Финансовый кризис 2007–2008 гг.

| Часть серии о |

| Великая рецессия |

|---|

| Хронология |

, Финансовый кризис 2007–2008 годов или глобальный финансовый кризис ( GFC ), был самым тяжелым мировым экономическим кризисом со времен Великой депрессии . Хищническое кредитование в форме субстандартных ипотечных кредитов, нацеленное на покупателей жилья с низкими доходами. [1] чрезмерный риск со стороны глобальных финансовых институтов , [2] Постоянное наращивание токсичных активов в банках и лопнувший пузырь на рынке жилья в Соединенных Штатах привели к « идеальному шторму », который привел к Великой рецессии .

Ценные бумаги, обеспеченные ипотекой (MBS), привязанные к американской недвижимости , а также обширная сеть деривативов , связанных с этими MBS, упали в цене . Финансовые учреждения во всем мире понесли серьезный ущерб, [3] достигнув кульминации с банкротством Lehman Brothers 15 сентября 2008 года и последующим международным банковским кризисом . [4]

Предпосылки финансового кризиса были сложными и имели множество причин. [5] [6] [7] Почти два десятилетия назад Конгресс США принял закон, поощряющий финансирование доступного жилья. [8] Однако в 1999 году некоторые части закона Гласса-Стигола , принятого в 1933 году, были отменены , что позволило финансовым учреждениям объединять свои коммерческие (избегающие риска) и собственные торговые (принимающие риск) операции. [9] Вероятно, самым большим фактором, способствующим созданию условий, необходимых для финансового краха, стало быстрое развитие хищнических финансовых продуктов, нацеленных на покупателей жилья с низкими доходами и малой информацией, которые в основном принадлежали к расовым меньшинствам . [10] Такое развитие рынка осталось без внимания регулирующих органов и, таким образом, застало правительство США врасплох. [11]

После начала кризиса правительства развернули масштабную помощь финансовым институтам и другие паллиативные денежно-кредитные и фискальные меры, чтобы предотвратить крах глобальной финансовой системы . [12] В США принятый 3 октября Закон о чрезвычайной экономической стабилизации на сумму 800 миллиардов долларов США 2008 года не смог замедлить свободное падение экономики, но аналогичный по масштабам американский Закон о восстановлении и реинвестировании 2009 года , который включал существенную налоговую льготу по заработной плате, привел к развороту экономических показателей. и стабилизируется менее чем через месяц после его вступления в силу 17 февраля. [13] Кризис спровоцировал Великую рецессию , которая привела к росту безработицы. [14] и самоубийство, [15] и снижение институционального доверия [16] и плодородие, [17] среди других показателей. Рецессия стала важной предпосылкой европейского долгового кризиса .

В 2010 году в США был принят Закон Додда-Фрэнка о реформе Уолл-стрит и защите потребителей как ответ на кризис, направленный на «содействие финансовой стабильности Соединенных Штатов». [18] Стандарты капитала и ликвидности Базель III также были приняты странами по всему миру. [19] [20]

Фон

[ редактировать ]

Кризис спровоцировал Великую рецессию , которая на тот момент была самой серьезной глобальной рецессией со времен Великой депрессии. [22] [23] [24] [25] [26] За ним также последовал европейский долговой кризис, который начался с дефицита в Греции в конце 2009 года, и исландский финансовый кризис 2008–2011 годов , который повлек за собой банкротство всех трех крупнейших банков Исландии и, по сравнению с размером ее экономики, стал крупнейшим экономическим коллапсом, который пережила любая страна в истории. [27] Это был один из пяти худших финансовых кризисов, которые когда-либо переживал мир, и он привел к потерям более 2 триллионов долларов мировой экономики. [28] [29] Задолженность по ипотечным кредитам в США по отношению к ВВП увеличилась в среднем с 46% в 1990-е годы до 73% в 2008 году, достигнув 10,5 триллионов долларов (~ 14,6 триллионов долларов в 2023 году). [30] Увеличение объемов рефинансирования наличными по мере роста стоимости домов способствовало увеличению потребления, которое больше не могло поддерживаться, когда цены на жилье падали. [31] [32] [33] Многие финансовые учреждения владели инвестициями, стоимость которых основывалась на ипотечных кредитах, таких как ценные бумаги с ипотечным покрытием или кредитные деривативы, используемые для страхования их от банкротства, стоимость которых значительно снизилась. [34] [35] [36] По оценкам Международного валютного фонда , с января 2007 года по сентябрь 2009 года крупные банки США и Европы потеряли более 1 триллиона долларов на токсичных активах и безнадежных кредитах. [37]

Отсутствие уверенности инвесторов в платежеспособности банков и снижение доступности кредитов привели к резкому падению цен на акции и сырьевые товары в конце 2008 года и начале 2009 года. [38] Кризис быстро перерос в глобальный экономический шок, приведший к банкротству нескольких банков . [39] В этот период темпы роста экономики во всем мире замедлились, поскольку ужесточение кредитной политики и сокращение международной торговли привели к замедлению темпов роста экономики во всем мире. [40] Рынки жилья пострадали, а безработица резко возросла, что привело к выселениям и лишению права выкупа заложенного имущества . Несколько предприятий потерпели крах. [41] [42] С пика во втором квартале 2007 года, составлявшего $61,4 трлн, благосостояние домохозяйств в США упало на $11 трлн до $50,4 трлн к концу первого квартала 2009 года, что привело к снижению потребления, а затем к снижению инвестиций в бизнес. [43] [44] В четвертом квартале 2008 года квартальное снижение реального ВВП в США составило 8,4%. [45] Уровень безработицы в США достиг пика в 11,0% в октябре 2009 года, что стало самым высоким показателем с 1983 года и примерно вдвое превысило докризисный уровень. Среднее количество часов в неделю снизилось до 33, самого низкого уровня с тех пор, как правительство начало собирать данные в 1964 году. [46] [47]

Экономический кризис начался в США, но распространился на остальной мир. [41] Потребление в США составляло более трети роста мирового потребления в период с 2000 по 2007 год, а остальной мир зависел от американского потребителя как источника спроса. [ нужна ссылка ] [48] [49] Токсичные ценные бумаги принадлежали корпоративным и институциональным инвесторам по всему миру. Производные финансовые инструменты, такие как кредитно-дефолтные свопы, также усилили связи между крупными финансовыми учреждениями. Сокращение заемных средств финансовых учреждений, поскольку активы продавались для погашения обязательств, которые не могли быть рефинансированы на замороженных кредитных рынках, еще больше ускорило кризис платежеспособности и вызвало сокращение международной торговли. Снижение темпов роста развивающихся стран было вызвано падением торговли, цен на сырьевые товары, инвестиций и денежных переводов, отправляемых трудящимися-мигрантами (пример: Армения [50] ). Государства с хрупкими политическими системами опасались, что инвесторы из западных стран заберут свои деньги из-за кризиса. [51]

В рамках национальной налогово-бюджетной политики в ответ на Великую рецессию правительства и центральные банки, включая Федеральную резервную систему , Европейский центральный банк и Банк Англии , предоставили беспрецедентные на тот момент триллионы долларов в виде финансовой помощи и стимулирования , включая экспансивную фискальную политику и денежно- кредитную политику. политика, призванная компенсировать снижение потребления и кредитного потенциала, избежать дальнейшего краха, стимулировать кредитование, восстановить веру в целостные рынки коммерческих бумаг , избежать риска дефляционной спирали и предоставить банкам достаточно средств, чтобы клиенты могли снимать средства. [52] По сути, центральные банки превратились из « кредитора последней инстанции » в «кредитора единственной инстанции» для значительной части экономики. В некоторых случаях ФРС считалась «покупателем последней инстанции». [53] [54] [55] [56] [57] В четвертом квартале 2008 года эти центральные банки выкупили у банков государственный долг и проблемные частные активы на сумму 2,5 триллиона долларов США (~ 3,47 триллиона долларов США в 2023 году). Это было крупнейшее вливание ликвидности на кредитный рынок и крупнейшая мера денежно-кредитной политики в мировой истории. Следуя модели, инициированной пакетом мер по спасению банков Соединенного Королевства в 2008 году , [58] [59] Правительства европейских стран и США гарантировали долги, выпущенные их банками, и привлекли капитал своих национальных банковских систем, в конечном итоге купив недавно выпущенные привилегированные акции крупных банков на сумму 1,5 триллиона долларов. [44] Федеральная резервная система создала значительные на тот момент объемы новой валюты в качестве метода борьбы с ловушкой ликвидности . [60]

Помощь пришла в форме триллионов долларов кредитов, покупки активов, гарантий и прямых расходов. [61] Помощь сопровождалась серьезными разногласиями, например, в случае разногласий по поводу бонусных выплат AIG , что привело к разработке различных «систем принятия решений», чтобы помочь сбалансировать конкурирующие политические интересы во время финансового кризиса. [62] Алистер Дарлинг Великобритании , министр финансов во время кризиса, заявил в 2018 году, что Британия пережила считанные часы после «нарушения закона и порядка» в тот день, когда Королевский банк Шотландии получил помощь. [63] Вместо финансирования большего количества внутренних кредитов некоторые банки вместо этого потратили часть стимулирующих денег в более прибыльные области, такие как инвестиции в развивающиеся рынки и иностранную валюту. [64]

В июле 2010 года в Соединенных Штатах был принят Закон Додда-Фрэнка о реформе Уолл-стрит и защите потребителей, призванный «содействовать финансовой стабильности Соединенных Штатов». [65] Стандарты капитала и ликвидности Базель III были приняты во всем мире. [66] После финансового кризиса 2008 года регуляторы прав потребителей в Америке стали более внимательно контролировать продавцов кредитных карт и ипотечных кредитов, чтобы сдержать антиконкурентную практику, которая привела к кризису. [67]

По крайней мере, два основных доклада о причинах кризиса были подготовлены Конгрессом США: доклад Комиссии по расследованию финансового кризиса , опубликованный в январе 2011 года, и доклад Постоянного подкомитета внутренней безопасности Сената США по расследованиям под названием «Уолл-стрит и финансовый кризис». : Анатомия финансового краха , выпущено в апреле 2011 года.

Всего в результате кризиса в тюрьме оказались 47 банкиров, более половины из которых были выходцами из Исландии , где кризис был самым тяжелым и привел к краху всех трех крупнейших исландских банков. [68] В апреле 2012 года Гейр Хаарде из Исландии стал единственным политиком, осужденным в результате кризиса. [69] [70] Только один банкир в США отбыл тюремное заключение в результате кризиса, Карим Серагельдин , банкир Credit Suisse, который был приговорен к 30 месяцам тюремного заключения и вернул 24,6 миллиона долларов в качестве компенсации за манипулирование ценами на облигации с целью сокрытия убытков в 1 миллиард долларов. [71] [68] Ни один человек в Соединенном Королевстве не был осужден в результате кризиса. [72] [73] Goldman Sachs заплатил 550 миллионов долларов для урегулирования обвинений в мошенничестве после того, как якобы предвидел кризис и продал своим клиентам токсичные инвестиции. [74]

Из-за меньшего количества ресурсов, которым можно было бы рисковать в результате творческого разрушения, количество патентных заявок осталось неизменным по сравнению с экспоненциальным ростом числа патентных заявок в предыдущие годы. [75]

Типичные американские семьи жили не очень хорошо, как и семьи «богатых, но не самых богатых», находящихся прямо под вершиной пирамиды. [76] [77] [78] Однако половина беднейших семей в Соединенных Штатах вообще не испытала снижения благосостояния во время кризиса, поскольку они, как правило, не владели финансовыми инвестициями, стоимость которых может колебаться. Федеральная резервная система обследовала 4000 домохозяйств в период с 2007 по 2009 год и обнаружила, что общее благосостояние 63% всех американцев снизилось за этот период, а у 77% самых богатых семей наблюдалось снижение общего благосостояния, в то время как только у 50% тех, кто находится на дне пирамида претерпела снижение. [79] [80] [81]

Хронология

[ редактировать ]The following is a timeline of the major events of the financial crisis, including government responses, and the subsequent economic recovery.[82][83][84][85]

Pre-2007

[edit]

- May 19, 2005: Fund manager Michael Burry closed a credit default swap against subprime mortgage bonds with Deutsche Bank valued at $60 million – the first such CDS. He projected they would become volatile within two years of the low "teaser rate" of the mortgages expiring.[86][87]

- 2006: After years of above-average price increases, housing prices peaked and mortgage loan delinquency rose, leading to the United States housing bubble.[88][89] Due to increasingly lax underwriting standards, one-third of all mortgages in 2006 were subprime or no-documentation loans,[90] which comprised 17 percent of home purchases that year.[91]

- May 2006: JPMorgan warns clients of housing downturn, especially sub-prime.[92]

- August 2006: The yield curve inverted, signaling a recession was likely within a year or two.[93]

- November 2006: UBS sounded "the alarm about an impending crisis in the U.S. housing market" [92]

2007 (January – August)

[edit]- February 27, 2007: Stock prices in China and the U.S. fell by the most since 2003 as reports of a decline in home prices and durable goods orders stoked growth fears, with Alan Greenspan predicting a recession.[94] Due to increased delinquency rates in subprime lending, Freddie Mac said that it would stop investing in certain subprime loans.[95]

- April 2, 2007: New Century, an American real estate investment trust specializing in subprime lending and securitization, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. This propagated the subprime mortgage crisis.[96][97][91][98][99]

- June 20, 2007: After receiving margin calls, Bear Stearns bailed out two of its hedge funds with $20 billion of exposure to collateralized debt obligations including subprime mortgages.[100]

- July 19, 2007: The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) closed above 14,000 for the first time at 14,000.41.[101]

- July 30, 2007: IKB Deutsche Industriebank, the first banking casualty of the crisis, announces its bailout by German public financial institution KfW.[102]

- July 31, 2007: Bear Stearns liquidated the two hedge funds.[98]

- August 6, 2007: American Home Mortgage filed bankruptcy.[98]

- August 9, 2007: BNP Paribas blocked withdrawals from three of its hedge funds with a total of $2.2 billion in assets under management, due to "a complete evaporation of liquidity", making valuation of the funds impossible – a clear sign that banks were refusing to do business with each other.[99][103][104]

- August 16, 2007: The DJIA closes at 12,945.78 after falling 12 out of the previous 20 trading days following its peak. It had fallen 1,164.63 or 8.3%.[101]

2007 (September – December)

[edit]

- September 14, 2007: Northern Rock, a medium-sized and highly leveraged British bank, received support from the Bank of England.[105] This led to investor panic and a bank run.[106]

- September 18, 2007: The Federal Open Market Committee began reducing the federal funds rate from its peak of 5.25% in response to worries about liquidity and confidence.[107][108]

- September 28, 2007: NetBank suffered from bank failure and filed bankruptcy due to exposure to home loans.[109]

- October 9, 2007: The DJIA hit its peak closing price of 14,164.53.[110]

- October 15, 2007: Citigroup, Bank of America, and JPMorgan Chase announced plans for the $80 billion Master Liquidity Enhancement Conduit to provide liquidity to structured investment vehicles. The plan was abandoned in December.[111]

- December 2007: Unemployment in the US hit 5%.[112][not specific enough to verify]

- December 12, 2007: The Federal Reserve instituted the Term auction facility to supply short-term credit to banks with sub-prime mortgages.[113]

- December 17, 2007: Delta Financial Corporation filed bankruptcy after failing to securitize subprime loans.[114]

- December 19, 2007: the Standard and Poor's rating agency downgrades the ratings of many monoline insurers which pay out bonds that fail.[citation needed]

2008 (January – August)

[edit]- January 11, 2008: Bank of America agreed to buy Countrywide Financial for $4 billion in stock.[115]

- January 18, 2008: Stock markets fell to a yearly low as the credit rating of Ambac, a bond insurance company, was downgraded. Meanwhile, an increase in the amount of withdrawals causes Scottish Equitable to implement up to 12 month delays on people wanting to withdraw money.[116]

- January 21, 2008: As US markets were closed for Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the FTSE 100 Index in the United Kingdom tumbled 323.5 points or 5.5% in its largest crash since the September 11 attacks.[117]

- January 22, 2008: The US Federal Reserve cut interest rates by 0.75% to stimulate the economy, the largest drop in 25 years and the first emergency cut since 2001.[117]

- January 2008: U.S. stocks had the worst January since 2000 over concerns about the exposure of companies that issue bond insurance.[118]

- February 13, 2008: The Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 was enacted, which included a tax rebate.[119][120]

- February 22, 2008: The nationalisation of Northern Rock was completed.[106]

- March 5, 2008: The Carlyle Group received margin calls on its mortgage bond fund.[121]

- March 17, 2008: Bear Stearns, with $46 billion of mortgage assets that had not been written down and $10 trillion in total assets, faced bankruptcy; instead, in its first emergency meeting in 30 years, the Federal Reserve agreed to guarantee its bad loans to facilitate its acquisition by JPMorgan Chase for $2/share. A week earlier, the stock was trading at $60/share and a year earlier it traded for $178/share. The buyout price was increased to $10/share the following week.[122][123][124]

- March 18, 2008: In a contentious meeting, the Federal Reserve cut the federal funds rate by 75 basis points, its 6th cut in 6 months.[125] It also allowed Fannie Mae & Freddie Mac to buy $200 billion in subprime mortgages from banks. Officials thought this would contain the possible crisis. The U.S. dollar weakened and commodity prices soared.[data missing][126][127][128]

- Late June 2008: Despite the U.S. stock market falling to a 20% drop off its highs, commodity-related stocks soared as oil traded above $140/barrel for the first time and steel prices rose above $1,000 per ton. Worries about inflation combined with strong demand from China encouraged people to invest in commodities during the 2000s commodities boom.[129][130]

- July 11, 2008: IndyMac failed. Oil prices peaked at $147.50[131][117]

- July 30, 2008: The Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 was enacted.[132]

- August 2008: Unemployment hit 6% in the US.[112]

2008 (September)

[edit]- September 7, 2008: The Federal takeover of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac was implemented.[133]

- September 15, 2008: After the Federal Reserve declined to guarantee its loans as it did for Bear Stearns, the Bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers led to a 504.48-point (4.42%) drop in the DJIA, its worst decline in seven years. To avoid bankruptcy, Merrill Lynch was acquired by Bank of America for $50 billion in a transaction facilitated by the government.[134] Lehman had been in talks to be sold to either Bank of America or Barclays but neither bank wanted to acquire the entire company.[135]

- September 16, 2008: The Federal Reserve took over American International Group with $85 billion in debt and equity funding. The Reserve Primary Fund "broke the buck" as a result of its exposure to Lehman Brothers securities.[136]

- September 17, 2008: Investors withdrew $144 billion from U.S. money market funds, the equivalent of a bank run on money market funds, which frequently invest in commercial paper issued by corporations to fund their operations and payrolls, causing the short-term lending market to freeze. The withdrawal compared to $7.1 billion in withdrawals the week prior. This interrupted the ability of corporations to rollover their short-term debt. The U.S. government extended insurance for money market accounts analogous to bank deposit insurance via a temporary guarantee[137] and with Federal Reserve programs to purchase commercial paper.

- September 18, 2008: In a dramatic meeting, United States Secretary of the Treasury Henry Paulson and Chair of the Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke met with Speaker of the United States House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi and warned that the credit markets were close to a complete meltdown. Bernanke requested a $700 billion fund to acquire toxic mortgages and reportedly told them: "If we don't do this, we may not have an economy on Monday".[138]

- September 19, 2008: The Federal Reserve created the Asset Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility to temporarily insure money market funds and allow the credit markets to continue operating.[citation needed]

- September 20, 2008: Paulson requested the U.S. Congress authorize a $700 billion fund to acquire toxic mortgages, telling Congress "If it doesn't pass, then heaven help us all".[139]

- September 21, 2008: Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley converted from investment banks to bank holding companies to increase their protection by the Federal Reserve.[140][141][142][143]

- September 22, 2008: MUFG Bank acquired 20% of Morgan Stanley.[144]

- September 23, 2008: Berkshire Hathaway made a $5 billion investment in Goldman Sachs.[145]

- September 26, 2008: Washington Mutual went bankrupt and was seized by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation after a bank run in which panicked depositors withdrew $16.7 billion in 10 days.[146]

- September 29, 2008: By a vote of 225–208, with most Democrats in support and Republicans against, the House of Representatives rejected the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, which included the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program. In response, the DJIA dropped 777.68 points, or 6.98%, then the largest point drop in history. The S&P 500 Index fell 8.8% and the Nasdaq Composite fell 9.1%.[147] Several stock market indices worldwide fell 10%. Gold prices soared to $900/ounce. The Federal Reserve doubled its credit swaps with foreign central banks as they all needed to provide liquidity. Wachovia reached a deal to sell itself to Citigroup; however, the deal would have made shares worthless and required government funding.[148]

- September 30, 2008: President George W. Bush addressed the country, saying "Congress must act. ... Our economy is depending on decisive action from the government. The sooner we address the problem, the sooner we can get back on the path of growth and job creation". The DJIA rebounded 4.7%.[149]

2008 (October)

[edit]- October 1, 2008: The U.S. Senate passed the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008.[150]

- October 2, 2008: Stock market indices fell 4% as investors were nervous ahead of a vote in the U.S. House of Representatives on the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008.[151]

- October 3, 2008: The House of Representatives passed the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 and the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program.[152] Bush signed the legislation that same day.[153] Wachovia reached a deal to be acquired by Wells Fargo in a deal that did not require government funding.[154]

- October 6–10, 2008: From October 6–10, 2008, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) closed lower in all five sessions. Volume levels were record-breaking. The DJIA fell 1,874.19 points, or 18.2%, in its worst weekly decline ever on both a points and percentage basis. The S&P 500 fell more than 20%.[155]

- October 7, 2008: In the U.S., per the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation increased deposit insurance coverage to $250,000 per depositor.[156]

- October 8, 2008: The Indonesian stock market halted trading after a 10% drop in one day.[158] Global central banks held emergency meetings and coordinated interest rate cuts before the US stock markets opened.[159]

- October 11, 2008: The head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) warned that the world financial system was teetering on the "brink of systemic meltdown".[160]

- October 14, 2008: Having been suspended for three successive trading days (October 9, 10 and 13), the Icelandic stock market reopened on October 14, with the main index, the OMX Iceland 15, closing at 678.4, which was about 77% lower than the 3,004.6 at the close on October 8, after the value of the three big banks, which had formed 73.2% of the value of the OMX Iceland 15, had been set to zero, leading to the 2008–2011 Icelandic financial crisis.[161] The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation created the Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program to guarantee the senior debt of all FDIC-insured institutions through June 30, 2009.[162]

- October 16, 2008: A rescue plan was unveiled for Swiss banks UBS AG and Credit Suisse.[163]

- October 24, 2008: Many of the world's stock exchanges experienced the worst declines in their history, with drops of around 10% in most indices.[164] In the U.S., the DJIA fell 3.6%, although not as much as other markets.[165] The United States dollar and Japanese yen and the Swiss franc soared against other major currencies, particularly the British pound and Canadian dollar, as world investors sought safe havens. A currency crisis developed, with investors transferring vast capital resources into stronger currencies, leading many governments of emerging economies to seek aid from the International Monetary Fund.[166][167] Later that day, the deputy governor of the Bank of England, Charlie Bean, suggested that "This is a once in a lifetime crisis, and possibly the largest financial crisis of its kind in human history".[168] In a transaction pushed by regulators, PNC Financial Services agreed to acquire National City Corp.[169]

2008 (November – December)

[edit]

- November 6, 2008: The IMF predicted a worldwide recession of −0.3% for 2009. On the same day, the Bank of England and the European Central Bank, respectively, reduced their interest rates from 4.5% to 3%, and from 3.75% to 3.25%.[170]

- November 10, 2008: American Express converted to a bank holding company.[171]

- November 20, 2008: Iceland obtained an emergency loan from the International Monetary Fund after the failure of banks in Iceland resulted in a devaluation of the Icelandic króna and threatened the government with bankruptcy.[172]

- November 25, 2008: The Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility was announced.[173]

- November 29, 2008: Economist Dean Baker observed:

There is a really good reason for tighter credit. Tens of millions of homeowners who had substantial equity in their homes two years ago have little or nothing today. Businesses are facing the worst downturn since the Great Depression. This matters for credit decisions. A homeowner with equity in her home is very unlikely to default on a car loan or credit card debt. They will draw on this equity rather than lose their car and/or have a default placed on their credit record. On the other hand, a homeowner who has no equity is a serious default risk. In the case of businesses, their creditworthiness depends on their future profits. Profit prospects look much worse in November 2008 than they did in November 2007 ... While many banks are obviously at the brink, consumers and businesses would be facing a much harder time getting credit right now even if the financial system were rock solid. The problem with the economy is the loss of close to $6 trillion in housing wealth and an even larger amount of stock wealth.[174]

- December 1, 2008: The NBER announced the US was in a recession and had been since December 2007. The Dow tumbled 679.95 points or 7.8% on the news.[175][101]

- December 6, 2008: The 2008 Greek riots began, sparked in part by economic conditions in the country.[citation needed]

- December 16, 2008: The federal funds rate was lowered to zero percent.[176]

- December 20, 2008: Financing under the Troubled Asset Relief Program was made available to General Motors and Chrysler.[177]

2009

[edit]

- January 6, 2009: Citi claimed that Singapore would experience "the most severe recession in Singapore's history" in 2009. In the end the economy grew in 2009 by 0.1% and in 2010 by 14.5%.[178][179][180]

- January 20–26, 2009: The 2009 Icelandic financial crisis protests intensified and the Icelandic government collapsed.[181]

- February 13, 2009: Congress approved the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, a $787 billion economic stimulus package. President Barack Obama signed it February 17.[182][13][183][184]

- February 20, 2009: The DJIA closed at a 6-year low amidst worries that the largest banks in the United States would have to be nationalized.[185]

- February 27, 2009: The DJIA closed its lowest value since 1997 as the U.S. government increased its stake in Citigroup to 36%, raising further fears of nationalization and a report showed that GDP shrank at the sharpest pace in 26 years.[186]

- Early March 2009: The drop in stock prices was compared to that of the Great Depression.[187][188]

- March 3, 2009: President Obama stated that "Buying stocks is a potentially good deal if you've got a long-term perspective on it".[189]

- March 6, 2009: The Dow Jones hit its lowest level of 6,469.95, a drop of 54% from its peak of 14,164 on October 9, 2007, over a span of 17 months, before beginning to recover.[190]

- March 10, 2009: Shares of Citigroup rose 38% after the CEO said that the company was profitable in the first two months of the year and expressed optimism about its capital position going forward. Major stock market indices rose 5–7%, marking the bottom of the stock market decline.[191]

- March 12, 2009: Stock market indices in the U.S. rose another 4% after Bank of America said it was profitable in January and February and would likely not need more government funding. Bernie Madoff was convicted.[192]

- First quarter of 2009: For the first quarter of 2009, the annualized rate of decline in GDP was 14.4% in Germany, 15.2% in Japan, 7.4% in the UK, 18% in Latvia,[193] 9.8% in the Euro area and 21.5% for Mexico.[41]

- April 2, 2009: Unrest over economic policy and bonuses paid to bankers resulted in the 2009 G20 London summit protests.

- April 10, 2009: Time magazine declared "More Quickly Than It Began, The Banking Crisis Is Over".[194]

- April 29, 2009: The Federal Reserve projected GDP growth of 2.5–3% in 2010; an unemployment plateau in 2009 and 2010 around 10% with moderation in 2011; and inflation rates around 1–2%.[195]

- May 1, 2009: People protested economic conditions globally during the 2009 May Day protests.

- May 20, 2009: President Obama signed the Fraud Enforcement and Recovery Act of 2009.

- June 2009: The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) declared June 2009 as the end date of the U.S. recession.[196] The Federal Open Market Committee release in June 2009 stated:

... the pace of economic contraction is slowing. Conditions in financial markets have generally improved in recent months. Household spending has shown further signs of stabilizing but remains constrained by ongoing job losses, lower housing wealth, and tight credit. Businesses are cutting back on fixed investment and staffing but appear to be making progress in bringing inventory stocks into better alignment with sales. Although economic activity is likely to remain weak for a time, the Committee continues to anticipate that policy actions to stabilize financial markets and institutions, fiscal and monetary stimulus, and market forces will contribute to a gradual resumption of sustainable economic growth in a context of price stability.[197]

- June 17, 2009: Barack Obama and key advisers introduced a series of regulatory proposals that addressed consumer protection, executive pay, bank capital requirements, expanded regulation of the shadow banking system and derivatives, and enhanced authority for the Federal Reserve to safely wind down systemically important institutions.[198][199][200]

- December 11, 2009: United States House of Representatives passed bill H.R. 4173, a precursor to what became the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act.[201]

2010

[edit]- January 22, 2010: President Obama introduced "The Volcker Rule" limiting the ability of banks to engage in proprietary trading, named after Paul Volcker, who publicly argued for the proposed changes.[202][203] Obama also proposed a Financial Crisis Responsibility Fee on large banks.

- January 27, 2010: President Obama declared on "the markets are now stabilized, and we've recovered most of the money we spent on the banks".[204]

- First quarter 2010: Delinquency rates in the United States peaked at 11.54%.[205]

- April 15, 2010: U.S. Senate introduced bill S.3217, Restoring American Financial Stability Act of 2010.[206]

- May 2010: The U.S. Senate passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. The Volcker Rule against proprietary trading was not part of the legislation.[207]

- July 21, 2010: Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act enacted.[208][209]

- September 12, 2010: European regulators introduced Basel III regulations for banks, which increased capital ratios, limits on leverage, narrowed the definition of capital to exclude subordinated debt, limited counter-party risk, and added liquidity requirements.[210][211] Critics argued that Basel III didn't address the problem of faulty risk-weightings. Major banks suffered losses from AAA-rated created by financial engineering (which creates apparently risk-free assets out of high risk collateral) that required less capital according to Basel II. Lending to AA-rated sovereigns has a risk-weight of zero, thus increasing lending to governments and leading to the next crisis.[212] Johan Norberg argued that regulations (Basel III among others) have indeed led to excessive lending to risky governments (see European sovereign-debt crisis) and the European Central Bank pursues even more lending as the solution.[213]

- November 3, 2010: To improve economic growth, the Federal Reserve announced another round of quantitative easing, dubbed QE2, which included the purchase of $600 billion in long-term Treasuries over the following eight months.[214]

Post-2010

[edit]- March 2011: Two years after the nadir of the crisis, many stock market indices were 75% above their lows set in March 2009. Nevertheless, the lack of fundamental changes in banking and financial markets worried many market participants, including the International Monetary Fund.[215]

- 2011: Median household wealth fell 35% in the U.S., from $106,591 to $68,839 between 2005 and 2011.[216]

- May 2012: The Manhattan District Attorney indicted Abacus Federal Savings Bank and 19 employees for selling fraudulent mortgages to Fannie Mae. The bank was acquitted in 2015. Abacus was the only bank prosecuted for misbehavior that precipitated the crisis.

- July 26, 2012: During the European debt crisis, President of the European Central Bank Mario Draghi announced that "The ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro".[217]

- August 2012: In the United States, many homeowners still faced foreclosure and could not refinance or modify their mortgages. Foreclosure rates remained high.[218]

- September 13, 2012: To improve lower interest rates, support mortgage markets, and make financial conditions more accommodative, the Federal Reserve announced another round of quantitative easing, dubbed QE3, which included the purchase of $40 billion in long-term Treasuries each month.[219]

- 2014: A report showed that the distribution of household incomes in the United States became more unequal during the post-2008 economic recovery, a first for the United States but in line with the trend over the last ten economic recoveries since 1949.[220][221] Income inequality in the United States grew from 2005 to 2012 in more than 2 out of 3 metropolitan areas.[222]

- June 2015: A study commissioned by the ACLU found that white home-owning households recovered from the financial crisis faster than black home-owning households, widening the racial wealth gap in the U.S.[223]

- 2017: Per the International Monetary Fund, from 2007 to 2017, "advanced" economies accounted for only 26.5% of global GDP (PPP) growth while emerging and developing economies accounted for 73.5% of global GDP (PPP) growth.[224]

- August 2023: UBS reaches an agreement with the United States Department of Justice to pay a combined $1.435 billion in civil penalties to settle a legacy matter from 2006–2007 related to the issuance, underwriting and sale of residential mortgage-backed securities.[225]

In the table, the names of emerging and developing economies are shown in boldface type, while the names of developed economies are in Roman (regular) type.

| Economy | Incremental GDP (billions in USD) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (01) | |||||||||

| (02) | |||||||||

| (03) | |||||||||

| (—) | |||||||||

| (04) | |||||||||

| (05) | |||||||||

| (06) | |||||||||

| (07) | |||||||||

| (08) | |||||||||

| (09) | |||||||||

| (10) | |||||||||

| (11) | |||||||||

| (12) | |||||||||

| (13) | |||||||||

| (14) | |||||||||

| (15) | |||||||||

| (16) | |||||||||

| (17) | |||||||||

| (18) | |||||||||

| (19) | |||||||||

| (20) | |||||||||

The twenty largest economies contributing to global GDP (PPP) growth (2007–2017)[226] | |||||||||

Fed's action towards crisis

[edit]

The expansion of central bank lending in response to the crisis was not only confined to the Federal Reserve's provision of aid to individual financial institutions. The Federal Reserve has also conducted a number of innovative lending programs with the goal of improving liquidity and strengthening different financial institutions and markets, such as Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae. In this case, the major problem among the market is the lack of free cash reserves and flows to secure the loans. The Federal Reserve took a number of steps to deal with worries about liquidity in the financial markets. One of these steps was a credit line for major traders, who act as the Fed's partners in open market activities.[227] Also, loan programs were set up to make the money market mutual funds and commercial paper market more flexible. Also, the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) was put in place thanks to a joint effort with the US Department of the Treasury. This plan was meant to make it easier for consumers and businesses to get credit by giving Americans who owned high-quality asset-backed securities more credit.

Before the crisis, the Federal Reserve's stocks of Treasury securities were sold to pay for the increase in credit. This method was meant to keep banks from trying to give out their extra savings, which could cause the federal funds rate to drop below where it was supposed to be.[228] However, in October 2008, the Federal Reserve was granted the power to provide banks with interest payments on their surplus reserves. This created a motivation for banks to retain their reserves instead of disbursing them, so reducing the need for the Federal Reserve to hedge its increased lending by decreases in alternative assets.[229]

Money market funds also went through runs when people lost faith in the market. To keep it from getting worse, the Fed said it would give money to mutual fund companies. Also, Department of Treasury said that it would briefly cover the assets of the fund. Both of these things helped get the fund market back to normal, which helped the commercial paper market, which most businesses use to run. The FDIC also did a number of things, like raise the insurance cap from $100,000 to $250,000, to boost customer trust.

They engaged in Quantitative Easing, which added more than $4 trillion to the financial system and got banks to start lending again, both to each other and to people. Many homeowners who were trying to keep their homes from going into default got housing credits. A package of policies was passed that let borrowers refinance their loans even though the value of their homes was less than what they still owed on their mortgages.[230]

Causes

[edit]

While the causes of the bubble and subsequent crash are disputed, the precipitating factor for the Financial Crisis of 2007–2008 was the bursting of the United States housing bubble and the subsequent subprime mortgage crisis, which occurred due to a high default rate and resulting foreclosures of mortgage loans, particularly adjustable-rate mortgages. Some or all of the following factors contributed to the crisis:[231][88][89]

- In its January 2011 report, the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC, a committee of U.S. congressmen) concluded that the financial crisis was avoidable and was caused by:[232][233][234][235][236]

- "widespread failures in financial regulation and supervision", including the Federal Reserve's failure to stem the tide of toxic assets.

- "dramatic failures of corporate governance and risk management at many systemically important financial institutions" including too many financial firms acting recklessly and taking on too much risk.

- "a combination of excessive borrowing, risky investments, and lack of transparency" by financial institutions and by households that put the financial system on a collision course with crisis.

- ill preparation and inconsistent action by government and key policy makers lacking a full understanding of the financial system they oversaw that "added to the uncertainty and panic".

- a "systemic breakdown in accountability and ethics" at all levels.

- "collapsing mortgage-lending standards and the mortgage securitization pipeline".

- deregulation of 'over-the-counter' derivatives, especially credit default swaps.

- "the failures of credit rating agencies" to correctly price risk.

- "Wall Street and the Financial Crisis: Anatomy of a Financial Collapse" (known as the Levin–Coburn Report) by the United States Senate concluded that the crisis was the result of "high risk, complex financial products; undisclosed conflicts of interest; the failure of regulators, the credit rating agencies, and the market itself to rein in the excesses of Wall Street".[237]

- The high delinquency and default rates by homeowners, particularly those with subprime credit, led to a rapid devaluation of mortgage-backed securities including bundled loan portfolios, derivatives and credit default swaps. As the value of these assets plummeted, buyers for these securities evaporated and banks who were heavily invested in these assets began to experience a liquidity crisis.

- Securitization, a process in which many mortgages were bundled together and formed into new financial instruments called mortgage-backed securities, allowed for shifting of risk and lax underwriting standards. These bundles could be sold as (ostensibly) low-risk securities partly because they were often backed by credit default swap insurance.[238] Because mortgage lenders could pass these mortgages (and the associated risks) on in this way, they could and did adopt loose underwriting criteria.

- Lax regulation allowed predatory lending in the private sector,[239][240] especially after the federal government overrode anti-predatory state laws in 2004.[241]

- The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA),[242] a 1977 U.S. federal law designed to help low- and moderate-income Americans get mortgage loans required banks to grant mortgages to higher risk families.[243][244][245][246] Granted, in 2009, Federal Reserve economists found that, "only a small portion of subprime mortgage originations [related] to the CRA", and that "CRA-related loans appear[ed] to perform comparably to other types of subprime loans". These findings "run counter to the contention that the CRA contributed in any substantive way to the [mortgage crisis]."[247]

- Reckless lending by lenders such as Bank of America's Countrywide Financial unit was increasingly incentivized and even mandated by government regulation.[248][249][250] This may have caused Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to lose market share and to respond by lowering their own standards.[251]

- Mortgage guarantees by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, quasi-government agencies, which purchased many subprime loan securitizations.[252] The implicit guarantee by the U.S. federal government created a moral hazard and contributed to a glut of risky lending.

- Government policies that encouraged home ownership, providing easier access to loans for subprime borrowers; overvaluation of bundled subprime mortgages based on the theory that housing prices would continue to escalate; questionable trading practices on behalf of both buyers and sellers; compensation structures by banks and mortgage originators that prioritize short-term deal flow over long-term value creation; and a lack of adequate capital holdings from banks and insurance companies to back the financial commitments they were making.[253][254]

- The 1999 Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, which partially repealed the Glass-Steagall Act, effectively removed the separation between investment banks and depository banks in the United States and increased speculation on the part of depository banks.[255]

- Credit rating agencies and investors failed to accurately price the financial risk involved with mortgage loan-related financial products, and governments did not adjust their regulatory practices to address changes in financial markets.[256][257][258]

- Variations in the cost of borrowing.[259]

- Fair value accounting was issued as U.S. accounting standard SFAS 157 in 2006 by the privately run Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB)—delegated by the SEC with the task of establishing financial reporting standards.[260] This required that tradable assets such as mortgage securities be valued according to their current market value rather than their historic cost or some future expected value. When the market for such securities became volatile and collapsed, the resulting loss of value had a major financial effect upon the institutions holding them even if they had no immediate plans to sell them.[261]

- Easy availability of credit in the US, fueled by large inflows of foreign funds after the 1998 Russian financial crisis and 1997 Asian financial crisis of the 1997–1998 period, led to a housing construction boom and facilitated debt-financed consumer spending. As banks began to give out more loans to potential home owners, housing prices began to rise. Lax lending standards and rising real estate prices also contributed to the real estate bubble. Loans of various types (e.g., mortgage, credit card, and auto) were easy to obtain and consumers assumed an unprecedented debt load.[262][231][263]

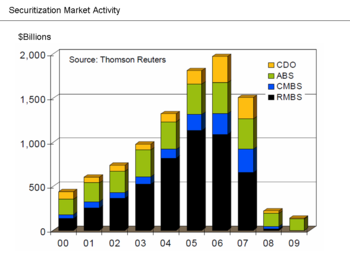

- As part of the housing and credit booms, the number of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDO), which derived their value from mortgage payments and housing prices, greatly increased. Such financial innovation enabled institutions and investors to invest in the U.S. housing market. As housing prices declined, these investors reported significant losses.[264]

- Falling prices also resulted in homes worth less than the mortgage loans, providing borrowers with a financial incentive to enter foreclosure. Foreclosure levels were elevated until early 2014.[265] drained significant wealth from consumers, losing up to $4.2 trillion[266] Defaults and losses on other loan types also increased significantly as the crisis expanded from the housing market to other parts of the economy. Total losses were estimated in the trillions of U.S. dollars globally.[264]

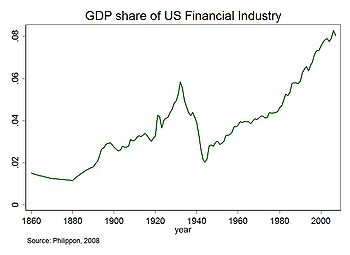

- Financialization – the increased use of leverage in the financial system.

- Financial institutions such as investment banks and hedge funds, as well as certain, differently regulated banks, assumed significant debt burdens while providing the loans described above and did not have a financial cushion sufficient to absorb large loan defaults or losses.[267] These losses affected the ability of financial institutions to lend, slowing economic activity.

- Some critics contend that government mandates forced banks to extend loans to borrowers previously considered uncreditworthy, leading to increasingly lax underwriting standards and high mortgage approval rates.[268][248][269][249] These, in turn, led to an increase in the number of homebuyers, which drove up housing prices. This appreciation in value led many homeowners to borrow against the equity in their homes as an apparent windfall, leading to over-leveraging.

Subprime lending

[edit]

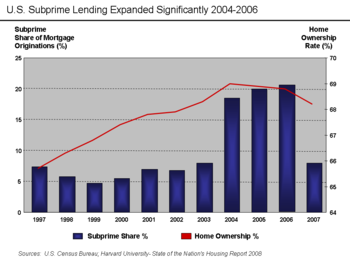

The relaxing of credit lending standards by investment banks and commercial banks allowed for a significant increase in subprime lending. Subprime had not become less risky; Wall Street just accepted this higher risk.[270]

Due to competition between mortgage lenders for revenue and market share, and when the supply of creditworthy borrowers was limited, mortgage lenders relaxed underwriting standards and originated riskier mortgages to less creditworthy borrowers. In the view of some analysts, the relatively conservative government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) policed mortgage originators and maintained relatively high underwriting standards prior to 2003. However, as market power shifted from securitizers to originators, and as intense competition from private securitizers undermined GSE power, mortgage standards declined and risky loans proliferated. The riskiest loans were originated in 2004–2007, the years of the most intense competition between securitizers and the lowest market share for the GSEs. The GSEs eventually relaxed their standards to try to catch up with the private banks.[271][272]

A contrarian view is that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac led the way to relaxed underwriting standards, starting in 1995, by advocating the use of easy-to-qualify automated underwriting and appraisal systems, by designing no-down-payment products issued by lenders, by the promotion of thousands of small mortgage brokers, and by their close relationship to subprime loan aggregators such as Countrywide.[273][274]

Depending on how "subprime" mortgages are defined, they remained below 10% of all mortgage originations until 2004, when they rose to nearly 20% and remained there through the 2005–2006 peak of the United States housing bubble.[275]

Role of affordable housing programs

[edit]The majority report of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, written by the six Democratic appointees, the minority report, written by three of the four Republican appointees, studies by Federal Reserve economists, and the work of several independent scholars generally contend that government affordable housing policy was not the primary cause of the financial crisis. Although they concede that governmental policies had some role in causing the crisis, they contend that GSE loans performed better than loans securitized by private investment banks, and performed better than some loans originated by institutions that held loans in their own portfolios.

In his dissent to the majority report of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, conservative American Enterprise Institute fellow Peter J. Wallison[276] stated his belief that the roots of the financial crisis can be traced directly and primarily to affordable housing policies initiated by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in the 1990s and to massive risky loan purchases by government-sponsored entities Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Based upon information in the SEC's December 2011 securities fraud case against six former executives of Fannie and Freddie, Peter Wallison and Edward Pinto estimated that, in 2008, Fannie and Freddie held 13 million substandard loans totaling over $2 trillion.[277]

In the early and mid-2000s, the Bush administration called numerous times for investigations into the safety and soundness of the GSEs and their swelling portfolio of subprime mortgages. On September 10, 2003, the United States House Committee on Financial Services held a hearing, at the urging of the administration, to assess safety and soundness issues and to review a recent report by the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight (OFHEO) that had uncovered accounting discrepancies within the two entities.[278][279] The hearings never resulted in new legislation or formal investigation of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, as many of the committee members refused to accept the report and instead rebuked OFHEO for their attempt at regulation.[280] Some, such as Wallison, believe this was an early warning to the systemic risk that the growing market in subprime mortgages posed to the U.S. financial system that went unheeded.[281]

A 2000 United States Department of the Treasury study of lending trends for 305 cities from 1993 to 1998 showed that $467 billion of mortgage lending was made by Community Reinvestment Act (CRA)-covered lenders into low and mid-level income (LMI) borrowers and neighborhoods, representing 10% of all U.S. mortgage lending during the period. The majority of these were prime loans. Sub-prime loans made by CRA-covered institutions constituted a 3% market share of LMI loans in 1998,[282] but in the run-up to the crisis, fully 25% of all subprime lending occurred at CRA-covered institutions and another 25% of subprime loans had some connection with CRA.[283] However, most sub-prime loans were not made to the LMI borrowers targeted by the CRA,[citation needed][284][285] especially in the years 2005–2006 leading up to the crisis,[citation needed][286][285][287] nor did it find any evidence that lending under the CRA rules increased delinquency rates or that the CRA indirectly influenced independent mortgage lenders to ramp up sub-prime lending.[288][verification needed]

To other analysts the delay between CRA rule changes in 1995 and the explosion of subprime lending is not surprising, and does not exonerate the CRA. They contend that there were two, connected causes to the crisis: the relaxation of underwriting standards in 1995 and the ultra-low interest rates initiated by the Federal Reserve after the terrorist attack on September 11, 2001. Both causes had to be in place before the crisis could take place.[289] Critics also point out that publicly announced CRA loan commitments were massive, totaling $4.5 trillion in the years between 1994 and 2007.[290] They also argue that the Federal Reserve's classification of CRA loans as "prime" is based on the faulty and self-serving assumption that high-interest-rate loans (3 percentage points over average) equal "subprime" loans.[291]

Others have pointed out that there were not enough of these loans made to cause a crisis of this magnitude. In an article in Portfolio magazine, Michael Lewis spoke with one trader who noted that "There weren't enough Americans with [bad] credit taking out [bad loans] to satisfy investors' appetite for the end product." Essentially, investment banks and hedge funds used financial innovation to enable large wagers to be made, far beyond the actual value of the underlying mortgage loans, using derivatives called credit default swaps, collateralized debt obligations and synthetic CDOs.

By March 2011, the FDIC had paid out $9 billion (c. $12 billion in 2023[292]) to cover losses on bad loans at 165 failed financial institutions.[293][294] The Congressional Budget Office estimated, in June 2011, that the bailout to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac exceeds $300 billion (c. $401 billion in 2023[292]) (calculated by adding the fair value deficits of the entities to the direct bailout funds at the time).[295]

Economist Paul Krugman argued in January 2010 that the simultaneous growth of the residential and commercial real estate pricing bubbles and the global nature of the crisis undermines the case made by those who argue that Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, CRA, or predatory lending were primary causes of the crisis. In other words, bubbles in both markets developed even though only the residential market was affected by these potential causes.[296]

Countering Krugman, Wallison wrote: "It is not true that every bubble—even a large bubble—has the potential to cause a financial crisis when it deflates." Wallison notes that other developed countries had "large bubbles during the 1997–2007 period" but "the losses associated with mortgage delinquencies and defaults when these bubbles deflated were far lower than the losses suffered in the United States when the 1997–2007 [bubble] deflated." According to Wallison, the reason the U.S. residential housing bubble (as opposed to other types of bubbles) led to financial crisis was that it was supported by a huge number of substandard loans—generally with low or no downpayments.[297]

Krugman's contention (that the growth of a commercial real estate bubble indicates that U.S. housing policy was not the cause of the crisis) is challenged by additional analysis. After researching the default of commercial loans during the financial crisis, Xudong An and Anthony B. Sanders reported (in December 2010): "We find limited evidence that substantial deterioration in CMBS [commercial mortgage-backed securities] loan underwriting occurred prior to the crisis."[298] Other analysts support the contention that the crisis in commercial real estate and related lending took place after the crisis in residential real estate. Business journalist Kimberly Amadeo reported: "The first signs of decline in residential real estate occurred in 2006. Three years later, commercial real estate started feeling the effects."[verification needed][299] Denice A. Gierach, a real estate attorney and CPA, wrote:

... most of the commercial real estate loans were good loans destroyed by a really bad economy. In other words, the borrowers did not cause the loans to go bad-it was the economy.[300]

Growth of the housing bubble

[edit]

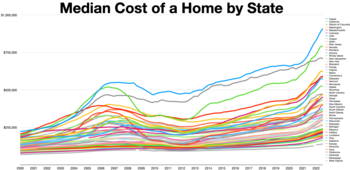

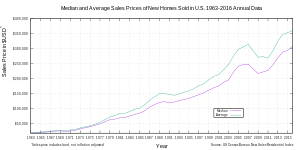

Between 1998 and 2006, the price of the typical American house increased by 124%.[301] During the 1980s and 1990s, the national median home price ranged from 2.9 to 3.1 times median household income. By contrast, this ratio increased to 4.0 in 2004, and 4.6 in 2006.[302] This housing bubble resulted in many homeowners refinancing their homes at lower interest rates, or financing consumer spending by taking out second mortgages secured by the price appreciation.

In a Peabody Award-winning program, NPR correspondents argued that a "Giant Pool of Money" (represented by $70 trillion in worldwide fixed income investments) sought higher yields than those offered by U.S. Treasury bonds early in the decade. This pool of money had roughly doubled in size from 2000 to 2007, yet the supply of relatively safe, income generating investments had not grown as fast. Investment banks on Wall Street answered this demand with products such as the mortgage-backed security and the collateralized debt obligation that were assigned safe ratings by the credit rating agencies.[3]

In effect, Wall Street connected this pool of money to the mortgage market in the US, with enormous fees accruing to those throughout the mortgage supply chain, from the mortgage broker selling the loans to small banks that funded the brokers and the large investment banks behind them. By approximately 2003, the supply of mortgages originated at traditional lending standards had been exhausted, and continued strong demand began to drive down lending standards.[3]

The collateralized debt obligation in particular enabled financial institutions to obtain investor funds to finance subprime and other lending, extending or increasing the housing bubble and generating large fees. This essentially places cash payments from multiple mortgages or other debt obligations into a single pool from which specific securities draw in a specific sequence of priority. Those securities first in line received investment-grade ratings from rating agencies. Securities with lower priority had lower credit ratings but theoretically a higher rate of return on the amount invested.[303]

By September 2008, average U.S. housing prices had declined by over 20% from their mid-2006 peak.[304][305] As prices declined, borrowers with adjustable-rate mortgages could not refinance to avoid the higher payments associated with rising interest rates and began to default. During 2007, lenders began foreclosure proceedings on nearly 1.3 million properties, a 79% increase over 2006.[306] This increased to 2.3 million in 2008, an 81% increase vs. 2007.[307] By August 2008, approximately 9% of all U.S. mortgages outstanding were either delinquent or in foreclosure.[308] By September 2009, this had risen to 14.4%.[309][310]

After the bubble burst, Australian economist John Quiggin wrote, "And, unlike the Great Depression, this crisis was entirely the product of financial markets. There was nothing like the postwar turmoil of the 1920s, the struggles over gold convertibility and reparations, or the Smoot-Hawley tariff, all of which have shared the blame for the Great Depression." Instead, Quiggin lays the blame for the 2008 near-meltdown on financial markets, on political decisions to lightly regulate them, and on rating agencies which had self-interested incentives to give good ratings.[311]

Easy credit conditions

[edit]Lower interest rates encouraged borrowing. From 2000 to 2003, the Federal Reserve lowered the federal funds rate target from 6.5% to 1.0%.[312][313] This was done to soften the effects of the collapse of the dot-com bubble and the September 11 attacks, as well as to combat a perceived risk of deflation.[314] As early as 2002, it was apparent that credit was fueling housing instead of business investment as some economists went so far as to advocate that the Fed "needs to create a housing bubble to replace the Nasdaq bubble".[315] Moreover, empirical studies using data from advanced countries show that excessive credit growth contributed greatly to the severity of the crisis.[316]

Additional downward pressure on interest rates was created by rising U.S. current account deficit, which peaked along with the housing bubble in 2006. Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke explained how trade deficits required the U.S. to borrow money from abroad, in the process bidding up bond prices and lowering interest rates.[317]

Bernanke explained that between 1996 and 2004, the U.S. current account deficit increased by $650 billion, from 1.5% to 5.8% of GDP. Financing these deficits required the country to borrow large sums from abroad, much of it from countries running trade surpluses. These were mainly the emerging economies in Asia and oil-exporting nations. The balance of payments identity requires that a country (such as the US) running a current account deficit also have a capital account (investment) surplus of the same amount. Hence large and growing amounts of foreign funds (capital) flowed into the U.S. to finance its imports.

All of this created demand for various types of financial assets, raising the prices of those assets while lowering interest rates. Foreign investors had these funds to lend either because they had very high personal savings rates (as high as 40% in China) or because of high oil prices. Ben Bernanke referred to this as a "saving glut".[318]

A flood of funds (capital or liquidity) reached the U.S. financial markets. Foreign governments supplied funds by purchasing Treasury bonds and thus avoided much of the direct effect of the crisis. U.S. households, used funds borrowed from foreigners to finance consumption or to bid up the prices of housing and financial assets. Financial institutions invested foreign funds in mortgage-backed securities.[citation needed]

The Fed then raised the Fed funds rate significantly between July 2004 and July 2006.[319] This contributed to an increase in one-year and five-year adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM) rates, making ARM interest rate resets more expensive for homeowners.[320] This may have also contributed to the deflating of the housing bubble, as asset prices generally move inversely to interest rates, and it became riskier to speculate in housing.[321][322] U.S. housing and financial assets dramatically declined in value after the housing bubble burst.[323][44]

Weak and fraudulent underwriting practices

[edit]Subprime lending standards declined in the U.S.: in early 2000, a subprime borrower had a FICO score of 660 or less. By 2005, many lenders dropped the required FICO score to 620, making it much easier to qualify for prime loans and making subprime lending a riskier business. Proof of income and assets were de-emphasized. Loans at first required full documentation, then low documentation, then no documentation. One subprime mortgage product that gained wide acceptance was the no income, no job, no asset verification required (NINJA) mortgage. Informally, these loans were aptly referred to as "liar loans" because they encouraged borrowers to be less than honest in the loan application process.[324] Testimony given to the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission by whistleblower Richard M. Bowen III, on events during his tenure as the Business Chief Underwriter for Correspondent Lending in the Consumer Lending Group for Citigroup, where he was responsible for over 220 professional underwriters, suggests that by 2006 and 2007, the collapse of mortgage underwriting standards was endemic. His testimony stated that by 2006, 60% of mortgages purchased by Citigroup from some 1,600 mortgage companies were "defective" (were not underwritten to policy, or did not contain all policy-required documents)—this, despite the fact that each of these 1,600 originators was contractually responsible (certified via representations and warrantees) that its mortgage originations met Citigroup standards. Moreover, during 2007, "defective mortgages (from mortgage originators contractually bound to perform underwriting to Citi's standards) increased ... to over 80% of production".[325]

In separate testimony to the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, officers of Clayton Holdings, the largest residential loan due diligence and securitization surveillance company in the United States and Europe, testified that Clayton's review of over 900,000 mortgages issued from January 2006 to June 2007 revealed that scarcely 54% of the loans met their originators' underwriting standards. The analysis (conducted on behalf of 23 investment and commercial banks, including 7 "too big to fail" banks) additionally showed that 28% of the sampled loans did not meet the minimal standards of any issuer. Clayton's analysis further showed that 39% of these loans (i.e. those not meeting any issuer's minimal underwriting standards) were subsequently securitized and sold to investors.[326][327]

Predatory lending

[edit]Predatory lending refers to the practice of unscrupulous lenders, enticing borrowers to enter into "unsafe" or "unsound" secured loans for inappropriate purposes.[328][329][330]

In June 2008, Countrywide Financial was sued by then California Attorney General Jerry Brown for "unfair business practices" and "false advertising", alleging that Countrywide used "deceptive tactics to push homeowners into complicated, risky, and expensive loans so that the company could sell as many loans as possible to third-party investors".[331] In May 2009, Bank of America modified 64,000 Countrywide loans as a result.[332] When housing prices decreased, homeowners in ARMs then had little incentive to pay their monthly payments, since their home equity had disappeared. This caused Countrywide's financial condition to deteriorate, ultimately resulting in a decision by the Office of Thrift Supervision to seize the lender. One Countrywide employee—who would later plead guilty to two counts of wire fraud and spent 18 months in prison—stated that, "If you had a pulse, we gave you a loan."[333]

Former employees from Ameriquest, which was United States' leading wholesale lender, described a system in which they were pushed to falsify mortgage documents and then sell the mortgages to Wall Street banks eager to make fast profits. There is growing evidence that such mortgage frauds may be a cause of the crisis.[334]

Deregulation and lack of regulation

[edit]According to Barry Eichengreen, the roots of the financial crisis lay in the deregulation of financial markets.[335] A 2012 OECD study[336] suggest that bank regulation based on the Basel accords encourage unconventional business practices and contributed to or even reinforced the financial crisis. In other cases, laws were changed or enforcement weakened in parts of the financial system. Key examples include:

- Jimmy Carter's Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 (DIDMCA) phased out several restrictions on banks' financial practices, broadened their lending powers, allowed credit unions and savings and loans to offer checkable deposits, and raised the deposit insurance limit from $40,000 to $100,000 (thereby potentially lessening depositor scrutiny of lenders' risk management policies).[337]

- In October 1982, U.S. President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Garn–St. Germain Depository Institutions Act, which provided for adjustable-rate mortgage loans, began the process of banking deregulation, and contributed to the savings and loan crisis of the late 1980s/early 1990s.[338][339]

- In November 1999, U.S. President Bill Clinton signed into law the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act, which repealed provisions of the Glass-Steagall Act that prohibited a bank holding company from owning other financial companies. The repeal effectively removed the separation that previously existed between Wall Street investment banks and depository banks, providing a government stamp of approval for a universal risk-taking banking model. Investment banks such as Lehman became competitors with commercial banks.[340] Some analysts say that this repeal directly contributed to the severity of the crisis, while others downplay its impact since the institutions that were greatly affected did not fall under the jurisdiction of the act itself.[341][342]

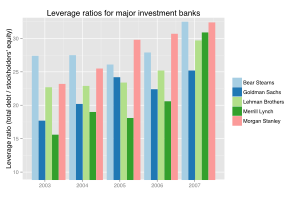

- In 2004, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission relaxed the net capital rule, which enabled investment banks to substantially increase the level of debt they were taking on, fueling the growth in mortgage-backed securities supporting subprime mortgages. The SEC conceded that self-regulation of investment banks contributed to the crisis.[343][344]

- Financial institutions in the shadow banking system are not subject to the same regulation as depository banks, allowing them to assume additional debt obligations relative to their financial cushion or capital base.[345] This was the case despite the Long-Term Capital Management debacle in 1998, in which a highly leveraged shadow institution failed with systemic implications and was bailed out.

- Regulators and accounting standard-setters allowed depository banks such as Citigroup to move significant amounts of assets and liabilities off-balance sheet into complex legal entities called structured investment vehicles, masking the weakness of the capital base of the firm or degree of leverage or risk taken. Bloomberg News estimated that the top four U.S. banks will have to return between $500 billion and $1 trillion to their balance sheets during 2009.[346] This increased uncertainty during the crisis regarding the financial position of the major banks.[347] Off-balance sheet entities were also used in the Enron scandal, which brought down Enron in 2001.[348]

- As early as 1997, Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan fought to keep the derivatives market unregulated.[349] With the advice of the Working Group on Financial Markets,[350] the U.S. Congress and President Bill Clinton allowed the self-regulation of the over-the-counter derivatives market when they enacted the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000. Written by Congress with lobbying from the financial industry, it banned the further regulation of the derivatives market. Derivatives such as credit default swaps (CDS) can be used to hedge or speculate against particular credit risks without necessarily owning the underlying debt instruments. The volume of CDS outstanding increased 100-fold from 1998 to 2008, with estimates of the debt covered by CDS contracts, as of November 2008, ranging from US$33 to $47 trillion. Total over-the-counter (OTC) derivative notional value rose to $683 trillion by June 2008.[351] Warren Buffett famously referred to derivatives as "financial weapons of mass destruction" in early 2003.[352][353]

A 2011 paper suggested that Canada's avoidance of a banking crisis in 2008 (as well as in prior eras) could be attributed to Canada possessing a single, powerful, overarching regulator, while the United States had a weak, crisis prone and fragmented banking system with multiple competing regulatory bodies.[354]

Increased debt burden or overleveraging

[edit]

Prior to the crisis, financial institutions became highly leveraged, increasing their appetite for risky investments and reducing their resilience in case of losses. Much of this leverage was achieved using complex financial instruments such as off-balance sheet securitization and derivatives, which made it difficult for creditors and regulators to monitor and try to reduce financial institution risk levels.[355][verification needed]

U.S. households and financial institutions became increasingly indebted or overleveraged during the years preceding the crisis.[356] This increased their vulnerability to the collapse of the housing bubble and worsened the ensuing economic downturn.[357] Key statistics include:

Free cash used by consumers from home equity extraction doubled from $627 billion in 2001 to $1,428 billion in 2005 as the housing bubble built, a total of nearly $5 trillion over the period, contributing to economic growth worldwide.[31][32][33] U.S. home mortgage debt relative to GDP increased from an average of 46% during the 1990s to 73% during 2008, reaching $10.5 trillion (c. $14.6 trillion in 2023[292]).[30]

U.S. household debt as a percentage of annual disposable personal income was 127% at the end of 2007, versus 77% in 1990.[356] In 1981, U.S. private debt was 123% of GDP; by the third quarter of 2008, it was 290%.[358]

From 2004 to 2007, the top five U.S. investment banks each significantly increased their financial leverage, which increased their vulnerability to a financial shock. Changes in capital requirements, intended to keep U.S. banks competitive with their European counterparts, allowed lower risk weightings for AAA-rated securities. The shift from first-loss tranches to AAA-rated tranches was seen by regulators as a risk reduction that compensated the higher leverage.[359] These five institutions reported over $4.1 trillion in debt for fiscal year 2007, about 30% of U.S. nominal GDP for 2007. Lehman Brothers went bankrupt and was liquidated, Bear Stearns and Merrill Lynch were sold at fire-sale prices, and Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley became commercial banks, subjecting themselves to more stringent regulation. With the exception of Lehman, these companies required or received government support.[360]

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, two U.S. government-sponsored enterprises, owned or guaranteed nearly $5 trillion (c. $6.95 trillion in 2023[292]) trillion in mortgage obligations at the time they were placed into conservatorship by the U.S. government in September 2008.[361][362]

These seven entities were highly leveraged and had $9 trillion in debt or guarantee obligations; yet they were not subject to the same regulation as depository banks.[345][363]

Behavior that may be optimal for an individual, such as saving more during adverse economic conditions, can be detrimental if too many individuals pursue the same behavior, as ultimately one person's consumption is another person's income. Too many consumers attempting to save or pay down debt simultaneously is called the paradox of thrift and can cause or deepen a recession. Economist Hyman Minsky also described a "paradox of deleveraging" as financial institutions that have too much leverage (debt relative to equity) cannot all de-leverage simultaneously without significant declines in the value of their assets.[357]

In April 2009, Federal Reserve vice-chair Janet Yellen discussed these paradoxes:

Once this massive credit crunch hit, it didn't take long before we were in a recession. The recession, in turn, deepened the credit crunch as demand and employment fell, and credit losses of financial institutions surged. Indeed, we have been in the grips of precisely this adverse feedback loop for more than a year. A process of balance sheet deleveraging has spread to nearly every corner of the economy. Consumers are pulling back on purchases, especially on durable goods, to build their savings. Businesses are cancelling planned investments and laying off workers to preserve cash. And financial institutions are shrinking assets to bolster capital and improve their chances of weathering the current storm. Once again, Minsky understood this dynamic. He spoke of the paradox of deleveraging, in which precautions that may be smart for individuals and firms—and indeed essential to return the economy to a normal state—nevertheless magnify the distress of the economy as a whole.[357]

Financial innovation and complexity

[edit]