хангыль

В этой статье есть несколько проблем. Пожалуйста, помогите улучшить его или обсудите эти проблемы на странице обсуждения . ( Узнайте, как и когда удалять эти шаблонные сообщения )

|

| корейский алфавит Хангыль / Чосоныль Хангыль ( Хангыль ) / Чосонгул | |

|---|---|

"Chosŏn'gŭl" (top) and "Hangul" (bottom) | |

| Script type | Featural |

| Creator | Sejong of Joseon |

Time period | 1443 CE – present |

| Direction |

|

| Languages | Korean and Jeju (standard) Cia-Cia (limited use) |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Hang (286), Hangul (Hangŭl, Hangeul) Jamo (for the jamo subset) |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Hangul |

|

| Korean writing systems |

|---|

| Hangul |

|

| Hanja |

| Mixed script |

| Braille |

| Transcription |

| Transliteration |

|

| Writing systems |

|---|

|

| Abjad |

| Abugida |

| Alphabetical |

| Logographic |

| Syllabic |

| Hybrids |

Japanese (Logographic and syllabic) Hangul (Alphabetic and syllabic) |

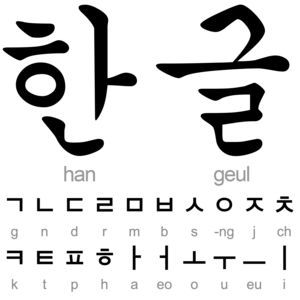

Корейский алфавит , известный как хангыль [а] или хангыль [б] в Южной Корее ( Английский: / ˈ h ɑː n ɡ uː l / HAHN -gool ; [1] Корейский : Хангыль ; Ханджа : 韓㐎 ; Корейское произношение: [ha(ː)n.ɡɯɭ] ) и Чосонгул в Северной Корее ( 조선글 ; Северная Корея 㐎 ; Северокорейское произношение [tsʰo.sʰɔn.ɡɯɭ] ) — современная система письма корейского языка . [2] [3] [4] Буквы пяти основных согласных отражают форму органов речи, используемых для их произношения. Они систематически модифицируются для обозначения фонетических особенностей. Гласные письма буквы систематически модифицируются для родственных звуков, что делает хангыль уникальной системой . [5][6][7] It has been described as a syllabic alphabet as it combines the features of alphabetic and syllabic writing systems.[8][6]

Hangul was created in 1443 CE by King Sejong the Great, fourth king of the Joseon dynasty. It was an attempt to increase literacy by serving as a complement (or alternative) to the logographic Sino-Korean Hanja, which had been used by Koreans as their primary script to write the Korean language since as early as the Gojoseon period (spanning more than a thousand years and ending around 108 BCE), along with the usage of Classical Chinese.[9][10][11]

Modern Hangul orthography uses 24 basic letters: 14 consonant letters[c] and 10 vowel letters.[d] There are also 27 complex letters that are formed by combining the basic letters: 5 tense consonant letters,[e] 11 complex consonant letters,[f] and 11 complex vowel letters.[g] Four basic letters in the original alphabet are no longer used: 1 vowel letter[h] and 3 consonant letters.[i] Korean letters are written in syllabic blocks with the alphabetic letters arranged in two dimensions. For example, the South Korean city of Seoul is written as 서울, not ㅅㅓㅇㅜㄹ.[12] The syllables begin with a consonant letter, then a vowel letter, and then potentially another consonant letter called a batchim (Korean: 받침). If the syllable begins with a vowel sound, the consonant ㅇ (ng) acts as a silent placeholder. However, when ㅇ starts a sentence or is placed after a long pause, it marks a glottal stop. Syllables may begin with basic or tense consonants but not complex ones. The vowel can be basic or complex, and the second consonant can be basic, complex or a limited number of tense consonants. How the syllable is structured depends if the baseline of the vowel symbol is horizontal or vertical. If the baseline is vertical, the first consonant and vowel are written above the second consonant (if present), but all components are written individually from top to bottom in the case of a horizontal baseline.[12]

As in traditional Chinese and Japanese writing, as well as many other texts in East Asia, Korean texts were traditionally written top to bottom, right to left, as is occasionally still the way for stylistic purposes. However, Korean is now typically written from left to right with spaces between words serving as dividers, unlike in Japanese and Chinese.[7] Hangul is the official writing system throughout Korea, both North and South. It is a co-official writing system in the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture and Changbai Korean Autonomous County in Jilin Province, China. Hangul has also seen limited use by speakers of the Cia-Cia language in Indonesia.[13]

Names

[edit]Official names

[edit]| Korean name (North Korea) | |

| Chosŏn'gŭl | |

|---|---|

| Hancha | |

| Revised Romanization | Joseon(-)geul |

| McCune–Reischauer | Chosŏn'gŭl |

| IPA | Korean pronunciation: [tsʰo.sʰɔn.ɡɯɭ] |

| Korean name (South Korea) | |

| Hangul | |

|---|---|

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Han(-)geul |

| McCune–Reischauer | Han'gŭl[14] |

| IPA | Korean pronunciation: [ha(ː)n.ɡɯɭ] |

The Korean alphabet was originally named Hunminjeong'eum (훈민정음) by King Sejong the Great in 1443.[10] Hunminjeong'eum is also the document that explained logic and science behind the script in 1446.

The name hangeul (한글) was coined by Korean linguist Ju Si-gyeong in 1912. The name combines the ancient Korean word han (한), meaning great, and geul (글), meaning script. The word han is used to refer to Korea in general, so the name also means Korean script.[15] It has been romanized in multiple ways:

- Hangeul or han-geul in the Revised Romanization of Korean, which the South Korean government uses in English publications and encourages for all purposes.

- Han'gŭl in the McCune–Reischauer system, is often capitalized and rendered without the diacritics when used as an English word, Hangul, as it appears in many English dictionaries.

- hān kul in the Yale romanization, a system recommended for technical linguistic studies.

North Koreans call the alphabet Chosŏn'gŭl (조선글), after Chosŏn, the North Korean name for Korea.[16] A variant of the McCune–Reischauer system is used there for romanization.

Other names

[edit]Until the mid-20th century, the Korean elite preferred to write using Chinese characters called Hanja. They referred to Hanja as jinseo (진서/真書) meaning true letters. Some accounts say the elite referred to the Korean alphabet derisively as 'amkeul (암클) meaning women's script, and 'ahaetgeul (아햇글) meaning children's script, though there is no written evidence of this.[17]

Supporters of the Korean alphabet referred to it as jeong'eum (정음/正音) meaning correct pronunciation, gungmun (국문/國文) meaning national script, and eonmun (언문/諺文) meaning vernacular script.[17]

History

[edit]Creation

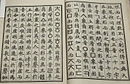

[edit]Koreans primarily wrote using Classical Chinese alongside native phonetic writing systems that predate Hangul by hundreds of years, including Idu script, Hyangchal, Gugyeol and Gakpil.[18][19][20][21] However, many lower class uneducated Koreans were illiterate due to the difficulty of learning the Korean and Chinese languages, as well as the large number of Chinese characters that are used.[22] To promote literacy among the common people, the fourth king of the Joseon dynasty, Sejong the Great, personally created and promulgated a new alphabet.[3][22][23] Although it is widely assumed that King Sejong ordered the Hall of Worthies to invent Hangul, contemporary records such as the Veritable Records of King Sejong and Jeong Inji's preface to the Hunminjeongeum Haerye emphasize that he invented it himself.[24]

The Korean alphabet was designed so that people with little education could learn to read and write.[25] According to the Hunminjeongeum Haerye Edition, King Sejong expressed his intention to understand the language of the people in his country and to express their meanings more conveniently in writing. He noted that the shapes of the traditional Chinese characters, as well as factors such as the thickness, stroke count, and order of strokes in calligraphy, were extremely complex, making it difficult for people to recognize and understand them individually. A popular saying about the alphabet is, "A wise man can acquaint himself with them before the morning is over; even a stupid man can learn them in the space of ten days."[26]

The project was completed in late December 1443 or January 1444, and described in 1446 in a document titled Hunminjeong'eum (The Proper Sounds for the Education of the People), after which the alphabet itself was originally named.[17] The publication date of the Hunminjeongeum, October 9, became Hangul Day in South Korea. Its North Korean equivalent, Chosŏn'gŭl Day, is on January 15.

Another document published in 1446 and titled Hunminjeong'eum Haerye (Hunminjeong'eum Explanation and Examples) was discovered in 1940. This document explains that the design of the consonant letters is based on articulatory phonetics and the design of the vowel letters is based on the principles of yin and yang and vowel harmony.[27] After the creation of Hangul, people from the lower class or the commoners had a chance to be literate. They learned how to read and write Korean, not just the upper classes and literary elite. They learn Hangul independently without formal schooling or such.[28]

Opposition

[edit]The Korean alphabet faced opposition in the 1440s by the literary elite, including Choe Manri and other Korean Confucian scholars. They believed Hanja was the only legitimate writing system. They also saw the circulation of the Korean alphabet as a threat to their status.[22] However, the Korean alphabet entered popular culture as King Sejong had intended, used especially by women and writers of popular fiction.[29]

King Yeonsangun banned the study and publication of the Korean alphabet in 1504, after a document criticizing the king was published.[30] Similarly, King Jungjong abolished the Ministry of Eonmun, a governmental institution related to Hangul research, in 1506.[31]

Revival

[edit]The late 16th century, however, saw a revival of the Korean alphabet as gasa and sijo poetry flourished. In the 17th century, the Korean alphabet novels became a major genre.[32] However, the use of the Korean alphabet had gone without orthographical standardization for so long that spelling had become quite irregular.[29]

In 1796, the Dutch scholar Isaac Titsingh became the first person to bring a book written in Korean to the Western world. His collection of books included the Japanese book Sangoku Tsūran Zusetsu (An Illustrated Description of Three Countries) by Hayashi Shihei.[33] This book, which was published in 1785, described the Joseon Kingdom[34] and the Korean alphabet.[35] In 1832, the Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland supported the posthumous abridged publication of Titsingh's French translation.[36]

Thanks to growing Korean nationalism, the Gabo Reformists' push, and Western missionaries' promotion of the Korean alphabet in schools and literature,[37] the Hangul Korean alphabet was adopted in official documents for the first time in 1894.[30] Elementary school texts began using the Korean alphabet in 1895, and Tongnip Sinmun, established in 1896, was the first newspaper printed in both Korean and English.[38]

Reforms and suppression under Japanese rule

[edit]After the Japanese annexation, which occurred in 1910, Japanese was made the official language of Korea. However, the Korean alphabet was still taught in Korean-established schools built after the annexation and Korean was written in a mixed Hanja-Hangul script, where most lexical roots were written in Hanja and grammatical forms in the Korean alphabet. Japan banned earlier Korean literature from public schooling, which became mandatory for children.[39]

The orthography of the Korean alphabet was partially standardized in 1912, when the vowel arae-a (ㆍ)—which has now disappeared from Korean—was restricted to Sino-Korean roots: the emphatic consonants were standardized to ㅺ, ㅼ, ㅽ, ㅆ, ㅾ and final consonants restricted to ㄱ, ㄴ, ㄹ, ㅁ, ㅂ, ㅅ, ㅇ, ㄺ, ㄻ, ㄼ. Long vowels were marked by a diacritic dot to the left of the syllable, but this was dropped in 1921.[29]

A second colonial reform occurred in 1930. The arae-a was abolished: the emphatic consonants were changed to ㄲ, ㄸ, ㅃ, ㅆ, ㅉ and more final consonants ㄷ, ㅈ, ㅌ, ㅊ, ㅍ, ㄲ, ㄳ, ㄵ, ㄾ, ㄿ, ㅄ were allowed, making the orthography more morphophonemic. The double consonant ㅆ was written alone (without a vowel) when it occurred between nouns, and the nominative particle 가 was introduced after vowels, replacing 이.[29]

Ju Si-gyeong, the linguist who had coined the term Hangul to replace Eonmun or Vulgar Script in 1912, established the Korean Language Research Society (later renamed the Hangul Society), which further reformed orthography with Standardized System of Hangul in 1933. The principal change was to make the Korean alphabet as morphophonemically practical as possible given the existing letters.[29] A system for transliterating foreign orthographies was published in 1940.

Japan banned the Korean language from schools and public offices in 1938 and excluded Korean courses from the elementary education in 1941 as part of a policy of cultural genocide.[40][41]

Further reforms

[edit]The definitive modern Korean alphabet orthography was published in 1946, just after Korean independence from Japanese rule. In 1948, North Korea attempted to make the script perfectly morphophonemic through the addition of new letters, and, in 1953, Syngman Rhee in South Korea attempted to simplify the orthography by returning to the colonial orthography of 1921, but both reforms were abandoned after only a few years.[29]

Both North Korea and South Korea have used the Korean alphabet or mixed script as their official writing system, with ever-decreasing use of Hanja especially in the North.

In South Korea

[edit]Beginning in the 1970s, Hanja began to experience a gradual decline in commercial or unofficial writing in the South due to government intervention, with some South Korean newspapers now only using Hanja as abbreviations or disambiguation of homonyms. However, as Korean documents, history, literature and records throughout its history until the contemporary period were written primarily in Literary Chinese using Hanja as its primary script, a good working knowledge of Chinese characters especially in academia is still important for anyone who wishes to interpret and study older texts from Korea, or anyone who wishes to read scholarly texts in the humanities.[42]

A high proficiency in Hanja is also useful for understanding the etymology of Sino-Korean words as well as to enlarge one's Korean vocabulary.[42]

In North Korea

[edit]North Korea instated Hangul as its exclusive writing system in 1949 on the orders of Kim Il Sung of the Workers' Party of Korea, and officially banned the use of Hanja.[43]

Non-Korean languages

[edit]Systems that employed Hangul letters with modified rules were attempted by linguists such as Hsu Tsao-te and Ang Ui-jin to transcribe Taiwanese Hokkien, a Sinitic language, but the usage of Chinese characters ultimately ended up being the most practical solution and was endorsed by the Ministry of Education (Taiwan).[44][45][46]

The Hunminjeong'eum Society in Seoul attempted to spread the use of Hangul to unwritten languages of Asia.[47] In 2009, it was unofficially adopted by the town of Baubau, in Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia, to write the Cia-Cia language.[48][49][50][51]

A number of Indonesian Cia-Cia speakers who visited Seoul generated large media attention in South Korea, and they were greeted on their arrival by Oh Se-hoon, the mayor of Seoul.[52]

Letters

[edit]

Letters in the Korean alphabet are called jamo (자모). There are 14 consonants (자음) and 10 vowels (모음) used in the modern alphabet. They were first named in Hunmongjahoe, a hanja textbook written by Choe Sejin. Additionally, there are 27 complex letters that are formed by combining the basic letters: 5 tense consonant letters, 11 complex consonant letters, and 11 complex vowel letters.

In typography design and in IME automata, the letters that make up a block are called jaso (자소).

Consonants

[edit]

The chart below shows all 19 consonants in South Korean alphabetic order with Revised Romanization equivalents for each letter and pronunciation in IPA (see Korean phonology for more).

| Hangul | ㄱ | ㄲ | ㄴ | ㄷ | ㄸ | ㄹ | ㅁ | ㅂ | ㅃ | ㅅ | ㅆ | ㅇ | ㅈ | ㅉ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅌ | ㅍ | ㅎ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Romanization | g | kk | n | d | tt | r | m | b | pp | s | ss | ' [j] | j | jj | ch | k | t | p | h |

| IPA | /k/ | /k͈/ | /n/ | /t/ | /t͈/ | /ɾ/ | /m/ | /p/ | /p͈/ | /s/ | /s͈/ | silent | /t͡ɕ/ | /t͈͡ɕ͈/ | /t͡ɕʰ/ | /kʰ/ | /tʰ/ | /pʰ/ | /h/ | |

| Final | Romanization | k | k | n | t | – | l | m | p | – | t | t | ng | t | – | t | k | t | p | t |

| g | kk | n | d | l | m | b | s | ss | ng | j | ch | k | t | p | h | |||||

| IPA | /k̚/ | /n/ | /t̚/ | – | /ɭ/ | /m/ | /p̚/ | – | /t̚/ | /ŋ/ | /t̚/ | – | /t̚/ | /k̚/ | /t̚/ | /p̚/ | /t̚/ | |||

ㅇ is silent syllable-initially and is used as a placeholder when the syllable starts with a vowel. ㄸ, ㅃ, and ㅉ are never used syllable-finally.

Consonants are broadly categorized into either obstruents (sounds produced when airflow either completely stops (i.e., a plosive consonant) or passes through a narrow opening (i.e., a fricative)) or sonorants (sounds produced when air flows out with little to no obstruction through the mouth, nose, or both).[53] The chart below lists the Korean consonants by their respective categories and subcategories.

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Alveolo-palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstruent | Stop (plosive) | Lax | p (ㅂ) | t (ㄷ) | k (ㄱ) | ||

| Tense | p͈ (ㅃ) | t͈ (ㄸ) | k͈ (ㄲ) | ||||

| Aspirated | pʰ (ㅍ) | tʰ (ㅌ) | kʰ (ㅋ) | ||||

| Fricative | Lax | s (ㅅ) | h (ㅎ) | ||||

| Tense | s͈ (ㅆ) | ||||||

| Affricate | Lax | t͡ɕ (ㅈ) | |||||

| Tense | t͈͡ɕ͈ (ㅉ) | ||||||

| Aspirated | t͡ɕʰ (ㅊ) | ||||||

| Sonorant | Nasal | m (ㅁ) | n (ㄴ) | ŋ (ㅇ) | |||

| Liquid (lateral approximant) | l (ㄹ) | ||||||

All Korean obstruents are voiceless in that the larynx does not vibrate when producing those sounds and are further distinguished by degree of aspiration and tenseness. The tensed consonants are produced by constricting the vocal cords while heavily aspirated consonants (such as the Korean ㅍ, /pʰ/) are produced by opening them.[53]

Korean sonorants are voiced.

Consonant assimilation

[edit]The pronunciation of a syllable-final consonant (which may already differ from its syllable-initial sound) may be affected by the following letter, and vice-versa. The table below describes these assimilation rules. Spaces are left blank when no modification is made to the normal syllable-final sound.

| Preceding syllable block's final letter-sound | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ㄱ (k) | ㄲ (k) | ㄴ (n) | ㄷ (t) | ㄹ (l) | ㅁ (m) | ㅂ (p) | ㅅ (t) | ㅆ (t) | ㅇ (ng) | ㅈ (t) | ㅊ (t) | ㅋ (k) | ㅌ (t) | ㅍ (p) | ㅎ (t) | ||

| Subsequent syllable block's initial letter | ㄱ(g) | k+k | n+g | t+g | l+g | m+g | b+g | t+g | - | t+g | t+g | t+g | p+g | h+k | |||

| ㄴ(n) | ng+n | n+n | l+n | m+n | m+n | t+n | n+t | t+n | t+n | t+n | p+n | h+n | |||||

| ㄷ(d) | k+d | n+d | t+t | l+d | m+d | p+d | t+t | t+t | t+t | t+t | k+d | t+t | p+d | h+t | |||

| ㄹ(r) | g+n | n+n | l+l | m+n | m+n | - | ng+n | r | |||||||||

| ㅁ(m) | g+m | n+m | t+m | l+m | m+m | m+m | t+m | - | ng+m | t+m | t+m | k+d | t+m | p+m | h+m | ||

| ㅂ(b) | g+b | p+p | t+b | - | |||||||||||||

| ㅅ (s) | ss+s | ||||||||||||||||

| ㅇ(∅) | g | kk+h | n | t | r | m | p | s | ss | ng+h | t+ch | t+ch | k+h | t+ch | p+h | h | |

| ㅈ(j) | t+ch | ||||||||||||||||

| ㅎ(h) | k | kk+h | n+h | t | r/ l+h | m+h | p | t | - | t+ch | t+ch | k | t | p | - | ||

Consonant assimilation occurs as a result of intervocalic voicing. When surrounded by vowels or sonorant consonants such as ㅁ or ㄴ, a stop will take on the characteristics of its surrounding sound. Since plain stops (like ㄱ /k/) are produced with relaxed vocal cords that are not tensed, they are more likely to be affected by surrounding voiced sounds (which are produced by vocal cords that are vibrating).[53]

Below are examples of how lax consonants (ㅂ /p/, ㄷ /t/, ㅈ /t͡ɕ/, ㄱ /k/) change due to location in a word. Letters in bolded interface show intervocalic weakening, or the softening of the lax consonants to their sonorous counterparts.[53]

ㅂ

- 밥 [bap̚] – 'rice'

- 보리밥 [boɾibap̚] – 'barley mixed with rice'

ㄷ

- 다 [da] – 'all'

- 맏 [mat̚] – 'oldest'

- 맏아들 [madadɯɭ] – 'oldest son'

ㅈ

- 죽 [t͡ɕuk] – 'porridge'

- 콩죽 [kʰoŋd͡ʑuk̚] – 'bean porridge'

ㄱ

- 공 [goŋ] – 'ball'

- 새 공 [sɛgoŋ] – 'new ball'

The consonants ㄹ and ㅎ also experience weakening. The liquid ㄹ, when in an intervocalic position, will be weakened to a [ɾ]. For example, the final ㄹ in the word 말 ([maɭ], 'word') changes when followed by the subject marker 이 (a vowel), and changes to a [ɾ] to become [maɾi].

ㅎ /h/ is very weak and is usually deleted in Korean words, as seen in words like 괜찮아요 /kwɛnt͡ɕʰanhajo/ [kwɛnt͡ɕʰanajo]. However, instead of being completely deleted, it leaves remnants by devoicing the following sound or by acting as a glottal stop.[53]

Lax consonants are tensed when following other obstruents due to the fact that the first obstruent's articulation is not released. Tensing can be seen in words like 입구 ('entrance') /ipku/ which is pronounced as [ip̚k͈u].

Consonants in the Korean alphabet can be combined into one of 11 consonant clusters, which always appear in the final position in a syllable block. They are: ㄳ, ㄵ, ㄶ, ㄺ, ㄻ, ㄼ, ㄽ, ㄾ, ㄿ, ㅀ, and ㅄ.

| Consonant cluster combinations (e.g. [in isolation] 닭 dak; [preceding another syllable block] 없다 – eop-da, 앉아 anj-a) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preceding syllable block's final letter | ㄳ (gs) | ㄵ (nj) | ㄶ (nh) | ㄺ (lg) | ㄻ (lm) | ㄼ (lb) | ㄽ (ls) | ㄾ (lt) | ㄿ (lp) | ㅀ (lh) | ㅄ (bs) | |

| (pronunciation in isolation) | k | n | n | k or l* | m | l or p** | l | l | p | l | p | |

| Subsequent block's initial letter | ㅇ(∅) | k+s | n+j | n+h | l+g | l+m | l+b | l+s | l+t | l+p | l+h | p+s |

| ㄷ(d) | k+d | n+d | n+t | k+d | m+d | l+d or p+d** | l+d | l+d | p+d | l+t | p+d | |

* Before ㄱ, the cluster ㄺ is pronounced as l (e.g., 맑게 malge [mal.k͈e]).

** For certain words, ㄼ may be pronounced as p (e.g., 밟다 bapda [pa:p̚.t͈a], 넓죽하다 neopjukhada [nʌp̚.t͈ɕu.kʰa.da]).

In cases where consonant clusters are followed by words beginning with ㅇ, the consonant cluster is resyllabified through a phonological phenomenon called liaison. In words where the first consonant of the consonant cluster is ㅂ,ㄱ, or ㄴ (the stop consonants), articulation stops and the second consonant cannot be pronounced without releasing the articulation of the first once. Hence, in words like 값 /kaps/ ('price'), the ㅅ cannot be articulated and the word is thus pronounced as [kap̚]. The second consonant is usually revived when followed by a word with initial ㅇ (값이 → [kap̚.si]. Other examples include 삶 (/salm/ [sam], 'life'). The ㄹ in the final consonant cluster is generally lost in pronunciation, however when followed by the subject marker 이, the ㄹ is revived and the ㅁ takes the place of the blank consonant ㅇ. Thus, 삶이 is pronounced as [sal.mi].

In cases where clusters are followed by syllables beginning with a consonant (e.g., ㄷ as shown above), the cluster generally maintains its isolated pronunciation; however, the cluster's lost consonant may sometimes revive and assimilate into the following syllable's consonant. For example, in 않다 (/anh.ta/ → [an.tʰa]) the lost ㅎ is assimilated into the following syllable and aspirates ㄷ. Similarly, in 앉하다 (/antɕ.ha.ta/ → [an.tɕʰa.da]) the lost ㅈ is revived and aspirated by the following ㅎ.[55]

Vowels

[edit]The chart below shows the 21 vowels used in the modern Korean alphabet in South Korean alphabetic order with Revised Romanization equivalents for each letter and pronunciation in IPA (see Korean phonology for more).

| Hangul | ㅏ | ㅐ | ㅑ | ㅒ | ㅓ | ㅔ | ㅕ | ㅖ | ㅗ | ㅘ | ㅙ | ㅚ | ㅛ | ㅜ | ㅝ | ㅞ | ㅟ | ㅠ | ㅡ | ㅢ | ㅣ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revised Romanization | a | ae | ya | yae | eo | e | yeo | ye | o | wa | wae | oe | yo | u | wo | we | wi | yu | eu | ui/ yi | i |

| IPA | /a/ | /ɛ/ | /ja/ | /jɛ/ | /ʌ/ | /e/ | /jʌ/ | /je/ | /o/ | /wa/ | /wɛ/ | /ø/ ~ [we] | /jo/ | /u/ | /wʌ/ | /we/ | /y/ ~ [ɥi] | /ju/ | /ɯ/ | /ɰi/ | /i/ |

The vowels are generally separated into two categories: monophthongs and diphthongs. Monophthongs are produced with a single articulatory movement (hence the prefix mono), while diphthongs feature an articulatory change. Diphthongs have two constituents: a glide (or a semivowel) and a monophthong. There is some disagreement about exactly how many vowels are considered Korean's monophthongs; the largest inventory features ten, while some scholars have proposed eight or nine.[who?] This divergence reveals two issues: whether Korean has two front rounded vowels (i.e. /ø/ and /y/); and, secondly, whether Korean has three levels of front vowels in terms of vowel height (i.e. whether /e/ and /ɛ/ are distinctive).[54] Actual phonological studies done by studying formant data show that current speakers of Standard Korean do not differentiate between the vowels ㅔ and ㅐ in pronunciation.[56]

Alphabetic order

[edit]Alphabetic order in the Korean alphabet is called the ganada order, (가나다순) after the first three letters of the alphabet. The alphabetical order of the Korean alphabet does not mix consonants and vowels. Rather, first are velar consonants, then coronals, labials, sibilants, etc. The vowels come after the consonants.[57]

The collation order of Korean in Unicode is based on the South Korean order.

Historical orders

[edit]The order from the Hunminjeongeum in 1446 was:[58]

- ㄱ ㄲ ㅋ ㆁ ㄷ ㄸ ㅌ ㄴ ㅥ ㅂ ㅃ ㅍ ㅁ ㅈ ㅉ ㅊ ㅅ ㅆ ㆆ ㅎ ㆅ ㅇ ㄹ ㅿ

- ㆍ ㅡ ㅣ ㅗ ㅏ ㅜ ㅓ ㅛ ㅑ ㅠ ㅕ

This is the basis of the modern alphabetic orders. It was before the development of the Korean tense consonants and the double letters that represent them, and before the conflation of the letters ㅇ (null) and ㆁ (ng). Thus, when the North Korean and South Korean governments implemented full use of the Korean alphabet, they ordered these letters differently, with North Korea placing new letters at the end of the alphabet and South Korea grouping similar letters together.[59][60]

North Korean order

[edit]The double letters are placed after all the single letters (except the null initial ㅇ, which goes at the end).

- ㄱ ㄴ ㄷ ㄹ ㅁ ㅂ ㅅ ㅈ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ ㄲ ㄸ ㅃ ㅆ ㅉ ㅇ

- ㅏ ㅑ ㅓ ㅕ ㅗ ㅛ ㅜ ㅠ ㅡ ㅣ ㅐ ㅒ ㅔ ㅖ ㅚ ㅟ ㅢ ㅘ ㅝ ㅙ ㅞ

All digraphs and trigraphs, including the old diphthongs ㅐ and ㅔ, are placed after the simple vowels, again maintaining Choe's alphabetic order.

The order of the final letters (받침) is:

- (none) ㄱ ㄳ ㄴ ㄵ ㄶ ㄷ ㄹ ㄺ ㄻ ㄼ ㄽ ㄾ ㄿ ㅀ ㅁ ㅂ ㅄ ㅅ ㅇ ㅈ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ ㄲ ㅆ

(None means there is no final letter.)

Unlike when it is initial, this ㅇ is pronounced, as the nasal ㅇ ng, which occurs only as a final in the modern language. The double letters are placed to the very end, as in the initial order, but the combined consonants are ordered immediately after their first element.[59]

South Korean order

[edit]In the Southern order, double letters are placed immediately after their single counterparts:

- ㄱ ㄲ ㄴ ㄷ ㄸ ㄹ ㅁ ㅂ ㅃ ㅅ ㅆ ㅇ ㅈ ㅉ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ

- ㅏ ㅐ ㅑ ㅒ ㅓ ㅔ ㅕ ㅖ ㅗ ㅘ ㅙ ㅚ ㅛ ㅜ ㅝ ㅞ ㅟ ㅠ ㅡ ㅢ ㅣ

The modern monophthongal vowels come first, with the derived forms interspersed according to their form: i is added first, then iotated, then iotated with added i. Diphthongs beginning with w are ordered according to their spelling, as ㅗ or ㅜ plus a second vowel, not as separate digraphs.

The order of the final letters is:

- (none) ㄱ ㄲ ㄳ ㄴ ㄵ ㄶ ㄷ ㄹ ㄺ ㄻ ㄼ ㄽ ㄾ ㄿ ㅀ ㅁ ㅂ ㅄ ㅅ ㅆ ㅇ ㅈ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ

Every syllable begins with a consonant (or the silent ㅇ) that is followed by a vowel (e.g. ㄷ + ㅏ = 다). Some syllables such as 달 and 닭 have a final consonant or final consonant cluster (받침). Thus, 399 combinations are possible for two-letter syllables and 10,773 possible combinations for syllables with more than two letters (27 possible final endings), for a total of 11,172 possible combinations of Korean alphabet letters to form syllables.[59]

The sort order including archaic Hangul letters defined in the South Korean national standard KS X 1026-1 is:[61]

- Initial consonants: ᄀ, ᄁ, ᅚ, ᄂ, ᄓ, ᄔ, ᄕ, ᄖ, ᅛ, ᅜ, ᅝ, ᄃ, ᄗ, ᄄ, ᅞ, ꥠ, ꥡ, ꥢ, ꥣ, ᄅ, ꥤ, ꥥ, ᄘ, ꥦ, ꥧ, ᄙ, ꥨ, ꥩ, ꥪ, ꥫ, ꥬ, ꥭ, ꥮ, ᄚ, ᄛ, ᄆ, ꥯ, ꥰ, ᄜ, ꥱ, ᄝ, ᄇ, ᄞ, ᄟ, ᄠ, ᄈ, ᄡ, ᄢ, ᄣ, ᄤ, ᄥ, ᄦ, ꥲ, ᄧ, ᄨ, ꥳ, ᄩ, ᄪ, ꥴ, ᄫ, ᄬ, ᄉ, ᄭ, ᄮ, ᄯ, ᄰ, ᄱ, ᄲ, ᄳ, ᄊ, ꥵ, ᄴ, ᄵ, ᄶ, ᄷ, ᄸ, ᄹ, ᄺ, ᄻ, ᄼ, ᄽ, ᄾ, ᄿ, ᅀ, ᄋ, ᅁ, ᅂ, ꥶ, ᅃ, ᅄ, ᅅ, ᅆ, ᅇ, ᅈ, ᅉ, ᅊ, ᅋ, ꥷ, ᅌ, ᄌ, ᅍ, ᄍ, ꥸ, ᅎ, ᅏ, ᅐ, ᅑ, ᄎ, ᅒ, ᅓ, ᅔ, ᅕ, ᄏ, ᄐ, ꥹ, ᄑ, ᅖ, ꥺ, ᅗ, ᄒ, ꥻ, ᅘ, ᅙ, ꥼ, (filler;

U+115F) - Medial vowels: (filler;

U+1160), ᅡ, ᅶ, ᅷ, ᆣ, ᅢ, ᅣ, ᅸ, ᅹ, ᆤ, ᅤ, ᅥ, ᅺ, ᅻ, ᅼ, ᅦ, ᅧ, ᆥ, ᅽ, ᅾ, ᅨ, ᅩ, ᅪ, ᅫ, ᆦ, ᆧ, ᅿ, ᆀ, ힰ, ᆁ, ᆂ, ힱ, ᆃ, ᅬ, ᅭ, ힲ, ힳ, ᆄ, ᆅ, ힴ, ᆆ, ᆇ, ᆈ, ᅮ, ᆉ, ᆊ, ᅯ, ᆋ, ᅰ, ힵ, ᆌ, ᆍ, ᅱ, ힶ, ᅲ, ᆎ, ힷ, ᆏ, ᆐ, ᆑ, ᆒ, ힸ, ᆓ, ᆔ, ᅳ, ힹ, ힺ, ힻ, ힼ, ᆕ, ᆖ, ᅴ, ᆗ, ᅵ, ᆘ, ᆙ, ힽ, ힾ, ힿ, ퟀ, ᆚ, ퟁ, ퟂ, ᆛ, ퟃ, ᆜ, ퟄ, ᆝ, ᆞ, ퟅ, ᆟ, ퟆ, ᆠ, ᆡ, ᆢ - Final consonants: (none), ᆨ, ᆩ, ᇺ, ᇃ, ᇻ, ᆪ, ᇄ, ᇼ, ᇽ, ᇾ, ᆫ, ᇅ, ᇿ, ᇆ, ퟋ, ᇇ, ᇈ, ᆬ, ퟌ, ᇉ, ᆭ, ᆮ, ᇊ, ퟍ, ퟎ, ᇋ, ퟏ, ퟐ, ퟑ, ퟒ, ퟓ, ퟔ, ᆯ, ᆰ, ퟕ, ᇌ, ퟖ, ᇍ, ᇎ, ᇏ, ᇐ, ퟗ, ᆱ, ᇑ, ᇒ, ퟘ, ᆲ, ퟙ, ᇓ, ퟚ, ᇔ, ᇕ, ᆳ, ᇖ, ᇗ, ퟛ, ᇘ, ᆴ, ᆵ, ᆶ, ᇙ, ퟜ, ퟝ, ᆷ, ᇚ, ퟞ, ퟟ, ᇛ, ퟠ, ᇜ, ퟡ, ᇝ, ᇞ, ᇟ, ퟢ, ᇠ, ᇡ, ᇢ, ᆸ, ퟣ, ᇣ, ퟤ, ퟥ, ퟦ, ᆹ, ퟧ, ퟨ, ퟩ, ᇤ, ᇥ, ᇦ, ᆺ, ᇧ, ᇨ, ᇩ, ퟪ, ᇪ, ퟫ, ᆻ, ퟬ, ퟭ, ퟮ, ퟯ, ퟰ, ퟱ, ퟲ, ᇫ, ퟳ, ퟴ, ᆼ, ᇰ, ᇬ, ᇭ, ퟵ, ᇱ, ᇲ, ᇮ, ᇯ, ퟶ, ᆽ, ퟷ, ퟸ, ퟹ, ᆾ, ᆿ, ᇀ, ᇁ, ᇳ, ퟺ, ퟻ, ᇴ, ᇂ, ᇵ, ᇶ, ᇷ, ᇸ, ᇹ

- Sort order of Hangul consonants defined in the South Korean national standard KS X 1026-1

- Sort order of Hangul vowels defined in the South Korean national standard KS X 1026-1

Letter names

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2021) |

Letters in the Korean alphabet were named by Korean linguist Choe Sejin in 1527. South Korea uses Choe's traditional names, most of which follow the format of letter + i + eu + letter. Choe described these names by listing Hanja characters with similar pronunciations. However, as the syllables 윽 euk, 읃 eut, and 읏 eut did not occur in Hanja, Choe gave those letters the modified names 기역 giyeok, 디귿 digeut, and 시옷 siot, using Hanja that did not fit the pattern (for 기역) or native Korean syllables (for 디귿 and 시옷).[62]

Originally, Choe gave ㅈ, ㅊ, ㅋ, ㅌ, ㅍ, and ㅎ the irregular one-syllable names of ji, chi, ḳi, ṭi, p̣i, and hi, because they should not be used as final consonants, as specified in Hunminjeongeum. However, after establishment of the new orthography in 1933, which let all consonants be used as finals, the names changed to the present forms.

In North Korea

[edit]The chart below shows names used in North Korea for consonants in the Korean alphabet. The letters are arranged in North Korean alphabetic order, and the letter names are romanised with the McCune–Reischauer system, which is widely used in North Korea. The tense consonants are described with the word 된 toen meaning hard.

| Consonant | ㄱ | ㄴ | ㄷ | ㄹ | ㅁ | ㅂ | ㅅ | ㅈ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅌ | ㅍ | ㅎ | ㄲ | ㄸ | ㅃ | ㅆ | ㅇ | ㅉ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | 기윽 | 니은 | 디읃 | 리을 | 미음 | 비읍 | 시읏 | 지읒 | 치읓 | 키읔 | 티읕 | 피읖 | 히읗 | 된기윽 | 된디읃 | 된비읍 | 된시읏 | 이응 | 된지읒 |

| McCR | kiŭk | niŭn | diŭt | riŭl | miŭm | piŭp | siŭt | jiŭt | chiŭt | ḳiŭk | ṭiŭt | p̣iŭp | hiŭt | toen'giŭk | toendiŭt | toenbiŭp | toensiŭt | 'iŭng | toenjiŭt |

In North Korea, an alternative way to refer to a consonant is letter + ŭ (ㅡ), for example, gŭ (그) for the letter ㄱ, and ssŭ (쓰) for the letter ㅆ.

As in South Korea, the names of vowels in the Korean alphabet are the same as the sound of each vowel.

In South Korea

[edit]The chart below shows names used in South Korea for consonants of the Korean alphabet. The letters are arranged in the South Korean alphabetic order, and the letter names are romanised in the Revised Romanization system, which is the official romanization system of South Korea. The tense consonants are described with the word 쌍 ssang meaning double.

| Consonant | ㄱ | ㄲ | ㄴ | ㄷ | ㄸ | ㄹ | ㅁ | ㅂ | ㅃ | ㅅ | ㅆ | ㅇ | ㅈ | ㅉ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅌ | ㅍ | ㅎ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name (Hangul) | 기역 | 쌍기역 | 니은 | 디귿 | 쌍디귿 | 리을 | 미음 | 비읍 | 쌍비읍 | 시옷 | 쌍시옷 | 이응 | 지읒 | 쌍지읒 | 치읓 | 키읔 | 티읕 | 피읖 | 히읗 |

| Name (romanised) | gi-yeok | ssang-giyeok | ni-eun | digeut | ssang-digeut | ri-eul | mi-eum | bi-eup | ssang-bi-eup | si-ot (shi-ot) | ssang-si-ot (ssang-shi-ot) | 'i-eung | ji-eut | ssang-ji-eut | chi-eut | ḳi-euk | ṭi-eut | p̣i-eup | hi-eut |

Stroke order

[edit]Letters in the Korean alphabet have adopted certain rules of Chinese calligraphy, although ㅇ and ㅎ use a circle, which is not used in printed Chinese characters.[63][64]

- ㄱ (giyeok 기역)

- ㄴ (nieun 니은)

- ㄷ (digeut 디귿)

- ㄹ (rieul 리을)

- ㅁ (mieum 미음)

- ㅂ (bieup 비읍)

- ㅅ (siot 시옷)

- ㅇ (ieung 이응)

- ㅈ (jieut 지읒)

- ㅊ (chieut 치읓)

- ㅋ (ḳieuk 키읔)

- ㅌ (ṭieut 티읕)

- ㅍ (p̣ieup 피읖)

- ㅎ (hieut 히읗)

- ㅏ (a)

- ㅐ (ae)

- ㅓ (eo)

- ㅔ (e)

- ㅗ (o)

- ㅜ (u)

- ㅡ (eu)

For the iotated vowels, which are not shown, the short stroke is simply doubled.

Letter design

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Calligraphy |

|---|

|

Scripts typically transcribe languages at the level of morphemes (logographic scripts like Hanja), of syllables (syllabaries like kana), of segments (alphabetic scripts like the Latin script used to write English and many other languages), or, on occasion, of distinctive features. The Korean alphabet incorporates aspects of the latter three, grouping sounds into syllables, using distinct symbols for segments, and in some cases using distinct strokes to indicate distinctive features such as place of articulation (labial, coronal, velar, or glottal) and manner of articulation (plosive, nasal, sibilant, aspiration) for consonants, and iotation (a preceding i-sound), harmonic class and i-mutation for vowels.

For instance, the consonant ㅌ ṭ [tʰ] is composed of three strokes, each one meaningful: the top stroke indicates ㅌ is a plosive, like ㆆ ʔ, ㄱ g, ㄷ d, ㅈ j, which have the same stroke (the last is an affricate, a plosive–fricative sequence); the middle stroke indicates that ㅌ is aspirated, like ㅎ h, ㅋ ḳ, ㅊ ch, which also have this stroke; and the bottom stroke indicates that ㅌ is alveolar, like ㄴ n, ㄷ d, and ㄹ l. (It is said to represent the shape of the tongue when pronouncing coronal consonants, though this is not certain.) Two obsolete consonants, ㆁ and ㅱ, have dual pronunciations, and appear to be composed of two elements corresponding to these two pronunciations: [ŋ]~silence for ㆁ and [m]~[w] for ㅱ.

With vowel letters, a short stroke connected to the main line of the letter indicates that this is one of the vowels that can be iotated; this stroke is then doubled when the vowel is iotated. The position of the stroke indicates which harmonic class the vowel belongs to, light (top or right) or dark (bottom or left). In the modern alphabet, an additional vertical stroke indicates i mutation, deriving ㅐ [ɛ], ㅚ [ø], and ㅟ [y] from ㅏ [a], ㅗ [o], and ㅜ [u]. However, this is not part of the intentional design of the script, but rather a natural development from what were originally diphthongs ending in the vowel ㅣ [i]. Indeed, in many Korean dialects,[citation needed] including the standard dialect of Seoul, some of these may still be diphthongs. For example, in the Seoul dialect, ㅚ may alternatively be pronounced [we̞], and ㅟ [ɥi]. Note: ㅔ [e] as a morpheme is ㅓ combined with ㅣ as a vertical stroke. As a phoneme, its sound is not by i mutation of ㅓ [ʌ].

Beside the letters, the Korean alphabet originally employed diacritic marks to indicate pitch accent. A syllable with a high pitch (거성) was marked with a dot (〮) to the left of it (when writing vertically); a syllable with a rising pitch (상성) was marked with a double dot, like a colon (〯). These are no longer used, as modern Seoul Korean has lost tonality. Vowel length has also been neutralized in Modern Korean[65] and is no longer written.

Consonant design

[edit]The consonant letters fall into five homorganic groups, each with a basic shape, and one or more letters derived from this shape by means of additional strokes. In the Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye account, the basic shapes iconically represent the articulations the tongue, palate, teeth, and throat take when making these sounds.

| Simple | Aspirated | Tense | |

|---|---|---|---|

| velar | ㄱ | ㅋ | ㄲ |

| fricatives | ㅅ | ㅆ | |

| palatal | ㅈ | ㅊ | ㅉ |

| coronal | ㄷ | ㅌ | ㄸ |

| bilabial | ㅂ | ㅍ | ㅃ |

- Velar consonants (아음, 牙音 a'eum "molar sounds")

- ㄱ g [k], ㅋ ḳ [kʰ]

- Basic shape: ㄱ is a side view of the back of the tongue raised toward the velum (soft palate). (For illustration, access the external link below.) ㅋ is derived from ㄱ with a stroke for the burst of aspiration.

- Sibilant consonants (fricative or palatal) (치음, 齒音 chieum "dental sounds"):

- ㅅ s [s], ㅈ j [tɕ], ㅊ ch [tɕʰ]

- Basic shape: ㅅ was originally shaped like a wedge ∧, without the serif on top. It represents a side view of the teeth.[citation needed] The line topping ㅈ represents firm contact with the roof of the mouth. The stroke topping ㅊ represents an additional burst of aspiration.

- Coronal consonants (설음, 舌音 seoreum "lingual sounds"):

- ㄴ n [n], ㄷ d [t], ㅌ ṭ [tʰ], ㄹ r [ɾ, ɭ]

- Basic shape: ㄴ is a side view of the tip of the tongue raised toward the alveolar ridge (gum ridge). The letters derived from ㄴ are pronounced with the same basic articulation. The line topping ㄷ represents firm contact with the roof of the mouth. The middle stroke of ㅌ represents the burst of aspiration. The top of ㄹ represents a flap of the tongue.

- Bilabial consonants (순음, 唇音 suneum "labial sounds"):

- ㅁ m [m], ㅂ b [p], ㅍ p̣ [pʰ]

- Basic shape: ㅁ represents the outline of the lips in contact with each other. The top of ㅂ represents the release burst of the b. The top stroke of ㅍ is for the burst of aspiration.

- Dorsal consonants (후음, 喉音 hueum "throat sounds"):

- ㅇ '/ng [ŋ], ㅎ h [h]

- Basic shape: ㅇ is an outline of the throat. Originally ㅇ was two letters, a simple circle for silence (null consonant), and a circle topped by a vertical line, ㆁ, for the nasal ng. A now obsolete letter, ㆆ, represented a glottal stop, which is pronounced in the throat and had closure represented by the top line, like ㄱㄷㅈ. Derived from ㆆ is ㅎ, in which the extra stroke represents a burst of aspiration.

Vowel design

[edit]

Vowel letters are based on three elements:

- A horizontal line representing the flat Earth, the essence of yin.

- A point for the Sun in the heavens, the essence of yang. (This becomes a short stroke when written with a brush.)

- A vertical line for the upright Human, the neutral mediator between the Heaven and Earth.

Short strokes (dots in the earliest documents) were added to these three basic elements to derive the vowel letter:

Simple vowels

[edit]- Horizontal letters: these are mid-high back vowels.

- bright ㅗ o

- dark ㅜ u

- dark ㅡ eu (ŭ)

- Vertical letters: these were once low vowels.

- bright ㅏ a

- dark ㅓ eo (ŏ)

- bright ㆍ

- neutral ㅣ i

Compound vowels

[edit]The Korean alphabet does not have a letter for w sound. Since an o or u before an a or eo became a [w] sound, and [w] occurred nowhere else, [w] could always be analyzed as a phonemic o or u, and no letter for [w] was needed. However, vowel harmony is observed: dark ㅜ u with dark ㅓ eo for ㅝ wo; bright ㅗ o with bright ㅏ a for ㅘ wa:

- ㅘ wa = ㅗ o + ㅏ a

- ㅝ wo = ㅜ u + ㅓ eo

- ㅙ wae = ㅗ o + ㅐ ae

- ㅞ we = ㅜ u + ㅔ e

The compound vowels ending in ㅣ i were originally diphthongs. However, several have since evolved into pure vowels:

- ㅐ ae = ㅏ a + ㅣ i (pronounced [ɛ])

- ㅔ e = ㅓ eo + ㅣ i (pronounced [e])

- ㅙ wae = ㅘ wa + ㅣ i

- ㅚ oe = ㅗ o + ㅣ i (formerly pronounced [ø], see Korean phonology)

- ㅞ we = ㅝ wo + ㅣ i

- ㅟ wi = ㅜ u + ㅣ i (formerly pronounced [y], see Korean phonology)

- ㅢ ui = ㅡ eu + ㅣ i

Iotated vowels

[edit]There is no letter for y. Instead, this sound is indicated by doubling the stroke attached to the baseline of the vowel letter. Of the seven basic vowels, four could be preceded by a y sound, and these four were written as a dot next to a line. (Through the influence of Chinese calligraphy, the dots soon became connected to the line: ㅓㅏㅜㅗ.) A preceding y sound, called iotation, was indicated by doubling this dot: ㅕㅑㅠㅛ yeo, ya, yu, yo. The three vowels that could not be iotated were written with a single stroke: ㅡㆍㅣ eu, (arae a), i.

| Simple | Iotated |

|---|---|

| ㅏ | ㅑ |

| ㅓ | ㅕ |

| ㅗ | ㅛ |

| ㅜ | ㅠ |

| ㅡ | |

| ㅣ |

The simple iotated vowels are:

- ㅑ ya from ㅏ a

- ㅕ yeo from ㅓ eo

- ㅛ yo from ㅗ o

- ㅠ yu from ㅜ u

There are also two iotated diphthongs:

- ㅒ yae from ㅐ ae

- ㅖ ye from ㅔ e

The Korean language of the 15th century had vowel harmony to a greater extent than it does today. Vowels in grammatical morphemes changed according to their environment, falling into groups that "harmonized" with each other. This affected the morphology of the language, and Korean phonology described it in terms of yin and yang: If a root word had yang ('bright') vowels, then most suffixes attached to it also had to have yang vowels; conversely, if the root had yin ('dark') vowels, the suffixes had to be yin as well. There was a third harmonic group called mediating (neutral in Western terminology) that could coexist with either yin or yang vowels.

The Korean neutral vowel was ㅣ i. The yin vowels were ㅡㅜㅓ eu, u, eo; the dots are in the yin directions of down and left. The yang vowels were ㆍㅗㅏ ə, o, a, with the dots in the yang directions of up and right. The Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye states that the shapes of the non-dotted letters ㅡㆍㅣ were chosen to represent the concepts of yin, yang, and mediation: Earth, Heaven, and Human. (The letter ㆍ ə is now obsolete except in the Jeju language.)

The third parameter in designing the vowel letters was choosing ㅡ as the graphic base of ㅜ and ㅗ, and ㅣ as the graphic base of ㅓ and ㅏ. A full understanding of what these horizontal and vertical groups had in common would require knowing the exact sound values these vowels had in the 15th century.

The uncertainty is primarily with the three letters ㆍㅓㅏ. Some linguists reconstruct these as *a, *ɤ, *e, respectively; others as *ə, *e, *a. A third reconstruction is to make them all middle vowels as *ʌ, *ɤ, *a.[66] With the third reconstruction, Middle Korean vowels actually line up in a vowel harmony pattern, albeit with only one front vowel and four middle vowels:

| ㅣ *i | ㅡ *ɯ | ㅜ *u |

| ㅓ *ɤ | ||

| ㆍ *ʌ | ㅗ *o | |

| ㅏ *a |

However, the horizontal letters ㅡㅜㅗ eu, u, o do all appear to have been mid to high back vowels, [*ɯ, *u, *o], and thus to have formed a coherent group phonetically in every reconstruction.

Traditional account

[edit]The traditionally accepted account[k][67][unreliable source?] on the design of the letters is that the vowels are derived from various combinations of the following three components: ㆍ ㅡ ㅣ. Here, ㆍ symbolically stands for the (sun in) heaven, ㅡ stands for the (flat) earth, and ㅣ stands for an (upright) human. The original sequence of the Korean vowels, as stated in Hunminjeongeum, listed these three vowels first, followed by various combinations. Thus, the original order of the vowels was: ㆍ ㅡ ㅣ ㅗ ㅏ ㅜ ㅓ ㅛ ㅑ ㅠ ㅕ. Two positive vowels (ㅗ ㅏ) including one ㆍ are followed by two negative vowels including one ㆍ, then by two positive vowels each including two of ㆍ, and then by two negative vowels each including two of ㆍ.

| Vowels | ||

|---|---|---|

| ㆍ | ㅡ | ㅣ |

| Cosonants | ||

| ○ | □ | △ |

The same theory provides the most simple explanation of the shapes of the consonants as an approximation of the shapes of the most representative organ needed to form that sound. The original order of the consonants in Hunminjeong'eum was: ㄱ ㅋ ㆁ ㄷ ㅌ ㄴ ㅂ ㅍ ㅁ ㅈ ㅊ ㅅ ㆆ ㅎ ㅇ ㄹ ㅿ.

- ㄱ representing the [k] sound geometrically describes its tongue back raised.

- ㅋ representing the [kʰ] sound is derived from ㄱ by adding another stroke.

- ㆁ representing the [ŋ] sound may have been derived from ㅇ by addition of a stroke.

- ㄷ representing the [t] sound is derived from ㄴ by adding a stroke.

- ㅌ representing the [tʰ] sound is derived from ㄷ by adding another stroke.

- ㄴ representing the [n] sound geometrically describes a tongue making contact with an upper palate.

- ㅂ representing the [p] sound is derived from ㅁ by adding a stroke.

- ㅍ representing the [pʰ] sound is a variant of ㅂ by adding another stroke.

- ㅁ representing the [m] sound geometrically describes a closed mouth.

- ㅈ representing the [t͡ɕ] sound is derived from ㅅ by adding a stroke.

- ㅊ representing the [t͡ɕʰ] sound is derived from ㅈ by adding another stroke.

- ㅅ representing the [s] sound geometrically describes the sharp teeth.[citation needed]

- ㆆ representing the [ʔ] sound is derived from ㅇ by adding a stroke.

- ㅎ representing the [h] sound is derived from ㆆ by adding another stroke.

- ㅇ representing the absence of a consonant geometrically describes the throat.

- ㄹ representing the [ɾ] and [ɭ] sounds geometrically describes the bending tongue.

- ㅿ representing a weak ㅅ sound describes the sharp teeth, but has a different origin than ㅅ.[clarification needed]

Ledyard's theory of consonant design

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

(Bottom) Derivation of 'Phags-pa w, v, f from variants of the letter [h] (left) plus a subscript [w], and analogous composition of the Korean alphabet w, v, f from variants of the basic letter [p] plus a circle.

Although the Hunminjeong'eum Haerye explains the design of the consonantal letters in terms of articulatory phonetics, as a purely innovative creation, several theories suggest which external sources may have inspired or influenced King Sejong's creation. Professor Gari Ledyard of Columbia University studied possible connections between Hangul and the Mongol 'Phags-pa script of the Yuan dynasty. He, however, also believed that the role of 'Phags-pa script in the creation of the Korean alphabet was quite limited, stating it should not be assumed that Hangul was derived from 'Phags-pa script based on his theory:

It should be clear to any reader that in the total picture, that ['Phags-pa script's] role was quite limited ... Nothing would disturb me more, after this study is published, than to discover in a work on the history of writing a statement like the following: "According to recent investigations, the Korean alphabet was derived from the Mongol's phags-pa script."[68]

Ledyard posits that five of the Korean letters have shapes inspired by 'Phags-pa; a sixth basic letter, the null initial ㅇ, was invented by Sejong. The rest of the letters were derived internally from these six, essentially as described in the Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye. However, the five borrowed consonants were not the graphically simplest letters considered basic by the Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye, but instead the consonants basic to Chinese phonology: ㄱ, ㄷ, ㅂ, ㅈ, and ㄹ.[citation needed]

The Hunmin Jeong-eum states that King Sejong adapted the 古篆 (gojeon, Gǔ Seal Script) in creating the Korean alphabet. The 古篆 has never been identified. The primary meaning of 古 gǔ is old (Old Seal Script), frustrating philologists because the Korean alphabet bears no functional similarity to Chinese 篆字 zhuànzì seal scripts. However, Ledyard believes 古 gǔ may be a pun on 蒙古 Měnggǔ "Mongol", and that 古篆 is an abbreviation of 蒙古篆字 "Mongol Seal Script", that is, the formal variant of the 'Phags-pa alphabet written to look like the Chinese seal script. There were 'Phags-pa manuscripts in the Korean palace library, including some in the seal-script form, and several of Sejong's ministers knew the script well. If this was the case, Sejong's evasion on the Mongol connection can be understood in light of Korea's relationship with Ming China after the fall of the Mongol Yuan dynasty, and of the literati's contempt for the Mongols.[citation needed]

According to Ledyard, the five borrowed letters were graphically simplified, which allowed for consonant clusters and left room to add a stroke to derive the aspirate plosives, ㅋㅌㅍㅊ. But in contrast to the traditional account, the non-plosives (ㆁ ㄴ ㅁ ㅅ) were derived by removing the top of the basic letters. He points out that while it is easy to derive ㅁ from ㅂ by removing the top, it is not clear how to derive ㅂ from ㅁ in the traditional account, since the shape of ㅂ is not analogous to those of the other plosives.[citation needed]

The explanation of the letter ng also differs from the traditional account. Many Chinese words began with ng, but by King Sejong's day, initial ng was either silent or pronounced [ŋ] in China, and was silent when these words were borrowed into Korean. Also, the expected shape of ng (the short vertical line left by removing the top stroke of ㄱ) would have looked almost identical to the vowel ㅣ [i]. Sejong's solution solved both problems: The vertical stroke left from ㄱ was added to the null symbol ㅇ to create ㆁ (a circle with a vertical line on top), iconically capturing both the pronunciation [ŋ] in the middle or end of a word, and the usual silence at the beginning. (The graphic distinction between null ㅇ and ng ㆁ was eventually lost.)

Another letter composed of two elements to represent two regional pronunciations was ㅱ, which transcribed the Chinese initial 微. This represented either m or w in various Chinese dialects, and was composed of ㅁ [m] plus ㅇ (from 'Phags-pa [w]). In 'Phags-pa, a loop under a letter represented w after vowels, and Ledyard hypothesized that this became the loop at the bottom of ㅱ. In 'Phags-pa the Chinese initial 微 is also transcribed as a compound with w, but in its case the w is placed under an h. Actually, the Chinese consonant series 微非敷 w, v, f is transcribed in 'Phags-pa by the addition of a w under three graphic variants of the letter for h, and the Korean alphabet parallels this convention by adding the w loop to the labial series ㅁㅂㅍ m, b, p, producing now-obsolete ㅱㅸㆄ w, v, f. (Phonetic values in Korean are uncertain, as these consonants were only used to transcribe Chinese.)

As a final piece of evidence, Ledyard notes that most of the borrowed Korean letters were simple geometric shapes, at least originally, but that ㄷ d [t] always had a small lip protruding from the upper left corner, just as the 'Phags-pa ꡊ d [t] did. This lip can be traced back to the Tibetan letter ད d.[citation needed]

There is also the argument that the original theory, which stated the Hangul consonants to have been derived from the shape of the speaker's lips and tongue during the pronunciation of the consonants (initially, at least), slightly strains credulity.[69]

Hangul supremacy

[edit]Hangul supremacy or Hangul scientific supremacy is the claim that the Hangul alphabet is the simplest and most logical writing system in the world.[70]

Proponents of the claim believe Hangul is the most scientific writing system because its characters are based on the shapes of the parts of the human body used to enunciate.[citation needed] For example, the first alphabet, ㄱ, is shaped like the root of the tongue blocking the throat and makes a sound between /k/ and /g/ in English. They also believe that Hangul was designed to be simple to learn, containing only 28 characters in its alphabet with simplistic rules.[citation needed]

Edwin O. Reischauer and John K. Fairbank of Harvard University wrote that "Hangul is perhaps the most scientific system of writing in general use in any country."[71]

Former professor of Leiden University Frits Vos stated that King Sejong "invented the world's best alphabet," adding, "It is clear that the Korean alphabet is not only simple and logical, but has, moreover, been constructed in a purely scientific way."[72]

Obsolete letters

[edit]This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Numerous obsolete Korean letters and sequences are no longer used in Korean. Some of these letters were only used to represent the sounds of Chinese rime tables. Some of the Korean sounds represented by these obsolete letters still exist in dialects.

| 13 obsolete consonants (IPA) | Soft consonants | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jamo | ᄛ | ㅱ | ㅸ | ᄼ | ᄾ | ㅿ | ㆁ | ㅇ | ᅎ | ᅐ | ᅔ | ᅕ | ㆄ | ㆆ | |

| IPA | /ɾ/ | first:/ɱ/ last:/w/ | /β/ | /s/ | /ɕ/ | /z/ | /ŋ/ | /∅/ | /t͡s/ | /t͡ɕ/ | /t͡sʰ/ | /t͡ɕʰ/ | /f/ | /ʔ/ | |

| Identified Chinese Character (Hanzi) | 微(미) /ɱ/ | 非(비) /f/ | 心(심) /s/ | 審(심) /ɕ/ | 日 (ᅀᅵᇙ>일)/z/ | final position: 業 /ŋ/ | initial position: 欲 /∅/ | 精(정) /t͡s/ | 照(조) /t͡ɕ/ | 淸(청) /t͡sʰ/ | 穿(천) /t͡ɕʰ/ | 敷(부) /fʰ/ | 挹(읍) /ʔ/ | ||

| Toneme | falling | mid to falling | mid to falling | mid | mid to falling | dipping/ mid | mid | mid to falling | mid (aspirated) | high (aspirated) | mid to falling (aspirated) | high/mid | |||

| Remark | lenis voiceless dental affricate/ voiced dental affricate | lenis voiceless retroflex affricate/ voiced retroflex affricate | aspirated /t͡s/ | aspirated /t͡ɕ/ | glottal stop | ||||||||||

| Equivalents | Standard Chinese Pinyin: 子 z [tsɨ]; English: z in zoo or zebra; strong z in English zip | identical to the initial position of ng in Cantonese | German pf | "읗" = "euh" in pronunciation | |||||||||||

| 10 obsolete double consonants (IPA) | Hard consonants | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jamo | ㅥ | ᄙ | ㅹ | ᄽ | ᄿ | ᅇ | ᇮ | ᅏ | ᅑ | ㆅ |

| IPA | /nː/ | /v/ | /sˁ/ | /ɕˁ/ | /j/ | /ŋː/ | /t͡s/ | /t͡ɕˁ/ | /hˁ/ | |

| Middle Chinese | hn/nn | hl/ll | bh, bhh | sh | zh | hngw/gh or gr | hng | dz, ds | dzh | hh or xh |

| Identified Chinese Character (Hanzi) | 邪(사) /z/ | 禪(선) /ʑ/ | 從(종) /d͡z/ | 牀(상) /d͡ʑ/ | 洪(홍) /ɦ/ | |||||

| Remark | aspirated | aspirated | unaspirated fortis voiceless dental affricate | unaspirated fortis voiceless retroflex affricate | guttural | |||||

- 66 obsolete clusters of two consonants: ᇃ, ᄓ /ng/ (like English think), ㅦ /nd/ (as English Monday), ᄖ, ㅧ /ns/ (as English Pennsylvania), ㅨ, ᇉ /tʰ/ (as ㅌ; nt in the language Esperanto), ᄗ /dg/ (similar to ㄲ; equivalent to the word 밖 in Korean), ᇋ /dr/ (like English in drive), ᄘ /ɭ/ (similar to French Belle), ㅪ, ㅬ /lz/ (similar to English tall zebra), ᇘ, ㅭ /t͡ɬ/ (tl or ll; as in Nahuatl), ᇚ /ṃ/ (mh or mg, mm in English hammer, Middle Korean: pronounced as 목 mog with the ㄱ in the word almost silent), ᇛ, ㅮ, ㅯ (similar to ㅂ in Korean 없다), ㅰ, ᇠ, ᇡ, ㅲ, ᄟ, ㅳ bd (assimilated later into ㄸ), ᇣ, ㅶ bj (assimilated later into ㅉ), ᄨ /bj/ (similar to 비추 in Korean verb 비추다 bit-chu-da but without the vowel), ㅷ, ᄪ, ᇥ /ph/ (pha similar to Korean word 돌입하지 dol ip-haji), ㅺ sk (assimilated later into ㄲ; English: pick), ㅻ sn (assimilated later into nn in English annal), ㅼ sd (initial position; assimilated later into ㄸ), ᄰ, ᄱ sm (assimilated later into nm), ㅽ sb (initial position; similar sound to ㅃ), ᄵ, ㅾ assimilated later into ㅉ), ᄷ, ᄸ, ᄹ /θ/, ᄺ/ɸ/, ᄻ, ᅁ, ᅂ /ð/, ᅃ, ᅄ /v/, ᅅ (assimilated later into ㅿ; English z), ᅆ, ᅈ, ᅉ, ᅊ, ᅋ, ᇬ, ᇭ, ㆂ, ㆃ, ᇯ, ᅍ, ᅒ, ᅓ, ᅖ, ᇵ, ᇶ, ᇷ, ᇸ

- 17 obsolete clusters of three consonants: ᇄ, ㅩ /rgs/ (similar to "rx" in English name Marx), ᇏ, ᇑ /lmg/ (similar to English Pullman), ᇒ, ㅫ, ᇔ, ᇕ, ᇖ, ᇞ, ㅴ, ㅵ, ᄤ, ᄥ, ᄦ, ᄳ, ᄴ

| 1 obsolete vowel (IPA) | Extremely soft vowel |

|---|---|

| Jamo | ㆍ |

| IPA | /ʌ/ (also commonly found in the Jeju language: /ɒ/, closely similar to vowel:ㅓeo) |

| Letter name | 아래아 (arae-a) |

| Remarks | formerly the base vowel ㅡ eu in the early development of hangeul when it was considered vowelless, later development into different base vowels for clarification; acts also as a mark that indicates the consonant is pronounced on its own, e.g. s-va-ha → ᄉᆞᄫᅡ 하 |

| Toneme | low |

- 44 obsolete diphthongs and vowel sequences: ᆜ (/j/ or /jɯ/ or /jɤ/, yeu or ehyu); closest similarity to ㅢ, when follow by ㄱ on initial position, pronunciation does not produce any difference: ᄀᆜ /gj/),ᆝ (/jɒ/; closest similarity to ㅛ,ㅑ, ㅠ, ㅕ, when follow by ㄱ on initial position, pronunciation does not produce any difference: ᄀᆝ /gj/), ᆢ(/j/; closest similarity to ㅢ, see former example inᆝ (/j/), ᅷ (/au̯/; Icelandic Á, aw/ow in English allow), ᅸ (/jau̯/; yao or iao; Chinese diphthong iao), ᅹ, ᅺ, ᅻ, ᅼ, ᅽ /ōu/ (紬 ㅊᅽ, ch-ieou; like Chinese: chōu), ᅾ, ᅿ, ᆀ, ᆁ, ᆂ (/w/, wo or wh, hw), ᆃ /ow/ (English window), ㆇ, ㆈ, ᆆ, ᆇ, ㆉ (/jø/; yue), ᆉ /wʌ/ or /oɐ/ (pronounced like u'a, in English suave), ᆊ, ᆋ, ᆌ, ᆍ (wu in English would), ᆎ /juə/ or /yua/ (like Chinese: 元 yuán), ᆏ /ū/ (like Chinese: 軍 jūn), ᆐ, ㆊ /ué/ jujə (ɥe; like Chinese: 瘸 qué), ㆋ jujəj (ɥej; iyye), ᆓ, ㆌ /jü/ or /juj/ (/jy/ or ɥi; yu.i; like German Jürgen), ᆕ, ᆖ (the same as ᆜ in pronunciation, since there is no distinction due to it extreme similarity in pronunciation), ᆗ ɰju (ehyu or eyyu; like English news), ᆘ, ᆙ /ià/ (like Chinese: 墊 diàn), ᆚ, ᆛ, ᆟ, ᆠ (/ʔu/), ㆎ (ʌj; oi or oy, similar to English boy).

In the original Korean alphabet system, double letters were used to represent Chinese voiced (濁音) consonants, which survive in the Shanghainese slack consonants and were not used for Korean words. It was only later that a similar convention was used to represent the modern tense (faucalized) consonants of Korean.

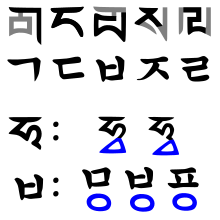

Свистящие (зубные) согласные были модифицированы, чтобы представлять две серии китайских шипящих, альвеолярные и ретрофлексные , различие между круглыми и резкими (аналогично s и sh ), которое никогда не проводилось в корейском языке и даже было потеряно из южного китайского языка. У альвеолярных букв были более длинные левые ножки, а у ретрофлексов - более длинные правые ножки:

| 5 Место артикуляции (오음, 五音) в китайской таблице иней | тонкий Чончхон (全淸) | Аспирируйте Ча Чеонг (次淸) | Озвученный Чон Так (全濁) | сонорант Чатак (次濁) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| шипящие стоматологический звук | 치두음 "головка зуба" | ᅎ 精(精) / тҡс / | ᅔ 淸(청) /t͡sʰ/ | ㅏ 從(слуга) / d̡z / | |

| ржу не могу 心 (сердце) / с / | час 邪(са) / z / | ||||

| политический звук «настоящий передний зуб» | ᅐ 照(照) / tɕ / | ᅕ 穿 (ткань) / tɕ ʰ/ | ᅑ 牀(牀) / dʡʑ / | ||

| ㄾ 審(審) / ɕ / | ㄿ Дзен / ʑ / | ||||

| Короналы звук языка | Звук языка "язык вверх" | ᅐ 知 (знание) / ʈ / | ᅕ 徹(철) / ʈ ʰ/ | ᅑ 澄(Цзин) / ɖ / | ты дочь(낭) / ɳ / |

Наиболее распространенный

[ редактировать ]- ㆍ ə (на современном корейском языке называется arae-a 아래아 «нижний а »): предположительно произносится [ ʌ ] , похоже на современный ㅓ ( eo ). Оно пишется в виде точки, расположенной под согласной. Араэ -а не совсем устарело, так как его можно встретить в различных торговых марках, а также в языке Чеджу , где оно произносится как [ ɒ ] . ə i образует собственную медиальную часть или встречается в дифтонге ㆎ əy , написанном с точкой под согласной и ㅣ ( ) справа от нее, так же, как ㅚ или ㅢ .

- ㅿ z ( бансиот 반시옷 «половина с », банчиеум 반치음 ): необычный звук, возможно, IPA [ʝ̃] ( назализованный небный фрикативный звук ). Современные корейские слова, ранее написанные с ㅿ заменой ㅅ или ㅇ .

- ㆆ ʔ ( yeorinhieut doenieung «легкий hieut» или « , сильный ieung»): гортанная остановка светлее, чем ㅎ , и жестче, чем ㅇ .

- ㆁ ŋ ( yedieung 옛이응 ) «old ieung»: исходное письмо для [ŋ] ; теперь путают с ㅇ Иенг . (В некоторых компьютерных шрифтах, таких как Arial Unicode MS , Yesieung отображается как сплющенная версия ieung, но правильная форма — с длинным пиком, более длинным, чем в с засечками версии ieung .)

- ㅸ β ( габёнбёп 가벼운비읍 , сунгёнымбип 순경음비읍 ): IPA [f] . Эта буква выглядит как диграф bieup и ieung , но она может быть более сложной — круг лишь случайно похож на ieung . В этом разделе китайских таблиц рифма были еще три, менее распространенные буквы для звуков : ㅱ w ( [w] или [m] ), ㆄ f и ㅹ ff [v̤] . Она действует как буква h в латинском алфавите (можно представить себе эти буквы как bh, mh, ph и pph соответственно). Корейцы не различают эти звуки сейчас, если вообще когда-либо различали, смешивая фрикативные звуки с соответствующими взрывными звуками .

Новая корейская орфография

[ редактировать ]

Чтобы корейский алфавит лучше морфофонологически соответствовал корейскому языку, Северная Корея ввела шесть новых букв, которые были опубликованы в « Новой орфографии корейского языка» и официально использовались с 1948 по 1954 год. [73]

Были восстановлены две устаревшие буквы: ⟨ ㅿ ⟩ ( 리읃 ), которые использовались для обозначения чередования в произношении начального /l/ и конечного /d/ ;

и ⟨ ㆆ ⟩ ( 히으 ), который произносился только между гласными.

Были введены две модификации буквы ㄹ : одна, которая завершается молчанием, и другая, которая удваивается между гласными. Гибридная буква ㅂ-ㅜ была введена для слов, в которых эти два звука чередовались (то есть /b/ , который стал /w/ перед гласной).

была введена гласная ⟨ 1 ⟩ Наконец, для переменной iotation .

| Письмо | Произношение | |

|---|---|---|

| перед гласный | перед согласный | |

| /л/ | — [1] | |

| /нн/ | /л/ | |

| ㅿ | /л/ | /т/ |

| ㆆ | — [2] | /◌͈/ [3] |

| /В/ [4] | /п/ | |

| /Дж/ [5] | /я/ | |

- ^ Тишина

- ^ Делает следующий согласный напряженным, как и финальный ㅅ.

- ^ В стандартной орфографии сочетается со следующей гласной как ㅘ, ㅙ, ㅚ, ㅝ, ㅞ, ㅟ

- ^ В стандартной орфографии сочетается со следующей гласной как ㅑ, ㅒ, ㅕ, ㅖ, ㅛ, ㅠ

Юникод

[ редактировать ]

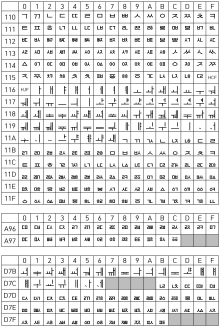

Хангыль Джамо (англ. U+1100– U+11FF) и Джамо совместимости с хангылем ( U+3130– U+318F) блоки были добавлены в стандарт Unicode в июне 1993 года с выпуском версии 1.1. Отдельный блок «Слоги хангыля» (не показан ниже из-за его длины) содержит предварительно составленные символы блока слогов, которые были впервые добавлены одновременно, хотя они были перемещены на свои нынешние места в июле 1996 года с выпуском версии 2.0. [74]

Хангыль Джамо Расширенный-А ( U+A960– U+A97F) и Hangul Jamo Extended-B ( U+D7B0– U+D7FF) блоки были добавлены в стандарт Unicode в октябре 2009 года с выпуском версии 5.2.

| Хангыль Джамо [1] Официальная таблица кодов Консорциума Unicode (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | А | Б | С | Д | И | Ф | |

| U + 110x | а | час | б | час | Да | ㄅ | ㄆ | Да | Да | ㄉ | Ой | Да | с | час | час | Хаха |

| U + 111x | ㄐ | ржу не могу | час | л | ㄔ | ржу не могу | Да | с | ㄘ | л | Да | час | час | Да | ㄞ | Да |

| U + 112x | ржу не могу | ᄡ | Ух ты | час | ㄤ | х | час | час | час | час | Да | ᄫ | ржу не могу | час | ᄮ | час |

| U + 113x | час | а | час | Да | ㄴ | час | а | час | час | час | ᄺ | Да | ржу не могу | час | ㄾ | ㄿ |

| U + 114x | ᅀ | ᅁ | ᅂ | ᅃ | ㅄ | ᅅ | ᅆ | ㅇ | ᅈ | Ух ты | ᅊ | ᅋ | ᅌ | ᅍ | ᅎ | ㅏ |

| U + 115x | ᅐ | ᅑ | ᅒ | ᅓ | ᅔ | ᅕ | ᅖ | Ух ты | ᅘ | ᅙ | ᅚ | ᅛ | ㅜ | ᅝ | ᅞ | ХК Ф |

| U + 116x | ГД Ф | ᅡ | ᅢ | ᅣ | х | х | ᅦ | ᅧ | ᅨ | ㅗ | ᅪ | ᅫ | ᅬ | ᅭ | ᅮ | ᅯ |

| U + 117x | ᅰ | ᅱ | ᅲ | ᅳ | ᅴ | ᅵ | ᅶ | ᅷ | ᅸ | ᅹ | ᅺ | ᅻ | ᅼ | ᅽ | ᅾ | ᅿ |

| U + 118x | ᆀ | ᆁ | ᆂ | ᆃ | ㆄ | ᆅ | ᆆ | ᆇ | ᆈ | ᆉ | ᆊ | ᆋ | ᆌ | ᆍ | ᆎ | ᆏ |

| U + 119x | ᆐ | ᆑ | ᆒ | ᆓ | ᆔ | ᆕ | ᆖ | ᆗ | ᆘ | ᆙ | ᆚ | ᆛ | ᆜ | ᆝ | ᆞ | ᆟ |

| U + 11 Топор | ᆠ | ᆡ | Ух ты | ᆣ | ᆤ | ᆥ | ᆦ | ᆧ | ᆨ | ᆩ | ᆪ | ᆫ | ᆬ | ᆭ | ᆮ | ᆯ |

| U + 11Bx | ᆰ | ᆱ | ᆲ | ᆳ | ᆴ | ᆵ | ᆶ | ᆷ | ᆸ | ᆹ | ᆺ | ᆻ | ᆼ | ᆽ | ᆾ | ᆿ |

| U + 11Cx | ᇀ | ᇁ | ᇂ | ᇃ | Да | ᇅ | ᇆ | ᇇ | ᇈ | ᇉ | ᇊ | ᇋ | ᇌ | ᇍ | ᇎ | ᇏ |

| U + 11Dx | ᇐ | ᇑ | ᇒ | ᇓ | ᇔ | ᇕ | ᇖ | ᇗ | ᇘ | ᇙ | ᇚ | ᇛ | ᇜ | ᇝ | ᇞ | ᇟ |

| U + 11Ex | ᇠ | ᇡ | ᇢ | ᇣ | ᇤ | х | ᇦ | ᇧ | ᇨ | ᇩ | ᇪ | ᇫ | ᇬ | ᇭ | ᇮ | ᇯ |

| U + 11Fx | ᇰ | ᇱ | ᇲ | ᇳ | ᇴ | ᇵ | ᇶ | ᇷ | ᇸ | ᇹ | ᇺ | ᇻ | ᇼ | ᇽ | ᇾ | ᇿ |

Примечания

| ||||||||||||||||

| Хангыль Джамо Расширенный-А [1] [2] Официальная таблица кодов Консорциума Unicode (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | А | Б | С | Д | И | Ф | |

| U + A96x | ꠠ | ꡡ | ꢢ | ꣣ | ꤤ | ꥥ | ꦦ | ꧧ | ꨨ | ꩩ | ꪪ | ꫫ | Ꜭ | Ух ты | ꮮ | Хорошо |

| U + A97x | Гюн | Ух ты | Ух ты | 곳 | ꜰ | Ух ты | 궶 | 꽷 | 길 | ꜱ | 꺺 | 꽻 | 꼼 | |||

| Примечания | ||||||||||||||||

| Хангыль Джамо Расширенный-B [1] [2] Официальная таблица кодов Консорциума Unicode (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | А | Б | С | Д | И | Ф | |

| U + D7Bx | Хе-хе | Привет | Хе-хе | Хе-хе | Привет | Привет | Хе-хе | Хе-хе | Ха | Привет | Хе-хе | Ударять | Привет | Ударять | Хе-хе | Хе-хе |

| U + D7Cx | Ух ты | Хе-хе | Хе-хе | Хе-хе | Хе-хе | Хе-хе | Ух ты | Хе-хе | Ух ты | Ух ты | Ух ты | Ух ты | ||||

| U + D7Dx | Ух ты | Ух ты | Ух ты | Хе-хе | Хе-хе | Ух ты | Ух ты | Хе-хе | Хе-хе | Ух ты | Ух ты | Хе-хе | Ух ты | Ух ты | Хе-хе | Хе-хе |

| U + D7Ex | Хе-хе | Ух ты | Ух ты | Ух ты | Хе-хе | Красная фасоль | Ух ты | Хе-хе | Хе-хе | Хе-хе | Хе-хе | Хе-хе | Ух ты | Цк | Ух ты | Хе-хе |

| U+D7Fx | Ух ты | Хе-хе | Хе-хе | Ух ты | Ух ты | Хе-хе | Ух ты | Хе-хе | Ух ты | Потрясающе | Хе-хе | Ух ты | ||||

| Примечания | ||||||||||||||||

| Совместимость с хангылем Джамо [1] [2] Официальная таблица кодов Консорциума Unicode (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | А | Б | С | Д | И | Ф | |

| U + 313x | идти | цветок | ㄳ | ты | ㄵ | ㄶ | делать | снова | ㄹ | ㄺ | ㄻ | ㄼ | ㄽ | ㄾ | ㄿ | |

| U + 314x | ㅀ | могила | сто | пердеть | ㅄ | корова | ㅆ | одеяло | триллион | хромой | поздравляю | ржу не могу | рамка | кровь | он | все |

| U + 315x | ага | привет | этот парень | да | к | женщина | да | ㅗ | ㅘ | ㅙ | ㅚ | одеяло | рыдать | ㅝ | ㅞ | ㅟ |

| U + 316x | ㅠ | ㅡ | ㅢ | зуб | ВЧ | ㅥ | ㅦ | ㅧ | ㅨ | ㅩ | ㅪ | ㅫ | ㅬ | ㅭ | ㅮ | ㅯ |

| U + 317x | ㅰ | а | ㅲ | ㅳ | ㅴ | ㅵ | ㅶ | ㅷ | ㅸ | ㅹ | ㅺ | ㅻ | ㅼ | ㅽ | ㅾ | ㅿ |

| U + 318x | ㆀ | ㆁ | ㆂ | ㆃ | ㆄ | ㆅ | ㆆ | ㆇ | ㆈ | ㆉ | ㆊ | ㆋ | ㆌ | точка | ㆎ | |

| Примечания | ||||||||||||||||

В скобках ( U+3200– U+321E) и обведено ( U+3260– U+327E) Символы совместимости с хангылем находятся в блоке «Закрытые буквы и месяцы CJK» :

| Подмножество закрытых букв и месяцев CJK на хангыле [1] [2] Официальная таблица кодов Консорциума Unicode (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | А | Б | С | Д | И | Ф | |

| U+320x | ㈀ | ㈁ | ㈂ | ㈃ | ㈄ | ㈅ | ㈆ | ㈇ | ㈈ | ㈉ | ㈊ | ㈋ | ㈌ | ㈍ | ㈎ | ㈏ |

| U + 321x | ㈐ | ㈑ | ㈒ | ㈓ | ㈔ | ㈕ | ㈖ | ㈗ | ㈘ | ㈙ | ㈚ | ㈛ | ㈜ | ㈝ | ㈞ | |

| ... | (U+3220–U+325F опущены) | |||||||||||||||

| U + 326x | ㉠ | ㉡ | ㉢ | ㉣ | ㉤ | ㉥ | ㉦ | ㉧ | ㉨ | ㉩ | ㉪ | ㉫ | ㉬ | ㉭ | ㉮ | ㉯ |

| U + 327x | ㉰ | ㉱ | ㉲ | ㉳ | ㉴ | ㉵ | ㉶ | ㉷ | ㉸ | ㉹ | ㉺ | ㉻ | ㉼ | ㉽ | ㉾ | |

| ... | (U+3280–U+32FF опущены) | |||||||||||||||

| Примечания | ||||||||||||||||

Символы совместимости с хангылем половинной ширины ( U+FFA0– U+FFDC) находятся в блоке «Формы половинной и полной ширины» :

| Подмножество форм половинной и полной ширины хангыль [1] [2] Официальная таблица кодов Консорциума Unicode (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | А | Б | С | Д | И | Ф | |

| ... | (U+FF00–U+FF9F опущены) | |||||||||||||||

| U+FFAx | HW ВЧ | ᄀ | ᄁ | ᆪ | ᄂ | ゥ | ᆭ | ᄃ | ᄄ | ᄅ | ᆰ | ᆱ | ᆲ | ᆳ | ᆴ | ᆵ |

| U+FFBx | ᄚ | ᄆ | ᄇ | ᄈ | ᄡ | ᄉ | ᄊ | ᄋ | ᄌ | ᄍ | ᄎ | ᄏ | ᄐ | ᄑ | ᄒ | |

| U+FFCx | ᅡ | ᅢ | ᅣ | ᅤ | ᅥ | ᅦ | ᅧ | ᅨ | ㅗ | ᅪ | ᅫ | ᅬ | ||||

| U+FFDx | ᅭ | ᅮ | ᅯ | ᅰ | ᅱ | ᅲ | ᅳ | ᅴ | ᅵ | |||||||

| ... | (U+FFE0–U+FFEF опущены) | |||||||||||||||

| Примечания | ||||||||||||||||

Корейский алфавит в других блоках Юникода:

- тона Знаки среднекорейского языка [75] [76] [77] находятся в блоке символов и пунктуации CJK : 〮 (

U+302E), 〯 (U+302F) - 11 172 заранее составленных слога корейского алфавита составляют блок слогов хангыль (

U+AC00–U+D7A3)

Морфо-слоговые блоки

[ редактировать ]За исключением нескольких грамматических морфем, существовавших до двадцатого века, ни одна буква не является отдельной буквой, обозначающей элементы корейского языка. Вместо этого буквы группируются в слоговые или морфемные блоки, по крайней мере, из двух, а часто и из трех: согласная или удвоенная согласная, называемая начальной ( 초성, 初聲 чхосон начало слога ), гласная или дифтонг, называемая средней ( 중성, 中聲 jungseong) . ядро слога ), и, необязательно, согласная или группа согласных в конце слога, называемая финальной ( 종성, 終聲 jongseong syllable coda ). Если в слоге нет начальной согласной, нулевая начальная буква ㅇ ieung в качестве заполнителя используется . (В современном корейском алфавите заполнители для конечной позиции не используются.) Таким образом, блок содержит минимум две буквы: начальную и среднюю. Хотя корейский алфавит исторически был организован в слоги, в современной орфографии он сначала организован в морфемы и только во вторую очередь в слоги внутри этих морфем, за исключением того, что односогласные морфемы не могут быть написаны отдельно.

Наборы начальных и конечных согласных неодинаковы. Например, ㅇ ng встречается только в конечной позиции, а удвоенные буквы, которые могут встречаться в конечной позиции, ограничены ㅆ ss и ㄲ kk .

Не считая устаревших букв, в корейском алфавите возможно 11 172 блока. [78]

Размещение букв внутри блока

[ редактировать ]Размещение или укладка букв в блоке следует установленным шаблонам, основанным на форме средней части.

Последовательности согласных и гласных, такие как ㅄ bs, ㅝ wo или устаревшие ㅵ bsd, ㆋ üye, пишутся слева направо.

Гласные (медиальные) пишутся под начальной согласной справа или обтекают начальную букву снизу направо, в зависимости от их формы: если гласная имеет горизонтальную ось, например ㅡ eu, то она пишется под начальной; если он имеет вертикальную ось типа ㅣ i, то он пишется справа от инициала; а если он сочетает в себе обе ориентации, как ㅢ ui, то он обтекает начальную снизу направо:

|

|

|

Конечная согласная, если она есть, всегда пишется внизу, под гласной. Это называется 받침 батчим «опорный пол»:

|

|

| ||||||||||||

Сложный финал пишется слева направо:

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

Блоки всегда пишутся в фонетическом порядке: начальный-средний-конечный. Поэтому:

- Слоги с горизонтальной средней частью пишутся вниз: 읍 eup ;

- Слоги с вертикальной средней частью и простым финалом пишутся по часовой стрелке: 쌍 ссанг ;

- Слоги с переключением медиального направления (вниз-вправо-вниз): 된 doen ;

- Слоги со сложным финалом пишутся внизу слева направо: 밟 balp .

Форма блока

[ редактировать ]Обычно результирующий блок записывается в квадрате. Некоторые последние шрифты (например, Eun, [79] HY Глубокая родниковая вода M [ нужна ссылка ] и Унджамо [ нужна ссылка ] ) перейти к европейской практике использования букв с фиксированным относительным размером и использовать пробелы для заполнения позиций букв, не используемых в конкретном блоке, а также отказаться от восточноазиатской традиции использования символов квадратных блоков ( 方块字 ). Они нарушают одно или несколько традиционных правил: [ нужны разъяснения ]

- Не растягивайте начальную согласную по вертикали, но оставьте пробел внизу, если нет нижней гласной и/или конечной согласной.

- Не растягивайте правую гласную вертикально, но оставьте пробел внизу, если нет конечной согласной. (Часто правая гласная простирается дальше вниз, чем левая согласная, как нижний гласный в европейской типографике.)

- Не растягивайте последнюю согласную по горизонтали, а оставьте пробел слева от нее.

- Не растягивайте и не дополняйте каждый блок до фиксированной ширины , но допускайте кернинг (переменную ширину), когда блоки слогов без правой гласной и двойной конечной согласной могут быть уже, чем блоки, в которых есть правая гласная или двойная конечная согласная. .

На корейском языке шрифты, которые не имеют фиксированного размера границ блока, называются 탈네모 글꼴 ( таллемо гёлккол , «неквадратный шрифт»). Если горизонтальный текст в шрифте выглядит выровненным по верхнему краю с неровным нижним краем , этот шрифт можно назвать 빨랫줄 글꼴 ( ppallaetjul geulkkol , «шрифт для бельевой веревки»). [ нужна ссылка ]

Эти шрифты использовались в качестве дизайнерских акцентов на знаках или заголовках, а не для набора больших объемов основного текста.

Линейный корейский

[ редактировать ]Вы можете помочь расширить этот раздел текстом, переведенным из соответствующей статьи на корейском языке . (сентябрь 2020 г.) Нажмите [показать], чтобы просмотреть важные инструкции по переводу. |

В начале двадцатого века было небольшое и безуспешное движение за отмену слоговых блоков и написание букв по отдельности и подряд, на манер латинского алфавита , вместо стандартного соглашения 모아쓰기 ( moa-sseugi «собранное письмо». "). Например, ㅎㅏㄴㄱㅡㄹ будет писаться для 한글 (хангыль). [80] Оно называется 풀어쓰기 ( пурео-ссэуги «неразборное письмо»).

Авангардный типограф Ан Сан Су создал для экспозиции «Хангыль Дада» шрифт, в котором разобраны слоговые блоки; но хотя буквы располагаются горизонтально, он сохраняет характерное вертикальное положение, которое каждая буква обычно имеет внутри блока, в отличие от старых предложений линейного письма. [81]

Орфография

[ редактировать ]До 20 века официальная орфография корейского алфавита не была установлена. Из-за связи, тяжелой ассимиляции согласных, диалектных вариантов и других причин корейское слово потенциально может писаться разными способами. Седжон, похоже, предпочитал морфонематическое написание (представляющее основные формы корня), а не фонематическое (представляющее реальные звуки). Однако в начале своей истории в корейском алфавите преобладала фонематическая орфография. На протяжении веков орфография стала частично морфонемной, сначала в существительных, а затем в глаголах. Современный корейский алфавит настолько морфонематичен, насколько это практически возможно. Разницу между фонетической латинизацией, фонематической орфографией и морфонематической орфографией можно проиллюстрировать фразой motaneun sarami :

- Фонетическая транскрипция и перевод:

посмотри на это

[mo.tʰa.nɯn.sa.ɾa.mi]

человек, который не может этого сделать - Фонематическая транскрипция:

Мота Ын Сарами

/mo.tʰa.nɯn.sa.la.mi/ - Морфонематическая транскрипция:

Люди, которые не могут этого сделать

|слово-ха-нɯн-са.лам-и| - Поморфемное толкование :

я не могу это сделать человек = это Мот-ха-Ын плата = я не могу-[ атрибутив ] человек=[тема]

После реформы Габо в 1894 году династия Чосон , а затем и Корейская империя начали писать все официальные документы на корейском алфавите. Под руководством правительства обсуждалось правильное использование корейского алфавита и ханджа, включая орфографию, до тех пор, пока Корейская империя не была аннексирована Японией в 1910 году.

Генерал -губернаторство Кореи популяризировало стиль письма, в котором смешались ханджа и корейский алфавит, и который использовался во времена поздней династии Чосон. Правительство пересмотрело правила правописания в 1912, 1921 и 1930 годах, сделав их относительно фонематическими. [ нужна ссылка ]

Общество хангыль , основанное Джу Сигёном , в 1933 году объявило о предложении новой, сильно морфонемной орфографии, которая стала прототипом современной орфографии как в Северной, так и в Южной Корее. После разделения Кореи Север и Юг отдельно пересмотрели орфографию. Руководящий текст по орфографии корейского алфавита называется Hangeul Matchumbeop , последняя южнокорейская версия которого была опубликована Министерством образования в 1988 году.

Смешанные сценарии

[ редактировать ]Начиная с периода поздней династии Чосон, различные смешанные системы ханджа-хангыль использовались . В этих системах ханджа использовалась для обозначения лексических корней, а корейский алфавит — для грамматических слов и флексий, так же как кандзи и кана используются в японском языке. Ханджа почти полностью выведена из повседневного использования в Северной Корее, а в Южной Корее они в основном ограничиваются глоссами в скобках для имен собственных и для устранения неоднозначности омонимов.

Индо-арабские цифры смешаны с корейским алфавитом, например 2007년 3월 22일 (22 марта 2007 г.).

Читабельность

[ редактировать ]Из-за кластеризации слогов слова на странице короче, чем их линейные аналоги, а границы между слогами легко видны (что может помочь при чтении, если сегментирование слов на слоги более естественно для читателя, чем деление их на фонемы). [82] Поскольку составные части слога представляют собой относительно простые фонематические символы, количество штрихов на иероглиф в среднем меньше, чем в китайских иероглифах. В отличие от слогов, таких как японская кана или китайские логограммы, ни одна из которых не кодирует составляющие фонемы внутри слога, графическая сложность корейских слоговых блоков варьируется в прямой зависимости от фонематической сложности слога. [83] Подобно японской кане или китайским иероглифам, и в отличие от линейных алфавитов, например, полученных из латыни , корейская орфография позволяет читателю использовать как горизонтальное, так и вертикальное поля зрения. [84] Поскольку корейские слоги представлены как наборами фонем, так и уникальными графами, они могут обеспечивать как визуальное, так и слуховое извлечение слов из лексикона . Подобные слоговые блоки, написанные небольшим размером, трудно отличить друг от друга и поэтому иногда их путают. Примеры: 홋/훗/흣 (горячий/хижина/хют), 퀼/퀄 (квиль/кволь), 홍/흥 (хонг/хын) и 핥/핣/핢 ( халп/халм ).

Стиль

[ редактировать ]