Шива

| Шива | |

|---|---|

Бог разрушения

| |

| Член Trimurti | |

| |

| Other names | |

| Affiliation |

|

| Abode | |

| Mantra | |

| Weapon | |

| Symbols | |

| Day | |

| Mount | Nandi[5] |

| Festivals | |

| Genealogy | |

| Consort | Sati, Parvati and other forms of Shakti[note 1] |

| Children |

|

Shiva ( / ˈ ʃ ɪ V ə / ; санскрит : शिव , Lit. महादेव : [ 11 ] [ 12 ] [ 13 ] или хара , [ 14 ] является одним из божеств индуизма . главных [ 15 ] Он является высшим существом в шейвизме , одной из главных традиций в индуизме. [ 16 ]

Шива известен как эсминец в Trimurti , индуистскую троицу, которая также включает Брахму и Вишну . [ 3 ] [ 17 ] В традиции Шайвита Шива - Верховный Господь, который создает, защищает и трансформирует вселенную. [ 11 ] [ 12 ] [ 13 ] , ориентированной на богини В традиции Шакты , верховная богиня ( Деви ) считается энергией и творческой силой ( Шакти ) и равным взаимодополняющим партнером Шивы. [ 18 ] [ 19 ] Шива является одним из пяти эквивалентных божеств в пудже умной панчаятананой традиции индуизма. [ 20 ]

Shiva has many aspects, benevolent as well as fearsome. In benevolent aspects, he is depicted as an omniscient Yogi who lives an ascetic life on Kailasa[3] as well as a householder with his wife Parvati and his two children, Ganesha and Kartikeya. In his fierce aspects, he is often depicted slaying demons. Shiva is also known as Adiyogi (the first Yogi), regarded as the patron god of yoga, meditation and the arts.[21] The iconographical attributes of Shiva are the serpent king Vasuki around his neck, the adorning crescent moon, the holy river Ganga flowing from his matted hair, the third eye on his forehead (the eye that turns everything in front of it into ashes when opened), the trishula or trident as his weapon, and the damaru. He is usually worshiped in the aniconic form of lingam.[4]

Shiva has pre-Vedic roots,[22] and the figure of Shiva evolved as an amalgamation of various older non-Vedic and Vedic deities, including the Rigvedic storm god Rudra who may also have non-Vedic origins,[23] into a single major deity.[24] Shiva is a pan-Hindu deity, revered widely by Hindus in India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Indonesia (especially in Java and Bali).[25]

| Part of a series on |

| Shaivism |

|---|

|

|

|

Etymology and other names

According to the Monier-Williams Sanskrit dictionary, the word "śiva" (Devanagari: शिव, also transliterated as shiva) means "auspicious, propitious, gracious, benign, kind, benevolent, friendly".[26] The root words of śiva in folk etymology are śī which means "in whom all things lie, pervasiveness" and va which means "embodiment of grace".[26][27]

The word Shiva is used as an adjective in the Rig Veda (c. 1700–1100 BCE), as an epithet for several Rigvedic deities, including Rudra.[28] The term Shiva also connotes "liberation, final emancipation" and "the auspicious one"; this adjectival usage is addressed to many deities in Vedic literature.[26][29] The term evolved from the Vedic Rudra-Shiva to the noun Shiva in the Epics and the Puranas, as an auspicious deity who is the "creator, reproducer and dissolver".[26][30]

Sharma presents another etymology with the Sanskrit root śarv-, which means "to injure" or "to kill",[31] interpreting the name to connote "one who can kill the forces of darkness".[32]

The Sanskrit word śaiva means "relating to the god Shiva", and this term is the Sanskrit name both for one of the principal sects of Hinduism and for a member of that sect.[33] It is used as an adjective to characterize certain beliefs and practices, such as Shaivism.[34]

Some authors associate the name with the Tamil word śivappu meaning "red", noting that Shiva is linked to the Sun (śivan, "the Red one", in Tamil) and that Rudra is also called Babhru (brown, or red) in the Rigveda.[35][36] The Vishnu sahasranama interprets Shiva to have multiple meanings: "The Pure One", and "the One who is not affected by three Guṇas of Prakṛti (Sattva, Rajas, and Tamas)".[37]

Shiva is known by many names such as Viswanatha (lord of the universe), Mahadeva, Mahandeo,[38] Mahasu,[39] Mahesha, Maheshvara, Shankara, Shambhu, Rudra, Hara, Trilochana, Devendra (chief of the gods), Neelakanta, Subhankara, Trilokinatha (lord of the three realms),[40][41][42] and Ghrneshwar (lord of compassion).[43] The highest reverence for Shiva in Shaivism is reflected in his epithets Mahādeva ("Great god"; mahā "Great" and deva "god"),[44][45] Maheśvara ("Great Lord"; mahā "great" and īśvara "lord"),[46][47] and Parameśvara ("Supreme Lord").[48]

Sahasranama are medieval Indian texts that list a thousand names derived from aspects and epithets of a deity.[49] There are at least eight different versions of the Shiva Sahasranama, devotional hymns (stotras) listing many names of Shiva.[50] The version appearing in Book 13 (Anuśāsanaparvan) of the Mahabharata provides one such list.[a] Shiva also has Dasha-Sahasranamas (10,000 names) that are found in the Mahanyasa. The Shri Rudram Chamakam, also known as the Śatarudriya, is a devotional hymn to Shiva hailing him by many names.[51][52]

Historical development and literature

Assimilation of traditions

The Shiva-related tradition is a major part of Hinduism, found all over the Indian subcontinent, such as India, Nepal, Sri Lanka,[53] and Southeast Asia, such as Bali, Indonesia.[54] Shiva has pre-Vedic tribal roots,[22] having "his origins in primitive tribes, signs and symbols."[55] The figure of Shiva as he is known today is an amalgamation of various older deities into a single figure, due to the process of Sanskritization and the emergence of the Hindu synthesis in post-Vedic times.[56] How the persona of Shiva converged as a composite deity is not well documented, a challenge to trace and has attracted much speculation.[57] According to Vijay Nath:

Vishnu and Siva [...] began to absorb countless local cults and deities within their folds. The latter were either taken to represent the multiple facets of the same god or else were supposed to denote different forms and appellations by which the god came to be known and worshipped. [...] Siva became identified with countless local cults by the sheer suffixing of Isa or Isvara to the name of the local deity, e.g., Bhutesvara, Hatakesvara, Chandesvara."[58]

An example of assimilation took place in Maharashtra, where a regional deity named Khandoba is a patron deity of farming and herding castes.[59] The foremost center of worship of Khandoba in Maharashtra is in Jejuri.[60] Khandoba has been assimilated as a form of Shiva himself,[61] in which case he is worshipped in the form of a lingam.[59][62] Khandoba's varied associations also include an identification with Surya[59] and Karttikeya.[63]

Myths about Shiva that were "roughly contemporary with early Christianity" existed that portrayed Shiva with many differences than how he is thought of now,[64] and these mythical portrayals of Shiva were incorporated into later versions of him. For instance, he and the other gods, from the highest gods to the least powerful gods, were thought of as somewhat human in nature, creating emotions they had limited control over and having the ability to get in touch with their inner natures through asceticism like humans.[65] In that era, Shiva was widely viewed as both the god of lust and of asceticism.[66] In one story, he was seduced by a prostitute sent by the other gods, who were jealous of Shiva's ascetic lifestyle he had lived for 1000 years.[64]

Pre-Vedic elements

Prehistoric art

Prehistoric rock paintings dating to the Mesolithic from Bhimbetka rock shelters have been interpreted by some authors as depictions of Shiva.[67][b] However, Howard Morphy states that these prehistoric rock paintings of India, when seen in their context, are likely those of hunting party with animals, and that the figures in a group dance can be interpreted in many different ways.[68]

Indus Valley and the Pashupati seal

Of several Indus valley seals that show animals, one seal that has attracted attention shows a large central figure, either horned or wearing a horned headdress and possibly ithyphallic,[note 2][69] seated in a posture reminiscent of the Lotus position, surrounded by animals. This figure was named by early excavators of Mohenjo-daro as Pashupati (Lord of Animals, Sanskrit paśupati),[70] an epithet of the later Hindu deities Shiva and Rudra.[71] Sir John Marshall and others suggested that this figure is a prototype of Shiva, with three faces, seated in a "yoga posture" with the knees out and feet joined.[72] Semi-circular shapes on the head were interpreted as two horns. Scholars such as Gavin Flood, John Keay and Doris Meth Srinivasan have expressed doubts about this suggestion.[73]

Gavin Flood states that it is not clear from the seal that the figure has three faces, is seated in a yoga posture, or even that the shape is intended to represent a human figure. He characterizes these views as "speculative", but adds that it is nevertheless possible that there are echoes of Shaiva iconographic themes, such as half-moon shapes resembling the horns of a bull.[74] John Keay writes that "he may indeed be an early manifestation of Lord Shiva as Pashu-pati", but a couple of his specialties of this figure does not match with Rudra.[75] Writing in 1997, Srinivasan interprets what John Marshall interpreted as facial as not human but more bovine, possibly a divine buffalo-man.[76]

The interpretation of the seal continues to be disputed. McEvilley, for example, states that it is not possible to "account for this posture outside the yogic account".[77] Asko Parpola states that other archaeological finds such as the early Elamite seals dated to 3000–2750 BCE show similar figures and these have been interpreted as "seated bull" and not a yogi, and the bovine interpretation is likely more accurate.[78] Gregory L. Possehl in 2002, associated it with the water buffalo, and concluded that while it would be appropriate to recognize the figure as a deity, and its posture as one of ritual discipline, regarding it as a proto-Shiva would "go too far".[79]

Proto-Indo-European elements

The Vedic beliefs and practices of the pre-classical era were closely related to the hypothesised Proto-Indo-European religion,[80] and the pre-Islamic Indo-Iranian religion.[81] The similarities between the iconography and theologies of Shiva with Greek and European deities have led to proposals for an Indo-European link for Shiva,[82][83] or lateral exchanges with ancient central Asian cultures.[84][85] His contrasting aspects such as being terrifying or blissful depending on the situation, are similar to those of the Greek god Dionysus,[86] as are their iconic associations with bull, snakes, anger, bravery, dancing and carefree life.[87][88] The ancient Greek texts of the time of Alexander the Great call Shiva "Indian Dionysus", or alternatively call Dionysus "god of the Orient".[87] Similarly, the use of phallic symbol[note 2] as an icon for Shiva is also found for Irish, Nordic, Greek (Dionysus[89]) and Roman deities, as was the idea of this aniconic column linking heaven and earth among early Indo-Aryans, states Roger Woodward.[82] Others contest such proposals, and suggest Shiva to have emerged from indigenous pre-Aryan tribal origins.[90]

Rudra

Shiva as we know him today shares many features with the Vedic god Rudra,[91] and both Shiva and Rudra are viewed as the same personality in Hindu scriptures. The two names are used synonymously. Rudra, a Rigvedic deity with fearsome powers, was the god of the roaring storm. He is usually portrayed in accordance with the element he represents as a fierce, destructive deity.[92] In RV 2.33, he is described as the "Father of the Rudras", a group of storm gods.[93][94]

Flood notes that Rudra is an ambiguous god, peripheral in the Vedic pantheon, possibly indicating non-Vedic origins.[23] Nevertheless, both Rudra and Shiva are akin to Wodan, the Germanic God of rage ("wütte") and the wild hunt.[95][96][page needed][97][page needed]

According to Sadasivan, during the development of the Hindu synthesis attributes of the Buddha were transferred by Brahmins to Shiva, who was also linked with Rudra.[55] The Rigveda has 3 out of 1,028 hymns dedicated to Rudra, and he finds occasional mention in other hymns of the same text.[98] Hymn 10.92 of the Rigveda states that deity Rudra has two natures, one wild and cruel (Rudra), another that is kind and tranquil (Shiva).[99]

The term Shiva also appears simply as an epithet, that means "kind, auspicious", one of the adjectives used to describe many different Vedic deities. While fierce ruthless natural phenomenon and storm-related Rudra is feared in the hymns of the Rigveda, the beneficial rains he brings are welcomed as Shiva aspect of him.[100] This healing, nurturing, life-enabling aspect emerges in the Vedas as Rudra-Shiva, and in post-Vedic literature ultimately as Shiva who combines the destructive and constructive powers, the terrific and the gentle, as the ultimate recycler and rejuvenator of all existence.[101]

The Vedic texts do not mention bull or any animal as the transport vehicle (vahana) of Rudra or other deities. However, post-Vedic texts such as the Mahabharata and the Puranas state the Nandi bull, the Indian zebu, in particular, as the vehicle of Rudra and of Shiva, thereby unmistakably linking them as same.[102]

Agni

Rudra and Agni have a close relationship.[note 3] The identification between Agni and Rudra in the Vedic literature was an important factor in the process of Rudra's gradual transformation into Rudra-Shiva.[note 4] The identification of Agni with Rudra is explicitly noted in the Nirukta, an important early text on etymology, which says, "Agni is also called Rudra."[103] The interconnections between the two deities are complex, and according to Stella Kramrisch:

The fire myth of Rudra-Śiva plays on the whole gamut of fire, valuing all its potentialities and phases, from conflagration to illumination.[104]

In the Śatarudrīya, some epithets of Rudra, such as Sasipañjara ("Of golden red hue as of flame") and Tivaṣīmati ("Flaming bright"), suggest a fusing of the two deities.[note 5] Agni is said to be a bull,[105] and Shiva possesses a bull as his vehicle, Nandi. The horns of Agni, who is sometimes characterized as a bull, are mentioned.[106][107] In medieval sculpture, both Agni and the form of Shiva known as Bhairava have flaming hair as a special feature.[108]

Indra

According to Wendy Doniger, the Saivite fertility myths and some of the phallic characteristics of Shiva are inherited from Indra.[109] Doniger gives several reasons for her hypothesis. Both are associated with mountains, rivers, male fertility, fierceness, fearlessness, warfare, the transgression of established mores, the Aum sound, the Supreme Self. In the Rig Veda the term śiva is used to refer to Indra. (2.20.3,[note 6] 6.45.17,[111][112] and 8.93.3.[113]) Indra, like Shiva, is likened to a bull.[114][115] In the Rig Veda, Rudra is the father of the Maruts, but he is never associated with their warlike exploits as is Indra.[116]

Indra himself may have been adopted by the Vedic Aryans from the Bactria–Margiana Culture.[81][117] According to Anthony,

Many of the qualities of Indo-Iranian god of might/victory, Verethraghna, were transferred to the adopted god Indra, who became the central deity of the developing Old Indic culture. Indra was the subject of 250 hymns, a quarter of the Rig Veda. He was associated more than any other deity with Soma, a stimulant drug (perhaps derived from Ephedra) probably borrowed from the BMAC religion. His rise to prominence was a peculiar trait of the Old Indic speakers.[118]

The texts and artwork of Jainism show Indra as a dancer, although not identical generally resembling the dancing Shiva artwork found in Hinduism, particularly in their respective mudras.[119] For example, in the Jain caves at Ellora, extensive carvings show dancing Indra next to the images of Tirthankaras in a manner similar to Shiva Nataraja. The similarities in the dance iconography suggests that there may be a link between ancient Indra and Shiva.[120]

Development

A few texts such as Atharvashiras Upanishad mention Rudra, and assert all gods are Rudra, everyone and everything is Rudra, and Rudra is the principle found in all things, their highest goal, the innermost essence of all reality that is visible or invisible.[121] The Kaivalya Upanishad similarly, states Paul Deussen – a German Indologist and professor of philosophy, describes the self-realized man as who "feels himself only as the one divine essence that lives in all", who feels identity of his and everyone's consciousness with Shiva (highest Atman), who has found this highest Atman within, in the depths of his heart.[122]

Rudra's evolution from a minor Vedic deity to a supreme being is first evidenced in the Shvetashvatara Upanishad (400–200 BCE), according to Gavin Flood, presenting the earliest seeds of theistic devotion to Rudra-Shiva.[123] Here Rudra-Shiva is identified as the creator of the cosmos and liberator of Selfs from the birth-rebirth cycle. The Svetasvatara Upanishad set the tone for early Shaivite thought, especially in chapter 3 verse 2 where Shiva is equated with Brahman: "Rudra is truly one; for the knowers of Brahman do not admit the existence of a second".[124][125] The period of 200 BC to 100 AD also marks the beginning of the Shaiva tradition focused on the worship of Shiva as evidenced in other literature of this period.[123] Other scholars such as Robert Hume and Doris Srinivasan state that the Shvetashvatara Upanishad presents pluralism, pantheism, or henotheism, rather than being a text just on Shiva theism.[126]

Self-realization and Shaiva Upanishads

He who sees himself in all beings,

And all beings in him,

attains the highest Brahman,

not by any other means.

Shaiva devotees and ascetics are mentioned in Patanjali's Mahābhāṣya (2nd-century BCE) and in the Mahabharata.[129]

The earliest iconic artworks of Shiva may be from Gandhara and northwest parts of ancient India. There is some uncertainty as the artwork that has survived is damaged and they show some overlap with meditative Buddha-related artwork, but the presence of Shiva's trident and phallic symbolism[note 2] in this art suggests it was likely Shiva.[130] Numismatics research suggests that numerous coins of the ancient Kushan Empire (30–375 CE) that have survived, were images of a god who is probably Shiva.[131] The Shiva in Kushan coins is referred to as Oesho of unclear etymology and origins, but the simultaneous presence of Indra and Shiva in the Kushan era artwork suggest that they were revered deities by the start of the Kushan Empire.[132][133]

The Shaiva Upanishads are a group of 14 minor Upanishads of Hinduism variously dated from the last centuries of the 1st millennium BCE through the 17th century.[134] These extol Shiva as the metaphysical unchanging reality Brahman and the Atman (Self),[121] and include sections about rites and symbolisms related to Shiva.[135]

The Shaiva Puranas, particularly the Shiva Purana and the Linga Purana, present the various aspects of Shiva, mythologies, cosmology and pilgrimage (Tirtha) associated with him.[136] The Shiva-related Tantra literature, composed between the 8th and 11th centuries, are regarded in devotional dualistic Shaivism as Sruti. Dualistic Shaiva Agamas which consider Self within each living being and Shiva as two separate realities (dualism, dvaita), are the foundational texts for Shaiva Siddhanta.[137] Other Shaiva Agamas teach that these are one reality (monism, advaita), and that Shiva is the Self, the perfection and truth within each living being.[138] In Shiva related sub-traditions, there are ten dualistic Agama texts, eighteen qualified monism-cum-dualism Agama texts and sixty-four monism Agama texts.[139][140][141]

Shiva-related literature developed extensively across India in the 1st millennium CE and through the 13th century, particularly in Kashmir and Tamil Shaiva traditions.[141] Shaivism gained immense popularity in Tamilakam as early as the 7th century CE, with poets such as Appar and Sambandar composing rich poetry that is replete with present features associated with the deity, such as his tandava dance, the mulavam (dumru), the aspect of holding fire, and restraining the proud flow of the Ganga upon his braid.[142] The monist Shiva literature posit absolute oneness, that is Shiva is within every man and woman, Shiva is within every living being, Shiva is present everywhere in the world including all non-living being, and there is no spiritual difference between life, matter, man and Shiva.[143] The various dualistic and monist Shiva-related ideas were welcomed in medieval southeast Asia, inspiring numerous Shiva-related temples, artwork and texts in Indonesia, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Thailand and Malaysia, with syncretic integration of local pre-existing theologies.[144]

Position within Hinduism

Shaivism

Shaivism is one of the four major sects of Hinduism, the others being Vaishnavism, Shaktism and the Smarta Tradition. Followers of Shaivism, called "Shaivas", revere Shiva as the Supreme Being. Shaivas believe that Shiva is All and in all, the creator, preserver, destroyer, revealer and concealer of all that is.[11][12] He is not only the creator in Shaivism, but he is also the creation that results from him, he is everything and everywhere. Shiva is the primal Self, the pure consciousness and Absolute Reality in the Shaiva traditions.[11] Shiva is also Part of 'Om' (ॐ) as a 'U' (उ). [145]

The Shaivism theology is broadly grouped into two: the popular theology influenced by Shiva-Rudra in the Vedas, Epics and the Puranas; and the esoteric theology influenced by the Shiva and Shakti-related Tantra texts.[146] The Vedic-Brahmanic Shiva theology includes both monist (Advaita) and devotional traditions (Dvaita), such as Tamil Shaiva Siddhanta and Lingayatism. Shiva temples feature items such as linga, Shiva-Parvati iconography, bull Nandi within the premises, and relief artwork showing aspects of Shiva.[147][148]

The Tantric Shiva ("शिव") tradition ignored the mythologies and Puranas related to Shiva, and depending on the sub-school developed a variety of practices. For example, historical records suggest the tantric Kapalikas (literally, the 'skull-men') co-existed with and shared many Vajrayana Buddhist rituals, engaged in esoteric practices that revered Shiva and Shakti wearing skulls, begged with empty skulls, and sometimes used meat as a part of ritual.[149] In contrast, the esoteric tradition within Kashmir Shaivism has featured the Krama and Trika sub-traditions.[150] The Krama sub-tradition focussed on esoteric rituals around Shiva-Kali pair.[151] The Trika sub-tradition developed a theology of triads involving Shiva, combined it with an ascetic lifestyle focusing on personal Shiva in the pursuit of monistic self-liberation.[150][152][153]

Vaishnavism

The Vaishnava (Vishnu-oriented) literature acknowledges and discusses Shiva. Like Shaiva literature that presents Shiva as supreme, the Vaishnava literature presents Vishnu as supreme. However, both traditions are pluralistic and revere both Shiva and Vishnu (along with Devi), their texts do not show exclusivism, and Vaishnava texts such as the Bhagavata Purana while praising Krishna as the Ultimate Reality, also present Shiva and Shakti as a personalized form an equivalent to the same Ultimate Reality.[154][155][156] The texts of Shaivism tradition similarly praise Vishnu. The Skanda Purana, for example, states:

Vishnu is no one but Shiva, and he who is called Shiva is but identical with Vishnu.

— Skanda Purana, 1.8.20–21[157]

Both traditions include legends about who is superior, about Shiva paying homage to Vishnu, and Vishnu paying homage to Shiva. However, in texts and artwork of either tradition, the mutual salutes are symbolism for complementarity.[158] The Mahabharata declares the unchanging Ultimate Reality (Brahman) to be identical to Shiva and to Vishnu,[159] that Vishnu is the highest manifestation of Shiva, and Shiva is the highest manifestation of Vishnu.[160]

Shaktism

The goddess-oriented Shakti tradition of Hinduism is based on the premise that the Supreme Principle and the Ultimate Reality called Brahman is female (Devi),[162][163][164] but it treats the male as her equal and complementary partner.[165] This partner is Shiva.[166][167]

The earliest evidence of the tradition of reverence for the feminine with Rudra-Shiva context, is found in the Hindu scripture Rigveda, in a hymn called the Devi Sukta.[168][169][168][169][170]

The Devi Upanishad in its explanation of the theology of Shaktism, mentions and praises Shiva such as in its verse 19.[171][172] Shiva, along with Vishnu, is a revered god in the Devi Mahatmya, a text of Shaktism considered by the tradition to be as important as the Bhagavad Gita.[173][174] The Ardhanarisvara concept co-mingles god Shiva and goddess Shakti by presenting an icon that is half-man and half woman, a representation and theme of union found in many Hindu texts and temples.[175][176]

Smarta tradition

In the Smarta tradition of Hinduism, Shiva is a part of its Panchayatana puja.[177] This practice consists of the use of icons or anicons of five deities considered equivalent,[177] set in a quincunx pattern.[178] Shiva is one of the five deities, others being Vishnu, Devi (such as Parvati), Surya and Ganesha or Skanda or any personal god of devotee's preference (Ishta Devata).[179]

Philosophically, the Smarta tradition emphasizes that all idols (murti) are icons to help focus on and visualize aspects of Brahman, rather than distinct beings. The ultimate goal in this practice is to transition past the use of icons, recognize the Absolute symbolized by the icons,[180] on the path to realizing the nondual identity of one's Atman (Self) and the Brahman.[181] Popularized by Adi Shankara, many Panchayatana mandalas and temples have been uncovered that are from the Gupta Empire period, and one Panchayatana set from the village of Nand (about 24 kilometers from Ajmer) has been dated to belong to the Kushan Empire era (pre-300 CE).[182] The Kushan period set includes Shiva, Vishnu, Surya, Brahma and one deity whose identity is unclear.[182]

Yoga

Shiva is considered the Great Yogi who is totally absorbed in himself – the transcendental reality. He is the Lord of Yogis, and the teacher of Yoga to sages.[183] As Shiva Dakshinamurthi, states Stella Kramrisch, he is the supreme guru who "teaches in silence the oneness of one's innermost self (atman) with the ultimate reality (brahman)."[184] Shiva is also an archetype for samhara (Sanskrit: संहार) or dissolution which includes transcendence of human misery by the dissolution of maya, which is why Shiva is associated with Yoga.[185][186]

The theory and practice of Yoga, in different styles, has been a part of all major traditions of Hinduism, and Shiva has been the patron or spokesperson in numerous Hindu Yoga texts.[187][188] These contain the philosophy and techniques for Yoga. These ideas are estimated to be from or after the late centuries of the 1st millennium CE, and have survived as Yoga texts such as the Isvara Gita (literally, 'Shiva's song'), which Andrew Nicholson – a professor of Hinduism and Indian Intellectual History – states have had "a profound and lasting influence on the development of Hinduism".[189]

Other famed Shiva-related texts influenced Hatha Yoga, integrated monistic (Advaita Vedanta) ideas with Yoga philosophy and inspired the theoretical development of Indian classical dance. These include the Shiva Sutras, the Shiva Samhita, and those by the scholars of Kashmir Shaivism such as the 10th-century scholar Abhinavagupta.[187][188][190] Abhinavagupta writes in his notes on the relevance of ideas related to Shiva and Yoga, by stating that "people, occupied as they are with their own affairs, normally do nothing for others", and Shiva and Yoga spirituality helps one look beyond, understand interconnectedness, and thus benefit both the individual and the world towards a more blissful state of existence.[191]

Trimurti

The Trimurti is a concept in Hinduism in which the cosmic functions of creation, maintenance, and destruction are personified by the forms of Brahma the creator, Vishnu the maintainer or preserver and Shiva the destroyer or transformer.[192][193] These three deities have been called "the Hindu triad"[194] or the "Great Triple deity".[195] However, the ancient and medieval texts of Hinduism feature many triads of gods and goddesses, some of which do not include Shiva.[196]

Attributes

- Third eye: Shiva is often depicted with a third eye, with which he burned Desire (Kāma) to ashes,[197] called "Tryambakam" (Sanskrit: त्र्यम्बकम्), which occurs in many scriptural sources.[198] In classical Sanskrit, the word ambaka denotes "an eye", and in the Mahabharata, Shiva is depicted as three-eyed, so this name is sometimes translated as "having three eyes".[199] However, in Vedic Sanskrit, the word ambā or ambikā means "mother", and this early meaning of the word is the basis for the translation "three mothers".[200][201] These three mother-goddesses who are collectively called the Ambikās.[202] Other related translations have been based on the idea that the name actually refers to the oblations given to Rudra, which according to some traditions were shared with the goddess Ambikā.[203]

- Crescent moon: Shiva bears on his head the crescent moon.[204] The epithet Candraśekhara (Sanskrit: चन्द्रशेखर "Having the moon as his crest" – candra = "moon"; śekhara = "crest, crown")[205][206][207] refers to this feature. The placement of the moon on his head as a standard iconographic feature dates to the period when Rudra rose to prominence and became the major deity Rudra-Shiva.[208] The origin of this linkage may be due to the identification of the moon with Soma, and there is a hymn in the Rig Veda where Soma and Rudra are jointly implored, and in later literature, Soma and Rudra came to be identified with one another, as were Soma and the moon.[209]

- Ashes: Shiva iconography shows his body covered with ashes (bhasma, vibhuti).[13][210] The ashes represent a reminder that all of material existence is impermanent, comes to an end becoming ash, and the pursuit of eternal Self and spiritual liberation is important.[211][212]

- Matted hair: Shiva's distinctive hair style is noted in the epithets Jaṭin, "the one with matted hair",[213] and Kapardin, "endowed with matted hair"[214] or "wearing his hair wound in a braid in a shell-like (kaparda) fashion".[215] A kaparda is a cowrie shell, or a braid of hair in the form of a shell, or, more generally, hair that is shaggy or curly.[216]

- Blue throat: The epithet Nīlakaṇtha (Sanskrit नीलकण्ठ; nīla = "blue", kaṇtha = "throat").[217][218] Since Shiva drank the Halahala poison churned up from the Samudra Manthana to eliminate its destructive capacity. Shocked by his act, Parvati squeezed his neck and stopped it in his neck to prevent it from spreading all over the universe, supposed to be in Shiva's stomach. However the poison was so potent that it changed the color of his neck to blue.[219][220] This attribute indicates that one can become Shiva by swallowing the worldly poisons in terms of abuses and insults with equanimity while blessing those who give them.[221]

- Meditating yogi: his iconography often shows him in a Yoga pose, meditating, sometimes on a symbolic Himalayan Mount Kailasa as the Lord of Yoga.[13]

- Sacred Ganga: The epithet Gangadhara, "Bearer of the river Ganga" (Ganges). The Ganga flows from the matted hair of Shiva.[222][223] The Gaṅgā (Ganga), one of the major rivers of the country, is said to have made her abode in Shiva's hair.[224]

- Tiger skin: Shiva is often shown seated upon a tiger skin.[13]

- Vasuki: Shiva is often shown garlanded with the serpent Vasuki.Vasuki is the second king of the nāgas (the first being Vishnu's mount, Shesha). According to a legend, Vasuki was blessed by Shiva and worn by him as an ornament after the Samudra Manthana.

- Trident: Shiva typically carries a trident called Trishula.[13] The trident is a weapon or a symbol in different Hindu texts.[225] As a symbol, the Trishul represents Shiva's three aspects of "creator, preserver and destroyer",[226] or alternatively it represents the equilibrium of three guṇas of sattva, rajas and tamas.[227]

- Drum: A small drum shaped like an hourglass is known as a damaru.[228][229] This is one of the attributes of Shiva in his famous dancing representation[230] known as Nataraja. A specific hand gesture (mudra) called ḍamaru-hasta (Sanskrit for "ḍamaru-hand") is used to hold the drum.[231] This drum is particularly used as an emblem by members of the Kāpālika sect.[232]

- Axe (Parashu) and Deer are held in Shiva's hands in Odisha & south Indian icons.[233]

- Rosary beads: he is garlanded with or carries a string of rosary beads in his right hand, typically made of Rudraksha.[13] This symbolises grace, mendicant life and meditation.[234][235]

- Nandī: Nandī, (Sanskrit: नन्दिन् (nandin)), is the name of the bull that serves as Shiva's mount.[236][237] Shiva's association with cattle is reflected in his name Paśupati, or Pashupati (Sanskrit: पशुपति), translated by Sharma as "lord of cattle"[238] and by Kramrisch as "lord of animals", who notes that it is particularly used as an epithet of Rudra.[239]

- Mount Kailāsa: Kailasa in the Himalayas is his traditional abode.[13][240] In Hindu mythology, Mount Kailāsa is conceived as resembling a Linga, representing the center of the universe.[241]

- Gaṇa: The Gaṇas are attendants of Shiva and live in Kailash. They are often referred to as the bhutaganas, or ghostly hosts, on account of their nature. Generally benign, except when their lord is transgressed against, they are often invoked to intercede with the lord on behalf of the devotee. His son Ganesha was chosen as their leader by Shiva, hence Ganesha's title gaṇa-īśa or gaṇa-pati, "lord of the gaṇas".[242]

- Varanasi: Varanasi (Benares) is considered to be the city specially loved by Shiva, and is one of the holiest places of pilgrimage in India. It is referred to, in religious contexts, as Kashi.[243]

Forms and depictions

Shiva is often depicted as embodying attributes of ambiguity and paradox. His depictions are marked by the opposing themes including fierceness and innocence. This duality can be seen in the diverse epithets attributed to him and the rich tapestry of narratives that delineate his persona within Hindu mythology.[244]

Destroyer and Benefactor

In Yajurveda, two contrary sets of attributes for both malignant or terrifying (Sanskrit: rudra) and benign or auspicious (Sanskrit: śiva) forms can be found, leading Chakravarti to conclude that "all the basic elements which created the complex Rudra-Śiva sect of later ages are to be found here".[246] In the Mahabharata, Shiva is depicted as "the standard of invincibility, might, and terror", as well as a figure of honor, delight, and brilliance.[247]

The duality of Shiva's fearful and auspicious attributes appears in contrasted names. The name Rudra reflects Shiva's fearsome aspects. According to traditional etymologies, the Sanskrit name Rudra is derived from the root rud-, which means "to cry, howl".[248] Stella Kramrisch notes a different etymology connected with the adjectival form raudra, which means "wild, of rudra nature", and translates the name Rudra as "the wild one" or "the fierce god".[249] R. K. Sharma follows this alternate etymology and translates the name as "terrible".[250] Hara is an important name that occurs three times in the Anushasanaparvan version of the Shiva sahasranama, where it is translated in different ways each time it occurs, following a commentorial tradition of not repeating an interpretation. Sharma translates the three as "one who captivates", "one who consolidates", and "one who destroys".[14] Kramrisch translates it as "the ravisher".[220] Another of Shiva's fearsome forms is as Kāla "time" and Mahākāla "great time", which ultimately destroys all things.[251] The name Kāla appears in the Shiva Sahasranama, where it is translated by Ram Karan Sharma as "(the Supreme Lord of) Time".[252] Bhairava "terrible" or "frightful"[253] is a fierce form associated with annihilation. In contrast, the name Śaṇkara, "beneficent"[32] or "conferring happiness"[254] reflects his benign form. This name was adopted by the great Vedanta philosopher Adi Shankara (c. 788 – c. 820),[255] who is also known as Shankaracharya.[44] The name Śambhu (Sanskrit: शम्भु swam-on its own; bhu-burn/shine) "self-shining/ shining on its own", also reflects this benign aspect.[44][256]

Ascetic and householder

Shiva is depicted as both an ascetic yogi and as a householder (grihasta), roles which have been traditionally mutually exclusive in Hindu society.[257] When depicted as a yogi, he may be shown sitting and meditating.[258] His epithet Mahāyogi ("the great Yogi: Mahā = "great", Yogi = "one who practices Yoga") refers to his association with yoga.[259] While Vedic religion was conceived mainly in terms of sacrifice, it was during the Epic period that the concepts of tapas, yoga, and asceticism became more important, and the depiction of Shiva as an ascetic sitting in philosophical isolation reflects these later concepts.[260]

As a family man and householder, he has a wife, Parvati, and two sons, Ganesha and Kartikeya. His epithet Umāpati ("The husband of Umā") refers to this idea, and Sharma notes that two other variants of this name that mean the same thing, Umākānta and Umādhava, also appear in the sahasranama.[261] Umā in epic literature is known by many names, including the benign Pārvatī.[262][263] She is identified with Devi, the Divine Mother; Shakti (divine energy) as well as goddesses like Tripura Sundari, Durga, Kali, Kamakshi and Minakshi. The consorts of Shiva are the source of his creative energy. They represent the dynamic extension of Shiva onto this universe.[264] His son Ganesha is worshipped throughout India and Nepal as the Remover of Obstacles, Lord of Beginnings and Lord of Obstacles. Kartikeya is worshipped in Southern India (especially in Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Karnataka) by the names Subrahmanya, Subrahmanyan, Shanmughan, Swaminathan and Murugan, and in Northern India by the names Skanda, Kumara, or Karttikeya.[265]

Some regional deities are also identified as Shiva's children. As one story goes, Shiva is enticed by the beauty and charm of Mohini, Vishnu's female avatar, and procreates with her. As a result of this union, Shasta – identified with regional deities Ayyappan and Aiyanar – is born.[266][267][268][269] In outskirts of Ernakulam in Kerala, a deity named Vishnumaya is stated to be offspring of Shiva and invoked in local exorcism rites, but this deity is not traceable in Hindu pantheon and is possibly a local tradition with "vaguely Chinese" style rituals, states Saletore.[270] In some traditions, Shiva has daughters like the serpent-goddess Manasa and Ashokasundari.[271][272] According to Doniger, two regional stories depict demons Andhaka and Jalandhara as the children of Shiva who war with him, and are later destroyed by Shiva.[273]

Iconographic forms

The depiction of Shiva as Nataraja (Sanskrit नटराज; Naṭarāja) is a form (mūrti) of Shiva as "Lord of Dance".[274][275] The names Nartaka ("dancer") and Nityanarta ("eternal dancer") appear in the Shiva Sahasranama.[276] His association with dance and also with music is prominent in the Puranic period.[277] In addition to the specific iconographic form known as Nataraja, various other types of dancing forms (Sanskrit: nṛtyamūrti) are found in all parts of India, with many well-defined varieties in Tamil Nadu in particular.[278] The two most common forms of the dance are the Tandava, which later came to denote the powerful and masculine dance as Kala-Mahakala associated with the destruction of the world. When it requires the world or universe to be destroyed, Shiva does it by the Tandava,[279] and Lasya, which is graceful and delicate and expresses emotions on a gentle level and is considered the feminine dance attributed to the goddess Parvati.[280][281] Lasya is regarded as the female counterpart of Tandava.[281] The Tandava-Lasya dances are associated with the destruction-creation of the world.[282][283][284]

Dakshinamurti (Sanskrit दक्षिणामूर्ति; Dakṣiṇāmūrti, "[facing] south form")[285] represents Shiva in his aspect as a teacher of yoga, music, and wisdom and giving exposition on the shastras.[286] Dakshinamurti is depicted as a figure seated upon a deer-throne surrounded by sages receiving instruction.[287] Dakshinamurti's depiction in Indian art is mostly restricted to Tamil Nadu.[288]

Bhikshatana (Sanskrit भिक्षाटन; Bhikṣāṭana, "wandering about for alms, mendicancy" [289]) depicts Shiva as a divine medicant. He is depicted as a nude four-armed man adorned with ornaments who holds a begging bowl in his hand and is followed by demonic attendants. He is associated with his penance for committing brahmicide as Bhirava and with his encounters with the sages and their wives in the Deodar forest.

Tripurantaka (Sanskrit त्रिपुरांतक; Tripurāntaka, "ender of Tripura"[290]) is associated with his destruction of the three cities (Tripura) of the Asuras.[291] He is depicted with four arms, the upper pair holding an axe and a deer, and the lower pair wielding a bow and arrow.

Ardhanarishvara (Sanskrit: अर्धनारीश्वर; Ardhanārīśvara, "the lord who is half woman"[292]) is conjunct form of Shiva with Parvati. Adhanarishvara is depicted with one half of the body as male and the other half as female. Ardhanarishvara represents the synthesis of masculine and feminine energies of the universe (Purusha and Prakriti) and illustrates how Shakti, the female principle of God, is inseparable from (or the same as, according to some interpretations) Shiva, the male principle of God, and vice versa.[293]

Kalyanasundara-murti (Sanskrit कल्याणसुन्दर-मूर्ति, literally "icon of beautiful marriage") is the depiction of Shiva's marriage to Parvati. The divine couple are often depicted performing the panigrahana (Sanskrit "accepting the hand") ritual from traditional Hindu wedding ceremonies.[294] The most basic form of this murti consists of only Shiva and Parvati together, but in more elaborate forms they are accompanied by other persons, sometimes including Parvati's parents, as well as deities (often with Vishnu and Lakshmi standing as Parvati's parents, Brahma as the officiating priest, and various other deities as attendants or guests).

Somaskanda is the depiction of Shiva, Parvati, and their son Skanda (Kartikeya), popular during the Pallava Dynasty in southern India.

Pañcānana (Sanskrit: पञ्चानन), also called the pañcabrahma, is a form of Shiva depicting him as having five faces which correspond to his five divine activities (pañcakṛtya): creation (sṛṣṭi), preservation (sthithi), destruction (saṃhāra), concealing grace (tirobhāva), and revealing grace (anugraha). Five is a sacred number for Shiva.[295] One of his most important mantras has five syllables (namaḥ śivāya).[296]

Shiva's body is said to consist of five mantras, called the pañcabrahman.[297] As forms of God, each of these have their own names and distinct iconography:[298] These are represented as the five faces of Shiva and are associated in various texts with the five elements, the five senses, the five organs of perception, and the five organs of action.[299][300] Doctrinal differences and, possibly, errors in transmission, have resulted in some differences between texts in details of how these five forms are linked with various attributes.[301] The overall meaning of these associations is summarized by Stella Kramrisch,

Through these transcendent categories, Śiva, the ultimate reality, becomes the efficient and material cause of all that exists.[302]

According to the Pañcabrahma Upanishad:

One should know all things of the phenomenal world as of a fivefold character, for the reason that the eternal verity of Śiva is of the character of the fivefold Brahman. (Pañcabrahma Upanishad 31)[303]

In the hymn of Manikkavacakar's Thiruvasagam, he testifies that Nataraja Temple, Chidambaram had, by the pre-Chola period, an abstract or 'cosmic' symbolism linked to five elements (Pancha Bhoota) including ether.[304] Nataraja is a significant visual interpretation of Brahman and a dance posture of Shiva.[305] Sharada Srinivasan notes that, Nataraja is described as Satcitananda or "Being, Consciousness and Bliss" in the Shaiva Siddhanta text Kunchitangrim Bhaje, resembling the Advaita doctrine, or "abstract monism," of Adi Shankara, "which holds the individual Self (Jīvātman) and supream Self (Paramātmā) to be one," while "an earlier hymn to Nataraja by Manikkavachakar identifies him with the unitary supreme consciousness, by using Tamil word Or Unarve, rather than Sanskrit Chit." This may point to an "osmosis" of ideas in medieval India, states Srinivasan.[306]

Lingam

The Linga Purana states, "Shiva is signless, without color, taste, smell, that is beyond word or touch, without quality, motionless and changeless".[307] The source of the universe is the signless, and all of the universe is the manifested Linga, a union of unchanging Principles and the ever changing nature.[307] The Linga Purana and the Shiva Gita texts builds on this foundation.[308][309] Linga, states Alain Daniélou, means sign.[307] It is an important concept in Hindu texts, wherein Linga is a manifested sign and nature of someone or something. It accompanies the concept of Brahman, which as invisible signless and existent Principle, is formless or linga-less.[307]

The Shvetashvatara Upanishad states one of the three significations, the primary one, of Lingam as "the imperishable Purusha", the absolute reality, where says the linga as "sign", a mark that provides the existence of Brahman, thus the original meaning as "sign".[310] Furthermore, it says "Shiva, the Supreme Lord, has no liūga", liuga (Sanskrit: लिऊग IAST: liūga) meaning Shiva is transcendent, beyond any characteristic and, specifically the sign of gender.[310]

Apart from anthropomorphic images of Shiva, he is also represented in aniconic form of a lingam.[311] These are depicted in various designs. One common form is the shape of a vertical rounded column in the centre of a lipped, disk-shaped object, the yoni, symbolism for the goddess Shakti.[312] In Shiva temples, the linga is typically present in its sanctum sanctorum and is the focus of votary offerings such as milk, water, flower petals, fruit, fresh leaves, and rice.[312] According to Monier Williams and Yudit Greenberg, linga literally means 'mark, sign or emblem', and also refers to a "mark or sign from which the existence of something else can be reliably inferred". It implies the regenerative divine energy innate in nature, symbolized by Shiva.[313][314]

Some scholars, such as Wendy Doniger, view linga as merely a phallic symbol,[315][316][317][318] although this interpretation is criticized by others, including Swami Vivekananda,[319] Sivananda Saraswati,[320] Stella Kramrisch,[321] Swami Agehananda Bharati,[322] S. N. Balagangadhara,[323] and others.[323][324][325][326] According to Moriz Winternitz, the linga in the Shiva tradition is "only a symbol of the productive and creative principle of nature as embodied in Shiva", and it has no historical trace in any obscene phallic cult.[327] According to Sivananda Saraswati, westerners who are curiously passionate and have impure understanding or intelligence, incorrectly assume Siva Linga as a phallus or sex organ.[320] Later on, Sivananda Saraswati mentions that, this is not only a serious mistake, but also a grave blunder.[320]

The worship of the lingam originated from the famous hymn in the Atharva-Veda Samhitâ sung in praise of the Yupa-Stambha, the sacrificial post. In that hymn, a description is found of the beginningless and endless Stambha or Skambha, and it is shown that the said Skambha is put in place of the eternal Brahman. Just as the Yajna (sacrificial) fire, its smoke, ashes, and flames, the Soma plant, and the ox that used to carry on its back the wood for the Vedic sacrifice gave place to the conceptions of the brightness of Shiva's body, his tawny matted hair, his blue throat, and the riding on the bull of the Shiva, the Yupa-Skambha gave place in time to the Shiva-Linga.[328][329] In the text Linga Purana, the same hymn is expanded in the shape of stories, meant to establish the glory of the great Stambha and the superiority of Shiva as Mahadeva.[329]

The oldest known archaeological linga as an icon of Shiva is the Gudimallam lingam from 3rd-century BCE.[312] In Shaivism pilgrimage tradition, twelve major temples of Shiva are called Jyotirlinga, which means "linga of light", and these are located across India.[330]

Avatars

Puranic scriptures contain occasional references to "ansh" – literally 'portion, or avatars of Shiva', but the idea of Shiva avatars is not universally accepted in Shaivism.[331] The Linga Purana mentions twenty-eight forms of Shiva which are sometimes seen as avatars,[332] however such mention is unusual and the avatars of Shiva is relatively rare in Shaivism compared to the well emphasized concept of Vishnu avatars in Vaishnavism.[333][334][335] Some Vaishnava literature reverentially link Shiva to characters in its Puranas. For example, in the Hanuman Chalisa, Hanuman is identified as the eleventh avatar of Shiva.[336][337][338] The Bhagavata Purana and the Vishnu Purana claim sage Durvasa to be a portion of Shiva.[339][340][341] Some medieval era writers have called the Advaita Vedanta philosopher Adi Shankara an incarnation of Shiva.[342]

Temple

Festivals

There is a Shivaratri in every lunar month on its 13th night/14th day,[343] but once a year in late winter (February/March) and before the arrival of spring, marks Maha Shivaratri which means "the Great Night of Shiva".[344]

Maha Shivaratri is a major Hindu festival, but one that is solemn and theologically marks a remembrance of "overcoming darkness and ignorance" in life and the world,[345] and meditation about the polarities of existence, of Shiva and a devotion to humankind.[343] It is observed by reciting Shiva-related poems, chanting prayers, remembering Shiva, fasting, doing Yoga and meditating on ethics and virtues such as self-restraint, honesty, noninjury to others, forgiveness, introspection, self-repentance and the discovery of Shiva.[346] The ardent devotees keep awake all night. Others visit one of the Shiva temples or go on pilgrimage to Jyotirlingam shrines. Those who visit temples, offer milk, fruits, flowers, fresh leaves and sweets to the lingam.[6] Some communities organize special dance events, to mark Shiva as the lord of dance, with individual and group performances.[347] According to Jones and Ryan, Maha Sivaratri is an ancient Hindu festival which probably originated around the 5th-century.[345]

Another major festival involving Shiva worship is Kartik Purnima, commemorating Shiva's victory over the three demons known as Tripurasura. Across India, various Shiva temples are illuminated throughout the night. Shiva icons are carried in procession in some places.[348]

Thiruvathira is a festival observed in Kerala dedicated to Shiva. It is believed that on this day, Parvati met Shiva after her long penance and Shiva took her as his wife.[349] On this day Hindu women performs the Thiruvathirakali accompanied by Thiruvathira paattu (folk songs about Parvati and her longing and penance for Shiva's affection).[350]

Regional festivals dedicated to Shiva include the Chithirai festival in Madurai around April/May, one of the largest festivals in South India, celebrating the wedding of Minakshi (Parvati) and Shiva. The festival is one where both the Vaishnava and Shaiva communities join the celebrations, because Vishnu gives away his sister Minakshi in marriage to Shiva.[351]

Some Shaktism-related festivals revere Shiva along with the goddess considered primary and Supreme. These include festivals dedicated to Annapurna such as Annakuta and those related to Durga.[352] In Himalayan regions such as Nepal, as well as in northern, central and western India, the festival of Teej is celebrated by girls and women in the monsoon season, in honor of goddess Parvati, with group singing, dancing and by offering prayers in Parvati-Shiva temples.[353][354]

The ascetic, Vedic and Tantric sub-traditions related to Shiva, such as those that became ascetic warriors during the Islamic rule period of India,[355][356] celebrate the Kumbha Mela festival.[357] This festival cycles every 12 years, in four pilgrimage sites within India, with the event moving to the next site after a gap of three years. The biggest is in Prayaga (renamed Allahabad during the Mughal rule era), where millions of Hindus of different traditions gather at the confluence of rivers Ganges and Yamuna. In the Hindu tradition, the Shiva-linked ascetic warriors (Nagas) get the honor of starting the event by entering the Sangam first for bathing and prayers.[357]

In Pakistan, major Shivaratri celebration occurs at the Umarkot Shiv Mandir in the Umarkot. The three-day Shivarathri celebration at the temple is attended by around 250,000 people.[358]

Beyond the Indian subcontinent and Hinduism

Indonesia

In Indonesian Shaivism the popular name for Shiva has been Batara Guru, which is derived from Sanskrit Bhattāraka which means "noble lord".[359] He is conceptualized as a kind spiritual teacher, the first of all Gurus in Indonesian Hindu texts, mirroring the Dakshinamurti aspect of Shiva in the Indian subcontinent.[360] However, the Batara Guru has more aspects than the Indian Shiva, as the Indonesian Hindus blended their spirits and heroes with him. Batara Guru's wife in Southeast Asia is the same Hindu deity Durga, who has been popular since ancient times, and she too has a complex character with benevolent and fierce manifestations, each visualized with different names such as Uma, Sri, Kali and others.[361][362] In contrast to Hindu religious texts, whether Vedas or Puranas, in Javanese puppetry (wayang) books, Batara Guru is the king of the gods who regulates and creates the world system. In the classic book that is used as a reference for the puppeteers, it is said that Sanghyang Manikmaya or Batara Guru was created from a sparkling light by Sang Hyang Tunggal, along with the blackish light which is the origin of Ismaya.[363][364] Shiva has been called Sadāśiva, Paramasiva, Mahādeva in benevolent forms, and Kāla, Bhairava, Mahākāla in his fierce forms.[362]

The Indonesian Hindu texts present the same philosophical diversity of Shaivite traditions found in the Indian subcontinent. However, among the texts that have survived into the contemporary era, the more common are of those of Shaiva Siddhanta (locally also called Siwa Siddhanta, Sridanta).[365]

During the pre-Islamic period on the island of Java, Shaivism and Buddhism were considered very close and allied religions, though not identical religions.[366] The medieval-era Indonesian literature equates Buddha with Siwa (Shiva) and Janardana (Vishnu).[367] This tradition continues in predominantly Hindu Bali Indonesia in the modern era, where Buddha is considered the younger brother of Shiva.[368]

Central Asia

The worship of Shiva became popular in Central Asia through the influence of the Hephthalite Empire[369] and Kushan Empire. Shaivism was also popular in Sogdia and the Kingdom of Yutian as found from the wall painting from Penjikent on the river Zervashan.[370] In this depiction, Shiva is portrayed with a sacred halo and a sacred thread (Yajnopavita).[370] He is clad in tiger skin while his attendants are wearing Sogdian dress.[370] A panel from Dandan Oilik shows Shiva in His Trimurti form with Shakti kneeling on her right thigh.[370][371] Another site in the Taklamakan Desert depicts him with four legs, seated cross-legged on a cushioned seat supported by two bulls.[370] It is also noted that the Zoroastrian wind god Vayu-Vata took on the iconographic appearance of Shiva.[371]

Sikhism

The Japuji Sahib of the Guru Granth Sahib says: "The Guru is Shiva, the Guru is Vishnu and Brahma; the Guru is Paarvati and Lakhshmi."[372] In the same chapter, it also says: "Shiva speaks, and the Siddhas listen." In Dasam Granth, Guru Gobind Singh has mentioned two avatars of Rudra: Dattatreya Avatar and Parasnath Avatar.[373]

Buddhism

Shiva is mentioned in the Buddhist Tantras and worshipped as the fierce deity Mahākāla in Vajrayana, Chinese Esoteric, and Tibetan Buddhism.[374] In the cosmologies of Buddhist Tantras, Shiva is depicted as passive, with Shakti being his active counterpart: Shiva as Prajña and Shakti as Upāya.[375][376]

In Mahayana Buddhism, Shiva is depicted as Maheshvara, a deva living in Akanishta Devaloka. In Theravada Buddhism, Shiva is depicted as Ishana, a deva residing in the 6th heaven of Kamadhatu along with Sakra Indra. In Vajrayana Buddhism, Shiva is depicted as Mahakala, a dharma protecting Bodhisattva. In most forms of Buddhism, the position of Shiva is lesser than that of Mahabrahma or Sakra Indra. In Mahayana Buddhist texts, Shiva (Maheshvara) becomes a buddha called Bhasmeshvara Buddha ("Buddha of ashes").[377]

In China and Taiwan, Shiva, better known there as Maheśvara (Chinese: 大自在天; pinyin: Dàzìzàitiān; or Chinese: 摩醯首羅天 pinyin: Móxīshǒuluótiān) is considered one of the Twenty Devas (Chinese: 二十諸天, pinyin: Èrshí Zhūtiān) or the Twenty-Four Devas (Chinese: 二十四諸天, pinyin: Èrshísì zhūtiān) who are a group of dharmapalas that manifest to protect the Buddhist dharma.[378] Statues of him are often enshrined in the Mahavira Halls of Chinese Buddhist temples along with the other devas. In Kizil Caves in Xinjiang, there are numerous caves that depict Shiva in the buddhist shrines through wall paintings.[379][380][381] In addition, he is also regarded as one of thirty-three manifestations of Avalokitesvara in the Lotus Sutra.[382] In Mahayana Buddhist cosmology, Maheśvara resides in Akaniṣṭha, highest of the Śuddhāvāsa ("Pure Abodes") wherein Anāgāmi ("Non-returners") who are already on the path to Arhathood and who will attain enlightenment are born.

Daikokuten, one of the Seven Lucky Gods in Japan, is considered to be evolved from Shiva. The god enjoys an exalted position as a household deity in Japan and is worshipped as the god of wealth and fortune.[383] The name is the Japanese equivalent of Mahākāla, the Buddhist name for Shiva.[384]

-

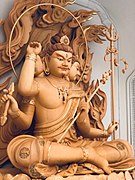

Statue of Shiva depicted as a Chinese Buddhist deva on Mount Putuo Guanyin Dharma Realm in Zhejiang, China

In popular culture

In contemporary culture, Shiva is depicted in art, films, and books. He has been referred to as "the god of cool things"[387] and a "bonafide rock hero".[388] One popular film was the 1967 Kannada movie Gange Gowri.[389]

A 1990s television series of DD National titled Om Namah Shivay was also based on legends of Shiva.[390] Amish Tripathi's 2010 book Shiva Trilogy has sold over a million copies.[387] Devon Ke Dev...Mahadev (2011–2014), a television serial about Shiva on the Life OK channel was among the most watched shows at its peak popularity.[391] Another popular film was the 2022 Gujarati language movie Har Har Mahadev.[389]

See also

Notes

- ^ This is the source for the version presented in Chidbhavananda, who refers to it being from the Mahabharata but does not explicitly clarify which of the two Mahabharata versions he is using. See Chidbhavananda 1997, p. 5.

- ^ Temporal range for Mesolithic in South Asia is from 12000 to 4000 years before present. The term "Mesolithic" is not a useful term for the periodization of the South Asian Stone Age, as certain tribes in the interior of the Indian subcontinent retained a mesolithic culture into the modern period, and there is no consistent usage of the term. The range 12,000–4,000 Before Present is based on the combination of the ranges given by Agrawal et al. (1978) and by Sen (1999), and overlaps with the early Neolithic at Mehrgarh. D.P. Agrawal et al., "Chronology of Indian prehistory from the Mesolithic period to the Iron Age", Journal of Human Evolution, Volume 7, Issue 1, January 1978, 37–44: "A total time bracket of c. 6,000–2,000 B.C. will cover the dated Mesolithic sites, e.g. Langhnaj, Bagor, Bhimbetka, Adamgarh, Lekhahia, etc." (p. 38). S.N. Sen, Ancient Indian History and Civilization, 1999: "The Mesolithic period roughly ranges between 10,000 and 6,000 B.C." (p. 23).

- ^ In scriptures, Shiva is paired with Shakti, the embodiment of power; who is known under various manifestations as Uma, Sati, Parvati, Durga, and Kali.[9] Sati is generally regarded as the first wife of Shiva, who reincarnated as Parvati after her death. Out of these forms of Shakti, Parvati is considered the main consort of Shiva.[10]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c The ithyphallic representation of the erect shape connotes the very opposite in this context.[392] It contextualize "seminal retention", practice of celibacy (Brahmacarya)[393] and illustration of Urdhva Retas[321][394][395][396] and represents Shiva as "he stands for complete control of the senses, and for the supreme carnal renunciation".[392]

- ^ For a general statement of the close relationship, and example shared epithets, see: Sivaramamurti 1976, p. 11. For an overview of the Rudra-Fire complex of ideas, see: Kramrisch 1981, pp. 15–19.

- ^ For quotation "An important factor in the process of Rudra's growth is his identification with Agni in the Vedic literature and this identification contributed much to the transformation of his character as Rudra-Śiva." see: Chakravarti 1986, p. 17.

- ^ For "Note Agni-Rudra concept fused" in epithets Sasipañjara and Tivaṣīmati see: Sivaramamurti 1976, p. 45.

- ^ For text of RV 2.20.3a as स नो युवेन्द्रो जोहूत्रः सखा शिवो नरामस्तु पाता । and translation as "May that young adorable Indra, ever be the friend, the benefactor, and protector of us, his worshipper".[110]

References

- ^ "Yogeshvara". Indian Civilization and Culture. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. 1998. p. 115. ISBN 978-81-7533-083-2.

- ^ "Hinduism". Encyclopedia of World Religions. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 2008. pp. 445–448. ISBN 978-1593394912.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Zimmer 1972, pp. 124–126.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Fuller 2004, p. 58.

- ^ Javid 2008, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dalal 2010, pp. 137, 186.

- ^ Cush, Robinson & York 2008, p. 78.

- ^ Williams 1981, p. 62.

- ^ "Shiva | Definition, Forms, God, Symbols, Meaning, & Facts | Britannica". 10 August 2024.

- ^ Kinsley 1998, p. 35.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Sharma 2000, p. 65.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Issitt & Main 2014, pp. 147, 168.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Flood 1996, p. 151.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sharma 1996, p. 314.

- ^ "Shiva In Mythology: Let's Reimagine The Lord". 28 October 2022. Archived from the original on 30 October 2022. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ Flood 1996, pp. 17, 153; Sivaraman 1973, p. 131.

- ^ Gonda 1969.

- ^ Kinsley 1988, pp. 50, 103–104.

- ^ Pintchman 2015, pp. 113, 119, 144, 171.

- ^ Flood 1996, pp. 17, 153.

- ^ Shiva Samhita, e.g. Mallinson 2007; Varenne 1976, p. 82; Marchand 2007 for Jnana Yoga.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sadasivan 2000, p. 148; Sircar 1998, pp. 3 with footnote 2, 102–105.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Flood 1996, p. 152.

- ^ Flood 1996, pp. 148–149; Keay 2000, p. xxvii; Granoff 2003, pp. 95–114; Nath 2001, p. 31.

- ^ Keay 2000, p. xxvii; Flood 1996, p. 17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Monier Monier-Williams (1899), Sanskrit to English Dictionary with Etymology Archived 27 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford University Press, pp. 1074–1076

- ^ Prentiss 2000, p. 199.

- ^ For use of the term śiva as an epithet for other Vedic deities, see: Chakravarti 1986, p. 28.

- ^ Chakravarti 1986, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Chakravarti 1986, pp. 1, 7, 21–23.

- ^ For root śarv- see: Apte 1965, p. 910.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sharma 1996, p. 306.

- ^ Ahmed, 8 n & Apte 1965, p. 927.

- ^ For the definition "Śaivism refers to the traditions which follow the teachings of Śiva (śivaśāna) and which focus on the deity Śiva... " see: Flood 1996, p. 149

- ^ van Lysebeth, Andre (2002). Tantra: Cult of the Feminine. Weiser Books. p. 213. ISBN 978-0877288459. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ Tyagi, Ishvar Chandra (1982). Shaivism in Ancient India: From the Earliest Times to C.A.D. 300. Meenakshi Prakashan. p. 81. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ Sri Vishnu Sahasranama 1986, pp. 47, 122; Chinmayananda 2002, p. 24.

- ^ Powell 2016, p. 27.

- ^ Berreman 1963, p. 385.

- ^ For translation see: Dutt 1905, Chapter 17 of Volume 13.

- ^ For translation see: Ganguli 2004, Chapter 17 of Volume 13.

- ^ Chidbhavananda 1997, Siva Sahasranama Stotram.

- ^ Lochtefeld 2002, p. 247.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kramrisch 1994a, p. 476.

- ^ For appearance of the name महादेव in the Shiva Sahasranama see: Sharma 1996, p. 297

- ^ Kramrisch 1994a, p. 477.

- ^ For appearance of the name in the Shiva Sahasranama see: Sharma 1996, p. 299

- ^ For Parameśhvara as "Supreme Lord" see: Kramrisch 1981, p. 479.

- ^ Sir Monier Monier-Williams, sahasranAman, A Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Etymologically and Philologically Arranged with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages, Oxford University Press (Reprinted: Motilal Banarsidass), ISBN 978-8120831056

- ^ Sharma 1996, pp. viii–ix

- ^ For an overview of the Śatarudriya see: Kramrisch 1981, pp. 71–74.

- ^ For complete Sanskrit text, translations, and commentary see: Sivaramamurti 1976.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 17; Keay 2000, p. xxvii.

- ^ Boon 1977, pp. 143, 205.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sadasivan 2000, p. 148.

- ^ Flood 1996, pp. 148–149; Keay 2000, p. xxvii; Granoff 2003, pp. 95–114.

- ^ For Shiva as a composite deity whose history is not well documented, see Keay 2000, p. 147

- ^ Nath 2001, p. 31.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Courtright 1985, p. 205.

- ^ For Jejuri as the foremost center of worship see: Mate 1988, p. 162.

- ^ Sontheimer 1976, pp. 180–198: "Khandoba is a local deity in Maharashtra and been Sanskritised as an incarnation of Shiva."

- ^ For worship of Khandoba in the form of a lingam and possible identification with Shiva based on that, see: Mate 1988, p. 176.

- ^ For use of the name Khandoba as a name for Karttikeya in Maharashtra, see: Gupta 1988, Preface, and p. 40.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hopkins 2001, p. 243.

- ^ Hopkins 2001, pp. 243–244, 261.

- ^ Hopkins 2001, p. 244.

- ^ Neumayer 2013, p. 104.

- ^ Howard Morphy (2014). Animals Into Art. Routledge. pp. 364–366. ISBN 978-1-317-59808-4. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ Singh 1989; Kenoyer 1998. For a drawing of the seal see Figure 1 in Flood 1996, p. 29

- ^ For translation of paśupati as "Lord of Animals" see: Michaels 2004, p. 312.

- ^ Vohra 2000; Bongard-Levin 1985, p. 45; Rosen & Schweig 2006, p. 45.

- ^ Flood 1996, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Flood 1996, pp. 28–29; Flood 2003, pp. 204–205; Srinivasan 1997, p. 181.

- ^ Flood 1996, pp. 28–29; Flood 2003, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Keay 2000, p. 14.

- ^ Srinivasan 1997, p. 181.

- ^ McEvilley, Thomas (1 March 1981). "An Archaeology of Yoga". Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics. 1: 51. doi:10.1086/RESv1n1ms20166655. ISSN 0277-1322. S2CID 192221643.

- ^ Asko Parpola(2009), Deciphering the Indus Script, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521795661, pp. 240–250

- ^ Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira. pp. 140–144. ISBN 978-0759116429. Archived from the original on 20 January 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ Roger D. Woodard (2006). Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman Cult. University of Illinois Press. pp. 242–. ISBN 978-0252092954.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Beckwith 2009, p. 32.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Roger D. Woodard (2010). Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman Cult. University of Illinois Press. pp. 60–67, 79–80. ISBN 978-0252-092954.

- ^ Alain Daniélou (1992). Gods of Love and Ecstasy: The Traditions of Shiva and Dionysus. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0892813742., Quote: "The parallels between the names and legends of Shiva, Osiris and Dionysus are so numerous that there can be little doubt as to their original sameness".

- ^ Namita Gokhale (2009). The Book of Shiva. Penguin Books. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0143067610.

- ^ Pierfrancesco Callieri (2005), A Dionysian Scheme on a Seal from Gupta India Archived 20 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, East and West, Vol. 55, No. 1/4 (December 2005), pp. 71–80

- ^ Long, J. Bruce (1971). "Siva and Dionysos: Visions of Terror and Bliss". Numen. 18 (3): 180–209. doi:10.2307/3269768. ISSN 0029-5973. JSTOR 3269768.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty (1980), Dionysus and Siva: Parallel Patterns in Two Pairs of Myths Archived 20 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, History of Religions, Vol. 20, No. 1/2 (Aug. – Nov., 1980), pp. 81–111

- ^ Патрик Лауд (2005). Божественная игра, священный смех и духовное понимание . Palgrave Macmillan. С. 41–60. ISBN 978-1403980588 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 31 марта 2024 года . Получено 6 октября 2016 года .

- ^ Уолтер Фридрих Отто; Роберт Б. Палмер (1965). Дионис: Миф и Культ . Издательство Университета Индианы. п. 164. ISBN 0253208912 .

- ^ Sircar 1998 , стр. 3 с сноской 2, 102–105.

- ^ Michaels 2004 , p. 316

- ^ Поток 2003 , с. 73.

- ^ Донигер, с. 221–223.

- ^ «Рудра | Индуизм, Шива, Веды | Британника» . www.britannica.com . Получено 8 июня 2024 года .

- ^ Циммер 2000 .

- ^ Storl 2004 .

- ^ Уинстедт 2020 .

- ^ Чакраварти 1986 , стр. 1–2.

- ^ Kramrisch 1994a , p. 7

- ^ Чакраварти 1986 , стр. 2–3.

- ^ Чакраварти 1986 , стр. 1–9.

- ^ Kramrisch 1994a , с. 14–15.

- ^ Для перевода из Nirukta 10.7, см.: Sarup 1998 , p. 155

- ^ Kramrisch 1994a , p. 18

- ^ «Риг Веда: Риг-Веда, Книга 6: Гимн XLVIII. Агни и другие» . Sacred-texts.com. Архивировано из оригинала 25 марта 2010 года . Получено 6 июня 2010 года .

- ^ Параллель между рогами Агни как быка, и Рудрой, см.: Чакраварти 1986 , с. 89

- ^ Rv 8.49; 10.155.

- ^ Для пылающих волос Агни и Бхайрава См.: Сиварамамурти, с. 11

- ^ Донигер, Венди (1973). «Ведические предшественники». Шива, эротический аскет . Oxford University Press США. С. 84–89.

- ^ Arya & Joshi 2001 , p. 48, том 2.

- ^ Для текста RV 6.45.17 как यो गृणतामिदासिथापिरूती शिवः सखा। स त्वं न इन्द्र मृलय॥॥॥ и перевод как « Индра , который когда -либо был другом тех, кто восхваляет вас, и страховщиком их счастья благодаря вашей защите, дайте нам Фелисити» Смотрите: Arya & Joshi 2001 , p. 91, том 3.

- ^ Для перевода RV 6.45.17 как «ты, кто был другом певцов, другом, благоприятным для твоей помощи, как таковой, о Индра, благосклонность нам» См.: Гриффит, 1973 , с. 310.

- ^ For text of RV 8.93.3 as स न इन्द्रः सिवः सखाश्चावद् गोमद्यवमत् । उरूधारेव दोहते ॥ and translation as "May Indra, our auspicious friend, milk for us, like a richly-streaming (cow), wealth of horses, kine, and barley" see: Arya & Joshi 2001, p. 48, volume 2.

- ^ Для быка параллель между Индрой и Рудрой См.: Чакраварти 1986 , с. 89

- ^ RV 7.19.

- ^ Об отсутствии воинственных связей и разницы между Индрой и Рудрой, см.: Чакраварти 1986 , с. 8

- ^ Энтони 2007 , с. 454–455.

- ^ Энтони 2007 , с. 454.

- ^ Owen 2012 , с. 25–29.

- ^ Sivaramamurti 2004 , стр. 41, 59; Owen 2012 , с. 25-29.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Deussen 1997 , p. 769.

- ^ Deussen 1997 , с. 792–793; Радхакришнан 1953 , с. 929.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Поток 2003 , с. 204–205.

- ^ «Светасватара Упанишад - глава 3 Высшая реальность» . Архивировано из оригинала 1 октября 2022 года . Получено 2 сентября 2022 года .

- ^ «Говорящее дерево: традиция Трики Кашмира Шайвизма» . The Times of India . 27 июля 2009 г. Архивировано с оригинала 2 сентября 2022 года . Получено 2 сентября 2022 года .

- ^ Юм 1921 , стр. 399, 403; Hiriyanna 2000 , стр. 32-36; Кунст 1968 ; Srinivasan 1997 , pp. 96-97 и глава 9.

- ^ Deussen 1997 , стр. 792–793.

- ^ Sassthe 1898 , стр. 80-82.

- ^ Поток 2003 , с. 205 Дата Махабхасьи См.: Шарф 1996 , стр. 1 с сноской.

- ^ Blurton 1993 , с. 84, 103.

- ^ Блюртон 1993 , с. 84

- ^ Pratapaditya Pal (1986). Индийская скульптура: около 500 г. до н.э. - АД 700 . Калифорнийский университет. С. 75–80 . ISBN 978-0520-059917 .

- ^ Sivaramamurti 2004 , стр. 41, 59.

- ^ Deussen 1997 , p. 556, 769 Сноска 1.

- ^ Klostermaier 1984 , с. 134, 371.

- ^ Поток 2003 , с. 205–206; Rocher 1986 , с. 187–188, 222–228.

- ^ Потоп 2003 , с. 208–212.

- ^ Шарма 1990 , с. 9–14; Дэвис 1992 , с. 167 ПРИМЕЧАНИЕ 21, Цитата (стр. 13): «Некоторые агамы утверждают монистическую метафизику, в то время как другие явно дуалистичны. Некоторые утверждают, что ритуал является наиболее эффективным средством религиозного достижения, в то время как другие утверждают, что знание более важно».

- ^ Марк Дайцковски (1989), Канон Шивагамы, Мотилальный Буртсдасс, 978-812080805958 , pl. 43–44

- ^ JS Vasugupta (2012), Шива Сутрас, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120804074 , стр. 252, 259

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Flup 1996 , pp. 162–169.

- ^ Somasundaram, Ottilingam; Мурти, Теджус (2017). «Шива - Безумный Лорд: пураническая перспектива» . Индийский журнал психиатрии . 59 (1): 119–122. doi : 10.4103/0019-5545.204441 . ISSN 0019-5545 . PMC 5418997 . PMID 28529371 .

- ^ Tagare 2002 , стр. 16-19.

- ^ Поток 2003 , с. 208–212; Gonda 1975 , с. 3–20, 35–36, 49–51; Thakur 1986 , с. 83–94.

- ^ «Деви Бхагват Пурана Скандх 5 Глава 1 Стих 22-23» .

{{cite web}}: Проверять|archive-url=значение ( справка ) CS1 Maint: URL-Status ( ссылка ) - ^ Michaels 2004 , p. 216

- ^ Michaels 2004 , с. 216–218.

- ^ Surendath Dasgupta (1973). История индийской философии Издательство Кембриджского университета. Стр. 17, 48–49, 65–67, 155–1 ISBN 978-81208-04166 .

- ^ Дэвид Н. Лоренцен (1972). Капалики и каламухас: две потерянные секты . Калифорнийский университет. С. 2–5, 15–17, 38, 80. ISBN 978-0520-018426 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 31 марта 2024 года . Получено 6 октября 2016 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Нарендранат Б. Патил (2003). Разнообразное оперение: встречи с индийской философией . Motilal Banarsidass. С. 125–126. ISBN 978-8120819535 .

- ^ Марк С.Г. Дицковский (1987). Учение о вибрации: анализ доктрин и практики, связанные с кашмирским шейвизмом . Государственный университет Нью -Йорк Пресс. п. 9. ISBN 978-0887064319 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 31 марта 2024 года . Получено 6 октября 2016 года .

- ^ Michaels 2004 , с. 215–216.

- ^ Дэвид Лоуренс, философия Кахмири Шайва, архивная 12 марта 2017 года на машине Wayback , Университет Манитобы, Канада, IEP, раздел 1 (D)

- ^ Эдвин Брайант (2003), Кришна: прекрасная легенда Бога: Шримад Бхагавата Пурана, Пингвин, ISBN 978-0141913377 , стр. 10–12, цитата: «(...) Принять и действительно превозносить трансцендентную и абсолютную природу другой, а также богини Деви тоже»

- ^ Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225 , с. 23 с сносками

- ^ Eo Джеймс (1997), «Древо жизни», Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004016125 , стр. 150-153

- ^ Грегор Мэйл (2009), Аштанга Йога, Новый Свет, ISBN 978-1577316695 , с. 17; Санскрит см.: Сканда Пурана Шанкара Самхита, часть 1, стихи 1.8.20–21 (санскрит)

- ^ Saroj Panthey (1987). Иконография Шивы в картинах Пахари . Миттал публикации. п. 94. ISBN 978-8170990161 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 31 марта 2024 года . Получено 6 октября 2016 года .

- ^ Барбара Холдреге (2012). Хананья Гудман (ред.). Между Иерусалимом и Бенаресом: сравнительные исследования по иудаизму и индуизму . Государственный университет Нью -Йорк Пресс. С. 120–125 с сносками. ISBN 978-1438404370 .

- ^ Чарльз Джонстон (1913). Атлантический ежемесячный . Тол. CXII. Riverside Press, Кембридж. С. 835–836.

- ^ Джонс и Райан 2006 , с. 43

- ^ Coburn 2002 , с. 1, 53–56, 280.

- ^ Lochtefeld 2002 , p. 426.

- ^ Кинсли, 1988 , с. 101–105.

- ^ Кинсли, 1988 , с. 50, 103–104; Pintchman 2015 , с. 113, 119, 144, 171.

- ^ Pintchman 2014 , с. 85–86, 119, 144, 171.

- ^ Кобурн 1991 , стр. 19–24, 40, 65, Нараяни с. 232.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный McDaniel 2004 , p. 90

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Браун 1998 , с. 26

- ^ Джеймисон, Стефани; Бреретон, Джоэл (2020). Ригведа . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0190633394 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 10 октября 2023 года . Получено 17 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ Браун 1998 , с. 77

- ^ Warrier 1967 , с. 77–84.

- ^ Rocher 1986 , p. 193.

- ^ Дэвид Р. Кинсли (1975). Меч и флейта: Кали и Кришна, темные видения ужасных и возвышенных в индуистской мифологии . Калифорнийский университет. с. 102 с сноской 42. ISBN 978-0520026759 Полем , Цитата: «В Деви Махатмая совершенно ясно, что Дурга - независимое божество, великое самостоятельно и только свободно связан с каким -либо из великих мужчин. И если кто -то из великих богов можно сказать Будь ее ближайшим партнером, это висну, а не Шива ».

- ^ Guptshw Prasad (1994). Иа Ричардс и индийский . SUPUP & SONS. стр. 117–118. ISBN 978-8185431376 .

- ^ Джайдева Васугупта (1991). Йога восторга, чуда и удивления . Государственный университет Нью -Йорк Пресс. п. xix. ISBN 978-0791410738 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Gudrun Bühnemann (2003). Мандалы и янтра в индуистских традициях . Brill Academic. п. 60. ISBN 978-9004129023 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 16 января 2024 года . Получено 6 октября 2016 года .

- ^ Джеймс С. Харл (1994). Искусство и архитектура индийского субконтинента . Издательство Йельского университета. С. 140–142 , 191, 201–203. ISBN 978-0300062175 .

- ^ Flup 1996 , p. 17