Music and politics

| Part of the Politics series |

| Politics |

|---|

|

|

This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (March 2024) |

The connection between music and politics has been seen in many cultures. People in the past and present – especially politicians, politically-engaged musicians and listeners – hold that music can 'express' political ideas and ideologies, such as rejection of the establishment ('anti-establishment') or protest against state or private actions, including war through anti-war songs, but also energize national sentiments and nationalist ideologies through national anthems and patriotic songs. Because people attribute these meanings and effects to the music they consider political, music plays an important role in political campaigns, protest marches as well as state ceremonies. Much (but not all) of the music that is considered political or related to politics are songs, and many of these are topical songs, i.e. songs with topical lyrics, made for a particular time and place.[1]

Introduction

[edit]Although the use of music to mobilise political activists (and their audiences) as well as to enhance the impact of political rituals on political actors and people observing the rituals from the outside suggests that music in political contexts has an impact on participants and audiences, it is not clear how or to what extent general audiences relate to music in political contexts.[2] Songs can be used to "transport" (or more precisely: accompany) lyrics with a political message. Like any political message, the political message of a song text set to music cannot be understood independently of its contemporary political context. It may have been clear to contemporaries, but historians studying past texts (with or without music) need to reconstruct the political 'content' of the lyrics and the political contexts in order to fully understand the texts (here: lyrics). In this everyday musical discourse, participants use the term "political music" to refer to songs (i.e. a combination of music with lyrics the latter set to the music and performed vocally). The political lyrics of such songs can in turn refer to an unlimited spectrum of political subjects, i.e. articulate both state-affirming and partisan opinions, or call for concrete political action. Additionally, a distinction can be made between the use of lyrics that raise awareness and support the formation of a certain political 'consciousness' and lyrics 'as advocacy'.[3]

Participants in the informed discourse about music are aware that music itself is not political. If music listeners (including performers, composers, politicians and authorities who know music because they listen to it) "see" a relationship between certain music and politics, this is because, as a result of consequential logic, they attribute to this music the capacity to initiate certain (political) beliefs or behaviours in listeners. This relationship is also due to the specific functioning of music as a sign system, which is primarily based on similarities, structural analogies and associations that listeners construct between the music they listen to and non-musical things and phenomena.[4][5]

Furthermore, some forms of music may be deemed political by cultural association, irrespective of political content, as evidenced by the way Western pop/rock bands such as The Beatles were censored by the State in the Eastern Bloc in the 1960s and 1970s, while being embraced by younger people as symbolic of social change.[6] This points to the possibilities for discrepancy between the political intentions of musicians (if any), and reception of their music by wider society. Conversely, there is the possibility of the meaning of deliberate political content being missed by its intended audience, reasons for which could include obscurity or delivery of message, or audience indifference or antipathy.

It is difficult to predict how audiences will respond to political music, in terms of aural or even visual cues.[2] For example, Bleich and Zillmann found that "counter to expectations, highly rebellious students did not enjoy defiant rock videos more than did their less rebellious peers, nor did they consume more defiant rock music than did their peers",[2] suggesting there may be little connection between behaviour and musical taste. Pedelty and Keefe argue that "It is not clear to what extent the political messages in and around music motivate fans, become a catalyst for discussion, [or] function aesthetically".

However, in contrast they cite research that concludes, based on interpretive readings of lyrics and performances with a strong emphasis on historical contexts and links to social groups, that "given the right historical circumstances, cultural conditions, and aesthetic qualities, popular music can help bring people together to form effective political communities".[2]

Recent research has also suggested that in many schools around the world, including in modern democratic nations, music education has sometimes been used for the ideological purpose of instilling patriotism in children, and that particularly during wartime patriotic singing can escalate to inspire destructive jingoism.[7]

Plato wrote: "musical innovation is full of danger to the whole state, and ought to be prohibited. When modes of music change, the fundamental laws of the state always change with them;"[8] although this was written as a warning it can be taken as a revolutionary statement that music is much more than just melodies and harmonies but an important movement in the life of all human beings.

Folk music

[edit]American folk revival

[edit]The song "We Shall Overcome" is perhaps the best-known example of political folk music, in this case a rallying-cry for the US Civil Rights Movement. Pete Seeger was involved in the popularisation of the song, as was Joan Baez.[9] During the early part of the 20th century, poor working conditions and class struggle lead to the growth of the Labour movement and numerous songs advocating social and political reform. The most famous songwriter of the early 20th century "Wobblies" was Joe Hill. Later, from the 1940s through the 1960s, groups like the Almanac Singers and The Weavers were influential in reviving this type of socio-political music. Woody Guthrie's "This Land Is Your Land" is one of the most famous American folk songs and its lyrics exemplify Guthrie's socialistic patriotism.[10] Pete Seeger's "Where Have All the Flowers Gone?", was a popular anti-war protest song.[11] Many of these types of songs became popular during the Vietnam War era. "Blowin' in the Wind", by Bob Dylan, was a hit for Peter, Paul and Mary, and suggested that a younger generation was becoming more aware of global problems than many of the older generation.[12] In 1964, Joan Baez had a top-ten hit in the UK[13] with "There but for Fortune" (by Phil Ochs); it was a plea for the innocent victim of prejudice or inhumane policies.[14] Many topical songwriters with social and political messages emerged from the folk music revival of the 1960s, including Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Phil Ochs,[15] Tom Paxton, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Judy Collins, Arlo Guthrie, and others.

The folk revival can be considered as a political re-invention of traditional song, a development encouraged by Left-leaning folk record labels and magazines such as Sing Out! and Broadside. The revival began in the 1930s[16] and continued after World War II. Folk songs of this time gained popularity by using old hymns and songs but adapting the lyrics to fit the current social and political conditions.[17] Archivists and artists such as Alan Lomax, Lead Belly and Woody Guthrie were crucial in popularising folk music, and the latter began to be known as the Lomax singers.[18] This was an era of folk music in which some artists and their songs expressed clear political messages with the intention of swaying public opinion and recruiting support.[19] In the UK, Ewan MacColl[20] and A. L. Lloyd performed similar roles, with Lloyd as folklorist[21] and MacColl (often with Peggy Seeger) releasing dozens of albums which blended traditional songs with newer political material influenced by their Communist activism.[22][23][24]

In the later, post-war revival, folk music found a new audience with college students, partly since universities provided the organisation necessary for sustaining music trends and an expanded, impressionable audience looking to rebel against the older generation.[25] Nevertheless, the rhetoric of the United States government during the Cold War era was very powerful and in some ways overpowered the message of folk artists, such as in relation to public opinion regarding Communist-backed political causes. Various Gallup Polls that were conducted during this time suggest that Americans consistently saw Communism as a threat; for example, a 1954 poll shows that at the time 51% of Americans said that admitted Communists should be arrested, and in relation to music 64% of respondents said that if a radio singer is an admitted Communist he should be fired.[26] Leading figures in the American folk revival such as Seeger, Earl Robinson and Irwin Silber were or had been members of the Communist Party, while others such as Guthrie (who had written a column for CPUSA magazine New Masses), Lee Hays and Paul Robeson were considered fellow travellers. As McCarthyism began to dominate the United States population and government, it was more difficult for folk artists to travel and perform since folk was pushed out of mainstream music.[27] Artists were blacklisted, denounced by politicians and the media, and in the case of the 1949 Peekskill Riots, subject to mob attack.

In general, the significance of lyrics within folk music reduced as it became influenced by rock and roll.[28] However, during the popular folk revival's last phase in the early 1960s, new folk artists such as Bob Dylan and Phil Ochs began writing their own, original topical music, as opposed to mainly adapting traditional folksong.[29]

Contemporary Western folk music

[edit]Although public attention shifted to rock music from the mid-1960s, folk singers such as Joan Baez and Tom Paxton continued to address political concerns in their music and activism. Baez's 1974 Gracias a la Vida[30] album was a response to events in Chile and included versions of songs by Nueva Canción Chilena singer-songwriters Violeta Parra and Victor Jara. Paxton albums such as Outward Bound[31] and Morning Again[32] continued to highlight political issues. They were joined by other activist musicians such as Holly Near,[33] Ray Korona, Charlie King, Anne Feeney, Jim Page, Utah Phillips and more recently David Rovics.

In the UK, the Ewan MacColl tradition of political folk has been continued since the 1960s by singer-songwriters such as Roy Bailey,[34] Leon Rosselson[35] and Dick Gaughan.[36] Since the 1980s, a number of artists have blended folk protest with influences from punk and elsewhere to produce topical and political songs for a modern independent rock music audience, including Billy Bragg,[37] Attila the Stockbroker,[38] Robb Johnson,[39] Alistair Hulett,[40] The Men They Couldn't Hang,[41] TV Smith,[42] Chumbawamba[43] and more recently Chris T-T[44] and Grace Petrie.[45]

Ireland

[edit]In Ireland, the Wolfe Tones is perhaps the best known band in the folk protest/rebel music tradition, recording political material since the late 1960s including songs by Dominic Behan on albums such as Let the People Sing and Rifles of the I.R.A. Christy Moore has also recorded much political material, including on debut solo album Paddy on the Road, produced by and featuring songs by Dominic Behan, and on albums such as Ride On (including "Viva la Quinta Brigada"), Ordinary Man and various artists LP H Block to which Moore contributed "Ninety Miles from Dublin", in response to the Republican prisoners' blanket protest of the late 1970s. Earlier in the decade, The Barleycorn had held the #1 spot on the Irish charts for five weeks in 1972 with their first release "The Men Behind the Wire", about internment, with all profits going to the families of internees; Republican label R&O Records likewise released several records around this time to fundraise for the same cause, including the live album Smash Internment,[46] recorded in Long Kesh, and The Wolfhounds' recording of Paddy McGuigan's "The Boys of the Old Brigade".[47]

Chicano folk

[edit]Chicano folk music has long been a platform for political resistance and social commentary. From the 1960s and onward, Chicano musicians used their music to express their personal experiences of discrimination and oppression faced as Mexican-Americans in the United States. Political themes like the fight for immigrant rights, labor struggles, Chicano identity, and police brutality have been common subjects of their music. Through their music, Chicano musicians have also encouraged community empowerment, activism, and unity throughout the development of the Chicano Movement. Joan Baez is the most recognized figure of this movement.[48]

Folk music around the world

[edit]Folk music had a strong connection with politics internationally. Hungary, for instance, experimented with a form of liberal Communism in the late Cold War era, which was reflected in much of their folk music.[49] During the late twentieth century folk music was crucial in Hungary, Romania, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia as it allowed ethnicities to express their national identity in a time of political uncertainty and chaos.[50]

In Communist China, exclusively national music was promoted. A flautist named Zhao Songtim – a member of the Zhejiang Song-and-Dance Troupe – attended an Arts festival in 1957 in Mexico but was punished for his international outlook by being expelled from the Troupe, and from 1966 to 1970 underwent "re-education". In 1973 he returned to the Troupe but was expelled again following accusations.[51]

An example of folk music being used for conservative, rather than radical, political ends is shown by the cultural activities of Edward Lansdale, a CIA chief who dedicated part of his career to counter-insurgency in the Philippines and Vietnam. Lansdale believed that the government's best weapon against Communist rebellion was the support and trust of the population. In 1953 he arranged for the release of a campaign song widely credited with helping to elect Philippine president Ramon Magsaysay, an important US anti-communist ally.[52] In 1965, intrigued by local Vietnamese customs and traditions, and the potential use of 'applied folklore' as a technique of raising consciousness, he began to record and curate tapes of folk songs for intelligence purposes. He also urged performers such as Phạm Duy to write and perform patriotic songs to raise morale in South Vietnam. Duy had written topical songs popular during the anti-French struggle but then broke with the Communist-dominated Viet Minh.[52]

Blues and African-American music

[edit]

Blues songs have the reputation of being resigned to fate rather than fighting against misfortune, but there have been exceptions. Bessie Smith recorded protest song "Poor Man Blues" in 1928. Josh White recorded "When Am I Going to be Called a Man" in 1936 – at this time it was common for white men to address black men as "boy" – before releasing two albums of explicitly political material, 1940's Chain Gang and 1941's Southern Exposure: An Album of Jim Crow Blues.[53] Lead Belly's "Bourgeois Blues" and Big Bill Broonzy's "Black, Brown and White" (aka "Get Back") protested racism. Billie Holiday recorded and popularized the song "Strange Fruit" in 1939. Written by Communist Lewis Allan, and also recorded by Josh White and Nina Simone, it addressed Southern racism, specifically the lynching of African-Americans, and was performed as a protest song in New York venues, including Madison Square Gardens. In the post-war era, J.B. Lenoir gained a reputation for political and social comment; his record label pulled the planned release of 1954 single "Eisenhower Blues" due to its title[54] and later material protested civil rights, racism and the Vietnam War.[55] John Lee Hooker also sang 'I Don't Wanna Go to Vietnam" on 1969 album Simply the Truth.[56]

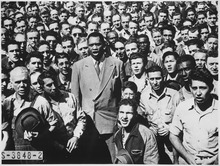

Paul Robeson, singer, actor, athlete, and civil rights activist, was investigated by the FBI and was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) for his outspoken political views. The State Department denied Robeson a passport and issued a "stop notice" at all ports, effectively confining him to the United States. In a symbolic act of defiance against the travel ban, labour unions in the U.S. and Canada organised a concert at the International Peace Arch on the border between Washington state and the Canadian province of British Columbia on May 18, 1952.[57] Robeson stood on the back of a flat bed truck on the U.S. side of the border and performed a concert for a crowd on the Canadian side, variously estimated at between 20,000 and 40,000 people. He returned to perform a second concert at the Peace Arch in 1953,[58] and over the next two years two further concerts were scheduled.

Jazz

[edit]

The development of new genres of jazz through experimentation was inherently connected to the social movements of their respective times, especially during the Civil Rights and Black Power movements of the '60's and '70's. The development of avant-garde, free, and Afrofuturist jazz was heavily connected to the desire to break free from societal norms and express the desire for a free voice. The music was also grounded in the Black Nationalists movements, and through their music, artists sought to reconnect African Americans with the traditional sounds of their ancestors.

In the development of avant-garde jazz, mainstream jazz magazines and critics (predominantly owned and operated by White people) harshly criticized the music and framed it as incoherent.[59] Unlike earlier forms of jazz, improvisation was central to avant-garde and many artists did not notate their music so that it followed a free expression of their emotions. However, as the mainstream jazz apparatus looked down upon Black musicians it praised White artists like John Cage. Cage and other musicians were heavily influenced by avant-garde sound, but their music was highly regarded by the media and hailed as genius.[60] Black musicians strived to break new grounds in music through the development of jazz to create methods of expression and autonomy. Meanwhile, structures of power within the jazz industry continuously placed pressures on this "new thing" so that it would assimilate in to normalized cultural standards, thus destroying its significance as a call for social and political change.[61]

The experimentation of certain artists, like Sun Ra, directly called for the liberation of the African American and a return to African traditions. In his Afrofuturist science fiction film, Space is the Place, Sun Ra creates a colony for Black people on a distant planet in the cosmos far away from the antagonisms of white society. This messaging remained consistent through Afrofuturist music as it contradicted Euro-American musical rules.

Unfortunately, the politics of jazz replicated the patriarchy of general society. Along with the portrayals of jazz as black music, it followed the belief that jazz experimentalism was masculine. Throughout jazz music and academia, women are left behind and forgotten despite the crucial role they play. For example, Alice Coltrane had a largely successful career by paving the way of new sounds through Far Eastern influences and spiritualism.[62] Yet, many of her accomplishments were overlooked because her husband, John Coltrane, had a more "relevant" career. Gender and womanhood are simple social constructs, similar to race, that have been replicated to create a hierarchy in jazz and academia.[63] Recently there have been calls to recognize the importance of Black women in the development of jazz as authors like Sherrie Tucker encourage readers to listen to the stylistic differences to understanding the role gender plays in jazz.

Dance music

[edit]Disco

[edit]Disco, contrary to popular belief, originated in Black queer communities and offered these communities a form of salvation or safe haven from social turmoil during the 1970s, in the Bronx and other parts of New York. It was agreed by many members prominent in the Disco scene that the music was about love and the vitality of "absorbing the feeling", but the question regarding its political import received mixed responses. Although the songs themselves may not have explicitly made political claims, it's important to note that disco, for many, was a "form of escape" and noted a "dissolve of restrictions on black/gay people".[64] The spirit of the 60s as well as the experience of Vietnam and black/gay liberation spurred the almost-frenzied energy pertinent in these discotheques. Not only did discos allow marginalized individuals an opportunity to express their sexuality and appreciate one another's diversity, they had the ability to influence popular music. Although once mutually exclusive, discotheques allowed for the coming together of black music and pop; this shows how disco music not only led to a social appreciation for diversity, but offered a platform on which Black artists could succeed. The eventual commercialization of disco set in motion its decline. This new commodified disco, very different than its diverse and queer roots, idealized the white individual and favored heteronormative relations. This not only allowed for the roots of such a diverse movement to be lost, but the erasure of the liberation and escapism it offered many minorities.[citation needed]

Latin American music

[edit]Latin American music has been intertwined with politics across the years. 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s protest songs played a critical role in the fight against authoritarian regimes in countries like Chile, Argentina, and Brazil. Today, Latin American musicians continue to tackle pressing social and political issues like immigration, inequality, and corruption through their work. As economist and musician Sumangala Damodaran explains, lyrics intertwined with activism are shaping the vast region's political landscape, creating a repertoire of new genres, and inspiring new generations of artists to do the same.[65]

Some notable political issues across the region include discrimination, toxic masculinity, and colonization. Musical artists from across Latin America have contributed to the fight political issues occurring in their specific countries, like Bad Bunny for Puerto Rico and Los Tigres del Norte for Mexico. Throughout history, artists across Latin America have used music as a political tool to bring awareness to social issues.

Nueva Canción

[edit]Nueva canción or "New Song" is a musical movement that emerged in Latin America in the late 1950s and early 1960s. In a Remezcla article, Julyssa Lopez discloses that the genre focused on socially and politically conscious lyrics, often addressing the oppression and inequality experienced by marginalized communities, especially the Indigenous culture.[66] Global languages and cultures professor Robert Neustadt affirms that artists like Violeta Parra, Victor Jara, and Inti-Ilimani used their music to speak out against censorship, state violence, and human rights abuses.

Nueva canción was relevant because it gave voice and visibility to social and political issues and provided a platform for marginalized communities to express their struggles and resistance through music. It also played a significant role in the fight against oppressive regimes and contributed to the development of cultural identity and social consciousness in Latin America.

Salsa

[edit]Salsa is most known for its rhythm and inclusion of various instruments. Cumbia is characterized by its energetic rhythm and fusion of African, Indigenous, and European influences. It has evolved over time, incorporating various musical styles and instruments, and continues to dominate dance floors in Latin America and beyond. Cumbia's relevance lies in its ability to bring people together, celebrate hybridity of the Latin American culture, while also serving as a marker of race and class differences in Latin American countries like Puerto, Rico, and Venezuela.[67][68] Political themes in salsa have included racial discrimination, white supremacy, colonialism, sexism, homophobia, environmental disaster.[69][70]

Reggaeton

[edit]As a musical genre born out of the Caribbean and Latin American regions, Reggaeton frequently engages with the tropes of other popular musical genres like love, money, and sexual conquests; but has also been used as a form of social commentary and has played a significant role in promoting social change. Reggaeton often addresses issues such as poverty, racism, police brutality, and political corruption in its lyrics. Additionally, many Reggaeton artists use their platforms to speak out against inequalities and social issues by organizing concerts, rallies, and charity events to raise awareness and funds for various social justice causes. Reggaeton also serves as a vehicle for empowering marginalized communities, particularly Black communities, Latin American people, women, and the LGBTQ+ community. Throughout its history, people have come to believe Reggaeton has become more than just a music genre but a voice for social justice and activism.[70]

Bad Bunny

[edit]Bad Bunny, whose real name is Benito Antonio Martinez Ocasio, is a Puerto Rican singer, rapper, and songwriter. He is known for his multiple chart-topping hits like “Titi Me Pregunto,” “DÁKITI”, “Yonaguni,” and “Callaita.” He also was the most listened to artists in 2022.[71] Additionally, Bad Bunny is recognized for his various awards, record-breaking achievement, and collaborations with major artist around the world.

One of his music video, "Yo Perreo Sola", translating to I twerk alone, from his second album YHLQMDLG caused controversy as he dressed up in 3 drag outfits. His music video became the most-watched Latin music video in 2020.[72]

In his most recent album, Un Verano Sin Ti, released May 2022, the 16th track was named “El Apagón,” translated to "The Blackout." Rather than just releasing a music video, he worked with Puerto Rican reporter Bianca Graulau to produce a 18-minute documentary about the impact of US colonialism on the island and the displacement of Puerto Ricans.[73] The documentary, “El Apagón" functions as a political statement from Puerto Rico about the ongoing modern-day colonization of the island, which has been happening since 1917. The song was inspired by Act 22, which is a law passed in the United States after Hurricane Maria which offered tax incentives to people in the US relocating to Puerto Rico. The law allows U.S. citizens to avoid paying taxes on their property, income, and wealth in Puerto Rico if they become bona fide residents. To qualify as a bona fide resident, a person must be a U.S. citizen who actively earns income from another country, has no intention of moving back to the United States, and has a permanent address in the other country.

It caused many millionaires and investors to buy multiple properties on the island, which has led to the displacement of many Puerto Ricans from their homes. The law was intended to improve the economy, but it has failed to do so.

Ivy Queen

[edit]Ivy Queen, also known as "La Reina del Reggaetón" (The Queen of Reggaeton), has been a prominent figure in Latin music since the beginning of her musical career in 1995. Throughout her career, she has produced hits like “Quiero Bailar” and “Quiero Saber” while also using her platform to advocate for social justice, particularly by crating narrative-based lyrics and videos exploring topics mentioning femininity, domestic violence, inequality, and sexuality. Gender and Women's studies scholar Dana E. Goldman explains that Ivy Queen's engagement with gender throughout her lyrics encourages dialogue to challenge gender norms, especially since male singers tend to perform Reggaeton more frequently and often express a desire for unattainable women or lament heartbreak.[74]

Regional Mexican Music

[edit]Regional Mexican music encompasses diverse Spanish language genres originating in Mexico, such as mariachi, banda, duranguense, nortenos, grupo, corridos, and more.[75] These genres hold significant popularity among Spanish-speaking audiences.[76] They are deeply rooted in Mexican identity and cultural traditions. Each genre serves as a platform for various forms of activism, addressing issues such as gun violence, immigration, drug crime, governmental matters in Mexico and the United States, and corruption through their powerful lyrics.

Los Tigres Del Norte

[edit]Los Tigres Del Norte is California-based norteño musical group that has used their platform on a variety of issues. The group consisted of four brothers and their cousin. Originally undocumented immigrants, they formed the group in 1968 while residing in San Jose, California.[77] They initially arrived in the United States with temporary visas to perform for incarcerated individuals, which marked the beginning of their journey as a grupo.

In 2013, Los Tigres del Norte, the renowned musical group, took the spotlight at a significant immigration rally in Washington D.C., advocating for immigration reform.[78] During the rally, they performed their popular songs "La Jaula de Oro," "Vivir En Las Sombras," and "Tres Veces Mojado." It's worth noting that this rally was not their only one, as they also organized an immigration rally at the National Mall in Hollywood in October of the same year. During the rally, their aim was to consistently address their themes. After each song, they engaged in discussions to reflect upon the messages conveyed.[79]

One of their biggest hits is "La Jaula de Oro," meaning "The Gilded Cage." This song has been performed numerous times and delves into the life of an immigrant and their American-born child who feels disconnected from their cultural heritage. The powerful message conveyed is, "What value does money hold when I feel trapped in this promising nation?"

Los Tigres Del Norte also tackle the topic of prison reform in their music. In 2019, they gave a memorable performance inside Folsom Prison, located in California, which led to the creation of a song called "La Prisión de Folsom" (Folsom Prison).[80] This performance was influenced by the legendary musician Johnny Cash. It is worth noting that the majority of the inmates present during the performance were Hispanic and Black, reflecting the demographic composition of the entire prison system. Los Tigres Del Norte documented their experience at Folsom Prison in a Netflix documentary titled "Los Tigres del Norte at Folsom Prison." The documentary explores the grupo's impact on inmates, both prior to and following their time in prison.

Rock music

[edit]Many rock artists, as varied as Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young,[81] Bruce Springsteen,[82] Little Steven,[83] Rage Against the Machine,[84] Radiohead,[85] Manic Street Preachers,[86] Megadeth,[87] Enter Shikari,[88] Architects,[89] Muse, System of a Down,[90] Sonic Boom Six[91] and Drive-By Truckers[92] have had openly political messages in their music. The use of political lyrics and the taking of political stances by rock musicians can be traced back to the 1960s counterculture,[93] specifically the influence of the early career of Bob Dylan,[12] itself shaped by the politicised folk revival.

1960s–70s counterculture

[edit]During the 1960s and early 1970s counterculture era, musicians such as John Lennon commonly expressed protest themes in their music,[94] for example on the Plastic Ono Band's 1969 single "Give Peace a Chance". Lennon later devoted an entire album to politics and wrote the song Imagine, widely considered to be a peace anthem. Its lyrics invoke a world without religion, national borders or private property.

In 1962–63, Bob Dylan sang about the evils of war, racism and poverty on his trademark political albums "The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan" and "The Times They Are a-Changin'" (released in 1964), popularising the cause of the Civil Rights Movement. Dylan was influenced by the folk revival, as well as by the Beat writers, and the political beliefs of the young generation of the era.[12] In turn, while Dylan's political phase comes under the 'folk' category, he was known as a rock artist from 1965 and remained associated with an anti-establishment stance that influenced other musicians – such as the British Invasion bands – and the rock music audience, by broadening the spectrum of subjects that could be addressed in popular song.[93]

The MC5 (Motor City 5) came out of the Detroit, Michigan underground scene of the late 1960s,[95] and embodied an aggressive evolution of garage rock which was often fused with socio-political and countercultural lyrics, such as in the songs "Motor City Is Burning", (a John Lee Hooker cover adapting the story of the Detroit Race Riot (1943) to the 1967 12th Street Detroit Riot), and "American Ruse" (which discusses U.S. police brutality as well as pollution, prison, materialism and rebellion). They had ties to radical leftist groups such as Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers and John Sinclair's White Panther Party. MC5 was the only band to perform a set before the August 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, as part of the Yippies' Festival of Life where an infamous riot subsequently broke out between police and students protesting the April assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Vietnam War.

Other rock groups that conveyed specific political messages in the late 1960s/early 1970s – often in regard to the Vietnam War – include The Fugs, Country Joe and the Fish, Jefferson Airplane, Creedence Clearwater Revival, and Third World War, while some bands, such as The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and Hawkwind, referenced political issues occasionally and in a more observational than engaged way, e.g. in songs like "Revolution", "Street Fighting Man", "Salt of the Earth" and "Urban Guerrilla".

Punk rock

[edit]Notable punk rock bands, such as Crass, Conflict, Sex Pistols, The Clash, Dead Kennedys, Black Flag, Refused, American Standards, Discharge, MDC, Aus-Rotten, Billy Talent, Anti-Flag, and Leftöver Crack have used political and sometimes controversial lyrics that attack the establishment, sexism, capitalism, racism, speciesism, colonialism, and other phenomena they see as sources of social problems.

Since the late 1970s, punk rock has been associated with various left-wing or anti-establishment ideologies,[96][97][98] including anarchism and socialism. Punk's DIY culture held an attraction for some on the Left, suggesting affinity with the ideals of workers' control, and empowerment of the powerless[99] (though it is arguable that the punk movement's partial focus on apathy towards the establishment, combined with the fact that in many situations, punk rock music generated income for major record companies, and the notable similarities between some strains of anarchism and capitalism, meant that the punk movement ran contrary to left-wing ideologies) – and the genre as a whole came, largely through the Sex Pistols, to be associated with anarchism. The sincerity of the early punk bands has been questioned – some critics saw their referencing of revolutionary politics as a provocative pose rather than an ideology[100][101] – but bands such as Crass[102] and Dead Kennedys[103] later emerged who held strong anarchist views, and over time this association strengthened, as they went on to influence other bands in the UK anarcho-punk and US hardcore subgenres, respectively.

The Sex Pistols song "God Save the Queen" was banned from broadcast by the BBC[104] in 1977 due to its presumed anti-Royalism, partly due to its apparent equation of the monarchy with a "fascist regime". The following year, the release of debut Crass album The Feeding Of the 5000 was initially obstructed when pressing plant workers refused to produce it due to sacrilegious lyrical content.[105] Crass later faced court charges of obscenity related to their Penis Envy album, as the Dead Kennedys later did over their Frankenchrist album artwork.[103]

The Clash are regarded as pioneers of political punk, and were seen to represent a progressive, socialistic worldview compared to the apparently anti-social or nihilistic attack of many early punk bands.[106][107] Partly inspired by 1960s protest music such as the MC5, their stance influenced other first and second wave punk/new wave bands such as The Jam, The Ruts, Stiff Little Fingers, Angelic Upstarts, TRB and Newtown Neurotics, and inspired a lyrical focus on subjects such as racial tension, unemployment, class resentment, urban alienation and police violence, as well as imperialism. Partially credited with aligning punk and reggae,[108][109] The Clash's anti-racism helped to cement punk's anti-fascist politics, and they famously headlined the first joint Rock Against Racism (RAR)/Anti Nazi League (ANL) carnival in Hackney, London, in April 1978.[110][111][112] The RAR/ANL campaign is credited with helping to destroy the UK National Front as a credible political force, aided by the support received from punk and reggae bands.

Many punk musicians, such as Vic Bondi (Articles of Faith), Joey Keithley (DOA), Tim McIlrath (Rise Against), The Crucifucks, Bad Religion, The Proletariat, Against All Authority, Dropkick Murphys and Crashdog have held and expressed left-wing views. Dead Kennedys singer Jello Biafra, as well as T.S.O.L. frontman Jack Grisham, have run as candidates for public office under left-wing platforms. However, some punk bands have expressed more populist and conservative opinions, and an ambiguous form of patriotism, beginning in the U.S. with many of the groups associated with 1980s New York hardcore,[113] and prior to that in the UK with a small section of the Oi! movement.[114][115]

An extremely small minority of punk rock bands, exemplified by (1980s-era) Skrewdriver and Skullhead, have held far-right and anti-communist stances, and were consequently reviled in the broader, largely Leftist punk subculture.

Latinx Rock/Punk

[edit]Music within the "Rock" genre have been linked to left-leaning political views, including views against racism and xenophobia.[116] Latin punk became a movement within the Rock genre. Within the genre, issues that are prevalent specifically within the Latinx communities were being discussed.[117] The issues pertained to the violation of immigrant rights, including within the workforce.[118] Many musicians within the genre paid homage to their cultural roots and adopted philosophies such as those that arose from the Zapatista Uprising.

The movement shed light on the Chicano/Latino scene within their communities.[119] This became a form of protest against the xenophobia that exists against the community in the US

Rage Against the Machine and Tigres del Norte

[edit]

Lead singer of Rage Against the Machine, Zach De La Rocha is introduced by Los Tigres del Norte for their MTV Unplugged performance in 2011.[120] Together, they perform a song of Los Tigres del Norte, "“Somos mas americanos." Zach De La Rocha is introduced as someone who “fights for the rights of us all.” Rage against the Machine is known for having socio-political commentary in their music as well as Los Tigres del Norte. Rage against the Machine's "political views and activism are central to the band's message." Zach De La Rocha has described being interested in "...spreading those ideas through art, because music has the power to cross borders, to break military sieges and to establish real dialogue."[121] Los Tigres del Norte also have a history of displaying their political views through their music. From supporting LGBT+ rights, prison abolition, and immigrant rights.[122]

Together, they perform ‘Somos Más Americanos.’ Los Tigres Del Norte being Regional Mexican music that dates back to the 60s while Zach's musical background coming from a heavy metal and rap background which originated in the 90s.

The performance gives historical and social commentary on the xenophobia and racism that is targeted against Mexican and Chicanx folks in the US. Both the group and Zach perform the song whilst adding anedoctes about the US government.

One of the introductory lyrics in the song is “I have to remind them that I didn't cross the border, the border crossed me.” These words directly reference US and Mexico history. Specifically to how a significant amount of what is now considered the Southwest US, was once Mexico. These words have also become a slogan for many Latinx movements and organizations in the US who aim to fight against xenophobic systems that target immigrants.[123] The lyrics that end the song are “Somos mas americanos que todititos los Gringos." Meaning, "we are more American than all of the White people."

Rock the Vote

[edit]Rock the Vote is an American 501(c)(3) non-profit, non-partisan organization founded in Los Angeles in 1990 by Jeff Ayeroff for the purposes of political advocacy. Rock the Vote works to engage youth in the political process by incorporating the entertainment community and youth culture into its activities.[124] Rock the Vote's stated mission is to "build the political clout and engagement of young people in order to achieve progressive change in our country."[125]

Hip hop

[edit]Hip hop music has been associated with protest since 1982, when "The Message" by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five became known as the first prominent rap record to make a serious “social statement”.[126][127] However the first political rap release has been credited to Brother D and the Collective Effort's 1980 single “How We Gonna Make the Black Nation Rise?” which called the USA a “police state” and rapped about historical injustices such as slavery and ethnic cleansing.[128]

Later in the decade hip hop band Public Enemy became "perhaps the most well-known and influential political rap group"[129] and released a series of records whose message and success "directed hip-hop toward an explicitly self-aware, pro-black consciousness that became the culture's signature throughout the next decade,"[130] helping to inspire a wave of politicised hip hop by artists such as X Clan,[131] Poor Righteous Teachers,[132] Brand Nubian,[133] 2 Black 2 Strong[134] and Paris.[135]

Eminem's tenth album, Kamikaze, contained many political messages, most of them revolving around his disapproval of Donald Trump being elected President of the United States. He stated he was willing to lose fans over this criticism and rapped: "And any fan of mine/who's a supporter of his/I'm drawing in the sand a line/you're either for or against,"[136]

During Donald Trump's presidential campaign, Kanye West took the opportunity to support the Republican candidate by urging his fans to vote for Trump.[137] Although West has historically been against the Republican administrations, he has been one of Donald Trumps most vocal supporters.[137] On April 27, 2018, Kanye West and fellow rapper, T.I., released a collaboration called "Ye vs. the People" that consisted of West and T.I.'s opposing political views.[138] The song, a conversation between the two rappers, became popular not for its musical touch, but because of the courage West and T.I. showed by releasing a controversial song in a time of high political disagreement.[139]

Reggae

[edit]Jamaican Reggae of the 1970s and the 1980s is an example of influential and powerful interaction between music and politics. A top figure-head in this music was Bob Marley. Though Marley was not in favor of politics, through his politicized lyrics he was seen as a political figure. In 1978 Bob Marley's One Love Peace Concert brought Prime Minister Michael Manley and the opposition leader Edward Seaga together (leaders connected to notorious rival gang leaders, Bucky Marshall and Claude Massop, respectively), to join hands with Marley during the performance; this was the "longest and most political reggae concert ever staged, and one of the most remarkable musical events recorded."[140] Throughout this period many reggae musicians played for and spoke or sung in support of Manley's People's National Party, a campaign credited with helping the PNP's victory in the 1972 and 1976 elections.[141]

Popular music

[edit]Popular music found throughout the world contains political messages such as those concerning social issues and racism. For example, Lady Gaga's song "Born This Way" has often been known as the international gay anthem,[142] as it discusses homosexuality in a positive light and expresses the idea that it is natural. Furthermore, the natural disaster of Hurricane Katrina received a great political response from the hip hop music community. The content of the music changed into a response showing the complex dynamic of the community, especially the black community, while also acting a sometimes contradictory protest of how the disaster was handled in the aftermath.[143] This topic even reached beyond the locality of New Orleans, as the issue of the disaster and racism was mentioned by other rappers from other regions of the country.[144]

Pop music is common for its sensationalized and mass-produced uplifting beats.[145] Many artists take advantage of their large followings to spread awareness of political issues in their music. Similar to Lady Gaga's "Born This Way," Macklemore's song "Same Love" also expresses support and homage to the LGBTQ+ community.[146] Furthermore, Beyoncé's album "Lemonade" has been hailed as awe-inspiring and eye-opening with many of the songs addressing political issues such as racism, stereotyping, police brutality, and infidelity.[147] These songs, aside from being catchy and uplifting, discuss serious issues in a lighthearted and simplified manner allowing people to understand while also commonly being influenced by the current political climate such as the violent attacks on the Bataclan Theater in Paris[148] and the Pulse Nightclub in Orlando.[149]

Country music

[edit]

American country music contains numerous images of traditional values and family and religious life, as well as patriotic themes. Songs such as Merle Haggard's "The Fightin' Side of Me" and "Okie from Muskogee" have been perceived as patriotic songs showing an "us versus them" mentality directed at the counterculture or "hippies" and the anti-war crowd, though these were actually misconceptions by listeners who failed to understand their satirical nature.[150]

Many American country songs addressed political and cultural views in the 1960s and 1970s, with mainstream and independent country artists releasing singles that conveyed support for conservative candidates or military action, anti-communist statements, or, in some cases, anti-hippie sentiments often framed as humorous put-downs.[151] These tropes have continued in such songs as Toby Keith's "Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue (The Angry American)" in 2002 and Bryan Lewis's "I Think My Dog's a Democrat" in 2016.[152]

More recent American country songs containing political messages include Keith Urban's "Female" which details the psychological and emotional impact on women of sexist language, slut-shaming, and lack of representation in politics.[153] The lyrics of Carrie Underwood's 2018 song "Love Wins" also identifies themes of prejudice, hatred, and politics.[154] Through this song, Underwood expresses the idea that the best way to close the political divide and strengthen what she sees to be a broken world is through unity, loving each other, and working together in times of crisis.[154]

Country artist Kacey Musgraves integrates politics into her lyrics, speaking about gay rights and cannabis consumption. Her song "Follow Your Arrow" is considered to be a radical perspective on same-sex marriage, in that it differs from the conservative point of view that is normally found in country music.[153]

African American country rapper Cowboy Troy, the stage name of Troy Lee Coleman III, incorporates real-life problems into his music, calling for societal change. He sheds light on concepts like class analysis, gender issues, and popular narratives about the "white" working class.[155] One of his songs, "I Play Chicken With The Train," acknowledges conservative and progressive ideas that tend to be brought up in presidential elections.[156]

Although race is a rarely addressed topic in country music, some artists have made an effort to approach this theme in their songs. Brad Paisley's 2013 album Wheelhouse included the track "Accidental Racist", which became controversial, generating many negative reviews. [citation needed] Will Hermes, in his critique in Rolling Stone, commented: "It's probably not going to win any awards for songcraft and rapping, but in the wake of movies like Django Unchained and Lincoln, it shows how fraught racial dialogue remains in America."[157] Paisley stated, "This song was meant to generate discussion among the people who listen to my albums."[158]

Classical music

[edit]Beethoven's third symphony was originally called "Bonaparte". In 1804 Napoleon crowned himself emperor, whereupon Beethoven rescinded the dedication. The symphony was renamed "Heroic Symphony composed to Celebrate the Memory of a Great Man".[citation needed]

Verdi's chorus of Hebrew slaves in the opera Nabucco is a kind of rallying-cry for Italians to throw off the yoke of Austrian domination (in the north) and French domination (near Rome)—the "Risorgimento". Following unification, Verdi was awarded a seat in the national parliament.[citation needed]

In late nineteenth century England, choral music was performed by mass choirs of workers and much music was written for them, by, for example, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and Ralph Vaughan Williams. When the young Vaughan Williams wondered what kind of music to write, Hubert Parry advised him to "write choral music as befits an Englishman and a democrat".[159] Others, including Frederick Delius and Vaughan Williams's friend Gustav Holst also wrote choral works, often using the words of Walt Whitman.

Richard Taruskin of the University of California accused John Adams of "romanticizing terrorists" in his opera The Death of Klinghoffer (1991).[160][clarification needed]

American classical composer Miguel del Aguila has written over 130 works many of which center on social issues such as the genocide of Native Americans during the European conquest, and the Guerra Sucia victims. More recent works like Bindfold Music deal with social injustice in contemporary US society.

In the Soviet Union

[edit]RAPM (The Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians) was formed in the early 1920s. In 1929 Stalin gave them his backing. Shostakovich had dedicated his first symphony to Mikhail Kvadri. In 1929 Kvardi was arrested and executed. In an article in The Worker and the Theatre, Shostakovich's Tahiti Trot (used with the ballet The Golden Age) was criticised; Ivan Yershov claimed it was part of "ideology harmful to the proletariat"". Shostakovich's response was to write his third symphony, The First of May (1929) to express "the festive mood of peaceful construction".[ 161 ] [ 162 ]

Прокофьев писал музыку на заказ для Советского Союза, в том числе Кантату к 20-летию Октябрьской революции (1937). Хачатуряна В балете «Спартак» (1954/6) речь идет о рабах-гладиаторах, восставших против своих бывших римских хозяев. Это рассматривалось как метафора свержения царя. [ нужна ссылка ] Точно так же музыка Прокофьева к фильму «Александр Невский» посвящена вторжению тевтонских рыцарей в Прибалтику. Это рассматривалось как метафора вторжения нацистов в СССР. [ нужна ссылка ] В целом советская музыка была неоромантической, а фашистская — неоклассической. [ нужна ссылка ]

Музыка в нацистской Германии

[ редактировать ]Стравинский заявил в 1930 году: «Я не верю, что кто-то почитает Муссолини больше, чем я»; [ 163 ] однако к 1943 году Стравинский был запрещен в нацистской Германии, поскольку он решил жить в США. Начиная с 1940 года Карла Орфа кантата «Кармина Бурана» исполнялась на мероприятиях нацистской партии и приобрела статус квазиофициального гимна. [ 164 ] В 1933 году Берлинское радио официально запретило трансляцию джаза. Однако по-прежнему можно было услышать свинг в исполнении немецких групп. Это произошло из-за сдерживающего влияния Геббельса , который знал ценность развлечения войск. В период 1933–45 музыка Густава Малера , австрийского еврея, практически исчезла из концертных выступлений Берлинской филармонии. [ 165 ] Рихарда Штрауса Опера «Безмолвная женщина» ( Die Schweigsame Frau ) была запрещена с 1935 по 1945 год, поскольку либреттист Стефан Цвейг был евреем. [ 166 ]

Музыка «Белая сила»

[ редактировать ]Расистская музыка или музыка власти белых — это музыка, связанная с неонацизмом и идеологиями превосходства белой расы и пропагандирующая их . [ 167 ] Хотя музыковеды отмечают, что во многих, если не в большинстве ранних культур, были песни, призванные рекламировать себя и очернять предполагаемых врагов, истоки расистской музыки восходят к 1970-м годам. К 2001 году существовало множество музыкальных жанров, наиболее часто представленным типом групп был «белый пауэр-рок», за которым следовал национал-социалистический блэк-метал . [ 168 ] «Расистская кантри-музыка» — это, главным образом, американский феномен, в то время как в Германии, Великобритании и Швеции более высокая концентрация белых групп власти. [ 168 ] Другие музыкальные жанры включают «фашистскую экспериментальную музыку» и «расистскую народную музыку». [ 168 ] Современные группы сторонников превосходства белой расы включают в себя «субкультурные фракции, которые в основном организованы вокруг продвижения и распространения расистской музыки». [ 169 ] По данным Комиссии по правам человека и равным возможностям , «расистская музыка в основном исходит от крайне правого движения скинхедов, и благодаря Интернету эта музыка стала, пожалуй, самым важным инструментом международного неонацистского движения для получения доходов и привлечения новых рекрутов». ." [ 170 ] [ 171 ] В новостном документальном фильме VH1 News Special: Inside Hate Rock (2002) отмечалось, что расистская музыка (также называемая «музыкой ненависти» и «скинхед-роком») является «питательной средой для доморощенных террористов ». [ 172 ] В 2004 году неонацистская звукозаписывающая компания запустила «Project Schoolyard» для распространения бесплатных компакт-дисков с музыкой среди до 100 000 подростков по всей территории США. На их веб-сайте говорилось: «Мы просто не развлекаем детей-расистов... Мы создаем их." [ 173 ] Брайан Хоутон из Национального мемориального института по предотвращению терроризма сказал, что расистская музыка была отличным инструментом вербовки: «С помощью музыки... можно захватить этих детей, научить их быть расистами и зацепить их на всю жизнь». [ 174 ]

По стране

[ редактировать ]Этот раздел , кажется, ориентирован на недавние события . ( Март 2024 г. ) |

Осознавая мотивирующую силу музыки, [ 2 ] политики всего мира стремятся включать в свои кампании разные песни. Однако точки зрения музыкантов и политиков, использующих их музыку, иногда расходятся. Помимо песен протеста, созданных специально для привлечения внимания к вопросам социальных перемен , музыканты всего мира противостоят политикам. Правительства и лидеры также различными способами заявляют о своем сопротивлении критикам музыкантов. В каждом национальном и культурном контексте сопротивление музыкантов и реакция политиков представляют собой уникальные взаимоотношения.

Бразилия

[ редактировать ]С момента своего избрания президентом Бразилии в 2018 году Жаир Болсонару становился все более противоречивым лидером. Как и его современники-правые Дональд Трамп и Нарендра Моди, Болсонару называют одновременно популистом и националистом. Хотя Болсонару напрямую поддерживает крайне правую политику в отношении прав геев и владения оружием, [ 175 ] более умеренные консерваторы также утверждают, что он поддерживает их интересы. [ 176 ] Чтобы заручиться поддержкой консервативных избирателей Бразилии, речи Болсонару были в значительной степени националистическими и патриотическими. [ 177 ] Хотя прямые обращения Болсонару к народу были более ограничены его национальными обращениями, он подчеркивал гордую разновидность бразильского национализма. Как фигура, чья политика и действия вызвали глубокую поляризацию и разногласия, [ 178 ] Болсонару стал основным источником презрения и критики бразильских музыкантов как внутри страны, так и за рубежом.

Музыкант Каэтано Велозу , который был сослан во время военной диктатуры Бразилии, продолжавшейся с 1964 по 1985 год, назвал деспотичную националистическую риторику и лидерство Болсонару «полным кошмаром». [ 179 ] Хотя музыкальный бренд Велосо не является музыкой протеста, он пользуется возможностью высказаться и использует свою известность для сопротивления. В августе 2020 года Велозу присоединился к хору видных бразильских деятелей, высмеивающих Болсонару за его предполагаемую роль в схеме хищений и отмывания денег. [ 180 ]

В то время как некоторые бразильские артисты, такие как Велозу, сопротивлялись в основном через свои аккаунты в социальных сетях, Бразилия имеет богатую историю музыки протеста против своего бывшего авторитарного диктаторского режима, которую продолжают многие современные артисты. [ 181 ] Художники со всей страны находили способы сопротивляться, критиковать и ссылаться на Болсонару в своих работах. Трубадур Чико Сезар использовал прямой подход, утверждая, что сторонники Болсонару были фашистами, композитор Ману да Куика завуалировал свою критику, включая предупреждение о Болсонару как об одном из опасных «мессий с оружием в руках», а певица Марина Ирис косвенно выступала в критике режима. как постоянные темы тревоги и разочарования по поводу нынешнего состояния Бразилии. [ 182 ] Эти традиционные формы бразильской музыки, уходящие корнями в местные музыкальные формы, являются ключевой формой музыки, направленной против статус-кво. [ 183 ] В ответ на сопротивление, вместо того чтобы перенимать музыку, как у Трампа, или полагаться на поддержку своих последователей, таких как Моди, Болсонару резко сократил общественную поддержку и ресурсы для музыкантов, кинематографистов и художников. Многие художники рассматривали этот поступок как расплату за свое сопротивление. [ 182 ] Однако несколько правых бразильских рэперов взяли на себя на музыкальной сцене задачу защищать и поддерживать Болсонару.

Китай

[ редактировать ]Эфиопия

[ редактировать ]Индия

[ редактировать ]После выборов в Лок Сабха 2014 года Нарендра Моди был приведен к присяге премьер-министра Индии. [ 184 ] Моди, известный своим эффективным националистическим обращением к индийскому народу, [ 185 ] быстро начали централизовать власть [ 186 ] и подвергнуть тщательному контролю как гражданские, так и иностранные неправительственные организации. [ 187 ]

Благодаря популистской поддержке Моди и растущей власти правительства музыканты сталкиваются с уникальным социальным и политическим ландшафтом в своих возможностях сопротивления. В мае 2020 года был выдан ордер на арест певца Майнула Ахсана Нобла за уничижительные комментарии в адрес Моди в Facebook. [ 188 ] При этом иск был подан частным гражданином Индии, который «не мог принять такие клеветнические высказывания в адрес премьер-министра [Индии]». С популистским поворотом Индии критика и сопротивление политикам стали более рискованными для музыкантов. Покойный певец С.П. Баласубрахманьям тщательно сопротивлялся действиям Моди, когда на собрании Моди Change Within 2019 года он предположил, что артисты из Южной Индии подвергаются другим ограничениям, чем артисты Болливуда. [ 189 ] В то время как открытые комментарии Ноубла вызвали гнев и судебные иски, приглушенная критика Баласубрахманьяма не вызвала такой же реакции. Поскольку популистский политический выбор Моди убедительно показывает индийскому народу, что он заботится о благосостоянии обычных граждан, [ 190 ] все больше граждан приходят к нему на помощь, и сопротивление Моди становится все труднее для современных индийских музыкантов.

Однако за рубежом критика Моди может быть менее осторожной. Дези-американские панки The Kominas и несколько других южноазиатских исполнителей организовали акцию против Моди в Нью-Йорке. [ 191 ] приурочено к организованному администрацией Трампа мероприятию в поддержку Моди в Хьюстоне . [ 192 ] Мероприятие оппозиции в поддержку Кашмира в Нью-Йорке вызвало нападки и осуждение со стороны некоторых индийцев в Интернете, но никаких международных судебных исков против участвующих групп и артистов не последовало. Несмотря на мероприятие оппозиции, подчеркивающее нарушения прав человека в связи с военным блокированием Кашмира, популистский взгляд на Моди как на очистителя от коррупции и защитника индийского народа сохраняется среди большей части Индии. [ 193 ] Чтобы еще больше расширить свое музыкальное сопротивление, Комина рассматривают возможность проведения панк-оппозиционных мероприятий против Моди в разных странах и даже, возможно, в Нью-Дели . [ 191 ]

Филиппины

[ редактировать ]ЮАР

[ редактировать ]

Режим апартеида в Южной Африке начался в 1948 году и продлился до 1994 года. Он включал систему институционализированной расовой сегрегации и белого превосходства , а также передал всю политическую власть в руки белого меньшинства . [ 200 ] [ 201 ] [ 202 ] Оппозиция апартеиду проявлялась по-разному, включая бойкоты, ненасильственные протесты и вооруженное сопротивление. [ 203 ] Музыка сыграла большую роль в движении против апартеида в Южной Африке, а также в международной оппозиции апартеиду. [ 204 ] [ 205 ] Влияние песен, выступающих против апартеида, включало повышение осведомленности, мобилизацию поддержки движения против апартеида, построение единства внутри этого движения и «представление альтернативного видения культуры в будущей демократической Южной Африке». [ 206 ]

Лирическое содержание и тон этой музыки отражали атмосферу, в которой она была написана. Музыка протеста 1950-х годов, вскоре после начала апартеида, явно обращалась к недовольству людей по поводу законов о пропусках и принудительного переселения. После резни в Шарпевиле в 1960 году и ареста или изгнания ряда лидеров песни стали более мрачными, а усиление цензуры вынудило их использовать тонкие и скрытые смыслы. [ 207 ] Песни и выступления также позволяли людям обходить более строгие ограничения на другие формы самовыражения. [ 205 ] В то же время песни сыграли роль в более воинственном сопротивлении, которое началось в 1960-х годах. Восстание в Соуэто в 1976 году привело к возрождению, а такие песни, как « Soweto Blues », поощряли более прямой вызов правительству апартеида. Эта тенденция усилилась в 1980-х годах, когда смешанные расово-смешанные группы проверяли законы апартеида, прежде чем они были демонтированы с освобождением Нельсона Манделы в 1990 году и возможным восстановлением правления большинства в 1994 году. [ 207 ] На протяжении всей своей истории музыка против апартеида в Южной Африке сталкивалась со значительной цензурой со стороны правительства, как напрямую, так и через Южноафриканскую радиовещательную корпорацию ; кроме того, музыканты, выступающие против правительства, столкнулись с угрозами, преследованиями и арестами.

Музыканты из других стран также участвовали в сопротивлении апартеиду, выпуская музыку, критикующую правительство Южной Африки, и участвуя в культурном бойкоте Южной Африки, начиная с 1980 года. Примеры включают « Бико » Питера Гэбриэла , « Город Солнца » группы «Объединенные художники против апартеида » и концерт в честь 70-летия Нельсона Манделы . Выдающиеся южноафриканские музыканты, такие как Мириам Макеба и Хью Масекела , вынужденные покинуть страну, также выпустили музыку, критикующую апартеид, и эта музыка оказала значительное влияние на западную популярную культуру, способствуя «моральному возмущению» по поводу апартеида. [ 208 ] Ученые заявили, что музыка против апартеида в Южной Африке, хотя ей и уделялось меньше внимания во всем мире, сыграла не менее важную роль в оказании давления на правительство Южной Африки.Соединенные Штаты

[ редактировать ]

В Соединенных Штатах музыканты, в том числе Нил Янг , Dropkick Murphys и Explosions in the Sky, выступили против таких политиков, как президент Дональд Трамп , губернатор штата Висконсин Скотт Уокер и сенатор от Техаса Тед Круз , или выступили против них . Эти конфликты между популярными музыкантами и политиками в Соединенных Штатах являются обычным явлением в предвыборном цикле, но проявляются по-разному.

Трамп использовал песню Янга « Rockin in the Free World » с самого начала своей президентской кампании против Хиллари Клинтон в 2015 году. Хотя Янг утверждал, что Трамп не имел права использовать эту песню в своей кампании, представитель Трампа заявил, что песня была получена законным путем через лицензию ASCAP и что кампания «продолжит использовать [его песню] независимо от политических взглядов Нила». [ 209 ] И хотя сама песня 1989 года может показаться одобрением американского образа жизни, при ближайшем рассмотрении обнаруживается критика администрации Джорджа Буша-старшего. [ 210 ] Это говорит о том, что влияние музыки в политической кампании не может ограничиваться только текстами песен. [ 211 ] Несмотря на резкие слова песни и продолжающееся сопротивление Янга, предвыборный штаб Трампа снова начал использовать эту песню в 2018 году в своей кампании по переизбранию президента. [ 212 ]

Точно так же в 2015 году Скотт Уокер использовал популярный кавер группы Dropkick Murphys на песню Вуди Гатри «I’m Shipping Up to Boston» на политическом мероприятии в Айове. Из-за разногласий по таким вопросам, как профсоюзы, группа написала в Твиттере: «Пожалуйста, прекратите использовать нашу музыку каким-либо образом… мы буквально ненавидим вас!!!» к Уокеру. [ 213 ] Хотя угрозы судебного иска не было, группа обратилась в социальные сети, чтобы дистанцироваться от Уокера и воспрепятствовать использованию им их песни.

Некоторые музыканты эффективно использовали закон об авторском праве, чтобы противостоять политическому использованию своей музыки. Когда Тед Круз включил песню Explosions in the Sky "Your Hand in Mine" в рекламный видеоролик губернатора Техаса Грега Эбботта , группа написала в Твиттере, что их "абсолютно это не устраивает". [ 214 ] Лейбл группы Temporary Residence вынудил кампанию Круза удалить видео из-за нарушения закона об авторских правах США. По закону политики могут лицензировать музыку, не консультируясь с самими исполнителями, заключая сделки с организациями по защите прав на исполнение. [ 215 ] В то время как предвыборный штаб Трампа уклонился от консультаций с Янгом и легальной лицензией «Rockin' in the Free World» от такой организации (ASCAP), усилия Круза не принесли ни того, ни другого.

В Соединенных Штатах также существует долгая и сложная история государственных школ, оказывающих поддержку военным посредством их музыкальной деятельности, а также учителей музыки, которые либо одобряли, либо сопротивлялись этим тенденциям. [ 216 ] Музыковеды отмечают влияние милитаризма на американское общество, утверждая, что «милитаризм ставит под угрозу музыкальное образование» и что, хотя военные модели не подходят для обучения школьников в условиях демократии, [ 217 ] Есть свидетельства того, что «В Соединенных Штатах мы находим множество проектов партнерства в области музыкального образования с военными, которые были бы немыслимы во многих других странах. [ 216 ]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Анархо-панк

- Да, Занг Усенандер

- Вместе

- Брексит в популярной культуре

- Краст-панк

- Экомузыкология

- Экологизм в музыке

- Песни свободы

- Хардлайн (субкультура)

- Ирландская повстанческая музыка

- Список музыкантов-анархистов

- Список антивоенных песен

- Список национальных гимнов

- Список политических панк-песен

- Список социалистических песен

- Список песен о терактах 11 сентября

- Список песен о войне во Вьетнаме

- Люблю музыку, ненавижу расизм

- Марш (музыка)

- Музыка и политическая война

- Новое музыковедение

- Ненасильственное сопротивление

- новая песня

- Привет!

- Народные песни

- Политические разногласия на конкурсе песни Евровидение

- Политическая песня в Египте

- Бунт грррл

- Рок против расизма Северный карнавал

- Рок против сексизма

- Роль музыки во Второй мировой войне.

- Остановите убийство, музыка

- Эта машина убивает фашистов

- Военная песня

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Родницкий, Джерри (2016). «Песня протеста» . Гроув Музыка онлайн .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и алио, нур (2010). «Политическая поп-музыка, политические фанаты?» . Музыка и политика . IV (1). дои : 10.3998/mp.9460447.0004.103 .

- ^ «Архивная копия» (PDF) . www.livingearth.org.uk . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 14 июля 2014 года . Проверено 17 января 2022 г.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: архивная копия в заголовке ( ссылка ) - ^ Кучке, Беате (2014). «Музыка и другие знаковые системы» . Теория музыки онлайн . 20 (4). дои : 10.30535/mto.20.4.3 .

- ^ Кучке, Беате (2016). «Политическая музыка и песня протеста». В Фаленбрахе, Катрин; Климке, Мартин; Шарлот, Иоахим (ред.). Протестные культуры . Нью-Йорк и Оксфорд: Берган. стр. 264–272.

- ^ «Новая Восточная Европа» . Neweasterneurope.eu . 29 ноября 2012 г. Архивировано из оригинала 29 марта 2014 г. Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Хеберт, Дэвид и Керц-Вельцель, Александра (2012). Патриотизм и национализм в музыкальном образовании . Олдершот, Великобритания: Ashgate Press ISBN 1409430804

- ^ Паттерсон, Арчи (19 июня 2018 г.). «Музыкальные инновации полны опасности для государства, поскольку, когда меняются музыкальные стили, фундаментально…» . Середина . Архивировано из оригинала 13 января 2020 г. Проверено 13 января 2020 г.

- ^ Адамс, Ной (15 января 1999 г.). «История «Мы победим» » . Проверено 17 февраля 2012 г.

- ^ Хайду, Дэвид (29 марта 2004 г.). «Рецензия: Народный герой» . Житель Нью-Йорка . Проверено 13 марта 2012 г.

- ^ «Сила песни» . Служба общественного вещания. 16 июня 2011 г. Проверено 18 марта 2012 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Политический Боб Дилан» . Журнал «Диссент». 13 ноября 2016 г. Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ «Фавориты Великобритании 1965» . Проверено 16 февраля 2012 г.

- ^ Унтербергер, Ричи. «Там, кроме Фортуны» . Корпорация Рови . Проверено 16 февраля 2012 г.

- ^ «Идеальный звук навсегда: Фил Окс» . Furious.com . 9 апреля 1976 г. Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Эйерман, Рон; Барретта. «С 30-х по 60-е годы: возрождение народной музыки в США» (PDF) . Спрингер. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 4 апреля 2013 года . Проверено 13 марта 2012 г.

- ^ Возрождение народной музыки 30-60-х годов, 1996, с. 508

- ^ Ройсс, Ричард; Ройсс, Джоанна (2000). Американская народная музыка и левая политика . Пугало Пресс. ISBN 9780810836846 .

- ^ Возрождение народной музыки 30-60-х годов, 1996, с. 502

- ^ «Биография Юэна МакКолла» . Ewanmaccoll.co.uk . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Ли, CP (2009), «Как ночь: прием и реакция, тур Дилана по Великобритании в 1966 году», в: Возвращение к шоссе 61: Дорога Боба Дилана из Миннесоты в мир , University of Minnesota Press, Миннеаполис, США, стр. 78– 84.

- ^ «Пегги Сигер и Юэн МакКолл – Песни борьбы» . Ewan-maccoll.info . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Нил Спенсер. «Юэн МакКолл: крестный отец народа, которого обожали и боялись | Музыка» . Хранитель . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Колин Ирвин. «Битва за британскую народную музыку | Музыка» . Хранитель . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Возрождение народной музыки 30-60-х годов 1996, с. 522

- ^ Уайт, Джон. «Видеть красное: холодная война и американское общественное мнение» . Проверено 10 апреля 2012 г.

- ^ Возрождение народной музыки 30-60-х годов, 1996, с. 520

- ^ Джеймс, Дэвид (1989). «Война во Вьетнаме и американская музыка». Социальный текст (23): 122–143. дои : 10.2307/466424 . JSTOR 466424 .

- ^ Возрождение народной музыки 30-60-х годов, 1996, с. 528

- ^ Уильям Рульманн. «Спасибо жизни - Джоан Баэз | Песни, обзоры, авторы» . Вся музыка . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Ричи Унтербергер . «Outward Bound – Том Пэкстон | Песни, обзоры, авторы» . Вся музыка . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Ричи Унтербергер . «Снова утро - Том Пэкстон | Песни, обзоры, авторы» . Вся музыка . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Уильям Рульманн. «Держись - Холли Нир | Песни, обзоры, авторы» . Вся музыка . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Рой Бэйли. «Рой Бейли | Биография и история» . Вся музыка . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Иэн Эйч. «Иэн Эйч знакомится с автором песен Леоном Россельсоном | Музыка» . Хранитель . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Джун Сойерс (18 июля 1995 г.). «Дик Гоган держит политику на переднем плане» . Статьи.chicagotribune.com . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ «Туринские тормоза» . Вместе Народ. 06 сентября 2015 г. Архивировано из оригинала 8 сентября 2016 г. Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ «Жизнь поэтов: Аттила Биржевой маклер Джастина Хоппера» . Фонд поэзии. 05 апреля 2010 г. Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ «Статья FolkWorld: Робб Джонсон» . Folkworld.eu . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Робин Денселоу. «Некролог Алистера Хьюлетта | Музыка» . Хранитель . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Робин Денселоу. «Обзор «Люди, которых они не могли повесить» - шумная вечеринка в честь 30-летия | Музыка» . Хранитель . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ «Статья для вашего информирования» (PDF) . TVsmith.com . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ «Чумбавамба: Их сбили с ног...» . Независимый . 11 марта 2008 г. Архивировано из оригинала 18 июня 2022 г. Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ «Новости» . Пространство. Апрель 2016 года . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ «Грейс Петри: Пение ради перемен» . Красный перец . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ «Виниловый альбом – Различные исполнители – Smash Internment And Injustice – Концертная запись в Лонг-Кеше – R&O – Ирландия» . 45worlds.com . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ «Волкодавы [Ирландия] – Мальчики из старой бригады / Эштаун-Роуд – R&O – Ирландия – RO.1001» . 45cat.com . 12 января 2012 г. Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Родницкий, Джером Л. «Шестидесятые между микроканавками: использование народной и протестной музыки для понимания американской истории, 1963–1973». Популярная музыка и общество 23, вып. 4 (декабрь 1999 г.): 105–22. дои : 10.1080/03007769908591755 .

- ^ Больман, Филип (2002). Мировая музыка: очень краткое введение . Оксфорд: Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 64–65.

- ^ Мировая музыка 2002, с. 65

- ^ Народная музыка Китая (1995) Стивена Джонса, стр. 55

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фиш, Лидия (1989). «Генерал Эдвард Г. Лэнсдейл и народные песни американцев во время войны во Вьетнаме». Журнал американского фольклора . 102 (406): 390–411. дои : 10.2307/541780 . JSTOR 541780 .

- ^ «Джош Уайт и протестный блюз, Элайджа Уолд» . Элайджавальд.com . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Билл Даль. «Ж. Б. Ленуар | Биография и история» . Вся музыка . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Джефф Швахтер. «Вьетнамский блюз: Полная запись L&R - Дж. Б. Ленуар | Песни, обзоры, авторы» . Вся музыка . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ «Джон Ли Хукер – Просто правда» . Discogs.com . 1969 год . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Дуберман, с. 400

- ^ Дуберман с. 411

- ^ Коулман, Квами (01 июля 2021 г.). «Фри-джаз и эстетика, идентичность и текстура «новинок», 1960–1966» . Журнал музыковедения . 38 (3): 261–295. дои : 10.1525/jm.2021.38.3.261 . ISSN 0277-9269 . S2CID 238815685 .

- ^ Льюис, Джордж Э. (2002). «Импровизационная музыка после 1950 года: афрологические и еврологические перспективы» . Журнал исследований черной музыки . 22 : 215–246. дои : 10.2307/1519950 . ISSN 0276-3605 . JSTOR 1519950 .

- ^ Коулман, Квами (2021). « Фри-джаз и «Новая вещь» » . Журнал музыковедения . 38 (3): 261–295. дои : 10.1525/jm.2021.38.3.261 . S2CID 238815685 . Проверено 10 мая 2023 г.

- ^ «Джон Колтрейн и стремление черной Америки к свободе: духовность и музыка» . Обзоры выбора в Интернете . 48 (6): 48–3180-48-3180. 01.02.2011. дои : 10.5860/выбор.48-3180 . ISSN 0009-4978 .

- ^ Такер, Шерри (2002). «Большие уши: учет гендера в джазовых исследованиях». Современное музыковедение (71–73). дои : 10.7916/cm.v0i71-73.4831 .

- ^ Лоуренс, Тим. «Дискотека и квиринг танцпола». Культурологические исследования . 25 : 230–243. doi : 10.1080/9502386.2011.535989 (неактивен 31 января 2024 г.).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI неактивен по состоянию на январь 2024 г. ( ссылка ) - ^ Дамодаран, Сумангала (5 августа 2016 г.). «Протест и музыка» . Оксфордская исследовательская энциклопедия политики . doi : 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.81 . ISBN 978-0-19-022863-7 . Проверено 4 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ «От Nueva Canción до Tropicália: 5 музыкальных жанров, рожденных латиноамериканским политическим сопротивлением» . Ремецкла . Проверено 4 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Апарисио, Фрэнсис Р. Слушание сальсы: пол, латинская популярная музыка и пуэрториканская культура . Музыка/Культура. Ганновер, Нью-Хэмпшир: Университетское издательство Новой Англии, 1998.

- ^ Рондон, Сезар Мигель. Книга сальсы. Хроника городской карибской музыки , Editorial Arte, 1980.

- ^ Агурто, Эндрю Спиноза. Сознательная сальса: политика, поэтика и латынь в мета-соседстве . Ист-Лансинг: Издательство Мичиганского государственного университета, 2021.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ривера-Ридо, Петра Р. Ремикс реггетона: расовая культурная политика в Пуэрто-Рико . Иллюстрированное издание. Дарем: Издательство Университета Дьюка, 2015.

- ^ «Лучшие артисты» . Рекламный щит . 2 января 2013 г. Проверено 7 августа 2023 г.

- ^ Фернандес, Сюзетт (16 апреля 2020 г.). «Все, что вам нужно знать о создании видео Bad Bunny «Yo Perreo Sola»» . Рекламный щит . Проверено 7 августа 2023 г.

- ^ Сисарио, Бен (19 сентября 2022 г.). «Плохой кролик, снова номер 1, обращает внимание на неравенство в Пуэрто-Рико» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 7 августа 2023 г.

- ^ Гольдман, Дара Э. (01 ноября 2017 г.). «Ходи как женщина, говори как мужчина: гендерные проблемы Ivy Queen» . Латиноамериканские исследования . 15 (4): 439–457. дои : 10.1057/s41276-017-0088-5 . ISSN 1476-3443 . S2CID 256517140 .