Израиль

Государство Израиль | |

|---|---|

| Гимн: Хатиква ( ). Надежда | |

Israel within internationally recognized borders shown in dark green; Israeli-occupied territories shown in light green | |

| Capital and largest city | Jerusalem (limited recognition)[fn 1][fn 2] 31°47′N 35°13′E / 31.783°N 35.217°E |

| Official language | Hebrew[8] |

| Special status | Arabic[fn 3] |

| Ethnic groups (2023)[12] | |

| Religion (2016)[13] | |

| Demonym(s) | Israeli |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Isaac Herzog | |

| Benjamin Netanyahu | |

| Amir Ohana | |

| Uzi Vogelman (acting) | |

| Legislature | Knesset |

| Establishment | |

| 14 May 1948 | |

| 11 May 1949 | |

| 19 July 2018 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 22,072 or 20,770[14][15] km2 (8,522 or 8,019 sq mi)[a] (149th) |

• Water (%) | 2.71[16] |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 9,900,000[17] (93rd) |

• 2022 census | 9,601,720[18][fn 4] |

• Density | 451/km2 (1,168.1/sq mi) (29th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2018) | 34.8[fn 4][20] medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | very high (25th) |

| Currency | New shekel (₪) (ILS) |

| Time zone | UTC+2:00 (IST) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3:00 (IDT) |

| Date format | |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +972 |

| ISO 3166 code | IL |

| Internet TLD | .il |

| |

Израиль , [ а ] официально Государство Израиль , [ б ] — страна в регионе Южного Леванта в Западной Азии . Она граничит с Ливаном и Сирией на севере, с Западным берегом реки Иордан и Иорданией на востоке, с сектором Газа и Египтом на юго-западе и со Средиземным морем на западе. [ 22 ] Страна также имеет небольшую береговую линию на Красном море в самой южной точке, а часть Мертвого моря проходит вдоль ее восточной границы. Провозглашенная столица Израиля находится в Иерусалиме . [ 23 ] в то время как Тель-Авив страны является крупнейшим городским районом и экономическим центром .

Израиль расположен в регионе, известном евреям как Земля Израиля , что является синонимом Палестинского региона , Святой Земли и Ханаана . В древности здесь проживала ханаанская цивилизация, за которой следовали царства Израиля и Иуды . Расположенный на перекрестке континентов , этот регион претерпел демографические изменения под властью различных империй, от Римской до Османской . [ 24 ] Европейский антисемитизм в конце 19 века активизировал сионизм , который искал еврейской родины в Палестине и получил поддержку Великобритании . После Первой мировой войны Великобритания оккупировала этот регион и в 1920 году основала Подмандатную Палестину. Увеличение еврейской иммиграции в преддверии Холокоста и британской колониальной политики привело к межобщинному конфликту между евреями и арабами . [25][26] которая переросла в гражданскую войну в 1947 году после того, как ООН предложила разделить землю между ними.

The State of Israel declared its establishment on 14 May 1948. The armies of neighboring Arab states invaded the area of the former Mandate the next day, beginning the First Arab–Israeli War. Subsequent armistice agreements established Israeli control over 77 percent of the former Mandate territory.[27][28][29] The majority of Palestinian Arabs were either expelled or fled in what is known as the Nakba, with those remaining becoming the new state's main minority.[30][31][32] Over the following decades, Israel's population increased massively as the country received an influx of Jews who emigrated, fled or were expelled from the Muslim world.[33][34] Following the 1967 Six-Day War Israel occupied the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Egyptian Sinai Peninsula and Syrian Golan Heights. Israel established and continues to expand settlements across the illegally occupied territories, contrary to international law, and has effectively annexed East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights in moves largely unrecognized internationally. After the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Israel signed peace treaties with Egypt—returning the Sinai in 1982—and Jordan. In the 2020s it normalized relations with more Arab countries. However, efforts to resolve the Israeli–Palestinian conflict after the interim Oslo Accords have not succeeded, and the country has engaged in several wars and clashes with Palestinian militant groups. Israel's practices in the occupied territories have drawn sustained international criticism, including accusations of war crimes against Palestinians from human rights advocates and United Nations officials.

The country's Basic Laws establish a unicameral parliament elected by proportional representation, the Knesset, which determines the makeup of the government headed by the prime minister and elects the figurehead president.[35] Israel is the only country to have a revived official language, Hebrew. Its culture comprises Jewish and Jewish diaspora elements alongside Arab influences, involving cuisine, music, and art. Israel has one of the biggest economies in the Middle East and among the highest GDP per capita and standards of living in Asia. One of the most technologically advanced and developed countries in the world, it spends proportionally more on research and development than any other and is widely believed to possess nuclear weapons.[36][37][38][39][40][41] The country joined the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in 2010 and has the only above-replacement fertility rate among its members.[42][43][44]

Etymology

Under the British Mandate (1920–1948), the whole region was known as Palestine.[45] Upon establishment in 1948, the country formally adopted the name State of Israel (Hebrew: מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, [mediˈnat jisʁaˈʔel]; Arabic: دَوْلَة إِسْرَائِيل, Dawlat Isrāʼīl, [dawlat ʔisraːˈʔiːl]) after other proposed names including Land of Israel (Eretz Israel), Ever (from ancestor Eber), Zion, and Judea, were considered but rejected.[46] The name Israel was suggested by Ben-Gurion and passed by a vote of 6–3.[47] In the early weeks after establishment, the government chose the term Israeli to denote a citizen of the Israeli state.[48]

The names Land of Israel and Children of Israel have historically been used to refer to the biblical Kingdom of Israel and the entire Jewish people respectively.[49] The name Israel (Hebrew: Yīsrāʾēl; Septuagint Greek: Ἰσραήλ, Israēl, "El (God) persists/rules", though after Hosea 12:4 often interpreted as "struggle with God") refers to the patriarch Jacob who, according to the Hebrew Bible, was given the name after he successfully wrestled with the angel of the Lord.[50] The earliest known archaeological artefact to mention the word Israel as a collective is the Merneptah Stele of ancient Egypt (dated to the late 13th century BCE).[51]

History

Prehistory

Early hominin presence in the Levant, where Israel is located, dates back at least 1.5 million years based on the Ubeidiya prehistoric site.[52] The Skhul and Qafzeh hominins, dating back 120,000 years, are some of the earliest traces of anatomically modern humans outside of Africa.[53] The Natufian culture emerged by the 10th millennium BCE,[54] followed by the Ghassulian culture by around 4,500 BCE.[55]

Bronze and Iron Ages

Early references to "Canaanites" and "Canaan" appear in Near Eastern and Egyptian texts (c. 2000 BCE); these populations were structured as politically independent city-states.[56][57] During the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 BCE), large parts of Canaan formed vassal states of the New Kingdom of Egypt.[58] As a result of the Late Bronze Age collapse, Canaan fell into chaos, and Egyptian control over the region collapsed.[59][60]

A people named Israel appear for the first time in the Merneptah Stele, an ancient Egyptian inscription which dates to about 1200 BCE.[61][62][fn 5][64] Ancestors of the Israelites are thought to have included ancient Semitic-speaking peoples native to this area.[65]: 78–79 Modern archaeological accounts suggest that the Israelites and their culture branched out of the Canaanite peoples[66] through the development of a distinct monolatristic—and later monotheistic—religion centered on Yahweh.[67][68] They spoke an archaic form of Hebrew, known as Biblical Hebrew.[69] Around the same time, the Philistines settled on the southern coastal plain.[70][71]

Modern archaeology has largely discarded the historicity of the narrative in the Torah and instead views the narrative as the Israelites' national myth.[72] However, some elements of these traditions do appear to have historical roots.[73][74][75] There is debate about the earliest existence of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah and their extent and power. While it is unclear if there was ever a United Kingdom of Israel,[76][77] historians and archaeologists agree that the northern Kingdom of Israel existed by ca. 900 BCE[78]: 169–195 [79] and the Kingdom of Judah by ca. 850 BCE.[80][81] The Kingdom of Israel was the more prosperous of the two and soon developed into a regional power, with a capital at Samaria;[82][83][84] during the Omride dynasty, it controlled Samaria, Galilee, the upper Jordan Valley, the Sharon and large parts of the Transjordan.[85]

The Kingdom of Israel was conquered around 720 BCE by the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[86] The Kingdom of Judah, under Davidic rule with its capital in Jerusalem, later became a client state of first the Neo-Assyrian Empire and then the Neo-Babylonian Empire. It is estimated that the region's population was around 400,000 in the Iron Age II.[87] In 587/6 BCE, following a revolt in Judah, King Nebuchadnezzar II besieged and destroyed Jerusalem and Solomon's Temple,[88][89] dissolved the kingdom and exiled much of the Judean elite to Babylon.[90]

Classical antiquity

After capturing Babylon in 539 BCE, Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid Empire, issued a proclamation allowing the exiled Judean population to return to Judah.[91][92] The construction of the Second Temple was completed c. 520 BCE.[91] The Achaemenids ruled the region as the province of Yehud Medinata.[93] In 332 BCE, Alexander the Great of Macedon conquered the region as part of his campaign against the Achaemenid Empire. After his death, the area was controlled by the Ptolemaic and Seleucid empires as a part of Coele-Syria. Over the ensuing centuries, the Hellenization of the region led to cultural tensions that came to a head during the reign of Antiochus IV, giving rise to the Maccabean Revolt of 167 BCE. The civil unrest weakened Seleucid rule and in the late 2nd century the semi-autonomous Hasmonean Kingdom of Judea arose, eventually attaining full independence and expanding into neighboring regions.[94][95][96]

The Roman Republic invaded the region in 63 BCE, first taking control of Syria, and then intervening in the Hasmonean Civil War. The struggle between pro-Roman and pro-Parthian factions in Judea led to the installation of Herod the Great as a dynastic vassal of Rome. In 6 CE, the area was annexed as the Roman province of Judaea; tensions with Roman rule led to a series of Jewish–Roman wars, resulting in widespread destruction. The First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE) resulted in the destruction of Jerusalem and the Second Temple and a sizable portion of the population being killed or displaced.[97]

A second uprising known as the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 CE) initially allowed the Jews to form an independent state, but the Romans brutally crushed the rebellion, devastating and depopulating Judea's countryside.[97][98][99][100][101] Jerusalem was rebuilt as a Roman colony (Aelia Capitolina), and the province of Judea was renamed Syria Palaestina.[102][103] Jews were expelled from the districts surrounding Jerusalem.[104][100] Nevertheless, there was a continuous small Jewish presence and Galilee became its religious center.[105][106]

Late antiquity and the medieval period

Early Christianity displaced Roman paganism in the 4th century CE, with Constantine embracing and promoting the Christian religion and Theodosius I making it the state religion. A series of laws were passed that discriminated against Jews and Judaism, and Jews were persecuted by both the church and the authorities.[108] Many Jews had emigrated to flourishing Diaspora communities,[109] while locally there was both Christian immigration and local conversion. By the middle of the 5th century, there was a Christian majority.[110][111] Towards the end of the 5th century, Samaritan revolts erupted, continuing until the late 6th century and resulting in a large decrease in the Samaritan population.[112] After the Sasanian conquest of Jerusalem and the short-lived Jewish revolt against Heraclius in 614 CE, the Byzantine Empire reconsolidated control of the area in 628.[113]

In 634–641 CE, the Rashidun Caliphate conquered the Levant.[109][114][115] Over the next six centuries, control of the region transferred between the Umayyad, Abbasid, Fatimid caliphates, and subsequently the Seljuks and Ayyubid dynasties.[116] The population drastically decreased during the following several centuries, dropping from an estimated 1 million during Roman and Byzantine periods to about 300,000 by the early Ottoman period, and there was a steady process of Arabization and Islamization.[115][114][117][87][24] The end of the 11th century brought the Crusades, papally-sanctioned incursions of Christian crusaders intent on wresting Jerusalem and the Holy Land from Muslim control and establishing Crusader States.[118] The Ayyubids pushed back the crusaders before Muslim rule was fully restored by the Mamluk sultans of Egypt in 1291.[119]

Modern period and the emergence of Zionism

In 1516, the Ottoman Empire conquered the region and ruled it as part of Ottoman Syria.[120] Two violent incidents took place against Jews, the 1517 Safed attacks and the 1517 Hebron attacks, after the Turkish Ottomans ousted the Mamluks during the Ottoman–Mamluk War.[121][122] Under the Ottoman Empire, the Levant was fairly cosmopolitan, with religious freedoms for Christians, Muslims, and Jews. In 1561 the Ottoman sultan invited Sephardi Jews escaping the Spanish Inquisition to settle in and rebuild the city of Tiberias.[123][124]

Under the Ottoman Empire's millet system, Christians and Jews were considered dhimmi (meaning "protected") under Ottoman law in exchange for loyalty to the state and payment of the jizya tax.[125][126] Non-Muslim Ottoman subjects faced geographic and lifestyle restrictions, though these were not always enforced.[127][128][129] The millet system organized non-Muslims into autonomous communities on the basis of religion.[130]

Since the existence of the Jewish diaspora, many Jews have aspired to return to "Zion".[131] The Jewish population of Palestine from the Ottoman rule to the beginning of the Zionist movement, known as the Old Yishuv, comprised a minority and fluctuated in size. During the 16th century, Jewish communities struck roots in the Four Holy Cities—Jerusalem, Tiberias, Hebron, and Safed—and in 1697, Rabbi Yehuda Hachasid led a group of 1,500 Jews to Jerusalem.[132] A 1660 Druze revolt against the Ottomans destroyed Safed and Tiberias.[120] In the second half of the 18th century, Eastern European Jews who were opponents of Hasidism, known as the Perushim, settled in Palestine.[133][134]

In the late 18th century, local Arab Sheikh Zahir al-Umar created a de facto independent Emirate in the Galilee. Ottoman attempts to subdue the Sheikh failed. After Zahir's death the Ottomans regained control of the area. In 1799, governor Jazzar Pasha repelled an assault on Acre by Napoleon's troops, prompting the French to abandon the Syrian campaign.[135] In 1834, a revolt by Palestinian Arab peasants against Egyptian conscription and taxation policies under Muhammad Ali was suppressed; Muhammad Ali's army retreated and Ottoman rule was restored with British support in 1840.[136] The Tanzimat reforms were implemented across the Ottoman Empire.

The first wave of modern Jewish migration to Ottoman-ruled Palestine, known as the First Aliyah, began in 1881, as Jews fled pogroms in Eastern Europe.[137] The 1882 May Laws increased economic discrimination against Jews, and restricted where they could live.[138][139] In response, political Zionism took form, a movement that sought to establish a Jewish state in the Land of Israel, thus offering a solution to the Jewish question of the European states.[140]

The Second Aliyah (1904–1914) began after the Kishinev pogrom; some 40,000 Jews settled in Palestine, although nearly half left eventually. Both the first and second waves of migrants were mainly Orthodox Jews.[141] The Second Aliyah included Zionist socialist groups who established the kibbutz movement based on the idea of establishing a separate Jewish economy based exclusively on Jewish labor.[142][143] Those of the Second Aliyah who became leaders of the Yishuv in the coming decades believed that the Jewish settler economy should not depend on Arab labor. This would be a dominant source of antagonism with the Arab population, with the new Yishuv's nationalist ideology overpowering its socialist one.[144] Though the immigrants of the Second Aliyah largely sought to create communal Jewish agricultural settlements, Tel Aviv was established as the first planned Jewish town in 1909. Jewish armed militias emerged during this period, the first being Bar-Giora in 1907. Two years later, the larger Hashomer organization was founded as its replacement.

British Mandate for Palestine

Chaim Weizmann's efforts to garner British support for the Zionist movement eventually secured the Balfour Declaration (1917),[145] stating Britain's support for the creation of a Jewish "national home" in Palestine.[146][147] Weizmann's interpretation of the declaration was that negotiations on the future of the country were to happen directly between Britain and the Jews, excluding Arabs. The years that followed would see Jewish-Arab relations in Palestine deteriorate dramatically.[148]

In 1918, the Jewish Legion, primarily Zionist volunteers, assisted in the British conquest of Palestine.[149] In 1920, the territory was divided between Britain and France under the mandate system, and the British-administered area (including modern Israel) was named Mandatory Palestine.[119][150][151] Arab opposition to British rule and Jewish immigration led to the 1920 Palestine riots and the formation of a Jewish militia known as the Haganah as an outgrowth of Hashomer, from which the Irgun and Lehi paramilitaries later split.[152] In 1922, the League of Nations granted Britain the Mandate for Palestine under terms which included the Balfour Declaration with its promise to the Jews, and with similar provisions regarding the Arab Palestinians.[153] The population of the area was predominantly Arab and Muslim, with Jews accounting for about 11%,[154] and Arab Christians about 9.5% of the population.[155]

The Third (1919–1923) and Fourth Aliyahs (1924–1929) brought an additional 100,000 Jews to Palestine. The rise of Nazism and the increasing persecution of Jews in 1930s Europe led to the Fifth Aliyah, with an influx of a quarter of a million Jews. This was a major cause of the Arab revolt of 1936–39, which was suppressed by British security forces and Zionist militias. Several hundred British security personnel and Jews were killed. 5,032 Arabs were killed, 14,760 were wounded, and 12,622 were detained.[156][157][158] An estimated ten percent of the adult male Palestinian Arab population was killed, wounded, imprisoned or exiled.[159]

The British introduced restrictions on Jewish immigration to Palestine with the White Paper of 1939. With countries around the world turning away Jewish refugees fleeing the Holocaust, a clandestine movement known as Aliyah Bet was organized to bring Jews to Palestine. By the end of World War II, 31% of the total population of Palestine was Jewish.[160] The UK found itself facing a Jewish insurgency over immigration restrictions and continued conflict with the Arab community over limit levels. The Haganah joined Irgun and Lehi in an armed struggle against British rule.[161] The Haganah attempted to bring tens of thousands of Jewish refugees and Holocaust survivors to Palestine by ship in a programme called Aliyah Bet. Most of the ships were intercepted by the Royal Navy and the refugees placed in detention camps in Atlit and Cyprus.[162][163]

On 22 July 1946, Irgun bombed the British administrative headquarters for Palestine, killing 91.[164][165][166][167][168][169] The attack was a response to Operation Agatha (a series of raids, including one on the Jewish Agency, by the British) and was the deadliest directed at the British during the Mandate era.[168][169] The Jewish insurgency continued throughout 1946 and 1947 despite concerted efforts by the British military and Palestine Police Force to suppress it. British efforts to mediate a negotiated solution with Jewish and Arab representatives also failed as the Jews were unwilling to accept any solution that did not involve a Jewish state and suggested a partition of Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, while the Arabs were adamant that a Jewish state in any part of Palestine was unacceptable and that the only solution was a unified Palestine under Arab rule. In February 1947, the British referred the Palestine issue to the newly formed United Nations. On 15 May 1947, the UN General Assembly resolved that a Special Committee be created "to prepare ... a report on the question of Palestine".[170] The Report of the Committee[171] proposed a plan to replace the British Mandate with "an independent Arab State, an independent Jewish State, and the City of Jerusalem [...] the last to be under an International Trusteeship System".[172] Meanwhile, the Jewish insurgency continued and peaked in July 1947, with a series of widespread guerrilla raids culminating in the Sergeants affair, in which the Irgun took two British sergeants hostage as attempted leverage against the planned execution of three Irgun operatives. After the executions were carried out, the Irgun killed the two British soldiers, hanged their bodies from trees, and left a booby trap at the scene which injured a British soldier. The incident caused widespread outrage in the UK.[173] In September 1947, the British cabinet decided to evacuate Palestine as the Mandate was no longer tenable.[174]

On 29 November 1947, the General Assembly adopted Resolution 181 (II).[175] The plan attached to the resolution was essentially that proposed in the report of 3 September. The Jewish Agency, the recognized representative of the Jewish community, accepted the plan, which assigned 55–56% of Mandatory Palestine to the Jews. At the time, the Jews were about a third of the population and owned around 6–7% of the land. Arabs constituted the majority and owned about 20% of the land, with the remainder held by the Mandate authorities or foreign landowners.[176][177][178][179][180][181][182] The Arab League and Arab Higher Committee of Palestine rejected it,[183] and indicated that they would reject any other plan of partition.[184][185] On 1 December 1947, the Arab Higher Committee proclaimed a three-day strike, and riots broke out in Jerusalem.[186] The situation spiraled into a civil war. Colonial Secretary Arthur Creech Jones announced that the British Mandate would end on 15 May 1948, at which point the British would evacuate. As Arab militias and gangs attacked Jewish areas, they were faced mainly by the Haganah, as well as the smaller Irgun and Lehi. In April 1948, the Haganah moved onto the offensive.[187][188] During this period 250,000 Palestinian Arabs fled or were expelled, due to numerous factors.[189]

State of Israel

Establishment and early years

On 14 May 1948, the day before the expiration of the British Mandate, David Ben-Gurion, the head of the Jewish Agency, declared "the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz-Israel".[190] The only reference in the text of the Declaration to the borders of the new state is the use of the term Eretz-Israel ("Land of Israel").[citation needed] The following day, the armies of four Arab countries—Egypt, Syria, Transjordan and Iraq—entered what had been Mandatory Palestine, launching the 1948 Arab–Israeli War;[191][192][193] contingents from Yemen, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and Sudan joined the war.[194][195] The apparent purpose of the invasion was to prevent the establishment of the Jewish state; some Arab leaders talked about "driving the Jews into the sea".[181][196][197] The Arab league stated the invasion was to restore order and prevent further bloodshed.[198]

After a year of fighting, a ceasefire was declared and temporary borders, known as the Green Line, were established.[199] Jordan annexed what became known as the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and Egypt occupied the Gaza Strip. Over 700,000 Palestinians were expelled by or fled by Zionist militias and the Israeli military—what would become known in Arabic as the Nakba ('catastrophe').[200] The events also led to the destruction of most of Palestine's predominantly Arab population's society, culture, identity, political rights, and national aspirations. Some 156,000 remained and became Arab citizens of Israel.[201]

Israel was admitted as a member of the UN on 11 May 1949.[202] In the early years of the state, the Labor Zionist movement led by Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion dominated Israeli politics.[203][204] Immigration to Israel during the late 1940s and early 1950s was aided by the Israeli Immigration Department and the non-government sponsored Mossad LeAliyah Bet (lit. "Institute for Immigration B").[205] The latter engaged in clandestine operations in countries, particularly in the Middle East and Eastern Europe, where the lives of Jews were believed to be in danger and exit was difficult. Mossad LeAliyah Bet was disbanded in 1953.[206] The immigration was in accordance with the One Million Plan. Some immigrants held Zionist beliefs or came for the promise of a better life, while others moved to escape persecution or were expelled.[207][208]

An influx of Holocaust survivors and Jews from Arab and Muslim countries to Israel during the first three years increased the number of Jews from 700,000 to 1,400,000. By 1958, the population had risen to two million.[209] Between 1948 and 1970, approximately 1,150,000 Jewish refugees relocated to Israel.[210] Some new immigrants arrived as refugees and were housed in temporary camps known as ma'abarot; by 1952, over 200,000 people were living in these tent cities.[211] Jews of European background were often treated more favorably than Jews from Middle Eastern and North African countries—housing units reserved for the latter were often re-designated for the former, so Jews newly arrived from Arab lands generally ended up staying longer in transit camps.[212][213] During this period, food, clothes and furniture were rationed in what became known as the austerity period. The need to solve the crisis led Ben-Gurion to sign a reparations agreement with West Germany that triggered mass protests by Jews angered at the idea that Israel could accept monetary compensation for the Holocaust.[214]

Arab–Israeli conflict

During the 1950s, Israel was frequently attacked by Palestinian fedayeen, nearly always against civilians,[215] mainly from the Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip,[216] leading to several Israeli reprisal operations. In 1956, the UK and France aimed at regaining control of the Suez Canal, which Egypt had nationalized. The continued blockade of the Suez Canal and Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping, together with increasing Fedayeen attacks against Israel's southern population and recent Arab threatening statements, prompted Israel to attack Egypt.[217][218][219] Israel joined a secret alliance with the UK and France and overran the Sinai Peninsula in the Suez Crisis, but was pressured to withdraw by the UN in return for guarantees of Israeli shipping rights.[220][221][222] The war resulted in significant reduction of Israeli border infiltration.[223]

In the early 1960s, Israel captured Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in Argentina and brought him to Israel for trial.[224] Eichmann remains the only person executed in Israel by conviction in an Israeli civilian court.[225] In 1963 Israel was engaged in a diplomatic standoff with the United States due to the Israeli nuclear programme.[226][227]

Since 1964, Arab countries, concerned over Israeli plans to divert waters of the Jordan River into the coastal plain,[228] had been trying to divert the headwaters to deprive Israel of water resources, provoking tensions between Israel on the one hand, and Syria and Lebanon on the other. Arab nationalists led by Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser refused to recognize Israel and called for its destruction.[229][230][231] By 1966, Israeli-Arab relations had deteriorated to the point of battles taking place between Israeli and Arab forces.[232]

In May 1967, Egypt massed its army near the border with Israel, expelled UN peacekeepers, stationed in the Sinai Peninsula since 1957, and blocked Israel's access to the Red Sea.[233][234][235] Other Arab states mobilized their forces.[236] Israel reiterated that these actions were a casus belli and launched a pre-emptive strike against Egypt in June. Jordan, Syria and Iraq attacked Israel. In the Six-Day War, Israel captured and occupied the West Bank from Jordan, the Gaza Strip and Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, and the Golan Heights from Syria.[237] Jerusalem's boundaries were enlarged, incorporating East Jerusalem. The 1949 Green Line became the administrative boundary between Israel and the occupied territories.[238]

Following the 1967 war and the "Three Nos" resolution of the Arab League, Israel faced attacks from the Egyptians in the Sinai Peninsula during the 1967–1970 War of Attrition, and from Palestinian groups targeting Israelis in the occupied territories, globally, and in Israel. Most important among the Palestinian and Arab groups was the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), established in 1964, which initially committed itself to "armed struggle as the only way to liberate the homeland".[239] In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Palestinian groups launched attacks[240][241] against Israeli and Jewish targets around the world,[242] including a massacre of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich. The Israeli government responded with an assassination campaign against the organizers of the massacre, a bombing and a raid on the PLO headquarters in Lebanon.

On 6 October 1973, the Egyptian and Syrian armies launched a surprise attack against Israeli forces in the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights, opening the Yom Kippur War. The war ended on 25 October with Israel repelling Egyptian and Syrian forces but suffering great losses.[243] An internal inquiry exonerated the government of responsibility for failures before and during the war, but public anger forced Prime Minister Golda Meir to resign.[244][better source needed] In July 1976, an airliner was hijacked in flight from Israel to France by Palestinian guerrillas; Israeli commandos rescued 102 out of 106 Israeli hostages.

Peace process

The 1977 Knesset elections marked a major turning point in Israeli political history as Menachem Begin's Likud party took control from the Labor Party.[245] Later that year, Egyptian President Anwar El Sadat made a trip to Israel and spoke before the Knesset in what was the first recognition of Israel by an Arab head of state.[246] Sadat and Begin signed the Camp David Accords (1978) and the Egypt–Israel peace treaty (1979).[247] In return, Israel withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula and agreed to enter negotiations over autonomy for Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.[247]

On 11 March 1978, a PLO guerilla raid from Lebanon led to the Coastal Road massacre. Israel responded by launching an invasion of southern Lebanon to destroy PLO bases. Most PLO fighters withdrew, but Israel was able to secure southern Lebanon until a UN force and the Lebanese army could take over. The PLO soon resumed its insurgency against Israel, and Israel carried out numerous retaliatory attacks.

Meanwhile, Begin's government provided incentives for Israelis to settle in the occupied West Bank, increasing friction with the Palestinians there.[248] The Jerusalem Law (1980) was believed by some to reaffirm Israel's 1967 annexation of Jerusalem by government decree, and reignited international controversy over the status of the city. No Israeli legislation has defined the territory of Israel and no act specifically included East Jerusalem therein.[249] In 1981 Israel effectively annexed the Golan Heights.[250] The international community largely rejected these moves, with the UN Security Council declaring both the Jerusalem Law and the Golan Heights Law null and void.[251][252] Several waves of Ethiopian Jews immigrated to Israel since the 1980s, while between 1990 and 1994, immigration from the post-Soviet states increased Israel's population by twelve percent.[253]

On 7 June 1981, during the Iran–Iraq War, the Israeli air force destroyed Iraq's sole nuclear reactor, then under construction, in order to impede the Iraqi nuclear weapons program.[254] Following a series of PLO attacks in 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon to destroy the PLO bases.[255] In the first six days, the Israelis destroyed the military forces of the PLO in Lebanon and decisively defeated the Syrians. An Israeli government inquiry (the Kahan Commission) held Begin and several Israeli generals indirectly responsible for the Sabra and Shatila massacre and held Defense minister Ariel Sharon as bearing "personal responsibility".[256] Sharon was forced to resign.[257] In 1985, Israel responded to a Palestinian terrorist attack in Cyprus by bombing the PLO headquarters in Tunisia. Israel withdrew from most of Lebanon in 1986, but maintained a borderland buffer zone in southern Lebanon until 2000, from where Israeli forces engaged in conflict with Hezbollah. The First Intifada, a Palestinian uprising against Israeli rule,[258] broke out in 1987, with waves of uncoordinated demonstrations and violence in the occupied West Bank and Gaza. Over the following six years, the Intifada became more organized and included economic and cultural measures aimed at disrupting the Israeli occupation. Over a thousand people were killed.[259] During the 1991 Gulf War, the PLO supported Saddam Hussein and Iraqi missile attacks against Israel. Despite public outrage, Israel heeded American calls to refrain from hitting back.[260][261]

In 1992, Yitzhak Rabin became prime minister following an election in which his party called for compromise with Israel's neighbours.[262][263] The following year, Shimon Peres on behalf of Israel, and Mahmoud Abbas for the PLO, signed the Oslo Accords, which gave the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) the right to govern parts of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.[264] The PLO also recognized Israel's right to exist and pledged an end to terrorism.[265] In 1994, the Israel–Jordan peace treaty was signed, making Jordan the second Arab country to normalize relations with Israel.[266] Arab public support for the Accords was damaged by the continuation of Israeli settlements[267] and checkpoints, and the deterioration of economic conditions.[268] Israeli public support for the Accords waned after Palestinian suicide attacks.[269] In November 1995, Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by Yigal Amir, a far-right Jew who opposed the Accords.[270]

During Benjamin Netanyahu's premiership at the end of the 1990s, Israel agreed to withdraw from Hebron,[271] though this was never ratified or implemented,[272] and signed the Wye River Memorandum, giving greater control to the PNA.[273] Ehud Barak, elected Prime Minister in 1999, withdrew forces from Southern Lebanon and conducted negotiations with PNA Chairman Yasser Arafat and U.S. President Bill Clinton at the 2000 Camp David Summit. Barak offered a plan for the establishment of a Palestinian state, including the entirety of the Gaza Strip and over 90% of the West Bank with Jerusalem as a shared capital.[274] Each side blamed the other for the failure of the talks.

21st century

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: the events of the last two decades outside of conflict is barely covered. (March 2023) |

In late 2000, after a controversial visit by Likud leader Ariel Sharon to the Temple Mount, the 4.5-year Second Intifada began. Suicide bombings were a recurrent feature.[276] Some commentators contend that the Intifada was pre-planned by Arafat due to the collapse of peace talks.[277][278][279][280] Sharon became prime minister in a 2001 election; he carried out his plan to unilaterally withdraw from the Gaza Strip and spearheaded the construction of the Israeli West Bank barrier,[281] ending the Intifada.[282] Between 2000 and 2008, 1,063 Israelis, 5,517 Palestinians and 64 foreign citizens were killed.[283]

In 2006, a Hezbollah artillery assault on Israel's northern border communities and a cross-border abduction of two Israeli soldiers precipitated the month-long Second Lebanon War.[284][285] In 2007, the Israeli Air Force destroyed a nuclear reactor in Syria. In 2008, a ceasefire between Hamas and Israel collapsed, resulting in the three-week Gaza War.[286][287] In what Israel described as a response to over a hundred Palestinian rocket attacks on southern Israeli cities,[288] Israel began an operation in the Gaza Strip in 2012, lasting eight days.[289] Israel started another operation in Gaza following an escalation of rocket attacks by Hamas in July 2014.[290] In May 2021, another round of fighting took place in Gaza and Israel, lasting eleven days.[291]

By the 2010s, increasing regional cooperation between Israel and Arab League countries have been established, culminating in the signing of the Abraham Accords. The Israeli security situation shifted from the traditional Arab–Israeli conflict towards the Iran–Israel proxy conflict and direct confrontation with Iran during the Syrian civil war. On 7 October 2023, Palestinian militant groups from Gaza, led by Hamas, launched a series of coordinated attacks on Israel, leading to the start of the Israel–Hamas war.[292] On that day, approximately 1300 Israelis, predominantly civilians, were killed in communities near the Gaza Strip border and during a music festival. Over 200 hostages were kidnapped and taken to the Gaza Strip.[293][294][295]

Geography

Israel is located in the Levant area of the Fertile Crescent. The country is at the eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea, bounded by Lebanon to the north, Syria to the northeast, Jordan and the West Bank to the east, and Egypt and the Gaza Strip to the southwest. It lies between latitudes 29° and 34° N, and longitudes 34° and 36° E.

The sovereign territory of Israel (according to the demarcation lines of the 1949 Armistice Agreements and excluding all territories captured by Israel during the 1967 Six-Day War) is approximately 20,770 square kilometers (8,019 sq mi), of which two percent is water.[296] However Israel is so narrow (100 km at its widest, compared to 400 km from north to south) that the exclusive economic zone in the Mediterranean is double the land area of the country.[297] The total area under Israeli law, including East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights, is 22,072 square kilometers (8,522 sq mi),[298] and the total area under Israeli control, including the military-controlled and partially Palestinian-governed territory of the West Bank, is 27,799 square kilometers (10,733 sq mi).[299]

Despite its small size, Israel is home to a variety of geographic features, from the Negev desert in the south to the inland fertile Jezreel Valley, mountain ranges of the Galilee, Carmel and toward the Golan in the north. The Israeli coastal plain on the shores of the Mediterranean is home to most of the nation's population.[300] East of the central highlands lies the Jordan Rift Valley, a small part of the 6,500-kilometer (4,039 mi) Great Rift Valley. The Jordan River runs along the Jordan Rift Valley, from Mount Hermon through the Hulah Valley and the Sea of Galilee to the Dead Sea, the lowest point on the surface of the Earth.[301] Further south is the Arabah, ending with the Gulf of Eilat, part of the Red Sea. Makhtesh, or "erosion cirques" are unique to the Negev and the Sinai Peninsula, the largest being the Makhtesh Ramon at 38 km in length.[302] Israel has the largest number of plant species per square meter of the countries in the Mediterranean Basin.[303] Israel contains four terrestrial ecoregions: Eastern Mediterranean conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf forests, Southern Anatolian montane conifer and deciduous forests, Arabian Desert, and Mesopotamian shrub desert.[304]

Forests accounted for 8.5% of the country's area in 2016, up from 2% in 1948, as the result of a large-scale forest planting program by the Jewish National Fund.[305][306]

Tectonics and seismicity

The Jordan Rift Valley is the result of tectonic movements within the Dead Sea Transform (DSF) fault system. The DSF forms the transform boundary between the African Plate to the west and the Arabian Plate to the east. The Golan Heights and all of Jordan are part of the Arabian Plate, while the Galilee, West Bank, Coastal Plain, and Negev along with the Sinai Peninsula are on the African Plate. This tectonic disposition leads to a relatively high seismic activity. The entire Jordan Valley segment is thought to have ruptured repeatedly, for instance during the last two major earthquakes along this structure in 749 and 1033. The deficit in slip that has built up since the 1033 event is sufficient to cause an earthquake of Mw ~7.4.[307]

The most catastrophic known earthquakes occurred in 31 BCE, 363, 749, and 1033 CE, that is every ca. 400 years on average.[308] Destructive earthquakes leading to serious loss of life strike about every 80 years.[309] While stringent construction regulations are in place and recently built structures are earthquake-safe, as of 2007[update] many public buildings as well as 50,000 residential buildings did not meet the new standards and were "expected to collapse" if exposed to a strong earthquake.[309]

Climate

Temperatures in Israel vary widely, especially during the winter. Coastal areas, such as those of Tel Aviv and Haifa, have a typical Mediterranean climate with cool, rainy winters and long, hot summers. The area of Beersheba and the Northern Negev have a semi-arid climate with hot summers, cool winters, and fewer rainy days. The Southern Negev and the Arava areas have a desert climate with very hot, dry summers, and mild winters with few days of rain. The highest temperature in the world outside Africa and North America as of 2021[update], 54 °C (129 °F), was recorded in 1942 in the Tirat Zvi kibbutz in the northern Jordan River valley.[310][311] Mountainous regions can be windy and cold, and areas at elevation of 750 metres (2,460 ft) or more (same elevation as Jerusalem) usually receive at least one snowfall each year.[312] From May to September, rain in Israel is rare.[313][314]

There are four different phytogeographic regions in Israel, due to the country's location between the temperate and tropical zones. For this reason, the flora and fauna are extremely diverse. There are 2,867 known species of plants in Israel. Of these, at least 253 species are introduced and non-native.[315] There are 380 Israeli nature reserves.[316]

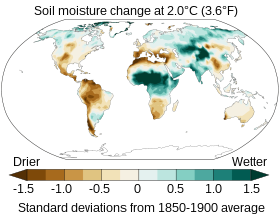

With scarce water resources, Israel has developed various water-saving technologies, including drip irrigation.[317][better source needed] The considerable sunlight available for solar energy makes Israel the leading nation in solar energy use per capita—practically every house uses solar panels for water heating.[318] The Israeli Ministry of Environmental Protection has reported that climate change "will have a decisive impact on all areas of life", particularly for vulnerable populations.[319]

Government and politics

Israel has a parliamentary system, proportional representation and universal suffrage. A member of parliament supported by a parliamentary majority becomes the prime minister—usually this is the chair of the largest party. The prime minister is the head of government and of cabinet.[320][321] The president is head of state, with limited and largely ceremonial duties.[320]

Israel is governed by a 120-member parliament, known as the Knesset. Membership of the Knesset is based on proportional representation of political parties,[322][better source needed] with a 3.25% electoral threshold, which in practice has resulted in coalition governments. Residents of Israeli settlements in the West Bank are eligible to vote[323] and after the 2015 election, 10 of the 120 members of the Knesset (8%) were settlers.[324] Parliamentary elections are scheduled every four years, but unstable coalitions or a no-confidence vote can dissolve a government earlier.[35] The first Arab-led party was established in 1988[325] and as of 2022, Arab-led parties hold about 10% of seats.[326] The Basic Law: The Knesset (1958) and its amendments prevent a party list from running for election to the Knesset if its objectives or actions include the "negation of the existence of the State of Israel as the state of the Jewish people".

The Basic Laws of Israel function as an uncodified constitution. In its Basic Laws, Israel defines itself as a Jewish and democratic state, and the nation-state of exclusively the Jewish people.[327] In 2003, the Knesset began to draft an official constitution based on these laws.[296][328]

Israel has no official religion,[329][330][331] but the definition of the state as "Jewish and democratic" creates a strong connection with Judaism. On 19 July 2018, the Knesset passed a Basic Law that characterizes the State of Israel as principally a "Nation State of the Jewish People", and Hebrew as its official language. The bill ascribes, an undefined, "special status" to the Arabic language.[332] The same bill gives Jews a unique right to national self-determination, and views the developing of Jewish settlement in the country as "a national interest", empowering the government to "take steps to encourage, advance and implement this interest".[333]

Administrative divisions

The State of Israel is divided into six main administrative districts, known as mehozot (Hebrew: מחוזות; sg.: mahoz)—Center, Haifa, Jerusalem, North, South, and Tel Aviv districts, as well as the Judea and Samaria Area in the West Bank. All of the Judea and Samaria Area and parts of the Jerusalem and Northern districts are not recognized internationally as part of Israel. Districts are further divided into fifteen sub-districts known as nafot (Hebrew: נפות; sg.: nafa), which are themselves partitioned into fifty natural regions.[334]

| District | Capital | Largest city | Population, 2021[335] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jews | Arabs | Total | note | |||

| Jerusalem | Jerusalem | 66% | 32% | 1,209,700 | a | |

| North | Nof HaGalil | Nazareth | 42% | 54% | 1,513,600 | |

| Haifa | Haifa | 67% | 25% | 1,092,700 | ||

| Center | Ramla | Rishon LeZion | 87% | 8% | 2,304,300 | |

| Tel Aviv | Tel Aviv | 92% | 2% | 1,481,400 | ||

| South | Beersheba | Ashdod | 71% | 22% | 1,386,000 | |

| Judea and Samaria Area | Ariel | Modi'in Illit | 98% | 0% | 465,400 | b |

- ^a Including 361,700 Arabs and 233,900 Jews in East Jerusalem, as of 2020[update].[336]

- ^b Israeli citizens only.

Israeli citizenship law

The two primary pieces of legislation relating to Israeli citizenship are the 1950 Law of Return and 1952 Citizenship Law. The law of return grants Jews the unrestricted right to immigrate to Israel and obtain Israeli citizenship. Individuals born within the country receive birthright citizenship if at least one parent is a citizen.[337]

Israeli law defines Jewish nationality as distinct from Israeli nationality, and the Supreme Court of Israel has ruled that an Israeli nationality does not exist.[338][339] Israeli law defines a Jewish national as any person practicing Judaism and their descendants.[338] Legislation has defined Israel as the nation state of the Jewish people since 2018.[340]

Israeli-occupied territories

| Area | Administered by | Recognition of governing authority | Sovereignty claimed by | Recognition of claim | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaza Strip | Palestinian National Authority (de jure) Controlled by Hamas (de facto) | Witnesses to the Oslo II Accord | State of Palestine | 145 UN member states | |

| West Bank | Palestinian enclaves (Areas A and B) | Palestinian National Authority and Israeli military | |||

| Area C | Israeli enclave law (Israeli settlements) and Israeli military (Palestinians under Israeli occupation) | ||||

| East Jerusalem | Israeli administration | Honduras, Guatemala, Nauru, and the United States | China, Russia | ||

| West Jerusalem | Russia, Czech Republic, Honduras, Guatemala, Nauru, and the United States | United Nations as an international city along with East Jerusalem | Various UN member states and the European Union; joint sovereignty also widely supported | ||

| Golan Heights | United States | Syria | All UN member states except the United States | ||

| Israel (Green Line border) | 165 UN member states | Israel | 165 UN member states | ||

In 1967, as a result of the Six-Day War, Israel captured and occupied the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, the Gaza Strip and the Golan Heights. Israel also captured the Sinai Peninsula, but returned it to Egypt as part of the 1979 Egypt–Israel peace treaty.[247] Between 1982 and 2000, Israel occupied part of southern Lebanon, in what was known as the Security Belt. Since Israel's capture of these territories, Israeli settlements and military installations have been built within each of them, except Lebanon.

The Golan Heights and East Jerusalem have been fully incorporated into Israel under Israeli law, but not under international law. Israel has applied civilian law to both areas and granted their inhabitants permanent residency status and the ability to apply for citizenship. The UN Security Council has declared the annexation of the Golan Heights and East Jerusalem to be "null and void" and continues to view the territories as occupied.[341][342] The status of East Jerusalem in any future peace settlement has at times been a difficult issue in negotiations between Israeli governments and representatives of the Palestinians.

The West Bank excluding East Jerusalem is known in Israeli law as the Judea and Samaria Area. The almost 400,000 Israeli settlers residing in the area are considered part of Israel's population, have Knesset representation, are subject to a large part of Israel's civil and criminal laws, and their output is considered part of Israel's economy.[343][fn 4] The land itself is not considered part of Israel under Israeli law, as Israel has consciously refrained from annexing the territory, without ever relinquishing its legal claim to the land or defining a border.[343] Israeli political opposition to annexation is primarily due to the perceived "demographic threat" of incorporating the West Bank's Palestinian population into Israel.[343] Outside of the Israeli settlements, the West Bank remains under direct Israeli military rule, and Palestinians in the area cannot become Israeli citizens. The international community maintains that Israel does not have sovereignty in the West Bank, and considers Israel's control of the area to be the longest military occupation in modern history.[346] The West Bank was occupied and annexed by Jordan in 1950, following the 1949 Armistice Agreements. Only Britain recognized this annexation and Jordan has since ceded its claim to the territory to the PLO. The population are mainly Palestinians, including refugees of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.[347] From their occupation in 1967 until 1993, the Palestinians living in these territories were under Israeli military administration. Since the Israel–PLO letters of recognition, most of the Palestinian population and cities have been under the internal jurisdiction of the Palestinian Authority, and only partial Israeli military control, although Israel has redeployed its troops and reinstated full military administration during periods of unrest. In response to increasing attacks during the Second Intifada, the Israeli government started to construct the Israeli West Bank barrier.[348] When completed, approximately 13% of the barrier will be constructed on the Green Line or in Israel with 87% inside the West Bank.[349][350]

Israel's claim of universal suffrage has been questioned due to its blurred territorial boundaries and its simultaneous extension of voting rights to Israeli settlers in the occupied territories and denial of voting rights to their Palestinian neighbours, as well as the alleged ethnocratic nature of the state.[351][352]

The Gaza Strip is considered to be a "foreign territory" under Israeli law. Israel and Egypt operate a land, air, and sea blockade of the Gaza Strip. The Gaza Strip was occupied by Israel after 1967. In 2005, as part of Israel's unilateral disengagement plan, Israel removed its settlers and forces from the territory but continues to maintain control of its airspace and waters. The international community, including numerous international humanitarian organizations and UN bodies, consider Gaza to remain occupied.[353][354][355][356][357] Following the 2007 Battle of Gaza, when Hamas assumed power in the Gaza Strip,[358] Israel tightened control of the Gaza crossings along its border, as well as by sea and air, and prevented persons from entering and exiting except for isolated cases it deemed humanitarian.[358] Gaza has a border with Egypt, and an agreement between Israel, the EU, and the PA governs how border crossings take place.[359] The application of democracy to its Palestinian citizens, and the selective application of Israeli democracy in the Israeli-controlled Palestinian territories, has been criticized.[360][361]

International opinion

The International Court of Justice said, in its 2004 advisory opinion on the legality of the construction of the Israeli West Bank barrier, that the lands captured by Israel in the Six-Day War, including East Jerusalem, are occupied territory and found that the construction of the wall within the occupied Palestinian territory violates international law.[362] Most negotiations relating to the territories have been on the basis of UN Security Council Resolution 242, which emphasizes "the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war", and calls on Israel to withdraw from occupied territories in return for normalization of relations with Arab states ("Land for peace").[363][364][365] Israel has been criticized for engaging in systematic and widespread violations of human rights in the occupied territories, including the occupation itself[366] and war crimes against civilians.[367][368][369][370] The allegations include violations of international humanitarian law[371] by the UN Human Rights Council.[372] The U.S. State Department has called reports of abuses of significant human rights of Palestinians "credible" both within Israel[373] and the occupied territories.[374] Amnesty International and other NGOs have documented mass arbitrary arrests, torture, unlawful killings, systemic abuses and impunity[375][376][377][378] in tandem with a denial of the right to Palestinian self-determination.[379][380][381][382][383] Prime Minister Netanyahu has defended the country's security forces for protecting the innocent from terrorists[384] and expressed contempt for what he describes as a lack of concern about the human rights violations committed by "criminal killers".[385]

The international community widely regards Israeli settlements in the occupied territories illegal under international law.[386] United Nations Security Council Resolution 2334 (passed 2016) states that Israel's settlement activity constitutes a "flagrant violation" of international law and demands that Israel stop such activity and fulfill its obligations as an occupying power under the Fourth Geneva Convention.[387] A United Nations special rapporteur concluded that the settlement program was a war crime under the Rome Statute,[388] and Amnesty International found that the settlement program constitutes an illegal transfer of civilians into occupied territory and "pillage", which is prohibited by the Hague Conventions and Geneva Conventions as well as being a war crime under the Rome Statute.[389]

Apartheid accusations

Israel's treatment of the Palestinians within the occupied territories have drawn widespread accusations that it is guilty of apartheid, a crime against humanity under the Rome Statute and the International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid.[390][391] The Washington Post's 2021 survey of scholars and academic experts on the Middle East found an increase from 59% to 65% of these scholars describing Israel as a "one-state reality akin to apartheid".[392][393] The claim that Israel's policies for Palestinians within Israel amount to apartheid has been affirmed by Israeli human rights organization B'tselem and international human rights organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.[391][394] Israeli human rights organization Yesh Din has also accused Israel of apartheid.[394] Amnesty's claim was criticised by politicians and representatives from Israel and its closest allies such as, the US,[395] the UK,[396] the European Commission,[397] Australia,[398] Netherlands[399] and Germany,[400] while said accusations were welcomed by Palestinians,[401] representatives from other states,[which?] and organizations such as the Arab League.[402] In 2022, Michael Lynk, a Canadian law professor appointed by the U.N. Human Rights Council said that the situation met the legal definition of apartheid, and concluded: "Israel has imposed upon Palestine an apartheid reality in a post-apartheid world".[403][404] Subsequent reports from his successor, Francesca Albanese and from Permanent United Nations Fact Finding Mission on the Israel Palestine conflict chair Navi Pillay echoed the opinion.[405][406]

In February 2024, The ICJ held public hearings in regards to the legal consequences arising from the policies and practices of Israel in the occupied Palestinian territory including East Jerusalem. During the hearings, 24 States and three international organizations said that Israeli practices amount to a breach of the prohibition of apartheid and/or amount to prohibited acts of racial discrimination.[407]

Foreign relations

Israel maintains diplomatic relations with 165 UN member states, as well as with the Holy See, Kosovo, the Cook Islands and Niue. It has 107 diplomatic missions;[408] countries with which it has no diplomatic relations include most Muslim countries.[409] Six out of twenty-two nations in the Arab League have normalized relations with Israel. Israel remains formally in a state of war with Syria, a status that dates back uninterrupted to 1948. It has been in a similarly formal state of war with Lebanon since the end of the Lebanese Civil War in 2000, with the Israel–Lebanon border remaining unagreed by treaty.

Despite the peace treaty between Israel and Egypt, Israel is still widely considered an enemy country among Egyptians.[410] Iran withdrew its recognition of Israel during the Islamic Revolution.[411] Israeli citizens may not visit Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen without permission from the Ministry of the Interior.[412] As a result of the 2008–09 Gaza War, Mauritania, Qatar, Bolivia, and Venezuela suspended political and economic ties with Israel,[413] though Bolivia renewed ties in 2019.[414]

The United States and the Soviet Union were the first two countries to recognize the State of Israel, having declared recognition roughly simultaneously.[415] Diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union were broken in 1967, following the Six-Day War, and renewed in October 1991.[416] The United States regards Israel as its "most reliable partner in the Middle East",[417] based on "common democratic values, religious affinities, and security interests".[418] The US has provided $68 billion in military assistance and $32 billion in grants to Israel since 1967, under the Foreign Assistance Act (period beginning 1962),[419] more than any other country for that period until 2003.[419][420][421] Most surveyed Americans have also held consistently favorable views of Israel.[422][423] The United Kingdom is seen as having a "natural" relationship with Israel because of the Mandate for Palestine.[424] By 2007[update], Germany had paid 25 billion euros in reparations to the Israeli state and individual Israeli Holocaust survivors.[425] Israel is included in the European Union's European Neighbourhood Policy.[426]

Although Turkey and Israel did not establish full diplomatic relations until 1991,[427] Turkey has cooperated with the Jewish state since its recognition of Israel in 1949. Turkey's ties to other Muslim-majority nations in the region have at times resulted in pressure from Arab and Muslim states to temper its relationship with Israel.[428] Relations between Turkey and Israel took a downturn after the 2008–09 Gaza War and Israel's raid of the Gaza flotilla.[429] Relations between Greece and Israel have improved since 1995 due to the decline of Israeli–Turkish relations.[430] The two countries have a defense cooperation agreement and in 2010, the Israeli Air Force hosted Greece's Hellenic Air Force in a joint exercise. The joint Cyprus-Israel oil and gas explorations centered on the Leviathan gas field are an important factor for Greece, given its strong links with Cyprus.[431] Cooperation in the world's longest submarine power cable, the EuroAsia Interconnector, has strengthened Cyprus–Israel relations.[432]

Azerbaijan is one of the few majority Muslim countries to develop strategic and economic relations with Israel.[433] Kazakhstan also has an economic and strategic partnership with Israel.[434] India established full diplomatic ties with Israel in 1992 and has fostered a strong military, technological and cultural partnership with the country since then.[435] India is the largest customer of the Israeli military equipment and Israel is the second-largest military partner of India after Russia.[436] Ethiopia is Israel's main ally in Africa due to common political, religious and security interests.[437]

Foreign aid

Israel has a history of providing emergency foreign aid and humanitarian response to disasters across the world.[438] In 1955 Israel began its foreign aid programme in Burma. The programme's focus subsequently shifted to Africa.[439] Israel's humanitarian efforts officially began in 1957, with the establishment of Mashav, the Israel's Agency for International Development Cooperation.[440] In this early period, whilst Israel's aid represented only a small percentage of total aid to Africa, its programme was effective in creating goodwill; however, following the 1967 war relations soured.[441] Israel's foreign aid programme subsequently shifted its focus to Latin America.[439] Since the late 1970s Israel's foreign aid has gradually decreased, although in recent years Israel has tried to reestablish aid to Africa.[442] There are additional Israeli humanitarian and emergency response groups that work with the Israel government, including IsraAid, a joint programme run by Israeli organizations and North American Jewish groups,[443] ZAKA,[444] The Fast Israeli Rescue and Search Team,[445] Israeli Flying Aid,[446] Save a Child's Heart[447] and Latet.[448] Between 1985 and 2015, Israel sent 24 delegations of IDF search and rescue unit, the Home Front Command, to 22 countries.[449] Currently Israeli foreign aid ranks low among OECD nations, spending less than 0.1% of its GNI on development assistance.[450] The country ranked 38th in the 2018 World Giving Index.[451]

Military

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) is the sole military wing of the Israeli security forces and is headed by its Chief of General Staff, the Ramatkal, subordinate to the Cabinet. The IDF consists of the army, air force and navy. It was founded during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War by consolidating paramilitary organizations—chiefly the Haganah.[452] The IDF also draws upon the resources of the Military Intelligence Directorate (Aman).[453] The IDF have been involved in several major wars and border conflicts, making it one of the most battle-trained armed forces in the world.[454]

Most Israelis are conscripted at age 18. Men serve two years and eight months and women two years.[455] Following mandatory service, Israeli men join the reserve forces and usually do up to several weeks of reserve duty every year until their forties. Most women are exempt from reserve duty. Arab citizens of Israel (except the Druze) and those engaged in full-time religious studies are exempt, although the exemption of yeshiva students has been a source of contention.[456][457] An alternative for those who receive exemptions on various grounds is Sherut Leumi, or national service, which involves a programme of service in social welfare frameworks.[458] A small minority of Israeli Arabs also volunteer in the army.[459] As a result of its conscription programme, the IDF maintains approximately 176,500 active troops and 465,000 reservists, giving Israel one of the world's highest percentage of citizens with military training.[460]

The military relies heavily on high-tech weapons systems designed and manufactured in Israel as well as some foreign imports. The Arrow missile is one of the world's few operational anti-ballistic missile systems.[461] The Python air-to-air missile series is often considered one of the most crucial weapons in its military history.[462] Israel's Spike missile is one of the most widely exported anti-tank guided missiles in the world.[463] Israel's Iron Dome anti-missile air defense system gained worldwide acclaim after intercepting hundreds of rockets fired by Palestinian militants from the Gaza Strip.[464][465] Since the Yom Kippur War, Israel has developed a network of reconnaissance satellites.[466] The Ofeq programme has made Israel one of seven countries capable of launching such satellites.[467]

Israel is widely believed to possess nuclear weapons[468] and per a 1993 report, chemical and biological weapons of mass destruction.[469][needs update] Israel has not signed the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons[470] and maintains a policy of deliberate ambiguity toward its nuclear capabilities.[471] The Israeli Navy's Dolphin submarines are believed to be armed with nuclear missiles offering second-strike capability.[472] Since the Gulf War in 1991, all homes in Israel are required to have a reinforced security room, Merkhav Mugan, impermeable to chemical and biological substances.[473]

Since Israel's establishment, military expenditure constituted a significant portion of the country's gross domestic product, with peak of 30.3% of GDP in 1975.[474] In 2021, Israel ranked 15th in the world by total military expenditure, with $24.3 billion, and 6th by defense spending as a percentage of GDP, with 5.2%.[475] Since 1974, the United States has been a particularly notable contributor of military aid.[476] Under a memorandum of understanding signed in 2016, the U.S. is expected to provide the country with $3.8 billion per year, or around 20% of Israel's defense budget, from 2018 to 2028.[477] Israel ranked 9th globally for arms exports in 2022.[478] The majority of Israel's arms exports are unreported for security reasons.[479] Israel is consistently rated low in the Global Peace Index, ranking 134th out of 163 nations in 2022.[480]

Legal system

Israel has a three-tier court system. At the lowest level are magistrate courts, situated in most cities across the country. Above them are district courts, serving as both appellate courts and courts of first instance; they are situated in five of Israel's six districts. The third and highest tier is the Supreme Court, located in Jerusalem; it serves a dual role as the highest court of appeals and the High Court of Justice. In the latter role, the Supreme Court rules as a court of first instance, allowing individuals, both citizens and non-citizens, to petition against the decisions of state authorities.[481]

Israel's legal system combines three legal traditions: English common law, civil law, and Jewish law.[296] It is based on the principle of stare decisis (precedent) and is an adversarial system. Court cases are decided by professional judges with no role for juries.[482][better source needed] Marriage and divorce are under the jurisdiction of the religious courts: Jewish, Muslim, Druze, and Christian. The election of judges is carried out by a selection committee chaired by the justice minister (currently Yariv Levin).[483] Israel's Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty seeks to defend human rights and liberties in Israel. The United Nations Human Rights Council and Israeli human rights organization Adalah have highlighted that this law does not in fact contain a general provision for equality and non-discrimination.[433][484] As a result of "Enclave law", large portions of Israeli civil law are applied to Israeli settlements and Israeli residents in the occupied territories.[485]

Economy

Israel is considered the most advanced country in Western Asia and the Middle East in economic and industrial development.[486][487] As of October 2023[update], the IMF estimated Israel's GDP at 521.7 billion dollars and Israel's GDP per capita at 53.2 thousand (ranking 13th worldwide).[488] It is the third richest country in Asia by nominal per capita income.[489] Israel has the highest average wealth per adult in the Middle East.[490]The Economist ranked Israel as the 4th most successful economy among the developed countries for 2022.[491] It has the most billionaires in the Middle East, and the 18th most in the world.[492] In recent years Israel had one of the highest growth rates in the developed world.[493] In 2010, it joined the OECD.[42][494] The country is ranked 20th in the World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Report[495] and 35th on the World Bank's Ease of Doing Business index.[496] Israel was also ranked 5th in the world by share of people in high-skilled employment.[497] Israeli economic data covers the economic territory of Israel, including the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank.[344]

Despite limited natural resources, intensive development of the agricultural and industrial sectors over the past decades has made Israel largely self-sufficient in food production, apart from grains and beef. Imports to Israel, totaling $96.5 billion in 2020, include raw materials, military equipment, investment goods, rough diamonds, fuels, grain, and consumer goods.[296] Leading exports include machinery, equipment, software, cut diamonds, agricultural products, chemicals, textiles, and apparel; in 2020, Israeli exports reached $114 billion.[296] The Bank of Israel holds $201 billion of foreign-exchange reserves, the 17th highest in the world.[296] Since the 1970s, Israel has received military aid from the United States, as well as economic assistance in the form of loan guarantees, which account for roughly half of Israel's external debt. Israel has one of the lowest external debts in the developed world, and is a lender in terms of net external debt (assets vs. liabilities abroad), which in 2015[update] stood at a surplus of $69 billion.[498]

Israel has the second-largest number of startup companies after the United States,[499] and the third-largest number of NASDAQ-listed companies.[500] It is the world leader for number of start-ups per capita.[501] Israel has been dubbed the "Start-Up Nation".[502][503][504][505] Intel[506] and Microsoft[507] built their first overseas research and development facilities in Israel, and other high-tech multinational corporations have opened research and development centres in the country.

The days which are allocated to working times in Israel are Sunday through Thursday (for a five-day workweek), or Friday (for a six-day workweek). In observance of Shabbat, in places where Friday is a work day and the majority of population is Jewish, Friday is a "short day". Several proposals have been raised to adjust the work week with the majority of the world.[508]

Science and technology

Israel's development of cutting-edge technologies in software, communications and the life sciences have evoked comparisons with Silicon Valley.[509][510] Israel is first in the world in expenditure on research and development as a percentage of GDP.[511] It is ranked 14th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023,[512] and fifth in the 2019 Bloomberg Innovation Index.[513] Israel has 140 scientists, technicians, and engineers per 10,000 employees, the highest number in the world.[514][515][516] Israel has produced six Nobel Prize-winning scientists since 2004[517] and has been frequently ranked as one of the countries with the highest ratios of scientific papers per capita.[518][519][520] Israeli universities are ranked among the top 50 world universities in computer science (Technion and Tel Aviv University), mathematics (Hebrew University of Jerusalem) and chemistry (Weizmann Institute of Science).[521]

In 2012, Israel was ranked ninth in the world by the Futron's Space Competitiveness Index.[522] The Israel Space Agency coordinates all Israeli space research programmes with scientific and commercial goals, and have designed and built at least 13 commercial, research and spy satellites.[523] Some of Israel's satellites are ranked among the world's most advanced space systems.[524] Shavit is a space launch vehicle produced by Israel to launch small satellites into low Earth orbit.[525] It was first launched in 1988, making Israel the eighth nation to have a space launch capability. In 2003, Ilan Ramon became Israel's first astronaut, serving on the fatal mission of Space Shuttle Columbia.[526]

The ongoing water shortage has spurred innovation in water conservation techniques, and a substantial agricultural modernization, drip irrigation, was invented in Israel. Israel is also at the technological forefront of desalination and water recycling. The Sorek desalination plant is the largest seawater reverse osmosis desalination facility in the world.[527] By 2014, Israel's desalination programmes provided roughly 35% of Israel's drinking water and it is expected to supply 70% by 2050.[528] As of 2015[update], over 50 percent of the water for Israeli households, agriculture and industry is artificially produced.[529] In 2011, Israel's water technology industry was worth around $2 billion a year with annual exports of products and services in the tens of millions of dollars. As a result of innovations in reverse osmosis technology, Israel is set to become a net exporter of water.[530]

Israel has embraced solar energy; its engineers are on the cutting edge of solar energy technology[532] and its solar companies work on projects around the world.[533][534] Over 90% of Israeli homes use solar energy for hot water, the highest per capita.[318][535] According to government figures, the country saves 8% of its electricity consumption per year because of its solar energy use in heating.[536] The high annual incident solar irradiance at its geographic latitude creates ideal conditions for what is an internationally renowned solar research and development industry in the Negev Desert.[532][533][534] Israel had a modern electric car infrastructure involving a countrywide network of charging stations.[537][538][539] However, Israel's electric car company Better Place shut down in 2013.[540]

Energy

Israel began producing natural gas from its own offshore gas fields in 2004. In 2009, a natural gas reserve, Tamar, was found near the coast of Israel. A second reserve, Leviathan, was discovered in 2010.[541] The natural gas reserves in these two fields could make Israel energy-secure for more than 50 years. In 2013, Israel began commercial production of natural gas from the Tamar field. As of 2014[update], Israel produced over 7.5 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas a year.[542] Israel had 199 billion bcm of proven reserves of natural gas as of 2016.[543] The Leviathan gas field started production in 2019.[544]

Ketura Sun is Israel's first commercial solar field. Built in 2011 by the Arava Power Company, the field consists of 18,500 photovoltaic panels made by Suntech, which will produce about 9 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of electricity per year.[545] In the next twenty years, the field will spare the production of some 125,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide.[546]

Transport

Israel has 19,224 kilometres (11,945 mi) of paved roads[547] and 3 million motor vehicles.[548] The number of motor vehicles per 1,000 persons is 365, relatively low among developed countries.[548] The country aims to have 30% of vehicles on its roads powered by electricity by 2030.[549]

Israel has 5,715 buses on scheduled routes,[550] operated by several carriers, the largest and oldest of which is Egged, serving most of the country.[551] Railways stretch across 1,277 kilometres (793 mi) and are operated by government-owned Israel Railways.[552] Following major investments beginning in the early to mid-1990s, the number of train passengers per year has grown from 2.5 million in 1990, to 53 million in 2015; railways transport 7.5 million tons of cargo per year.[552]

Israel is served by three international airports: Ben Gurion Airport, the country's main hub for international air travel; Ramon Airport; and Haifa Airport. Ben Gurion, Israel's largest airport, handled over 21.1 million passengers in 2023.[553] The country has three main ports: the Port of Haifa, the country's oldest and largest, on the Mediterranean coast, Ashdod Port; and the smaller Port of Eilat on the Red Sea.

Tourism

Tourism, especially religious tourism, is an important industry in Israel, with the country's beaches, archaeological, other historical and biblical sites, and unique geography also drawing tourists. Israel's security problems have taken their toll on the industry, but the number of tourists is on the rebound.[554] In 2017, a record 3.6 million tourists visited Israel, yielding a 25 percent growth since 2016 and contributed NIS 20 billion to the Israeli economy.[555][556][557][558]

Real estate