История театра

История театра отражает развитие театра за последние 2500 лет. Хотя перформативные элементы присутствуют в каждом обществе, принято признавать различие между театром как формой искусства и развлечения и театральными или перформативными элементами в других видах деятельности. История театра прежде всего связана с возникновением и последующим развитием театра как самостоятельной деятельности. Начиная с классических Афин в V веке до нашей эры, яркие традиции театра процветали в культурах по всему миру. [1]

Происхождение

[ редактировать ]Не существует убедительных доказательств того, что театр развился из ритуала, несмотря на сходство между исполнением ритуальных действий и театром и значимость этой связи. [2] Об этом сходстве раннего театра с ритуалом отрицательно свидетельствует Аристотель , который в своей «Поэтике» определил театр в отличие от представлений священных мистерий : театр не требовал от зрителя поститься, пить кикеон или маршировать в процессии; однако театр действительно напоминал священные мистерии в том смысле, что он приносил зрителю очищение и исцеление посредством видения, theama . Физическое место проведения таких представлений было соответственно названо театроном . [3]

According to the historians Oscar Brockett and Franklin Hildy, rituals typically include elements that entertain or give pleasure, such as costumes and masks as well as skilled performers. As societies grew more complex, these spectacular elements began to be acted out under non-ritualistic conditions. As this occurred, the first steps towards theatre as an autonomous activity were being taken.[4]

European theatre

[edit]Greek theatre

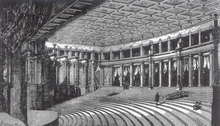

[edit]

Greek theatre, most developed in Athens, is the root of the Western tradition; theatre is a word of Greek origin.[2] It was part of a broader culture of theatricality and performance in classical Greece that included festivals, religious rituals, politics, law, athletics and gymnastics, music, poetry, weddings, funerals, and symposia.[6][a] Participation in the city-state's many festivals—and attendance at the City Dionysia as an audience member (or even as a participant in the theatrical productions) in particular—was an important part of citizenship.[7] Civic participation also involved the evaluation of the rhetoric of orators evidenced in performances in the law-court or political assembly, both of which were understood as analogous to the theatre and increasingly came to absorb its dramatic vocabulary.[8] The theatre of ancient Greece consisted of three types of drama: tragedy, comedy, and the satyr play.[9]

Athenian tragedy—the oldest surviving form of tragedy—is a type of dance-drama that formed an important part of the theatrical culture of the city-state.[10][b] Having emerged sometime during the 6th century BC, it flowered during the 5th century BC (from the end of which it began to spread throughout the Greek world) and continued to be popular until the beginning of the Hellenistic period.[11][c] No tragedies from the 6th century and only 32 of the more than a thousand that were performed in during the 5th century have survived.[12][d] We have complete texts extant by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides.[13][e] The origins of tragedy remain obscure, though by the 5th century it was institutionalised in competitions (agon) held as part of festivities celebrating Dionysos (the god of wine and fertility).[14] As contestants in the City Dionysia's competition (the most prestigious of the festivals to stage drama), playwrights were required to present a tetralogy of plays (though the individual works were not necessarily connected by story or theme), which usually consisted of three tragedies and one satyr play.[15][f] The performance of tragedies at the City Dionysia may have begun as early as 534 BC; official records (didaskaliai) begin from 501 BC, when the satyr play was introduced.[16] [g] Most Athenian tragedies dramatise events from Greek mythology, though The Persians—which stages the Persian response to news of their military defeat at the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC—is the notable exception in the surviving drama.[17][h] When Aeschylus won first prize for it at the City Dionysia in 472 BC, he had been writing tragedies for more than 25 years, yet its tragic treatment of recent history is the earliest example of drama to survive.[18] More than 130 years later, the philosopher Aristotle analysed 5th-century Athenian tragedy in the oldest surviving work of dramatic theory—his Poetics (c. 335 BC). Athenian comedy is conventionally divided into three periods, "Old Comedy", "Middle Comedy", and "New Comedy". Old Comedy survives today largely in the form of the eleven surviving plays of Aristophanes, while Middle Comedy is largely lost (preserved only in relatively short fragments in authors such as Athenaeus of Naucratis). New Comedy is known primarily from the substantial papyrus fragments of plays by Menander. Aristotle defined comedy as a representation of laughable people that involves some kind of error or ugliness that does not cause pain or destruction.[19]

Roman theatre

[edit]

Western theatre developed and expanded considerably under the Romans. The Roman historian Livy wrote that the Romans first experienced theatre in the 4th century BC, with a performance by Etruscan actors.[20] Beacham argues that Romans had been familiar with "pre-theatrical practices" for some time before that recorded contact.[21] The theatre of ancient Rome was a thriving and diverse art form, ranging from festival performances of street theatre, nude dancing, and acrobatics, to the staging of Plautus's broadly appealing situation comedies, to the high-style, verbally elaborate tragedies of Seneca. Although Rome had a native tradition of performance, the Hellenization of Roman culture in the 3rd century BC had a profound and energizing effect on Roman theatre and encouraged the development of Latin literature of the highest quality for the stage.

Following the expansion of the Roman Republic (509–27 BC) into several Greek territories between 270 and 240 BC, Rome encountered Greek drama.[22] From the later years of the republic and by means of the Roman Empire (27 BC-476 AD), theatre spread west across Europe, around the Mediterranean and reached England; Roman theatre was more varied, extensive and sophisticated than that of any culture before it.[23] While Greek drama continued to be performed throughout the Roman period, the year 240 BC marks the beginning of regular Roman drama.[22][i] From the beginning of the empire, however, interest in full-length drama declined in favour of a broader variety of theatrical entertainments.[24]

The first important works of Roman literature were the tragedies and comedies that Livius Andronicus wrote from 240 BC.[25] Five years later, Gnaeus Naevius also began to write drama.[25] No plays from either writer have survived. While both dramatists composed in both genres, Andronicus was most appreciated for his tragedies and Naevius for his comedies; their successors tended to specialise in one or the other, which led to a separation of the subsequent development of each type of drama.[25] By the beginning of the 2nd century BC, drama was firmly established in Rome and a guild of writers (collegium poetarum) had been formed.[26]

The Roman comedies that have survived are all fabula palliata (comedies based on Greek subjects) and come from two dramatists: Titus Maccius Plautus (Plautus) and Publius Terentius Afer (Terence).[27] In re-working the Greek originals, the Roman comic dramatists abolished the role of the chorus in dividing the drama into episodes and introduced musical accompaniment to its dialogue (between one-third of the dialogue in the comedies of Plautus and two-thirds in those of Terence).[28] The action of all scenes is set in the exterior location of a street and its complications often follow from eavesdropping.[28] Plautus, the more popular of the two, wrote between 205 and 184 BC and twenty of his comedies survive, of which his farces are best known; he was admired for the wit of his dialogue and his use of a variety of poetic meters.[29] All of the six comedies that Terence wrote between 166 and 160 BC have survived; the complexity of his plots, in which he often combined several Greek originals, was sometimes denounced, but his double-plots enabled a sophisticated presentation of contrasting human behaviour.[29]

No early Roman tragedy survives, though it was highly regarded in its day; historians know of three early tragedians—Quintus Ennius, Marcus Pacuvius and Lucius Accius.[28] From the time of the empire, the work of two tragedians survives—one is an unknown author, while the other is the Stoic philosopher Seneca.[30] Nine of Seneca's tragedies survive, all of which are fabula crepidata (tragedies adapted from Greek originals); his Phaedra, for example, was based on Euripides' Hippolytus.[31] Historians do not know who wrote the only extant example of the fabula praetexta (tragedies based on Roman subjects), Octavia, but in former times it was mistakenly attributed to Seneca due to his appearance as a character in the tragedy.[30]

In contrast to Ancient Greek theatre, the theatre in Ancient Rome did allow female performers. While the majority were employed for dancing and singing, a minority of actresses are known to have performed speaking roles, and there were actresses who achieved wealth, fame and recognition for their art, such as Eucharis, Dionysia, Galeria Copiola and Fabia Arete: they also formed their own acting guild, the Sociae Mimae, which was evidently quite wealthy.[32]

Transition and early medieval theatre, 500–1050

[edit]As the Western Roman Empire fell into decay through the 4th and 5th centuries, the seat of Roman power shifted to Constantinople and the Eastern Roman Empire, today called the Byzantine Empire. While surviving evidence about Byzantine theatre is slight, existing records show that miming, scenes or recitations from tragedies and comedies, dances, and other entertainments were very popular. Constantinople had two theatres that were in use as late as the 5th century.[33] However, the true importance of the Byzantines in theatrical history is their preservation of many classical Greek texts and the compilation of a massive encyclopedia called the Suda, from which is derived a large amount of contemporary information on Greek theatre.

From the 5th century, Western Europe was plunged into a period of general disorder that lasted (with a brief period of stability under the Carolingian Empire in the 9th century) until the 10th century. As such, most organized theatrical activities disappeared in Western Europe.[citation needed] While it seems that small nomadic bands travelled around Europe throughout the period, performing wherever they could find an audience, there is no evidence that they produced anything but crude scenes.[34] These performers were denounced by the Church during the Dark Ages as they were viewed as dangerous and pagan.

By the Early Middle Ages, churches in Europe began staging dramatized versions of particular biblical events on specific days of the year. These dramatizations were included in order to vivify annual celebrations.[35] Symbolic objects and actions – vestments, altars, censers, and pantomime performed by priests – recalled the events which Christian ritual celebrates. These were extensive sets of visual signs that could be used to communicate with a largely illiterate audience. These performances developed into liturgical dramas, the earliest of which is the Whom do you Seek (Quem-Quaeritis) Easter trope, dating from ca. 925.[35] Liturgical drama was sung responsively by two groups and did not involve actors impersonating characters. However, sometime between 965 and 975, Æthelwold of Winchester composed the Regularis Concordia (Monastic Agreement) which contains a playlet complete with directions for performance.[36]

Hrosvitha (c. 935 – 973), a canoness in northern Germany, wrote six plays modeled on Terence's comedies but using religious subjects. These six plays – Abraham, Callimachus, Dulcitius, Gallicanus, Paphnutius, and Sapientia – are the first known plays composed by a female dramatist and the first identifiable Western dramatic works of the post-classical era.[36] They were first published in 1501 and had considerable influence on religious and didactic plays of the sixteenth century. Hrosvitha was followed by Hildegard of Bingen (d. 1179), a Benedictine abbess, who wrote a Latin musical drama called Ordo Virtutum in 1155.

High and late medieval theatre, 1050–1500

[edit]

As the Viking invasions ceased in the middle of the 11th century, liturgical drama had spread from Russia to Scandinavia to Italy. Only in Muslim-occupied Iberian Peninsula were liturgical dramas not presented at all. Despite the large number of liturgical dramas that have survived from the period, many churches would have only performed one or two per year and a larger number never performed any at all.[37]

The Feast of Fools was especially important in the development of comedy. The festival inverted the status of the lesser clergy and allowed them to ridicule their superiors and the routine of church life. Sometimes plays were staged as part of the occasion and a certain amount of burlesque and comedy crept into these performances. Although comic episodes had to truly wait until the separation of drama from the liturgy, the Feast of Fools undoubtedly had a profound effect on the development of comedy in both religious and secular plays.[38]

Performance of religious plays outside of the church began sometime in the 12th century through a traditionally accepted process of merging shorter liturgical dramas into longer plays which were then translated into vernacular and performed by laymen. The Mystery of Adam (1150) gives credence to this theory as its detailed stage direction suggest that it was staged outdoors. A number of other plays from the period survive, including La Seinte Resurrection (Norman), The Play of the Magi Kings (Spanish), and Sponsus (French).

The importance of the High Middle Ages in the development of theatre was the economic and political changes that led to the formation of guilds and the growth of towns. This would lead to significant changes in the Late Middle Ages. In the British Isles, plays were produced in some 127 different towns during the Middle Ages. These vernacular Mystery plays were written in cycles of a large number of plays: York (48 plays), Chester (24), Wakefield (32) and Unknown (42). A larger number of plays survive from France and Germany in this period and some type of religious dramas were performed in nearly every European country in the Late Middle Ages. Many of these plays contained comedy, devils, villains and clowns.[39]

The majority of actors in these plays were drawn from the local population. For example, at Valenciennes in 1547, more than 100 roles were assigned to 72 actors.[40] Plays were staged on pageant wagon stages, which were platforms mounted on wheels used to move scenery. Often providing their own costumes, amateur performers in England were exclusively male, but other countries had female performers. The platform stage, which was an unidentified space and not a specific locale, allowed for abrupt changes in location.

Morality plays emerged as a distinct dramatic form around 1400 and flourished until 1550. The most interesting morality play[according to whom?] is The Castle of Perseverance which depicts mankind's progress from birth to death. However, the most famous morality play and perhaps best known medieval drama is Everyman. Everyman receives Death's summons, struggles to escape and finally resigns himself to necessity. Along the way, he is deserted by Kindred, Goods, and Fellowship – only Good Deeds goes with him to the grave.

There were also a number of secular performances staged in the Middle Ages, the earliest of which is The Play of the Greenwood by Adam de la Halle in 1276. It contains satirical scenes and folk material such as faeries and other supernatural occurrences. Farces also rose dramatically in popularity after the 13th century. The majority of these plays come from France and Germany and are similar in tone and form, emphasizing sex and bodily excretions.[41] The best known playwright of farces is Hans Sachs (1494–1576) who wrote 198 dramatic works. In England, The Second Shepherds' Play of the Wakefield Cycle is the best known early farce. However, farce did not appear independently in England until the 16th century with the work of John Heywood (1497–1580).

A significant forerunner of the development of Elizabethan drama was the Chambers of Rhetoric in the Low Countries.[42] These societies were concerned with poetry, music and drama and held contests to see which society could compose the best drama in relation to a question posed.

At the end of the Late Middle Ages, professional actors began to appear in England and Europe. Richard III and Henry VII both maintained small companies of professional actors. Their plays were performed in the Great Hall of a nobleman's residence, often with a raised platform at one end for the audience and a "screen" at the other for the actors. Also important were Mummers' plays, performed during the Christmas season, and court masques. These masques were especially popular during the reign of Henry VIII who had a House of Revels built and an Office of Revels established in 1545.[43]

The end of medieval drama came about due to a number of factors, including the weakening power of the Catholic Church, the Protestant Reformation and the banning of religious plays in many countries. Elizabeth I forbid all religious plays in 1558 and the great cycle plays had been silenced by the 1580s. Similarly, religious plays were banned in the Netherlands in 1539, the Papal States in 1547 and in Paris in 1548. The abandonment of these plays destroyed the international theatre that had thereto existed and forced each country to develop its own form of drama. It also allowed dramatists to turn to secular subjects and the reviving interest in Greek and Roman theatre provided them with the perfect opportunity.[43]

Italian Commedia dell'arte and Renaissance

[edit]

Commedia dell'arte (lit. 'comedy of the profession')[44] was an early form of professional theatre, originating from Italian theatre, that was popular throughout Europe between the 16th and 18th centuries.[45][46] It was formerly called "Italian comedy" in English and is also known as commedia alla maschera, commedia improvviso, and commedia dell'arte all'improvviso.[47] Characterized by masked "types", commedia was responsible for the rise of actresses such as Isabella Andreini[48] and improvised performances based on sketches or scenarios.[49][50] A commedia, such as The Tooth Puller, is both scripted and improvised.[49][51] Characters' entrances and exits are scripted. A special characteristic of commedia is the lazzo, a joke or "something foolish or witty", usually well known to the performers and to some extent a scripted routine.[51][52] Another characteristic of commedia is pantomime, which is mostly used by the character Arlecchino, now better known as Harlequin.[53]

The characters of the commedia usually represent fixed social types and stock characters, such as foolish old men, devious servants, or military officers full of false bravado.[49][54] The characters are exaggerated "real characters", such as a know-it-all doctor called Il Dottore, a greedy old man called Pantalone, or a perfect relationship like the Innamorati.[48] Many troupes were formed to perform commedia, including I Gelosi (which had actors such as Andreini and her husband Francesco Andreini),[55] Confidenti Troupe, Desioi Troupe, and Fedeli Troupe.[48][49] Commedia was often performed outside on platforms or in popular areas such as a piazza (town square).[47][49] The form of theatre originated in Italy, but travelled throughout Europe - sometimes to as far away as Moscow.[56]

The genesis of commedia may be related to carnival in Venice, where the author and actor Andrea Calmo had created the character Il Magnifico, the precursor to the vecchio (old man) Pantalone, by 1570. In the Flaminio Scala scenario, for example, Il Magnifico persists and is interchangeable with Pantalone into the 17th century. While Calmo's characters (which also included the Spanish Capitano and a dottore type) were not masked, it is uncertain at what point the characters donned the mask. However, the connection to carnival (the period between Epiphany and Ash Wednesday) would suggest that masking was a convention of carnival and was applied at some point. The tradition in Northern Italy is centred in Florence, Mantua, and Venice, where the major companies came under the protection of the various dukes. Concomitantly, a Neapolitan tradition emerged in the south and featured the prominent stage figure Pulcinella, which has been long associated with Naples and derived into various types elsewhere—most famously as the puppet character Punch (of the eponymous Punch and Judy shows) in England.

The commedia dell’arte allowed professional women to perform early on: Lucrezia Di Siena, whose name is on a contract of actors from 1564, has been referred to as the first Italian actress known by name, with Vincenza Armani and Barbara Flaminia as the first primadonna and the well-documented actresses in Europe.[57]

English Elizabethan theatre

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2011) |

English Renaissance theatre derived from several medieval theatre traditions, such as, the mystery plays that formed a part of religious festivals in England and other parts of Europe during the Middle Ages. Other sources include the "morality plays" and the "University drama" that attempted to recreate Athenian tragedy. The Italian tradition of Commedia dell'arte, as well as the elaborate masques frequently presented at court, also contributed to the shaping of public theatre.

Since before the reign of Elizabeth I, companies of players were attached to households of leading aristocrats and performed secular pieces seasonally in various locations.[58] These became the foundation for the professional players that performed on the Elizabethan stage. The tours of these players gradually replaced the performances of the mystery and morality plays by local players.[58] A 1572 law eliminated any unlicensed companies lacking formal patronage by labelling them vagabonds.[58]

The City of London authorities were generally hostile to public performances, but its hostility was overmatched by the Queen's taste for plays and the Privy Council's support.[59] Theatres sprang up in suburbs, especially in the liberty of Southwark, accessible across the Thames to city dwellers but beyond the authorities' control. The companies maintained the pretence that their public performances were mere rehearsals for the frequent performances before the Queen, but while the latter did grant prestige, the former were the real source of the income for the professional players.

Along with the economics of the profession, the character of the drama changed toward the end of the period. Under Elizabeth, the drama was a unified expression as far as social class was concerned: the Court watched the same plays the commoners saw in the public playhouses. With the development of the private theatres, drama became more oriented toward the tastes and values of an upper-class audience. By the later part of the reign of Charles I, few new plays were being written for the public theatres, which sustained themselves on the accumulated works of the previous decades.[60]

Puritan opposition to the stage (informed by the arguments of the early Church Fathers who had written screeds against the decadent and violent entertainments of the Romans) argued not only that the stage in general was pagan, but that any play that represented a religious figure was inherently idolatrous. In 1642, at the outbreak of the English Civil War, the Puritan authorities banned the performance of all plays within the city limits of London. A sweeping assault against the alleged immoralities of the theatre crushed whatever remained in England of the dramatic tradition.

Counter-Reformation theatre

[edit]If Protestantism was characterized by an ambivalent relationship to theatricality, Counter-Reformation Catholicism was to use it for explicitly affective and evangelical purposes.[61] The decorative innovations of baroque Catholic churches evolved symbiotically with the increasingly sophisticated art of scenography. Medieval theatrical traditions could be retained and developed in Catholic countries, wherever they were thought to be edifying. Sacre rappresentazioni in Italy, and Corpus Christi celebrations across Europe, are examples of this. Autos sacramentales, the one-act plays at the centre of Corpus Christi celebrations in Spain, gave concrete and triumphal realization to the abstractions of Catholic eucharistic theology, most famously in the hands of Pedro Calderón de la Barca. While the emphasis on predestination in Protestant theology had brought about a new appreciation of fatalism in classical drama, this could be counteracted. The very idea of tragicomedy was controversial because the genre was a post-classical development, but tragicomedies became a popular Counter-Reformation form because they were suited to demonstrating the benign workings of divine providence, and endorsing the concept of free will. Giovanni Battista Guarini’s Il pastor fido (The Faithful Shepherd, written 1580s, published 1602) was the most influential tragicomedy of the period, while Tirso de Molina is especially notable for ingeniously subverting the implications of his tragic plots by means of comic endings. A similar theologically motivated overturning of generic expectation lies behind tragœdiæ sacræ such as Francesco Sforza Pallavicino’s Ermenegildo.[61] This type of sacred tragedy developed from medieval dramatizations of saints’ lives; in them, martyr-protagonists die in a manner both tragic and triumphant. Enhancing Counter-Reformation Catholicism's encouragement of martyr cults, such plays could celebrate contemporary figures like Sir Thomas More — hero of several dramas across Europe — or be used to foment nationalistic sentiment.[61]

Spanish Golden age theatre

[edit]

During its Golden Age, roughly from 1590 to 1681,[62] Spain saw a monumental increase in the production of live theatre as well as in the importance of theatre within Spanish society. It was an accessible art form for all participants in Renaissance Spain, being both highly sponsored by the aristocratic class and highly attended by the lower classes.[63] The volume and variety of Spanish plays during the Golden Age was unprecedented in the history of world theatre, surpassing, for example, the dramatic production of the English Renaissance by a factor of at least four.[62][63][64] Although this volume has been as much a source of criticism as praise for Spanish Golden Age theatre, for emphasizing quantity before quality,[65] a large number of the 10,000[63] to 30,000[65] plays of this period are still considered masterpieces.[66][67]

Major artists of the period included Lope de Vega, a contemporary of Shakespeare, often, and contemporaneously, seen his parallel for the Spanish stage,[68] and Calderon de la Barca, inventor of the zarzuela[69] and Lope's successor as the preeminent Spanish dramatist.[70] Gil Vicente, Lope de Rueda, and Juan del Encina helped to establish the foundations of Spanish theatre in the mid-sixteenth centuries,[71][72][73] while Francisco de Rojas Zorrilla and Tirso de Molina made significant contributions in the latter half of the Golden Age.[74][75] Important performers included Lope de Rueda (previously mentioned among the playwrights) and later Juan Rana.[76][77]

The sources of influence for the emerging national theatre of Spain were as diverse as the theatre that nation ended up producing. Storytelling traditions originating in Italian Commedia dell'arte[78] and the uniquely Spanish expression of Western Europe's traveling minstrel entertainments[79][80] contributed a populist influence on the narratives and the music, respectively, of early Spanish theatre. Neo-Aristotelian criticism and liturgical dramas, on the other hand, contributed literary and moralistic perspectives.[81][82] In turn, Spanish Golden Age theatre has dramatically influenced the theatre of later generations in Europe and throughout the world. Spanish drama had an immediate and significant impact on the contemporary developments in English Renaissance theatre.[66] It has also had a lasting impact on theatre throughout the Spanish speaking world.[83] Additionally, a growing number of works are being translated, increasing the reach of Spanish Golden Age theatre and strengthening its reputation among critics and theatre patrons.[84]

French Classical theatre

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2024) |

Notable playwrights:

- Pierre Corneille (1606–84)

- Molière (1622–73)

- Jean Racine (1639–99)

Cretan Renaissance theatre

[edit]Greek theater was alive and flourishing on the island of Crete. During the Cretan Renaissance two notable Greek playwrights Georgios Chortatzis and Vitsentzos Kornaros were present in the latter part of the 16th century.[85][86]

Restoration comedy

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2011) |

After public stage performances had been banned for 18 years by the Puritan regime, the re-opening of the theatres in 1660 signalled a renaissance of English drama. With the restoration of the monarch in 1660 came the restoration of and the reopening of the theatre. English comedies written and performed in the Restoration period from 1660 to 1710 are collectively called "Restoration comedy". Restoration comedy is notorious for its sexual explicitness, a quality encouraged by Charles II (1660–1685) personally and by the rakish aristocratic ethos of his court. For the first time women were allowed to act, putting an end to the practice of the boy-player taking the parts of women. Socially diverse audiences included both aristocrats, their servants and hangers-on, and a substantial middle-class segment. Restoration audiences liked to see good triumph in their tragedies and rightful government restored. In comedy they liked to see the love-lives of the young and fashionable, with a central couple bringing their courtship to a successful conclusion (often overcoming the opposition of the elders to do so). Heroines had to be chaste, but were independent-minded and outspoken; now that they were played by women, there was more mileage for the playwright in disguising them in men's clothes or giving them narrow escape from rape. These playgoers were attracted to the comedies by up-to-the-minute topical writing, by crowded and bustling plots, by the introduction of the first professional actresses, and by the rise of the first celebrity actors. To non-theatre-goers these comedies were widely seen as licentious and morally suspect, holding up the antics of a small, privileged, and decadent class for admiration. This same class dominated the audiences of the Restoration theatre. This period saw the first professional woman playwright, Aphra Behn.

As a reaction to the decadence of Charles II era productions, sentimental comedy grew in popularity. This genre focused on encouraging virtuous behavior by showing middle class characters overcoming a series of moral trials. Playwrights like Colley Cibber and Richard Steele believed that humans were inherently good but capable of being led astray. Through plays such as The Conscious Lovers and Love's Last Shift they strove to appeal to an audience's noble sentiments in order that viewers could be reformed.[87][88]

Restoration spectacular

[edit]The Restoration spectacular, or elaborately staged "machine play", hit the London public stage in the late 17th-century Restoration period, enthralling audiences with action, music, dance, moveable scenery, baroque illusionistic painting, gorgeous costumes, and special effects such as trapdoor tricks, "flying" actors, and fireworks. These shows have always had a bad reputation as a vulgar and commercial threat to the witty, "legitimate" Restoration drama; however, they drew Londoners in unprecedented numbers and left them dazzled and delighted.

Basically home-grown and with roots in the early 17th-century court masque, though never ashamed of borrowing ideas and stage technology from French opera, the spectaculars are sometimes called "English opera". However, the variety of them is so untidy that most theatre historians despair of defining them as a genre at all.[89] Only a handful of works of this period are usually accorded the term "opera", as the musical dimension of most of them is subordinate to the visual. It was spectacle and scenery that drew in the crowds, as shown by many comments in the diary of the theatre-lover Samuel Pepys.[90] The expense of mounting ever more elaborate scenic productions drove the two competing theatre companies into a dangerous spiral of huge expenditure and correspondingly huge losses or profits. A fiasco such as John Dryden's Albion and Albanius would leave a company in serious debt, while blockbusters like Thomas Shadwell's Psyche or Dryden's King Arthur would put it comfortably in the black for a long time.[91]

Neoclassical theatre

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2011) |

Neoclassicism was the dominant form of theatre in the 18th century. It demanded decorum and rigorous adherence to the classical unities. Neoclassical theatre as well as the time period is characterized by its grandiosity. The costumes and scenery were intricate and elaborate. The acting is characterized by large gestures and melodrama. Neoclassical theatre encompasses the Restoration, Augustan, and Johnstinian Ages. In one sense, the neo-classical age directly follows the time of the Renaissance.

Theatres of the early 18th century – sexual farces of the Restoration were superseded by politically satirical comedies, 1737 Parliament passed the Stage Licensing Act 1737 which introduced state censorship of public performances and limited the number of theatres in London to two.

Nineteenth-century theatre

[edit]Theatre in the 19th century is divided into two parts: early and late. The early period was dominated by melodrama and Romanticism.

Beginning in France, melodrama became the most popular theatrical form. August von Kotzebue's Misanthropy and Repentance (1789) is often considered the first melodramatic play. The plays of Kotzebue and René Charles Guilbert de Pixérécourt established melodrama as the dominant dramatic form of the early 19th century.[92]

In Germany, there was a trend toward historical accuracy in costumes and settings, a revolution in theatre architecture, and the introduction of the theatrical form of German Romanticism. Influenced by trends in 19th-century philosophy and the visual arts, German writers were increasingly fascinated with their Teutonic past and had a growing sense of nationalism. The plays of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, and other Sturm und Drang playwrights inspired a growing faith in feeling and instinct as guides to moral behavior.

In Britain, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron were the most important dramatists of their time although Shelley's plays were not performed until later in the century. In the minor theatres, burletta and melodrama were the most popular. Kotzebue's plays were translated into English and Thomas Holcroft's A Tale of Mystery was the first of many English melodramas. Pierce Egan, Douglas William Jerrold, Edward Fitzball, and John Baldwin Buckstone initiated a trend towards more contemporary and rural stories in preference to the usual historical or fantastical melodramas. James Sheridan Knowles and Edward Bulwer-Lytton established a "gentlemanly" drama that began to re-establish the former prestige of the theatre with the aristocracy.[93]

The later period of the 19th century saw the rise of two conflicting types of drama: realism and non-realism, such as Symbolism and precursors of Expressionism.

Realism began earlier in the 19th century in Russia than elsewhere in Europe and took a more uncompromising form.[94] Beginning with the plays of Ivan Turgenev (who used "domestic detail to reveal inner turmoil"), Aleksandr Ostrovsky (who was Russia's first professional playwright), Aleksey Pisemsky (whose A Bitter Fate (1859) anticipated Naturalism), and Leo Tolstoy (whose The Power of Darkness (1886) is "one of the most effective of naturalistic plays"), a tradition of psychological realism in Russia culminated with the establishment of the Moscow Art Theatre by Konstantin Stanislavski and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko.[95]

The most important theatrical force in later 19th-century Germany was that of Georg II, Duke of Saxe-Meiningen and his Meiningen Ensemble, under the direction of Ludwig Chronegk. The Ensemble's productions are often considered the most historically accurate of the 19th century, although his primary goal was to serve the interests of the playwright. The Meiningen Ensemble stands at the beginning of the new movement toward unified production (or what Richard Wagner would call the Gesamtkunstwerk) and the rise of the director (at the expense of the actor) as the dominant artist in theatre-making.[96]

Naturalism, a theatrical movement born out of Charles Darwin's The Origin of Species (1859) and contemporary political and economic conditions, found its main proponent in Émile Zola. The realisation of Zola's ideas was hindered by a lack of capable dramatists writing naturalist drama. André Antoine emerged in the 1880s with his Théâtre Libre that was only open to members and therefore was exempt from censorship. He quickly won the approval of Zola and began to stage Naturalistic works and other foreign realistic pieces.[97]

In Britain, melodramas, light comedies, operas, Shakespeare and classic English drama, Victorian burlesque, pantomimes, translations of French farces and, from the 1860s, French operettas, continued to be popular. So successful were the comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan, such as H.M.S. Pinafore (1878) and The Mikado (1885), that they greatly expanded the audience for musical theatre.[98] This, together with much improved street lighting and transportation in London and New York led to a late Victorian and Edwardian theatre building boom in the West End and on Broadway. Later, the work of Henry Arthur Jones and Arthur Wing Pinero initiated a new direction on the English stage.

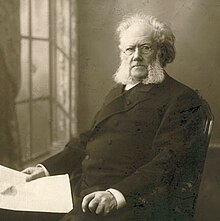

While their work paved the way, the development of more significant drama owes itself most to the playwright Henrik Ibsen. Ibsen was born in Norway in 1828. He wrote twenty-five plays, the most famous of which are A Doll's House (1879), Ghosts (1881), The Wild Duck (1884), and Hedda Gabler (1890). In addition, his works Rosmersholm (1886) and When We Dead Awaken (1899) evoke a sense of mysterious forces at work in human destiny, which was to be a major theme of symbolism and the so-called "Theatre of the Absurd".[citation needed]

After Ibsen, British theatre experienced revitalization with the work of George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, John Galsworthy, William Butler Yeats, and Harley Granville Barker. Unlike most of the gloomy and intensely serious work of their contemporaries, Shaw and Wilde wrote primarily in the comic form. Edwardian musical comedies were extremely popular, appealing to the tastes of the middle class in the Gay Nineties[99] and catering to the public's preference for escapist entertainment during World War 1.

Twentieth-century theatre

[edit]While much 20th-century theatre continued and extended the projects of realism and Naturalism, there was also a great deal of experimental theatre that rejected those conventions. These experiments form part of the modernist and postmodernist movements and included forms of political theatre as well as more aesthetically orientated work. Examples include: Epic theatre, the Theatre of Cruelty, and the so-called "Theatre of the Absurd".

The term theatre practitioner came to be used to describe someone who both creates theatrical performances and who produces a theoretical discourse that informs their practical work.[100] A theatre practitioner may be a director, a dramatist, an actor, or—characteristically—often a combination of these traditionally separate roles. "Theatre practice" describes the collective work that various theatre practitioners do.[101] It is used to describe theatre praxis from Konstantin Stanislavski's development of his 'system', through Vsevolod Meyerhold's biomechanics, Bertolt Brecht's epic and Jerzy Grotowski's poor theatre, down to the present day, with contemporary theatre practitioners including Augusto Boal with his Theatre of the Oppressed, Dario Fo's popular theatre, Eugenio Barba's theatre anthropology and Anne Bogart's viewpoints.[102]

Other key figures of 20th-century theatre include: Antonin Artaud, August Strindberg, Anton Chekhov, Max Reinhardt, Frank Wedekind, Maurice Maeterlinck, Federico García Lorca, Eugene O'Neill, Luigi Pirandello, George Bernard Shaw, Gertrude Stein, Ernst Toller, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams, Jean Genet, Eugène Ionesco, Samuel Beckett, Harold Pinter, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Heiner Müller, and Caryl Churchill.

A number of aesthetic movements continued or emerged in the 20th century, including:

- Naturalism

- Realism

- Dadaism

- Expressionism

- Surrealism and the Theatre of Cruelty

- Theatre of the Absurd

- Postmodernism

- Agitprop

After the great popularity of the British Edwardian musical comedies, the American musical theatre came to dominate the musical stage, beginning with the Princess Theatre musicals, followed by the works of the Gershwin brothers, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, Rodgers and Hart, and later Rodgers and Hammerstein.

American theatre

[edit]1752 to 1895 Romanticism

[edit]Throughout most of history, English belles lettres and theatre have been separated, but these two art forms are interconnected.[103] However, if they do not learn how to work hand-in-hand, it can be detrimental to the art form.[104] The prose of English literature and the stories it tells needs to be performed and theatre has that capacity.[105] From the start American theatre has been unique and diverse, reflecting society as America chased after its National identity.[106] The very first play performed, in 1752 in Williamsburg Virginia, was Shakespeare's "The Merchant of Venice."[107] Due to a temporary Puritan society, theatre was banned from 1774 until 1789.[108] This societal standard was due to the Puritan morality being permitted and any other entertainment were seen as inappropriate, frivolous (without purpose), and sensual (pleasurable).[109] During the ban, theatre often hid by titling itself as moral lectures.[110] Theatre took a brief pause because of the revolutionary war, but quickly resumed after the war ended in 1781.[108] Theatre began to spread west, and often towns had theatres before they had sidewalks or sewers.[111] There were several leading professional theatre companies early on, but one of the most influential was in Philadelphia (1794–1815); however, the company had shaky roots because of the ban on theatre.[108]

As the country expanded so did theatre; following the war of 1812 theatre headed west.[108] Many of the new theatres were community run, but in New Orleans a professional theatre had been started by the French in 1791.[108] Several troupes broke off and established a theatre in Cincinnati, Ohio.[108] The first official west theatre came in 1815 when Samuel Drake (1769–1854) took his professional theatre company from Albany to Pittsburgh to the Ohio River and Kentucky.[108] Along with this circuit he would sometimes take the troupe to Lexington, Louisville, and Frankfort.[108] At times, he would lead the troupe to Ohio, Indiana, Tennessee, and Missouri.[108] While there were circuit riding troupes, more permanent theatre communities out west often sat on rivers so there would be easy boat access.[108] During this time period very few theatres were above the Ohio River, and in fact Chicago did not have a permanent theatre until 1833.[108] Because of the turbulent times in America and the economic crisis happening due to wars, theatre during its most expansive time, experienced bankruptcy and change of management.[108] Also most early American theatre had great European influence because many of the actors had been English born and trained.[108] Between 1800 and 1850 neoclassical philosophy almost completely passed away under romanticism which was a great influence of 19th century American theatre that idolized the "noble savage."[108] Due to new psychological discoveries and acting methods, eventually romanticism would give birth to realism.[108] This trend toward realism occurred between 1870 and 1895.[108]

1895 to 1945 Realism

[edit]In this era of theatre, the moral hero shifts to the modern man who is a product of his environment.[112] This major shift is due in part to the civil war because America was now stained with its own blood, having lost its innocence.[113]

1945 to 1990

[edit]During this period of theatre, Hollywood emerged and threatened American theatre.[114] However theatre during this time didn't decline but in fact was renowned and noticed worldwide.[114] Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller achieved worldwide fame during this period.

African theatre

[edit]Egyptian theatre

[edit]Ancient Egyptian quasi-theatrical events

[edit]The earliest recorded quasi-theatrical event dates back to 2000 BC with the "passion plays" of Ancient Egypt. The story of the god Osiris was performed annually at festivals throughout the civilization.[115]

Modern Egyptian theater

[edit]In the modern era, the art of theater was evolved in the second half of the nineteenth century through interaction with Europe. As well as the development of popular theatrical forms that Egypt knew thousands of years before this date.[116][117][118]

The beginning was by Yaqub Sanu and Abu Khalil Qabbani, then the situation was divided into free theatrical groups, including the Youssef Wahbi troupe such as Fatima Rushdi, which presents tragedy or tragedy, and Abo El Seoud El Ebiary, Ismail Yassine, Badie' Khayri, Ali El Kassar and Naguib El-Rihani in presenting comedy in another way.[119][120][121]

More than 350 plays were presented in the so-called halls theater in the 1930s and 1940s, co-presented by Bayram El-Tunisi, Amin Sedky, Badie' Khayri and Abo El Seoud El Ebiary and directed by Aziz Eid, Bishara Wakim and Abdel Aziz Khalil. In addition to important statistics, including that the longest-lived private sector group is the Rihani band. Its activity lasted 67 years, starting from 1916 until 1983, nearly seventy years. The most prolific private sector group is the Ramses Troupe, which produced more than 240 plays from 1923 to 1960. The longest-lived state theater troupe is the National Theater Troupe, which lasted for over 80 years, starting from 1935 until now.[122][123]

After the 1952 revolution, there was a group of playwrights such as Alfred Farag, and Ali Salem, Noaman Ashour, Saad Eddin Wahba and others. Zaki, as for the country teams, the most prolific directors in production are the artists Fattouh Nashati, and Zaki Tulaimat.[124]

Among the Egyptian playwrights whose works were presented on stage are Amin Sedky, Badi’ Khairy, Abu Al-Saud Al-Ebiary, and Tawfiq Al-Hakim. Most of the world's playwrights whose works were presented on the stage are Molière, Pierre Corneille and William Shakespeare.[125][126]

The women's imprint was clear in the history of Egyptian theater, which Mounira El Mahdeya started as the first Egyptian singer and actress, and the founder of a theater group in her name at the beginning of the twentieth century instead of Levantines and Jews. Before that time, women were forbidden to act, which caused a noise that contributed to the increase in her fame. And Mounira El Mahdeya was also the one who discovered the musician of the generations, Mohammed Abdel Wahab, and gave him the opportunity to complete the melodies of Cleopatra and Mark Antony's play after the sudden death of Sayed Darwish. She encouraged him to stand in front of her, embodying the role of Mark Antonio in the same show. Starting from early 1960s, movie stars started invading theaters such as Salah Zulfikar in A Bullet in the Heart of 1964, based on Tawfiq Al-Hakim's 1933 novel, and many others. In the 1970s, the comedy was the dominant such as Al Ayal Kibrit of 1979.

In 2020, the Egyptian Minister of Culture, Dr. Ines Abdel-Dayem dedicates the next session of the National Festival of Egyptian Theater to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the beginning of the modern Egyptian theater. It will review the findings of the research team, consisting of Amr Dawara, the theater memory guard, who started since 1993 to prepare the largest Egyptian theater encyclopedia that includes all the details of professional theatrical performances during fifteen decades, starting from 1870 by Yacub Sanu until 2019, during which the number of performances reached 6300 professional works, which were presented to the public for a fee at the box office. And addressed the book body to print the encyclopedia. And that encyclopedia will help the reader and researcher to know the masterpieces and creations of Egyptian theater throughout its history.[127][128][122]

West African theatre

[edit]Ghanaian theatre

[edit]Modern theatre in Ghana emerged in the early 20th century.[129]It emerged first as literary comment on the colonization of Africa by Europe.[129] Among the earliest work in which this can be seen is The Blinkards written by Kobina Sekyi in 1915. The Blinkards is a blatant satire about the Africans who embraced the European culture that was brought to them. In it Sekyi demeans three groups of individuals: anyone European, anyone who imitates the Europeans, and the rich African cocoa farmer. This sudden rebellion though was just the beginning spark of Ghanaian literary theatre.[129]

A play that has similarity in its satirical view is Anowa. Written by Ghanaian author Ama Ata Aidoo, it begins with its eponymous heroine Anowa rejecting her many arranged suitors' marriage proposals. She insists on making her own decisions as to whom she is going to marry. The play stresses the need for gender equality, and respect for women.[129] This ideal of independence, as well as equality leads Anowa down a winding path of both happiness and misery. Anowa chooses a man of her own to marry. Anowa supports her husband Kofi both physically and emotionally. Through her support Kofi does prosper in wealth, but becomes poor as a spiritual being. Through his accumulation of wealth Kofi loses himself in it. His once happy marriage with Anowa becomes changed when he begins to hire slaves rather than doing any labor himself. This to Anowa does not make sense because it makes Kofi no better than the European colonists whom she detests for the way that she feels they have used the people of Africa. Their marriage is childless, which is presumed to have been caused by a ritual that Kofi has done trading his manhood for wealth. Anowa's viewing Kofi's slave-gotten wealth and inability to have a child leads to her committing suicide.[129] The name Anowa means "Superior moral force" while Kofi's means only "Born on Friday". This difference in even the basis of their names seems to implicate the moral superiority of women in a male run society.[129]

Another play of significance is The Marriage of Anansewa, written in 1975 by Efua Sutherland. The entire play is based upon an Akan oral tradition called Anansesem (folk tales). The main character of the play is Ananse (the spider). The qualities of Ananse are one of the most prevalent parts of the play. Ananse is cunning, selfish, has great insight into human and animal nature, is ambitious, eloquent, and resourceful. By putting too much of himself into everything that he does Ananse ruins each of his schemes and ends up poor.[129] Ananse is used in the play as a kind of Everyman. He is written in an exaggerated sense in order to force the process of self-examination. Ananse is used as a way to spark a conversation for change in the society of anyone reading. The play tells of Ananse attempting to marry off his daughter Anansewa off to any of a selection of rich chiefs, or another sort of wealthy suitor simultaneously, in order to raise money. Eventually all the suitors come to his house at once, and he has to use all of his cunning to defuse the situation.[129] The storyteller not only narrates but also enacts, reacts to, and comments on the action of the tale. Along with this, Mbuguous is used, Mbuguous is the name given to very specialized sect of Ghanaian theatre technique that allows for audience participation. The Mbuguous of this tale are songs that embellish the tale or comment on it. Spontaneity through this technique as well as improvisation are used enough to meet any standard of modern theatre.[129]

Yoruba theatre

[edit]In his pioneering study of Yoruba theatre, Joel Adedeji traced its origins to the masquerade of the Egungun (the "cult of the ancestor").[130] The traditional ceremony culminates in the essence of the masquerade where it is deemed that ancestors return to the world of the living to visit their descendants.[131] In addition to its origin in ritual, Yoruba theatre can be "traced to the 'theatrogenic' nature of a number of the deities in the Yoruba pantheon, such as Obatala the arch divinity, Ogun the divinity of creativeness, as well as Iron and technology,[132] and Sango the divinity of the storm", whose reverence is imbued "with drama and theatre and the symbolic overall relevance in terms of its relative interpretation."[133]

The Aláàrìnjó theatrical tradition sprang from the Egungun masquerade in the 16th century. The Aláàrìnjó was a troupe of traveling performers whose masked forms carried an air of mystique. They created short, satirical scenes that drew on a number of established stereotypical characters. Their performances utilised mime, music and acrobatics. The Aláàrìnjó tradition influenced the popular traveling theatre, which was the most prevalent and highly developed form of theatre in Nigeria from the 1950s to the 1980s. In the 1990s, the popular traveling theatre moved into television and film and now gives live performances only rarely.[134][135]

"Total theatre" also developed in Nigeria in the 1950s. It utilised non-Naturalistic techniques, surrealistic physical imagery, and exercised a flexible use of language. Playwrights writing in the mid-1970s made use of some of these techniques, but articulated them with "a radical appreciation of the problems of society."[136]

Traditional performance modes have strongly influenced the major figures in contemporary Nigerian theatre. The work of Hubert Ogunde (sometimes referred to as the "father of contemporary Yoruban theatre") was informed by the Aláàrìnjó tradition and Egungun masquerades.[137] Wole Soyinka, who is "generally recognized as Africa's greatest living playwright", gives the divinity Ogun a complex metaphysical significance in his work.[138] In his essay "The Fourth Stage" (1973),[139] Soyinka contrasts Yoruba drama with classical Athenian drama, relating both to the 19th-century German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche's analysis of the latter in The Birth of Tragedy (1872). Ogun, he argues, is "a totality of the Dionysian, Apollonian and Promethean virtues."[140]

The proponents of the travelling theatre in Nigeria include Duro Ladipo and Moses Olaiya (a popular comic act). These practitioners contributed much to the field of African theatre during the period of mixture and experimentation of the indigenous with the Western theatre.

African Diaspora theatre

[edit]African-American theatre

[edit]The history of African-American theatre has a dual origin. The first is rooted in local theatre where African Americans performed in cabins and parks. Their performances (folk tales, songs, music, and dance) were rooted in the African culture before being influenced by the American environment. African Grove Theatre was the first African-American theatre established in 1821 by William Henry Brown.[141]

Азиатский театр

[ редактировать ]

Индийский театр

[ редактировать ]Обзор индийского театра

[ редактировать ]Самой ранней формой индийского театра был санскритский театр . [142] Он возник где-то между 15 веком до нашей эры и 1 веком и процветал между 1 и 10 веками, что было периодом относительного мира в истории Индии, во время которого были написаны сотни пьес. [143] Ведические тексты, такие как Ригведа, свидетельствуют о драматических спектаклях, разыгрываемых во время Яджны церемоний . Диалоги, упомянутые в текстах, варьируются от монолога одного человека до диалога трех человек, например, диалог между Индрой, Индрани и Вришакапи. Диалоги не только религиозные по своему контексту, но и светские, например, один ригведический монолог посвящен игроку, чья жизнь из-за этого разрушена и который отдалил свою жену, а его родители также ненавидят его. Панини в V веке до нашей эры упоминает драматический текст «Натасутра», написанный двумя индийскими драматургами Шилалином и Кришашвой. Патанджали также упоминает названия утраченных пьес, таких как «Кемсавадха» и «Балибандха». Пещеры Ситабенга, построенные в III веке до нашей эры, и пещеры Кхандагири, построенные во II веке до нашей эры, являются самыми ранними примерами театральной архитектуры в Индии. [144] С исламскими завоеваниями , начавшимися в 10 и 11 веках, театр был обескуражен или полностью запрещен. [145] Позже, в попытке восстановить ценности и идеи коренных народов, деревенский театр получил распространение по всему субконтиненту, развиваясь на большом количестве региональных языков с 15 по 19 века. [146] Современный индийский театр развивался в период колониального правления Британской империи , с середины 19 века до середины 20 века. [147]

Санскритский театр

[ редактировать ]Самые ранние сохранившиеся фрагменты санскритской драмы датируются I веком. [148] Богатство археологических свидетельств более ранних периодов не дает никаких указаний на существование театральной традиции. [149] Веды ( самая ранняя индийская литература, датируемая 1500–600 гг. до н. э.) не содержат ни малейшего намека на это; хотя небольшое количество гимнов составлено в форме диалога, ритуалы ведического периода, похоже , не переросли в театр. [149] « Махабхашья» содержит Патанджали самое раннее упоминание о том, что, возможно, было зародышем санскритской драмы. [150] Этот трактат по грамматике, датируемый 140 г. до н.э., указывает вероятную дату возникновения театра в Индии . [150]

Однако, хотя до этой даты не сохранилось никаких фрагментов какой-либо драмы, вполне возможно, что ранняя буддийская литература представляет собой самое раннее свидетельство существования индийского театра. Палийские . сутты (датированные с V по III века до н.э.) относятся к существованию трупп актеров (во главе с главным актером), которые разыгрывали драмы на сцене Указывается, что эти драмы включали танец, но были указаны как отдельная форма представления наряду с танцами, пением и декламацией рассказов. [151] (Согласно более поздним буддийским текстам, король Бимбисара , современник Гаутамы Будды , разыграл драму для другого царя. Это было уже в V веке до нашей эры, но это событие описано только в гораздо более поздних текстах, начиная с III-го века. IV век нашей эры.) [152]

Основным источником свидетельств существования санскритского театра является «Трактат о театре» ( Натьяшастра ), сборник, дата составления которого неизвестна (по оценкам, от 200 г. до н.э. до 200 г. н.э.) и чье авторство приписывается Бхарате Муни . « Трактат» — наиболее полное произведение драматургии древнего мира. В нем рассматриваются актерское мастерство , танец , музыка , драматическое построение , архитектура , костюмы , грим , реквизит , организация трупп, публика, конкурсы, а также предлагается мифологическое объяснение происхождения театра. [150] При этом он дает представление о природе реальных театральных практик. Санскритский театр исполнялся на священной земле священниками, которые были обучены необходимым навыкам (танцу, музыке и декламации) в [наследственном процессе]. Его цель заключалась как в обучении, так и в развлечении.

Под покровительством королевских дворов исполнители принадлежали профессиональным труппам, которыми руководил постановщик ( сутрадхара ), который, возможно, также выступал. [153] Эту задачу считали аналогичной задаче кукольника — буквальное значение слова « сутрадхара » — «держатель веревочек или нитей». [150] Исполнители прошли тщательную подготовку вокальной и физической технике. [154] Никаких запретов в отношении исполнительниц не было; компании были полностью мужскими, полностью женскими и смешанного пола. Однако некоторые чувства считались неприемлемыми для проявления мужчинами и считались более подходящими для женщин. Некоторые исполнители играли персонажей своего возраста, другие — персонажей, отличных от них (младших или старше). Из всех элементов театра в «Трактате» больше всего внимания уделяется актерскому мастерству ( абхиная ), которое состоит из двух стилей: реалистического ( локадхарми ) и традиционного ( натьядхарми ), хотя основное внимание уделяется последнему. [155]

Его драматургия считается высшим достижением санскритской литературы . [156] В нем использовались стандартные персонажи , такие как герой ( наяка ), героиня ( найика ) или клоун ( видусака ). Актеры могут специализироваться на определенном типе. Калидаса, живший в I веке до нашей эры, возможно, считается древней Индии величайшим санскритским драматургом . Три знаменитые романтические пьесы, написанные Калидасом, — это « Малавикагнимитрам» ( «Малавика и Агнимитра» ), «Викрамуурвашиия» ( «Относящийся к Викраме и Урваши» ) и «Абхиджнянашакунтала» ( «Признание Шакунталы» ). Последний был вдохновлен историей из Махабхараты и является самым известным. Это был первый перевод на английский и немецкий языки . Сакунтала (в английском переводе) оказала влияние на Гете « Фауста» (1808–1832). [156]

Следующим великим индийским драматургом был Бхавабхути (ок. VII в.). Говорят, что он написал следующие три пьесы: «Малати-Мадхава» , «Махавирачарита» и «Уттар Рамачарита» . Среди этих трех последние два охватывают весь эпос Рамаяны . Могущественному индийскому императору Харше (606–648) приписывают написание трёх пьес: комедии «Ратнавали» , «Приядаршика» и буддийской драмы «Нагананда» .

Традиционный индийский театр

[ редактировать ]Кутияттам — единственный сохранившийся образец древнего санскритского театра, который, как полагают, возник примерно в начале нашей эры , и официально признан ЮНЕСКО шедевром устного и нематериального наследия человечества . Кроме того, существует множество форм индийского народного театра. Бхаваи (бродячие актеры) — популярная форма народного театра Гуджарата , возникшая, как говорят, в 14 веке нашей эры. Бхаона и Анкия Натс практикуют в Ассаме с начала 16 века, они были созданы и инициированы Махапурушой Шримантой Санкардевой . Джатра была популярна в Бенгалии , и ее происхождение восходит к движению Бхакти в 16 веке. Другая форма народного театра, популярная в Харьяне , Уттар-Прадеше и малва регионе Мадхья-Прадеша, — это сванг , который ориентирован скорее на диалог, чем на движение, и считается, что он возник в своей нынешней форме в конце 18 — начале 19 веков. Якшагана — очень популярное театральное искусство в Карнатаке, существующее под разными названиями, по крайней мере, с 16 века. Он носит полуклассический характер и включает в себя музыку и песни, основанные на Карнатическая музыка , богатые костюмы, сюжетные линии, основанные на Махабхарате и Рамаяне . Между песнями в нем также используются устные диалоги, что придает ему оттенок народного искусства . Катхакали форма танцевальной драмы, — характерная для Кералы возникшая в 17 веке, развивающаяся на основе пьес храмового искусства «Кришнанаттам» и «Раманаттам» .

Катхакали

[ редактировать ]Катхакали - это сильно стилизованная классическая индийская танцевальная драма, известная привлекательным макияжем персонажей, тщательно продуманными костюмами, детальными жестами и четко выраженными движениями тела, представленными в гармонии с основной воспроизводимой музыкой и дополнительной перкуссией. Он возник в современном штате Керала в 17 веке. [157] и с годами развивался с улучшенным внешним видом, утонченными жестами и добавлением тем, помимо более богатого пения и точной игры на барабанах.

Современный индийский театр

[ редактировать ]Рабиндранат Тагор был новаторским современным драматургом, написавшим пьесы, известные своим исследованием и сомнением в вопросах национализма, идентичности, спиритуализма и материальной жадности. [158] Его пьесы написаны на бенгали и включают «Читру» ( Читрангада , 1892), «Король темной палаты» ( Раджа , 1910), «Почтовое отделение» ( Дакгар , 1913) и «Красный олеандр» ( Рактакараби , 1924). [158]

Другим драматургом-новатором бенгальского театра , заслуженно ставшим преемником Рабиндраната Тагора , был Натьягуру Нурул Момен . В то время как его предшественник Тагор положил начало модернизму в бенгальской литературе XIX века; Нурул Момен держал переданную им эстафету модернизма и поднял ее на высоту театра мирового класса 20-го века через свои дебютные пьесы «Рупантар» и «Немезида» (спектакль «Момен») .

Китайский театр

[ редактировать ]Этот раздел нуждается в дополнительных цитатах для проверки . ( Апрель 2011 г. ) |

Шан театр

[ редактировать ]Есть упоминания о театральных развлечениях в Китае уже в 1500 г. до н.э. во времена династии Шан ; они часто включали музыку, клоунаду и акробатические представления.

Театр Хан и Тан

[ редактировать ]Во времена династии Хань театр теней впервые стал признанной формой театра в Китае. Существовали две различные формы теневого кукольного театра: южный кантонский и северный пекинесский. Эти два стиля различались методом изготовления марионеток и расположением стержней на марионетках, а не типом игры, которую играли марионетки. Оба стиля обычно ставили пьесы, изображающие великие приключения и фэнтези, и эта очень стилизованная форма театра редко использовалась для политической пропаганды. Кантонские теневые куклы были более крупными из двух. Они были сделаны из толстой кожи, которая создавала более существенные тени. Символический цвет также был очень распространен; черное лицо олицетворяло честность, красное — храбрость. Стержни, используемые для управления кантонскими марионетками, были прикреплены перпендикулярно их головам. Таким образом, зрители не видели их, когда создавалась тень. Пекинесы были более тонкими и маленькими. Их делали из тонкой полупрозрачной кожи, обычно снимаемой с брюха осла. Они были нарисованы яркими красками, поэтому отбрасывали очень красочную тень. Тонкие стержни, управлявшие их движениями, были прикреплены к кожаному ошейнику на шее куклы. Стержни шли параллельно телу марионетки, а затем поворачивались под углом девяносто градусов и соединялись с шеей. Хотя эти стержни были видны, когда отбрасывалась тень, они лежали вне тени марионетки; таким образом, они не мешали внешнему виду фигуры. Стержни прикреплены к шеям для облегчения использования нескольких головок с одним телом. Когда головы не использовались, их хранили в муслиновой книге или коробке на тканевой подкладке. Головы всегда снимали ночью. Это соответствовало старому суеверию, согласно которому, если оставить марионеток нетронутыми, они оживут ночью. Некоторые кукловоды заходили так далеко, что хранили головы в одной книге, а тела — в другой, чтобы еще больше снизить вероятность реанимации марионеток. Говорят, что теневой кукольный театр достиг высшей точки художественного развития в 11 веке, прежде чем стал инструментом правительства.

Династию Тан иногда называют «Эпохой 1000 развлечений». В это время император Сюаньцзун основал актерскую школу, известную как «Дети грушевого сада», чтобы создавать драматические формы, которые были в первую очередь музыкальными.

Театр Сун и Юань

[ редактировать ]Во времена династии Сун было много популярных пьес с акробатикой и музыкой. они приобрели Во времена династии Юань более сложную форму с четырех- или пятиактной структурой.

Юаньская драма распространилась по Китаю и разделилась на многочисленные региональные формы, самой известной из которых является Пекинская опера, популярная и сегодня.

Индонезийский театр

[ редактировать ]

Индонезийский театр стал важной частью местной культуры, театральные постановки в Индонезии развивались уже сотни лет. Большинство старых театральных форм Индонезии напрямую связаны с местными литературными традициями (устными и письменными). Известные кукольные театры — ваянг голек (кукольный спектакль с деревянным стержнем) на суданском языке и ваянг кулит (спектакль с кожаными тенями) на яванском и балийском языках — черпают большую часть своего репертуара из местных версий Рамаяны и Махабхараты . Эти сказки также служат исходным материалом для ваянг вонга (человеческого театра) на Яве и Бали , в котором используются актеры. Ваянг вонг — это разновидность классического яванского танцевального театрального представления, темы которого взяты из эпизодов Рамаяны или Махабхараты. Барельефные панели храма Прамбанан IX века изображают эпизоды эпоса Рамаяна. Адаптация эпизодов Махабхараты была интегрирована в яванскую литературную традицию со времен Кахурипана и Кедири, с такими яркими примерами, как Арджунавиваха , сочиненная Мпу Канвой в 11 веке. Храм Пенатаран на Восточной Яве изображает на своих барельефах темы Рамаяны и Махабхараты. Ваянг вонг представлял собой спектакль в стиле ваянг кулит (театр теней Центральной Явы), в котором роли марионеток исполняли актеры и актрисы. Первое письменное упоминание об этой форме содержится в каменной надписи Вималарама из Восточной Явы, датированной 930 годом нашей эры. В настоящее время этот жанр существует в замаскированных и немаскированных вариациях на Центральной Яве , Бали и Чиребоне , а также на сунданском языке ( Западная Ява ). [159] [160] [161]

Кхмерский театр

[ редактировать ]В Камбодже , в древней столице Ангкор-Ват сюжеты из индийского эпоса Рамаяна и Махабхарата , на стенах храмов и дворцов вырезаны .

Тайский театр

[ редактировать ]В Таиланде со времен Средневековья существует традиция ставить спектакли по сюжетам индийского эпоса. В частности, в Таиланде и сегодня остается популярной театральная версия национального эпоса Таиланда «Рамакиен» , версия индийской «Рамаяны» .

Филиппинский театр

[ редактировать ]В течение 333-летнего правления испанского правительства они привнесли на острова католическую религию и испанский образ жизни, которые постепенно слились с местной культурой, сформировав «равнинную народную культуру», которую сейчас разделяют основные этнолингвистические группы. Сегодня драматические формы, привнесенные Испанией или находящиеся под ее влиянием, продолжают жить в сельских районах по всему архипелагу. К этим формам относятся комедия, пьесы, синакуло, сарсвела и драма. В последние годы некоторые из этих форм были обновлены, чтобы сделать их более чувствительными к условиям и потребностям развивающейся страны.

Японский театр

[ редактировать ]Хорошо

[ редактировать ]В XIV веке в Японии были небольшие труппы актеров, которые исполняли короткие, иногда вульгарные комедии. У директора одной из этих трупп, Канами (1333–1384), был сын Дзеами Мотокиё (1363–1443), который считался одним из лучших детей-актеров Японии. Когда труппа Канами выступала перед Асикага Ёсимицу (1358–1408), сёгуном Японии, он умолял Дзеами получить придворное образование в области искусств. После того, как Зеами стал преемником своего отца, он продолжил выступать и адаптировать свой стиль к тому, что сегодня называется Но . Смесь пантомимы и вокальной акробатики, этот стиль очаровывал японцев на протяжении сотен лет.

Бунраку

[ редактировать ]Япония после длительного периода гражданских войн и политического беспорядка обрела единство и мир, прежде всего благодаря сёгуну Токугава Иэясу (1543–1616). Однако, встревоженный ростом христианства, он прервал контакты Японии с Европой и Китаем и объявил христианство вне закона. Когда мир действительно наступил, расцвет культурного влияния и рост торгового класса потребовали собственных развлечений. Первой процветающей формой театра был Нингё дзёрури (обычно называемый Бунраку ). Основатель и главный участник Нингё дзёрури Чикамацу Мондзаэмон (1653–1725) превратил свой театр в настоящую форму искусства. Нингё дзёрури — это сильно стилизованная форма театра с использованием кукол, которые сегодня составляют примерно 1/3 размера человека. Мужчины, которые управляют марионетками, всю свою жизнь тренируются, чтобы стать искусными кукловодами, а затем смогут управлять головой и правой рукой марионетки и решать показывать свои лица во время представления. Остальные кукловоды, контролирующие менее важные конечности марионетки, закрывают себя и лица черным костюмом, чтобы подчеркнуть свою невидимость. Диалоги ведет один человек, который использует разные тона голоса и манеры речи, чтобы имитировать разных персонажей. За свою карьеру Чикамацу написал тысячи пьес, большинство из которых используются до сих пор. Вместо тщательно продуманного макияжа они носили маски. Маски определяют пол, личность и настроение актера.

Кабуки

[ редактировать ]Кабуки зародился вскоре после Бунраку, легенда гласит, что его положила актриса по имени Окуни, жившая примерно в конце 16 века. Большая часть материала Кабуки взята из Но и Бунраку, и его беспорядочные танцевальные движения также являются результатом Бунраку. Однако Кабуки менее формален и более отстранен, чем Но, но при этом очень популярен среди японской публики. Актеров обучают множеству разнообразных вещей, включая танцы, пение, пантомиму и даже акробатику. Кабуки сначала исполняли молодые девушки, затем мальчики, а к концу XVI века труппы Кабуки состояли только из мужчин. Мужчины, изображавшие женщин на сцене, были специально обучены выявлять женскую сущность в своих тонких движениях и жестах.

Буто

[ редактировать ]

Буто — это собирательное название для разнообразных видов деятельности, техник и мотиваций для танцев, представлений или движений, вдохновленных движением Анкоку-Буто ( 暗黒 舞踏 , анкоку буто ) . Обычно он включает в себя игривые и гротескные образы, табуированные темы, экстремальную или абсурдную обстановку и традиционно исполняется в белом гриме с медленными гиперконтролируемыми движениями, с аудиторией или без нее. Не существует определенного стиля, и он может быть чисто концептуальным, без какого-либо движения. Его происхождение приписывают легендам японского танца Тацуми Хиджиката и Кадзуо Оно . Буто впервые появился в Японии после Второй мировой войны и особенно после студенческих беспорядков . Роли власти теперь подвергались сомнению и подрывной деятельности. Это также появилось как реакция на сцену современного танца в Японии, которая, по мнению Хиджиката, была основана, с одной стороны, на подражании Западу, а с другой - на подражании Но . Он раскритиковал нынешнее состояние танца как чрезмерно поверхностное.

Турецкий театр

[ редактировать ]Первые упоминания о театральных постановках в Османской империи связаны с появлением там испанских евреев в конце пятнадцатого – шестнадцатого веков. Позже в эту сферу включились и другие меньшинства, такие как цыгане, греки и армяне. Впоследствии турецкий аналог комедии дель арте - Орта оюну стал очень популярен по всей Империи. [162]

Персидский театр

[ редактировать ]Средневековый исламский театр

[ редактировать ]Самыми популярными формами театра в средневековом исламском мире были кукольный театр (который включал ручные куклы , пьесы теней и постановки марионеток ) и живые страстные пьесы, известные как тазия , в которых актеры воспроизводят эпизоды из мусульманской истории . В частности, шиитские исламские пьесы вращались вокруг шахида (мученичества) Али сыновей Хасана ибн Али и Хусейна ибн Али . Светские пьесы, известные как ахраджа, были записаны в средневековой адабской литературе, хотя они были менее распространены, чем кукольный театр и театр тазия . [163]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Антитеатральность

- Кембриджская история британского театра

- Развитие музыкального театра

- История искусства

- История танца

- История фигурного катания

- История фильма

- История литературы

- История оперы

- История профессионального рестлинга

- История телевидения

- Игра (театр)

- Радио драма

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ↑ Голдхилл утверждает, что, хотя действия, которые составляют «неотъемлемую часть осуществления гражданства» (например, когда «афинский гражданин выступает в Ассамблее, занимается в гимназии, поет на симпозиуме или ухаживает за мальчиком»), каждая из них имеет свои «собственный режим проявления и регулирования», тем не менее, термин «производительность» обеспечивает «полезную эвристическую категорию для изучения связей и совпадений между этими различными областями деятельности» (1999, 1).

- ↑ Таксиду говорит, что «большинство учёных теперь называют «греческую» трагедию «афинской» трагедией, что исторически верно» (2004, 104).

- ↑ Картледж пишет, что, хотя афиняне IV века считали Эсхила , Софокла и Еврипида «непревзойденными представителями жанра и регулярно удостаивали их пьес возрождением, трагедия сама по себе не была просто феноменом V века, продуктом короткометражного романа». пережили золотой век , хотя и не достигли качества и высоты «классики» пятого века, оригинальные трагедии, тем не менее, продолжали писаться, создаваться и конкурировать с ними в больших количествах на протяжении всего оставшегося существования демократии — и за ее пределами» (1997, 33).

- ^ У нас есть семь Эсхила , семь Софокла и восемнадцать Еврипида . Кроме того, у нас также есть « Циклоп» , сатирская пьеса Еврипида. Некоторые критики, начиная с 17 века, утверждали, что одна из трагедий, которую классическая традиция называет трагедией Еврипида, — «Резус» — представляет собой пьесу неизвестного автора IV века; современная наука соглашается с классическими авторитетами и приписывает пьесу Еврипиду; см. Уолтон (1997, viii, xix). (Эта неопределенность объясняет цифру Брокетта и Хильди — 31 трагедию, а не 32.)