Ливерпуль

Ливерпуль | |

|---|---|

| Девиз(ы): | |

Ливерпуль показан в Мерсисайде | |

| Координаты: 53 ° 24'34 "N 2 ° 58'43" W / 53,4094 ° N 2,9785 ° W | |

| Суверенное государство | Великобритания |

| Страна | Англия |

| Область | Северо-Запад |

| Церемониальное графство | Мерсисайд |

| Район города | Ливерпуль |

| Основан | 1207 |

| Статус города | 1880 |

| Столичный район | 1 апреля 1974 г. |

| Административный штаб | Здание Кунарда |

| Районы города | Список |

| Правительство | |

| • Тип | Столичный район |

| • Тело | Городской совет Ливерпуля |

| • Исполнительный | Лидер и кабинет |

| • Контроль | Труд |

| • Лидер | Лиам Робинсон ( L ) |

| • Лорд-мэр | Мэри Расмуссен |

| • депутаты | 5 депутатов |

| Область | |

| • Общий | 52 квадратных миль (134 км ) 2 ) |

| • Земля | 43 квадратных миль (112 км ) 2 ) |

| • Классифицировать | 185-й |

| Население (2022) [3] | |

| • Общий | 496,770 |

| • Классифицировать | 12-е |

| • Плотность | 11 500/кв. миль (4442/км) 2 ) |

| Демонимы |

|

| Этническая принадлежность ( 2021 ) | |

| • Этнические группы | Список |

| Религия (2021) | |

| • Религия | Список |

| Часовой пояс | UTC+0 ( GMT ) |

| • Лето ( летнее время ) | UTC+1 ( летнее время ) |

| Область почтового индекса | |

| Телефонный код | 0151 |

| Код ISO 3166 | ГБ ЖИЗНЬ |

| Код ГСС | E08000012 |

| Веб-сайт | Ливерпуль |

Ливерпуль — собор , портовый город столичный район Мерсисайда и , Англия. В 2022 году его население составляло 496 770 человек. [3] Город расположен на восточной стороне устья Мерси , рядом с Ирландским морем , и находится примерно в 178 милях (286 км) от Лондона . Ливерпуль — пятый по величине город Соединенного Королевства, крупнейший населенный пункт Мерсисайда и часть городского округа Ливерпуль , объединенного органа власти с населением более 1,5 миллиона человек. [5]

Ливерпуль был основан как район в 1207 году в графстве Ланкашир и стал важным городом в конце семнадцатого века, когда порт в соседнем Честере начал заиливать. Порт Ливерпуля стал активно участвовать в работорговле в Атлантическом океане : первый невольничий корабль покинул город в 1699 году. Порт также импортировал большую часть хлопка, необходимого соседним текстильным фабрикам Ланкашира , и стал основным отправным пунктом для англичан и Ирландские эмигранты в Северной Америке. В 19 веке Ливерпуль приобрел мировое экономическое значение, находясь в авангарде промышленной революции , и построил первую междугородную железную дорогу , первую складскую систему из негорючих материалов ( Королевский Альберт-док ) и новаторскую надземную электрическую железную дорогу ; ему был предоставлен статус города в 1880 году. Как и многие британские города, город вступил в период упадка в середине 20-го века, хотя он пережил возрождение после того, как был выбран культурной столицей Европы в 2008 году. [6] [7]

Ливерпуля Современная экономика диверсифицирована. В нем есть такие сектора, как туризм, культура , морское судоходство , гостиничный бизнес , здравоохранение , науки о жизни , передовое производство, креатив и цифровые технологии . [8] [9] [10] Город занимает второе место в Великобритании по количеству национальных музеев , памятников архитектуры и парков , больше только в Лондоне. [11] Город часто используется в качестве места съемок благодаря своей архитектуре, и в 2022 году он вошел в пятерку городов Великобритании, наиболее посещаемых иностранными туристами. [12] Это единственный в Англии , внесенный в список ЮНЕСКО город музыки , и здесь появилось множество выдающихся музыкальных коллективов , в первую очередь «Битлз» , а музыканты из города выпустили больше хит-синглов номер один в Великобритании, чем где-либо еще в мире. [13] Он также выпустил много актеров , художников , поэтов и писателей . В спорте город известен как дом Премьер-лиги футбольных команд «Эвертон» и «Ливерпуль» . Порт города был четвертым по величине в Великобритании в 2023 году. [14] Здесь расположены штаб-квартиры и офисы многочисленных судоходных и грузовых линий.

Жителей Ливерпуля часто называют «скаузерами» в отношении скаузера , местного тушеного мяса, которое стало популярным среди моряков в городе, и это название также применяется к отчетливому местному акценту . В городе проживает культурно и этнически разнообразное население, и исторически он привлекал множество иммигрантов, особенно из Ирландии, Скандинавии и Уэльса. Это дом самой ранней черной общины в Великобритании , самой ранней китайской общины в Европе и первой мечети в Англии. [15]

Топонимия

Название происходит от древнеанглийского lifer , что означает густую или мутную воду, и pōl , что означает заводь или ручей, и впервые упоминается около 1190 года как Liuerpul . [16] [17] Согласно Кембриджскому словарю топонимов английского языка , «первоначально речь шла о бассейне или приливном ручье, который теперь заполнился, и в который впадают два ручья». [18] Место, обозначенное как Лейрпол в юридической записи 1418 года, также может относиться к Ливерпулю. [19] Было предложено другое происхождение названия, в том числе «элверпул», ссылка на большое количество угрей в Мерси . [20] Прилагательное «ливерпульский» впервые было записано в 1833 году. [17]

Хотя древнеанглийское происхождение названия «Ливерпуль» не подлежит сомнению, иногда высказываются утверждения, что название «Ливерпуль» имеет валлийское происхождение, но это необоснованно. Валлийское название Ливерпуля — Lerpwl , от бывшего английского местного названия Leerpool. Это сокращение формы «Леверпул» с потерей интервокального [v] (встречается в других английских именах и словах, например, Давентри (Нортгемптоншир) > Данетри, никогда не преуспевающий > неуспевающий).

В 19 веке в некоторых валлийских публикациях использовалось название « Lle'r Pwll » («(место) бассейна»), реинтерпретация слова «Lerpwl» , вероятно, полагая, что « Lle'r Pwll » было оригиналом. форма.

Другое название, широко известное даже сегодня, — Ллинллейфиад , опять-таки чеканка 19-го века. « Ллин » — это пул, но « леефиада » не имеет очевидного значения. Дж. Мелвилл Ричардс (1910–1973), пионер научной топонимики в Уэльсе, в «Топонимах Северного Уэльса», [21] не пытается объяснить это, за исключением того, что отмечает, что « леефиада » используется как валлийский эквивалент слова «Печень».

Производная форма ученого заимствования в валлийский язык ( * llaf ) латинского lāma (трясина, болото, болото) для образования « lleifiad » возможна, но не доказана.

История

Ранняя история

В средние века Ливерпуль существовал сначала как сельскохозяйственные угодья в пределах Западной Дерби-Сотни. [22] прежде чем превратиться в небольшой городок фермеров, рыбаков и торговцев и тактическую военную базу короля Англии Джона . Город планировался с собственным замком , хотя из-за вспышек болезней и его подчинения близлежащему римскому порту Честер рост и процветание города застопорились до конца 17 - начала 18 веков. Существенный рост произошел в середине-конце 18 века, когда город стал наиболее активно вовлеченным европейским портом в работорговлю в Атлантическом океане . [23]

короля Джона от В патенте на письма 1207 года было объявлено об основании городка Ливерпуль (тогда называвшегося Люэрпул ). Нет никаких свидетельств того, что это место ранее было центром какой-либо торговли. Создание городка, вероятно, произошло из-за того, что король Джон решил, что это будет удобное место для погрузки людей и припасов для его ирландских кампаний , в частности ирландской кампании Джона 1209 года . [24] [25] Говорят, что первоначальный план улиц Ливерпуля был разработан королем Джоном примерно в то же время, когда ему была предоставлена королевская хартия , сделавшая его городком. Первоначальные семь улиц были расположены в форме двойного креста: Бэнк-стрит (ныне Уотер-стрит ), Касл-стрит , Чапел -стрит , Дейл-стрит , Джагглер-стрит (ныне Хай-стрит ), Мур-стрит (ныне Титебарн-стрит ) и Уайтакр-стрит. (ныне Олд-Холл-стрит ). [25] Ливерпульский замок был построен до 1235 года, он просуществовал до тех пор, пока не был снесен в 1720-х годах. [26] К середине 16-го века население все еще составляло около 600 человек, хотя, вероятно, оно упало с более раннего пика в 1000 человек из-за медленной торговли и последствий чумы . [27] [28] [29]

В 17 веке наблюдался медленный прогресс в торговле и росте населения. Бои за контроль над городом велись во время гражданской войны в Англии , включая короткую осаду в 1644 году. [30] В 1699 году, в том же году, когда его первый зарегистрированный невольничий корабль « Ливерпульский торговец » отправился в Африку, [31] Ливерпуль стал приходом согласно парламентскому акту . Но, возможно, закон 1695 года, реформировавший совет Ливерпуля, имел большее значение для его последующего развития. [32] Со времен Римской империи близлежащий город Честер на реке Ди был главным портом региона на Ирландском море . Однако, когда Ди начал заиливаться , морская торговля из Честера становилась все более затруднительной и переместилась в сторону Ливерпуля на соседней реке Мерси . Первый из доков Ливерпуля был построен в 1715 году, и система доков постепенно превратилась в большую взаимосвязанную систему. [33]

Поскольку торговля из Вест-Индии , включая сахар, превзошла торговлю с Ирландией и Европой, а река Ди продолжала заиливать, Ливерпуль начал расти все быстрее. Первый коммерческий мокрый док был построен в Ливерпуле в 1715 году. [34] [35] Существенные доходы от работорговли и табака помогли городу процветать и быстро расти, хотя несколько видных местных мужчин, в том числе Уильям Рэтбоун , Уильям Роско и Эдвард Раштон , были в авангарде местного аболиционистского движения . [36]

19 век

В 19 веке Ливерпуль приобрел мировое экономическое значение. В городе открылись новаторские, первые в мире технологические и гражданские объекты для обслуживания растущего населения, вызванного притоком этнических и религиозных общин со всего мира.

К началу XIX века через Ливерпуль проходил большой объем торговли, и строительство крупных зданий отражало это богатство. В 1830 году Ливерпуль и Манчестер стали первыми городами, имеющими междугороднее железнодорожное сообщение через Ливерпульско-Манчестерскую железную дорогу . Население продолжало быстро расти, особенно в 1840-х годах, когда ирландские мигранты начали прибывать сотнями тысяч в результате Великого голода . Хотя многие ирландцы поселились в это время в городе, большой процент также эмигрировал в Соединенные Штаты или переехал в промышленные центры Ланкашира , Йоркшира и Мидлендса . [37]

В своей поэтической иллюстрации «Ливерпуль» (1832 г.), воспевающей мировую торговлю города, Летиция Элизабет Лэндон конкретно обращается к экспедиции Макгрегора Лэрда на реку Нигер, которая в то время продолжалась. [38] Это картина Сэмюэля Остина , Ливерпуль, из Мерси . [39]

Великобритания была крупным рынком для хлопка, импортируемого с глубокого юга Соединенных Штатов, который питал текстильную промышленность страны. Учитывая решающее место, которое хлопок занимал в экономике города, во время Гражданской войны в США Ливерпуль был, по словам историка Свена Беккерта , «самым проконфедеративным местом в мире за пределами самой Конфедерации ». [40] Ливерпульские купцы помогали вывозить хлопок из портов, блокированных ВМС Союза , строили военные корабли для Конфедерации и поставляли хлопок.Юг с военной техникой и кредитами. [41]

Во время войны ВМС Конфедерации корабль CSS «Алабама » был построен в Биркенхеде на реке Мерси, и там же сдался CSS «Шенандоа» (это была окончательная капитуляция в конце войны). Город также был центром закупок Конфедерацией военной техники, включая оружие и боеприпасы, униформу и военно-морские припасы, которые контрабандой переправлялись британскими участниками блокады на юг . [42]

В течение некоторых периодов XIX века богатство Ливерпуля превышало богатство Лондона. [43] и Ливерпульская таможня вносила самый крупный вклад в британское казначейство . [44] Ливерпуль был единственным британским городом, когда-либо имевшим собственный офис в Уайтхолле . [45] В этом столетии через Ливерпуль проходило не менее 40% всей мировой торговли. [46]

В начале 19 века Ливерпуль играл важную роль в в Антарктике промысле тюленей , в знак признания этого пляж Ливерпуля на Южных Шетландских островах назван в честь города. [47]

Еще в 1851 году город называли «Нью-Йорком Европы». [48] В конце 19 - начале 20 века Ливерпуль привлекал иммигрантов со всей Европы. Это привело к строительству в городе множества религиозных зданий для новых этнических и религиозных групп, многие из которых используются до сих пор. Немецкая церковь Ливерпуля , Греческая православная церковь Святого Николая , Церковь Густава Адольфа и синагога Принсес-Роуд были основаны в 1800-х годах для обслуживания растущей немецкой, греческой, нордической и еврейской общин Ливерпуля соответственно. Одна из старейших сохранившихся церквей Ливерпуля, Римско-католическая церковь Святого Петра , в последние годы своего существования служила польской общине местом поклонения.

20 век

В 20-м веке устоявшийся статус Ливерпуля как мировой экономической державы был поставлен под сомнение. Стратегическое расположение международного морского порта сделало его особенно уязвимым в двух мировых войнах . Экономическая депрессия (как в Соединенном Королевстве, так и во всем мире), изменение структуры жилищного строительства и контейнеризация в морской отрасли способствовали снижению производительности и процветания города. Несмотря на это, влияние города на мировую популярную культуру было превосходным, и к концу века продолжающийся процесс обновления города проложил путь к новому современному городу 21 века.

Период после Великой войны был отмечен социальными волнениями, поскольку общество боролось с огромными военными потерями молодых людей, а также пыталось реинтегрировать ветеранов в гражданскую жизнь и экономику. Безработица и низкий уровень жизни постигли многих бывших военнослужащих. Организация профсоюзов и забастовки происходили во многих местах, включая в Ливерпуле забастовку городской полиции . Многочисленные колониальные солдаты и моряки из Африки и Индии, служившие в британских вооруженных силах , поселились в Ливерпуле и других портовых городах. В июне 1919 года они подверглись нападению белых во время расовых беспорядков; Среди жителей порта были шведские иммигранты , и обеим группам приходилось конкурировать с коренными жителями Ливерпуля за рабочие места и жилье. В этот период расовые беспорядки имели место и в других портовых городах. [49]

Закон о жилье 1919 года привел к массовому строительству муниципального жилья по всему Ливерпулю в 1920-х и 1930-х годах. В 1920-х и 1930-х годах до 15% населения города (около 140 000 человек) было переселено из центральной части города в специально построенные пригородные жилые комплексы с меньшей плотностью населения, исходя из убеждения, что это улучшит их уровень жизни. , хотя общие преимущества были оспорены. [50] [51] В это время также было построено множество частных домов. Во время Великой депрессии начала 1930-х годов безработица в городе достигла пика - около 30%. Великобритании Ливерпуль был местом расположения первого провинциального аэропорта , работавшего с 1930 года.

Во время Второй мировой войны решающее стратегическое значение Ливерпуля признавалось и Гитлером , и Черчиллем . Город подвергся сильным бомбардировкам со стороны немцев, уступив лишь Лондону. [52] Решающая битва за Атлантику была спланирована, проведена и выиграна Ливерпулем. [53]

Люфтваффе , убив 2500 человек и причинив совершило 80 воздушных налетов на Мерсисайд ущерб почти половине домов в столичном регионе. После войны последовала значительная реконструкция, включая огромные жилые комплексы и док Сифорт , крупнейший доковый проект в Великобритании. С 1952 года Ливерпуль является побратимом немецкого Кёльна , города, который также пострадал от серьёзных бомбардировок с воздуха во время войны. В 1950-х и 1960-х годах большая часть немедленной реконструкции, проводившейся в центре города, оказалась крайне непопулярной. Исторические части города, пережившие немецкие бомбардировки, сильно пострадали во время обновления города. Утверждалось, что так называемый «План Шенкленда» 1960-х годов, названный в честь градостроителя Грэма Шенкленда , привел к нарушению городского планирования и обширным схемам строительства дорог, которые опустошили и разделили центральные районы города. конкретная бруталистская архитектура Предметом осуждения стала , скомпрометированные идеи, неудачные проекты и грандиозные замыслы, которые так и не были реализованы. Историк Рафаэль Сэмюэл назвал Грэма Шенкленда «мясником Ливерпуля». [54] [55] [56] [57]

Значительная чернокожая община Вест-Индии существовала в городе с первых двух десятилетий 20-го века. Как и большинство британских и промышленных городов, Ливерпуль стал домом для значительного числа иммигрантов из Содружества , начиная с Первой мировой войны с колониальными солдатами и моряками, служившими в этом районе. После Второй мировой войны прибыло больше иммигрантов, в основном поселившихся в старых городских районах, таких как Токстет , где жилье было дешевле. В 2011 году черное население Ливерпуля составляло 1,90%. По данным переписи 2021 года 5,2% назвали себя чернокожими африканцами, выходцами из Карибского бассейна, смешанными белыми и черными африканцами, смешанными белыми и карибскими или «другими черными». [58] [59]

В 1960-х годах Ливерпуль был центром звучания « Merseybeat », которое стало синонимом «Битлз» и других ливерпульских рок-групп. Под влиянием американского ритм-н-блюза и рок-музыки они, в свою очередь, сильно повлияли на американскую музыку. The Beatles стали всемирно известными в начале 1960-х годов и вместе выступали по всему миру ; они были и продолжают оставаться самой коммерчески успешной и музыкально влиятельной группой в истории популярности. Их соучредитель, певец и композитор Джон Леннон был убит в Нью-Йорке в 1980 году. В 2002 году в его честь был переименован аэропорт Ливерпуля , став первым британским аэропортом, названным в честь человека. [60] [61]

Ливерпуль, ранее входивший в состав Ланкашира и являвшийся городским округом с 1889 года, в 1974 году стал столичным районом в рамках вновь созданного столичного графства Мерсисайд . С середины 1970-х годов доки Ливерпуля и традиционные обрабатывающие отрасли пришли в упадок из-за реструктуризации судоходства и тяжелой промышленности, что приводит к массовым потерям рабочих мест. Появление контейнеризации означало, что городские доки в значительной степени устарели, а докеры остались без работы. К началу 1980-х годов уровень безработицы в Ливерпуле был одним из самых высоких в Великобритании. [62] к январю 1982 года этот показатель составлял 17%, хотя это было примерно вдвое меньше уровня безработицы, который затронул город во время Великой депрессии около 50 лет назад. [63] В этот период Ливерпуль стал центром ожесточенной левой оппозиции центральному правительству в Лондоне. [64] Ливерпуль в 1980-е годы называли британским «шоковым городом». Когда-то второй город Британской империи , соперничавший со столицей по мировому значению, Ливерпуль рухнул в свой «надир» в глубинах постколониальной , постиндустриальной Британии. [65] [66] В конце 20 века экономика Ливерпуля начала восстанавливаться. В конце 1980-х годов был открыт обновленный Альберт-Док , который стал катализатором дальнейшего возрождения. [67] В середине 1990-х годов темпы роста города были выше, чем в среднем по стране. В конце 20-го века «Ливерпуль» сосредоточился на возрождении, и этот процесс продолжается и сегодня.

21 век

Продолжающееся восстановление в сочетании с проведением мероприятий международного значения помогло превратить Ливерпуль в один из самых посещаемых и ориентированных на туристов городов Соединенного Королевства. Руководители города сосредоточены на долгосрочных стратегиях роста населения и экономики города, в то время как национальное правительство изучает постоянный потенциал передачи полномочий в городе.

В 2002 году королева Елизавета II и принц Филипп, герцог Эдинбургский посетили Ливерпуль, чтобы отметить золотой юбилей . Выступая перед аудиторией в ратуше Ливерпуля , королева признала Ливерпуль «одной из самых самобытных и энергичных частей Соединенного Королевства» и отдала дань уважения «крупным оркестрам, музеям и галереям мирового уровня». Она также признала заявку Ливерпуля на звание культурной столицы Европы . [68] [69] Чтобы отпраздновать золотой юбилей Елизаветы II в 2002 году, природоохранная благотворительная организация Plantlife организовала конкурс по выбору окружных цветов ; морской падуб был окончательным выбором Ливерпуля. Инициатива была разработана, чтобы подчеркнуть растущую угрозу видам цветов Великобритании, а также спросить общественность о том, какие цветы лучше всего представляют их графство. [70]

Благодаря популярности рок-групп 1960-х годов, таких как «Битлз» , а также городским художественным галереям мирового класса, музеям и достопримечательностям, туризм и культура стали важным фактором экономики Ливерпуля.

В 2004 году застройщик Grosvenor запустил проект Paradise Project , стоимостью 920 миллионов фунтов стерлингов, на базе Paradise Street . Это привело к одному из самых значительных изменений в центре Ливерпуля со времен послевоенной реконструкции. переименованный в Liverpool One Центр, , открылся в мае 2008 года.

В 2007 году прошли мероприятия и торжества в честь 800-летия основания района Ливерпуль. Ливерпуль был объявлен объединенной культурной столицей Европы в 2008 году. В рамках празднования было воздвигнуто Принцессу , большого механического паука высотой 20 метров и весом 37 тонн, который олицетворял «восемь ног» Ливерпуля: честь, историю, музыку, Мерси, порты, управление, солнечный свет и культура. Во время торжества Принцесса бродила по улицам города и завершила свое выступление входом в туннель Квинсуэй .

Возрождение , возглавляемое многомиллиардным проектом Liverpool ONE, продолжалось на протяжении 2010-х годов. Некоторые из наиболее значительных проектов реконструкции включали новые здания в Коммерческом районе , Королевском доке , острове Манн , вокруг Лайм-стрит , Балтийском треугольнике , RopeWalks и Edge Lane . [71] [72] [73]

Изменения в управлении Ливерпулем произошли в 2014 году. Местные власти городского совета Ливерпуля решили объединить свою власть и ресурсы с окружающими районами путем формирования Объединенного управления городского региона Ливерпуля в форме передачи полномочий . Благодаря децентрализованному бюджету, предоставленному центральным правительством , власти теперь контролируют и инвестируют в важнейшие стратегические дела по всему региону Ливерпуля , включая крупные проекты восстановления. Власти вместе с самим городским советом Ливерпуля приступили к реализации долгосрочных планов по росту населения и экономики города. [74] [75] [76] [77]

К 2020-м годам регенерация города продолжится. Liverpool Waters , многофункциональный комплекс в заброшенных северных доках города, был признан одним из крупнейших мегапроектов в истории Великобритании. Новый стадион «Эвертона» в доке Брэмли-Мур на момент строительства считался крупнейшим проектом частного сектора в Соединенном Королевстве. [78] [79]

В городе регулярно проходят крупные мероприятия, деловые и политические конференции, которые составляют важную часть экономики. В июне 2014 года премьер-министр Дэвид Кэмерон открыл Международный фестиваль бизнеса в Ливерпуле, крупнейшее в мире деловое мероприятие 2014 года. [80] и крупнейший в Великобритании со времен Фестиваля Британии в 1951 году. [81] Начиная с середины 2010-х годов, Лейбористская партия неоднократно выбирала Ливерпуль для проведения своей ежегодной конференции Лейбористской партии . Ливерпуль принимал конкурс песни «Евровидение-2023» .

Изобретения и инновации

Ливерпуль был центром изобретений и инноваций. Железные дороги, трансатлантические пароходы , муниципальные трамваи, [82] и электрички были впервые использованы в Ливерпуле как виды общественного транспорта. В 1829 и 1836 годах под Ливерпулем были построены первые в мире железнодорожные туннели ( Wapping Tunnel ). курсировало первое в мире регулярное пассажирское вертолетное сообщение С 1950 по 1951 год между Ливерпулем и Кардиффом . [83]

Первая школа для слепых , [84] Механический институт , [85] Средняя школа для девочек, [86] [87] муниципальный дом, [88] и суд по делам несовершеннолетних [89] все были основаны в Ливерпуле. Благотворительные организации, такие как RSPCA , [90] НСПЦК , [91] Возрастная озабоченность , [92] Relate и Бюро консультаций граждан [93] все сложилось из работы в городе.

Первая спасательная станция, общественная баня и прачечная, [94] санитарный акт, [95] медицинский работник ( Уильям Генри Дункан ), участковая медсестра, расчистка трущоб , [96] специально построенная машина скорой помощи, [97] рентгенологическая медицинская диагностика, [98] школа тропической медицины ( Ливерпульская школа тропической медицины ), моторизованная муниципальная пожарная машина, [99] бесплатное школьное питание, [100] центр онкологических исследований, [101] и зоонозов научно-исследовательский центр [102] все зародилось в Ливерпуле. Первая британская Нобелевская премия была присуждена в 1902 году Рональду Россу , профессору Школы тропической медицины, первой школы такого рода в мире. [103] Ортопедическая хирургия была впервые разработана в Ливерпуле Хью Оуэном Томасом . [104] и современные медицинские анестетики Томаса Сесила Грея .

Первая в мире интегрированная канализационная система была построена в Ливерпуле Джеймсом Ньюлендсом , назначенным в 1847 году первым городским инженером Великобритании. [105] [106] Ливерпуль также основал первую в Великобритании страховщиков. Ассоциацию [107] и первый институт бухгалтеров . Первые финансовые деривативы (фьючерсы на хлопок) в западном мире торговались на Ливерпульской хлопковой бирже в конце 1700-х годов. [108]

В сфере искусства Ливерпуль был домом для первой библиотеки ( Лицей ), общества атенеума ( Ливерпульский Атенеум ), центра искусств ( Bluecoat Chambers ), [109] и центр консервации общественного искусства ( Национальный центр консервации ). [110] Здесь также находится старейший сохранившийся классический оркестр Великобритании ( Королевский филармонический оркестр Ливерпуля ). [111] и репертуарный театр ( Liverpool Playhouse ). [112]

В 1864 году Питер Эллис построил первое в мире с навесными стенами офисное здание и железным каркасом — Oriel Chambers , которое было прототипом небоскреба. Первым специально построенным универмагом в Великобритании был Compton House , построенный в 1867 году для розничного торговца JR Jeffrey. [113] В то время это был самый большой магазин в мире. [114]

Между 1862 и 1867 годами в Ливерпуле проводился ежегодный Большой Олимпийский фестиваль . Эти игры, разработанные Джоном Халли и Чарльзом Пьером Мелли , были первыми, которые носили полностью любительский характер и международный характер. [115] [116] Программа первой современной Олимпиады в Афинах 1896 года была практически идентична программе Олимпийских игр в Ливерпуле. [117] В 1865 году Халли стал соучредителем Национальной олимпийской ассоциации в Ливерпуле, предшественницы Британской олимпийской ассоциации . Ее устав лег в основу Олимпийской хартии .

Концепция, разработанная розничным предпринимателем Дэвидом Льюисом , — первый рождественский грот, открытый в Льюиса в Ливерпуле в 1879 году. универмаге [118] Сэр Альфред Льюис Джонс , судовладелец, привез бананы в Великобританию через доки Ливерпуля в 1884 году. [119] Железная дорога Мерси , открытая в 1886 году, включала первый в мире туннель под приливным устьем. [120] и первые в мире станции метро глубокого уровня ( железнодорожная станция Liverpool James Street ).

В 1889 году городской инженер Джон Александр Броди изобрел сетку для футбольных ворот. Он также был пионером в использовании сборных домов. [122] и курировал строительство первой в Великобритании кольцевой дороги ( А5058 ) и междугородного шоссе ( Ист-Ланкашир-роуд ), а также туннеля Куинсуэй, соединяющего Ливерпуль и Биркенхед . Описываемый как «восьмое чудо света» на момент постройки, он был самым длинным подводным туннелем в мире на протяжении 24 лет.

В 1897 году братья Люмьер сняли фильм «Ливерпуль». [123] включая то, что считается первым в мире следящим выстрелом , [124] взято с Ливерпульской надземной железной дороги , первой в мире надземной электрифицированной железной дороги. Надземная железная дорога была первой железной дорогой в мире, которая использовала электропоезда , автоматическую сигнализацию и установила эскалатор.

Изобретатель из Ливерпуля Фрэнк Хорнби был провидцем в разработке и производстве игрушек, создав три самые популярные линии игрушек в 20 веке: Meccano , Hornby Model Railways и Dinky Toys . Британское межпланетное общество , основанное в Ливерпуле в 1933 году Филиппом Эллаби Клитором, является старейшей в мире существующей организацией, занимающейся продвижением космических полетов . Его журнал, «Журнал Британского межпланетного общества» , является старейшим астронавтическим изданием в мире. [125]

В 1999 году Ливерпуль стал первым городом за пределами Лондона, награжденным голубыми мемориальными досками от организации English Heritage в знак признания «значительного вклада, внесенного его сыновьями и дочерьми во всех сферах жизни». [126]

Правительство

Для целей местного самоуправления город Ливерпуль классифицируется как столичный район . Столичный район расположен как в графстве Мерсисайд , так и в городском регионе Ливерпуля . Каждая из этих географических зон рассматривается как административная территория, к каждой из которой применяются разные уровни местного управления.

Городской совет Ливерпуля является руководящим органом исключительно города Ливерпуль и выполняет функции, стандартные для английского унитарного органа власти . оставляет Объединенное управление городского региона Ливерпуля за собой основные стратегические полномочия в отношении таких вопросов, как транспорт, экономическое развитие и восстановление города, а также пяти прилегающих районов городского региона Ливерпуля. Объединенный орган власти обладает компетенцией в отношении территорий, переданных национальным правительством и специфичных для данного региона. [127]

Тем не менее, помимо этих двух структур, из местного управления есть несколько исключений. Ливерпуль находился под управлением Совета графства Мерсисайд в период с 1974 по 1986 год, и некоторые остаточные аспекты организации, относящиеся к этому времени, сохранились. Когда Совет графства был распущен в 1986 году, большинство гражданских функций было передано городскому совету Ливерпуля. Однако некоторые органы власти, такие как полиция , пожарно-спасательная служба , продолжают управляться на уровне округа. Таким образом, графство Мерсисайд продолжает существовать как административная территория только для нескольких ограниченных служб, в то время как возможности и возможности Объединенного управления региона города Ливерпуль со временем развиваются. [128]

Город также избирает пять членов парламента (депутатов) в Вестминстерский парламент , все от лейбористской партии по состоянию на всеобщие выборы 2024 года.

Лидер городского совета и кабинет министров

Городской совет Ливерпуля действует в соответствии с конституцией, состоящей из 85 членов городского совета, которые избираются прямым голосованием избирателей Ливерпуля каждые 4 года и представляют множество различных политических партий . Члены городского совета принимают решения о местных услугах для жителей города.

На каждых выборах политическая партия, получившая большинство из 85 мест в совете, возглавляет совет в течение следующих 4 лет. Местный лидер этой партии берет на себя роль лидера городского совета, который затем возглавляет кабинет из 9 советников, на которых возложены конкретные обязанности, известные как «портфели».

Действующим лидером городского совета Ливерпуля является советник Лиам Робинсон , который представляет Лейбористскую партию , которая получила значительное большинство на местных выборах 2023 года . [130]

Решения городского совета и проверка его деятельности осуществляются рядом различных комитетов и комиссий, в том числе обзорных и контрольных комитетов, контрольных комиссий, регулирующих комитетов и других комитетов. Повседневное управление советом осуществляется управленческой командой, в которую входят генеральный директор, а также несколько директоров и старших должностных лиц. Команда управления работает с Кабинетом министров и советниками для определения стратегического направления и приоритетов, таких как бюджет и план города. [131] [132]

Выборы в городской совет Ливерпуля

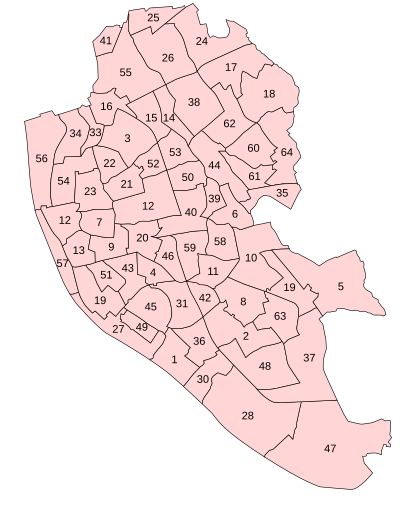

Каждые 4 года город избирает 85 членов совета местных советов из 64 округов . [133] которые в алфавитном порядке:

Во время выборов в городской совет Ливерпуля в 2023 году Лейбористская партия укрепила свой контроль над городским советом Ливерпуля после предыдущих выборов. Из общего числа 85 мест в городском совете, выставленных на выборы, Лейбористская партия получила 61 место (53,13% от общего числа голосов избирателей), Либерал-демократы получили 15 мест (21,61% голосов), Партия зеленых получила 3 места (9,76). % голосов), Независимые от сообщества Ливерпуля получили 3 места (4,64% голосов), а Либеральная партия получила оставшиеся 3 места (3,21% голосов). Консервативная партия , политическая партия, находящаяся у власти в национальном правительстве , не имела представительства в городском совете Ливерпуля. Только 27,27% имеющих право голоса избирателей Ливерпуля пришли на голосование. [134]

На протяжении большей части XIX и начала XX веков Ливерпуль был муниципальным оплотом ториизма . Однако поддержка Консервативной партии в последнее время была одной из самых низких в любой части Британии, особенно после монетаристской экономической политики бывшего премьер-министра Маргарет Тэтчер . После всеобщих выборов 1979 года многие утверждали, что ее победа способствовала давнему высокому уровню безработицы и упадку города. [135] Ливерпуль — один из ключевых оплотов Лейбористской партии; однако город также пережил тяжелые времена при лейбористском правительстве. Особенно зимой недовольства (конец 1978 - начало 1979 года), когда Ливерпуль, как и остальная часть Соединенного Королевства, пострадал от забастовок в государственном секторе, но также и когда он пережил особенно унизительное несчастье, когда могильщики объявили забастовку, оставив мертвых непогребенными. в течение длительных периодов времени. [136]

Критика и улучшение городского совета

В последние годы городской совет Ливерпуля начал обширную программу улучшений, призванную обеспечить эффективное использование властями денег налогоплательщиков и стимулировать рост бизнеса и инвестиций в город. Grosvenor Group , компания по недвижимости, ответственная за Liverpool One , оценила изменения как «возможность для смелого мышления в Ливерпуле». [137]

В 2021 году крайне критическая правительственная проверка и последующий отчет городского совета Ливерпуля (именуемый отчетом Звонящего) выявили множество недостатков в городском совете Ливерпуля. Государственный секретарь по делам жилищного строительства, сообществ и местного самоуправления Роберт Дженрик направил правительственных комиссаров для наблюдения за шоссейными дорогами городского совета, восстановлением, управлением собственностью, управлением и принятием финансовых решений. Власти были вынуждены принять трехлетний план улучшений, согласно которому вся структура совета будет пересмотрена. В результате вмешательства к местным выборам в Соединенном Королевстве в 2023 году произошли серьезные структурные изменения в городском совете , которые были названы «самыми непредсказуемыми [выборами] в истории города». Число избирательных округов в городе было увеличено вдвое с 30 до 64, а общее число членов городского совета, выставляемых на выборы, сократилось с 90 до 85. В будущем совет также будет переходить на «всеобщие» выборы каждые четыре года, в результате чего каждый член городского совета будет иметь право на переизбрание одновременно. Роль избранный мэр города также был упразднен, и Совет вернулся к прежнему лидера и кабинета министров стилю руководства . Результаты выборов рассматривались не только как проверка того, как широкая общественность отреагирует на вмешательство правительства в дела города, но и как проверка того, как широкая общественность отреагирует на вмешательство правительства в дела города. Правительство премьер-министра Риши Сунака в целом. [138] [139] [140] [141]

Член совета Лиам Робинсон стал новым лидером городского совета Ливерпуля на выборах в городской совет 2023 года. Была создана Ливерпульская консультативная группа по стратегическому будущему под председательством мэра городского региона Ливерпуля Стива Ротерама , в состав которой вошли несколько высокопоставленных деятелей, имеющих опыт работы в местном самоуправлении . Перед комиссией была поставлена задача определить долгосрочное будущее совета, не ограничиваясь мерами государственного вмешательства, а также дать рекомендации относительно планов и приоритетов, которым городу следует следовать. [142]

В феврале 2008 года городской совет Ливерпуля был признан советом с наихудшими показателями в стране, получившим всего одну звезду (классифицированным как неадекватный). Основная причина низкого рейтинга связана с плохим обращением совета с деньгами налогоплательщиков, в том числе с накоплением дефицита в 20 миллионов фунтов стерлингов, когда город носил титул культурной столицы Европы . [143] В апреле 2024 года Управление местного самоуправления опубликовало рейтинг местных органов власти, поставив городской совет Ливерпуля на 317-е место из 318 возможных. [144]

Лорд-мэр Ливерпуля

Лорд -мэр Ливерпуля — древняя церемониальная должность. Члены городского совета Ливерпуля (а не широкая общественность) ежегодно избирают лорд-мэра, который затем избирается сроком на один год. Лорд-мэр считается «первым гражданином» и избирается для того, чтобы представлять город на общественных мероприятиях и мероприятиях, продвигать его в более широком мире, поддерживать местные благотворительные организации и общественные группы, посещать религиозные мероприятия, встречаться с делегатами из городов-побратимов Ливерпуля , председательствовать заседания совета и присвоение почетных граждан и ассоциаций . [145]

Мэр метрополитена Ливерпульского городского округа

Город Ливерпуль — один из шести округов местного самоуправления, входящих в состав городского региона Ливерпуля . Мэр метрополитена городского региона Ливерпуля раз в четыре года посещает жителей этих шести районов и курирует Объединенное управление городского региона Ливерпуля . Объединенная администрация является высшим административным органом местного управления городским регионом, и ей поручено принимать важные стратегические решения по таким вопросам, как транспорт и инвестиции, экономическое развитие, занятость и профессиональная подготовка, туризм, культура, жилье и физическая инфраструктура. Нынешний мэр метро - Стив Ротерам.

Парламентские округа и депутаты

Ливерпуль включен в пять парламентских округов , через которые избираются депутаты, представляющие город в Вестминстере : Ливерпуль Риверсайд , Ливерпуль Уолтон , Ливерпуль Уэвертри , Ливерпуль Вест Дерби и Гарстон и Хейлвуд . [146] На последних всеобщих выборах все были выиграны Лейбористской партией, представленной Ким Джонсоном , Дэном Карденом , Полой Баркер и Яном Бирном соответственно. [147] Из-за изменений границ перед выборами 2010 года округ Ливерпуль-Гарстон был объединен с большей частью Ноусли-Саут , чтобы сформировать Гарстон и Хейлвуд трансграничный округ . На последних выборах 2024 года это место получила Мария Игл от Лейбористской партии. [147]

География

Среда

Ливерпуль называют «самым великолепным местом среди всех английских городов». [148] В 53 ° 24'0 "N 2 ° 59'0" W / 53,40000 ° N 2,98333 ° W (53,4, -2,98), в 176 милях (283 километрах) к северо-западу от Лондона, в Ливерпульском заливе Ирландского моря . Город Ливерпуль построен на гряде холмов из песчаника, поднимающихся на высоту около 230 футов ( 70 м) над уровнем моря на холме Эвертон, который представляет собой южную границу прибрежной равнины Западного Ланкашира .

Устье Мерси отделяет Ливерпуль от полуострова Уиррал . Границы Ливерпуля примыкают к Бутлу , Кросби и Магхаллу на юге Сефтона на севере, а также Киркби , Хайтону , Прескоту и Хейлвуду в Ноусли на востоке.

Климат

| Ливерпуль | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Климатическая карта ( пояснение ) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

В Ливерпуле умеренный морской климат ( Köppen : Cfb ), как и на большей части Британских островов, с относительно мягким летом, прохладной зимой и осадками, распределяющимися довольно равномерно в течение года. Записи об осадках и температуре велись в Бидстон-Хилле с 1867 года, но записи атмосферного давления датируются как минимум 1846 годом. [149] Бидстон закрылся в 2002 году, но у метеорологического бюро также есть метеостанция в Кросби . С момента начала регистрации в 1867 году температура колебалась от -17,6 ° C (0,3 ° F) 21 декабря 2010 г. до 34,5 ° C (94,1 ° F) 2 августа 1990 г., хотя в аэропорту Ливерпуля была зафиксирована температура 35,0 ° C (95,0 °). F) 19 июля 2006 г. [150]

Наименьшее количество солнечного света за всю историю наблюдений составило 16,5 часов в декабре 1927 года, тогда как наибольшее — 314,5 часов в июле 2013 года. [151] [152]

Активность торнадо или образование воронкообразных облаков очень редки в районе Ливерпуля и его окрестностях, а образующиеся торнадо обычно слабы. Последние торнадо или воронкообразные облака в Мерсисайде наблюдались в 1998 и 2014 годах. [153] [154]

В период 1981–2010 гг. Кросби регистрировал в среднем 32,8 дней заморозков в году, что является низким показателем для Соединенного Королевства. [155] Зимой довольно часто бывает снег, хотя сильный снегопад бывает редко. Снег обычно выпадает в период с ноября по март, но иногда может выпасть раньше или позже. В последнее время самый ранний снегопад выпал 1 октября 2008 года. [156] а последнее произошло 15 мая 2012 года. [157] Хотя исторически самый ранний снегопад выпал 10 сентября 1908 года. [158] и последний раз 2 июня 1975 г. [159]

Осадки, хотя и небольшие, являются довольно распространенным явлением в Ливерпуле: самым влажным месяцем за всю историю наблюдений был август 1956 года, когда было зарегистрировано 221,2 мм (8,71 дюйма) дождя, а самым засушливым - февраль 1932 года - 0,9 мм (0,035 дюйма). [160] Самым засушливым годом за всю историю наблюдений был 1991 год с выпадением 480,5 мм (18,92 дюйма) осадков, а самым влажным был 1872 год с выпадением 1159,9 мм (45,67 дюйма). [161]

| Климатические данные для Кросби [а] Идентификатор ВМО : 03316; координаты 53 ° 29'50 "N 3 ° 03'28" W / 53,49721 ° N 3,05767 ° W ; высота: 30 м (98 футов); 1991–2020 гг. Нормальные, [б] [с] крайности 1867 – настоящее время [д] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Месяц | Ян | февраль | Мар | апрель | Может | июнь | июль | август | Сентябрь | октябрь | ноябрь | декабрь | Год |

| Рекордно высокий °C (°F) | 15.1 (59.2) | 18.9 (66.0) | 21.2 (70.2) | 24.6 (76.3) | 28.2 (82.8) | 30.7 (87.3) | 35.5 (95.9) | 34.5 (94.1) | 30.4 (86.7) | 25.9 (78.6) | 18.7 (65.7) | 15.8 (60.4) | 35.5 (95.9) |

| Среднесуточный максимум °C (°F) | 7.5 (45.5) | 7.9 (46.2) | 9.9 (49.8) | 12.8 (55.0) | 15.9 (60.6) | 18.4 (65.1) | 20.0 (68.0) | 19.7 (67.5) | 17.7 (63.9) | 14.2 (57.6) | 10.5 (50.9) | 8.0 (46.4) | 13.6 (56.5) |

| Среднесуточное значение °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) | 5.3 (41.5) | 6.9 (44.4) | 9.2 (48.6) | 12.1 (53.8) | 14.9 (58.8) | 16.7 (62.1) | 16.6 (61.9) | 14.5 (58.1) | 11.4 (52.5) | 8.1 (46.6) | 5.6 (42.1) | 10.5 (50.9) |

| Среднесуточный минимум °C (°F) | 2.8 (37.0) | 2.7 (36.9) | 3.9 (39.0) | 5.6 (42.1) | 8.3 (46.9) | 11.3 (52.3) | 13.5 (56.3) | 13.5 (56.3) | 11.2 (52.2) | 8.5 (47.3) | 5.7 (42.3) | 3.1 (37.6) | 7.5 (45.5) |

| Рекордно низкий °C (°F) | −13.1 (8.4) | −11.3 (11.7) | −8.6 (16.5) | −5.6 (21.9) | −1.7 (28.9) | 1.0 (33.8) | 5.0 (41.0) | 3.1 (37.6) | 1.7 (35.1) | −2.9 (26.8) | −7.5 (18.5) | −17.6 (0.3) | −17.6 (0.3) |

| Среднее количество осадков , мм (дюймы) | 69.4 (2.73) | 57.1 (2.25) | 53.3 (2.10) | 49.8 (1.96) | 52.5 (2.07) | 64.4 (2.54) | 65.5 (2.58) | 72.1 (2.84) | 76.6 (3.02) | 89.7 (3.53) | 82.2 (3.24) | 91.9 (3.62) | 824.3 (32.45) |

| Среднее количество осадков в дни (≥ 1,0 мм) | 13.8 | 11.5 | 11.3 | 10.0 | 9.8 | 10.4 | 11.0 | 12.2 | 11.8 | 14.4 | 15.5 | 15.4 | 146.9 |

| Среднее количество снежных дней | 6 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 22 |

| Средняя относительная влажность (%) | 85.1 | 83.5 | 80.7 | 77.9 | 76.6 | 78.9 | 79.0 | 80.1 | 81.9 | 84.6 | 85.1 | 85.6 | 80.8 |

| Среднемесячное количество солнечных часов | 56.0 | 70.3 | 105.1 | 154.2 | 207.0 | 191.5 | 197.0 | 175.2 | 132.7 | 97.3 | 65.8 | 46.8 | 1,499.1 |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 8.2 | 9.9 | 11.9 | 14.1 | 15.9 | 16.9 | 16.4 | 14.7 | 12.7 | 10.5 | 8.6 | 7.6 | 12.3 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Source 1: Met Office[162] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Oceanography Centre[163] WeatherAtlas[164] CEDA Archive[165] | |||||||||||||

- ^ Weather station is located 7 miles (11 km) from the Liverpool city centre.

- ^ Sunshine hours were recorded at the Bidston Observatory from the period of 1971–2000.

- ^ Humidity was recorded at the Bidston Observatory for the period of 1975–June 2002. The period Jul–Sep 1992 has no record, with Jan–May 2001 reporting unreliabe data.

- ^ From 1867–2002, extremes were recorded at the Bidston Observatory in Wirral. Since 1983, extremes were recorded at Crosby, Sefton.

Human

Suburbs and districts

Suburbs and districts of Liverpool include:

- Aigburth

- Allerton

- Anfield

- Belle Vale

- Broadgreen

- Canning

- Childwall

- Chinatown

- City Centre

- Clubmoor

- Croxteth

- Dingle

- Dovecot

- Edge Hill

- Everton

- Fairfield

- Fazakerley

- Garston

- Gateacre

- Gillmoss

- Grassendale

- Hunt's Cross

- Kensington

- Kirkdale

- Knotty Ash

- Mossley Hill

- Netherley

- Norris Green

- Oglet

- Old Swan

- Orrell Park

- St Michael's Hamlet

- Speke

- Stoneycroft

- Toxteth

- Tuebrook

- Vauxhall

- Walton

- Wavertree

- West Derby

- Woolton

Green Liverpool

| UK core cities – Population and population density (Number of usual residents per km2) (2021)[166][167][168][169] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Core City | Population | Population density | |

| Birmingham | 1,144,900 | 4275.4 | |

| Leeds | 812,000 | 1471.7 | |

| Glasgow | 635,130 | 3637 | |

| Sheffield | 556,500 | 1512.5 | |

| Manchester | 552,000 | 4772.7 | |

| Liverpool | 486,100 | 4346.1 | |

| Bristol | 472,400 | 4308.1 | |

| Cardiff | 362,400 | 2571.3 | |

| Belfast | 345,418 | 2597.8 | |

| Nottingham | 323,700 | 4337.6 | |

| Newcastle | 300,200 | 2646.1 | |

In 2010, Liverpool City Council and the Primary Care Trust commissioned the Mersey Forest to complete "A Green Infrastructure Strategy" for the city.[170]

Green belt

Liverpool is a core urban element of a green belt region that extends into the wider surrounding counties, which is in place to reduce urban sprawl, prevent the towns in the conurbation from further convergence, protect the identity of outlying communities, encourage brownfield reuse, and preserve nearby countryside. This is achieved by restricting inappropriate development within the designated areas and imposing stricter conditions on permitted building.[171]

Due to being already highly built up, the city contains limited portions of protected green belt area within greenfield throughout the borough at Fazakerley, Croxteth Hall and country park and Craven Wood, Woodfields Park and nearby golf courses in Netherley, small greenfield tracts east of the Speke area by the St Ambrose primary school, and the small hamlet of Oglet and the surrounding area south of Liverpool Airport.[172]

The green belt was first drawn up in 1983 under Merseyside County Council[173] and the size in the city amounts to 530 hectares (5.3 km2; 2.0 sq mi).[174]

Demonyms

Scouser

Since the mid-20th century, Scouser has become the predominant demonym for the inhabitants of Liverpool, and is strongly associated with the Scouse accent and dialect of the city.[175] The Scouse accent is described as progressively diverging from the Lancastrian accent in the late 19th century.[176][177][178][179][180]

The etymology of Scouser is derived from the traditional dish Scouse brought to the area by sailors travelling through Liverpool's port.[181][180][182]

Other demonyms

Prior to the establishment of Scouser as there have been a number of different terms used to refer to inhabitants of Liverpool of varying popularity and longevity:

- Liverpoldon (17th century)[183]

- Leeirpooltonian (17th Century)[180]

- Liverpolitan (19th century)[184]

- Liverpudlian (19th century to present)[185]

Professor Tony Crowley argues that up until the 1950s, inhabitants of Liverpool were generally referred to by a number of demonyms. He argues that there was a debate in the mid 20th century between the two rival terms of 'Liverpolitan' and 'Liverpudlian'. The debate surrounded the lexicology of these terms and their connotations of social class.[182][186]

Professor John Belchem suggests that a series of other nicknames such as 'Dick Liver', 'Dicky Sam' and 'whacker' were used, but gradually fell out of use. Belchem and Philip Boland suggest that comedic radio presenters and entertainers brought the Liverpool identity to a national audience, which in turn encouraged locals to be gradually more known as 'scousers'. By the time that Frank Shaw's My Liverpool, a Celebration of 'Scousetown' was published in 1971, Belchem argues that 'Scouser' had firmly become the dominant demonym.[175][187][188]

Demography

Population

| Historical population of Liverpool (numbers vary by source) Sources:[189][190][191][192][193][194][195][196][197][198][199] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Population | Notes | |

| 1207 | Borough of Liverpool founded by John, King of England. The economy was focused on agricultural and food processing, grain mills and warehouses until the 16th century. | ||

| 1272 | 840 | ||

| 14th century | 1,000 – 1,200 | Population roughly 1,000 in 1300. Because Liverpool was a port, it was more at risk from the spread of disease. Townspeople lived partly by farming and fishing. Some were craftsmen or tradesmen such as bakers, brewers, butchers, blacksmiths, and carpenters. A watermill existed to ground grain into flour for the townspeople's bread, and there was a windmill. Black Death wiped out whole families and bodies were buried in a mass grave at St Nicholas's churchyard. | |

| 16th century | Ireland was still Liverpool's main trading partner. In 1540, a writer said: "Irish merchants come much hither as to a good harbor". He also said there was "good merchandise at Liverpool and much Irish yarn, that Manchester men buy there". Skins and hides were still imported from Ireland. Exports from Liverpool included coal, woolen cloth, knives and leather goods. There were still many fishermen in Liverpool. In the mid 16th century, the town was under the control of the country gentry and trade was slow. The population dropped to below 600, in part due to deaths in the 1558 plague when a third of the townspeople died. Further plague outbreaks took place in 1609, 1647 and 1650 which led to static or retrogressive population levels. The town was regarded as subordinate to Chester until the 1650s. | ||

| 1600 | <2,000 | English troops bound for rebellions in Ireland settled in the 16th and early 17th centuries. | |

| 1626 | Charles I of England issued new Charter for the town. Trade with other cities, Ireland, Isle of Man, France and Spain increased. Fish and wool was exported to the Continent, and wines, iron and other commodities imported. In the following decades, merchants invested in Liverpool and its importance grew. Regular shipping began to America and West Indies. Liverpool was controlled by the Crown, the Molyneux and Stanley families. | ||

| 1642 | 2,500 | Liverpool overtook Chester in exporting coal and salt in early 17th century, especially to Ireland. | |

| 1644 | During English Civil War, Prince Rupert led a royalist army to capture Liverpool. He described the town as a "mere crow's nest which a parcel of boys could take". He stormed Liverpool Castle in the 'Siege of Liverpool' with considerable slaughter. | ||

| 1647 | Liverpool was made a free and independent port, no longer subject to Chester. | ||

| 1648 | First recorded cargo from America landed at Liverpool. | ||

| Late 17th century | Liverpool grew rapidly with the growth of English colonies in North America and West Indies. Liverpool was well placed to trade across Atlantic Ocean. The writer Celia Fiennes visited Liverpool and said: "Liverpool is built on the River Mersey. It is mostly newly built, of brick and stone after the London fashion. The original (town) was a few fishermen's houses. It has now grown into a large, fine town. It is but one parish with one church though there be 24 streets in it, there is indeed a little chapel and there are a great many dissenters in the town (Protestants who did not belong to the Church of England). It's a very rich trading town, the houses are of brick and stone, built high and even so that a street looks very handsome. The streets are well paved. There is an abundance of persons who are well dressed and fashionable. The streets are fair and long. It's London in miniature as much as I ever saw anything. There is a very pretty exchange. It stands on 8 pillars, over which is a very handsome Town Hall." | ||

| 1700 | 5,714 | First recorded Liverpool slave ship, the 'Liverpool Merchant', sold a cargo of 220 slaves in Barbados. In the early 1700s, the writer Daniel Defoe said: "Liverpool has an opulent, flourishing and increasing trade to Virginia and English colonies in America. They trade around the whole island (of Great Britain), send ships to Norway, to Hamburg, and to the Baltic as also to Holland and Flanders (roughly modern Belgium)." Welsh people in search of work and opportunity made up a large amount of population in early 18th century. | |

| 1715 | World's first wet dock opened in Liverpool, symbolising a new era in the town's growth, the starting point of the 18th century boom in Liverpool's fortunes. | ||

| 1720s | Liverpool Castle demolished (built in the 1230s) | ||

| 1750 | 20,000 | ||

| 1795 | Influx of Irish, Welsh, Scandinavian and Dutch communities grew the town rapidly. Most of the population were not native to Liverpool. | ||

| 1797 | 77,708 | ||

| 1801 | 77,000 – 85,000 | ||

| 1811 | 94,376 | ||

| 1821 | 118,972 | ||

| 1831 | 165,175 | ||

| 1835 | Boundary of Liverpool expanded to include Everton, Kirkdale and parts of Toxteth and West Derby. Liverpool was second only to London in importance. Poor, overcrowded and unsanitary living conditions led to disease and epidemics of cholera in 1830s to 1860s. | ||

| 1841 | 286,487 | ||

| 1851 | 375,955 | At the height of the potato famine, Liverpool's Irish born population peaked to about 83,000–90,000. 43,000 were settled in the area around the docks. More Irish people lived in Liverpool than the majority of Irish towns. 40% of the world's trade was passing through Liverpool's docks. | |

| 1861 | 413,000 – 462,749 | ||

| 1871 | 493,405 – 539,248 | ||

| 1880 | Liverpool officially became a city. | ||

| 1881 | 552,508 – 648,616 | ||

| 1891 | 617,032 – 644,243 | ||

| 1895 | Boundary of Liverpool expanded to include Wavertree, Walton, and parts of Toxteth and West Derby. | ||

| 1901 | 684,958 – 711,030 | ||

| 1902 | Boundary of Liverpool expanded to include Garston, Aigburth, Cressington and Grassendale. | ||

| 1904 | Boundary of Liverpool expanded to include Fazakerley. | ||

| 1907 | 746,144 | ||

| 1911 | 746,421 – 766,044 | ||

| 1913 | Boundary of Liverpool expanded to include Woolton and Gateacre. | ||

| 1921 | 805,046 – 821,000 | ||

| 1931 | 855,688 | ||

| 1937 | 867,000 | The highest recorded population of Liverpool city proper. | |

| 1941 | 806,271 | Liverpool's population fell in the following decades, largely due to the new towns movement and the British government's policy to displace thousands of people from major British cities (including Central Liverpool) to various new towns such as Kirkby, Skelmersdale, Runcorn and Warrington. Liverpool's downward population trend continued until the early 21st century as people escaped rising unemployment and increasing deprivation. | |

| 1951 | 765,641 – 768,337 | ||

| 1961 | 683,133 – 737,637 | ||

| 1971 | 595,252 – 607,454 | ||

| 1981 | 492,164 – 503,726 | High levels of unemployment led to significant numbers of people leaving the city. | |

| 1991 | 448,629 – 480,196 | ||

| 2001 | 439,428 – 439,476 | Liverpool's population steadily increased again, partly attributed to a rise in students, student accommodation, young professionals, and increased job opportunities through urban regeneration. | |

| 2011 | 466,415 | ||

| 2021 | 486,100 | ||

The city

The city of Liverpool is at the core of a much larger and more populous metropolitan area, however, at the most recent UK Census in 2021, the area governed by Liverpool City Council had a population of 486,100, a 4.2% increase from the previous Census in 2011. This figure increased to 500,500 people by 2022, according to data from Liverpool City Council.

Taking in to account how local government is organised within the cities and metropolitan areas of England, the city of Liverpool was the fifth largest of England's 'core cities' and had the second overall highest population density of those, by 2021.[200][201][202]

The population of the city has steadily risen since the 2001 Census. As well as having a growing population, the population density also grew at the 2021 Census compared to the previous Census. This makes Liverpool the second most densely populated local authority in North West England, after Manchester.

The population of the city is comparatively younger than that of England as a whole. Family life in the city is also growing at odds with the North West England region as a whole: At the 2021 Census, the percentage of households including a couple without children increased in Liverpool, but fell across the North West. The percentage of people aged 16 years and over (excluding full-time students) who were employed also increased in Liverpool compared to the overall North West region where it fell.

The 2021 Census also showed that Liverpool's ethnic and international population was growing. The number of residents in the city born outside of England has increased since the previous Census, while the number of residents who did not identify with any national identity associated with the UK has also increased at a faster rate than England as a whole. The overall share of the city's population who identified as Asian and Black increased, while the percentage who identified as white decreased in the city compared with previous Census.[203]

It has been argued that the city can claim to have one of the strongest Irish heritages in the United Kingdom, with as many as 75 percent (estimated) of Liverpool's population with some form of Irish ancestry.[204]

The growing population of Liverpool in the 21st century reverses a trend which took place between the 1930s and 2001, when the population of the city proper effectively halved.

At the 1931 United Kingdom census, Liverpool's population reached an all-time high of 846,302. Following this peak, in response to central government policy, the Council authority of Liverpool then built and owned large several 'new town' council estates in the suburbs within Liverpool's metropolitan area. Tens of thousands of people were systematically relocated to new housing in areas such as Halton, Knowsley, St Helens, Sefton, Wirral, Cheshire West and Chester, West Lancashire, Warrington and as far as North Wales.

Such a mass relocation and population loss during this time was common practice for many British cities, including London and Manchester, In contrast, satellite towns such as Kirkby, Skelmersdale and Runcorn saw a corresponding rise in their populations (Kirkby being the fastest growing town in Britain during the 1960s).[205][206][207][208]

Urban and metropolitan area

Liverpool is typically grouped with the wider Merseyside (plus Halton) area for the purpose of defining its metropolitan footprint, and there are several methodologies. Sometimes, this metropolitan area is broadened to encompass urban settlements in the neighbouring counties of Lancashire and Cheshire.[209][210]

The Office for National Statistics in the United Kingdom uses the international standardised International Territorial Levels (ITLs) to divide up the economic territory of the UK. This enables the ONS to calculate regional and local statistics and data. The ONS uses a series of codes to identify these areas. In order of hierarchy from largest area to smallest area, Liverpool is part of the following regions:[211][212][213]

ITL 1 region

North West England (code TLD)

At the 2021 Census, the ITL 1 region of North West England had a usual resident population of 7,417,300.[214]

ITL 2 region

Merseyside (code TLD7)

The ITL 2 region of Merseyside is defined as the area comprising East Merseyside (TLD71) plus Liverpool (TLD72), Sefton (TLD73) and Wirral (TLD74).

At the 2021 Census, the population of this area was as follows:[215]

East Merseyside (TLD71):

- Halton = 128,200

- Knowsley = 154,500

- St. Helens = 183,200

Liverpool (TLD72) = 486,100

Sefton (TLD73) = 279,300

Wirral (TLD74) = 320,200

Therefore, the total population of the ITL 2 Merseyside region was 1,551,500 based on the 2021 Census.

ITL 3 region

The smallest ITL 3 area classed as Liverpool (code TLD72), therefore, had a population of 486,100 at the 2021 Census.

Other definitions

At the 2021 Census, the ONS used a refreshed concept of built-up areas (BUAs) based on the physical built environment, using satellite imagery to recognise developed land, such as cities, towns, and villages. This allows the ONS to investigate economic and social statistics based on actual settlements where most people live. Data from the 2021 Census is not directly comparable with 2011 Census data due to this revised methodology. Using the population figures of BUAs at the 2021 Census (excluding London), Liverpool Built-up Area is the third largest in England with some 506,565 usual residents (behind only Birmingham and Leeds). Liverpool's built-up area is, therefore, larger than the major English cities of Bristol, Manchester, Newcastle upon Tyne, Nottingham and Sheffield.[216]

Excluding London, the Liverpool City Region was the 4th largest combined authority area in England, by 2021. The population is approximately 1.6 million. The Liverpool City Region is a political and economic partnership between local authorities including Liverpool, plus the Metropolitan boroughs of Knowsley, Sefton, St Helens, Wirral and the Borough of Halton. The Liverpool City Region Combined Authority exercises strategic governance powers for the region in many areas. The economic data of the Liverpool city region is of particular policy interest to the Office for National Statistics, particularly as the British Government continuously explores the potential to negotiate increased devolved powers for each combined authority area.[217][218][219][220]

A 2011 report, Liverpool City Region – Building on its Strengths, by Lord Heseltine and Terry Leahy, stated that "what is now called Liverpool City Region has a population of around 1.5 million", but also referred to "an urban region that spreads from Wrexham and Flintshire to Chester, Warrington, West Lancashire and across to Southport", with a population of 2.3 million.[221]

In 2006, in an attempt to harmonise the series of metropolitan areas across the European Union, ESPON (now European Observation Network for Territorial Development and Cohesion) released a study defining a "Liverpool/Birkenhead Metropolitan area" with an estimated population of 2,241,000 people. The metro area comprised a functional urban area consisting of a contiguous urban sprawl, labour pool, and commuter Travel to work areas. The analysis defined this metropolitan area as Liverpool itself, combined with the surrounding areas of Birkenhead, Wigan/Ashton, Warrington, Widnes/Runcorn, Chester, Southport, Ellesmere Port, Ormskirk and Skelmersdale.[222]

Liverpool and Manchester are sometimes considered as one large polynuclear metropolitan area,[223][224][225] or megalopolis.

Ethnicity

In recent decades, Liverpool's population is becoming more multicultural. According to the 2021 census, 77% of all Liverpool residents described their ethnic group as White English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish or British. The remaining 23% were described as non-White English/British. Between 2011 and 2021, there was population growth across all ethnic groups, except 'White English/British' and 'Any Other', where there were overall losses. The number of 'Other White residents' in Liverpool also increased by almost 12,000 people, with notable increases in the 'Other Asian', 'Arab', and 'Other Mixed/Multiple' population categories. The non-White English/British population as a percentage of the total population across the 'newly organised city electoral wards' ranged from 5% in the Orrell Park ward to 69% in the Princes Park ward. 9 out of 10 Liverpool residents regarded English as their main language. The highest non-English languages in the city were Arabic (5,743 main speakers) followed by Polish (4,809 main speakers). Overall, almost 45,000 residents had a main language that was not English.[226]

According to a 2014 survey, the ten most popular surnames of Liverpool and their occurrence in the population are:[227][228]

- 1. Jones – 23,012

- 2. Smith – 16,276

- 3. Williams – 13,997

- 4. Davies – 10,149

- 5. Hughes – 9,787

- 6. Roberts – 9,571

- 7. Taylor – 8,219

- 8. Johnson – 6,715

- 9. Brown – 6,603

- 10. Murphy – 6,495

Liverpool is home to Britain's oldest Black community, dating to at least the 1730s. Some Liverpudlians can trace their black ancestry in the city back ten generations.[229] Early Black settlers in the city included seamen, the children of traders sent to be educated, and freed slaves, since slaves entering the country after 1722 were deemed free men.[230] Since the 20th century, Liverpool is also noted for its large African-Caribbean,[4] Ghanaian,[231] and Somali[232] communities, formed of more recent African-descended immigrants and their subsequent generations.

The city is also home to the oldest Chinese community in Europe; the first residents of the city's Chinatown arrived as seamen in the 19th century.[233] The traditional Chinese gateway erected in Liverpool's Chinatown is the largest gateway outside China. Liverpool also has a long-standing Filipino community. Lita Roza, a singer from Liverpool who was the first woman to achieve a UK number one hit, had Filipino ancestry.

| Ethnic breakdown in Liverpool – (UK Census 2021)[234][226] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic group | Population | Percentage | |

| White: English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish or British | 375,785 | 77.3 | |

| White: Other White | 24,162 | 5 | |

| Black, Black British, Black Welsh, Caribbean or African: African | 12,709 | 2.6 | |

| Asian, Asian British or Asian Welsh: Chinese | 8,841 | 1.8 | |

| Other ethnic group: Arab | 8,312 | 1.7 | |

| Other ethnic group: Any other ethnic group | 7,722 | 1.6 | |

| Asian, Asian British or Asian Welsh: Other Asian | 7,085 | 1.5 | |

| White: Irish | 6,826 | 1.4 | |

| Asian, Asian British or Asian Welsh: Indian | 6,251 | 1.3 | |

| Mixed or multiple ethnic groups: Other mixed or multiple ethnic groups | 4,934 | 1 | |

| Mixed or multiple ethnic groups: White and Black African | 4,157 | 0.9 | |

| Mixed or multiple ethnic groups: White and Black Caribbean | 4,127 | 0.8 | |

| Asian, Asian British or Asian Welsh: Pakistani | 3,673 | 0.8 | |

| Mixed or multiple ethnic groups: White and Asian | 3,662 | 0.8 | |

| Black, Black British, Black Welsh, Caribbean or African: Other Black | 2,762 | 0.6 | |

| Asian, Asian British or Asian Welsh: Bangladeshi | 1,917 | 0.4 | |

| Black, Black British, Black Welsh, Caribbean or African: Caribbean | 1,493 | 0.3 | |

| White: Roma | 1,169 | 0.2 | |

| White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller | 501 | 0.1 | |

The city is also known for its large Irish and Welsh populations.[235] In 1813, 10 per cent of Liverpool's population was Welsh, leading to the city becoming known as "the capital of North Wales."[235]

During, and in the decades following, the Great Irish Famine in the mid-19th century, up to two million Irish people travelled to Liverpool within one decade, with many subsequently departing for the United States.[236] By 1851, more than 20 per cent of the population of Liverpool was Irish.[237] At the 2001 Census, 1.17 per cent of the population were Welsh-born and 0.75 per cent were born in the Republic of Ireland, while 0.54 per cent were born in Northern Ireland,[238] but many more Liverpudlians are of legacy Welsh or Irish ancestry.[239]

Other contemporary ethnicities include Indian,[4] Latin American,[240] Malaysian,[241] and Yemeni[242] communities, which number several thousand each.

Religion

The thousands of migrants and sailors passing through Liverpool resulted in a religious diversity that is still apparent today. This is reflected in the equally diverse collection of religious buildings,[244] including two Christian cathedrals.

Liverpool is known to be England's 'most Catholic city', with a Catholic population much larger than in other parts of England.[245] This is mainly due to high historic Irish migration to the city and their descendants since.[246]

The parish church of Liverpool is the Anglican Our Lady and St Nicholas, colloquially known as "the sailors church", which has existed near the waterfront since 1257. It regularly plays host to Catholic masses. Other notable churches include the Greek Orthodox Church of St Nicholas (built in the Neo-Byzantine architecture style), and the Gustav Adolf Church (the Swedish Seamen's Church, reminiscent of Nordic styles).

Liverpool's wealth as a port city enabled the construction of two enormous cathedrals in the 20th century. The Anglican Cathedral, which was designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott and plays host to the annual Liverpool Shakespeare Festival, has one of the longest naves, largest organs and heaviest and highest peals of bells in the world. The Roman Catholic Metropolitan Cathedral, on Mount Pleasant next to Liverpool Science Park, was initially planned to be even larger. Of Sir Edwin Lutyens's original design, only the crypt was completed. The cathedral was eventually built to a simpler design by Sir Frederick Gibberd. While this is on a smaller scale than Lutyens' original design, it still incorporates the largest panel of stained glass in the world. The road running between the two cathedrals is called Hope Street. The cathedral has long been colloquially referred to as "Paddy's Wigwam" due to its shape.[247]

Liverpool contains several synagogues, of which the Grade I listed Moorish Revival Princes Road Synagogue is architecturally the most notable. Princes Road is widely considered to be the most magnificent of Britain's Moorish Revival synagogues and one of the finest buildings in Liverpool.[248] Liverpool has a thriving Jewish community with a further two orthodox Synagogues, one in the Allerton district of the city and a second in the Childwall district of the city where a significant Jewish community reside. A third orthodox Synagogue in the Greenbank Park area of L17 has recently closed and is a listed 1930s structure. There is also a Lubavitch Chabad House and a reform Synagogue. Liverpool has had a Jewish community since the mid-18th century. The Jewish population of Liverpool is around 5,000.[249] The Liverpool Talmudical College existed from 1914 until 1990, when its classes moved to the Childwall Synagogue.[citation needed]

Liverpool also has a Hindu community, with a Mandir on Edge Lane, Edge Hill. The Shri Radha Krishna Temple from the Hindu Cultural Organisation in Liverpool is located there.[250] Liverpool also has the Guru Nanak Sikh Gurdwara in Wavertree[251] and a Baháʼí Centre in the same area.[252]

The city had the earliest Mosque in England and possibly the UK, founded in 1887 by William Abdullah Quilliam, a lawyer who had converted to Islam who set up the Liverpool Muslim Institute in a terraced house on West Derby Road.[253] Apart from the first mosque in England which now houses a museum,[254][255] the largest and main one, Al-Rahma mosque, was also the third purpose built mosque in the United Kingdom.[256] The second largest mosque in Liverpool is the Masjid Al-Taiseer.[257] Other mosques in the city include the Bait ul Lateef Ahmadiyya Mosque,[258] Hamza Center (Community Center),[259] Islamic community centre,[260] Liverpool Mosque and Islamic Institute,[261] Liverpool Towhid Centre,[262] Masjid Annour,[263] and the Shah Jalal Mosque.[264]

Economy

City and region

The Liverpool City Region GDP in 2021 was £40.479 billion. The 6 contributing boroughs to this GDP were as follows:[268]

The City of Liverpool forms an integral part of North West England's economy, the third largest regional economy in the United Kingdom. The city is also a major contributor to the economy of Liverpool City Region, worth over £40 billion per year.[269][270][271]

The local authority area governed by Liverpool City Council accounts for 39% of the Liverpool city region's total jobs, 40% of its total GVA and 35% of its total businesses. At the local authority level, the city's GVA (balanced) at current basic prices was £14.3 billion in 2021. Its GDP at current market prices was £15.9 billion. This equates to £32,841 per head of the population.[272][273]

At the 2021 United Kingdom census, 51.1% of Liverpool's population aged 16 years and over was classed as employed, 44.2% economically inactive and 4.8% unemployed. Of those employed, the most popular industries providing the employment were human health and social work activities (18.7%), wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motor cycles (15%), education (10.8%), public administration and defence; compulsory social security (7.3%), accommodation and food service activities (6.8%), construction (6.5%), transport and storage (5.8%), manufacturing (5.5%) and professional, scientific and technical activities (5.2%).[274]

According to the ONS Business Register and Employment Survey 2021, some industries within Liverpool perform strongly compared to other local authorities in Great Britain. In terms of absolute number of jobs per industry in Great Britain's local authority areas, Liverpool features in the national top 10 for human health and social work activities; arts, entertainment and recreation; public administration and defence; compulsory social security; accommodation and food service activities and real estate activities. Liverpool features in the national top 20 for number of jobs in education; construction; wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles; transportation and storage; financial and insurance activities and professional, scientific and technical activities.[275]

In 2023, Liverpool City Council set out an economic growth plan for the city over the following 20 years. The City Council will have particular focus on economic sectors such as the visitor economy (tourism), culture, life sciences, digital and creative sectors, and advanced car manufacturing.[276]

According to the International passenger Survey, from the ONS, Liverpool was one of the top 5 most visited cities in the UK by overseas tourists in 2022. As of the same year, the city's tourist industry was worth a total of £3.5 billion annually and was part of a larger city region tourist industry worth £5 billion. A consistent calendar of major events, as well as a plethora of cultural attractions, continue to provide a significant draw for tourists. Tourism related to the Beatles is worth an estimated £100m to the Liverpool economy each year alone. Liverpool One, as well as a growing retail offer overall, has led to the city being one of the most prominent destinations for shopping in the UK. Liverpool Cruise Terminal, which is situated close to the Pier Head, enables tourists to berth in the centre of the city.[277][278][279][280][281][282][283]