Перформанс

Перформанс — это произведение искусства или художественная выставка, созданная в результате действий художника или других участников. Его можно наблюдать вживую или через документацию, спонтанно разработанную или написанную, и он традиционно представляется публике в контексте изобразительного искусства в междисциплинарном режиме. [1] Также известный как художественное действие , он с годами развивался как отдельный жанр, в котором искусство представлено вживую. Он сыграл важную и фундаментальную роль в авангардном искусстве 20-го века . [2] [3]

Он включает в себя пять основных элементов: время, пространство, тело и присутствие художника, а также отношения между творцом и публикой. Действия, обычно разворачивающиеся в художественных галереях и музеях, могут происходить на улице, в любой обстановке и пространстве и в любой период времени. [4] Его цель — вызвать реакцию, иногда при поддержке импровизации и чувства эстетики. Темы обычно связаны с жизненным опытом самого художника, потребностью в разоблачении или социальной критике, а также с духом трансформации. [5]

The term "performance art" and "performance" became widely used in the 1970s, even though the history of performance in visual arts dates back to futurist productions and cabarets from the 1910s.[6][1] Art critic and performance artist John Perreault credits Marjorie Strider with the invention of the term in 1969.[7] The main pioneers of performance art include Carolee Schneemann,[8] Marina Abramović,[9] Ana Mendieta,[10] Chris Burden,[11] Hermann Nitsch, Joseph Beuys, Nam June Paik, Tehching Hsieh, Yves Klein and Vito Acconci.[12] Some of the main exponents more recently are Tania Bruguera,[13] Abel Azcona,[14] Regina José Galindo,[15] Marta Minujín,[16] Melati Suryodarmo and Petr Pavlensky. The discipline is linked to the happenings and "events" of the Fluxus movement, Viennese Actionism, body art and conceptual art.[17]

Definition[edit]

The definition and historical and pedagogical contextualization of performance art is controversial. One of the handicaps comes from the term itself, which is polysemic, and one of its meanings relates to the scenic arts. This meaning of performance in the scenic arts context is opposite to the meaning of performance art, since performance art emerged with a critical and antagonistic position towards scenic arts. Performance art only adjoins the scenic arts in certain aspects such as the audience and the present body, and still not every performance art piece contains these elements.[19]

The meaning of the term in the narrower sense is related to postmodernist traditions in Western culture. From about the mid-1960s into the 1970s, often derived from concepts of visual art, with respect to Antonin Artaud, Dada, the Situationists, Fluxus, installation art, and conceptual art, performance art tended to be defined as an antithesis to theatre, challenging orthodox art forms and cultural norms. The ideal had been an ephemeral and authentic experience for performer and audience in an event that could not be repeated, captured or purchased.[20] The widely discussed difference, how concepts of visual arts and concepts of performing arts are used, can determine the meanings of a performance art presentation.[19]

Performance art is a term usually reserved to refer to a conceptual art which conveys a content-based meaning in a more drama-related sense, rather than being simple performance for its own sake for entertainment purposes. It largely refers to a performance presented to an audience, but which does not seek to present a conventional theatrical play or a formal linear narrative, or which alternately does not seek to depict a set of fictitious characters in formal scripted interactions. It therefore can include action or spoken word as a communication between the artist and audience, or even ignore expectations of an audience, rather than following a script written beforehand.

Some types of performance art nevertheless can be close to performing arts. Such performance may use a script or create a fictitious dramatic setting, but still constitute performance art in that it does not seek to follow the usual dramatic norm of creating a fictitious setting with a linear script which follows conventional real-world dynamics; rather, it would intentionally seek to satirize or to transcend the usual real-world dynamics which are used in conventional theatrical plays.

Performance artists often challenge the audience to think in new and unconventional ways, break conventions of traditional arts, and break down conventional ideas about "what art is". As long as the performer does not become a player who repeats a role, performance art can include satirical elements; use robots and machines as performers, as in pieces of the Survival Research Laboratories; involve ritualised elements (e.g. Shaun Caton); or borrow elements of any performing arts such as dance, music, and circus. It can also involve intersection with architecture.

Some artists, e.g. the Viennese Actionists and neo-Dadaists, prefer to use the terms "live art", "action art", "actions", "intervention" (see art intervention) or "manoeuvre" to describe their performing activities. As genres of performance art appear body art, fluxus-performance, happening, action poetry, and intermedia.

Origins[edit]

Performance art is a form of expression that was born as an alternative artistic manifestation. The discipline emerged in 1916 parallel to dadaism, under the umbrella of conceptual art. The movement was led by Tristan Tzara, one of the pioneers of Dada. Western culture theorists have set the origins of performance art in the beginnings of the 20th century, along with constructivism, Futurism and Dadaism. Dada was an important inspiration because of their poetry actions, which drifted apart from conventionalisms, and futurist artists, specially some members of Russian futurism, could also be identified as part of the starting process of performance art.[21][22]

Cabaret Voltaire[edit]

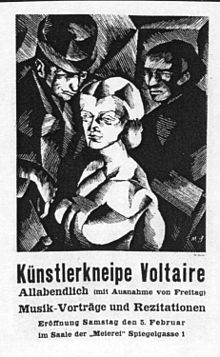

The Cabaret Voltaire was founded in Zürich, Switzerland by the couple Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings for artistic and political purposes, and was a place where new tendencies were explored. Located on the upper floor of a theater, whose exhibitions they mocked in their shows, the works interpreted in the cabaret were avant garde and experimental. It is thought that the Dada movement was founded in the ten-meter-square locale.[23][24] Moreover, Surrealists, whose movement descended directly from Dadaism, used to meet in the Cabaret. On its brief existence—barely six months, closing the summer of 1916—the Dadaist Manifesto was read and it held the first Dada actions, performances, and hybrid poetry, plastic art, music and repetitive action presentations. Founders such as Richard Huelsenbeck, Marcel Janco, Tristan Tzara, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Jean Arp participated in provocative and scandalous events that were fundamental and the basis of the foundation for the anarchist movement called Dada.[25]

Dadaism was born with the intention of destroying any system or established norm in the art world.[27] It is an anti-art movement, anti-literary and anti-poetry, that questioned the existence of art, literature and poetry itself. Not only was it a way of creating, but of living; it created a whole new ideology.[28] It was against eternal beauty, the eternity of principles, the laws of logic, the immobility of thought and clearly against anything universal. It promoted change, spontaneity, immediacy, contradiction, randomness and the defense of chaos against the order and imperfection against perfection, ideas similar to those of performance art. They stood for provocation, anti-art protest and scandal, through ways of expression many times satirical and ironic. The absurd or lack of value and the chaos protagonized[clarification needed] their breaking actions with traditional artistic form.[27][28][29][30]

Cabaret Voltaire closed in 1916, but was revived in the 21st century.

Futurism[edit]

Futurism was an artistic avant garde movement that appeared in 1909. It first started as a literary movement, even though most of the participants were painters. In the beginning it also included sculpture, photography, music and cinema. The First World War put an end to the movement, even though in Italy it went on until the 1930s. One of the countries where it had the most impact was Russia.[31] In 1912 manifestos such as the Futurist Sculpture Manifesto and the Futurist Architecture arose, and in 1913 the Manifesto of Futurist Lust by Valentine de Saint-Point, dancer, writer and French artist. The futurists spread their theories through encounters, meetings and conferences in public spaces, that got close to the idea of a political concentration, with poetry and music-halls, which anticipated performance art.[31][32][33]

Bauhaus[edit]

The Bauhaus, an art school founded in Weimar in 1919, included an experimental performing arts workshops with the goal of exploring the relationship between the body, space, sound and light. The Black Mountain College, founded in the United States by instructors of the original Bauhaus who were exiled by the Nazi Party, continued incorporating experimental performing arts in the scenic arts training twenty years before the events related to the history of performance in the 1960s.[34] The name Bauhaus derives from the German words Bau, construction and Haus, house; ironically, despite its name and the fact that his founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department the first years of its existence.[35][36]

Action painting[edit]

In the 1940s and 1950s, the action painting technique or movement gave artists the possibility of interpreting the canvas as an area to act in, rendering the paintings as traces of the artist's performance in the studio [37] According to art critic Harold Rosenberg, it was one of the initiating processes of performance art, along with abstract expressionism. Jackson Pollock is the action painter par excellence, who carried out many of his actions live.[38] In Europe Yves Klein did his Anthropométries using (female) bodies to paint canvasses as a public action. Names to be highlighted are Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline, whose work include abstract and action painting.[37][39][40]

Nouveau réalisme[edit]

Nouveau réalisme is another one of the artistic movements cited in the beginnings of performance art. It was a painting movement founded in 1960 by art critic Pierre Restany and painter Yves Klein, during the first collective exhibition in the Apollinaire Gallery in Milan. Nouveau réalisme was, along with Fluxus and other groups, one of the many avant garde tendencies of the 1960s. Pierre Restany created various performance art assemblies in the Tate Modern, amongst other spaces.[41] Yves Klein is one of the main exponents of the movement. He was a clear pioneer of performance art, with his conceptual pieces like Zone de Sensibilité Picturale Immatérielle (1959–62), Anthropométries (1960), and the photomontage Saut dans le vide.[42][43] All his works have a connection with performance art, as they are created as a live action, like his best-known artworks of paintings created with the bodies of women. The members of the group saw the world as an image, from which they took parts and incorporated them into their work; they sought to bring life and art closer together.[44][45][46]

Gutai[edit]

One of the other movements that anticipated performance art was the Japanese movement Gutai, who made action art or happening. It emerged in 1955 in the region of Kansai (Kyōto, Ōsaka, Kōbe). The main participants were Jirō Yoshihara, Sadamasa Motonaga, Shozo Shimamoto, Saburō Murakami, Katsuō Shiraga, Seichi Sato, Akira Ganayama and Atsuko Tanaka.[47] The Gutai group arose after World War II. They rejected capitalist consumerism, carrying out ironic actions with latent aggressiveness (object breaking, actions with smoke). They influenced groups such as Fluxus and artists like Joseph Beuys and Wolf Vostell.[47][48][49]

Land art and performance[edit]

In the late 1960s, diverse land art artists such as Robert Smithson or Dennis Oppenheim created environmental pieces that preceded performance art in the 1970s. Works by conceptual artists from the early 1980s, such as Sol LeWitt, who made mural drawing into a performance act, were influenced by Yves Klein and other land art artists.[50][51][52] Land art is a contemporary art movement in which the landscape and the artwork are deeply bound. It uses nature as a material (wood, soil, rocks, sand, wind, fire, water, etc.) to intervene on itself. The artwork is generated with the place itself as a starting point. The result is sometimes a junction between sculpture and architecture, and sometimes a junction between sculpture and landscaping that is increasingly taking a more determinant role in contemporary public spaces. When incorporating the artist's body in the creative process, it acquires similarities with the beginnings of performance art.

- Portrait of Valentine de Saint-Point in the space of creation

- Intervened cover by Russian Futurist Olga Rozanova (1912)

- Portrait of Willem de Kooning, action painting painter in his studio

- Installation by Gutai Group, in the 2009 Venice Biennial

- Installation by Dennis Oppenheim in Hesse, Germany

- Land art work by Robert Smithson

- Portrait of Pierre Restany in one of his openings

- Freeing of 1001 blue balloons, "sculpture aérostatique" by Yves Klein

1960s[edit]

In the 1960s, with the purpose of evolving the generalized idea of art and with similar principles of those originary from Cabaret Voltaire or Futurism, a variety of new works, concepts and a growing number of artists led to new kinds of performance art. Movements clearly differentiated from Viennese Actionism, avant garde performance art in New York City, process art, the evolution of The Living Theatre or happening, but most of all the consolidation of the pioneers of performance art.[53]

Viennese actionism[edit]

The term Viennese Actionism (Wiener Aktionismus) comprehends a brief and controversial art movement of the 20th century, which is remembered for the violence, grotesque and visual of their artworks.[54] It is located in the Austrian vanguard of the 1960s, and it had the goal of bringing art to the ground of performance art, and is linked to Fluxus and Body Art. Amongst their main exponents are Günter Brus, Otto Muehl and Hermann Nitsch, who developed most of their actionist activities between 1960 and 1971. Hermann, pioneer of performance art, presented in 1962 his Theatre of Orgies and Mysteries (Orgien und Mysterien Theater).[55][56][57] Marina Abramović participated as a performer in one of his performances in 1975.

New York and avant-garde performance[edit]

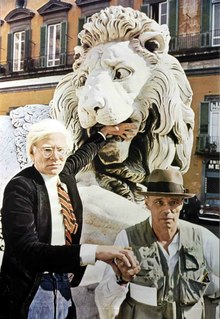

In the early 1960s, New York City harbored many movements, events and interests regarding performance art. Amongst others, Andy Warhol began creating films and videos,[58] and mid decade he sponsored The Velvet Underground and staged events and performative actions in New York, such as the Exploding Plastic Inevitable (1966), that included live rock music, explosive lights and films.[59][60][61][62]

The Living Theatre[edit]

Indirectly influential for art-world performance, particularly in the United States, were new forms of theatre, embodied by the San Francisco Mime Troupe and the Living Theatre and showcased in Off-Off Broadway theaters in SoHO and at La MaMa in New York City. The Living Theatre is a theater company created in 1947 in New York. It is the oldest experimental theatre in the United States.[63] Throughout its history it has been led by its founders: actress Judith Malina, who had studied theatre with Erwin Piscator, with whom she studied Bertolt Brecht's and Meyerhold's theory; and painter and poet Julian Beck. After Beck's death in 1985, the company member Hanon Reznikov became co-director along with Malina. Because it is one of the oldest random theatre or live theatre groups nowadays, it is looked upon by the rest.[clarification needed] They understood theatre as a way of life, and the actors lived in a community under libertary[clarification needed] principles. It was a theatre campaign dedicated to transformation of the power organization of an authoritarian society and hierarchical structure. The Living Theatre chiefly toured in Europe between 1963 and 1968, and in the U.S. in 1968. A work of this period, Paradise Now, was notorious for its audience participation and a scene in which actors recited a list of social taboos that included nudity, while disrobing.[64]

Fluxus[edit]

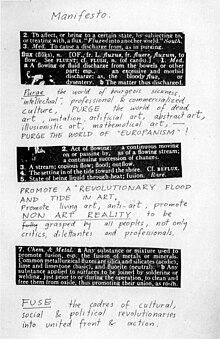

Fluxus, a Latin word that means flow, is a visual arts movement related to music, literature, and dance. Its most active moment was in the 1960s and 1970s. They proclaimed themselves against the traditional artistic object as a commodity and declared themselves a sociological art movement. Fluxus was informally organized in 1962 by George Maciunas (1931–1978). This movement had representation in Europe, the United States and Japan.[65] The Fluxus movement, mostly developed in North America and Europe under the stimulus of John Cage, did not see the avant-garde as a linguistic renovation, but it sought to make a different use of the main art channels that separate themselves from specific language; it tries to be interdisciplinary and to adopt mediums and materials from different fields. Language is not the goal, but the mean for a renovation of art, seen as a global art.[66] As well as Dada, Fluxus escaped any attempt for a definition or categorization. As one of the movement's founders, Dick Higgins, stated:

Fluxus started with the work, and then came together, applying the name Fluxus to work which already existed. It was as if it started in the middle of the situation, rather than at the beginning.[67][68]

Robert Filliou places Fluxus opposite to conceptual art for its direct, immediate and urgent reference to everyday life, and turns around Duchamp's proposal, who starting from Ready-made, introduced the daily into art, whereas Fluxus dissolved art into the daily, many times with small actions or performances.[69]

John Cage was an American composer, music theorist, artist, and philosopher. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading figures of the post-war avant-garde. Critics have lauded him as one of the most influential composers of the 20th century.[70][71][72][73] He was also instrumental in the development of modern dance, mostly through his association with choreographer Merce Cunningham, who was also Cage's romantic partner for most of their lives.[74][75]

Cage's friend Sari Dienes can be seen as an important link between the Abstract Expressionists, Neo-Dada artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Ray Johnson, and Fluxus. Dienes inspired all these artists to blur the lines between life, Zen, performative art-making techniques and "events," in both pre-meditated and spontaneous ways.[76]

Process art[edit]

Process art is an artistic movement where the end product of art and craft, the objet d’art (work of art/found object), is not the principal focus; the process of its making is one of the most relevant aspects if not the most important one: the gathering, sorting, collating, associating, patterning, and moreover the initiation of actions and proceedings. Process artists saw art as pure human expression. Process art defends the idea that the process of creating the work of art can be an art piece itself. Artist Robert Morris predicated "anti-form", process and time over an objectual finished product.[77][78][79]

Happening[edit]

Wardrip-Fruin and Montfort in The New Media Reader, "The term 'Happening' has been used to describe many performances and events, organized by Allan Kaprow and others during the 1950s and 1960s, including a number of theatrical productions that were traditionally scripted and invited only limited audience interaction."[80] A happening allows the artist to experiment with the movement of the body, recorded sounds, written and talked texts, and even smells. One of Kaprow's first works was Happenings in the New York Scene, written in 1961.[81] Allan Kaprow's happenings turned the public into interpreters. Often the spectators became an active part of the act without realizing it. Other actors who created happenings were Jim Dine, Al Hansen, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Whitman and Wolf Vostell: Theater is in the Street (Paris, 1958).[82][83]

Main artists[edit]

The works by performance artists after 1968 showed many times influences from the political and cultural situation that year. Barbara T. Smith with Ritual Meal (1969) was at the vanguard of body and scenic feminist art in the seventies, which included, amongst others, Carolee Schneemann and Joan Jonas. These, along with Yoko Ono, Joseph Beuys, Nam June Paik, Wolf Vostell, Allan Kaprow, Vito Acconci, Chris Burden and Dennis Oppenheim were pioneers in the relationship between body art and performance art, as well as the Zaj collective in Spain with Esther Ferrer and Juan Hidalgo.

Barbara Smith is an artist and United States activist. She is one of the main African-American exponents of feminism and LGBT activism in the United States. In the beginning of the 1970s she worked as a teacher, writer and defender of the black feminism current.[84] She has taught at numerous colleges and universities in the last five years. Smith's essays, reviews, articles, short stories and literary criticism have appeared in a range of publications, including The New York Times, The Guardian, The Village Voice and The Nation.[85][86][87]

Carolee Schneemann[88] was an American visual experimental artist, known for her multi-media works on the body, narrative, sexuality and gender.[89] She created pieces such as Meat Joy (1964) and Interior Scroll (1975).[90] Schneemann considered her body a surface for work.[91] She described herself as a "painter who has left the canvas to activate the real space and the lived time."[92][failed verification]

Joan Jonas (born July 13, 1936) is an American visual artist and a pioneer of video and performance art, who is one of the most important female artists to emerge in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[93] Jonas' projects and experiments provided the foundation on which much video performance art would be based. Her influences also extended to conceptual art, theatre, performance art and other visual media. She lives and works in New York and Nova Scotia, Canada.[94][95] Immersed in New York's downtown art scene of the 1960s, Jonas studied with the choreographer Trisha Brown for two years.[96]Jonas also worked with choreographers Yvonne Rainer and Steve Paxton.[97]

Yoko Ono was part of the avant-garde movement of the 1960s. She was part of the Fluxus movement.[98] She is known for her performance art pieces in the late 1960s, works such as Cut Piece, where visitors could intervene in her body until she was left naked.[99] One of her best known pieces is Wall piece for orchestra (1962).[100][101]

Joseph Beuys was a German Fluxus, happening, performance artist, painter, sculptor, medallist and installation artist. In 1962 his actions alongside the Fluxus neodadaist movement started, group in which he ended up becoming the most important member. His most relevant achievement was his socialization of art, making it more accessible for every kind of public.[102] In How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965) he covered his face with honey and gold leaf and explained his work to a dead hare that lay in his arms. In this work he linked spacial and sculptural, linguistic and sonorous factors to the artist's figure, to his bodily gesture, to the conscience of a communicator whose receptor is an animal.[103] Beuys acted as a shaman with healing and saving powers toward the society that he considered dead.[104] In 1974 he carried out the performance I Like America and America Likes Me where Beuys, a coyote and materials such as paper, felt and thatch constituted the vehicle for its creation. He lived with the coyote for three days. He piled United States newspapers, a symbol of capitalism.[105] With time, the tolerance between Beuys and the coyote grew and he ended up hugging the animal. Beuys repeats many elements used in other works.[106] Objects that differ form Duchamp's ready-mades, not for their poor[clarification needed] and ephemerality, but because they are part of Beuys's own life, who placed them after living with them and leaving his mark on them. Many have an autobiographical meaning, like the honey or the grease used by the tartars who saved[clarification needed] in World War Two. In 1970 he made his Felt Suit. Also in 1970, Beuys taught sculpture in the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf.[107] In 1979, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum of New York City exhibited a retrospective of his work from the 1940s to 1970.[108][109][110]

- Portrait of Barbara Smith

- Conference by Yoko Ono in the Viena Biennial, 2012

- Portrait of Yoko Ono

- Video art piece from the Brooklyn Museum with an interview with Carolee Schneemann

- Joan Jonas during a performance documented on video and installed, 1972

- Portrait of artist Joan Jonas

- Portrait of Joseph Beuys in a conference-performance, 1978

- Joseph Beuys in a video art piece

Nam June Paik was a South Korean performance artist, composer and video artist from the second half of the 20th century. He studied music and art history in the University of Tokyo. Later, in 1956, he traveled to Germany, where he studied Music Theory in Munich, then continued in Cologne in the Freiburg conservatory. While studying in Germany, Paik met the composers Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage and the conceptual artists Sharon Grace as well as George Maciunas, Joseph Beuys and Wolf Vostell and was from 1962 on, a member of the experimental art movement Fluxus.[111][112] Nam June Paik then began participating in the Neo-Dada art movement, known as Fluxus, which was inspired by the composer John Cage and his use of everyday sounds and noises in his music.[113] He was mates with Yoko Ono as a member of Fluxus.[114]

Wolf Vostell was a German artist, one of the most representative of the second half of the 20th century, who worked with various mediums and techniques such as painting, sculpture, installation, decollage, video art, happening and fluxus.[115]

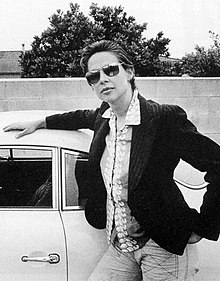

Vito Acconci[116][117] was an influential American performance, video and installation artist, whose diverse practice eventually included sculpture, architectural design, and landscape design. His foundational performance and video art[118] was characterized by "existential unease," exhibitionism, discomfort, transgression and provocation, as well as wit and audacity,[117] and often involved crossing boundaries such as public–private, consensual–nonconsensual, and real world–art world.[119][120] His work is considered to have influenced artists including Laurie Anderson, Karen Finley, Bruce Nauman, and Tracey Emin, among others.[119] Acconci was initially interested in radical poetry, but by the late 1960s, he began creating Situationist-influenced performances in the street or for small audiences that explored the body and public space. Two of his most famous pieces were Following Piece (1969), in which he selected random passersby on New York City streets and followed them for as long as he was able, and Seedbed (1972), in which he claimed that he masturbated while under a temporary floor at the Sonnabend Gallery, as visitors walked above and heard him speaking.[121]

Chris Burden was an American artist working in performance, sculpture and installation art. Burden became known in the 1970s for his performance art works, including Shoot (1971), in which he arranged for a friend to shoot him in the arm with a small-caliber rifle. A prolific artist, Burden created many well-known installations, public artworks and sculptures before his death in 2015.[122][123][124] Burden began to work in performance art in the early 1970s. He made a series of controversial performances in which the idea of personal danger as artistic expression was central. His first significant performance work, Five Day Locker Piece (1971), was created for his master's thesis at the University of California, Irvine,[122] and involved his being locked in a locker for five days.[125]

Dennis Oppenheim was an American conceptual artist, performance artist, earth artist, sculptor and photographer. Dennis Oppenheim's early artistic practice is an epistemological questioning about the nature of art, the making of art and the definition of art: a meta-art which arose when strategies of the Minimalists were expanded to focus on site and context. As well as an aesthetic agenda, the work progressed from perceptions of the physical properties of the gallery to the social and political context, largely taking the form of permanent public sculpture in the last two decades of a highly prolific career, whose diversity could exasperate his critics.[126]

Yayoi Kusama is a Japanese artist who, throughout her career, has worked with a great variety of media including:sculpture, installation, painting, performance, film, fashion, poetry, fiction, and other arts; the majority of them exhibited her interest in psychedelia, repetition and patterns. Kusama is a pioneer of the pop art, minimalism and feminist art movements and influenced her coetaneous, Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg.[127] She has been acknowledged as one of the most important living artists to come out of Japan and a very relevant voice in avant garde art.[128][129]

- Video-installation-performance by Nam June Paik in 2008

- Video-installation-performance by Nam June Paik in Düsseldorf

- Portrait of Wolf Vostell in 1980

- Portrait of Allan Kaprow in 1973

- Vito Acconci during a video-performance in 1973

- Installation by Vito Acconci in the Luigi Pecci Contemporary Art Centre

- Installation by Dennis Oppenheim in the Vancouver Sculpture Biennial

1970s[edit]

In the 1970s, artists that had derived to works related to performance art evolved and consolidated themselves as artists with performance art as their main discipline, deriving into installations created through performance, video performance, or collective actions, or in the context of a socio-historical and political context.

Video performance[edit]

In the early 1970s the use of video format by performance artists was consolidated. Some exhibitions by Joan Jonas and Vito Acconci were made entirely of video, activated by previous performative processes. In this decade, various books that talked about the use of the means of communication, video and cinema by performance artists, like Expanded Cinema, by Gene Youngblood, were published. One of the main artists who used video and performance, with notorious audiovisual installations, is the South Korean artist Nam June Paik, who in the early 1960s had already been in the Fluxus movement until becoming a media artist and evolving into the audiovisual installations he is known for.

Carolee Schneemann's and Robert Whitman's 1960s work regarding their video-performances must be taken into consideration as well. Both were pioneers of performance art, turning it into an independent art form in the early seventies.[130]

Joan Jonas started to include video in her experimental performances in 1972, while Bruce Nauman scenified[clarification needed] his acts to be directly recorded on video.[131] Nauman is an American multimedia artist, whose sculptures, videos, graphic work and performances have helped diversify and develop culture from the 1960s on. His unsettling artworks emphasized the conceptual nature of art and the creation process.[132] His priority is the idea and the creative process over the result. His art uses an incredible array of materials and especially his own body.[133][134]

Gilbert and George are Italian artist Gilbert Proesch and English artist George Passmore, who have developed their work inside conceptual art, performance and body art. They were best known for their live-sculpture acts.[135][136] One of their first makings was The Singing Sculpture, where the artists sang and danced "Underneath the Arches", a song from the 1930s. Since then they have forged a solid reputation as live-sculptures, making themselves works of art, exhibited in front of spectators through diverse time intervals. They usually appear dressed in suits and ties, adopting diverse postures that they maintain without moving, though sometimes they also move and read a text, and occasionally they appear in assemblies or artistic installations.[137] Apart from their sculptures, Gilbert and George have also made pictorial works, collages and photomontages, where they pictured themselves next to diverse objects from their immediate surroundings, with references to urban culture and a strong content; they addressed topics such as sex, race, death and HIV, religion or politics,[138] critiquing many times the British government and the established power. The group's most prolific and ambitious work was Jack Freak Pictures, where they had a constant presence of the colors red, white and blue in the Union Jack. Gilbert and George have exhibited their work in museums and galleries around the world, like the Stedelijk van Abbemuseum of Eindhoven (1980), the Hayward Gallery in London (1987), and the Tate Modern (2007). They have participated in the Venice Biennale. In 1986 they won the Turner Prize.[139]

Endurance art[edit]

Endurance performance art deepens the themes of trance, pain, solitude, deprivation of freedom, isolation or exhaustion.[140] Some of the works, based on the passing of long periods of time are also known as long-durational performances.[141] One of the pioneering artists was Chris Burden in California since the 1970s.[142] In one of his best known works, Five days in a locker (1971) he stayed for five days inside a school locker, in Shoot (1971) he was shot with a firearm, and inhabited for twenty two days a bed inside an art gallery in Bed Piece (1972).[143] Another example of endurance artist is Tehching Hsieh. During a performance created in 1980–1981 (Time Clock Piece), where he stayed a whole year repeating the same action around a metaphorical clock. Hsieh is also known for his performances about deprivation of freedom; he spent an entire year confined.[144] In The House With the Ocean View (2003), Marina Abramović lived silently for twelve days without food.[145] The Nine Confinements or The Deprivation of Liberty is a conceptual endurance artwork of critical content carried out in the years 2013 and 2016. All of them have in common the illegitimate deprivation of freedom.

Performance in a political context[edit]

In the mid-1970s, behind the Iron Curtain, in major Eastern Europe cities such as Budapest, Kraków, Belgrade, Zagreb, Novi Sad and others, scenic arts of a more experimental content flourished. Against political and social control, different artists who made performance of political content arose. Orshi Drozdik's performance series, titled Individual Mythology 1975–77 and the NudeModel 1976–77. All her actions were critical of the patriarchal discourse in art and the forced emancipation programme and constructed by the equally patriarchal state.[146] Drozdik showed a pioneer and feminist point of view on both, becoming one of the precursors of this type of critical art in Eastern Europe.[147] In the 1970s, performance art, due to its fugacity,[clarification needed] had a solid presence in the Eastern European avant-garde, specially in Poland and Yugoslavia, where dozens of artists who explored the body conceptually and critically emerged.

The Other[edit]

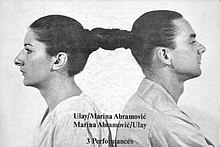

In the mid-1976s, Ulay and Marina Abramović founded the collective The Other in the city of Amsterdam. When Abramović and Ulay[148] started their collaboration. The main concepts they explored were the ego and artistic identity. This was the start of a decade of collaborative work.[149] Both artists were interested in the tradition of their cultural heritage and the individual's desire for rituals.[150] In consecuense,[clarification needed] they formed a collective named The Other. They dressed and behaved as one, and created a relation of absolute confidence. They created a series of works in which their bodies created additional spaces for the audience's interaction. In Relation in Space they ran around the room, two bodies like two planets, meshing masculine and feminine energies into a third component they called "that self".[151] Relation in Movement (1976) had the couple driving their car inside the museum, doing 365 spins. A black liquid dripped out of the car, forming a sculpture, and each round represented a year.[152] After this, they created Breathing In/Breathing Out, where both of them united their lips and inspired the air expired by the other one until they used up all oxygen. Exactly 17 minutes after the start of the performance, both of them fell unconscious, due to their lungs filling with carbon dioxide. This piece explored the idea of the ability of a person to absorb the life out of another one, changing them and destroying them. In 1988, after some years of a tense relationship, Abramović and Ulay decided to make a spiritual travel that would put an end to the collective. They walked along the Great Wall of China, starting on opposite ends and finding each other halfway. Abramović conceived this walk on a dream, and it gave her what she saw as an appropriate and romantic ending to the relationship full of mysticism, energy and attraction.[153] Ulay started on the Gobi dessert and Abramovic in the Yellow sea. Each one of them walked 2500 kilometres, found each other in the middle and said goodbye.

Main artists[edit]

In 1973, Laurie Anderson interpreted Duets on Ice in the streets of New York. Marina Abramović, in the performance Rhythm 10, included conceptually the violation of a body.[154] Thirty years later, the topic of rape, shame and sex exploitation would be reimagined in the works of contemporary artists such as Clifford Owens,[155] Gillian Walsh, Pat Oleszko and Rebecca Patek, amongst others.[156] New artists with radical acts consolidated themselves as the main precursors of performance, like Chris Burden, with the 1971 work Shoot, where an assistant shot him in the arm from a five-meter distance, and Vito Acconci the same year with Seedbed. The work Eye Body (1963) by Carolee Schneemann en 1963, had already been considered a prototype of performance art. In 1975, Schneemann recurred to innovative solo acts such as Interior Scroll, that showed the feminine body as an artistic media.

One of the main artists was Gina Pane,[157] French artist of Italian origins. She studied at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in París from 1960 until 1965[158] and was a member of the performance art movement in the 1970 in France, called "Art Corporel".[159] Parallel to her art, Pane taught in the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Mans from 1975 until 1990 and directed an atelier dedicated to performance art in the Pompidou Centre from 1978 to 1979.[159] One of her best known works is The Conditioning (1973), in which she was lied into a metal bed spring over an area of lit candles. The Conditioning was created as an homage to Marina Abramović, part of her Seven Easy Pieces(2005) in the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City in 2005. Great part of her works are protagonized by self-inflicted pain, separating her from most of other woman artists in the 1970s. Through the violence of cutting her skin with razors or extinguishing fires with her bare hands and feet, Pane has the intention of inciting a real experience in the visitor, who would feel moved for its discomfort.[157] The impactful nature of these first performance art pieces or actions, as she preferred to call them, many times eclipsed her prolific photographic and sculptural work. Nonetheless, the body was the main concern in Panes's work, either literally or conceptually.

- Portrait of Ulay in 1972

- Abramovic and Ulay's Furgone

- Exhibition of Marina Abramović's first works in Stockholm

- Installation by Bruce Nauman in Germany

- Video installation by Nam June Paik

- Gilbert and George in a presentation

- Orshi Drozdik in one of her exhibitions

1980s[edit]

The technique of performance art[edit]

Until the 1980s, performance art has demystified virtuosism,[clarification needed] this being one of its key characteristics. Nonetheless, from the 1980s on it started to adopt some technical brilliancy.[160] In reference to the work Presence and Resistance[161] by Philip Auslander, the dance critic Sally Banes writes, "... by the end of the 1980s, performance art had become so widely known that it no longer needed to be defined; mass culture, especially television, had come to supply both structure and subject matter for much performance art; and several performance artists, including Laurie Anderson, Spalding Gray, Eric Bogosian, Willem Dafoe, and Ann Magnuson, had indeed become crossover artists in mainstream entertainment."[162] In this decade the parameters and technicalities built to purify and perfect performance art were defined.

Critique and investigation of performance art[edit]

Despite the fact that many performances are held within the circle of a small art-world group, Roselee Goldberg notes in Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present that "performance has been a way of appealing directly to a large public, as well as shocking audiences into reassessing their own notions of art and its relation to culture. Conversely, public interest in the medium, especially in the 1980s, stems from an apparent desire of that public to gain access to the art world, to be a spectator of its ritual and its distinct community, and to be surprised by the unexpected, always unorthodox presentations that the artists devise." In this decade, publications and compilations about performance art and its best known artists emerged.

Performance art from a political context[edit]

In the 1980s, the political context played an important role in the artistic development and especially in performance, as almost every one of the works created with a critical and political discourse were in this discipline. Until the decline of the European Eastern bloc during the late 1980s, performance art had actively been rejected by most communist governments. With the exception of Poland and Yugoslavia, performance art was more or less banned in countries where any independent public event was feared. In the GDR, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Latvia it happened in apartments, at seemingly spontaneous gatherings in artist studios, in church-controlled settings, or was covered as another activity, like a photo-shoot. Isolated from the western conceptual context, in different settings it could be like a playful protest or a bitter comment, using subversive metaphors to express dissent with the political situation.[163] Amongst the most remarkable performance art works of political content in this time were those of Tehching Hsieh between July 1983 and July 1984, Art/Life: One Year Performance (Rope Piece).[164]

Performance poetry[edit]

In 1982 the terms "poetry" and "performance" were first used together. Performance poetry appeared to distinguish text-based vocal performances from performance art, especially the work of escenic[clarification needed] and musical performance artists, such as Laurie Anderson, who worked with music at that time. Performance poets relied more on the rhetorical and philosophical expression in their poetics than performance artists, who arose from the visual art genres of painting and sculpture. Many artists since John Cage fuse performance with a poetical base.

Feminist performance art[edit]

Since 1973 the Feminist Studio Workshop in the Woman's Building of Los Ángeles had an impact in the wave of feminist acts, but until 1980 they did not completely fuse. The conjunction between feminism and performance art progressed through the last decade. In the first two decades of performance art development, works that had not been conceived as feminist are seen as such now.[clarification needed]

Still, not until 1980 did artists self-define themselves as feminists. Artist groups in which women influenced by the 1968 student movement as well as the feminist movement stood out.[165] This connection has been treated in contemporary art history research. Some of the women whose innovative input in representations and shows was the most relevant were Pina Bausch and the Guerrilla Girls who emerged in 1985 in New York City,[166] anonymous feminist and anti-racist art collective.[167][168][169][170] They chose that name because they used guerrilla tactics in their activism [167] to denounce discrimination against women in art through political and performance art.[171][172][173][174] Their first performance was placing posters and making public appearances in museums and galleries in New York, to critique the fact that some groups of people were discriminated against for their gender or race.[175] All of this was done anonymously; in all of these appearances they covered their faces with gorilla masks (this was due to the similar pronunciation of the words "gorilla" and "guerrilla"). They used as nicknames the names of female artists who had died.[176] From the 1970s until the 1980s, amongst the works that challenged the system and their usual strategies of representation, the main ones feature women's bodies, such as Ana Mendieta's works in New York City where her body is outraged and abused, or the artistic representations by Louise Bourgeois with a rather minimalist discourse that emerge in the late seventies and eighties. Special mention to the works created with feminine and feminist corporeity[clarification needed] such as Lynda Benglis and her phallic performative actions, who reconstructed the feminine image to turn it into more than a fetish. Through feminist performance art the body becomes a space for developing these new discourses and meanings. Artist Eleanor Antin, creator in the 1970s and 1980s, worked on the topics of gender, race and class. Cindy Sherman, in her first works in the seventies and already in her artistic maturity in the eighties, continues her critical line of overturning the imposed self, through her use of the body as an object of privilege.

Cindy Sherman is an American photographer and artist. She is one of the most representative post-war artists and exhibited more than the work of three decades of her work in the MoMA. Even though she appears in most of her performative photographies, she does not consider them self-portraits. Sherman uses herself as a vehicle to represent a great array of topics of the contemporary world, such as the part women play in our society and the way they are represented in the media as well as the nature of art creation. In 2020 she was awarded with the Wolf prize in arts.[177]

Judy Chicago is an artist and pioneer of feminist art and performance art in the United States. Chicago is known for her big collaborative art installation pieces on images of birth and creation, that examine women's part in history and culture. In the 1970s, Chicago has founded the first feminist art programme in the United States. Chicago's work incorporates a variety of artistic skills such as sewing, in contrast with skills that required a lot of workforce, like welding and pyrotechnics. Chicago's best known work is The Dinner Party, that was permanently installed in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art in the Brooklyn Museum. The Dinner Party celebrated the achievements of women throughout history and is widely considered as the first epic feminist artwork. Other remarkable projects include International Honor Quilt, The Birth Project,[178] Powerplay,[179] and The Holocaust Project.[180]

- Students in a Martha Rosler exhibition

- The Guerrilla Girls in an opening in London

- Works of the 'Guerrilla Girls' in an exhibition in the Museum of Modern Art, Manhattan, New York

- Guerrilla Girls exhibition

- Installation by Louise Bourgeois in a Brazilian museum

- Portrait of Judy Chicago

Expansion to Latin America[edit]

In this decade performance art spread until reaching Latin America through the workshops and programmes that universities and academic institutions offered. It mainly developed in Mexico, Colombia -with artists such as Maria Teresa Hincapié—, in Brasil and in Argentina.[181]

Ana Mendieta was a conceptual and performance artist born in Cuba and raised in the United States. She's mostly known for her artworks and performance art pieces in land art. Mendieta's work was known mostly in the feminist art critic environment. Years after her death, specially since the Whitney Museum of American Art retrospective in 2004[182] and the retrospective in the Haywart Gallery in London in 2013[183] she is considered a pioneer of performance art and other practices related to body art and land art, sculpture and photography.[184] She described her own work as earth-body art.[185][186]

Tania Bruguera is a Cuban artist specialized in performance art and political art. Her work mainly consists of her interpretation of political and social topics.[187]She has developed concepts such as "conduct art" to define her artistic practices with a focus on the limits of language and the body confronted to the reaction and behavior of the spectators. She also came up with "useful art", that it ought to transform certain political and legal aspects of society. Brugera's work revolves around power and control topics, and a great portion of her work questions the current state of her home country, Cuba. In 2002 she created the Cátedra Arte de Conducta in La Habana.[188][189][190]

Regina José Galindo is a Guatemalan artist specialized in performance art. Her work is characterized by its explicit political and critical content, using her own body as a tool of confrontation and social transformation.[191] Her artistic career has been marked by the Guatemalan Civil War that took place from 1960 to 1996, which triggered a genocide of more than 200 thousand people, many of them indigenous, farmers, women and children.[181] With her work, Galindo denounces violence, sexism (one of her the main topics is femicide), the western beauty standards, the repression of the estates and the abuse of power, especially in the context of her country, even though her language transgresses borders. Since her beginnings she only used her body as media, which she occasionally takes to extreme situations (like in Himenoplasty (2004) where she goes through a hymen reconstruction, a work that won the Golden Lyon in the Venice Biennale), to later have volunteers or hired people to interact with her, so that she loses control over the action.[192]

1990s[edit]

The 1990s was a period of absence for classic European performance, so performance artists kept a low profile. Nevertheless, Eastern Europe experienced a peak. On the other hand, Latin American performance continued to boom, as well as feminist performance art. There also was a peak of this discipline in Asian countries, whose motivation emerged from the Butō dance in the 1950s, but in this period they professionalized and new Chinese artists arose, earning great recognition. There was also a general professionalization in the increase of exhibitions dedicated to performance art, at the opening of the Venice Art Biennial to performance art, where various artists of this discipline have won the Leone d'Oro, including Anne Imhof, Regina José Galindo or Santiago Sierra.

Performance with political context[edit]

While the Soviet Bloc dissolved, some forbidden performance art pieces began to spread. Young artists from the former Eastern Bloc, including Russia, devoted themselves to performance art. Scenic arts emerged around the same time in Cuba, the Caribbean and China. "In these contexts, performance art became a new critical voice with a social strength similar to that of Western Europe, the United States and South America in the sixties and early seventies. It must be emphasized that the rise of performance art in the 1990s in Eastern Europe, China, South Africa, Cuba and other places must not be considered secondary or an imitation of the West".[193]

Professionalization of performance art[edit]

In the Western World, in the 1990s, performance art joined the mainstream culture. Diverse performance artworks, live, photographed or through documentation started to become part of galleries and museums that began to understand performance art as an art discipline.[194] Nevertheless, it was not until the next decade that a major institutionalization happened, when every museum started to incorporate performance art pieces into their collections and dedicating great exhibitions and retrospectives, museums such as the Tate Modern in London, the MoMA in New York City or the Pompidou Centre in Paris. From the 1990s on, many more performance artists were invited to important biennials like the Venice Biennale, the Sao Paulo Biennial and the Lyon Biennial.

Performance in China[edit]

In the late 1990s, Chinese contemporary art and performance art received great recognition internationally, as 19 Chinese artists were invited to the Venice Biennial.[195][196] Performance art in China and its history had been growing since the 1970s due to the interest between art, process and tradition in Chinese culture, but it gained recognition from the 1990s on.[197][193] In China, performance art is part of the fine arts education programme, and is becoming more and more popular.[197][198] In the early 1990s, Chinese performance art was already acclaimed in the international art scene.[199][197][200]

- Performance art in the Lyon Biennale

- Performance art in the Lyon Biennale

- Performance at the entrance of the Romanian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

- Performative installation by Joseph Beuys in the Tate Modern of London

- Video installation with the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei

- Tehching Hsieh exhibition in downtown New York City

- China Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

- Portrait of Wang Xiaoshuai

- Liu Xiaodong during a performance artwork

Since the 2000s[edit]

New-media performance[edit]

In the late 1990s and into the 2000s, a number of artists incorporated technologies such as the World Wide Web, digital video, webcams, and streaming media, into performance artworks.[201] Artists such as Coco Fusco, Shu Lea Cheang, and Prema Murthy produced performance art that drew attention to the role of gender, race, colonialism, and the body in relation to the Internet.[202] Other artists, such as Critical Art Ensemble, Electronic Disturbance Theater, and Yes Men, used digital technologies associated with hacktivism and interventionism to raise political issues concerning new forms of capitalism and consumerism.[203][204]

In the second half of the decade, computer-aided forms of performance art began to take place.[205] Many of these works led to the development of algorithmic art, generative art, and robotic art, in which the computer itself, or a computer-controlled robot, becomes the performer.[206]

Coco Fusco is an interdisciplinary Cuban-American artist, writer and curator who lives and works in the United States. Her artistic career began in 1988. In her work, she explores topics such as identity, race, power and gender through performance. She also makes videos, interactive installations and critical writing.[207][19]

Radical performance[edit]

During the 2000s and 2010s, artists such as Pussy Riot, Tania Bruguera, and Petr Pavlensky have been judged for diverse artistic actions.[208]

On February 21, 2012, as a part of their protest against the re-election of Vladímir Putin, various women of the artistic collective Pussy Riot entered the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour of Moscow of the Russian Orthodox Church. They made the sign of the cross, bowed before the shrine, and started to interpret a performance compound by a song and a dance under the motto "Virgin Mary, put Putin Away". On March 3, they were detained.[209] On March 3, 2012, Maria Alyokhina and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova,[210][211] Pussy Riot members, were arrested by the Russian authorities and accused of vandalism. At first, they both denied being members of the group and started a hunger strike for being incarcerated and taken apart from their children until the trials began in April.[212] On March 16 another woman, Yekaterina Samutsévitch, who had been previously interrogated as a witness, was arrested and accused as well.[citation needed] On July 5, formal charges against the group and a 2800-page accusation were filed.[213] That same day they were notified that they had until July 9 to prepare their defense. In reply, they announced a hunger strike, pleading that two days was an inappropriate time frame to prepare their defense.[214] On July 21, the court extended their preventive prison to last six more months.[215] The three detained members were recognized as political prisoners by the Union of Solidarity with Political Prisoners.[216] Amnesty International considers them to be prisoners of conscience for "the severity of the response of the Russian authorities".[217]

Since 2012, artist Abel Azcona has been prosecuted for some of his works. The demand that gained the most repercussion[clarification needed] was the one carried out by the Archbishopric of Pamplona and Tudela,[218] in representation of the Catholic Church.[219] The Church demanded Azcona for desecration and blasphemy crimes, hate crime and attack against the religious freedom and feelings for his work Amen or The Pederasty.[220][221] In 2016, Azcona was denounced for extolling terrorism[222][223] for his exhibition Natura Morta,[224] in which the artist recreated situations of violence, historical memory, terrorism or war conflicts through performance and hyperrealistic sculptures and installations.[225]

In December 2014 Tania Bruguera was detained in La Habana to prevent her from carrying out new reivindicative[clarification needed] works. Her performance art pieces have earned her harsh critiques, and she has been accused of promoting resistance and public disturbances.[226][227] In December 2015 and January 2016, Bruguera was detained for organizing a public performance in the plaza de la Revolución of La Habana. She was detained along with other Cuban artists, activists and reporters who took part in the campaign Yo También Exijo, which was created after the declarations of Raúl Castro and Barack Obama in favor of restoring their diplomatic relationship. During the performance El Susurro de Tatlin #6 she set microphones and talkers[clarification needed] in the Plaza de la Revolución so the Cubans could express their feelings regarding the new political climate. The event had great repercussion in international media, including a presentation of El Susurro de Tatlin #6 in Times Square, and an action in which various artists and intellectuals expressed themselves in favour of the liberation of Bruguera by sending an open letter to Raúl Castro signed by thousands of people around the world asking for the return of her passport and claiming criminal injustice, as she only gave a microphone to the people so they could give their opinion.[228][229][230][231][232]

In November 2015 and October 2017 Petr Pavlensky was arrested for carrying out a radical performance art piece in which he set on fire the entry of the Lubyanka Building, headquarters of the Federal Security Service of Russia, and a branch office of the Bank of France.[233] On both occasions he sprayed the main entrance with gasoline; in the second performance he sprayed the inside as well, and ignited it with a lighter. The doors of the building were partially burnt. Both times Pavlenski was arrested without resistance and accused of debauchery. A few hours after the actions, several political and artistic reivindicative videos appeared on the internet.[234]

Institutionalization of performance art / performance collecting processes[edit]

Since the 2000s, big museums, institutions and collections have supported performance art. Since January 2003, Tate Modern in London has had a curated programme of live art and performance.[235] With exhibitions by artists such as Tania Bruguera or Anne Imhof.[236] In 2012 The Tanks at Tate Modern were opened: the first dedicated spaces for performance, film and installation in a major modern and contemporary art museum.

С 14 по 31 марта 2010 года в Музее современного искусства прошла масштабная ретроспектива и перформанс работ Марины Абрамович , крупнейшая выставка перформанса в истории МоМА. [237][238] В экспозицию вошли более двадцати работ художника, большинство из них — 1960–1980-х годов. Многие из них были повторно активированы другими молодыми артистами разных национальностей, выбранными для шоу. [239] Параллельно с выставкой Абрамович исполнила «Художник присутствует» — статическую немую пьесу продолжительностью 726 часов и 30 минут, в которой она неподвижно сидела в атриуме музея, а зрителям предлагалось по очереди сесть напротив нее. [240] Работа представляет собой обновленную репродукцию одного из произведений 1970 года, представленных на выставке, где Абрамович целыми днями оставался рядом с Улаем, который был ее сентиментальным спутником. Представление привлекло таких знаменитостей, как Бьорк , Орландо Блум и Джеймс Франко. [241] которые участвовали и получили освещение в СМИ. [242]

На фоне институционализации производительности брюссельская инициатива A Performance Affair [243] и лондонский формат Performance Exchange [244] поинтересоваться коллекционностью исполнительских произведений. В выпуске The Non-fungible Body? австрийский музейный и культурный центр OÖLKG/OK размышляет о последних событиях в институционализации перформанса посредством дискурсивного фестивального формата, который был впервые представлен в июне 2022 года.

- Фасад музея Гуггенхайма в Бильбао с Йоко Оно баннером

- Работа Дорис Сальседо в галерее Тейт Модерн в Лондоне, 2007 г.

- Марина Абрамович во время своих семи выступлений в спектакле «Семь простых пьес» (2005) в Музее Соломона Р. Гуггенхайма.

- Зенитный кадр спектакля «Художник присутствует» в Музее современного искусства

- Работа Марины Абрамович воспроизведена для ретроспективы в Болонье , Италия, 2018 г.

- Герман Нитч проводит перформанс в своем одноименном музее (2009 г.)

- Спектакль Брайана Занисника « Когда я был ребенком, я поймал мимолетный взгляд» , 2009 г.

искусство Коллективное возрождения

В 2014 году создается перформанс Carry That Weight , также известный как «матрасный перформанс». Автором этого произведения является Эмма Сулкович , которая закончила диссертацию по изобразительному искусству в Колумбийском университете в Нью-Йорке. В сентябре 2014 года работа Сулкович началась, когда она начала носить свой матрас по кампусу Колумбийского университета . [245] Эта работа была создана художницей с целью обличить ее изнасилование на том же матрасе много лет назад, в ее собственном общежитии, о чем она сообщила и не было услышано ни университетом, ни судом. [246] поэтому она решила носить матрас с собой весь семестр, ни разу не покидая его, вплоть до выпускной церемонии в мае 2015 года. Статья вызвала бурную полемику, но была поддержана группой ее товарищей и активистов, присоединившихся к группе Сулковича. раз при переноске матраса, что делает эту работу международным признанием. Искусствовед Джерри Сальц назвал эту работу одной из самых важных работ 2014 года. [247]

был создан коллективный перформанс « Насильник на твоем пути» В 2019 году феминистской группой из Вальпараисо , Чили, под названием Lastesis , который представлял собой демонстрацию против нарушений прав женщин в контексте чилийских протестов 2019–2020 годов . [248] [249] [250] Впервые оно было исполнено перед вторым полицейским участком карабинеров Чили в Вальпараисо 18 ноября 2019 года. [251] Второе выступление 2000 чилийских женщин 25 ноября 2019 года в рамках Международного дня борьбы за ликвидацию насилия в отношении женщин было снято на видео и стало вирусным в социальных сетях. [252] Его охват стал глобальным [253] [254] после того, как феминистские движения в десятках стран приняли и перевели спектакль для своих собственных протестов и требований прекращения и наказания фемиубийства и сексуального насилия, среди прочего. [255]

- Спутники Эммы Сулкович и сама художница несли матрас на выпускной в качестве жалобы

- Сулкович с инструкциями по ее выступлению в Колумбийском университете.

- Часть перформанса Сулковича, акция под названием «Llevemos el peso entre todas» (« Несите этот груз вместе »).

- Портрет Сулковича в одной из презентаций работы

- Роберта Смит , New York Times арт-критик (слева), обсуждает производительность матраса с Сулковичем, Бруклинский музей , 14 декабря 2014 г.

- Мексиканская интерпретация фильма «Насильник на твоем пути» в Оахаке , 27 ноября 2019 г.

- Насильник на твоем пути представлен в контексте протестов в Чили 2019–2020 гг.

- Перуанская интерпретация фильма «Насильник на твоем пути» в Лиме, 12 декабря 2019 г.

- Насильник на твоем пути представлен в контексте протестов в Чили 2019–2020 гг.

- Ребенок вмешивается во время спектакля « Насильник на твоем пути».

См. также [ править ]

Ссылки [ править ]

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Искусство перформанса» . Тейт Модерн . Проверено 20 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Обзор движения исполнительского искусства» . История искусства . Проверено 12 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Медиа и перформанс» . Мома Музей современного искусства . Проверено 20 мая 2020 г.

- ^ Тейлор и Фуэнтес, Диана и Масела (2011). «Расширенные исследования производительности» (PDF) . Фонд экономической культуры. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 14 февраля 2019 года . Проверено 8 февраля 2019 г.

- ^ Франко Пепло, Фернандо (2014). «Концепция спектакля по Эрвингу Гоффману и Джудит Батлер» (PDF) . Сборник рабочих документов. Издательство ЦЭА. Год1. Номер 3 . Проверено 8 февраля 2019 г.

- ^ «Этимология спектакля» . Этимология Чили. 2019 . Проверено 20 мая 2020 г.

- ^ Перро, Джон (1982). «Марджори Страйдер: Обзор». Ван Вагнер, Джудит К. (ред.). Марджори Страйдер: 10 лет, 1970–1980 . Галерея изящных искусств Майерса. стр. 11–15.

- ^ Карреньо Рио, Родриго. «Кэроли Шнееманн, пионер и справочник» . Ле Миау Нуар . Проверено 8 июня 2020 г.

- ^ «Марина Абрамович, пионер перформанса» . Хранилище . 8 апреля 2018 г. Проверено 8 июня 2020 г.

- ^ «Ана Мендьета, пионер кубинского перформанса, находится в Мадриде» . Кубинский дневник . 14 февраля 2020 г. . Проверено 8 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Кальво, Ирен (14 мая 2015 г.). «Крис Берден, боди-арт и перформанс 70-х: актуальные ссылки» . Ах журнал . Проверено 8 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Дэвис, Бен (28 апреля 2017 г.). «Вито Аккончи, трансгрессивный прародитель исполнительского искусства, умер в возрасте 77 лет» . Лондонская неделя искусств . Проверено 30 июня 2020 г.

- ^ «10 лучших ныне живущих художников 2015 года» . Артистичный . 2015 . Проверено 30 июня 2020 г.

- ^ «Абель Аскона, лучший артист-спектакль» . Хою — это искусство. 22 февраля 2016 года . Проверено 30 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Толедо, Мануэль (10 июня 2005 г.). «Гватемальский ганский Леон де Оро» . Мир Би-би-си . Проверено 28 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Э. Куэ, Карлос (17 февраля 2017 г.). «Марта Минухин «Ничего нового в искусстве не было сделано с шестидесятых годов» » . Страна . Проверено 30 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Фишер-Лихте, Эрика. Преобразующая сила перформанса: новая эстетика. Нью-Йорк и Лондон, 2008 г., Routledge. ISBN 978-0415458566 .

- ^ Моллер, Хелен Данэм, Кертис, танцующий с Хелен Моллер. Нью-Йорк: компания Джона Лейна. — 1918.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Карлсон, Марвин (1998) [1996]. Производительность: критическое введение . Лондон и Нью-Йорк: Рутледж. стр. 2, 103–105 . ISBN 0-415-13703-9 .

- ^ Парр, Адриан (2005). Адриан Парр (ред.). Становление + Перформанс . Издательство Эдинбургского университета. стр. 25, 2. ISBN 0748618996 . Проверено 26 октября 2010 г.

{{cite book}}:|work=игнорируется ( помогите ) - ^ «Перформансеры и дадаисты» . С а. 2020 . Проверено 23 мая 2020 г.

- ^ Рохас, Диего (20 мая 2017 г.). «Перформанс, эта радикальная и тревожная форма современного искусства» . Инфобаэ . Проверено 23 мая 2020 г.

- ^ Сук, Аластер (20 июля 2016 г.). «Кабаре Вольтер: вечер в самом диком ночном клубе в истории» . BBC Культура .

- ^ Туризм, Швейцария. «Кабаре Вольтер» . Suiza Turismo (на испанском языке) . Проверено 16 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Сук, Аластер. «Кабаре Вольтер: вечер в самом диком ночном клубе в истории» . Проверено 4 марта 2018 г.

- ^ Первая мировая война и дадаизм , Музей современного искусства (МоМА).

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Ломели, Наталья (23 декабря 2015 г.). «Кабаре Вольтер: Начало дадаизма» . Коллективная культура . Проверено 23 мая 2020 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Де Микели, Марио: Художественный авангард двадцатого века , 1959.

- ^ Олбрайт, Дэниел: Модернизм и музыка: антология источников . Издательство Чикагского университета , 2004. ISBN 0-226-01266-2 .

- ^ Элгер, Дитмар: Дадаизм . Алемания : Сумки , 2004. ISBN 3-8228-2946-3 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Эль Футуризм» . CКапиталия. 14 июля 2005 года . Проверено 5 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Лахо Перес, Розина (1990). Художественный лексикон . Мадрид – Испания: Акал. п. 87. ИСБН 978-84-460-0924-5 .

- ^ Брокколи, Бетина (29 июня 2009 г.). «Футуризм: сто лет после эстетики скорости» . Аргентина проводит расследование . Проверено 5 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Эссерс, В., «Классическая современность. Живопись первой половины 20-го века», в «Мастерах западной живописи» , том II, Taschen, 2005. ISBN 3-8228-4744-5 , с. 555

- ^ Исаак, Шелли (3 июля 2019 г.). «Перформанс 1960-х-настоящее время» . Мысль КО . Проверено 7 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Касадеваль, Хема (1 сентября 1997 г.). «ЮНЕСКО объявляет Баухаус объектом Всемирного наследия» . Мир . Проверено 7 июня 2020 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Техника живописи действием: определение, характеристика» . Проверено 26 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Джексон Поллок, художник боевиков» . Тотенарт . 2019 . Проверено 20 мая 2020 г.

- ^ Розенберг, Гарольд. « Американские художники действия » . Проверено 26 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Живопись Действия Художественная» . Проверено 26 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Пьер Рестани, «Современная магия в Тейт», Studio International, июнь 1968 года» . Тейт Модерн . Июнь 1968 года . Проверено 20 мая 2020 г.

- ^ Ханна Вайтемайер ( де ), Ив Кляйн, 1928–1962: Internacional Klein Blue (Кёльн, Лиссабон, Париж: Taschen, 2001), 8. ISBN 3-8228-5842-0 .

- ^ Гилберт Перлейн и Бруно Кора (редакторы) и др., Ив Кляйн: Да здравствует нематериальное! («Антологическая ретроспектива», каталог выставки 2000 г.), Нью-Йорк: Делано Гринидж, 2000 г., ISBN 978-0-929445-08-3 , с. 226

- ^ Ойбин Марина (31 января 2016 г.). «Цветная революция: по следам Ива Кляйна» . Нация . Проверено 20 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Прыжок в пустоту. Ив Кляйн и новое искусство 20 века» . Латиноамериканский факультет социальных наук . Проверено 20 мая 2020 г.

- ^ Селфриджес, Камилла (23 октября 2017 г.). «Художественные движения (по мотивам Ива Кляйна)» . Крусибл сегодня . Проверено 20 мая 2020 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Все освещено» . NYMag.com . 23 сентября 2004 г.

- ^ Барнс, Рэйчел (2001). Книга по искусству ХХ века (перепечатано под ред.). Лондон: Phaidon Press. ISBN 0714835420 .

- ^ «Визуальный очерк о Гутае». Флеш-арт . Том. 45, нет. 287. Флэш Арт Интернэшнл. 2012. с. 111. ISSN 0394-1493 .

- ^ Лопес, Янко (3 ноября 2017 г.). «Лэнд-Арт: искусство загадок земли» . Журнал АД . Проверено 22 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Искусство Земли или природа в музее» . www.elcultural.com . 13 ноября 2009 года . Проверено 5 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Национальная художественная галерея. «От Лос-Анджелеса до Нью-Йорка: Галерея Дван, 1959–1971» . Проверено 5 июня 2020 г.

- ^ «Эволюция производительности с 60-70-х годов» . Университет Саламанки. 4 мая 2011 года . Проверено 5 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Лапидарио, Хосеп. «Живопись, кровь, секс и смерть: во внутренностях венского акционизма» . ДжотДаун . Проверено 27 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Венский акционизм» (PDF) . Андалузский центр современного искусства . Проверено 27 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Венский акционизм или жестокий язык тела» . Середина . 18 июля 2016 г. Проверено 5 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Рамис, Мариано (21 апреля 1965 г.). «Венский акционизм» . ИДИС . Проверено 5 июня 2020 г.

- ^ «Фильмы Энди Уорхола» . www.warholstars.org .

- ^ «Из исследовательских лабораторий Энди Уорхола вышел этот номер журнала Aspen» . Вечнозеленый обзор. Апрель 1967 года.

- ^ Джозеф, Бранден В. (лето 2002 г.). « Мой разум раскололся: взрыв пластика Энди Уорхола неизбежен». Серая комната . 8 : 80–107. дои : 10.1162/15263810260201616 . S2CID 57560227 .

- ^ Остервейл, Ара; Блетц, Робин (2007). Женское экспериментальное кино: критические рамки . Издательство Университета Дьюка . п. 143. ИСБН 9780822340447 .

- ^ Мартин Торгофф, Мартин (2004). Не могу найти дорогу домой: Америка в великий каменный век, 1945–2000 гг . Нуэва-Йорк: Саймон и Шустер. п. 156. ИСБН 0-7432-3010-8 .

- ^ Бек, Дж., Живой театр Эль , Мадрид, Fundamentos, 1974, с. 255

- ^ Бек, Дж., Живой театр Эль , Мадрид, Fundamentos, 1974, стр.102.

- ^ Происходящий симпозиум , Флюксус и другие художественные явления второй половины 20 века . Касерес, 1999, Региональная редакция Эстремадуры, ISBN 84-7671-607-9 .

- ^ Флюксус в 50 лет . Стефан Фрике, Александр Клар, Сара Маске, Кербер Верлаг, 2012 г., ISBN 978-3-86678-700-1 .

- ↑ Дик Хиггинс о Fluxus , интервью 1986 года.

- ↑ Среди самых ранних произведений, которые позже будут опубликованы Fluxus, были партитуры событий Брехта, самые ранние из которых датированы примерно 1958/9 годом, и такие работы, как «Валош», который первоначально был выставлен на персональной выставке Брехта «Навстречу событиям» в 1959 году.

- ^ «Флюксус» . Masdearte.com . Проверено 8 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Притчетт, Кун и Гарретт, 2012 , с. «Он оказал большее влияние на музыку ХХ века, чем любой другой американский композитор».

- ^ Козинн, Аллан (13 августа 1992 г.). «Умер Джон Кейдж, 79 лет, минималист, очарованный звуком» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 21 июля 2007 г.

Джон Кейдж, плодовитый и влиятельный композитор, чьи минималистские произведения долгое время были движущей силой в мире музыки, танца и искусства, умер вчера в больнице Святого Винсента на Манхэттене. Ему было 79 лет, и он жил на Манхэттене.

- ^ Леонард, Джордж Дж. (1995). В свете вещей: искусство обыденности от Вордсворта до Джона Кейджа . Издательство Чикагского университета. п. 120 («... когда издательство Гарвардского университета назвало его в рекламе книги 1990 года «без сомнения, самым влиятельным композитором последней половины столетия», как ни удивительно, это было слишком скромно».). ISBN 978-0-226-47253-9 .

- ^ Грин, Дэвид Мейсон (2007). Биографическая энциклопедия композиторов Грина . Воспроизведение Piano Roll Fnd. п. 1407 («... Джон Кейдж, вероятно, самый влиятельный ... из всех американских композиторов на сегодняшний день»). ISBN 978-0-385-14278-6 .

- ^ Перлофф, Юнкерман, 1994, 93.

- ^ Бернштейн, Хэтч, 2001, 43–45.

- ^ Блох, Марк (июль 2023 г.). «Новая книга и музейная выставка Сари Динес» . Журнал Уайтхот . Проверено 8 сентября 2023 г.

- ^ Готлиб, Барух (2010). «Жизненно важные признаки процессуального искусства» . Центр трудового искусства . Проверено 17 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Процессуальное искусство» . Тейт Модерн . Проверено 10 июня 2020 г.

- ^ «Процессуальное искусство» . Гуггенхайм . Проверено 10 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Ной Уордрип-Фруин и Ник Монфор, ред., The New Media Reader (Кембридж: MIT Press, 2003): стр. 83. ISBN 0-262-23227-8 .

- ^ Монфор, Ник и Ной Уордрип-Фруин. Читатель новых медиа. Кембридж, Массачусетс [ua: MIT, 2003]. Распечатать.

- ^ Патрис Павис , «Театральный словарь», с. 232

- ^ Факультет. «Искусство действия: событие, представление и поток» (PDF) . Университет Кастилии Ла Манча. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 8 марта 2021 г. Проверено 7 ноября 2021 г.

- ^ Интервью Смита с Лореттой Росс, Проект устной истории «Голоса феминизма» , стр. 5–6.

- ↑ Смит, Барбара, интервью Лоретты Росс, расшифровка видеозаписи, 7 мая 2003 г., Проект устной истории «Голоса феминизма» , Коллекция Софии Смит, стр. 2.

- ^ Интервью Смита с Лореттой Росс, Проект устной истории «Голоса феминизма» , стр. 3–4.

- ^ Смит, Барбара. Домашние девушки: Антология черных феминисток , Кухонный стол: Цветная пресса для женщин, 1983, ISBN 0-913175-02-1 , с. хх, Введение

- ^ «Кэроли Шнеманн, художница-новаторка-феминистка, умерла в возрасте 79 лет» .

- ^ «Кэроли Шниман о феминизме, активизме и старении» . Другой журнал . Проверено 19 марта 2016 г.

- ^ «Кэроли Шнееманн: «Еще предстоит увидеть: новые и восстановленные фильмы и видео» » . Тайм-аут Нью-Йорк . 25 октября 2007. Архивировано из оригинала 5 января 2013 года . Проверено 10 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Стайлз, Кристина (2003). «Художник как инструмент реального времени». Изображение ее эротики: эссе, интервью, проекты . Кембридж, Массачусетс : MIT Press . п. 3. ISBN 026269297X .

- ^ Выступление Кэроли Шнеманн , Журнал эстетических исследований Новой Англии . Опубликовано 11 октября 2007 г. [ самостоятельный источник ]

- ^ Факультет: Джоан Джонас ACT в Массачусетском технологическом институте - Программа Массачусетского технологического института в области искусства, культуры и технологий.

- ^ «Художница Джоан Джонас» , Венецианская биеннале, дата обращения 17 августа 2014 г.

- ↑ «Джоан Джонас: Биография». Архивировано 21 января 2011 года в Wayback Machine , Electronic Arts Intermix, проверено 6 июня 2020 года.

- ^ «Онлайн-коллекция - Джоан Джонас» . Музей Соломона Р. Гуггенхайма . Архивировано из оригинала 16 апреля 2014 года . Проверено 8 июня 2014 г.

- ^ «Джоан Джонас» . pbs.org .

- ^ «Йоко Оно: Самый известный неизвестный художник в мире» .

- ^ «Йоко Оно, Cut Piece и феминистский спектакль» . Миралл . 12 июля 2017 г. Проверено 21 мая 2020 г.

- ^ Ана Лопес-Варела (сентябрь 2017 г.). «Джон Леннон, Йоко Оно и Гибралтар» . Ярмарка тщеславия . Проверено 26 мая 2020 г.