Французская революция

| Часть атлантических революций | |

Взятие Бастилии , 14 июля 1789 года. | |

| Дата | 5 мая 1789 г. - 9 ноября 1799 г. (10 лет, 6 месяцев и 4 дня) |

|---|---|

| Расположение | Королевство Франция |

| Исход |

|

Французская революция [а] был периодом политических и социальных перемен во Франции , который начался с Генеральных штатов 1789 года и закончился переворотом 18 брюмера в ноябре 1799 года и образованием французского консульства . Многие из его идей считаются фундаментальными принципами либеральной демократии . [1] в то время как ее ценности и институты остаются центральными в современном французском политическом дискурсе. [2]

Принято считать, что его причинами является сочетание социальных, политических и экономических факторов, с которыми « Старый режим» оказался неспособен справиться. Финансовый кризис и широкомасштабные социальные бедствия привели в мае 1789 года к созыву , Генеральных штатов которые в июне были преобразованы в Национальное собрание . Штурм Бастилии 14 июля привел к ряду радикальных мер Ассамблеи, среди которых отмена феодализма , государственный контроль над католической церковью во Франции и декларация прав .

Следующие три года прошли под знаком борьбы за политический контроль, усугубленной экономической депрессией . Военные поражения после начала французских революционных войн в апреле 1792 года привели к восстанию 10 августа 1792 года . Монархия была упразднена и заменена Первой французской республикой в сентябре, а Людовик XVI был казнен в январе 1793 года.

После очередного восстания в июне 1793 года действие конституции было приостановлено, и эффективная политическая власть перешла от Национального собрания к Комитету общественной безопасности . Около 16 000 человек были казнены во время правления террора , закончившегося в июле 1794 года . Ослабленная внешними угрозами и внутренней оппозицией, Республика была заменена в 1795 году Директорией . Четыре года спустя, в 1799 году, Консульство захватило власть в результате военного переворота под предводительством Наполеона Бонапарта . Обычно это рассматривается как окончание революционного периода.

Причины

| История Франции |

|---|

|

| Темы |

| Хронология |

Революция стала результатом множества долгосрочных и краткосрочных факторов, кульминацией которых стал социальный, экономический, финансовый и политический кризис в конце 1780-х годов. [3] [4] [5] В сочетании с сопротивлением реформам со стороны правящей элиты и нерешительной политикой Людовика XVI и его министров государство не смогло справиться с кризисом. [6] [7]

Между 1715 и 1789 годами население Франции выросло примерно с 21 до 28 миллионов человек. [8] Доля городского населения увеличилась до 20%, а в одном только Париже проживало более 600 000 жителей. [8] Крестьяне составляли около 80% населения, но средний класс утроился за столетие, достигнув почти 10% населения к 1789 году. [9] Хотя XVIII век был периодом растущего благосостояния, блага распределялись неравномерно по регионам и социальным группам. Больше всего выиграли те, чей доход был получен от сельского хозяйства, ренты, процентов и торговли товарами из рабовладельческих колоний Франции, в то время как уровень жизни наемных рабочих и фермеров на арендованной земле упал. [10] [11] Рост неравенства привел к усилению социальных конфликтов. [12] Экономический спад 1785 года и неурожаи в 1787 и 1788 годах привели к высокому уровню безработицы и росту цен на продукты питания, что совпало с финансовым и политическим кризисом монархии. [3] [13] [14] [15]

Хотя государство также пережило долговой кризис, сам уровень долга был невысоким по сравнению с британским. [16] Основная проблема заключалась в том, что ставки налогов сильно различались от региона к региону, часто отличались от официальных сумм и собирались непоследовательно. Его сложность означала неопределенность в отношении суммы, которую фактически вносил любой утвержденный налог, и вызывала недовольство среди всех налогоплательщиков. [17] [б] Попытки упростить систему были заблокированы региональными парламентами , утвердившими финансовую политику. Возникший тупик привел к созыву Генеральных штатов , которые стали радикальными из-за борьбы за контроль над государственными финансами. [19]

Людовик XVI был готов рассмотреть реформы, но часто отступал, сталкиваясь с противодействием консервативных элементов дворянства. Критика социальных институтов в духе Просвещения широко обсуждалась среди образованной французской элиты, в то время как американская революция и европейские восстания 1780-х годов вдохновили общественные дебаты по таким вопросам, как патриотизм, свобода, равенство и участие людей в принятии законов. Эти дебаты помогли сформировать реакцию образованной общественности на кризис, с которым столкнулось государство. [20] Серия публичных скандалов, таких как « Дело с бриллиантовым ожерельем», также усилила народный гнев на суд, дворянство и церковных чиновников. [21]

Кризис старого режима

Финансовый и политический кризис

В XVIII веке монархия столкнулась с серией бюджетных кризисов, поскольку доходы не успевали за расходами на армию и государственные пенсии. [22] [23] Хотя французская экономика уверенно росла, налоговая система не отразила новое богатство. [22] Сбор налогов поручался фермерам и получателям налогов , которые часто оставляли большую часть собранных налогов в качестве личной прибыли. Поскольку дворянство и церковь пользовались многими льготами, налоговое бремя легло в основном на крестьян. [24] Реформа была трудной, поскольку новые налоговые законы нужно было регистрировать в региональных судебных органах, известных как парламенты , которые могли отказать в регистрации, если законы противоречили существующим правам и привилегиям. Король мог вводить законы своим указом, но это грозило открытым конфликтом с парламентами , дворянством и теми, кто облагался новыми налогами. [25]

Франция в основном финансировала англо-французскую войну 1778–1783 годов за счет займов. После заключения мира монархия продолжала брать крупные займы, что привело к долговому кризису. К 1788 году половина государственных доходов требовалась для обслуживания долга. [26] В 1786 году министр финансов Франции Калонн предложил пакет реформ, включая всеобщий земельный налог, отмену контроля за зерном и внутренних тарифов, а также новые провинциальные ассамблеи, назначаемые королем. Новые налоги, однако, были отклонены сначала тщательно отобранным собранием знати, в котором доминировала знать, а затем парламентами, представленными преемницей Калонна Бриенной . Знатные люди и парламенты утверждали, что предложенные налоги могут быть одобрены только Генеральными штатами, представительным органом, который последний раз собирался в 1614 году. [27]

Конфликт между короной и парламентами превратился в национальный политический кризис. Обе стороны выступили с серией публичных заявлений: правительство утверждало, что оно борется с привилегиями, а парламенты – что оно защищает древние права нации. Общественное мнение было твердо на стороне парламентов, и в нескольких городах вспыхнули беспорядки. Попытки Бриенны получить новые займы потерпели неудачу, и 8 августа 1788 года он объявил, что король созовет Генеральные штаты на совещание в мае следующего года. Бриенна подала в отставку, и ее заменил Неккер . [28]

В сентябре 1788 года парижский парламент постановил, что Генеральные штаты должны собираться в той же форме, что и в 1614 году, а это означает, что три сословия (духовенство, дворянство и третье сословие или «община») будут собираться и голосовать отдельно, а голоса будут считаться по сословию, а не по головам. В результате духовенство и дворянство могли объединиться, чтобы перевесить голоса Третьего сословия, несмотря на то, что они составляли менее 5% населения. [29] [30]

После ослабления цензуры и законов против политических клубов группа либеральных дворян и активистов среднего класса, известная как «Общество Тридцати», начала кампанию за удвоение представительства третьего сословия и голосования по головам. В ходе публичных дебатов, начиная с 25 сентября 1788 года, в неделю публиковалось в среднем 25 новых политических брошюр. [31] Аббат Сийес выпустил влиятельные брошюры, осуждающие привилегии духовенства и дворянства и утверждающие, что третье сословие представляет нацию и должно заседать единолично в качестве Национального собрания. Такие активисты, как Мунье , Барнав и Робеспьер, организовывали собрания, петиции и литературу от имени третьего сословия в региональных городах. [32] В декабре король согласился удвоить представительство третьего сословия, но оставил на усмотрение Генеральных штатов вопрос о подсчете голосов по главам. [33]

Генеральные штаты 1789 г.

Генеральные штаты состояли из трех отдельных органов: первое сословие представляло 100 000 духовенства, второе - дворянство, а третье - «общину». [34] Поскольку каждое из них собиралось отдельно, а любые предложения должны были быть одобрены как минимум двумя, первое и второе сословия могли перевесить голоса третьего, несмотря на то, что они представляли менее 5% населения. [29]

Хотя католическая церковь во Франции владела почти 10% всей земли, а также получала ежегодную десятину , выплачиваемую крестьянами, [35] три четверти из 303 избранных священнослужителей были приходскими священниками, многие из которых зарабатывали меньше, чем неквалифицированные чернорабочие, и имели больше общего со своими бедными прихожанами, чем с епископами первого сословия. [36] [37]

Второе сословие избрало 322 депутата, представляющих около 400 000 мужчин и женщин, владевших около 25% земли и собиравших сеньорические пошлины и ренту со своих арендаторов. Большинство делегатов были горожанами, представителями дворянства или традиционной аристократии. Придворные и представители дворянства ( те, кто получил звание на судебных или административных должностях) были недостаточно представлены. [38]

Из 610 депутатов третьего сословия около двух третей имели юридическую квалификацию и почти половина были продажными должностными лицами. Менее 100 человек занимались торговлей или промышленностью, и никто не был крестьянином или ремесленником. [39] Чтобы помочь делегатам, каждый регион составил список жалоб, известный как Cahiers de doléances . [40] Налоговое неравенство и сеньорские сборы (феодальные платежи, причитающиеся землевладельцам) возглавляли жалобы в кассах поместья. [41]

5 мая 1789 года Генеральные штаты собрались в Версале . Неккер изложил государственный бюджет и подтвердил решение короля о том, что каждое сословие должно решить, по каким вопросам оно согласится собираться и голосовать совместно с другими сословиями. На следующий день каждое сословие должно было отдельно проверить полномочия своих представителей. Третье сословие, однако, проголосовало за то, чтобы предложить другим сословиям присоединиться к ним для общей проверки всех представителей Генеральных штатов и согласиться с тем, что голоса должны подсчитываться по головам. Бесплодные переговоры продолжались до 12 июня, когда третье сословие начало проверку своих членов. 17 июня Третье сословие объявило себя Национальным собранием Франции и объявило все существующие налоги незаконными. [42] За два дня к ним присоединилось более 100 представителей духовенства. [43]

Потрясенный этим вызовом своей власти, король согласился на пакет реформ, о котором он объявит на королевской сессии Генеральных штатов. был Государственный зал закрыт для подготовки к совместному заседанию, но члены Генеральных штатов не были проинформированы заранее. 20 июня, когда члены «третьего сословия» обнаружили, что место их встреч закрыто, они перебрались на близлежащий теннисный корт и поклялись не расходиться до тех пор, пока не будет согласована новая конституция. [44]

На королевской сессии король объявил о серии налоговых и других реформ и заявил, что никакие новые налоги или займы не будут вводиться без согласия Генеральных штатов. Однако он заявил, что три сословия неприкосновенны, и каждое сословие должно согласиться отказаться от своих привилегий и решить, по каким вопросам они будут голосовать совместно с другими сословиями. В конце заседания третье сословие отказалось покинуть зал и подтвердило свою клятву не расходиться до тех пор, пока не будет согласована конституция. В последующие дни к Национальному собранию присоединилось еще больше представителей духовенства. 27 июня, столкнувшись с народными демонстрациями и мятежами в своей французской гвардии , Людовик XVI капитулировал. Он приказал членам первого и второго сословий присоединиться к третьему в Национальном собрании. [45]

Конституционная монархия (июль 1789 г. - сентябрь 1792 г.)

Отмена старого режима

Даже ограниченные реформы, объявленные королем, зашли слишком далеко для Марии-Антуанетты и младшего брата Людовика, графа д'Артуа . По их совету 11 июля Луи снова уволил Неккера с поста главного министра. [46] 12 июля Ассамблея приступила к непрерывной сессии после того, как распространились слухи, что он планировал использовать швейцарскую гвардию , чтобы заставить ее закрыться. Эта новость привела к тому, что на улицы вышли толпы протестующих, а солдаты элитного полка французской гвардии отказались их разгонять. [47]

14 числа многие из этих солдат присоединились к толпе, атакующей Бастилию , королевскую крепость с большими запасами оружия и боеприпасов. Его губернатор Бернар-Рене де Лоне сдался после нескольких часов боев, унесших жизни 83 нападавших. Его доставили в ратушу де Виль , казнили, возложили голову на пику и пронесли по городу; затем крепость была снесена за удивительно короткое время. Хотя, по слухам, в Бастилии содержалось много заключенных, в Бастилии содержалось только семь человек: четыре фальсификатора, сумасшедший, неудавшийся убийца и дворянин-девиант. Тем не менее, как мощный символ Старого режима , его разрушение рассматривалось как триумф, и День взятия Бастилии до сих пор отмечается каждый год. [48] Некоторые представители французской культуры считают ее падение началом революции. [49]

Встревоженный перспективой потери контроля над столицей, Людовик назначил маркиза де Лафайета командующим Национальной гвардией , а Жана-Сильвена Байи — главой новой административной структуры, известной как Коммуна . 17 июля Людовик посетил Париж в сопровождении 100 депутатов, где его приветствовал Байи и принял трехцветную кокарду под громкие аплодисменты . Однако было ясно, что власть перешла от его двора; его приветствовали как «Людовика XVI, отца французов и короля свободного народа». [50]

Недолговечное единство, навязанное Ассамблее общей угрозой, быстро рассеялось. Депутаты спорили о конституционных формах, а гражданская власть быстро ухудшалась. 22 июля бывший министр финансов Жозеф Фуллон и его сын были линчеваны парижской мафией, и ни Байи, ни Лафайет не смогли этому помешать. В сельской местности дикие слухи и паранойя привели к формированию милиции и аграрному восстанию, известному как la Grande Peur . [51] Нарушение правопорядка и частые нападения на аристократическую собственность привели к тому, что большая часть дворянства бежала за границу. Эти эмигранты финансировали реакционные силы во Франции и призывали иностранных монархов поддержать контрреволюцию . [52]

В ответ Ассамблея опубликовала Августовские декреты , отменившие феодализм . Свыше 25% французских сельскохозяйственных угодий облагались феодальными сборами , обеспечивая дворянству большую часть их доходов; теперь они были отменены вместе с церковной десятиной. Хотя бывшие арендаторы должны были выплатить им компенсацию, получить ее оказалось невозможно, и обязательство было аннулировано в 1793 году. [53] Другие указы включали равенство перед законом, открытие государственных должностей для всех, свободу вероисповедания и отмену особых привилегий, которыми пользовались провинции и города. [54]

После приостановки работы 13 региональных парламентов в ноябре все ключевые институциональные основы старого режима были упразднены менее чем за четыре месяца. Таким образом, с самых ранних этапов революция демонстрировала признаки своего радикального характера; что оставалось неясным, так это конституционный механизм воплощения намерений в практическое применение. [55]

Создание новой конституции

| Часть серии о |

| Политическая революция |

|---|

|

9 июля Национальное собрание назначило комитет для разработки конституции и заявления о правах. [56] Было представлено двадцать проектов, которые были использованы подкомитетом для создания Декларации прав человека и гражданина , Мирабо . наиболее видным членом которого был [57] Декларация была одобрена Ассамблеей и опубликована 26 августа как принципиальное заявление. [58]

The Assembly now concentrated on the constitution itself. Mounier and his monarchist supporters advocated a bicameral system, with an upper house appointed by the king, who would also have the right to appoint ministers and veto legislation. On 10 September, the majority of the Assembly, led by Sieyès and Talleyrand, voted in favour of a single body, and the following day approved a "suspensive veto" for the king, meaning Louis could delay implementation of a law, but not block it indefinitely. In October, the Assembly voted to restrict political rights, including voting rights, to "active citizens", defined as French males over the age of 25 who paid direct taxes equal to three days' labour. The remainder were designated "passive citizens", restricted to "civil rights", a distinction opposed by a significant minority, including the Jacobin clubs.[59][60] By mid-1790, the main elements of a constitutional monarchy were in place, although the constitution was not accepted by Louis until 1791.[61]

Food shortages and the worsening economy caused frustration at the lack of progress, and led to popular unrest in Paris. This came to a head in late September 1789, when the Flanders Regiment arrived in Versailles to reinforce the Royal bodyguard, and were welcomed with a formal banquet as was common practice. The radical press described this as a 'gluttonous orgy', and claimed the tricolour cockade had been abused, while the Assembly viewed their arrival as an attempt to intimidate them.[62]

On 5 October, crowds of women assembled outside the Hôtel de Ville, agitating against high food prices and shortages.[63] These protests quickly turned political, and after seizing weapons stored at the Hôtel de Ville, some 7,000 of them marched on Versailles, where they entered the Assembly to present their demands. They were followed to Versailles by 15,000 members of the National Guard under Lafayette, who was virtually "a prisoner of his own troops".[64]

When the National Guard arrived later that evening, Lafayette persuaded Louis the safety of his family required their relocation to Paris. Next morning, some of the protestors broke into the Royal apartments, searching for Marie Antoinette, who escaped. They ransacked the palace, killing several guards. Order was eventually restored, and the Royal family and Assembly left for Paris, escorted by the National Guard.[65] Louis had announced his acceptance of the August Decrees and the Declaration, and his official title changed from 'King of France' to 'King of the French'.[66]

The Revolution and the Church

Historian John McManners argues "in eighteenth-century France, throne and altar were commonly spoken of as in close alliance; their simultaneous collapse ... would one day provide the final proof of their interdependence." One suggestion is that after a century of persecution, some French Protestants actively supported an anti-Catholic regime, a resentment fuelled by Enlightenment thinkers such as Voltaire.[67] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, considered a philosophical founder of the revolution,[68][69][70] wrote it was "manifestly contrary to the law of nature... that a handful of people should gorge themselves with superfluities, while the hungry multitude goes in want of necessities."[71]

The Revolution caused a massive shift of power from the Catholic Church to the state; although the extent of religious belief has been questioned, elimination of tolerance for religious minorities meant by 1789 being French also meant being Catholic.[72] The church was the largest individual landowner in France, controlling nearly 10% of all estates and levied tithes, effectively a 10% tax on income, collected from peasant farmers in the form of crops. In return, it provided a minimal level of social support.[73]

The August decrees abolished tithes, and on 2 November the Assembly confiscated all church property, the value of which was used to back a new paper currency known as assignats. In return, the state assumed responsibilities such as paying the clergy and caring for the poor, the sick and the orphaned.[74] On 13 February 1790, religious orders and monasteries were dissolved, while monks and nuns were encouraged to return to private life.[75]

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy of 12 July 1790 made them employees of the state, as well as establishing rates of pay and a system for electing priests and bishops. Pope Pius VI and many French Catholics objected to this since it denied the authority of the Pope over the French Church. In October, thirty bishops wrote a declaration denouncing the law, further fuelling opposition.[76]

When clergy were required to swear loyalty to the Civil Constitution in November 1790, it split the church between the 24% who complied, and the majority who refused.[77] This stiffened popular resistance against state interference, especially in traditionally Catholic areas such as Normandy, Brittany and the Vendée, where only a few priests took the oath and the civilian population turned against the revolution.[76] The result was state-led persecution of "Refractory clergy", many of whom were forced into exile, deported, or executed.[78]

Political divisions

The period from October 1789 to spring 1791 is usually seen as one of relative tranquility, when some of the most important legislative reforms were enacted. However, conflict over the source of legitimate authority was more apparent in the provinces, where officers of the Ancien Régime had been swept away, but not yet replaced by new structures. This was less obvious in Paris, since the National Guard made it the best policed city in Europe, but disorder in the provinces inevitably affected members of the Assembly.[79]

Centrists led by Sieyès, Lafayette, Mirabeau and Bailly created a majority by forging consensus with monarchiens like Mounier, and independents including Adrien Duport, Barnave and Alexandre Lameth. At one end of the political spectrum, reactionaries like Cazalès and Maury denounced the Revolution in all its forms, with radicals like Maximilien Robespierre at the other. He and Jean-Paul Marat opposed the criteria for "active citizens", gaining them substantial support among the Parisian proletariat, many of whom had been disenfranchised by the measure.[80]

On 14 July 1790, celebrations were held throughout France commemorating the fall of the Bastille, with participants swearing an oath of fidelity to "the nation, the law and the king." The Fête de la Fédération in Paris was attended by the Royal family, with Talleyrand performing a mass. Despite this show of unity, the Assembly was increasingly divided, while external players like the Paris Commune and National Guard competed for power. One of the most significant was the Jacobin club; originally a forum for general debate, by August 1790 it had over 150 members, split into different factions.[81]

The Assembly continued to develop new institutions; in September 1790, the regional Parlements were abolished and their legal functions replaced by a new independent judiciary, with jury trials for criminal cases. However, moderate deputies were uneasy at popular demands for universal suffrage, labour unions and cheap bread, and over the winter of 1790 and 1791, they passed a series of measures intended to disarm popular radicalism. These included exclusion of poorer citizens from the National Guard, limits on use of petitions and posters, and the June 1791 Le Chapelier Law suppressing trade guilds and any form of worker organisation.[82]

The traditional force for preserving law and order was the army, which was increasingly divided between officers, who largely came from the nobility, and ordinary soldiers. In August 1790, the loyalist General Bouillé suppressed a serious mutiny at Nancy; although congratulated by the Assembly, he was criticised by Jacobin radicals for the severity of his actions. Growing disorder meant many professional officers either left or became émigrés, further destabilising the institution.[83]

Varennes and after

Held in the Tuileries Palace under virtual house arrest, Louis XVI was urged by his brother and wife to re-assert his independence by taking refuge with Bouillé, who was based at Montmédy with 10,000 soldiers considered loyal to the Crown.[84] The royal family left the palace in disguise on the night of 20 June 1791; late the next day, Louis was recognised as he passed through Varennes, arrested and taken back to Paris. The attempted escape had a profound impact on public opinion; since it was clear Louis had been seeking refuge in Austria, the Assembly now demanded oaths of loyalty to the regime, and began preparing for war, while fear of 'spies and traitors' became pervasive.[85]

Despite calls to replace the monarchy with a republic, Louis retained his position but was generally regarded with acute suspicion and forced to swear allegiance to the constitution. A new decree stated retracting this oath, making war upon the nation, or permitting anyone to do so in his name would be considered abdication. However, radicals led by Jacques Pierre Brissot prepared a petition demanding his deposition, and on 17 July, an immense crowd gathered in the Champ de Mars to sign. Led by Lafayette, the National Guard was ordered to "preserve public order" and responded to a barrage of stones by firing into the crowd, killing between 13 and 50 people.[86]

The massacre badly damaged Lafayette's reputation; the authorities responded by closing radical clubs and newspapers, while their leaders went into exile or hiding, including Marat.[87] On 27 August, Emperor Leopold II and King Frederick William II of Prussia issued the Declaration of Pillnitz declaring their support for Louis, and hinting at an invasion of France on his behalf. In reality, the meeting between Leopold and Frederick was primarily to discuss the Partitions of Poland; the Declaration was intended to satisfy Comte d'Artois and other French émigrés but the threat rallied popular support behind the regime.[88]

Based on a motion proposed by Robespierre, existing deputies were barred from elections held in early September for the French Legislative Assembly. Although Robespierre himself was one of those excluded, his support in the clubs gave him a political power base not available to Lafayette and Bailly, who resigned respectively as head of the National Guard and the Paris Commune. The new laws were gathered together in the 1791 Constitution, and submitted to Louis XVI, who pledged to defend it "from enemies at home and abroad". On 30 September, the Constituent Assembly was dissolved, and the Legislative Assembly convened the next day.[89]

Fall of the monarchy

The Legislative Assembly is often dismissed by historians as an ineffective body, compromised by divisions over the role of the monarchy, an issue exacerbated when Louis attempted to prevent or reverse limitations on his powers.[90] At the same time, restricting the vote to those who paid a minimal amount of tax disenfranchised a significant proportion of the 6 million Frenchmen over 25, while only 10% of those able to vote actually did so. Finally, poor harvests and rising food prices led to unrest among the urban class known as Sans-culottes, who saw the new regime as failing to meet their demands for bread and work.[91]

This meant the new constitution was opposed by significant elements inside and outside the Assembly, itself split into three main groups. 264 members were affiliated with Barnave's Feuillants, constitutional monarchists who considered the Revolution had gone far enough, while another 136 were Jacobin leftists who supported a republic, led by Brissot and usually referred to as Brissotins.[92] The remaining 345 belonged to La Plaine, a centrist faction who switched votes depending on the issue, but many of whom shared doubts as to whether Louis was committed to the Revolution.[92] After he officially accepted the new Constitution, one recorded response was "Vive le roi, s'il est de bon foi!", or "Long live the king – if he keeps his word".[93]

Although a minority in the Assembly, control of key committees allowed the Brissotins to provoke Louis into using his veto. They first managed to pass decrees confiscating émigré property, and threatening them with the death penalty.[94] This was followed by measures against non-juring priests, whose opposition to the Civil Constitution led to a state of near civil war in southern France, which Barnave tried to defuse by relaxing the more punitive provisions. On 29 November, the Assembly approved a decree giving refractory clergy eight days to comply, or face charges of 'conspiracy against the nation', an act opposed even by Robespierre.[95] When Louis vetoed both, his opponents were able to portray him as opposed to reform in general.[96]

Brissot accompanied this with a campaign for war against Austria and Prussia, often interpreted as a mixture of calculation and idealism. While exploiting popular anti-Austrianism, it reflected a genuine belief in exporting the values of political liberty and popular sovereignty.[97] Simultaneously, conservatives headed by Marie Antoinette also favoured war, seeing it as a way to regain control of the military, and restore royal authority. In December 1791, Louis made a speech in the Assembly giving foreign powers a month to disband the émigrés or face war, an act greeted with enthusiasm by supporters, but suspicion from opponents.[98]

Barnave's inability to build a consensus in the Assembly resulted in the appointment of a new government, chiefly composed of Brissotins. On 20 April 1792, the French Revolutionary Wars began when French armies attacked Austrian and Prussian forces along their borders, before suffering a series of disastrous defeats. In an effort to mobilise popular support, the government ordered non-juring priests to swear the oath or be deported, dissolved the Constitutional Guard and replaced it with 20,000 fédérés; Louis agreed to disband the Guard, but vetoed the other two proposals, while Lafayette called on the Assembly to suppress the clubs.[99]

Popular anger increased when details of the Brunswick Manifesto reached Paris on 1 August, threatening 'unforgettable vengeance' should any oppose the Allies in seeking to restore the power of the monarchy. On the morning of 10 August, a combined force of the Paris National Guard and provincial fédérés attacked the Tuileries Palace, killing many of the Swiss Guards protecting it.[100] Louis and his family took refuge with the Assembly and shortly after 11:00 am, the deputies present voted to 'temporarily relieve the king', effectively suspending the monarchy.[101]

First Republic (1792–1795)

Proclamation of the First Republic

In late August, elections were held for the National Convention. New restrictions on the franchise meant the number of votes cast fell to 3.3 million, versus 4 million in 1791, while intimidation was widespread.[102] The Brissotins now split between moderate Girondins led by Brissot, and radical Montagnards, headed by Robespierre, Georges Danton and Jean-Paul Marat. While loyalties constantly shifted, voting patterns suggest roughly 160 of the 749 deputies can generally be categorised as Girondists, with another 200 Montagnards. The remainder were part of a centrist faction known as La Plaine, headed by Bertrand Barère, Pierre Joseph Cambon and Lazare Carnot.[103]

In the September Massacres, between 1,100 and 1,600 prisoners held in Parisian jails were summarily executed, the vast majority being common criminals.[104] A response to the capture of Longwy and Verdun by Prussia, the perpetrators were largely National Guard members and fédérés on their way to the front. While responsibility is still disputed, even moderates expressed sympathy for the action, which soon spread to the provinces. One suggestion is that the killings stemmed from concern over growing lawlessness, rather than political ideology.[105]

On 20 September, the French defeated the Prussians at the Battle of Valmy, in what was the first major victory by the army of France during the Revolutionary Wars. Emboldened by this, on 22 September the Convention replaced the monarchy with the French First Republic (1792–1804) and introduced a new calendar, with 1792 becoming "Year One".[106] The next few months were taken up with the trial of Citoyen Louis Capet, formerly Louis XVI. While evenly divided on the question of his guilt, members of the convention were increasingly influenced by radicals based within the Jacobin clubs and Paris Commune. The Brunswick Manifesto made it easy to portray Louis as a threat to the Revolution, especially when extracts from his personal correspondence showed him conspiring with Royalist exiles.[107]

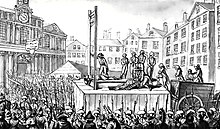

On 17 January 1793, Louis was sentenced to death for "conspiracy against public liberty and general safety". 361 deputies were in favour, 288 against, while another 72 voted to execute him, subject to delaying conditions. The sentence was carried out on 21 January on the Place de la Révolution, now the Place de la Concorde.[108] Conservatives across Europe now called for the destruction of revolutionary France, and in February the Convention responded by declaring war on Britain and the Dutch Republic. Together with Austria and Prussia, these two countries were later joined by Spain, Portugal, Naples, and Tuscany in the War of the First Coalition (1792–1797).[109]

Political crisis and fall of the Girondins

The Girondins hoped war would unite the people behind the government and provide an excuse for rising prices and food shortages, but found themselves the target of popular anger. Many left for the provinces. The first conscription measure or levée en masse on 24 February sparked riots in Paris and other regional centres. Already unsettled by changes imposed on the church, in March the traditionally conservative and royalist Vendée rose in revolt. On 18th, Dumouriez was defeated at Neerwinden and defected to the Austrians. Uprisings followed in Bordeaux, Lyon, Toulon, Marseilles and Caen. The Republic seemed on the verge of collapse.[110]

The crisis led to the creation on 6 April 1793 of the Committee of Public Safety, an executive committee accountable to the convention.[111] The Girondins made a fatal political error by indicting Marat before the Revolutionary Tribunal for allegedly directing the September massacres; he was quickly acquitted, further isolating the Girondins from the sans-culottes. When Jacques Hébert called for a popular revolt against the "henchmen of Louis Capet" on 24 May, he was arrested by the Commission of Twelve, a Girondin-dominated tribunal set up to expose 'plots'. In response to protests by the Commune, the Commission warned "if by your incessant rebellions something befalls the representatives of the nation,...Paris will be obliterated".[110]

Growing discontent allowed the clubs to mobilise against the Girondins. Backed by the Commune and elements of the National Guard, on 31 May they attempted to seize power in a coup. Although the coup failed, on 2 June the convention was surrounded by a crowd of up to 80,000, demanding cheap bread, unemployment pay and political reforms, including restriction of the vote to the sans-culottes, and the right to remove deputies at will.[112] Ten members of the commission and another twenty-nine members of the Girondin faction were arrested, and on 10 June, the Montagnards took over the Committee of Public Safety.[113]

Meanwhile, a committee led by Robespierre's close ally Saint-Just was tasked with preparing a new Constitution. Completed in only eight days, it was ratified by the convention on 24 June, and contained radical reforms, including universal male suffrage. However, normal legal processes were suspended following the assassination of Marat on 13 July by the Girondist Charlotte Corday, which the Committee of Public Safety used as an excuse to take control. The 1793 Constitution was suspended indefinitely in October.[114]

Key areas of focus for the new government included creating a new state ideology, economic regulation and winning the war.[115] They were helped by divisions among their internal opponents; while areas like the Vendée and Brittany wanted to restore the monarchy, most supported the Republic but opposed the regime in Paris. On 17 August, the Convention voted a second levée en masse; despite initial problems in equipping and supplying such large numbers, by mid-October Republican forces had re-taken Lyon, Marseilles and Bordeaux, while defeating Coalition armies at Hondschoote and Wattignies.[116] The new class of military leaders included a young colonel named Napoleon Bonaparte, who was appointed commander of artillery at the siege of Toulon thanks to his friendship with Augustin Robespierre. His success in that role resulted in promotion to the Army of Italy in April 1794, and the beginning of his rise to military and political power.[117]

Reign of Terror

Although intended to bolster revolutionary fervour, the Reign of Terror rapidly degenerated into the settlement of personal grievances. At the end of July, the Convention set price controls on a wide range of goods, with the death penalty for hoarders. On 9 September, 'revolutionary groups' were established to enforce these controls, while the Law of Suspects on 17th approved the arrest of suspected "enemies of freedom". This initiated what has become known as the "Terror". From September 1793 to July 1794, around 300,000 were arrested,[118] with some 16,600 people executed on charges of counter-revolutionary activity, while another 40,000 may have been summarily executed, or died awaiting trial.[119]

Price controls made farmers reluctant to sell their produce in Parisian markets, and by early September, the city was suffering acute food shortages. At the same time, the war increased public debt, which the Assembly tried to finance by selling confiscated property. However, few would buy assets that might be repossessed by their former owners, a concern that could only be achieved by military victory. This meant the financial position worsened as threats to the Republic increased, while printing assignats to deal with the deficit further increased inflation.[120]

On 10 October, the Convention recognised the Committee of Public Safety as the supreme Revolutionary Government, and suspended the Constitution until peace was achieved.[114] In mid-October, Marie Antoinette was convicted of a long list of crimes, and guillotined; two weeks later, the Girondist leaders arrested in June were also executed, along with Philippe Égalité. The "Terror" was not confined to Paris, with over 2,000 killed in Lyons after its recapture.[121]

At Cholet on 17 October, the Republican army won a decisive victory over the Vendée rebels, and the survivors escaped into Brittany. Another defeat at Le Mans on 23 December ended the rebellion as a major threat, although the insurgency continued until 1796. The extent of the repression that followed has been debated by French historians since the mid-19th century.[122] Between November 1793 to February 1794, over 4,000 were drowned in the Loire at Nantes under the supervision of Jean-Baptiste Carrier. Historian Reynald Secher claims that as many as 117,000 died between 1793 and 1796. Although those numbers have been challenged, François Furet concluded it "not only revealed massacre and destruction on an unprecedented scale, but a zeal so violent that it has bestowed as its legacy much of the region's identity."[123] [c]

At the height of the Terror, not even its supporters were immune from suspicion, leading to divisions within the Montagnard faction between radical Hébertists and moderates led by Danton.[d] Robespierre saw their dispute as de-stabilising the regime, and, as a deist, objected to the anti-religious policies advocated by the atheist Hébert, who was arrested and executed on 24 March with 19 of his colleagues, including Carrier.[127] To retain the loyalty of the remaining Hébertists, Danton was arrested and executed on 5 April with Camille Desmoulins, after a show trial that arguably did more damage to Robespierre than any other act in this period.[128]

The Law of 22 Prairial (10 June) denied "enemies of the people" the right to defend themselves. Those arrested in the provinces were now sent to Paris for judgement; from March to July, executions in Paris increased from five to twenty-six a day.[129] Many Jacobins ridiculed the festival of the Cult of the Supreme Being on 8 June, a lavish and expensive ceremony led by Robespierre, who was also accused of circulating claims he was a second Messiah. Relaxation of price controls and rampant inflation caused increasing unrest among the sans-culottes, but the improved military situation reduced fears the Republic was in danger. Fearing their own survival depended on Robespierre's removal, on 29 June three members of the Committee of Public Safety openly accused him of being a dictator.[130]

Robespierre responded by refusing to attend Committee meetings, allowing his opponents to build a coalition against him. In a speech made to the convention on 26 July, he claimed certain members were conspiring against the Republic, an almost certain death sentence if confirmed. When he refused to provide names, the session broke up in confusion. That evening he repeated these claims at the Jacobins club, where it was greeted with demands for execution of the 'traitors'. Fearing the consequences if they did not act first, his opponents attacked Robespierre and his allies in the Convention next day. When Robespierre attempted to speak, his voice failed, one deputy crying "The blood of Danton chokes him!"[131]

After the Convention authorised his arrest, he and his supporters took refuge in the Hotel de Ville, which was defended by elements of the National Guard. Other units loyal to the Convention stormed the building that evening and detained Robespierre, who severely injured himself attempting suicide. He was executed on 28 July with 19 colleagues, including Saint-Just and Georges Couthon, followed by 83 members of the Commune.[132] The Law of 22 Prairial was repealed, any surviving Girondists reinstated as deputies, and the Jacobin Club was closed and banned.[133]

There are various interpretations of the Terror and the violence with which it was conducted. François Furet argues that the intense ideological commitment of the revolutionaries and their utopian goals required the extermination of any opposition.[134] A middle position suggests violence was not inevitable but the product of a series of complex internal events, exacerbated by war.[135]

Thermidorian reaction

The bloodshed did not end with the death of Robespierre; Southern France saw a wave of revenge killings, directed against alleged Jacobins, Republican officials and Protestants. Although the victors of Thermidor asserted control over the Commune by executing their leaders, some of those closely involved in the "Terror" retained their positions. They included Paul Barras, later chief executive of the French Directory, and Joseph Fouché, director of the killings in Lyon who served as Minister of Police under the Directory, the Consulate and Empire.[136] Despite his links to Augustin Robespierre, military success in Italy meant Napoleon Bonaparte escaped censure.[137]

The December 1794 Treaty of La Jaunaye ended the Chouannerie in western France by allowing freedom of worship and the return of non-juring priests.[138] This was accompanied by military success; in January 1795, French forces helped the Dutch Patriots set up the Batavian Republic, securing their northern border.[139] The war with Prussia was concluded in favour of France by the Peace of Basel in April 1795, while Spain made peace shortly thereafter.[140]

However, the Republic still faced a crisis at home. Food shortages arising from a poor 1794 harvest were exacerbated in Northern France by the need to supply the army in Flanders, while the winter was the worst since 1709.[141] By April 1795, people were starving and the assignat was worth only 8% of its face value; in desperation, the Parisian poor rose again.[142] They were quickly dispersed and the main impact was another round of arrests, while Jacobin prisoners in Lyon were summarily executed.[143]

A committee drafted a new constitution, approved by plebiscite on 23 September 1795 and put into place on 27th.[144] Largely designed by Pierre Daunou and Boissy d'Anglas, it established a bicameral legislature, intended to slow down the legislative process, ending the wild swings of policy under the previous unicameral systems. The Council of 500 was responsible for drafting legislation, which was reviewed and approved by the Council of Ancients, an upper house containing 250 men over the age of 40. Executive power was in the hands of five Directors, selected by the Council of Ancients from a list provided by the lower house, with a five-year mandate.[145]

Deputies were chosen by indirect election, a total franchise of around 5 million voting in primaries for 30,000 electors, or 0.6% of the population. Since they were also subject to stringent property qualification, it guaranteed the return of conservative or moderate deputies. In addition, rather than dissolving the previous legislature as in 1791 and 1792, the so-called 'law of two-thirds' ruled only 150 new deputies would be elected each year. The remaining 600 Conventionnels kept their seats, a move intended to ensure stability.[146]

The Directory (1795–1799)

Jacobin sympathisers viewed the Directory as a betrayal of the Revolution, while Bonapartists later justified Napoleon's coup by emphasising its corruption.[147] The regime also faced internal unrest, a weak economy, and an expensive war, while the Council of 500 could block legislation at will. Since the Directors had no power to call new elections, the only way to break a deadlock was rule by decree, or use force. As a result, the Directory was characterised by "chronic violence, ambivalent forms of justice, and repeated recourse to heavy-handed repression."[148]

Retention of the Conventionnels ensured the Thermidorians held a majority in the legislature and three of the five Directors, but they were increasingly challenged by the right. On 5 October, Convention troops led by Napoleon put down a royalist rising in Paris; when the first elections were held two weeks later, over 100 of the 150 new deputies were royalists of some sort.[149] The power of the Parisian sans-culottes had been broken by the suppression of the May 1795 revolt; relieved of pressure from below, the Jacobin clubs became supporters of the Directory, largely to prevent restoration of the monarchy.[150]

Removal of price controls and a collapse in the value of the assignat led to inflation and soaring food prices. By April 1796, over 500,000 Parisians were unemployed, resulting in the May insurrection known as the Conspiracy of the Equals. Led by the revolutionary François-Noël Babeuf, their demands included immediate implementation of the 1793 Constitution, and a more equitable distribution of wealth. Despite support from sections of the military, the revolt was easily crushed, while Babeuf and other leaders were executed.[151] Nevertheless, by 1799 the economy had been stabilised, and important reforms made allowing steady expansion of French industry. Many of these remained in place for much of the 19th century.[152]

Prior to 1797, three of the five Directors were firmly Republican; Barras, Révellière-Lépeaux and Jean-François Rewbell, as were around 40% of the legislature. The same percentage were broadly centrist or unaffiliated, along with two Directors, Étienne-François Letourneur and Lazare Carnot. Although only 20% were committed Royalists, many centrists supported the restoration of the exiled Louis XVIII of France in the belief this would bring peace.[153] The elections of May 1797 resulted in significant gains for the right, with Royalists Jean-Charles Pichegru elected President of the Council of 500, and Barthélemy appointed a Director.[154]

With Royalists apparently on the verge of power, Republicans attempted a pre-emptive coup on 4 September. Using troops from Napoleon's Army of Italy under Pierre Augereau, the Council of 500 was forced to approve the arrest of Barthélemy, Pichegru and Carnot. The elections were annulled, sixty-three leading Royalists deported to French Guiana, and new laws passed against émigrés, Royalists and ultra-Jacobins. The removal of his conservative opponents opened the way for direct conflict between Barras, and those on the left.[155]

Fighting continued despite general war weariness, and the 1798 elections saw a resurgence in Jacobin strength. Napoleon's invasion of Egypt in July 1798 confirmed European fears of French expansionism, and the War of the Second Coalition began in November. Without a majority in the legislature, the Directors relied on the army to enforce decrees, and extract revenue from conquered territories. Generals like Napoleon and Joubert were now central to the political process, while both the army and Directory became notorious for their corruption.[156]

It has been suggested the Directory collapsed because by 1799, many 'preferred the uncertainties of authoritarian rule to the continuing ambiguities of parliamentary politics'.[157] The architect of its end was Sieyès, who when asked what he had done during the Terror allegedly answered "I survived". Nominated to the Directory, his first action was to remove Barras, with the help of allies including Talleyrand, and Napoleon's brother Lucien, President of the Council of 500.[158] On 9 November 1799, the Coup of 18 Brumaire replaced the five Directors with the French Consulate, which consisted of three members, Napoleon, Sieyès, and Roger Ducos. Most historians consider this the end point of the French Revolution.[159]

Role of ideology

| Part of the Politics series |

| Republicanism |

|---|

The role of ideology in the Revolution is controversial with Jonathan Israel stating that the "radical Enlightenment" was the primary driving force of the Revolution.[160] Cobban, however, argues "[t]he actions of the revolutionaries were most often prescribed by the need to find practical solutions to immediate problems, using the resources at hand, not by pre-conceived theories."[161]

The identification of ideologies is complicated by the profusion of revolutionary clubs, factions and publications, absence of formal political parties, and individual flexibility in the face of changing circumstances.[162] In addition, although the Declaration of the Rights of Man was a fundamental document for all revolutionary factions, its interpretation varied widely.[163]

While all revolutionaries professed their devotion to liberty in principle, "it appeared to mean whatever those in power wanted."[164] For example, the liberties specified in the Rights of Man were limited by law when they might "cause harm to others, or be abused". Prior to 1792, Jacobins and others frequently opposed press restrictions on the grounds these violated a basic right.[165] However, the radical National Convention passed laws in September 1793 and July 1794 imposing the death penalty for offences such as "disparaging the National Convention", and "misleading public opinion."[166]

While revolutionaries also endorsed the principle of equality, few advocated equality of wealth since property was also viewed as a right.[167] The National Assembly opposed equal political rights for women,[168] while the abolition of slavery in the colonies was delayed until February 1794 because it conflicted with the property rights of slave owners, and many feared it would disrupt trade.[169] Political equality for male citizens was another divisive issue, with the 1791 constitution limiting the right to vote and stand for office to males over 25 who met a property qualification, so-called "active citizens". This restriction was opposed by many activists, including Robespierre, the Jacobins, and Cordeliers.[170]

The principle that sovereignty resided in the nation was a key concept of the Revolution.[171] However, Israel argues this obscures ideological differences over whether the will of the nation was best expressed through representative assemblies and constitutions, or direct action by revolutionary crowds, and popular assemblies such as the sections of the Paris commune.[172] Many considered constitutional monarchy as incompatible with the principle of popular sovereignty,[173] but prior to 1792, there was a strong bloc with an ideological commitment to such a system, based on the writings of Hobbes, Locke, Montesquieu and Voltaire.[174]

Israel argues the nationalisation of church property and the establishment of the Constitutional Church reflected an ideological commitment to secularism, and a determination to undermine a bastion of old regime privilege.[175] While Cobban agrees the Constitutional Church was motivated by ideology, he sees its origins in the anti-clericalism of Voltaire and other Enlightenment figures.[176]

Jacobins were hostile to formal political parties and factions which they saw as a threat to national unity and the general will, with "political virtue" and "love of country" key elements of their ideology.[177][178] They viewed the ideal revolutionary as selfless, sincere, free of political ambition, and devoted to the nation.[179] The disputes leading to the departure first of the Feuillants, then later the Girondists, were conducted in terms of the relative political virtue and patriotism of the disputants. In December 1793, all members of the Jacobin clubs were subject to a "purifying scrutiny", to determine whether they were "men of virtue".[180]

French Revolutionary Wars

The Revolution initiated a series of conflicts that began in 1792 and ended only with Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo in 1815. In its early stages, this seemed unlikely; the 1791 Constitution specifically disavowed "war for the purpose of conquest", and although traditional tensions between France and Austria re-emerged in the 1780s, Emperor Joseph II cautiously welcomed the reforms. Austria was at war with the Ottomans, as were the Russians, while both were negotiating with Prussia over partitioning Poland. Most importantly, Britain preferred peace, and as Emperor Leopold II stated after the Declaration of Pillnitz, "without England, there is no case".[181]

In late 1791, factions within the Assembly came to see war as a way to unite the country and secure the Revolution by eliminating hostile forces on its borders and establishing its "natural frontiers".[182] France declared war on Austria in April 1792 and issued the first conscription orders, with recruits serving for twelve months. By the time peace finally came in 1815, the conflict had involved every major European power as well as the United States, redrawn the map of Europe and expanded into the Americas, the Middle East, and the Indian Ocean.[183]

From 1701 to 1801, the population of Europe grew from 118 to 187 million; combined with new mass production techniques, this allowed belligerents to support large armies, requiring the mobilisation of national resources. It was a different kind of war, fought by nations rather than kings, intended to destroy their opponents' ability to resist, but also to implement deep-ranging social change. While all wars are political to some degree, this period was remarkable for the emphasis placed on reshaping boundaries and the creation of entirely new European states.[184]

In April 1792, French armies invaded the Austrian Netherlands but suffered a series of setbacks before victory over an Austrian-Prussian army at Valmy in September. After defeating a second Austrian army at Jemappes on 6 November, they occupied the Netherlands, areas of the Rhineland, Nice and Savoy. Emboldened by this success, in February 1793 France declared war on the Dutch Republic, Spain and Britain, beginning the War of the First Coalition.[185] However, the expiration of the 12-month term for the 1792 recruits forced the French to relinquish their conquests. In August, new conscription measures were passed and by May 1794 the French army had between 750,000 and 800,000 men.[186] Despite high rates of desertion, this was large enough to manage multiple internal and external threats; for comparison, the combined Prussian-Austrian army was less than 90,000.[187]

By February 1795, France had annexed the Austrian Netherlands, established their frontier on the left bank of the Rhine and replaced the Dutch Republic with the Batavian Republic, a satellite state. These victories led to the collapse of the anti-French coalition; Prussia made peace in April 1795, followed soon after by Spain, leaving Britain and Austria as the only major powers still in the war.[188] In October 1797, a series of defeats by Bonaparte in Italy led Austria to agree to the Treaty of Campo Formio, in which they formally ceded the Netherlands and recognised the Cisalpine Republic.[189]

Fighting continued for two reasons; first, French state finances had come to rely on indemnities levied on their defeated opponents. Second, armies were primarily loyal to their generals, for whom the wealth achieved by victory and the status it conferred became objectives in themselves. Leading soldiers like Hoche, Pichegru and Carnot wielded significant political influence and often set policy; Campo Formio was approved by Bonaparte, not the Directory, which strongly objected to terms it considered too lenient.[189]

Despite these concerns, the Directory never developed a realistic peace programme, fearing the destabilising effects of peace and the consequent demobilisation of hundreds of thousands of young men. As long as the generals and their armies stayed away from Paris, they were happy to allow them to continue fighting, a key factor behind sanctioning Bonaparte's invasion of Egypt. This resulted in aggressive and opportunistic policies, leading to the War of the Second Coalition in November 1798.[190]

Slavery and the colonies

In 1789, the most populous French colonies were Saint-Domingue (today Haiti), Martinique, Guadeloupe, the Île Bourbon (Réunion) and the Île de la France. These colonies produced commodities such as sugar, coffee and cotton for exclusive export to France. There were about 700,000 slaves in the colonies, of which about 500,000 were in Saint-Domingue. Colonial products accounted for about a third of France's exports.[191]

In February 1788, the Société des Amis des Noirs (Society of the Friends of Blacks) was formed in France with the aim of abolishing slavery in the empire. In August 1789, colonial slave owners and merchants formed the rival Club de Massiac to represent their interests. When the Constituent Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in August 1789, delegates representing the colonial landowners successfully argued that the principles should not apply in the colonies as they would bring economic ruin and disrupt trade. Colonial landowners also gained control of the Colonial Committee of the Assembly from where they exerted a powerful influence against abolition.[192][193]

People of colour also faced social and legal discrimination in mainland France and its colonies, including a bar on their access to professions such as law, medicine and pharmacy.[194] In 1789–90, a delegation of free coloureds, led by Vincent Ogé and Julien Raimond, unsuccessfully lobbied the Assembly to end discrimination against free coloureds. Ogé left for Saint-Domingue where an uprising against white landowners broke out in October 1790. The revolt failed and Ogé was killed.[195][193]

In May 1791, the National Assembly granted full political rights to coloureds born of two free parents, but left the rights of freed slaves to be determined by the colonial assemblies. The assemblies refused to implement the decree and fighting broke out between the coloured population of Saint-Domingue and white colonists, each side recruiting slaves to their forces. A major slave revolt followed in August.[196]

In March 1792, the Legislative Assembly responded to the revolt by granting citizenship to all free coloureds and sending two commissioners, Sonthonax and Polvérel, and 6,000 troops to Saint-Domingue to enforce the decree. On arrival in September, the commissioners announced that slavery would remain in force. Over 72,00 slaves were still in revolt, mostly in the north.[197]

Brissot and his supporters envisaged an eventual abolition of slavery but their immediate concern was securing trade and the support of merchants for the revolutionary wars. After Brissot's fall, the new constitution of June 1793 included a new Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, but excluded the colonies from its provisions. In any event, the new constitution was suspended until France was at peace.[198]

In early 1793, royalist planters from Guadeloupe and Saint-Domingue formed an alliance with Britain. The Spanish supported insurgent slaves, led by Jean-François Papillon and Georges Biassou, in the north of Saint-Domingue. White planters loyal to the republic sent representatives to Paris to convince the Jacobin controlled Convention that those calling for the abolition of slavery were British agents and supporters of Brissot, hoping to disrupt trade.[199]

In June, the commissioners in Saint-Domingue freed 10,000 slaves fighting for the republic. As the royalists and their British and Spanish supporters were also offering freedom for slaves willing to fight for their cause, the commissioners outbid them by abolishing slavery in the north in August, and throughout the colony in October. Representatives were sent to Paris to gain the approval of the convention for the decision.[199][200]

The Convention voted for the abolition of slavery in the colonies on 4 February 1794 and decreed that all residents of the colonies had the full rights of French citizens irrespective of colour.[201] An army of 1,000 sans-culottes led by Victor Hugues was sent to Guadeloupe to expel the British and enforce the decree. The army recruited former slaves and eventually numbered 11,000, capturing Guadeloupe and other smaller islands. Abolition was also proclaimed on Guyane. Martinique remained under British occupation, while colonial landowners in Réunion and the Îles Mascareignes repulsed the republicans.[202] Black armies drove the Spanish out of Saint-Domingue in 1795, and the last of the British withdrew in 1798.[203]

In republican controlled areas from 1793 to 1799, freed slaves were required to work on their former plantations or for their former masters if they were in domestic service. They were paid a wage and gained property rights. Black and coloured generals were effectively in control of large areas of Guadeloupe and Saint-Domingue, including Toussaint Louverture in the north of Saint-Domingue, and André Rigaud in the south. Historian Fréderic Régent states that the restrictions on the freedom of employment and movement of former slaves meant that, "only whites, persons of color already freed before the decree, and former slaves in the army or on warships really benefited from general emancipation."[202]

Media and symbolism

Newspapers

Newspapers and pamphlets played a central role in stimulating and defining the Revolution. Prior to 1789, there have been a small number of heavily censored newspapers that needed a royal licence to operate, but the Estates-General created an enormous demand for news, and over 130 newspapers appeared by the end of the year. Among the most significant were Marat's L'Ami du peuple and Elysée Loustallot's Revolutions de Paris.[204] Over the next decade, more than 2,000 newspapers were founded, 500 in Paris alone. Most lasted only a matter of weeks but they became the main communication medium, combined with the very large pamphlet literature.[205]

Newspapers were read aloud in taverns and clubs, and circulated hand to hand. There was a widespread assumption that writing was a vocation, not a business, and the role of the press was the advancement of civic republicanism.[206] By 1793 the radicals were most active but initially the royalists flooded the country with their publication the "L'Ami du Roi" (Friends of the King) until they were suppressed.[207]

Revolutionary symbols

To illustrate the differences between the new Republic and the old regime, the leaders needed to implement a new set of symbols to be celebrated instead of the old religious and monarchical symbols. To this end, symbols were borrowed from historic cultures and redefined, while those of the old regime were either destroyed or reattributed acceptable characteristics. These revised symbols were used to instil in the public a new sense of tradition and reverence for the Enlightenment and the Republic.[208]

La Marseillaise

"La Marseillaise" (French pronunciation: [la maʁsɛjɛːz]) became the national anthem of France. The song was written and composed in 1792 by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle, and was originally titled "Chant de guerre pour l'Armée du Rhin". The French National Convention adopted it as the First Republic's anthem in 1795. It acquired its nickname after being sung in Paris by volunteers from Marseille marching on the capital.

The song is the first example of the "European march" anthemic style, while the evocative melody and lyrics led to its widespread use as a song of revolution and incorporation into many pieces of classical and popular music. De Lisle was instructed to 'produce a hymn which conveys to the soul of the people the enthusiasm which it (the music) suggests.'[210]

Guillotine

The guillotine remains "the principal symbol of the Terror in the French Revolution."[211] Invented by a physician during the Revolution as a quicker, more efficient and more distinctive form of execution, the guillotine became a part of popular culture and historic memory. It was celebrated on the left as the people's avenger, for example in the revolutionary song La guillotine permanente,[212] and cursed as the symbol of the Terror by the right.[213]

Its operation became a popular entertainment that attracted great crowds of spectators. Vendors sold programmes listing the names of those scheduled to die. Many people came day after day and vied for the best locations from which to observe the proceedings; knitting women (tricoteuses) formed a cadre of hardcore regulars, inciting the crowd. Parents often brought their children. By the end of the Terror, the crowds had thinned drastically. Repetition had staled even this most grisly of entertainments, and audiences grew bored.[214]

Cockade, tricolore, and liberty cap

Cockades were widely worn by revolutionaries beginning in 1789. They now pinned the blue-and-red cockade of Paris onto the white cockade of the Ancien Régime. Camille Desmoulins asked his followers to wear green cockades on 12 July 1789. The Paris militia, formed on 13 July, adopted a blue and red cockade. Blue and red are the traditional colours of Paris, and they are used on the city's coat of arms. Cockades with various colour schemes were used during the storming of the Bastille on 14 July.[215]

The Liberty cap, also known as the Phrygian cap, or pileus, is a brimless, felt cap that is conical in shape with the tip pulled forward. It reflects Roman republicanism and liberty, alluding to the Roman ritual of manumission, in which a freed slave receives the bonnet as a symbol of his newfound liberty.[216]

Role of women

Deprived of political rights by the Ancien Régime, the Revolution initially allowed women to participate, although only to a limited degree. Activists included Girondists like Olympe de Gouges, author of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen, and Charlotte Corday, killer of Marat. Others like Théroigne de Méricourt, Pauline Léon and the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women supported the Jacobins, staged demonstrations in the National Assembly and took part in the October 1789 March to Versailles. Despite this, the 1791 and 1793 constitutions denied them political rights and democratic citizenship.[217]

In 1793, the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women campaigned for strict price controls on bread, and a law that would compel all women to wear the tricolour cockade. Although both demands were successful, in October the male-dominated Jacobins who then controlled the government denounced the Society as dangerous rabble-rousers, and made all women's clubs and associations illegal. Organised women were permanently shut out of the French Revolution after 30 October 1793.[218]

At the same time, especially in the provinces, women played a prominent role in resisting social changes introduced by the Revolution. This was particularly so in terms of the reduced role of the Catholic Church; for those living in rural areas, closing of the churches meant a loss of normality.[219] This sparked a counter-revolutionary movement led by women; while supporting other political and social changes, they opposed the dissolution of the Catholic Church and revolutionary cults like the Cult of the Supreme Being.[220] Olwen Hufton argues some wanted to protect the Church from heretical changes enforced by revolutionaries, viewing themselves as "defenders of faith".[221]

Prominent women

Olympe de Gouges was an author whose publications emphasised that while women and men were different, this should not prevent equality under the law. In her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen she insisted women deserved rights, especially in areas concerning them directly, such as divorce and recognition of illegitimate children.[222][full citation needed] Along with other Girondists, she was executed in November 1793 during the Terror.

Madame Roland, also known as Manon or Marie Roland, was another important female activist whose political focus was not specifically women but other aspects of the government. A Girondist, her personal letters to leaders of the Revolution influenced policy; in addition, she often hosted political gatherings of the Brissotins, a political group which allowed women to join. She too was executed in November 1793.[223]

Economic policies

The Revolution abolished many economic constraints imposed by the Ancien Régime, including church tithes and feudal dues although tenants often paid higher rents and taxes.[224] All church lands were nationalised, along with those owned by Royalist exiles, which were used to back paper currency known as assignats, and the feudal guild system eliminated.[225] It also abolished the highly inefficient system of tax farming, whereby private individuals would collect taxes for a hefty fee. The government seized the foundations that had been set up (starting in the 13th century) to provide an annual stream of revenue for hospitals, poor relief, and education. The state sold the lands but typically local authorities did not replace the funding and so most of the nation's charitable and school systems were massively disrupted.[226]

Between 1790 and 1796, industrial and agricultural output dropped, foreign trade plunged, and prices soared, forcing the government to finance expenditure by issuing ever increasing quantities assignats. When this resulted in escalating inflation, the response was to impose price controls and persecute private speculators and traders, creating a black market. Between 1789 and 1793, the annual deficit increased from 10% to 64% of gross national product, while annual inflation reached 3,500% after a poor harvest in 1794 and the removal of price controls. The assignats were withdrawn in 1796 but inflation continued until the introduction of the gold-based Franc germinal in 1803.[227]

Impact

The French Revolution had a major impact on western history, by ending feudalism in France and creating a path for advances in individual freedoms throughout Europe.[228][2] The revolution represented the most significant challenge to political absolutism up to that point in history and spread democratic ideals throughout Europe and ultimately the world.[229] Its impact on French nationalism was profound, while also stimulating nationalist movements throughout Europe.[230] Some modern historians argue the concept of the nation state was a direct consequence of the revolution.[231] As such, the revolution is often seen as marking the start of modernity and the modern period.[232]

France

The long-term impact on France was profound, shaping politics, society, religion and ideas, and polarising politics for more than a century. Historian François Aulard wrote:

"From the social point of view, the Revolution consisted in the suppression of what was called the feudal system, in the emancipation of the individual, in greater division of landed property, the abolition of the privileges of noble birth, the establishment of equality, the simplification of life.... The French Revolution differed from other revolutions in being not merely national, for it aimed at benefiting all humanity."[233][title missing]

The revolution permanently crippled the power of the aristocracy and drained the wealth of the Church, although the two institutions survived. Hanson suggests the French underwent a fundamental transformation in self-identity, evidenced by the elimination of privileges and their replacement by intrinsic human rights.[234] After the collapse of the First French Empire in 1815, the French public lost many of the rights and privileges earned since the revolution, but remembered the participatory politics that characterised the period. According to Paul Hanson, "Revolution became a tradition, and republicanism an enduring option."[235]

The Revolution meant an end to arbitrary royal rule and held out the promise of rule by law under a constitutional order. Napoleon as emperor set up a constitutional system and the restored Bourbons were forced to retain one. After the abdication of Napoleon III in 1871, the French Third Republic was launched with a deep commitment to upholding the ideals of the Revolution.[236][237] The Vichy regime (1940–1944), tried to undo the revolutionary heritage, but retained the republic. However, there were no efforts by the Bourbons, Vichy or any other government to restore the privileges that had been stripped away from the nobility in 1789. France permanently became a society of equals under the law.[235]

Agriculture was transformed by the Revolution. With the breakup of large estates controlled by the Church and the nobility and worked by hired hands, rural France became more a land of small independent farms. Harvest taxes were ended, such as the tithe and seigneurial dues. Primogeniture was ended both for nobles and peasants, thereby weakening the family patriarch, and led to a fall in the birth rate since all children had a share in the family property.[238] Cobban argues the Revolution bequeathed to the nation "a ruling class of landowners."[239]

Economic historians are divided on the economic impact of the Revolution. One suggestion is the resulting fragmentation of agricultural holdings had a significant negative impact in the early years of 19th century, then became positive in the second half of the century because it facilitated the rise in human capital investments.[240] Others argue the redistribution of land had an immediate positive impact on agricultural productivity, before the scale of these gains gradually declined over the course of the 19th century.[241]

In the cities, entrepreneurship on a small scale flourished, as restrictive monopolies, privileges, barriers, rules, taxes and guilds gave way. However, the British blockade virtually ended overseas and colonial trade, hurting the cities and their supply chains. Overall, the Revolution did not greatly change the French business system, and probably helped freeze in place the horizons of the small business owner. The typical businessman owned a small store, mill or shop, with family help and a few paid employees; large-scale industry was less common than in other industrialising nations.[242]

Europe outside France

Historians often see the impact of the Revolution as through the institutions and ideas exported by Napoleon. Economic historians Dan Bogart, Mauricio Drelichman, Oscar Gelderblom, and Jean-Laurent Rosenthal describe Napoleon's codified law as the French Revolution's "most significant export."[243] According to Daron Acemoglu, Davide Cantoni, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson the French Revolution had long-term effects in Europe. They suggest that "areas that were occupied by the French and that underwent radical institutional reform experienced more rapid urbanization and economic growth, especially after 1850. There is no evidence of a negative effect of French invasion."[244]

The Revolution sparked intense debate in Britain. The Revolution Controversy was a "pamphlet war" set off by the publication of A Discourse on the Love of Our Country, a speech given by Richard Price to the Revolution Society on 4 November 1789, supporting the French Revolution. Edmund Burke responded in November 1790 with his own pamphlet, Reflections on the Revolution in France, attacking the French Revolution as a threat to the aristocracy of all countries.[245][246] William Coxe opposed Price's premise that one's country is principles and people, not the State itself.[247]

Conversely, two seminal political pieces of political history were written in Price's favour, supporting the general right of the French people to replace their State. One of the first of these "pamphlets" into print was A Vindication of the Rights of Men by Mary Wollstonecraft . Wollstonecraft's title was echoed by Thomas Paine's Rights of Man, published a few months later. In 1792 Christopher Wyvill published Defence of Dr. Price and the Reformers of England, a plea for reform and moderation.[248] This exchange of ideas has been described as "one of the great political debates in British history".[249]