Река Темза

| Река Темза | |

|---|---|

Река Темза в Воксхолле, Лондон. | |

Course of the Thames | |

| Etymology | Proto-Celtic *tamēssa, possibly meaning "dark" |

| Location | |

| Country | England |

| Counties | Gloucestershire, Wiltshire, Oxfordshire, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Surrey, Greater London, Kent, Essex |

| Towns/cities | Cricklade, Lechlade, Oxford, Abingdon, Wallingford, Reading, Henley-on-Thames, Marlow, Maidenhead, Windsor, Staines-upon-Thames, Walton-on-Thames, Sunbury-on-Thames, Kingston upon Thames, London (inc. Twickenham, the City), Dagenham, Erith, Dartford, Grays, Gravesend |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Thames Head, Gloucestershire, UK |

| • coordinates | 51°41′40″N 02°01′47″W / 51.69444°N 2.02972°W |

| • elevation | 110 m (360 ft) |

| 2nd source | |

| • location | Ullenwood, Gloucestershire, UK |

| • coordinates | 51°50′49″N 02°04′41″W / 51.84694°N 2.07806°W |

| • elevation | 214 m (702 ft) |

| Mouth | Thames Estuary, North Sea |

• location | Southend-on-Sea, Essex, UK |

• coordinates | 51°30′00″N 00°36′36″E / 51.50000°N 0.61000°E |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 346 km (215 mi) |

| Basin size | 12,935 km2 (4,994 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | London |

| • average | 65.8 m3/s (2,320 cu ft/s) |

| • maximum | 370 m3/s (13,000 cu ft/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | entering Oxford |

| • average | 17.6 m3/s (620 cu ft/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | leaving Oxford |

| • average | 24.8 m3/s (880 cu ft/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Reading, Berkshire |

| • average | 39.7 m3/s (1,400 cu ft/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Windsor |

| • average | 59.3 m3/s (2,090 cu ft/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Windrush, Cherwell, Colne, Lea, Roding |

| • right | Kennet, Wey, Mole |

Thames summary route map |

|---|

Thameside settlements Towns/villages by parish beside the river blank spaces indicate as place above (") |

|---|

Thames bridges |

|---|

Река Темза ( / t ɛ m z / TEMZ ), также известная в некоторых частях как река Исида , — река, протекающая через южную Англию, включая Лондон . При длине 215 миль (346 км) это самая длинная река в Англии и вторая по длине в Соединенном Королевстве после реки Северн .

Река берет свое начало в районе Темз-Хед в Глостершире и впадает в Северное море недалеко от Тилбери , Эссекс, и Грейвсенда , Кент, через устье Темзы . С запада она протекает через Оксфорд (где ее иногда называют Исидой), Рединг , Хенли-на-Темзе и Виндзор . Темза также истощает весь Большой Лондон . [1]

Нижнее течение реки называется Tideway , полученное из-за ее длинного приливного течения до шлюза Теддингтон . Его приливная часть включает большую часть лондонского участка и имеет высоту подъема и падения 23 фута (7 м). От Оксфорда до устья Темза падает на 55 метров (180 футов). Протекающая через некоторые из более засушливых частей материковой Британии и сильно отбираемая для питья, расход Темзы невелик, учитывая ее длину и ширину: расход реки Северн в среднем почти в два раза больше, несмотря на меньший водосборный бассейн . В Шотландии расход реки Тэй более чем в два раза превышает средний расход Темзы из водосборного бассейна, который на 60% меньше.

Along its course are 45 navigation locks with accompanying weirs. Its catchment area covers a large part of south-eastern and a small part of western England; the river is fed by at least 50 named tributaries. The river contains over 80 islands. With its waters varying from freshwater to almost seawater, the Thames supports a variety of wildlife and has a number of adjoining Sites of Special Scientific Interest, with the largest being in the North Kent Marshes and covering 20.4 sq mi (5,289 ha).[2]

Name

[edit]Brittonic origin

[edit]

According to Mallory and Adams, the Thames, from Middle English Temese, is derived from the Brittonic name for the river, Tamesas (from *tamēssa),[3] recorded in Latin as Tamesis and yielding modern Welsh Tafwys "Thames".

The name element Tam may have meant "dark" and can be compared to other cognates such as Russian темно (Proto-Slavic *tĭmĭnŭ), Lithuanian tamsi "dark", Latvian tumsa "darkness", Sanskrit tamas and Welsh tywyll "darkness" and Middle Irish teimen "dark grey".[3][b] The origin is shared by many other river names in Britain, such as the River Tamar at the border of Devon and Cornwall, several rivers named Tame in the Midlands and North Yorkshire, the Tavy on Dartmoor, the Team of the North East, the Teifi and Teme of Wales, the Teviot in the Scottish Borders and a Thames tributary the Thame.

Kenneth H. Jackson proposed that the name of the Thames is not Indo-European (and of unknown meaning),[5] while Peter Kitson suggested that it is Indo-European but originated before the Britons and has a name indicating "muddiness" from a root *tā-, 'melt'.[6]

Name history

[edit]Early variants of the name include:

- Tamesa (Brittonic)[4]

- Tamesis (Latin)[4]

- Tamis, Temes (Old English)[4]

- Tamise, Thamis (1220) (Middle English, Anglo-Norman French)[c]

Indirect evidence for the antiquity of the name "Thames" is provided by a Roman potsherd found at Oxford, bearing the inscription Tamesubugus fecit (Tamesubugus made [this]). It is believed that Tamesubugus' name was derived from that of the river.[7] Tamese was referred to as a place, not a river in the Ravenna Cosmography (c. AD 700).

The river's name has always been pronounced with a simple t /t/; the Middle English spelling was typically Temese and the Brittonic form Tamesis. A similar spelling from 1210, "Tamisiam" (the accusative case of "Tamisia"; see Kingston upon Thames § Early history), is found in Magna Carta.[8]

The Isis

[edit]The Thames through Oxford is sometimes[when?] called the Isis. Historically, and especially in Victorian times, gazetteers and cartographers insisted that the entire river was correctly named the Isis from its source down to Dorchester on Thames and that only from this point, where the river meets the Thame and becomes the "Thame-isis" (supposedly subsequently abbreviated to Thames) should it be so called.[citation needed] Ordnance Survey maps still label the Thames as "River Thames or Isis" down to Dorchester. Since the early 20th century this distinction has been lost in common usage outside of Oxford, and some historians [who?] suggest the name Isis is nothing more than a truncation of Tamesis, the Latin name for the Thames. Sculptures titled Tamesis and Isis by Anne Seymour Damer are located on the bridge at Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire (the original terracotta and plaster models were exhibited at the Royal Academy, London, in 1785. They are now[when?] on show at the River and Rowing Museum in Henley).[9]

Name legacy

[edit]Richard Coates suggests that while the river was as a whole called the Thames, part of it, where it was too wide to ford, was called *(p)lowonida. This gave the name to a settlement on its banks, which became known as Londinium, from the Indo-European roots *pleu- "flow" and *-nedi "river" meaning something like the flowing river or the wide flowing unfordable river.[10][11]

The river gives its name to three informal areas: the Thames Valley, a region of England around the river between Oxford and West London; the Thames Gateway; and the greatly overlapping Thames Estuary around the tidal Thames to the east of London and including the waterway itself. Thames Valley Police is a formal body that takes its name from the river, covering three counties. In non-administrative use, the river's name is used in those of Thames Valley University, Thames Water, Thames Television, publishing company Thames & Hudson, Thameslink (north–south rail service passing through central London) and South Thames College. An example of its use in the names of historic entities is the Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company.

History

[edit]Marks of human activity, in some cases dating back to Pre-Roman Britain, are visible at various points along the river. These include a variety of structures connected with use of the river, such as navigations, bridges and watermills, as well as prehistoric burial mounds.

The lower Thames in the Roman era was a shallow waterway winding through marshes. But centuries of human intervention have transformed it into a deep tidal canal flowing between 200 miles of solid walls; these defend a floodplain where 1.5 million people work and live.

A major maritime route is formed for much of its length for shipping and supplies: through the Port of London for international trade, internally along its length and by its connection to the British canal system. The river's position has put it at the centre of many events in British history, leading to it being described by John Burns as "liquid history".

Two broad canals link the river to other rivers: the Kennet and Avon Canal (Reading to Bath) and the Grand Union Canal (London to the Midlands). The Grand Union effectively bypassed the earlier, narrow and winding Oxford Canal which remains open as a popular scenic recreational route. Three further cross-basin canals are disused but are in various stages of reconstruction: the Thames and Severn Canal (via Stroud), which operated until 1927 (to the west coast of England), the Wey and Arun Canal to Littlehampton, which operated until 1871 (to the south coast), and the Wilts & Berks Canal.

Rowing and sailing clubs are common along the Thames, which is navigable to such vessels. Kayaking and canoeing also take place. Major annual events include the Henley Royal Regatta and the Boat Race, while the Thames has been used during two Summer Olympic Games: 1908 (rowing) and 1948 (rowing and canoeing). Safe headwaters and reaches are a summer venue for organised swimming, which is prohibited on safety grounds in a stretch centred on Central London.

Conversion of marshland

[edit]After the river took its present-day course, many of the banks of the Thames Estuary and the Thames Valley in London were partly covered in marshland, as was the adjoining Lower Lea Valley. Streams and rivers like the River Lea, Tyburn Brook and Bollo Brook drained into the river, while some islands, e.g. Thorney Island, formed over the ages. The northern tip of the ancient parish of Lambeth, for example, was marshland known as Lambeth Marshe, but it was drained in the 18th century; the street names Lower Marsh and Upper Marsh preserve a memory.[12]

Until the middle of the Victorian era, malaria was commonplace beside the River Thames, even in London, and was frequently lethal. Some cases continued to occur into the early 20th century. Draining of the marshes helped with its eradication, but the causes are complex and unclear.

The East End of London, also known simply as the East End, was the area of London east of the medieval walled City of London and north of the River Thames, although it is not defined by universally accepted formal boundaries; the River Lea can be considered another boundary.[13] Most of the local riverside was also marshland. The land was drained and became farmland; it was built on after the Industrial Revolution.

Canvey Island in southern Essex (area 18.45 km2, 7.12 sq mi; population 40,000[14]) was once marshy, but is now a fully reclaimed island in the Thames estuary, separated from the mainland of south Essex by a network of creeks. Lying below sea level, it is prone to flooding at exceptional tides, but has nevertheless been inhabited since Roman times.

Course

[edit]

The usually quoted source of the Thames is at Thames Head (at grid reference ST980994). This is about 1.5 mi (2.4 km)[15] north of the village of Kemble in southern Gloucestershire, near the town of Cirencester, in the Cotswolds.[16] However, Seven Springs near Cheltenham, where the Churn (which feeds into the Thames near Cricklade) rises, is also sometimes quoted as the Thames' source,[17][18] as this location is farthest from the mouth and adds some 14 mi (23 km) to the river's length. At Seven Springs above the source is a stone with the Latin hexameter inscription "Hic tuus o Tamesine pater septemgeminus fons", which means "Here, O Father Thames, [is] your sevenfold source".[19]

The springs at Seven Springs flow throughout the year, while those at Thames Head are seasonal (a winterbourne). With a length of 215 mi (346 km),[20] the Thames is the longest river entirely in England. (The longest river in the United Kingdom, the Severn, flows partly in Wales.) However, as the River Churn, sourced at Seven Springs, is 14 mi (23 km) longer than the section of the Thames from its traditional source at Thames Head to the confluence, the overall length of the Thames measured from Seven Springs, at 229 mi (369 km), is greater than the Severn's length of 220 mi (350 km).[21] Thus, the "Churn/Thames" river may be regarded as the longest natural river in the United Kingdom. The stream from Seven Springs is joined at Coberley by a longer tributary which could further increase the length of the Thames, with its source in the grounds of the National Star College at Ullenwood.

The Thames flows through or alongside Ashton Keynes, Cricklade, Lechlade, Oxford, Abingdon-on-Thames, Wallingford, Goring-on-Thames and Streatley (at the Goring Gap), Pangbourne and Whitchurch-on-Thames, Reading, Wargrave, Henley-on-Thames, Marlow, Maidenhead, Windsor and Eton, Staines-upon-Thames and Egham, Chertsey, Shepperton, Weybridge, Sunbury-on-Thames, Walton-on-Thames, Molesey and Thames Ditton. The river was subject to minor redefining and widening of the main channel around Oxford, Abingdon and Marlow before 1850, when further cuts to ease navigation reduced distances further.

Molesey faces Hampton, and in Greater London the Thames passes Hampton Court Palace, Surbiton, Kingston upon Thames, Teddington, Twickenham, Richmond (with a famous view of the Thames from Richmond Hill), Syon House, Kew, Brentford, Chiswick, Barnes, Hammersmith, Fulham, Putney, Wandsworth, Battersea and Chelsea. In central London, the river passes Pimlico and Vauxhall, and then forms one of the principal axes of the city, from the Palace of Westminster to the Tower of London. At this point, it historically formed the southern boundary of the medieval city, with Southwark, on the opposite bank, then being part of Surrey.

Beyond central London, the river passes Bermondsey, Wapping, Shadwell, Limehouse, Rotherhithe, Millwall, Deptford, Greenwich, Cubitt Town, Blackwall, New Charlton and Silvertown, before flowing through the Thames Barrier, which protects central London from flooding by storm surges. Below the barrier, the river passes Woolwich, Thamesmead, Dagenham, Erith, Purfleet, Dartford, West Thurrock, Northfleet, Tilbury and Gravesend before entering the Thames Estuary near Southend-on-Sea.

Sea level

[edit]The sea level in the Thames estuary is rising and the rate of rise is increasing.[22][23]

Sediment cores up to 10 m deep collected by the British Geological Survey from the banks of the tidal River Thames contain geochemical information and fossils which provide a 10,000-year record of sea-level change.[24] Combined, this and other studies suggest that the Thames sea-level has risen more than 30 m during the Holocene at a rate of around 5–6 mm per year from 10,000 to 6,000 years ago.[24] The rise of sea level dramatically reduced when the ice melt nearly concluded[clarification needed] over the past 4,000 years. Since the beginning of the 20th century, rates of sea level rise range from 1.22 mm per year to 2.14 mm per year.[24]

Catchment area and discharge

[edit]The Thames River Basin[25] District, including the Medway catchment, covers an area of 6,229 sq mi (16,130 km2).[26] The entire river basin is a mixture of urban and rural, with rural landscape predominating in the western part. The area is among the driest in the United Kingdom. Water resources consist of groundwater from aquifers and water taken from the Thames and its tributaries, much of it stored in large bank-side reservoirs.[26]

The Thames itself provides two-thirds of London's drinking water, while groundwater supplies about 40 per cent of public water supplies in the overall catchment area. Groundwater is an important water source, especially in the drier months, so maintaining its quality and quantity is extremely important. Groundwater is vulnerable to surface pollution, especially in highly urbanised areas.[26]

Non-tidal section

[edit]

Brooks, canals and rivers, within an area of 3,842 sq mi (9,951 km2),[27] combine to form 38 main tributaries feeding the Thames between its source and Teddington Lock. This is the usual tidal limit; however, high spring tides can raise the head water level in the reach above Teddington and can occasionally reverse the river flow for a short time. In these circumstances, tidal effects can be observed upstream to the next lock beside Molesey weir,[27] which is visible from the towpath and bridge beside Hampton Court Palace. Before Teddington Lock was built in 1810–12, the river was tidal at peak spring tides as far as Staines upon Thames.

In descending order, non-related tributaries of the non-tidal Thames, with river status, are the Churn, Leach, Cole, Ray, Coln, Windrush, Evenlode, Cherwell, Ock, Thame, Pang, Kennet, Loddon, Colne, Wey and Mole. In addition, there are occasional backwaters and artificial cuts that form islands, distributaries (most numerous in the case of the Colne), and man-made distributaries such as the Longford River. Three canals intersect this stretch: the Oxford Canal, Kennet and Avon Canal and Wey Navigation.

Its longest artificial secondary channel (cut), the Jubilee River, was built between Maidenhead and Windsor for flood relief and completed in 2002.[28][29]

The non-tidal section of the river is managed by the Environment Agency, which is responsible for managing the flow of water to help prevent and mitigate flooding, and providing for navigation: the volume and speed of water downstream is managed by adjusting the sluices at each of the weirs and, at peak high water, levels are generally dissipated over preferred flood plains adjacent to the river. Occasionally, flooding of inhabited areas is unavoidable and the agency issues flood warnings. Due to stiff penalties applicable on the non-tidal river, which is a drinking water source before treatment, sanitary sewer overflow from the many sewage treatment plants covering the upper Thames basin should be rare in the non-tidal Thames. However, storm sewage overflows are still common in almost all the main tributaries of the Thames[30][31] despite claims by Thames Water to the contrary.[32]

Tidal section

[edit]

Below Teddington Lock (about 55 mi or 89 km upstream of the Thames Estuary), the river is subject to tidal activity from the North Sea. Before the lock was installed, the river was tidal as far as Staines, about 16 mi (26 km) upstream.[33] London, capital of Roman Britain, was established on two hills, now known as Cornhill and Ludgate Hill. These provided a firm base for a trading centre at the lowest possible point on the Thames.[34]

A river crossing was built at the site of London Bridge. London Bridge is now used as the basis for published tide tables giving the times of high tide. High tide reaches Putney about 30 minutes later than London Bridge, and Teddington about an hour later. The tidal stretch of the river is known as "the Tideway". Tide tables are published by the Port of London Authority and are available online. Times of high and low tides are also posted on Twitter.

The principal tributaries of the River Thames on the Tideway include the rivers Crane, Brent, Wandle, Ravensbourne (the final part of which is called Deptford Creek), Lea (the final part of which is called Bow Creek), Roding (Barking Creek), Darent and Ingrebourne. In London, the water is slightly brackish with sea salt, being a mix of sea and fresh water.

This part of the river is managed by the Port of London Authority. The flood threat here comes from high tides and strong winds from the North Sea, and the Thames Barrier was built in the 1980s to protect London from this risk.

The Nore is the sandbank that marks the mouth of the Thames Estuary, where the outflow from the Thames meets the North Sea. It is roughly halfway between Havengore Creek in Essex and Warden Point on the Isle of Sheppey in Kent. Until 1964 it marked the seaward limit of the Port of London Authority. As the sandbank was a major hazard for shipping coming in and out of London, in 1732 it received the world's first lightship. This became a major landmark, and was used as an assembly point for shipping. Today it is marked by Sea Reach No. 1 Buoy.[35]

Islands

[edit]

The River Thames contains over 80 islands ranging from the large estuarial marshlands of the Isle of Sheppey and Canvey Island to small tree-covered islets like Rose Isle in Oxfordshire and Headpile Eyot in Berkshire. They are found all the way from Fiddler's Island in Oxfordshire to the Isle of Sheppey in Kent. Some of the largest inland islands, for example Formosa Island near Cookham and Andersey Island at Abingdon, were created naturally when the course of the river divided into separate streams.

In the Oxford area the river splits into several streams across the floodplain (Seacourt Stream, Castle Mill Stream, Bulstake Stream and others), creating several islands (Fiddler's Island, Osney and others). Desborough Island, Ham Island at Old Windsor and Penton Hook Island were artificially created by lock cuts and navigation channels. Chiswick Eyot is a landmark on the Boat Race course, while Glover's Island forms the centre of a view from Richmond Hill.

Islands of historical interest include Magna Carta Island at Runnymede, Fry's Island at Reading, and Pharaoh's Island near Shepperton. In more recent times Platts Eyot at Hampton was the place where Motor Torpedo Boats (MTB)s were built, Tagg's Island near Molesey was associated with the impresario Fred Karno and Eel Pie Island at Twickenham was the birthplace of the South East's R&B music scene.

Westminster Abbey and the Palace of Westminster (commonly known today as the Houses of Parliament) were built on Thorney Island, which used to be an eyot.

Geology

[edit]

Researchers have identified the River Thames as a discrete drainage line flowing as early as 58 million years ago, in the Thanetian stage of the late Palaeocene epoch.[36] Until around 500,000 years ago, the Thames flowed on its existing course through what is now Oxfordshire, before turning to the north-east through Hertfordshire and East Anglia and reaching the North Sea near present-day Ipswich.[37]

At this time the river-system headwaters lay in the English West Midlands and may, at times, have received drainage from the Berwyn Mountains in North Wales.

Ice age

[edit]About 450,000 years ago, in the most extreme Ice Age of the Pleistocene, the Anglian, the furthest southern extent of the ice sheet reached Hornchurch[38] in east London, the Vale of St Albans, and the Finchley Gap.

It dammed the river in Hertfordshire, resulting in the formation of large ice lakes, which eventually burst their banks and caused the river to divert onto its present course through the area of present-day London.

The ice lobe which stopped at present-day Finchley deposited about 14 metres of boulder clay there.[39] Its torrent of meltwater gushed through the Finchley Gap and south towards the new course of the Thames, and proceeded to carve out the Brent Valley in the process.[40]

The Anglian ice advance resulted in a new course for the Thames through Berkshire and on into London, after which the river rejoined its original course in southern Essex, near the present River Blackwater estuary. Here it entered a substantial freshwater lake in the southern North Sea basin, south of what is called Doggerland. The overspill of this lake caused the formation of the Channel River and later the Dover Strait gap between present-day Britain and France. Subsequent development led to the continuation of the course that the river follows at the present day.[41]

Most of the bedrock of the Vale of Aylesbury comprises clay and chalk that formed at the end of the ice age and at one time was under the Proto-Thames. At this time the vast underground reserves of water formed that make the water table higher than average in the Vale of Aylesbury.[42]

At the height of the last ice age, around 20,000 BC, Britain was connected to mainland Europe by a large expanse of land known as Doggerland in the southern North Sea Basin. At this time, the Thames' course did not continue to Doggerland but flowed southwards from the eastern Essex coast where it met the waters of the proto-Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta[41] flowing from what are now the Netherlands and Belgium. These rivers formed a single river – the Channel River (Fleuve Manche) – that passed through the Dover Strait and drained into the Atlantic Ocean in the western English Channel.

Upon the valley sides of the Thames and some of its tributaries can be seen other terraces of brickearth, laid over and sometimes interlayered with the clays. These deposits were brought in by the winds during the periglacial periods, suggesting that wide, flat marshes were then part of the landscape, which the new rivers proceeded to cut into.

The steepness of some valley sides indicates very much lower mean sea levels caused by the glaciation locking up so much water upon the land masses, thus causing the river water to flow rapidly seaward and so erode its bed quickly downwards.

The original land surface was around 350 to 400 ft (110 to 120 m) above the current sea-level. The surface had sandy deposits from an ancient sea, laid over sedimentary clay (this is the blue London Clay). All the erosion down from this higher land surface, and the sorting action by these changes of water flow and direction, formed what is known as the Thames River Gravel Terraces.

Since Roman times and perhaps earlier, the isostatic rebound from the weight of previous ice sheets, and its interplay with the eustatic change in sea level, have resulted in the old valley of the River Brent, together with that of the Thames, silting up again. Thus, along much of the Brent's present-day course, one can make out the water-meadows of rich alluvium, which is augmented by frequent floods.

Wildlife

[edit]

Various species of birds feed off the river or nest on it, some being found both at sea and inland. These include cormorant, black-headed gull and herring gull. The mute swan is a familiar sight on the river but the escaped black swan is more rare. The annual ceremony of Swan Upping is an old tradition of counting stocks.

Non-native geese that can be seen include Canada geese, Egyptian geese and bar-headed geese, and ducks include the familiar native mallard, plus introduced Mandarin duck and wood duck. Other water birds to be found on the Thames include the great crested grebe, coot, moorhen, heron and kingfisher. Many types of British birds also live alongside the river, although they are not specific to the river habitat.

The Thames contains both sea water and fresh water, thus providing support for seawater and freshwater fish. However, many populations of fish are at risk and are being killed in tens of thousands because of pollutants leaking into the river from human activities.[43] Salmon, which inhabit both environments, have been reintroduced and a succession of fish ladders have been built into weirs to enable them to travel upstream.

On 5 August 1993, the largest non-tidal salmon in recorded history was caught close to Boulters Lock in Maidenhead. The specimen weighed 14+1⁄2 lb (6.6 kg) and measured 22 in (56 cm) in length. The eel is particularly associated with the Thames and there were formerly many eel traps. Freshwater fish of the Thames and its tributaries include brown trout, chub, dace, roach, barbel, perch, pike, bleak and flounder. Colonies of short-snouted seahorses as well as tope and starry smooth-hound sharks have also recently been discovered in the river.[44][45] The Thames is also host to some invasive crustaceans, including the signal crayfish and the Chinese mitten crab.

Aquatic mammals are also known to inhabit the Thames. The population of grey and harbour seals numbers up to 700 in the Thames Estuary. These animals have been sighted as far upriver as Richmond.[46] Bottlenose dolphins and harbour porpoises are also sighted in the Thames.[47]

On 20 January 2006, a 16–18 ft (4.9–5.5 m) northern bottle-nosed whale was seen in the Thames as far upstream as Chelsea. This was extremely unusual: this whale is generally found in deep sea waters. Crowds gathered along the riverbanks to witness the spectacle but there was soon concern, as the animal came within yards of the banks, almost beaching, and crashed into an empty boat causing slight bleeding. About 12 hours later, the whale is believed to have been seen again near Greenwich, possibly heading back to sea. A rescue attempt lasted several hours, but the whale died on a barge. See River Thames whale.[48]

Human history

[edit]

The River Thames has played several roles in human history: as an economic resource, a maritime route, a boundary, a fresh water source, a source of food and more recently a leisure facility. In 1929, John Burns, one-time MP for Battersea, responded to an American's unfavourable comparison of the Thames with the Mississippi by coining the expression "The Thames is liquid history".

There is evidence of human habitation living off the river along its length dating back to Neolithic times.[49] The British Museum has a decorated bowl (3300–2700 BC), found in the river at Hedsor, Buckinghamshire, and a considerable amount of material was discovered during the excavations of Dorney Lake.[50] A number of Bronze Age sites and artefacts have been discovered along the banks of the river including settlements at Lechlade, Cookham and Sunbury-on-Thames.[51]

So extensive have the changes to this landscape been that what little evidence there is of man's presence before the ice came has inevitably shown signs of transportation here by water and reveals nothing specifically local. Likewise, later evidence of occupation, even since the arrival of the Romans, may lie next to the original banks of the Brent but have been buried under centuries of silt.[51]

Roman Britain

[edit]Some of the earliest written references to the Thames (Latin: Tamesis) occur in Julius Caesar's account of his second expedition to Britain in 54 BC,[52] when the Thames presented a major obstacle and he encountered the Iron Age Belgic tribes (Catuvellauni and Atrebates) along the river. At the confluence of the Thames and Cherwell was the site of early settlements and the River Cherwell marked the boundary between the Dobunni tribe to the west and the Catuvellauni to the east (these were pre-Roman Celtic tribes). In the late 1980s a large Romano-British settlement was excavated on the edge of the village of Ashton Keynes in Wiltshire.

Starting in AD 43, under the Emperor Claudius, the Romans occupied England and, recognising the river's strategic and economic importance, built fortifications along the Thames valley including a major camp at Dorchester. Cornhill and Ludgate Hill provided a defensible site near a point on the river both deep enough for the era's ships and narrow enough to be bridged; Londinium (London) grew up around the Walbrook on the north bank around the year 47. Boudica's Iceni razed the settlement in AD 60 or 61, but it was soon rebuilt; and once the bridge was built, it grew to become the provincial capital of the island.

The next Roman bridges upstream were at Staines on the Devil's Highway between Londinium and Calleva (Silchester). Boats could be swept up to it on the rising tide, with no need for wind or muscle power.

Middle Ages

[edit]A Romano-British settlement grew up north of the confluence, partly because the site was naturally protected from attack on the east side by the River Cherwell and on the west by the River Thames. This settlement dominated the pottery trade in what is now central southern England, and pottery was distributed by boats on the Thames and its tributaries.

Competition for the use of the river created the centuries-old conflict between those who wanted to dam the river to build millraces and fish traps and those who wanted to travel and carry goods on it. Economic prosperity and the foundation of wealthy monasteries by the Anglo-Saxons attracted unwelcome visitors and by around AD 870 the Vikings were sweeping up the Thames on the tide and creating havoc as in their destruction of Chertsey Abbey.

Once King William had won total control of the strategically important Thames Valley, he went on to invade the rest of England. He had many castles built, including those at Wallingford, Rochester, Windsor and most importantly the Tower of London. Many details of Thames activity are recorded in the Domesday Book. The following centuries saw the conflict between king and barons coming to a head in AD 1215 when King John was forced to sign Magna Carta on an island in the Thames at Runnymede. Among a host of other things, this granted the barons the right of Navigation under Clause 23.

Another major consequence of John's reign was the completion of the multi-piered London Bridge, which acted as a barricade and barrage on the river, affecting the tidal flow upstream and increasing the likelihood of the river freezing over. In Tudor and Stuart times, various kings and queens built magnificent riverside palaces at Hampton Court, Kew, Richmond on Thames, Whitehall and Greenwich.

As early as the 1300s, the Thames was used to dispose of waste matter produced in the city of London, thus turning the river into an open sewer. In 1357, Edward III described the state of the river in a proclamation: "... dung and other filth had accumulated in divers places upon the banks of the river with ... fumes and other abominable stenches arising therefrom."[53]

The growth of the population of London greatly increased the amount of waste that entered the river, including human excrement, animal waste from slaughter houses, and waste from manufacturing processes. According to historian Peter Ackroyd, "a public lavatory on London Bridge showered its contents directly onto the river below, and latrines were built over all the tributaries that issued into the Thames."[53]

Early modern period

[edit]

During a series of cold winters the Thames froze over above London Bridge: in the first Frost Fair in 1607, a tent city was set up on the river, along with a number of amusements, including ice bowling.

In good conditions, barges travelled daily from Oxford to London carrying timber, wool, foodstuffs and livestock. The stone from the Cotswolds used to rebuild St Paul's Cathedral after the Great Fire in 1666 was brought all the way down from Radcot. The Thames provided the major route between the City of London and Westminster in the 16th and 17th centuries; the clannish guild of watermen ferried Londoners from landing to landing and tolerated no outside interference. In 1715, Thomas Doggett was so grateful to a local waterman for his efforts in ferrying him home, pulling against the tide, that he set up a rowing race for professional watermen known as "Doggett's Coat and Badge".

By the 18th century, the Thames was one of the world's busiest waterways, as London became the centre of the vast, mercantile British Empire, and progressively over the next century the docks expanded in the Isle of Dogs and beyond. Efforts were made to resolve the navigation conflicts upstream by building locks along the Thames. After temperatures began to rise again, starting in 1814, the river stopped freezing over.[54] The building of a new London Bridge in 1825, with fewer piers (pillars) than the old, allowed the river to flow more freely and prevented it from freezing over in cold winters.[55]

Throughout early modern history the population of London and its industries discarded their rubbish in the river.[56] This included the waste from slaughterhouses, fish markets, and tanneries. The buildup in household cesspools could sometimes overflow, especially when it rained, and was washed into London's streets and sewers which eventually led to the Thames.[57] In the late 18th and 19th centuries people known as mudlarks scavenged in the river mud for a meagre living.

Victorian era

[edit]

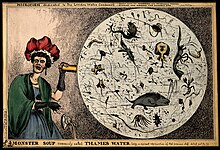

In the 19th century the quality of water in the Thames deteriorated further. The discharge of raw sewage into the Thames was formerly only common in the City of London, making its tideway a harbour for many harmful bacteria. Gasworks were built alongside the river, and their by-products leaked into the water, including spent lime, ammonia, cyanide, and carbolic acid. The river had an unnaturally warm temperature caused by chemical reactions in the water, which also removed the water's oxygen.[58] Four serious cholera outbreaks killed tens of thousands of people between 1832 and 1865. Historians have attributed Prince Albert's death in 1861 to typhoid that had spread in the river's dirty waters beside Windsor Castle.[59] Wells with water tables that mixed with tributaries (or the non-tidal Thames) faced such pollution with the widespread installation of the flush toilet in the 1850s.[59] In the 'Great Stink' of 1858, pollution in the river reached such an extreme that sittings of the House of Commons at Westminster had to be abandoned. Chlorine-soaked drapes were hung in the windows of Parliament in an attempt to stave off the smell of the river, but to no avail.[60]

There followed a concerted effort to contain the city's sewage by constructing massive sewer systems on the north and south river embankments, under the supervision of engineer Joseph Bazalgette. Meanwhile, there were similar huge projects to ensure the water supply: reservoirs and pumping stations were built on the river to the west of London, slowly helping the quality of water to improve.

The Victorian era was one of imaginative engineering. The coming of the railways added railway bridges to the earlier road bridges and also reduced commercial activity on the river. However, sporting and leisure use increased with the establishment of regattas such as Henley and the Boat Race. One of the worst river disasters in England was on 3 September 1878, when the crowded pleasure boat Princess Alice collided with the Bywell Castle, killing over 640 people.

20th century

[edit]

The growth of road transport, and the decline of the Empire in the years following 1914, reduced the economic prominence of the river. During the Second World War, the protection of certain Thames-side facilities, particularly docks and water treatment plants, was crucial to the munitions and water supply of the country. The river's defences included the Maunsell forts in the estuary, and the use of barrage balloons to counter German bombers using the reflectivity and shapes of the river to navigate during the Blitz.

In the post-war era, although the Port of London remains one of the UK's three main ports, most trade has moved downstream from central London. In the late 1950s, the discharge of methane gas in the depths of the river caused the water to bubble, and the toxins wore away at boats' propellers.[61]

The decline of heavy industry and tanneries, reduced use of oil-pollutants and improved sewage treatment have led to much better water quality compared to the late 19th and early- to mid-20th centuries and aquatic life has returned to its formerly 'dead' stretches.

Alongside the entire river runs the Thames Path, a National Route for walkers and cyclists.

In the early 1980s a pioneering flood control device, the Thames Barrier, was opened. It is closed to tides several times a year to prevent water damage to London's low-lying areas upstream (the 1928 Thames flood demonstrated the severity of this type of event).

In the late 1990s, the 7 mi (11 km) long Jubilee River was built as a wide "naturalistic" flood relief channel from Taplow to Eton to help reduce the flood risk in Maidenhead, Windsor and Eton,[62] although it appears to have increased flooding in the villages immediately downstream.

21st century

[edit]In 2010, the Thames won the largest environmental award in the world: the $350,000 International Riverprize.[63]

In August 2022, the first few miles of the river dried up due to the previous month's heatwave, and the source of the river temporarily moved five miles to beyond Somerford Keynes.[64]

The active river

[edit]

One of the major resources provided by the Thames is the water distributed as drinking water by Thames Water, whose area of responsibility covers the length of the River Thames. The Thames Water Ring Main is the main distribution mechanism for water in London, with one major loop linking the Hampton, Walton, Ashford and Kempton Park Water Treatment Works with central London.

In the past, commercial activities on the Thames included fishing (particularly eel trapping), coppicing willows and osiers which provided wood and baskets, and the operation of watermills for flour and paper production and metal beating. These activities have largely disappeared.

The Thames is popular for a wide variety of riverside housing, including high-rise flats in central London and chalets on the banks and islands upstream. Some people live in houseboats, typically around Brentford and Tagg's Island.

Transport and tourism

[edit]Tidal river

[edit]

In London there are many sightseeing tours in tourist boats, past riverside attractions such as the Houses of Parliament and the Tower of London. There are also regular riverboat services co-ordinated by London River Services. London City Airport is situated on the Thames, in East London. Previously it was a dock.

Upper river

[edit]The leisure navigation and sporting activities on the river have given rise to a number of businesses including boatbuilding, marinas, ships chandlers and salvage services.

In summer, passenger services operate along the entire non-tidal river from Oxford to Teddington. The two largest operators are Salters Steamers and French Brothers. Salters operate services between Folly Bridge, Oxford and Staines. The whole journey takes four days and requires several changes of boat.[65] French Brothers operate passenger services between Maidenhead and Hampton Court.[66]Along the course of the river a number of smaller private companies also offer river trips at Oxford, Wallingford, Reading and Hampton Court.[67] Many companies also provide boat hire on the river.

Cable car

[edit]

The London Cable Car over the Thames from the Greenwich Peninsula to the Royal Docks has been in operation since the 2012 Summer Olympics.

Police and lifeboats

[edit]

The river is policed by five police forces. The Thames Division is the River Police arm of London's Metropolitan Police, while Surrey Police, Thames Valley Police, Essex Police and Kent Police have responsibilities on their parts of the river outside the metropolitan area. There is also a London Fire Brigade fire boat on the river. The river claims a number of lives each year.[68]

As a result of the Marchioness disaster in 1989 when 51 people died, the Government asked the Maritime and Coastguard Agency, the Port of London Authority and the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) to work together to set up a dedicated Search and Rescue service for the tidal River Thames. As a result, there are four lifeboat stations on the River Thames: at Teddington, Chiswick, Tower (based at Victoria Embankment/Waterloo Bridge) and Gravesend.[69]

Navigation

[edit]

The Thames is maintained for navigation by powered craft from the estuary as far as Lechlade in Gloucestershire and for very small craft to Cricklade. The original towpath extends upstream from Putney Bridge as far as the connection with the now disused Thames and Severn Canal at Inglesham, one and a half miles upstream of the last boat lock near Lechlade. From Teddington Lock to the head of navigation, the navigation authority is the Environment Agency. Between the sea and Teddington Lock, the river forms part of the Port of London and navigation is administered by the Port of London Authority. Both the tidal river through London and the non-tidal river upstream are intensively used for leisure navigation.

The non-tidal River Thames is divided into reaches by the 45 locks. The locks are staffed for the greater part of the day, but can be operated by experienced users out of hours. This part of the Thames links to existing navigations at the River Wey Navigation, the River Kennet and the Oxford Canal. All craft using it must be licensed. The Environment Agency has patrol boats (named after tributaries of the Thames) and can enforce the limit strictly since river traffic usually has to pass through a lock at some stage. A speed limit of 8 km/h (4.3 kn) applies. There are pairs of transit markers at various points along the non-tidal river that can be used to check speed – a boat travelling legally taking a minute or more to pass between the two markers.

The tidal river is navigable to large ocean-going ships as far upstream as the Pool of London and London Bridge. Although London's upstream enclosed docks have closed and central London sees only the occasional visiting cruise ship or warship, the tidal river remains one of Britain's main ports. Around 60 active terminals cater for shipping of all types including ro-ro ferries, cruise liners and vessels carrying containers, vehicles, timber, grain, paper, crude oil, petroleum products, liquified petroleum gas etc.[70] There is a regular traffic of aggregate or refuse vessels, operating from wharves in the west of London. The tidal Thames links to the canal network at the River Lea Navigation, the Regent's Canal at Limehouse Basin and the Grand Union Canal at Brentford.

Upstream of Wandsworth Bridge a speed limit of 8 kn (15 km/h) is in force for powered craft to protect the riverbank environment and to provide safe conditions for rowers and other river users. There is no absolute speed limit on most of the Tideway downstream of Wandsworth Bridge, although boats are not allowed to create undue wash. Powered boats are limited to 12 knots between Lambeth Bridge and downstream of Tower Bridge, with some exceptions. Boats can be approved by the harbour master to travel at speeds of up to 30 knots from below Tower Bridge to past the Thames Barrier.[71]

Management

[edit]The administrative powers of the Thames Conservancy to control river traffic and manage flows have been taken on with some modifications by the Environment Agency and, in respect of the Tideway part of the river, such powers are split between the agency and the Port of London Authority.

In the Middle Ages the Crown exercised general jurisdiction over the Thames, one of the four royal rivers, and appointed water bailiffs to oversee the river upstream of Staines. The City of London exercised jurisdiction over the tidal Thames. However, navigation was increasingly impeded by weirs and mills, and in the 14th century the river probably ceased to be navigable for heavy traffic between Henley and Oxford. In the late 16th century the river seems to have been reopened for navigation from Henley to Burcot.[72]

The first commission concerned with the management of the river was the Oxford-Burcot Commission, formed in 1605 to make the river navigable between Burcot and Oxford.

In 1751 the Thames Navigation Commission was formed to manage the whole non-tidal river above Staines. The City of London long claimed responsibility for the tidal river. A long running dispute between the City and the Crown over ownership of the river was not settled until 1857, when the Thames Conservancy was formed to manage the river from Staines downstream. In 1866 the functions of the Thames Navigation Commission were transferred to the Thames Conservancy, which thus had responsibility for the whole river.

In 1909 the powers of the Thames Conservancy over the tidal river, below Teddington, were transferred to the Port of London Authority.

In 1974 the Thames Conservancy became part of the new Thames Water Authority. When Thames Water was privatised in 1990, its river management functions were transferred to the National Rivers Authority, in 1996 subsumed into the Environment Agency.

In 2010, the Thames won the world's largest environmental award at the time, the $350,000 International Riverprize, presented at the International Riversymposium in Perth, WA in recognition of the substantial and sustained restoration of the river by many hundreds of organisations and individuals since the 1950s.

As a boundary

[edit]Until enough crossings were established, the river presented a formidable barrier, with Belgic tribes and Anglo-Saxon kingdoms being defined by which side of the river they were on. When English counties were established their boundaries were partly determined by the Thames. On the northern bank were the ancient counties of Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Middlesex and Essex. On the southern bank were the counties of Wiltshire, Berkshire, Surrey and Kent.

Counting bridges to the far bank or to an island connected to such, the Thames has 223. From source to mouth a channel can be found with 138 bridges, plus the temporary footbridge often added during Reading Festival. The river is heavily splayed in Ashton Keynes and Oxford. Where the river is wide 17 tunnels that have been built, many of which for rail or notable electricity cables. The crossings have changed the dynamics and made cross-river development and shared responsibilities more practicable. In 1965, upon the creation of Greater London, the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames incorporated the former 'Middlesex and Surrey' banks, Spelthorne moved from Middlesex to Surrey; and further changes in 1974 moved some of the boundaries away from the river. For example, some areas were transferred from Berkshire to Oxfordshire, and from Buckinghamshire to Berkshire. In many river sports and traditions – for example in rowing – the banks are referred to by their traditional county names.

Crossings

[edit]

Many of the present-day road bridges are on the site of earlier fords, ferries and wooden bridges. Swinford Bridge, known as the five pence toll bridge, replaced a ferry that in turn replaced a ford. The earliest known major crossings of the Thames by the Romans were at London Bridge and Staines Bridge. At Folly Bridge in Oxford the remains of an original Saxon structure can be seen, and medieval stone bridges such as Newbridge, Wallingford Bridge[73] and Abingdon Bridge are still in use.

Kingston's growth is believed to stem from its having the only crossing between London Bridge and Staines until the beginning of the 18th century. During the 18th century, many stone and brick road bridges were built from new or to replace existing bridges both in London and along the length of the river. These included Putney Bridge, Westminster Bridge, Datchet Bridge, Windsor Bridge and Sonning Bridge.

Several central London road bridges were built in the 19th century, most conspicuously Tower Bridge, the only Bascule bridge on the river, designed to allow ocean-going ships to pass beneath it. The most recent road bridges are the bypasses at Isis Bridge and Marlow By-pass Bridge and the motorway bridges, most notably the two on the M25 route: Queen Elizabeth II Bridge and M25 Runnymede Bridge.

Railway development in the 19th century resulted in a spate of bridge building including Blackfriars Railway Bridge and Charing Cross (Hungerford) Railway Bridge in central London, and the railway bridges by Isambard Kingdom Brunel at Maidenhead Railway Bridge, Gatehampton Railway Bridge and Moulsford Railway Bridge.

The world's first underwater tunnel was Marc Brunel's Thames Tunnel built in 1843 and now used to carry the East London Line. The Tower Subway was the first railway under the Thames, which was followed by all the deep-level tube lines. Road tunnels were built in East London at the end of the 19th century, being the Blackwall Tunnel and the Rotherhithe Tunnel. The latest tunnels are the Dartford Crossings.

Через плотины, построенные на не приливной реке, было установлено множество пешеходных переходов, и некоторые из них остались, когда были построены шлюзы - например, в шлюзе Бенсон . Другие были заменены пешеходными мостами, когда плотину сняли, как на пешеходном мосту Hart's Weir Footbridge . Примерно в 2000 году вдоль Темзы было добавлено несколько пешеходных мостов либо как часть Пути Темзы, либо в ознаменование тысячелетия. К ним относятся пешеходный мост Темпл , пешеходный мост Блумерс-Хоул , пешеходные мосты Хангерфорд и мост Миллениум , каждый из которых имеет отличительные конструктивные особенности.

До того, как были построены мосты, основным способом переправы через реку был паром. Значительное количество паромов было предусмотрено специально для навигационных целей. Когда тропа меняла направление, приходилось переправлять лошадь-буксировщика и ее возницу через реку. В этом больше не было необходимости, когда баржи приводились в движение паром. Некоторые паромы до сих пор курсируют по реке. Паром Вулиджа перевозит автомобили и пассажиров через реку через Ворота Темзы и соединяет Северную и Южную кольцевые дороги. Выше по течению находятся меньшие пешеходные паромы, например, Hampton Ferry и Shepperton to Weybridge Ferry , последний из которых является единственной непостоянной переправой, которая остается на Пути Темзы.

Гидроэнергетика

[ редактировать ]Хотя использование реки для привода водяных мельниц в значительной степени вымерло, в последнее время появилась тенденция использовать напор воды, обеспечиваемый существующими плотинами реки винтовых , для привода небольших гидроэлектростанций с использованием турбин Архимеда . Операционные схемы включают в себя:

- открылся частный завод В 2011 году в Mapledurham Watermill , работающий параллельно с от водяного колеса с приводом кукурузной мельницей , которая время от времени работает до сих пор. [74]

- Гидроэлектростанция в Ромни-Локе, питающая Виндзорский замок с помощью двух винтов Архимеда, открыта в 2013 году королевой Елизаветой II . [75]

- Osney Lock Hydro , общественная схема в Osney Lock в Оксфорде , также открылась в 2013 году. [76]

- Sandford Hydro , общественная схема в Сэндфорд-Лок к югу от Оксфорда, открылась в 2017 году. [77]

- Reading Hydro , общественная схема в Caversham Lock в Ридинге , открылась в 2021 году. [78]

Загрязнение

[ редактировать ]Очищенные и неочищенные сточные воды

[ редактировать ]Очищенные сточные воды из всех городов и деревень водосбора Темзы стекают в Темзу через очистные сооружения. Сюда входит все, что есть в Суиндоне, Оксфорде, Беркшире и почти во всем Суррее.

Однако неочищенные сточные воды все равно часто попадают в Темзу во время дождливой погоды. Когда была построена канализационная система Лондона , канализационные трубы были спроектированы таким образом, чтобы во время сильных штормов они могли переливаться через точки сброса вдоль реки. Первоначально это происходило один или два раза в год, однако теперь переполнение происходит в среднем раз в неделю. [79] В 2013 году более 55 миллионов тонн разбавленных неочищенных сточных вод вылилось в приливную Темзу. Эти сбросы убивают рыбу, оставляют неочищенные сточные воды на берегах рек и ухудшают качество воды в реке. [80] [81] Расследование Агентства по охране окружающей среды, проведенное в 2022 году, выявило «широко распространенное и серьезное несоблюдение соответствующих правил». [82] [83] Thames Water также опубликовала интерактивную карту, показывающую происходящие сбросы. [84] [85]

Чтобы уменьшить выбросы этого вещества в реку, в настоящее время строится схема прилива Темзы стоимостью 4,2 миллиарда фунтов стерлингов. Этот проект будет собирать сточные воды из района Большого Лондона до того, как они переполнятся , а затем направлять их по туннелю длиной 25 км (15 миль) под приливной Темзой, чтобы их можно было очищать на очистных сооружениях Бектона . [86] [87] Планируется, что проект позволит сократить сброс сточных вод в Темзу в районе Большого Лондона на 90%, что значительно повысит качество воды. [88] Предполагается, что после его завершения каждый год в Темзу будет поступать два миллиона тонн сточных вод. [89]

Уровни ртути

[ редактировать ]Ртуть (Hg) представляет собой экологически стойкий тяжелый металл, который может быть токсичным для морской жизни и человека. Шестьдесят кернов отложений глубиной 1 м, охватывающих всю приливную реку Темзу между Брентфордом и островом Грейн , были проанализированы на содержание общего содержания ртути. Записи отложений показывают явный рост и снижение уровня загрязнения ртутью на протяжении всей истории. [90] Концентрации ртути в Темзе снижаются вниз по течению от Лондона к внешнему устью, при этом общий уровень ртути колеблется от 0,01 до 12,07 мг/кг, что дает среднее значение 2,10 мг/кг, что выше, чем во многих других устьях рек Великобритании и Европы. [91] [90]

Наибольшее загрязнение ртутью в устье Темзы, вызванное осадками, происходит в центральном районе Лондона между мостом Воксхолл и Вулиджем. [90] В большинстве кернов отложений наблюдается явное снижение концентрации ртути вблизи поверхности, что объясняется общим сокращением загрязняющей деятельности, а также повышением эффективности недавней экологической легализации и управления реками (например, Осло-Парижская конвенция).

Пластиковое загрязнение

[ редактировать ]Темза имеет относительно высокий уровень загрязнения пластиком: около 94 000 микропластиков по некоторым частям реки перемещается в секунду. Этот микропластик образуется в результате распада более крупных предметов, а также блесток и микрочастиц косметики. [92]

Одно исследование показало, что пятая часть макропластика, обнаруженного в реке, приходится на упаковку пищевых продуктов. [93]

Спорт

[ редактировать ]На Темзе распространено несколько водных видов спорта, многие клубы поощряют участие и организуют скачки и межклубные соревнования.

Гребля

[ редактировать ]

Темза — исторический центр гребли в Соединенном Королевстве. На реке расположено более 200 клубов и более 8000 членов British Rowing (более 40% ее членов). [94] В большинстве городов и районов любого размера на реке есть хотя бы один клуб. Международно посещаемые центры - это Оксфорд , Хенли-он-Темз , а также мероприятия и клубы на участке реки от Чизвика до Путни .

Два соревнования по гребле на Темзе традиционно являются частью более широкого английского спортивного календаря:

Университетские гонки на лодках (между Оксфордом и Кембриджем ) проходят в конце марта или начале апреля на трассе чемпионата от Путни до Мортлейка на западе Лондона.

Королевская регата Хенли проходит в течение пяти дней в начале июля в городе Хенли-на-Темзе , расположенном вверх по течению . Помимо своего спортивного значения, регата является важной датой в английском общественном календаре наряду с такими событиями, как Royal Ascot и Wimbledon .

Другие важные или исторические соревнования по гребле на Темзе включают:

- Руководитель речной гонки и руководитель женских восьмерок (8+) (т.е. восьмерки с рулевым), руководитель школы , руководитель ветеранов , руководитель гребли , руководитель четверок (HOR4) и руководитель пар (короче) на чемпионской трассе

- Wingfield Sculls на одной и той же трассе: (1x) ( одиночка ) чемпионат

- Пальто и значок Доггетта для учеников лондонских водников, одного из старейших спортивных мероприятий в мире.

- Женская регата Хенли

- В настоящее время проводятся гребные гонки в Хенли для экипажей легкого веса (мужских и женских) Оксфордского и Кембриджского университетов.

- В Оксфордском университете проводятся скачки, известные как «Неделя восьмерок» и «Торпиды».

Другие регаты , гонки на головы и университетские гонки проводятся вдоль Темзы, которые описаны в разделе «Гребля по реке Темзе» .

Парусный спорт

[ редактировать ]

Парусный спорт практикуется как на приливных, так и на неприливных участках реки. Самый высокий клуб вверх по течению находится в Оксфорде. Самыми популярными парусными судами, используемыми на Темзе, являются лазеры , GP14 и Wayfarers . Одна уникальная парусная лодка для Темзы — Thames Rater , которая курсирует вокруг Рэйвенс-Айт .

Скиффинг

[ редактировать ]Скиффинг сократился в пользу частных моторных лодок, но в летние месяцы на реке проводятся соревнования. Шесть клубов и такое же количество регат для лодочных лодок существуют в Skiff Club , Теддингтон , вверх по течению.

Пунтинг

[ редактировать ]В отличие от «развлекательного плавания на лодке », распространенного на Черуэлле в Оксфорде и Кэме в Кембридже , катание на лодке по Темзе носит как соревновательный, так и развлекательный характер и использует более узкие суда, обычно базирующиеся в нескольких скиф-клубах.

Каякинг и каноэ

[ редактировать ]Каякинг и гребля на каноэ являются обычным явлением, а морские каякеры используют приливные участки для прогулок. Каякеры и каноисты используют приливные и неприливные участки для тренировок, гонок и путешествий. Уайтуотера Плавники и гребцы слалома обслуживаются на плотинах , таких как плотины в Херли-Лок , Санбери-Лок и Боултер-Лок . В Теддингтоне, непосредственно перед началом приливного участка реки, находится Королевский каноэ-клуб , который считается старейшим в мире и основан в 1866 году. С 1950 года почти каждый год на Пасху каноисты на длинные дистанции соревнуются в том, что сейчас известно как Девайс на Вестминстерскую международную гонку на каноэ , [95] который следует по руслу каналов Кеннет и Эйвон , впадает в Темзу в Рединге и заканчивается у Вестминстерского моста .

Плавание

[ редактировать ]В 2006 году британский пловец и активист по защите окружающей среды Льюис Пью стал первым человеком, который переплыл всю длину Темзы от Кембла до Саутенд-он-Си, чтобы привлечь внимание к сильной засухе в Англии, где наблюдались рекордные температуры, свидетельствующие о степени глобальной потепление. Заплыв на 202 мили (325 км) занял у него 21 день. Официальный истоок реки перестал течь из-за засухи, что вынудило Пью пробежать первые 26 миль (42 км). [96]

С июня 2012 года администрация лондонского порта издала постановление , которое оно обеспечивает соблюдением, запрещающее плавание между мостом Патни и Кросснессом , Темзмидом (таким образом, включая весь центр Лондона) без предварительного разрешения на том основании, что пловцы в этот участок реки подвергает опасности не только себя из-за сильного течения реки, но и других пользователей реки. [97]

Организованные соревнования по плаванию проводятся в различных точках, как правило, выше по течению от Хэмптон-Корта , включая Виндзор, Марлоу и Хенли. [98] [99] [100] В 2011 году комик Дэвид Уоллиамс проплыл 140 миль (230 км) от Лехлейда до Вестминстерского моста и собрал более 1 миллиона фунтов стерлингов на благотворительность. [101]

На участках без прилива плавание было и остается развлечением и фитнесом для опытных пловцов, когда во время низкого течения используются безопасные и более глубокие внешние каналы. [102]

Меандры

[ редактировать ]Меандр Темзы — это путешествие на большие расстояния по всей Темзе или ее части путем бега, плавания или использования любого из вышеперечисленных способов. Это часто проводится как спортивное соревнование или попытка установления рекорда.

Темза в искусстве

[ редактировать ]Изобразительное искусство

[ редактировать ]Река Темза на протяжении веков была темой для художников, великих и второстепенных. Четырьмя крупными художниками, чьи работы основаны на Темзе, являются Каналетто , Дж. М. У. Тернер , Клод Моне и Джеймс Эбботт Макнил Уистлер . [103] Британский художник 20-го века Стэнли Спенсер создал множество работ в Кукхэме . [104]

Джона Кауфмана Скульптура «Дайвер: Регенерация» расположена в Темзе недалеко от Рейнхема . [105]

Река и мосты изображены разрушенными – вместе с большей частью Лондона – в фильме « День независимости 2» . [106]

- Темза в искусстве

- Эффект солнечного света в здании парламента — Клод Моне

- Первый Вестминстерский мост , нарисованный Каналетто в 1746 году.

- Железнодорожный мост Мейденхед , каким его видел Тернер в 1844 году.

- Туманное утро на Темзе — Джеймс Гамильтон (между 1872 и 1878 годами)

- Катание на лодке по Темзе — Джон Лавери , ок. 1890 г.

- На Темзе — Джеймс Тиссо , ок. 1874 г.

Литература

[ редактировать ]

Темза упоминается во многих литературных произведениях, включая романы, дневники и поэзию. В частности, это центральная тема в трех:

«Трое мужчин в лодке» Джерома К. Джерома , впервые опубликованное в 1889 году, представляет собой юмористический рассказ о путешествии на лодке по Темзе между Кингстоном и Оксфордом . Изначально книга задумывалась как серьезный путеводитель с рассказами о местной истории мест вдоль маршрута, но со временем юмористические элементы взяли верх. Пейзаж и особенности Темзы, описанные Джеромом, практически не изменились, а непреходящая популярность книги привела к тому, что ее издание ни разу не вышло из печати с момента ее первой публикации.

Книга Чарльза Диккенса « Наш общий друг» (написанная в 1864–1865 годах) описывает реку в более мрачном свете. Он начинается с того, что мусорщик и его дочь вытаскивают мертвеца из реки возле Лондонского моста, чтобы спасти то, что у тела может быть в карманах, и заканчивается смертью злодеев, утонувших в шлюзе Плашуотер выше по течению. Работа реки и влияние приливов и отливов описаны с большой точностью. Диккенс открывает роман этим наброском реки и людей, которые над ней работают:

В наше время, хотя нет необходимости указывать точный год, лодка грязного и неприглядного вида с двумя фигурами в ней плыла по Темзе между железным мостом Саутварк и Лондонским мостом , который был сделан из железа. из камня, поскольку приближался осенний вечер. В этой лодке были фигуры сильного мужчины с взлохмаченными седыми волосами и загорелым лицом и девушки лет девятнадцати или двадцати. Девушка грела, очень легко тянув пару весел; человек с провисшими в руках рулями направления и свободно за поясом не спускал глаз.

Кеннета Грэма Действие книги «Ветер в ивах» , написанной в 1908 году, происходит в среднем и верхнем течении реки. Он начинается как рассказ об антропоморфных персонажах, «просто возящихся в лодках», но развивается в более сложную историю, сочетающую элементы мистицизма с приключениями и размышлениями об эдвардианском обществе. Его вообще считают одним из самых любимых произведений детской литературы. [107] а на иллюстрациях Э. Х. Шепарда и Артура Рэкхема изображена Темза и ее окрестности.

Река почти неизбежно фигурирует во многих книгах, действие которых происходит в Лондоне. В большинстве других романов Диккенса есть некоторые аспекты Темзы. Оливер Твист финиширует в трущобах и лежбищах на южном берегу. Рассказы Шерлоке Холмсе о Артура Конан Дойла часто посещают прибрежные районы, как в «Знаке четырех» . В «Сердце тьмы » Джозефа Конрада безмятежность современной Темзы контрастирует с дикостью реки Конго и с дикой природой Темзы, какой она казалась римскому солдату, отправленному в Британию две тысячи лет назад. Описание подхода к Лондону со стороны устья Темзы Конрад дает также в своем эссе «Зеркало моря» (1906). Вверх по течению, Генри Джеймса » в «Портрете дамы в качестве одного из ключевых мест используется большой особняк на берегу реки Темзы.

Литературные научно-популярные произведения включают дневник Сэмюэля Пеписа , в котором он записал множество событий, связанных с Темзой, включая лондонский пожар . Когда он писал это в июне 1667 года, его потревожили звуки выстрелов, когда голландские военные корабли прорвались через Королевский флот на Темзе.

В поэтическом плане Уильяма Вордсворта сонет «На Вестминстерском мосту» завершается такими строками:

- Никогда я не видел и никогда не чувствовал такого глубокого спокойствия!

- Река скользит по своей сладкой воле:

- О, Боже! сами дома кажутся спящими;

- И все это могучее сердце лежит неподвижно!

Т.С. Элиот несколько раз упоминает Темзу в «Огненной проповеди», раздел III книги «Бесплодная земля» .

Линия « Сладкая Темза» взята из Эдмунда Спенсера » «Проталамиона , который представляет собой более идиллический образ:

- Вдоль берега серебряных струящихся Темм;

- Чей ухабистый берег, который перекрывает его река,

- Раскрашено все переменными цветами.

- И все медовухи украшены изысканными драгоценными камнями

- Подходит для палубных луков Maydens.

О верховьях также пишет Мэтью Арнольд в «Ученом цыгане» :

- Пересечение молодой Темзы в Бэблок-Хите.

- Плывешь в прохладном ручье, твои мокрые пальцы

- Когда медленный пант разворачивается

- О, рожденный в те дни, когда ум был свежим и ясным

- И жизнь текла весело, как сверкающая Темза;

- До этой странной болезни современной жизни.

Венди Коуп Действие стихотворения «После обеда» происходит на мосту Ватерлоо и начинается так:

- На мосту Ватерлоо, где мы прощались,

- Погодные условия вызывают слезы на глазах.

- Я вытираю их черной шерстяной перчаткой,

- И постарайся не заметить, что я влюбился.

Дилан Томас упоминает Темзу в своем стихотворении «Отказ оплакивать смерть ребенка в Лондоне от пожара». «Дочь Лондона», тема стихотворения, лежит «глубоко среди первых мертвецов… в тайне у не скорбящих вод верховой Темзы».

В научно-фантастических романах широко используется футуристическая Темза. Утопические «Вести из ниоткуда» Уильяма Морриса — это, главным образом, рассказ о путешествии по долине Темзы в социалистическое будущее. Темза фигурирует в книге Герберта Уэллса « Война миров» . Темза также занимает видное место в трилогии Филипа Пулмана « Темные начала » как коммуникационная артерия для водного цыганского народа Оксфорда и Фенса , а также как известное место действия его романа «Прекрасная дикарь» .

В «Дептфордские мыши» трилогии Робина Джарвиса Темза появляется несколько раз. В одной книге персонажи-крысы плывут по нему в Дептфорд . Лауреат премии детской книжной премии Nestlé Золотой I «Кориандр » Салли Гарднер — это фэнтезийный роман, в котором героиня живет на берегу Темзы. Марк Уоллингтон описывает путешествие вверх по Темзе на походной лодке в своей книге 1989 года «Буги вверх по реке» .

Многие из главных героев «Реки Лондона» городского фэнтезийного сериала Бена Аароновича - это genii locorum (местные боги), связанные с рекой Темзой и ее притоками. Сюда входят Отец Темза , первоначальный бог Темзы, но теперь (в книгах) ограниченный неприливными территориями над шлюзом Теддингтон , и Мама Темза, богиня приливной Темзы ниже Теддингтона.

Музыка

[ редактировать ]Премьера « Музыки воды», сочиненной Георгом Фридрихом Генделем, состоялась 17 июля 1717 года, когда король Георг I попросил дать концерт на Темзе. Концерт был исполнен для короля Георга I на его барже, и, как говорят, он настолько понравился ему, что он приказал 50 измученным музыкантам трижды сыграть сюиты за время путешествия.

Песня «Old Father Thames» была записана Питером Доусоном на студии Abbey Road Studios в 1933 году и Грейси Филдс пять лет спустя. Джесси Мэтьюз поет «Мою реку» в фильме 1938 года «Плавание вдоль» , и эта мелодия является центральной частью основного танцевального номера ближе к концу фильма.

Sex Pistols отыграли концерт на речном судне Королевы Елизаветы 7 июня 1977 года, в год серебряного юбилея королевы Елизаветы II , во время плавания по реке. Хоровая линия «(I) (связывается) жить у реки» в песне « London Calling » группы Clash относится к реке Темзе.

В двух песнях The Kinks Темза упоминается в названии первой песни, а во второй песне, возможно, упоминается «река»: « Waterloo Sunset » повествует о встречах пары на мосту Ватерлоо в Лондоне и начинается так: «Старая грязная река, ты должна продолжать катиться, утекая в ночь?» и продолжает: «Терри встречает Джули, станция Ватерлоо » и «... но Терри и Джули переходят реку, где они чувствуют себя в безопасности и невредимости...». « See My Friends » постоянно относится к друзьям певца, «играющим в «пересечь реку», а не к девушке, которая «только что ушла». Кроме того, Рэй Дэвис как сольный исполнитель упоминает Темзу в своей «Лондонской песне». [108]

«Сладкая Темза, течь мягко» Юэна Макколла , написанная в начале 1960-х годов, представляет собой трагическую балладу о любви, действие которой происходит во время путешествия вверх по реке (см Эдмунда Спенсера . выше припев любовного стихотворения ). Культурный клуб путешествует по Темзе на речном катере в клипе « Карма Хамелеон ». Английская музыкантша Имоджен Хип написала песню с видом на Темзу под названием «Ты знаешь, где меня найти». Песня была выпущена 18 октября 2012 года как шестой сингл с ее четвертого альбома Sparks . [109]

Крупные наводнения

[ редактировать ]Лондонское наводнение 1928 года.

[ редактировать ]Наводнение Темзы 1928 года было катастрофическим наводнением на реке Темзе, которое затронуло большую часть прибрежного Лондона 7 января 1928 года, а также места ниже по реке. Четырнадцать человек утонули в Лондоне, а тысячи остались без крова, когда паводковые воды захлестнули набережную Темзы и обрушилась часть набережной Челси . Это было последнее крупное наводнение, затронувшее центр Лондона , и, особенно после катастрофического наводнения в Северном море в 1953 году , оно помогло привести к принятию новых мер по борьбе с наводнениями, кульминацией которых стало строительство Темзского барьера в 1970-х годах.

Наводнение в долине Темзы 1947 года.

[ редактировать ]Наводнение Темзы 1947 года в целом было самым сильным наводнением на Темзе в 20 веке, затронувшим большую часть долины Темзы , а также другие районы Англии в середине марта 1947 года после очень суровой зимы .

Наводнение было вызвано выпадением 4,6 дюймов (120 мм) осадков (включая снег); пиковый расход составил 61,7 × 10 9 Л (13,6 × 10 9 имп галлонов воды в день, а ремонт ущерба обошелся в общей сложности в 12 миллионов фунтов стерлингов. [110] Повреждения в результате войны некоторых шлюзов еще больше усугубили ситуацию.

Другие значительные наводнения на Темзе с 1947 года произошли в 1968, 1993, 1998, 2000, 2003, 2006 и 2014 годах.

Наводнение на острове Канви в 1953 году.

[ редактировать ]В ночь на 31 января наводнение в Северном море 1953 года опустошило остров, унеся жизни 58 жителей острова и вынудив временную эвакуацию 13 000 жителей. [111] Таким образом, Канви защищен современной морской защитой, состоящей из бетонной дамбы длиной 15 миль (24 км). [112] Многие из жертв находились в праздничных бунгало поместья Ньюлендс на востоке и погибли, когда вода достигла уровня потолка. Небольшая деревня на острове находится примерно на два фута (0,6 м) над уровнем моря и, следовательно, избежала последствий наводнения.

См. также

[ редактировать ]Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ См . Реку Тамса.

- ^ Глава 5: Кельтский элемент (П.Х. Рини) . . . Считается, что это название связано с санскритским Тамаса («темная вода»), названием притока. [а] реки Ганг. [4]

- ^ Глава 5: Кельтский элемент (П.Х. Рини). Общее ME Tamise — это французская форма, как и современное написание французского Th- вместо T- (Thamis 1220). [4]

Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ «Карта артиллерийской разведки» . Английское наследие . Архивировано из оригинала 24 апреля 2012 года . Проверено 11 декабря 2018 г.

- ^ «Вид на выделенные места: устье и болота Южной Темзы» . Сайты особого научного интереса. Натуральная Англия. Архивировано из оригинала 2 марта 2018 года . Проверено 28 февраля 2018 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Мэллори, Дж. П. и Д. К. Адамс (1947). Энциклопедия индоевропейской культуры . Лондон: Фицрой и Дирборн. п. 147.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Рини 1969 , с. 72.

- ^ Джексон, Кеннет Х (1955). Пиктский язык . в FT Уэйнрайт (ред.). Проблема пиктов . Эдинбург: Нельсон. стр. 129–166.

- ^ Китсон, Питер Р. (1996). «Британские и европейские названия рек ». Труды Филологического общества . 94 (2): 73–118. дои : 10.1111/j.1467-968X.1996.tb01178.x .

- ^ Хениг М. и Бут П. (2000). Роман Оксфордшир , стр. 118–119.

- ^ Сандоз, Эллис (ред.). Корни свободы: Великая хартия вольностей.. . Индианаполис: Амаги/Фонд Свободы. стр. 39, 347.

- ^ Кендал, Роджер; Боуэн, Джейн; Уортли, Лаура (2002). Гений и благородство: Хенли в эпоху Просвещения . Хенли-он-Темз: Музей реки и гребли. стр. 12–13. ISBN 9780953557127 .

- ^ Коутс, Ричард (1998). «Новое объяснение названия Лондона». Труды Филологического общества . 96 (2): 203–229. дои : 10.1111/1467-968X.00027 .

- ^ Ресурсы культурного наследия (2005). Легендарное происхождение и происхождение топонима Лондона. Архивировано 9 июля 2011 года в Wayback Machine . Проверено 1 ноября 2005 г.

- ^ Энтони Дэвид Миллс (2001). Оксфордский словарь топонимов Лондона . Издательство Оксфордского университета . ISBN 978-0-19-280106-7 . Архивировано из оригинала 13 сентября 2016 года . Проверено 25 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Новый Оксфордский словарь английского языка (1998) ISBN 0-19-861263-X с. 582 « Ист-Энд, часть Лондона к востоку от Сити до реки Ли, включая Доклендс».

- ^ «Краткая история острова Канви» . Городской совет Канви-Айленда. Архивировано из оригинала 27 августа 2020 года . Проверено 27 августа 2020 г.

- ^ «Хед Темзы, исток реки Темзы» . Британия Экспресс .

- ^ «Источник» . Путь Темзы. Архивировано из оригинала 27 августа 2020 года . Проверено 27 августа 2020 г.

- ^ Бейли, Дэвид (15 мая 2012 г.). «По следам истока Темзы» . Новости Би-би-си . Архивировано из оригинала 27 августа 2020 года . Проверено 12 сентября 2018 г.

- ^ Харт, Дороти (9 мая 2004 г.). «Семь источников и маслобойка» . The-river-thames.co.uk. Архивировано из оригинала 16 мая 2010 года . Проверено 17 мая 2010 г.

- ^ Винн, Кристофер (19 апреля 2018 г.). Я никогда не знал этого о реке Темзе . Издательство Эбери. ISBN 9780091933579 . Архивировано из оригинала 27 августа 2020 года . Проверено 20 января 2019 г. - через Google Книги.