Манхэттен

Манхэттен

округ Нью-Йорк | |

|---|---|

Мидтаун Манхэттен в мире , крупнейший центральный деловой район , на переднем плане, Нижний Манхэттен и его финансовый район на заднем плане. | |

| Etymology: Lenape: Manaháhtaan (the place where we get bows) | |

| Nickname: The City | |

Interactive map outlining Manhattan | |

Map of Manhattan in New York | |

Location within New York City | |

| Coordinates: 40°42′46″N 74°00′21″W / 40.7127°N 74.0059°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | New York County (coterminous) |

| City | New York City |

| Settled | 1624 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Borough (New York City) |

| • Borough President | Mark Levine (D) — (Borough of Manhattan) |

| • District Attorney | Alvin Bragg (D) — (New York County) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 33.58 sq mi (87.0 km2) |

| • Land | 22.83 sq mi (59.1 km2) |

| • Water | 10.76 sq mi (27.9 km2) 32% |

| Dimensions —width at 14th Street, widest | |

| • Length | 13 mi (21 km) |

| • Width | 2.3 mi (3.7 km) |

| Highest elevation | 265 ft (81 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,694,250 |

| • Estimate (2022)[3] | 1,596,273 |

| • Density | 74,781.6/sq mi (28,873.3/km2) |

| Demonyms | Manhattanite[4] Knickerbocker (historical) |

| GDP | |

| • Total | US$780.966 billion (2022) · 2nd by U.S. county; 1st per capita |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code format | 100xx, 101xx, 102xx |

| Area code | 212/646/332, 917[a] |

| Website | Manhattan Borough President |

Манхэттен ( / m æ n ˈ h æ t ên , m - ə n / ) — самый густонаселенный и географически самый маленький из пяти районов Нью -Йорка . Манхэттен , совпадающий с округом Нью-Йорк , является самым маленьким по географической площади округом в американском штате Нью -Йорк . Расположенный почти полностью на острове Манхэттен, недалеко от южной оконечности штата, Манхэттен представляет собой центр северо -восточного мегаполиса и городское ядро агломерации Нью-Йорка . [ 6 ] центром Нью-Йорка Манхэттен является экономическим и административным и считается культурной, финансовой, медиа- столицей и столицей развлечений мира. [ 7 ] [ 8 ] [ 9 ] [ 10 ]

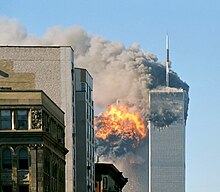

Современный Манхэттен изначально был частью территории Ленапе . [ 11 ] Европейское заселение началось с основания поста торгового голландскими колонистами в 1624 году на юге острова Манхэттен; пост был назван Новым Амстердамом в 1626 году. Территория и ее окрестности перешли под контроль Англии в 1664 году и были переименованы в Нью-Йорк после того, как король Англии Карл II пожаловал земли своему брату, герцогу Йоркскому . [12] New York, based in present-day Lower Manhattan, served as the capital of the United States from 1785 until 1790.[13] The Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor greeted millions of arriving immigrants in the late 19th century and is a world symbol of the United States and its ideals.[14] Manhattan became a borough during the consolidation of New York City in 1898, and houses New York City Hall, the seat of the city's government.[15] The Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, part of the Stonewall National Monument, is considered the birthplace of the modern gay rights movement, cementing Manhattan's central role in LGBT culture.[16][17] Здесь также находился Всемирный торговый центр , разрушенный во время террористических атак 11 сентября .

Situated on one of the world's largest natural harbors, the borough is bounded by the Hudson, East, and Harlem rivers and includes several small adjacent islands, including Roosevelt, U Thant, and Randalls and Wards Islands. It also includes the small neighborhood of Marble Hill now on the U.S. mainland. Manhattan Island is divided into three informally bounded components, each cutting across the borough's long axis: Lower Manhattan, Midtown, and Upper Manhattan. Manhattan is one of the most densely populated locations in the world, with a 2020 census population of 1,694,250 living in a land area of 22.66 square miles (58.69 km2),[3][18] or 72,918 residents per square mile (28,154 residents/km2), and coextensive with New York County, its residential property has the highest sale price per square foot in the United States.[19]

Manhattan is home to the world's two largest stock exchanges by total market capitalization, the New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq.[20] Many multinational media conglomerates are based in Manhattan, as are numerous colleges and universities, such as Columbia University and New York University. The headquarters of the United Nations is located in the Turtle Bay neighborhood of Midtown Manhattan. Manhattan hosts three of the world's top 10 most-visited tourist attractions: Times Square, Central Park, and Grand Central Terminal.[21] Penn Station is the busiest transportation hub in the Western Hemisphere.[22] Chinatown incorporates the highest concentration of Chinese people in the Western Hemisphere.[23] Fifth Avenue is the most expensive shopping street in the world.[24]The borough hosts many prominent bridges and tunnels, and skyscrapers including the Empire State Building, Chrysler Building, and One World Trade Center.[25] It is also home to the National Basketball Association's New York Knicks and the National Hockey League's New York Rangers.

History

[edit]Lenape settlement

[edit]Manhattan was historically part of the Lenapehoking territory inhabited by the Munsee, Lenape,[26] and Wappinger tribes.[27] There were several Lenape settlements in the area including Sapohanikan, Nechtanc, and Konaande Kongh, which were interconnected by a series of trails. The primary trail on the island, which would later become Broadway, ran from what is now Inwood in the north to Battery Park in the south.[28] There were various sites for fishing and planting established by the Lenape throughout Manhattan.[11] The name Manhattan originated from the Lenape's language, Munsee, manaháhtaan (where manah- means "gather", -aht- means "bow", and -aan is an abstract element used to form verb stems). The Lenape word has been translated as "the place where we get bows" or "place for gathering the (wood to make) bows". According to a Munsee tradition recorded by Albert Seqaqkind Anthony in the 19th century, the island was named so for a grove of hickory trees at its southern end that was considered ideal for the making of bows.[29]

Colonial era

[edit]| History of New York City |

|---|

|

Lenape and New Netherland, to 1664 New Amsterdam British and Revolution, 1665–1783 Federal and early American, 1784–1854 Tammany and Consolidation, 1855–1897 (Civil War, 1861–1865) Early 20th century, 1898–1945 Post–World War II, 1946–1977 Modern and post-9/11, 1978–present |

| See also |

|

Transportation Timelines: NYC • Bronx • Brooklyn • Queens • Staten Island Category |

In April 1524, Florentine explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano, sailing in service of Francis I of France, became the first documented European to visit the area that would become New York City.[30] Verrazzano entered the tidal strait now known as The Narrows and named the land around Upper New York Harbor New Angoulême, in reference to the family name of King Francis I; he sailed far enough into the harbor to sight the Hudson River, and he named the Bay of Santa Margarita – what is now Upper New York Bay – after Marguerite de Navarre, the elder sister of the king.[31][32]

Manhattan was first mapped during a 1609 voyage of Henry Hudson.[33] Hudson came across Manhattan Island and the native people living there, and continued up the river that would later bear his name, the Hudson River.[34] Manhattan was first recorded in writing as Manna-hata, in the logbook of Robert Juet, an officer on the voyage.[35]

A permanent European presence in New Netherland began in 1624, with the founding of a Dutch fur trading settlement on Governors Island.[36] In 1625, construction was started on the citadel of Fort Amsterdam on Manhattan Island, later called New Amsterdam (Nieuw Amsterdam), in what is now Lower Manhattan.[37][38] The establishment of Fort Amsterdam is recognized as the birth of New York City.[39] In 1647, Peter Stuyvesant was appointed as the last Dutch Director-General of the colony.[40] New Amsterdam was formally incorporated as a city on February 2, 1653.[41] In 1664, English forces conquered New Netherland and renamed it "New York" after the English Duke of York and Albany, the future King James II.[42] In August 1673, the Dutch reconquered the colony, renaming it "New Orange", but permanently relinquished it back to England the following year under the terms of the Treaty of Westminster that ended the Third Anglo-Dutch War.[43][44]

American Revolution

[edit]

Manhattan was at the heart of the New York Campaign, a series of major battles in the early stages of the American Revolutionary War. The Continental Army was forced to abandon Manhattan after the Battle of Fort Washington on November 16, 1776.[46] The city, greatly damaged by the Great Fire of New York during the campaign, became the British military and political center of operations in North America for the remainder of the war.[47] British occupation lasted until November 25, 1783, when George Washington returned to Manhattan, a day celebrated as Evacuation Day, marking when the last British forces left the city.[48]

From January 11, 1785, until 1789, New York City was the fifth of five capitals of the United States under the Articles of Confederation, with the Continental Congress meeting at New York City Hall (then at Fraunces Tavern).[49] New York was the first capital under the newly enacted Constitution of the United States, from March 4, 1789, to August 12, 1790, at Federal Hall.[50] Federal Hall was where the United States Supreme Court met for the first time,[51] the United States Bill of Rights were drafted and ratified,[52] and where the Northwest Ordinance was adopted, establishing measures for admission to the Union of new states.[53]

19th century

[edit]New York grew as an economic center, first as a result of Alexander Hamilton's policies and practices as the first Secretary of the Treasury to expand the city's role as a center of commerce and industry.[54] By 1810, New York City, then confined to Manhattan, had surpassed Philadelphia as the most populous city in the United States.[55] The Commissioners' Plan of 1811 laid out the island of Manhattan in its familiar grid plan.[56] The city's role as an economic center grew with the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, cutting transportation costs by 90% compared to road transport and connecting the Atlantic port to the vast agricultural markets of the Midwestern United States and Canada.[57][58][59]

Tammany Hall, a Democratic Party political machine, began to grow in influence with the support of many of the immigrant Irish, culminating in the election of the first Tammany mayor, Fernando Wood, in 1854.[60] Covering 840 acres (340 ha) in the center of the island, Central Park, which opened its first portions to the public in 1858, became the first landscaped public park in an American city.[61][62][63][64]

New York City played a complex role in the American Civil War. The city had strong commercial ties to the South, but anger around conscription, resentment against Lincoln's war policies and paranoia about free Blacks taking the jobs of poor immigrants[65] culminated in the three-day-long New York Draft Riots of July 1863, among the worst incidents of civil disorder in American history.[66] The rate of immigration from Europe grew steeply after the Civil War, and Manhattan became the first stop for millions seeking a new life in the United States, a role acknowledged by the dedication of the Statue of Liberty in 1886.[67][68] This immigration brought further social upheaval. In a city of tenements packed with poorly paid laborers from dozens of nations, the city became a hotbed of revolution (including anarchists and communists among others), syndicalism, racketeering, and unionization.[citation needed]

In 1883, the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge across the East River established a road connection to Brooklyn and the rest of Long Island.[69] In 1898, New York City consolidated with three neighboring counties to form "the City of Greater New York", and Manhattan was established as one of the five boroughs of New York City.[70][71] The Bronx remained part of New York County until 1914, when Bronx County was established.[72]

20th century

[edit]

The construction of the New York City Subway, which opened in 1904, helped bind the new city together,[73] as did the completion of the Williamsburg Bridge (1903) and Manhattan Bridge (1909) connecting to Brooklyn and the Queensboro Bridge (1909) connecting to Queens.[74] In the 1920s, Manhattan experienced large arrivals of African-Americans as part of the Great Migration from the southern United States, and the Harlem Renaissance,[75] part of a larger boom time in the Prohibition era that included new skyscrapers competing for the skyline, with the Woolworth Building (1913), 40 Wall Street (1930), Chrysler Building (1930) and the Empire State Building (1931) leapfrogging each other to take their place as the world's tallest building.[76] Manhattan's majority white ethnic group declined from 98.7% in 1900 to 58.3% by 1990.[77] On March 25, 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in Greenwich Village killed 146 garment workers,[78] leading to overhauls of the city's fire department, building codes, and workplace safety regulations.[79] In 1912, about 20,000 workers, a quarter of them women, marched upon Washington Square Park to commemorate the fire. Many of the women wore fitted tucked-front blouses like those manufactured by the company, a clothing style that became the working woman's uniform and a symbol of women's liberation, reflecting the alliance of the labor and suffrage movements.[80]

Despite the Great Depression, some of the world's tallest skyscrapers were completed in Manhattan during the 1930s, including numerous Art Deco masterpieces that are still part of the city's skyline, most notably the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, and 30 Rockefeller Plaza.[81] A postwar economic boom led to the development of huge housing developments targeted at returning veterans, the largest being Stuyvesant Town–Peter Cooper Village, which opened in 1947.[82][83] The United Nations relocated to a new headquarters that was completed in 1952 along the East River.[84][85][86]

The Stonewall riots were a series of spontaneous, violent protests by members of the gay community against a police raid that took place in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Lower Manhattan. They are widely considered to constitute the single most important event leading to the gay liberation movement[87][88] and the modern fight for LGBT rights.[89][90]

In the 1970s, job losses due to industrial restructuring caused New York City, including Manhattan, to suffer from economic problems and rising crime rates.[91] While a resurgence in the financial industry greatly improved the city's economic health in the 1980s, New York's crime rate continued to increase through the decade and into the beginning of the 1990s.[92] The 1980s saw a rebirth of Wall Street, and Manhattan reclaimed its role as the world's financial center, with Wall Street employment doubling from 1977 to 1987.[93] The 1980s also saw Manhattan at the heart of the AIDS crisis, with Greenwich Village at its epicenter.[94]

In the 1970s, Times Square and 42nd Street – with its sex shops, peep shows, and adult theaters, along with its sex trade, street crime, and public drug use – became emblematic of the city's decline, with a 1981 article in Rolling Stone magazine calling the stretch of West 42nd Street between 7th and 8th Avenues the "sleaziest block in America".[95] By the late 1990s, led by efforts by the city and the Walt Disney Company, the area had been revived as a center of tourism to the point where it was described by The New York Times as "arguably the most sought-after 13 acres of commercial property in the world."[96]

By the 1990s, crime rates began to drop dramatically[97][98] and the city once again became the destination of immigrants from around the world, joining with low interest rates and Wall Street bonus payments to fuel the growth of the real estate market.[99] Important new sectors, such as Silicon Alley, emerged in the Flatiron District, cementing technology as a key component of Manhattan's economy.[100]

The 1993 World Trade Center bombing, described by the FBI as "something of a deadly dress rehearsal for 9/11", was a terrorist attack in which six people were killed when a van bomb filled with explosives was detonated in a parking lot below the North Tower of the World Trade Center complex.[101]

21st century

[edit]

On September 11, 2001, the Twin Towers of the original World Trade Center were struck by hijacked aircraft and collapsed in the September 11 attacks launched by al-Qaeda terrorists. The collapse caused extensive damage to surrounding buildings and skyscrapers in Lower Manhattan, and resulted in the deaths of 2,606 of the 17,400 who had been in the buildings when the planes hit, in addition to those on the planes.[102] Since 2001, most of Lower Manhattan has been restored, although there has been controversy surrounding the rebuilding. In 2014, the new One World Trade Center, at 1,776 feet (541 m) measured to the top if its spire, became the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere[103] and is the world's seventh-tallest building (as of 2023).[104]

The Occupy Wall Street protests in Zuccotti Park in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan began on September 17, 2011, receiving global attention and spawning the Occupy movement against social and economic inequality worldwide.[105][106]

On October 29 and 30, 2012, Hurricane Sandy caused extensive destruction in the borough, ravaging portions of Lower Manhattan with record-high storm surge from New York Harbor,[107] severe flooding, and high winds, causing power outages for hundreds of thousands of city residents[108] and leading to gasoline shortages[109] and disruption of mass transit systems.[110][111][112][113] The storm and its profound impacts have prompted discussion of constructing seawalls and other coastal barriers around the shorelines of the borough and the metropolitan area to minimize the risk of destructive consequences from another such event in the future.[114]

On October 31, 2017, a terrorist drove a truck down a bike path alongside the West Side Highway in Lower Manhattan, killing eight.[115]

Geography

[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, New York County has a total area of 33.6 square miles (87 km2), of which 22.8 square miles (59 km2) is land and 10.8 square miles (28 km2) (32%) is water.[1] The northern segment of Upper Manhattan represents a geographic panhandle. Manhattan Island is 22.7 square miles (59 km2) in area, 13.4 miles (21.6 km) long and 2.3 miles (3.7 km) wide, at its widest point, near 14th Street.[116]

The borough consists primarily of Manhattan Island, along with the Marble Hill neighborhood and several small islands, including Randalls Island and Wards Island and Roosevelt Island in the East River; and Governors Island and Liberty Island to the south in New York Harbor.[117]

Manhattan Island

[edit]Manhattan Island is loosely divided into Downtown (Lower Manhattan), Midtown (Midtown Manhattan), and Uptown (Upper Manhattan), with Fifth Avenue dividing Manhattan lengthwise into its East Side and West Side.[118] Manhattan Island is bounded by the Hudson River to the west and the East River to the east. To the north, the Harlem River divides Manhattan Island from the Bronx and the mainland United States. Early in the 19th century, land reclamation was used to expand Lower Manhattan from the natural Hudson shoreline at Greenwich Street to West Street.[119] When building the World Trade Center in 1968, 1.2 million cubic yards (920,000 m3) of material excavated from the site[120] was used to expand the Manhattan shoreline across West Street, creating Battery Park City.[121] Constructed on piers at a cost of $260 million, Little Island opened on the Hudson River in May 2021, connected to the western termini of 13th and 14th Streets by footbridges.[122]

Marble Hill

[edit]Marble Hill was part of the northern tip of Manhattan Island, but the Harlem River Ship Canal, dug in 1895 to better connect the Harlem and Hudson rivers, separated it from the remainder of Manhattan.[123] Before World War I, the section of the original Harlem River channel separating Marble Hill from the Bronx was filled in, and Marble Hill became part of the mainland.[124] After a May 1984 court ruling that Marble Hill was simultaneously part of the Borough of Manhattan (not the Borough of the Bronx) and part of Bronx County (not New York County),[125] the matter was definitively settled later that year when the New York Legislature overwhelmingly passed legislation declaring the neighborhood part of both New York County and the Borough of Manhattan.[126][127]

Smaller islands

[edit]

Within New York Harbor, there are three smaller islands:

- Ellis Island, shared with New Jersey[128]

- Governors Island[129]

- Liberty Island (administered by the National Park Service)[130]

Other smaller islands, in the East River, include (from north to south):

- Randalls and Wards Islands, joined by landfill

- Mill Rock

- Roosevelt Island, which has a population of 14,000, extends for 2 miles (3.2 km), and was renamed in 1973 from Welfare Island to honor President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[131]

- U Thant Island (legally Belmont Island)

Geology

[edit]The bedrock underlying much of Manhattan consists of three rock formations: Inwood marble, Fordham gneiss, and Manhattan schist, and is well suited for the foundations of Manhattan's skyscrapers.[132] It is part of the Manhattan Prong physiographic region.

Adjacent counties

[edit]Climate

[edit]

Under the Köppen climate classification, New York City features both a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) and a humid continental climate (Dfa);[133] it is the northernmost major city on the North American continent with a humid subtropical climate. The city averages 234 days with at least some sunshine annually.[134]

Winters are cold and damp, and prevailing wind patterns that blow offshore temper the moderating effects of the Atlantic Ocean, yet the Atlantic and the partial shielding from colder air by the Appalachians keep the city warmer in the winter than inland North American cities at similar or lesser latitudes. The daily mean temperature in January, the area's coldest month, is 32.6 °F (0.3 °C);[135] temperatures usually drop to 10 °F (−12 °C) several times per winter,[135][136] and reach 60 °F (16 °C) several days in the coldest winter month.[135] Spring and autumn are unpredictable and can range from chilly to warm, although they are usually mild with low humidity. Summers are typically warm to hot and humid, with a daily mean temperature of 76.5 °F (24.7 °C) in July.[135] Nighttime conditions are often exacerbated by the urban heat island phenomenon, which causes heat absorbed during the day to be radiated back at night, raising temperatures by as much as 7 °F (4 °C) when winds are slow.[137] Daytime temperatures exceed 90 °F (32 °C) on average of 17 days each summer[138] and in some years exceed 100 °F (38 °C). Extreme temperatures have ranged from −15 °F (−26 °C), recorded on February 9, 1934, up to 106 °F (41 °C) on July 9, 1936.[138]

Manhattan receives 49.9 inches (1,270 mm) of precipitation annually, which is relatively evenly spread throughout the year. Average winter snowfall between 1981 and 2010 has been 25.8 inches (66 cm); this varies considerably from year to year.[138]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

78 (26) |

86 (30) |

96 (36) |

99 (37) |

101 (38) |

106 (41) |

104 (40) |

102 (39) |

94 (34) |

84 (29) |

75 (24) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 60.4 (15.8) |

60.7 (15.9) |

70.3 (21.3) |

82.9 (28.3) |

88.5 (31.4) |

92.1 (33.4) |

95.7 (35.4) |

93.4 (34.1) |

89.0 (31.7) |

79.7 (26.5) |

70.7 (21.5) |

62.9 (17.2) |

97.0 (36.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 39.5 (4.2) |

42.2 (5.7) |

49.9 (9.9) |

61.8 (16.6) |

71.4 (21.9) |

79.7 (26.5) |

84.9 (29.4) |

83.3 (28.5) |

76.2 (24.6) |

64.5 (18.1) |

54.0 (12.2) |

44.3 (6.8) |

62.6 (17.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 33.7 (0.9) |

35.9 (2.2) |

42.8 (6.0) |

53.7 (12.1) |

63.2 (17.3) |

72.0 (22.2) |

77.5 (25.3) |

76.1 (24.5) |

69.2 (20.7) |

57.9 (14.4) |

48.0 (8.9) |

39.1 (3.9) |

55.8 (13.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 27.9 (−2.3) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

35.8 (2.1) |

45.5 (7.5) |

55.0 (12.8) |

64.4 (18.0) |

70.1 (21.2) |

68.9 (20.5) |

62.3 (16.8) |

51.4 (10.8) |

42.0 (5.6) |

33.8 (1.0) |

48.9 (9.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 9.8 (−12.3) |

12.7 (−10.7) |

19.7 (−6.8) |

32.8 (0.4) |

43.9 (6.6) |

52.7 (11.5) |

61.8 (16.6) |

60.3 (15.7) |

50.2 (10.1) |

38.4 (3.6) |

27.7 (−2.4) |

18.0 (−7.8) |

7.7 (−13.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −6 (−21) |

−15 (−26) |

3 (−16) |

12 (−11) |

32 (0) |

44 (7) |

52 (11) |

50 (10) |

39 (4) |

28 (−2) |

5 (−15) |

−13 (−25) |

−15 (−26) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.64 (92) |

3.19 (81) |

4.29 (109) |

4.09 (104) |

3.96 (101) |

4.54 (115) |

4.60 (117) |

4.56 (116) |

4.31 (109) |

4.38 (111) |

3.58 (91) |

4.38 (111) |

49.52 (1,258) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 8.8 (22) |

10.1 (26) |

5.0 (13) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.5 (1.3) |

4.9 (12) |

29.8 (76) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.8 | 10.0 | 11.1 | 11.4 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 10.5 | 10.0 | 8.8 | 9.5 | 9.2 | 11.4 | 125.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.7 | 3.2 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 2.1 | 11.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 61.5 | 60.2 | 58.5 | 55.3 | 62.7 | 65.2 | 64.2 | 66.0 | 67.8 | 65.6 | 64.6 | 64.1 | 63.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 162.7 | 163.1 | 212.5 | 225.6 | 256.6 | 257.3 | 268.2 | 268.2 | 219.3 | 211.2 | 151.0 | 139.0 | 2,534.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 54 | 55 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 59 | 63 | 59 | 61 | 51 | 48 | 57 |

| Source 1: NOAA[138][135][134] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas[140] | |||||||||||||

Neighborhoods

[edit]

Manhattan's many neighborhoods are not named according to any particular convention, nor do they have official boundaries. Some are geographical (the Upper East Side), or ethnically descriptive (Little Italy). Others are acronyms, such as TriBeCa (for "TRIangle BElow CAnal Street") or SoHo ("SOuth of HOuston"), NoLIta ("NOrth of Little ITAly"), and NoMad ("NOrth of MADison Square Park").[141][142][143][144][145] Harlem is a name from the Dutch colonial era after Haarlem, a city in the Netherlands.[146] Some have simple folkloric names, such as Hell's Kitchen, alongside their more official but lesser used title (in this case, Clinton).[147]

Some neighborhoods, such as SoHo, which is mixed use, are known for upscale shopping as well as residential use.[148] Others, such as Greenwich Village, the Lower East Side, Alphabet City and the East Village, have long been associated with the Bohemian subculture.[149][150][151] Chelsea is one of several Manhattan neighborhoods with large gay populations and has become a center of both the international art industry and New York's nightlife.[152] Chinatown has the highest concentration of people of Chinese descent outside of Asia.[153][154] Koreatown is roughly centered on 32nd Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues.[155] Rose Hill features a growing number of Indian restaurants and spice shops along a stretch of Lexington Avenue between 25th and 30th Streets which has become known as Curry Hill.[156] Washington Heights in Uptown Manhattan is home to the largest Dominican immigrant community in the United States.[157] Harlem, also in Upper Manhattan, is the historical epicenter of African American culture.[158] Since 2010, a Little Australia has emerged and is growing in Nolita, Lower Manhattan.[159]

Manhattan has two central business districts, the Financial District at the southern tip of the island, and Midtown Manhattan. The term uptown also refers to the northern part of Manhattan above 72nd Street and downtown to the southern portion below 14th Street,[160] with Midtown covering the area in between, though definitions can be fluid. Fifth Avenue roughly bisects Manhattan Island and acts as the demarcation line for east/west designations.[160][161] South of Waverly Place, Fifth Avenue terminates and Broadway becomes the east/west demarcation line.[citation needed] In Manhattan, uptown means north and downtown means south.[162] This usage differs from that of most American cities, where downtown refers to the central business district.

Boroughscape

[edit]Demographics

[edit]

As of the 2020 census, Manhattan's population had increased by 6.8% over the decade to 1,694,250, representing 19.2% of New York City's population of 8,804,194 and 8.4% of New York State's population of 20,201,230.[3] The population density of New York County was 70,450.8 inhabitants per square mile (27,201.2/km2) in 2022, the highest population density of any county in the United States and higher than the density of any individual U.S. city.[163][164] At the 2010 census, there were 1,585,873 people living in Manhattan, an increase of 3.2% from the 1,537,195 counted in the 2000 census.[165]

| Racial composition | 2020[167] | 2010[168] | 2000[169] | 1990[77] | 1950[77] | 1900[77] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 50.0% | 57.4% | 54.3% | 58.3% | 79.4% | 97.8% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 46.8% | 48% | 45.7% | 48.9% | n/a | n/a |

| Black or African American | 13.5% | 15.6% | 17.3% | 22.0% | 19.6% | 2.0% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 23.8% | 25.4% | 27.1% | 26.0% | n/a | n/a |

| Asian | 13.1% | 11.3% | 9.4% | 7.4% | 0.8% | 0.3% |

Religion

[edit]In 2010, the largest organized religious group in Manhattan was the Archdiocese of New York, with 323,325 Catholics worshiping at 109 parishes, followed by 64,000 Orthodox Jews with 77 congregations, an estimated 42,545 Muslims with 21 congregations, 42,502 non-denominational adherents with 54 congregations, 26,178 TEC Episcopalians with 46 congregations, 25,048 ABC-USA Baptists with 41 congregations, 24,536 Reform Jews with 10 congregations, 23,982 Mahayana Buddhists with 35 congregations, 10,503 PC-USA Presbyterians with 30 congregations, and 10,268 RCA Presbyterians with 10 congregations. Altogether, 44.0% of the population was claimed as members by religious congregations, although members of historically African-American denominations were underrepresented due to incomplete information.[170] In 2014, Manhattan had 703 religious organizations, the seventeenth most out of all US counties.[171] There is a large Buddhist temple in Manhattan located at the foot of the Manhattan Bridge in Chinatown.[172]

Languages

[edit]As of 2015, 60.0% (927,650) of Manhattan residents, aged five and older, spoke only English at home, while 22.63% (350,112) spoke Spanish, 5.37% (83,013) Chinese, 2.21% (34,246) French, 0.85% (13,138) Korean, 0.72% (11,135) Russian, and 0.70% (10,766) Japanese. In total, 40.0% of Manhattan's population, aged five and older, spoke a language other than English at home.[173]

Landmarks and architecture

[edit]Points of interest on Manhattan Island include the American Museum of Natural History; the Battery; Broadway and the Theater District; Bryant Park; Central Park, Chinatown; the Chrysler Building; The Cloisters; Columbia University; Curry Hill; the Empire State Building; Flatiron Building; the Financial District (including the New York Stock Exchange Building; Wall Street; and the South Street Seaport); Grand Central Terminal; Greenwich Village (including New York University; Washington Square Arch; and Stonewall Inn); Harlem and Spanish Harlem; the High Line; Koreatown; Lincoln Center; Little Australia; Little Italy; Madison Square Garden; Museum Mile on Fifth Avenue (including the Metropolitan Museum of Art); Penn Station, Port Authority Bus Terminal; Rockefeller Center (including Radio City Music Hall); Times Square; and the World Trade Center (including the National September 11 Museum and One World Trade Center).

There are also numerous iconic bridges across rivers that connect to Manhattan Island, as well as an emerging number of supertall skyscrapers. The Statue of Liberty rests on Liberty Island, an exclave of Manhattan, and part of Ellis Island is also an exclave of Manhattan. The borough has many energy-efficient office buildings, such as the Hearst Tower, the rebuilt 7 World Trade Center,[174] and the Bank of America Tower—the first skyscraper designed to attain a Platinum LEED Certification.[175][176]

The skyscraper, which has shaped Manhattan's distinctive skyline, has been closely associated with New York City's identity since the end of the 19th century.[177] Structures such as the Equitable Building of 1915, which rises vertically forty stories from the sidewalk, prompted the passage of the 1916 Zoning Resolution, requiring new buildings to contain setbacks withdrawing progressively at a defined angle from the street as they rose, in order to preserve a view of the sky at street level.[178] Manhattan's skyline includes several buildings that are symbolic of New York, in particular the Chrysler Building[179]: 14 and the Empire State Building, which sees about 4 million visitors a year.[180]

In 1961, the struggling Pennsylvania Railroad unveiled plans to tear down the old Penn Station and replace it with a new Madison Square Garden and office building complex.[181] Organized protests were aimed at preserving the McKim, Mead & White-designed structure completed in 1910, widely considered a masterpiece of the Beaux-Arts style and one of the architectural jewels of New York City.[182] Despite these efforts, demolition of the structure began in October 1963.[183] The loss of Penn Station led directly to the enactment in 1965 of a local law establishing the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, which is responsible for preserving the "city's historic, aesthetic, and cultural heritage".[184] The historic preservation movement triggered by Penn Station's demise has been credited with the retention of some one million structures nationwide, including over 1,000 in New York City.[185] In 2017, a multibillion-dollar rebuilding plan was unveiled to restore the historic grandeur of Penn Station, in the process of upgrading the landmark's status as a critical transportation hub.[186]

The 700,000 sq ft (65,000 m2) Moynihan Train Hall, developed as a $1.6 billion renovation and expansion of Penn Station into the James A. Farley Building, the city's former main post office building, was opened in January 2021.[187]

National protected areas

[edit]- African Burial Ground National Monument

- Castle Clinton National Monument

- Federal Hall National Memorial

- General Grant National Memorial

- Governors Island National Monument

- Hamilton Grange National Memorial

- Lower East Side Tenement National Historic Site

- Statue of Liberty National Monument (part)

- Theodore Roosevelt Birthplace National Historic Site

Parkland

[edit]

Parkland covers a total of 2,659 acres (10.76 km2), accounting for 18.2% of the borough's land area; the 840-acre (3.4 km2) Central Park is the borough's largest park, comprising 31.6% of Manhattan's parkland.[188] Designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, the park is anchored by the 12-acre (4.9 ha) Great Lawn[189] and offers extensive walking tracks, two ice-skating rinks, a wildlife sanctuary, and several lawns and sporting areas, as well as 21 playgrounds,[190] and a 6-mile (9.7 km) road from which automobile traffic has been banned since 2018.[191] While much of the park looks natural, it is almost entirely landscaped; the construction of Central Park in the 1850s was one of the era's most massive public works projects, with some 20,000 workers moving 5 million cubic yards (3.8 million cubic meters) of material to shape the topography and create the English-style pastoral landscape that Olmsted and Vaux sought.[192]

The remaining 70% of Manhattan's parkland includes 204 playgrounds, 251 Greenstreets, 371 basketball courts, and many other amenities.[193] The next-largest park in Manhattan, the Hudson River Park, stretches 4.5 miles (7.2 km) along the Hudson River and comprises 550 acres (220 ha).[194] Other major parks include:[188]

- Bowling Green

- Bryant Park

- City Hall Park

- DeWitt Clinton Park

- East River Greenway

- Fort Tryon Park

- Fort Washington Park

- Harlem River Park

- Rucker Park

- Imagination Playground

- Inwood Hill Park

- Isham Park

- J. Hood Wright Park

- Jackie Robinson Park

- Madison Square Park

- Marcus Garvey Park

- Morningside Park

- Randall's Island Park

- Riverside Park

- Sara D. Roosevelt Park

- Seward Park

- St. Nicholas Park

- Stuyvesant Square

- The Battery

- The High Line

- Thomas Jefferson Park

- Tompkins Square Park

- Union Square Park

- Washington Square Park

Economy

[edit]

Manhattan is the economic engine of New York City, with its 2.45 million workers drawn from the entire New York metropolitan area accounting for almost more than half of all jobs in New York City.[195] Manhattan's workforce is overwhelmingly focused on white collar professions. In 2010, Manhattan's daytime population was swelling to 3.94 million, with commuters adding a net 1.48 million people to the population, along with visitors, tourists, and commuting students. The commuter influx of 1.61 million workers coming into Manhattan was the largest of any county or city in the country.[196]

Manhattan had the highest per capita income, at $186,848 in 2022, among United States counties with more than 50,000 residents.[197] Based on census data for New York County for 2018–2022, the median household income was $99,880 and the poverty rate was 17.2%.[3] In the second quarter of 2023, Manhattan had an average weekly wage of $2,590, ranked fourth-highest among the nation's 360 largest counties.[195] Data for 2022 from the Census Bureau showed growing inequality, with those in the top 20% having an average household income of $545,549, more than 50 times higher than the $10,529 average income in the lowest 20% of households, the largest gap of any county in the country and "larger ... than in many developing countries",[198][199] with inequality growing steadily since 2010.[200] As of 2023[update], Manhattan's cost of living was the highest in the United States.[201]

Financial sector

[edit]

Manhattan's most important economic sector lies in its role as the headquarters for the U.S. financial industry, metonymously known as Wall Street. Manhattan is home to the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), at 11 Wall Street in Lower Manhattan, and the Nasdaq, now located at 4 Times Square in Midtown Manhattan, representing the world's largest and second-largest stock exchanges, respectively, when measured both by overall share trading value and by total market capitalization of their listed companies in 2023.[20] The NYSE American (formerly the American Stock Exchange, AMEX), New York Board of Trade, and the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) are also located downtown.

Corporate sector

[edit]New York City is home to the most corporate headquarters of any city in the United States, the overwhelming majority based in Manhattan.[202] Manhattan had more than 520 million square feet (48 million square meters) of office space in 2022,[203] making it the largest office market in the United States; while Midtown Manhattan, with more than 400 million square feet (37 million square meters) is the largest central business district in the world.[204] Lower Manhattan is the third-largest U.S. central business district (following the Chicago Loop).[205][206] New York City's role as the top global center for the advertising industry is metonymously known as "Madison Avenue".[207]

Tech and biotech

[edit]

Manhattan has driven New York's status as a top-tier global high technology hub.[209][210] Silicon Alley, once a metonym for the sphere encompassing the metropolitan region's high tech industries,[211] is no longer a relevant moniker as the city's tech environment has expanded dramatically both in location and in its scope. New York City's current tech sphere encompasses a universal array of applications involving artificial intelligence, the internet, new media, financial technology (fintech) and cryptocurrency, biotechnology, game design, and other fields within information technology that are supported by its entrepreneurship ecosystem and venture capital investments. As of 2014[update], New York City hosted 300,000 employees in the tech sector.[212][213] In 2015, Silicon Alley generated over US$7.3 billion in venture capital investment,[214] most based in Manhattan, as well as in Brooklyn, Queens, and elsewhere in the region. High technology startup companies and employment are growing in Manhattan and across New York City, bolstered by the city's emergence as a global node of creativity and entrepreneurship,[214] social tolerance,[215] and environmental sustainability,[216][217] as well as New York's position as the leading Internet hub and telecommunications center in North America, including its vicinity to several transatlantic fiber optic trunk lines, the city's intellectual capital, and its extensive outdoor wireless connectivity.[218] Verizon Communications, headquartered at 140 West Street in Lower Manhattan, was at the final stages in 2014 of completing a US$3 billion fiberoptic telecommunications upgrade throughout New York City.[219]

The biotechnology sector is also growing in Manhattan based upon the city's strength in academic scientific research and public and commercial financial support. By mid-2014, Accelerator, a biotech investment firm, had raised more than US$30 million from investors, including Eli Lilly and Company, Pfizer, and Johnson & Johnson, for initial funding to create biotechnology startups at the Alexandria Center for Life Science, which encompasses more than 700,000 square feet (65,000 m2) on East 29th Street and promotes collaboration among scientists and entrepreneurs at the center and with nearby academic, medical, and research institutions. The New York City Economic Development Corporation's Early Stage Life Sciences Funding Initiative and venture capital partners, including Celgene, General Electric Ventures, and Eli Lilly, committed a minimum of US$100 million to help launch 15 to 20 ventures in life sciences and biotechnology.[220] In 2011, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg had announced his choice of Cornell University and Technion-Israel Institute of Technology to build a US$2 billion graduate school of applied sciences on Roosevelt Island, Manhattan, with the goal of transforming New York City into the world's premier technology capital.[221][222][needs update]

Tourism

[edit]

Tourism is vital to Manhattan's economy, and the landmarks of Manhattan are the focus of New York City's tourists, with a record 66.6 million visiting the city in 2019, bringing in $47.4 billion in tourism revenue. Visitor numbers dropped by two-thirds in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, climbing back to 63.3 million visitors in 2023.[223][224]

According to The Broadway League, shows on Broadway sold approximately US$1.54 billion worth of tickets in the 2022–2023 and the 2023–2024 seasons with attendance of approximately 12.3 million each.[225]

Real estate

[edit]Real estate is a major force driving Manhattan's economy. Manhattan has perennially been home to some of the world's most valuable real estate, including the Time Warner Center, which had the highest-listed market value in the city in 2006 at US$1.1 billion,[226] to be subsequently surpassed in October 2014 by the Waldorf Astoria New York, which became the most expensive hotel ever sold after being purchased by the Anbang Insurance Group, based in China, for US$1.95 billion.[227] When 450 Park Avenue was sold on July 2, 2007, for US$510 million, about US$1,589 per square foot (US$17,104/m²), it broke the barely month-old record for an American office building of US$1,476 per square foot (US$15,887/m²) based on the sale of 660 Madison Avenue.[228] In 2014, Manhattan was home to six of the top ten zip codes in the United States by median housing price.[229] In 2019, the most expensive home sale ever in the United States occurred in Manhattan, at a selling price of US$238 million, for a 24,000-square-foot (2,200 m2) penthouse apartment overlooking Central Park,[230] while Central Park Tower, topped out at 1,550 feet (472 m) in 2019, is the world's tallest residential building, followed globally in height by 111 West 57th Street and 432 Park Avenue, both also located in Midtown Manhattan.

Media

[edit]Manhattan has been described as the media capital of the world.[231][232] A significant array of media outlets and their journalists report about international, American, business, entertainment, and New York metropolitan area–related matters from Manhattan.

Manhattan is served by the major New York City daily news publications, including The New York Times, which has won the most Pulitzer Prizes for journalism[233] and is considered the U.S. media's newspaper of record;[234] the New York Daily News; and the New York Post, which are all headquartered in the borough. The nation's largest newspaper by circulation, The Wall Street Journal, is also based in Manhattan.[235] Other daily newspapers include AM New York and The Villager. The New York Amsterdam News, based in Harlem, is one of the leading Black-owned weekly newspapers in the United States. The Village Voice, historically the largest alternative newspaper in the United States, announced in 2017 that it would cease publication of its print edition and convert to a fully digital venture.[236]

The television industry developed in Manhattan and is a significant employer in the borough's economy. The four major American broadcast networks, ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox,[237] as well as Univision, are all headquartered in Manhattan, as are many cable channels, including CNN, MSNBC, MTV, Fox News, HBO, and Comedy Central. In 1971, WLIB became New York City's first Black-owned radio station[238] and began broadcasts geared toward the African-American community in 1949.[239] WQHT, also known as Hot 97, claims to be the premier hip-hop station in the United States.[240] WNYC, broadcasting on both an AM and FM signal, has the largest public radio audience in the nation and is the most-listened to commercial or non-commercial radio station in Manhattan.[241] WBAI, owned by the non-profit Pacifica Foundation, broadcasts eclectic music, as well as political news, talk and opinion from a left-leaning viewpoint.[242]

The oldest public-access television cable TV channel in the United States is the Manhattan Neighborhood Network, founded in 1971, offers eclectic local programming that ranges from a jazz hour to discussions of labor issues to foreign language and religious programming.[243] NY1, Charter Communications's local news channel, is known for its beat coverage of City Hall and state politics.[244]

Education

[edit]

Education in Manhattan is provided by a vast number of public and private institutions. Non-charter public schools in the borough are operated by the New York City Department of Education,[247] the largest public school system in the United States. Charter schools include Success Academy Harlem 1 through 5, Success Academy Upper West, and Public Prep.

Several notable New York City public high schools are located in Manhattan, including A. Philip Randolph Campus High School, Beacon High School, Stuyvesant High School, Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School, High School of Fashion Industries, Eleanor Roosevelt High School, NYC Lab School, Manhattan Center for Science and Mathematics, Hunter College High School, and High School for Math, Science and Engineering at City College. Bard High School Early College, a hybrid school created by Bard College, serves students from around the city.

Many private preparatory schools are also situated in Manhattan, including the Upper East Side's Brearley School, Dalton School, Browning School, Spence School, Chapin School, Nightingale-Bamford School, Convent of the Sacred Heart, Hewitt School, Saint David's School, Loyola School, and Regis High School. The Upper West Side is home to the Collegiate School and Trinity School. The borough is also home to Manhattan Country School, Trevor Day School, Xavier High School and the United Nations International School.

Based on data from the 2011–2015 American Community Survey, 59.9% of Manhattan residents over age 25 have a bachelor's degree.[248] As of 2005, about 60% of residents were college graduates and some 25% had earned advanced degrees, giving Manhattan one of the nation's densest concentrations of highly educated people.[249]

Manhattan has various colleges and universities, including Columbia University (and its affiliate Barnard College), Cooper Union, Marymount Manhattan College, New York Institute of Technology, New York University (NYU), The Juilliard School, Pace University, Berkeley College, The New School, Yeshiva University, and a campus of Fordham University. Other schools include Bank Street College of Education, Boricua College, Jewish Theological Seminary of America, Manhattan School of Music, Metropolitan College of New York, Parsons School of Design, School of Visual Arts, Touro College, and Union Theological Seminary. Several other private institutions maintain a Manhattan presence, among them Mercy College, St. John's University, Adelphi University, The King's College, and Pratt Institute. Cornell Tech, part of Cornell University, is developing on Roosevelt Island.

The City University of New York (CUNY), the municipal college system of New York City, is the largest urban university system in the United States, serving more than 226,000 degree students and a roughly equal number of adult, continuing and professional education students.[250] A third of college graduates in New York City graduate from CUNY, with the institution enrolling about half of all college students in New York City. CUNY senior colleges located in Manhattan include: Baruch College, City College of New York, Hunter College, John Jay College of Criminal Justice and William E. Macaulay Honors College; graduate studies and doctorate-granting institutions are Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York, CUNY Graduate Center, CUNY Graduate School of Public Health & Health Policy, CUNY School of Labor and Urban Studies and CUNY School of Professional Studies.[251][252] The only CUNY community college located in Manhattan is the Borough of Manhattan Community College.[253] The State University of New York is represented by the Fashion Institute of Technology, State University of New York State College of Optometry, and Stony Brook University – Manhattan.[254]

Manhattan is a world center for training and education in medicine and the life sciences.[255] The city as a whole receives the second-highest amount of annual funding from the National Institutes of Health among all U.S. cities,[256] the bulk of which goes to Manhattan's research institutions, including Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Rockefeller University, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Weill Cornell Medical College, and New York University School of Medicine.

Manhattan is served by the New York Public Library, which has the largest collection of any public library system in the country.[257] The five units of the Central Library—Mid-Manhattan Library, 53rd Street Library, the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Andrew Heiskell Braille and Talking Book Library, and the Science, Industry and Business Library—are all located in Manhattan.[258] More than 35 other branch libraries are located in the borough.[259]

Culture

[edit]This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (August 2024) |

Manhattan is the borough most closely associated with New York City by non-residents; residents within the New York City metropolitan area, including New York City's boroughs outside Manhattan, will often describe a trip to Manhattan as "going to the City".[260] Poet Walt Whitman characterized the streets of Manhattan as being traversed by "hurrying, feverish, electric crowds".[261]

Manhattan has been the scene of many important global and American cultural movements. The Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s established the African-American literary canon in the United States and introduced writers Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. Manhattan's visual art scene in the 1950s and 1960s was a center of the pop art movement, which gave birth to such giants as Jasper Johns and Roy Lichtenstein. The downtown pop art movement of the late 1970s included artist Andy Warhol and clubs like Serendipity 3 and Studio 54, where he socialized.

Broadway theatre is considered the highest professional form of theatre in the United States. Plays and musicals are staged in one of the 39 larger professional theatres with at least 500 seats, almost all in and around Times Square. Off-Broadway theatres feature productions in venues with 100–500 seats.[262][263] Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, anchoring Lincoln Square on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, is home to 12 influential arts organizations, including the Metropolitan Opera, New York Philharmonic, and New York City Ballet, as well as the Vivian Beaumont Theater, the Juilliard School, Jazz at Lincoln Center, and Alice Tully Hall. Performance artists displaying diverse skills are ubiquitous on the streets of Manhattan.

Manhattan is also home to some of the most extensive art collections in the world, both contemporary and classical art, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), the Frick Collection, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Guggenheim Museum. The Upper East Side has many art galleries,[264][265] and the downtown neighborhood of Chelsea is known for its more than 200 art galleries that are home to modern art from both upcoming and established artists.[266][267] Many of the world's most lucrative art auctions are held in Manhattan.[268][269]

Manhattan is the epicenter of LGBT culture and the central node of the LGBTQ+ sociopolitical ecosystem.[272] The borough is widely acclaimed as the cradle of the modern LGBTQ rights movement, with its inception at the 1969 Stonewall Riots.[88][273][274][89][275] Brian Silverman, the author of Frommer's New York City from $90 a Day, wrote the city has "one of the world's largest, loudest, and most powerful LGBT communities", and "Gay and lesbian culture is as much a part of New York's basic identity as yellow cabs, high-rise buildings, and Broadway theatre"—[276] radiating from this central hub, as LGBT travel guide Queer in the World states, "The fabulosity of Gay New York is unrivaled on Earth, and queer culture seeps into every corner of its five boroughs".[277] Multiple gay villages have developed, spanning the length of the borough from the Lower East Side, East Village, and Greenwich Village, through Chelsea and Hell's Kitchen, uptown to Morningside Heights.

The annual NYC Pride March (or gay pride parade) traverses southward down Fifth Avenue and ends at Greenwich Village; the Manhattan parade is the largest pride parade in the world, attracting tens of thousands of participants and millions of sidewalk spectators each June.[270][271] Stonewall 50 – WorldPride NYC 2019 was the largest international Pride celebration in history, produced by Heritage of Pride. The events were in partnership with the I ❤ NY program's LGBT division, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, with 150,000 participants and five million spectators attending in Manhattan.[278]

The borough is represented in several prominent idioms. The phrase New York minute is meant to convey an extremely short time such as an instant,[279] sometimes in hyperbolic form, as in "perhaps faster than you would believe is possible," referring to the rapid pace of life in Manhattan.[280][281] The expression "melting pot" was first popularly coined to describe the densely populated immigrant neighborhoods on the Lower East Side in Israel Zangwill's play The Melting Pot, which was an adaptation of William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet set in New York City in 1908.[282] The iconic Flatiron Building is said to have been the source of the phrase "23 skidoo" or scram, from what cops would shout at men who tried to get glimpses of women's dresses being blown up by the winds created by the triangular building.[283] The "Big Apple" dates back to the 1920s, when a reporter heard the term used by New Orleans stable-hands to refer to New York City's horse racetracks and named his racing column "Around The Big Apple". Jazz musicians adopted the term to refer to the city as the world's jazz capital, and a 1970s ad campaign by the New York Convention and Visitors Bureau helped popularize the term.[284]

Manhattan is well known for its street parades, which celebrate a broad array of themes, including holidays, nationalities, human rights, and major league sports team championship victories. The majority of higher profile parades in New York City are held in Manhattan. The primary orientation of the annual street parades is typically from north to south, marching along major avenues. The annual Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade is the world's largest parade,[285] beginning alongside Central Park and processing southward to the flagship Macy's Herald Square store;[288] the parade is viewed on telecasts worldwide and draws millions of spectators in person.[285]

Other notable parades including the world's oldest St. Patrick's Day Parade, held annually in March since 1762,[289][290] the Greenwich Village Halloween Parade in October,[291] and numerous parades commemorating the independence days of many nations.[292] Ticker-tape parades celebrating sporting championships won as well as other national accomplishments march northward on Broadway from Bowling Green to City Hall Park in Lower Manhattan, along the Canyon of Heroes.[293] New York Fashion Week, held at various locations in Manhattan, is a high-profile semiannual event featuring models displaying the latest wardrobes created by prominent fashion designers worldwide in advance of these fashions proceeding to the retail marketplace.

Sports

[edit]

Manhattan is home to the NBA's New York Knicks and the NHL's New York Rangers, both of which play their home games at Madison Square Garden, the only major professional sports arena in the borough.[294] The Garden was also home to the WNBA's New York Liberty through the 2017 season, but that team's primary home is now the Barclays Center in Brooklyn. The New York Jets proposed a West Side Stadium for their home field, but the proposal was defeated in June 2005, and they now play at MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey.[295]

Manhattan does not currently host a professional baseball franchise. The original New York Giants played primarily in the various incarnations of the Polo Grounds from their inception in 1883 until they headed to California with the Brooklyn Dodgers after the 1957 season.[296] The New York Yankees began their franchise as the Highlanders, named for Hilltop Park, where they played from their creation in 1903 until 1912.[297] The team moved to the Polo Grounds with the 1913 season, where they were officially christened the New York Yankees, remaining there until they moved across the Harlem River in 1923 to Yankee Stadium.[298] The New York Mets played in the Polo Grounds in 1962 and 1963, their first two seasons, before Shea Stadium was completed in 1964.[299] After the Mets departed, the Polo Grounds was demolished in April 1964.[300][301]

The first national college-level basketball championship, the National Invitation Tournament, was held in New York in 1938 and remains in the city.[302] The New York Knicks started play in 1946 as one of the National Basketball Association's original teams, playing their first home games at the 69th Regiment Armory, before making Madison Square Garden their permanent home.[303] The New York Liberty of the WNBA shared the Garden with the Knicks from their creation in 1997 as one of the league's original eight teams through the 2017 season,[304] after which the team moved nearly all of its home schedule to White Plains, New York.[305] Rucker Park in Harlem is a playground court, famed for its streetball style of play, where many NBA athletes have played in the summer league.[306]

Although both of New York City's football teams play today in MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey, both teams started out playing in the Polo Grounds. The New York Giants played side-by-side with their baseball namesakes from the time they entered the National Football League in 1925, until crossing over to Yankee Stadium in 1956.[307] The New York Jets, originally known as the Titans of New York, started out in 1960 at the Polo Grounds, before joining the Mets in Queens at Shea Stadium in 1964.[308]

The New York Rangers of the National Hockey League have played in the various locations of Madison Square Garden since the team's founding in the 1926–1927 season. The Rangers were predated by the New York Americans, who started play in the Garden the previous season, lasting until the team folded after the 1941–1942 NHL season, a season it played in the Garden as the Brooklyn Americans.[309]

The New York Cosmos of the North American Soccer League played their home games at Downing Stadium for two seasons, starting in 1974. The playing pitch and facilities at Downing Stadium were in unsatisfactory condition, however, and as the team's popularity grew they too left for Yankee Stadium, and then Giants Stadium. The stadium was demolished in 2002 to make way for the $45 million, 4,754-seat Icahn Stadium.[310][311]

Government

[edit]

Since New York City's consolidation in 1898, Manhattan has been governed by the New York City Charter; its 1989 revision provided for a strong mayor–council system.[312] The centralized New York City government is responsible for public education, correctional institutions, libraries, public safety, recreational facilities, sanitation, water supply, and welfare services in Manhattan.

The office of Borough President was created in the consolidation of 1898 to balance centralization with local authority. Each borough president had a powerful administrative role derived from having a vote on the New York City Board of Estimate, which was responsible for creating and approving the city's budget and proposals for land use. In 1989, the US Supreme Court declared the Board of Estimate unconstitutional because Brooklyn, the most populous borough, had no greater effective representation on the Board than Staten Island, the least populous borough, a violation of the Equal Protection Clause.[313] Since 1990, the largely powerless Borough President has acted as an advocate for the borough at the mayoral agencies, the City Council, the New York state government, and corporations.[citation needed] Manhattan's current Borough President is Mark Levine, elected as a Democrat in November 2021.

Alvin Bragg, a Democrat, is the District Attorney of New York County. Manhattan has ten City Council members, the third largest contingent among the five boroughs. It also has twelve administrative districts, each served by a local Community Board. Community Boards are representative bodies that field complaints and serve as advocates for local residents.

As the host of the United Nations, the borough is home to the world's largest international consular corps, comprising 105 consulates, consulates general and honorary consulates.[314] It is also the home of New York City Hall, the seat of New York City government housing the Mayor of New York City and the New York City Council. The mayor's staff and thirteen municipal agencies are located in the nearby Manhattan Municipal Building, completed in 1914, one of the largest governmental buildings in the world.[315]

Politics

[edit]

| Year | Republican / Whig | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 85,185 | 12.21% | 603,040 | 86.42% | 9,588 | 1.37% |

| 2016 | 64,930 | 9.71% | 579,013 | 86.56% | 24,997 | 3.74% |

| 2012 | 89,559 | 14.92% | 502,674 | 83.74% | 8,058 | 1.34% |

| 2008 | 89,949 | 13.47% | 572,370 | 85.70% | 5,566 | 0.83% |

| 2004 | 107,405 | 16.73% | 526,765 | 82.06% | 7,781 | 1.21% |

| 2000 | 82,113 | 14.38% | 454,523 | 79.60% | 34,370 | 6.02% |

| 1996 | 67,839 | 13.76% | 394,131 | 79.96% | 30,929 | 6.27% |

| 1992 | 84,501 | 15.88% | 416,142 | 78.20% | 31,475 | 5.92% |

| 1988 | 115,927 | 22.89% | 385,675 | 76.14% | 4,949 | 0.98% |

| 1984 | 144,281 | 27.39% | 379,521 | 72.06% | 2,869 | 0.54% |

| 1980 | 115,911 | 26.23% | 275,742 | 62.40% | 50,245 | 11.37% |

| 1976 | 117,702 | 25.54% | 337,438 | 73.22% | 5,698 | 1.24% |

| 1972 | 178,515 | 33.38% | 354,326 | 66.25% | 2,022 | 0.38% |

| 1968 | 135,458 | 25.59% | 370,806 | 70.04% | 23,128 | 4.37% |

| 1964 | 120,125 | 19.20% | 503,848 | 80.52% | 1,746 | 0.28% |

| 1960 | 217,271 | 34.19% | 414,902 | 65.28% | 3,394 | 0.53% |

| 1956 | 300,004 | 44.26% | 377,856 | 55.74% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1952 | 300,284 | 39.30% | 446,727 | 58.47% | 16,974 | 2.22% |

| 1948 | 241,752 | 32.75% | 380,310 | 51.51% | 116,208 | 15.74% |

| 1944 | 258,650 | 33.47% | 509,263 | 65.90% | 4,864 | 0.63% |

| 1940 | 292,480 | 37.59% | 478,153 | 61.45% | 7,466 | 0.96% |

| 1936 | 174,299 | 24.51% | 517,134 | 72.71% | 19,820 | 2.79% |

| 1932 | 157,014 | 27.78% | 378,077 | 66.89% | 30,114 | 5.33% |

| 1928 | 186,396 | 35.74% | 317,227 | 60.82% | 17,935 | 3.44% |

| 1924 | 190,871 | 41.20% | 183,249 | 39.55% | 89,206 | 19.25% |

| 1920 | 275,013 | 59.22% | 135,249 | 29.12% | 54,158 | 11.66% |

| 1916 | 113,254 | 42.65% | 139,547 | 52.55% | 12,759 | 4.80% |

| 1912 | 63,107 | 18.15% | 166,157 | 47.79% | 118,391 | 34.05% |

| 1908 | 154,958 | 44.71% | 160,261 | 46.24% | 31,393 | 9.06% |

| 1904 | 155,003 | 42.11% | 189,712 | 51.54% | 23,357 | 6.35% |

| 1900 | 153,001 | 44.16% | 181,786 | 52.47% | 11,700 | 3.38% |

| 1896 | 156,359 | 50.73% | 135,624 | 44.00% | 16,249 | 5.27% |

| 1892 | 98,967 | 34.73% | 175,267 | 61.50% | 10,750 | 3.77% |

| 1888 | 106,922 | 39.20% | 162,735 | 59.67% | 3,076 | 1.13% |

| 1884 | 90,095 | 39.54% | 133,222 | 58.47% | 4,530 | 1.99% |

| 1880 | 81,730 | 39.79% | 123,015 | 59.90% | 636 | 0.31% |

| 1876 | 58,561 | 34.17% | 112,530 | 65.66% | 289 | 0.17% |

| 1872 | 54,676 | 41.27% | 77,814 | 58.73% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1868 | 47,738 | 30.59% | 108,316 | 69.41% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1864 | 36,681 | 33.23% | 73,709 | 66.77% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1860 | 33,290 | 34.83% | 62,293 | 65.17% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1856 | 17,771 | 22.32% | 41,913 | 52.65% | 19,922 | 25.03% |

| 1852 | 23,124 | 39.98% | 34,280 | 59.27% | 436 | 0.75% |

| 1848 | 29,070 | 54.51% | 18,973 | 35.57% | 5,290 | 9.92% |

| 1844 | 26,385 | 48.15% | 28,296 | 51.64% | 117 | 0.21% |

| 1840 | 20,958 | 48.69% | 21,936 | 50.96% | 153 | 0.36% |

| 1836 | 16,348 | 48.42% | 17,417 | 51.58% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1832 | 12,506 | 40.97% | 18,020 | 59.03% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1828 | 9,638 | 38.44% | 15,435 | 61.56% | 0 | 0.00% |

The Democratic Party holds most public offices. Registered Republicans are a minority in the borough, constituting 9.88% of the electorate as of April 2016[update]. Registered Republicans are more than 20% of the electorate only in the neighborhoods of the Upper East Side and the Financial District as of 2016[update]. Democrats accounted for 68.41% of those registered to vote, while 17.94% of voters were unaffiliated.[319][320]

As of 2023, three Democrats represented Manhattan in the United States House of Representatives.[321]

- Dan Goldman (first elected in 2022) represents New York's 10th congressional district, which includes Lower Manhattan, as well as a portion of Brooklyn.

- Jerry Nadler (first elected in 1992) represents New York's 12th congressional district, which includes the Upper West Side, Upper East Side, and Midtown Manhattan.

- Adriano Espaillat (first elected in 2016) represents New York's 13th congressional district, which includes the Upper Manhattan, as well as part of the northwest Bronx.

Federal offices

[edit]The United States Postal Service operates post offices in Manhattan. The James Farley Post Office in Midtown Manhattan is New York City's main post office.[322] Both the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York and United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit are located in Lower Manhattan's Foley Square, and the U.S. Attorney and other federal offices and agencies maintain locations in that area.

Crime and public safety

[edit]Starting in the mid-19th century, the United States became a magnet for immigrants seeking to escape poverty in their home countries. After arriving in New York, many new arrivals ended up living in squalor in the slums of the Five Points neighborhood, an area between Broadway and the Bowery, northeast of New York City Hall. By the 1820s, the area was home to many gambling dens and brothels, and was known as a dangerous place to go. In 1842, Charles Dickens visited the area and was appalled at the horrendous living conditions he had seen.[323] The predominantly Irish Five Points Gang was one of the country's first major organized crime entities.

As Italian immigration grew in the early 20th century many joined ethnic gangs, including Al Capone, who got his start in crime with the Five Points Gang.[324] The Mafia (also known as Cosa Nostra) first developed in the mid-19th century in Sicily and spread to the US East Coast during the late 19th century following waves of Sicilian and Southern Italian emigration. Lucky Luciano established Cosa Nostra in Manhattan, forming alliances with other criminal enterprises, including the Jewish mob, led by Meyer Lansky, the leading Jewish gangster of that period.[325] From 1920 to 1933, Prohibition helped create a thriving black market in liquor, upon which the Mafia was quick to capitalize.[325]

New York City as a whole experienced a sharp increase in crime during the post-war period.[326] The murder rate in Manhattan hit an all-time high of 42 murders per 100,000 residents in 1979.[327] Manhattan retained the highest murder rate in the city until 1985 when it was surpassed by the Bronx.[327] Most serious violent crime has been historically concentrated in Upper Manhattan and the Lower East Side, though robbery in particular was a major quality of life concern throughout the borough. Through the 1990s and 2000s, levels of violent crime in Manhattan plummeted to levels not seen since the 1950s,[328] with murders in Manhattan dropping from 503 in 1990, at the citywide peak, to 78 in 2022, a decline of 84%.[329]

Today crime rates in most of Lower Manhattan, Midtown, the Upper East Side, and the Upper West Side are consistent with other major city centers in the United States. However, crime rates remain high in the Upper Manhattan neighborhoods of East Harlem, Harlem, Washington Heights, Inwood, and New York City Housing Authority developments across the borough, despite significant reductions. After the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, there had been an increase in violent crime, particularly in Upper Manhattan.[330] Mirroring a nationwide trend, rates of shootings and violent crimes in 2023 declined from their peaks during the pandemic.[331][332][333]

Housing

[edit]

The rise of immigration near the turn of the 20th century left major portions of Manhattan, especially the Lower East Side, densely packed with recent arrivals, crammed into unhealthy and unsanitary housing. Tenements were usually five stories high, constructed on the then-typical 25 by 100 feet (7.6 by 30.5 m) lots, with "cockroach landlords" exploiting the new immigrants.[334][335] By 1929, a new housing code effectively ended construction of tenements, though some survive today on the East Side of the borough.[335] Conversely, there were also areas with luxury apartment developments, the first of which was the Dakota on the Upper West Side.[336]

Manhattan offers a wide array of private housing, as well as public housing, which is administered by the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). Affordable rental and co-operative housing units throughout the borough were created under the Mitchell–Lama Housing Program.[337] There were 923,302 housing units in 2022[3] at an average density of 40,745 units per square mile (15,732/km2). As of 2003[update], only 24.3% of Manhattan residents lived in owner-occupied housing, the second-lowest rate of all counties in the nation, after the Bronx.[338] Public housing administered by NYCHA accounts for nearly 100,000 residents in more than 50,000 units in 2023.[339] Completed in 1935, the First Houses in the East Village were one of the country's first publicly-funded low-income housing projects.[340][341] At $2,024 in 2022, Manhattan has the highest average cost for rent of any county in the US, although a lower percentage of annual income than in several other American cities.[342]

Manhattan's real estate market for luxury housing continues to be among the most expensive in the world,[343] and Manhattan residential property continues to have the highest sale price per square foot in the United States.[19] Manhattan's apartments cost $1,773 per square foot ($19,080/m2), compared to San Francisco housing at $1,185 per square foot ($12,760/m2), Boston housing at $751 per square foot ($8,080/m2), and Los Angeles housing at $451 per square foot ($4,850/m2).[344] As of the fourth quarter of 2021, the median value of homes in Manhattan was $1,306,208, second highest among US counties.[345]

Infrastructure

[edit]Transportation

[edit]This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (August 2023) |

Public transportation

[edit]

Manhattan is unique in the U.S. for intense use of public transportation and lack of private car ownership. While 88% of Americans nationwide drive to their jobs, with only 5% using public transport, mass transit is the dominant form of travel for residents of Manhattan, with 72% of borough residents using public transport to get to work, while only 18% drove.[346][347] According to the 2000 United States Census, 77.5% of Manhattan households do not own a car.[348] In 2008, Mayor Michael Bloomberg proposed a congestion pricing system to regulate entering Manhattan south of 60th Street, but the state legislature rejected the proposal.[349]

The New York City Subway, the largest subway system in the world by number of stations, is the primary means of travel within the city, linking every borough except Staten Island. There are 151 subway stations in Manhattan, out of the 472 stations.[350] A second subway, the PATH system, connects six stations in Manhattan to northern New Jersey. Passengers pay fares with pay-per-ride MetroCards, which are valid on all city buses and subways, as well as on PATH trains.[351][352] Commuter rail services operating to and from Manhattan are the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR), which connects Manhattan and other New York City boroughs to Long Island; the Metro-North Railroad, which connects Manhattan to Upstate New York and Southwestern Connecticut; and NJ Transit trains, which run to various points in New Jersey.

The US$11.1 billion East Side Access project, which brings LIRR trains to Grand Central Terminal, opened in 2023; this project utilized a pre-existing train tunnel beneath the East River, connecting the East Side of Manhattan with Long Island City, Queens.[353][354] Four multi-billion-dollar projects were completed in the mid-2010s: the $1.4 billion Fulton Center in November 2014,[355] the $2.4 billion 7 Subway Extension in September 2015,[356] the $4 billion World Trade Center Transportation Hub in March 2016,[357][358] and Phase 1 of the $4.5 billion Second Avenue Subway in January 2017.[359][360]

MTA New York City Transit offers a wide variety of local buses within Manhattan under the brand New York City Bus. An extensive network of express bus routes serves commuters and other travelers heading into Manhattan.[361] The bus system served 784 million passengers citywide in 2011, placing the bus system's ridership as the highest in the nation, and more than double the ridership of the second-place Los Angeles system.[362]

The Roosevelt Island Tramway, one of two commuter cable car systems in North America, takes commuters between Roosevelt Island and Manhattan in less than five minutes, and has been serving the island since 1978.[363][364]