Анаболический стероид

| Анаболико-андрогенные стероиды | |

|---|---|

| Класс препарата | |

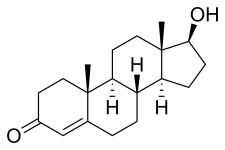

Химическая структура природного ААС тестостерона (андрост-4-ен-17β-ол-3-он). | |

| Идентификаторы классов | |

| Синонимы | Анаболические стероиды; Андрогены |

| Использовать | Различный |

| код АТС | A14A |

| Биологическая цель | Андрогенный рецептор (АР) |

| Chemical class | Steroids; Androstanes; Estranes |

| Clinical data | |

| Drugs.com | Drug Classes |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D045165 |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| In Wikidata | |

Анаболические стероиды , также известные как анаболически-андрогенные стероиды (ААС), представляют собой класс препаратов, которые структурно родственны тестостерону , основному мужскому половому гормону , и оказывают действие путем связывания с андрогенным рецептором (АР). Анаболические стероиды имеют ряд медицинских применений. [1] но также используются спортсменами для увеличения размера мышц, силы и производительности.

Риск для здоровья может быть вызван длительным применением или чрезмерными дозами ААС. [2] [3] Эти эффекты включают вредные изменения уровня холестерина (повышение уровня липопротеинов низкой плотности и снижение уровня липопротеинов высокой плотности ), прыщи , высокое кровяное давление , поражение печени (в основном при приеме большинства пероральных ААС) и гипертрофию левого желудочка . [4] Эти риски еще больше увеличиваются, когда спортсмены принимают стероиды вместе с другими препаратами, что наносит значительно больший вред их организму. [5] Влияние анаболических стероидов на сердце может вызвать инфаркт миокарда и инсульты. [5] Состояния, связанные с гормональным дисбалансом, такие как гинекомастия и уменьшение размера яичек, также могут быть вызваны ААС. [6] In women and children, AAS can cause irreversible masculinization.[6]

Ergogenic uses for AAS in sports, racing, and bodybuilding as performance-enhancing drugs are controversial because of their adverse effects and the potential to gain advantage in physical competitions. Their use is referred to as doping and banned by most major sporting bodies. Athletes have been looking for drugs to enhance their athletic abilities since the Olympics started in Ancient Greece.[5] For many years, AAS have been by far the most detected doping substances in IOC-accredited laboratories.[7][8] Anabolic steroids are classified as Schedule III controlled substances in many countries,[9] meaning that AAS have recognized medical use but are also recognized as having a potential for abuse and dependence, leading to their regulation and control. In countries where AAS are controlled substances, there is often a black market in which smuggled, clandestinely manufactured or even counterfeit drugs are sold to users.

Uses

[edit]Medical

[edit]

Since the discovery and synthesis of testosterone in the 1930s, AAS have been used by physicians for many purposes, with varying degrees of success. These can broadly be grouped into anabolic, androgenic, and other uses.

Anabolic

[edit]- Bone marrow stimulation: For decades, AAS were the mainstay of therapy for hypoplastic anemias due to leukemia, kidney failure or aplastic anemia.[10]

- Growth stimulation: AAS can be used by pediatric endocrinologists to treat children with growth failure.[11] However, the availability of synthetic growth hormone, which has fewer side effects, makes this a secondary treatment.[medical citation needed]

- Stimulation of appetite and preservation and increase of muscle mass: AAS have been given to people with chronic wasting conditions such as cancer and AIDS.[12][13]

- Stimulation of lean body mass and prevention of bone loss in elderly men, as some studies indicate.[14][15][16] However, a 2006 placebo-controlled trial of low-dose testosterone supplementation in elderly men with low levels of testosterone found no benefit on body composition, physical performance, insulin sensitivity, or quality of life.[17]

- Prevention or treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women.[18][19] Nandrolone decanoate is approved for this use.[20] Although they have been indicated for this indication, AAS saw very little use for this purpose due to their virilizing side effects.[18][21]

- Aiding weight gain following surgery or physical trauma, during chronic infection, or in the context of unexplained weight loss.[22][23]

- Counteracting the catabolic effect of long-term corticosteroid therapy.[22][23]

- Oxandrolone improves both short-term and long-term outcomes in people recovering from severe burns, and is well-established as a safe treatment for this indication.[24][25]

- Treatment of idiopathic short stature, hereditary angioedema, alcoholic hepatitis, and hypogonadism.[26][27]

- Methyltestosterone is used in the treatment of delayed puberty, hypogonadism, cryptorchidism, and erectile dysfunction in males, and in low doses to treat menopausal symptoms (specifically for osteoporosis, hot flashes, and to increase libido and energy), postpartum breast pain and engorgement, and breast cancer in women.[28][29][30]

- Growth hormones used in veterinary medicine (e.g. trenbolone acetate) are also used in intensive animal farming for faster gains in muscle mass for higher yields of meat from livestock and higher milk production in the dairy industry.[31]

Androgenic

[edit]- Androgen replacement therapy for men with low levels of testosterone, such as those associated with late-onset hypogonadism;[32] also effective in improving libido for elderly males.[33][34][35][36]

- Induction of male puberty: Androgens are given to many boys distressed about extreme delay of puberty. Testosterone is now nearly the only androgen used for this purpose and has been shown to increase height, weight, and fat-free mass in boys with delayed puberty.[37]

- Masculinizing hormone therapy for transgender men, other transmasculine people, and intersex people, by producing masculine secondary sexual characteristics such as a voice deepening, increased bone and muscle mass, masculine fat distribution, facial and body hair, and clitoral enlargement, as well as mental changes such as alleviation of gender dysphoria and increased sex drive.[38][39][40][41][42]

Other

[edit]- Treatment of breast cancer in women, although they are now very rarely used for this purpose due to their marked virilizing side effects.[43][18][44]

- In low doses as a component of hormone therapy for postmenopausal and transgender women, for instance to increase energy, well-being, libido, and quality of life, as well as to reduce hot flashes.[45][46][47][48] Testosterone is usually used for this purpose, although methyltestosterone is also used.[48][49]

- Male hormonal contraception; currently experimental, but potential for use as effective, safe, reliable, and reversible male contraceptives.[50]

- Assistant in the treatment of Raynaud's Phenomenon and peripheral acrocyanosis. Testosterone and other anabolics tend to be potent vasodilators, which can significantly improve bloodflow in individuals prone to vasoconstriction.[51]

Enhancing performance

[edit]

Most steroid users are not athletes.[52] In the United States, between 1 million and 3 million people (1% of the population) are thought to have used AAS.[53] Studies in the United States have shown that AAS users tend to be mostly middle-class men with a median age of about 25 who are noncompetitive bodybuilders and non-athletes and use the drugs for cosmetic purposes.[54] "Among 12- to 17-year-old boys, use of steroids and similar drugs jumped 25 percent from 1999 to 2000, with 20 percent saying they use them for looks rather than sports, a study by insurer Blue Cross Blue Shield found."[55] Another study found that non-medical use of AAS among college students was at or less than 1%.[56] According to a recent survey, 78.4% of steroid users were noncompetitive bodybuilders and non-athletes, while about 13% reported unsafe injection practices such as reusing needles, sharing needles, and sharing multidose vials,[57] though a 2007 study found that sharing of needles was extremely uncommon among individuals using AAS for non-medical purposes, less than 1%.[58] Another 2007 study found that 74% of non-medical AAS users had post-secondary degrees and more had completed college and fewer had failed to complete high school than is expected from the general populace.[58] The same study found that individuals using AAS for non-medical purposes had a higher employment rate and a higher household income than the general population.[58] AAS users tend to research the drugs they are taking more than other controlled-substance users;[citation needed] however, the major sources consulted by steroid users include friends, non-medical handbooks, internet-based forums, blogs, and fitness magazines, which can provide questionable or inaccurate information.[59]

AAS users tend to be unhappy with the portrayal of AAS as deadly in the media and in politics.[60] According to one study, AAS users also distrust their physicians and in the sample 56% had not disclosed their AAS use to their physicians.[61] Another 2007 study had similar findings, showing that, while 66% of individuals using AAS for non-medical purposes were willing to seek medical supervision for their steroid use, 58% lacked trust in their physicians, 92% felt that the medical community's knowledge of non-medical AAS use was lacking, and 99% felt that the public has an exaggerated view of the side-effects of AAS use.[58] A recent study has also shown that long term AAS users were more likely to have symptoms of muscle dysmorphia and also showed stronger endorsement of more conventional male roles.[62] A recent study in the Journal of Health Psychology showed that many users believed that steroids used in moderation were safe.[63]

AAS have been used by men and women in many different kinds of professional sports to attain a competitive edge or to assist in recovery from injury. These sports include bodybuilding, weightlifting, shot put and other track and field, cycling, baseball, wrestling, mixed martial arts, boxing, football, and cricket. Such use is prohibited by the rules of the governing bodies of most sports. AAS use occurs among adolescents, especially by those participating in competitive sports. It has been suggested that the prevalence of use among high-school students in the U.S. may be as high as 2.7%.[64]

Dosages

[edit]| Medication | Route | Dosage range[a] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Danazol | Oral | 100–800 mg/day | ||

| Drostanolone propionate | Injection | 100 mg 3 times/week | ||

| Ethylestrenol | Oral | 2–8 mg/day | ||

| Fluoxymesterone | Oral | 2–40 mg/day | ||

| Mesterolone | Oral | 25–150 mg/day | ||

| Metandienone | Oral | 2.5–15 mg/day | ||

| Metenolone acetate | Oral | 10–150 mg/day | ||

| Metenolone enanthate | Injection | 25–100 mg/week | ||

| Methyltestosterone | Oral | 1.5–200 mg/day | ||

| Nandrolone decanoate | Injection | 12.5–200 mg/week[b] | ||

| Nandrolone phenylpropionate | Injection | 6.25–200 mg/week[b] | ||

| Norethandrolone | Oral | 20–30 mg/day | ||

| Oxandrolone | Oral | 2.5–20 mg/day | ||

| Oxymetholone | Oral | 1–5 mg/kg/day or 50–150 mg/day | ||

| Stanozolol | Oral | 2–6 mg/day | ||

| Injection | 50 mg up to every two weeks | |||

| Testosterone | Oral[c] | 400–800 mg/day[b] | ||

| Injection | 25–100 mg up to three times weekly | |||

| Testosterone cypionate | Injection | 50–400 mg up to every four weeks | ||

| Testosterone enanthate | Injection | 50–400 mg up to every four weeks | ||

| Testosterone propionate | Injection | 25–50 mg up to three times weekly | ||

| Testosterone undecanoate | Oral | 80–240 mg/day[b] | ||

| Injection | 750–1000 mg up to every 10 weeks | |||

| Trenbolone HBC | Injection | 75 mg every 10 days | ||

| Sources: [65][66][67][68][18][69][70][71][72][73] | ||||

Available forms

[edit]The AAS that have been used most commonly in medicine are testosterone and its many esters (but most typically testosterone undecanoate, testosterone enanthate, testosterone cypionate, and testosterone propionate),[74] nandrolone esters (typically nandrolone decanoate and nandrolone phenylpropionate), stanozolol, and metandienone (methandrostenolone).[75] Others that have also been available and used commonly but to a lesser extent include methyltestosterone, oxandrolone, mesterolone, and oxymetholone, as well as drostanolone propionate (dromostanolone propionate), metenolone (methylandrostenolone) esters (specifically metenolone acetate and metenolone enanthate), and fluoxymesterone.[75] Dihydrotestosterone (DHT), known as androstanolone or stanolone when used medically, and its esters are also notable, although they are not widely used in medicine.[70] Boldenone undecylenate and trenbolone acetate are used in veterinary medicine.[75]

Designer steroids are AAS that have not been approved and marketed for medical use but have been distributed through the black market.[76] Examples of notable designer steroids include 1-testosterone (dihydroboldenone), methasterone, trenbolone enanthate, desoxymethyltestosterone, tetrahydrogestrinone, and methylstenbolone.[76]

Routes of administration

[edit]

There are four common forms in which AAS are administered: oral pills; injectable steroids; creams/gels for topical application; and skin patches. Oral administration is the most convenient. Testosterone administered by mouth is rapidly absorbed, but it is largely converted to inactive metabolites, and only about one-sixth is available in active form. In order to be sufficiently active when given by mouth, testosterone derivatives are alkylated at the 17α position, e.g. methyltestosterone and fluoxymesterone. This modification reduces the liver's ability to break down these compounds before they reach the systemic circulation.

Testosterone can be administered parenterally, but it has more irregular prolonged absorption time and greater activity in muscle in enanthate, undecanoate, or cypionate ester form. These derivatives are hydrolyzed to release free testosterone at the site of injection; absorption rate (and thus injection schedule) varies among different esters, but medical injections are normally done anywhere between semi-weekly to once every 12 weeks. A more frequent schedule may be desirable in order to maintain a more constant level of hormone in the system.[77] Injectable steroids are typically administered into the muscle, not into the vein, to avoid sudden changes in the amount of the drug in the bloodstream. In addition, because estered testosterone is dissolved in oil, intravenous injection has the potential to cause a dangerous embolism (clot) in the bloodstream.

Transdermal patches (adhesive patches placed on the skin) may also be used to deliver a steady dose through the skin and into the bloodstream. Testosterone-containing creams and gels that are applied daily to the skin are also available, but absorption is inefficient (roughly 10%, varying between individuals) and these treatments tend to be more expensive. Individuals who are especially physically active and/or bathe often may not be good candidates, since the medication can be washed off and may take up to six hours to be fully absorbed. There is also the risk that an intimate partner or child may come in contact with the application site and inadvertently dose themselves; children and women are highly sensitive to testosterone and can develop unintended masculinization and health effects, even from small doses. Injection is the most common method used by individuals administering AAS for non-medical purposes.[58]

The traditional routes of administration do not have differential effects on the efficacy of the drug. Studies indicate that the anabolic properties of AAS are relatively similar despite the differences in pharmacokinetic principles such as first-pass metabolism. However, the orally available forms of AAS may cause liver damage in high doses.[8][78]

Adverse effects

[edit]

Known possible side effects of AAS include:[6][80][81][82][83]

- Dermatological/integumental: oily skin, acne vulgaris, acne conglobata, seborrhea, stretch marks (due to rapid muscle enlargement), hypertrichosis (excessive body hair growth), androgenic alopecia (pattern hair loss; scalp baldness), fluid retention/edema.

- Reproductive/endocrine: libido changes, reversible infertility, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.

- Male-specific: spontaneous erections, nocturnal emissions, priapism, erectile dysfunction, gynecomastia (mostly only with aromatizable and hence estrogenic AAS), oligospermia/azoospermia, testicular atrophy, intratesticular leiomyosarcoma, prostate hypertrophy, prostate cancer.

- Female-specific: masculinization, irreversible voice deepening, hirsutism (excessive facial/body hair growth), menstrual disturbances (e.g., anovulation, oligomenorrhea, amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea), clitoral enlargement, breast atrophy, uterine atrophy, teratogenicity (in female fetuses).

- Child-specific: premature epiphyseal closure and associated short stature, precocious puberty in boys, delayed puberty and contrasexual precocity in girls.

- Psychiatric/neurological: mood swings, irritability, aggression, violent behavior, impulsivity/recklessness, hypomania/mania, euphoria, depression, anxiety, dysphoria, suicidality, delusions, psychosis, withdrawal, dependence, neurotoxicity, cognitive impairment.[84][85]

- Musculoskeletal: muscle hypertrophy, muscle strains, tendon ruptures, rhabdomyolysis.

- Cardiovascular: dyslipidemia (e.g., increased LDL levels, decreased HDL levels, reduced apo-A1 levels), atherosclerosis, elevated hematocrit, hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, cardiomyopathy, myocardial hypertrophy, polycythemia/erythrocytosis, arrhythmias, thrombosis (e.g., embolism, stroke), myocardial infarction, sudden death.[86][87]

- Hepatic: elevated liver function tests (AST, ALT, bilirubin, LDH, ALP), hepatotoxicity, jaundice, hepatic steatosis, hepatocellular adenoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, cholestasis, peliosis hepatis; all mostly or exclusively with 17α-alkylated AAS.[88]

- Renal: renal hypertrophy, nephropathy, acute renal failure (secondary to rhabdomyolysis), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, renal cell carcinoma.

- Others: glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, immune dysfunction.[89]

Physiological

[edit]Depending on the length of drug use, there is a chance that the immune system can be damaged. Most of these side-effects are dose-dependent, the most common being elevated blood pressure, especially in those with pre-existing hypertension.[90] In addition to morphological changes of the heart which may have a permanent adverse effect on cardiovascular efficiency.

AAS have been shown to alter fasting blood sugar and glucose tolerance tests.[91] AAS such as testosterone also increase the risk of cardiovascular disease[2] or coronary artery disease.[92][93] Acne is fairly common among AAS users, mostly due to stimulation of the sebaceous glands by increased testosterone levels.[7][94] Conversion of testosterone to DHT can accelerate the rate of premature baldness for males genetically predisposed, but testosterone itself can produce baldness in females.[95]

A number of severe side effects can occur if adolescents use AAS. For example, AAS may prematurely stop the lengthening of bones (premature epiphyseal fusion through increased levels of estrogen metabolites), resulting in stunted growth. Other effects include, but are not limited to, accelerated bone maturation, increased frequency and duration of erections, and premature sexual development. AAS use in adolescence is also correlated with poorer attitudes related to health.[96]

Cancer

[edit]WHO organization International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) list AAS under Group 2A: Probably carcinogenic to humans.[97]

Cardiovascular

[edit]Other side-effects can include alterations in the structure of the heart, such as enlargement and thickening of the left ventricle, which impairs its contraction and relaxation, and therefore reducing ejected blood volume.[4] Possible effects of these alterations in the heart are hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, heart attacks, and sudden cardiac death.[98] These changes are also seen in non-drug-using athletes, but steroid use may accelerate this process.[99][100] However, both the connection between changes in the structure of the left ventricle and decreased cardiac function, as well as the connection to steroid use have been disputed.[101][102]

AAS use can cause harmful changes in cholesterol levels: Some steroids cause an increase in LDL cholesterol and a decrease in HDL cholesterol.[103]

Growth defects

[edit]AAS use in adolescents quickens bone maturation and may reduce adult height in high doses.[citation needed] Low doses of AAS such as oxandrolone are used in the treatment of idiopathic short stature, but this may only quicken maturation rather than increasing adult height.[104]

Feminization

[edit]

Although all anabolic steroids have androgenic effects, some of them paradoxically results in feminization, such as breast tissue in males, a condition called gynecomastia. These side effect are caused by the natural conversion of testosterone into estrogen and estradiol by the action of aromatase enzyme, encoded by the CYP19A1 gene.[105]

Prolonged use of androgenic-anabolic steroids by men results in temporary shut down of their natural testosterone production due to an inhibition of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. This manifests in testicular atrophy, inhibition of the production of sperm, sexual function and infertility.[106][107][108] A short (1–2 months) use of androgenic-anabolic steroids by men followed by a course of testosterone-boosting therapy (e.g. clomifene and human chorionic gonadotropin) usually results in return to normal testosterone production.[109])

Masculinization

[edit]Female-specific side effects include increases in body hair, permanent deepening of the voice, enlarged clitoris, and temporary decreases in menstrual cycles. Alteration of fertility and ovarian cysts can also occur in females.[110] When taken during pregnancy, AAS can affect fetal development by causing the development of male features in the female fetus and female features in the male fetus.[111]

Kidney problems

[edit]Kidney tests revealed that nine of the ten steroid users developed a condition called focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, a type of scarring within the kidneys. The kidney damage in the bodybuilders has similarities to that seen in morbidly obese patients, but appears to be even more severe.[112]

Liver problems

[edit]High doses of oral AAS compounds can cause liver damage.[3] Peliosis hepatis has been increasingly recognised with the use of AAS.

Neuropsychiatric

[edit]

A 2005 review in CNS Drugs determined that "significant psychiatric symptoms including aggression and violence, mania, and less frequently psychosis and suicide have been associated with steroid abuse. Long-term steroid abusers may develop symptoms of dependence and withdrawal on discontinuation of AAS".[85] High concentrations of AAS, comparable to those likely sustained by many recreational AAS users, produce apoptotic effects on neurons,[citation needed] raising the specter of possibly irreversible neurotoxicity. Recreational AAS use appears to be associated with a range of potentially prolonged psychiatric effects, including dependence syndromes, mood disorders, and progression to other forms of substance use, but the prevalence and severity of these various effects remains poorly understood.[114] There is no evidence that steroid dependence develops from therapeutic use of AAS to treat medical disorders, but instances of AAS dependence have been reported among weightlifters and bodybuilders who chronically administered supraphysiologic doses.[115] Mood disturbances (e.g. depression, [hypo-]mania, psychotic features) are likely to be dose- and drug-dependent, but AAS dependence or withdrawal effects seem to occur only in a small number of AAS users.[7] Large-scale long-term studies of psychiatric effects on AAS users are not currently available.[114]

Diagnostic Statistical Manual assertion

[edit]DSM-IV lists General diagnostic criteria for a personality disorder guideline that "The pattern must not be better accounted for as a manifestation of another mental disorder, or to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g. drug or medication) or a general medical condition (e.g. head trauma).". As a result, AAS users may get misdiagnosed by a psychiatrist not told about their habit.[116]

Personality profiles

[edit]Cooper, Noakes, Dunne, Lambert, and Rochford identified that AAS-using individuals are more likely to score higher on borderline (4.7 times), antisocial (3.8 times), paranoid (3.4 times), schizotypal (3.1 times), histrionic (2.9 times), passive-aggressive (2.4 times), and narcissistic (1.6 times) personality profiles than non-users.[117] Other studies have suggested that antisocial personality disorder is slightly more likely among AAS users than among non-users (Pope & Katz, 1994).[116] Bipolar dysfunction,[118] substance dependency, and conduct disorder have also been associated with AAS use.[119]

Mood and anxiety

[edit]Affective disorders have long been recognised as a complication of AAS use. Case reports describe both hypomania and mania, along with irritability, elation, recklessness, racing thoughts and feelings of power and invincibility that did not meet the criteria for mania/hypomania.[120] Of 53 bodybuilders who used AAS, 27 (51%) reported unspecified mood disturbance.[121]

Aggression and hypomania

[edit]From the mid-1980s onward, the media reported "roid rage" as a side effect of AAS.[122]: 23

A 2005 review determined that some, but not all, randomized controlled studies have found that AAS use correlates with hypomania and increased aggressiveness, but pointed out that attempts to determine whether AAS use triggers violent behavior have failed, primarily because of high rates of non-participation.[123] A 2008 study on a nationally representative sample of young adult males in the United States found an association between lifetime and past-year self-reported AAS use and involvement in violent acts. Compared with individuals that did not use steroids, young adult males that used AAS reported greater involvement in violent behaviors even after controlling for the effects of key demographic variables, previous violent behavior, and polydrug use.[124] A 1996 review examining the blind studies available at that time also found that these had demonstrated a link between aggression and steroid use, but pointed out that with estimates of over one million past or current steroid users in the United States at that time, an extremely small percentage of those using steroids appear to have experienced mental disturbance severe enough to result in clinical treatments or medical case reports.[125]

The relationship between AAS use and depression is inconclusive. A 1992 review[needs update] found that AAS may both relieve and cause depression, and that cessation or diminished use of AAS may also result in depression, but called for additional studies due to disparate data.[126]

Reproductive

[edit]Androgens such as testosterone, androstenedione and dihydrotestosterone are required for the development of organs in the male reproductive system, including the seminal vesicles, epididymis, vas deferens, penis and prostate.[127] AAS are testosterone derivatives designed to maximize the anabolic effects of testosterone.[75] AAS are consumed by elite athletes competing in sports like weightlifting, bodybuilding, and track and field.[128] Male recreational athletes take AAS to achieve an "enhanced" physical appearance.[129]

AAS consumption disrupts the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis (HPG axis) in males.[127] In the HPG axis, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is secreted from the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus and stimulates the anterior pituitary to secrete the two gonadotropins, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH).[130] In adult males, LH stimulates the Leydig cells in the testes to produce testosterone which is required to form new sperm through spermatogenesis.[127] AAS consumption leads to dose-dependent suppression of gonadotropin release through suppression of GnRH from the hypothalamus (long-loop mechanism) or from direct negative feedback on the anterior pituitary to inhibit gonadotropin release (short-loop mechanism), leading to AAS-induced hypogonadism.[127]

Pharmacology

[edit]Mechanism of action

[edit]

The pharmacodynamics of AAS are unlike peptide hormones. Water-soluble peptide hormones cannot penetrate the fatty cell membrane and only indirectly affect the nucleus of target cells through their interaction with the cell's surface receptors. However, as fat-soluble hormones, AAS are membrane-permeable and influence the nucleus of cells by direct action. The pharmacodynamic action of AAS begin when the exogenous hormone penetrates the membrane of the target cell and binds to an androgen receptor (AR) located in the cytoplasm of that cell. From there, the compound hormone-receptor diffuses into the nucleus, where it either alters the expression of genes[132] or activates processes that send signals to other parts of the cell.[133] Different types of AAS bind to the AAR with different affinities, depending on their chemical structure.[7]

The effect of AAS on muscle mass is caused in at least two ways:[134] first, they increase the production of proteins; second, they reduce recovery time by blocking the effects of stress hormone cortisol on muscle tissue, so that catabolism of muscle is greatly reduced. It has been hypothesized that this reduction in muscle breakdown may occur through AAS inhibiting the action of other steroid hormones called glucocorticoids that promote the breakdown of muscles.[64] AAS also affect the number of cells that develop into fat-storage cells, by favouring cellular differentiation into muscle cells instead.[135]

Molecular Interaction of AAS with Androgen Receptors

[edit]Anabolic steroids interact with ARs across various tissues, including muscle, bone, and reproductive systems.[136] Upon binding to the AR, anabolic steroids trigger a translocation of the hormone-receptor complex to the cell nucleus, where they either alter gene expression or activate cellular signaling pathways; this results in increased protein synthesis, enhanced muscle growth, and reduced muscle catabolism.[137]

Anabolic steroids influence cellular differentiation while favoring the development of muscle cells over fat-storage cells.[138] Research in this field has shown that structural modifications in anabolic steroids are critical in determining their binding affinity to ARs and their resulting anabolic and androgenic activities.[82] These modifications affect a steroid's ability to influence gene expression and cellular processes, highlighting the complex biophysical interactions of anabolic steroids at the cellular level.[136]

Anabolic and androgenic effects

[edit]| Medication | Ratioa |

|---|---|

| Testosterone | ~1:1 |

| Androstanolone (DHT) | ~1:1 |

| Methyltestosterone | ~1:1 |

| Methandriol | ~1:1 |

| Fluoxymesterone | 1:1–1:15 |

| Metandienone | 1:1–1:8 |

| Drostanolone | 1:3–1:4 |

| Metenolone | 1:2–1:30 |

| Oxymetholone | 1:2–1:9 |

| Oxandrolone | 1:3–1:13 |

| Stanozolol | 1:1–1:30 |

| Nandrolone | 1:3–1:16 |

| Ethylestrenol | 1:2–1:19 |

| Norethandrolone | 1:1–1:20 |

| Notes: In rodents. Footnotes: a = Ratio of androgenic to anabolic activity. Sources: See template. | |

As their name suggests, AAS have two different, but overlapping, types of effects: anabolic, meaning that they promote anabolism (cell growth), and androgenic (or virilizing), meaning that they affect the development and maintenance of masculine characteristics.

Some examples of the anabolic effects of these hormones are increased protein synthesis from amino acids, increased appetite, increased bone remodeling and growth, and stimulation of bone marrow, which increases the production of red blood cells. Through a number of mechanisms AAS stimulate the formation of muscle cells and hence cause an increase in the size of skeletal muscles, leading to increased strength.[139][12][140]

The androgenic effects of AAS are numerous. Depending on the length of use, the side effects of the steroid can be irreversible. Processes affected include pubertal growth, sebaceous gland oil production, and sexuality (especially in fetal development). Some examples of virilizing effects are growth of the clitoris in females and the penis in male children (the adult penis size does not change due to steroids[medical citation needed] ), increased vocal cord size, increased libido, suppression of natural sex hormones, and impaired production of sperm.[141] Effects on women include deepening of the voice, facial hair growth, and possibly a decrease in breast size. Men may develop an enlargement of breast tissue, known as gynecomastia, testicular atrophy, and a reduced sperm count.[citation needed]The androgenic:anabolic ratio of an AAS is an important factor when determining the clinical application of these compounds. Compounds with a high ratio of androgenic to an anabolic effects are the drug of choice in androgen-replacement therapy (e.g., treating hypogonadism in males), whereas compounds with a reduced androgenic:anabolic ratio are preferred for anemia and osteoporosis, and to reverse protein loss following trauma, surgery, or prolonged immobilization. Determination of androgenic:anabolic ratio is typically performed in animal studies, which has led to the marketing of some compounds claimed to have anabolic activity with weak androgenic effects. This disassociation is less marked in humans, where all AAS have significant androgenic effects.[77]

A commonly used protocol for determining the androgenic:anabolic ratio, dating back to the 1950s, uses the relative weights of ventral prostate (VP) and levator ani muscle (LA) of male rats. The VP weight is an indicator of the androgenic effect, while the LA weight is an indicator of the anabolic effect. Two or more batches of rats are castrated and given no treatment and respectively some AAS of interest. The LA/VP ratio for an AAS is calculated as the ratio of LA/VP weight gains produced by the treatment with that compound using castrated but untreated rats as baseline: (LAc,t–LAc)/(VPc,t–VPc). The LA/VP weight gain ratio from rat experiments is not unitary for testosterone (typically 0.3–0.4), but it is normalized for presentation purposes, and used as basis of comparison for other AAS, which have their androgenic:anabolic ratios scaled accordingly (as shown in the table above).[142][143] In the early 2000s, this procedure was standardized and generalized throughout OECD in what is now known as the Hershberger assay.

Body composition and strength improvements

[edit]Anabolic steroids notably influence muscle fiber characteristics, affecting both the size and type of muscle fibers. This alteration significantly contributes to enhanced muscle strength and endurance.[144] Anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) cause these changes by directly impacting the muscle tissue's cellular components. Studies have shown that these changes are not merely superficial but represent a profound transformation in the muscle's structural and functional properties. This transformation is a key factor in the steroids' ability to enhance physical performance and endurance.[145]

Body weight in men may increase by 2 to 5 kg as a result of short-term (<10 weeks) AAS use, which may be attributed mainly to an increase of lean mass. Animal studies also found that fat mass was reduced, but most studies in humans failed to elucidate significant fat mass decrements. The effects on lean body mass have been shown to be dose-dependent. Both muscle hypertrophy and the formation of new muscle fibers have been observed. The hydration of lean mass remains unaffected by AAS use, although small increments of blood volume cannot be ruled out.[7]

The upper region of the body (thorax, neck, shoulders, and upper arm) seems to be more susceptible for AAS than other body regions because of predominance of ARs in the upper body.[citation needed] The largest difference in muscle fiber size between AAS users and non-users was observed in type I muscle fibers of the vastus lateralis and the trapezius muscle as a result of long-term AAS self-administration. After drug withdrawal, the effects fade away slowly, but may persist for more than 6–12 weeks after cessation of AAS use.[7]

Strength improvements in the range of 5 to 20% of baseline strength, depending largely on the drugs and dose used as well as the administration period. Overall, the exercise where the most significant improvements were observed is the bench press.[7] For almost two decades, it was assumed that AAS exerted significant effects only in experienced strength athletes.[146][147] A randomized controlled trial demonstrated, however, that even in novice athletes a 10-week strength training program accompanied by testosterone enanthate at 600 mg/week may improve strength more than training alone does.[7][148] This dose is sufficient to significantly improve lean muscle mass relative to placebo even in subjects that did not exercise at all.[148] The anabolic effects of testosterone enanthate were highly dose dependent.[7][149]

Dissociation of effects

[edit]Endogenous/natural AAS like testosterone and DHT and synthetic AAS mediate their effects by binding to and activating the AR.[75] On the basis of animal bioassays, the effects of these agents have been divided into two partially dissociable types: anabolic (myotrophic) and androgenic.[75] Dissociation between the ratios of these two types of effects relative to the ratio observed with testosterone is observed in rat bioassays with various AAS.[75] Theories for the dissociation include differences between AAS in terms of their intracellular metabolism, functional selectivity (differential recruitment of coactivators), and non-genomic mechanisms (i.e., signaling through non-AR membrane androgen receptors, or mARs).[75] Support for the latter two theories is limited and more hypothetical, but there is a good deal of support for the intracellular metabolism theory.[75]

The measurement of the dissociation between anabolic and androgenic effects among AAS is based largely on a simple but outdated and unsophisticated model using rat tissue bioassays.[75] It has been referred to as the "myotrophic–androgenic index".[75] In this model, myotrophic or anabolic activity is measured by change in the weight of the rat bulbocavernosus/levator ani muscle, and androgenic activity is measured by change in the weight of the rat ventral prostate (or, alternatively, the rat seminal vesicles), in response to exposure to the AAS.[75] The measurements are then compared to form a ratio.[75]

Intracellular metabolism

[edit]Testosterone is metabolized in various tissues by 5α-reductase into DHT, which is 3- to 10-fold more potent as an AR agonist, and by aromatase into estradiol, which is an estrogen and lacks significant AR affinity.[75] In addition, DHT is metabolized by 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD) and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD) into 3α-androstanediol and 3β-androstanediol, respectively, which are metabolites with little or no AR affinity.[75] 5α-reductase is widely distributed throughout the body, and is concentrated to various extents in skin (particularly the scalp, face, and genital areas), prostate, seminal vesicles, liver, and the brain.[75] In contrast, expression of 5α-reductase in skeletal muscle is undetectable.[75] Aromatase is highly expressed in adipose tissue and the brain, and is also expressed significantly in skeletal muscle.[75] 3α-HSD is highly expressed in skeletal muscle as well.[70]

Natural AAS like testosterone and DHT and synthetic AAS are analogues and are very similar structurally.[75] For this reason, they have the capacity to bind to and be metabolized by the same steroid-metabolizing enzymes.[75] According to the intracellular metabolism explanation, the androgenic-to-anabolic ratio of a given AR agonist is related to its capacity to be transformed by the aforementioned enzymes in conjunction with the AR activity of any resulting products.[75] For instance, whereas the AR activity of testosterone is greatly potentiated by local conversion via 5α-reductase into DHT in tissues where 5α-reductase is expressed, an AAS that is not metabolized by 5α-reductase or is already 5α-reduced, such as DHT itself or a derivative (like mesterolone or drostanolone), would not undergo such potentiation in said tissues.[75] Moreover, nandrolone is metabolized by 5α-reductase, but unlike the case of testosterone and DHT, the 5α-reduced metabolite of nandrolone has much lower affinity for the AR than does nandrolone itself, and this results in reduced AR activation in 5α-reductase-expressing tissues.[75] As so-called "androgenic" tissues such as skin/hair follicles and male reproductive tissues are very high in 5α-reductase expression, while skeletal muscle is virtually devoid of 5α-reductase, this may primarily explain the high myotrophic–androgenic ratio and dissociation seen with nandrolone, as well as with various other AAS.[75]

Aside from 5α-reductase, aromatase may inactivate testosterone signaling in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, so AAS that lack aromatase affinity, in addition to being free of the potential side effect of gynecomastia, might be expected to have a higher myotrophic–androgenic ratio in comparison.[75] In addition, DHT is inactivated by high activity of 3α-HSD in skeletal muscle (and cardiac tissue), and AAS that lack affinity for 3α-HSD could similarly be expected to have a higher myotrophic–androgenic ratio (although perhaps also increased long-term cardiovascular risks).[75] In accordance, DHT, mestanolone (17α-methyl-DHT), and mesterolone (1α-methyl-DHT) are all described as very poorly anabolic due to inactivation by 3α-HSD in skeletal muscle, whereas other DHT derivatives with other structural features like metenolone, oxandrolone, oxymetholone, drostanolone, and stanozolol are all poor substrates for 3α-HSD and are described as potent anabolics.[70]

The intracellular metabolism theory explains how and why remarkable dissociation between anabolic and androgenic effects might occur despite the fact that these effects are mediated through the same signaling receptor, and why this dissociation is invariably incomplete.[75] In support of the model is the rare condition congenital 5α-reductase type 2 deficiency, in which the 5α-reductase type 2 enzyme is defective, production of DHT is impaired, and DHT levels are low while testosterone levels are normal.[150][151] Males with this condition are born with ambiguous genitalia and a severely underdeveloped or even absent prostate gland.[150][151] In addition, at the time of puberty, such males develop normal musculature, voice deepening, and libido, but have reduced facial hair, a female pattern of body hair (i.e., largely restricted to the pubic triangle and underarms), no incidence of male pattern hair loss, and no prostate enlargement or incidence of prostate cancer.[151][152][153][154][155] They also notably do not develop gynecomastia as a consequence of their condition.[153]

Functional selectivity

[edit]An animal study found that two different kinds of androgen response elements could differentially respond to testosterone and DHT upon activation of the AR.[10][156] Whether this is involved in the differences in the ratios of anabolic-to-myotrophic effect of different AAS is unknown however.[10][156][75]

Non-genomic mechanisms

[edit]Testosterone signals not only through the nuclear AR, but also through mARs, including ZIP9 and GPRC6A.[157][158] It has been proposed that differential signaling through mARs may be involved in the dissociation of the anabolic and androgenic effects of AAS.[75] Indeed, DHT has less than 1% of the affinity of testosterone for ZIP9, and the synthetic AAS metribolone and mibolerone are ineffective competitors for the receptor similarly.[158] This indicates that AAS do show differential interactions with the AR and mARs.[158] However, women with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS), who have a 46,XY ("male") genotype and testes but a defect in the AR such that it is non-functional, are a challenge to this notion.[159] They are completely insensitive to the AR-mediated effects of androgens like testosterone, and show a perfectly female phenotype despite having testosterone levels in the high end of the normal male range.[159] These women have little or no sebum production, incidence of acne, or body hair growth (including in the pubic and axillary areas).[159] Moreover, CAIS women have lean body mass that is normal for females but is of course greatly reduced relative to males.[160] These observations suggest that the AR is mainly or exclusively responsible for masculinization and myotrophy caused by androgens.[159][160][161] The mARs have however been found to be involved in some of the health-related effects of testosterone, like modulation of prostate cancer risk and progression.[158][162]

Antigonadotropic effects

[edit]Changes in endogenous testosterone levels may also contribute to differences in myotrophic–androgenic ratio between testosterone and synthetic AAS.[70] AR agonists are antigonadotropic – that is, they dose-dependently suppress gonadal testosterone production and hence reduce systemic testosterone concentrations.[70] By suppressing endogenous testosterone levels and effectively replacing AR signaling in the body with that of the exogenous AAS, the myotrophic–androgenic ratio of a given AAS may be further, dose-dependently increased, and this hence may be an additional factor contributing to the differences in myotrophic–androgenic ratio among different AAS.[70] In addition, some AAS, such as 19-nortestosterone derivatives like nandrolone, are also potent progestogens, and activation of the progesterone receptor (PR) is antigonadotropic similarly to activation of the AR.[70] The combination of sufficient AR and PR activation can suppress circulating testosterone levels into the castrate range in men (i.e., complete suppression of gonadal testosterone production and circulating testosterone levels decreased by about 95%).[50][163] As such, combined progestogenic activity may serve to further increase the myotrophic–androgenic ratio for a given AAS.[70]

GABAA receptor modulation

[edit]Some AAS, such as testosterone, DHT, stanozolol, and methyltestosterone, have been found to modulate the GABAA receptor similarly to endogenous neurosteroids like allopregnanolone, 3α-androstanediol, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, and pregnenolone sulfate.[75] It has been suggested that this may contribute as an alternative or additional mechanism to the neurological and behavioral effects of AAS.[75][164][165][166][167][168][169]

Comparison of AAS

[edit]AAS differ in a variety of ways including in their capacities to be metabolized by steroidogenic enzymes such as 5α-reductase, 3-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases, and aromatase, in whether their potency as AR agonists is potentiated or diminished by 5α-reduction, in their ratios of anabolic/myotrophic to androgenic effect, in their estrogenic, progestogenic, and neurosteroid activities, in their oral activity, and in their capacity to produce hepatotoxicity.[70][75][170]

5α-Reductase and androgenicity

[edit]Testosterone can be robustly converted by 5α-reductase into DHT in so-called androgenic tissues such as skin, scalp, prostate, and seminal vesicles, but not in muscle or bone, where 5α-reductase either is not expressed or is only minimally expressed.[75] As DHT is 3- to 10-fold more potent as an agonist of the AR than is testosterone, the AR agonist activity of testosterone is thus markedly and selectively potentiated in such tissues.[75] In contrast to testosterone, DHT and other 4,5α-dihydrogenated AAS are already 5α-reduced, and for this reason, cannot be potentiated in androgenic tissues.[75] 19-Nortestosterone derivatives like nandrolone can be metabolized by 5α-reductase similarly to testosterone, but 5α-reduced metabolites of 19-nortestosterone derivatives (e.g., 5α-dihydronandrolone) tend to have reduced activity as AR agonists, resulting in reduced androgenic activity in tissues that express 5α-reductase.[75] In addition, some 19-nortestosterone derivatives, including trestolone (7α-methyl-19-nortestosterone (MENT)), 11β-methyl-19-nortestosterone (11β-MNT), and dimethandrolone (7α,11β-dimethyl-19-nortestosterone), cannot be 5α-reduced.[171] Conversely, certain 17α-alkylated AAS like methyltestosterone are 5α-reduced and potentiated in androgenic tissues similarly to testosterone.[75][70] 17α-Alkylated DHT derivatives cannot be potentiated via 5α-reductase however, as they are already 4,5α-reduced.[75][70]

The capacity to be metabolized by 5α-reductase and the AR activity of the resultant metabolites appears to be one of the major, if not the most important determinant of the androgenic–myotrophic ratio for a given AAS.[75] AAS that are not potentiated by 5α-reductase or that are weakened by 5α-reductase in androgenic tissues have a reduced risk of androgenic side effects such as acne, androgenic alopecia (male-pattern baldness), hirsutism (excessive male-pattern hair growth), benign prostatic hyperplasia (prostate enlargement), and prostate cancer, while incidence and magnitude of other effects such as muscle hypertrophy, bone changes,[172] voice deepening, and changes in sex drive show no difference.[75][173]

Aromatase and estrogenicity

[edit]Testosterone can be metabolized by aromatase into estradiol, and many other AAS can be metabolized into their corresponding estrogenic metabolites as well.[75] As an example, the 17α-alkylated AAS methyltestosterone and metandienone are converted by aromatase into methylestradiol.[174] 4,5α-Dihydrogenated derivatives of testosterone such as DHT cannot be aromatized, whereas 19-nortestosterone derivatives like nandrolone can be but to a greatly reduced extent.[75][175] Some 19-nortestosterone derivatives, such as dimethandrolone and 11β-MNT, cannot be aromatized due to steric hindrance provided by their 11β-methyl group, whereas the closely related AAS trestolone (7α-methyl-19-nortestosterone), in relation to its lack of an 11β-methyl group, can be aromatized.[175] AAS that are 17α-alkylated (and not also 4,5α-reduced or 19-demethylated) are also aromatized but to a lesser extent than is testosterone.[75][176] However, it is notable that estrogens that are 17α-substituted (e.g., ethinylestradiol and methylestradiol) are of markedly increased estrogenic potency due to improved metabolic stability,[174] and for this reason, 17α-alkylated AAS can actually have high estrogenicity and comparatively greater estrogenic effects than testosterone.[174][70]

The major effect of estrogenicity is gynecomastia (woman-like breasts).[75] AAS that have a high potential for aromatization like testosterone and particularly methyltestosterone show a high risk of gynecomastia at sufficiently high dosages, while AAS that have a reduced potential for aromatization like nandrolone show a much lower risk (though still potentially significant at high dosages).[75] In contrast, AAS that are 4,5α-reduced, and some other AAS (e.g., 11β-methylated 19-nortestosterone derivatives), have no risk of gynecomastia.[75] In addition to gynecomastia, AAS with high estrogenicity have increased antigonadotropic activity, which results in increased potency in suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and gonadal testosterone production.[177]

Progestogenic activity

[edit]Many 19-nortestosterone derivatives, including nandrolone, trenbolone, ethylestrenol (ethylnandrol), metribolone (R-1881), trestolone, 11β-MNT, dimethandrolone, and others, are potent agonists of the progesterone receptor (PR) and hence are progestogens in addition to AAS.[75][178] Similarly to the case of estrogenic activity, the progestogenic activity of these drugs serves to augment their antigonadotropic activity.[178] This results in increased potency and effectiveness of these AAS as antispermatogenic agents and male contraceptives (or, put in another way, increased potency and effectiveness in producing azoospermia and reversible male infertility).[178]

Oral activity and hepatotoxicity

[edit]Non-17α-alkylated testosterone derivatives such as testosterone itself, DHT, and nandrolone all have poor oral bioavailability due to extensive first-pass hepatic metabolism and hence are not orally active.[75] A notable exception to this are AAS that are androgen precursors or prohormones, including dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), androstenediol, androstenedione, boldione (androstadienedione), bolandiol (norandrostenediol), bolandione (norandrostenedione), dienedione, mentabolan (MENT dione, trestione), and methoxydienone (methoxygonadiene) (although these are relatively weak AAS).[179][180] AAS that are not orally active are used almost exclusively in the form of esters administered by intramuscular injection, which act as depots and function as long-acting prodrugs.[75] Examples include testosterone, as testosterone cypionate, testosterone enanthate, and testosterone propionate, and nandrolone, as nandrolone phenylpropionate and nandrolone decanoate, among many others (see here for a full list of testosterone and nandrolone esters).[75] An exception is the very long-chain ester testosterone undecanoate, which is orally active, albeit with only very low oral bioavailability (approximately 3%).[181] In contrast to most other AAS, 17α-alkylated testosterone derivatives show resistance to metabolism due to steric hindrance and are orally active, though they may be esterified and administered via intramuscular injection as well.[75]

In addition to oral activity, 17α-alkylation also confers a high potential for hepatotoxicity, and all 17α-alkylated AAS have been associated, albeit uncommonly and only after prolonged use (different estimates between 1 and 17%),[182][183] with hepatotoxicity.[75][184][185] In contrast, testosterone esters have only extremely rarely or never been associated with hepatotoxicity,[183] and other non-17α-alkylated AAS only rarely,[citation needed] although long-term use may reportedly still increase the risk of hepatic changes (but at a much lower rate than 17α-alkylated AAS and reportedly not at replacement dosages).[182][186][74][additional citation(s) needed] In accordance, D-ring glucuronides of testosterone and DHT have been found to be cholestatic.[187]

Aside from prohormones and testosterone undecanoate, almost all orally active AAS are 17α-alkylated.[188] A few AAS that are not 17α-alkylated are orally active.[75] Some examples include the testosterone 17-ethers cloxotestosterone, quinbolone, and silandrone,[citation needed] which are prodrugs (to testosterone, boldenone (Δ1-testosterone), and testosterone, respectively), the DHT 17-ethers mepitiostane, mesabolone, and prostanozol (which are also prodrugs), the 1-methylated DHT derivatives mesterolone and metenolone (although these are relatively weak AAS),[75][74] and the 19-nortestosterone derivatives dimethandrolone and 11β-MNT, which have improved resistance to first-pass hepatic metabolism due to their 11β-methyl groups (in contrast to them, the related AAS trestolone (7α-methyl-19-nortestosterone) is not orally active).[75][178] As these AAS are not 17α-alkylated, they show minimal potential for hepatotoxicity.[75]

Neurosteroid activity

[edit]DHT, via its metabolite 3α-androstanediol (produced by 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD)), is a neurosteroid that acts via positive allosteric modulation of the GABAA receptor.[75] Testosterone, via conversion into DHT, also produces 3α-androstanediol as a metabolite and hence has similar activity.[75] Some AAS that are or can be 5α-reduced, including testosterone, DHT, stanozolol, and methyltestosterone, among many others, can or may modulate the GABAA receptor, and this may contribute as an alternative or additional mechanism to their central nervous system effects in terms of mood, anxiety, aggression, and sex drive.[75][164][165][166][167][168][169]

Chemistry

[edit]AAS are androstane or estrane steroids. They include testosterone (androst-4-en-17β-ol-3-one) and derivatives with various structural modifications such as:[75][189][70]

- 17α-Alkylation: methyltestosterone, metandienone, fluoxymesterone, oxandrolone, oxymetholone, stanozolol, norethandrolone, ethylestrenol

- 19-Demethylation: nandrolone, trenbolone, norethandrolone, ethylestrenol, trestolone, dimethandrolone

- 5α-Reduction: androstanolone, drostanolone, mestanolone, mesterolone, metenolone, oxandrolone, oxymetholone, stanozolol

- 3β- and/or 17β-esterification: testosterone enanthate, nandrolone decanoate, drostanolone propionate, boldenone undecylenate, trenbolone acetate

As well as others such as 1-dehydrogenation (e.g., metandienone, boldenone), 1-substitution (e.g., mesterolone, metenolone), 2-substitution (e.g., drostanolone, oxymetholone, stanozolol), 4-substitution (e.g., clostebol, oxabolone), and various other modifications.[75][189][70]

Structural conversions of anabolic steroids

[edit]Testosterone to derivatives

[edit]Conversion to DHT,[190] nandrolone,[75] metandienone (Dianabol),[191] chlorodehydromethyltestosterone (Turinabol),[192] fluoxymesterone (Halotestin),[193] and boldenone (Equipoise):[194]

DHT to derivatives

[edit]DHT to stanozolol (Winstrol),[195] metenolone acetate (Primobolan),[196] oxymetholone (Anadrol),[197] and methasterone (Superdrol):[198]

Nandrolone to derivatives

[edit]Nandrolone to trestolone,[199] trenbolone,[200] norboletone,[201] and ethylestrenol:[202]

Detection in body fluids

[edit]The most commonly employed human physiological specimen for detecting AAS usage is urine, although both blood and hair have been investigated for this purpose. The AAS, whether of endogenous or exogenous origin, are subject to extensive hepatic biotransformation by a variety of enzymatic pathways. The primary urinary metabolites may be detectable for up to 30 days after the last use, depending on the specific agent, dose and route of administration. A number of the drugs have common metabolic pathways, and their excretion profiles may overlap those of the endogenous steroids, making interpretation of testing results a very significant challenge to the analytical chemist. Methods for detection of the substances or their excretion products in urine specimens usually involve gas chromatography–mass spectrometry or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry.[203][204][205][206]

History

[edit]| Generic name | Class[a] | Brand name | Route[b] | Intr. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Androstanolone[c][d] | DHT | Andractim | PO,[e] IM, TD | 1953 | ||

| Boldenone undecylenate[f] | Ester | Equipoise[g] | IM | 1960s | ||

| Danazol | Alkyl | Danocrine | PO | 1971 | ||

| Drostanolone propionate[e] | DHT Ester | Masteron | IM | 1961 | ||

| Ethylestrenol[d] | 19-NT Alkyl | Maxibolin[g] | PO | 1961 | ||

| Fluoxymesterone[d] | Alkyl | Halotestin[g] | PO | 1957 | ||

| Mestanolone[e] | DHT Alkyl | Androstalone[g] | PO | 1950s | ||

| Mesterolone | DHT | Proviron | PO | 1967 | ||

| Metandienone[d] | Alkyl | Dianabol | PO, IM | 1958 | ||

| Metenolone acetate[d] | DHT Ester | Primobolan | PO | 1961 | ||

| Metenolone enanthate[d] | DHT Ester | Primobolan Depot | IM | 1962 | ||

| Methyltestosterone[d] | Alkyl | Metandren | PO | 1936 | ||

| Nandrolone decanoate | 19-NT Ester | Deca-Durabolin | IM | 1962 | ||

| Nandrolone phenylpropionate[d] | 19-NT Ester | Durabolin | IM | 1959 | ||

| Norethandrolone[d] | 19-NT Alkyl | Nilevar[g] | PO | 1956 | ||

| Oxandrolone[d] | DHT Alkyl | Oxandrin[g] | PO | 1964 | ||

| Oxymetholone[d] | DHT Alkyl | Anadrol[g] | PO | 1961 | ||

| Prasterone[h] | Prohormone | Intrarosa[g] | PO, IM, vaginal | 1970s | ||

| Stanozolol[e] | DHT Alkyl | Winstrol[g] | PO, IM | 1962 | ||

| Testosterone cypionate | Ester | Depo-Testosterone | IM | 1951 | ||

| Testosterone enanthate | Ester | Delatestryl | IM | 1954 | ||

| Testosterone propionate | Ester | Testoviron | IM | 1937 | ||

| Testosterone undecanoate | Ester | Andriol[g] | PO, IM | 1970s | ||

| Trenbolone acetate[f] | 19-NT Ester | Finajet[g] | IM | 1970s | ||

| ||||||

Discovery of androgens

[edit]The use of gonadal steroids pre-dates their identification and isolation. Use of cow urine for treatment of ascites, heart failure, renal failure and vitiligo has been elaborately described in Sushruta Samhita, suggesting that ancient Indians had some understanding of steroidal properties of cow urine around 6th century BCE.[207] Extraction of hormones from urines began in China around 100 BCE.[citation needed] Medical use of testicle extract began in the late 19th century while its effects on strength were still being studied.[141] The isolation of gonadal steroids can be traced back to 1931, when Adolf Butenandt, a chemist in Marburg, purified 15 milligrams of the male hormone androstenone from tens of thousands of litres of urine. This steroid was subsequently synthesized in 1934 by Leopold Ružička, a chemist in Zurich.[208]

In the 1930s, it was already known that the testes contain a more powerful androgen than androstenone, and three groups of scientists, funded by competing pharmaceutical companies in the Netherlands, Germany, and Switzerland, raced to isolate it.[208][209] This hormone was first identified by Karoly Gyula David, E. Dingemanse, J. Freud and Ernst Laqueur in a May 1935 paper "On Crystalline Male Hormone from Testicles (Testosterone)."[210] They named the hormone testosterone, from the stems of testicle and sterol, and the suffix of ketone. The chemical synthesis of testosterone was achieved in August that year, when Butenandt and G. Hanisch published a paper describing "A Method for Preparing Testosterone from Cholesterol."[211] Only a week later, the third group, Ruzicka and A. Wettstein, announced a patent application in a paper "On the Artificial Preparation of the Testicular Hormone Testosterone (Androsten-3-one-17-ol)."[212] Ruzicka and Butenandt were offered the 1939 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work, but the Nazi government forced Butenandt to decline the honor, although he accepted the prize after the end of World War II.[208][209]

Clinical trials on humans, involving either PO doses of methyltestosterone or injections of testosterone propionate, began as early as 1937.[208] There are often reported rumors that German soldiers were administered AAS during the Second World War, the aim being to increase their aggression and stamina, but these are, as yet, unproven.[122]: 6 Adolf Hitler himself, according to his physician, was injected with testosterone derivatives to treat various ailments.[213] AAS were used in experiments conducted by the Nazis on concentration camp inmates,[213] and later by the allies attempting to treat the malnourished victims that survived Nazi camps.[122]: 6 President John F. Kennedy was administered steroids both before and during his presidency.[214]

Development of synthetic AAS

[edit]The development of muscle-building properties of testosterone was pursued in the 1940s, in the Soviet Union and in Eastern Bloc countries such as East Germany, where steroid programs were used to enhance the performance of Olympic and other amateur weight lifters. In response to the success of Russian weightlifters, the U.S. Olympic Team physician John Ziegler worked with synthetic chemists to develop an AAS with reduced androgenic effects.[215] Ziegler's work resulted in the production of methandrostenolone, which Ciba Pharmaceuticals marketed as Dianabol. The new steroid was approved for use in the U.S. by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1958. It was most commonly administered to burn victims and the elderly. The drug's off-label users were mostly bodybuilders and weight lifters. Although Ziegler prescribed only small doses to athletes, he soon discovered that those having used Dianabol developed enlarged prostates and atrophied testes.[216] AAS were placed on the list of banned substances of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1976, and a decade later, the committee introduced "out-of-competition" doping tests because many athletes used AAS in their training period rather than during competition.[7]

Three major ideas governed modifications of testosterone into a multitude of AAS: Alkylation at C17α position with methyl or ethyl group created POly active compounds because it slows the degradation of the drug by the liver; esterification of testosterone and nortestosterone at the C17β position allows the substance to be administered parenterally and increases the duration of effectiveness because agents soluble in oily liquids may be present in the body for several months; and alterations of the ring structure were applied for both PO and parenteral agents to seeking to obtain different anabolic-to-androgenic effect ratios.[7]

Society and culture

[edit]Etymology

[edit]Androgens were discovered in the 1930s and were characterized as having effects described as androgenic (i.e., virilizing) and anabolic (e.g., myotrophic, renotrophic).[70][75] The term anabolic steroid can be dated as far back as at least the mid-1940s, when it was used to describe the at-the-time hypothetical concept of a testosterone-derived steroid with anabolic effects but with minimal or no androgenic effects.[217] This concept was formulated based on the observation that steroids had ratios of renotrophic to androgenic potency that differed significantly, which suggested that anabolic and androgenic effects might be dissociable.[217]

In 1953, a testosterone-derived steroid known as norethandrolone (17α-ethyl-19-nortestosterone) was synthesized at G. D. Searle & Company and was studied as a progestin, but was not marketed.[218] Subsequently, in 1955, it was re-examined for testosterone-like activity in animals and was found to have similar anabolic activity to testosterone, but only one-sixteenth of its androgenic potency.[218][219] It was the first steroid with a marked and favorable separation of anabolic and androgenic effect to be discovered, and has accordingly been described as the "first anabolic steroid".[220][221] Norethandrolone was introduced for medical use in 1956, and was quickly followed by numerous similar steroids, for instance nandrolone phenylpropionate in 1959 and stanozolol in 1962.[220][221][222][223] With these developments, anabolic steroid became the preferred term to refer to such steroids (over "androgen"), and entered widespread use.

Although anabolic steroid was originally intended to specifically describe testosterone-derived steroids with a marked dissociation of anabolic and androgenic effect, it is applied today indiscriminately to all steroids with AR agonism-based anabolic effects regardless of their androgenic potency, including even non-synthetic and non-preferentially-anabolic steroids like testosterone.[70][75][218] While many anabolic steroids have diminished androgenic potency in comparison to anabolic potency, there is no anabolic steroid that is exclusively anabolic, and hence all anabolic steroids retain at least some degree of androgenicity.[70][75][218] (Likewise, all "androgens" are inherently anabolic.)[70][75][218] Indeed, it is probably not possible to fully dissociate anabolic effects from androgenic effects, as both types of effects are mediated by the same signaling receptor, the AR.[75] As such, the distinction between the terms anabolic steroid and androgen is questionable, and this is the basis for the revised and more recent term anabolic–androgenic steroid (AAS).[70][75][218]

David Handelsman has criticized terminology and understanding surrounding AAS in many publications.[224][225][226][227][228][229][230][231] According to Handelsman, the pharmaceutical industry attempted to dissociate the so-called "androgenic" and "anabolic" effects of AAS in the mid-20th-century in order to create non-masculinizing anabolic agents that would be more suitable for use in women and children.[224] However, this effort failed comprehensively and was abandoned by the 1970s.[224][225] This failure was due to the subsequent discovery of a singular androgen receptor (AR) mediating the effects of AAS in both muscle and reproductive tissue, along with misinterpretation of flawed animal androgen bioassays employed to distinguish between androgenic or virilizing effects and anabolic or myotrophic effects (i.e., the Hershberger assay involving the unrepresentative levator ani muscle).[224][225] In reality, all AAS have essentially similar AR-mediated effects,[231] even if some may differ in potency to a degree in certain tissues (e.g., skin, hair follicles, prostate gland) based on susceptibility to 5α-reduction and associated metabolic amplification or inactivation or lack thereof.[231][8] Per Handelsman, the terms "anabolic steroid" and "anabolic–androgenic steroid" are obsolete, meaningless, and falsely distinguish these agents from androgens when there is no physiological basis for such distinction.[224][225] In fact, it has been noted that the use and distinction of the concepts "anabolic" and "androgenic" as well as the term "anabolic–androgenic steroid" are oxymoronic, as anabolic refers to muscle-building while androgenic refers to induction and maintenance of male secondary sexual characteristics (which in principle would include anabolic or muscle-building effects).[224][225][232] Handelsman has argued that these terms should be discarded and instead, AAS should all simply be referred to as "androgens", with him using this term exclusively to refer to these agents in his publications.[224][225] Although the term "anabolic–androgenic steroid" is technically valid in describing two types of actions of these agents, Handelsman considers the term unnecessary and redundant and likens it to hypothetical never-used terms like "luteal–gestational progestins" or "mammary–uterine estrogens".[224] Handelsman also notes that "anabolic steroid" is easily and unnecessarily confusable with corticosteroids.[224] Aside from AAS, Handelsman has criticized the term "selective androgen receptor modulator (SARM)" and claims about these agents as well.[226][224][225][230]

Legal status

[edit]

The legal status of AAS varies from country to country: some have stricter controls on their use or prescription than others though in many countries they are not illegal. In the U.S., AAS are currently listed as Schedule III controlled substances under the Controlled Substances Act, which makes simple possession of such substances without a prescription a federal crime punishable by up to one year in prison for the first offense. Unlawful distribution or possession with intent to distribute AAS as a first offense is punished by up to ten years in prison.[233] In Canada, AAS and their derivatives are part of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act and are Schedule IV substances, meaning that it is illegal to obtain or sell them without a prescription; however, possession is not punishable, a consequence reserved for schedule I, II, or III substances. Those guilty of buying or selling AAS in Canada can be imprisoned for up to 18 months.[234] Import and export also carry similar penalties.

In Canada, researchers have concluded that steroid use among student athletes is extremely widespread. A study conducted in 1993 by the Canadian Centre for Drug-Free Sport found that nearly 83,000 Canadians between the ages of 11 and 18 use steroids.[235] AAS are also illegal without prescription in Australia,[236] Argentina,[citation needed] Brazil,[citation needed] and Portugal,[citation needed] and are listed as Class C Controlled Drugs in the United Kingdom. AAS are readily available without a prescription in some countries such as Mexico and Thailand.

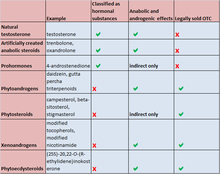

| Substance | Example | Classified as hormonal substances | Anabolic and androgenic effects | Legally sold OTC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural testosterone | testosterone | hormonal | yes | not legal |

| Artificially created anabolic steroids | trenbolone, oxandrolone | hormonal | yes | not legal |

| Prohormones | 4-androstenedione | hormonal | indirect only | not legal |

| Phytoandrogens | daidzein, gutta-percha triterpenoids | no | yes | legal |

| Phytosteroids | campesterol, beta-sitosterole, stigmasterol | no | indirect only | legal |

| Xenoandrogens | modified tocopherols, modified nicotinamide | no | yes | legal |

| Phytoecdysteroids | (25S)-20, 22-O-(R-ethylidene)inokosterone | no | yes | legal |

| Selective androgen receptor modulators | ostarine | anabolic[237] | not for human consumption[238][239] |

United States

[edit]

The history of the U.S. legislation on AAS goes back to the late 1980s, when the U.S. Congress considered placing AAS under the Controlled Substances Act following the controversy over Ben Johnson's victory at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul. AAS were added to Schedule III of the Controlled Substances Act in the Anabolic Steroids Control Act of 1990.[240]

The same act also introduced more stringent controls with higher criminal penalties for offenses involving the illegal distribution of AAS and human growth hormone. By the early 1990s, after AAS were scheduled in the U.S., several pharmaceutical companies stopped manufacturing or marketing the products in the U.S., including Ciba, Searle, Syntex, and others. In the Controlled Substances Act, AAS are defined to be any drug or hormonal substance chemically and pharmacologically related to testosterone (other than estrogens, progestins, and corticosteroids) that promote muscle growth. The act was amended by the Anabolic Steroid Control Act of 2004, which added prohormones to the list of controlled substances, with effect from 20 January 2005.[241]

Even though they can still be prescribed by a medical doctor in the U.S., the use of anabolic steroids for injury recovery purposes has been a taboo subject, even amongst the majority of sports medicine doctors and endocrinologists.

United Kingdom

[edit]In the United Kingdom, AAS are classified as class C drugs, which puts them in the same class as benzodiazepines. AAS are in Schedule 4, which is divided in 2 parts; Part 1 contains most of the benzodiazepines and Part 2 contains the AAS.

Part 1 drugs are subject to full import and export controls with possession being an offence without an appropriate prescription. There is no restriction on the possession when it is part of a medicinal product. Part 2 drugs require a Home Office licence for importation and export unless the substance is in the form of a medicinal product and is for self-administration by a person.[242]

Status in sports

[edit]

AAS are banned by all major sports bodies including Association of Tennis Professionals, Major League Baseball, Fédération Internationale de Football Association,[243] the Olympics,[244] the National Basketball Association,[245] the National Hockey League,[246] World Wrestling Entertainment and the National Football League.[247] The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) maintains the list of performance-enhancing substances used by many major sports bodies and includes all anabolic agents, which includes all AAS and precursors as well as all hormones and related substances.[248][249]

Usage

[edit]Law enforcement

[edit]United States federal law enforcement officials have expressed concern about AAS use by police officers. "It's a big problem, and from the number of cases, it's something we shouldn't ignore. It's not that we set out to target cops, but when we're in the middle of an active investigation into steroids, there have been quite a few cases that have led back to police officers," says Lawrence Payne, a spokesman for the United States Drug Enforcement Administration.[250] The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin stated that "Anabolic steroid abuse by police officers is a serious problem that merits greater awareness by departments across the country".[251] It is also believed that police officers across the United Kingdom "are using criminals to buy steroids" which he claims to be a top risk factor for police corruption.

Professional wrestling

[edit]Following the Chris Benoit double-murder and suicide in 2007, the Oversight and Government Reform Committee investigated steroid usage in the wrestling industry.[252] The Committee investigated WWE and Total Nonstop Action Wrestling (now known as Impact Wrestling), asking for documentation of their companies' drug policies. WWE CEO and chairman, Linda and Vince McMahon respectively, both testified. The documents stated that 75 wrestlers—roughly 40 percent—had tested positive for drug use since 2006, most commonly for steroids.[253][254]

Economics

[edit]

AAS are frequently produced in pharmaceutical laboratories, but, in nations where stricter laws are present, they are also produced in small home-made underground laboratories, usually from raw substances imported from abroad.[255] In these countries, the majority of steroids are obtained illegally through black market trade.[256][257] These steroids are usually manufactured in other countries, and therefore must be smuggled across international borders. As with most significant smuggling operations, organized crime is involved.[258]

In the late 2000s, the worldwide trade in illicit AAS increased significantly, and authorities announced record captures on three continents. In 2006, Finnish authorities announced a record seizure of 11.8 million AAS tablets. A year later, the DEA seized 11.4 million units of AAS in the largest U.S. seizure ever. In the first three months of 2008, Australian customs reported a record 300 seizures of AAS shipments.[114]