Польша

Республика Польша Республика Польша ( польский ) | |

|---|---|

| Гимн: « Мазурка Домбровского ». [а] («Польша еще не потеряна») | |

Location of Poland (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Warsaw 52°13′N 21°02′E / 52.217°N 21.033°E |

| Official language | Polish[1] |

| Ethnic groups (2021)[3] |

|

| Religion (2021[4]) |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Andrzej Duda | |

| Donald Tusk | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| Sejm | |

| Formation | |

| c. 960 | |

| 966 | |

| 18 April 1025 | |

| 1 July 1569 | |

| 24 October 1795 | |

| 11 November 1918 | |

| 17 September 1939 | |

| 22 July 1944 | |

| 31 December 1989[6] | |

| Area | |

• Total | 312,696 km2 (120,733 sq mi)[7][8] (69th) |

• Water (%) | 1.48 (2015)[9] |

| Population | |

• 2022 census | |

• Density | 122/km2 (316.0/sq mi) (75th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2022) | low |

| HDI (2022) | very high (36th) |

| Currency | Złoty (PLN) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy (CE) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +48 |

| ISO 3166 code | PL |

| Internet TLD | .pl [a] |

| |

Польша , [и] официально Республика Польша , [ф] это страна в Центральной Европе . Польша разделена на шестнадцать воеводств и является пятым по численности населения государством-членом Европейского Союза (ЕС) с населением более 38 миллионов человек и седьмой по величине страной ЕС , общая площадь которой составляет 312 696 км². 2 (120 733 квадратных миль). Он простирается от Балтийского моря на севере до Судетов и Карпат на юге, гранича с семью странами. [г] Территория характеризуется разнообразным ландшафтом, разнообразными экосистемами и умеренным переходным климатом. Столица и крупнейший город — Варшава ; другие крупные города включают Краков , Вроцлав , Лодзь , Познань и Гданьск .

Люди присутствовали на польской земле со времен нижнего палеолита , с постоянным заселением с конца последнего ледникового периода более 12 000 лет назад. Культурно разнообразный на протяжении всей поздней античности , в период раннего средневековья этот регион был заселен племенами полянов , которые дали Польше ее название . Процесс становления государственности совпал с обращением языческого правителя полян в христианство под эгидой Римско-католической церкви в 966 г. Последующая территориальная экспансия привела к созданию Царства Польского в 1025 г. К середине 14 в. столетия Польша стала крупной европейской державой и начала постепенно интегрироваться с Литвой , что привело к образованию Речи Посполитой в 1569 году. В течение следующих двух столетий Речь Посполитая была одной из великих держав Европы, управляемой уникально либеральной системой правления. политическая система, принявшая первую современную конституцию Европы в 1791 году.

With the passing of the Renaissance and the prosperous Polish Golden Age in the late 16th century, Poland–Lithuania was weakened by social and political turmoil that led to its partition by neighbouring states at the end of the 18th century. Poland regained its independence at the end of World War I with the founding of the Second Polish Republic. In September 1939, the invasion of Poland by Germany and the Soviet Union marked the beginning of World War II, which resulted in the Holocaust and millions of Polish casualties. Forced into the Eastern Bloc during the global Cold War, the Polish People's Republic was a founding signatory of the Warsaw Pact. Through the emergence and contributions of the Solidarity movement, the communist government was dissolved and Poland re-established itself as a democratic state in 1989.

Poland is a unitary parliamentary republic, with its bicameral legislature comprising the Sejm and the Senate. The country is considered a middle power, with a developed market and high-income economy that is the sixth largest in the EU by nominal GDP and the fifth largest by GDP (PPP). Poland enjoys a very high standard of living, safety, and economic freedom, as well as free university education and universal health care. The country has 17 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, 15 of which are cultural. Poland is a founding member state of the United Nations and a member of the World Trade Organization, OECD, NATO, and the European Union (including the Schengen Area).

Etymology

The native Polish name for Poland is Polska.[13] The name is derived from the Polans, a West Slavic tribe who inhabited the Warta River basin of present-day Greater Poland region (6th–8th century CE).[14] The tribe's name stems from the Proto-Slavic noun pole meaning field, which in-itself originates from the Proto-Indo-European word *pleh₂- indicating flatland.[15] The etymology alludes to the topography of the region and the flat landscape of Greater Poland.[16][17] During the Middle Ages, the Latin form Polonia was widely used throughout Europe.[18]

The country's alternative archaic name is Lechia and its root syllable remains in official use in several languages, notably Hungarian, Lithuanian, and Persian.[19] The exonym possibly derives from either Lech, a legendary ruler of the Lechites, or from the Lendians, a West Slavic tribe that dwelt on the south-easternmost edge of Lesser Poland.[20][21] The origin of the tribe's name lies in the Old Polish word lęda (plain).[22] Initially, both names Lechia and Polonia were used interchangeably when referring to Poland by chroniclers during the Middle Ages.[23]

History

Prehistory and protohistory

The first Stone Age archaic humans and Homo erectus species settled what was to become Poland approximately 500,000 years ago, though the ensuing hostile climate prevented early humans from founding more permanent encampments.[24] The arrival of Homo sapiens and anatomically modern humans coincided with the climatic discontinuity at the end of the Last Glacial Period (Northern Polish glaciation 10,000 BC), when Poland became habitable.[25] Neolithic excavations indicated broad-ranging development in that era; the earliest evidence of European cheesemaking (5500 BC) was discovered in Polish Kuyavia,[26] and the Bronocice pot is incised with the earliest known depiction of what may be a wheeled vehicle (3400 BC).[27]

The period spanning the Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age (1300 BC–500 BC) was marked by an increase in population density, establishment of palisaded settlements (gords) and the expansion of Lusatian culture.[28][29] A significant archaeological find from the protohistory of Poland is a fortified settlement at Biskupin, attributed to the Lusatian culture of the Late Bronze Age (mid-8th century BC).[30]

Throughout antiquity (400 BC–500 AD), many distinct ancient populations inhabited the territory of present-day Poland, notably Celtic, Scythian, Germanic, Sarmatian, Baltic and Slavic tribes.[31] Furthermore, archaeological findings confirmed the presence of Roman Legions sent to protect the amber trade.[32] The Polish tribes emerged following the second wave of the Migration Period around the 6th century AD;[18] they were Slavic and may have included assimilated remnants of peoples that earlier dwelled in the area.[33][34] Beginning in the early 10th century, the Polans would come to dominate other Lechitic tribes in the region, initially forming a tribal federation and later a centralised monarchical state.[35]

Kingdom of Poland

Poland began to form into a recognisable unitary and territorial entity around the middle of the 10th century under the Piast dynasty.[36] In 966, ruler of the Polans Mieszko I accepted Christianity under the auspices of the Roman Church with the Baptism of Poland.[37] In 968, a missionary bishopric was established in Poznań. An incipit titled Dagome iudex first defined Poland's geographical boundaries with its capital in Gniezno and affirmed that its monarchy was under the protection of the Apostolic See.[38] The country's early origins were described by Gallus Anonymus in Gesta principum Polonorum, the oldest Polish chronicle.[39] An important national event of the period was the martyrdom of Saint Adalbert, who was killed by Prussian pagans in 997 and whose remains were reputedly bought back for their weight in gold by Mieszko's successor, Bolesław I the Brave.[38]

In 1000, at the Congress of Gniezno, Bolesław obtained the right of investiture from Otto III, Holy Roman Emperor, who assented to the creation of additional bishoprics and an archdioceses in Gniezno.[38] Three new dioceses were subsequently established in Kraków, Kołobrzeg, and Wrocław.[40] Also, Otto bestowed upon Bolesław royal regalia and a replica of the Holy Lance, which were later used at his coronation as the first King of Poland in c. 1025, when Bolesław received permission for his coronation from Pope John XIX.[41][42] Bolesław also expanded the realm considerably by seizing parts of German Lusatia, Czech Moravia, Upper Hungary and southwestern regions of the Kievan Rus'.[43]

The transition from paganism in Poland was not instantaneous and resulted in the pagan reaction of the 1030s.[44] In 1031, Mieszko II Lambert lost the title of king and fled amidst the violence.[45] The unrest led to the transfer of the capital to Kraków in 1038 by Casimir I the Restorer.[46] In 1076, Bolesław II re-instituted the office of king, but was banished in 1079 for murdering his opponent, Bishop Stanislaus.[47] In 1138, the country fragmented into five principalities when Bolesław III Wrymouth divided his lands among his sons.[20] These comprised Lesser Poland, Greater Poland, Silesia, Masovia and Sandomierz, with intermittent hold over Pomerania.[48] In 1226, Konrad I of Masovia invited the Teutonic Knights to aid in combating the Baltic Prussians; a decision that later led to centuries of warfare with the Knights.[49]

In the first half of the 13th century, Henry I the Bearded and Henry II the Pious aimed to unite the fragmented dukedoms, but the Mongol invasion and the death of Henry II in battle hindered the unification.[50][51] As a result of the devastation which followed, depopulation and the demand for craft labour spurred a migration of German and Flemish settlers into Poland, which was encouraged by the Polish dukes.[52] In 1264, the Statute of Kalisz introduced unprecedented autonomy for the Polish Jews, who came to Poland fleeing persecution elsewhere in Europe.[53]

In 1320, Władysław I the Short became the first king of a reunified Poland since Przemysł II in 1296,[54] and the first to be crowned at Wawel Cathedral in Kraków.[55] Beginning in 1333, the reign of Casimir III the Great was marked by developments in castle infrastructure, army, judiciary and diplomacy.[56][57] Under his authority, Poland transformed into a major European power; he instituted Polish rule over Ruthenia in 1340 and imposed quarantine that prevented the spread of Black Death.[58][59] In 1364, Casimir inaugurated the University of Kraków, one of the oldest institutions of higher learning in Europe.[60] Upon his death in 1370, the Piast dynasty came to an end.[61] He was succeeded by his closest male relative, Louis of Anjou, who ruled Poland, Hungary and Croatia in a personal union.[62] Louis' younger daughter Jadwiga became Poland's first female monarch in 1384.[62]

In 1386, Jadwiga of Poland entered a marriage of convenience with Władysław II Jagiełło, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, thus forming the Jagiellonian dynasty and the Polish–Lithuanian union which spanned the late Middle Ages and early Modern Era.[63] The partnership between Poles and Lithuanians brought the vast multi-ethnic Lithuanian territories into Poland's sphere of influence and proved beneficial for its inhabitants, who coexisted in one of the largest European political entities of the time.[64]

In the Baltic Sea region, the struggle of Poland and Lithuania with the Teutonic Knights continued and culminated at the Battle of Grunwald in 1410, where a combined Polish-Lithuanian army inflicted a decisive victory against them.[65] In 1466, after the Thirteen Years' War, king Casimir IV Jagiellon gave royal consent to the Peace of Thorn, which created the future Duchy of Prussia under Polish suzerainty and forced the Prussian rulers to pay tributes.[20] The Jagiellonian dynasty also established dynastic control over the kingdoms of Bohemia (1471 onwards) and Hungary.[66] In the south, Poland confronted the Ottoman Empire (at the Varna Crusade) and the Crimean Tatars, and in the east helped Lithuania to combat Russia.[20]

Poland was developing as a feudal state, with a predominantly agricultural economy and an increasingly powerful landed nobility that confined the population to private manorial farmstead known as folwarks.[67] In 1493, John I Albert sanctioned the creation of a bicameral parliament composed of a lower house, the Sejm, and an upper house, the Senate.[68] The Nihil novi act adopted by the Polish General Sejm in 1505, transferred most of the legislative power from the monarch to the parliament, an event which marked the beginning of the period known as Golden Liberty, when the state was ruled by the seemingly free and equal Polish nobles.[69]

The 16th century saw Protestant Reformation movements making deep inroads into Polish Christianity, which resulted in the establishment of policies promoting religious tolerance, unique in Europe at that time.[70] This tolerance allowed the country to avoid the religious turmoil and wars of religion that beset Europe.[70] In Poland, Nontrinitarian Christianity became the doctrine of the so-called Polish Brethren, who separated from their Calvinist denomination and became the co-founders of global Unitarianism.[71]

The European Renaissance evoked under Sigismund I the Old and Sigismund II Augustus a sense of urgency in the need to promote a cultural awakening.[20] During the Polish Golden Age, the nation's economy and culture flourished.[20] The Italian-born Bona Sforza, daughter of the Duke of Milan and queen consort to Sigismund I, made considerable contributions to architecture, cuisine, language and court customs at Wawel Castle.[20]

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Union of Lublin of 1569 established the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a unified federal state with an elective monarchy, but largely governed by the nobility.[72] The latter coincided with a period of prosperity; the Polish-dominated union thereafter becoming a leading power and a major cultural entity, exercising political control over parts of Central, Eastern, Southeastern and Northern Europe. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth occupied approximately 1 million km2 (390,000 sq mi) at its peak and was the largest state in Europe.[73][74] Simultaneously, Poland imposed Polonisation policies in newly acquired territories which were met with resistance from ethnic and religious minorities.[72]

In 1573, Henry de Valois of France, the first elected king, approbated the Henrician Articles which obliged future monarchs to respect the rights of nobles.[75] When he left Poland to become King of France, his successor, Stephen Báthory, led a successful campaign in the Livonian War, granting Poland more lands across the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea.[76] State affairs were then headed by Jan Zamoyski, the Crown Chancellor.[77] Stephen’s successor, Sigismund III, defeated a rival Habsburg electoral candidate, Archduke Maximilian III, in the War of the Polish Succession (1587–1588). In 1592, Sigismund succeeded his father and John Vasa, in Sweden.[78] The Polish-Swedish union endured until 1599, when he was deposed by the Swedes.[79]

In 1609, Sigismund invaded Russia which was engulfed in a civil war,[20] and a year later the Polish winged hussar units under Stanisław Żółkiewski occupied Moscow for two years after defeating the Russians at Klushino.[20] Sigismund also countered the Ottoman Empire in the southeast; at Khotyn in 1621 Jan Karol Chodkiewicz achieved a decisive victory against the Turks, which ushered the downfall of Sultan Osman II.[80][81]

Sigismund's long reign in Poland coincided with the Silver Age.[82] The liberal Władysław IV effectively defended Poland's territorial possessions but after his death the vast Commonwealth began declining from internal disorder and constant warfare.[83][84] In 1648, the Polish hegemony over Ukraine sparked the Khmelnytsky Uprising,[85] followed by the decimating Swedish Deluge during the Second Northern War,[86] and Prussia's independence in 1657.[86] In 1683, John III Sobieski re-established military prowess when he halted the advance of an Ottoman Army into Europe at the Battle of Vienna.[87] The Saxon era, under Augustus II and Augustus III, saw neighboring powers grow in strength at the expense of Poland. Both Saxon kings faced opposition from Stanisław Leszczyński during the Great Northern War (1700) and the War of the Polish Succession (1733).[88]

Partitions

The royal election of 1764 resulted in the elevation of Stanisław II Augustus Poniatowski to the monarchy.[89] His candidacy was extensively funded by his sponsor and former lover, Empress Catherine II of Russia.[90] The new king maneuvered between his desire to implement necessary modernising reforms, and the necessity to remain at peace with surrounding states.[91] His ideals led to the formation of the 1768 Bar Confederation, a rebellion directed against the Poniatowski and all external influence, which ineptly aimed to preserve Poland's sovereignty and privileges held by the nobility.[92] The failed attempts at government restructuring as well as the domestic turmoil provoked its neighbours to intervene.[93]

In 1772, the First Partition of the Commonwealth by Prussia, Russia and Austria took place; an act which the Partition Sejm, under considerable duress, eventually ratified as a fait accompli.[94] Disregarding the territorial losses, in 1773 a plan of critical reforms was established, in which the Commission of National Education, the first government education authority in Europe, was inaugurated.[95] Corporal punishment of schoolchildren was officially prohibited in 1783. Poniatowski was the head figure of the Enlightenment, encouraged the development of industries, and embraced republican neoclassicism.[96] For his contributions to the arts and sciences he was awarded a Fellowship of the Royal Society.[97]

In 1791, Great Sejm parliament adopted the 3 May Constitution, the first set of supreme national laws, and introduced a constitutional monarchy.[98] The Targowica Confederation, an organisation of nobles and deputies opposing the act, appealed to Catherine and caused the 1792 Polish–Russian War.[99] Fearing the reemergence of Polish hegemony, Russia and Prussia arranged and in 1793 executed, the Second Partition, which left the country deprived of territory and incapable of independent existence. On 24 October 1795, the Commonwealth was partitioned for the third time and ceased to exist as a territorial entity.[100][101] Stanisław Augustus, the last King of Poland, abdicated the throne on 25 November 1795.[102]

Era of insurrections

The Polish people rose several times against the partitioners and occupying armies. An unsuccessful attempt at defending Poland's sovereignty took place in the 1794 Kościuszko Uprising, where a popular and distinguished general Tadeusz Kościuszko, who had several years earlier served under George Washington in the American Revolutionary War, led Polish insurgents.[103] Despite the victory at the Battle of Racławice, his ultimate defeat ended Poland's independent existence for 123 years.[104]

In 1806, an insurrection organised by Jan Henryk Dąbrowski liberated western Poland ahead of Napoleon's advance into Prussia during the War of the Fourth Coalition. In accordance with the 1807 Treaty of Tilsit, Napoleon proclaimed the Duchy of Warsaw, a client state ruled by his ally Frederick Augustus I of Saxony. The Poles actively aided French troops in the Napoleonic Wars, particularly those under Józef Poniatowski who became Marshal of France shortly before his death at Leipzig in 1813.[105] In the aftermath of Napoleon's exile, the Duchy of Warsaw was abolished at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 and its territory was divided into Russian Congress Kingdom of Poland, the Prussian Grand Duchy of Posen, and Austrian Galicia with the Free City of Kraków.[106]

In 1830, non-commissioned officers at Warsaw's Officer Cadet School rebelled in what was the November Uprising.[107] After its collapse, Congress Poland lost its constitutional autonomy, army and legislative assembly.[108] During the European Spring of Nations, Poles took up arms in the Greater Poland Uprising of 1848 to resist Germanisation, but its failure saw duchy's status reduced to a mere province; and subsequent integration into the German Empire in 1871.[109] In Russia, the fall of the January Uprising (1863–1864) prompted severe political, social and cultural reprisals, followed by deportations and pogroms of the Polish-Jewish population. Towards the end of the 19th century, Congress Poland became heavily industrialised; its primary exports being coal, zinc, iron and textiles.[110][111]

Second Polish Republic

In the aftermath of World War I, the Allies agreed on the reconstitution of Poland, confirmed through the Treaty of Versailles of June 1919.[112] A total of 2 million Polish troops fought with the armies of the three occupying powers, and over 450,000 died.[113] Following the armistice with Germany in November 1918, Poland regained its independence as the Second Polish Republic.[114]

The Second Polish Republic reaffirmed its sovereignty after a series of military conflicts, most notably the Polish–Soviet War, when Poland inflicted a crushing defeat on the Red Army at the Battle of Warsaw.[115]

The inter-war period heralded a new era of Polish politics. Whilst Polish political activists had faced heavy censorship in the decades up until World War I, a new political tradition was established in the country. Many exiled Polish activists, such as Ignacy Jan Paderewski, who would later become prime minister, returned home. A significant number of them then went on to take key positions in the newly formed political and governmental structures. Tragedy struck in 1922 when Gabriel Narutowicz, inaugural holder of the presidency, was assassinated at the Zachęta Gallery in Warsaw by a painter and right-wing nationalist Eligiusz Niewiadomski.[116]

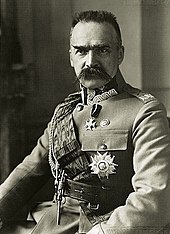

In 1926, the May Coup, led by the hero of the Polish independence campaign Marshal Józef Piłsudski, turned rule of the Second Polish Republic over to the nonpartisan Sanacja (Healing) movement to prevent radical political organisations on both the left and the right from destabilizing the country.[117] By the late 1930s, due to increased threats posed by political extremism inside the country, the Polish government became increasingly heavy-handed, banning a number of radical organisations, including communist and ultra-nationalist political parties, which threatened the stability of the country.[118]

World War II

World War II began with the Nazi German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, followed by the Soviet invasion of Poland on 17 September. On 28 September 1939, Warsaw fell. As agreed in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Poland was split into two zones, one occupied by Nazi Germany, the other by the Soviet Union. In 1939–1941, the Soviets deported hundreds of thousands of Poles. The Soviet NKVD executed thousands of Polish prisoners of war (among other incidents in the Katyn massacre) ahead of Operation Barbarossa.[119] German planners had in November 1939 called for "the complete destruction of all Poles" and their fate as outlined in the genocidal Generalplan Ost.[120]

Poland made the fourth-largest troop contribution in Europe,[121][122][123] and its troops served both the Polish Government in Exile in the west and Soviet leadership in the east. Polish troops played an important role in the Normandy, Italian, North African Campaigns and Netherlands and are particularly remembered for the Battle of Britain and Battle of Monte Cassino.[124][125] Polish intelligence operatives proved extremely valuable to the Allies, providing much of the intelligence from Europe and beyond,[126] Polish code breakers were responsible for cracking the Enigma cipher and Polish scientists participating in the Manhattan Project were co-creators of the American atomic bomb. In the east, the Soviet-backed Polish 1st Army distinguished itself in the battles for Warsaw and Berlin.[127]

The wartime resistance movement, and the Armia Krajowa (Home Army), fought against German occupation. It was one of the three largest resistance movements of the entire war, and encompassed a range of clandestine activities, which functioned as an underground state complete with degree-awarding universities and a court system.[128] The resistance was loyal to the exiled government and generally resented the idea of a communist Poland; for this reason, in the summer of 1944 it initiated Operation Tempest, of which the Warsaw Uprising that began on 1 August 1944 is the best-known operation.[127][129]

Nazi German forces under orders from Adolf Hitler set up six German extermination camps in occupied Poland, including Treblinka, Majdanek and Auschwitz. The Germans transported millions of Jews from across occupied Europe to be murdered in those camps.[130][131] Altogether, 3 million Polish Jews[132][133] – approximately 90% of Poland's pre-war Jewry – and between 1.8 and 2.8 million ethnic Poles[134][135][136] were killed during the German occupation of Poland, including between 50,000 and 100,000 members of the Polish intelligentsia – academics, doctors, lawyers, nobility and priesthood. During the Warsaw Uprising alone, over 150,000 Polish civilians were killed, most were murdered by the Germans during the Wola and Ochota massacres.[137][138] Around 150,000 Polish civilians were killed by Soviets between 1939 and 1941 during the Soviet Union's occupation of eastern Poland (Kresy), and another estimated 100,000 Poles were murdered by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) between 1943 and 1944 in what became known as the Wołyń Massacres.[139][140] Of all the countries in the war, Poland lost the highest percentage of its citizens: around 6 million perished – more than one-sixth of Poland's pre-war population – half of them Polish Jews.[141][142][143] About 90% of deaths were non-military in nature.[144]

In 1945, Poland's borders were shifted westwards. Over two million Polish inhabitants of Kresy were expelled along the Curzon Line by Stalin.[145] The western border became the Oder-Neisse line. As a result, Poland's territory was reduced by 20%, or 77,500 square kilometres (29,900 sq mi). The shift forced the migration of millions of other people, most of whom were Poles, Germans, Ukrainians, and Jews.[146][147][148]

Post-war communism

At the insistence of Joseph Stalin, the Yalta Conference sanctioned the formation of a new provisional pro-Communist coalition government in Moscow, which ignored the Polish government-in-exile based in London. This action angered many Poles who considered it a betrayal by the Allies. In 1944, Stalin had made guarantees to Churchill and Roosevelt that he would maintain Poland's sovereignty and allow democratic elections to take place. However, upon achieving victory in 1945, the elections organised by the occupying Soviet authorities were falsified and were used to provide a veneer of legitimacy for Soviet hegemony over Polish affairs. The Soviet Union instituted a new communist government in Poland, analogous to much of the rest of the Eastern Bloc. As elsewhere in Communist Europe, the Soviet influence over Poland was met with armed resistance from the outset which continued into the 1950s.[149]

Despite widespread objections, the new Polish government accepted the Soviet annexation of the pre-war eastern regions of Poland[150] (in particular the cities of Wilno and Lwów) and agreed to the permanent garrisoning of Red Army units on Poland's territory. Military alignment within the Warsaw Pact throughout the Cold War came about as a direct result of this change in Poland's political culture. In the European scene, it came to characterise the full-fledged integration of Poland into the brotherhood of communist nations.[151]

The new communist government took control with the adoption of the Small Constitution on 19 February 1947. The Polish People's Republic (Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa) was officially proclaimed in 1952. In 1956, after the death of Bolesław Bierut, the régime of Władysław Gomułka became temporarily more liberal, freeing many people from prison and expanding some personal freedoms. Collectivisation in the Polish People's Republic failed. A similar situation repeated itself in the 1970s under Edward Gierek, but most of the time persecution of anti-communist opposition groups persisted. Despite this, Poland was at the time considered to be one of the least oppressive states of the Eastern Bloc.[152]

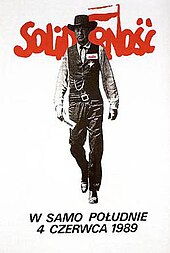

Labour turmoil in 1980 led to the formation of the independent trade union "Solidarity" ("Solidarność"), which over time became a political force. Despite persecution and imposition of martial law in 1981 by General Wojciech Jaruzelski, it eroded the dominance of the Polish United Workers' Party and by 1989 had triumphed in Poland's first partially free and democratic parliamentary elections since the end of the Second World War. Lech Wałęsa, a Solidarity candidate, eventually won the presidency in 1990. The Solidarity movement heralded the collapse of communist regimes and parties across Europe.[153]

Third Polish Republic

A shock therapy program, initiated by Leszek Balcerowicz in the early 1990s, enabled the country to transform its Soviet-style planned economy into a market economy.[154] As with other post-communist countries, Poland suffered temporary declines in social, economic, and living standards,[155] but it became the first post-communist country to reach its pre-1989 GDP levels as early as 1995, although the unemployment rate increased.[156] Poland became a member of the Visegrád Group in 1991,[157] and joined NATO in 1999.[158] Poles then voted to join the European Union in a referendum in June 2003,[159] with Poland becoming a full member on 1 May 2004, following the consequent enlargement of the organisation.[160]

Poland joined the Schengen Area in 2007, as a result of which, the country's borders with other member states of the European Union were dismantled, allowing for full freedom of movement within most of the European Union.[161] On 10 April 2010, the President of Poland Lech Kaczyński, along with 89 other high-ranking Polish officials died in a plane crash near Smolensk, Russia.[162]

In 2011, the ruling Civic Platform won parliamentary elections.[163] In 2014, the Prime Minister of Poland, Donald Tusk, was chosen to be President of the European Council, and resigned as prime minister.[164] The 2015 and 2019 elections were won by the national-conservative Law and Justice Party (PiS) led by Jarosław Kaczyński,[165][166] resulting in increased Euroscepticism and increased friction with the European Union.[167] In December 2017, Mateusz Morawiecki was sworn in as the Prime Minister, succeeding Beata Szydlo, in office since 2015. President Andrzej Duda, supported by Law and Justice party, was re-elected in the 2020 presidential election.[168] As of November 2023[update], the Russian invasion of Ukraine had led to 17 million Ukrainian refugees crossing the border to Poland.[169] As of November 2023[update], 0.9 million of those had stayed in Poland.[169] In October 2023, the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party won the largest share of the vote in the election, but lost its majority in parliament. In December 2023, Donald Tusk became the new Prime Minister leading a coalition called Civic Coalition made up of Civic Platform, Third Way, and The Left. Law and Justice became the leading opposition party.[170]

Geography

Poland covers an administrative area of 312,722 km2 (120,743 sq mi), and is the ninth-largest country in Europe. Approximately 311,895 km2 (120,423 sq mi) of the country's territory consists of land, 2,041 km2 (788 sq mi) comprises internal waters and 8,783 km2 (3,391 sq mi) is territorial sea.[171] Topographically, the landscape of Poland is characterised by diverse landforms, water bodies and ecosystems.[172] The central and northern region bordering the Baltic Sea lie within the flat Central European Plain, but its south is hilly and mountainous.[173] The average elevation above the sea level is estimated at 173 metres.[171]

The country has a coastline spanning 770 km (480 mi); extending from the shores of the Baltic Sea, along the Bay of Pomerania in the west to the Gulf of Gdańsk in the east.[171] The beach coastline is abundant in sand dune fields or coastal ridges and is indented by spits and lagoons, notably the Hel Peninsula and the Vistula Lagoon, which is shared with Russia.[174] The largest Polish island on the Baltic Sea is Wolin, located within Wolin National Park.[175] Poland also shares the Szczecin Lagoon and the Usedom island with Germany.[176]

The mountainous belt in the extreme south of Poland is divided into two major mountain ranges; the Sudetes in the west and the Carpathians in the east. The highest part of the Carpathian massif are the Tatra Mountains, extending along Poland's southern border.[177] Poland's highest point is Mount Rysy at 2,501 metres (8,205 ft) in elevation, located in the Tatras.[178] The highest summit of the Sudetes massif is Mount Śnieżka at 1,603.3 metres (5,260 ft), shared with the Czech Republic.[179] The lowest point in Poland is situated at Raczki Elbląskie in the Vistula Delta, which is 1.8 metres (5.9 ft) below sea level.[171]

Poland's longest rivers are the Vistula, the Oder, the Warta, and the Bug.[171] The country also possesses one of the highest densities of lakes in the world, numbering around ten thousand and mostly concentrated in the north-eastern region of Masuria, within the Masurian Lake District.[180] The largest lakes, covering more than 100 square kilometres (39 sq mi), are Śniardwy and Mamry, and the deepest is Lake Hańcza at 108.5 metres (356 ft) in depth.[171]

Climate

The climate of Poland is temperate transitional, and varies from oceanic in the north-west to continental in the south-east.[181] The mountainous southern fringes are situated within an alpine climate.[181] Poland is characterised by warm summers, with a mean temperature of around 20 °C (68.0 °F) in July, and moderately cold winters averaging −1 °C (30.2 °F) in December.[182] The warmest and sunniest part of Poland is Lower Silesia in the southwest and the coldest region is the northeast corner, around Suwałki in Podlaskie province, where the climate is affected by cold fronts from Scandinavia and Siberia.[183] Precipitation is more frequent during the summer months, with highest rainfall recorded from June to September.[182]

There is a considerable fluctuation in day-to-day weather and the arrival of a particular season can differ each year.[181] Climate change and other factors have further contributed to interannual thermal anomalies and increased temperatures; the average annual air temperature between 2011 and 2020 was 9.33 °C (48.8 °F), around 1.11 °C higher than in the 2001–2010 period.[183] Winters are also becoming increasingly drier, with less sleet and snowfall.[181]

Biodiversity

Phytogeographically, Poland belongs to the Central European province of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. The country has four Palearctic ecoregions – Central, Northern, Western European temperate broadleaf and mixed forest, and the Carpathian montane conifer. Forests occupy 31% of Poland's land area, the largest of which is the Lower Silesian Wilderness.[184] The most common deciduous trees found across the country are oak, maple, and beech; the most common conifers are pine, spruce, and fir.[185] An estimated 69% of all forests are coniferous.[186]

The flora and fauna in Poland is that of Continental Europe, with the wisent, white stork and white-tailed eagle designated as national animals, and the red common poppy being the unofficial floral emblem.[187] Among the most protected species is the European bison, Europe's heaviest land animal, as well as the Eurasian beaver, the lynx, the gray wolf and the Tatra chamois.[171] The region was also home to the extinct aurochs, the last individual dying in Poland in 1627.[188] Game animals such as red deer, roe deer, and wild boar are found in most woodlands.[189] Poland is also a significant breeding ground for migratory birds and hosts around one quarter of the global population of white storks.[190]

Around 315,100 hectares (1,217 sq mi), equivalent to 1% of Poland's territory, is protected within 23 Polish national parks, two of which – Białowieża and Bieszczady – are UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[191] There are 123 areas designated as landscape parks, along with numerous nature reserves and other protected areas under the Natura 2000 network.[192]

Government and politics

Poland is a unitary parliamentary republic and a representative democracy, with a president as the head of state.[193] The executive power is exercised further by the Council of Ministers and the prime minister who acts as the head of government.[193] The council's individual members are selected by the prime minister, appointed by the president and approved by parliament.[193] The head of state is elected by popular vote for a five-year term.[194] The current president is Andrzej Duda and the prime minister is Donald Tusk.

Poland's legislative assembly is a bicameral parliament consisting of a 460-member lower house (Sejm) and a 100-member upper house (Senate).[195] The Sejm is elected under proportional representation according to the d'Hondt method for vote-seat conversion.[196] The Senate is elected under the first-past-the-post electoral system, with one senator being returned from each of the one hundred constituencies.[197] The Senate has the right to amend or reject a statute passed by the Sejm, but the Sejm may override the Senate's decision with a majority vote.[198]

With the exception of ethnic minority parties, only candidates of political parties receiving at least 5% of the total national vote can enter the Sejm.[197] Both the lower and upper houses of parliament in Poland are elected for a four-year term and each member of the Polish parliament is guaranteed parliamentary immunity.[199] Under current legislation, a person must be 21 years of age or over to assume the position of deputy, 30 or over to become senator and 35 to run in a presidential election.[199]

Members of the Sejm and Senate jointly form the National Assembly of the Republic of Poland.[200] The National Assembly, headed by the Sejm Marshal, is formed on three occasions – when a new president takes the oath of office; when an indictment against the president is brought to the State Tribunal; and in case a president's permanent incapacity to exercise his duties due to the state of his health is declared.[200]

Administrative divisions

Poland is divided into 16 provinces or states known as voivodeships.[201] As of 2022, the voivodeships are subdivided into 380 counties (powiats), which are further fragmented into 2,477 municipalities (gminas).[201] Major cities normally have the status of both gmina and powiat.[201] The provinces are largely founded on the borders of historic regions, or named for individual cities.[202] Administrative authority at the voivodeship level is shared between a government-appointed governor (voivode), an elected regional assembly (sejmik) and a voivodeship marshal, an executive elected by the assembly.[202]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Law

The Constitution of Poland is the enacted supreme law, and Polish judicature is based on the principle of civil rights, governed by the code of civil law.[204] The current democratic constitution was adopted by the National Assembly of Poland on 2 April 1997; it guarantees a multi-party state with freedoms of religion, speech and assembly, prohibits the practices of forced medical experimentation, torture or corporal punishment, and acknowledges the inviolability of the home, the right to form trade unions, and the right to strike.[205]

The judiciary in Poland is composed of the Supreme Court as the country's highest judicial organ, the Supreme Administrative Court for the judicial control of public administration, Common Courts (District, Regional, Appellate) and the Military Court.[206] The Constitutional and State Tribunals are separate judicial bodies, which rule the constitutional liability of people holding the highest offices of state and supervise the compliance of statutory law, thus protecting the Constitution.[207] Judges are nominated by the National Council of the Judiciary and are appointed for life by the president.[207] With the approval of the Senate, the Sejm appoints an ombudsman for a five-year term to guard the observance of social justice.[197]

Poland has a low homicide rate at 0.7 murders per 100,000 people, as of 2018.[208] Rape, assault and violent crime remain at a very low level.[209] The country has imposed strict regulations on abortion, which is permitted only in cases of rape, incest or when the woman's life is in danger; congenital disorder and stillbirth are not covered by the law, prompting some women to seek abortion abroad.[210]

Historically, the most significant Polish legal act is the Constitution of 3 May 1791. Instituted to redress long-standing political defects of the federative Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and its Golden Liberty, it was the first modern constitution in Europe and influenced many later democratic movements across the globe.[211][212][213] In 1918, the Second Polish Republic became one of the first countries to introduce universal women's suffrage.[214]

Foreign relations

Poland is a middle power and is transitioning into a regional power in Europe.[215][216] It has a total of 52 representatives in the European Parliament as of 2022.[217] Warsaw serves as the headquarters for Frontex, the European Union's agency for external border security as well as ODIHR, one of the principal institutions of the OSCE.[218][219] Apart from the European Union, Poland has been a member of NATO, the United Nations, and the WTO.

In recent years, Poland significantly strengthened its relations with the United States, thus becoming one of its closest allies and strategic partners in Europe.[220] Historically, Poland maintained strong cultural and political ties to Hungary; this special relationship was recognised by the parliaments of both countries in 2007 with the joint declaration of 23 March as "The Day of Polish-Hungarian Friendship".[221]

Military

The Polish Armed Forces are composed of five branches – the Land Forces, the Navy, the Air Force, the Special Forces and the Territorial Defence Force.[222] The military is subordinate to the Ministry of National Defence of the Republic of Poland.[222] However, its commander-in-chief in peacetime is the president, who nominates officers, the Minister for National Defence and the chief of staff.[222] Polish military tradition is generally commemorated by the Armed Forces Day, celebrated annually on 15 August.[223] As of 2022, the Polish Armed Forces have a combined strength of 114,050 active soldiers, with a further 75,400 active in the gendarmerie and defence force.[224]

Poland ranks 14th in the world in terms of military expenditures; the country allocates 3.8% of its total GDP on military spending, equivalent to approximately US$31.6 billion in 2023.[225] From 2022, Poland initiated a programme of mass modernisation of its armed forces, in close cooperation with American, South Korean and local Polish defence manufacturers.[226] Also, the Polish military is set to increase its size to 250,000 enlisted and officers, and 50,000 defence force personnel.[227] According to SIPRI, the country exported €487 million worth of arms and armaments to foreign countries in 2020.[228]

Compulsory military service for men, who previously had to serve for nine months, was discontinued in 2008.[229] Polish military doctrine reflects the same defensive nature as that of its NATO partners and the country actively hosts NATO's military exercises.[224] Since 1953, the country has been a large contributor to various United Nations peacekeeping missions,[230] and currently maintains military presence in the Middle East, Africa, the Baltic states and southeastern Europe.[224]

Security, law enforcement and emergency services

Thanks to its location, Poland is a country essentially free from the threat of natural disasters such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, tornadoes and tropical cyclones. However, floods have occurred in low-lying areas from time to time during periods of extreme rainfall (e.g. during the 2010 Central European floods).

Law enforcement in Poland is performed by several agencies which are subordinate to the Ministry of Interior and Administration – the State Police (Policja), assigned to investigate crimes or transgression; the Municipal City Guard, which maintains public order; and several specialised agencies, such as the Polish Border Guard.[231] Private security firms are also common, although they possess no legal authority to arrest or detain a suspect.[231][232] Municipal guards are primarily headed by provincial, regional or city councils; individual guards are not permitted to carry firearms unless instructed by the superior commanding officer.[233] Security service personnel conduct regular patrols in both large urban areas or smaller suburban localities.[234]

The Internal Security Agency (ABW, or ISA in English) is the chief counterintelligence instrument safeguarding Poland's internal security, along with Agencja Wywiadu (AW) which identifies threats and collects secret information abroad.[235] The Central Investigation Bureau of Police (CBŚP) and the Central Anticorruption Bureau (CBA) are responsible for countering organised crime and corruption in state and private institutions.[236][237]

Emergency services in Poland consist of the emergency medical services, search and rescue units of the Polish Armed Forces and State Fire Service. Emergency medical services in Poland are operated by local and regional governments,[238] but are a part of the centralised national agency – the National Medical Emergency Service (Państwowe Ratownictwo Medyczne).[239]

Economy

| GDP (PPP) | $1.801 trillion (2024)[10] |

|---|---|

| Nominal GDP | $844.6 billion (2024)[10] |

| Real GDP growth | 5.3% (2022)[240] |

| CPI inflation | 14.4% (2022)[241] |

| Employment-to-population ratio | 57% (2022)[242] |

| Unemployment | 2.8% (2023)[243] |

| Total public debt | $340 billion (2022)[244] |

As of 2023[update], Poland's economy and gross domestic product (GDP) is the sixth largest in the European Union by nominal standards and the fifth largest by purchasing power parity. It is also one of the fastest growing within the Union and reached a developed market status in 2018.[245] The unemployment rate published by Eurostat in 2023 amounted to 2.8%, which was the second-lowest in the EU.[243] As of 2023[update], around 62% of the employed population works in the service sector, 29% in manufacturing, and 8% in the agricultural sector.[246] Although Poland is a member of the European single market, the country has not adopted the Euro as legal tender and maintains its own currency – the Polish złoty (zł, PLN).

Poland is the regional economic leader in Central Europe, with nearly 40 per cent of the 500 biggest companies in the region (by revenues) as well as a high globalisation rate.[247] The country's largest firms compose the WIG20 and WIG30 indexes, which is traded on the Warsaw Stock Exchange. According to reports made by the National Bank of Poland, the value of Polish foreign direct investments reached almost 300 billion PLN at the end of 2014. The Central Statistical Office estimated that in 2014 there were 1,437 Polish corporations with interests in 3,194 foreign entities.[248]

Poland has the largest banking sector in Central Europe,[249] with 32.3 branches per 100,000 adults.[250] It was the only European economy to have avoided the recession of 2008.[251] The country is the 20th largest exporter of goods and services in the world.[252] Exports of goods and services are valued at approximately 56% of GDP, as of 2020.[253] In 2019, Poland passed a law that would exempt workers under the age of 26 from income tax.[254]

Tourism

In 2020, the total value of the tourism industry in Poland was 104.3 billion PLN, then equivalent to 4.5% of the Polish GDP.[255] Tourism contributes considerably to the overall economy and makes up a relatively large proportion of the country's service market.[256] Nearly 200,000 people were employed in the accommodation and catering (hospitality) sector in 2020.[255] In 2021, Poland ranked 12th most visited country in the world by international arrivals.[257]

Tourist attractions in Poland vary, from the mountains in the south to the beaches in the north, with a trail of rich architectural and cultural heritage. Among the most recognisable landmarks are Old Towns in Kraków, Warsaw, Wrocław (dwarf statues), Gdańsk, Poznań, Lublin, Toruń and Zamość as well as museums, zoological gardens, theme parks and the Wieliczka Salt Mine, with its labyrinthine tunnels, underground lake and chapels carved by miners out of rock salt beneath the ground. There are over 100 castles in the country, largely within the Lower Silesian Voivodeship, and also on the Trail of the Eagles' Nests; the largest castle in the world by land area is situated in Malbork.[258][259] The German Auschwitz concentration camp in Oświęcim, and the Skull Chapel in Kudowa-Zdrój constitute dark tourism.[260] Regarding nature based travel, notable sites include the Masurian Lake District and Białowieża Forest in the east; on the south Karkonosze, the Table Mountains and the Tatra Mountains, where Rysy and the Eagle's Path trail are located. The Pieniny and Bieszczady Mountains lie in the extreme south-east.[261]

Transport

Transport in Poland is provided by means of rail, road, marine shipping and air travel. The country is part of EU's Schengen Area and is an important transport hub due to its strategic geographical position in Central Europe.[262] Some of the longest European routes, including the E30 and E40, run through Poland. The country has a good network of highways comprising express roads and motorways. As of August 2023, Poland has the world's 21st-largest road network, maintaining over 5,000 km (3,100 mi) of highways in use.[263]

In 2022, the nation had 19,393 kilometres (12,050 mi) of railway track, the third longest in the European Union after Germany and France.[264] The Polish State Railways (PKP) is the dominant railway operator, with certain major voivodeships or urban areas possessing their own commuter and regional rail.[265] Poland has a number of international airports, the largest of which is Warsaw Chopin Airport.[266] It is the primary global hub for LOT Polish Airlines, the country's flag carrier.[267]

Seaports exist all along Poland's Baltic coast, with most freight operations using Świnoujście, Police, Szczecin, Kołobrzeg, Gdynia, Gdańsk and Elbląg as their base. The Port of Gdańsk is the only port in the Baltic Sea adapted to receive oceanic vessels. Polferries and Unity Line are the largest Polish ferry operators, with the latter providing roll-on/roll-off and train ferry services to Scandinavia.[268]

Energy

The electricity generation sector in Poland is largely fossil-fuel–based. Coal production in Poland is a major source of employment and the largest source of the nation's greenhouse gas emissions.[269] Many power plants nationwide use Poland's position as a major European exporter of coal to their advantage by continuing to use coal as the primary raw material in the production of their energy. The three largest Polish coal mining firms (Węglokoks, Kompania Węglowa and JSW) extract around 100 million tonnes of coal annually.[270] After coal, Polish energy supply relies significantly on oil—the nation is the third-largest buyer of Russian oil exports to the EU.[271]

The new Energy Policy of Poland until 2040 (EPP2040) would reduce the share of coal and lignite in electricity generation by 25% from 2017 to 2030. The plan involves deploying new nuclear plants, increasing energy efficiency, and decarbonising the Polish transport system in order to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and prioritise long-term energy security.[269][272]

Science and technology

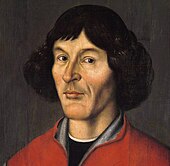

Over the course of history, the Polish people have made considerable contributions in the fields of science, technology and mathematics.[274] Perhaps the most renowned Pole to support this theory was Nicolaus Copernicus (Mikołaj Kopernik), who triggered the Copernican Revolution by placing the Sun rather than the Earth at the center of the universe.[275] He also derived a quantity theory of money, which made him a pioneer of economics. Copernicus' achievements and discoveries are considered the basis of Polish culture and cultural identity.[276] Poland was ranked 41st in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[277]

Poland's tertiary education institutions; traditional universities, as well as technical, medical, and economic institutions, employ around tens of thousands of researchers and staff members. There are hundreds of research and development institutes.[278] However, in the 19th and 20th centuries many Polish scientists worked abroad; one of the most important of these exiles was Marie Curie, a physicist and chemist who lived much of her life in France. In 1925, she established Poland's Radium Institute.[273]

In the first half of the 20th century, Poland was a flourishing centre of mathematics. Outstanding Polish mathematicians formed the Lwów School of Mathematics (with Stefan Banach, Stanisław Mazur, Hugo Steinhaus, Stanisław Ulam) and Warsaw School of Mathematics (with Alfred Tarski, Kazimierz Kuratowski, Wacław Sierpiński and Antoni Zygmund). Numerous mathematicians, scientists, chemists or economists emigrated due to historic vicissitudes, among them Benoit Mandelbrot, Leonid Hurwicz, Alfred Tarski, Joseph Rotblat and Nobel Prize laureates Roald Hoffmann, Georges Charpak and Tadeusz Reichstein.

Demographics

Poland has a population of approximately 38.2 million as of 2021, and is the ninth-most populous country in Europe, as well as the fifth-most populous member state of the European Union.[279] It has a population density of 122 inhabitants per square kilometre (320 inhabitants/sq mi).[280] The total fertility rate was estimated at 1.33 children born to a woman in 2021, which is among the world's lowest.[281] Furthermore, Poland's population is aging significantly, and the country has a median age of 42.2.[282]

Around 60% of the country's population lives in urban areas or major cities and 40% in rural zones.[283] In 2020, 50.2% of Poles resided in detached dwellings and 44.3% in apartments.[284] The most populous administrative province or state is the Masovian Voivodeship and the most populous city is the capital, Warsaw, at 1.8 million inhabitants with a further 2–3 million people living in its metropolitan area.[285][286][287] The metropolitan area of Katowice is the largest urban conurbation with a population between 2.7 million[288] and 5.3 million residents.[289] Population density is higher in the south of Poland and mostly concentrated between the cities of Wrocław and Kraków.[290]

In the 2011 Polish census, 37,310,341 people reported Polish identity, 846,719 Silesian, 232,547 Kashubian and 147,814 German. Other identities were reported by 163,363 people (0.41%) and 521,470 people (1.35%) did not specify any nationality.[291] Official population statistics do not include migrant workers who do not possess a permanent residency permit or Karta Polaka.[292] More than 1.7 million Ukrainian citizens worked legally in Poland in 2017.[293] The number of migrants is rising steadily; the country approved 504,172 work permits for foreigners in 2021 alone.[294] According to the Council of Europe, 12,731 Romani people live in Poland.[295]

| Rank | Name | Voivodeship | Pop. | Rank | Name | Voivodeship | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Warsaw  Kraków | 1 | Warsaw | Masovian | 1,860,281 | 11 | Katowice | Silesian | 285,711 |  Wrocław  Łódź |

| 2 | Kraków | Lesser Poland | 800,653 | 12 | Gdynia | Pomeranian | 245,222 | ||

| 3 | Wrocław | Lower Silesian | 672,929 | 13 | Częstochowa | Silesian | 213,107 | ||

| 4 | Łódź | Łódź | 670,642 | 14 | Radom | Masovian | 201,601 | ||

| 5 | Poznań | Greater Poland | 546,859 | 15 | Toruń | Kuyavian-Pomeranian | 198,273 | ||

| 6 | Gdańsk | Pomeranian | 486,022 | 16 | Rzeszów | Subcarpathian | 195,871 | ||

| 7 | Szczecin | West Pomeranian | 396,168 | 17 | Sosnowiec | Silesian | 193,660 | ||

| 8 | Bydgoszcz | Kuyavian-Pomeranian | 337,666 | 18 | Kielce | Świętokrzyskie | 186,894 | ||

| 9 | Lublin | Lublin | 334,681 | 19 | Gliwice | Silesian | 174,016 | ||

| 10 | Białystok | Podlaskie | 294,242 | 20 | Olsztyn | Warmian-Masurian | 170,225 | ||

Languages

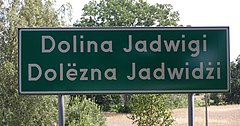

Polish is the official and predominant spoken language in Poland, and is one of the official languages of the European Union.[298] It is also a second language in parts of neighbouring Lithuania, where it is taught in Polish-minority schools.[299][300] Contemporary Poland is a linguistically homogeneous nation, with 97% of respondents declaring Polish as their mother tongue.[301] There are currently 15 minority languages in Poland,[302] including one recognised regional language, Kashubian, which is spoken by approximately 100,000 people on a daily basis in the northern regions of Kashubia and Pomerania.[303] Poland also recognises secondary administrative languages or auxiliary languages in bilingual municipalities, where bilingual signs and placenames are commonplace.[304] According to the Centre for Public Opinion Research, around 32% of Polish citizens declared knowledge of the English language in 2015.[305]

Religion

According to the 2021 census, 71.3% of all Polish citizens adhere to the Roman Catholic Church, with 6.9% identifying as having no religion and 20.6% refusing to answer.[4]

Poland is one of the most religious countries in Europe, where Roman Catholicism remains a part of national identity and Polish-born Pope John Paul II is widely revered.[306][307] In 2015, 61.6% of respondents outlined that religion is of high or very high importance.[308] However, church attendance has greatly decreased in recent years; only 28% of Catholics attended mass weekly in 2021, down from around half in 2000.[309] According to The Wall Street Journal, "Of [the] more than 100 countries studied by the Pew Research Center in 2018, Poland was secularizing the fastest, as measured by the disparity between the religiosity of young people and their elders."[306]

Freedom of religion in Poland is guaranteed by the Constitution, and Poland's concordat with the Holy See enables the teaching of religion in public schools.[310] Historically, the Polish state maintained a high degree of religious tolerance and provided asylum for refugees fleeing religious persecution in other parts of Europe.[311] Poland hosted Europe's largest Jewish diaspora, and the country was a centre of Ashkenazi Jewish culture and traditional learning until the Holocaust.[312]

Contemporary religious minorities include Orthodox Christians, Protestants, including Lutherans of the Evangelical-Augsburg Church, Pentecostals in the Pentecostal Church in Poland, Adventists in the Seventh-day Adventist Church, and other smaller Evangelical denominations, including Jehovah's Witnesses, Eastern Catholics, Mariavites, Jews, Muslims (Tatars), and neopagans, some of whom are members of the Native Polish Church.[313]

Pilgrimages to the Jasna Góra Monastery, a shrine dedicated to the Black Madonna, take place annually.[314]

Health

Medical service providers and hospitals (szpitale) in Poland are subordinate to the Ministry of Health; it provides administrative oversight and scrutiny of general medical practice, and is obliged to maintain a high standard of hygiene and patient care. Poland has a universal healthcare system based on an all-inclusive insurance system; state subsidised healthcare is available to all citizens covered by the general health insurance program of the National Health Fund (NFZ). Private medical complexes exist nationwide; over 50% of the population uses both public and private sectors.[315][316][317]

According to the Human Development Report from 2020, the average life expectancy at birth is 79 years (around 75 years for an infant male and 83 years for an infant female);[318] the country has a low infant mortality rate (4 per 1,000 births).[319] In 2019, the principal cause of death was ischemic heart disease; diseases of the circulatory system accounted for 45% of all deaths.[320] In the same year, Poland was also the 15th-largest importer of medications and pharmaceutical products.[321]

Education

The Jagiellonian University founded in 1364 by Casimir III in Kraków was the first institution of higher learning established in Poland, and is one of the oldest universities still in continuous operation.[322] Poland's Commission of National Education (Komisja Edukacji Narodowej), established in 1773, was the world's first state ministry of education.[323][324]

The framework for primary, secondary and higher tertiary education are established by the Ministry of Education and Science. Kindergarten attendance is optional for children aged between three and five, with one year being compulsory for six-year-olds.[325][326] Primary education traditionally begins at the age of seven, although children aged six can attend at the request of their parents or guardians.[326] Elementary school spans eight grades and secondary schooling is dependent on student preference – a four-year high school (liceum), a five-year technical school (technikum) or various vocational studies (szkoła branżowa) can be pursued by each individual pupil.[326] A liceum or technikum is concluded with a maturity exit exam (matura), which must be passed in order to apply for a university or other institutions of higher learning.[327]

In Poland, there are over 500 university-level institutions,[328] with technical, medical, economic, agricultural, pedagogical, theological, musical, maritime and military faculties.[329] The University of Warsaw and Warsaw Polytechnic, the University of Wrocław, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań and the University of Technology in Gdańsk are among the most prominent.[330] There are three conventional academic degrees in Poland – licencjat or inżynier (first cycle qualification), magister (second cycle qualification) and doktor (third cycle qualification).[331] In 2018, the Programme for International Student Assessment, coordinated by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ranked Poland's educational system higher than the OECD average; the study showed that students in Poland perform better academically than in most OECD countries.[332]

Culture

The culture of Poland is closely connected with its intricate 1,000-year history, and forms an important constituent in the Western civilisation.[333] The Poles take great pride in their national identity which is often associated with the colours white and red, and exuded by the expression biało-czerwoni ("whitereds").[334] National symbols, chiefly the crowned white-tailed eagle, are often visible on clothing, insignia and emblems.[335] The architectural monuments of great importance are protected by the National Heritage Board of Poland.[336] Over 100 of the country's most significant tangible wonders were enlisted onto the Historic Monuments Register,[337] with further 17 being recognised by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites.[338]

Holidays and traditions

There are 13 government-approved annual public holidays – New Year on 1 January, Three Kings' Day on 6 January, Easter Sunday and Easter Monday, Labour Day on 1 May, Constitution Day on 3 May, Pentecost, Corpus Christi, Feast of the Assumption on 15 August, All Saints' Day on 1 November, Independence Day on 11 November and Christmastide on 25 and 26 December.[339]

Particular traditions and superstitious customs observed in Poland are not found elsewhere in Europe. Though Christmas Eve (Wigilia) is not a public holiday, it remains the most memorable day of the entire year. Trees are decorated on 24 December, hay is placed under the tablecloth to resemble Jesus' manger, Christmas wafers (opłatek) are shared between gathered guests and a twelve-dish meatless supper is served that same evening when the first star appears.[340] An empty plate and seat are symbolically left at the table for an unexpected guest.[341] On occasion, carolers journey around smaller towns with a folk Turoń creature until the Lent period.[342]

A widely-popular doughnut and sweet pastry feast occurs on Fat Thursday, usually 52 days prior to Easter.[343] Eggs for Holy Sunday are painted and placed in decorated baskets that are previously blessed by clergymen in churches on Easter Saturday. Easter Monday is celebrated with pagan dyngus festivities, where the youth is engaged in water fights.[344][343] Cemeteries and graves of the deceased are annually visited by family members on All Saints' Day; tombstones are cleaned as a sign of respect and candles are lit to honour the dead on an unprecedented scale.[345]

Music

Artists from Poland, including famous musicians such as Frédéric Chopin, Artur Rubinstein, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Krzysztof Penderecki, Henryk Wieniawski, Karol Szymanowski, and traditional, regionalised folk composers create a lively and diverse music scene, which even recognises its own music genres, such as sung poetry and disco polo.[346]

The origins of Polish music can be traced to the 13th century; manuscripts have been found in Stary Sącz containing polyphonic compositions related to the Parisian Notre Dame School. Other early compositions, such as the melody of Bogurodzica and God Is Born (a coronation polonaise tune for Polish kings by an unknown composer), may also date back to this period, however, the first known notable composer, Nicholas of Radom, lived in the 15th century. Diomedes Cato, a native-born Italian who lived in Kraków, became a renowned lutenist at the court of Sigismund III; he not only imported some of the musical styles from southern Europe but blended them with native folk music.[347]

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Polish baroque composers wrote liturgical music and secular compositions such as concertos and sonatas for voices or instruments. At the end of the 18th century, Polish classical music evolved into national forms like the polonaise. Wojciech Bogusławski is accredited with composing the first Polish national opera, titled Krakowiacy i Górale, which premiered in 1794.[348]

Poland today has an active music scene, with the jazz and metal genres being particularly popular among the contemporary populace. Polish jazz musicians such as Krzysztof Komeda created a unique style, which was most famous in the 1960s and 1970s and continues to be popular to this day. Poland has also become a major venue for large-scale music festivals, chief among which are the Pol'and'Rock Festival,[349] Open'er Festival, Opole Festival and Sopot Festival.[350]

Art

Art in Poland has invariably reflected European trends, with Polish painting pivoted on folklore, Catholic themes, historicism and realism, but also on impressionism and romanticism. An important art movement was Young Poland, developed in the late 19th century for promoting decadence, symbolism and art nouveau. Since the 20th century Polish documentary art and photography has enjoyed worldwide fame, especially the Polish School of Posters.[351] One of the most distinguished paintings in Poland is Lady with an Ermine (1490) by Leonardo da Vinci.[352]

Internationally renowned Polish artists include Jan Matejko (historicism), Jacek Malczewski (symbolism), Stanisław Wyspiański (art nouveau), Henryk Siemiradzki (Roman academic art), Tamara de Lempicka (art deco), and Zdzisław Beksiński (dystopian surrealism).[353] Several Polish artists and sculptors were also acclaimed representatives of avant-garde, constructivist, minimalist and contemporary art movements, including Katarzyna Kobro, Władysław Strzemiński, Magdalena Abakanowicz, Alina Szapocznikow, Igor Mitoraj and Wilhelm Sasnal.

Notable art academies in Poland include the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts, Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, Art Academy of Szczecin, University of Fine Arts in Poznań and the Geppert Academy of Fine Arts in Wrocław. Contemporary works are exhibited at Zachęta, Ujazdów, and MOCAK art galleries.[354]

Architecture

The architecture of Poland reflects European architectural styles, with strong historical influences derived from Italy, Germany, and the Low Countries.[355] Settlements founded on Magdeburg Law evolved around central marketplaces (plac, rynek), encircled by a grid or concentric network of streets forming an old town (stare miasto).[356] Poland's traditional landscape is characterised by ornate churches, city tenements and town halls.[357] Cloth hall markets (sukiennice) were once an abundant feature of Polish urban architecture.[358] The mountainous south is known for its Zakopane chalet style, which originated in Poland.[359]

The earliest architectonic trend was Romanesque (c. 11th century), but its traces in the form of circular rotundas are scarce.[360] The arrival of brick Gothic (c. 13th century) defined Poland's most distinguishable medieval style, exuded by the castles of Malbork, Lidzbark, Gniew and Kwidzyn as well as the cathedrals of Gniezno, Gdańsk, Wrocław, Frombork and Kraków.[361] The Renaissance (16th century) gave rise to Italianate courtyards, defensive palazzos and mausoleums.[362] Decorative attics with pinnacles and arcade loggias are elements of Polish Mannerism, found in Poznań, Lublin and Zamość.[363][364] Foreign artisans often came at the expense of kings or nobles, whose palaces were built thereafter in the Baroque, Neoclassical and Revivalist styles (17th–19th century).[365]

Primary building materials comprising timber or red brick were extensively utilised in Polish folk architecture,[366] and the concept of a fortified church was commonplace.[367] Secular structures such as dworek manor houses, farmsteads, granaries, mills and country inns are still present in some regions or in open air museums (skansen).[368] However, traditional construction methods faded in the early-mid 20th century due to urbanisation and the construction of functionalist housing estates and residential areas.[369]

Literature

The literary works of Poland have traditionally concentrated around the themes of patriotism, spirituality, social allegories and moral narratives.[370] The earliest examples of Polish literature, written in Latin, date to the 12th century.[371] The first Polish phrase Day ut ia pobrusa, a ti poziwai (officially translated as "Let me, I shall grind, and you take a rest") was documented in the Book of Henryków and reflected the use of a quern-stone.[372] It has been since included in UNESCO's Memory of World Register.[373] The oldest extant manuscripts of fine prose in Old Polish are the Holy Cross Sermons and the Bible of Queen Sophia,[374] and Calendarium cracoviense (1474) is Poland's oldest surviving print.[375]

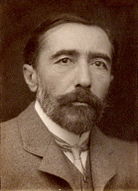

The poets Jan Kochanowski and Nicholas Rey became the first Renaissance authors to write in Polish.[376] Prime literarians of the period included Dantiscus, Modrevius, Goslicius, Sarbievius and theologian John Laski. In the Baroque era, Jesuit philosophy and local culture greatly influenced the literary techniques of Jan Andrzej Morsztyn (Marinism) and Jan Chryzostom Pasek (sarmatian memoirs).[377] During the Enlightenment, playwright Ignacy Krasicki composed the first Polish-language novel.[378] Poland's leading 19th-century romantic poets were the Three Bards – Juliusz Słowacki, Zygmunt Krasiński and Adam Mickiewicz, whose epic poem Pan Tadeusz (1834) is a national classic.[379] In the 20th century, the English impressionist and early modernist writings of Joseph Conrad made him one of the most eminent novelists of all time.[380][381]

Contemporary Polish literature is versatile, with its fantasy genre having been particularly praised.[382] The philosophical sci-fi novel Solaris by Stanisław Lem and The Witcher series by Andrzej Sapkowski are celebrated works of world fiction.[383] Poland has six Nobel-Prize winning authors – Henryk Sienkiewicz (Quo Vadis; 1905), Władysław Reymont (The Peasants; 1924), Isaac Bashevis Singer (1978), Czesław Miłosz (1980), Wisława Szymborska (1996), and Olga Tokarczuk (2018).[384][385][386]

Cuisine

The cuisine of Poland is eclectic and shares similarities with other regional cuisines. Among the staple or regional dishes are pierogi (filled dumplings), kielbasa (sausage), bigos (hunter's stew), kotlet schabowy (breaded cutlet), gołąbki (cabbage rolls), barszcz (borscht), żurek (soured rye soup), oscypek (smoked cheese), and tomato soup.[387][388] Bagels, a type of bread roll, also originated in Poland.[389]

Traditional dishes are hearty and abundant in pork, potatoes, eggs, cream, mushrooms, regional herbs, and sauce.[390] Polish food is characteristic for its various kinds of kluski (soft dumplings), soups, cereals and a variety of breads and open sandwiches. Salads, including mizeria (cucumber salad), coleslaw, sauerkraut, carrot and seared beets, are common. Meals conclude with a dessert such as sernik (cheesecake), makowiec (poppy seed roll), or napoleonka (mille-feuille) cream pie.[391]

Traditional alcoholic beverages include honey mead, widespread since the 13th century, beer, wine and vodka.[392] The world's first written mention of vodka originates from Poland.[393] The most popular alcoholic drinks at present are beer and wine which took over from vodka more popular in the years 1980–1998.[394] Grodziskie, sometimes referred to as "Polish Champagne", is an example of a historical beer style from Poland.[395] Tea remains common in Polish society since the 19th century, whilst coffee is drunk widely since the 18th century.[396]

Fashion and design

Several Polish designers and stylists left a legacy of beauty inventions and cosmetics; including Helena Rubinstein and Maksymilian Faktorowicz, who created a line of cosmetics company in California known as Max Factor and formulated the term "make-up" which is now widely used as an alternative for describing cosmetics.[397] Faktorowicz is also credited with inventing modern eyelash extensions.[398][399] As of 2020, Poland possesses the sixth-largest cosmetic market in Europe. Inglot Cosmetics is the country's largest beauty products manufacturer,[400] and the retail store Reserved is the country's most successful clothing store chain.[401]

Historically, fashion has been an important aspect of Poland's national consciousness or cultural manifestation, and the country developed its own style known as Sarmatism at the turn of the 17th century.[402] The national dress and etiquette of Poland also reached the court at Versailles, where French dresses inspired by Polish garments included robe à la polonaise and the witzchoura. The scope of influence also entailed furniture; rococo Polish beds with canopies became fashionable in French châteaus.[403] Sarmatism eventually faded in the wake of the 18th century.[402]

Cinema

The cinema of Poland traces its origins to 1894, when inventor Kazimierz Prószyński patented the Pleograph and subsequently the Aeroscope, the first successful hand-held operated film camera.[404][405] In 1897, Jan Szczepanik constructed the Telectroscope, a prototype of television transmitting images and sounds.[404] They are both recognised as pioneers of cinematography.[404] Poland has also produced influential directors, film producers and actors, many of whom were active in Hollywood, chiefly Roman Polański, Andrzej Wajda, Pola Negri, Samuel Goldwyn, the Warner brothers, Max Fleischer, Agnieszka Holland, Krzysztof Zanussi and Krzysztof Kieślowski.[406]

The themes commonly explored in Polish cinema include history, drama, war, culture and black realism (film noir).[404][405] In the 21st-century, two Polish productions won the Academy Awards – The Pianist (2002) by Roman Polański and Ida (2013) by Paweł Pawlikowski.[405] Polish cinematography also created many well-received comedies. The most known of them were made by Stanisław Bareja and Juliusz Machulski.

Media

According to the Eurobarometer Report (2015), 78 percent of Poles watch the television daily.[407] In 2020, 79 percent of the population read the news more than once a day, placing it second behind Sweden.[408] Poland has a number of major domestic media outlets, chiefly the public broadcasting corporation TVP, free-to-air channels TVN and Polsat as well as 24-hour news channels TVP Info, TVN 24 and Polsat News.[409] Public television extends its operations to genre-specific programmes such as TVP Sport, TVP Historia, TVP Kultura, TVP Rozrywka, TVP Seriale and TVP Polonia, the latter a state-run channel dedicated to the transmission of Polish-language telecasts for the Polish diaspora. In 2020, the most popular types of newspapers were tabloids and socio-political news dailies.[407]

Poland is a major European hub for video game developers and among the most successful companies are CD Projekt, Techland, The Farm 51, CI Games and People Can Fly.[410] Some of the popular video games developed in Poland include The Witcher trilogy and Cyberpunk 2077.[410] The Polish city of Katowice also hosts Intel Extreme Masters, one of the biggest esports events in the world.[410]

Sports