Иран

Исламская Республика Иран | |

|---|---|

| Девиз: Независимость, свобода, Исламская Республика. Эстеклаль, Азади, Джомхури-йе Эслами «Независимость, свобода, Исламская Республика» ( фактически ) [1] | |

| Гимн: Государственный гимн Исламской Республики Иран. Спросите Исламскую Республику Иран « Государственный гимн Исламской Республики Иран » | |

| Capital and largest city | Tehran 35°41′N 51°25′E / 35.683°N 51.417°E |

| Official languages | Persian |

| Recognised regional languages | |

| National language | Persian |

| Ethnic groups (2003 estimate)[5] | All |

| Demonym(s) | Iranian |

| Government | Unitary Khomeinist presidential theocratic Islamic republic |

| Ali Khamenei | |

| Masoud Pezeshkian | |

| Mohammad Reza Aref | |

| Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf | |

| Gholam-Hossein Mohseni-Eje'i | |

| Ahmad Jannati | |

| Legislature | Islamic Consultative Assembly |

| Formation | |

| c. 678 BC | |

| 550 BC | |

| 247 BC | |

| 224 AD | |

| 1501 | |

| 1736 | |

| 1751 | |

| 1789 | |

| 12 December 1905 | |

| 15 December 1925 | |

| 11 February 1979 | |

| 3 December 1979 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,648,195 km2 (636,372 sq mi) (17th) |

• Water (%) | 1.63 (as of 2015)[6] |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | |

• Density | 55/km2 (142.4/sq mi) (132nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2019) | 40.9[9] medium |

| HDI (2022) | high (78th) |

| Currency | Iranian rial (ریال) (IRR) |

| Time zone | UTC+3:30 (IRST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IR |

| Internet TLD | |

Иран , [а] официально Исламская Республика Иран ( ИРИ ), [б] также известный как Персия , [с] это страна в Западной Азии . Граничит с Турцией на северо-западе и Ираком на западе, с Азербайджаном , Арменией , Каспийским морем и Туркменистаном на севере, с Афганистаном на востоке, с Пакистаном на юго-востоке, с Оманским заливом и Персидским заливом на юге. С населением в основном персидского происхождения , составляющим почти 90 миллионов человек, на площади 1 648 195 км². 2 (636 372 квадратных миль), Иран занимает 17-е место в мире как по географическому размеру , так и по численности населения . Это шестая по величине страна в Азии стран мира и одна из самых гористых . Официально являясь исламской республикой , Иран имеет мусульманское большинство населения . Страна разделена на пять регионов с 31 провинцией . Тегеран страны – столица , крупнейший город и финансовый центр .

A cradle of civilization, Iran has been inhabited since the Lower Palaeolithic. It was first unified as a state by Deioces in the seventh century BC, and reached its territorial height in the sixth century BC, when Cyrus the Great founded the Achaemenid Empire, one of the largest in ancient history. Alexander the Great conquered the empire in the fourth century BC. An Iranian rebellion established the Parthian Empire in the third century BC and liberated the country, which was succeeded by the Sasanian Empire in the third century AD. Ancient Iran saw some of the earliest developments of writing, agriculture, urbanisation, religion and central government. Muslims conquered the region in the seventh century AD, leading to Iran's Islamization. The blossoming literature, philosophy, mathematics, medicine, astronomy and art became major elements for Iranian civilization during the Islamic Golden Age. A series of Iranian Muslim dynasties ended Arab rule, revived the Persian language and ruled the country until the Сельджукские и монгольские завоевания XI-XIV веков.

In the 16th century, the native Safavids re-established a unified Iranian state with Twelver Shi'ism as the official religion. During the Afsharid Empire in the 18th century, Iran was a leading world power, though by the 19th century, it had lost significant territory through conflicts with the Russian Empire. The early 20th century saw the Persian Constitutional Revolution and the establishment of the Pahlavi dynasty. Attempts by Mohammad Mosaddegh to nationalize the oil industry led to an Anglo-American coup in 1953. After the Iranian Revolution, the monarchy was overthrown in 1979 and the Islamic Republic of Iran was established by Ruhollah Khomeini, who became the country's first Supreme Leader. In 1980, Iraq invaded Iran, sparking the eight-year-long Iran–Iraq War, which ended in stalemate.

Iran is officially governed as a unitary Islamic Republic with a Presidential system, with ultimate authority vested in a Supreme Leader. The government is authoritarian and has attracted widespread criticism for its significant violations of human rights and civil liberties. Iran is a major regional power, due to its large reserves of fossil fuels, including the world's second largest natural gas supply, third largest proven oil reserves, its geopolitically significant location, military capabilities, cultural hegemony, regional influence, and role as the world's focal point of Shia Islam. The Iranian economy is the world's 19th-largest by PPP. Iran is an active and founding member of the United Nations, OIC, OPEC, ECO, NAM, SCO and BRICS. Iran is home to 27 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, the 10th highest in the world, and ranks 5th in Intangible Cultural Heritage, or human treasures. Iran was the world's third fastest-growing tourism destination in 2019.[12]

Etymology

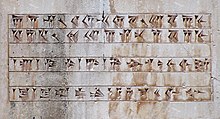

The term Iran 'the land of the Aryans' derives from Middle Persian Ērān, first attested in a 3rd-century inscription at Naqsh-e Rostam, with the accompanying Parthian inscription using Aryān, in reference to the Iranians.[13] Ērān and Aryān are oblique plural forms of gentilic nouns ēr- (Middle Persian) and ary- (Parthian), deriving from Proto-Iranian language *arya- (meaning 'Aryan', i.e. of the Iranians),[13][14] recognised as a derivative of Proto-Indo-European language *ar-yo-, meaning 'one who assembles (skilfully)'.[15] According to Iranian mythology, the name comes from Iraj, a legendary king.[16]

Iran was referred to as Persia by the West, due to Greek historians who referred to all of Iran as Persís, meaning 'the land of the Persians'.[17][18][19][20] Persia is the Fars province in southwest Iran, the 4th largest province, also known as Pârs.[21][22] The Persian Fârs (فارس), derived from the earlier form Pârs (پارس), which is in turn derived from Pârsâ (Old Persian: 𐎱𐎠𐎼𐎿). Due to Fars' historical importance,[23][24] Persia originated from this territory through Greek in around 550 BC,[25] and Westerners referred to the entire country as Persia,[26][27] until 1935, when Reza Shah requested the international community to use its native and original name, Iran;[28] Iranians called their nation Iran since at least 1000 BC.[21] Today, both Iran and Persia are used culturally, while Iran remains mandatory in official use.[29][30][31][32][33]

The Persian pronunciation of Iran is [ʔiːˈɾɒːn]. Commonwealth English pronunciations of Iran are listed in the Oxford English Dictionary as /ɪˈrɑːn/ and /ɪˈræn/,[34] while American English dictionaries provide pronunciations which map to /ɪˈrɑːn, -ˈræn, aɪˈræn/,[35] or /ɪˈræn, ɪˈrɑːn, aɪˈræn/. The Cambridge Dictionary lists /ɪˈrɑːn/ as the British pronunciation and /ɪˈræn/ as the American pronunciation. Voice of America's pronunciation guide provides /ɪˈrɑːn/.[36]

History

Prehistory

Archaeological artifacts confirm human presence in Iran since the Lower Palaeolithic.[37] Neanderthal artifacts have been found in the Zagros region.[38][39][40] From the 10th to the 7th millennium BC, agricultural communities flourished around the Zagros region, including Chogha Golan,[41][42] Chogha Bonut,[43][44] and Chogha Mish.[45][46][47] The occupation of grouped hamlets in the area of Susa ranges from 4395 to 3490 BC.[48] There are several prehistoric sites across the country, such as Shahr-e Sukhteh and Teppe Hasanlu, all pointing to ancient cultures and civilizations.[49][50][51] From the 34th to the 20th century BC, northwest Iran was part of the Kura-Araxes culture, which stretched into the neighbouring Caucasus and Anatolia.

Since the Bronze Age, the area has been home to Iranian civilization,[52][53] including Elam, Jiroft, and Zayanderud. Elam, the most prominent, continued until the Plateau was unified as a state by the Medes in 7th century BC. The advent of writing in Elam was parallelled to Sumer; the Elamite cuneiform developed beginning in the third millennium BC.[54] Elam was part of the early urbanization of the Near East during the Chalcolithic period. Diverse artifacts from the Bronze Age and huge structures from the Iron Age indicates suitable conditions for human civilization over the past 8,000 years in Piranshahr and other areas.[55][56]

Ancient Iran and unification

By the 2nd millennium BC, ancient Iranian peoples arrived from the Eurasian Steppe.[57][58][59] As the Iranians dispersed into Greater Iran, it was dominated by Median, Persian, and Parthian tribes.[60] From the 10th to 7th century BC, Iranian peoples, together with pre-Iranian kingdoms, fell under the Assyrian Empire, based in Mesopotamia.[61] The Medes and Persians entered into an alliance with Babylonian ruler Nabopolassar, and attacked the Assyrians. Civil war ravaged the Assyrian Empire between 616 and 605 BC, freeing peoples from three centuries of Assyrian rule.[62] The interference of the Assyrians in Zagros unified the Median tribes by Deioces in 728 BC, the foundation of the Medes Kingdom and their capital Ecbatana, unifying Iran as a state and nation for the first time in 678 BC.[63] By 612 BC, the Medes with the Babylonians overthrown the Assyrian Empire.[64] This ended the Kingdom of Urartu.[65][66]

In 550 BC, Cyrus the Great defeated the last Median king, Astyages, and established the Achaemenid Empire. Conquests under Cyrus and his successors expanded it to include Lydia, Babylon, Egypt, parts of the Eastern Europe, and lands west of the Indus and Oxus rivers. In 539 BC, Persian forces defeated the Babylonians at Opis, ending four centuries of Mesopotamian domination by the Neo-Babylonian Empire.[67] In 518 BC, Persepolis was founded by Darius the Great as the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire, then the largest ever empire; it ruled over 40% of the world's population.[68][69] The Empire had a successful model of centralized bureaucracy, multiculturalism, road system, postal system, use of official languages, civil service and large, professional army. It inspired similar governance by later empires.[70] In 334 BC, Alexander the Great defeated the last Achaemenid king, Darius III and burned down Persepolis. After Alexander's death in 323 BC, Iran fell under the Seleucid Empire, and divided into several Hellenistic states.

Iran remained under Seleucid occupation until 250–247 BC, when the native Parthians liberated Parthia in the northeast, and rebelled against the Seleucids, founding the Parthian Empire. Parthians became the main power, and the geopolitical arch-rivalry between the Romans and the Parthians began, culminating in the Roman–Parthian Wars. At its height, the Parthian Empire stretched from the north reaches of the Euphrates in present-day Turkey, to Afghanistan and Pakistan. Located on the Silk Road trade route between the Roman Empire and China, it became a commercial center. As the Parthians expanded west, they conflicted with Armenia and the Roman Republic.[71]

After five centuries of Parthian rule, civil war proved more dangerous to stability, than invasion. Parthian power evaporated when Persian ruler Ardashir I, killed Artabanus IV, and founded the Sasanian Empire in 224 AD. Sassanids and their arch-rival, the Roman-Byzantines, were the world's dominant powers for four centuries. Late antiquity is one of Iran's most influential periods,[72] its influence reached ancient Rome,[73][74] Africa,[75] China, and India,[76] and played a prominent role in the mediaeval art of Europe and Asia.[77][78] Sasanian rule was a high point, characterized by sophisticated bureaucracy, and revitalized Zoroastrianism as a legitimizing and unifying force.[79]

Mediaeval Iran and Iranian Intermezzo

Following early Muslim conquests, the influence of Sasanian art, architecture, music, literature and philosophy on Islamic culture, spread Iranian culture, knowledge and ideas in the Muslim world. The Byzantine–Sasanian wars, and conflict within the Sasanian Empire, allowed Arab invasion in the 7th century.[80][81] The empire was defeated by the Rashidun Caliphate, which was succeeded by the Umayyad Caliphate, then the Abbasid Caliphate. Islamization followed, which targeted Iran's Zoroastrian majority and included religious persecution,[82][83][84] demolition of libraries[85] and fire temples,[86] a tax penalty ("jizya"),[87][88] and language shift.[89][90]

In 750, the Abbasids overthrew the Umayyads.[91] Arab and Persians Muslims made up the rebel army together, which was united by Persian Abu Muslim.[92][93] In their struggle for power, society became cosmopolitan. Persians and Turks replaced Arabs. A hierarchy of officials emerged, a bureaucracy at first Persian and later Turkish which decreased Abbasid prestige and power for good.[94] After two centuries of Arab rule, Iranian Muslim dynasties in the Plateau rose, appearing on the fringes of the declining Abbasid Caliphate.[95] The Iranian Intermezzo was an interlude between Abbasid rule by Arabs, and the "Sunni Revival", with the 11th-century emergence of the Seljuks. The Intermezzo ended the Arab rule over Iran, revived the Iranian national spirit and culture in Islamic form, and the Persian language. The most significant literature was Shahnameh by Ferdowsi, the national epic.[96][97][98][99]

The blossoming literature, philosophy, mathematics, medicine, astronomy and art became major elements in the Islamic Golden Age.[100][101] This Golden Age peaked in the 10th and 11th centuries, when Iran was the main theatre of scientific activities.[102] The 10th century saw a mass migration of Turkic tribes from Central Asia to Iran. Turkic tribesmen were first used in the Abbasid army as mamluks (slave-warriors);[103] and gained significant political power. Portions of Iran were occupied by the Seljuk and Khwarezmian empires.[104][105] The result of the adoption and patronage of Iranian culture by Turkish rulers was the development of a distinct Turco-Persian tradition.

Between 1219 and 1221, under the Khwarazmian Empire, Iran suffered under the Mongol invasion of the Khwarazmian Empire. According to Steven Ward, "Mongol violence... killed up to three-fourths of the population of the Iranian Plateau, possibly 10 to 15 million people....Iran's population did not...reach its pre-Mongol levels until the mid-20th century." Others believe this to be an exaggeration by Muslim chroniclers.[106][107][108] Following the fracture of the Mongol Empire in 1256, Hulegu Khan established the Ilkhanate Empire in Iran. In 1357, the capital Tabriz was occupied by the Golden Horde and centralised power collapsed, resulting in rivalling dynasties. In 1370, yet another Mongol, Timur, took control of Iran, and established the Timurid Empire. In 1387, Timur ordered the complete massacre of Isfahan, killing 70,000 people.[109]

Early modern period

Safavids

In 1501, Ismail I established the Safavid Empire, and chose Tabriz as capital.[110] Beginning with Azerbaijan, he extended his authority over Iranian territories, and established Iranian hegemony over Greater Iran.[111] The Safavids, along with the Ottomans and Mughals, were creators of the "Gunpowder empires", flourished from mid-16th, to the early 18th century. Iran was predominantly Sunni, but Ismail forced conversion to Shia, a turning point in the history of Islam;[112][113][114][115][116] Iran is the world's only official Shia nation today.[117][118]

Relations between Safavids and the West began with the Portuguese, in the Persian Gulf, from the 16th century, oscillating between alliances and war up to the 18th century. The Safavid era saw integration from Caucasian populations and their resettlement within Iran's heartlands. In 1588, Abbas the Great ascended during a troubled period. Iran developed the ghilman system where thousands of Circassian, Georgian, and Armenian slave-soldiers joined the administration and military. The Christian Iranian-Armenian community is the largest minority in Iran today.[119]

Abbas eclipsed the power of the Qizilbash in the civil administration, royal house and military. He relocated the capital from Qazvin to Isfahan, making it the focal point of Safavid architecture. Tabriz returned to Iran from the Ottomans under his rule. Following court intrigue, Abbas became suspicious of his sons and had them killed or blinded. Following a gradual decline in the late 1600s and early 1700s, caused by internal conflicts, wars with the Ottomans, and foreign interference, the Safavid rule was ended by the Pashtun rebels who besieged Isfahan, and defeated Soltan Hoseyn in 1722. Safavids' legacy was the revival of Iran as an economic stronghold between East and West, an efficient bureaucracy based upon "checks and balances", their architectural innovations, and patronage for fine arts. They established Twelver Shīʿīsm as the state religion-it still is-and spread Shīʿa Islam across the Middle East, Central Asia, Caucasus, Anatolia, the Persian Gulf, and Mesopotamia.[120]

Afsharids and Zands

In 1729, Nader Shah Afshar drove out Pashtun invaders, and founded the Afsharid Empire. He took back the Caucasian territories which were divided among the Ottoman and Russian authorities. Iran reached its greatest extent since the Sasanian Empire, reestablishing hegemony over the Caucasus, west and central Asia, arguably the most powerful empire at that time.[121] Nader invaded India and sacked Delhi by the 1730s, his army defeated the Mughals at the Battle of Karnal and captured their capital. Historians have described him as the "Napoleon of Iran" and "the Second Alexander".[122][123] Nader's territorial expansion and military successes declined following campaigns in the Northern Caucasus against revolting Lezgins. Nader became cruel as a result of illness and desire to extort more taxes to pay for campaigns. Nader crushed revolts, building towers from victims' skulls in imitation of his hero Timur.[124][125] After his assassination in 1747, most of Nader's empire was divided between the Zands, Durranis, Georgians, and Caucasian khanates, while Afsharid rule was limited to a small local state in Khorasan. His death sparked civil war, after which Karim Khan Zand came to power in 1750.[126]

Compared to preceding dynasties, the Zands' geopolitical reach was limited. Many Iranian territories in the Caucasus gained autonomy and ruled through Caucasian khanates. However, they remained subjects and vassals to the Zand kingdom. It expanded to include much of Iran as well as parts of modern Iraq. The lands of present-day Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia were controlled by khanates - legally part of Zand rule, but actually autonomous.[127] The reign of its most important ruler, Karim Khan, was marked by prosperity and peace. With his capital in Shiraz, arts and architecture flourished in the city. Following Khan's death in 1779, Iran went into decline due to civil war within the Zand dynasty. Its last ruler, Lotf Ali Khan, was executed by Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar in 1794.

Qajars

The Qajars took control in 1794 and founded the Qajar Empire. In 1795, following the disobedience of Georgians and their Russian alliance, the Qajars captured Tbilisi at the Battle of Krtsanisi, and drove the Russians out of the Caucasus, re-establishing Iranian suzerainty. In 1796, Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar seized Mashhad with ease, and ended the Afsharid rule. He was crowned king and chose Tehran as capital; it still is today. His reign saw a return to a centralized and unified Iran. He was cruel and rapacious, while also viewed as a pragmatic, calculating, and shrewd military and political leader.[128][129]

The Russo-Iranian wars of 1804–1813 and 1826–1828 resulted in territorial losses for Iran in the Caucasus: South Caucasus and Dagestan.[130] The Russians took over Iran's integral territories in the region, which was confirmed in the treaties of Gulistan and Turkmenchay.[131][132][133][134] The weakening of Iran made it a victim of the struggle between Russia and Britain known as the Great Game.[135] Especially after the treaty of Turkmenchay, Russia was the dominant force in Iran,[136] while the Qajars would play a role in 'Great Game' battles such as the sieges of Herat in 1837 and 1856. As Iran shrank, many South Caucasian and North Caucasian Muslims moved towards Iran,[137] especially until the Circassian genocide, and the decades afterwards, while Iran's Armenians were encouraged to settle in the newly incorporated Russian territories,[138][139] causing demographic shifts. Around 1.5 million people—20 to 25% of the population—died as a result of the Persian famine of 1870–1872.[140]

Constitutional Revolution and Pahlavis

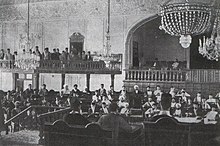

Between 1872 and 1905, protesters objected to the sale of concessions to foreigners by Qajar monarchs, leading to the Persian Constitutional Revolution in 1905. The first Iranian constitution and national parliament were founded in 1906; the Constitution recognised Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians. This was followed by the Triumph of Tehran in 1909, when Mohammad Ali was forced to abdicate. The event ended the Minor Tyranny; the revolution was the first of its kind in the Islamic world.

The old order was replaced by new institutions. In 1907, the Anglo-Russian Convention divided Iran into influence zones. The Russians occupied north Iran and Tabriz and maintained a military presence for years. This did not end the civil uprisings and was followed by Mirza Kuchik Khan's Jungle Movement against the Qajar monarchy and foreign invaders.

Despite Iran's neutrality during World War I, the Ottoman, Russian, and British Empires occupied west Iran and fought the Persian campaign before withdrawing in 1921. At least 2 million civilians died in the fighting, the Ottoman-perpetrated anti-Christian genocides or the war-induced famine of 1917–1919. Iranian Assyrian and Iranian Armenian Christians, as well Muslims who tried to protect them, were victims of mass murders committed by the invading Ottoman troops.[141][142][143][144]

Apart from Agha Mohammad Khan, Qajar rule was incompetent.[145] The inability to prevent occupation during, and immediately after, World War I, led to the British-directed 1921 Persian coup d'état. Military officer Reza Pahlavi took power in 1925, becoming Prime Minister, monarch and establishing the Pahlavi dynasty. In 1941, during World War II, the British demanded Iran expel all Germans. Pahlavi refused so the British and Soviets launched a successful surprise invasion,[146] which secured a supply line to the USSR and limited German influence. Pahlavi was quickly surrendered, went to exile and replaced by his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.[147][148][149]Iran became a major conduit for British and American aid to the Soviet Union and through which over 120,000 Polish refugees and Polish Armed Forces fled.[150] At the 1943 Tehran Conference, the Allies issued the Tehran Declaration to guarantee the independence and boundaries of Iran. However, the Soviets established puppet states in north-west Iran: the People's Government of Azerbaijan and Republic of Mahabad. This led to the Iran crisis of 1946, one of the first confrontations of the Cold War, which ended after oil concessions were promised to the USSR, which withdrew in 1946. The puppet states were overthrown, and the concessions revoked.[151][152]

1951–1978: Mosaddegh, Pahlavi and Khomeini

In 1951, Mohammad Mosaddegh was democratically elected Prime Minister of Iran. Mosaddegh became popular after he nationalized the oil industry, which had been controlled by foreign interests. He worked to weaken the monarchy until he was removed in the 1953 Iran coup—an Anglo-American covert operation.[153] Before its removal, Mosaddegh's administration introduced social and political measures such as social security, land reforms and higher taxes, including the introduction of tax on the rent of land. Mosaddegh was imprisoned, then put under house arrest until his death and buried in his home to prevent a political furore. In 2013, the US government acknowledged its role in the coup, including paying protestors and bribing officials.[154] After the coup, Pahlavi aligned Iran with the Western Bloc and cultivated a close relationship with the United States to consolidate his power as an authoritarian ruler, relying heavily on American support amidst the Cold War.

The Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini first came to political prominence in 1963, when he led opposition to Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and his White Revolution. Khomeini was arrested after declaring Mohammad Reza a "wretched miserable man" who had "embarked on the...destruction of Islam in Iran."[155] Major riots followed, with 15,000 killed by the police.[156] Khomeini was released after eight months of house arrest and continued his agitation, condemning Iran's cooperation with Israel and its capitulations, or extension of diplomatic immunity, to US government personnel. In November 1964, Khomeini was re-arrested and sent into exile, where he remained for 15 years.

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi became autocratic and sultanistic, and Iran entered a decade of controversially-close relations with the US.[157] While Mohammad Reza modernised Iran and claimed to retain it as a secular state,[158] arbitrary arrests and torture by his secret police, the SAVAK, were used for crushing opposition.[159] Due to the 1973 oil crisis, the economy was flooded with foreign currency, causing inflation. By 1974, Iran was experiencing double-digit inflation, and despite large modernising projects, corruption was rampant. By 1976, a recession increased unemployment, especially among youths who had migrated to the cities for construction jobs during the boom years of the early 1970s. By the late 1970s, they protested against Pahlavi's regime.[160]

Iranian Revolution

As ideological and political tensions persisted between Pahlavi and Khomeini, demonstrations began in October 1977, developing into civil resistance, including secularism and Islamism.[161] In 1978, the death of hundreds in the Cinema Rex fire in August, and September's Black Friday—catalysed the revolutionary movement, with nation-wide strikes and demonstrations paralyzing the country.[162][163][164] After a year of strikes and demonstrations, in January 1979, Pahlavi fled to the US,[165] and Khomeini returned in February, forming a new government.[166] Millions of people gathered to greet him as he landed in the capital city Tehran.[167]

Following the March 1979 referendum, in which 98% of voters approved the shift to an Islamic republic, the government began to draft a Constitution, and Ayatollah Khomeini emerged as Supreme Leader of Iran in December 1979. He became Time magazine's Man of the Year in 1979 for his international influence, and been described as the "virtual face of Shia Islam in Western popular culture".[168] Following Khomeini's order to purge officials loyal to Pahlavi, many former ministers and officials, were executed.[169] In the aftermath of the revolution, Iran began to back Shia militancy around the world to combat Sunni influence and establish Iranian dominance within the Muslim world. The Cultural Revolution began in 1980, with threats to close universities which did not conform to Islamization. All universities were closed in 1980, and reopened in 1983.[170][171][172]

In November 1979, after the US refused the extradition of Pahlavi, Iranian students seized its embassy and took 53 Americans hostage.[173] Jimmy Carter's administration attempted to negotiate their release, and to rescue them. On Carter's final day in office, the last hostages were set free under the Algiers Accords. The US and Iran severed diplomatic relations in April 1980, and have had no formal diplomatic relationship since.[174] The crisis was a pivotal episode in Iran–United States relations.

Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988)

In September 1980, Iraq invaded Khuzestan, initiating the Iran–Iraq War. While Iraq hoped to take advantage of Iran's post-revolutionary chaos, the Iraqi military only made progress for three months, and by December 1980, the forces of Saddam Hussein had stalled. By mid-1982, Iranian forces began to gain momentum, successfully driving the Iraqis back into Iraq, and regaining all lost territory by June 1982. Iran rejected United Nations Security Council Resolution 514 and launched an invasion, capturing cities such as Basra. Iranian offensives in Iraq lasted for five years, with Iraq launching counter-offensives.

War continued until 1988, when Iraq defeated Iranian forces inside Iraq, and pushed Iranian troops back across the border. Khomeini accepted a truce mediated by the United Nations: both withdrew to their pre-war borders. It was the longest conventional war of the 20th century and second longest after the Vietnam War. Total Iranian casualties were estimated to be 123,000–160,000 KIA, 61,000 MIA, and 11,000–16,000 civilians killed.[176][177] Since the downfall of Saddam Hussein, Iran has shaped Iraq's politics, and relations between the two has warmed immensely.[178][179][180] Significant military assistance has been provided by Iran to Iraq, resulting in Iran holding a large amount of influence and foothold. Iraq is heavily dependent on the more stable and developed Iran for its energy needs.[181][182]

Since the 1990s

In 1989, Akbar Rafsanjani concentrated on a pro-business policy of rebuilding the economy without breaking with the ideology of the revolution. He supported a free market domestically, favoring privatization of state industries and a moderate position internationally.

In 1997, Rafsanjani was succeeded by moderate reformist Mohammad Khatami, whose government advocated freedom of expression, constructive diplomatic relations with Asia and the European Union, and an economic policy that supported a free market and foreign investment.

The 2005 presidential election brought conservative populist and nationalist candidate Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to power. He was known for his hardline views, nuclearisation, and hostility towards Israel, Saudi Arabia, the UK, the US and other states. He was the first president to be summoned by the parliament to answer questions regarding his presidency.[183]

In 2013, centrist and reformist Hassan Rouhani was elected president. In domestic policy, he encouraged personal freedom, free access to information, and improved women's rights. He improved Iran's diplomatic relations through exchanging conciliatory letters.[184] The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was reached in Vienna in 2015, between Iran, the P5+1 (UN Security Council + Germany) and the EU. The negotiations centered around ending the economic sanctions in exchange for Iran's restriction in producing enriched uranium.[185] In 2018, however, the US under Trump Administration withdrew from the deal and new sanctions were imposed. This nulled the economic provisions, left the agreement in jeopardy, and brought Iran to nuclear threshold status.[186] In 2020, IRGC general, Qasem Soleimani, the 2nd-most powerful person in Iran,[187] was assassinated by the US, heightening tensions between them.[188] Iran retaliated against US airbases in Iraq, the largest ballistic missile attack ever on Americans;[189] 110 sustained brain injuries.[190][191][192]

Hardliner Ebrahim Raisi ran for president again in 2021, succeeding Hassan Rouhani. During Raisi's term, Iran intensified uranium enrichment, hindered international inspections, joined SCO and BRICS, supported Russia in its invasion of Ukraine and restored diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia. In April 2024, Israel's airstrike on an Iranian consulate, killed an IRGC commander.[193][194] Iran retaliated with UAVs, cruise and ballistic missiles; 9 hit Israel.[195][196][197] Western and Jordanian military helped Israel down some Iranian drones.[198][199] It was the largest drone strike in history,[200] biggest missile attack in Iranian history,[201] its first ever direct attack on Israel[202][203] and the first time since 1991 Israel was directly attacked by a state force.[204] This occurred during heightened tensions amid the Israeli invasion of the Gaza Strip.

In May 2024, President Raisi was killed in a helicopter crash, and Iran held a presidential election in June according to the constitution, which reformist politician and former Minister of Health, Masoud Pezeshkian, came to power.[205][206]

Geography

Iran has an area of 1,648,195 km2 (636,372 sq mi). It is the sixth-largest country entirely in Asia and the second-largest in West Asia.[207] It lies between latitudes 24° and 40° N, and longitudes 44° and 64° E. It is bordered to the northwest by Armenia (35 km or 22 mi), the Azeri exclave of Nakhchivan (179 km or 111 mi),[208] and the Republic of Azerbaijan (611 km or 380 mi); to the north by the Caspian Sea; to the northeast by Turkmenistan (992 km or 616 mi); to the east by Afghanistan (936 km or 582 mi) and Pakistan (909 km or 565 mi); to the south by the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman; and to the west by Iraq (1,458 km or 906 mi) and Turkey (499 km or 310 mi).

Iran is in a seismically active area.[209] On average, an earthquake of magnitude seven on the Richter scale occurs once every ten years.[210] Most earthquakes are shallow-focus and can be very devastating, such as the 2003 Bam earthquake.

Iran consists of the Iranian Plateau. It is one of the world's most mountainous countries, its landscape is dominated by rugged mountain ranges that separate basins or plateaus. The populous west part is the most mountainous, with ranges such as the Caucasus, Zagros, and Alborz, the last containing Mount Damavand, Iran's highest point, at 5,610 m (18,406 ft), which is the highest volcano in Asia. Iran's mountains have impacted its politics and economics for centuries.

The north part is covered by the lush lowland Caspian Hyrcanian forests, near the southern shores of the Caspian Sea. The east part consists mostly of desert basins, such as the Kavir Desert, which is the country's largest desert, and the Lut Desert, as well as salt lakes. The Lut Desert is the hottest recorded spot on the Earth's surface, with 70.7 °C recorded in 2005.[211][212][213][214] The only large plains are found along the coast of the Caspian and at the north end of the Persian Gulf, where the country borders the mouth of the Arvand river. Smaller, discontinuous plains are found along the remaining coast of the Persian Gulf, the Strait of Hormuz, and Gulf of Oman.[215][216][217]

Islands

Iranian islands are mainly located in the Persian Gulf. Iran has 102 islands in Urmia Lake, 427 in Aras River, several in Anzali Lagoon, Ashurade Island in the Caspian Sea, Sheytan Island in the Oman Sea and other inland islands. Iran has an uninhabited island at the far end of the Gulf of Oman, near Pakistan. A few islands can be visited by tourists. Most are owned by the military or used for wildlife protection, and entry is prohibited or requires a permit.[218][219][220]

Iran took control of Bumusa, and the Greater and Lesser Tunbs in 1971, in the Strait of Hormuz between the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman. Despite the islands being small and having little natural resources or population, they are highly valuable for their strategic location.[221][222][223][224][225] Although the United Arab Emirates claims sovereignty,[226][227][228] it has consistently been met with a strong response from Iran,[229][230][231] based on their historical and cultural background.[232] Iran has full-control over the islands.[233]

Kish island, as a free trade zone, is touted as a consumer's paradise, with malls, shopping centres, tourist attractions, and luxury hotels. Qeshm is the largest island in Iran, and a UNESCO Global Geopark since 2016.[234][235][236] Its salt cave, Namakdan, is the largest in the world, and one of the world's longest caves.[237][238][239][240]

Climate

Iran's climate is diverse, ranging from arid and semi-arid, to subtropical along the Caspian coast and northern forests.[241] On the north edge of the country, temperatures rarely fall below freezing and the area remains humid. Summer temperatures rarely exceed 29 °C (84.2 °F).[242] Annual precipitation is 680 mm (26.8 in) in the east part of the plain and more than 1,700 mm (66.9 in) in the west part. The UN Resident Coordinator for Iran, has said that "Water scarcity poses the most severe human security challenge in Iran today".[243]

To the west, settlements in the Zagros basin experience lower temperatures, severe winters with freezing average daily temperatures and heavy snowfall. The east and central basins are arid, with less than 200 mm (7.9 in) of rain and have occasional deserts.[244] Average summer temperatures rarely exceed 38 °C (100.4 °F). The southern coastal plains of the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman have mild winters, and very humid and hot summers. The annual precipitation ranges from 135 to 355 mm (5.3 to 14.0 in).[245]

Biodiversity

More than one-tenth of the country is forested.[246] About 120 million hectares of forests and fields are government-owned for national exploitation.[247][248] Iran's forests can be divided into five vegetation regions: Hyrcanian region which forms the green belt of the north side of the country; the Turan region, which are mainly scattered in the center of Iran; Zagros region, which mainly contains oak forests in the west; the Persian Gulf region, which is scattered in the southern coastal belt; the Arasbarani region, which contains rare and unique species. More than 8,200 plant species are grown. The land covered by natural flora is four times that of Europe's.[249] There are over 200 protected areas to preserve biodiversity and wildlife, with over 30 being national parks.

Iran's living fauna includes 34 bat species, Indian grey mongoose, small Indian mongoose, golden jackal, Indian wolf, foxes, striped hyena, leopard, Eurasian lynx, brown bear and Asian black bear. Ungulate species include wild boar, urial, Armenian mouflon, red deer, and goitered gazelle.[250][251] One of the most famous animals is the critically endangered Asiatic cheetah, which survives only in Iran. Iran lost all its Asiatic lions and the extinct Caspian tigers by the early 20th century.[252] Domestic ungulates are represented by sheep, goat, cattle, horse, water buffalo, donkey and camel. Bird species like pheasant, partridge, stork, eagles and falcons are native.[253][254]

Government and politics

Supreme Leader

The Supreme Leader, "Rahbar", Leader of the Revolution or Supreme Leadership Authority, is head of state and responsible for supervision of policy. The president has limited power compared to the Rahbar. Key ministers are selected with the Rahbar's agreement and they have the ultimate say on foreign policy.[255] The Rahbar is directly involved in ministerial appointments for Defence, Intelligence and Foreign Affairs, as well as other top ministries after submission of candidates from the president.

Regional policy is directly controlled by the Rahbar, with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs' task limited to protocol and ceremonial occasions. Ambassadors to Arab countries, for example, are chosen by the Quds Force, which directly reports to the Rahbar.[256] The Rahbar can order laws to be amended.[257] Setad was estimated at $95 billion in 2013 by Reuters, accounts of which are secret even to the parliament.[258][259]

The Rahbar is the commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces, controls military intelligence and security operations, and has sole power to declare war or peace. The heads of the judiciary, state radio and television networks, commanders of the police and military, and the members of the Guardian Council are appointed by the Rahbar.

The Assembly of Experts is responsible for electing the Rahbar, and has the power to dismiss him on the basis of qualifications and popular esteem.[260] To date, the Assembly of Experts has not challenged any of the Rahbar's decisions nor attempted to dismiss him. The previous head of the judicial system, Sadeq Larijani, appointed by the Rahbar, said that it is illegal for the Assembly of Experts to supervise the Rahbar.[261] Many believe the Assembly of Experts has become a ceremonial body without any real power.[262][263][264]

The political system is based on the country's constitution.[265] Iran ranked 154th in the 2022 The Economist Democracy Index.[266] Juan José Linz wrote in 2000 that "the Iranian regime combines the ideological bent of totalitarianism with the limited pluralism of authoritarianism".[267]

President

The President is head of government and the second highest-ranking authority, after the Supreme Leader. The President is elected by universal suffrage for 4 years. Before elections, nominees to become a presidential candidate must be approved by the Guardian Council.[268] The Council's members are chosen by the Leader, with the Leader having the power to dismiss the president.[269] The President can only be re-elected for one term.[270] The president is the deputy commander-in-chief of the Army, the head of Supreme National Security Council, and has the power to declare a state of emergency after passage by the parliament.

The President is responsible for the implementation of the constitution, and for the exercise of executive powers in implementing the decrees and general policies as outlined by the Rahbar, except for matters directly related to the Rahbar, who has the final say.[271] The President functions as the executive of affairs such as signing treaties and other international agreements, and administering national planning, budget, and state employment affairs, all as approved by the Rahbar.[272][273]

The President appoints ministers, subject to the approval of the Parliament, and the Rahbar, who can dismiss or reinstate any minister.[274][275][276] The President supervises the Council of Ministers, coordinates government decisions, and selects government policies to be placed before the legislature.[277] Eight Vice Presidents serve under the President, as well as a cabinet of 22 ministers, all appointed by the president.[278]

Guardian Council

Presidential and parliamentary candidates must be approved by the 12-member Guardian Council (all members of which are appointed by the Leader) or the Leader, before running to ensure their allegiance.[279] The Leader rarely does the vetting, but has the power to do so, in which case additional approval of the Guardian Council is not needed. The Leader can revert the decisions of the Guardian Council.[280]

The constitution gives the council three mandates: veto power over legislation passed by the parliament,[281][282] supervision of elections[283] and approving or disqualifying candidates seeking to run in local, parliamentary, presidential, or Assembly of Experts elections.[284] The council can nullify a law based on two accounts: being against Sharia (Islamic law), or being against the constitution.[285]

Supreme National Security Council

The Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) is at the top of the foreign policy decisions process.[286][287][288] The council was formed during the 1989 Iranian constitutional referendum for the protection and support of national interests, the revolution, territorial integrity and national sovereignty.[289] It is mandated by Article 176 of the Constitution to be presided over by the President.[290][291]

The Leader selects the secretary of the Supreme Council, and the decisions of the council are effective after the confirmation by the Leader. The SNSC formulates nuclear policy, and would become effective if they are confirmed by the Leader.[292][293]

Legislature

The legislature, known as the Islamic Consultative Assembly (ICA), Iranian Parliament or "Majles", is a unicameral body comprising 290 members elected for four-years.[294] It drafts legislation, ratifies international treaties, and approves the national budget. All parliamentary candidates and legislation from the assembly must be approved by the Guardian Council.[295][296] The Guardian Council can and has dismissed elected members of the parliament.[297][298] The parliament has no legal status without the Guardian Council, and the Council holds absolute veto power over legislation.[299]

The Expediency Discernment Council has the authority to mediate disputes between Parliament and the Guardian Council, and serves as an advisory body to the Supreme Leader, making it one of the most powerful governing bodies in Iran.[300][301]

The Parliament has 207 constituencies, including the 5 reserved seats for religious minorities. The remaining 202 are territorial, each covering one or more of Iran's counties.

Law

Iran uses a form of Sharia law as its legal system, with elements of European Civil law. The Supreme Leader appoints the head of the Supreme Court and chief public prosecutor. There are several types of courts, including public courts that deal with civil and criminal cases, and revolutionary courts which deal with certain offences, such as crimes against national security. The decisions of the revolutionary courts are final and cannot be appealed.

The Chief Justice is the head of the judicial system and responsible for its administration and supervision. He is the highest judge of the Supreme Court of Iran. The Chief Justice nominates candidates to serve as minister of justice, and the President selects one. The Chief Justice can serve for two five-year terms.[302]

The Special Clerical Court handles crimes allegedly committed by clerics, although it has taken on cases involving laypeople. The Special Clerical Court functions independently of the regular judicial framework and is accountable only to the Rahbar. The Court's rulings are final and cannot be appealed.[303] The Assembly of Experts, which meets for one week annually, comprises 86 "virtuous and learned" clerics elected by adult suffrage for 8-year terms.

Administrative divisions

Iran is subdivided into thirty-one provinces (Persian: استان ostân), each governed from a local centre, usually the largest local city, which is called the capital (Persian: مرکز, markaz) of that province. The provincial authority is headed by a governor-general (استاندار ostândâr), who is appointed by the Minister of the Interior subject to approval of the cabinet.[304]

Foreign relations

Iran maintains diplomatic relations with 165 countries, but not the United States and Israel—a state which Iran derecognised in 1979.[305]

Iran has an adversarial relationship with Saudi Arabia due to different political and ideologies. Iran and Turkey have been involved in modern proxy conflicts such as in Syria, Libya, and the South Caucasus.[306][307][308] However, they have shared common interests, such as the issue of Kurdish separatism and the Qatar diplomatic crisis.[309][310] Iran has a close and strong relationship with Tajikistan.[311][312][313][314] Iran has deep economic relations and alliance with Iraq, Lebanon and Syria, with Syria often described as Iran's "closest ally".[315][316][317]

Russia is a key trading partner, especially in regard to its excess oil reserves.[318][319] Both share a close economic and military alliance, and are subject to heavy sanctions by Western nations.[320][321][322][323] Iran is the only country in Western Asia that has been invited to join the CSTO, the Russia-based international treaty organization that parallels NATO.[324]

Relations between Iran and China is strong economically; they have developed a friendly, economic and strategic relationship. In 2021, Iran and China signed a 25-year cooperation agreement that will strengthen the relations between the two countries and would include "political, strategic and economic" components.[325] Iran-China relations dates back to at least 200 BC and possibly earlier.[326][327] Iran is one of the few countries in the world that has a good relationship with both North and South Korea.[328]

Iran is a member of dozens of international organizations, including the G-15, G-24, G-77, IAEA, IBRD, IDA, NAM, IDB, IFC, ILO, IMF, IMO, Interpol, OIC, OPEC, WHO, and the UN, and currently has observer status at the WTO.

Military

The military is organized under a unified structure, the Islamic Republic of Iran Armed Forces, comprising the Islamic Republic of Iran Army, which includes the Ground Forces, Air Defence Force, Air Force, and Navy; the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, which consists of the Ground Forces, Aerospace Force, Navy, Quds Force, and Basij; and the Law Enforcement Command (Faraja), which serves an analogous function to a gendarme. While the IRIAF protects the country's sovereignty in a traditional capacity, the IRGC is mandated to ensure the integrity of the Republic, against foreign interference, coups, and internal riots.[329] Since 1925, it is mandatory for all male citizen aged 18 to serve around 14 months in the IRIAF or IRGC.[330][331]

Iran has over 610,000 active troops and around 350,000 reservists, totalling over 1 million military personnel, one of the world's highest percentage of citizens with military training.[332][333][334][335] The Basij, a paramilitary volunteer militia within the IRGC, has over 20 million members, 600,000 available for immediate call-up, 300,000 reservists, and a million that could be mobilized when necessary.[336][337][338][339] Faraja, the Iranian uniformed police force, has over 260,000 active personnel. Most statistical organizations do not include the Basij and Faraja in their ratings report.

Excluding the Basij and Faraja, Iran has been identified as a major military power, owing it to the size and capabilities of its armed forces. It possesses the world's 14th strongest military.[340] It ranks 13th globally in terms of overall military strength, 7th in the number of active military personnel,[341] and 9th in the size of both its ground force and armoured force. Iran's armed forces are the largest in West Asia and comprise the greatest Army Aviation fleet in the Middle East.[342][343][344] Iran is among the top 15 countries in terms of military budget.[345] In 2021, its military spending increased for the first time in four years, to $24.6 billion, 2.3% of the national GDP.[346] Funding for the IRGC accounted for 34% of Iran's total military spending in 2021.[347]

Since the Revolution, to overcome foreign embargoes, Iran has developed a domestic military industry capable of producing indigenous tanks, armoured personnel carriers, missiles, submarines, missile destroyer, radar systems, helicopters, naval vessels, and fighter planes.[348] Official announcements have highlighted the development of advanced weaponry, particularly in rocketry.[349][n 1] Consequently, Iran has the largest and most diverse ballistic missile arsenal in the Middle East and is only the 5th country in the world with hypersonic missile technology.[350][351] It is the world's 6th missile power.[352] Iran designs and produces a variety of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and is considered a global leader and superpower in drone warfare and technology.[353][354][355] It is one of the world's five countries with cyberwarfare capabilities and is identified as "one of the most active players in the international cyber arena".[356][357][358] Iran is an key exporter of arms since 2000s.[359]

Following Russia's purchase of Iranian drones during the invasion of Ukraine,[360][361][362] in November 2023, the Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force (IRIAF) finalized arrangements to acquire Russian Sukhoi Su-35 fighter jets, Mil Mi-28 attack helicopters, air defence and missile systems.[363][364] The Iranian Navy has had joint exercises with Russia and China.[365]

Nuclear program

Iran's nuclear program dates back to the 1950s.[366] Iran revived it after the Revolution, and its extensive nuclear fuel cycle, including enrichment capabilities, became the subject of intense international negotiations and sanctions.[367] Many countries have expressed concern Iran could divert civilian nuclear technology into a weapons programme.[368] In 2015, Iran and the P5+1 agreed to the Joint Comprehensive Plan on Action (JCPOA), aiming to end economic sanctions in exchange for restriction in producing enriched uranium.[369]

In 2018, however, the US withdrew from the deal under the Trump administration, and reimposed sanctions. This was met with resistance by Iran and other members of the P5+1.[370][371][372] A year later, Iran began decreasing its compliance.[373] By 2020, Iran announced it would no longer observe any limit set by the agreement.[374][375] Progress since then has brought Iran to the nuclear threshold status.[376][377][378] As of November 2023[update], Iran had uranium enriched to up to 60% fissile content, close to weapon grade.[379][380][381][382] Some analysts already regard Iran as a de facto nuclear power.[383][384][385]

Regional influence

Since the Revolution, Iran has grown its influence across and beyond the region.[390][391][392][393] It has built military forces with a wide network of state and none-state actors, starting with Hezbollah in Lebanon in 1982.[394][395] The IRGC has been key to Iranian influence, through its Quds Force.[396][397][398] The instability in Lebanon (from the 1980s),[399] Iraq (from 2003) [400] and Yemen (from 2014) [401] has allowed Iran to build strong alliances and footholds beyond its borders. Iran has a prominent influence in the social services, education, economy and politics of Lebanon,[402][403] and Lebanon provides Iran access to the Mediterranean Sea.[404][405] Hezbollah's strategic successes against Israel, such as its symbolic victory during the 2006 Israel–Hezbollah War, elevated Iran's influence in the Levant and strengthened its appeal across the Muslim World.[406][407]

Since the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the arrival of ISIS in the mid-2010s, Iran has financed and trained militia groups in Iraq.[408][409][410] Since the Iran-Iraq war in 1980s and the fall of Saddam Hussein, Iran has shaped Iraq's politics.[411][412][413] Following Iraq's struggle against ISIS in 2014, companies linked to the IRGC such as Khatam al-Anbiya, started to build roads, power plants, hotels and businesses in Iraq, creating an economic corridor worth around $9 billion before COVID-19.[414] This is expected to grow to $20 billion.[415][416]

During Yemen's civil war, Iran provided military support to the Houthis,[420][421][422] a Zaydi Shiite movement fighting Yemen's Sunni government since 2004.[423][424] They gained significant power in recent years.[425][426][427] Iran has considerable influence in Afghanistan and Pakistan through militant groups such as Liwa Fatemiyoun and Liwa Zainebiyoun.[428][429][430]

In Syria, Iran has supported President Bashar al-Assad;[431][432] the two countries are long-standing allies.[433][434] Iran has provided significant military and economic support to Assad's government,[435][436] so has a considerable foothold in Syria.[437][438] Iran has long supported the anti-Israel fronts in North Africa in countries like Algeria and Tunisia, embracing Hamas in part to help undermine the popularity of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO).[439] Iran's support of Hamas emerged more clearly in later years.[440][441][442][443] According to US intelligence, Iran does not have full control over these state and non-state groups.[444]

Human rights and censorship

The Iranian government has been denounced by various international organizations and governments for violating human rights.[446] The government has frequently persecuted and arrested critics of the government. Iranian law does not recognize sexual orientations. Sexual activity between members of the same sex is illegal and is punishable by death.[447][448] Capital punishment is a legal punishment, and according to the BBC, Iran "carries out more executions than any other country, except China".[449] UN Special Rapporteur Javaid Rehman has reported discrimination against several ethnic minorities in Iran.[450] A group of UN experts in 2022 urged Iran to stop "systematic persecution" of religious minorities, adding that members of the Baháʼí Faith were arrested, barred from universities, or had their homes demolished.[451][452]

Censorship in Iran is ranked among the most extreme worldwide.[453][454][455] Iran has strict internet censorship, with the government persistently blocking social media and other sites.[456][457][458] Since January 2021, Iranian authorities have blocked a list of social media platforms; Instagram, WhatsApp, Facebook, Telegram, Twitter and YouTube.[459]

The 2006 election results were widely disputed, resulting in protests.[460][461][462][463] The 2017–18 Iranian protests swept across the country in response to the economic and political situation.[464] It was formally confirmed that thousands of protesters were arrested.[465] The 2019–20 Iranian protests started on 15 November in Ahvaz, and spread across the country after the government announced increases in fuel prices of up to 300%.[466] A week-long total Internet shutdown marked one of the most severe Internet blackouts in any country, and the bloodiest governmental crackdown of the protestors.[467] Tens of thousands were arrested and hundreds were killed within a few days according to multiple international observers, including Amnesty International.[468]

Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752, was a scheduled international civilian passenger flight from Tehran to Kyiv, operated by Ukraine International Airlines. On 8 January 2020, the Boeing 737–800 flying the route was shot down by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) shortly after takeoff, killing all 176 occupants on board and leading to protests. An international investigation led to the government admitting to the shootdown, calling it a "human error".[469][470] Another Protests against the government began on 16 September 2022 after a woman named Mahsa Amini died in police custody following her arrest by the Guidance Patrol, known commonly as the "morality police".[471][472][473][474]

Economy

As of 2024[update], Iran has the world's 19th largest economy (by PPP). It is a mixture of central planning, state ownership of oil and other large enterprises, village agriculture, and small-scale private trading and service ventures.[475] Services contribute the largest percentage of GDP, followed by industry (mining and manufacturing) and agriculture.[476] The economy is characterized by its hydrocarbon sector, in addition to manufacturing and financial services.[477] With 10% of the world's oil reserves and 15% of gas reserves, Iran is an energy superpower. Over 40 industries are directly involved in the Tehran Stock Exchange.

Tehran is the economic powerhouse of Iran.[478] About 30% of Iran's public-sector workforce and 45% of its large industrial firms are located there, and half those firms' employees work for government.[479] The Central Bank of Iran is responsible for developing and maintaining the currency: the Iranian rial. The government does not recognise trade unions other than the Islamic labour councils, which are subject to the approval of employers and the security services.[480] Unemployment was 9% in 2022.[481]

Budget deficits have been a chronic problem, mostly due to large state subsidies, that include foodstuffs and especially petrol, totalling $100 billion in 2022 for energy alone.[483][484] In 2010, the economic reform plan was to cut subsidies gradually and replace them with targeted social assistance. The objective is to move towards free market prices and increase productivity and social justice.[485] The administration continues reform, and indicates it will diversify the oil-reliant economy. Iran has developed a biotechnology, nanotechnology, and pharmaceutical industry.[486] The government is privatising industries.

Iran has leading manufacturing industries in automobile manufacture, transportation, construction materials, home appliances, food and agricultural goods, armaments, pharmaceuticals, information technology, and petrochemicals in the Middle East.[487] Iran is among the world's top five producers of apricots, cherries, cucumbers and gherkins, dates, figs, pistachios, quinces, walnuts, Kiwifruit and watermelons.[488] International sanctions against Iran have damaged the economy.[489]

Tourism

Tourism had been rapidly growing before the COVID-19 pandemic, reaching nearly 9 million foreign visitors in 2019, the world's third fastest-growing tourism destination.[491][492] In 2022 it expanded its share to 5% of the economy.[493] Iran's tourism experienced a growth of 43% in 2023, attracting 6 million foreign tourists.[494] The government ended visa requirements for 60 countries in 2023.[495]

98% of visits are for leisure, while 2% are for business, indicating the country's appeal as a tourist destination.[496] Alongside the capital, the most popular tourist destinations are Isfahan, Shiraz and Mashhad.[497] Iran is emerging as a preferred destination for medical tourism.[498][499] Travellers from other West Asian countries grew 31% in the first seven months of 2023, surpassing Bahrain, Kuwait, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia.[500] Domestic tourism is one of the world's largests; Iranian tourists spent $33bn in 2021.[501][502][503] Iran projects investment of $32 billion in the tourism sector by 2026.[504]

Agriculture and fishery

Roughly one-third of Iran's total surface area is suited for farmland. Only 12% of the total land area is under cultivation, but less than one-third of the cultivated area is irrigated; the rest is devoted to dryland farming. Some 92% of agricultural products depend on water.[505] The western and northwestern portions of the country have the most fertile soils. Iran's food security index stands at around 96 percent.[506][507] 3% of the total land area is used for grazing and fodder production. Most of the grazing is done on mostly semi-dry rangeland in mountain areas and on areas surrounding the large deserts of Central Iran. Progressive government efforts and incentives during the 1990s, improved agricultural productivity, helping Iran toward its goal of reestablishing national self-sufficiency in food production.

Access to the Caspian Sea, the Persian Gulf, the Gulf of Oman, and many river basins provides Iran the potential to develop excellent fisheries. The government assumed control of commercial fishing in 1952. Expansion of the fishery infrastructure enabled the country to harvest an estimated 700,000 tons of fish annually from the southern waters. Since the Revolution, increased attention has been focused on producing fish from inland waters. Between 1976 and 2004, the combined take from inland waters by the state and private sectors increased from 1,100 tons to 110,175 tons.[508] Iran is the world's largest producer and exporter of caviar, exporting more than 300 tonnes annually.[509][510]

Industry and services

Iran is globally ranked 16th in car manufacturing, ahead of the UK, Italy, and Russia.[512][513] It has outputted 1.188 million cars in 2023, a 12% growth compared to the previous years. Iran has exported various cars to countries such as Venezuela, Russia and Belarus. From 2008 to 2009, Iran leaped to 28th place from 69th in annual industrial production growth rate.[514] Iranian contractors have been awarded several foreign tender contracts in different fields of construction of dams, bridges, roads, buildings, railroads, power generation, and gas, oil and petrochemical industries. As of 2011, some 66 Iranian industrial companies are carrying out projects in 27 countries.[515] Iran exported over $20 billion worth of technical and engineering services over 2001–2011. The availability of local raw materials, rich mineral reserves, experienced manpower have all played crucial role in winning the bids.[516]

45% of large industrial firms are located in Tehran, and almost half of their workers work for government.[517] The Iranian retail industry is largely in the hands of cooperatives, many of them government-sponsored, and of independent retailers in the bazaars. The bulk of food sales occur at street markets, where the Chief Statistics Bureau sets the prices.[518] Iran's main exports are to Iraq, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Oman, Syria, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, France, Canada, Venezuela, Japan, South Korea and Turkey.[519][520] Iran's automotive industry is the second most active industry of the country, after its oil and gas industry. Iran Khodro is the largest car manufacturer in the Middle East, and ITMCO is the biggest tractor manufacturer. Iran is the 12th largest automaker in the world. Construction is one of the most important sectors in Iran accounting for 20–50% of the total private investment.

Iran is one of the most important mineral producers in the world, ranked among 15 major mineral-rich countries.[521][522] Iran has become self-sufficient in designing, building and operating dams and power plants. Iran is one of the six countries in the world that manufacture gas- and steam-powered turbines.[523]

Transport

In 2011 Iran had 173,000 kilometres (107,000 mi) of roads, of which 73% were paved.[524] In 2008 there were nearly 100 passenger cars for every 1,000 inhabitants.[525]Tehran Metro is the largest in the Middle East,[526][527] it carries more than 3 million passengers daily and in 2018, 820 million trips.[528][529] Trains operate on 11,106 km (6,901 mi) of track.[530] The country's major port of entry is Bandar Abbas on the Strait of Hormuz. Imported goods are distributed through the country by trucks and freight trains. The Tehran–Bandar Abbas railroad connects Bandar-Abbas to the railroad system of Central Asia, via Tehran and Mashhad. Other major ports include Bandar e-Anzali and Bandar e-Torkeman on the Caspian Sea and Khorramshahr and Bandar-e Emam Khomeyni on the Persian Gulf.

Dozens of cities have airports that serve passenger and cargo planes. Iran Air, the national airline, operates domestic and international flights. All large cities have mass transit systems using buses, and private companies provide bus services between cities. Over a million people work in transport, accounting for 9% of GDP.[531]

Energy

Iran is an energy superpower and petroleum plays a key part.[533][534] As of 2023[update], Iran produced 4% of the world's crude oil (3.6 million barrels (570,000 m3) per day),[535] which generates US$36bn[536] of export revenue and is the main source of foreign currency.[537] Oil and gas reserves are estimated at 1.2 trn barrels;[538] Iran holds 10% of world oil reserves and 15% for gas. It ranks 3rd in oil reserves[539] and is OPEC's 2nd largest exporter. It has the 2nd largest gas reserves,[540] and 3rd largest natural gas production. In 2019, Iran discovered a southern oil field of 50 bn barrels[541][542][543][544] and in April 2024, the NIOC discovered 10 giant shale oil deposits, totalling 2.6 bn barrels.[545][546][547] Iran plans to invest $500 billion in oil by 2025.[548]

Iran manufactures 60–70% of its industrial equipment domestically, including turbines, pumps, catalysts, refineries, oil tankers, drilling rigs, offshore platforms, towers, pipes, and exploration instruments.[549] The addition of new hydroelectric stations and streamlining of conventional coal and oil-fired stations increased installed capacity to 33 GW; about 75% was based on natural gas, 18% on oil, and 7% on hydroelectric power. In 2004, Iran opened its first wind-powered and geothermal plants, and the first solar thermal plant began in 2009. Iran is the world's third country to develop GTL technology.[550]

Demographic trends and intensified industrialization have caused electric power demand to grow by 8% per year. The government's goal of 53 GW of installed capacity by 2010 is to be reached by bringing on line new gas-fired plants, and adding hydropower and nuclear generation capacity. Iran's first nuclear power plant went online in 2011.[551][552]

Science and technology

Iran has made considerable advances in science and technology, despite international sanctions. In the biomedical sciences, Iran's Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics has a UNESCO chair in biology.[553] In 2006, Iranian scientists successfully cloned a sheep at the Royan Research Center in Tehran.[554] Stem cell research is among the top 10 in the world.[555] Iran ranks 15th in the world in nanotechnologies.[556][557][558] Iranian scientists outside Iran have made major scientific contributions. In 1960, Ali Javan co-invented the first gas laser, and fuzzy set theory was introduced by Lotfi A. Zadeh.[559]

Cardiologist Tofy Mussivand invented and developed the first artificial cardiac pump, the precursor of the artificial heart. Furthering research in diabetes, the HbA1c was discovered by Samuel Rahbar. Many papers in string theory are published in Iran.[560] In 2014, Iranian mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani became the first woman, and Iranian, to receive the Fields Medal, the highest prize in mathematics.[561]

Iran increased its publication output nearly tenfold from 1996 through 2004, and ranked first in output growth rate, followed by China.[562] According to a study by SCImago in 2012, Iran would rank fourth in research output by 2018, if the trend persisted.[563] The Iranian humanoid robot Sorena 2, which was designed by engineers at the University of Tehran, was unveiled in 2010. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) has placed the name of Surena among the five most prominent robots, after analyzing its performance.[564]

Iranian Space Agency

The Iranian Space Agency (ISA) was established in 2004. Iran became an orbital-launch-capable nation in 2009,[565] and is a founding member of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. Iran placed its domestically built satellite Omid into orbit on the 30th anniversary of the Revolution, in 2009,[566] through its first expendable launch vehicle Safir. It became the 9th country capable of both producing a satellite and sending it into space from a domestically made launcher.[567] Simorgh's launch in 2016, is the successor of Safir.[568]

In January 2024, Iran launched the Soraya satellite into its highest orbit yet (750 km),[569][570] a new space launch milestone for the country.[571][572] It was launched by Qaem 100 rocket.[573][574] Iran also successfully launched 3 indigenous satellites, The Mahda, Kayan and Hatef,[575] into orbit using the Simorgh carrier rocket.[576][577] It was the first time in country's history that it simultaneously sent three satellites into space.[578][579] The three satellites are designed for testing advanced satellite subsystems, space-based positioning technology, and narrowband communication.[580]

In February 2024, Iran launched its domestically developed imaging satellite, Pars 1, from Russia into orbit.[581][582] This was the second time since August 2022, when Russia launched another Iranian remote-sensing, Khayyam satellite, into orbit from Kazakhstan, reflecting deep scientific cooperation between the countries.[583][584]

Iran is the world's 7th country to produce uranium hexafluoride, and controls the entire nuclear fuel cycle.[585]

Telecommunication

Iran's telecommunications industry is almost entirely state-owned, dominated by the Telecommunication Company of Iran (TCI). As of 2020, 70 million Iranians use high-speed mobile internet. Iran is among the first five countries which have had a growth rate of over 20 percent and the highest level of development in telecommunication.[586] Iran has been awarded the UNESCO special certificate for providing telecommunication services to rural areas.

Globally, Iran ranks 75th in mobile internet speed and 153rd in fixed internet speed.[587]

Demographics

Iran's population grew rapidly from about 19 million in 1956 to about 85 million by February 2023.[588] However, Iran's fertility rate has dropped dramatically, from 6.5 children born per woman to about 1.7 two decades later,[589][590][591] leading to a population growth rate of about 1.39% as of 2018.[592] Due to its young population, studies project that the growth will continue to slow until it stabilises around 105 million by 2050.[593][594][595]

Iran hosts one of the largest refugee populations, with almost one million,[596] mostly from Afghanistan and Iraq.[597] According to the Iranian Constitution, the government is required to provide every citizen with access to social security, covering retirement, unemployment, old age, disability, accidents, calamities, health and medical treatment and care services.[598] This is covered by tax revenues and income derived from public contributions.[599]

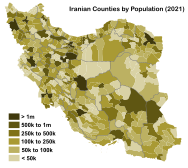

The country has one of the highest urban growth rates in the world. From 1950 to 2002, the urban proportion of the population increased from 27% to 60%.[600] Iran's population is concentrated in its western half, especially in the north, north-west and west.[601]

Tehran, with a population of around 9.4 million, is Iran's capital and largest city. The country's second most populous city, Mashhad, has a population of around 3.4 million, and is capital of the province of Razavi Khorasan. Isfahan has a population of around 2.2 million and is Iran's third most populous city. It is the capital of Isfahan province and was also the third capital of the Safavid Empire.

Largest cities or towns in Iran 2016 census | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

Tehran  Mashhad | 1 | Tehran | Tehran | 8,693,706 | 11 | Rasht | Gilan | 679,995 |  Isfahan  Karaj |

| 2 | Mashhad | Razavi Khorasan | 3,001,184 | 12 | Zahedan | Sistan and Baluchestan | 587,730 | ||

| 3 | Isfahan | Isfahan | 1,961,260 | 13 | Hamadan | Hamadan | 554,406 | ||

| 4 | Karaj | Alborz | 1,592,492 | 14 | Kerman | Kerman | 537,718 | ||

| 5 | Shiraz | Fars | 1,565,572 | 15 | Yazd | Yazd | 529,673 | ||

| 6 | Tabriz | East Azarbaijan | 1,558,693 | 16 | Ardabil | Ardabil | 529,374 | ||

| 7 | Qom | Qom | 1,201,158 | 17 | Bandar Abbas | Hormozgan | 526,648 | ||

| 8 | Ahvaz | Khuzestan | 1,184,788 | 18 | Arak | Markazi | 520,944 | ||

| 9 | Kermanshah | Kermanshah | 946,651 | 19 | Eslamshahr | Tehran | 448,129 | ||

| 10 | Urmia | West Azarbaijan | 736,224 | 20 | Zanjan | Zanjan | 430,871 | ||

Ethnic groups

Ethnic group composition remains a point of debate, mainly regarding the largest and second largest ethnic groups, the Persians and Azerbaijanis, due to the lack of Iranian state censuses based on ethnicity. The World Factbook has estimated that around 79% of the population of Iran is a diverse Indo-European ethno-linguistic group,[602] with Persians (including Mazenderanis and Gilaks) constituting 61% of the population, Kurds 10%, Lurs 6%, and Balochs 2%. Peoples of other ethnolinguistic groups make up the remaining 21%, with Azerbaijanis constituting 16%, Arabs 2%, Turkmens and other Turkic tribes 2%, and others (such as Armenians, Talysh, Georgians, Circassians, Assyrians) 1%.

The Library of Congress issued slightly different estimates: 65% Persians (including Mazenderanis, Gilaks, and the Talysh), 16% Azerbaijanis, 7% Kurds, 6% Lurs, 2% Baloch, 1% Turkic tribal groups (including Qashqai and Turkmens), and non-Iranian, non-Turkic groups (including Armenians, Georgians, Assyrians, Circassians, and Arabs) less than 3%.[603][604]

Languages

Most of the population speaks Persian, the country's official and national language.[3] Others include speakers of other Iranian languages, within the greater Indo-European family, and languages belonging to other ethnicities. The Gilaki and Mazenderani languages are widely spoken in Gilan and Mazenderan, northern Iran. The Talysh language is spoken in parts of Gilan. Varieties of Kurdish are concentrated in the province of Kurdistan and nearby areas. In Khuzestan, several dialects of Persian are spoken. South Iran also houses the Luri and Lari languages.

Azerbaijani, the most-spoken minority language in the country,[605] and other Turkic languages and dialects are found in various regions, especially Azerbaijan. Notable minority languages include Armenian, Georgian, Neo-Aramaic, and Arabic. Khuzi Arabic is spoken by the Arabs in Khuzestan, and the wider group of Iranian Arabs. Circassian was also once widely spoken by the large Circassian minority, but, due to assimilation, no sizable number of Circassians speak the language anymore.[606][607][608][609]

Percentages of spoken language continue to be a point of debate, most notably regarding the largest and second largest ethnicities in Iran, the Persians and Azerbaijanis. Percentages given by the CIA's World Factbook include 53% Persian, 16% Azerbaijani, 10% Kurdish, 7% Mazenderani and Gilaki, 7% Luri, 2% Turkmen, 2% Balochi, 2% Arabic, and 2% the remainder Armenian, Georgian, Neo-Aramaic, and Circassian.[4]

Religion

| Religion | Percent | Number |

| Muslim | 99.4% | 74,682,938 |

| Christian | 0.2% | 117,704 |

| Zoroastrian | 0.03% | 25,271 |

| Jewish | 0.01% | 8,756 |

| Other | 0.07% | 49,101 |

| Undeclared | 0.4% | 265,899 |

Twelver Shia Islam is the state religion, to which 90%-95% of Iranians adhere;[611][612][613][614] about 5–10% are in the Sunni and Sufi branches of Islam.[615] 96% of Iranians believe in Islam, but 14% identify as not religious.[616][page needed]

There is a large population of adherents to Yarsanism, a Kurdish indigenous religion, estimated to be over half a million to one million followers.[617][618][619][620][621] The Baháʼí Faith is not officially recognized and has been subject to official persecution.[622] Since the Revolution, the persecution of Baháʼís has increased.[623][624] Irreligion is not recognized by the government.