Лесбиянка

| Сексуальная ориентация |

|---|

|

| Сексуальная ориентация |

| Связанные термины |

| Исследовать |

| Животные |

| Связанные темы |

| Часть серии о |

| ЛГБТ-темы |

|---|

|

|

Лесбиянка женщина или девушка – это гомосексуальная . [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [ 5 ] Это слово также используется для женщин в отношении их сексуальной идентичности или сексуального поведения , независимо от сексуальной ориентации , или как прилагательное для характеристики или ассоциации существительных с женской гомосексуальностью или однополым влечением. [ 6 ] [ 7 ] Понятие «лесбиянка», позволяющее различать женщин с общей сексуальной ориентацией, появилось в 20 веке. На протяжении всей истории женщины не имели такой же свободы и независимости, как мужчины, в гомосексуальных отношениях, но и не подвергались такому же суровому наказанию, как мужчины-геи в некоторых обществах. Вместо этого лесбийские отношения часто считались безобидными, если только их участники не пытались отстаивать привилегии, традиционно которыми пользовались мужчины. В результате в истории было мало документально подтверждено точное описание того, как выражался женский гомосексуальность. Когда первые сексологи в конце 19 века начали классифицировать и описывать гомосексуальное поведение, чему мешал недостаток знаний о гомосексуализме или женской сексуальности, они различали лесбиянок как женщин, не придерживающихся женских гендерных ролей . Они классифицировали их как психически больных — определение, которое с конца 20-го века изменилось в мировом научном сообществе.

Женщины в гомосексуальных отношениях в Европе и США ответили на дискриминацию и репрессии либо скрывая свою личную жизнь, либо приняв ярлык изгоя и создав субкультуру и идентичность . После Второй мировой войны , в период социальных репрессий, когда правительства активно преследовали гомосексуалистов, женщины создали сети для общения и обучения друг друга. Обретение большей экономической и социальной свободы позволило им определить, как они могут формировать отношения и семьи. Со второй волной феминизма и ростом исследований женской истории и сексуальности в конце 20-го века определение лесбиянки расширилось, что привело к спорам об использовании этого термина. Хотя исследование Лизы М. Даймонд выявило, что сексуальное желание является основным компонентом определения лесбиянок, [ 8 ] [ а ] некоторые женщины, вступающие в однополую сексуальную активность, могут отказаться идентифицировать себя не только как лесбиянки, но как бисексуалы и . Самоидентификация других женщин как лесбиянок может не совпадать с их сексуальной ориентацией или сексуальным поведением. Сексуальная идентичность не обязательно совпадает с сексуальной ориентацией или сексуальным поведением по разным причинам, например, из-за страха выявить свою сексуальную ориентацию в гомофобной среде.

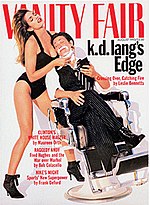

Изображения лесбиянок в средствах массовой информации позволяют предположить, что общество в целом одновременно заинтриговано и угрожает женщинам, бросающим вызов женским гендерным ролям , а также очаровано и потрясено женщинами, которые находятся в романтических отношениях с другими женщинами. Женщины, принявшие лесбийскую идентичность, разделяют опыт, который формирует мировоззрение, подобное этнической идентичности: как гомосексуалистов их объединяет гетеросексистская дискриминация и потенциальное неприятие, с которым они сталкиваются со стороны своих семей, друзей и других людей в результате гомофобии. Как женщины, они сталкиваются с проблемами отдельно от мужчин. Лесбиянки могут сталкиваться с определенными проблемами физического или психического здоровья, возникающими из-за дискриминации, предрассудков и стресса, связанного с меньшинствами . Политические условия и социальные установки также влияют на формирование лесбийских отношений и семей на открытом воздухе.

Этимология

Слово «лесбиянка» — это демоним греческого острова Лесбос , где жила поэтесса VI века до нашей эры Сафо . [ 3 ] Из различных древних писаний историки пришли к выводу, что группа молодых женщин была оставлена под опекой Сафо для их обучения или культурного назидания. [ 9 ] Немногое из стихов Сафо сохранилось, но оставшиеся ее стихи отражают темы, о которых она писала: повседневная жизнь женщин, их отношения и ритуалы. Она сосредоточилась на красоте женщин и заявила о своей любви к девушкам. [ 10 ] До середины 19 века, [ 11 ] Слово «лесбиянка» относилось к любому производному или аспекту Лесбоса, включая сорт вина . [ б ]

В стихотворении Алджернона Чарльза Суинберна «Сапфики» 1866 года термин «лесбиянка» появляется дважды, но оба раза пишется с заглавной буквы после двойного упоминания острова Лесбос, поэтому его можно истолковать как « с острова Лесбос » . [ 13 ] В 1875 году Джордж Сэйнтсбери , описывая поэзию Бодлера, ссылается на свои «Лесбийские исследования», в которые он включает свое стихотворение о «страсти Дельфины», которое представляет собой стихотворение просто о любви между двумя женщинами, в котором не упоминается остров Лесбос. , хотя другое упомянутое стихотворение, озаглавленное «Лесбос», имеет такое значение. [ 14 ] Использование слова лесбиянство для описания эротических отношений между женщинами было задокументировано в 1870 году. [ 15 ] В 1890 году термин «лесбиянка» использовался в медицинском словаре как прилагательное для описания трибадизма (как «лесбийской любви»). Термины «лесбиянка» , «инвертированный » и «гомосексуалист» были взаимозаменяемы с сапфистом и сапфизмом . на рубеже 20-го века [ 15 ] Использование лесбиянок в медицинской литературе стало заметным; к 1925 году это слово было записано как существительное, обозначающее женский эквивалент содомита . [ 15 ] [ 16 ]

Развитие медицинских знаний стало важным фактором в дальнейшем значении термина « лесбиянка». В середине XIX века писатели-медики попытались найти способы выявления мужского гомосексуализма, который считался серьезной социальной проблемой в большинстве западных обществ. назвал « инверсией При классификации поведения, указывающего на то, что немецкий сексолог Магнус Хиршфельд » , исследователи классифицировали то, что является нормальным сексуальным поведением для мужчин и женщин, и, следовательно, в какой степени мужчины и женщины отличаются от «идеального мужского сексуального типа» и «идеальный женский сексуальный тип». [ 17 ]

Гораздо меньше литературы посвящено женскому гомосексуальному поведению, чем мужскому гомосексуализму, поскольку медицинские работники не считают это серьезной проблемой. В некоторых случаях его существование не признавалось. Сексологи Рихард фон Краффт-Эбинг из Германии и британский Хэвлок Эллис написали некоторые из самых ранних и наиболее устойчивых классификаций женского однополого влечения , рассматривая его как форму безумия (категоризация Эллисом «лесбиянства» как медицинской проблемы в настоящее время дискредитирована). ). [ 18 ] Краффт-Эбинг, считавшая лесбиянство неврологическим заболеванием, и Эллис, находившийся под влиянием работ Крафт-Эбинга, расходились во мнениях относительно того, является ли сексуальная инверсия в целом состоянием на протяжении всей жизни. Эллис считал, что многие женщины, исповедующие любовь к другим женщинам, изменили свое отношение к таким отношениям после того, как пережили брак и «практическую жизнь». [ 19 ]

Эллис признал, что существуют «настоящие извращенцы», которые посвятят свою жизнь эротическим отношениям с женщинами. Это были представители « третьего пола », которые отвергали роль женщины как подчиненной, женственной и домашней. [ 20 ] Инверт описал противоположные гендерные роли, а также связанное с этим влечение к женщинам, а не к мужчинам; поскольку женщины в викторианский период считались неспособными инициировать сексуальные контакты, считалось, что женщины, которые делали это с другими женщинами, обладали мужскими сексуальными желаниями. [ 21 ]

Работы Краффт-Эбинга и Эллиса получили широкое распространение и помогли сформировать общественное сознание о женском гомосексуализме. [ с ] Заявления сексологов о том, что гомосексуальность является врожденной аномалией, в целом были хорошо приняты гомосексуальными мужчинами; это указывало на то, что их поведение не было вызвано преступным пороком и не должно рассматриваться как широко признанное явление. В отсутствие какого-либо другого материала для описания своих эмоций гомосексуалы приняли обозначение «иных» или «извращенных» и использовали свой статус вне закона для формирования социальных кругов в Париже и Берлине. Лесбиянку стали описывать элементы субкультуры. [ 24 ]

Лесбиянки в западных культурах, в частности, часто относят себя к людям, имеющим идентичность , определяющую их индивидуальную сексуальность, а также их принадлежность к группе, имеющей общие черты. [ 25 ] Женщины во многих культурах на протяжении всей истории вступали в сексуальные отношения с другими женщинами, но их редко считали частью группы людей на основании того, с кем они имели физические отношения. Поскольку женщины, как правило, составляли политическое меньшинство в западных культурах, добавленное медицинское обозначение гомосексуализма стало причиной развития субкультурной идентичности. [ 26 ]

Сексуальность и идентичность

Представление о том, что сексуальная активность между женщинами необходима для определения лесбийских или лесбийских отношений, продолжает обсуждаться. По мнению писательницы-феминистки Наоми Маккормик , женскую сексуальность конструируют мужчины, для которых основным показателем лесбийской сексуальной ориентации является сексуальный опыт с другими женщинами. Этот же показатель не является обязательным для идентификации женщины как гетеросексуальной. Маккормик утверждает, что эмоциональные, умственные и идеологические связи между женщинами так же или даже более важны, чем генитальные. [ 32 ] Тем не менее, в 1980-х годах значительное движение отвергло десексуализацию лесбиянства со стороны культурных феминисток, что вызвало острую полемику, названную феминистскими секс-войнами . [ 33 ] Роли Буча и женщины вернулись, хотя и не так строго соблюдались, как в 1950-х годах. Для некоторых женщин в 1990-е годы они стали способом избранного сексуального самовыражения. И снова женщины почувствовали себя в большей безопасности, утверждая, что они более склонны к сексуальным приключениям, а сексуальная гибкость стала более приемлемой. [ 34 ]

В центре дебатов часто оказывается феномен, названный сексологом Пеппер Шварц в 1983 году. Шварц обнаружил, что лесбийские пары, длительно живущие в браке, сообщают о меньшем количестве сексуальных контактов, чем гетеросексуальные или гомосексуальные мужские пары, называя это смертью лесбиянок в постели . Некоторые лесбиянки оспаривают определение сексуального контакта, данное в исследовании, и вводят другие факторы, такие как более глубокие связи, существующие между женщинами, которые делают частые сексуальные отношения излишними, большую сексуальную изменчивость у женщин, заставляющую их переходить от гетеросексуалов к бисексуалам и к лесбиянкам множество раз в жизни - или полностью отказаться от ярлыков. Дальнейшие аргументы подтвердили, что исследование было ошибочным и искажало точные сексуальные контакты между женщинами, или что сексуальные контакты между женщинами увеличились с 1983 года, поскольку многие лесбиянки стали более свободны в сексуальном самовыражении. [ 35 ]

Расширение дискуссий о гендере и сексуальной ориентации повлияло на то, как много женщин навешивают ярлыки или воспринимают себя. Большинство людей в западной культуре учат, что гетеросексуальность — это врожденное качество всех людей. Когда женщина осознает свое романтическое и сексуальное влечение к другой женщине, это может вызвать «экзистенциальный кризис»; многие из тех, кто проходит через это, принимают личность лесбиянок, бросая вызов стереотипам общества о гомосексуалистах, чтобы научиться функционировать в рамках гомосексуальной субкультуры. [ 36 ] Лесбиянки в западных культурах обычно разделяют идентичность, аналогичную идентичности, основанной на этнической принадлежности; у них общая история и субкультура, а также схожий опыт дискриминации, из-за которой многие лесбиянки отвергают гетеросексуальные принципы. Эта идентичность уникальна для геев и гетеросексуальных женщин и часто создает напряженность в отношениях с бисексуальными женщинами. [ 25 ] Одним из спорных вопросов являются лесбиянки, которые занимались сексом с мужчинами, в то время как лесбиянок, которые никогда не занимались сексом с мужчинами, можно назвать « лесбиянками с золотой звездой ». Те, кто имел половые контакты с мужчинами, могут столкнуться с насмешками со стороны других лесбиянок или проблемами идентичности при определении того, что значит быть лесбиянкой. [ 37 ]

Исследователи, в том числе социологи , заявляют, что часто поведение и идентичность не совпадают: женщины могут называть себя гетеросексуальными, но вступать в сексуальные отношения с женщинами, самоидентифицированные лесбиянки могут заниматься сексом с мужчинами, или женщины могут обнаружить то, что они считали неизменной сексуальной идентичностью. изменилось с течением времени. [ 7 ] [ 38 ] Исследование Лизы М. Даймонд и др. сообщили, что «лесбиянки и подвижные женщины были более исключительными, чем бисексуальные женщины, в своем сексуальном поведении» и что «женщины-лесбиянки, похоже, склонялись исключительно к однополым влечениям и поведению». В нем сообщалось, что лесбиянки «по всей видимости, демонстрируют «основную» лесбийскую ориентацию». [ 8 ]

В статье 2001 года о различении лесбиянок для медицинских исследований и исследований в области здравоохранения предлагалось идентифицировать лесбиянок, используя только три характеристики идентичности, только сексуальное поведение или оба вместе взятых. В статье отказались включать желание или влечение, поскольку они редко имеют отношение к измеримым проблемам со здоровьем или психосоциальным состоянием. [ 39 ] Исследователи заявляют, что не существует стандартного определения лесбиянки , поскольку «этот термин использовался для описания женщин, занимающихся сексом с женщинами, либо исключительно, либо в дополнение к сексу с мужчинами (т. е. поведение ); женщин, которые идентифицируют себя как лесбиянки (т. е. , идентичность ); и женщины, чьи сексуальные предпочтения относятся к женщинам (т.е. желание или влечение )»… «Отсутствие стандартного определения лесбиянок и стандартных вопросов для оценки того, кто является лесбиянкой, затрудняет четкое определение популяции. женщин-лесбиянок». [ 7 ] То, как и где были получены образцы для исследования, также может повлиять на определение. [ 7 ]

Женский гомосексуальность без идентичности в западной культуре

The varied meanings of lesbian since the early 20th century have prompted some historians to revisit historic relationships between women before the wide usage of the word was defined by erotic proclivities. Discussion from historians caused further questioning of what qualifies as a lesbian relationship. As lesbian-feminists asserted, a sexual component was unnecessary in declaring oneself a lesbian if the primary and closest relationships were with women. When considering past relationships within appropriate historic context, there were times when love and sex were separate and unrelated notions.[40] В 1989 году академическая группа под названием «Группа истории лесбиянок» написала:

Because of society's reluctance to admit that lesbians exist, a high degree of certainty is expected before historians or biographers are allowed to use the label. Evidence that would suffice in any other situation is inadequate here... A woman who never married, who lived with another woman, whose friends were mostly women, or who moved in known lesbian or mixed gay circles, may well have been a lesbian. ... But this sort of evidence is not 'proof'. What our critics want is incontrovertible evidence of sexual activity between women. This is almost impossible to find.[41]

Female sexuality is often not adequately represented in texts and documents. Until very recently, much of what has been documented about women's sexuality has been written by men, in the context of male understanding, and relevant to women's associations to men—as their wives, daughters, or mothers, for example.[42] Often artistic representations of female sexuality suggest trends or ideas on broad scales, giving historians clues as to how widespread or accepted erotic relationships between women were.

Ancient Greece and Rome

Women in ancient Greece were sequestered with one another, and men were segregated likewise. In this homosocial environment, erotic and sexual relationships between males were common and recorded in literature, art, and philosophy. Very little was recorded about homosexual activity between Greek women. There is some speculation that similar relationships existed between women and girls — the poet Alcman used the term aitis, as the feminine form of aites — which was the official term for the younger participant in a pederastic relationship.[44] Aristophanes, in Plato's Symposium, mentions women who are romantically attracted to other women, but uses the term trepesthai (to be focused on) instead of eros, which was applied to other erotic relationships between men, and between men and women.[45]

Historian Nancy Rabinowitz argues that ancient Greek red vase images which portray women with their arms around another woman's waist, or leaning on a woman's shoulders can be construed as expressions of romantic desire.[46] Much of the daily lives of women in ancient Greece is unknown, in particular their expressions of sexuality. Although men participated in pederastic relationships outside marriage, there is no clear evidence that women were allowed or encouraged to have same-sex relationships before or during marriage as long as their marital obligations were met. Women who appear on Greek pottery are depicted with affection, and in instances where women appear only with other women, their images are eroticized: bathing, touching one another, with dildos placed in and around such scenes, and sometimes with imagery also seen in depictions of heterosexual marriage or pederastic seduction. Whether this eroticism is for the viewer or an accurate representation of life is unknown.[44][47] Rabinowitz writes that the lack of interest from 19th-century historians who specialized in Greek studies regarding the daily lives and sexual inclinations of women in Greece was due to their social priorities. She postulates that this lack of interest led the field to become over male-centric and was partially responsible for the limited information available on female topics in ancient Greece.[48]

Women in ancient Rome were similarly subject to men's definitions of sexuality. Modern scholarship indicates that men viewed female homosexuality with hostility. They considered women who engaged in sexual relations with other women to be biological oddities that would attempt to penetrate women—and sometimes men—with "monstrously enlarged" clitorises.[49] According to scholar James Butrica, lesbianism "challenged not only the Roman male's view of himself as the exclusive giver of sexual pleasure but also the most basic foundations of Rome's male-dominated culture". No historical documentation exists of women who had other women as sex partners.[50]

Early modern Europe

Female homosexuality did not receive the same negative response from religious or criminal authorities as male homosexuality or adultery did throughout history. Whereas sodomy between men, men and women, and men and animals was punishable by death in England, acknowledgment of sexual contact between women was nonexistent in medical and legal texts. The earliest law against female homosexuality appeared in France in 1270.[51] In Spain, Italy, and the Holy Roman Empire, sodomy between women was included in acts considered unnatural and punishable by burning to death, although few instances are recorded of this taking place.[52]

The earliest such execution occurred in Speier, Germany, in 1477. Forty days' penance was demanded of nuns who "rode" each other or were discovered to have touched each other's breasts. An Italian nun named Sister Benedetta Carlini was documented to have seduced many of her sisters when possessed by a Divine spirit named "Splenditello"; to end her relationships with other women, she was placed in solitary confinement for the last 40 years of her life.[53] Female homoeroticism was so common in English literature and theater that historians suggest it was fashionable for a period during the Renaissance.[54] Englishwoman Mary Frith has been described as lesbian in academic study.[55]

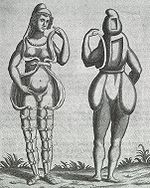

Ideas about women's sexuality were linked to contemporary understanding of female physiology. The vagina was considered an inward version of the penis; where nature's perfection created a man, often nature was thought to be trying to right itself by prolapsing the vagina to form a penis in some women.[56] These sex changes were later thought to be cases of hermaphrodites, and hermaphroditism became synonymous with female same-sex desire. Medical consideration of hermaphroditism depended upon measurements of the clitoris; a longer, engorged clitoris was thought to be used by women to penetrate other women. Penetration was the focus of concern in all sexual acts, and a woman who was thought to have uncontrollable desires because of her engorged clitoris was called a "tribade" (literally, one who rubs).[57] Not only was an abnormally engorged clitoris thought to create lusts in some women that led them to masturbate, but pamphlets warning women about masturbation leading to such oversized organs were written as cautionary tales. For a while, masturbation and lesbian sex carried the same meaning.[58]

Class distinction became linked as the fashion of female homoeroticism passed. Tribades were simultaneously considered members of the lower class trying to ruin virtuous women, and representatives of an aristocracy corrupt with debauchery. Satirical writers began to suggest that political rivals (or more often, their wives) engaged in tribadism in order to harm their reputations. Queen Anne was rumored to have a passionate relationship with Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough, her closest adviser and confidante. When Churchill was ousted as the queen's favorite, she purportedly spread allegations of the queen having affairs with her bedchamberwomen.[59] Marie Antoinette was also the subject of such speculation for some months between 1795 and 1796.[60]

Female husbands

Hermaphroditism appeared in medical literature enough to be considered common knowledge, although cases were rare. Homoerotic elements in literature were pervasive, specifically the masquerade of one gender for another to fool an unsuspecting woman into being seduced. Such plot devices were used in Shakespeare's Twelfth Night (1601), The Faerie Queene by Edmund Spenser in 1590, and James Shirley's The Bird in a Cage (1633).[61] Cases during the Renaissance of women taking on male personae and going undetected for years or decades have been recorded, though whether these cases would be described as transvestism by homosexual women,[62][63] or in contemporary sociology characterised as transgender, is debated and depends on the individual details of each case.

If discovered, punishments ranged from death, to time in the pillory, to being ordered never to dress as a man again. Henry Fielding wrote a pamphlet titled The Female Husband in 1746, based on the life of Mary Hamilton, who was arrested after marrying a woman while masquerading as a man, and was sentenced to public whipping and six months in jail. Similar examples were procured of Catharine Linck in Prussia in 1717, executed in 1721; Swiss Anne Grandjean married and relocated with her wife to Lyons, but was exposed by a woman with whom she had had a previous affair and sentenced to time in the stocks and prison.[64]

Queen Christina of Sweden's tendency to dress as a man was well known during her time and excused because of her noble birth. She was brought up as a male and there was speculation at the time that she was a hermaphrodite. Even after Christina abdicated the throne in 1654 to avoid marriage, she was known to pursue romantic relationships with women.[65]

Some historians view cases of cross-dressing women to be manifestations of women seizing power they would naturally be unable to enjoy in feminine attire, or their way of making sense out of their desire for women. Lillian Faderman argues that Western society was threatened by women who rejected their feminine roles. Catharine Linck and other women who were accused of using dildos, such as two nuns in 16th century Spain executed for using "material instruments", were punished more severely than those who did not.[51][64] Two marriages between women were recorded in Cheshire, England, in 1707 (between Hannah Wright and Anne Gaskill) and 1708 (between Ane Norton and Alice Pickford) with no comment about both parties being female.[66][67] Reports of clergymen with lax standards who performed weddings—and wrote their suspicions about one member of the wedding party—continued to appear for the next century.

Outside Europe, women were able to dress as men and go undetected. Deborah Sampson fought in the American Revolution under the name Robert Shurtlieff, and pursued relationships with women.[68] Edward De Lacy Evans was born female in Ireland, but took a male name during the voyage to Australia and lived as a man for 23 years in Victoria, marrying three times.[69] Percy Redwood created a scandal in New Zealand in 1909 when she was found to be Amy Bock, who had married a woman from Port Molyneaux; newspapers argued whether it was a sign of insanity or an inherent character flaw.[70]

Re-examining romantic friendships

During the 17th through 19th centuries, a woman expressing passionate love for another woman was fashionable, accepted, and encouraged.[67] These relationships were termed romantic friendships, Boston marriages, or "sentimental friends", and were common in the U.S., Europe, and especially in England. Documentation of these relationships is possible by a large volume of letters written between women. Whether the relationship included any genital component was not a matter for public discourse, but women could form strong and exclusive bonds with each other and still be considered virtuous, innocent, and chaste; a similar relationship with a man would have destroyed a woman's reputation. In fact, these relationships were promoted as alternatives to and practice for a woman's marriage to a man.[71][d]

One such relationship was between Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who wrote to Anne Wortley in 1709: "Nobody was so entirely, so faithfully yours ... I put in your lovers, for I don't allow it possible for a man to be so sincere as I am."[73] Similarly, English poet Anna Seward had a devoted friendship to Honora Sneyd, who was the subject of many of Seward's sonnets and poems. When Sneyd married despite Seward's protest, Seward's poems became angry. Seward continued to write about Sneyd long after her death, extolling Sneyd's beauty and their affection and friendship.[74] As a young woman, writer and philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft was attached to a woman named Fanny Blood. Writing to another woman by whom she had recently felt betrayed, Wollstonecraft declared, "The roses will bloom when there's peace in the breast, and the prospect of living with my Fanny gladdens my heart:—You know not how I love her."[75][e]

The two women had a relationship that was hailed as devoted and virtuous, after eloping and living 51 years together in Wales.

Perhaps the most famous of these romantic friendships was between Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby, nicknamed the Ladies of Llangollen. Butler and Ponsonby eloped in 1778, to the relief of Ponsonby's family (concerned about their reputation had she run away with a man)[77] to live together in Wales for 51 years and be thought of as eccentrics.[78] Their story was considered "the epitome of virtuous romantic friendship" and inspired poetry by Anna Seward and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.[79] Diarist Anne Lister, captivated by Butler and Ponsonby, recorded her affairs with women between 1817 and 1840. Some of it was written in code, detailing her sexual relationships with Marianna Belcombe and Maria Barlow.[80] Both Lister and Eleanor Butler were considered masculine by contemporary news reports, and though there were suspicions that these relationships were sapphist in nature, they were nonetheless praised in literature.[72][81]

Romantic friendships were also popular in the U.S. Enigmatic poet Emily Dickinson wrote over 300 letters and poems to Susan Gilbert, who later became her sister-in-law, and engaged in another romantic correspondence with Kate Scott Anthon. Anthon broke off their relationship the same month Dickinson entered self-imposed lifelong seclusion.[82] Nearby in Hartford, Connecticut, African American freeborn women Addie Brown and Rebecca Primus left evidence of their passion in letters: "No kisses is like youres".[83] In Georgia, Alice Baldy wrote to Josie Varner in 1870, "Do you know that if you touch me, or speak to me there is not a nerve of fibre in my body that does not respond with a thrill of delight?"[84]

Around the turn of the 20th century, the development of higher education provided opportunities for women. In all-female surroundings, a culture of romantic pursuit was fostered in women's colleges. Older students mentored younger ones, called on them socially, took them to all-women dances, and sent them flowers, cards, and poems that declared their undying love for each other.[85] These were called "smashes" or "spoons", and they were written about quite frankly in stories for girls aspiring to attend college in publications such as Ladies Home Journal, a children's magazine titled St. Nicholas, and a collection called Smith College Stories, without negative views.[86] Enduring loyalty, devotion, and love were major components to these stories, and sexual acts beyond kissing were consistently absent.[85]

Women who had the option of a career instead of marriage labeled themselves New Women and took their new opportunities very seriously.[f] Faderman calls this period "the last breath of innocence" before 1920 when characterizations of female affection were connected to sexuality, marking lesbians as a unique and often unflatteringly portrayed group.[85] Specifically, Faderman connects the growth of women's independence and their beginning to reject strictly prescribed roles in the Victorian era to the scientific designation of lesbianism as a type of aberrant sexual behavior.[87]

Identity and gender role in western culture

Construction

For some women, the realization that they participated in behavior or relationships that could be categorized as lesbian caused them to deny or conceal it, such as professor Jeannette Augustus Marks at Mount Holyoke College, who lived with the college president, Mary Woolley, for 36 years. Marks discouraged young women from "abnormal" friendships and insisted happiness could only be attained with a man.[26][g] Other women embraced the distinction and used their uniqueness to set themselves apart from heterosexual women and gay men.[89]

From the 1890s to the 1930s, American heiress Natalie Clifford Barney held a weekly salon in Paris to which major artistic celebrities were invited and where lesbian topics were the focus. Combining Greek influences with contemporary French eroticism, she attempted to create an updated and idealized version of Lesbos in her salon.[90] Her contemporaries included artist Romaine Brooks, who painted others in her circle; writers Colette, Djuna Barnes, social host Gertrude Stein, and novelist Radclyffe Hall.

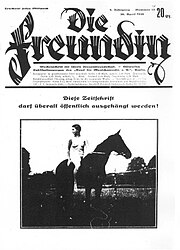

Berlin had a vibrant homosexual culture in the 1920s, and about 50 clubs catered to lesbians. Die Freundin (The Girlfriend) magazine, published between 1924 and 1933, targeted lesbians. Garçonne (aka Frauenliebe (Woman Love)) was aimed at lesbians and male transvestites.[91] These publications were controlled by men as owners, publishers, and writers. Around 1926, Selli Engler founded Die BIF – Blätter Idealer Frauenfreundschaften (The BIF – Papers on Ideal Women Friendships), the first lesbian publication owned, published and written by women. In 1928, the lesbian bar and nightclub guide Berlins lesbische Frauen (The Lesbians of Berlin) by Ruth Margarite Röllig[92] further popularized the German capital as a center of lesbian activity. Clubs varied between large establishments that became tourist attractions, to small neighborhood cafes where local women went to meet other women. The cabaret song "Das lila Lied" ("The Lavender Song") became an anthem to the lesbians of Berlin. Although it was sometimes tolerated, homosexuality was illegal in Germany and law enforcement used permitted gatherings as an opportunity to register the names of homosexuals for future reference.[93] Magnus Hirschfeld's Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, which promoted tolerance for homosexuals in Germany, welcomed lesbian participation, and a surge of lesbian-themed writing and political activism in the German feminist movement became evident.[94]

In 1928, Radclyffe Hall published a novel titled The Well of Loneliness. The novel's plot centers around Stephen Gordon, a woman who identifies herself as an invert after reading Krafft-Ebing's Psychopathia Sexualis, and lives within the homosexual subculture of Paris. The novel included a foreword by Havelock Ellis and was intended to be a call for tolerance for inverts by publicizing their disadvantages and accidents of being born inverted.[95] Hall subscribed to Ellis and Krafft-Ebing's theories and rejected Freud's theory that same-sex attraction was caused by childhood trauma and was curable. The publicity Hall received was due to unintended consequences; the novel was tried for obscenity in London, a spectacularly scandalous event described as "the crystallizing moment in the construction of a visible modern English lesbian subculture" by professor Laura Doan.[96]

Newspaper stories frankly divulged that the book's content includes "sexual relations between Lesbian women", and photographs of Hall often accompanied details about lesbians in most major print outlets within a span of six months.[97] Hall reflected the appearance of a "mannish" woman in the 1920s: short cropped hair, tailored suits (often with pants), and monocle that became widely recognized as a "uniform". When British women supported the war effort during the First World War, they became familiar with masculine clothing, and were considered patriotic for wearing uniforms and pants. Postwar masculinization of women's clothing became associated primarily with lesbianism.[98]

In the United States, the 1920s was a decade of social experimentation, particularly with sex. This was heavily influenced by the writings of Sigmund Freud, who theorized that sexual desire would be sated unconsciously, despite an individual's wish to ignore it. Freud's theories were much more pervasive in the U.S. than in Europe. With the well-publicized notion that sexual acts were a part of lesbianism and their relationships, sexual experimentation was widespread. Large cities that provided a nightlife were immensely popular, and women began to seek out sexual adventure. Bisexuality became chic, particularly in America's first gay neighborhoods.[99]

No location saw more visitors for its possibilities of homosexual nightlife than Harlem, the predominantly African American section of New York City. White "slummers" enjoyed jazz, nightclubs, and anything else they wished. Blues singers Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, Ethel Waters, and Gladys Bentley sang about affairs with women to visitors such as Tallulah Bankhead, Beatrice Lillie, and the soon-to-be-named Joan Crawford.[100][101] Homosexuals began to draw comparisons between their newly recognized minority status and that of African Americans.[102] Among African American residents of Harlem, lesbian relationships were common and tolerated, though not overtly embraced. Some women staged lavish wedding ceremonies, even filing licenses using masculine names with New York City.[103] Most homosexual women were married to men and participated in affairs with women regularly.[104]

Across town, Greenwich Village also saw a growing homosexual community; both Harlem and Greenwich Village provided furnished rooms for single men and women, which was a major factor in their development as centers for homosexual communities.[105] The tenor was different in Greenwich Village than Harlem. Bohemians—intellectuals who rejected Victorian ideals—gathered in the Village. Homosexuals were predominantly male, although figures such as poet Edna St. Vincent Millay and social host Mabel Dodge were known for their affairs with women and promotion of tolerance of homosexuality.[106] Women in the U.S. who could not visit Harlem or live in Greenwich Village for the first time were able to visit saloons in the 1920s without being considered prostitutes. The existence of a public space for women to socialize in bars that were known to cater to lesbians "became the single most important public manifestation of the subculture for many decades", according to historian Lillian Faderman.[107]

Great Depression

The primary component necessary to encourage lesbians to be public and seek other women was economic independence, which virtually disappeared in the 1930s with the Great Depression. Most women in the U.S. found it necessary to marry to a "front" such as a gay man where both could pursue homosexual relationships with public discretion, or to a man who expected a traditional wife. Independent women in the 1930s were generally seen as holding jobs that men should have.[108]

The social attitude made very small and close-knit communities in large cities that centered around bars, while simultaneously isolating women in other locales. Speaking of homosexuality in any context was socially forbidden, and women rarely discussed lesbianism even amongst themselves; they referred to openly gay people as "in the Life".[109][h] Freudian psychoanalytic theory was pervasive in influencing doctors to consider homosexuality as a neurosis afflicting immature women. Homosexual subculture disappeared in Germany with the rise of the Nazis in 1933.[111]

World War II

The onset of World War II caused a massive upheaval in people's lives as military mobilization engaged millions of men. Women were also accepted into the military in the U.S. Women's Army Corps (WACs) and U.S. Navy's Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES). Unlike processes to screen out male homosexuals, which had been in place since the creation of the American military, there were no methods to identify or screen for lesbians; they were put into place gradually during World War II. Despite common attitudes regarding women's traditional roles in the 1930s, independent and masculine women were directly recruited by the military in the 1940s, and frailty discouraged.[112]

Some women arrived at the recruiting station in a man's suit, denied ever being in love with another woman, and were easily inducted.[112] Sexual activity was forbidden and blue discharge was almost certain if one identified oneself as a lesbian. As women found each other, they formed into tight groups on base, socialized at service clubs, and began to use code words. Historian Allan Bérubé documented that homosexuals in the armed forces either consciously or subconsciously refused to identify themselves as homosexual or lesbian, and also never spoke about others' orientation.[113]

The most masculine women were not necessarily common, though they were visible, so they tended to attract women interested in finding other lesbians. Women had to broach the subject about their interest in other women carefully, sometimes taking days to develop a common understanding without asking or stating anything outright.[114] Women who did not enter the military were aggressively called upon to take industrial jobs left by men, in order to continue national productivity. The increased mobility, sophistication, and independence of many women during and after the war made it possible for women to live without husbands, something that would not have been feasible under different economic and social circumstances, further shaping lesbian networks and environments.[115]

Lesbians were not included under Paragraph 175 of the German Criminal Code, which made homosexual acts between males a crime. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) stipulates that this is because women were seen as subordinate to men, and the Nazi state feared lesbians less than gay men. Many lesbians were arrested and imprisoned for "asocial" behaviour,[i] a label which was applied to women who did not conform to the ideal Nazi image of a woman (child raising, kitchen work, churchgoing and passivity). These women were identified with an inverted black triangle.[117] Although lesbianism was not specifically criminalized by Paragraph 175, some lesbians reclaimed the black triangle symbol as gay men reclaimed the pink triangle, and many lesbians also reclaimed the pink triangle.[116]

Postwar

Following World War II, a nationwide movement pressed to return to pre-war society as quickly as possible in the U.S.[118] When combined with the increasing national paranoia about communism and psychoanalytic theory that had become pervasive in medical knowledge, homosexuality became an undesired characteristic of employees working for the U.S. government in 1950. Homosexuals were thought to be vulnerable targets to blackmail, and the government purged its employment ranks of open homosexuals, beginning a widespread effort to gather intelligence about employees' private lives.[119] State and local governments followed suit, arresting people for congregating in bars and parks, and enacting laws against cross-dressing for men and women.[120]

The U.S. military and government conducted many interrogations, asking if women had ever had sexual relations with another woman and essentially equating even a one-time experience to a criminal identity, thereby severely delineating heterosexuals from homosexuals.[121] In 1952, homosexuality was listed as a pathological emotional disturbance in the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual.[122] The view that homosexuality was a curable sickness was widely believed in the medical community, general population, and among many lesbians themselves.[123]

Attitudes and practices to ferret out homosexuals in public service positions extended to Australia[124] and Canada.[125] A section to create an offence of "gross indecency" between females was added to a bill in the United Kingdom House of Commons and passed there in 1921, but was rejected in the House of Lords, apparently because they were concerned any attention paid to sexual misconduct would also promote it.[126]

Underground socializing

Very little information was available about homosexuality beyond medical and psychiatric texts. Community meeting places consisted of bars that were commonly raided by police once a month on average, with those arrested exposed in newspapers. In response, eight women in San Francisco met in their living rooms in 1955 to socialize and have a safe place to dance. When they decided to make it a regular meeting, they became the first organization for lesbians in the U.S., titled the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB). The DOB began publishing a magazine titled The Ladder in 1956. Inside the front cover of every issue was their mission statement, the first of which stated was "Education of the variant". It was intended to provide women with knowledge about homosexuality—specifically relating to women and famous lesbians in history. By 1956, the term "lesbian" had such a negative meaning that the DOB refused to use it as a descriptor, choosing "variant" instead.[127]

The DOB spread to Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles, and The Ladder was mailed to hundreds—eventually thousands—of DOB members discussing the nature of homosexuality, sometimes challenging the idea that it was a sickness, with readers offering their own reasons why they were lesbians and suggesting ways to cope with the condition or society's response to it.[123] British lesbians followed with the publication of Arena Three beginning in 1964, with a similar mission.[128]

Butch and femme dichotomy

As a reflection of categories of sexuality so sharply defined by the government and society at large, early lesbian subculture developed rigid gender roles between women, particularly among the working class in the United States and Canada. For working class lesbians who wanted to live as homosexuals, "A functioning couple ... meant dichotomous individuals, if not male and female, then butch and femme", and the only models they had to go by were "those of the traditional female-male [roles]".[129] Although many municipalities enacted laws against cross-dressing, some women would socialize in bars as butches: dressed in men's clothing and mirroring traditional masculine behavior. Others wore traditionally feminine clothing and assumed the role of femmes. Butch and femme modes of socialization were so integral within lesbian bars that women who refused to choose between the two would be ignored, or at least unable to date anyone, and butch women becoming romantically involved with other butch women or femmes with other femmes was unacceptable.[129]

Butch women were not a novelty in the 1950s; even in Harlem and Greenwich Village in the 1920s some women assumed these personae. In the 1950s and 1960s, the roles were pervasive and not limited to North America: from 1940 to 1970, butch/femme bar culture flourished in Britain, though there were fewer class distinctions.[130] They further identified members of a group that had been marginalized; women who had been rejected by most of society had an inside view of an exclusive group of people that took a high amount of knowledge to function in.[131] Butch and femme were considered coarse by American lesbians of higher social standing during this period. Many wealthier women married men to satisfy their familial obligations, and others left North America to live as expatriates in Europe.[132]

Fiction

Regardless of the lack of information about homosexuality in scholarly texts, another forum for learning about lesbianism was growing. A paperback book titled Women's Barracks describing a woman's experiences in the Free French Forces was published in 1950. It told of a lesbian relationship the author had witnessed. After 4.5 million copies were sold, it was consequently named in the House Select Committee on Current Pornographic Materials in 1952.[133] Its publisher, Gold Medal Books, followed with the novel Spring Fire in 1952, which sold 1.5 million copies. Gold Medal Books was overwhelmed with mail from women writing about the subject matter, and followed with more books, creating the genre of lesbian pulp fiction.[134]

Between 1955 and 1969, over 2,000 books were published using lesbianism as a topic, and they were sold in corner drugstores, train stations, bus stops, and newsstands all over the U.S. and Canada. Literary scholar, Yvonne Keller created several subclasses for lesbian pulp fiction, to help highlight the differences between the types of pulp fiction being released.[135] Virile adventures were written by authors using male pseudonyms, and almost all were marketed to heterosexual men. During this time, another subclass emerged called "Pro-Lesbian". The emergence of pro-lesbian fiction began with authors seeing the voyeuristic and homophobic nature of virile adventures. With only a handful of lesbian pulp fiction authors were women writing for lesbians, including Ann Bannon, Valerie Taylor, Paula Christian, and Vin Packer/Ann Aldrich. These authors deliberately defied the standard of virile adventures by focusing on the relationship between the pair, instead of writing sexually explicit material like virile adventures. [135]

The differences between virile adventures and pro-lesbian covers and titles were distinct enough that Bannon, who also purchased lesbian pulp fiction, later stated that women identified the material iconically by the cover art.[136] Pro-lesbian covers were innocuous and hinted at their lesbian themes, and virile adventures ranged from having one woman partially undressed to sexually explicit covers, to demonstrate the invariably salacious material inside.[135] In addition to this, coded words and images were used on the covers. Instead of "lesbian", terms such as "strange", "twilight", "queer", and "third sex", were used in the titles, and cover art was invariably salacious.[137] Many of the books used cultural references: naming places, terms, describing modes of dress and other codes to isolated women. As a result, pulp fiction helped to proliferate a lesbian identity simultaneously to lesbians and heterosexual readers.[138]

Second-wave feminism

The social rigidity of the 1950s and early 1960s encountered a backlash as social movements to improve the standing of African Americans, the poor, women, and gays all became prominent. Of the latter two, the gay rights movement and the feminist movement connected after a violent confrontation occurred in New York City in the 1969 Stonewall riots.[139] What followed was a movement characterized by a surge of gay activism and feminist consciousness that further transformed the definition of lesbian.

The sexual revolution in the 1970s introduced the differentiation between identity and sexual behavior for women. Many women took advantage of their new social freedom to try new experiences. Women who previously identified as heterosexual tried sex with women, though many maintained their heterosexual identity.[140] With the advent of second-wave feminism, lesbian as a political identity grew to describe a social philosophy among women, often overshadowing sexual desire as a defining trait. A militant feminist organization named Radicalesbians published a manifesto in 1970 entitled "The Woman-Identified Woman" that declared "A lesbian is the rage of all women condensed to the point of explosion".[141][j]

Militant feminists expressed their disdain with an inherently sexist and patriarchal society, and concluded the most effective way to overcome sexism and attain the equality of women would be to deny men any power or pleasure from women. For women who subscribed to this philosophy—dubbing themselves lesbian-feminists—lesbian was a term chosen by women to describe any woman who dedicated her approach to social interaction and political motivation to the welfare of women. Sexual desire was not the defining characteristic of a lesbian-feminist, but rather her focus on politics. Independence from men as oppressors was a central tenet of lesbian-feminism, and many believers strove to separate themselves physically and economically from traditional male-centered culture. In the ideal society, named Lesbian Nation, "woman" and "lesbian" were interchangeable.[143]

Although lesbian-feminism was a significant shift, not all lesbians agreed with it. Lesbian-feminism was a youth-oriented movement: its members were primarily college educated, with experience in New Left and radical causes, but they had not seen any success in persuading radical organizations to take up women's issues.[144] Many older lesbians who had acknowledged their sexuality in more conservative times felt maintaining their ways of coping in a homophobic world was more appropriate. The Daughters of Bilitis folded in 1970 over which direction to focus on: feminism or gay rights issues.[145]

As equality was a priority for lesbian-feminists, disparity of roles between men and women or butch and femme were viewed as patriarchal. Lesbian-feminists eschewed gender role play that had been pervasive in bars, as well as the perceived chauvinism of gay men; many lesbian-feminists refused to work with gay men, or take up their causes.[146] Lesbians who held more essentialist views that they were born homosexual, and used the descriptor "lesbian" to define sexual attraction, often considered the separatist, angry opinions of lesbian-feminists to be detrimental to the cause of gay rights.[147]

In 1980, poet and essayist Adrienne Rich expanded upon the political meaning of lesbian by proposing a continuum of lesbian existence based on "woman-identified experience" in her essay "Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence".[148] All relationships between women, Rich proposed, have some lesbian element, regardless if they claim a lesbian identity: mothers and daughters, women who work together, and women who nurse each other, for example. Such a perception of women relating to each other connects them through time and across cultures, and Rich considered heterosexuality a condition forced upon women by men.[148] Several years earlier, DOB founders Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon similarly relegated sexual acts as unnecessary in determining what a lesbian is, by providing their definition: "a woman whose primary erotic, psychological, emotional and social interest is in a member of her own sex, even though that interest may not be overtly expressed".[149]

Outside western culture

Middle East

Arabic-language historical records have used various terms to describe sexual practices between women.[150] A common one is "sahq", which refers to rubbing. Lesbian practices and identities are largely absent from the historical record. The common term to describe lesbianism in Arabic today is essentially the same term used to describe men, and thus the distinction between male and female homosexuality is to a certain extent linguistically obscured in contemporary queer discourse.[150] Overall, the study of contemporary lesbian experience in the region is complicated by power dynamics in the postcolonial context, shaped even by what some scholars refer to as "homonationalism", the use of politicized understanding of sexual categories to advance specific national interests on the domestic and international stage.[151]

Female homosexual behavior may be present in every culture, although the concept of a lesbian as a woman who pairs exclusively with other women is not. Attitudes about female homosexual behavior are dependent upon women's roles in each society and each culture's definition of sex. Women in the Middle East have been historically segregated from men. In the 7th and 8th centuries, some extraordinary women dressed in male attire when gender roles were less strict, but the sexual roles that accompanied European women were not associated with Islamic women. The Caliphal court in Baghdad featured women who dressed as men, including false facial hair, but they competed with other women for the attentions of men.[152][153]

According to the 12th-century writings of Sharif al-Idrisi, highly intelligent women were more likely to be lesbians; their intellectual prowess put them on a more even par with men.[152] Relations between women who lived in harems and fears of women being sexually intimate in Turkish baths were expressed in writings by men. Women were mostly silent, and men likewise rarely wrote about lesbian relationships. It is unclear to historians if the rare instances of lesbianism mentioned in literature are an accurate historical record, or if they were only intended to serve as fantasies for men. A 1978 treatise about repression in Iran asserted that women were completely silenced: "In the whole of Iranian history, [no woman] has been allowed to speak out for such tendencies ... To attest to lesbian desires would be an unforgivable crime."[152]

Although the authors of Islamic Homosexualities argued this did not mean women could not engage in lesbian relationships, a lesbian anthropologist in 1991 visited Yemen and reported that women in the town she visited were unable to comprehend her romantic relationship to another woman. Women in Pakistan are expected to marry men; those who do not are ostracized. Women may have intimate relations with other women as long as their wifely duties are met, their private matters are kept quiet, and the woman with whom they are involved is somehow related by family or logical interest to her lover.[154]

Individuals identifying with or otherwise engaging in lesbian practices in the region can face family violence and societal persecution, including what are commonly referred to as "honor killings." The justifications provided by murderers relate to a person's perceived sexual immorality, loss of virginity (outside of acceptable frames of marriage), and target female victims primarily.[155]

Americas

Both male and female homosexuality were known in Aztec culture. Although both were generally disapproved of, there is no evidence that homosexuality was actively suppressed until after the Spanish Conquest.[156] Female homosexuality is described in the Florentine Codex, a 16th-century study of the Aztec world written by the Spanish Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún. It describes Aztec lesbians as masculine in appearance and behavior and never wishing to be married.[156] The book Monarquía indiana by Fray Juan de Torquemada, published in 1615, briefly mentions the persecution of Aztec lesbians: "The woman, who with another woman had carnal pleasures, for which they were called Patlache, which means: female incubus, they both died for it."[156][k]

In Latin America, lesbian consciousness and associations appeared in the 1970s, increasing while several countries transitioned to or reformed democratic governments. Harassment and intimidation have been common even in places where homosexuality is legal, and laws against child corruption, morality, or "the good ways" (faltas a la moral o las buenas costumbres), have been used to persecute homosexuals.[157] From the Hispanic perspective, the conflict between the lesbophobia of some feminists and the misogyny from gay men has created a difficult path for lesbians and associated groups.[158]

Argentina was the first Latin American country with a gay rights group, Nuestro Mundo (NM, or Our World), created in 1969. Six mostly secret organizations concentrating on gay or lesbian issues were founded around this time, but persecution and harassment were continuous and grew worse with the dictatorship of Jorge Rafael Videla in 1976, when all groups were dissolved in the Dirty War. Lesbian rights groups have gradually formed since 1986 to build a cohesive community that works to overcome philosophical differences with heterosexual women.[159]

The Latin American lesbian movement has been the most active in Mexico but has encountered similar problems in effectiveness and cohesion. While groups try to promote lesbian issues and concerns, they also face misogynistic attitudes from gay men and homophobic views from heterosexual women. In 1977, Lesbos, the first lesbian organization for Mexicans, was formed. Several incarnations of political groups promoting lesbian issues have evolved; 13 lesbian organizations were active in Mexico City in 1997. Ultimately, lesbian associations had little influence on the homosexual and feminist movements.[160]

In Chile, the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet forbade the creation of lesbian groups until 1984, when Ayuquelén ("joy of being" in Mapuche) was first founded, prompted by the very public beating death of a woman amid shouts of "Damned lesbian!" from her attacker. The lesbian movement has been closely associated with the feminist movement in Chile, although the relationship has been sometimes strained. Ayuquelén worked with the International Lesbian Information Service, the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, and the Chilean gay rights group Movimiento de Integración y Liberación Homosexual (Movement to Integrate and Liberate Homosexuals) to remove the sodomy law still in force in Chile.[158]

Lesbian consciousness became more visible in Nicaragua in 1986, when the Sandinista National Liberation Front expelled gay men and lesbians from its midst. State persecution prevented the formation of associations until AIDS became a concern, when educational efforts forced sexual minorities to band together. The first lesbian organization was Nosotras, founded in 1989. An effort to promote visibility from 1991 to 1992 provoked the government to declare homosexuality illegal in 1994, effectively ending the movement, until 2004, when Grupo Safo – Grupo de Mujeres Lesbianas de Nicaragua was created, four years before homosexuality became legal again.[161]

The meetings of feminist lesbians of Latin America and the Caribbean, sometimes shortened to "Lesbian meetings", have been an important forum for the exchange of ideas for Latin American lesbians since the late 1980s. With rotating hosts and biannual gatherings, its main aims are the creation of communication networks, to change the situation of lesbians in Latin America (both legally and socially), to increase solidarity between lesbians and to destroy the existing myths about them.[162]

Some Indigenous peoples of the Americas conceptualize a third gender for women who dress as, and fulfill the roles usually filled by, men in their cultures.[163][164] In other cases they may see gender as a spectrum, and use different terms for feminine women and masculine women.[165] These identities are rooted in the context of the ceremonial and cultural lives of the particular Indigenous cultures, and "simply being gay and Indian does not make someone a Two-Spirit."[166] These ceremonial and social roles, which are conferred and confirmed by the person's elders, "do not make sense" when defined by non-Native concepts of sexual orientation and gender identity.[164] Rather, they must be understood in an Indigenous context, as traditional spiritual and social roles held by the person in their Indigenous community.[166][164][167]

Africa

Cross-gender roles and marriage between women has also been recorded in over 30 African societies.[168] Women may marry other women, raise their children, and be generally thought of as men in societies in Nigeria, Cameroon, and Kenya. The Hausa people of Sudan have a term equivalent to lesbian, kifi, that may also be applied to males to mean "neither party insists on a particular sexual role".[169]

Near the Congo River, a female who participates in strong emotional or sexual relationships with another female among the Nkundo people is known as yaikya bonsángo (a woman who presses against another woman). Lesbian relationships are also known in matrilineal societies in Ghana among the Akan people. In Lesotho, females engage in what is commonly considered sexual behavior to the Western world: they kiss, sleep together, rub genitals, participate in cunnilingus, and maintain their relationships with other females vigilantly. Since the people of Lesotho believe sex requires a penis, they do not consider their behavior sexual, nor label themselves lesbians.[170]

In Tanzania, lesbians are known as or called "Msagaji" (singular), "Wasagaji" (plural), which in Swahili means grinder or grinding because of the perceived nature of lesbian sex that would involve the mutual rubbing of vulvas.[citation needed]

In South Africa, lesbians are sometimes raped by heterosexual men with a goal of punishment of "abnormal" behavior and reinforcement of societal norms.[171] The crime was first identified in South Africa[172] where it is sometimes supervised by members of the woman's family or local community,[173] and is a major contributor to HIV infection in South African lesbians.[171] "Corrective rape" is not recognized by the South African legal system as a hate crime despite the fact that the South African Constitution states that no person shall be discriminated against based on their social status and identity, including sexual orientation.[174][175][176] Legally, South Africa protects gay rights extensively, but the government has not taken proactive action to prevent corrective rape, and women do not have much faith in the police and their investigations.[177][178]

Corrective rape is reported to be on the rise in South Africa. The South African nonprofit "Luleki Sizwe" estimates that more than 10 lesbians are raped or gang-raped on a weekly basis.[179] As made public by the Triangle Project in 2008, at least 500 lesbians become victims of corrective rape every year and 86% of black lesbians in the Western Cape live in fear of being sexually assaulted.[177] Victims of corrective rape are less likely to report the crime because of their society's negative beliefs about homosexuality.[177]

Asia

China before westernization was another society that segregated men from women. Historical Chinese culture has not recognized a concept of sexual orientation, or a framework to divide people based on their same-sex or opposite-sex attractions.[180] Although there was a significant culture surrounding homosexual men, there was none for women. Outside their duties to bear sons to their husbands, women were perceived as having no sexuality at all.[181]

This did not mean that women could not pursue sexual relationships with other women, but that such associations could not impose upon women's relationships to men. Rare references to lesbianism were written by Ying Shao, who identified same-sex relationships between women in imperial courts who behaved as husband and wife as dui shi (paired eating). "Golden Orchid Associations" in Southern China existed into the 20th century and promoted formal marriages between women, who were then allowed to adopt children.[182] Westernization brought new ideas that all sexual behavior not resulting in reproduction was aberrant.[183]

The liberty of being employed in silk factories starting in 1865 allowed some women to style themselves tzu-shu nii (never to marry) and live in communes with other women. Other Chinese called them sou-hei (self-combers) for adopting hairstyles of married women. These communes passed because of the Great Depression and were subsequently discouraged by the communist government for being a relic of feudal China.[184] In contemporary Chinese society, tongzhi (same goal or spirit) is the term used to refer to homosexuals; most Chinese are reluctant to divide this classification further to identify lesbians.[185]

In Japan, the term rezubian, a Japanese pronunciation of "lesbian", was used during the 1920s. Westernization brought more independence for women and allowed some Japanese women to wear pants.[186] The cognate tomboy is used in the Philippines, and particularly in Manila, to denote women who are more masculine.[187] Virtuous women in Korea prioritize motherhood, chastity, and virginity; outside this scope, very few women are free to express themselves through sexuality, although there is a growing organization for lesbians named Kkirikkiri.[188] The term pondan is used in Malaysia to refer to gay men, but since there is no historical context to reference lesbians, the term is used for female homosexuals as well.[189] As in many Asian countries, open homosexuality is discouraged in many social levels, so many Malaysians lead double lives.[190]

In India, a 14th-century Indian text mentioning a lesbian couple who had a child as a result of their lovemaking is an exception to the general silence about female homosexuality. According to Ruth Vanita, this invisibility disappeared with the release of a film titled Fire in 1996, prompting some theaters in India to be attacked by religious extremists. Terms used to label homosexuals are often rejected by Indian activists for being the result of imperialist influence, but most discourse on homosexuality centers on men. Women's rights groups in India continue to debate the legitimacy of including lesbian issues in their platforms, as lesbians and material focusing on female homosexuality are frequently suppressed.[191]

Demographics

Kinsey Report

The most extensive early study of female homosexuality was provided by the Institute for Sex Research, who published an in-depth report of the sexual experiences of American women in 1953. More than 8,000 women were interviewed by Alfred Kinsey and the staff of the Institute for Sex Research in a book titled Sexual Behavior in the Human Female, popularly known as part of the Kinsey Report. The Kinsey Report's dispassionate discussion of homosexuality as a form of human sexual behavior was revolutionary. Up to this study, only physicians and psychiatrists studied sexual behavior, and almost always the results were interpreted with a moral view.[192]

Kinsey and his staff reported that 28% of women had been aroused by another female, and 19% had a sexual contact with another female.[193][l] Of women who had sexual contact with another female, half to two-thirds of them had orgasmed. Single women had the highest prevalence of homosexual activity, followed by women who were widowed, divorced, or separated. The lowest occurrence of sexual activity was among married women; those with previous homosexual experience reported they married to stop homosexual activity.[195]

Most of the women who reported homosexual activity had not experienced it more than ten times. Fifty-one percent of women reporting homosexual experience had only one partner.[196] Women with post-graduate education had a higher prevalence of homosexual experience, followed by women with a college education; the smallest occurrence was among women with education no higher than eighth grade.[197] Some criticized Kinsey's methodology.[198][199]

Based on Kinsey's scale where 0 represents a person with an exclusively heterosexual response and 6 represents a person with an exclusively homosexual one, and numbers in between represent a gradient of responses with both sexes, 6% of those interviewed ranked as a 6: exclusively homosexual. Apart from those who ranked 0 (71%), the largest percentage in between 0 and 6 was 1 at approximately 15%.[200] The Kinsey Report remarked that the ranking described a period in a person's life, and that a person's orientation may change.[200] Among the criticisms the Kinsey Report received, a particular one addressed the Institute for Sex Research's tendency to use statistical sampling, which facilitated an over-representation of same-sex relationships by other researchers who did not adhere to Kinsey's qualifications of data.[192]

Hite Report

In 1976, sexologist Shere Hite published a report on the sexual encounters of 3,019 women who had responded to questionnaires, under the title The Hite Report. Hite's questions differed from Kinsey's, focusing more on how women identified, or what they preferred rather than experience. Respondents to Hite's questions indicated that 8% preferred sex with women and 9% answered that they identified as bisexual or had sexual experiences with men and women, though they refused to indicate preference.[201]

Hite's conclusions are more based on respondents' comments than quantifiable data. She found it "striking" that many women who had no lesbian experiences indicated they were interested in sex with women, particularly because the question was not asked.[202] Hite found the two most significant differences between respondents' experience with men and women were the focus on clitoral stimulation, and more emotional involvement and orgasmic responses.[203] Since Hite performed her study during the popularity of feminism in the 1970s, she also acknowledged that women may have chosen the political identity of a lesbian.

Population estimates

Lesbians in the U.S. are estimated to be about 2.6% of the population, according to a National Opinion Research Center survey of sexually active adults who had had same-sex experiences within the past year, completed in 2000.[204] A survey of same-sex couples in the United States showed that between 2000 and 2005, the number of people claiming to be in same-sex relationships increased by 30%—five times the rate of population growth in the U.S. The study attributed the jump to people being more comfortable self-identifying as homosexual to the federal government.[m]

The government of the United Kingdom does not ask citizens to define their sexuality. A survey by the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) in 2010 found that 1.5% of Britons identified themselves as gay or bisexual, and the ONS suggests that this is in line with other surveys showing the number between 0.3% and 3%.[206][207] Estimates of lesbians are sometimes not differentiated in studies of same-sex households, such as those performed by the U.S. census, and estimates of total gay, lesbian, or bisexual population by the UK government. Polls in Australia recorded a range of self-identified lesbian or bisexual women from 1.3% to 2.2% of the total population.[208]

Health

Physical

In terms of medical issues, lesbians are referred to as women who have sex with women (WSW) because of the misconceptions and assumptions about women's sexuality and some women's hesitancy to disclose their accurate sexual histories even to a physician.[209] Many self-identified lesbians neglect to see a physician because they do not participate in heterosexual activity and require no birth control, which is the initiating factor for most women to seek consultation with a gynecologist when they become sexually active.[210] As a result, many lesbians are not screened regularly with Pap smears. The U.S. government reports that some lesbians neglect seeking medical screening in the U.S.; they lack health insurance because many employers do not offer health benefits to domestic partners.[211]

The result of the lack of medical information on WSW is that medical professionals and some lesbians perceive lesbians as having lower risks of acquiring sexually transmitted infections or types of cancer. When women do seek medical attention, medical professionals often fail to take a complete medical history. In a 2006 study of 2,345 lesbian and bisexual women, only 9.3% had claimed they had ever been asked their sexual orientation by a physician. A third of the respondents believed disclosing their sexual history would result in a negative reaction, and 30% had received a negative reaction from a medical professional after identifying themselves as lesbian or bisexual.[212] A patient's complete history helps medical professionals identify higher risk areas and corrects assumptions about the personal histories of women. In a similar survey of 6,935 lesbians, 77% had had sexual contact with one or more male partners, and 6% had that contact within the previous year.[212][n]

Heart disease is listed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services as the number one cause of death for all women. Factors that add to risk of heart disease include obesity and smoking, both of which are more prevalent among lesbians. Studies show that lesbians have a higher body mass and are generally less concerned about weight issues than heterosexual women; and lesbians consider women with higher body masses to be more attractive than heterosexual women do. Lesbians are more likely to exercise regularly than heterosexual women, and lesbians do not generally exercise for aesthetic reasons, although heterosexual women do.[214] Research is needed to determine specific causes of obesity in lesbians.[211][212]

Lack of differentiation between homosexual and heterosexual women in medical studies that concentrate on health issues for women skews results for lesbians and non-lesbian women. Reports are inconclusive about occurrence of breast cancer in lesbians.[212] It has been determined that the lower rate of lesbians tested by regular Pap smears makes it more difficult to detect cervical cancer at early stages in lesbians. The risk factors for developing ovarian cancer rates are higher in lesbians than heterosexual women, perhaps because many lesbians lack protective factors of pregnancy, abortion, contraceptives, breast feeding, and miscarriages.[215]

Some sexually transmitted infections are communicable between women, including human papillomavirus (HPV)—specifically genital warts—squamous intraepithelial lesions, trichomoniasis, syphilis, and herpes simplex virus (HSV). Transmission of specific sexually transmitted infections among women who have sex with women depends on the sexual practices women engage in. Any object that comes in contact with cervical secretions, vaginal mucosa, or menstrual blood, including fingers or penetrative objects may transmit sexually transmitted infections.[216] Orogenital contact may indicate a higher risk of acquiring HSV,[217] even among women who have had no prior sex with men.[218]

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) occurs more often in lesbians, but it is unclear if BV is transmitted by sexual contact; it occurs in celibate as well as sexually active women. BV often occurs in both partners in a lesbian relationship;[219] a recent study of women with BV found that 81% had partners with BV.[220] Lesbians are not included in a category of frequency of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission, although transmission is possible through vaginal and cervical secretions. The highest rate of transmission of HIV to lesbians is among women who participate in intravenous drug use or have sexual intercourse with bisexual men.[221][222]

Mental

Since medical literature began to describe homosexuality, it has often been approached from a view that sought to find an inherent psychopathology as the root cause, influenced by the theories of Sigmund Freud. Although he considered bisexuality inherent in all people and said that most have phases of homosexual attraction or experimentation, exclusive same-sex attraction he attributed to stunted development resulting from trauma or parental conflicts.[223][o] Much literature on mental health and lesbians centered on their depression, substance abuse, and suicide. Although these issues exist among lesbians, discussion about their causes shifted after homosexuality was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual in 1973. Instead, social ostracism, legal discrimination, internalization of negative stereotypes, and limited support structures indicate factors homosexuals face in Western societies that often adversely affect their mental health.[225]

Women who identify as lesbian report feeling significantly different and isolated during adolescence.[225][226] These emotions have been cited as appearing on average at 15 years old in lesbians and 18 years old in women who identify as bisexual.[227] On the whole, women tend to work through developing a self-concept internally, or with other women with whom they are intimate. Women also limit who they divulge their sexual identities to, and more often see being lesbian as a choice, as opposed to gay men, who work more externally and see being gay as outside their control.[226]