Калечащие операции на женских половых органах

Дорожный знак против КОЖПО возле Капчорвы , Уганда, 2004 г. | |||

| Определение | «Частичное или полное удаление наружных женских половых органов или иное повреждение женских половых органов по немедицинским причинам» ( ВОЗ , ЮНИСЕФ и ЮНФПА , 1997). [1] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Области | Africa, Southeast Asia, Middle East, and within communities from these areas[2] | ||

| Numbers | Over 230 million women and girls worldwide: 144 million in Africa, 80 million in Asia, 6 million in Middle East, and 1-2 million in other parts of the world (as of 2024)[3][4] | ||

| Age | Days after birth to puberty[5] | ||

| Prevalence | |||

| |||

| |||

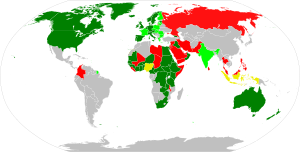

Калечащие операции на женских половых органах ( КОЖПО ) (также известные как обрезание женских половых органов , калечащие операции на женских половых органах/обрезание ( КОЖПО/К ) и женское обрезание [а] ) — это ритуальное обрезание или удаление части или всей вульвы . Распространенность КЖПО варьируется во всем мире, но в основном она присутствует в некоторых странах Африки, Азии и Ближнего Востока, а также в их диаспорах. По состоянию на 2024 год [update] , По оценкам ЮНИСЕФ 230 миллионов девочек и женщин во всем мире (144 миллиона в Африке, 80 миллионов в Азии, 6 миллионов на Ближнем Востоке и 1-2 миллиона в других частях мира) подверглись одному или нескольким видам КОЖПО. [3]

Обрезание женских половых органов обычно проводится традиционным специалистом по обрезанию с использованием лезвия. Обрезание проводится со нескольких дней после рождения до полового созревания и далее. В половине стран, по которым доступна национальная статистика, большинство девочек стригутся в возрасте до пяти лет. [7] Процедуры различаются в зависимости от страны или этнической группы. Они включают удаление капюшона клитора (тип 1-а) и головки клитора (1-б); удаление внутренних половых губ (2-а); удаление внутренних и наружных половых губ и закрытие вульвы (тип 3). При этой последней процедуре, известной как инфибуляция , оставляют небольшое отверстие для прохождения мочи и менструальной жидкости , влагалище открывается для полового акта и далее открывается для родов . [8]

The practice is rooted in gender inequality, religious beliefs, attempts to control female sexuality, and ideas about purity, modesty, and beauty. It is usually initiated and carried out by women, who see it as a source of honour, and who fear that failing to have their daughters and granddaughters cut will expose the girls to social exclusion.[9] Adverse health effects depend on the type of procedure; they can include recurrent infections, difficulty urinating and passing menstrual flow, chronic pain, the development of cysts, an inability to get pregnant, complications during childbirth, and fatal bleeding.[8] There are no known health benefits.[10]

There have been international efforts since the 1970s to persuade practitioners to abandon FGM, and it has been outlawed or restricted in most of the countries in which it occurs, although the laws are often poorly enforced. Since 2010, the United Nations has called upon healthcare providers to stop performing all forms of the procedure, including reinfibulation after childbirth and symbolic "nicking" of the clitoral hood.[11] The opposition to the practice is not without its critics, particularly among anthropologists, who have raised questions about cultural relativism and the universality of human rights.[12] According to the UNICEF, international FGM rates have risen significantly in recent years, from an estimated 200 million in 2016 to 230 million in 2024, with progress towards its abandonment stalling or reversing in many affected countries.[13]

Terminology

Until the 1980s, FGM was widely known in English as "female circumcision", implying an equivalence in severity with male circumcision.[6] From 1929 the Kenya Missionary Council referred to it as the sexual mutilation of women, following the lead of Marion Scott Stevenson, a Church of Scotland missionary.[14] References to the practice as mutilation increased throughout the 1970s.[15] In 1975 Rose Oldfield Hayes, an American anthropologist, used the term female genital mutilation in the title of a paper in American Ethnologist,[16] and four years later Fran Hosken called it mutilation in her influential The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females.[17] The Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children began referring to it as female genital mutilation in 1990, and the World Health Organization (WHO) followed suit in 1991.[18] Other English terms include female genital cutting (FGC) and female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), preferred by those who work with practitioners.[15]

In countries where FGM is common, the practice's many variants are reflected in dozens of terms, often alluding to purification.[19] In the Bambara language, spoken mostly in Mali, it is known as bolokoli ("washing your hands")[20] and in the Igbo language in eastern Nigeria as isa aru or iwu aru ("having your bath").[b] A common Arabic term for purification has the root t-h-r, used for male and female circumcision (tahur and tahara).[22] It is also known in Arabic as khafḍ or khifaḍ.[23] Communities may refer to FGM as "pharaonic" for infibulation and "sunna" circumcision for everything else;[24] sunna means "path or way" in Arabic and refers to the tradition of Muhammad, although none of the procedures are required within Islam.[23] The term infibulation derives from fibula, Latin for clasp; the Ancient Romans reportedly fastened clasps through the foreskins or labia of slaves to prevent sexual intercourse. The surgical infibulation of women came to be known as pharaonic circumcision in Sudan and as Sudanese circumcision in Egypt.[25] In Somalia, it is known simply as qodob ("to sew up").[26]

Methods

The procedures are generally performed by a traditional circumciser (cutter or exciseuse) in the girls' homes, with or without anaesthesia. The cutter is usually an older woman, but in communities where the male barber has assumed the role of health worker, he will also perform FGM.[27][c] When traditional cutters are involved, non-sterile devices are likely to be used, including knives, razors, scissors, glass, sharpened rocks, and fingernails.[29] According to a nurse in Uganda, quoted in 2007 in The Lancet, a cutter would use one knife on up to 30 girls at a time.[30] In several countries, health professionals are involved; in Egypt, 77 percent of FGM procedures, and in Indonesia over 50 percent, were performed by medical professionals as of 2008 and 2016.[31][4]

Classification

Variation

The WHO, UNICEF, and UNFPA issued a joint statement in 1997 defining FGM as "all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs whether for cultural or other non-therapeutic reasons".[15] The procedures vary according to ethnicity and individual practitioners; during a 1998 survey in Niger, women responded with over 50 terms when asked what was done to them.[19] Translation problems are compounded by the women's confusion over which type of FGM they experienced, or even whether they experienced it.[32] Studies have suggested that survey responses are unreliable. A 2003 study in Ghana found that in 1995 four percent said they had not undergone FGM, but in 2000 said they had, while 11 percent switched in the other direction.[33] In Tanzania in 2005, 66 percent reported FGM, but a medical exam found that 73 percent had undergone it.[34] In Sudan in 2006, a significant percentage of infibulated women and girls reported a less severe type.[35]

Types

Standard questionnaires from United Nations bodies ask women whether they or their daughters have undergone the following: (1) cut, no flesh removed (symbolic nicking); (2) cut, some flesh removed; (3) sewn closed; or (4) type not determined/unsure/doesn't know.[d] The most common procedures fall within the "cut, some flesh removed" category and involve complete or partial removal of the clitoral glans.[36] The World Health Organization (a UN agency) created a more detailed typology in 1997: Types I–II vary in how much tissue is removed; Type III is equivalent to the UNICEF category "sewn closed"; and Type IV describes miscellaneous procedures, including symbolic nicking.[37]

Type I

Type I is "partial or total removal of the clitoral glans (the external and visible part of the clitoris, which is a sensitive part of the female genitals), and/or the prepuce/clitoral hood (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoral glans)".[38] Type Ia[e] involves removal of the clitoral hood only. This is rarely performed alone.[f] The more common procedure is Type Ib (clitoridectomy), the complete or partial removal of the clitoral glans (the visible tip of the clitoris) and clitoral hood.[1][41] The circumciser pulls the clitoral glans with her thumb and index finger and cuts it off.[g]

Type II

Type II (excision) is the complete or partial removal of the inner labia, with or without removal of the clitoral glans and outer labia. Type IIa is removal of the inner labia; Type IIb, removal of the clitoral glans and inner labia; and Type IIc, removal of the clitoral glans, inner and outer labia. Excision in French can refer to any form of FGM.[1]

Type III

Type III (infibulation or pharaonic circumcision), the "sewn closed" category, is the removal of the external genitalia and fusion of the wound. The inner and/or outer labia are cut away, with or without removal of the clitoral glans.[h] Type III is found largely in northeast Africa, particularly Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan (although not in South Sudan). According to one 2008 estimate, over eight million women in Africa are living with Type III FGM.[i] According to UNFPA in 2010, 20 percent of women with FGM have been infibulated.[44] In Somalia, according to Edna Adan Ismail, the child squats on a stool or mat while adults pull her legs open; a local anaesthetic is applied if available:

The element of speed and surprise is vital and the circumciser immediately grabs the clitoris by pinching it between her nails aiming to amputate it with a slash. The organ is then shown to the senior female relatives of the child who will decide whether the amount that has been removed is satisfactory or whether more is to be cut off.

After the clitoris has been satisfactorily amputated ... the circumciser can proceed with the total removal of the labia minora and the paring of the inner walls of the labia majora. Since the entire skin on the inner walls of the labia majora has to be removed all the way down to the perineum, this becomes a messy business. By now, the child is screaming, struggling, and bleeding profusely, which makes it difficult for the circumciser to hold with bare fingers and nails the slippery skin and parts that are to be cut or sutured together. ...

Having ensured that sufficient tissue has been removed to allow the desired fusion of the skin, the circumciser pulls together the opposite sides of the labia majora, ensuring that the raw edges where the skin has been removed are well approximated. The wound is now ready to be stitched or for thorns to be applied. If a needle and thread are being used, close tight sutures will be placed to ensure that a flap of skin covers the vulva and extends from the mons veneris to the perineum, and which, after the wound heals, will form a bridge of scar tissue that will totally occlude the vaginal introitus.[45]

The amputated parts might be placed in a pouch for the girl to wear.[46] A single hole of 2–3 mm is left for the passage of urine and menstrual fluid.[j] The vulva is closed with surgical thread, or agave or acacia thorns, and might be covered with a poultice of raw egg, herbs, and sugar. To help the tissue bond, the girl's legs are tied together, often from hip to ankle; the bindings are usually loosened after a week and removed after two to six weeks.[47][29] If the remaining hole is too large in the view of the girl's family, the procedure is repeated.[48]

The vagina is opened for sexual intercourse, for the first time either by a midwife with a knife or by the woman's husband with his penis.[49] In some areas, including Somaliland, female relatives of the bride and groom might watch the opening of the vagina to check that the girl is a virgin.[47] The woman is opened further for childbirth (defibulation or deinfibulation), and closed again afterwards (reinfibulation). Reinfibulation can involve cutting the vagina again to restore the pinhole size of the first infibulation. This might be performed before marriage, and after childbirth, divorce and widowhood.[k][50] Hanny Lightfoot-Klein interviewed hundreds of women and men in Sudan in the 1980s about sexual intercourse with Type III:

The penetration of the bride's infibulation takes anywhere from 3 or 4 days to several months. Some men are unable to penetrate their wives at all (in my study over 15%), and the task is often accomplished by a midwife under conditions of great secrecy, since this reflects negatively on the man's potency. Some who are unable to penetrate their wives manage to get them pregnant in spite of the infibulation, and the woman's vaginal passage is then cut open to allow birth to take place. ... Those men who do manage to penetrate their wives do so often, or perhaps always, with the help of the "little knife". This creates a tear which they gradually rip more and more until the opening is sufficient to admit the penis.[51]

Type IV

Type IV is "[a]ll other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes", including pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterization.[1] It includes nicking of the clitoris (symbolic circumcision), burning or scarring the genitals, and introducing substances into the vagina to tighten it.[52][53] Labia stretching is also categorized as Type IV.[54] Common in southern and eastern Africa, the practice is supposed to enhance sexual pleasure for the man and add to the sense of a woman as a closed space. From the age of eight, girls are encouraged to stretch their inner labia using sticks and massage. Girls in Uganda are told they may have difficulty giving birth without stretched labia.[l][56]

A definition of FGM from the WHO in 1995 included gishiri cutting and angurya cutting, found in Nigeria and Niger. These were removed from the WHO's 2008 definition because of insufficient information about prevalence and consequences.[54] Angurya cutting is excision of the hymen, usually performed seven days after birth. Gishiri cutting involves cutting the vagina's front or back wall with a blade or penknife, performed in response to infertility, obstructed labour, and other conditions. In a study by Nigerian physician Mairo Usman Mandara, over 30 percent of women with gishiri cuts were found to have vesicovaginal fistulae (holes that allow urine to seep into the vagina).[57]

Complications

Short term

FGM harms women's physical and emotional health throughout their lives.[58][59] It has no known health benefits.[10] The short-term and late complications depend on the type of FGM, whether the practitioner has had medical training, and whether they used antibiotics and sterilized or single-use surgical instruments. In the case of Type III, other factors include how small a hole was left for the passage of urine and menstrual blood, whether surgical thread was used instead of agave or acacia thorns, and whether the procedure was performed more than once (for example, to close an opening regarded as too wide or re-open one too small).[8]

Common short-term complications include swelling, excessive bleeding, pain, urine retention, and healing problems/wound infection. A 2014 systematic review of 56 studies suggested that over one in ten girls and women undergoing any form of FGM, including symbolic nicking of the clitoris (Type IV), experience immediate complications, although the risks increased with Type III. The review also suggested that there was under-reporting.[m] Other short-term complications include fatal bleeding, anaemia, urinary infection, septicaemia, tetanus, gangrene, necrotizing fasciitis (flesh-eating disease), and endometritis.[61] It is not known how many girls and women die as a result of the practice, because complications may not be recognized or reported. The practitioners' use of shared instruments is thought to aid the transmission of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV, although no epidemiological studies have shown this.[62]

Long term

Late complications vary depending on the type of FGM.[8] They include the formation of scars and keloids that lead to strictures and obstruction, epidermoid cysts that may become infected, and neuroma formation (growth of nerve tissue) involving nerves that supplied the clitoris.[63][64] An infibulated girl may be left with an opening as small as 2–3 mm, which can cause prolonged, drop-by-drop urination, pain while urinating, and a feeling of needing to urinate all the time. Urine may collect underneath the scar, leaving the area under the skin constantly wet, which can lead to infection and the formation of small stones. The opening is larger in women who are sexually active or have given birth by vaginal delivery, but the urethra opening may still be obstructed by scar tissue. Vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistulae can develop (holes that allow urine or faeces to seep into the vagina).[8][65] This and other damage to the urethra and bladder can lead to infections and incontinence, pain during sexual intercourse and infertility.[63]

Painful periods are common because of the obstruction to the menstrual flow, and blood can stagnate in the vagina and uterus. Complete obstruction of the vagina can result in hematocolpos and hematometra (where the vagina and uterus fill with menstrual blood).[8] The swelling of the abdomen and lack of menstruation can resemble pregnancy.[65] Asma El Dareer, a Sudanese physician, reported in 1979 that a girl in Sudan with this condition was killed by her family.[66]

Pregnancy, childbirth

FGM may place women at higher risk of problems during pregnancy and childbirth, which are more common with the more extensive FGM procedures.[8] Infibulated women may try to make childbirth easier by eating less during pregnancy to reduce the baby's size.[67]: 99 In women with vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistulae, it is difficult to obtain clear urine samples as part of prenatal care, making the diagnosis of conditions such as pre-eclampsia harder.[63] Cervical evaluation during labour may be impeded and labour prolonged or obstructed. Third-degree laceration (tears), anal-sphincter damage and emergency caesarean section are more common in infibulated women.[8][67]

Neonatal mortality is increased. The WHO estimated in 2006 that an additional 10–20 babies die per 1,000 deliveries as a result of FGM. The estimate was based on a study conducted on 28,393 women attending delivery wards at 28 obstetric centres in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, and Sudan. In those settings all types of FGM were found to pose an increased risk of death to the baby: 15 percent higher for Type I, 32 percent for Type II, and 55 percent for Type III. The reasons for this were unclear, but may be connected to genital and urinary tract infections and the presence of scar tissue. According to the study, FGM was associated with an increased risk to the mother of damage to the perineum and excessive blood loss, as well as a need to resuscitate the baby, and stillbirth, perhaps because of a long second stage of labour.[68][69]

Psychological effects, sexual function

According to a 2015 systematic review there is little high-quality information available on the psychological effects of FGM. Several small studies have concluded that women with FGM develop anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.[62] Feelings of shame and betrayal can develop when women leave the culture that practices FGM and learn that their condition is not the norm, but within the practicing culture, they may view their FGM with pride because for them it signifies beauty, respect for tradition, chastity and hygiene.[8] Studies on sexual function have also been small.[62] A 2013 meta-analysis of 15 studies involving 12,671 women from seven countries concluded that women with FGM were twice as likely to report no sexual desire and 52 percent more likely to report dyspareunia (painful sexual intercourse). One-third reported reduced sexual feelings.[70]

Distribution

According to the UNICEF, international FGM rates have risen significantly in recent years, rising from an estimated 200 million in 2016 to 230 million in 2024, with progress towards its abandonment stalling or reversing in many effected countries.[13]

Household surveys

Aid agencies define the prevalence of FGM as the percentage of the 15–49 age group that has experienced it.[72] These figures are based on nationally representative household surveys known as Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), developed by Macro International and funded mainly by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID); and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) conducted with financial and technical help from UNICEF.[32] These surveys have been carried out in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and elsewhere roughly every five years since 1984 and 1995 respectively.[73] The first to ask about FGM was the 1989–1990 DHS in northern Sudan. The first publication to estimate FGM prevalence based on DHS data (in seven countries) was written by Dara Carr of Macro International in 1997.[74]

Type of FGM

Questions the women are asked during the surveys include: "Was the genital area just nicked/cut without removing any flesh? Was any flesh (or something) removed from the genital area? Was your genital area sewn?"[75] Most women report "cut, some flesh removed" (Types I and II).[76]

Type I is the most common form in Egypt,[77] and in the southern parts of Nigeria.[78] Type III (infibulation) is concentrated in northeastern Africa, particularly Djibouti, Eritrea, Somalia, and Sudan.[43] In surveys in 2002–2006, 30 percent of cut girls in Djibouti, 38 percent in Eritrea, and 63 percent in Somalia had experienced Type III.[79] There is also a high prevalence of infibulation among girls in Niger and Senegal,[80] and in 2013 it was estimated that in Nigeria three percent of the 0–14 age group had been infibulated.[81] The type of procedure is often linked to ethnicity. In Eritrea, for example, a survey in 2002 found that all Hedareb girls had been infibulated, compared with two percent of the Tigrinya, most of whom fell into the "cut, no flesh removed" category.[19]

Prevalence

FGM is mostly found in what Gerry Mackie called an "intriguingly contiguous" zone in Africa—east to west from Somalia to Senegal, and north to south from Egypt to Tanzania.[82] Nationally representative figures are available for 27 countries in Africa, as well as Indonesia, Iraqi Kurdistan and Yemen. Over 200 million women and girls are thought to be living with FGM in those 30 countries.[3][4][83]

The highest concentrations among the 15–49 age group are in Somalia (98 percent), Guinea (97 percent), Djibouti (93 percent), Egypt (91 percent), and Sierra Leone (90 percent).[84] As of 2013, 27.2 million women had undergone FGM in Egypt, 23.8 million in Ethiopia, and 19.9 million in Nigeria.[85] There is a high concentration in Indonesia, where according to UNICEF Type I (clitoridectomy) and Type IV (symbolic nicking) are practised; the Indonesian Ministry of Health and Indonesian Ulema Council both say the clitoris should not be cut. The prevalence rate for the 0–11 group in Indonesia is 49 percent (13.4 million).[83]: 2 Smaller studies or anecdotal reports suggest that various types of FGM are also practised in various circumstances in Colombia, Jordan, Oman, Saudi Arabia,[86][87] Malaysia,[88] the United Arab Emirates,[4] and India,[89] but there are no representative data on the prevalence in these countries.[4] As of 2023[update], UNICEF reported that "The highest levels of support for FGM can be found in Mali, Sierra Leone, Guinea, the Gambia, Somalia, and Egypt, where more than half of the female population thinks the practice should continue".[3]

Prevalence figures for the 15–19 age group and younger show a downward trend.[n] For example, Burkina Faso fell from 89 percent (1980) to 58 percent (2010); Egypt from 97 percent (1985) to 70 percent (2015); and Kenya from 41 percent (1984) to 11 percent (2014).[91] Beginning in 2010, household surveys asked women about the FGM status of all their living daughters.[92] The highest concentrations among girls aged 0–14 were in Gambia (56 percent), Mauritania (54 percent), Indonesia (49 percent for 0–11) and Guinea (46 percent).[4] The figures suggest that a girl was one third less likely in 2014 to undergo FGM than she was 30 years ago.[93] According to a 2018 study published in BMJ Global Health, the prevalence within the 0–14 year old group fell in East Africa from 71.4 percent in 1995 to 8 percent in 2016; in North Africa from 57.7 percent in 1990 to 14.1 percent in 2015; and in West Africa from 73.6 percent in 1996 to 25.4 percent in 2017.[94] If the current rate of decline continues, the number of girls cut will nevertheless continue to rise because of population growth, according to UNICEF in 2014; they estimate that the figure will increase from 3.6 million a year in 2013 to 4.1 million in 2050.[o]

Rural areas, wealth, education

Surveys have found FGM to be more common in rural areas, less common in most countries among girls from the wealthiest homes, and (except in Sudan and Somalia) less common in girls whose mothers had access to primary or secondary/higher education. In Somalia and Sudan the situation was reversed: in Somalia, the mothers' access to secondary/higher education was accompanied by a rise in prevalence of FGM in their daughters, and in Sudan, access to any education was accompanied by a rise.[96]

Age, ethnicity

FGM is not invariably a rite of passage between childhood and adulthood but is often performed on much younger children.[97] Girls are most commonly cut shortly after birth to age 15. In half the countries for which national figures were available in 2000–2010, most girls had been cut by age five.[5] Over 80 percent (of those cut) are cut before the age of five in Nigeria, Mali, Eritrea, Ghana and Mauritania.[98] The 1997 Demographic and Health Survey in Yemen found that 76 percent of girls had been cut within two weeks of birth.[99] The percentage is reversed in Somalia, Egypt, Chad, and the Central African Republic, where over 80 percent (of those cut) are cut between five and 14.[98] Just as the type of FGM is often linked to ethnicity, so is the mean age. In Kenya, for example, the Kisi cut around age 10 and the Kamba at 16.[100]

A country's national prevalence often reflects a high sub-national prevalence among certain ethnicities, rather than a widespread practice.[101] In Iraq, for example, FGM is found mostly among the Kurds in Erbil (58 percent prevalence within age group 15–49, as of 2011), Sulaymaniyah (54 percent) and Kirkuk (20 percent), giving the country a national prevalence of eight percent.[102] The practice is sometimes an ethnic marker, but it may differ along national lines. For example, in the northeastern regions of Ethiopia and Kenya, which share a border with Somalia, the Somali people practise FGM at around the same rate as they do in Somalia.[103] But in Guinea all Fulani women responding to a survey in 2012 said they had experienced FGM,[104] against 12 percent of the Fulani in Chad, while in Nigeria the Fulani are the only large ethnic group in the country not to practise it.[105] In Sierra Leone, the predominantly Christian Creole people are the only ethnicity not known to practice FGM or participate in Bondo society rituals.[106][107][108]

Reasons

Support from women

Dahabo Musa, a Somali woman, described infibulation in a 1988 poem as the "three feminine sorrows": the procedure itself, the wedding night when the woman is cut open, then childbirth when she is cut again.[110] Despite the evident suffering, it is women who organize all forms of FGM.[111][p] Anthropologist Rose Oldfield Hayes wrote in 1975 that educated Sudanese men who did not want their daughters to be infibulated (preferring clitoridectomy) would find the girls had been sewn up after the grandmothers arranged a visit to relatives.[116] Gerry Mackie has compared the practice to footbinding. Like FGM, footbinding was carried out on young girls, nearly universal where practised, tied to ideas about honour, chastity, and appropriate marriage, and "supported and transmitted" by women.[q]

FGM practitioners see the procedures as marking not only ethnic boundaries but also gender differences. According to this view, male circumcision defeminizes men while FGM demasculinizes women.[119]

Fuambai Ahmadu, an anthropologist and member of the Kono people of Sierra Leone, who in 1992 underwent clitoridectomy as an adult during a Sande society initiation, argued in 2000 that it is a male-centred assumption that the clitoris is important to female sexuality. African female symbolism revolves instead around the concept of the womb.[118] Infibulation draws on that idea of enclosure and fertility. "[G]enital cutting completes the social definition of a child's sex by eliminating external traces of androgyny," Janice Boddy wrote in 2007. "The female body is then covered, closed, and its productive blood bound within; the male body is unveiled, opened, and exposed."[120]

In communities where infibulation is common, there is a preference for women's genitals to be smooth, dry and without odour, and both women and men may find the natural vulva repulsive.[121] Some men seem to enjoy the effort of penetrating an infibulation.[122] The local preference for dry sex causes women to introduce substances into the vagina to reduce lubrication, including leaves, tree bark, toothpaste and Vicks menthol rub.[123] The WHO includes this practice within Type IV FGM, because the added friction during intercourse can cause lacerations and increase the risk of infection.[124] Because of the smooth appearance of an infibulated vulva, there is also a belief that infibulation increases hygiene.[125]

Common reasons for FGM cited by women in surveys are social acceptance, religion, hygiene, preservation of virginity, marriageability and enhancement of male sexual pleasure.[126] In a study in northern Sudan, published in 1983, only 17.4 percent of women opposed FGM (558 out of 3,210), and most preferred excision and infibulation over clitoridectomy.[127] Attitudes are changing slowly. In Sudan in 2010, 42 percent of women who had heard of FGM said the practice should continue.[128] In several surveys since 2006, over 50 percent of women in Mali, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Somalia, the Gambia, and Egypt supported FGM's continuance, while elsewhere in Africa, Iraq, and Yemen most said it should end, although in several countries only by a narrow margin.[129]

Social obligation, poor access to information

Against the argument that women willingly choose FGM for their daughters, UNICEF calls the practice a "self-enforcing social convention" to which families feel they must conform to avoid uncut daughters facing social exclusion.[131] Ellen Gruenbaum reported that, in Sudan in the 1970s, cut girls from an Arab ethnic group would mock uncut Zabarma girls with Ya, ghalfa! ("Hey, unclean!"). The Zabarma girls would respond Ya, mutmura! (A mutmara was a storage pit for grain that was continually opened and closed, like an infibulated woman.) But despite throwing the insult back, the Zabarma girls would ask their mothers, "What's the matter? Don't we have razor blades like the Arabs?"[132]

Because of poor access to information, and because practitioners downplay the causal connection, women may not associate the health consequences with the procedure. Lala Baldé, president of a women's association in Medina Cherif, a village in Senegal, told Mackie in 1998 that when girls fell ill or died, it was attributed to evil spirits. When informed of the causal relationship between FGM and ill health, Mackie wrote, the women broke down and wept. He argued that surveys taken before and after this sharing of information would show very different levels of support for FGM.[133] The American non-profit group Tostan, founded by Molly Melching in 1991, introduced community-empowerment programs in several countries that focus on local democracy, literacy, and education about healthcare, giving women the tools to make their own decisions.[134] In 1997, using the Tostan program, Malicounda Bambara in Senegal became the first village to abandon FGM.[135] By August 2019, 8,800 communities in eight countries had pledged to abandon FGM and child marriage.[r]

Religion

Surveys have shown a widespread belief, particularly in Mali, Mauritania, Guinea, and Egypt, that FGM is a religious requirement.[137] Gruenbaum has argued that practitioners may not distinguish between religion, tradition, and chastity, making it difficult to interpret the data.[138] FGM's origins in northeastern Africa are pre-Islamic, but the practice became associated with Islam because of that religion's focus on female chastity and seclusion.[s]

According to a 2013 UNICEF report, in 18 African countries at least 10 percent of Muslim females had experienced FGM, and in 13 of those countries, the figure rose to 50–99 percent.[140] There is no mention of the practice in the Quran.[141] It is praised in a few daʻīf (weak) hadith (sayings attributed to Muhammad) as noble but not required,[142][t] although it is regarded as obligatory by the Shafi'i version of Sunni Islam.[143] In 2007 the Al-Azhar Supreme Council of Islamic Research in Cairo ruled that FGM had "no basis in core Islamic law or any of its partial provisions".[144][u] FGM in India is particularly prevalent amongst the Shia Islam members of the Bohra Muslim community who practice it as a religious custom.[146][147]

There is no mention of FGM in the Bible.[v] The Skoptsy Christian sect in Europe practices FGM as part of redemption from sin and to remain chaste.[149] Christian missionaries in Africa were among the first to object to FGM,[150] but Christian communities in Africa do practise it. In 2013 UNICEF identified 19 African countries in which at least 10 percent of Christian females aged 15 to 49 had undergone FGM;[w] in Niger, 55 percent of Christian women and girls had experienced it, compared with two percent of their Muslim counterparts.[152] The only Jewish group known to have practised it is the Beta Israel of Ethiopia. Judaism requires male circumcision but does not allow FGM.[153] FGM is also practised by animist groups, particularly in Guinea and Mali.[140]

History

Antiquity

But if a man wants to know how to live, he should recite it [a magical spell] every day, after his flesh has been rubbed with the b3d [unknown substance] of an uncircumcised girl ['m't] and the flakes of skin [šnft] of an uncircumcised bald man.

—From an Egyptian sarcophagus, c. 1991–1786 BCE[154]

The practice's origins are unknown. Gerry Mackie has suggested that, because FGM's east–west, north–south distribution in Africa meets in Sudan, infibulation may have begun there with the Meroite civilization (c. 800 BCE – c. 350 CE), before the rise of Islam, to increase confidence in paternity.[155] According to historian Mary Knight, Spell 1117 (c. 1991–1786 BCE) of the Ancient Egyptian Coffin Texts may refer in hieroglyphs to an uncircumcised girl ('m't):

| |

The spell was found on the sarcophagus of Sit-hedjhotep, now in the Egyptian Museum, and dates to Egypt's Middle Kingdom.[154][x] (Paul F. O'Rourke argues that 'm't probably refers instead to a menstruating woman.)[156] The proposed circumcision of an Egyptian girl, Tathemis, is also mentioned on a Greek papyrus, from 163 BCE, in the British Museum: "Sometime after this, Nephoris [Tathemis's mother] defrauded me, being anxious that it was time for Tathemis to be circumcised, as is the custom among the Egyptians."[y]

The examination of mummies has shown no evidence of FGM. Citing the Australian pathologist Grafton Elliot Smith, who examined hundreds of mummies in the early 20th century, Knight writes that the genital area may resemble Type III because during mummification the skin of the outer labia was pulled toward the anus to cover the pudendal cleft, possibly to prevent a sexual violation. It was similarly not possible to determine whether Types I or II had been performed, because soft tissues had deteriorated or been removed by the embalmers.[158]

The Greek geographer Strabo (c. 64 BCE – c. 23 CE) wrote about FGM after visiting Egypt around 25 BCE: "This is one of the customs most zealously pursued by them [the Egyptians]: to raise every child that is born and to circumcise [peritemnein] the males and excise [ektemnein] the females ..."[159][z][aa] Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BCE – 50 CE) also made reference to it: "the Egyptians by the custom of their country circumcise the marriageable youth and maid in the fourteenth (year) of their age when the male begins to get seed, and the female to have a menstrual flow."[162] It is mentioned briefly in a work attributed to the Greek physician Galen (129 – c. 200 CE): "When [the clitoris] sticks out to a great extent in their young women, Egyptians consider it appropriate to cut it out."[ab] Another Greek physician, Aëtius of Amida (mid-5th to mid-6th century CE), offered more detail in book 16 of his Sixteen Books on Medicine, citing the physician Philomenes. The procedure was performed in case the clitoris, or nymphê, grew too large or triggered sexual desire when rubbing against clothing. "On this account, it seemed proper to the Egyptians to remove it before it became greatly enlarged," Aëtius wrote, "especially at that time when the girls were about to be married":

The surgery is performed in this way: Have the girl sit on a chair while a muscled young man standing behind her places his arms below the girl's thighs. Have him separate and steady her legs and whole body. Standing in front and taking hold of the clitoris with a broad-mouthed forceps in his left hand, the surgeon stretches it outward, while with the right hand, he cuts it off at the point next to the pincers of the forceps. It is proper to let a length remain from that cut off, about the size of the membrane that's between the nostrils, so as to take away the excess material only; as I have said, the part to be removed is at that point just above the pincers of the forceps. Because the clitoris is a skinlike structure and stretches out excessively, do not cut off too much, as a urinary fistula may result from cutting such large growths too deeply.[164]

The genital area was then cleaned with a sponge, frankincense powder and wine or cold water, and wrapped in linen bandages dipped in vinegar, until the seventh day when calamine, rose petals, date pits, or a "genital powder made from baked clay" might be applied.[165]

Red Sea slave trade

Whatever the practice's origins, infibulation became linked to slavery. Research has indicated that linkes between the Red Sea slave trade and female genital mutilation.[166] An investigation combining contemporary from data on slave shipments from 1400 to 1900 with data from 28 African countries has found that women belonging to ethnic groups historically victimized by the Red Sea slave trade were "significantly" more likely to suffer genital mutilation in the 21st-century, as well as "more in favour of continuing the practice".[166][167]Women trafficked in the Red Sea slave trade were sold as concubines (sex slaves) in the Islamic Middle East up until as late as in the mid 20th-century, and the practice of infibulation was used to temporarily signal the virginity of girls, increasing their value on the slave market: "According to descriptions by early travellers, infibulated female slaves had a higher price on the market because infibulation was thought to ensure chastity and loyalty to the owner and prevented undesired pregnancies".[166][167]Mackie cites the Portuguese missionary João dos Santos, who in 1609 wrote of a group near Mogadishu who had a "custome to sew up their Females, especially their slaves being young to make them unable for conception, which makes these slaves sell dearer, both for their chastitie, and for better confidence which their Masters put in them". Thus, Mackie argues, a "practice associated with shameful female slavery came to stand for honor".[168]

Europe and the United States

Some gynaecologists in 19th-century Europe and the United States removed the clitoris to treat insanity and masturbation.[170] A British doctor, Robert Thomas, suggested clitoridectomy as a cure for nymphomania in 1813.[171] In 1825 The Lancet described a clitoridectomy performed in 1822 in Berlin by Karl Ferdinand von Graefe on a 15-year-old girl who was masturbating excessively.[172]

Isaac Baker Brown, an English gynaecologist, president of the Medical Society of London and co-founder in 1845 of St. Mary's Hospital, believed that masturbation, or "unnatural irritation" of the clitoris, caused hysteria, spinal irritation, fits, idiocy, mania, and death.[173] He, therefore "set to work to remove the clitoris whenever he had the opportunity of doing so", according to his obituary.[169] Brown performed several clitoridectomies between 1859 and 1866.[169] In the United States, J. Marion Sims followed Brown's work and in 1862 slit the neck of a woman's uterus and amputated her clitoris, "for the relief of the nervous or hysterical condition as recommended by Baker Brown".[174] When Brown published his views in On the Curability of Certain Forms of Insanity, Epilepsy, Catalepsy, and Hysteria in Females (1866), doctors in London accused him of quackery and expelled him from the Obstetrical Society.[175]

Later in the 19th century, A. J. Bloch, a surgeon in New Orleans, removed the clitoris of a two-year-old girl who was reportedly masturbating.[176] According to a 1985 paper in the Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, clitoridectomy was performed in the United States into the 1960s to treat hysteria, erotomania and lesbianism.[177] From the mid-1950s, James C. Burt, a gynaecologist in Dayton, Ohio, performed non-standard repairs of episiotomies after childbirth, adding more stitches to make the vaginal opening smaller. From 1966 until 1989, he performed "love surgery" by cutting women's pubococcygeus muscle, repositioning the vagina and urethra, and removing the clitoral hood, thereby making their genital area more appropriate, in his view, for intercourse in the missionary position.[178] "Women are structurally inadequate for intercourse," he wrote; he said he would turn them into "horny little mice".[179] In the 1960s and 1970s he performed these procedures without consent while repairing episiotomies and performing hysterectomies and other surgery; he said he had performed a variation of them on 4,000 women by 1975.[178] Following complaints, he was required in 1989 to stop practicing medicine in the United States.[180]

Opposition and legal status

Colonial opposition in Kenya

Little knives in their sheaths

That they may fight with the church,

The time has come.

Elders (of the church)

When Kenyatta comes

You will be given women's clothes

And you will have to cook him his food.

— From the Muthirigu (1929), Kikuyu dance-songs against church opposition to FGM[181]

Protestant missionaries in British East Africa (present-day Kenya) began campaigning against FGM in the early 20th century, when Dr. John Arthur joined the Church of Scotland Mission (CSM) in Kikuyu. An important ethnic marker, the practice was known by the Kikuyu, the country's main ethnic group, as irua for both girls and boys. It involved excision (Type II) for girls and removal of the foreskin for boys. Unexcised Kikuyu women (irugu) were outcasts.[182]

Jomo Kenyatta, general secretary of the Kikuyu Central Association and later Kenya's first prime minister, wrote in 1938 that, for the Kikuyu, the institution of FGM was the "conditio sine qua non of the whole teaching of tribal law, religion and morality". No proper Kikuyu man or woman would marry or have sexual relations with someone who was not circumcised, he wrote. A woman's responsibilities toward the tribe began with her initiation. Her age and place within tribal history were traced to that day, and the group of girls with whom she was cut was named according to current events, an oral tradition that allowed the Kikuyu to track people and events going back hundreds of years.[183]

Beginning with the CSM in 1925, several missionary churches declared that FGM was prohibited for African Christians; the CSM announced that Africans practising it would be excommunicated, which resulted in hundreds leaving or being expelled.[184] In 1929 the Kenya Missionary Council began referring to FGM as the "sexual mutilation of women", and a person's stance toward the practice became a test of loyalty, either to the Christian churches or to the Kikuyu Central Association.[185] The stand-off turned FGM into a focal point of the Kenyan independence movement; the 1929–1931 period is known in the country's historiography as the female circumcision controversy.[186] When Hulda Stumpf, an American missionary who opposed FGM in the girls' school she helped to run, was murdered in 1930, Edward Grigg, the governor of Kenya, told the British Colonial Office that the killer had tried to circumcise her.[187]

There was some opposition from Kenyan women themselves. At the mission in Tumutumu, Karatina, where Marion Scott Stevenson worked, a group calling themselves Ngo ya Tuiritu ("Shield of Young Girls"), the membership of which included Raheli Warigia (mother of Gakaara wa Wanjaũ), wrote to the Local Native Council of South Nyeri on 25 December 1931: "[W]e of the Ngo ya Tuiritu heard that there are men who talk of female circumcision, and we get astonished because they (men) do not give birth and feel the pain and even some die and even others become infertile, and the main cause is circumcision. Because of that, the issue of circumcision should not be forced. People are caught like sheep; one should be allowed to cut her own way of either agreeing to be circumcised or not without being dictated on one's own body."[188]

Elsewhere, support for the practice from women was strong. In 1956 in Meru, eastern Kenya, when the council of male elders (the Njuri Nchecke) announced a ban on FGM in 1956, thousands of girls cut each other's genitals with razor blades over the next three years as a symbol of defiance. The movement came to be known as Ngaitana ("I will circumcise myself"), because to avoid naming their friends the girls said they had cut themselves. Historian Lynn Thomas described the episode as significant in the history of FGM because it made clear that its victims were also its perpetrators.[189] FGM was eventually outlawed in Kenya in 2001, although the practice continued, reportedly driven by older women.[190]

Growth of opposition

| FGM opposition |

|---|

|

One of the earliest campaigns against FGM began in Egypt in the 1920s, when the Egyptian Doctors' Society called for a ban.[ac] There was a parallel campaign in Sudan, run by religious leaders and British women. Infibulation was banned there in 1946, but the law was unpopular and barely enforced.[192][ad] The Egyptian government banned infibulation in state-run hospitals in 1959, but allowed partial clitoridectomy if parents requested it.[195] (Egypt banned FGM entirely in 2007.)

In 1959, the UN asked the WHO to investigate FGM, but the latter responded that it was not a medical matter.[196] Feminists took up the issue throughout the 1970s.[197] The Egyptian physician and feminist Nawal El Saadawi criticized FGM in her book Women and Sex (1972); the book was banned in Egypt and El Saadawi lost her job as director-general of public health.[198] She followed up with a chapter, "The Circumcision of Girls", in her book The Hidden Face of Eve: Women in the Arab World (1980), which described her own clitoridectomy when she was six years old:

I did not know what they had cut off from my body, and I did not try to find out. I just wept, and called out to my mother for help. But the worst shock of all was when I looked around and found her standing by my side. Yes, it was her, I could not be mistaken, in flesh and blood, right in the midst of these strangers, talking to them and smiling at them, as though they had not participated in slaughtering her daughter just a few moments ago.[199]

In 1975, Rose Oldfield Hayes, an American social scientist, became the first female academic to publish a detailed account of FGM, aided by her ability to discuss it directly with women in Sudan. Her article in American Ethnologist called it "female genital mutilation", rather than female circumcision, and brought it to wider academic attention.[200] Edna Adan Ismail, who worked at the time for the Somalia Ministry of Health, discussed the health consequences of FGM in 1977 with the Somali Women's Democratic Organization.[201][202] Two years later Fran Hosken, an Austrian-American feminist, published The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females (1979),[17] the first to offer global figures. She estimated that 110,529,000 women in 20 African countries had experienced FGM.[203] The figures were speculative but consistent with later surveys.[204] Describing FGM as a "training ground for male violence", Hosken accused female practitioners of "participating in the destruction of their own kind".[205] The language caused a rift between Western and African feminists; African women boycotted a session featuring Hosken during the UN's Mid-Decade Conference on Women in Copenhagen in July 1980.[206]

In 1979, the WHO held a seminar, "Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children", in Khartoum, Sudan, and in 1981, also in Khartoum, 150 academics and activists signed a pledge to fight FGM after a workshop held by the Babiker Badri Scientific Association for Women's Studies (BBSAWS), "Female Circumcision Mutilates and Endangers Women – Combat it!" Another BBSAWS workshop in 1984 invited the international community to write a joint statement for the United Nations.[207] It recommended that the "goal of all African women" should be the eradication of FGM and that, to sever the link between FGM and religion, clitoridectomy should no longer be referred to as sunna.[208]

The Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children, founded in 1984 in Dakar, Senegal, called for an end to the practice, as did the UN's World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna in 1993. The conference listed FGM as a form of violence against women, marking it as a human-rights violation, rather than a medical issue.[209] Throughout the 1990s and 2000s governments in Africa and the Middle East passed legislation banning or restricting FGM. In 2003 the African Union ratified the Maputo Protocol on the rights of women, which supported the elimination of FGM.[210] By 2015 laws restricting FGM had been passed in at least 23 of the 27 African countries in which it is concentrated, although several fell short of a ban.[ae]

As of 2023[update], UNICEF reported that "in most countries in Africa and the Middle East with representative data on attitudes (23 out of 30), the majority of girls and women think the practice should end", and that "even among communities that practice FGM, there is substantial opposition to its continuation".[3]

United Nations

In December 1993, the United Nations General Assembly included FGM in resolution 48/104, the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women, and from 2003 sponsored International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation, held every 6 February.[214][215] UNICEF began in 2003 to promote an evidence-based social norms approach, using ideas from game theory about how communities reach decisions about FGM, and building on the work of Gerry Mackie on the demise of footbinding in China.[216] In 2005 the UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre in Florence published its first report on FGM.[28] UNFPA and UNICEF launched a joint program in Africa in 2007 to reduce FGM by 40 percent within the 0–15 age group and eliminate it from at least one country by 2012, goals that were not met and which they later described as unrealistic.[217][af] In 2008 several UN bodies recognized FGM as a human-rights violation,[219] and in 2010 the UN called upon healthcare providers to stop carrying out the procedures, including reinfibulation after childbirth and symbolic nicking.[11] In 2012 the General Assembly passed resolution 67/146, "Intensifying global efforts for the elimination of female genital mutilations".[220]

Non-practising countries

Overview

Immigration spread the practice to Australia, New Zealand, Europe, and North America, all of which outlawed it entirely or restricted it to consenting adults.[221] Sweden outlawed FGM in 1982 with the Act Prohibiting the Genital Mutilation of Women, the first Western country to do so.[222] Several former colonial powers, including Belgium, Britain, France, and the Netherlands, introduced new laws or made clear that it was covered by existing legislation.[223] As of 2013[update], legislation banning FGM had been passed in 33 countries outside Africa and the Middle East.[211]

North America

In the United States, an estimated 513,000 women and girls had experienced FGM or were at risk as of 2012.[224][225][ag] A Nigerian woman successfully contested deportation in March 1994, asking for "cultural asylum" on the grounds that her young daughters (who were American citizens) might be cut if she took them to Nigeria,[227] and in 1996 Fauziya Kasinga from Togo became the first to be officially granted asylum to escape FGM.[228] In 1996 the Federal Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act made it illegal to perform FGM on minors for non-medical reasons, and in 2013 the Transport for Female Genital Mutilation Act prohibited transporting a minor out of the country for the purpose of FGM.[224]: 2 The first FGM conviction in the US was in 2006, when Khalid Adem, who had emigrated from Ethiopia, was sentenced to ten years for aggravated battery and cruelty to children after severing his two-year-old daughter's clitoris with a pair of scissors.[229] A federal judge ruled in 2018 that the 1996 Act was unconstitutional, arguing that FGM is a "local criminal activity" that should be regulated by states.[230][ah] Twenty-four states had legislation banning FGM as of 2016,[224]: 2 and in 2021 the STOP FGM Act of 2020 was signed into federal law.[231] The American Academy of Pediatrics opposes all forms of the practice, including pricking the clitoral skin.[ai]

Canada recognized FGM as a form of persecution in July 1994, when it granted refugee status to Khadra Hassan Farah, who had fled Somalia to avoid her daughter being cut.[233] In 1997 section 268 of its Criminal Code was amended to ban FGM, except where "the person is at least eighteen years of age and there is no resulting bodily harm".[234][211] As of February 2019[update], there had been no prosecutions. Officials have expressed concern that thousands of Canadian girls are at risk of being taken overseas to undergo the procedure, so-called "vacation cutting".[235]

Europe

According to the European Parliament, 500,000 women in Europe had undergone FGM as of March 2009[update].[236] In France up to 30,000 women were thought to have experienced it as of 1995. According to Colette Gallard, a family-planning counsellor, when FGM was first encountered in France, the reaction was that Westerners ought not to intervene. It took the deaths of two girls in 1982, one of them three months old, for that attitude to change.[237][238] In 1991 a French court ruled that the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees offered protection to FGM victims; the decision followed an asylum application from Aminata Diop, who fled an FGM procedure in Mali.[239] The practice is outlawed by several provisions of France's penal code that address bodily harm causing permanent mutilation or torture.[240][238] The first civil suit was in 1982,[237] and the first criminal prosecution in 1993.[233] In 1999 a woman was given an eight-year sentence for having performed FGM on 48 girls.[241] By 2014 over 100 parents and two practitioners had been prosecuted in over 40 criminal cases.[238]

Around 137,000 women and girls living in England and Wales were born in countries where FGM is practised, as of 2011.[242] Performing FGM on children or adults was outlawed under the Prohibition of Female Circumcision Act 1985.[243] This was replaced by the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003 and Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation (Scotland) Act 2005, which added a prohibition on arranging FGM outside the country for British citizens or permanent residents.[244][aj] The United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) asked the government in July 2013 to "ensure the full implementation of its legislation on FGM".[246] The first charges were brought in 2014 against a physician and another man; the physician had stitched an infibulated woman after opening her for childbirth. Both men were acquitted in 2015.[247]

Criticism of opposition

Tolerance versus human rights

Anthropologists[who?] have accused FGM eradicationists of cultural colonialism, and have been criticized in turn for their moral relativism and failure to defend the idea of universal human rights.[249] According to critics of the eradicationist position, the biological reductionism of the opposition to FGM, and the failure to appreciate FGM's cultural context, serves to "other" practitioners and undermine their agency—in particular when parents are referred to as "mutilators".[250]

Africans who object to the tone of FGM opposition risk appearing to defend the practice. The feminist theorist Obioma Nnaemeka, herself strongly opposed to FGM, argued in 2005 that renaming the practice female genital mutilation had introduced "a subtext of barbaric African and Muslim cultures and the West's relevance (even indispensability) in purging [it]".[251] According to Ugandan law professor Sylvia Tamale, the early Western opposition to FGM stemmed from a Judeo-Christian judgment that African sexual and family practices, including not only FGM but also dry sex, polygyny, bride price and levirate marriage, required correction. African feminists "take strong exception to the imperialist, racist and dehumanising infantilization of African women", she wrote in 2011.[252] Commentators highlight the voyeurism in the treatment of women's bodies as exhibits. Examples include images of women's vulvas after FGM or girls undergoing the procedure.[253] The 1996 Pulitzer-prize-winning photographs of a 16-year-old Kenyan girl experiencing FGM were published by 12 American newspapers, without her consent either to be photographed or to have the images published.[254]

The debate has highlighted a tension between anthropology and feminism, with the former's focus on tolerance and the latter's on equal rights for women. According to the anthropologist Christine Walley, a common position in anti-FGM literature has been to present African women as victims of false consciousness participating in their own oppression, a position promoted by feminists in the 1970s and 1980s, including Fran Hosken, Mary Daly and Hanny Lightfoot-Klein.[255] It prompted the French Association of Anthropologists to issue a statement in 1981, at the height of the early debates, that "a certain feminism resuscitates (today) the moralistic arrogance of yesterday's colonialism".[197]

Comparison with other procedures

Cosmetic procedures

Nnaemeka argues that the crucial question, broader than FGM, is why the female body is subjected to so much "abuse and indignity", including in the West.[256] Several authors have drawn a parallel between FGM and cosmetic procedures.[257] Ronán Conroy of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland wrote in 2006 that cosmetic genital procedures were "driving the advance" of FGM by encouraging women to see natural variations as defects.[258] Anthropologist Fadwa El Guindi compared FGM to breast enhancement, in which the maternal function of the breast becomes secondary to men's sexual pleasure.[259] Benoîte Groult, the French feminist, made a similar point in 1975, citing FGM and cosmetic surgery as sexist and patriarchal.[260] Against this, the medical anthropologist Carla Obermeyer argued in 1999 that FGM may be conducive to a subject's social well-being in the same way that rhinoplasty and male circumcision are.[261] Despite the 2007 ban in Egypt, Egyptian women wanting FGM for their daughters seek amalyet tajmeel (cosmetic surgery) to remove what they see as excess genital tissue.[262]

Cosmetic procedures such as labiaplasty and clitoral hood reduction do fall within the WHO's definition of FGM, which aims to avoid loopholes, but the WHO notes that these elective practices are generally not regarded as FGM.[ak] Some legislation banning FGM, such as in Canada and the United States, covers minors only, but several countries, including Sweden and the United Kingdom, have banned it regardless of consent. Sweden, for example, has banned operations "on the outer female sexual organs with a view to mutilating them or bringing about some other permanent change in them, regardless of whether or not consent has been given for the operation".[222] Gynaecologist Birgitta Essén and anthropologist Sara Johnsdotter argue that the law seems to distinguish between Western and African genitals, and deems only African women (such as those seeking reinfibulation after childbirth) unfit to make their own decisions.[264]

The philosopher Martha Nussbaum argues that a key concern with FGM is that it is mostly conducted on children using physical force. The distinction between social pressure and physical force is morally and legally salient, comparable to the distinction between seduction and rape. She argues further that the literacy of women in practising countries is generally poorer than in developed nations, which reduces their ability to make informed choices.[265][266]

Analogy to other genital-altering procedures

FGM has been compared to other procedures that modify the human genitalia. Conservatives in the United States during the late 2010s and early 2020s have argued that FGM is similar to gender-affirming surgery for transgender individuals, which has led to bills being drafted in Republican states equating the two. Criticism of these ideas include the fact that the gender-affirming surgeries are approved by American medical authorities, are rare for minors, and are done after reviews by multiple medical professionals.[267][268] Formerly, FGM was widely referred to as "female circumcision" in the academic literature, but this "was rejected by international medical practitioners because it suggests a fallacious analogy to male circumcision."[6] It has been argued that the genital alteration of intersex infants and children, who are born with anomalies that physicians choose to "fix", is analogous to FGM.[269]

See also

- Dishonour (a short film on FGM)

- Emasculation

- Genital modification and mutilation

- International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation

- No FGM Australia

References

Notes

- ^ Martha Nussbaum (Sex and Social Justice, 1999): "Although discussions sometimes use the terms 'female circumcision' and 'clitoridectomy', 'female genital mutilation' (FGM) is the standard generic term for all these procedures in the medical literature ... The term 'female circumcision' has been rejected by international medical practitioners because it suggests the fallacious analogy to male circumcision ..."[6]

- ^ For example, "a young woman must 'have her bath' before she has a baby."[21]

- ^ UNICEF 2005: "The large majority of girls and women are cut by a traditional practitioner, a category which includes local specialists (cutters or exciseuses), traditional birth attendants and, generally, older members of the community, usually women. This is true for over 80 percent of the girls who undergo the practice in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea, Mali, Niger, Tanzania, and Yemen. In most countries, medical personnel, including doctors, nurses, and certified midwives, are not widely involved in the practice."[28]

- ^ UNICEF 2013: "These categories do not fully match the WHO typology. Cut, no flesh removed describes a practice known as nicking or pricking, which currently is categorized as Type IV. Cut, some flesh removed corresponds to Type I (clitoridectomy) and Type II (excision) combined. And sewn closed corresponds to Type III, infibulation."[19]

- ^ A diagram in WHO 2016, copied from Abdulcadir et al. 2016, refers to Type 1a as circumcision.[39]

- ^ WHO (2018): Type 1 ... the partial or total removal of the clitoris ... and in very rare cases, only the prepuce (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoris)."[10]

WHO (2008): "[There is a] common tendency to describe Type I as removal of the prepuce, whereas this has not been documented as a traditional form of female genital mutilation. However, in some countries, medicalized female genital mutilation can include removal of the prepuce only (Type Ia) (Thabet and Thabet, 2003), but this form appears to be relatively rare (Satti et al., 2006). Almost all known forms of female genital mutilation that remove tissue from the clitoris also cut all or part of the clitoral glans itself."[40]

- ^ Susan Izett and Nahid Toubia (WHO, 1998): "[T]he clitoris is held between the thumb and index finger, pulled out and amputated with one stroke of a sharp object."[42]

- ^ WHO 2014: "Narrowing of the vaginal orifice with creation of a covering seal by cutting and appositioning the labia minora and/or the labia majora, with or without excision of the clitoris (infibulation)."Type IIIa, removal and apposition of the labia minora; Type IIIb, removal and apposition of the labia majora."[1]

- ^ USAID 2008: "Infibulation is practiced largely in countries located in northeastern Africa: Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan. ... Sudan alone accounts for about 3.5 million of the women. ... [T]he estimate of the total number of women infibulated in [Djibouti, Somalia, Eritrea, northern Sudan, Ethiopia, Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, Senegal, Chad, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Tanzania, for women 15–49 years old] comes to 8,245,449, or just over eight million women."[43]

- ^ Jasmine Abdulcadir (Swiss Medical Weekly, 2011): "In the case of infibulation, the urethral opening and part of the vaginal opening are covered by the scar. In a virgin infibulated woman the small opening left for the menstrual fluid and the urine is not wider than 2–3 mm; in sexually active women and after the delivery the vaginal opening is wider but the urethral orifice is often still covered by the scar."[8]

- ^ Elizabeth Kelly, Paula J. Adams Hillard (Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2005): "Women commonly undergo reinfibulation after a vaginal delivery. In addition to reinfibulation, many women in Sudan undergo a second type of re-suturing called El-Adel, which is performed to recreate the size of the vaginal orifice to be similar to the size created at the time of primary infibulation. Two small cuts are made around the vaginal orifice to expose new tissues to suture, and then sutures are placed to tighten the vaginal orifice and perineum. This procedure, also called re-circumcision, is primarily performed after vaginal delivery, but can also be performed before marriage, after cesarean section, after divorce, and sometimes even in elderly women as a preparation before death."[29]

- ^ WHO 2005: "In some areas (e.g. parts of Congo and mainland Tanzania), FGM entails the pulling of the labia minora and/or clitoris over a period of about 2 to 3 weeks. The procedure is initiated by an old woman designated for this task, who puts sticks of a special type in place to hold the stretched genital parts so that they do not revert back to their original size. The girl is instructed to pull her genitalia every day, to stretch them further, and to put additional sticks in to hold the stretched parts from time to time. This pulling procedure is repeated daily for a period of about two weeks, and usually, no more than four sticks are used to hold the stretched parts, as further pulling and stretching would make the genital parts unacceptably long."[55]

- ^ Берг и Андерланд (Норвежский центр знаний о службах здравоохранения, 2014): «Имеются свидетельства занижения сведений об осложнениях. Однако результаты показывают, что процедура КОЖПО/К однозначно вызывает немедленные, а обычно несколько, осложнения со здоровьем во время Процедура FGM/C и краткосрочный период. Каждое из наиболее распространенных осложнений возникало более чем у одной из каждых десяти девушек и женщин, подвергшихся FGM/C. Участники этих исследований имели типы FGM/C от I до IV, то есть немедленные. такие осложнения, как кровотечение и отек, возникают при всех формах КОЖПО/К. Даже КОЖПО/К типа I и типа IV «надрез», формы КОЖПО/С с наименьшей анатомической степенью, вызывают немедленные осложнения. Результаты подтверждают, что множественные. КОЖПО/К могут привести к немедленным и весьма серьезным осложнениям. Эти результаты следует рассматривать в свете долгосрочных осложнений, таких как акушерские и гинекологические проблемы, а также защиты прав человека». [60]

- ^ ЮНИСЕФ, 2013: «Процент девочек и женщин репродуктивного возраста (от 15 до 49 лет), подвергшихся любой форме КОЖПО/К, является первым показателем, используемым для того, чтобы показать, насколько широко распространена эта практика в конкретной стране… Второй показатель Национальная распространенность измеряет масштабы проведения обрезания среди дочерей в возрасте от 0 до 14 лет, о которых сообщают их матери. Данные о распространенности среди девочек отражают их текущий, а не окончательный статус КЖПО/К, поскольку многие из них, возможно, не достигли обычного возраста для проведения обрезания. на момент проведения опроса они считаются неразрезанными, но все еще рискуют подвергнуться этой процедуре. Поэтому статистику по девочкам в возрасте до 15 лет следует интерпретировать с высокой степенью осторожности..." [88] Дополнительная сложность в оценке распространенности среди девочек заключается в том, что в странах, проводящих кампании против КОЖПО, женщины могут не сообщать о том, что их дочери были обрезаны. [90]

- ^ ЮНИСЕФ, 2014: «Если до 2050 года эта практика не сократится, число девочек, подвергающихся обрезанию каждый год, вырастет с 3,6 миллиона в 2013 году до 6,6 миллиона в 2050 году. Но если темпы прогресса, достигнутые за последние 30 лет, сохраняется, число девочек, страдающих ежегодно, увеличится с 3,6 миллиона сегодня до 4,1 миллиона в 2050 году. «В любом сценарии общее число сокращенных девочек и женщин будет продолжать увеличиваться из-за роста населения. Если ничего не предпринять, число пострадавших девочек и женщин вырастет со 133 миллионов сегодня до 325 миллионов в 2050 году. достигнутый на данный момент прогресс устойчив, их число вырастет со 133 миллионов до 196 миллионов в 2050 году, и почти 130 миллионов девочек будут избавлены от этого серьезного посягательства на их права человека». [95]

- ^ Gerry Mackie (1996): "Virtually every ethnography and report states that FGM is defended and transmitted by the women."[112]Fadwa El Guindi (2007): "Female circumcision belongs to the women's world, and ordinarily men know little about it or how it is performed—a fact that is widely confirmed in ethnographic studies."[113]Bettina Shell-Duncan (2008): "[T]he fact that the decision to perform FGC is often firmly in the control of women weakens the claim of gender discrimination."[114]

Bettina Shell-Duncan (2015): "[W]hen you talk to people on the ground, you also hear people talking about the idea that it's women's business. As in, it's for women to decide this. If we look at the data across Africa, the support for the practice is stronger among women than among men."[115]

- ^ Gerry Mackie, 1996: "Footbinding and infibulation correspond as follows. Both customs are nearly universal where practised; they are persistent and are practised even by those who oppose them. Both control sexual access to females and ensure female chastity and fidelity. Both are necessary for proper marriage and family honor. Both are believed to be sanctioned by tradition. Both are said to be ethnic markers, and distinct ethnic minorities may lack the practices. Both seem to have a past of contagious diffusion. Both are exaggerated over time and both increase with status. Both are supported and transmitted by women, are performed on girls about six to eight years old, and are generally not initiation rites. Both are believed to promote health and fertility. Both are defined as aesthetically pleasing compared with the natural alternative. Both are said to properly exaggerate the complementarity of the sexes, and both are claimed to make intercourse more pleasurable for the male."[117]

- ^ The eight countries are Djibouti, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Mauritania, Senegal, Somalia, and the Gambia.[136]

- ^ Gerry Mackie, 1996: "FGM is pre-Islamic but was exaggerated by its intersection with the Islamic modesty code of family honor, female purity, virginity, chastity, fidelity, and seclusion."[139]

- ^ Gerry Mackie, 1996: "The Koran is silent on FGM, but several hadith (sayings attributed to Mohammed) recommend attenuating the practice for the woman's sake, praise it as noble but not commanded, or advise that female converts refrain from mutilation because even if pleasing to the husband it is painful to the wife."[141]

- ^ Maggie Michael, Associated Press, 2007: "[Egypt's] supreme religious authorities stressed that Islam is against female circumcision. It's prohibited, prohibited, prohibited," Grand Mufti Ali Gomaa said on the privately-owned al-Mahwar network."[145]

- ^ Samuel Waje Kunhiyop, 2008: "Nowhere in all of Scripture or in any of recorded church history is there even a hint that women were to be circumcised."[148]

- ^ The countries were Benin, Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, Chad, Cote d'Ivoire, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Sudan, and Tanzania.[151]

- ^ Knight adds that Egyptologists are uncomfortable with the translation to uncircumcised, because there is no information about what constituted the circumcised state.[154]

- ^ "Sometime after this, Nephoris [Tathemis's mother] defrauded me, being anxious that it was time for Tathemis to be circumcised, as is the custom among the Egyptians. She asked that I give her 1,300 drachmae ... to clothe her ... and to provide her with a marriage dowry ... if she didn't do each of these or if she did not circumcise Tathemis in the month of Mecheir, year 18 [163 BCE], she would repay me 2,400 drachmae on the spot."[157]

- ^ Strabo, Geographica, c. 25 BCE: "One of the customs most zealously observed among the Aegyptians is this, that they rear every child that is born, and circumcise [περιτέμνειν, peritemnein] the males, and excise [ektemnein] the females, as is also customary among the Jews, who are also Aegyptians in origin, as I have already stated in my account of them."[160]

Book XVI, chapter 4, 16.4.9: "And then to the Harbour of Antiphilus, and, above this, to the Creophagi [meat-eaters], of whom the males have their sexual glands mutilated [kolobos] and the women are excised [ektemnein] in the Jewish fashion."

- ^ Knight 2001 writes that there is one extant reference from antiquity, from Xanthus of Lydia in the fifth century BCE, that may allude to FGM outside Egypt. Xanthus wrote, in a history of Lydia: "The Lydians arrived at such a state of delicacy that they were even the first to 'castrate' their women." Knight argues that the "castration", which is not described, may have kept women youthful, in the sense of allowing the Lydian king to have intercourse with them without pregnancy. Knight concludes that it may have been a reference to sterilization, not FGM.[161]

- ^ Knight adds that the attribution to Galen is suspect.[163]

- ^ UNICEF 2013 calls the Egyptian Doctors' Society opposition the "first known campaign" against FGM.[191]

- ^ Некоторые штаты Судана запретили КОЖПО в 2008–2009 годах, но с 2013 года [update], не было национального законодательства. [193] Распространенность КОЖПО среди женщин в возрасте 14–49 лет в 2014 году составила 89 процентов. [194]

- ^ Например, в отчете ЮНИСЕФ за 2013 год указано, что Мавритания приняла закон против КОЖПО, но (с того года) его проведение было запрещено только в государственных учреждениях или медицинским персоналом. [211] Ниже приведены страны, в которых КОЖПО является обычным явлением и в которых действуют ограничения по состоянию на 2013 год. Звездочка обозначает запрет: Бенин (2003 г.), Буркина-Фасо (1996 г.*), Центральноафриканская Республика (1966 г., поправки 1996 г.), Чад (2003 г.), Кот-д'Ивуар (1998 г.), Джибути (1995 г., поправки 2009 г. *), Египет (2008 г. *), Эритрея (2007 г.*), Эфиопия (2004 г. *), Гана (1994 г., поправки 2007 г.), Гвинея (1965 г., поправки 2000 г. *), Гвинея-Бисау (2011 г. *), Ирак (2011 г. *), Кения (2001 г., поправки 2011 г. *) ), Мавритания (2005 г.), Нигер (2003 г.), Нигерия (2015*), Сенегал (1999*), Сомали (2012*), Судан, некоторые штаты (2008–2009), Танзания (1998), Того (1998), Уганда (2010*), Йемен (2001*). [212] [213]

- ^ Пятнадцать стран присоединились к программе: Джибути, Египет, Эфиопия, Гвинея, Гвинея-Бисау, Кения, Сенегал и Судан в 2008 году; Буркина-Фасо, Гамбия, Уганда и Сомали в 2009 г.; и Эритрея, Мали и Мавритания в 2011 году. [218]

- ^ Предыдущая оценка Центров по контролю заболеваний составляла 168 000 по состоянию на 1990 год. [226]

- ↑ Судья вынес свое решение по делу против членов общины Давуди Бора в Мичигане, обвиняемых в проведении КОЖПО. [230]

- ↑ В 2010 году Американская академия педиатрии предположила, что «прокалывание или надрез кожи клитора» является безвредной процедурой, которая могла бы удовлетворить родителей, но отозвала это заявление после жалоб. [232]