Внешняя политика Соединенных Штатов

Эта статья требует дополнительных цитат для проверки . ( июль 2021 г. ) |

| История нас расширение и влияние |

|---|

| Колониализм |

|

|

| Милитаризм |

|

|

| Внешняя политика |

|

| Concepts |

Официально заявленные цели внешней политики Соединенных Штатов Америки , включая все бюро и офисы в Государственном департаменте США , [ 1 ] Как упомянуто в повестке дня по внешней политике Государственного департамента, «построить и поддерживать более демократический, надежный и процветающий мир в интересах американского народа и международного сообщества». [ 2 ] Либерализм был ключевым компонентом внешней политики США с момента ее независимости от Великобритании. [ 3 ] После окончания Второй мировой войны Соединенные Штаты имели грандиозную стратегию, которая была охарактеризована как ориентированная на первенство, «глубокое взаимодействие» и/или либеральную гегемонию . [ 4 ] [ 5 ] Эта стратегия влечет за собой то, что Соединенные Штаты поддерживают военные преобладания; строит и поддерживает обширную сеть союзников (примером которой является НАТО, двусторонние альянсы и иностранные военные базы США); интегрирует другие государства в международные институты, разработанные в США (такие как МВФ, ВТО/ГАТТ и Всемирный банк); и ограничивает распространение ядерного оружия. [ 3 ] [ 5 ]

The United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs states as some of its jurisdictional goals: "export controls, including nonproliferation of nuclear technology and nuclear hardware; measures to foster commercial interaction with foreign nations and to safeguard American business abroad; international commodity agreements; international education; protection of American citizens abroad; and expulsion".[6] Внешняя политика США и иностранная помощь были предметом многого обсуждения, похвалы и критики, как внутри страны, так и за рубежом.

Foreign policy development

[edit]Article Two of the United States Constitution grants power of foreign policy to the President of the United States,[7] including powers to command the military, negotiate treaties, and appoint ambassadors. The Department of State carries out the president's foreign policy. The State Department is usually pulled between the wishes of Congress, and the wishes of the residing president.[8] The Department of Defense carries out the president's military policy. The Central Intelligence Agency is an independent agency responsible for gathering intelligence on foreign activity. Some checks and balances are applied to the president's powers of foreign policy. Treaties negotiated by the president require ratification by the Senate to take force as United States law. The president's ambassadorial nominations also require Senate approval before taking office. Military actions must first be approved by both chambers of Congress.

The Constitution grants Congress the power to approve the president's picks for ambassadors and the power to declare war. The president is commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces. He appoints a Secretary of State and ambassadors with the advice and consent of the Senate. The Secretary acts similarly to a foreign minister, because they are the primary conductor of foreign affairs.[9] While foreign policy has varied slightly from president to president, there have generally been consistently similar goals throughout different administrations.[10]

Generally speaking there are 4 schools of thought regarding foreign policy. First is Neo-Isolationists, who believe the United States should maintain a very narrow focus and avoid all involvement in the rest of the world. Second is selective-engagement which avoids all conflicts with other nations, and is semi-restrictive on its foreign policy. Third is cooperative security, which requires more involvement throughout the world, occasionally countering threats to the country. Finally is the idea of primacy which seeks to advance the United States well beyond all other nations of the world, placing it first in all matters.[11]

International law

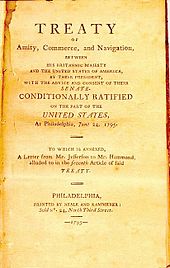

[edit]Much of American foreign policy consists of international agreements made with other countries. Treaties are governed by the Treaty Clause of the United States Constitution. This clause dictates that the president negotiates treaties with other countries or political entities, and signs them. For a treaty to be ratified, it must be approved by the Committee on Foreign Relations and then be approved by at least two-thirds of the United States Senate in a floor vote. If approved, the United States exchanges the instruments of ratification with the relevant foreign states.[12] In Missouri v. Holland, the Supreme Court ruled that the power to make treaties under the U.S. Constitution is a power separate from the other enumerated powers of the federal government, and hence the federal government can use treaties to legislate in areas which would otherwise fall within the exclusive authority of the states.[13] Between 1789 and 1990, the Senate approved more than 1,500 treaties, rejected 21 and withdrew 85 without further action.[14] As of 2019, 37 treaties were pending Senate approval.[15]

In addition to treaties, the president can also make executive agreements. These agreements are made under the president's power of setting foreign policy, but they are not ratified by the Senate and as a result are not legally binding. In contrast to most other nations, the United States regards treaties and executive agreements as legally distinct.[citation needed] Congress may pass a resolution to enshrine an executive agreement into law, but the constitutionality of this action has been questioned.[16]

The State Department has taken the position that the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties represents established law. Following ratification, the United States incorporates treaty law into the body of U.S. federal law. As a result, Congress can modify or repeal treaties after they are ratified. This can overrule an agreed-upon treaty obligation even if that is seen as a violation of the treaty under international law. Several U.S. court rulings confirmed this understanding, including Supreme Court decisions in Paquete Habana v. the United States (1900), and Reid v. Covert (1957), as well as a lower court ruling in Garcia-Mir v. Meese (1986).[citation needed] As a result of the Reid v. Covert decision, the United States adds a reservation to the text of every treaty that says in effect that the United States intends to abide by the treaty but that if the treaty is found to be in violation of the Constitution, the United States legally is then unable to abide by the treaty since the American signature would be ultra vires.[17]

Historical overview

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2022) |

The main trend regarding the history of U.S. foreign policy since the American Revolution is the shift from non-interventionism before and after World War I, to its growth as a world power and global hegemon during World War II and throughout the Cold War in the 20th century.[18] Since the 19th century, U.S. foreign policy also has been characterized by a shift from the realist school to the idealistic or Wilsonian school of international relations.[19] Over time, other themes, key goals, attitudes, or stances have been variously expressed by presidential 'doctrines'.[20]

18th century

[edit]

Foreign policy themes were expressed considerably in George Washington's farewell address; these included, among other things, observing good faith and justice towards all nations and cultivating peace and harmony with all, excluding both "inveterate antipathies against particular nations, and passionate attachments for others", "steer[ing] clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world", and advocating trade with all nations.[21] Foreign policy in the first years of American independence constituted the balancing of relations with Great Britain and France. The Federalist Party supported Washington's foreign policy and sought close ties with Britain, but the Democratic-Republican Party favored France.[22] Under the Federalist government of John Adams, the United States engaged in conflict with France in the Quasi-War, but the rival Jeffersonians feared Britain and favored France in the 1790s, declaring the War of 1812 on Britain. Jeffersonians vigorously opposed a large standing army and any navy until attacks against American shipping by Barbary corsairs spurred the country into developing a navy, resulting in the First Barbary War in 1801.[23]

19th century

[edit]American foreign policy was mostly peaceful and marked by steady expansion of its foreign trade during the 19th century.[citation needed] As the Jeffersonians took power in the 1800s, they opposed a large standing army and any navy until attacks against American shipping by Barbary corsairs spurred the country into developing a naval force projection capability, resulting in the First Barbary War in 1801.[23] The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 doubled the nation's geographical area. The American policy of neutrality had caused tensions to rise with Britain in the Atlantic and with Native American nations in the frontier. This led to the War of 1812 and helped cement American foreign policy as independent of Europe.[24] After the War of 1812, there were diagreements between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton as to whether the United States should be isolated or be more involved in global activities.[11]

In the 1820s, the Monroe Doctrine was established as the primary foreign policy doctrine of the United States, establishing Latin America as an American sphere of influence and rejecting European colonization in the region. The 1830s and 1840s were marked by increasing conflict with Mexico, exacerbated by the Texas annexation and culminating in the Mexican–American War in 1846. Following the war, the United States claimed much of what is now the Southwestern United States, and the Gadsden Purchase further expanded this territory. Relations with Britain continued to be strained as a result of border conflicts until they were resolved by the Webster–Ashburton Treaty in 1842. The Perry Expedition of 1853 led to Japan establishing relations with the United States.

The Diplomacy of the American Civil War emphasized preventing European involvement in the war. During the Civil War, Spain and France defied the Monroe Doctrine and expanded their colonial influence in the Dominican Republic and Mexico, respectively.[25] The Alaska Purchase was negotiated with Russia in 1867 and the Newlands Resolution annexed Hawaii in 1898. The Spanish–American War took place during 1898, resulting in the United States claiming Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, and causing Spain to retract claims upon Cuba.[11] Generally speaking the Foreign Policy of the United States during this era was anchored in a policy of wealth building for the nation.[10]

20th century

[edit]Following the Spanish–American War, the United States entered the 20th century as an emerging great power with colonies in the Caribbean and the Pacific. Under Theodore Roosevelt, the United States adopted the Roosevelt Corollary, which indicated American willingness to use its military strength to end conflicts and wrongdoings in Latin America. Following the independence of Panama, the United States and Panama negotiated the construction of the Panama Canal, during which time the Panama Canal Zone was placed under American jurisdiction. The United States established the Open Door Policy with China during this time as well.[11] The 20th century was marked by two world wars in which Allied powers, along with the United States, defeated their enemies, and through this participation the United States increased its international reputation.

World War I and Interbellum

[edit]Entry into the First World War was a hotly debated issue in the 1916 presidential election.[26]

In response to the Russian revolutions,

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2023) |

President Wilson's Fourteen Points was developed from his idealistic Wilsonianism program of spreading democracy and fighting militarism to prevent future wars. It became the basis of the German Armistice (which amounted to a military surrender) and the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. The resulting Treaty of Versailles, due to European allies' punitive and territorial designs, showed insufficient conformity with these points, and the U.S. signed separate treaties with each of its adversaries; due to Senate objections also, the U.S. never joined the League of Nations, which was established as a result of Wilson's initiative. In the 1920s, the United States followed an independent course, and succeeded in a program of naval disarmament, and refunding the German economy. Operating outside the League it became a dominant player in diplomatic affairs. New York became the financial capital of the world,[27] but the Wall Street Crash of 1929 hurled the Western industrialized world into the Great Depression. American trade policy relied on high tariffs under the Republicans, and reciprocal trade agreements under the Democrats, but in any case exports were at very low levels in the 1930s.[citation needed] Post WWI, the United States entered back into isolation from world events. This was largely due to the Great Depression of 1929.[11]

World War II

[edit]

The United States adopted an isolationist foreign policy from 1932 to 1938, but this position was challenged by the outbreak of World War II in 1939.[11] Franklin D. Roosevelt advocated strong support of the allies, establishing the United States as the Arsenal of Democracy by providing military equipment without entering the war. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States joined the allies as combatants in World War II.

Roosevelt mentioned four fundamental freedoms, which ought to be enjoyed by people "everywhere in the world"; these included the freedom of speech and religion, as well as freedom from want and fear. Roosevelt helped establish terms for a post-war world among potential allies at the Atlantic Conference; specific points were included to correct earlier failures, which became a step toward the United Nations.[11] American policy was to counter Japan, to force out of China, and to prevent attacking the Soviet Union. Japan reacted with an attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, and the United States was at war with Japan, Germany, and Italy. Instead of the loans given to allies in World War I, the

United States provided Lend-Lease grants of $50,000,000,000. Working closely with Winston Churchill of Britain, and Joseph Stalin of the Soviet Union, Roosevelt sent his forces into the Pacific against Japan, then into North Africa against Italy and Germany, and finally into Europe starting with France and Italy in 1944 against the Germans. The American economy roared forward, doubling industrial production, and building vast quantities of airplanes, ships, tanks, munitions, and, finally, the atomic bomb. The culmination of World War II ended in the defeat of Nazi Germany, and the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The post World War II era saw the rise of the United States as the global leader, which necessitated an effort by the United States to instill liberal democracy around the world.[11]

Cold War

[edit]After the war, the U.S. rose to become the dominant economic power with broad influence in much of the world, with the key policies of the Marshall Plan and the Truman Doctrine. Almost immediately, two broad camps formed during the Cold War; one side was led by the U.S. and the other by the Soviet Union, but this situation also led to the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement. This period lasted until almost the end of the 20th century and is thought to be both an ideological and power struggle between the two superpowers. The United States extended its influence in the years after World War II, enacting the Marshall Plan to support the reconstruction process in European countries and seeking to combat Communism through containment.[11] This strategy of containment resulted in the Korean War and the Vietnam War. The Vietnam War in particular was highly controversial, and its perceived failures reduced popularity for foreign intervention in the United States.[28] The invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviet Union contributed directly to fueling tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union. This began with President Carter announcing the United States interests in maintaining the status quo within the Persian Gulf region, resulting in the Carter Doctrine. The Regan administration escalated the tensions by supporting freedom fighters around the world, most notably in Afghanistan during the Soviet invasion. The Soviet Union and the United States did not engage in

direct conflict, but rather supported small proxies that opposed the other.[20][11] In 1991, the Soviet Union dissolved into separate nations, and the Cold War formally ended as the United States gave separate diplomatic recognition to the Russian Federation and other former Soviet states.[citation needed]

In domestic politics, foreign policy was not usually a central issue. In 1945–1970, the Democratic Party took a strong anti-Communist line and supported wars in Korea and Vietnam. Then the party split with a strong, "dovish", pacifist element (typified by 1972 presidential candidate George McGovern). Many "hawks", advocates for war, joined the neoconservative movement and started supporting the Republicans—especially Reagan—based on foreign policy.[29] Meanwhile, down to 1952 the Republican Party was split between an isolationist wing, based in the Midwest and led by Senator Robert A. Taft, and an internationalist wing based in the East and led by Dwight D. Eisenhower. Eisenhower defeated Taft for the 1952 nomination largely on foreign policy grounds. Since then the Republicans have been characterized by American nationalism, strong opposition to Communism, and strong support for Israel.[30]

21st century

[edit]

Following the end of the Cold War, the United States entered the 21st century as the sole superpower, though this status has been challenged by China, India, Russia, and the European Union.[31] Substantial problems remain, such as climate change, nuclear proliferation, and the specter of international terrorism.[citation needed]

The September 11 attacks in 2001 caused a policy shift, in which America declared a "war on terror". The United States invaded Afghanistan in 2001 and invaded Iraq in 2003, emphasizing nation-building and the neutralization of terrorist threats in the Middle East. During the war on terror, the United States significantly expanded its military and intelligence capacities while also pursuing economic methods of targeting opposing governments. After a phased withdrawal from Iraq, In 2014, the Islamic State emerged as a major hostile power in the Middle East, and the United States led a military intervention in Iraq and Syria to combat it. The extended nature of American involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan has resulted in support for isolationism and reduced involvement in foreign conflicts.[32]

In 2011, the United States led a NATO intervention in Libya. In 2013, disclosures of American surveillance programs revealed that United States intelligence policy included extensive global surveillance activities against foreign governments and citizens.[33]

In 2017, diplomats from other countries developed new tactics to engage with President Donald Trump's brand of American nationalism. Peter Baker of The New York Times reported on the eve of his first foreign trip as president that the global diplomatic community had devised a strategy of keeping interactions brief, complimenting him, and giving him something he can consider a victory.[34] Before the Trump presidency, foreign policy in the U.S. was the result of bipartisan consensus on an agenda of strengthening its position as the number one power. That consensus has since fractured, with Republican and Democratic politicians increasingly calling for a more restrained approach.[35] Foreign policy under the Trump administration involved heightened tensions with Iran, a trade war through increased tariffs, and a reduced role in international organizations.

Advancing a "Free and Open Indo-Pacific" has become the core of the U.S. national security strategy and has been embraced by both Democratic and Republican administrations.[36] The United States ended its wars in the Greater Middle East with the withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021.[37] Unlike the Trump administration, which is more concerned with containing China's influence, foreign policy of the Biden-Harris administration shifted to an increased focus on Russia following the attempted Russian election interference in 2016 and developments in the Russo-Ukrainian War. With the rise of Russia and China as co-superpowers, the United States has had to shift its relations to more cooperation rather than coercion, with Russia and China pursuing a more self serving global system.[38][39]

In early 2023, when China brokered the long-awaited reconciliation of Saudi-Arabia Iran relations, the U.S. found itself on the sidelines of political developments in the Middle East. The JCPOA, which attempted to control the nuclear capabilities of Iran, was not fully reinstated after the Trump administration abandoned the international agreement supported by European powers in 2018. As China attempted to fill this vacuum, the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine further tested the international alliances with the U.S. Iran and other larger powers such as India as well as Arab nations did not adopt any of the economic sanctions imposed on Russia but to the contrary, increased their economic and strategic alliances with Russia or China. As China is focussing primarily on the global expansion of its economy, Russia was able to maintain its military and energy-related influence not only in Asia but also in Africa and South America. With regard to the Middle East, trade from these nations with China is three times greater than the trade with the U.S. As China is extending its mid-East reach, Russia despite its battered economy from sanctions still remains influential in South America with trade relations that are difficult to deconstruct through U.S. American influence. While China's influence in the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Africa is still hindered by commercial and currency-related U.S. trade policies, it is perceived more and more as a peace negotiator than a communist aggressor, particularly outside of Europe and North America. While the U.S. still upholds its moral dominance by advocating for democracy, its foreign policies are increasingly marked by a perceived inability to defend its image as an exporter of peace and prosperity.[40][41][42]

Diplomatic policy

[edit]The diplomatic policy of the United States is created by the president and carried out by the Department of State. The department's stated mission is to "protect and promote U.S. security, prosperity, and democratic values and shape an international environment in which all Americans can thrive."[43] Its objectives during the 2022-2026 period include renewing U.S. leadership, promoting global prosperity, strengthening democratic institutions, revitalizing the diplomatic workforce and institutions, and serving U.S. citizens abroad.[44] As of 2022, the United States has bilateral relations with all but four United Nations members.[45]

The United States government emphasizes human rights in foreign policy.[46] Annual reports produced by the Department of State, such as "Advancing Freedom and Democracy" and the "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices", track the status of human rights around the world.[47][48][49] The National Endowment for Democracy provides financial aid to promote democracy internationally.[50]

International agreements

[edit]The United States is party to thousands of international agreements with other countries, territories, and international organizations. These include arms control agreements, human rights treaties, environmental protocols, and free trade agreements.[51] Under the Compact of Free Association, the United States also maintains a relationship of free association with the countries of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and Palau, grants the United States military access to the countries in exchange for military protection, foreign aid, and access domestic American agencies.[52]

The United States is a member of many international organizations. It is a founding member of the United Nations and holds a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council. The United States is also a member of other global organizations, including the World Trade Organization. Regional organizations in which the United States is a member include NATO, Organization of American States, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement, and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. As the largest economy in the world, the United States is also a member of organizations for the most developed nations, including the OECD, the Group of Seven, and the G20.

Non-participation in multi-lateral agreements

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2022) |

This section may contain material not related to its topic. (June 2022) |

This section may lend undue weight to treaties unrelated to American foreign policy. Please help to create a more balanced presentation. Discuss and resolve this issue before removing this message. (June 2022) |

The United States notably does not participate in various international agreements adhered to by almost all other industrialized countries, by almost all the countries of the Americas, or by almost all other countries in the world. With a large population and economy, on a practical level this can undermine the effect of certain agreements,[53][54] or give other countries a precedent to cite for non-participation in various agreements.[55]

In some cases the arguments against participation include that the United States should maximize its sovereignty and freedom of action, or that ratification would create a basis for lawsuits that would treat American citizens unfairly.[56] In other cases, the debate became involved in domestic political issues, such as gun control, climate change, and the death penalty.[citation needed]

Examples include:

- Versailles Treaty and the League of Nations covenant (in force 1920–45, signed but not ratified)

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (took effect in 1976, ratified with substantial reservations)

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (took effect in 1976, signed but not ratified)

- American Convention on Human Rights (took effect in 1978)

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (took effect in 1981, signed but not ratified)

- Convention on the Rights of the Child (took effect in 1990, signed but not ratified)

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (took effect in 1994)

- Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (signed in 1996 but never ratified and never took effect)

- Mine Ban Treaty (took effect in 1999)

- International Criminal Court (took effect in 2002)

- Kyoto Protocol (in force 2005–12, signed but not ratified)

- Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture (took effect in 2006)

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (took effect in 2008, signed but not ratified)

- Convention on Cluster Munitions (took effect in 2010)

- International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (took effect in 2010)

- Arms Trade Treaty (took effect in 2014)

- Other human rights treaties

- Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (took effect in 2016 as part of the United Nations Security Council Resolution 2231. Signed by the U.S., France, Germany, European Union, UK, Russia, China and Iran, but abandoned by the U.S. in 2018)

Foreign aid

[edit]Foreign assistance is a core component of the State Department's international affairs budget, and aid is considered an essential instrument of U.S. foreign policy.[57] There are four major categories of non-military foreign assistance: bilateral development aid, economic assistance supporting U.S. political and security goals, humanitarian aid, and multilateral economic contributions (for example, contributions to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund).[58][failed verification] In absolute dollar terms, the United States government is the largest international aid donor.[57] The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) manages the bulk of bilateral economic assistance, while the Treasury Department handles most multilateral aid.[59] Foreign aid is a highly partisan issue in the United States, with liberals, on average, supporting foreign aid much more than conservatives do.[60]

The United States first began distributing regular foreign aid in the aftermath of World War II and the onset of the Cold War. Foreign aid has been used to foster closer relations with foreign nations, strengthen countries that could potentially become future allies and trading partners, and provide assistance for people of countries most in need. American foreign aid contributed to the Green Revolution in the 1960s and the democratization of Taiwan and Colombia.[61] Since the 1970s, issues of human rights have become increasingly important in American foreign policy, and several acts of Congress served to restrict foreign aid from governments that "engage in a consistent pattern of gross violations of internationally recognized human rights".[62][63] In 2011, President Obama instructed agencies to consider LGBT rights when issuing financial aid to foreign countries.[64] In the 2019 fiscal year, the United States spent $39.2 billion in foreign aid, constituting less than one percent of the federal budget.[65]

War on Drugs

[edit]United States foreign policy is influenced by the efforts of the U.S. government to control imports of illicit drugs, including cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, and cannabis. This is especially true in Latin America, a focus for the U.S. War on Drugs. These foreign policy efforts date back to at least the 1900s, when the U.S. banned the importation of non-medical opium and participated in the 1909 International Opium Commission, one of the first international drug conferences.[66]

Over a century later, the Foreign Relations Authorization Act requires the President to identify the major drug transit or major illicit drug-producing countries. In September 2005,[67] the following countries were identified: Bahamas, Bolivia, Brazil, Burma, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Haiti, India, Jamaica, Laos, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Peru and Venezuela. Two of these, Burma and Venezuela are countries that the U.S. considers to have failed to adhere to their obligations under international counternarcotics agreements during the previous 12 months. Notably absent from the 2005 list were Afghanistan, the People's Republic of China and Vietnam; Canada was also omitted in spite of evidence that criminal groups there are increasingly involved in the production of MDMA destined for the United States and that large-scale cross-border trafficking of Canadian-grown cannabis continues. The U.S. believes that the Netherlands are successfully countering the production and flow of MDMA to the U.S.[citation needed]

In 2011, overdose deaths in the U.S. were on a decline mostly due to interdiction efforts and international cooperation to reduce the production of illicit drugs. Since about 2014, a reversal of this trend could be clearly seen as legal semi-synthetic opioids and cocaine stimulants were replaced by the fully synthetic fentanyl and methamphetamine. By 2022, overdose deaths caused by illicit fentanyl led to the worst drug crisis the U.S. has ever experienced in its history, with 1,500 people dying every week of overdose-related cases. By 2022, deaths caused by fentanyl significantly reduced the life expectancy in the U.S. and were also seen as a major drag on the U.S. economy. Despite efforts to control the trade of chemicals used in the synthesis of fentanyl, the tide of fentanyl-related deaths continues to be a major threat to U.S. national security.[68]

Regional diplomacy

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2022) |

Africa

[edit]American involvement with Africa has historically been limited. During the war on terror, the United States increased its activities in Africa to fight terrorism in conjunction with African countries as well as to support democracy in Africa through the Millennium Challenge Corporation. Africa has also been the subject of competition between American and Chinese investment strategies.[69] In 2007 the U.S. was Sub-Saharan Africa's largest single export market accounting for 28% of exports (second in total to the EU at 31%). 81% of U.S. imports from this region were petroleum products.[70]

Asia

[edit]America's relations with Asia have tended to be based on a "hub and spoke" model instead of multilateral relations, using a series of bilateral relationships where states coordinate with the United States instead of through a unified bloc.[71] On May 30, 2009, at the Shangri-La Dialogue, Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates urged the nations of Asia to build on this hub and spoke model as they established and grew multilateral institutions such as ASEAN, APEC and the ad hoc arrangements in the area.[citation needed] In 2011, Gates said the United States must serve as the "indispensable nation", for building multilateral cooperation.[72] As of 2022, the Department of Defense considers China to be the greatest threat to the policy goals of the United States.[73]

Canada

[edit]Canada has historically been a close ally to the United States, and their foreign policies often work in conjunction. The armed forces of Canada and the United States have a high level of interoperability, and domestic air force operations have been fully integrated between the two countries through NORAD.[74] Almost all of Canada's energy exports go to the United States, making it the largest foreign source of U.S. energy imports; Canada is consistently among the top sources for U.S. oil imports, and it is the largest source of U.S. natural gas and electricity imports.[75] Trade between the United States and Canada as well as Mexico is facilitated through the USMCA.

Europe

[edit]The United States has close ties with the European Union, and it is a member of NATO along with several European countries. The United States has close relations with most countries of Europe. Much of American foreign policy has involved combating the Soviet Union in the 20th century and Russia in the 21st century.

Latin America

[edit]The Monroe Doctrine has historically made up the foreign policy of the United States in regard to Latin America. Under this policy, the United States would consider Latin America to be under its sphere of influence and defend Latin American countries from European hostilities. The United States was heavily involved in the politics of Panama during the early-20th century in order to construct the Panama Canal. Cuba was an ally of the United States following its independence, but it was identified as a major national security threat following the Cuban Revolution; Cuba–United States relations remain poor.

Middle East

[edit]

The Middle East region was first proclaimed to be of national interest to the United States during World War II, and relations were secured with Saudi Arabia to secure additional oil supplies.[76] The Middle East continued to be regarded as an area of vital importance to the United States during the Cold War, and American containment policy emphasized preventing Soviet influence from taking hold in the Middle East.[77] The Truman Doctrine, the Eisenhower Doctrine, and the Nixon Doctrine all played roles in the formulation of the Carter Doctrine, which stated that the United States would use military force if necessary to defend its national interests in the Persian Gulf region.[78] Carter's successor, President Ronald Reagan, extended the policy in October 1981 with the Reagan Doctrine, which proclaimed that the United States would intervene to protect Saudi Arabia, whose security was threatened after the outbreak of the Iran–Iraq War.[79] During the so-called war on terror, the United States increased its involvement in the region; some analysts have argued that the implementation of the Carter Doctrine and the Reagan Doctrine also played a role in the outbreak of the 2003 Iraq War.[80][81][82][83]

Two-thirds of the world's proven oil reserves are estimated to be found in the Persian Gulf,[84][85] and the United States imports oil from several Middle Eastern countries. While its imports have exceeded domestic production since the early 1990s, new hydraulic fracturing techniques and discovery of shale oil deposits in Canada and the American Dakotas offer the potential for increased energy independence from oil exporting countries such as OPEC.[86]

Oceania

[edit]Australia and New Zealand are close allies of the United States. Together, the three countries compose the ANZUS collective security agreement. The United States and the United Kingdom also have a separate agreement, AUKUS, with Australia. After it captured the islands from Japan during World War II, the United States administered the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands from 1947 to 1986 (1994 for Palau). The Northern Mariana Islands became a U.S. territory (part of the United States), while Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and Palau became independent countries. Each has signed a Compact of Free Association that gives the United States exclusive military access in return for U.S. defense protection and conduct of military foreign affairs (except the declaration of war) and a few billion dollars of aid. These agreements also generally allow citizens of these countries to live and work in the United States with their spouses (and vice versa), and provide for largely free trade. The federal government also grants access to services from domestic agencies, including the Federal Emergency Management Agency, National Weather Service, the United States Postal Service, the Federal Aviation Administration, the Federal Communications Commission, and U.S. representation to the International Frequency Registration Board of the International Telecommunication Union.[citation needed]

Defense policy

[edit]

Defense policy of the United States is established by the president under the role of commander-in-chief, and it is carried out by the Department of Defense and the Department of Homeland Security. As of 2022, the stated objective of the Department of Defense is to deter attacks against the United States and its allies in order to protect the American people, expand America's prosperity, and defend democratic values. The department recognizes China as the greatest foreign threat to the United States, with Russia, North Korea, Iran, and violent extremist organizations recognized as other major foreign threats.[73] Most American troops stationed in foreign countries operate in non-combat roles. As of 2021, about 173,000 troops are deployed in 159 countries. Japan, Germany, and South Korea are host to the largest numbers of American troops due to continued military cooperation following World War II and the Korean War.[87] The United States has not been involved in a major war since the conclusion of the War in Afghanistan in 2021, though American forces continue to operate against terrorist groups in the Middle East and Africa through the Authorization for Use of Military Force of 2001.[37] The United States also provides billions of dollars of military aid to allied countries each year.[88]

The Constitution of the United States requires that Congress authorize any military conflict initiated by the president. This has been carried out through formal declarations of war, Congressional authorizations without formal declaration, and through United Nations Security Council Resolutions that are legally recognized by Congress. The War Powers Resolution of 1973 limited the ability of the president to use the military without Congressional authorization. Prior to 2001, 125 instances of American presidents using military force without Congressional authorization had been identified.[89] Since 2001, the Authorization for Use of Military Force of 2001 (AUMF) has granted the president the power to engage in military conflict with any country, organization, or person that was involved in carrying out the September 11 attacks. American presidents have since interpreted the AUMF to authorize military campaigns against terrorist groups associated with Al-Qaeda in several countries.[90]

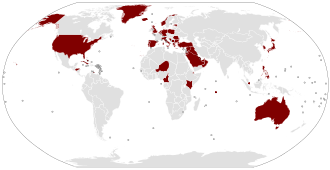

Alliances and partnerships

[edit]The Department of Defense considers cooperation with American allies and partners to be "critical" to achieving American defense objectives.[73] The department makes a distinction between alliances, which are formal military agreements between countries through a treaty, and strategic partnerships, which are military cooperation agreements that aren't bound by specific terms.[91] The United States military works in cooperation with many national governments, and the United States has approximately 750 military bases in at least 80 different countries.[87] In addition to military agreements, the United States is a member of multiple international disarmament organizations, including the International Atomic Energy Agency and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons.

The United States is a founding member of NATO, an alliance of 29 North American and European nations formed to defend Western Europe against the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Under the NATO charter, the United States legally recognizes any attack on a NATO member as an attack on all NATO members. The United States is also a founding member of the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance, an alliance of 19 North and South American nations. The United States is one of the three members of ANZUS, along with Australia and New Zealand, and it also has military alliances with Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Thailand.[92] Under the Compact of Free Association, the United States is responsible for the defense of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and Palau.[52] The United States has also designated several countries as major non-NATO allies. These are countries that are not members of NATO but are granted certain privileges in regard to defense trade and security cooperation, including eligibility for certain trade deals and research collaboration. The president is empowered to designate additional foreign countries as major non-NATO allies.[93]

Since it became a superpower in the mid-20th century, the United States has primarily carried out defense operations by leading and participating in multilateral coalitions. These coalitions may be constructed around existing defensive alliances, such as NATO, or through separate coalitions constructed through diplomatic negotiations and acting in a common interest. The United States has not engaged in unilateral military action since the invasion of Panama in 1989.[94] United States military action may take place in accordance with or in opposition to the wishes of the United Nations. The United States has opposed the expansion of United Nations peacekeeping beyond its previous scope, instead supporting the use of multilateral coalitions in hostile countries and territories.[95]

Military aid

[edit]

The U.S. provides military aid through many channels, including direct funding, support for training, or distribution of military equipment. Military aid spending has varied over time, with spending reaching as high as $35 billion in 1952, adjusted for inflation.[88] The United States established a cohesive military aid policy during World War II, when the Lend-Lease program was implemented to support the Allied powers. After the war, the United States continued to provide military aid in line with other foreign aid programs to support American allies. Programs such as Foreign Military Financing and Foreign Military Sales oversee distribution of military aid.

According to a 2016 report by the Congressional Research Service, the U.S. topped the market in global weapon sales for 2015, with $40 billion sold. The largest buyers were Qatar, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Pakistan, Israel, the United Arab Emirates and Iraq.[96] In 2020, the United States distributed $11.6 billion in military aid, the lowest since 2004. Military aid is one of the main forms of foreign aid, with 23% of American foreign aid in 2020 taking the form of military aid. Afghanistan was the primary recipient of American military aid in the 2010s. In 2022, military aid policy in the United States shifted from Afghanistan to Ukraine following the end of the War in Afghanistan and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[88] As of 2021, the United States has military bases in at least 80 countries.[87]

The table below outlines the ten largest recipients of United States military aid in 2020 and their estimated aid in billions.[88]

| Recipient | Military aid 2020 (USD Billions) |

|---|---|

| 3.30 | |

| 2.76 | |

| 1.30 | |

| 0.5481 | |

| 0.5040 | |

| 0.2840 | |

| 0.2445 | |

| 0.1651 | |

| 0.1384 | |

| 0.1021 |

Missile defense

[edit]The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) was a proposal by U.S. President Ronald Reagan on March 23, 1983[97] to use ground and space-based systems to protect the United States from attack by strategic nuclear ballistic missiles,[98] later dubbed "Star Wars".[99] The initiative focused on strategic defense rather than the prior strategic offense doctrine of mutual assured destruction (MAD). Though it was never fully developed or deployed, the research and technologies of SDI paved the way for some anti-ballistic missile systems of today.[100]

In February 2007, the U.S. started formal negotiations with Poland and Czech Republic concerning construction of missile shield installations in those countries for a Ground-Based Midcourse Defense system[101] (in April 2007, 57% of Poles opposed the plan).[102] According to press reports, the government of the Czech Republic agreed (while 67% Czechs disagree)[103] to host a missile defense radar on its territory while a base of missile interceptors is supposed to be built in Poland.[104][105]

Russia threatened to place short-range nuclear missiles on the Russia's border with NATO if the United States refuses to abandon plans to deploy 10 interceptor missiles and a radar in Poland and the Czech Republic.[106][107] In April 2007, Putin warned of a new Cold War if the Americans deployed the shield in Central Europe.[108] Putin also said that Russia is prepared to abandon its obligations under an Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty of 1987 with the United States.[109]

On August 14, 2008, the United States and Poland announced a deal to implement the missile defense system in Polish territory, with a tracking system placed in the Czech Republic.[110] "The fact that this was signed in a period of very difficult crisis in the relations between Russia and the United States over the situation in Georgia shows that, of course, the missile defense system will be deployed not against Iran but against the strategic potential of Russia", Dmitry Rogozin, Russia's NATO envoy, said.[101][111]

Keir A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press, argue in Foreign Affairs that U.S. missile defenses are designed to secure Washington's nuclear primacy and are chiefly directed at potential rivals, such as Russia and China. The authors note that Washington continues to eschew nuclear first strike and contend that deploying missile defenses "would be valuable primarily in an offensive context, not a defensive one; as an adjunct to a US First Strike capability, not as a stand-alone shield":

If the United States launched a nuclear attack against Russia (or China), the targeted country would be left with only a tiny surviving arsenal, if any at all. At that point, even a relatively modest or inefficient missile defense system might well be enough to protect against any retaliatory strikes.[112]

This analysis is corroborated by the Pentagon's 1992 Defense Planning Guidance (DPG), prepared by then Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney and his deputies. The DPG declares that the United States should use its power to "prevent the reemergence of a new rival" either on former Soviet territory or elsewhere. The authors of the Guidance determined that the United States had to "Field a missile defense system as a shield against accidental missile launches or limited missile strikes by 'international outlaws'" and also must "Find ways to integrate the 'new democracies' of the former Soviet bloc into the U.S.-led system". The National Archive notes that Document 10 of the DPG includes wording about "disarming capabilities to destroy" which is followed by several blacked out words. "This suggests that some of the heavily excised pages in the still-classified DPG drafts may include some discussion of preventive action against threatening nuclear and other WMD programs."[113]

Robert David English, writing in Foreign Affairs, observes that the DPG's second recommendation has also been proceeding on course. "Washington has pursued policies that have ignored Russian interests (and sometimes international law as well) in order to encircle Moscow with military alliances and trade blocs conducive to U.S. interests."[114]

On September 12, 2024, the U.S. disclosed that Russia obtained ballistic missiles from Iran for its war in Ukraine, leading to new sanctions on Russian entities involved. The U.S. also targeted Iran Air and other organizations linked to Iran’s missile activities, though Iran denies supplying the weapons. Secretary of State Antony Blinken is set to visit Ukraine and Poland to discuss further support, as Ukraine urges stronger actions.[115][116]

Exporting democracy

[edit]

Studies have been devoted to the historical success rate of the U.S. in exporting democracy abroad. Some studies of American intervention have been pessimistic about the overall effectiveness of U.S. efforts to encourage democracy in foreign nations.[117] Until recently, scholars have generally agreed with international relations professor Abraham Lowenthal that U.S. attempts to export democracy have been "negligible, often counterproductive, and only occasionally positive".[118][119] Other studies find U.S. intervention has had mixed results,[117] and another by Hermann and Kegley has found that military interventions have improved democracy in other countries.[120]

Intelligence policy

[edit]

Intelligence policy is developed by the president and carried out by the United States Intelligence Community, led by the Director of National Intelligence. The Intelligence Community includes 17 offices and bureaus within various executive departments as well as the Central Intelligence Agency.[121][122] Its stated purpose is to utilize insights, protected information, and understanding of adversaries to advance national security, economic strength, and technological superiority.[123]

The Intelligence Community provides support for all diplomatic and military action undertaken by the United States and serves to inform government and military decision-making, as well as collecting and analyzing global economic and environmental information. The primary functions of the Intelligence Community are the collection and analysis of information, and it is responsible for collecting information on foreign subjects that is not available publicly or through diplomatic channels. Collection of information typically takes the form of signals intelligence, imagery intelligence, and human intelligence. Information collected by American intelligence is used to counter foreign intelligence, terrorism, narcotics trafficking, WMD proliferation, and international organized crime.[124]

Counterintelligence

[edit]The Intelligence Community is responsible for counterintelligence to protect the United States from foreign intelligence services. The Central Intelligence Agency is responsible for counterintelligence activities abroad, while the Federal Bureau of Investigation is responsible for combating foreign intelligence operations in the United States. The goal of American counterintelligence is to protect classified government information as well as trade secrets of American industry. Offensive counterintelligence operations undertaken by the United States include recruiting foreign intelligence agents, monitoring suspected foreign agents, and collecting information on the intentions of foreign intelligence services, while defensive counterintelligence operations include investigating suspected cases of espionage and producing analyses of foreign intelligence threats.[124]

Counterintelligence operations in the United States began when the Espionage Act of 1917 was used to prosecute German infiltrators and saboteurs during World War I. Today, counterintelligence is applied in the United States as a tool of national security. Due to its global influence, the United States is considered to be the world's greatest target for intelligence operations. Terrorists, tyrants, foreign adversaries, and economic competitors have all been found to engage in "a range of intelligence activities" directed against the United States. Terrorist organizations such as al Qaeda have been found to employ intelligence practices similar to those of foreign powers, and American counterintelligence operations play a significant role in counterterrorism.[125]

Covert action

[edit]In addition to intelligence gathering, the Central Intelligence Agency is authorized by the National Security Act of 1947 to engage in covert action. Covert action is undertaken to influence conditions in foreign countries without evidence of American involvement. This may include enacting propaganda campaigns, offering support to factions within a country, providing logistical assistance to foreign governments, or disrupting illegal activities. The use of covert action is controversial within the Intelligence Community due to the potential harm to foreign relations and public image, but most individuals involved in American intelligence cite it as an "essential" option to prevent terrorism, drug trafficking, and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.[124]

Examples of covert involvement in regime change

[edit]| United States involvement in regime change |

|---|

United States foreign policy also includes covert actions to topple foreign governments that have been opposed to the United States. According to J. Dana Stuster, writing in Foreign Policy, there are seven "confirmed cases" where the U.S.—acting principally through the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), but sometimes with the support of other parts of the U.S. government, including the Navy and State Department—covertly assisted in the overthrow of a foreign government: Iran in 1953, Guatemala in 1954, Congo in 1960, the Dominican Republic in 1961, South Vietnam in 1963, Brazil in 1964, and Chile in 1973. Stuster states that this list excludes "U.S.-supported insurgencies and failed assassination attempts" such as those directed against Cuba's Fidel Castro, as well as instances where U.S. involvement has been alleged but not proven (such as Syria in 1949).[126]

In 1953 the CIA, working with the British government, initiated Operation Ajax against the Prime Minister of Iran Mohammad Mossadegh who had attempted to nationalize Iran's oil, threatening the interests of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. This had the effect of restoring and strengthening the authoritarian monarchical reign of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.[127] In 1957, the CIA and Israeli Mossad aided the Iranian government in establishing its intelligence service, SAVAK, later blamed for the torture and execution of the regime's opponents.[128][129]

A year later, in Operation PBSuccess, the CIA assisted the local military in toppling the democratically elected left-wing government of Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala and installing the military dictator Carlos Castillo Armas. The United Fruit Company lobbied for Árbenz's overthrow as his land reforms jeopardized their land holdings in Guatemala, and painted these reforms as a communist threat. The coup triggered a decades long civil war which claimed the lives of an estimated 200,000 people (42,275 individual cases have been documented), mostly through 626 massacres against the Maya population perpetrated by the U.S.-backed Guatemalan military.[130][131][132][133] An independent Historical Clarification Commission found that U.S. corporations and government officials "exercised pressure to maintain the country's archaic and unjust socio-economic structure",[131] and that U.S. military assistance had a "significant bearing on human rights violations during the armed confrontation".[134]

During the massacre of at least 500,000 alleged communists in 1960s Indonesia, U.S. government officials encouraged and applauded the mass killings while providing covert assistance to the Indonesian military which helped facilitate them.[135][136][137][138][139] This included the U.S. Embassy in Jakarta supplying Indonesian forces with lists of up to 5,000 names of suspected members of the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI), who were subsequently killed in the massacres.[140][141][142][143] In 2001, the CIA attempted to prevent the publication of the State Department volume Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, which documents the U.S. role in providing covert assistance to the Indonesian military for the express purpose of the extirpation of the PKI.[139][144][145] In July 2016, an international panel of judges ruled the killings constitute crimes against humanity, and that the US, along with other Western governments, were complicit in these crimes.[146]

In 1970, the CIA worked with coup-plotters in Chile in the attempted kidnapping of General René Schneider, who was targeted for refusing to participate in a military coup upon the election of Salvador Allende. Schneider was shot in the botched attempt and died three days later. The CIA later paid the group $35,000 for the failed kidnapping.[147][148]

According to one peer-reviewed study, the U.S. intervened in 81 foreign elections between 1946 and 2000.[149][150]

The failed 1961 CIA Bay of Pigs Invasion in Cuba was an attempt by the U.S. government to overthrow a regime.[151][152] Not only did this cause a diplomatic embarrassment, it also damaged the CIA's credibility internationally.[153]

Public image

[edit]United States foreign policy has been the subject of debate, receiving praise and criticism domestically and abroad. As of 2019, public opinion in the United States is closely divided on American involvement in world affairs. 53% of Americans wish for the United States to be active in world affairs, while 46% of Americans wish for less involvement overseas. American involvement in the global economy is received more positively by the American people, with 73% considering it to be a "good thing".[154]

Global opinion

[edit]

Overall, the United States is viewed positively by the rest of the world. The Eurasia Group Foundation reported that as of 2021, 85% of respondents from 10 countries have a favorable opinion of the United States and 81% favor American hegemony over Chinese hegemony. Those with an unfavorable view of the United States most commonly cited interventionism, and in particular the War in Afghanistan, as their reason. It was also found that the exercise of soft power increased favorable opinions while the exercise of hard power decreased favorable opinions. Citizens of Brazil, Nigeria, and India were found to have more favorable opinions of the United States, while citizens of China and Germany were found to have less favorable opinions of the United States.[155]

International opinion about the US has often changed with different executive administrations. For example, in 2009, the French public favored the United States when President Barack Obama (75% favorable) replaced President George W. Bush (42%). After President Donald Trump took the helm in 2017, French public opinion about the US fell from 63% to 46%. These trends were also seen in other European countries.[156]

Many democracies have voluntary military ties with the United States. See NATO, ANZUS, U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, Mutual Defense Treaty with South Korea, and Major non-NATO ally. Those nations with military alliances with the U.S. can spend less on the military since they can count on U.S. protection. This may give a false impression that the U.S. is less peaceful than those nations.[157][158] A 2013 global poll in 65 countries found that the United States is perceived as the biggest threat to world peace, with 24% of respondents identifying it as such. A majority of Russian respondents named the United States as the greatest threat, as well as significant minorities in China, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Argentina, Greece, Turkey, and Pakistan.[159]

Foreign intervention

[edit]

Empirical studies (see democide) have found that democracies, including the United States, inflict significantly fewer civilian casualties than dictatorships.[160][161] Media may be biased against the U.S. regarding reporting human rights violations. Studies have found that The New York Times coverage of worldwide human rights violations predominantly focuses on the human rights violations in nations where there is clear U.S. involvement, while having relatively little coverage of the human rights violations in other nations.[162][163] For example, the bloodiest war in recent time, involving eight nations and killing millions of civilians, was the Second Congo War, which was almost completely ignored by the media.[164]

Журналисты и правозащитные организации критиковали авиаудары под руководством США и целенаправленные убийства беспилотниками , которые в некоторых случаях привели к сопутствующему повреждению гражданского населения. [ 165 ] [ 166 ] [ 167 ] В начале 2017 года США столкнулись с критикой со стороны некоторых ученых, активистов и средств массовой информации за то, что они сбросили 26 171 бомб на семи странах в течение 2016 года: Сирия, Ирак, Афганистан, Ливия, Йемен, Сомали и Пакистан. [ 168 ] [ 169 ] [ 170 ]

Исследования по теории демократического мира , как правило, показали, что демократии, в том числе Соединенные Штаты, не вступили в войну друг с другом. Была поддержка США для переворотов против некоторых демократий, но, например, Спенсер Р. Уорут утверждает, что частью объяснения было восприятие, правильное или нет, что эти государства превращались в коммунистические диктатуры. Также важной была роль редко прозрачных правительственных учреждений Соединенных Штатов, которые иногда вводят в заблуждение или не полностью реализовали решения избранных гражданских лидеров. [ 171 ]

Критики из левых цитируют эпизоды, которые подрывают левые правительства или оказали поддержку Израилю. Другие ссылаются на нарушения прав человека и нарушения международного права. Критики утверждают, что президенты США использовали демократию для оправдания военного вмешательства за границей. [ 172 ] [ 173 ] Критики также указывают на рассекреченные записи, которые указывают на то, что ЦРУ под Алленом Даллесом и ФБР под руководством Дж. Эдгара Гувера агрессивно набрали более 1000 нацистов, включая тех, кто ответственен за военные преступления, использовать в качестве шпионов и информаторов против Советского Союза в холодной войне. Полем [ 174 ] [ 175 ]

Исследования были посвящены историческому уровню успеха США в экспорте демократии за рубежом. Некоторые исследования американского вмешательства были пессимистичными в отношении общей эффективности усилий США по стимулированию демократии в иностранных странах. [ 117 ] Некоторые ученые в целом согласились с профессором международных отношений Абрахама Лоуенталя, что мы пытаются экспортировать демократию, «незначительны, часто контрпродуктивны и лишь изредка позитивны». [ 118 ] [ 119 ] Другие исследования обнаруживают, что вмешательство имело смешанные результаты, [ 117 ] И еще один от Германа и Кегли обнаружил, что военные вмешательства улучшили демократию в других странах. [ 120 ]

История невмешательства Америки также подверглась критике. В своем мировом политическом журнале обзор книги Билла Кауфмана «Америка» 1995 года! Его история, культура и политика , Бенджамин Шварц описал историю изоляционизма Америки как «трагедию» и укоренившиеся в пуританском мышлении. [ 176 ]

Сегодня США утверждают, что демократические нации лучше всего поддерживают национальные интересы США. По данным Государственного департамента США, «демократия - это единственный национальный интерес, который помогает защитить всех остальных. Демократически управляемые страны с большей вероятностью обеспечат мир, сдерживают агрессию, расширяют открытые рынки, способствуют экономическому развитию, защищают американских граждан, боевой международный Терроризм и преступность, поддерживать права человека и работников, избегать гуманитарных кризисов и потоков беженцев, улучшать глобальную среду и защищать здоровье человека ». [ 177 ] По словам бывшего президента США Билла Клинтона , «в конечном итоге лучшая стратегия обеспечения нашей безопасности и создания долговечного мира - это поддержать продвижение демократии в других местах. Демократии не нападают друг на друга». [ 178 ] С одной стороны, упомянутой Государственным департаментом США, демократия также хороша для бизнеса. Страны, которые охватывают политические реформы, также с большей вероятностью будут проводить экономические реформы, которые повышают производительность бизнеса. Соответственно, с середины 1980-х годов при президенте Рональде Рейгане наблюдается увеличение уровней прямых иностранных инвестиций, направленных на демократии на развивающихся рынках по сравнению со странами, которые не провели политические реформы. [ 179 ] Утечка кабелей в 2010 году предположил, что «темная тень терроризма все еще доминирует в отношениях Соединенных Штатов с миром». [ 180 ]

Соединенные Штаты официально утверждают, что она поддерживает демократию и права человека с помощью нескольких инструментов. [ 46 ] Примеры этих инструментов следующие:

- Опубликованный ежегодный отчет Государственного департамента под названием «продвижение свободы и демократии», [ 47 ] Выдается в соответствии с Законом о предварительной демократии 2007 года (ранее доклад был известен как «поддержка прав человека и демократии: протокол США» и был выпущен в соответствии с законом 2002 года). [ 48 ]

- Ежегодно опубликованные « страновые отчеты о практике прав человека ». [ 49 ]

- В 2006 году (при президенте Джорджу Буше ) Соединенные Штаты создали «Фонд правозащитников» и «Фонд свободы». [ 181 ]

- Награда «Премии по правам человека и демократии» признает исключительное достижение сотрудников иностранных агентств, размещенных за границей. [ 182 ]

- «Амбассадориальная серия круглых столов», созданная в 2006 году, представляют собой неофициальные дискуссии между вновь подтвержденными послами США и правонарушениями человека и неправительственными организациями демократии. [ 183 ]

- Национальный фонд демократии , частная некоммерческая организация, созданная Конгрессом в 1983 году (и подписанный президентом Рональдом Рейганом ), которая в основном финансируется правительством США и дает денежные гранты для укрепления демократических институтов по всему миру. [ 184 ]

Поддержка авторитарных правительств

[ редактировать ]

Как в настоящее время, так и исторически, Соединенные Штаты были готовы сотрудничать с авторитарными правительствами для достижения своих геополитических целей. [ 186 ] США столкнулись с критикой за поддержку правых диктаторов, которые систематически нарушали права человека, такие как Аугусто Пиночет из Чили, [ 187 ] Альфредо Стросснер из Парагвая, [ 188 ] Эфраин Риос Монтт из Гватемалы, [ 189 ] Jorge Rafael Videla of Argentina, [ 190 ] ХЕБЕР ХИССЕН [ 191 ] [ 192 ] Яхья Хан из Пакистана [ 193 ] и Сухарто из Индонезии. [ 138 ] [ 142 ] Критики также обвинили Соединенные Штаты в содействии и поддержке государственного терроризма на мировом юге во время холодной войны, таких как операция Condor , международная кампания политического убийства и государственного террора, организованного правыми военными диктатурами в южном конусе Южной Америки Полем [ 194 ] [ 195 ] [ 188 ] [ 196 ]

Что касается поддержки определенных антикоммунистических диктатур во время холодной войны , то ответ заключается в том, что они считались необходимым злом, а альтернативы еще хуже коммунистические или фундаменталистские диктатуры. Дэвид Шмитц говорит, что эта политика не служила нам интересам. Дружественные тираны сопротивлялись необходимым реформам и уничтожили политический центр (хотя и не в Южной Корее), в то время как политика « реалистических » диктаторов ткдлинга принесла обратную реакцию среди иностранных групп населения с длинными воспоминаниями. [ 197 ] [ 198 ] Некоторые критические ученые и журналисты, в том числе Джейсон Хикель и Винсент Бевинс , утверждают, что США поддержали таких диктаторов, чтобы укрепить западные деловые интересы и расширить капитализм в страны мирового юга, которые пытались пройти альтернативные пути . [ 199 ] [ 194 ] [ 200 ]

США были обвинены в соучастии в военных преступлениях за поддержку вмешательства под руководством Саудовской Аравии в гражданскую войну в Йемени , которая вызвала гуманитарную катастрофу, включая вспышку холеры и миллионы, сталкивающиеся с голодом . [ 201 ] [ 202 ] [ 203 ]

Найл Фергюсон утверждает, что США неправильно обвиняются во всех нарушениях прав человека, совершенных правительствами, поддерживаемыми США. Фергюсон пишет, что существует общее согласие о том, что Гватемала была худшим из поддерживаемых США режимов во время холодной войны, но США не могут быть достоверно обвинены во всех примерно 200 000 смертей во время Длинной Гватемальской гражданской войны . [ 198 ] Совет по надзору за разведкой США пишет, что военная помощь была сокращена в течение длительных периодов из -за таких нарушений, что США помогли остановить переворот в 1993 году, и были предприняты усилия по улучшению поведения служб безопасности. [ 204 ]

Права человека

[ редактировать ]

С 1970 -х годов проблемы прав человека становятся все более важными во внешней политике американской. [ 205 ] [ 206 ] Конгресс взял на себя инициативу в 1970 -х годах. [ 207 ] После войны во Вьетнаме чувство, что внешняя политика США выросла помимо традиционных американских ценностей, было извлечено представителем Дональдом М. Фрейзером (D, MN) , что возглавило подкомитет по международным организациям и движениям, критикуя республиканскую внешнюю политику в соответствии с Никсоном. администрация . В начале 1970 -х годов Конгресс завершил войну во Вьетнаме и принял Закон о военных полномочиях . Как часть растущей уверенности Конгресса о многих аспектах внешней политики », [ 208 ] Проблемы прав человека стали полем битвы между законодательными и исполнительными ветвями в разработке внешней политики. Дэвид Форсайт указывает на три конкретных ранних примеров Конгресса, вмешивающего свои собственные мысли о внешней политике:

- Подраздел (а) Закона о международной финансовой помощи 1977 года: обеспечение помощи через международные финансовые учреждения будет ограничена странами, «другими теми, чьи правительства участвуют в последовательной модели грубых нарушений международных прав человека». [ 208 ]

- Раздел 116 Закона о иностранной помощи 1961 года, с поправками в 1984 году: отчасти гласит: «По этой части не может быть оказана помощь правительству любой страны, которая участвует в последовательных схемах грубых нарушений во всемирно признанных правах человека». [ 208 ]

- Раздел 502B Закона о иностранной помощи 1961 года, с поправками в 1978 году: «Не может быть предоставлена помощь в безопасности любой страны, правительству, в которой участвует постоянная модель грубых нарушений международных прав человека». [ 208 ]

Эти меры неоднократно использовались Конгрессом с различным успехом, чтобы повлиять на внешнюю политику США в отношении включения проблем с правами человека. Конкретные примеры включают Сальвадор , Никарагуа , Гватемалу и Южную Африку . Исполнительный директор (от Никсона до Рейгана) утверждал, что холодная война требовала, чтобы региональная безопасность в пользу интересов США по сравнению с любыми поведенческими проблемами национальных союзников. Конгресс утверждал обратное, в пользу дистанции Соединенных Штатов от репрессивных режимов. [ 207 ] Тем не менее, по словам историка Даниэля Голдхагена , в течение последних двух десятилетий холодной войны число американских клиентских государств, практикующих массовые убийства по численности числа Советского Союза . [ 209 ] Джон Генри Котсворт , историк Латинской Америки и проректора Колумбийского университета, предполагает, что число жертв репрессий только в Латинской Америке намного превзошло, что у СССР и его восточно -европейских спутников в период с 1960 по 1990 год. [ 210 ] У. Джон Грин утверждает, что Соединенные Штаты были «важным фактором» из «Латинской Америки привычки к политическим убийствам, выявляя и позволяя процветать некоторых из худших тенденций региона». [ 211 ]

6 декабря 2011 года Обама поручил агентствам рассмотреть права ЛГБТ при выдаче финансовой помощи иностранным странам. [ 212 ] Он также раскритиковал закон России, дискриминационный в отношении геев, [ 213 ] Присоединяясь к другим западным лидерам в бойкоте в зимних Олимпийских игр 2014 года России. [ 214 ]

В июне 2014 года чилийский суд постановил, что Соединенные Штаты сыграли ключевую роль в убийствах Чарльза Хормана и Фрэнка Теругги , оба американских граждане, вскоре после числа -переворота 1973 года . [ 215 ]

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]- Американский вступление в Первую мировую войну

- Международные отношения, 1648–1814

- Международные отношения великих держав (1814–1919)

- Международные отношения (1919–1939)

- Соединенные Штаты и спонсируемый государством терроризм

- Восприятие санкций Соединенных Штатов

- Критика внешней политики США

Дипломатия

[ редактировать ]- Ковбойская дипломатия

- Список дипломатических миссий в Соединенных Штатах

- Список дипломатических миссий Соединенных Штатов

- Соединенные Штаты и Организация Объединенных Наций

- Иностранные противники США

Интеллект

[ редактировать ]Политика и доктрина

[ редактировать ]- Антиамериканизм

- Буш доктрина

- Китайская политика сдерживания

- Расслабление

- Права человека в Соединенных Штатах

- Правозащитные записи Соединенных Штатов ( китайская публикация )

- Kirkpatrick Dectrine

- Пауэлл Доктрина

- Особые отношения

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ «Алфавитный список бюро и офисов» . Государственный департамент США . Получено 20 апреля 2016 года .

- ^ «Бюро бюджета и планирования» . State.gov . Получено 18 февраля 2015 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Деш, Майкл С. (2007). «Либеральный нелиберализм Америки: идеологическое происхождение чрезмерной реакции во внешней политике США» . Международная безопасность . 32 (3): 7–43. doi : 10.1162/isec.2008.32.3.7 . ISSN 0162-2889 . JSTOR 30130517 . S2CID 57572097 .

- ^ Брукс, Стивен Дж.; Wohlforth, William C. (2016). Америка за границей: глобальная роль Соединенных Штатов в 21 -м веке . Издательство Оксфордского университета. С. 73–77. ISBN 978-0-19-046425-7 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ikenberry, G. John (2001). После победы: институты, стратегическая сдержанность и восстановление порядка после крупных войн . ПРИЗНАЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТА ПРИСЕТА. ISBN 978-0-691-05091-1 .

- ^ «О комитете» . Архивировано с оригинала 15 апреля 2012 года . Получено 18 февраля 2015 года .

- ^ «Сенат США: международные отношения» . www.senate.gov . Получено 10 мая 2023 года .

- ^ Государственный департамент credoreference.com

- ^ «Государственный секретарь» . Государственный департамент США . Получено 15 октября 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Внешняя политика». Оксфордская энциклопедия американской военной и дипломатической истории - посредством ссылки на кредо.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж Поиск внешней политики США credoreference.com

- ^ «О договорах» . Сенат.gov . Сенат Соединенных Штатов . Получено 24 июля 2021 года .

- ^ «Миссури против Холландии, 252 США 416 (1920)» . Юстия закон . Получено 5 мая 2022 года .

- ^ Деннис Джетт (26 декабря 2014 г.). «Республиканцы блокируют ратификацию даже самых разумных международных договоров» . Новая республика . Получено 24 июля 2021 года .

- ^ «Договоры, находящиеся на рассмотрении в Сенате» . Государственный департамент США . 22 октября 2019 года . Получено 16 июня 2022 года .

- ^ Laurence H. Tribe, «Серьезное текст и структуру: размышления о методе свободной формы в конституционном толковании» , 108 Гарвардский закон . 1221, 1227 (1995).

- ^ «Договоры и другие международные соглашения: роль Сената Соединенных Штатов» . www.govinfo.gov . Получено 16 сентября 2022 года .

- ^ Джордж С. Херринг, от колонии до сверхдержавы: иностранные отношения США с 1776 года (2008)

- ^ Ричард Рассел, «Американский дипломатический реализм: традиция, практикуемая и проповедоваемая Джорджем Ф. Кеннаном», Diplomacy and Statecraft , ноябрь 2000 г., Vol. 11 Выпуск 3, с. 159–83

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Американская внешняя политика». Политочная наука 21 -го века: справочное справочник - через справочник Credo.

- ^ Вашингтон, Джордж. «Прощальный адрес Вашингтона» (PDF) . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 26 сентября 2018 года.

- ^ «1784–1800 гг.: Дипломатия ранней республики» . Государственный департамент США . Получено 4 мая 2022 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Орен, Майкл Б. (3 ноября 2005 г.). «Ближний Восток и создание Соединенных Штатов, с 1776 по 1815 год» .