Epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called theory of knowledge, it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowledge in the form of skills, and knowledge by acquaintance as a familiarity through experience. Epistemologists study the concepts of belief, truth, and justification to understand the nature of knowledge. To discover how knowledge arises, they investigate sources of justification, such as perception, introspection, memory, reason, and testimony.

The school of skepticism questions the human ability to attain knowledge while fallibilism says that knowledge is never certain. Empiricists regard sense experience as the primary source of knowledge, whereas rationalists view reason as an additional source. Coherentists argue that a belief is justified if it coheres with other beliefs. Foundationalists, by contrast, maintain that the justification of basic beliefs does not depend on other beliefs. Internalism and externalism disagree about whether justification is determined solely by mental states or also by external circumstances.

Separate branches of epistemology are dedicated to knowledge found in specific fields, like scientific, mathematical, moral, and religious knowledge. Naturalized epistemology relies on empirical methods and discoveries, whereas formal epistemology uses formal tools from logic. Social epistemology investigates the communal aspect of knowledge and historical epistemology examines its historical conditions. Epistemology is closely related to psychology, which describes the beliefs people hold, while epistemology studies the norms governing the evaluation of beliefs. It also intersects with fields such as decision theory, education, and anthropology.

Early reflections on the nature, sources, and scope of knowledge are found in ancient Greek and ancient Indian philosophy. The relation between reason and faith was a central topic in the medieval period. The modern era was characterized by the contrasting perspectives of empiricism and rationalism. Epistemologists in the 20th century examined the components, structure, and value of knowledge while integrating insights from the natural sciences and linguistics.

Definition

[edit]Epistemology is the philosophical study of knowledge. Also called theory of knowledge,[a] it examines what knowledge is and what types of knowledge there are. It further investigates the sources of knowledge, like perception, inference, and testimony, to determine how knowledge is created. Another topic is the extent and limits of knowledge, confronting questions about what people can and cannot know.[2] Other central concepts include belief, truth, justification, evidence, and reason.[3] Epistemology is one of the main branches of philosophy besides fields like ethics, logic, and metaphysics.[4] The term can also be used in a slightly different sense to refer not to the branch of philosophy but to a particular position within that branch, as in Plato's epistemology and Immanuel Kant's epistemology.[5]

As a normative field of inquiry, epistemology explores how people should acquire beliefs. This way, it determines which beliefs fulfill the standards or epistemic goals of knowledge and which ones fail, thereby providing an evaluation of beliefs. Descriptive fields of inquiry, like psychology and cognitive sociology, are also interested in beliefs and related cognitive processes. Unlike epistemology, they study the beliefs people have and how people acquire them instead of examining the evaluative norms of these processes.[6][b] Epistemology is relevant to many descriptive and normative disciplines, such as the other branches of philosophy and the sciences, by exploring the principles of how they may arrive at knowledge.[9]

The word epistemology comes from the ancient Greek terms ἐπιστήμη (episteme, meaning knowledge or understanding) and λόγος (logos, meaning study of or reason), literally, the study of knowledge. Even though ancient Greek philosophers practiced epistemology, they did not use this word. The term was only coined in the 19th century to label this field and conceive it as a distinct branch of philosophy.[10][c]

Central concepts

[edit]Knowledge

[edit]Knowledge is an awareness, familiarity, understanding, or skill. Its various forms all involve a cognitive success through which a person establishes epistemic contact with reality.[15] Knowledge is typically understood as an aspect of individuals, generally as a cognitive mental state that helps them understand, interpret, and interact with the world. While this core sense is of particular interest to epistemologists, the term also has other meanings. Understood on a social level, knowledge is a characteristic of a group of people that share ideas, understanding, or culture in general.[16] The term can also refer to information stored in documents, such as "knowledge housed in the library"[17] or knowledge stored in computers in the form of the knowledge base of an expert system.[18]

Knowledge contrasts with ignorance, which is often simply defined as the absence of knowledge. Knowledge is usually accompanied by ignorance since people rarely have complete knowledge of a field, forcing them to rely on incomplete or uncertain information when making decisions.[19] Even though many forms of ignorance can be mitigated through education and research, there are certain limits to human understanding that are responsible for inevitable ignorance.[20] Some limitations are inherent in the human cognitive faculties themselves, such as the inability to know facts too complex for the human mind to conceive.[21] Others depend on external circumstances when no access to the relevant information exists.[22]

Epistemologists disagree on how much people know, for example, whether fallible beliefs about everyday affairs can amount to knowledge or whether absolute certainty is required. The most stringent position is taken by radical skeptics, who argue that there is no knowledge at all.[23]

Types

[edit]

Epistemologists distinguish between different types of knowledge.[25] Their primary interest is in knowledge of facts, called propositional knowledge.[26] It is a theoretical knowledge that can be expressed in declarative sentences using a that-clause, like "Ravi knows that kangaroos hop". For this reason, it is also called knowledge-that.[27][d] Epistemologists often understand it as a relation between a knower and a known proposition, in the case above between the person Ravi and the proposition "kangaroos hop".[28] It is use-independent since it is not tied to one specific purpose. It is a mental representation that relies on concepts and ideas to depict reality.[29] Because of its theoretical nature, it is often held that only relatively sophisticated creatures, such as humans, possess propositional knowledge.[30]

Propositional knowledge contrasts with non-propositional knowledge in the form of knowledge-how and knowledge by acquaintance.[31] Knowledge-how is a practical ability or skill, like knowing how to read or how to prepare lasagna.[32] It is usually tied to a specific goal and not mastered in the abstract without concrete practice.[33] To know something by acquaintance means to be familiar with it as a result of experiental contact. Examples are knowing the city of Perth, knowing the taste of tsampa, and knowing Marta Vieira da Silva personally.[34]

Another influential distinction is between a posteriori and a priori knowledge.[35] A posteriori knowledge is knowledge of empirical facts based on sensory experience, like seeing that the sun is shining and smelling that a piece of meat has gone bad.[36] Knowledge belonging to the empirical science and knowledge of everyday affairs belongs to a posteriori knowledge. A priori knowledge is knowledge of non-empirical facts and does not depend on evidence from sensory experience. It belongs to fields such as mathematics and logic, like knowing that .[37] The contrast between a posteriori and a priori knowledge plays a central role in the debate between empiricists and rationalists on whether all knowledge depends on sensory experience.[38]

A closely related contrast is between analytic and synthetic truths. A sentence is analytically true if its truth depends only on the meaning of the words it uses. For instance, the sentence "all bachelors are unmarried" is analytically true because the word "bachelor" already includes the meaning "unmarried". A sentence is synthetically true if its truth depends on additional facts. For example, the sentence "snow is white" is synthetically true because its truth depends on the color of snow in addition to the meanings of the words snow and white. A priori knowledge is primarily associated with analytic sentences while a posteriori knowledge is primarily associated with synthetic sentences. However, it is controversial whether this is true for all cases. Some philosophers, such as Willard Van Orman Quine, reject the distinction, saying that there are no analytic truths.[40]

Analysis

[edit]The analysis of knowledge is the attempt to identify the essential components or conditions of all and only propositional knowledge states. According to the so-called traditional analysis,[e] knowledge has three components: it is a belief that is justified and true.[42] In the second half of the 20th century, this view was put into doubt by a series of thought experiments that aimed to show that some justified true beliefs do not amount to knowledge.[43] In one of them, a person is unaware of all the fake barns in their area. By coincidence, they stop in front of the only real barn and form a justified true belief that it is a real barn.[44] Many epistemologists agree that this is not knowledge because the justification is not directly relevant to the truth.[45] More specifically, this and similar counterexamples involve some form of epistemic luck, that is, a cognitive success that results from fortuitous circumstances rather than competence.[46]

Following these thought experiments, philosophers proposed various alternative definitions of knowledge by modifying or expanding the traditional analysis.[47] According to one view, the known fact has to cause the belief in the right way.[48] Another theory states that the belief is the product of a reliable belief formation process.[49] Further approaches require that the person would not have the belief if it was false,[50] that the belief is not inferred from a falsehood,[51] that the justification cannot be undermined,[52] or that the belief is infallible.[53] There is no consensus on which of the proposed modifications and reconceptualizations is correct.[54] Some philosophers, such as Timothy Williamson, reject the basic assumption underlying the analysis of knowledge by arguing that propositional knowledge is a unique state that cannot be dissected into simpler components.[55]

Value

[edit]The value of knowledge is the worth it holds by expanding understanding and guiding action. Knowledge can have instrumental value by helping a person achieve their goals.[56] For example, knowledge of a disease helps a doctor cure their patient, and knowledge of when a job interview starts helps a candidate arrive on time.[57] The usefulness of a known fact depends on the circumstances. Knowledge of some facts may have little to no uses, like memorizing random phone numbers from an outdated phone book.[58] Being able to assess the value of knowledge matters in choosing what information to acquire and transmit to others. It affects decisions like which subjects to teach at school and how to allocate funds to research projects.[59]

Of particular interest to epistemologists is the question of whether knowledge is more valuable than a mere opinion that is true.[60] Knowledge and true opinion often have a similar usefulness since both are accurate representations of reality. For example, if a person wants to go to Larissa, a true opinion about how to get there may help them in the same way as knowledge does.[61] Plato already considered this problem and suggested that knowledge is better because it is more stable.[62] Another suggestion focuses on practical reasoning. It proposes that people put more trust in knowledge than in mere true beliefs when drawing conclusions and deciding what to do.[63] A different response says that knowledge has intrinsic value, meaning that it is good in itself independent of its usefulness.[64]

Belief and truth

[edit]Beliefs are mental states about what is the case, like believing that snow is white or that God exists.[65] In epistemology, they are often understood as subjective attitudes that affirm or deny a proposition, which can be expressed in a declarative sentence. For instance, to believe that snow is white is to affirm the proposition "snow is white". According to this view, beliefs are representations of what the world is like. They are kept in memory and can be retrieved when actively thinking about reality or when deciding how to act.[66] A different view understands beliefs as behavioral patterns or dispositions to act rather than as representational items stored in the mind. This view says that to believe that there is mineral water in the fridge is nothing more than a group of dispositions related to mineral water and the fridge. Examples are the dispositions to answer questions about the presence of mineral water affirmatively and to go to the fridge when thirsty.[67] Some theorists deny the existence of beliefs, saying that this concept borrowed from folk psychology is an oversimplification of much more complex psychological processes.[68] Beliefs play a central role in various epistemological debates, which cover their status as a component of propositional knowledge, the question of whether people have control over and are responsible for their beliefs, and the issue of whether there are degrees of beliefs, called credences.[69]

As propositional attitudes, beliefs are true or false depending on whether they affirm a true or a false proposition.[70] According to the correspondence theory of truth, to be true means to stand in the right relation to the world by accurately describing what it is like. This means that truth is objective: a belief is true if it corresponds to a fact.[71] The coherence theory of truth says that a belief is true if it belongs to a coherent system of beliefs. A result of this view is that truth is relative since it depends on other beliefs.[72] Further theories of truth include pragmatist, semantic, pluralist, and deflationary theories.[73] Truth plays a central role in epistemology as a goal of cognitive processes and a component of propositional knowledge.[74]

Justification

[edit]In epistemology, justification is a property of beliefs that fulfill certain norms about what a person should believe.[75] According to a common view, this means that the person has sufficient reasons for holding this belief because they have information that supports it.[75] Another view states that a belief is justified if it is formed by a reliable belief formation process, such as perception.[76] The terms reasonable, warranted, and supported are closely related to the idea of justification and are sometimes used as synonyms.[77] Justification is what distinguishes justified beliefs from superstition and lucky guesses.[78] However, justification does not guarantee truth. For example, if a person has strong but misleading evidence, they may form a justified belief that is false.[79]

Epistemologists often identify justification as one component of knowledge.[80] Usually, they are not only interested in whether a person has a sufficient reason to hold a belief, known as propositional justification, but also in whether the person holds the belief because or based on[f] this reason, known as doxastic justification. For example, if a person has sufficient reason to believe that a neighborhood is dangerous but forms this belief based on superstition then they have propositional justification but lack doxastic justification.[82]

Sources

[edit]Sources of justification are ways or cognitive capacities through which people acquire justification. Often-discussed sources include perception, introspection, memory, reason, and testimony, but there is no universal agreement to what extent they all provide valid justification.[83] Perception relies on sensory organs to gain empirical information. There are various forms of perception corresponding to different physical stimuli, such as visual, auditory, haptic, olfactory, and gustatory perception.[84] Perception is not merely the reception of sense impressions but an active process that selects, organizes, and interprets sensory signals.[85] Introspection is a closely related process focused not on external physical objects but on internal mental states. For example, seeing a bus at a bus station belongs to perception while feeling tired belongs to introspection.[86]

Rationalists understand reason as a source of justification for non-empirical facts. It is often used to explain how people can know about mathematical, logical, and conceptual truths. Reason is also responsible for inferential knowledge, in which one or several beliefs are used as premises to support another belief.[87] Memory depends on information provided by other sources, which it retains and recalls, like remembering a phone number perceived earlier.[88] Justification by testimony relies on information one person communicates to another person. This can happen by talking to each other but can also occur in other forms, like a letter, a newspaper, and a blog.[89]

Other concepts

[edit]Rationality is closely related to justification and the terms rational belief and justified belief are sometimes used as synonyms. However, rationality has a wider scope that encompasses both a theoretical side, covering beliefs, and a practical side, covering decisions, intentions, and actions.[90] There are different conceptions about what it means for something to be rational. According to one view, a mental state is rational if it is based on or responsive to good reasons. Another view emphasizes the role of coherence, stating that rationality requires that the different mental states of a person are consistent and support each other.[91] A slightly different approach holds that rationality is about achieving certain goals. Two goals of theoretical rationality are accuracy and comprehensiveness, meaning that a person has as few false beliefs and as many true beliefs as possible.[92]

Epistemic norms are criteria to assess the cognitive quality of beliefs, like their justification and rationality. Epistemologists distinguish between deontic norms, which are prescriptions about what people should believe or which beliefs are correct, and axiological norms, which identify the goals and values of beliefs.[93] Epistemic norms are closely related to intellectual or epistemic virtues, which are character traits like open-mindedness and conscientiousness. Epistemic virtues help individuals form true beliefs and acquire knowledge. They contrast with epistemic vices and act as foundational concepts of virtue epistemology.[94]

Evidence for a belief is information that favors or supports it. Epistemologists understand evidence primarily in terms of mental states, for example, as sensory impressions or as other propositions that a person knows. But in a wider sense, it can also include physical objects, like bloodstains examined by forensic analysts or financial records studied by investigative journalists.[95] Evidence is often understood in terms of probability: evidence for a belief makes it more likely that the belief is true.[96] A defeater is evidence against a belief or evidence that undermines another piece of evidence. For instance, witness testimony connecting a suspect to a crime is evidence for their guilt while an alibi is a defeater.[97] Evidentialists analyze justification in terms of evidence by saying that to be justified, a belief needs to rest on adequate evidence.[98]

The presence of evidence usually affects doubt and certainty, which are subjective attitudes toward propositions that differ regarding their level of confidence. Doubt involves questioning the validity or truth of a proposition. Certainty, by contrast, is a strong affirmative conviction, meaning that the person is free of doubt that the proposition is true. In epistemology, doubt and certainty play central roles in attempts to find a secure foundation of all knowledge and in skeptical projects aiming to establish that no belief is immune to doubt.[99]

While propositional knowledge is the main topic in epistemology, some theorists focus on understanding rather than knowledge. Understanding is a more holistic notion that involves a wider grasp of a subject. To understand something, a person requires awareness of how different things are connected and why they are the way they are. For example, knowledge of isolated facts memorized from a textbook does not amount to understanding. According to one view, understanding is a special epistemic good that, unlike knowledge, is always intrinsically valuable.[100] Wisdom is similar in this regard and is sometimes considered the highest epistemic good. It encompasses a reflective understanding with practical applications. It helps people grasp and evaluate complex situations and lead a good life.[101]

Schools of thought

[edit]Skepticism, fallibilism, and relativism

[edit]Philosophical skepticism questions the human ability to arrive at knowledge. Some skeptics limit their criticism to certain domains of knowledge. For example, religious skeptics say that it is impossible to have certain knowledge about the existence of deities or other religious doctrines. Similarly, moral skeptics challenge the existence of moral knowledge and metaphysical skeptics say that humans cannot know ultimate reality.[102]

Global skepticism is the widest form of skepticism, asserting that there is no knowledge in any domain.[103] In ancient philosophy, this view was accepted by academic skeptics while Pyrrhonian skeptics recommended the suspension of belief to achieve a state of tranquility.[104] Overall, not many epistemologists have explicitly defended global skepticism. The influence of this position derives mainly from attempts by other philosophers to show that their theory overcomes the challenge of skepticism. For example, René Descartes used methodological doubt to find facts that cannot be doubted.[105]

One consideration in favor of global skepticism is the dream argument. It starts from the observation that, while people are dreaming, they are usually unaware of this. This inability to distinguish between dream and regular experience is used to argue that there is no certain knowledge since a person can never be sure that they are not dreaming.[106][g] Some critics assert that global skepticism is a self-refuting idea because denying the existence of knowledge is itself a knowledge claim. Another objection says that the abstract reasoning leading to skepticism is not convincing enough to overrule common sense.[108]

Fallibilism is another response to skepticism.[109] Fallibilists agree with skeptics that absolute certainty is impossible. Most fallibilists disagree with skeptics about the existence of knowledge, saying that there is knowledge since it does not require absolute certainty.[110] They emphasize the need to keep an open and inquisitive mind since doubt can never be fully excluded, even for well-established knowledge claims like thoroughly tested scientific theories.[111]

Epistemic relativism is a related view. It does not question the existence of knowledge in general but rejects the idea that there are universal epistemic standards or absolute principles that apply equally to everyone. This means that what a person knows depends on the subjective criteria or social conventions used to assess epistemic status.[112]

Empiricism and rationalism

[edit]The debate between empiricism and rationalism centers on the origins of human knowledge. Empiricism emphasizes that sense experience is the primary source of all knowledge. Some empiricists express this view by stating that the mind is a blank slate that only develops ideas about the external world through the sense data it receives from the sensory organs. According to them, the mind can arrive at various additional insights by comparing impressions, combining them, generalizing to arrive at more abstract ideas, and deducing new conclusions from them. Empiricists say that all these mental operations depend on material from the senses and do not function on their own.[113]

Even though rationalists usually accept sense experience as one source of knowledge,[h] they also say that important forms of knowledge come directly from reason without sense experience,[115] like knowledge of mathematical and logical truths.[116] According to some rationalists, the mind possesses inborn ideas which it can access without the help of the senses. Others hold that there is an additional cognitive faculty, sometimes called rational intuition, through which people acquire nonempirical knowledge.[117] Some rationalists limit their discussion to the origin of concepts, saying that the mind relies on inborn categories to understand the world and organize experience.[115]

Foundationalism and coherentism

[edit]Foundationalists and coherentists disagree about the structure of knowledge.[118][i] Foundationalism distinguishes between basic and non-basic beliefs. A belief is basic if it is justified directly, meaning that its validity does not depend on the support of other beliefs.[j] A belief is non-basic if it is justified by another belief.[121] For example, the belief that it rained last night is a non-basic belief if it is inferred from the observation that the street is wet.[122] According to foundationalism, basic beliefs are the foundation on which all other knowledge is built while non-basic beliefs constitute the superstructure resting on this foundation.[121]

Coherentists reject the distinction between basic and non-basic beliefs, saying that the justification of any belief depends on other beliefs. They assert that a belief must be in tune with other beliefs to amount to knowledge. This is the case if the beliefs are consistent and support each other. According to coherentism, justification is a holistic aspect determined by the whole system of beliefs, which resembles an interconnected web.[123]

The view of foundherentism is an intermediary position combining elements of both foundationalism and coherentism. It accepts the distinction between basic and non-basic beliefs while asserting that the justification of non-basic beliefs depends on coherence with other beliefs.[124]

Infinitism presents another approach to the structure of knowledge. It agrees with coherentism that there are no basic beliefs while rejecting the view that beliefs can support each other in a circular manner. Instead, it argues that beliefs form infinite justification chains, in which each link of the chain supports the belief following it and is supported by the belief preceding it.[125]

Internalism and externalism

[edit]

The disagreement between internalism and externalism is about the sources of justification.[127][k] Internalists say that justification depends only on factors within the individual. Examples of such factors include perceptual experience, memories, and the possession of other beliefs. This view emphasizes the importance of the cognitive perspective of the individual in the form of their mental states. It is commonly associated with the idea that the relevant factors are accessible, meaning that the individual can become aware of their reasons for holding a justified belief through introspection and reflection.[129]

Externalism rejects this view, saying that at least some relevant factors are external to the individual. This means that the cognitive perspective of the individual is less central while other factors, specifically the relation to truth, become more important.[129] For instance, when considering the belief that a cup of coffee stands on the table, externalists are not only interested in the perceptual experience that led to this belief but also consider the quality of the person's eyesight, their ability to differentiate coffee from other beverages, and the circumstances under which they observed the cup.[130]

Evidentialism is an influential internalist view. It says that justification depends on the possession of evidence.[131] In this context, evidence for a belief is any information in the individual's mind that supports the belief. For example, the perceptual experience of rain is evidence for the belief that it is raining. Evidentialists have suggested various other forms of evidence, including memories, intuitions, and other beliefs.[132] According to evidentialism, a belief is justified if the individual's evidence supports the belief and they hold the belief on the basis of this evidence.[133]

Reliabilism is an externalist theory asserting that a reliable connection between belief and truth is required for justification.[134] Some reliabilists explain this in terms of reliable processes. According to this view, a belief is justified if it is produced by a reliable belief-formation process, like perception. A belief-formation process is reliable if most of the beliefs it causes are true. A slightly different view focuses on beliefs rather than belief-formation processes, saying that a belief is justified if it is a reliable indicator of the fact it presents. This means that the belief tracks the fact: the person believes it because it is a fact but would not believe it otherwise.[135]

Virtue epistemology is another type of externalism and is sometimes understood as a form of reliabilism. It says that a belief is justified if it manifests intellectual virtues. Intellectual virtues are capacities or traits that perform cognitive functions and help people form true beliefs. Suggested examples include faculties like vision, memory, and introspection.[136]

Others

[edit]In the epistemology of perception, direct and indirect realists disagree about the connection between the perceiver and the perceived object. Direct realists say that this connection is direct, meaning that there is no difference between the object present in perceptual experience and the physical object causing this experience. According to indirect realism, the connection is indirect since there are mental entities, like ideas or sense data, that mediate between the perceiver and the external world. The contrast between direct and indirect realism is important for explaining the nature of illusions.[137]

Constructivism in epistemology is the theory that how people view the world is not a simple reflection of external reality but an invention or a social construction. This view emphasizes the creative role of interpretation while undermining objectivity since social constructions may differ from society to society.[138]

According to contrastivism, knowledge is a comparative term, meaning that to know something involves distinguishing it from relevant alternatives. For example, if a person spots a bird in the garden, they may know that it is a sparrow rather than an eagle but they may not know that it is a sparrow rather than an indistinguishable sparrow hologram.[139]

Epistemic conservatism is a view about belief revision. It gives preference to the beliefs a person already has, asserting that a person should only change their beliefs if they have a good reason to. One motivation for adopting epistemic conservatism is that the cognitive resources of humans are limited, meaning that it is not feasible to constantly reexamine every belief.[140]

Pragmatist epistemology is a form of fallibilism that emphasizes the close relation between knowing and acting. It sees the pursuit of knowledge as an ongoing process guided by common sense and experience while always open to revision.[141]

Bayesian epistemology is a formal approach based on the idea that people have degrees of belief representing how certain they are. It uses probability theory to define norms of rationality that govern how certain people should be about their beliefs.[142]

Phenomenological epistemology emphasizes the importance of first-person experience. It distinguishes between the natural and the phenomenological attitudes. The natural attitude focuses on objects belonging to common sense and natural science. The phenomenological attitude focuses on the experience of objects and aims to provide a presuppositionless description of how objects appear to the observer.[143]

Particularism and generalism disagree about the right method of conducting epistemological research. Particularists start their inquiry by looking at specific cases. For example, to find a definition of knowledge, they rely on their intuitions about concrete instances of knowledge and particular thought experiments. They use these observations as methodological constraints that any theory of more general principles needs to follow. Generalists proceed in the opposite direction. They give preference to general epistemic principles, saying that it is not possible to accurately identify and describe specific cases without a grasp of these principles.[144] Other methods in contemporary epistemology aim to extract philosophical insights from ordinary language or look at the role of knowledge in making assertions and guiding actions.[145]

Postmodern epistemology criticizes the conditions of knowledge in advanced societies. This concerns in particular the metanarrative of a constant progress of scientific knowledge leading to a universal and foundational understanding of reality.[147] Feminist epistemology critiques the effect of gender on knowledge. Among other topics, it explores how preconceptions about gender influence who has access to knowledge, how knowledge is produced, and which types of knowledge are valued in society.[148] Decolonial scholarship criticizes the global influence of Western knowledge systems, often with the aim of decolonizing knowledge to undermine Western hegemony.[149]

Various schools of epistemology are found in traditional Indian philosophy. Many of them focus on the different sources of knowledge, called pramāṇa. Perception, inference, and testimony are sources discussed by most schools. Other sources only considered by some schools are non-perception, which leads to knowledge of absences, and presumption.[150] Buddhist epistemology tends to focus on immediate experience, understood as the presentation of unique particulars without the involvement of secondary cognitive processes, like thought and desire.[151] Nyāya epistemology discusses the causal relation between the knower and the object of knowledge, which happens through reliable knowledge-formation processes. It sees perception as the primary source of knowledge, drawing a close connection between it and successful action.[152] Mīmāṃsā epistemology understands the holy scriptures known as the Vedas as a key source of knowledge while discussing the problem of their right interpretation.[153] Jain epistemology states that reality is many-sided, meaning that no single viewpoint can capture the entirety of truth.[154]

Branches

[edit]Some branches of epistemology focus on the problems of knowledge within specific academic disciplines. The epistemology of science examines how scientific knowledge is generated and what problems arise in the process of validating, justifying, and interpreting scientific claims. A key issue concerns the problem of how individual observations can support universal scientific laws. Further topics include the nature of scientific evidence and the aims of science.[155] The epistemology of mathematics studies the origin of mathematical knowledge. In exploring how mathematical theories are justified, it investigates the role of proofs and whether there are empirical sources of mathematical knowledge.[156]

Epistemological problems are found in most areas of philosophy. The epistemology of logic examines how people know that an argument is valid. For example, it explores how logicians justify that modus ponens is a correct rule of inference or that all contradictions are false.[157] Epistemologists of metaphysics investigate whether knowledge of ultimate reality is possible and what sources this knowledge could have.[158] Knowledge of moral statements, like the claim that lying is wrong, belongs to the epistemology of ethics. It studies the role of ethical intuitions, coherence among moral beliefs, and the problem of moral disagreement.[159] The ethics of belief is a closely related field covering the interrelation between epistemology and ethics. It examines the norms governing belief formation and asks whether violating them is morally wrong.[160]

Religious epistemology studies the role of knowledge and justification for religious doctrines and practices. It evaluates the weight and reliability of evidence from religious experience and holy scriptures while also asking whether the norms of reason should be applied to religious faith.[161] Social epistemology focuses on the social dimension of knowledge. While traditional epistemology is mainly interested in knowledge possessed by individuals, social epistemology covers knowledge acquisition, transmission, and evaluation within groups, with specific emphasis on how people rely on each other when seeking knowledge.[162] Historical epistemology examines how the understanding of knowledge and related concepts has changed over time. It asks whether the main issues in epistemology are perennial and to what extent past epistemological theories are relevant to contemporary debates. It is particularly concerned with scientific knowledge and practices associated with it.[163] It contrasts with the history of epistemology, which presents, reconstructs, and evaluates epistemological theories of philosophers in the past.[164][l]

Naturalized epistemology is closely associated with the natural sciences, relying on their methods and theories to examine knowledge. Naturalistic epistemologists focus on empirical observation to formulate their theories and are often critical of approaches to epistemology that proceed by a priori reasoning.[166] Evolutionary epistemology is a naturalistic approach that understands cognition as a product of evolution, examining knowledge and the cognitive faculties responsible for it from the perspective of natural selection.[167] Epistemologists of language explore the nature of linguistic knowledge. One of their topics is the role of tacit knowledge, for example, when native speakers have mastered the rules of grammar but are unable to explicitly articulate those rules.[168] Epistemologists of modality examine knowledge about what is possible and necessary.[169] Epistemic problems that arise when two people have diverging opinions on a topic are covered by the epistemology of disagreement.[170] Epistemologists of ignorance are interested in epistemic faults and gaps in knowledge.[171]

There are distinct areas of epistemology dedicated to specific sources of knowledge. Examples are the epistemology of perception,[172] the epistemology of memory,[173] and the epistemology of testimony.[174]

Some branches of epistemology are characterized by their research method. Formal epistemology employs formal tools found in logic and mathematics to investigate the nature of knowledge.[175][m] Experimental epistemologists rely in their research on empirical evidence about common knowledge practices.[177] Applied epistemology focuses on the practical application of epistemological principles to diverse real-world problems, like the reliability of knowledge claims on the internet, how to assess sexual assault allegations, and how racism may lead to epistemic injustice.[178][n]

Metaepistemologists examine the nature, goals, and research methods of epistemology. As a metatheory, it does not directly defend a position about which epistemological theories are correct but examines their fundamental concepts and background assumptions.[180][o]

Related fields

[edit]Epistemology and psychology were not defined as distinct fields until the 19th century; earlier investigations about knowledge often do not fit neatly into today's academic categories.[182] Both contemporary disciplines study beliefs and the mental processes responsible for their formation and change. One important contrast is that psychology describes what beliefs people have and how they acquire them, thereby explaining why someone has a specific belief. The focus of epistemology is on evaluating beliefs, leading to a judgment about whether a belief is justified and rational in a particular case.[183] Epistemology has a similar intimate connection to cognitive science, which understands mental events as processes that transform information.[184] Artificial intelligence relies on the insights of epistemology and cognitive science to implement concrete solutions to problems associated with knowledge representation and automatic reasoning.[185]

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. For epistemology, it is relevant to inferential knowledge, which arises when a person reasons from one known fact to another.[186] This is the case, for example, if a person does not know directly that but comes to infer it based on their knowledge that , , and .[187] Whether an inferential belief amounts to knowledge depends on the form of reasoning used, in particular, that the process does not violate the laws of logic.[188] Another overlap between the two fields is found in the epistemic approach to fallacy theory.[189] Fallacies are faulty arguments based on incorrect reasoning.[190] The epistemic approach to fallacies explains why they are faulty, stating that arguments aim to expand knowledge. According to this view, an argument is a fallacy if it fails to do so.[189] A further intersection is found in epistemic logic, which uses formal logical devices to study epistemological concepts like knowledge and belief.[191]

Both decision theory and epistemology are interested in the foundations of rational thought and the role of beliefs. Unlike many approaches in epistemology, the main focus of decision theory lies less in the theoretical and more in the practical side, exploring how beliefs are translated into action.[192] Decision theorists examine the reasoning involved in decision-making and the standards of good decisions.[193] They identify beliefs as a central aspect of decision-making. One of their innovations is to distinguish between weaker and stronger beliefs. This helps them take the effect of uncertainty on decisions into consideration.[194]

Epistemology and education have a shared interest in knowledge, with one difference being that education focuses on the transmission of knowledge, exploring the roles of both learner and teacher.[195] Learning theory examines how people acquire knowledge.[196] Behavioral learning theories explain the process in terms of behavior changes, for example, by associating a certain response with a particular stimulus.[197] Cognitive learning theories study how the cognitive processes that affect knowledge acquisition transform information.[198] Pedagogy looks at the transmission of knowledge from the teacher's side, exploring the teaching methods they may employ.[199] In teacher-centered methods, the teacher takes the role of the main authority delivering knowledge and guiding the learning process. In student-centered methods, the teacher mainly supports and facilitates the learning process while the students take a more active role.[200] The beliefs students have about knowledge, called personal epistemology, affect their intellectual development and learning success.[201]

The anthropology of knowledge examines how knowledge is acquired, stored, retrieved, and communicated. It studies the social and cultural circumstances that affect how knowledge is reproduced and changes, covering the role of institutions like university departments and scientific journals as well as face-to-face discussions and online communications. It understands knowledge in a wide sense that encompasses various forms of understanding and culture, including practical skills. Unlike epistemology, it is not interested in whether a belief is true or justified but in how understanding is reproduced in society.[202] The sociology of knowledge is a closely related field with a similar conception of knowledge. It explores how physical, demographic, economic, and sociocultural factors impact knowledge. It examines in what sociohistorical contexts knowledge emerges and the effects it has on people, for example, how socioeconomic conditions are related to the dominant ideology in a society.[203]

History

[edit]Early reflections on the nature and sources of knowledge are found in ancient history. In ancient Greek philosophy, Plato (427–347 BCE) studied what knowledge is, examining how it differs from true opinion by being based on good reasons.[204] According to him, the process of learning something is a form of recollection in which the soul remembers what it already knew before.[205][p] Aristotle (384–322 BCE) was particularly interested in scientific knowledge, exploring the role of sensory experience and how to make inferences from general principles.[206] The Hellenistic schools began to arise in the 4th century BCE. The Epicureans had an empiricist outlook, stating that sensations are always accurate and act as the supreme standard of judgments.[207] The Stoics defended a similar position but limited themselves to clear and distinct sensations, which they regarded as true.[208] The skepticists questioned that knowledge is possible, recommending instead suspension of judgment to arrive at a state of tranquility.[209]

The Upanishads, philosophical scriptures composed in ancient India between 700 and 300 BCE, examined how people acquire knowledge, including the role of introspection, comparison, and deduction.[211] In the 6th century BCE, the school of Ajñana developed a radical skepticism questioning the possibility and usefulness of knowledge.[212] The school of Nyaya emerged in the 2nd century BCE and provided a systematic treatment of how people acquire knowledge, distinguishing between valid and invalid sources.[213] When Buddhist philosophers later became interested in epistemology, they relied on concepts developed in Nyaya and other traditions.[214] Buddhist philosopher Dharmakirti (6th or 7th century CE)[215] analyzed the process of knowing as a series of causally related events.[210]

The relation between reason and faith was a central topic in the medieval period.[216] In Arabic–Persian philosophy, al-Farabi (c. 870–950) and Averroes (1126–1198) discussed how philosophy and theology interact and which is the better vehicle to truth.[217] Al-Ghazali (c. 1056–1111) criticized many of the core teachings of previous Islamic philosophers, saying that they rely on unproven assumptions that do not amount to knowledge.[218] In Western philosophy, Anselm of Canterbury (1033–1109) proposed that theological teaching and philosophical inquiry are in harmony and complement each other.[219] Peter Abelard (1079–1142) argued against unquestioned theological authorities and said that all things are open to rational doubt.[220] Influenced by Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) developed an empiricist theory, stating that "nothing is in the intellect unless it first appeared in the senses".[221] According to an early form of direct realism proposed by William of Ockham (c. 1285–1349), perception of mind-independent objects happens directly without intermediaries.[222]

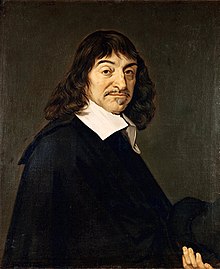

The course of modern philosophy was shaped by René Descartes (1596–1650), who claimed that philosophy must begin from a position of indubitable knowledge of first principles. Inspired by skepticism, he aimed to find absolutely certain knowledge by encountering truths that cannot be doubted. He thought that this is the case for the assertion "I think, therefore I am", from which he constructed the rest of his philosophical system.[223] Descartes, together with Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), belonged to the school of rationalism, which asserts that the mind possesses innate ideas independent of experience.[224] John Locke (1632–1704) rejected this view in favor of an empiricism according to which the mind is a blank slate. This means that all ideas depend on sense experience, either as "ideas of sense", which are directly presented through the senses, or as "ideas of reflection", which the mind creates by reflecting on ideas of sense.[225] David Hume (1711–1776) used this idea to explore the limits of what people can know. He said that knowledge of facts is never certain, adding that knowledge of relations between ideas, like mathematical truths, can be certain but contains no information about the world.[226] Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) tried to find a middle position between rationalism and empiricism by identifying a type of knowledge that Hume had missed. For Kant, this is knowledge about principles that underlie all experience and structure it, such as spatial and temporal relations and fundamental categories of understanding.[227]

In the 19th-century, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) argued against empiricism, saying that sensory impressions on their own cannot amount to knowledge since all knowledge is actively structured by the knowing subject.[228] John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) defended a wide-sweeping form of empiricism and explained knowledge of general truths through inductive reasoning.[229] Charles Peirce (1839–1914) thought that all knowledge is fallible, emphasizing that knowledge seekers should always be ready to revise their beliefs if new evidence is encountered. He used this idea to argue against Cartesian foundationalism seeking absolutely certain truths.[230]

In the 20th century, fallibilism was further explored by J. L. Austin (1911–1960) and Karl Popper (1902–1994).[231] In continental philosophy, Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) applied the skeptic idea of suspending judgment to the study of experience. By not judging whether an experience is accurate or not, he tried to describe the internal structure of experience instead.[232] Logical positivists, like A. J. Ayer (1910–1989), said that all knowledge is either empirical or analytic.[233] Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) developed an empiricist sense-datum theory, distinguishing between direct knowledge by acquaintance of sense data and indirect knowledge by description, which is inferred from knowledge by acquaintance.[234] Common sense had a central place in G. E. Moore's (1873–1958) epistemology. He used trivial observations, like the fact that he has two hands, to argue against abstract philosophical theories that deviate from common sense.[235] Ordinary language philosophy, as practiced by the late Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951), is a similar approach that tries to extract epistemological insights from how ordinary language is used.[236]

Edmund Gettier (1927–2021) conceived counterexamples against the idea that knowledge is the same as justified true belief. These counterexamples prompted many philosophers to suggest alternative definitions of knowledge.[237] One of the alternatives considered was reliabilism, which says that knowledge requires reliable sources, shifting the focus away from justification.[238] Virtue epistemology, a closely related response, analyses belief formation in terms of the intellectual virtues or cognitive competencies involved in the process.[239] Naturalized epistemology, as conceived by Willard Van Orman Quine (1908–2000), employs concepts and ideas from the natural sciences to formulate its theories.[240] Other developments in late 20th-century epistemology were the emergence of social, feminist, and historical epistemology.[241]

See also

[edit]- Epistemological pluralism – term used in philosophy, economics, and virtually any field of study to refer to different ways of knowing things, different epistemological methodologies for attaining a fuller description of a particular field

- Knowledge falsification – Deliberate misrepresentation of knowledge

- Reformed epistemology – School of philosophical thought

- Theory of Knowledge (IB Course) – Compulsory International Baccalaureate subject

References

[edit]Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Реже термин « гносеология » используется также как синоним. [ 1 ]

- ^ Несмотря на этот контраст, эпистемологи могут полагаться на идеи эмпирических наук при формулировании своих нормативных теорий. [ 7 ] Согласно одной из интерпретаций, цель натурализованной эпистемологии — ответить на описательные вопросы, но эта характеристика оспаривается. [ 8 ]

- ^ В качестве обозначения раздела философии термин «эпистемология» впервые был использован в 1854 году Джеймсом Э. Ферье. [ 11 ] В другом контексте это слово использовалось еще в 1847 году в нью-йоркском журнале Eclectic Magazine . [ 12 ] Поскольку этот термин не был придуман до XIX века, более ранние философы не называли свои теории явно эпистемологией и часто исследовали ее в сочетании с психологией . [ 13 ] По мнению философа Томаса Штурма, остается открытым вопрос, насколько актуальны эпистемологические проблемы, к которым обращались философы прошлого, для современной философии. [ 14 ]

- ^ Другие синонимы включают декларативные знания и описательные знания . [ 28 ]

- ^ Точность термина « традиционный анализ» обсуждается, поскольку он предполагает широкое признание в истории философии - идея, которую разделяют не все ученые. [ 41 ]

- ^ Отношение между убеждением и основанием, на котором оно основано, называется отношением основания . [ 81 ]

- ^ Мозг в чане — это аналогичный мысленный эксперимент , предполагающий, что у человека нет тела, а есть просто мозг, получающий электрические стимулы, неотличимые от стимулов, которые получал бы мозг в теле. Этот аргумент также приводит к выводу о глобальном скептицизме, основанном на утверждении, что невозможно отличить стимулы, представляющие реальный мир, от симулированных стимулов. [ 107 ]

- ^ Некоторые формы крайнего рационализма, встречающиеся в древнегреческой философии , рассматривают разум как единственный источник знания. [ 114 ]

- ^ Оба могут быть поняты как ответы на проблему регресса . [ 119 ]

- ^ Теория классического фундаментализма предъявляет более строгие требования, утверждая, что основные убеждения самоочевидны или неоспоримы. [ 120 ]

- ^ Споры интерналистов-экстерналистов в эпистемологии отличаются от дебатов интернализма-экстернализма в философии разума , которые задаются вопросом, зависят ли психические состояния только от человека или также от его окружения. [ 128 ]

- ^ Точная характеристика контраста оспаривается. [ 165 ]

- ^ Это тесно связано с вычислительной эпистемологией , которая исследует взаимосвязь между знаниями и вычислительными процессами. [ 176 ]

- ^ Эпистемическая несправедливость возникает, когда обоснованные утверждения о знаниях отклоняются или искажаются. [ 179 ]

- ^ Тем не менее, метаэпистемологические идеи могут иметь различное косвенное влияние на споры в эпистемологии. [ 181 ]

- ^ Чтобы аргументировать эту точку зрения, Платон использует пример мальчика-раба, которому удается ответить на ряд вопросов по геометрии, хотя он никогда не изучал геометрию. [ 205 ]

Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Мерриам-Вебстер, 2024 г.

- ^

- Тручеллито , ведущий отдел

- Blaauw & Pritchard 2005 , стр. 101–111. 49–50

- Крамли II 2009 , с. 16

- Картер и Литтлджон, 2021 г. , Введение: 1. Что такое эпистемология?

- Мозер 2005 , с. 3

- ^

- Фумертон, 2006 г. , стр. 1–2.

- Мозер 2005 , с. 4

- ^

- Бреннер 1993 , с. 16

- Палмквист 2010 , с. 800

- Дженичек 2018 , с. 31

- ^

- Steup & Neta 2024 , Ведущая секция

- Мосс 2021 , стр. 1–2

- ^

- Крамли II 2009 , с. 16

- Картер и Литтлджон, 2021 г. , Введение: 1. Что такое эпистемология?

- ^ О'Донохью и Китченер 1996 , стр. 2

- ^

- Крамли II 2009 , с. 192

- Среда 2007 г. , стр. 113, 115.

- ^

- Ауди 2003 , стр. 258–259

- Воленски, 2004 г. , стр. 3–4.

- Кэмпбелл 2024 , Ведущий раздел

- ^

- Steup & Neta 2024 , Ведущая секция

- Скотт 2002 , с. 30

- Воленски 2004 , с. 3

- ^ Воленски 2004 , с. 3

- ^ Издательство Оксфордского университета, 2024 г.

- ^ Олстон 2006 , стр. 1–2.

- ^ Штурм 2011 , стр. 308–309.

- ^

- Загжебский 1999 , с. 109

- Steup & Neta 2020 , Ведущая секция, § 1. Разновидности когнитивного успеха

- ХарперКоллинз 2022а

- ^

- Клаузен 2015 , стр. 813–818

- Лакей 2021 , стр. 111–112.

- ^

- ^

- ХарперКоллинз 2022b

- Уолтон 2005 , стр. 59, 64.

- ^

- Гросс и Макгоуи, 2015 г. , стр. 1–4.

- Haas & Vogt 2015 , стр. 17–18.

- Блау и Притчард 2005 , с. 79

- ^

- Маркие и Фолеску 2023 , § 1. Введение

- Исследователь 2009 , с. 2, 6

- Штольц 2021 , с. 120

- ^

- Исследователь 2009 , с. 10, 93

- Решер 2009a , стр. x–xi, 57–58.

- По состоянию на 2023 год , с. 163

- ^

- Исследователь 2009 , с. 2, 6

- Решер 2009a , стр. 140–141.

- ^

- Уилсон 2008 , с. 314

- Причард 2005 , с. 18

- Хетерингтон, « Фаллибилизм » , Главный раздел, § 8. Последствия фаллибилизма: нет знаний?

- ^ Браун 2016 , с. 104

- ^

- Хетерингтон, « Знание » , § 1. Виды познания

- Барнетт 1990 , стр. 40.

- Лилли, Лайтфут и Амарал, 2004 г. , стр. 162–163.

- ^

- Кляйн 1998 , § 1. Разновидности знаний

- Хетерингтон, « Познание » , § 1б. Знание-Это

- Прогулка 2023 , § Природа знаний

- ^

- Хетерингтон, « Познание » , § 1б. Знание-Это

- Прогулка 2023 , § Природа знаний

- Загжебский 1999 , с. 92

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хетерингтон, « Познание » , § 1б. Знание-Это

- ^

- Моррисон 2005 , с. 371

- Рейф 2008 , с. 33

- Загжебский 1999 , с. 93

- ^ Причард 2013 , с. 4

- ^

- Хетерингтон, « Знание » , § 1. Виды познания

- Прогулка 2023 , § Природа знаний

- Стэнли и Уилламсон 2001 , стр. 411–412.

- ^

- Хетерингтон, « Знание » , § 1г. Ноу-хау

- Причард 2013 , с. 3

- ^

- Мерриенбур 1997 , с. 32

- Клауер и др. 2016 , стр. 105–6

- Павезе 2022 , Ведущий раздел

- ^

- Хетерингтон, « Познание » , § 1а. Знание по знакомству

- Прогулка 2023 , § Святой Ансельм Кентерберийский

- Загжебский 1999 , с. 92

- Бентон 2024 , с. 4

- ^

- Прогулка 2023 , § Априорные и апостериорные знания

- Бэр, « Априори и апостериори » , ведущий раздел.

- Рассел 2020 , Ведущий раздел

- ^

- Бэр, « Априори и апостериори » , ведущий раздел.

- Мозер 2016 , Ведущий раздел

- ^

- Рассел 2020 , Ведущий раздел

- Бэр, « Априори и апостериори » , Главный раздел, § 1. Первоначальная характеристика

- Мозер 2016 , Ведущий раздел

- ^

- ^ Юль и Лумис 2009 , с. 4

- ^

- ^

- Крамли II, 2009 г. , стр. 54–55.

- Айерс 2019 , с. 4

- ^

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018 , Ведущий раздел

- Крамли II, 2009 г. , стр. 53–54.

- ^

- Крамли II, 2009 г. , стр. 61–62.

- Итикава и Штеуп 2018 , § 3. Проблема Геттье

- ^

- Родригес 2018 , стр. 29–32

- Гольдман 1976 , стр. 771–773.

- Суддут , § 2б. Анализ осуществимости и пропозициональные победители

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018 , § 10.2 Фальшивые дела в сарае

- ^

- Крамли II, 2009 г. , стр. 61–62.

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018 , § 8. Эпистемическая удача

- ^

- Причард 2005 , стр. 1–4.

- Broncano-Berrocal & Carter 2017 , Ведущий раздел

- ^

- Крамли II 2009 , с. 65

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018 , Ведущий раздел, § 3. Проблема Геттье

- ^ Крамли II 2009 , стр. 67–68.

- ^ Ichikawa & Steup 2018 , § 6.1 Релайабилистские теории познания

- ^ Ichikawa & Steup 2018 , § 5.1 Чувствительность

- ^

- Крамли II 2009 , с. 75

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018 , § 4. Никаких ложных лемм

- ^ Крамли II 2009 , с. 69

- ^

- Хетерингтон, « Знание » , § 5в. Ставя под сомнение проблему Геттье, § 6. Стандарты познания

- Крафт 2012 , стр. 49–50.

- ^

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018 , § 3. Проблема Геттье, § 7. Поддаются ли знания анализу?

- Загзебский 1999 , стр. 93–94, 104–105.

- Steup & Neta 2020 , § 2.3 Знание фактов

- ^ Ichikawa & Steup 2018 , § 7. Поддаются ли знания анализу?

- ^

- Дегенхардт 2019 , стр. 1–6.

- Причард 2013 , стр. 10–11.

- Олссон 2011 , стр. 874–875

- ^

- Причард 2013 , с. 11

- Маккормик 2014 , с. 42

- ^ Причард 2013 , стр. 11–12.

- ^

- Штер и Адольф, 2016 , стр. 483–485.

- Пауэлл 2020 , стр. 132–133.

- Мейрманс и др. 2019 , стр. 754–756

- Дегенхардт 2019 , стр. 1–6.

- ^

- Причард, Турри и Картер 2022 , § 1. Проблемы ценностей

- Олссон 2011 , стр. 874–875

- Греко 2021 , § Ценность знаний

- ^

- Олссон 2011 , стр. 874–875

- Причард, Турри и Картер 2022 , § 1. Проблемы ценностей

- Платон 2002 , стр. 89–90, 97б–98а.

- ^

- Олссон 2011 , с. 875

- Греко 2021 , § Ценность знаний

- ^ Причард, Турри и Картер 2022 , § 6. Другие оценки ценности знаний

- ^

- Причард 2013 , стр. 15–16.

- Греко 2021 , § Ценность знаний

- ^

- Брэддон-Митчелл и Джексон 2011 , Ведущий раздел

- Баннин и Ю, 2008 , стр. 80–81.

- Дрецке 2005 , с. 85

- Крамли II 2009 , с. 18

- ^

- Брэддон-Митчелл и Джексон 2011 , Ведущий раздел

- Schwitzgebel 2024 , Ведущий раздел, § 1.1 Репрезентационализм

- Швицгебель 2011 , стр. 14–15.

- ^

- Schwitzgebel 2024 , § 1.2 Диспозиционализм

- Швицгебель 2011 , стр. 17–18.

- ^

- Schwitzgebel 2024 , § 1.5 Элиминативизм, инструментализм и фикционализм

- Швицгебель 2011 , с. 20

- ^

- Blaauw & Pritchard 2005 , стр. 101–111. 14–15

- Schwitzgebel 2024 , § 2.3 Степень веры, § 2.5 Вера и знание

- ^

- Дрецке 2005 , с. 85

- Лоу 2005 , с. 926

- Крамли II 2009 , с. 18

- ^

- Лоу 2005 , с. 926

- Дауден и Шварц , § 3. Теория соответствия

- Линч, 2011 г. , стр. 3–5.

- Крамли II 2009 , с. 58

- ^

- Гланцберг 2023 , § 1.2 Теория когерентности

- Лоу, 2005 , стр. 926–927.

- Линч 2011 , с. 3

- Крамли II 2009 , с. 58

- ^

- Линч 2011 , стр. 5–7, 10.

- Гланцберг 2023 , § 1. Неоклассические теории истины, § 2. Теория истины Тарского, § 4.4 Плюрализм истины, § 5. Дефляционизм

- Blaauw & Pritchard 2005 , стр. 101–111. 148–149

- ^

- Линч 2011 , с. 5

- Блау и Притчард 2005 , с. 148

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б

- Голдман и Бендер 2005 , с. 465

- Кванвиг 2011 , стр. 25–26

- ^

- Крамли II, 2009 г. , стр. 83–84.

- Олссон 2016

- ^

- Кванвиг 2011 , с. 25

- Фоли 1998 , Ведущий раздел

- ^ Ichikawa & Steup 2018 , § 1.3 Условие обоснования

- ^

- Крамли II 2009 , с. 149

- Comesaña & Comesaña 2022 , с. 44

- ^ Blaauw & Pritchard 2005 , с. 92–93

- ^ Сильва и Оливейра, 2022 , стр. 1–4

- ^

- Итикава и Штеуп 2018 , § 1.3.2 Виды обоснования

- Сильва и Оливейра 2022 , стр. 1–4

- ^

- Керн 2017 , стр. 8–10, 133.

- Смит 2023 , с. 3

- Steup & Neta 2024 , § 5. Источники знаний и обоснование

- Хетерингтон, « Познание » , § 3. Способы познания

- ^

- Steup & Neta 2024 , § 5.1 Восприятие

- Хетерингтон, « Познание » , § 3. Способы познания

- ^

- Хатун 2012 , с. 104

- Мартин 1998 , Ведущий раздел

- ^ Steup & Neta 2024 , § 5.2 Самоанализ

- ^

- Хетерингтон, « Познание » , § 3г. Познание посредством мышления плюс наблюдения

- Steup & Neta 2024 , § 5.4 Причина

- Ауди 2002 , стр. 85, 90–91

- Ауди 2006 г. , с. 38

- ^

- Steup & Neta 2024 , § 5.3 Память

- Ауди 2002 , стр. 72–75

- Гардинер 2001 , стр. 1351–1352.

- Михаэлиан и Саттон, 2017 г.

- ^

- Steup & Neta 2024 , § 5.5 Свидетельские показания

- Леонард 2021 , Ведущий раздел, § 1. Редукционизм и нередукционизм

- Зеленый 2022 , Ведущий раздел

- ^

- Blaauw & Pritchard 2005 , стр. 101–111. 123–124

- Фоли 2011 , стр. 37, 39–40.

- Харман 2013 , § Теоретическая и практическая рациональность

- Мел и Роулинг 2004 , стр. 3–4

- ^

- Хайнцельманн 2023 , стр. 312–314.

- Кизеветтер 2020 , стр. 332–334.

- ^

- Фоли, 2011 , стр. 39–40.

- Blaauw & Pritchard 2005 , стр. 101–111. 123–124

- ^

- Блау и Притчард 2005 , с. 109

- Энгель 2011 , с. 47

- ^

- Блау и Притчард 2005 , с. 88

- Чу, 2016 , стр. 91–92.

- Монмарке, 1987 , стр. 482–483]

- ^

- Blaauw & Pritchard 2005 , стр. 101–111. 50–51

- DiFate , Ведущий раздел, § 1. Природа доказательств: что это такое и что оно делает?

- Келли 2016 , Ведущий раздел

- МакГрю, 2011 , стр. 58–59.

- ^ МакГрю 2011 , с. 59

- ^

- Суддут , Свинцовый раздел, § 2c. Ограничения на пропозициональных победителей

- Макферсон 2020 , с. 10

- ^

- Блау и Притчард 2005 , с. 51

- Келли 2016 , § 1. Доказательства как то, что оправдывает веру

- ^

- Blaauw & Pritchard 2005 , стр. 101–111. 18–19,

- Хуквей 2005а , с. 134

- Хуквей 2005b , с. 220

- ^

- Блау и Притчард 2005 , с. 150

- Гримм 2011 , стр. 84, 88.

- Гордон , ведущий отдел

- ^

- Кекес 2005 , с. 959

- Блау и Притчард 2005 , с. 157

- Уиткомб 2011 , с. 95

- ^

- Коэн 1998 , § Краткое содержание статьи

- Хуквей 2005 , с. 838

- Мозер 2011 , с. 200

- ^

- Хуквей 2005 , с. 838

- Бергманн 2021 , с. 57

- ^

- Хэзлетт 2014 , с. 18

- Левин 1999 , с. 11

- ^

- Хуквей 2005 , с. 838

- Comesana & Klein 2024 , Ведущая секция

- ^

- Виндт 2021 , § 1.1 Скептицизм картезианской мечты

- Кляйн 1998 , § 8. Эпистемические принципы и скептицизм.

- Хетерингтон, « Познание » , § 4. Скептические сомнения относительно познания

- ^

- Хуквей 2005 , с. 838

- Steup & Neta 2024 , § 6.1 Общий скептицизм и выборочный скептицизм

- ^

- Steup & Neta 2024 , § 6.2 Ответы на аргумент закрытия

- Рид 2015 , с. 75

- ^ Коэн 1998 , § 1. Философская проблема скептицизма, § 2. Ответы на скептицизм

- ^

- Хетерингтон, « Фаллибилизм » , Ведущий раздел, § 9. Последствия фаллибилизма: знание ошибочности?

- Решер 1998 , § Краткое содержание статьи

- ^

- Решер 1998 , § Краткое содержание статьи

- Хетерингтон, « Фаллибилизм » , § 9. Последствия фаллибилизма: знание ошибочности?

- ^

- Картер 2017 , с. 292

- Лупер 2004 , стр. 271–272

- ^

- Лейси 2005 , с. 242

- Markie & Folescu 2023 , Ведущий раздел, § 1.2 Эмпиризм

- ^ Лейси 2005a , с. 783

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б

- Лейси 2005a , с. 783

- Markie & Folescu 2023 , Ведущий раздел, § 1. Введение

- ^ Тиезен 2005 , с. 175

- ^

- Лейси 2005a , с. 783

- Markie & Folescu 2023 , Ведущий раздел, § 1. Введение

- Хейлз 2009 , с. 29

- ^

- Ауди 1988 , стр. 407–408

- Лестница 2017 , стр. 155–156.

- Марголис 2007 , с. 214

- ^ Брэдли 2015 , с. 170

- ^ Blaauw & Pritchard 2005 , с. 64

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б

- Лестница 2017 , стр. 155–156.

- Марголис 2007 , с. 214

- ^ Лестница 2017 , с. 155

- ^

- Лестница 2017 , стр. 156–157.

- О'Брайен 2006 , с. 77

- ^

- Рупперт, Шлютер и Зайде, 2016 , с. 59

- Трамел 2008 , стр. 215–216.

- ^

- Брэдли 2015 , стр. 170–171.

- Лестница 2017 , стр. 155–156.

- ^ Привет, 2016 год .

- ^

- Паппас 2023 , Ведущий раздел

- Крамли II, 2009 г. , стр. 159–160.

- Фумертон 2011 , Ведущая секция

- ^

- Бернекер 2013 г. , 1 класс

- Уилсон 2023

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б

- Паппас 2023 , Ведущий раздел

- Постон , Ведущий раздел

- Крамли II, 2009 г. , стр. 159–160.

- ^ Крамли II 2009 , с. 160

- ^

- Крамли II 2009 , стр. 99, 298.

- Картер и Литтлджон 2021 , § 9.3.3 Эвиденциалистский аргумент

- Обед , Ведущая секция

- ^ Полдень , § 2б. Доказательство

- ^ Крамли II 2009 , стр. 99, 298.

- ^

- Крамли II 2009 , стр. 83, 301.

- Олссон 2016

- ^

- Крамли II 2009 , с. 84

- Лион, 2016 г. , стр. 160–162.

- Олссон 2016

- ^

- Крамли II, 2009 г. , стр. 175–176.

- Бэр, « Эпистемология добродетели » , Ведущий раздел, § 1. Введение в эпистемологию добродетели.

- ^

- Браун 1992 , с. 341

- Крамли II 2009 , стр. 268–269, 277–278, 300–301.

- ^

- Кьяри и Нуццо 2009 , с. 21

- Крамли II 2009 , стр. 215–216, 301.

- ^

- Кокрам и Мортон 2017

- Бауманн, 2016 , стр. 59–60.

- ^

- ^

- Legg & Hookway 2021 , Ведущий раздел, § 4. Прагматическая эпистемология

- Келли и Кордейро 2020 , с. 1

- ^

- ^

- Питерсма 2000 , стр. 3–4

- Howarth 1998 , § Краткое содержание статьи

- ^

- Греко 2021 , § 1. Методология в эпистемологии: партикуляризм и генерализм

- Лемос 2005 , стр. 488–489

- Дэнси 2010 , стр. 532–533.

- ^

- Greco 2021 , § 2. Методология в эпистемологии: за пределами партикуляризма

- Гардинер 2015 , стр. 31, 33–35.

- ^

- Клаф и МакХью 2020 , с. 177

- Грассвик 2018 , Ведущая секция

- ^

- Шарп 2018 , стр. 318–319.

- Бест и Келлнер 1991 , с. 165

- ^

- Андерсон 1995 , с. 50

- Андерсон 2024 , Ведущий раздел

- ^

- Ли 2017 , с. 67

- Драйер, 2017 , стр. 1–7.

- ^

- Филлипс 1998 , Ведущий раздел

- Phillips & Vaidya 2024 , Ведущая секция

- Бхатт и Мехротра, 2017 , стр. 12–13.

- ^

- Филлипс 1998 , § 1. Буддийский прагматизм и когерентизм.

- Сидеритс 2021 , с. 332

- ^ Филлипс 1998 , § 2. Ньяя Релайабилизм

- ^ Филлипс 1998 , § 2. Самосертификационизм Мимамсы.

- ^

- Уэбб , § 2. Эпистемология и логика

- Сетия 2004 , с. 93

- ^

- Маккейн и Кампуракис, 2019 г. , стр. xiii–xiv.

- Птица 2010 , с. 5

- Мерритт 2020 , стр. 1–2.

- ^

- Муравский 2004 , стр. 571–572

- Серпинская и Лерман 1996 , стр. 827–828

- ^ Уоррен 2020 , § 6. Эпистемология логики.

- ^

- МакДэниел 2020 , § 7.2 Эпистемология метафизики

- Ван Инваген, Салливан и Бернштейн 2023 , § 5. Возможна ли метафизика?

- ^

- ДеЛапп , Ведущий раздел, § 6. Эпистемологические проблемы метаэтики

- Сэйр-МакКорд 2023 , § 5. Моральная эпистемология

- ^ Chignell 2018 , Ведущий раздел

- ^

- Макнабб, 2019 г. , стр. 1–3, 22–23.

- Ховард-Снайдер и МакКоган, 2023 г. , стр. 96–97.

- ^

- Танини 2017 , Ведущий раздел

- О'Коннор, Голдберг и Голдман, 2024 г. , Ведущий раздел, § 1. Что такое социальная эпистемология?

- ^

- Авила и Алмейда 2023 , с. 235

- Вермейр 2013 , стр. 65–66

- Штурм 2011 , стр. 303–304, 306, 308.

- ^ Штурм 2011 , стр. 303–304, 08–309.

- ^ Штурм 2011 , с. 304

- ^

- Крамли II 2009 , стр. 183–184, 188–189, 300.

- Ренн , ведущий отдел

- Рысев 2021 , § 2. «Натурализованная эпистемология»

- ^

- Bradie & Harms 2023 , Ведущая секция

- Гонтье , ведущий отдел

- ^ Барбер 2003 , стр. 1–3, 10–11, 15.

- ^ Вайдья и Валлнер, 2021 , стр. 1909–1910 гг.

- ^ Кроче 2023 , Ведущий раздел

- ^ Магуайр 2015 , стр. 33–34.

- ^ Сигел, Силинс и Маттен, 2014 , с. 781

- ^ Кони 1998 , Ведущий раздел

- ^ Причард 2004 , с. 326

- ^ Douven & Schupbach 2014 , Ведущий раздел

- ^

- Сегура 2009 , стр. 557–558

- Хендрикс 2006 , с. 115

- ^ Beebe 2017 , Ведущий раздел

- ^ Лакей 2021 , стр. 3, 8–9, 13.

- ^

- Фрикер 2007 , стр. 1–2.

- Крайтон, Карел и Кидд, 2017 , стр. 65–66

- ^

- Геркен 2018 , Ведущий раздел

- Мчуг, Уэй и Уайтинг, 2019 г. , стр. 1–2.

- ^ Геркен 2018 , Ведущий раздел

- ^ Олстон 2006 , с. 2

- ^

- Китченер 1992 , с. 119

- Крамли II 2009 , с. 16

- Шмитт 2004 , стр. 841–842.

- ^

- Шмитт 2004 , стр. 841–842.

- Фриденберг, Сильверман и Спиви, 2022 г. , стр. 2–3.

- ^ Уиллер и Перейра 2004 , стр. 469–470, 472, 491.

- ^

- Розенберг 2002 , с. 184

- Steup & Neta 2024 , § 4.1 Фундаментализм

- Ауди 2002 г. , с. 90

- ^ Кларк 2009 , с. 516

- ^ Лестница 2017 , с. 156

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хансен 2023 , § 3.5 Эпистемический подход к заблуждениям

- ^

- Хансен 2023 , Ведущий раздел

- Чатфилд 2017 , с. 194

- ^

- Исследователь 2005 , с. 1

- Рендсвиг, Симонс и Ван 2024 , Ведущий раздел

- ^

- Каплан 2005 , стр. 434, 443–444.

- Steele & Stefánsson 2020 , Ведущий раздел, § 7. Заключительные замечания

- Хукер, Лич и МакКленнен, 2012 г. , стр. xiii–xiv.

- ^ Стил и Стефанссон 2020 , Ведущий раздел

- ^

- Каплан 2005 , стр. 434, 443–444.

- Steele & Stefánsson 2020 , § 7. Заключительные замечания

- ^

- ^

- Келли 2004 , стр. 183–184.

- Харасим 2017 , с. 4

- ^ Харасим 2017 , с. 11

- ^ Харасим 2017 , с. 11–12

- ^

- Уоткинс и Мортимор, 1999 , стр. 1–3.

- Пейн 2003 , с. 264

- Габриэль 2022 , стр. 16.

- Турути, Ньяги и Чемвей 2017 , стр. 365

- ^ Эмалиана 2017 , стр. 59–61

- ^

- Хофер 2008 , стр. 3–4.

- Хофер 2001 , стр. 353–354, 369–370.

- ^

- Оллвуд, 2013 , стр. 69–72.

- Барт 2002 , стр. 1–2.

- ^

- ^

- Хэмлин 2005 , с. 260

- Паппас 1998 , § Античная философия

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Паппас 1998 , § Античная философия

- ^

- Паппас 1998 , § Античная философия

- Хэмлин 2005 , с. 260

- Воленски 2004 , с. 7

- ^

- Хэмлин 2006 , стр. 287–288

- Воленски 2004 , с. 8

- ^

- Хэмлин 2006 , с. 288

- Фогт 2011 , с. 44

- ^

- Воленски 2004 , с. 8

- Паппас 1998 , § Античная философия

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Данн 2006 , с. 753

- ^ Черный , Ведущий раздел

- ^

- Фунтулакис 2021 , с. 23

- Уордер 1998 , стр. 43–44.

- Флетчер и др. 2020 , с. 46

- ^

- Прасад 1987 , с. 48

- Дасти , Ведущий раздел

- Бхатт 1989 , с. 72

- ^

- Прасад 1987 , с. 6

- Данн 2006 , с. 753

- ^ Боневак 2023 , с. восемнадцатый

- ^

- Воленски 2004 , стр. 10–11.

- Котерский 2011 , стр. 9–10

- ^

- Воленски 2004 , с. 11

- Шенбаум 2015 , с. 181

- ^

- Griffel 2020 , Ведущий раздел, § 3. «Опровержения» Аль-Газали фальсафы и исмаилизма

- Василопулу и Кларк 2009 , с. 303

- ^

- Воленски 2004 , с. 11

- Холопайнен 2010 , с. 75

- ^ Воленски 2004 , стр. 11.

- ^

- Воленски 2004 , с. 11

- Хэмлин 2006 , стр. 289–290

- ^

- Кэй , Свинцовый раздел, § 4а. Прямой реалистический эмпиризм

- Антоньяцца 2024 , с. 86

- ^

- Воленски 2004 , стр. 14–15.

- Хэмлин 2006 , с. 291

- ^

- Хэмлин 2005 , с. 261

- Эванс 2018 , с. 298

- ^

- Воленски 2004 , стр. 17–18.

- Хэмлин 2006 , стр. 298–299

- Хэмлин 2005 , с. 261

- ^

- Ковентри и Меррилл 2018 , с. 161

- Паппас 1998 , § Современная философия: от Юма до Пирса

- Воленски 2004 , стр. 22–23.

- ^

- Воленски 2004 , стр. 27–30.

- Паппас 1998 , § Современная философия: от Юма до Пирса

- ^

- Паппас 1998 , § Современная философия: от Юма до Пирса

- Хэмлин 2005 , с. 262

- ^

- Хэмлин 2005 , с. 262

- Хэмлин 2006 , с. 312

- ^ Паппас 1998 , § Современная философия: от Юма до Пирса

- ^

- Паппас 1998 , § Двадцатый век

- Квас и Зеленяк 2009 , с. 71

- ^

- Рокмор, 2011 г. , стр. 131–132.

- Воленски 2004 , с. 44

- Хэмлин 2006 , с. 312

- ^ Хэмлин 2005 , с. 262

- ^

- Паппас 1998 , § Двадцатый век

- Хэмлин 2006 , с. 315

- Воленски 2004 , стр. 48–49.

- ^

- Болдуин 2010 , § 6. Здравый смысл и уверенность

- Воленски 2004 , с. 49

- ^ Хэмлин 2006 , стр. 317–318

- ^

- Хэмлин 2005 , с. 262

- Бейлби 2017 , с. 74

- Паппас 1998 , § Двадцатый век

- ^

- Goldman & Beddor 2021 , Ведущий раздел, § 1. Смена парадигмы в аналитической эпистемологии

- Паппас 1998 , § Двадцатый век, § Последние выпуски

- ^

- Goldman & Beddor 2021 , § 4.1 Релайабилизм добродетели

- Крамли II 2009 , с. 175

- ^ Крамли II 2009 , стр. 183–184, 188–189.

- ^

- Паппас 1998 , § Недавние выпуски

- Вагелли 2019 , с. 96

Библиография

[ редактировать ]- Оллвуд, Карл Мартин (2013). «Антропология знания». Энциклопедия межкультурной психологии . John Wiley & Sons, Inc., стр. 69–72. дои : 10.1002/9781118339893.wbeccp025 . ISBN 978-1-118-33989-3 . Архивировано из оригинала 26 сентября 2022 года . Проверено 26 сентября 2022 г.

- Олстон, Уильям Пейн (2006). За пределами оправдания: аспекты эпистемической оценки . Издательство Корнельского университета. ISBN 978-0-8014-4291-9 .

- Андерсон, Элизабет (1995). «Феминистская эпистемология: интерпретация и защита» . Гипатия . 10 (3): 50–84. дои : 10.1111/j.1527-2001.1995.tb00737.x . ISSN 0887-5367 . JSTOR 3810237 . Архивировано из оригинала 2 августа 2024 года . Проверено 3 августа 2024 г.

- Андерсон, Элизабет (2024). «Феминистская эпистемология и философия науки» . Стэнфордская энциклопедия философии . Лаборатория метафизических исследований Стэнфордского университета. Архивировано из оригинала 14 октября 2019 года . Проверено 2 августа 2024 г.