История рабства в мусульманском мире

| Часть серии о |

| Принудительный труд и рабство |

|---|

|

| Часть серии о |

| Islam |

|---|

|

История рабства в мусульманском мире началась с институтов, унаследованных от доисламской Аравии . [1] [2] [3] [4]

На протяжении всей мусульманской истории рабы выполняли различные социальные и экономические функции: от могущественных эмиров до жестоких рабочих. Рабы широко использовались в ирригации, горнодобывающей промышленности и животноводстве, но чаще всего в качестве солдат, охранников, домашней прислуги и т.д. [5] и наложницы (секс-рабыни). [6] Использование рабов для тяжелого физического труда на ранних этапах мусульманской истории привело к нескольким разрушительным восстаниям рабов. [5] наиболее заметным из них было Занджское восстание 869–883 годов, приведшее к прекращению этой практики. [7] Многие правители также использовали рабов в армии и управлении до такой степени, что рабы могли захватить власть, как это делали мамлюки . [5]

Большинство рабов были импортированы из-за пределов мусульманского мира. [8] Рабство в исламском праве в принципе не имеет расовой основы, хотя на практике это не всегда имело место. [9] The Arab slave trade was most active in West Asia, North Africa (Trans-Saharan slave trade), and Southeast Africa (Red Sea slave trade and Indian Ocean slave trade), and rough estimates place the number of Africans enslaved in the twelve centuries prior to the 20th century at between six million to ten million.[10][11][12][13][14] Османская работорговля возникла в результате набегов на Восточную и Центральную Европу и Кавказ , связанных с крымской работорговлей , в то время как работорговцы с Берберийского побережья совершали набеги на средиземноморские побережья Европы и даже на Британские острова и Исландию .

In the early 20th century, the authorities in Muslim states gradually outlawed and suppressed slavery, largely due to pressure exerted by Western nations such as Britain and France.[15] Slavery in Zanzibar was abolished in 1909, when slave concubines were freed, and the open slave market in Morocco was closed in 1922. Slavery in the Ottoman Empire was abolished in 1924 when the new Turkish Constitution disbanded the Imperial Harem and made the last concubines and eunuchs free citizens of the newly proclaimed republic.[16]

Slavery in Iran and slavery in Jordan was abolished in 1929. In the Persian Gulf, slavery in Bahrain was first to be abolished in 1937, followed by slavery in Kuwait in 1949 and slavery in Qatar in 1952, while Saudi Arabia and Yemen abolished it in 1962,[17] while Oman followed in 1970. Mauritania became the last state to abolish slavery, in 1981. In 1990 the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam declared that "no one has the right to enslave" another human being.[18] As of 2001, however, instances of modern slavery persisted in areas of the Sahel,[19][20] and several 21st-century terroristic jihadist groups have attempted to use historic slavery in the Muslim world as a pretext for reviving slavery in the 21st century.

Scholars point to the various difficulties in studying this amorphous phenomenon which occurs over a large geographic region (between East Africa and the Near East), a lengthy period of history (from the seventh century to the present day), and which only received greater attention after the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade.[21][22][23][24] The terms "Arab slave trade" and "Islamic slave trade" (and other similar terms) are invariably used to refer to this phenomenon.

Slavery in pre-Islamic Arabia

[edit]Slavery was widely practiced in pre-Islamic Arabia,[25] as well as in the rest of the ancient and early medieval world. The minority were European and Caucasus slaves of foreign extraction, likely brought in by Arab caravaners (or the product of Bedouin captures) stretching back to biblical times. Native Arab slaves had also existed, a prime example being Zayd ibn Harithah, later to become Muhammad's adopted son. Arab slaves, however, usually obtained as captives, were generally ransomed off among nomad tribes.[15] The Red Sea slave trade of Africans to the Arabian Peninsula are known to have been ongoing already during the antiquity.[26]

The slave population increased by the custom of child abandonment (see also infanticide), and by the kidnapping or sale of small children.[27] Whether enslavement for debt or the sale of children by their families was common is disputed. (historian Henri Brunschvig argues it was rare,[15] but according to Jonathan E. Brockopp, debt slavery was persistent.[28]) Free persons could sell their offspring, or even themselves, into slavery. Enslavement was also possible as a consequence of committing certain offenses against the law, as in the Roman Empire.[27]

Two classes of slave existed: a purchased slave, and a slave born in the master's home. Over the latter, the master had complete rights of ownership, though these slaves were unlikely to be sold or disposed of by the master. Female slaves were at times forced into prostitution for the benefit of their masters, in accordance with Near Eastern customs.[15][29][30]

Slavery in Islamic Arabia

[edit]

Early Islamic history

[edit]W. Montgomery Watt points out that Muhammad's expansion of Pax Islamica to the Arabian peninsula reduced warfare and raiding, and therefore cut off the basis for enslaving freemen.[31] According to Patrick Manning, Islamic legislations against abuse of slaves limited the extent of enslavement in the Arabian peninsula and, to a lesser degree, for the area of the entire Umayyad Caliphate, where slavery had existed since the most ancient times.[32]

Constant Umayyad raids into Byzantine territory flooded the slave market with Greek captives. When Caliph Sulayman was in Medina on his way back from pilgrimage, he gifted 400 Greek slaves to his local favorites, "who could think of nothing better to do with them than slaughter them", boasted Jarir ibn Atiyah, a poet who took part in this.[33]

According to Bernard Lewis, the growth of internal slave populations through natural increase was insufficient to maintain slave numbers through to modern times, which contrasts markedly with rapidly rising slave populations in the New World. This was due to a number of factor including liberation of the children born by slave mothers, liberation of slaves as an act of piety, liberation of military slaves who rose through the ranks, and restrictions on procreation, since casual sex and marriage was discouraged among the menial, domestic, and manual worker slaves.[1]

A fair proportion of male slaves were also imported as eunuchs. Levy states that according to the Quran and Islamic traditions, such emasculation was objectionable. Some jurists such as al-Baydawi considered castration to be mutilation, stipulating laws to prevent it. However, in practice, emasculation was frequent.[34] In eighteenth-century Mecca, the majority of eunuchs were in the service of the mosques.[35]

There were also high death tolls among all classes of slaves. Slaves usually came from remote places and, lacking immunities, died in large numbers. Segal notes that the recently enslaved, weakened by their initial captivity and debilitating journey, would have been easy victims of an unfamiliar climate and infection.[36]

Children were especially at risk, and the Islamic market demand for children was much greater than the American one. Many Black slaves lived in conditions conducive to malnutrition and disease, with effects on their own life expectancy, the fertility of women, and the infant mortality rate.[36] As late as the 19th century, Western travellers in North Africa and Egypt noted the high death rate among imported Black slaves.[37]

Another factor was the Zanj Rebellion against the plantation economy of ninth-century southern Iraq. Due to fears of a similar uprising among slave gangs occurring elsewhere, Muslims came to realize that large concentrations of slaves were not a suitable organization of labour and that slaves were best employed in smaller concentrations.[38] As such, large-scale employment of slaves for manual labour became the exception rather than the norm, and the medieval Islamic world did not need to import vast numbers of slaves.[39]

Arab slave trade

[edit]

Bernard Lewis writes: "In one of the sad paradoxes of human history, it was the humanitarian reforms brought by Islam that resulted in a vast development of the slave trade inside, and still more outside, the Islamic empire." He notes that the Islamic injunctions against the enslavement of Muslims led to the massive importation of slaves from the outside.[40] According to Patrick Manning, Islam by recognizing and codifying slavery seems to have done more to protect and expand slavery than the reverse.[32]

The 'Arab' slave trade was part of the broader 'Islamic' slave trade. Bernard Lewis writes that "polytheists and idolaters were seen primarily as sources of slaves, to be imported into the Islamic world and molded-in Islamic ways, and, since they possessed no religion of their own worth the mention, as natural recruits for Islam."[41] Patrick Manning states that religion was hardly the point of this slavery.[42] Also, this term suggests comparison between Islamic slave trade and Christian slave trade. Propagators of Islam in Africa often revealed a cautious attitude towards proselytizing because of its effect in reducing the potential reservoir of slaves.[43]

In the 8th century, Africa was dominated by Arab-Berbers in the north: Islam moved southwards along the Nile and along the desert trails. One supply of slaves was the Solomonic dynasty of Ethiopia which often exported Nilotic slaves from their western borderland provinces. Native Muslim Somali sultanates exported slaves as well as the Sultanate of Adal. According to Al-Maqrizi, Sultan Jamal ad-Din sold numerous Amhara into slavery as far away as Greece and India after a victorious military campaign.[44][45] Historian Ulrich Braukämper states that these works of Islamic historiography, while demonstrating the influence and military presence of the Adal sultanate in southern Ethiopia, tend to overemphasize the importance of military victories that at best led to temporary territorial control in regions such as Bale. They nevertheless demonstrate Adal's strong impact in this hotly contested frontier province[46] The supply of European slaves came from Muslim outposts in Europe such as Fraxinetum.[47]

Up until the early 18th century, the Crimean Khanate maintained a massive slave trade with the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East. Between 1530 and 1780, there were almost certainly one million and quite possibly as many as 1.25 million white, European Christians enslaved by the Muslims of the Barbary Coast of North Africa.[48]

On the coast of the Indian Ocean too, slave-trading posts were set up by Muslim Arabs.[49] The archipelago of Zanzibar, along the coast of present-day Tanzania, is undoubtedly the most notorious example of these trading colonies. Southeast Africa and the Indian Ocean continued as an important region for the Oriental slave trade up until the 19th century.[15] Livingstone and Stanley were then the first Europeans to penetrate to the interior of the Congo basin and to discover the scale of slavery there.[49] The Arab Tippu Tib extended his influence and made many people slaves.[49] After Europeans had settled in the Gulf of Guinea, the trans-Saharan slave trade became less important. In Zanzibar, slavery was abolished late, in 1897, under Sultan Hamoud bin Mohammed.[50] The rest of Africa had no direct contact with Muslim slave-traders.

Roles of slaves

[edit]While slaves were employed for manual labour during the Arab slave trade, although most agricultural labor in the medieval Islamic world consisted of paid labour. Exceptions include the plantation economy of Southern Iraq (which led to the Zanj Revolt), in 9th-century Ifriqiya (modern-day Tunisia), and in 11th-century Bahrain (during the Karmatian state).[39]

A system of plantation labor, much like that which would emerge in the Americas, developed early on, but with such dire consequences that subsequent engagements were relatively rare and reduced.[5] Slaves in Islam were mainly directed at the service sector – concubines and cooks, porters and soldiers – with slavery itself primarily a form of consumption rather than a factor of production.[5] The most telling evidence for this is found in the gender ratio; among slaves traded in Islamic empire across the centuries, there were roughly two females to every male.[5] Outside of explicit sexual slavery, most female slaves had domestic occupations. Often, this also included sexual relations with their masters – a lawful motive for their purchase and the most common one.[51][6]

Military slavery was also a common role for slaves. Barbarians from the "martial races" beyond the frontiers were widely recruited into the imperial armies. These recruits often advanced in the imperial and eventually metropolitan forces, sometimes obtaining high ranks.[52]

Arab views of African peoples

[edit]Though the Qur'an expresses no racial prejudice against black Africans, Bernard Lewis argues that ethnocentric prejudice later developed among Arabs, for a variety of reasons:[53] their extensive conquests and slave trade; the influence of Aristotelian ideas regarding slavery, which some Muslim philosophers directed towards Zanj (Bantu[54]) and Turkic peoples;[55] and the influence of religious ideas regarding divisions among humankind.[56] By the 8th century, anti-black prejudice among Arabs resulted in discrimination. A number of medieval Arabic authors argued against this prejudice, urging respect for all black people and especially Ethiopians.[57]

The dominating Islamic view, expressed by contemporary Arab writers, was that slavery was benevolent since the supply source of slaves were the non-Islamic outside world of Polytheist-Idolators and Barbaric infidels, who thanks to their enslavement would convert to Islam and enjoy the benefits of Islamic civilisation.[58] In the first two centuries of Islam, Muslim were viewed as synonymous to Arab ethnicity, and the non-Arab mawla (converts) freedmen, who were captured, enslaved, converted and manumitted, were considered inferior Muslims and fiscally, politically, socially and military discriminated against also as freedmen.[59] During the Umayyad Caliphate, when the Islamic Caliphate expanded to a truly international empire composed of many different ethnicities, and Islam a universal civilization, with people of different races making the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, the Muslim world developed different stereotypical views on different races, creating a racial hierarchy among slaves of different ethnicity.[60]

The hajin, half-Arab sons of Muslim Arab men and their slave concubines, were viewed differently depending on the ethnicity of their mothers. Abduh Badawi noted that "there was a consensus that the most unfortunate of the hajins and the lowest in social status were those to whom blackness had passed from their mothers", since a son of African mother more visibly recognizable as non-Arab than the son of a white slave mother, and consequently, "son of a black woman" was used as an insult, while "son of a white woman" was used as a praise and as boasting.[61]

By the 14th century, a significant number of slaves came from sub-Saharan Africa; Lewis argues that this led to the likes of Egyptian historian Al-Abshibi (1388–1446) writing that "[i]t is said that when the [black] slave is sated, he fornicates, when he is hungry, he steals."[62]

As late as the 20th century, some authors argued that slavery in Islamic societies was free of racism. However, recent research has revealed racist attitudes in Islamic history—especially anti-Black racism and a link between Blackness and slavery—dating back to at least the ninth century CE.[63]

In 2010, at the Second Afro-Arab summit Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi apologized for Arab involvement in the African slave trade, saying: "I regret the behavior of the Arabs... They brought African children to North Africa, they made them slaves, they sold them like animals, and they took them as slaves and traded them in a shameful way. I regret and I am ashamed when we remember these practices. I apologize for this."[64][65]

Abolition

[edit]One of the early calls for abolition of the Arab slave trade in Africa was issued in the 19th century by the French Catholic cardinal, Charles Lavigerie.[66] European political leaders in the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 cited the slave trade as reason for colonial efforts in the region.[67] This call was due in part for the need to gain public acceptance of the colonial efforts.[68][69]

The conference resolved to end slavery by African and Islamic powers. Thus, an international prohibition of the slave trade throughout their respected spheres was signed by the European members. In his novella Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad sarcastically referred to one of the participants at the conference, the International Association of the Congo (also called "International Congo Society"), as "the International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs".[70][71] The first name of this Society had been the "International Association for the Exploration and Civilization of Central Africa".

Female slaves

[edit]

In Classical Arabic terminology, female slaves were generally called jawāri (Arabic: جَوار, s. jāriya Arabic: جارِية). Slave-girls specifically might be called imā’ (Arabic: اِماء, s. ama Arabic: اَمة), while female slaves who had been trained as entertainers or courtesans were usually called qiyān (Arabic: قِيان, IPA /qi'jaːn/; singular qayna, Arabic: قَينة, IPA /'qaina/).[72]

The cultural perception and role of women in society drastically differentiated the experience that women had as slaves from that of men.[73] In medieval Islam, lack of agency was associated with femininity[74] which differentiated how women were enslaved in context of how they were traded, treated, freed and labelled.

While male slaves were typically captured during warfare, women and children were captured during raids.[74] Although, the enslavement of any Muslim, male or female, was prohibited. On the other hand, female relatives were often used as payment by patriarchs of the family.[73]

“Suria," which is commonly translated as concubine, referred to female slaves who had sexual relations with their masters but were not married to them. The accuracy of this translation has been criticized: "this act placed the woman who gave birth to a child from her 'master' into the legal category of suria, which was a type of marriage and not the European 'concubinage.'"[75] She became free at his death and the master was unable to sell her, which also meant he could not divorce her as his suria. This clear critique of "European" pertaining to a facet of Swahili culture suggests that usuria, a phenomenon governed by Islamic law, was quite legitimate and performed as such on the coast of East Africa. However, usuria was not treated similarly in all Islamic legal systems.[73]

Ibn Battuta's Accounts

[edit]The 14th century Maghrebi traveller, Ibn Battuta, rarely travelled without the company of his concubines. Although he was a scholar of Muslim Law, his accounts provide insight into how women slave were traded and treated.[citation needed]

Ibn Battuta initially describes buying slave girls in Anatolia, and it seems that even though he lost his wealth and belongings multiple times, he never ventured out without a concubine if he could avoid it. Up until the nineteenth century, the importation of slaves from the non-Islamic world became an ever-expanding business due to the prohibition on Muslims being forced into slavery for debts or crimes, as well as the prohibition on Muslims ability to legally enslave Arabs. Because of this, any slave owned by a Muslim was distinct from its owner in terms of ethnicity, and any slave owned by a Muslim Arab was unquestionably a foreigner. Due to the recognized dubious status of slave merchants, it has been inferred that Ibn Battuta employed an intermediary, an agent to complete the trade.[74]

Women were also traded as gifts across the Muslim world. Ibn Battuta writes about his exchanges with the amir Dawlasa in the Maldives as he brought two slave girls to his accommodation. Similarly, Ibn Battuta gifted "a white slave, a horse, and some raisins and almonds" to the governor of Multan. As a result, he solidified his relationship with powerful men.[citation needed]

Political uprisings

[edit]Rebellion

[edit]In some cases, slaves would join domestic rebellions or even rise up against governors. The most renowned of these rebellions was known as the Zanj Rebellion.[76][77] The Zanj Rebellion took place near the port city of Basra, located today in southern Iraq, over a period of fifteen years (869–883 AD). It grew to involve over 50,000 slaves imported from across the Muslim empire, and claimed over "tens of thousands of lives in lower Iraq".[78]

The revolt was said to have been led by Ali ibn Muhammad, who claimed to be a descendant of Caliph Ali ibn Abu Talib.[78] Several historians, such as Al-Tabari and Al-Masudi, consider and view this revolt as one of the "most vicious and brutal uprising[s]" out of the many disturbances that plagued the Abbasid central government.[78]

When the Russian general Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufmann and his army approached the city of Khiva during the Khivan campaign of 1873, the Khan Muhammad Rahim Khan II of Khiva fled to hide among the Yomuts, and the slaves in Khiva rebelled, informed about the eminent downfall of the city, resulting in the Khivan slave uprising.[79] When Kaufmann's Russian army entered Khiva on 28 March, he was approached by Khivans who begged him to put down the ongoing slave uprising, during which slaves avenged themselves on their former enslavers.[80] When the Khan returned to his capital after the Russian conquest, the Russian General Kaufmann presented him with a demand to abolish the Khivan slave trade and slavery, which he did.[81]

Political power

[edit]

The Mamluks were slave-soldiers who were converted to Islam, and served the Muslim caliphs and the Ayyubid sultans during the Middle Ages. Over time, they became a powerful military caste, often defeating the Crusaders and, on more than one occasion, they seized power for themselves, for example, ruling Egypt in the Mamluk Sultanate from 1250 to 1517.

European slaves

[edit]Saqaliba is a term used in medieval Arabic sources to refer to Slavs and other peoples of Central, Southern, and Eastern Europe, or in a broad sense to European slaves under Arab Islamic rule.

Through the Middle Ages up until the early modern period,[82] a major source of slaves sent to Muslim lands was Central and Eastern Europe. Slaves of Northwestern Europe were also favored. The slaves captured were sent to Islamic lands like Spain and Egypt through France and Venice via the Prague slave trade and the Venetian slave trade. Prague served as a major centre for castration of Slavic captives.[83][84] The Emirate of Bari also served as an important port for trade of such slaves.[85] After the Byzantine Empire and Venice blocked Arab merchants from European ports, Arabs started importing slaves from the Caucasus and Caspian Sea regions, shipping them off as far east as Transoxiana in Central Asia.[86] Despite this, slaves taken in battle or from minor raids in continental Europe remained a steady resource in many regions. The Ottoman Empire used slaves from the Balkans and Eastern Europe via the Crimean slave trade. The Janissaries were primarily composed of enslaved Europeans. Slaving raids by Barbary Pirates on the coasts of Western Europe as far as Iceland remained a source of slaves until suppressed in the early 19th century. Common roles filled by European slaves ranged from laborers to concubines, and even soldiers.

Christians became part of harems as slaves in the Balkans and Asia Minor when the Turks invaded. Muslim qadis owned Christian slave girls. Greek girls who were pretty were forced into prostitution after being enslaved to Turks who took all their earnings in the 14th century according to Ibn Battuta.[87]

Slavery in Central Asia

[edit]

Central Asian Sunni Kazakhs, Sunni Karakalpaks, Sunni Uzbeks and Sunni Turkmen would raid Shia Hazaras in Hazarajat and Shia Persians living in Khorasan province of Qajar Iran and Christian Russian and Volga German settlers in areas of Russia for slaves and sell them in markets of the Emirate of Bukhara, Khanate of Khiva and Khanate of Kokand.[88]

Muslim prisoners of Turkmen were coerced into admitting to heterodoxy by their Turkmen masters who justified enslaving fellow Muslims.[89]

Prior to the Battle of Geok Tepe in January 1881 and subsequent conquest of Merv in 1884, the Turkmen "retained the condition of predatory, horse-riding nomads, who were greatly feared by their neighbours as 'man-stealing Turks.' Until subjugated by the Russians, the Turkmens were a warlike people, who conquered their neighbours and regularly captured ethnic Persians for sale at the Khivan slave market. It was their boast that not one Persian had crossed their frontier except with a rope round his neck."[90]

Oirats were given as slaves to the Turfani Turkic Muslims of Emin Khoja by the Qing during the Qing conquest of the Dzungars.[91]

Hui Muslims were targeted in slave raids by Muslims of the Kokand Khanate.[92] Enslavement didn't depend on religious status but political allegiance, since Turkic Muslim Ishaqi and Turfanis who served the Qing against fellow Turkic Muslim Afaqi and Khokandis were also enslaved by their fellow Turkic Muslims led by Jahangir.[93] Kashgari Muslims purchased Ghalcha Mountain Tajiks as slaves.[94]

Two Uyghurs named Isma'il and Adir were sentenced to be sliced to death in public in 1841 after killing their Xibo master Dasanbu while they were sentenced to penal slavery in Ili. Isma'il was a thief and Adir was the son of a rebel with Jahanir Khoja in 1828. Adir was originally the slave of a Xibe named Dasangga before Dasanbu.[95]

Persians in northeast Iran were targeted by Turkmen slave raiders.[96][97] [98]

Kazakh Khanate slave trade on Russian settlement

[edit]During the 18th century, raids by Kazakhs on Russia's territory of Orenburg were common; the Kazakhs captured many Russians and sold them as slaves in the Central Asian market. The Volga Germans were also victims of Kazakh raids; they were ethnic Germans living along the River Volga in the region of southeastern European Russia around Saratov.[citation needed]

In 1717, 3,000 Russian slaves, men, women, and children, were sold in Khiva by Kazakh and Kyrgyz tribesmen.[99]

In 1730, the Kazakhs' frequent raids into Russian lands were a constant irritant and resulted in the enslavement of many of the Tsar's subjects, who were sold on the Kazakh steppe.[100]

In 1736, urged on by Kirilov, the Kazakhs of the Lesser and Middle Hordes launched raids into Bashkir lands, killing or capturing many Bashkirs in the Siberian and Nogay districts.[101]

In 1743, an order was given by the senate in response to the failure to defend against the Kazakh attack on a Russian settlement, which resulted in 14 Russians killed, 24 wounded. In addition, 96 Cossacks were captured by Kazakhs.[102]

In 1755, Nepliuev tried to enlist Kazakh support by ending the reprisal raids and promising that the Kazakhs could keep the Bashkir women and children living among them (a long-standing point of contention between Nepliuev and Khan Nurali of the Junior Jüz).[103] Thousands of Bashkirs would be massacred or taken captive by Kazakhs over the course of the uprising, whether in an effort to demonstrate loyalty to the Tsarist state, or as a purely opportunistic maneuver.[104][105]

In the period between 1764 and 1803, according to data collected by the Orenburg Commission, twenty Russian caravans were attacked and plundered. Kazakh raiders attacked even big caravans which were accompanied by numerous guards.[106]

In spring 1774, the Russians demanded the Khan return 256 Russians captured by a recent Kazakh raid.[107]

In summer 1774, when Russian troops in the Kazan region were suppressing the rebellion led by the Cossack leader Pugachev, the Kazakhs launched more than 240 raids and captured many Russians and herds along the border of Orenburg.[107]

In 1799, the biggest Russian caravan which was plundered at that time lost goods worth 295,000 rubles.[108]

By 1830, the Russian government estimated that two hundred Russians were kidnapped and sold into slavery in Khiva every year.[109]

Slavery in India

[edit]In the Muslim conquests of the 8th century, the armies of the Umayyad commander Muhammad bin Qasim enslaved tens of thousands of Indian prisoners, including both soldiers and civilians.[110][111] In the early 11th century Tarikh al-Yamini, the Arab historian Al-Utbi recorded that in 1001 the armies of Mahmud of Ghazna conquered Peshawar and Waihand (the capital city of Gandhara) after the Battle of Peshawar in 1001, "in the midst of the land of Hindustan", and captured some 100,000 youths.[112][113]

Later, following his twelfth expedition into India in 1018–19, Mahmud is reported to have returned with such a large number of slaves that their value was reduced to only two to ten dirhams each. This unusually low price made, according to Al-Utbi, "merchants [come] from distant cities to purchase them, so that the countries of Central Asia, Iraq and Khurasan were swelled with them, and the fair and the dark, the rich and the poor, mingled in one common slavery". Elliot and Dowson refer to "five thousand slaves, beautiful men, and women."[114][115][116] Later, during the Delhi Sultanate period (1206–1555), references to the abundant availability of low-priced Indian slaves abound. Levi attributes this primarily to the vast human resources of India, compared to its neighbors to the north and west (India's Mughal population being approximately 12 to 20 times that of Turan and Iran at the end of the 16th century).[117]

The Delhi sultanate obtained thousands of slaves and eunuch servants from the villages of Eastern Bengal (a widespread practice which Mughal emperor Jahangir later tried to stop). Wars, famines and pestilences drove many villagers to sell their children as slaves. The Muslim conquest of Gujarat in Western India had two main objectives. The conquerors demanded and more often forcibly wrested both Hindu women as well as land owned by Hindus. Enslavement of women invariably led to their conversion to Islam.[118] In battles waged by Muslims against Hindus in Malwa and the Deccan plateau, a large number of captives were taken. Muslim soldiers were permitted to retain and enslave prisoners of war as plunder.[119]

The first Bahmani sultan, Alauddin Bahman Shah is noted to have captured 1,000 singing and dancing girls from Hindu temples after he battled the northern Carnatic chieftains. The later Bahmanis also enslaved civilian women and children in wars; many of them were converted to Islam in captivity.[120][121][122][123][124]

During the rule of Shah Jahan, many peasants were compelled to sell their women and children into slavery to meet the land revenue demand.[125]

Slavery in the Seljuk and Ottoman Empires

[edit]There was a very extensive slave trade of Christians in Anatolia by the Seljuk Turks in the eleventh and twelfth centuries which caused a significant decline in the numbers of Christians in Asia minor. After Edessa was captured and pillaged, 16,000 Christians were enslaved. Michael the Syrian reported that 16,000 Christians were enslaved and sold at Aleppo when the Turks, led by Nur ad-Din invaded Cilicia. Major raids in the Greek provinces of western Anatolia led to the enslavement of thousands of Greeks. 26,000 people from Armenia, Mesopotamia and Cappadocia were captured and taken to slave markets during Turkic raids in the year 1185. "Asia Minor continued to be a major source of slaves for the Islamic world through the 14th century" according to Speros Vryonis.[126]

After the Seljuks conquered parts of Asia Minor, they brought to the devastated lands Greek, Armenian and Syrian farmers after enslaving entire Byzantine and Armenian villages and towns.[127]

Arab historians and geographers noted that the Turkmen tribes in Anatolia were constantly raiding Greek lands and carrying off large numbers of slaves. The historians Abul Fida and al-Umari relate that the Turkmens especially singled out the Greek children for enslavement, and describe that the numbers of slaves available were so great that, "one saw ... arriving daily those merchants who indulged in this trade."[128][129]

Western Anatolia in the late 13th and the early 14th century was the center of a flourishing trade in Christian slaves. Matthew, metropolitan of Ephesus describes this slave trade:[128]

Also distressing is the multitude of prisoners, some of whom are miserably enslaved to the Ismaelites and others to the Jews .... And the prisoners brought back to this new enslavement are numbered by the thousands; those [prisoners] arising from the enslavement of Rhomaioi through the capture of their lands and cities from all times by comparison would be found to be smaller or [at most] equal.

Ibn Battuta often spoke of slaves that the Turks used as domestic servants or sex slaves during his travels through Anatolia during the 1300s. There was a large number of slaves at Laodicea, in the harems of the prominent citizens. Some of the slaves had arrived in the marketplaces in large quantities, and Batouta himself acquired a slave woman at Balıkesir, close to Pergamon. According to Ibn Battuta, the emir of Smyrna, Omour Beg, among the most famous of slave traders during this period (and often went into expeditions for slaves in the Aegean Sea) personally presented him with the gift of a slave woman. The slaves often sought to escape at any costs. Battuta describes how his slave fled from Magnesia together with another slave and how the two fugitives were later captured.[87][128][130][page needed]

In the year 1341, The Turkish bey Umur of Aydin terrorized the Christians in the Aegean sea with his 350 ships and 15,000 men from a captured port in Smyrna, capturing many slaves.[131]

According to professor Ehud R. Toledano, slavery in the Ottoman Empire was "Accepted by custom, perpetuated by tradition and sanctioned by religion". Abolitionism was considered a foreign idea, barely understood and vigorously resisted.[132] Slavery was a legal and important part of the economy of the Ottoman Empire and Ottoman society[133] until the slavery of Caucasians was banned in the early 19th century, although slaves from other groups were still permitted.[134] In Constantinople (present-day Istanbul), the administrative and political center of the Empire, about a fifth of the population consisted of slaves in 1609.[135] Even after several measures to ban slavery in the late 19th century, the practice continued largely uninterrupted into the early 20th century. As late as 1908, female slaves were still sold in the Ottoman Empire. Concubinage was a central part of the Ottoman slave system throughout the history of the institution.[136][137]

A member of the Ottoman slave class, called a kul in Turkish, could achieve high status. Black castrated slaves were tasked to guard the imperial harems, while white castrated slaves filled administrative functions. Janissaries were the elite soldiers of the imperial armies, collected in childhood as a "blood tax", while galley slaves captured in slave raids or as prisoners of war, staffed the imperial vessels. Slaves were often to be found at the forefront of Ottoman politics. The majority of officials in the Ottoman government were bought slaves, raised free, and integral to the success of the Ottoman Empire from the 14th century into the 19th. Many officials themselves owned a large number of slaves, although the Sultan himself owned by far the largest number.[138] By raising and specially training slaves as officials in palace schools such as Enderun, the Ottomans created administrators with intricate knowledge of government and a fanatic loyalty.

Ottomans practiced devşirme, a sort of "blood tax" or "child collection": young Christian boys from Eastern Europe and Anatolia were taken from their homes and families, brought up as Muslims, and enlisted into the most famous branch of the Kapıkulu, the Janissaries, a special soldier class of the Ottoman army that became a decisive faction in the Ottoman invasions of Europe.[citation needed] Most of the military commanders of the Ottoman forces, imperial administrators, and de facto rulers of the Empire, such as Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha and Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, were recruited in this way.[139][140][unreliable source?]

Slavery in the sultanates of Southeast Asia

[edit]In the East Indies, slavery was common until the end of the 19th century. The slave trade was centered on the Muslim sultanates in the Sulu Sea: the Sultanate of Sulu, the Sultanate of Maguindanao, and the Confederation of Sultanates in Lanao (the modern Moro people). Also the Aceh Sultanate on Sumatra took part in the slave trade.[141] The economies of these sultanates relied heavily on the slave trade.[142]

It is estimated that from 1770 to 1870, around 200,000 to 300,000 people were enslaved by Iranun and Banguingui slavers. These were taken by piracy from passing ships as well as coastal raids on settlements as far as the Malacca Strait, Java, the southern coast of China and the islands beyond the Makassar Strait. Most of the slaves were Tagalogs, Visayans, and "Malays" (including Bugis, Mandarese, Iban, and Makassar). There were also occasional European and Chinese captives who were usually ransomed off through Tausug intermediaries of the Sulu Sultanate.[142]

The scale of this activity was so massive that the word for "pirate" in Malay became Lanun, an exonym of the Iranun people. Male captives of the Iranun and the Banguingui were treated brutally, even fellow Muslim captives were not spared. They were usually forced to serve as galley slaves on the lanong and garay warships of their captors. Within a year of capture, most of the captives of the Iranun and Banguingui would be bartered off in Jolo usually for rice, opium, bolts of cloth, iron bars, brassware, and weapons. The buyers were usually Tausug datu from the Sultanate of Sulu who had preferential treatment, but buyers also included European (Dutch and Portuguese) and Chinese traders as well as Visayan pirates (renegados).[142]

The economy of the Sulu sultanates was largely based on slaves and the slave trade. Slaves were the primary indicators of wealth and status, and they were the source of labor for the farms, fisheries, and workshops of the sultanates. While personal slaves were rarely sold, slave traders trafficked extensively in slaves purchased from the Iranun and Banguingui slave markets. By the 1850s, slaves constituted 50% or more of the population of the Sulu archipelago.[142]

Chattel slaves, known as banyaga, bisaya, ipun, or ammas were distinguished from the traditional debt bondsmen (the kiapangdilihan, known as alipin elsewhere in the Philippines). The bondsmen were natives enslaved to pay off debt or crime. They were slaves only in terms of their temporary service requirement to their master, but retained most of the rights of the freemen, including protection from physical harm and the fact that they could not be sold. The banyaga, on the other hand, had little to no rights.[142]

Some slaves were treated like serfs and servants. Educated and skilled male slaves were largely treated well. Since most of the aristocratic classes in Sulu were illiterate, they were often dependent on the educated banyaga as scribes and interpreters. Slaves were often given their own houses and lived in small communities with slaves of similar ethnic and religious backgrounds. Harsh punishment and abuse were not uncommon, despite Islamic laws, especially for slave laborers and slaves who attempt to escape.[142]

Spanish authorities and native Christian Filipinos responded to the Moro slave raids by building watchtowers and forts across the Philippine archipelago, many of which are still standing today. Some provincial capitals were also moved further inland. Major command posts were built in Manila, Cavite, Cebu, Iloilo, Zamboanga, and Iligan. Defending ships were also built by local communities, especially in the Visayas Islands, including the construction of war "barangayanes" (balangay) that were faster than the Moro raiders' ships and could give chase. As resistance against raiders increased, Lanong warships of the Iranun were eventually replaced by the smaller and faster garay warships of the Banguingui in the early 19th century. The Moro raids were eventually subdued by several major naval expeditions by the Spanish and local forces from 1848 to 1891, including retaliatory bombardment and capture of Moro settlements. By this time, the Spanish had also acquired steam gunboats (vapor), which could easily overtake and destroy the native Moro warships.[143][144][145]

The slave raids on merchant ships and coastal settlements disrupted traditional trade in goods in the Sulu Sea. While this was temporarily offset by the economic prosperity brought by the slave trade, the decline of slavery in the mid-19th century also led to the economic decline of the Sultanates of Brunei, Sulu, and Maguindanao. This eventually led to the collapse of the latter two states and contributed to the widespread poverty of the Moro region in the Philippines today. By the 1850s, most slaves were local-born from slave parents as the raiding became more difficult. By the end of the 19th century and the conquest of the Sultanates by the Spanish and the Americans, the slave population was largely integrated into the native population as citizens under the Philippine government.[143][142][144]

The Sultanate of Gowa of the Bugis people also became involved in the Sulu slave trade. They purchased slaves (as well as opium and Bengali cloth) from the Sulu Sea sultanates, then re-sold the slaves in the slave markets in the rest of Southeast Asia. Several hundred slaves (mostly Christian Filipinos) were sold by the Bugis annually in Batavia, Malacca, Bantam, Cirebon, Banjarmasin, and Palembang by the Bugis. The slaves were usually sold to Dutch and Chinese families as servants, sailors, laborers, and concubines. The sale of Christian Filipinos (who were Spanish subjects) in Dutch-controlled cities led to formal protests by the Spanish Empire to the Netherlands and its prohibition in 1762 by the Dutch, but it had little effect due to lax or absent enforcement. The Bugis slave trade was only stopped in the 1860s, when the Spanish navy from Manila started patrolling Sulu waters to intercept Bugis slave ships and rescue Filipino captives. Also contributing to the decline was the hostility of the Sama-Bajau raiders in Tawi-Tawi who broke off their allegiance to the Sultanate of Sulu in the mid-1800s and started attacking ships trading with the Tausug ports.[142]

Both non-Muslims and Muslims in Southeast Asia during the end of the 19th century bought Japanese girls as slaves who were imported to the region by sea.[146] The Japanese women were sold as concubines both to Muslim Malay men as well as non-Muslim Chinese men and British men of the British ruled Straits Settlements of British Malaya after being trafficked from Japan to Hong Kong and Port Darwin in Australia. In Hong Kong the Japanese consul Miyagawa Kyujiro said these Japanese women were taken by Malay and Chinese men who "lead them off to wild and savage lands where they suffered unimaginable hardship." One Chinese man paid 40 British pounds for 2 Japanese women and a Malay man paid 50 British pounds for a Japanese woman in Port Darwin, Australia after they were trafficked there in August 1888 by a Japanese pimp, Takada Tokijirō.[147][148][149][150][151][152]

However, the buying of Chinese girls in Singapore was forbidden for Muslims by a Batavia (Jakarta) based Arab Muslim Mufti, Usman bin Yahya in a fatwa because he ruled that in Islam it was illegal to buy free non-Muslims or marry non-Muslim slave girls during peace time from slave dealers and non-Muslims could only be enslaved and purchased during holy war (jihad).[153]

Girls and women sold into prostitution from China to Australia, San Francisco, Singapore were ethnic Tanka people, and they served the men of the oversees Chinese community there.[154] The Tanka were regarded as a non-Han ethnicity during the Late Qing and Republican period of China.[155]

A Chinese non-Muslim man had a female concubine who was of Muslim Arab Hadhrami Sayyid origin in Solo, the Dutch East Indies, in 1913 which was scandalous in the eyes of Ahmad Surkati and his Al-Irshad Al-Islamiya.[156][157]

In Jeddah, Kingdom of Hejaz on the Arabian peninsula, the Arab king Ali bin Hussein, King of Hejaz had in his palace 20 young pretty Javanese girls from Java (modern day Indonesia).[158]

In the 1760s the Arab Syarif Abdurrahman Alkadrie mass enslaved other Muslims while raiding coastal Borneo in violation of sharia, before he founded the Pontianak Sultanate.[89]

Slavery in the Maghreb

[edit]When Amr ibn al-As conquered Tripoli in 643, he forced the Jewish and Christian Berbers to give their wives and children as slaves to the Arab army as part of their jizya.[159][160]

Uqba ibn Nafi would often enslave for himself (and to sell to others) countless Berber girls, "the likes of which no one in the world had ever seen."[161]

The Muslim historian Ibn Abd al-Hakam recounts that the Arab General Hassan ibn al-Nu'man would often abduct "young, female Berber slaves of unparalled beauty, some of which were worth a thousand dinars." Al-Hakam confirms that up to 150,000 slaves were captured by Musa ibn Nusayr and his son and nephew during the conquest of North Africa. In Tangier, Musa ibn Nusayr enslaved all of the Berber inhabitants. Musa sacked a fortress near Kairouan and took with him all the children as slaves.[162] The number of Berbers enslaved "amounted to a number never before heard of in any of the countries subject to the rule of Islam" up to that time. As a result, "most of the African cities were depopulated [and] the fields remained without cultivation." Even so, Musa "never ceased pushing his conquests until he arrived before Tangiers, the citadel of their [Berbers’] country and the mother of their cities, which he also besieged and took, obliging its inhabitants to embrace Islam."[163]

The historian Pascual de Gayangos observed: "Owing to the system of warfare adopted by the Arabs in those times, it is not improbable that the number of captives here specified fell into Musa's hands. It appears both from Christian and Arabian authorities that populous towns were not infrequently besieged and their inhabitants, amounting to thousands, led into captivity."[164][165]

Successive Muslim rulers of north Africa continued to attack and enslave the berbers en masse. Historian Hugh Kennedy says that "The Islamic Jihad looks uncomfortably like a giant slave trade"[166] Arab chronicles record vast numbers of Berber slaves taken, especially in the accounts of Musa ibn Nusayr, who became the governor of Africa in 689, and "who was cruel and ruthless against any tribe that opposed the tenets of the Muslim faith, but generous and lenient to those who converted"[167][168] Muslim Historian Ibn Qutaybah recounts Musa ibn Nusayr waging battles of extermination" against the Berbers and how he "killed myriads of them and made a surprising number of prisoners".[168]

According to the historian As-sadfi, the number of Berber slaves taken by Musa ibn Nusayr was greater than in any of the previous Islamic conquests:[169]

Musa went out against the Berbers, and pursued them far into their native deserts, leaving wherever he went traces of his passage, killing numbers of them, taking thousands of prisoners, and carrying on the work of havoc and destruction. When the nations inhabiting the dreary plains of Africa saw what had befallen the Berbers of the coast and of the interior, they hastened to ask for peace and place themselves under the obedience of Musa, whom they solicited to enlist them in the ranks of his army

Arab world

[edit]Ibn Battuta met a Syrian Arab Damascene girl who was a slave of a black African governor in Mali. Ibn Battuta engaged in a conversation with her in Arabic.[170][171][172][173][174] The black man was a scholar of Islam and his name was Farba Sulayman.[175][176] Syrian girls were trafficked from Syria to Saudi Arabia right before World War II and married to legally bring them across the border but then divorced and given to other men. A Syrian Dr. Midhat and Shaikh Yusuf were accused of engaging in this traffic of Syrian girls to supply them to Saudis.[177][178]

Emily Ruete (Salama bint Said) was born to Sultan Said bin Sultan and Jilfidan, a Circassian slave, turned concubine (some accounts also note her as Georgian[179][180][181]) An Indian girl slave who was named Mariam (originally Fatima) ended up in Zanzibar after being sold by multiple men. She originally came from Bombay. There were also Georgian girl slaves in Zanzibar.[182] Egypt and Hejaz were also the recipients of Indian women trafficked via Aden and Goa.[183][184] Since Britain banned the slave trade in its colonies, 19th century British ruled Aden was no longer a recipient of slaves and the slaves sent from Ethiopia to Arabia were shipped to Hejaz instead.[185] Eunuchs, female concubines and male labourers were the occupations of slaves sent from Ethiopia to Jidda and other parts of Hejaz.[186] The southwest and southern parts of Ethiopia supplied most of the girls being exported by Ethiopian slave traders to India and Arabia.[187] Female and male slaves from Ethiopia made up the main supply of slaves to India and the Middle East.[188]

Raoul du Bisson was traveling down the Red Sea when he saw the chief black eunuch of the Sharif of Mecca being brought to Constantinople for trial for impregnating a Circassian concubine of the Sharif and having sex with his entire harem of Circassian and Georgian women. The chief black eunuch was not castrated correctly so he was still able to impregnate and the women were drowned as punishment.[189][190][a] 12 Georgian women were shipped to replace the drowned concubines.[191]

Iran

[edit]The Gulf of Bengal and Malabar in India were sources of eunuchs for the Safavid court of Iran according to Jean Chardin.[192] Sir Thomas Herbert accompanied Robert Shirley in 1627–9 to Safavid Iran. He reported seeing Indian slaves sold to Iran, "above three hundred slaves whom the Persians bought in India: Persees, Ientews (gentiles [i.e. Hindus]) Bannaras [Bhandaris?], and others." brought to Bandar Abbas via ship from Surat in 1628.[193]

Ethiopian slaves, both females imported as concubines and men imported as eunuchs were imported in 19th century Iran.[194][195] Sudan, Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zanzibar exported the majority of slaves to 19th century Iran.[196]

19th and 20th centuries

[edit]The strong abolitionist movement in the 19th century in England and later in other Western countries influenced slavery in Muslim lands.

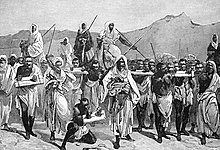

By 1870, chattel slavery had been at least formally banned in most areas of the world, with the exception of Muslim territories in the Middle East, in Caucasus, Africa, and the Gulf.[197] While slavery was by the 1870s viewed as morally unacceptable in the West, slavery was not considered to be imoral in the Muslim world since it was an institution recognized in the Quran and morally justified under the guise of warfare against non-Muslims, and non-Muslims were kidnapped and enslaved by Muslims around the Muslim world: in the Balkans, the Caucasus, the Baluchistan, India, South West Asia and the Philippines.[198] Slaves where marsched in schackles to the coasts of Sudan, Ethiopia and Somali, placed upon dhows and trafficked accross the Indian Ocean to the Gulf or Aden, or across the Red Sea to Arabia and Aden, while weak slaves being thrown in the sea; or across the Sahara desert via the Trans-Saharan slave trade to the Nile, while dying from exposure and swollen feet.[199] Ottoman anti slavery laws where not enforced in the late 19th-century, particularly not in Hejaz; the first attempt to ban the Red Sea slave trade in 1857 resulted in a rebellion in the Hejaz Province, which resulted in Hejza exempted from the ban.[200] The Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1880 formally banned the Red Sea slave trade, but it was not enforced in the Ottoman Provinces in the Arabian Peninsula.[201] In the late 19th-century, the Sultan of Morocco stated to Western diplomats that it was impossible for him to ban slavery because such a ban would not be enforcable, but the British asked him to ensure that the slave trade in Morocco would at least be handled discreet and away from the eyes of foreign wittnesses.[202]

Appalling loss of life and hardships often resulted from the processes of acquisition and transportation of slaves to Muslim lands and this drew the attention of European opponents of slavery. Continuing pressure from European countries eventually overcame the strong resistance of religious conservatives who were holding that forbidding what God permits is just as great an offense as to permit what God forbids. Slavery, in their eyes, was "authorized and regulated by the holy law".[203] Even masters persuaded of their own piety and benevolence sexually exploited their concubines, without a thought of whether this constituted a violation of their humanity.[204] There were also many pious Muslims who refused to have slaves and persuaded others not to do so.[205][full citation needed] Eventually, the Ottoman Empire's orders against the traffic of slaves were issued and put into effect.[206]

According to Brockopp, in the 19th century, "Some authorities made blanket pronouncements against slavery, arguing that it violated the Qurʾānic ideals of equality and freedom. The great slave markets of Cairo were closed down at the end of the nineteenth century and even conservative Qurʾān interpreters continue to regard slavery as opposed to Islamic principles of justice and equality."[28]

Slavery in the forms of carpet weavers, sugarcane cutters, camel jockeys, sex slaves, and even chattel exists even today in some Muslim countries (though some have questioned the use of the term slavery as an accurate description).[207][208]

According to a March 1886 article in The New York Times, the Ottoman Empire allowed a slave trade in girls to thrive during the late 1800s, while publicly denying it. Girl sexual slaves sold in the Ottoman Empire were mainly of three ethnic groups: Circassian, Syrian, and Nubian. Circassian girls were described by the American journalist as fair and light-skinned. They were frequently sent by Circassian leaders as gifts to the Ottomans. They were the most expensive, reaching up to 500 Turkish lira and the most popular with the Turks. The next most popular slaves were Syrian girls, with "dark eyes and hair", and light brown skin. Their price could reach to thirty lira. They were described by the American journalist as having "good figures when young". Throughout coastal regions in Anatolia, Syrian girls were sold. The New York Times journalist stated Nubian girls were the cheapest and least popular, fetching up to 20 lira.[209]

Murray Gordon said that, unlike Western societies which developed anti-slavery movements, no such organizations developed in Muslim societies. In Muslim politics, the state interpreted Islamic law. This then extended legitimacy to the traffic in slaves.[210]

Writing about the Arabia he visited in 1862, the English traveler W. G. Palgrave met large numbers of slaves. The effects of slave concubinage were apparent in the number of persons of mixed race and in the emancipation of slaves he found to be common.[211] Charles Doughty, writing about 25 years later, made similar reports.[212]

According to British explorer (and abolitionist) Samuel Baker, who visited Khartoum in 1862 six decades after the British had declared slave trade illegal, slave trade was the industry "that kept Khartoum going as a bustling town". From Khartoum slave raiders attacked African villages to the south, looting and destroying so that "surviving inhabitants would be forced to collaborate with slavers on their next excursion against neighboring villages," and taking back captured women and young adults to sell in slave markets.[213]

In the 1800s, the slave trade from Africa to the Islamic countries picked up significantly when the European slave trade dropped around the 1850s only to be ended with European colonisation of Africa around 1900.[214][full citation needed]

In 1814, Swiss explorer Johann Burckhardt wrote of his travels in Egypt and Nubia, where he saw the practice of slave trading: "I frequently witnessed scenes of the most shameless indecency, which the traders, who were the principal actors, only laughed at. I may venture to state, that very few female slaves who have passed their tenth year, reach Egypt or Arabia in a state of virginity."[215]

Richard Francis Burton wrote about the Medina slaves, during his 1853 Haj, "a little black boy, perfect in all his points, and tolerably intelligent, costs about a thousand piastres; girls are dearer, and eunuchs fetch double that sum." In Zanzibar, Burton found slaves owning slaves.[216]

David Livingstone wrote of the slave trade in the African Great Lakes region, which he visited in the mid-nineteenth century:

To overdraw its evils is a simple impossibility ...

19th June 1866 – We passed a woman tied by the neck to a tree and dead, the people of the country explained that she had been unable to keep up with the other slaves in a gang, and her master had determined that she should not become anyone's property if she recovered.

26th June. – ...We passed a slave woman shot or stabbed through the body and lying on the path: a group of men stood about a hundred yards off on one side, and another of the women on the other side, looking on; they said an Arab who passed early that morning had done it in anger at losing the price he had given for her, because she was unable to walk any longer.

27th June 1866 – To-day we came upon a man dead from starvation, as he was very thin. One of our men wandered and found many slaves with slave-sticks on, abandoned by their masters from want of food; they were too weak to be able to speak or say where they had come from; some were quite young.[217][218][219]

The strangest disease I have seen in this country seems really to be broken-heartedness, and it attacks free men who have been captured and made slaves... Twenty one were unchained, as now safe; however all ran away at once; but eight with many others still in chains, died in three days after the crossing. They described their only pain in the heart, and placed the hand correctly on the spot, though many think the organ stands high up in the breast-bone.[220]

Zanzibar was once East Africa's main slave-trading port, and under Omani Arabs in the 19th century as many as 50,000 slaves were passing through the city each year.[221] Livingstone wrote in a letter to the editor of the New York Herald:

And if my disclosures regarding the terrible Ujijian slavery should lead to the suppression of the East Coast slave trade, I shall regard that as a greater matter by far than the discovery of all the Nile sources together.[222]

The Anglo-Egyptian Slave Trade Convention of 1877 officially banned the slave trade from Sudan, thus formally putting an end on the import of slaves from Sudan,[223] which was at this point the main suppluyer of slaves to slavery in Egypt. This ban was followed in 1884 by a ban on the import of white slave girls; this law was directed against the import of white women (mainly from Caucasus), which were the preferred choice for harem concubines among the Egyptian upper class.[223][224]

20th-century: suppression and prohibition

[edit]At Istanbul, the sale of black and Circassian women was conducted openly, even well past the granting of the Constitution in 1908.[225]

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, slavery gradually became outlawed and suppressed in Muslim lands, due to a combination of pressures exerted by Western nations such as Britain and France, internal pressure from Islamic abolitionist movements, and economic pressures.[15]

The Brussels Anti-Slavery Conference 1889–90 had adressed the slavery in a semi-global level and concluded with the Brussels Conference Act of 1890, which was revised by the Convention of Saint-Germain-en-Laye 1919. When the League of Nations was founded, they conducted an international investigation of slavery via the Temporary Slavery Commission (TSC), and a convention was drawn up to hasten the total abolition of slavery and the slave trade.[226] The 1926 Slavery Convention, which was founded upon the investigation of the TSC of the League of Nations, was a turning point in banning global slavery. By this point in time, chattel slavery was mainly legal in the Muslim world.

By the Treaty of Jeddah, May 1927 (art.7), concluded between the British Government and Ibn Sa'ud (King of Nejd and the Hijaz) it was agreed to suppress the slave trade in Saudi Arabia, mainly supplyed by the ancient Red Sea slave trade. In the 1932, the League of Nations asked all member countries to include anti-slavery commitment in any treaties they made with all Arab states.[227] In 1932 the League formed the Committee of Experts on Slavery (CES) to review the result and enforcement of the 1926 Slavery Convention, which resulted in a new international investigation under the first permanent slavery committee, the Advisory Committee of Experts on Slavery (ACE) in 1934–1939.[228] In the 1930s, Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Arabian Peninsula was the main center of legal chattel slavery. By a decree issued in 1936, the importation of slaves into Saudi Arabia was prohibited unless it could be proved that they were slaves at the treaty date.[225] Slavery in Bahrain was abolished by efforts of George Maxwell of the ACE in 1937.

Article 4 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948 by the UN General Assembly, explicitly banned slavery. After World War II, chattel slavery was formally abolished by law in almost the entire world, with the exception of the Arabian Peninsula and some parts of Africa. Chattel slavery was still legal in Saudi Arabia, in Yemen, in the Trucial States and in Oman, and slaves were supplied to the Arabian Peninsula via the Red Sea slave trade. At this point in time, Anti-Slavery International campaigned against the chattel slavery in the Arabian Peninsula and urged the UN to form a committee to adress the issue.

When the League of Nations was succeeded by the United Nations (UN) after World War II, Charles Wilton Wood Greenidge of the Anti-Slavery International worked for the UN to continue the investigation of global slavery conducted by the ACE of the League, and in February 1950 the Ad hoc Committee on Slavery of the United Nations was inaugurated,[229] which ultimately resulted in the introduction of the Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery of 1956.[230] At this time, Saudi Arabia and the other states in the Arabian Peninsula were put under growing international pressure.

In 1962, all slavery practices or trafficking in Saudi Arabia was prohibited.[231][232]

By 1969, it could be observed that most Muslim states had abolished slavery, although it existed in the deserts of Iraq bordering Arabia and it still flourished in Saudi Arabia, Yemen and Oman.[225] Slavery was not formally abolished in Yemen and Oman until the following year.[233] The last nation to formally enact the abolition of slavery practice and slave trafficking was the Islamic Republic of Mauritania in 1981.[234]

During the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005) people were taken into slavery; estimates of abductions range from 14,000 to 200,000.[235]

Slavery in Mauritania was legally abolished by laws passed in 1905, 1961, and 1981.[236] It was finally criminalized in August 2007.[237] It is estimated that up to 600,000 Mauritanians, or 20% of Mauritania's population, are currently[when?] in conditions which some consider to be "slavery", namely, many of them used as bonded labour due to poverty.[238]

Slavery in the late 20th and 21st-century Muslim world

[edit]The issue of slavery in the Islamic world in modern times is controversial. Critics argue there is hard evidence of its existence and destructive effects. According to the Oxford Dictionary of Islam, slavery in central Islamic lands has been "virtually extinct" since the mid-20th century, though there are reports indicating that it is still practiced in some areas of Sudan and Somalia as a result of warfare.[239]

Islamist opinions

[edit]Earlier in the 20th century, prior to the "reopening" of slavery by Salafi scholars like Shaykh al-Fawzan, Islamist authors declared slavery outdated without actually clearly supporting its abolition. This has caused at least one scholar, William Clarence-Smith,[240] to bemoan the "dogged refusal of Mawlana Mawdudi to give up on slavery"[241] and the notable "evasions and silences of Muhammad Qutb".[242][243]

Muhammad Qutb, brother and promoter of the Egyptian author and revolutionary Sayyid Qutb, vigorously defended Islamic slavery from Western criticism, telling his audience that "Islam gave spiritual enfranchisement to slaves" and "in the early period of Islam the slave was exalted to such a noble state of humanity as was never before witnessed in any other part of the world."[244] He contrasted the adultery, prostitution,[245] and (what he called) "that most odious form of animalism" casual sex, found in Europe,[246] with (what he called) "that clean and spiritual bond that ties a maid [i.e. slave girl] to her master in Islam."[245]

Salafi support for slavery

[edit]In recent years, according to some scholars,[247] there has been a "reopening"[248] of the issue of slavery by some conservative Salafi Islamic scholars after its "closing" earlier in the 20th century when Muslim countries banned slavery.

In 2003, Shaykh Saleh Al-Fawzan, a member of Saudi Arabia's highest religious body, the Senior Council of Clerics, issued a fatwa claiming "Slavery is a part of Islam. Slavery is part of jihad, and jihad will remain as long there is Islam."[249] Muslim scholars who said otherwise were "infidels". In 2016, Shaykh al-Fawzan responded to a question about taking Yazidi women as sex slaves by reiterating that "Enslaving women in war is not prohibited in Islam", he added that those who forbid enslavement are either "ignorant or infidel".[250]

While Saleh Al-Fawzan's fatwa does not repeal Saudi laws against slavery,[citation needed] the fatwa carries weight among many Salafi Muslims. According to reformist jurist and author Khaled Abou El Fadl, it "is particularly disturbing and dangerous because it effectively legitimates the trafficking in and sexual exploitation of so-called domestic workers in the Gulf region and especially Saudi Arabia."[251] "Organized criminal gangs smuggle children into Saudi Arabia where they are enslaved, sometimes mutilated, and forced to work as beggars. When caught, the children are deported as illegal aliens."[252]

Mauritania and Sudan

[edit]In Mauritania slavery was abolished in the country's first constitution of 1961 after independence, and abolished yet again, by presidential decree, in July 1980. The "catch" of these abolitions was that slave ownership was not abolished. The edict "recognized the rights of owners by stipulating that they should be compensated for their loss of property". No financial payment was provided by the state, so that the abolition amounted to "little more than propaganda for foreign consumption". Religious authorities within Mauritania assailed abolition. One leader, El Hassan Ould Benyamine, imam of a mosque in Tayarat attacked it as

"not only illegal because it is contrary to the teachings of the fundamental text of Islamic law, the Koran. The abolition also amounts to the expropriation from Muslims of their goods, goods that were acquired legally. The state, if it is Islamic, does not have the right to seize my house, my wife or my slave."[19][253]

In 1994–95, a Special Rapporteur of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights documented the physical and emotional abuse of captives by the Sudanese Army and allied militia and army. The captives were "sold as slaves or forced to work under conditions amounting to slavery". The Sudanese government responded with "fury", accusing the author, Gaspar Biro of "harboring anti-Islam and Anti-Arab sentiments". In 1999, the UN Commission sent another Special Rapporteur who "also produced a detailed examination of the question of slavery incriminating the government of Sudan."[254] At least in the 1980s, slavery in Sudan was developed enough for slaves to have a market price – the price of a slave boy fluctuating between $90 and $10 in 1987 and 1988.[255]

Saudi Arabia

[edit]In 1962, Saudi Arabia abolished slavery officially; however, unofficial slavery is rumored to exist.[256][257][258]

According to the U.S. State Department as of 2005:

Saudi Arabia is a destination for men and women from South and East Asia and East Africa trafficked for the purpose of labor exploitation, and for children from Yemen, Afghanistan, and Africa trafficking for forced begging. Hundreds of thousands of low-skilled workers from India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Kenya migrate voluntarily to Saudi Arabia; some fall into conditions of involuntary servitude, suffering from physical and sexual abuse, non-payment or delayed payment of wages, the withholding of travel documents, restrictions on their freedom of movement and non-consensual contract alterations. The Government of Saudi Arabia does not comply with the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking and is not making significant efforts to do so.[259]

Libya and Algeria

[edit]Libya is a major exit point for African migrants heading to Europe. International Organization for Migration (IOM) published a report in April 2017 showing that many of the migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa heading to Europe are sold as slaves after being detained by people smugglers or militia groups. African countries south of Libya were targeted for slave trading and transferred to Libyan slave markets instead. According to the victims, the price is higher for migrants with skills like painting and tiling.[260][261] Slaves are often ransomed to their families and – in the meantime until ransom can be paid – tortured, forced to work, sometimes to death and eventually executed or left to starve if they can't pay for too long. Women are often raped and used as sex slaves and sold to brothels and private Libyan clients.[260][261][262] Many child migrants also suffer from abuse and child rape in Libya.[263][264]

In November 2017, hundreds of African migrants were being forced into slavery by human smugglers who were themselves facilitating their arrival in the country. Most of the migrants are from Nigeria, Senegal and Gambia. They however end up in cramped warehouses due to the crackdown by the Libyan Coast Guard, where they are held until they are ransomed or are sold for labor.[265] Libyan authorities of the Government of National Accord announced that they had opened up an investigation into the auctions.[266] A human trafficker told Al-Jazeera that hundreds of the migrants are bought and sold across the country every week.[267] Dozens of African migrants headed for a new life in Europe in 2018 said they were sold for labor and trapped in slavery in Algeria.[268]

Jihadists

[edit]Militants insurgencies have raged in recent times in the Muslim world in places like the Palestinian territories, Syria, Chechnya, Yemen, Kashmir and Somalia, and many of them have taken prisoners of war.[269] Despite Taliban fighting in Afghanistan for decades, they have never sought to enslave their war captives (as of 2019).[269] The Palestinian group Hamas has held Israeli prisoners (such as Gilad Shalit). Yet Hamas, which claims to uphold Islamic law, has also never sought to enslave its prisoners.[269]

However, other jihadist groups have enslaved their captives, claiming sanction from Islam. In 2014, Islamic terrorist groups in the Middle East (ISIS also known as Islamic State) and Northern Nigeria (Boko Haram) have not only justified the taking of slaves in war but actually enslaved women and girls. Abubakar Shekau, the leader of the Nigerian extremist group Boko Haram said in an interview, "I shall capture people and make them slaves".[270] In the digital magazine Dabiq, ISIS claimed religious justification for enslaving Yazidi women. ISIS claimed that the Yazidi are idol worshipers and their enslavement part of the old shariah practice of spoils of war.[271][272][273][274][275] The Economist reports that ISIS has taken "as many as 2,000 women and children" captive, selling and distributing them as sexual slaves.[276] ISIS appealed to apocalyptic beliefs and "claimed justification by a Hadith that they interpret as portraying the revival of slavery as a precursor to the end of the world."[277]

In response to Boko Haram's Quranic justification for kidnapping and enslaving people and ISIS's religious justification for enslaving Yazidi women, 126 Islamic scholars from around the Muslim world signed an open letter in late September 2014 to the Islamic State's leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, rejecting his group's interpretations of the Qur'an and hadith to justify its actions.[278][279] The letter accuses the group of instigating fitna – sedition – by instituting slavery under its rule in contravention of the anti-slavery consensus of the Islamic scholarly community.[280]

Geography of the slave trade

[edit]"Supply" zones

[edit]There is historical evidence of North African Muslim slave raids all along the Mediterranean coasts across Christian Europe.[281] The majority of slaves traded across the Mediterranean region were predominantly of European origin from the 7th to 15th centuries.[282] In the 15th century, Ethiopians sold slaves from western borderland areas (usually just outside the realm of the Emperor of Ethiopia) or Ennarea.[283]

Barter

[edit]

Slaves were often bartered for objects of various kinds: in the Sudan, they were exchanged for cloth, trinkets and so on. In the Maghreb, slaves were swapped for horses. In the desert cities, lengths of cloth, pottery, Venetian glass slave beads, dyestuffs and jewels were used as payment. The trade in black slaves was part of a diverse commercial network. Alongside gold coins, cowrie shells from the Indian Ocean or the Atlantic (Canaries, Luanda) were used as money throughout sub-saharan Africa (merchandise was paid for with sacks of cowries).[284]

Slave markets and fairs

[edit]

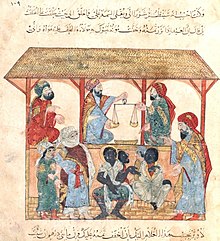

Enslaved Africans were sold in the towns of the Arab World. In 1416, al-Maqrizi told how pilgrims coming from Takrur (near the Senegal River) brought 1,700 slaves with them to Mecca. In North Africa, the main slave markets were in Morocco, Algiers, Tripoli and Cairo. Sales were held in public places or in souks.

Potential buyers made a careful examination of the "merchandise": they checked the state of health of a person who was often standing naked with wrists bound together. In Cairo, transactions involving eunuchs and concubines happened in private houses. Prices varied according to the slave's quality. Thomas Smee, the commander of the British research ship Ternate, visited such a market in Zanzibar in 1811 and gave a detailed description:

'The show' commences about four o'clock in the afternoon. The slaves, set off to the best advantage by having their skins cleaned and burnished with cocoa-nut oil, their faces painted with red and white stripes and the hands, noses, ears and feet ornamented with a profusion of bracelets of gold and silver and jewels, are ranged in a line, commencing with the youngest, and increasing to the rear according to their size and age. At the head of this file, which is composed of all sexes and ages from 6 to 60, walks the person who owns them; behind and at each side, two or three of his domestic slaves, armed with swords and spears, serve as guard. Thus ordered the procession begins, and passes through the market-place and the principle streets... when any of them strikes a spectator's fancy the line immediately stops, and a process of examination ensues, which, for minuteness, is unequalled in any cattle market in Europe. The intending purchaser having ascertained there is no defect in the faculties of speech, hearing, etc., that there is no disease present, next proceeds to examine the person; the mouth and the teeth are first inspected and afterwards every part of the body in succession, not even excepting the breasts, etc., of the girls, many of whom I have seen handled in the most indecent manner in the public market by their purchasers; indeed there is every reasons to believe that the slave-dealers almost universally force the young girls to submit to their lust previous to their being disposed of. From such scenes one turns away with pity and indignation.[285]

Africa: 8th through 19th centuries

[edit]In April 1998, Elikia M'bokolo, wrote in Le Monde diplomatique. "The African continent was bled of its human resources via all possible routes. Across the Sahara, through the Red Sea, from the Indian Ocean ports and across the Atlantic. At least ten centuries of slavery for the benefit of the Muslim countries (from the ninth to the nineteenth)." He continues: "Four million slaves exported via the Red Sea, another four million through the Swahili ports of the Indian Ocean, perhaps as many as nine million along the trans-Saharan caravan route, and eleven to twenty million (depending on the author) across the Atlantic Ocean"[286]

In the 8th century, Africa was dominated by Arab-Berbers in the north: Islam moved southwards along the Nile and along the desert trails.