Неоклассицизм (музыка)

Неклассицизм в музыке был тенденцией двадцатого века, особенно в межвоенном периоде , в которой композиторы стремились вернуться к эстетическим заповедям, связанным с широко определенной концепцией « классицизма », а также порядок, баланс, ясности, экономики и эмоциональной сдержанности. Таким образом, неоклассицизм был реакцией против безудержного эмоциональности и воспринимаемого бесформенного романтизма , а также «призыв к порядку» после экспериментального брожения первых двух десятилетий двадцатого века. Неоклассический импульс обнаружил, что его выражение в таких особенностях, как использование окрашенных исполняющих сил, акцент на ритме и контрапунтальной текстуре, обновленной или расширенной тональной гармонии и концентрации на абсолютной музыке , в отличие от романтической программы музыки .

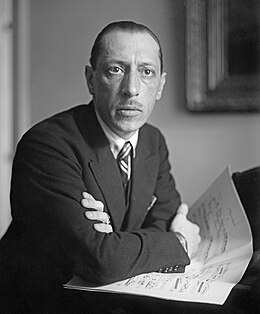

В форме и тематической технике неоклассическая музыка часто черпала вдохновение из музыки восемнадцатого века, хотя вдохновляющий канон принадлежал так же часто в барокко (и даже более ранние периоды), как и в классический период - по этой причине, музыка, которая черпает вдохновение специально из Барокко иногда называют нео-бароковой музыкой. Неклассицизм имел две разные национальные линии развития: французский (отчасти от влияния Эрика Сати и представлена Игором Стравинским , который на самом деле был русским языком) и немецкий (исходя из « новой объективности » Ferruccio Busoni , который на самом деле был на самом деле. Итальянец, и представлен Полом Хиндемтом ). Неклассицизм был эстетической тенденцией, а не организованным движением; Даже многие композиторы обычно не считаются «неоклассицистами», поглощающими элементы стиля.

Люди и работают

[ редактировать ]Хотя термин «неоклассицизм» относится к движению двадцатого века, были важные предшественники XIX века. В таких кусочках, как Франц Лишт, Шипл Шестел (1862), Эдварда Грига ( Сюита 1884 г.), Пиано Энеску дивертизирование «Королевы Спел» 1890 из ( г. Стиль (1897) и концерт Макса Регера в старом стиле (1912), композиторы «одели свою музыку в старую одежду, чтобы создать улыбающееся или задумчивое воспоминание о прошлом». [ 1 ]

Симфония Сергея Прокофьева № 1 ( 1917 ) иногда называют предшественником неоклассицизма. [ 2 ] Сам Прокофьев подумал, что его композиция была «фазой прохождения», тогда как неоклассицизм Стравинского был к 1920 -м годам «стал основной линией его музыки». [ 3 ] Ричард Штраус также ввел в свою музыку неоклассические элементы, особенно в его оркестровом люксе Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme Op. 60, написано в ранней версии в 1911 году и ее окончательной версии в 1917 году. [ 4 ]

Оторино Респиги также был одним из предшественников неоклассицизма с его древним воздухом и танцами , составленным в 1917 году. Вместо того, чтобы смотреть на музыкальные формы восемнадцатого века, Респиги, который, помимо того, что он был известным композитором и дирижером. Был также известным музыкологом, вернулся к итальянской музыке шестнадцатого и семнадцатого веков. Его коллега -современный композитор Джан Франческо Малипьеро , также музыколог, собрал полное издание произведений Клаудио Монтеверди . Отношение Малипьеро с древней итальянской музыкой было не просто нацелено на возрождение антикварных форм в рамках «возвращения к порядку», но и попытка возродить подход к композиции, который позволил бы композитору освободиться от ограничений сонаты Форма и из чрезмерных механизмов тематического развития. [ 5 ]

Первый набег Игоря Стравинского в стиль начался в 1919/20 годах, когда он сочинил балет -пульцинелла , используя темы, которые, по его мнению, Джованни Баттиста Перголесси (позже выяснилось, что многие из них не были, хотя они были современниками). Американский композитор Эдвард Т. Коне описывает балет «[Стравинский] противостоит вызванной исторической манере в каждой точке с его собственной версией современного языка; Результатом является полная переосмысление и преобразование более раннего стиля ». [ 6 ] Более поздние примеры- октет для ветров, концерт «Дамбартон-дубов» , концерт в D , симфония псалмов , симфония в C и симфония в трех движениях , а также оперотореаторию Эдип Рекс и балеты Аполлон и Орфей. , в котором неоклассицизм приобрел явную «классическую греческую» ауру. Неоклассицизм Стравинского завершился в его опере «Прогресс граблей » с либретто Уауеном . [ 7 ] Стравинский неоклассицизм оказал решающее влияние на французских композиторов Дариуса Милхауда , Фрэнсиса Поленса , Артура Хонеггера и Жермене Тайлферре , а также на Бохуслава Мартина , которые возродили форму барочной концертной концертной формы в своих работах. [ 8 ] Pulcinella , как подкатегория перестройки существующих композиций в барокке, породила ряд подобных произведений, в том числе Соединенное место Scarlattiana (1927) Альфредо Казеллы (1927), » , «Ототорино», древний воздух и танцы и тон « [9] and Richard Strauss's Dance Suite from Keyboard Pieces by François Couperin and the related Divertimento after Keyboard Pieces by Couperin, Op. 86 (1923 and 1943, respectively).[10] Starting around 1926 Béla Bartók's music shows a marked increase in neoclassical traits, and a year or two later acknowledged Stravinsky's "revolutionary" accomplishment in creating novel music by reviving old musical elements while at the same time naming his colleague Zoltán Kodály as another Hungarian adherent of neoclassicism.[11]

A German strain of neoclassicism was developed by Paul Hindemith, who produced chamber music, orchestral works, and operas in a heavily contrapuntal, chromatically inflected style, best exemplified by Mathis der Maler. Roman Vlad contrasts the "classicism" of Stravinsky, which consists in the external forms and patterns of his works, with the "classicality" of Busoni, which represents an internal disposition and attitude of the artist towards works.[12] Busoni wrote in a letter to Paul Bekker, "By 'Young Classicalism' I mean the mastery, the sifting and the turning to account of all the gains of previous experiments and their inclusion in strong and beautiful forms".[13]

Neoclassicism found a welcome audience in Europe and America, as the school of Nadia Boulanger promulgated ideas about music based on her understanding of Stravinsky's music. Boulanger taught and influenced many notable composers, including Grażyna Bacewicz, Lennox Berkeley, Elliott Carter, Francis Chagrin, Aaron Copland, David Diamond, Irving Fine, Harold Shapero, Jean Françaix, Roy Harris, Igor Markevitch, Darius Milhaud, Astor Piazzolla, Walter Piston, Ned Rorem, and Virgil Thomson.

In Spain, Manuel de Falla's neoclassical Concerto for Harpsichord, Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Violin, and Cello of 1926 was perceived as an expression of "universalism" (universalismo), broadly linked to an international, modernist aesthetic.[14] In the first movement of the concerto, Falla quotes fragments of the fifteenth-century villancico "De los álamos, vengo madre". He had similarly incorporated quotations from seventeenth-century music when he first embraced neoclassicism in the puppet-theatre piece El retablo de maese Pedro (1919–23), an adaptation from Cervantes's Don Quixote. Later neoclassical compositions by Falla include the 1924 chamber cantata Psyché and incidental music for Pedro Calderón de la Barca's, El gran teatro del mundo, written in 1927.[15] In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Roberto Gerhard composed in the neoclassical style, including his Concertino for Strings, the Wind Quintet, the cantata L'alta naixença del rei en Jaume, and the ballet Ariel.[16] Other important Spanish neoclassical composers are found amongst the members of the Generación de la República (also known as the Generación del 27), including Julián Bautista, Fernando Remacha, Salvador Bacarisse, and Jesús Bal y Gay.[17][18][19][20]

A neoclassical aesthetic was promoted in Italy by Alfredo Casella, who had been educated in Paris and continued to live there until 1915, when he returned to Italy to teach and organize concerts, introducing modernist composers such as Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg to the provincially minded Italian public. His neoclassical compositions were perhaps less important than his organizing activities, but especially representative examples include Scarlattiana of 1926, using motifs from Domenico Scarlatti's keyboard sonatas, and the Concerto romano of the same year.[21] Casella's colleague Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco wrote neoclassically inflected works which hark back to early Italian music and classical models: the themes of his Concerto italiano in G minor of 1924 for violin and orchestra echo Vivaldi as well as sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Italian folksongs, while his highly successful Guitar Concerto No. 1 in D of 1939 consciously follows Mozart's concerto style.[22]

Portuguese representatives of neoclassicism include two members of the "Grupo de Quatro", Armando José Fernandes and Jorge Croner de Vasconcellos, both of whom studied with Nadia Boulanger.[23]

In South America, neoclassicism was of particular importance in Argentina, where it differed from its European model in that it did not seek to redress recent stylistic upheavals which had simply not occurred in Latin America. Argentine composers associated with neoclassicism include Jacobo Ficher, José María Castro, Luis Gianneo, and Juan José Castro.[24] The most important twentieth-century Argentine composer, Alberto Ginastera, turned from nationalistic to neoclassical forms in the 1950s (e.g., Piano Sonata No. 1 and the Variaciones concertantes) before moving on to a style dominated by atonal and serial techniques. Roberto Caamaño, professor of Gregorian chant at the Institute of Sacred Music in Buenos Aires, employed a dissonant neoclassical style in some works and a serialist style in others.[25]

Although the well-known Bachianas Brasileiras of Heitor Villa-Lobos (composed between 1930 and 1947) are cast in the form of Baroque suites, usually beginning with a prelude and ending with a fugal or toccata-like movement and employing neoclassical devices such as ostinato figures and long pedal notes, they were not intended so much as stylized recollections of the style of Bach as a free adaptation of Baroque harmonic and contrapuntal procedures to music in a Brazilian style.[26][27] Brazilian composers of the generation after Villa-Lobos more particularly associated with neoclassicism include Radamés Gnattali (in his later works), Edino Krieger, and the prolific Camargo Guarnieri, who had contact with but did not study under Nadia Boulanger when he visited Paris in the 1920s. Neoclassical traits figure in Guarnieri's music starting with the second movement of the Piano Sonatina of 1928, and are particularly notable in his five piano concertos.[26][28][29]

The Chilean composer Domingo Santa Cruz Wilson was so strongly influenced by the German variety of neoclassicism that he became known as the "Chilean Hindemith".[30]

In Cuba, José Ardévol initiated a neoclassical school, though he himself moved on to a modernistic national style later in his career.[31][32][30]

Even the atonal school, represented for example by Arnold Schoenberg, showed the influence of neoclassical ideas. After his early style of 'Late Romanticism' (exemplified by his string sextet Verklärte Nacht) had been supplanted by his Atonal period, and immediately before he embraced twelve-tone serialism, the forms of Schoenberg's works after 1920, beginning with opp. 23, 24, and 25 (all composed at the same time), have been described as "openly neoclassical", and represent an effort to integrate the advances of 1908 to 1913 with the inheritance of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[33] Schoenberg attempted in those works to offer listeners structural points of reference with which they could identify, beginning with the Serenade, op. 24, and the Suite for piano, op. 25.[34] Schoenberg's pupil Alban Berg actually came to neoclassicism before his teacher, in his Three Pieces for Orchestra, op. 6 (1913–14), and the opera Wozzeck,[35] which uses closed forms such as suite, passacaglia, and rondo as organizing principles within each scene. Anton Webern also achieved a sort of neoclassical style through an intense concentration on the motif.[36] However, his 1935 orchestration of the six-part ricercar from Bach's Musical Offering is not regarded as neoclassical because of its concentration on the fragmentation of instrumental colours.[9]

Other neoclassical composers

[edit]Some composers below may have only written music in a neoclassical style during a portion of their careers.

- Arthur Berger (1912–2003)

- Carlos Chávez (1899–1978)[37]

- Salvador Contreras (1910–1982)

- Pierre Gabaye (1930–2019)

- Harald Genzmer (1909–2007)

- Giorgio Federico Ghedini (1892–1965)

- Vagn Holmboe (1909–1996)

- Stefan Kisielewski (1911–1991)

- Iša Krejčí (1904–1968)

- Ernst Krenek (1900–1991)

- Franco Margola (1908-1992)

- Marcel Mihalovici (1898–1985)

- Giorgio Pacchioni (born 1947)

- Goffredo Petrassi (1904–2003)

- Gabriel Pierné (1863–1937)[38][39][40]

- Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)

- Knudåge Riisager (1897–1974)

- Albert Roussel (1869–1937)

- Alexandre Tansman (1897–1986)

- Michael Tippett (1905–1998)

- Dag Wirén (1905–1986)

See also

[edit]Sources

[edit]- Bónis, Ferenc (1983). "Zoltán Kodály, a Hungarian Master of Neoclassicism". Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 25 (1–4): 73–91.

- Cone, Edward T. (July 1962). "The Uses of Convention: Stravinsky and His Models". The Musical Quarterly. XLVIII (3): 287–299. doi:10.1093/mq/XLVIII.3.287.

- Cowell, Henry (March–April 1933). "Towards Neo-Primitivism". Modern Music. 10 (3): 149–53. Reprinted in Essential Cowell: Selected Writings on Music by Henry Cowell 1921–1964, edited by Richard Carter Higgins and Bruce McPherson, preface by Kyle Gann, pp. 299–303. Kingston, New York City: Documentext, 2002. ISBN 978-0-929701-63-9.

- Hess, Carol A. (Spring 2013). "Copland in Argentina: Pan Americanist Politics, Folklore, and the Crisis in Modern Music". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 66 (1): 191–250. doi:10.1525/jams.2013.66.1.191.

- Malipiero, Gian Francesco. 1952. [Essay?]. In L'opera di Gian Francesco Malipiero: Saggi di scrittori italiani e stranieri con una introduzione di Guido M. Gatti, seguiti dal catalogo delle opere con annotazioni dell'autore e da ricordi e pensieri dello stesso, edited by Guido Maggiorino Gatti, [page needed] Treviso: Edizioni di Treviso.

- Moody, Ivan (1996). "'Mensagens': Portuguese Music in the 20th Century". Tempo, new series, no. 198 (October): 2–10.

- Rosen, Charles (1975). Arnold Schoenberg. Modern Masters. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-13316-7 (cloth) ISBN 0-670-01986-0 (pbk). UK edition, titled simply Schoenberg. London: Boyars; Glasgow: W. Collins ISBN 0-7145-2566-9 Paperback reprint, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981. ISBN 0-691-02706-4.

- Ross, Alex (2010). "Strauss's Place in the Twentieth Century". In Charles Youmans (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Richard Strauss. Cambridge Companions to Music Series. Cambridge and New York City: Cambridge University Press. pp. 195–212. ISBN 9780521728157.

- Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 9780195170672.

- Sorce Keller, Marcello (1978). "A Bent for Aphorisms: Some Remarks about Music and about His Own Music by Gian Francesco Malipiero". The Music Review. 39 (3–4): 231–239.

Footnotes

- ^ Albright, Daniel (2004). Modernism and Music: An Anthology of Sources. University of Chicago Press. p. 276. ISBN 0-226-01267-0.

- ^ Whittall, Arnold (1980). "Neo-classicism". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, edited by Stanley Sadie. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- ^ Prokofiev, Sergey (1991). "Short Autobiography", translated by Rose Prokofieva, revised and corrected by David Mather. In Soviet Diary 1927 and Other Writings. London: Faber and Faber. p. 273. ISBN 0-571-16158-8.

- ^ Ross 2010, p. 207.

- ^ Malipiero 1952, p. 340, cited from Sorce Keller 1978.[page needed][failed verification]

- ^ Cone 1962, p. 291.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001, "Stravinsky, Igor" (§8) by Stephen Walsh.

- ^ Large, Brian (1976). Martinu. Teaneck NJ: Holmes & Meier. p. 100. ISBN 978-0841902565.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Simms, Bryan R. 1986. "Twentieth-Century Composers Return to the Small Ensemble". In The Orchestra: A Collection of 23 Essays on Its Origins and Transformations, edited by Joan Peyser, 453–74. New York City: Charles Scribner's Sons p. 462. Reprinted in paperback, Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2006. ISBN 978-1-4234-1026-3.

- ^ Heisler, Wayne (2009). The Ballet Collaborations of Richard Strauss. Rochester: University of Rochester Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-58046-321-8 .

- ^ Bónis 1983 , стр. 73-4.

- ^ Самсон, Джим (1977). Музыка в переходе: исследование тональной экспансии и атональности, 1900–1920 . Нью -Йорк: WW Norton & Company. п. 28 ISBN 0-393-02193-9 .

- ^ Busoni, Ferruccio (1957). Суть музыки и другие бумаги . Перевод Розамонд Лей. Лондон: Роклифф. п. 20

- ^ Хесс, Кэрол А. (2001). Мануэль де Фалла и модернизм в Испании, 1898–1936 . Университет Чикагской Прессы. С. 3–8. ISBN 9780226330389 .

- ^ New Grove Dikc. 2001 , "Фалла, Мануэль де" Кэрол А. Хесс.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001 , «Герхард, Роберто [Герхард Оттенвелдер, Роберт]» Малком Макдональд.

- ^ New Grove Dikc. 2001 , «Испания: художественная музыка 6: 20 век.

- ^ New Grove Dikc. 2001 , Шория, Сальвадан Хейн.

- ^ New Grove Dikc. 2001 , Фернандо (Виллар).

- ^ New Grove Dikc. 2001 , "Баутиста, Юлиан" Сусана Сальгадо.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001 , «Казелла, Альфредо» Джона К.Г. Уотерхауса и Вирджилио Бернардони.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001 , «Кастельнуово-подъездной, Марио» Джеймса Уэстби.

- ^ Муди 1996 , с. 4

- ^ Hess 2013 , с. 205–6.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001 , «Аргентина» (i) Джерарда Бехагу и Ирма Руиза.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный New Grove Dict. 2001 , «Бразилия» Джерарда Бехагу .

- ^ New Grove Dikc. 2001 , "Лобос, Гитор "

- ^ New Grove Dikc. 2001 , "Гуарнирри, Джерард Бехаг .

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001 , «Кригер, Эдино» Джерарда Бехагу .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Hess 2013 , p. 205.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001 , «Куба, Республика» Джерарда Бехагу и Робин Мур.

- ^ New Grove Dict. . Эли Родригес

- ^ Коуэлл 1933 , с. 150; Розен 1975 , с. 70–3.

- ^ Кейлор, Джон (2009). « Вариации для оркестра, соч. 31 ». allmusic.com Сайт . (Доступ 4 апреля 2010 г.).

- ^ Розен 1975 , с. 87

- ^ Розен 1975 , с. 102

- ^ Oja, Кэрол Дж. 2000. Создание музыки современной: Нью -Йорк в 1920 -х годах . Оксфорд и Нью -Йорк: издательство Оксфордского университета. С. 275–9. ISBN 978-0-19-516257-8 .

- ^ Huritz, David (ND). " Пьерн Тен С ". Classicstoday.com (Acesde 1 июля 2015 г.).

- ^ Льюис, дядя Дейв (ND). « Кристиан Ивальди / Солисты из Люксембургского филармонического оркестра: Габриэль Пьерн: камерная музыка, вып. 2 ”Allmusic Review (Accesed 1 июля 2015 г.).

- ^ Шарп, Родерик Л. (2009). Габриэль Пьерн (Б. Мец, Лорейн, 16 августа 1863 г. - д . « Конрад фон Абель и феноменология музыки: Repcoptoire & Opera Explorer : Vorworte - Префексы. Мюнхен: Musikproduktion Юрген Холих.

Дальнейшее чтение

[ редактировать ]- Lanza, Andrea (2008). «Схема итальянской инструментальной музыки в 20 -м веке». Сонус: Журнал исследований глобальных музыкальных возможностей 29, нет. 1: 1–21. ISSN 0739-229X

- Мессы, Скотт (1988). Неклассицизм в музыке: от генезиса концепции через полемику Шенберга/Стравинского . Рочестер, Нью -Йорк: Университет Рочестер Пресс. ISBN 978-1-878822-73-4 .

- Саладо, Сьюзен (2001b). "Камано, Роберто" под экраном Стэнли Сэди. Лондон: Macmillan Pubbashers.

- Стравинский, Игорь (1970). Поэтика музыки в форме шести уроков (от лекций Чарльза Элиота Нортона, проведенных в 1939–1940 годах). Гарвардский колледж, 1942. Английский перевод Артура Кноделла и Ингольфа Даля, Предисловие Джорджа Сефериса. Кембридж: издательство Гарвардского университета. ISBN 0-674-67855-9 .

- New Grove Dict. 2001 , «Неоклассизм» Арнольда Уитталла.