Маргарет Тэтчер

Баронесса Тэтчер | |||

|---|---|---|---|

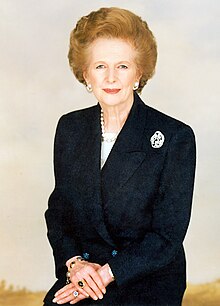

Студийный портрет, c. 1995–96 | |||

| Премьер -министр Соединенного Королевства | |||

| В офисе 4 мая 1979 г. - 28 ноября 1990 г. | |||

| Монарх | Элизабет II | ||

| Депутат | Джеффри Хоу (1989–90) | ||

| Предшествует | Джеймс Каллаган | ||

| Преуспевает | Джон Майо | ||

| Лидер оппозиции | |||

| В офисе 11 февраля 1975 г. - 4 мая 1979 г. | |||

| Монарх | Элизабет II | ||

| премьер-министр |

| ||

| Депутат | Уильям Уайтлау | ||

| Предшествует | Эдвард Хит | ||

| Преуспевает | Джеймс Каллаган | ||

| Лидер консервативной партии | |||

| В офисе 11 февраля 1975 - 28 ноября 1990 г. | |||

| Депутат | Виконт белый | ||

| Председатель | Смотрите список | ||

| Предшествует | Эдвард Хит | ||

| Преуспевает | Джон Майо | ||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Личные данные | |||

| Рожденный | Маргарет Хильда Робертс 13 октября 1925 г. Грантхам , Линкольншир, Англия | ||

| Умер | 8 апреля 2013 г. (в возрасте 87 лет) Лондон, Англия | ||

| Место отдыха | Королевская больница Челси 51 ° 29 "21 ″ с.ш. 0 ° 09'2'2 ″ с 51,489057 ° с.ш. 0,156195 ° С | ||

| Политическая партия | Консервативный | ||

| Супруг | |||

| Дети | |||

| Родительский |

| ||

| Альма -матер | |||

| Занятие | |||

| Награды | Полный список | ||

| Подпись | |||

| Веб -сайт | Фундамент | ||

| Прозвище | "Железная леди" | ||

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Государственный секретарь по образованию и науке

Лидер оппозиции

Премьер -министр Соединенного Королевства

Политики

Назначения

Статьи министерства и срока: 1979–1983

1983–1987

1987–1990

Пост-предпринимательство

Публикации

|

||

Маргарет Хильда Тэтчер, Баронесса Тэтчер , Л.Г. , Ом , DSTJ , PC , FRS , HONFRSC ( урожденная Робертс ; 13 октября 1925 г. - 8 апреля 2013 г.) была британской государственной женщиной и консервативным политиком, который был премьер -министром Соединенного Королевства с 1979 по 1990 Лидер Консервативной партии с 1975 по 1990 год. Она была самой долгосрочной премьер-министром 20-го века британцами и первой женщиной, которая занимала эту должность. Будучи премьер -министром, она осуществила экономическую политику, известную как тэтчеризм . Советский журналист назвал ее « Железная леди », прозвище, которое стало связано с ее бескомпромиссной политикой и стилем лидерства .

Тэтчер изучала химию в Сомервилле, в Оксфорде , и кратко работал как химик исследования, прежде чем стать адвокатом . Она была избрана членом парламента в Финчли в 1959 году . Эдвард Хит назначил своего государственного секретаря по образованию и науке в своем правительстве 1970–1974 годов . В 1975 году она победила Хита на выборах на руководство Консервативной партии, чтобы стать лидером оппозиции , первой женщиной, которая возглавила крупную политическую партию в Великобритании.

Став премьер -министром после победы на всеобщих выборах 1979 года , Тэтчер ввела ряд экономической политики, предназначенной для того, чтобы обратить вспять высокую инфляцию и британскую борьбу после зимы недовольства и встречной рецессии . [ NB 2 ] Ее политическая философия и экономическая политика подчеркивали большую личную свободу , приватизацию государственных компаний и снижение власти и влияния профсоюзов . Ее популярность в ее первых годах в офисе уменьшилась на фоне рецессии и роста безработицы. Победа в Войне Фолклендских островов 1982 года и восстановительной экономике привела к возрождению поддержки, что привело к ее оползням в 1983 году . Она пережила попытку убийства временной IRA в бомбардировке в Блайтоне в 1984 году и оказала политическую победу над Национальным союзом минных рабочих в результате забастовки шахтеров 1984–85 годов . В 1986 году Тэтчер курировала дерегулирование британских финансовых рынков , что привело к экономическому буму , в том, что стало известно как Большой взрыв .

Тэтчер была переизбран на третий срок с другим оползнем в 1987 году , но ее последующая поддержка обвинения сообщества (также известное как «налог на опрос») была широко непопулярной, и ее все более евроскептические взгляды на европейское сообщество не разделялось другие в ее кабинете. Она ушла в отставку с поста премьер -министра и лидера партии в 1990 году после того, как ее лидерство была вызова , и ее сменил Джон Майор , ее канцлер казначейства . [ NB 3 ] После ухода из общин в 1992 году ей дали пожизненный пэры в роли баронессы Тэтчер (из Кестеена в графстве Линкольншир ), которая дала ей право сидеть в Палате лордов . В 2013 году она умерла от инсульта в отеле Ritz, Лондон , в возрасте 87 лет.

Поляризующая фигура в британской политике, тем не менее, благоприятно рассматривается в историческом рейтинге и общественном мнении британских премьер -министров. Ее пребывание в должности представляло собой перестройку в отношении неолиберальной политики в Британии; Сложное наследие, приписываемое этой сдвиге, продолжает обсуждаться в 21 -м веке.

Ранняя жизнь и образование

Семья и детство (1925–1943)

Маргарет Хильда Робертс родилась 13 октября 1925 года в Грантаме , Линкольншир. Ее родителями были Альфред Робертс (1892–1970), из Нортгемптоншира, и Беатрис Этель Стивенсон (1888–1960) из Линкольншира. [ 7 ] Бабушка по материнской линии ее отца, Кэтрин Салливан, родилась в графстве Керри , Ирландия . [ 8 ]

Робертс провела свое детство в Грэнтэме, где ее отец владел табакконом и продуктовым магазином. В 1938 году, до Второй мировой войны , семья Робертса ненадолго дала святилище подростковой еврейской девушке, которая сбежала от нацистской Германии . С ее подъемом пожилой сестрой Мюриэль Маргарет сэкономила карманные деньги, чтобы помочь оплатить путешествие подростка. [ 9 ]

Альфред был олдерменом и методистским местным проповедником . [ 10 ] Он воспитывал свою дочь в качестве строгого методиста Уэслиан , [ 11 ] посещение методистской церкви на улице Финкин , [ 12 ] Но Маргарет была более скептической; Будущий ученый сказала другу, что она не может поверить в ангелов , рассчитав, что им нужна длинная грудь 6 футов (1,8 м) для поддержки крыльев. [ 13 ] Альфред приехал из либеральной семьи, но стоял (как тогда было обычным в местном правительстве) в качестве независимого . Он занимал пост мэра Грэнтэма с 1945 по 1946 год и потерял свою должность Олдермана в 1952 году после того, как лейбористская партия выиграла свое первое большинство в Совете Грантама в 1950 году. [ 10 ]

Робертс учился в начальной школе Huntingtower Road и выиграл стипендию в школе Kesteven и Grantham Girls , гимназии. [ 14 ] Ее школьные отчеты показали тяжелую работу и постоянное улучшение; Ее внеклассные занятия включали пианино, полевой хоккей, поэтические концерты, плавание и ходьба. [ 15 ] Она была главной девушкой в 1942–43 годах, [ 16 ] И вне школы, в то время как вторая мировая война продолжалась, она добровольно работала пожарным наблюдателем в местной службе ARP . [ 17 ] Другие студенты считали Робертса как «звездного ученых», хотя ошибочные советы относительно очистки чернил из паркета почти вызывали отравление газовым газом . На старшем шестом курсе Робертс была принята на стипендию для изучения химии в Колледже Сомервилля, Оксфорд , женского колледжа, начиная с 1944 года. После того, как еще один кандидат отозвал, Робертс поступил в Оксфорд в октябре 1943 года. [ 18 ] [ 13 ]

Оксфорд (1943–1947)

После ее прибытия в Оксфорд Робертс начал обучение у рентгеновского кристаллографа Дороти Ходжкин , преподавателя по химии в Сомервилле Колледж с 1934 года. [ 19 ] [ 20 ] Ходжкин считал Робертса «хорошим» студентом, а затем вспомнил: «Всегда можно было бы полагаться на то, что она создает разумное, хорошо прочитанное эссе». [ 21 ] Она решила читать для классифицированной степени с отличием , что влечет за собой дополнительный год контролируемых исследований. [ 21 ] Как ее диссертация, Ходжкин поручил Робертсу работать с Герхардом Шмидтом , исследователем в лаборатории Ходжкина, чтобы определить структуру антибиотического пептидного грамицидина . [ 22 ] Хотя исследование достигло некоторого прогресса, структура пептида оказалась более сложной, чем предполагалось, и Шмидт будет определять только полную структуру намного позже; Робертс (к тому времени Тэтчер) узнал об этом в 1960 -х годах во время посещения Института Вайзманна , где тогда работал ее бывший партнер по исследованию. [ 21 ]

Робертс окончил в 1947 году степень почетов второго сорта по химии, а в 1950 году также получила степень магистра искусств (как Оксфордский бакалавр, она имела право на степень 21 после своего зачисления ). [ 23 ] Хотя Ходжкин позже будет критиковать политику своего бывшего студента, они продолжали соответствовать 1980-м годам, и Робертс в ее мемуарах описывает ее наставника как «вечно удивленного», «блестящего ученого и одаренного учителя». [ 21 ] Будучи премьер -министром, она оставит портрет Ходжкина на 10 Даунинг -стрит . [ 21 ] Позже, она, как сообщается, была более охвачена тем, что стала первым премьер -министром с научной степенью, чем первой женщиной -премьер -министром. [ 24 ] В то время как премьер -министр она попыталась сохранить Сомервилль как женский колледж. [ 25 ] Дважды в неделю за пределами учебы она работала в столовой местных сил. [ 26 ]

Во время своего пребывания в Оксфорде Робертс была отмечена своим изолированным и серьезным отношением. [ 13 ] Ее первый парень, Тони Брей (1926–2014), вспомнил, что она «очень вдумчива и очень хороший разговорник. Это, вероятно, меня интересовало. Она была хороша по общим предметам». [ 13 ] [ 27 ]

Курсовая работа Робертса включала субъекты за пределами химии [ 28 ] как она уже размышляла о входе в закон и политику. [ 29 ] Ее энтузиазм по поводу политики в качестве девушки заставил Брей думать о ней как о «необычной», а ее родители - как «слегка строго» и «очень правильно». [ 13 ] [ 27 ] Робертс стал президентом Консервативной ассоциации Оксфордского университета в 1946 году. [ 30 ] На нее повлияли в университете политическими работами, такими как Фридриха Хайека » «Дорога (1944), [ 31 ] который осудил экономическое вмешательство правительством в качестве предшественника авторитарного государства. [ 32 ]

Карьера после Оксфорда (1947–1951)

После окончания учебы Робертс получил должность химика исследования британского ксилонита ( BX Plastics ) после серии интервью, организованных Оксфордом; Впоследствии она переехала в Колчестер в Эссексе, чтобы работать в фирме. [ 33 ] Мало что известно о ее коротком времени там. [ 34 ] По ее собственной учетной записи она первоначально была в восторге от этой должности, поскольку она была предназначена для того, чтобы выступить в качестве личного помощника руководителя по исследованиям и разработкам компании, предоставляя возможности для изучения управления операциями : «Но по моему прибытию было решено, что что было решено, что было решено, что было решено Там было недостаточно, чтобы сделать в этом качестве ». [ 21 ] Вместо этого она, кажется, исследовала методы прикрепления поливинилхлорида (ПВХ) к металлам. [ 34 ] В то время как с фирмой она присоединилась к Ассоциации научных работников . [ 34 ] В 1948 году она подала заявку на работу в Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI), но была отвергнута после того, как кадровый департамент оценил ее как «упрямую, упрямую и опасно самоопинированную». [ 35 ] Джон Агар в заметках и записях утверждает, что ее понимание современных научных исследований впоследствии повлияло на ее взгляды как премьер -министра. [ 34 ]

Робертс присоединился к местной консервативной ассоциации и принял участие в партийной конференции в Лландадно , Уэльс, в 1948 году в качестве представителя Ассоциации выпускников университета. [ 36 ] Тем временем она стала высокопоставленным филиалом клуба Vermin , [ 37 ] [ 38 ] Группа массовых консерваторов, сформированных в ответ на уничижительный комментарий, сделанный аневрином Беваном . [ 38 ] Одна из ее друзей из Оксфорда была также другом председателя консервативной ассоциации Дартфорда в Кенте , которая искала кандидатов. [ 36 ] Чиновники ассоциации были настолько впечатлены ею, что попросили ее подать заявку, хотя она не была в утвержденном списке партии; Она была выбрана в январе 1950 года (в возрасте 24 лет) и добавлена в утвержденный список Post Ante . [ 39 ]

На ужине после ее официального усыновления в качестве кандидата консерваторов в Дартфорде в феврале 1949 года она встретила «Разводя» Денис Тэтчер , успешного и богатого бизнесмена, который отвез ее в свой поезд Эссекса. [ 40 ] После их первой встречи она назвала его Мюриэль как «не очень привлекательного существа - очень сдержанного, но довольно приятного». [ 13 ] Подготовившись к выборам, Робертс переехала в Дартфорд, в то время как она поддерживала себя, работая химиком исследований для J. Lyons and Co. в Хаммерсмите , как сообщается, в рамках команды, разрабатывающей эмульгаторы для мороженого . [ 41 ] Поскольку работа носила более теоретическую по своей природе, чем во время ее предыдущей роли в BX Plastics, Робертс нашел это «более удовлетворительным». [ 21 ] Находясь в Лионе, она работала под надзором Ганса Джеллинека, который возглавлял раздел физической химии компании. [ 42 ] Jellinek назначил ее для изучения опонирования α-моностеарина ( моностеарат глицерина ), который обладает свойствами в качестве эмульгатора, стабилизатора и пищевого консерванта. Агар отметил, что исследование, возможно, было связано с эмульгированием мороженого, но только как возможность. [ 21 ] В сентябре 1951 года их исследования были опубликованы в журнале «Наука о продуктах питания и сельском хозяйстве» , недавно выпущенной публикации Общества химической промышленности , [ 21 ] как «омыление α-моностеарина в монослое». [ 43 ] Это было бы единственной научной публикацией Робертса. [ 21 ] В 1979 году, после выборов своего бывшего помощника в качестве премьер -министра Джеллинека, к тому времени профессором физической химии в Университете Кларксона в Соединенных Штатах, сказала, что она сделала «очень хорошую работу» в проекте, «демонстрируя большую решимость». [ 44 ] Она послала Джеллинек поздравительное письмо после его выхода на пенсию в 1984 году и еще одно письмо незадолго до его смерти два года спустя. [ 45 ]

Робертс женился в часовне Уэсли , а ее дети были крещены там, [ 46 ] Но она и ее муж начали посещать службы церкви Англии , а затем обратились в англиканство . [ 47 ] [ 48 ]

Ранняя политическая карьера

На всеобщих выборах в 1950 и 1951 годах Робертс был кандидатом на рабочую силу в Дартфорде . Местная партия выбрала ее в качестве кандидата, потому что, хотя и не динамичный оратор, Робертс была хорошо подготовлена и бесстрашна в своих ответах. Проспективный кандидат, Билл Дейдес , вспомнил: «Как только она открыла рот, остальные из нас начали выглядеть довольно второстепенным». [ 24 ] Она привлекала внимание средств массовой информации как самую младшую и единственную женщину -кандидат; [ 49 ] В 1950 году она была самым молодым консервативным кандидатом в стране. [ 50 ] Она проиграла в обоих случаях Норман Доддс, но сократила трудовое большинство на 6000, а затем еще 1000. [ 51 ] Во время кампаний ее поддерживали ее родители и будущий муж Денис Тэтчер, на котором она вышла замуж в декабре 1951 года. [ 51 ] [ 52 ] Денис финансировал учебу своей жены для бара ; [ 53 ] Она квалифицировалась в качестве адвоката в 1953 году и специализировалась на налогообложении. [ 54 ] Позже в том же году их близнецы Кэрол и Марк родились, преждевременно поставленные кесарева сечением. [ 55 ]

Член парламента (1959–1970)

В 1954 году Тэтчер потерпела поражение, когда она искала отбор в качестве кандидата Консервативной партии на дополнительные выборы в Орпингтоне в январе 1955 года. Она решила не выступать в качестве кандидата на всеобщих выборах 1955 года , в последующие годы, заявив: «Я действительно просто просто. Чувствовал, что близнецы были [...] только два, я действительно чувствовал, что это было слишком рано. [ 56 ] После этого Тэтчер начал искать консервативное безопасное место и был выбран в качестве кандидата в Финчли в апреле 1958 года (узко избивая Яна Монтегю Фрейзер ). Она была избрана депутатом на место после тяжелой кампании на выборах 1959 года . [ 57 ] [ 58 ] Выгода от ее счастливого результата, чтобы лотерея для Backbenchers предложила новое законодательство, [ 24 ] Первая речь Тэтчер необычайно была в поддержке законопроекта ее частного члена , Закона о государственных органах (поступление на собрания) 1960 года , требуя, чтобы местные власти проводят свои советы публично; Законопроект был успешным и стал законом. [ 59 ] [ 60 ] В 1961 году она пошла против официальной должности Консервативной партии, проголосовав за восстановление Бедчинга как судебного телесного наказания . [ 61 ]

На передовых

Талант и драйв Тэтчер заставили ее упомянуть в качестве будущего премьер -министра в возрасте 20 лет [ 24 ] Хотя она сама была более пессимистичной, заявив, что еще в 1970 году: «В моей жизни не будет женщина -премьер -министр - мужское население слишком предвзято». [ 62 ] В октябре 1961 года она была назначена на фронтбету в качестве парламентского секретаря в министерстве пенсий Гарольдом Макмилланом . [ 63 ] Тэтчер была самой молодой женщиной в истории, получившей такой пост, и среди первых депутатов, избранных в 1959 году, которые были повышены. [ 64 ] После того, как консерваторы проиграли выборы 1964 года , она стала пресс -секретарем в жилье и земле. На этой должности она выступала за политику своей партии предоставить арендаторам право покупать свои домы совета . [ 65 ] Она переехала в теневую казначейство в 1966 году и, как пресс -секретарь казначейства, выступила против обязательной цены лейбористов и контроля доходов, утверждая, что они непреднамеренно дадут последствия, которые искажат экономику. [ 65 ]

Джим Приор предложил Тэтчер в качестве члена теневого кабинета консерваторов после поражения 1966 года , но лидер партии Эдвард Хит и главный кнут Уильям Уайтлау в конечном итоге выбрали Мервин Пайк в качестве консервативного теневого шкафа . единственного члена [ 64 ] На конференции Консервативной партии 1966 года Тэтчер критиковала политику высокого налога лейбористского правительства как шаги «не только в отношении социализма, но и на коммунизм», утверждая, что более низкие налоги послужили стимулом для тяжелой работы. [ 65 ] Тэтчер была одним из немногих консервативных депутатов, чтобы поддержать Лео Абсе для декриминализации мужской гомосексуализма. законопроект [ 66 ] Она проголосовала за Дэвида Стила о легализации абортов, законопроект [ 67 ] [ 68 ] а также запрет на посещение заяц . [ 69 ] Она поддержала сохранение смертной казни [ 70 ] и проголосовали против расслабления законов о разводе. [ 71 ] [ 72 ]

В теневой шкафу

В 1967 году посольство Соединенных Штатов выбрало Тэтчер принять участие в Международной программе лидерства посетителей (тогда называемой программой иностранного лидера), программы профессионального обмена, которая позволила ей провести около шести недель, посещая различные города США и политические деятели, а также институты. такие как Международный валютный фонд . Хотя она еще не была членом кабинета теневого кабинета, посольство, как сообщается, описала ее в Государственный департамент как возможный будущий премьер -министр. Описание помогло Тэтчер встретиться с выдающимися людьми во время занятого маршрута, посвященного экономическим вопросам, включая Пола Самуэльсона , Уолта Ростоу , Пьер-Поля Швейцера и Нельсона Рокфеллера . После визита Хит назначил Тэтчер в теневой шкаф [ 64 ] Как пресс -секретарь топлива и электроэнергии. [ 73 ] До всеобщих выборов 1970 года она была повышена до пресс -секретаря Shadow Transport, а затем на образование. [ 74 ]

В 1968 году Енох Пауэлл произнес свою речь «реки крови» , в которой он сильно критиковал иммиграцию Содружества в Соединенное Королевство и тогдашний законопроект о расовых отношениях . Когда Хит позвонила Тэтчер, чтобы сообщить ей, что он уволит Пауэлл из теневого шкафа, она вспомнила, что она «действительно думала, что лучше позволить вещам остыть в настоящее время, а не усилить кризис». Она считала, что его основные моменты об иммиграции Содружества были правильными и что выбранные цитаты из его речи были выведены из контекста. [ 75 ] В интервью 1991 года на сегодняшний день Тэтчер заявила, что, по ее мнению, Пауэлл «выступила с действительным аргументом, если иногда в прискорбных терминах». [ 76 ]

Примерно в это же время она произнесла свою первую речь в общих в качестве министра теневого транспорта и подчеркнула необходимость инвестиций в British Rail . Она утверждала: «[Я] мы строим большие и лучшие дороги, они скоро будут насыщены большим количеством транспортных средств, и мы не будем ближе к решению проблемы». [ 77 ] Тэтчер совершила свой первый визит в Советский Союз летом 1969 года в качестве представителя оппозиции транспорта, а в октябре выступила с речью, посвященной ее десять лет в парламенте. В начале 1970 года она сказала The Finchley Press , что хотела бы увидеть «изменение разрешающего общества». [ 78 ]

Секретарь образования (1970–1974)

Консервативная партия, возглавляемая Эдвардом Хитом, выиграла всеобщие выборы 1970 года, а Тэтчер был назначен в кабинет министра образования и науки . Тэтчер вызвала противоречие, когда, после нескольких дней пребывания в должности, она сняла циркуляр лейбористов 10/65 , что пыталось создать понимание , не проходя процесс консультации. Она была сильно критикована за скорость, с которой она это вынесла. [ 79 ] Следовательно, она разработала свою новую политику ( циркуляр 10/70 ), которая гарантировала, что местные власти не были вынуждены стать всеобъемлющими. Ее новая политика не должна была остановить развитие новых полных полей; Она сказала: «Мы будем ожидать, что планы будут основаны на образовательных соображениях, а не на всеобъемлющем принципе». [ 80 ]

Тэтчер поддержала предложение лорда Ротшильда 1971 года о рыночных силах повлиять на государственное финансирование исследований. Хотя многие ученые выступили против этого предложения, ее исследование, вероятно, скептически оказалась в своем утверждении, что посторонние не должны мешать финансированию. [ 29 ] Департамент оценил предложения по большему количеству местных органов образования для закрытия гимназических школ и принятия комплексного среднего образования . Хотя Тэтчер была привержена многоуровневой средней современной школьной системе образования и попыталась сохранить гимназию, [ 81 ] Во время своего пребывания в качестве министра образования она отказалась только 326 из 3612 предложений (примерно 9 процентов) [ 82 ] Для школ становятся вселенными; Доля учеников, посещающих всеобъемлющие школы, выросла с 32 до 62 процентов. [ 83 ] Тем не менее, ей удалось сэкономить 94 гимназии. [ 80 ]

В течение первых месяцев пребывания в должности она привлекла внимание общественности из -за попыток правительства сократить расходы. Она отдала приоритет академическим потребностям в школах, [ 81 ] При управлении государственными расходами сокращается государственная система образования, что приводит к отмене свободного молока для школьников в возрасте от семи до одиннадцати. [ 84 ] Она считала, что немногие дети пострадают, если бы школам будет предъявлено обвинение за молоко, но согласилась предоставить младшим детям 0,3 имперских пинты (0,17 л) в день для питательных целей. [ 84 ] Она также утверждала, что она просто продолжала с тем, что начало правительство лейбористов с тех пор, как они перестали давать бесплатное молоко в средние школы. [ 85 ] Молоко все еще будет предоставлено тем детям, которые требовали его по медицинским соображениям, и школы все еще могут продавать молоко. [ 85 ] Последствия молочного ряда утверждали ее решимость; Она рассказала редактору-пропринятору Гарольду Крейтону из зрителя : «Не стоит меня недооценивать, я увидел, как они сломали Кейта [Джозефа] , но они не сломают меня». [ 86 ]

Позже документы кабинета показали, что она выступила против политики, но была вынуждена казначейство. [ 87 ] Ее решение вызвало шторм протеста от лейбористов и прессы, [ 88 ] Ведущая к ее общеизвестному прозвищу «Маргарет Тэтчер, Руководитель молока». [ 84 ] [ 89 ] По сообщениям, она подумала о том, чтобы оставить политику в последствии, а затем написала в своей автобиографии: «Я усвоил ценный урок. Я взял на себя максимум политического сидия для минимума политической выгоды». [ 90 ]

Лидер оппозиции (1975–1979)

| Внешний аудио | |

|---|---|

| Речь 1975 года в Национальном пресс -клубе США | |

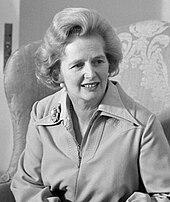

Тэтчер в конце 1975 года | |

Правительство Хита продолжало испытывать трудности с нефтяными эмбарго и профсоюзными требованиями к повышению заработной платы в 1973 году, впоследствии проиграв всеобщие выборы в феврале 1974 года . [ 88 ] Труд сформировал правительство меньшинства и выиграл узкое большинство на всеобщих выборах в октябре 1974 года . Руководство Хита в консервативной партии все больше выглядело под сомнением. Тэтчер изначально не рассматривалась как очевидная замена, но в конечном итоге она стала главным претендентом, обещая новое начало. [ 93 ] Ее главная поддержка пришла из комитета парламентского 1922 года. [ 93 ] и зритель , [ 94 ] Но время в должности Тэтчер дало ей репутацию прагматика, а не идеолога. [ 24 ] Она победила Хита в первом бюллетене, и он ушел из руководства. [ 95 ] Во втором избирательном бюллетене она победила Уайтлоу, предпочтительный преемник Хита. Выборы Тэтчер оказали поляризационное влияние на партию; Ее поддержка была сильнее среди депутатов справа, а также среди тех, кто из южной Англии, и тех, кто не посещал государственные школы или Оксбридж . [ 96 ]

Тэтчер стал лидером консервативной партии и лидером оппозиции 11 февраля 1975 года; [ 97 ] Она назначила Уайтлоу своим заместителем . Хит никогда не примирился с лидерством Тэтчер в партии. [ 98 ]

Телевизионный критик Клайв Джеймс , пишущая в «Обозревателе» до ее выборов в качестве лидера консервативной партии, сравнила свой голос 1973 года с «кошкой, скользящей по доске». [ NB 4 ] Тэтчер уже начала работать над своей презентацией по совету Гордона Риса , бывшего телевизионного продюсера. Случайно, Рис встретил актера Лоуренса Оливье , который организовал уроки с голосовым тренером Национального театра . [ 100 ] [ 101 ] [ NB 5 ]

Тэтчер начал регулярно посещать обеды в Институте экономических дел (IEA), аналитическом центре, основанном хайекианским птицеводством Антони Фишером ; Она посещала IEA и читала ее публикации с начала 1960 -х годов. Там на нее повлияли идеи Ральфа Харриса и Артура Селдона и стали лицом идеологического движения, противостоящего британскому государству всеобщего благосостояния . Кейнсианская экономика , полагали, ослабила Великобританию. Брошюры института предложили меньше правительства, более низкие налоги и большую свободу для бизнеса и потребителей. [ 104 ]

Тэтчер намеревалась продвигать неолиберальные экономические идеи дома и за рубежом. Несмотря на определение направления ее внешней политики для консервативного правительства, Тэтчер была обеспокоена ее повторной неспособностью сиять в палате общин. Следовательно, Тэтчер решила, что, когда «ее голос несет в себе маленький вес дома», она «будет слышна в более широком мире». [ 105 ] Тэтчер совершила посещения по всей Атлантике, создавая международный профиль и продвигая ее экономическую и иностранную политику. Она совершила поездку по Соединенным Штатам в 1975 году и встретила президента Джеральда Форда , [ 106 ] Посещение снова в 1977 году, когда она встретила президента Джимми Картера . [ 107 ] Среди других иностранных поездок она познакомилась с Шахом Мохаммадом Реза Пахлави во время визита в Иран в 1978 году. [ 108 ] Тэтчер решила путешествовать без сопровождения ее министра иностранных дел теневого Реджинальда Модлинга , пытаясь оказать более смелое личное влияние. [ 107 ]

В домашних делах Тэтчер выступила против шотландской передачи ( домашнего правила ) и создания шотландского собрания . Она поручила консервативным депутатам проголосовать против законопроекта о Шотландии и Уэльсе в декабре 1976 года, который был успешно побежден, а затем, когда были предложены новые законопроекты, она поддержала поправки в законодательство, позволяющее англичанам голосовать на референдуме 1979 года по шотландскому деволюции. [ 109 ]

Британская экономика в 1970 -х годах была настолько слабой, что тогдашний министр иностранных дел Джеймс Каллаган предупредил своих коллег по трудовым кабинету в 1974 году о возможности «срыва демократии», сказав им: «Если бы я был молодым человеком, я бы эмигрировал». [ 110 ] В середине 1978 года экономика начала восстанавливаться, и опросы мнений показали лейбористы в лидере, причем всеобщие выборы ожидаются позже в том же году, а лейбористская партия выиграет серьезную возможность. Теперь премьер -министр Каллаган удивил многих, объявив 7 сентября, что в этом году не будет всеобщих выборов, и что он будет ждать до 1979 года, прежде чем отправиться на выборы. Тэтчер отреагировала на это, заливая лейбористского правительства «цыплята», и присоединился лидер Либеральной партии Дэвид Стил, критикуя труд за «испуганный бег». [ 111 ]

Затем лейбористское правительство столкнулось с новым общественным беспокойством по поводу направления страны и поврежденной серии ударов зимой 1978–79 гг . Консерваторы напали на протокол безработицы лейбористского правительства, используя рекламу с лозунгом « труд не работает ». Всеобщие выборы были вызваны после того, как министерство Каллаган не потеряло ходатайство о том, как в начале 1979 года не доверяла. Консерваторы выиграли 44-местное большинство в Палате общин, а Тэтчер стала первой женщиной-премьер-министром. [ 112 ]

"Железная леди"

| Внешние видео | |

|---|---|

| Речь 1976 года консерваторам Финчли | |

Я стою перед тобой сегодня вечером в моем красном шифоновом вечернем платье, мое лицо мягко придумано, и мои честные волосы нежно махали, Железная Леди Западного мира. [ 113 ]

- Тэтчер обнимает ее советский прозвище в 1976 году

В 1976 году Тэтчер произносила ей «бодрствование в Британии», которая пробила Советский Союз, заявив, что это «склонилось к мировому доминированию». [ 114 ] Журнал Советской Армии Красная Звезда сообщила о своей позиции в статье, озаглавленной «Железная леди, повышает страхи», [ 115 ] ссылаясь на ее замечания на железной занавеске . [ 114 ] The Sunday Times освещала статью Red Star на следующий день, [ 116 ] И Тэтчер обнял эпитет через неделю; В речи с консерваторами Финчли она сравнивала это с прозвищем герцога Веллингтона "Iron Duke". [ 113 ] следовала «Железная» метафора за ней с тех пор, с тех пор, [ 117 ] и станет общим требитом для других волевых женщин-политиков. [ 118 ]

Премьер -министр Соединенного Королевства (1979–1990)

| Внешние видео | |

|---|---|

| Замечания 1979 года о том, как стать премьер -министром | |

10 Даунинг -стрит , c. 1979 | |

Тэтчер стала премьер -министром 4 мая 1979 года. Прибыв на Даунинг -стрит, по ее словам, перефразируя молитву Святого Франциска :

Там, где есть разногласия, можем ли мы принести гармонию;

Там, где есть ошибка, можем ли мы принести правду;

Где есть сомнения, пусть мы принесем веру;

И где есть отчаяние, можем ли мы принести надежду. [ 119 ]

В офисе в течение 1980 -х годов Тэтчер часто называли самой влиятельной женщиной в мире. [ 120 ] [ 121 ] [ 122 ]

Домашние дела

Меньшинства

Тэтчер был лидером оппозиции и премьер -министром во времена расовой напряженности в Британии. Во время местных выборов в 1977 году экономист прокомментировал : «Прилив Тори завалл, в частности, национальный фронт [NF] , который получил явное снижение с прошлого года». [ 123 ] [ 124 ] Ее положение в выборах выросло на 11% после интервью 1978 года для мира в действии , в котором она сказала: «Британский персонаж так много сделал для демократии, для закона и сделал так много во всем мире, что если есть какой -либо страх, что это Может быть, люди будут реагировать и быть довольно враждебными по отношению к тем, кто приходит », а также« во многих отношениях [меньшинства] добавляют к богатству и разнообразию этой страны. напуган ». [ 125 ] [ 126 ] На всеобщих выборах 1979 года консерваторы привлекли голоса от НФ, чья поддержка почти рухнула. [ 127 ] На заседании в июле 1979 года с министром иностранных дел лорда Каррингтона и министром внутренних дел Уильям Уайтлау Тэтчер возражал против числа азиатских иммигрантов в контексте ограничения общего числа вьетнамских лодок , которые разрешали поселиться в Великобритании до менее чем 10 000 в течение двух лет. [ 128 ]

Королева

Будучи премьер -министром, Тэтчер встретился еженедельно с королевой Елизаветой II , чтобы обсудить правительственный бизнес, и их отношения подвергались тщательному тщательному тщательному пристальности. [ 129 ] Кэмпбелл (2011a , p. 464) Государства:

Одним из вопросов, который продолжал очаровывать общественность о явлении премьер -министра женщины, был то, как она поступила с королевой. Ответ заключается в том, что их отношения были актуально правильными, но с обеих сторон было мало любви. Как две женщины очень похожих возрастов - миссис Тэтчер была на шесть месяцев старше - занимая параллельные позиции на вершине социальной пирамиды, одна глава правительства, другой глава государства, они должны были быть в некотором смысле соперниками. Отношение миссис Тэтчер к королеве было двойственным. С одной стороны, она имела почти мистическое почтение к институту монархии [...], но в то же время она пыталась модернизировать страну и сместить многие ценности и практики, которые увековечила монархия.

Майкл Ши , пресс -секретарь королевы, в 1986 году просочил истории о глубоком расколе The Sunday Times . Он сказал, что она чувствовала, что политика Тэтчер была «безразличной, конфронтационной и социально спорной». [ 130 ] Позже Тэтчер написала: «Я всегда обнаружил, что отношение королевы к работе правительства абсолютно правильные [...] истории о столкновениях между« двумя могущественными женщинами »было слишком хорошим, чтобы не составить наверстать». [ 131 ]

Экономика и налогообложение

| Экономический рост и государственные расходы % Изменение в реальных терминах : 1979/80–289/90 | |

|---|---|

| Экономический рост (ВВП) | +23.3 |

| Общие государственные расходы | +12.9 |

| Закон и порядок | +53.3 |

| Занятость и обучение | +33.3 |

| NHS | +31.8 |

| Социальное обеспечение | +31.8 |

| Образование | +13.7 |

| Защита | +9.2 |

| Среда | +7.9 |

| Транспорт | −5.8 |

| Торговля и промышленность | −38.2 |

| Жилье | −67.0 |

На экономическую политику Тэтчер влияли монетаристское мышление и экономисты, такие как Милтон Фридман и Алан Уолтерс . [ 132 ] Вместе со своим первым канцлером , Джеффри Хоу , она снизила прямые налоги на доход и увеличила косвенные налоги. [ 133 ] Она увеличила процентные ставки, чтобы замедлить рост денежной массы и тем самым снизить инфляцию; [ 132 ] введены денежные ограничения на государственные расходы и сократили расходы на социальные услуги, такие как образование и жилье. [ 133 ] Сокращение высшего образования привело к тому, что Тэтчер стал первым оксонским послевоенным премьер-министром без почетного доктора из Оксфордского университета после 738–319 голосов руководящего собрания и студенческого ходатайства. [ 134 ]

Некоторые консерваторы Хитита в кабинете, так называемые « милины », выразили сомнение в политике Тэтчер. [ 135 ] Британские беспорядки в 1981 году привели к тому, что британские СМИ обсуждали необходимость в политической развороте . На конференции консервативной партии 1980 года Тэтчер обратилась к этому вопросу непосредственно с речью, написанной драматургом Рональдом Милларом , [ 136 ] Это особенно включало следующие строки:

Для тех, кто ожидает задыхаемого дыхания для этой любимой категории медиа -фразы, поворота «U», у меня есть только одна вещь, чтобы сказать. «Ты поворачиваешься, если хочешь. Леди не для поворота ». [ 137 ]

Рейтинг одобрения работы в Тэтчер упал до 23% к декабрю 1980 года, что ниже, чем зарегистрирован для любого предыдущего премьер -министра. [ 138 ] Когда рецессия начала 1980 -х годов углубилась, она увеличила налоги, [ 139 ] Несмотря на опасения, выраженные в заявлении 1981 года, подписанном 364 ведущими экономистами, [ 140 ] который утверждал, что «нет оснований в экономической теории [...] для убеждения правительства, что, снижая спрос, они будут постоянно контролировать инфляцию», добавив, что «нынешняя политика углубит депрессию, разрушает промышленную базу нашей экономики и и угрожать его социальной и политической стабильности ». [ 141 ]

К 1982 году Великобритания начала испытывать признаки восстановления экономики; [ 142 ] Инфляция снизилась до 8,6% с максимума 18%, но безработица была более 3 миллионов впервые с 1930 -х годов. [ 143 ] К 1983 году общий экономический рост был сильнее, а ставки по инфляции и ипотечным кредитам упали до самого низкого уровня за 13 лет, хотя занятость в производстве как доля общей занятости снизилась чуть более 30%,, чтобы [ 144 ] Поскольку общая безработица осталась высокой, достигает 3,3 миллиона в 1984 году. [ 145 ]

Во время конференции Консервативной партии 1982 года Тэтчер сказал: «Мы сделали больше, чтобы отбросить границы социализма, чем любое предыдущее консервативное правительство». [ 146 ] Она сказала на партийной конференции в следующем году, что британский народ полностью отверг государственный социализм и понял: «У государства нет источника денег, кроме денег, которые люди зарабатывают сами [...] нет таких вещей, как государственные деньги; там там это только деньги налогоплательщиков ». [ 147 ]

К 1987 году безработица падала, экономика была стабильной и сильной, а инфляция была низкой. Опросы общественного мнения показали удобное консервативное лидерство, и результаты выборов местного совета также были успешными, что побудило Тэтчер назвать всеобщие выборы на 11 июня того же года, несмотря на крайний срок на выборы, которые еще 12 месяцев. Выборы увидели , что Тэтчер переизбран на третий последовательный термин. [ 148 ]

Тэтчер твердо против британского членства в механизме обменного курса (EM, предшественник Европейского экономического и валютного союза ), полагая, что это ограничит британскую экономику, [ 149 ] Несмотря на побуждение канцлера казначейства Найджела Лоусона и министра иностранных дел Джеффри Хоу; [ 150 ] В октябре 1990 года ее убежден Джон Майор , преемник Лоусона в качестве канцлера, присоединиться к ERM в том, что оказалось слишком высоким. [ 151 ]

Тэтчер реформировала налоги местного самоуправления, заменив внутренние ставки (налог на номинальную аренду дома дома) с обвинением в сообществе (или налогах на опросы), в ходе которого та же сумма была взималась каждому взрослому жителю. [ 152 ] Новый налог был введен в Шотландии в 1989 году и в Англии и Уэльсе в следующем году, [ 153 ] и оказалась одной из самых непопулярных политик ее премьерства. [ 152 ] Общественный беспокойство завершилось в 70 000-200 000-силовых [ 154 ] демонстрация в Лондоне в марте 1990 года; Демонстрация вокруг Трафальгарской площади ухудшилась в беспорядках , оставив 113 человек ранены и 340 под арестом. [ 155 ] Общественное обвинение было отменено в 1991 году ее преемником Джоном Мейджором. [ 155 ] С тех пор выяснилось, что сама Тэтчер не зарегистрировалась на налог, и ей угрожали финансовые штрафы, если она не вернет свою форму. [ 156 ]

Промышленные отношения

Тэтчер полагала, что профсоюзы были вредны как обычным профсоюзным, так и для общественности. [ 157 ] Она была привержена сокращению власти профсоюзов, чье руководство, которое она обвинила в подрыве парламентской демократии и экономических результатов посредством забастовок. [ 158 ] Несколько профсоюзов нанесли удары в ответ на законодательство, введенное для ограничения их власти, но сопротивление в конечном итоге рухнуло. [ 159 ] Только 39% членов профсоюза проголосовали за лейбористов на всеобщих выборах 1983 года. [ 160 ] Согласно политическому корреспонденту Би -би -си в 2004 году, Тэтчер «удалось уничтожить власть профсоюзов почти на поколение». [ 161 ] была Забастовка шахтеров в 1984–85 годах самой большой и самой разрушительной конфронтацией между профсоюзами и правительством Тэтчер. [ 162 ]

В марте 1984 года Национальный угольный совет (NCB) предложил закрыть 20 из 174 государственных шахт и сократить 20 000 рабочих мест из 187 000 человек. [ 163 ] [ 164 ] [ 165 ] Две трети шахтеров страны во главе с Национальным союзом мин-работников (NUM) под Артуром Скаргиллом начали забастовку в знак протеста. [ 163 ] [ 166 ] [ 167 ] Тем не менее, Скаргилл отказался удерживать голосование на забастовке, [ 168 ] ранее потеряв три бюллетеня на национальной забастовке (в январе и октябре 1982 года и март 1983 г.). [ 169 ] Это привело к тому, что забастовка была объявлена незаконной Высоким судом . [ 170 ] [ 171 ]

Тэтчер отказалась удовлетворить требования Союза и сравнить спор шахтеров с войной Фолклендс , объявив в речи в 1984 году: «Мы должны были сражаться с врагом без Фолклендских островов. Гораздо сложнее сражаться и более опасно для свободы ». [ 172 ] Оппоненты Тэтчер охарактеризовали ее слова как указывающие на презрение к рабочему классу и с тех пор используются в критике ее. [ 173 ]

После года в забастовке в марте 1985 года руководство NUM уступило без сделки. Стоимость экономики оценивалась не менее 1,5 млрд. Фунтов стерлингов, и забастовка была обвинена в том, что большая часть фунта упала против доллара США. [ 174 ] Тэтчер размышляла о конце забастовки в своем заявлении, что «если кто -то выиграл», это были «шахтеры, которые остались на работе», и все те, кто заставил Британия идти ». [ 175 ]

Правительство закрыло 25 убыточных угольных шахт в 1985 году, и к 1992 году было закрыто 97 шахт; [ 165 ] Те, кто остался, были приватизированы в 1994 году. [ 176 ] Получающееся закрытие 150 угольных шахт, некоторые из которых не теряли деньги, привело к потере десятков тысяч рабочих мест и имело влияние разрушительных целых сообществ. [ 165 ] Ударные удары помогли сбить правительство Хита, и Тэтчер был полон решимости добиться успеха там, где он потерпел неудачу. Ее стратегия приготовления топлива, назначая хардлинар Яна Макгрегора лидером NCB и обеспечение адекватного обучения полиции и оснащена беспорядками, способствовала ее триумфу над яркими шахтерами. [ 177 ]

Количество остановок по всей Великобритании достигло максимума на 4583 в 1979 году, когда было потеряно более 29 миллионов рабочих дней. В 1984 году, в течение года забастовки шахтеров, было 1221, что привело к потере более 27 миллионов рабочих дней. Затем остановки постоянно падали на оставшуюся часть премьерства Тэтчер; В 1990 году было потеряно 630 и менее 2 миллионов рабочих дней, и после этого они продолжали падать. [ 178 ] Срок пребывания в Тэтчер также стал свидетелем резкого снижения плотности профсоюзов, поскольку процент работников, принадлежащих к профсоюзам, упал с 57,3% в 1979 году до 49,5% в 1985 году. [ 179 ] В 1979 году до последнего года пребывания в должности Тэтчер членство профсоюза также упало с 13,5 миллионов в 1979 году до менее 10 миллионов. [ 180 ]

Приватизация

Политика приватизации была названа «важнейшим компонентом тэтчеризма». [ 181 ] После выборов 1983 года продажа государственных коммунальных услуг ускорилась; [ 182 ] Более 29 миллиардов фунтов стерлингов было собрано в результате продажи национализированных отраслей промышленности и еще 18 миллиардов фунтов стерлингов от продажи домов советов. [ 183 ] Процесс приватизации, особенно подготовка национализированных отраслей приватизации, был связан с заметным улучшением эффективности, особенно с точки зрения производительности труда . [ 184 ]

Некоторые из приватизированных отраслей, в том числе газ, вода и электричество, были естественными монополиями , за которые приватизация включала небольшой рост конкуренции. Приватизированные отрасли, которые продемонстрировали улучшение, иногда делали это, все еще находящиеся в государственной собственности. British Steel Corporation добилась больших успехов в прибыльности, в то время как национализированная отрасль под назначенным правительством председательство Макгрегора, которая столкнулась с оппозицией торговли, чтобы закрыть растения и вдвое увеличило рабочую силу. [ 185 ] Регулирование также было значительно расширено, чтобы компенсировать потерю прямого государственного контроля, поскольку основание регулирующих органов, таких как Oftel ( 1984 ), Ofgas ( 1986 ) и Национальное управление реки ( 1989 ). [ 186 ] Не было четкой схемы до степени конкуренции, регулирования и эффективности среди приватизированных отраслей. [ 184 ]

В большинстве случаев приватизация приносила пользу потребителям с точки зрения более низких цен и повышения эффективности, но результаты в целом были смешаны. [ 187 ] Не все приватизированные компании имели успешные траектории цены акций в долгосрочной перспективе. [ 188 ] Обзор 2010 года, проведенный IEA, гласит: «[I] T, похоже, имеет место, что после введения конкуренции и/или эффективного регулирования, производительность заметно улучшилась [...], но я спешу подчеркнуть, что литература не единодушна . " [ 189 ]

Тэтчер всегда сопротивлялась приватизированию британской железной дороги и, как говорили, говорил министру транспорта Николасу Ридли : «Приватизация железной дороги будет Ватерлоо этого правительства. Пожалуйста, никогда больше не упоминайте мне железные дороги». Незадолго до своей отставки в 1990 году она приняла аргументы в пользу приватизации, которые ее преемник Джон Майл реализовал в 1994 году. [ 190 ]

Приватизация государственных активов была сочетается с финансовой дерегулированием для экономического роста. Канцлер Джеффри Хоу отменил обмен контроля Великобритании в 1979 году, [ 191 ] что позволило инвестировать больше капитала на иностранные рынки, и большой взрыв 1986 года удалил много ограничений на Лондонскую фондовую биржу . [ 191 ]

Северная Ирландия

В 1980 и 1981 годах заключенных Временной Ирландской республиканской армии (PIRA) и Ирландской национальной армии освобождения Северной Ирландии (INLA) в тюрьме Мейзинга совершили голод , чтобы восстановить статус политических заключенных, который был удален в 1976 году предыдущим правительством лейбористов. [ 192 ] Бобби Сэндс начал забастовку 1981 года, заявив, что он постится до смерти, если заключенные заключенные не выиграют уступки от условий жизни. [ 192 ] Тэтчер отказалась поддержать возвращение к политическому статусу для заключенных, объявив, что «преступление - это преступление, это преступление; это не политическое». [ 192 ] Тем не менее, британское правительство в частном порядке связалось с республиканскими лидерами, чтобы завершить голода. [ 193 ] После смерти песков и девяти других ударов закончился. Некоторые права были восстановлены на военизированные заключенные, но не официальное признание политического статуса. [ 194 ] Насилие в Северной Ирландии значительно усилилось во время голода. [ 195 ]

Тэтчер едва избежала травмы в попытке убийства ИРА в Брайтонском отеле рано утром 12 октября 1984 года. [ 196 ] Пять человек были убиты, в том числе жена министра Джона Уэйкхэма . Тэтчер оставалась в отеле, чтобы подготовиться к конференции Консервативной партии, которая, как она настаивала, должна открыться в соответствии с графиком на следующий день. [ 196 ] Она произнесла свою речь, как и планировалось, [ 197 ] хотя переписана из ее первоначального драфта, [ 198 ] в шаге, который был поддержан по всему политическому спектру и повысила ее популярность среди общественности. [ 199 ]

6 ноября 1981 года Тэтчер и Таоисейч (премьер-министр ирландцы) Гаррет Фицджеральд создал англо-ирландский межправительный совет, форум для встреч между двумя правительствами. [ 194 ] 15 ноября 1985 года Тэтчер и Фицджеральд подписали Англо-ирландское соглашение Хиллсборо , которое отмечало впервые британское правительство дало Республике Ирландия консультативная роль в управлении Северной Ирландией. В знак протеста Ольстер говорит, что ни одно движение во главе с Яном Пейсли не привлекло 100 000 на митинг в Белфасте, [ 200 ] Ян Гоу , позже убитый Пирой, ушел в отставку с поста государственного министра в Казначействе Хм , [ 201 ] [ 202 ] и все 15 профсоюзных депутатов подали в отставку в парламентских местах; Только один не был возвращен в последующих выборах 23 января 1986 года. [ 203 ]

Среда

Тэтчер поддержал активную политику защиты климата ; Она сыграла важную роль в принятии Закона о защите окружающей среды 1990 года , [ 204 ] Основание Центра по исследованиям и прогнозированию Хэдли , [ 205 ] Создание межправительственной группы по изменению климата , [ 206 ] и ратификация протокола Монреаля при сохранении озона . [ 207 ]

Тэтчер помогла изменить климат , кислотный дождь и общее загрязнение в британском мейнстриме в конце 1980 -х годов, [ 206 ] [ 208 ] Призыв к глобальному договору об изменении климата в 1989 году. [ 209 ] Ее выступления включали один в Королевское общество в 1988 году, [ 210 ] с последующим другим в Генеральной Ассамблее ООН в 1989 году.

Иностранные дела

Тэтчер назначил лорда Каррингтона, обстрелянного члена партии и бывшего государственного секретаря по обороне , управляющим министерством иностранных дел в 1979 году. [ 211 ] Несмотря на то, что он считался «влажным», он избегал домашних дел и хорошо ладил с Тэтчер. Одна проблема заключалась в том, что делать с Родезией , где белое меньшинство решило править процветающей колонией в черном большинстве перед лицом подавляющей международной критики. С португальским крахом в 1975 году на континенте Южная Африка (которая была главным сторонником Родезии) поняла, что их союзник является обязательством; Черное правило было неизбежным, и правительство Тэтчер заключило мирное решение, чтобы положить конец родезийскому Буш -войне в декабре 1979 года через Соглашение о Ланкастере . На конференции в Lancaster House приняли участие Родезийский премьер -министр Ян Смит , а также ключевые чернокожие лидеры: Музорева , Мугабе , Нкомо и Тонгогара . Результатом стала новая зимбабвская нация под черным правлением в 1980 году. [ 212 ]

Холодная война

Первый кризис в иностранной политике Тэтчер произошел с советским вторжением в Афганистане 1979 года . Она осудила это вторжение, сказала, что оно продемонстрировало банкротство политики разрядки и помогла убедить некоторых британских спортсменов бойкотировать Олимпийские игры 1980 года в Москве . Она оказала слабую поддержку президенту США Джимми Картеру, который пытался наказать СССР экономическими санкциями. Экономическая ситуация в Великобритании была ненадежной, и большая часть НАТО не хотела сокращать торговые связи. [ 213 ] Тэтчер, тем не менее, дал Уайтхолл , чтобы одобрить MI6 (вместе с SAS), чтобы предпринять «разрушительные действия» в Афганистане . [ 214 ] Помимо работы с ЦРУ в операции Cyclone , они также поставляли оружие, обучение и интеллект для муджахеддина . [ 215 ]

В 2011 году Financial Times сообщила, что ее правительство тайно предоставило Ирак под командованием Саддама Хусейна года «нелетальной» военной техникой с 1981 . [ 216 ] [ 217 ]

Отозвав формальное признание с режима Pol Pot в 1979 году, [ 218 ] Правительство Тэтчер поддержало кхмерскую рубежу , сохранив свое место ООН после того, как они были вытеснены из власти в Камбодже камбоджийской и вьетнамской войной . Хотя Тэтчер отрицал это в то время, [ 219 ] В 1991 году выяснилось, что, хотя и не обучал ни одного кхмерского роуж, [ 220 ] С 1983 года Специальная авиационная служба (SAS) была отправлена в тайное обучение «вооруженным силам камбоджийского некоммунистического сопротивления », которые оставались верными принцу Нородому Сиануку и его бывшему премьер-министру Санн в борьбе против во Вьетнамском режиме. Полем [ 221 ] [ 222 ]

Тэтчер была одним из первых западных лидеров, которые тепло реагировали на реформистского советского лидера Михаила Горбачева . После встреч и реформ на саммите Рейгана -Горбачева, введенных Горбачевом в СССР, она заявила в ноябре 1988 года, что «w] не в холодной войне», а скорее в «новых отношениях гораздо шире, чем когда -либо холодная война, была ". [ 223 ] Она отправилась в государственный визит в Советский Союз в 1984 году и встретилась с Горбачевом и председателем Совета министров Николаем Ричков . [ 224 ]

Ties with the US

Despite opposite personalities, Thatcher bonded quickly with US president Ronald Reagan.[nb 6] She gave strong support to the Reagan administration's Cold War policies based on their shared distrust of communism.[159] A sharp disagreement came in 1983 when Reagan did not consult with her on the invasion of Grenada.[225][226]

During her first year as prime minister, she supported NATO's decision to deploy US nuclear cruise and Pershing II missiles in Western Europe,[159] permitting the US to station more than 160 cruise missiles at RAF Greenham Common, starting in November 1983 and triggering mass protests by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.[159] She bought the Trident nuclear missile submarine system from the US to replace Polaris, tripling the UK's nuclear forces[227] at an eventual cost of more than £12 billion (at 1996–97 prices).[228] Thatcher's preference for defence ties with the US was demonstrated in the Westland affair of 1985–86 when she acted with colleagues to allow the struggling helicopter manufacturer Westland to refuse a takeover offer from the Italian firm Agusta in favour of the management's preferred option, a link with Sikorsky Aircraft. Defence Secretary Michael Heseltine, who had supported the Agusta deal, resigned from the government in protest.[229]

In April 1986 she permitted US F-111s to use Royal Air Force bases for the bombing of Libya in retaliation for the alleged Libyan bombing of a Berlin discothèque,[230] citing the right of self-defence under Article 51 of the UN Charter.[231][nb 7] Polls suggested that fewer than one in three British citizens approved of her decision.[233]

Thatcher was in the US on a state visit when Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in August 1990.[234] During her talks with President George H. W. Bush, who succeeded Reagan in 1989, she recommended intervention,[234] and put pressure on Bush to deploy troops in the Middle East to drive the Iraqi Army out of Kuwait.[235] Bush was apprehensive about the plan, prompting Thatcher to remark to him during a telephone conversation: "This was no time to go wobbly!"[236][237] Thatcher's government supplied military forces to the international coalition in the build-up to the Gulf War, but she had resigned by the time hostilities began on 17 January 1991.[238][239] She applauded the coalition victory on the backbenches, while warning that "the victories of peace will take longer than the battles of war".[240] It was disclosed in 2017 that Thatcher had suggested threatening Saddam with chemical weapons after the invasion of Kuwait.[241][242]

Crisis in the South Atlantic

On 2 April 1982, the ruling military junta in Argentina ordered the invasion of the British Overseas Territories of the Falkland Islands and South Georgia, triggering the Falklands War.[243] The subsequent crisis was "a defining moment of [Thatcher's] premiership".[244] At the suggestion of Harold Macmillan and Robert Armstrong,[244] she set up and chaired a small War Cabinet (formally called ODSA, Overseas and Defence committee, South Atlantic) to oversee the conduct of the war,[245] which by 5–6 April had authorised and dispatched a naval task force to retake the islands.[246] Argentina surrendered on 14 June and Operation Corporate was hailed a success, notwithstanding the deaths of 255 British servicemen and three Falkland Islanders. Argentine fatalities totalled 649, half of them after the nuclear-powered submarine HMS Conqueror torpedoed and sank the cruiser ARA General Belgrano on 2 May.[247]

Thatcher was criticised for the neglect of the Falklands' defence that led to the war, and especially by Labour MP Tam Dalyell in Parliament for the decision to torpedo the General Belgrano, but overall, she was considered a competent and committed war leader.[248] The "Falklands factor", an economic recovery beginning early in 1982, and a bitterly divided opposition all contributed to Thatcher's second election victory in 1983.[249] Thatcher frequently referred after the war to the "Falklands spirit";[250] Hastings & Jenkins (1983, p. 329) suggests that this reflected her preference for the streamlined decision-making of her War Cabinet over the painstaking deal-making of peacetime cabinet government.

Negotiating Hong Kong

In September 1982, she visited China to discuss with Deng Xiaoping the sovereignty of Hong Kong after 1997. China was the first communist state Thatcher had visited as prime minister, and she was the first British prime minister to visit China. Throughout their meeting, she sought the PRC's agreement to a continued British presence in the territory. Deng insisted that the PRC's sovereignty over Hong Kong was non-negotiable but stated his willingness to settle the sovereignty issue with the British government through formal negotiations. Both governments promised to maintain Hong Kong's stability and prosperity.[251] After the two-year negotiations, Thatcher conceded to the PRC government and signed the Sino-British Joint Declaration in Beijing in 1984, agreeing to hand over Hong Kong's sovereignty in 1997.[252]

Apartheid in South Africa

Despite saying that she was in favour of "peaceful negotiations" to end apartheid,[253][254] Thatcher opposed sanctions imposed on South Africa by the Commonwealth and the European Economic Community (EEC).[255] She attempted to preserve trade with South Africa while persuading its government to abandon apartheid. This included "[c]asting herself as President Botha's candid friend" and inviting him to visit the UK in 1984,[256] despite the "inevitable demonstrations" against his government.[257] Alan Merrydew of the Canadian broadcaster BCTV News asked Thatcher what her response was "to a reported ANC statement that they will target British firms in South Africa?" to which she later replied: "[...] when the ANC says that they will target British companies [...] This shows what a typical terrorist organisation it is. I fought terrorism all my life and if more people fought it, and we were all more successful, we should not have it and I hope that everyone in this hall will think it is right to go on fighting terrorism."[258] During his visit to Britain five months after his release from prison, Nelson Mandela praised Thatcher: "She is an enemy of apartheid [...] We have much to thank her for."[256]

Europe

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| 1988 speech to the College of Europe | |

Thatcher and her party supported British membership of the EEC in the 1975 national referendum[260] and the Single European Act of 1986, and obtained the UK rebate on contributions,[261] but she believed that the role of the organisation should be limited to ensuring free trade and effective competition, and feared that the EEC approach was at odds with her views on smaller government and deregulation.[262] Believing that the single market would result in political integration,[261] Thatcher's opposition to further European integration became more pronounced during her premiership and particularly after her third government in 1987.[263] In her Bruges speech in 1988, Thatcher outlined her opposition to proposals from the EEC,[259] forerunner of the European Union, for a federal structure and increased centralisation of decision-making:

We have not successfully rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain, only to see them re-imposed at a European level, with a European super-state exercising a new dominance from Brussels.[262]

Sharing the concerns of French president François Mitterrand,[264] Thatcher was initially opposed to German reunification,[nb 8] telling Gorbachev that it "would lead to a change to postwar borders, and we cannot allow that because such a development would undermine the stability of the whole international situation and could endanger our security". She expressed concern that a united Germany would align itself more closely with the Soviet Union and move away from NATO.[266]

In March 1990, Thatcher held a Chequers seminar on the subject of German reunification that was attended by members of her cabinet and historians such as Norman Stone, George Urban, Timothy Garton Ash and Gordon A. Craig. During the seminar, Thatcher described "what Urban called 'saloon bar clichés' about the German character, including 'angst, aggressiveness, assertiveness, bullying, egotism, inferiority complex [and] sentimentality'". Those present were shocked to hear Thatcher's utterances and "appalled" at how she was "apparently unaware" about the post-war German collective guilt and Germans' attempts to work through their past.[267] The words of the meeting were leaked by her foreign-policy advisor Charles Powell and, subsequently, her comments were met with fierce backlash and controversy.[268]

During the same month, German chancellor Helmut Kohl reassured Thatcher that he would keep her "informed of all his intentions about unification",[269] and that he was prepared to disclose "matters which even his cabinet would not know".[269]

Challenges to leadership and resignation

During her premiership, Thatcher had the second-lowest average approval rating (40%) of any post-war prime minister. Since Nigel Lawson's resignation as chancellor in October 1989,[270] polls consistently showed that she was less popular than her party.[271] A self-described conviction politician, Thatcher always insisted that she did not care about her poll ratings and pointed instead to her unbeaten election record.[272]

In December 1989, Thatcher was challenged for the leadership of the Conservative Party by the little-known backbench MP Sir Anthony Meyer.[273] Of the 374 Conservative MPs eligible to vote, 314 voted for Thatcher and 33 for Meyer. Her supporters in the party viewed the result as a success and rejected suggestions that there was discontent within the party.[273]

Opinion polls in September 1990 reported that Labour had established a 14% lead over the Conservatives,[274] and by November, the Conservatives had been trailing Labour for 18 months.[271] These ratings, together with Thatcher's combative personality and tendency to override collegiate opinion, contributed to further discontent within her party.[275]

In July 1989, Thatcher removed Geoffrey Howe as foreign secretary after he and Lawson had forced her to agree to a plan for Britain to join the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM). Britain joined the ERM in October 1990.

On 1 November 1990, Howe, by then the last remaining member of Thatcher's original 1979 cabinet, resigned as deputy prime minister, ostensibly over her open hostility to moves towards European monetary union.[274][276] In his resignation speech on 13 November, which was instrumental in Thatcher's downfall,[277] Howe attacked Thatcher's openly dismissive attitude to the government's proposal for a new European currency competing against existing currencies (a "hard ECU"):

How on earth are the Chancellor and the Governor of the Bank of England, commending the hard ECU as they strive to, to be taken as serious participants in the debate against that kind of background noise? I believe that both the Chancellor and the Governor are cricketing enthusiasts, so I hope that there is no monopoly of cricketing metaphors. It is rather like sending your opening batsmen to the crease only for them to find, the moment the first balls are bowled, that their bats have been broken before the game by the team captain.[278][279]

On 14 November, Michael Heseltine mounted a challenge for the leadership of the Conservative Party.[280][281] Opinion polls had indicated that he would give the Conservatives a national lead over Labour.[282] Although Thatcher led on the first ballot with the votes of 204 Conservative MPs (54.8%) to 152 votes (40.9%) for Heseltine, with 16 abstentions, she was four votes short of the required 15% majority. A second ballot was therefore necessary.[283] Thatcher initially declared her intention to "fight on and fight to win" the second ballot, but consultation with her cabinet persuaded her to withdraw.[275][284] After holding an audience with the Queen, calling other world leaders, and making one final Commons speech,[285] on 28 November she left Downing Street in tears. She reportedly regarded her ousting as a betrayal.[286] Her resignation was a shock to many outside Britain, with such foreign observers as Henry Kissinger and Gorbachev expressing private consternation.[287]

Chancellor John Major replaced Thatcher as head of government and party leader, whose lead over Heseltine in the second ballot was sufficient for Heseltine to drop out. Major oversaw an upturn in Conservative support in the 17 months leading to the 1992 general election and led the party to a fourth successive victory on 9 April 1992.[288] Thatcher had lobbied for Major in the leadership contest against Heseltine, but her support for him waned in later years.[289]

Later life

Return to backbenches (1990–1992)

After leaving the premiership, Thatcher returned to the backbenches as a constituency parliamentarian.[290] Her domestic approval rating recovered after her resignation, though public opinion remained divided on whether her government had been good for the country.[270][291] Aged 66, she retired from the House of Commons at the 1992 general election, saying that leaving the Commons would allow her more freedom to speak her mind.[292]

Post-Commons (1992–2003)

On leaving the Commons, Thatcher became the first former British prime minister to set up a foundation;[293] the British wing of the Margaret Thatcher Foundation was dissolved in 2005 due to financial difficulties.[294] She wrote two volumes of memoirs, The Downing Street Years (1993) and The Path to Power (1995). In 1991, she and her husband Denis moved to a house in Chester Square, a residential garden square in central London's Belgravia district.[295]

Thatcher was hired by the tobacco company Philip Morris as a "geopolitical consultant" in July 1992 for $250,000 per year and an annual contribution of $250,000 to her foundation.[296] Thatcher earned $50,000 for each speech she delivered.[297]

Thatcher became an advocate of Croatian and Slovenian independence.[298] Commenting on the Yugoslav Wars, in a 1991 interview for Croatian Radiotelevision, she was critical of Western governments for not recognising the breakaway republics of Croatia and Slovenia as independent and for not supplying them with arms after the Serbian-led Yugoslav Army attacked.[299] In August 1992, she called for NATO to stop the Serbian assault on Goražde and Sarajevo to end ethnic cleansing during the Bosnian War, comparing the situation in Bosnia–Herzegovina to "the barbarities of Hitler's and Stalin's".[300]

She made a series of speeches in the Lords criticising the Maastricht Treaty,[292] describing it as "a treaty too far" and stated: "I could never have signed this treaty."[301] She cited A. V. Dicey when arguing that, as all three main parties were in favour of the treaty, the people should have their say in a referendum.[302]

Thatcher served as honorary chancellor of the College of William & Mary in Virginia from 1993 to 2000,[303] while also serving as chancellor of the private University of Buckingham from 1992 to 1998,[304][305] a university she had formally opened in 1976 as the former education secretary.[305]

After Tony Blair's election as Labour Party leader in 1994, Thatcher praised Blair as "probably the most formidable Labour leader since Hugh Gaitskell", adding: "I see a lot of socialism behind their front bench, but not in Mr Blair. I think he genuinely has moved."[306] Blair responded in kind: "She was a thoroughly determined person, and that is an admirable quality."[307]

In 1998, Thatcher called for the release of former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet when Spain had him arrested and sought to try him for human rights violations. She cited the help he gave Britain during the Falklands War.[308] In 1999, she visited him while he was under house arrest near London.[309] Pinochet was released in March 2000 on medical grounds by Home Secretary Jack Straw.[310]

At the 2001 general election, Thatcher supported the Conservative campaign, as she had done in 1992 and 1997, and in the Conservative leadership election following its defeat, she endorsed Iain Duncan Smith over Kenneth Clarke.[311] In 2002 she encouraged George W. Bush to aggressively tackle the "unfinished business" of Iraq under Saddam Hussein,[312] and praised Blair for his "strong, bold leadership" in standing with Bush in the Iraq War.[313]

She broached the same subject in her Statecraft: Strategies for a Changing World, which was published in April 2002 and dedicated to Ronald Reagan, writing that there would be no peace in the Middle East until Saddam was toppled. Her book also said that Israel must trade land for peace and that the European Union (EU) was a "fundamentally unreformable", "classic utopian project, a monument to the vanity of intellectuals, a programme whose inevitable destiny is failure".[314] She argued that Britain should renegotiate its terms of membership or else leave the EU and join the North American Free Trade Area.[315]

Following several small strokes, her doctors advised her not to engage in further public speaking.[316] In March 2002 she announced that, on doctors' advice, she would cancel all planned speaking engagements and accept no more.[317]

Being Prime Minister is a lonely job. In a sense, it ought to be: you cannot lead from the crowd. But with Denis there I was never alone. What a man. What a husband. What a friend.

Thatcher (1993, p. 23)

On 26 June 2003, Thatcher's husband, Sir Denis, died aged 88;[318] his body was cremated on 3 July at Mortlake Crematorium in London.[319]

Final years (2003–2013)

On 11 June 2004, Thatcher (against doctors' orders) attended the state funeral service for Ronald Reagan.[320] She delivered her eulogy via videotape; in view of her health, the message had been pre-recorded several months earlier.[321][322] Thatcher flew to California with the Reagan entourage, and attended the memorial service and interment ceremony for the president at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.[323]

In 2005, Thatcher criticised how Blair had decided to invade Iraq two years previously. Although she still supported the intervention to topple Saddam Hussein, she said that (as a scientist) she would always look for "facts, evidence and proof" before committing the armed forces.[239] She celebrated her 80th birthday on 13 October at the Mandarin Oriental Hotel in Hyde Park, London; guests included the Queen, the Duke of Edinburgh, Princess Alexandra and Tony Blair.[324] Geoffrey Howe, Baron Howe of Aberavon, was also in attendance and said of his former leader: "Her real triumph was to have transformed not just one party but two, so that when Labour did eventually return, the great bulk of Thatcherism was accepted as irreversible."[325]

In 2006, Thatcher attended the official Washington memorial service to commemorate the fifth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks on the US. She was a guest of Vice President Dick Cheney and met Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice during her visit.[326] In February 2007 Thatcher became the first living British prime minister to be honoured with a statue in the Houses of Parliament. The bronze statue stood opposite that of her political hero, Winston Churchill,[327] and was unveiled on 21 February 2007 with Thatcher in attendance; she remarked in the Members' Lobby of the Commons: "I might have preferred iron – but bronze will do [...] It won't rust."[327]

Thatcher was a public supporter of the Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism and the resulting Prague Process and sent a public letter of support to its preceding conference.[328]

After collapsing at a House of Lords dinner, Thatcher, suffering low blood pressure,[329] was admitted to St Thomas' Hospital in central London on 7 March 2008 for tests. In 2009 she was hospitalised again when she fell and broke her arm.[330] Thatcher returned to 10 Downing Street in late November 2009 for the unveiling of an official portrait by artist Richard Stone,[331] an unusual honour for a living former prime minister. Stone was previously commissioned to paint portraits of the Queen and Queen Mother.[331]

On 4 July 2011, Thatcher was to attend a ceremony for the unveiling of a 10 ft (3.0 m) statue of Ronald Reagan outside the US embassy in London, but was unable to attend due to her frail health.[332] She last attended a sitting of the House of Lords on 19 July 2010,[333] and on 30 July 2011 it was announced that her office in the Lords had been closed.[1] Earlier that month, Thatcher was named the most competent prime minister of the past 30 years in an Ipsos MORI poll.[334]

Thatcher's daughter Carol first revealed that her mother had dementia in 2005,[335] saying "Mum doesn't read much any more because of her memory loss". In her 2008 memoir, Carol wrote that her mother "could hardly remember the beginning of a sentence by the time she got to the end".[335] She later recounted how she was first struck by her mother's dementia when, in conversation, Thatcher confused the Falklands and Yugoslav conflicts; she recalled the pain of needing to tell her mother repeatedly that her husband Denis was dead.[336]

Death and funeral (2013)

Thatcher died on 8 April 2013, at the age of 87, after suffering a stroke. She had been staying at a suite in the Ritz Hotel in London since December 2012 after having difficulty with stairs at her Chester Square home in Belgravia.[337] Her death certificate listed the primary causes of death as a "cerebrovascular accident" and "repeated transient ischaemic attack";[338] secondary causes were listed as a "carcinoma of the bladder" and dementia.[338]

Reactions to the news of Thatcher's death were mixed across the UK, ranging from tributes lauding her as Britain's greatest-ever peacetime prime minister to public celebrations of her death and expressions of hatred and personalised vitriol.[339]

Details of Thatcher's funeral had been agreed upon with her in advance.[340] She received a ceremonial funeral, including full military honours, with a church service at St Paul's Cathedral on 17 April.[341][342]

Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh attended her funeral,[343] marking only the second and final time in the Queen's reign that she attended the funeral of any of her former prime ministers, after that of Churchill, who received a state funeral in 1965.[344]

After the service at St Paul's, Thatcher's body was cremated at Mortlake, where her husband's had been cremated. On 28 September, a service for Thatcher was held in the All Saints Chapel of the Royal Hospital Chelsea's Margaret Thatcher Infirmary. In a private ceremony, Thatcher's ashes were interred in the hospital's grounds, next to her husband's.[345][346]

Legacy

Political impact

| Part of the politics series on |

| Thatcherism |

|---|

|

Thatcherism represented a systematic and decisive overhaul of the post-war consensus, whereby the major political parties largely agreed on the central themes of Keynesianism, the welfare state, nationalised industry, and close regulation of the economy, and high taxes. Thatcher generally supported the welfare state while proposing to rid it of abuses.[nb 9]

She promised in 1982 that the highly popular National Health Service was "safe in our hands".[347] At first, she ignored the question of privatising nationalised industries; heavily influenced by right-wing think tanks, and especially by Sir Keith Joseph,[348] Thatcher broadened her attack. Thatcherism came to refer to her policies as well as aspects of her ethical outlook and personal style, including moral absolutism, nationalism, liberal individualism, and an uncompromising approach to achieving political goals.[349][350][nb 10]

Thatcher defined her political philosophy, in a major and controversial break with the one-nation conservatism[351] of her predecessor Edward Heath, in a 1987 interview published in Woman's Own magazine:

I think we have gone through a period when too many children and people have been given to understand "I have a problem, it is the Government's job to cope with it!" or "I have a problem, I will go and get a grant to cope with it!" "I am homeless, the Government must house me!" and so they are casting their problems on society and who is society? There is no such thing! There are individual men and women and there are families and no government can do anything except through people and people look to themselves first. It is our duty to look after ourselves and then also to help look after our neighbour and life is a reciprocal business and people have got the entitlements too much in mind without the obligations.[352]

Overview

The number of adults owning shares rose from 7 per cent to 25 per cent during her tenure, and more than a million families bought their council houses, increasing from 55 per cent to 67 per cent in owner-occupiers from 1979 to 1990. The houses were sold at a discount of 33–55 per cent, leading to large profits for some new owners. Personal wealth rose by 80 per cent in real terms during the 1980s, mainly due to rising house prices and increased earnings. Shares in the privatised utilities were sold below their market value to ensure quick and wide sales rather than maximise national income.[353][354]

The "Thatcher years" were also marked by periods of high unemployment and social unrest,[355][356] and many critics on the left of the political spectrum fault her economic policies for the unemployment level; many of the areas affected by mass unemployment as well as her monetarist economic policies remained blighted for decades, by such social problems as drug abuse and family breakdown.[357] Unemployment did not fall below its May 1979 level during her tenure,[358] only falling below its April 1979 level in 1990.[359] The long-term effects of her policies on manufacturing remain contentious.[360][361]

Speaking in Scotland in 2009, Thatcher insisted she had no regrets and was right to introduce the poll tax and withdraw subsidies from "outdated industries, whose markets were in terminal decline", subsidies that created "the culture of dependency, which had done such damage to Britain".[362] Political economist Susan Strange termed the neoliberal financial growth model "casino capitalism", reflecting her view that speculation and financial trading were becoming more important to the economy than industry.[363]