Латиноамериканцы и латиноамериканцы

| Часть серии о |

| латиноамериканцы и Латиноамериканцы |

|---|

Латиноамериканцы и латиноамериканцы ( испанский : Estadounidenses hispanos y latinos ; португальский : Estadunidenses hispânicos e latinos ) — американцы полного или частичного испанского и/или латиноамериканского происхождения, культуры или семейного происхождения. [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [ 5 ] [ 6 ] В эту демографическую группу входят все американцы, которые идентифицируют себя как латиноамериканцы или латиноамериканцы, независимо от расы. [ 7 ] [ 8 ] [ 9 ] [ 10 ] [ 11 ] [ 12 ] проживало почти 65,3 миллиона выходцев из Латинской Америки и Латинской Америки По оценкам Бюро переписи населения, по состоянию на 2020 год в Соединенных Штатах и на их территориях .

«Происхождение» можно рассматривать как происхождение, национальную группу, происхождение или страну рождения человека или его родителей или предков до его прибытия в Соединенные Штаты Америки. Люди, идентифицирующие себя как латиноамериканцы или латиноамериканцы, могут принадлежать к любой расе, поскольку, подобно тому, что произошло во время колонизации и после обретения независимости Соединенными Штатами, население латиноамериканских стран состояло из потомков белых европейских колонизаторов (в данном случае португальцев и Испанцы ), коренные народы Америки , потомки африканских рабов , иммигранты после обретения независимости, прибывшие из Европы , Ближнего Востока и Восточной Азии , а также потомки многорасовых союзов между этими разными этническими группами. [ 13 ] [ 14 ] [ 15 ] [ 16 ] Являясь одной из двух специально обозначенных категорий этнической принадлежности в Соединенных Штатах , латиноамериканцы и латиноамериканцы образуют панэтническую группу , включающую в себя разнообразие взаимосвязанных культурных и языковых наследий, при этом использование испанского и португальского языков является наиболее важным из всех. . Большинство латиноамериканцев и латиноамериканцев имеют мексиканское , пуэрториканское , кубинское , сальвадорское , доминиканское , колумбийское , гватемальское , гондурасское , эквадорское , перуанское , венесуэльское или никарагуанское происхождение. Преобладающее происхождение регионального латиноамериканского и латиноамериканского населения широко варьируется в разных местах по всей стране. [ 14 ] [ 17 ] [ 18 ] [ 19 ] [ 20 ] В 2012 году американцы латиноамериканского происхождения были второй по темпам роста этнической группой в США по процентному росту после американцев азиатского происхождения . [ 21 ]

Многорасовые выходцы из Латинской Америки ( метисы ) коренного и испанского происхождения являются вторыми старейшими этническими группами (после коренных американцев ), населяющими большую часть территории современных Соединенных Штатов. [ 22 ] [ 23 ] [ 24 ] [ 25 ] Испания колонизировала большие территории того, что сегодня является Америки юго-западным и западным побережьем , а также Флоридой. Его владения включали современные Калифорнию, Техас, Нью-Мексико, Неваду, Юту, Аризону и Флориду, все из которых входили в состав вице-королевства Новой Испании , базирующегося в Мехико . Позже эта обширная территория стала частью Мексики после ее независимости от Испании в 1821 году и до конца американо-мексиканской войны в 1848 году. Латиноамериканские иммигранты в столичный регион Нью-Йорка / Нью-Джерси происходят из широкого спектра латиноамериканских стран. [ 26 ]

Терминология

[ редактировать ]

Термины « латиноамериканец » и « латиноамериканец » относятся к этнической принадлежности . «Латиноамериканец» впервые стал широко использоваться для обозначения лиц, происходящих из испаноязычных стран, после того, как Административно-бюджетное управление создало классификацию в 1977 году, как было предложено подкомитетом, состоящим из трех государственных служащих, кубинца, мексиканца и пуэрто-американца. Риканский американец. [ 27 ] Бюро переписи населения США определяет латиноамериканцев как принадлежность к какой-либо этнической принадлежности, а не как принадлежность к определенной расе , и, таким образом, люди, являющиеся членами этой группы, также могут быть членами любой расы. [ 14 ] [ 28 ] [ 29 ] В национальном опросе латиноамериканцев, назвавших себя латиноамериканцами в 2015 году, 56% заявили, что латиноамериканцы являются частью их расовой и этнической принадлежности, в то время как меньшие числа считали это частью только своей этнической принадлежности (19%) или только расовой принадлежности (11%). . [ 28 ] Выходцы из Латинской Америки могут иметь любое лингвистическое происхождение; в опросе 2015 года 71% выходцев из Латинской Америки согласились с тем, что «человеку не обязательно говорить по-испански, чтобы считаться латиноамериканцем / латиноамериканцем». [ 30 ] Латиноамериканцы и латиноамериканцы могут иметь некоторые общие черты в своем языке, культуре, истории и наследии. По данным Смитсоновского института , термин «латиноамериканец» включает в себя народы с португальскими корнями, например бразильцев , а также людей испаноязычного происхождения. [ 31 ] [ 32 ] Разница между терминами «латиноамериканец» и «латиноамериканец» для некоторых людей неоднозначна. [ 33 ] Бюро переписи населения США приравнивает эти два термина и определяет их как относящихся к любому жителю Испании или испано- или португалоязычных стран Америки. После завершения американо-мексиканской войны в 1848 году термин «латиноамериканец» или «американец испанского происхождения» в основном использовался для описания латиноамериканцев Нью-Мексико на юго-западе Америки . Перепись населения США 1970 года неоднозначно расширила это определение до «лица мексиканской, пуэрториканской, кубинской, доминиканской, южно- или центральноамериканской или другой испанской культуры или происхождения, независимо от расы». Сейчас это общепринятое формальное и разговорное определение этого термина в Соединенных Штатах, за пределами Нью-Мексико. [ 34 ] [ 35 ] Это определение согласуется с использованием в 21 веке Бюро переписи населения США и OMB , поскольку эти два агентства используют оба термина «латиноамериканец» и «латиноамериканец» как взаимозаменяемые. Исследовательский центр Pew считает, что термин «латиноамериканец» строго ограничен Испанией , Пуэрто-Рико и всеми странами, где испанский является единственным официальным языком, тогда как «латиноамериканец» включает в себя все страны Латинской Америки (даже Бразилию, несмотря на то, что португальский язык является это единственный официальный язык), но он не включает Испанию и Португалию. [ 3 ]

Термины Latino и Latina заимствованы из Италии и, в конечном счете, из Древнего Рима . В английском языке термин «латиноамериканец» представляет собой сокращенную форму «latinoamericano» , испанского термина, обозначающего латиноамериканца или выходца из Латинской Америки. Термин «латиноамериканец» имеет ряд определений. Это определение как «мужской латиноамериканский житель Соединенных Штатов» [ 36 ] Это самое старое определение, которое используется в Соединенных Штатах. Впервые оно было использовано в 1946 году. [ 36 ] Например, согласно этому определению американец мексиканского происхождения или пуэрториканец является одновременно латиноамериканцем и латиноамериканцем. Американец бразильского происхождения также является латиноамериканцем по этому определению, которое включает в себя португалоязычных выходцев из Латинской Америки. [ 37 ] [ 38 ] [ 39 ] [ 40 ] [ 41 ] [ 42 ] На английском языке американцы итальянского происхождения считаются не «латиноамериканцами», поскольку они по большей части происходят от иммигрантов из Европы, а не из Латинской Америки, если только у них не было недавнего опыта проживания в какой-либо латиноамериканской стране.

Предпочтение использования терминов выходцами из Латинской Америки в Соединенных Штатах часто зависит от того, где проживают пользователи соответствующих терминов. Жители восточной части Соединенных Штатов, как правило, предпочитают термин «латиноамериканец» , тогда как жители Запада, как правило, предпочитают термин «латиноамериканец» . [ 13 ]

Этническое обозначение «латиноамериканец» в США абстрагировано от более длинной формы «латиноамерикано» . [ 43 ] Элемент latino- на самом деле является несклоняемой композиционной формой на -o (т.е. elemento compositivo ), которая используется для чеканки сложных образований (аналогично franc o- в franc o canadiense «французско-канадский» или ibero- в iberorrománico , [ 44 ] и т. д.).

Термин Latinx (и аналогичный неологизм Xicanx ) получил некоторое распространение. [ 46 ] [ 47 ] Принятие X будет «отражать новое сознание, вдохновленное недавней работой ЛГБТКИ и феминистских движений, некоторые испаноязычные активисты все чаще используют еще более инклюзивное «x» для замены «a» и «o». , в полном разрыве с гендерной бинарностью . [ 48 ] Среди сторонников термина LatinX одна из наиболее часто цитируемых жалоб на гендерную предвзятость в испанском языке заключается в том, что группа смешанного или неизвестного пола будет называться латиноамериканцами , тогда как латиноамериканцы относятся только к группе женщин (но это немедленно меняется на латиноамериканцев , если к этой женской группе присоединяется хотя бы одинокий мужчина). [ 49 ] Опрос Pew Research Center 2020 года показал, что около 3% латиноамериканцев используют этот термин (в основном женщины), и только около 23% вообще слышали об этом термине. Из них 65% заявили, что это слово не следует использовать для описания их этнической группы. [ 50 ]

Некоторые отмечают, что термин «латиноамериканец» относится к панэтнической идентичности, охватывающей целый ряд рас, национального происхождения и языкового происхождения. «Такие термины, как латиноамериканец и латиноамериканец, не полностью отражают то, как мы видим себя», — говорит Джеральдо Кадава, доцент кафедры истории и латиноамериканских исследований Северо-Западного университета . [ 51 ]

Согласно данным исследования американского сообщества 2017 года , небольшое меньшинство иммигрантов из Бразилии (2%), Португалии (2%) и Филиппин (1%) идентифицировали себя как латиноамериканцы. [ 11 ]

История

[ редактировать ]Этот раздел нуждается в дополнении : подробнее о XIX и XX веках. Вы можете помочь, добавив к нему . ( январь 2010 г. ) |

16 и 17 века

[ редактировать ]

Испанские исследователи были пионерами на территории современных Соединенных Штатов. Первая подтвержденная высадка европейцев в континентальной части Соединенных Штатов была совершена Хуаном Понсе де Леоном , который высадился в 1513 году на пышном берегу, который он назвал Флоридой . В следующие три десятилетия испанцы стали первыми европейцами, достигшими Аппалачей , реки Миссисипи , Большого Каньона и Великих равнин . Испанские корабли плыли вдоль Атлантического побережья , проникнув до современного Бангора, штат Мэн , и вверх по Тихоокеанскому побережью до Орегона . С 1528 по 1536 год Альвар Нуньес Кабеса де Вака и трое его товарищей (включая африканца по имени Эстеванико ) из провалившейся испанской экспедиции отправились из Флориды в Калифорнийский залив . В 1540 году Эрнандо де Сото предпринял обширное исследование территории нынешних Соединенных Штатов.

Также в 1540 году Франсиско Васкес де Коронадо повел 2000 испанцев и мексиканских туземцев через сегодняшнюю границу Аризоны и Мексики и дошел до центрального Канзаса , недалеко от точного географического центра того, что сейчас является континентальной частью Соединенных Штатов. Среди других испанских исследователей территории США: Алонсо Альварес де Пинеда , Лукас Васкес де Айльон , Панфило де Нарваес , Себастьян Вискайно , Гаспар де Портола , Педро Менендес де Авилес , Альвар Нуньес Кабеса де Вака , Тристан де Луна и Арельяно , и Хуан де Оньяте , а также неиспанские исследователи, работающие на испанскую корону, такие как Хуан Родригес Кабрильо . В 1565 году испанцы создали первое постоянное европейское поселение на континентальной части Соединенных Штатов, в Сент-Огастине, штат Флорида . Испанские миссионеры и колонисты основали поселения, в том числе на территории современных Санта-Фе, Нью-Мексико , Эль-Пасо , Сан-Антонио , Тусона , Альбукерке , Сан-Диего , Лос-Анджелеса и Сан-Франциско . [ 52 ]

Испанские поселения в Америке были частью более широкой сети торговых путей, соединявших Европу, Африку и Америку. Испанцы установили торговые связи с коренными народами, обменивая такие товары, как меха , шкуры , сельскохозяйственную продукцию и промышленные товары. Эти торговые сети способствовали экономическому развитию испанских колоний и способствовали культурному обмену между различными группами.

18 и 19 века

[ редактировать ]

Еще в 1783 году, в конце Войны за независимость США (конфликт, в котором Испания помогала повстанцам и сражалась вместе с ними), Испания претендовала примерно на половину территории сегодняшних континентальных Соединенных Штатов. С 1819 по 1848 год Соединенные Штаты увеличили свою территорию примерно на треть за счет Испании и Мексики, приобретя современные штаты Калифорния американские , Техас , Невада , Юта , большую часть Колорадо , Нью-Мексико и Аризоны , а также части Оклахомы. , Канзас и Вайоминг по Договору Гуадалупе-Идальго после американо-мексиканской войны , [ 53 ] а также Флорида через договор Адамса-Ониса , [ 54 ] и территория США в Пуэрто-Рико во время испано-американской войны 1898 года. [ 55 ] Многие латиноамериканцы, проживавшие в этих регионах в тот период, получили гражданство США. Тем не менее, многие давние латиноамериканцы столкнулись со значительными трудностями после получения гражданства. С приходом англо-американцев в эти недавно присоединенные территории латиноамериканские жители изо всех сил пытались сохранить свои земельные владения, политическое влияние и культурные традиции. [ 56 ] [ 57 ]

Открытие золота в Калифорнии в 1848 году привлекло людей разного происхождения, в том числе латиноамериканских и латиноамериканских горняков, торговцев и поселенцев. Золотая лихорадка привела к демографическому буму и быстрому экономическому росту в Калифорнии, изменив социальный и политический ландшафт региона.

Многие выходцы из Латинской Америки жили на территориях, приобретенных Соединенными Штатами, и новая волна иммигрантов из Мексики, Центральной Америки, Карибского бассейна и Южной Америки переехала в Соединенные Штаты в поисках новых возможностей. Это было началом демографической ситуации, которая с годами резко выросла. [ 58 ]

20 и 21 века

[ редактировать ]

В течение 20-го и 21-го веков иммиграция латиноамериканцев в Соединенные Штаты заметно увеличилась после изменений в иммиграционном законе в 1965 году. [ 61 ] Во время мировых войн американцы латиноамериканского происхождения и иммигранты помогли стабилизировать американскую экономику от падения из-за промышленного бума на Среднем Западе в таких штатах, как Мичиган, Огайо, Индиана, Иллинойс, Айова, Висконсин и Миннесота. В то время как часть американцев покинула свои рабочие места из-за войны, выходцы из Латинской Америки устроились на работу в промышленном мире. Это может объяснить, почему существует такая высокая концентрация американцев латиноамериканского происхождения в таких агломерациях, как Чикаго-Элгин-Нейпервилл, Детройт-Уоррен-Дирборн и Кливленд-Элирия. [ 58 ]

Латиноамериканцы и латиноамериканцы активно участвовали в более широком движении за гражданские права 20-го века, выступая за равные права, социальную справедливость и прекращение дискриминации и сегрегации. Такие организации, как Лига объединенных латиноамериканских граждан (LULAC) и Объединение сельскохозяйственных рабочих (UFW), боролись за права латиноамериканских и латиноамериканских рабочих и сообществ.

Вклад латиноамериканцев в историческое прошлое и настоящее Соединенных Штатов более подробно рассматривается ниже (см. « Выдающиеся личности и их вклад »). Чтобы отметить нынешний и исторический вклад американцев латиноамериканского происхождения, 17 сентября 1968 года президент Линдон Б. Джонсон неделю в середине сентября Неделей национального латиноамериканского наследия объявил с разрешения Конгресса . В 1988 году президент Рональд Рейган продлил этот праздник до месяца, получившего название « Месяц национального латиноамериканского наследия» . [ 62 ] [ 63 ] Американцы латиноамериканского происхождения стали крупнейшим меньшинством в 2004 году. [ 64 ]

Латиноамериканцы и латиноамериканцы все чаще стремились к политическому представительству и расширению прав и возможностей в течение 20 века. Избрание в Конгресс таких людей, как Эдвард Ройбал , Генри Б. Гонсалес и Деннис Чавес , ознаменовало важные вехи в политическом представительстве латиноамериканцев. Кроме того, назначение таких людей, как Лауро Кавасос и Билл Ричардсон, на должности в кабинете министров подчеркнуло растущее влияние латиноамериканских и латиноамериканских лидеров в правительстве.

Латиноамериканцы и латиноамериканцы стали крупнейшей группой меньшинства в Соединенных Штатах, внося значительный вклад в рост населения страны. Усилия по сохранению и продвижению латиноамериканской и латиноамериканской культуры и наследия продолжались и в 21 веке, включая инициативы по поддержке двуязычного образования, празднованию культурных традиций и фестивалей, а также признанию вклада латиноамериканских и латиноамериканских людей и сообществ в американское общество.

Демография

[ редактировать ]

По состоянию на 2020 год выходцы из Латинской Америки составляли 19–20% населения США, или 62–65 миллионов человек. [ 65 ] Бюро переписи населения США позже подсчитало, что латиноамериканцы были занижены на 5,0% или 3,3 миллиона человек в переписи населения США, что объясняет диапазон в 3 миллиона в приведенном выше числе. Напротив, количество белых было пересчитано примерно на 3 миллиона. [ 66 ] Темпы роста латиноамериканского населения за период с 1 апреля 2000 г. по 1 июля 2007 г. составили 28,7%, что примерно в четыре раза превышает темпы общего прироста населения страны (7,2%). [ 67 ] Только с 1 июля 2005 г. по 1 июля 2006 г. темп роста составил 3,4%. [ 68 ] - примерно в три с половиной раза превышает темпы общего прироста населения страны (на 1,0%). [ 67 ] По данным переписи 2010 года, выходцы из Латинской Америки в настоящее время являются крупнейшей группой меньшинства в 191 из 366 мегаполисов США. [ 69 ] Прогнозируемая численность латиноамериканского населения Соединенных Штатов на 1 июля 2050 года составит 132,8 миллиона человек, или 30,2% от общей прогнозируемой численности населения страны на эту дату. [ 70 ]

Географическое распространение

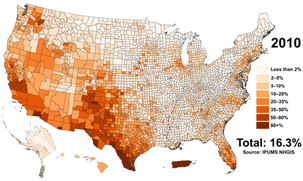

[ редактировать ]- Распределение латиноамериканского и латиноамериканского населения с течением времени

-

1980

-

1990

-

2000

-

2010

-

2020

Статистические районы мегаполисов США с населением более 1 миллиона выходцев из Латинской Америки (2014 г.) [ 71 ]

| Классифицировать | Агломерация | латиноамериканец население |

Процент латиноамериканцев |

|---|

Штаты и территории с наибольшей долей выходцев из Латинской Америки (2021 г.) [ 72 ]

| Классифицировать | Штат/территория | Латиноамериканское население | Процент латиноамериканцев |

|---|

Из общей численности латиноамериканского населения страны 49% (21,5 миллиона человек) проживают в Калифорнии или Техасе . [ 73 ] В 2022 году Нью-Йорк и Вашингтон, округ Колумбия, начали принимать значительное количество латиноамериканских мигрантов из штата Техас, в основном выходцев из Венесуэлы , Эквадора , Колумбии и Гондураса . [ 74 ]

Более половины латиноамериканского населения сосредоточено в Юго-Западном регионе, в основном состоящее из американцев мексиканского происхождения. В Калифорнии и Техасе проживает одно из самых больших поселений мексиканцев и выходцев из Центральной Америки в Соединенных Штатах. В северо-восточном регионе преобладают американцы доминиканского происхождения и пуэрториканцы , где самая высокая концентрация обоих в стране. В Среднеатлантическом регионе, с центром в районе метро округа Колумбия , сальвадорские американцы являются самой крупной из латиноамериканских групп. Во Флориде преобладают американцы кубинского происхождения и пуэрториканцы. И в штатах Великих озер , и в штатах Южной Атлантики преобладают мексиканцы и пуэрториканцы. Мексиканцы доминируют в остальной части страны, включая Западные , Южно-Центральные и Великие равнины штаты.

Национальное происхождение

[ редактировать ]

| латиноамериканец происхождение |

Население | % из латиноамериканцы |

% из олень |

|---|---|---|---|

| Мексиканский | 37,145,956 | 60.15% | 11.22% |

| Пуэрториканец | 5,902,402 | 9.56% | 1.78% |

| Кубинский | 2,405,080 | 3.89% | 0.73% |

| Сальвадор | 2,389,469 | 3.87% | 0.72% |

| Доминиканский | 2,267,142 | 3.67% | 0.68% |

| гватемальский | 1,669,094 | 2.70% | 0.50% |

| Колумбийский | 1,357,798 | 2.20% | 0.41% |

| Гондурасский | 1,068,265 | 1.73% | 0.32% |

| эквадорский | 803,854 | 1.30% | 0.24% |

| Перуанский | 712,740 | 1.15% | 0.22% |

| Венесуэльский | 627,961 | 1.02% | 0.19% |

| Никарагуа | 441,378 | 0.71% | 0.13% |

| аргентинец | 304,672 | 0.49% | 0.09% |

| Панамский | 224,385 | 0.36% | 0.07% |

| Чилийский | 182,671 | 0.30% | 0.06% |

| Коста-Риканец | 173,375 | 0.28% | 0.05% |

| Боливийский | 128,584 | 0.21% | 0.04% |

| уругвайский | 71,984 | 0.12% | 0.02% |

| Парагвайский | 27,522 | 0.04% | 0.01% |

| Другая Центральная Америка | 36,629 | 0.06% | 0.01% |

| Другая южноамериканская | 30,622 | 0.05% | 0.01% |

| испанский [ 76 ] | 1,756,181 | 2.84% | 0.53% |

| Все остальные | 2,028,102 | 3.28% | 0.61% |

| Общий | 61,755,866 | 100.00% | 18.65% |

По состоянию на 2022 год примерно 60,1% латиноамериканского населения страны были мексиканского происхождения (см. таблицу). Еще 9,6% были выходцами из Пуэрто-Рико , примерно по 3,9% - кубинцами и сальвадорцами и около 3,7% - доминиканцами . [ 75 ] Остальные были выходцами из других стран Центральной Америки, Южной Америки или непосредственно из Испании. В 2017 году две трети всех американцев латиноамериканского происхождения родились в Соединенных Штатах. [ 77 ]

Иммигрантов непосредственно из Испании немного, поскольку испанцы исторически эмигрировали в латиноамериканскую Америку, а не в англоязычные страны. Из-за этого большинство выходцев из Латинской Америки, считающих себя испанцами или испанцами, также идентифицируют себя с латиноамериканским национальным происхождением. По оценкам переписи 2017 года, около 1,76 миллиона американцев указали, что они являются испанцами в той или иной форме , независимо от того, были ли они непосредственно из Испании или нет. [ 75 ]

На севере Нью-Мексико и на юге Колорадо проживает значительная часть выходцев из Латинской Америки, которые ведут свое происхождение от поселенцев из Новой Испании (Мексика), а иногда и самой Испании в конце 16-17 веков. Люди этого происхождения часто идентифицируют себя как «испаносцы», «испанцы» или «латиноамериканцы». Многие из этих поселенцев также вступали в брак с местными коренными американцами, создавая популяцию метисов . [ 78 ] Точно так же южная Луизиана является домом для общин выходцев с Канарских островов , известных как Исленьос , в дополнение к другим людям испанского происхождения. Калифорнийцы , новомексиканцы и теханос — американцы испанского и/или мексиканского происхождения, с подгруппами, которые иногда называют себя чикано . Нуевомексиканос и теханос - это отдельные латиноамериканские культуры юго-запада со своей собственной кухней, диалектами и музыкальными традициями.

Нуйориканцы — американцы пуэрториканского происхождения из района Нью-Йорка . В Соединенных Штатах проживает около двух миллионов нуйоринцев. Среди выдающихся жителей Нуйорики - конгрессмен Александрия Окасио-Кортес , судья Верховного суда США Соня Сотомайор и певица Дженнифер Лопес .

Раса и этническая принадлежность

[ редактировать ]Выходцы из Латинской Америки происходят из многорасовых и многоэтнических стран с разным происхождением; следовательно, латиноамериканец может быть представителем любой расы или смеси рас. Наиболее распространенные предки: коренные американцы, европейцы и африканцы. колониальной эпохи . Многие из них также имеют новохристианское сефардско-еврейское происхождение [ 79 ] В результате своего расового разнообразия выходцы из Латинской Америки образуют этническую группу, разделяющую язык ( испанский ) и культурное наследие, а не расу .

называет его «этнической принадлежностью» Латиноамериканское происхождение не зависит от расы и Бюро переписи населения США .

По данным переписи населения США 2020 года , 20,3% выходцев из Латинской Америки выбрали «белых» в качестве своей расы. Это стало большим падением по сравнению с переписью населения США 2010 года , согласно которой 53,0% выходцев из Латинской Америки идентифицировали себя как «белые». [ 80 ] Эти выходцы из Латинской Америки составляют 12 579 626 человек или 3,8% населения.

Более 42% латиноамериканцев идентифицируют себя с « какой-то другой расой ». [ 81 ] Из всех американцев, отметивших галочку «Другая раса», 97 процентов были латиноамериканцами. [ 82 ] Эти выходцы из Латинской Америки составляют 26 225 882 человека или 42,2% латиноамериканского населения.

Почти треть респондентов « двух или более рас » составляли выходцы из Латинской Америки. [ 83 ] Эти выходцы из Латинской Америки составляют 20 299 960 человек или 32,7% латиноамериканского населения.

Наибольшее количество чернокожих выходцев из Латинской Америки проживает с испанских островов Карибского бассейна, включая кубинские, доминиканские , панамские и пуэрториканские общины.

В Пуэрто-Рико люди имеют некоторое происхождение от коренных американцев, а также от европейцев и жителей Канарских островов. Есть также население преимущественно африканского происхождения, а также население индейского происхождения, а также люди смешанного происхождения. Кубинцы в основном имеют иберийское и канарское происхождение, а также имеют некоторое наследие от коренных жителей Карибского бассейна. Есть также группы чернокожего происхождения, живущие к югу от Сахары, и представители разных рас. [ 84 ] [ 85 ] [ 86 ] Раса и культура каждой латиноамериканской страны и их диаспоры в Соединенных Штатах различаются в зависимости от истории и географии.

Уэлч и Сигельман обнаружили, что по состоянию на 2000 год взаимодействие между латиноамериканцами разных национальностей (например, между кубинцами и мексиканцами) ниже, чем между латиноамериканцами и нелатиноамериканцами. [ 87 ] Это напоминание о том, что, хотя к ним часто относятся как к таковым, латиноамериканцы в Соединенных Штатах не являются монолитом и часто рассматривают свою этническую или национальную идентичность как сильно отличающуюся от идентичности других латиноамериканцев. [ 87 ]

| Race/Ethnic Group | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population | 9,072,602 | 14,608,673 | 22,354,059 | 35,305,818 | 50,477,594 | 62,080,044 |

| White alone | 8,466,126 (93.3%) | 8,115,256 (55.6%) | 11,557,774 (51.7%) | 16,907,852 (47.9%) | 26,735,713 (53.0%) | 12,579,626 (20.3%) |

| Black alone | 454,934 (5.0%) | 390,852 (2.7%) | 769,767 (3.4%) | 710,353 (2.0%) | 1,243,471 (2.5%) | 1,163,862 (1.9%) |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone | 26,859 (0.3%) | 94,745 (0.6%) | 165,461 (0.7%) | 407,073 (1.2%) | 685,150 (1.4%) | 1,475,436 (2.4%) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander alone | x | 166,010 (1.1%) | 305,303 (1.4%) | 165,155 (0.5%) | 267,565 (0.5%) | 335,278 (0.5%) |

| Some other race alone | 124,683 (1.4%)[a] | 5,841,810 (40.0%) | 9,555,754 (42.7%) | 14,891,303 (42.2%) | 18,503,103 (36.7%) | 26,225,882 (42.2%) |

| Two or more races | x[b] | x[b] | x[b] | 2,224,082 (6.3%) | 3,042,592 (6.0%) | 20,299,960 (32.7%) |

Genetics

[edit]An automosal DNA study published in 2019, focusing specifically on Native American ancestry in different ethnic/racial groups within the US, found that self-identified Hispanic Americans had a higher average amount of Native American ancestry compared to Black and non-Hispanic White Americans. On average, Hispanic Americans were found to be just over half European, around 38% Native American, and less than 10% African.[93][94] However, these results, being an average of the entire Hispanic population, vary sharply between individuals and between regions. Hispanic participants from the West Coast and West South Central regions, where the Hispanic population is predominantly Mexican-American,[95] had an average of 43% Native American ancestry.[94] On the other hand, those from the Mid-Atlantic region, where the Hispanic population is predominantly of Puerto Rican or Dominican descent,[96] averaged only 11% Native American ancestry.[94]

Age

[edit]As of 2014, one third, or 17.9 million, of the Hispanic population was younger than 18 and a quarter, 14.6 million, were Millennials. This makes them more than half of the Hispanic population within the United States.[97]

Education

[edit]Hispanic K–12 education

[edit]

With the increasing Hispanic population in the United States, Hispanics have had a considerable impact on the K–12 system. In 2011–12, Hispanics comprised 24% of all enrollments in the United States, including 52% and 51% of enrollment in California and Texas, respectively.[98] Further research shows the Hispanic population will continue to grow in the United States, implicating that more Hispanics will populate US schools.

The state of Hispanic education shows some promise. First, Hispanic students attending pre-K or kindergarten were more likely to attend full-day programs.[98] Second, Hispanics in elementary education were the second largest group represented in gifted and talented programs.[98] Third, Hispanics' average NAEP math and reading scores have consistently increased over the last 10 years.[98] Finally, Hispanics were more likely than other groups, including White people, to go to college.[98]

However, their academic achievement in early childhood, elementary, and secondary education lag behind other groups.[98] For instance, their average math and reading NAEP scores were lower than every other group, except African Americans, and have the highest dropout rate of any group, 13% despite decreasing from 24%.[98]

To explain these disparities, some scholars have suggested there is a Hispanic "Education Crisis" due to failed school and social policies.[99] To this end, scholars have further offered several potential reasons including language barriers, poverty, and immigrant/nativity status resulting in Hispanics not performing well academically.[100][101]

English language learners

[edit]

Currently, Hispanic students make up 80% of English language learners in the United States.[102] In 2008–2009, 5.3 million students were classified as English Language Learners (ELLs) in pre-K to 12th grade.[103] This is a result of many students entering the education system at different ages, although the majority of ELLs are not foreign born.[103] In order to provide English instruction for Hispanic students there have been a multitude of English Language programs. Schools make demands when it comes to English fluency. There are test requirements to certify students who are non-native English speakers in writing, speaking, reading, and listening, for example. They take an ELPAC test, which evaluates their English efficiency. This assessment determines whether they are considered ELL students or not. For Hispanic students, being an ELL student will have a big impact because it's additional pressure to pass an extra exam apart from their own original classes. Furthermore, if the exam is not passed before they attend high school, the student will fall behind in their courses due to the additional ELD courses instead of taking their normal classes in that year.[104] However, the great majority of these programs are English Immersion, which arguably undermines the students' culture and knowledge of their primary language.[101] As such, there continues to be great debate within schools as to which program can address these language disparities.

Immigration status

[edit]There are more than five million ELLs from all over the world attending public schools in the United States and speaking at least 460 different languages.[104] Undocumented immigrants have not always had access to compulsory education in the United States. However, since the landmark Supreme Court case Plyler v. Doe in 1982, immigrants have received access to K-12 education. This significantly impacted all immigrant groups, including Hispanics. However, their academic achievement is dependent upon several factors including, but not limited to time of arrival and schooling in country of origin.[105] When non-native speakers arrive to the United States, the student not only enters a new country, language or culture, but they also enter a testing culture to determine everything from their placements to advancement into the next grade level in their education.[104] Moreover, Hispanics' immigration/nativity status plays a major role regarding their academic achievement. For instance, first- and second- generation Hispanics outperform their later generational counterparts.[106] Additionally, their aspirations appear to decrease as well.[107] This has major implications on their postsecondary futures.

Simultaneous bilingualism

[edit]There is a term “simultaneous bilinguals" it is emerged on the research from Guadalupe Valdez [108] she states that it is used by individuals who acquire two languages as a “first” language; that most American circumstantial bilinguals acquire their ethnic or immigrant language first and then acquire English. The period of acquisition of the second language is known as incipient bilingualism.

Hispanic higher education

[edit]

Those with a bachelor's degree or higher ranges from 50% of Venezuelans compared to 18% for Ecuadorians 25 years and older. Amongst the largest Hispanic groups, those with a bachelor's or higher was 25% for Cubans, 16% of Puerto Ricans, 15% of Dominicans, and 11% for Mexicans. Over 21% of all second-generation Dominican Americans have college degrees, slightly below the national average (28%) but significantly higher than US-born Mexican Americans (13%) and US-born Puerto Rican Americans (12%).[110]

Hispanics make up the second or third largest ethnic group in Ivy League universities, considered to be the most prestigious in the United States. Hispanic enrollment at Ivy League universities has gradually increased over the years. Today, Hispanics make up between 8% of students at Yale University to 15% at Columbia University.[111] For example, 18% of students in the Harvard University Class of 2018 are Hispanic.[112]

Hispanics have significant enrollment in many other top universities such as University of Texas at El Paso (70% of students), Florida International University (63%), University of Miami (27%), and MIT, UCLA and UC-Berkeley at 15% each. At Stanford University, Hispanics are the third largest ethnic group behind non-Hispanic White people and Asians, at 18% of the student population.[113]

Hispanic university enrollments

[edit]| 2019 -2020 Total Enrollment 4-Year Schools[114] |

|---|

While Hispanics study in colleges and universities throughout the country, some choose to attend federally-designated Hispanic-serving institutions, institutions that are accredited, degree-granting, public or private nonprofit institutions of higher education with 25 percent or more total undergraduate Hispanic full-time equivalent (FTE) student enrollment. There are over 270 institutions of higher education that have been designated as an HSI.[115]

Health

[edit]Longevity

[edit]

As of 2016, life expectancy for Hispanic Americans is 81.8 years, which is higher than the life expectancy for White Americans (78.6 years).[130] Research on the "Hispanic paradox"—the well-established apparent mortality advantage of Hispanic Americans compared to White Americans, despite the latter's more advantaged socioeconomic status—has been principally explained by "(1) health-related migration to and from the US; and (2) social and cultural protection mechanisms, such as maintenance of healthy lifestyles and behaviors adopted in the countries of origin, and availability of extensive social networks in the US."[131] The "salmon bias" hypothesis, which suggests that the Hispanic health advantage is attributable to higher rates of return migration among less-healthy migrants, has received some support in the scholarly literature.[132] A 2019 study, examining the comparatively better health of foreign-born American Hispanics, challenged the hypothesis that a stronger orientation toward the family (familism) contributed to this advantage.[133] Some scholars have suggested that the Hispanic mortality advantage is likely to disappear due to the higher rates of obesity and diabetes among Hispanics relative to White people, although lower rates of smoking (and thus smoking-attributable mortality) among Hispanics may counteract this to some extent.[131]

Healthcare

[edit]As of 2017, about 19% of Hispanic Americans lack health insurance coverage, which is the highest of all ethnic groups except for Indigenous Americans and Alaska Natives.[134] In terms of extending health coverage, Hispanics benefited the most among US ethnic groups from the Affordable Care Act (ACA); among non-elderly Hispanics, the uninsured rate declined from 26.7% in 2013 to 14.2% in 2017.[134] Among the population of non-elderly uninsured Hispanic population in 2017, about 53% were non-citizens, about 39% were US-born citizens, and about 9% were naturalized citizens.[134] (The ACA does not help undocumented immigrants or legal immigrants with less than five years' residence in the United States gain coverage).[134]

According to a 2013 study, Mexican women have the highest uninsured rate (54.6%) as compared to other immigrants (26.2%), Black (22.5%) and White (13.9%).[135] According to the study, Mexican women are the largest female immigrant group in the United States and are also the most at risk for developing preventable health conditions.[135] Multiple factors such as limited access to health care, legal status and income increase the risk of developing preventable health conditions because many undocumented immigrants postpone routine visits to the doctor until they become seriously ill.

Mental health

[edit]Family separation

[edit]

Some families who are in the process of illegally crossing borders can suffer being caught and separated by border patrol agents. Migrants are also in danger of separation if they do not bring sufficient resources such as water for all members to continue crossing. Once illegal migrants have arrived to the new country, they may fear workplace raids where illegal immigrants are detained and deported.

Family separation puts US-born children, undocumented children and their illegal immigrant parents at risk for depression and family maladaptive syndrome. The effects are often long-term and the impact extends to the community level. Children may experience emotional traumas and long-term changes in behaviors. Additionally, when parents are forcefully removed, children often develop feelings of abandonment and they might blame themselves for what has happened to their family. Some children that are victims to illegal border crossings that result in family separation believe in the possibility of never seeing their parents again. These effects can cause negative parent-child attachment. Reunification may be difficult because of immigration laws and re-entry restrictions which further affect the mental health of children and parents.[136] Parents who leave their home country also experience negative mental health experiences. According to a study published in 2013, 46% of Mexican migrant men who participated in the study reported elevated levels of depressive symptoms.[137] In recent years, the length of stay for migrants has increased, from 3 years to nearly a decade.[137] Migrants who were separated from their families, either married or single, experienced greater depression than married men accompanied by their spouses.[137] Furthermore, the study also revealed that men who are separated from their families are more prone to harsher living conditions such as overcrowded housing and are under a greater deal of pressure to send remittance to support their families. These conditions put additional stress on the migrants and often worsen their depression. Families who migrated together experience better living conditions, receive emotional encouragement and motivation from each other, and share a sense of solidarity. They are also more likely to successfully navigate the employment and health care systems in the new country, and are not pressured to send remittances back home.

Vulnerabilities

[edit]

The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 significantly changed how the United States dealt with immigration. Under this new law, immigrants who overstayed their visas or were found to be in the United States illegally were subject to be detained and/or deported without legal representation. Immigrants who broke these laws may not be allowed back into the country. Similarly, this law made it more difficult for other immigrants who want to enter the United States or gain legal status. These laws also expanded the types of offenses that can be considered worthy of deportation for documented immigrants.[136] Policies enacted by future presidents further limit the number of immigrants entering the country and their expedited removal.

Many illegal immigrant families cannot enjoy doing everyday activities without exercising caution because they fear encountering immigration officers which limits their involvement in community events. Undocumented families also do not trust government institutions and services. Because of their fear of encountering immigration officers, illegal immigrants often feel ostracized and isolated which can lead to the development of mental health issues such as depression and anxiety.[136] The harmful effects of being ostracized from the rest of society are not limited to just that of undocumented immigrants but it affects the entire family even if some of the members are of legal status. Children often reported having been victims of bullying in school by classmates because their parents are undocumented.[138] This can cause them to feel isolated and develop a sense of inferiority which can negatively impact their academic performance.

Stress

[edit]

Despite the struggles Hispanic families encounter, they have found ways to keep motivated. Many immigrants use religion as a source of motivation. Mexican immigrants believed that the difficulties they face are a part of God's bigger plan and believe their life will get better in the end. They kept their faith strong and pray every day, hoping that God will keep their families safe.[138] Immigrants participate in church services and bond with other immigrants that share the same experiences.<[136] Undocumented Hispanics also find support from friends, family and the community that serve as coping mechanisms. Some Hispanics state that their children are the reason they have the strength to keep on going. They want their children to have a future and give them things they are not able to have themselves.[138] The community is able to provide certain resources that immigrant families need such as tutoring for their children, financial assistance and counseling services.[136] Some identified that maintaining a positive mental attitude helped them cope with the stresses they experience. Many immigrants refuse to live their life in constant fear which leads to depression in order to enjoy life in the United States.[138] Since many immigrants have unstable sources of income, many plan ahead in order to prevent future financial stress. They put money aside and find ways to save money instead of spend it such as learning to fix appliances themselves.[138]

Poverty

[edit]

Many Hispanic families migrate to find better economic opportunities in order to send remittances back home. Being undocumented limits the possibilities of jobs that immigrants undertake and many struggle to find a stable job. Many Hispanics report that companies turned them down because they do not have a Social Security number. If they are able to obtain a job, immigrants risk losing it if their employer finds out they are unable to provide proof of residency or citizenship. Many look towards agencies that do not ask for identification, but those jobs are often unreliable. In order to prevent themselves from being detained and deported, many have to work under exploitation. In a study, a participant reported "If someone knows that you don't have the papers ... that person is a danger. Many people will con them ... if they know you don't have the papers, with everything they say 'hey I'm going to call immigration on you.'".[138] These conditions lower the income that Hispanic families bring to their household and some find living each day very difficult. When an undocumented parent is deported or detained, income will be lowered significantly if the other parent also supports the family financially. The parent who is left has to look after the family and might find working difficult to manage along with other responsibilities. Even if families are not separated, Hispanics are constantly living in fear that they will lose their economic footing.

Living in poverty has been linked to depression, low self-esteem, loneliness, crime activities and frequent drug use among youth.[136] Families with low incomes are unable to afford adequate housing and some of them are evicted. The environment in which the children of undocumented immigrants grow up in is often composed of poor air quality, noise, and toxins which prevent healthy development.[136] Furthermore, these neighborhoods are prone to violence and gang activities, forcing the families to live in constant fear which can contribute to the development of PTSD, aggression and depression.

Economic outlook

[edit]| Ethnicity | Income | |

|---|---|---|

| Spanish | $60,640 | |

| Argentinian | $60,000 | |

| Colombian | $56,800 | |

| Cuban | $56,000 | |

| Puerto Rican | $54,500 | |

| Venezuelan | $51,000 | |

| Chilean | $51,000 | |

| Peruvian | $47,600 | |

| Bolivian | $44,400 | |

| Ecuadorian | $44,200 | |

| Mexican | $40,500 | |

| Honduran | $40,200 | |

| Salvadoran | $36,800 | |

| Guatemalan | $36,800 | |

| Sources:[139][failed verification] | ||

Median income

[edit]In 2017, the US Census reported the median household incomes of Hispanic Americans to be $50,486. This is the third consecutive annual increase in median household income for Hispanic-origin households.[90]

Poverty

[edit]According to the US Census, the poverty rate Hispanics was 18.3 percent in 2017, down from 19.4 percent in 2016. Hispanics accounted for 10.8 million individuals in poverty.[90] In comparison, the average poverty rates in 2017 for non-Hispanic White Americans was 8.7 percent with 17 million individuals in poverty, Asian Americans was 10.0 percent with 2 million individuals in poverty, and African Americans was 21.2 percent with 9 million individuals in poverty.[90]

Among the largest Hispanic groups during 2015 was: Honduran Americans & Dominican Americans (27%), Guatemalan Americans (26%), Puerto Ricans (24%), Mexican Americans (23%), Salvadoran Americans (20%), Cuban Americans and Venezuelan Americans (17%), Ecuadorian Americans (15%), Nicaraguan Americans (14%), Colombian Americans (13%), Argentinian Americans (11%) and Peruvian Americans (10%).[140]

Poverty affects many underrepresented students as racial/ethnic minorities tend to stay isolated within pockets of low-income communities. This results in several inequalities, such as "school offerings, teacher quality, curriculum, counseling and all manner of things that both keep students engaged in school and prepare them to graduate".[141] In the case of Hispanics, the poverty rate for Hispanic children in 2004 was 28.6 percent.[102] Moreover, with this lack of resources, schools reproduce these inequalities for generations to come. In order to assuage poverty, many Hispanic families can turn to social and community services as resources.

Cultural matters

[edit]

The geographic, political, social, economic and racial diversity of Hispanic Americans makes all Hispanics very different depending on their family heritage and/or national origin. Many times, there are many cultural similarities between Hispanics from neighboring countries than from more distant countries, i.e. Spanish Caribbean, Southern Cone, Central America etc. Yet several features tend to unite Hispanics from these diverse backgrounds.

Language

[edit]Spanish

[edit]

As one of the most important uniting factors of Hispanic Americans, Spanish is an important part of Hispanic culture. Teaching Spanish to children is often one of the most valued skills taught amongst Hispanic families. Spanish is not only closely tied with the person's family, heritage, and overall culture, but valued for increased opportunities in business and one's future professional career. A 2013 Pew Research survey showed that 95% of Hispanics adults said "it's important that future generations of Hispanics speak Spanish".[142][143] Given the United States' proximity to other Spanish-speaking countries, Spanish is being passed on to future American generations. Amongst second-generation Hispanics, 80% speak fluent Spanish, and amongst third-generation Hispanics, 40% speak fluent Spanish.[144] Spanish is also the most popular language taught in the United States.[145][146]

Hispanics have revived the Spanish language in the United States, first brought to North America during the Spanish colonial period in the 16th century. Spanish is the oldest European language in the United States, spoken uninterruptedly for four and a half centuries, since the founding of Saint Augustine, Florida in 1565.[147][148][149][150] Today, 90% of all Hispanics speak English, and at least 78% speak fluent Spanish.[151] Additionally, 2.8 million non-Hispanic Americans also speak Spanish at home for a total of 41.1 million.[92]

With 40% of Hispanic Americans being immigrants,[152] and with many of the 60% who are US-born being the children or grandchildren of immigrants, bilingualism is the norm in the community at large. At home, at least 69% of all Hispanics over the age of five are bilingual in English and Spanish, whereas up to 22% are monolingual English-speakers, and 9% are monolingual Spanish speakers. Another 0.4% speak a language other than English and Spanish at home.[151]

American Spanish dialects

[edit]| Year | Number of speakers |

Percent of population |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 11.0 million | 5% |

| 1990 | 17.3 million | 7% |

| 2000 | 28.1 million | 10% |

| 2010 | 37.0 million | 13% |

| 2012 | 38.3 million | 13% |

| 2020* | 40.0 million | 14% |

| *-Projected; sources:[142][153][154][155] | ||

The Spanish dialects spoken in the United States differ depending on the country of origin of the person or the person's family heritage. However, generally, Spanish spoken in the Southwest is Mexican Spanish or Chicano Spanish. A variety of Spanish native to the Southwest spoken by descendants of the early Spanish colonists in New Mexico and Colorado is known as Traditional New Mexican Spanish. One of the major distinctions of Traditional New Mexican Spanish is its use of distinct vocabulary and grammatical forms that make New Mexican Spanish unique amongst Spanish dialects. The Spanish spoken in the East Coast is generally Caribbean Spanish and is heavily influenced by the Spanish of Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico. Isleño Spanish, descended from Canarian Spanish, is the historic Spanish dialect spoken by the descendants of the earliest Spanish colonists beginning in the 18th century in Louisiana. Spanish spoken elsewhere throughout the country varies, although is generally Mexican Spanish.[92][156]

Heritage Spanish speakers tend to speak Spanish with near-native level phonology, but a more limited command of morphosyntax.[157] Hispanics who speak Spanish as a second language often speak with English accents.

Spanglish and English dialects

[edit]

Hispanics have influenced the way Americans speak with the introduction of many Spanish words into the English language. Amongst younger generations of Hispanics, Spanglish, a term for any mix of Spanish and English, is common in speaking. As they are fluent in both languages, speakers will often switch between Spanish and English throughout the conversation. Spanglish is particularly common in Hispanic-majority cities and communities such as Miami, Hialeah, San Antonio, Los Angeles and parts of New York City.[158]

Hispanics have also influenced the way English is spoken in the United States. In Miami, for example, the Miami dialect has evolved as the most common form of English spoken and heard in Miami today. This is a native dialect of English, and was developed amongst second and third generations of Cuban Americans in Miami. Today, it is commonly heard everywhere throughout the city. Gloria Estefan and Enrique Iglesias are examples of people who speak with the Miami dialect. Another major English dialect, is spoken by Chicanos and Tejanos in the Southwestern United States, called Chicano English. George Lopez and Selena are examples of speakers of Chicano English.[159] An English dialect spoken by Puerto Ricans and other Hispanic groups is called New York Latino English; Jennifer Lopez and Cardi B are examples of people who speak with the New York Latino dialect.

When speaking in English, American Hispanics may often insert Spanish tag and filler items such as tú sabes, este, and órale, into sentences as a marker of ethnic identity and solidarity. The same often occurs with grammatical words like pero.[160]

Religion

[edit]

According to a Pew Center study which was conducted in 2019, the majority of Hispanic Americans are Christians (72%),[161] Among American Hispanics, as of 2018–19, 47% are Catholic, 24% are Protestant, 1% are Mormon, less than 1% are Orthodox Christian, 3% are members of non-Christian faiths, and 23% are unaffiliated.[161] The proportion of Hispanics who are Catholic has dropped from 2009 (when it was 57%), while the proportion of unaffiliated Hispanics has increased since 2009 (when it was 15%).[161] Among Hispanic Protestant community, most are evangelical, but some belong to mainline denominations.[162] Compared to Catholic, unaffiliated, and mainline Protestant Hispanics; Evangelical Protestant Hispanics are substantially more likely to attend services weekly, pray daily, and adhere to biblical liberalism.[162] As of 2014, about 67% of Hispanic Protestants and about 52% of Hispanic Catholics were renewalist, meaning that they described themselves as Pentecosal or charismatic Christians (in the Catholic tradition, called Catholic charismatic renewal).[163]

Catholic affiliation is much higher among first-generation Hispanic immigrants than it is among second and third-generation Hispanic immigrants, who exhibit a fairly high rate of conversion to Protestantism or the unaffiliated camp.[164] According to Andrew Greeley, as many as 600,000 American Hispanics leave Catholicism for Protestant churches every year, and this figure is much higher in Texas and Florida.[165] Hispanic Catholics are developing youth and social programs to retain members.[166]

Hispanics make up a substantial proportion (almost 40%) of Catholics in the United States,[167] although the number of American Hispanic priests is low relative to Hispanic membership in the church.[168] In 2019, José Horacio Gómez, Archbishop of Los Angeles and a naturalized American citizen born in Mexico, was elected as president of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops.[167]

| Date | Catholicism | Unaffiliated | Evangelical Protestant | Non-Evangelical Protestant | Other religion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 43 | 30 | 15 | 6 | 4 |

| 2021 | 46 | 25 | 14 | 7 | 5 |

| 2018 | 49 | 20 | 19 | 7 | 3 |

| 2016 | 54 | 17 | 15 | 7 | 5 |

| 2015 | 54 | 17 | 18 | 7 | 4 |

| 2014 | 58 | 12 | 14 | 7 | 7 |

| 2013 | 55 | 18 | 17 | 7 | 3 |

| 2012 | 58 | 13 | 15 | 6 | 3 |

| 2011 | 62 | 14 | 13 | 6 | 3 |

| 2010 | 67 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 3 |

Media

[edit]

The United States is home to thousands of Spanish-language media outlets, which range in size from giant commercial and some non-commercial broadcasting networks and major magazines with circulations numbering in the millions, to low-power AM radio stations with listeners numbering in the hundreds. There are hundreds of Internet media outlets targeting US Hispanic consumers. Some of the outlets are online versions of their printed counterparts and some online exclusively.

Increased use of Spanish-language media leads to increased levels of group consciousness, according to survey data. The differences in attitudes are due to the diverging goals of Spanish-language and English-language media. The effect of using Spanish-language media serves to promote a sense of group consciousness among Hispanics by reinforcing roots in the Hispanic world and the commonalities among Hispanics of varying national origin.[170][171]

The first Hispanic-American owned major film studio in the United States is based in Atlanta, Georgia. In 2017, Ozzie and Will Areu purchased Tyler Perry's former studio to establish Areu Bros. Studios.[172][173]

Radio

[edit]Spanish language radio is the largest non-English broadcasting media.[174] While other foreign language broadcasting declined steadily, Spanish broadcasting grew steadily from the 1920s to the 1970s. The 1930s were boom years.[175] The early success depended on the concentrated geographical audience in Texas and the Southwest.[176] American stations were close to Mexico which enabled a steady circular flow of entertainers, executives and technicians, and stimulated the creative initiatives of Hispanic radio executives, brokers, and advertisers. Ownership was increasingly concentrated in the 1960s and 1970s. The industry sponsored the now-defunct trade publication Sponsor from the late 1940s to 1968.[177] Spanish-language radio has influenced American and Hispanic discourse on key current affairs issues such as citizenship and immigration.[178]

Networks

[edit]Notable Hispanic-oriented media outlets include:

- CNN en Español, a Spanish-language news network based in Atlanta, Georgia;

- ESPN Deportes and Fox Deportes, two Spanish-language sports television networks.

- Telemundo, the second-largest Spanish-language television network in the United States, with affiliates in nearly every major U.S. market, and numerous affiliates internationally;

- Univisión, the largest Spanish-language television network in the United States, with affiliates in nearly every major U.S. market, and numerous affiliates internationally. It is the country's fourth-largest network overall;[179]

- UniMás, an American Spanish language free-to-air television network owned by Univision Communications.

- Fusion TV, an English television channel targeting Hispanic audiences with news and satire programming;

- Galavisión, a Spanish-language television channel targeting Hispanic audiences with general entertainment programming;

- Estrella TV, an American Spanish-language broadcast television network owned by the Estrella Media.

- V-me, a Spanish-language television network;

- Primo TV, an English-language cable channel aimed at Hispanic youth.;

- Azteca América, a Spanish-language television network in the United States, with affiliates in nearly every major U.S. market, and numerous affiliates internationally;

- Fuse, a former music channel that merged with the Hispanic-oriented NuvoTV in 2015.

- FM, a music-centric channel that replaced NuvoTV following the latter's merger with Fuse in 2015.

- 3ABN Latino, a Spanish-language Christian television network based in West Frankfort, Illinois;

- TBN Enlace USA, a Spanish-language Christian television network based in Tustin, California;

- La Opinión, a Spanish-language daily newspaper published in Los Angeles, California and distributed throughout the six counties of Southern California. It is the largest Spanish-language newspaper in the United States

- El Nuevo Herald and Diario Las Américas, Spanish-language daily newspapers serving the greater Miami, Florida, market

- El Tiempo Latino a Spanish-language free-circulation weekly newspaper published in Washington, D.C.

- Latina, a magazine for bilingual, bicultural Hispanic women

- People en Español, a Spanish-language magazine counterpart of People

- Vida Latina, a Spanish-language entertainment magazine distributed throughout the Southern United States

Sports and music

[edit]Because of different cultures throughout the Hispanic world, there are various music forms throughout Hispanic countries, with different sounds and origins. Reggaeton and hip hop are genres that are most popular to Hispanic youth in the United States. Recently Latin trap, trap corridos, and Dominican dembow have gained popularity.[180][181][182]

Soccer is a common sport for Hispanics from outside of the Caribbean region, particularly immigrants. Baseball is a common among Caribbean Hispanics. Other popular sports include boxing, gridiron football, and basketball.

Cuisine

[edit]

Hispanic food, particularly Mexican food, has influenced American cuisine and eating habits. Mexican cuisine has become mainstream in American culture. Across the United States, tortillas and salsa are arguably becoming as common as hamburger buns and ketchup. Tortilla chips have surpassed potato chips in annual sales, and plantain chips popular in Caribbean cuisines have continued to increase sales.[183] The avocado has been described as "America's new favorite fruit"; its largest market within the US is among Hispanic Americans.[184]

Due to the large Mexican-American population in the Southwestern United States, and its proximity to Mexico, Mexican food there is believed to be some of the best in the United States. Cubans brought Cuban cuisine to Miami and today, cortaditos, pastelitos de guayaba and empanadas are common mid-day snacks in the city. Cuban culture has changed Miami's coffee drinking habits, and today a café con leche or a cortadito is commonly had at one of the city's numerous coffee shops.[185] The Cuban sandwich, developed in Miami, is now a staple and icon of the city's cuisine and culture.[186]

Familial situations

[edit]Family life and values

[edit]

Hispanic culture places a strong value on family, and is commonly taught to Hispanic children as one of the most important values in life. Statistically, Hispanic families tend to have larger and closer knit families than the American average. Hispanic families tend to prefer to live near other family members. This may mean that three or sometimes four generations may be living in the same household or near each other, although four generations is uncommon in the United States. The role of grandparents is believed to be very important in the upbringing of children.[187]

Hispanics tend to be very group-oriented, and an emphasis is placed on the well-being of the family above the individual. The extended family plays an important part of many Hispanic families, and frequent social, family gatherings are common. Traditional rites of passages, particularly Roman Catholic sacraments: such as baptisms, birthdays, first Holy Communions, quinceañeras, Confirmations, graduations and weddings are all popular moments of family gatherings and celebrations in Hispanic families.[188][189]

Education is another important priority for Hispanic families. Education is seen as the key towards continued upward mobility in the United States among Hispanic families. A 2010 study by the Associated Press showed that Hispanics place a higher emphasis on education than the average American. Hispanics expect their children to graduate university.[190][191]

Hispanic youth today stay at home with their parents longer than before. This is due to more years spent studying and the difficulty of finding a paid job that meets their aspirations.[192]

Intermarriage

[edit]

Hispanic Americans, like many immigrant groups before them, are out-marrying at high rates. Out-marriages comprised 17.4% of all existing Hispanic marriages in 2008.[197] The rate was higher for newlyweds (which excludes immigrants who are already married): Among all newlyweds in 2010, 25.7% of all Hispanics married a non-Hispanic (this compares to out-marriage rates of 9.4% of White people, 17.1% of Black people, and 27.7% of Asians). The rate was larger for native-born Hispanics, with 36.2% of native-born Hispanics (both men and women) out-marrying compared to 14.2% of foreign-born Hispanics.[198] The difference is attributed to recent immigrants tending to marry within their immediate immigrant community due to commonality of language, proximity, familial connections, and familiarity.[197]

In 2008, 81% of Hispanics who married out married non-Hispanic White people, 9% married non-Hispanic Black people, 5% non-Hispanic Asians, and the remainder married non-Hispanic, multi-racial partners.[197]

Of approximately 275,500 new interracial or interethnic marriages in 2010, 43.3% were White-Hispanic (compared to White-Asian at 14.4%, White-Black at 11.9%, and other combinations at 30.4%; "other combinations" consists of pairings between different minority groups and multi-racial people).[198] Unlike those for marriage to Black people and Asians, intermarriage rates of Hispanics to White people do not vary by gender. The combined median earnings of White/Hispanic couples are lower than those of White/White couples but higher than those of Hispanic/Hispanic couples. 23% of Hispanic men who married White women have a college degree compared to only 10% of Hispanic men who married a Hispanic woman. 33% of Hispanic women who married a White husband are college-educated compared to 13% of Hispanic women who married a Hispanic man.[198]

Attitudes among non-Hispanics toward intermarriage with Hispanics are mostly favorable, with 81% of White people, 76% of Asians and 73% of Black people "being fine" with a member of their family marrying a Hispanic and an additional 13% of White people, 19% of Asians and 16% of Black people "being bothered but accepting of the marriage". Only 2% of White people, 4% of Asians, and 5% of Black people would not accept a marriage of their family member to a Hispanic.[197]

Hispanic attitudes toward intermarriage with non-Hispanics are likewise favorable, with 81% "being fine" with marriages to White people and 73% "being fine" with marriages to Black people. A further 13% admitted to "being bothered but accepting" of a marriage of a family member to a White and 22% admitted to "being bothered but accepting" of a marriage of a family member to a Black. Only 5% of Hispanics objected outright marriage of a family member to a non-Hispanic Black and 2% to a non-Hispanic White.[197]

Unlike intermarriage with other racial groups, intermarriage with non-Hispanic Black people varies by nationality of origin. Puerto Ricans have by far the highest rates of intermarriage with Black people, of all major Hispanic national groups, who also has the highest overall intermarriage rate among Hispanics.[190][200][201][202][203][204][205][206][207][208][excessive citations] Cubans have the highest rate of intermarriage with non-Hispanic White people, of all major Hispanic national groups, and are the most assimilated into White American culture.[209][210]

Cultural adjustment

[edit]

As Hispanic migrants become the norm in the United States, the effects of this migration on the identity of these migrants and their kin becomes most evident in the younger generations. Crossing the borders changes the identities of both the youth and their families. Often "one must pay special attention to the role expressive culture plays as both entertainment and as a site in which identity is played out, empowered, and reformed" because it is "sometimes in opposition to dominant norms and practices and sometimes in conjunction with them".[211] The exchange of their culture of origin with American culture creates a dichotomy within the values that the youth find important, therefore changing what it means to be Hispanic in the global sphere.

Transnationalism

[edit]Along with feeling that they are neither from the country of their ethnic background nor the United States, a new identity within the United States is formed called latinidad. This is especially seen in cosmopolitan social settings like New York City, Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles and San Francisco. Underway is "the intermeshing of different Latino subpopulations has laid the foundations for the emergence and ongoing evolution of a strong sense of latinidad" which establishes a "sense of cultural affinity and identity deeply rooted in what many Hispanics perceive to be a shared historical, spiritual, aesthetic and linguistic heritage, and a growing sense of cultural affinity and solidarity in the social context of the United States."[211] This unites Hispanics as one, creating cultural kin with other Hispanic ethnicities.

Gender roles

[edit]In a 1998 study of Mexican Americans it was found that males were more likely to endorse the notion than men should be the sole breadwinners of the family, while Mexican American women did not endorse this notion.[212]

Prior to the 1960s countercultural movement, Mexican men often felt an exaggerated need to be the sole breadwinner of their families.[213] There are two sides to machismo, the man who has a strong work ethic and lives up to his responsibilities, or the man who heavily drinks and therefore displays acts of unpleasant behavior towards his family.[212]

The traditional roles of women in a Hispanic community are of housewife and mother, a woman's role is to cook, clean, and care for her children and husband; putting herself and her needs last.[214] The typical structure of a Hispanic family forces women to defer authority to her husband, allowing him to make the important decisions, that both the woman and children must abide by.[215] In traditional Hispanic households, women and young girls are homebodies or muchachas de la casa ("girls of the house"), showing that they abide "by the cultural norms ... [of] respectability, chastity, and family honor [as] valued by the [Hispanic] community".[216]

Migration to the United States can change the identity of Hispanic youth in various ways, including how they carry their gendered identities.[217] However, when Hispanic women come to the United States, they tend to adapt to the perceived social norms of this new country and their social location changes as they become more independent and able to live without the financial support of their families or partners.[217] The unassimilated community views these adapting women as being de la calle ("of [or from] the street"), transgressive, and sexually promiscuous.[217] A women's motive for pursuing an education or career is to prove she can care and make someone of herself, breaking the traditional gender role that a Hispanic woman can only serve as a mother or housewife, thus changing a woman's role in society.[218] Some Hispanic families in the United States "deal with young women's failure to adhere to these culturally prescribed norms of proper gendered behavior in a variety of ways, including sending them to live in ... [the sending country] with family members, regardless of whether or not ... [the young women] are sexually active".[219] Now there has been a rise in the Hispanic community where both men and women are known to work and split the household chores among themselves; women are encouraged to gain an education, degree, and pursue a career.[220]

Sexuality

[edit]

According to polling data released in 2022, 11% of Hispanic American adults identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender. This is more than twice the rate of White Americans or African Americans. Over 20% of Hispanic Millennials and Gen Z claimed an LGBT identity.[221] The growth of the young Hispanic population is driving an increase of the LGBT community in the United States.[222] Studies have shown that Hispanic Americans are over-represented among transgender people in the United States.[223][224]

According to Gattamorta, et al. (2018), the socially constructed notion of machismo reinforces male gender roles in Hispanic culture, which can lead to internalized homophobia in Hispanic gay men and increase mental health issues and suicidal ideation.[225] However, according to Reyes Salinas, more recent research shows that there has been an explosive growth of LGBT self-identification among young Hispanic Americans, which may signal that the Hispanic attitudes towards LGBT have broken down.[221] According to Marina Franco, polling conducted in 2022 suggests that the Hispanic community in America is largely accepting of LGBT people and gay marriage, which is significant in light of the rapid growth of LGBT self-identification among Hispanics.[226]

Relations with other minority groups

[edit]

As a result of the rapid growth of the Hispanic population, there has been some tension with other minority populations, especially the African-American population, as Hispanics have increasingly moved into once exclusively Black areas.[227][228] There has also been increasing cooperation between minority groups to work together to attain political influence.[229][230]

- A 2007 UCLA study reported that 51% of Black people felt that Hispanics were taking jobs and political power from them and 44% of Hispanics said they feared African-Americans, identifying them (African-Americans) with high crime rates. That said, large majorities of Hispanics credited American Black people and the civil rights movement with making life easier for them in the United States.[231][232]

- A Pew Research Center poll from 2006 showed that Black people overwhelmingly felt that Hispanic immigrants were hard working (78%) and had strong family values (81%); 34% believed that immigrants took jobs from Americans, 22% of Black people believed that they had directly lost a job to an immigrant, and 34% of Black people wanted immigration to be curtailed. The report also surveyed three cities: Chicago (with its well-established Hispanic community); Washington, D.C. (with a less-established but quickly growing Hispanic community); and Raleigh-Durham (with a very new but rapidly growing Hispanic community). The results showed that a significant proportion of Black people in those cities wanted immigration to be curtailed: Chicago (46%), Raleigh-Durham (57%), and Washington, DC (48%).[233]

- Per a 2008 University of California, Berkeley Law School research brief, a recurring theme to Black/Hispanic tensions is the growth in "contingent, flexible, or contractor labor", which is increasingly replacing long term steady employment for jobs on the lower-rung of the pay scale (which had been disproportionately filled by Black people). The transition to this employment arrangement corresponds directly with the growth in the Hispanic immigrant population. The perception is that this new labor arrangement has driven down wages, removed benefits, and rendered temporary, jobs that once were stable (but also benefiting consumers who receive lower-cost services) while passing the costs of labor (healthcare and indirectly education) onto the community at large.[234]

- A 2008 Gallup poll indicated that 60% of Hispanics and 67% of Black people believe that good relations exist between US Black people and Hispanics[235] while only 29% of Black people, 36% of Hispanics and 43% of White people, say Black–Hispanic relations are bad.[235]

- In 2009, in Los Angeles County, Hispanics committed 30% of the hate crimes against Black victims and Black people committed 70% of the hate crimes against Hispanics.[236]

Politics

[edit]| Name | Political party | State | First elected | Ancestry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supreme Court | ||||

| Sonia Sotomayor | — | 2009[c] | Puerto Rican | |

| Census Bureau | ||||

| Robert Santos | 2022 | Mexican American | ||

| State Governors | ||||

| Chris Sununu | Republican | New Hampshire | 2016 | Salvadoran, Cuban |

| Michelle Lujan Grisham | Democratic | New Mexico | 2018 | Hispanos of New Mexico |

| US Senate | ||||

| Bob Menéndez | Democratic | New Jersey | 2006 | Cuban |

| Marco Rubio | Republican | Florida | 2010 | Cuban |

| Ted Cruz | Republican | Texas | 2012 | Cuban |

| Catherine Cortez Masto | Democratic | Nevada | 2016 | Mexican |

| Ben Ray Luján | Democratic | New Mexico | 2020 | Hispanos of New Mexico |

| Alex Padilla | Democratic | California | 2021[d] | Mexican |

| US House of Representatives | ||||

| Nydia Velázquez | Democratic | New York | 1992 | Puerto Rican |

| Grace Napolitano | Democratic | California | 1998 | Mexican |

| Mario Díaz-Balart | Republican | Florida | 2002 | Cuban |

| Raúl Grijalva | Democratic | Arizona | 2002 | Mexican |

| Linda Sánchez | Democratic | California | 2002 | Mexican |

| Henry Roberto Cuellar | Democratic | Texas | 2004 | Mexican |

| John Garamendi | Democratic | California | 2009 | Spanish |

| Tony Cárdenas | Democratic | California | 2012 | Mexican |

| Joaquin Castro | Democratic | Texas | 2012 | Mexican |

| Raúl Ruiz | Democratic | California | 2012 | Mexican |

| Juan Vargas | Democratic | California | 2012 | Mexican |

| Pete Aguilar | Democratic | California | 2014 | Mexican |

| Ruben Gallego | Democratic | Arizona | 2014 | Colombian |

| Alex Mooney | Republican | West Virginia | 2014 | Cuban |

| Norma Torres | Democratic | California | 2014 | Guatemalan |

| Nanette Barragán | Democratic | California | 2016 | Mexican |

| Salud Carbajal | Democratic | California | 2016 | Mexican |

| Lou Correa | Democratic | California | 2016 | Mexican |

| Adriano Espaillat | Democratic | New York | 2016 | Dominican |

| Vicente González | Democratic | Texas | 2016 | Mexican |

| Brian Mast | Republican | Florida | 2016 | Mexican |

| Darren Soto | Democratic | Florida | 2016 | Puerto Rican |