Ashoka

| Ashoka | |

|---|---|

| Universal Monarch Beloved of the Gods Humane King of Magadha King of Kings | |

| |

| Emperor of Magadha | |

| Reign | c. 268 BCE – c. 232 BCE[3] |

| Coronation | c. 269 BCE[3] |

| Predecessor | Bindusara |

| Successor | Dasharatha |

| Crown Prince of Magadha | |

| Predecessor | Susima |

| Successor | Kunala |

| Viceroy of Avantirastra | |

| Born | c. 304 BCE Pataliputra, Magadha, Mauryan Empire |

| Died | 232 BCE (aged c. 71 – 72) Pataliputra, Magadha, Mauryan Empire |

| Spouses |

|

| Issue | |

| Dynasty | Maurya |

| Father | Bindusara |

| Mother | Subhadrangi or Dharma[note 1] |

| Religion | Supported Buddhism[4][5] but also other religions, propagated dharma ("righteousness") |

| Maurya Empire (322–180 BCE) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Ashoka (/əˈʃoʊkə/[6] ə-SHOH-kə; Sanskrit pronunciation: [ɐˈɕoːkɐ], IAST: Aśoka; c. 304 – 232 BCE), and popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was Emperor of Magadha[7] from c. 268 BCE until his death in c. 232 BCE, and the third ruler from the Mauryan dynasty. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, stretching from present-day Afghanistan in the west to present-day Bangladesh in the east, with its capital at Pataliputra. A patron of Buddhism, he is credited with playing an important role in the spread of Buddhism across ancient Asia.

Ashoka's edicts state that during his eighth regnal year (c. 260 BCE), he conquered Kalinga after a brutal war. Ashoka subsequently devoted himself to the propagation of "dhamma" or righteous conduct, the major theme of the edicts. Ashoka's edicts suggest that a few years after the Kalinga War, he was gradually drawn towards Buddhism. The Buddhist legends credit Ashoka with establishing a large number of stupas, patronising the Third Buddhist council, supporting Buddhist missionaries, making generous donations to the sangha.

Ashoka's existence as a historical emperor had almost been forgotten, but since the decipherment in the 19th century of sources written in the Brahmi script, Ashoka holds a reputation as one of the greatest Indian emperors. The emblem of the modern Republic of India is an adaptation of the Lion Capital of Ashoka. Ashoka's wheel, the Ashoka Chakra, is adopted at the centre of the National Flag of India.

Sources of information

[edit]Information about Ashoka from his inscriptions; other inscriptions that mention him or are possibly from his reign; and ancient literature, especially Buddhist texts.[8] These sources often contradict each other, although various historians have attempted to correlate their testimony.[9]

Inscriptions

Ashoka's inscriptions are the earliest self-representations of imperial power in the Indian subcontinent.[10] However, these inscriptions are focused mainly on the topic of dhamma, and provide little information regarding other aspects of the Maurya state or society.[9] Even on the topic of dhamma, the content of these inscriptions cannot be taken at face value. In the words of American academic John S. Strong, it is sometimes helpful to think of Ashoka's messages as propaganda by a politician whose aim is to present a favourable image of himself and his administration, rather than record historical facts.[11]

A small number of other inscriptions also provide some information about Ashoka.[9] For example, he finds a mention in the 2nd century Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman.[12] An inscription discovered at Sirkap mentions a lost word beginning with "Priyadari", which is theorised to be Ashoka's title "Priyadarshi" since it has been written in Aramaic of 3rd century BCE, although this is not certain.[13] Some other inscriptions, such as the Sohgaura copper plate inscription and the Mahasthan inscription, have been tentatively dated to Ashoka's period by some scholars, although others contest this.[14]

Buddhist legends

[edit]Much of the information about Ashoka comes from Buddhist legends, which present him as a great, ideal emperor.[15] These legends appear in texts that are not contemporary to Ashoka and were composed by Buddhist authors, who used various stories to illustrate the impact of their faith on Ashoka. This makes it necessary to exercise caution while relying on them for historical information.[16] Among modern scholars, opinions range from downright dismissal of these legends as mythological to acceptance of all historical portions that seem plausible.[17]

The Buddhist legends about Ashoka exist in several languages, including Sanskrit, Pali, Tibetan, Chinese, Burmese, Khmer, Sinhala, Thai, Lao, and Khotanese. All these legends can be traced to two primary traditions:[18]

- the North Indian tradition preserved in the Sanskrit-language texts such as Divyavadana (including its constituent Ashokavadana); and Chinese sources such as A-yü wang chuan and A-yü wang ching.[18]

- the Sri Lankan tradition preserved in Pali-language texts, such as Dipavamsa, Mahavamsa, Vamsatthapakasini (a commentary on Mahavamsa), Buddhaghosha's commentary on the Vinaya, and Samanta-pasadika.[12][18]

There are several significant differences between the two traditions. For example, the Sri Lankan tradition emphasizes Ashoka's role in convening the Third Buddhist council, and his dispatch of several missionaries to distant regions, including his son Mahinda to Sri Lanka.[18] However, the North Indian tradition makes no mention of these events. It describes other events not found in the Sri Lankan tradition, such as a story about another son named Kunala.[19]

Even while narrating the common stories, the two traditions diverge in several ways. For example, both Ashokavadana and Mahavamsa mention that Ashoka's empress Tishyarakshita had the Bodhi Tree destroyed. In Ashokavadana, the empress manages to have the tree healed after she realises her mistake. In the Mahavamsa, she permanently destroys the tree, but only after a branch of the tree has been transplanted in Sri Lanka.[20] In another story, both the texts describe Ashoka's unsuccessful attempts to collect a relic of Gautama Buddha from Ramagrama. In Ashokavadana, he fails to do so because he cannot match the devotion of the Nāgas who hold the relic; however, in the Mahavamsa, he fails to do so because the Buddha had destined the relic to be enshrined by King Dutthagamani of Sri Lanka.[21] Using such stories, the Mahavamsa glorifies Sri Lanka as the new preserve of Buddhism.[22]

Other sources

[edit]Numismatic, sculptural, and archaeological evidence supplements research on Ashoka.[23] Ashoka's name appears in the lists of Mauryan emperors in the various Puranas. However, these texts do not provide further details about him, as their Brahmanical authors were not patronised by the Mauryans.[24] Other texts, such as the Arthashastra and Indica of Megasthenes, which provide general information about the Maurya period, can also be used to make inferences about Ashoka's reign.[25] However, the Arthashastra is a normative text that focuses on an ideal rather than a historical state, and its dating to the Mauryan period is a subject of debate. The Indica is a lost work, and only parts of it survive in the form of paraphrases in later writings.[9]

The 12th-century text Rajatarangini mentions a Kashmiri king Ashoka of Gonandiya dynasty who built several stupas: some scholars, such as Aurel Stein, have identified this king with the Maurya emperor Ashoka; others, such as Ananda W. P. Guruge dismiss this identification as inaccurate.[26]

Alternative interpretation of the epigraphic evidence

This section relies largely or entirely upon a single source. (January 2023) |

For Christopher I. Beckwith, Ashoka, whose name only appears in the Minor Rock Edicts, is not the same as king Piyadasi, or Devanampiya Piyadasi (i.e. "Beloved of the Gods Piyadasi", "Beloved of the Gods" being a fairly widespread title for "King"), who is named as the author of the Major Pillar Edicts and the Major Rock Edicts.[27]

Beckwith suggests that Piyadasi was living in the 3rd century BCE, was probably the son of Chandragupta Maurya known to the Greeks as Amitrochates, and only advocated for piety ("Dharma") in his Major Pillar Edicts and Major Rock Edicts, without ever mentioning Buddhism, the Buddha, or the Sangha (the single notable exception is the 7th Edict of the Major Pillar Edicts which does mention the Sangha, but is a considered a later fake by Beckwith).[27] Also, the geographical spread of his inscription shows that Piyadasi ruled a vast Empire, contiguous with the Seleucid Empire in the West.[27]

On the contrary, for Beckwith, Ashoka was a later king of the 1st–2nd century CE, whose name only appears explicitly in the Minor Rock Edicts and allusively in the Minor Pillar Edicts, and who does mention the Buddha and the Sangha, explicitly promoting Buddhism.[27] The name "Priyadarsi" does occur in two of the minor edicts (Gujarra and Bairat), but Beckwith again considers them as later fabrications.[27] The minor inscriptions cover a very different and much smaller geographical area, clustering in Central India.[27] According to Beckwith, the inscriptions of this later Ashoka were typical of the later forms of "normative Buddhism", which are well attested from inscriptions and Gandhari manuscripts dated to the turn of the millennium, and around the time of the Kushan Empire.[27] The quality of the inscriptions of this Ashoka is significantly lower than the quality of the inscriptions of the earlier Piyadasi.[27]

However, many of Beckwith's methodologies and interpretations concerning early Buddhism, inscriptions, and archaeological sites have been criticized by other scholars, such as Johannes Bronkhorst and Osmund Bopearachchi.

Names and titles

[edit]The name "A-shoka" literally means "without sorrow". According to an Ashokavadana legend, his mother gave him this name because his birth removed her sorrows.[28]

The name Priyadasi is associated with Ashoka in the 3rd–4th century CE Dipavamsa.[29][30] The term literally means "he who regards amiably", or "of gracious mien" (Sanskrit: Priya-darshi). It may have been a regnal name adopted by Ashoka.[31][32] A version of this name is used for Ashoka in Greek-language inscriptions: βασιλεὺς Πιοδασσης ("Basileus Piodassēs").[32]

Ashoka's inscriptions mention his title Devanampiya (Sanskrit: Devanampriya, "Beloved of the Gods"). The identification of Devanampiya and Ashoka as the same person is established by the Maski and Gujarra inscriptions, which use both these terms for the king.[33][34] The title was adopted by other kings, including the contemporary king Devanampiya Tissa of Anuradhapura and Ashoka's descendant Dasharatha Maurya.[35]

Date

[edit]

The exact date of Ashoka's birth is not certain, as the extant contemporary Indian texts did not record such details. It is known that he lived in the 3rd century BCE, as his inscriptions mention several contemporary rulers whose dates are known with more certainty, such as Antiochus II Theos, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, Antigonus II Gonatas, Magas of Cyrene, and Alexander (of Epirus or Corinth).[36] Thus, Ashoka must have been born sometime in the late 4th century BCE or early 3rd century BCE (c. 304 BCE),[37] and ascended the throne around 269-268 BCE.[36]

Ancestry

[edit]Ashoka's own inscriptions are fairly detailed but make no mention of his ancestors.[38] Other sources, such as the Puranas and the Mahavamsa state that his father was the Mauryan emperor Bindusara, and his grandfather was Chandragupta – the founder of the Empire.[39] The Ashokavadana also names his father as Bindusara, but traces his ancestry to Buddha's contemporary king Bimbisara, through Ajatashatru, Udayin, Munda, Kakavarnin, Sahalin, Tulakuchi, Mahamandala, Prasenajit, and Nanda.[40] The 16th century Tibetan monk Taranatha, whose account is a distorted version of the earlier traditions,[25] describes Ashoka as the illegitimate son of king Nemita of Champarana from the daughter of a merchant.[41]

Ashokavadana states that Ashoka's mother was the daughter of a Brahmin from Champa, and was prophesied to marry a king. Accordingly, her father took her to Pataliputra, where she was inducted into Bindusara's harem, and ultimately, became his chief empress.[42] The Ashokavadana does not mention her by name,[43] although other legends provide different names for her.[44] For example, the Asokavadanamala calls her Subhadrangi.[45][46] The Vamsatthapakasini or Mahavamsa-tika, a commentary on Mahavamsa, calls her "Dharma" ("Dhamma" in Pali), and states that she belonged to the Moriya Kshatriya clan.[46] A Divyavadana legend calls her Janapada-kalyani;[47] according to scholar Ananda W. P. Guruge, this is not a name, but an epithet.[45]

According to the 2nd-century historian Appian, Chandragupta entered into a marital alliance with the Greek ruler Seleucus I Nicator, which has led to speculation that either Chandragupta or his son Bindusara married a Greek princess. However, there is no evidence that Ashoka's mother or grandmother was Greek, and most historians have dismissed the idea.[48]

As a prince

[edit]Ashoka's own inscriptions do not describe his early life, and much of the information on this topic comes from apocryphal legends written hundreds of years after him.[49] While these legends include obviously fictitious details such as narratives of Ashoka's past lives, they have some plausible historical information about Ashoka's period.[49][47]

According to the Ashokavadana, Bindusara disliked Ashoka because of his rough skin. One day, Bindusara asked the ascetic Pingala-vatsajiva to determine which of his sons was worthy of being his successor. He asked all the princes to assemble at the Garden of the Golden Pavilion on the ascetic's advice. Ashoka was reluctant to go because his father disliked him, but his mother convinced him to do so. When minister Radhagupta saw Ashoka leaving the capital for the Garden, he offered to provide the prince with an imperial elephant for the travel.[50] At the Garden, Pingala-vatsajiva examined the princes and realised that Ashoka would be the next emperor. To avoid annoying Bindusara, the ascetic refused to name the successor. Instead, he said that one who had the best mount, seat, drink, vessel and food would be the next king; each time, Ashoka declared that he met the criterion. Later, he told Ashoka's mother that her son would be the next emperor, and on her advice, left the empire to avoid Bindusara's wrath.[51]

While legends suggest that Bindusara disliked Ashoka's ugly appearance, they also state that Bindusara gave him important responsibilities, such as suppressing a revolt in Takshashila (according to north Indian tradition) and governing Ujjain (according to Sri Lankan tradition). This suggests that Bindusara was impressed by the other qualities of the prince.[52] Another possibility is that he sent Ashoka to distant regions to keep him away from the imperial capital.[53]

Rebellion at Taxila

[edit]

According to the Ashokavadana, Bindusara dispatched prince Ashoka to suppress a rebellion in the city of Takshashila[54] (present-day Bhir Mound[55] in Pakistan). This episode is not mentioned in the Sri Lankan tradition, which instead states that Bindusara sent Ashoka to govern Ujjain. Two other Buddhist texts – Ashoka-sutra and Kunala-sutra – state that Bindusara appointed Ashoka as a viceroy in Gandhara (where Takshashila was located), not Ujjain.[52]

The Ashokavadana states that Bindusara provided Ashoka with a fourfold-army (comprising cavalry, elephants, chariots and infantry) but refused to provide any weapons for this army. Ashoka declared that weapons would appear before him if he was worthy of being an emperor, and then, the deities emerged from the earth and provided weapons to the army. When Ashoka reached Takshashila, the citizens welcomed him and told him that their rebellion was only against the evil ministers, not the emperor. Sometime later, Ashoka was similarly welcomed in the Khasa territory and the gods declared that he would go on to conquer the whole earth.[54]

Takshashila was a prosperous and geopolitically influential city, and historical evidence proves that by Ashoka's time, it was well-connected to the Mauryan capital Pataliputra by the Uttarapatha trade route.[56] However, no extant contemporary source mentions the Takshashila rebellion, and none of Ashoka's records states that he ever visited the city.[57] That said, the historicity of the legend about Ashoka's involvement in the Takshashila rebellion may be corroborated by an Aramaic-language inscription discovered at Sirkap near Taxila. The inscription includes a name that begins with the letters "prydr", and most scholars restore it as "Priyadarshi", which was the title of Ashoka.[52] Another evidence of Ashoka's connection to the city may be the name of the Dharmarajika Stupa near Taxila; the name suggests that it was built by Ashoka ("Dharma-raja").[58]

The story about the deities miraculously bringing weapons to Ashoka may be the text's way of deifying Ashoka; or indicating that Bindusara – who disliked Ashoka – wanted him to fail in Takshashila.[59]

Viceroy of Ujjain

[edit]According to the Mahavamsa, Bindusara appointed Ashoka as the Viceroy of Avantirastra (present day Ujjain district),[52] which was an important administrative and commercial province in central India.[60] This tradition is corroborated by the Saru Maru inscription discovered in central India; this inscription states that he visited the place as a prince.[61] Ashoka's own rock edict mentions the presence of a prince viceroy at Ujjain during his reign,[62] which further supports the tradition that he himself served as a viceroy at Ujjain.[63]

Pataliputra was connected to Ujjain by multiple routes in Ashoka's time, and on the way, Ashoka entourage may have encamped at Rupnath, where his inscription has been found.[64]

According to the Sri Lankan tradition, Ashoka visited Vidisha, where he fell in love with a beautiful woman on his way to Ujjain. According to the Dipamvamsa and Mahamvamsa, the woman was Devi – the daughter of a merchant. According to the Mahabodhi-vamsa, she was Vidisha-Mahadevi and belonged to the Shakya clan of Gautama Buddha. The Buddhist chroniclers may have fabricated the Shakya connection to connect Ashoka's family to Buddha.[65] The Buddhist texts allude to her being a Buddhist in her later years but do not describe her conversion to Buddhism. Therefore, it is likely that she was already a Buddhist when she met Ashoka.[66]

The Mahavamsa states that Devi gave birth to Ashoka's son Mahinda in Ujjain, and two years later, to a daughter named Sanghamitta.[67] According to the Mahavamsa, Ashoka's son Mahinda was ordained at the age of 20 years, during the sixth year of Ashoka's reign. That means Mahinda must have been 14 years old when Ashoka ascended the throne. Even if Mahinda was born when Ashoka was as young as 20 years old, Ashoka must have ascended the throne at 34 years, which means he must have served as a viceroy for several years.[68]

Ascension to the throne

[edit]Legends suggest that Ashoka was not the crown prince, and his ascension on the throne was disputed. [69]

Ashokavadana states that Bindusara's eldest son Susima once slapped a bald minister on his head in jest. The minister worried that after ascending the throne, Susima may jokingly hurt him with a sword. Therefore, he instigated five hundred ministers to support Ashoka's claim to the throne when the time came, noting that Ashoka was predicted to become a chakravartin (universal ruler).[70] Sometime later, Takshashila rebelled again, and Bindusara dispatched Susima to curb the rebellion. Shortly after, Bindusara fell ill and was expected to die soon. Susima was still in Takshashila, having been unsuccessful in suppressing the rebellion. Bindusara recalled him to the capital and asked Ashoka to march to Takshashila.[71] However, the ministers told him that Ashoka was ill and suggested that he temporarily install Ashoka on the throne until Susmia's return from Takshashila.[70] When Bindusara refused to do so, Ashoka declared that if the throne were rightfully his, the gods would crown him as the next emperor. At that instance, the gods did so, Bindusara died, and Ashoka's authority extended to the entire world, including the Yaksha territory located above the earth and the Naga territory located below the earth.[71] When Susima returned to the capital, Ashoka's newly appointed prime minister Radhagupta tricked him into a pit of charcoal. Susima died a painful death, and his general Bhadrayudha became a Buddhist monk.[72]

The Mahavamsa states that when Bindusara fell sick, Ashoka returned to Pataliputra from Ujjain and gained control of the capital. After his father's death, Ashoka had his eldest brother killed and ascended the throne.[66] The text also states that Ashoka killed ninety-nine of his half-brothers, including Sumana.[62] The Dipavamsa states that he killed a hundred of his brothers and was crowned four years later.[70] The Vamsatthapakasini adds that an Ajivika ascetic had predicted this massacre based on the interpretation of a dream of Ashoka's mother.[75] According to these accounts, only Ashoka's uterine brother Tissa was spared.[76] Other sources name the surviving brother Vitashoka, Vigatashoka, Sudatta (So-ta-to in A-yi-uang-chuan), or Sugatra (Siu-ka-tu-lu in Fen-pie-kung-te-hun).[76]

The figures such as 99 and 100 are exaggerated and seem to be a way of stating that Ashoka killed several of his brothers.[70] Taranatha states that Ashoka, who was an illegitimate son of his predecessor, killed six legitimate princes to ascend the throne.[41] It is possible that Ashoka was not the rightful heir to the throne and killed a brother (or brothers) to acquire the throne. However, the Buddhist sources have exaggerated the story, which attempts to portray him as evil before his conversion to Buddhism. Ashoka's Rock Edict No. 5 mentions officers whose duties include supervising the welfare of "the families of his brothers, sisters, and other relatives". This suggests that more than one of his brothers survived his ascension. However, some scholars oppose this suggestion, arguing that the inscription talks only about the families of his brothers, not the brothers themselves.[76]

Date of ascension

[edit]According to the Sri Lankan texts Mahavamsa and the Dipavamsa, Ashoka ascended the throne 218 years after the death of Gautama Buddha and ruled for 37 years.[77] The date of the Buddha's death is itself a matter of debate,[78] and the North Indian tradition states that Ashoka ruled a hundred years after the Buddha's death, which has led to further debates about the date.[19]

Assuming that the Sri Lankan tradition is correct, and assuming that the Buddha died in 483 BCE – a date proposed by several scholars – Ashoka must have ascended the throne in 265 BCE.[78] The Puranas state that Ashoka's father Bindusara reigned for 25 years, not 28 years as specified in the Sri Lankan tradition.[39] If this is true, Ashoka's ascension can be dated three years earlier, to 268 BCE. Alternatively, if the Sri Lankan tradition is correct, but if we assume that the Buddha died in 486 BCE (a date supported by the Cantonese Dotted Record), Ashoka's ascension can be dated to 268 BCE.[78] The Mahavamsa states that Ashoka consecrated himself as the emperor four years after becoming a sovereign. This interregnum can be explained assuming that he fought a war of succession with other sons of Bindusara during these four years.[79]

The Ashokavadana contains a story about Ashoka's minister Yashas hiding the sun with his hand. Professor P. H. L. Eggermont theorised that this story was a reference to a partial solar eclipse that was seen in northern India on 4 May 249 BCE.[80] According to the Ashokavadana, Ashoka went on a pilgrimage to various Buddhist sites sometime after this eclipse. Ashoka's Rummindei pillar inscription states that he visited Lumbini during his 21st regnal year. Assuming this visit was a part of the pilgrimage described in the text, and assuming that Ashoka visited Lumbini around 1–2 years after the solar eclipse, the ascension date of 268–269 BCE seems more likely.[78][36] However, this theory is not universally accepted. For example, according to John S. Strong, the event described in the Ashokavadana has nothing to do with chronology, and Eggermont's interpretation grossly ignores the literary and religious context of the legend.[81]

Reign before Buddhist influence

[edit]Both Sri Lankan and North Indian traditions assert that Ashoka was a violent person before Buddhism.[82] Taranatha also states that Ashoka was initially called "Kamashoka" because he spent many years in pleasurable pursuits (kama); he was then called "Chandashoka" ("Ashoka the fierce") because he spent some years performing evil deeds; and finally, he came to be known as Dhammashoka ("Ashoka the righteous") after his conversion to Buddhism.[83]

The Ashokavadana also calls him "Chandashoka", and describes several of his cruel acts:[84]

- The ministers who had helped him ascend the throne started treating him with contempt after his ascension. To test their loyalty, Ashoka gave them the absurd order of cutting down every flower-and fruit-bearing tree. When they failed to carry out this order, Ashoka personally cut off the heads of 500 ministers.[84]

- One day, during a stroll at a park, Ashoka and his concubines came across a beautiful Ashoka tree. The sight put him in an amorous mood, but the women did not enjoy caressing his rough skin. Sometime later, when Ashoka fell asleep, the resentful women chopped the flowers and the branches of his namesake tree. After Ashoka woke up, he burnt 500 of his concubines to death as punishment.[85]

- Alarmed by the king's involvement in such massacres, prime minister Radha-Gupta proposed hiring an executioner to carry out future mass killings to leave the king unsullied. Girika, a Magadha village boy who boasted that he could execute the whole of Jambudvipa, was hired for the purpose. He came to be known as Chandagirika ("Girika the fierce"), and on his request, Ashoka built a jail in Pataliputra.[85] Called Ashoka's Hell, the jail looked pleasant from the outside, but inside it, Girika brutally tortured the prisoners.[86] but was last executed during the demolition of ashoka"s hell.

The 5th-century Chinese traveller Faxian states that Ashoka personally visited the underworld to study torture methods there and then invented his methods. The 7th-century traveller Xuanzang claims to have seen a pillar marking the site of Ashoka's "Hell".[83]

The Mahavamsa also briefly alludes to Ashoka's cruelty, stating that Ashoka was earlier called Chandashoka because of his evil deeds but came to be called Dharmashoka because of his pious acts after his conversion to Buddhism.[87] However, unlike the north Indian tradition, the Sri Lankan texts do not mention any specific evil deeds performed by Ashoka, except his killing of 99 of his brothers.[82]

Such descriptions of Ashoka as an evil person before his conversion to Buddhism appear to be a fabrication of the Buddhist authors,[83] who attempted to present the change that Buddhism brought to him as a miracle.[82] In an attempt to dramatise this change, such legends exaggerate Ashoka's past wickedness and his piousness after the conversion.[88]

Kalinga war and conversion to Buddhism

[edit]

Ashoka's inscriptions mention that he conquered the Kalinga region during his 8th regnal year: the destruction caused during the war made him repent violence, and in the subsequent years, he was drawn towards Buddhism.[90] Edict 13 of the Edicts of Ashoka Rock Inscriptions expresses the great remorse the king felt after observing the destruction of Kalinga:

Directly, after the Kalingas had been annexed, began His Sacred Majesty's zealous protection of the Law of Piety, his love of that Law, and his inculcation of that Law. Thence arises the remorse of His Sacred Majesty for having conquered the Kalingas because the conquest of a country previously unconquered involves the slaughter, death, and carrying away captive of the people. That is a matter of profound sorrow and regret to His Sacred Majesty.[91]

On the other hand, the Sri Lankan tradition suggests that Ashoka was already a devoted Buddhist by his 8th regnal year, converted to Buddhism during his 4th regnal year, and constructed 84,000 viharas during his 5th–7th regnal years.[90] The Buddhist legends make no mention of the Kalinga campaign.[92]

Based on Sri Lankan tradition, some scholars, such as Eggermont, believe Ashoka converted to Buddhism before the Kalinga war.[93] Critics of this theory argue that if Ashoka were already a Buddhist, he would not have waged the violent Kalinga War. Eggermont explains this anomaly by theorising that Ashoka had his own interpretation of the "Middle Way".[94]

Some earlier writers believed that Ashoka dramatically converted to Buddhism after seeing the suffering caused by the war since his Major Rock Edict 13 states that he became closer to the dhamma after the annexation of Kalinga.[92] However, even if Ashoka converted to Buddhism after the war, epigraphic evidence suggests that his conversion was a gradual process rather than a dramatic event.[92] For example, in a Minor Rock Edict issued during his 13th regnal year (five years after the Kalinga campaign), he states that he had been an upasaka (lay Buddhist) for more than two and a half years, but did not make much progress; in the past year, he was drawn closer to the sangha and became a more ardent follower.[92]

Kalinga war

[edit]According to Ashoka's Major Rock Edict 13, he conquered Kalinga 8 years after ascending to the throne. The edict states that during his conquest of Kalinga, 100,000 men and animals were killed in action; many times that number "perished"; and 150,000 men and animals were carried away from Kalinga as captives. Ashoka states that the repentance of these sufferings caused him to devote himself to the practice and propagation of dharma.[95] He proclaims that he now considered the slaughter, death and deportation caused during the conquest of a country painful and deplorable; and that he considered the suffering caused to the religious people and householders even more deplorable.[95]

This edict has been inscribed at several places, including Erragudi, Girnar, Kalsi, Maneshra, Shahbazgarhi and Kandahar.[96] However, it is omitted in Ashoka's inscriptions found in the Kalinga region, where the Rock Edicts 13 and 14 have been replaced by two separate edicts that make no mention of Ashoka's remorse. It is possible that Ashoka did not consider it politically appropriate to make such a confession to the people of Kalinga.[97] Another possibility is the Kalinga war and its consequences, as described in Ashoka's rock edicts, are "more imaginary than real". This description is meant to impress those far removed from the scene, thus unable to verify its accuracy.[98]

Ancient sources do not mention any other military activity of Ashoka, although the 16th-century writer Taranatha claims that Ashoka conquered the entire Jambudvipa.[93]

First contact with Buddhism

[edit]Different sources give different accounts of Ashoka's conversion to Buddhism.[83]

According to Sri Lankan tradition, Ashoka's father, Bindusara, was a devotee of Brahmanism, and his mother Dharma was a devotee of Ajivikas.[99] The Samantapasadika states that Ashoka followed non-Buddhist sects during the first three years of his reign.[100] The Sri Lankan texts add that Ashoka was not happy with the behaviour of the Brahmins who received his alms daily. His courtiers produced some Ajivika and Nigantha teachers before him, but these also failed to impress him.[101]

The Dipavamsa states that Ashoka invited several non-Buddhist religious leaders to his palace and bestowed great gifts upon them in the hope that they would answer a question posed by the king. The text does not state what the question was but mentions that none of the invitees were able to answer it.[102] One day, Ashoka saw a young Buddhist monk called Nigrodha (or Nyagrodha), who was looking for alms on a road in Pataliputra.[102] He was the king's nephew, although the king was not aware of this:[103] he was a posthumous son of Ashoka's eldest brother Sumana, whom Ashoka had killed during the conflict for the throne.[104] Ashoka was impressed by Nigrodha's tranquil and fearless appearance, and asked him to teach him his faith. In response, Nigrodha offered him a sermon on appamada (earnestness).[102] Impressed by the sermon, Ashoka offered Nigrodha 400,000 silver coins and 8 daily portions of rice.[105] The king became a Buddhist upasaka, and started visiting the Kukkutarama shrine at Pataliputra. At the temple, he met the Buddhist monk Moggaliputta Tissa, and became more devoted to the Buddhist faith.[101] The veracity of this story is not certain.[105] This legend about Ashoka's search for a worthy teacher may be aimed at explaining why Ashoka did not adopt Jainism, another major contemporary faith that advocates non-violence and compassion. The legend suggests that Ashoka was not attracted to Buddhism because he was looking for such a faith, rather, for a competent spiritual teacher.[106] The Sri Lankan tradition adds that during his sixth regnal year, Ashoka's son Mahinda became a Buddhist monk, and his daughter became a Buddhist nun.[107]

A story in Divyavadana attributes Ashoka's conversion to the Buddhist monk Samudra, who was an ex-merchant from Shravasti. According to this account, Samudra was imprisoned in Ashoka's "Hell", but saved himself using his miraculous powers. When Ashoka heard about this, he visited the monk, and was further impressed by a series of miracles performed by the monk. He then became a Buddhist.[108] A story in the Ashokavadana states that Samudra was a merchant's son, and was a 12-year-old boy when he met Ashoka; this account seems to be influenced by the Nigrodha story.[93]

The A-yu-wang-chuan states that a 7-year-old Buddhist converted Ashoka. Another story claims that the young boy ate 500 Brahmanas who were harassing Ashoka for being interested in Buddhism; these Brahmanas later miraculously turned into Buddhist bhikkus at the Kukkutarama monastery, which Ashoka visited.[108]

Several Buddhist establishments existed in various parts of India by the time of Ashoka's ascension. It is not clear which branch of the Buddhist sangha influenced him, but the one at his capital Pataliputra is a good candidate.[109] Another good candidate is the one at Mahabodhi: the Major Rock Edict 8 records his visit to the Bodhi Tree – the place of Buddha's enlightenment at Mahabodhi – after his tenth regnal year, and the minor rock edict issued during his 13th regnal year suggests that he had become a Buddhist around the same time.[92][109]

Reign after Buddhist influence

[edit]Construction of stupas and temples

[edit]

Both Mahavamsa and Ashokavadana state that Ashoka constructed 84,000 stupas or viharas.[110] According to the Mahavamsa, this activity took place during his fifth–seventh regnal years.[107]

The Ashokavadana states that Ashoka collected seven out of the eight relics of Gautama Buddha, and had their portions kept in 84,000 boxes made of gold, silver, cat's eye, and crystal. He ordered the construction of 84,000 stupas throughout the earth, in towns that had a population of 100,000 or more. He told Elder Yashas, a monk at the Kukkutarama monastery, that he wanted these stupas to be completed on the same day. Yashas stated that he would signal the completion time by eclipsing the sun with his hand. When he did so, the 84,000 stupas were completed at once.[21]

The Mahavamsa states that Ashoka ordered construction of 84,000 viharas (monasteries) rather than the stupas to house the relics.[114] Like Ashokavadana, the Mahavamsa describes Ashoka's collection of the relics, but does not mention this episode in the context of the construction activities.[114] It states that Ashoka decided to construct the 84,000 viharas when Moggaliputta Tissa told him that there were 84,000 sections of the Buddha's Dhamma.[115] Ashoka himself began the construction of the Ashokarama vihara, and ordered subordinate kings to build the other viharas. Ashokarama was completed by the miraculous power of Thera Indagutta, and the news about the completion of the 84,000 viharas arrived from various cities on the same day.[21]

The construction of following stupas and viharas is credited to Ashoka:[citation needed]

- Sanchi, Madhya Pradesh, India

- Dhamek Stupa, Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh, India

- Mahabodhi Temple, Bihar, India

- Barabar Caves, Bihar, India

- Nalanda Mahavihara (some portions like Sariputta Stupa), Bihar, India

- Taxila University (some portions like Dharmarajika Stupa and Kunala Stupa), Taxila, Pakistan

- Bhir Mound (reconstructed), Taxila, Pakistan

- Bharhut stupa, Madhya Pradesh, India

- Deorkothar Stupa, Madhya Pradesh, India

- Butkara Stupa, Swat, Pakistan

- Sannati Stupa, Karnataka, India

- Mir Rukun Stupa, Nawabshah, Pakistan

Propagation of Dhamma

[edit]Ashoka's rock edicts suggest that during his eighth–ninth regnal years, he made a pilgrimage to the Bodhi Tree, started propagating dhamma, and performed social welfare activities. The welfare activities included establishment of medical treatment facilities for humans and animals; plantation of medicinal herbs; and digging of wells and plantation of trees along the roads. These activities were conducted in the neighbouring kingdoms, including those of the Cholas, the Pandyas, the Satiyaputras, Tamraparni, the Greek kingdom of Antiyoka.[116]

The edicts also state that during his tenth–eleventh regnal years, Ashoka became closer to the Buddhist sangha, and went on a tour of the empire that lasted for at least 256 days.[116]

By his 12th regnal year, Ashoka had started inscribing edicts to propagate dhamma, having ordered his officers (rajjukas and pradesikas) to tour their jurisdictions every five years for inspection and for preaching dhamma. By the next year, he had set up the post of the dharma-mahamatra.[116]

During his 14th regnal year, he commissioned the enlargement of the stupa of Buddha Kanakamuni.[116]

Third Buddhist Council

[edit]The Sri Lankan tradition presents a greater role for Ashoka in the Buddhist community.[18] In this tradition, Ashoka starts feeding monks on a large scale. His lavish patronage to the state patronage leads to many fake monks joining the sangha. The true Buddhist monks refuse to co-operate with these fake monks, and therefore, no uposatha ceremony is held for seven years. The king attempts to eradicate the fake monks, but during this attempt, an over-zealous minister ends up killing some real monks. The king then invites the elder monk Moggaliputta-Tissa, to help him expel non-Buddhists from the monastery founded by him at Pataliputra.[103] 60,000 monks (bhikkhus) convicted of being heretical are de-frocked in the ensuing process.[18] The uposatha ceremony is then held, and Tissa subsequently organises the Third Buddhist council,[117] during the 17th regnal year of Ashoka.[118] Tissa compiles Kathavatthu, a text that reaffirms Theravadin orthodoxy on several points.[117]

The North Indian tradition makes no mention of these events, which has led to doubts about the historicity of the Third Buddhist council.[19]

Richard Gombrich argues that the non-corroboration of this story by inscriptional evidence cannot be used to dismiss it as completely unhistorical, as several of Ashoka's inscriptions may have been lost.[117] Gombrich also argues that Asohka's inscriptions prove that he was interested in maintaining the "unanimity and purity" of the Sangha.[119] For example, in his Minor Rock Edict 3, Ashoka recommends the members of the Sangha to study certain texts (most of which remain unidentified). Similarly, in an inscription found at Sanchi, Sarnath, and Kosam, Ashoka mandates that the dissident members of the sangha should be expelled, and expresses his desire to the Sangha remain united and flourish.[120][121]

The 8th century Buddhist pilgrim Yijing records another story about Ashoka's involvement in the Buddhist sangha. According to this story, the earlier king Bimbisara, who was a contemporary of the Gautama Buddha, once saw 18 fragments of a cloth and a stick in a dream. The Buddha interpreted the dream to mean that his philosophy would be divided into 18 schools after his death, and predicted that a king called Ashoka would unite these schools over a hundred years later.[75]

Buddhist missions

[edit]In the Sri Lankan tradition, Moggaliputta-Tissa – who is patronised by Ashoka – sends out nine Buddhist missions to spread Buddhism in the "border areas" in c. 250 BCE. This tradition does not credit Ashoka directly with sending these missions. Each mission comprises five monks, and is headed by an elder.[122] To Sri Lanka, he sent his own son Mahinda, accompanied by four other Theras – Itthiya, Uttiya, Sambala and Bhaddasala.[18] Next, with Moggaliputta-Tissa's help, Ashoka sent Buddhist missionaries to distant regions such as Kashmir, Gandhara, Himalayas, the land of the Yonas (Greeks), Maharashtra, Suvannabhumi, and Sri Lanka.[18]

The Sri Lankan tradition dates these missions to Ashoka's 18th regnal year, naming the following missionaries:[116]

- Mahinda to Sri Lanka

- Majjhantika to Kashmir and Gandhara

- Mahadeva to Mahisa-mandala (possibly modern Mysore region)

- Rakkhita to Vanavasa

- Dhammarakkhita the Greek to Aparantaka (western India)

- Maha-dhamma-rakkhita to Maharashtra

- Maharakkhita to the Greek country

- Majjhima to the Himalayas

- Soṇa and Uttara to Suvaṇṇabhūmi (possibly Lower Burma and Thailand)

The tradition adds that during his 19th regnal year, Ashoka's daughter Sanghamitta went to Sri Lanka to establish an order of nuns, taking a sapling of the sacred Bodhi Tree with her.[122][118]

The North Indian tradition makes no mention of these events.[19] Ashoka's own inscriptions also appear to omit any mention of these events, recording only one of his activities during this period: in his 19th regnal year, he donated the Khalatika Cave to ascetics to provide them a shelter during the rainy season. Ashoka's Pillar Edicts suggest that during the next year, he made pilgrimage to Lumbini – the place of Buddha's birth, and to the stupa of the Buddha Kanakamuni.[118]

The Rock Edict XIII states that Ashoka's won a "dhamma victory" by sending messengers to five kings and several other kingdoms. Whether these missions correspond to the Buddhist missions recorded in the Buddhist chronicles is debated.[123] Indologist Etienne Lamotte argues that the "dhamma" missionaries mentioned in Ashoka's inscriptions were probably not Buddhist monks, as this "dhamma" was not same as "Buddhism".[124] Moreover, the lists of destinations of the missions and the dates of the missions mentioned in the inscriptions do not tally the ones mentioned in the Buddhist legends.[125]

Other scholars, such as Erich Frauwallner and Richard Gombrich, believe that the missions mentioned in the Sri Lankan tradition are historical.[125] According to these scholars, a part of this story is corroborated by archaeological evidence: the Vinaya Nidana mentions names of five monks, who are said to have gone to the Himalayan region; three of these names have been found inscribed on relic caskets found at Bhilsa (near Vidisha). These caskets have been dated to the early 2nd century BCE, and the inscription states that the monks are of the Himalayan school.[122] The missions may have set out from Vidisha in central India, as the caskets were discovered there, and as Mahinda is said to have stayed there for a month before setting out for Sri Lanka.[126]

According to Gombrich, the mission may have included representatives of other religions, and thus, Lamotte's objection about "dhamma" is not valid. The Buddhist chroniclers may have decided not to mention these non-Buddhists, so as not to sideline Buddhism.[127] Frauwallner and Gombrich also believe that Ashoka was directly responsible for the missions, since only a resourceful ruler could have sponsored such activities. The Sri Lankan chronicles, which belong to the Theravada school, exaggerate the role of the Theravadin monk Moggaliputta-Tissa in order to glorify their sect.[127]

Some historians argue that Buddhism became a major religion because of Ashoka's royal patronage.[128] However, epigraphic evidence suggests that the spread of Buddhism in north-western India and Deccan region was less because of Ashoka's missions, and more because of merchants, traders, landowners and the artisan guilds who supported Buddhist establishments.[129]

Violence after conversion

[edit]According to the 5th century Buddhist legend Ashokavadana, Ashoka resorted to violence even after converting to Buddhism. For example:[130]

- He slowly tortured Chandagirika to death in the "hell" prison.[130]

- He ordered a massacre of 18,000 heretics for a misdeed of one.[130]

- He launched a pogrom against the Jains, announcing a bounty on the head of any heretic; this resulted in the beheading of his own brother – Vitashoka.[130]

According to the Ashokavadana, a non-Buddhist in Pundravardhana drew a picture showing the Buddha bowing at the feet of the Nirgrantha leader Jnatiputra. The term nirgrantha ("free from bonds") was originally used for a pre-Jaina ascetic order, but later came to be used for Jaina monks.[131] "Jnatiputra" is identified with Mahavira, 24th Tirthankara of Jainism. The legend states that on complaint from a Buddhist devotee, Ashoka issued an order to arrest the non-Buddhist artist, and subsequently, another order to kill all the Ajivikas in Pundravardhana. Around 18,000 followers of the Ajivika sect were executed as a result of this order.[132][133] Sometime later, another Nirgrantha follower in Pataliputra drew a similar picture. Ashoka burnt him and his entire family alive in their house.[133] He also announced an award of one dinara to anyone who brought him the head of a Nirgrantha heretic. According to Ashokavadana, as a result of this order, his own brother was mistaken for a heretic and killed by a cowherd.[132] Ashoka realised his mistake, and withdrew the order.[131]

For several reasons, scholars say, these stories of persecutions of rival sects by Ashoka appear to be clear fabrications arising out of sectarian propaganda.[133][134][135] Additionally, these stories do not appear in the Jain texts themselves who do mention Ashoka, such as the Parishtaparvan or Theravali.[136][137]

Family

[edit]

Consorts

[edit]Various sources mention five consorts of Ashoka: Devi (or Vedisa-Mahadevi-Shakyakumari), Asandhimitra, Padmavati, Karuvaki and Tishyarakshita.[139]

Karuvaki is the only queen of Ashoka known from his own inscriptions: she is mentioned in an edict inscribed on a pillar at Allahabad. The inscription names her as the mother of prince Tivara, and orders the imperial officers (mahamattas) to record her religious and charitable donations.[79] According to one theory, Tishyarakshita was the regnal name of Kaurvaki.[79]

According to the Mahavamsa, Ashoka's chief empress was Asandhimitta, who died four years before him.[79] It states that she was born as Ashoka's empress because in a previous life, she directed a pratyekabuddha to a honey merchant (who was later reborn as Ashoka).[140] Some later texts also state that she additionally gave the pratyekabuddha a piece of cloth made by her.[141] These texts include the Dasavatthuppakarana, the so-called Cambodian or Extended Mahavamsa (possibly from 9th–10th centuries), and the Trai Bhumi Katha (15th century).[141] These texts narrate another story: one day, Ashoka mocked Asandhamitta was enjoying a tasty piece of sugarcane without having earned it through her karma. Asandhamitta replied that all her enjoyments resulted from merit resulting from her own karma. Ashoka then challenged her to prove this by procuring 60,000 robes as an offering for monks.[141] At night, the guardian gods informed her about her past gift to the pratyekabuddha, and next day, she was able to miraculously procure the 60,000 robes. An impressed Ashoka makes her his favourite empress, and even offers to make her a sovereign ruler. Asandhamitta refuses the offer, but still invokes the jealousy of Ashoka's 16,000 other women. Ashoka proves her superiority by having 16,000 identical cakes baked with his imperial seal hidden in only one of them. Each wife is asked to choose a cake, and only Asandhamitta gets the one with the imperial seal.[142] The Trai Bhumi Katha claims that it was Asandhamitta who encouraged her husband to become a Buddhist, and to construct 84,000 stupas and 84,000 viharas.[143]

According to Mahavamsa, after Asandhamitta's death, Tissarakkha became the chief empress.[79] The Ashokavadana does not mention Asandhamitta at all, but does mention Tissarakkha as Tishyarakshita.[144] The Divyavadana mentions another empress called Padmavati, who was the mother of the crown-prince Kunala.[79]

As mentioned above, according to the Sri Lankan tradition, Ashoka fell in love with Devi (or Vidisha-Mahadevi), as a prince in central India.[65] After Ashoka's ascension to the throne, Devi chose to remain at Vidisha than move to the imperial capital Pataliputra. According to the Mahavmsa, Ashoka's chief empress was Asandhamitta, not Devi: the text does not talk of any connection between the two women, so it is unlikely that Asandhamitta was another name for Devi.[145] The Sri Lankan tradition uses the word samvasa to describe the relationship between Ashoka and Devi, which modern scholars variously interpret as sexual relations outside marriage, or co-habitation as a married couple.[146] Those who argue that Ashoka did not marry Devi argue that their theory is corroborated by the fact that Devi did not become Ashoka's chief empress in Pataliputra after his ascension.[63] The Dipavamsa refers to two children of Ashoka and Devi – Mahinda and Sanghamitta.[147]

Sons

[edit]Tivara, the fourth son of Ashoka and Karuvaki, is the only of Ashoka's sons to be mentioned by name in the inscriptions.[79]

According to North Indian tradition, Ashoka had a second son named Kunala.[19] Kunala had a son named Samprati.[79]

The Sri Lankan tradition mentions a son called Mahinda, who was sent to Sri Lanka as a Buddhist missionary; this son is not mentioned at all in the North Indian tradition.[18] The Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang states that Mahinda was Ashoka's younger brother (Vitashoka or Vigatashoka) rather than his illegitimate son.[148]

The Divyavadana mentions the crown-prince Kunala alias Dharmavivardhana, who was a second son of Ashoka and empress Padmavati. According to Faxian, Dharmavivardhana was appointed as the governor of Gandhara.[79]

The Rajatarangini mentions Jalauka as a third son of Ashoka.[79]

Daughters

[edit]According to Sri Lankan tradition, Ashoka had a daughter named Sanghamitta, who became a Bhikkhunī.[107] A section of historians, such as Romila Thapar, doubt the historicity of Sanghamitta, based on the following points:[149]

- The name "Sanghamitta", which literally means the friend of the Buddhist order (sangha), is unusual, and the story of her going to Ceylon so that the Ceylonese queen could be ordained appears to be an exaggeration.[145]

- The Mahavamsa states that she married Ashoka's nephew Agnibrahma, and the couple had a son named Sumana. The contemporary laws regarding exogamy would have forbidden such a marriage between first cousins.[148]

- According to the Mahavamsa, she was 18 years old when she was ordained as a nun.[145] The narrative suggests that she was married two years earlier, and that her husband as well as her child were ordained. It is unlikely that she would have been allowed to become a nun with such a young child.[148]

Another source mentions that Ashoka had a daughter named Charumati, who married a kshatriya named Devapala.[79]

Brothers

[edit]According to the Ashokavadana, Ashoka had an elder half-brother named Susima.[40]

- According to Sri Lankan tradition, this brother was Tissa, who initially lived a luxurious life, without worrying about the world. To teach him a lesson, Ashoka put him on the throne for a few days, then accused him of being an usurper, and sentenced him to die after seven days. During these seven days, Tissa realised that the Buddhist monks gave up pleasure because they were aware of the eventual death. He then left the palace, and became an arhat.[76]

- The Theragatha commentary calls this brother Vitashoka. According to this legend, one day, Vitashoka saw a grey hair on his head, and realised that he had become old. He then retired to a monastery, and became an arhat.[131]

- Faxian calls the younger brother Mahendra, and states that Ashoka shamed him for his immoral behaviour. The brother then retired to a dark cave, where he meditated, and became an arhat. Ashoka invited him to return to the family, but he preferred to live alone on a hill. So, Ashoka had a hill built for him within Pataliputra.[131]

- The Ashoka-vadana states that Ashoka's brother was mistaken for a non-Buddhist Jain, and killed during a massacre of the Jains ordered by Ashoka.[131]

Imperial extent

[edit]

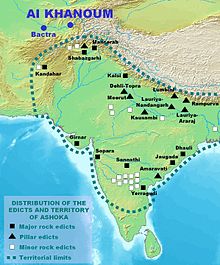

The extent of the territory controlled by Ashoka's predecessors is not certain, but it is possible that the empire of his grandfather Chandragupta extended across northern India from the western coast (Arabian Sea) to the eastern coast (Upto borders of Burma) covering nearly most of the Indian subcontinent. Bindusara and Ashoka seem to have extended the empire southwards.[151] The distribution of Ashoka's inscriptions suggests that his empire included almost the entire Indian subcontinent, except its southernmost parts. The Rock Edicts 2 and 13 suggest that these southernmost parts were controlled by the Cholas, the Pandyas, the Keralaputras, and the Satiyaputras. In the north-west, Ashoka's kingdom extended up to Herat, to the east of the Seleucid Empire ruled by Antiochus II.[2] The capital of Ashoka's empire was Pataliputra in the Magadha region.[151]

Religion and philosophy

[edit]Relationship with Buddhism

[edit]

The Buddhist legends state that Ashoka converted to Buddhism,[152] although this has been debated by a section of scholars.[153] The Minor Rock Edict 1 leaves no doubt that Ashoka was a follower of Buddhism. In this edict, he calls himself an upasaka (a lay follower of Buddhism) and a sakya (i.e. Buddhist, after Gautama Buddha's title Shakya-Muni).[154] This and several other edicts are evidence of his Buddhist affiliation:[155]

- In his Minor Rock Edict 1, Ashoka adds that he did not make much progress for a year after becoming an upasaka, but then, he "went to" the Sangha, and made more progress. It is not certain what "going to" the Sangha means – the Buddhist tradition that he lived with monks may be an exaggeration, but it clearly means that Ashoka was drawn closer to Buddhism.[156]

- In his Minor Rock Edict 3, he calls himself an upasaka, and records his faith in the Buddha and the Sangha.[157][158]

- In the Major Rock Edict 8, he records his visit to Sambodhi (the sacred Bodhi Tree at Bodh Gaya), ten years after his coronation.[158]

- In the Lumbini (Rumminidei) inscription, he records his visit to the Buddha's birthplace, and declares his reverence for the Buddha and the sangha.[81]

- In the Nigalisagar inscription, he records his doubling in size of a stupa dedicated to a former Buddha, and his visit to the site for worship.[120]

- Some of his inscriptions reflect his interest in maintaining the Buddhist sangha.[120]

- The Saru Maru inscription states that Ashoka dispatched the message while travelling to Upunita-vihara in Manema-desha. Although the identity of the destination is not certain, it was obviously a Buddhist monastery (vihara).[159]

Other religions

[edit]A legend in the Buddhist text Vamsatthapakasini states that an Ajivika ascetic invited to interpret a dream of Ashoka's mother had predicted that he would patronise Buddhism and destroy 96 heretical sects.[75] However, such assertions are directly contradicted by Ashoka's own inscriptions. Ashoka's edicts, such as the Rock Edicts 6, 7, and 12, emphasise tolerance of all sects.[160] Similarly, in his Rock Edict 12, Ashoka honours people of all faiths.[161] In his inscriptions, Ashoka dedicates caves to non-Buddhist ascetics, and repeatedly states that both Brahmins and shramanas deserved respect. He also tells people "not to denigrate other sects, but to inform themselves about them".[156]

In fact, there is no evidence that Buddhism was a state religion under Ashoka.[162] None of Ashoka's extant edicts record his direct donations to the Buddhists. One inscription records donations by his Queen Karuvaki, while the emperor is known to have donated the Barabar Caves to the Ajivikas.[163] There are some indirect references to his donations to Buddhists. For example, the Nigalisagar Pillar inscription records his enlargement of the Konakamana stupa.[164] Similarly, the Lumbini (Rumminidei) inscription states that he exempted the village of Buddha's birth from the land tax, and reduced the revenue tax to one-eighth.[165]

Ashoka appointed the dhamma-mahamatta officers, whose duties included the welfare of various religious sects, including the Buddhist sangha, Brahmins, Ajivikas, and Nirgranthas. The Rock Edicts 8 and 12, and the Pillar Edict 7, mandate donations to all religious sects.[166]

Ashoka's Minor Rock Edict 1 contains the phrase "amissā devā". According to one interpretation, the term "amissā" derives from the word "amṛṣa" ("false"), and thus, the phrase is a reference to Ashoka's belief in "true" and "false" gods. However, it is more likely that the term derives from the word "amiśra" ("not mingled"), and the phrase refers to celestial beings who did not mingle with humans. The inscription claims that the righteousness generated by adoption of dhamma by the humans attracted even the celestial gods who did not mingle with humans.[167]

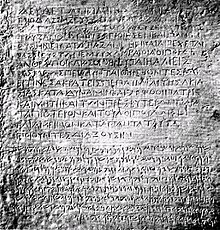

Dharma

[edit]Ashoka's various inscriptions suggest that he devoted himself to the propagation of "Dharma" (Pali: Dhamma), a term that refers to the teachings of Gautama Buddha in the Buddhist circles.[168] However, Ashoka's own inscriptions do not mention Buddhist doctrines such as the Four Noble Truths or Nirvana.[81] The word "Dharma" has various connotations in the Indian religions, and can be generally translated as "law, duty, or righteousness".[168] In the Kandahar inscriptions of Ashoka, the word "Dharma" has been translated as eusebeia (Greek) and qsyt (Aramaic), which further suggests that his "Dharma" meant something more generic than Buddhism.[153]

The inscriptions suggest that for Ashoka, Dharma meant "a moral polity of active social concern, religious tolerance, ecological awareness, the observance of common ethical precepts, and the renunciation of war."[168] For example:

- Abolition of the death penalty (Pillar Edict IV)[156]

- Plantation of banyan trees and mango groves, and construction of resthouses and wells, every 800 metres (1⁄2 mile) along the roads. (Pillar Edict 7).[161]

- Restriction on killing of animals in the imperial kitchen (Rock Edict 1); [161] the number of animals killed was limited to two peacocks and a deer daily, and in future, even these animals were not to be killed.[156]

- Provision of medical facilities for humans and animals (Rock Edict 2).[161]

- Encouragement of obedience to parents, "generosity toward priests and ascetics, and frugality in spending" (Rock Edict 3).[161]

- He "commissions officers to work for the welfare and happiness of the poor and aged" (Rock Edict 5)[161]

- Promotion of "the welfare of all beings so as to pay off his debt to living creatures and to work for their happiness in this world and the next." (Rock Edict 6)[161]

Modern scholars have variously understood this dhamma as a Buddhist lay ethic, a set of politico-moral ideas, a "sort of universal religion", or as an Ashokan innovation. On the other hand, it has also been interpreted as an essentially political ideology that sought to knit together a vast and diverse empire.[10]

Ashoka instituted a new category of officers called the dhamma-mahamattas, who were tasked with the welfare of the aged, the infirm, the women and children, and various religious sects. They were also sent on diplomatic missions to the Hellenistic kingdoms of west Asia, in order to propagate the dhamma.[166]

Historically, the image of Ashoka in the global Buddhist circles was based on legends (such as those mentioned in the Ashokavadana) rather than his rock edicts. This was because the Brahmi script in which these edicts were written was forgotten soon and remained undeciphered until its study by James Prinsep in the 19th century.[169] The writings of the Chinese Buddhist pilgrims such as Faxian and Xuanzang suggest that Ashoka's inscriptions mark the important sites associated with Gautama Buddha. These writers attribute Buddhism-related content to Ashoka's edicts, but this content does not match with the actual text of the inscriptions as determined by modern scholars after the decipherment of the Brahmi script. It is likely that the script was forgotten by the time of Faxian, who probably relied on local guides; these guides may have made up some Buddhism-related interpretations to gratify him, or may have themselves relied on faulty translations based on oral traditions. Xuanzang may have encountered a similar situation, or may have taken the supposed content of the inscriptions from Faxian's writings.[170] This theory is corroborated by the fact that some Brahmin scholars are known to have similarly come up with a fanciful interpretation of Ashoka pillar inscriptions, when requested to decipher them by the 14th century Muslim Tughlaq emperor Firuz Shah Tughlaq. According to Shams-i Siraj's Tarikh-i Firoz Shahi, after the king had these pillar transported from Topra and Mirat to Delhi as war trophies, these Brahmins told him that the inscriptions prophesied that nobody would be able to remove the pillars except a king named Firuz. Moreover, by this time, there were local traditions that attributed the erection of these pillars to the legendary hero Bhima.[171]

According to scholars such as Richard Gombrich, Ashoka's dharma shows Buddhist influence. For example, the Kalinga Separate Edict I seems to be inspired by Buddha's Advice to Sigala and his other sermons.[156]

Animal welfare

[edit]Ashoka's rock edicts declare that injuring living things is not good, and no animal should be slaughtered for sacrifice.[172] However, he did not prohibit common cattle slaughter or beef eating.[173]

He imposed a ban on killing of "all four-footed creatures that are neither useful nor edible", and of specific animal species including several birds, certain types of fish and bulls among others. He also banned killing of female goats, sheep and pigs that were nursing their young; as well as their young up to the age of six months. He also banned killing of all fish and castration of animals during certain periods such as Chaturmasa and Uposatha.[174][175]

Ashoka also abolished the imperial hunting of animals and restricted the slaying of animals for food in the imperial residence.[176] Because he banned hunting, created many veterinary clinics and eliminated meat eating on many holidays, the Mauryan Empire under Ashoka has been described as "one of the very few instances in world history of a government treating its animals as citizens who are as deserving of its protection as the human residents".[177]

Foreign relations

[edit]

It is well known that Ashoka sent dütas or emissaries to convey messages or letters, written or oral (rather both), to various people. The VIth Rock Edict about "oral orders" reveals this. It was later confirmed that it was not unusual to add oral messages to written ones, and the content of Ashoka's messages can be inferred likewise from the XIIIth Rock Edict: They were meant to spread his dhammavijaya, which he considered the highest victory and which he wished to propagate everywhere (including far beyond India). There is obvious and undeniable trace of cultural contact through the adoption of the Kharosthi script, and the idea of installing inscriptions might have travelled with this script, as Achaemenid influence is seen in some of the formulations used by Ashoka in his inscriptions. This indicates to us that Ashoka was indeed in contact with other cultures, and was an active part in mingling and spreading new cultural ideas beyond his own immediate walls.[180]

Hellenistic world

[edit]In his rock edicts, Ashoka states that he had encouraged the transmission of Buddhism to the Hellenistic kingdoms to the west and that the Greeks in his dominion were converts to Buddhism and recipients of his envoys:

Теперь это завоевано Дхаммой, что любимые боги считают лучшим завоеванием. И это (завоевание Дхаммы) было выиграно здесь, на границах, даже в шести сотнях йоджан, где правила греческого короля Антиохоса , за пределами там, где четыре царя по имени Птолемей , Антигоны , Магас и Александер Правительство, также на юге среди среди среди Чолас, Пандия, и до Тамрапарни. Здесь, в домене короля, среди греков, Камбоджас, Набхаки, Набхапамктис, Бходжас, Питиники, Андхры и Палидас, везде люди следят за инструкциями любимых богов в Дхамме. Даже там, где посланники любимых богов тоже не были, эти люди, услышав о практике Дхаммы и таинствах и инструкциях в Дхамме, данных любимыми богами, следуют за ним и будут продолжать Сделай это.

Возможно, но не уверен, что Ашока получила письма от греческих правителей и был знаком с эллинистическими королевскими орденами так же, как он, возможно, знал о надписях ахеменидных королей, учитывая присутствие послов эллинистических королей в Индии (Индия (Индия (Индия (Индия ( а также Дюты , отправленные самим Ашокой). [ 180 ] Сообщается, что Дионисий был таким греческим послом в дворе Ашоки, отправленный Птолемей II Филадельфус , [ 182 ] который сам упоминается в «Эдиктах Ашоки» как получатель буддийского прозелитизма Ашоки. Некоторые эллинистические философы, такие как Hegesias из Кирена , которые, вероятно, жили под правлением короля Магаса , одного из предполагаемых получателей буддийских эмиссаров из Ашоки, иногда считают, что буддийские учения. [ 183 ]

Греки в Индии, похоже, даже сыграли активную роль в распространении буддизма, поскольку некоторые из эмиссаров Ашоки, таких как Дхармараксита , описываются в источниках пали как ведущие греческие ( Йону ) буддийские монахи, активные в распространении буддизма (The Махавамса , XII). [ 184 ]

Некоторые греки (явана), возможно, сыграли административную роль на территориях, которым управляет Ашока. Гиннарская надпись Рудрадамана записывает, что во время правления Ашоки губернатор Яваны отвечал в районе Гиннара , Гуджарат , упомянув его роль в строительстве водохранилища. [ 185 ]

Считается, что дворец Ашоки в Патне был смоделирован после Ахеменидского дворца Персеполиса . [ 186 ]

Легенды о прошлой жизни

[ редактировать ]

Буддийские легенды упоминают истории о прошлых жизнях Ашоки. Согласно истории Махавамсы , Ашока, Ниграда и Девнампия Тисаса были братьями в прошлой жизни. В этой жизни Пратиекабудда искал мед, чтобы вылечить другого, больного Пратиекабудха. Женщина направила его в магазин с медом, принадлежащий трем братьям. Ашока щедро пожертвовал меда Пратиекабуддхе и хотела стать суверенным правителем Джамбудвипы для этого акта заслуг. [ 187 ] Женщина хотела стать его королевой и возродилась как жена Ашока Асандхамитта. [ 140 ] Позднее Пали тексты почитают ее дополнительным актом заслуг: она подарила Pratyekabuddha кусок ткани, сделанный ею. Эти тексты включают Dasavatthuppakarana , так называемую камбоджийскую или расширенную махавамсу (возможно, с 9 по 10 веков) и Trai Bhumi Katha (15 век). [ 141 ]

Согласно истории Ашокавадана , Ашока родилась как Джая в выдающейся семье Раджагриха. Когда он был маленьким мальчиком, он дал грязь Гаутамы Будды, воображая, что это еда. Будда одобрил пожертвование, и Джая заявил, что он станет королем в соответствии с этим актом заслуг. В тексте также говорится, что спутник Джая Виджая возродился в качестве главного министерства Ашоки Радхагупта. [ 188 ] В более поздней жизни буддийский монк Упагупта говорит Ашоке, что его грубая кожа была вызвана нечистым даром грязи в предыдущей жизни. [ 130 ] Некоторые более поздние тексты повторяют эту историю, не упомянув негативные последствия подарка грязи; Кумаралаты Эти тексты включают Кальпана-Мандитика Арьяшуры , Джатака-Мала и Маха-Карма-Вибхага . Китайский писатель Pao Ch'eng's Shih Chia Ju Lai Ying Hua Lu утверждает, что незначительный поступка, подобный дару грязи, не мог быть достаточно заслуженным, чтобы вызвать будущее величие Ашоки. Вместо этого текст утверждает, что в другой прошлой жизни Ашока заказала большое количество статуй Будды как король, и этот акт заслуг заставил его стать великим императором в следующей жизни. [ 189 ]

Сказья на языке паликанья 14-го века Дасаваттуппакарана (возможно, из C. 14-го века ) сочетает в себе истории о дар купца медового и дар мультяни. В нем рассказывается немного другая версия истории Махавамсы , заявляя, что она произошла до рождения Будды Гаутамы. Затем говорится, что торговец возродился как мальчик, который подарил грязь Будде; Однако в этом случае Будда его сопровождающего в Ананде создает штукатурку из грязи, которая используется ремонтные трещины в стенах монастыря. [ 190 ]

В последние годы

[ редактировать ]Борьба как императрица

[ редактировать ]Последняя устаревшая надпись Ашоки - указатель 4 столба от его 26 -го года. [ 118 ] Единственный источник информации о более поздних годах Ашоки - буддийские легенды. Шри -ланкийская традиция гласит, что императрица Ашоки Асандхамитта умер в течение его 29 -го года, и в его 32 -м решающем году его жене Мисараккха получила титул императрицы. [ 118 ]

Как Махавамса , так и Ашокавадана утверждают, что Ашока расширила услуги и внимание к дереву Бодхи , а ревнивая Тисараккха приняла «Бодхи» за любовницу Ашоки. Затем она использовала черную магию, чтобы сделать дерево. [ 191 ] Согласно Ашокавадане , она наняла колдунья для выполнения работы, и когда Ашока объяснила, что «Бодхи» был названием дерева, она заставила колдунья исцелить дерево. [ 192 ] Согласно Махавамсе , она полностью уничтожила дерево, [ 193 ] Во время 34 -го года Редлента Ашоки. [ 118 ]

Ашокавадана утверждает , что Мисараккха (называемый «Тишаракшита» здесь) сделал сексуальные достижения в отношении сына Ашоки Кунала, но Кунала отверг ее. Впоследствии Ашока предоставила Императорству Мисаракки в течение семи дней, и в этот период она пылала и ослепила Кунала. [ 144 ] Затем Ашока угрожала «вырвать глаза, разорвать ее тело острыми границами, пробивать ее живым на косе, отрезать нос пилой, вырезать язык бритвой». Кунала чудесным образом восстановил зрение и умолял о пощаде за императрицу, но Ашока все равно казнила. [ 191 ] Кшемендры Авадана-кальпа-лата также рассказывает эту легенду, но стремится улучшить образ Ашоки, заявив, что он простил императрицу после того, как Кунала восстановил свое зрение. [ 194 ]

Смерть

[ редактировать ]Согласно традиции Шри -Ланки, Ашока умер во время своего 37 -го года, [ 118 ] что предполагает, что он умер около 232 г. до н.э. [ 195 ]

Согласно Ашокавадане , император заболел сильно болен в последние дни. Он начал использовать государственные средства, чтобы сделать пожертвования в буддийскую Сангху, побуждая своих министров отказать ему в доступе к государственной казначейству. Затем Ашока начал пожертвовать свои личные имущества, но также был ограничен от этого. На смертном одре его единственным владением была половина миробаланского фрукта , который он предложил Сангхе в качестве последнего пожертвования. [ 196 ] Такие легенды поощряют щедрые пожертвования для Сангхи и подчеркивают роль Императорства в поддержке буддийской веры. [ 47 ]

Легенда утверждает, что во время его кремации его тело горело в течение семи дней и ночей. [ 197 ]

Наследие

[ редактировать ]Во время его правления империя Маурья стала одной из самых больших империй в мире с точки зрения области, экономики и военных. Достижения в области науки и образования сделали период Маурья золотым веком Индии . [ Цитация необходима ]

Архитектура

[ редактировать ]Помимо различных стулей, приписываемых Ашоке, устанавливаемые им колонны выживают в разных местах индийского субконтинента.

Ашоке часто приписывают начало каменной архитектуры в Индии, что, возможно, после введения каменных техник греков в честь Александра Великого . [ 198 ] До времен Ашоки здания, вероятно, были построены в непостоянном материале, таком как дерево, бамбук или сот . [ 198 ] [ 199 ] Ашока, возможно, восстановил свой дворец в Паталипутре , заменив деревянный материал на камне, [ 200 ] и мог также использовать помощь иностранных ремесленников. [ 201 ] Ашока также внедрировал, используя постоянные качества камня для своих письменных указов , а также свои колонны с буддийской символикой.

-

Алмазный трон в храме Махабодхи , приписываемый Ашоке

-

Передний фриз алмаза трона

-

Маурен Рингстоун , с стоящей богиней. Северо -западный Пакистан. 3 -й век до н.э. Британский музей

-

Рампурва Булл Столичный , деталь абакуса , с двумя «пламенными пальмтками», обрамляющими лотос, окруженный небольшими цветами розетки.

Символы

[ редактировать ]Ашоканские столицы были очень реалистичными и использовали характерную полированную отделку, лак Маурьян , придавая блестящему появлению на каменной поверхности. [ 202 ] Столица Lion of Ashoka , столица одного из столпов, установленных Ashoka, содержит резьбу из спикера, известного как Ashoka Chakra . Это колесо представляет собой колесо Дхаммы, приведенное в движении Буддой Гаутамы, и появляется на флаге современной Индии. В этой столице также есть скульптуры львов, которые появляются на печать Индии. [ 151 ]

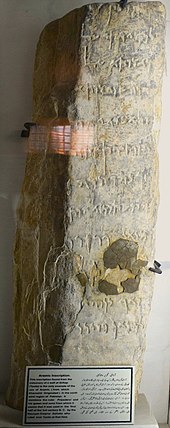

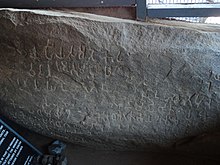

Надписи

[ редактировать ]

Эдикты Ашоки представляют собой коллекцию из 33 надписей на столпах Ашоки , а также валуны и стены пещеры, выпущенные во время его правления. [ 202 ] Эти надписи рассеяны по всему современному Пакистану и Индии и представляют собой первое ощутимое доказательство буддизма. Эдии подробно описывают первое широкое расширение буддизма посредством спонсорства одного из самых влиятельных королей истории индийской истории, предлагая больше информации о проселитизме Ашоки, моральных заповедях, религиозных заповеди и его представлениях о социальном и благополучии животных. [ 204 ]

Перед Ашокой королевские сообщения, по -видимому, были написаны на скоропортящихся материалах, таких как пальмовые листья, березовые лаки, хлопчатобумажная ткань и, возможно, деревянные доски. В то время как администрация Ашоки продолжала бы использовать эти материалы, Ашока также написал свои сообщения на скальцевых направлениях. [ 205 ] Ашока, вероятно, получила идею поставить эти надписи из соседней империи Ахеменидов . [ 156 ] Вполне вероятно, что сообщения Ашоки также были надписаны на более скоропортящиеся материалы, такие как древесина, и отправлены в различные части империи. Ни одна из этих записей не сохранится сейчас. [ 13 ]

Ученые по -прежнему пытаются проанализировать как выраженные, так и подразумеваемые политические идеи эдии (особенно в отношении имперского видения), и сделать выводы, относящиеся к тому, как это видение сталкивается с проблемами и политическими реалиями «практически субконтинентальных и культурных и экономически экономически Высоко разнообразной, индийской империи 3 -го века. [ 9 ] Тем не менее, остается ясным, что надписи Ашоки представляют собой самый ранний корпус королевских надписей на индийском субконтиненте, и, следовательно, оказываются очень важными инновациями в королевских практиках ». [ 204 ]

Большинство надписей Ашоки написаны в смеси различных пракритских диалектов, в сценарии Брахми . [ 206 ]

Несколько надписей Ашоки, по -видимому, были созданы рядом с городами, на важных маршрутах и в местах религиозного значения. [ 207 ] Многие из надписей были обнаружены на холмах, каменных укрытиях и местах местного значения. [ 208 ] Были выдвинуты различные теории о том, почему Ашока или его чиновники выбрали такие места, в том числе то, что они были центрами мегалитических культур, [ 209 ] считались священными пятнами во времена Ашоки или что их физическое величие может быть символом духовного доминирования. [ 210 ] Надписи Ашоки не были обнаружены в крупных городах империи Маурья, таких как Паталипутра, Видиша, Уджайнини и Таксила. [ 208 ] Возможно, что многие из этих надписей потеряны; Китайский паломник 7 -го века Сюансанг относится к некоторым из указов Ашоки, которые не были обнаружены современными исследователями. [ 207 ]

Похоже, что Ашока отправила каждое сообщение своим губернаторам провинции, которые, в свою очередь, передали его различным чиновникам на своей территории. [ 211 ] Например, второстепенный рок -эдикт 1 появляется в нескольких версиях в нескольких местах: все версии утверждают, что Ашока выпустила прокламацию во время тура, проведя 256 дней в туре. Число 256 указывает, что сообщение было отправлено одновременно в различные места. [ 212 ] Три версии сообщения, найденные в Эдиктах в соседних местах в штате Карнатака (Брахмагири, Сиддапура и Джатинга-Рамешвара), были отправлены из столицы южной провинции в различных местах. Все три версии содержат одно и то же послание, в котором предшествует первоначальное приветствие от Арья-Путра (предположительно сына Ашоки и губернатора провинции) и махаматров (чиновников) в Суварнагири. [ 211 ]

Монет

[ редактировать ]Caduceus . появляется как символ маркированных монет империи Маурья в Индии, в 3-м-2 веке до нашей эры Нумизматические исследования показывают, что этот символ был символом императора Ашоки, его личной « мудры ». [ 213 ] Этот символ не использовался не на монетах с маркированным домарьеном, но только на монетах периода Маурья, вместе с тремя арочными хиллыми символом , «павлином на холме», Трискелис и отметка Таньила . [ 214 ]

-

в эпоху Маурья Символ Caduceus на монете, отмеченной

-

Монета с маркировкой, приписываемая Ashoka [ 215 ]