Вторая мировая война

| Вторая мировая война | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Участники | |||||||

| Союзники | Ось | ||||||

| Командиры и лидеры | |||||||

| Основные лидеры союзников : | Основные лидеры оси : | ||||||

| Потери и потери | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Вторая мировая война |

|---|

| Навигация |

|

|

Вторая мировая война [ B ] Или вторая мировая война (1 сентября 1939 - 2 сентября 1945 года) была глобальным конфликтом между двумя коалициями: союзниками и державами Оси . Почти все страны мира , в том числе все великие державы , участвующие в участии, при этом многие инвестируют все доступные экономические, промышленные и научные возможности в стремление к полной войне , стимулируя различие между военными и гражданскими ресурсами. Танки и самолеты сыграли главные роли , причем последние позволяют стратегическому бомбардировке населенных пунктов и доставку единственных двух ядерных оружия, когда -либо использовавшихся на войне. Вторая мировая война стала самым смертоносным конфликтом в истории, в результате чего от 70 до 85 миллионов смертельств более половины из которых были гражданскими лицами. Миллионы погибли в геноцидах , включая Холокост европейских евреев, а также от убийств, голода и болезней. После победы союзных держав, Германия , Австрия , Япония и Корея были заняты, а военных преступлений трибуналы были проведены против немецких и японских лидеров .

Причины Второй мировой войны включали неразрешенную напряженность в последствиях Первой мировой войны и роста фашизма в Европе и милитаризма в Японии , и ему предшествовали события, включая японское вторжение в Маньчжурию , гражданскую войну в Испании , вспышка второго Синоя -Японская война и немецкие аннексии Австрии и Судетенленда . Считается, что Вторая мировая война началась 1 сентября 1939 года, когда нацистская Германия под руководством Адольфа Гитлера вторглась в Польшу . Соединенное Королевство и Франция объявили войну Германии 3 сентября. Под их пактом Молотова -Риббентропа , Германия и Советский Союз разбили Польшу и отметили « сферы влияния » по всей Восточной Европе; В 1940 году Советы аннексировали Балтийские государства и части Финляндии и Румынии . После падения Франции в июне 1940 года война продолжалась в первую очередь между Германией и Британской империей , с кампаниями в Северной и Восточной Африке и на Балканах , воздушной битвой в Великобритании и Блица Великобритании и военно -морской битвой Атлантики Полем К середине 1941 года, благодаря ряду кампаний и договоров, Германия занимала или контролировала большую часть континентальной Европы и сформировала союз оси с Италией , Японией и другими странами. В июне 1941 года Германия возглавила Европейскую Ось в вторжении в Советский Союз , открыв восточный фронт .

Япония стремилась доминировать в Восточной Азии и Азиатско-Тихоокеанском регионе , и к 1937 году находилась на войне с Китайской Республикой . В декабре 1941 года Япония напала на американские и британские территории в Юго -Восточной Азии и центральной части Тихого океана , включая нападение на Перл -Харбор , в результате чего Соединенные Штаты и Соединенное Королевство объявили войну против Японии. Европейские державы оси объявили войну в США солидарностью. Япония вскоре победила большую часть западной части Тихого океана , но ее достижения были остановлены в 1942 году после поражения в военно -морской битве на Мидуэй ; Германия и Италия были побеждены в Северной Африке и в Сталинграде в Советском Союзе. Ключевые неудачи в 1943 году, в том числе немецкие поражения на Восточном фронте, вторжения союзников Сицилии и Материкала Италии , а также союзные наступления в Тихом океане - заставляют оси приводит их инициативу и заставили их попасть в стратегическое отступление на всех фронтах. В 1944 году западные союзники вторглись в Германии, занятую Францию в Нормандии , в то время как Советский Союз восстановил свои территориальные потери и подтолкнул Германию и ее союзников на запад. В 1944 и 1945 годах Япония перенесла изменения в материковую Азию, в то время как союзники нанесли ущерб японскому флоту и захватили ключевые острова западной части Тихого океана . Война в Европе завершилась освобождением территорий, занятых немецким языком ; вторжение в Германию западными союзниками и Советским Союзом, кульминацией которого является падение Берлина в советские войска; Самоубийство Гитлера ; и немецкая безусловная сдача 8 мая 1945 года . После отказа Японии сдаться на условиях Декларации Потсдама , США сбросили первые атомные бомбы на Хиросиму 6 августа и Нагасаки 9 августа. Столкнулся с неизбежным вторжением в японский архипелаг , возможность более атомных взрывов и советской декларацией войны против Японии и ее вторжения в Маньчжурию , Япония объявила о своей безусловной сдаче 15 августа и подписала документ с капитуляцией 2 1945 сентября конец конфликта.

Вторая мировая война изменила политическое выравнивание и социальную структуру мира, и она создала основу международных отношений до конца 20 -го века и в 21 -м веке. Организация Объединенных Наций была создана для развития международного сотрудничества и предотвращения конфликтов, когда победоносные великие державы - Китай, Франция, Советский Союз, Великобритания и США - являются постоянными членами его Совета Безопасности . Советский Союз и Соединенные Штаты стали конкурирующими суперспособниками , создав почву для холодной войны . После европейского опустошения влияние его великих держав уменьшилось, вызвав деколонизацию Африки и Азии . Большинство стран, чьи отрасли были повреждены, двинулись в направлении восстановления экономики и расширения .

Начало и окончание даты

| Сроки Второй мировой войны |

|---|

| Хронологический |

| Прелюдия |

| По теме |

| Театр |

Вторая мировая война началась в Европе 1 сентября 1939 года [ 1 ] [ 2 ] С немецким вторжением в Польшу и Соединенным Королевствам и Франции Декларация войны в Германии два дня спустя, 3 сентября 1939 года. Даты начала Тихоокеанской войны включают начало второй китайско-японской войны 7 июля 1937 года, [ 3 ] [ 4 ] или более раннее вторжение в японское в Маньчжурию 19 сентября 1931 года. [ 5 ] [ 6 ] Другие следуют за британским историком AJP Taylor , который заявил, что китайско-японская война и война в Европе и его колония произошли одновременно, и две войны стали Второй мировой войной в 1941 году. [ 7 ] Другие предложенные даты начала Второй мировой войны включают в себя итальянское вторжение в Абиссинию 3 октября 1935 года. [ 8 ] Британский историк Энтони Бивор рассматривает начало Второй мировой войны, когда битвы Халхин Гол сражались между Японией и силами Монголии и Советским Союзом с мая по сентябрь 1939 года. [ 9 ] Другие рассматривают гражданскую войну в Испании как начало или прелюдию ко Второй мировой войне. [ 10 ] [ 11 ]

Точная дата конца войны также не согласована с повсеместной. В то время было принято, что война закончилась перемирием от 15 августа 1945 года ( VJ Day ), а не официальной сдачей Японии 2 сентября 1945 года, которая официально закончила войну в Азии . Мирный договор между Японией и союзниками был подписан в 1951 году. [ 12 ] Договор 1990 года, касающийся будущего Германии, позволил воссоединению Восточной и Западной Германии пройти и решить большинство проблем после Второй войны после Второй мировой войны. [ 13 ] Никакого формального мирного договора между Японией и Советским Союзом никогда не было подписано, [ 14 ] Хотя состояние войны между этими двумя странами было прекращено Совместной японской декларацией 1956 года , которая также восстановила полные дипломатические отношения между ними. [ 15 ]

История

Фон

Последствия Первой мировой войны

Первая мировая война радикально изменила политическую европейскую карту с поражением центральных держав , включая Австрийскую-Венгрию , Германию , Болгарию и Османскую империю 1917 года -и большевистский захват власти , 1917 года . что привело к основанию Советского Совета Союз Тем временем победоносные союзники Первой мировой войны , такие как Франция, Бельгия, Италия, Румыния и Греция, получили территорию, и новые национальные государства были созданы из роспуска австро-венгерских, османских и русских империй. [ 16 ]

Чтобы предотвратить будущую мировую войну, Лига Наций была основана в 1920 году Парижской мирной конференцией . Основные цели организации состояли в том, чтобы предотвратить вооруженные конфликты посредством коллективной безопасности, военных и военно -морских разоружение , а также урегулирование международных споров посредством мирных переговоров и арбитража. [ 17 ]

Несмотря на сильные пацифистские настроения мировой войны после Первой , [ 18 ] Ирредентист и для отдыха национализм в нескольких европейских государствах. Эти чувства были особенно отмечены в Германии из -за значительных территориальных, колониальных и финансовых потерь, нанесенных Версальским договором . В соответствии с договором Германия потеряла около 13 процентов своей домашней территории и всех своих зарубежных владений , в то время как немецкая аннексия других государств была запрещена, были наложены репарации страны , и были установлены ограничения на размер и возможности вооруженных сил . [ 19 ]

Германия

Немецкая империя была распущена в немецкой революции 1918–1919 годов , и было создано демократическое правительство, позже известное как Республика Веймара . Межвоенный период увидел раздоры между сторонниками Новой Республики и противниками противника как политического правого, так и слева. Италия, как союзник-энтента, добилась некоторых послевоенных территориальных выгод; Тем не менее, итальянские националисты были возмущены тем, что обещания, выданные Соединенным Королевством и Францией о обеспечении итальянского входа в войну, не были выполнены в мирном поселении. С 1922 по 1925 год фашистское движение, возглавляемое Бенито Муссолини, захватило власть в Италии с националистической, тоталитарной и классовой повесткой дня, которая отменила представительную демократию, репрессируемую социалистическую, левую и либеральную силу и преследуется агрессивная экспункция, прицеленная внешняя политика Сделать Италию мировой властью, обещая создание « новой Римской империи ». [ 20 ]

Адольф Гитлер , после неудачной попытки свергнуть немецкое правительство в 1923 году, в конечном итоге стало канцлером Германии в 1933 году, когда его назначил Пол фон Хинденбург и Рейхстаг. После смерти Гинденбурга в 1934 году Гитлер провозгласил себя фюрером Германии и отменил демократию, поддерживая радикальный, расово мотивированный пересмотр мирового порядка , и вскоре начал массовую кампанию по переоборудованию . [ 21 ] Франция, стремясь обеспечить свой союз с Италией, позволила Италии свободную руку в Эфиопии , которую Италия желала колониальному владению. Ситуация усугублялась в начале 1935 года, когда территория бассейна Саара была юридически воссоединена с Германией, и Гитлер отвергли Версальский договор, ускорил свою программу поощрения и представил призыв. [ 22 ]

Европейские договоры

Соединенное Королевство, Франция и Италия сформировали фронт Стреса в апреле 1935 года, чтобы сдержать Германию, что является ключевым шагом к военной глобализации ; Однако в июне Соединенное Королевство заключило независимое военно -морское соглашение с Германией, облегчив предварительные ограничения. Советский Союз, обеспокоенный целями Германии по захвату обширных районов Восточной Европы , составил договор о взаимной помощи с Францией. Перед тем, как вступить в силу, Франко-Советский Пакт должен был пройти через бюрократию Лиги Наций, что сделало его по существу беззубым. [ 23 ] Соединенные Штаты, озабоченные событиями в Европе и Азии, приняли Закон о нейтралитете в августе того же года. [ 24 ]

Гитлер бросил вызов договорам Версаля и Локарно , ремилитарируя Рейнланд в марте 1936 года, столкнувшись с небольшим противодействием из -за политики умиротворения . [ 25 ] В октябре 1936 года Германия и Италия сформировали ось Рим -Берлин . Месяц спустя Германия и Япония подписали антикоминальный пакт , к которому Италия присоединилась в следующем году. [ 26 ]

Азия

Партия Kuomintang (KMT) в Китае начала объединительную кампанию против региональных военнослужащих и номинально объединенного Китая в середине 1920-х годов, но вскоре была вовлечена в гражданскую войну против ее бывшей коммунистической партии Китая (CCP) [ 27 ] и новые региональные военачальники . В 1931 году все более милитаристическая империя Японии , которая давно искала влияние в Китае [ 28 ] что его правительство считало правом страны управлять Азией , устроил инцидент с Мукденом в качестве предлога для вторжения в Маньчжурию и установить марионеточное состояние Маньчукуо В качестве первого шага того , . [ 29 ]

Китай обратился к Лиге Наций, чтобы остановить японское вторжение в Маньчжурию. Япония вышла из Лиги Наций после того, как была осуждена за его вторжение в Маньчжурию. Затем две страны сражались в несколько сражений, в Шанхае , Рехе и Хэбэй , пока не было подписано перемирие Тангу в 1933 году. После этого китайские волонтерские силы продолжали сопротивление японской агрессии в Маньчжурии , а Чахар и Суйюань . [ 30 ] После инцидента XI'AN 1936 года силы Куминтана и КПК согласились с прекращением огня, чтобы представить объединенный фронт , чтобы противостоять Японии. [ 31 ]

Довоенные события

Итальянское вторжение в Эфиопию (1935)

Вторая италоопическая война была краткой колониальной войной , которая началась в октябре 1935 года и закончилась в мае 1936 года. Война началась с вторжения в Эфиопскую империю (также известную как Абиссиния ) вооруженными силами Королевства Италии ( Регно Д. «Италия ), которая была запущена из итальянского Сомалиленда и Эритреи . [ 32 ] Война привела к военной оккупации Эфиопии и ее аннексии в недавно созданную колонию Итальянской Восточной Африки ( Африка Ориентал Итальян , или AOI); Кроме того, он выявил слабость Лиги Наций как силы, чтобы сохранить мир. И Италия, и Эфиопия были странами -членами, но лига мало что сделала, лиги когда бывшая явно нарушенная статья X Завета . [ 33 ] Соединенное Королевство и Франция поддержали внедрение санкций в Италию для вторжения, но санкции не были полностью принуждены и не смогли положить конец итальянскому вторжению. [ 34 ] Впоследствии Италия отбросила свои возражения против цели Германии по поглощению Австрии . [ 35 ]

Гражданская война в Испании (1936–1939)

Когда в Испании началась гражданская война, Гитлер и Муссолини оказали военную поддержку националистическим повстанцам во главе с генералом Франциско Франко . Италия в большей степени поддерживала националистов, чем нацисты: Муссолини послал более 70 000 сухопутных войск, 6000 авиационных сотрудников и 720 самолетов в Испанию. [ 36 ] Советский Союз поддержал существующее правительство испанской республики . Более 30 000 иностранных добровольцев, известных как Международные бригады , также боролись против националистов. И Германия, и Советский Союз использовали эту доверенную войну как возможность проверить в борьбе с их наиболее продвинутым оружием и тактикой. Националисты выиграли гражданскую войну в апреле 1939 года; Франко, ныне диктатор, оставался официально нейтральным во время Второй мировой войны, но в целом предпочитал ось . [ 37 ] Его самым большим сотрудничеством с Германией была отправка добровольцев , чтобы сражаться на восточном фронте . [ 38 ]

Японское вторжение в Китай (1937)

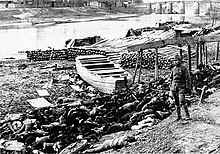

В июле 1937 года Япония захватила бывшую китайскую имперскую столицу Пекина после того, как спровоцировал инцидент с мостом Марко Поло , который завершился японской кампанией, чтобы вторгнуться в во всем Китае. [ 39 ] Советы быстро подписали неагрессивный пакт с Китаем для оказания поддержки материалам , эффективно прекратив арестованное сотрудничество Китая с Германией . С сентября по ноябрь японцы атаковали Тайюань , вовлекая армию Куминтанга вокруг Сюйнку , [ 40 ] и боролся с коммунистическими силами в Пинсинггуане . [ 41 ] [ 42 ] Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek развернул свою лучшую армию для защиты Шанхая , но после трех месяцев боевых действий Шанхай упал. Японцы продолжали отталкивать китайские силы назад, захватив столицу Нанкин в декабре 1937 года. После падения нанкинга, десятков или сотен тысяч китайских гражданских лиц и разоруженных комбатантов японцы были убиты . [ 43 ] [ 44 ]

В марте 1938 года националистические китайские войска одержали свою первую крупную победу в Тайерзхуанге город Сюжжоу . японцы одержали , но затем в мае [ 45 ] В июне 1938 года китайские силы остановили продвижение японцев, наводнив Желтую реку ; Этот маневр купил время для китайцев, чтобы подготовить свою защиту в Ухане , но город был взят к октябрю. [ 46 ] Японские военные победы не привели к краху сопротивления Китая, которого Япония надеялась достичь; Вместо этого китайское правительство переехало внутри страны в Чунцин и продолжило войну. [ 47 ] [ 48 ]

Советские -японские пограничные конфликты

В середине до 1930-х годов японские войска в Маньчукуо столкнулись с спорадическими границами с Советским Союзом и Монголией . Японская доктрина Хокушин-Рон , которая подчеркивала расширение Японии на север, была одобрена имперской армией в течение этого времени. Эта политика оказалась бы трудной для поддержания в свете поражения Японии в Khalkin GOL в 1939 году, продолжающейся второй китайско-японской войны [ 49 ] и союзник нацистская Германия, преследуя нейтралитет с Советами. Япония и Советский Союз в конечном итоге подписали договор о нейтралитете в апреле 1941 года, и Япония приняла доктрину Наншин-Рон , продвигаемой военно-морским флотом, которая сосредоточилась на юге и в конечном итоге привела к войне с Соединенными Штатами и Западными союзниками. [ 50 ] [ 51 ]

Европейские занятия и соглашения

В Европе Германия и Италия стали более агрессивными. В марте 1938 года Германия аннексировала Австрию , вновь вызывая небольшой отклик со стороны других европейских держав. [ 52 ] Поощряемый, Гитлер начал нажимать на получение немецких заявлений о Судетенленде , районе Чехословакии с преимущественно этническим немецким населением. Вскоре Соединенное Королевство и Франция следовали политике умиротворения премьер -министра Британского Невилла Чемберлена и уступили этой территории Германии в Мюнхенском соглашении , которое было вынесено против желаний чехословацкого правительства, в обмен на обещание дальнейших территориальных требований. [ 53 ] Вскоре после этого Германия и Италия вынудили Чехословакию уступить дополнительную территорию в Венгрию, а Польша аннексировала Транс-Ольза в Чехословакии. [ 54 ]

Хотя все заявленные требования Германии были удовлетворены соглашением, частный Гитлер был в ярости, что британское вмешательство помешало ему захватить всю Чехословакию в одной операции. В последующих выступлениях Гитлер напал на британских и еврейских «военных монтиров» и в январе 1939 года тайно приказал значительно создать немецкий военно-морской флот, чтобы бросить вызов британскому военно-морскому превосходству. В марте 1939 года Германия вторглась в оставшуюся часть Чехословакии и впоследствии разделила ее на немецкую протекторат Богемии и Моравии и про-герман -государство , Словацкая Республика . [ 55 ] Гитлер также доставил ультиматум в Литву 20 марта 1939 года, заставив концессию в регионе Клайпхада , бывшего немецкого мемелланда . [ 56 ]

Очень встревожено, и Гитлер предъявляет дополнительные требования к свободному городу Данциг , Великобритания и Франция гарантировали свою поддержку независимости польского языка ; Когда Италия завоевала Албанию в апреле 1939 года, такая же гарантия была расширена до королевства Румынии и Греции . [ 57 ] Вскоре после того, как Франко - Британское обещание в Польшу, Германии и Италии официально формализовало свой собственный союз с договором стали . [ 58 ] Гитлер обвинил Соединенное Королевство и Польшу в попытке «окружить» Германию и отказался от англо-германского военно-морского соглашения и немецко-полистской декларации о неагрессии . [ 59 ]

Ситуация стала кризисом в конце августа, когда немецкие войска продолжали мобилизоваться против польской границы. 23 августа Советский Союз подписал неагрессивный договор с Германией, [ 60 ] После трехсторонних переговоров о военном альянсе между Францией, Великобритании и Советским Союзом остановились. [ 61 ] У этого договора был секретный протокол, который определил немецкие и советские «сферы влияния» (Западная Польша и Литва для Германии; Восточная Польша , Финляндия, Эстония , Латвия и Бессарабия для Советского Союза) и подняли вопрос постоянной польской независимости. [ 62 ] Пакт нейтрализовал возможность советской оппозиции кампании против Польши и заверил, что Германия не придется столкнуться с перспективой войны с двумя фронтами, как это было в Первой мировой войне, Гитлер приказал атаку продолжить 26 Август, но, услышав, что Соединенное Королевство завершило официальный пакт об взаимной помощи с Польшей и что Италия будет поддерживать нейтралитет, он решил отложить его. [ 63 ]

В ответ на британские запросы о прямых переговорах по избежанию войны Германия предъявляла требования по Польше, которые послужили предлогом ухудшения отношений. [ 64 ] 29 августа Гитлер потребовал, чтобы польская уплательница немедленно отправилась в Берлин, чтобы договориться о передаче Данцига и разрешил плебисцит в Польском коридоре , в котором немецкое меньшинство будет голосовать за отделение. [ 64 ] Поляки отказались соблюдать требования Германии, а в ночь на 30–31 августа на конфронтационной встрече с британским послом Невилом Хендерсоном Риббентроп заявил, что Германия считала, что его претензии отвергнуты. [ 65 ]

Курс войны

Война разрывается в Европе (1939–1940)

1 сентября 1939 года Германия вторглась в Польшу после того, как устроила несколько инцидентов по границе ложного флага в качестве предлога, чтобы инициировать вторжение. [ 66 ] Первая немецкая атака войны произошла против польской защиты в Вестерплатте . [ 67 ] Соединенное Королевство ответило ультиматумом, чтобы Германия прекратила военные операции, а 3 сентября, после того, как ультиматум был проигнорирован, Британия и Франция объявили войну Германии. [ 68 ] Затем следует Австралия , Новая Зеландия , Южная Африка и Канада . В период Фони -войны Альянс не оказывал прямой военной поддержки Польше, за пределами осторожного французского расследования в Саарланде . [ 69 ] Западные союзники также начали военно -морскую блокаду Германии , целью которой было нанести ущерб экономике страны и военным усилиям. [ 70 ] Германия ответила, заказав войну подводной лодки против торговца союзниками и военных кораблей, которые впоследствии переразится в битву за Атлантику . [ 71 ]

8 сентября немецкие войска достигли пригородов Варшавы . Польское противодействие на запад остановило аванс Германии в течение нескольких дней, но оно было охвачено и окружено Вермачтом . Остатки польской армии прорвались, чтобы осадить Варшаву . 17 сентября 1939 года, через два дня после подписания прекращения огня с Японией , Советский Союз вторгся в Польшу [ 72 ] Под предполагаемым предлогом, что польское государство перестало существовать. [ 73 ] 27 сентября Варшавский гарнизон сдался немцам, и последняя крупная оперативная единица польской армии сдалась 6 октября . Несмотря на военное поражение, Польша никогда не сдалась; Вместо этого он сформировал польское правительство в избытке , а тайный государственный аппарат остался в оккупированной Польше. [ 74 ] Значительная часть польского военнослужащего, эвакуированного в Румынии и Латвии; Многие из них позже боролись против оси в других кинотеатрах войны. [ 75 ]

Германия аннексировала западную Польшу и заняла центральную Польшу ; Советский Союз аннексировал Восточную Польшу ; Небольшие акции польской территории были перенесены в Литву и Словакию . 6 октября Гитлер сделал общественное мирное владение Соединенным Королевством и Францией, но сказал, что будущее Польши должно быть определено исключительно Германией и Советским Союзом. Предложение было отклонено [ 65 ] и Гитлер приказал немедленно наступление на Францию, [ 76 ] который был отложен до весны 1940 года из -за плохой погоды. [ 77 ] [ 78 ] [ 79 ]

После начала войны в Польше Сталин угрожал Эстонии , Латвии и Литве с военным вторжением, заставляя три страны Балтии подписать договорные договоры , позволяющие создавать советские военные базы в этих странах; В октябре 1939 года там были перенесены значительные советские военные контингенты. [ 80 ] [ 81 ] [ 82 ] Финляндия отказалась подписать аналогичный договор и отклонила уединительную часть своей территории в Советский Союз. Советский союз вторгся в Финляндию в ноябре 1939 года, [ 83 ] и впоследствии был исключен из Лиги Наций за это преступление агрессии. [ 84 ] Несмотря на подавляющее числовое превосходство, советский военный успех во время зимней войны был скромным, [ 85 ] и Финно-Советская война закончилась в марте 1940 года с некоторыми финскими уступками территории . [ 86 ]

В июне 1940 года Советский Союз занял все территории Эстонии, Латвии и Литвы, [ 81 ] а также румынские регионы Бессарабии, Северной Буковины и региона Герц . В августе 1940 года Гитлер ввел вторую венку на Румынию, которая привела к передаче северной Трансильвании в Венгрию. [ 87 ] В сентябре 1940 года Болгария потребовала южного Добруджи из Румынии с немецкой и итальянской поддержкой, что привело к Крайовой договору . [ 88 ] Потеря одной трети территории Румынии в 1939 году вызвала переворот против короля Кэрол II, превратив Румынию в фашистскую диктатуру под руководством маршала Антонеску , с курсом, проведенным в сторону оси в надежде на немецкую гарантию. [ 89 ] Между тем, немецко-советские политические отношения и экономическое сотрудничество [ 90 ] [ 91 ] постепенно остановился, [ 92 ] [ 93 ] И оба государства начали подготовку к войне. [ 94 ]

Западная Европа (1940–1941)

В апреле 1940 года Германия вторглась в Данию и Норвегию, чтобы защитить поставки железной руды от Швеции , которые союзники пытались отрезать . [ 95 ] Дания капитулировала через шесть часов , и, несмотря на поддержку союзников , Норвегия была завоевана в течение двух месяцев. [ 96 ] Британское недовольство норвежской кампанией привело к отставке премьер -министра Невилла Чемберлена мая 1940 года заменил Уинстон Черчилль , которого 10 . [ 97 ]

В тот же день Германия начала наступление против Франции . Чтобы обойти сильные укрепления линии Магино на границе с франко Германом, Германия направила свою атаку на нейтральные народы Бельгии , Нидерланды и Люксембург . [ 98 ] Немцы провели фланкировочный маневр через регион Арденнс , [ 99 ] который был ошибочно воспринимается союзниками как непроницаемый естественный барьер против бронированных транспортных средств. [ 100 ] [ 101 ] Успешно внедрив новую Blitzkrieg тактику , Wehrmacht быстро продвинулся к каналу и отключил союзные силы в Бельгии, захватывая основную часть союзных армий в котле на границе Франко-Бельджия недалеко от Лилля. Соединенное Королевство смогло эвакуировать значительное количество союзных войск с континента к началу июня, хотя им пришлось отказаться почти от всего их оборудования. [ 102 ]

10 июня Италия вторглась в Францию , объявив войну как Франции, так и в Соединенное Королевство. [ 103 ] Немцы повернулись на юг против ослабленной французской армии, а Париж упал на них 14 июня. Восемь дней спустя Франция подписала перемирие с Германией ; он был разделен на немецкие и итальянские оккупационные зоны , [ 104 ] и незанятое государство Румба под режимом Виши , которое, хотя и официально нейтральное, обычно было связано с Германией. Франция сохранила свой флот, который Соединенное Королевство атаковало 3 июля, пытаясь предотвратить его захват Германией. [ 105 ]

Воздушная битва за Британию [ 106 ] Начало в начале июля с атаки Люфтваффе на доставку и остатки . [ 107 ] Немецкая кампания по превосходству воздуха началась в августе, но ее неспособность победить истребитель RAF заставила неопределенную отложенность предложенного немецкого вторжения в Великобританию . Немецкое стратегическое бомбардировочное наступление усилилось ночными атаками на Лондон и другие города в Блице , но в значительной степени закончилось в мае 1941 года. [ 108 ] После того, как не удалось значительно нарушить британские военные усилия. [ 107 ]

Используя недавно захваченные французские порты, Немецкий флот добился успеха против чрезмерно расширенного Королевского флота , используя подводные лодки против британской судоходства в Атлантике . [ 109 ] Британский домашний флот одержал значительную победу 27 мая 1941 года, тонув немецкий линкор Бисмарк . [ 110 ]

В ноябре 1939 года Соединенные Штаты помогли Китаю и западным союзникам и внесли изменения в Закон о нейтралитете, чтобы позволить покупку «наличные и носить» союзников. [ 111 ] В 1940 году, после немецкого захвата Парижа, размер ВМС США был значительно увеличен . В сентябре Соединенные Штаты также согласились на торговлю американскими эсминцами на британские базы . [ 112 ] Тем не менее, подавляющее большинство американской общественности продолжали выступать против любого прямого военного вмешательства в конфликте до 1941 года. [ 113 ] В декабре 1940 года Рузвельт обвинил Гитлера в завоевании мира по планированию и исключил любые переговоры как бесполезные, призывая Соединенные Штаты стать « арсеналом демократии » и продвигая программы лизирования с лизом военной и гуманитарной помощи в поддержку британских военных усилий; Lend-Lease был позже распространен на других союзников, включая Советский Союз после того, как в него вторгли Германию . [ 114 ] Соединенные Штаты начали стратегическое планирование, чтобы подготовиться к полномасштабному наступлению на Германию. [ 115 ]

В конце сентября 1940 года Трехсторонний пакт официально объединился в Японии, Италии и Германии в качестве держав Оси . Трехсторонний пакт предусматривал, что любая страна - за исключением Советского Союза - которая напала на любую силу оси, будет вынуждена пойти на войну против всех трех. [ 116 ] Ось расширилась в ноябре 1940 года, когда Венгрия , Словакия и Румыния . присоединились [ 117 ] Румыния и Венгрия позже внесли большой вклад в войну оси против Советского Союза, в случае Румынии частично, чтобы вернуть территорию, уступившуюся в Советский Союз . [ 118 ]

Средиземноморье (1940–1941)

В начале июня 1940 года итальянская Regia Aeronautica атаковала и осадила Мальту , британское владение. С конца лета до начала осени Италия завоевала британский Сомалиленд и принесла вторжение в Британский Египет . В октябре Италия напала на Грецию , но атака была отталкивана тяжелыми итальянскими жертвами; Кампания закончилась в течение нескольких месяцев с незначительными территориальными изменениями. [ 119 ] Чтобы помочь Италии и предотвратить застройку Британии, Германия подготовилась к вторжению на Балкан, что угрожает румынским нефтяным месторождениям и нанести удар по британскому доминированию Средиземного моря. [ 120 ]

В декабре 1940 года силы Британской империи начали противодействовать итальянским войскам в Египте и Итальянской Восточной Африке . [ 121 ] Нападающие были успешными; К началу февраля 1941 года Италия потеряла контроль над Восточной Ливией, и большое количество итальянских войск было взято в плен. Итальянский военно -морской флот также потерпел значительные поражения, когда Королевский флот вынес три итальянские линкоры из комиссии после атаки перевозчика в Таранто и нейтрализовать еще несколько военных кораблей в битве при Кейп -Матапане . [ 122 ]

Итальянские поражения побудили Германию развернуть экспедиционную силу в Северную Африку; В конце марта 1941 года Роммеля из Африка Корпс начала наступление , которое отодвинуло силы Содружества. [ 123 ] Менее чем через месяц силы Оси вышли в Западный Египет и осадили порт Тобрук . [ 124 ]

К концу марта 1941 года Болгария и Югославия подписали трехсторонний пакт ; Тем не менее, югославское правительство было свергнуто через два дня пробуртскими националистами. Германия и Италия ответили одновременными вторжениями как Югославии , так и Греции , начиная с 6 апреля 1941 года; Обе страны были вынуждены сдаться в течение месяца. [ 125 ] Вторжение в воздухе на греческом острове Крит в конце мая завершило немецкое завоевание Балкан. [ 126 ] Партизанская война впоследствии разразилась против оккупации оси Югославии , которая продолжалась до конца войны. [ 127 ]

На Ближнем Востоке в мае силы Содружества отменили восстание в Ираке , которое было поддержано немецкими самолетами с баз в Сирии, контролируемой Виши . [ 128 ] В период с июня по июль, британские силы вторглись и заняли французские владения Сирии и Ливана , которым помогал свободный французский . [ 129 ]

Атака оси на Советский Союз (1941)

С ситуацией в Европе и Азии относительно стабильной, Германия, Япония и Советский Союз подготовились к войне. Поскольку Советы опасаются растущей напряженности с Германией, и японцы планируют воспользоваться европейской войной, захватывая богатые ресурсами европейские владения в Юго-Восточной Азии , две силы подписали соглашение о нейтралитете Советского Союза в апреле 1941 года. [ 130 ] Напротив, немцы постоянно готовились к нападению на Советский Союз, массирующие силы на советской границе. [ 131 ]

Гитлер полагал, что отказ Соединенного Королевства положить конец войне был основан на надежде, что Соединенные Штаты и Советский Союз рано или поздно войдут в войну против Германии. [ 132 ] 31 июля 1940 года Гитлер решил, что Советский Союз должен быть устранен и направлен на завоевание Украины , Балтийских государств и Биолоруссии . [ 133 ] Тем не менее, другие высокопоставленные немецкие чиновники, такие как Ribbentrop, увидели возможность создать евро-азиатский блок против Британской империи, пригласив Советский Союз в трехсторонний пакт. [ 134 ] В ноябре 1940 года состоялись переговоры , чтобы определить, присоединится ли Советский Союз в договор. Советы проявили некоторый интерес, но попросили уступить от Финляндии, Болгарии, Турции и Японии, которые Германия считала неприемлемой. 18 декабря 1940 года Гитлер выпустил директиву для подготовки к вторжению в Советский Союз. [ 135 ]

22 июня 1941 года, Германия, поддержала Италию и Румынию, вторгся в Советский Союз в операции «Барбаросса» , когда Германия обвинила Советы в заговоре против них ; Вскоре к ним присоединились Финляндия и Венгрия. [ 136 ] Основные цели этого неожиданного оскорбления [ 137 ] были Балтийскими регионами , Москвой и Украиной, с конечной целью прекращения кампании 1941 года возле линии Архангелска-Астрахан -от каспии до белых морей . Цели Гитлера состояли в том, чтобы устранить Советский Союз как военную власть, уничтожить коммунизм , генерировать Лебенсраум («Живое пространство») [ 138 ] лишая коренного населения , [ 139 ] и гарантировать доступ к стратегическим ресурсам, необходимым для победы над оставшимися конкурентами Германии. [ 140 ]

Хотя Красная Армия готовилась к стратегическим противоречиям перед войной, [ 141 ] Операция Barbarossa вынудила советскую высшую команду принять стратегическую защиту . В течение лета ось добилась значительных успехов в советской территории, нанеся огромные потери как персонала, так и у материального. Однако к середине августа Верховное командование немецкой армии решило приостановить наступление значительно истощенного армейского центра армии и отвлечь 2-ю танковую группу, чтобы укрепить войска, продвигающиеся к Центральной Украине и Ленинграду. [ 142 ] Наступление в Киеве было в подавляющем большинстве успешных, что привело к окружению и устранению четырех советских армий и сделало возможным дальнейший продвижение в Крыму и разработанную промышленность Восточную Украину ( Первая битва за Харков ). [ 143 ]

Отвращение трех четвертей войск оси и большинства их воздушных сил из Франции и центрального Средиземноморья на восточный фронт [ 144 ] побудил Великобритания пересмотреть свою грандиозную стратегию . [ 145 ] В июле Великобритания и Советский Союз сформировали военный альянс против Германии [ 146 ] А в августе Соединенное Королевство и Соединенные Штаты совместно выпустили Атлантическую хартию , в которой изложены британские и американские цели для послевоенного мира. [ 147 ] В конце августа англичане и Советы вторглись в нейтральный Иран, чтобы обеспечить персидский коридор Ирана , нефтяные месторождения и предотвратить любые достижения оси через Иран в направлении нефтяных месторождений Баку или Индии. [ 148 ]

К октябрю Axis Powers достиг оперативных целей в Украине и Балтийском регионе, только с осадками Ленинграда [ 149 ] и Севастополь продолжается. [ 150 ] Основное наступление на Москву было обновлено; После двух месяцев ожесточенных сражений в все более суровой погоде немецкая армия почти достигла внешних пригородов Москвы, где истощенные войска [ 151 ] были вынуждены приостановить наступление. [ 152 ] Большие территориальные выгоды были достигнуты силами оси, но их кампания не смогла достичь своих основных целей: в советских руках остались два ключевых города, советская способность сопротивляться не была сломана, а Советский Союз сохранил значительную часть своего военного потенциала. закончилась . Фаза войны Блицкрига в Европе [ 153 ]

К началу декабря свежие мобилизованные резервы [ 154 ] позволил Советам достичь численного паритета с войсками оси. [ 155 ] Это, а также данные разведки , которые установили, что минимальное количество советских войск на Востоке было бы достаточным, чтобы удержать любую атаку японской армии Квантунга , [ 156 ] позволил Советам начать массовое противодействие , которое началось 5 декабря по всему фронту и подтолкнуло немецкие войска 100–250 километров (62–155 миль) на запад. [ 157 ]

Война разрывается в Тихом океане (1941)

После японского ложного флага Мукдена в 1931 году японский обстрел американской канонечной лодки USS Panay в 1937 году и резня на Нанкине 1937–1938 гг ., Японские американские отношения ухудшились . В 1939 году Соединенные Штаты уведомили Японию о том, что они не будут расширять свой торговый договор, и американское общественное мнение, противостоящее японскому экспансионизму, привело к ряду экономических санкций - акты экспорта , которые запретили экспорт химических веществ, минералов и военных частей США в Японию, в которые запретили экспорт химических веществ, минералов и военных. и повышение экономического давления на японский режим. [ 114 ] [ 158 ] [ 159 ] В течение 1939 года Япония начала свою первую атаку на Чаншу , но к концу сентября была отталкивана. [ 160 ] Несмотря на несколько наступлений обеих сторон, к 1940 году война между Китаем и Японией была в тупике. Чтобы повысить давление на Китай, блокируя маршруты поставок и лучшую позицию японских сил в случае войны с западными державами, Япония вторглась и заняла северный Индокитай в сентябре 1940 года. [ 161 ]

Китайские националистические силы начали масштабное противодействие в начале 1940 года. В августе китайские коммунисты начали наступление в центральном Китае ; В ответ Япония внедрила жесткие меры в оккупированных районах, чтобы уменьшить человеческие и материальные ресурсы для коммунистов. [ 162 ] Продолжающаяся антипатия между китайскими коммунистическими и националистическими войсками завершилась вооруженными столкновениями в январе 1941 года , что эффективно положило конец их сотрудничеству. [ 163 ] В марте японская 11 -я армия напала на штаб -квартиру китайской 19 -й армии, но была отталкивана во время битвы при Шангао . [ 164 ] В сентябре Япония снова попыталась взять город Чанша и столкнуться с китайскими националистическими войсками. [ 165 ]

Немецкие успехи в Европе побудили Японию повысить давление на европейские правительства в Юго -Восточной Азии . Правительство Голландии согласилось предоставить Японии нефтяные принадлежности от Голландской Ост -Индии , но переговоры о дополнительном доступе к их ресурсам закончились неудачей в июне 1941 года. [ 166 ] В июле 1941 года Япония отправила войска в южный Индокитай, тем самым угрожая британским и голландским владениям на Дальнем Востоке. Соединенные Штаты, Великобритания и другие западные правительства отреагировали на этот шаг с замораживанием японских активов и полным нефтяным эмбарго. [ 167 ] [ 168 ] В то же время Япония планировала вторжение в Советский Дальний Восток , намереваясь воспользоваться вторжением Германии на Западе, но отказалась от операции после санкций. [ 169 ]

С начала 1941 года Соединенные Штаты и Япония участвовали в переговорах в попытке улучшить свои напряженные отношения и положить конец войне в Китае. В ходе этих переговоров Япония выдвинула ряд предложений, которые были отклонены американцами как неадекватные. [ 170 ] В то же время Соединенные Штаты, Соединенное Королевство и Нидерланды участвовали в тайных дискуссиях о совместной защите своих территорий, в случае нападения японцев на любого из них. [ 171 ] Рузвельт укрепил Филиппины (американский протекторат, запланированный на независимость в 1946 году) и предупредил Японию, что Соединенные Штаты отреагируют на нападения японцев на любые «соседние страны». [ 171 ]

Разочарованная из -за отсутствия прогресса и ощущения щепотки санкций американского и брюк -брус, Япония подготовилась к войне. Император Хирохито , после первоначального колебания о шансах Японии на победу, [ 172 ] начал отдавать предпочтение вступлению Японии в войну. [ 173 ] В результате премьер -министр Фумимаро Коноэ подал в отставку. [ 174 ] [ 175 ] Хирохито отказался от рекомендации назначить принца Нарухико Хигашикуни на его месте, выбрав военного министра Хидеки Тоджо . [ 176 ] 3 ноября Нагано подробно объяснил план нападения на Перл -Харбор Императору. [ 177 ] 5 ноября Хирохито одобрил на Имперской конференции План операций для войны. [ 178 ] 20 ноября новое правительство представило промежуточное предложение в качестве окончательного предложения. Он призвал к окончанию американской помощи в Китае и для поднятия эмбарго на поставку нефти и других ресурсов в Японию. В обмен, Япония пообещала не начинать атаки в Юго -Восточной Азии и отказаться от своих сил из южного Индокитая. [ 170 ] Американская контр-протомация от 26 ноября требовала, чтобы Япония эвакуировала весь Китай без условий и заключал дошкольные договорки со всеми тимическими державами. [ 179 ] Это означало, что Япония была по сути вынуждена выбирать между отказом от своих амбиций в Китае или изъятия природных ресурсов, которые им необходимы в голландской Ост -Индии силой; [ 180 ] [ 181 ] Японские военные не рассмотрели прежний вариант, и многие офицеры считали нефтяное эмбарго невысказанным декларацией войны. [ 182 ]

Япония планировала захватить европейские колонии в Азии для создания большого оборонительного периметра, простирающегося в центральную часть Тихого океана. Затем японцы могут свободно использовать ресурсы Юго-Восточной Азии, исчерпая чрезмерно растянутых союзников, сражаясь с защитной войной. [ 183 ] [ 184 ] Чтобы предотвратить американское вмешательство при обеспечении периметра, было дополнительно запланировано нейтрализовать тихоокеанский флот Соединенных Штатов и американское военное присутствие на Филиппинах с самого начала. [ 185 ] 7 декабря 1941 года (8 декабря в азиатских часовых поясах) Япония напала на британские и американские Холдингс с почти сильными наступлениями против Юго-Восточной Азии и центральной части Тихого океана . [ 186 ] Они включали нападение на американских флотов в Перл -Харборе и на Филиппинах , а также вторжения Гуама , острова Уэйк , Малайя , [ 186 ] Таиланд и Гонконг . [ 187 ]

Эти атаки возглавляли Соединенные Штаты , Великобритания , Китай, Австралия и несколько других штатов, официально объявили войну Японии, тогда как Советский Союз активно участвует в крупномасштабных военных действиях с европейскими странами оси, сохранил соглашение о нейтралитете с Японией. [ 188 ] Германия, за которыми следуют другие штаты Оси, объявила войну в Соединенные Штаты [ 189 ] В солидарности с Японией, ссылаясь на оправдание американские нападения на немецкие военные суда, которые были заказаны Рузвельтом. [ 136 ] [ 190 ]

Авансовые киоски оси (1942–1943)

1 января 1942 года, большая четверка союзников [ 191 ] - Советский Союз, Китай, Великобритания и Соединенные Штаты - и 22 небольших или изгнанных правительства выпустили Декларацию Организацией Объединенных Наций , что подтверждает Атлантическую хартию [ 192 ] и согласие не подписывать отдельный мир с полномочиями оси. [ 193 ]

В течение 1942 года союзные чиновники обсуждали соответствующую грандиозную стратегию для выполнения. Все согласились с тем, что побеждение Германии было основной целью. Американцы предпочитали прямое, крупномасштабное нападение на Германию через Францию. Советы потребовали второй фронт. Британцы утверждали, что военные операции должны быть нацелены на периферийные районы для изнашивания в немецкой силе, что приводит к увеличению деморализации, а также усиливает силы сопротивления; Сама Германия будет подвергаться тяжелой бомбардировке. Наступление на Германию будет запущено в основном в основном доспехами, не используя крупномасштабные армии. [ 194 ] В конце концов британцы убедили американцев, что посадка во Франции была невозможна в 1942 году, и вместо этого они должны сосредоточиться на выезде из оси из Северной Африки. [ 195 ]

На конференции Касабланки в начале 1943 года союзники подтвердили заявления, опубликованные в декларации 1942 года, и потребовали безусловную сдачу своих врагов. Британские и американцы согласились продолжать нажимать на инициативу в Средиземноморье, вторгся на Сицилию, чтобы полностью обеспечить середины маршрутов снабжения. [ 196 ] Хотя англичане выступали за дальнейшие операции на Балканах, чтобы ввести Турцию в войну, в мае 1943 года американцы достали британское обязательство ограничить операции союзников в Средиземноморье к вторжению в материковую часть Италии и вторгнуться в Францию в 1944 году. [ 197 ]

Pacific (1942–1943)

К концу апреля 1942 года Япония и ее союзник Таиланд почти завоевали Бирму , Малайю , Голландскую Ост -Индию , Сингапур и Рабаул , нанесли серьезные потери союзным войскам и приняли большое количество заключенных. [ 198 ] Несмотря на упорное сопротивление со стороны филиппинских и американских сил , Филиппинское Содружество было в конечном итоге захвачено в мае 1942 года, что заставило его правительство в изгнание. [ 199 ] 16 апреля в Бирме 7000 британских солдат были окружены японским дивизионом во время битвы при Йенангьянге и спасены китайской 38 -й дивизией. [ 200 ] Японские войска также достигли военно -морских побед в Южно -Китайском море , Джава -Море и Индийском океане , [ 201 ] и бомбил союзную военно -морскую базу в Дарвине , Австралия. В январе 1942 года единственным союзником успеха против Японии была китайская победа в Чанше . [ 202 ] Эти легкие победы над неподготовленными противниками США и европейски оставили Японию самоуверенными и чрезмерными. [ 203 ]

В начале мая 1942 года Япония инициировала операции, чтобы захватить порт Moresby путем амфибийного нападения и, следовательно, вырубленных линий связи и снабжения между Соединенными Штатами и Австралией. Запланированное вторжение было сорвано, когда целевая группа союзников, сосредоточенную на двух американских авианосцах флота, сражалась с японскими военно -морскими силами, чтобы ничья в битве при Коралловом море . [ 204 ] Следующий план Японии, мотивированный более ранним набегом Дулиттла , состоял в том, чтобы захватить атолл Мидуэй и привлечь американских перевозчиков в битву, чтобы быть ликвидированными; В качестве диверсии Япония также послала бы силы, чтобы занять алеутские острова на Аляске. [ 205 ] В середине мая Япония начала кампанию Чжэцзян-Цзингкси в Китае, с целью нанести возмездие китайца, которые помогли выжившим американским летчикам во время рейда Дулиттла путем уничтожения китайских воздушных баз и борьбы с китайскими 23-м и 32-й армии. [ 206 ] [ 207 ] В начале июня Япония вступила в действие, но американцы разбили японские военно -морские коды в конце мая и были полностью осведомлены о планах и порядок битвы и использовали эти знания для достижения решающей победы в середине Имперского Японского флота Полем [ 208 ]

В результате сражения с агрессивным действием в результате битвы на полпути Япония попыталась захватить Порт -Морсби из -за сухопутной кампании на территории Папуа . [ 209 ] Американцы планировали контратаку против японских позиций на южных Соломоновых островах , в первую очередь Гуадалканал , в качестве первого шага к захвату Рабаула , главной японской базы в Юго -Восточной Азии. [ 210 ]

Оба плана начались в июле, но к середине сентября битва за Гуадалканал уделял приоритет для японцев, а войска в Новой Гвинеи было приказано уйти из района Порт-Морсби в северную часть острова , где они столкнулись с австралийскими и объединенными Государства войск в битве при Буна -Гане . [ 211 ] Гуадалканал вскоре стал центром для обеих сторон с тяжелыми обязательствами войск и кораблей в битве за Гуадалканал. К началу 1943 года японцы потерпели поражение на острове и сняли свои войска . [ 212 ] В Бирме силы Содружества установили две операции. Первым было катастрофическое наступление в регионе Аракан в конце 1942 года, которое вынудило отступление в Индию к маю 1943 года. [ 213 ] Вторым была вставка нерегулярных сил, стоящих за японскими фронтами в феврале, которые к концу апреля достиг смешанных результатов. [ 214 ]

Восточный фронт (1942–1943)

Несмотря на значительные потери, в начале 1942 года Германия и ее союзники остановили крупное советское наступление в Центральной и Южной России , сохраняя большинство территориальных прибылей, которых они достигли в течение предыдущего года. [ 215 ] В мае немцы победили советские наступления на полуострове Керч и в Харкове , [ 216 ] А затем в июне 1942 года начало свое главное летнее наступление на южную Россию, чтобы захватить нефтяные месторождения Кавказа и занять Кубанское Степи , сохраняя при этом должности на северных и центральных районах фронта. Группа немцев разделила армейскую группу на юг на две группы: армейская группа А вышла до реки Нижней Дон и ударил на юго-восток до Кавказа, в то время как армейская группа В направилась к реке Волга . Советы решили встать на Сталинград на Волге. [217]

By mid-November, the Germans had nearly taken Stalingrad in bitter street fighting. The Soviets began their second winter counter-offensive, starting with an encirclement of German forces at Stalingrad,[218] and an assault on the Rzhev salient near Moscow, though the latter failed disastrously.[219] By early February 1943, the German Army had taken tremendous losses; German troops at Stalingrad had been defeated,[220] and the front-line had been pushed back beyond its position before the summer offensive. In mid-February, after the Soviet push had tapered off, the Germans launched another attack on Kharkov, creating a salient in their front line around the Soviet city of Kursk.[221]

Western Europe/Atlantic and Mediterranean (1942–1943)

Exploiting poor American naval command decisions, the German navy ravaged Allied shipping off the American Atlantic coast.[222] By November 1941, Commonwealth forces had launched a counter-offensive in North Africa, Operation Crusader, and reclaimed all the gains the Germans and Italians had made.[223] The Germans also launched a North African offensive in January, pushing the British back to positions at the Gazala line by early February,[224] followed by a temporary lull in combat which Germany used to prepare for their upcoming offensives.[225] Concerns that the Japanese might use bases in Vichy-held Madagascar caused the British to invade the island in early May 1942.[226] An Axis offensive in Libya forced an Allied retreat deep inside Egypt until Axis forces were stopped at El Alamein.[227] On the Continent, raids of Allied commandos on strategic targets, culminating in the failed Dieppe Raid,[228] demonstrated the Western Allies' inability to launch an invasion of continental Europe without much better preparation, equipment, and operational security.[229]

In August 1942, the Allies succeeded in repelling a second attack against El Alamein[230] and, at a high cost, managed to deliver desperately needed supplies to the besieged Malta.[231] A few months later, the Allies commenced an attack of their own in Egypt, dislodging the Axis forces and beginning a drive west across Libya.[232] This attack was followed up shortly after by Anglo-American landings in French North Africa, which resulted in the region joining the Allies.[233] Hitler responded to the French colony's defection by ordering the occupation of Vichy France;[233] although Vichy forces did not resist this violation of the armistice, they managed to scuttle their fleet to prevent its capture by German forces.[233][234] Axis forces in Africa withdrew into Tunisia, which was conquered by the Allies in May 1943.[233][235]

In June 1943, the British and Americans began a strategic bombing campaign against Germany with a goal to disrupt the war economy, reduce morale, and "de-house" the civilian population.[236] The firebombing of Hamburg was among the first attacks in this campaign, inflicting significant casualties and considerable losses on infrastructure of this important industrial centre.[237]

Allies gain momentum (1943–1944)

After the Guadalcanal campaign, the Allies initiated several operations against Japan in the Pacific. In May 1943, Canadian and U.S. forces were sent to eliminate Japanese forces from the Aleutians.[238] Soon after, the United States, with support from Australia, New Zealand and Pacific Islander forces, began major ground, sea and air operations to isolate Rabaul by capturing surrounding islands, and breach the Japanese Central Pacific perimeter at the Gilbert and Marshall Islands.[239] By the end of March 1944, the Allies had completed both of these objectives and had also neutralised the major Japanese base at Truk in the Caroline Islands. In April, the Allies launched an operation to retake Western New Guinea.[240]

In the Soviet Union, both the Germans and the Soviets spent the spring and early summer of 1943 preparing for large offensives in central Russia. On 5 July 1943, Germany attacked Soviet forces around the Kursk Bulge. Within a week, German forces had exhausted themselves against the Soviets' well-constructed defences,[241] and for the first time in the war, Hitler cancelled an operation before it had achieved tactical or operational success.[242] This decision was partially affected by the Western Allies' invasion of Sicily launched on 9 July, which, combined with previous Italian failures, resulted in the ousting and arrest of Mussolini later that month.[243]

On 12 July 1943, the Soviets launched their own counter-offensives, thereby dispelling any chance of German victory or even stalemate in the east. The Soviet victory at Kursk marked the end of German superiority,[244] giving the Soviet Union the initiative on the Eastern Front.[245][246] The Germans tried to stabilise their eastern front along the hastily fortified Panther–Wotan line, but the Soviets broke through it at Smolensk and the Lower Dnieper Offensive.[247]

On 3 September 1943, the Western Allies invaded the Italian mainland, following Italy's armistice with the Allies and the ensuing German occupation of Italy.[248] Germany, with the help of fascists, responded to the armistice by disarming Italian forces that were in many places without superior orders, seizing military control of Italian areas,[249] and creating a series of defensive lines.[250] German special forces then rescued Mussolini, who then soon established a new client state in German-occupied Italy named the Italian Social Republic,[251] causing an Italian civil war. The Western Allies fought through several lines until reaching the main German defensive line in mid-November.[252]

German operations in the Atlantic also suffered. By May 1943, as Allied counter-measures became increasingly effective, the resulting sizeable German submarine losses forced a temporary halt of the German Atlantic naval campaign.[253] In November 1943, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill met with Chiang Kai-shek in Cairo and then with Joseph Stalin in Tehran.[254] The former conference determined the post-war return of Japanese territory[255] and the military planning for the Burma campaign,[256] while the latter included agreement that the Western Allies would invade Europe in 1944 and that the Soviet Union would declare war on Japan within three months of Germany's defeat.[257]

From November 1943, during the seven-week Battle of Changde, the Chinese awaited allied relief as they forced Japan to fight a costly war of attrition.[258][259][260] In January 1944, the Allies launched a series of attacks in Italy against the line at Monte Cassino and tried to outflank it with landings at Anzio.[261]

On 27 January 1944, Soviet troops launched a major offensive that expelled German forces from the Leningrad region, thereby ending the most lethal siege in history.[262] The following Soviet offensive was halted on the pre-war Estonian border by the German Army Group North aided by Estonians hoping to re-establish national independence. This delay slowed subsequent Soviet operations in the Baltic Sea region.[263] By late May 1944, the Soviets had liberated Crimea, largely expelled Axis forces from Ukraine, and made incursions into Romania, which were repulsed by the Axis troops.[264] The Allied offensives in Italy had succeeded and, at the expense of allowing several German divisions to retreat, Rome was captured on 4 June.[265]

The Allies had mixed success in mainland Asia. In March 1944, the Japanese launched the first of two invasions, an operation against Allied positions in Assam, India,[266] and soon besieged Commonwealth positions at Imphal and Kohima.[267] In May 1944, British and Indian forces mounted a counter-offensive that drove Japanese troops back to Burma by July,[267] and Chinese forces that had invaded northern Burma in late 1943 besieged Japanese troops in Myitkyina.[268] The second Japanese invasion of China aimed to destroy China's main fighting forces, secure railways between Japanese-held territory and capture Allied airfields.[269] By June, the Japanese had conquered the province of Henan and begun a new attack on Changsha.[270]

Allies close in (1944)

On 6 June 1944 (commonly known as D-Day), after three years of Soviet pressure,[271] the Western Allies invaded northern France. After reassigning several Allied divisions from Italy, they also attacked southern France.[272] These landings were successful and led to the defeat of the German Army units in France. Paris was liberated on 25 August by the local resistance assisted by the Free French Forces, both led by General Charles de Gaulle,[273] and the Western Allies continued to push back German forces in western Europe during the latter part of the year. An attempt to advance into northern Germany spearheaded by a major airborne operation in the Netherlands failed.[274] After that, the Western Allies slowly pushed into Germany, but failed to cross the Rur river. In Italy, the Allied advance slowed due to the last major German defensive line.[275]

On 22 June, the Soviets launched a strategic offensive in Belarus ("Operation Bagration") that nearly destroyed the German Army Group Centre.[276] Soon after that, another Soviet strategic offensive forced German troops from Western Ukraine and Eastern Poland. The Soviets formed the Polish Committee of National Liberation to control territory in Poland and combat the Polish Armia Krajowa; the Soviet Red Army remained in the Praga district on the other side of the Vistula and watched passively as the Germans quelled the Warsaw Uprising initiated by the Armia Krajowa.[277] The national uprising in Slovakia was also quelled by the Germans.[278] The Soviet Red Army's strategic offensive in eastern Romania cut off and destroyed the considerable German troops there and triggered a successful coup d'état in Romania and in Bulgaria, followed by those countries' shift to the Allied side.[279]

In September 1944, Soviet troops advanced into Yugoslavia and forced the rapid withdrawal of German Army Groups E and F in Greece, Albania and Yugoslavia to rescue them from being cut off.[280] By this point, the communist-led Partisans under Marshal Josip Broz Tito, who had led an increasingly successful guerrilla campaign against the occupation since 1941, controlled much of the territory of Yugoslavia and engaged in delaying efforts against German forces further south. In northern Serbia, the Soviet Red Army, with limited support from Bulgarian forces, assisted the Partisans in a joint liberation of the capital city of Belgrade on 20 October. A few days later, the Soviets launched a massive assault against German-occupied Hungary that lasted until the fall of Budapest in February 1945.[281] Unlike impressive Soviet victories in the Balkans, bitter Finnish resistance to the Soviet offensive in the Karelian Isthmus denied the Soviets occupation of Finland and led to a Soviet-Finnish armistice on relatively mild conditions,[282] although Finland was forced to fight their former German allies.[283]

By the start of July 1944, Commonwealth forces in Southeast Asia had repelled the Japanese sieges in Assam, pushing the Japanese back to the Chindwin River[284] while the Chinese captured Myitkyina. In September 1944, Chinese forces captured Mount Song and reopened the Burma Road.[285] In China, the Japanese had more successes, having finally captured Changsha in mid-June and the city of Hengyang by early August.[286] Soon after, they invaded the province of Guangxi, winning major engagements against Chinese forces at Guilin and Liuzhou by the end of November[287] and successfully linking up their forces in China and Indochina by mid-December.[288]

In the Pacific, U.S. forces continued to push back the Japanese perimeter. In mid-June 1944, they began their offensive against the Mariana and Palau islands and decisively defeated Japanese forces in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. These defeats led to the resignation of the Japanese Prime Minister, Hideki Tojo, and provided the United States with air bases to launch intensive heavy bomber attacks on the Japanese home islands. In late October, American forces invaded the Filipino island of Leyte; soon after, Allied naval forces scored another large victory in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, one of the largest naval battles in history.[289]

Axis collapse and Allied victory (1944–1945)

On 16 December 1944, Germany made a last attempt to split the Allies on the Western Front by using most of its remaining reserves to launch a massive counter-offensive in the Ardennes and along the French-German border, hoping to encircle large portions of Western Allied troops and prompt a political settlement after capturing their primary supply port at Antwerp. By 16 January 1945, this offensive had been repulsed with no strategic objectives fulfilled.[290] In Italy, the Western Allies remained stalemated at the German defensive line. In mid-January 1945, the Red Army attacked in Poland, pushing from the Vistula to the Oder river in Germany, and overran East Prussia.[291] On 4 February Soviet, British, and U.S. leaders met for the Yalta Conference. They agreed on the occupation of post-war Germany, and on when the Soviet Union would join the war against Japan.[292]

In February, the Soviets entered Silesia and Pomerania, while the Western Allies entered western Germany and closed to the Rhine river. By March, the Western Allies crossed the Rhine north and south of the Ruhr, encircling the German Army Group B.[293] In early March, in an attempt to protect its last oil reserves in Hungary and retake Budapest, Germany launched its last major offensive against Soviet troops near Lake Balaton. Within two weeks, the offensive had been repulsed, the Soviets advanced to Vienna, and captured the city. In early April, Soviet troops captured Königsberg, while the Western Allies finally pushed forward in Italy and swept across western Germany capturing Hamburg and Nuremberg. American and Soviet forces met at the Elbe river on 25 April, leaving unoccupied pockets in southern Germany and around Berlin.

Soviet troops stormed and captured Berlin in late April.[294] In Italy, German forces surrendered on 29 April, while the Italian Social Republic capitulated two days later. On 30 April, the Reichstag was captured, signalling the military defeat of Nazi Germany.[295]

Major changes in leadership occurred on both sides during this period. On 12 April, President Roosevelt died and was succeeded by his vice president, Harry S. Truman. Benito Mussolini was killed by Italian partisans on 28 April.[296] On 30 April, Hitler committed suicide in his headquarters, and was succeeded by Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz (as President of the Reich) and Joseph Goebbels (as Chancellor of the Reich); Goebbels also committed suicide on the following day and was replaced by Lutz Graf Schwerin von Krosigk, in what would later be known as the Flensburg Government. Total and unconditional surrender in Europe was signed on 7 and 8 May, to be effective by the end of 8 May.[297] German Army Group Centre resisted in Prague until 11 May.[298] On 23 May all remaining members of the German government were arrested by the Allied Forces in Flensburg, while on 5 June all German political and military institutions were transferred under the control of the Allies through the Berlin Declaration.[299]

In the Pacific theatre, American forces accompanied by the forces of the Philippine Commonwealth advanced in the Philippines, clearing Leyte by the end of April 1945. They landed on Luzon in January 1945 and recaptured Manila in March. Fighting continued on Luzon, Mindanao, and other islands of the Philippines until the end of the war.[300] Meanwhile, the United States Army Air Forces launched a massive firebombing campaign of strategic cities in Japan in an effort to destroy Japanese war industry and civilian morale. A devastating bombing raid on Tokyo of 9–10 March was the deadliest conventional bombing raid in history.[301]

In May 1945, Australian troops landed in Borneo, overrunning the oilfields there. British, American, and Chinese forces defeated the Japanese in northern Burma in March, and the British pushed on to reach Rangoon by 3 May.[302] Chinese forces started a counterattack in the Battle of West Hunan that occurred between 6 April and 7 June 1945. American naval and amphibious forces also moved towards Japan, taking Iwo Jima by March, and Okinawa by the end of June.[303] At the same time, a naval blockade by submarines was strangling Japan's economy and drastically reducing its ability to supply overseas forces.[304][305]

On 11 July, Allied leaders met in Potsdam, Germany. They confirmed earlier agreements about Germany,[306] and the American, British and Chinese governments reiterated the demand for unconditional surrender of Japan, specifically stating that "the alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction".[307] During this conference, the United Kingdom held its general election, and Clement Attlee replaced Churchill as Prime Minister.[308]

The call for unconditional surrender was rejected by the Japanese government, which believed it would be capable of negotiating for more favourable surrender terms.[309] In early August, the United States dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Between the two bombings, the Soviets, pursuant to the Yalta agreement, declared war on Japan, invaded Japanese-held Manchuria and quickly defeated the Kwantung Army, which was the largest Japanese fighting force.[310] These two events persuaded previously adamant Imperial Army leaders to accept surrender terms.[311] The Red Army also captured the southern part of Sakhalin Island and the Kuril Islands. On the night of 9–10 August 1945, Emperor Hirohito announced his decision to accept the terms demanded by the Allies in the Potsdam Declaration.[312] On 15 August, the Emperor communicated this decision to the Japanese people through a speech broadcast on the radio (Gyokuon-hōsō, literally "broadcast in the Emperor's voice").[313] On 15 August 1945, Japan surrendered, with the surrender documents finally signed at Tokyo Bay on the deck of the American battleship USS Missouri on 2 September 1945, ending the war.[314]

Aftermath

The Allies established occupation administrations in Austria and Germany, both initially divided between western and eastern occupation zones controlled by the Western Allies and the Soviet Union, respectively. However, their paths soon diverged. In Germany, the western and eastern occupation zones controlled by the Western Allies and the Soviet Union officially ended in 1949, with the respective zones becoming separate countries, West Germany and East Germany.[315] In Austria, however, occupation continued until 1955, when a joint settlement between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union permitted the reunification of Austria as a democratic state officially non-aligned with any political bloc (although in practice having better relations with the Western Allies). A denazification program in Germany led to the prosecution of Nazi war criminals in the Nuremberg trials and the removal of ex-Nazis from power, although this policy moved towards amnesty and re-integration of ex-Nazis into West German society.[316]

Germany lost a quarter of its pre-war (1937) territory. Among the eastern territories, Silesia, Neumark and most of Pomerania were taken over by Poland,[317] and East Prussia was divided between Poland and the Soviet Union, followed by the expulsion to Germany of the nine million Germans from these provinces,[318][319] as well as three million Germans from the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia. By the 1950s, one-fifth of West Germans were refugees from the east. The Soviet Union also took over the Polish provinces east of the Curzon Line,[320] from which 2 million Poles were expelled;[319][321] north-east Romania,[322][323] parts of eastern Finland,[324] and the Baltic states were annexed into the Soviet Union.[325][326] Italy lost its monarchy, colonial empire and some European territories.[327]

In an effort to maintain world peace,[328] the Allies formed the United Nations,[329] which officially came into existence on 24 October 1945,[330] and adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 as a common standard for all member nations.[331] The great powers that were the victors of the war—France, China, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and the United States—became the permanent members of the UN's Security Council.[332] The five permanent members remain so to the present, although there have been two seat changes, between the Republic of China and the People's Republic of China in 1971, and between the Soviet Union and its successor state, the Russian Federation, following the dissolution of the USSR in 1991. The alliance between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union had begun to deteriorate even before the war was over.[333]

Besides Germany, the rest of Europe was also divided into Western and Soviet spheres of influence.[334] Most eastern and central European countries fell into the Soviet sphere, which led to establishment of Communist-led regimes, with full or partial support of the Soviet occupation authorities. As a result, East Germany,[335] Poland, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, and Albania[336] became Soviet satellite states. Communist Yugoslavia conducted a fully independent policy, causing tension with the Soviet Union.[337] A Communist uprising in Greece was put down with Anglo-American support and the country remained aligned with the West.[338]

Post-war division of the world was formalised by two international military alliances, the United States-led NATO and the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact.[339] The long period of political tensions and military competition between them—the Cold War—would be accompanied by an unprecedented arms race and number of proxy wars throughout the world.[340]

In Asia, the United States led the occupation of Japan and administered Japan's former islands in the Western Pacific, while the Soviets annexed South Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands.[341] Korea, formerly under Japanese colonial rule, was divided and occupied by the Soviet Union in the North and the United States in the South between 1945 and 1948. Separate republics emerged on both sides of the 38th parallel in 1948, each claiming to be the legitimate government for all of Korea, which led ultimately to the Korean War.[342]

In China, nationalist and communist forces resumed the civil war in June 1946. Communist forces were victorious and established the People's Republic of China on the mainland, while nationalist forces retreated to Taiwan in 1949.[343] In the Middle East, the Arab rejection of the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine and the creation of Israel marked the escalation of the Arab–Israeli conflict. While European powers attempted to retain some or all of their colonial empires, their losses of prestige and resources during the war rendered this unsuccessful, leading to decolonisation.[344][345]

The global economy suffered heavily from the war, although participating nations were affected differently. The United States emerged much richer than any other nation, leading to a baby boom, and by 1950 its gross domestic product per person was much higher than that of any of the other powers, and it dominated the world economy.[346] The Allied occupational authorities pursued a policy of industrial disarmament in Western Germany from 1945 to 1948.[347] Due to international trade interdependencies, this policy led to an economic stagnation in Europe and delayed European recovery from the war for several years.[348][349]

At the Bretton Woods Conference in July 1944, the Allied nations drew up an economic framework for the post-war world. The agreement created the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which later became part of the World Bank Group. The Bretton Woods system lasted until 1973.[350] Recovery began with the mid-1948 currency reform in Western Germany, and was sped up by the liberalisation of European economic policy that the U.S. Marshall Plan economic aid (1948–1951) both directly and indirectly caused.[351][352] The post-1948 West German recovery has been called the German economic miracle.[353] Italy also experienced an economic boom[354] and the French economy rebounded.[355] By contrast, the United Kingdom was in a state of economic ruin,[356] and although receiving a quarter of the total Marshall Plan assistance, more than any other European country,[357] it continued in relative economic decline for decades.[358] The Soviet Union, despite enormous human and material losses, also experienced rapid increase in production in the immediate post-war era,[359] having seized and transferred most of Germany's industrial plants and exacted war reparations from its satellite states.[c][360] Japan recovered much later.[361] China returned to its pre-war industrial production by 1952.[362]

Impact

Casualties and war crimes

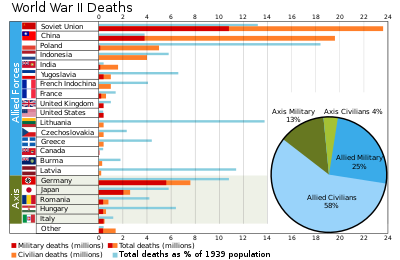

Estimates for the total number of casualties in the war vary, because many deaths went unrecorded.[363] Most suggest that some 60 million people died in the war, including about 20 million military personnel and 40 million civilians.[364][365][366]

The Soviet Union alone lost around 27 million people during the war,[367] including 8.7 million military and 19 million civilian deaths.[368] A quarter of the total people in the Soviet Union were wounded or killed.[369] Germany sustained 5.3 million military losses, mostly on the Eastern Front and during the final battles in Germany.[370]

An estimated 11[371] to 17 million[372] civilians died as a direct or as an indirect result of Hitler's racist policies, including mass killing of around 6 million Jews, along with Roma, homosexuals, at least 1.9 million ethnic Poles[373][374] and millions of other Slavs (including Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians), and other ethnic and minority groups.[375][372] Between 1941 and 1945, more than 200,000 ethnic Serbs, along with Roma and Jews, were persecuted and murdered by the Axis-aligned Croatian Ustaše in Yugoslavia.[376] Concurrently, Muslims and Croats were persecuted and killed by Serb nationalist Chetniks,[377] with an estimated 50,000–68,000 victims (of which 41,000 were civilians).[378] Also, more than 100,000 Poles were massacred by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army in the Volhynia massacres, between 1943 and 1945.[379] At the same time, about 10,000–15,000 Ukrainians were killed by the Polish Home Army and other Polish units, in reprisal attacks.[380]

In Asia and the Pacific, the number of people killed by Japanese troops remains contested. According to R.J. Rummel, the Japanese killed between 3 million and more than 10 million people, with the most probable case of almost 6,000,000 people.[381] According to the British historian M. R. D. Foot, civilian deaths are between 10 million and 20 million, whereas Chinese military casualties (killed and wounded) are estimated to be over five million.[382] Other estimates say that up to 30 million people, most of them civilians, were killed.[383][384] The most infamous Japanese atrocity was the Nanjing Massacre, in which fifty to three hundred thousand Chinese civilians were raped and murdered.[385] Mitsuyoshi Himeta reported that 2.7 million casualties occurred during the Three Alls policy. General Yasuji Okamura implemented the policy in Hebei and Shandong.[386]

Axis forces employed biological and chemical weapons. The Imperial Japanese Army used a variety of such weapons during its invasion and occupation of China (see Unit 731)[387][388] and in early conflicts against the Soviets.[389] Both the Germans and the Japanese tested such weapons against civilians,[390] and sometimes on prisoners of war.[391]

The Soviet Union was responsible for the Katyn massacre of 22,000 Polish officers,[392] and the imprisonment or execution of hundreds of thousands of political prisoners by the NKVD secret police, along with mass civilian deportations to Siberia, in the Baltic states and eastern Poland annexed by the Red Army.[393] Soviet soldiers committed mass rapes in occupied territories, especially in Germany.[394][395] The exact number of German women and girls raped by Soviet troops during the war and occupation is uncertain, but historians estimate their numbers are likely in the hundreds of thousands, and possibly as many as two million,[396] while figures for women raped by German soldiers in the Soviet Union go as far as ten million.[397][398]

The mass bombing of cities in Europe and Asia has often been called a war crime, although no positive or specific customary international humanitarian law with respect to aerial warfare existed before or during World War II.[399] The USAAF bombed a total of 67 Japanese cities, killing 393,000 civilians, including the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and destroying 65% of built-up areas.[400]

Genocide, concentration camps, and slave labour