Hillary Clinton

Hillary Clinton | |

|---|---|

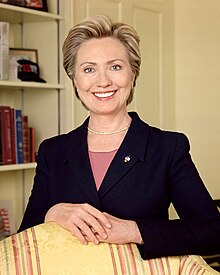

Клинтон в 2016 году | |

| 67-й государственный секретарь США | |

| In office 21 января 2009 г. - 1 февраля 2013 г. | |

| President | Barack Obama |

| Deputy | |

| Preceded by | Condoleezza Rice |

| Succeeded by | John Kerry |

| United States Senator from New York | |

| In office January 3, 2001 – January 21, 2009 | |

| Preceded by | Daniel Patrick Moynihan |

| Succeeded by | Kirsten Gillibrand |

| First Lady of the United States | |

| In role January 20, 1993 – January 20, 2001 | |

| President | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Barbara Bush |

| Succeeded by | Laura Bush |

| First Lady of Arkansas | |

| In role January 11, 1983 – December 12, 1992 | |

| Governor | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Gay Daniels White |

| Succeeded by | Betty Tucker |

| In role January 9, 1979 – January 19, 1981 | |

| Governor | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Barbara Pryor |

| Succeeded by | Gay Daniels White |

| 11th Chancellor of Queen's University Belfast | |

| Assumed office January 2, 2020 | |

| President | Ian Greer |

| Preceded by | Thomas J. Moran |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hillary Diane Rodham October 26, 1947 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic (1968–present) |

| Other political affiliations | Republican (1965–1968) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Chelsea Clinton |

| Parents | |

| Relatives | Clinton family |

| Residences |

|

| Education | Wellesley College (BA) Yale University (JD) |

| Awards | List of honors and awards |

| Signature | |

| Website | hillaryclinton |

Хиллари Дайан Родэм Клинтон ( урожденная Родэм ; родилась 26 октября 1947 года) — американский политик и дипломат, занимавшая должность 67-го государственного секретаря США в администрации Барака Обамы с 2009 по 2013 год, а также сенатора США, представляющего Нью-Йорк с 2001 года. до 2009 года, а также в качестве первой леди США при бывшем президенте Билле Клинтоне с 1993 по 2001. Член Демократической партии , она была кандидатом от партии на президентских выборах 2016 года , став первой женщиной, выигравшей выдвижение в президенты от крупной политической партии США, и первой женщиной, выигравшей всенародное голосование за президента США. На сегодняшний день она единственная первая леди Соединенных Штатов, баллотировавшаяся на выборную должность.

Raised in Park Ridge, Illinois, Rodham graduated from Wellesley College in 1969 and from Yale Law School in 1973. After serving as a congressional legal counsel, she moved to Arkansas and, in 1975, married Bill Clinton, whom she had met at Yale. In 1977, Clinton co-founded Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families. She was appointed the first female chair of the Legal Services Corporation in 1978 and became the first woman partner at Little Rock's Rose Law Firm the following year. The National Law Journal twice listed her as one of the hundred most influential lawyers in America. Clinton was the first lady of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and again from 1983 to 1992. As the first lady of the U.S., Clinton advocated for healthcare reform. In 1994, her health care plan failed to gain approval from Congress. In 1997 and 1999, Clinton played a leading role in promoting the creation of the State Children's Health Insurance Program, the Adoption and Safe Families Act, and the Foster Care Independence Act. Она также выступала за гендерное равенство на Всемирной конференции по положению женщин 1995 года . В 1998 году супружеские отношения Клинтон оказались под пристальным вниманием общественности во время скандала с Левински , который побудил ее сделать заявление, в котором подтвердила свою приверженность браку.

Clinton was first elected to the U.S. Senate in 2000, becoming the first female senator from New York and the first First Lady to simultaneously hold elected office. As a senator, she chaired the Senate Democratic Steering and Outreach Committee from 2003 to 2007. She advocated for medical benefits for September 11 first responders.[1] She supported the resolution authorizing the Iraq War in 2002, but opposed the surge of U.S. troops in 2007. Clinton ran for president in 2008, but lost to Barack Obama in the Democratic primaries. After resigning from the Senate to become Obama's secretary of state in 2009, she established the Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review. She responded to the Arab Spring by advocating the 2011 military intervention in Libya, but was harshly criticized by Republicans for the failure to prevent or adequately respond to the 2012 Benghazi attack. Clinton helped to organize a diplomatic isolation and a regime of international sanctions against Iran in an effort to force it to curtail its nuclear program, which eventually led to the multinational Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action in 2015. The strategic pivot to Asia was a central aspect of her tenure, underscoring the strategic shift in U.S. foreign policy focus from the Middle East and Europe towards Asia. She had a key role in launching the United States Global Health Initiative, which aimed to increase U.S. investment in global public health, including combating HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. Her use of a private email server as secretary was the subject of intense scrutiny; while no charges were filed against Clinton, the email controversy was the single most covered topic during the 2016 presidential election.

Clinton made a second presidential run in 2016, winning the Democratic nomination, but losing the general election to Republican opponent Donald Trump in the Electoral College, despite winning the popular vote. Following her loss, she wrote multiple books and launched Onward Together, a political action organization dedicated to fundraising for progressive political groups.

In 2011, Clinton was appointed the Honorary Founding Chair of the Institute for Women, Peace and Security at Georgetown University, and the awards named in her name has been awarded annually at the university. Since 2020, she has served as the chancellor of the Queen's University Belfast. In 2023, Clinton joined Columbia University as a Professor of Practice at the School of International and Public Affairs.

Early life and education

Early life

Hillary Diane Rodham[2] was born on October 26, 1947, at Edgewater Hospital in Chicago, Illinois.[3][4] She was raised in a Methodist family who first lived in Chicago. When she was three years old, her family moved to the Chicago suburb of Park Ridge.[5] Her father, Hugh Rodham, was of English and Welsh descent,[6] and managed a small but successful textile business, which he had founded.[7] Her mother, Dorothy Howell, was a homemaker of Dutch, English, French Canadian (from Quebec), Scottish, and Welsh descent.[6][8][9] She has two younger brothers, Hugh and Tony.[10]

As a child, Rodham was a favorite student among her teachers at the public schools she attended in Park Ridge.[11] She participated in swimming and softball and earned numerous badges as a Brownie and a Girl Scout.[11] She was inspired by U.S. efforts during the Space Race and sent a letter to NASA around 1961 asking what she could do to become an astronaut, only to be informed that women were not being accepted into the program.[12] She attended Maine South High School,[13][14] where she participated in the student council and school newspaper and was selected for the National Honor Society.[3][15] She was elected class vice president for her junior year but then lost the election for class president for her senior year against two boys, one of whom told her that "you are really stupid if you think a girl can be elected president".[16] For her senior year, she and other students were transferred to the then-new Maine South High School. There she was a National Merit Finalist and was voted "most likely to succeed." She graduated in 1965 in the top five percent of her class.[17]

Rodham's mother wanted her to have an independent, professional career.[9] Her father, who was otherwise a traditionalist, felt that his daughter's abilities and opportunities should not be limited by gender.[18] She was raised in a politically conservative household,[9] and she helped canvass Chicago's South Side at age 13 after the very close 1960 U.S. presidential election. She stated that, while investigating with a fellow teenage friend shortly after the election, she saw evidence of electoral fraud (a voting list entry showing a dozen addresses that was an empty lot) against Republican candidate Richard Nixon;[19] she later volunteered to campaign for Republican candidate Barry Goldwater in the 1964 election.[20]

Rodham's early political development was shaped mostly by her high school history teacher (like her father, a fervent anti-communist), who introduced her to Goldwater's The Conscience of a Conservative and by her Methodist youth minister (like her mother, concerned with issues of social justice), with whom she saw and afterwards briefly met civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. at a 1962 speech in Chicago's Orchestra Hall.[21]

Wellesley College years

In 1965, Rodham enrolled at Wellesley College, where she majored in political science.[22][23] During her first year, she was president of the Wellesley Young Republicans.[24][25] As the leader of this "Rockefeller Republican"-oriented group,[26] she supported the elections of moderate Republicans John Lindsay to mayor of New York City and Massachusetts attorney general Edward Brooke to the United States Senate.[27] She later stepped down from this position. In 2003, Clinton would write that her views concerning the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War were changing in her early college years.[24] In a letter to her youth minister at that time, she described herself as "a mind conservative and a heart liberal".[28] In contrast to the factions in the 1960s that advocated radical actions against the political system, she sought to work for change within it.[29][30]

By her junior year, Rodham became a supporter of the antiwar presidential nomination campaign of Democrat Eugene McCarthy.[31] In early 1968, she was elected president of the Wellesley College Government Association, a position she held until early 1969.[29][32] Following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Rodham organized a two-day student strike and worked with Wellesley's black students to recruit more black students and faculty.[31] In her student government role, she played a role in keeping Wellesley from being embroiled in the student disruptions common to other colleges.[29][33] A number of her fellow students thought she might some day become the first female president of the United States.[29]

To help her better understand her changing political views, Professor Alan Schechter assigned Rodham to intern at the House Republican Conference, and she attended the "Wellesley in Washington" summer program.[31] Rodham was invited by moderate New York Republican representative Charles Goodell to help Governor Nelson Rockefeller's late-entry campaign for the Republican nomination.[31] Rodham attended the 1968 Republican National Convention in Miami Beach. However, she was upset by the way Richard Nixon's campaign portrayed Rockefeller and by what she perceived as the convention's "veiled" racist messages, and she left the Republican Party for good.[31] Rodham wrote her senior thesis, a critique of the tactics of radical community organizer Saul Alinsky, under Professor Schechter.[34] Years later, while she was the first lady, access to her thesis was restricted at the request of the White House and it became the subject of some speculation. The thesis was later released.[34]

In 1969, she graduated with a Bachelor of Arts,[35] with departmental honors in political science.[34] After some fellow seniors requested that the college administration allow a student speaker at commencement, she became the first student in Wellesley College history to speak at the event. Her address followed that of the commencement speaker, Senator Edward Brooke.[32][36] After her speech, she received a standing ovation that lasted seven minutes.[29][37][38] She was featured in an article published in Life magazine,[39][40] because of the response to a part of her speech that criticized Senator Brooke.[36] She also appeared on Irv Kupcinet's nationally syndicated television talk show as well as in Illinois and New England newspapers.[41] She was asked to speak at the 50th anniversary convention of the League of Women Voters in Washington, D.C., the next year.[42] That summer, she worked her way across Alaska, washing dishes in Mount McKinley National Park and sliming salmon in a fish processing cannery in Valdez (which fired her and shut down overnight when she complained about unhealthy conditions).[43]

Yale Law School and postgraduate studies

Rodham then entered Yale Law School, where she was on the editorial board of the Yale Review of Law and Social Action.[44] During her second year, she worked at the Yale Child Study Center,[45] learning about new research on early childhood brain development and working as a research assistant on the seminal work, Beyond the Best Interests of the Child (1973).[46][47] She also took on cases of child abuse at Yale–New Haven Hospital,[46] and volunteered at New Haven Legal Services to provide free legal advice for the poor.[45] In the summer of 1970, she was awarded a grant to work at Marian Wright Edelman's Washington Research Project, where she was assigned to Senator Walter Mondale's Subcommittee on Migratory Labor. There she researched various migrant workers' issues including education, health and housing.[48] Edelman later became a significant mentor.[49] Rodham was recruited by political advisor Anne Wexler to work on the 1970 campaign of Connecticut U.S. Senate candidate Joseph Duffey. Rodham later crediting Wexler with providing her first job in politics.[50]

In the spring of 1971, she began dating fellow law student Bill Clinton. During the summer, she interned at the Oakland, California, law firm of Treuhaft, Walker and Burnstein. The firm was well known for its support of constitutional rights, civil liberties and radical causes (two of its four partners were current or former Communist Party members);[51] Rodham worked on child custody and other cases.[a] Clinton canceled his original summer plans and moved to live with her in California;[55] the couple continued living together in New Haven when they returned to law school.[52] The following summer, Rodham and Clinton campaigned in Texas for unsuccessful 1972 Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern.[56] She received a Juris Doctor degree from Yale in 1973,[35] having stayed on an extra year to be with Clinton.[57] He first proposed marriage to her following graduation, but she declined, uncertain if she wanted to tie her future to his.[57]

Rodham began a year of postgraduate study on children and medicine at the Yale Child Study Center.[58] In late 1973, her first scholarly article, "Children Under the Law", was published in the Harvard Educational Review.[59] Discussing the new children's rights movement, the article stated that "child citizens" were "powerless individuals"[60] and argued that children should not be considered equally incompetent from birth to attaining legal age, but instead that courts should presume competence on a case-by-case basis, except when there is evidence otherwise.[61] The article became frequently cited in the field.[62]

Marriage, family, legal career and first ladyship of Arkansas

From the East Coast to Arkansas

During her postgraduate studies, Rodham was staff attorney for Edelman's newly founded Children's Defense Fund in Cambridge, Massachusetts,[63] and as a consultant to the Carnegie Council on Children.[64] In 1974, she was a member of the impeachment inquiry staff in Washington, D.C., and advised the House Committee on the Judiciary during the Watergate scandal.[65] The committee's work culminated with the resignation of President Richard Nixon in August 1974.[65]

By then, Rodham was viewed as someone with a bright political future. Democratic political organizer and consultant Betsey Wright moved from Texas to Washington the previous year to help guide Rodham's career.[66] Wright thought Rodham had the potential to become a future senator or president.[67] Meanwhile, boyfriend Bill Clinton had repeatedly asked Rodham to marry him, but she continued to demur.[68] After failing the District of Columbia bar exam[69] and passing the Arkansas exam, Rodham came to a key decision. As she later wrote, "I chose to follow my heart instead of my head".[70] She thus followed Clinton to Arkansas, rather than staying in Washington, where career prospects were brighter. He was then teaching law and running for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in his home state. In August 1974, Rodham moved to Fayetteville, Arkansas, and became one of only two female faculty members at the University of Arkansas School of Law in Fayetteville, Arkansas.[71][72]

Early Arkansas years

Rodham became the first director of a new legal aid clinic at the University of Arkansas School of Law.[74] During her time in Fayetteville, Rodham and several other women founded the city's first rape crisis center.[74]

In 1974, Bill Clinton lost an Arkansas congressional race, facing incumbent Republican John Paul Hammerschmidt.[75] Rodham and Bill Clinton bought a house in Fayetteville in the summer of 1975 and she agreed to marry him.[76] The wedding took place on October 11, 1975, in a Methodist ceremony in their living room.[77] A story about the marriage in the Arkansas Gazette indicated that she decided to retain the name Hillary Rodham.[77][78] Her motivation was threefold. She wanted to keep the couple's professional lives separate, avoid apparent conflicts of interest, and as she told a friend at the time, "it showed that I was still me".[79] The decision upset both mothers, who were more traditional.[80]

In 1976, Rodham temporarily relocated to Indianapolis to work as an Indiana state campaign organizer for the presidential campaign of Jimmy Carter.[81][82] In November 1976, Bill Clinton was elected Arkansas attorney general, and the couple moved to the state capital of Little Rock.[75] In February 1977, Rodham joined the venerable Rose Law Firm, a bastion of Arkansan political and economic influence.[83] She specialized in patent infringement and intellectual property law[44] while working pro bono in child advocacy.[84] In 1977, Rodham cofounded Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families, a state-level alliance with the Children's Defense Fund.[44][85]

Later in 1977, President Jimmy Carter (for whom Rodham had been the 1976 campaign director of field operations in Indiana)[86] appointed her to the board of directors of the Legal Services Corporation.[87] She held that position from 1978 until the end of 1981.[88] From mid-1978 to mid-1980,[b] she served as the first female chair of that board.[89]

Following her husband's November 1978 election as governor of Arkansas, Rodham became that state's first lady in January 1979. She would hold that title for twelve nonconsecutive years (1979–1981, 1983–1992). Clinton appointed his wife to be the chair of the Rural Health Advisory Committee the same year,[90] in which role she secured federal funds to expand medical facilities in Arkansas's poorest areas without affecting doctors' fees.[91]

In 1979, Rodham became the first woman to be made a full partner in Rose Law Firm.[92] From 1978 until they entered the White House, she had a higher salary than her husband.[93] During 1978 and 1979, while looking to supplement their income, Rodham engaged in the trading of cattle futures contracts;[94] an initial $1,000 investment generated nearly $100,000 when she stopped trading after ten months.[95] At this time, the couple began their ill-fated investment in the Whitewater Development Corporation real estate venture with Jim and Susan McDougal.[94] Both of these became subjects of controversy in the 1990s.[citation needed]

On February 27, 1980, Rodham gave birth to the couple's only child, a daughter whom they named Chelsea. In November 1980, Bill Clinton was defeated in his bid for re-election.[96]

Later Arkansas years

Two years after leaving office, Bill Clinton returned to the governorship of Arkansas after winning the election of 1982. During her husband's campaign, Hillary began to use the name "Hillary Clinton", or sometimes "Mrs. Bill Clinton", to assuage the concerns of Arkansas voters; she also took a leave of absence from Rose Law to campaign for him full-time.[97] During her second stint as the first lady of Arkansas, she made a point of using Hillary Rodham Clinton as her name.[c]

Clinton became involved in state education policy. She was named chair of the Arkansas Education Standards Committee in 1983, where worked to reform the state's public education system.[103][104] In one of the Clinton governorship's most important initiatives, she fought a prolonged but ultimately successful battle against the Arkansas Education Association to establish mandatory teacher testing and state standards for curriculum and classroom size.[90][103] In 1985, she introduced Arkansas's Home Instruction Program for Preschool Youth, a program that helps parents work with their children in preschool preparedness and literacy.[105]

Clinton continued to practice law with the Rose Law Firm while she was the first lady of Arkansas.[106][107] The firm considered her a "rainmaker" because she brought in clients, partly thanks to the prestige she lent it and to her corporate board connections. She was also very influential in the appointment of state judges.[107] Bill Clinton's Republican opponent in his 1986 gubernatorial reelection campaign accused the Clintons of conflict of interest because Rose Law did state business; the Clintons countered the charge by saying that state fees were walled off by the firm before her profits were calculated.[108] Clinton was twice named by The National Law Journal as one of the 100 most influential lawyers in America—in 1988 and 1991.[109] When Bill Clinton thought about not running again for governor in 1990, Hillary Clinton considered running. Private polls were unfavorable, however, and in the end he ran and was reelected for the final time.[110]

From 1982 to 1988, Clinton was on the board of directors, sometimes as chair, of the New World Foundation,[111] which funded a variety of New Left interest groups.[112] Clinton was chairman of the board of the Children's Defense Fund[3][113] and on the board of the Arkansas Children's Hospital's Legal Services (1988–92).[114] In addition to her positions with nonprofit organizations, she also held positions on the corporate board of directors of TCBY (1985–92),[115] Wal-Mart Stores (1986–92)[116] and Lafarge (1990–92).[117] TCBY and Wal-Mart were Arkansas-based companies that were also clients of Rose Law.[107][118] Clinton was the first female member on Wal-Mart's board, added following pressure on chairman Sam Walton to name a woman to it.[118] Once there, she pushed successfully for Wal-Mart to adopt more environmentally friendly practices. She was largely unsuccessful in her campaign for more women to be added to the company's management and was silent about the company's famously anti-labor union practices.[116][118][119] According to Dan Kaufman, awareness of this later became a factor in her loss of credibility with organized labor, helping contribute to her loss in the 2016 election, where slightly less than half of union members voted for Donald Trump.[120][121]

Bill Clinton 1992 presidential campaign

Clinton received sustained national attention for the first time when her husband became a candidate for the 1992 Democratic presidential nomination. Before the New Hampshire primary, tabloid publications printed allegations that Bill Clinton had engaged in an extramarital affair with Gennifer Flowers.[122] In response, the Clintons appeared together on 60 Minutes, where Bill denied the affair, but acknowledged "causing pain in my marriage".[123] This joint appearance was credited with rescuing his campaign.[124] During the campaign, Hillary made culturally disparaging remarks about Tammy Wynette's outlook on marriage as described in her classic song "Stand by Your Man".[d] Later in the campaign, she commented she could have chosen to be like women staying home and baking cookies and having teas, but wanted to pursue her career instead.[e] The remarks were widely criticized, particularly by those who were, or defended, stay-at-home mothers. In retrospect, she admitted they were ill-considered. Bill said that in electing him, the nation would "get two for the price of one", referring to the prominent role his wife would assume.[130] Beginning with Daniel Wattenberg's August 1992 The American Spectator article "The Lady Macbeth of Little Rock", Hillary's own past ideological and ethical record came under attack from conservatives.[131] At least twenty other articles in major publications also drew comparisons between her and Lady Macbeth.[132]

First Lady of the United States (1993–2001)

When Bill Clinton took office as president in January 1993, Hillary Rodham Clinton became the first lady. Her press secretary reiterated she would be using that form of her name.[c] She was the first in this role to have a postgraduate degree and her own professional career up to the time of entering the White House.[133] She was also the first to have an office in the West Wing of the White House in addition to the usual first lady offices in the East Wing.[58][134] During the presidential transition, she was part of the innermost circle vetting appointments to the new administration. Her choices filled at least eleven top-level positions and dozens more lower-level ones.[135][136] After Eleanor Roosevelt, Clinton was regarded as the most openly empowered presidential wife in American history.[137][138]

Some critics called it inappropriate for the first lady to play a central role in public policy matters. Supporters pointed out that Clinton's role in policy was no different from that of other White House advisors, and that voters had been well aware she would play an active role in her husband's presidency.[139]

Health care and other policy initiatives

In January 1993, President Clinton named Hillary to chair a task force on National Health Care Reform, hoping to replicate the success she had in leading the effort for Arkansas education reform.[140] The recommendation of the task force became known as the Clinton health care plan. This was a comprehensive proposal that would require employers to provide health coverage to their employees through individual health maintenance organizations. Its opponents quickly derided the plan as "Hillarycare" and it even faced opposition from some Democrats in Congress.[141]

Failing to gather enough support for a floor vote in either the House or the Senate (although Democrats controlled both chambers), the proposal was abandoned in September 1994.[142] Clinton later acknowledged in her memoir that her political inexperience partly contributed to the defeat but cited many other factors. The first lady's approval ratings, which had generally been in the high-50 percent range during her first year, fell to 44 percent in April 1994 and 35 percent by September 1994.[143]

The Republican Party negatively highlighted the Clinton health care plan in their campaign for the 1994 midterm elections.[144] The Republican Party saw strong success in the midterms, and many analysts and pollsters found the healthcare plan to be a major factor in the Democrats' defeat, especially among independent voters.[145] After this, the White House subsequently sought to downplay Clinton's role in shaping policy.[146]

Along with senators Ted Kennedy and Orrin Hatch, Clinton was a force behind the passage of the State Children's Health Insurance Program in 1997, which gave state support to children whose parents could not provide them health coverage. She participated in campaigns to promote the enrollment of children in the program after it took effect.[147]

Enactment of welfare reform was a major goal of Bill Clinton's presidency. When the first two bills on the issue came from a Republican-controlled Congress lacking protections for people coming off welfare, Hillary urged her husband to veto the bills, which he did.[148][149] A third version came up during his 1996 general election campaign that restored some of the protections but cut the scope of benefits in other areas. While Clinton was urged to persuade the president to similarly veto the bill,[148] she decided to support the bill, which became the Welfare Reform Act of 1996, as the best political compromise available.[148][149]

Together with Attorney General Janet Reno, Clinton helped create the Office on Violence Against Women at the Department of Justice.[58] In 1997, she initiated and shepherded the Adoption and Safe Families Act, which she regarded as her greatest accomplishment as the first lady.[58][150] In 1999, she was instrumental in the passage of the Foster Care Independence Act, which doubled federal monies for teenagers aging out of foster care.[150]

International diplomacy and promotion of women's rights

Clinton traveled to 79 countries as first lady,[151] breaking the record for most-traveled first lady previously held by Pat Nixon.[152] She did not hold a security clearance or attend National Security Council meetings, but played a role in U.S. diplomacy attaining its objectives.[153]

In a September 1995 speech before the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, Clinton argued forcefully against practices that abused women around the world and in the People's Republic of China itself. She declared, "it is no longer acceptable to discuss women's rights as separate from human rights".[154] Delegates from over 180 countries heard her declare,

If there is one message that echoes forth from this conference, let it be that human rights are women's rights and women's rights are human rights, once and for all."[155]

In delivering these remarks, Clinton resisted both internal administration and Chinese pressure to soften her remarks.[151][155] The speech became a key moment in the empowerment of women and years later women around the world would recite Clinton's key phrases.[156]

During the late 1990s, Clinton was one of the most prominent international figures to speak out against the treatment of Afghan women by the Taliban.[157][158] She helped create Vital Voices, an international initiative sponsored by the U.S. to encourage the participation of women in the political processes of their countries.[159]

Scandals and investigations

One prominent investigation regarding Clinton was the Whitewater controversy, which arose out of real estate investments by the Clintons and associates made in the 1970s.[160][161][160] As part of this investigation, on January 26, 1996, Clinton became the first spouse of a U.S. president to be subpoenaed to testify before a federal grand jury.[162] After several Independent Counsels had investigated, a final report was issued in 2000 that stated there was insufficient evidence that either Clinton had engaged in criminal wrongdoing.[163]

Another investigated scandal involving Clinton was the White House travel office controversy, often referred to as "Travelgate".[164] Another scandal that arose was the Hillary Clinton cattle futures controversy, which related to cattle futures trading Clinton had made in 1978 and 1979.[165] Some in the press had alleged that Clinton had engaged in a conflict of interest and disguised a bribery. Several individuals analyzed her trading records; however, no formal investigation was made and she was never charged with any wrongdoing in relation to this.[166]

An outgrowth of the "Travelgate" investigation was the June 1996 discovery of improper White House access to hundreds of FBI background reports on former Republican White House employees, an affair that some called "Filegate".[167] Accusations were made that Clinton had requested these files and she had recommended hiring an unqualified individual to head the White House Security Office.[168] The 2000 final Independent Counsel report found no substantial or credible evidence that Clinton had any role or showed any misconduct in the matter.[167]

In early 2001, a controversy arose over gifts that were sent to the White House; there was a question whether the furnishings were White House property or the Clintons' personal property. During the last year of Bill Clinton's time in office, those gifts were shipped to the Clintons' private residence.[169][170]

It Takes a Village and other writings

In 1996, Clinton presented a vision for American children in the book It Takes a Village: And Other Lessons Children Teach Us. In January 1996, she went on a ten-city book tour and made numerous television appearances to promote the book,[171] although she was frequently hit with questions about her involvement in the Whitewater and Travelgate controversies.[172][173] The book spent 18 weeks on the New York Times Best Seller List that year, including three weeks at number one.[174] By 2000, it had sold 450,000 copies in hardcover and another 200,000 in paperback.[175] Clinton received the Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Album in 1997 for the book's audio recording.[176]

Other books published by Clinton when she was the first lady include Dear Socks, Dear Buddy: Kids' Letters to the First Pets (1998) and An Invitation to the White House: At Home with History (2000). In 2001, she wrote an afterword to the children's book Beatrice's Goat.[177]

Clinton also published a weekly syndicated newspaper column titled "Talking It Over" from 1995 to 2000.[178][179] It focused on her experiences and those of women, children and families she met during her travels around the world.[3]

Response to Lewinsky scandal

In 1998, the Clintons' private concerns became the subject of much speculation when investigations revealed the president had engaged in an extramarital affair with 22-year-old White House intern Monica Lewinsky.[180] Events surrounding the Lewinsky scandal eventually led to the impeachment of the president by the House of Representatives; he was later acquitted by the Senate. When the allegations against her husband were first made public, Hillary Clinton stated that the allegations were part of a "vast right-wing conspiracy".[181][182] Clinton characterized the Lewinsky charges as the latest in a long, organized, collaborative series of charges by Bill's political enemies[f] rather than any wrongdoing by her husband. She later said she had been misled by his initial claims that no affair had taken place.[184] After the evidence of President Clinton's encounters with Lewinsky became incontrovertible, she issued a public statement reaffirming her commitment to their marriage. Privately, she was reported to be furious at him and was unsure if she wanted to remain in the marriage.[185] The White House residence staff noticed a pronounced level of tension between the couple during this period.[186]

Public response to Clinton's handling of the matter varied. Women variously admired her strength and poise in private matters that were made public. They sympathized with her as a victim of her husband's insensitive behavior and criticized her as being an enabler to her husband's indiscretions. They also accused her of cynically staying in a failed marriage as a way of keeping or even fostering her own political influence. In the wake of the revelations, her public approval ratings shot upward to around 70 percent, the highest they had ever been.[187]

Save America's Treasures initiative

Clinton was the founding chair of Save America's Treasures, a nationwide effort matching federal funds with private donations to preserve and restore historic items and sites.[188] This included the flag that inspired "The Star-Spangled Banner" and the First Ladies National Historic Site in Canton, Ohio.[58]

Traditional duties

Clinton was the head of the White House Millennium Council[189] and hosted Millennium Evenings,[190] a series of lectures that discussed futures studies, one of which became the first live simultaneous webcast from the White House.[58] Clinton also created the first White House Sculpture Garden, located in the Jacqueline Kennedy Garden.[191]

Working with Arkansas interior decorator Kaki Hockersmith over an eight-year period, Clinton oversaw extensive, privately funded redecoration efforts of the White House.[192] Overall the redecoration received a mixed reaction.[192]

Clinton hosted many large-scale events at the White House. Examples include a state dinner for visiting Chinese dignitaries, a New Year's Eve celebration at the turn of the 21st century, and a state dinner honoring the bicentennial of the White House in November 2000.[58]

U.S. Senate (2001–2009)

2000 U.S. Senate election

When New York's long-serving U.S. senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan announced his retirement in November 1998, several prominent Democratic figures, including Representative Charles Rangel of New York, urged Clinton to run for his open seat in the Senate election of 2000.[193] Once she decided to run, the Clintons purchased a home in Chappaqua, New York, north of New York City, in September 1999.[194] She became the first wife of the president of the United States to be a candidate for elected office.[195] Initially, Clinton expected to face Rudy Giuliani—the mayor of New York City—as her Republican opponent in the election. Giuliani withdrew from the race in May 2000 after being diagnosed with prostate cancer and matters related to his failing marriage became public. Clinton then faced Rick Lazio, a Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives who represented New York's 2nd congressional district. Throughout the campaign, opponents accused Clinton of carpetbagging, because she had never resided in New York State or participated in the state's politics before the 2000 Senate race.[196]

Bill de Blasio was Clinton's campaign manager. She began her drive to the U.S. Senate by visiting all 62 counties in the state, in a "listening tour" of small-group settings.[197] She devoted considerable time in traditionally Republican Upstate New York regions. Clinton vowed to improve the economic situation in those areas, promising to deliver 200,000 jobs to the state over her term. Her plan included tax credits to reward job creation and encourage business investment, especially in the high-tech sector. She called for personal tax cuts for college tuition and long-term care.[198]

The contest drew national attention. During a September debate, Lazio blundered when he seemed to invade Clinton's personal space by trying to get her to sign a fundraising agreement.[199] Their campaigns, along with Giuliani's initial effort, spent a record combined $90 million.[200] Clinton won the election on November 7, 2000, with 55 percent of the vote to Lazio's 43 percent.[199] She was sworn in as U.S. senator on January 3, 2001, and as George W. Bush was still 17 days away from being inaugurated as president after winning the 2000 presidential election, that meant from January 3–20, she simultaneously held the titles of First Lady and Senator – a first in U.S. history.[201]

First term

Because Bill Clinton's term as president did not end until 17 days after she was sworn in, upon entering the Senate, Clinton became the first and so far only first lady to serve as a senator and first lady concurrently. Clinton maintained a low public profile and built relationships with senators from both parties when she started her term.[202] She forged alliances with religiously inclined senators by becoming a regular participant in the Senate Prayer Breakfast.[203][204] She sat on five Senate committees: Committee on Budget (2001–02),[205] Committee on Armed Services (2003–09),[206] Committee on Environment and Public Works (2001–09), Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (2001–09)[205] and Special Committee on Aging.[207] She was also a member of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe[208] (2001–09).[209]

Following the September 11 terrorist attacks, Clinton sought to obtain funding for the recovery efforts in New York City and security improvements in her state. Working with New York's senior senator, Chuck Schumer, she was instrumental in securing $21 billion in funding for the World Trade Center site's redevelopment.[210] She subsequently took a leading role in investigating the health issues faced by 9/11 first responders.[211] Clinton voted for the USA Patriot Act in October 2001. In 2005, when the act was up for renewal, she expressed concerns with the USA Patriot Act Reauthorization Conference Report regarding civil liberties.[212] In March 2006, she voted in favor of the USA PATRIOT Improvement and Reauthorization Act of 2005 that had gained large majority support.[213]

Clinton strongly supported the 2001 U.S. military action in Afghanistan, saying it was a chance to combat terrorism while improving the lives of Afghan women who suffered under the Taliban government.[214] Clinton voted in favor of the October 2002 Iraq War Resolution, which authorized President George W. Bush to use military force against Iraq.[215]

After the Iraq War began, Clinton made trips to Iraq and Afghanistan to visit American troops stationed there. On a visit to Iraq in February 2005, Clinton noted that the insurgency had failed to disrupt the democratic elections held earlier and that parts of the country were functioning well.[216] Observing that war deployments were draining regular and reserve forces, she co-introduced legislation to increase the size of the regular U.S. Army by 80,000 soldiers to ease the strain.[217] In late 2005, Clinton said that while immediate withdrawal from Iraq would be a mistake, Bush's pledge to stay "until the job is done" was also misguided, as it gave Iraqis "an open-ended invitation not to take care of themselves".[218] Her stance caused frustration among those in the Democratic Party who favored quick withdrawal.[219] Clinton supported retaining and improving health benefits for reservists and lobbied against the closure of several military bases, especially those in New York.[220][221] She used her position on the Armed Services Committee to forge close relationships with a number of high-ranking military officers.[221] By 2014 and 2015 Clinton had fully reversed herself on the Iraq War Resolution, saying she "got it wrong" and the vote in support had been a "mistake".[222]

Clinton voted against President Bush's two major tax cut packages, the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 and the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003.[223] In 2003, Simon & Schuster released her memoir Living History.[224] The book set a first-week sales record for a nonfiction work,[225] went on to sell more than one million copies in the first month following publication,[226] and was translated into twelve foreign languages.[227] Clinton's audio recording of the book earned her a nomination for the Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Album.[228]

Clinton voted against the 2005 confirmation of John Roberts as chief justice of the United States and the 2006 confirmation of Samuel Alito to the U.S. Supreme Court, filibustering the latter.[229][230]

In 2005, Clinton called for the Federal Trade Commission to investigate how hidden sex scenes showed up in the controversial video game Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas.[231] Along with senators Joe Lieberman and Evan Bayh, she introduced the Family Entertainment Protection Act, intended to protect children from inappropriate content found in video games. In 2004 and 2006, Clinton voted against the Federal Marriage Amendment that sought to prohibit same-sex marriage.[223][232]

Looking to establish a "progressive infrastructure" to rival that of American conservatism, Clinton played a formative role in conversations that led to the 2003 founding of former Clinton administration chief of staff John Podesta's Center for American Progress, shared aides with Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, founded in 2003 and advised the Clintons' former antagonist David Brock's Media Matters for America, created in 2004.[233] Following the 2004 Senate elections, she successfully pushed new Democratic Senate leader Harry Reid to create a Senate war room to handle daily political messaging.[234]

2006 reelection campaign

In November 2004, Clinton announced she would seek a second Senate term. She easily won the Democratic nomination over opposition from antiwar activist Jonathan Tasini.[235][236] The early frontrunner for the Republican nomination, Westchester County District Attorney Jeanine Pirro, withdrew from the contest after several months of poor campaign performance.[237] Clinton's eventual opponent in the general election was Republican candidate John Spencer, a former mayor of Yonkers. Clinton won the election on November 7, 2006, with 67 percent of the vote to Spencer's 31 percent,[238] carrying all but four of New York's sixty-two counties.[239] Her campaign spent $36 million for her reelection, more than any other candidate for Senate in the 2006 elections. Some Democrats criticized her for spending too much in a one-sided contest, while some supporters were concerned she did not leave more funds for a potential presidential bid in 2008.[240] In the following months, she transferred $10 million of her Senate funds toward her presidential campaign.[241]

Second term

Clinton opposed the Iraq War troop surge of 2007, for both military and domestic political reasons (by the following year, she was privately acknowledging the surge had been successful).[g] In March of that year, she voted in favor of a war-spending bill that required President Bush to begin withdrawing troops from Iraq by a deadline; it passed almost completely along party lines[243] but was subsequently vetoed by Bush. In May, a compromise war funding bill that removed withdrawal deadlines but tied funding to progress benchmarks for the Iraqi government passed the Senate by a vote of 80–14 and would be signed by Bush; Clinton was one of those who voted against it.[244] She responded to General David Petraeus's September 2007 Report to Congress on the Situation in Iraq by saying, "I think that the reports that you provide to us really require a willing suspension of disbelief."[245]

In March 2007, in response to the dismissal of U.S. attorneys controversy, Clinton called on Attorney General Alberto Gonzales to resign.[246] Regarding the high-profile, hotly debated immigration reform bill known as the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007, Clinton cast several votes in support of the bill, which eventually failed to gain cloture.[247]

As the financial crisis of 2007–08 reached a peak with the liquidity crisis of September 2008, Clinton supported the proposed bailout of the U.S. financial system, voting in favor of the $700 billion law that created the Troubled Asset Relief Program, saying it represented the interests of the American people. It passed the Senate 74–25.[248]

In 2007, Clinton and Virginia senator Jim Webb called for an investigation into whether the body armor issued to soldiers in Iraq was adequate.[249]

2008 presidential campaign

Clinton had been preparing for a potential candidacy for U.S. president since at least early 2003.[250] On January 20, 2007, she announced via her website the formation of a presidential exploratory committee for the United States presidential election of 2008, stating: "I'm in and I'm in to win."[251] No woman had ever been nominated by a major party for the presidency, and no first lady had ever run for president. When Bill Clinton became president in 1993, a blind trust was established; in April 2007, the Clintons liquidated the blind trust to avoid the possibility of ethical conflicts or political embarrassments as Hillary undertook her presidential race. Later disclosure statements revealed the couple's worth was now upwards of $50 million.[252] They had earned over $100 million since 2000—most of it coming from Bill's books, speaking engagements and other activities.[253]

Throughout the first half of 2007, Clinton led candidates competing for the Democratic presidential nomination in opinion polls for the election. Senator Barack Obama of Illinois and former senator John Edwards of North Carolina were her strongest competitors.[215] The biggest threat to her campaign was her past support of the Iraq War, which Obama had opposed from the beginning.[215] Clinton and Obama both set records for early fundraising, swapping the money lead each quarter.[254] At the end of October, Clinton fared poorly in her debate performance against Obama, Edwards, and her other opponents.[255][256] Obama's message of change began to resonate with the Democratic electorate better than Clinton's message of experience.[257]

In the first vote of 2008, she placed third in the January 3 Iowa Democratic caucus behind Obama and Edwards.[258] Obama gained ground in national polling in the next few days, with all polls predicting a victory for him in the New Hampshire primary.[259] Clinton gained a surprise win there on January 8, narrowly defeating Obama.[260] It was the first time a woman had won a major American party's presidential primary for the purposes of delegate selection.[261] Explanations for Clinton's New Hampshire comeback varied but often centered on her being seen more sympathetically, especially by women, after her eyes welled with tears and her voice broke while responding to a voter's question the day before the election.[262]

The nature of the contest fractured in the next few days. Several remarks by Bill Clinton and other surrogates,[263] and a remark by Hillary Clinton concerning Martin Luther King Jr. and Lyndon B. Johnson,[h] were perceived by many as, accidentally or intentionally, limiting Obama as a racially oriented candidate or otherwise denying the post-racial significance and accomplishments of his campaign.[264] Despite attempts by both Hillary and Obama to downplay the issue, Democratic voting became more polarized as a result, with Clinton losing much of her support among African Americans.[263][265] She lost by a two-to-one margin to Obama in the January 26, South Carolina primary,[265] setting up, with Edwards soon dropping out, an intense two-person contest for the twenty-two February 5 Super Tuesday states. The South Carolina campaign had done lasting damage to Clinton, eroding her support among the Democratic establishment and leading to the prized endorsement of Obama by Ted Kennedy.[266]

On Super Tuesday, Clinton won the largest states, such as California, New York, New Jersey and Massachusetts, while Obama won more states;[267] they almost evenly split the total popular vote.[268] But Obama was gaining more pledged delegates for his share of the popular vote due to better exploitation of the Democratic proportional allocation rules.[269]

The Clinton campaign had counted on winning the nomination by Super Tuesday and was unprepared financially and logistically for a prolonged effort; lagging in Internet fundraising as Clinton began loaning money to her campaign.[257][270] There was continuous turmoil within the campaign staff, and she made several top-level personnel changes.[270][271] Obama won the next eleven February contests across the country, often by large margins and took a significant pledged delegate lead over Clinton.[269][270] On March 4, Clinton broke the string of losses by winning in Ohio among other places,[270] where her criticism of NAFTA, a major legacy of her husband's presidency, helped in a state where the trade agreement was unpopular.[272] Throughout the campaign, Obama dominated caucuses, for which the Clinton campaign largely ignored and failed to prepare.[257][269] Obama did well in primaries where African Americans or younger, college-educated, or more affluent voters were heavily represented; Clinton did well in primaries where Hispanics or older, non-college-educated, or working-class white voters predominated.[273][274] Behind in delegates, Clinton's best hope of winning the nomination came in persuading uncommitted, party-appointed superdelegates.[275]

Following the final primaries on June 3, 2008, Obama had gained enough delegates to become the presumptive nominee.[276] In a speech before her supporters on June 7, Clinton ended her campaign and endorsed Obama.[277] By campaign's end, Clinton had won 1,640 pledged delegates to Obama's 1,763;[278] at the time of the clinching, Clinton had 286 superdelegates to Obama's 395,[279] with those numbers widening to 256 versus 438 once Obama was acknowledged the winner.[278] Clinton and Obama each received over 17 million votes during the nomination process[i] with both breaking the previous record.[280] Clinton was the first woman to run in the primary or caucus of every state and she eclipsed, by a very wide margin, Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm's 1972 marks for most votes garnered and delegates won by a woman.[261] Clinton gave a passionate speech supporting Obama at the 2008 Democratic National Convention and campaigned frequently for him in fall 2008, which concluded with his victory over McCain in the general election on November 4.[281]

Secretary of State (2009–2013)

Nomination and confirmation

In mid-November 2008, President-elect Obama and Clinton discussed the possibility of her serving as secretary of state in his administration.[282] She was initially quite reluctant, but on November 20 she told Obama she would accept the position.[283][284] On December 1, President-elect Obama formally announced that Clinton would be his nominee for secretary of state.[285][286] Clinton said she did not want to leave the Senate, but that the new position represented a "difficult and exciting adventure".[286] As part of the nomination and to relieve concerns of conflict of interest, Bill Clinton agreed to accept several conditions and restrictions regarding his ongoing activities and fundraising efforts for the William J. Clinton Foundation and the Clinton Global Initiative.[287]

The appointment required a Saxbe fix, passed and signed into law in December 2008.[288] Confirmation hearings before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee began on January 13, 2009, a week before the Obama inauguration; two days later, the committee voted 16–1 to approve Clinton.[289] By this time, her public approval rating had reached 65 percent, the highest point since the Lewinsky scandal.[290] On January 21, 2009, Clinton was confirmed in the full Senate by a vote of 94–2.[291] Clinton took the oath of office of secretary of state, resigning from the Senate later that day.[292] She became the first former first lady to be a member of the United States Cabinet.[293]

Tenure

During her tenure as secretary of state, Clinton and President Obama forged a positive working relationship that lacked power struggles. Clinton was regarded to be a team player within the Obama administration. She was also considered a defender of the administration to the public. She was regarded to be cautious to prevent herself or her husband from upstaging the president.[294][295] Obama and Clinton both approached foreign policy as a largely non-ideological, pragmatic exercise.[283] Clinton met with Obama weekly, but did not have the close, daily relationship that some of her predecessors had had with their presidents.[295] Nevertheless, Obama was trusting of Clinton's actions.[283] Clinton also formed an alliance with Secretary of Defense Robert Gates with whom she shared similar strategic outlooks.[296]

As secretary of state, Clinton sought to lead a rehabilitation of the United States' reputation on the world stage. After taking office, Clinton spent several days telephoning dozens of world leaders and indicating that U.S. foreign policy would change direction. Days into her tenure, she remarked, "We have a lot of damage to repair."[297]

Clinton advocated an expanded role in global economic issues for the State Department, and cited the need for an increased U.S. diplomatic presence, especially in Iraq where the Defense Department had conducted diplomatic missions.[298] Clinton announced the most ambitious of her departmental reforms, the Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review, which establishes specific objectives for the State Department's diplomatic missions abroad; it was modeled after a similar process in the Defense Department that she was familiar with from her time on the Senate Armed Services Committee.[299] The first such review was issued in late 2010 and called for the U.S. to lead through "civilian power".[300] and prioritize the empowerment of women throughout the world.[155] One cause that Clinton promoted throughout her tenure was the adoption of cookstoves in the developing world, to foster cleaner and more environmentally sound food preparation and reduce smoke dangers to women.[283]

In a 2009 internal Obama administration debate regarding the War in Afghanistan, Clinton sided with the military's recommendations for a maximal "Afghanistan surge", recommending 40,000 troops and no public deadline for withdrawal. She prevailed over Vice President Joe Biden's opposition but eventually supported Obama's compromise plan to send an additional 30,000 troops and tie the surge to a timetable for eventual withdrawal.[221][301]

In March 2009, Clinton presented Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov with a "reset button" symbolizing U.S. attempts to rebuild ties with that country under its new president, Dmitry Medvedev.[302][303] The policy, which became known as the Russian reset, led to improved cooperation in several areas during Medvedev's presidency.[302] However Clinton noted at the time that the US was concerned about Russia's use of energy as a tool of intimidation.[304] Bilateral relations, however, would decline considerably, after Medvedev's presidency ended in 2012 and Vladimir Putin's return to the Russian presidency.[305]

In October 2009, on a trip to Switzerland, Clinton's intervention overcame last-minute snafues and managed to secure the final signing of an historic Turkish–Armenian accord that established diplomatic relations and opened the border between the two long-hostile nations.[306][307] Beginning in 2010, she helped organize a diplomatic isolation and international sanctions regime against Iran, in an effort to force curtailment of that country's nuclear program; this would eventually lead to the multinational Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action being agreed to in 2015.[283][308][309]

In a prepared speech in January 2010, Clinton drew analogies between the Iron Curtain and the free and unfree Internet,[310] which marked the first time that a senior American government official had clearly defined the Internet as a key element of American foreign policy.[311]

In July 2010, she visited South Korea, where she and Cheryl Mills successfully worked to convince SAE-A, a large apparel subcontractor, to invest in Haiti despite the company's deep concerns about plans to raise the minimum wage.[312] This tied into the "build back better" program initiated by her husband after he was named the UN Special Envoy to Haiti in 2009 following a tropical storm season that caused $1 billion in damages to Haiti.[313]

The 2011 Egyptian protests posed the most challenging foreign policy crisis yet for the Obama administration.[314] Clinton's public response quickly evolved from an early assessment that the government of Hosni Mubarak was "stable", to a stance that there needed to be an "orderly transition [to] a democratic participatory government", to a condemnation of violence against the protesters.[315][316] Obama came to rely upon Clinton's advice, organization and personal connections in the behind-the-scenes response to developments.[314] As Arab Spring protests spread throughout the region, Clinton was at the forefront of a U.S. response that she recognized was sometimes contradictory, backing some regimes while supporting protesters against others.[317]

As the Libyan Civil War took place, Clinton's shift in favor of military intervention aligned her with Ambassador to the UN Susan Rice and National Security Council figure Samantha Power. This was a key turning point in overcoming internal administration opposition from Defense Secretary Gates, security advisor Thomas E. Donilon and counterterrorism advisor John Brennan in gaining the backing for, and Arab and U.N. approval of, the 2011 military intervention in Libya.[317][318][319] Secretary Clinton testified to Congress that the administration did not need congressional authorization for its military intervention in Libya, despite objections from some members of both parties that the administration was violating the War Powers Resolution. The State Department's legal advisor argued the same point when the Resolution's 60-day limit for unauthorized wars was passed (a view that prevailed in a legal debate within the Obama administration).[320] Clinton later used U.S. allies and what she called "convening power" to promote unity among the Libyan rebels as they eventually overthrew the Gaddafi regime.[318] The aftermath of the Libyan Civil War saw the country becoming a failed state.[321] The wisdom of the intervention and interpretation of what happened afterward would become the subject of considerable debate.[322][323][324]

During April 2011, internal deliberations of the president's innermost circle of advisors over whether to order U.S. special forces to conduct a raid into Pakistan against Osama bin Laden, Clinton was among those who argued in favor, saying the importance of getting bin Laden outweighed the risks to the U.S. relationship with Pakistan.[325][326] Following the completion of the mission on May 2 resulting in bin Laden's death, Clinton played a key role in the administration's decision not to release photographs of the dead al-Qaeda leader.[327] During internal discussions regarding Iraq in 2011, Clinton argued for keeping a residual force of up to 10,000–20,000 U.S. troops there. (All of them ended up being withdrawn after negotiations for a revised U.S.–Iraq Status of Forces Agreement failed.)[221][328]

In a speech before the United Nations Human Rights Council in December 2011, Clinton said that, "Gay rights are human rights", and that the U.S. would advocate for gay rights and legal protections of gay people abroad.[329] The same period saw her overcome internal administration opposition with a direct appeal to Obama and stage the first visit to Burma by a U.S. secretary of state since 1955. She met with Burmese leaders as well as opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi and sought to support the 2011 Burmese democratic reforms.[330][331] She also said the 21st century would be "America's Pacific century",[332] a declaration that was part of the Obama administration's "pivot to Asia".[333]

During the Syrian Civil War, Clinton and the Obama administration initially sought to persuade Syrian president Bashar al-Assad to engage popular demonstrations with reform. As government violence allegedly rose in August 2011, they called for him to resign from the presidency.[334] The administration joined several countries in delivering non-lethal assistance to so-called rebels opposed to the Assad government and humanitarian groups working in Syria.[335] During mid-2012, Clinton formed a plan with CIA Director David Petraeus to further strengthen the opposition by arming and training vetted groups of Syrian rebels. The proposal was rejected by White House officials who were reluctant to become entangled in the conflict, fearing that extremists hidden among the rebels might turn the weapons against other targets.[330][336]

In December 2012, Clinton was hospitalized for a few days for treatment of a blood clot in her right transverse venous sinus.[337] Her doctors had discovered the clot during a follow-up examination for a concussion she had sustained when she fainted and fell nearly three weeks earlier, as a result of severe dehydration from a viral intestinal ailment acquired during a trip to Europe.[337][338] The clot, which caused no immediate neurological injury, was treated with anticoagulant medication, and her doctors have said she has made a full recovery.[338][339][j]

Overall themes

Throughout her time in office (and mentioned in her final speech concluding it), Clinton viewed "smart power" as the strategy for asserting U.S. leadership and values. In a world of varied threats, weakened central governments and increasingly important nongovernmental entities, smart power combined military hard power with diplomacy and U.S. soft power capacities in global economics, development aid, technology, creativity and human rights advocacy.[318][344] As such, she became the first secretary of state to methodically implement the smart power approach.[345] In debates over use of military force, she was generally one of the more hawkish voices in the administration.[221][296][328] In August 2011 she hailed the ongoing multinational military intervention in Libya and the initial U.S. response towards the Syrian Civil War as examples of smart power in action.[346]

Clinton greatly expanded the State Department's use of social media, including Facebook and Twitter, to get its message out and to help empower citizens of foreign countries vis-à-vis their governments.[318] And in the Mideast turmoil, Clinton particularly saw an opportunity to advance one of the central themes of her tenure, the empowerment and welfare of women and girls worldwide.[155] Moreover, in a formulation that became known as the "Hillary Doctrine", she viewed women's rights as critical for U.S. security interests, due to a link between the level of violence against women and gender inequality within a state, and the instability and challenge to international security of that state.[294][347] In turn, there was a trend of women around the world finding more opportunities, and in some cases feeling safer, as the result of her actions and visibility.[348]

Clinton visited 112 countries during her tenure, making her the most widely traveled secretary of state[349][k] (Time magazine wrote that "Clinton's endurance is legendary".)[318] The first secretary of state to visit countries like Togo and East Timor, she believed that in-person visits were more important than ever in the virtual age.[352] As early as March 2011, she indicated she was not interested in serving a second term as secretary of state should Obama be re-elected in 2012;[319] in December 2012, following that re-election, Obama nominated Senator John Kerry to be Clinton's successor.[338] Her last day as secretary of state was February 1, 2013.[353] Upon her departure, analysts commented that Clinton's tenure did not bring any signature diplomatic breakthroughs as some other secretaries of state had accomplished,[354][355] and highlighted her focus on goals she thought were less tangible but would have more lasting effect.[356] She has also been criticized for accepting millions in dollars in donations from foreign governments to the Clinton Foundation during her tenure as Secretary of State.[357]

Benghazi attack and subsequent hearings

On September 11, 2012, the U.S. diplomatic mission in Benghazi, Libya, was attacked, resulting in the deaths of the U.S. Ambassador, J. Christopher Stevens and three other Americans. The attack, questions surrounding the security of the U.S. consulate, and the varying explanations given afterward by administration officials for what had happened became politically controversial in the U.S.[358] On October 15, Clinton took responsibility for the question of security lapses saying the differing explanations were due to the inevitable fog of war confusion after such events.[358][359]

On December 19, a panel led by Thomas R. Pickering and Michael Mullen issued its report on the matter. It was sharply critical of State Department officials in Washington for ignoring requests for more guards and safety upgrades and for failing to adapt security procedures to a deteriorating security environment.[360] It focused its criticism on the department's Bureau of Diplomatic Security and Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs; four State Department officials at the assistant secretary level and below were removed from their posts as a consequence.[361] Clinton said she accepted the conclusions of the report and that changes were underway to implement its suggested recommendations.[360]

Clinton gave testimony to two congressional foreign affairs committees on January 23, 2013, regarding the Benghazi attack. She defended her actions in response to the incident, and while still accepting formal responsibility, said she had had no direct role in specific discussions beforehand regarding consulate security.[362] Congressional Republicans challenged her on several points, to which she responded. In particular, after persistent questioning about whether or not the administration had issued inaccurate "talking points" after the attack, Clinton responded with the much-quoted rejoinder, "With all due respect, the fact is we had four dead Americans. Was it because of a protest or was it because of guys out for a walk one night who decided that they'd they go kill some Americans? What difference at this point does it make? It is our job to figure out what happened and do everything we can to prevent it from ever happening again, Senator."[362][363] In November 2014, the House Intelligence Committee issued a report that concluded there had been no wrongdoing in the administration's response to the attack.[364]

The Republican-led House Select Committee on Benghazi was created in May 2014 and conducted a two-year investigation related to the 2012 attack.[365] The committee was criticized as partisan,[365][366] including by one of its ex-staffers.[367] Some Republicans admitted that the committee aimed to lower Clinton's poll numbers.[368][369] On October 22, 2015, Clinton testified at an all-day and nighttime session before the committee.[370][371] Clinton was widely seen as emerging largely unscathed from the hearing, because of what the media perceived as a calm and unfazed demeanor and a lengthy, meandering, repetitive line of questioning from the committee.[372] The committee issued competing final reports in June 2016; the Republican report offered no evidence of culpability by Clinton.[366][365]

Email controversy

During her tenure as secretary of state, Clinton conducted official business exclusively through her private email server, as opposed to her government email account.[373] Some experts, officials, members of Congress and political opponents contended that her use of private messaging system software and a private server violated State Department protocols and procedures, and federal laws and regulations governing recordkeeping requirements. The controversy occurred against the backdrop of Clinton's 2016 presidential election campaign and hearings held by the House Select Committee on Benghazi.[374][375]

In a joint statement released on July 15, 2015, the inspector general of the State Department and the inspector general of the intelligence community said their review of the emails found information that was classified when sent, remained so at the time of their inspection and "never should have been transmitted via an unclassified personal system". They also stated unequivocally this classified information should never have been stored outside of secure government computer systems. Clinton had said over a period of months that she kept no classified information on the private server that she set up in her house.[376] Government policy, reiterated in the nondisclosure agreement signed by Clinton as part of gaining her security clearance, is that sensitive information can be considered as classified even if not marked as such.[377] After allegations were raised that some of the emails in question fell into the so-called "born classified" category, an FBI probe was initiated regarding how classified information was handled on the Clinton server.[378] The New York Times reported in February 2016 that nearly 2,100 emails stored on Clinton's server were retroactively marked classified by the State Department. Additionally, the intelligence community's inspector general wrote Congress to say that some of the emails "contained classified State Department information when originated".[379] In May 2016, the inspector general of the State Department criticized her use of a private email server while secretary of state, stating that she had not requested permission for this and would not have received it if she had asked.[380]

Clinton maintained she did not send or receive any emails from her personal server that were confidential at the time they were sent. In a Democratic debate with Bernie Sanders on February 4, 2016, Clinton said, "I never sent or received any classified material—they are retroactively classifying it." On July 2, 2016, Clinton stated: "Let me repeat what I have repeated for many months now, I never received nor sent any material that was marked classified."[381][382]

On July 5, 2016, the FBI concluded its investigation. In a statement, FBI director James Comey said:

110 e-mails in 52 e-mail chains have been determined by the owning agency to contain classified information at the time they were sent or received. Eight of those chains contained information that was Top Secret at the time they were sent; 36 chains contained Secret information at the time; and eight contained Confidential information, which is the lowest level of classification. Separate from those, about 2,000 additional e-mails were "up-classified" to make them Confidential; the information in those had not been classified at the time the e-mails were sent.[383][384]

Out of 30,000, three emails were found to be marked as classified, although they lacked classified headers and were marked only with a small "c" in parentheses, described as "portion markings" by Comey. He also said it was possible Clinton was not "technically sophisticated" enough to understand what the three classified markings meant.[384] The probe found Clinton used her personal email extensively while outside the United States, both sending and receiving work-related emails in the territory of sophisticated adversaries. Comey acknowledged that it was "possible that hostile actors gained access to Secretary Clinton's personal email account". He added that "[although] we did not find clear evidence that Secretary Clinton or her colleagues intended to violate laws governing the handling of classified information, there is evidence that they were extremely careless in their handling of very sensitive, highly classified information". Nevertheless, Comey asserted that "no reasonable prosecutor" would bring criminal charges in this case, despite the existence of "potential violations of the statutes regarding the handling of classified information". The FBI recommended that the Justice Department decline to prosecute.[383] On July 6, 2016, U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch confirmed that the probe into Clinton's use of private email servers would be closed without criminal charges.[385]

Two weeks before the election, on October 28, 2016, Comey notified Congress that the FBI had begun looking into newly discovered Clinton emails. On November 6, Comey notified Congress that the FBI had not changed the conclusion it had reached in July.[386] The notification was later cited by Clinton as a factor in her loss in the 2016 presidential election.[387] The emails controversy received more media coverage than any other topic during the 2016 presidential election.[388][389][390]

The State Department finished its internal review in September 2019. It found that Clinton's use of a personal email server increased the risk of information being compromised, but concluded there was no evidence of "systemic, deliberate mishandling of classified information".[391]

Clinton Foundation, Hard Choices, and speeches

When Clinton left the State Department, she returned to private life for the first time in thirty years.[392] She and her daughter joined her husband as named members of the Bill, Hillary & Chelsea Clinton Foundation in 2013.[393] There she focused on early childhood development efforts, including an initiative called Too Small to Fail and a $600 million initiative to encourage the enrollment of girls in secondary schools worldwide, led by former Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard.[393][394]

In 2014, Clinton published a second memoir, Hard Choices, which focused on her time as secretary of state. As of July 2015[update], the book had sold about 280,000 copies.[395] Clinton also led the No Ceilings: The Full Participation Project, a partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to gather and study data on the progress of women and girls around the world since the Beijing conference in 1995.[396] The foundation began accepting new donations from foreign governments, which it had stopped doing while she was secretary of state.[l] However, even though the Clinton Foundation had stopped taking donations from foreign governments, they continued to take large donations from foreign citizens who were sometimes linked to their governments.[399]

She began work on another volume of memoirs and made appearances on the paid speaking circuit.[400] There she received $200,000–225,000 per engagement, often appearing before Wall Street firms or at business conventions.[400][401] She also made some unpaid speeches on behalf of the foundation.[400] For the fifteen months ending in March 2015, Clinton earned over $11 million from her speeches.[402] For the overall period 2007–14, the Clintons earned almost $141 million, paid some $56 million in federal and state taxes and donated about $15 million to charity.[403] As of 2015[update], she was estimated to be worth over $30 million on her own, or $45–53 million with her husband.[404]

Clinton resigned from the board of the Clinton Foundation in April 2015, when she began her presidential campaign. The foundation said it would accept new foreign governmental donations from six Western nations only.[l]

2016 presidential campaign