T. S. Eliot

T. S. Eliot | |

|---|---|

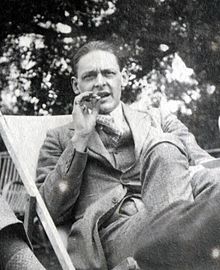

Eliot in 1934 | |

| Born | Thomas Stearns Eliot 26 September 1888 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | 4 January 1965 (aged 76) London, England |

| Occupation |

|

| Citizenship |

|

| Education | |

| Period | 1905–1965 |

| Literary movement | Modernism |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouses | |

| Parents | |

| Relatives | Eliot family |

| Signature | |

Thomas Stearns Eliot OM (26 September 1888 – 4 January 1965) was a poet, essayist and playwright.[1] He is considered to be one of the 20th century's greatest poets, as well as a central figure in English-language Modernist poetry. His use of language, writing style, and verse structure reinvigorated English poetry. He is also noted for his critical essays, which often re-evaluated long-held cultural beliefs.[2]

Born in St. Louis, Missouri, to a prominent Boston Brahmin family, he moved to England in 1914 at the age of 25 and went on to settle, work, and marry there.[3] He became a British subject in 1927 at the age of 39 and renounced his American citizenship.[4]

Eliot first attracted widespread attention for his poem "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" from 1914 to 1915, which, at the time of its publication, was considered outlandish.[5] It was followed by The Waste Land (1922), "The Hollow Men" (1925), "Ash Wednesday" (1930), and Four Quartets (1943).[6] He wrote seven plays, notably Murder in the Cathedral (1935) and The Cocktail Party (1949). He was awarded the 1948 Nobel Prize in Literature, "for his outstanding, pioneer contribution to present-day poetry".[7][8]

Life

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]The Eliots were a Boston Brahmin family, with roots in England and New England. Eliot's paternal grandfather, William Greenleaf Eliot, had moved to St. Louis, Missouri,[6][9] to establish a Unitarian Christian church there. His father, Henry Ware Eliot, was a successful businessman, president and treasurer of the Hydraulic-Press Brick Company in St Louis. His mother, Charlotte Champe Stearns, who wrote poetry, was a social worker, which was a new profession in the U.S. in the early 20th century. Eliot was the last of six surviving children. Known to family and friends as Tom, he was the namesake of his maternal grandfather, Thomas Stearns.

Eliot's childhood infatuation with literature can be ascribed to several factors. First, he had to overcome physical limitations as a child. Struggling from a congenital double inguinal hernia, he could not participate in many physical activities and thus was prevented from socialising with his peers. As he was often isolated, his love for literature developed. Once he learned to read, the young boy immediately became obsessed with books, favouring tales of savage life, the Wild West, or Mark Twain's Tom Sawyer.[10] In his memoir about Eliot, his friend Robert Sencourt comments that the young Eliot "would often curl up in the window-seat behind an enormous book, setting the drug of dreams against the pain of living."[11] Secondly, Eliot credited his hometown with fuelling his literary vision: "It is self-evident that St. Louis affected me more deeply than any other environment has ever done. I feel that there is something in having passed one's childhood beside the big river, which is incommunicable to those people who have not. I consider myself fortunate to have been born here, rather than in Boston, or New York, or London."[12]

From 1898 to 1905, Eliot attended Smith Academy, the boys college preparatory division of Washington University, where his studies included Latin, Ancient Greek, French, and German. He began to write poetry when he was 14 under the influence of Edward Fitzgerald's translation of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. He said the results were gloomy and despairing and he destroyed them.[13] His first published poem, "A Fable For Feasters", was written as a school exercise and was published in the Smith Academy Record in February 1905.[14] Also published there in April 1905 was his oldest surviving poem in manuscript, an untitled lyric, later revised and reprinted as "Song" in The Harvard Advocate, Harvard University's student literary magazine.[15] He published three short stories in 1905, "Birds of Prey", "A Tale of a Whale" and "The Man Who Was King". The last mentioned story reflected his exploration of the Igorot Village while visiting the 1904 World's Fair of St. Louis.[16][17][18] His interest in indigenous peoples thus predated his anthropological studies at Harvard.[19]

Eliot lived in St. Louis, Missouri, for the first 16 years of his life at the house on Locust Street where he was born. After going away to school in 1905, he returned to St. Louis only for vacations and visits. Despite moving away from the city, Eliot wrote to a friend that "Missouri and the Mississippi have made a deeper impression on me than any other part of the world."[20]

Following graduation from Smith Academy, Eliot attended Milton Academy in Massachusetts for a preparatory year, where he met Scofield Thayer who later published The Waste Land. He studied at Harvard College from 1906 to 1909, earning a Bachelor of Arts in an elective program similar to comparative literature in 1909 and a Master of Arts in English literature the following year.[1][6] Because of his year at Milton Academy, Eliot was allowed to earn his Bachelor of Arts after three years instead of the usual four.[21] Frank Kermode writes that the most important moment of Eliot's undergraduate career was in 1908 when he discovered Arthur Symons's The Symbolist Movement in Literature. This introduced him to Jules Laforgue, Arthur Rimbaud, and Paul Verlaine. Without Verlaine, Eliot wrote, he might never have heard of Tristan Corbière and his book Les amours jaunes, a work that affected the course of Eliot's life.[22] The Harvard Advocate published some of his poems and he became lifelong friends with Conrad Aiken, the American writer and critic.[23]

After working as a philosophy assistant at Harvard from 1909 to 1910, Eliot moved to Paris where, from 1910 to 1911, he studied philosophy at the Sorbonne. He attended lectures by Henri Bergson and read poetry with Henri Alban-Fournier.[6][22] From 1911 to 1914, he was back at Harvard studying Indian philosophy and Sanskrit.[6][24] Whilst a member of the Harvard Graduate School, Eliot met and fell in love with Emily Hale.[25] Eliot was awarded a scholarship to Merton College, Oxford, in 1914. He first visited Marburg, Germany, where he planned to take a summer programme, but when the First World War broke out he went to Oxford instead. At the time so many American students attended Merton that the Junior Common Room proposed a motion "that this society abhors the Americanization of Oxford". It was defeated by two votes after Eliot reminded the students how much they owed American culture.[26]

Eliot wrote to Conrad Aiken on New Year's Eve 1914: "I hate university towns and university people, who are the same everywhere, with pregnant wives, sprawling children, many books and hideous pictures on the walls [...] Oxford is very pretty, but I don't like to be dead."[26] Escaping Oxford, Eliot spent much of his time in London. This city had a monumental and life-altering effect on Eliot for several reasons, the most significant of which was his introduction to the influential American literary figure Ezra Pound. A connection through Aiken resulted in an arranged meeting and on 22 September 1914, Eliot paid a visit to Pound's flat. Pound instantly deemed Eliot "worth watching" and was crucial to Eliot's fledgling career as a poet, as he is credited with promoting Eliot through social events and literary gatherings. Thus, according to biographer John Worthen, during his time in England Eliot "was seeing as little of Oxford as possible". He was instead spending long periods of time in London, in the company of Ezra Pound and "some of the modern artists whom the war has so far spared [...] It was Pound who helped most, introducing him everywhere."[27] In the end, Eliot did not settle at Merton and left after a year. In 1915 he taught English at Birkbeck College, University of London.[28]

In 1916, he completed a doctoral dissertation for Harvard on "Knowledge and Experience in the Philosophy of F. H. Bradley", but failed to return for the viva voce examination.[6][29]

Marriage

[edit]

Before leaving the US, Eliot had told Emily Hale that he was in love with her. He exchanged letters with her from Oxford during 1914 and 1915, but they did not meet again until 1927.[25][30] In a letter to Aiken late in December 1914, Eliot, aged 26, wrote: "I am very dependent upon women (I mean female society)."[31] Less than four months later, Thayer introduced Eliot to Vivienne Haigh-Wood, a Cambridge governess. They were married at Hampstead Register Office on 26 June 1915.[32]

After a short visit, alone, to his family in the United States, Eliot returned to London and took several teaching jobs, such as lecturing at Birkbeck College, University of London. The philosopher Bertrand Russell took an interest in Vivienne while the newlyweds stayed in his flat. Some scholars have suggested that she and Russell had an affair, but the allegations were never confirmed.[33]

The marriage seems to have been markedly unhappy, in part because of Vivienne's health problems. In a letter addressed to Ezra Pound, she covers an extensive list of her symptoms, which included a habitually high temperature, fatigue, insomnia, migraines, and colitis.[34] This, coupled with apparent mental instability, meant that she was often sent away by Eliot and her doctors for extended periods of time in the hope of improving her health. As time went on, he became increasingly detached from her. According to witnesses, both Eliots were frequent complainers of illness, physical and mental, while Eliot would drink excessively and Vivienne is said to have developed a liking for opium and ether, drugs prescribed for medical issues. It is claimed that the couple's wearying behaviour caused some visitors to vow never to spend another evening in the company of both together.[35] The couple formally separated in 1933, and in 1938 Vivienne's brother, Maurice, had her committed to a mental hospital, against her will, where she remained until her death of heart disease in 1947. When told via a phone call from the asylum that Vivienne had died unexpectedly during the night, Eliot is said to have buried his face in his hands and cried out 'Oh God, oh God.'[35]

Their relationship became the subject of a 1984 play Tom & Viv, which in 1994 was adapted as a film of the same name.

In a private paper written in his sixties, Eliot confessed: "I came to persuade myself that I was in love with Vivienne simply because I wanted to burn my boats and commit myself to staying in England. And she persuaded herself (also under the influence of [Ezra] Pound) that she would save the poet by keeping him in England. To her, the marriage brought no happiness. To me, it brought the state of mind out of which came The Waste Land."[36]

Teaching, banking, and publishing

[edit]

After leaving Merton, Eliot worked as a schoolteacher, most notably at Highgate School in London, where he taught French and Latin: his students included John Betjeman.[6] He subsequently taught at the Royal Grammar School, High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire. To earn extra money, he wrote book reviews and lectured at evening extension courses at University College London and Oxford. In 1917, he took a position at Lloyds Bank in London, working on foreign accounts. On a trip to Paris in August 1920 with the artist Wyndham Lewis, he met the writer James Joyce. Eliot said he found Joyce arrogant, and Joyce doubted Eliot's ability as a poet at the time, but the two writers soon became friends, with Eliot visiting Joyce whenever he was in Paris.[37] Eliot and Wyndham Lewis also maintained a close friendship, leading to Lewis's later making his well-known portrait painting of Eliot in 1938.

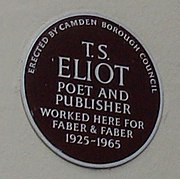

Charles Whibley recommended T. S. Eliot to Geoffrey Faber.[38] In 1925 Eliot left Lloyds to become a director in the publishing firm Faber and Gwyer (later Faber and Faber), where he remained for the rest of his career.[39][40] At Faber and Faber, he was responsible for publishing distinguished English poets, including W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender, Charles Madge and Ted Hughes.[41]

Conversion to Anglicanism and British citizenship

[edit]

On 29 June 1927, Eliot converted from Unitarianism to Anglicanism, and in November that year he took British citizenship, thereby renouncing his United States citizenship in the event he had not officially done so previously.[42] He became a churchwarden of his parish church, St Stephen's, Gloucester Road, London, and a life member of the Society of King Charles the Martyr.[43][44] He specifically identified as Anglo-Catholic, proclaiming himself "classicist in literature, royalist in politics, and anglo-catholic [sic] in religion".[45][46]

About 30 years later Eliot commented on his religious views that he combined "a Catholic cast of mind, a Calvinist heritage, and a Puritanical temperament".[47] He also had wider spiritual interests, commenting that "I see the path of progress for modern man in his occupation with his own self, with his inner being" and citing Goethe and Rudolf Steiner as exemplars of such a direction.[48]

One of Eliot's biographers, Peter Ackroyd, commented that "the purposes of [Eliot's conversion] were two-fold. One: the Church of England offered Eliot some hope for himself, and I think Eliot needed some resting place. But secondly, it attached Eliot to the English community and English culture."[41]

Separation and remarriage

[edit]By 1932, Eliot had been contemplating a separation from his wife for some time. When Harvard offered him the Charles Eliot Norton professorship for the 1932–1933 academic year, he accepted and left Vivienne in England. Upon his return, he arranged for a formal separation from her, avoiding all but one meeting with her between his leaving for America in 1932 and her death in 1947. Vivienne was committed to the Northumberland House mental hospital in Woodberry Down, Manor House, London, in 1938, and remained there until she died. Although Eliot was still legally her husband, he never visited her.[49] From 1933 to 1946 Eliot had a close emotional relationship with Emily Hale. Eliot later destroyed Hale's letters to him, but Hale donated Eliot's to Princeton University Library where they were sealed, following Eliot's and Hale's wishes, for 50 years after both had died, until 2020.[50] When Eliot heard of the donation he deposited his own account of their relationship with Harvard University to be opened whenever the Princeton letters were.[25]

From 1938 to 1957 Eliot's public companion was Mary Trevelyan of London University, who wanted to marry him and left a detailed memoir.[51][52][53]

From 1946 to 1957, Eliot shared a flat at 19 Carlyle Mansions, Chelsea, with his friend John Davy Hayward, who collected and managed Eliot's papers, styling himself "Keeper of the Eliot Archive".[54][55] Hayward also collected Eliot's pre-Prufrock verse, commercially published after Eliot's death as Poems Written in Early Youth. When Eliot and Hayward separated their household in 1957, Hayward retained his collection of Eliot's papers, which he bequeathed to King's College, Cambridge, in 1965.

On 10 January 1957, at the age of 68, Eliot married Esmé Valerie Fletcher, who was 30. In contrast to his first marriage, Eliot knew Fletcher well, as she had been his secretary at Faber and Faber since August 1949. They kept their wedding secret; the ceremony was held in St Barnabas Church, Kensington, London,[56] at 6:15 am with virtually no one in attendance other than his wife's parents. In the early 1960s, by then in failing health, Eliot worked as an editor for the Wesleyan University Press, seeking new poets in Europe for publication. After Eliot's death, Valerie dedicated her time to preserving his legacy, by editing and annotating The Letters of T. S. Eliot and a facsimile of the draft of The Waste Land.[57] Valerie Eliot died on 9 November 2012 at her home in London.[58]

Eliot had no children with either of his wives.

Death and honours

[edit]

Eliot died of emphysema at his home in Kensington in London, on 4 January 1965,[59] and was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium.[60] In accordance with his wishes, his ashes were taken to St Michael and All Angels' Church, East Coker, the village in Somerset from which his Eliot ancestors had emigrated to America.[61] A wall plaque in the church commemorates him with a quotation from his poem East Coker: "In my beginning is my end. In my end is my beginning."[62]

In 1967, on the second anniversary of his death, Eliot was commemorated by the placement of a large stone in the floor of Poets' Corner in London's Westminster Abbey. The stone, cut by designer Reynolds Stone, is inscribed with his life dates, his Order of Merit, and a quotation from his poem Little Gidding, "the communication / of the dead is tongued with fire beyond / the language of the living."[63]

In 1986, a blue plaque was placed on the apartment block - No. 3 Kensington Court Gardens - where he lived and died.[64]

Poetry

[edit]For a poet of his stature, Eliot produced relatively few poems. He was aware of this even early in his career; he wrote to J. H. Woods, one of his former Harvard professors, "My reputation in London is built upon one small volume of verse, and is kept up by printing two or three more poems in a year. The only thing that matters is that these should be perfect in their kind, so that each should be an event."[65]

Typically, Eliot first published his poems individually in periodicals or in small books or pamphlets and then collected them in books. His first collection was Prufrock and Other Observations (1917). In 1920, he published more poems in Ara Vos Prec (London) and Poems: 1920 (New York). These had the same poems (in a different order) except that "Ode" in the British edition was replaced with "Hysteria" in the American edition. In 1925, he collected The Waste Land and the poems in Prufrock and Poems into one volume and added The Hollow Men to form Poems: 1909–1925. From then on, he updated this work as Collected Poems. Exceptions are Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats (1939), a collection of light verse; Poems Written in Early Youth, posthumously published in 1967 and consisting mainly of poems published between 1907 and 1910 in The Harvard Advocate, and Inventions of the March Hare: Poems 1909–1917, material Eliot never intended to have published, which appeared posthumously in 1996.[66]

During an interview in 1959, Eliot said of his nationality and its role in his work: "I'd say that my poetry has obviously more in common with my distinguished contemporaries in America than with anything written in my generation in England. That I'm sure of. ... It wouldn't be what it is, and I imagine it wouldn't be so good; putting it as modestly as I can, it wouldn't be what it is if I'd been born in England, and it wouldn't be what it is if I'd stayed in America. It's a combination of things. But in its sources, in its emotional springs, it comes from America."[13]

Cleo McNelly Kearns notes in her biography that Eliot was deeply influenced by Indic traditions, notably the Upanishads. From the Sanskrit ending of The Waste Land to the "What Krishna meant" section of Four Quartets shows how much Indic religions and more specifically Hinduism made up his philosophical basic for his thought process.[67] It must also be acknowledged, as Chinmoy Guha showed in his book Where the Dreams Cross: T S Eliot and French Poetry (Macmillan, 2011) that he was deeply influenced by French poets from Baudelaire to Paul Valéry. He himself wrote in his 1940 essay on W.B. Yeats: "The kind of poetry that I needed to teach me the use of my own voice did not exist in English at all; it was only to be found in French." ("Yeats", On Poetry and Poets, 1948).

"The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock"

[edit]In 1915, Ezra Pound, overseas editor of Poetry magazine, recommended to Harriet Monroe, the magazine's founder, that she should publish "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock".[68] Although the character Prufrock seems to be middle-aged, Eliot wrote most of the poem when he was only twenty-two. Its now-famous opening lines, comparing the evening sky to "a patient etherised upon a table", were considered shocking and offensive, especially at a time when Georgian Poetry was hailed for its derivations of the 19th-century Romantic Poets.[69]

The poem's structure was heavily influenced by Eliot's extensive reading of Dante and refers to a number of literary works, including Hamlet and those of the French Symbolists. Its reception in London can be gauged from an unsigned review in The Times Literary Supplement on 21 June 1917. "The fact that these things occurred to the mind of Mr. Eliot is surely of the very smallest importance to anyone, even to himself. They certainly have no relation to poetry."[70]

The Waste Land

[edit]

In October 1922, Eliot published The Waste Land in The Criterion. Eliot's dedication to il miglior fabbro ('the better craftsman') refers to Ezra Pound's significant hand in editing and reshaping the poem from a longer manuscript to the shortened version that appears in publication.[71]

It was composed during a period of personal difficulty for Eliot—his marriage was failing, and both he and Vivienne were suffering from nervous disorders.[72] Before the poem's publication as a book in December 1922, Eliot distanced himself from its vision of despair. On 15 November 1922, he wrote to Richard Aldington, saying, "As for The Waste Land, that is a thing of the past so far as I am concerned and I am now feeling toward a new form and style."[73]

The poem is often read as a representation of the disillusionment of the post-war generation.[74] Dismissing this view, Eliot commented in 1931, "When I wrote a poem called The Waste Land, some of the more approving critics said that I had expressed 'the disillusion of a generation', which is nonsense. I may have expressed for them their own illusion of being disillusioned, but that did not form part of my intention."[75]

The poem is known for its disjointed nature due to its usage of allusion and quotation and its abrupt changes of speaker, location, and time. This structural complexity is one of the reasons that the poem has become a touchstone of modern literature, a poetic counterpart to a novel published in the same year, James Joyce's Ulysses.[76][page needed]

Among its best-known phrases are "April is the cruellest month", "I will show you fear in a handful of dust", and "These fragments I have shored against my ruins".[77]

"The Hollow Men"

[edit]"The Hollow Men" appeared in 1925. For the critic Edmund Wilson, it marked "The nadir of the phase of despair and desolation given such effective expression in 'The Waste Land'."[78] It is Eliot's major poem of the late 1920s. Similar to Eliot's other works, its themes are overlapping and fragmentary. Post-war Europe under the Treaty of Versailles (which Eliot despised), the difficulty of hope and religious conversion, Eliot's failed marriage.[79]

Allen Tate perceived a shift in Eliot's method, writing, "The mythologies disappear altogether in 'The Hollow Men'." This is a striking claim for a poem as indebted to Dante as anything else in Eliot's early work, to say little of the modern English mythology—the "Old Guy Fawkes" of the Gunpowder Plot—or the colonial and agrarian mythos of Joseph Conrad and James George Frazer, which, at least for reasons of textual history, echo in The Waste Land.[80] The "continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity" that is so characteristic of his mythical method remained in fine form.[81] "The Hollow Men" contains some of Eliot's most famous lines, notably its conclusion:

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.

"Ash-Wednesday"

[edit]"Ash-Wednesday" is the first long poem written by Eliot after his 1927 conversion to Anglicanism. Published in 1930, it deals with the struggle that ensues when a person who has lacked faith acquires it. Sometimes referred to as Eliot's "conversion poem", it is richly but ambiguously allusive, and deals with the aspiration to move from spiritual barrenness to hope for human salvation. Eliot's style of writing in "Ash-Wednesday" showed a marked shift from the poetry he had written prior to his 1927 conversion, and his post-conversion style continued in a similar vein. His style became less ironic, and the poems were no longer populated by multiple characters in dialogue. Eliot's subject matter also became more focused on his spiritual concerns and his Christian faith.[82]

Many critics were particularly enthusiastic about "Ash-Wednesday". Edwin Muir maintained that it is one of the most moving poems Eliot wrote, and perhaps the "most perfect", though it was not well received by everyone. The poem's groundwork of orthodox Christianity discomfited many of the more secular literati.[6][83]

Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats

[edit]In 1939, Eliot published a book of light verse, Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats. ("Old Possum" was Ezra Pound's friendly nickname for Eliot.) The first edition had an illustration of the author on the cover. In 1954, the composer Alan Rawsthorne set six of the poems for speaker and orchestra in a work titled Practical Cats. After Eliot's death, the book was the basis of the musical Cats by Andrew Lloyd Webber, first produced in London's West End in 1981 and opening on Broadway the following year.[84]

Four Quartets

[edit]Eliot regarded Four Quartets as his masterpiece, and it is the work that most of all led him to being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.[6] It consists of four long poems, each first published separately: "Burnt Norton" (1936), "East Coker" (1940), "The Dry Salvages" (1941) and "Little Gidding" (1942). Each has five sections. Although they resist easy characterisation, each poem includes meditations on the nature of time in some important respect—theological, historical, physical—and its relation to the human condition. Each poem is associated with one of the four classical elements, respectively: air, earth, water, and fire.

"Burnt Norton" is a meditative poem that begins with the narrator trying to focus on the present moment while walking through a garden, focusing on images and sounds such as the bird, the roses, clouds and an empty pool. The meditation leads the narrator to reach "the still point" in which there is no attempt to get anywhere or to experience place and/or time, instead experiencing "a grace of sense". In the final section, the narrator contemplates the arts ("words" and "music") as they relate to time. The narrator focuses particularly on the poet's art of manipulating "Words [which] strain, / Crack and sometimes break, under the burden [of time], under the tension, slip, slide, perish, decay with imprecision, [and] will not stay in place, / Will not stay still." By comparison, the narrator concludes that "Love is itself unmoving, / Only the cause and end of movement, / Timeless, and undesiring."

"East Coker" continues the examination of time and meaning, focusing in a famous passage on the nature of language and poetry. Out of darkness, Eliot offers a solution: "I said to my soul, be still, and wait without hope."

"The Dry Salvages" treats the element of water, via images of river and sea. It strives to contain opposites: "The past and future / Are conquered, and reconciled."

"Little Gidding" (the element of fire) is the most anthologised of the Quartets.[85] Eliot's experiences as an air raid warden in the Blitz power the poem, and he imagines meeting Dante during the German bombing. The beginning of the Quartets ("Houses / Are removed, destroyed") had become a violent everyday experience; this creates an animation, where for the first time he talks of love as the driving force behind all experience. From this background, the Quartets end with an affirmation of Julian of Norwich: "All shall be well and / All manner of thing shall be well."[86]

The Four Quartets draws upon Christian theology, art, symbolism and language of such figures as Dante, and mystics St. John of the Cross and Julian of Norwich.[86]

Plays

[edit]With the important exception of Four Quartets, Eliot directed much of his creative energies after Ash Wednesday to writing plays in verse, mostly comedies or plays with redemptive endings. He was long a critic and admirer of Elizabethan and Jacobean verse drama; witness his allusions to Webster, Thomas Middleton, William Shakespeare and Thomas Kyd in The Waste Land. In a 1933 lecture he said "Every poet would like, I fancy, to be able to think that he had some direct social utility . . . . He would like to be something of a popular entertainer and be able to think his own thoughts behind a tragic or a comic mask. He would like to convey the pleasures of poetry, not only to a larger audience but to larger groups of people collectively; and the theatre is the best place in which to do it."[87]

After The Waste Land (1922), he wrote that he was "now feeling toward a new form and style". One project he had in mind was writing a play in verse, using some of the rhythms of early jazz. The play featured "Sweeney", a character who had appeared in a number of his poems. Although Eliot did not finish the play, he did publish two scenes from the piece. These scenes, titled Fragment of a Prologue (1926) and Fragment of an Agon (1927), were published together in 1932 as Sweeney Agonistes. Although Eliot noted that this was not intended to be a one-act play, it is sometimes performed as one.[14]

A pageant play by Eliot called The Rock was performed in 1934 for the benefit of churches in the Diocese of London. Much of it was a collaborative effort; Eliot accepted credit only for the authorship of one scene and the choruses.[14] George Bell, the Bishop of Chichester, had been instrumental in connecting Eliot with producer E. Martin Browne for the production of The Rock, and later commissioned Eliot to write another play for the Canterbury Festival in 1935. This one, Murder in the Cathedral, concerning the martyrdom of Thomas Becket, was more under Eliot's control. Eliot biographer Peter Ackroyd comments that "for [Eliot], Murder in the Cathedral and succeeding verse plays offered a double advantage; it allowed him to practice poetry but it also offered a convenient home for his religious sensibility."[41] After this, he worked on more "commercial" plays for more general audiences: The Family Reunion (1939), The Cocktail Party (1949), The Confidential Clerk, (1953) and The Elder Statesman (1958) (the latter three were produced by Henry Sherek and directed by E. Martin Browne[88]). The Broadway production in New York of The Cocktail Party received the 1950 Tony Award for Best Play. Eliot wrote The Cocktail Party while he was a visiting scholar at the Institute for Advanced Study.[89][90]

Regarding his method of playwriting, Eliot explained, "If I set out to write a play, I start by an act of choice. I settle upon a particular emotional situation, out of which characters and a plot will emerge. And then lines of poetry may come into being: not from the original impulse but from a secondary stimulation of the unconscious mind."[41]

Literary criticism

[edit]Eliot also made significant contributions to the field of literary criticism, and strongly influenced the school of New Criticism. He was somewhat self-deprecating and minimising of his work and once said his criticism was merely a "by-product" of his "private poetry-workshop". But the critic William Empson once said, "I do not know for certain how much of my own mind [Eliot] invented, let alone how much of it is a reaction against him or indeed a consequence of misreading him. He is a very penetrating influence, perhaps not unlike the east wind."[91]

In his critical essay "Tradition and the Individual Talent", Eliot argues that art must be understood not in a vacuum, but in the context of previous pieces of art. "In a peculiar sense [an artist or poet] ... must inevitably be judged by the standards of the past."[92] This essay was an important influence over the New Criticism by introducing the idea that the value of a work of art must be viewed in the context of the artist's previous works, a "simultaneous order" of works (i.e., "tradition"). Eliot himself employed this concept on many of his works, especially on his long-poem The Waste Land.[93]

Also important to New Criticism was the idea—as articulated in Eliot's essay "Hamlet and His Problems"—of an "objective correlative", which posits a connection among the words of the text and events, states of mind, and experiences.[94] This notion concedes that a poem means what it says, but suggests that there can be a non-subjective judgment based on different readers' different—but perhaps corollary—interpretations of a work.

More generally, New Critics took a cue from Eliot in regard to his "'classical' ideals and his religious thought; his attention to the poetry and drama of the early seventeenth century; his deprecation of the Romantics, especially Shelley; his proposition that good poems constitute 'not a turning loose of emotion but an escape from emotion'; and his insistence that 'poets... at present must be difficult'."[95]

Эссе Элиота стали важным фактором возрождения интереса к поэтам-метафизикам . Элиот особенно похвалил способность поэтов-метафизиков показать опыт как психологический, так и чувственный, в то же время наполняя это изображение, по мнению Элиота, остроумием и уникальностью. Эссе Элиота «Метафизические поэты», наряду с приданием метафизической поэзии нового значения и внимания, представило его теперь хорошо известное определение «единой чувствительности», которое, по мнению некоторых, означает то же самое, что и термин «метафизический». [ 96 ] [ 97 ]

Его стихотворение 1922 года «Бесплодная земля». [ 98 ] также может быть лучше понято в свете его работы в качестве критика. Он утверждал, что поэт должен писать «программную критику», то есть поэт должен писать для продвижения своих собственных интересов, а не для продвижения «исторической науки». Если смотреть с критической точки зрения Элиота, «Бесплодная земля», вероятно, показывает его личное отчаяние по поводу Первой мировой войны, а не объективное историческое понимание ее. [ 99 ]

В конце своей карьеры Элиот сосредоточил большую часть своей творческой энергии на написании сценариев для театра; некоторые из его ранних критических работ, в таких эссе, как «Поэзия и драма», [ 100 ] «Гамлет и его проблемы», [ 94 ] и «Возможность поэтической драмы», [ 101 ] сосредоточился на эстетике написания драмы в стихах.

Критический прием

[ редактировать ]Ответы на его стихи

[ редактировать ]Писатель Рональд Буш отмечает, что ранние стихи Элиота, такие как «Любовная песня Дж. Альфреда Пруфрока», «Портрет дамы», «La Figlia Che Piange», «Прелюдии» и «Рапсодия в ветреную ночь», имели «[ эффект, [который] был одновременно уникальным и убедительным, и их уверенность ошеломила современников [Элиота], которым была предоставлена честь читать их в рукописи, например, [Конрад] Эйкен поражался тому, «насколько четко, полно и уникально все это». была с самого начала. Целостность здесь, с самого начала». [ 1 ]

Первоначальная критическая реакция на «Бесплодную землю» Элиота была неоднозначной. Буш отмечает, что поначалу это произведение было правильно воспринято как произведение, напоминающее джазовую синкопу, и, как и джаз 1920-х годов , по сути иконоборческое». [ 1 ] Некоторые критики, такие как Эдмунд Уилсон , Конрад Эйкен и Гилберт Селдес, считали, что это лучшая поэзия, написанная на английском языке, в то время как другие считали ее эзотерической и намеренно сложной. Эдмунд Уилсон, будучи одним из критиков, хваливших Элиота, назвал его «одним из наших единственных подлинных поэтов». [ 102 ] Уилсон также указал на некоторые слабости Элиота как поэта. Что касается «Бесплодной земли» , Уилсон признает ее недостатки («отсутствие структурного единства»), но приходит к выводу: «Я сомневаюсь, что существует хоть одно другое стихотворение такой же длины, написанное современным американцем, которое демонстрирует столь высокое и столь разнообразное мастерство». английского стиха». [ 102 ]

Чарльз Пауэлл негативно критиковал Элиота, назвав его стихи непонятными. [ 103 ] Авторы журнала Time были также сбиты с толку таким сложным стихотворением, как «Бесплодная земля» . [ 104 ] Джон Кроу Рэнсом отрицательно критиковал работу Элиота, но также мог сказать и положительное. Например, хотя Рэнсом негативно раскритиковал «Бесплодную землю » за ее «крайнюю разобщенность», Рэнсом не полностью осудил творчество Элиота и признал, что Элиот был талантливым поэтом. [ 105 ]

Обращаясь к некоторым распространённым критическим замечаниям, направленным в то время в адрес «Бесплодной земли» , Гилберт Селдес заявил: «На первый взгляд стихотворение кажется удивительно бессвязным и запутанным… [однако] более пристальный взгляд на стихотворение не просто проясняет трудности; он раскрывает скрытая форма произведения [и] указывает, как каждая вещь становится на свои места». [ 106 ]

Репутация Элиота как поэта, а также его влияние в академии достигли пика после публикации «Четырех квартетов» . В эссе об Элиоте, опубликованном в 1989 году, писательница Синтия Озик называет этот пик влияния (с 1940-х по начало 1960-х годов) «эпохой Элиота», когда Элиот «казался чистым зенитом, колоссом, не чем иным, как постоянным светило, закрепленное на небосводе, как солнце и луна». [ 107 ] Но в этот послевоенный период другие, такие как Рональд Буш, заметили, что это время также ознаменовало начало упадка литературного влияния Элиота:

Поскольку консервативные религиозные и политические убеждения Элиота стали казаться менее близкими по духу в послевоенном мире, другие читатели с подозрением отнеслись к его утверждениям авторитета, очевидным в «Четырех квартетах» и подразумеваемым в более ранней поэзии. Результатом, вызванным периодическим повторным открытием антисемитской риторики Элиота, стал постепенный пересмотр в сторону понижения его некогда высокой репутации. [ 1 ]

Буш также отмечает, что после его смерти репутация Элиота «значительно упала». Он пишет: «Иногда Элиота считали слишком академичным ( по мнению Уильяма Карлоса Уильямса ), его также часто критиковали за умерщвляющий неоклассицизм (как он сам — возможно, столь же несправедливо — критиковал Мильтона ). Однако разнообразные дани уважения со стороны практикующих поэтов из многих школ, опубликованных во время его столетия в 1988 году, было убедительным свидетельством продолжающегося устрашающего присутствия его поэтического голоса». [ 1 ]

Литературоведы, такие как Гарольд Блум [ 108 ] и Стивен Гринблатт , [ 109 ] признать поэзию Элиота центральной частью литературного английского канона. Например, редакторы «Антологии английской литературы Нортона» пишут: «Нет разногласий относительно важности [Элиота] как одного из величайших обновителей диалекта английской поэзии, влияние которого на целое поколение поэтов, критиков и интеллектуалов в целом был огромен, [Однако] его диапазон как поэта [был] ограничен, а его интерес к великой золотой середине человеческого опыта (в отличие от крайностей святого и грешника) [был] недостаточным». Несмотря на эту критику, эти ученые также признают «поэтическую хитрость [Элиота], его прекрасное мастерство, его оригинальный акцент, его историческую и репрезентативную значимость как поэта современного символиста - метафизической традиции». [ 109 ]

Антисемитизм

[ редактировать ]Изображение евреев в некоторых стихотворениях Элиота побудило некоторых критиков обвинить его в антисемитизме , особенно решительно Энтони Джулиуса в его книге «Т. С. Элиот, антисемитизм и литературная форма» (1996). [ 110 ] [ 111 ] В « Геронтионе » Элиот пишет голосом пожилого рассказчика стихотворения: «И еврей сидит на подоконнике, владелец [моего здания] / Породился в каком-то Антверпена » эстаминете . [ 112 ] Другой пример появляется в стихотворении «Бербанк с Бедекером: Блейстейн с сигарой», в котором Элиот написал: «Крысы под сваями. / Еврей под партией. / Деньги в мехах». [ 113 ] Юлиус пишет: «Антисемитизм очевиден. Он доносится до читателя как ясный сигнал». Точку зрения Юлиуса поддержал Гарольд Блум . [ 114 ] Кристофер Рикс , [ 115 ] Джордж Штайнер , [ 115 ] Том Полин [ 116 ] и Джеймс Фентон . [ 115 ]

В лекциях, прочитанных в Университете Вирджинии в 1933 году (опубликованных в 1934 году под названием « После странных богов: учебник современной ереси »), Элиот писал о социальных традициях и согласованности: «Что еще важнее [чем культурная однородность] — это единство религиозное происхождение, а также причины расы и религии в совокупности делают любое большое количество свободомыслящих евреев нежелательным». [ 117 ] Элиот никогда не переиздавал эту книгу/лекцию. [ 115 ] В своей театрализованной пьесе 1934 года «Скала » Элиот дистанцируется от фашистских движений 1930-х годов, изображая Освальда Мосли , чернорубашечников которые «категорически отказываются/ Спускаться к болтовне с антропоидными евреями». [ 118 ] «Новые евангелы» [ 118 ] тоталитаризма представляются как антитеза духу христианства .

В книгах «В защиту Т.С. Элиота» (2001) и Т.С. Элиота (2006) Крейг Рейн защищал Элиота от обвинений в антисемитизме. [ нужны разъяснения ] Пола Дина аргументы Рейна не убедили, но он, тем не менее, заключил: «В конечном счете, как настаивают и Рейн, и, отдать ему должное, Джулиус, как бы сильно Элиот ни был скомпрометирован как личность, как и все мы в разных отношениях, его величие как остается поэт». [ 115 ] Критик Терри Иглтон также поставил под сомнение всю основу книги Рейна, написав: «Почему критики чувствуют необходимость защищать авторов, о которых пишут, подобно любящим родителям, глухим к любой критике своих неприятных детей? Заслуженная репутация Элиота [как поэта] ] установлен вне всякого сомнения, и выставление его таким же безупречным, как архангел Гавриил, не оказывает ему никакой пользы». [ 119 ]

Влияние

[ редактировать ]Элиот оказал влияние на многих поэтов, писателей и авторов песен, в том числе Шона О Риордайна , Майртина О Дирейна , Вирджинию Вульф , Эзру Паунда , Боба Дилана , Харта Крэйна , Уильяма Гэддиса , Аллена Тейта , Эндрю Ллойда Уэббера , Тревора Нанна , Теда Хьюза , Джеффри Хилла , Шеймус Хини , Ф. Скотт Фицджеральд , Рассел Кирк , [ 120 ] Джордж Сеферис (который в 1936 году опубликовал современный греческий перевод « Бесплодной земли ») и Джеймс Джойс . [ сомнительно – обсудить ] [ 121 ] Т. С. Элиот оказал сильное влияние на карибскую поэзию 20-го века , написанную на английском языке, в том числе на эпос «Омерос» (1990) нобелевского лауреата Дерека Уолкотта . [ 122 ] и острова (1969) барбадосца Камау Брэтуэйта . [ 123 ]

Почести и награды

[ редактировать ]Ниже приведен неполный список наград и наград, полученных Элиотом, врученных или созданных в его честь.

Национальные или государственные награды

[ редактировать ]Эти награды отображаются в порядке старшинства в зависимости от национальности Элиота и правил протокола, а не даты награждения.

| Национальные или государственные награды | |||

| Орден «За заслуги» | Великобритания | 1948 [ 124 ] [ 125 ] | |

| Президентская медаль Свободы | Соединенные Штаты | 1964 | |

| Офицер Почетного легиона | Франция | 1951 | |

| Кавалер Ордена Искусств и литературы | Франция | 1960 | |

Литературные награды

[ редактировать ]- Нобелевская премия по литературе «за выдающийся новаторский вклад в современную поэзию» (1948). [ 8 ]

- Ганзейская премия Гете (Гамбург) (1955)

- Медаль Данте (Флоренция) (1959)

Драматические награды

[ редактировать ]- Премия Тони 1950 года за лучшую пьесу в бродвейской постановке «Коктейльная вечеринка»

- Премия Тони 1983 года за лучшую книгу мюзикла за стихи, использованные в мюзикле « Кошки » (посмертная награда).

- Премия Тони 1983 года за лучший оригинальный саундтрек за стихи, использованные в мюзикле « Кошки » (совместно с Эндрю Ллойдом Уэббером ) (посмертная награда) [ 126 ]

Музыкальные награды

[ редактировать ]- Премия Айвора Новелло за лучшую песню в музыкальном и лирическом плане за стихи, использованные в песне « Memory » (1982). [ 127 ]

Научные награды

[ редактировать ]- Введен в должность Фи Бета Каппа (1935). [ 128 ]

- Избран в Американскую академию искусств и наук (1954 г.). [ 129 ]

- Избран в Американское философское общество (1960). [ 130 ]

- Тринадцать почетных докторских степеней (в том числе Оксфорда, Кембриджа, Сорбонны и Гарварда)

Другие награды

[ редактировать ]- Колледж Элиота в Кентского университета Англии, названный в его честь

- Отмечен на памятных почтовых марках США.

- Звезда на Аллее славы в Сент-Луисе

Работает

[ редактировать ]Источник: «Нобелевская премия по литературе 1948 года | Т. С. Элиот | Библиография» . nobelprize.org . Архивировано из оригинала 7 ноября 2012 года.

Самые ранние работы

[ редактировать ]- Проза

- Стихи

- «Басня для праздников» (1905)

- «[Лирика:]« Если время и пространство, как говорят мудрецы »» (1905)

- «[На выпускном 1905]» (1905)

- «Песня: 'Если пространство и время, как говорят мудрецы'» (1907)

- «Перед утром» (1908)

- «Дворец Цирцеи» (1908 г.)

- «Песня: «Когда мы вернулись домой через холм»» (1909).

- «На портрете» (1909)

- «Песня: «Лунный цветок открывается мотыльку»» (1909). [ 133 ]

- «Ноктюрн» (1909)

- «Юмореска» (1910)

- «Сплин» (1910)

- «[Класс] Ода» (1910)

- «Смерть святого Нарцисса» ( ок. 1911-15 ) [ 133 ]

Поэзия

[ редактировать ]- Пруфрок и другие наблюдения (1917)

- Песня о любви Дж. Альфреда Пруфрока

- Портрет дамы

- Прелюдии

- Рапсодия в ветреную ночь

- Утро у окна

- The Boston Evening Transcript (о Boston Evening Transcript )

- тетя Хелен

- Кузина Нэнси

- г-н Аполлинакс

- истерия

- Разговор Галанте

- Плачущая дочь

- Стихи (1920)

- Геронтион

- Бербанк с Бедекером: Блейстейн с сигарой

- Суини Эрект

- Кулинарное яйцо

- Директор

- Прелюбодейная смесь всего

- Медовый месяц

- Бегемот

- В ресторане

- Шепот бессмертия

- Воскресная утренняя служба мистера Элиота

- Суини среди соловьев

- Пустошь (1922)

- Полые люди (1925)

- Стихи Ариэля (1927–1954)

- Путешествие волхвов (1927)

- Песня для Симеона (1928)

- Животное (1929)

- Марина (1930)

- Триумфальный марш (1931)

- Выращивание рождественских елок (1954)

- Макавити : Таинственный кот

- Пепельная среда (1930)

- Кориолан (1931)

- Книга практичных кошек старого опоссума (1939)

- Марширующая песня собак-полликлов и Билли Маккоу: Замечательный попугай (1939) в Королевской книге Красного Креста

- Четыре квартета (1945)

Пьесы

[ редактировать ]- Суини Агонистес (опубликовано в 1926 году, впервые исполнено в 1934 году)

- Скала (1934)

- Убийство в соборе (1935)

- Воссоединение семьи (1939)

- Коктейльная вечеринка (1949)

- Секретный клерк (1953)

- The Elder Statesman (впервые исполнено в 1958 году, опубликовано в 1959 году)

Научная литература

[ редактировать ]- Христианство и культура (1939, 1948)

- Разум второго порядка (1920)

- Традиции и индивидуальный талант (1920)

- Священный лес: очерки поэзии и критики (1920)

- Посвящение Джону Драйдену (1924)

- Шекспир и стоицизм Сенеки (1928)

- Для Ланселота Эндрюса (1928)

- Данте (1929)

- Избранные очерки 1917–1932 гг. (1932)

- Использование поэзии и использование критики (1933)

- После странных богов (1934)

- Елизаветинские очерки (1934)

- Очерки древних и современных (1936)

- Идея христианского общества (1939)

- Выбор стиха Киплинга (1941), сделанный Элиотом, с эссе о Редьярде Киплинге

- Заметки к определению культуры (1948)

- Поэзия и драма (1951)

- Три голоса поэзии (1954)

- Границы критики (1956)

- О поэзии и поэтах (1943)

Посмертные публикации

[ редактировать ]- Критиковать критика (1965)

- Стихи, написанные в ранней юности (1967)

- Пустошь: факсимильное издание (1974)

- Изобретения мартовского зайца: Стихи 1909–1917 (1996)

Критические издания

[ редактировать ]- Сборник стихов, 1909–1962 (1963), отрывок и текстовый поиск.

- Книга практичных кошек старого опоссума, иллюстрированное издание (1982), отрывок и текстовый поиск

- Избранная проза Т. С. Элиота под редакцией Фрэнка Кермода (1975), отрывок и текстовый поиск

- The Waste Land (Norton Critical Editions), под редакцией Майкла Норта (2000), отрывок и текстовый поиск

- Стихи Т. С. Элиота , том 1 (Собрание и несобранные стихи) и том 2 (Практические кошки и дальнейшие стихи), под редакцией Кристофера Рикса и Джима МакКью (2015), Faber & Faber

- Избранные очерки (1932); увеличенный (1960)

- Письма Т. С. Элиота под редакцией Валери Элиот и Хью Хотона, том 1: 1898–1922 (1988, переработка 2009 г.)

- Письма Т. С. Элиота под редакцией Валери Элиот и Хью Хотона, том 2: 1923–1925 (2009)

- Письма Т. С. Элиота под редакцией Валери Элиот и Джона Хаффендена, том 3: 1926–1927 (2012)

- Письма Т. С. Элиота под редакцией Валери Элиот и Джона Хаффендена, том 4: 1928–1929 (2013)

- Письма Т. С. Элиота под редакцией Валери Элиот и Джона Хаффендена, том 5: 1930–1931 (2014)

- Письма Т. С. Элиота под редакцией Валери Элиот и Джона Хаффендена, том 6: 1932–1933 (2016)

- Письма Т. С. Элиота под редакцией Валери Элиот и Джона Хаффендена, том 7: 1934–1935 (2017)

- Письма Т. С. Элиота под редакцией Валери Элиот и Джона Хаффендена, том 8: 1936–1938 (2019)

- Письма Т. С. Элиота под редакцией Валери Элиот и Джона Хаффендена, том 9: 1939–1941 (2021 г.)

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Буш, Рональд. «Жизнь и карьера Т. С. Элиота», в книге Джона А. Гаррати и Марка К. Карнса (редакторы), American National Biography . Нью-Йорк: Oxford University Press, 1999, через [1]. Архивировано 17 апреля 2022 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ «Т.С. Элиот | Биография, стихи, произведения, значение и факты | Британника» . Britannica.com . Проверено 12 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ «Нобелевская премия по литературе 1948 года» . NobelPrize.org . Проверено 20 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ Санна, Эллин (2003). «Биография Т. С. Элиота». В Блуме, Гарольд (ред.). ТС Элиот . Биокритика Блума. Брумолл: Издательство Chelsea House. стр. (3–44) 30 .

- ^ Элиот, Т.С. (21 декабря 2010 г.). «Бесплодная земля» и другие стихи . Бродвью Пресс. п. 133. ИСБН 978-1-77048-267-8 . Проверено 9 июля 2017 года . (цитата по неподписанной рецензии в «Литературном мире» , 5 июля 1917 г., т. lxxxiii, 107.)

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я «Томас Стернс Элиот» , Британская энциклопедия . Проверено 7 ноября 2009 г.

- ^ «Нобелевская премия по литературе 1948 года» . Нобелевский фонд . Проверено 26 апреля 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Нобелевская премия по литературе 1948 года - Т. С. Элиот» , Нобелевский фонд, взято у Френца, Хорста (ред.). Нобелевские лекции по литературе 1901–1967 гг . Амстердам: Издательская компания Elsevier, 1969. Проверено 6 марта 2012 г.

- ^ Буш, Рональд (1991). Т.С. Элиот: Модернист в истории . Нью-Йорк: Издательство Кембриджского университета . п. 72. ИСБН 978-0-52139-074-3 .

- ^ Уортен, Джон (2009). Т. С. Элиот: Краткая биография . Лондон: Издательство Haus. п. 9.

- ^ Сенкур, Роберт (1971). Т. С. Элиот, Мемуары . Лондон: Гарнстон Лимитед. п. 18.

- ↑ Письмо маркизу Чайлдсу, цитируемое в газете St. Louis Post Dispatch (15 октября 1930 г.) и в обращении «Американская литература и американский язык», произнесенном в Вашингтонском университете в Сент-Луисе (9 июня 1953 г.), опубликованном в журнале Washington University Studies, New. Серия: Литература и язык , вып. 23 (Сент-Луис: Издательство Вашингтонского университета, 1953), стр. 6.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Элиот, Т.С. (весна – лето 1959 г.). «Искусство поэзии №1» . Парижское обозрение (интервью). № 21. Беседовал Дональд Холл . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 3 октября 2009 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Гэллап, Дональд (1969). Т. С. Элиот: Библиография (пересмотренное и расширенное издание). Нью-Йорк: Харкорт, Брейс и мир. п. 195. АСИН B000TM4Z00 .

- ^ Элиот, Т.С. (1967). Хейворд, Джон Дэви (ред.). Стихи, написанные в ранней юности . Нью-Йорк: Фаррар, Штраус и Жиру . стр. 33–34.

- ^ Нарита, Тацуши (ноябрь 1994 г.). «Молодой Т. С. Элиот и инопланетные культуры: его филиппинские взаимодействия». Обзор исследований английского языка . 45 (180): 523–525. дои : 10.1093/res/XLV.180.523 .

- ^ Нарита, Тацуши (2013). Т. С. Элиот, Всемирная выставка в Сент-Луисе и «автономия» . Нагоя, Япония: Когаку Шуппан. стр. 9–104. ISBN 9784903742212 .

- ^ Буш, Рональд (1995). «Присутствие прошлого: этнографическое мышление / литературная политика». В Баркане Эльзар; Буш, Рональд (ред.). Предыстория будущего . Стэнфорд, Калифорния: Издательство Стэнфордского университета . стр. 3–5, 25–31.

- ^ Марш, Алекс; Даумер, Элизабет (2005). «Паунд и Т.С. Элиот». Американская литературная стипендия . п. 182.

- ^ Литературный Сент-Луис . Сотрудники библиотек Университета Сент-Луиса, Inc. и Ассоциации достопримечательностей Сент-Луиса, Inc., 1969 г.

- ^ Миллер, Джеймс Эдвин (2001). Т. С. Элиот: Становление американского поэта, 1888–1922 гг . Государственный колледж, Пенсильвания: Издательство Пенсильванского государственного университета. п. 62. ИСБН 0271027622 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кермод, Фрэнк. «Введение» к «Бесплодной земле и другим стихотворениям» , Penguin Classics, 2003.

- ^ Дэвис, Гаррик (2008). Хвала новому: лучшее из новой критики . Swallow Press/Издательство Университета Огайо. п. 2. ISBN 978-0-8040-1108-2 .

Через год после того, как Элиот переехал в Лондон в 1914 году, он был представлен Эзре Паунду через общего друга Конрада Эйкена. Паунд и Элиот вскоре стали друзьями и литературными союзниками на всю жизнь.

- ^ Перл, Джеффри М. и Эндрю П. Так. «Скрытое преимущество традиции: о значении индийских исследований Т. С. Элиота» , Philosophy East & West V. 35, № 2, апрель 1985 г., стр. 116–131.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Заявление Т. С. Элиота по поводу вскрытия писем Эмили Хейл в Принстоне» . ТС Элиот . 2 января 2020 г. Проверено 6 января 2020 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сеймур-Джонс, Кэрол. Нарисованная тень: жизнь Вивьен Элиот, первой жены Т. С. Элиота , Издательская группа Knopf, стр. 1

- ^ Уортен, Джон (2009). Т. С. Элиот: Краткая биография . Лондон: Издательство Haus. стр. 34–36.

- ^ «Известные биркбекианцы» . Биркбек . Проверено 6 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ О прочтении диссертации см. Бразил, Грегори (осень 2007 г.). «Предполагаемый прагматизм Т. С. Элиота». Философия и литература . 31 (1): 248–264. ССНР 1738642 .

- ^ Скемер, Дон (16 мая 2017 г.). «Запечатанное сокровище: письма Т. С. Элиота Эмили Хейл» . Новости рукописей ПУЛ . Проверено 6 января 2020 г.

- ^ Элиот, Т.С. Письма Т.С. Элиота, Том 1, 1898–1922 гг . п. 75.

- ^ Ричардсон, Джон , Священные монстры, Священные мастера . Рэндом Хаус, 2001, с. 20.

- ^ Сеймур-Джонс, Кэрол. Нарисованная тень: жизнь Вивьен Элиот . Издательская группа Кнопф, 2001, с. 17.

- ^ Письма Т. С. Элиота: Том 1, 1898–1922 гг . Лондон: Фабер и Фабер. 1988. с. 533.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пуарье, Ришар (3 апреля 2003 г.). «В Гиацинтовом саду» . Лондонское обозрение книг . 25 (7).

- ^ Элиот, Т.С. Письма Т.С. Элиота, Том 1, 1898–1922. Лондон: Фабер и Фабер. 1988. с. XVIII.

- ^ Эллманн, Ричард . Джеймс Джойс . стр. 492–495.

- ^ Коджеки, Роджер (1972). Социальная критика Т. С. Элиота . Фабер и Фабер. п. 55 . ISBN 978-0571096923 .

- ^ Джейсон Хардинг (31 марта 2011 г.). Т.С. Элиот в контексте . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 73. ИСБН 978-1-139-50015-9 . Проверено 26 октября 2017 г.

- ^ ФБ Пиньон (27 августа 1986 г.). Компаньон Т. С. Элиота: жизнь и творчество . Пэлгрейв Макмиллан, Великобритания. п. 32. ISBN 978-1-349-07449-5 . Проверено 26 октября 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д ТС Элиот. Серия «Голоса и видения» . Нью-Йоркский центр визуальной истории: PBS, 1988. [2]

- ^ Боягода, Рэнди (21 июля 2015 г.). «ТС Элиот, американец» . Американский консерватор .

- ^ Мемориальная доска на внутренней стене собора Святого Стефана.

- ↑ Некролог в журнале Church and King , Vol. XVII, № 4, 28 февраля 1965 г., стр. 3.

- ^ Конкретная цитата: «Общую точку зрения [эссе] можно охарактеризовать как классицистическую в литературе, роялистскую в политике и англо-католическую [ sic ] в религии», в предисловии Т. С. Элиота к книге « Для Ланселота Эндрюса : Очерки о стиль и порядок (1929).

- ↑ Книги: роялист, классицист, англо-католик , Time , 25 мая 1936 года.

- ^ Элиот, Т.С. (1986). О поэзии и поэтах . Лондон: Фабер и Фабер. п. 209 . ISBN 978-0571089833 .

- ↑ Радиоинтервью от 26 сентября 1959 года, Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk , цитируется по Уилсон, Колин (1988). За пределами оккультизма . Лондон: Бантам Пресс. стр. 335–336.

- ^ Сеймур-Джонс, Кэрол. Нарисованная тень: жизнь Вивьен Элиот . Констебль 2001, с. 561.

- ^ Хелмор, Эдвард (2 января 2020 г.). «Скрытые любовные письма Т.С. Элиота раскрывают напряженный, душераздирающий роман» . Хранитель . ISSN 0261-3077 . Проверено 6 января 2020 г.

- ^ Буш, Рональд, Т.С. Элиот: Модернист в истории 1991, с. 11: «Мэри Тревельян, которой тогда было сорок лет, имела меньшее значение для творчества Элиота. Там, где Эмили Хейл и Вивьен были частью частной фантасмагории Элиота, Мэри Тревельян играла свою роль в том, что по сути было общественной дружбой. Она сопровождала Элиота почти двадцать лет. до его второго брака в 1957 году. Умная женщина, с бодрящей организационной энергией Флоренс Найтингейл , она поддерживала внешнюю структуру жизни Элиота, но и для него она тоже олицетворяла…»

- ^ Сюретт, Леон, Современная дилемма: Уоллес Стивенс, Т.С. Элиот и гуманизм , 2008, стр. 343: «Позже разумная и работоспособная Мэри Тревельян долгое время служила ей опорой в годы покаяния. Для нее их дружба была обязательством; для Элиота — совершенно второстепенной. Его страсть к бессмертию была настолько властной, что позволила ему… "

- ^ Халдар, Сантвана, Т.С. Элиот – Взгляд XXI века 2005, стр. xv: «Подробности дружбы Элиота с Эмили Хейл, которая была очень близка с ним в бостонские дни, и с Мэри Тревельян, которая хотела выйти за него замуж и оставила захватывающие воспоминания о самых непостижимых годах славы Элиота, проливают новый свет на этот период. в...."

- ^ «Валери Элиот» , The Daily Telegraph , 11 ноября 2012 г. Проверено 1 июля 2017 г.

- ^ Гордон, Линдалл . Т.С. Элиот: Несовершенная жизнь . Нортон 1998, с. 455.

- ^ «Брак. Мистер Т.С. Элиот и мисс Э.В. Флетчер» . Таймс . № 53736. 11 января 1957 г. с. 10. ISSN 0140-0460 . Проверено 3 марта 2020 г.

- ^ Гордон, Джейн. «Университет стихов» , The New York Times , 16 октября 2005 г.; Хронология прессы Уэслианского университета. Архивировано 1 декабря 2010 года в Wayback Machine , 1957 год.

- ^ Лоулесс, Джилл (11 ноября 2012 г.). «Вдова Т. С. Элиота Валери Элиот умирает в возрасте 86 лет» . Associated Press через Yahoo News . Проверено 12 ноября 2012 г.

- ^ Грантк, Майкл (1997). Т. С. Элиот: Критическое наследие, Том 1 . Психология Пресс. п. 55. ИСБН 9780415159470 .

- ^ МакСмит, Энди (16 марта 2010 г.). «Знаменитые имена, конечной остановкой которых был крематорий Голдерс-Грин» . Независимый . Архивировано из оригинала 26 мая 2022 года . Проверено 3 января 2018 г.

- ^ Премьер (2014). «Национальный день поэзии в Премьере 2013 – Премьера» . Премьер . Проверено 27 февраля 2018 г.

- ^ Дженкинс, Саймон (6 апреля 2007 г.). «Ист Кокер не заслуживает налета нарциссической мрачности Т. С. Элиота» . Хранитель . Проверено 3 января 2018 г.

- ^ «Томас Стернс Элиот» . www.westminster-abbey.org . Проверено 1 декабря 2016 г.

- ^ "Синяя табличка ТС Элиота" . openplaques.org . Проверено 23 ноября 2013 г.

- ^ Элиот, Т.С. «Письмо Дж. Х. Вудсу, 21 апреля 1919 г.». Письма Т. С. Элиота , том. И. Валери Элиот (редактор), Нью-Йорк: Harcourt Brace, 1988, с. 285.

- ^ «Т.С. Элиот: Стихи Гарвардского адвоката » . Theworld.com . Проверено 3 августа 2009 г.

- ^ Кернс, Клео МакНелли (1987). Т. С. Элиот и индийские традиции: исследование поэзии и веры . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-52132-439-7 . Проверено 8 марта 2016 г.

- ^ Мертенс, Ричард. «Письмо за письмом» в журнале Чикагского университета (август 2001 г.). Проверено 23 апреля 2007 г.

- ^ См., например, Элиот, Т.С. (21 декабря 2010 г.). «Бесплодная земля» и другие стихи . Бродвью Пресс. п. 133. ISBN 978-1-77048-267-8 . Проверено 27 февраля 2019 г. (со ссылкой на неподписанную рецензию в Literary World от 5 июля 1917 г., том lxxxiii, 107.)

- ^ Во, Артур. «Новая поэзия» , Ежеквартальное обозрение , октябрь 1916 г., стр. 226, со ссылкой на Литературное приложение Times от 21 июня 1917 г., вып. 805, 299; Вагнер, Эрика (2001), «Вспышка ярости» , The Guardian , письма в редакцию, 4 сентября 2001 г. Вагнер опускает слово «очень» из цитаты.

- ^ Миллер, Джеймс Х. младший (2005). Т. С. Элиот: становление американского поэта, 1888–1922 гг . Юниверсити-Парк, Пенсильвания: Издательство Пенсильванского государственного университета. стр. 387–388. ISBN 978-0-271-02681-7 .

- ^ Экройд, Питер (1984). ТС Элиот . Нью-Йорк: Саймон и Шустер. п. 113. ОЛ 24766653М .

- ^ Письма Т. С. Элиота , Том. 1, с. 596.

- ^ Льюис, Перикл (2007). Кембриджское введение в модернизм . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 129. ИСБН 9780521828093 . ОЛ 22749928М .

- ^ Стихи Т. С. Элиота, Том 1: Сборник и несобранные стихи . Под редакцией Кристофера Рикса и Джима МакКью, Faber & Faber, 2015, стр. 576

- ^ Маккейб, Колин. ТС Элиот . Тависток: Норткот Хаус, 2006.

- ^ Тирл, Оливер (4 февраля 2021 г.). «10 самых известных строк Т.С. Элиота» . Интересная литература . Проверено 3 февраля 2024 г.

- ^ Уилсон, Эдмунд . «Обзор Пепельной среды», Новая Республика , 20 августа 1930 года.

- ↑ См., например, биографически ориентированную работу одного из редакторов и главных критиков Элиота, Рональда Шухарда.

- ^ Грант, Майкл (ред.). Т. С. Элиот: критическое наследие . Рутледж и Кеган Пол, 1982.

- ^ «Улисс, порядок и миф», Избранные эссе Т. С. Элиота (оригинал 1923 г.).

- ^ Рейн, Крейг. Т. С. Элиот (Нью-Йорк: Oxford University Press, 2006).

- ^ Унтермейер, Луи . Современная американская поэзия . Харткорт Брейс, 1950, стр. 395–396.

- ^ «Введение в Книгу практичных кошек Старого Опоссума» . Британская библиотека . Архивировано из оригинала 25 марта 2019 года . Проверено 27 февраля 2018 г.

- ^ «Полная простота Т.С. Элиота» . Джошуа Сподек . 22 декабря 2013 года . Проверено 7 ноября 2020 г. .

Литтл Гиддинг (стихия огня) — наиболее антологизированный из квартетов.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ньюман, Барбара (2011). «Позитивный путь Элиота: Джулиан Норвичский, Чарльз Уильямс и Литтл Гиддинг» . Современная филология . 108 (3): 427–461. дои : 10.1086/658355 . ISSN 0026-8232 . JSTOR 10.1086/658355 . S2CID 162999145 .

- ^ Элиот, Т.С. Использование поэзии и использование критики , издательство Гарвардского университета, 1933 (предпоследний абзац).

- ^ Дарлингтон, Вашингтон (2004). «Генри Шерек» . Оксфордский национальный биографический словарь (онлайн-изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета. doi : 10.1093/ref:odnb/36063 . Проверено 27 июля 2014 г. (Требуется подписка или членство в публичной библиотеке Великобритании .)

- ^ Т. С. Элиот из Института перспективных исследований , Письмо института , весна 2007 г., стр. 6.

- ↑ Элиот, Томас Стернс. Архивировано 19 января 2015 г. в профиле IAS Wayback Machine .

- ^ цитируется Роджером Кимбаллом, «Тяга к реальности», The New Criterion Vol. 18, 1999.

- ^ Элиот, Т.С. (1930). «Традиции и индивидуальный талант» . Священный лес . Бартлби.com . Проверено 3 августа 2009 г.

- ^ Дирк Вайдманн: И я, Тиресий, претерпел все... . В: ЛИТЕРАТУРА 51 (3), 2009, стр. 98–108.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Элиот, Т.С. (1921). «Гамлет и его проблемы» . Священный лес . Бартлби.com . Проверено 3 августа 2009 г.

- ^ Берт, Стивен и Левин, Дженнифер. «Поэзия и новая критика». Товарищ поэзии двадцатого века , Нил Робертс, изд. Молден, Массачусетс: Blackwell Publishers, 2001. с. 154

- ^ Бейкер, Кристофер Пол (2003). «Роза Порфирона: «Метафизические поэты» Китса и Т.С. Элиота ». Журнал современной литературы . 27 (1): 57–62. дои : 10.1353/jml.2004.0051 . S2CID 162044168 . Проект МУЗА 171830 .

- ^ Маллок, А.Е. (1953). «Единая чувствительность и метафизическая поэзия». Колледж английского языка . 15 (2): 95–101. дои : 10.2307/371487 . JSTOR 371487 . S2CID 149839426 .

- ^ Элиот, Т.С. (1922). «Бесплодная земля» . Бартлби.com . Проверено 3 августа 2009 г.

- ^ «Т. С. Элиот :: Пустошь и критика» . Британская энциклопедия . 4 января 1965 года . Проверено 3 августа 2009 г.

- ^ Элиот, Т.С. (1 января 2000 г.). Поэзия и драма . Фабер и Фабер Лимитед . Проверено 26 января 2017 г. - из Интернет-архива.

- ^ Элиот, Т.С. (1921). «Возможность поэтической драмы» . Священный лес: очерки поэзии и критики . bartleby.com . Проверено 26 января 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уилсон, Эдмунд, «Поэзия Друта». Циферблат 73. Декабрь 1922. 611–16.

- ^ Пауэлл, Чарльз, «Так много макулатуры». Манчестер Гардиан , 31 октября 1923 года.

- ↑ Время , 3 марта 1923 г., 12.

- ^ Рэнсом, Джон Кроу. «Бесплодные земли». Литературное обозрение New York Evening Post , 14 июля 1923 г., стр. 825–26.

- ^ Селдес, Гилберт. «ТС Элиот». Нация , 6 декабря 1922 г., стр. 614–616.

- ^ Озик, Синтия (20 ноября 1989 г.). «ТС ЭЛИОТ НА 101» . Житель Нью-Йорка . Проверено 1 декабря 2016 г.

- ^ Блум, Гарольд. Западный канон: книги и школы веков . Нью-Йорк: Риверхед, 1995.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Стивен Гринблатт и др. (ред.), Антология английской литературы Нортона, Том 2 . «ТС Элиот». Нью-Йорк, штат Нью-Йорк: WW Norton & Co.: Нью-Йорк, Нью-Йорк, 2000.

- ^ Гросс, Джон . Был ли Т.С. Элиот негодяем? , журнал «Комментарий» , ноябрь 1996 г.

- ^ Энтони, Юлиус . Т. С. Элиот, антисемитизм и литературная форма . Издательство Кембриджского университета, 1996 г. ISBN 0-521-58673-9

- ^ Элиот, Т.С. "Геронтион". Сборник стихов . Харкорт, 1963 год.

- ^ Элиот, Т.С. «Бербанк с Бедекером: Блейстейн с сигарой». Сборник стихов . Харкорт, 1963 год.

- ^ Блум, Гарольд (7 мая 2010 г.). «Еврейский вопрос: британский антисемитизм» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 9 апреля 2012 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Дин, Пол (апрель 2007 г.). Крейга Рейна «Академический: о Т. С. Элиоте » . Новый критерий . Проверено 7 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Полин, Том (9 мая 1996 г.). «Нежелательно» . Лондонское обозрение книг .

- ^ Кирк, Рассел (осень 1997 г.). «Т. С. Элиот о литературной морали: о Т. С. Элиоте после странных богов » . Журнал Touchstone . Том. 10, нет. 4.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Т. С. Элиот, Скала (Лондон: Фабер и Фабер, 1934), 44.

- ^ Иглтон, Терри (22 марта 2007 г.). «Стерильный гром Рейн» . Перспектива .

- ^ «www.beingpoet.com» . Архивировано из оригинала 3 февраля 2014 года . Проверено 1 декабря 2016 г.

- ^ Сорел, Нэнси Колдуэлл (18 ноября 1995 г.). «ПЕРВЫЕ ВСТРЕЧИ: Когда Джеймс Джойс встретил Т.С. Элиота» . Независимый . Архивировано из оригинала 26 мая 2022 года . Проверено 1 декабря 2016 г.

- ^ Вашингтон, Канцелярия (6 января 2020 г.). «Дерек Уолкотт (1930–2017)» . Проверено 7 ноября 2020 г. .

Находясь под сильным влиянием поэтов-модернистов Т. С. Элиота и Эзры Паунда, Уолкотт стал всемирно известным благодаря сборнику «В зеленой ночи: стихи 1948–1960» (1962).

- ^ Брэтуэйт, Камау (1993). «Корни». История Голоса . Анн-Арбор, Мичиган: Издательство Мичиганского университета . п. 286.

- ^ «Поэт Т. С. Элиот умирает в Лондоне» . Этот день в истории . Проверено 16 февраля 2012 г.

- ^ МакКрири, Кристофер (2005). Орден Канады: его истоки, история и развитие . Университет Торонто Пресс. ISBN 9780802039408 .

- ^ «ТС Элиот» . Афиша . Архивировано из оригинала 3 мая 2019 года . Проверено 3 мая 2019 г.

- ^ «Айворс 1982» . Академия Айворса. Архивировано из оригинала 3 мая 2019 года . Проверено 3 мая 2019 г.

- ^ : «Фото в Instagram, сделанное Обществом Фи Бета Каппа • 15 июля 2015 г., 19:44 по всемирному координированному времени» . instagram.com. Архивировано из оригинала 23 декабря 2021 года . Проверено 1 декабря 2016 г.

- ^ «Томас Стернс Элиот» . Американская академия искусств и наук . Проверено 1 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ «История участников APS» . search.amphilsoc.org . Проверено 1 декабря 2022 г.

- ↑ О трех рассказах, опубликованных в журнале Smith Academy Record (1905), никогда не вспоминали ни в какой форме, и ими практически пренебрегали.

- ^ Что касается сравнительного исследования этого рассказа и » Редьярда Киплинга « Человека, который хотел бы стать королем , см. Тацуши Нарита, Т. С. Элиот и его юность как «Литературный Колумб» (Нагоя: Когаку Шуппан, 2011), 21– 30.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Стихи Т. С. Элиота «Гарвардский адвокат»» . Архивировано из оригинала 28 сентября 2007 года.

Дальнейшее чтение

[ редактировать ]- Экройд, Питер . Т. С. Элиот: Жизнь (1984).

- Адамсон, Дональд (ред.) и Сенкур, Роберт. Т. С. Элиот: Мемуары , Додд Мид (1971).

- Али, Ахмед. Пенни-мир г-на Элиота: эссе по интерпретации поэзии Т. С. Элиота , опубликовано для Университета Лакхнау издательством New Book Co., Бомбей, PS King & Staples Ltd, Вестминстер, Лондон, 1942, 138 стр.

- Ашер, Кеннет Т.С. Элиот и идеология (1995).

- Боттум, Джозеф , «Во что почти верил Т. С. Элиот» , First Things 55 (август/сентябрь 1995 г.): 25–30.

- Брэнд, Клинтон А. «Голос этого призвания: непреходящее наследие Т. С. Элиота», Modern Age, том 45, номер 4; Осень 2003 г., консервативная точка зрения.

- Браун, Алек. «Лирический импульс в поэзии Элиота», Исследование , том. 2.

- Буш, Рональд. Т. С. Элиот: исследование характера и стиля (1984).

- Буш, Рональд, «Присутствие прошлого: этнографическое мышление / литературная политика». В «Преисториях будущего» под ред. Эльзар Баркан и Рональд Буш, издательство Стэнфордского университета (1995).

- Кроуфорд, Роберт. Дикарь и город в творчестве Т. С. Элиота (1987).

- Кроуфорд, Роберт. Молодой Элиот: От Сент-Луиса до «Бесплодной земли» (2015).

- Кроуфорд, Роберт. Элиот. После «Бесплодной земли» (2022).

- Кристенсен, Карен. «Дорогая миссис Элиот», The Guardian Review (29 января 2005 г.).

- Дас, Джолли. «Призматические пьесы Элиота: многогранный поиск». Нью-Дели: Атлантика, 2007.

- Доусон, Дж. Л., П. Д. Холланд и DJ МакКиттерик, Согласие к «Полному собранию стихов и пьес Т. С. Элиота», Итака и Лондон: Cornell University Press, 1995.

- Форстер, Э.М. Эссе о Т.С. Элиоте в журнале Life and Letters , июнь 1929 г.

- Гарднер, Хелен . Искусство Т. С. Элиота (1949).

- Гордон, Линдалл . Т. С. Элиот: Несовершенная жизнь (1998).

- Гуха, Чинмой. Где пересекаются мечты: Т. С. Элиот и французская поэзия (2000, 2011).

- Хардинг, У.Д. Т.С. Элиот, 1925–1935 гг ., Исследование, сентябрь 1936 г.: Обзор.

- Харгроув, Нэнси Дюваль. Пейзаж как символ в поэзии Т. С. Элиота . Университетское издательство Миссисипи (1978).

- Хирн, Шейла Г., Традиции и отдельные шотландцы]: Эдвин Мьюир и Т.С. Элиот , в Cencrastus № 13, лето 1983 г., стр. 21–24, ISSN 0264-0856

- Хирн, Парижский год Шейлы Дж. Т. С. Элиот . Университетское издательство Флориды (2009).

- Юлиус, Энтони . Т. С. Элиот, антисемитизм и литературная форма . Издательство Кембриджского университета (1995).

- Кеннер, Хью . Невидимый поэт: Т. С. Элиот (1969).

- Кеннер, Хью . редактор, Т. С. Элиот: Сборник критических эссе , Прентис-Холл (1962).

- Кирк, Рассел Элиот и его век: Т.С., Моральное воображение Элиота в двадцатом веке (Введение Бенджамина Г. Локерда-младшего). Уилмингтон: Институт межвузовских исследований , переиздание исправленного второго издания, 2008 г.

- Коджеки, Роджер. Социальная критика Т. С. Элиота , Faber & Faber, Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1972, переработанное издание Kindle. 2014.

- Лал, П. (редактор), Т. С. Элиот: Посвящение Индии: памятный том из 55 эссе и элегий , Мастерская писателей, Калькутта, 1965.

- Письма Т. С. Элиота . Эд. Валери Элиот. Том. Я, 1898–1922. Сан-Диего [и др.], 1988. Том. 2, 1923–1925. Под редакцией Валери Элиот и Хью Хотона, Лондон: Faber, 2009. ISBN 978-0-571-14081-7

- Леви, Уильям Тернер и Виктор Шерл. С любовью, Т. С. Элиот: История дружбы: 1947–1965 (1968).

- Мэтьюз, Т.С. Великий Том: Примечания к определению Т.С. Элиота (1973)

- Максвелл, Д.С. Поэзия Т.С. Элиота , Рутледжа и Кегана Пола (1960).

- Миллер, Джеймс Э.-младший Т.С. Элиот. Становление американского поэта, 1888–1922 гг . Издательство Пенсильванского государственного университета. 2005.

- Норт, Майкл (ред.) Пустошь (Norton Critical Editions) . Нью-Йорк: WW Нортон , 2000.

- Рейн, Крейг . ТС Элиот . Издательство Оксфордского университета (2006).

- Рикс, Кристофер . Т. С. Элиот и предубеждение (1988).

- Робинсон, Ян «Английские пророки» , The Brynmill Press Ltd (2001)

- Шухард, Рональд. Темный ангел Элиота: пересечения жизни и искусства (1999).

- Скофилд, доктор Мартин, «Т. С. Элиот: Стихи», издательство Кембриджского университета (1988).

- Сеферис, Джордж; Матиас, Сьюзен (2009). «Введение в TS Элиота Джорджа Сефериса». Модернизм/Модернизм . 16 (1): 146–160. дои : 10.1353/мод.0.0068 . S2CID 143631556 . Проект МУЗА 258704 .

- Сеймур-Джонс, Кэрол . Нарисованная тень: жизнь Вивьен Элиот (2001).

- Синха, Арун Кумар и Викрам, Кумар. Т. С. Элиот: Интенсивное исследование избранных стихов , Нью-Дели: Spectrum Books Pvt. ООО (2005).

- Спендер, Стивен . ТС Элиот (1975)

- Сперр, Барри, англо-католик в религии: Т. С. Элиот и христианство , The Lutterworth Press (2009)

- Тейт, Аллен , редактор. Т. С. Элиот: Человек и его работа (1966; переиздано издательством Penguin, 1971).

Внешние ссылки

[ редактировать ]Биография

[ редактировать ]- Т. С. Элиот в Poetry Foundation

- Биография из TS Eliot Lives' and Legacies. Архивировано 14 февраля 2007 г. в Wayback Machine.

- Генеалогия семьи Элиотов , включая Т. С. Элиота

- Могила Элиота

- Линдалл Гордон , Ранние годы Элиота, Оксфорд и Нью-Йорк: Oxford University Press , 1977, ISBN 978-0-19-812078-0 .

- Профиль Т.С. Элиота, стихи, эссе на Poets.org

- Т.С. Элиот на Nobelprize.org

Работает

[ редактировать ]- Работы Т. С. Элиота в форме электронных книг в Standard Ebooks

- Работы Т.С. Элиота в Project Gutenberg

- Работы Т.С. (Томас Стернс) Элиота в Faded Page (Канада)

- Работы Т.С. Элиота или о нем в Интернет-архиве

- Работы Т.С. Элиота в LibriVox (аудиокниги, являющиеся общественным достоянием)

- официальный список работ Т.С. Элиота, некоторые из которых доступны полностью

- Список работ Т.С. Элиота, написанных для сцены на doollee.com. Архивировано 22 ноября 2016 г. в Wayback Machine.

- Стихи Т.С. Элиота и биография на PoetryFoundation.org

- Текст ранних стихов (1907–1910), напечатанных в The Harvard Advocate.

- Коллекция TS Eliot на Bartleby.com

- Кошки Т.С. Элиота

- Священный лес: очерки поэзии и критики . Кнопф, 1921. Через HathiTrust.

Веб-сайты

[ редактировать ]- Ресурсный центр Общества TS Элиота (Великобритания)

- Гипертекстовый проект TS Eliot

- Официальный сайт (TS Eliot Estate)

- Общества Т. С. Элиота (США) Домашняя страница

Архивы

[ редактировать ]- «Архивные материалы, касающиеся Т. С. Элиота» . Национальный архив Великобритании .

- Найдите Т.С. Элиота в Гарвардском университете

- Коллекция TS Элиота. Архивировано 28 февраля 2009 года в Wayback Machine в Центре выкупа Гарри при Техасском университете в Остине.

- Коллекция Т. С. Элиота в Мертон-колледже Оксфордского университета

- Коллекция Т. С. Элиота в Университете Виктории, специальные коллекции

- Коллекция Т.С. Элиота в библиотеках Университета Мэриленда

- Коллекция Т. С. Элиота . Йельская коллекция американской литературы, Библиотека редких книг и рукописей Бейнеке.

Разнообразный

[ редактировать ]- Ссылки на аудиозаписи чтения Элиотом своих работ

- Интервью с Элиотом: Дональд Холл (весна – лето 1959 г.). «Т. С. Элиот, Искусство поэзии № 1» . Парижское обозрение . Весна-лето 1959 (21).

- Лекция Йельского колледжа по аудио, видео и полным стенограммам открытых курсов Йельского университета Т. С. Элиота

- TS Eliot. Архивировано 21 апреля 2019 года в Wayback Machine Британской библиотеки.

- Вырезки из газет о Т.С. Элиоте в 20-м веке Пресс- ZBW архив

- ТС Элиот

- 1888 рождений

- 1965 смертей

- Американские эмигранты в Соединенном Королевстве

- Американские эмигранты во Франции

- Семья Элиот (США)

- Люди, отказавшиеся от гражданства США

- Натурализованные граждане Соединенного Королевства

- Писатели из Сент-Луиса

- Американские поэты 20-го века

- Британские поэты 20-го века

- Американские поэты-мужчины

- Англиканские поэты

- Британские поэты-мужчины

- Эпические поэты

- Модернистская поэзия на английском языке

- Американские поэты-модернисты

- Британские поэты-модернисты

- Поэты из Миссури

- Американские писатели-мужчины 20-го века

- Американские писатели научно-популярной литературы XX века

- Американские писатели XX века

- Британские писатели-мужчины XX века

- Американские эссеисты XX века

- Британские эссеисты XX века

- Авторы рассказов XX века

- Американские эссеисты-мужчины

- Американские писатели-мужчины научной литературы

- Американские авторы рассказов мужского пола

- Англо-католические писатели

- Британские эссеисты-мужчины

- Британские писатели-мужчины

- Авторы потерянного поколения

- Модернизм

- Неоклассические писатели

- Писатели об активизме и социальных изменениях

- Писатели, иллюстрировавшие свои произведения