Возраст викингов

| Часть серии на |

| Скандинавия |

|---|

|

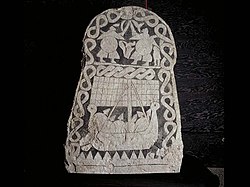

Возраст викингов (около 800–1050 гг. Н.э. ) был периодом в средние века , когда нонсманцы , известные как викинги . [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] Возраст викингов относится не только к их родине Скандинавии , но и к любому месту, значительно обоснованному скандинавтами в течение периода. [ 3 ] Скандинавцы эпохи викингов часто называют викингами, а также норсителями , хотя немногие из них были викингами в смысле участия в пиратстве. [ 4 ]

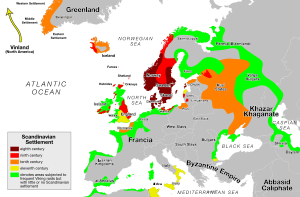

Voyaging by sea from their homelands in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, the Norse people settled in the British Isles, Ireland, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Greenland, Normandy, and the Baltic coast and along the Dnieper and Volga trade routes in eastern Europe, where they were also known as Varangians. They also briefly settled in Newfoundland, becoming the first Europeans to reach North America. The Norse-Gaels, Normans, Rus' people, Faroese, and Icelanders emerged from these Norse colonies. The Vikings founded several kingdoms and earldoms in Europe: the Kingdom of the Isles (Suðreyjar), Orkney (Norðreyjar), York (Jórvík) and the Danelaw (Danalǫg), Dublin (Dyflin), Normandy, and Kievan Rus' (Garðaríki). The Norse homelands were also unified into larger kingdoms during the Viking Age, and the short-lived North Sea Empire included large swathes of Scandinavia and Britain. In 1021, the Vikings achieved the feat of reaching North America—the date of which was not determined until a millennium later.[5]

Several things drove this expansion. The Vikings were drawn by the growth of wealthy towns and monasteries overseas and weak kingdoms. They may also have been pushed to leave their homeland by overpopulation, lack of good farmland, and political strife arising from the unification of Norway. The aggressive expansion of the Carolingian Empire and forced conversion of the neighbouring Saxons to Christianity may also have been a factor.[6] Sailing innovations had allowed the Vikings to sail farther and longer to begin with.

Information about the Viking Age is drawn largely from primary sources written by those the Vikings encountered, as well as archaeology, supplemented with secondary sources such as the Icelandic Sagas.

Context

[edit]In England, the Viking attack of 8 June 793 that destroyed the abbey on Lindisfarne, a centre of learning on an island off the northeast coast of England in Northumberland, is regarded as the beginning of the Viking Age.[7][8][9] Judith Jesch has argued that the start of the Viking Age can be pushed back to 700–750, as it was unlikely that the Lindisfarne attack was the first attack, and given archeological evidence that suggests contacts between Scandinavia and the British isles earlier in the century.[7] The earliest raids were most likely small in scale, but expanded in scale during the 9th century.[10]

In the Lindisfarne attack, monks were killed in the abbey, thrown into the sea to drown, or carried away as slaves along with the church treasures, giving rise to the traditional (but unattested) prayer—A furore Normannorum libera nos, Domine, "Free us from the fury of the Northmen, Lord."[11] Three Viking ships had beached in Weymouth Bay four years earlier (although due to a scribal error the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle dates this event to 787 rather than 789), but that incursion may have been a trading expedition that went wrong rather than a piratical raid. Lindisfarne was different. The Viking devastation of Northumbria's Holy Island was reported by the Northumbrian scholar Alcuin of York, who wrote: "Never before in Britain has such a terror appeared".[12] Vikings were portrayed as wholly violent and bloodthirsty by their enemies. Robert of Gloucester's Chronicle, c. 1300, mentions Viking attacks on the people of East Anglia wherein they are described as "wolves among sheep".[13]

The first challenges to the many negative depictions of Vikings in Britain emerged in the 17th century. Pioneering scholarly works on the Viking Age reached only a small readership there, while linguists traced the Viking Age origins of rural idioms and proverbs. New dictionaries and grammars of the Old Icelandic language appeared, enabling more Victorian scholars to read the primary texts of the Icelandic Sagas.[14]

In Scandinavia, the 17th-century Danish scholars Thomas Bartholin and Ole Worm and Swedish scholar Olaus Rudbeck were the first to use runic inscriptions and Icelandic Sagas as primary historical sources. During the Enlightenment and Nordic Renaissance, historians such as the Icelandic-Norwegian Thormodus Torfæus, Danish-Norwegian Ludvig Holberg, and Swedish Olof von Dalin developed a more "rational" and "pragmatic" approach to historical scholarship.

By the latter half of the 18th century, while the Icelandic sagas were still used as important historical sources, the Viking Age had again come to be regarded as a barbaric and uncivilised period in the history of the Nordic countries. Scholars outside Scandinavia did not begin to extensively reassess the achievements of the Vikings until the 1890s, recognising their artistry, technological skills, and seamanship.[15]

Background

[edit]

The Vikings who invaded western and eastern Europe were mainly pagans from the same area as present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. They also settled in the Faroe Islands, Ireland, Iceland, peripheral Scotland (Caithness, the Hebrides and the Northern Isles), Greenland, and Canada.

Their North Germanic language, Old Norse, became the precursor to present-day Scandinavian languages. By 801, a strong central authority appears to have been established in Jutland, and the Danes were beginning to look beyond their own territory for land, trade, and plunder.

In Norway, mountainous terrain and fjords formed strong natural boundaries. Communities remained independent of each other, unlike the situation in lowland Denmark. By 800, some 30 small kingdoms existed in Norway.

The sea was the easiest way of communication between the Norwegian kingdoms and the outside world. In the eighth century, Scandinavians began to build ships of war and send them on raiding expeditions which started the Viking Age. The North Sea rovers were traders, colonisers, explorers, and plunderers who were notorious in England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales and other places in Europe for being brutal.

Probable causes

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Norsemen |

|---|

|

| WikiProject Norse history and culture |

Many theories are posited for the cause of the Viking invasions; the will to explore likely played a major role. At the time, England, Wales, and Ireland were vulnerable to attack, being divided into many different warring kingdoms in a state of internal disarray, while the Franks were well defended. Overpopulation, especially near the Scandes, was a possible reason, although some disagree with this theory.[16] Technological advances like the use of iron and a shortage of women due to selective female infanticide also likely had an impact.[17] Tensions caused by Frankish expansion to the south of Scandinavia, and their subsequent attacks upon the Viking peoples, may have also played a role in Viking pillaging.[citation needed] Harald I of Norway ("Harald Fairhair") had united Norway around this time and displaced many peoples. As a result, these people sought for new bases to launch counter-raids against Harald.

Debate among scholars is ongoing as to why the Scandinavians began to expand from the eighth through 11th centuries. Various factors have been highlighted: demographic, economic, ideological, political, technological, and environmental models.[18]

Demographic models

[edit]Barrett considers that prior scholarship having examined causes of the Viking Age in terms of demographic determinism, the resulting explanations have generated a "wide variety of possible models". While admitting that Scandinavia did share in the general European population and settlement expansion at the end of the first millennium, he dismisses 'population pressure' as a realistic cause of the Viking Age.[19] Bagge alludes to the evidence of demographic growth at the time, manifested in an increase of new settlements, but he declares that a warlike people do not require population pressure to resort to plundering abroad. He grants that although population increase was a factor in this expansion, it was not the incentive for such expeditions.[20] According to Ferguson, the proliferation of the use of iron in Scandinavia at the time increased agricultural yields, allowing for demographic growth that strained the limited capacity of the land.[21] As a result, many Scandinavians found themselves with no property and no status. To remedy this, these landless men took to piracy to obtain material wealth. The population continued to grow, and the pirates looked further and further beyond the borders of the Baltic, and eventually into all of Europe.[22] Historian Anders Winroth has also challenged the "overpopulation" thesis, arguing that scholars are "simply repeating an ancient cliché that has no basis in fact."[23]

Economic model

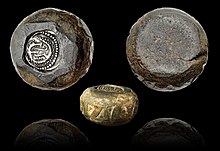

[edit]The economic model states that the Viking Age was the result of growing urbanism and trade throughout mainland Europe. As the Islamic world grew, so did its trade routes, and the wealth which moved along them was pushed further and further north.[24] In Western Europe, proto-urban centres such as those with names ending in wich, the so-called -wich towns of Anglo-Saxon England, began to boom during the prosperous era known as the "Long Eighth Century".[25] The Scandinavians, like many other Europeans, were drawn to these wealthier "urban" centres, which soon became frequent targets of Viking raids. The connection of the Scandinavians to larger and richer trade networks lured the Vikings into Western Europe, and soon the rest of Europe and parts of the Middle East. In England, hoards of Viking silver, such as the Cuerdale Hoard and the Vale of York Hoard, offer insight into this phenomenon. Barrett rejects this model, arguing that the earliest recorded Viking raids were in Western Norway and northern Britain, which were not highly economically integrated areas. He proposes a version of the economic model that points to new economic incentives stemming from a "bulge" in the population of young Scandinavian men, impelling them to engage in maritime activity due to limited economic alternatives.[18]

Ideological model

[edit]This era coincided with the Medieval Warm Period (800–1300) and stopped with the start of the Little Ice Age (about 1250–1850). The start of the Viking Age, with the sack of Lindisfarne, also coincided with Charlemagne's Saxon Wars, or Christian wars with pagans in Saxony. Bruno Dumézil theorises that the Viking attacks may have been in response to the spread of Christianity among pagan peoples.[26][27][28][29][30] Because of the penetration of Christianity in Scandinavia, serious conflict divided Norway for almost a century.[31]

Political model

[edit]The first of two main components to the political model is the external "pull" factor, which suggests that the weak political bodies of Britain and Western Europe made for an attractive target for Viking raiders.[citation needed] The reasons for these weaknesses vary, but generally can be simplified into decentralised polities, or religious sites. As a result, Viking raiders found it easy to sack and then retreat from these areas which were thus frequently raided. The second case is the internal "push" factor, which coincides with a period just before the Viking Age in which Scandinavia was undergoing a mass centralisation of power in the modern-day countries of Denmark, Sweden, and especially Norway. This centralisation of power forced hundreds of chieftains from their lands, which were slowly being appropriated by the kings and dynasties that began to emerge. As a result, many of these chiefs sought refuge elsewhere, and began harrying the coasts of the British Isles and Western Europe.[32] Anders Winroth argues that purposeful choices by warlords "propelled the Viking Age movement of people from Scandinavia."[23]

- Technological model

- This model suggests that the Viking Age occurred as a result of technological innovations that allowed the Vikings to go on their raids in the first place.[33] There is no doubt that piracy existed in the Baltic before the Viking Age, but developments in sailing technology and practice made it possible for early Viking raiders to attack lands farther away.[34][20] Among these developments are included the use of larger sails, tacking practices, and 24-hour sailing.[19] Anders Winroth writes, "If early medieval Scandinavians had not become exquisite shipwrights, there would have been no Vikings and no Viking Age."[35]

These models constitute much of what is known about the motivations for and the causes of the Viking Age. In all likelihood, the beginning of this age was the result of some combination of the aforementioned hypotheses.

The Viking colonisation of islands in the North Atlantic has in part been attributed to a period of favourable climate (the Medieval Climactic Optimum), as the weather was relatively stable and predictable, with calm seas.[36] Sea ice was rare, harvests were typically strong, and fishing conditions were good.[36]

Overview

[edit]

The earliest date given for the coming of Vikings to England is 789 during the reign of King Beorhtric of Wessex. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle three Norwegian boats from Hordaland (Old Norse: Hǫrðalandi) landed at the Isle of Portland off the coast of Dorset. They apparently were mistaken for merchants by a royal official, Beaduhard,[37] a king's reeve who attempted to force them to come to the king's manor, whereupon they killed the reeve and his men.[38] The beginning of the Viking Age in the British Isles is often set at 793. It was recorded in the Anglo–Saxon Chronicle that the Northmen raided the important island monastery of Lindisfarne (the generally accepted date is actually 8 June, not January[9]):

A.D. 793. This year came dreadful fore-warnings over the land of the Northumbrians, terrifying the people most woefully: these were immense sheets of light rushing through the air, and whirlwinds, and fiery dragons flying across the firmament. These tremendous tokens were soon followed by a great famine: and not long after, on the sixth day before the ides of January in the same year, the harrowing inroads of heathen men made lamentable havoc in the church of God in Holy-island (Lindisfarne), by rapine and slaughter.

— Anglo Saxon Chronicle.[39]

In 794, according to the Annals of Ulster, a serious attack was made on Lindisfarne's mother-house of Iona, which was followed in 795 by raids upon the northern coast of Ireland. From bases there, the Norsemen attacked Iona again in 802, causing great slaughter amongst the Céli Dé Brethren, and burning the abbey to the ground.

The Vikings primarily targeted Ireland until 830, as England and the Carolingian Empire were able to fight the Vikings off.[40] However, after 830 CE, the Vikings had considerable success against England, the Carolingian Empire, and other parts of Western Europe.[40] After 830, the Vikings exploited disunity within the Carolingian Empire, as well as pitting the English kingdoms against each other.[40]

The Kingdom of the Franks under Charlemagne was particularly devastated by these raiders, who could sail up the Seine with near impunity. Near the end of Charlemagne's reign (and throughout the reigns of his sons and grandsons), a string of Norse raids began, culminating in a gradual Scandinavian conquest and settlement of the region now known as Normandy in 911. Frankish King Charles the Simple granted the Duchy of Normandy to Viking warleader Rollo (a chieftain of disputed Norwegian or Danish origins)[41] in order to stave off attacks by other Vikings.[40] Charles gave Rollo the title of duke. In return, Rollo swore fealty to Charles, converted to Christianity, and undertook to defend the northern region of France against the incursions of other Viking groups. Several generations later, the Norman descendants of these Viking settlers not only identified themselves as Norman, but also carried the Norman language (either a French dialect or a Romance language which can be classified as one of the Oïl languages along with French, Picard and Walloon), and their Norman culture, into England in 1066. With the Norman Conquest, they became the ruling aristocracy of Anglo–Saxon England.

The clinker-built longships used by the Scandinavians were uniquely suited to both deep and shallow waters. They extended the reach of Norse raiders, traders, and settlers along coastlines and along the major river valleys of north-western Europe. Rurik also expanded to the east, and in 859 became ruler either by conquest or invitation by local people of the city of Novgorod (which means "new city") on the Volkhov River. His successors moved further, founding the early East Slavic state of Kievan Rus' with the capital in Kiev. This persisted until 1240, when the Mongols invaded Kievan Rus'.

Other Norse people continued south to the Black Sea and then on to Constantinople. The eastern connections of these "Varangians" brought Byzantine silk, a cowrie shell from the Red Sea, and even coins from Samarkand, to Viking York.

In 884, an army of Danish Vikings was defeated at the Battle of Norditi (also called the Battle of Hilgenried Bay) on the Germanic North Sea coast by a Frisian army under Archbishop Rimbert of Bremen-Hamburg, which precipitated the complete and permanent withdrawal of the Vikings from East Frisia. In the 10th and 11th centuries, Saxons and Slavs began to use trained mobile cavalry successfully against Viking foot soldiers, making it hard for Viking invaders to fight inland.[42]

In Scandinavia, the Viking Age is considered by some scholars to have ended with the establishment of royal authority and the establishment of Christianity as the dominant religion.[43] Scholars have proposed different end dates for the Viking Age, but many argue it ended in the 11th century. The year 1000 is sometimes used, as that was the year in which Iceland converted to Christianity, marking the conversion of all of Scandinavia to Christianity. The death of Harthacnut, the Danish King of England, in 1042 has also been used as an end date.[7] History does not often allow such clear-cut separation between arbitrary "ages", and it is not easy to pin down a single date that applies to all the Viking world. The Viking Age was not a "monolithic chronological period" across three or four hundred years, but was characterised by various distinct phases of Viking activity. It is unlikely that the Viking Age could be so neatly assigned a terminal event.[44] The end of the Viking era in Norway is marked by the Battle of Stiklestad in 1030, in which Óláfr Haraldsson (later known as Olav the Holy), a fervent Christianiser who dealt harshly with those suspected of clinging to pagan cult, was killed.[45] Although Óláfr's army lost the battle, Christianity continued to spread, and after his death he became one of the subjects of the three miracle stories given in the Manx Chronicle.[46] In Sweden, the reign of king Olof Skötkonung (c. 995–1020) is considered to be the transition from the Viking Age to the Middle Ages, because he was the first Christian king of the Swedes, and he is associated with a growing influence of the church in what is today southwestern and central Sweden. Norse beliefs persisted until the 12th century; Olof was the last king in Scandinavia to adopt Christianity.

The end of the Viking Age is traditionally marked in England by the failed invasion attempted by the Norwegian king Harald III (Haraldr Harðráði), who was defeated by Saxon King Harold Godwinson in 1066 at the Battle of Stamford Bridge;[7] in Ireland, the capture of Dublin by Strongbow and his Hiberno-Norman forces in 1171; and 1263 in Scotland by the defeat of King Hákon Hákonarson at the Battle of Largs by troops loyal to Alexander III.[citation needed] Godwinson was subsequently defeated within a month by another Viking descendant, William, Duke of Normandy. Scotland took its present form when it regained territory from the Norse between the 13th and the 15th centuries; the Western Isles and the Isle of Man remained under Scandinavian authority until 1266. Orkney and Shetland belonged to the king of Norway as late as 1469. Consequently, a "long Viking Age" may stretch into the 15th century.[7]

Northern Europe

[edit]England

[edit]

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, Viking raiders struck England in 793 and raided Lindisfarne, the monastery that held Saint Cuthbert's relics, killing the monks and capturing the valuables. The raid marked the beginning of the "Viking Age of Invasion". Great but sporadic violence continued on England's northern and eastern shores, with raids continuing on a small scale across coastal England. While the initial raiding groups were small, a great amount of planning is believed to have been involved. The Vikings raided during the winter of 840–841, rather than the usual summer, having waited on an island off Ireland.[47]

In 850, the Vikings overwintered for the first time in England, on the island of Thanet, Kent. In 854, a raiding party overwintered a second time, at the Isle of Sheppey in the Thames estuary. In 864, they reverted to Thanet for their winter encampment.[47]

The following year, the Great Heathen Army, led by brothers Ivar the Boneless, Halfdan and Ubba, and also by another Viking Guthrum, arrived in East Anglia. They proceeded to cross England into Northumbria and captured York, establishing a Viking community in Jorvik, where some settled as farmers and craftsmen. Most of the English kingdoms, being in turmoil, could not stand against the Vikings. In 867, Northumbria became the northern kingdom of the coalescing Danelaw, after its conquest by the Ragnarsson brothers, who installed an Englishman, Ecgberht, as a puppet king. By 870, the "Great Summer Army" arrived in England, led by a Viking leader called Bagsecg and his five earls. Aided by the Great Heathen Army (which had already overrun much of England from its base in Jorvik), Bagsecg's forces, and Halfdan's forces (through an alliance), the combined Viking forces raided much of England until 871, when they planned an invasion of Wessex. On 8 January 871, Bagsecg was killed at the Battle of Ashdown along with his earls. As a result, many of the Vikings returned to northern England, where Jorvic had become the centre of the Viking kingdom, but Alfred of Wessex managed to keep them out of his country. Alfred and his successors continued to drive back the Viking frontier and take York. A new wave of Vikings appeared in England in 947, when Eric Bloodaxe captured York.

In 1003, the Danish King Sweyn Forkbeard started a series of raids against England to avenge the St. Brice's Day massacre of England's Danish inhabitants, culminating in a full-scale invasion that led to Sweyn being crowned king of England in 1013.[48][49] Sweyn was also king of Denmark and parts of Norway at this time.[50] The throne of England passed to Edmund Ironside of Wessex after Sweyn's death in 1014. Sweyn's son, Cnut the Great, won the throne of England in 1016 through conquest. When Cnut the Great died in 1035 he was a king of Denmark, England, Norway, and parts of Sweden.[51][52] Harold Harefoot became king of England after Cnut's death, and Viking rule of England ceased.[clarification needed]

The Viking presence declined until 1066, when they lost their final battle with the English at Stamford Bridge. The death in the battle of King Harald Hardrada of Norway ended any hope of reviving Cnut's North Sea Empire, and it is because of this, rather than the Norman conquest, that 1066 is often taken as the end of the Viking Age. Nineteen days later, a large army containing and led by senior Normans, themselves mostly male-line descendants of Norsemen, invaded England and defeated the weakened English army at the Battle of Hastings. The army invited others from across Norman gentry and ecclesiastical society to join them. There were several unsuccessful attempts by Scandinavian kings to regain control of England, the last of which took place in 1086.[53]

In 1152, Eystein II of Norway led a plundering raid down the east coast of Britain.[54]

Ireland

[edit]

In 795, small bands of Vikings began plundering monastic settlements along the coast of Gaelic Ireland. The Annals of Ulster state that in 821 the Vikings plundered Howth and "carried off a great number of women into captivity".[55] From 840 the Vikings began building fortified encampments, longphorts, on the coast and overwintering in Ireland. The first were at Dublin and Linn Duachaill.[56] Their attacks became bigger and reached further inland, striking larger monastic settlements such as Armagh, Clonmacnoise, Glendalough, Kells, and Kildare, and also plundering the ancient tombs of Brú na Bóinne.[57] Viking chief Thorgest is said to have raided the whole midlands of Ireland until he was killed by Máel Sechnaill I in 845.

In 853, Viking leader Amlaíb (Olaf) became the first king of Dublin. He ruled along with his brothers Ímar (possibly Ivar the Boneless) and Auisle.[58] Over the following decades, there was regular warfare between the Vikings and the Irish, and between two groups of Vikings: the Dubgaill and Finngaill (dark and fair foreigners). The Vikings also briefly allied with various Irish kings against their rivals. In 866, Áed Findliath burnt all Viking longphorts in the north, and they never managed to establish permanent settlements in that region.[59] The Vikings were driven from Dublin in 902.[60]

They returned in 914, now led by the Uí Ímair (House of Ivar).[61] During the next eight years the Vikings won decisive battles against the Irish, regained control of Dublin, and founded settlements at Waterford, Wexford, Cork, and Limerick, which became Ireland's first large towns. They were important trading hubs, and Viking Dublin was the biggest slave port in western Europe.[62]

These Viking territories became part of the patchwork of kingdoms in Ireland. Vikings intermarried with the Irish and adopted elements of Irish culture, becoming the Norse-Gaels. Some Viking kings of Dublin also ruled the kingdom of the Isles and York; such as Sitric Cáech, Gofraid ua Ímair, Olaf Guthfrithson, and Olaf Cuaran. Sigtrygg Silkbeard was "a patron of the arts, a benefactor of the church, and an economic innovator" who established Ireland's first mint, in Dublin.[63]

In 980 CE, Máel Sechnaill Mór defeated the Dublin Vikings and forced them into submission.[64] Over the following thirty years, Brian Boru subdued the Viking territories and made himself High King of Ireland. The Dublin Vikings, together with Leinster, twice rebelled against him, but they were defeated in the battles of Glenmama (999 CE) and Clontarf (1014 CE). After the battle of Clontarf, the Dublin Vikings could no longer "single-handedly threaten the power of the most powerful kings of Ireland".[65] Brian's rise to power and conflict with the Vikings is chronicled in Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib ("The War of the Irish with the Foreigners").

Scotland

[edit]While few records are known, the Vikings are thought to have led their first raids in Scotland on the holy island of Iona in 794, the year following the raid on the other holy island of Lindisfarne, Northumbria.

In 839, a large Norse fleet invaded via the River Tay and River Earn, both of which were highly navigable, and reached into the heart of the Pictish kingdom of Fortriu. They defeated Eogán mac Óengusa, king of the Picts, his brother Bran, and the king of the Scots of Dál Riata, Áed mac Boanta, along with many members of the Pictish aristocracy in battle. The sophisticated kingdom that had been built fell apart, as did the Pictish leadership, which had been stable for more than 100 years since the time of Óengus mac Fergusa (The accession of Cináed mac Ailpín as king of both Picts and Scots can be attributed to the aftermath of this event).

In 870, the Britons of the Old North around the Firth of Clyde came under Viking attack as well. The fortress atop Alt Clut ("Rock of the Clyde", the Brythonic name for Dumbarton Rock, which had become the metonym for their kingdom) was besieged by the Viking kings Amlaíb and Ímar. After four months, its water supply failed, and the fortress fell. The Vikings are recorded to have transported a vast prey of British, Pictish, and English captives back to Ireland. These prisoners may have included the ruling family of Alt Clut including the king Arthgal ap Dyfnwal, who was slain the following year under uncertain circumstances. The fall of Alt Clut marked a watershed in the history of the realm. Afterwards, the capital of the restructured kingdom was relocated about 12 miles (20 km) up the River Clyde to the vicinity of Govan and Partick (within present-day Glasgow), and became known as the Kingdom of Strathclyde, which persisted as a major regional political player for another 150 years.

The land that now comprises most of the Scottish Lowlands had previously been the northernmost part of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria, which fell apart with its Viking conquest; these lands were never regained by the Anglo-Saxons, or England. The upheaval and pressure of Viking raiding, occupation, conquest and settlement resulted in alliances among the formerly enemy peoples that comprised what would become present-day Scotland. Over the subsequent 300 years, this Viking upheaval and pressure led to the unification of the previously contending Gaelic, Pictish, British, and English kingdoms, first into the Kingdom of Alba, and finally into the greater Kingdom of Scotland.[66] The Viking Age in Scotland came to an end after another 100 years. The last vestiges of Norse power in the Scottish seas and islands were completely relinquished after another 200 years.

Earldom of Orkney

[edit]By the mid-9th century, the Norsemen had settled in Shetland, Orkney (the Nordreys- Norðreyjar), the Hebrides and Isle of Man, (the Sudreys- Suðreyjar—this survives in the Diocese of Sodor and Man) and parts of mainland Scotland. The Norse settlers were to some extent integrating with the local Gaelic population (see Norse-Gaels) in the Hebrides and Man. These areas were ruled over by local Jarls, originally captains of ships or hersirs. The Jarl of Orkney and Shetland, however, claimed supremacy.

In 875, King Harald Fairhair led a fleet from Norway to Scotland. In his attempt to unite Norway, he found that many of those opposed to his rise to power had taken refuge in the Isles. From here, they were raiding not only foreign lands but were also attacking Norway itself. After organising a fleet, Harald was able to subdue the rebels, and in doing so brought the independent Jarls under his control, many of the rebels having fled to Iceland. He found himself ruling not only Norway, but also the Isles, Man, and parts of Scotland.

Kings of the Isles

[edit]In 876, the Norse-Gaels of Mann and the Hebrides rebelled against Harald. A fleet was sent against them led by Ketil Flatnose to regain control. On his success, Ketil was to rule the Sudreys as a vassal of King Harald. His grandson, Thorstein the Red, and Sigurd the Mighty, Jarl of Orkney, invaded Scotland and were able to exact tribute from nearly half the kingdom until their deaths in battle. Ketil declared himself King of the Isles. Ketil was eventually outlawed and, fearing the bounty on his head, fled to Iceland.

The Norse-Gaelic Kings of the Isles continued to act semi independently, in 973 forming a defensive pact with the Kings of Scotland and Strathclyde. In 1095, the King of Mann and the Isles Godred Crovan was killed by Magnus Barelegs, King of Norway. Magnus and King Edgar of Scotland agreed on a treaty. The islands would be controlled by Norway, but mainland territories would go to Scotland. The King of Norway nominally continued to be king of the Isles and Man. However, in 1156, The kingdom was split into two. The Western Isles and Man continued as to be called the "Kingdom of Man and the Isles", but the Inner Hebrides came under the influence of Somerled, a Gaelic speaker, who was styled 'King of the Hebrides'. His kingdom was to develop latterly into the Lordship of the Isles.

In eastern Aberdeenshire, the Danes invaded at least as far north as the area near Cruden Bay.[67]

The Jarls of Orkney continued to rule much of northern Scotland until 1196, when Harald Maddadsson agreed to pay tribute to William the Lion, King of Scots, for his territories on the mainland.

The end of the Viking Age proper in Scotland is generally considered to be in 1266. In 1263, King Haakon IV of Norway, in retaliation for a Scots expedition to Skye, arrived on the west coast with a fleet from Norway and Orkney. His fleet linked up with those of King Magnus of Man and King Dougal of the Hebrides. After peace talks failed, his forces met with the Scots at Largs, in Ayrshire. The battle proved indecisive, but it did ensure that the Norse were not able to mount a further attack that year. Haakon died overwintering in Orkney, and by 1266, his son Magnus the Law-Mender ceded the Kingdom of Man and the Isles, with all territories on mainland Scotland to Alexander III, through the Treaty of Perth.

Orkney and Shetland continued to be ruled as autonomous Jarldoms under Norway until 1468, when King Christian I pledged them as security on the dowry of his daughter, who was betrothed to James III of Scotland. Although attempts were made during the 17th and 18th centuries to redeem Shetland, without success,[68] and Charles II ratifying the pawning in the Act for annexation of Orkney and Shetland to the Crown 1669, explicitly exempting them from any "dissolution of His Majesty's lands",[69] they are currently considered as being officially part of the United Kingdom.[70][71]

Wales

[edit]Incursions in Wales were decisively reversed at the Battle of Buttington in Powys, in 893, when a combined Welsh and Mercian army under Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians, defeated a Danish band.

Wales was not colonised by the Vikings as heavily as eastern England. The Vikings did, however, settle in the south around St. David's, Haverfordwest, and Gower, among other places. Place names such as Skokholm, Skomer, and Swansea remain as evidence of the Norse settlement.[72] The Vikings, however, did not subdue the Welsh mountain kingdoms.

Iceland

[edit]According to the Icelandic sagas, Iceland was discovered by Naddodd, a Viking from the Faroe Islands, after which it was settled by mostly Norwegians fleeing the oppressive rule of Harald Fairhair in 985 CE. While harsh, the land allowed for a pastoral farming life familiar to the Norse. According to the saga of Erik the Red, when Erik was exiled from Iceland, he sailed west and pioneered Greenland.

Kvenland

[edit]Kvenland, known as Cwenland, Kænland, and similar terms in medieval sources, is an ancient name for an area in Scandinavia and Fennoscandia. A contemporary reference to Kvenland is provided in an Old English account written in the 9th century. It used the information provided by the Norwegian adventurer and traveller named Ohthere. Kvenland, in that or close to that spelling, is also known from Nordic sources, primarily Icelandic, but also one that was possibly written in the modern-day area of Norway.

All the remaining Nordic sources discussing Kvenland, using that or close to that spelling, date to the 12th and 13th centuries, but some of them—in part at least—are believed to be rewrites of older texts. Other references and possible references to Kvenland by other names and/or spellings are discussed in the main article of Kvenland.

Estonia

[edit]

During the Viking Age, Estonia was a Finnic area divided between two major cultural regions, a coastal and an inland one, corresponding to the historical cultural and linguistic division between Northern and Southern Estonian.[73] These two areas were further divided between loosely allied regions.[74] The Viking Age in Estonia is considered to be part of the Iron Age period which started around 400 CE and ended c. 1200 CE, soon after Estonian raiders were recorded in the Eric Chronicle to have sacked Sigtuna in 1187.[74]

The society, economy, settlement and culture of the territory of what is in the present-day the country of Estonia is studied mainly through archaeological sources. The era is seen to have been a period of rapid change. The Estonian peasant culture came into existence by the end of the Viking Age. The overall understanding of the Viking Age in Estonia is deemed to be fragmentary and superficial, because of the limited amount of surviving source material. The main sources for understanding the period are remains of the farms and fortresses of the era, cemeteries and a large amount of excavated objects.[75]

The landscape of Ancient Estonia featured numerous hillforts, some later hillforts on Saaremaa heavily fortified during the Viking Age and on to the 12th century.[76] There were a number of late prehistoric or medieval harbour sites on the coast of Saaremaa, but none have been found that are large enough to be international trade centres.[76] The Estonian islands also have a number of graves from the Viking Age, both individual and collective, with weapons and jewellery.[76] Weapons found in Estonian Viking Age graves are common to types found throughout Northern Europe and Scandinavia.[77]

Curonians

[edit]The Curonians[78] were known as fierce warriors, excellent sailors and pirates. They were involved in several wars and alliances with Swedish, Danish, and Icelandic Vikings.[79]

In c. 750, according to Norna-Gests þáttr saga from c. 1157, Sigurd Hring ("ring"), a legendary king of Denmark and Sweden, fought against the invading Curonians and Kvens (Kvænir) in the southern part of what today is Sweden:

- "Sigurd Ring (Sigurðr) was not there, since he had to defend his land, Sweden (Svíþjóð), since Curonians (Kúrir) and Kvænir were raiding there."[80]

Curonians are mentioned among other participants of the Battle of Brávellir.

Grobin (Grobiņa) was the main centre of the Curonians during the Vendel Age.[81] From the 10th to 13th century, Palanga served as an important economical, political and cultural centre for the Curonians.[82] Chapter 46 of Egils Saga describes one Viking expedition by the Vikings Thorolf and Egill Skallagrímsson in Courland. According to some opinions, they took part in attacking Sweden's main city Sigtuna in 1187.[83] Curonians established temporary settlements near Riga and in overseas regions including eastern Sweden and the islands of Gotland[84] and Bornholm.

Scandinavian settlements existed along the southeastern Baltic coast in Truso and Kaup (Old Prussia), Palanga[85] (Samogitia, Lithuania) as well as Grobin (Courland, Latvia).

Eastern Europe

[edit]The Varangians or Varyagi were Scandinavians, often Swedes, who migrated eastwards and southwards through what is now Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine, mainly in the 9th and 10th centuries. Engaging in trade, piracy, and mercenary activities, they roamed the river systems and portages of Gardariki, reaching the Caspian Sea and Constantinople.[86] Contemporary English publications also use the name "Viking" for early Varangians in some contexts.[87][88]

The term Varangian remained in usage in the Byzantine Empire until the 13th century, largely disconnected from its Scandinavian roots by then. Having settled Aldeigja (Ladoga) in the 750s, Scandinavian colonists were probably an element in the early ethnogenesis of the Rus' people, and likely played a role in the formation of the Rus' Khaganate.[89][90] The Varangians are first mentioned by the Primary Chronicle as having exacted tribute from the Slavic and Finnic tribes in 859 CE.[91] It was the time of rapid expansion of the Vikings in Northern Europe; England began to pay Danegeld in 859 CE, and the Curonians of Grobin faced an invasion by the Swedes at about the same date.

The text of the Primary Chronicle says that in 860–862, the Finnic and Slavic tribes rebelled against the Varangian Rus', driving them back to Scandinavia, but soon started to conflict with each other. The disorder prompted the tribes to invite back the Varangian Rus' to "Come and rule and reign over us" and bring peace to the region. This was a somewhat bilateral relation with the Varangians defending the cities that they ruled. Led by Rurik and his brothers Truvor and Sineus, the Varangians settled around the town of Novgorod (Holmgarðr).[92].

In the 9th century, the Rus' operated the Volga trade route, which connected northern Russia (Gardariki) with the Middle East (Serkland). As the Volga route declined by the end of the century, the trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks rapidly overtook it in popularity. Apart from Ladoga and Novgorod, Gnezdovo and Gotland were major centres for Varangian trade.[93][94]

The consensus among western scholars, disputed by Russian scholars, who believe them to be a Slavic tribe,[95] is that the Rus' people originated in what is currently coastal eastern Sweden around the 8th century, and that their name has the same origin as that of Roslagen in Sweden.[96] The maritime districts of East Götland and Uppland were known in earlier times as Roþer or Roþin, and later as Roslagen.[97] According to Thorsten Andersson, the Russian folk name Rus' ultimately derives from the noun roþer ('rowing'), a word also used in naval campaigns in the leþunger (Old Norse: leiðangr) system of organizing a coastal fleet. The Old Swedish place name Roþrin, in the older iteration Roþer, contains the word roþer and is still used in the form of Roden as a historical name for the coastal areas of Svealand. In modern times the name still exists as Roslagen, the name of the coastal area of Uppland province.[98] According to Stefan Brink, the name Rus' derives from the words ro (row) and rodd (a rowing session).[99]

The term "Varangian" became more common from the 11th century onwards.[100] In these years, Swedish men left to enlist in the Byzantine Varangian Guard in such numbers that a medieval Swedish law, Västgötalagen, used in the province Västergötland, declared that no one could inherit while staying in "Greece"—the then Scandinavian term for the Byzantine Empire—to stop the emigration,[101] especially as two other European courts simultaneously also recruited Scandinavians:[102] Kievan Rus' c. 980–1060 and London 1018–1066 (the Þingalið).[102]

In contrast to the notable Scandinavian influence in Normandy and the British Isles, Varangian culture did not survive to a great extent in the East. Instead, the Varangian ruling classes of the two powerful city-states of Novgorod and Kiev were thoroughly Slavicised by the beginning of the 11th century. Some evidence suggests that Old Norse may have been spoken amongst the Rus' later, however. Old East Norse was probably still spoken in Kievan Rus' at Novgorod until the 13th century, according to the Nationalencyklopedin (Swedish National Encyclopedia).[103]

Central Europe

[edit]

Viking Age Scandinavian settlements were set up along the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, primarily for trade purposes. Their emergence appears to coincide with the settlement and consolidation of the coastal Slavic tribes in the respective areas.[104] The archaeological record indicates that substantial cultural exchange between Scandinavian and Slavic traditions and technologies occurred.[105] It is known that Slavic and Scandinavian craftsmen had different processes in crafts and productions. In the lagoons and delta of the eastern and southern Baltic there is evidence of Slavic boatbuilding practices somewhat divergent from the Viking tradition, and of a fusion of the two in a shipyard site from the Viking Age on the island of Falster in Denmark.[106]

Slavic-Scandinavian settlements on the Mecklenburgian coast include the maritime trading center Reric (Groß Strömkendorf) on the eastern coast of Wismar Bay,[107] and the multi-ethnic trade emporium Dierkow (near Rostock).[108] Reric was set up around the year 700,[107] but following later warfare between Obodrites and Danes, the inhabitants, who were subject to the Danish king, were resettled to Haithabu by him.[108] Dierkow apparently belongs to the late 8th to the early 9th century.[109]

Scandinavian settlements on the Pomeranian coast include Wolin (on the isle of Wolin), Ralswiek (on the isle of Rügen), Altes Lager Menzlin (on the lower Peene river),[110] and Bardy-Świelubie near modern Kołobrzeg.[111] Menzlin was set up in the mid-8th century.[107] Wolin and Ralswiek began to prosper in the course of the 9th century.[108] A merchants' settlement has also been suggested near Arkona, but no archeological evidence supports this theory.[112] Menzlin and Bardy-Świelubie were vacated in the late 9th century,[113] Ralswiek survived into the new millennium, but by the time written chronicles reported news of the island of Rügen in the 12th century, it had lost all its importance.[108] Wolin, thought to be identical with the legendary Vineta and the semilegendary Jomsborg,[114] base of the Jomsvikings, was destroyed in 1043 by Dano-Norwegian king Magnus the Good,[115] according to the Heimskringla.[116] Castle building by the Slavs seems to have reached a high level on the southern Baltic coast in the 8th and 9th centuries, possibly explained by a threat coming from the sea or from the trade emporiums, as Scandinavian arrowheads found in the area indicate advances penetrating as far as the lake chains in the Mecklenburgian and Pomeranian hinterlands.[108]

Western Europe

[edit]Frisia

[edit]Frisia was a region which spanned from around modern-day Bruges to the islands on the west coast of Jutland—including large parts of the Low Countries. This region was progressively brought under Frankish control (Frisian-Frankish wars), but the Christianization of the local population and cultural assimilation was a slow process. However, several Frisian towns, most notably Dorestad were raided by Vikings. Rorik of Dorestad was a famous Viking raider in Frisia. On Wieringen the Vikings most likely had a base of operations. Viking leaders took an active role in Frisian politics, such as Godfrid, Duke of Frisia, as well as Rorik.

France

[edit]The French region of Normandy takes its name from the Viking invaders who were called Normanni, which means 'men of the North'.

The first Viking raids began between 790 and 800 along the coasts of western France. They were carried out primarily in the summer, as the Vikings wintered in Scandinavia. Several coastal areas were lost to Francia during the reign of Louis the Pious (814–840). But the Vikings took advantage of the quarrels in the royal family caused after the death of Louis the Pious to settle their first colony in the south-west (Gascony) of the kingdom of Francia, which was more or less abandoned by the Frankish kings after their two defeats at Roncevaux. The incursions in 841 CE caused severe damage to Rouen and Jumièges. The Viking attackers sought to capture the treasures stored at monasteries, easy prey given the monks' lack of defensive capacity. In 845 CE an expedition up the Seine reached Paris. The presence of Carolingian deniers of c. 847, found in 1871 among a hoard at Mullaghboden, County Limerick, where coins were neither minted nor normally used in trade, probably represents booty from the raids of 843–846.[117]

However, from 885 to 886, Odo of Paris (Eudes de Paris) succeeded in defending Paris against Viking raiders.[118] His military success allowed him to replace the Carolingians.[119] In 911, a band of Viking warriors attempted to siege Chartres but was defeated by Robert I of France. Robert's victory later paved way for the baptism, and settlement in Normandy, of Viking leader Rollo.[120] Rollo reached an agreement with Charles the Simple to sign the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte, under which Charles gave Rouen and the area of present-day Upper Normandy to Rollo, establishing the Duchy of Normandy. In exchange, Rollo pledged vassalage to Charles in 940, agreed to be baptised, and vowed to guard the estuaries of the Seine from further Viking attacks. During Rollo's baptism Robert I of France stood as his godfather.[121] The Duchy of Normandy also annexed further areas in Northern France, expanding the territory which was originally negotiated.

The Scandinavian expansion included Danish and Norwegian as well as Swedish elements, all under the leadership of Rollo. By the end of the reign of Richard I of Normandy in 996 (aka Richard the Fearless / Richard sans Peur), all descendants of Vikings became, according to Cambridge Medieval History (Volume 5, Chapter XV), 'not only Christians but in all essentials Frenchmen'.[122] During the Middle Ages, the Normans created one of the most powerful feudal states of Western Europe. The Normans conquered England and southern Italy in 11th century, and played a key role in the Crusades.

Southern Europe

[edit]Italy

[edit]In 860, according to an account by the Norman monk Dudo of Saint-Quentin, a Viking fleet, probably under Björn Ironside and Hastein, landed at the Ligurian port of Luni and sacked the city. The Vikings then moved another 60 miles down the Tuscan coast to the mouth of the Arno, sacking Pisa and then, following the river upstream, also the hill-town of Fiesole above Florence, among other victories around the Mediterranean (including in Sicily and Nekor (Morocco), North Africa).[123][124]

Many Anglo-Danish and Varangian mercenaries fought in Southern Italy, including Harald Hardrada and William de Hauteville who conquered parts of Sicily between 1038 and 1040,[125][126] and Edgar the Ætheling who fought in the Norman conquest of southern Italy.[127] Runestones were raised in Sweden in memory of warriors who died in Langbarðaland (Land of the Lombards), the Old Norse name for southern Italy.[128]

Several Anglo-Danish and Norwegian nobles participated in the Norman conquest of southern Italy, like Edgar the Ætheling, who left England in 1086,[127] and Jarl Erling Skakke, who won his nickname ("Skakke", meaning bent head) after a battle against Arabs in Sicily.[129] On the other hand, many Anglo-Danish rebels fleeing William the Conqueror, joined the Byzantines in their struggle against the Robert Guiscard, duke of Apulia, in Southern Italy.[130]

Spain

[edit]

After 842, the Vikings set up a permanent base at the mouth of the river Loire from whence they could strike as far as northern Spain.[131] These Vikings were Hispanicised in all the Christian kingdoms, while they kept their ethnic identity and culture in al-Andalus.[132]

The southern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, both sides of the Strait of Gibraltar, and much of the Iberian peninsula were under Muslim rule when Vikings first entered the Mediterranean in the 9th century. The Vikings launched their campaigns from their strongholds in Francia into this realm of Muslim influence; following the coastline of the Kingdom of Asturias they sailed through the Gibraltar strait (known to them as Nǫrvasund, the 'Narrow Sound') into what they called Miðjarðarhaf, literally 'Middle of the earth' sea,[133] with the same meaning as the Late Latin Mare Mediterrāneum.[134]

The first Viking attacks in al-Andalus in AD 844 greatly affected the region.[135] Medieval texts such as the Chronicon albeldense and the Annales Bertiniani tell of a Viking fleet that left Toulouse and made raids in Asturias and Galicia. According to the Historia silense it had 60 ships. Being repulsed in Galicia (Ghilīsīa), the fleet sailed southward around the peninsula, raiding coastal towns along the way.[136]

In Irene García Losquiño's telling, these Vikings navigated their boats up the river Guadalquivir towards Išbīliya (Seville) and destroyed Qawra (Coria del Río), a small town about 15 km south of the city. Then they took Išbīliya, from which they controlled the region for several weeks.[136] Their attack on the city forced its inhabitants to flee to Qarmūnâ (Carmona), a fortified city. The Emirate of Qurṭuba made great exertions to recover Išbīliya, and succeeded with the assistance of Qurṭuba (Córdoba) and the Banu Qasi, who ruled over a semi-autonomous state in the Upper March of the Ebro Valley.[137] Consequently, defensive walls were built at Išbīliya, and the emir Abd al-Raḥmān II invested in the construction of a large fleet of ships to protect the entrance of the Guadalquivir and the coast of southern al-Andalus, after which Viking fleets had difficulties battling the Andalusī armada.[136]

Gwyn Jones writes that this Viking raid had occurred on 1 October 844, when most of the Iberian peninsula was controlled by the emirate. His account says a flotilla of about 80 Viking ships, after attacking Asturias, Galicia and Lisbon, had ascended the Guadalquivir to Išbīliya, and besieged it for seven days, inflicting many casualties and taking numerous hostages with the intent to ransom them. Another group of Vikings had gone to Qādis (Cádiz) to plunder while those in Išbīliya waited on Qubtil (Isla Menor), an island in the river, for the ransom money to arrive.[138] Meantime, the emir of Qurṭuba, Abd ar-Rahman II, prepared a military contingent to meet them, and on 11 November a pitched battle ensued on the grounds of Talayata (Tablada).[139] The Vikings held their ground, but the results were catastrophic for the invaders, who suffered a thousand casualties; four hundred were captured and executed, some thirty ships were destroyed.[140] It was not a total victory for the emir's forces, but the Viking survivors had to negotiate a peace to leave the area, surrendering their plunder and the hostages they had taken to sell as slaves, in exchange for food and clothing. According to the Arabist Lévi-Provençal, over time, the few Norse survivors converted to Islam and settled as farmers in the area of Qawra, Qarmūnâ, and Moron, where they engaged in animal husbandry and made dairy products (reputedly the origin of Sevillian cheese).[141][142] Knutson and Caitlin write that Lévi-Provençal offered no sources for the proposition of conversion to Islam by northern Europeans in al-Andalus and thus it "remains unsubstantiated".[143]

By the year 859 a large Viking force again invaded al-Andalus, beginning a campaign along the coast of the Iberian Peninsula with smaller groups that assaulted various locations. They attacked Išbīliya (Seville), but were driven off and they returned down the Guadalquivir to the Strait of Gibraltar. The Vikings then sailed round Cape Gata and followed the coastline to the Kūra (cora) of Tudmir, raiding various settlements, as mentioned by the 10th-century historian Ibn Hayyān. They finally ventured inland, entering the mouth of the river Segura and sailing towards ḥiṣn Ūriyūla (Orihuela), whose inhabitants had fled. The assailants sacked this important town, and according to the Arab sources, they attacked the fortress and burnt it to the ground. There is only brief mention in the historical record of this Viking army's attacks on south-eastern al-Andalus, including at al-Jazīra al-Khadrā (Algeciras), Ūriyūla, and the Juzur al-Balyār (جزُر البليار) (Balearic Islands).[136]

Ibn Hayyān wrote about the Viking campaign of 859–861 in al-Andalus, perhaps relying on the account given by Muslim historian Aḥmad al-Rāzī, who tells of a Viking fleet of sixty-two ships that sailed up to Išbīliya and occupied al-Jazīra al-Khadrā. The Muslims seized two of their ships, laden with goods and coins, off the coast of Shidūnah (Sidonia). The ships were destroyed and their Viking crews killed. The remaining vessels continued up the Atlantic coast and landed near (Pampeluna), called Banbalūna in Arabic,[144] where they took their emir Gharsīa ibn Wanaqu (García Iñiquez) prisoner until in 861 he was ransomed for 70,000 dinars.[145]

According to the Annales Bertiniani, Danish Vikings embarked on a long voyage in 859, sailing eastward through the Strait of Gibraltar then up the river Rhône, where they raided monasteries and towns and established a base in the Camargue.[146] Afterwards they raided Nakūr in what is now Morocco, kidnapped women of the royal family, and returned them when the emir of Córdoba paid their ransoms.[147]

The Vikings made several incursions in the years 859, 966 and 971, with intentions more diplomatic than bellicose, although an invasion in 971 was repelled when the Viking fleet was totally annihilated.[148] Vikings attacked Talayata again in 889 at the instigation of Kurayb ibn Khaldun of Išbīliya. In 1015, a Viking fleet entered the river Minho and sacked the episcopal city of Tui Galicia; no new bishop was appointed until 1070.[149]

Portugal

[edit]In 844, a fleet of several dozen Viking longships with square brown sails appeared in the Mar da Palha ("Sea of Straw"), i.e., the mouth of the river Tagus.[21] At the time, the city later called Lisbon was under Muslim rule and known in Arabic as al-Us̲h̲būna or al-ʾIšbūnah (الأشبونة).[150][151] After a thirteen-day siege in which they plundered the surrounding countryside, the Vikings conquered al-Us̲h̲būna, but eventually retreated in the face of continued resistance by the townspeople led by their governor, Wahb Allah ibn Hazm.[152][153][154]

The chronicler Ibn Hayyān, who wrote the most reliable early history of al-Andalus, in his Kitāb almuqtabis, quoted the Muslim historian Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Rāzī:

At the end of the year 229/844, the ships of the Norsemen [ al-Urdumaniyin ], who were known in al-Andalus as majus, appeared off the western coast of al-Andalus, landing at Lisbon, their first point of entry to the forbidden lands. It was a Wednesday, the first day of Dhu al-Hijjah [20 August] in that year, and they remained there thirteen days, during which time they engaged in three battles with the Muslims.[155]

North America

[edit]Greenland

[edit]

The Viking-Age settlements in Greenland were established in the sheltered fjords of the southern and western coast. They settled in three separate areas along roughly 650 km (350 nmi; 400 mi) of the western coast. While harsh, the microclimates along some fjords allowed for a pastoral lifestyle similar to that of Iceland, until the climate changed for the worse with the Little Ice Age c. 1400.[156]

- The Eastern Settlement: The remains of about 450 farms have been found here. Erik the Red settled at Brattahlid on Ericsfjord.

- The Middle Settlement, near modern Ivigtut, consisted of about 20 farms.

- The Western Settlement at modern Godthåbsfjord, was established before the 12th century. It has been extensively excavated by archaeologists.

Mainland North America

[edit]In about 986, the Norwegian Vikings Bjarni Herjólfsson, Leif Ericson, and Þórfinnr Karlsefni from Greenland reached Mainland North America, over 500 years before Christopher Columbus, and they attempted to settle the land they called Vinland. They created a small settlement on the northern peninsula of present-day Newfoundland, near L'Anse aux Meadows. Conflict with indigenous peoples and lack of support from Greenland brought the Vinland colony to an end within a few years. The archaeological remains are now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[157]

Technology

[edit]

The Vikings were among the most advanced of all societies of the time in their naval technology, and were noted in other technological works as well. The Vikings were equipped with the technologically superior longships; for purposes of conducting trade however, another type of ship, the knarr, wider and deeper in draft, were customarily used. The Vikings were competent sailors, adept in land warfare as well as at sea, and they often struck at accessible and poorly defended targets, usually with near impunity. The effectiveness of these tactics earned Vikings a formidable reputation as raiders and pirates.

The Vikings used their longships to travel vast distances and attain certain tactical advantages in battle. They could perform highly efficient hit-and-run attacks, in which they quickly approached a target, then left as rapidly as possible before a counter-offensive could be launched. Because of the ships' negligible draft, the Vikings could sail in shallow waters, allowing them to invade far inland along rivers. The ships were agile, and light enough to be carried over land from one river system to another. "Under sail, the same boats could tackle open water and cross the unexplored wastes of the North Atlantic."[158] The ships' speed was also prodigious for the time, estimated at a maximum of 14–15 knots (26–28 km/h). The use of the longships ended when technology changed, and ships began to be constructed using saws instead of axes, resulting in inferior vessels.

While battles at sea were rare, they would occasionally occur when Viking ships attempted to board European merchant vessels in Scandinavian waters. When larger scale battles ensued, Viking crews would rope together all nearby ships and slowly proceed towards the enemy targets. While advancing, the warriors hurled spears, arrows, and other projectiles at the opponents. When the ships were sufficiently close, melee combat would ensue using axes, swords, and spears until the enemy ship could be easily boarded. The roping technique allowed Viking crews to remain strong in numbers and act as a unit, but this uniformity also created problems. A Viking ship in the line could not retreat or pursue hostiles without breaking the formation and cutting the ropes, which weakened the overall Viking fleet and was a burdensome task to perform in the heat of battle. In general, these tactics enabled Vikings to quickly destroy the meagre opposition posted during raids.[159]

Together with an increasing centralisation of government in the Scandinavian countries, the old system of leidang—a fleet mobilisation system, where every skipreide (ship community) had to maintain one ship and a crew—was discontinued as a purely military institution, as the duty to build and man a ship soon was converted into a tax. The Norwegian leidang was called under Haakon Haakonson for his 1263 expedition to Scotland during the Scottish–Norwegian War, and the last recorded calling of it was in 1603. However, already by the 11th and 12th centuries, perhaps in response to the longships, European fighting ships were built with raised platforms fore and aft, from which archers could shoot down into the relatively low longships. This led to the defeat of longship navies in most subsequent naval engagements—e.g., with the Hanseatic League.

The Vikings were also said to have fine weapons. Generally, Vikings used axes as weapons due to the lessened amount of iron required for their creations; swords were typically seen as a mark of wealth. Spears were also a common weapon among Vikings. Great amounts of time and artistry were expended in the creation of Viking weapons; ornamentation is commonly seen among them.[160] Scandinavian architecture during the Viking Age most often involved wood, due to the abundance of the material. Longhouses, a form of home, often featuring ornamentation, are commonly seen as the defining building of the Viking Age.[161]

Exactly how the Vikings navigated the open seas with such success is unclear. A study published by the Royal Society in its journal, Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical and Physical Sciences, suggests that the Vikings made use of an optical compass as a navigation aid, using the light-splitting and polarisation-filtering properties of Iceland spar to find the location of the sun when it was not directly visible.[162] While some evidence points to such use of calcite "sunstones" to find the sun's location, modern reproductions of Viking "sky-polarimetric" navigation have found these sun compasses to be highly inaccurate, and not usable in cloudy or foggy weather.[163]

The archaeological find known as the Visby lenses from the Swedish island of Gotland may be components of a telescope. It appears to date from long before the invention of the telescope in the 17th century.[164]

Religion

[edit]For most of the Viking Age, Scandinavian society generally followed Norse paganism. The traditions of this faith, including Valhalla and the Æsir, are sometimes cited as a factor in the creation of Viking warrior culture.[165] However, Scandinavia was eventually Christianised towards the later Viking Age, with early centres of Christianity especially in Denmark.

Trade

[edit]

Some of the most important trading ports founded by the Norse during the period include both existing and former cities such as Aarhus (Denmark), Ribe (Denmark), Hedeby (Germany), Vineta (Pomerania), Truso (Poland), Bjørgvin (Norway), Kaupang (Norway), Skiringssal (Norway), Birka (Sweden), Bordeaux (France), York (England), Dublin (Ireland) and Aldeigjuborg (Russia).[166]

As Viking ships carried cargo and trade goods throughout the Baltic area and beyond, their active trading centres grew into thriving towns.[167] One important centre of trade was at Hedeby. Close to the border with the Franks, it was effectively a crossroads between the cultures, until its eventual destruction by the Norwegians in an internecine dispute around 1050. York was the centre of the kingdom of Jórvík from 866, and discoveries there (e.g., a silk cap, a counterfeit of a coin from Samarkand, and a cowry shell from the Red Sea or the Persian Gulf) suggest that Scandinavian trade connections in the 10th century reached beyond Byzantium. However, those items could also have been Byzantine imports, and there is no reason to assume that the Varangians travelled significantly beyond Byzantium and the Caspian Sea.

Торговые маршруты викингов простирались далеко за пределы Скандинавии. Когда скандинавские корабли проникли на юг по рекам Восточной Европы, чтобы приобрести финансовый капитал, они столкнулись с кочевыми народами степи, что привело к началу торговой системы, которая соединила Россию и Скандинавию с северными маршрутами евразийской сети шелковой дороги . [168] During the Middle Ages, the Volga trade route connected Northern Europe and Northwestern Russia with the Caspian Sea, via the Volga River. The international trade routes that enabled the passage of goods by ship from Scandinavia to the east were mentioned in early medieval literature as the Austrrvegr passing through the eastern Baltic region. Ships headed to the river Volga sailed through the Gulf of Finland, while those destined for Byzantium might take one of several routes through present-day north-eastern Poland or the Baltic lands.[ 169 ]

Викинги удовлетворили спрос на рабов на южных рабских рынках в ортодоксальной Восточной Римской империи и мусульманской эмайяд Халифат , оба из которых желали рабы религии, отличной от их собственной. [ 170 ] Торговый маршрут от варанганцев к грекам связал Скандинавию , Киеван Рус и Восточную Римскую империю . Рус был отмечен как торговцы , которые поставляли мед, воск и рабы в Константинополь. [ 171 ] Васанганцы служили наемниками русских князей, тогдашних шведских князей, которые основали и управляли скандинавскими королевствами в Восточной Европе, таких как Киев и Новгород. [ 172 ]

Культура

[ редактировать ]В возрасте викингов многие из самых ранних скандинавских культурных событий. Традиционные исландские саги , до сих пор часто читаются сегодня, рассматриваются как характерные литературные произведения Северной Европы. Старые английские произведения, такие как Беовульф , написанные в традиции германской героической легенды , демонстрируют влияние викингов; В Беовульфе это влияние наблюдается на языке и обстановке стихотворения. Другим примером культурного влияния викинга является старое норвежское влияние на английском языке ; Это влияние является в первую очередь наследием различных вторжений в Англию. [ 173 ]

Женщины в обществе викингов

[ редактировать ]По словам археолога Лива Хельги Доммаснес в 1998 году, хотя археологические источники, относящиеся к изучению роли женщин в Скандинавии, были наиболее многочисленными с возраста викингов по сравнению с другими историческими эрами, не многие археологи воспользовались возможностями, которые они представляли. Она намекает на тот факт, что картина, обычно представленная об обществе викингов в эпоху викингов, была общества мужчин, занимающихся их различными профессиями или должностями, с скудным упоминанием о женщинах и детях, которые также были его частью. [ 174 ]

По ее мнению, учитывая этот основной недостаток в современном образе общества викингов, как следует учитывать знание прошлого. Соответственно, язык является неотъемлемой частью этой организации знаний, и концепции современных языков являются инструментами для понимания реалий прошлого и для организации этого знания, даже если они являются артефактами нашего собственного времени и воспринимаемой реальности. Письменные источники, хотя и скудные, по -видимому, были приоритетными, хотя понятно, что эти письменные источники предвзяты. Почти все они происходят из других культур, так как литература из общества викингов редка. Поскольку он однозначно передает значение в литературном терминах, совершенно ясно, что это значение не происходит от идеологии людей викингов, а скорее от раннего северного христианства. Средневековые исследования Ученый Гро Стейнсленд утверждает, что трансформация из язычника в христианскую религию в обществе викингов была «радикальным разрывом», а не постепенным переходом, и Доммаснес говорит в литературе 12-го или 13-го века. По этой причине изменение культурных ценностей обязательно сильно повлияло на восприятие женщин, особенно гендерных ролей в целом. [ 174 ]

Джудит Джэч , профессор исследований эпохи викингов в Университете Ноттингема , предполагает, что в ее женщинах в эпоху викингов «если историки акцент на викингах как воины невидимым женщинами на заднем плане, то не всегда ясно, где более видимые Женщины -коллеги новых городских викингов взялись ». Она говорит, что невозможно изучить викингов без концепции всего исторического периода, в котором они жили, о культуре, которая их произвела, и других культур, на которые они повлияли. По ее огням, не учитывая, что наполовину половина населения будет смешным. [ 175 ]

Опубликовано в 1991 году, женщины в эпохе викингов разрабатывают тезис Джэша о том, что тексты исландских саг ( íslendingasögur ) являются записями мифологических повествований, сохранившихся в формах, в которых они были написаны антикварными платами 13-го века в Исландии. Их нельзя интерпретировать буквально как «подлинный голос викингов», воплощая в том, что они делают предвзятые представления этих средневековых исландцев. Эти саги, которые ранее считались основанными на реальных исторических традициях, в настоящее время обычно рассматриваются как творческие творения. С их происхождением в устных традициях, в них мало уверенности в их исторической истине, но они выражают то, что они говорят более напрямую, чем «сухие кости археологии» или краткие сообщения о руне. Современный взгляд на эпоху викингов полностью переплетен со знаниями, передаваемыми сагами, и они являются основным источником широкого убеждения, что женщины в эпоху викингов были независимыми, напористыми и обладающими агентством . [ 3 ]

Джез описывает содержание рунических надписей как связывания людей, которые живут в наше время с женщинами эпохи викингов, аналогично археологическим данным, часто рассказывая больше о жизни женщин, чем материал, выявленные в археологических раскопках . Она рассматривает эти надписи как современные доказательства, возникающие в культуре, а не с неполной или предвзятой точки зрения культурного постороннего, и рассматривает большинство из них как повествования в узком смысле, что детали снабжения освещают общую картину, полученную из археологических источников. Они позволяют идентифицировать реальных людей и раскрывать информацию о них, такую как их семейные отношения, их имена и, возможно, факты, касающиеся их индивидуальной жизни. [ 176 ]

Биргит Сойер говорит, что ее книга «Руны-камни викинга» направлены на то, чтобы показать, что корпус рунных камней, рассматриваемый в целом, является плодотворным источником знаний о религиозной, политической, социальной и экономической истории Скандинавии в 10-м и 11-м веках. Используя данные из своей базы данных, она обнаруживает, что Runestones прокладывают свет на узоры урегулирования, коммуникации, родство и обычаи на обычаях, а также эволюцию языка и поэзии. Систематическое исследование материала приводит к ее гипотезе о том, что рунические надписи отражали обычаи наследования, влечет за собой не только земли или товары, но и права, обязательства и ранжирование в обществе. [ 177 ] Хотя женщины в обществе викингов, как и мужчины, имели надгробия над могилами, Рунстоны воспитывались в основном для увековечивания мужчин, причем жизни немногих женщин отмечались Рунстонами (Сойер говорит только 7 процентов), и половина из них была с мужчинами. Поскольку в железном веке в железном веке было гораздо больше процентных центров с богатыми назначениями, сравнительно меньшее количество Runestones, мемориальных женщин, указывает на то, что эта тенденция отражает изменения в обычаях и религии только частично. Большинство из тех, кто удостоен Runestones, были мужчинами, и акцент делался на тех, кто спонсировал памятники. Типичные средневековые могильные памятники называют только умершего, но Runestones Viking Age приоритет спонсорам, в первую очередь; Поэтому они «являются памятниками для жизни так же, как и мертвым ». [ 178 ]

Язык

[ редактировать ]12-го века Исландские законы о серо-гусях ( исландский : Грагас ) утверждают, что шведы, норвежцы, исландцы и датчаны говорили на том же языке, dǫnsk Tunga («датский язык»; спикеры старого восточного норвея сказали бы Данск Тунга ). Другим термином был Норр, не Мал («Северная речь»). Старый норвеж превратился в современные северные германские языки : исландские , фаруэрские , норвежские , датские, датские , шведские и другие северные германские сорта, которые норвежские, датские и шведские сохраняют значительную взаимопонимающуюся разборчивость, в то время как исландский язык остается самым близким к старым норve. В современных школах Исландии могут читать исландские саги 12-го века на исходном языке (в изданиях с нормализованным правописанием). [ 179 ]

Письменные источники старого норвежского эпохи викингов редки: есть рунические камни , но надписи в основном короткие. Большое количество словарного запаса, морфологии и фонологии рунических надписей (мало что известно об их синтаксисе), «может быть показано, что он регулярно развивается в рефлексы викинга, средневековые и современные скандинавские рефлексы »,-говорит Майкл Барнс. [ 180 ]

По словам Дэвида Артера, старый норвеж некоторое время был в эпоху викингов лингва франка, на которой говорилось не только в Скандинавии, но и в судах скандинавских правителей в Ирландии, Шотландии, Англии, Франции и России. Норвежское происхождение некоторых слов, используемых сегодня, очевидно, как и в слове , ссылаясь на холодный морской туман на восточном побережье Шотландии и Англии; [ 181 ] Это происходит от старого норвежского хаарра . [ 182 ]

Старое норвежское влияние на другие языки

[ редактировать ]Долгосрочные лингвистические последствия поселений викингов в Англии были в три раза: более тысячи старых норвежских слов в конечном итоге стали частью стандартного английского языка ; Многочисленные места на востоке и северо-востоке Англии имеют датские имена, и многие английские личные имена имеют скандинавское происхождение. [ 183 ] Скандинавские слова, которые вошли в английский язык, включали в себя посадку, счет, Бек, парень, взрыв, разрушение и управляющий . [ 183 ] Подавляющее большинство ссудных слов не появлялось в документах до начала 12 -го века; Они включали много современных слов, которые использовали SK- звуки, такие как юбка, небо и кожа ; Другие слова, появляющиеся в письменных источниках, включали снова, неловкие, рождение, торт, древа, туман, веснушки, задыхание, закон, мох, шея, разграбление, корень, хмурый взгляд, сестра, сиденье, хитрый, улыбка, желание, слабые и окно от старых норвежских значений «ветровой глаз». [ 183 ] Некоторые из слов, которые вступили в использование, являются одними из самых распространенных на английском языке, например , идти, прийти, сидеть, слушать, есть, оба, то же самое, получить и давать . Система личных местоимений была затронута, с ними, их и их заменой более ранних форм. глагол Старый норвежский повлиял на ; Замена Sindon By является третьего человека почти наверняка скандинавской по происхождению, как и конец-с-сингл- конец в настоящем времени глаголов. [ 183 ]

В Англии насчитывается более 1500 имен скандинавских мест, в основном в Йоркшире и Линкольншире (в рамках прежних границ Данелау ) : более 600 заканчиваются -скандинавским словом «деревня» -например , Гримсби, Насеби и Уитби ; [ 184 ] Многие другие заканчиваются в -торп («ферма»), -то, что («очистка») и -toft («Усадьба»). [ 183 ]

Согласно анализу имен, заканчивающихся в -соном , распределение фамилии, показывающих влияние скандинавского, все еще сосредоточено на севере и востоке, что соответствует районам бывшего поселения викингов. Ранние средневековые записи показывают, что более 60% личных имен в Йоркшире и Северном Линкольншире оказали скандинавское влияние. [ 183 ]

Генетика