Reading

| Part of a series on |

| Reading |

|---|

|

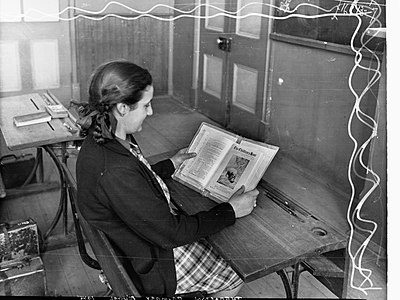

Reading is the process of taking in the sense or meaning of letters, symbols, etc., especially by sight or touch.[1][2][3][4]

For educators and researchers, reading is a multifaceted process involving such areas as word recognition, orthography (spelling), alphabetics, phonics, phonemic awareness, vocabulary, comprehension, fluency, and motivation.[5][6]

Other types of reading and writing, such as pictograms (e.g., a hazard symbol and an emoji), are not based on speech-based writing systems.[7] The common link is the interpretation of symbols to extract the meaning from the visual notations or tactile signals (as in the case of braille).[8]

Overview[edit]

Reading is generally an individual activity, done silently, although on occasion a person reads out loud for other listeners; or reads aloud for one's own use, for better comprehension. Before the reintroduction of separated text (spaces between words) in the late Middle Ages, the ability to read silently was considered rather remarkable.[10][11]

Major predictors of an individual's ability to read both alphabetic and non-alphabetic scripts are oral language skills,[12] phonological awareness, rapid automatized naming and verbal IQ.[13]

As a leisure activity, children and adults read because it is enjoyable and interesting. In the US, about half of all adults read one or more books for pleasure each year.[14] About 5% read more than 50 books per year.[14] Americans read more if they: have more education, read fluently and easily, are female, live in cities, and have higher socioeconomic status.[14] Children become better readers when they know more about the world in general, and when they perceive reading as fun rather than as a chore to be performed.[14]

Reading vs. literacy[edit]

Reading is an essential part of literacy, yet from a historical perspective literacy is about having the ability to both read and write.[15][16][17][18]

Since the 1990s, some organizations have defined literacy in a wide variety of ways that may go beyond the traditional ability to read and write. The following are some examples:

- "the ability to read and write ... in all media (print or electronic), including digital literacy"[19]

- "the ability to ... understand ... using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts"[20][21][22]

- "the ability to read, write, speak and listen"[23]

- "having the skills to be able to read, write and speak to understand and create meaning"[24]

- "the ability to ... communicate using visual, audible, and digital materials"[25][26]

- "the ability to use printed and written information to function in society, to achieve one's goals, and to develop one's knowledge and potential".[27] It includes three types of adult literacy: prose (e.g., a newspaper article), documents (e.g., a bus schedule), and quantitative literacy (e.g., using arithmetic operations in a product advertisement).[28][29]

In the academic field, some view literacy in a more philosophical manner and propose the concept of "multiliteracies". For example, they say, "this huge shift from traditional print-based literacy to 21st century multiliteracies reflects the impact of communication technologies and multimedia on the evolving nature of texts, as well as the skills and dispositions associated with the consumption, production, evaluation, and distribution of those texts (Borsheim, Meritt, & Reed, 2008, p. 87)".[30][31] According to cognitive neuroscientist Mark Seidenberg these "multiple literacies" have allowed educators to change the topic from reading and writing to "Literacy". He goes on to say that some educators, when faced with criticisms of how reading is taught, "didn't alter their practices, they changed the subject".[32]

Also, some organizations might include numeracy skills and technology skills separately but alongside of literacy skills.[33]

In addition, since the 1940s the term literacy is often used to mean having knowledge or skill in a particular field (e.g., computer literacy, ecological literacy, health literacy, media literacy, quantitative literacy (numeracy)[29] and visual literacy).[34][35][36][37]

Writing systems[edit]

In order to understand a text, it is usually necessary to understand the spoken language associated with that text. In this way, writing systems are distinguished from many other symbolic communication systems.[38] Once established, writing systems on the whole change more slowly than their spoken counterparts, and often preserve features and expressions which are no longer current in the spoken language. The great benefit of writing systems is their ability to maintain a persistent record of information expressed in a language, which can be retrieved independently of the initial act of formulation.[38]

Cognitive benefits[edit]

Reading for pleasure has been linked to increased cognitive progress in vocabulary and mathematics during adolescence.[39][40] Sustained high volume lifetime reading has been associated with high levels of academic attainment.[41]

Research suggests that reading can improve stress management,[42] memory,[42] focus,[43] writing skills,[43] and imagination.[44]

The cognitive benefits of reading continue into mid-life and the senior years.[45][46][47]

Research suggests that reading books and writing are among the brain-stimulating activities that can slow down cognitive decline in seniors.[48]

State of reading achievement[edit]

Reading has been the subject of considerable research and reporting for decades. Many organizations measure and report on reading achievement for children and adults (e.g., NAEP, PIRLS, PISA PIAAC, and EQAO).

Researchers have concluded that approximately 95% of students can be taught to read by the end of the first or second year of school, yet in many countries 20% or more do not meet that expectation.[49][50]

A 2012 study in the U.S. found that 33% of grade three children had low reading scores – however, they comprised 63% of the children who did not graduate from high school. Poverty also had an additional negative impact on high school graduation rates.[51]

According to the 2019 Nation's Report card, 34% of grade four students in the United States failed to perform at or above the Basic reading level. There was a significant difference by race and ethnicity (e.g., black students at 52% and white students at 23%). After the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic the average basic reading score dropped by 3% in 2022.[52] See more about the breakdown by ethnicity in 2019 and 2022 here. According to a 2023 study in California, many teenagers who've spent time in California's juvenile detention facilities get high school diplomas with grade-school reading skills. "There are kids getting their high school diplomas who aren't able to even read and write." During a five-year span beginning in 2018, 85% of these students who graduated from high school did not pass a 12th-grade reading assessment.[53]

Between 2013 and 2024, 37 US States passed laws or implemented new policies related to evidence-based reading instruction.[54] In 2023, New York City set about to require schools to teach reading with an emphasis on phonics. In that city, less than half of the students from the third grade to the eighth grade of school scored as proficient on state reading exams. More than 63% of Black and Hispanic test-takers did not make the grade.[55]

Globally, the COVID-19 pandemic created a substantial overall learning deficit in reading abilities and other academic areas. It arose early in the pandemic and persists over time, and is particularly large among children from low socio-economic backgrounds.[56][57] In the US, several research studies show that, in the absence of additional support, there is nearly a 90 percent chance that a poor reader in Grade 1 will remain a poor reader.[58]

In Canada, the province of Ontario reported that 27% of grade three students did not meet the provincial reading standards in 2023.[59] Also in Ontario, 53% of grade three students with special education needs (students who have an Individual Education Plan), were not meeting the provincial standards in 2022.[60] The province of Nova Scotia reported that 32% of grade three students did not meet the provincial reading standards in 2022.[61] The province of New Brunswick reported that 43.4% and 30.7% did not meet the Reading Comprehension Achievement Levels for grades four and six respectively in 2023.[62]

The Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) publishes reading achievement for fourth graders in 50 countries.[63] The five countries with the highest overall reading average are the Russian Federation, Singapore, Hong Kong SAR, Ireland and Finland. Some others are: England 10th, United States 15th, Australia 21st, Canada 23rd, and New Zealand 33rd.[64][65][66]

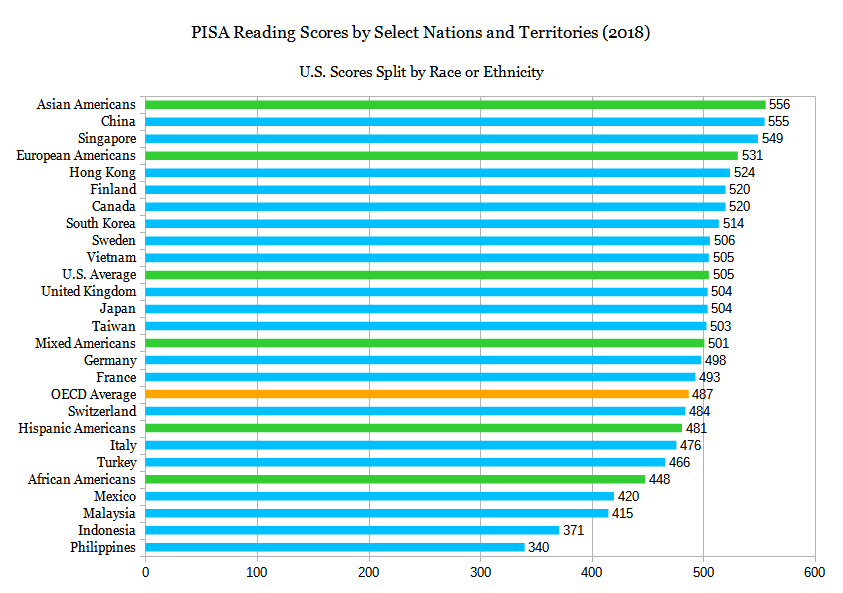

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) measures 15-year-old school pupils scholastic performance on mathematics, science, and reading.[67] Critics, however, say PISA is fundamentally flawed in its underlying view of education, its implementation, and its interpretation and impact on education globally.[68][69][70]

The reading levels of adults, ages 16–65, in 39 countries are reported by the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC).[71] Between 2011 and 2018, PIAAC reports the percentage of adults reading at-or-below level one (the lowest of five levels). Some examples are Japan 4.9%, Finland 10.6%, Netherlands 11.7%, Australia 12.6%, Sweden 13.3%, Canada 16.4%, England (UK) 16.4%, and the United States 16.9%.[72]

According to the World Bank, 53% of all children in low-and-middle-income countries suffer from 'learning poverty'. In 2019, using data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, they published a report entitled Ending Learning Poverty: What will it take?.[73] Learning poverty is defined as being unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10.

Although they say that all foundational skills are important, include reading, numeracy, basic reasoning ability, socio-emotional skills, and others – they focus specifically on reading. Their reasoning is that reading proficiency is an easily understood metric of learning, reading is a student's gateway to learning in every other area, and reading proficiency can serve as a proxy for foundational learning in other subjects.

They suggest five pillars to reduce learning poverty:

- Learners are prepared and motivated to learn

- Teachers at all levels are effective and valued

- Classrooms are equipped for learning

- Schools are safe and inclusive spaces, and

- Education systems are well-managed.

Learning to read[edit]

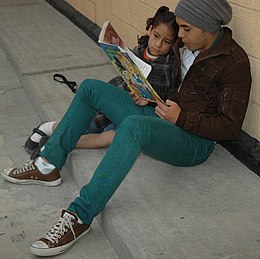

Learning to read or reading skills acquisition is the acquisition and practice of the skills necessary to understand the meaning behind printed words. For a skilled reader, the act of reading feels simple, effortless, and automatic.[74] However, the process of learning to read is complex and builds on cognitive, linguistic, and social skills developed from a very early age. As one of the four core language skills (listening, speaking, reading and writing),[75][76] reading is vital to gaining a command of written language.

In the United States and elsewhere, it is widely believed that students who lack proficiency in reading by the end of grade three may face obstacles for the rest of their academic career.[77][78][79] For example, it is estimated that they would not be able to read half of the material they will encounter in grade four.[80]

In 2019, among American fourth-graders in public schools, only 58% of Asian, 45% of Caucasian, 23% of Hispanic, and 18% of Black students performed at or above the proficient level of the Nation's Report Card.[81] Also, in 2012, in the United Kingdom it has been reported that 15-year-old students are reading at the level expected of 12-year-old students.[82]

As a result, many governments put practices in place to ensure that students are reading at grade level by the end of grade three. An example of this is the Third Grade Reading Guarantee created by the State of Ohio in 2017. This is a program to identify students from kindergarten through grade three that are behind in reading, and provide support to make sure they are on track for reading success by the end of grade three.[83][84] This is also known as remedial education. Another example is the policy in England whereby any pupil who is struggling to decode words properly by year three must "urgently" receive help through a "rigorous and systematic phonics programme".[85]

In 2016, out of 50 countries, the United States achieved the 15th highest score in grade-four reading ability.[86] The ten countries with the highest overall reading average are the Russian Federation, Singapore, Hong Kong SAR, Ireland, Finland, Poland, Northern Ireland, Norway, Chinese Taipei and England (UK). Some others are: Australia (21st), Canada (23rd), New Zealand (33rd), France (34th), Saudi Arabia (44th), and South Africa (50th).

Spoken language: the foundation of reading[edit]

Spoken language is the foundation of learning to read (long before children see any letters) and children's knowledge of the phonological structure of language is a good predictor of early reading ability. Spoken language is dominant for most of childhood; however, reading ultimately catches up and surpasses speech.[87][88][89][90]

By their first birthday most children have learned all the sounds in their spoken language. However, it takes longer for them to learn the phonological form of words and to begin developing a spoken vocabulary.[12]

Children acquire a spoken language in a few years. Five-to-six-year-old English learners have vocabularies of 2,500 to 5,000 words, and add 5,000 words per year for the first several years of schooling. This rapid learning rate cannot be accounted for by the instruction they receive. Instead, children learn that the meaning of a new word can be inferred because it occurs in the same context as familiar words (e.g., lion is often seen with cowardly and king).[91] As British linguist John Rupert Firth says, "You shall know a word by the company it keeps".

The environment in which children live may also impact their ability to acquire reading skills. Children who are regularly exposed to chronic environmental noise pollution, such as highway traffic noise, have been known to show decreased ability to discriminate between phonemes (oral language sounds) as well as lower reading scores on standardized tests.[92]

Reading to children: necessary but not sufficient[edit]

Children learn to speak naturally – by listening to other people speak. However, reading is not a natural process, and many children need to learn to read through a process that involves "systematic guidance and feedback".[95][96][97][98]

So, "reading to children is not the same as teaching children to read".[99] Nonetheless, reading to children is important because it socializes them to the activity of reading; it engages them; it expands their knowledge of spoken language; and it enriches their linguistic ability by hearing new and novel words and grammatical structures.

However, there is some evidence that "shared reading" with children does help to improve reading if the children's attention is directed to the words on the page as they are being read to.[93][94]

Stages to skilled reading[edit]

The path to skilled reading involves learning the alphabetic principle, phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension.[100]

British psychologist Uta Frith introduced a three stages model to acquire skilled reading. Stage one is the logographic or pictorial stage where students attempt to grasp words as objects, an artificial form of reading. Stage two is the phonological stage where students learn the relationship between the graphemes (letters) and the phonemes (sounds). Stage three is the orthographic stage where students read familiar words more quickly than unfamiliar words, and word length gradually ceases to play a role.[101]

Optimum age for learning[edit]

There is some debate as to the optimum age to teach children to read.

The Common Core State Standards Initiative (CCSS) in the United States has standards for foundational reading skills in kindergarten and grade one that include instruction in print concepts, phonological awareness, phonics, word recognition and fluency.[102] However, some critics of CCSS say that "To achieve reading standards usually calls for long hours of drill and worksheets – and reduces other vital areas of learning such as math, science, social studies, art, music and creative play".[103]

The PISA 2007 OECD data from 54 countries demonstrates "no association between school entry age ... and reading achievement at age 15".[104] Also, a German study of 50 kindergartens compared children who, at age 5, had spent a year either "academically focused", or "play-arts focused" and found that in time the two groups became inseparable in reading skill.[105] The authors conclude that the effects of early reading are like "watering a garden before a rainstorm; the earlier watering is rendered undetectable by the rainstorm, the watering wastes precious water, and the watering detracts the gardener from other important preparatory groundwork".[104]

Some scholars favor a developmentally appropriate practice (DPA) in which formal instruction on reading begins when children are about six or seven years old. And to support that theory some point out that children in Finland start school at age seven (Finland ranked 5th in the 2016 PIRLS international grade four reading achievement.)[106] In a discussion on academic kindergartens, professor of child development David Elkind has argued that, since "there is no solid research demonstrating that early academic training is superior to (or worse than) the more traditional, hands-on model of early education", educators should defer to developmental approaches that provide young children with ample time and opportunity to explore the natural world on their own terms.[107] Elkind emphasized the principle that "early education must start with the child, not with the subject matter to be taught".[107] In response, Grover J. Whitehurst, Director, Brown Center on Education Policy, (part of Brookings Institution)[108] said David Elkind is relying too much on philosophies of education rather than science and research. He continues to say education practices are "doomed to cycles of fad and fancy" until they become more based on evidence-based practice.[109]

On the subject of Finland's academic results, as some researchers point out, prior to starting school Finnish children must participate in one year of compulsory free pre-primary education and most are reading before they start school.[110][111] And, with respect to developmentally appropriate practice (DPA), in 2019 the National Association for the Education of Young Children, Washington, D.C., released a draft position paper on DPA saying "The notion that young children are not ready for academic subject matter is a misunderstanding of developmentally appropriate practice; particularly in grades 1 through 3, almost all subject matter can be taught in ways that are meaningful and engaging for each child".[112] And, researchers at The Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential say it is a myth that early readers are bored or become trouble makers in school.[113]

Other researchers and educators favor limited amounts of literacy instruction at the age of four and five, in addition to non-academic, intellectually stimulating activities.[114]

Reviews of the academic literature by the Education Endowment Foundation in the UK have found that starting literacy teaching in preschool has "been consistently found to have a positive effect on early learning outcomes"[115] and that "beginning early years education at a younger age appears to have a high positive impact on learning outcomes".[116] This supports current standard practice in the UK which includes developing children's phonemic awareness in preschool and teaching reading from age four.

A study in Chicago reports that an early education program for children from low-income families is estimated to generate $4 to $11 of economic benefits over a child's lifetime for every dollar spent initially on the program, according to a cost-benefit analysis funded by the National Institutes of Health. The program is staffed by certified teachers and offers "instruction in reading and math, group activities and educational field trips for children ages 3 through 9".[117][118]

There does not appear to be any definitive research about the "magic window" to begin reading instruction.[111] However, there is also no definitive research to suggest that starting early causes any harm. Researcher and educator Timothy Shanahan, suggests, "Start teaching reading from the time you have kids available to teach, and pay attention to how they respond to this instruction – both in terms of how well they are learning what you are teaching, and how happy and invested they seem to be. If you haven't started yet, don't feel guilty, just get going".[111]

Reading instruction by grade level[edit]

Some education researchers suggest the teaching of the various reading components by specific grade levels.[119] The following is one example from Carol Tolman, Ed.D. and Louisa Moats, Ed.D. that corresponds in many respects with the United States Common Core State Standards Initiative:[102]

| Reading instruction component | Tolman & Moats | US Common Core |

|---|---|---|

| Phonological awareness | K–1 | K–1 |

| Basic phonics | K–1 | K–1 |

| Vocabulary | K–6+ | K–6+ |

| Comprehension | K–6+ | K–6+ |

| Written expression | 1–6+ | K–6+ |

| Fluency | 1–3 | 1–5 |

| Advanced phonics/decoding | 2–6+ | 2–5 |

Reading development[edit]

According to some researchers, learners (children and adults) progress through several stages while first learning to read in English, and then refining their reading skills. One of the recognized experts in this area is Harvard professor Jeanne Sternlicht Chall. In 1983 she published a book entitled Stages of Reading Development that proposed six stages.[120][121]

Subsequently, in 2008 Maryanne Wolf, UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, published a book entitled Proust and the Squid in which she describes her view of the following five stages of reading development.[122][123] It is normal that children will move through these stages at different rates; however, typical ages for children in the United States are shown below.

Emerging pre-reader: 6 months to 6 years old[edit]

The emerging pre-reader stage, also known as reading readiness, usually lasts for the first five years of a child's life.[126] Children typically speak their first few words before their first birthday.[127] Educators and parents help learners to develop their skills in listening, speaking, reading and writing.[128]

Reading to children helps them to develop their vocabulary, a love of reading, and phonemic awareness, i.e. the ability to hear and manipulate the individual sounds (phonemes) of oral language. Children will often "read" stories they have memorized. However, in the late 1990s United States' researchers found that the traditional way of reading to children made little difference in their later ability to read because children spend relatively little time actually looking at the text. Yet, in a shared reading program with four-year-old children, teachers found that directing children's attention to the letters and words (e.g. verbally or pointing to the words) made a significant difference in early reading, spelling and comprehension.[129][94][130][131]

Novice reader: 6 to 7 years old[edit]

Novice readers continue to develop their phonemic awareness, and come to realize that the letters (graphemes) connect to the sounds (phonemes) of the language; known as decoding, phonics, and the alphabetic principle.[132] They may also memorize the most common letter patterns and some of the high-frequency words that do not necessarily follow basic phonological rules (e.g. have and who). However, it is a mistake to assume a reader understands the meaning of a text merely because they can decode it. Vocabulary and oral language comprehension are also important parts of text comprehension as described in the Simple view of reading, Scarborough's reading rope, and The active view of reading model. Reading and speech are codependent: reading promotes vocabulary development and a richer vocabulary facilitates skilled reading.[133]

Decoding reader: 7 to 9 years old[edit]

The transition from the novice reader stage to the decoding stage is marked by a reduction of painful pronunciations and in its place the sounds of a smoother, more confident reader.[134] In this phase the reader adds at least 3,000 words to what they can decode. For example, in the English language, readers now learn the variations of the vowel-based rimes (e.g. sat, mat, cat)[135] and vowel pairs (also digraph) (e.g. rain, play, boat)[136]

As readers move forward, they learn the make up of morphemes (i.e. stems, roots, prefixes and suffixes). They learn the common morphemes such as "s" and "ed" and see them as "sight chunks". "The faster a child can see that beheaded is be + head + ed", the faster they will become a more fluent reader.

In the beginning of this stage a child will often be devoting so much mental capacity to the process of decoding that they will have no understanding of the words being read. It is nevertheless an important stage, allowing the child to achieve their ultimate goal of becoming fluent and automatic.

It is in the decoding phase that the child will get to what the story is really about, and to learn to re-read a passage when necessary so as to truly understand it.

Fluent, comprehending reader: 9 to 15 years old[edit]

The goal of this stage is to "go below the surface of the text", and in the process the reader will build their knowledge of spelling substantially.[137]

Teachers and parents may be tricked by fluent-sounding reading into thinking that a child understands everything that they are reading. As the content of what they are able to read becomes more demanding, good readers will develop knowledge of figurative language and irony which helps them to discover new meanings in the text.

Children improve their comprehension when they use a variety of tools such as connecting prior knowledge, predicting outcomes, drawing inferences, and monitoring gaps in their understanding. One of the most powerful moments is when fluent comprehending readers learn to enter into the lives of imagined heroes and heroines.

When teaching comprehension, the educational psychologist, G. Michael Pressley, says a strong case can be made for instruction in decoding, vocabulary, word knowledge, active comprehension strategies, and self-monitoring.[138]

At the end of this stage, many processes are starting to become automatic, allowing the reader to focus on meaning. With the decoding process almost automatic by this point, the brain learns to integrate more metaphorical, inferential, analogical, background and experiential knowledge. This stage in learning to read will often last until early adulthood.[139]

Expert reader: 16 years and older[edit]

At the expert stage it will usually only take a reader one-half second to read almost any word.[140] The degree to which expert reading will change over the course of an adult's life depends on what they read and how much they read.

Science of reading[edit]

There is no single definition of the science of reading (SOR).[144] Foundational skills such as phonics, decoding, and phonemic awareness are considered to be important parts of the science of reading, but they are not the only ingredients. SOR includes any research and evidence about how humans learn to read, and how reading should be taught. This includes areas such as oral reading fluency, vocabulary, morphology, reading comprehension, text, spelling and pronunciation, thinking strategies, oral language proficiency, working memory training, and written language performance (e.g., cohesion, sentence combining/reducing).[145]

In addition, some educators feel that SOR should include digital literacy; background knowledge; content-rich instruction; infrastructural pillars (curriculum, reimagined teacher preparation, and leadership); adaptive teaching (recognizing the student's individual, culture and linguistic strengths); bi-literacy development; equity, social justice and supporting underserved populations (e.g., students from low-income backgrounds).[144]

Some researchers suggest there is a need for more studies on the relationship between theory and practice. They say "we know more about the science of reading than about the science of teaching based on the science of reading", and "there are many layers between basic science findings and teacher implementation that must be traversed".[144]

In cognitive science there is likely no area that has been more successful than the study of reading. Yet, in many countries reading levels are considered low. In the United States, the 2019 Nation's Report Card reported that 34% of grade-four public school students performed at or above the NAEP proficient level (solid academic performance) and 65% performed at or above the basic level (partial mastery of the proficient level skills).[146] As reported in the PIRLS study, the United States ranked 15th out of 50 countries, for reading comprehension levels of fourth-graders.[64][65] In addition, according to the 2011–2018 PIAAC study, out of 39 countries the United States ranked 19th for literacy levels of adults 16 to 65; and 16.9% of adults in the United States read at or below level one (out of five levels).[147][72]

Many researchers are concerned that low reading levels are due to the manner in which reading is taught. They point to three areas:

- Contemporary reading science has had very little impact on educational practice—mainly because of a "two-cultures problem separating science and education".

- Current teaching practice rests on outdated assumptions that make learning to read harder than it needs to be.

- Connecting evidence-based practice to educational practice would be beneficial, but is extremely difficult to achieve due to a lack of adequate training in the science of reading among many teachers.[148][149][150][50]

Simple view of reading[edit]

The simple view of reading is a scientific theory about reading comprehension.[151] According to the theory, in order to comprehend what they are reading students need both decoding skills and oral language (listening) comprehension ability. Neither is enough on their own. In other words, they need the ability to recognize and process (e.g., sound out) the text, and the ability to understand the language in which the text is written (i.e., vocabulary, grammar and background knowledge). Students are not reading if they can decode words but do not understand their meaning. Similarly, students are not reading if they cannot decode words that they would ordinarily recognize and understand if they heard them spoken out loud.[152][153][154]

It is expressed in this equation:Decoding × Oral Language Comprehension = Reading Comprehension.[155]

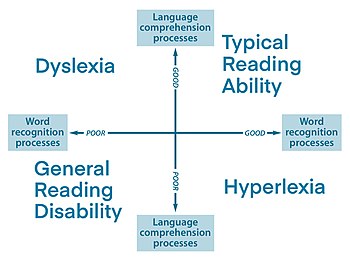

As shown in the graphic, the Simple View of Reading proposes four broad categories of developing readers: typical readers; poor readers (general reading disability); dyslexics;[156] and hyperlexics.[157][158]

Scarborough's reading rope[edit]

Hollis Scarborough, the creator of the Reading Rope and senior scientist at Haskins Laboratories, is a leading researcher of early language development and its connection to later literacy.[159]

Scarborough published the Reading Rope infographics in 2001 using strands of rope to illustrate the many ingredients that are involved in becoming a skilled reader. The upper strands represent language-comprehension and reinforce one another. The lower strands represent word-recognition and work together as the reader becomes accurate, fluent, and automatic through practice. The upper and lower strands all weave together to produce a skilled reader.[160]

| Language-comprehension (Upper strands) |

|---|

| Background knowledge (facts, concepts, etc.) |

| Vocabulary (breadth, precision, links, etc.) |

| Language structures (syntax, semantics, etc.) |

| Verbal reasoning (inference, metaphor, etc.) |

| Literacy knowledge (print concepts, genres, etc.) |

| Word-recognition (Lower strands) |

| Phonological awareness (syllable, phonemes, etc.) |

| Decoding (alphabetic principle, spelling-sound correspondence) |

| Sight recognition (of familiar words) |

More recent research by Laurie E. Cutting and Hollis S. Scarborough has highlighted the importance of executive function processes (e.g. working memory, planning, organization, self-monitoring, and similar abilities) to reading comprehension.[161][162] Easy texts do not require much executive functions; however, more difficult text require more "focus on the ideas". Reading comprehension strategies, such as summarizing, may help.

Active view of reading model[edit]

The active view of reading (AVR) model (May 7, 2021), Nell K. Duke and Kelly B. Cartwright,[163] offers an alternative to the simple view of reading (SVR), and a proposed update to Scarborough's reading rope (SRR). It reflects key insights from scientific research on reading that are not captured in the SVR and SRR. Although the AVR model has not been tested as a whole in research, "each element within the model has been tested in instructional research demonstrating positive, causal influences on reading comprehension".[164] This model is more complete than the simple view of reading and does a better job of accommodating some of the knowledge about reading developed over the past several decades. However, it does not explain how these variables fit together, how their relative importance changes with development, or many other issues relevant to reading instruction.[165]

The model lists contributors to reading (and potential causes of reading difficulty) within, across, and beyond word recognition and language comprehension; including the elements of self-regulation. This feature of the model reflects the research documenting that not all profiles of reading difficulty are explained by low word recognition and/or low language comprehension. A second feature of the model is that it shows how word recognition and language comprehension overlap, and identifies processes that "bridge" these constructs.

The following chart shows the ingredients in the authors' infographic. In addition, the authors point out that reading is also impacted by text, task and sociocultural context.

| Active Self Regulation |

|---|

| Motivation and engagement |

| Executive function skills |

| Strategy use (related to word recognition, comprehension, vocabulary, etc.) |

| Word recognition (WR) |

| Phonological awareness (syllables, phonemes, etc.) |

| Alphabetic principle |

| Phonics knowledge |

| Decoding skills |

| Recognition of words at sight |

| Bridging processes (the overlapping of WR and LC) |

| Print concepts |

| Reading fluency |

| Vocabulary knowledge |

| Morphological awareness (the structure of words and parts of words such as stems, root words, prefixes, and suffixes) |

| Graphophonological-semantic cognitive flexibility (letter-sound-meaning flexibility) |

| Language comprehension (LC) |

| Cultural and other content knowledge |

| Reading-specific background knowledge (genre, text, etc.) |

| Verbal reasoning (inference, metaphor, etc.) |

| Language structure (syntax, semantic, etc.) |

| Theory of mind (the ability to attribute mental states to ourselves and others)[166] |

Automaticity[edit]

In the field of psychology, automaticity is the ability to do things without occupying the mind with the low-level details required, allowing it to become an automatic response pattern or a habit. When reading is automatic, precious working memory resources can be devoted to considering the meaning of a text, etc.

The unexpected finding from cognitive science is that practice does not make perfect. For a new skill to become automatic, sustained practice beyond the point of mastery is necessary.[167][168]

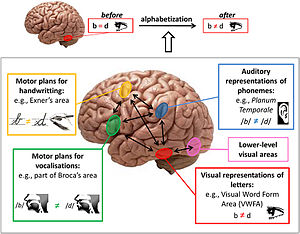

How the brain reads[edit]

Several researchers and neuroscientists have attempted to explain how the brain reads. They have written articles and books, and created websites and YouTube videos to help the average consumer.[169][170][171][172]

Neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene says that a few simple truths should be accepted by all, namely: a) all children have similar brains, are well tuned to systematic grapheme-phoneme correspondences, "and have everything to gain from phonics – the only method that will give them the freedom to read any text", b) classroom size is largely irrelevant if the proper teaching methods are used, c) it is essential to have standardized screening tests for dyslexia, followed by appropriate specialized training, and d) while decoding is essential, vocabulary enrichment is equally important.[173]

A study conducted at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in 2022 indicates that "greater left-brain asymmetry can predict both better and average performance on a foundational level of reading ability, depending on whether analysis is conducted over the whole brain or in specific regions".[174][175] There have been correlations between specific brain regions in the left hemisphere of the cerebral cortex during different reading activities.[176]

Although it is not included in most meta-analytical studies, the sensorimotor cortex of the brain is the most active region of the brain during reading. This is often disregarded because it is associated solely with movement;[177] however, a 2014 fMRI study involving adults and children participants, where bodily movement was restricted, demonstrated strong evidence revealing that this region may be correlated with automatic word processing and decoding.[178] The results of this study found this portion of the brain to be highly active in persons who were learning/struggling to read (children, those diagnosed with dyslexia, and those new to the English language) and less active in fluent adult readers.[178]

The occipital and parietal lobes, or more specifically fusiform gyrus, include the brain's visual word form area (VWFA).[179] The VWFA is believed to be responsible for the brain's ability to read visually.[179] This area of the brain tends to be activated when words are presented orthographically, as found in a study in 2002 where participants were presented with word and non-word stimuli.[180] During presentation of word stimuli, this portion of the brain was extremely active; however, during presentation of stimuli that did not involve graphemes the brain was less active. Participants with dyslexia remained outliers, with this area of the brain being consistently under active in both scenarios.[180]

The two major regions of the brain associated with phonological skills are the temporal-parietal region and the Perisylvian Region.[181] In an fMRI study conducted in 2001, participants were presented with written words, verbal frequency words, and verbal pseudo-words.[182] The dorsal (upper) portion of the temporal-parietal region was the most active during the pseudo-words and the ventral (lower) portion was more active during frequency words, with the exception of subjects diagnosed with dyslexia, who showed no impairment to their ventral region but under-activation in the dorsal portion.[182]

The Perisylvian Region, which is the portion of the brain believed to connect Broca's and Wernicke's area,[183] is another region that is highly active during phonological activities where participants are asked to verbalize known and unknown words.[184] Damage to this portion of this brain directly affects a person's ability to speak cohesively and with sense; furthermore, this portion of the brain activity remains consistent for both dyslexic and non-dyslexic readers.[185][186]

The inferior frontal region is a much more complex region of the brain, and its association with reading is not necessarily linear, for it is active in several reading related activities.[187] Several studies have recorded its activity in association with comprehension and processing skills, as well as spelling and working memory.[188] Although the exact role of this portion of the brain is still debatable, several studies indicate that this area of the brain tends to be more active in readers who have been diagnosed with dyslexia and less active when treatment is successfully undergone.[189]

In addition to regions on the cortex, which is considered gray matter on fMRI's, there are several white matter fasciculus that are also active during different reading activities.[190] These three regions are what connects the three respected cortex regions as the brain reads, thus it is responsible for the brains cross-model integration involved in reading.[191] Three connective fasciculus that are prominently active during reading are the following: the left arcuate faciculus, the left inferior longitudinal faciculus, and the superior longitudinal fasciculus.[192] All three areas are found to be weaker in readers diagnosed with dyslexia.[190][191][192]

The cerebellum, which is not a part of the cerebral cortex, is also believed to play an important role in reading.[193] When the cerebellum is impaired, victims struggle with many executive functioning and organizational skills both inside and outside of their reading ability.[193] In a synthetic fMRI study, specific activities that displayed significant cerebellum involvement included automation, word accuracy, and reading speed.[194]

Eye movement and silent reading rate[edit]

Reading is an intensive process in which the eye quickly moves to assimilate the text – seeing just accurately enough to interpret groups of symbols.[195] It is necessary to understand visual perception and eye movement in reading to understand the reading process.

When reading, the eye moves continuously along a line of text, but makes short rapid movements (saccades) intermingled with short stops (fixations). There is considerable variability in fixations (the point at which a saccade jumps to) and saccades between readers, and even for the same person reading a single passage of text. When reading, the eye has a perceptual span of about 20 slots. In the best-case scenario and reading English, when the eye is fixated on a letter, four to five letters to the right and three to four letters to the left can be clearly identified. Beyond that, only the general shape of some letters can be identified.[196]

The eye movements of deaf readers differ from that of readers that can hear, and skilled deaf readers have shown to have shorter fixations and fewer refixations when reading.[197]

Research published in 2019 concluded that the silent reading rate of adults in English for non-fiction is in the range of 175 to 300 words per minute (wpm); and for fiction the range is 200 to 320 words per minute.[198][199]

Dual-route hypothesis to reading aloud[edit]

In the early 1970s the dual-route hypothesis to reading aloud was proposed, according to which there are two separate mental mechanisms involved in reading aloud, with output from both contributing to the pronunciation of written words.[201][202][203] One mechanism is the lexical route whereby skilled readers can recognize a word as part of their sight vocabulary. The other is the nonlexical or sublexical route, in which the reader "sounds out" (decodes) written words.[203][204]

The production effect (reading out loud)[edit]

There is robust evidence that saying a word out loud makes it more memorable than simply reading it silently or hearing someone else say it. This is because self-reference and self-control over speaking produce more engagement with the words. The memory benefit of "hearing oneself" is referred to as the production effect.[205] This has implications for students such as those who are learning to read. The results of studies imply that oral production is beneficial because it entails two distinctive components: speaking (a motor act) and hearing oneself (the self-referential auditory input). It is also thought that the "optimal benefit would probably come from reading aloud from notes that the student took at the time of initial exposure to new information".[206][207]

Evidence-based reading instruction[edit]

Evidence-based reading instruction refers to practices having research evidence showing their success in improving reading achievement.[208][209][210][211][212] It is related to evidence-based education.

Several organizations report on research about reading instruction, for example:

- Best Evidence Encyclopedia (BEE) is a free website created by the Johns Hopkins University School of Education's Center for Data-Driven Reform in Education and is funded by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.[213] In 2021, BEE released a review of research on 51 different programs for struggling readers in elementary schools.[214] Many of the programs used phonics-based teaching and/or one or more other approaches. The conclusions of this report are shown at the section entitled Effectiveness of programs.

- Evidence for ESSA[215] began in 2017 and is produced by the Center for Research and Reform in Education (CRRE)[216] at Johns Hopkins University School of Education, Baltimore, MD.[217] It offers free up-to-date information on current PK–12 programs in reading, math, social-emotional learning, and attendance that meet the standards of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) (the United States K–12 public education policy signed by President Obama in 2015).[218]

- ProvenTutoring.org[219] is a non-profit organization, a separate subsidiary of the non-profit Success for All. It is a resource for school systems and educators interested in research-proven tutoring programs. It lists programs that deliver tutoring programs that are proven effective in rigorous research as defined in the 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act. The Center for Research and Reform in Education at Johns Hopkins University provides the technical support to inform program selection.[220][221]

- What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) of Washington, DC,[222] was established in 2002 and evaluates numerous educational programs in twelve categories by the quality and quantity of the evidence and the effectiveness. It is operated by the federal National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), part of the Institute of Education Sciences (IES)[222] Individual studies are available that have been reviewed by WWC and categorized according to the evidence tiers of the United States Every student succeeds act (ESSA).[223]

- Intervention reports are provided for programs according to twelve topics (e.g. literacy, mathematics, science, behavior, etc.).[224]

- The British Educational Research Association (BERA)[225] claims to be the home of educational research in the United Kingdom.[226][227]

- Florida Center for Reading Research is a research center at Florida State University that explores all aspects of reading research. Its Resource Database allows you to search for information based on a variety of criteria.[228]

- Institute of Education Sciences (IES), Washington, DC,[229] is the statistics, research, and evaluation arm of the U.S. Department of Education. It funds independent education research, evaluation and statistics. It published a Synthesis of its Research on Early Intervention and Early Childhood Education in 2013.[230] Its publications and products can be searched by author, subject, etc.[231]

- National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER)[232] is a non-profit research and development organization based in Berkshire, England. It produces independent research and reports about issues across the education system, such as Using Evidence in the Classroom: What Works and Why.[233]

- Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted), in England, conducts research on schools, early education, social care, further education and skills.[234]

- The Ministry of Education, Ontario, Canada offers a site entitled What Works? Research Into Practice. It is a collection of research summaries of promising teaching practice written by experts at Ontario universities.[235]

- RAND Corporation, with offices throughout the world, funds research on early childhood, K–12, and higher education.[236]

- ResearchED,[237] a U.K. based non-profit since 2013 has organized education conferences around the world (e.g. Africa, Australia, Asia, Canada, the E.U., the Middle East, New Zealand, the U.K. and the U.S.) featuring researchers and educators in order to "promote collaboration between research-users and research-creators". It has been described as a "grass-roots teacher-led project that aims to make teachers research-literate and pseudo-science proof".[238]

Reading from paper vs. screens[edit]

A systematic review and meta‐analysis was conducted on the advantages of reading from paper vs. screens. It found no difference in reading times; however, reading from paper has a small advantage in reading performance and metacognition.[239] Other studies conclude that many children understand more from reading books vs. screens.[240][241]

Teacher training and legislation[edit]

According to some researchers, having a highly qualified teacher in every classroom is an educational necessity, and a 2023 study of 512 classroom teachers in 112 schools showed that teachers' knowledge of language and literacy reliably predicted students' reading foundational skills scores, but not reading comprehension scores.[242] Yet, some teachers, even after obtaining a master's degree in education, think they lack the necessary knowledge and skills to teach all students how to read.[243] A 2019 survey of K-2 and special education teachers found that only 11 percent said they felt "completely prepared" to teach early reading after finishing their preservice programs. And, a 2021 study found that most U.S. states do not measure teachers' knowledge of the 'science of reading'.[244] In addition, according to one study, as few as 2% of school districts use reading programs that follow the science of reading.[245][246] Mark Seidenberg, a neuroscientist, states that, with few exceptions, teachers are not taught to teach reading and "don't know what they don't know".[247]

A survey in the United States reported that 70% of teachers believe in a balanced literacy approach to teaching reading – however, balanced literacy "is not systematic, explicit instruction".[243] Teacher, researcher and author, Louisa Moats,[248] in a video about teachers and science of reading, says that sometimes when teachers talk about their "philosophy" of teaching reading, she responds by saying, "But your 'philosophy' doesn't work".[249] She says this is evidenced by the fact that so many children are struggling with reading.[250] On another occasion, when asked about the most common questions teachers ask her, she replied, "over and over" they ask "why didn't anyone teach me this before?".[251]In an Education Week Research Center survey of more than 530 professors of reading instruction, only 22 percent said their philosophy of teaching early reading centered on explicit, systematic phonics with comprehension as a separate focus.[243]

As of January 24, 2024, after Mississippi became the only state to improve reading results between 2017 and 2019,[252] 37 U.S. states and the District of Columbia have since passed laws or implemented new policies related to evidence-based reading instruction.[54] These requirements relate to six areas: teacher preparation; teacher certification or license renewal; professional development or coaching; assessment; material; and instruction or intervention. As a result, many schools are moving away from balanced literacy programs that encourage students to guess a word, and are introducing phonics where they learn to "decode" (sound out) words.[253] However, the adoption of these new requirements are by no means uniform. For example, only ten states have requirements in all six areas, and five have requirements in only one or two areas. Only nineteen states have requirements related to pre-service teacher certification or license renewal. Thirty-six states have requirements for professional development or coaching, and thirty-one require teachers to use specific instructional methods or interventions for struggling readers. Furthermore, eight states do not allow or require 3rd-grade retention for students who are behind in reading. Experts say it is uncertain whether these new initiatives will lead to real improvements in children's reading results because old practices prove hard to shake.[254][255]

As more state legislatures seek to pass science of reading legislation, some teachers' unions are mounting opposition, citing concerns about mandates that would limit teachers' professional autonomy in the classroom, uneven implementation, unreasonable timelines, and the amount of time and compensation teachers receive for additional training.[256] Some teachers' unions, in particular, have protested attempts to ban the three-cueing system that encourages students to guess at the pronunciation of words, using pictures, etc. (rather than to decode them). In April 2024, the California Teachers Union was successful in stopping a bill that would have required teachers to use the science of reading.[257]

Arkansas required every elementary and special education teacher to be proficient in the scientific research on reading by 2021; causing Amy Murdoch, an associate professor and the director of the reading science program at Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati to say "We still have a long way to go – but I do see some hope".[243][258][259]

In 2021, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development of New Brunswick appears to be the first in Canada to revise its K-2 reading curriculum based on "research-based instructional practice". For example, it replaced the various cueing systems with "mastery in the consolidated alphabetic to skilled reader phase".[260][261] Although one document on the site, dated 1998, contains references to such practices as using "cueing systems" which is at odds with the department's current shift to using evidence-based practices.[262] The Minister of Education in Ontario, Canada followed by stating plans to revise the elementary language curriculum and the Grade 9 English course with "scientific, evidence-based approaches that emphasize direct, explicit and systematic instruction and removing references to unscientific discovery and inquiry-based learning, including the three-cueing system, by 2023."[263]

Some non-profit organizations, such as the Center for Development and Learning (Louisiana) and the Reading League (New York State), offer training programs for teachers to learn about the science of reading.[264][265][266][267] ResearchED, a U.K. based non-profit since 2013 has organized education conferences around the world featuring researchers and educators in order to promote collaboration between research-users and research-creators.[237]

Researcher and educator Timothy Shanahan acknowledges that comprehensive research does not always exist for specific aspects of reading instruction. However, "the lack of evidence doesn't mean something doesn't work, only that we don't know". He suggests that teachers make use of the research that is available in such places as Journal of Educational Psychology, Reading Research Quarterly, Reading & Writing Quarterly, Review of Educational Research, and Scientific Studies of Reading. If a practice lacks supporting evidence, it can be used with the understanding that it is based upon a claim, not science.[268]

Teaching reading[edit]

Alphabetic languages[edit]

Educators have debated for years about which method is best to teach reading for the English language. There are three main methods, phonics, whole language and balanced literacy. There are also a variety of other areas and practices such as phonemic awareness, fluency, reading comprehension, sight words and sight vocabulary, the three-cueing system (the searchlights model in England), guided reading, shared reading, and leveled reading. Each practice is employed in different manners depending on the country and the specific school division.

In 2001, some researchers reached two conclusions: 1) "mastering the alphabetic principle is essential" and 2) "instructional techniques (namely, phonics) that teach this principle directly are more effective than those that do not". However, while they make it clear they have some fundamental disagreements with some of the claims made by whole-language advocates, some principles of whole language have value such as the need to ensure that students are enthusiastic about books and eager to learn to read.[74]

[edit]

Phonics emphasizes the alphabetic principle – the idea that letters (graphemes) represent the sounds of speech (phonemes).[271] It is taught in a variety of ways; some are systematic and others are unsystematic. Unsystematic phonics teaches phonics on a "when needed" basis and in no particular sequence. Systematic phonics uses a planned, sequential introduction of a set of phonic elements along with explicit teaching and practice of those elements. The National Reading Panel (NRP) concluded that systematic phonics instruction is more effective than unsystematic phonics or non-phonics instruction.

Phonics approaches include analogy phonics, analytic phonics, embedded phonics with mini-lessons, phonics through spelling, and synthetic phonics.[272][273][274][74][275]

According to a 2018 review of research related to English speaking poor readers, phonics training is effective for improving literacy-related skills, particularly the fluent reading of words and non-words, and the accurate reading of irregular words.[276]

In addition, phonics produces higher achievement for all beginning readers, and the greatest improvement is experienced by students who are at risk of failing to learn to read. While some children are able to infer these rules on their own, some need explicit instruction on phonics rules. Some phonics instruction has marked benefits such as expansion of a student's vocabulary. Overall, children who are directly taught phonics are better at reading, spelling and comprehension.[277]

A challenge in teaching phonics is that in some languages, such as English, complex letter-sound correspondences can cause confusion for beginning readers. For this reason, it is recommended that teachers of English-reading begin by introducing the "most frequent sounds" and the "common spellings", and save the less frequent sounds and complex spellings for later (e.g. the sounds /s/ and /t/ before /v/ and /w/; and the spellings cake before eight and cat before duck).[74][278][279]

Phonics is gaining world-wide acceptance.

Combining phonics with other literacy instruction[edit]

Phonics is taught in many different ways and it is often taught together with some of the following: oral language skills,[280][281] concepts about print,[282] phonological awareness, phonemic awareness, phonology, oral reading fluency, vocabulary, syllables, reading comprehension, spelling, word study,[283][284][285] cooperative learning, multisensory learning, and guided reading. And, phonics is often featured in discussions about science of reading,[286][287] and evidence-based practices.

The National Reading Panel (U.S. 2000) is clear that "systematic phonics instruction should be integrated with other reading instruction to create a balanced reading program".[288] It suggests that phonics be taught together with phonemic awareness, oral fluency, vocabulary and comprehension. Researcher and educator Timothy Shanahan, a member of that panel, recommends that primary students receive 60–90 minutes per day of explicit, systematic, literacy instruction time; and that it be divided equally between a) words and word parts (e.g. letters, sounds, decoding and phonemic awareness), b) oral reading fluency, c) reading comprehension, and d) writing.[289] Furthermore, he states that "the phonemic awareness skills found to give the greatest reading advantage to kindergarten and first-grade children are segmenting and blending".[290]

The Ontario Association of Deans of Education (Canada) published research Monograph # 37 entitled Supporting early language and literacy with suggestions for parents and teachers in helping children prior to grade one. It covers the areas of letter names and letter-sound correspondence (phonics), as well as conversation, play-based learning, print, phonological awareness, shared reading, and vocabulary.[291]

Effectiveness of programs[edit]

Some researchers report that teaching reading without teaching phonics is harmful to large numbers of students; yet not all phonics teaching programs produce effective results. The reason is that the effectiveness of a program depends on using the right curriculum together with the appropriate approach to instruction techniques, classroom management, grouping, and other factors.[292] Louisa Moats, a teacher, psychologist and researcher, has long advocated for reading instruction that is direct, explicit and systematic, covering phoneme awareness, decoding, comprehension, literature appreciation, and daily exposure to a variety of texts.[293] She maintains that "reading failure can be prevented in all but a small percentage of children with serious learning disorders. It is possible to teach most students how to read if we start early and follow the significant body of research showing which practices are most effective".[294]

Interest in evidence-based education appears to be growing.[237] In 2021, Best evidence encyclopedia (BEE) released a review of research on 51 different programs for struggling readers in elementary schools.[214] Many of the programs used phonics-based teaching and/or one or more of the following: cooperative learning, technology-supported adaptive instruction (see Educational technology), metacognitive skills, phonemic awareness, word reading, fluency, vocabulary, multisensory learning, spelling, guided reading, reading comprehension, word analysis, structured curriculum, and balanced literacy (non-phonetic approach).

The BEE review concludes that a) outcomes were positive for one-to-one tutoring, b) outcomes were positive, but not as large, for one-to-small group tutoring, c) there were no differences in outcomes between teachers and teaching assistants as tutors, d) technology-supported adaptive instruction did not have positive outcomes, e) whole-class approaches (mostly cooperative learning) and whole-school approaches incorporating tutoring obtained outcomes for struggling readers as large as those found for one- to-one tutoring, and benefitted many more students, and f) approaches mixing classroom and school improvements, with tutoring for the most at-risk students, have the greatest potential for the largest numbers of struggling readers.[214]

Robert Slavin, of BEE, goes so far as to suggest that states should "hire thousands of tutors" to support students scoring far below grade level – particularly in elementary school reading. Research, he says, shows "only tutoring, both one-to-one and one-to-small group, in reading and mathematics, had an effect size larger than +0.10 ... averages are around +0.30", and "well-trained teaching assistants using structured tutoring materials or software can obtain outcomes as good as those obtained by certified teachers as tutors".[295][296]

What works clearinghouse allows you to see the effectiveness of specific programs. For example, as of 2020 they have data on 231 literacy programs. If you filter them by grade 1 only, all class types, all school types, all delivery methods, all program types, and all outcomes you receive 22 programs. You can then view the program details and, if you wish, compare one with another.[297]

Evidence for ESSA[215] (Center for Research and Reform in Education)[216] offers free up-to-date information on current PK–12 programs in reading, writing, math, science, and others that meet the standards of the Every Student Succeeds Act (U.S.).[298]

ProvenTutoring.org[219] a non-profit organization, is a resource for educators interested in research-proven tutoring programs. The programs it lists are proven effective in rigorous research as defined in the 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act. The Center for Research and Reform in Education at Johns Hopkins University provides the technical support to inform program selection.[216]

Systematic phonics[edit]

Systematic phonics is not one specific method of teaching phonics; it is a term used to describe phonics approaches that are taught explicitly and in a structured, systematic manner. They are systematic because the letters and the sounds they relate to are taught in a specific sequence, as opposed to incidentally or on a "when needed" basis.[300]

The National Reading Panel (NRP) concluded that systematic phonics instruction is more effective than unsystematic phonics or non-phonics instruction. The NRP also found that systematic phonics instruction is effective (with varying degrees) when delivered through one-to-one tutoring, small groups, and teaching classes of students; and is effective from kindergarten onward, the earlier the better. It helps significantly with word-reading skills and reading comprehension for kindergartners and 1st graders as well as for older struggling readers and reading disabled students. Benefits to spelling were positive for kindergartners and 1st graders but not for older students.[301]

Systematic phonics is sometimes mischaracterised as "skill and drill" with little attention to meaning. However, researchers point out that this impression is false. Teachers can use engaging games or materials to teach letter-sound connections, and it can also be incorporated with the reading of meaningful text.[302]

Phonics can be taught systematically in a variety of ways, such as: analogy phonics, analytic phonics, phonics through spelling, and synthetic phonics. However, their effectiveness vary considerably because the methods differ in such areas as the range of letter-sound coverage, the structure of the lesson plans, and the time devoted to specific instructions.[303]

Systematic phonics has gained increased acceptance in different parts of the world since the completion of three major studies into teaching reading; one in the US in 2000,[304][305] another in Australia in 2005,[306] and the other in the UK in 2006.[307]

In 2009, the UK Department of Education published a curriculum review that added support for systematic phonics. In fact, systematic phonics in the UK is known as Synthetic phonics.[308]

Beginning as early as 2014, several states in the United States have changed their curriculum to include systematic phonics instruction in elementary school.[309][310][311][312]

In 2018, the State Government of Victoria, Australia, published a website containing a comprehensive Literacy Teaching Toolkit including Effective Reading Instruction, Phonics, and Sample Phonics Lessons.[313]

Analytic phonics and analogy phonics[edit]

Analytic phonics does not involve pronouncing individual sounds (phonemes) in isolation and blending the sounds, as is done in synthetic phonics. Rather, it is taught at the word level and students learn to analyze letter-sound relationships once the word is identified. For example, students analyze letter-sound correspondences such as the ou spelling of /aʊ/ in shrouds. Also, students might be asked to practice saying words with similar sounds such as ball, bat and bite. Furthermore, students are taught consonant blends (separate, adjacent consonants) as units, such as break or shrouds.[314][315]

Analogy phonics is a particular type of analytic phonics in which the teacher has students analyze phonic elements according to the speech sounds (phonograms) in the word. For example, a type of phonogram (known in linguistics as a rime) is composed of the vowel and the consonant sounds that follow it (e.g. in the words cat, mat and sat, the rime is "at".) Teachers using the analogy method may have students memorize a bank of phonograms, such as -at or -am, or use word families (e.g. can, ran, man, or may, play, say).[316][314]

There have been studies on the effectiveness of instruction using analytic phonics vs. synthetic phonics. Johnston et al. (2012) conducted experimental research studies that tested the effectiveness of phonics learning instruction among 10-year-old boys and girls.[317] They used comparative data from the Clackmannanshire Report and chose 393 participants to compare synthetic phonics instruction and analytic phonics instruction.[318][317] The boys taught by the synthetic phonics method had better word reading than the girls in their classes, and their spelling and reading comprehension was as good. On the other hand, with analytic phonics teaching, although the boys performed as well as the girls in word reading, they had inferior spelling and reading comprehension. Overall, the group taught by synthetic phonics had better word reading, spelling, and reading comprehension. And, synthetic phonics did not lead to any impairment in the reading of irregular words.[317]

Embedded phonics with mini-lessons[edit]

Embedded phonics, also known as incidental phonics, is the type of phonics instruction used in whole language programs. It is not systematic phonics.[319] Although phonics skills are de-emphasised in whole language programs, some teachers include phonics "mini-lessons" when students struggle with words while reading from a book. Short lessons are included based on phonics elements the students are having trouble with, or on a new or difficult phonics pattern that appears in a class reading assignment. The focus on meaning is generally maintained, but the mini-lesson provides some time for focus on individual sounds and the letters that represent them. Embedded phonics is different from other methods because instruction is always in the context of literature rather than in separate lessons about distinct sounds and letters; and skills are taught when an opportunity arises, not systematically.[320][321]

Phonics through spelling[edit]

For some teachers this is a method of teaching spelling by using the sounds (phonemes).[322] However, it can also be a method of teaching reading by focusing on the sounds and their spelling (i.e. phonemes and syllables). It is taught systematically with guided lessons conducted in a direct and explicit manner including appropriate feedback. Sometimes mnemonic cards containing individual sounds are used to allow the student to practice saying the sounds that are related to a letter or letters (e.g. a, e, i, o, u). Accuracy comes first, followed by speed. The sounds may be grouped by categories such as vowels that sound short (e.g. c-a-t and s-i-t). When the student is comfortable recognizing and saying the sounds, the following steps might be followed: a) the tutor says a target word and the student repeats it out loud, b) the student writes down each individual sound (letter) until the word is completely spelled, saying each sound as it is written, and c) the student says the entire word out loud. An alternate method would be to have the student use mnemonic cards to sound-out (spell) the target word.

Typically, the instruction starts with sounds that have only one letter and simple CVC words such as sat and pin. Then it progresses to longer words, and sounds with more than one letter (e.g. hear and day), and perhaps even syllables (e.g. wa-ter). Sometimes the student practices by saying (or sounding-out) cards that contain entire words.[323]

Synthetic phonics[edit]

Synthetic phonics, also known as blended phonics, is a systematic phonics method employed to teach students to read by sounding out the letters then blending the sounds to form the word. This method involves learning how letters or letter groups represent individual sounds, and that those sounds are blended to form a word. For example, shrouds would be read by pronouncing the sounds for each spelling, sh, r, ou, d, s (IPA /ʃ, r, aʊ, d, z/), then blending those sounds orally to produce a spoken word, sh – r – ou – d – s = shrouds (IPA /ʃraʊdz/). The goal of a synthetic phonics instructional program is that students identify the sound-symbol correspondences and blend their phonemes automatically. Since 2005, synthetic phonics has become the accepted method of teaching reading (by phonics instruction) in England, Scotland and Australia.[324][325][326][327]

The 2005 Rose Report from the UK concluded that systematic synthetic phonics was the most effective method for teaching reading. It also suggests the "best teaching" included a brisk pace, engaging children's interest with multi-sensory activities and stimulating resources, praise for effort and achievement; and above all, the full backing of the headteacher.[328]

It also has considerable support in some States in the U.S.[305] and some support from expert panels in Canada.[329]

In the US, a pilot program using the Core Knowledge Early Literacy program that used this type of phonics approach showed significantly higher results in K–3 reading compared with comparison schools.[330] In addition, several States such as California, Ohio, New York and Arkansas, are promoting the principles of synthetic phonics (see synthetic phonics in the United States).

Resources for teaching phonics are available here.

Related areas[edit]

Phonemic awareness[edit]

Phonemic awareness is the process by which the phonemes (sounds of oral language) are heard, interpreted, understood and manipulated – unrelated to their grapheme (written language). It is a sub-set of Phonological awareness that includes the manipulation of rhymes, syllables, and onsets and rimes, and is most prevalent in alphabetic systems.[331] The specific part of speech depends on the writing system employed. The National Reading Panel (NPR) concluded that phonemic awareness improves a learner's ability to learn to read. When teaching phonemic awareness, the NRP found that better results were obtained with focused and explicit instruction of one or two elements, over five or more hours, in small groups, and using the corresponding graphemes (letters).[332] See also Speech perception. As mentioned earlier, some researchers feel that the most effective way of teaching phonemic awareness is through segmenting and blending, a key part of synthetic phonics.[290]

Vocabulary[edit]

A critical aspect of reading comprehension is vocabulary development.[333] When a reader encounters an unfamiliar word in print and decodes it to derive its spoken pronunciation, the reader understands the word if it is in the reader's spoken vocabulary. Otherwise, the reader must derive the meaning of the word using another strategy, such as context. If the development of the child's vocabulary is impeded by things such as ear infections that inhibit the child from hearing new words consistently then the development of reading will also be impaired.[334]

Sight vocabulary vs. sight words[edit]

Sight words (i.e. high-frequency or common words), sometimes called the look-say or whole-word method, are not a part of the phonics method.[335] They are usually associated with whole language and balanced literacy where students are expected to memorize common words such as those on the Dolch word list and the Fry word list (e.g. a, be, call, do, eat, fall, gave, etc.).[336][337] The supposition (in whole language and balanced literacy) is that students will learn to read more easily if they memorize the most common words they will encounter, especially words that are not easily decoded (i.e. exceptions).

On the other hand, using sight words as a method of teaching reading in English is seen as being at odds with the alphabetic principle and treating English as though it was a logographic language (e.g. Chinese or Japanese).[338]

In addition, according to research, whole-word memorization is "labor-intensive", requiring on average about 35 trials per word.[339] Also, phonics advocates say that most words are decodable, so comparatively few words have to be memorized. And because a child will over time encounter many low-frequency words, "the phonological recoding mechanism is a very powerful, indeed essential, mechanism throughout reading development".[74] Furthermore, researchers suggest that teachers who withhold phonics instruction to make it easier on children "are having the opposite effect" by making it harder for children to gain basic word-recognition skills. They suggest that learners should focus on understanding the principles of phonics so they can recognize the phonemic overlaps among words (e.g. have, had, has, having, haven't, etc.), making it easier to decode them all.[340][341][342]