Атомные взрывы Хиросимы и Нагасаки

| Атомные взрывы Хиросимы и Нагасаки | |

|---|---|

| Часть Тихоокеанской войны войны Второй мировой | |

атомной бомбы Грибные грибные облака над Хиросимой (слева) и Нагасаки (справа) | |

| Тип | Ядерная бомбардировка |

| Расположение | 34 ° 23′41 ″ N 132 ° 27′17 ″ E / 34,39472 ° N 132,45472 ° E 32 ° 46′25 ″ с.ш. 129 ° 51′48 ″ E / 32,77361 ° N 129,86333 ° E |

| Дата | 6 и 9 августа 1945 г. |

| Выполнено | |

| Жертвы | Хиросима:

Нагасаки:

Всего убито (к концу 1945 года):

|

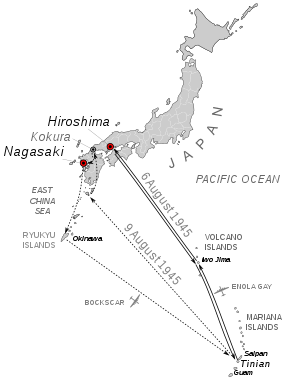

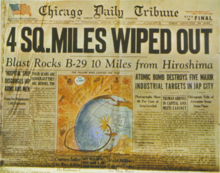

6 и 9 августа 1945 года Соединенные Штаты взорвали две атомные бомбы над японскими городами Хиросима и Нагасаки соответственно. В результате взрывов погибли между 150 000 и 246 000 человек, большинство из которых были гражданскими лицами, и остаются единственным использованием ядерного оружия в вооруженном конфликте. Япония сдалась союзникам 15 августа, через шесть дней после бомбардировки Нагасаки и Декларации войны Советского Союза против Японии и вторжения в японскую Маньчжурию . Правительство Японии подписало инструмент капитуляции 2 сентября, фактически положив конец войне .

В последний год Второй мировой войны союзники подготовились к дорогостоящему вторжению в японское материк . Этому начинанию предшествовали обычная кампания по бомбардировке и бомбардировке , которая опустошила 64 японских города, в том числе операция на Токио . Война в европейском театре завершилась, когда Германия сдалась 8 мая 1945 года, и союзники обратили все внимание на Тихоокеанскую войну . » союзников К июлю 1945 года проект «Манхэттен произвел два типа атомных бомб: « Маленький мальчик », обогащенное оружие с урановым оружием и « толстый человек », плутония ядерное оружие типа . 509- я композитная группа была ВВС армии Соединенных Штатов обучена и оснащена специализированной Silverplate версией Superfortress B-29 и развернута на Тиниан на Марианских островах . Союзники призвали к безусловной капитуляции имперских японских вооруженных сил в Потсдамской декларации 26 июля 1945 года, альтернативным является «быстрое и полное разрушение». Японское правительство проигнорировал ультиматум.

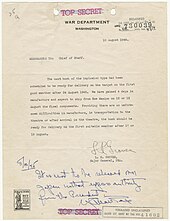

Согласие Соединенного Королевства было получено на бомбардировку, как требовалось Соглашение Квебека , и приказы были изданы 25 июля генералом Томасом Хэнди , исполняющим обязанности начальника штаба Армии Соединенных Штатов , на атомные бомбы, которые будут использоваться против Хиросима, Кокура , Ниигата и Нагасаки. Эти цели были выбраны потому, что они были крупными городскими районами, которые также содержали значительные средства. 6 августа маленький мальчик был сброшен на Хиросиму. Три дня спустя толстый человек был сброшен на Нагасаки. В течение следующих двух -четырех месяцев последствия атомных взрывов погибли от 90 000 до 166 000 человек в Хиросиме и от 60 000 до 80 000 человек в Нагасаки; Примерно половина произошла в первый день. В течение нескольких месяцев после этого многие люди продолжали умирать от последствий ожогов, радиационной болезни и других травм, усугубляемых болезнью и недоеданием. Хотя у Хиросимы был значительный военный гарнизон, большинство мертвых были гражданскими лицами.

Ученые широко изучали влияние взрывов на социальную и политическую характер последующей мировой истории и популярной культуры , и все еще есть много споров о этическом и юридическом оправдании для взрывов. По словам сторонников, атомные взрывы были необходимы, чтобы положить конец войне с минимальными жертвами и в конечном итоге предотвращали большую потерю жизни; По словам критиков, взрывы были ненужными для конца войны и были военным преступлением, что приводит к моральным и этическим последствиям.

Фон

Тихоокеанская война

Белый и зеленый: области, контролируемые Японией

Красный: области, контролируемые союзниками

Серый: области, контролируемые Советским Союзом (нейтральный)

В 1945 году Тихоокеанская война между империей Японии и союзниками вступила в четвертый год. Большинство японских военных подразделений яростно сражались, гарантируя, что победа союзников достигнет огромных затрат. 1,25 млн. Пострадавших от боевых действий, понесенных в общей сложности Соединенными Штатами во Второй мировой войне, включали оба военнослужащих, убитых в бою и раненых в бою . по июнь 1945 года около миллиона жертв произошли в течение последнего года войны С июня 1944 года . Взволнованный потерь, потерпевшие потери, президент Рузвельт предложил как можно скорее использование атомных бомб на Германии, но был проинформирован о первом полезном атомном оружии, которые были еще месяцами. [ 1 ] Американские резервы рабочей силы выходили. Отсрочки для таких групп, как работники сельского хозяйства, были ужесточены, и было рассмотрено составление женщин. В то же время публика становилась уставленной войной и требовала, чтобы давние военнослужащие были отправлены домой. [ 2 ]

В Тихом океане союзники вернулись на Филиппины , [ 3 ] Верно [ 4 ] и вторгся Борнео . [ 5 ] Нападали, чтобы уменьшить японские силы, оставшиеся в Бугенвилле , Новой Гвинее и на Филиппинах. [ 6 ] В апреле 1945 года американские войска приземлились на Окинаве , где тяжелые боевые действия продолжались до июня. Попутно соотношение японских и американских жертв упало с пяти к одному на Филиппинах до двух к одному на Окинаве. [ 2 ] Хотя некоторые японские солдаты были взяты в плен , большинство из них сражались, пока они не были убиты или совершены самоубийства . Почти 99 процентов из 21 000 защитников Иво -Джимы были убиты. Из 117 000 Окинаван и японских войск, защищающих Окинаву в апреле по июнь 1945 года, 94 процента были убиты; [ 7 ] 7,401 японские солдаты сдались, беспрецедентно большое количество. [ 8 ]

По мере того, как союзники продвинулись в сторону Японии, условия стали неуклонно хуже для японцев. Японский торговый флот снизился с 5 250 000 тонн валового регистра в 1941 году до 1 560 000 тонн в марте 1945 года и 557 000 тонн в августе 1945 года. Отсутствие сырья вынудило японскую военную экономику в резкое снижение после середины 1944 года. Гражданская экономика, которая привела медленно ухудшился на протяжении всей войны, достиг катастрофического уровня к середине 1945 года. Потеря доставки также повлияла на рыболовную флот, а улов 1945 года составлял только 22 процента от этого в 1941 году. Убор риса 1945 года был худшим с 1909 года, и и и и и худший. Голод и недоедание стали широко распространенными. Промышленное производство США в подавляющем большинстве превосходило Японию. К 1943 году США производили почти 100 000 самолетов в год по сравнению с производством Японии 70 000 за всю войну. В феврале 1945 года принц Фумимаро Коноэ посоветовал императору Хирохито , что поражение было неизбежным и призвал его отречься. [ 9 ]

Подготовка к вторжению в Японию

Еще до капитуляции нацистской Германии 8 мая 1945 года начались планы по крупнейшей деятельности Тихоокеанской войны, «Операция» , вторжение союзников в Японию. [ 10 ] В операции было две части: началось в октябре 1945 года, операция «Олимпийская игра» включала серию посадков шестой армии США , намеченной для захвата южной трети самого южного главного японского острова, Кьюшу . [ 11 ] Это должно было последовать в марте 1946 года «Операция Коронет» , захват равнины Канто , недалеко от Токио на главном японском острове Хоншу в американских восьмом , десятом и состоящего армиях, а также корпуса Содружества, из австралийского британского, британского и канадские подразделения. Целевая дата была выбрана для того, чтобы Олимпийские игры выполняли свои цели, чтобы войска были перевязаны из Европы, а японская зима проходила. [ 12 ]

География Японии сделала этот план вторжения очевидным для японцев; Они смогли точно предсказать планы вторжения союзников и, таким образом, скорректировать свой защитный план, операция Ketsugō , соответственно. Японцы запланировали тотальную защиту Кьюшу, и мало осталось в резерве. [ 13 ] В целом, было подготовлено 2,3 миллиона войск японской армии для защиты домашних островов, поддержанных гражданским ополчением в 28 миллионов. Прогнозы жертва сильно варьировались, но были чрезвычайно высокими. Вице -начальник Генерального штаба Императорского японского военно -морского флота , вице -адмирал Такиджиро Аниши , предсказал до 20 миллионов японских смертей. [ 14 ]

Американцы были встревожены японским накоплением, которое точно отслеживалось через Ultra Intelligence. [ 15 ] 15 июня 1945 года исследование Комитета Объединенного военных планов, [ 16 ] Опираясь на опыт битвы при Лейте , подсчитал, что падение приведет к от 132 500 до 220 000 жертв в США, причем мы погибшие и пропали бы в диапазоне от 27 500 до 50 000. [ 17 ] Министр военного министра Генри Л. Стимсон заказал свое собственное исследование Куинси Райта и Уильяма Шокли , которые, по оценкам, вторгающиеся союзники понесут от 1,7 до 4 миллионов жертв, из которых от 400 000 до 800 000 человек были бы мертвы, в то время как японские невыполнения были бы около 5 до 10 миллионов. [ 18 ] [ 19 ] На встрече с президентом и командирами 18 июня 1945 года генерал Джордж С. Маршалл заявил, что «есть основания полагать» потери в течение первых 30 дней не превышает цену, уплаченную за Лусона . Кроме того, с японской позицией, оказанной «безнадежным» вторжением в их материк, Маршалл предположил, что вступление советского в войну может быть «решающим действием», необходимым для окончательного «[использовать] их в капитуляции». [ 20 ]

Маршалл начал размышлять над использованием оружия, которое было «легко доступно и которое, несомненно, может снизить стоимость в американской жизни»: ядовитый газ . [ 21 ] Количество фосгене , горчичного газа , слезоточивого газа и хлорида цианогена были перемещены в Лусон из запасов в Австралии и Новой Гвинеи при подготовке к операции олимпийских игр, и Макартур гарантировал, что подразделения службы химической войны были обучены их использованию. [ 21 ] Рассмотрение также было уделено использованию биологического оружия . [ 22 ]

Воздушные налеты на Японию

В то время как Соединенные Штаты разработали планы на воздушную кампанию против Японии до Тихоокеанской войны, захват союзных баз в западной части Тихого океана в первые недели конфликта означал, что это наступление не началось до середины 1944 года, когда долгосрочные стала Boeing B-29 Superfortress Boeing B-29 готовой к использованию в бою. [ 23 ] Операция Материалхорн участвовал в индийском базирующемся в области B-29, проведенных по базам вокруг Чэнду в Китае, чтобы провести ряд рейдов на стратегические цели в Японии. [ 24 ] Этим усилиям не удалось достичь стратегических целей, которые предполагали его планировщики, в основном из -за логистических проблем, механических трудностей бомбардировщика, уязвимости китайских стадивших баз и крайнего диапазона, необходимых для достижения ключевых японских городов. [ 25 ]

Бригадный генерал Хейвуд С. Ханселл определил, что Гуам , Тиниан и Сайпан на островах Марианы будут лучше служить базами B-29, но они находились в японских руках. [ 26 ] Стратегии были сдвинуты, чтобы приспособить воздушную войну, [ 27 ] и острова были захвачены в период с июня по август 1944 года. Были разработаны авиационные базы, [ 28 ] и операции B-29 начались с Марианских в октябре 1944 года. [ 29 ] Командование XXI Bomber начало миссии против Японии 18 ноября 1944 года. [ 30 ] Ранние попытки бомбить Японию из Марианы оказались такими же неэффективными, как и китайские B-29. Ханселл продолжил практику проведения так называемой высокой точной бомбардировки , нацеленной на ключевые отрасли и транспортные сети, даже после того, как эта тактика не дала приемлемых результатов. [ 31 ] Эти усилия оказались неудачными из -за логистических трудностей с удаленным местоположением, технических проблем с новыми и передовыми самолетами, неблагоприятных погодных условий и действий противника. [ 32 ] [ 33 ]

Преемник Ханселла, генерал -майор Кертис Лемей , принял командование в январе 1945 года и первоначально продолжал использовать ту же точную тактику бомбардировки с одинаково неудовлетворительными результатами. Первоначально атаки были направлены на ключевые промышленные объекты, но большая часть японского производственного процесса была проведена в небольших мастерских и частных домах. [ 37 ] Под давлением штаб-квартиры ВВС Армии Соединенных Штатов (USAAF) в Вашингтоне Лемей изменил тактику и решил, что низкоуровневые зажигательные рейды против японских городов были единственным способом уничтожить их производственные возможности, переходя от точной бомбардировки к бомбардировке с зажиганиями. [ 38 ] Как и большинство стратегических бомбардировок во время Второй мировой войны , целью воздушного наступления на Японию было уничтожение военной промышленности противника, убийства или инъекции гражданских работников в этих отраслях и подорвать гражданский моральный дух . [ 39 ] [ 40 ]

В течение следующих шести месяцев командование Bomber XXI под командованием Lemay Fire бомбардировало 64 японских города. [ 41 ] Пожарная бомбардировка Токио , под кодовым названием «Собрание» , 9–10 марта убили примерно 100 000 человек и уничтожили 41 км 2 (16 кв. Миль) города и 267 000 зданий за одну ночь. Это был самый смертельный рейд войны, по цене 20 B-29, сбитых Flak and Fighters. [ 42 ] К маю 75 процентов сброшенных бомб были зажиганиями, предназначенными для сжигания Японских «бумажных городов». К середине июня шесть крупнейших городов Японии были опустошены. [ 43 ] Конец боевых действий на Окинаве в этом месяце обеспечил аэродромы еще ближе к материковой части Японии, что позволило бомбардировке быть дополнительно обостренными. союзников Самолеты, летящие из авианосцев и острова Рюкю, также регулярно выбивали цели в Японии в течение 1945 года, готовясь к падению операции. [ 44 ] Огненная бомбардировка переключилась на небольшие города, с населением от 60 000 до 350 000 человек. По словам Юки Танаки , США бомбардировали более ста японских городов и городов. [ 45 ]

страны Японские военные не смогли остановить нападения союзников, а подготовка к гражданской обороне оказалась неадекватной. Японские бойцы и зенитные орудия испытывали трудности с привлечением бомбардировщиков, летящих на большой высоте. [ 46 ] С апреля 1945 года японские перехватчики также должны были встретиться с американскими сопровождающими истребителями, основанными на Иво -Джиме и Окинаве. [ 47 ] В этом месяце авиационная служба имперской японской армии и авиационная служба Императорского японского флота перестали пытаться перехватить воздушные налеты, чтобы сохранить истребительные самолеты, чтобы противостоять ожидаемому вторжению. [ 48 ] К середине 1945 года японцы лишь изредка экранировали самолеты, чтобы перехватить отдельные B-29, проводящие разведывательные вылеты по стране, чтобы сохранить поставки топлива. [ 49 ] В июле 1945 года у японцев было 137 800 000 литров (1156 000 американских баррелей в АВГАС , закупленное вторжением в Японию. Около 72 000 000 литров (604 000 BBL США) было потреблено в районе домашних островов в апреле, мае и июне 1945 года. [ 50 ] В то время как японские военные решили возобновить атаки на бомбардировщиков союзников с конца июня, к этому времени было слишком мало операционных боевиков, доступных для этой смены тактики, чтобы препятствовать авиационным налетам союзников. [ 51 ]

Разработка атомной бомбы

Открытие ядерного деления в 1938 году сделало развитие атомной бомбы теоретической возможностью. [ 52 ] Опасения в том, что в первую очередь ученые, которые были беженцами из нацистской Германии и других фашистских стран, были выражены в письме Эйнштейн -Силард из Рузвельта в 1939 году. 1939. [ 53 ] Прогресс был медленным до появления отчета Британского комитета Мод в конце 1941 года, в котором указывалось, что только от 5 до 10 килограммов изотопно -обработанного труда урана -235 были необходимы для бомбы вместо тонн естественного урана и модератора нейтронов , такой как тяжелая вода . [ 54 ] Следовательно, работа была ускорена, сначала в качестве пилотной программы, и, наконец, в соглашении Рузвельта о передаче работы Инженерному корпусу армии США построить производственные мощности, необходимые для производства урана-235 и плутония-239 . Эта работа была консолидирована в недавно созданном районе Манхэттенского инженера, который стал более известным как проект Манхэттена , в конечном итоге под руководством генерала майора Лесли Р. Гроувса -младшего . [ 55 ]

Работа проекта Манхэттена состоялась на десятках участков по всей территории Соединенных Штатов, а даже некоторые за пределами его границ. В конечном итоге это будет стоить более 2 миллиардов долларов США (эквивалентно около 27 миллиардов долларов в 2023 году) [ 56 ] и нанимают более 125 000 человек одновременно на пике. Гроувс назначил Дж. Роберта Оппенгеймера организовать и руководить лабораторией проекта в Лос -Аламосе в Нью -Мексико , где были выполнены работы по проектированию бомб. [ 57 ] В конечном итоге были разработаны два разных типа бомб: оружие деления типа оружия , в котором использовался уран-235, называемый Little Boy , и более сложное ядерное оружие , которое использовало плутоний-239, называемый Fat Man . [ 58 ]

Была японская программа ядерного оружия , но ей не хватало человеческих, минеральных и финансовых ресурсов проекта Манхэттена, и никогда не достигали большого прогресса в разработке атомной бомбы. [ 59 ]

Подготовка

Организация и обучение

509 -я композитная группа была составлена 9 декабря 1944 года и активирована 17 декабря 1944 года на авиационном поле Армии Вендовера , штат Юта под командованием полковника Пола Тиббетса . [ 60 ] Tibbets был назначен для организации и командования боевой группой для разработки средств доставки атомного оружия против целей в Германии и Японии. Поскольку летающие эскадрильи группы состояли как из бомбардировщика, так и транспортных самолетов, группа была обозначена как «композитный», а не как «бомбардировка». [ 61 ] Из -за своей удаленности Тиббетс выбрал Вендовера для своей тренировочной базы над Грейт Бенд, Канзас и Маунтин -Дом, Айдахо . [ 62 ] Каждый бомбардировщик завершил по меньшей мере 50 практик инертных или обычных взрывных тыквенных бомб , нацеленных на острова вокруг Тиниана, а затем на японские домашние острова, до 14 августа 1945 года. [ 63 ] [ 64 ] Некоторые из миссий по Японии были выполнены одинокими бессипрерными бомбардировщиками с одной полезной нагрузкой, чтобы привыкнуть японцев к этой модели. Они также смоделировали фактические атомные бомбардировки, в том числе направления входа и выхода по отношению к ветру. Самому Тиббету было запрещено летать большинство миссий по Японии из -за страха, что он может быть захвачен и допрошен. [ 64 ] 5 апреля 1945 года было назначено Code name Central Board. Сотрудник, ответственный за его ассигнование в отделе операций военного департамента, не был прояснен, чтобы узнать какие -либо подробности об этом. Первая бомбардировка была поздней под кодовой названием «Центральный доска I», а вторая - Operation Centerboard II. [ 65 ]

У 509 -й композитной группы была разрешенная сила 225 офицеров и 1542 зачисленных мужчин, почти все из которых в конечном итоге развернулись в Тиниане. В дополнение к своей уполномоченной силе, 509 -й приложил к нему на Tinian 51 гражданский и военнослужащий из проекта Альберта , [ 66 ] известный как 1 -й технический отряд. [ 67 ] 509-й композитной группы 393D-бомбардировка была оснащена 15 Silverplate B-29. Эти самолеты были специально адаптированы для ношения ядерного оружия и были оснащены двигателями, впрыскиваемыми в топливе Curtiss Electric обратимого шага , винтами , пневматическими приводами для быстрого открытия и закрытия дверей залива бомб и других улучшений. [ 68 ]

Эшелон наземной поддержки 509 -й композитной группы, перенесенный на железной дороге 26 апреля 1945 года в свой порт посадки в Сиэтле , штат Вашингтон. 6 мая элементы поддержки плыли на победе SS Cape для Мариан, в то время как Group Materiel был отправлен на SS Emile Berliner . Победа на мысе сделала краткие портовые звонки в Гонолулу и Эниветоке, но пассажирам не было разрешено покинуть зону дока. Предварительная вечеринка воздушного эшелона, состоящая из 29 офицеров и 61 зачисленных мужчин, летала по С-54 на Северное поле на Тиниане, с 15 по 22 мая. [ 69 ] Были также два представителя из Вашингтона, округ Колумбия, бригадный генерал Томас Фаррелл , заместитель командира проекта Манхэттена, и контр -адмирал Уильям Р. Пурнелл из Комитета по военной политике, [ 70 ] которые были под рукой, чтобы решить более высокие вопросы политики на месте. Вместе с капитаном Уильямом С. Парсонсом , командиром проекта Альберты, они стали известны как «совместные вождя Тиниан». [ 71 ]

Выбор целей

В апреле 1945 года Маршалл попросил Гроувса назначить конкретные цели для бомбардировки для окончательного одобрения самим собой и Симсоном. Гроувс сформировал целевой комитет, который возглавлял его самим, в который вошли Фаррелл, майор Джон А. Дерри, полковник Уильям П. Фишер, Джойс С. Стернс и Дэвид М. Деннисон из USAAF; и ученые Джон фон Нейман , Роберт Р. Уилсон и Уильям Пенни из проекта Манхэттена. Целевой комитет встретился в Вашингтоне 27 апреля; в Лос -Аламосе 10 мая, где он смог поговорить с учеными и техническими специалистами; и, наконец, в Вашингтоне 28 мая, где его проинформировал Тиббетс и командир Фредериком Эшвортом из Project Alberta, и научный консультант проекта Манхэттена Ричард С. Толман . [ 72 ]

Целевой комитет назначил пять целей: Кокура (ныне Китакюшу ), место одного из крупнейших заводов в Японии; Хиросима , порт посадки и промышленный центр, который был местом крупной военной штаб -квартиры; Йокохама , городской центр производства самолетов, машины, доки, электрическое оборудование и нефтеперерабатывающие заводы; Niigata , порт с промышленными объектами, включая стальные и алюминиевые заводы и нефтеперерабатывающий завод; и Киото , крупный промышленный центр. Выбор цели был подчинен следующим критериям:

- Цель была диаметром больше 4,8 км (3 мили) и была важной целью в большом городе.

- Взрывная волна приведет к эффективному повреждению.

- Цель вряд ли будет атакована к августу 1945 года. [ 73 ]

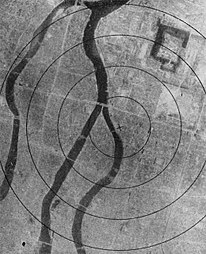

Эти города были в значительной степени нетронуты во время ночных бомбардировок, и военно -воздушные силы армии согласились оставить их из списка целей, настолько точную оценку ущерба, причиненного атомными бомбами. Хиросима был описан как «важный армейский депо и порт посадки в центре городской промышленной зоны. Это хорошая радарная цель, и это такой размер, что большая часть города может быть сильно повреждена. Прилегающие холмы есть. которые могут создать фокус -эффект, который значительно увеличит ущерб от . взрыва [ 73 ]

Целевой комитет заявил, что «было решено, что психологические факторы в отборе целей имели большое значение. Два аспекта этого - (1) получение наибольшего психологического эффекта против Японии и (2), что делает первоначальное использование достаточно впечатляющим для важности которое должно быть признано на международном уровне, когда публикуется. Оружие , что большая часть города может быть уничтожена. гор , Возможные фокусировки из соседних [ 73 ]

Эдвин О. Рейшауэр , эксперт Японии для разведывательной службы армии США , был неправильно, как говорилось в том, что он помешал бомбардировке Киото. [ 73 ] В своей автобиографии Рейшауэр специально опроверг это утверждение:

... Единственным человеком, заслуживающим заслуга за спасение Киото от разрушения, является Генри Л. Смимсон, военный министр в то время, который знал и восхищался Киото с со времен своего медового месяца там несколькими десятилетиями ранее. [ 74 ] [ 75 ]

Экспадиционные источники показывают, что, хотя Симсон был лично знаком с Киото, это было результатом визита через десятилетия после его брака, а не потому, что он там прошел медовый месяц. [ 76 ] [ 77 ] 30 мая Стимсон попросил Гроувса удалить Киото из списка целей из -за его исторического, религиозного и культурного значения, но Гровс указал на его военное и промышленное значение. [ 78 ] Затем Симсон обратился к президенту Гарри С. Трумэну по этому поводу. Трумэн согласился со Стимой, и Киото был временно удален из целевого списка. [ 79 ] Гроувс попытался восстановить Киото в список целей в июле, но Стимсон оставался непреклонным. [ 80 ] [ 81 ] 25 июля Нагасаки был помещен в список целевых людей вместо Киото. Это был крупный военный порт, один из крупнейших центров судостроения и ремонта в Японии, и важный производитель военно -морских боеприпасов. [ 81 ]

Предложенная демонстрация

В начале мая 1945 года Стимусон был создан временным комитетом по настоянию лидеров проекта Манхэттена и с одобрением Трумэна для консультирования по вопросам, касающимся ядерных технологий . [ 82 ] Они согласились с тем, что атомная бомба должна быть использована (1) против Японии при первой же возможности, (2) без особого предупреждения и (3) на «двойной цели» военной установки, окруженной другими зданиями, подверженными повреждениям. [ 64 ]

Во время встреч 31 мая и 1 июня ученый Эрнест Лоуренс предложил дать японским демонстрации нечастота. [ 83 ] Артур Комптон позже вспомнил, что:

Было очевидно, что все будут подозревать обманы. Если в Японии была взорвана бомба с предыдущим уведомлением, японская воздушная энергия все еще была достаточной, чтобы придать серьезные помехи. Атомная бомба была замысловатым устройством, все еще на стадии развития. Его операция будет далеко не рутиной. Если во время окончательной корректировки бомбы, японские защитники должны атаковать, неисправное движение может легко привести к какому -либо неудачу. Такой конец рекламируемой демонстрации власти был бы намного хуже, чем если бы попытка не была предпринята. Теперь стало очевидно, что когда пришло время для использования бомб, у нас должен быть только один из них, а затем следовал за другими с полными интервалами. Мы не могли позволить себе шанс, что один из них может быть безумным. Если бы тест был проведен на какой -то нейтральной территории, было трудно поверить, что решительные и фанатичные военные Японии были бы впечатлены. Если бы такой открытый тест был проведен в первую очередь и не смог принести сдачу, шанс исчез, чтобы дать шок удивления, который оказался настолько эффективным. Напротив, это сделало бы японцы готовыми вмешиваться в атомную атаку, если бы они могли. Хотя возможность демонстрации, которая не разрушила бы человеческую жизнь, была привлекательной, никто не мог бы предложить способ, которым она может быть сделана настолько убедительной, что это, вероятно, остановит войну. [ 84 ]

Возможность демонстрации была снова поднята в отчете Франка, опубликованном физиком Джеймсом Франком 11 июня, и научная консультативная группа отвергла его отчет 16 июня, заявив, что «мы не можем предложить техническую демонстрацию, вероятно, положить конец войне; Мы не видим приемлемой альтернативы прямому военному использованию ». Затем Франк отправил отчет в Вашингтон, округ Колумбия, где временный комитет встретился 21 июня, чтобы пересмотреть свои предыдущие выводы; Но это подтвердило, что не было альтернативы использованию бомбы на военной цели. [ 85 ]

Как и Комптон, многие американские чиновники и ученые утверждали, что демонстрация пожертвовала бы шоковой ценностью атомной атаки, и японцы могли отрицать, что атомная бомба была смертельной, что делает миссию менее вероятной сдачей. Союзные военнопленные могут быть перенесены на демонстрационную площадку и быть убиты бомбой. Они также обеспокоены тем, что бомба может потерпеть неудачу, так как тест Троицы был бомбой о неподвижном устройстве, а не бомбой с воздухом. Кроме того, хотя в производстве было больше бомб, только два будут доступны в начале августа, и они стоят миллиарды долларов, поэтому использование одного для демонстрации было бы дорого. [ 86 ] [ 87 ]

Листочки

В течение нескольких месяцев США предупредили гражданских лиц о потенциальных воздушных налетах, уронив более 63 миллионов листовок по всей Японии. Многие японские города получили ужасный ущерб от воздушных взрывов; Некоторые были уничтожены на 97 процентов. Лемей подумал, что листочки увеличат психологическое воздействие бомбардировки и уменьшат международную стигму бомбардировочных городов. Даже с предупреждениями японское оппозиция войне оставалась неэффективной. В целом, японцы рассматривали листочные сообщения как правдивые: многие японцы решили покинуть крупные города. Листовки вызвали такую обеспокоенность, что правительство приказало арестовать всех, кто поймал листовку. [ 88 ] [ 89 ] Тексты из листовок были подготовлены недавними японскими военнопленными, потому что они считали лучшим выбором, «чтобы обратиться к своим соотечественникам». [ 90 ]

под руководством Оппенгеймера Подготовившись к тому, чтобы сбросить атомную бомбу на Хиросиму, научная коллегия промежуточного комитета решила против демонстрационной бомбы и против специального предупреждения о листовке. Эти решения были реализованы из -за неопределенности успешной детонации, а также из -за желания максимизировать шок в руководстве . [ 91 ] Хиросиме не было предупреждено о том, что новая и гораздо более разрушительная бомба будет сброшена. [ 92 ] Различные источники давали противоречивую информацию о том, когда последние листочки были сброшены на Хиросиму до атомной бомбы. Роберт Джей Лифтон написал, что было 27 июля, [ 92 ] И Теодор Х. Макнелли написал, что это 30 июля. [ 91 ] История USAAF отметила, что одиннадцать городов были нацелены на листочки 27 июля, но Хиросима не был одним из них, и 30 июля не было никаких листочных вылетов. [ 89 ] Листочки были предприняты 1 и 4 августа. Хиросима, возможно, была листовка в конце июля или начале августа, так как рассказы Survivor рассказывают о доставке листовок за несколько дней до того, как атомная бомба была сброшена. [ 92 ] Три версии были напечатаны из листовки, в которой перечислены 11 или 12 городов, предназначенных для бомбардировки; В общей сложности 33 города перечислены. С текстом этого чтения листовки на японском языке «... мы не можем обещать, что только эти города будут среди тех, кто атаковал ...» [ 88 ] Хиросима не был перечислен. [ 93 ] [ 94 ]

Консультация с Британией и Канадой

В 1943 году Соединенные Штаты и Соединенное Королевство подписали соглашение Квебека , которое предусматривает, что ядерное оружие не будет использоваться против другой страны без взаимного согласия. Поэтому Симсон должен был получить британское разрешение. Заседание комбинированного комитета по политике , в которую входили один канадский представитель, состоялось в Пентагоне 4 июля 1945 года. [ 95 ] Полевой маршал сэр Генри Мейтленд Уилсон объявил, что британское правительство согласилось с использованием ядерного оружия против Японии, которое будет официально зарегистрировано в качестве решения комбинированного политического комитета. [ 95 ] [ 96 ] [ 97 ] Поскольку выпуск информации третьим лицам также контролировался соглашением Квебека, обсуждение обратилось к тому, что научные детали будут раскрыты в объявлении о бомбеде. Встреча также рассмотрела то, что Трумэн может показать Джозефу Сталину , лидеру Советского Союза , на предстоящей конференции Потсдама , поскольку это также требовало британского согласия. [ 95 ]

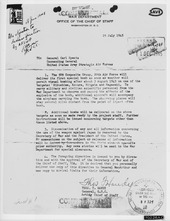

Заказы о нападении были изданы генералу Карлу Спаацу 25 июля под подписью генерала Томаса Т. Хэнди , исполняющего обязанности начальника штаба, так как Маршалл был на конференции Потсдама с Трумэном. [ 98 ] Он читается:

- 509 -я композитная группа, 20 -я воздушная сила, доставит свою первую специальную бомбу, как только погода позволит визуальной бомбардировке после 3 августа 1945 года по одной из целей: Хиросима, Кокура, Ниигата и Нагасаки. Чтобы нести военные и гражданские научные сотрудники из военного департамента, чтобы наблюдать и записать влияние взрыва бомбы, дополнительные самолеты будут сопровождать самолет, несущий бомбу. Наблюдательные самолеты останутся в нескольких милях от удара от удара бомбы.

- Дополнительные бомбы будут доставлены по вышеуказанным целям, как только готовится сотрудники проекта. Будут изданы дополнительные инструкции по вопросам, отличным от перечисленных выше. [ 99 ]

В тот день Трумэн отметил в своем дневнике, что:

Это оружие следует использовать против Японии в период с настоящего момента до 10 августа. Я сказал SEC. Война, г -н Симсон, чтобы использовать его так, чтобы военные цели, а также солдаты и моряки - цель, а не женщины и дети. Даже если японки являются дикарями, безжалостными, беспощадными и фанатичными, мы, как лидер мира по общему благосостоянию, не можем отбросить эту ужасную бомбу на старую столицу [Киото] или новую [Токио]. Он и я в согласии. Цель будет чисто военной. [ 100 ]

Потсдам Декларация

Успех Trinity Test в пустыне Нью -Мексико от 16 июля превзошел ожидания. [ 101 ] 26 июля лидеры союзников выпустили Декларацию Потсдама , в которой изложены условия капитуляции для Японии. Декларация была представлена в качестве ультиматума и заявила, что без капитуляции союзники нападут на Японию, что привело к «неизбежному и полному разрушению японских вооруженных сил и, как и неизбежно, в полном разрушении японской родины». Атомная бомба не упоминалась в коммюнике. [ 102 ]

28 июля японские документы сообщили, что декларация была отвергнута правительством японцев. В тот день премьер -министр Кантаро Сузуки заявил на пресс -конференции, что Декларация Потсдама является не более чем перефразированием ( Якинаоши ) Каирского декларации , что правительство намеревалось игнорировать его ( Мокусацу , «убийство за молча сразится до конца. [ 103 ] Заявление было сделано как японским, так и иностранным документом как явное отказ от декларации. Император Хирохито, который ждал советского ответа на не связанные с общественностью японских мирных чувств, не предпринимал шага, чтобы изменить правительственную позицию. [ 104 ] Готовность Японии к сдаче оставалась условной в отношении сохранения кокутаи ( имперского учреждения и национального государства ), предположения имперской штаб -квартиры ответственности за разоружение и демобилизацию, без оккупации японских домашних островов , Кореи или Формозы и делегирования наказания Военные преступники в японское правительство. [ 105 ]

В Потсдаме Трумэн согласился на просьбу Уинстона Черчилля о том, что Британия будет представлена, когда атомная бомба была сброшена. Уильям Пенни и капитан группы Леонард Чешир были отправлены в Тиниан, но обнаружили, что Лемей не позволит им сопровождать миссию. Все, что они могли сделать, это отправить решительно сформулированный сигнал Уилсону. [ 106 ]

Бомбы

Маленькая бомба, за исключением полезной нагрузки урана, была готова в начале мая 1945 года. [ 107 ] Было два компонента урана-235, полый цилиндрический снаряд и цилиндрическая вставка мишени. Снаряд был завершен 15 июня, а целевой вставка 24 июля. [ 108 ] Снаряд и восемь бомб предварительных сборов (частично собравшихся бомб без заряда порошка и расщепляющих компонентов) оставили военно-морской верфь Хантерс-Пойнт , штат Калифорния, 16 июля на борту крейсера USS Indianapolis и прибыли на Тиниан 26 июля. [ 109 ] Целевая вставка, за которой следуют Air 30 июля, в сопровождении командира Фрэнсиса Берча из Project Alberta. [ 108 ] Отвечая на опасения, выраженные 509-й композитной группой о возможности сбоя B-29 при взлете, Берч изменил дизайн Little Boy, чтобы включить съемную казенную пробку, которая позволила бы вооруженной бомбе во время полета. [ 107 ]

Первое ядро плутония , наряду с его Polonium - Beryllium инициатором ежа , было транспортировано под стражей проекта Alberta Courier Raemer Schreiber в поле с магний, предназначенное для цели Филиппа Моррисона . Магний был выбран, потому что он не действует как отражатель нейтронов . [ 110 ] Ядро отправилось от авиационного поля армии Киртланда на транспортном самолете C-54 509-й композитной группы от 320-й эскадрильи для авианосцев . Три жира с высокими эксплуатационными докладами, обозначенные F31, F32 и F33, были подняты в Киртланде 28 июля тремя B-29, два из 393-й эскадрильи бомбардировки плюс из 216-й базовой авиационной базы армии и и перевозит на северное поле, прибыв 2 августа. [ 111 ]

Хиросима

Хиросима во время Второй мировой войны

Во время бомбардировки Хиросима был городом промышленного и военного значения. Ряд военных подразделений был расположен поблизости, наиболее важной из которых была штаб -квартира маршала Шунроку Хата , полевого которая командовала защитой всей южной Японии, [ 112 ] и был расположен в замке Хиросима . Команда Хаты состояла из примерно 400 000 человек, большинство из которых находились на Кюшу, где правильно ожидалось вторжение союзников. [ 113 ] В Хиросиме также присутствовали штаб -квартира 59 -й армии , 5 -й дивизион и 224 -й дивизии , недавно сформированного мобильного подразделения. [ 114 ] Город был защищен пятью батареями 70 мм и 80 мм (2,8 и 3,1 дюйма) зенитных орудий 3-го зенитного подразделения, включая единицы из 121-го и 122-го зенитного полка и 22-й и 45-й отдельной анти- Самолетные батальоны. В общей сложности в городе было размещено около 40 000 японских военнослужащих. [ 115 ]

Хиросима была базой снабжения и логистики для японских военных. [ 116 ] Город был центром связи, ключевым портом для доставки и зоной сборки для войск. [ 78 ] Он поддерживал крупную военную индустрию, производственные детали для самолетов и лодок, для бомб, винтовки и пистолетов. [ 117 ] Центр города содержал несколько железобетонных зданий. За пределами центра эта область была перегружена плотной коллекцией небольших семинаров по дереву, установленной среди японских домов. Несколько крупных промышленных предприятий лежали рядом с окраиной города. Дома были построены из древесины с крышами плитки, и многие из промышленных зданий были также построены вокруг лесных рам. Город в целом был очень восприимчив к повреждению огня. [ 118 ] Это был второй по величине город в Японии после Киото, который все еще не был поврежден воздушными налетами, [ 119 ] В первую очередь потому, что ему не хватало промышленности самолетов, которая была приоритетной целью XXI Bomber Command. 3 июля Объединенные начальники штаба установили его от бомбардировщиков, а также Кокура, Ниигата и Киото. [ 120 ]

Население Хиросимы достигла пика более 381 000 ранее в войне, но до атомной бомбардировки население неуклонно уменьшалось из -за систематической эвакуации, расположенной правительством Японии . Во время нападения население составляло приблизительно 340 000–350 000. [ 121 ] Жители задавались вопросом, почему Хиросима был избавлен от разрушения от пожарной бомбардировки. [ 122 ] Некоторые предполагают, что город должен быть спасен для штаб -квартиры оккупации США, другие считали, что их родственники на Гавайях и Калифорнии ходатайствовали о правительстве США, чтобы избежать бомбардировок Хиросимы. [ 123 ] Более реалистичные городские чиновники приказали разорвать здания, чтобы создать длинные прямые пожарные разбивки . [ 124 ] Они продолжали расширяться и распространяться до утра 6 августа 1945 года. [ 125 ]

Бомбардировка Хиросимы

Хиросима была основной целью первой миссии по бомбардировке атомной бомбардировки 6 августа, а Кокура и Нагасаки были альтернативными целями. 393-й бомбардировочной эскадрильи B-29 Enola Gay , названная в честь матери Тиббета и пилотируемой Тиббетсом, вылетел из Северного Филда, Тиниан , около шести часов полета из Японии, [ 126 ] в 02:45 по местному времени. [ 127 ] Энола Гэй сопровождал два других B-29: великий артист , которым командовал майор Чарльз Суини , который несущих, и тогдашний самолет, который позже назвал необходимый зло , под командованием капитана Джорджа Маркварда. Необходимым злом был фотоаппарат . [ 128 ]

| Самолеты | Пилот | Знак вызова | Роль миссии |

|---|---|---|---|

| Прямой флеш | Майор Клод Р. Этерли | Ямочки 85 | Погода разведка (Хиросима) |

| Джабит III | Майор Джон А. Уилсон | Ямочки 71 | Погода разведка (кокура) |

| Аншлаг | Майор Ральф Р. Тейлор | Ямочки 83 | Погода разведка (Нагасаки) |

| Инола Гей | Полковник Пол В. Тиббетс | Ямочки 82 | Доставка оружия |

| Великий артист | Майор Чарльз В. Суини | Ямочки 89 | Приборы измерения взрыва |

| Необходимое зло | Капитан Джордж В. Марквардт | Ямочки 91 | Ударные наблюдения и фотография |

| Секрет | Капитан Чарльз Ф. Макнайт | Ямочки 72 | Запасной удар - не выполнил миссию |

Покинув Тиниан, самолет отправился отдельно в Иво Джиму, чтобы встретиться с Суини и Марквардтом в 05:55 на 2800 метрах (9 200 футов), [ 130 ] и установить курс для Японии. Самолет прибыл через цель с четкой видимостью на уровне 9 470 метров (31 060 футов). [ 131 ] Парсонс, который командовал миссией, вооружил бомбу в полете, чтобы минимизировать риски во время взлета. Он стал свидетелем того, как четыре B-29-й разбиты и сжигали при взлете, и опасался, что ядерный взрыв произойдет, если B-29 разбился с вооруженным маленьким мальчиком на борту. [ 132 ] Его помощник, второй лейтенант Моррис Р. Джепсон , удалил устройства безопасности за 30 минут до достижения целевой области. [ 133 ]

В течение ночи 5–6 августа радар японского раннего предупреждения обнаружил подход многочисленных американских самолетов, направляющихся в южную часть Японии. Радар обнаружил 65 бомбардировщиков, направленных на сагу , 102, связанный с Маебаши , 261 на пути к Нишиномии , 111, направившись в UBE и 66, направлявшись в Имабари . Было дано предупреждение, и радиовещание остановилось во многих городах, среди которых Хиросима. Все язвы звучали в Хиросиме в 00:05. [ 135 ] Примерно за час до бомбардировки, вновь звучал оповещение о воздушном налете, так как прямой флеш пролетел над городом. Он транслировал короткое сообщение, которое было поднято Энолой Гэй . Он гласит: «Облачное покрытие менее 3/10 во всех высотах. Совет: Бомба первичная». [ 136 ] В целом в 07:09 снова прозвучали все ячейки. [ 137 ]

В 08:09 Тиббетс начал свою бомбу и передал контроль своему бомбардировщику, майор Томас Фереби . [ 138 ] Выпуск в 08:15 (время Хиросимы) пошел в соответствии с планированием, и маленький мальчик, содержащий около 64 кг (141 фунт) урана-235 Высота около 580 метров (1900 футов) над городом. [ 139 ] [ 140 ] Энола Гэй был в 18,5 км (11,5 миль), прежде чем он почувствовал ударные волны от взрыва. [ 141 ]

Из -за бомба бомба пропустила точку прицеливания , мост AIOI , примерно на 240 м (800 футов) и взорвался непосредственно через хирургическую клинику Шима . [ 142 ] Он выпустил эквивалентную энергию 16 ± 2 килотона TNT (66,9 ± 8,4 TJ). [ 139 ] Оружие считалось очень неэффективным , только 1,7 процента его материала. [ 143 ] Радиус общего разрушения составлял около 1,6 километра (1 миль), с полученными пожарами на 11 км 2 (4,4 кв. МИ). [ 144 ]

Энола Гэй оставался над целевой зоной в течение двух минут и находился в 16 километрах (10 миль), когда бомба взорвалась. Только Тиббетс, Парсонс и Фереби знали о природе оружия; Другим на бомбардировщике было сказано только ожидать ослепительную вспышку и дать черные очки. «Трудно было поверить в то, что мы видели»,-сказал Тиббетс журналистам, в то время как Парсонс сказал: «Все это было огромным и внушающим страх ... люди на борту со мной ахнули« мой Бог ». Он и Тиббетс сравнили ударную волну с «близким всплеском огня ACK-ACK ». [ 145 ]

События на земле

сообщили о пике - - звучанием блестящей вспышке света - с последующим громким доном Люди на земле . [ 146 ] Опыт выживших в городе варьировался в зависимости от их местоположения и обстоятельств, но общим фактором в рассказах о выжившем было ощущение, что обычное оружие (иногда цитируемое как магниевая бомба , у которой появилось ярко -белая вспышка), у которого появилась ярко -белая вспышка) Сразу по их окрестностям, нанося огромный ущерб (бросая людей в комнаты, разбитое стекло, разбивающие здания). После выхода из руин выжившие постепенно понимали, что весь город подвергся нападению в тот же момент. В учетных записях оставшихся в живых часто появляются ходьба по руинам города без четкого ощущения того, куда идти, и сталкиваясь с криками людей, пойманных в ловушку в раздавленных сооружениях, или людей с ужасными ожогами. Когда многочисленные небольшие пожары, взрывом созданные Полем [ 147 ] [ 148 ] Фотограф Йошито Мацусиге сделал единственные фотографии Хиросимы сразу после бомбардировки. В более позднем интервью он описал, что сразу после бомбардировки: «Повсюду была пыль; она сделала серовавую тьму над всем». Всего он сделал пять фотографий, прежде чем он не смог продолжить: «Это была действительно ужасная сцена. Это было похоже на что -то из ада». [ 149 ] Учетные записи выживших также заметно показывают случаи выживших, которые казались не пострадавшими, но которые поддались бы в течение нескольких часов или дней тому, что впоследствии будет идентифицировано как радиационная болезнь .

Точное количество людей, убитых в результате взрыва, огненного шторма и радиационных эффектов бомбардировки, неизвестно. Трудность придумать правильную фигуру обусловлена неточным ведением записей во время войны, хаосом, вызванным атакой, отсутствием согласия того, сколько людей было в городе утром после нападения, и неопределенность в методологии. Отчеты по проекту Манхэттена в 1946 году и Объединенной комиссии США по расследованию атомной бомбы в Японии в 1951 году оценили 66 000 погибших и 69 000 раненых и 64 500 погибших и 72 000 раненых соответственно, в то время как японские пересмотр По оценкам, в 1970 -х годах 140 000 погибших в Хиросиме к концу года. [ 150 ] Оценки также различаются по количеству убитых японских военнослужащих. подсчитано Обследование стратегических бомбардировок Соединенных Штатов в 1946 году, что в Хиросиме присутствовало 24 158 солдат во время нападения, и в результате 6 789 были убиты или отсутствуют; Пересмотр 1970 -х годов оценивается около 10 000 военных погибших. [ 150 ] Современная оценка, проведенная Фондом исследований радиационных эффектов (RERF), оценивает население города от 340 000 до 350 000 во время бомбардировки, из которых от 90 000 до 166 000 умерли к концу года. [ 121 ]

Американские опросы подсчитали, что 12 км 2 (4,7 кв. Миль) города были уничтожены. Японские чиновники определили, что 69 процентов зданий Хиросимы были разрушены, а еще 6-7 процентов повреждены. [ 151 ] Некоторые из железобетонных зданий в Хиросиме были очень сильно построены из -за опасности землетрясения в Японии, и их рамки не рухнули, даже если они были довольно близки к взрывному центру. С тех пор, как бомба взорвалась в воздухе, взрыв был направлен более вниз, чем в сторону, что было в значительной степени ответственным за выживание префектурного промышленного промо-зала , который теперь обычно известен как купол Генбаку (бомба), который составлял всего 150 м ( 490 футов) от земли ноль ( гипоцентр ). Руины были названы Мемориалом мира Хиросимы и стали местом Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО в 1996 году по поводу возражений Соединенных Штатов и Китая, которые выражали оговорки на том основании, что другие азиатские нации были теми, кто потерпел наибольшую потерю жизни и собственности, И сосредоточение внимания на Японии не хватало исторической перспективы. [ 152 ]

-

Хиросима после бомбардировки

-

Руины Хиросимы

-

Купол Хиросимы Генбаку после бомбардировки

-

Образец кимоно, который носил выживший выживший, сгорел в ее коже в плотно подходящих областях.

-

Прямые, тепловые сжигания

-

22-летняя жертва Toyo Kugata лечит в больнице Хиросимы Красного Креста (6 октября 1945 года)

-

Фотография последствий бомбардировки Хиросимы

-

Мемориал в Andersonville NHS для американских летчиков, которые погибли в результате взрыва

-

Жертва с ожогами

-

Жертва со всем телом ожогами

-

Жертва со всем телом ожогами

-

Жертва с ожогами на спине

-

Corpse near the Western Parade Ground

-

A mobilized school girl suffered burns to face

-

Elder sister and younger brother who suffered radiation disease. The brother died in 1949 and the sister in 1965.

The air raid warning had been cleared at 07:31, and many people were outside, going about their activities.[156] Eizō Nomura was the closest known survivor, being in the basement of a reinforced concrete building (it remained as the Rest House after the war) only 170 meters (560 ft) from ground zero at the time of the attack.[157][158] He died in 1982, aged 84.[159] Akiko Takakura was among the closest survivors to the hypocenter of the blast. She was in the solidly-built Bank of Hiroshima only 300 meters (980 ft) from ground-zero at the time of the attack.[160]

Over 90 percent of the doctors and 93 percent of the nurses in Hiroshima were killed or injured—most had been in the downtown area which received the greatest damage.[161] The hospitals were destroyed or heavily damaged. Only one doctor, Terufumi Sasaki, remained on duty at the Red Cross Hospital.[162] Nonetheless, by early afternoon the police and volunteers had established evacuation center at hospitals, schools and tram stations, and a morgue was established in the Asano library.[163] Survivors of the blast gathered for medical treatment, but many would die before receiving any help, leaving behind rings of corpses around hospitals.[164]

Most elements of the Japanese Second General Army headquarters were undergoing physical training on the grounds of Hiroshima Castle, barely 820 meters (900 yd) from the hypocenter. The attack killed 3,243 troops on the parade ground.[165] The communications room of Chugoku Military District Headquarters that was responsible for issuing and lifting air raid warnings was located in a semi-basement in the castle. Yoshie Oka, a Hijiyama Girls High School student who had been mobilized to serve as a communications officer, had just sent a message that the alarm had been issued for Hiroshima and neighboring Yamaguchi, when the bomb exploded. She used a special phone to inform Fukuyama Headquarters (some 100 kilometers (62 mi) away) that "Hiroshima has been attacked by a new type of bomb. The city is in a state of near-total destruction."[166]

Since Mayor Senkichi Awaya had been killed while eating breakfast with his son and granddaughter at the mayoral residence, Field Marshal Shunroku Hata, who was only slightly wounded, took over the administration of the city, and coordinated relief efforts. Many of his staff had been killed or fatally wounded, including Lieutenant Colonel Yi U, a prince of the Korean imperial family who was serving as a General Staff Officer.[167][168] Hata's senior surviving staff officer was the wounded Colonel Kumao Imoto, who acted as his chief of staff. Soldiers from the undamaged Hiroshima Ujina Harbor used Shin'yō-class suicide motorboats, intended to repel the American invasion, to collect the wounded and take them down the rivers to the military hospital at Ujina.[167] Trucks and trains brought in relief supplies and evacuated survivors from the city.[169]

Twelve American airmen were imprisoned at the Chugoku Military Police Headquarters, about 400 meters (1,300 ft) from the hypocenter of the blast.[170] Most died instantly, although two were reported to have been executed by their captors, and two prisoners badly injured by the bombing were left next to the Aioi Bridge by the Kempei Tai, where they were stoned to death.[171][172] Eight U.S. prisoners of war killed as part of the medical experiments program at Kyushu University were falsely reported by Japanese authorities as having been killed in the atomic blast as part of an attempted cover up.[173]

Japanese realization of the bombing

The Tokyo control operator of the Japan Broadcasting Corporation noticed that the Hiroshima station had gone off the air. He tried to re-establish his program by using another telephone line, but it too had failed.[174] About 20 minutes later the Tokyo railroad telegraph center realized that the main line telegraph had stopped working just north of Hiroshima. From some small railway stops within 16 km (10 mi) of the city came unofficial and confused reports of a terrible explosion in Hiroshima. All these reports were transmitted to the headquarters of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff.[175]

Military bases repeatedly tried to call the Army Control Station in Hiroshima. The complete silence from that city puzzled the General Staff; they knew that no large enemy raid had occurred and that no sizable store of explosives was in Hiroshima at that time. A young officer was instructed to fly immediately to Hiroshima, to land, survey the damage, and return to Tokyo with reliable information for the staff. It was felt that nothing serious had taken place and that the explosion was just a rumor.[175]

The staff officer went to the airport and took off for the southwest. After flying for about three hours, while still nearly 160 km (100 mi) from Hiroshima, he and his pilot saw a great cloud of smoke from the firestorm created by the bomb. After circling the city to survey the damage they landed south of the city, where the staff officer, after reporting to Tokyo, began to organize relief measures. Tokyo learned that the city had been destroyed by a new type of bomb from President Truman's announcement of the strike, sixteen hours later.[175]

Events of 7–9 August

After the Hiroshima bombing, Truman issued a statement announcing the use of the new weapon. He stated, "We may be grateful to Providence" that the German atomic bomb project had failed, and that the United States and its allies had "spent two billion dollars on the greatest scientific gamble in history—and won". Truman then warned Japan: "If they do not now accept our terms, they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with the fighting skill of which they are already well aware."[176] This was a widely broadcast speech picked up by Japanese news agencies.[177]

The 50,000-watt standard wave station on Saipan, the OWI radio station, broadcast a similar message to Japan every 15 minutes about Hiroshima, stating that more Japanese cities would face a similar fate in the absence of immediate acceptance of the terms of the Potsdam Declaration and emphatically urged civilians to evacuate major cities. Radio Japan, which continued to extoll victory for Japan by never surrendering[88] had informed the Japanese of the destruction of Hiroshima by a single bomb.[178]

Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov had informed Tokyo of the Soviet Union's unilateral abrogation of the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact on 5 April.[179] At two minutes past midnight on 9 August, Tokyo time, Soviet infantry, armor, and air forces had launched the Manchurian Strategic Offensive Operation.[180] Four hours later, word reached Tokyo of the Soviet Union's official declaration of war. The senior leadership of the Japanese Army began preparations to impose martial law on the nation, with the support of Minister of War Korechika Anami, to stop anyone attempting to make peace.[181]

On 7 August, a day after Hiroshima was destroyed, Yoshio Nishina and other atomic physicists arrived at the city, and carefully examined the damage. They then went back to Tokyo and told the cabinet that Hiroshima was indeed destroyed by a nuclear weapon. Admiral Soemu Toyoda, the Chief of the Naval General Staff, estimated that no more than one or two additional bombs could be readied, so they decided to endure the remaining attacks, acknowledging "there would be more destruction but the war would go on".[182] American Magic codebreakers intercepted the cabinet's messages.[183]

Purnell, Parsons, Tibbets, Spaatz, and LeMay met on Guam that same day to discuss what should be done next.[184] Since there was no indication of Japan surrendering,[183] they decided to proceed with dropping another bomb. Parsons said that Project Alberta would have it ready by 11 August, but Tibbets pointed to weather reports indicating poor flying conditions on that day due to a storm, and asked if the bomb could be readied by 9 August. Parsons agreed to try to do so.[185][184]

Nagasaki

Nagasaki during World War II

The city of Nagasaki had been one of the largest seaports in southern Japan, and was of great wartime importance because of its wide-ranging industrial activity, including the production of ordnance, ships, military equipment, and other war materials. The four largest companies in the city were Mitsubishi Shipyards, Electrical Shipyards, Arms Plant, and Steel and Arms Works, which employed about 90 percent of the city's labor force, and accounted for 90 percent of the city's industry.[186] Although an important industrial city, Nagasaki had been spared from firebombing because its geography made it difficult to locate at night with AN/APQ-13 radar.[120]

Unlike the other target cities, Nagasaki had not been placed off limits to bombers by the Joint Chiefs of Staff's 3 July directive,[120][187] and was bombed on a small scale five times. During one of these raids on 1 August, a number of conventional high-explosive bombs were dropped on the city. A few hit the shipyards and dock areas in the southwest portion of the city, and several hit the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works.[186] By early August, the city was defended by the 134th Anti-Aircraft Regiment of the 4th Anti-Aircraft Division with four batteries of 7 cm (2.8 in) anti-aircraft guns and two searchlight batteries.[115]

In contrast to Hiroshima, almost all of the buildings were of old-fashioned Japanese construction, consisting of timber or timber-framed buildings with timber walls (with or without plaster) and tile roofs. Many of the smaller industries and business establishments were also situated in buildings of timber or other materials not designed to withstand explosions. Nagasaki had been permitted to grow for many years without conforming to any definite city zoning plan; residences were erected adjacent to factory buildings and to each other almost as closely as possible throughout the entire industrial valley. On the day of the bombing, an estimated 263,000 people were in Nagasaki, including 240,000 Japanese residents, 10,000 Korean residents, 2,500 conscripted Korean workers, 9,000 Japanese soldiers, 600 conscripted Chinese workers, and 400 Allied prisoners of war in a camp to the north of Nagasaki.[188]

Bombing of Nagasaki

Responsibility for the timing of the second bombing was delegated to Tibbets. Scheduled for 11 August, the raid was moved earlier by two days to avoid a five-day period of bad weather forecast to begin on 10 August.[189] Three bomb pre-assemblies had been transported to Tinian, labeled F-31, F-32, and F-33 on their exteriors. On 8 August, a dress rehearsal was conducted off Tinian by Sweeney using Bockscar as the drop airplane. Assembly F-33 was expended testing the components and F-31 was designated for the 9 August mission.[190]

| Aircraft | Pilot | Call sign | Mission role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enola Gay | Captain George W. Marquardt | Dimples 82 | Weather reconnaissance (Kokura) |

| Laggin' Dragon | Captain Charles F. McKnight | Dimples 95 | Weather reconnaissance (Nagasaki) |

| Bockscar | Major Charles W. Sweeney | Dimples 77 | Weapon delivery |

| The Great Artiste | Captain Frederick C. Bock | Dimples 89 | Blast measurement instrumentation |

| Big Stink | Major James I. Hopkins, Jr. | Dimples 90 | Strike observation and photography |

| Full House | Major Ralph R. Taylor | Dimples 83 | Strike spare – did not complete mission |

At 03:47 Tinian time (GMT+10), 02:47 Japanese time,[127] on the morning of 9 August 1945, Bockscar, flown by Sweeney's crew, lifted off from Tinian island with the Fat Man, with Kokura as the primary target and Nagasaki the secondary target. The mission plan for the second attack was nearly identical to that of the Hiroshima mission, with two B-29s flying an hour ahead as weather scouts and two additional B-29s in Sweeney's flight for instrumentation and photographic support of the mission. Sweeney took off with his weapon already armed but with the electrical safety plugs still engaged.[192]

During pre-flight inspection of Bockscar, the flight engineer notified Sweeney that an inoperative fuel transfer pump made it impossible to use 2,400 liters (640 U.S. gal) of fuel carried in a reserve tank. This fuel would still have to be carried all the way to Japan and back, consuming still more fuel. Replacing the pump would take hours; moving the Fat Man to another aircraft might take just as long and was dangerous as well, as the bomb was live. Tibbets and Sweeney therefore elected to have Bockscar continue the mission.[193][194]

This time Penney and Cheshire were allowed to accompany the mission, flying as observers on the third plane, Big Stink, flown by the group's operations officer, Major James I. Hopkins, Jr. Observers aboard the weather planes reported both targets clear. When Sweeney's aircraft arrived at the assembly point for his flight off the coast of Japan, Big Stink failed to make the rendezvous.[192] According to Cheshire, Hopkins was at varying heights including 2,700 meters (9,000 ft) higher than he should have been, and was not flying tight circles over Yakushima as previously agreed with Sweeney and Captain Frederick C. Bock, who was piloting the support B-29 The Great Artiste. Instead, Hopkins was flying 64-kilometer (40 mi) dogleg patterns.[195] Though ordered not to circle longer than fifteen minutes, Sweeney continued to wait for Big Stink for forty minutes. Before leaving the rendezvous point, Sweeney consulted Ashworth, who was in charge of the bomb. As commander of the aircraft, Sweeney made the decision to proceed to the primary, the city of Kokura.[196]

After exceeding the original departure time limit by nearly a half-hour, Bockscar, accompanied by The Great Artiste, proceeded to Kokura, thirty minutes away. The delay at the rendezvous had resulted in clouds and drifting smoke over Kokura from fires started by a major firebombing raid by 224 B-29s on nearby Yahata the previous day.[197] Additionally, the Yahata Steel Works intentionally burned coal tar, to produce black smoke.[198] The clouds and smoke resulted in 70 percent of the area over Kokura being covered, obscuring the aiming point. Three bomb runs were made over the next 50 minutes, burning fuel and exposing the aircraft repeatedly to the heavy defenses around Kokura, but the bombardier was unable to drop visually. By the time of the third bomb run, Japanese anti-aircraft fire was getting close, and Second Lieutenant Jacob Beser, who was monitoring Japanese communications, reported activity on the Japanese fighter direction radio bands.[199]

With fuel running low because of the failed fuel pump, Bockscar and The Great Artiste headed for their secondary target, Nagasaki.[192] Fuel consumption calculations made en route indicated that Bockscar had insufficient fuel to reach Iwo Jima and would be forced to divert to Okinawa, which had become entirely Allied-occupied territory only six weeks earlier. After initially deciding that if Nagasaki were obscured on their arrival the crew would carry the bomb to Okinawa and dispose of it in the ocean if necessary, Ashworth agreed with Sweeney's suggestion that a radar approach would be used if the target was obscured.[200][201] At about 07:50 Japanese time, an air raid alert was sounded in Nagasaki, but the "all clear" signal was given at 08:30. When only two B-29 Superfortresses were sighted at 10:53 Japanese Time (GMT+9), the Japanese apparently assumed that the planes were only on reconnaissance and no further alarm was given.[202]

A few minutes later at 11:00 Japanese Time, The Great Artiste dropped instruments attached to three parachutes. These instruments also contained an unsigned letter to Professor Ryokichi Sagane, a physicist at the University of Tokyo who studied with three of the scientists responsible for the atomic bomb at the University of California, Berkeley, urging him to tell the public about the danger involved with these weapons of mass destruction. The messages were found by military authorities but not turned over to Sagane until a month later.[203] In 1949, one of the authors of the letter, Luis Alvarez, met with Sagane and signed the letter.[204]

At 11:01 Japanese Time, a last-minute break in the clouds over Nagasaki allowed Bockscar's bombardier, Captain Kermit Beahan, to visually sight the target as ordered. The Fat Man weapon, containing a core of about 5 kg (11 lb) of plutonium, was dropped over the city's industrial valley. It exploded 47 seconds later at 11:02 Japanese Time[127] at 503 ± 10 m (1,650 ± 33 ft), above a tennis court,[205] halfway between the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works in the south and the Nagasaki Arsenal in the north. This was nearly 3 km (1.9 mi) northwest of the planned hypocenter; the blast was confined to the Urakami Valley and a major portion of the city was protected by the intervening hills.[206] The resulting explosion released the equivalent energy of 21 ± 2 kt (87.9 ± 8.4 TJ).[139] Big Stink spotted the explosion from 160 kilometers (100 mi) away, and flew over to observe.[207]

Bockscar flew on to Okinawa, arriving with only sufficient fuel for a single approach. Sweeney tried repeatedly to contact the control tower for landing clearance, but received no answer. He could see heavy air traffic landing and taking off from Yontan Airfield. Firing off every flare on board to alert the field to his emergency landing, the Bockscar came in fast, landing at 230 km/h (140 mph) instead of the normal 190 kilometers per hour (120 mph). The number two engine died from fuel starvation as he began the final approach. Touching down on only three engines midway down the landing strip, Bockscar bounced up into the air again for about 7.6 meters (25 ft) before slamming back down hard. The heavy B-29 slewed left and towards a row of parked B-24 bombers before the pilots managed to regain control. Its reversible propellers were insufficient to slow the aircraft adequately, and with both pilots standing on the brakes, Bockscar made a swerving 90-degree turn at the end of the runway to avoid running off it. A second engine died from fuel exhaustion before the plane came to a stop.[208]

Following the mission, there was confusion over the identification of the plane. The first eyewitness account by war correspondent William L. Laurence of The New York Times, who accompanied the mission aboard the aircraft piloted by Bock, reported that Sweeney was leading the mission in The Great Artiste. He also noted its "Victor" number as 77, which was that of Bockscar.[209] Laurence had interviewed Sweeney and his crew, and was aware that they referred to their airplane as The Great Artiste. Except for Enola Gay, none of the 393d's B-29s had yet had names painted on the noses, a fact which Laurence himself noted in his account. Unaware of the switch in aircraft, Laurence assumed Victor 77 was The Great Artiste,[210] which was in fact, Victor 89.[211]

Events on the ground

Although the bomb was more powerful than the one used on Hiroshima, its effects were confined by hillsides to the narrow Urakami Valley.[212] Of 7,500 Japanese employees who worked inside the Mitsubishi Munitions plant, including "mobilized" students and regular workers, 6,200 were killed. Some 17,000–22,000 others who worked in other war plants and factories in the city died as well.[213] The 1946 Manhattan Project report estimated 39,000 dead and 25,000 injured, and the 1951 U.S.-led Joint Commission report estimated 39,214 dead and 25,153 injured; Japanese-led reconsiderations in the 1970s estimated 70,000 dead in Nagasaki by the end of the year.[150] A modern estimate by the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF) estimates a city population of 250,000 to 270,000 at the time of the bombing, of which 60,000 to 80,000 died by the end of the year.[121]

Unlike Hiroshima's military death toll, only 150 Japanese soldiers were killed instantly, including 36 from the 134th AAA Regiment of the 4th AAA Division.[115] At least eight Allied prisoners of war (POWs) died from the bombing, and as many as thirteen may have died. The eight confirmed deaths included a British POW, Royal Air Force Corporal Ronald Shaw,[216] and seven Dutch POWs.[217] One American POW, Joe Kieyoomia, was in Nagasaki at the time of the bombing but survived, reportedly having been shielded from the effects of the bomb by the concrete walls of his cell.[218] There were 24 Australian POWs in Nagasaki, all of whom survived.[219]

The radius of total destruction was about 1.6 km (1 mi), followed by fires across the northern portion of the city to 3.2 km (2 mi) south of the bomb.[144][220] About 58 percent of the Mitsubishi Arms Plant was damaged, and about 78 percent of the Mitsubishi Steel Works. The Mitsubishi Electric Works suffered only 10 percent structural damage as it was on the border of the main destruction zone. The Nagasaki Arsenal was destroyed in the blast.[221] Although many fires likewise burnt following the bombing, in contrast to Hiroshima where sufficient fuel density was available, no firestorm developed in Nagasaki as the damaged areas did not furnish enough fuel to generate the phenomenon. Instead, ambient wind pushed the fire spread along the valley.[222] Had the bomb been dropped more precisely at the intended aiming point, which was downtown Nagasaki at the heart of the historic district, the destruction to medical and administrative infrastructure would have been even greater.[64]

As in Hiroshima, the bombing badly dislocated the city's medical facilities. A makeshift hospital was established at the Shinkozen Primary School, which served as the main medical center. The trains were still running, and evacuated many victims to hospitals in nearby towns. A medical team from a naval hospital reached the city in the evening, and fire-fighting brigades from the neighboring towns assisted in fighting the fires.[223] Takashi Nagai was a doctor working in the radiology department of Nagasaki Medical College Hospital. He received a serious injury that severed his right temporal artery, but joined the rest of the surviving medical staff in treating bombing victims.[224]

Plans for more atomic attacks on Japan

There were plans for further attacks on Japan following Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Groves expected to have another "Fat Man" atomic bomb ready for use on 19 August, with three more in September and a further three in October.[87] A second Little Boy bomb (using U-235) would not be available until December 1945.[225][226] On 10 August, he sent a memorandum to Marshall in which he wrote that "the next bomb ... should be ready for delivery on the first suitable weather after 17 or 18 August." The memo today contains hand-written comment written by Marshall: "It is not to be released over Japan without express authority from the President."[87] At the cabinet meeting that morning, Truman discussed these actions. James Forrestal paraphrased Truman as saying "there will be further dropping of the atomic bomb," while Henry A. Wallace recorded in his diary that: "Truman said he had given orders to stop atomic bombing. He said the thought of wiping out another 100,000 people was too horrific. He didn't like the idea of killing, as he said, 'all those kids.'"[227] The previous order that the target cities were to be attacked with atomic bombs "as made ready" was thus modified.[228] There was already discussion in the War Department about conserving the bombs then in production for Operation Downfall, and Marshall suggested to Stimson that the remaining cities on the target list be spared attack with atomic bombs.[229]

Two more Fat Man assemblies were readied, and scheduled to leave Kirtland Field for Tinian on 11 and 14 August,[230] and Tibbets was ordered by LeMay to return to Albuquerque, New Mexico, to collect them.[231] At Los Alamos, technicians worked 24 hours straight to cast another plutonium core.[232] Although cast, it still needed to be pressed and coated, which would take until 16 August.[233] Therefore, it could have been ready for use on 19 August. Unable to reach Marshall, Groves ordered on his own authority on 13 August that the core should not be shipped.[228]

Surrender of Japan and subsequent occupation

Until 9 August, Japan's war council still insisted on its four conditions for surrender. The full cabinet met at 14:30 on 9 August, and spent most of the day debating surrender. Anami conceded that victory was unlikely, but argued in favor of continuing the war. The meeting ended at 17:30, with no decision having been reached. Suzuki went to the palace to report on the outcome of the meeting, where he met with Kōichi Kido, the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal of Japan. Kido informed him that the emperor had agreed to hold an imperial conference, and gave a strong indication that the emperor would consent to surrender on condition that kokutai be preserved. A second cabinet meeting was held at 18:00. Only four ministers supported Anami's position of adhering to the four conditions, but since cabinet decisions had to be unanimous, no decision was reached before it ended at 22:00.[234]

Calling an imperial conference required the signatures of the prime minister and the two service chiefs, but the Chief Cabinet Secretary Hisatsune Sakomizu had already obtained signatures from Toyoda and General Yoshijirō Umezu in advance, and he reneged on his promise to inform them if a meeting was to be held. The meeting commenced at 23:50. No consensus had emerged by 02:00 on 10 August, but the emperor gave his "sacred decision",[235] authorizing the Foreign Minister, Shigenori Tōgō, to notify the Allies that Japan would accept their terms on one condition, that the declaration "does not comprise any demand which prejudices the prerogatives of His Majesty as a Sovereign ruler."[236]

On 12 August, the Emperor informed the imperial family of his decision to surrender. One of his uncles, Prince Asaka, asked whether the war would be continued if the kokutai could not be preserved. Hirohito simply replied, "Of course."[237] As the Allied terms seemed to leave intact the principle of the preservation of the Throne, Hirohito recorded on 14 August his capitulation announcement which was broadcast to the Japanese nation the next day despite an attempted military coup d'état by militarists opposed to the surrender.[238]

In his declaration's fifth paragraph, Hirohito solely mentions the duration of the conflict; and did not explicitly mention the Soviets as a factor for surrender:

But now the war has lasted for nearly four years. Despite the best that has been done by every one—the gallant fighting of military and naval forces, the diligence and assiduity of Our servants of the State and the devoted service of Our one hundred million people, the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan's advantage, while the general trends of the world have all turned against her interest.

The sixth paragraph by Hirohito specifically mentions the use of nuclear ordnance devices, from the aspect of the unprecedented damage they caused:

Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.

The seventh paragraph gives the reason for the ending of hostilities against the Allies:

Such being the case, how are we to save the millions of our subjects, or to atone ourselves before the hallowed spirits of our imperial ancestors? This is the reason why we have ordered the acceptance of the provisions of the joint declaration of the powers.[239]

In his "Rescript to the Soldiers and Sailors" delivered on 17 August, Hirohito did not refer to the atomic bombs or possible human extinction, and instead described the Soviet declaration of war as "endangering the very foundation of the Empire's existence."[240]

Reportage

On 10 August 1945, the day after the Nagasaki bombing, military photographer Yōsuke Yamahata, correspondent Higashi, and artist Yamada arrived in the city with instructions to record the destruction for propaganda purposes. Yamahata took scores of photographs, and on 21 August, they appeared in Mainichi Shimbun, a popular Japanese newspaper. After Japan's surrender and the arrival of American forces, copies of his photographs were seized amid the ensuing censorship, but some records have survived.[241]

Leslie Nakashima, a former United Press (UP) journalist, filed the first personal account of the scene to appear in American newspapers. He observed that large numbers of survivors continued to die from what later became recognized as radiation poisoning.[242] On 31 August, The New York Times published an abbreviated version of his 27 August UP article. Nearly all references to uranium poisoning were omitted. An editor's note was added to say that, according to American scientists, "the atomic bomb will not have any lingering after-effects."[243][242]

Wilfred Burchett was also one of the first Western journalists to visit Hiroshima after the bombing. He arrived alone by train from Tokyo on 2 September, defying the traveling ban put in place on Western correspondents.[244] Burchett's dispatch, "The Atomic Plague", was printed by the Daily Express newspaper in London on 5 September 1945. The reports from Nakashima and Burchett informed the public for the first time of the gruesome effects of radiation and nuclear fallout—radiation burns and radiation poisoning, sometimes lasting more than thirty days after the blast.[245][246] Burchett especially noted that people were dying "horribly" after bleeding from orifices, and their flesh would rot away from the injection holes where vitamin A was administered, to no avail.[244]

The New York Times then apparently reversed course and ran a front-page story by Bill Lawrence confirming the existence of a terrifying affliction in Hiroshima, where many had symptoms such as hair loss and vomiting blood before dying.[244] Lawrence had gained access to the city as part of a press junket promoting the U.S. Army Air Force. Some reporters were horrified by the scene, however, referring to what they saw as a "death laboratory" littered with "human guinea pigs". General MacArthur found the reporting to have turned from good PR into bad PR and threatened to court martial the entire group. He withdrew Burchett's press accreditation and expelled the journalist from the occupation zones.[247] The authorities also accused him of being under the sway of Japanese propaganda and later suppressed another story, on the Nagasaki bombing, by George Weller of the Chicago Daily News. Less than a week after his New York Times story was published, Lawrence also backtracked and dismissed the reports on radiation sickness as Japanese efforts to undermine American morale.[248][244]