Неаполь

Неаполь

| |

|---|---|

| Муниципалитет Неаполя | |

| Nickname: Partenope | |

Location of Naples | |

| Coordinates: 40°50′9″N 14°14′55″E / 40.83583°N 14.24861°E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Campania |

| Metropolitan city | Naples (NA) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Gaetano Manfredi (Independent) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 117.27 km2 (45.28 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 99.8 m (327.4 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 453 m (1,486 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (30 June 2022)[2] | |

| • Total | 909,048 |

| • Density | 7,800/km2 (20,000/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Napoletano Partenopeo Napulitano (Neapolitan) Neapolitan (English) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 80100, 80121-80147 |

| Dialing code | 081 |

| ISTAT code | 063049 |

| Patron saint | Januarius |

| Saint day | 19 September |

| Website | comune |

Неаполь ( / ˈ n eɪ p əl z / nay -plz ; итальянский : наполи [ˈnaːpoli] ; Neapolitan : napule [nːpail] ) [ А ] является региональной столицей Кампании и третьего по величине городом Италии , [ 3 ] После Рима и Милана население 909 048 человек в пределах административных пределов города по состоянию на 2022 год. [ 4 ] Его муниципалитет на уровне провинции является третьим по численным жильем столичного города в Италии с населением 3115 320 жителей, [ 5 ] и его столичный район простирается за границами городской стены примерно в 30 километрах (20 миль).

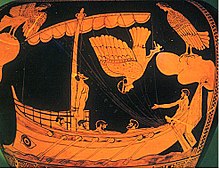

Основанный греками в первом тысячелетии до нашей эры, Неаполь является одним из старейших постоянно населенных городских районов в мире. В восьмом веке до н.э. колония, известная как Партеноп ( древнегреческий : παρθενόπη ), была установлена на холме пиццефалкона. В шестом веке до н.э. он был восстановлен как Neápolis. [ 6 ] Город был важной частью Magna Graecia , сыграл главную роль в слиянии греческого и римского общества и был значительным культурным центром при римлянах. [7]

Naples served as the capital of the Duchy of Naples (661–1139), subsequently as the capital of the Kingdom of Naples (1282–1816), and finally as the capital of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies — until the unification of Italy in 1861. Naples is also considered a capital of the Baroque, beginning with the artist Caravaggio's career in the 17th century and the artistic revolution he inspired.[8] It was also an important centre of humanism and Enlightenment.[9][10] The city has long been a global point of reference for classical music and opera through the Neapolitan School.[11] Between 1925 and 1936, Naples was expanded and upgraded by the Fascist regime. During the later years of World War II, it sustained severe damage from Allied bombing as they invaded the peninsula. The city underwent extensive reconstruction work after the war.[12]

Since the late 20th century, Naples has had significant economic growth, helped by the construction of the Centro Direzionale business district and an advanced transportation network, which includes the Alta Velocità high-speed rail link to Rome and Salerno and an expanded subway network. Naples is the third-largest urban economy in Italy by GDP, after Milan and Rome.[13] The Port of Naples is one of the most important in Europe. In addition to commercial activities, it is home to NATO's Allied Joint Force Command Naples[14] and of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Mediterranean.

Naples' historic city centre is the largest in Europe and has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. A wide range of culturally and historically significant sites are nearby, including the Palace of Caserta and the Roman ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Naples is also known for its natural beauties, such as Posillipo, Phlegraean Fields, Nisida and Vesuvius.[15] Neapolitan cuisine is noted for its association with pizza, which originated in the city, as well as numerous other local dishes. Restaurants in the Naples' area have earned the most stars from the Michelin Guide of any Italian province.[16] Naples' Centro Direzionale was built in 1994 as the first grouping of skyscrapers in Italy, remaining the only such grouping in Italy until 2009. The most widely-known sports team in Naples is the Serie A football club Napoli, three-time Italian champions (most recently in 2023), who play at the Stadio Diego Armando Maradona in the west of the city, in the Fuorigrotta quartier.

History

[edit]Greek birth and Roman acquisition

[edit]

Naples has been inhabited since the Neolithic period.[18] In the second millennium BC, a first Mycenaean settlement arose not far from the geographical position of the future city of Parthenope.[19]

Sailors from the Greek island of Rhodes established probably a small commercial port called Parthenope (Παρθενόπη, meaning "Pure Eyes", a Siren in Greek mythology) on the island of Megaride in the ninth century BC.[20] By the eighth century BC, the settlement was expanded by Cumaeans, as evidenced by the archaeological findings, to include Monte Echia.[21] In the sixth century BC the city was refounded as Neápolis (Νεάπολις), eventually becoming one of the foremost cities of Magna Graecia.[22]

The city grew rapidly due to the influence of the powerful Greek city-state of Syracuse,[23] and became an ally of the Roman Republic against Carthage. During the Samnite Wars, the city, now a bustling centre of trade, was captured by the Samnites;[24] however, the Romans soon captured the city from them and made it a Roman colony.[25] During the Punic Wars, the strong walls surrounding Neápolis repelled the invading forces of the Carthaginian general Hannibal.[25]

The Romans greatly respected Naples as a paragon of Hellenistic culture. During the Roman era, the people of Naples maintained their Greek language and customs. At the same time, the city was expanded with elegant Roman villas, aqueducts, and public baths. Landmarks such as the Temple of Dioscures were built, and many emperors chose to holiday in the city, including Claudius and Tiberius.[25] Virgil, the author of Rome's national epic, the Aeneid, received part of his education in the city, and later resided in its environs.

It was during this period that Christianity first arrived in Naples; the apostles Peter and Paul are said[according to whom?] to have preached in the city. Januarius, who would become Naples' patron saint, was martyred there in the fourth century AD.[26] The last emperor of the Western Roman Empire, Romulus Augustulus, was exiled to Naples by the Germanic king Odoacer in the fifth century AD.

Duchy of Naples

[edit]

Following the decline of the Western Roman Empire, Naples was captured by the Ostrogoths, a Germanic people, and incorporated into the Ostrogothic Kingdom.[27] However, Belisarius of the Byzantine Empire recaptured Naples in 536, after entering the city via an aqueduct.[28]

In 543, during the Gothic Wars, Totila briefly took the city for the Ostrogoths, but the Byzantines seized control of the area following the Battle of Mons Lactarius on the slopes of Vesuvius.[27] Naples was expected to keep in contact with the Exarchate of Ravenna, which was the centre of Byzantine power on the Italian Peninsula.[29]

After the exarchate fell, a Duchy of Naples was created. Although Naples' Greco-Roman culture endured, it eventually switched allegiance from Constantinople to Rome under Duke Stephen II, putting it under papal suzerainty by 763.[29]

The years between 818 and 832 saw tumultuous relations with the Byzantine Emperor, with numerous local pretenders feuding for possession of the ducal throne.[30] Theoctistus was appointed without imperial approval; his appointment was later revoked and Theodore II took his place. However, the disgruntled general populace chased him from the city and elected Stephen III instead, a man who minted coins with his initials rather than those of the Byzantine Emperor. Naples gained complete independence by the early ninth century.[30] Naples allied with the Muslim Saracens in 836 and asked for their support to repel the siege of Lombard troops coming from the neighbouring Duchy of Benevento. However, during the 850s, Muslim general Muhammad I Abu 'l-Abbas sacked Miseno, but only for Khums purposes (Islamic booty), without conquering the territories of Campania.[31][32]

The duchy was under the direct control of the Lombards for a brief period after the capture by Pandulf IV of the Principality of Capua, a long-term rival of Naples; however, this regime lasted only three years before the Greco-Roman-influenced dukes were reinstated.[30] By the 11th century, Naples had begun to employ Norman mercenaries to battle their rivals; Duke Sergius IV hired Rainulf Drengot to wage war on Capua for him.[33]

By 1137, the Normans had attained great influence in Italy, controlling previously independent principalities and duchies such as Capua, Benevento, Salerno, Amalfi, Sorrento and Gaeta; it was in this year that Naples, the last independent duchy in the southern part of the peninsula, came under Norman control. The last ruling duke of the duchy, Sergius VII, was forced to surrender to Roger II, who had been proclaimed King of Sicily by Antipope Anacletus II seven years earlier. Naples thus joined the Kingdom of Sicily, with Palermo as the capital.[34]

As part of the Kingdom of Sicily

[edit]

After a period of Norman rule, in 1189, the Kingdom of Sicily was in a succession dispute between Tancred, King of Sicily of an illegitimate birth and the Hohenstaufens, a Germanic royal house,[35] as its Prince Henry had married Princess Constance the last legitimate heir to the Sicilian throne. In 1191 Henry invaded Sicily after being crowned as Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor, and many cities surrendered. Still, Naples resisted him from May to August under the leadership of Richard, Count of Acerra, Nicholas of Ajello, Aligerno Cottone and Margaritus of Brindisi before the Germans suffered from disease and were forced to retreat. Conrad II, Duke of Bohemia and Philip I, Archbishop of Cologne died of disease during the siege. During his counterattack, Tancred captured Constance, now empress. He had the empress imprisoned at Castel dell'Ovo at Naples before her release on May 1192 under the pressure of Pope Celestine III. In 1194 Henry started his second campaign upon the death of Tancred, but this time Aligerno surrendered without resistance, and finally, Henry conquered Sicily, putting it under the rule of Hohenstaufens.

The University of Naples, the first university in Europe dedicated to training secular administrators,[36] was founded by Frederick II, making Naples the intellectual centre of the kingdom. Conflict between the Hohenstaufens and the Papacy led in 1266 to Pope Innocent IV crowning the Angevin duke Charles I King of Sicily:[37] Charles officially moved the capital from Palermo to Naples, where he resided at the Castel Nuovo.[38] Having a great interest in architecture, Charles I imported French architects and workmen and was personally involved in several building projects in the city.[39] Many examples of Gothic architecture sprang up around Naples, including the Naples Cathedral, which remains the city's main church.[40]

Kingdom of Naples

[edit]

In 1282, after the Sicilian Vespers, the Kingdom of Sicily was divided into two. The Angevin Kingdom of Naples included the southern part of the Italian peninsula, while the island of Sicily became the Aragonese Kingdom of Sicily.[37] Wars between the competing dynasties continued until the Peace of Caltabellotta in 1302, which saw Frederick III recognised as king of Sicily, while Charles II was recognised as king of Naples by Pope Boniface VIII.[37] Despite the split, Naples grew in importance, attracting Pisan and Genoese merchants,[41] Tuscan bankers, and some of the most prominent Renaissance artists of the time, such as Boccaccio, Petrarch and Giotto.[42] During the 14th century, the Hungarian Angevin king Louis the Great captured the city several times. In 1442, Alfonso I conquered Naples after his victory against the last Angevin king, René, and Naples was unified with Sicily again for a brief period.[43]

Aragonese and Spanish

[edit]Sicily and Naples were separated since 1282, but remained dependencies of Aragon under Ferdinand I.[44] The new dynasty enhanced Naples' commercial standing by establishing relations with the Iberian Peninsula. Naples also became a centre of the Renaissance, with artists such as Laurana, da Messina, Sannazzaro and Poliziano arriving in the city.[45] In 1501, Naples came under direct rule from France under Louis XII, with the Neapolitan king Frederick being taken as a prisoner to France; however, this state of affairs did not last long, as Spain won Naples from the French at the Battle of Garigliano in 1503.[46]

Following the Spanish victory, Naples became part of the Spanish Empire, and remained so throughout the Spanish Habsburg period.[46] The Spanish sent viceroys to Naples to directly deal with local issues: the most important of these viceroys was Pedro Álvarez de Toledo, who was responsible for considerable social, economic and urban reforms in the city; he also tried to introduce the Inquisition.[47][better source needed] In 1544, around 7,000 people were taken as slaves by Barbary pirates and brought to the Barbary Coast of North Africa (see Sack of Naples).[48]

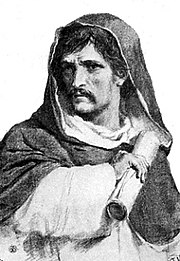

By the 17th century, Naples had become Europe's second-largest city – second only to Paris – and the largest European Mediterranean city, with around 250,000 inhabitants.[49] The city was a major cultural centre during the Baroque era, being home to artists such as Caravaggio, Salvator Rosa and Bernini, philosophers such as Bernardino Telesio, Giordano Bruno, Tommaso Campanella and Giambattista Vico, and writers such as Giambattista Marino. A revolution led by the local fisherman Masaniello saw the creation of a brief independent Neapolitan Republic in 1647. However, this lasted only a few months before Spanish rule was reasserted.[46] In 1656, an outbreak of bubonic plague killed about half of Naples' 300,000 inhabitants.[50]

In 1714, Spanish rule over Naples came to an end as a result of the War of the Spanish Succession; the Austrian Charles VI ruled the city from Vienna through viceroys of his own.[51] However, the War of the Polish Succession saw the Spanish regain Sicily and Naples as part of a personal union, with the 1738 Treaty of Vienna recognising the two polities as independent under a cadet branch of the Spanish Bourbons.[52]

In 1755, the Duke of Noja commissioned an accurate topographic map of Naples, later known as the Map of the Duke of Noja, employing rigorous surveying accuracy and becoming an essential urban planning tool for Naples.

During the time of Ferdinand IV, the effects of the French Revolution were felt in Naples: Horatio Nelson, an ally of the Bourbons, arrived in the city in 1798 to warn against the French republicans. Ferdinand was forced to retreat and fled to Palermo, where he was protected by a British fleet.[53] However, Naples' lower class lazzaroni were strongly pious and royalist, favouring the Bourbons; in the mêlée that followed, they fought the Neapolitan pro-Republican aristocracy, causing a civil war.[53]

Eventually, the Republicans conquered Castel Sant'Elmo and proclaimed a Parthenopaean Republic, secured by the French Army.[53] A counter-revolutionary religious army of lazzaroni known as the sanfedisti under Cardinal Fabrizio Ruffo was raised; they met with great success, and the French were forced to surrender the Neapolitan castles, with their fleet sailing back to Toulon.[53]

Ferdinand IV was restored as king; however, after only seven years, Napoleon conquered the kingdom and installed Bonapartist kings, including installing his brother Joseph Bonaparte.[54] With the help of the Austrian Empire and its allies, the Bonapartists were defeated in the Neapolitan War. Ferdinand IV once again regained the throne and the kingdom.[54]

Independent Two Sicilies

[edit]The Congress of Vienna in 1815 saw the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily combine to form the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies,[54] with Naples as the capital city. In 1839, Naples became the first city on the Italian Peninsula to have a railway, with the construction of the Naples–Portici railway.[55]

Italian unification to the present day

[edit]

After the Expedition of the Thousand led by Giuseppe Garibaldi, which culminated in the controversial siege of Gaeta, Naples became part of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861 as part of the Italian unification, ending the era of Bourbon rule. The economy of the area formerly known as the Two Sicilies as dependant on agriculture suffered the international pressure on prices of wheat, and together with lower sea fares prices lead to an unprecedented wave of emigration,[56] with an estimated 4 million people emigrating from the Naples area between 1876 and 1913.[57] In the forty years following unification, the population of Naples grew by only 26%, vs. 63% for Turin and 103% for Milan; however, by 1884, Naples was still the largest city in Italy with 496,499 inhabitants, or roughly 64,000 per square kilometre (more than twice the population density of Paris).[58]: 11–14, 18

Public health conditions in certain areas of the city were poor, with twelve epidemics of cholera and typhoid fever claiming some 48,000 people between 1834 and 1884. A death rate 31.84 per thousand, high even for the time, insisted in the absence of epidemics between 1878 and 1883.[58] Then in 1884, Naples fell victim to a major cholera epidemic, caused largely by the city's poor sewerage infrastructure. In response to these problems, in 1885,[59] the government prompted a radical transformation of the city called risanamento to improve the sewerage infrastructure and replace the most clustered areas, considered the main cause of insalubrity, with large and airy avenues. The project proved difficult to accomplish politically and economically due to corruption, as shown in the Saredo Inquiry, land speculation and extremely long bureaucracy. This led to the project to massive delays with contrasting results. The most notable transformations made were the construction of Via Caracciolo in place of the beach along the promenade, the creation of Galleria Umberto I and Galleria Principe and the construction of Corso Umberto.[60][61]

Naples was the most-bombed Italian city during World War II.[12] Though Neapolitans did not rebel under Italian Fascism, Naples was the first Italian city to rise up against German military occupation; for the first time in Europe, the Nazis, whose leader in this case was Colonel Scholl, negotiated a surrender in the face of insurgents. The city was already completely freed by 1 October 1943,[62] when British and American forces entered the city.[63] Departing Germans burned the library of the university, as well as the Italian Royal Society. They also destroyed the city archives. Time bombs planted throughout the city continued to explode into November.[64] The symbol of the rebirth of Naples was the rebuilding of the church of Santa Chiara, which had been destroyed in a United States Army Air Corps bombing raid.[12]

Special funding from the Italian government's Fund for the South was provided from 1950 to 1984, helping the Neapolitan economy to improve somewhat, with city landmarks such as the Piazza del Plebiscito being renovated.[65] However, high unemployment continues to affect Naples.

Italian media attributed the city's recent illegal waste disposal issues to the Camorra, the organized crime network centered in Campania.[66] Due to illegal waste dumping, as exposed by Roberto Saviano in his book Gomorrah, severe environmental contamination and increased health risks remain prevalent.[67] In 2007, Silvio Berlusconi's government held senior meetings in Naples to demonstrate their intention to solve these problems.[68] However, the late-2000s recession had a severe impact on the city, intensifying its waste-management and unemployment problems.[69] By August 2011, the number of unemployed in the Naples area had risen to 250,000, sparking public protests against the economic situation.[70] In June 2012, allegations of blackmail, extortion, and illicit contract tendering emerged concerning the city's waste management issues.[71][72]

Naples hosted the sixth World Urban Forum in September 2012[73] and the 63rd International Astronautical Congress in October 2012.[74] In 2013, it was the host of the Universal Forum of Cultures and the host for the 2019 Summer Universiade.

Architecture

[edit]UNESCO World Heritage Site

[edit]| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv |

| Reference | 726 |

| Inscription | 1995 (19th Session) |

| Area | 1,021 ha |

| Buffer zone | 1,350 ha |

Naples' 2,800-year history has left it with a wealth of historical buildings and monuments, from medieval castles to classical ruins, and a wide range of culturally and historically significant sites nearby, including the Palace of Caserta and the Roman ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum. In 2017 the BBC defined Naples as "the Italian city with too much history to handle".[75]

The most prominent forms of architecture visible in present-day Naples are the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque styles.[76] Naples has a total of 448 historical churches (1000 in total[77]), making it one of the most Catholic cities in the world in terms of the number of places of worship.[78] In 1995, the historic centre of Naples was listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, a United Nations programme which aims to catalogue and conserve sites of outstanding cultural or natural importance to the common heritage of mankind.

Naples is one of the most ancient cities in Europe, whose contemporary urban fabric preserves the elements of its long and eventful history. The rectangular grid layout of the ancient Greek foundation of Neapolis is still discernible. It has indeed continued to provide the layout for the present-day Historic Centre of Naples, one of the major Mediterranean port cities. From the Middle Ages to the 18th century, Naples was a focal point in terms of art and architecture, expressed in its ancient forts, the royal ensembles such as the Royal Palace of 1600, and the palaces and churches sponsored by the noble families.

— UNESCO's Criterion

Piazzas, palaces and castles

[edit]

The main city square or piazza of the city is the Piazza del Plebiscito. Its construction was begun by the Bonapartist king Joachim Murat and finished by the Bourbon king Ferdinand IV. The piazza is bounded on the east by the Royal Palace and on the west by the church of San Francesco di Paola, with the colonnades extending on both sides. Nearby is the Teatro di San Carlo, which is the oldest opera house in Italy. Directly across San Carlo is Galleria Umberto.

Naples is well known for its castles: The most ancient is Castel dell'Ovo ("Egg Castle"), which was built on the tiny islet of Megarides, where the original Cumaean colonists had founded the city. In Roman times the islet became part of Lucullus's villa, later hosting Romulus Augustulus, the exiled last western Roman emperor.[79] It had also been the prison for Empress Constance between 1191 and 1192 after her being captured by Sicilians, and Conradin and Giovanna I of Naples before their executions.

Castel Nuovo, also known as Maschio Angioino, is one of the city's top landmarks; it was built during the time of Charles I, the first king of Naples. Castel Nuovo has seen many notable historical events: for example, in 1294, Pope Celestine V resigned as pope in a hall of the castle, and following this Pope Boniface VIII was elected pope by the cardinal collegium, before moving to Rome.[80]

Castel Capuano was built in the 12th century by William I, the son of Roger II of Sicily, the first monarch of the Kingdom of Naples. It was expanded by Frederick II and became one of his royal palaces. The castle was the residence of many kings and queens throughout its history. In the 16th century, it became the Hall of Justice.[81]

Another Neapolitan castle is Castel Sant'Elmo, which was completed in 1329 and is built in the shape of a star. Its strategic position overlooking the entire city made it a target of various invaders. During the uprising of Masaniello in 1647, the Spanish took refuge in Sant'Elmo to escape the revolutionaries.[82]

The Carmine Castle, built in 1392 and highly modified in the 16th century by the Spanish, was demolished in 1906 to make room for the Via Marina, although two of the castle's towers remain as a monument. The Vigliena Fort, built in 1702, was destroyed in 1799 during the royalist war against the Parthenopean Republic and is now abandoned and in ruin.[83]

Museums

[edit]

Naples is widely known for its wealth of historical museums. The Naples National Archaeological Museum is one of the city's main museums, with one of the most extensive collections of artefacts of the Roman Empire in the world.[84] It also houses many of the antiques unearthed at Pompeii and Herculaneum, as well as some artefacts from the Greek and Renaissance periods.[84]

Previously a Bourbon palace, now a museum and art gallery, the Museo di Capodimonte is another museum of note. The gallery features paintings from the 13th to the 18th centuries, including major works by Simone Martini, Raphael, Titian, Caravaggio, El Greco, Jusepe de Ribera and Luca Giordano. The royal apartments are furnished with antique 18th-century furniture and a collection of porcelain and majolica from the various royal residences: the famous Capodimonte Porcelain Factory once stood just adjacent to the palace.

In front of the Royal Palace of Naples stands the Galleria Umberto I, which contains the Coral Jewellery Museum. Occupying a 19th-century palazzo renovated by the Portuguese architect Álvaro Siza, the Museo d'Arte Contemporanea Donnaregina (MADRE) features an enfilade procession of permanent installations by artists such as Francesco Clemente, Richard Serra, and Rebecca Horn.[85] The 16th-century palace of Roccella hosts the Palazzo delle Arti Napoli, which contains the civic collections of art belonging to the City of Naples, and features temporary exhibits of art and culture. Palazzo Como, which dates from the 15th century, hosts the Museo Civico Filangieri of plastic arts, created in 1883 by Gaetano Filangieri.

Churches and other religious structures

[edit]

Naples is the seat of the Archdiocese of Naples; there are hundreds of churches in the city.[78] The Cathedral of Naples is the city's premier place of worship; each year on 19 September, it hosts the longstanding Miracle of Saint Januarius, the city's patron saint.[86] During the miracle, which thousands of Neapolitans flock to witness, the dried blood of Januarius is said to turn to liquid when brought close to holy relics said to be of his body.[86] Below is a selective list of Naples' major churches, chapels, and monastery complexes:

- Certosa di San Martino

- Naples Cathedral

- San Francesco di Paola

- Gesù Nuovo

- Girolamini

- San Domenico Maggiore

- Santa Chiara

- San Paolo Maggiore

- Santa Maria della Sanità, Naples

- Santa Maria del Carmine

- Sant'Agostino alla Zecca

- Madre del Buon Consiglio

- Santa Maria Donna Regina Nuova

- San Lorenzo Maggiore

- Santa Maria Donna Regina Vecchia

- Santa Caterina a Formiello

- Santissima Annunziata Maggiore

- San Gregorio Armeno

- San Giovanni a Carbonara

- Santa Maria La Nova

- Sant'Anna dei Lombardi

- Sant'Eligio Maggiore

- Santa Restituta

- Sansevero Chapel

- San Pietro a Maiella

- San Gennaro extra Moenia

- San Ferdinando

- Pio Monte della Misericordia

- Santa Maria di Montesanto

- Sant'Antonio Abate

- Santa Caterina a Chiaia

- San Pietro Martire

- Hermitage of Camaldoli

- Archbishop's Palace

Other features

[edit]

Aside from the Piazza del Plebiscito, Naples has two other major public squares: the Piazza Dante and the Piazza dei Martiri. The latter originally had only a memorial to religious martyrs, but in 1866, after the Italian unification, four lions were added, representing the four rebellions against the Bourbons.[87]

The San Gennaro dei Poveri is a Renaissance-era hospital for the poor, erected by the Spanish in 1667. It was the forerunner of a much more ambitious project, the Bourbon Hospice for the Poor started by Charles III. This was for the destitute and ill of the city; it also provided a self-sufficient community where the poor would live and work. Though a notable landmark, it is no longer a functioning hospital.[88]

Subterranean Naples

[edit]

Underneath Naples lies a series of caves and structures created by centuries of mining, and the city rests atop a major geothermal zone. There are also several ancient Greco-Roman reservoirs dug out from the soft tufo stone on which, and from which, much of the city is built. Approximately one kilometre (0.62 miles) of the many kilometres of tunnels under the city can be visited from the Napoli Sotteranea, situated in the historic centre of the city in Via dei Tribunali. This system of tunnels and cisterns underlies most of the city and lies approximately 30 metres (98 ft) below ground level. During World War II, these tunnels were used as air-raid shelters, and there are inscriptions on the walls depicting the suffering endured by the refugees of that era.

There are large catacombs in and around the city, and other landmarks such as the Piscina Mirabilis, the main cistern serving the Bay of Naples during Roman times.

Several archaeological excavations are also present; they revealed in San Lorenzo Maggiore the macellum of Naples, and in Santa Chiara, the biggest thermal complex of the city in Roman times.

Parks, gardens, villas, fountains and stairways

[edit]

Of the various public parks in Naples, the most prominent are the Villa Comunale, which was built by the Bourbon king Ferdinand IV in the 1780s;[89] the park was originally a "Royal Garden", reserved for members of the royal family, but open to the public on special holidays. The Bosco di Capodimonte, the city's largest green space, served as a royal hunting reserve. The Park has 16 additional historical buildings, including residences, lodges, churches, fountains, statues, orchards and woods.[90]

Another important park is the Parco Virgiliano, which looks towards the tiny volcanic islet of Nisida; beyond Nisida lie Procida and Ischia.[91] Parco Virgiliano was named after Virgil, the classical Roman poet and Latin writer who is thought to be entombed nearby.[91] Naples is noted for its numerous stately villas, fountains and stairways, such as the Neoclassical Villa Floridiana, the Fountain of Neptune and the Pedamentina stairway.

Neo-Gothic, Liberty Napoletano and modern architecture

[edit]

Various buildings inspired by the Gothic Revival are extant in Naples, due to the influence that this movement had on the Scottish-Indian architect Lamont Young, one of the most active Neapolitan architects of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Young left a significant footprint in the cityscape and designed many urban projects, such as the city's first subway (metro).

In the first years of the 20th century, a local version of the Art Nouveau phenomenon, known as "Liberty Napoletano", developed in the city, creating many buildings which still stand today. In 1935, the Rationalist architect Luigi Cosenza designed a new fish market for the city. During the Benito Mussolini era, the first structures of the city's "service center" were built, all in a Rationalist-Functionalist style, including the Palazzo delle Poste and the Pretura buildings. The Centro Direzionale di Napoli is the only adjacent cluster of skyscrapers in southern Europe.

Geography

[edit]

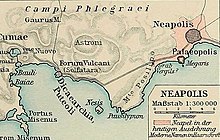

The city is situated on the Gulf of Naples, on the western coast of southern Italy; it rises from sea level to an elevation of 450 metres (1,480 ft). The small rivers that formerly crossed the city's centre have since been covered by construction. It lies between two notable volcanic regions, Mount Vesuvius and the Campi Flegrei (Phlegraean Fields). Campi Flegrei is considered a supervolcano.[92] The islands of Procida, Capri and Ischia can all be reached from Naples by hydrofoils and ferries. Sorrento and the Amalfi Coast are situated south of the city. At the same time, the Roman ruins of Pompeii, Herculaneum, Oplontis and Stabiae, which were destroyed in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, are also visible nearby. The port towns of Pozzuoli and Baia, which were part of the Roman naval facility of Portus Julius, lie to the west of the city.

Quarters

[edit]

The thirty quarters (quartieri) of Naples are listed below. For administrative purposes, these thirty districts are grouped together into ten governmental community boards.[93]

|

1. Pianura |

11. Montecalvario |

21. Piscinola |

Climate

[edit]Naples has a Mediterranean climate (Csa) in the Köppen climate classification.[94][95] The climate and fertility of the Gulf of Naples made the region famous during Roman times, when emperors such as Claudius and Tiberius holidayed near the city.[25] Maritime features mitigate the winters but occasionally cause heavy rainfall, particularly in the autumn and winter. Summers feature high temperatures and humidity.

Winters are mild, and snow is rare in the city area but frequent on Mount Vesuvius. November is the wettest month in Naples, while July is the driest.

| Climate data for Naples-Capodichino, district on the outskirts (altitude: 72 metres (236 feet) above sea level.[96]) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.1 (70.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

27.8 (82.0) |

27.4 (81.3) |

34.8 (94.6) |

37.4 (99.3) |

39.0 (102.2) |

40.0 (104.0) |

37.2 (99.0) |

31.5 (88.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

24.4 (75.9) |

40.0 (104.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 13.0 (55.4) |

13.1 (55.6) |

15.6 (60.1) |

17.4 (63.3) |

23.0 (73.4) |

26.5 (79.7) |

29.8 (85.6) |

30.8 (87.4) |

26.8 (80.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

14.3 (57.7) |

20.9 (69.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.7 (47.7) |

8.8 (47.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

12.9 (55.2) |

17.8 (64.0) |

21.3 (70.3) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.9 (76.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

17.1 (62.8) |

12.5 (54.5) |

9.9 (49.8) |

15.9 (60.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 4.4 (39.9) |

4.5 (40.1) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.4 (47.1) |

12.6 (54.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

18.8 (65.8) |

19.1 (66.4) |

16.0 (60.8) |

12.1 (53.8) |

7.8 (46.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −5.6 (21.9) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

0.8 (33.4) |

5.0 (41.0) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.2 (52.2) |

11.4 (52.5) |

5.6 (42.1) |

2.6 (36.7) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 92.1 (3.63) |

95.3 (3.75) |

77.9 (3.07) |

98.6 (3.88) |

59.0 (2.32) |

32.8 (1.29) |

28.5 (1.12) |

35.5 (1.40) |

88.9 (3.50) |

135.5 (5.33) |

152.1 (5.99) |

112.0 (4.41) |

1,008.2 (39.69) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 9.3 | 9.1 | 8.6 | 9.3 | 6.1 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 3.7 | 6.1 | 8.5 | 10.2 | 9.9 | 86.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75 | 73 | 71 | 70 | 70 | 72 | 70 | 69 | 73 | 74 | 76 | 75 | 72 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 114.7 | 127.6 | 158.1 | 189.0 | 244.9 | 279.0 | 313.1 | 294.5 | 234.0 | 189.1 | 126.0 | 105.4 | 2,375.4 |

| Source: Servizio Meteorologico[97] and NOAA (1961–1990, humidity)[98] | |||||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14.6 °C (58.3 °F) | 13.9 °C (57.0 °F) | 14.2 °C (57.6 °F) | 15.6 °C (60.1 °F) | 19.0 °C (66.2 °F) | 23.6 °C (74.5 °F) | 25.9 °C (78.6 °F) | 26.0 °C (78.8 °F) | 24.9 °C (76.8 °F) | 21.5 °C (70.7 °F) | 19.2 °C (66.6 °F) | 16.4 °C (61.5 °F) | 19.6 °C (67.3 °F) |

Demographics

[edit]

As of 2022[update], the population of the comune di Napoli totals around 910,000. Naples' wider metropolitan area, sometimes known as Greater Naples, has a population of approximately 4.4 million.[104] The demographic profile for the Neapolitan province in general is relatively young: 19% are under the age of 14, while 13% are over 65, compared to the national average of 14% and 19%, respectively.[104] Naples has a higher percentage of females (52.5%) than males (47.5%).[100] Naples currently has a higher birth rate than other parts of Italy, with 10.46 births per 1,000 inhabitants, compared to the Italian average of 9.45 births.[105]

Naples's population rose from 621,000 in 1901 to 1,226,000 in 1971, declining to 910,000 in 2022 as city dwellers moved to the suburbs. According to different sources, Naples' metropolitan area is either the second-most-populated metropolitan area in Italy after Milan (with 4,434,136 inhabitants according to Svimez Data)[106] or the third (with 3.5 million inhabitants according to the OECD).[107] In addition, Naples is Italy's most densely populated major city, with approximately 8,182 people per square kilometre;[100] however, it has seen a notable decline in population density since 2003, when the figure was over 9,000 people per square kilometre.[108]

| 2023 largest resident foreign-born groups[109] |

|---|

In contrast to many northern Italian cities, there are relatively few foreign immigrants in Naples; 94.3% of the city's inhabitants are Italian nationals. In 2023, there were a total of 56,153 foreigners in the city of Naples; the majority of these are mostly from Sri Lanka, China, Ukraine, Pakistan and Romania.[109] Statistics show that, in the past, the vast majority of immigrants in Naples were female; this happened because male immigrants in Italy tended to head to the wealthier north.[104][110]

Education

[edit]

Naples is noted for its numerous higher education institutes and research centres. Naples hosts what is thought to be the oldest state university in the world, in the form of the University of Naples Federico II, which was founded by Frederick II in 1224. The university is among the most prominent in Italy, with around 70,000 students and over 6,000 professors in 2022.[111] It is host to the Botanical Garden of Naples, which was opened in 1807 by Joseph Bonaparte, using plans drawn up under the Bourbon king Ferdinand IV. The garden's 15 hectares feature around 25,000 samples of over 10,000 species.[112]

Naples is also served by the University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, a modern university which opened in 1989, and which has strong links to the nearby province of Caserta.[113] Another notable centre of education is the University of Naples "L'Orientale", which specialises in Eastern culture, and was founded by the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ripa in 1732, after he returned from the court of Kangxi, the emperor of the Manchu Qing dynasty of China.[114]

Other prominent universities in Naples include the Parthenope University of Naples, the private Suor Orsola Benincasa University of Naples, and the Jesuit Theological Seminary of Southern Italy.[115][116] The San Pietro a Maiella music conservatory is the city's foremost institution of musical education; the earliest Neapolitan music conservatories were founded in the 16th century under the Spanish.[117] The Academy of Fine Arts located on the Via Santa Maria di Costantinopoli is the city's foremost art school and one of the oldest in Italy.[118] Naples hosts also the Astronomical Observatory of Capodimonte, established in 1812 by the king Joachim Murat and the astronomer Federigo Zuccari,[119] the oldest marine zoological study station in the world, Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, created in 1872 by German scientist Anton Dohrn, and the world's oldest permanent volcano observatory, the Vesuvius Observatory, founded in 1841. The Observatory lies on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius, near the city of Ercolano, and is now a permanent specialised institute of the Italian National Institute of Geophysics.

Politics

[edit]

Governance

[edit]Each of the 7,896 comune in Italy is today represented locally by a city council headed by an elected mayor, known as a sindaco and informally called the first citizen (primo cittadino). This system, or one very similar to it, has been in place since the invasion of Italy by Napoleonic forces in 1808. When the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was restored, the system was kept in place with members of the nobility filling mayoral roles. By the end of the 19th century, party politics had begun to emerge; during the fascist era, each commune was represented by a podestà. Since World War II, the political landscape of Naples has been neither strongly right-wing nor left-wing – both Christian democrats and democratic socialists have governed the city at different times, with roughly equal frequency. Since the early 1990s, the mayors of Naples have all belonged to left-wing or center-left political groups.

Since 2021, the mayor of Naples is Gaetano Manfredi, an independent politician candidated by the center-left coalition, former minister of university and research in the second Conte government, and former rector of the University of Naples Federico II.

Administrative subdivisions

[edit]Economy

[edit]

Naples, within its administrative limits, is Italy's fourth-largest economy after Milan, Rome and Turin, and is the world's 103rd-largest urban economy by purchasing power, with an estimated 2011 GDP of US$83.6 billion, equivalent to $28,749 per capita.[120][121] Naples is a major cargo terminal, and the port of Naples is one of the Mediterranean's largest and busiest. The city has experienced significant economic growth since World War II, but joblessness remains a major problem,[122][123][124] and the city is characterised by high levels of political corruption and organised crime.

Naples is a major national, and international tourist destination, one of Italy's and Europe's top tourist cities.[125] Tourists began visiting Naples in the 18th century during the Grand Tour.

In the last decades, there has been a move away from a traditional agriculture-based economy in the province of Naples to one based on service industries.[citation needed] The service sector employs the majority of Neapolitans, although more than half of these are small enterprises with fewer than 20 workers; about 70 companies are said to be medium-sized with more than 200 workers, and about 15 have more than 500 workers.[citation needed]

Tourism

[edit]Naples is, with Florence, Rome, Venice and Milan, one of the main Italian tourist destinations. With 3,700,000 visitors in 2018,[126] the city has completely emerged from the strong tourist depression of past decades (due primarily to the unilateral destination of an industrial city but also due to the damage to the city's image caused by the Italian media,[127][128] from the 1980 Irpinia earthquake and the waste crisis, in favour of the coastal centres of its metropolitan area).[129] To adequately assess the phenomenon, however, it must be considered that a large slice of tourists visit Naples per year, staying in the numerous localities in its surroundings,[130] connected to the city with both private and public direct lines.[131][132] Daily visits to Naples are carried out by various Roman tour operators and by all the main tourist resorts of Campania: as of 2019, Naples is the tenth most visited municipality in Italy and the first in the South.[133]

The sector is constantly growing[134][135] and the prospect of reaching the art cities of its level is once again expected in a relatively short time;[136] tourism is increasingly assuming a decisive weight for the city's economy, which is why, exactly as happened for example in the case of Venice or Florence, the risk of gentrification of the historic centre is now high.[137][138]

Transport

[edit]

Naples is served by several major motorways (it: autostrade). The Autostrada A1, the longest motorway in Italy, links Naples to Milan.[141] The A3 runs southwards from Naples to Salerno, where the motorway to Reggio Calabria begins, while the A16 runs east to Canosa.[142] The A16 is nicknamed the autostrada dei Due Mari ("Motorway of the Two Seas") because it connects the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Adriatic Sea.[143]

Suburban rail services are provided by Trenitalia, Circumvesuviana, Ferrovia Cumana and Metronapoli.

The city's main railway station is Napoli Centrale, which is located in Piazza Garibaldi; other significant stations include the Napoli Campi Flegrei[144] and Napoli Mergellina. Napoli Afragola serves high-speed trains that do not start or finish at Napoli Centrale railway station. Naples' streets are famously narrow (it was the first city in the world to set up a pedestrian one-way street),[145] so the general public commonly use compact hatchback cars and scooters for personal transit.[146] Since 2007, trains running at 300 km/h (186 mph) have connected Naples with Rome with a journey time of under an hour,[147] and direct high speed services also operate to Florence, Bologna, Milan, Turin and Salerno. Direct sleeper 'boat train' services operate nightly to cities in Sicily.

The port of Naples runs several ferry, hydrofoil, and SWATH catamaran lines to Capri, Ischia and Sorrento, Salerno, Positano and Amalfi.[148] Services are also available to Sicily, Sardinia, Ponza and the Aeolian Islands.[148] The port serves over 6 million local passengers annually,[149] plus a further 1 million international cruise ship passengers.[150] A regional hydrofoil transport service, the "Metropolitana del Mare", runs annually from July to September, maintained by a consortium of shipowners and local administrations.[151]

The Naples International Airport is located in the suburb of San Pietro a Patierno. It is the largest airport in southern Italy, with around 250 national and international flights arriving or departing daily.[152]

The average commute with public transit in Naples on a weekday is 77 minutes. Nineteen per cent of public transit commuters ride for more than 2 hours every day. The average time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 27 minutes, while 56% of riders wait for over 20 minutes. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 7.1 km (4.4 mi), while 11% travel for over 12 km (7.5 mi) in a single direction.[153]

Urban public transport

[edit]Naples has an extensive public transport network, including trams, buses and trolleybuses,[154] most of which are operated by the municipally owned company Azienda Napoletana Mobilità (ANM). Some suburban services are operated by AIR Campania.

The city furthermore operates the Naples Metro (Italian: metropolitana di Napoli), an underground rapid transit railway system which integrates both surface railway lines and the city's metro stations, many of which are noted for their decorative architecture and public art. In fact, the station of Via Toledo is often in the top spots of the rankings of the most beautiful metro stations in the world.[154]

There are also four funiculars in the city (operated by ANM): Centrale, Chiaia, Montesanto and Mergellina.[155] Four public elevators are in operation in the city: within the bridge of Chiaia, in via Acton, near the Sanità Bridge,[156] and in the Ventaglieri Park, accompanied by two public escalators.[157]

Culture

[edit]Art

[edit]

Naples has long been a centre of art and architecture, dotted with Medieval-, Baroque- and Renaissance-era churches, castles and palaces. A critical factor in the development of the Neapolitan school of painting was Caravaggio's arrival in Naples in 1606. In the 18th century, Naples went through a period of neoclassicism, following the discovery of the remarkably intact Roman ruins of Herculaneum and Pompeii.

The Neapolitan Academy of Fine Arts, founded by Charles III of Bourbon in 1752 as the Real Accademia di Disegno (en: Royal Academy of Design), was the centre of the artistic School of Posillipo in the 19th century. Artists such as Domenico Morelli, Giacomo Di Chirico, Francesco Saverio Altamura and Gioacchino Toma worked in Naples during this period, and many of their works are now exhibited in the academy's art collection. The modern Academy offers courses in painting, decorating, sculpture, design, restoration, and urban planning. Naples is also known for its theatres, which are among the oldest in Europe: the Teatro di San Carlo opera house dates back to the 18th century.

Naples is also the home of the artistic tradition of Capodimonte porcelain. In 1743, Charles of Bourbon founded the Royal Factory of Capodimonte, many of whose artworks are now on display in the Museum of Capodimonte. Several of Naples' mid-19th-century porcelain factories remain active today.

Cuisine

[edit]

Naples is internationally famous for its cuisine and wine; it draws culinary influences from the numerous cultures which have inhabited it throughout its history, including the Greeks, Spanish and French. Neapolitan cuisine emerged as a distinct form in the 18th century. The ingredients are typically rich in taste while remaining affordable to the general populace.[158]

Naples is traditionally credited as the home of pizza.[159] This originated as a meal of the poor, but under Ferdinand IV it became popular among the upper classes: famously, the Margherita pizza was named after Queen Margherita of Savoy after her visit to the city.[159] Cooked traditionally in a wood-burning oven, the ingredients of Neapolitan pizza have been strictly regulated by law since 2004, and must include wheat flour type "00" with the addition of flour type "0" yeast, natural mineral water, peeled tomatoes or fresh cherry tomatoes, mozzarella, sea salt and extra virgin olive oil.[160]

Spaghetti is also associated with the city, and is commonly eaten with clams vongole or lupini di mare. A popular Neapolitan folkloric symbol is the comic figure Pulcinella eating a plate of spaghetti.[161] Other dishes popular in Naples include Parmigiana di melanzane, spaghetti alle vongole and casatiello.[162] As a coastal city, Naples is furthermore known for numerous seafood dishes, including impepata di cozze (peppered mussels), purpetiello affogato (octopus poached in broth), alici marinate (marinated anchovies), baccalà alla napoletana (salt cod) and baccalà fritto (fried cod), a dish commonly eaten during the Christmas period.

Naples is well known for its sweet dishes, including colourful gelato, which is similar to ice cream, though more fruit-based. Popular Neapolitan pastry dishes include zeppole, babà, sfogliatelle and pastiera, the latter of which is prepared specially for Easter celebrations.[163] Another seasonal sweet is struffoli, a sweet-tasting honey dough decorated and eaten around Christmas.[164] Neapolitan coffee is also widely acclaimed. The traditional Neapolitan flip coffee pot, known as the cuccuma or cuccumella, was the basis for the invention of the espresso machine, and also inspired the Moka pot.

Wineries in the Vesuvius area produce wines such as the Lacryma Christi ("tears of Christ") and Terzigno. Naples is also the home of limoncello, a popular lemon liqueur.[165][166]

Фестивали

[ редактировать ]Культурное значение Неаполя часто представлено через серию фестивалей, проводимых в городе. Ниже приведен список нескольких фестивалей, которые проходят в Неаполе (примечание: некоторые фестивали не проводятся на ежегодной основе).

- Festa di Piedigrotta («Пьеротта -фестиваль») - музыкальное мероприятие, обычно проводимое в сентябре, в память о знаменитой Мадонне Пьегретта. В течение месяца серия музыкальных семинаров, концертов, религиозных мероприятий и детских мероприятий проводятся для развлечения граждан Неаполя и прилегающих районов. [ 167 ]

- PizzaFest -Поскольку Неаполь известен тем, что является домом для Pizza, в городе проходит одиннадцать дней фестиваля, посвященного этому культовому блюду. Это ключевое событие как для неаполитанцев, так и для туристов, так как различные станции открыты для дегустации широкого спектра настоящей неаполитанской пиццы. В дополнение к дегустации пиццы выставлены различные развлекательные шоу. [ 168 ]

- Maggio Dei Monumenti («Май из памятников») - культурное событие, где в городе проводится множество специальных мероприятий, посвященных рождению короля Чарльза из Бурбона. ИТ -фестиваль представляет собой искусство и музыку 18 -го века, и многие здания, которые обычно могут быть закрыты в течение всего года, открыты для посетителей. [ 169 ]

- IL Ritorno Della Festa Di San Gennaro («Возвращение праздника Сан -Геннаро ») - ежегодный праздник и праздник веры, проводимый в течение трех дней, посвященный Сен -Геннаро . На протяжении всего фестиваля представлены парады, религиозные шествия и музыкальные развлечения. Ежегодный праздник также проводится в « Маленькой Италии » на Манхэттене. [ 170 ] [ 171 ]

Язык

[ редактировать ]Неаполитенский язык , который считается отдельным языком и в основном говорящим в городе, также встречается в регионе Кампании и был распространен в других районах южной Италии неаполитанскими мигрантами и во многих различных местах в мире. 14 октября 2008 года Кампания принял региональный закон, который оказывает влияние использования неаполитанского языка. [ 172 ]

Термин «неаполитанский язык» часто используется для описания языка всей Кампании (кроме Cilento ) и иногда применяется ко всему южно -итальянскому языку ; Этнолог называет последнее как Наполетано-Калабрезе . [ 173 ] На этой лингвистической группе говорится по большей части южной континентальной Италии, в том числе в районе Гаэта и Сора Южного Лацио , южной части Марче и Абриццо , Молизы, Базиликаты , Северной Калабрии , а также в Северной и Центральной Апулии . В 1976 году было около 7 047 399 носителей этой группы диалектов. [ 173 ]

Литература и философия

[ редактировать ]В этом разделе есть несколько проблем. Пожалуйста, помогите улучшить его или обсудить эти вопросы на странице разговоров . ( Узнайте, как и когда удалить эти сообщения )

|

Неаполь является одним из ведущих центров итальянской литературы . История неаполитанского языка была глубоко перепутана с историей тосканского диалекта , который затем стал нынешним итальянским языком. Первыми письменными свидетельствами итальянского языка являются документы Placiti Cassinensi , датированные 960 г. юридические н.э. Тосканский поэт Боккаччо много лет жил во дворе короля Роберта Мудреца и его преемника Джоанны из Неаполя , используя Неаполь в качестве обстановки для Декамерона и ряда его более поздних романов. Его работы содержат несколько слов, которые взяты из неаполитанского вместо соответствующего итальянского, например, « Тесто » (Neap.: « Testa »), что в Неаполе указывает на большую терракотную банку, используемую для культивирования кустарников и маленьких деревьев. Король Альфонсо V из Арагона заявил в 1442 году, что неаполитанский язык должен быть использован вместо латинского в официальных документах.

Позже неаполитан был заменен итальянцем в первой половине 16 -го века, [ 174 ] [ 175 ] Во время доминирования в испанском языке. В 1458 году в Неаполе была основана академия Понтаниана , одна из первых академий в Италии как бесплатная инициатива «Люди писем, науки и литературы». В 1480 году писатель и поэт Якопо Саннаццаро написал первый пастырский роман «Аркадия» , который повлиял на итальянскую литературу. В 1634 году Giambattista Basile собрал Lo Cunto de Li Cunti пять книг древних рассказов, написанных на неаполитанском диалекте, а не итальянском. Философ Джордано Бруно , который теоретизировал существование бесконечных солнечных систем и бесконечность всей вселенной, завершил свои исследования в Университете Неаполя. Из -за таких философов, как Джамбаттиста Вико , Неаполь стал одним из центров итальянского полуострова для исторической и философии истории исследований.

Исследования юриспруденции были улучшены в Неаполе благодаря выдающимся личностям юристов, таких как Бернардо Тануччи , Гаэтано Филангиери и Антонио Геновиси . В 18 -м веке Неаполь вместе с Миланом стал одним из самых важных мест, из которых Просвещение проникло в Италию. Поэт и философ Джакомо Леопарди посетили город в 1837 году и умерли там. Его работы повлияли на Франческо де Сантис , который учился в Неаполе и в конечном итоге стал министром наставления во время итальянского королевства. Де Сантис был одним из первых литературных критиков, которые обнаружили, изучали и распространяли стихи и литературные произведения великого поэта из Реканати .

Писатель и журналист Матильда Серао соучредила газету Ир Маттино со своим мужем Эдоардо Скарфоглио в 1892 году. Серао была известным романистом и писателем в течение ее дня. Поэт Сальваторе Ди Джакомо был одним из самых известных писателей на неаполитанском диалекте, и многие из его стихов были адаптированы к музыке, став известными неаполитанскими песнями. В 20 -м веке такие философы, как Бенедетто Кроче, проводили давнюю традицию философических исследований в Неаполе, а личности, такие как юристы и адвокат Энрико де Никола, проводили юридические и конституционные исследования. Позже Де Никола помог составить современную конституцию итальянской республики и в конечном итоге был избран на канцелярию президента Итальянской Республики. Другими известными неаполитанскими писателями и журналистами являются Антонио де Кертис , Керзио Малапарт , Джанкарло Сиани , Роберто Савиано и Елена Ферранте . [ 176 ] В Неаполе 44 года, офицер разведки в итальянском лабиринте (Лондон, Eland, 2002), известный британский путешественник Норман Льюис записывает жизнь народа наполя после освобождения города от нацистских сил в 1943 году.

Театр

[ редактировать ]В этом разделе нужны дополнительные цитаты для проверки . ( Июнь 2013 г. ) |

Неаполь был одним из центров полуострова, из которого возник современный жанр театра, как наверняка, развивались из 16 -го века Commedia Dell'arte . Маскированный характер Pulcinella - это всемирная известная фигура либо в виде театрального персонажа, либо кукольного характера.

Жанр музыкальной оперы в оперной баффе был создан в Неаполе в 18 -м веке, а затем распространился на Рим и Северную Италию. В период Belle Epoque Неаполь соперничал с Парижом за его кафе-шансы , и изначально были созданы многие известные неаполитанские песни, чтобы развлечь публику в кафе Неаполя. Возможно, самая известная песня-"Ninì tirabusciò". История того, как родилась эта песня, была драматизирована в одноименном комедийном фильме « Ninì Tirabusciò: La Donna Che Inventò La Mossa » с Моникой Витти в главной роли .

Неаполитанский популярный жанр Sceneggiata - это важный жанр современного народного театра во всем мире, драматизирующие общие темы канонов сорванных любовных историй, комедий, рассказов о слезах, как правило, о честных людях, становящихся чемоданом Каморры из -за неудачных событий. Сценаггиата стала очень популярной среди неаполитанцев и, в конечном итоге, одним из самых известных жанров итальянской кинематографии благодаря актерам и певцам, таким как Марио Мерола и Нино Д'Анджело . Многие писатели и драматурги, такие как Раффаэле Вивиани , писали комедии и драмы для этого жанра. Актеры и комики, такие как Эдуардо Скарпетта , а затем его сыновья Эдуардо де Филиппо , Пеппино де Филиппо и Титина де Филиппо внесли свой вклад в создание неаполитанского театра. Его комедии и трагедии, такие как « Filumena Marturano » и « Napoli Milionaria », хорошо известны.

Музыка

[ редактировать ]

Неаполь играл важную роль в истории западной европейской художественной музыки более четырех веков. [ 177 ] Первые музыкальные консерватории были созданы в городе под испанским правлением в 16 веке. Музыкальная консерватория San Pietro Majella, основанная в 1826 году Франческо I из Бурбона , продолжает работать сегодня как престижный центр музыкального образования и музыкальный музей.

В течение позднего барокко периода Алессандро Скарлатти , отец Доменико Скарлатти , основал неаполитанскую школу оперы; Это было в форме Opera Seria , которая была новой разработкой для своего времени. [ 178 ] Другая форма оперы, происходящей в Неаполе, - это оперная буффа , стиль комической оперы, тесно связанной с Баттиста Перголесси и Пикцинни ; Более поздние участники жанра включали Россини и Вольфганг Амадеус Моцарт . [ 179 ] Teatro Di San Carlo , построенный в 1737 году, является самым старым рабочим театром в Европе и остается оперным центром Неаполя. [ 180 ]

Самая ранняя шестипринг-гитара была создана неаполитанской Гаетано Виначча в 1779 году; Инструмент теперь называется романтической гитарой . Семейство Vinaccia также разработало мандолину . [ 181 ] [ 182 ] Под влиянием испанских, неаполитанцы стали пионерами классической гитарной музыки, а Фердинандо Карулли и Мауро Джулиани стали выдающимися показателями. [ 183 ] Джулиани, который был на самом деле из Апулии , но жил и работал в Неаполе, широко считается одним из величайших гитаристов и композиторов 19 -го века, а также его каталонский современный Фернандо Сор . [ 184 ] [ 185 ] Другим неаполитанским музыкантом Note был оперный певец Энрико Карузо , один из самых выдающихся оперных теноров всех времен: [ 186 ] Его считали человеком людей в Неаполе, родом из рабочего класса. [ 187 ]

Популярный традиционный танец в южной части Италии и Неаполя - это Тарантелла , которая возникла в Апулии и распространилась по всему Королевству двух сицилий . Neapolitan Tarantella - это танец ухаживания, исполняемый парами, чьи «ритмы, мелодии, жесты и сопровождающие песни довольно четко», показывают более быструю, более веселую музыку.

Примечательным элементом популярной неаполитанской музыки является стиль Canzone Napoletana , по сути, традиционная музыка города, с репертуаром из сотен народных песен, некоторые из которых можно отследить до 13 -го века. [ 188 ] Этот жанр стал формальным учреждением в 1835 году после введения ежегодного фестиваля конкурса написания песенга . [ 188 ] Некоторые из самых известных звукозаписывающих артистов в этой области включают Роберто Муроло , Серхио Бруни и Ренато Каросон . [ 189 ] Кроме того, существуют различные формы музыки, популярные в Неаполе, но не известны на улице, такие как Cantautore («певец-автор песен») и Sceneggiata , которая была описана как музыкальная мыльная оперство; Самым известным показателем этого стиля является Марио Мерола . [ 190 ]

Кино и телевидение

[ редактировать ]В этом разделе есть несколько проблем. Пожалуйста, помогите улучшить его или обсудить эти вопросы на странице разговоров . ( Узнайте, как и когда удалить эти сообщения )

|

Неаполь оказал значительное влияние на итальянское кино . Из -за актуальности города многие фильмы и телевизионные шоу установлены (полностью или частично) в Неаполе. В дополнение к выступлению на фоне нескольких фильмов и шоу, многие талантливые знаменитости (актеры, актрисы, режиссеры и продюсеры) родом из Неаполя.

Неаполь был местом для нескольких ранних итальянских шедевров кино. Assunta Spina (1915) была немое фильмом, адаптированным из театральной драмы неаполитанского писателя Сальваторе Ди Джакомо . Фильм был снят неаполитанским Густаво Сереной . Серена также снялась в фильме 1912 года «Ромео и Джульетта» . [ 191 ] [ 192 ] [ 193 ]

Список некоторых известных фильмов, которые происходят (полностью или частично) в Неаполе, включает в себя: [ 194 ]

- Shoeshine (1946), режиссер Neapolitan, Vittorio de Sica

- Руки над городом (1963), режиссер Неаполитан, Франческо Рози

- Путешествие в Италию (1954), режиссер Роберто Росселлини

- Брак итальянский стиль (1964), режиссер Neapolitan, Vittorio de Sica

- Это началось в Неаполе (1960), режиссер Мелвилл Шейвельсон

- Рука Бога (2021), режиссер Паоло Соррентино

Неаполь является домом для одного из первых итальянских цветных фильмов, Toto in Color (1952), в главной роли Totò (Antonio de Curtis), известного комедийного актера, родившегося в Неаполе. [ 195 ]

Некоторые известные комедии, установленные в Неаполе, включают Ieri, Oggi E Domani ( вчера, сегодня и завтра ), Витторио де Сика, в главных ролях София Лорен и Марчелло Мастроанни , Аделина из Неаполя (фильм, получивший премию Академии), он начался в Неаполе , L ' Оро Ди Наполи снова от Витторио де Сика, драматических фильмов, таких как Дино Риси » «Аромат женщины , военные фильмы, такие как Сардинского режиссера Нанни Лой , фильмы « Музыка четыре Неаполя дня Певица и актер и актер Марио Марио Мерола , криминальные фильмы, такие как Ил Каморриста , с Беном Газзарой, играющая роль печально известного Кафура босса Раффаээээээээле Кауло , и исторические или костюмированные фильмы, подобные этой женщине Гамильтона с Вивьен Ли и Лоуренсом Оливье .

Более современные неаполитанские фильмы включают Ricomincio Da Tre , в котором изображены несчастные случаи молодого эмигранта в конце 20 -го века. Фильм 2008 года «Гоморра» , основанная на книге Роберто Савиано , исследует мрачный живот города Неаполя через пять переплетений о мощном неаполитанском преступном синдикате , а также о одном именивом сериале .

Несколько эпизодов анимационного сериала Тома и Джерри также имеют ссылки/влияние Неаполя. Песня " Санта-Люсия ", сыгранная Томом Кэт в Кошке и Дупле-Кате, имеет свое происхождение в Неаполе. Неаполитанская мышь происходит в том же городе.

Японская серия Jojo's Bizarre Adventure, часть 5 , Vento Aureo, проходит в городе.

Неаполь появился в эпизодах телевизионных сериалов, таких как «Сопрано» и версия графа Монте -Кристо в главной роли в 1998 году с Герардом Депардье .

Спорт

[ редактировать ]

Футбол , безусловно, самый популярный вид спорта в Неаполе. Привезено в город британцами в начале 20 -го века, [ 196 ] Спорт глубоко встроен в местную культуру: он популярен на всех уровнях общества, от Скагницци ( уличных детей ) до богатых специалистов. города Самым известным футбольным клубом является Наполи , который играет свои домашние игры на стадионе Марадона в Фуориглотте . Стадион клуба был переименован в стадион Диего Армандо Марандона в честь атакующего полузащитника аргентинца, который играл за них в течение семи лет. [ 197 ] Команда играет в Серии А выигрывала Скудетто и три раза , шесть раз, Коппа Италия и Суперкоппа Итальянская . Команда также выиграла Кубок УЕФА , [ 198 ] и однажды назвал FIFA Player of the Century Diego Maradona среди своих игроков. Неаполь является местом рождения многочисленных выдающихся профессиональных футболистов, в том числе Сиро Феррара и Фабио Каннаваро . Каннаваро был капитаном сборной Италии до 2010 года и привел команду к победе на чемпионате мира 2006 года . Следовательно, он был назван мировым игроком года .

Некоторые из небольших клубов города включают Sporting Neapolis и Internapoli , которые играют на стадионе Arturo Collana . В городе также есть команды во множестве других видов спорта: Эльдо Наполи представляет город в серии баскетбола и играет в городе Багноли . Город совместил с евробаскеткой 1969 года . в городе Partenope Rugby-самая известная сторона регби : команда выиграла «Союз регби » в два раза. Другие популярные местные виды спорта включают футзал , водное поло , скачки, парусный спорт , фехтование, бокс и боевые искусства. названия «Мастер меча» и «Мастер Кендо ». Accademia Nazionale Di Scherma (Национальная академия и школа фехтования Неаполя) - единственное место в Италии, где можно получить [ 199 ]

Пошив

[ редактировать ]Неаполитанский пошив родился как попытка ослабить жесткость английского пошива, что не соответствовало неаполитанскому образу жизни. [ 200 ] Неаполитанская куртка короче, легче, с квартальной подставкой или безделенной, и не имеет наплечника.

Международные отношения

[ редактировать ]Города -близнецы и родственные города

[ редактировать ] ГАФСА , Тунис

ГАФСА , Тунис  Крагуевак , Сербия

Крагуевак , Сербия  Palma de Mallorca , Испания

Palma de Mallorca , Испания  Афины , Греция

Афины , Греция  Сантьяго де Куба , Куба

Сантьяго де Куба , Куба  Сантьяго -де -Куба провинция , Куба

Сантьяго -де -Куба провинция , Куба  Любопытный , Мадагаскар

Любопытный , Мадагаскар  Наблус , Палестина

Наблус , Палестина  Лимерик , Ирландия

Лимерик , Ирландия  Сассари , Италия

Сассари , Италия  Салманский , Ирак [ 202 ]

Салманский , Ирак [ 202 ]

Партнерство

[ редактировать ]Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Из латыни : Неаполис , от древнегреческого : Неаполь , романизированный : neápolis , горит. «Новый город».

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Основная географическая статистика о муниципалитетах» . www.istat.it (на итальянском языке). 28 февраля 2019 года. Архивировано с оригинала 2 марта 2020 года . Получено 1 апреля 2019 года .

- ^ «Демографический баланс за 2022 - июньская провинция: Наполи» . Demo.istat.it . ISTAT - ISTITUTO NAZIONALE DI Statistica. Архивировано из оригинала 25 сентября 2022 года . Получено 25 сентября 2022 года .

- ^ Маззео, Джузеппе (2009). "Неаполь" Города 26 (6): 363–376. два 10.1016/j.cities.2009.06.001:

- ^ «Запалость цитирует плотность населения» . Все это (в Италии). Архив жарить оригинал 10 февраля 2023 года . Получено 10 февраля 2023 года .

- ^ «Внешний контекст-анализ демографического и социально-экономического контекста столичного города Неаполь-год 2021 года» . Cittametropolyanan.na.it . 28 апреля 2021 года . Получено 10 февраля 2023 года . [ Постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Даниэла Джампаола, Франческа Лонгбардо (2000). Неаполь Греческий и Роман . Electa.

- ^ «Вирджил в Неаполе» . naplesldm.com. Архивировано с оригинала 2 апреля 2017 года . Получено 9 мая 2017 года .

- ^ Алессандро Джардино (2017), Корпоративность и перформативность в барокко Неаполь. Тело Неаполя. Лексингтон.

- ^ "Уманесимо в" Энсиклопедии Дей Рагацци " . www.treccani.it (на итальянском языке). Архивировано из оригинала 11 сентября 2020 года . Получено 28 декабря 2020 года .

- ^ Муси, Аурелио. Неаполь, столица и его королевство (на итальянском языке). Гастролинг. стр. 118, 156.

- ^ Флоримо, Франческо. Исторический кивок в музыкальной школе де Наполи (на итальянском языке). Набу Пресс.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Бомбардировка Неаполя» . naplesldm.com. 7 октября 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 27 июня 2017 года . Получено 9 мая 2017 года .

- ^ "Sr-M.it" (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 8 февраля 2018 года.

- ^ «Неаполь, инаугурация стратегического центра НАТО» . La Repubblica . 5 сентября 2017 года. Архивировано с оригинала 5 сентября 2017 года.

- ^ "Rivistameridiana.it" (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 26 декабря 2014 года.

- ^ «Какие рестораны в Италии в Италии? Вот гид Michelin 2021» . Itlaian Touring Club . Архивировано из оригинала 24 июля 2021 года . Получено 24 июля 2021 года .

- ^ «Центр Неаполя, Италия» . Чадаба Наполи. 24 июня 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 11 октября 2007 года.

- ^ «Станция Neapolis - археологические дворы», архивные 20 мая 2013 года на машине Wayback . VirtualTourist.com. 12 июня 2005 года. Получено 7 сентября 2012 года.

- ^ Дэвид Дж. Блэкман; Мария Костанса Лентини (2010). Госпитализации для военных кораблей в портах древнего и средневекового Средиземноморья: семинарные документы, Равелло, 4-5 ноября 2005 года . Edipuglia srl. п. 99. ISBN 978-88-7228-565-7 .

- ^ «Порт Неаполя» архивировал 28 апреля 2012 года на машине Wayback . Всемирный источник порта. Получено 15 мая 2012 года.

- ^ Archemail. Это архивировано 29 марта 2013 года на машине Wayback . Получено 3 декабря 2012 года.

- ^ «Исторический центр Неаполя» . Архивировано из оригинала 4 октября 2022 года . Получено 4 октября 2022 года .

- ^ «Греческий Неаполь» . naplesldm.com. Архивировано из оригинала 21 марта 2017 года . Получено 9 мая 2017 года .

- ^ «Туристический клуб Италии, Неаполь: город и его знаменитый залив, Капри, Сорренто, Ишия и Амальфи, Милано» . Туристический клуб Италии. 2003. с. 11. ISBN 88-365-2836-8 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый «Антино -неаполь» . Неаполь. 8 января 2008 года. Архивировано с оригинала 25 декабря 2008 года.

- ^ Герберманн, Чарльз, изд. (1913). . Католическая энциклопедия . Нью -Йорк: Роберт Эпплтон Компания.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Wolfram, Herwig (1997). Римская империя и ее германские народы . Калифорнийский университет. ISBN 978-0-520-08511-4 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 18 апреля 2024 года . Получено 27 октября 2020 года .

- ^ «Белисарий - знаменитый византийский генерал» . ОБЛЮДА. 8 января 2008 года. Архивировано с оригинала 19 апреля 2009 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Кляйнхенц, Кристофер (2004). Средневековая Италия: энциклопедия . Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-22126-9 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 18 апреля 2024 года . Получено 27 октября 2020 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в McKitterick, Rosamond (2004). Новая Кембриджская средневековая история . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-521-85360-6 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 18 апреля 2024 года . Получено 27 октября 2020 года .

- ^ Magnusson & Goring 1990

- ^ Хилмар С. Крюгер. «Итальянские города и арабы до 1095 года» в истории крестовых походов: первые сто лет , том. Кеннет Мейер Сеттон, Маршалл В. Болдуин (ред., 1955). Университет Пенсильвании Пресс. с.48.

- ^ Брэдбери, Джим (8 апреля 2004 г.). Спутник Routledge для средневековой войны . Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-22126-9 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 18 апреля 2024 года . Получено 27 октября 2020 года .

- ^ "Царство Сицилия, или Тринацила " Британская январь 2008 8 , г.

- ^ "Swabian Naples" . naplesldm.com. 7 октября 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 19 марта 2017 года . Получено 9 мая 2017 года .

- ^ Astarita, Tommaso (2013). «Введение:« Неаполь - это весь мир » . Компаньон раннего современного Неаполя . Брилль п. 2

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Сицилийская история» . Dieli.net. 7 октября 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 4 мая 2009 года . Получено 26 февраля 2008 года .

- ^ «Неаполь - Кастель Нуово» . 7 октября 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 23 апреля 2023 года . Получено 23 апреля 2023 года .

- ^ Уор, Корделия; Эллиотт, Janis (2010). Искусство и архитектура в Неаполе, 1266–1713: новые подходы . Джон Уайли и сыновья. С. 154 –155. ISBN 9781405198615 .

- ^ Брузелиус, Кэролайн (1991). « Ad Modum Franciae»: Чарльз Анжу и готическая архитектура в Королевстве Сицилии ». Журнал Общества архитектурных историков . 50 (4). Университет Калифорнии Пресс: 402–420. doi : 10.2307/990664 . JSTOR 990664 .

- ^ Констебль, Оливия Реми (1 августа 2002 г.). Размещение незнакомца в средиземноморском мире: проживание, торговля и путешествия . Humana Press. ISBN 978-1-58829-171-4 .

- ^ "Ангиоино -замок, Неаполь" . Неаполь-City.info. 7 октября 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 29 сентября 2008 года . Получено 26 февраля 2008 года .

- ^ «Арагонский зарубежный расширение, 1282–1479» . Zum.de. 7 октября 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 29 декабря 2008 года.

- ^ «Ferrante of Naples: государственное управление принца Ренессанса» . 7 октября 2007 г. [ мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ «Неаполь средних лет» . Неаполь. 7 октября 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 10 апреля 2008 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Испанский приобретение Неаполя» . Encyclopædia Britannica . 7 октября 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 18 февраля 2008 года.

- ^ Мэтьюз, Джефф (2005). "Дон Педро де Толедо" . Вокруг Неаполя Энциклопедии . Faculty.ed.umuc.edu. Архивировано из оригинала 9 мая 2008 года.

- ^ Ниаз, Илхан (2014). Империи Старого Света: культура власти и управления в Евразии . Routledge. п. 399. ISBN 978-1317913795 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 18 апреля 2024 года . Получено 3 марта 2019 года .

- ^ Колин Мкеджи (2010), Атлас пингвинов современной истории (до 1815 года) . Пингвин . п. 39

- ^ Бирн, Джозеф П. (2012). Энциклопедия черной смерти . ABC-Clio. п. 249. ISBN 978-1598842548 .

- ^ «Чарльз VI, Священная Римская Император» . Bartleby.com. 7 октября 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 2 февраля 2009 года.

- ^ «Чарльз Бурбона - реставратор Королевства Неаполя» . Realcasadiborbone.it. 7 октября 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 26 сентября 2009 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый «Партенопейская республика» . Faculty.ed.umuc.edu. 7 октября 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 6 марта 2001 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Австрия Неаполя - неаполитская война 1815» . Onwar.com. 7 октября 2007 года. Архивировано из оригинала 31 июля 2001 года.

- ^ Уэбб, Диана (6 июня 1996 г.). «La Dolce Vita? Италия по железной дороге, 1839–1914» . История сегодня . Архивировано с оригинала 24 сентября 2015 года.

- ^ «Итальянцы по всему миру: обучение итальянской миграции с транснациональной точки зрения» . Oah.org. 7 октября 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 27 ноября 2010 года.

- ^ Моретти, Энрико (1999). «Социальные сети и миграции: Италия 1876–1913». Международный обзор миграции . 33 (3): 640–657. doi : 10.2307/2547529 . JSTOR 2547529 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Сноуден, Фрэнк М. (2002). Неаполь во времена холеры, 1884–1911 . Издательство Кембриджского университета.

- ^ «План реконструкции Неаполя» . Эддибург (на итальянском языке) . Получено 4 июля 2024 года .

- ^ «Архивная копия» (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 5 марта 2016 года . Получено 9 июля 2018 года .

{{cite web}}: CS1 Maint: архивная копия как заголовок ( ссылка ) - ^ "Эддибург. Полем 25 января 2012 года. Архивировано с оригинала 25 января 2012 года.

- ^ Неаполь, муниципалитет. «Четыре дня Неаполя» . www.comune.napoli.it (на итальянском языке) . Получено 4 июля 2024 года .

- ^ Хьюз, Дэвид (1999). Британские бронированные и кавалерийские подразделения . Нафцигер. С. 39–40.

- ^ Аткинсон, Рик (2 октября 2007 г.). День битвы . 4889: Генри Холт и Ко. ISBN 9780805062892 .