Языки Индии

| Языки Индии | |

|---|---|

| |

| Official | |

| Signed | |

| Keyboard layout | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of India |

|---|

|

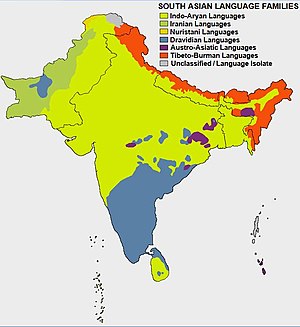

Языки, на которых говорят в Республике Индия , принадлежат к нескольким языковым семьям , основными из которых являются индоарийские языки, на которых говорят 78,05% индийцев , и дравидийские языки, на которых говорят 19,64% индийцев; [5] [6] обе семьи вместе иногда называют индийскими языками . [7] [8] [9] [а] Языки, на которых говорят оставшиеся 2,31% населения, принадлежат к австроазиатским , сино-тибетским , тай-кадайским и нескольким другим второстепенным языковым семьям и изолированным языкам . [10] : 283 По данным Народного лингвистического опроса Индии , Индия занимает второе место по количеству языков (780) после Папуа-Новой Гвинеи (840). [11] «Этнолог» называет меньшее число — 456. [12]

Article 343 of the Constitution of India stated that the official language of the Union is Hindi in Devanagari script, with official use of English to continue for 15 years from 1947. Later, a constitutional amendment, The Official Languages Act, 1963, allowed for the continuation of English alongside Hindi in the Indian government indefinitely until legislation decides to change it.[2] The form of numerals to be used for the official purposes of the Union are "the international form of Indian numerals",[13][14] which are referred to as Arabic numerals in most English-speaking countries.[1] Despite some misconceptions, Hindi is not the national language of India; the Constitution of India does not give any language the status of national language.[15][16]

The Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution lists 22 languages,[17] which have been referred to as scheduled languages and given recognition, status and official encouragement. In addition, the Government of India has awarded the distinction of classical language to Kannada, Malayalam, Odia, Sanskrit, Tamil and Telugu. This status is given to languages that have a rich heritage and independent nature.[citation needed]

According to the Census of India of 2001, India has 122 major languages and 1599 other languages. However, figures from other sources vary, primarily due to differences in the definition of the terms "language" and "dialect". The 2001 Census recorded 30 languages which were spoken by more than a million native speakers and 122 which were spoken by more than 10,000 people.[18] Two contact languages have played an important role in the history of India: Persian[19] and English.[20] Persian was the court language during the Mughal period in India and reigned as an administrative language for several centuries until the era of British colonisation.[21] English continues to be an important language in India. It is used in higher education and in some areas of the Indian government.[citation needed]

Hindi, which has the largest number of first-language speakers in India today,[22] serves as the lingua franca across much of northern and central India. However, there have been concerns raised with Hindi being imposed in South India, most notably in the states of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka.[23][24] Some in Maharashtra, West Bengal, Assam, Punjab and other non-Hindi regions have also started to voice concerns about imposition of Hindi.[25] Bengali is the second most spoken and understood language in the country with a significant number of speakers in eastern and northeastern regions. Marathi is the third most spoken and understood language in the country with a significant number of speakers in the southwest,[26] followed closely by Telugu, which is most commonly spoken in southeastern areas.[27]

Hindi is the fastest growing language of India, followed by Kashmiri in the second place, with Meitei (officially called Manipuri) as well as Gujarati, in the third place, and Bengali in the fourth place, according to the 2011 census of India.[28]

According to the Ethnologue, India has 148 Sino-Tibetan, 140 Indo-European, 84 Dravidian, 32 Austro-Asiatic, 14 Andamanese, 5 Kra-Dai languages.[29]

History

The Southern Indian languages are from the Dravidian family. The Dravidian languages are indigenous to the Indian subcontinent.[30] Proto-Dravidian languages were spoken in India in the 4th millennium BCE and started disintegrating into various branches around 3rd millennium BCE.[31] The Dravidian languages are classified in four groups: North, Central (Kolami–Parji), South-Central (Telugu–Kui), and South Dravidian (Tamil-Kannada).[32]

The Northern Indian languages from the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European family evolved from Old Indo-Aryan by way of the Middle Indo-Aryan Prakrit languages and Apabhraṃśa of the Middle Ages. The Indo-Aryan languages developed and emerged in three stages — Old Indo-Aryan (1500 BCE to 600 BCE), Middle Indo-Aryan stage (600 BCE and 1000 CE), and New Indo-Aryan (between 1000 CE and 1300 CE). The modern north Indian Indo-Aryan languages all evolved into distinct, recognisable languages in the New Indo-Aryan Age.[33]

In the Northeast India, among the Sino-Tibetan languages, Meitei language (officially known as Manipuri language) was the court language of the Manipur Kingdom (Meitei: Meeteileipak). It was honoured before and during the darbar sessions before Manipur was merged into the Dominion of the Indian Republic. Its history of existence spans from 1500 to 2000 years according to most eminent scholars including Padma Vibhushan awardee Suniti Kumar Chatterji.[34][35] Even according to the "Manipur State Constitution Act, 1947" of the once independent Manipur, Manipuri and English were made the court languages of the kingdom (before merging into Indian Republic).[36][37]

Persian, or Farsi, was brought into India by the Ghaznavids and other Turko-Afghan dynasties as the court language. Culturally Persianized, they, in combination with the later Mughal dynasty (of Turco-Mongol origin), influenced the art, history, and literature of the region for more than 500 years, resulting in the Persianisation of many Indian tongues, mainly lexically. In 1837, the British replaced Persian with English and Hindustani in Perso-Arabic script for administrative purposes and the Hindi movement of the 19th Century replaced Persianised vocabulary with Sanskrit derivations and replaced or supplemented the use of Perso-Arabic script for administrative purposes with Devanagari.[19][38]

Each of the northern Indian languages had different influences. For example, Hindustani was strongly influenced by Sanskrit, Arabic and Persian, leading to the emergence of Modern Standard Hindi and Modern Standard Urdu as registers of the Hindustani language.Bangla on the other hand has retained its Sanskritic roots while heavily expanding its vocabulary with words from Persian, English, French and other foreign languages.[39][40]

Inventories

The first official survey of language diversity in the Indian subcontinent was carried out by Sir George Abraham Grierson from 1898 to 1928. Titled the Linguistic Survey of India, it reported a total of 179 languages and 544 dialects.[41] However, the results were skewed due to ambiguities in distinguishing between "dialect" and "language",[41] use of untrained personnel and under-reporting of data from South India, as the former provinces of Burma and Madras, as well as the princely states of Cochin, Hyderabad, Mysore and Travancore were not included in the survey.[42]

Languages of India by language families (Ethnologue)[43]

Different sources give widely differing figures, primarily based on how the terms "language" and "dialect" are defined and grouped. Ethnologue, produced by the Christian evangelist organisation SIL International, lists 435 tongues for India (out of 6,912 worldwide), 424 of which are living, while 11 are extinct. The 424 living languages are further subclassified in Ethnologue as follows:[43][44]

- Institutional– 45

- Stable– 248

- Endangered– 131

- Extinct– 11

The People's Linguistic Survey of India, a privately owned research institution in India, has recorded over 66 different scripts and more than 780 languages in India during its nationwide survey, which the organisation claims to be the biggest linguistic survey in India.[45]

The People of India (POI) project of Anthropological Survey of India reported 325 languages which are used for in-group communication by 5,633 Indian communities.[46]

Census of India figures

The Census of India records and publishes data with respect to the number of speakers for languages and dialects, but uses its own unique terminology, distinguishing between language and mother tongue. The mother tongues are grouped within each language. Many of the mother tongues so defined could be considered a language rather than a dialect by linguistic standards. This is especially so for many mother tongues with tens of millions of speakers that are officially grouped under the language Hindi.

Separate figures for Hindi, Urdu, and Punjabi were not issued, due to the fact the returns were intentionally recorded incorrectly in states such as East Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Delhi, PEPSU, and Bilaspur.[47]

The 1961 census recognised 1,652 mother tongues spoken by 438,936,918 people, counting all declarations made by any individual at the time when the census was conducted.[48] However, the declaring individuals often mixed names of languages with those of dialects, subdialects and dialect clusters or even castes, professions, religions, localities, regions, countries and nationalities.[48] The list therefore includes languages with barely a few individual speakers as well as 530 unclassified mother tongues and more than 100 idioms that are non-native to India, including linguistically unspecific demonyms such as "African", "Canadian" or "Belgian".[48]

The 1991 census recognises 1,576 classified mother tongues.[49] According to the 1991 census, 22 languages had more than a million native speakers, 50 had more than 100,000 and 114 had more than 10,000 native speakers. The remaining accounted for a total of 566,000 native speakers (out of a total of 838 million Indians in 1991).[49][50]

According to the census of 2001, there are 1635 rationalised mother tongues, 234 identifiable mother tongues and 22 major languages.[18] Of these, 29 languages have more than a million native speakers, 60 have more than 100,000 and 122 have more than 10,000 native speakers.[51] There are a few languages like Kodava that do not have a script but have a group of native speakers in Coorg (Kodagu).[52]

According to the most recent census of 2011, after thorough linguistic scrutiny, edit, and rationalization on 19,569 raw linguistic affiliations, the census recognizes 1369 rationalized mother tongues and 1474 names which were treated as ‘unclassified’ and relegated to ‘other’ mother tongue category.[53] Among, the 1369 rationalized mother tongues which are spoken by 10,000 or more speakers, are further grouped into appropriate set that resulted into total 121 languages. In these 121 languages, 22 are already part of the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India and the other 99 are termed as "Total of other languages" which is one short as of the other languages recognized in 2001 census.[54]

Multilingualism

2011 Census India

| Language | First language speakers | Second language | Third language | Total speakers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers[55] | As % of total population | Speakers (millions) | (millions)[56] | As % of total population[57] | ||

| Hindi | 528,347,193 | 43.63 | 139 | 24 | 692 | 57.1 |

| Bengali | 97,237,669 | 8.30 | 9 | 1 | 107 | 8.9 |

| Marathi | 83,026,680 | 6.86 | 13 | 3 | 99 | 8.2 |

| Telugu | 81,127,740 | 6.70 | 12 | 1 | 95 | 7.8 |

| Tamil | 69,026,881 | 5.70 | 7 | 1 | 77 | 6.3 |

| Gujarati | 55,492,554 | 4.58 | 4 | 1 | 60 | 5.0 |

| Urdu | 50,772,631 | 4.19 | 11 | 1 | 63 | 5.2 |

| Kannada | 43,706,512 | 3.61 | 14 | 1 | 59 | 4.9 |

| Odia | 37,521,324 | 3.10 | 5 | 0.03 | 43 | 3.5 |

| Malayalam | 34,838,819 | 2.88 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 36 | 2.9 |

| Punjabi | 33,124,726 | 2.74 | 0.03 | 0.003 | 36 | 3.0 |

| Assamese | 15,311,351 | 1.26 | 7.48 | 0.74 | 24 | 2.0 |

| Maithili | 13,583,464 | 1.12 | 0.03 | 0.003 | 14 | 1.2 |

| Meitei (Manipuri) | 1,761,079 | 0.15 | 0.4 | 0.04 | 2.25 | 0.2 |

| English | 259,678 | 0.02 | 83 | 46 | 129 | 10.6 |

| Sanskrit | 24,821 | 0.00185 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.025 | 0.002 |

Language families

Ethnolinguistically, the languages of South Asia, echoing the complex history and geography of the region, form a complex patchwork of language families, language phyla and isolates.[10] Languages spoken in India belong to several language families, the major ones being the Indo-Aryan languages spoken by 78.05% of Indians and the Dravidian languages spoken by 19.64% of Indians. The most important language families in terms of speakers are:[58][5][6][10][59]

| Language family | Population (2011 census)[60] |

|---|---|

| Indo-European language family | 945,333,910 (78.07%) |

| Dravidian language family | 237,840,116 (19.64%) |

| Austroasiatic language family | 13,493,080 (1.11%) |

| Tibeto-Burman language family | 12,257,382 (1.01%) |

| Semito-Hamitic language family | 54,947 (0%) |

| Other languages | 1,875,542 (0.15%) |

| Total speaker/population | 1,210,854,977 (100%) |

Indo-Aryan language family

The largest of the language families represented in India, in terms of speakers, is the Indo-Aryan language family, a branch of the Indo-Iranian family, itself the easternmost, extant subfamily of the Indo-European language family. This language family predominates, accounting for some 1035 million speakers, or over 76.5 of the population, per a 2018 estimate. The most widely spoken languages of this group are Hindi,[n 1] Bengali, Marathi, Gujarati, Bhojpuri, Awadhi, Odia, Maithili, Punjabi, Marwari, Kashmiri, Assamese (Asamiya), Chhattisgarhi and Sindhi.[61][62] Aside from the Indo-Aryan languages, other Indo-European languages are also spoken in India, the most prominent of which is English, as a lingua franca.

Dravidian language family

The second largest language family is the Dravidian language family, accounting for some 277 million speakers, or approximately 20.5% per 2018 estimate. The Dravidian languages are spoken mainly in southern India and parts of eastern and central India as well as in parts of northeastern Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Nepal and Bangladesh. The Dravidian languages with the most speakers are Telugu, Tamil, Kannada and Malayalam.[6] Besides the mainstream population, Dravidian languages are also spoken by small scheduled tribe communities, such as the Oraon and Gond tribes.[63] Only two Dravidian languages are exclusively spoken outside India, Brahui in Balochistan, Pakistan and Dhangar, a dialect of Kurukh, in Nepal.[64]

Austroasiatic language family

Families with smaller numbers of speakers are Austroasiatic and numerous small Sino-Tibetan languages, with some 10 and 6 million speakers, respectively, together 3% of the population.[65]

The Austroasiatic language family (austro meaning South) is the autochthonous language in Southeast Asia, arrived by migration. Austroasiatic languages of mainland India are the Khasi and Munda languages, including Bhumij and Santali. The languages of the Nicobar islands also form part of this language family. With the exceptions of Khasi and Santali, all Austroasiatic languages on Indian territory are endangered.[10]: 456–457

Tibeto-Burman language family

The Tibeto-Burman language family is well represented in India. However, their interrelationships are not discernible, and the family has been described as "a patch of leaves on the forest floor" rather than with the conventional metaphor of a "family tree".[10]: 283–5

Padma Vibhushan awardee Indian Bengali scholar Suniti Kumar Chatterjee said, "Among the various Tibeto-Burman languages, the most important and in literature certainly of much greater importance than Newari, is the Meitei or Manipuri language".[66][67][68]

In India, Tibeto-Burman languages are spoken across the Himalayas in the regions of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam (hills and autonomous councils), Himachal Pradesh, Ladakh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, Tripura and West Bengal.[69][70][71]

Sino-Tibetan languages spoken in India include two constitutionally recognised official languages, Meitei (officially known as Manipuri) and Bodo as well as the non-scheduled languages like Karbi, Lepcha, and many varieties of several related Tibetic, West Himalayish, Tani, Brahmaputran, Angami–Pochuri, Tangkhul, Zeme, Kukish sub linguistic branches, amongst many others.

Tai-Kadai language family

The Ahom language, a Southwestern Tai language, had been once the dominant language of the Ahom Kingdom in modern-day Assam, but was later replaced by the Assamese language (known as Kamrupi in ancient era which is the pre-form of the Kamrupi dialect of today). Nowadays, small Tai communities and their languages remain in Assam and Arunachal Pradesh together with Sino-Tibetans, e.g. Tai Phake, Tai Aiton and Tai Khamti, which are similar to the Shan language of Shan State, Myanmar; the Dai language of Yunnan, China; the Lao language of Laos; the Thai language of Thailand; and the Zhuang language in Guangxi, China.

Andamanese language families

The languages of the Andaman Islands form another group:[72]

- the Great Andamanese languages, comprising a number of extinct, and one highly endangered language Aka-Jeru.

- the Ongan family of the southern Andaman Islands, comprising two extant languages, Önge and Jarawa, and one extinct language, Jangil.

In addition, Sentinelese is thought likely to be related to the above languages.[72]

Language isolates

The only language found in the Indian mainland that is considered a language isolate is Nihali.[10]: 337 The status of Nihali is ambiguous, having been considered as a distinct Austroasiatic language, as a dialect of Korku and also as being a "thieves' argot" rather than a legitimate language.[73][74]

The other language isolates found in the rest of South Asia include Burushaski, a language spoken in Gilgit–Baltistan (administered by Pakistan), Kusunda (in western Nepal), and Vedda (in Sri Lanka).[10]: 283 The validity of the Great Andamanese language group as a language family has been questioned and it has been considered a language isolate by some authorities.[10]: 283 [75][76] The Hruso language, which is long assumed to be a Sino-Tibetan language, it may actually be a language isolate.[77][78] Roger Blench classifies the Shompen language of the Nicobar Islands as a language isolate.[79] Roger Blench also considers Puroik to be a language isolate.[80]

In addition, a Bantu language, Sidi, was spoken until the mid-20th century in Gujarat by the Siddi.[10]: 528

Official languages

Federal level

Prior to Independence, in British India, English was the sole language used for administrative purposes as well as for higher education purposes.[84]

In 1946, the issue of national language was a bitterly contested subject in the proceedings of the Constituent Assembly of India, specifically what should be the language in which the Constitution of India is written and the language spoken during the proceedings of Parliament and thus deserving of the epithet "national".The Constitution of India does not give any language the status of national language.[15][16]

Members belonging to the northern parts of India insisted that the Constitution be drafted in Hindi with the unofficial translation in English. This was not agreed to by the drafting committee on the grounds that English was much better to craft the nuanced prose on constitutional subjects. The efforts to make Hindi the pre-eminent language were bitterly resisted by the members from those parts of India where Hindi was not spoken natively.

Eventually, a compromise was reached not to include any mention of a national language. Instead, Hindi in Devanagari script was declared to be the official language of the union, but for "fifteen years from the commencement of the Constitution, the English Language shall continue to be used for all the official purposes of the Union for which it was being used immediately before such commencement."[84]

Article 343 (1) of the Constitution of India states "The Official Language of the Union government shall be Hindi in Devanagari script."[85]: 212 [86] Unless Parliament decided otherwise, the use of English for official purposes was to cease 15 years after the constitution came into effect, i.e. on 26 January 1965.[85]: 212 [86]

As the date for changeover approached, however, there was much alarm in the non-Hindi-speaking areas of India, especially in Kerala, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Punjab, West Bengal, Karnataka, Puducherry and Andhra Pradesh. Accordingly, Jawaharlal Nehru ensured the enactment of the Official Languages Act, 1963,[87][88] which provided that English "may" still be used with Hindi for official purposes, even after 1965.[84] The wording of the text proved unfortunate in that while Nehru understood that "may" meant shall, politicians championing the cause of Hindi thought it implied exactly the opposite.[84]

In the event, as 1965 approached, India's new Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri prepared to make Hindi paramount with effect from 26 January 1965. This led to widespread agitation, riots, self-immolations, and suicides in Tamil Nadu. The split of Congress politicians from the South from their party stance, the resignation of two Union ministers from the South, and the increasing threat to the country's unity forced Shastri to concede.[84][24]

As a result, the proposal was dropped,[89][90] and the Act itself was amended in 1967 to provide that the use of English would not be ended until a resolution to that effect was passed by the legislature of every state that had not adopted Hindi as its official language, and by each house of the Indian Parliament.[87]

Hindi

In the 2001 census, 422 million (422,048,642) people in India reported Hindi to be their native language.[91] This figure not only included Hindi speakers of Hindustani, but also people who identify as native speakers of related languages who consider their speech to be a dialect of Hindi, the Hindi belt. Hindi (or Hindustani) is the native language of most people living in Delhi and Western Uttar Pradesh.[92]

"Modern Standard Hindi", a standardised language is one of the official languages of the Union of India. In addition, it is one of only two languages used for business in Parliament. However, the Rajya Sabha now allows all 22 official languages on the Eighth Schedule to be spoken.[93]

Hindustani, evolved from khari boli (खड़ी बोली), a prominent tongue of Mughal times, which itself evolved from Apabhraṃśa, an intermediary transition stage from Prakrit, from which the major North Indian Indo-Aryan languages have evolved.[citation needed]

By virtue of its being a lingua franca, Hindi has also developed regional dialects such as Bambaiya Hindi in Mumbai. In addition, a trade language, Andaman Creole Hindi has also developed in the Andaman Islands.[94] In addition, by use in popular culture such as songs and films, Hindi also serves as a lingua franca across North-Central India.[citation needed]

Hindi is widely taught both as a primary language and language of instruction and as a second tongue in many states.

English

British colonialism in India resulted in English becoming a language for governance, business, and education. English, along with Hindi, is one of the two languages permitted in the Constitution of India for business in Parliament. Despite the fact that Hindi has official Government patronage and serves as a lingua franca over large parts of India, there was considerable opposition to the use of Hindi in the southern states of India, and English has emerged as a de facto lingua franca over much of India.[84][24] Journalist Manu Joseph, in a 2011 article in The New York Times, wrote that due to the prominence and usage of the language and the desire for English-language education, "English is the de facto national language of India. It is a bitter truth."[95] English language proficiency is highest among urban residents, wealthier Indians, Indians with higher levels of educational attainment, Christians, men and younger Indians.[96] In 2017, more than 58 percent of rural teens could read basic English, and 53 percent of fourteen year-olds & sixty percent of 18-year-olds could read English sentences.[97]

Scheduled languages

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2016) |

Until the Twenty-first Amendment of the Constitution of India in 1967, the country recognised 14 official regional languages. The Eighth Schedule and the Seventy-First Amendment provided for the inclusion of Sindhi, Konkani, Meitei and Nepali, thereby increasing the number of official regional languages of India to 18. The Eighth Schedule of the Constitution of India, as of 1 December 2007, lists 22 languages,[85]: 330 which are given in the table below together with the regions where they are used.[91]

The individual states, the borders of most of which are or were drawn on socio-linguistic lines, can legislate their own official languages, depending on their linguistic demographics. The official languages chosen reflect the predominant as well as politically significant languages spoken in that state. Certain states having a linguistically defined territory may have only the predominant language in that state as its official language, examples being Karnataka and Gujarat, which have Kannada and Gujarati as their sole official language respectively. Telangana, with a sizeable Urdu-speaking Muslim population, and Andhra Pradesh[100] has two languages, Telugu and Urdu, as its official languages.

Some states buck the trend by using minority languages as official languages. Jammu and Kashmir used to have Urdu, which is spoken by fewer than 1% of the population, as the sole official language until 2020. Meghalaya uses English spoken by 0.01% of the population. This phenomenon has turned majority languages into "minority languages" in a functional sense.[101]

In addition to official languages, a few states also designate official scripts.

| Union territory | Official language(s)[111] | Additional official language(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Andaman and Nicobar Islands[139] | Hindi, English | |

| Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu[140][141] | Gujarati | |

| Delhi[142] | Urdu, Punjabi | |

| Ladakh | ||

| Chandigarh[143] | English | |

| Lakshadweep[144][145] | Malayalam[145] | |

| Jammu and Kashmir | Kashmiri, Dogri, Hindi, Urdu, English[146] | |

| Puducherry | Tamil, Telugu (in Yanam), Malayalam (in Mahe)[b][147][148] | English, French[149] |

In addition to states and union territories, India has autonomous administrative regions which may be permitted to select their own official language – a case in point being the Bodoland Territorial Council in Assam which has declared the Bodo language as official for the region, in addition to Assamese and English already in use.[150] and Bengali in the Barak Valley,[151] as its official languages.

Prominent languages of India

Hindi

In British India, English was the sole language used for administrative purposes as well as for higher education purposes. When India became independent in 1947, the Indian legislators had the challenge of choosing a language for official communication as well as for communication between different linguistic regions across India. The choices available were:

- Making "Hindi", which a plurality of the people (41%)[91] identified as their native language, the official language.

- Making English, as preferred by non-Hindi speakers, particularly Kannadigas and Tamils, and those from Mizoram and Nagaland, the official language. See also Anti-Hindi agitations.

- Declare both Hindi and English as official languages and each state is given freedom to choose the official language of the state.

The Indian constitution, in 1950, declared Hindi in Devanagari script to be the official language of the union.[85] Unless Parliament decided otherwise, the use of English for official purposes was to cease 15 years after the constitution came into effect, i.e. on 26 January 1965.[85] The prospect of the changeover, however, led to much alarm in the non-Hindi-speaking areas of India, especially in South India whose native tongues are not related to Hindi. As a result, Parliament enacted the Official Languages Act in 1963,[152][153][154][155][156][157] which provided for the continued use of English for official purposes along with Hindi, even after 1965.

Bengali

Native to the Bengal region, comprising the nation of Bangladesh and the states of West Bengal, Tripura and Barak Valley region[158][159] of Assam. Bengali (also spelt as Bangla: বাংলা) is the sixth most spoken language in the world.[158][159] After the partition of India (1947), refugees from East Pakistan were settled in Tripura, and Jharkhand and the union territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands. There is also a large number of Bengali-speaking people in Maharashtra and Gujarat where they work as artisans in jewellery industries. Bengali developed from Abahattha, a derivative of Apabhramsha, itself derived from Magadhi Prakrit. The modern Bengali vocabulary contains the vocabulary base from Magadhi Prakrit and Pali, also borrowings from Sanskrit and other major borrowings from Persian, Arabic, Austroasiatic languages and other languages in contact with.

Like most Indian languages, Bengali has a number of dialects. It exhibits diglossia, with the literary and standard form differing greatly from the colloquial speech of the regions that identify with the language.[160] Bengali language has developed a rich cultural base spanning art, music, literature, and religion. Bengali has some of the oldest literature of all modern Indo-Aryan languages, dating from about 10th to 12th century ('Chargapada' Buddhist songs). There have been many movements in defence of this language and in 1999 UNESCO declared 21 Feb as the International Mother Language Day in commemoration of the Bengali Language Movement in 1952.[161]

Assamese

Asamiya or Assamese language is most spoken in the state of Assam.[162] It is an Eastern Indo-Aryan language with more than 23 million total speakers including more than 15 million native speakers and more than 7 million L2 speakers per the 2011 Census of India.[163] Along with other Eastern Indo-Aryan languages, Assamese evolved at least before the 7th century CE[164] from the middle Indo-Aryan Magadhi Prakrit. Assamese is unusual among Eastern Indo-Aryan languages for the presence of the /x/ (which, phonetically, varies between velar ([x]) and a uvular ([χ]) pronunciations). The first characteristics of this language are seen in the Charyapadas composed in between the eighth and twelfth centuries. The first examples emerged in writings of court poets in the fourteenth century, the finest example of which is Madhav Kandali's Saptakanda Ramayana composed during 14th century CE, which was the first translation of the Ramayana into an Indo-Aryan language.

Marathi

Marathi is an Indo-Aryan language. It is the official language and co-official language in Maharashtra and Goa states of Western India respectively, and is one of the official languages of India. There were 83 million speakers of the language in 2011.[165] Marathi has the third-largest number of native speakers in India and ranks 10th in the list of most spoken languages in the world. Marathi has some of the oldest literature of all modern Indo-Aryan languages; Oldest stone inscriptions from 8th century & literature dating from about 1100 AD (Mukundraj's Vivek Sindhu dates to the 12th century). The major dialects of Marathi are Standard Marathi (Pramaan Bhasha) and the Varhadi dialect. There are other related languages such as Ahirani, Dangi, Vadvali, Samavedi. Malvani Konkani has been heavily influenced by Marathi varieties. Marathi is one of several languages that descend from Maharashtri Prakrit. The further change led to the Apabhraṃśa languages like Old Marathi.

Marathi Language Day (मराठी दिन/मराठी दिवस (transl. Marathi Dina/Marathi Diwasa) is celebrated on 27 February every year across the Indian states of Maharashtra and Goa. This day is regulated by the State Government. It is celebrated on the birthday of eminent Marathi Poet Vishnu Vaman Shirwadkar, popularly known as Kusumagraj .

Marathi is the official language of Maharashtra and co-official language in the union territories of Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu. In Goa, Konkani is the sole official language; however, Marathi may also be used for all official purposes.[166]

Over a period of many centuries the Marathi language and people came into contact with many other languages and dialects. The primary influence of Prakrit, Maharashtri, Apabhraṃśa and Sanskrit is understandable. Marathi has also been influenced by the Austroasiatic, Dravidian and foreign languages such as Persian and Arabic. Marathi contains loanwords from Persian, Arabic, English and a little from French and Portuguese.

Meitei

Meitei language (officially known as Manipuri language) is the most widely spoken Indian Sino-Tibetan language of Tibeto-Burman linguistic sub branch. It is the sole official language in Manipur and is one of the official languages of India. It is one of the two Sino-Tibetan languages with official status in India, beside Bodo. It has been recognized as one of the advanced modern languages of India by the National Sahitya Academy for its rich literature.[167] It uses both Meitei script as well as Bengali script for writing.[168][169]

Meitei language is currently proposed to be included in the elite category of "Classical Languages" of India.[170][171][172] Besides, it is also currently proposed to be an associate official language of Government of Assam. According to Leishemba Sanajaoba, the present titular king of Manipur and a Rajya Sabha member of Manipur state, by recognising Meitei as an associate official language of Assam, the identity, history, culture and tradition of Manipuris residing in Assam could be protected.[173][174][175]

Meitei Language Day (Manipuri Language Day) is celebrated on 20 August every year by the Manipuris across the Indian states of Manipur, Assam and Tripura. This day is regulated by the Government of Manipur. It is the commemoration of the day on which Meitei was included in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India on the 20 August 1992.[176][177][178][179][180]

Telugu

Telugu is the most widely spoken Dravidian language in India and around the world. Telugu is an official language in Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Yanam, making it one of the few languages (along with Hindi, Bengali, and Urdu) with official status in more than one state. It is also spoken by a significant number of people in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Chhattisgarh, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, and by the Sri Lankan Gypsy people. It is one of six languages with classical status in India. Telugu ranks fourth by the number of native speakers in India (81 million in the 2011 Census),[165] fifteenth in the Ethnologue list of most-spoken languages worldwide and is the most widely spoken Dravidian language.

Tamil

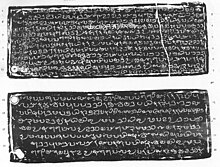

Tamil is a Dravidian language predominantly spoken in Tamil Nadu, Puducherry and many parts of Sri Lanka. It is also spoken by large minorities in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Kerala, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Malaysia, Singapore, Mauritius and throughout the world. Tamil ranks fifth by the number of native speakers in India (61 million in the 2001 Census)[181] and ranks 20th in the list of most spoken languages.[citation needed] It is one of the 22 scheduled languages of India and was the first Indian language to be declared a classical language by the Government of India in 2004. Tamil is one of the longest surviving classical languages in the world.[182][183] It has been described as "the only language of contemporary India which is recognisably continuous with a classical past".[184] The two earliest manuscripts from India,[185][186] acknowledged and registered by UNESCO Memory of the World register in 1997 and 2005, are in Tamil.[187] Tamil is an official language of Tamil Nadu, Puducherry, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Sri Lanka and Singapore. It is also recognized as a minority language in Canada, Malaysia, Mauritius and South Africa.

Urdu

After independence, Modern Standard Urdu, the Persianised register of Hindustani became the national language of Pakistan. During British colonial times, knowledge of Hindustani or Urdu was a must for officials. Hindustani was made the second language of British Indian Empire after English and considered as the language of administration.[citation needed] The British introduced the use of Roman script for Hindustani as well as other languages. Urdu had 70 million speakers in India (per the Census of 2001), and, along with Hindi, is one of the 22 officially recognised regional languages of India and also an official language in the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh[100], Jammu and Kashmir, Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Telangana that have significant Muslim populations.

Gujarati

Gujarati is an Indo-Aryan language. It is native to the west Indian region of Gujarat. Gujarati is part of the greater Indo-European language family. Gujarati is descended from Old Gujarati (c. 1100 – 1500 CE), the same source as that of Rajasthani. Gujarati is the chief and official language in the Indian state of Gujarat. It is also an official language in the union territories of Daman and Diu and Dadra and Nagar Haveli. According to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), 4.5% of population of India (1.21 billion according to 2011 census) speaks Gujarati. This amounts to 54.6 million speakers in India.[188]

Kannada

Kannada is a Dravidian language which branched off from Kannada-Tamil sub group around 500 B.C.E according to the Dravidian scholar Zvelebil.[189] It is the official language of Karnataka. According to the Dravidian scholars Steever and Krishnamurthy, the study of Kannada language is usually divided into three linguistic phases: Old (450–1200 CE), Middle (1200–1700 CE) and Modern (1700–present).[190][191] The earliest written records are from the 5th century,[192] and the earliest available literature in rich manuscript (Kavirajamarga) is from c. 850.[193][194] Kannada language has the second oldest written tradition of all languages of India.[195][196] Current estimates of the total number of epigraph present in Karnataka range from 25,000 by the scholar Sheldon Pollock to over 30,000 by the Sahitya Akademi,[197] making Karnataka state "one of the most densely inscribed pieces of real estate in the world".[198] According to Garg and Shipely, more than a thousand notable writers have contributed to the wealth of the language.[199][200]

Malayalam

Malayalam (/mæləˈjɑːləm/;[201] [maləjaːɭəm]) has official language status in the state of Kerala and in the union territories of Lakshadweep and Puducherry. It belongs to the Dravidian family of languages and is spoken by some 38 million people. Malayalam is also spoken in the neighboring states of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka; with some speakers in the Nilgiris, Kanyakumari and Coimbatore districts of Tamil Nadu, and the Dakshina Kannada and the Kodagu district of Karnataka.[202][203][204] Malayalam originated from Middle Tamil (Sen-Tamil) in the 7th century.[205] As Malayalam began to freely borrow words as well as the rules of grammar from Sanskrit, the Grantha alphabet was adopted for writing and came to be known as Arya Eluttu.[206] This developed into the modern Malayalam script.[207]

Odia

Odia (formerly spelled Oriya)[208] is the only modern language officially recognized as a classical language from the Indo-Aryan group. Odia is primarily spoken and has official language status in the Indian state of Odisha and has over 40 million speakers. It was declared as a classical language of India in 2014. Native speakers comprise 91.85% of the population in Odisha.[209][210] Odia originated from Odra Prakrit which developed from Magadhi Prakrit, a language spoken in eastern India over 2,500 years ago. The history of Odia language can be divided to Old Odia (3rd century BC −1200 century AD),[211] Early Middle Odia (1200–1400), Middle Odia (1400–1700), Late Middle Odia (1700–1870) and Modern Odia (1870 until present day). The National Manuscripts Mission of India have found around 213,000 unearthed and preserved manuscripts written in Odia.[212]

Santali

Santali is a Munda language, a branch of Austroasiatic languages spoken widely in Jharkhand and other states of eastern India by Santhal community of tribal and non-tribal.[213] It is written in Ol Chiki script invented by Raghunath Murmu at the end of 19th century.[214] Santali is spoken by 0.67% of India's population.[215][216] About 7 million people speak this language.[217] It is also spoken in Bangladesh and Nepal.[218][219] The language is major tribal language of Jharkhand and thus Santhal community is demanding to make it as the official language of Jharkhand.[220]

Punjabi

Punjabi, written in the Gurmukhi script in India, is one of the prominent languages of India with about 32 million speakers. In Pakistan it is spoken by over 80 million people and is written in the Shahmukhi alphabet. It is mainly spoken in Punjab but also in neighboring areas. It is an official language of Delhi and Punjab.

Maithili

Maithili (/ˈmaɪtɪli/;[221] Maithilī) is an Indo-Aryan language native to India and Nepal. In India, it is widely spoken in the Bihar and Jharkhand states.[222][223] Native speakers are also found in other states and union territories of India, most notably in Uttar Pradesh and the National Capital Territory of Delhi.[224] In the 2011 census of India, It was reported by 13,583,464 people as their mother tongue comprising about 1.12% of the total population of India.[225]In Nepal, it is spoken in the eastern Terai, and is the second most prevalent language of Nepal.[226] Tirhuta was formerly the primary script for written Maithili. Less commonly, it was also written in the local variant of Kaithi.[227] Today it is written in the Devanagari script.[228]

In 2003, Maithili was included in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution as a recognised regional language of India, which allows it to be used in education, government, and other official contexts.[229]

Classical languages of India

In 2004, the Government of India declared that languages that met certain requirements could be accorded the status of a "Classical Language" of India.[230]

Languages thus far declared to be Classical:

- Tamil (in 2004),[231]

- Sanskrit (in 2005),[232]

- Kannada (in 2008),[233]

- Telugu (in 2008),[233]

- Malayalam (in 2013),[234]

- Odia (in 2014).[235][236]

Over the next few years, several languages were granted the Classical status, and demands have been made for other languages, including Pali, Bengali,[237][238] Marathi,[239] Maithili[240] and Meitei (officially called Manipuri).[241][242][243]

Other regional languages and dialects

The 2001 census identified the following native languages having more than one million speakers. Most of them are dialects/variants grouped under Hindi.[91]

| Languages | No. of native speakers[91] |

|---|---|

| Bhojpuri | 33,099,497 |

| Rajasthani | 18,355,613 |

| Magadhi/Magahi | 13,978,565 |

| Chhattisgarhi | 13,260,186 |

| Haryanvi | 7,997,192 |

| Marwari | 7,936,183 |

| Malvi | 5,565,167 |

| Mewari | 5,091,697 |

| Khorth/Khotta | 4,725,927 |

| Bundeli | 3,072,147 |

| Bagheli | 2,865,011 |

| Pahari | 2,832,825 |

| Laman/Lambadi | 2,707,562 |

| Awadhi | 2,529,308 |

| Harauti | 2,462,867 |

| Garhwali | 2,267,314 |

| Nimadi | 2,148,146 |

| Sadan/Sadri | 2,044,776 |

| Kumauni | 2,003,783 |

| Dhundhari | 1,871,130 |

| Tulu | 1,722,768 |

| Surgujia | 1,458,533 |

| Bagri Rajasthani | 1,434,123 |

| Banjari | 1,259,821 |

| Nagpuria | 1,242,586 |

| Surajpuri | 1,217,019 |

| Kangri | 1,122,843 |

Practical problems

India has several languages in use; choosing any single language as an official language presents problems to all those whose "mother tongue" is different. However, all the boards of education across India recognise the need for training people to one common language.[244] There are complaints that in North India, non-Hindi speakers have language trouble. Similarly, there are complaints that North Indians have to undergo difficulties on account of language when travelling to South India. It is common to hear of incidents that result due to friction between those who strongly believe in the chosen official language, and those who follow the thought that the chosen language(s) do not take into account everyone's preferences.[245] Local official language commissions have been established and various steps are being taken in a direction to reduce tensions and friction.[citation needed]

Languages by earliest known inscriptions

Earliest known manuscripts are often subjected to debates and disputes, due to the conflicting opinions and assumptions of different scholars, claiming high antiquity of the languages. So, inscriptions are studied more in depth for understanding the chronology of the oldest known languages of the Indian subcontinent.

| Date | Language | Earliest known inscriptions | Images | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| early 2nd century BC | Old Tamil | rock inscription ARE 465/1906 at Mangulam caves, Tamil Nadu[246] (Other authors give dates from late 3rd century BC to 1st century AD.[247][248]) |  | |

| 1st century BC | Sanskrit | Ayodhya Inscription of Dhana, and Hathibada Ghosundi Inscriptions (both near Chittorgarh)[249] | The Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman (shortly after 150 AD) is the oldest long text.[250] | |

| c. 450 | Old Kannada | Halmidi inscription[251] |  | |

| c. 568 CE | Meitei | Yumbanlol copper plate inscriptions about literature of sexuality, the relationships between husbands and wives, and instructions on how to run a household.[252][253] |  | |

| c. 575 CE | Telugu | Kalamalla inscription[254] | ||

| c. 849/850 CE | Malayalam | Quilon Syrian copper plates[255] |  | |

| c. 1012 CE | Marathi | A stone inscription from Akshi taluka of Raigad district[256] | ||

| c. 1051 CE | Odia | Urajam inscription[257][258] |  |

Language policy

The Union Government of India formulated the Three language formula.

In the Prime Minister's Office

The official website of the Prime Minister's Office of India publishes its official information in 11 Indian official languages, namely Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Kannada, Malayalam, Meitei (Manipuri), Marathi, Odia, Punjabi, Tamil and Telugu, out of the 22 official languages of the Indian Republic, in addition to English and Hindi.[259]

In the Press Information Bureau

The Press Information Bureau (PIB) selects 14 Indian official languages, which are Dogri, Punjabi, Bengali, Oriya, Gujarati, Marathi, Meitei (Manipuri), Tamil, Kannada, Telugu, Malayalam, Konkani and Urdu, in addition to Hindi and English, out of the 22 official languages of the Indian Republic to render its information about all the Central Government press releases.[c][260][261]

In the Staff Selection Commission

The Staff Selection Commission (SSC) selected 13 Indian official languages, which are Urdu, Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu, Kannada, Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Konkani, Meitei (Manipuri), Marathi, Odia and Punjabi, in addition to Hindi and English, out of the 22 official languages of the Indian Republic, to conduct the Multi-Tasking (Non-Technical) Staff examination for the first time in its history.[262][263]

In the Central Armed Police Forces

The Union Government of India selected Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Marathi, Malayalam, Meitei (Manipuri), Kannada, Tamil, Telugu, Odia, Urdu, Punjabi, and Konkani, 13 out of the 22 official languages of the Indian Republic, in addition to Hindi & English, to be used in the recruitment examination of the Central Armed Police Forces (CAPF). The decision was taken by the Home Minister after having an agreement between the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Staff Selection Commission.[264][265] The official decision will be converted into action from 1 January 2024.[266]

Language conflicts

There are conflicts over linguistic rights in India. The first major linguistic conflict, known as the Anti-Hindi agitations of Tamil Nadu, took place in Tamil Nadu against the implementation of Hindi as the official language of India. Political analysts consider this as a major factor in bringing DMK to power and leading to the ousting and nearly total elimination of the Congress party in Tamil Nadu.[267] Strong cultural pride based on language is also found in other Indian states such as Assam, Odisha, Karnataka, West Bengal, Punjab and Maharashtra. To express disapproval of the imposition of Hindi on its states' people as a result of the central government, the government of Maharashtra made the state language Marathi mandatory in educational institutions of CBSE and ICSE through Class/Grade 10.[268]

The Government of India attempts to assuage these conflicts with various campaigns, coordinated by the Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore, a branch of the Department of Higher Education, Language Bureau, and the Ministry of Human Resource Development.[clarification needed][citation needed]

Linguistic movements

In the history of India, various linguistic movements were and are undertaken by different literary, political and social associations as well as organisations, advocating for the changes and the developments of several languages, dialects and vernaculars in diverse critical, discriminative and unfavorable circumstances and situations.

Bengali

Meitei (Manipuri)

- Meitei language movements (aka Manipuri language movements), various linguistic movements for the cause of Meitei language (officially called Manipuri language)

- Meitei linguistic purism movement, an ongoing linguistic movement, aimed to attain linguistic purism in Meitei language

- Scheduled language movement, a historical linguistic movement in Northeast India, aimed at the recognition of Meitei language as one of the scheduled languages of Indian Republic

- Meitei classical language movement, an ongoing linguistic movement in Northeast India, aimed at the recognition of Meitei language as an officially recognized "classical language"

- Meitei associate official language movement, a semi active linguistic movement in Northeast India, aimed at the recognition of Meitei language as an "associate" official language of Assam

Rajasthani

- Rajasthani language movement, a linguistic movement that has been campaigning for greater recognition for the Rajasthani language since 1947

Tamil

- Tanittamil Iyakkam (Pure Tamil Movement), a linguistic purism movement for the Tamil language, to ignore the loanwords borrowed from Sanskrit

Developmental works

In the age of technological advancements, the Google Translate supports the following Indian languages: Bengali, Bhojpuri,[269] Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Maithili, Malayalam, Marathi, Meiteilon (Manipuri)[d] (in Meitei script[e]), Odia, Punjabi (in Gurmukhi script[f]), Sanskrit, Tamil, Telugu, Urdu.

Meitei (Manipuri)

On the 4 September 2013, the Directorate of Language Planning and Implementation (DLPI) was established for the development and the promotion of Meitei language (officially called Manipuri language) and the Meitei script (Manipuri script) in Manipur.[270][271]

The Manipuri Sahitya Parishad is given annual financial support of ₹500,000 (equivalent to ₹750,000 or US$9,000 in 2023) by the Government of Manipur.[272][273][274]

Since 2020, the Government of Assam is giving annual financial support of ₹500,000 (equivalent to ₹590,000 or US$7,100 in 2023) to the Assam Manipuri Sahitya Parishad. Besides, the Assam government financed ₹6 crore (equivalent to ₹7.1 crore or US$850,000 in 2023) for the creation of a corpus for the development of the Meitei language (officially called Manipuri language).[275]

In September 2021, the Central Government of India released ₹180 million (US$2.2 million) as the first instalment for the development and the promotion of the Meitei language (officially called Manipuri language) and the Meitei script (Manipuri script) in Manipur.[276][277][278]

The Department of Language Planning and Implementation of the Government of Manipur offers a sum of ₹5,000 (equivalent to ₹8,500 or US$100 in 2023), to every individual who learns Meitei language (officially called Manipuri language), having certain terms and conditions.[279][280]

Sanskrit

Центральное правительство Индии выделило 6438,4 миллиона фунтов стерлингов за последние три года на развитие и продвижение санскрита , 2311,5 миллиона фунтов стерлингов в 2019–2020 годах, около 2143,8 миллиона фунтов стерлингов в 2018–19 годах и 1983,1 миллиона фунтов стерлингов в 2017–2018 годах. [281] [282]

тамильский

Центральное правительство Индии выделило 105,9 миллиона рупий в 2017–18 годах, 46,5 миллиона рупий в 2018–19 годах и 77 миллионов рупий в 2019–20 годах «Центральному институту классического тамильского языка» на развитие и продвижение тамильского языка. . [281] [283]

Телугу и каннада

Центральное правительство Индии выделило 10 миллионов рупий в 2017–18 годах, 9,9 миллиона рупий в 2018–19 годах и 10,7 миллиона рупий в 2019–2020 годах каждый на развитие и продвижение языков телугу и языка каннада . [281] [283]

Компьютеризация

| Язык | Код языка | Гугл переводчик [284] | Бхашини [285] | Microsoft переводчик [286] | Яндекс Переводчик [287] | IBM Ватсон [288] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Бенгальский | млрд | Да | Да | Да | Да | Да |

| Гуджарати | к | Да | Да | Да | Да | Да |

| Неа | привет | Да | Да | Да | Да | Да |

| Каннада | знать | Да | Да | Да | Да | Да |

| Майтхили | Может | Да | Бета | Да | Нет | Нет |

| малаялам | мл | Да | Да | Да | Да | Да |

| Маратхи | Мистер | Да | Да | Да | Да | Да |

| Мэйтей (Манипури) | mni (в конкретном случае сценария mni-Mtei) | Да | Да | Да | Нет | Нет |

| Одия (Ория) | или | Да | Да | Да | Нет | Нет |

| панджаби | хорошо | Да | Да | Да | Да | Да |

| тамильский | лицом к лицу | Да | Да | Да | Да | Да |

| телугу | тот | Да | Да | Да | Да | Да |

Системы письма

Большинство языков в Индии написаны письменностью, полученной от Брахми . [289] К ним относятся деванагари , тамильский , телугу , каннада , мейтей майек , одиа , восточный нагари – ассамский/бенгальский, гурумукхи и другие. Урду написан алфавитом, заимствованным из арабского языка . Несколько второстепенных языков, таких как сантали, используют независимые сценарии (см. сценарий Ол Чики ).

В разных индийских языках есть свои сценарии. хинди , маратхи , майтхили [290] и Ангика — языки, написанные с использованием сценария деванагари . Большинство основных языков записываются с использованием специфического для них алфавита, например ассамского (асамия). [291] [292] с ассамским , [293] Бенгальский с бенгальским , пенджабский с гурмукхи , мейтей с мейтей майек , одия с письмом одиа , гуджарати с гуджарати и т. д. Урду и кашмири , сараики и синдхи написаны модифицированными вариантами персидско -арабского письма . За этим единственным исключением, письменность индийских языков является родной для Индии. Некоторые языки, такие как Kodava , у которых не было сценария, а также некоторые языки, такие как Tulu , у которых уже был сценарий, приняли сценарий каннада из-за его легкодоступных настроек печати. [294]

- Надпись языке мейтей на камне на шрифтом мейтей о королевском указе короля мейтей, найденная в священном месте Бога Панам Нинтоу в Андро, Восток Импхал , Манипур.

- Разработка сценария Одиа

- Серебряная монета, выпущенная во время правления Рудры Сингхи, с ассамскими надписями.

- Североиндийский брахми найден в столбе Ашока

- Надпись Хальмиди , старейшая известная надпись на языке каннада. Надпись датирована периодом 450–500 гг. н.э.

См. также

- Карибский хиндустани

- Фиджи Хинди

- Индо-португальские креолы

- Языки Бангладеш

- Языки Бутана

- Языки Китая

- Языки Фиджи

- Языки Гайаны

- Языки Малайзии

- Языки Мальдив

- Языки Маврикия

- Языки Мьянмы

- Языки Непала

- Языки Пакистана

- Языки Реюньона

- Языки Сингапура

- Языки Шри-Ланки

- Языки Тринидада и Тобаго

- Список исчезающих языков в Индии

- Список языков по количеству носителей языка в Индии

- Национальная миссия переводов

- Романизация синдхи

- Тамильская диаспора

- телугу диаспора

Примечания

- ^ В современном и разговорном контексте термин « индийский » также в более общем смысле относится к языкам Индийского субконтинента , включая, таким образом, и неиндоарийские языки. См., например Рейнольдс, Майк; Верма, Махендра (2007). «Индийские языки» . В Великобритании Дэвид (ред.). Язык на Британских островах . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета . стр. 293–307. ISBN 978-0-521-79488-6 . Проверено 4 октября 2021 г.

- ^ См . Официальные языки Пудучерри.

- ^ Версии пресс-релизов на языке Meitei (официально называемые Manipuri планируется изменить этот сценарий на сценарий Meitei ( скрипт Manipuri ). ) в настоящее время доступны на бенгальском языке, но со временем

- ^ Google Translate упоминает как « Мейтейлон », так и « Манипури » (в скобках одновременно ) для языка мейтей (официально известного как язык манипури ).

- ^ В языке Meitei официально используется как сценарий Meitei , так и бенгальский сценарий , но Google Translate использует только сценарий Meitei .

- ^ Пенджабский язык официально использует как сценарий Гурмухи, так и сценарий Шахмукхи , но Google Translate использует только сценарий Гурмукхи .

- ^ Хотя лингвистически хинди и урду — это один и тот же язык, называемый хиндустани , правительство классифицирует их как отдельные языки, а не как разные стандартные регистры одного и того же языка.

Ссылки

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Конституция Индии» . Архивировано из оригинала 2 апреля 2012 года . Проверено 21 марта 2012 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Закон об официальном языке | Правительство Индии, Министерство электроники и информационных технологий» . meity.gov.in . Проверено 24 января 2017 г.

- ^ Зальцманн, Зденек; Стэнлоу, Джеймс; Адачи, Нобуко (8 июля 2014 г.). Язык, культура и общество: введение в лингвистическую антропологию . Вествью Пресс. ISBN 9780813349558 – через Google Книги.

- ^ «Официальный язык – Профиль Союза – Знай Индию: Национальный портал Индии» . Archive.india.gov.in . Проверено 28 декабря 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Индоарийские языки» . Британская онлайн-энциклопедия . Проверено 10 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Языки хинди» . Британская онлайн-энциклопедия . Проверено 10 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Как, Субхаш (январь 1996 г.). «Индские языковые семьи и индоевропейские» . Яваника .

В индийскую семью входят подсемейства североиндийской и дравидийской.

- ^ Рейнольдс, Майк; Верма, Махендра (2007), Великобритания, Дэвид (редактор), «Индские языки» , Язык на Британских островах , Кембридж: Cambridge University Press, стр. 293–307, ISBN 978-0-521-79488-6 , получено 4 октября 2021 г.

- ^ Как, Субхаш. «О классификации индийских языков» (PDF) . Университет штата Луизиана .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я Мозли, Кристофер (10 марта 2008 г.). Энциклопедия языков мира, находящихся под угрозой исчезновения . Рутледж. ISBN 978-1-135-79640-2 .

- ^ Ситхараман, Г. (13 августа 2017 г.). «Спустя семь десятилетий после обретения независимости многим малым языкам Индии грозит исчезновение» . Экономические времена .

- ^ «В каких странах больше всего языков?» . Этнолог . 22 мая 2019 г.

- ^ Аадитиян, Кавин (10 ноября 2016 г.). «Примечания и цифры: как новая валюта может возродить дебаты о старом языке» . Проверено 5 марта 2020 г.

- ^ «Статья 343 Конституции Индии 1949 года» . Проверено 5 марта 2020 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хан, Саид (25 января 2010 г.). «В Индии нет национального языка: Высокий суд Гуджарата» . Таймс оф Индия . Проверено 5 мая 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Press Trust of India (25 января 2010 г.). «Хинди, а не национальный язык: Суд» . Индус . Ахмедабад . Проверено 23 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Языки, включенные в восьмой список Конституции Индии [ sic ] . Архивировано 4 июня 2016 года в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Данные переписи населения 2001 года: общее примечание» . Перепись Индии . Проверено 11 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Абиди, Саха; Гаргеш, Равиндер (2008). «4. Персы в Южной Азии » В Качру, Брадж Б. (ред.). Язык в Южной Азии Качру, Ямуна и Шридхар, издательство SN Cambridge University Press. стр. 100-1 103–120. ISBN 978-0-521-78141-1 .

- ^ Бхатия, Тедж К. и Уильям К. Ричи. (2006) Двуязычие в Южной Азии. В: Справочник по двуязычию, стр. 780–807. Оксфорд: издательство Blackwell Publishing

- ^ «Упадок языка фарси - The Times of India» . Таймс оф Индия . 7 января 2012 года . Проверено 26 октября 2015 г.

- ^ «Родной язык хинди для 44% жителей Индии, второй по распространенности бенгальский - The Times of India» . Таймс оф Индия . 28 июня 2018 года . Проверено 6 ноября 2021 г.

- ^ Неру, Джавахарлал ; Ганди, Мохандас (1937). Вопрос языка: выпуск 6 политических и экономических исследований Конгресса . КМ Ашраф.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Хардгрейв, Роберт Л. (август 1965 г.). Беспорядки в Тамилнаде: проблемы и перспективы языкового кризиса Индии . Азиатский опрос. Издательство Калифорнийского университета.

- ^ «Махараштра присоединится к движению против хинди в Бангалоре» . www.nagpurtoday.in .

- ^ «Всемирная книга фактов» . www.cia.gov . Проверено 25 октября 2015 г.

- ^ «Язык телугу | Происхождение, история и факты | Британника» . www.britanica.com . 20 октября 2023 г. Проверено 28 октября 2023 г.

- ^ — «Что данные переписи населения говорят об использовании индийских языков» . Декан Вестник . Проверено 16 ноября 2023 г.

— «За десять лет на хинди появилось 100 миллионов говорящих; кашмирский второй быстрорастущий язык» . 28 июня 2018 года . Проверено 16 ноября 2023 г.

— «Хинди — самый быстрорастущий язык в Индии, на нем появилось 100 миллионов новых носителей» .

— «Хинди быстро рос в нехинди-государствах даже без официального мандата» . Индия сегодня . 11 апреля 2022 г. Проверено 16 ноября 2023 г. - ^ «Индия» . Этнолог (Бесплатно Все) . Проверено 26 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ Авари, Бурджор (11 июня 2007 г.). Индия: Древнее прошлое: история Индийского субконтинента с 7000 г. до н.э. по 1200 г. н.э. Рутледж. ISBN 9781134251629 .

- ^ Андронов Михаил Сергеевич (1 января 2003 г.). Сравнительная грамматика дравидийских языков . Отто Харрасовиц Верлаг. п. 299. ИСБН 9783447044554 .

- ^ Кришнамурти, Бхадрираджу (2003). Дравидийские языки . Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. 19–20. ISBN 0521771110 .

- ^ Качру, Ямуна (1 января 2006 г.). Хинди . Лондонская библиотека восточных и африканских языков. Издательство Джона Бенджамина. п. 1. ISBN 90-272-3812-Х .

- ^ Санаджаоба, Наорем (1988). Манипур, Прошлое и настоящее: наследие и испытания цивилизации . Публикации Миттала. п. 290. ИСБН 978-81-7099-853-2 .

- ^ Моханти, ПК (2006). Энциклопедия зарегистрированных племен Индии: в пяти томах . Издательство Гян. п. 149. ИСБН 978-81-8205-052-5 .

- ^ Санаджаоба, Наорем (1993). Манипур: Трактат и документы . Публикации Миттала. п. 369. ИСБН 978-81-7099-399-5 .

- ^ Санаджаоба, Наорем (1993). Манипур: Трактат и документы . Публикации Миттала. п. 255. ИСБН 978-81-7099-399-5 .

- ^ Брасс, Пол Р. (2005). Язык, религия и политика в Северной Индии . iUniverse. п. 129. ИСБН 978-0-595-34394-2 .

- ^ Кулшрешта, Маниша; Матур, Рамкумар (24 марта 2012 г.). Особенности диалектного акцента для установления личности говорящего: пример . Springer Science & Business Media. п. 16. ISBN 978-1-4614-1137-6 .

- ^ Роберт Э. Нанли; Северин М. Робертс; Джордж Вубрик; Дэниел Л. Рой (1999), Культурный ландшафт: введение в человеческую географию , Прентис Холл, ISBN 0-13-080180-1 ,

...хиндустани является основой обоих языков...

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Айджазуддин Ахмад (2009). География Южноазиатского субконтинента: критический подход . Концептуальное издательство. стр. 123–124. ISBN 978-81-8069-568-1 . Проверено 17 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Нахид Саба (18 сентября 2013 г.). «2. Многоязычие». Лингвистическая неоднородность и многоязычие в Индии: лингвистическая оценка индийской языковой политики (PDF) . Алигарх: Мусульманский университет Алигарха. стр. 61–68 . Проверено 17 декабря 2014 г. [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Льюис, М. Пол; Саймонс, Гэри Ф.; Фенниг, Чарльз Д., ред. (2014). «Этнолог: Языки мира (семнадцатое издание): Индия» . Даллас, Техас: SIL International . Проверено 29 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ Этнолог: Языки мира (семнадцатое издание): Статистические сводки. Архивировано 17 декабря 2014 года в Wayback Machine . Проверено 17 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Сингх, Шив Сахай (22 июля 2013 г.). «Языковое исследование выявляет разнообразие» . Индус . Проверено 15 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Банерджи, Паула; Чаудхури, Сабьясачи Басу Рэй; Дас, Самир Кумар; Бишну Адхикари (2005). Внутреннее перемещение в Южной Азии: актуальность руководящих принципов ООН . Публикации SAGE. п. 145. ИСБН 978-0-7619-3329-8 . Проверено 17 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Дасгупта, Джйотириндра (1970). Языковой конфликт и национальное развитие: групповая политика и национальная языковая политика в Индии . Беркли: Калифорнийский университет, Беркли. Центр исследований Южной и Юго-Восточной Азии. п. 47. ИСБН 9780520015906 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Малликарджун, Б. (5 августа 2002 г.). «Родные языки Индии по данным переписи 1961 года» . Языки в Индии . 2 . МС Тирумалай. ISSN 1930-2940 . Проверено 11 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Виджаянунни, М. (26–29 августа 1998 г.). «Планирование переписи населения Индии 2001 года на основе переписи 1991 года» (PDF) . 18-я конференция по переписи населения . Гонолулу, Гавайи, США: Ассоциация директоров национальных переписей и статистики Америки, Азии и Тихоокеанского региона. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 19 ноября 2008 года . Проверено 17 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Малликарджун, Б. (7 ноября 2001 г.). «Языки Индии по данным переписи 2001 года» . Языки в Индии . Проверено 17 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Вишенбарт, Рюдигер (11 февраля 2013 г.). Мировой рынок электронных книг: текущие условия и прогнозы на будущее . «О'Рейли Медиа, Инк.». п. 62. ИСБН 978-1-4493-1999-1 . Проверено 18 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Шиффрин, Дебора; Фина, Анна Де; Нюлунд, Анастасия (2010). Рассказывание историй: язык, повествование и социальная жизнь . Издательство Джорджтаунского университета. п. 95. ИСБН 978-1-58901-674-3 . Проверено 18 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ «Перепись Индии 2011 г., Документ 1 2018 г., Язык – Индия, штаты и союзные территории» (PDF) . Веб-сайт переписи населения Индии . Проверено 29 августа 2019 г.

- ^ Данные переписи населения 2001 г. Общие примечания | дата доступа = 29 августа 2019 г.

- ^ Перепись Индии: Сравнительная сила говорящих на зарегистрированных языках в 1951, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991, 2001 и 2011 годах (PDF) (Отчет). Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 27 июня 2018 года.

- ^ «Со сколькими индейцами ты можешь поговорить?» . www.hindustantimes.com .

- ^ «Как языки пересекаются в Индии» . Индостан Таймс. 22 ноября 2018 г.

- ^ «Индия: Языки» . Британская онлайн-энциклопедия . Проверено 2 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ СТАТИСТИЧЕСКИЙ ОТЧЕТ ИНДИИ

- ^ Таблица C-16: ЯЗЫК ИНДИЯ, ШТАТЫ И СОЮЗНЫЕ ТЕРРИТОРИИ (PDF) . Перепись населения Индии 2011 г. (Отчет). ДОКУМЕНТ 1 2018 ГОДА. УПРАВЛЕНИЕ ГЕНЕРАЛЬНОГО РЕГИСТРАТОРА, ИНДИЯ. п. 21. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 20 февраля 2019 года.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: другие ( ссылка ) - ^ «Индоарийские языки » энциклопедия Британская Октябрь 2023 г.

- ^ Мандрык, Джейсон (15 октября 2010 г.). Operation World: Полное молитвенное руководство для каждой нации . Межвузовская пресса. ISBN 978-0-8308-9599-1 .

- ^ Уэст, Барбара А. (1 января 2009 г.). Энциклопедия народов Азии и Океании . Издательство информационной базы. п. 713. ИСБН 978-1-4381-1913-7 .

- ^ Левинсон, Дэвид; Кристенсен, Карен (2002). Энциклопедия современной Азии: Китайско-индийские отношения до Хёго . Сыновья Чарльза Скрибнера. п. 299. ИСБН 978-0-684-31243-9 .

- ^ Иштиак, М. (1999). Языковые сдвиги среди зарегистрированных племен в Индии: географическое исследование . Дели: Издательство Motilal Banarsidass. стр. 26–27. ISBN 9788120816176 . Проверено 7 сентября 2012 г.

- ^ Деви, Нунглекпам Преми (14 апреля 2018 г.). Взгляд на литературные произведения Манипури . п. 5.

- ^ Сингх, Ч. Манихар (1996). История литературы Манипури . Сахитья Академия . п. 8. ISBN 978-81-260-0086-9 .

- ^ Антология статей индийских и советских ученых (1975). Проблемы современной индийской литературы . : Мичиганский университет Статистический паб. Общество: дистрибьютор, КП Багчи. п. 23.

- ^ «Меморандум об урегулировании территориального совета Бодоланда (БТС)» . www.satp.org .

- ^ Качру, Брадж Б.; Качру, Ямуна; Шридхар, С.Н. (27 марта 2008 г.). Язык в Южной Азии Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 9780521781411 . Проверено 28 декабря 2017 г.

- ^ Роббинс Берлинг. «О «Камарупане» » (PDF) . Sealang.net . Проверено 28 декабря 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Никлас Буренхульт. «Глубокая лингвистическая предыстория с особым упором на андаманский язык» (PDF) . Рабочие документы (45). Лундский университет, факультет лингвистики: 5–24 . Проверено 2 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Андерсон, Грегори Д.С. (2007). Глагол мунда: типологические перспективы . Вальтер де Грюйтер. п. 6. ISBN 978-3-11-018965-0 .

- ^ Андерсон, GDS (6 апреля 2010 г.). «Австроазиатские языки» . В Брауне, Кейт; Огилви, Сара (ред.). Краткая энциклопедия языков мира . Эльзевир. п. 94. ИСБН 978-0-08-087775-4 .

- ^ Гринберг, Джозеф (1971). «Индо-Тихоокеанская гипотеза». Современные тенденции в лингвистике вып. 8 , изд. Томас А. Себеок, 807.71. Гаага: Мутон.

- ^ Абби, Анвита (2006). Вымирающие языки Андаманских островов. Германия: Линком ГмбХ.

- ^ Бленч, Роджер; Пост, Марк (2011), (Де)классификация языков Аруначал: реконструкция доказательств (PDF) , заархивировано из оригинала (PDF) 26 мая 2013 г.

- ^ Хаммарстрем, Харальд; Форк, Роберт; Хаспельмат, Мартин; Банк, Себастьян, ред. (2020). «Хрусо» . Глоттолог 4.3 .

- ^ Бленч, Роджер (2007). «5. Классификация языка шом пен». Язык Шом Пен: язык, изолированный на Никобарских островах (PDF) . стр. 20–21.

- ^ Бленч, Роджер. 2011. (Де)классификация языков аруначал: пересмотр доказательств. Архивировано 26 мая 2013 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ «50-й отчет комиссара по делам языковых меньшинств в Индии (июль 2012 г. - июнь 2013 г.)» (PDF) . Комиссар по делам языковых меньшинств Министерства по делам меньшинств правительства Индии. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 26 декабря 2014 года . Проверено 17 сентября 2016 г.

- ^ «C-17: Население в результате двуязычия и трехъязычия» . Веб-сайт переписи населения Индии .

- ^ «Веб-сайт переписи населения Индии: Управление генерального регистратора и комиссара по переписи населения Индии» . censusindia.gov.in .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Гуха, Рамачандра (10 февраля 2011 г.). «6. Идеи Индии (раздел IX)». Индия после Ганди: история крупнейшей демократии в мире . Пан Макмиллан. стр. 117–120. ISBN 978-0-330-54020-9 . Проверено 3 января 2015 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и «Конституция Индии от 29 июля 2008 г.» (PDF) . Конституция Индии . Министерство права и юстиции. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 21 июня 2014 года . Проверено 13 апреля 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Томас Бенедиктер (2009). Языковая политика и языковые меньшинства в Индии: оценка языковых прав меньшинств в Индии . ЛИТ Верлаг Мюнстер. стр. 32–35. ISBN 978-3-643-10231-7 . Проверено 19 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Закон об официальных языках 1963 года (с поправками)» (PDF) . Индийские железные дороги . 10 мая 1963 года . Проверено 3 января 2015 г.

- ^ «Глава 7 – Соответствие разделу 3 (3) Закона об официальных языках 1963 года» (PDF) . Отчет комитета парламента по государственному языку . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 20 февраля 2012 года.

- ^ «Сила слова» . Время . 19 февраля 1965 года. Архивировано из оригинала 14 октября 2007 года . Проверено 3 января 2015 г.

- ^ Форрестер, Дункан Б. (весна – лето 1966 г.), «Мадрасская агитация против хинди, 1965 г.: политический протест и его влияние на языковую политику в Индии», Pacific Relations , 39 (1/2): 19–36, doi : 10.2307/2755179 , АКБ 2755179

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и «Утверждение 1 – Резюме отчета о силе языков и родных языков говорящих – 2001 г.» . Правительство Индии. Архивировано из оригинала 14 октября 2013 года . Проверено 11 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Хинди (2005). Кейт Браун (ред.). Энциклопедия языка и лингвистики (2-е изд.). Эльзевир. ISBN 0-08-044299-4 .

- ^ «Депутаты Раджья Сабхи теперь могут говорить на любом из 22 запланированных языков в палате» . Проверено 24 июля 2018 г.

- ^ Карпентер, Юдит; Пайкосси, Каталин; Корнаи, Андраш (2017). «Цифровая жизнеспособность уральских языков» (PDF) . Acta Linguistica Academica . 64 (3): 327–345. дои : 10.1556/2062.2017.64.3.1 . S2CID 57699700 .

- ^ Джозеф, Ману (17 февраля 2011 г.). «Индия сталкивается с лингвистической правдой: здесь говорят по-английски» . Нью-Йорк Таймс .

- ^ С. Рукмини (14 мая 2019 г.). «Кто и где в Индии говорит по-английски?» . мята . Проверено 11 октября 2022 г.

- ^ Пратим Гохайн, Манаш (22 января 2018 г.). «58% сельских подростков умеют читать на базовом английском языке: опрос» . Таймс оф Индия . Проверено 11 октября 2022 г.

- ^ Сной, Юре. «20 карт Индии, объясняющих страну» . Зов путешествия . Архивировано из оригинала 17 августа 2017 года . Проверено 17 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ — «Что данные переписи населения говорят об использовании индийских языков» . Декан Вестник . Проверено 16 ноября 2023 г.

— «За десять лет на хинди появилось 100 миллионов говорящих; кашмирский второй быстрорастущий язык» . 28 июня 2018 года . Проверено 16 ноября 2023 г.

— «Хинди — самый быстрорастущий язык в Индии, на нем появилось 100 миллионов новых носителей» .

— «Хинди быстро рос в нехинди-государствах даже без официального мандата» . Индия сегодня . 11 апреля 2022 г. Проверено 16 ноября 2023 г. - ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Урду второй официальный язык в Андхра-Прадеше» . Деканская хроника . 24 марта 2022 г. Проверено 26 марта 2022 г.

- ^ Пандхарипанде, Раджешвари (2002), «Вопросы меньшинств: проблемы языков меньшинств в Индии» (PDF) , Международный журнал мультикультурных обществ , 4 (2): 3–4

- ^ «Языки» . APOnline . 2002. Архивировано из оригинала 8 февраля 2012 года . Проверено 25 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ «Закон об официальном языке Андхра-Прадеша, 1966 год» . Courtkutchehry.com . Проверено 23 июня 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б 52-й отчет Комиссара по делам языковых меньшинств (PDF) (Отчет). Министерство по делам меньшинств . п. 18. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 25 мая 2017 года . Проверено 15 февраля 2018 г.

- ^ «Закон об официальном языке Ассама 1960 года» . Код Индии . Законодательный департамент Министерства права и юстиции правительства Индии . Проверено 28 февраля 2024 г.

- ^ АНИ (10 сентября 2014 г.). «Правительство Ассама отменяет ассамский язык в качестве официального языка в долине Барак и восстанавливает бенгали» . ДНК Индии . Проверено 25 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Закон об официальном языке Бихара, 1950 г.» (PDF) . Национальная комиссия по делам языковых меньшинств. 29 ноября 1950 г. с. 31. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 8 июля 2016 года . Проверено 26 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ «Закон об официальном языке Чхаттисгарха (поправка) 2007 г.» (PDF) . Индийский код. 2008 год . Проверено 25 декабря 2022 г.

- ↑ Национальная комиссия по делам языковых меньшинств, 1950 г. (там же) не упоминает чхаттисгархи как дополнительный государственный язык, несмотря на уведомление правительства штата от 2007 г., предположительно потому, что чхаттисгархи считается диалектом хинди.

- ^ «Закон об официальном языке Гоа, Даман и Диу, 1987 г.» (PDF) . UT Администрация Дамана и Диу . 19 декабря 1987 года . Проверено 26 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час «Отчет комиссара по делам языковых меньшинств: 50-й отчет (июль 2012 г. – июнь 2013 г.)» (PDF) . Комиссар по делам языковых меньшинств Министерства по делам меньшинств правительства Индии. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 8 июля 2016 года . Проверено 26 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Курзон, Деннис (2004). «3. Споры Конкани-Маратхи: версия 2000-01 гг.» . «Там, где Восток смотрит на Запад: успех в английском языке в Гоа и на побережье Конкан» . Многоязычные вопросы. стр. 42–58. ISBN 978-1-85359-673-5 . Проверено 26 декабря 2014 г. Устарело, но дает хороший обзор разногласий по поводу придания маратхи полного «официального статуса».

- ^ Бенедиктер, Томас (2009). Языковая политика и языковые меньшинства в Индии: оценка языковых прав меньшинств в Индии . ЛИТ Верлаг Мюнстер. п. 89. ИСБН 978-3-643-10231-7 .

- ^ «Закон об официальном языке штата Харьяна 1969 года» . Код Индии . Законодательный департамент Министерства права и юстиции правительства Индии . Проверено 28 февраля 2024 г.

- ^ «Харьяна предоставляет панджаби статус второго языка» . Индостан Таймс . 28 января 2010 г. Архивировано из оригинала 3 сентября 2015 г.

- ^ «Закон об официальном языке штата Химачал-Прадеш, 1975 г.» . Код Индии . Законодательный департамент Министерства права и юстиции правительства Индии.