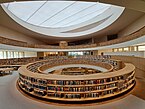

Современная еврейская историография

Современная еврейская историография – это развитие еврейского исторического повествования в современную эпоху . Хотя еврейская устная история и сборник комментариев к Мидрашу и Талмуду являются древними, с появлением печатного станка и подвижных литер в период раннего Нового времени были опубликованы еврейские истории и ранние издания Торы/Танаха, посвященные истории. еврейской религии и, во все большей степени, истории евреев и , еврейского народа национальной идентичности . Это был переход от культуры рукописей или писцов к культуре печати . Еврейские историки писали отчеты о своем коллективном опыте, но также все чаще использовали историю для политических, культурных, научных или философских исследований. Писатели использовали корпус текстов, унаследованных от культуры, пытаясь построить логическое повествование для критики или продвижения современного уровня техники. Современная еврейская историография переплетается с интеллектуальными движениями, такими как европейский Ренессанс и эпоха Просвещения. но опирался на более ранние работы позднего средневековья и различные источники античности.

Предыстория и контекст

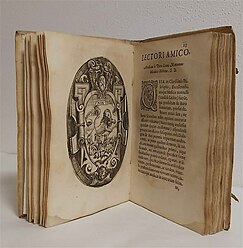

[ редактировать ]Самые ранние книги на иврите печатались в Риме, начиная с 1469 года, и ранние печатники знали о сильной традиции создания еврейских писцов . [1] Переход к печати устранил разнообразие и вариации, присущие рукописям, и позволил текстам дойти до большего числа людей. [2] Хотя эллинистическая еврейская историография была забыта основной еврейской мыслью на многие годы, она сохранилась Церковью и в Книге Маккавеев из Хасмонейского царства . [3]

Основные публикации по еврейской истории раннего Нового времени были созданы под влиянием политического климата того времени. [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] Некоторые еврейские историки, руководствуясь желанием добиться еврейского равенства, использовали еврейскую историю как инструмент еврейской эмансипации и религиозной реформы. Что касается еврейских историков 18-го и 19-го веков, Майкл А. Мейер пишет: «Рассматривая еврейскую идентичность как по существу религиозную, они создали еврейское прошлое, которое сосредоточилось на еврейской религиозной рациональности и подчеркнуло еврейскую интеграцию в общества, в которых жили евреи. " [9]

Отношение к исторической литературе

[ редактировать ]Талмудические авторитеты не поощряли написание истории в эпоху средневековья и раннего Нового времени; степень, в которой это было эффективно в препятствовании реальному историческому производству, неясна. Мориц Штайншнейдер и Арнальдо Момильяно заметили, что еврейская историография, похоже, замедлилась в конце периода Второго Храма , и даже Маймонид (1138–1204) считал историю пустой тратой времени. [11] [12] Официально светская философия рассматривалась как нееврейская деятельность и запрещалась. Еврейским ученым высшего класса было предложено изучать медицину . Астрология также была разрешена. [13] Медицина, астрономия и космография представляли собой приемлемое сочетание религии и науки, основанное на вавилонянах. [14] Историю время от времени читали, но считали занятием, которым занимаются другие группы; однако средневековые еврейские власти в арабском мире относились к практике светской философии с благотворным пренебрежением , хотя и были запрещены, но на ее практику закрывали глаза. Фактически, как отмечает Дэвид Бергер , испанское еврейство явно было гостеприимно к философии, литературному искусству и наукам. [15] Джозеф Каро называл книги по истории «книгами войн», чтение которых он запрещал как «сидение в скоплении бездумных людей», а геонимы , такие как Саадия Гаон , подразумевали корни ереси или просто недостаток образования. [16] Некоторые ранние попытки написать историю были встречены противоречиями или наложены санкции или запреты, такие как выборочные или общие запреты, приказные сожжения, бойкоты и эффективный саботаж успеха публикации. [17] [18] Общепринятое мнение в еврейской историографии, воплощенное Сало Виттмайером Бароном и Йосефом Хаимом Йерушалми , состоит в том, что галахические взгляды серьезно ограничивали деятельность средневековых еврейских историков, хотя это частично оспаривалось Робертом Бонфилом , Амосом Функенштейном и Бергером, бывшим считая Ренессанс «лебединой песней» более ранних работ, что, по мнению ученика Йерушалми Дэвида Н. Майерса , сформировало важные дебаты Йерушалми-Бонфил в еврейской историографии . [19] [20] [16] [15] [21]

Амрам Троппер объяснил, что интеллектуальная элита использовала классическую литературу и схоластику для построения идентичности в Римской империи после неудавшихся еврейских восстаний. [22] Объясняя на примере Маймонида, Ха-Коэна и Илии Капсали (1485-1550) отношение к истории, Бонфил показывает, что, тем не менее, существует средневековая историография, унаследованная более поздними авторами, хотя он признает скудность еврейской средневековой историографии и влияние негативной галахической позиции, которое не следует недооценивать. [16] Capsali, an important historian of Muslim and Ottoman history, has a medieval historical approach, with early modern subject matter.[23][24] Capsali's chronicle may be the first example of a diasporic Jew writing a history of their own location (Venice).[25]

Bonfil surmises that the return to traditionalism in orthodoxy was actually a later phenomenon, a reactionary response to modernity.[16] When those among the halakhic authorities who valued philosophy studied it, such as Moses Isserles, they justified it with a continuity to Hellenistic philosophy.[26][27]

Notably, Baruch Spinoza was excommunicated for transgressing the bounds of Rabbinic thought into the growing domain of Enlightenment philosophy in 1656.[28] Spinoza and rabbi Joseph Solomon Delmedigo, who studied with Galileo, shared a goal to liberate science from theology, and combined it with scriptural references.[29] Spinoza and other heretics such as Abraham Abulafia or ibn Caspi became figures in the conflict between emancipation and traditionalism in Jewish political and historical ideology.[30][31] Israël Salvator Révah, per Marina Rustow, has stressed that the anti-rabbinic themes expressed by both Uriel da Costa (1585-1640) and Spinoza had emerged from the crucible of Iberian crypto-Jewish culture.[32][33] Early modern philology (i.e. the study of historical texts) had an important impact on the development of the Enlightenment intellectual movements through work such as that of Spinoza.[34] Richard Simon also had his work of historical biblical criticism suppressed by the Catholic authorities in France in 1678.[35] While some Jews were willing to express doubt or disbelief privately, they feared the judgment or ostracism of the community to go too far in criticism of the establishment.[36]

Medieval sources

[edit]About 90% of world Jewry inhabited the Muslim world around the Mediterranean in the medieval period.[37] Jews of the medieval Islamic world such as Andalusia, North Africa, Syria, Palestine, and Iraq were prolific producers and consumers of historical works in Hebrew, Judeo-Arabic, Arabic and rarely Aramaic.[38] David B. Ruderman has stated that Bonfil's perspective on the complex dialectic between Jews and non-Jews, rather than a simplistic understanding of "influence," is a revisionist perspective with implications for understanding historiography in context be it Christian or Ottoman; Ruderman is a proponent of Bonfil's interpretation.[39][40]

Over 400,000 manuscript fragments in the Cairo Geniza are an important historical source from the Fatimid period, rediscovered as a historical source in the 18th and 19th centuries. The Geniza has been called a "lost archive." The Geniza is a storeroom in the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fustat which contained scrap documents dating to the 9th century, and now exists at various academic institutions for study.[41][42][43][37][44]

Iggeret of Rabbi Sherira Gaon (987)[45][46][47] and Sefer ha-Qabbalah (1161)[48] by Abraham ibn Daud (ibn David)[49] were two medieval sources available to and trusted by Jewish early modern historians.[50][51][52] Ibn David is considered one of the first rationalist Spanish Jewish philosophers.[53] The 10th century responsa of the Geonim are an important corpus of correspondence. Iraqi Jews in areas such as Baghdad and Basra, were an important community in this time period and corresponded with the Talmudic academies in Babylonia.[54]

Josippon

[edit]Josippon (or Sefer/Sepher Josippon), also called "Josephus of the Jews," was a key medieval source familiar to Hasdai ibn Shaprut and Ibn Hazm, one of if not the most influential historical works in pre-modern Jewish historiography, probably composed by a pseudonymous "Joseph ben Gorion" in the 10th century based on the earlier Josephus Flavius and his work Antiquities of the Jews.[56][57] It relies on the Hegesippus (or Pseudo-Hegesippus), a Latin translator of Antiquities and Josephus' The Jewish War.[58] The author had access to a decent library of material and drew on 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, Jerome's translation of Eusebius, the Aeneid, Macrobius, Orosius, and Livy.[59] Like its namesake and inspiration, the work commingles Roman history and Jewish history.[60] Yosippon was republished in the 16th century and was a historical chronicle of critical importance to medieval Jews.[61] It was relied on by Abraham ibn Ezra and Isaac Abravanel.[62] These books were frequently reprinted through the 18th century.[63][64][65][66][67][68]

The work emerged from the context of Hellenistic Judaism or Romaniote Judaism in the Jewish Byzantine Empire.[69] The version of Josippon by the young Balkan scholar Yehudah ibn Moskoni (1328-1377), printed in Constantinople in 1510 and translated to English in 1558, became the most popular book published by Jews and about Jews for non-Jews, who ascribed its authenticity to the Roman Josephus, until the 20th century.[70] Born in Byzantium, Moskoni's library of 198 volumes was once considered by historians to be the largest individual Jewish library in medieval Western Europe, although as Eleazar Gutwirth notes, there were numerous Jewish and converso libraries 1229-1550, citing Jocelyn Nigel Hillgarth. He further notes that Moskoni's library was sold in 1375 for a high price, and that Moskoni specifically commented on the use of non-Jewish sources in Josippon.[71] Moskoni was part of a Byzantine Greek-Jewish milieu that produced a number of philosophical works in Hebrew and a common intellectual community of Jews in the Mediterranean.[72]

Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406) 's Muqaddimah (1377) also contains a post-biblical Jewish history of the "Israelites in Syria" and he relied on Jewish sources, such as the Arabic translation of Josippon by Zachariah ibn Said, a Yemenite Jew, according to Khalifa (d. 1655).[73][74] Saskia Dönitz has analyzed an earlier Egyptian version older than the version reconstructed by David Flusser, drawing on the work of a parallel Judaeo-Arabic Josippon by Shulamit Sela and fragments in the Cairo Geniza, which indicate that Josippon is a composite text written by multiple authors over time.[75][76][77][78][79]

Josippon was also a popular work or a volksbuch, and had further influence such as its Latin translation by Christian Hebraist Sebastian Münster which was translated into English by Peter Morvyn, a fellow of Magdalen College in Oxford and a Canon of Lichfield, printed by Richard Jugge, printer to the Queen in England, and according to Lucien Wolf may have played a role in the resettlement of the Jews in England.[80][81] Munster also translated the historical work of ibn Daud which was included with Morwyng's edition.[82] Steven Bowman notes that Josippon is an early work that inspired Jewish nationalism and had a significant influence on midrashic literature and talmudic chroniclers as well as secular historians, though considered aggadah by mainstream Jewish thought, and acted as an ur-text for 19th century efforts in Jewish national history.[70]

Jewish expulsions and the Spanish Inquisition

[edit]

Jewish expulsions accelerated in the 15th century and influenced the growth in Jewish historiography.[83][32] Sephardic Jews from Spain, Portugal, and France settled in Italy and the Ottoman Empire during this period, shifting the nexus of Jewry east.[84] The Languedoc region, which had a large population and respected rabbis known collectively as the Hachmei Provence, were forced to convert or flee in the 14th century, and they sought to avoid detection, which creates a paucity of documentation and a difficult scenario for historians.[85] Within Italy, there was also considerable upheaval with the migration and expulsion of Jews in the Papal States in the late 1500s.[86]

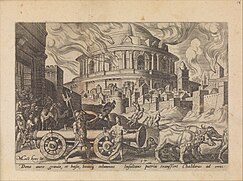

The Spanish Inquisition attempted to burn any parchment or paper containing Hebrew, and any book known to have been translated from Hebrew. This led to an estimated millions of texts destroyed in Spain and Portugal, especially centers of academic learning as Salamanca and Coimbra, rendering surviving manuscripts in foreign libraries rare and hard to come by.[87]

Whether the Spanish Inquisition's records are truthful or worthy of trust is the subject of debate. Historians such as Yitzhak Baer and Haim Beinart have taken the view that the crypto-Jews were sincerely Jewish; Benzion Netanyahu has argued they were sincerely Christian converts, and their secret practice of Judaism a myth, before changing his view; Norman Roth has also argued the Inquisition's records can be trusted, which is disputed.[88]

Early modern histories in the post-medieval and Renaissance era

[edit]The 16th century is considered something of a blossoming of Jewish historiography by some historians, such as Yerushalmi, who characterizes the focus as shifting social and post-biblical.[61][20] Although some historians focus on the 19th century as an important period in the development of modern Jewish historiography, the 16th century is also considered an important period.[89] Religion figured prominently and the differences in martyrdom and messianic figures in Sephardic and Askenazic communities post-expulsion are the subject of historiographical debate.[90] Some historians, such as Bonfil, have disagreed with Yerushalmi that this period produced a significant sea change in historiography.[91][12]

The Book of the Honeycomb's Flow (1476) by Italian rabbi Judah Messer Leon (c.1420-1498) (Judah ben Jehiel, alias Leone di Vitale) is an early work of humanistic classical rhetorical analysis that was also noted by Graetz, which was noted by Bonfil, and paraphrasing Israel Zinberg stated, he "was a child not only of the old people of Israel, but also of the youthful Renaissance." Nofet Zufim drew on the classical theoretical writings of Cicero, Averroes and Quintilian[92] While not a work of history, it was a precursor to Azariah dei Rossi and cited by him as opening the door to the value of secular studies. It was printed by Abraham Conat.[93] David ben Judah Messer Leon, his son, published a humanistic work defending the literary arts in Constantinople in 1497.[94]

The 1504 historic work of the Portuguese royal astronomer[95] Abraham Zacuto (1452-1515),[96][97] Sefer ha-Yuḥasin (Book of the Genealogies), contains anti-Christian historiographical polemic and urging of strength in the face of persecution and Jewish martyrdom.[98] Still, Zacuto was aware of and depended on secular work.[2] Zacuto was an important scientist who befriended Columbus and provided a meaningful new astrolabe for the Portuguese explorers in addition to his work in history and commentary. Abraham A. Neuman writes,

Sefer Yuhasin is a medley of historical biographical notes, reminiscences, comments and observations which often express his inner thoughts. Here, he appears in his strength and weakness, a man of numerous contradictions. He was necessarily a many-sided figure, for he lived and participated in the adventures of an explosive age, midway between medievalism and modernism, holding in its grasp the Inquisition and the discovery of new worlds.[99]

It is primarily a world history with specific attention to the Jewish plight, from creation to 1500.[100] Sefer Yuhasin traces the chronology and development of the Oral Torah, and contains critical appraisal of Talmudic evidence. Zacuto expresses his view of the importance of familiarity with Roman history. He was familiar with Josippon but was apparently unfamiliar with the genuine Josephus; Samuel Shullam, his editor who published his annotated version in 1566, was familiar with the original Josephus, and inserted comments and glosses with corrections.[101]

Italian talmudic chronologer Gedaliah ibn Yahya ben Joseph's (1515-1587) 1587 Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah (Chain of Tradition) was also of significance during this period.[102][61] It included a justification of Aristotelian and Neoplatonic philosophy.[103] The "chain of tradition" or the successor tradition is also used to refer to the continuation aspect of historians building on the shared reference base of works by creating introductions or citations to prior work, key to rabbinic textual analysis in the mishnah or mesorah well as Jewish historiography.[83][104]Italian Jewry in particular benefitted from factors such as education, geography, and access to printing. They enjoyed relative freedom during the period and had contact with Christian scholars. Besides their interest in Jewish text, they also pursued the sciences, medicine, music, and history.[105] The liberal dukes of d'Este practiced toleration of Jewish faith.[106]

ibn Verga

[edit]Solomon ibn Verga (1460-1554)'s 1520 Scepter of Judah (Shevret Yehudah) was a notable chronicle of Jewish persecutions, written in Italy and published in the Ottoman Empire in 1550.[19][107][108][109][110][111][112] It contains some 75 stories of Jewish persecution,[113] and is a transitional work between the medieval and modern periods of Jewish history.[114][115] Born in Spain, Verga's views were shaped by the expulsion in 1492, his forced baptism, and the massacres as he fled Portugal.[113][116] Shevret Yehudah was "the first Jewish work whose main concern was the struggle against ritual murder accusations."[114] It was cited by his contemporary Samuel Usque, Consolação às Tribulações de Israel ("Consolation for the Tribulations of Israel"), Ferrara, 1553.[117][118][119] Usque was a trader.[120] Rebecca Rist has called it a satirical work that blends fiction with history.[121] Jeremy Cohen has said Verga was a pragmatist who presented benevolent and enlightened characters with a happy ending.[122][123][124]

ha-Cohen

[edit]Joseph ha-Cohen (1496-1575) was a Sephardic physician and chronicler who is considered one of the most significant 16th century Jewish historians and Renaissance scholars.[125][126][127] Born in Avignon to Castilian and Aragonian Jewish parents and later in Genoa, he was cited and highly regarded by later historians such as Basnage.[128][129][130] His Emek Ha-Bakha (Vale of Tears), appeared in 1558[131] and is considered an important historical work.[61] The name comes from Psalm 84, and it is a history of Jewish martyrdom.[132] It consisted of the narrative of Jewish persecution that extracted from and built on the Jewish part of his earlier world histories, and inspired Salo Baron's idea of the "lachrymose" conception of Jewish history.[20] Yerushalmi notes that it begins in the post-biblical era.[61] Bonfil notes that ha-Cohen's historiography is specifically shaped by the Jewish expulsion from Spain and France that ha-Cohen personally experienced.[20] ha-Cohen's sources included Samuel Usque.[133] ha-Cohen and Usque are sources for early documentation of Jewish blood libels.[134] He was a contemporary of the Italian-Jewish geographer Abraham Farissol, a scribe from Avignon who worked for Judah Messer Leon,[135] and drew upon his work.[136] It incorporates earlier medieval chronicles almost verbatim.[137]

dei Rossi

[edit]

Azariah dei Rossi (1511-1578) was an Italian-Jewish physician, rabbi, and a leading Torah scholar during the Italian Renaissance. Born in Mantua, he translated classical works such as Aristotle, and was known to quote Roman and Greek writers along with Hebrew in his work.[138][139][140] He is often considered the father of modern Jewish historiography.[141] He was the first major author in Jewish historiography to incorporate and edit non-Jewish texts into his work.[89] His 1573 work Me'or Einayim (Light of the Eyes) is an important early work of humanistic 16th century Jewish historiography.[142][61][143][20][144] It includes a polemic critique of Philo noted by Baron and Norman Bentwich; Philo's work was popular among contemporary Italian Jews.[56] Rossi drew on the Latin Josephus, with specific annotations on source text versions for the Jewish academies at Ferrara, and investigated the Septuagint.[101] Bonfil writes that it was an attempt at a "New History" of the Jews and a work of ecclesiastical historiography, that adopted as its main tool, logical and philological criticism.[16] Rossi also cited rabbinical material and Jewish writers such as Zacuto; Baron has also noted it was an apologetic work, and Bonfil has asserted ultimately a conservative work with a medieval worldview, but nonetheless pioneering in its critical study and methods.[145]

De Rossi's work was critical of the rabbinical establishment, questioning the historicity of post-biblical Jewish legends, and was met with condemnation, opprobrium and bans; Joseph Caro called for it to be burned, though he died before this was carried out, and Samuel Judah Katzenellenbogen, the leader of the Venetian rabbis at the time, published herem prior to publication prohibiting owning or reading the book without permission.[146][147][148][17][149] Rossi's work mixed the world of secular Renaissance scholarship with Jewish rabbinical textual analysis, addressing contradictions, which offended the sensibilities of religious leaders such as the Rabbi Judah Loew of Prague, known as the Maharal, who said the words of Torah should not mix with those of science.[150] Signatories to the ban included important Jewish community scholars Yehiel Nissim da Pisa and Yehiel Trabot.[151] Nonetheless, the rabbis of Mantua, Judah Moscato and David Provençal, although critical in some ways, still considered him a respectable Jew with great value.[18]

Rossi went to Venice to argue his case with the rabbis who had charged him with heresy, who said he could publish if he would include David's brother Moses Provençal's defense of the traditional chronology, which he did along with his own response to the response. They also requested some passages to be deleted, which he yielded to; Abraham Coen Porto rescinded his veto, but the 1574 decree still held sway in limiting publication. Rossi sought help from the Catholics interested in bible study, and obtained an imprimatur from Marco Marini, a teacher of Hebrew and Latin in Venice. Marini taught Giacomo Boncompagno who requested Rossi translate Me'or Einyanim into Italian. Like Elijah Levita, Rossi became known for teaching Hebrew to Christians, earning disapproval from fellow Jews, but he did not convert.[18] Rossi was cited by Christian Hebraists such as Bartolocci, Bochart, Buxtorf, Hottinger, Lowth, Voisin, and Morin.[56]

Despite its controversial status, Rossi's work was known in the 17th and 18th centuries, per David Cassel and Zunz as relayed by Joanna Weinberg, individuals such as Joseph Solomon Delmedigo and Menasseh ben Israel considered it required reading. Baron considered Rossi an antiquarian; Bonfil argues he had a nationalistic view of Jewish history.[152][153] Rossi's work is considered by some to be an early example of the construction of Jewish identity through modern historical methods.[154]

Gans

[edit]David Gans (1541–1613) was a German-Jewish rabbi, astronomer, historian, and chronicler from Lippstadt, Westphalia, whose historical work Tzemach David, published in 1592, was a pioneering study of Jewish history.[155][156][157][158] Gans wrote on a variety of liberal arts and scientific topics, making him unique among the Ashkenazi for his production of secular scholarship.[159] Gans was a student of the Maharal, whom Yerushalmi says had the more profound ideas about Jewish history,[61] and of Moses Isserles.[150] Gans was the first Jewish scholar to use a telescope and the science of Copernicus.[26] Gans also corresponded with secular astronomers such as Johannes Kepler and Tycho Brahe, and drew on August Gottlieb Spangenberg.[160] Gans took inspiration from Josippon and Maimonides.[161] Gans' work is a hybrid of two parallel stories of world and Jewish history.[20][162] While not as cutting-edge a historian as his contemporary, de Rossi, his books introduced historiography to the Ashkenazi audience, making him a forerunner of subsequent developments in Jewish culture.[149] Gans' work can be seen as a defense of the traditional dissemination of knowledge.[163]

17th century

[edit]Abraham Portaleone was another Italian-Jewish Renaissance physician who, as discussed by Peter Miller and Moses Shulvass, published the historiographical work, Shilte ha-Giborim (Shields of the Heroes) in Mantua in 1612[164] which contained detailed descriptions of ancient life. Miller calls it a "complex" and "strange" "encyclopedic study."[140][138][165][21] While ostensibly on the subject of the levitical tasks of the Temple, it touches on diverse topics such as botany, music, warfare, zoology, mineralogy, chemistry, and philology, and appears as a work of Renaissance scholarship per Samuel S. Kottek.[166]

Hannover

[edit]Nathan ben Moses Hannover's Yeven Mezulah (Abyss of Despair) (1653)[167][168][169][170] is a chronicle of the Khmelnytsky massacres or pogroms in eastern Europe in the mid 17th century. While a massacre certainly occurred, accounts and casualty numbers differ among Ukrainian, Polish, and Jewish historians.[171][172] All three groups also use the story as part of their own national ideologies.[173]

Basnage

[edit]

Jacques Basnage (1653-1723), a Huguenot living in the Netherlands, was one of the first authors in the modern era to publish a comprehensive post-biblical history of the Jews.[175] Basnage aimed to recount the story of the Jewish religion in his work Histoire des juifs, depuis Jésus-Christ jusqu'a present. Pour servir de continuation à l'histoire de Joseph (1706, in 15 volumes). Basnage heavily cites early modern and medieval Sephardic Jewish historians, such as Isaac Cardoso, Leon Modena, Abraham ibn Daud, Josippon, and Joseph ha-Cohen (whom he called "the best historian this nation has had since Josephus"), but also drew on Christian sources such as Jesuit Juan de Mariana.[128]

It was said to be the first comprehensive post-biblical history of Judaism and became the authoritative work for 100 years;[176] Basnage was aware that no such work had ever been published before.[177] Basnage sought to provide an objective account of the history of Judaism.[178][179] His work was widely influential, and developed further by other authors such as Hannah Adams.[180][181] Basnage's work is considered the birth of the "Christian historiography" of Jewish history.[128]

18th century

[edit]In the 18th century, reformists such as Moses Mendelssohn (1729-1786) invoked Maimonides to pursue a rational emancipationist movement for German Jews.[182][183] Mendelssohn has a significant role in Jewish history and the Haskalah or Jewish enlightenment. One of Mendelssohn's central goals concerned a grounding in Jewish history.[184] Isaac Euchel (1756-1804)'s Toledot Rabbenu Moshe ben Menahem (1788) was the first biography of Mendelssohn and significant in beginning a movement of biographical studies in Jewish historiography.[185][186] Meyer notes that Euchel acknowledges that Mendelssohn began his secular studies in history.[187] Israel Zamosz, one of Mendelssohn's teachers, also published a work applying reason and science to the statements of talmudic authorities.[188][189][190]

According to David B. Ruderman, the maskilim were inspired by such medieval and early modern historians and thinkers as Judah Messer Leon, de Rossi, ibn Verga, Moscato, Portaleone, Tobias Cohen, Simone Luzzatto, Menasseh ben Israel, and Isaac Orobio de Castro. Rossi's Me'or Einayim was republished by Isaac Satanow in 1794.[191] Satanow wrote on education and encouraged the study of science and enlightenment philosophy, citing David Gans.[192] According to Funkenstein as related by David Sorkin, the development of the Haskalah was related to classical liberalism, citing Mendelssohn's influence by Thomas Hobbes.[193]

The Haskalah made education a priority and produced pedagogical literature in the humanistic vein, such as that of Satanow and David Friedländer.[194] The Haskalah became interested in Sephardic Jewish sources and had an idea of historiography with an eye toward reformism.[195][196] The scholarship of the Sephardim held a mystique for emancipated German Jews who had an opportunity to redefine their identities.[197] They held manuscripts in held esteem, and superior to other types of sources.[1]

The travel diary of Chaim Yosef David Azulai (1724-1806) is one important source for information on the broader Jewish world during this period.[198][199] The Vilna Gaon was another figure that encouraged critical reading of text and scientific study during this period.[200]

Prague was a major center of Jewish scholarship before the 19th century, with maskilim Peter Beer (1758-1838), Salomo Löwisohn (1789-1821), and Marcus Fischer (1788-1858) making it a center for Jewish historical production.[201]

There was also significant progression in Yiddish historiography during the 18th century such as the work of Menahem Amelander (also called Menahem ben Solomon ha-Levi or Menahem Mann) in the Netherlands, who translated Josippon.[89][202][203][204][205][64][206] He also drew on Basnage.[207] His 1743 work Sheyris Yisroel (Remnant of Israel) picks up where Josippon left off.[203] It is a continuation of his Yiddish translation of Josippon with a general history of the Jews in the diaspora until 1740.[202] Max Erik and Israel Zinberg considered it the foremost representative of its genre.[208] It was cited by Abraham Trebitsch with his Qorot ha-'Ittim and Abraham Chaim Braatbard with his Ayn Naye Kornayk.[83] Zinberg called it "the most important work of Old Yiddish historiographical literature".[209]

The Lithuanian rabbi Jehiel ben Solomon Heilprin (1660-1746)'s Seder HaDoroth (1768) was another 18th century historical work which cited the earlier work by Gans, ibn Yahya and Zacuto as well as other medieval work such as the itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela.[210][211]

19th century and birth of modern Jewish studies

[edit]Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi wrote that first modern professional Jewish historians appeared in the early 19th century,[212] writing that "[v]irtually all nineteenth-century Jewish ideologies, from Reform to Zionism, would feel a need to appeal to history for validation".[213] He has further explained that the 19th century themes of martyrology and the chain of rabbinic tradition were a line of continuation from the medieval era; Daniel Frank has suggested a corollary, that Jewish history had tended to focus on these themes and ignore threads without clear expression of them.[214]

The German Wissenschaft des Judentums (or the "science of Judaism" or "Jewish studies") movement, was founded by Isaac Marcus Jost, Leopold Zunz, Heinrich Heine,[215] Solomon Judah Loeb Rapoport, and Eduard Gans, and was the birth of modern academic Jewish studies. Although a rationalist movement, it also drew on spiritual sources such as Yehuda Halevi's Kuzari.[216] Zunz started the movement in 1818 with his Etwas.[217]

Another important father of the movement was Immanuel Wolf whose essay Über den Begriff einer Wissenschaft des Judentums (On the Concept of Jewish Studies) in 1822 proposed a structure for Jewish studies, and indicated a modern notion of Jewish peoplehood.[218] Wolf was a German idealist who dealt with Judaism in systematic, universal, Hegelian terms.[217]

David Cassel was a notable historian and student of Zunz.[219] Edouard Gans was one of Hegel's students.[220]

Abraham Geiger founded the Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums or school/seminary for Jewish studies, in Berlin in 1872, which remained until it was shuttered by the Nazis in 1942.[221]

Solomon Schechter was an important Moldavian-born, later British-American rabbi. A student of the Hochschule, he went on to start his own American school, become president of synagogues and was influential in the development of Conservative Judaism in the United States. He was also influential in British and American Jewish education. Schechter became aware of the Cairo Geniza and was instrumental in bringing the documents to Cambridge University Library and the Jewish Theological Seminary for study.[222][223]

Adolph Jellinek was a rabbi, publisher and pamphleteer who spoke and wrote emphatically against antisemitism, and republished medieval works from the Crusades era and history from the early modern period such as ha-Kohen's Emeq ha-Bakha.[224]

The Wissenschaft has been called "institutionalized German historicism," and a number of historians from Funkenstein to Meyer to Shmuel Feiner and Louise Hecht have challenged Yerushalmi's interpretation that the 19th century narrative is the salient shift in the characterization of Jewish historiography into modernity.[201]

Significant work from the 19th century included Moritz Steinschneider (1816-1907)'s Geschichtsliteratur der Juden.[225][226][227] Steinschneider became the preeminent scholar of the period.[217] The work of Julius Fürst was also significant.[224][228]

Théodore Reinach (1860-1928)'s Histoire des Israelites (1884) is the most significant example of 19th-century French-Jewish historiography which is something of a counterpoint to the mainstream German development in this time.[229] Marco Mortara (1815-1894) can be considered an Italian-Jewish version.[230] Isidore Loeb (1839-1892) founded the Revue des Études Juives or Jewish studies review, in 1880 in Paris. British Jews Claude Montefiore and Israel Abrahams founded The Jewish Quarterly Review, an English counterpart, in 1889.[231] Emmanuel Levinas, a Lithuanian-French philosopher, offered a "new science of Judaism" critique of the Wissenschaft pertaining to Jewish particularism.[232]

Forerunners to Jewish national Zionist historiography from the 19th century include Peretz Smolenskin, Abraham Shalom Friedberg, and Saul Pinchas Rabinowitz, part of the Hibbat Zion movement, leading to Ahad Ha'am.[233]

Jost

[edit]Isaak Markus Jost (1793-1860) was the first Jewish author to publish a comprehensive post-biblical modern history of the Jews.[234] His Geschichte der Israeliten seit den Zeit der Maccabaer, in 9 volumes (1820–1829), was the first comprehensive history of Judaism from Biblical to modern times by a Jewish author. It primarily focused on recounting the history of the Jewish religion.[235]

Jost's history left "the differences among various phases of the Jewish past clearly apparent". He was criticized for this by later scholars such as Graetz, who worked to create an unbroken narrative.[236]

Unlike Zunz, Jost has an anti-rabbinical stance, and sought to free Jewish history from Christian theology. He saw influence from Greco-Roman law and philosophy in Jewish philosophy, and sought to secularize Jewish history.[237]

Zunz

[edit]Leopold Zunz (1794-1886), a colleague of Jost, was considered the father of academic Jewish studies in universities, or Wissenschaft des Judentums (or the "science of Judaism").[238] Zunz' article Etwas über die rabbinische Litteratur ("On Rabbinical Literature"), published in 1818, was a manifesto for modern Jewish scholarship.[148] Zunz was influenced by Rossi's philological and comparative linguistics approach.[200] Though they were childhood friends, Zunz had a harsh and perhaps jealous criticism of Jost's earlier work and sought to improve on it.[239] Zunz was a student of August Böckh and Friedrich August Wolf and they influenced his work.[148]

Zunz urged his contemporaries to, through the embrace of study of a wide swath of literature, grasp the geist or "spirit" of the Jewish people.[240] Zunz proposed an ambitious Jewish historiography and further proposed that Jewish people adopt history as a way of life.[148] Zunz not only proposed a university vision of Jewish studies, but believed Jewish history to be an inseparable part of human culture.[241] Zunz's historiographical view aligns with the "lachrymose" view of Jewish history of persecution.[242] Zunz was the least philosophically inclined of the Wissenschaft but the most devoted to scholarship.[243] Zunz called for an "emanicipation" of Jewish scholarship "from the theologians."[244] He was the editor of Nachman Krochmal.[245]

Contrasting with earlier bible printing, Zunz adopted a re-Hebraization of names.[246]

Zunz was politically active and was elected to office. He believed that Jewish emancipation would come out of universal human rights.[247] The revolutionary year of 1848 had an influence on Zunz, and he expressed a messianic eagerness in the ideals of equality.[248] Zunz's stated goal was to transform Prussia into a democratic republic.[249]

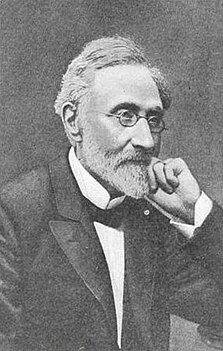

Graetz

[edit]Heinrich Graetz (1817-1891) was one of the first modern historians to write a comprehensive history of the Jewish people from a specifically Jewish perspective.[250][251] Geschichte der Juden (History of the Jews) (1853-1876) had a dual focus. While he provided a comprehensive history of the Jewish religion, he also highlighted the emergence of a Jewish national identity and the role of Jews in modern nation-states.[252][253] Graetz sought to improve on Jost's work, which he disdained for lacking warmth and passion.[254]

Salo Baron later identified Graetz with the "lachrymose conception" of Jewish history which he sought to critique.[255]

Baruch Ben-Jacob (1886-1943) likewise criticized Graetz' "sad and bitter" narrative for omitting Ottoman Jews.[229] Graetz was also meaningfully challenged by Hermann Cohen and Zecharias Frankel.[256]

20th century histories

[edit]The 20th century saw the Shoah and the establishment of Israel, both of which had a major impact on Jewish historiography.[257][258]

Ephraim Deinard (1846–1930) was a notable 20th century historian of American Jews.[259] The writings of Gershom Scholem and Hannah Arendt are also important in modern Jewish historiography of the 1940s.[260][261][262][263] Scholem was a critic of the Wissenschaft for their history that had omitted Jewish mysticism.[264] Martin Buber also was a significant exponent of Jewish mysticism building on the work of Scholem in the 20th century.[265]

While most of the historians associated with the Wissenschaft were men, Selma Stern (1890-1981) was the first woman associated with the movement and one of the first professional female historians in Germany.[266]

Dubnow

[edit]

Simon Dubnow (1860-1941) wrote Weltgeschichte des Jüdischen Volkes (World History of the Jewish People), which focused on the history of Jewish communities across the world. His scholarship developed a unified Jewish national narrative, especially in the context of the Russian Revolution and Zionism.[267] Dubnow's work nationalized and secularized Jewish history, whilst also moving its modern center of gravity from Germany to Eastern Europe and shifting its focus from intellectual history to social history.[268] Michael Brenner commented that Yerushalmi's "faith of fallen Jews" observation "is probably applicable to no one more than to Dubnow, who claimed to be praying in the temple of history that he himself erected."[269]

Dinur

[edit]Ben-Zion Dinur (1884 – 1973) followed Dubnow with a Zionist version of Jewish history. Conforti writes that Dinur "provided Jewish historiography with a clear Zionist-nationalist structure... [and] established the Palestine-centric approach, which viewed the entire Jewish past through the prism of Eretz Israel".[270]

Dinur was the first Zionist scholar to study the fate of Jewish communities in Palestine during the Crusades.[271]

Baron

[edit]

Salo Wittmayer Baron (1895-1989), a professor at Columbia University, became the first chair in Jewish history at a secular university; the chair at Columbia is now named after him.[212] Born in Tarnów, he was ordained at the Jewish Theological Seminary in Vienna, Austria in 1920. He joined the faculty at Columbia in 1930, and starting in 1950 he directed Columbia's Institute for Israel and Jewish Studies, where he worked until retirement in 1963. He published 13 works of Jewish history. His student Yerushalmi called him the greatest 20th century historian of Jewish history.[272] His A Social and Religious History of the Jews (18 vols., 2d ed. 1952–1983) covered both the religious and social aspects of Jewish history. His work is the most recent comprehensive multi-volume Jewish history.[273]

Baron's work further developed the Jewish national history, particularly in the wake of the Holocaust and the establishment of Israel.[274] Baron called for Jews and Jewish historical studies to be integrated into traditional general world history as a key part.[275][276] Baron sought to balance the tendencies toward extremes of traditionalism or modernity, seeking a third way on the question of emancipation.[277] While Baron's earlier work was periodic, in The Jewish Community he analyzed a Jewish community that transcended time, per Elisheva Carlebach.[278][279][280] Amnon Raz‐Krakotzkin says Baron's historiography is a call to view Jewish history as counter-history.[281] In contrast to Baer and the Zionist historians, Baron believed the diaspora to be a critical source of strength and vitality.[282] While Baron was mainly criticizing the lachrymose conception of medieval Jewish history, "neobaronianism" has been proposed by David Engel to apply more generally.[283]

Baron admired and even revered Graetz, who was an influence on him, but he sought to counter and critique the historical view espoused by the older historian.[284] Engel says the Baronian view of history stresses continuities, rather than ruptures.[255] Baron's analysis of Jewish historiography runs through Zacuto, Hacohen, Ibn Verga, to Jost, Graetz, and Dubnow.[285] Baron believed older work to be "parochial."[286] Adam Teller says his work is an alternative to history motivated by persecution and antisemitism, at the risk of de-emphasizing the impact of violence on Jewish history.[255] Esther Benbassa is another critic of the lachrymose conception and says that Baron is joined by Cecil Roth and to a lesser extent Schorsch in restoring a less tragic vision of Jewish fate.[287][288]

Baer

[edit]Yitzhak Baer (1888-1980) made a significant contribution to medieval and modern Jewish historiography. He had a critique of Baron's view that had failed to take into account his friend Gershom Sholem's studies of Jewish mysticism and Jewish messianism. Baer aligned his approach with Israeli Zionist historians such as Dinur and Hayim Hillel Ben-Sasson.[289][276] Moshe Idel considers Baer a "historian's historian" and possibly the most important historian at the Hebrew University since its inception, and the founder of the Jerusalem School of Jewish history.[265] Baer's periodization considers Jewish history one long period from the end of the Second Temple until the Enlightenment.[290]

Later 20th century: history of historiography

[edit]Jewish historiography also developed uniquely in Jewish diaspora communities[291][292] such as Anglo-Jewish historiography,[293] Polish-Jewish historiography,[294] and American-Jewish historiography.[295] History of women and Jewish women in particular became more widespread in the 1980s, such as the work of Paula Hyman and Judith Baskin.[296][297]

Beginning around 1970, a new Polish-Jewish historiography gradually arose, driven by reprints of works by Zinberg, Dubnow, and Baron, as well as new consideration by Bernard Dov Weinryb. Relevant authors in Polish-Jewish historiography are Meier Balaban, Yitzhak Schipper and Moses Schorr.[298][299]

The concept of microhistory has also arisen to describe a new movement in Jewish history led by Francesca Trivellato and Carlo Ginzburg.[300] Steven Bowman is the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship and filled a gap in the study of Greek Jews.[301]

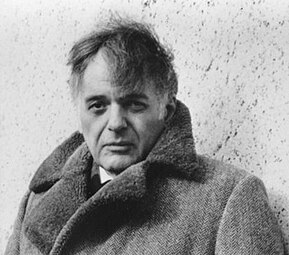

Yerushalmi

[edit]

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi (1932-2009) wrote Zakhor: Jewish History and Jewish Memory (1982) which explored the intersection of historical scholarship and Jewish collective memory, including mythology, religion and assimilation. The term Zakhor is an imperative "Remember," and the book discusses the author's perception of the decay in memory and the impact on the Jewish psyche; his core belief is that one can never stop being Jewish.[302][303] It has been described as the "pathbreaking study on the relationship between Jewish historiography and memory from the biblical period to the modern age".[304]

Yerushalmi's work can be viewed largely as critique of the Wissenschaft.[305] He was influenced by his teacher, Salo Baron, whose classes he attended at Columbia University where he later taught, and saw himself as a social historian of Jews, not of Judaism.[306] Yerushalmi was born and lived most of his life in New York City, aside from a stint at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[21] Whilst Yerushalmi's work largely centered on premodern Jewish histories, it set the stage for future analysis of modern Jewish histories, per his student Brenner.[307] Yerushalmi deeply studied the Sephardim, such as Isaac Cardoso, particularly the marrano or converso, i.e. crypto-Jewish or forced Catholic secular Jews, which were a core historical interest.[32][308] In addition to his work on the Sephardim, Yerushalmi's history also focused on German Jewish, not Eastern European Jewish social history, despite being American Eastern European Jewish himself.[309] Yerushalmi wrote that:

...the secularization of Jewish history is a break with the past, [and] the historicizing of Judaism itself has been an equally significant departure... Only in the modern era do we really find, for the first time, a Jewish historiography divorced from Jewish collective memory and, in crucial respects, thoroughly at odds with it. To a large extent, of course, this reflects a universal and ever-growing modern dichotomy... Intrinsically, modern Jewish historiography cannot replace an eroded group memory which, as we have seen throughout, never depended on historians in the first place. The collective memories of the Jewish people were a function of the shared faith, cohesiveness, and will of the group itself, transmitting and recreating its past through an entire complex of interlocking social and religious institutions that functioned organically to achieve this. The decline of Jewish collective memory in modern times is only a symptom of the unraveling of that common network of belief and praxis through whose mechanisms, some of which we have examined, the past was once made present. Therein lies the root of the malady. Ultimately Jewish memory cannot be "healed" unless the group itself finds healing, unless its wholeness is restored or rejuvenated. But for the wounds inflicted upon Jewish life by the disintegrative blows of the last two hundred years the historian seems at best a pathologist, hardly a physician.[310]

Some scholars such as Bonfil, Yerushalmi's students David N. Myers and Marina Rustow, and Amos Funkenstein took issue with Yerushalmi's interpretation of the importance of Jewish historiography or its relative abundance in the medieval period. In particular, Funkenstein argues that collective memory is an earlier form of historical consciousness, not a fundamental break.[19][311][111] Rustow says that Yerushalmi's core thesis rests on a narrow definition of historiography and explores the issue of historical particularism.[312] Gavriel D. Rosenfeld writes that Yerushalmi's fear that history would overtake memory was unfounded.[313] Myers writes that his teacher took the criticism of his paper, which contextualized the work as a post-Shoah malaise and a postmodern authorial perspective, hard, and did not know how to respond to it, leading to estrangement that lasted years before reconnecting shortly before his professor's death.[21]

Yerushalmi is also described by Rustow as practicing microhistory, that he did not believe in traditional methods, "heritage", "contributions", but sought a spirituality and "immanence" in his study of history.[32] Yerushalmi was frustrated by "antiquarianism" and the anachronistic view of history. He had a complex relationship with the Jerusalem school of historians including Baer, whom he disagreed with, but was influenced by, and Scholem. He was also influenced by Lucien Febvre. Rustow, writes that Yerushalmi, like his teacher Baron, believed modernity to be a trade-off and that the role of the Church in protecting, as well as persecuting, the Jewish people of premodern Europe was "anti-lachrymose," and drew admiration from his teacher. However she writes that he agreed with Baer and Scholem that history could be only understood in Jewish terms, and disagreed with Baron's more integrationist view. Ultimately, he is criticized for accepting the sources of the Spanish Inquisition without characterizing their motive as anti-Jewish.[32] One of Yerushalmi's major themes as expressed in the foreword to Zakhor is about a proposed return to previous modes of thinking.[314]

Meyer

[edit]Michael A. Meyer's Ideas of Jewish History (1974) is a milestone in the study of modern Jewish histories, and Meyer's ideas were developed further by Ismar Schorsch's "From Text to Context" (1994). These works emphasized the transformation of Jewish historical understanding in the modern era and are significant in summarizing the evolution of modern Jewish histories. According to Michael Brenner, these works – like Yerushalmi's before them – underlined the "break between a traditional Jewish understanding of history and its modern transformation".[315]

Brenner

[edit]

Michael Brenner's Prophets of the Past, first published in German in 2006, was described by Michael A. Meyer as "the first broadly conceived history of modern Jewish historiography".[316] Born in Weiden in der Oberpfalz, Brenner studied under Yerushalmi at Columbia.[317]

Rustow

[edit]Marina Rustow, a Princeton University professor and student of Yerushalmi's at Columbia, was a recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship and a Guggenheim Fellowship[318] and specializes in medieval Egypt, particularly the Cairo Geniza.[319][41] Her 2008 work has changed the scholarly view of heresy with respect to the relative community interaction with the Karaites, a divergent group from the Rabbanite sect dominant in Judaism.[320][44]

References

[edit] Media related to Jewish history at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jewish history at Wikimedia Commons Media related to Collections of the National Library of Israel at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Collections of the National Library of Israel at Wikimedia Commons

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schrijver, Emile G. L. (2017-11-16), "Jewish Book Culture Since the Invention of Printing (1469 – c. 1815)", The Cambridge History of Judaism, Cambridge University Press, pp. 291–315, doi:10.1017/9781139017169.013, ISBN 978-1-139-01716-9, retrieved 2023-11-24

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chabás, José; Goldstein, Bernard R. (2000). "Astronomy in the Iberian Peninsula: Abraham Zacut and the Transition from Manuscript to Print". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 90 (2): iii–196. doi:10.2307/1586015. ISSN 0065-9746. JSTOR 1586015.

- ^ Jelinčič Boeta, Klemen (2023). "Jewish Historiography". Edinost in Dialog. 78 (1). doi:10.34291/edinost/78/01/jelincic. ISSN 2385-8907. S2CID 263821644.

- ^ Brenner 2010, p. 15: "Along with periodization we can also see the differing titles of works on Jewish history that cover more than one era as indexes of their respective orientations. It is no accident that Jost’s work on the history of religion is called The History of the Israelites; that Graetz titles his already nationally oriented work History of the Jews; that Dubnow, as a convinced diasporic nationalist, chooses the title World History of the Jewish People, in which both the national character of the Jews and their dispersal over the whole world are contained; and that in his monumental work Dinur distinguishes between Israel in Its Own Land and Israel in Dispersal. In all these cases the title is already a program."

- ^ Brenner 2010, p. 49, 50: "At the same time, however, they shaped a scholarly discipline that used the weapons of historiography to elaborate new Jewish identities. All over Europe, during the nineteenth century historiography was part of the battle among Jews for their emancipation, their identification with their respective nation-states, and their striving for religious reform. What for Jews had earlier been one Jewish history was now transformed by historians into several Jewish histories in the respective national contexts.At the same time, during the second half of the nineteenth century a new variant of Jewish historiography developed that put passionate emphasis on the existence of a unified Jewish national history. Its begin- nings are found in the work of the most important Jewish historian of the nineteenth century, Heinrich Graetz."

- ^ Meyer 2007, p. 661: "A constant temptation within Jewish historiography has been and is still today its instrumentalization, whether for the sake of emancipation, religious reform, a socialist or Zionist ideology, or the resuscitation and reshaping of Jewish memory for the sake of Jewish survival - all of these standing against the Rankean ideal of historical writing for its own sake."

- ^ Yerushalmi 1982, p. 85: "It should be manifest by now that it did not derive from prior Jewish historical writing or historical thought. Nor was it the fruit of a gradual and organic evolution, as was the case with general modern historiography whose roots extend back to the Renaissance. Modern Jewish historiography began precipitously out of that assimilation from without and collapse from within which characterized the sudden emergence of Jews out of the ghetto. It originated, not as scholarly curiosity, but as ideology, one of a gamut of responses to the crisis of Jewish emancipation and the struggle to attain it."

- ^ Biale 1994, p. 3: "The question of Jewish politics lies at the very heart of any attempt to understand Jewish history. The dialectic between power and powerlessness that threads its way from biblical to modern times is one of the central themes in the long history of the Jews and, especially in the modern period, defines one of the key ideological issues in Jewish life. How one understands the history of Jewish politics may well determine the stance one takes on the possibility of Jewish existence in diaspora or the necessity for a Jewish state. Or conversely, perhaps the ideological position one takes on this political question may determine how one interprets Jewish history. It may therefore not be an exaggeration to say that modern Jewish historiography is the historiography of Jewish politics, even when its explicit concerns appear to lie elsewhere. Since the modern historian writes in a context in which political questions are so important, he or she brings them to bear--consciously or not--on the broad field of Jewish history. To take but one famous example, Gershom Scholem's magisterial history of Jewish mysticism cannot be separated from his commitment to Zionism, although in no sense can one speak of a crudely direct correspondence between the one and the other."

- ^ Meyer 2007, p. 662.

- ^ "[Genealogy of the Exilarchs to David and Adam]: manuscript. - Colenda Digital Repository". colenda.library.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2023-11-28.

- ^ Momigliano, Arnaldo (1990). The Classical Foundations of Modern Historiography. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07870-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tropper, Amram (2004). "The Fate of Jewish Historiography after the Bible: A New Interpretation". History and Theory. 43 (2): 179–197. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2303.2004.00274.x. ISSN 0018-2656. JSTOR 3590703.

- ^ Veltri, Giuseppe (1998). "On the Influence of "Greek Wisdom": Theoretical and Empirical Sciences in Rabbinic Judaism". Jewish Studies Quarterly. 5 (4): 300–317. ISSN 0944-5706. JSTOR 40753221.

- ^ Yoshiko Reed, Annette (2020-12-31), "8. "Ancient Jewish Sciences" and the Historiography of Judaism", Ancient Jewish Sciences and the History of Knowledge in Second Temple Literature, New York University Press, pp. 195–254, doi:10.18574/nyu/9781479823048.003.0008, ISBN 9781479873975, retrieved 2023-12-20

- ^ Jump up to: a b Berger, David (2011), "Judaism and General Culture in Medieval and Early Modern Times", Cultures in Collision and Conversation, Essays in the Intellectual History of the Jews, Academic Studies Press, pp. 21–116, doi:10.2307/j.ctt21h4xrd.5, ISBN 978-1-936235-24-7, JSTOR j.ctt21h4xrd.5, retrieved 2023-11-04

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Bonfil, Robert (1997). "Jewish Attitudes toward History and Historical Writing in Pre-Modern Times". Jewish History. 11 (1): 7–40. doi:10.1007/BF02335351. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 20101283. S2CID 161957265.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Whitfield, S. J. (2002-10-01). "Where They Burn Books ..." Modern Judaism. 22 (3): 213–233. doi:10.1093/mj/22.3.213. ISSN 0276-1114.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Weinberg, Joanna (1978). "Azariah Dei Rossi: Towards a Reappraisal of the Last Years of His Life". Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia. 8 (2): 493–511. ISSN 0392-095X. JSTOR 24304990.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Funkenstein, Amos (1989). "Collective Memory and Historical Consciousness". History and Memory. 1 (1): 5–26. ISSN 0935-560X. JSTOR 25618571.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Bonfil, Robert (1988). "How Golden was the Age of the Renaissance in Jewish Historiography?". History and Theory. 27 (4): 78–102. doi:10.2307/2504998. ISSN 0018-2656. JSTOR 2504998.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Myers, David N. (2014). "Introduction". Jewish History. 28 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1007/s10835-014-9197-y. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 24709807. S2CID 254333935.

- ^ Stern, Sacha (2006). "Review of Wisdom, Politics, and Historiography. Tractate Avot in the Context of the Graeco-Roman Near East (Oxford Oriental Monographs)". Biblica. 87 (1): 140–143. ISSN 0006-0887. JSTOR 42614660.

- ^ Jacobs, Martin (April 2005). "Exposed to All the Currents of the Mediterranean—A Sixteenth-Century Venetian Rabbi on Muslim History". AJS Review. 29 (1): 33–60. doi:10.1017/s0364009405000024. ISSN 0364-0094. S2CID 162151514.

- ^ Shmuelevitz, Aryeh (August 1978). "Capsali as a Source for Ottoman History, 1450–1523". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 9 (3): 339–344. doi:10.1017/s0020743800033614. ISSN 0020-7438. S2CID 162799564.

- ^ Corazzol, Giacomo (December 2012). "On the sources of Elijah Capsali's Chronicle of the 'Kings' of Venice". Mediterranean Historical Review. 27 (2): 151–160. doi:10.1080/09518967.2012.730796. ISSN 0951-8967. S2CID 154974512.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fuss, Abraham M. (1994). "The Study of Science and Philosophy Justified by Jewish Tradition". The Torah U-Madda Journal. 5: 101–114. ISSN 1050-4745. JSTOR 40914819.

- ^ Feldman, Louis H. (2006). Judaism And Hellenism Reconsidered. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-14906-9.

- ^ Schwartz, Daniel B. (2015-06-30), 1. Our Rabbi Baruch: Spinoza and Radical Jewish Enlightenment, University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 25–47, doi:10.9783/9780812291513-003, ISBN 978-0-8122-9151-3, retrieved 2023-11-04

- ^ Rudavsky, Tamar (March 2013). "Galileo and Spinoza: The Science of Naturalizing Scripture". Intellectual History Review. 23 (1): 119–139. doi:10.1080/17496977.2012.738002. ISSN 1749-6977. S2CID 170150253.

- ^ Wertheim, David J. (2006). "Spinoza's Eyes: The Ideological Motives of German-Jewish Spinoza scholarship". Jewish Studies Quarterly. 13 (3): 234–246. doi:10.1628/094457006778994786. ISSN 0944-5706. JSTOR 40753405.

- ^ Idel, Moshe (2007). "Yosef H. Yerushalmi's "Zakhor": Some Observations". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 97 (4): 491–501. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 25470222.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Rustow, Marina (2014). "Yerushalmi and the Conversos". Jewish History. 28 (1): 11–49. doi:10.1007/s10835-014-9198-x. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 24709808. S2CID 254599514.

- ^ Lacerda, Daniel (2009-10-23). "Israël Salvator Révah, Uriel da Costa et les marranes de Porto". Lusotopie. 16 (2): 265–269. doi:10.1163/17683084-01602022. ISBN 978-972-8462-37-6. ISSN 1257-0273.

- ^ Bod, Rens (2015), van Kalmthout, Ton; Zuidervaart, Huib (eds.), "The Importance of the History of Philology, or the Unprecedented Impact of the Study of Texts", The Practice of Philology in the Nineteenth-Century Netherlands, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 17–36, ISBN 978-90-8964-591-3, JSTOR j.ctt130h8j8.4, retrieved 2023-11-04

- ^ Lambe, Patrick J. (1985). "Biblical Criticism and Censorship in Ancien Régime France: The Case of Richard Simon". The Harvard Theological Review. 78 (1/2): 149–177. doi:10.1017/S0017816000027425. ISSN 0017-8160. JSTOR 1509597. S2CID 162945310.

- ^ Davis, Joseph M. (2012-03-19). "Judaism and Science in the Age of Discovery". The Wiley-Blackwell History of Jews and Judaism. pp. 257–276. doi:10.1002/9781118232897.ch15. ISBN 9781405196376.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Discarded history: Cairo Genizah treasures". University of Cambridge. 2022-05-31. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

- ^ Vehlow, Katja (2021), Lieberman, Phillip I. (ed.), "Historiography", The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 5: Jews in the Medieval Islamic World, The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 5, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 974–992, doi:10.1017/9781139048873.037, ISBN 978-0-521-51717-1, retrieved 2023-11-08

- ^ Aziz, Jeff (July 2012). "Early Modern Jewry: A New Cultural History by David B. Ruderman Princeton University Press, 2010, 340 pp, ISBN 978-0691144641". Critical Quarterly. 54 (2): 82–86. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8705.2012.02063.x.

- ^ "The World of a Renaissance Jew: The Life and Thought of Abraham ben Mordecai Farissol". The American Historical Review (Monographs of the Hebrew Union College, Number 6.) Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press; Distributed by KTAV, New York. 1981. Pp. Xvi, 265. $20.00. December 1982. doi:10.1086/ahr/87.5.1417. ISSN 1937-5239.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rustow, Marina (2020-01-14). The Lost Archive. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15647-7.

- ^ Greenhouse, Emily (2013-03-01). "Treasures in the Wall". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

- ^ Nirenberg, David (2011-06-01). "From Cairo to Córdoba: The Story of the Cairo Geniza". ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rustow, Marina (2014-10-03). Heresy and the Politics of Community. doi:10.7591/9780801455308. ISBN 9780801455308.

- ^ גפני, ישעיהו; Gafni, Isaiah (1987). "On the Talmudic Chronology in "Iggeret Rav Sherira Gaon" / לחקר הכרונולוגיה התלמודית באיגרת רב שרירא גאון". Zion / ציון. נב (א): 1–24. ISSN 0044-4758. JSTOR 23559516.

- ^ גפני, ישעיהו; Gafni, Isaiah M. (2008). "On Talmudic Historiography in the Epistle of Rav Sherira Gaon: Between Tradition and Creativity / ההיסטוריוגרפיה התלמודית באיגרת רב שרירא גאון: בין מסורת ליצירה". Zion / ציון. עג (ג): 271–296. ISSN 0044-4758. JSTOR 23568181.

- ^ Gross, Simcha (2017). "When the Jews Greeted Ali: Sherira Gaon's Epistle in Light of Arabic and Syriac Historiography". Jewish Studies Quarterly. 24 (2): 122–144. doi:10.1628/094457017X14909690198980. ISSN 0944-5706. JSTOR 44861517.

- ^ Kraemer, Joel L. (1971). Cohen, Gerson D. (ed.). "A Critical Edition with a Translation and Notes of the Book of Tradition". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 62 (1): 61–71. doi:10.2307/1453863. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 1453863.

- ^ Halivni, David Weiss (1996). "Reflections on Classical Jewish Hermeneutics". Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research. 62: 21–127. doi:10.2307/3622592. ISSN 0065-6798. JSTOR 3622592.

- ^ Chazan, Robert (1994). "The Timebound and the Timeless: Medieval Jewish Narration of Events". History and Memory. 6 (1): 5–34. ISSN 0935-560X. JSTOR 25618660.

- ^ Gil, Moshe (1990). "The Babylonian Yeshivot and the Maghrib in the Early Middle Ages". Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research. 57: 69–120. doi:10.2307/3622655. ISSN 0065-6798. JSTOR 3622655.

- ^ Marcus, Ivan G. (1990). "History, Story and Collective Memory: Narrativity in Early Ashkenazic Culture". Prooftexts. 10 (3): 365–388. ISSN 0272-9601. JSTOR 20689283.

- ^ Singer, David G. (2004). "God in Nature or the Lord of the Universe?: The Encounter of Judaism and Science from Hellenistic Times to the Present". Shofar. 22 (4): 80–93. ISSN 0882-8539. JSTOR 42943720.

- ^ Mann, Jacob (1917). "The Responsa of the Babylonian Geonim as a Source of Jewish History". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 7 (4): 457–490. doi:10.2307/1451354. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 1451354.

- ^ Nemoy, Leon (1929). "The Yiddish Yosippon of 1546 in the Alexander Kohut Memorial Collection of Judaica". The Yale University Library Gazette. 4 (2): 36–39. ISSN 0044-0175. JSTOR 40856706.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Marcus, Ralph (1948). "A 16TH CENTURY HEBREW CRITIQUE OF PHILO (Azariah dei Rossi's "Meor Eynayim", Pt. I, cc. 3–6)". Hebrew Union College Annual. 21: 29–71. ISSN 0360-9049. JSTOR 23503688.

- ^ Dönitz, Saskia (2012-01-01), "Historiography Among Byzantine Jews: The Case Of Sefer Yosippon", Jews in Byzantium, Brill, pp. 951–968, doi:10.1163/ej.9789004203556.i-1010.171, ISBN 978-90-04-21644-0, retrieved 2023-10-29

- ^ Avioz, Michael (2019). "The Place of Josephus in Abravanel's Writings". Hebrew Studies. 60: 357–374. ISSN 0146-4094. JSTOR 26833120.

- ^ Sepher Yosippon: A Tenth-Century History of Ancient Israel. Wayne State University Press. 2022-11-09. ISBN 978-0-8143-4945-8.

- ^ Bowman, Steven (2010). "Jewish Responses to Byzantine Polemics from the Ninth through the Eleventh Centuries". Shofar. 28 (3): 103–115. ISSN 0882-8539. JSTOR 10.5703/shofar.28.3.103.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Yerushalmi, Yosef Hayim (1979). "Clio and the Jews: Reflections on Jewish Historiography in the Sixteenth Century". Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research. 46/47: 607–638. doi:10.2307/3622374. ISSN 0065-6798. JSTOR 3622374.

- ^ Нойман, Авраам А. (1952). «Иосиппон и апокрифы» . Еврейский ежеквартальный обзор . 43 (1): 1–26. дои : 10.2307/1452910 . ISSN 0021-6682 . JSTOR 1452910 .

- ^ Гертнер, Хаим (2007). «Эпигонизм и начало православной исторической письменности в Восточной Европе девятнадцатого века» . Студия Розенталиана . 40 : 217–229. дои : 10.2143/SR.40.0.2028846 . ISSN 0039-3347 . JSTOR 41482513 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Шац, Андреа (2019). Иосиф Флавий в современной еврейской культуре . Исследования еврейской истории и культуры. Лейден Бостон (Нью-Йорк): Брилл. ISBN 978-90-04-39308-0 .

- ^ «Иосиппон» . www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org . Проверено 6 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ Цейтлин, Соломон (1963). «Иосиппон» . Еврейский ежеквартальный обзор . 53 (4): 277–297. дои : 10.2307/1453382 . ISSN 0021-6682 . JSTOR 1453382 .

- ^ Дёниц, Саския (15 декабря 2015 г.), Чепмен, Онора Хауэлл; Роджерс, Зулейка (ред.), «Сефер Йосиппон (Джосиппон)» , Спутник Иосифа Флавия (1-е изд.), Wiley, стр. 382–389, doi : 10.1002/9781118325162.ch25 , ISBN 978-1-4443-3533-0 , получено 6 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ Гудман, Мартин; Вайнберг, Джоанна (2016). «Прием Иосифа Флавия в период раннего Нового времени» . Международный журнал классической традиции . 23 (3): 167–171. дои : 10.1007/s12138-016-0398-2 . ISSN 1073-0508 . JSTOR 45240038 . S2CID 255509625 .

- ^ Боуман, Стивен (2 ноября 2021 г.). «Платон и Аристотель в еврейской одежде: обзор Дова Шварца, еврейская мысль в Византии в позднем средневековье» . Иудаика . Neue Digitale Folge. 2 . дои : 10.36950/jndf.2r5 . ISSN 2673-4273 . S2CID 243950830 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Боуман, Стивен (1995). « Иосиппон» и еврейский национализм» . Труды Американской академии еврейских исследований . 61 : 23–51. ISSN 0065-6798 . JSTOR 4618850 .

- ^ Элеазар, Гутвирт (2022). «Лео Греч/Иегуда Москони: еврейская историография и коллекционизм в четырнадцатом веке» . Гельмантика . 73 (207): 221–237.

- ^ Саксон, Адриан (2014). «Иосиф бен Моисей Килти: предварительное исследование греко-еврейского философа» . Ежеквартальный журнал еврейских исследований . 21 (4): 328–361. дои : 10.1628/094457014X14127716907065 . ISSN 0944-5706 . JSTOR 24751788 .

- ^ Бланд, Кальман (1986-01-01), «Исламская теория еврейской истории: случай Ибн Халдуна» , Ибн Халдун и исламская идеология , Брилл, стр. 37–45, doi : 10.1163/9789004474000_006 , ISBN 978-90-04-47400-0 , получено 8 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ Фишель, Уолтер Дж. (1961). «Использование Ибн Халдуном исторических источников» . Студия Исламика (14): 109–119. дои : 10.2307/1595187 . ISSN 0585-5292 . JSTOR 1595187 .

- ^ Илан, Нахем. «Иосиппон, Книга» . Де Грюйтер . doi : 10.1515/ebr.josipponbookof . Проверено 8 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ Села, Суламит (1991). Книга Иосиппона и ее параллельные версии на арабском и иудео-арабском языках (на иврите). Университет Тель-Авива, ха-Хуг ле-История шел ам Исраэль.

- ^ Дёниц, Саския (01 января 2013 г.), «Иосиф, разорванный на части — фрагменты Сефера Йосиппона в Genizat Germania» , Книги внутри книг , Brill, стр. 83–95, doi : 10.1163/9789004258501_007 , ISBN 978-90-04-25850-1 , получено 8 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ Волландт, Ронни (19 ноября 2014 г.). «Древняя еврейская историография в арабской одежде: Сефер Иосиппон между Южной Италией и коптским Каиром» . Зутот . 11 (1): 70–80. дои : 10.1163/18750214-12341264 . ISSN 1571-7283 .

- ^ «Боуман на Селе, Сефер Йосеф бен Гурьон ха-Арви» | H-Net» . network.h-net.org . Проверено 8 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ Вольф, Люсьен (1908). « Джосиппон» в Англии» . Сделки (Еврейское историческое общество Англии) . 6 : 277–288. ISSN 2047-2331 . JSTOR 29777757 .

- ^ Райнер, Джейкоб (1967). «Английский Йосиппон» . Еврейский ежеквартальный обзор . 58 (2): 126–142. дои : 10.2307/1453342 . ISSN 0021-6682 . JSTOR 1453342 .

- ^ Велов, Катя (2017). «Очарованные Иосифом Флавием: читатели раннего Нового времени и еврейское воплощение Иосиппона Ибн Дауда в двенадцатом веке» . Журнал шестнадцатого века . 48 (2): 413–435. дои : 10.1086/SCJ4802005 . ISSN 0361-0160 . JSTOR 44816356 . S2CID 166029181 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Кошелек, Барт (2007). «Непрерывная история: традиция-преемница в еврейской историографии раннего Нового времени» . Студия Розенталиана . 40 : 183–194. дои : 10.2143/SR.40.0.2028843 . ISSN 0039-3347 . JSTOR 41482510 .

- ^ Рэй, Джонатан (2009). «Иберийское еврейство между Западом и Востоком: еврейское поселение в Средиземноморье шестнадцатого века» . Средиземноморские исследования . 18 : 44–65. дои : 10.2307/41163962 . ISSN 1074-164X . JSTOR 41163962 .

- ^ Ментцер, Раймонд А. (1982). «Марраны Южной Франции в начале шестнадцатого века» . Еврейский ежеквартальный обзор . 72 (4): 303–311. дои : 10.2307/1454184 . ISSN 0021-6682 . JSTOR 1454184 .

- ^ Сегре, Рената (декабрь 1991 г.). «Сефардские поселения в Италии шестнадцатого века: историко-географический обзор» . Исторический обзор Средиземноморья . 6 (2): 112–137. дои : 10.1080/09518969108569618 . ISSN 0951-8967 .

- ^ Родити, Эдуард (1970). «Сефардские картографы» . Европейский иудаизм: журнал для новой Европы . 4 (2): 35–37. ISSN 0014-3006 . JSTOR 41431091 .

- ^ Эдвардс, Джон (1997). Нетаньяху, Б.; Рот, Норман (ред.). «Была ли правдива испанская инквизиция?» . Еврейский ежеквартальный обзор . 87 (3/4): 351–366. дои : 10.2307/1455191 . ISSN 0021-6682 . JSTOR 1455191 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Рутковский, Анна (2010). «Между историей и легендой» . ПАРДЕС: Журнал Ассоциации еврейских исследований (16): 50–56. ISSN 1614-6492 .

- ^ Бергер, Дэвид (2011), «Сефардский и ашкеназский мессианизм в средние века: оценка историографических дебатов» , «Культуры в столкновении и разговоре» , «Очерки интеллектуальной истории евреев», Academic Studies Press, стр. 289–311, doi : 10.2307/j.ctt21h4xrd.16 , ISBN 978-1-936235-24-7 , JSTOR j.ctt21h4xrd.16 , получено 4 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ Питерс, Эдвард (1995). «Еврейская история и языческая память: изгнание 1492 года» . Еврейская история . 9 (1): 9–34. дои : 10.1007/BF01669187 . ISSN 0334-701X . JSTOR 20101210 . S2CID 159523585 .

- ^ Бонфил, Роберт (1992). «Книга сотового потока» Иуды Мессера Леона: риторическое измерение еврейского гуманизма в Италии пятнадцатого века» . Еврейская история . 6 (1/2): 21–33. дои : 10.1007/BF01695207 . ISSN 0334-701X . JSTOR 20101117 . S2CID 161950742 .

- ^ Лесли, Артур М.; Леон, Иуда Мессер (1983). «Нофет Зуфим, о еврейской риторике» . Риторика: Журнал истории риторики . 1 (2): 101–114. дои : 10.1525/рх.1983.1.2.101 . ISSN 0734-8584 . JSTOR 10.1525/rh.1983.1.2.101 .

- ^ Тирош-Ротшильд, Хава (1988). «В защиту еврейского гуманизма» . Еврейская история . 3 (2): 31–57. дои : 10.1007/BF01698568 . ISSN 0334-701X . JSTOR 20085218 . S2CID 162257827 .

- ^ Бэйнс, Дэниел (1988). «Португальские путешествия открытий и возникновение современной науки» . Журнал Вашингтонской академии наук . 78 (1): 47–58. ISSN 0043-0439 . JSTOR 24536958 .

- ^ Нойман, Авраам А. (1965). «Авраам Закуто: историограф». Американская академия еврейских исследований . Юбилейный том Гарри Острина Вольфсона, посвященный его семьдесят пятому дню рождения, изд. Саул Либерман (2): 597–629.

- ^ «Закуто, Авраам Бен Самуэль» . www.jewishencyclepedia.com . Проверено 5 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ Бен-Шалом, Рам (2017). «Антихристианская историографическая полемика в «Сефер Юхасин» » . Испания иудаика . 13 : 1–42. ISSN 1565-0073 .

- ^ Нойман, Авраам А. (1967). «Парадоксы и судьба еврейского медиевиста» . Еврейский ежеквартальный обзор . 57 : 398–408. дои : 10.2307/1453505 . ISSN 0021-6682 . JSTOR 1453505 .

- ^ Леви, Рафаэль (1936). Бургос, Франсиско Кантера (ред.). «Астрономическая деятельность Закуто» . Еврейский ежеквартальный обзор . 26 (4): 385–388. дои : 10.2307/1452099 . ISSN 0021-6682 . JSTOR 1452099 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Вайнберг, Джоанна (2016). «Ранние современные еврейские читатели Иосифа Флавия» . Международный журнал классической традиции . 23 (3): 275–289. дои : 10.1007/s12138-016-0409-3 . ISSN 1073-0508 . JSTOR 45240047 . S2CID 255519719 .

- ^ «Ибн Яхья (или Ибн Йихья), Гедалия бен Иосиф | Encyclepedia.com» . www.энциклопедия.com . Проверено 5 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ «Глава восьмая. Соломон, Аристотель Иудейский и изобретение псевдосоломоновой библиотеки», Воображаемое трио , Де Грюйтер, стр. 172–190, 10 августа 2020 г., doi : 10.1515/9783110677263-010 , ISBN 9783110677263 , S2CID 241221279

- ^ Салдарини, Энтони Дж. (1974). «Конец раввинской цепи традиций» . Журнал библейской литературы . 93 (1): 97–106. дои : 10.2307/3263869 . ISSN 0021-9231 . JSTOR 3263869 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б «3. Между еврейскими и христианскими картами: карта странствий израильтян из Мантуи в шестнадцатом веке» , «Изображая землю » , Де Грюйтер, стр. 80–101, 22 мая 2018 г., doi : 10.1515/9783110570656-006 , ISBN 9783110570656 , получено 24 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ Тоафф, Ариэль; Шварцфукс, Саймон; Горовиц, Эллиот С. (1989). Средиземноморье и евреи: общество, культура и экономика раннего Нового времени . Издательство Университета Бар-Илан. ISBN 978-965-226-221-9 .

- ^ Мелтон, Дж. Гордон (2014). Веры во времени: 5000 лет истории религии [4 тома]: 5000 лет истории религии . АВС-КЛИО. п. 1514. ИСБН 978-1-61069-026-3 .

- ^ Коэн, Джереми (2017). Историк в изгнании: Соломон ибн Верга, «Шевет Иегуда» и еврейско-христианская встреча . Издательство Пенсильванского университета. ISBN 978-0-8122-4858-6 . JSTOR j.ctv2t4c2k .

- ^ «Ибн Верга, Соломон» . www.jewishencyclepedia.com . Проверено 5 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ «Шебет Иегуда» и историография шестнадцатого века | Статья РАМБИ990004793790705171 | Национальная библиотека Израиля» . www.nli.org.il. Проверено 5 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Раз-Кракоцкин, Амнон (2007). «Еврейская память между изгнанием и историей» . Еврейский ежеквартальный обзор . 97 (4): 530–543. ISSN 0021-6682 . JSTOR 25470226 .

- ^ Гамильтон, Мишель М.; Сильерас-Фернандес, Нурия (30 апреля 2021 г.). В Средиземноморье и в Средиземноморье: средневековые и ранние современные иберийские исследования . Издательство Университета Вандербильта. ISBN 978-0-8265-0361-9 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Коэн, Джереми (2013). «Межрелигиозные дебаты и литературное творчество: Соломон ибн Верга о споре о Тортосе» . Ежеквартальный журнал еврейских исследований . 20 (2): 159–181. дои : 10.1628/094457013X13661210446274 . ISSN 0944-5706 . JSTOR 24751814 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Коэн, Джереми (2009), «Кровавый навет в «Шевет Иегуда» Соломона ибн Верги» , Jewish Blood , Routledge, стр. 128–147, doi : 10.4324/9780203876404-13 , ISBN 978-0-203-87640-4 , получено 5 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ Рудерман, Давид; Велтри, Джузеппе; Рабочая группа Вольфенбюттеля по исследованиям эпохи Возрождения; Центр Леопольда Цунца по изучению европейского еврейства; Библиотека Герцога Августа, ред. (2004). Культурные посредники: еврейские интеллектуалы в Италии раннего Нового времени . Еврейская культура и контексты. Филадельфия, Пенсильвания: Издательство Пенсильванского университета. ISBN 978-0-8122-3779-5 .

- ^ Вакс, Дэвид А. (2015). Двойная диаспора в сефардской литературе: еврейское культурное производство до и после 1492 года . Издательство Университета Индианы. ISBN 978-0-253-01572-3 . JSTOR j.ctt16gzfs2 .

- ^ Дайнер, Хасия Р. (2021). Оксфордский справочник еврейской диаспоры . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-024094-3 .

- ^ Шуартц, Мириам Сильвия (5 октября 2011 г.). «Присутствие возвышенного в утешении скорбей Израиля, Сэмюэль Уске» . Вершин : 140–158. дои : 10.11606/issn.2179-5894.ip140-158 . ISSN 2179-5894 . S2CID 193200054 .

- ^ Леб, Исидор (1892). «Еврейский фольклор в хронике Ибн Верги Шебет Ихуда» . Обзор иудаики . 24 (47): 1–29. дои : 10.3406/rjuiv.1892.3805 . S2CID 263176489 .

- ^ Монж, Матильда; Мучник, Наталья (27 апреля 2022 г.). Диаспоры раннего Нового времени: европейская история . Рутледж. ISBN 978-1-000-57214-8 .

- ^ Рист, Ребекка (17 декабря 2015 г.). «Папская власть и защита в Шебет-Иуде» . Журнал истории религии . 40 (4): 490–507. дои : 10.1111/1467-9809.12324 . ISSN 0022-4227 .