Чтение

| Часть серии о |

| Чтение |

|---|

|

Чтение — это процесс восприятия смысла или значения букв , символов и т. д., особенно посредством зрения или осязания . [1] [2] [3] [4]

Для преподавателей и исследователей чтение — это многогранный процесс, включающий такие области, как распознавание слов, орфография (правописание), алфавит , фонетика , фонематическое восприятие , словарный запас, понимание, беглость речи и мотивация. [5] [6]

Другие типы чтения и письма, такие как пиктограммы (например, символ опасности и эмодзи ), не основаны на речевых системах письма . [7] Общей связью является интерпретация символов для извлечения значения из визуальных обозначений или тактильных сигналов (как в случае со шрифтом Брайля ). [8]

Обзор

[ редактировать ]

Чтение — это, как правило, индивидуальное занятие, совершаемое молча, хотя иногда человек читает вслух для других слушателей; или читает вслух для собственного использования, для лучшего понимания. До повторного введения разделенного текста (пробелов между словами) в позднем Средневековье способность читать молча считалась весьма примечательной. [10] [11]

Основными предикторами способности человека читать как алфавитные, так и неалфавитные сценарии являются навыки устной речи, [12] фонологическая осведомленность , быстрое автоматическое наименование и вербальный IQ . [13]

В качестве досуга дети и взрослые читают, потому что это приятно и интересно. В США около половины взрослых каждый год читают одну или несколько книг ради удовольствия. [14] Около 5% читают более 50 книг в год. [14] Американцы читают больше, если они: имеют более высокий уровень образования, читают бегло и легко, являются женщинами, живут в городах и имеют более высокий социально-экономический статус . [14] Дети становятся лучше читающими, когда они больше знают о мире в целом и когда они воспринимают чтение как развлечение, а не как рутинную работу. [14]

Чтение против грамотности

[ редактировать ]Чтение является неотъемлемой частью грамотности , однако с исторической точки зрения грамотность подразумевает умение читать и писать. [15] [16] [17] [18]

С 1990-х годов некоторые организации определяют грамотность по-разному, выходя за рамки традиционного умения читать и писать. Ниже приведены некоторые примеры:

- «умение читать и писать... на всех носителях (печатных или электронных), включая цифровую грамотность» [19]

- «способность... понимать... использование печатных и письменных материалов, связанных с различными контекстами» [20] [21] [22]

- «умение читать, писать, говорить и слушать» [23]

- «иметь навыки, позволяющие читать, писать и говорить, чтобы понимать и создавать смысл» [24]

- «способность... общаться с использованием визуальных, звуковых и цифровых материалов» [25] [26]

- «способность использовать печатную и письменную информацию для функционирования в обществе, достижения своих целей и развития своих знаний и потенциала». [27] Она включает в себя три типа грамотности взрослых: прозу (например, газетная статья), документальную (например, расписание автобусов) и количественную грамотность (например, использование арифметических операций в рекламе продукта). [28] [29]

В академической сфере некоторые рассматривают грамотность более философски и предлагают концепцию «мультиграмотности». Например, по их словам, «этот огромный переход от традиционной печатной грамотности к мультиграмотности XXI века отражает влияние коммуникационных технологий и мультимедиа на развивающуюся природу текстов, а также на навыки и склонности, связанные с потреблением, производством, оценкой». и распространение этих текстов (Боршейм, Меритт и Рид, 2008, стр. 87)». [30] [31] По словам когнитивного нейробиолога Марка Зайденберга, эта «множественная грамотность» позволила педагогам сменить тему с чтения и письма на «Грамотность». Далее он говорит, что некоторые преподаватели, столкнувшись с критикой в отношении преподавания чтения, «не изменили свою практику, они изменили предмет». [32]

Кроме того, некоторые организации могут включать навыки счета и технологические навыки отдельно, но вместе с навыками грамотности. [33]

Кроме того, с 1940-х годов термин «грамотность» часто используется для обозначения обладания знаниями или навыками в определенной области (например, компьютерная грамотность , экологическая грамотность , медицинская грамотность , медиаграмотность , количественная грамотность ( счёт ) [29] и визуальная грамотность ). [34] [35] [36] [37]

Системы письма

[ редактировать ]Чтобы понять текст, обычно необходимо понимать разговорный язык, связанный с этим текстом. Этим системы письма отличаются от многих других систем символической коммуникации. [38] После своего создания системы письменности в целом изменяются медленнее, чем их разговорные аналоги, и часто сохраняют черты и выражения, которые больше не используются в разговорном языке. Большим преимуществом систем письменности является их способность поддерживать постоянную запись информации, выраженной на языке, которую можно получить независимо от первоначального акта формулирования. [38]

Когнитивные преимущества

[ редактировать ]

Чтение ради удовольствия связано с увеличением когнитивного прогресса в словарном запасе и математике в подростковом возрасте. [39] [40] Постоянное большое количество чтения в течение всей жизни было связано с высоким уровнем академической успеваемости. [41]

Исследования показывают, что чтение может улучшить управление стрессом. [42] память, [42] фокус, [43] навыки письма, [43] и воображение . [44]

Когнитивные преимущества чтения сохраняются в среднем и старшем возрасте. [45] [46] [47]

Исследования показывают, что чтение книг и письмо относятся к числу видов деятельности, стимулирующих мозг, которые могут замедлить снижение когнитивных функций у пожилых людей. [48]

Состояние достижений в чтении

[ редактировать ]Чтение было предметом серьезных исследований и репортажей на протяжении десятилетий. Многие организации измеряют и сообщают об успеваемости детей и взрослых по чтению (например, NAEP , PIRLS , PISA PIAAC и EQAO ).

Исследователи пришли к выводу, что примерно 95% учащихся можно научить читать к концу первого или второго года обучения, однако во многих странах 20% и более не оправдывают этих ожиданий. [49] [50]

Исследование, проведенное в США в 2012 году, показало, что 33% детей третьего класса имели низкие оценки по чтению, однако они составляли 63% детей, не окончивших среднюю школу. Бедность также оказала дополнительное негативное влияние на количество выпускников средних школ. [51]

Согласно Национальному отчету за 2019 год , 34% учащихся четвертых классов в США не смогли достичь базового уровня чтения или выше его . Была значительная разница по расе и этнической принадлежности (например, чернокожие студенты - 52% и белые студенты - 23%). После воздействия пандемии COVID-19 средний балл по базовому чтению упал на 3% в 2022 году. [52] Подробнее о разбивке по этническому признаку в 2019 и 2022 годах можно узнать здесь . В 2022 году 30% учащихся восьмых классов не смогли достичь базового уровня НАЭП или выше, что было на 3 балла ниже по сравнению с 2019 годом. [53] Согласно исследованию 2023 года, проведенному в Калифорнии, только 46,6% учащихся третьего класса достигли стандартов чтения по английскому языку. [54] [55] В другом отчете говорится, что многие подростки, которые провели время в исправительных учреждениях для несовершеннолетних Калифорнии, получают аттестаты средней школы с навыками чтения начальной школы. «Есть дети, получающие аттестаты об окончании средней школы, которые даже не умеют читать и писать». За пять лет, начиная с 2018 года, 85% учащихся, окончивших среднюю школу, не сдали экзамен по чтению в 12-м классе. [56]

В период с 2013 по 2024 год 37 штатов США приняли законы или внедрили новую политику, связанную с обучением чтению на основе фактических данных. [57] В 2023 году Нью-Йорк начал требовать от школ преподавания чтения с упором на фонетику . В этом городе менее половины учащихся с третьего по восьмой класс школы получили хорошие оценки на государственных экзаменах по чтению. Более 63% чернокожих и латиноамериканцев не сдали экзамен. [58]

Во всем мире пандемия COVID-19 привела к существенному общему дефициту навыков чтения и других академических областей. Оно возникло на ранних стадиях пандемии и сохраняется с течением времени, и особенно распространено среди детей из семей с низким социально-экономическим статусом. [59] [60] В США несколько исследований показывают, что при отсутствии дополнительной поддержки существует почти 90-процентная вероятность того, что плохой читатель в первом классе так и останется плохим читателем. [61]

В Канаде провинция Онтарио сообщила, что в 2023 году 27% учащихся третьего класса не соответствовали провинциальным стандартам чтения. [62] Также в Онтарио 53% учащихся третьего класса с особыми образовательными потребностями (учащиеся, имеющие индивидуальный план обучения) не соответствовали провинциальным стандартам в 2022 году. [63] Провинция Новая Шотландия сообщила, что в 2022 году 32% учащихся третьего класса не соответствовали провинциальным стандартам чтения. [64] В провинции Нью-Брансуик сообщили, что в 2023 году 43,4% и 30,7% не достигли уровня понимания прочитанного для четвертого и шестого классов соответственно. [65]

Исследование Progress in International Reading Literacy Study ( PIRLS ) публикует данные об успеваемости четвероклассников в 50 странах. [66] В пятерку стран с самым высоким общим средним показателем чтения входят Российская Федерация, Сингапур, САР Гонконг, Ирландия и Финляндия. Некоторые другие: Англия 10-е, США 15-е, Австралия 21-е, Канада 23-е и Новая Зеландия 33-е. [67] [68] [69]

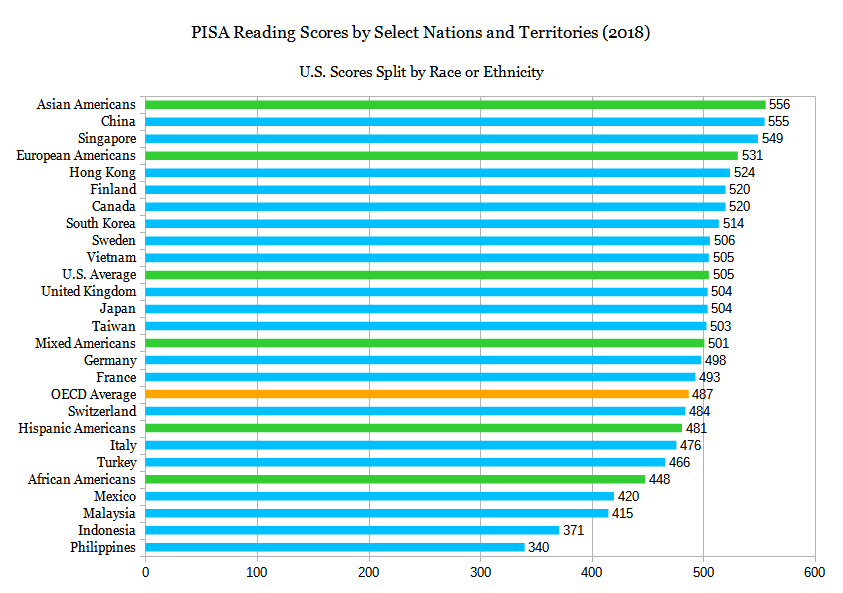

Программа международной оценки учащихся ( PISA ) измеряет успеваемость 15-летних школьников по математике, естественным наукам и чтению. [70] Критики, однако, говорят, что PISA в корне ошибочна в своем базовом взгляде на образование, его реализации, интерпретации и влиянии на образование во всем мире. [71] [72] [73]

Уровень чтения взрослых в возрасте 16–65 лет в 39 странах сообщается Программой международной оценки компетенций взрослых (PIAAC). [74] В период с 2011 по 2018 год PIAAC сообщает о проценте взрослых, читающих на первом уровне или ниже (самый низкий из пяти уровней). Некоторые примеры: Япония 4,9%, Финляндия 10,6%, Нидерланды 11,7%, Австралия 12,6%, Швеция 13,3%, Канада 16,4%, Англия (Великобритания) 16,4% и США 16,9%. [75]

По данным Всемирного банка , 53% всех детей в странах с низким и средним уровнем дохода страдают от «учебной бедности». В 2019 году, используя данные Статистического института ЮНЕСКО , они опубликовали отчет под названием « Покончить с бедностью в обучении: что для этого нужно?» . [76] Бедность в обучении определяется как неспособность читать и понимать простой текст к 10 годам.

Хотя они говорят, что важны все базовые навыки, включая чтение, умение считать, базовые способности к рассуждению, социально-эмоциональные навыки и другие, они уделяют особое внимание чтению. Они аргументируют это тем, что умение читать — это легко понимаемый показатель обучения, чтение — это путь учащегося к обучению во всех других областях, а умение читать может служить показателем базового обучения по другим предметам.

Они предлагают пять столпов для сокращения бедности в обучении:

- Учащиеся подготовлены и мотивированы к обучению

- Учителя на всех уровнях эффективны и ценятся

- Классы оборудованы для обучения

- Школы являются безопасными и инклюзивными пространствами, и

- Системы образования хорошо управляются.

Учимся читать

[ редактировать ]

Обучение чтению или приобретение навыков чтения – это приобретение и практика навыков, необходимых для понимания значения печатных слов. Опытному читателю процесс чтения кажется простым, легким и автоматическим. [77] Однако процесс обучения чтению сложен и основан на когнитивных, лингвистических и социальных навыках, развиваемых с самого раннего возраста. В качестве одного из четырех основных языковых навыков (аудирование, говорение, чтение и письмо) [78] [79] чтение жизненно важно для овладения письменным языком.

В США и других странах широко распространено мнение, что учащиеся, не умеющие читать к концу третьего класса, могут столкнуться с препятствиями на протяжении всей своей академической карьеры. [80] [81] [82] Например, по оценкам, они не смогут прочитать половину материала, с которым они столкнутся в четвертом классе. [83]

В 2019 году среди американских четвероклассников государственных школ только 58% азиатов, 45% европеоидов, 23% латиноамериканцев и 18% чернокожих учеников показали результаты на уровне или выше, указанном успеваемости в Национальном табеле . [84] Кроме того, в 2012 году в Великобритании сообщалось, что 15-летние учащиеся читают на уровне, ожидаемом от 12-летних. [85]

В результате многие правительства ввели практику, гарантирующую, что к концу третьего класса учащиеся будут читать на уровне своего класса. Примером этого является Гарантия чтения в третьем классе, созданная штатом Огайо в 2017 году. Это программа для выявления учащихся от детского сада до третьего класса, которые отстают в чтении, и оказания поддержки, чтобы убедиться, что они на пути к успеху в чтении. к концу третьего класса. [86] [87] Это также известно как коррекционное образование . Другим примером является политика в Англии, согласно которой любой ученик, который пытается правильно расшифровать слова к третьему году обучения, должен «срочно» получить помощь через «строгую и систематическую программу фонетики». [88]

В 2016 году из 50 стран США заняли 15-е место по уровню навыков чтения среди учащихся четвертого класса. [89] В десятку стран с самым высоким общим средним показателем чтения вошли Российская Федерация, Сингапур, САР Гонконг, Ирландия, Финляндия, Польша, Северная Ирландия, Норвегия, Китайский Тайбэй и Англия (Великобритания). Некоторые другие: Австралия (21-е), Канада (23-е), Новая Зеландия (33-е), Франция (34-е), Саудовская Аравия (44-е) и Южная Африка (50-е).

Разговорный язык: основа чтения

[ редактировать ]Разговорный язык является основой обучения чтению (задолго до того, как дети увидят какие-либо буквы), а знание детьми фонологической структуры языка является хорошим предиктором ранних способностей к чтению. Разговорная речь является доминирующей на протяжении большей части детства; однако чтение в конечном итоге догоняет и превосходит речь. [90] [91] [92] [93]

К своему первому дню рождения большинство детей выучили все звуки разговорной речи. Однако им требуется больше времени, чтобы выучить фонологическую форму слов и начать развивать разговорный словарный запас. [12]

Дети овладевают разговорной речью за несколько лет. Словарный запас детей пяти-шести лет, изучающих английский язык, составляет от 2500 до 5000 слов, и в течение первых нескольких лет обучения они добавляют по 5000 слов в год. Столь высокая скорость обучения не может быть объяснена инструкциями, которые они получают. Вместо этого дети узнают, что значение нового слова можно сделать вывод, потому что оно встречается в том же контексте, что и знакомые слова (например, лев часто встречается с трусливым и королем ). [94] Как говорит британский лингвист Джон Руперт Ферт : «Вы узнаете слово по тому, в какой компании оно находится».

Среда, в которой живут дети, также может влиять на их способность приобретать навыки чтения. Известно, что дети, которые регулярно подвергаются хроническому шумовому загрязнению окружающей среды, например шуму дорожного движения, демонстрируют снижение способности различать фонемы (звуки устной речи), а также более низкие оценки по чтению в стандартизированных тестах. [95]

Чтение детям: необходимо, но недостаточно

[ редактировать ]

Дети учатся говорить естественно, слушая, как говорят другие люди. Однако чтение не является естественным процессом, и многим детям необходимо учиться читать посредством процесса, который включает «систематическое руководство и обратную связь». [98] [99] [100] [101]

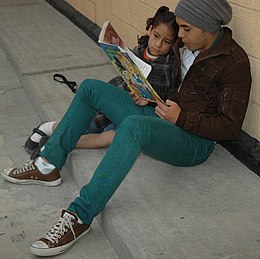

Итак, «чтение детям – это не то же самое, что обучение детей чтению». [102] Тем не менее, чтение детям важно, поскольку оно приобщает их к чтению; это их привлекает; это расширяет их знания разговорной речи; и это обогащает их лингвистические способности, слушая новые и новые слова и грамматические структуры.

Однако есть некоторые свидетельства того, что «совместное чтение» с детьми действительно помогает улучшить чтение, если внимание детей направлено на слова на странице, когда их читают. [96] [97]

Оптимальный возраст для обучения чтению

[ редактировать ]Ведутся споры относительно оптимального возраста для обучения детей чтению.

Инициатива Common Core State Standards Initiative (CCSS) в США разработала стандарты базовых навыков чтения в детском саду и первом классе, которые включают обучение основам печати, фонологическую осведомленность, фонетику, распознавание слов и беглость речи. [103] Однако некоторые критики CCSS говорят, что «для достижения стандартов чтения обычно требуются долгие часы тренировок и рабочих листов – и сокращаются другие жизненно важные области обучения, такие как математика, естествознание, обществознание, искусство, музыка и творческие игры». [104]

Данные ОЭСР PISA за 2007 год из 54 стран демонстрируют «отсутствие связи между возрастом поступления в школу... и успеваемостью по чтению в возрасте 15 лет». [105] Кроме того, немецкое исследование 50 детских садов сравнило детей, которые в возрасте 5 лет провели год либо «сосредоточенными на учебе», либо «сосредоточенными на игровых искусствах», и обнаружило, что со временем эти две группы стали неразделимы в навыках чтения. [106] Авторы приходят к выводу, что эффект раннего чтения подобен «поливу сада перед ливнем; более ранний полив становится незаметным из-за ливня, полив тратит драгоценную воду, а полив отвлекает садовника от других важных подготовительных работ». [105]

Некоторые ученые отдают предпочтение практике, соответствующей развитию (DPA), при которой формальное обучение чтению начинается, когда детям исполняется около шести или семи лет. В поддержку этой теории некоторые указывают, что дети в Финляндии идут в школу в семь лет (Финляндия заняла 5-е место в международном рейтинге PIRLS по чтению в четвертом классе в 2016 году). [107] В обсуждении академических детских садов профессор развития детей Дэвид Элкинд утверждал, что, поскольку «нет серьезных исследований, демонстрирующих, что раннее академическое обучение превосходит (или хуже) более традиционную практическую модель дошкольного образования», Педагогам следует полагаться на подходы к развитию, которые предоставляют маленьким детям достаточно времени и возможностей исследовать мир природы на своих собственных условиях. [108] Элкинд подчеркнул принцип, согласно которому «раннее образование должно начинаться с ребенка, а не с предмета, который ему преподают». [108] В ответ Гровер Дж. Уайтхерст , директор Брауновского центра образовательной политики (часть Брукингского института ) [109] сказал, что Дэвид Элкинд слишком полагается на философию образования, а не на науку и исследования. Он продолжает говорить, что образовательная практика «обречена на циклы причуд и фантазий» до тех пор, пока она не станет в большей степени основываться на научно обоснованной практике . [110]

Что касается академических результатов в Финляндии, то, как отмечают некоторые исследователи, перед тем, как пойти в школу, финские дети должны пройти один год обязательного бесплатного дошкольного образования, и большинство из них читают до того, как пойдут в школу. [111] [112] Что касается практики, соответствующей развитию (DPA), в 2019 году Национальная ассоциация образования детей раннего возраста в Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия, опубликовала проект позиционного документа по DPA, в котором говорится: «Идея о том, что маленькие дети не готовы к академическим предметам, является неправильное понимание практики, соответствующей уровню развития; особенно в 1–3 классах почти все предметы можно преподавать таким образом, чтобы они были значимыми и интересными для каждого ребенка». [113] А исследователи из Института развития человеческого потенциала говорят, что то, что ранние читатели скучают или становятся создателями проблем в школе, — это миф. [114]

Другие исследователи и преподаватели отдают предпочтение ограниченному объему обучения грамоте в возрасте четырех и пяти лет в дополнение к неакадемической, интеллектуально стимулирующей деятельности. [115]

Обзоры научной литературы, проведенные Фондом образовательных фондов в Великобритании, показали, что начало обучения грамоте в дошкольных учреждениях «неизменно оказывает положительное влияние на результаты раннего обучения». [116] и что «начало дошкольного образования в более молодом возрасте, по-видимому, оказывает большое положительное влияние на результаты обучения». [117] Это поддерживает текущую стандартную практику в Великобритании, которая включает развитие фонематического восприятия детей в дошкольных учреждениях и обучение чтению с четырехлетнего возраста.

Исследование, проведенное в Чикаго, показало, что программа раннего образования для детей из семей с низкими доходами, согласно оценкам, принесет от 4 до 11 долларов экономической выгоды в течение жизни ребенка на каждый доллар, первоначально потраченный на программу, согласно анализу затрат и выгод, финансируемому Национальные институты здравоохранения . В программе работают сертифицированные преподаватели, и она предлагает «обучение чтению и математике, групповые занятия и образовательные экскурсии для детей в возрасте от 3 до 9 лет». [118] [119]

Похоже, что не существует каких-либо окончательных исследований о «волшебном окне», позволяющем начать обучение чтению. [112] Тем не менее, также не существует окончательных исследований, позволяющих предположить, что раннее начало лечения причиняет какой-либо вред. Исследователь и педагог Тимоти Шанахан предлагает: «Начинайте обучать чтению с того момента, как у вас есть дети, готовые обучать, и обращайте внимание на то, как они реагируют на эту инструкцию – как с точки зрения того, насколько хорошо они усваивают то, чему вы учите, так и с точки зрения того, насколько они счастливы. и они, похоже, вложены. Если вы еще не начали, не чувствуйте себя виноватыми, просто начинайте». [112]

Рекомендуемые инструкции по чтению в зависимости от класса

[ редактировать ]Некоторые исследователи в области образования предлагают преподавать различные компоненты чтения в определенных классах. [120] Ниже приводится пример Кэрол Толман, Эд.Д. и Луиза Моутс, Ed.D. США это во многом соответствует Инициативе по общим основным государственным стандартам : [103]

| Компонент инструкции по чтению | Толман и Рвы | Общее ядро США |

|---|---|---|

| Фонологическая осведомленность | К–1 | К–1 |

| Базовая фонетика | К–1 | К–1 |

| Словарный запас | К–6+ | К–6+ |

| Понимание | К–6+ | К–6+ |

| Письменное выражение | 1–6+ | К–6+ |

| Беглость | 1–3 | 1–5 |

| Расширенная фонетика/декодирование | 2–6+ | 2–5 |

Практика обучения базовым навыкам чтения, от детского сада до 12 класса.

[ редактировать ]Процент американских учащихся, не сумевших достичь в соответствии с Табель успеваемости Наций базового уровня чтения или выше , составил 4 класс (37% в 2022 г.), 8 класс (30% в 2022 г.) и 12 класс (30% в 2019 г.). [121] В результате многие учителя средних школ посвящают некоторое время занятиям, связанным с базовыми навыками чтения. [122]

На следующей диаграмме показан процент учителей английского языка K-12, которые участвовали в базовых занятиях по чтению с учащимися (т. е. вовлекали каждого учащегося в классе в занятия, связанные с базовыми навыками чтения, в течение более чем нескольких минут в течение последних пяти занятий). уроки). [123]

| Мероприятия / Оценки | К-1 | 2-5 | 6-8 | 9-12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Концепции печати | 73% | 56% | 35% | 40% |

| Фонологическая осведомленность | 85% | 59% | 29% | 22% |

| Акустика | 92% | 61% | 25% | 22% |

| Беглость | 80% | 65% | 36% | 36% |

Учителя средних школ ELA в штатах, где действует закон о чтении, значительно чаще сообщали о частом привлечении своих учеников к этим занятиям, чем учителя средних школ ELA в штатах без такого законодательства, даже несмотря на то, что только четверть штатов, где действуют эти законы, включают требования, касающиеся преподавания ELA в средней школе. [124]

Этапы умелого чтения

[ редактировать ]Путь к умелому чтению включает в себя изучение алфавитного принципа , фонематического восприятия , фонетики , беглости речи, словарного запаса и понимания. [125]

Британский психолог Ута Фрит представила трехэтапную модель освоения навыков чтения. Первый этап — это логографический или графический этап , на котором учащиеся пытаются воспринять слова как объекты, искусственную форму чтения. Второй этап — это фонологический этап , на котором учащиеся изучают взаимосвязь между графемами (буквами) и фонемами (звуками). Третий этап — орфографический этап , на котором учащиеся читают знакомые слова быстрее, чем незнакомые, и длина слова постепенно перестает играть роль. [126]

Еще одним признанным экспертом в этой области является Гарварда профессор Джин Штернлихт Чалл . В 1983 году она опубликовала книгу под названием «Стадии развития чтения» , в которой предложила шесть стадий. [127] [128]

Впоследствии, в 2008 году Мэриэнн Вольф , Высшая школа образования и информационных исследований Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе , опубликовала книгу под названием «Пруст и кальмар» , в которой она описывает свой взгляд на следующие пять стадий развития чтения. [129] [130] Обычно дети проходят эти стадии с разной скоростью; однако типичный возраст детей в Соединенных Штатах показан ниже.

Начинающий читатель: от 6 месяцев до 6 лет.

[ редактировать ]

Формирующаяся стадия подготовки к чтению, также известная как готовность к чтению , обычно длится в течение первых пяти лет жизни ребенка. [133] Дети обычно произносят свои первые несколько слов еще до своего первого дня рождения. [134] Педагоги и родители помогают учащимся развивать навыки аудирования, говорения, чтения и письма. [135]

Чтение детям помогает им развивать словарный запас, любовь к чтению и фонематическую осведомленность , то есть способность слышать и манипулировать отдельными звуками ( фонемами ) устной речи. Дети часто «читают» истории, которые они запомнили. Однако в конце 1990-х годов исследователи из США обнаружили, что традиционный способ чтения детям мало повлиял на их способность читать в дальнейшем, поскольку дети тратят относительно мало времени на просмотр текста. Тем не менее, в программе совместного чтения с четырехлетними детьми учителя обнаружили, что направление внимания детей на буквы и слова (например, устно или указание на слова) существенно влияет на раннее чтение, правописание и понимание. [136] [97] [137] [138]

Начинающий читатель: от 6 до 7 лет.

[ редактировать ]Начинающие читатели продолжают развивать свое фонематическое восприятие и приходят к пониманию того, что буквы ( графемы ) связаны со звуками ( фонемами ) языка; известный как декодирование, фонетика и алфавитный принцип . [139] Они также могут запомнить наиболее распространенные сочетания букв и некоторые часто встречающиеся слова, которые не обязательно следуют основным фонологическим правилам (например, « have» и «who» ). Однако было бы ошибкой предполагать, что читатель понимает смысл текста только потому, что может его расшифровать. Понимание словарного запаса и устной речи также являются важными частями понимания текста, как описано в разделах « Простой вид чтения» , «Скакалка для чтения Скарборо» и «Модель активного представления чтения» . Чтение и речь взаимозависимы: чтение способствует развитию словарного запаса, а более богатый словарный запас способствует умелому чтению. [140]

Расшифровка читателя: от 7 до 9 лет.

[ редактировать ]Переход от стадии начинающего читателя к стадии декодирования отмечен уменьшением болезненного произношения и на его месте появляются звуки более плавного и уверенного чтения. [141] На этом этапе читатель добавляет не менее 3000 слов к тому, что он может декодировать. Например, в английском языке читатели теперь изучают варианты римов , основанных на гласных (например, s at , m at , c at ). [142] и гласных пары (также диграф ) (например , дождь , игра , лодка ) [143]

По мере продвижения вперед читатели изучают состав морфем (т.е. основ, корней, приставок и суффиксов ). Они изучают общие морфемы, такие как «s» и «ed», и видят в них «куски зрения». «Чем быстрее ребенок поймет, что обезглавлено — это быть + голова + ed» , тем быстрее он станет более свободно читать.

В начале этого этапа ребенок часто отдает столько умственных способностей процессу декодирования, что не понимает читаемых слов. Тем не менее, это важный этап, позволяющий ребенку достичь своей конечной цели – стать беглым и автоматическим.

Именно на этапе расшифровки ребенок поймет, о чем на самом деле история, и научится перечитывать отрывок, когда это необходимо, чтобы по-настоящему понять его.

Свободный, понимающий читатель: от 9 до 15 лет.

[ редактировать ]Цель этого этапа — «пойти под поверхность текста», и в процессе этого читатель существенно расширит свои знания орфографии. [144]

Учителя и родители могут быть обмануты беглым чтением, заставляя их думать, что ребенок понимает все, что они читают. Поскольку содержание того, что они могут прочитать, становится более требовательным, хорошие читатели будут развивать знания образного языка и иронии , которые помогают им открывать новые значения в тексте.

Дети улучшают свое понимание, когда используют различные инструменты, такие как объединение предыдущих знаний, прогнозирование результатов, формирование выводов и отслеживание пробелов в их понимании. Один из самых ярких моментов — это когда бегло понимающие читатели учатся входить в жизнь воображаемых героев и героинь.

считает, что при обучении пониманию Педагогический психолог Дж . Майкл Прессли можно привести веские аргументы в пользу обучения расшифровке, словарному запасу, знанию слов, стратегиям активного понимания и самоконтролю. [145]

В конце этого этапа многие процессы начинают становиться автоматическими, позволяя читателю сосредоточиться на смысле. Поскольку к этому моменту процесс декодирования почти автоматический, мозг учится интегрировать больше метафорических , логических выводов, аналогий , фоновых и экспериментальных знаний . Этот этап обучения чтению часто длится до раннего взросления. [146]

Экспертный читатель: 16 лет и старше

[ редактировать ]На этапе эксперта читателю обычно требуется всего полсекунды, чтобы прочитать практически любое слово. [147] Степень изменения профессионального чтения на протяжении жизни взрослого человека зависит от того, что и сколько он читает.

Наука чтения

[ редактировать ]

Единого определения науки чтения (СОР) не существует. [151] Базовые навыки, такие как фонетика , декодирование и фонематическое восприятие, считаются важными частями науки чтения, но они не являются единственными составляющими. SOR включает в себя любые исследования и данные о том, как люди учатся читать и как следует обучать чтению. Сюда входят такие области, как беглость устного чтения, словарный запас, морфология , понимание прочитанного, текст, правописание и произношение, стратегии мышления, владение устной речью, тренировка рабочей памяти и качество письменной речи (например, связность, объединение/сокращение предложений). [152]

Кроме того, некоторые преподаватели считают, что SOR должен включать цифровую грамотность; фоновые знания; содержательная инструкция; инфраструктурные основы (учебная программа, обновленная подготовка учителей и лидерство); адаптивное обучение (признание индивидуальных, культурных и языковых способностей учащегося); развитие двойной грамотности; равенство, социальная справедливость и поддержка малообеспеченных групп населения (например, студентов из семей с низкими доходами). [151]

Некоторые исследователи предполагают, что существует необходимость в дополнительных исследованиях взаимосвязи теории и практики. Они говорят: «Мы знаем больше о науке чтения, чем о науке преподавания, основанной на науке чтения», и «между фундаментальными научными открытиями и их внедрением учителями необходимо преодолеть множество слоев». [151]

В когнитивной науке, вероятно, нет более успешной области, чем изучение чтения. Тем не менее, во многих странах уровень чтения считается низким. В Соединенных Штатах в Национальном табеле успеваемости за 2019 год сообщается, что 34% учащихся четвертых классов государственных школ показали результаты на NAEP уровне владения или выше (хорошая академическая успеваемость), а 65% показали результаты на базовом уровне или выше (частичное владение языком на профессиональном уровне). уровень навыков). [153] Как сообщается в исследовании PIRLS , Соединенные Штаты заняли 15-е место из 50 стран по уровню понимания прочитанного четвероклассниками. [67] [68] Кроме того, согласно исследованию PIAAC 2011–2018 годов , из 39 стран США заняли 19-е место по уровню грамотности взрослого населения от 16 до 65 лет; и 16,9% взрослых в США читают на первом уровне или ниже (из пяти уровней). [154] [75]

Многие исследователи обеспокоены тем, что низкий уровень чтения обусловлен тем, как учат чтению. Они указывают на три направления:

- Современная наука о чтении оказала очень незначительное влияние на образовательную практику - главным образом из-за «проблемы двух культур, разделяющих науку и образование».

- Современная практика преподавания основана на устаревших предположениях, которые усложняют обучение чтению, чем это необходимо.

- Соединение научно обоснованной практики с образовательной практикой было бы полезным, но достичь этого чрезвычайно сложно из-за отсутствия у многих учителей адекватной подготовки в области науки чтения. [155] [156] [157] [50]

Простой взгляд на чтение

[ редактировать ]

Простой взгляд на чтение — это научная теория понимания прочитанного. [158] Согласно теории, чтобы понять то, что они читают, учащимся необходимы как навыки декодирования , так и способность к пониманию устной речи (аудирование) . Ни того, ни другого недостаточно. Другими словами, им нужна способность распознавать и обрабатывать (например, озвучивать) текст, а также способность понимать язык, на котором написан текст (т. е. словарный запас, грамматика и базовые знания). Учащиеся не читают, если могут расшифровать слова, но не понимают их значения. Точно так же учащиеся не читают, если они не могут расшифровать слова, которые они обычно узнали бы и поняли, если бы услышали их вслух. [159] [160] [161]

Это выражается в этом уравнении:Декодирование × Понимание устной речи = Понимание прочитанного. [162]

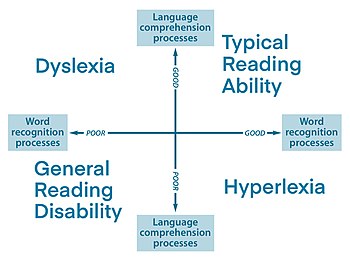

Как показано на рисунке, «Простой взгляд на чтение» предлагает четыре широкие категории развивающихся читателей: типичные читатели; плохие читатели (общая неспособность к чтению); дислексики ; [163] и гиперлексика . [164] [165]

Веревка для чтения Скарборо

[ редактировать ]Холлис Скарборо , создатель «Скакалки для чтения» и старший научный сотрудник Haskins Laboratories , является ведущим исследователем раннего языкового развития и его связи с последующей грамотностью. [166]

В 2001 году Скарборо опубликовал инфографику «Веревка для чтения», используя пряди веревки, чтобы проиллюстрировать множество ингредиентов, необходимых для того, чтобы стать умелым читателем. Верхние нити представляют понимание языка и усиливают друг друга. Нижние нити представляют собой распознавание слов и работают вместе, поскольку благодаря практике читатель становится точным, беглым и автоматическим. Верхняя и нижняя нити переплетаются вместе, создавая опытного читателя. [167]

| Понимание языка (Верхние нити) |

|---|

| Базовые знания (факты, концепции и т. д.) |

| Словарный запас (широта, точность, связи и т. д.) |

| Языковые структуры (синтаксис, семантика и т. д.) |

| Вербальное рассуждение (вывод, метафора и т. д.) |

| Грамотные знания (концепции печати, жанры и т. д.) |

| Распознавание слов (нижние нити) |

| Фонологическая осведомленность (слоги, фонемы и т. д.) |

| Расшифровка (алфавитный принцип, орфографо-звуковое соответствие) |

| Распознавание взглядов (знакомых слов) |

Более поздние исследования Лори Э. Каттинг и Холлис С. Скарборо подчеркнули важность процессов исполнительных функций (например, рабочей памяти, планирования, организации, самоконтроля и подобных способностей) для понимания прочитанного. [168] [169] Легкие тексты не требуют многих исполнительных функций; однако более сложный текст требует большего «сосредоточения на идеях». Стратегии понимания прочитанного , такие как обобщение, могут помочь.

Активный просмотр модели чтения

[ редактировать ]Модель активного взгляда на чтение (AVR) (7 мая 2021 г.), Нелл К. Дьюк и Келли Б. Картрайт, [170] предлагает альтернативу простому представлению о чтении (SVR) и предлагаемое обновление веревки для чтения Скарборо (SRR). Он отражает ключевые выводы научных исследований по чтению, которые не отражены в SVR и SRR. Хотя модель AVR в целом не тестировалась в исследованиях, «каждый элемент модели был протестирован в учебных исследованиях, демонстрирующих положительное причинно-следственное влияние на понимание прочитанного». [171] Эта модель является более полной, чем простой взгляд на чтение, и лучше учитывает некоторые знания о чтении, полученные за последние несколько десятилетий. Однако он не объясняет, как эти переменные сочетаются друг с другом, как их относительная важность меняется с развитием, или многие другие вопросы, имеющие отношение к обучению чтению. [172]

В модели перечислены факторы, способствующие чтению (и потенциальные причины трудностей с чтением) в рамках, помимо и за пределами распознавания слов и понимания языка; включая элементы саморегуляции. Эта особенность модели отражает исследования, показавшие, что не все профили трудностей с чтением объясняются плохим распознаванием слов и/или низким пониманием языка. Вторая особенность модели заключается в том, что она показывает, как распознавание слов и понимание языка перекрываются, и определяет процессы, которые «связывают» эти конструкции.

На следующей диаграмме показаны ингредиенты инфографики авторов. Кроме того, авторы отмечают, что на чтение также влияют текст, задача и социокультурный контекст .

| Активное саморегуляция |

|---|

| Мотивация и вовлеченность |

| Навыки исполнительной функции |

| Использование стратегии (связанной с распознаванием слов, пониманием, словарным запасом и т. д.) |

| Распознавание слов (WR) |

| Фонологическая осведомленность (слоги, фонемы и т. д.) |

| Алфавитный принцип |

| акустики Знание |

| Навыки декодирования |

| Распознавание слов с первого взгляда |

| Переходные процессы (перекрытие WR и LC) |

| Концепции печати |

| Беглое чтение |

| Словарный запас |

| Морфологическая осведомленность (структура слов и частей слов, таких как основы, корни слов, приставки и суффиксы) |

| Графонолого-семантическая когнитивная гибкость (буквенно-звукозначительная гибкость) |

| Понимание языка (LC) |

| Знание культуры и другого содержания |

| Специальные знания по чтению (жанр, текст и т. д.) |

| Вербальное рассуждение (вывод, метафора и т. д.) |

| Структура языка (синтаксис, семантика и т. д.) |

| Теория разума (способность приписывать психические состояния себе и другим) [173] |

Автоматичность

[ редактировать ]В области психологии автоматизм — это способность делать что-то, не занимая разум необходимыми деталями низкого уровня, что позволяет этому стать автоматическим шаблоном реакции или привычкой . Когда чтение происходит автоматически, драгоценные ресурсы рабочей памяти могут быть направлены на обдумывание смысла текста и т. д.

Неожиданный вывод когнитивной науки заключается в том, что практика не приводит к совершенству. Чтобы новый навык стал автоматическим, необходима постоянная практика, достигающая уровня мастерства. [174] [175]

Как читает мозг

[ редактировать ]Несколько исследователей и нейробиологов попытались объяснить, как читает мозг. Они написали статьи и книги, создали веб-сайты и видеоролики на YouTube, чтобы помочь обычному потребителю. [176] [177] [178] [179]

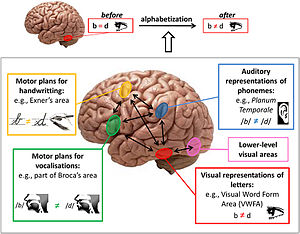

Нейробиолог Станислас Деэн говорит, что все должны принять несколько простых истин, а именно: а) все дети имеют одинаковый мозг, хорошо настроены на систематические соответствия графема-фонема «и имеют все преимущества от фонемы – единственного метода, который даст им свободу читать любой текст», б) размер классной комнаты в значительной степени не имеет значения, если используются правильные методы обучения, в) важно иметь стандартизированные скрининговые тесты на дислексию с последующей соответствующей специализированной подготовкой, и г) при этом важно декодирование Не менее важно и обогащение словарного запаса. [180]

Исследование, проведенное в Медицинском университете Южной Каролины (MUSC) в 2022 году, показывает, что «большая асимметрия левого полушария может предсказать как лучшую, так и среднюю производительность на базовом уровне способности к чтению, в зависимости от того, проводится ли анализ всего мозга или в конкретных регионах». [181] [182] Были выявлены корреляции между конкретными областями мозга в левом полушарии коры головного мозга во время различных видов деятельности по чтению. [183]

головного мозга , хотя и не включена в большинство метааналитических исследований, Сенсомоторная кора является наиболее активной областью мозга во время чтения. На это часто не обращают внимания, поскольку оно связано исключительно с движением; [184] Однако исследование фМРТ 2014 года с участием взрослых и детей, в которых движения тела были ограничены, продемонстрировало убедительные доказательства того, что эта область может быть коррелирована с автоматической обработкой и декодированием текста. [185] Результаты этого исследования показали, что эта часть мозга очень активна у людей, которые учатся или испытывают трудности с чтением (дети, люди с диагнозом дислексии и новички в английском языке) и менее активна у свободно бегло читающих взрослых. [185]

Затылочная теменная и доли , или, точнее, веретенообразная извилина мозга , включают в себя область зрительных словесных форм (VWFA). [186] Считается, что VWFA отвечает за способность мозга визуально читать. [186] Эта область мозга имеет тенденцию активироваться, когда слова представлены орфографически, как было обнаружено в исследовании 2002 года, в котором участникам предъявлялись словесные и несловесные стимулы. [187] Во время предъявления словесных стимулов эта часть мозга была чрезвычайно активна; однако при предъявлении стимулов, не связанных с графемами, мозг был менее активен. Участники с дислексией оставались в стороне, причем эта область мозга постоянно была недостаточно активна в обоих сценариях. [187]

Двумя основными областями мозга, связанными с фонологическими навыками, являются височно-теменная область и перисильвийская область. [188] В исследовании фМРТ, проведенном в 2001 году, участникам предлагались письменные слова, слова, повторяющиеся в устной форме, и вербальные псевдослова. [189] Дорсальная (верхняя) часть височно-теменной области была наиболее активной во время псевдослов, а вентральная (нижняя) часть была более активной во время частотных слов, за исключением субъектов с диагнозом дислексия, у которых не было выявлено нарушений вентральной области, но недостаточная активация в дорсальной части. [189]

Перисильвийская область — часть мозга, которая, как полагают, соединяет зоны Брока и Вернике. [190] Это еще одна область, которая очень активна во время фонологической деятельности, когда участников просят вербализовать известные и неизвестные слова. [191] Повреждение этой части этого мозга напрямую влияет на способность человека говорить связно и осмысленно; более того, эта часть мозговой активности остается неизменной как для читателей с дислексией, так и для читателей без дислексии. [192] [193]

Нижняя лобная область — гораздо более сложная область мозга, и ее связь с чтением не обязательно линейна, поскольку она активна в нескольких видах деятельности, связанных с чтением. [194] В нескольких исследованиях была зафиксирована связь его активности с навыками понимания и обработки информации, а также с правописанием и рабочей памятью. [195] Хотя точная роль этой части мозга до сих пор остается дискуссионной, некоторые исследования показывают, что эта область мозга имеет тенденцию быть более активной у читателей, у которых диагностирована дислексия, и менее активной после успешного лечения. [196]

Помимо областей коры головного мозга, которые на фМРТ считаются серым веществом , существует несколько пучков белого вещества , которые также активны во время различных действий по чтению. [197] Эти три области соединяют три уважаемые области коры головного мозга во время чтения и, таким образом, отвечают за интеграцию кросс-моделей мозга, участвующих в чтении. [198] Три соединительных пучка, которые заметно активны во время чтения: левый дугообразный пучок , левый нижний продольный пучок и верхний продольный пучок . [199] Все три области оказываются слабее у читателей с диагнозом дислексия. [197] [198] [199]

, Считается, что мозжечок который не является частью коры головного мозга, также играет важную роль в чтении. [200] Когда мозжечок поврежден, у жертв возникают проблемы со многими исполнительными функциями и организационными навыками как внутри, так и за пределами способности к чтению. [200] В синтетическом исследовании фМРТ конкретные действия, которые показали значительное вовлечение мозжечка, включали автоматизацию, точность слов и скорость чтения. [201]

Движение глаз и скорость чтения без звука

[ редактировать ]Чтение — это интенсивный процесс, в ходе которого глаз быстро усваивает текст и видит достаточно точно, чтобы интерпретировать группы символов. [202] необходимо понимать зрительное восприятие и движение глаз при чтении Чтобы понять процесс чтения, .

При чтении глаз движется непрерывно по строке текста, но совершает короткие быстрые движения (саккады), перемежающиеся короткими остановками (фиксациями). Существует значительная вариативность фиксаций (точки, в которой происходит саккада) и саккад между читателями и даже для одного и того же человека, читающего один отрывок текста. При чтении глаз имеет диапазон восприятия около 20 щелей. В лучшем случае и при чтении по-английски, когда взгляд фиксируется на букве, можно четко идентифицировать четыре-пять букв справа и три-четыре буквы слева. Помимо этого, можно определить только общую форму некоторых букв. [203]

Движения глаз глухих читателей отличаются от движений глаз слышащих читателей, и было показано, что у опытных глухих читателей фиксация короче и меньше рефиксаций при чтении. [204]

Исследование, опубликованное в 2019 году, пришло к выводу, что скорость молчаливого чтения взрослыми на английском языке документальной литературы находится в диапазоне от 175 до 300 слов в минуту (слов в минуту), а для художественной литературы — от 200 до 320 слов в минуту. [205] [206]

Dual-route hypothesis to reading aloud

[edit]In the early 1970s, the dual-route hypothesis to reading aloud was proposed, according to which there are two separate mental mechanisms involved in reading aloud, with output from both contributing to the pronunciation of written words.[208][209][210] One mechanism is the lexical route whereby skilled readers can recognize a word as part of their sight vocabulary. The other is the nonlexical or sublexical route, in which the reader "sounds out" (decodes) written words.[210][211]

The production effect (reading out loud)

[edit]There is robust evidence that saying a word out loud makes it more memorable than simply reading it silently or hearing someone else say it. This is because self-reference and self-control over speaking produce more engagement with the words. The memory benefit of "hearing oneself" is referred to as the production effect.[212] This has implications for students such as those who are learning to read. The results of studies imply that oral production is beneficial because it entails two distinctive components: speaking (a motor act) and hearing oneself (the self-referential auditory input). It is also thought that the "optimal benefit would probably come from reading aloud from notes that the student took at the time of initial exposure to new information".[213][214]

Evidence-based reading instruction

[edit]Evidence-based reading instruction refers to practices having research evidence showing their success in improving reading achievement.[215][216][217][218][219] It is related to evidence-based education.

Several organizations report on research about reading instruction, for example:

- Best Evidence Encyclopedia (BEE) is a free website created by the Johns Hopkins University School of Education's Center for Data-Driven Reform in Education and is funded by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.[220] In 2021, BEE released a review of research on 51 different programs for struggling readers in elementary schools.[221] Many of the programs used phonics-based teaching and/or one or more other approaches. The conclusions of this report are shown in the section entitled Effectiveness of programs.

- Evidence for ESSA[222] began in 2017 and is produced by the Center for Research and Reform in Education (CRRE)[223] at Johns Hopkins University School of Education, Baltimore, MD.[224] It offers free up-to-date information on current PK–12 programs in reading, math, social-emotional learning, and attendance that meet the standards of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) (the United States K–12 public education policy signed by President Obama in 2015).[225]

- ProvenTutoring.org[226] is a non-profit organization, a separate subsidiary of the non-profit Success for All. It is a resource for school systems and educators interested in research-proven tutoring programs. It lists programs that deliver tutoring programs that are proven effective in rigorous research as defined in the 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act. The Center for Research and Reform in Education at Johns Hopkins University provides the technical support to inform program selection.[227][228]

- What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) of Washington, DC,[229] was established in 2002 and evaluates numerous educational programs in twelve categories by the quality and quantity of the evidence and the effectiveness. It is operated by the federal National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), part of the Institute of Education Sciences (IES)[229] Individual studies are available that have been reviewed by WWC and categorized according to the evidence tiers of the United States Every student succeeds act (ESSA).[230]

- Intervention reports are provided for programs according to twelve topics (e.g. literacy, mathematics, science, behavior, etc.).[231]

- The British Educational Research Association (BERA)[232] claims to be the home of educational research in the United Kingdom.[233][234]

- Florida Center for Reading Research is a research center at Florida State University that explores all aspects of reading research. Its Resource Database allows you to search for information based on a variety of criteria.[235]

- Institute of Education Sciences (IES), Washington, DC,[236] is the statistics, research, and evaluation arm of the U.S. Department of Education. It funds independent education research, evaluation and statistics. It published a Synthesis of its Research on Early Intervention and Early Childhood Education in 2013.[237] Its publications and products can be searched by author, subject, etc.[238]

- National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER)[239] is a non-profit research and development organization based in Berkshire, England. It produces independent research and reports about issues across the education system, such as Using Evidence in the Classroom: What Works and Why.[240]

- Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted), in England, conducts research on schools, early education, social care, further education and skills.[241]

- The Ministry of Education, Ontario, Canada offers a site entitled What Works? Research Into Practice. It is a collection of research summaries of promising teaching practice written by experts at Ontario universities.[242]

- RAND Corporation, with offices throughout the world, funds research on early childhood, K–12, and higher education.[243]

- ResearchED,[244] a U.K. based non-profit since 2013 has organized education conferences around the world (e.g. Africa, Australia, Asia, Canada, the E.U., the Middle East, New Zealand, the U.K. and the U.S.) featuring researchers and educators to "promote collaboration between research-users and research-creators". It has been described as a "grass-roots teacher-led project that aims to make teachers research-literate and pseudo-science proof".[245]

Reading from paper vs. screens

[edit]A systematic review and meta‐analysis was conducted on the advantages of reading from paper vs. screens. It found no difference in reading times; however, reading from paper has a small advantage in reading performance and metacognition.[246] Other studies conclude that many children understand more from reading books vs. screens.[247][248]

Teacher training and legislation

[edit]According to some researchers, having a highly qualified teacher in every classroom is an educational necessity, and a 2023 study of 512 classroom teachers in 112 schools showed that teachers' knowledge of language and literacy reliably predicted students' reading foundational skills scores, but not reading comprehension scores.[249] Yet, some teachers, even after obtaining a master's degree in education, think they lack the necessary knowledge and skills to teach all students how to read.[250] A 2019 survey of K-2 and special education teachers found that only 11 percent said they felt "completely prepared" to teach early reading after finishing their preservice programs. And, a 2021 study found that most U.S. states do not measure teachers' knowledge of the 'science of reading'.[251] In addition, according to one study, as few as 2% of school districts use reading programs that follow the science of reading.[252][253] Mark Seidenberg, a neuroscientist, states that, with few exceptions, teachers are not taught to teach reading and "don't know what they don't know".[254]

A survey in the United States reported that 70% of teachers believe in a balanced literacy approach to teaching reading – however, balanced literacy "is not systematic, explicit instruction".[250] Teacher, researcher, and author, Louisa Moats,[255] in a video about teachers and science of reading, says that sometimes when teachers talk about their "philosophy" of teaching reading, she responds by saying, "But your 'philosophy' doesn't work".[256] She says this is evidenced by the fact that so many children are struggling with reading.[257] On another occasion, when asked about the most common questions teachers ask her, she replied, "over and over" they ask "why didn't anyone teach me this before?".[258]In an Education Week Research Center survey of more than 530 professors of reading instruction, only 22 percent said their philosophy of teaching early reading centered on explicit, systematic phonics with comprehension as a separate focus.[250]

As of January 24, 2024, after Mississippi became the only state to improve reading results between 2017 and 2019,[259] 37 U.S. states and the District of Columbia have since passed laws or implemented new policies related to evidence-based reading instruction.[57] These requirements relate to six areas: teacher preparation; teacher certification or license renewal; professional development or coaching; assessment; material; and instruction or intervention. As a result, many schools are moving away from balanced literacy programs that encourage students to guess a word, and are introducing phonics where they learn to "decode" (sound out) words.[260] However, the adoption of these new requirements are by no means uniform. For example, only ten states have requirements in all six areas, and five have requirements in only one or two areas. Only nineteen states have requirements related to pre-service teacher certification or license renewal. Thirty-six states have requirements for professional development or coaching, and thirty-one require teachers to use specific instructional methods or interventions for struggling readers. Furthermore, eight states do not allow or require 3rd-grade retention for students who are behind in reading. Experts say it is uncertain whether these new initiatives will lead to real improvements in children's reading results because old practices prove hard to shake.[261][262]

As more state legislatures seek to pass science of reading legislation, some teachers' unions are mounting opposition, citing concerns about mandates that would limit teachers' professional autonomy in the classroom, uneven implementation, unreasonable timelines, and the amount of time and compensation teachers receive for additional training.[263] Some teachers' unions, in particular, have protested attempts to ban the three-cueing system that encourages students to guess at the pronunciation of words, using pictures, etc. (rather than to decode them). In April 2024, the California Teachers Union was successful in stopping a bill that would have required teachers to use the science of reading.[264]

Arkansas required every elementary and special education teacher to be proficient in the scientific research on reading by 2021; causing Amy Murdoch, an associate professor and the director of the reading science program at Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati to say "We still have a long way to go – but I do see some hope".[250][265][266]

In 2021, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development of New Brunswick appears to be the first in Canada to revise its K-2 reading curriculum based on "research-based instructional practice". For example, it replaced the various cueing systems with "mastery in the consolidated alphabetic to skilled reader phase".[267][268] Although one document on the site, dated 1998, contains references to such practices as using "cueing systems" which is at odds with the department's current shift to using evidence-based practices.[269] The Minister of Education in Ontario, Canada followed by stating plans to revise the elementary language curriculum and the Grade 9 English course with "scientific, evidence-based approaches that emphasize direct, explicit and systematic instruction and removing references to unscientific discovery and inquiry-based learning, including the three-cueing system, by 2023."[270]

Some non-profit organizations, such as the Center for Development and Learning (Louisiana) and the Reading League (New York State), offer training programs for teachers to learn about the science of reading.[271][272][273][274] ResearchED, a U.K. based non-profit since 2013 has organized education conferences around the world featuring researchers and educators in order to promote collaboration between research-users and research-creators.[244]

Researcher and educator Timothy Shanahan acknowledges that comprehensive research does not always exist for specific aspects of reading instruction. However, "the lack of evidence doesn't mean something doesn't work, only that we don't know". He suggests that teachers make use of the research that is available in such places as Journal of Educational Psychology, Reading Research Quarterly, Reading & Writing Quarterly, Review of Educational Research, and Scientific Studies of Reading. If a practice lacks supporting evidence, it can be used with the understanding that it is based upon a claim, not science.[275]

Teaching reading

[edit]

Alphabetic languages

[edit]Educators have debated for years about which method is best to teach reading for the English language. There are three main methods, phonics, whole language and balanced literacy. There are also a variety of other areas and practices such as phonemic awareness, fluency, reading comprehension, sight words and sight vocabulary, the three-cueing system (the searchlights model in England), guided reading, shared reading, and leveled reading. Each practice is employed in different manners depending on the country and the specific school division.

In 2001, some researchers reached two conclusions: 1) "mastering the alphabetic principle is essential" and 2) "instructional techniques (namely, phonics) that teach this principle directly are more effective than those that do not". However, while they make it clear they have some fundamental disagreements with some of the claims made by whole-language advocates, some principles of whole-language have value such as the need to ensure that students are enthusiastic about books and eager to learn to read.[77]

Phonics and related areas

[edit]

Phonics emphasizes the alphabetic principle – the idea that letters (graphemes) represent the sounds of speech (phonemes).[278] It is taught in a variety of ways; some are systematic and others are unsystematic. Unsystematic phonics teaches phonics on a "when needed" basis and in no particular sequence. Systematic phonics uses a planned, sequential introduction of a set of phonic elements along with explicit teaching and practice of those elements. The National Reading Panel (NRP) concluded that systematic phonics instruction is more effective than unsystematic phonics or non-phonics instruction.

Phonics approaches include analogy phonics, analytic phonics, embedded phonics with mini-lessons, phonics through spelling, and synthetic phonics.[279][280][281][77][282]

According to a 2018 review of research related to English speaking poor readers, phonics training is effective for improving literacy-related skills, particularly the fluent reading of words and non-words, and the accurate reading of irregular words.[283]

In addition, phonics produces higher achievement for all beginning readers, and the greatest improvement is experienced by students who are at risk of failing to learn to read. While some children can infer these rules on their own, some need explicit instruction on phonics rules. Some phonics instruction has marked benefits such as the expansion of a student's vocabulary. Overall, children who are directly taught phonics are better at reading, spelling, and comprehension.[284]

A challenge in teaching phonics is that in some languages, such as English, complex letter-sound correspondences can confuse beginning readers. For this reason, it is recommended that teachers of English reading begin by introducing the "most frequent sounds" and the "common spellings", and save the less frequent sounds and complex spellings for later (e.g. the sounds /s/ and /t/ before /v/ and /w/; and the spellings cake before eight and cat before duck).[77][285][286]

Phonics is gaining world-wide acceptance.

Combining phonics with other literacy instruction

[edit]Phonics is taught in many different ways and it is often taught together with some of the following: oral language skills,[287][288] concepts about print,[289] phonological awareness, phonemic awareness, phonology, oral reading fluency, vocabulary, syllables, reading comprehension, spelling, word study,[290][291][292] cooperative learning, multisensory learning, and guided reading. And, phonics is often featured in discussions about science of reading,[293][294] and evidence-based practices.

The National Reading Panel (U.S. 2000) is clear that "systematic phonics instruction should be integrated with other reading instruction to create a balanced reading program".[295] It suggests that phonics be taught together with phonemic awareness, oral fluency, vocabulary and comprehension. Researcher and educator Timothy Shanahan, a member of that panel, recommends that primary students receive 60–90 minutes per day of explicit, systematic, literacy instruction time; and that it be divided equally between a) words and word parts (e.g. letters, sounds, decoding and phonemic awareness), b) oral reading fluency, c) reading comprehension, and d) writing.[296] Furthermore, he states that "the phonemic awareness skills found to give the greatest reading advantage to kindergarten and first-grade children are segmenting and blending".[297]

The Ontario Association of Deans of Education (Canada) published research Monograph # 37 entitled Supporting early language and literacy with suggestions for parents and teachers in helping children prior to grade one. It covers the areas of letter names and letter-sound correspondence (phonics), as well as conversation, play-based learning, print, phonological awareness, shared reading, and vocabulary.[298]

Effectiveness of programs

[edit]Some researchers report that teaching reading without teaching phonics is harmful to large numbers of students, yet not all phonics teaching programs produce effective results. The reason is that the effectiveness of a program depends on using the right curriculum together with the appropriate approach to instruction techniques, classroom management, grouping, and other factors.[299] Louisa Moats, a teacher, psychologist and researcher, has long advocated for reading instruction that is direct, explicit and systematic, covering phoneme awareness, decoding, comprehension, literature appreciation, and daily exposure to a variety of texts.[300] She maintains that "reading failure can be prevented in all but a small percentage of children with serious learning disorders. It is possible to teach most students how to read if we start early and follow the significant body of research showing which practices are most effective".[301]

Interest in evidence-based education appears to be growing.[244] In 2021, Best evidence encyclopedia (BEE) released a review of research on 51 different programs for struggling readers in elementary schools.[221] Many of the programs used phonics-based teaching and/or one or more of the following: cooperative learning, technology-supported adaptive instruction (see Educational technology), metacognitive skills, phonemic awareness, word reading, fluency, vocabulary, multisensory learning, spelling, guided reading, reading comprehension, word analysis, structured curriculum, and balanced literacy (non-phonetic approach).

The BEE review concludes that a) outcomes were positive for one-to-one tutoring, b) outcomes were positive, but not as large, for one-to-small group tutoring, c) there were no differences in outcomes between teachers and teaching assistants as tutors, d) technology-supported adaptive instruction did not have positive outcomes, e) whole-class approaches (mostly cooperative learning) and whole-school approaches incorporating tutoring obtained outcomes for struggling readers as large as those found for one-to-one tutoring, and benefitted many more students, and f) approaches mixing classroom and school improvements, with tutoring for the most at-risk students, have the greatest potential for the largest numbers of struggling readers.[221]

Robert Slavin, of BEE, goes so far as to suggest that states should "hire thousands of tutors" to support students scoring far below grade level – particularly in elementary school reading. Research, he says, shows "only tutoring, both one-to-one and one-to-small group, in reading and mathematics, had an effect size larger than +0.10 ... averages are around +0.30", and "well-trained teaching assistants using structured tutoring materials or software can obtain outcomes as good as those obtained by certified teachers as tutors".[302][303]

What works clearinghouse allows you to see the effectiveness of specific programs. For example, as of 2020 they have data on 231 literacy programs. If you filter them by grade 1 only, all class types, all school types, all delivery methods, all program types, and all outcomes you receive 22 programs. You can then view the program details and, if you wish, compare one with another.[304]

Evidence for ESSA[222] (Center for Research and Reform in Education)[223] offers free up-to-date information on current PK–12 programs in reading, writing, math, science, and others that meet the standards of the Every Student Succeeds Act (U.S.).[305]

ProvenTutoring.org[226] a non-profit organization, is a resource for educators interested in research-proven tutoring programs. The programs it lists are proven effective in rigorous research as defined in the 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act. The Center for Research and Reform in Education at Johns Hopkins University provides the technical support to inform program selection.[223]

Systematic phonics

[edit]

Systematic phonics is not one specific method of teaching phonics; it is a term used to describe phonics approaches that are taught explicitly and in a structured, systematic manner. They are systematic because the letters and the sounds they relate to are taught in a specific sequence, as opposed to incidentally or on a "when needed" basis.[307]

The National Reading Panel (NRP) concluded that systematic phonics instruction is more effective than unsystematic phonics or non-phonics instruction. The NRP also found that systematic phonics instruction is effective (with varying degrees) when delivered through one-to-one tutoring, small groups, and teaching classes of students; and is effective from kindergarten onward, the earlier the better. It helps significantly with word-reading skills and reading comprehension for kindergartners and 1st graders as well as for older struggling readers and reading-disabled students. Benefits to spelling were positive for kindergartners and 1st graders but not for older students.[308]

Systematic phonics is sometimes mischaracterised as "skill and drill" with little attention to meaning. However, researchers point out that this impression is false. Teachers can use engaging games or materials to teach letter-sound connections, and it can also be incorporated with the reading of meaningful text.[309]

Phonics can be taught systematically in a variety of ways, such as analogy phonics, analytic phonics, phonics through spelling, and synthetic phonics. However, their effectiveness varies considerably because the methods differ in such areas as the range of letter-sound coverage, the structure of the lesson plans, and the time devoted to specific instructions.[310]

Systematic phonics has gained increased acceptance in different parts of the world since the completion of three major studies into teaching reading; one in the US in 2000,[311][312] another in Australia in 2005,[313] and the other in the UK in 2006.[314]

In 2009, the UK Department of Education published a curriculum review that added support for systematic phonics. In fact, systematic phonics in the UK is known as Synthetic phonics.[315]

Beginning as early as 2014, several states in the United States have changed their curriculum to include systematic phonics instruction in elementary school.[316][317][318][319]

In 2018, the State Government of Victoria, Australia, published a website containing a comprehensive Literacy Teaching Toolkit including Effective Reading Instruction, Phonics, and Sample Phonics Lessons.[320]

Analytic phonics and analogy phonics

[edit]Analytic phonics does not involve pronouncing individual sounds (phonemes) in isolation and blending the sounds, as is done in synthetic phonics. Rather, it is taught at the word level and students learn to analyze letter-sound relationships once the word is identified. For example, students analyze letter-sound correspondences such as the ou spelling of /aʊ/ in shrouds. Also, students might be asked to practice saying words with similar sounds such as ball, bat and bite. Furthermore, students are taught consonant blends (separate, adjacent consonants) as units, such as break or shrouds.[321][322]

Analogy phonics is a particular type of analytic phonics in which the teacher has students analyze phonic elements according to the speech sounds (phonograms) in the word. For example, a type of phonogram (known in linguistics as a rime) is composed of the vowel and the consonant sounds that follow it (e.g. in the words cat, mat and sat, the rime is "at".) Teachers using the analogy method may have students memorize a bank of phonograms, such as -at or -am, or use word families (e.g. can, ran, man, or may, play, say).[323][321]

There have been studies on the effectiveness of instruction using analytic phonics vs. synthetic phonics. Johnston et al. (2012) conducted experimental research studies that tested the effectiveness of phonics learning instruction among 10-year-old boys and girls.[324] They used comparative data from the Clackmannanshire Report and chose 393 participants to compare synthetic phonics instruction and analytic phonics instruction.[325][324] The boys taught by the synthetic phonics method had better word reading than the girls in their classes, and their spelling and reading comprehension was as good. On the other hand, with analytic phonics teaching, although the boys performed as well as the girls in word reading, they had inferior spelling and reading comprehension. Overall, the group taught by synthetic phonics had better word reading, spelling, and reading comprehension. And, synthetic phonics did not lead to any impairment in the reading of irregular words.[324]

Embedded phonics with mini-lessons

[edit]Embedded phonics, also known as incidental phonics, is the type of phonics instruction used in whole language programs. It is not systematic phonics.[326] Although phonics skills are de-emphasised in whole language programs, some teachers include phonics "mini-lessons" when students struggle with words while reading from a book. Short lessons are included based on phonics elements the students are having trouble with, or on a new or difficult phonics pattern that appears in a class reading assignment. The focus on meaning is generally maintained, but the mini-lesson provides some time for focus on individual sounds and the letters that represent them. Embedded phonics is different from other methods because instruction is always in the context of literature rather than in separate lessons about distinct sounds and letters; and skills are taught when an opportunity arises, not systematically.[327][328]

Phonics through spelling

[edit]For some teachers, this is a method of teaching spelling by using the sounds (phonemes).[329] However, it can also be a method of teaching reading by focusing on the sounds and their spelling (i.e. phonemes and syllables). It is taught systematically with guided lessons conducted in a direct and explicit manner including appropriate feedback. Sometimes mnemonic cards containing individual sounds are used to allow the student to practice saying the sounds that are related to a letter or letters (e.g. a, e, i, o, u). Accuracy comes first, followed by speed. The sounds may be grouped by categories such as vowels that sound short (e.g. c-a-t and s-i-t). When the student is comfortable recognizing and saying the sounds, the following steps might be followed: a) the tutor says a target word and the student repeats it out loud, b) the student writes down each individual sound (letter) until the word is completely spelled, saying each sound as it is written, and c) the student says the entire word out loud. An alternate method would be to have the student use mnemonic cards to sound-out (spell) the target word.

Typically, the instruction starts with sounds that have only one letter and simple CVC words such as sat and pin. Then it progresses to longer words, and sounds with more than one letter (e.g. hear and day), and perhaps even syllables (e.g. wa-ter). Sometimes the student practices by saying (or sounding-out) cards that contain entire words.[330]

Synthetic phonics

[edit]Synthetic phonics, also known as blended phonics, is a systematic phonics method employed to teach students to read by sounding out the letters and then blend the sounds to form the word. This method involves learning how letters or letter groups represent individual sounds, and that those sounds are blended to form a word. For example, shrouds would be read by pronouncing the sounds for each spelling, sh, r, ou, d, s (IPA /ʃ, r, aʊ, d, z/), then blending those sounds orally to produce a spoken word, sh – r – ou – d – s = shrouds (IPA /ʃraʊdz/). The goal of a synthetic phonics instructional program is that students identify the sound-symbol correspondences and blend their phonemes automatically. Since 2005, synthetic phonics has become the accepted method of teaching reading (by phonics instruction) in England, Scotland and Australia.[331][332][333][334]

The 2005 Rose Report from the UK concluded that systematic synthetic phonics was the most effective method for teaching reading. It also suggests the "best teaching" includes a brisk pace, engaging children's interest with multi-sensory activities and stimulating resources, praise for effort and achievement; and above all, the full backing of the headteacher.[335]

It also has considerable support in some States in the U.S.[312] and some support from expert panels in Canada.[336]

In the US, a pilot program using the Core Knowledge Early Literacy program that used this type of phonics approach showed significantly higher results in K–3 reading compared with comparison schools.[337] In addition, several States such as California, Ohio, New York and Arkansas, are promoting the principles of synthetic phonics (see synthetic phonics in the United States).

Resources for teaching phonics are available here.

Related areas

[edit]

Phonemic awareness