Рабиндранат Тагор

Рабиндранат Тагор | |

|---|---|

| |

| Родное имя | Рабиндранат Тагор ( бенгальский ) |

| Born | Rabindranath Tagore 7 May 1861 Calcutta, Bengal, British India |

| Died | 7 August 1941 (aged 80) Calcutta, Bengal, British India |

| Pen name | Bhanusimha |

| Occupation |

|

| Language | |

| Citizenship | British India (1861–1941) |

| Period | Bengali Renaissance |

| Literary movement | Contextual Modernism |

| Notable works | |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1913 |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 5, including Rathindranath Tagore |

| Relatives | Tagore family |

| Signature | |

Raindranath Fras ( / Tagore ˈbɪndrənɑːt tæˈɡɔːrr ; произносится [roˈbindɾonatʰ ˈʈʰakuɾ] ; [ 1 ] 7 мая 1861 года [ 2 ] - 7 августа 1941 года [ 3 ] ) был бенгальским поэтом, писателем, драматургом, композитором, философом, социальным реформатором и художником бенгальского эпохи Возрождения . [ 4 ] [ 5 ] [ 6 ] Он изменил бенгальскую литературу и музыку , а также индийское искусство с контекстуальным модернизмом в конце 19 -го и начале 20 -го веков. Автор «глубоко чувствительной, свежей и красивой» поэзии Гитанджали , [ 7 ] В 1913 году Тагор стал первым невропейским и первым лириком, получившим Нобелевскую премию по литературе . [ 8 ] Поэтические песни Тагора рассматривались как духовные и ртутные; где его элегантная проза и магическая поэзия были широко популярны на индийском субконтиненте . [ 9 ] Он был членом Королевского азиатского общества . Называется « Баргальским », [ 10 ] [ 5 ] [ 6 ] Тагор был известен под сорта Gurudeb , Kobiguru и Biswokobi . [ А ]

A Bengali Brahmin from Calcutta with ancestral gentry roots in Burdwan district[12] and Jessore, Tagore wrote poetry as an eight-year-old.[13] At the age of sixteen, he released his first substantial poems under the pseudonym Bhānusiṃha ("Sun Lion"), which were seized upon by literary authorities as long-lost classics.[14] By 1877 he graduated to his first short stories and dramas, published under his real name. As a humanist, universalist, internationalist, and ardent critic of nationalism,[15] he denounced the British Raj and advocated independence from Britain. As an exponent of the Bengal Renaissance, he advanced a vast canon that comprised paintings, sketches and doodles, hundreds of texts, and some two thousand songs; his legacy also endures in his founding of Visva-Bharati University.[16][17]

Tagore modernised Bengali art by spurning rigid classical forms and resisting linguistic strictures. His novels, stories, songs, dance dramas, and essays spoke to topics political and personal. Gitanjali (Song Offerings), Gora (Fair-Faced) and Ghare-Baire (The Home and the World) are his best-known works, and his verse, short stories, and novels were acclaimed—or panned—for their lyricism, colloquialism, naturalism, and unnatural contemplation. His compositions were chosen by two nations as national anthems: India's "Jana Gana Mana" and Bangladesh's "Amar Shonar Bangla" .The Sri Lankan national anthem was also inspired by his work.[18] His Song "Banglar Mati Banglar Jol" has been adopted as the state anthem of West Bengal.

Family Background

The name Tagore is the anglicised transliteration of Thakur.[19] The original surname of the Tagores was Kushari. They were Pirali Brahmin ('Pirali' historically carried a stigmatized and pejorative connotation)[20][21] who originally belonged to a village named Kush in the district named Burdwan in West Bengal. The biographer of Rabindranath Tagore, Prabhat Kumar Mukhopadhyaya wrote in the first volume of his book Rabindrajibani O Rabindra Sahitya Prabeshak that

The Kusharis were the descendants of Deen Kushari, the son of Bhatta Narayana; Deen was granted a village named Kush (in Burdwan zilla) by Maharaja Kshitisura, he became its chief and came to be known as Kushari.[12]

Life and events

Early life: 1861–1878

The last two days a storm has been raging, similar to the description in my song—Jhauro jhauro borishe baridhara [... amidst it] a hapless, homeless man drenched from top to toe standing on the roof of his steamer [...] the last two days I have been singing this song over and over [...] as a result the pelting sound of the intense rain, the wail of the wind, the sound of the heaving Gorai River, [...] have assumed a fresh life and found a new language and I have felt like a major actor in this new musical drama unfolding before me.

— Letter to Indira Devi.[22]

The youngest of 13 surviving children, Tagore (nicknamed "Rabi") was born on 7 May 1861 in the Jorasanko mansion in Calcutta,[23] the son of Debendranath Tagore (1817–1905) and Sarada Devi (1830–1875).[b]

Tagore was raised mostly by servants; his mother had died in his early childhood and his father travelled widely.[29] The Tagore family was at the forefront of the Bengal renaissance. They hosted the publication of literary magazines; theatre and recitals of Bengali and Western classical music featured there regularly. Tagore's father invited several professional Dhrupad musicians to stay in the house and teach Indian classical music to the children.[30] Tagore's oldest brother Dwijendranath was a philosopher and poet. Another brother, Satyendranath, was the first Indian appointed to the elite and formerly all-European Indian Civil Service. Yet another brother, Jyotirindranath, was a musician, composer, and playwright.[31] His sister Swarnakumari became a novelist.[32] Jyotirindranath's wife Kadambari Devi, slightly older than Tagore, was a dear friend and powerful influence. Her abrupt suicide in 1884, soon after he married, left him profoundly distraught for years.[33]

Tagore largely avoided classroom schooling and preferred to roam the manor or nearby Bolpur and Panihati, which the family visited.[34][35] His brother Hemendranath tutored and physically conditioned him—by having him swim the Ganges or trek through hills, by gymnastics, and by practising judo and wrestling. He learned drawing, anatomy, geography and history, literature, mathematics, Sanskrit, and English—his least favourite subject.[36] Tagore loathed formal education—his scholarly travails at the local Presidency College spanned a single day. Years later he held that proper teaching does not explain things; proper teaching stokes curiosity.[37]

After his upanayan (coming-of-age rite) at age eleven, Tagore and his father left Calcutta in February 1873 to tour India for several months, visiting his father's Santiniketan estate and Amritsar before reaching the Himalayan hill station of Dalhousie. There Tagore read biographies, studied history, astronomy, modern science, and Sanskrit, and examined the classical poetry of Kālidāsa.[38][39] During his 1-month stay at Amritsar in 1873 he was greatly influenced by melodious gurbani and Nanak bani being sung at Golden Temple for which both father and son were regular visitors. He writes in his My Reminiscences (1912):

The golden temple of Amritsar comes back to me like a dream. Many a morning have I accompanied my father to this Gurudarbar of the Sikhs in the middle of the lake. There the sacred chanting resounds continually. My father, seated amidst the throng of worshippers, would sometimes add his voice to the hymn of praise, and finding a stranger joining in their devotions they would wax enthusiastically cordial, and we would return loaded with the sanctified offerings of sugar crystals and other sweets.[40]

He wrote 6 poems relating to Sikhism and several articles in Bengali children's magazine about Sikhism.[41]

- Poems on Guru Gobind Singh: নিষ্ফল উপহার Nishfal-upahaar (1888, translated as "Futile Gift"), গুরু গোবিন্দ Guru Gobinda (1899) and শেষ শিক্ষা Shesh Shiksha (1899, translated as "Last Teachings")[41]

- Poem on Banda Bahadur: বন্দী বীর Bandi-bir (The Prisoner Warrior written in 1888 or 1898)[41]

- Poem on Bhai Torusingh: প্রার্থনাতীত দান (prarthonatit dan – Unsolicited gift) written in 1888 or 1898[41]

- Poem on Nehal Singh: নীহাল সিংহ (Nihal Singh) written in 1935.[41]

Tagore returned to Jorosanko and completed a set of major works by 1877, one of them a long poem in the Maithili style of Vidyapati. As a joke, he claimed that these were the lost works of newly discovered 17th-century Vaiṣṇava poet Bhānusiṃha.[42] Regional experts accepted them as the lost works of the fictitious poet.[43] He debuted in the short-story genre in Bengali with "Bhikharini" ("The Beggar Woman").[44][45] Published in the same year, Sandhya Sangit (1882) includes the poem "Nirjharer Swapnabhanga" ("The Rousing of the Waterfall").

Shilaidaha: 1878–1901

Because Debendranath wanted his son to become a barrister, Tagore enrolled at a public school in Brighton, East Sussex, England in 1878.[22] He stayed for several months at a house that the Tagore family owned near Brighton and Hove, in Medina Villas; in 1877 his nephew and niece—Suren and Indira Devi, the children of Tagore's brother Satyendranath—were sent together with their mother, Tagore's sister-in-law, to live with him.[46] He briefly read law at University College London, but again left, opting instead for independent study of Shakespeare's plays Coriolanus, and Antony and Cleopatra and the Religio Medici of Thomas Browne. Lively English, Irish, and Scottish folk tunes impressed Tagore, whose own tradition of Nidhubabu-authored kirtans and tappas and Brahmo hymnody was subdued.[22][47] In 1880 he returned to Bengal degree-less, resolving to reconcile European novelty with Brahmo traditions, taking the best from each.[48] After returning to Bengal, Tagore regularly published poems, stories, and novels. These had a profound impact within Bengal itself but received little national attention.[49] In 1883 he married 10-year-old[50] Mrinalini Devi, born Bhabatarini, 1873–1902 (this was a common practice at the time). They had five children, two of whom died in childhood.[51]

In 1890 Tagore began managing his vast ancestral estates in Shelaidaha (today a region of Bangladesh); he was joined there by his wife and children in 1898. Tagore released his Manasi poems (1890), among his best-known work.[52] As Zamindar Babu, Tagore criss-crossed the Padma River in command of the Padma, the luxurious family barge (also known as "budgerow"). He collected mostly token rents and blessed villagers who in turn honoured him with banquets—occasionally of dried rice and sour milk.[53] He met Gagan Harkara, through whom he became familiar with Baul Lalon Shah, whose folk songs greatly influenced Tagore.[54] Tagore worked to popularise Lalon's songs. The period 1891–1895, Tagore's Sadhana period, named after one of his magazines, was his most productive;[29] in these years he wrote more than half the stories of the three-volume, 84-story Galpaguchchha.[44] Its ironic and grave tales examined the voluptuous poverty of an idealised rural Bengal.[55]

Santiniketan: 1901–1932

In 1901 Tagore moved to Santiniketan to found an ashram with a marble-floored prayer hall—The Mandir—an experimental school, groves of trees, gardens, a library.[56] There his wife and two of his children died. His father died in 1905. He received monthly payments as part of his inheritance and income from the Maharaja of Tripura, sales of his family's jewellery, his seaside bungalow in Puri, and a derisory 2,000 rupees in book royalties.[57] He gained Bengali and foreign readers alike; he published Naivedya (1901) and Kheya (1906) and translated poems into free verse.

In 1912, Tagore translated his 1910 work Gitanjali into English. While on a trip to London, he shared these poems with admirers including William Butler Yeats and Ezra Pound. London's India Society published the work in a limited edition, and the American magazine Poetry published a selection from Gitanjali.[58] In November 1913, Tagore learned he had won that year's Nobel Prize in Literature: the Swedish Academy appreciated the idealistic—and for Westerners—accessible nature of a small body of his translated material focused on the 1912 Gitanjali: Song Offerings.[59] He was awarded a knighthood by King George V in the 1915 Birthday Honours, but Tagore renounced it after the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre.[60] Renouncing the knighthood, Tagore wrote in a letter addressed to Lord Chelmsford, the then British Viceroy of India, "The disproportionate severity of the punishments inflicted upon the unfortunate people and the methods of carrying them out, we are convinced, are without parallel in the history of civilised governments...The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in their incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part wish to stand, shorn of all special distinctions, by the side of my countrymen."[61][62]

In 1919, he was invited by the president and chairman of Anjuman-e-Islamia, Syed Abdul Majid to visit Sylhet for the first time. The event attracted over 5000 people.[63]

In 1921, Tagore and agricultural economist Leonard Elmhirst set up the "Institute for Rural Reconstruction", later renamed Shriniketan or "Abode of Welfare", in Surul, a village near the ashram. With it, Tagore sought to moderate Gandhi's Swaraj protests, which he occasionally blamed for British India's perceived mental – and thus ultimately colonial – decline.[64] He sought aid from donors, officials, and scholars worldwide to "free village[s] from the shackles of helplessness and ignorance" by "vitalis[ing] knowledge".[65][66] In the early 1930s he targeted ambient "abnormal caste consciousness" and untouchability. He lectured against these, he penned Dalit heroes for his poems and his dramas, and he campaigned—successfully—to open Guruvayoor Temple to Dalits.[67][68]

Twilight years: 1932–1941

Dutta and Robinson describe this phase of Tagore's life as being one of a "peripatetic litterateur". It affirmed his opinion that human divisions were shallow. During a May 1932 visit to a Bedouin encampment in the Iraqi desert, the tribal chief told him that "Our Prophet has said that a true Muslim is he by whose words and deeds not the least of his brother-men may ever come to any harm ..." Tagore confided in his diary: "I was startled into recognizing in his words the voice of essential humanity."[69] To the end Tagore scrutinized orthodoxy—and in 1934, he struck. That year, an earthquake hit Bihar and killed thousands. Gandhi hailed it as seismic karma, as divine retribution avenging the oppression of Dalits. Tagore rebuked him for his seemingly ignominious implications.[70] He mourned the perennial poverty of Calcutta and the socioeconomic decline of Bengal and detailed this newly plebeian aesthetics in an unrhymed hundred-line poem whose technique of searing double-vision foreshadowed Satyajit Ray's film Apur Sansar.[71][72] Fifteen new volumes appeared, among them prose-poem works Punashcha (1932), Shes Saptak (1935), and Patraput (1936). Experimentation continued in his prose-songs and dance-dramas— Chitra (1914), Shyama (1939), and Chandalika (1938)— and in his novels— Dui Bon (1933), Malancha (1934), and Char Adhyay (1934).[73]

Clouds come floating into my life, no longer to carry rain or usher storm, but to add color to my sunset sky.

—Verse 292, Stray Birds, 1916.

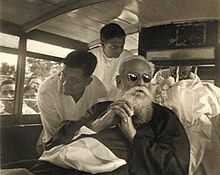

Tagore's remit expanded to science in his last years, as hinted in Visva-Parichay, a 1937 collection of essays. His respect for scientific laws and his exploration of biology, physics, and astronomy informed his poetry, which exhibited extensive naturalism and verisimilitude.[74] He wove the process of science, the narratives of scientists, into stories in Se (1937), Tin Sangi (1940), and Galpasalpa (1941). His last five years were marked by chronic pain and two long periods of illness. These began when Tagore lost consciousness in late 1937; he remained comatose and near death for a time. This was followed in late 1940 by a similar spell, from which he never recovered. Poetry from these valetudinary years is among his finest.[75][76] A period of prolonged agony ended with Tagore's death on 7 August 1941, aged 80.[23] He was in an upstairs room of the Jorasanko mansion in which he grew up.[77][78] The date is still mourned.[79] A. K. Sen, brother of the first chief election commissioner, received dictation from Tagore on 30 July 1941, a day before a scheduled operation: his last poem.[80]

I'm lost in the middle of my birthday. I want my friends, their touch, with the earth's last love. I will take life's final offering, I will take the human's last blessing. Today my sack is empty. I have given completely whatever I had to give. In return, if I receive anything—some love, some forgiveness—then I will take it with me when I step on the boat that crosses to the festival of the wordless end.

Travels

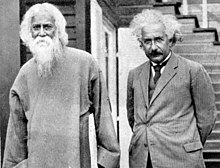

Our passions and desires are unruly, but our character subdues these elements into a harmonious whole. Does something similar to this happen in the physical world? Are the elements rebellious, dynamic with individual impulse? And is there a principle in the physical world that dominates them and puts them into an orderly organization?

— Interviewed by Einstein, 14 April 1930.[81]

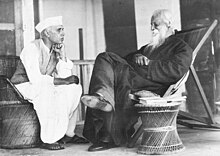

Between 1878 and 1932, Tagore set foot in more than thirty countries on five continents.[82] In 1912, he took a sheaf of his translated works to England, where they gained attention from missionary and Gandhi protégé Charles F. Andrews, Irish poet William Butler Yeats, Ezra Pound, Robert Bridges, Ernest Rhys, Thomas Sturge Moore, and others.[83] Yeats wrote the preface to the English translation of Gitanjali; Andrews joined Tagore at Santiniketan. In November 1912 Tagore began touring the United States[84] and the United Kingdom, staying in Butterton, Staffordshire with Andrews's clergymen friends.[85] From May 1916 until April 1917, he lectured in Japan[86] and the United States.[87] He denounced nationalism.[88] His essay "Nationalism in India" was scorned and praised; it was admired by Romain Rolland and other pacifists.[89]

Shortly after returning home, the 63-year-old Tagore accepted an invitation from the Peruvian government. He travelled to Mexico. Each government pledged US$100,000 to his school to commemorate the visits.[90] A week after his 6 November 1924 arrival in Buenos Aires,[91] an ill Tagore shifted to the Villa Miralrío at the behest of Victoria Ocampo. He left for home in January 1925. In May 1926 Tagore reached Naples; the next day he met Mussolini in Rome.[92] Their warm rapport ended when Tagore pronounced upon Il Duce's fascist finesse.[93] He had earlier enthused: "[w]without any doubt he is a great personality. There is such a massive vigor in that head that it reminds one of Michael Angelo's chisel." A "fire-bath" of fascism was to have educed "the immortal soul of Italy ... clothed in quenchless light".[94]

On 1 November 1926 Tagore arrived in Hungary and spent some time on the shore of Lake Balaton in the city of Balatonfüred, recovering from heart problems at a sanitarium. He planted a tree, and a bust statue was placed there in 1956 (a gift from the Indian government, the work of Rasithan Kashar, replaced by a newly gifted statue in 2005) and the lakeside promenade still bears his name since 1957.[95]

On 14 July 1927, Tagore and two companions began a four-month tour of Southeast Asia. They visited Bali, Java, Kuala Lumpur, Malacca, Penang, Siam, and Singapore. The resultant travelogues compose Jatri (1929).[96] In early 1930 he left Bengal for a nearly year-long tour of Europe and the United States. Upon returning to Britain—and as his paintings were exhibited in Paris and London—he lodged at a Birmingham Quaker settlement. He wrote his Oxford Hibbert Lectures[c] and spoke at the annual London Quaker meet.[97] There, addressing relations between the British and the Indians – a topic he would tackle repeatedly over the next two years – Tagore spoke of a "dark chasm of aloofness".[98] He visited Aga Khan III, stayed at Dartington Hall, toured Denmark, Switzerland, and Germany from June to mid-September 1930, then went on into the Soviet Union.[99] In April 1932 Tagore, intrigued by the Persian mystic Hafez, was hosted by Reza Shah Pahlavi.[100][101] In his other travels, Tagore interacted with Henri Bergson, Albert Einstein, Robert Frost, Thomas Mann, George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, and Romain Rolland.[102][103] Visits to Persia and Iraq (in 1932) and Sri Lanka (in 1933) composed Tagore's final foreign tour, and his dislike of communalism and nationalism only deepened.[69] Vice-president of India M. Hamid Ansari has said that Rabindranath Tagore heralded the cultural rapprochement between communities, societies and nations much before it became the liberal norm of conduct. Tagore was a man ahead of his time. He wrote in 1932, while on a visit to Iran, that "each country of Asia will solve its own historical problems according to its strength, nature and needs, but the lamp they will each carry on their path to progress will converge to illuminate the common ray of knowledge."[104]

Works

Known mostly for his poetry, Tagore wrote novels, essays, short stories, travelogues, dramas, and thousands of songs. Of Tagore's prose, his short stories are perhaps the most highly regarded; he is indeed credited with originating the Bengali-language version of the genre. His works are frequently noted for their rhythmic, optimistic, and lyrical nature. Such stories mostly borrow from the lives of common people. Tagore's non-fiction grappled with history, linguistics, and spirituality. He wrote autobiographies. His travelogues, essays, and lectures were compiled into several volumes, including Europe Jatrir Patro (Letters from Europe) and Manusher Dhormo (The Religion of Man). His brief chat with Einstein, "Note on the Nature of Reality", is included as an appendix to the latter. On the occasion of Tagore's 150th birthday, an anthology (titled Kalanukromik Rabindra Rachanabali) of the total body of his works is currently being published in Bengali in chronological order. This includes all versions of each work and fills about eighty volumes.[105] In 2011, Harvard University Press collaborated with Visva-Bharati University to publish The Essential Tagore, the largest anthology of Tagore's works available in English; it was edited by Fakrul Alam and Radha Chakravarthy and marks the 150th anniversary of Tagore's birth.[106]

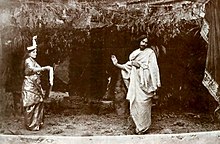

Drama

Tagore's experiences with drama began when he was sixteen, with his brother Jyotirindranath. He wrote his first original dramatic piece when he was twenty – Valmiki Pratibha which was shown at the Tagore's mansion. Tagore stated that his works sought to articulate "the play of feeling and not of action". In 1890 he wrote Visarjan (an adaptation of his novella Rajarshi), which has been regarded as his finest drama. In the original Bengali language, such works included intricate subplots and extended monologues. Later, Tagore's dramas used more philosophical and allegorical themes. The play Dak Ghar (The Post Office; 1912), describes the child Amal defying his stuffy and puerile confines by ultimately "fall[ing] asleep", hinting his physical death. A story with borderless appeal—gleaning rave reviews in Europe—Dak Ghar dealt with death as, in Tagore's words, "spiritual freedom" from "the world of hoarded wealth and certified creeds".[107][108] Another is Tagore's Chandalika (Untouchable Girl), which was modelled on an ancient Buddhist legend describing how Ananda, the Gautama Buddha's disciple, asks a tribal girl for water.[109] In Raktakarabi ("Red" or "Blood Oleanders") is an allegorical struggle against a kleptocrat king who rules over the residents of Yaksha puri.[110]

Chitrangada, Chandalika, and Shyama are other key plays that have dance-drama adaptations, which together are known as Rabindra Nritya Natya.

Short stories

Tagore began his career in short stories in 1877—when he was only sixteen—with "Bhikharini" ("The Beggar Woman").[111] With this, Tagore effectively invented the Bengali-language short story genre.[112] The four years from 1891 to 1895 are known as Tagore's "Sadhana" period (named for one of Tagore's magazines). This period was among Tagore's most fecund, yielding more than half the stories contained in the three-volume Galpaguchchha, which itself is a collection of eighty-four stories.[111] Such stories usually showcase Tagore's reflections upon his surroundings, on modern and fashionable ideas, and on interesting mind puzzles (which Tagore was fond of testing his intellect with). Tagore typically associated his earliest stories (such as those of the "Sadhana" period) with an exuberance of vitality and spontaneity; these characteristics were intimately connected with Tagore's life in the common villages of, among others, Patisar, Shajadpur, and Shilaida while managing the Tagore family's vast landholdings.[111] There, he beheld the lives of India's poor and common people; Tagore thereby took to examining their lives with a penetrative depth and feeling that was singular in Indian literature up to that point.[113] In particular, such stories as "Kabuliwala" ("The Fruitseller from Kabul", published in 1892), "Kshudita Pashan" ("The Hungry Stones") (August 1895), and "Atithi" ("The Runaway", 1895) typified this analytic focus on the downtrodden.[114] Many of the other Galpaguchchha stories were written in Tagore's Sabuj Patra period from 1914 to 1917, also named after one of the magazines that Tagore edited and heavily contributed to.[111]

Novels

Tagore wrote eight novels and four novellas, among them Nastanirh (1901), Noukadubi (1906), Chaturanga (1916) and Char Adhyay (1934).

In Chokher Bali (1902-1903), Tagore inscribes Bengali society via its heroine: a rebellious widow who would live for herself alone. He pillories the custom of perpetual mourning on the part of widows, who were not allowed to remarry, who were consigned to seclusion and loneliness.

Ghare Baire (The Home and the World, 1916), through the lens of the idealistic zamindar protagonist Nikhil, excoriates rising Indian nationalism, terrorism, and religious zeal in the Swadeshi movement; a frank expression of Tagore's conflicted sentiments, it emerged from a 1914 bout of depression. The novel ends in Hindu-Muslim violence and Nikhil's likely mortal—wounding.[115]

His longest novel, Gora (1907-1910), raises controversial questions regarding the Indian identity. As with Ghare Baire, matters of self-identity (jāti), personal freedom, and religion are developed in the context of a family story and love triangle.[116] In it an Irish boy orphaned in the Sepoy Mutiny is raised by Hindus as the titular gora—"whitey". Ignorant of his foreign origins, he chastises Hindu religious backsliders out of love for the indigenous Indians and solidarity with them against his hegemon-compatriots. He falls for a Brahmo girl, compelling his worried foster father to reveal his lost past and cease his nativist zeal. As a "true dialectic" advancing "arguments for and against strict traditionalism", it tackles the colonial conundrum by "portray[ing] the value of all positions within a particular frame [...] not only syncretism, not only liberal orthodoxy but the extremist reactionary traditionalism he defends by an appeal to what humans share." Among these Tagore highlights "identity [...] conceived of as dharma."[117]

In Jogajog (Yogayog, Relationships, 1929), the heroine Kumudini—bound by the ideals of Śiva-Sati, exemplified by Dākshāyani—is torn between her pity for the sinking fortunes of her progressive and compassionate elder brother and his foil: her roué of a husband. Tagore flaunts his feminist leanings; pathos depicts the plight and ultimate demise of women trapped by pregnancy, duty, and family honor; he simultaneously trucks with Bengal's putrescent landed gentry.[118] The story revolves around the underlying rivalry between two families—the Chatterjees, aristocrats now on the decline (Biprodas) and the Ghosals (Madhusudan), representing new money and new arrogance. Kumudini, Biprodas' sister, is caught between the two as she is married off to Madhusudan. She had risen in an observant and sheltered traditional home, as had all her female relations.

Others were uplifting: Shesher Kabita (1929) — translated twice as Last Poem and Farewell Song — is his most lyrical novel, with poems and rhythmic passages written by a poet protagonist. It contains elements of satire and postmodernism and has stock characters who gleefully attack the reputation of an old, outmoded, oppressively renowned poet who, incidentally, goes by a familiar name: "Rabindranath Tagore".

Though his novels remain among the least-appreciated of his works, they have been given renewed attention via film adaptations, by Satyajit Ray for Charulata (based on Nastanirh) in 1964 and Ghare Baire in 1984, and by several others filmmakers such as Satu Sen for Chokher Bali already in 1938, when Tagore was still alive.

Poetry

Internationally, Gitanjali (Bengali: গীতাঞ্জলি) is Tagore's best-known collection of poetry, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. Tagore was the first non-European to receive a Nobel Prize in Literature and the second non-European to receive a Nobel Prize after Theodore Roosevelt.[119]

Besides Gitanjali, other notable works include Manasi, Sonar Tori ("Golden Boat"), Balaka ("Wild Geese" – the title being a metaphor for migrating souls)[120]

Tagore's poetic style, which proceeds from a lineage established by 15th- and 16th-century Vaishnava poets, ranges from classical formalism to the comic, visionary, and ecstatic. He was influenced by the atavistic mysticism of Vyasa and other rishi-authors of the Upanishads, the Bhakti-Sufi mystic Kabir, and Ramprasad Sen.[121] Tagore's most innovative and mature poetry embodies his exposure to Bengali rural folk music, which included mystic Baul ballads such as those of the bard Lalon.[122][123] These, rediscovered and re-popularized by Tagore, resemble 19th-century Kartābhajā hymns that emphasize inward divinity and rebellion against bourgeois bhadralok religious and social orthodoxy.[124][125] During his Shelaidaha years, his poems took on a lyrical voice of the moner manush, the Bāuls' "man within the heart" and Tagore's "life force of his deep recesses", or meditating upon the jeevan devata—the demiurge or the "living God within".[22] This figure connected with divinity through appeal to nature and the emotional interplay of human drama. Such tools saw use in his Bhānusiṃha poems chronicling the Radha-Krishna romance, which was repeatedly revised over seventy years.[126][127]

Later, with the development of new poetic ideas in Bengal – many originating from younger poets seeking to break with Tagore's style – Tagore absorbed new poetic concepts, which allowed him to further develop a unique identity. Examples of this include Africa and Camalia, which are among the better-known of his latter poems.

Songs (Rabindra Sangeet)

Tagore was a prolific composer with around 2,230 songs to his credit.[128] His songs are known as rabindrasangit ("Tagore Song"), which merges fluidly into his literature, most of which—poems or parts of novels, stories, or plays alike—were lyricized. Influenced by the thumri style of Hindustani music, they ran the entire gamut of human emotion, ranging from his early dirge-like Brahmo devotional hymns to quasi-erotic compositions.[129] They emulated the tonal color of classical ragas to varying extents. Some songs mimicked a given raga's melody and rhythm faithfully, others newly blended elements of different ragas.[130] Yet about nine-tenths of his work was not bhanga gaan, the body of tunes revamped with "fresh value" from select Western, Hindustani, Bengali folk and other regional flavors "external" to Tagore's own ancestral culture.[22]

In 1971, Amar Shonar Bangla became the national anthem of Bangladesh. It was written – ironically – to protest the 1905 Partition of Bengal along communal lines: cutting off the Muslim-majority East Bengal from Hindu-dominated West Bengal was to avert a regional bloodbath. Tagore saw the partition as a cunning plan to stop the independence movement, and he aimed to rekindle Bengali unity and tar communalism. Jana Gana Mana was written in shadhu-bhasha, a Sanskritised form of Bengali,[131] and is the first of five stanzas of the Brahmo hymn Bharot Bhagyo Bidhata that Tagore composed. It was first sung in 1911 at a Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress[132] and was adopted in 1950 by the Constituent Assembly of the Republic of India as its national anthem.

Sri Lanka's National Anthem was inspired by his work.[18]

For Bengalis, the songs' appeal, stemming from the combination of emotive strength and beauty described as surpassing even Tagore's poetry, was such that the Modern Review observed that "[t]here is in Bengal no cultured home where Rabindranath's songs are not sung or at least attempted to be sung... Even illiterate villagers sing his songs".[133] Tagore influenced sitar maestro Vilayat Khan and sarodiyas Buddhadev Dasgupta and Amjad Ali Khan.[130]

Art works

At sixty, Tagore took up drawing and painting; successful exhibitions of his many works—which made a debut appearance in Paris upon encouragement by artists he met in the south of France[135]—were held throughout Europe. He was likely red, green color blind, resulting in works that exhibited strange color schemes and off-beat aesthetics. Tagore was influenced by numerous styles, including scrimshaw by the Malanggan people of northern New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, Haida carvings from the Pacific Northwest region of North America, and woodcuts by the German Max Pechstein.[134] His artist's eye for handwriting was revealed in the simple artistic and rhythmic leitmotifs embellishing the scribbles, cross-outs, and word layouts of his manuscripts. Some of Tagore's lyrics corresponded in a synesthetic sense with particular paintings.[22]

Surrounded by several painters Rabindranath had always wanted to paint. Writing and music, playwriting and acting came to him naturally and almost without training, as it did to several others in his family, and in even greater measure. But painting eluded him. Yet he tried repeatedly to master the art and there are several references to this in his early letters and reminiscence. In 1900 for instance, when he was nearing forty and already a celebrated writer, he wrote to Jagadish Chandra Bose, "You will be surprised to hear that I am sitting with a sketchbook drawing. Needless to say, the pictures are not intended for any salon in Paris, they cause me not the least suspicion that the national gallery of any country will suddenly decide to raise taxes to acquire them. But, just as a mother lavishes most affection on her ugliest son, so I feel secretly drawn to the very skill that comes to me least easily." He also realized that he was using the eraser more than the pencil, and dissatisfied with the results he finally withdrew, deciding it was not for him to become a painter.[136]

India's National Gallery of Modern Art lists 102 works by Tagore in its collections.[138][139]

In 1937, Tagore's paintings were removed from Berlin's baroque Crown Prince Palace by the Nazi regime and five were included in the inventory of "degenerate art" compiled by the Nazis in 1941–1942.[140]

Politics

Tagore opposed imperialism and supported Indian nationalists,[141][142][143] and these views were first revealed in Manast, which was mostly composed in his twenties.[52] Evidence produced during the Hindu–German Conspiracy Trial and latter accounts affirm his awareness of the Ghadarites and stated that he sought the support of Japanese Prime Minister Terauchi Masatake and former Premier Ōkuma Shigenobu.[144] Yet he lampooned the Swadeshi movement; he rebuked it in The Cult of the Charkha, an acrid 1925 essay.[145] According to Amartya Sen, Tagore rebelled against strongly nationalist forms of the independence movement, and he wanted to assert India's right to be independent without denying the importance of what India could learn from abroad.[146] He urged the masses to avoid victimology and instead seek self-help and education, and he saw the presence of British administration as a "political symptom of our social disease". He maintained that, even for those at the extremes of poverty, "there can be no question of blind revolution"; preferable to it was a "steady and purposeful education".[147][148]

So I repeat we never can have a true view of man unless we have a love for him. Civilisation must be judged and prized, not by the amount of power it has developed, but by how much it has evolved and given expression to, by its laws and institutions, the love of humanity.

— Sādhanā: The Realisation of Life, 1916.[149]

Such views enraged many. He escaped assassination—and only narrowly—by Indian expatriates during his stay in a San Francisco hotel in late 1916; the plot failed when his would-be assassins fell into an argument.[150] Tagore wrote songs lionizing the Indian independence movement.[151] Two of Tagore's more politically charged compositions, "Chitto Jetha Bhayshunyo" ("Where the Mind is Without Fear") and "Ekla Chalo Re" ("If They Answer Not to Thy Call, Walk Alone"), gained mass appeal, with the latter favored by Gandhi.[152] Though somewhat critical of Gandhian activism,[153] Tagore was key in resolving a Gandhi–Ambedkar dispute involving separate electorates for untouchables, thereby mooting at least one of Gandhi's fasts "unto death".[154][155]

Repudiation of knighthood

Tagore renounced his knighthood in response to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919. In the repudiation letter to the Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, he wrote[156]

The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part, wish to stand, shorn, of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen who, for their so-called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings.

Santiniketan and Visva-Bharati

Tagore despised rote classroom schooling, as shown in his short story, "The Parrot's Training", wherein a bird is caged and force-fed textbook pages—to death.[157][158] Visiting Santa Barbara in 1917, Tagore conceived a new type of university: he sought to "make Santiniketan the connecting thread between India and the world [and] a world center for the study of humanity somewhere beyond the limits of nation and geography."[150] The school, which he named Visva-Bharati,[d] had its foundation stone laid on 24 December 1918 and was inaugurated precisely three years later.[159] Tagore employed a brahmacharya system: gurus gave pupils personal guidance—emotional, intellectual, and spiritual. Teaching was often done under trees. He staffed the school, he contributed his Nobel Prize monies,[160] and his duties as steward-mentor at Santiniketan kept him busy: mornings he taught classes; afternoons and evenings he wrote the students' textbooks.[161] He fundraised widely for the school in Europe and the United States between 1919 and 1921.[162]

Theft of Nobel Prize

On 25 March 2004, Tagore's Nobel Prize was stolen from the safety vault of the Visva-Bharati University, along with several other of his belongings.[163] On 7 December 2004, the Swedish Academy decided to present two replicas of Tagore's Nobel Prize, one made of gold and the other made of bronze, to the Visva-Bharati University.[164] It inspired the fictional film Nobel Chor. In 2016, a baul singer named Pradip Bauri, accused of sheltering the thieves, was arrested.[165][166]

Impact and legacy

Every year, many events pay tribute to Tagore: Kabipranam, his birth anniversary, is celebrated by groups scattered across the globe; the annual Tagore Festival held in Urbana, Illinois (US); Rabindra Path Parikrama walking pilgrimages from Kolkata to Santiniketan; and recitals of his poetry, which are held on important anniversaries.[84][167][168] Bengali culture is fraught with this legacy: from language and arts to history and politics. Amartya Sen deemed Tagore a "towering figure", a "deeply relevant and many-sided contemporary thinker".[168][146] Tagore's Bengali originals—the 1939 Rabīndra Rachanāvalī—is canonized as one of his nation's greatest cultural treasures, and he was roped into a reasonably humble role: "the greatest poet India has produced".[169]

Тагор был известен в большей части Европы, Северной Америки и Восточной Азии. Он соучредил Дартингтон-Холл Школу , прогрессивного совместного учреждения; [ 170 ] В Японии он повлиял на такие фигуры, как Нобелевский лауреат Ясунари Кавабата . [ 171 ] В колониальном Вьетнаме Тагор был руководством для беспокойного духа радикального писателя и публициста Нгуена и нийн [ 172 ] Работы Тагора были широко переведены на английский, голландский, немецкий, испанский и другие европейские языки чешского индолога Винсенка Лесни , [ 173 ] Французский нобелевский лауреат Андре Гид , русский поэт Анна Ахматова , [ 174 ] Бывший премьер -министр Турции Бюлент Эквит , [ 175 ] и другие. В Соединенных Штатах лекции Тагора, особенно в 1916–1917 годах, были широко посещены и высоко оценены. Некоторые споры [ E ] С учетом Тагора, возможно, вымышленного, разрушил его популярность и продажи в Японии и Северной Америке после конца 1920 -х годов, завершив его «почти полным затмением» за пределами Бенгалии. [ 9 ] И все же скрытое почтение к Тагору было обнаружено удивленным Салманом Рушди во время поездки в Никарагуа. [ 181 ]

В качестве переводов Тагор оказал влияние на чилийцев Пабло Неруда и Габриэлы Мистраль ; Мексиканский писатель Октавио Пас ; и испанцы Жозе Ортега Y Gasset , Zenobia Camprubí и Хуан Рамон Джименес . В период 1914–1922 гг. Пара Хименес-Кампробия создала двадцать два испанских перевода английского корпуса Тагора; Они сильно пересмотрели полумесяц и другие ключевые названия. В эти годы Джименес разработал «обнаженную поэзию». [ 182 ] Ortega Y Gasset написал, что «широкая привлекательность Тагора [обязан тому, как] он говорит о стремлении к совершенству, что у всех нас есть [...] Тагор пробуждает бездействующее чувство детского чуда, и он насыщает воздух всевозможными очаровательными обещаниями Читатель, который [...] уделяет мало внимания более глубокому импорту восточной мистики ». Работы Тагора распространялись в свободных изданиях около 1920 года - наряду с работами Платона , Данте , Сервантеса , Гете и Толстоя .

Тагор был признан чрезмерным рейтингом некоторыми. Грэм Грин сомневался, что «любой, кроме мистера Йейтса, все еще может относиться к своим стихам очень серьезно». Несколько выдающихся западных поклонников, включая фунт и, в меньшей степени, даже Йейтс, критиковали работу Тагора. Йейтс, не впечатленный своими английскими переводами, выступил против этого «чертового Тагора [...] мы получили три хороших книгах, Стердж Мур и я, а затем, потому что он думал, что более важно видеть и знать английский, чем быть великим Поэт, он вынес сентиментальный мусор и разрушил свою репутацию. [ 9 ] [ 183 ] Уильям Радис , который «английский [ed]» его стихи спросил: «Каково их место в мировой литературе?» [ 184 ] Он видел его как «своего рода контркультуры [Al]», неся «новый вид классицизма», который излечил бы «разрушенную романтическую путаницу и хаос 20-го века». [ 183 ] [ 185 ] Переведенный Тагор был «почти бессмысленным», [ 186 ] и подпадные английские предложения уменьшили его транснациональную апелляцию:

Любой, кто знает стихи Тагора в их первоначальном бенгальском языке, не может чувствовать себя довольным каким -либо из переводов (сделанные с помощью или без помощи Йейтса). Даже переводы его прозы в некоторой степени страдают от искажений. Эм Форстер отметил [из] дома и мира [который] «[t] тема он настолько прекрасна», но чары «исчезли в переводе» или, возможно, «в эксперименте, который не совсем оторвался».

- Амартия Сен , «Тагор и его Индия». [ 9 ]

Музеи

Есть восемь музеев Тагора, три в Индии и пять в Бангладеш:

- Музей Рабиндры Бхарати, в Йорасанко Такур Бари , Калькута, Индия

- Мемориальный музей Тагора, в Шилайдахе Катибади , Шилайдаха , Бангладеш

- Мемориальный музей Рабиндра в Шахзадпуре Качхарибари , Шахзадпур , Бангладеш

- Музей Рабиндры Бхаван, в Сантиникетан , Индия

- Музей Рабиндры , в Мунгпу, недалеко от Калимпонг, Индия

- Патисар Рабиндра Качарибари, Патисар, Атраи , Наогаон , Бангладеш

- Мемориальный комплекс Pithavoge Rabindra, Питавоге, Рупша , Хулна, Бангладеш

- Комплекс Рабиндры , Деревня Дахиндихи, Фуланла Упазила , Хулна , Бангладеш

Jorasanko Thakur Bari ( Бенгали : Дом Такурс ; Англизированный до Тагора ) в Йорасанко , к северу от Калькутты, является наследственным домом семьи Тагора. В настоящее время он расположен в кампусе Университета Рабиндры Бхарати по адресу 6/4 Dwarakanath Tagore Lane [ 187 ] Jorasanko, Kolkata 700007. [ 188 ] Это дом, в котором родился Тагор, а также место, где он провел большую часть своего детства и где он умер 7 августа 1941 года.

Список работ

Кто вы, читатель, читаете мои стихи сто лет отсюда?

Я не могу отправить вам один цветок из этого богатства весны, одной отдельной полосы золота из Yonder Clouds.

Откройте свои двери и посмотрите за границу.

Из вашего цветущего сада собирайте ароматные воспоминания о исчезнувших цветах сто лет назад.

В радости вашего сердца вы можете почувствовать живую радость, которая пела одно весеннее утро, посылая его радостный голос на сотню лет.

Садовник , 1915 [ 189 ]

SNLTR проводит 1415 Be Edition полных бенгальских работ Тагора. Tagore Web также проводит издание работ Тагора, включая аннотированные песни. Переводы встречаются в Project Gutenberg и Wikisource . Больше источников ниже .

Оригинал

| Бенгальский титул | Транслитерированный заголовок | Перевод названия | Год |

|---|---|---|---|

| Бханусингх Тагор | Бханусфорта | Песни бханусиха ṭākur | 1884 |

| Мани | Значение | Идеальный | 1890 |

| Золото | Сонар | Золотая лодка | 1894 |

| Гитанджали | Гитанджали | Предложения песен | 1910 |

| Жест | Обрезанный | Венок из песен | 1914 |

| Болт | Балака | Полет кранов | 1916 |

| Бенгальский титул | Транслитерированный заголовок | Перевод названия | Год |

|---|---|---|---|

| Балмики | Валмики-Пратибха | Гений Валмики | 1881 |

| Церковь | Кал-Мригайя | Фатальная охота | 1882 |

| Майер | Майар Хела | Пьеса иллюзий | 1888 |

| Погружение | Висарджан | Жертва | 1890 |

| Рисование | Чирангада | Чирангада | 1892 |

| Король | Король | Король темной камеры | 1910 |

| Почтовое отделение | ДАК ГАР | Почтовое отделение | 1912 |

| Неудержимый | Ахалаятан | Недовидимый | 1912 |

| Свободный поток | Понедельник | Водопад | 1922 |

| Кровь | Груз | Красные олеандерс | 1926 |

| Похожая | Проверить | Неприкасаемая девушка | 1933 |

| Бенгальский титул | Транслитерированный заголовок | Перевод названия | Год |

|---|---|---|---|

| Противный | Аскат | Сломанное гнездо | 1901 |

| Шепот | Вверх | Ярко-лицо | 1910 |

| Из комнаты | Гаре Байр | Дом и мир | 1916 |

| Коммуникация | Йогайог | Перекрестная тока | 1929 |

| Бенгальский титул | Транслитерированный заголовок | Перевод названия | Год |

|---|---|---|---|

| Память о жизни | Jivansmriti | Мои воспоминания | 1912 |

| Детство | Челебела | Мои детства дни | 1940 |

| Заголовок | Год |

|---|---|

| Мыслители реликвии | 1921 [ Оригинал 1 ] |

Переведенный

| Год | Работа |

|---|---|

| 1914 | Хитра [ текст 1 ] |

| 1922 | Творческое единство [ Текст 2 ] |

| 1913 | Полумесяц [ Текст 3 ] |

| 1917 | Цикл пружины [ Текст 4 ] |

| 1928 | Светлячки |

| 1916 | Фрукты [ Текст 5 ] |

| 1916 | Беглец [ Текст 6 ] |

| 1913 | Садовник [ Текст 7 ] |

| 1912 | Гитанджали: предложения песен [ Текст 8 ] |

| 1920 | Проблески Бенгалии [ Текст 9 ] |

| 1921 | Дом и мир [ Текст 10 ] |

| 1916 | Голодные камни [ Текст 11 ] |

| 1991 | Я не отпущу тебя: выбранные стихи |

| 1914 | Король темной камеры [ Текст 12 ] |

| 2012 | Письма от экспатрианта в Европе |

| 2003 | Любитель Бога |

| 1918 | Копье [ Текст 13 ] |

| 1928 | Мои детства дни |

| 1917 | Мои воспоминания [ Текст 14 ] |

| 1917 | Национализм |

| 1914 | Почтовое отделение [ Текст 15 ] |

| 1913 | Садхана: реализация жизни [ Текст 16 ] |

| 1997 | Избранные буквы |

| 1994 | Избранные стихи |

| 1991 | Выбранные рассказы |

| 1915 | Песни Кабира [ Текст 17 ] |

| 1916 | Дух Японии [ Текст 18 ] |

| 1918 | Истории от Тагора [ Текст 19 ] |

| 1916 | Бездомные птицы [ Текст 20 ] |

| 1913 | Призвание [ 190 ] |

| 1921 | Крушение |

В популярной культуре

- Рабиндранат Тагор - индийский документальный фильм 1961 года, написанный и режиссер Сатьяджит Рэй , выпущенный во время столетия рождения Тагора. Это было произведено правительства Индии Отделом фильмов .

- Сербский композитор Даринка Симик-Митрович использовала текст Тагора для своего песенного цикла Gradinar в 1962 году. [ 191 ]

- В 1969 году американский композитор Э. Энн Швердтфгер был поручен составить две части : работа для женского хора на основе текста Тагора. [ 192 ]

- Суканта Роя В бенгальском фильме Чхелебела (2002) Джисху Сенгупта изобразил Тагора. [ 193 ]

- В бенгальском фильме Банданы Мукхопадхьяй Хиросаха Хе (2007) Саяндип Бхаттачарья сыграл Тагора. [ 194 ]

- В бенгальском документальном фильме Rituparno 's Ghosh Дживан Смрити (2011) Самадарши Датта сыграл Тагора. [ 195 ]

- В Саман Гош» бенгальском фильме « Кадамбари (2015) Парамабрата Чаттерджи изобразил Тагора. [ 196 ]

Смотрите также

- Работы Рабиндраната Тагора

- Список работ Рабиндраната Тагора

- Адаптация произведений Рабиндраната Тагора в кино и телевидении

- Список индийских писателей

- Кази Назрул Ислам

- Рабиндра Джаянти

- Рабиндра Пураскар

- Семья Тагор

- Художник в жизни - биография Нихарранджана Рэя

- Таптапади

- Временная шкала Рабиндраната Тагора

- Музыка Бенгалии

Ссылки

Примечания

- ^ Гурудев переводится как «божественный наставник», Бишокоби переводит как «поэт мира», а Кобигуру переводится как «великий поэт». [ 11 ]

- ^ Тагор родился в № 6 Дварканатх Тагоре Лейн, Йорасанко - адрес главного особняка ( Йорасанко Тхакурбари ), населенный отделением Йорасанко клана Тагора, который ранее перенес удивительный раскол. Йорасанко был расположен в бенгальской секции Калькутты, недалеко от Читпур -роуд. [ 24 ] [ 25 ] Дварканат Тагор был его дедушкой по отцовской линии. [ 26 ] Дебендранат сформулировал брахмоистскую философию, поддерживаемую его другом Рамом Моханом Роем , и стал центром в обществе Брахмо после смерти Роя. [ 27 ] [ 28 ]

- ^ Об «идее человечества нашего Бога или Божественности человека вечного».

- ^ Этимология «Вишва-бхарати»: от санскрита для «мира» или «вселенной» и имени Ригвидской Богини («Бхарати»), связанного с Сарасвати , индуистским покровителем обучения. [ 159 ] «Вишва-Бхарати» также переводится как «Индия в мире».

- ^ Тагор был не привыкать к противоречиям: его отношения с индийскими националистами Subhas Chandra Bose [ 9 ] И Rash Behari Bose , [ 176 ] его иена для советского коммунизма, [ 177 ] [ 178 ] и документы, конфискованные от индийских националистов в Нью -Йорке, предположительно, в том числе Тагора в заговор, чтобы свергнуть Радж через немецкие фонды. [ 179 ] Это уничтожило изображение Тагора - и продажи книг - в Соединенных Штатах. [ 176 ] Его отношения с и амбивалентным мнением Муссолини восстали много; [ 94 ] Близкий друг Ромен Роллан отчаровал, что «[h] e отказывается от его роли морального руководства независимых духов Европы и Индии». [ 180 ]

Цитаты

- ^ «Как произнести Рабиндранат Тагор» . Forvo.com .

- ^ 25 Байсах 1268 ( Бангабда )

- ^ 21 Шраван 1368 ( Бангабда )

- ^ Любет, Алекс (17 октября 2016 г.). «Тагор, а не Дилан: первый лирик, выигравший Нобелевскую премию за литературу, был фактически индийским» . Кварц Индия . Получено 17 августа 2022 года .

- «Анита Десаи и Эндрю Робинсон - современный резонанс Рабиндраната Тагора» . На Бытие . Получено 30 июля 2019 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Стерн, Роберт В. (2001). Демократия и диктатура в Южной Азии: доминирующие классы и политические результаты в Индии, Пакистане и Бангладеш . Greenwood Publishing Group. п. 6. ISBN 978-0-275-97041-3 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Ньюман, Генри (1921). Обзор Калькутты . Университет Калькутты . п. 252.

Я также обнаружил, что Бомбей - это Индия, Сатара - это Индия, Бангалор - это Индия, Мадрас - это Индия, Дели, Лахор, Хайбер, Лакхнау, Калькутта, Каттак, Шиллонг и т. Д.

- ^ Нобелевский фонд .

- ^ О'Коннелл 2008 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый и Его 1997 .

- ^ «Работа Рабиндраната Тагора отмечалась в Лондоне» . BBC News . Получено 15 июля 2015 года .

- ^ Sil 2005 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный * Тагор, Ратиндранат (декабрь 1978 г.). На краях времени (новое изд.). Greenwood Press. п. 2. ISBN 978-0-313-20760-0 .

- Мукерджи, Мани Шанкар (май 2010 г.). «Вечный гений». Праваси Бхаратия : 89, 90.

- Томпсон, Эдвард (1948). Рабиндранат Тагор: поэт и драматург . Издательство Оксфордского университета . п. 13

- 4. ? 2

- ^ Томпсон 1926 , с. 27–28; Dasgupta 1993 , p. 20

- ^ «Национализм - это великая угроза» Тагор и национализм, Радхакришнан М. и Ройчоудхури Д. из Хогана, ПК; Пандит Л. (2003), Рабиндранат Тагор: Универсальность и традиция, стр. 29–40

- ^ «Вишва-Бхарти-Факты и фигуры с первого взгляда» . Архивировано из оригинала 23 мая 2007 года.

- ^ Датта 2002 , с. 2; Kripalani 2005a , pp. 6–8; Kripalani 2005b , pp. 2–3; Томпсон 1926 , с. 12

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный * де Сильва, Км ; Wriggins, Howard (1988). JR Jayewardene из Шри -Ланки: политическая биография - Том первый: первые пятьдесят лет . Университет Гавайи Пресс . п. 368. ISBN 0-8248-1183-6 .

- «Человек серии: Нобелевский лауреат Тагор» . The Times of India . Times News Network . 3 апреля 2011 года.

- «Как Тагор вдохновил национальный гимн Шри -Ланки» . IBN Live . 8 мая 2012 года. Архивировано из оригинала 10 мая 2012 года.

- ^ Насрин, Митхун Б.; Вурф, Ван Ван дер (2015). Разговорный бенгальский . Routledge . п. 1. ISBN 978-1-317-30613-9 .

- ^ Ахмад, Зарин (14 июня 2018 г.). Мясные пейзажи Дели: мусульманские мясники в трансформирующемся мегацине . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-909538-4 .

- ^ Фразы, Башаби (15 сентября 2019 г.). Рабиндранат Тагор . Реакционные книги. ISBN 978-1-78914-178-8 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Гош 2011 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный «Рабиндранат Тагор - факты» . Нобелевский фонд.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 34

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 37

- ^ Новости сегодня 2011 .

- ^ Рой 1977 , с. 28–30.

- ^ Тагор 1997b , с. 8–9.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Томпсон 1926 , с. 20

- ^ Я 2010 , с. 16

- ^ Tagore 1997b , p. 10

- ^ Sree, S. Prasanna (2003). Женщина в романах Шаши Дешпанде: исследование (1 -е изд.). Нью -Дели: Sarup & Sons. п. 13. ISBN 81-7625-381-2 Полем Получено 12 апреля 2016 года .

- ^ Пол, С.К. (1 января 2006 г.). Полные стихи из Гитанджали Рабиндрената Тагора: тексты и критическая оценка Сарп и сыновья. П. 2. ISBN 978-81-7625-660-5 Полем Получено 12 апреля 2016 года .

- ^ Томпсон 1926 , с. 21–24.

- ^ 2009 .

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 48–49.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 50.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 55–56.

- ^ Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003 , p. 91

- ^ «Путешествие с моим отцом» . Мои воспоминания .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый и Dev, Amiya (2014). «Тагор и сикхизм» . Мейнстрим еженедельно .

- ^ Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003 , p. 3

- ^ Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003 , p. 3

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Тагор и Чакраварти 1961 , с. 45

- ^ Tagore 1997b , p. 265

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 68

- ^ Томпсон 1926 , с. 31

- ^ Tagore 1997b , pp. 11–12.

- ^ Гуха, Рамачандра (2011). Создатели современной Индии . Кембридж, Массачусетс: Белкнап Пресс из Гарвардского университета. п. 171.

- ^ Датта, Кришна; Робинсон, Эндрю (1997). Избранные буквы Рабиндраната Тагора . Издательство Кембриджского университета . п. 13. ISBN 978-0-521-59018-1 Полем Получено 27 апреля 2016 года .

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 373.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Скотт 2009 , с. 10

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 109–111.

- ^ Chowadry, AA, AA (1992), Taloh Shah , Dang , Bangladshes: Happy Academy , ISBN 984-07-2597-1

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 109

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 133.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 139–140.

- ^ "Рабиндранат Тагор" . Поэтический фонд . 7 мая 2022 года . Получено 8 мая 2022 года .

- ^ Hjärne 1913 .

- ^ Анил Сети; Гуха; Хуллар; Наир; Прасад; Анвар; Сингх; Мохапатра, ред. (2014). «Роулатт Сатьяграха». Наше прошлое: том 3, часть 2 (учебник по истории) (пересмотренный 2014 Ed.). Индия: Ncert . п. 148. ISBN 978-81-7450-838-6 .

- ^ «Письмо из Рабиндраната Тагора лорду Челмсфорду, вице -король Индии» . Цифровые антропологические ресурсы для преподавания, Колумбийский университет и Лондонская школа экономики. Архивировано с оригинала 25 августа 2019 года . Получено 29 августа 2018 года .

- ^ «Тагор отказался от своего рыцарства в знак протеста за убийство в Jalianwalla Bagh Mass» . The Times of India . 13 апреля 2011 года.

- ^ Мортада, Сайед Ахмед. «Когда Тагор приехал в Силхет» .

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 239–240.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 242

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 308–309.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 303.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 309

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Dutta & Robinson 1995 , p. 317

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 312–313.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 335–338.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 342.

- ^ «100 лет назад Рабиндранат Тагор был удостоен Нобелевской премии за поэзию. Но его романы более устойчивы» . Индус . Получено 17 сентября 2019 года .

- ^ TAGORE & RADICE 2004 , с. 28

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 338.

- ^ Индо-азиатская служба новостей 2005 .

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 367

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 363.

- ^ The Daily Star 2009 .

- ^ Sigi 2006 , p. 89

- ^ Тагор 1930 , с. 222–225.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 374–376.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 178–179.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Университет Иллинойса в Урбана-Шампейн .

- ^ Тагор и Чакраварти 1961 , с. 1–2.

- ^ Натан, Ричард (12 марта 2021 года). «Изменяющиеся нации: японская девушка с книгой» . Красные авторы .

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 206

- ^ Hogan & Pandit 2003 , с. 56–58.

- ^ Тагор и Чакраварти 1961 , с. 182.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 253.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 256

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 267.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 270–271.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Кунду 2009 .

- ^ "Соединение Тагора" . Free Press Journal . Получено 5 мая 2022 года .

- ^ Тагор и Чакраварти 1961 , с. 1

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 289–292.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 303–304.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 292–293.

- ^ Тагор и Чакраварти 1961 , с. 2

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 315

- ^ Тагор и Чакраварти 1961 , с. 99

- ^ Tagore & Chakravarty 1961 , с. 100–103.

- ^ «Вице -президент выступает на Рабиндранате Тагоре» . Newkerala.com. 8 мая 2012 года. Архивировано с оригинала 4 июня 2012 года . Получено 7 августа 2016 года .

- ^ Пандей 2011 .

- ^ Essential Tagore , издательство Гарвардского университета , архивировано из оригинала 12 марта 2021 года , извлечен 19 декабря 2011 года

- ^ Tagore 1997b , pp. 21–22.

- ^ Tagore & Chakravarty 1961 , с. 123–124.

- ^ Тагор и Чакраварти 1961 , с. 124

- ^ Рэй 2007 , с. 147–148.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Тагор и Чакраварти 1961 , с. 45

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1997 , с. 265

- ^ Tagore & Chakravarty 1961 , с. 45–46

- ^ Тагор и Чакраварти 1961 , с. 46

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 192–194.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 154–155.

- ^ Hogan 2000 , с. 213–214.

- ^ Мукерджи 2004 .

- ^ «Все Нобелевские призы» . Нобелевский фонд . Получено 22 февраля 2020 года .

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 1

- ^ Рой 1977 , с. 201.

- ^ Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003 , p. 94

- ^ Urban 2001 , p. 18

- ^ Urban 2001 , с. 6–7.

- ^ Urban 2001 , p. 16

- ^ Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003 , p. 95

- ^ Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003 , p. 7

- ^ Сандзюкта Дасгупта; Чинмой Гуха (2013). Тагор-в доме в мире . SAGE Publications. п. 254. ISBN 978-81-321-1084-2 .

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 94

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Дасгупта 2001 .

- ^ «10 вещей, которые нужно знать о гимне Индии» . Архивировано из оригинала 21 июля 2021 года . Получено 21 июля 2021 года .

- ^ Чаттерджи, Мониш Р. (13 августа 2003 г.). «Тагор и Яна Гана Мана» . Contracurents.org.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 359.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Дайсон 2001 .

- ^ Tagore 1997b , p. 222

- ^ Р. Шива Кумар (2011) Последний урожай: картины Рабиндраната Тагора .

- ^ Я 2010 , стр. 144–145.

- ^ «Национальная галерея современного искусства - Мумбаи: виртуальные галереи» . Получено 23 октября 2017 года .

- ^ «Национальная галерея современного искусства: коллекции» . Получено 23 октября 2017 года .

- ^ «Рабиндранат Тагор: Когда Гитлер очистил картины лауреата Нобелевского нобелевского индийского нобелевского лауреата» . BBC News. 21 ноября 2022 года . Получено 21 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Tagore 1997b , p. 127

- ^ Tagore 1997b , p. 210.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 304

- ^ Браун 1948 , с. 306

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 261.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Сен, Амартия. «Тагор и его Индия» . Contracurents.org . Получено 1 января 2021 года .

- ^ Tagore 1997b , pp. 239–240.

- ^ Тагор и Чакраварти 1961 , с. 181.

- ^ Тагор 1916 , с. 111.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Dutta & Robinson 1995 , p. 204

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 215–216.

- ^ Chakraborty & Bhattacharya 2001 , p. 157

- ^ Мехта 1999 .

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 306–307.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 339.

- ^ «Тагор отказался от своего рыцарства в знак протеста за убийство в Jalianwalla Bagh Mass» . The Times of India . Мумбаи. 13 апреля 2011 года. Архивировано с оригинала 12 мая 2013 года . Получено 17 февраля 2012 года .

- ^ Tagore 1997b , p. 267.

- ^ Tagore & Pal 2004 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Dutta & Robinson 1995 , p. 220.

- ^ Рой 1977 , с. 175.

- ^ Тагор и Чакраварти 1961 , с. 27

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 221

- ^ «Нобелевская премия Тагора украдена» . The Times of India . 25 марта 2004 года. Архивировано с оригинала 19 августа 2013 года . Получено 10 июля 2013 года .

- ^ «Швеция, чтобы представить Индийские реплики Нобелевы Тагора» . The Times of India . 7 декабря 2004 года. Архивировано с оригинала 10 июля 2013 года . Получено 10 июля 2013 года .

- ^ «Кража Нобелевской медали Тагора: арестован Баул Певица» . The Times of India . Получено 31 марта 2019 года .

- ^ «Кража Нобелевской медали Тагора: народный певец арестован из Бенгалии» . News18 . Получено 31 марта 2019 года .

- ^ Чакрабарти 2001 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Хэтчер 2001 .

- ^ Kämpchen 2003 .

- ^ Фаррелл 2000 , с. 162.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 202

- ^ Hue-Tam Ho Tai, радикализм и происхождение вьетнамской революции , с. 76-82

- ^ Кэмерон 2006 .

- ^ Его 2006 г. , с.

- ^ Kinzer 2006 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Dutta & Robinson 1995 , p. 214

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 297

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 214–215.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 212.

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 273

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 255

- ^ Датта и Робинсон 1995 , с. 254–255.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Bhattacharya 2001 .

- ^ TAGORE & RADICE 2004 , с. 26

- ^ Tagor & Root 2004 , стр. 26-31.

- ^ Tagor & Root 2004 , стр. 18-19.

- ^ «Музей Рабиндра Бхарти (Jorasanko Thakurbari)» . Архивировано с оригинала 9 февраля 2012 года.

- ^ «Дом Тагора (Jorasanko Thakurbari) - Калькута» . Wikimapia.org .

- ^ Tagore & Ray 2007 , p. 104

- ^ Призвание , Ратна Сагар, 2007, с. 64, ISBN 978-81-8332-175-4

- ^ Коэн, Аарон И. (1987). Международная энциклопедия женщин -композиторов . Книги и музыка (США). ISBN 978-0-9617485-2-4 .

- ^ Генрих, Адель (1991). Органная и клавесина музыка женщин композиторов: аннотированный каталог . Нью -Йорк: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-38790-6 Полем OCLC 650307517 .

- ^ «Челебела поймает детство поэта» . Rediff.com . Получено 12 апреля 2020 года .

- ^ «Тагор или сенсорный-не» . The Times of India . 13 июля 2007 г. Получено 12 апреля 2020 года .

- ^ «Празднование Тагора» . Индус . 7 августа 2013 года . Получено 12 апреля 2020 года .

- ^ Банерджи, Катхакали (12 января 2017 г.). «Кадамбари исследует Тагора и его невестки ответственно» . The Times of India . Получено 12 апреля 2020 года .

Библиография

Начальный

Антологии

- Тагор, Рабиндранат (1952), собранные стихи и пьесы Рабиндраната Тагора , Macmillan Publishing (опубликовано в январе 1952 г.), ISBN 978-0-02-615920-3

- Тагор, Рабиндранат (1984), некоторые песни и стихи из Рабиндраната Тагора , публикации восток-запад, ISBN 978-0-85692-055-4

- Тагор, Рабиндранат (2011), Алам, Ф.; Чакраварти, Р. (ред.), Основной Тагор , издательство Гарвардского университета (опубликовано 15 апреля 2011 г.), с. 323, ISBN 978-0-674-05790-6

- Тагор, Рабиндранат (1961), Чакраварти, А. (ред.), Читатель Tagore , Beacon Press (опубликовано 1 июня 1961 года), ISBN 978-0-8070-5971-5

- Тагор, Рабиндранат (1997a), Датта, К.; Робинсон, А. (ред.), Избранные письма Рабиндраната Тагора , издательство Кембриджского университета (опубликовано 28 июня 1997 г.), ISBN 978-0-521-59018-1

- Тагор, Рабиндранат (1997b), Датта, К.; Робинсон, А. (ред.), Рабиндранат Тагор: Антология , Пресса Святого Мартина (опубликовано ноябрь 1997 г.), ISBN 978-0-312-16973-2

- Тагор, Рабиндранат (2007), Рэй, М.К. (ред.), Английские сочинения Рабиндраната Тагора , том. 1, Atlantic Publishing (опубликовано 10 июня 2007 г.), ISBN 978-81-269-0664-2

Оригиналы

- Тагор, Рабиндранат (1916), Садхана: реализация жизни , Макмиллан

- Тагор, Рабиндранат (1930), «Религия человека» , Макмиллан

Переводы

- Тагор, Рабиндранат (1914), почтовое отделение , перевод Mukerjea, D., London: Macmillan

- Tagore, Rabindrenath (2004), «Сказка попугая» , Парабас , перевод PAL, PB (опубликовано 1 декабря 2004 г.)

- Тагор, Рабиндранат (1995), Рабиндранат Тагор: Выбранные стихи , переведенные Радисом, В. (1 -е изд.), Лондон: Пингвин (опубликовано 1 июня 1995 г.), ISBN 978-0-14-018366-5

- Tagore, Rabindranath (2004), частицы, Jottings, Sparks: собранные краткие стихи , переведенные Radice, W , Angel Books (опубликовано 28 декабря 2004 г.), ISBN 978-0-946162-66-6

- Тагор, Рабиндранат (2003), Рабиндранат Тагор: любитель Бога , литературные выборы Ланнана, перевод Стюарта, Т.К.; Twichell, C., Copper Canyon Press (опубликовано 1 ноября 2003 г.), ISBN 978-1-55659-196-9

Второстепенный

Статьи

- Bhattacharya, S. (2001), «Перевод Tagore» , The Hindu , Chennai, Индия (опубликовано 2 сентября 2001 г.), архивировано из оригинала 1 ноября 2003 года , полученная 9 сентября 2011 г.

- Браун, GT (1948), «Индуистский заговор: 1914–1917», The Pacific Historical Review , 17 (3), Университет Калифорнийской Прессы (опубликовано в августе 1948 г.): 299–310, doi : 10.2307/3634258 , ISSN 0030- 8684 , JSTOR 3634258

- Cameron, R. (2006), «Выставка Бенгальских фильмов открывается в Праге» , Radio Prague (опубликовано 31 марта 2006 г.) , получено 29 сентября 2011 г.

- Чакрабарти И. (2001), «Народный поэт или литературное божество?» , Parabas (опубликовано 15 июля 2001 г.) , переиздание 17 сентября

- Das, S. (2009), «Эдемский сад Тагора» , The Telegraph , Калькутта, Индия (опубликовано 2 августа 2009 г.), архивировав с оригинала 3 марта 2010 года , полученная 29 сентября 2011 г.

- Dasgupta, A. (2001), «Рабиндра-сангги в качестве ресурса для индийских классических бандитов » , Parabas (опубликовано 15 июля 2001 года) , получено 17 сентября

- Dyson, KK (2001), «Рабиндранат Тагор и его мир цветов» , Parabaas (опубликовано 15 июля 2001 года) , извлечено 26 ноября 2009 г.

- Ghosh, B. (2011), «В мире музыки Тагора» , Parabaas (опубликовано в августе 2011 г.) , извлечено 17 сентября 2011 года.

- Харви, Дж. (1999), В поисках духа: мысли о музыке , издательство Калифорнийского университета, архивировано из оригинала 6 мая 2001 года , получено 10 сентября 2011 г.

- Хэтчер, Б.А. (2001), « Паре столети Тагор что Аджи Хоте : говорит нам Сатабарша

- Hjärne, H. (1913), Нобелевская премия по литературе в 1913 году: Рабиндранат Тагор - речь на церемонии навеса , Нобелевский фонд (опубликован 10 декабря 1913 г.) , получено 17 сентября 2011 г.

- Jha, N. (1994), «Рабиндранат Тагор» (PDF) , Перспективы: Ежеквартальный обзор образования , 24 (3/4), Париж: ЮНЕСКО: Международное бюро образования: 603–19, doi : 10.1007/bf02195291 , S2CID 144526531 , архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 10 ноября 2011 года , извлеченные 30 августа 2011 г.

- Kämpchen, M. (2003), «Рабиндранат Тагор в Германии» , Parabaas (опубликовано 25 июля 2003 г.) , извлечен 28 сентября 2011 г.

- Kinzer, S. (2006), «Бюлент Эквит, который повернул Турцию на запад, умирает» , «Нью -Йорк Таймс» (опубликовано 5 ноября 2006 г.) , получено 28 сентября 2011 года.

- Kundu, K. (2009), «Муссолини и Тагор» , Parabaas (опубликовано 7 мая 2009 г.) , получено 17 сентября 2011 года.

- Мехта, С. (1999), «Первый азиатский нобелевский лауреат» , «Время » (опубликовано 23 августа 1999 г.), архивировано с оригинала 10 февраля 2001 года , получено 30 августа 2011 г.

- Meyer, L. (2004), «Тагор в Нидерландах» , Parabaas (опубликовано 15 июля 2004 г.) , извлечен 30 августа 2011 г.

- Mukherjee, M. (2004), « йогайог (« Nexus ») Рабиндранат Тагор: обзор книги» , Parabaas (опубликовано 25 марта 2004 г.) , получено 29 сентября 2011 г.

- Pandey, JM (2011), «Оригинальные сценарии Рабиндраната Тагора в печати вскоре» , The Times of India (опубликовано 8 августа 2011 г.), архивировав с оригинала 24 сентября 2012 года , полученная 1 сентября 2011 г.

- О'Коннелл, К.М. (2008), « Красные олеандерс ( Рактакараби ) Рабиндранат Тагор - новый перевод и адаптация: два обзора» , Парабаас (опубликованная декабрь 2008 г.) , извлеченные 28 сентября 2011 г.

- Radice, W. (2003), «Поэтическое величие Тагора» , Parabaas (опубликовано 7 мая 2003 г.) , извлечено 30 августа 2011 г.

- Sen, A. (1997), «Тагор и его Индия» , «Нью -Йорк Обзор книг» , полученные 30 августа 2011 г.

- SIL, NP (2005), « Devotio Humana : Rabindranth's Sipems Repisited» , Parabas (опубликовано 15 февраля 2005 г.) , извлечено 13 августа

Книги

- Рэй, Нихарранджан (1967). Художник в жизни . Университет Кералы .

- Ayyub, AS (1980), квест Тагора , папирус

- Чакраборти, SK; Bhattacharya, P. (2001), Лидерство и власть: этические исследования , издательство Оксфордского университета (опубликовано 16 августа 2001 г.), ISBN 978-0-19-565591-9

- Dasgupta, T. (1993), Социальная мысль о Рабиндранате Тагоре: исторический анализ , публикации Abhinav (опубликовано 1 октября 1993 г.), ISBN 978-81-7017-302-1

- Датта, П.К. (2002), Рабиндранат Тагор «Дом и мир : критический компаньон» (1 -е изд.), Постоянный черный (опубликовано 1 декабря 2002 г.), ISBN 978-81-7824-046-6

- Датта, К.; Робинсон, А. (1995), Рабиндранат Тагор: бесчисленное множество человек , пресса Святого Мартина (опубликовано декабрь 1995 г.), ISBN 978-0-312-14030-4

- Фаррелл, Г. (2000), Индийская музыка и Запад , серия «Кларендонскую обложку» (3 Ed.), Oxford University Press (опубликовано 9 марта 2000 г.), ISBN 978-0-19-816717-4

- Hogan, PC (2000), Колониализм и культурная идентичность: кризисы традиции в англоязычной литературе Индии, Африки и Карибском бассейне , Государственный университет Нью -Йорк Пресс (опубликовано 27 января 2000 г.), ISBN 978-0-7914-4460-3

- Хоган, ПК; Пандит Л. (2003), Рабиндранат Тагор: Универсальность и традиция , издательство Университета Фэрли Дикинсон (опубликовано в мае 2003 г.), ISBN 978-0-8386-3980-1

- Крипалани, К. (2005), Дварканатх Тагор: забытый пионер - жизнь , Национальное книжное доверие Индии, ISBN 978-81-237-3488-0

- Крипалани, К. (2005), Тагор - жизнь , Национальное книжное доверие Индии, ISBN 978-81-237-1959-7

- Лаго, М. (1977), Рабиндранат Тагор , Бостон: издатели Твейн (опубликовано апрель 1977 г.), ISBN 978-0-8057-6242-6

- Lifton, BJ; Wiesel, E. (1997), король детей: жизнь и смерть Януша Корчака , Гриффин Святого Мартина (опубликовано 15 апреля 1997 г.), ISBN 978-0-312-15560-5

- Прасад, Ан; Саркар, Б. (2008), Критическая реакция на индийскую поэзию на английском языке , сарап и сыновьях, ISBN 978-81-7625-825-8

- Рэй, М.К. (2007), Исследования Рабиндраната Тагора , вып. 1, Атлантика (опубликовано 1 октября 2007 г.), ISBN 978-81-269-0308-5 , Получено 16 сентября 2011 г.

- Рой, Б.К. (1977), Рабиндранат Тагор: Человек и его поэзия , издание библиотеки Фолкрофта, ISBN 978-0-8414-7330-0

- Скотт, Дж. (2009), Бенгальский цветок: 50 отобранных стихов из Индии и Бангладеш (опубликовано 4 июля 2009 г.), ISBN 978-1-4486-3931-1

- Sen, A. (2006), Аргументативный индийский: писания по истории индийской истории, культуры и идентичности (1 -е изд.), Picador (опубликовано 5 сентября 2006 г.), ISBN 978-0-312-42602-6

- Сиги Р. (2006), Гурудев Рабиндранат Тагор - биография , бриллиантовые книги (опубликовано 1 октября 2006 г.), ISBN 978-81-89182-90-8

- Синха, С. (2015), Диалектика Бога: теософские взгляды Тагора и Ганди , Partridge Publishing India, ISBN 978-1-4828-4748-2

- SOM, R. (2010), Рабиндранат Тагор: Певец и его песня , Viking (опубликовано 26 мая 2010 г.), ISBN 978-0-670-08248-3 , OL 23720201M

- Томпсон, Э. (1926), Рабиндранат Тагор: поэт и драматурги , Pierides Press, ISBN 978-1-4067-8927-0

- Урбан, HB (2001), «Песни экстази: тантрические и религиозные песни из колониальной Бенгалии , издательство Оксфордского университета» (опубликовано 22 ноября 2001 г.), ISBN 978-0-19-513901-3

Другой

- «68 -я годовщина смерти Рабиндраната Тагора» , The Daily Star , Dhaka (опубликовано 7 августа 2009 г.), 2009 г. , извлеченная 29 сентября 2011 г.

- «Чтение поэзии смерти Тагора», Hindustan Times , 2005

- «Археологи отслеживают дом наследия Тагора в Хулне» , The News Today (опубликовано 28 апреля 2011 года), 2011 год, архивировав с оригинала 28 марта 2012 года , полученная 9 сентября 2011 г.

- Нобелевская премия по литературе в 1913 году , Нобелевский фонд , получил 14 августа 2009 г.

- История фестиваля Тагора , Университет Иллинойса в Урбана-Шампейн: Комитет по фестивалям Тагора, архивный из оригинала 13 июня 2015 года , извлечен 29 ноября 2009 г.

Тексты

Оригинал

- ^ Реликвии мыслей , интернет -священный текстовый архив

Переведенный

- ^ Читра в проекте Гутенберг

- ^ Творческий единство в проекте Гутенберг

- ^ Луна полумесяца в проекте Гутенберг

- ^ Цикл весны в проекте Гутенберг

- ^ Фрукты в Project Gutenberg

- ^ Бегство в проекте Гутенберг

- ^ Садовник в Project Gutenberg

- ^ Гитанджали в Project Gutenberg

- ^ Проблески Бенгалии в проекте Гутенберг

- ^ Дом и мир в проекте Гутенберг

- ^ Голодные камни в Project Gutenberg

- ^ Король Темной Палаты в проекте Гутенберг

- ^ Маши в проекте Гутенберг

- ^ Мои воспоминания в проекте Гутенберг

- ^ Почтовое отделение в проекте Гутенберг

- ^ Садхана: реализация жизни в Project Gutenberg

- ^ Песни Кабира в Project Gutenberg

- ^ Дух Японии в проекте Гутенберг

- ^ Истории от Тагора в Project Gutenberg

- ^ Берегнутые птицы в проекте Гутенберг

Дальнейшее чтение

- Абу Закария, Г., изд. Рабиндранат Тагор - путешественники между мирами . Klemm и Oelschläger. ISBN 978-3-86281-018-5 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 28 марта 2012 года . Получено 15 мая 2011 года .

- Бхаттачарья, Сабьясачи (2011). Рабиндранат Тагор: интерпретация . Нью -Дели: Викинг, Пингвин Книги Индия. ISBN 978-0-670-08455-5 .

- Chaudhuri, A., ed. (2004). Винтажная книга современной индийской литературы (1 -е изд.). Vintage (опубликовано 9 ноября 2004 г.). ISBN 978-0-375-71300-2 .

- Deutsch, A .; Робинсон, А. , ред. (1989). Искусство Рабиндраната Тагора (1 -е изд.). Ежемесячная обзорная пресса (опубликовано в августе 1989 г.). ISBN 978-0-233-98359-2 .

- Шамсуд Дула, ABM (2016). Рабиндранат Тагор, Нобелевская премия за литературу в 1913 году и Британский Радж: некоторые невыразимые истории . Partridge Publishing Сингапур. ISBN 978-1-4828-6403-8 .

- Синха, Сатья (2015). Диалектика Бога: теософские взгляды Тагора и Ганди . Partridge Publishing India. ISBN 978-1-4828-4748-2 .

Внешние ссылки

- Рабиндранат Тагор в Encyclopædia Britannica

- Рабиндранат Тагор в IMDB

- Школа мудрости

- Газетные вырезки о Рабиндранате Тагоре в пресс -архивах 20 -го ZBW века

Анализы

- Эзра Паунд: «Рабиндранат Тагор» , «Две», обзор , март 1913 г.

- Коллекция Мэри Лаго , Университет Миссури

Аудиокниги

- Работы Рабиндраната Тагора в Librivox (общественные аудиокниги)

Тексты

- Работы Рабиндраната Тагора в форме электронных книг в Standard Ebooks

- Bichitra: онлайн Тагор различные

- Работы Рабиндраната Тагора в Project Gutenberg

- Работает у Рабиндраната Тагора в интернет -архиве

Разговоры

- Писатели из Калькутты

- Рабиндранат Тагор

- 1861 Рождение

- 1941 Смерть

- Президентский университет, выпускники Калькутты

- Выпускники университетского колледжа Лондон

- Бенгальские индусы

- Бенгальские философы

- Бенгальские Заминдары

- Брахмос

- Основатели индийских школ и колледжей

- Индийские нобелевские лауреаты

- Национальные писатели гимна

- Нобелевские лауреаты в литературе