Рейс 007 Корейских авиалиний

HL7442, самолет, сбитый в 1983 году, в аэропорту Цюриха в 1980 году. | |

| Перестрелка | |

|---|---|

| Дата | 1 сентября 1983 г. |

| Краткое содержание | Сбит советскими войсками ПВО из-за навигационной ошибки пилотов, приведшей к поломке в полете. |

| Сайт | Японское море , недалеко от острова Монерон , к западу от острова Сахалин , РСФСР , Советский Союз. 46 ° 34' с.ш., 141 ° 17' в.д. / 46,567 ° с.ш., 141,283 ° в.д. |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 747-230B |

| Operator | Korean Air Lines |

| IATA flight No. | KE007 |

| ICAO flight No. | KAL007 |

| Call sign | KOREAN AIR 007 |

| Registration | HL7442 |

| Flight origin | John F. Kennedy International Airport, New York City, U.S. |

| Stopover | Anchorage International Airport, Anchorage, Alaska, U.S. |

| Destination | Gimpo International Airport, Gangseo District, Seoul, South Korea |

| Occupants | 269 |

| Passengers | 246[1] |

| Crew | 23[note 1] |

| Fatalities | 269 |

| Survivors | 0 |

Рейс 007 Korean Air Lines ( KE007 / KAL007 ) [примечание 2] Это был регулярный рейс Korean Air Lines из Нью-Йорка в Сеул через Анкоридж, Аляска . 1 сентября 1983 года самолет был сбит советским самолетом Су-15 - перехватчиком . Авиалайнер Boeing 747 следовал из Анкориджа в Сеул, но из-за навигационной ошибки, допущенной экипажем, авиалайнер отклонился от запланированного маршрута и пролетел через запрещенное советское воздушное пространство . Советские ВВС сочли неопознанный самолет вторгшимся американским самолетом-шпионом и уничтожили его ракетами класса «воздух-воздух» после предупредительных выстрелов. Корейский авиалайнер в конечном итоге рухнул в море недалеко от острова Монерон к западу от Сахалина в Японском море , в результате чего погибли все 269 пассажиров и члены экипажа, находившиеся на борту, включая Ларри Макдональда , представителя США . Советский Союз нашел обломки под водой две недели спустя, 15 сентября, и обнаружил бортовые самописцы в октябре, но эта информация хранилась советскими властями в секрете до 1992 года, после распада страны .

Советский Союз первоначально отрицал, что знает об инциденте. [2] but later admitted to shooting down the aircraft, claiming that it was on a MASINT spy mission.[3] The Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union said it was a deliberate provocation by the United States[4] to probe the Soviet Union's military preparedness, or even to provoke a war. The US accused the Soviet Union of obstructing search and rescue operations.[5] The Soviet Armed Forces suppressed evidence sought by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) investigation, such as the flight recorders,[6] which were released ten years later, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[7]

As a result of the incident, the United States altered tracking procedures for aircraft departing from Alaska, and president Ronald Reagan issued a directive making American satellite-based radio navigation Global Positioning System freely available for civilian use, once it was sufficiently developed, as a common good.[8]

Aircraft

[edit]

The aircraft flying as Korean Air Lines Flight 007 was a Boeing 747-230B jet airliner with Boeing serial number 20559. The aircraft was powered by four Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7A engines.[9]

Details of the flight

[edit]Passengers and crew

[edit]| Nation | Victims | |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | 2 | |

| British Hong Kong | 12 | |

| Canada | 8 | |

| Dominican Republic | 1 | |

| India | 1 | |

| Iran | 1 | |

| Japan | 28 | |

| Malaysia | 1 | |

| Philippines | 16 | |

| South Korea | 105 | |

| Sweden | 1 | |

| Taiwan | 23 | |

| Thailand | 5 | |

| United Kingdom | 2 | |

| United States | 62 | |

| Vietnam | 1 | |

| Total (16 Nationalities) | 269 | |

* 76 passengers, 23 active crew and 6 deadheading crew[10] | ||

The aircraft flying as Korean Air Lines Flight 007 departed from Gate 15 of John F. Kennedy International Airport, New York City, on August 31, 1983, at 00:25 EDT (04:25 UTC), bound for Kimpo International Airport in Gangseo District, Seoul, 35 minutes behind its scheduled departure time of 23:50 EDT, August 30 (03:50 UTC, August 31). The flight was carrying 246 passengers and 23 crew members.[note 1][13] After refueling at Anchorage International Airport in Anchorage, Alaska, the aircraft departed for Seoul at 04:00 AHDT (13:00 UTC) on August 31, 1983. This leg of the journey was piloted by Captain Chun Byung-in (45), First Officer Son Dong-hui (47), and Flight Engineer Kim Eui-dong (31).[14][15] Captain Chun had a total of 10,627 flight hours, including 6,618 hours in the 747. First Officer Son had a total of 8,917 flight hours, including 3,411 hours in the 747. Flight Engineer Kim had a total of 4,012 flight hours, including 2,614 hours on the 747.[16]

The aircrew had an unusually high ratio of crew to passengers, as six deadheading crew were on board.[17] Twelve passengers occupied the upper deck first class, while in business class almost all of the 24 seats were taken; in economy class, approximately 80 seats were empty. There were 22 children under the age of 12 years aboard. 130 passengers planned to connect to other destinations such as Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Taipei.[18]

United States Congressman Larry McDonald from Georgia, who at the time was also the second president of the conservative John Birch Society, was on the flight. Senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina, Senator Steve Symms of Idaho, and Representative Carroll Hubbard of Kentucky (who cancelled his reservations for the trip at the last moment) were aboard sister flight KAL 015, which flew 15 minutes behind KAL 007; they were headed, along with McDonald on KAL 007, to Seoul, South Korea, in order to attend the ceremonies for the thirtieth anniversary of the U.S.–South Korea Mutual Defense Treaty.[19] The Soviets contended former U.S. president Richard Nixon was to have been seated next to Larry McDonald on KAL 007 but that the CIA warned him not to go, according to the New York Post and Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS); this was denied by Nixon.[20]

Flight deviation from assigned route

[edit]Less than a half-minute after taking off from Anchorage, KAL 007 was directed by air traffic control (ATC) to turn to a magnetic heading of 220°.[10]: 31 This sharp turn, 100° to the left, was only to transition the plane from its initial heading at take-off (320° magnetic, in line with the runway it used),[10]: 41 to bring it closer to a route known as J501, which KAL 007 was to take to Bethel. Approximately 90 seconds later, ATC directed the flight to "proceed direct Bethel when able."[21][22] In response, the plane immediately began a slight turn to the right, to align it with route J501, and less than a minute later (3 minutes after take-off) was on a magnetic heading of approximately 245°,[10]: 31 roughly toward Bethel.

Upon KAL 007’s arrival over Bethel, its flight plan called for it to take the northernmost of five 50-mile-wide (80 km) airways, known as the NOPAC (North Pacific) routes, that bridge the Alaskan and Japanese coasts. That particular airway, R20 (Romeo Two Zero), passed as close as 20 miles (32 km) from what was then Soviet airspace off the coast of the Kamchatka Peninsula.

The lateral navigation half of the autopilot system of the 747-200 has four basic control modes: HEADING, VOR/LOC, ILS, and INS. The HEADING mode maintained a constant magnetic course selected by the pilot. The VOR/LOC mode maintained the plane on a specific course, transmitted from a VOR (VHF omnidirectional range, a type of short-range radio signal transmitted from ground beacons) or Localizer (LOC) beacon selected by the pilot. The ILS (instrument landing system) mode caused the plane to track both vertical and lateral course beacons, which led to a specific runway selected by the pilot. The INS (inertial navigation system) mode maintained the plane on lateral course lines between selected flight plan waypoints programmed into the INS computer.

When the INS navigation systems were properly programmed with the filed flight plan waypoints, the pilot could turn the autopilot mode selector switch to the INS position and the plane would then automatically track the programmed INS course line, provided the plane was headed in the proper direction and within 7.5 nautical miles (13.9 km) of that course line.[10]: 42 If, however, the plane was more than 7.5 nautical miles (13.9 km) from the flight-planned course line when the pilot turned the autopilot mode selector from HEADING to INS, the plane would continue to track the heading selected in HEADING mode as long as the actual position of the plane was more than 7.5 nautical miles (13.9 km) from the programmed INS course line. The autopilot computer software commanded the INS mode to remain in the "armed" condition until the plane had moved to a position less than 7.5 nautical miles (13.9 km) from the desired course line. Once that happened, the INS mode would change from "armed" to "capture" and the plane would track the flight-planned course from then on.[23][10]: 42

The HEADING mode of the autopilot would normally be engaged sometime after takeoff in order to follow vectors from ATC, and then after receiving appropriate ATC clearance, to guide the plane to intercept the desired INS course line.[23]

The Anchorage VOR beacon was not operational at the time, as it was undergoing maintenance.[24] The crew received a NOTAM (Notice to Airmen) of this fact, which was not seen as a problem, as the captain could still check his position at the next VORTAC beacon at Bethel, 346 nautical miles (641 km) away. The aircraft was required to maintain the assigned heading of 220 degrees until it could receive the signals from Bethel, then it could fly direct to Bethel, as instructed by ATC, by centering the VOR "to" course deviation indicator (CDI) and then engaging the autopilot in the VOR/LOC mode. Then, when over the Bethel beacon, the flight could start using INS mode to follow the waypoints that makeup route Romeo-20 around the coast of the U.S.S.R. to Seoul. The INS mode was necessary for this route since after Bethel the plane would be mostly out of range from VOR stations.

At about 10 minutes after take-off, flying on a heading of 245 degrees, KAL 007 began to deviate to the right (north) of its assigned route to Bethel and continued to fly on this constant heading for the next five and a half hours.[25]

International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) simulation and analysis of the flight data recorder determined that this deviation was probably caused by the aircraft's autopilot system operating in HEADING mode, after the point that it should have been switched to the INS mode.[26][27] According to the ICAO, the autopilot was not operating in the INS mode either because the crew did not switch the autopilot to the INS mode (as they should have shortly after Cairn Mountain), or they did select the INS mode, but the computer did not transition from "armed" to "capture" condition because the aircraft had already deviated off track by more than the 7.5-nautical-mile (13.9 km) tolerance permitted by the inertial navigation computer. Whatever the reason, the autopilot remained in HEADING mode, and the problem was not detected by the crew.[26]

At 27 minutes after KAL 007's take-off, civilian radar at Kenai, located about 50 nautical miles (90 km) southwest of Anchorage and with coverage of up to 175 nautical miles (320 km),[10]: 10 showed it passing near Cairn Mountain, about 160 nautical miles (300 km) west of Anchorage.[10]: 15 It also showed that the aircraft by then was already off course—about 6 nautical miles (11 km) north of its expected route to Bethel.[10]: 4–5, 43

Later, at 13:49 UTC (49 minutes after take-off), KAL 007 reported that it had reached its Bethel waypoint, about 346 nautical miles (641 km) west of Anchorage.[10]: 5 But traces from military radar at King Salmon, Alaska, showed that the aircraft then was actually about 12 nautical miles (22 km) north of that location[10]: 5, 43 —and apparently heading farther off course.[10]: 44 There is no evidence to indicate that anyone with access to King Salmon radar output that night—civil air traffic controllers or military radar personnel—was aware in real-time of KAL 007's deviation and in a position to warn the aircraft.[28] But had the aircraft been steered under INS control, as was intended, such an error would have been far greater than the INS's nominal navigational accuracy of less than 2 nautical miles (3.7 km) per hour of flight.[10]: 43 [29]

KAL 007's divergence prevented the aircraft from transmitting its position via shorter-range very-high-frequency radio (VHF). It therefore requested KAL 015, also en route to Seoul, to relay reports to air traffic control on its behalf.[30] KAL 007 requested KAL 015 to relay its position three times. At 14:43 UTC, KAL 007 directly transmitted a change of estimated time of arrival for its next waypoint, NEEVA, to the international flight service station at Anchorage,[31] but it did so over the longer range high frequency radio (HF) rather than VHF. HF transmissions are able to carry a longer distance than VHF, but are vulnerable to electromagnetic interference and static; VHF is clearer with less interference, and is preferred by flight crews. The inability to establish direct radio communications to be able to transmit their position directly did not alert the pilots of KAL 007 of their ever-increasing divergence[32] and was not considered unusual by air traffic controllers.[30] Halfway between Bethel and waypoint NABIE, KAL 007 passed through the southern portion of the North American Aerospace Defense Command buffer zone. This zone is north of Romeo 20 and off-limits to civilian aircraft.

Sometime after leaving American territorial waters, KAL Flight 007 crossed the International Date Line, where the local date shifted from August 31, 1983, to September 1, 1983.

KAL 007 continued its journey, ever increasing its deviation—60 nautical miles (110 km) off course at waypoint NABIE, 100 nautical miles (190 km) off course at waypoint NUKKS, and 160 nautical miles (300 km) off course at waypoint NEEVA—until it reached the Kamchatka Peninsula.[10]: 13

| Route J501 / R20 waypoint[10]: 13 | Flight-planned coordinates | ATC | KAL 007 deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAIRN MOUNTAIN | 61°06.0′N 155°33.0′W / 61.1000°N 155.5500°W[33] | Anchorage | 6 nmi (11 km)[10]: 43 |

| BETHEL | 60°47.1′N 161°49.3′W / 60.7850°N 161.8217°W[33] | Anchorage | 12 nmi (22 km)[10]: 43 |

| NABIE | 59°18.0′N 171°45.4′W / 59.3000°N 171.7567°W | Anchorage | 60 nmi (110 km) |

| NUKKS | 57°15.1′N 179°44.3′E / 57.2517°N 179.7383°E[33] | Anchorage | 100 nmi (190 km) |

| NEEVA | 54°40.7′N 172°11.8′E / 54.6783°N 172.1967°E | Anchorage | 160 nmi (300 km) |

| NINNO | 52°21.5′N 165°22.8′E / 52.3583°N 165.3800°E | Anchorage | |

| NIPPI | 49°41.9′N 159°19.3′E / 49.6983°N 159.3217°E | Anchorage/Tokyo | 180 mi (290 km)[34] |

| NYTIM | 46°11.9′N 153°00.5′E / 46.1983°N 153.0083°E | Tokyo | 500 nmi (930 km) to point of impact |

| NOKKA | 42°23.3′N 147°28.8′E / 42.3883°N 147.4800°E | Tokyo | 350 nmi (650 km) to point of impact |

| NOHO | 40°25.0′N 145°00.0′E / 40.4167°N 145.0000°E | Tokyo | 390 nmi (720 km) to point of impact |

Shoot-down

[edit]

In 1983, Cold War tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union had escalated to a level not seen since the Cuban Missile Crisis because of several factors. These included the United States' Strategic Defense Initiative, its planned deployment of the Pershing II weapon system in Europe in March and April, and FleetEx '83-1, the largest naval exercise held to date in the North Pacific.[35] The military hierarchy of the Soviet Union (particularly the old guard led by Soviet General Secretary Yuri Andropov and Minister of Defence Dmitry Ustinov) viewed these actions as bellicose and destabilizing; they were deeply suspicious of U.S. President Ronald Reagan's intentions and openly fearful he was planning a pre-emptive nuclear strike against the Soviet Union. These fears culminated in RYAN, the code name for a secret intelligence-gathering program initiated by Andropov to detect a potential nuclear sneak attack which he believed Reagan was plotting.[36]

Aircraft from USS Midway and USS Enterprise repeatedly overflew Soviet military installations in the Kuril Islands during FleetEx '83 naval exercise (29 March to 17 April 1983),[37] resulting in the dismissal or reprimanding of Soviet military officials who had been unable to shoot them down.[38] On the Soviet side, RYAN was expanded.[38] Lastly, there was a heightened alert around the Kamchatka Peninsula at the time that KAL 007 was in the vicinity, because of a Soviet missile test at the Kura Missile Test Range that was scheduled for the same day. A United States Air Force Boeing RC-135 reconnaissance aircraft flying in the area was monitoring the missile test off the peninsula.[39]

At 15:51 UTC, according to Soviet sources,[32] KAL 007 entered the restricted airspace of the Kamchatka Peninsula. The buffer zone extended 200 kilometres (120 mi; 110 nmi) from Kamchatka's coast and is known as a flight information region (FIR). The 100-kilometre (62 mi; 54 nmi) radius of the buffer zone nearest to Soviet territory had the additional designation of prohibited airspace. When KAL 007 was about 130 kilometres (81 mi; 70 nmi) from the Kamchatka coast, four MiG-23 fighters were scrambled to intercept the Boeing 747.[26]

Significant command and control problems were experienced trying to vector the fast military jets onto the 747 before they ran out of fuel. In addition, the pursuit was made more difficult, according to Soviet Air Force Captain Aleksandr Zuyev, who defected to the West in 1989, because, ten days before, Arctic gales had knocked out the key warning radar on the Kamchatka Peninsula. Furthermore, he stated that local officials responsible for repairing the radar lied to Moscow, falsely reporting that they had successfully fixed the radar. Had this radar been operational, it would have enabled an intercept of the stray airliner roughly two hours earlier with plenty of time for proper identification as a civilian aircraft. Instead, the unidentified jetliner crossed over the Kamchatka Peninsula back into international airspace over the Sea of Okhotsk without being intercepted.[40] In his explanation to 60 Minutes, Zuyev stated: "Some people lied to Moscow, trying to save their ass."[41]

The Commander of the Soviet Far East District Air Defense Forces, General Valeri Kamensky,[42] was adamant that KAL 007 was to be destroyed even over neutral waters but only after positive identification showed it not to be a passenger plane. His subordinate, General Anatoly Kornukov, commander of Sokol Air Base and later to become commander of the Russian Air Force, insisted that there was no need to make positive identification as the intruder aircraft had already flown over the Kamchatka Peninsula.

General Kornukov (to Military District Headquarters-Gen. Kamensky): (5:47) "...simply destroy [it] even if it is over neutral waters? Are the orders to destroy it over neutral waters? Oh, well."

Kamensky: "We must find out, maybe it is some civilian craft or God knows who."

Kornukov: "What civilian? [It] has flown over Kamchatka! It [came] from the ocean without identification. I am giving the order to attack if it crosses the State border."

Units of the Soviet Air Defence Forces that had been tracking the South Korean aircraft for more than an hour while it entered and left Soviet airspace now classified the aircraft as a military target when it re-entered their airspace over Sakhalin.[26] After a protracted ground-controlled interception, the three Su-15 fighters (from nearby Dolinsk-Sokol airbase) and the MiG-23[43] (from Smirnykh Air Base) managed to make visual contact with the Boeing, but, owing to the black of night, failed to make critical identification of the aircraft which Russian communications reveal. The pilot of the lead Su-15 fighter fired warning shots with its cannon, but recalled later in 1991, "I fired four bursts, more than 200 rounds. For all the good it did. After all, I was loaded with armor-piercing shells, not incendiary shells. It's doubtful whether anyone could see them."[44]

At this point, KAL 007 contacted Tokyo Area Control Center, requesting clearance to ascend to a higher flight level for reasons of fuel economy; the request was granted, so the Boeing started to climb, gradually slowing as it exchanged speed for altitude. The decrease in speed caused the pursuing fighter to overshoot the Boeing and was interpreted by the Soviet pilot as an evasive maneuver. The order to shoot KAL 007 down was given as it was about to leave Soviet airspace for the second time. At around 18:26 UTC, under pressure from General Kornukov and ground controllers not to let the aircraft escape into international airspace, the lead fighter was able to move back into a position where it could fire two K-8 (NATO reporting name: AA-3 "Anab") air-to-air missiles at the plane.[45]

Soviet pilot's recollection of shoot-down

[edit]In a 1991 interview with Izvestia, Major Gennadiy Osipovich, pilot of the Su-15 interceptor that shot the aircraft down, spoke about his recollections of the events leading up to the shoot-down. Contrary to official Soviet statements at the time, he recalled telling ground controllers that there were "blinking lights".[46] He continued, saying of the 747-230B, "I saw two rows of windows and knew that this was a Boeing. I knew this was a civilian plane. But for me this meant nothing. It is easy to turn a civilian type of plane into one for military use."[46] Osipovich stated, "I did not tell the ground that it was a Boeing-type plane; they did not ask me."[44][46]

Commenting on the moment that KAL 007 slowed as it ascended from flight level 330 to flight level 350, and then on his maneuvering for a missile launch, Osipovich said:

They [KAL 007] quickly lowered their speed. They were flying at 400 km/h (249 mph). My speed was more than 400. I was simply unable to fly slower. In my opinion, the intruder's intentions were plain. If I did not want to go into a stall, I would be forced to overshoot them. That's exactly what happened. We had already flown over the island [Sakhalin]. It is narrow at that point, the target was about to get away... Then the ground [controller] gave the command: "Destroy the target...!" That was easy to say. But how? With shells? I had already expended 243 rounds. Ram it? I had always thought of that as poor taste. Ramming is the last resort. Just in case, I had already completed my turn and was coming down on top of him. Then, I had an idea. I dropped below him about two thousand metres (6,600 ft)... afterburners. Switched on the missiles and brought the nose up sharply. Success! I have a lock on.We shot down the plane legally ... Later we began to lie about small details: the plane was supposedly flying without running lights or strobe light, that tracer bullets were fired, or that I had radio contact with them on the emergency frequency of 121.5 megahertz.[47]

Osipovich died on September 23, 2015, after a protracted illness.[48]

Soviet command hierarchy of shoot-down

[edit]The Soviet real-time military communication transcripts of the shoot-down suggest the chain of command from the top general to Major Osipovich, the Su-15 interceptor pilot who shot down KAL 007.[49][50] In reverse order, they are:

- Major Gennadiy Nikolayevich Osipovich,

- Captain Titovnin, Combat Control Center – Fighter Division

- Lt. Colonel Maistrenko, Smirnykh Air Base Fighter Division Acting Chief of Staff, who confirmed the shoot-down order to Titovnin.

Titovnin: "You confirm the task?"

Maistrenko: "Yes." - Lt. Colonel Gerasimenko, Acting Commander, 41st Fighter Regiment.

Gerasimenko: (to Kornukov) "Task received. Destroy target 60–65 with missile fire. Accept control of fighter from Smirnikh.

- General Anatoly Kornukov, Commander of Sokol Air Base – Sakhalin.

Kornukov: (to Gerasimenko) "I repeat the task, Fire the missiles, Fire on target 60–65. Destroy target 60–65 ... Take control of the MiG 23 from Smirnikh, call sign 163, call sign 163. He is behind the target at the moment. Destroy the target!... Carry out the task! Destroy it!"

- General Valery Kamensky, Commander of Far East Military District Air Defense Forces.

Kornukov: (To Kamensky) "... simply destroy [it] even if it is over neutral waters? Are the orders to destroy it over neutral waters? Oh, well."

- Army General Ivan Moiseevich Tretyak, Commander of the Far East Military District.

"Weapons were used, weapons authorized at the highest level. Ivan Moiseevich authorized it. Hello, hello.", "Say again.", "I cannot hear you clearly now.", "He gave the order. Hello, hello, hello.", "Yes, yes.", "Ivan Moiseevich gave the order, Tretyak.", "Roger, roger.", "Weapons were used at his order."[51]

Post-attack flight

[edit]At the time of the attack, the plane had been cruising at an altitude of about 35,000 feet (11,000 m). Tapes recovered from the airliner's cockpit voice recorder indicate that the crew was unaware that they were off course and violating Soviet airspace. Immediately after missile detonation, the airliner began a 113-second arc upward because of a damaged crossover cable between the left inboard and right outboard elevators.[52]

At 18:26:46 UTC (03:26 Japan Time; 06:26 Sakhalin time),[53] at the apex of the arc at altitude 38,250 feet (11,660 m),[52] the autopilot disengaged (this was either done by the pilots, or it disengaged automatically). Now being controlled manually, the plane began to descend to 35,000 feet (11,000 m). From 18:27:01 until 18:27:09, the flight crew reported to Tokyo Area Control Center informing that KAL 007 would "descend to 10,000" [feet; 3,000 m]. At 18:27:20, ICAO graphing of Digital Flight Data Recorder tapes showed that after a descent phase and a 10-second "nose-up", KAL 007 was leveled out at pre-missile detonation altitude of 35,000 ft (11,000 m), forward acceleration was back to pre-missile detonation rate of zero acceleration, and airspeed had returned to pre-detonation velocity.

Yaw oscillations, beginning at the time of missile detonation, continued decreasingly until the end of the 1-minute 44-second section of the tape. The Boeing did not break up, explode, or plummet immediately after the attack; it continued its gradual descent for four minutes, then leveled off at 16,424 ft (5,006 m) (18:30–18:31 UTC), rather than continuing to descend to 10,000 ft (3,000 m) as previously reported to Tokyo Area Control Center. It continued at this altitude for almost five more minutes (18:35 UTC).

The last cockpit voice recorder entry occurred at 18:27:46 while in this phase of the descent. At 18:28 UTC, the aircraft was reported turning to the north.[54] ICAO analysis concluded that the flight crew "retained limited control" of the aircraft.[55] However, this lasted for only five minutes. The crew then lost all control. The aircraft began to descend rapidly in spirals over Moneron Island for 2.6 miles (4.2 km). The aircraft then broke apart in mid-air and crashed into the ocean, just off the west coast of Sakhalin Island. All 269 people on board were killed.[note 3] The aircraft was last seen visually by Osipovich, "somehow descending slowly" over Moneron Island. The aircraft disappeared off long-range military radar at Wakkanai, Japan, at a height of 1,000 feet (300 m).[56]

KAL 007 was probably attacked in international airspace, with a 1993 Russian report listing the location of the missile firing outside its territory at 46°46′27″N 141°32′48″E / 46.77417°N 141.54667°E,[38][57] although the intercepting pilot stated otherwise in a subsequent interview. Initial reports that the airliner had been forced to land on Sakhalin were soon proven false[citation needed]. One of these reports conveyed via phone by Orville Brockman, the Washington office spokesman of the Federal Aviation Administration, to the press secretary of Larry McDonald, was that the FAA in Tokyo had been informed by the Japanese Civil Aviation Bureau that "Japanese self-defense force radar confirms that the Hokkaido radar followed Air Korea to a landing in Soviet territory on the island of Sakhalinska and it is confirmed by the manifest that Congressman McDonald is on board".[58]

A Japanese fisherman aboard 58th Chidori Maru later reported to the Japanese Maritime Safety Agency (this report was cited by ICAO analysis) that he had heard a plane at low altitude, but had not seen it. Then he heard "a loud sound followed by a bright flash of light on the horizon, then another dull sound and a less intense flash of light on the horizon"[59] and smelled aviation fuel.[60]

Soviet command response to post-detonation flight

[edit]Though the interceptor pilot reported to ground control, "Target destroyed", the Soviet command, from general on down, indicated surprise and consternation at KAL 007's continued flight, and ability to regain its altitude and maneuver. This consternation continued through to KAL 007's subsequent level flight at altitude 16,424 ft (5,006 m), and then, after almost five minutes, through its spiral descent over Moneron Island. (See Korean Air Lines Flight 007 transcripts from 18:26 UTC onwards: "Lt. Col. Novoseletski: Well, what is happening? What is the matter? Who guided him in? He locked on; why didn't he shoot it down?")

Missile damage to plane

[edit]The following damage to the aircraft was determined by the ICAO from its analysis of the flight data recorder and cockpit voice recorder:

Hydraulics

[edit]KAL 007 had four redundant hydraulic systems of which systems one, two, and three were damaged or destroyed. There was no evidence of damage to system four.[53] The hydraulics provided actuation of all primary and secondary flight controls (except leading edge slats in the latter) as well as landing gear retraction, extension, gear steering, and wheel braking. Each primary flight control axis received power from all four hydraulic systems.[61] Upon missile detonation, the jumbo jet began to experience oscillations (yawing) as the dual channel yaw damper was damaged. Yawing would not have occurred if hydraulic systems one or two were fully operational. The result is that the control column did not thrust forward upon impact (it should have done so as the plane was on autopilot) to bring down the plane to its former altitude of 35,000 feet (11,000 m). This failure of the autopilot to correct the rise in altitude indicates that hydraulic system number three, which operates the autopilot actuator, a system controlling the plane's elevators, was damaged or out. KAL 007's airspeed and acceleration rate both began to decrease as the plane began to climb. At twenty seconds after the missile detonation, a click was heard in the cabin, which is identified as the "automatic pilot disconnect warning" sound. Either the pilot or co-pilot had disconnected the autopilot and was manually thrusting the control column forward in order to bring the plane lower. Though the autopilot had been turned off, manual mode did not begin functioning for another twenty seconds. This failure of the manual system to engage upon command indicates failure in hydraulic systems one and two. With wing flaps up, "control was reduced to the right inboard aileron and the innermost of spoiler section of each side".[53]

Left wing

[edit]Contrary to Major Osipovich's statement in 1991 that he had taken off half of KAL 007's left wing,[44] ICAO analysis found that the wing was intact: "The interceptor pilot stated that the first missile hit near the tail, while the second missile took off half the left wing of the aircraft... The interceptor's pilot's statement that the second missile took off half of the left wing was probably incorrect. The missiles were fired at a two-second interval and would have detonated at an equal interval. The first detonated at 18:26:02 UTC. The last radio transmissions from KE007 to Tokyo Radio were between 18:26:57 and 18:27:15 UTC using HF [high frequency]. The HF 1 radio aerial of the aircraft was positioned in the left wing tip suggesting that the left wing tip was intact at this time. Also, the aircraft's maneuvers after the attack did not indicate extensive damage to the left wing."[62]

Engines

[edit]The co-pilot reported to Captain Chun twice during the flight after the missiles' detonation, "Engines normal, sir."[63]

Tail section

[edit]The first missile was radar-controlled and proximity fuzed, and detonated 50 metres (160 ft) behind the aircraft. Sending fragments forward, it either severed or unraveled the crossover cable from the left inboard elevator to the right elevator.[52] This, with damage to one of the four hydraulic systems, caused KAL 007 to ascend from 35,000 to 38,250 feet (10,670 to 11,660 m), at which point the autopilot was disengaged.

Fuselage

[edit]Fragments from the proximity fuzed air-to-air missile that detonated 50 metres (160 ft) behind the aircraft, punctured the fuselage and caused rapid decompression of the pressurised cabin. The interval of 11 seconds between the sound of missile detonation picked up by the cockpit voice recorder and the sound of the alarm sounding in the cockpit enabled ICAO analysts to determine that the size of the ruptures to the pressurised fuselage was 1.75 square feet (0.163 m2).[64]

Search and rescue

[edit]As a result of Cold War tensions, the search and rescue operations of the Soviet Union were not coordinated with those of the United States, South Korea, and Japan. Consequently, no information was shared, and each side endeavored to harass or obtain evidence to implicate the other.[65] The flight data recorders were the key pieces of evidence sought by both governments, with the United States insisting that an independent observer from the ICAO be present on one of its search vessels in the event that they were found.[66] International boundaries are not well defined on the open sea, leading to numerous confrontations between the large number of opposing naval ships that were assembled in the area.[67]

Soviet search and rescue mission to Moneron Island

[edit]The Soviets did not acknowledge shooting down the aircraft until September 6, five days after the flight was shot down.[68] Eight days after the shoot-down, Marshal of the Soviet Union and Chief of General Staff Nikolai Ogarkov denied knowledge of where KAL 007 had gone down; "We could not give the precise answer about the spot where it [KAL 007] fell because we ourselves did not know the spot in the first place."[69]

Nine years later, the Russian Federation handed over transcripts of Soviet military communications that showed that at least two documented search and rescue (SAR) missions were ordered within a half-hour of the attack, to the last Soviet verified location of the descending jumbo jet over Moneron Island. The first search was ordered from Smirnykh Air Base in central Sakhalin at 18:47 UTC, nine minutes after KAL 007 had disappeared from Soviet radar screens and brought rescue helicopters from Khomutovo Air Base (the military unit at Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk Airport in southern Sakhalin), and Soviet Border Troops boats to the area.[64]

The second search was ordered eight minutes later by the Deputy Commander of the Far Eastern Military District, General Strogov, and involved civilian trawlers that were in the area around Moneron. "The border guards. What ships do we now have near Moneron Island? If they are civilians, send [them] there immediately."[70] Moneron is just 4.5 miles (7.2 km) long and 3.5 miles (5.6 km) wide, located 24 miles (39 km) due west of Sakhalin Island at 46°15′N 141°14′E / 46.250°N 141.233°E; it is the only land mass in the whole Tatar Straits.

Search for KAL 007 in international waters

[edit]

Immediately after the shoot-down, South Korea, the owner of the aircraft and therefore prime considerant for jurisdiction, designated the United States and Japan as search and salvage agents, thereby making it illegal for the Soviet Union to salvage the aircraft, providing it was found outside Soviet territorial waters. If it did so, the United States would now be legally entitled to use force against the Soviets, if necessary, to prevent retrieval of any part of the plane.[71]

On the same day as the shoot-down, Rear Admiral William A. Cockell, Commander, Task Force 71, and a skeleton staff, taken by helicopter from Japan, embarked in USS Badger (stationed off Vladivostok at time of the flight)[71] on September 9 for further transfer to the destroyer USS Elliot to assume duties as Officer in Tactical Command (OTC) of the Search and Rescue (SAR) effort. A surface search began immediately and on into September 13. U.S. underwater operations began on September 14. On September 10, 1983, with no further hope of finding survivors, Task Force 71's mission was reclassified from a "Search and Rescue" (SAR) operation to a "Search and Salvage" (SAS).[72]

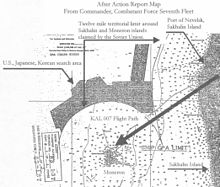

On October 17, Rear Admiral Walter T. Piotti, Jr. took command of the task force and its search and salvage mission from Rear Admiral Cockell. First to be searched was a 60-square-mile (160 km2) "high probability" area. This was unsuccessful. On October 21, Task Force 71 extended its search within coordinates encompassing, in an arc around the Soviet territorial boundaries north of Moneron Island, an area of 225 square miles (583 km2), reaching to the west of Sakhalin Island. This was the "large probability" area. The search areas were outside the 12-nautical-mile (22 km) Soviet-claimed territorial boundaries. The northwesternmost point of the search touched the Soviet territorial boundary closest to the naval port of Nevelsk on Sakhalin. Nevelsk was 46 nautical miles (85 km) from Moneron. This larger search was also unsuccessful.[72]

The vessels used in the search, for the Soviet side as well as the US side (US, South Korea, Japan) were both civilian trawlers, specially equipped for both the SAR and SAS operations, and various types of warships and support ships. The Soviet side also employed both civilian and military divers. The Soviet search, beginning on the day of the shoot-down and continuing until November 6, was confined to the 60-square-mile (160 km2) "high probability" area in international waters, and within Soviet territorial waters to the north of Moneron Island. The area within Soviet territorial waters was off-limits to the U.S., South Korean, and Japanese boats. From September 3 to 29, four ships from South Korea joined in the search.

Piotti Jr, commander of Task Force 71 of the 7th Fleet would summarize the US and Allied, and then the Soviets', Search and Salvage operations:

Not since the search for the hydrogen bomb lost off Palomares, Spain, has the U.S. Navy undertaken a search effort of the magnitude or import of the search for the wreckage of KAL Flight 007.

Within six days of the downing of KAL 007, the Soviets had deployed six ships to the general crash site area. Over the next 8 weeks of observation by U.S. naval units this number grew to a daily average of 19 Soviet naval, naval-associated, and commercial (but undoubtedly naval-subordinated) ships in the Search and Salvage (SAS) area. The number of Soviet ships in the SAS area over this period ranged from a minimum of six to a maximum of thirty-two and included at least forty-eight different ships comprising forty different ship classes.[73]

These missions met with interference by the Soviets,[74] in violation of the 1972 Incidents at Sea agreement, and included false flag and fake light signals, sending an armed boarding party to threaten to board a U.S.-chartered Japanese auxiliary vessel (blocked by U.S. warship interposition), interfering with a helicopter coming off the USS Elliot (Sept. 7), attempted ramming of rigs used by the South Koreans in their quadrant search, hazardous maneuvering of Gavril Sarychev and near-collision with the USS Callaghan (September 15, 18), removing U.S. sonars, setting false pingers in deep international waters, sending Backfire bombers armed with air-to-surface nuclear-armed missiles to threaten U.S. naval units, criss-crossing in front of U.S. combatant vessels (October 26), cutting and attempted cutting of moorings of Japanese auxiliary vessels, particularly Kaiko Maru III, and radar lock-ons by a Soviet Kara-class cruiser, Petropavlovsk, and a Kashin-class destroyer, Odarennyy, targeting U.S. naval ships and the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter USCGC Douglas Munro (WHEC-724), USS Towers, escorting USS Conserver, experienced all of the above interference and was involved in a near-collision with Odarennyy (September 23–27).[75][76]

According to the ICAO: "The location of the main wreckage was not determined... the approximate position was 46°34′N 141°17′E / 46.567°N 141.283°E, which was in international waters." This point is about 41 miles (66 km) from Moneron Island, about 45 miles (72 km) from the shore of Sakhalin and 33 miles (53 km) from the point of attack.[77]

Piotti Jr, commander of Task Force 71 of 7th Fleet, believed the search for KAL 007 in international waters to have been a search in the wrong place and assessed:[78]

Had TF [task force] 71 been permitted to search without restriction imposed by claimed territorial waters, the aircraft stood a good chance of having been found. No wreckage of KAL 007 was found. However, the operation established, with a 95% or above confidence level, that the wreckage, or any significant portion of the aircraft, does not lie within the probability area outside the 12 nautical mile area claimed by the Soviets as their territorial limit.[45]

At a hearing of the ICAO on September 15, 1983, J. Lynn Helms, the head of the Federal Aviation Administration, stated:[5] "The USSR has refused to permit search and rescue units from other countries to enter Soviet territorial waters to search for the remains of KAL 007. Moreover, the Soviet Union has blocked access to the likely crash site and has refused to cooperate with other interested parties, to ensure prompt recovery of all technical equipment, wreckage, and other material."

Human remains and artifacts

[edit]Surface finds

[edit]No body parts were recovered by the Soviet search team from the surface of the sea in their territorial waters, though they would later turn over clothes and shoes to a joint U.S.–Japanese delegation at Nevelsk on Sakhalin. On Monday, September 26, 1983, a delegation of seven Japanese and U.S. officials arriving aboard the Japanese patrol boat Tsugaru, had met a six-man Soviet delegation at the port of Nevelsk on Sakhalin Island. KGB Major General A. I. Romanenko, the Commander of the Sakhalin and Kuril Islands frontier guard, headed the Soviet delegation. Romanenko handed over to the U.S. and the Japanese, among other things, single and paired footwear. With footwear that the Japanese also retrieved, the total came to 213 men's, women's, and children's dress shoes, sandals, and sports shoes.[79] The Soviets indicated these items were all that they had retrieved floating or on the shores of Sakhalin and Moneron islands.

Family members of KAL 007 passengers later stated that these shoes were worn by their loved ones for the flight. Sonia Munder had no difficulty recognizing the sneakers of her children, one from Christian, age 14, and one from Lisi, age 17, by the intricate way her children laced them. Another mother says, "I recognized them just like that. You see, there are all kinds of inconspicuous marks that strangers do not notice. This is how I recognized them. My daughter loved to wear them."[80]

Another mother, Nan Oldham, identified her son John's sneakers from a photo in Life magazine of 55 of the 213 shoes—apparently a random array on display those first days at Chitose Air Force Base in Japan. "We saw photos of his shoes in a magazine," says Oldham, "We followed up through KAL and a few weeks later, a package arrived. His shoes were inside: size 11 sneakers with cream white paint."[81] John Oldham had taken his seat in row 31 of KAL 007 wearing those cream white paint-spattered sneakers.[81]

Nothing was found by the joint U.S.–Japanese–South Korean search and rescue/salvage operations in international waters at the designated crash site or within the 225-square-nautical-mile (770 km2) search area.[82]

Hokkaido finds

[edit]Eight days after the shoot-down, human remains and other types of objects appeared on the north shore of Hokkaido, Japan. Hokkaido is about 30 miles (48 km) below the southern tip of Sakhalin across the La Pérouse Strait (the southern tip of Sakhalin is 35 miles (56 km) from Moneron Island which is west of Sakhalin). The ICAO concluded that these bodies, body parts, and objects were carried from Soviet waters to the shores of Hokkaido by the southerly current west of Sakhalin Island. All currents of the Strait of Tartary relevant to Moneron Island flow to the north, except this southerly current between Moneron Island and Sakhalin Island.[83]

These human remains, including body parts, tissues, and two partial torsos, totaled 13. All were unidentifiable, but one partial torso was that of a Caucasian woman as indicated by auburn hair on a partial skull, and one partial body was of an Asian child (with glass embedded). There was no luggage recovered. Of the non-human remains that the Japanese recovered were various items including dentures, newspapers, seats, books, eight KAL paper cups, shoes, sandals, and sneakers, a camera case, a "please fasten seat belt" sign, an oxygen mask, a handbag, a bottle of dishwashing fluid, several blouses, an identity card belonging to 25-year-old passenger Mary Jane Hendrie of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada, and the business cards of passengers Kathy Brown-Spier and Mason Chang.[84][85] These items generally came from the passenger cabin of the aircraft. None of the items found generally came from the cargo hold of the plane, such as suitcases, packing boxes, industrial machinery, instruments, and sports equipment.

Russian diver reports

[edit]

In 1991, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian newspaper Izvestia published a series of interviews with Soviet military personnel who had been involved in salvage operations to find and recover parts of the aircraft.[44] After three days of searching using trawlers, side-scan sonar, and diving bells, Soviet searchers located the aircraft wreckage at a depth of 174 metres (571 ft) near Moneron Island.[44][86] Since no human remains or luggage were found on the surface in the impact area, the divers expected to find the remains of passengers who had been trapped in the submerged wreckage of the aircraft on the seabed. When they visited the site two weeks after the shoot-down, they found that the wreckage was in small pieces, and found no bodies:

I had the idea that it would be intact. Well, perhaps a little banged up... The divers would go inside the aircraft and see everything there was to see. In fact, it was completely demolished, scattered about like kindling. The largest things we saw were the braces which are especially strong—they were about one and a half or two meters long and 50–60 centimeters wide. As for the rest—broken into tiny pieces...[44]

According to Izvestia, the divers had only ten encounters with passenger remains (tissues and body parts) in the debris area, including one partial torso.[87]

Tinro ll submersible Captain Mikhail Igorevich Girs' diary: Submergence 10 October. Aircraft pieces, wing spars, pieces of aircraft skin, wiring, and clothing. But—no people. The impression is that all of this has been dragged here by a trawl rather than falling down from the sky...[88]

Vyacheslav Popov: "I will confess that we felt great relief when we found out that there were no bodies at the bottom. Not only were no bodies; there were also no suitcases or large bags. I did not miss a single dive. I have quite a clear impression: The aircraft was filled with garbage, but there were really no people there. Why? Usually when an aircraft crashes, even a small one... As a rule, there are suitcases and bags, or at least the handles of the suitcases."[citation needed]

A number of civilian divers, whose first dive was on September 15, two weeks after the shoot-down, state that Soviet military divers and trawls had been at work before them:

Diver Vyacheslav Popov: "As we learned then, before us the trawlers had done some 'work' in the designated quadrant. It is hard to understand what sense the military saw in the trawling operation. First, drag everything haphazardly around the bottom by the trawls, and then send in the submersibles?...It is clear that things should have been done in the reverse order."

ICAO also interviewed a number of these divers for its 1993 report: "In addition to the scraps of metal, they observed personal items, such as clothing, documents, and wallets. Although some evidence of human remains was noticed by the divers, they found no bodies."[89]

Political events

[edit]Initial Soviet denial

[edit]General Secretary Yuri Andropov, on the advice of Defense Minister Dmitriy Ustinov, but against the advice of the Foreign Ministry, initially decided not to make any admission of downing the airliner, on the premise that no one would find out or be able to prove otherwise.[68] Consequently the TASS news agency reported twelve hours after the shoot-down only that an unidentified aircraft, flying without lights, had been intercepted by Soviet fighters after it violated Soviet airspace over Sakhalin. The aircraft had allegedly failed to respond to warnings and "continued its flight toward the Sea of Japan".[68][90] Some commentators believe that the inept manner in which the political events were handled by the Soviet government[91] was affected by the failing health of Andropov, who was permanently hospitalised in late September or early October 1983 (Andropov died the following February).[92]

In a 2015 interview Igor Kirillov, the senior Soviet news anchor said that he was initially given a printed TASS report to announce over the news on September 1, which included an "open and honest" admission that the plane was shot down by mistake (a wrong judgment call by the Far Eastern Air Defence Command). However, at the moment the opening credits of the Vremya evening news programme rolled in, an editor ran in and snatched the sheet of paper from his hand, handing him another TASS report which was "completely opposite" to the first one and to the truth.[93]

U.S. reaction and further developments

[edit]

The shoot-down happened at a very tense time in the U.S.–Soviet relations during the Cold War. The U.S. adopted a strategy of releasing a substantial amount of hitherto highly classified intelligence information in order to exploit a major propaganda advantage over the Soviet Union.[94]

Six hours after the plane was downed, the South Korean government issued an announcement that the plane had merely been forced to land abruptly by the Soviets and that all passengers and crew were safe.[95][page needed] U.S. Secretary of State George P. Shultz held a press conference about the incident at 10:45 on September 1, during which he divulged some details of intercepted Soviet communications and denounced the actions of the Soviet Union.[90]

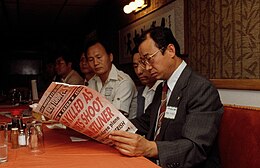

On September 5, 1983, President Reagan condemned the shooting down of the airplane as the "Korean airline massacre", a "crime against humanity [that] must never be forgotten" and an "act of barbarism... [and] inhuman brutality".[96] The following day, the U.S. ambassador to the UN Jeane Kirkpatrick delivered an audio-visual presentation in the United Nations Security Council, using audio tapes of the Soviet pilots' radio conversations and a map of Flight 007's path in depicting its shooting down. Following this presentation, TASS acknowledged for the first time that the aircraft had indeed been shot down after warnings were ignored. The Soviets challenged many of the facts presented by the U.S. and revealed the previously unknown presence of a USAF RC-135 surveillance aircraft whose path had crossed that of KAL 007.

On September 7, Japan and the United States jointly released a transcript of Soviet communications, intercepted by the listening post at Wakkanai, to an emergency session of the United Nations Security Council.[97] Reagan issued a National Security Directive stating that the Soviets were not to be let off the hook, and initiating "a major diplomatic effort to keep international and domestic attention focused on the Soviet action".[36] The move was seen by the Soviet leadership as confirmation of the West's bad intentions.

A high-level U.S.–Soviet summit, the first in nearly a year, was scheduled for September 8, 1983, in Madrid.[68] The Shultz–Gromyko meeting went ahead but was overshadowed by the KAL 007 events.[68] It ended acrimoniously, with Shultz stating: "Foreign Minister Gromyko's response to me today was even more unsatisfactory than the response he gave in public yesterday. I find it totally unacceptable."[68] Reagan ordered the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) on September 15, 1983, to revoke the license of Aeroflot Soviet Airlines to operate flights to and from the United States. Aeroflot flights to North America were consequently available only through Canadian and Mexican cities, forcing the Soviet foreign minister to cancel his scheduled trip to the UN. Aeroflot service to the U.S. was not restored until April 29, 1986.[98]

An emergency session of the ICAO was held in Montreal, Canada.[99] On September 12, 1983, the Soviet Union used its veto to block a United Nations resolution condemning it for shooting down the aircraft.[67]

Shortly after the Soviet Union shot down KAL 007, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, operating the commercial airports around New York City, denied Soviet aircraft landing rights, in violation of the United Nations Charter that required the host nation to allow all member countries access to the UN. In reaction, TASS and some at the UN raised the question of whether the UN should move its headquarters from the United States. Charles Lichenstein, acting U.S. permanent representative to the UN under Ambassador Kirkpatrick, responded, "We will put no impediment in your way. The members of the U.S. mission to the United Nations will be down at the dockside waving you a fond farewell as you sail off into the sunset." Administration officials were quick to announce that Lichenstein was speaking only for himself.[100]

In the Cold War context of Operation RYAN, the Strategic Defence Initiative, Pershing II missile deployment in Europe, and the upcoming Exercise Able Archer, the Soviet Government perceived the incident with the South Korean airliner to be a portent of war.[92] The Soviet hierarchy took the official line that KAL Flight 007 was on a spy mission, as it "flew deep into Soviet territory for several hundred kilometres [miles], without responding to signals and disobeying the orders of interceptor fighter planes".[3] They claimed its purpose was to probe the air defences of highly sensitive Soviet military sites in the Kamchatka Peninsula and Sakhalin Island.[3] The Soviet government expressed regret over the loss of life, but offered no apology and did not respond to demands for compensation.[101] Instead, the Soviet Union blamed the CIA for this "criminal, provocative act".[3]

In a comparative study of the two tragedies published in 1991, political scientist Robert Entman points out that with KAL 007, "the angle taken by the US media emphasised the moral bankruptcy and guilt of the perpetrating nation. With Iran Air 655, the frame de-emphasised guilt and focused on the complex problems of operating military high technology".[102]

Investigations

[edit]NTSB

[edit]Since the aircraft had departed from U.S. soil and U.S. nationals had died in the incident, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) was legally required to investigate. On the morning of September 1, the NTSB chief in Alaska, James Michelangelo, received an order from the NTSB in Washington at the behest of the State Department requiring all documents relating to the NTSB investigation to be sent to Washington and notifying him that the State Department would now conduct the investigation.[103]

The U.S. State Department, after closing the NTSB investigation on the grounds that it was not an accident, pursued an ICAO investigation instead. Commentators such as Johnson point out that this action was illegal, and that in deferring the investigation to the ICAO, the Reagan administration effectively precluded any politically or militarily sensitive information from being subpoenaed that might have embarrassed the administration or contradicted its version of events.[104] Unlike the NTSB, ICAO can subpoena neither persons nor documents and is dependent on the governments involved—in this incident, the United States, the Soviet Union, Japan, and South Korea—to supply evidence voluntarily.

Initial ICAO investigation (1983)

[edit]The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) had only one experience of investigation of an air disaster before the KAL 007 shoot-down. This was the incident of February 21, 1973, when Libyan Arab Airlines Flight 114 was shot down by Israeli F-4 jets over the Sinai Peninsula. ICAO convention required the state in whose territory the incident had taken place (the Soviet Union) to conduct an investigation together with the country of registration (South Korea), the country whose air traffic control the aircraft was flying under (Japan), as well as the country of the aircraft's manufacturer (US).

The ICAO investigation, led by Caj Frostell,[105] did not have the authority to compel the states involved to hand over evidence, instead having to rely on what they voluntarily submitted.[106] Consequently, the investigation did not have access to sensitive evidence such as radar data, intercepts, ATC tapes, or the Flight Data Recorder (FDR) and Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) (whose discovery the U.S.S.R. had kept secret). A number of simulations were conducted with the assistance of Boeing and Litton (the manufacturer of the navigation system).[107]

The ICAO released their report on December 2, 1983, which concluded that the violation of Soviet airspace was accidental: One of two explanations for the aircraft's deviation was that the autopilot had remained in HEADING hold instead of INS mode after departing Anchorage. They postulated that this inflight navigational error was caused by either the crew's failure to select INS mode or the inertial navigation not activating when selected because the aircraft was already too far off track.[26] It was determined that the crew did not notice this error or subsequently perform navigational checks, which would have revealed that the aircraft was diverging further and further from its assigned route. This was later deemed to be caused by a "lack of situational awareness and flight deck coordination".[108]

The report included a statement by the Soviet Government claiming "no remains of the victims, the instruments or their components or the flight recorders have so far been discovered".[109] This statement was subsequently shown to be untrue by Boris Yeltsin's release in 1993 of a November 1983 memo from KGB head Viktor Chebrikov and Defence Minister Dmitriy Ustinov to Yuri Andropov. This memo stated, "In the third decade of October this year the equipment in question (the recorder of in-flight parameters and the recorder of voice communications by the flight crew with ground air traffic surveillance stations and between themselves) was brought aboard a search vessel and forwarded to Moscow by air for decoding and translation at the Air Force Scientific Research Institute."[110] The Soviet Government statement would further be contradicted by Soviet civilian divers who later recalled that they viewed the wreckage of the aircraft on the bottom of the sea for the first time on September 15, two weeks after the plane had been shot down.[111]

Following the publication of the report, the ICAO adopted a resolution condemning the Soviet Union for the attack.[112] Furthermore, the report led to a unanimous amendment in May 1984—though not coming into force until October 1, 1998—to the Convention on International Civil Aviation that defined the use of force against civilian airliners in more detail.[113] The amendment to section 3(d) reads in part: "The contracting States recognize that every State must refrain from resorting to the use of weapons against civil aircraft in flight and that, in case of interception, the lives of persons on board and the safety of aircraft must not be endangered."[114]

U.S. Air Force radar data

[edit]It is customary for the Air Force to impound radar trackings involving possible litigation in cases of aviation accidents.[115] In the civil litigation for damages, the United States Department of Justice explained that the tapes from the Air Force radar installation at King Salmon, Alaska, pertinent to KAL 007's flight in the Bethel area had been destroyed and could therefore not be supplied to the plaintiffs. At first Justice Department lawyer Jan Van Flatern stated that they were destroyed 15 days after the shoot-down. Later, he said he had "misspoken" and changed the time of destruction to 30 hours after the event. A Pentagon spokesman concurred, saying that the tapes are recycled for re-use from 24–30 hours afterward;[116] the fate of KAL 007 was known inside this timeframe.[115]

Interim developments

[edit]

Hans Ephraimson-Abt, whose daughter Alice Ephraimson-Abt had died on the flight, chaired the American Association for Families of KAL 007 Victims. He single-handedly pursued three U.S. administrations for answers about the flight, flying to Washington 250 times and meeting with 149 State Department officials. Following the dissolution of the U.S.S.R., Ephraimson-Abt persuaded U.S. Senators Ted Kennedy, Sam Nunn, Carl Levin, and Bill Bradley to write to the Soviet President, Mikhail Gorbachev requesting information about the flight.[117]

Glasnost reforms in the same year brought about a relaxation of press censorship; consequently reports started to appear in the Soviet press suggesting that the Soviet military knew the location of the wreckage and had possession of the flight data recorders.[44][118] On December 10, 1991, Senator Jesse Helms of the Committee on Foreign Relations, wrote to Boris Yeltsin requesting information concerning the survival of passengers and crew of KAL 007 including the fate of Congressman Larry McDonald.[119]

17 июня 1992 года президент Ельцин сообщил, что после неудавшейся попытки государственного переворота в 1991 году были предприняты согласованные попытки найти документы советской эпохи, относящиеся к KAL 007. Он упомянул об обнаружении «меморандума КГБ Центральному комитету Коммунистической партии». ", заявив, что произошла трагедия, и добавив, что есть документы, "которые прояснят всю картину". Ельцин заявил, что в меморандуме далее говорится, что "эти документы настолько хорошо спрятаны, что сомнительно, что наши дети смогут их найти". [120] 11 сентября 1992 года Ельцин официально признал существование самописцев и пообещал предоставить правительству Южной Кореи стенограмму содержимого бортовых самописцев, обнаруженную в файлах КГБ.

В октябре 1992 года Ханс Эфраимсон-Абт возглавил делегацию семей и представителей Госдепартамента США в Москву по приглашению президента Ельцина. [121] Во время торжественной церемонии в Екатерининском зале Кремля делегации семьи КАЛ был вручен портфель, содержащий частичные расшифровки диктофона кабины КАЛ 007, переведенные на русский язык, и документы Политбюро, имеющие отношение к трагедии.

Во время официального визита в Сеул в ноябре 1992 года с целью улучшения двусторонних отношений президент Ельцин вручил президенту Кореи Но Тэ У два контейнера для магнитофонов , но не сами кассеты. В следующем месяце ИКАО проголосовала за возобновление расследования KAL 007, чтобы принять во внимание недавно опубликованную информацию. Ленты были переданы в ИКАО в Париже 8 января 1993 года. [7] Тогда же были переданы и записи переговоров советских военных «земля-воздух». [122] Записи были расшифрованы Бюро опросов и анализа по безопасности гражданской авиации (BEA) в Париже в присутствии представителей Японии, Российской Федерации, Южной Кореи и США. [122]

Официальное расследование, проведенное Российской Федерацией в 1993 году, сняло с советской иерархии вину, установив, что инцидент был случаем ошибочной идентификации. [92] 28 мая 1993 года ИКАО представила свой второй доклад Генеральному секретарю ООН .

Советские меморандумы

[ редактировать ]

В 1992 году президент России Борис Ельцин раскрыл пять сверхсекретных записок, датированных несколькими неделями после крушения KAL 007 в 1983 году. [примечание 4] В записках содержались советские сообщения (от главы КГБ Виктора Чебрикова и министра обороны Дмитрия Устинова генеральному секретарю Юрию Андропову), в которых указывалось, что они знали местонахождение обломков KAL 007, когда имитировали поиск и преследовали американский флот; искомый диктофон в кабине экипажа они нашли 20 октября 1983 года (через 50 дней после инцидента), [123] и решили сохранить эти сведения в секрете, поскольку записи не могли однозначно подтвердить их твердое мнение о том, что полет KAL 007 на советскую территорию был намеренно спланированной разведывательной миссией. [124] [125]

В настоящее время нашими судами проводятся имитационные поисковые работы в Японском море с целью дезинформации США и Японии. Данная деятельность будет прекращена в соответствии с конкретным планом...

Поэтому, если бортовые самописцы будут переданы западным странам, их объективные данные могут в равной степени быть использованы СССР и западными странами для доказательства противоположных точек зрения на характер полета южнокорейского самолета. В таких условиях нельзя исключать новую фазу антисоветской истерии.

В связи со всем вышеизложенным представляется весьма предпочтительным не передавать бортовые самописцы Международной организации гражданской авиации (ИКАО) или какой-либо третьей стороне, желающей расшифровать их содержимое. Тот факт, что самописцы находятся в распоряжении СССР, должен храниться в тайне...

Насколько нам известно, ни США, ни Япония не имеют никакой информации о бортовых самописцах. Мы предприняли необходимые усилия, чтобы предотвратить любое раскрытие информации в будущем.

Ждем вашего одобрения.

D. Ustinov, V. Chebrikov (photo) [примечание 5] декабрь 1983 г.

В третьей записке подтверждается, что анализ записей самописца не выявил никаких доказательств попыток советского перехватчика связаться с KAL 007 по радио, а также никаких указаний на то, что KAL 007 был произведен предупредительные выстрелы.

Однако в случае, если бортовые самописцы станут доступны западным странам, их данные могут быть использованы для подтверждения отсутствия попыток перехватывающего самолета установить радиосвязь с самолетом-нарушителем на частоте 121,5 МГц и отсутствия предупредительных выстрелов трассеров на последнем участке полета. [126]

О том, что советские поиски были смоделированы (хотя они знали, что обломки лежат в другом месте), свидетельствует и статья заместителя директора Российского государственного архива новейшей истории Михаила Прозуменщикова , посвященная двадцатой годовщине сбития самолета. Комментируя советские и американские поиски: "Поскольку СССР по естественным причинам лучше знал, где был сбит Боинг... вернуть что-либо было очень проблематично, тем более, что СССР особо не интересовался". [127]

Пересмотренный отчет ИКАО (1993 г.)

[ редактировать ]18 ноября 1992 года президент России Борис Ельцин в знак доброй воли Южной Корее во время визита в Сеул для ратификации нового договора выпустил в свет самописец полетных данных (FDR) и диктофон кабины (CVR) KAL 007. [128] Первоначальные южнокорейские исследования показали, что FDR пуст, а CVR имеет неразборчивую копию. Затем русские передали записи генеральному секретарю ИКАО. [129] Отчет ИКАО продолжает поддерживать первоначальное утверждение о том, что KAL 007 случайно пролетел в советском воздушном пространстве. [108] после прослушивания разговоров летного экипажа, записанных CVR, и подтверждения того, что либо самолет летел по постоянному магнитному курсу вместо активации ИНС и следовал назначенным путевым точкам, либо, если он активировал ИНС, он был активирован, когда самолет уже отклонился за пределы 7 1 / 2 — морская миля Конверт желаемого пути, в пределах которого должны быть зафиксированы путевые точки.

Кроме того, Российская Федерация предоставила ИКАО стенограммы «Стенограммы переговоров. Командные центры ПВО СССР на острове Сахалин» - это новое доказательство послужило основой для пересмотренного отчета ИКАО в 1993 году «Отчет о завершении расследования по установлению фактов». [130] и присоединяется к нему. Эти расшифровки (две катушки ленты, каждая из которых содержит несколько дорожек) представляют собой, с точностью до секунды, записи переговоров между различными командными пунктами и другими военными объектами на Сахалине с момента первоначального приказа о сбитии и затем через преследование KAL 007 майором Осиповичем на его перехватчике Су-15, нападение, как его видел и комментировал генерал Корнуков, командующий авиабазой «Сокол» , вплоть до боевого диспетчера капитана Титовнина. [131]

Стенограммы включают в себя полет KAL 007 после нападения, пока он не достиг острова Монерон, спуск KAL 007 над Монероном, первые советские поисково-спасательные миссии на Монерон, тщетные поиски вспомогательных перехватчиков KAL 007 на воде и окончание с разбором полетов Осиповича по возвращении на базу. Некоторые виды связи представляют собой телефонные разговоры между вышестоящими офицерами и подчиненными и включают в себя команды, подаваемые им, в то время как другие коммуникации включают записанные ответы на то, что затем просматривалось на радаре слежения KAL 007. Эти многоканальные сообщения с различных командных пунктов, осуществляющие телекоммуникационную связь на те же минуты и секунды, в течение которых общались другие командные пункты, дают «композитную» картину происходящего. [131]

Данные CVR и FDR показали, что записи прервались после первой минуты и 44 секунд 12-минутного полета KAL 007 после взрыва ракеты. Оставшиеся минуты полета будут предоставлены Россией в 1992 году, представившей в ИКАО советские военные сообщения в режиме реального времени о сбитии и последствиях. Тот факт, что обе ленты самописца остановились точно в одно и то же время через 1 минуту и 44 секунды после взрыва ракеты (18:38:02 UTC) без частей ленты в течение более чем 10 минут полета KAL 007 после взрыва, прежде чем он опустился за пределы радара. слежение (18:38 UTC) не находит объяснения в анализе ИКАО: «Не удалось установить, почему оба бортовых самописца одновременно перестали работать через 104 секунды после атаки. Кабели электропитания подведены к задней части самолета по кабельным каналам на противоположных сторонах фюзеляжа, пока они не сошлись за двумя записывающими устройствами». [52]

Боль и страдания пассажиров

[ редактировать ]пассажиров Боль и страдания были важным фактором при определении уровня компенсации, выплачиваемой Korean Air Lines.

Осколки ракеты класса «воздух-воздух» Р-98 средней дальности с неконтактным взрывателем , взорвавшиеся в 50 метрах (160 футов) за хвостом, вызвали пробои герметичного пассажирского салона . [64] Когда один из членов летного экипажа связался по радио с диспетчерской службой района Токио через минуту и две секунды после взрыва ракеты, его дыхание уже было «усиленным», что указывало аналитикам ИКАО на то, что он говорил через микрофон, расположенный в его кислородной маске: «Korean Air 007 ах.. .Мы... Быстрое сжатие до 10 000». [132]

Два свидетеля-эксперта давали показания на суде перед тогдашним мировым судьей Наоми Райс Бухвальд из Окружного суда США Южного округа Нью-Йорка. Они затронули проблему предсмертной боли и страданий. Капитан Джеймс Макинтайр, опытный пилот Боинга 747 и следователь авиационных происшествий, показал, что осколки ракеты вызвали быструю декомпрессию салона, но оставили пассажирам достаточно времени, чтобы надеть кислородные маски: «Макинтайр показал, что, основываясь на его оценке По мнению эксперта Макинтайра, между попаданием шрапнели и падением самолета прошло не менее 12 минут, и пассажиры все время оставались в сознании. ." [133]

Альтернативные теории

[ редактировать ]Рейс 007 был предметом постоянных споров и породил ряд теорий заговора . [134] Многие из них основаны на сокрытии таких доказательств, как самописцы полетных данных, [123] необъяснимые детали, такие как роль самолета-разведчика ВВС США RC-135 , [39] [135] несвоевременное уничтожение данных радара King Salmon ВВС США, дезинформация и пропаганда времен Холодной войны, а также заявление Геннадия Осиповича (советского летчика-истребителя, сбившего рейс 007) о том, что, хотя он знал, что это был гражданский самолет, он подозревал, что он мог использовался как самолет-разведчик. [136] [137] [138]

Последствия

[ редактировать ]

Об этом инциденте было снято два телевизионных фильма; оба фильма были сняты до того, как распад Советского Союза позволил получить доступ к архивам. «Стрельба» (1988), телефильм с Анджелой Лэнсбери , Джоном Каллумом и Кайлом Секором в главных ролях , был основан на одноименной книге Р. У. Джонсона о попытках Нэн Мур (Лэнсбери), матери пассажира, получить ответы. со стороны правительств США и СССР. британского телевидения Гранады « Затем документальная драма Кодированный враждебно» , показанная на канале ITV 7 сентября 1989 года, подробно описала военное и правительственное расследование США, подчеркнув вероятную путаницу рейса 007 с самолетом ВВС США RC-135 в контексте обычных миссий SIGINT / COMINT США. в этом районе. Написанный Брайаном Феланом и поставленный Дэвидом Дарлоу , в нем снимались Майкл Мерфи , Майкл Мориарти и Крис Сарандон . Обновленная версия была показана на канале Channel 4 в Великобритании 31 августа 1993 года и включала подробности расследования ООН 1992 года.

26 сентября 1983 года произошел инцидент ложной ядерной тревоги , который едва не привел к ядерной войне. После сбития авиалайнера советская военная система была настроена на обнаружение первого удара и немедленное принятие ответных мер, а оптическая иллюзия привела к неисправности системы раннего предупреждения и срабатыванию ложной тревоги.

Дыхательные пути закрыты

[ редактировать ]2 сентября ФАУ временно закрыло Airway R-20, воздушный коридор, по которому должен был следовать рейс 007 Korean Air. [139] Авиакомпании яростно сопротивлялись закрытию этого популярного маршрута, самого короткого из пяти коридоров между Аляской и Восточной Азией. Поэтому 2 октября он был вновь открыт после проверки средств безопасности и навигации. [140] [141]

Под руководством администрации Рейгана НАТО приняло решение разместить «Першинг-2» и крылатые ракеты «Грифон» в Западной Германии . [142] В результате такого развертывания ракеты были бы размещены всего на расстоянии 6–10 минут удара от Москвы. [ нужна ссылка ] Поддержка развертывания колебалась, и казалось сомнительным, что оно будет осуществлено. Когда Советский Союз сбил рейс 007, США смогли заручиться достаточной поддержкой внутри страны и за рубежом, чтобы развертывание могло продолжиться. [143]

Беспрецедентное раскрытие сообщений, перехваченных Соединенными Штатами и Японией, позволило раскрыть значительный объем информации об их разведывательных системах и возможностях. Агентства национальной безопасности Директор Линкольн Д. Форер прокомментировал: «...в результате дела Korean Air Lines за последние две недели вы уже услышали о моем бизнесе больше, чем мне хотелось бы... По большей части это это не было результатом нежелательных утечек информации. Это результат сознательного и ответственного решения разобраться с невероятным ужасом». [144] Изменения, которые Советы впоследствии внесли в свои коды и частоты, снизили эффективность этого мониторинга на 60%. [145]

Ассоциация жертв катастрофы KAL 007 США под руководством Ханса Эфраимсона-Абта успешно лоббировала Конгресс США и авиационную отрасль с целью принятия соглашения, которое гарантировало бы, что будущие жертвы авиационных происшествий будут получать быструю и справедливую компенсацию за счет увеличения размера компенсации и снижения размера вознаграждения. бремя доказывания неправомерных действий авиалайнера. [121] Этот закон имел далеко идущие последствия для жертв последующих авиакатастроф.

США решили использовать военные радары , чтобы расширить зону действия радаров управления воздушным движением с 200 до 1200 миль (от 320 до 1930 км) от Анкориджа. [примечание 7] ФАУ также установило вторичную радиолокационную систему (ATCBI-5) на острове Сент-Пол . В 1986 году США, Япония и Советский Союз создали совместную систему управления воздушным движением для наблюдения за самолетами над северной частью Тихого океана, тем самым возложив на Советский Союз официальную ответственность за наблюдение за гражданским воздушным движением и установив прямую связь между диспетчерами. из трёх стран. [146]

16 сентября 1983 года пресс-секретарь Белого дома зачитал заявление о сбитии рейса 007 Korean Air Lines. Сообщается, что система GPS должна быть доступна для гражданской авиации с запланированным завершением в 1988 году. [147] Это сообщение иногда понималось как обнародование военного проекта для широкой публики. Однако система GPS с самого начала разрабатывалась для военной и гражданской навигации. [148]

Регулярное воздушное сообщение между Сеулом и Москвой началось в апреле 1990 года в результате Nordpolitik политики Южной Кореи , которой управляли Аэрофлот и Korean Air ; Между тем, все девять европейских маршрутов Korean Air начнут проходить через советское воздушное пространство. Это был первый раз, когда самолету Korean Air было официально разрешено пролетать через воздушное пространство СССР. [149]