Научный расизм

| Раса |

|---|

| История |

| Общество |

| Гонка и... |

| По местоположению |

| Связанные темы |

| Часть серии о |

| Дискриминация |

|---|

|

Научный расизм , иногда называемый биологическим расизмом , — это псевдонаучная вера в то, что человеческий вид разделен на биологически различные таксоны, называемые « расами ». [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] и что существуют эмпирические данные , подтверждающие или оправдывающие расовую дискриминацию , расовую неполноценность или расовое превосходство . [ 4 ] [ 5 ] [ 6 ] [ 7 ] До середины 20 века научный расизм был принят во всем научном сообществе, но больше не считается научным. [ 5 ] [ 6 ] Разделение человечества на биологически отдельные группы, а также присвоение этим группам определенных физических и психических характеристик посредством построения и применения соответствующих объяснительных моделей называют расизмом , расовым реализмом или расовой наукой те, кто поддерживает эти идеи, . Современный научный консенсус отвергает эту точку зрения как несовместимую с современными генетическими исследованиями . [ 8 ]

Научный расизм неправильно применяет, неверно истолковывает или искажает антропологию (особенно физическую антропологию ), краниометрию , эволюционную биологию и другие дисциплины или псевдодисциплины, предлагая антропологические типологии для классификации человеческих популяций на физически дискретные человеческие расы, некоторые из которых можно считать высшими. или уступает другим. Научный расизм был распространен в период с 1600-х годов до конца Второй мировой войны и был особенно заметен в европейских и американских академических трудах с середины 19-го века до начала 20-го века. Со второй половины 20-го века научный расизм дискредитировался и критиковался как устаревший, однако он постоянно использовался для поддержки или подтверждения расистских мировоззрений, основанных на вере в существование и значение расовых категорий и иерархии высших и низших. гонки. [ 9 ]

В XX веке антрополог Франц Боас и биологи Джулиан Хаксли и Ланселот Хогбен были одними из первых ведущих критиков научного расизма. Скептицизм по отношению к обоснованности научного расизма вырос в межвоенный период . [ 10 ] а к концу Второй мировой войны научный расизм в теории и на практике был официально осужден, особенно в заявлении ЮНЕСКО раннем антирасистском « Расовый вопрос » (1950 г.): «Биологический факт расы и миф о «расе». Следует различать «расу» во всех практических социальных целях – это не столько биологический феномен, сколько социальный миф. В последние годы миф о «расе» нанес огромный человеческий и социальный ущерб. тяжелые человеческие жертвы и причинили невыразимые страдания». [ 11 ] С тех пор достижения в области эволюционной генетики человека и физической антропологии привели к новому консенсусу среди антропологов о том, что человеческие расы являются социально-политическим явлением, а не биологическим. [ 12 ] [ 13 ] [ 14 ] [ 15 ]

Термин «научный расизм» обычно используется в уничижительном смысле применительно к более современным теориям, например, в «Геллорсе» (1994). Критики утверждают, что такие работы постулируют расистские выводы, такие как генетическая связь между расой и интеллектом , которые не подтверждаются имеющимися доказательствами. [ 16 ] Такие публикации, как « Mankind Quarterly» , основанный явно как «расовый» журнал, обычно рассматриваются как платформы научного расизма, поскольку они публикуют маргинальные интерпретации человеческой эволюции , интеллекта , этнографии , языка , мифологии , археологии и расы.

Предшественники

Мыслители Просвещения

В эпоху Просвещения (эпоха с 1650-х по 1780-е годы) концепции моногенизма и полигенизма стали популярными, хотя эпистемологически они были систематизированы только в XIX веке. Моногенизм утверждает, что все расы имеют единое происхождение, тогда как полигенизм — это идея, что каждая раса имеет отдельное происхождение. До XVIII века слова «раса» и «вид» были взаимозаменяемыми. [ 17 ]

François Bernier

François Bernier (1620–1688) was a French physician and traveller. In 1684, he published a brief essay dividing humanity into what he called "races", distinguishing individuals, and particularly women, by skin color and a few other physical traits. The article was published anonymously in the Journal des Savants, the earliest academic journal published in Europe, and titled "New Division of the Earth by the Different Species or 'Races' of Man that Inhabit It."[18]

In the essay, he distinguished four different races:

- The first race included populations from Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, India, south-east Asia, and the Americas

- The second race consisted of the sub-Saharan Africans

- The third race consisted of the east- and northeast Asians

- The fourth race consisted of Sámi people.

A product of French salon culture, the essay placed an emphasis on different kinds of female beauty. Bernier emphasized that his novel classification was based on his personal experience as a traveler in different parts of the world. Bernier offered a distinction between essential genetic differences and accidental ones that depended on environmental factors. He also suggested that the latter criterion might be relevant to distinguish sub-types.[19] His biological classification of racial types never sought to go beyond physical traits, and he also accepted the role of climate and diet in explaining degrees of human diversity. Bernier had been the first to extend the concept of "species of man" to racially classify the entirety of humanity, but he did not establish a cultural hierarchy between the so-called "races" that he had conceived. On the other hand, he clearly placed white Europeans as the norm from which other "races" deviated.[20][19]

The qualities which he attributed to each race were not strictly Eurocentric, because he thought that peoples of temperate Europe, the Americas, and India—although culturally very different from one another—belonged to roughly the same racial group, and he explained the differences between the civilizations of India (his main area of expertise) and Europe through climate and institutional history. By contrast, he emphasized the biological difference between Europeans and Africans, and made very negative comments towards the Sámi (Lapps) of the coldest climates of Northern Europe,[20] and about Africans living at the Cape of Good Hope. For example, Bernier wrote: "The 'Lappons' compose the 4th race. They are a small and short race with thick legs, wide shoulders, a short neck, and a face that I don't know how to describe, except that it's long, truly awful, and seems reminiscent of a bear's face. I've only ever seen them twice in Danzig, but according to the portraits I've seen, and from what I've heard from a number of people, they're ugly animals."[21] The significance of Bernier's ideology for the emergence of what Joan-Pau Rubiés called the "modern racial discourse" has been debated, with Siep Stuurman considering it the beginning of modern racial thought,[20] while Rubiés believes it is less significant if Bernier's entire view of humanity is taken into account.[19]

Robert Boyle

An early scientist who studied race was Robert Boyle (1627–1691), an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, and inventor. Boyle believed in what today is called monogenism, that is, that all races, no matter how diverse, came from the same source: Adam and Eve. He studied reported stories of parents' giving birth to differently coloured albinos, so he concluded that Adam and Eve were originally white, and that whites could give birth to different coloured races. Theories of Robert Hooke and Isaac Newton about color and light via optical dispersion in physics were also extended by Robert Boyle into discourses of polygenesis,[17] speculating that perhaps these differences were due to "seminal impressions." However, Boyle's writings mentioned that at his time, for "European Eyes," beauty was not measured so much in colour, but in "stature, comely symmetry of the parts of the body, and good features in the face."[22] Various members of the scientific community rejected his views, and described them as "disturbing" or "amusing."[23]

Richard Bradley

Richard Bradley (1688–1732) was an English naturalist. In his book titled Philosophical Account of the Works of Nature (1721), Bradley claimed there to be "five sorts of men" based on their skin colour and other physical characteristics: white Europeans with beards; white men in America without beards (meaning Native Americans); men with copper-coloured skin, small eyes, and straight black hair; Blacks with straight black hair; and Blacks with curly hair. It has been speculated that Bradley's account inspired Linnaeus' later categorisation.[24]

Lord Kames

The Scottish lawyer Henry Home, Lord Kames (1696–1782) was a polygenist; he believed God had created different races on Earth in separate regions. In his 1734 book Sketches on the History of Man, Home claimed that the environment, climate, or state of society could not account for racial differences, so the races must have come from distinct, separate stocks.[25]

Carl Linnaeus

This section may be unbalanced towards certain viewpoints. (June 2020) |

Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778), the Swedish physician, botanist, and zoologist, modified the established taxonomic bases of binomial nomenclature for fauna and flora, and also made a classification of humans into different subgroups. In the twelfth edition of Systema Naturae (1767), he labeled five[26] "varieties"[27][28] of human species. Each one was described as possessing the following physiognomic characteristics "varying by culture and place":[29]

- The Americanus: red, choleric, upright; black, straight, thick hair; nostrils flared; face freckled; beardless chin; stubborn, zealous, free; painting themself with red lines; governed by habit.[30]

- The Europeanus: white, sanguine, muscular; with yellowish, long hair; blue eyes; gentle, acute, inventive; covered with close vestments; governed by customs.[31]

- The Asiaticus: yellow, melancholic, stiff; black hair, dark eyes; austere, haughty, greedy; covered with loose clothing; governed by beliefs.[32]

- The Afer or Africanus: black, phlegmatic, relaxed; black, frizzled hair; silky skin, flat nose, tumid lips; females with elongated labia; mammary glands give milk abundantly; sly, lazy, negligent; anoints themself with grease; governed by caprice.[33][34][35][36]

- The Monstrosus were mythologic humans which did not appear in the first editions of Systema Naturae. The sub-species included: the "four-footed, mute, hairy" Homo feralis (Feral man); the animal-reared Juvenis lupinus hessensis (Hessian wolf boy); the Juvenis hannoveranus (Hannoverian boy); the Puella campanica (Wild-girl of Champagne); the agile, but faint-hearted Homo monstrosus (Monstrous man); the Patagonian giant; the Dwarf of the Alps; and the monorchid Khoikhoi (Hottentot). In Amoenitates academicae (1763), Linnaeus presented the mythologic Homo anthropomorpha (Anthropomorphic man), or humanoid creatures, such as the troglodyte, the satyr, the hydra, and the phoenix, incorrectly identified as simian creatures.[37]

There are disagreements about the basis for Linnaeus' human taxa. On the one hand, his harshest critics say the classification was not only ethnocentric, but seemed to be based upon skin colour. Renato G. Mazzolini argued that classifications based on skin colour, at its core, were a white/black polarity, and that Linnaeus' thinking became paradigmatic for later racist beliefs.[38] On the other hand, Quintyn (2010) points out that some authors believed that Linnaeus' classification was based upon geographical distribution, being cartographically-based, and not hierarchical.[39] In the opinion of Kenneth A. R. Kennedy (1976), Linnaeus certainly considered his own culture as superior, but his motives for the classification of human varieties were not race-centered.[40] Paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould (1994) argued that the taxa was "not in the ranked order favored by most Europeans in the racist tradition," and that Linnaeus' division was influenced by the medical theory of humors, which said that a person's temperament may be related to biological fluids.[41][42] In a 1994 essay, Gould added: "I don't mean to deny that Linnaeus held conventional beliefs about the superiority of his own European variety over others... nevertheless, and despite these implications, the overt geometry of Linnaeus' model is not linear or hierarchical."[43]

In a 2008 essay published by the Linnean Society of London, Marie-Christine Skuncke interpreted Linnaeus' statements as reflecting a view that "Europeans' superiority resides in "culture," and that the decisive factor in Linnaeus' taxa was "culture," not race." Thus, regarding this topic, Skuncke considers Linnaeus' view as merely "eurocentric," arguing that Linnaeus never called for racist action, and did not use the word "race," which was only introduced later "by his French opponent, Buffon."[44] However, the anthropologist Ashley Montagu, in his book Man's Most Dangerous Myth: the Fallacy of Race, points out that Buffon, indeed "the enemy of all rigid classifications,"[45] was diametrically opposed to such broad categories, and did not use the word "race" to describe them. "It was quite clear, after reading Buffon, that he uses the word in no narrowly defined, but rather in a general sense,"[45] wrote Montagu, pointing out that Buffon did employ the French word la race, but as a collective term for whatever population he happened to be discussing at the time; for instance: "The Danish, Swedish, and Muscovite Laplanders, the inhabitants of Nova-Zembla, the Borandians, the Samoiedes, the Ostiacks of the old continent, the Greenlanders, and the savages to the north of the Esquimaux Indians, of the new continent, appear to be of one common race."[46]

Scholar Stanley A. Rice agrees that Linnaeus' classification was not meant to "imply a hierarchy of humanness or superiority";[47] however, modern critics regard Linnaeus' classification as obviously stereotyped and erroneous for having included anthropological, non-biological features, such as customs or traditions.

John Hunter

John Hunter (1728–1793), a Scottish surgeon, believed that the Negroid race was originally white at birth. He thought that over time, because of the sun, the people turned dark-skinned, or "black." Hunter also stated that blisters and burns would likely turn white on a Negro, which he asserted was evidence that their ancestors were originally white.[48]

Charles White

Charles White (1728–1813), an English physician and surgeon, believed that races occupied different stations in the "Great Chain of Being", and he tried to scientifically prove that human races had distinct origins from each other. He speculated that whites and Negroes were two different species. White was a believer in polygeny, the idea that different races had been created separately. His Account of the Regular Gradation in Man (1799) provided an empirical basis for this idea. White defended the theory of polygeny by rebutting French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon's interfertility argument, which said that only the same species can interbreed. White pointed to species hybrids, such as foxes, wolves, and jackals, which were separate groups that were still able to interbreed. For White, each race was a separate species, divinely created for its own geographical region.[25]

Buffon and Blumenbach

The French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707–1788) and the German anatomist Johann Blumenbach (1752–1840) were proponents of monogenism, the concept that all races have a single origin.[49] Buffon and Blumenbach believed a "degeneration theory" of the origins of racial difference.[49] Both asserted that Adam and Eve were white, and that other races came about by degeneration owing to environmental factors, such as climate, disease, and diet.[49] According to this model, Negroid pigmentation arose because of the heat of the tropical sun; that cold wind caused the tawny colour of the Eskimos; and that the Chinese had fairer skins than the Tartars, because the former kept mostly in towns, and were protected from environmental factors.[49] Environmental factors, poverty, and hybridization could make races "degenerate", and differentiate them from the original white race by a process of "raciation".[49] Interestingly, both Buffon and Blumenbach believed that the degeneration could be reversed if proper environmental control was taken, and that all contemporary forms of man could revert to the original white race.[49]

According to Blumenbach, there are five races, all belonging to a single species: Caucasian, Mongolian, Negroid, American, and the Malay race. Blumenbach stated: "I have allotted the first place to the Caucasian for the reasons given below, which make me esteem it the primeval one."[50]

Before James Hutton and the emergence of scientific geology, many believed the Earth was only 6,000 years old. Buffon had conducted experiments with heated balls of iron, which he believed were a model for the Earth's core, and concluded that the Earth was 75,000 years old, but did not extend the time since Adam and the origin of humanity back more than 8,000 years—not much further than the 6,000 years of the prevailing Ussher chronology subscribed to by most of the monogenists.[49] Opponents of monogenism believed that it would have been difficult for races to change markedly in such a short period of time.[49]

Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Rush (1745–1813), a Founding Father of the United States and a physician, proposed that being black was a hereditary skin disease, which he called "negroidism," and that it could be cured. Rush believed non-whites were actually white underneath, but that they were stricken with a non-contagious form of leprosy, which darkened their skin color. Rush drew the conclusion that "whites should not tyrannize over [blacks], for their disease should entitle them to a double portion of humanity. However, by the same token, whites should not intermarry with them, for this would tend to infect posterity with the 'disorder'… attempts must be made to cure the disease."[51]

Christoph Meiners

Christoph Meiners (1747–1810) was a German polygenist, and believed that each race had a separate origin. Meiners studied the physical, mental, and moral characteristics of each race, and built a race hierarchy based on his findings. Meiners split mankind into two divisions, which he labelled the "beautiful white race" and the "ugly black race". In his book titled The Outline of History of Mankind, Meiners argued that a main characteristic of race is either beauty or ugliness. Meiners thought only the white race to be beautiful, and considered ugly races to be inferior, immoral, and animal-like. Meiners wrote about how the dark, ugly peoples were differentiated from the white, beautiful peoples by their "sad" lack of virtue and their "terrible vices".[52]

Meiners hypothesized about how the Negro felt less pain than any other race, and lacked in emotions. Meiners wrote that the Negro had thick nerves, and thus, was not sensitive like the other races. He went so far as to say that the Negro possessed "no human, barely any animal, feeling." Meiners described a story where a Negro was condemned to death by being burned alive. Halfway through the burning, the Negro asked to smoke a pipe, and smoked it like nothing was happening while he continued to be burned alive. Meiners studied the anatomy of the Negro, and came to the conclusion that Negroes were all carnivores, based upon his observations that Negroes had bigger teeth and jaws than any other race. Meiners claimed the skull of the Negro was larger, but the brain of the Negro was smaller than any other race. Meiners theorized that the Negro was the most unhealthy race on Earth because of its poor diet, mode of living, and lack of morals.[53]

Meiners studied the diet of the Americans, and said they fed off any kind of "foul offal", and consumed copious amounts of alcohol. He believed their skulls were so thick that the blades of Spanish swords shattered on them. Meiners also claimed the skin of an American is thicker than that of an ox.[53]

Meiners wrote that the noblest race was the Celts. This was based upon assertions that they were able to conquer various parts of the world, they were more sensitive to heat and cold, and their delicacy is shown by the way they are selective about what they eat. Meiners claimed that Slavs are an inferior race, "less sensitive and content with eating rough food." He described stories of Slavs allegedly eating poisonous fungi without coming to any harm. He claimed that their medical techniques were also counterproductive; as an example, Meiners described their practice of warming up sick people in ovens, then making them roll in the snow.[53]

Later thinkers

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) was an American politician, scientist,[54][55] and slave owner. His contributions to scientific racism have been noted by many historians, scientists, and scholars. According to an article published in the McGill Journal of Medicine: "One of the most influential pre-Darwinian racial theorists, Jefferson's call for science to determine the obvious 'inferiority' of African Americans is an extremely important stage in the evolution of scientific racism."[56] Writing for The New York Times, historian Paul Finkelman described how as "a scientist, Jefferson nevertheless speculated that blackness might come 'from the color of the blood,' and concluded that blacks were 'inferior to the whites in the endowments of body and mind'."[57] In his "Notes on the State of Virginia," Jefferson described black people as follows:[58]

They seem to require less sleep. A black, after hard labor through the day, will be induced by the slightest amusements to sit up till midnight, or later, though knowing he must be out with the first dawn of the morning. They are at least as brave, and more adventuresome. But, this may perhaps proceed from a want of forethought, which prevents their seeing a danger till it be present. When present, they do not go through it with more coolness or steadiness than the whites. They are more ardent after their female: but love seems with them to be more an eager desire, than a tender delicate mixture of sentiment and sensation. Their griefs are transient. Those numberless afflictions, which render it doubtful whether heaven has given life to us in mercy or in wrath, are less felt, and sooner forgotten with them. In general, their existence appears to participate more of sensation than reflection... Comparing them by their faculties of memory, reason, and imagination, it appears to me, that in memory, they are equal to the whites; in reason, much inferior, as I think one [black] could scarcely be found capable of tracing and comprehending the investigations of Euclid; and that in imagination, they are dull, tasteless, and anomalous... I advance it, therefore, as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.

However, by 1791, Jefferson had to reassess his earlier suspicions of whether blacks were capable of intelligence when he was presented with a letter and almanac from Benjamin Banneker, an educated black mathematician. Delighted to have discovered scientific proof for the existence of black intelligence, Jefferson wrote to Banneker:[59]

No body wishes more than I do to see such proofs as you exhibit, that nature has given to our black brethren, talents equal to those of the other colors of men, & that the appearance of a want of them is owing merely to the degraded condition of their existence both in Africa & America. I can add with truth that no body wishes more ardently to see a good system commenced for raising the condition both of their body & mind to what it ought to be, as fast as the imbecility of their present existence, and other circumstance which cannot be neglected, will admit.

Samuel Stanhope Smith

Samuel Stanhope Smith (1751–1819) was an American Presbyterian minister and author of the Essay on the Causes of Variety of Complexion and Figure in the Human Species (1787). Smith claimed that Negro pigmentation was nothing more than a huge freckle that covered the whole body as a result of an oversupply of bile, which was caused by tropical climates.[60]

Georges Cuvier

Racial studies by Georges Cuvier (1769–1832), the French naturalist and zoologist, influenced both scientific polygenism and scientific racism. Cuvier believed there were three distinct races: the Caucasian (white), Mongolian (yellow), and the Ethiopian (black). He rated each for the beauty or ugliness of the skull and quality of their civilizations. Cuvier wrote about Caucasians: "The white race, with oval face, straight hair and nose, to which the civilised people of Europe belong, and which appear to us the most beautiful of all, is also superior to others by its genius, courage, and activity."[61]

Regarding Negroes, Cuvier wrote:[62]

The Negro race … is marked by black complexion, crisped or woolly hair, compressed cranium, and a flat nose. The projection of the lower parts of the face, and the thick lips, evidently approximate it to the monkey tribe: the hordes of which it consists have always remained in the most complete state of barbarism.

He thought Adam and Eve were Caucasian, and hence, the original race of mankind. The other two races arose by survivors escaping in different directions after a major catastrophe hit the earth approximately 5,000 years ago. Cuvier theorized that the survivors lived in complete isolation from each other, and developed separately as a result.[63][64]

One of Cuvier's pupils, Friedrich Tiedemann, was among the first to make a scientific contestation of racism. Tiedemann asserted that based upon his documentation of craniometric and brain measurements of Europeans and black people from different parts of the world, that the then-common European belief that Negroes have smaller brains, and are thus intellectually inferior, was scientifically unfounded, and based merely on the prejudice of travellers and explorers.[65]

Arthur Schopenhauer

The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) attributed civilizational primacy to the white races, who gained sensitivity and intelligence via the refinement caused by living in the rigorous Northern climate:[66]

The highest civilization and culture, apart from the ancient Hindus and Egyptians, are found exclusively among the white races; and even with many dark peoples, the ruling caste, or race, is fairer in colour than the rest, and has, therefore, evidently immigrated, for example, the Brahmins, the Inca, and the rulers of the South Sea Islands. All this is due to the fact that necessity is the mother of invention, because those tribes that emigrated early to the north, and there gradually became white, had to develop all their intellectual powers, and invent and perfect all the arts in their struggle with need, want, and misery, which, in their many forms, were brought about by the climate. This they had to do to make up for the parsimony of nature, and out of it all came their high civilization.

Franz Ignaz Pruner

Franz Ignaz Pruner (1808–1882) was a German physician, ophthalmologist, and anthropologist who studied the racial structure of Negroes in Egypt. In a book Pruner wrote in 1846, he claimed that Negro blood had a negative influence on the Egyptian moral character. He published a monograph on Negroes in 1861. He claimed that the main feature of the Negro's skeleton is prognathism, which he claimed was the Negro's relation to the ape. He also claimed that Negroes had brains very similar to those of apes and that Negroes have a shortened big toe, a characteristic, he said, that connected Negroes closely to apes.[67]

Racial theories in physical anthropology (1850–1918)

The scientific classification established by Carl Linnaeus is requisite to any human racial classification scheme. In the 19th century, unilineal evolution, or classical social evolution, was a conflation of competing sociologic and anthropologic theories proposing that Western European culture was the acme of human socio-cultural evolution. The Christian Bible was interpreted to sanction slavery and from the 1820s to the 1850s was often used in the antebellum Southern United States, by writers such as the Rev. Richard Furman and Thomas R. Cobb, to enforce the idea that Negroes had been created inferior, and thus suited to slavery.[68]

Arthur de Gobineau

The French aristocrat and writer Arthur de Gobineau (1816–1882), is best known for his book An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races (1853–55) which proposed three human races (black, white and yellow) were natural barriers and claimed that race mixing would lead to the collapse of culture and civilization. He claimed that "The white race originally possessed the monopoly of beauty, intelligence and strength" and that any positive accomplishments or thinking of blacks and Asians were due to an admixture with whites. His works were praised by many white supremacist American pro-slavery thinkers such as Josiah C. Nott and Henry Hotze.

Gobineau believed that the different races originated in different areas, the white race had originated somewhere in Siberia, the Asians in the Americas and the blacks in Africa. He believed that the white race was superior, writing:

I will not wait for the friends of equality to show me such and such passages in books written by missionaries or sea captains, who declare some Wolof is a fine carpenter, some Hottentot a good servant, that a Kaffir dances and plays the violin, that some Bambara knows arithmetic… Let us leave aside these puerilities and compare together not men, but groups.[69]

Gobineau later used the term "Aryans" to describe the Germanic peoples (la race germanique).[70]

Gobineau's works were also influential to the Nazi Party, which published his works in German. They played a key role in the master race theory of Nazism.

Carl Vogt

Another polygenist evolutionist was Carl Vogt (1817–1895) who believed that the Negro race was related to the ape. He wrote the white race was a separate species to Negroes. In Chapter VII of his Lectures of Man (1864) he compared the Negro to the white race whom he described as "two extreme human types". The difference between them, he claimed are greater than those between two species of ape; and this proves that Negroes are a separate species from the whites.[71]

Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin's views on race have been a topic of much discussion and debate. According to Jackson and Weidman, Darwin was a moderate in the 19th century debates about race. "He was not a confirmed racist — he was a staunch abolitionist, for example — but he did think that there were distinct races that could be ranked in a hierarchy."[72]

Darwin's influential 1859 book On the Origin of Species did not discuss human origins. The extended wording on the title page, which adds by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, uses the general terminology of biological races as an alternative for "varieties" such as "the several races, for instance, of the cabbage", and does not carry the modern connotation of human races. In The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871), Darwin examined the question of "Arguments in favour of, and opposed to, ranking the so-called races of man as distinct species" and reported no racial distinctions that would indicate that human races are discrete species.[68][73]

The historian Richard Hofstadter wrote:

Although Darwinism was not the primary source of the belligerent ideology and dogmatic racism of the late nineteenth century, it did become a new instrument in the hands of the theorists of race and struggle... The Darwinist mood sustained the belief in Anglo-Saxon racial superiority which obsessed many American thinkers in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The measure of world domination already achieved by the 'race' seemed to prove it the fittest.[74]

According to the historian Gertrude Himmelfarb, "The subtitle of [The Origin of Species] made a convenient motto for racists: 'The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life.' Darwin, of course, took 'races' to mean varieties or species; but it was no violation of his meaning to extend it to human races.... Darwin himself, in spite of his aversion to slavery, was not averse to the idea that some races were more fit than others."[75]

On the other hand, Robert Bannister defended Darwin on the issue of race, writing that "Upon closer inspection, the case against Darwin himself quickly unravels. An ardent opponent of slavery, he consistently opposed the oppression of nonwhites... Although by modern standards The Descent of Man is frustratingly inconclusive on the critical issues of human equality, it was a model of moderation and scientific caution in the context of midcentury racism."[76]

According to Myrna Perez Sheldon, Darwin believed that different races gained their 'population-level characteristics' via sexual selection. Previously, race theorists conceptualized race as a 'stable blood essence' and that these 'essences' mixed when miscegenation occurred.[77]

Herbert Hope Risley

As an exponent of "race science", colonial administrator Herbert Hope Risley (1851–1911) used the ratio of the width of a nose to its height to divide Indian people into Aryan and Dravidian races, as well as seven castes.[78][79]

Ernst Haeckel

Like most of Darwin's supporters,[citation needed] Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919) put forward a doctrine of evolutionary polygenism based on the ideas of the linguist and polygenist August Schleicher, in which several different language groups had arisen separately from speechless prehuman Urmenschen (German for 'original humans'), which themselves had evolved from simian ancestors. These separate languages had completed the transition from animals to man, and, under the influence of each main branch of languages, humans had evolved as separate species, which could be subdivided into races. Haeckel divided human beings into ten races, of which the Caucasian was the highest and the primitives were doomed to extinction.[80] Haeckel was also an advocate of the out of Asia theory by writing that the origin of humanity was to be found in Asia; he believed that Hindustan (South Asia) was the actual location where the first humans had evolved. Haeckel argued that humans were closely related to the primates of Southeast Asia and rejected Darwin's hypothesis of Africa.[81][82]

Haeckel also wrote that Negroes have stronger and more freely movable toes than any other race which is evidence that Negroes are related to apes because when apes stop climbing in trees they hold on to the trees with their toes. Haeckel compared Negroes to "four-handed" apes. Haeckel also believed Negroes were savages and that whites were the most civilised.[71]

Nationalism of Lapouge and Herder

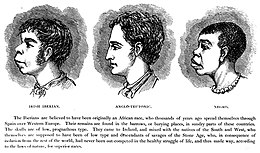

At the 19th century's end, scientific racism conflated Greco-Roman eugenicism with Francis Galton's concept of voluntary eugenics to produce a form of coercive, anti-immigrant government programs influenced by other socio-political discourses and events. Such institutional racism was effected via phrenology, telling character from physiognomy; craniometric skull and skeleton studies; thus skulls and skeletons of black people and other colored volk, were displayed between apes and white men.

In 1906, Ota Benga, a Pygmy, was displayed as the "Missing Link", in the Bronx Zoo, New York City, alongside apes and animals. The most influential theorists included the anthropologist Georges Vacher de Lapouge (1854–1936) who proposed "anthroposociology"; and Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803), who applied "race" to nationalist theory, thereby developing the first conception of ethnic nationalism. In 1882, Ernest Renan contradicted Herder with a nationalism based upon the "will to live together", not founded upon ethnic or racial prerequisites (see Civic nationalism). Scientific racist discourse posited the historical existence of "national races" such as the Deutsche Volk in Germany, and the "French race" being a branch of the basal "Aryan race" extant for millennia, to advocate for geopolitical borders parallel to the racial ones.

Craniometry and physical anthropology

The Dutch scholar Pieter Camper (1722–89), an early craniometric theoretician, used "craniometry" (interior skull-volume measurement) to scientifically justify racial differences. In 1770, he conceived of the facial angle to measure intelligence among species of men. The facial angle was formed by drawing two lines: a horizontal line from nostril to ear; and a vertical line from the upper-jawbone prominence to the forehead prominence. Camper's craniometry reported that antique statues (the Greco-Roman ideal) had a 90-degree facial angle, whites an 80-degree angle, blacks a 70-degree angle, and the orangutan a 58-degree facial angle—thus he established a racist biological hierarchy for mankind, per the Decadent conception of history. Such scientific racist researches were continued by the naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1772–1844) and the anthropologist Paul Broca (1824–1880).

Samuel George Morton

In the 19th century, an early American physical anthropologist, physician and polygenist Samuel George Morton (1799–1851), collected human skulls from worldwide, and attempted a logical classification scheme. Influenced by contemporary racialist theory, Dr Morton said he could judge racial intellectual capacity by measuring the interior cranial capacity, hence a large skull denoted a large brain, thus high intellectual capacity. Conversely, a small skull denoted a small brain, thus low intellectual capacity; superior and inferior established. After inspecting three mummies from ancient Egyptian catacombs, Morton concluded that Caucasians and Negroes were already distinct three thousand years ago. Since interpretations of the bible indicated that Noah's Ark had washed up on Mount Ararat only a thousand years earlier, Morton claimed that Noah's sons could not possibly account for every race on earth. According to Morton's theory of polygenesis, races have been separate since the start.[83]

In Morton's Crania Americana, his claims were based on craniometry data, that the Caucasians had the biggest brains, averaging 87 cubic inches, Native Americans were in the middle with an average of 82 cubic inches and Negroes had the smallest brains with an average of 78 cubic inches.[83]

In The Mismeasure of Man (1981), the evolutionary biologist and historian of science Stephen Jay Gould argued that Samuel Morton had falsified the craniometric data, perhaps inadvertently over-packing some skulls, to so produce results that would legitimize the racist presumptions he was attempting to prove. A subsequent study by the anthropologist John Michael found Morton's original data to be more accurate than Gould describes, concluding that "[c]ontrary to Gould's interpretation... Morton's research was conducted with integrity".[84] Jason Lewis and colleagues reached similar conclusions as Michael in their reanalysis of Morton's skull collection; however, they depart from Morton's racist conclusions by adding that "studies have demonstrated that modern human variation is generally continuous, rather than discrete or "racial", and that most variation in modern humans is within, rather than between, populations".[85]

In 1873, Paul Broca, founder of the Anthropological Society of Paris (1859), found the same pattern of measures—that Crania Americana reported—by weighing specimen brains at autopsy. Other historical studies, proposing a black race–white race, intelligence–brain size difference, include those by Bean (1906), Mall (1909), Pearl (1934), and Vint (1934).

Nicolás Palacios

After the War of the Pacific (1879–83) there was a rise of racial and national superiority ideas among the Chilean ruling class.[86] In his 1918 book physician Nicolás Palacios argued for the existence of Chilean race and its superiority when compared to neighboring peoples. He thought Chileans were a mix of two martial races: the indigenous Mapuches and the Visigoths of Spain, who descended ultimately from Götaland in Sweden. Palacios argued on medical grounds against immigration to Chile from southern Europe claiming that Mestizos who are of south European stock lack "cerebral control" and are a social burden.[87]

Monogenism and polygenism

Samuel Morton's followers, especially Dr Josiah C. Nott (1804–1873) and George Gliddon (1809–1857), extended Dr Morton's ideas in Types of Mankind (1854), claiming that Morton's findings supported the notion of polygenism (mankind has discrete genetic ancestries; the races are evolutionarily unrelated), which is a predecessor of the modern human multiregional origin hypothesis. Moreover, Morton himself had been reluctant to espouse polygenism, because it theologically challenged the Christian creation myth espoused in the Bible.

Later, in The Descent of Man (1871), Charles Darwin proposed the single-origin hypothesis, i.e., monogenism—mankind has a common genetic ancestry, the races are related, opposing everything that the polygenism of Nott and Gliddon proposed.

Typologies

One of the first typologies used to classify various human races was invented by Georges Vacher de Lapouge (1854–1936), a theoretician of eugenics, who published in 1899 L'Aryen et son rôle social ("The Aryan and his social role"). In this book, he classified humanity into various, hierarchized races, spanning from the "Aryan white race, dolichocephalic", to the "brachycephalic", "mediocre and inert" race, best represented by Southern European, Catholic peasants".[88] Between these, Vacher de Lapouge identified the "Homo europaeus" (Teutonic, Protestant, etc.), the "Homo alpinus" (Auvergnat, Turkish, etc.), and finally the "Homo mediterraneus" (Neapolitan, Andalus, etc.) Jews were dolichocephalic like the Aryans, according to Lapouge, but exactly for this reason he considered them to be dangerous; they were the only group, he thought, threatening to displace the Aryan aristocracy.[89] Vacher de Lapouge became one of the leading inspirators of Nazi antisemitism and Nazi racist ideology.[90]

Vacher de Lapouge's classification was mirrored in William Z. Ripley in The Races of Europe (1899), a book which had a large influence on American white supremacism. Ripley even made a map of Europe according to the alleged cephalic index of its inhabitants. He was an important influence of the American eugenist Madison Grant.

Furthermore, according to John Efron of Indiana University, the late 19th century also witnessed "the scientizing of anti-Jewish prejudice", stigmatizing Jews with male menstruation, pathological hysteria, and nymphomania.[91][92] At the same time, several Jews, such as Joseph Jacobs or Samuel Weissenberg, also endorsed the same pseudoscientific theories, convinced that the Jews formed a distinct race.[91][92] Chaim Zhitlovsky also attempted to define Yiddishkayt (Ashkenazi Jewishness) by turning to contemporary racial theory.[93]

Joseph Deniker (1852–1918) was one of William Z. Ripley's principal opponents; whereas Ripley maintained, as did Vacher de Lapouge, that the European populace comprised three races, Joseph Deniker proposed that the European populace comprised ten races (six primary and four sub-races). Furthermore, he proposed that the concept of "race" was ambiguous, and in its stead proposed the compound word "ethnic group", which later prominently featured in the works of Julian Huxley and Alfred C. Haddon. Moreover, Ripley argued that Deniker's "race" idea should be denoted a "type", because it was less biologically rigid than most racial classifications.

Ideological applications

Nordicism

Joseph Deniker's contribution to racist theory was La Race nordique (the Nordic race), a generic, racial-stock descriptor, which the American eugenicist Madison Grant (1865–1937) presented as the white racial engine of world civilization. Having adopted Ripley's three-race European populace model, but disliking the Teuton race name, he transliterated la race nordique into 'the Nordic race', the acme of the concocted racial hierarchy, based upon his racial classification theory, popular in the 1910s and 1920s.

The State Institute for Racial Biology (Swedish: Statens Institut för Rasbiologi) and its director Herman Lundborg in Sweden were active in racist research. Furthermore, much of early research on Ural-Altaic languages was coloured by attempts at justifying the view that European peoples east of Sweden were Asian and thus of an inferior race, justifying colonialism, eugenics and racial hygiene.[citation needed] The book The Passing of the Great Race (Or, The Racial Basis of European History) by American eugenicist, lawyer, and amateur anthropologist Madison Grant was published in 1916. Though influential, the book was largely ignored when it first appeared, and it went through several revisions and editions. Nevertheless, the book was used by people who advocated restricted immigration as justification for what became known as scientific racism.[94]

Justification of slavery in the United States

In the United States, scientific racism justified Black African slavery to assuage moral opposition to the Atlantic slave trade. Alexander Thomas and Samuell Sillen described black men as uniquely fitted for bondage, because of their "primitive psychological organization."[95] In 1851, in antebellum Louisiana, the physician Samuel A. Cartwright (1793–1863) wrote of slave escape attempts as "drapetomania," a treatable mental illness, that "with proper medical advice, strictly followed, this troublesome practice that many Negroes have of running away can be almost entirely prevented." The term drapetomania (mania of the runaway slave) derives from the Greek δραπέτης (drapetes, 'a runaway [slave]') and μανία (mania, 'madness, frenzy').[96] Cartwright also described dysaesthesia aethiopica, called "rascality" by overseers. The 1840 United States Census claimed that Northern, free blacks suffered mental illness at higher rates than did their Southern, enslaved counterparts. Though the census was later found to have been severely flawed by the American Statistical Association, it became a political weapon against abolitionists. Southern slavers concluded that escaping Negroes were suffering from "mental disorders."[97]

At the time of the American Civil War (1861–1865), the matter of miscegenation prompted studies of ostensible physiological differences between Caucasians and Negroes. Early anthropologists, such as Josiah Clark Nott, George Robins Gliddon, Robert Knox, and Samuel George Morton, aimed to scientifically prove that Negroes were a human species different from the white people; that the rulers of Ancient Egypt were not African; and that mixed-race offspring (the product of miscegenation) tended to physical weakness and infertility. After the Civil War, Southern (Confederacy) physicians wrote textbooks of scientific racism based upon studies claiming that black freemen (ex-slaves) were becoming extinct, because they were inadequate to the demands of being a free man—implying that black people benefited from enslavement.

In Medical Apartheid, Harriet A. Washington noted the prevalence of two different views on blacks in the 19th century: the belief that they were inferior and "riddled with imperfections from head to toe", and the idea that they did not know true pain and suffering because of their primitive nervous systems (and that slavery was therefore justifiable). Washington noted the failure of scientists to accept the inconsistency between these two viewpoints, writing that:

in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, scientific racism was simply science, and it was promulgated by the very best minds at the most prestigious institutions of the nation. Other, more logical medical theories stressed the equality of Africans and laid poor black health at the feet of their abusers, but these never enjoyed the appeal of the medical philosophy that justified slavery and, along with it, our nation's profitable way of life.[98]

Even after the end of the Civil War, some scientists continued to justify the institution of slavery by citing the effect of topography and climate on racial development. Nathaniel Shaler, a prominent geologist at Harvard University from 1869 to 1906, published the book Man and the Earth in 1905 describing the physical geography of different continents and linking these geologic settings to the intelligence and strength of human races that inhabited these spaces. Shaler argued that North American climate and geology was ideally suited for the institution of slavery.[99]

South African apartheid

Scientific racism played a role in establishing apartheid in South Africa. In South Africa, white scientists, like Dudly Kidd, who published The essential Kafir in 1904, sought to "understand the African mind". They believed that the cultural differences between whites and blacks in South Africa might be caused by physiological differences in the brain. Rather than suggesting that Africans were "overgrown children", as early white explorers had, Kidd believed that Africans were "misgrown with a vengeance". He described Africans as at once "hopelessly deficient", yet "very shrewd".[100]

The Carnegie Commission on the Poor White Problem in South Africa played a key role in establishing apartheid in South Africa. According to one memorandum sent to Frederick Keppel, then president of the Carnegie Corporation, there was "little doubt that if the natives were given full economic opportunity, the more competent among them would soon outstrip the less competent whites".[101] Keppel's support for the project of creating the report was motivated by his concern with the maintenance of existing racial boundaries.[101] The preoccupation of the Carnegie Corporation with the so-called poor white problem in South Africa was at least in part the outcome of similar misgivings about the state of poor whites in the southern United States.[101]

The report was five volumes in length.[102] Around the start of the 20th century, white Americans, and whites elsewhere in the world, felt uneasy because poverty and economic depression seemed to strike people regardless of race.[102]

Though the ground work for apartheid began earlier, the report provided support for this central idea of black inferiority. This was used to justify racial segregation and discrimination[103] in the following decades.[104] The report expressed fear about the loss of white racial pride, and in particular pointed to the danger that the poor white would not be able to resist the process of "Africanisation".[101]

Although scientific racism played a role in justifying and supporting institutional racism in South Africa, it was not as important in South Africa as it has been in Europe and the United States. This was due in part to the "poor white problem", which raised serious questions for supremacists about white racial superiority.[100] Since poor whites were found to be in the same situation as natives in the African environment, the idea that intrinsic white superiority could overcome any environment did not seem to hold. As such, scientific justifications for racism were not as useful in South Africa.[100]

Eugenics

Stephen Jay Gould described Madison Grant's The Passing of the Great Race (1916) as "the most influential tract of American scientific racism." In the 1920s–30s, the German racial hygiene movement embraced Grant's Nordic theory. Alfred Ploetz (1860–1940) coined the term Rassenhygiene in Racial Hygiene Basics (1895), and founded the German Society for Racial Hygiene in 1905. The movement advocated selective breeding, compulsory sterilization, and a close alignment of public health with eugenics.

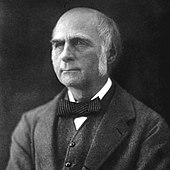

Racial hygiene was historically tied to traditional notions of public health, but with emphasis on heredity—what philosopher and historian Michel Foucault has called state racism. In 1869, Francis Galton (1822–1911) proposed the first social measures meant to preserve or enhance biological characteristics, and later coined the term eugenics. Galton, a statistician, introduced correlation and regression analysis and discovered regression toward the mean. He was also the first to study human differences and inheritance of intelligence with statistical methods. He introduced the use of questionnaires and surveys to collect data on population sets, which he needed for genealogical and biographical works and for anthropometric studies. Galton also founded psychometrics, the science of measuring mental faculties, and differential psychology, a branch of psychology concerned with psychological differences between people rather than common traits.

Like scientific racism, eugenics grew popular in the early 20th century, and both ideas influenced Nazi racial policies and Nazi eugenics. In 1901, Galton, Karl Pearson (1857–1936) and Walter F. R. Weldon (1860–1906) founded the Biometrika scientific journal, which promoted biometrics and statistical analysis of heredity. Charles Davenport (1866–1944) was briefly involved in the review. In Race Crossing in Jamaica (1929), he made statistical arguments that biological and cultural degradation followed white and black interbreeding. Davenport was connected to Nazi Germany before and during World War II. In 1939 he wrote a contribution to the festschrift for Otto Reche (1879–1966), who became an important figure within the plan to remove populations considered "inferior" from eastern Germany.[105]

Interbellum to World War II

Scientific racism continued through the early 20th century, and soon intelligence testing became a new source for racial comparisons. Before World War II (1939–45), scientific racism remained common to anthropology, and was used as justification for eugenics programs, compulsory sterilization, anti-miscegenation laws, and immigration restrictions in Europe and the United States. The war crimes and crimes against humanity of Nazi Germany (1933–45) discredited scientific racism in academia,[citation needed] but racist legislation based upon it remained in some countries until the late 1960s.

Early intelligence testing and the Immigration Act of 1924

Before the 1920s, social scientists agreed that whites were superior to blacks, but they needed a way to prove this to back social policy in favor of whites. They felt the best way to gauge this was through testing intelligence. By interpreting the tests to show favor to whites these test makers' research results portrayed all minority groups very negatively.[16][106] In 1908, Henry Goddard translated the Binet intelligence test from French and in 1912 began to apply the test to incoming immigrants on Ellis Island.[107] Some claim that in a study of immigrants Goddard reached the conclusion that 87% of Russians, 83% of Jews, 80% of Hungarians, and 79% of Italians were feeble-minded and had a mental age less than 12.[108] Some have also claimed that this information was taken as "evidence" by lawmakers and thus it affected social policy for years.[109] Bernard Davis has pointed out that, in the first sentence of his paper, Goddard wrote that the subjects of the study were not typical members of their groups but were selected because of their suspected sub-normal intelligence. Davis has further noted that Goddard argued that the low IQs of the test subjects were more likely due to environmental rather than genetic factors, and that Goddard concluded that "we may be confident that their children will be of average intelligence and if rightly brought up will be good citizens".[110] In 1996 the American Psychological Association's Board of Scientific Affairs stated that IQ tests were not discriminatory towards any ethnic/racial groups.[111]

In his book The Mismeasure of Man, Stephen Jay Gould argued that intelligence testing results played a major role in the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924 that restricted immigration to the United States.[112] However, Mark Snyderman and Richard J. Herrnstein, after studying the Congressional Record and committee hearings related to the Immigration Act, concluded "the [intelligence] testing community did not generally view its findings as favoring restrictive immigration policies like those in the 1924 Act, and Congress took virtually no notice of intelligence testing".[113]

Juan N. Franco contested the findings of Snyderman and Herrnstein. Franco stated that even though Snyderman and Herrnstein reported that the data collected from the results of the intelligence tests were in no way used to pass The Immigration Act of 1924, the IQ test results were still taken into consideration by legislators. As suggestive evidence, Franco pointed to the following fact: Following the passage of the immigration act, information from the 1890 census was used to set quotas based on percentages of immigrants coming from different countries. Based on these data, the legislature restricted the entrance of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe into the United States and allowed more immigrants from northern and Western Europe into the country. The use of the 1900, 1910 or 1920 census data sets would have resulted in larger numbers of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe being allowed into the U.S. However, Franco pointed out that using the 1890 census data allowed congress to exclude southern and eastern Europeans (who performed worse on IQ tests of the time than did western and northern Europeans) from the U.S. Franco argued that the work Snyderman and Herrnstein conducted on this matter neither proved or disproved that intelligence testing influenced immigration laws.[114]

Sweden

После создания первого общества по пропаганде расовой гигиены, Немецкого общества расовой гигиены в 1905 году, шведское общество было основано в 1909 году как Svenska sällskapet för rashygien , третье в мире. [115][116] By lobbying Swedish parliamentarians and medical institutes the society managed to pass a decree creating a government-run institute in the form of the Swedish State Institute for Racial Biology in 1921.[115] By 1922 the institute was built and opened in Uppsala.[115] It was the first such government-funded institute in the world performing research into "racial biology" and remains highly controversial to this day.[115][117] It was the most prominent institution for the study of "racial science" in Sweden.[118] The goal was to cure criminality, alcoholism and psychiatric problems through research in eugenics and racial hygiene.[115] As a result of the institute's work, a law permitting compulsory sterilization of certain groups was enacted in Sweden in 1934.[119] The second president of the institute Gunnar Dahlberg was highly critical of the validity of the science performed at the institute and reshaped the institute toward a focus on genetics.[ 120 ] В 1958 году он закрылся, а все оставшиеся исследования были переведены на факультет медицинской генетики Уппсальского университета. [ 120 ]

Нацистская Германия

Нацистская партия и ее сторонники опубликовали множество книг о научном расизме, опираясь на евгенические и антисемитские идеи, с которыми они были широко связаны, хотя эти идеи были в обращении с 19 века. Такие книги, как Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes («Расовая наука немецкого народа») Ганса Гюнтера . [ 121 ] (впервые опубликовано в 1922 г.) [ 122 ] и «Раса и душа» («Раса и душа») Людвига Фердинанда Клауса [ 123 ] (опубликовано под разными названиями в период с 1926 по 1934 год) [ 124 ] : 394 пытался научно определить различия между немецкими, нордическими или арийскими народами и другими, предположительно низшими, группами. [ нужна ссылка ] Немецкие школы использовали эти книги в качестве текстов во времена нацизма. [ 125 ] В начале 1930-х годов нацисты использовали расистскую научную риторику, основанную на социальном дарвинизме. [ нужна ссылка ] продвигать свою ограничительную и дискриминационную социальную политику.

Во время Второй мировой войны нацистские расистские убеждения стали анафемой в Соединенных Штатах, и боасианцы, такие как Рут Бенедикт, укрепили свою институциональную власть. После войны открытие Холокоста и злоупотреблений нацистами научными исследованиями (таких как Йозефа Менгеле этические нарушения и другие военные преступления, раскрытые на Нюрнбергском процессе ) заставило большую часть научного сообщества отказаться от научной поддержки расизма.

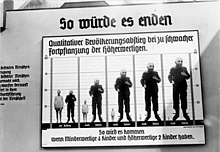

Пропаганда нацистской программы евгеники началась с пропаганды евгенической стерилизации. Статьи в Neues Volk описывали появление психически больных и важность предотвращения таких рождений. [ 126 ] Фотографии умственно отсталых детей сопоставлялись с фотографиями здоровых детей. [ 127 ] : 119 В фильме «Das Erbe» показан конфликт по своей природе с целью узаконить Закон о предотвращении наследственных заболеваний потомства путем стерилизации.

Хотя ребенок был «самым главным сокровищем народа», это распространялось не на всех детей, даже немецких, а только на тех, у кого не было наследственных слабостей. [ 128 ] Социальная политика нацистской Германии, основанная на расовой принадлежности, поставила улучшение арийской расы посредством евгеники в центр нацистской идеологии. В число мишеней этой политики входили преступники, «дегенераты» , «диссиденты», выступавшие против нацификации Германии, «слабоумные», евреи, гомосексуалисты , безумные, праздные и «слабые». Поскольку их считали людьми, которые соответствовали критериям « жизни, недостойной жизни » (нем. Lebensunwertes Leben ), им не следует разрешать производить потомство и передавать свои гены или наследие . [ нужна ссылка ] Хотя их по-прежнему считали «арийцами», нацистская идеология считала славян (т. е. поляков, русских, украинцев и т. д.) расово низшими по отношению к германской господствующей расой , пригодными для изгнания, порабощения или даже истребления. [ 129 ] : 180

Адольф Гитлер запретил тестирование коэффициента интеллекта (IQ) на предмет того, что он «еврей». [ 130 ] : 16

Соединенные Штаты

В 20-м веке концепции научного расизма, которые стремились доказать физическую и умственную неадекватность групп, считавшихся «неполноценными», использовались для оправдания принудительной стерилизации . программ [ 131 ] [ 132 ] Такие программы, продвигаемые евгениками, такими как Гарри Х. Лафлин , были признаны конституционными Верховным судом США в деле Бак против Белла (1927). Всего принудительной стерилизации подверглись от 60 000 до 90 000 американцев. [ 131 ]

Научный расизм также использовался в качестве оправдания Закона о чрезвычайных квотах 1921 года и Закона об иммиграции 1924 года (Закон Джонсона-Рида), которые ввели расовые квоты, ограничивающие иммиграцию итальянских американцев в Соединенные Штаты и иммиграцию из других стран Южной и Восточной Европы. . Сторонники этих квот, стремившиеся заблокировать «нежелательных» иммигрантов, оправдывали ограничения ссылками на научный расизм. [ 133 ]

Лотроп Стоддард опубликовал множество расистских книг о том, что он считал опасностью иммиграции, его самая известная из них - «Восходящая волна цветного населения против белого мирового превосходства» в 1920 году. В этой книге он представил взгляд на мировую ситуацию, касающуюся расы, уделяя особое внимание проблемам предстоящий демографический взрыв среди «цветных» народов мира и то, как «мировое превосходство белых» уменьшилось после Первой мировой войны и краха колониализма.

Анализ Стоддарда разделил мировую политику и ситуацию на «белых», «желтых», «черных», «индейцев» и «коричневых» народов и их взаимодействие. Стоддард утверждал, что раса и наследственность являются ведущими факторами истории и цивилизации, и что уничтожение или поглощение «белой» расы «цветными» расами приведет к разрушению западной цивилизации. Как и Мэдисон Грант, Стоддард разделил белую расу на три основных подразделения: нордическую, альпийскую и средиземноморскую. Он считал, что все три имеют хорошее происхождение и намного превосходят по качеству цветные расы, но утверждал, что нордические расы являются величайшими из трех и их необходимо сохранить посредством евгеники. В отличие от Гранта, Стоддарда меньше интересовало, какие разновидности европейцев превосходят других (нордическая теория), а больше интересовало то, что он называл «двурасовым», считая мир состоящим просто из «цветных» и «белых». "расы. Через годы после Великой миграции и Первой мировой войны расовая теория Гранта потеряла популярность в США и уступила место модели, более близкой к модели Стоддарда. [ нужна ссылка ]

Влиятельной публикацией стала «Расы Европы » (1939) Карлтона С. Куна , президента Американской ассоциации физических антропологов с 1930 по 1961 год. Кун был сторонником мультирегионального происхождения современных людей . Он разделил Homo sapiens на пять основных рас: европеоидную, монголоидную (включая коренных американцев), австралоидную, конгоидную и капоидную .

Школа мысли Куна стала объектом растущей оппозиции в основной антропологии после Второй мировой войны. Эшли Монтегю особенно активно осуждал Куна, особенно в его «Самом опасном мифе о человеке: расовая ошибка» . К 1960-м годам подход Куна стал устаревшим в основной антропологии, но его система продолжала появляться в публикациях его ученика Джона Лоуренса Энджела даже в 1970-х годах.

В конце XIX века по делу «Плесси против Фергюсона» (1896 г.) решение Верховного суда США , подтвердившее конституционную законность расовой сегрегации в соответствии с доктриной « отдельного, но равного », интеллектуально коренилось в расизме той эпохи, как и народная поддержка этого решения. [ 134 ] Позже, в середине 20-го века, решение Верховного суда по делу Браун против Совета по образованию Топики (1954 г.) отвергло расистские аргументы о «необходимости» расовой сегрегации, особенно в государственных школах .

После 1945 г.

К 1954 году, через 58 лет после того, как дело Плесси против Фергюсона поддержало расовую сегрегацию в Соединенных Штатах, американские популярные и научные мнения о научном расизме и его социологической практике изменились. [ 134 ]

В 1960 году был основан журнал Mankind Quarterly , который обычно называют местом научного расизма и превосходства белой расы. [ 135 ] [ 136 ] [ 137 ] и как не имеющее законной научной цели. [ 138 ] Журнал был основан в 1960 году, отчасти в ответ на решение Верховного суда «Браун против Совета по образованию», которое десегрегировало американскую систему государственных школ. [ 139 ] [ 138 ]

В апреле 1966 года Алекс Хейли взял интервью у американской нацистской партии основателя Джорджа Линкольна Роквелла для журнала Playboy . Роквелл обосновал свое убеждение в том, что черные уступают белым, цитируя длинное исследование Г.О. Фергюсона, проведенное в 1916 году, в котором утверждалось, что интеллектуальные достижения чернокожих студентов коррелируют с процентом их белого происхождения, утверждая, что «чистые негры, негры на три четверти чистые, мулаты и квадруны имеют примерно 60, 70, 80 и 90 процентов соответственно белой интеллектуальной эффективности». [ 140 ] Позже Playboy опубликовал интервью с редакционной заметкой, в которой утверждалось, что исследование было «дискредитированным… псевдонаучным обоснованием расизма». [ 141 ]

Международные организации, такие как ЮНЕСКО, пытались разработать резолюции, обобщающие состояние научных знаний о расе, и призывали к разрешению расовых конфликтов. В своей работе « Расовый вопрос » 1950 года ЮНЕСКО не отвергла идею биологической основы расовых категорий. [ 142 ] но вместо этого определил расу как: «Поэтому раса с биологической точки зрения может быть определена как одна из групп популяций, составляющих вид Homo sapiens», которые в широком смысле определялись как европеоидная , монголоидная , негроидная расы, но заявляли, что « В настоящее время общепризнано, что тесты интеллекта сами по себе не позволяют нам безопасно различать то, что обусловлено врожденными способностями, и то, что является результатом влияния окружающей среды, обучения и образования». [ 143 ]

Несмотря на то, что научный расизм в значительной степени отвергся научным сообществом после Второй мировой войны, некоторые исследователи продолжали предлагать теории расового превосходства в последние несколько десятилетий. [ 144 ] [ 145 ] Сами эти авторы, считая свою работу научной, могут оспаривать термин «расизм» и предпочитать такие термины, как «расовый реализм» или «расизм». [ 146 ] В 2018 году британский научный журналист и писатель Анджела Сайни выразила серьёзную обеспокоенность по поводу возвращения этих идей в мейнстрим. [ 147 ] Сайни продолжила эту идею в своей книге 2019 года «Высшее: Возвращение расовой науки» . [ 148 ]

Одним из таких научных исследователей расизма после Второй мировой войны является Артур Дженсен . Его самая известная работа — «Фактор g: наука об умственных способностях» , в которой он поддерживает теорию о том, что чернокожие люди по своей природе менее умны, чем белые. Дженсен выступает за дифференциацию образования по признаку расы, заявляя, что преподаватели должны «в полной мере учитывать все факты характера [студентов]». [ 149 ] В ответах Дженсену критиковалось отсутствие внимания к факторам окружающей среды. [ 150 ] Психолог Сандра Скарр описывает работу Дженсена как «вызывание в воображении образов чернокожих, обреченных на неудачу из-за своих собственных недостатков». [ 151 ]

Дж. Филипп Раштон , президент Фонда пионеров ( Раса, эволюция и поведение Дженсена ) и защитник «Фактора g» , [ 152 ] также имеет множество публикаций, увековечивающих научный расизм. Раштон утверждает, что «расовые различия в размере мозга, вероятно, лежат в основе их разнообразных результатов в истории жизни». [ 153 ] Теории Раштона защищают другие научные расисты, такие как Глэйд Уитни . Уитни опубликовала работы, предполагающие, что более высокий уровень преступности среди людей африканского происхождения частично можно объяснить генетикой. [ 154 ] Уитни делает такой вывод на основе данных, показывающих более высокий уровень преступности среди лиц африканского происхождения в разных регионах. Другие исследователи отмечают, что сторонники связи генетической преступности и расы игнорируют смешанные социальные и экономические переменные, делая выводы на основе корреляций. [ 155 ]

Кристофер Брэнд был сторонником работы Артура Дженсена о расовых различиях в интеллекте. [ 156 ] В книге Брэнда «Фактор g: общий интеллект и его последствия» утверждается, что чернокожие люди интеллектуально уступают белым. [ 157 ] Он утверждает, что лучший способ борьбы с неравенством IQ — это поощрять женщин с низким IQ воспроизводить потомство с мужчинами с высоким IQ. [ 157 ] Он столкнулся с резкой общественной реакцией, а его деятельность была описана как пропаганда евгеники. [ 158 ] Книга Брэнда была отозвана издателем, и он был уволен со своей должности в Эдинбургском университете .

Среди других выдающихся современных сторонников научного расизма — Чарльз Мюррей и Ричард Хернштейн ( «Геллорсовая кривая »).

Кевин Макдональд в своей серии «Культура критики» использовал аргументы эволюционной психологии для продвижения антисемитских теорий о том, что евреи как группа биологически эволюционировали и стали крайне этноцентричными и враждебными интересам белых людей . Он утверждает, что еврейское поведение и культура являются основными причинами антисемитизма, и продвигает теории заговора о предполагаемом еврейском контроле и влиянии на государственную политику и политические движения.

Психолог Ричард Линн опубликовал множество статей и книгу, поддерживающую теории научного расизма. В книге «IQ и богатство народов» Линн утверждает, что национальный ВВП во многом определяется средним национальным IQ. [ 159 ] Он делает этот вывод на основе корреляции между средним IQ и ВВП и утверждает, что низкий интеллект в африканских странах является причиной их низкого уровня роста. Теорию Линна критиковали за объяснение причинно-следственной связи между коррелирующими статистическими данными. [ 160 ] [ 161 ] Линн более непосредственно поддерживает научный расизм в своей статье 2002 года «Цвет кожи и интеллект афроамериканцев», где он предполагает, что «уровень интеллекта афроамериканцев в значительной степени определяется долей европеоидных генов». [ 162 ] Как и в случае с IQ и богатством народов , методология Линна ошибочна, и он предполагает наличие причинно-следственной связи, основанной на простой корреляции. [ 163 ]

Николаса Уэйда Книга ( «Проблемное наследство ») вызвала резкую реакцию научного сообщества: 142 генетика и биолога подписали письмо, описывающее работу Уэйда как «незаконное присвоение исследований в нашей области для поддержки аргументов о различиях между человеческими обществами». [ 164 ]

17 июня 2020 года Elsevier объявил, что отзывает статью, которую Дж. Филипп Раштон и Дональд Темплер опубликовали в 2012 году в журнале Elsevier «Личность и индивидуальные различия» . [ 165 ] В статье ложно утверждалось, что существуют научные доказательства того, что цвет кожи связан с агрессией и сексуальностью у людей. [ 166 ]

Йенская декларация , опубликованная Немецким зоологическим обществом , отвергает идею человеческих рас и дистанцируется от расовых теорий учёных 20 века. В нем говорится, что генетические различия между человеческими популяциями меньше, чем внутри них, демонстрируя, что биологическая концепция «рас» недействительна. В заявлении подчеркивается, что не существует конкретных генов или генетических маркеров , которые соответствовали бы общепринятым расовым категориям . Это также указывает на то, что идея «рас» основана на расизме, а не на каких-либо научных фактах. [ 167 ] [ 168 ]

Кларенс Гравли пишет, что различия в частоте таких заболеваний, как диабет, инсульт, рак и низкий вес при рождении, следует рассматривать через призму общества. Он утверждает, что социальное неравенство причиной этих различий является , а не генетические различия между расами. Он пишет, что генетические различия между различными группами населения основаны на климате и географии, а не на расе, и призывает заменить неверные биологические объяснения расовых различий анализом социальных условий, которые приводят к несопоставимым медицинским результатам. [ 169 ] В своей книге «Расизм в науке » Джонатан Маркс аналогичным образом утверждает, что расы существуют, хотя им не хватает естественной классификации в области биологии. Культурные правила, такие как « правило одной капли », должны быть разработаны для установления категорий расы, даже если они противоречат естественным закономерностям внутри нашего вида. По мнению Маркса, расистские идеи, пропагандируемые учеными, делают науку расистской. [ 170 ]

В своей книге «Медицинский апартеид». [ 171 ] Гарриет Вашингтон описывает жестокое обращение с чернокожими во время медицинских исследований и экспериментов. Чернокожих людей обманом заставляли участвовать в медицинских экспериментах, используя неясные формулировки в формах согласия и не перечисляя риски и побочные эффекты лечения. Вашингтон упоминает, что, поскольку чернокожим людям было отказано в адекватной медицинской помощи , они часто отчаянно нуждались в медицинской помощи, и медицинские экспериментаторы смогли воспользоваться этой потребностью. Вашингтон также подчеркивает, что, когда методы лечения были усовершенствованы и усовершенствованы в результате этих экспериментов, чернокожие люди почти никогда не получали от них пользы. [ 172 ]

В заявлении Американского общества генетики человека (ASHG) от 2018 года выражается тревога по поводу «возрождения групп, отвергающих ценность генетического разнообразия и использующих дискредитированные или искаженные генетические концепции для поддержки фиктивных заявлений о превосходстве белой расы ». ASHG осудил это как «неправильное использование генетики для подпитки расистских идеологий» и выделил несколько фактических ошибок, на которых основывались утверждения сторонников превосходства белой расы. В заявлении подтверждается, что генетика «демонстрирует, что люди не могут быть разделены на биологически различные подкатегории» и что она «разоблачает концепцию «расовой чистоты» как научно бессмысленную». [ 173 ]

См. также

- Предвзятость

- Биологический детерминизм

- Экологический детерминизм

- Фрик-шоу

- История расы и споров об разведке

- Человеческий зоопарк

- Институт изучения академического расизма

- Итальянский фашизм и расизм

- Итальянские расовые законы

- Нацизм и раса

- Объективация

- Пионерский фонд

- Расовая политика нацистской Германии

- Раса и генетика

- Раса и здоровье

- Раса и интеллект

- Научный империализм

Ссылки

- ^ Гаррос, Джоэл З. (9 января 2006 г.). «Храбрый старый мир: анализ научного расизма и БиДил» . Медицинский журнал Макгилла . 9 (1): 54–60. ПМЦ 2687899 . ПМИД 19529811 .

- ^ Нортон, Хизер Л.; Куиллен, Эллен Э.; Бигэм, Эбигейл В.; Пирсон, Лорел Н.; Дансворт, Холли (9 июля 2019 г.). «Человеческие расы не похожи на породы собак: опровергая расистскую аналогию» . Эволюция: образование и информационно-пропагандистская деятельность . 12 (1): 17. дои : 10.1186/s12052-019-0109-y . ISSN 1936-6434 . S2CID 255479613 .

- ^ Кеньон-Флэтт, Британи (19 марта 2021 г.). «Как научная систематика создала миф о расе» . Сапиенс.