Майлз Дэвис

Майлз Дэвис | |

|---|---|

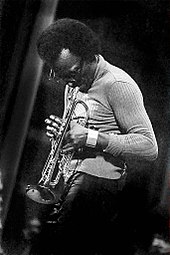

Дэвис в своем доме в Нью -Йорке, ок. 1955–1956; Фотография Тома Палумбо | |

| Справочная информация | |

| Имя рода | Майлз Дьюи Дэвис III |

| Рожденный | 26 мая 1926 г. Альтон, Иллинойс , США |

| Умер | September 28, 1991 (aged 65) Санта -Моника, Калифорния , США |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Discography | Miles Davis discography |

| Years active |

|

| Labels | |

| Formerly of | Miles Davis Quintet |

| Spouses | |

| Website | milesdavis |

| Education | Juilliard School (no degree) |

Майлз Дьюи Дэвис III (26 мая 1926 г. - 28 сентября 1991 г.) был американским джазовым трубачом, лидером группы и композитором. Он является одним из самых влиятельных и известных фигур в истории джаза и музыки 20-го века . Дэвис принял множество музыкальных направлений в примерно пяти десятилетней карьере, которая держала его в авангарде многих крупных стилистических событий в джазе. [ 1 ]

Родился в высшем среднем классе [ 2 ] Семья в Альтоне, штат Иллинойс , и выросла в Восточном Сент -Луисе , Дэвис начал на трубе в его раннем подростковом возрасте. Он уехал, чтобы учиться в Джульярде в Нью -Йорке, прежде чем бросить учебу и дебютировать в качестве своего профессионального дебюта в качестве члена квинтета саксофониста Паркера с Чарли 1944 по 1948 год. Вскоре после этого он записал рождение крутых сессий для Capitol Records , которые сыграли важную роль в разработке прохладного джаза . В начале 1950 -х годов Дэвис записал одну из самых ранних жестких боп -музыки, находясь на престижных записях , но это случайно делал из -за героиновой зависимости. После широко известного выступления на Джазовом фестивале в Ньюпорте он подписал долгосрочный контракт с Columbia Records и записал альбом Round около полуночи в 1955 году. [3] It was his first work with saxophonist John Coltrane and bassist Paul Chambers, key members of the sextet he led into the early 1960s. During this period, he alternated between orchestral jazz collaborations with arranger Gil Evans, such as the Spanish music-influenced Sketches of Spain (1960), and band recordings, such as Milestones (1958) and Kind of Blue (1959).[4] The latter recording remains one of the most popular jazz albums of all time,[5] Продав более пяти миллионов копий в США

Davis made several lineup changes while recording Someday My Prince Will Come (1961), his 1961 Blackhawk concerts, and Seven Steps to Heaven (1963), another commercial success that introduced bassist Ron Carter, pianist Herbie Hancock, and drummer Tony Williams.[4] After adding saxophonist Wayne Shorter to his new quintet in 1964,[4] Davis led them on a series of more abstract recordings often composed by the band members, helping pioneer the post-bop genre with albums such as E.S.P. (1965) and Miles Smiles (1967),[6] before transitioning into his electric period. During the 1970s, he experimented with rock, funk, African rhythms, emerging electronic music technology, and an ever-changing lineup of musicians, including keyboardist Joe Zawinul, drummer Al Foster, bassist Michael Henderson, and guitarist John McLaughlin.[7] This period, beginning with Davis's 1969 studio album In a Silent Way and concluding with the 1975 concert recording Agharta, was the most controversial in his career, alienating and challenging many in jazz.[8] His million-selling 1970 record Bitches Brew helped spark a resurgence in the genre's commercial popularity with jazz fusion as the decade progressed.[9]

After a five-year retirement due to poor health, Davis resumed his career in the 1980s, employing younger musicians and pop sounds on albums such as The Man with the Horn (1981), You're Under Arrest (1985) and Tutu (1986). Critics were often unreceptive but the decade garnered Davis his highest level of commercial recognition. He performed sold-out concerts worldwide, while branching out into visual arts, film, and television work, before his death in 1991 from the combined effects of a stroke, pneumonia and respiratory failure.[10] In 2006, Davis was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame,[11] which recognized him as "one of the key figures in the history of jazz".[11] Rolling Stone described him as "the most revered jazz trumpeter of all time, not to mention one of the most important musicians of the 20th century,"[10] while Gerald Early called him inarguably one of the most influential and innovative musicians of that period.[12]

Early life

[edit]Davis was born on May 26, 1926, to an affluent African-American family in Alton, Illinois, 15 miles (24 kilometres) north of St. Louis.[13][14] He had an older sister, Dorothy Mae (1925–1996), and a younger brother, Vernon (1929–1999). His mother, Cleota Mae Henry of Arkansas, was a music teacher and violinist, and his father, Miles Dewey Davis Jr., also of Arkansas, was a dentist. They owned a 200-acre (81 ha) estate near Pine Bluff, Arkansas, with a profitable pig farm. In Pine Bluff, he and his siblings fished, hunted, and rode horses.[15][16] Davis's grandparents were the owners of an Arkansas farm where he would spend many summers.[17]

In 1927, the family moved to East St. Louis, Illinois. They lived on the second floor of a commercial building behind a dental office in a predominantly white neighborhood. Davis's father would soon become distant to his children as the Great Depression caused him to become increasingly consumed by his job; typically working six days a week.[17] From 1932 to 1934, Davis attended John Robinson Elementary School, an all-black school,[14] then Crispus Attucks, where he performed well in mathematics, music, and sports.[16] Davis had previously attended Catholic school.[17] At an early age he liked music, especially blues, big bands, and gospel.[15]

In 1935, Davis received his first trumpet as a gift from John Eubanks, a friend of his father.[18] He then took weekly lessons from "the biggest influence on my life," Elwood Buchanan, a teacher and musician who was a patient of his father.[13][19] His mother wanted him to play the violin instead.[20] Against the fashion of the time, Buchanan stressed the importance of playing without vibrato and encouraged him to use a clear, mid-range tone. Davis said that whenever he started playing with heavy vibrato, Buchanan slapped his knuckles.[20][13][21] In later years Davis said, "I prefer a round sound with no attitude in it, like a round voice with not too much tremolo and not too much bass. Just right in the middle. If I can't get that sound I can't play anything."[22] The family soon moved to 1701 Kansas Avenue in East St. Louis.[17]

In his autobiography, Davis stated, "By the age of 12, music had become the most important thing in my life."[19] On his thirteenth birthday his father bought him a new trumpet,[18] and Davis began to play in local bands. He took additional trumpet lessons from Joseph Gustat, principal trumpeter of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra.[18] Davis would also play the trumpet in talent shows he and his siblings would put on.[17]

In 1941, the 15-year-old attended East St. Louis Lincoln High School, where he joined the marching band directed by Buchanan and entered music competitions. Years later, Davis said that he was discriminated against in these competitions due to his race, but he added that these experiences made him a better musician.[16] When a drummer asked him to play a certain passage of music, and he couldn't do it, he began to learn music theory. "I went and got everything, every book I could get to learn about theory."[23] At Lincoln, Davis met his first girlfriend, Irene Birth (later Cawthon).[24] He had a band that performed at the Elks Club.[25] Part of his earnings paid for his sister's education at Fisk University.[26] Davis befriended trumpeter Clark Terry, who suggested he play without vibrato, and performed with him for several years.[18][26]

With encouragement from his teacher and girlfriend, Davis filled a vacant spot in the Rhumboogie Orchestra, also known as the Blue Devils, led by Eddie Randle. He became the band's musical director, which involved hiring musicians and scheduling rehearsal.[27][26] Years later, Davis considered this job one of the most important of his career.[23] Sonny Stitt tried to persuade him to join the Tiny Bradshaw band, which was passing through town, but his mother insisted he finish high school before going on tour. He said later, "I didn't talk to her for two weeks. And I didn't go with the band either."[28] In January 1944, Davis finished high school and graduated in absentia in June. During the next month, his girlfriend gave birth to a daughter, Cheryl.[26]

In July 1944, Billy Eckstine visited St. Louis with a band that included Art Blakey, Dizzy Gillespie, and Charlie Parker. Trumpeter Buddy Anderson was too sick to perform,[13] so Davis was invited to join. He played with the band for two weeks at Club Riviera.[26][29] After playing with these musicians, he was certain he should move to New York City, "where the action was".[30] His mother wanted him to go to Fisk University, like his sister, and study piano or violin. Davis had other interests.[28]

Career

[edit]1944–1948: New York City and the bebop years

[edit]

In September 1944, Davis accepted his father's idea of studying at the Juilliard School of Music in New York City.[26] After passing the audition, he attended classes in music theory, piano and dictation.[31] Davis often skipped his classes.[32]

Much of Davis's time was spent in clubs seeking his idol, Charlie Parker. According to Davis, Coleman Hawkins told him "finish your studies at Juilliard and forget Bird [Parker]".[33][29] After finding Parker, he joined a cadre of regulars at Minton's and Monroe's in Harlem who held jam sessions every night. The other regulars included J. J. Johnson, Kenny Clarke, Thelonious Monk, Fats Navarro, and Freddie Webster. Davis reunited with Cawthon and their daughter when they moved to New York City. Parker became a roommate.[29][26] Around this time Davis was paid an allowance of $40 (equivalent to $690 in 2023[34]).[35]

In mid-1945, Davis failed to register for the year's autumn term at Juilliard and dropped out after three semesters[15][36][26] because he wanted to perform full-time.[37] Years later he criticized Juilliard for concentrating too much on classical European and "white" repertoire, but he praised the school for teaching him music theory and improving his trumpet technique.

Davis began performing at clubs on 52nd Street with Coleman Hawkins and Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis. He recorded for the first time on April 24, 1945, when he entered the studio as a sideman for Herbie Fields's band.[26][29] During the next year, he recorded as a leader for the first time with the Miles Davis Sextet plus Earl Coleman and Ann Baker, one of the few times he accompanied a singer.[38]

In 1945, Davis replaced Dizzy Gillespie in Charlie Parker's quintet. On November 26, he participated in several recording sessions as part of Parker's group Reboppers that also involved Gillespie and Max Roach,[26] displaying hints of the style he would become known for. On Parker's tune "Now's the Time", Davis played a solo that anticipated cool jazz. He next joined a big band led by Benny Carter, performing in St. Louis and remaining with the band in California. He again played with Parker and Gillespie.[39] In Los Angeles, Parker had a nervous breakdown that put him in the hospital for several months.[39][40] In March 1946, Davis played in studio sessions with Parker and began a collaboration with bassist Charles Mingus that summer. Cawthon gave birth to Davis's second child, Gregory, in East St. Louis before reuniting with Davis in New York City the following year.[39] Davis noted that by this time, "I was still so much into the music that I was even ignoring Irene." He had also turned to alcohol and cocaine.[41]

Davis was a member of Billy Eckstine's big band in 1946 and Gillespie's in 1947.[42] He joined a quintet led by Parker that also included Max Roach. Together they performed live with Duke Jordan and Tommy Potter for much of the year, including several studio sessions.[39] In one session that May, Davis wrote the tune "Cheryl", for his daughter. Davis's first session as a leader followed in August 1947, playing as the Miles Davis All Stars that included Parker, pianist John Lewis, and bassist Nelson Boyd; they recorded "Milestones", "Half Nelson", and "Sippin' at Bells".[43][39] After touring Chicago and Detroit with Parker's quintet, Davis returned to New York City in March 1948 and joined the Jazz at the Philharmonic tour, which included a stop in St. Louis on April 30.[39]

1948–1950: Miles Davis Nonet and Birth of the Cool

[edit]In August 1948, Davis declined an offer to join Duke Ellington's orchestra as he had entered rehearsals with a nine-piece band featuring baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan and arrangements by Gil Evans, taking an active role on what soon became his own project.[44][39] Evans' Manhattan apartment had become the meeting place for several young musicians and composers such as Davis, Roach, Lewis, and Mulligan who were unhappy with the increasingly virtuoso instrumental techniques that dominated bebop.[45] These gatherings led to the formation of the Miles Davis Nonet, which included atypical modern jazz instruments such as French horn and tuba, leading to a thickly textured, almost orchestral sound.[32] The intent was to imitate the human voice through carefully arranged compositions and a relaxed, melodic approach to improvisation. In September, the band completed their sole engagement as the opening band for Count Basie at the Royal Roost for two weeks. Davis had to persuade the venue's manager to write the sign "Miles Davis Nonet. Arrangements by Gil Evans, John Lewis and Gerry Mulligan". Davis returned to Parker's quintet, but relationships within the quintet were growing tense mainly due to Parker's erratic behavior caused by his drug addiction.[39] Early in his time with Parker, Davis abstained from drugs, chose a vegetarian diet, and spoke of the benefits of water and juice.[46]

In December 1948, Davis quit, saying he was not being paid.[39] His departure began a period when he worked mainly as a freelancer and sideman. His nonet remained active until the end of 1949. After signing a contract with Capitol Records, they recorded sessions in January and April 1949, which sold little but influenced the "cool" or "west coast" style of jazz.[39] The lineup changed throughout the year and included tuba player Bill Barber, alto saxophonist Lee Konitz, pianist Al Haig, trombone players Mike Zwerin with Kai Winding, French horn players Junior Collins with Sandy Siegelstein and Gunther Schuller, and bassists Al McKibbon and Joe Shulman. One track featured singer Kenny Hagood. The presence of white musicians in the group angered some black players, many of whom were unemployed at the time, yet Davis rebuffed their criticisms.[47] Recording sessions with the nonet for Capitol continued until April 1950. The Nonet recorded a dozen tracks which were released as singles and subsequently compiled on the 1957 album Birth of the Cool.[32]

In May 1949, Davis performed with the Tadd Dameron Quintet with Kenny Clarke and James Moody at the Paris International Jazz Festival. On his first trip abroad Davis took a strong liking to Paris and its cultural environment, where he felt black jazz musicians and people of color in general were better respected than in the U.S. The trip, he said, "changed the way I looked at things forever".[48] He began an affair with singer and actress Juliette Gréco.[48]

1949–1955: Signing with Prestige, heroin addiction, and hard bop

[edit]After returning from Paris in mid-1949, he became depressed and found little work except a short engagement with Powell in October and guest spots in New York City, Chicago, and Detroit until January 1950.[49] He was falling behind in hotel rent and attempts were made to repossess his car. His heroin use became an expensive addiction, and Davis, not yet 24 years old, "lost my sense of discipline, lost my sense of control over my life, and started to drift".[50][39] In August 1950, Cawthon gave birth to Davis's second son, Miles IV. Davis befriended boxer Johnny Bratton which began his interest in the sport. Davis left Cawthon and his three children in New York City in the hands of one his friends, jazz singer Betty Carter.[49] He toured with Eckstine and Billie Holiday and was arrested for heroin possession in Los Angeles. The story was reported in DownBeat magazine, which led to a further reduction in work, though he was acquitted weeks later.[51] By the 1950s, Davis had become more skilled and was experimenting with the middle register of the trumpet alongside harmonies and rhythms.[32]

In January 1951, Davis's fortunes improved when he signed a one-year contract with Prestige after owner Bob Weinstock became a fan of the nonet. [52] Davis chose Lewis, trombonist Bennie Green, bassist Percy Heath, saxophonist Sonny Rollins, and drummer Roy Haynes; they recorded what became part of Miles Davis and Horns (1956). Davis was hired for other studio dates in 1951[51] and began to transcribe scores for record labels to fund his heroin addiction. His second session for Prestige was released on The New Sounds (1951), Dig (1956), and Conception (1956).[53]

Davis supported his heroin habit by playing music and by living the life of a hustler, exploiting prostitutes, and receiving money from friends. By 1953, his addiction began to impair his playing. His drug habit became public in a DownBeat interview with Cab Calloway, whom he never forgave as it brought him "all pain and suffering".[54] He returned to St. Louis and stayed with his father for several months.[54] After a brief period with Roach and Mingus in September 1953,[55] he returned to his father's home, where he concentrated on addressing his addiction.[56]

Davis lived in Detroit for about six months, avoiding New York City, where it was easy to get drugs. Though he used heroin, he was still able to perform locally with Elvin Jones and Tommy Flanagan as part of Billy Mitchell's house band at the Blue Bird club. He was also "pimping a little".[57] However, he was able to end his addiction, and, in February 1954, Davis returned to New York City, feeling good "for the first time in a long time", mentally and physically stronger, and joined a gym.[58] He informed Weinstock and Blue Note that he was ready to record with a quintet, which he was granted. He considered the albums that resulted from these and earlier sessions – Miles Davis Quartet and Miles Davis Volume 2 – "very important" because he felt his performances were particularly strong.[59] He was paid roughly $750 (equivalent to $8,500 in 2023[34]) for each album and refused to give away his publishing rights.[60]

Davis abandoned the bebop style and turned to the music of pianist Ahmad Jamal, whose approach and use of space influenced him.[61] When he returned to the studio in June 1955 to record The Musings of Miles, he wanted a pianist like Jamal and chose Red Garland.[61] Blue Haze (1956), Bags' Groove (1957), Walkin' (1957), and Miles Davis and the Modern Jazz Giants (1959) documented the evolution of his sound with the Harmon mute placed close to the microphone, and the use of more spacious and relaxed phrasing. He assumed a central role in hard bop, less radical in harmony and melody, and used popular songs and American standards as starting points for improvisation. Hard bop distanced itself from cool jazz with a harder beat and music inspired by the blues.[62] A few critics consider Walkin' (April 1954) the album that created the hard bop genre.[22]

Davis gained a reputation for being cold, distant, and easily angered. He wrote that in 1954 Sugar Ray Robinson "was the most important thing in my life besides music", and he adopted Robinson's "arrogant attitude".[63] He showed contempt for critics and the press.

Davis had an operation to remove polyps from his larynx in October 1955.[64] The doctors told him to remain silent after the operation, but he got into an argument that permanently damaged his vocal cords and gave him a raspy voice for the rest of his life.[65] He was called the "prince of darkness", adding a patina of mystery to his public persona.[a]

1955–1959: Signing with Columbia, first quintet, and modal jazz

[edit]In July 1955, Davis's fortunes improved considerably when he played at the Newport Jazz Festival, with a lineup of Monk, Heath, drummer Connie Kay, and horn players Zoot Sims and Gerry Mulligan.[69][70] The performance was praised by critics and audiences alike, who considered it to be a highlight of the festival as well as helping Davis, the least well known musician in the group, to increase his popularity among affluent white audiences.[71][70] He tied with Dizzy Gillespie for best trumpeter in the 1955 DownBeat magazine Readers' Poll.[72]

George Avakian of Columbia Records heard Davis perform at Newport and wanted to sign him to the label. Davis had one year left on his contract with Prestige, which required him to release four more albums. He signed a contract with Columbia that included a $4,000 advance (equivalent to $45,500 in 2023[34]) and required that his recordings for Columbia remain unreleased until his agreement with Prestige expired.[73][74]

At the request of Avakian, he formed the Miles Davis Quintet for a performance at Café Bohemia. The quintet contained Sonny Rollins on tenor saxophone, Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on double bass, and Philly Joe Jones on drums. Rollins was replaced by John Coltrane, completing the membership of the first quintet. To fulfill Davis' contract with Prestige, this new group worked through two marathon sessions in May and October 1956 that were released by the label as four LPs: Cookin' with the Miles Davis Quintet (1957), Relaxin' with the Miles Davis Quintet (1958), Workin' with the Miles Davis Quintet (1960) and Steamin' with the Miles Davis Quintet (1961). Each album was critically acclaimed and helped establish Davis's quintet as one of the best.[75][76][77]

The style of the group was an extension of their experience playing with Davis. He played long, legato, melodic lines, while Coltrane contrasted with energetic solos. Their live repertoire was a mix of bebop, standards from the Great American Songbook and pre-bop eras, and traditional tunes. They appeared on 'Round About Midnight, Davis's first album for Columbia.

In 1956, he left his quintet temporarily to tour Europe as part of the Birdland All-Stars, which included the Modern Jazz Quartet and French and German musicians. In Paris, he reunited with Gréco and they "were lovers for many years".[78][79] He then returned home, reunited his quintet and toured the US for two months. Conflict arose on tour when he grew impatient with the drug habits of Jones and Coltrane. Davis was trying to live a healthier life by exercising and reducing his alcohol. But he continued to use cocaine.[80] At the end of the tour, he fired Jones and Coltrane and replaced them with Sonny Rollins and Art Taylor.[81]

In November 1957, Davis went to Paris and recorded the soundtrack to Ascenseur pour l'échafaud.[42] directed by Louis Malle and starring Jeanne Moreau. Consisting of French jazz musicians Barney Wilen, Pierre Michelot, and René Urtreger, and American drummer Kenny Clarke, the group avoided a written score and instead improvised while they watched the film in a recording studio.

After returning to New York, Davis revived his quintet with Adderley[42] and Coltrane, who was clean from his drug habit. Now a sextet, the group recorded material in early 1958 that was released on Milestones, an album that demonstrated Davis's interest in modal jazz. A performance by Les Ballets Africains drew him to slower, deliberate music that allowed the creation of solos from harmony rather than chords.[82]

By May 1958, he had replaced Jones with drummer Jimmy Cobb, and Garland left the group, leaving Davis to play piano on "Sid's Ahead" for Milestones.[83] He wanted someone who could play modal jazz, so he hired Bill Evans, a young pianist with a background in classical music.[84] Evans had an impressionistic approach to piano. His ideas greatly influenced Davis. But after eight months of touring, a tired Evans left. Wynton Kelly, his replacement, brought to the group a swinging style that contrasted with Evans's delicacy. The sextet made their recording debut on Jazz Track (1958).[84]

1957–1963: Collaborations with Gil Evans and Kind of Blue

[edit]By early 1957, Davis was exhausted from recording and touring and wished to pursue new projects. In March, the 30-year-old Davis told journalists of his intention to retire soon and revealed offers he had received to teach at Harvard University and be a musical director at a record label.[85][86] Avakian agreed that it was time for Davis to explore something different, but Davis rejected his suggestion of returning to his nonet as he considered that a step backward.[86] Avakian then suggested that he work with a bigger ensemble, similar to Music for Brass (1957), an album of orchestral and brass-arranged music led by Gunther Schuller featuring Davis as a guest soloist.

Davis accepted and worked with Gil Evans in what became a five-album collaboration from 1957 to 1962.[87] Miles Ahead (1957) showcased Davis on flugelhorn and a rendition of "The Maids of Cadiz" by Léo Delibes, the first piece of classical music that Davis recorded. Evans devised orchestral passages as transitions, thus turning the album into one long piece of music.[88][89] Porgy and Bess (1959) includes arrangements of pieces from George Gershwin's opera. Sketches of Spain (1960) contained music by Joaquín Rodrigo and Manuel de Falla and originals by Evans. The classical musicians had trouble improvising, while the jazz musicians couldn't handle the difficult arrangements, but the album was a critical success, selling over 120,000 copies in the US.[90] Davis performed with an orchestra conducted by Evans at Carnegie Hall in May 1961 to raise money for charity.[91] The pair's final album was Quiet Nights (1963), a collection of bossa nova songs released against their wishes. Evans stated it was only half an album and blamed the record company; Davis blamed producer Teo Macero and refused to speak to him for more than two years.[92] The boxed set Miles Davis & Gil Evans: The Complete Columbia Studio Recordings (1996) won the Grammy Award for Best Historical Album and Best Album Notes in 1997.

In March and April 1959, Davis recorded what some consider his greatest album, Kind of Blue. He named the album for its mood.[93] He called back Bill Evans, as the music had been planned around Evans's piano style.[94] Both Davis and Evans were familiar with George Russell's ideas about modal jazz.[95][96] But Davis neglected to tell pianist Wynton Kelly that Evans was returning, so Kelly appeared on only one song, "Freddie Freeloader". [94] The sextet had played "So What" and "All Blues" at performances, but the remaining three compositions they saw for the first time in the studio.

Released in August 1959, Kind of Blue was an instant success, with widespread radio airplay and rave reviews from critics.[93] It has remained a strong seller over the years. In 2019, the album achieved 5× platinum certification from the Recording Industry Association of America for sales of over five million copies in the US, making it one of the most successful jazz albums in history.[97] In 2009, the US House of Representatives passed a resolution that honored it as a national treasure.[98][99]

In August 1959, during a break in a recording session at the Birdland nightclub in New York City, Davis was escorting a blonde-haired woman to a taxi outside the club when policeman Gerald Kilduff told him to "move on".[100][101] Davis said that he was working at the club, and he refused to move.[102] Kilduff arrested and grabbed Davis as he tried to protect himself. Witnesses said the policeman hit Davis in the stomach with a nightstick without provocation. Two detectives held the crowd back, while a third approached Davis from behind and beat him over the head. Davis was taken to jail, charged with assaulting an officer, then taken to the hospital where he received five stitches.[101] By January 1960, he was acquitted of disorderly conduct and third-degree assault. He later stated the incident "changed my whole life and whole attitude again, made me feel bitter and cynical again when I was starting to feel good about the things that had changed in this country".[103]

Davis and his sextet toured to support Kind of Blue.[93] He persuaded Coltrane to play with the group on one final European tour in the spring of 1960. Coltrane then departed to form his quartet, though he returned for some tracks on Davis's album Someday My Prince Will Come (1961). Its front cover shows a photograph of his wife, Frances Taylor, after Davis demanded that Columbia depict black women on his album covers.[104]

1963–1968: Second quintet

[edit]

In December 1962, Davis, Kelly, Chambers, Cobb, and Rollins played together for the last time as the first three wanted to leave and play as a trio. Rollins left them soon after, leaving Davis to pay over $25,000 (equivalent to $251,800 in 2023[34]) to cancel upcoming gigs and quickly assemble a new group. Following auditions, he found his new band in tenor saxophonist George Coleman, bassist Ron Carter, pianist Victor Feldman, and drummer Frank Butler.[105] By May 1963, Feldman and Butler were replaced by 23-year-old pianist Herbie Hancock and 17-year-old drummer Tony Williams who made Davis "excited all over again".[106] With this group, Davis completed the rest of what became Seven Steps to Heaven (1963) and recorded the live albums Miles Davis in Europe (1964), My Funny Valentine (1965), and Four & More (1966). The quintet played essentially the same bebop tunes and standards that Davis's previous bands had played, but they approached them with structural and rhythmic freedom and occasionally breakneck speed.

In 1964, Coleman was briefly replaced by saxophonist Sam Rivers (who recorded with Davis on Miles in Tokyo) until Wayne Shorter was persuaded to leave the Jazz Messengers. The quintet with Shorter lasted through 1968, with Shorter becoming the group's principal composer. The album E.S.P. (1965) was named after his composition. While touring Europe, the group made its first album, Miles in Berlin (1965).[107]

Davis needed medical attention for hip pain, which had worsened since his Japanese tour during the previous year.[108] He underwent hip replacement surgery in April 1965, with bone taken from his shin, but it failed. After his third month in the hospital, he discharged himself due to boredom and went home. He returned to the hospital in August after a fall required the insertion of a plastic hip joint.[109] In November 1965, he had recovered enough to return to performing with his quintet, which included gigs at the Plugged Nickel in Chicago. Teo Macero returned as his record producer after their rift over Quiet Nights had healed.[110][111]

In January 1966, Davis spent three months in the hospital with a liver infection. When he resumed touring, he performed more at colleges because he had grown tired of the typical jazz venues.[112] Columbia president Clive Davis reported in 1966 his sales had declined to around 40,000–50,000 per album, compared to as many as 100,000 per release a few years before. Matters were not helped by the press reporting his apparent financial troubles and imminent demise.[113] After his appearance at the 1966 Newport Jazz Festival, he returned to the studio with his quintet for a series of sessions. He started a relationship with actress Cicely Tyson, who helped him reduce his alcohol consumption.[114]

Material from the 1966–1968 sessions was released on Miles Smiles (1966), Sorcerer (1967), Nefertiti (1967), Miles in the Sky (1968), and Filles de Kilimanjaro (1968). The quintet's approach to the new music became known as "time no changes"—which referred to Davis's decision to depart from chordal sequences and adopt a more open approach, with the rhythm section responding to the soloists' melodies.[115] Through Nefertiti the studio recordings consisted primarily of originals composed by Shorter, with occasional compositions by the other sidemen. In 1967, the group began to play their concerts in continuous sets, each tune flowing into the next, with only the melody indicating any sort of change. His bands performed this way until his hiatus in 1975.

Miles in the Sky and Filles de Kilimanjaro—which tentatively introduced electric bass, electric piano, and electric guitar on some tracks—pointed the way to the fusion phase of Davis's career. He also began experimenting with more rock-oriented rhythms on these records. By the time the second half of Filles de Kilimanjaro was recorded, bassist Dave Holland and pianist Chick Corea had replaced Carter and Hancock. Davis soon took over the compositional duties of his sidemen.

1968–1975: The electric period

[edit]In a Silent Way was recorded in a single studio session in February 1969, with Shorter, Hancock, Holland, and Williams alongside keyboardists Chick Corea and Joe Zawinul and guitarist John McLaughlin. The album contains two side-long tracks that Macero pieced together from different takes recorded at the session. When the album was released later that year, some critics accused him of "selling out" to the rock and roll audience. Nevertheless, it reached number 134 on the US Billboard Top LPs chart, his first album since My Funny Valentine to reach the chart. In a Silent Way was his entry into jazz fusion. The touring band of 1969–1970—with Shorter, Corea, Holland, and DeJohnette—never completed a studio recording together, and became known as Davis's "lost quintet", though radio broadcasts from the band's European tour have been extensively bootlegged.[116][117]

For the double album Bitches Brew (1970), he hired Jack DeJohnette, Harvey Brooks, and Bennie Maupin. The album contained long compositions, some over twenty minutes, that more often than not, were constructed from several takes by Macero and Davis via splicing and tape loops amid epochal advances in multitrack recording technologies.[118] Bitches Brew peaked at No. 35 on the Billboard Album chart.[119] In 1976, it was certified gold for selling over 500,000 records. By 2003, it had sold one million copies.[97]

In March 1970, Davis began to perform as the opening act for rock bands, allowing Columbia to market Bitches Brew to a larger audience. He shared a Fillmore East bill with the Steve Miller Band and Neil Young with Crazy Horse on March 6 and 7.[120] Biographer Paul Tingen wrote, "Miles' newcomer status in this environment" led to "mixed audience reactions, often having to play for dramatically reduced fees, and enduring the 'sell-out' accusations from the jazz world", as well as being "attacked by sections of the black press for supposedly genuflecting to white culture".[121] The 1970 tours included the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival on August 29 when he performed to an estimated 600,000 people, the largest of his career.[122] Plans to record with Hendrix ended after the guitarist's death; his funeral was the last one that Davis attended.[123] Several live albums with a transitional sextet/septet including Corea, DeJohnette, Holland, Airto Moreira, saxophonist Steve Grossman, and keyboardist Keith Jarrett were recorded during this period, including Miles Davis at Fillmore (1970) and Black Beauty: Miles Davis at Fillmore West (1973).[11]

By 1971, Davis had signed a contract with Columbia that paid him $100,000 a year (equivalent to $752,340 in 2023[34]) for three years in addition to royalties.[124] He recorded a soundtrack album (Jack Johnson) for the 1970 documentary film about heavyweight boxer Jack Johnson, containing two long pieces of 25 and 26 minutes in length with Hancock, McLaughlin, Sonny Sharrock, and Billy Cobham. He was committed to making music for African-Americans who liked more commercial, pop, groove-oriented music. By November 1971, DeJohnette and Moreira had been replaced in the touring ensemble by drummer Leon "Ndugu" Chancler and percussionists James Mtume and Don Alias.[125] Live-Evil was released in the same month. Showcasing bassist Michael Henderson, who had replaced Holland in 1970, the album demonstrated that Davis's ensemble had transformed into a funk-oriented group while retaining the exploratory imperative of Bitches Brew.

In 1972, composer-arranger Paul Buckmaster introduced Davis to the music of avant-garde composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, leading to a period of creative exploration. Biographer J. K. Chambers wrote, "The effect of Davis' study of Stockhausen could not be repressed for long ... Davis' own 'space music' shows Stockhausen's influence compositionally."[126] His recordings and performances during this period were described as "space music" by fans, Feather, and Buckmaster, who described it as "a lot of mood changes—heavy, dark, intense—definitely space music".[127][128] The studio album On the Corner (1972) blended the influence of Stockhausen and Buckmaster with funk elements. Davis invited Buckmaster to New York City to oversee the writing and recording of the album with Macero.[129] The album reached No. 1 on the Billboard jazz chart but peaked at No. 156 on the more heterogeneous Top 200 Albums chart. Davis felt that Columbia marketed it to the wrong audience. "The music was meant to be heard by young black people, but they just treated it like any other jazz album and advertised it that way, pushed it on the jazz radio stations. Young black kids don't listen to those stations; they listen to R&B stations and some rock stations."[130] In October 1972, he broke his ankles in a car crash. He took painkillers and cocaine to cope with the pain.[131] Looking back at his career after the incident, he wrote, "Everything started to blur."[132]

After recording On the Corner, he assembled a group with Henderson, Mtume, Carlos Garnett, guitarist Reggie Lucas, organist Lonnie Liston Smith, tabla player Badal Roy, sitarist Khalil Balakrishna, and drummer Al Foster. In striking contrast to that of his previous lineups, the music emphasized rhythmic density and shifting textures instead of solos. This group was recorded live in 1972 for In Concert, but Davis found it unsatisfactory, leading him to drop the tabla and sitar and play organ himself. He also added guitarist Pete Cosey. The compilation studio album Big Fun contains four long improvisations recorded between 1969 and 1972.

This was music that polarized audiences, provoking boos and walk-outs amid the ecstasy of others. The length, density, and unforgiving nature of it mocked those who said that Miles was interested only in being trendy and popular. Some have heard in this music the feel and shape of a musician's late work, an egoless music that precedes its creator's death. As Theodor Adorno said of the late Beethoven, the disappearance of the musician into the work is a bow to mortality. It was as if Miles were testifying to all that he had been witness to for the past thirty years, both terrifying and joyful.

— John Szwed on Agharta (1975) and Pangaea (1976)[133]

Studio sessions throughout 1973 and 1974 led to Get Up with It, an album which included four long pieces alongside four shorter recordings from 1970 and 1972. The track "He Loved Him Madly", a thirty-minute tribute to the recently deceased Duke Ellington, influenced Brian Eno's ambient music.[134] In the United States, it performed comparably to On the Corner, reaching number 8 on the jazz chart and number 141 on the pop chart. He then concentrated on live performance with a series of concerts that Columbia released on the double live albums Agharta (1975), Pangaea (1976), and Dark Magus (1977). The first two are recordings of two sets from February 1, 1975, in Osaka, by which time Davis was troubled by several physical ailments; he relied on alcohol, codeine, and morphine to get through the engagements. His shows were routinely panned by critics who mentioned his habit of performing with his back to the audience.[135] Cosey later asserted that "the band really advanced after the Japanese tour",[136] but Davis was again hospitalized, for his ulcers and a hernia, during a tour of the US while opening for Herbie Hancock.

After appearances at the 1975 Newport Jazz Festival in July and the Schaefer Music Festival in New York in September, Davis dropped out of music.[137][138]

1975–1980: Hiatus

[edit]In his autobiography, Davis wrote frankly about his life during his hiatus from music. He called his Upper West Side brownstone a wreck and chronicled his heavy use of alcohol and cocaine, in addition to sexual encounters with many women.[139] He also stated that "Sex and drugs took the place music had occupied in my life." Drummer Tony Williams recalled that by noon (on average) Davis would be sick from the previous night's intake.[140]

In December 1975, he had regained enough strength to undergo a much needed hip replacement operation.[141] In December 1976, Columbia was reluctant to renew his contract and pay his usual large advances. But after his lawyer started negotiating with United Artists, Columbia matched their offer, establishing the Miles Davis Fund to pay him regularly. Pianist Vladimir Horowitz was the only other musician with Columbia who had a similar status.[142]

In 1978, Davis asked fusion guitarist Larry Coryell to participate in sessions with keyboardists Masabumi Kikuchi and George Pavlis, bassist T. M. Stevens, and drummer Al Foster.[143] Davis played the arranged piece uptempo, abandoned his trumpet for the organ, and had Macero record the session without the band's knowledge. After Coryell declined a spot in a band that Davis was beginning to put together, Davis returned to his reclusive lifestyle in New York City.[144][145] Soon after, Marguerite Eskridge had Davis jailed for failing to pay child support for their son Erin, which cost him $10,000 (equivalent to $46,710 in 2023[34]) for release on bail.[143][141] A recording session that involved Buckmaster and Gil Evans was halted,[146] with Evans leaving after failing to receive the payment he was promised. In August 1978, Davis hired a new manager, Mark Rothbaum, who had worked with him since 1972.[147]

1980–1985: Comeback

[edit]Having played the trumpet little throughout the previous three years, Davis found it difficult to reclaim his embouchure. His first post-hiatus studio appearance took place in May 1980.[148] A day later, Davis was hospitalized due to a leg infection.[149] He recorded The Man with the Horn from June 1980 to May 1981 with Macero producing. A large band was abandoned in favor of a combo with saxophonist Bill Evans and bassist Marcus Miller. Both would collaborate with him during the next decade.

The Man with the Horn received a poor critical reception despite selling well. In June 1981, Davis returned to the stage for the first time since 1975 in a ten-minute guest solo as part of Mel Lewis's band at the Village Vanguard.[150] This was followed by appearances with a new band.[151][152] Recordings from a mixture of dates from 1981, including from the Kix in Boston and Avery Fisher Hall, were released on We Want Miles,[153] which earned him a Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance by a Soloist.[154]

In January 1982, while Tyson was working in Africa, Davis "went a little wild" with alcohol and suffered a stroke that temporarily paralyzed his right hand.[155][156] Tyson returned home and cared for him. After three months of treatment with a Chinese acupuncturist, he was able to play the trumpet again. He listened to his doctor's warnings and gave up alcohol and drugs. He credited Tyson with helping his recovery, which involved exercise, piano playing, and visits to spas. She encouraged him to draw, which he pursued for the rest of his life.[155] Takao Ogawa, a Japanese jazz journalist who befriended Davis during this period, took pictures of his drawings and put them in his book along with the interviews of Davis at his apartment in New York. Davis told Ogawa: "I'm interested in line and color, line is like phrase and coating colors is like code. When I see good paintings, I hear good music. That is why my paintings are the same as my music. They are different than any paintings."[157]

Davis resumed touring in May 1982 with a lineup that included percussionist Mino Cinelu and guitarist John Scofield, with whom he worked closely on the album Star People (1983). In mid-1983, he worked on the tracks for Decoy, an album mixing soul music and electronica that was released in 1984. He brought in producer, composer, and keyboardist Robert Irving III, who had collaborated with him on The Man with the Horn. With a seven-piece band that included Scofield, Evans, Irving, Foster, and Darryl Jones, he played a series of European performances that were positively received. In December 1984, while in Denmark, he was awarded the Léonie Sonning Music Prize. Trumpeter Palle Mikkelborg had written "Aura", a contemporary classical piece, for the event which impressed Davis to the point of returning to Denmark in early 1985 to record his next studio album, Aura.[158] Columbia was dissatisfied with the recording and delayed its release.

In May 1985, one month into a tour, Davis signed a contract with Warner Bros. that required him to give up his publishing rights.[159][160] You're Under Arrest, his final album for Columbia, was released in September. It included cover versions of two pop songs: "Time After Time" by Cyndi Lauper and Michael Jackson's "Human Nature". He considered releasing an album of pop songs, and he recorded dozens of them, but the idea was rejected. He said that many of today's jazz standards had been pop songs in Broadway theater and that he was simply updating the standards repertoire.

Davis collaborated with a number of figures from the British post-punk and new wave movements during this period, including Scritti Politti.[161] This period also saw Davis move from his funk inspired sound of the early 1970s to a more melodic style.[35]

1986–1991: Final years

[edit]

After taking part in the recording of the 1985 protest song "Sun City" as a member of Artists United Against Apartheid, Davis appeared on the instrumental "Don't Stop Me Now" by Toto for their album Fahrenheit (1986). Davis collaborated with Prince on a song titled "Can I Play With U," which went unreleased until 2020.[162] Davis also collaborated with Zane Giles and Randy Hall on the Rubberband sessions in 1985 but those would remain unreleased until 2019.[163] Instead, he worked with Marcus Miller, and Tutu (1986) became the first time he used modern studio tools such as programmed synthesizers, sampling, and drum loops. Released in September 1986, its front cover is a photographic portrait of Davis by Irving Penn.[160] In 1987, he won a Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Soloist. Also in 1987, Davis contacted American journalist Quincy Troupe to work with him on his autobiography.[164] The two men had met the previous year when Troupe conducted a two-day-long interview, which was published by Spin as a 45-page article.[164]

В 1988 году Дэвис имел небольшую роль в качестве уличного музыканта в рождественском комедийном фильме « Скругед» в главной роли с Биллом Мюрреем . Он также сотрудничал с Zucchero Fornaciari в версии Dune Mosse ( Blue's ), опубликованной в 2004 году в Zu & Co. Итальянского блюзмена. В ноябре 1988 года он был введен в суверенный военный орден Мальты на церемонии во дворце Алхамбры в Испании [165][166][167] (this was part of the reasoning for his daughter's decision to include the honorific "Sir" on his headstone).[168] Later that month, Davis cut his European tour short after he collapsed and fainted after a two-hour show in Madrid and flew home.[169] Ходили слухи о том, что американская звезда журнала сообщила о том, что американская звезда журнала 21 февраля 1989 года, издание, в котором опубликовано утверждение о том, что Дэвис заключил контракт с СПИДом, что побудило своего менеджера Питера Шуката выступить на следующий день. Шукат сказал, что Дэвис был в больнице для легкого случая пневмонии и удаления доброкачественного полипа в его вокальных связках и удобно отдыхал, готовясь к своим турам 1989 года. [ 170 ] Позже Дэвис обвинил одну из своих бывших жен или подруг за то, что он начал слух, и решил не предпринимать судебных исков. [ 171 ] Он дал интервью 60 минут Гарри Рассудом. В октябре 1989 года он получил Гранд Медайл де Вермейл от мэра Парижа Жака Чирака . [ 172 ] В 1990 году он получил награду Грэмми пожизненной достижения . [ 173 ] В начале 1991 года он появился в «Рольф де Хиер» фильме в качестве джазового музыканта.

Дэвис последовал за Туту с Амандлой (1989) и саундтреками к четырем фильмам: Street Smart , Siesta , The Hot Spot и Dingo . под влиянием хип-хопа Его последние альбомы были выпущены посмертно: Doo-Bop (1992) и Miles & Quincy Live в Montreux (1993), сотрудничество с Куинси Джонсом из джазового фестиваля в Montreux 1991 года , где впервые за три десятилетия Он исполнял песни с Майлза впереди , Порги и Бесс , а также наброски Испании . [ 174 ]

8 июля 1991 года Дэвис вернулся к исполнению материала из своего прошлого на Джазовом фестивале в Монтре 1991 года с группой и оркестром, проведенным Куинси Джонсом. [ 175 ] Набор состоял из аранжировок из его альбомов, записанных с Джилом Эвансом. [ 176 ] За шоу последовал концерт, объявленный «Майлзом и друзьями» в Гранде Галле де ла Виллетт в Париже два дня спустя, с выступлениями приглашенных музыкантов на протяжении всей его карьеры, включая Джона Маклафлина, Херби Хэнкок и Джо Завинула. [ 176 ] В Париже он был награжден рыцарством, шеверием министра французской культуры Легиона Французской культуры Джека Ланга, который назвал его «Пикассо джаза». [ 173 ] Вернувшись в Америку, он остановился в Нью-Йорке, чтобы записать материал для Doo-Bop, а затем вернулся в Калифорнию, чтобы сыграть в Hollywood Bowl 25 августа, его финальное живое выступление. [ 175 ] [ 177 ]

Личная жизнь

[ редактировать ]В 1957 году, [ 178 ] Дэвис начал отношения с Фрэнсис Тейлор , танцовщицей, с которой он встретил в 1953 году в Ciro's в Лос -Анджелесе. [ 179 ] [ 180 ] Они поженились в декабре 1959 года в Толедо, штат Огайо . [ 181 ] Отношения были омрачены многочисленными случаями домашнего насилия в отношении Тейлора. Позже он писал: «Каждый раз, когда я ударил ее, мне было плохо, потому что во многом это было не ее вина, но имел отношение к тем, что я темпераментирован и ревнив». [ 182 ] [ 183 ] [ 184 ] Одна теория его поведения заключалась в том, что в 1963 году он увеличил употребление алкоголя и кокаина, чтобы облегчить боль в суставах, вызванную анемией серповидноклеточной клеток . [ 185 ] [ 186 ] Он галлюцинировал, «ищет этого воображаемого человека» в своем доме, владея кухонным ножом. Вскоре после того, как была сделана фотография альбома ESP (1965), Тейлор оставил его в последний раз. [ 187 ] Она подала на развод в 1966 году; Он был завершен в феврале 1968 года. [ 188 ] [ 189 ]

В сентябре 1968 года Дэвис женился на 23-летней модели и авторе песен Бетти Мабри . [ 190 ] В своей автобиографии Дэвис описал ее как «гриплу высокого класса, которая была очень талантлива, но не верила в свой собственный талант». [ 191 ] Мабри, знакомое лицо в контркультуре Нью -Йорка, представила Дэвиса популярным рок, душевным и фанк -музыкантам. [ 192 ] Джаз -критик Леонард Фетер посетил квартиру Дэвиса и был шокирован, обнаружив, что он слушает альбомы Бердса , Ареты Франклин и Дионн Уорвик . Ему также понравились Джеймс Браун , Хриплый и Семейный камень , и Джими Хендрикс , [ 193 ] чья группа Gypsys особенно впечатлила Дэвиса. [ 194 ] Дэвис подал на развод от Мабри в 1969 году, обвинив ее в романе с Хендриксом. [ 191 ]

В октябре 1969 года Дэвис был застрелен пять раз в его машине с Маргаритой Эскридж, одним из двух его любовников. Инцидент оставил его с пасом, и Эскридж невредился. [ 120 ] В 1970 году Маргарита родила своего сына Эрин. К 1979 году Дэвис возродил свои отношения с актрисой Сюли Тайсоном , которая помогла ему преодолеть свою зависимость от кокаина и восстановить его энтузиазм по поводу музыки. Они поженились в ноябре 1981 года, [ 195 ] [ 196 ] Но их бурный брак закончился тем, что Тайсон подал заявку на развод в 1988 году, который был завершен в 1989 году. [ 197 ]

В 1984 году Дэвис встретился с 34-летним скульптором Джо Гелбардом. [ 198 ] Гелбард научит Дэвиса, как рисовать; Эти двое были частыми сотрудниками и вскоре были романтически вовлечены. [ 198 ] [ 164 ] К 1985 году Дэвис был диабетом и требовал ежедневных инъекций инсулина. [ 199 ] Дэвис становился все более агрессивным в последний год из -за того, что он принимал лекарства, которые он принимал, [ 198 ] и его агрессия проявилась как насилие по отношению к Гельбарду. [ 198 ]

Смерть

[ редактировать ]

В начале сентября 1991 года Дэвис зарегистрировался в больнице Святого Иоанна возле своего дома в Санта -Монике, штат Калифорния, на обычные испытания. [ 201 ] Врачи предположили, что у него есть трахеальная трубка, имплантированная, чтобы облегчить его дыхание после повторных приступов бронхиальной пневмонии . Предложение спровоцировало вспышки Дэвиса, которая привела к внутримощному кровоизлиянию, за которой последовала кома. По словам Джо Гелбарда, 26 сентября Дэвис нарисовал свою последнюю картину, состоящую из темных, призрачных фигур, капающей кровь и «его неизбежной кончины». [ 140 ] После нескольких дней поддержки жизнеобеспечения его машина была выключена, и он умер 28 сентября 1991 года в руках Гельбарда. [ 202 ] [ 164 ] Ему было 65 лет. Его смерть была связана с комбинированными эффектами инсульта, пневмонии и дыхательной недостаточности. [ 11 ] Согласно Troupe, Дэвис принимал азидотимидин (AZT), тип антиретровирусного препарата, используемого для лечения ВИЧ и СПИДа, во время его лечения в больнице. [ 203 ] Похоронная служба состоялась 5 октября 1991 года в лютеранской церкви Святого Петра на Лексингтон -авеню в Нью -Йорке [ 204 ] [ 205 ] В нем приняли участие около 500 друзей, членов семьи и музыкальных знакомых, и многие фанаты стояли под дождем. [ 206 ] Он был похоронен на кладбище Вудлон в Бронксе , штат Нью -Йорк, с одной из его трубы, недалеко от места могилы герцога Эллингтона . [ 207 ] [ 206 ]

На момент его смерти поместье Дэвиса оценивалось в размере более 1 миллиона долларов (эквивалентно примерно 2,2 миллиона долларов в 2023 году. [ 34 ] ) В своем завещании Дэвис оставил 20 процентов своей дочери Шерил Дэвис; 40 процентов его сыну Эрин Дэвис; 10 процентов его племяннику Винсенту Уилберн -младшему и 15 процентов каждому своему брату Вернону Дэвису и его сестре Дороти Уилберн. Он исключил своих двух сыновей Грегори и Майлза IV. [ 208 ]

Взгляды на его предыдущую работу

[ редактировать ]В конце своей жизни, начиная с «электрического периода», Дэвис неоднократно объяснял свои причины не желая выполнять свои предыдущие работы, такие как рождение прохладного или типа синего . По его мнению, оставшиеся стилистически статичные были неправильным вариантом. [ 209 ] Он прокомментировал: « Так что», или, как бы ни с синим , они были сделаны в ту эпоху, в правильный час, в правильный день, и это произошло. Все кончено ... что я играл с Биллом Эвансом, все эти разные режимы и заменить аккорды, у нас была энергия, и нам это понравилось. [ 210 ] Когда в 1990 году Ширли Хорн настаивала на том, что Майлз пересмотрел баллады и модальные мелодии своего рода синего периода, он сказал: «Нет, это больно моей губой». [ 210 ] Билл Эванс , который играл на пианино в родом синего цвета , сказал: «Я хотел бы услышать больше о непревзойденном мелодичном мастере, но я чувствую, что большой бизнес и его звукозаписывающая компания оказали коррупционное влияние на его материал. The Rock and Pop Thing Конечно, привлекает более широкую аудиторию ». [ 210 ] На протяжении всей своей более поздней карьеры Дэвис отказался от предложений восстановить свой квинтет 1960 -х годов. [ 140 ]

Многие книги и документальные фильмы сосредоточены на его работе до 1975 года. [ 140 ] Согласно статье Independent , с 1975 года началось снижение критической похвалы за результаты Дэвиса, и многие рассматривали эпоху «бесполезной»: «Есть удивительно широко распространенное мнение, что с точки зрения достоинств его мюзикла Выход, Дэвис мог бы также погибнуть в 1975 году ». [ 140 ] В интервью 1982 года в Downbeat сказал: «Они называют материал Майлза джаз. Это не джаз, чувак. Только потому , Уинтон Марсалис что кто -то играл в джаз одновременно, это не значит, что они все еще играют». [ 140 ] Несмотря на его презрение к «более поздней работе Дэвиса», работа Марсалиса «нагружена ироничными ссылками на музыку Дэвиса 60 -х». [ 35 ] Дэвис не обязательно не согласился; Лумбастинг того, что он видел как стилистический консерватизм Марсалиса, Дэвис сказал: «Джаз мертв ... это финито! Все кончено, и нет смысла обнять дерьмо». [ 211 ] Писатель Стэнли Крауч раскритиковал работу Дэвиса в молчании . [ 140 ]

Наследие и влияние

[ редактировать ]

Майлз Дэвис считается одной из самых инновационных, влиятельных и уважаемых фигур в истории музыки. Хранитель назвал его «пионером музыки 20-го века, ведущего многие из ключевых событий в мире джаза». [ 212 ] Его называли "одним из великих новаторов в джазе", [ 213 ] и получил названия принца тьмы, а Пикассо Джаза даровал ему. [ 214 ] Энциклопедия Rock & Roll Rolling Stone) сказал: «Майлз Дэвис сыграл решающую и неизбежно противоречивую роль в каждом крупном развитии в джазе с середины 40-х годов, и ни один другой джазовый музыкант не оказал настолько глубокого влияния на рок. Майлз Дэвис был был Самый широко известный джазовый музыкант своей эпохи, откровенный социальный критик и арбитр стиля - в отношении и моде - а также музыка ». [ 215 ]

Уильям Рулманн из Allmusic писал: «Чтобы изучить его карьеру, значит изучить историю джаза с середины 1940-х годов до начала 1990-х годов, так как он был в гуще практически всех важных инноваций и стилистического развития в музыке в течение этого периода. I. [ 1 ] Фрэнсис Дэвис из Атлантики отметил, что карьеру Дэвиса можно рассматривать как «постоянную критику Бебопа: происхождение« крутого »джаза ..., жесткий боп или« фанк »..., модальная импровизация ... и джаз -Рок Фьюжн ... можно проследить до его усилий, чтобы снести бибопа до самого необходимого ». [ 216 ]

Его подход, в значительной степени из-за афроамериканской традиции исполнения, которая была сосредоточена на индивидуальном выражении, решительном взаимодействии и творческом отклике на изменение содержания, оказал глубокое влияние на поколения джазовых музыкантов. [ 217 ] В 2016 году цифровое публикация The Pudding в статье, посвященной наследию Дэвиса, показало, что 2452 страницы Википедии упоминают Дэвиса, причем более 286 ссылается на него как влияние. [ 218 ]

5 ноября 2009 года представитель США Джон Коньерс из Мичигана спонсировал меру в Палате представителей Соединенных Штатов, чтобы ознаменовать вид синего цвета на 50 -летие. Эта мера также подтверждает джаз как национальное сокровище и «поощряет правительство Соединенных Штатов сохранять и продвигать искусство джазовой музыки». [ 219 ] Он прошел с голосованием 409–0 15 декабря 2009 года. [ 220 ] Труба, которую Дэвис использовал на записи, отображается в кампусе Университета Северной Каролины в Гринсборо . Он был пожертвован в школу Артуром «Бадди» Гистом, который встретил Дэвиса в 1949 году и стал близким другом. Подарок был причиной, по которой джазовая программа в UNCG названа программой Miles Davis Jazz Study. [ 221 ]

В 1986 году консерватория Новой Англии присудила Дэвису почетную докторскую степень за его вклад в музыку. [ 222 ] С 1960 года Национальная академия звукозаписывающих искусств и наук ( Нарас ) удостоила его восемь премий Грэмми, премией Грэмми пожизненной достижением и тремя наградами Зала Славы Грэмми.

В 2001 году Miles Davis Story , двухчасовой документальный фильм Майка Дибба , выиграл Международную премию Эмми за искусство года. [ 223 ] С 2005 года Джазовый комитет Майлза Дэвиса провел ежегодный джазовый фестиваль Miles Davis. [ 224 ] биография Дэвиса, «Последние мили» , Также в 2005 году была опубликована [ 225 ] и лондонская выставка была проведена на его картинах, «Последние мили: музыка Майлза Дэвиса », 1980–1991 гг. Подписание в Columbia Records. [ 140 ] В 2006 году Дэвис был введен в Зал славы рок -н -ролла. [ 226 ] В 2012 году почтовая служба США выпустила памятные марки с участием Дэвиса. [ 226 ]

Мили вперед был американским музыкальным фильмом 2015 года, снятым Дон Чидл , написанным в соавторстве Чидл со Стивеном Байжелманом , Стивеном Дж. Ривеле и Кристофером Уилкинсоном , которые интерпретируют жизнь и сочинения Дэвиса. Премьера состоялась на Нью -Йоркском кинофестивале в октябре 2015 года. Звезды фильма «Чидл», Emayatzy Corinealdi в роли Фрэнсис Тейлор, Эван МакГрегор , Майкл Стулбарг и Лейк -Стэнфилд . [ 227 ] В том же году его статуя была возведена в его родном городе, Альтоне, Иллинойсе , и слушатели BBC Radio и Jazz FM проголосовали за Дэвиса величайшего джазового музыканта. [ 228 ] [ 224 ] Такие публикации, как The Guardian, также оценили Дэвиса среди лучших из всех джазовых музыкантов. [ 229 ]

В 2018 году американский рэппер Q-Tip сыграл Майлза Дэвиса в театральной постановке « Мой забавный Валентин» . [ 230 ] Q-Tip ранее играл в Дэвисе в 2010 году. [ 230 ] В 2019 году документальный фильм Майлз Дэвис: Рождение прохладного , режиссер Стэнли Нельсон , состоялась на кинофестивале Sundance . [ 231 ] Позже он был выпущен в PBS серии American Masters . [ 232 ]

Дэвис, однако, подвергся критике. В 1990 году писатель Стэнли Крауч , известный критик джазового фьюжн, назвал Дэвиса «самой блестящей распродажей в истории джаза». [ 140 ] Эссе 1993 года Роберта Уолсера в музыкальном квартале утверждает, что «Дэвис долгое время был печально известен тем, что пропустил больше нот, чем любой другой крупный труба». [ 233 ] Также в эссе находится цитата музыкального критика Джеймса Линкольна Коллиера , который заявляет, что «если его влияние было глубоким, конечная ценность его работы - это другое дело» и называет Дэвиса «адекватным инструменталистом», но «не великим». [ 233 ] В 2013 году AV Club опубликовал статью под названием «Майлз Дэвис победил своих жен и сделал прекрасную музыку». В статье писательница Соня Сарая хвалит Дэвиса как музыканта, но критикует его как человека, в частности, его злоупотребление своими женами. [ 234 ] Другие, такие как Фрэнсис Дэвис, критиковали его обращение с женщинами, назвав его «презренным». [ 216 ]

Награды и награды

[ редактировать ]Грэмми награды

- Майлз Дэвис получил восемь премий Грэмми и получил тридцать две номинации. [ 235 ]

| Год | Категория | Работа |

|---|---|---|

| 1960 | Лучшая джазовая композиция более пяти минут продолжительностью | Эскизы Испании |

| 1970 | Лучшее джазовое выступление, большая группа или солист с большой группой | Суки пиво |

| 1982 | Лучший джазовый инструментальный исполнение, солист | Мы хотим Майлза |

| 1986 | Лучший джазовый инструментальный исполнение, солист | Холодный |

| 1989 | Лучший джазовый инструментальный исполнение, солист | Аура |

| 1989 | Лучшее джазовое инструментальное исполнение, биг -бэнд | Аура |

| 1990 | Награда за достижения в жизни | |

| 1992 | Лучший инструментальный результат R & B | Doo-bop |

| 1993 | Лучший большой джазовый ансамбль | Miles & Quincy Live в Montreux |

Другие награды

| Год | Премия | Источник |

|---|---|---|

| 1955 | Проголосовал за лучшего трубача, опрос читателей Downbeat Readers ' | |

| 1957 | Проголосовал за лучшего трубача, опрос читателей Downbeat Readers ' | |

| 1961 | Проголосовал за лучшего трубача, опрос читателей Downbeat Readers ' | |

| 1984 | Награда Sonning за жизненные достижения в музыке | |

| 1986 | Доктор музыки, Honoris Causa , консерватория Новой Англии | |

| 1988 | Рыцарство рыцарей Мальты | [ 167 ] |

| 1989 | Награда губернатора от Совета штата Нью -Йорк по искусству | [ 236 ] |

| 1990 | Св. | [ 237 ] |

| 1991 | Награда австралийского института кино за лучшую оригинальную музыкальную партитуру для Dingo , поделившись с Мишелем Леграндом | |

| 1991 | Рыцарь Легиона Чести | |

| 1998 | Голливудская прогулка славы | |

| 2006 | Зал славы рок -н -ролла | [ 226 ] |

| 2006 | Голливудский роквок | |

| 2008 | Четырехкратная платиновая сертификация для типа синего | |

| 2019 | Quintuple Platinum сертификация для вида синего цвета |

Дискография

[ редактировать ]Следующий список намеревается наметить основные работы Дэвиса, особенно студийные альбомы. Более полную дискографию можно найти в основной статье.

- Новые звуки (1951)

- Молодой человек с рогом (1952)

- Синий период (1953)

- Композиции Аль -Кона (1953)

- Майлз Дэвис Том 2 (1954)

- Майлз Дэвис Том 3 (1954)

- Майлз Дэвис Квинтет (1954)

- С Сонни Роллинсом (1954)

- Майлз Дэвис Квартет (1954)

- All-Stars, том 1 (1955)

- All-Stars, том 2 (1955)

- All Star Sextet (1955)

- Размышления мили (1955)

- Синее настроение (1955)

- Майлз Дэвис, вып. 1 (1956)

- Майлз Дэвис, вып. 2 (1956)

- Ты (1956)

- Майлз: Новый квинтет Майлза Дэвис (1956)

- Quintet/Sextet (1956)

- Предметы коллекционеров (1956)

- Рождение прохладного (1957)

- 'Round около полуночи (1957)

- Walkin ' (1957)

- Cookin ' (1957)

- Мили вперед (1957)

- Релагин (1958)

- Вехи (1958)

- Майлз Дэвис и современные джазовые гиганты (1959)

- Порги и Бесс (1959)

- Вид синего (1959)

- Работа (1960)

- Эскизы Испании (1960)

- Steam ' (1961)

- Когда -нибудь мой принц придет (1961)

- Семь шагов на небеса (1963)

- Тихие ночи (1963)

- ESP (1965)

- Майлз улыбается (1967)

- Волшебник (1967)

- Нефертити (1968)

- Мили в небе (1968)

- Девочки Килиманджаро (1968)

- Молчаливым образом (1969)

- Суки Брево (1970)

- Джек Джонсон (1971)

- Live-Evil (1971)

- На углу (1972)

- В концерте (1973)

- Большое веселье (1974)

- Встать с этим (1974)

- Фронт (1975)

- Родитель (1975)

- Dark Magus (1977)

- Человек с рогом (1981)

- Мы хотим Майлз (1982)

- Звездные люди (1983)

- Приманка (1984)

- Ты арестоваешь (1985)

- Cold (1986)

- Власть (1989)

- Аура (1989)

- Doo-Bop (1992)

- Резиновая полоса (2019)

Фимография

[ редактировать ]| Год | Фильм | Зачислен как | Роль | Примечания | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Композитор | Исполнитель | Актер | ||||

| 1958 | Лифт на виселицу | Да | Да | — | Описанный критиком Филом Джонсоном как «самый одинокий звук трубы, который вы когда-либо слышали, и с тех пор модель для музыки с грустным ядром. Слушайте это и плачет». [ 238 ] | |

| 1968 | Symbiopsychotaxiplasm | Да | Да | — | Музыка Дэвиса, из тихого пути [ 239 ] [ 240 ] | |

| 1970 | Джек Джонсон | Да | Да | Основа для альбома 1971 года Джек Джонсон | ||

| 1972 | Представлять себе | Да | Сам | Камея, некредитованная | ||

| 1985 | Майами Вицт | Да | Ivory Jones | Сериал (1 эпизод - "Junk Love") | ||

| 1986 | Криминальная история | Да | Джазовый музыкант | Камея, сериал (1 эпизод - «Война») | ||

| 1987 | Сиеста | Да | Да | — | Только одна песня написана Майлзом Дэвисом в сотрудничестве с Маркусом Миллером («Тема для Августина»). | |

| 1988 | Скруг | Да | Да | Уличный музыкант | Камея | |

| 1990 | Горячая точка | Да | Составлен Джеком Ницше , также с участием Джона Ли Хукера | |||

| 1991 | Динго | Да | Да | Да | Билли Кросс | Саундтрек состоит из Майлза Дэвиса в сотрудничестве с Мишелем Леграндом . |

Примечания

[ редактировать ]Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Рулманн, Уильям. «Биография Майлза Дэвис» . Allmusic . Архивировано с оригинала 21 июня 2016 года . Получено 16 июня 2016 года .

- ^ Аговино, Майкл Дж. (11 марта 2016 г.). «Ансамбли Майлза Дэвиса охладили» . New York Times . ISSN 0362-4331 . Получено 12 февраля 2024 года .

- ^ Yanow 2005 , p. 176

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Майлз Дэвис, инновационная, влиятельная и уважаемая джазовая легенда» . Афроамериканский реестр. Архивировано с оригинала 9 августа 2016 года . Получено 11 июня 2016 года .

- ^ McCurdy 2004 , p. 61.

- ^ Бейли, С. Майкл (11 апреля 2008 г.). «Майлз Дэвис, Майлз улыбается и изобретение Post Bop» . Все о джазе . Архивировано с оригинала 8 июня 2016 года . Получено 20 июня 2016 года .

- ^ Freeman 2005 , с. 9–11, 155–156.

- ^ Кристгау 1997 ; Freeman 2005 , с. 10–11, задняя крышка

- ^ Сегелл, Майкл (28 декабря 1978 г.). «Дети« Бруки Бревота » . Катящий камень . Архивировано с оригинала 14 июня 2016 года . Получено 12 июня 2016 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Макни, Джим. «Биография Майлза Дэвис» . Катящий камень . Архивировано с оригинала 9 августа 2017 года . Получено 11 июня 2016 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый «Майлз Дэвис» . Зал славы рок -н -ролла . Архивировано из оригинала 3 мая 2016 года . Получено 1 мая 2016 года .

- ^ Джеральд Лин, Ранний (1998). Не только место: антология афроамериканских писаний о Сент -Луисе . Музей истории Миссури . п. 205 . ISBN 1-883982-28-6 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Кук 2007 , с. 9

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный В начале 2001 , с. 209

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Полная иллюстрированная история 2007 , с. 17

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Нос 2012 , с. 11

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Warner 2014 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый В начале 2001 , с. 210.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Жизнь в картинках: Майлз Дэвис - Дайджест читателя» . Digest Reader . Получено 29 июня 2020 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Полная иллюстрированная история 2007 , с. 19

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 32

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Кан 2001 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Полная иллюстрированная история 2007 , с. 23

- ^ Мортон 2005 , с. 10

- ^ Аронс, Рэйчел (21 марта 2014 г.). «Слайд -шоу: американские публичные библиотеки велики и маленькие» (PDF) . Фонд Грэма . п. 5. Архивированный (PDF) из оригинала 9 мая 2018 года . Получено 8 мая 2018 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж В начале 2001 , с. 211.

- ^ Нос 2012 , с. 12

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Нос 2012 , с. 13

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Кук 2007 , с. 10

- ^ Полная иллюстрированная история 2007 , с. 29

- ^ Полная иллюстрированная история 2007 , с. 32

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый «Майлз Дэвис» . Encyclopædia Britannica . 22 мая 2020 года. Архивировано с оригинала 26 мая 2020 года . Получено 22 июня 2020 года .

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 56

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин 1634–1699: McCusker, JJ (1997). Сколько это в реальных деньгах? Исторический индекс цен для использования в качестве дефлятора денег в экономике Соединенных Штатов: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF) . Американское антикварное общество . 1700–1799: McCusker, JJ (1992). Сколько это в реальных деньгах? Исторический индекс цен для использования в качестве дефлятора денег в экономике Соединенных Штатов (PDF) . Американское антикварное общество . 1800 - Present: Федеральный резервный банк Миннеаполиса. «Индекс потребительской цены (оценка) 1800–» . Получено 29 февраля 2024 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Кук, Ричард (13 июля 1985 г.). «Майлз Дэвис: Майлз управляет вуду вниз». NME - Via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Начало 2001 , с. 38

- ^ Начало 2001 , с. 68

- ^ «Смотрите базу данных сеанса Plosin» . Plosin.com. 18 октября 1946 года. Архивировано из оригинала 11 мая 2011 года . Получено 18 июля 2011 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж k В начале 2001 , с. 212.

- ^ В этом случае Мингус горько раскритиковал Дэвиса за то, что он оставил своего «музыкального отца» (см. Автобиографию ).

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 105

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Кернфельд, Барри (2002). Кернфельд, Барри (ред.). Новая роща словарь джаза . Тол. 1 (2 -е изд.). Нью -Йорк: словаря Гроув. п. 573. ISBN 1-56159-284-6 .

- ^ Кук 2007 , с. 12

- ^ Маллиган, Джерри. «Я слышу поет Америку» (PDF) . gerrymulligan.com . Джерри Маллиган. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 3 марта 2016 года.

Майлз, руководитель группы. Он взял на себя инициативу и поставил теории на работу. Он назвал репетиции, нанял залы, называл игроков и, как правило, взломал кнут.

- ^ Кук 2007 , с. 14

- ^ Кук 2007 , с. 2

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 117

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Дэвис и Труппа 1989 , с. 126

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Swede 2004 , p.

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 129

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Кук 2007 , с. 25

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , с. 175–176.

- ^ Кук 2007 , с. 26

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Дэвис и Труппа 1989 , с. 164.

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , с. 164–165.

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , с. 169–170.

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 171.

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , с. 174, 175, 184.

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 175.

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 176

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Дэвис и Труппа 1989 , с. 190.

- ^ Открытые ссылки на блюз в джазовой игре были довольно недавними. До середины 1930-х годов, как заявил Коулман Хокинс Алану Ломаксу ( земля, где началась блюз. Нью-Йорк: Pantheon, 1993), афроамериканские игроки, работающие в белых заведениях, будут избежать ссылок на блюз.

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 183.

- ^ Swede 2004 .

- ^ Приобретено, кричащим на продюсера записей, еще более больно после недавней операции в горле - автобиографии .

- ^ Санторо, Джин (ноябрь 1991). «Принц тьмы. (Майлз Дэвис) (некролог)» . Нация . Архивировано из оригинала 8 августа 2013 года.

- ^ «Майлз Дэвис» . Pbs .org . Архивировано с оригинала 31 марта 2016 года.

- ^ Челл, Самуил (29 июня 2008 г.). «Майлз Дэвис: Когда -нибудь придет мой принц» . allaboutjazz.com . Архивировано из оригинала 2 февраля 2009 года.

- ^ Полная иллюстрированная история 2007 , с. 73.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Натам, Кофи (22 сентября 2014 г.). «Майлз Дэвис: новая революция в звуке» . Черный ренессанс/ренессанс Нуар . 14 (2): 36–40 . Получено 27 июня 2020 года .

- ^ Мортон 2005 , с. 27

- ^ Кук 2007 , с. 43–44.

- ^ Карр 1998 , с. 96

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 192.

- ^ Chambers 1998 , p. 223

- ^ Кук 2007 , с. 45

- ^ Карр 1998 , с. 99

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 186

- ^ Начало 2001 , с. 215

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 209

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 214

- ^ Полная иллюстрированная история 2007 , с. 97

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 224

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Дэвис и Труппа 1989 , с. 229

- ^ Szwed 2004 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Карр 1998 , с. 107

- ^ Szwed 2004 , с.

- ^ Szwed 2004 , p.

- ^ Кук, соч. Цит -

- ^ Полная иллюстрированная история 2007 , с. 108

- ^ Полная иллюстрированная история 2007 , с. 109

- ^ Карр 1998 , с. 192–193.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Полная иллюстрированная история 2007 , с. 106

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Кан 2001 , с. 95

- ^ Кан 2001 , с. 29–30.

- ^ Кан 2001 , с. 74

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный "Gold & Platinum - поиск" Майлз Дэвис " . Ассоциация звукозаписывающей промышленности Америки. Архивировано с оригинала 24 июня 2016 года . Получено 7 мая 2017 года .

- ^ «Американские политики чествуют альбом Майлза Дэвиса | Rnw Media» . Rnw.nl. Архивировано из оригинала 3 декабря 2013 года . Получено 17 июля 2015 года .

- ^ «Us House Of Reps Honors Miles Davis Альбом - ABC News (Австралийская вещательная корпорация)» . ABC News . Австралийская вещательная корпорация. 16 декабря 2009 г. Архивировано с оригинала 5 декабря 2010 года . Получено 6 января 2011 года .

- ^ Полная иллюстрированная история 2007 , с. 100

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный "Был ли Майлз Дэвис победил Блондин?" Полем Балтимор Афроамериканский . 1 сентября 1959 года. С. 1–13. Архивировано из оригинала 9 августа 2013 года . Получено 20 декабря 2020 года .

- ^ «Джазовый трубач Майлз Дэвис в Джусте с полицейскими» . Сарасота Журнал . 26 августа 1959 года. Архивировано с оригинала 9 августа 2013 года . Получено 27 августа 2010 года .

- ^ Начало 2001 , с. 89

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 252

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , с. 260–262.

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 262

- ^ Einarson 2005 , с. 56–57.

- ^ Карр 1998 , с. 202

- ^ Карр 1998 , с. 203.

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , с. 282–283.

- ^ Карр 1998 , с. 204

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 283.

- ^ Карр 1998 , с. 209–210.

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 284

- ^ Мортон 2005 , с. 49

- ^ Луна, Том (30 января 2013 г.). «Бутлега 1969 года обнаруживает Майлз Дэвис» «Потерянный» квинтет » . ЭНЕРГЕТИЧЕСКИЙ ЯДЕРНЫЙ РЕАКТОР. Архивировано с оригинала 27 апреля 2018 года . Получено 5 апреля 2018 года .

- ^ Shteamer, Hank (31 января 2013 г.). «Майлз Дэвис» . Pitchfork . Архивировано с оригинала 11 апреля 2019 года . Получено 20 апреля 2020 года .

- ^ Freeman 2005 , с. 83–84.

- ^ «Майлз Дэвис» . Billboard . Архивировано с оригинала 16 марта 2018 года . Получено 10 мая 2018 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Полная иллюстрированная история 2007 , с. 150

- ^ Вещь 2001 , с.

- ^ Полная иллюстрированная история 2007 , с. 153

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , с. 318–319.

- ^ Карр 1998 , с. 302

- ^ "Roio" Архив блога »Майлз - Белград 1971» . Figozine2.com. Архивировано из оригинала 21 июля 2015 года . Получено 17 июля 2015 года .

- ^ Chambers 1998 , p. 246

- ^ Карр 1998 .

- ^ Тинген, Пол (1999). «Создание полных сессий пивоваренных сессий» . Архивировано из оригинала 5 марта 2017 года . Получено 15 апреля 2017 года .

- ^ Мортон 2005 , с. 72–73.

- ^ Davis & Troupe 1989 , p. 328.

- ^ Коул 2005 , с. 28

- ^ & Полная иллюстрированная история 2007 , с. 154

- ^ Szwed 2004 , p.

- ^ Тинген, Пол (26 октября 2007 г.). «Самый ненавистный альбом в джазе» . Хранитель . Архивировано из оригинала 2 августа 2019 года . Получено 13 июня 2019 года .

- ^ Полная иллюстрированная история 2007 , с. 177.

- ^ Вещь 2001 , с.

- ^ Полная иллюстрированная история 2007 , с. 177.