Человеческий мозг

| Человеческий мозг | |

|---|---|

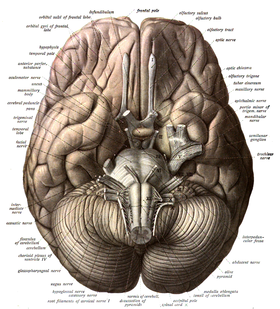

Человеческий мозг, полученный после вскрытия | |

Human brain and skull | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Neural tube |

| System | Central nervous system |

| Artery | Internal carotid arteries, vertebral arteries |

| Vein | Internal jugular vein, internal cerebral veins; external veins: (superior, middle, and inferior cerebral veins), basal vein, and cerebellar veins |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cerebrum |

| Greek | ἐγκέφαλος (enképhalos)[1] |

| TA98 | A14.1.03.001 |

| TA2 | 5415 |

| FMA | 50801 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

является Головной мозг центральным органом человека нервной системы и вместе со спинным мозгом составляет центральную нервную систему . Головной мозг состоит из головного мозга , ствола мозга и мозжечка . Он контролирует большую часть деятельности тела , обрабатывая, интегрируя и координируя информацию, которую он получает от органов чувств , и принимая решения относительно инструкций, посылаемых остальной части тела. Мозг находится внутри костей черепа и защищен ими .

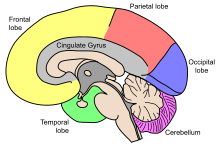

The cerebrum, the largest part of the human brain, consists of two cerebral hemispheres. Each hemisphere has an inner core composed of white matter, and an outer surface – the cerebral cortex – composed of grey matter. The cortex has an outer layer, the neocortex, and an inner allocortex. The neocortex is made up of six neuronal layers, while the allocortex has three or four. Each hemisphere is divided into four lobes – the frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes. The frontal lobe is associated with executive functions including self-control, planning, reasoning, and abstract thought, while the occipital lobe is dedicated to vision. Within each lobe, cortical areas are associated with specific functions, such as the sensory, motor, and association regions. Although the left and right hemispheres are broadly similar in shape and function, some functions are associated with one side, such as language in the left and visual-spatial ability in the right. The hemispheres are connected by комиссуральные нервные пути , самый крупный из которых — мозолистое тело .

The cerebrum is connected by the brainstem to the spinal cord. The brainstem consists of the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla oblongata. The cerebellum is connected to the brainstem by three pairs of nerve tracts called cerebellar peduncles. Within the cerebrum is the ventricular system, consisting of four interconnected ventricles in which cerebrospinal fluid is produced and circulated. Underneath the cerebral cortex are several important structures, including the thalamus, the epithalamus, the pineal gland, the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the subthalamus; the limbic structures, including the amygdalae and the hippocampi, the claustrum, the various nuclei of the basal ganglia, the basal forebrain structures, and the three circumventricular organs. Brain structures that are not on the midplane exist in pairs, for example, there are two hippocampi and two amygdalae. The cells of the brain include neurons and supportive glial cells. There are more than 86 billion neurons in the brain, and a more or less equal number of other cells. Brain activity is made possible by the interconnections of neurons and their release of neurotransmitters in response to nerve impulses. Neurons connect to form neural pathways, neural circuits, and elaborate network systems. The whole circuitry is driven by the process of neurotransmission.

The brain is protected by the skull, suspended in cerebrospinal fluid, and isolated from the bloodstream by the blood–brain barrier. However, the brain is still susceptible to damage, disease, and infection. Damage can be caused by trauma, or a loss of blood supply known as a stroke. The brain is susceptible to degenerative disorders, such as Parkinson's disease, dementias including Alzheimer's disease, and multiple sclerosis. Psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia and clinical depression, are thought to be associated with brain dysfunctions. The brain can also be the site of tumours, both benign and malignant; these mostly originate from other sites in the body.

The study of the anatomy of the brain is neuroanatomy, while the study of its function is neuroscience. Numerous techniques are used to study the brain. Specimens from other animals, which may be examined microscopically, have traditionally provided much information. Medical imaging technologies such as functional neuroimaging, and electroencephalography (EEG) recordings are important in studying the brain. The medical history of people with brain injury has provided insight into the function of each part of the brain. Neuroscience research has expanded considerably, and research is ongoing.

In culture, the philosophy of mind has for centuries attempted to address the question of the nature of consciousness and the mind–body problem. The pseudoscience of phrenology attempted to localise personality attributes to regions of the cortex in the 19th century. In science fiction, brain transplants are imagined in tales such as the 1942 Donovan's Brain.

Structure

[edit]

Gross anatomy

[edit]The adult human brain weighs on average about 1.2–1.4 kg (2.6–3.1 lb) which is about 2% of the total body weight,[2][3] with a volume of around 1260 cm3 in men and 1130 cm3 in women.[4] There is substantial individual variation,[4] with the standard reference range for men being 1,180–1,620 g (2.60–3.57 lb)[5] and for women 1,030–1,400 g (2.27–3.09 lb).[6]

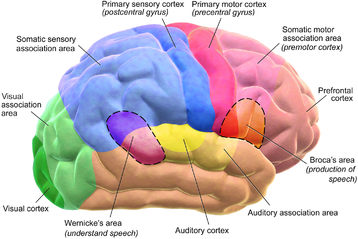

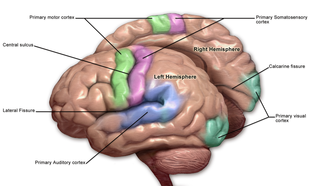

The cerebrum, consisting of the cerebral hemispheres, forms the largest part of the brain and overlies the other brain structures.[7] The outer region of the hemispheres, the cerebral cortex, is grey matter, consisting of cortical layers of neurons. Each hemisphere is divided into four main lobes – the frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe, and occipital lobe.[8] Three other lobes are included by some sources which are a central lobe, a limbic lobe, and an insular lobe.[9] The central lobe comprises the precentral gyrus and the postcentral gyrus and is included since it forms a distinct functional role.[9][10]

The brainstem, resembling a stalk, attaches to and leaves the cerebrum at the start of the midbrain area. The brainstem includes the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla oblongata. Behind the brainstem is the cerebellum (Latin: little brain).[7]

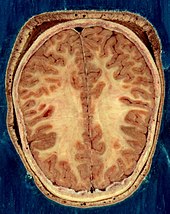

The cerebrum, brainstem, cerebellum, and spinal cord are covered by four[11] membranes called meninges. The membranes are the tough dura mater; the middle arachnoid mater and the more delicate inner pia mater. Between the arachnoid mater and the pia mater is the subarachnoid space and subarachnoid cisterns, which contain the cerebrospinal fluid.[12] The outermost membrane of the cerebral cortex is the basement membrane of the pia mater called the glia limitans and is an important part of the blood–brain barrier.[13]The living brain is very soft, having a gel-like consistency similar to soft tofu.[14] The cortical layers of neurons constitute much of the cerebral grey matter, while the deeper subcortical regions of myelinated axons, make up the white matter.[7] The white matter of the brain makes up about half of the total brain volume.[15]

Cerebrum

[edit]

The cerebrum is the largest part of the brain and is divided into nearly symmetrical left and right hemispheres by a deep groove, the longitudinal fissure.[16] Asymmetry between the lobes is noted as a petalia.[17] The hemispheres are connected by five commissures that span the longitudinal fissure, the largest of these is the corpus callosum.[7]Each hemisphere is conventionally divided into four main lobes; the frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe, and occipital lobe, named according to the skull bones that overlie them.[8] Each lobe is associated with one or two specialised functions though there is some functional overlap between them.[18] The surface of the brain is folded into ridges (gyri) and grooves (sulci), many of which are named, usually according to their position, such as the frontal gyrus of the frontal lobe or the central sulcus separating the central regions of the hemispheres. There are many small variations in the secondary and tertiary folds.[19]

The outer part of the cerebrum is the cerebral cortex, made up of grey matter arranged in layers. It is 2 to 4 millimetres (0.079 to 0.157 in) thick, and deeply folded to give a convoluted appearance.[20] Beneath the cortex is the cerebral white matter. The largest part of the cerebral cortex is the neocortex, which has six neuronal layers. The rest of the cortex is of allocortex, which has three or four layers.[7]

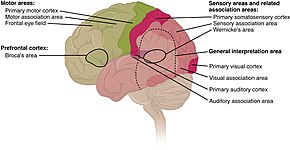

The cortex is mapped by divisions into about fifty different functional areas known as Brodmann's areas. These areas are distinctly different when seen under a microscope.[21] The cortex is divided into two main functional areas – a motor cortex and a sensory cortex.[22] The primary motor cortex, which sends axons down to motor neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord, occupies the rear portion of the frontal lobe, directly in front of the somatosensory area. The primary sensory areas receive signals from the sensory nerves and tracts by way of relay nuclei in the thalamus. Primary sensory areas include the visual cortex of the occipital lobe, the auditory cortex in parts of the temporal lobe and insular cortex, and the somatosensory cortex in the parietal lobe. The remaining parts of the cortex are called the association areas. These areas receive input from the sensory areas and lower parts of the brain and are involved in the complex cognitive processes of perception, thought, and decision-making.[23] The main functions of the frontal lobe are to control attention, abstract thinking, behaviour, problem-solving tasks, and physical reactions and personality.[24][25] The occipital lobe is the smallest lobe; its main functions are visual reception, visual-spatial processing, movement, and colour recognition.[24][25] There is a smaller occipital lobule in the lobe known as the cuneus. The temporal lobe controls auditory and visual memories, language, and some hearing and speech.[24]

The cerebrum contains the ventricles where the cerebrospinal fluid is produced and circulated. Below the corpus callosum is the septum pellucidum, a membrane that separates the lateral ventricles. Beneath the lateral ventricles is the thalamus and to the front and below is the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus leads on to the pituitary gland. At the back of the thalamus is the brainstem.[26]

The basal ganglia, also called basal nuclei, are a set of structures deep within the hemispheres involved in behaviour and movement regulation.[27] The largest component is the striatum, others are the globus pallidus, the substantia nigra and the subthalamic nucleus.[27] The striatum is divided into a ventral striatum, and dorsal striatum, subdivisions that are based upon function and connections. The ventral striatum consists of the nucleus accumbens and the olfactory tubercle whereas the dorsal striatum consists of the caudate nucleus and the putamen. The putamen and the globus pallidus lie separated from the lateral ventricles and thalamus by the internal capsule, whereas the caudate nucleus stretches around and abuts the lateral ventricles on their outer sides.[28] At the deepest part of the lateral sulcus between the insular cortex and the striatum is a thin neuronal sheet called the claustrum.[29]

Below and in front of the striatum are a number of basal forebrain structures. These include the nucleus basalis, diagonal band of Broca, substantia innominata, and the medial septal nucleus. These structures are important in producing the neurotransmitter, acetylcholine, which is then distributed widely throughout the brain. The basal forebrain, in particular the nucleus basalis, is considered to be the major cholinergic output of the central nervous system to the striatum and neocortex.[30]

Cerebellum

[edit]

The cerebellum is divided into an anterior lobe, a posterior lobe, and the flocculonodular lobe.[31] The anterior and posterior lobes are connected in the middle by the vermis.[32] Compared to the cerebral cortex, the cerebellum has a much thinner outer cortex that is narrowly furrowed into numerous curved transverse fissures.[32]Viewed from underneath between the two lobes is the third lobe the flocculonodular lobe.[33] The cerebellum rests at the back of the cranial cavity, lying beneath the occipital lobes, and is separated from these by the cerebellar tentorium, a sheet of fibre.[34]

It is connected to the brainstem by three pairs of nerve tracts called cerebellar peduncles. The superior pair connects to the midbrain; the middle pair connects to the medulla, and the inferior pair connects to the pons.[32] The cerebellum consists of an inner medulla of white matter and an outer cortex of richly folded grey matter.[34] The cerebellum's anterior and posterior lobes appear to play a role in the coordination and smoothing of complex motor movements, and the flocculonodular lobe in the maintenance of balance[35] although debate exists as to its cognitive, behavioural and motor functions.[36]

Brainstem

[edit]The brainstem lies beneath the cerebrum and consists of the midbrain, pons and medulla. It lies in the back part of the skull, resting on the part of the base known as the clivus, and ends at the foramen magnum, a large opening in the occipital bone. The brainstem continues below this as the spinal cord,[37] protected by the vertebral column.

Ten of the twelve pairs of cranial nerves[a] emerge directly from the brainstem.[37] The brainstem also contains many cranial nerve nuclei and nuclei of peripheral nerves, as well as nuclei involved in the regulation of many essential processes including breathing, control of eye movements and balance.[38][37] The reticular formation, a network of nuclei of ill-defined formation, is present within and along the length of the brainstem.[37] Many nerve tracts, which transmit information to and from the cerebral cortex to the rest of the body, pass through the brainstem.[37]

Microanatomy

[edit]The human brain is primarily composed of neurons, glial cells, neural stem cells, and blood vessels. Types of neuron include interneurons, pyramidal cells including Betz cells, motor neurons (upper and lower motor neurons), and cerebellar Purkinje cells. Betz cells are the largest cells (by size of cell body) in the nervous system.[39] The adult human brain is estimated to contain 86±8 billion neurons, with a roughly equal number (85±10 billion) of non-neuronal cells.[40] Out of these neurons, 16 billion (19%) are located in the cerebral cortex, and 69 billion (80%) are in the cerebellum.[3][40]

Types of glial cell are astrocytes (including Bergmann glia), oligodendrocytes, ependymal cells (including tanycytes), radial glial cells, microglia, and a subtype of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Astrocytes are the largest of the glial cells. They are stellate cells with many processes radiating from their cell bodies. Some of these processes end as perivascular endfeet on capillary walls.[41] The glia limitans of the cortex is made up of astrocyte foot processes that serve in part to contain the cells of the brain.[13]

Mast cells are white blood cells that interact in the neuroimmune system in the brain.[42] Mast cells in the central nervous system are present in a number of structures including the meninges;[42] they mediate neuroimmune responses in inflammatory conditions and help to maintain the blood–brain barrier, particularly in brain regions where the barrier is absent.[42][43] Mast cells serve the same general functions in the body and central nervous system, such as effecting or regulating allergic responses, innate and adaptive immunity, autoimmunity, and inflammation.[42] Mast cells serve as the main effector cell through which pathogens can affect the biochemical signaling that takes place between the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system.[44][45]

Some 400 genes are shown to be brain-specific. In all neurons, ELAVL3 is expressed, and in pyramidal cells, NRGN and REEP2 are also expressed. GAD1 – essential for the biosynthesis of the neurotransmitter GABA – is expressed in interneurons. Proteins expressed in glial cells include astrocyte markers GFAP and S100B whereas myelin basic protein and the transcription factor OLIG2 are expressed in oligodendrocytes.[46]

Cerebrospinal fluid

[edit]

Cerebrospinal fluid is a clear, colourless transcellular fluid that circulates around the brain in the subarachnoid space, in the ventricular system, and in the central canal of the spinal cord. It also fills some gaps in the subarachnoid space, known as subarachnoid cisterns.[47] The four ventricles, two lateral, a third, and a fourth ventricle, all contain a choroid plexus that produces cerebrospinal fluid.[48] The third ventricle lies in the midline and is connected to the lateral ventricles.[47] A single duct, the cerebral aqueduct between the pons and the cerebellum, connects the third ventricle to the fourth ventricle.[49] Three separate openings, the middle and two lateral apertures, drain the cerebrospinal fluid from the fourth ventricle to the cisterna magna, one of the major cisterns. From here, cerebrospinal fluid circulates around the brain and spinal cord in the subarachnoid space, between the arachnoid mater and pia mater.[47]At any one time, there is about 150mL of cerebrospinal fluid – most within the subarachnoid space. It is constantly being regenerated and absorbed, and is replaced about once every 5–6 hours.[47]

A glymphatic system has been described[50][51][52] as the lymphatic drainage system of the brain. The brain-wide glymphatic pathway includes drainage routes from the cerebrospinal fluid, and from the meningeal lymphatic vessels that are associated with the dural sinuses, and run alongside the cerebral blood vessels.[53][54] The pathway drains interstitial fluid from the tissue of the brain.[54]

Blood supply

[edit]

The internal carotid arteries supply oxygenated blood to the front of the brain and the vertebral arteries supply blood to the back of the brain.[55] These two circulations join in the circle of Willis, a ring of connected arteries that lies in the interpeduncular cistern between the midbrain and pons.[56]

The internal carotid arteries are branches of the common carotid arteries. They enter the cranium through the carotid canal, travel through the cavernous sinus and enter the subarachnoid space.[57] They then enter the circle of Willis, with two branches, the anterior cerebral arteries emerging. These branches travel forward and then upward along the longitudinal fissure, and supply the front and midline parts of the brain.[58] One or more small anterior communicating arteries join the two anterior cerebral arteries shortly after they emerge as branches.[58] The internal carotid arteries continue forward as the middle cerebral arteries. They travel sideways along the sphenoid bone of the eye socket, then upwards through the insula cortex, where final branches arise. The middle cerebral arteries send branches along their length.[57]

The vertebral arteries emerge as branches of the left and right subclavian arteries. They travel upward through transverse foramina which are spaces in the cervical vertebrae. Each side enters the cranial cavity through the foramen magnum along the corresponding side of the medulla.[57] They give off one of the three cerebellar branches. The vertebral arteries join in front of the middle part of the medulla to form the larger basilar artery, which sends multiple branches to supply the medulla and pons, and the two other anterior and superior cerebellar branches.[59] Finally, the basilar artery divides into two posterior cerebral arteries. These travel outwards, around the superior cerebellar peduncles, and along the top of the cerebellar tentorium, where it sends branches to supply the temporal and occipital lobes.[59] Each posterior cerebral artery sends a small posterior communicating artery to join with the internal carotid arteries.

Blood drainage

[edit]Cerebral veins drain deoxygenated blood from the brain. The brain has two main networks of veins: an exterior or superficial network, on the surface of the cerebrum that has three branches, and an interior network. These two networks communicate via anastomosing (joining) veins.[60] The veins of the brain drain into larger cavities of the dural venous sinuses usually situated between the dura mater and the covering of the skull.[61] Blood from the cerebellum and midbrain drains into the great cerebral vein. Blood from the medulla and pons of the brainstem have a variable pattern of drainage, either into the spinal veins or into adjacent cerebral veins.[60]

The blood in the deep part of the brain drains, through a venous plexus into the cavernous sinus at the front, and the superior and inferior petrosal sinuses at the sides, and the inferior sagittal sinus at the back.[61] Blood drains from the outer brain into the large superior sagittal sinus, which rests in the midline on top of the brain. Blood from here joins with blood from the straight sinus at the confluence of sinuses.[61]

Blood from here drains into the left and right transverse sinuses.[61] These then drain into the sigmoid sinuses, which receive blood from the cavernous sinus and superior and inferior petrosal sinuses. The sigmoid drains into the large internal jugular veins.[61][60]

The blood–brain barrier

[edit]The larger arteries throughout the brain supply blood to smaller capillaries. These smallest of blood vessels in the brain, are lined with cells joined by tight junctions and so fluids do not seep in or leak out to the same degree as they do in other capillaries; this creates the blood–brain barrier.[43] Pericytes play a major role in the formation of the tight junctions.[62] The barrier is less permeable to larger molecules, but is still permeable to water, carbon dioxide, oxygen, and most fat-soluble substances (including anaesthetics and alcohol).[43] The blood-brain barrier is not present in the circumventricular organs—which are structures in the brain that may need to respond to changes in body fluids—such as the pineal gland, area postrema, and some areas of the hypothalamus.[43] There is a similar blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier, which serves the same purpose as the blood–brain barrier, but facilitates the transport of different substances into the brain due to the distinct structural characteristics between the two barrier systems.[43][63]

Development

[edit]

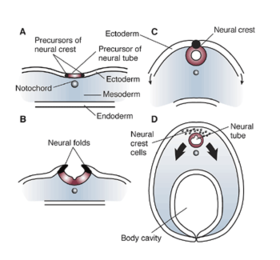

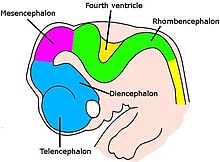

At the beginning of the third week of development, the embryonic ectoderm forms a thickened strip called the neural plate.[64] By the fourth week of development the neural plate has widened to give a broad cephalic end, a less broad middle part and a narrow caudal end. These swellings are known as the primary brain vesicles and represent the beginnings of the forebrain (prosencephalon), midbrain (mesencephalon), and hindbrain (rhombencephalon).[65][66]

Neural crest cells (derived from the ectoderm) populate the lateral edges of the plate at the neural folds. In the fourth week—during the neurulation stage—the neural folds close to form the neural tube, bringing together the neural crest cells at the neural crest.[67] The neural crest runs the length of the tube with cranial neural crest cells at the cephalic end and caudal neural crest cells at the tail. Cells detach from the crest and migrate in a craniocaudal (head to tail) wave inside the tube.[67] Cells at the cephalic end give rise to the brain, and cells at the caudal end give rise to the spinal cord.[68]

The tube flexes as it grows, forming the crescent-shaped cerebral hemispheres at the head. The cerebral hemispheres first appear on day 32.[69]Early in the fourth week, the cephalic part bends sharply forward in a cephalic flexure.[67] This flexed part becomes the forebrain (prosencephalon); the adjoining curving part becomes the midbrain (mesencephalon) and the part caudal to the flexure becomes the hindbrain (rhombencephalon). These areas are formed as swellings known as the three primary brain vesicles. In the fifth week of development five secondary brain vesicles have formed.[70] The forebrain separates into two vesicles – an anterior telencephalon and a posterior diencephalon. The telencephalon gives rise to the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, and related structures. The diencephalon gives rise to the thalamus and hypothalamus. The hindbrain also splits into two areas – the metencephalon and the myelencephalon. The metencephalon gives rise to the cerebellum and pons. The myelencephalon gives rise to the medulla oblongata.[71] Also during the fifth week, the brain divides into repeating segments called neuromeres.[65][72] In the hindbrain these are known as rhombomeres.[73]

A characteristic of the brain is the cortical folding known as gyrification. For just over five months of prenatal development the cortex is smooth. By the gestational age of 24 weeks, the wrinkled morphology showing the fissures that begin to mark out the lobes of the brain is evident.[74] Why the cortex wrinkles and folds is not well-understood, but gyrification has been linked to intelligence and neurological disorders, and a number of gyrification theories have been proposed.[74] These theories include those based on mechanical buckling,[75][18] axonal tension,[76] and differential tangential expansion.[75] What is clear is that gyrification is not a random process, but rather a complex developmentally predetermined process which generates patterns of folds that are consistent between individuals and most species.[75][77]

The first groove to appear in the fourth month is the lateral cerebral fossa.[69] The expanding caudal end of the hemisphere has to curve over in a forward direction to fit into the restricted space. This covers the fossa and turns it into a much deeper ridge known as the lateral sulcus and this marks out the temporal lobe.[69] By the sixth month other sulci have formed that demarcate the frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes.[69] A gene present in the human genome (ARHGAP11B) may play a major role in gyrification and encephalisation.[78]

Function

[edit]

Motor control

[edit]The frontal lobe is involved in reasoning, motor control, emotion, and language. It contains the motor cortex, which is involved in planning and coordinating movement; the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for higher-level cognitive functioning; and Broca’s area, which is essential for language production.[79] The motor system of the brain is responsible for the generation and control of movement.[80] Generated movements pass from the brain through nerves to motor neurons in the body, which control the action of muscles. The corticospinal tract carries movements from the brain, through the spinal cord, to the torso and limbs.[81] The cranial nerves carry movements related to the eyes, mouth and face.

Gross movement – such as locomotion and the movement of arms and legs – is generated in the motor cortex, divided into three parts: the primary motor cortex, found in the precentral gyrus and has sections dedicated to the movement of different body parts. These movements are supported and regulated by two other areas, lying anterior to the primary motor cortex: the premotor area and the supplementary motor area.[82] The hands and mouth have a much larger area dedicated to them than other body parts, allowing finer movement; this has been visualised in a motor homunculus.[82] Impulses generated from the motor cortex travel along the corticospinal tract along the front of the medulla and cross over (decussate) at the medullary pyramids. These then travel down the spinal cord, with most connecting to interneurons, in turn connecting to lower motor neurons within the grey matter that then transmit the impulse to move to muscles themselves.[81] The cerebellum and basal ganglia, play a role in fine, complex and coordinated muscle movements.[83] Connections between the cortex and the basal ganglia control muscle tone, posture and movement initiation, and are referred to as the extrapyramidal system.[84]

Sensory

[edit]

The sensory nervous system is involved with the reception and processing of sensory information. This information is received through the cranial nerves, through tracts in the spinal cord, and directly at centres of the brain exposed to the blood.[85] The brain also receives and interprets information from the special senses of vision, smell, hearing, and taste. Mixed motor and sensory signals are also integrated.[85]

From the skin, the brain receives information about fine touch, pressure, pain, vibration and temperature. From the joints, the brain receives information about joint position.[86] The sensory cortex is found just near the motor cortex, and, like the motor cortex, has areas related to sensation from different body parts. Sensation collected by a sensory receptor on the skin is changed to a nerve signal, that is passed up a series of neurons through tracts in the spinal cord. The dorsal column–medial lemniscus pathway contains information about fine touch, vibration and position of joints. The pathway fibres travel up the back part of the spinal cord to the back part of the medulla, where they connect with second-order neurons that immediately send fibres across the midline. These fibres then travel upwards into the ventrobasal complex in the thalamus where they connect with third-order neurons which send fibres up to the sensory cortex.[86] The spinothalamic tract carries information about pain, temperature, and gross touch. The pathway fibres travel up the spinal cord and connect with second-order neurons in the reticular formation of the brainstem for pain and temperature, and also terminate at the ventrobasal complex of the thalamus for gross touch.[87]

Vision is generated by light that hits the retina of the eye. Photoreceptors in the retina transduce the sensory stimulus of light into an electrical nerve signal that is sent to the visual cortex in the occipital lobe. Visual signals leave the retinas through the optic nerves.Optic nerve fibres from the retinas' nasal halves cross to the opposite sides joining the fibres from the temporal halves of the opposite retinas to form the optic tracts.The arrangements of the eyes' optics and the visual pathways mean vision from the left visual field is received by the right half of each retina, is processed by the right visual cortex, and vice versa. The optic tract fibres reach the brain at the lateral geniculate nucleus, and travel through the optic radiation to reach the visual cortex.[88]

Hearing and balance are both generated in the inner ear. Sound results in vibrations of the ossicles which continue finally to the hearing organ, and change in balance results in movement of liquids within the inner ear. This creates a nerve signal that passes through the vestibulocochlear nerve. From here, it passes through to the cochlear nuclei, the superior olivary nucleus, the medial geniculate nucleus, and finally the auditory radiation to the auditory cortex.[89]

The sense of smell is generated by receptor cells in the epithelium of the olfactory mucosa in the nasal cavity. This information passes via the olfactory nerve which goes into the skull through a relatively permeable part. This nerve transmits to the neural circuitry of the olfactory bulb from where information is passed to the olfactory cortex.[90][91]Taste is generated from receptors on the tongue and passed along the facial and glossopharyngeal nerves into the solitary nucleus in the brainstem. Some taste information is also passed from the pharynx into this area via the vagus nerve. Information is then passed from here through the thalamus into the gustatory cortex.[92]

Regulation

[edit]Autonomic functions of the brain include the regulation, or rhythmic control of the heart rate and rate of breathing, and maintaining homeostasis.

Blood pressure and heart rate are influenced by the vasomotor centre of the medulla, which causes arteries and veins to be somewhat constricted at rest. It does this by influencing the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems via the vagus nerve.[93] Information about blood pressure is generated by baroreceptors in aortic bodies in the aortic arch, and passed to the brain along the afferent fibres of the vagus nerve. Information about the pressure changes in the carotid sinus comes from carotid bodies located near the carotid artery and this is passed via a nerve joining with the glossopharyngeal nerve. This information travels up to the solitary nucleus in the medulla. Signals from here influence the vasomotor centre to adjust vein and artery constriction accordingly.[94]

The brain controls the rate of breathing, mainly by respiratory centres in the medulla and pons.[95] The respiratory centres control respiration, by generating motor signals that are passed down the spinal cord, along the phrenic nerve to the diaphragm and other muscles of respiration. This is a mixed nerve that carries sensory information back to the centres. There are four respiratory centres, three with a more clearly defined function, and an apneustic centre with a less clear function. In the medulla a dorsal respiratory group causes the desire to breathe in and receives sensory information directly from the body. Also in the medulla, the ventral respiratory group influences breathing out during exertion. In the pons the pneumotaxic centre influences the duration of each breath,[95] and the apneustic centre seems to have an influence on inhalation. The respiratory centres directly senses blood carbon dioxide and pH. Information about blood oxygen, carbon dioxide and pH levels are also sensed on the walls of arteries in the peripheral chemoreceptors of the aortic and carotid bodies. This information is passed via the vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves to the respiratory centres. High carbon dioxide, an acidic pH, or low oxygen stimulate the respiratory centres.[95] The desire to breathe in is also affected by pulmonary stretch receptors in the lungs which, when activated, prevent the lungs from overinflating by transmitting information to the respiratory centres via the vagus nerve.[95]

The hypothalamus in the diencephalon, is involved in regulating many functions of the body. Functions include neuroendocrine regulation, regulation of the circadian rhythm, control of the autonomic nervous system, and the regulation of fluid, and food intake. The circadian rhythm is controlled by two main cell groups in the hypothalamus. The anterior hypothalamus includes the suprachiasmatic nucleus and the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus which through gene expression cycles, generates a roughly 24 hour circadian clock. In the circadian day an ultradian rhythm takes control of the sleeping pattern. Sleep is an essential requirement for the body and brain and allows the closing down and resting of the body's systems. There are also findings that suggest that the daily build-up of toxins in the brain are removed during sleep.[96] Whilst awake the brain consumes a fifth of the body's total energy needs. Sleep necessarily reduces this use and gives time for the restoration of energy-giving ATP. The effects of sleep deprivation show the absolute need for sleep.[97]

The lateral hypothalamus contains orexinergic neurons that control appetite and arousal through their projections to the ascending reticular activating system.[98][99] The hypothalamus controls the pituitary gland through the release of peptides such as oxytocin, and vasopressin, as well as dopamine into the median eminence. Through the autonomic projections, the hypothalamus is involved in regulating functions such as blood pressure, heart rate, breathing, sweating, and other homeostatic mechanisms.[100] The hypothalamus also plays a role in thermal regulation, and when stimulated by the immune system, is capable of generating a fever. The hypothalamus is influenced by the kidneys: when blood pressure falls, the renin released by the kidneys stimulates a need to drink. The hypothalamus also regulates food intake through autonomic signals, and hormone release by the digestive system.[101]

Language

[edit]

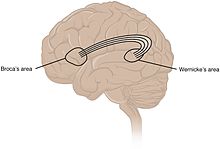

While language functions were traditionally thought to be localised to Wernicke's area and Broca's area,[102] it is now mostly accepted that a wider network of cortical regions contributes to language functions.[103][104][105]

The study on how language is represented, processed, and acquired by the brain is called neurolinguistics, which is a large multidisciplinary field drawing from cognitive neuroscience, cognitive linguistics, and psycholinguistics.[106]

Lateralisation

[edit]The cerebrum has a contralateral organisation with each hemisphere of the brain interacting primarily with one half of the body: the left side of the brain interacts with the right side of the body, and vice versa. This is theorized to be caused by a developmental axial twist.[107] Motor connections from the brain to the spinal cord, and sensory connections from the spinal cord to the brain, both cross sides in the brainstem. Visual input follows a more complex rule: the optic nerves from the two eyes come together at a point called the optic chiasm, and half of the fibres from each nerve split off to join the other.[108] The result is that connections from the left half of the retina, in both eyes, go to the left side of the brain, whereas connections from the right half of the retina go to the right side of the brain.[109] Because each half of the retina receives light coming from the opposite half of the visual field, the functional consequence is that visual input from the left side of the world goes to the right side of the brain, and vice versa.[110] Thus, the right side of the brain receives somatosensory input from the left side of the body, and visual input from the left side of the visual field.[111][112]

The left and right sides of the brain appear symmetrical, but they function asymmetrically.[113] For example, the counterpart of the left-hemisphere motor area controlling the right hand is the right-hemisphere area controlling the left hand. There are, however, several important exceptions, involving language and spatial cognition. The left frontal lobe is dominant for language. If a key language area in the left hemisphere is damaged, it can leave the victim unable to speak or understand,[113] whereas equivalent damage to the right hemisphere would cause only minor impairment to language skills.

A substantial part of current understanding of the interactions between the two hemispheres has come from the study of "split-brain patients"—people who underwent surgical transection of the corpus callosum in an attempt to reduce the severity of epileptic seizures.[114] These patients do not show unusual behaviour that is immediately obvious, but in some cases can behave almost like two different people in the same body, with the right hand taking an action and then the left hand undoing it.[114][115] These patients, when briefly shown a picture on the right side of the point of visual fixation, are able to describe it verbally, but when the picture is shown on the left, are unable to describe it, but may be able to give an indication with the left hand of the nature of the object shown.[115][116]

Emotion

[edit]Emotions are generally defined as two-step multicomponent processes involving elicitation, followed by psychological feelings, appraisal, expression, autonomic responses, and action tendencies.[117] Attempts to localise basic emotions to certain brain regions have been controversial; some research found no evidence for specific locations corresponding to emotions, but instead found circuitry involved in general emotional processes. The amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, mid and anterior insula cortex and lateral prefrontal cortex, appeared to be involved in generating the emotions, while weaker evidence was found for the ventral tegmental area, ventral pallidum and nucleus accumbens in incentive salience.[118] Others, however, have found evidence of activation of specific regions, such as the basal ganglia in happiness, the subcallosal cingulate cortex in sadness, and amygdala in fear.[119]

Cognition

[edit]The brain is responsible for cognition,[120][121] which functions through numerous processes and executive functions.[121][122][123] Executive functions include the ability to filter information and tune out irrelevant stimuli with attentional control and cognitive inhibition, the ability to process and manipulate information held in working memory, the ability to think about multiple concepts simultaneously and switch tasks with cognitive flexibility, the ability to inhibit impulses and prepotent responses with inhibitory control, and the ability to determine the relevance of information or appropriateness of an action.[122][123] Higher order executive functions require the simultaneous use of multiple basic executive functions, and include planning, prospection and fluid intelligence (i.e., reasoning and problem solving).[123]

The prefrontal cortex plays a significant role in mediating executive functions.[121][123][124] Planning involves activation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), anterior cingulate cortex, angular prefrontal cortex, right prefrontal cortex, and supramarginal gyrus.[124] Working memory manipulation involves the DLPFC, inferior frontal gyrus, and areas of the parietal cortex.[121][124] Inhibitory control involves multiple areas of the prefrontal cortex, as well as the caudate nucleus and subthalamic nucleus.[123][124][125]

Physiology

[edit]Neurotransmission

[edit]Brain activity is made possible by the interconnections of neurons that are linked together to reach their targets.[126] A neuron consists of a cell body, axon, and dendrites. Dendrites are often extensive branches that receive information in the form of signals from the axon terminals of other neurons. The signals received may cause the neuron to initiate an action potential (an electrochemical signal or nerve impulse) which is sent along its axon to the axon terminal, to connect with the dendrites or with the cell body of another neuron. An action potential is initiated at the initial segment of an axon, which contains a specialised complex of proteins.[127] When an action potential reaches the axon terminal it triggers the release of a neurotransmitter at a synapse that propagates a signal that acts on the target cell.[128] These chemical neurotransmitters include dopamine, serotonin, GABA, glutamate, and acetylcholine.[129] GABA is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain, and glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter.[130] Neurons link at synapses to form neural pathways, neural circuits, and large elaborate network systems such as the salience network and the default mode network, and the activity between them is driven by the process of neurotransmission.

Metabolism

[edit]

The brain consumes up to 20% of the energy used by the human body, more than any other organ.[131] In humans, blood glucose is the primary source of energy for most cells and is critical for normal function in a number of tissues, including the brain.[132] The human brain consumes approximately 60% of blood glucose in fasted, sedentary individuals.[132] Brain metabolism normally relies upon blood glucose as an energy source, but during times of low glucose (such as fasting, endurance exercise, or limited carbohydrate intake), the brain uses ketone bodies for fuel with a smaller need for glucose. The brain can also utilize lactate during exercise.[133] The brain stores glucose in the form of glycogen, albeit in significantly smaller amounts than that found in the liver or skeletal muscle.[134] Long-chain fatty acids cannot cross the blood–brain barrier, but the liver can break these down to produce ketone bodies. However, short-chain fatty acids (e.g., butyric acid, propionic acid, and acetic acid) and the medium-chain fatty acids, octanoic acid and heptanoic acid, can cross the blood–brain barrier and be metabolised by brain cells.[135][136][137]

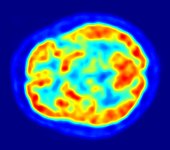

Although the human brain represents only 2% of the body weight, it receives 15% of the cardiac output, 20% of total body oxygen consumption, and 25% of total body glucose utilization.[138] The brain mostly uses glucose for energy, and deprivation of glucose, as can happen in hypoglycemia, can result in loss of consciousness.[139] The energy consumption of the brain does not vary greatly over time, but active regions of the cortex consume somewhat more energy than inactive regions, which forms the basis for the functional neuroimaging methods of PET and fMRI.[140] These techniques provide a three-dimensional image of metabolic activity.[141] A preliminary study showed that brain metabolic requirements in humans peak at about five years old.[142]

The function of sleep is not fully understood; however, there is evidence that sleep enhances the clearance of metabolic waste products, some of which are potentially neurotoxic, from the brain and may also permit repair.[52][143][144] Evidence suggests that the increased clearance of metabolic waste during sleep occurs via increased functioning of the glymphatic system.[52] Sleep may also have an effect on cognitive function by weakening unnecessary connections.[145]

Research

[edit]The brain is not fully understood, and research is ongoing.[146] Neuroscientists, along with researchers from allied disciplines, study how the human brain works. The boundaries between the specialties of neuroscience, neurology and other disciplines such as psychiatry have faded as they are all influenced by basic research in neuroscience.

Neuroscience research has expanded considerably. The "Decade of the Brain", an initiative of the United States Government in the 1990s, is considered to have marked much of this increase in research,[147] and was followed in 2013 by the BRAIN Initiative.[148] The Human Connectome Project was a five-year study launched in 2009 to analyse the anatomical and functional connections of parts of the brain, and has provided much data.[146]

An emerging phase in research may be that of simulating brain activity.[149]

Methods

[edit]Information about the structure and function of the human brain comes from a variety of experimental methods, including animals and humans. Information about brain trauma and stroke has provided information about the function of parts of the brain and the effects of brain damage. Neuroimaging is used to visualise the brain and record brain activity. Electrophysiology is used to measure, record and monitor the electrical activity of the cortex. Measurements may be of local field potentials of cortical areas, or of the activity of a single neuron. An electroencephalogram can record the electrical activity of the cortex using electrodes placed non-invasively on the scalp.[150][151]

Invasive measures include electrocorticography, which uses electrodes placed directly on the exposed surface of the brain. This method is used in cortical stimulation mapping, used in the study of the relationship between cortical areas and their systemic function.[152] By using much smaller microelectrodes, single-unit recordings can be made from a single neuron that give a high spatial resolution and high temporal resolution. This has enabled the linking of brain activity to behaviour, and the creation of neuronal maps.[153]

The development of cerebral organoids has opened ways for studying the growth of the brain, and of the cortex, and for understanding disease development, offering further implications for therapeutic applications.[154][155]

Imaging

[edit]

Functional neuroimaging techniques show changes in brain activity that relate to the function of specific brain areas. One technique is functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) which has the advantages over earlier methods of SPECT and PET of not needing the use of radioactive materials and of offering a higher resolution.[156] Another technique is functional near-infrared spectroscopy. These methods rely on the haemodynamic response that shows changes in brain activity in relation to changes in blood flow, useful in mapping functions to brain areas.[157] Resting state fMRIlooks at the interaction of brain regions whilst the brain is not performing a specific task.[158] This is also used to show the default mode network.

Any electrical current generates a magnetic field; neural oscillations induce weak magnetic fields, and in functional magnetoencephalography the current produced can show localised brain function in high resolution.[159] Tractography uses MRI and image analysis to create 3D images of the nerve tracts of the brain. Connectograms give a graphical representation of the neural connections of the brain.[160]

Differences in brain structure can be measured in some disorders, notably schizophrenia and dementia. Different biological approaches using imaging have given more insight for example into the disorders of depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder. A key source of information about the function of brain regions is the effects of damage to them.[161]

Advances in neuroimaging have enabled objective insights into mental disorders, leading to faster diagnosis, more accurate prognosis, and better monitoring.[162]

Gene and protein expression

[edit]Bioinformatics is a field of study that includes the creation and advancement of databases, and computational and statistical techniques, that can be used in studies of the human brain, particularly in the areas of gene and protein expression. Bioinformatics and studies in genomics, and functional genomics, generated the need for DNA annotation, a transcriptome technology, identifying genes, their locations and functions.[163][164][165] GeneCards is a major database.

As of 2017[update], just under 20,000 protein-coding genes are seen to be expressed in the human,[163] and some 400 of these genes are brain-specific.[166][167] The data that has been provided on gene expression in the brain has fuelled further research into a number of disorders. The long term use of alcohol for example, has shown altered gene expression in the brain, and cell-type specific changes that may relate to alcohol use disorder.[168] These changes have been noted in the synaptic transcriptome in the prefrontal cortex, and are seen as a factor causing the drive to alcohol dependence, and also to other substance abuses.[169]

Other related studies have also shown evidence of synaptic alterations and their loss, in the ageing brain. Changes in gene expression alter the levels of proteins in various neural pathways and this has been shown to be evident in synaptic contact dysfunction or loss. This dysfunction has been seen to affect many structures of the brain and has a marked effect on inhibitory neurons resulting in a decreased level of neurotransmission, and subsequent cognitive decline and disease.[170][171]

Clinical significance

[edit]Injury

[edit]Injury to the brain can manifest in many ways. Traumatic brain injury, for example received in contact sport, after a fall, or a traffic or work accident, can be associated with both immediate and longer-term problems. Immediate problems may include bleeding within the brain, this may compress the brain tissue or damage its blood supply. Bruising to the brain may occur. Bruising may cause widespread damage to the nerve tracts that can lead to a condition of diffuse axonal injury.[172] A fractured skull, injury to a particular area, deafness, and concussion are also possible immediate developments. In addition to the site of injury, the opposite side of the brain may be affected, termed a contrecoup injury. Longer-term issues that may develop include posttraumatic stress disorder, and hydrocephalus. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy can develop following multiple head injuries.[173]

Disease

[edit]Neurodegenerative diseases result in progressive damage to, or loss of neurons affecting different functions of the brain, that worsen with age. Common types are dementias including Alzheimer's disease, alcoholic dementia, vascular dementia, and Parkinson's disease dementia. Other rarer infectious, genetic, or metabolic types include Huntington's disease, motor neuron diseases, HIV dementia, syphilis-related dementia and Wilson's disease. Neurodegenerative diseases can affect different parts of the brain, and can affect movement, memory, and cognition.[174] Rare prion diseases including Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease and its variant, and kuru are fatal neurodegenerative dieases.[175]

Cerebral atherosclerosis is atherosclerosis that affects the brain. It results from the build-up of plaques formed of cholesterol, in the large arteries of the brain, and can be mild to significant. When significant, arteries can become narrowed enough to reduce blood flow. It contributes to the development of dementia, and has protein similarities to those found in Alzheimer’s disease.[176]

The brain, although protected by the blood–brain barrier, can be affected by infections including viruses, bacteria and fungi. Infection may be of the meninges (meningitis), the brain matter (encephalitis), or within the brain matter (such as a cerebral abscess).[175]

Tumours

[edit]Brain tumours can be either benign or cancerous. Most malignant tumours arise from another part of the body, most commonly from the lung, breast and skin.[177] Cancers of brain tissue can also occur, and originate from any tissue in and around the brain. Meningioma, cancer of the meninges around the brain, is more common than cancers of brain tissue.[177] Cancers within the brain may cause symptoms related to their size or position, with symptoms including headache and nausea, or the gradual development of focal symptoms such as gradual difficulty seeing, swallowing, talking, or as a change of mood.[177] Cancers are in general investigated through the use of CT scans and MRI scans. A variety of other tests including blood tests and lumbar puncture may be used to investigate for the cause of the cancer and evaluate the type and stage of the cancer.[177] The corticosteroid dexamethasone is often given to decrease the swelling of brain tissue around a tumour. Surgery may be considered, however given the complex nature of many tumours or based on tumour stage or type, radiotherapy or chemotherapy may be considered more suitable.[177]

Mental disorders

[edit]Mental disorders, such as depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, Tourette syndrome, and addiction, are known to relate to the functioning of the brain.[125][129][178] Treatment for mental disorders may include psychotherapy, psychiatry, social intervention and personal recovery work or cognitive behavioural therapy; the underlying issues and associated prognoses vary significantly between individuals.[179]

Epilepsy

[edit]Epileptic seizures are thought to relate to abnormal electrical activity.[180] Seizure activity can manifest as absence of consciousness, focal effects such as limb movement or impediments of speech, or be generalized in nature.[180] Status epilepticus refers to a seizure or series of seizures that have not terminated within five minutes.[181] Seizures have a large number of causes, however many seizures occur without a definitive cause being found. In a person with epilepsy, risk factors for further seizures may include sleeplessness, drug and alcohol intake, and stress. Seizures may be assessed using blood tests, EEG and various medical imaging techniques based on the medical history and medical examination findings.[180] In addition to treating an underlying cause and reducing exposure to risk factors, anticonvulsant medications can play a role in preventing further seizures.[180]

Congenital

[edit]Some brain disorders, such as Tay–Sachs disease,[182] are congenital and linked to genetic and chromosomal mutations.[183] A rare group of congenital cephalic disorders known as lissencephaly is characterised by the lack of, or inadequacy of, cortical folding.[184] Normal development of the brain can be affected during pregnancy by nutritional deficiencies,[185] teratogens,[186] infectious diseases,[187] and by the use of recreational drugs, including alcohol (which may result in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders).[185][188]Most cerebral arteriovenous malformations are congenital, these tangled networks of blood vessels may remain without symptoms but at their worst may rupture and cause intracranial hemorrhaging.[189]

Stroke

[edit]

A stroke is a decrease in blood supply to an area of the brain causing cell death and brain injury. This can lead to a wide range of symptoms, including the "FAST" symptoms of facial droop, arm weakness, and speech difficulties (including with speaking and finding words or forming sentences).[190] Symptoms relate to the function of the affected area of the brain and can point to the likely site and cause of the stroke. Difficulties with movement, speech, or sight usually relate to the cerebrum, whereas imbalance, double vision, vertigo and symptoms affecting more than one side of the body usually relate to the brainstem or cerebellum.[191]

Most strokes result from loss of blood supply, typically because of an embolus, rupture of a fatty plaque causing thrombus, or narrowing of small arteries. Strokes can also result from bleeding within the brain.[192] Transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs) are strokes in which symptoms resolve within 24 hours.[192] Investigation into the stroke will involve a medical examination (including a neurological examination) and the taking of a medical history, focusing on the duration of the symptoms and risk factors (including high blood pressure, atrial fibrillation, and smoking).[193] Further investigation is needed in younger patients.[194] An ECG and biotelemetry may be conducted to identify atrial fibrillation; an ultrasound can investigate narrowing of the carotid arteries; an echocardiogram can be used to look for clots within the heart, diseases of the heart valves or the presence of a patent foramen ovale.[194] Blood tests are routinely done as part of the workup including diabetes tests and a lipid profile.[194]

Some treatments for stroke are time-critical. These include clot dissolution or surgical removal of a clot for ischaemic strokes, and decompression for haemorrhagic strokes.[195][196] As stroke is time critical,[197] hospitals and even pre-hospital care of stroke involves expedited investigations – usually a CT scan to investigate for a haemorrhagic stroke and a CT or MR angiogram to evaluate arteries that supply the brain.[194] MRI scans, not as widely available, may be able to demonstrate the affected area of the brain more accurately, particularly with ischaemic stroke.[194]

Having experienced a stroke, a person may be admitted to a stroke unit, and treatments may be directed as preventing future strokes, including ongoing anticoagulation (such as aspirin or clopidogrel), antihypertensives, and lipid-lowering drugs.[195] A multidisciplinary team including speech pathologists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and psychologists plays a large role in supporting a person affected by a stroke and their rehabilitation.[198][194] A history of stroke increases the risk of developing dementia by around 70%, and recent stroke increases the risk by around 120%.[199]

Brain death

[edit]Brain death refers to an irreversible total loss of brain function.[200][201] This is characterised by coma, loss of reflexes, and apnoea,[200] however, the declaration of brain death varies geographically and is not always accepted.[201] In some countries there is also a defined syndrome of brainstem death.[202] Declaration of brain death can have profound implications as the declaration, under the principle of medical futility, will be associated with the withdrawal of life support,[203] and as those with brain death often have organs suitable for organ donation.[201][204] The process is often made more difficult by poor communication with patients' families.[205]

When brain death is suspected, reversible differential diagnoses such as, electrolyte, neurological and drug-related cognitive suppression need to be excluded.[200][203] Testing for reflexes[b] can be of help in the decision, as can the absence of response and breathing.[203] Clinical observations, including a total lack of responsiveness, a known diagnosis, and neural imaging evidence, may all play a role in the decision to pronounce brain death.[200]

Society and culture

[edit]Neuroanthropology is the study of the relationship between culture and the brain. It explores how the brain gives rise to culture, and how culture influences brain development.[206] Cultural differences and their relation to brain development and structure are researched in different fields.[207]

The mind

[edit]

The philosophy of the mind studies such issues as the problem of understanding consciousness and the mind–body problem. The relationship between the brain and the mind is a significant challenge both philosophically and scientifically. This is because of the difficulty in explaining how mental activities, such as thoughts and emotions, can be implemented by physical structures such as neurons and synapses, or by any other type of physical mechanism. This difficulty was expressed by Gottfried Leibniz in the analogy known as Leibniz's Mill:

One is obliged to admit that perception and what depends upon it is inexplicable on mechanical principles, that is, by figures and motions. In imagining that there is a machine whose construction would enable it to think, to sense, and to have perception, one could conceive it enlarged while retaining the same proportions, so that one could enter into it, just like into a windmill. Supposing this, one should, when visiting within it, find only parts pushing one another, and never anything by which to explain a perception.

- — Leibniz, Monadology[209]

Doubt about the possibility of a mechanistic explanation of thought drove René Descartes, and most other philosophers along with him, to dualism: the belief that the mind is to some degree independent of the brain.[210] There has always, however, been a strong argument in the opposite direction. There is clear empirical evidence that physical manipulations of, or injuries to, the brain (for example by drugs or by lesions, respectively) can affect the mind in potent and intimate ways.[211][212] In the 19th century, the case of Phineas Gage, a railway worker who was injured by a stout iron rod passing through his brain, convinced both researchers and the public that cognitive functions were localised in the brain.[208] Following this line of thinking, a large body of empirical evidence for a close relationship between brain activity and mental activity has led most neuroscientists and contemporary philosophers to be materialists, believing that mental phenomena are ultimately the result of, or reducible to, physical phenomena.[213]

Brain size

[edit]The size of the brain and a person's intelligence are not strongly related.[214] Studies tend to indicate small to moderate correlations (averaging around 0.3 to 0.4) between brain volume and IQ.[215] The most consistent associations are observed within the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, the hippocampi, and the cerebellum, but these only account for a relatively small amount of variance in IQ, which itself has only a partial relationship to general intelligence and real-world performance.[216][217]

Other animals, including whales and elephants have larger brains than humans. However, when the brain-to-body mass ratio is taken into account, the human brain is almost twice as large as that of a bottlenose dolphin, and three times as large as that of a chimpanzee. However, a high ratio does not of itself demonstrate intelligence: very small animals have high ratios and the treeshrew has the largest quotient of any mammal.[218]

In popular culture

[edit]

Earlier ideas about the relative importance of the different organs of the human body sometimes emphasised the heart.[219]Modern Western popular conceptions, in contrast, have placed increasing focus on the brain.[220]

Research has disproved some common misconceptions about the brain. These include both ancient and modern myths. It is not true (for example) that neurons are not replaced after the age of two; nor that normal humans use only ten per cent of the brain.[221] Popular culture has also oversimplified the lateralisation of the brain by suggesting that functions are completely specific to one side of the brain or the other. Akio Mori coined the term "game brain" for the unreliably supported theory that spending long periods playing video games harmed the brain's pre-frontal region, and impaired the expression of emotion and creativity.[222]

Historically, particularly in the early-19th century, the brain featured in popular culture through phrenology, a pseudoscience that assigned personality attributes to different regions of the cortex. The cortex remains important in popular culture as covered in books and satire.[223][224]

The human brain can feature in science fiction, with themes such as brain transplants and cyborgs (beings with features like partly artificial brains).[225] The 1942 science-fiction book (adapted three times for the cinema) Donovan's Brain tells the tale of an isolated brain kept alive in vitro, gradually taking over the personality of the book's protagonist.[226]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

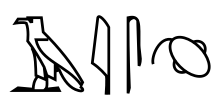

The Edwin Smith Papyrus, an ancient Egyptian medical treatise written in the 17th century BC, contains the earliest recorded reference to the brain. The hieroglyph for brain, occurring eight times in this papyrus, describes the symptoms, diagnosis, and prognosis of two traumatic injuries to the head. The papyrus mentions the external surface of the brain, the effects of injury (including seizures and aphasia), the meninges, and cerebrospinal fluid.[227][228]

In the fifth century BC, Alcmaeon of Croton in Magna Grecia, first considered the brain to be the seat of the mind.[228] Also in the fifth century BC in Athens, the unknown author of On the Sacred Disease, a medical treatise which is part of the Hippocratic Corpus and traditionally attributed to Hippocrates, believed the brain to be the seat of intelligence. Aristotle, in his biology initially believed the heart to be the seat of intelligence, and saw the brain as a cooling mechanism for the blood. He reasoned that humans are more rational than the beasts because, among other reasons, they have a larger brain to cool their hot-bloodedness.[229] Aristotle did describe the meninges and distinguished between the cerebrum and cerebellum.[230]

Herophilus of Chalcedon in the fourth and third centuries BC distinguished the cerebrum and the cerebellum, and provided the first clear description of the ventricles; and with Erasistratus of Ceos experimented on living brains. Their works are now mostly lost, and we know about their achievements due mostly to secondary sources. Some of their discoveries had to be re-discovered a millennium after their deaths.[228] Anatomist physician Galen in the second century AD, during the time of the Roman Empire, dissected the brains of sheep, monkeys, dogs, and pigs. He concluded that, as the cerebellum was denser than the brain, it must control the muscles, while as the cerebrum was soft, it must be where the senses were processed. Galen further theorised that the brain functioned by movement of animal spirits through the ventricles.[228][229]

Renaissance

[edit]

In 1316, Mondino de Luzzi's Anathomia began the modern study of brain anatomy.[231]Niccolò Massa discovered in 1536 that the ventricles were filled with fluid.[232] Archangelo Piccolomini of Rome was the first to distinguish between the cerebrum and cerebral cortex.[233] In 1543 Andreas Vesalius published his seven-volume De humani corporis fabrica.[233][234][235] The seventh book covered the brain and eye, with detailed images of the ventricles, cranial nerves, pituitary gland, meninges, structures of the eye, the vascular supply to the brain and spinal cord, and an image of the peripheral nerves.[236] Vesalius rejected the common belief that the ventricles were responsible for brain function, arguing that many animals have a similar ventricular system to humans, but no true intelligence.[233]

René Descartes proposed the theory of dualism to tackle the issue of the brain's relation to the mind. He suggested that the pineal gland was where the mind interacted with the body, serving as the seat of the soul and as the connection through which animal spirits passed from the blood into the brain.[232] This dualism likely provided impetus for later anatomists to further explore the relationship between the anatomical and functional aspects of brain anatomy.[237]

Thomas Willis is considered a second pioneer in the study of neurology and brain science. He wrote Cerebri Anatome (Latin: Anatomy of the brain)[c] in 1664, followed by Cerebral Pathology in 1667. In these he described the structure of the cerebellum, the ventricles, the cerebral hemispheres, the brainstem, and the cranial nerves, studied its blood supply; and proposed functions associated with different areas of the brain.[233] The circle of Willis was named after his investigations into the blood supply of the brain, and he was the first to use the word "neurology".[238] Willis removed the brain from the body when examining it, and rejected the commonly held view that the cortex only consisted of blood vessels, and the view of the last two millennia that the cortex was only incidentally important.[233]

In the middle of 19th century Emil du Bois-Reymond and Hermann von Helmholtz were able to use a galvanometer to show that electrical impulses passed at measurable speeds along nerves, refuting the view of their teacher Johannes Peter Müller that the nerve impulse was a vital function that could not be measured.[239][240][241] Richard Caton in 1875 demonstrated electrical impulses in the cerebral hemispheres of rabbits and monkeys.[242] In the 1820s, Jean Pierre Flourens pioneered the experimental method of damaging specific parts of animal brains describing the effects on movement and behavior.[243]

Современный период

[ редактировать ]

Исследования мозга стали более сложными с использованием микроскопа и разработкой окрашивания серебром метода Камилло Гольджи в 1880-х годах. Это позволило показать сложные структуры отдельных нейронов. [244] Это было использовано Сантьяго Рамоном-и-Кахалем и привело к формированию доктрины нейронов , революционной на тот момент гипотезы о том, что нейрон является функциональной единицей мозга. Он использовал микроскопию, чтобы обнаружить многие типы клеток, и предложил функции клеток, которые он видел. [244] За это Гольджи и Кахаля считают основателями нейробиологии двадцатого века , оба получили Нобелевскую премию 1906 года за свои исследования и открытия в этой области. [244]

Чарльз Шеррингтон опубликовал в 1906 году свою влиятельную работу «Интегративное действие нервной системы», в которой исследуется функция рефлексов, эволюционное развитие нервной системы, функциональная специализация мозга, а также расположение и клеточные функции центральной нервной системы. [245] В 1942 году он ввел термин « зачарованный ткацкий станок» как метафору мозга. Джон Фаркуар Фултон основал Журнал нейрофизиологии и опубликовал первый всеобъемлющий учебник по физиологии нервной системы в 1938 году. [246] Нейронаука в двадцатом веке стала признаваться как отдельная единая академическая дисциплина, а Дэвид Риоч , Фрэнсис О. Шмитт и Стивен Каффлер сыграли решающую роль в становлении этой области. [247] Риоч инициировал интеграцию фундаментальных анатомических и физиологических исследований с клинической психиатрией в Армейском исследовательском институте Уолтера Рида , начиная с 1950-х годов. [248] В тот же период Шмитт учредил Программу нейробиологических исследований — межуниверситетскую и международную организацию, объединяющую биологию, медицину, психологию и поведенческие науки. Само слово «нейронаука» возникло из этой программы. [249]

Поль Брока связал области мозга с определенными функциями, в частности, речью в зоне Брока , после работы с пациентами с повреждением головного мозга. [250] Джон Хьюлингс Джексон описал функцию моторной коры , наблюдая за развитием эпилептических припадков по всему телу. Карл Вернике описал область, связанную с пониманием и производством языка. Корбиниан Бродманн разделил области мозга в зависимости от внешнего вида клеток. [250] К 1950 году Шеррингтон, Папес и Маклин определили многие функции ствола мозга и лимбической системы. [251] [252] Способность мозга к реорганизации и изменению с возрастом, а также признанный критический период развития были приписаны нейропластичности , впервые разработанной Маргарет Кеннард , которая экспериментировала на обезьянах в 1930-40-х годах. [253]

Харви Кушинг (1869–1939) признан первым опытным нейрохирургом . в мире [254] В 1937 году Уолтер Денди начал практику сосудистой нейрохирургии , выполнив первое хирургическое клипирование внутричерепной аневризмы . [255]

Сравнительная анатомия

[ редактировать ]Человеческий мозг обладает многими свойствами, общими для мозга всех позвоночных . [256] Многие из его особенностей являются общими для мозга всех млекопитающих . [257] в первую очередь шестислойная кора головного мозга и набор связанных с ней структур, [258] включая гиппокамп и миндалевидное тело . [259] Кора головного мозга у человека пропорционально больше, чем у многих других млекопитающих. [260] У людей больше ассоциативной коры, сенсорных и моторных частей, чем у более мелких млекопитающих, таких как крыса и кошка. [261]

Как и мозг приматов , человеческий мозг имеет гораздо большую кору головного мозга (пропорционально размеру тела), чем у большинства млекопитающих. [259] и высокоразвитая зрительная система. [262] [263]

Как мозг гоминида , человеческий мозг существенно увеличен даже по сравнению с мозгом типичной обезьяны. Последовательность эволюции человека от австралопитека (четыре миллиона лет назад) до человека разумного (современного человека) была отмечена устойчивым увеличением размера мозга. [264] [265] Увеличение размера мозга привело к изменению размера и формы черепа. [266] примерно от 600 см 3 у Homo habilis в среднем около 1520 см. 3 у неандертальца [267] Различия в ДНК , экспрессии генов и взаимодействиях генов и окружающей среды помогают объяснить различия между функциями мозга человека и других приматов. [268]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Очертание человеческого мозга

- Очерк нейробиологии

- Церебральная атрофия

- Кортикальная распространяющаяся депрессия

- Эволюция человеческого интеллекта

- Крупномасштабные мозговые сети

- Поверхностные вены головного мозга

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ « Энцефало -этимология» . Интернет-словарь этимологии . Архивировано из оригинала 2 октября 2017 года . Проверено 24 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Родитель, А.; Карпентер, МБ (1995). «Ч. 1». Нейроанатомия человека Карпентера . Уильямс и Уилкинс. ISBN 978-0-683-06752-1 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бигос, КЛ; Харири, А.; Вайнбергер, Д. (2015). Нейровизуализационная генетика: принципы и практика . Издательство Оксфордского университета . п. 157. ИСБН 978-0-19-992022-8 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Косгроув, КП; Мазуре, СМ; Стейли, Дж. К. (2007). «Развитие знаний о половых различиях в структуре, функциях и химии мозга» . Биологическая психиатрия . 62 (8): 847–855. doi : 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.001 . ПМК 2711771 . ПМИД 17544382 .

- ^ Молина, Д. Кимберли; ДиМайо, Винсент Дж. М. (2012). «Нормальный вес органов у мужчин». Американский журнал судебной медицины и патологии . 33 (4): 368–372. дои : 10.1097/PAF.0b013e31823d29ad . ISSN 0195-7910 . ПМИД 22182984 . S2CID 32174574 .

- ^ Молина, Д. Кимберли; ДиМайо, Винсент Дж. М. (2015). «Нормальный вес органов у женщин». Американский журнал судебной медицины и патологии . 36 (3): 182–187. дои : 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000175 . ISSN 0195-7910 . ПМИД 26108038 . S2CID 25319215 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Анатомия Грея 2008 , стр. 227–9.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Анатомия Грея 2008 , стр. 335–7.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Рибас, ГК (2010). «Мозговые борозды и извилины» . Нейрохирургический фокус . 28 (2): 7. doi : 10.3171/2009.11.FOCUS09245 . ПМИД 20121437 .

- ^ Фригери, Т.; Пальоли, Э.; Де Оливейра, Э.; Ротон-младший, Алабама (2015). «Микрохирургическая анатомия центральной доли». Журнал нейрохирургии . 122 (3): 483–98. дои : 10.3171/2014.11.JNS14315 . ПМИД 25555079 .

- ^ Мёллгорд, Кьельд; Бейнлих, Феликс Р.М.; Куск, Питер; Миякоши, Лео М.; Делле, Кристина; Пла, Вирджиния; Хаугланд, Натали Л.; Эсмаил, Тина; Расмуссен, Мартин К.; Гомолка, Рышард С.; Мори, Юки; Недергаард, Майкен (2023). «Мезотелий делит субарахноидальное пространство на функциональные отсеки» . Наука . 379 (6627): 84–88. Бибкод : 2023Sci...379...84M . doi : 10.1126/science.adc8810 . ПМИД 36603070 . S2CID 255440992 .

- Медицинский центр Рочестерского университета (5 января 2023 г.). «Недавно открытая анатомия защищает и контролирует мозг» . Медицинский Экспресс . Архивировано из оригинала 7 января 2023 года . Проверено 15 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Первес 2012 , с. 724.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Чиполла, MJ (1 января 2009 г.). «Анатомия и ультраструктура» . Церебральное кровообращение . Морган и Клейпул Науки о жизни. Архивировано из оригинала 1 октября 2017 года на NCBI Bookshelf.

- ^ «Взгляд на мозг глазами хирурга» . ЭНЕРГЕТИЧЕСКИЙ ЯДЕРНЫЙ РЕАКТОР . Свежий воздух. 10 мая 2006 г. Архивировано из оригинала 7 ноября 2017 г.

- ^ Сампайо-Баптиста, К; Йохансен-Берг, Х. (20 декабря 2017 г.). «Пластичность белого вещества в мозгу взрослого человека» . Нейрон . 96 (6): 1239–1251. дои : 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.11.026 . ПМК 5766826 . ПМИД 29268094 .

- ^ Дэйви, Г. (2011). Прикладная психология . Джон Уайли и сыновья . п. 153. ИСБН 978-1-4443-3121-9 .

- ^ Арсава, EY; Арсава, Э.М.; Огуз, КК; Топчуоглу, Массачусетс (2019). «Затылочные петалии как прогностический признак доминирования поперечного синуса». Неврологические исследования . 41 (4): 306–311. дои : 10.1080/01616412.2018.1560643 . ПМИД 30601110 . S2CID 58546404 .