Франция

Французская Республика Французская Республика ( французский ) | |

|---|---|

| Девиз: « Свобода, равенство, братство ». («Свобода, Равенство, Братство») | |

| Гимн: « Марсельеза ». | |

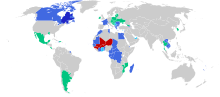

Дипломатическая эмблема  | |

Расположение Франции (синий или темно-зеленый) – в Европе (зеленый и темно-серый) | |

| Капитал и крупнейший город | Париж 48 ° 51' с.ш. 2 ° 21' в.д. / 48,850 ° с.ш. 2,350 ° в.д. |

| Официальный язык и национальный язык | Французский [ II ] |

| Национальность (2021) [ 3 ] | |

| Религия (2023) [ 4 ] |

|

| Демон(ы) | Французский |

| Правительство | Унитарная полупрезидентская республика |

| Эммануэль Макрон | |

| Габриэль Атталь | |

| Жерар Ларше | |

| Яэль Браун-Пиве | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| National Assembly | |

| Establishment | |

| 10 August 843 | |

| 22 September 1792 | |

| 4 October 1958 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 643,801 km2 (248,573 sq mi)[5] (43rd) |

• Water (%) | 0.86[6] |

| 551,695 km2 (213,011 sq mi)[III] (50th) | |

• Metropolitan France (Cadastre) | 543,940.9 km2 (210,016.8 sq mi)[IV][7] (50th) |

| Population | |

• January 2024 estimate | |

• Density | 106.20274/km2 (106th) |

• Metropolitan France, estimate as of January 2024[update] | |

• Density | 122/km2 (316.0/sq mi) (89th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2022) | low inequality |

| HDI (2022) | very high (28th) |

| Currency | |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET[VII]) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Calling code | +33[VIII] |

| ISO 3166 code | FR |

| Internet TLD | .fr[IX] |

Source gives area of metropolitan France as 551,500 km2 (212,900 sq mi) and lists overseas regions separately, whose areas sum to 89,179 km2 (34,432 sq mi). Adding these give the total shown here for the entire French Republic. The World Factbook reports the total as 643,801 km2 (248,573 sq mi). | |

Франция , [ а ] официально Французская Республика , [ б ] Это страна, расположенная преимущественно в Западной Европе . Сюда также входят заморские регионы и территории в Северной и Южной Америке , а также в Атлантическом , Тихом и Индийском океанах . [ Х ] что дает ему одну из крупнейших несмежных исключительных экономических зон в мире . Метрополия Франция граничит с Бельгией и Люксембургом на севере, с Германией на северо-востоке, со Швейцарией на востоке, с Италией и Монако на юго-востоке, с Андоррой и Испанией на юге, а также имеет морскую границу с Соединенным Королевством на северо-западе. Ее агломерация простирается от Рейна до Атлантического океана и от Средиземного моря до Ла-Манша и Северного моря . Ее заморские территории включают Французскую Гвиану в Южной Америке , Сен-Пьер и Микелон в Северной Атлантике, Французскую Вест-Индию и множество островов в Океании и Индийском океане . Его восемнадцать составных регионов (пять из которых находятся за рубежом) занимают общую площадь 643 801 км . 2 (248 573 квадратных миль), а общая численность населения по состоянию на январь 2024 года составляет 68,4 миллиона человек. [update]. [ 5 ] [ 8 ] Франция — полупрезидентская республика со столицей в Париже , крупнейшем городе страны и главном культурном и торговом центре.

Метрополия Франции была заселена в железном веке известными кельтскими племенами, как галлы, до того, как Рим аннексировал эту территорию в 51 г. до н.э., что привело к возникновению особой галло-римской культуры . В раннем средневековье франки образовали Королевство Франкия , которое стало центром Каролингской империи . 843 Верденский договор года разделил империю, и Западная Франция превратилась в Королевство Франции . В эпоху Высокого Средневековья Франция была могущественным, но децентрализованным феодальным королевством, но с середины 14 по середину 15 веков Франция была погружена в династический конфликт с Англией, известный как Столетняя война . В 16 веке французский Ренессанс стал свидетелем расцвета культуры и возникновения Французской колониальной империи . [ 13 ] Внутри Франции доминировали конфликт с Домом Габсбургов и религиозные войны между католиками и гугенотами . Франция добилась успеха в Тридцатилетней войне и еще больше усилила свое влияние во время правления Людовика XIV . [ 14 ]

Французская революция 1789 года свергла Ancien Régime и создала Декларацию прав человека , которая по сей день выражает идеалы нации. Франция достигла своего политического и военного зенита в начале 19 века при Наполеоне Бонапарте , подчинив себе часть континентальной Европы и основав Первую Французскую империю . Французская революция и наполеоновские войны существенно повлияли на ход европейской истории. Распад империи положил начало периоду относительного упадка, в течение которого Франция пережила Реставрацию Бурбонов до основания Второй французской республики , на смену которой пришла Вторая Французская империя после прихода к власти Наполеона III . Его империя рухнула во время франко-прусской войны в 1870 году. Это привело к созданию Третьей Французской республики , а последующие десятилетия стали периодом экономического процветания, культурного и научного расцвета, известного как Belle Époque . Франция была одним из крупнейших участников , Первой мировой войны из которой вышла победительницей. ценой огромных человеческих и экономических затрат. Он был среди союзников во Второй мировой войне , но сдался и был оккупирован странами Оси в 1940 году. После его освобождения в 1944 году была создана недолговечная Четвертая республика , которая позже распалась в ходе поражения в Алжирской войне . Нынешняя Пятая республика была основана в 1958 году Шарлем де Голлем . Алжир и большинство французских колоний стали независимыми в 1960-х годах, при этом большинство из них сохранило тесные экономические и военные связи с Францией .

France retains its centuries-long status as a global centre of art, science, and philosophy. It hosts the fourth-largest number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites and is the world's leading tourist destination, receiving 100 million foreign visitors in 2023.[15] France is a developed country with a high nominal per capita income globally, and its advanced economy ranks among the largest in the world. It is a great power,[16] being one of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council and an official nuclear-weapon state. France is a founding and leading member of the European Union and the eurozone,[17] as well as a member of the Group of Seven, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and Francophonie.

Etymology and pronunciation

Originally applied to the whole Frankish Empire, the name France comes from the Latin Francia, or "realm of the Franks".[18] The name of the Franks is related to the English word frank ("free"): the latter stems from the Old French franc ("free, noble, sincere"), and ultimately from the Medieval Latin word francus ("free, exempt from service; freeman, Frank"), a generalisation of the tribal name that emerged as a Late Latin borrowing of the reconstructed Frankish endonym *Frank.[19][20] It has been suggested that the meaning "free" was adopted because, after the conquest of Gaul, only Franks were free of taxation,[21] or more generally because they had the status of freemen in contrast to servants or slaves.[20] The etymology of *Frank is uncertain. It is traditionally derived from the Proto-Germanic word *frankōn, which translates as "javelin" or "lance" (the throwing axe of the Franks was known as the francisca),[22] although these weapons may have been named because of their use by the Franks, not the other way around.[20]

In English, 'France' is pronounced /fræns/ FRANSS in American English and /frɑːns/ FRAHNSS or /fræns/ FRANSS in British English. The pronunciation with /ɑː/ is mostly confined to accents with the trap-bath split such as Received Pronunciation, though it can be also heard in some other dialects such as Cardiff English.[23]

History

Pre-6th century BC

The oldest traces of archaic humans in what is now France date from approximately 1.8 million years ago.[24] Neanderthals occupied the region into the Upper Paleolithic era but were slowly replaced by Homo sapiens around 35,000 BC.[25] This period witnessed the emergence of cave painting in the Dordogne and Pyrenees, including at Lascaux, dated to c. 18,000 BC.[24] At the end of the Last Glacial Period (10,000 BC), the climate became milder;[24] from approximately 7,000 BC, this part of Western Europe entered the Neolithic era, and its inhabitants became sedentary.

After demographic and agricultural development between the 4th and 3rd millennia BC, metallurgy appeared, initially working gold, copper and bronze, then later iron.[26] France has numerous megalithic sites from the Neolithic, including the Carnac stones site (approximately 3,300 BC).

Antiquity (6th century BC – 5th century AD)

In 600 BC, Ionian Greeks from Phocaea founded the colony of Massalia (present-day Marseille).[27] Celtic tribes penetrated parts of eastern and northern France, spreading through the rest of the country between the 5th and 3rd century BC.[28] Around 390 BC, the Gallic chieftain Brennus and his troops made their way to Roman Italy, defeated the Romans in the Battle of the Allia, and besieged and ransomed Rome.[29] This left Rome weakened, and the Gauls continued to harass the region until 345 BC when they entered into a peace treaty.[30] But the Romans and the Gauls remained adversaries for centuries.[31]

Around 125 BC, the south of Gaul was conquered by the Romans, who called this region Provincia Nostra ("Our Province"), which evolved into Provence in French.[32] Julius Caesar conquered the remainder of Gaul and overcame a revolt by Gallic chieftain Vercingetorix in 52 BC.[33] Gaul was divided by Augustus into provinces[34] and many cities were founded during the Gallo-Roman period, including Lugdunum (present-day Lyon), the capital of the Gauls.[34] In 250-290 AD, Roman Gaul suffered a crisis with its fortified borders attacked by barbarians.[35] The situation improved in the first half of the 4th century, a period of revival and prosperity.[36] In 312, Emperor Constantine I converted to Christianity. Christians, who had been persecuted, increased.[37] But from the 5th century, the Barbarian Invasions resumed.[38] Teutonic tribes invaded the region, the Visigoths settling in the southwest, the Burgundians along the Rhine River Valley, and the Franks in the north.[39]

Early Middle Ages (5th–10th century)

In Late antiquity, ancient Gaul was divided into Germanic kingdoms and a remaining Gallo-Roman territory. Celtic Britons, fleeing the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, settled in west Armorica; the Armorican peninsula was renamed Brittany and Celtic culture was revived.

The first leader to unite all Franks was Clovis I, who began his reign as king of the Salian Franks in 481, routing the last forces of the Roman governors in 486. Clovis said he would be baptised a Christian in the event of victory against the Visigothic Kingdom, which was said to have guaranteed the battle. Clovis regained the southwest from the Visigoths and was baptised in 508. Clovis I was the first Germanic conqueror after the Fall of the Western Roman Empire to convert to Catholic Christianity; thus France was given the title "Eldest daughter of the Church" by the papacy,[40] and French kings called "the Most Christian Kings of France".

The Franks embraced the Christian Gallo-Roman culture, and ancient Gaul was renamed Francia ("Land of the Franks"). The Germanic Franks adopted Romanic languages. Clovis made Paris his capital and established the Merovingian dynasty, but his kingdom would not survive his death. The Franks treated land as a private possession and divided it among their heirs, so four kingdoms emerged from that of Clovis: Paris, Orléans, Soissons, and Rheims. The last Merovingian kings lost power to their mayors of the palace (head of household). One mayor of the palace, Charles Martel, defeated an Umayyad invasion of Gaul at the Battle of Tours (732). His son, Pepin the Short, seized the crown of Francia from the weakened Merovingians and founded the Carolingian dynasty. Pepin's son, Charlemagne, reunited the Frankish kingdoms and built an empire across Western and Central Europe.

Proclaimed Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Leo III and thus establishing the French government's longtime historical association with the Catholic Church,[41] Charlemagne tried to revive the Western Roman Empire and its cultural grandeur. Charlemagne's son, Louis I kept the empire united, however in 843, it was divided between Louis' three sons, into East Francia, Middle Francia and West Francia. West Francia approximated the area occupied by modern France and was its precursor.[42]

During the 9th and 10th centuries, threatened by Viking invasions, France became a decentralised state: the nobility's titles and lands became hereditary, and authority of the king became more religious than secular, and so was less effective and challenged by noblemen. Thus was established feudalism in France. Some king's vassals grew so powerful they posed a threat to the king. After the Battle of Hastings in 1066, William the Conqueror added "King of England" to his titles, becoming vassal and the equal of the king of France, creating recurring tensions.

High and Late Middle Ages (10th–15th century)

The Carolingian dynasty ruled France until 987, when Hugh Capet was crowned king of the Franks.[43] His descendants unified the country through wars and inheritance. From 1190, the Capetian rulers began to be referred as "kings of France" rather than "kings of the Franks".[44] Later kings expanded their directly possessed domaine royal to cover over half of modern France by the 15th century. Royal authority became more assertive, centred on a hierarchically conceived society distinguishing nobility, clergy, and commoners.

The nobility played a prominent role in Crusades to restore Christian access to the Holy Land. French knights made up most reinforcements in the 200 years of the Crusades, in such a fashion that the Arabs referred to crusaders as Franj.[45] French Crusaders imported French into the Levant, making Old French the base of the lingua franca ("Frankish language") of the Crusader states.[45] The Albigensian Crusade was launched in 1209 to eliminate the heretical Cathars in the southwest of modern-day France.[46]

From the 11th century, the House of Plantagenet, rulers of the County of Anjou, established its dominion over the surrounding provinces of Maine and Touraine, then built an "empire" from England to the Pyrenees, covering half of modern France. Tensions between France and the Plantagenet empire would last a hundred years, until Philip II of France conquered, between 1202 and 1214, most continental possessions of the empire, leaving England and Aquitaine to the Plantagenets.

Charles IV the Fair died without an heir in 1328.[47] The crown passed to Philip of Valois, rather than Edward of Plantagenet, who became Edward III of England. During the reign of Philip, the monarchy reached the height of its medieval power.[47] However Philip's seat on the throne was contested by Edward in 1337, and England and France entered the off-and-on Hundred Years' War.[48] Boundaries changed, but landholdings inside France by English Kings remained extensive for decades. With charismatic leaders, such as Joan of Arc, French counterattacks won back most English continental territories. France was struck by the Black Death, from which half of the 17 million population died.[49]

Early modern period (15th century–1789)

The French Renaissance saw cultural development and standardisation of French, which became the official language of France and Europe's aristocracy. France became rivals of the House of Habsburg during the Italian Wars, which would dictate much of their later foreign policy until the mid-18th century. French explorers claimed lands in the Americas, paving expansion of the French colonial empire. The rise of Protestantism led France to a civil war known as the French Wars of Religion.[50] This forced Huguenots to flee to Protestant regions such as the British Isles and Switzerland. The wars were ended by Henry IV's Edict of Nantes, which granted some freedom of religion to the Huguenots. Spanish troops,[51] assisted the Catholics from 1589 to 1594 and invaded France in 1597. Spain and France returned to all-out war between 1635 and 1659. The war cost France 300,000 casualties.[52]

Under Louis XIII, Cardinal Richelieu promoted centralisation of the state and reinforced royal power. He destroyed castles of defiant lords and denounced the use of private armies. By the end of the 1620s, Richelieu established "the royal monopoly of force".[53] France fought in the Thirty Years’ War, supporting the Protestant side against the Habsburgs. From the 16th to the 19th century, France was responsible for about 10% of the transatlantic slave trade.[54]

During Louis XIV's minority, trouble known as The Fronde occurred. This rebellion was driven by feudal lords and sovereign courts as a reaction to the royal absolute power. The monarchy reached its peak during the 17th century and reign of Louis XIV. By turning lords into courtiers at the Palace of Versailles, his command of the military went unchallenged. The "Sun King" made France the leading European power. France became the most populous European country and had tremendous influence over European politics, economy, and culture. French became the most-used language in diplomacy, science, and literature until the 20th century.[55] France took control of territories in the Americas, Africa and Asia. In 1685, Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, forcing thousands of Huguenots into exile and published the Code Noir providing the legal framework for slavery and expelling Jews from French colonies.[56]

Under the wars of Louis XV (r. 1715–74), France lost New France and most Indian possessions after its defeat in the Seven Years' War (1756–63). Its European territory kept growing, however, with acquisitions such as Lorraine and Corsica. Louis XV's weak rule, including the decadence of his court, discredited the monarchy, which in part paved the way for the French Revolution.[57]

Louis XVI (r. 1774–93) supported America with money, fleets and armies, helping them win independence from Great Britain. France gained revenge, but verged on bankruptcy—a factor that contributed to the Revolution. Some of the Enlightenment occurred in French intellectual circles, and scientific breakthroughs, such as the naming of oxygen (1778) and the first hot air balloon carrying passengers (1783), were achieved by French scientists. French explorers took part in the voyages of scientific exploration through maritime expeditions. Enlightenment philosophy, in which reason is advocated as the primary source of legitimacy, undermined the power of and support for the monarchy and was a factor in the Revolution.

Revolutionary France (1789–1799)

The French Revolution was a period of political and societal change that began with the Estates General of 1789, and ended with the coup of 18 Brumaire in 1799 and the formation of the French Consulate. Many of its ideas are fundamental principles of liberal democracy,[58] while its values and institutions remain central to modern political discourse.[59]

Its causes were a combination of social, political and economic factors, which the Ancien Régime proved unable to manage. A financial crisis and social distress led in May 1789 to the convocation of the Estates General, which was converted into a National Assembly in June. The Storming of the Bastille on 14 July led to a series of radical measures by the Assembly, among them the abolition of feudalism, state control over the Catholic Church in France, and a declaration of rights.

The next three years were dominated by struggle for political control, exacerbated by economic depression. Military defeats following the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars in April 1792 resulted in the insurrection of 10 August 1792. The monarchy was abolished and replaced by the French First Republic in September, while Louis XVI was executed in January 1793.

After another revolt in June 1793, the constitution was suspended and power passed from the National Convention to the Committee of Public Safety. About 16,000 people were executed in a Reign of Terror, which ended in July 1794. Weakened by external threats and internal opposition, the Republic was replaced in 1795 by the Directory. Four years later in 1799, the Consulate seized power in a coup led by Napoleon.

Napoleon and 19th century (1799–1914)

Napoleon became First Consul in 1799 and later Emperor of the French Empire (1804–1814; 1815). Changing sets of European coalitions declared wars on Napoleon's empire. His armies conquered most of continental Europe with swift victories such as the battles of Jena-Auerstadt and Austerlitz. Members of the Bonaparte family were appointed monarchs in some of the newly established kingdoms.[61]

These victories led to the worldwide expansion of French revolutionary ideals and reforms, such as the metric system, Napoleonic Code and Declaration of the Rights of Man. In 1812 Napoleon attacked Russia, reaching Moscow. Thereafter his army disintegrated through supply problems, disease, Russian attacks, and finally winter. After this catastrophic campaign and the ensuing uprising of European monarchies against his rule, Napoleon was defeated. About a million Frenchmen died during the Napoleonic Wars.[61] After his brief return from exile, Napoleon was finally defeated in 1815 at the Battle of Waterloo, and the Bourbon monarchy was restored with new constitutional limitations.

The discredited Bourbon dynasty was overthrown by the July Revolution of 1830, which established the constitutional July Monarchy; French troops began the conquest of Algeria. Unrest led to the French Revolution of 1848 and the end of the July Monarchy. The abolition of slavery and introduction of male universal suffrage was re-enacted in 1848. In 1852, president of the French Republic, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, Napoleon I's nephew, was proclaimed emperor of the Second Empire, as Napoleon III. He multiplied French interventions abroad, especially in Crimea, Mexico and Italy. Napoleon III was unseated following defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, and his regime replaced by the Third Republic. By 1875, the French conquest of Algeria was complete, with approximately 825,000 Algerians killed from famine, disease, and violence.[62]

France had colonial possessions since the beginning of the 17th century, but in the 19th and 20th centuries its empire extended greatly and became the second-largest behind the British Empire.[13] Including metropolitan France, the total area reached almost 13 million square kilometres in the 1920s and 1930s, 9% of the world's land. Known as the Belle Époque, the turn of the century was characterised by optimism, regional peace, economic prosperity and technological, scientific and cultural innovations. In 1905, state secularism was officially established.

Early to mid-20th century (1914–1946)

France was invaded by Germany and defended by Great Britain at the start of World War I in August 1914. A rich industrial area in the north was occupied. France and the Allies emerged victorious against the Central Powers at tremendous human cost. It left 1.4 million French soldiers dead, 4% of its population.[63][64] Interwar was marked by intense international tensions and social reforms introduced by the Popular Front government (e.g., annual leave, eight-hour workdays, women in government).

In 1940, France was invaded and quickly defeated by Nazi Germany. France was divided into a German occupation zone in the north, an Italian occupation zone and an unoccupied territory, the rest of France, which consisted of the southern France and the French empire. The Vichy government, an authoritarian regime collaborating with Germany, ruled the unoccupied territory. Free France, the government-in-exile led by Charles de Gaulle, was set up in London.[65]

From 1942 to 1944, about 160,000 French citizens, including around 75,000 Jews,[66] were deported to death and concentration camps.[67] On 6 June 1944, the Allies invaded Normandy, and in August they invaded Provence. The Allies and French Resistance emerged victorious, and French sovereignty was restored with the Provisional Government of the French Republic (GPRF). This interim government, established by de Gaulle, continued to wage war against Germany and to purge collaborators from office. It made important reforms e.g. suffrage extended to women and the creation of a social security system.

1946–present

A new constitution resulted in the Fourth Republic (1946–1958), which saw strong economic growth (les Trente Glorieuses). France was a founding member of NATO and attempted to regain control of French Indochina, but was defeated by the Viet Minh in 1954. France faced another anti-colonialist conflict in Algeria, then part of France and home to over one million European settlers (Pied-Noir). The French systematically used torture and repression, including extrajudicial killings to keep control.[68] This conflict nearly led to a coup and civil war.[69]

During the May 1958 crisis, the weak Fourth Republic gave way to the Fifth Republic, which included a strengthened presidency.[70] The war concluded with the Évian Accords in 1962 which led to Algerian independence, at a high price: between half a million and one million deaths and over 2 million internally-displaced Algerians.[71] Around one million Pied-Noirs and Harkis fled from Algeria to France.[72] A vestige of empire is the French overseas departments and territories.

During the Cold War, de Gaulle pursued a policy of "national independence" towards the Western and Eastern blocs. He withdrew from NATO's military-integrated command (while remaining within the alliance), launched a nuclear development programme and made France the fourth nuclear power. He restored cordial Franco-German relations to create a European counterweight between American and Soviet spheres of influence. However, he opposed any development of a supranational Europe, favouring sovereign nations. The revolt of May 1968 had an enormous social impact; it was a watershed moment when a conservative moral ideal (religion, patriotism, respect for authority) shifted to a more liberal moral ideal (secularism, individualism, sexual revolution). Although the revolt was a political failure (the Gaullist party emerged stronger than before) it announced a split between the French and de Gaulle, who resigned.[73]

In the post-Gaullist era, France remained one of the most developed economies in the world but faced crises that resulted in high unemployment rates and increasing public debt. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, France has been at the forefront of the development of a supranational European Union, notably by signing the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, establishing the eurozone in 1999 and signing the Treaty of Lisbon in 2007.[74] France has fully reintegrated into NATO and since participated in most NATO-sponsored wars.[75] Since the 19th century, France has received many immigrants, often male foreign workers from European Catholic countries who generally returned home when not employed.[76] During the 1970s France faced an economic crisis and allowed new immigrants (mostly from the Maghreb, in northwest Africa)[76] to permanently settle in France with their families and acquire citizenship. It resulted in hundreds of thousands of Muslims living in subsidised public housing and suffering from high unemployment rates.[77] The government had a policy of assimilation of immigrants, where they were expected to adhere to French values and norms.[78]

Since the 1995 public transport bombings, France has been targeted by Islamist organisations, notably the Charlie Hebdo attack in 2015 which provoked the largest public rallies in French history, gathering 4.4 million people,[79] the November 2015 Paris attacks which resulted in 130 deaths, the deadliest attack on French soil since World War II[80] and the deadliest in the European Union since the Madrid train bombings in 2004.[81] Opération Chammal, France's military efforts to contain ISIS, killed over 1,000 ISIS troops between 2014 and 2015.[82]

Geography

Location and borders

The vast majority of France's territory and population is situated in Western Europe and is called Metropolitan France. It is bordered by the North Sea in the north, the English Channel in the northwest, the Atlantic Ocean in the west and the Mediterranean Sea in the southeast. Its land borders consist of Belgium and Luxembourg in the northeast, Germany and Switzerland in the east, Italy and Monaco in the southeast, and Andorra and Spain in the south and southwest. Except for the northeast, most of France's land borders are roughly delineated by natural boundaries and geographic features: to the south and southeast, the Pyrenees and the Alps and the Jura, respectively, and to the east, the Rhine river. Metropolitan France includes various coastal islands, of which the largest is Corsica. Metropolitan France is situated mostly between latitudes 41° and 51° N, and longitudes 6° W and 10° E, on the western edge of Europe, and thus lies within the northern temperate zone. Its continental part covers about 1000 km from north to south and from east to west.

Metropolitan France covers 551,500 square kilometres (212,935 sq mi),[83] the largest among European Union members.[17] France's total land area, with its overseas departments and territories (excluding Adélie Land), is 643,801 km2 (248,573 sq mi), 0.45% of the total land area on Earth. France possesses a wide variety of landscapes, from coastal plains in the north and west to mountain ranges of the Alps in the southeast, the Massif Central in the south-central and Pyrenees in the southwest.

Due to its numerous overseas departments and territories scattered across the planet, France possesses the second-largest exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the world, covering 11,035,000 km2 (4,261,000 sq mi). Its EEZ covers approximately 8% of the total surface of all the EEZs of the world.

Geology, topography and hydrography

Metropolitan France has a wide variety of topographical sets and natural landscapes. During the Hercynian uplift in the Paleozoic Era, the Armorican Massif, the Massif Central, the Morvan, the Vosges and Ardennes ranges and the island of Corsica were formed. These massifs delineate several sedimentary basins such as the Aquitaine Basin in the southwest and the Paris Basin in the north. Various routes of natural passage, such as the Rhône Valley, allow easy communication. The Alpine, Pyrenean and Jura mountains are much younger and have less eroded forms. At 4,810.45 metres (15,782 ft)[84] above sea level, Mont Blanc, located in the Alps on the France–Italy border, is the highest point in Western Europe. Although 60% of municipalities are classified as having seismic risks (though moderate).

The coastlines offer contrasting landscapes: mountain ranges along the French Riviera, coastal cliffs such as the Côte d'Albâtre, and wide sandy plains in the Languedoc. Corsica lies off the Mediterranean coast. France has an extensive river system consisting of the four major rivers Seine, the Loire, the Garonne, the Rhône and their tributaries, whose combined catchment includes over 62% of the metropolitan territory. The Rhône divides the Massif Central from the Alps and flows into the Mediterranean Sea at the Camargue. The Garonne meets the Dordogne just after Bordeaux, forming the Gironde estuary, the largest estuary in Western Europe which after approximately 100 kilometres (62 mi) empties into the Atlantic Ocean.[85] Other water courses drain towards the Meuse and Rhine along the northeastern borders. France has 11,000,000 km2 (4,200,000 sq mi) of marine waters within three oceans under its jurisdiction, of which 97% are overseas.

Environment

France was one of the first countries to create an environment ministry, in 1971.[86] France is ranked 19th by carbon dioxide emissions due to the country's heavy investment in nuclear power following the 1973 oil crisis,[87] which now accounts for 75 per cent of its electricity production[88] and results in less pollution.[89][90] According to the 2020 Environmental Performance Index conducted by Yale and Columbia, France was the fifth most environmentally conscious country in the world.[91][92]

Like all European Union state members, France agreed to cut carbon emissions by at least 20% of 1990 levels by 2020.[93] As of 2009[update], French carbon dioxide emissions per capita were lower than that of China.[94] The country was set to impose a carbon tax in 2009;[95] however, the plan was abandoned due to fears of burdening French businesses.[96]

Forests account for 31 per cent of France's land area—the fourth-highest proportion in Europe—representing an increase of 7 per cent since 1990.[97][98][99] French forests are some of the most diverse in Europe, comprising more than 140 species of trees.[100] France had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.52/10, ranking it 123rd globally.[101] There are nine national parks[102] and 46 natural parks in France.[103] A regional nature park[104] (French: parc naturel régional or PNR) is a public establishment in France between local authorities and the national government covering an inhabited rural area of outstanding beauty, to protect the scenery and heritage as well as setting up sustainable economic development in the area.[105][106] As of 2019[update] there are 54 PNRs in France.[107]

Government and politics

Government

France is a representative democracy organised as a unitary semi-presidential republic.[108] Democratic traditions and values are deeply rooted in French culture, identity and politics.[109] The Constitution of the Fifth Republic was approved by referendum on 28 September 1958, establishing a framework consisting of executive, legislative and judicial branches.[110] It sought to address the instability of the Third and Fourth Republics by combining elements of both parliamentary and presidential systems, while greatly strengthening the authority of the executive relative to the legislature.[109]

The executive branch has two leaders. The President of the Republic, currently Emmanuel Macron, is the head of state, elected directly by universal adult suffrage for a five-year term.[111] The Prime Minister, currently Gabriel Attal, is the head of government, appointed by the President to lead the government. The President has the power to dissolve Parliament or circumvent it by submitting referendums directly to the people; the President also appoints judges and civil servants, negotiates and ratifies international agreements, as well as serves as commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces. The Prime Minister determines public policy and oversees the civil service, with an emphasis on domestic matters.[112] In the 2022 presidential election, president Macron was re-elected.[113] Two months later, in the June 2022 legislative elections, Macron lost his parliamentary majority and had to form a minority government.[114]

The legislature consists of the French Parliament, a bicameral body made up of a lower house, the National Assembly (Assemblée nationale) and an upper house, the Senate.[115] Legislators in the National Assembly, known as députés, represent local constituencies and are directly elected for five-year terms.[116] The Assembly has the power to dismiss the government by majority vote. Senators are chosen by an electoral college for six-year terms, with half the seats submitted to election every three years.[117] The Senate's legislative powers are limited; in the event of disagreement between the two chambers, the National Assembly has the final say.[118] The parliament is responsible for determining the rules and principles concerning most areas of law, political amnesty, and fiscal policy; however, the government may draft specific details concerning most laws.

From World War II until 2017, French politics was dominated by two politically opposed groupings: one left-wing, the French Section of the Workers' International, which was succeeded by the Socialist Party (in 1969); and the other right-wing, the Gaullist Party, whose name changed over time to the Rally of the French People (1947), the Union of Democrats for the Republic (1958), the Rally for the Republic (1976), the Union for a Popular Movement (2007) and The Republicans (since 2015). In the 2017 presidential and legislative elections, the radical centrist party La République En Marche! (LREM) became the dominant force, overtaking both Socialists and Republicans. LREM's opponent in the second round of the 2017 and 2022 presidential elections was the growing far-right party National Rally (RN). Since 2020, Europe Ecology – The Greens (EELV) have performed well in mayoral elections in major cities[119] while on a national level, an alliance of Left parties (the NUPES) was the second-largest voting block elected to the lower house in 2022.[120] Right-wing populist RN became the largest opposition party in the National Assembly in 2022.[121]

The electorate is constitutionally empowered to vote on amendments passed by the Parliament and bills submitted by the president. Referendums have played a key role in shaping French politics and even foreign policy; voters have decided on such matters as Algeria's independence, the election of the president by popular vote, the formation of the EU, and the reduction of presidential term limits.[122]

Administrative divisions

The French Republic is divided into 18 regions (located in Europe and overseas), five overseas collectivities, one overseas territory, one special collectivity—New Caledonia and one uninhabited island directly under the authority of the Minister of Overseas France—Clipperton.

Regions

Since 2016, France is divided into 18 administrative regions: 13 regions in metropolitan France (including Corsica),[123] and five overseas.[83] The regions are further subdivided into 101 departments,[124] which are numbered mainly alphabetically. The department number is used in postal codes and was formerly used on vehicle registration plates. Among the 101 French departments, five (French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Mayotte, and Réunion) are in overseas regions (ROMs) that are simultaneously overseas departments (DOMs), enjoying the same status as metropolitan departments and are thereby included in the European Union.

The 101 departments are subdivided into 335 arrondissements, which are, in turn, subdivided into 2,054 cantons.[125] These cantons are then divided into 36,658 communes, which are municipalities with an elected municipal council.[125] Three communes—Paris, Lyon and Marseille—are subdivided into 45 municipal arrondissements.

Overseas territories and collectivities

In addition to the 18 regions and 101 departments, the French Republic has five overseas collectivities (French Polynesia, Saint Barthélemy, Saint Martin, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, and Wallis and Futuna), one sui generis collectivity (New Caledonia), one overseas territory (French Southern and Antarctic Lands), and one island possession in the Pacific Ocean (Clipperton Island). Overseas collectivities and territories form part of the French Republic, but do not form part of the European Union or its fiscal area (except for Saint Barthélemy, which seceded from Guadeloupe in 2007). The Pacific Collectivities (COMs) of French Polynesia, Wallis and Futuna, and New Caledonia continue to use the CFP franc[126] whose value is strictly linked to that of the euro. In contrast, the five overseas regions used the French franc and now use the euro.[127]

Foreign relations

France is a founding member of the United Nations and serves as one of the permanent members of the UN Security Council with veto rights.[128] In 2015, it was described as "the best networked state in the world" due to its membership in more international institutions than any other country;[129] these include the G7, World Trade Organization (WTO),[130] the Pacific Community (SPC)[131] and the Indian Ocean Commission (COI).[132] It is an associate member of the Association of Caribbean States (ACS)[133] and a leading member of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF) of 84 French-speaking countries.[134]

As a significant hub for international relations, France has the third-largest assembly of diplomatic missions, second only to China and the United States, which are far more populous. It also hosts the headquarters of several international organisations, including the OECD, UNESCO, Interpol, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, and the OIF.[137]

French foreign policy after World War II has been largely shaped by membership in the European Union, of which it was a founding member. Since the 1960s, France has developed close ties with reunified Germany to become the most influential driving force of the EU.[138] Since 1904, France has maintained an "Entente cordiale" with the United Kingdom, and there has been a strengthening of links between the countries, especially militarily.

France is a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), but under President de Gaulle excluded itself from the joint military command, in protest of the Special Relationship between the United States and Britain, and to preserve the independence of French foreign and security policies. Under Nicolas Sarkozy, France rejoined the NATO joint military command on 4 April 2009.[139][140][141]

France retains strong political and economic influence in its former African colonies (Françafrique)[142] and has supplied economic aid and troops for peacekeeping missions in Ivory Coast and Chad.[143] From 2012 to 2021, France and other African states intervened in support of the Malian government in the Northern Mali conflict.

In 2017, France was the world's fourth-largest donor of development aid in absolute terms, behind the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom.[144] This represents 0.43% of its GNP, the 12th highest among the OECD.[145] Aid is provided by the governmental French Development Agency, which finances primarily humanitarian projects in sub-Saharan Africa,[146] with an emphasis on "developing infrastructure, access to health care and education, the implementation of appropriate economic policies and the consolidation of the rule of law and democracy".[146]

Military

The French Armed Forces (Forces armées françaises) are the military and paramilitary forces of France, under the President of the Republic as supreme commander. They consist of the French Army (Armée de Terre), the French Navy (Marine Nationale, formerly called Armée de Mer), the French Air and Space Force (Armée de l'Air et de l’Espace), and the National Gendarmerie (Gendarmerie nationale), which serves as both military police and civil police in rural areas. Together they are among the largest armed forces in the world and the largest in the EU. According to a 2018 study by Crédit Suisse, the French Armed Forces ranked as the world's sixth-most powerful military, and the second most powerful in Europe.[147] France's annual military expenditure in 2022 was US$53.6 billion, or 1.9% of its GDP, making it the eighth biggest military spender in the world.[148] There has been no national conscription since 1997.[149]

France has been a recognised nuclear state since 1960. It is a party to both the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT)[150] and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. The French nuclear force (formerly known as "Force de Frappe") consists of four Triomphant class submarines equipped with submarine-launched ballistic missiles. In addition to the submarine fleet, it is estimated that France has about 60 ASMP medium-range air-to-ground missiles with nuclear warheads;[151] 50 are deployed by the Air and Space Force using the Mirage 2000N long-range nuclear strike aircraft, while around 10 are deployed by the French Navy's Super Étendard Modernisé (SEM) attack aircraft, which operate from the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle.

France has major military industries and one of the largest aerospace sectors in the world.[152] The country has produced such equipment as the Rafale fighter, the Charles de Gaulle aircraft carrier, the Exocet missile and the Leclerc tank among others. France is a major arms seller,[153][154] with most of its arsenal's designs available for the export market, except for nuclear-powered devices.

One French intelligence unit, the Directorate-General for External Security (Direction générale de la sécurité extérieure), is considered to be a component of the Armed Forces under the authority of the Ministry of Defense. The other, the Directorate-General for Internal Security (Direction générale de la Sécurité intérieure) operates under the authority of the Ministry of the Interior.[155] France's cybersecurity capabilities are regularly ranked as some of the most robust of any nation in the world.[156][157]

French weapons exported totaled 27 billion euros in 2022, up from 11.7 billion euros the previous year 2021. Additionally, the UAE alone contributed more than 16 billion euros arms to the French total.[158] Among the largest French defence companies are Dassault, Thales and Safran.[159]

Law

France uses a civil legal system, wherein law arises primarily from written statutes;[83] judges are not to make law, but merely to interpret it (though the amount of judicial interpretation in certain areas makes it equivalent to case law in a common law system). Basic principles of the rule of law were laid in the Napoleonic Code (which was largely based on the royal law codified under Louis XIV). In agreement with the principles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, the law should only prohibit actions detrimental to society.

French law is divided into two principal areas: private law and public law. Private law includes, in particular, civil law and criminal law. Public law includes, in particular, administrative law and constitutional law. However, in practical terms, French law comprises three principal areas of law: civil law, criminal law, and administrative law. Criminal laws can only address the future and not the past (criminal ex post facto laws are prohibited).[160] While administrative law is often a subcategory of civil law in many countries, it is completely separated in France and each body of law is headed by a specific supreme court: ordinary courts (which handle criminal and civil litigation) are headed by the Court of Cassation and administrative courts are headed by the Council of State. To be applicable, every law must be officially published in the Journal officiel de la République française.[citation needed]

France does not recognise religious law as a motivation for the enactment of prohibitions; it has long abolished blasphemy laws and sodomy laws (the latter in 1791). However, "offences against public decency" (contraires aux bonnes mœurs) or disturbing public order (trouble à l'ordre public) have been used to repress public expressions of homosexuality or street prostitution.[citation needed]

France generally has a positive reputation regarding LGBT rights.[161] Since 1999, civil unions for homosexual couples have been permitted, and since 2013, same-sex marriage and LGBT adoption are legal.[162] Laws prohibiting discriminatory speech in the press are as old as 1881. Some consider hate speech laws in France to be too broad or severe, undermining freedom of speech.[163] France has laws against racism and antisemitism,[164] while the 1990 Gayssot Act prohibits Holocaust denial. In 2024, France became the first nation in the European Union to explicitly protect abortion in its constitution.[165]

Freedom of religion is constitutionally guaranteed by the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. The 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State is the basis for laïcité (state secularism): the state does not formally recognise any religion, except in Alsace-Moselle, which continues to subsidize education and clergy of Catholicism, Lutheranism, Calvinism, and Judaism. Nonetheless, France does recognise religious associations. The Parliament has listed many religious movements as dangerous cults since 1995 and has banned wearing conspicuous religious symbols in schools since 2004. In 2010, it banned the wearing of face-covering Islamic veils in public; human rights groups such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch described the law as discriminatory towards Muslims.[166][167] However, it is supported by most of the population.[168]

Economy

Overview

France has a mixed market economy, characterised by sizeable government involvement, and economic diversity. For roughly two centuries, the French economy has consistently ranked among the ten largest globally; it is currently the world's ninth-largest by purchasing power parity, the seventh-largest by nominal GDP, and the second-largest in the European Union by both metrics.[170] France is considered an economic power, with membership in the Group of Seven leading industrialised countries, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the Group of Twenty largest economies.

France's economy is highly diversified; services represent two-thirds of both the workforce and GDP,[171] while the industrial sector accounts for a fifth of GDP and a similar proportion of employment. France is the third-biggest manufacturing country in Europe, behind Germany and Italy, and ranks eighth in the world by share of global manufacturing output, at 1.9 per cent.[172] Less than 2 per cent of GDP is generated by the primary sector, namely agriculture;[173] however, France's agricultural sector is among the largest in value and leads the EU in terms of overall production.[174]

In 2018, France was the fifth-largest trading nation in the world and the second-largest in Europe, with the value of exports representing over a fifth of GDP.[175] Its membership in the eurozone and the broader European single market facilitates access to capital, goods, services, and skilled labour.[176] Despite protectionist policies over certain industries, particularly in agriculture, France has generally played a leading role in fostering free trade and commercial integration in Europe to enhance its economy.[177][178] In 2019, it ranked first in Europe and 13th in the world in foreign direct investment, with European countries and the United States being leading sources.[179] According to the Bank of France (founded in 1800),[180] the leading recipients of FDI were manufacturing, real estate, finance and insurance.[181] The Paris Region has the highest concentration of multinational firms in mainland Europe.[181]

Under the doctrine of Dirigisme, the government historically played a major role in the economy; policies such as indicative planning and nationalisation are credited for contributing to three decades of unprecedented postwar economic growth known as Trente Glorieuses. At its peak in 1982, the public sector accounted for one-fifth of industrial employment and over four-fifths of the credit market. Beginning in the late 20th century, France loosened regulations and state involvement in the economy, with most leading companies now being privately owned; state ownership now dominates only transportation, defence and broadcasting.[182] Policies aimed at promoting economic dynamism and privatisation have improved France's economic standing globally: it is among the world's 10 most innovative countries in the 2020 Bloomberg Innovation Index,[183] and the 15th most competitive, according to the 2019 Global Competitiveness Report (up two places from 2018).[184]

The Paris stock exchange (French: La Bourse de Paris) is one of the oldest in the world, created in 1724.[185] In 2000, it merged with counterparts in Amsterdam and Brussels to form Euronext,[186] which in 2007 merged with the New York stock exchange to form NYSE Euronext, the world's largest stock exchange.[186] Euronext Paris, the French branch of NYSE Euronext, is Europe's second-largest stock exchange market. Some examples of the most valuable French companies include LVMH, L'Oréal and Sociéte Générale.[187]

France has historically been one of the world's major agricultural centres and remains a "global agricultural powerhouse"; France is the world's sixth-biggest exporter of agricultural products, generating a trade surplus of over €7.4 billion.[188][189] Nicknamed "the granary of the old continent",[190] over half its total land area is farmland, of which 45 per cent is devoted to permanent field crops such as cereals. The country's diverse climate, extensive arable land, modern farming technology, and EU subsidies have made it Europe's leading agricultural producer and exporter.[191]

Tourism

With 100 million international tourist arrivals in 2023,[15] France is the world's top tourist destination, ahead of Spain (85 million) and the United States (66 million). However, it ranks third in tourism-derived income due to the shorter duration of visits.[192] The most popular tourist sites include (annual visitors): Eiffel Tower (6.2 million), Château de Versailles (2.8 million), Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle (2 million), Pont du Gard (1.5 million), Arc de Triomphe (1.2 million), Mont Saint-Michel (1 million), Sainte-Chapelle (683,000), Château du Haut-Kœnigsbourg (549,000), Puy de Dôme (500,000), Musée Picasso (441,000), and Carcassonne (362,000).[193]

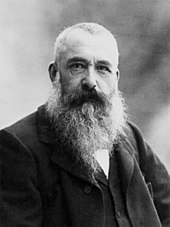

France, especially Paris, has some of the world's largest and most renowned museums, including the Louvre, which is the most visited art museum in the world (7.7 million visitors in 2022), the Musée d'Orsay (3.3 million), mostly devoted to Impressionism, the Musée de l'Orangerie (1.02 million), which is home to eight large Water Lily murals by Claude Monet, as well as the Centre Georges Pompidou (3 million), dedicated to contemporary art. Disneyland Paris is Europe's most popular theme park, with 15 million combined visitors to the resort's Disneyland Park and Walt Disney Studios Park in 2009.[194] With more than 10 million tourists a year, the French Riviera (French: Côte d'Azur), in Southeast France, is the second leading tourist destination in the country, after the Paris Region.[195] With 6 million tourists a year, the castles of the Loire Valley (French: châteaux) and the Loire Valley itself are the third leading tourist destination in France.[196][197]

France has 52 sites inscribed in UNESCO's World Heritage List and features cities of high cultural interest, beaches and seaside resorts, ski resorts, as well as rural regions that many enjoy for their beauty and tranquillity (green tourism). Small and picturesque French villages are promoted through the association Les Plus Beaux Villages de France (literally "The Most Beautiful Villages of France"). The "Remarkable Gardens" label is a list of the over 200 gardens classified by the Ministry of Culture. This label is intended to protect and promote remarkable gardens and parks. France attracts many religious pilgrims on their way to St. James, or to Lourdes, a town in the Hautes-Pyrénées that hosts several million visitors a year.

Energy

France is the world's tenth-largest producer of electricity.[198] Électricité de France (EDF), which is majority-owned by the French government, is the country's main producer and distributor of electricity, and one of the world's largest electric utility companies, ranking third in revenue globally.[199] In 2018, EDF produced around one-fifth of the European Union's electricity, primarily from nuclear power.[200] As of 2021, France was the biggest energy exporter in Europe, mostly to the U.K. and Italy,[201] and the largest net exporter of electricity in the world.[201]

Since the 1973 oil crisis, France has pursued a strong policy of energy security,[201] namely through heavy investment in nuclear energy. It is one of 32 countries with nuclear power plants, ranking second in the world by the number of operational nuclear reactors, at 56.[202] Consequently, 70% of France's electricity is generated by nuclear power, the highest proportion in the world by a wide margin;[203] only Slovakia and Ukraine also derive a majority of electricity from nuclear power, at roughly 53% and 51%, respectively.[204] France is considered a world leader in nuclear technology, with reactors and fuel products being major exports.[201]

France's significant reliance on nuclear power has resulted in comparatively slower development of renewable energy sources than in other Western nations. Nevertheless, between 2008 and 2019, France's production capacity from renewable energies rose consistently and nearly doubled.[205] Hydropower is by far the leading source, accounting for over half the country's renewable energy sources[206] and contributing 13% of its electricity,[205] the highest proportion in Europe after Norway and Turkey.[206] As with nuclear power, most hydroelectric plants, such as Eguzon, Étang de Soulcem, and Lac de Vouglans, are managed by EDF.[206] France aims to further expand hydropower into 2040.[205]

Transport

France's railway network, which stretches 29,473 kilometres (18,314 mi) as of 2008,[208] is the second most extensive in Western Europe after Germany.[209] It is operated by the SNCF, and high-speed trains include the Thalys, the Eurostar and TGV, which travels at 320 km/h (199 mph).[210] The Eurostar, along with the Eurotunnel Shuttle, connects with the United Kingdom through the Channel Tunnel. Rail connections exist to all other neighbouring countries in Europe except Andorra. Intra-urban connections are also well developed, with most major cities having underground or tramway services complementing bus services.

There are approximately 1,027,183 kilometres (638,262 mi) of serviceable roadway in France, ranking it the most extensive network of the European continent.[211] The Paris Region is enveloped with the densest network of roads and highways, which connect it with virtually all parts of the country. French roads also handle substantial international traffic, connecting with cities in neighbouring Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Spain, Andorra and Monaco. There is no annual registration fee or road tax; however, usage of the mostly privately owned motorways is through tolls except in the vicinity of large communes. The new car market is dominated by domestic brands such as Renault, Peugeot and Citroën.[212] France possesses the Millau Viaduct, the world's tallest bridge,[213] and has built many important bridges such as the Pont de Normandie. Diesel and petrol-driven cars and lorries cause a large part of the country's air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.[214][215]

There are 464 airports in France.[83] Charles de Gaulle Airport, located in the vicinity of Paris, is the largest and busiest airport in the country, handling the vast majority of popular and commercial traffic and connecting Paris with virtually all major cities across the world. Air France is the national carrier airline, although numerous private airline companies provide domestic and international travel services. There are ten major ports in France, the largest of which is in Marseille,[216] which also is the largest bordering the Mediterranean Sea.[217] 12,261 kilometres (7,619 mi) of waterways traverse France including the Canal du Midi, which connects the Mediterranean Sea to the Atlantic Ocean through the Garonne river.[83]

Science and technology

Since the Middle Ages, France has contributed to scientific and technological achievement. In the early 11th century, the French-born Pope Sylvester II reintroduced the abacus and armillary sphere and introduced Arabic numerals and clocks to much of Europe.[219] The University of Paris, founded in the mid-12th century, is still one of the most important academic institutions in the Western world.[220] In the 17th century, mathematician and philosopher René Descartes pioneered rationalism as a method for acquiring scientific knowledge, while Blaise Pascal became famous for his work on probability and fluid mechanics; both were key figures of the Scientific Revolution, which blossomed in Europe during this period. The French Academy of Sciences, founded in the mid-17th century by Louis XIV to encourage and protect French scientific research, was one of the earliest national scientific institutions in history.

The Age of Enlightenment was marked by the work of biologist Buffon, one of the first naturalists to recognize ecological succession, and chemist Lavoisier, who discovered the role of oxygen in combustion. Diderot and D'Alembert published the Encyclopédie, which aimed to give the public access to "useful knowledge" that could be applied to everyday life.[221] The Industrial Revolution of the 19th century saw spectacular scientific developments in France, with Augustin Fresnel founding modern optics, Sadi Carnot laying the foundations of thermodynamics, and Louis Pasteur pioneering microbiology. Other eminent French scientists of the period have their names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

Famous French scientists of the 20th century include the mathematician and physicist Henri Poincaré; physicists Henri Becquerel, Pierre and Marie Curie, who remain famous for their work on radioactivity; physicist Paul Langevin; and virologist Luc Montagnier, co-discoverer of HIV AIDS. Hand transplantation was developed in Lyon in 1998 by an international team that included Jean-Michel Dubernard, who afterward performed the first successful double hand transplant.[222] Telesurgery was first performed by French surgeons led by Jacques Marescaux on 7 September 2001 across the Atlantic Ocean.[223] A face transplant was first done on 27 November 2005 by Bernard Devauchelle.[224][225] France ranked 11th in the 2023 Global Innovation Index, compared to 16th in 2019.[226][227][228][229]

Demographics

With an estimated January 2024 population of 68,373,433 people,[8] France is the 20th most populous country in the world, the third-most populous in Europe (after Russia and Germany), and the second most populous in the European Union (after Germany).

France is an outlier among developed countries, particularly in Europe, for its relatively high rate of natural population growth: By birth rates alone, it was responsible for almost all natural population growth in the European Union in 2006.[230] Between 2006 and 2016, France saw the second-highest overall increase in population in the EU and was one of only four EU countries where natural births accounted for the most population growth.[231] This was the highest rate since the end of the baby boom in 1973 and coincides with the rise of the total fertility rate from a nadir of 1.7 in 1994 to 2.0 in 2010.

As of January 2021[update], the fertility rate declined slightly to 1.84 children per woman, below the replacement rate of 2.1, and considerably below the high of 4.41 in 1800.[232][233][234][235] France's fertility rate and crude birth rate nonetheless remain among the highest in the EU. However, like many developed nations, the French population is aging; the average age is 41.7 years, while about a fifth of French people are 65 or over.[236] The life expectancy at birth is 82.7 years, the 12th highest in the world.

From 2006 to 2011, population growth averaged 0.6 per cent per year;[237] since 2011, annual growth has been between 0.4 and 0.5 per cent annually.[238] Immigrants are major contributors to this trend; in 2010, 27 per cent of newborns in metropolitan France had at least one foreign-born parent and another 24 per cent had at least one parent born outside Europe (excluding French overseas territories).[239]

Major cities

France is a highly urbanised country, with its largest cities (in terms of metropolitan area population in 2021[240]) being Paris (13,171,056 inh.), Lyon (2,308,818), Marseille (1,888,788), Lille (1,521,660), Toulouse (1,490,640), Bordeaux (1,393,764), Nantes (1,031,953), Strasbourg (864,993), Montpellier (823,120), and Rennes (771,320). (Note: since its 2020 revision of metropolitan area borders, INSEE considers that Nice is a metropolitan area separate from the Cannes-Antibes metropolitan area; these two combined would have a population of 1,019,905, as of the 2021 census). Rural flight was a perennial political issue throughout most of the 20th century.

Largest metropolitan areas in France

2021 census | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

Paris  Lyon |

1 | Paris | Île-de-France | 13,171,056 | 11 | Grenoble | Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 722,904 | |

| 2 | Lyon | Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 2,308,818 | 12 | Rouen | Normandy | 709,065 | ||

| 3 | Marseille | Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur | 1,888,788 | 13 | Nice | Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur | 626,218 | ||

| 4 | Lille | Hauts-de-France | 1,521,660 | 14 | Toulon | Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur | 581,948 | ||

| 5 | Toulouse | Occitania | 1,490,640 | 15 | Tours | Centre-Val de Loire | 522,597 | ||

| 6 | Bordeaux | Nouvelle-Aquitaine | 1,393,764 | 16 | Nancy | Grand Est | 508,793 | ||

| 7 | Nantes | Pays de la Loire | 1,031,953 | 17 | Clermont-Ferrand | Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 508,699 | ||

| 8 | Strasbourg | Grand Est | 864,993 | 18 | Saint-Étienne | Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 500,562 | ||

| 9 | Montpellier | Occitania | 823,120 | 19 | Caen | Normandy | 478,105 | ||

| 10 | Rennes | Brittany | 771,320 | 20 | Orléans | Centre-Val de Loire | 456,452 | ||

Ethnic groups

Historically, French people were mainly of Celtic-Gallic origin, with a significant admixture of Italic (Romans) and Germanic (Franks) groups reflecting centuries of respective migration and settlement.[241] Through the course of the Middle Ages, France incorporated various neighbouring ethnic and linguistic groups, as evidenced by Breton elements in the west, Aquitanian in the southwest, Scandinavian in the northwest, Alemannic in the northeast, and Ligurian in the southeast.

Large-scale immigration over the last century and a half have led to a more multicultural society; beginning with the French Revolution, and further codified in the French Constitution of 1958, the government is prohibited from collecting data on ethnicity and ancestry; most demographic information is drawn from private sector organisations or academic institutions. In 2004, the Institut Montaigne estimated that within Metropolitan France, 51 million people were White (85% of the population), 6 million were Northwest African (10%), 2 million were Black (3.3%), and 1 million were Asian (1.7%).[242][243]

A 2008 poll conducted jointly by the Institut national d'études démographiques and the French National Institute of Statistics[244][245] estimated that the largest minority ancestry groups were Italian (5 million), followed by Northwest African (3–6 million),[246][247][248] Sub-Saharan African (2.5 million), Armenian (500,000), and Turkish (200,000).[249] There are also sizeable minorities of other European ethnic groups, namely Spanish, Portuguese, Polish, and Greek.[246][250][251] France has a significant Gitan (Romani) population, numbering between 20,000 and 400,000;[252] many foreign Roma are expelled back to Bulgaria and Romania frequently.[253]

Immigration

It is currently estimated that 40% of the French population is descended at least partially from the different waves of immigration since the early 20th century;[254] between 1921 and 1935 alone, about 1.1 million net immigrants came to France.[255] The next largest wave came in the 1960s when around 1.6 million pieds noirs returned to France following the independence of its Northwest African possessions, Algeria and Morocco.[256][257] They were joined by numerous former colonial subjects from North and West Africa, as well as numerous European immigrants from Spain and Portugal.

France remains a major destination for immigrants, accepting about 200,000 legal immigrants annually.[258] In 2005, it was Western Europe's leading recipient of asylum seekers, with an estimated 50,000 applications (albeit a 15% decrease from 2004).[259] In 2010, France received about 48,100 asylum applications—placing it among the top five asylum recipients in the world.[260] In subsequent years it saw the number of applications increase, ultimately doubling to 100,412 in 2017.[261] The European Union allows free movement between the member states, although France established controls to curb Eastern European migration.[citation needed] Foreigners' rights are established in the Code of Entry and Residence of Foreigners and of the Right to Asylum. Immigration remains a contentious political issue.[262]

In 2008, the INSEE (National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies) estimated that the total number of foreign-born immigrants was around 5 million (8% of the population), while their French-born descendants numbered 6.5 million, or 11% of the population. Thus, nearly a fifth of the country's population were either first or second-generation immigrants, of which more than 5 million were of European origin and 4 million of Maghrebi ancestry.[263][264][265] In 2008, France granted citizenship to 137,000 persons, mostly from Morocco, Algeria and Turkey.[266] In 2022, more than 320,000 migrants came to France, with the majority coming from Africa.[267]

In 2014, the INSEE reported a significant increase in the number of immigrants coming from Spain, Portugal and Italy between 2009 and 2012. According to the institute, this increase resulted from the financial crisis that hit several European countries in that period.[268] Statistics on Spanish immigrants in France show a growth of 107 per cent between 2009 and 2012, with the population growing from 5,300 to 11,000.[268] Of the total of 229,000 foreigners coming to France in 2012, nearly 8% were Portuguese, 5% British, 5% Spanish, 4% Italian, 4% German, 3% Romanian, and 3% Belgian.[268]

Language

The official language of France is French,[269] a Romance language derived from Latin. Since 1635, the Académie française has been France's official authority on the French language, although its recommendations carry no legal weight. There are also regional languages spoken in France, such as Occitan, Breton, Catalan, Flemish (Dutch dialect), Alsatian (German dialect), Basque, and Corsican (Italian dialect). Italian was the official language of Corsica until 9 May 1859.[270]

The Government of France does not regulate the choice of language in publications by individuals, but the use of French is required by law in commercial and workplace communications. In addition to mandating the use of French in the territory of the Republic, the French government tries to promote French in the European Union and globally through institutions such as the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie. Besides French, there exist 77 vernacular minority languages of France, eight spoken in French metropolitan territory and 69 in the French overseas territories. It is estimated that between 300 million[271] and 500 million[272] people worldwide can speak French, either as a mother tongue or as a second language.

According to the 2007 Adult Education survey, part of a project by the European Union and carried out in France by the INSEE and based on a sample of 15,350 persons, French was the native language of 87.2% of the total population, or roughly 55.81 million people, followed by Arabic (3.6%, 2.3 million), Portuguese (1.5%, 960,000), Spanish (1.2%, 770,000) and Italian (1.0%, 640,000). Native speakers of other languages made up the remaining 5.2% of the population.[273]

Religion

France is a secular country in which freedom of religion is a constitutional right. The French policy on religion is based on the concept of laïcité, a strict separation of church and state under which the government and public life are kept completely secular, detached from any religion. The region of Alsace and Moselle is an exception to the general French norm since the local law stipulates official status and state funding for Lutheranism, Catholicism, and Judaism. According to the national survey of 2020 held by the INSEE,[XII] 34-38% of the French population adhered to Christianity, of whom approximately 25-29% were Catholics and 9% other Christians (without further specification); at the same time, 10-11% of the French population adhered to Islam, 0.5% to Buddhism, 0.5% to Judaism, and 1% to other religions.[4] 51-53% of the population declared that they had no religion.[4]

Catholicism was the main religion in France for more than a millennium, and it was once the country's state religion. Its role nowadays, however, has been greatly reduced, although, as of 2012, among the 47,000 religious buildings in France 94% were still Catholic churches.[274] After alternating between royal and secular republican governments during the 19th century, in 1905 France passed the 1905 law on the Separation of the Churches and the State, which established the aforementioned principle of laïcité.[275]

The government is prohibited from recognising specific rights to any religious community (with the exception of legacy statutes like those of military chaplains and the aforementioned local law in Alsace-Moselle). It recognises religious organisations according to formal legal criteria that do not address religious doctrine, and religious organisations are expected to refrain from intervening in policymaking.[276] Some religious groups, such as Scientology, the Children of God, the Unification Church, and the Order of the Solar Temple, are considered cults (sectes in French, which is considered a pejorative term[277]) in France, and therefore they are not granted the same status as recognised religions.[278]

Health

The French health care system is one of universal health care largely financed by government national health insurance. In its 2000 assessment of world health care systems, the World Health Organization found that France provided the "close to best overall health care" in the world.[280] The French health care system was ranked first worldwide by the World Health Organization in 1997.[281][282] In 2011, France spent 11.6% of its GDP on health care, or US$4,086 per capita,[283] a figure much higher than the average spent by countries in Europe but less than in the United States. Approximately 77% of health expenditures are covered by government-funded agencies.[284]

Care is generally free for people affected by chronic diseases (affections de longues durées) such as cancer, AIDS or cystic fibrosis. The life expectancy at birth is 78 years for men and 85 years for women, one of the highest in the European Union and the World.[285][286] There are 3.22 physicians for every 1000 inhabitants in France,[287] and average health care spending per capita was US$4,719 in 2008.[288] As of 2007[update], approximately 140,000 inhabitants (0.4%) of France are living with HIV/AIDS.[83]

Education

In 1802, Napoleon created the lycée, the second and final stage of secondary education that prepares students for higher education studies or a profession.[290] Jules Ferry is considered the father of the French modern school, leading reforms in the late 19th century that established free, secular and compulsory education (currently mandatory until the age of 16).[291][292]

French education is centralised and divided into three stages: primary, secondary, and higher education. The Programme for International Student Assessment, coordinated by the OECD, ranked France's education as near the OECD average in 2018.[293][294] France was one of the PISA-participating countries where school children perceived some of the lowest levels of support and feedback from their teachers.[294] Schoolchildren in France reported greater concern about the disciplinary climate and behaviour in classrooms compared to other OECD countries.[294]

Higher education is divided between public universities and the prestigious and selective Grandes écoles, such as Sciences Po Paris for political studies, HEC Paris for economics, Polytechnique, the École des hautes études en sciences sociales for social studies and the École nationale supérieure des mines de Paris that produce high-profile engineers, or the École nationale d'administration for careers in the Grands Corps of the state. The Grandes écoles have been criticised for alleged elitism, producing many if not most of France's high-ranking civil servants, CEOs and politicians.[295]

Culture

Art

The origins of French art were very much influenced by Flemish art and by Italian art at the time of the Renaissance. Jean Fouquet, the most famous medieval French painter, is said to have been the first to travel to Italy and experience the Early Renaissance firsthand. The Renaissance painting School of Fontainebleau was directly inspired by Italian painters such as Primaticcio and Rosso Fiorentino, who both worked in France. Two of the most famous French artists of the time of the Baroque era, Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, lived in Italy.

French artists developed the rococo style in the 18th century, as a more intimate imitation of the old baroque style, the works of the court-endorsed artists Antoine Watteau, François Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard being the most representative in the country. The French Revolution brought great changes, as Napoleon favoured artists of neoclassic style such as Jacques-Louis David and the highly influential Académie des Beaux-Arts defined the style known as Academism.

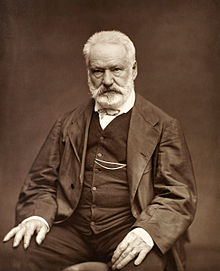

In the second part of the 19th century, France's influence over painting grew, with the development of new styles of painting such as Impressionism and Symbolism. The most famous impressionist painters of the period were Camille Pissarro, Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir.[296] The second generation of impressionist-style painters, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Toulouse-Lautrec and Georges Seurat, were also at the avant-garde of artistic evolutions,[297] as well as the fauvist artists Henri Matisse, André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck.[298][299]