Нью-Мексико

Эта статья может быть слишком длинной для удобного чтения и навигации . Когда этот тег был добавлен, его читаемый размер составлял 19 000 слов. ( июнь 2023 г. ) |

Нью-Мексико

| |

|---|---|

| Штат Нью-Мексико Штат Нью-Мексико ( испанский ) | |

| Прозвище : Страна волшебства | |

| Девиз : Он растет дела по ходу | |

Гимн:

| |

Карта Соединенных Штатов с выделенным Нью-Мексико | |

| Страна | Соединенные Штаты |

| До государственности |

|

| Принят в Союз | 6 января 1912 г. (47-е) |

| Капитал | Санта Фе |

| Крупнейший город | Альбукерке |

| Крупнейшие метро и городские районы | Столичный округ Альбукерке |

| Правительство | |

| • Губернатор | Мишель Лухан Гришэм ( З ) |

| • Вице-губернатор | Хауи Моралес (З) |

| Законодательная власть | Законодательное собрание Нью-Мексико |

| • Верхняя палата | Сенат |

| • Нижняя палата | Палата представителей |

| судебная власть | Верховный суд Нью-Мексико |

| Сенаторы США |

|

| Делегация Палаты представителей США |

|

| Область | |

| • Общий | 121,591 [ 1 ] квадратных миль (314 915 км ) 2 ) |

| • Земля | 121,298 [ 1 ] квадратных миль (314 161 км ) 2 ) |

| • Вода | 292 [ 1 ] квадратных миль (757 км 2 ) 0.24% |

| • Классифицировать | 5-е место |

| Размеры | |

| • Длина | 371 миль (596 км) |

| • Ширина | 344 миль (552 км) |

| Высота | 5701 фут (1741 м) |

| Самая высокая точка | 13 161 футов (4011,4 м) |

| Самая низкая высота | 2845 футов (868 м) |

| Население (2020) | |

| • Общий | 2,117,522 |

| • Классифицировать | 36-е |

| • Плотность | 17,2/кв. миль (6,62/км) 2 ) |

| • Классифицировать | 45-е место |

| • Средний доход домохозяйства | $51,945 |

| • Рейтинг дохода | 45-е место |

| Демон(ы) | Новый мексиканец (исп. Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano ) [ 4 ] |

| Язык | |

| • Официальный язык | Никто |

| • Разговорный язык | Английский, испанский ( Нью-Мексико ), навахо , керес , зуни [ 5 ] |

| Часовой пояс | UTC– 07:00 ( Гора ) |

| • Лето ( летнее время ) | UTC–06:00 ( МСК ) |

| Аббревиатура USPS | Нью-Мексико |

| Код ISO 3166 | США-Нью-Мексико |

| Традиционная аббревиатура | Нью-Мексико, Северная Мексика. |

| Широта | От 31 ° 20 'с.ш. до 37 ° с.ш. |

| Долгота | От 103 ° з.д. до 109 ° 3 'з.д. |

| Веб-сайт | нм |

| Список государственных символов | |

|---|---|

| Живые знаки отличия | |

| Птица | Большой роудраннер |

| Рыба | Головорезная форель Рио-Гранде |

| Цветок | Юкка |

| Трава | Синяя грама |

| Насекомое | Тарантул Ястребиная оса |

| млекопитающее | Американский черный медведь |

| Рептилия | Хлыстохвост Нью-Мексико |

| Дерево | Двухигольный пиньон |

| Неодушевленные знаки различия | |

| Цвет (а) | Красный и желтый |

| Еда | Перец Чили , фасоль пинто и бискочито. |

| Ископаемое | Целофиз |

| драгоценный камень | Бирюзовый |

| Другой | Запах жареного зеленого чили [ 6 ] |

| Указатель государственного маршрута | |

| |

| Государственный квартал | |

Выпущен в 2008 году | |

| Списки государственных символов США | |

Нью-Мексико (исп. Nuevo México [ Примечание 2 ] [ 7 ] [ˈnweβo ˈМексика] ; Навахо : Юто Хахудзо. Произношение навахо: [jòːtʰó hɑ̀hòːtsò] ) — штат в юго-западном регионе США. Это один из горных штатов на юге Скалистых гор , разделяющий регион Четырех Углов с Ютой , Колорадо и Аризоной . Он также граничит со штатом Техас на востоке и юго-востоке, с Оклахомой на северо-востоке и граничит с мексиканскими штатами Чиуауа . и Сонора на юге Крупнейшим городом Нью-Мексико является Альбукерке , а столицей штата — Санта-Фе , старейшая столица штата США, основанная в 1610 году как правительственная резиденция Нуэво-Мексико в Новой Испании .

Нью-Мексико является пятым по величине из пятидесяти штатов по площади, но с населением чуть более 2,1 миллиона человек, занимает 36-е место по численности населения и 46-е место по плотности населения . [ 8 ] Его климат и география очень разнообразны: от лесистых гор до редких пустынь; северные восточные и регионы характеризуются более холодным альпийским климатом , тогда как запад и юг более теплые и засушливые . Река Рио-Гранде и ее плодородная долина текут с севера на юг, создавая прибрежный климат в центре штата , который поддерживает среду обитания босков и особый климат бассейна Альбукерке . Одна треть земли Нью-Мексико находится в федеральной собственности, и в штате находится множество охраняемых территорий дикой природы и национальных памятников, в том числе три объекта Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО , больше, чем в любом штате США. [ 9 ]

Экономика Нью-Мексико очень диверсифицирована, включая разведение крупного рогатого скота , сельское хозяйство, лесозаготовку, научные и технологические исследования, туризм и искусство; Основные сектора включают горнодобывающую, нефтегазовую, аэрокосмическую, медиа и киноиндустрию. [ 10 ] [ 11 ] [ 12 ] [ 13 ] Ее общий валовой внутренний продукт (ВВП) в 2020 году составил 95,73 миллиарда долларов, при этом ВВП на душу населения составил примерно 46 300 долларов. [ 14 ] [ 15 ] Государственная налоговая политика характеризуется низким или умеренным налогообложением доходов резидентов по национальным стандартам, с налоговыми льготами, льготами и особыми соображениями для военнослужащих и благоприятных отраслей. Нью-Мексико имеет значительное военное присутствие США , [ 16 ] включая ракетный полигон Уайт-Сэндс , а также стратегически важные федеральные исследовательские центры, такие как Сандия и Национальные лаборатории Лос-Аламос . В штате располагалось несколько ключевых объектов Манхэттенского проекта , в рамках которого была разработана первая в мире атомная бомба , а также место первого ядерного испытания « Тринити» .

В доисторические времена Нью-Мексико был домом для предков пуэблоанцев , культуры Моголлонов и предков юте . [ 17 ] Навахо и апачи прибыли в конце 15 века, а команчи - в начале 18 века. Народы пуэбло заняли несколько десятков деревень, в основном в долине Рио-Гранде на севере Нью-Мексико. [ 18 ] [ 19 ] Испанские исследователи и поселенцы прибыли в 16 веке из современной Мексики. [ 20 ] [ 21 ] [ 22 ] Изолированный своей пересеченной местностью, Нью-Мексико был периферийной частью вице-королевства Новая Испания, где доминировала Команчерия . После обретения Мексикой независимости в 1821 году он стал автономным регионом Мексики, хотя ему все больше угрожала политика централизации мексиканского правительства, кульминацией которой стало восстание 1837 года ; в то же время регион стал более экономически зависимым от США. После американо-мексиканской войны в 1848 году США аннексировали Нью-Мексико как часть более крупной территории Нью-Мексико . Он сыграл центральную роль в расширении США на запад и был принят в Союз как 47-й штат 6 января 1912 года.

История Нью-Мексико способствовала формированию его уникального демографического и культурного характера. Это один из семи штатов с большинством меньшинств , с самым высоким в стране процентом латиноамериканцев и латиноамериканцев и вторым по величине процентом коренных американцев после Аляски . [ 23 ] В штате проживает одна треть народа навахо , 19 признанных на федеральном уровне общин пуэбло и три признанных на федеральном уровне племени апачей . Его большое латиноамериканское население включает латиноамериканцев, произошедших от поселенцев испанской эпохи . [ 24 ] [ 25 ] и более поздние группы американцев мексиканского происхождения с 19 века. Флаг Новой Мексики , который является одним из самых узнаваемых в США, [ 26 ] отражает эклектичное происхождение штата, показывая древний солнечный символ Зия , племени пуэбло, а также алый и золотой цвета испанского флага . [ 27 ] Слияние коренных, латиноамериканских (испанских и мексиканских) и американских Нью-Мексико влияний также очевидно в уникальной кухне , музыкальных жанрах и архитектурных стилях .

Этимология

[ редактировать ]Нью-Мексико получил свое название задолго до того, как нынешняя Мексика завоевала независимость от Испании и приняла это название в 1821 году. Название «Мексика» происходит от языка науатль и первоначально относилось к центру Мексики , правителей Империи ацтеков . в долине Мехико . История Мексики поместила происхождение их народа в Ацтлан , место на севере, откуда они мигрировали в Мексику. Этот отчет и отчеты испанских исследователей торговой сети пуэбло и других в конечном итоге превратились в фольклор Семи золотых городов . 1609 года на языке науатль В «Crónica Mexicayotl» четко идентифицируются Нью-Мексико и Ацтлан, описывая, как жители Мексики покинули «свой дом там, в Старой Мексике, Ацтлан Квинеуайан Чикомосток, который сегодня они называют Нью-Мексико ( янкуикская Мексика )». [ 28 ] [ 29 ]

После завоевания ацтеков в начале 16 века испанцы начали исследовать территорию, которая сейчас является юго-западом Соединенных Штатов, называя ее Новой Мексикой . В 1581 году экспедиция Чамускадо и Родригеса назвала регион к северу от Рио-Гранде Сан-Фелипе-дель-Нуэво-Мексика . [ 30 ] Испанцы надеялись найти богатые коренные культуры, подобные мексиканской. Однако коренные культуры Нью-Мексико оказались не связанными с Мексикой и лишены богатства, но название сохранилось. [ 31 ] [ 32 ]

До обретения статуса штата в 1912 году название «Нью-Мексико» широко применялось к различным конфигурациям территорий на одной и той же территории, которая развивалась на протяжении испанского, мексиканского и американского периодов , но обычно охватывала большую часть современного Нью-Мексико вместе с частями штата. соседние государства. [ 33 ]

История

[ редактировать ]

Предыстория

[ редактировать ]Мексико были представителями культуры Кловис палеоиндейской Первые известные жители Нью - . [ 34 ] : 19 Следы, обнаруженные в 2017 году, позволяют предположить, что люди могли обитать в этом регионе еще в 21 000–23 000 лет до нашей эры. [ 35 ] Среди более поздних жителей - культуры Моголлонов и предков пуэбло , для которых характерны сложная гончарная работа и городское развитие; [ 36 ] : 52 пуэбло или их остатки, например, в Акоме , Таосе и Национальном историческом парке культуры Чако , указывают на масштаб жилищ предков пуэбло в этом районе. Эти культуры являются частью более широкого региона Оазисамерики доколумбовой Северной Америки.

Обширные торговые сети предков-пуэблоанцев привели к появлению легенд по всей Мезоамерике и Империи ацтеков ( Мексика ) о невидимой северной империи, которая соперничала с их собственной, которую они называли Янкуик-Мексико , что буквально переводится как «Новая Мексика».

Нью-Мексико

[ редактировать ]Новая эпоха Испании

[ редактировать ]

Легенды ацтеков о процветающей империи на севере стали основной основой мифических семи золотых городов , которые стимулировали исследования испанских конкистадоров после их завоевания ацтеков в начале 16 века; Среди выдающихся исследователей были Альвар Нуньес Кабеса де Вака , Андрес Дорантес де Карранса , Алонсо дель Кастильо Мальдонадо , Эстеванико и Маркос де Ниса .

Поселение Ла-Вилья-Реал-де-ла-Санта-Фе-де-Сан-Франциско-де-Асис (современный Санта-Фе) было основано Педро де Перальта как более постоянная столица у подножия гор Сангре-де-Кристо в 1610 году. [ 37 ] : 182 К концу 17 века восстание пуэбло изгнало испанцев и оккупировало эти первые города более чем на десять лет. [ 38 ] После смерти лидера пуэбло Диего Попе де Варгас восстановил эту территорию под властью Испании. [ 36 ] : 68–75 с пуэблоанцами предлагалось больше культурных и религиозных свобод. [ 39 ] [ 40 ] [ 34 ] : 6, 48 Вернувшиеся поселенцы основали La Villa de Alburquerque в 1706 году в Старом городе Альбукерке как торговый центр для существующих окружающих сообществ, таких как Барелас , Ислета , Лос-Ранчо и Сандия ; [ 36 ] : 84 он был назван в честь вице-короля Новой Испании Франсиско Фернандеса де ла Куэва, 10-го герцога Альбуркерке . [ 41 ] Губернатор Франсиско Куэрво-и-Вальдес основал виллу в Тигексе, чтобы обеспечить свободный доступ к торговле и облегчить культурный обмен в регионе.

Помимо улучшения отношений с пуэбло, губернаторы были снисходительны в своем подходе к коренным народам, как это было с губернатором Томасом Велесом Качупином ; [ 42 ] сравнительно большие резервации в Нью-Мексико и Аризоне отчасти являются наследием испанских договоров, признающих притязания коренных народов на землю в Нуэво-Мексико. [ 43 ] Тем не менее, отношения между различными группами коренных народов и испанскими поселенцами оставались туманными и сложными, варьируясь от торговли и коммерции до культурной ассимиляции, смешанных браков и тотальных войн. На протяжении большей части XVIII века набеги навахо , апачей и особенно команчей препятствовали росту и процветанию Нью-Мексико. Суровые условия и удаленность региона, окруженного враждебными коренными американцами, способствовали большей степени самообеспеченности, а также прагматическому сотрудничеству между народами пуэбло и колонистами. Многие общины коренных народов пользовались значительной автономией даже в конце 19 века благодаря улучшению управления.

Чтобы стимулировать заселение своей уязвимой периферии, Испания предоставила земельные гранты европейским поселенцам в Нуэво-Мексико; из-за нехватки воды во всем регионе подавляющее большинство колонистов проживало в центральной долине Рио-Гранде и ее притоков. Большинство общин представляли собой обнесенные стеной анклавы, состоящие из глинобитных домов, выходивших на площадь, от которой четыре улицы вели наружу к небольшим частным сельскохозяйственным участкам и фруктовым садам; они орошались асекиями , ирригационными каналами, принадлежащими и управляемыми общинами. Сразу за стеной располагалось эхидо , общинная земля для выпаса скота, дров или отдыха. К 1800 году население Нью-Мексико достигло 25 000 человек (не считая коренных жителей), что намного превышает территории Калифорнии и Техаса. [ 44 ]

Мексика была

[ редактировать ]

В составе Новой Испании провинция Нью-Мексико стала частью Первой Мексиканской империи в 1821 году после Мексиканской войны за независимость . [ 36 ] : 109 После отделения от Мексики в 1836 году Республика Техас претендовала на часть к востоку от Рио-Гранде , основываясь на ошибочном предположении, что старые латиноамериканские поселения в верховьях Рио-Гранде были такими же, как недавно созданные мексиканские поселения в Техасе. Техасская экспедиция в Санта-Фе была начата с целью захвата спорной территории, но потерпела неудачу: вся армия была захвачена и заключена в тюрьму латиноамериканским ополчением Нью-Мексико.

На рубеже XIX века крайняя северо-восточная часть Нью-Мексико, к северу от реки Канадиан и к востоку от хребта Сангре-де-Кристо, все еще принадлежала Франции, которая продала ее в 1803 году в рамках покупки Луизианы. . Когда в 1812 году территория Луизианы была признана штатом, США реклассифицировали оставшуюся землю как часть территории Миссури . Этот регион (вместе с территорией, включающей современный юго-восточный Колорадо, Техас и Оклахому Панхандлс и юго-западный Канзас ) был передан Испании по договору Адамса-Ониса в 1819 году.

Когда Первая Мексиканская республика начала превращаться в Централистскую Республику Мексика , они начали централизовать власть, игнорируя суверенитет Санта-Фе и игнорируя земельные права пуэбло. Это привело к восстанию Чимайо в 1837 году, которое возглавил генизаро Хосе Гонсалес. [ 45 ] Смерть тогдашнего губернатора Альбино Переса во время восстания была встречена с дальнейшей враждебностью. Хотя Хосе Гонсалес был казнен из-за его причастности к смерти губернатора, последующие губернаторы Мануэль Армихо и Хуан Баутиста Виджил-и-Аларид согласились с некоторыми из основных мнений. Это привело к тому, что Нью-Мексико стал финансово и политически привязан к США и отдал предпочтение торговле по тропе Санта-Фе .

Территориальный этап

[ редактировать ]После победы Соединенных Штатов в американо-мексиканской войне (1846–1848 гг.) Мексика свои северные территории , включая Калифорнию, Техас и Нью-Мексико. уступила США [ 36 ] : 132 Поначалу американцы жестко обращались с бывшими гражданами Мексики, что спровоцировало восстание Таос в 1847 году, организованное латиноамериканцами и их союзниками-пуэбло; восстание привело к смерти губернатора территории Чарльза Бента и краху гражданского правительства, установленного Стивеном Кирни . В ответ правительство США назначило местного жителя Донасиано Виджила , чтобы он лучше представлял Нью-Мексико. губернатором [ 46 ] а также поклялся признать земельные права жителей Новой Мексики и предоставить им гражданство. В 1864 году президент Авраам Линкольн символизировал признание прав коренных народов на землю тростями Линкольна, скипетрами должностными , подаренными каждому из пуэбло, традиция, восходящая к испанской и мексиканской эпохам. [ 47 ] [ 48 ]

После того, как Республика Техас была признана штатом в 1846 году, она попыталась претендовать на восточную часть Нью-Мексико к востоку от Рио-Гранде, в то время как Калифорнийская Республика и штат Дезерет претендовали на части западного Нью-Мексико. В соответствии с Компромиссом 1850 года правительство США вынудило эти регионы отказаться от своих претензий, Техас получил 10 миллионов долларов из федеральных фондов, Калифорния получила статус штата и официально учредила территорию Юта ; тем самым признавая большинство исторически сложившихся земельных претензий Нью-Мексико. [ 36 ] : 135 В соответствии с компромиссом Конгресс учредил территорию Нью-Мексико ; в сентябре того же года [ 49 ] он включал большую часть современной Аризоны и Нью-Мексико, а также Лас-Вегаса долину и то, что позже станет округом Кларк в Неваде .

В 1853 году США приобрели преимущественно пустынную юго-западную часть штата, а также земли Аризоны к югу от реки Хила в рамках сделки Гадсдена , которая была необходима для получения полосы отвода для стимулирования строительства трансконтинентальной железной дороги . [ 36 ] : 136

Гражданская война в США, войны с американскими индейцами и американская граница

[ редактировать ]Когда гражданская война в США в 1861 году разразилась , правительства Конфедерации и Союза заявили о своей собственности и территориальных правах на территорию Нью-Мексико. Конфедерация провозгласила южный тракт своей собственной территорией Аризоны и в рамках Транс-Миссисипи театра военных действий вела амбициозную кампанию в Нью-Мексико по контролю над юго-западом Америки и открытию доступа к Союзу Калифорния. Власть Конфедерации на территории Нью-Мексико была фактически сломлена после битвы при перевале Глориета в 1862 году, хотя правительство территории Конфедерации продолжало действовать за пределами Техаса. Более 8000 солдат с территории Нью-Мексико служили в армии Союза . [ 50 ]

Конец войны ознаменовался быстрым экономическим развитием и заселением Нью-Мексико, что привлекло поселенцев, владельцев ранчо, ковбоев, бизнесменов и преступников; [ 51 ] Многие фольклорные персонажи западного жанра родом из Нью-Мексико, в первую очередь бизнесвумен Мария Гертрудис Барсело , преступник Билли Кид и законники Пэт Гарретт и Эльфего Бака . Приток «англо-американцев» из восточной части США (включая афроамериканцев и недавних иммигрантов из Европы) изменил экономику, культуру и политику штата. В конце 19 века большинство жителей Новой Мексики оставались этническими метисами смешанного испанского и индейского происхождения (в первую очередь пуэбло, навахо, апачи, генизаро и команчи), многие из которых имели корни, уходящие корнями в испанские поселения в 16 веке; эта явно новомексиканская этническая группа стала известна как латиноамериканцы и приобрела более выраженную идентичность по сравнению с новыми англо-прибывшими. В политическом отношении они по-прежнему контролировали большинство городских и окружных офисов посредством местных выборов, а богатые семьи фермеров пользовались значительным влиянием, предпочитая деловые, законодательные и судебные отношения с другими коренными группами Нью-Мексико. Напротив, англо-американцы, которые были «превзойдены численностью, но хорошо организованы и росли». [ 52 ] как правило, имели больше связей с правительством территории, должностные лица которого назначались федеральным правительством США; впоследствии новые жители Нью-Мексико в целом выступали за сохранение территориального статуса, что они рассматривали как сдерживание влияния коренных жителей и латиноамериканцев.

Последствием гражданской войны стало усиление конфликта с коренными народами, который был частью более широких войн с американскими индейцами вдоль границы. Вывод войск и материалов для военных действий спровоцировал набеги враждебных племен, и федеральное правительство предприняло шаги по подчинению многих коренных общин, которые фактически были автономными на протяжении всего колониального периода. После устранения угрозы со стороны Конфедерации бригадный генерал Джеймс Карлтон , принявший на себя командование военным департаментом Нью-Мексико в 1862 году, возглавил то, что он назвал «беспощадной войной против всех враждебных племен», целью которой было «заставить их встать на колени». , а затем заключить их в резервации, где они могли бы быть обращены в христианство и обучены сельскому хозяйству». [ 51 ] Когда знаменитый пограничник Кит Карсон был назначен командующим войсками в полевых условиях, могущественные группы коренных народов, такие как навахо , мескалеро- апачи, кайова и команчи , были жестоко усмирены с помощью политики выжженной земли, а затем вынуждены жить в бесплодных и отдаленных резервациях. Спорадические конфликты продолжались до конца 1880-х годов, в первую очередь партизанские кампании, возглавляемые вождями апачей Викторио и его зятем Наной .

Политические и культурные столкновения между этими конкурирующими этническими группами иногда заканчивались массовым насилием, включая линчевания коренных жителей, латиноамериканцев и мексиканцев, как это было при попытке перестрелки во Фриско в 1884 году. Демократическая и Республиканская партии попытались бороться с этим предрассудком и создать более сплоченную, многонациональную идентичность Новой Мексики; в их число входят законники Бака и Гарретт , а также губернаторы Карри , Хагерман и Отеро . [ 53 ] [ 54 ] Действительно, некоторые губернаторы территорий, такие как Лью Уоллес , служили как в мексиканской, так и в американской армии. [ 55 ]

Государственность

[ редактировать ]

Конгресс США признал Нью-Мексико 47-м штатом 6 января 1912 года. [ 36 ] : 166 Он имел право на получение статуса штата 60 лет назад, но было отложено из-за того, что большинство его латиноамериканского населения было «чуждо» культуре и политическим ценностям США. [ 56 ] Когда примерно пять лет спустя США вступили в Первую мировую войну, жители Новой Мексики в значительном количестве пошли добровольцами, отчасти для того, чтобы доказать свою лояльность как полноправные граждане США. Штат занял пятое место в стране по военной службе, набрав более 17 000 новобранцев. из всех 33 округов; более 500 жителей Нью-Мексико погибли в войне. [ 57 ]

Семьи коренных латиноамериканцев существовали уже давно, начиная с испанской и мексиканской эпохи. [ 58 ] но у большинства американских поселенцев в штате были непростые отношения с крупными индейскими племенами. [ 59 ] Большинство коренных жителей Новой Мексики жили в резервациях и вблизи старых пласита и вилл . В 1924 году Конгресс принял закон, предоставляющий всем коренным американцам гражданство США и право голосовать на федеральных выборах и выборах штата. Однако прибытие англо-американцев в Нью-Мексико привело к принятию законов Джима Кроу против выходцев из Латинской Америки, латиноамериканцев и тех, кто не платил налоги, направленных против лиц, связанных с коренными народами; [ 60 ] поскольку выходцы из Латинской Америки часто имели межличностные отношения с коренными народами, они часто подвергались сегрегации , социальному неравенству и дискриминации при приеме на работу . [ 59 ]

Во время борьбы за избирательное право женщин в Соединенных Штатах , испаноязычные и мексиканские женщины Нью-Мексико в авангарде были Тринидад Кабеса де Бака, Долорес «Лола» Армихо, миссис Джеймс Чавес, Аврора Лусеро, Анита «Миссис Секундино» Ромеро, Арабелла «Миссис Клеофас» Ромеро и ее дочь Мари. [ 61 ] [ 62 ]

Крупное открытие нефти в 1928 году недалеко от города Хоббс принесло еще большее богатство штату, особенно в округе Ли . [ 63 ] Бюро горнодобывающей промышленности и минеральных ресурсов Нью-Мексико назвало это «самым важным открытием нефти в истории Нью-Мексико». [ 64 ] Тем не менее, сельское хозяйство и скотоводство оставались основными видами экономической деятельности.

Нью-Мексико сильно изменился после вступления США во Вторую мировую войну в декабре 1941 года. Как и в Первую мировую войну, патриотизм был высоким среди жителей Нью-Мексико, в том числе среди маргинализированных латиноамериканских и коренных общин; В расчете на душу населения Нью-Мексико произвел больше добровольцев и понес больше потерь, чем любой другой штат. Война также стимулировала экономическое развитие, особенно в добывающих отраслях: государство стало ведущим поставщиком ряда стратегических ресурсов. Пересеченная местность и географическая изоляция Нью-Мексико сделали его привлекательным местом для размещения нескольких важных военных и научных объектов; самым известным был Лос-Аламос , один из центральных объектов Манхэттенского проекта первые атомные бомбы , где были спроектированы и изготовлены . Первая бомба была испытана на полигоне Тринити в пустыне между Сокорро и Аламогордо , который сегодня является частью ракетного полигона Уайт-Сэндс . [ 36 ] : 179–180

В результате Второй мировой войны Нью-Мексико продолжает получать большие суммы расходов федерального правительства на крупные военные и исследовательские учреждения. Помимо ракетного полигона Уайт-Сэндс, в штате расположены три базы ВВС США, которые были созданы или расширены во время войны. Хотя большое военное присутствие принесло значительные инвестиции, оно также стало центром споров; 22 мая 1957 года B-36 случайно сбросил ядерную бомбу в 4,5 милях от диспетчерской вышки при приземлении на базе ВВС Киртланд в Альбукерке; сработал только его обычный «спусковой крючок». [ 65 ] [ 66 ] Национальная лаборатория Лос-Аламоса и Национальные лаборатории Сандии страны , два ведущих федеральных научно-исследовательских центра , возникли в результате Манхэттенского проекта. Сосредоточение внимания на высоких технологиях по-прежнему является главным приоритетом штата, поскольку он стал центром неопознанных летающих объектов , особенно после инцидента в Розуэлле в 1947 году .

В Нью-Мексико население почти удвоилось с примерно 532 000 в 1940 году до более 954 000 к 1960 году. [ 67 ] [ 68 ] Помимо федерального персонала и агентств, многие жители и предприятия переехали в штат, особенно с северо-востока, часто из-за его теплого климата и низких налогов. [ 69 ] Эта тенденция сохраняется и в 21 веке: в период с 2000 по 2020 год в Нью-Мексико проживало более 400 000 человек.

Коренные американцы из Нью-Мексико сражались на стороне Соединенных Штатов в обеих мировых войнах. Вернувшиеся ветераны были разочарованы, обнаружив, что их гражданские права ограничены государственной дискриминацией. В Аризоне и Нью-Мексико ветераны оспорили законы и практику штатов, запрещающие им голосовать. ветерану Мигелю Трухильо-старшему с острова Пуэбло В 1948 году, после того как регистратор округа сказал , что он не может зарегистрироваться для голосования, он подал иск против округа в федеральный окружной суд. Коллегия из трех судей отменила как неконституционное положение Нью-Мексико, согласно которому коренные американцы, которые не платили налоги (и не могли документально подтвердить, заплатили ли они налоги), не могли голосовать. [ 60 ] [ Примечание 3 ]

В начале-середине 20 века присутствие искусства в Санта-Фе выросло, и он стал известен как один из величайших центров искусства в мире. [ 70 ] Присутствие таких художников, как Джорджия О'Киф, привлекло многих других, в том числе тех, кто жил на Каньон-роуд . [ 71 ] В конце 20-го века федеральный закон разрешил коренным американцам открывать игровые казино в своих резервациях при определенных условиях в штатах, которые разрешили такие игры. Такие объекты помогли племенам, расположенным вблизи населенных пунктов, получать доходы для реинвестирования в экономическое развитие и благосостояние своих народов. расположено В результате в столичном регионе Альбукерке несколько казино. [ 72 ]

В 21 веке области роста занятости в Нью-Мексико включают электронные схемы , научные исследования , информационные технологии, казино , искусство юго-запада Америки , еду, кино и средства массовой информации, особенно в Альбукерке . [ 73 ] Штат был местом основания компании Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems , что привело к основанию Microsoft в Альбукерке. [ 74 ] Intel имеет свой F11X в Рио-Ранчо , где также находится ИТ-центр HP Inc. [ 75 ] [ 76 ] Кулинарная сцена Нью-Мексико получила признание и теперь является источником дохода для штата. [ 77 ] [ 78 ] [ 79 ] Albuquerque Studios стала центром съемок Netflix , и сюда были привлечены международные медиа-компании, такие как NBCUniversal . [ 80 ] [ 81 ] [ 82 ]

Было подтверждено, что пандемия COVID-19 достигла американского штата Нью-Мексико 11 марта 2020 года. 23 декабря 2020 года Министерство здравоохранения Нью-Мексико сообщило о 1174 новых случаях заболевания COVID-19 и 40 случаях смерти, в результате чего совокупные показатели по штату до 133 242 случаев и 2243 смертей с начала пандемии. [ 83 ] В последнем квартале 2020 года количество госпитализаций по поводу COVID-19 в Нью-Мексико увеличилось, достигнув пика в 947 госпитализаций 3 декабря.

В наиболее густонаселенных округах штата зарегистрировано наибольшее количество инфекций, но к середине апреля северо-западные округа Мак-Кинли и Сан-Хуан стали наиболее зараженными районами штата, а в округе Сандовал также наблюдался высокий уровень заражения. Во всех этих округах проживает большое количество коренных американцев . Согласно информационной панели штата, по состоянию на 15 мая на долю американских индейцев приходилось почти 58 процентов всех случаев заражения по всему штату. 25 апреля в округе Мак-Кинли было самое большое общее количество случаев, а в округе Сан-Хуан - самое большое количество смертей к 26 апреля. Однако к концу июля среди латиноамериканцев/латиноамериканцев было зарегистрировано множество случаев. Доля случаев среди американских индейцев продолжала снижаться и к середине февраля 2021 года оказалась ниже, чем среди белых. [ 83 ]

География

[ редактировать ]

Общая площадь 121 590 квадратных миль (314 900 км²). 2 ), [ 1 ] Нью-Мексико — пятый по величине штат после Аляски, Техаса, Калифорнии и Монтаны. Его восточная граница проходит вдоль 103° западной долготы со штатом Оклахома и в 2,2 мили (3,5 километра) к западу от 103° западной долготы с Техасом из-за ошибки геодезии 19-го века. [ 84 ] [ 85 ] На южной границе Техас составляет две трети восточных территорий, а мексиканские штаты Чиуауа и Сонора составляют западную треть, причем Чиуауа составляет около 90% этой территории. Западная граница с Аризоной проходит по 109°03’з.д. долготы. [ 86 ] Юго-западный угол штата известен как Бутил . Параллель 37 ° с.ш. образует северную границу с Колорадо. Штаты Нью-Мексико, Колорадо, Аризона и Юта объединяются в «Четырех углах» в северо-западной части Нью-Мексико. Площадь его поверхностных вод составляет около 292 квадратных миль (760 км²). 2 ). [ 1 ]

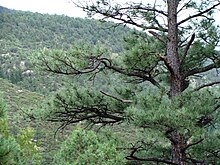

Несмотря на популярное представление о засушливой пустыне, Нью-Мексико имеет один из самых разнообразных ландшафтов среди всех штатов США: от широких рыжевато-красных пустынь и зеленых лугов до разбитых гор и высоких заснеженных вершин. [ 87 ] Около трети штата покрыто лесами , а на севере преобладают густо засаженные деревьями горные пустыни. Горы Сангре-де-Кристо , самая южная часть Скалистых гор , тянутся примерно с севера на юг вдоль восточного берега Рио-Гранде , на суровом пасторальном севере. Великие равнины простираются на восточную треть штата, в первую очередь на Льяно Эстакадо («Ставленная равнина»), самая западная граница которого отмечена откосом Мескалеро хребта . В северо-западном квадранте Нью-Мексико преобладает плато Колорадо , характеризующееся уникальными вулканическими образованиями, сухими лугами и кустарниками, открытыми пиньонно-можжевеловыми лесами и горными лесами. [ 88 ] Пустыня Чиуауа , крупнейшая в Северной Америке, простирается на юге.

Более четырех пятых Нью-Мексико находится на высоте более 4000 футов (1200 метров) над уровнем моря. Средняя высота колеблется от 8000 футов (2400 метров) над уровнем моря на северо-западе до менее 4000 футов на юго-востоке. [ 87 ] Самая высокая точка — пик Уиллер на высоте более 13 160 футов (4010 метров) в горах Сангре-де-Кристо, а самая низкая — водохранилище Ред-Блафф на высоте около 2840 футов (870 метров) в юго-восточном углу штата.

Помимо Рио-Гранде, которая является четвертой по длине рекой в США , в Нью-Мексико есть еще четыре крупные речные системы: Пекос , Канадская , Сан-Хуан и Хила . [ 89 ] Рио-Гранде, почти разделяющий Нью-Мексико пополам с севера на юг, сыграл влиятельную роль в истории региона; его плодородная пойма служила местом проживания людей с доисторических времен, а европейские поселенцы первоначально жили исключительно в ее долинах и вдоль ее притоков. [ 87 ] Река Пекос, текущая примерно параллельно Рио-Гранде на востоке, была популярным маршрутом для исследователей, как и река Канадская, которая берет начало на гористом севере и течет на восток через засушливые равнины. Сан-Хуан и Хила лежат к западу от континентального водораздела , на северо-западе и юго-западе соответственно. За исключением Хилы, все основные реки Нью-Мексико перекрыты плотинами и служат основным источником воды для орошения и борьбы с наводнениями.

Эксперты по охране природы, охотники и любители активного отдыха выразили признательность за природную среду Нью-Мексико и беспристрастность Департамента дичи и рыбы штата Нью-Мексико . [ 90 ] Автор Н. Скотт Момадей обсудил приграничную обстановку коренных народов, выходцев из Латинской Америки и Америки в Нью-Мексико и ее общее отношение к этой земле. [ 91 ] который был освещен в документальном фильме под названием « Вспомнинная земля », который он рассказал , о высокогорной пустыне Нью-Мексико. [ 92 ] Охотники на крупную дичь, такие как Роберт Л. Раннелс, [ 93 ] эксперты по рыбной ловле Ван Бичем и Тай Пайпер , [ 94 ] [ 95 ] и охотники на уток, такие как Сай Робертсон из Duck Commander , [ 96 ] признали условия охоты и рыбалки на диких животных в Нью-Мексико. [ 97 ]

Климат

[ редактировать ]Нью-Мексико издавна известен своим сухим умеренным климатом. [ 87 ] В целом штат является полузасушливым или засушливым, с районами континентального и альпийского климата на возвышенностях. Среднее количество осадков по всему штату Нью-Мексико составляет 13,7 дюймов (350 мм) в год, причем среднемесячное количество осадков достигает максимума летом, особенно в более суровых северо-центральных районах вокруг Альбукерке и на юге. Как правило, восточная треть штата получает больше всего осадков, а западная треть - меньше всего. На больших высотах высота составляет около 40 дюймов (1000 мм), а на самых низких — всего от 8 до 10 дюймов (от 200 до 250 миллиметров). [ 87 ]

| Климатические данные для Нью-Мексико | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Месяц | Ян | февраль | Мар | апрель | Может | июнь | июль | август | Сентябрь | октябрь | ноябрь | декабрь | Год |

| Среднесуточный максимум °F (°C) | 49.7 (9.8) |

54.0 (12.2) |

61.8 (16.6) |

69.2 (20.7) |

78.1 (25.6) |

87.8 (31.0) |

88.8 (31.6) |

86.3 (30.2) |

80.4 (26.9) |

70.6 (21.4) |

58.6 (14.8) |

49.4 (9.7) |

69.6 (20.9) |

| Среднесуточный минимум °F (°C) | 21.7 (−5.7) |

25.0 (−3.9) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

36.5 (2.5) |

45.2 (7.3) |

54.4 (12.4) |

59.5 (15.3) |

58.1 (14.5) |

51.1 (10.6) |

39.7 (4.3) |

29.0 (−1.7) |

22.0 (−5.6) |

39.4 (4.1) |

| Среднее количество осадков в дюймах (мм) | 0.67 (17) |

0.59 (15) |

0.69 (18) |

0.62 (16) |

0.91 (23) |

1.02 (26) |

2.44 (62) |

2.33 (59) |

1.76 (45) |

1.17 (30) |

0.68 (17) |

0.81 (21) |

13.69 (349) |

| Источник 1: Служба наблюдения за экстремальной погодой. [ 98 ] | |||||||||||||

| Источник 2: НОАА. [ 99 ] | |||||||||||||

Годовая температура может варьироваться от 65 ° F (18 ° C) на юго-востоке до ниже 40 ° F (4 ° C) в северных горах. [ 86 ] средний показатель составляет около 50 ° F (12 ° C). Летом дневные температуры часто могут превышать 100 ° F (38 ° C) на высоте ниже 5000 футов (1500 м); средняя высокая температура в июле колеблется от 99 ° F (37 ° C) на более низких высотах до 78 ° F (26 ° C) на возвышенностях. В более холодные месяцы с ноября по март во многих городах Нью-Мексико ночные температуры могут достигать подросткового уровня выше нуля или ниже. Самая высокая температура, зарегистрированная в Нью-Мексико, составила 122 ° F (50 ° C) на экспериментальной установке по изоляции отходов (WIPP) недалеко от Ловинга 27 июня 1994 года; самая низкая зарегистрированная температура составляет -57 ° F (-49 ° C) в Чинизе (недалеко от Джеймстауна ) 13 января 1963 года. [ 100 ]

Стабильный климат и редкое население Нью-Мексико обеспечивают более ясное небо и меньшее световое загрязнение , что делает его популярным местом для нескольких крупных астрономических обсерваторий , в том числе обсерватории Апач-Пойнт , Очень большого массива и обсерватории Магдалена-Ридж , среди других. [ 101 ] [ 102 ]

Флора и фауна

[ редактировать ]

Благодаря разнообразной топографии Нью-Мексико имеет шесть различных растительных зон , которые обеспечивают разнообразные среды обитания для многих растений и животных. [ 103 ] Зона Верхнего Соноры, безусловно, является самой заметной, составляя около трех четвертей штата; он включает большую часть равнин, предгорий и долин высотой более 4500 футов и определяется степными травами, низкими пиньонскими соснами и кустарниками можжевельника. Льяно -Эстакадо на востоке представляет собой прерию Шортграсс с голубой грамой , на которой обитают зубры . Пустыня Чиуауа на юге характеризуется кустарниковым креозотом . Плато Колорадо в северо-западном углу Нью-Мексико представляет собой высокогорную пустыню с холодной зимой, где растут полынь , теневая чешуя , жирное дерево и другие растения, приспособленные к солончаковой и селеноносной почве.

На гористом севере встречается широкий спектр типов растительности, соответствующих градиентам высот, таких как пиньон-можжевеловые леса у подножия, вечнозеленые хвойные , елово - пихтовые и осиновые леса в переходной зоне, а также Круммхольц и альпийская тундра на самой вершине. . [ 103 ] Апачская зона, расположенная на юго-западной окраине штата, имеет почву с высоким содержанием кальция, дубовые леса , аризонский кипарис и другие растения, которые не встречаются в других частях штата. [ 104 ] [ 105 ] Южные части долин Рио-Гранде и Пекос занимают 20 000 квадратных миль (52 000 квадратных километров) лучших пастбищ и орошаемых сельскохозяйственных угодий Нью-Мексико.

Разнообразный климат и растительные зоны Нью-Мексико, следовательно, поддерживают разнообразие дикой природы. Черные медведи , снежные бараны , рыси , пумы , олени и лоси живут в местах обитания на высоте более 7000 футов, в то время как койоты , зайцы , кенгуровые крысы , дротики , дикобразы , вилорогие антилопы , западные ромбовидные и дикие индейки живут в менее гористых и возвышенных регионах. [ 106 ] [ 107 ] [ 108 ] Знаменитый дорожный бегун , который является государственной птицей, в изобилии встречается на юго-востоке. К исчезающим видам относятся мексиканский серый волк , который постепенно вновь интродуцируется в мир, и серебристый гольян Рио-Гранде . [ 109 ] Через Нью-Мексико обитает или мигрирует более 500 видов птиц, уступая только Калифорнии и Мексике. [ 110 ]

Сохранение

[ редактировать ]На Нью-Мексико и 12 других западных штатов вместе приходится 93% всей земли, находящейся в федеральной собственности в США. Примерно треть штата, или 24,7 миллиона из 77,8 миллиона акров, принадлежит правительству США, что является десятым по величине процентом в США. страна. Более половины этих земель находится в ведении Бюро землеустройства в качестве земель общественного достояния или национальных заповедников , а еще одна треть находится в ведении Лесной службы США как национальные леса . [ 111 ]

в начале 20-го века Нью-Мексико занимал центральное место в движении по сохранению природы : в 1924 году Гила Уайлдернесс была признана первой в мире зоной дикой природы . [ 112 ] страны В штате также находятся девять из 84 национальных памятников , больше, чем в любом другом штате после Аризоны; к ним относятся второй старейший памятник, Эль Морро , который был создан в 1906 году, и жилища Хила-Клифф , провозглашенные в 1907 году. [ 112 ]

Национальные леса Нью-Мексико

[ редактировать ]| Национальный лес Карсон |  |

| Национальный лес Сибола |  |

| Национальный лес Линкольна |  |

| Национальный лес Санта-Фе |  |

| Национальный лес Гила |  |

| Хила Уайлдернесс |  |

| Национальный лес Коронадо (в округе Идальго ) |  |

Национальные парки Нью-Мексико

[ редактировать ]Нью-Мексико Национальные парки , а также национальные памятники и тропы, находящиеся в ведении Службы национальных парков , перечислены следующим образом: [ 113 ]

- Национальный памятник ацтекских руин в Ацтеке

- Национальный памятник Банделье в Уайт-Роке

- Национальная историческая тропа Баттерфилд-Оверленд

- Национальный памятник вулкан Капулин возле Капулина

- Национальный парк Карловарские пещеры недалеко от Карловых Вар

- Национальный исторический парк культуры Чако в Нагизи

- Национальная историческая тропа Эль-Камино-Реал-де-Тьерра-Адентро

- Национальный памятник Эль-Мальпаис возле Грантса

- Национальный памятник Эль Морро в Раме

- Национальный памятник Форт-Юнион в Уотрусе

- Национальный памятник Жилище Гила-Клифф недалеко от Силвер-Сити

- Национальный исторический парк Манхэттенского проекта в Лос-Аламосе

- Старая национальная историческая тропа Испании

- Национальный исторический парк Пекос в Пекосе

- Национальный памятник Петроглиф недалеко от Альбукерке

- Национальный памятник миссии Салинас Пуэбло в Маунтинэйре

- Национальная историческая тропа Санта-Фе

- Национальный заповедник Валлес Кальдера в горах Джемез

- Национальный парк Уайт-Сэндс недалеко от Аламогордо

Национальные заповедные земли в Нью-Мексико

[ редактировать ]Национальные памятники, заповедники и другие подразделения Национальной системы охраны ландшафтов Нью-Мексико находятся в ведении Бюро землеустройства . Единицы включают, помимо прочего: [ 114 ]

- Дикая местность Бисти/Де-На-Зин недалеко от Фармингтона

- Национальная историческая тропа Эль-Камино-Реал-де-Тьерра-Адентро

- Национальный заповедник Эль-Мальпаис возле Грантс

- Национальный памятник Каша-Катуве «Тент-Скалы» в Кочити-Пуэбло

- Национальный памятник «Доисторические тропы» возле Лас-Крусес

- Старая национальная историческая тропа Испании

- Национальный памятник «Горы Орган и Пики пустыни» недалеко от Лас-Крусеса

- Национальный памятник Рио-Гранде-дель-Норте недалеко от Таоса

- Дикая и живописная река Рио-Чама недалеко от Абикиу

- Рио-Гранде и Ред-Ривер Дикие и живописные реки возле Квесты

Национальные заповедники дикой природы в Нью-Мексико

[ редактировать ]Нью-Мексико Национальные заповедники дикой природы находятся в ведении Службы охраны рыбы и дикой природы США . В состав единиц входят:

- Национальный заповедник дикой природы «Горькое озеро»

- Национальный заповедник дикой природы Боске-дель-Апач

- Национальный заповедник дикой природы Грулла

- Национальный заповедник дикой природы Лас-Вегаса

- Национальный заповедник дикой природы Максвелл

- Национальный заповедник дикой природы Сан-Андрес

- Национальный заповедник дикой природы Севильеты

- Национальный заповедник дикой природы Валле-де-Оро

Государственные парки в Нью-Мексико

[ редактировать ]Территории, находящиеся в ведении Управления парков штата Нью-Мексико: [ 115 ] [ Примечание 4 ]

- Государственный парк Блууотер-Лейк

- Государственный парк «Бездонные озера»

- Государственный парк Брантли-Лейк

- Государственный парк Серрильос-Хиллз

- Государственный парк озера Кабалло

- Государственный парк Симаррон-Каньон

- Государственный парк Город Рокс

- Государственный парк Клейтон-Лейк

- озера Кончас Государственный парк

- Государственный парк Койот-Крик

- Государственный парк озера Игл-Нест

- Государственный парк Элефант-Бьютт-Лейк

- озера Эль-Вадо Государственный парк

- Херон-Лейк Государственный парк

- Государственный парк Гайд-Мемориал

- Государственный парк Лисбург Дам

- Государственный парк «Живой пустынный зоопарк и сады»

- Государственный парк гор Мансано

- Государственный парк Лесная долина Месилья

- Государственный парк Морфи-Лейк

- Озеро Навахо ( Ап-Ривер , Нью-Мексико и Сан-Хуан, Нью-Мексико )

- Государственный парк Оазис

- Государственный парк Мемориала Оливера Ли

- Государственный парк Панчо-Вилла

- Государственный парк плотины Перча

- Государственный парк природного центра Рио-Гранде

- Государственный парк долины Рио-Гранде

- Государственный парк Рокхаунд

- Государственный парк Санта-Роза-Лейк

- Государственный парк Сторри-Лейк

- Государственный парк Шугарит-Каньон

- Государственный парк Самнер-Лейк

- Государственный парк Фентон-Лейк

- Государственный парк Ют-Лейк

- Государственный парк Вильянуэва

Другие заповедники в Нью-Мексико

[ редактировать ]Примеры природных заповедников местного управления включают:

- Whitfield Wildlife Conservation Area in Valencia County[116][117]

- Albuquerque Open Space, see Open Space Visitor Center[118]

Environmental issues

[edit]In January 2016, New Mexico sued the United States Environmental Protection Agency over negligence after the 2015 Gold King Mine waste water spill. The spill had caused heavy metals such as cadmium and lead and toxins such as arsenic to flow into the Animas River, polluting water basins of several states.[119] The state has since implemented or considered stricter regulations and harsher penalties for spills associated with resource extraction.[120]

New Mexico is a major producer of greenhouse gases.[121] A study by Colorado State University showed that the state's oil and gas industry generated 60 million metric tons of greenhouse gases in 2018, over four times greater than previously estimated.[121] The fossil fuels sector accounted for over half the state's overall emissions, which totaled 113.6 million metric tons, about 1.8% of the country's total and more than twice the national average per capita.[121][122] The New Mexico government has responded with efforts to regulate industrial emissions, promote renewable energy, and incentivize the use of electric vehicles.[122][123]

Settlements

[edit]

With just 17 people per square mile (6.6 people/km2), New Mexico is one of the least densely populated states, ranking 45th out of 50; by contrast, the overall population density of the U.S. is 90 people per square mile (35 people/km2). The state is divided into 33 counties and 106 municipalities, which include cities, towns, villages, and a consolidated city-county, Los Alamos. Only three cities have at least 100,000 residents: Albuquerque, Rio Rancho, and Las Cruces, whose respective metropolitan areas together account for the majority of New Mexico's population.

Residents are concentrated in the north-central region of New Mexico, anchored by the state's largest city, Albuquerque. Centered in Bernalillo County, the Albuquerque metropolitan area includes New Mexico's third-largest city, Rio Rancho, and has a population of over 918,000, accounting for one-third of all New Mexicans. It is adjacent to Santa Fe, the capital and fourth-largest city. Altogether, the Albuquerque–Santa Fe–Los Alamos combined statistical area includes more than 1.17 million people, or nearly 60% of the state population.

New Mexico's other major center of population is in south-central area around Las Cruces, its second-largest city and the largest city in the southern region of the state. The Las Cruces metropolitan area includes roughly 214,000 residents, but with neighboring El Paso, Texas forms a combined statistical area numbering over 1 million.[124]

New Mexico hosts 23 federally recognized tribal reservations, including part of the Navajo Nation, the largest and most populous tribe; of these, 11 hold off-reservation trust lands elsewhere in the state. The vast majority of federally recognized tribes are concentrated in the northwest, followed by the north-central region.

Like several other southwestern states, New Mexico hosts numerous colonias, unincorporated, low-income slums characterized by abject poverty, the absence of basic services (such as water and sewage), and scarce housing and infrastructure.[125] The University of New Mexico estimates there are 118 colonias in the state, though the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development identifies roughly 150.[126] The majority are located along the Mexico-U.S. border.

Largest cities or towns in New Mexico

Source: 2017 U.S. Census Bureau estimate | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||||||

Albuquerque  Las Cruces |

1 | Albuquerque | Bernalillo | 558,545 |  Rio Rancho  Santa Fe | ||||

| 2 | Las Cruces | Doña Ana | 101,712 | ||||||

| 3 | Rio Rancho | Sandoval / Bernalillo | 96,159 | ||||||

| 4 | Santa Fe | Santa Fe | 83,776 | ||||||

| 5 | Roswell | Chaves | 47,775 | ||||||

| 6 | Farmington | San Juan | 45,450 | ||||||

| 7 | Clovis | Curry | 38,962 | ||||||

| 8 | Hobbs | Lea | 37,764 | ||||||

| 9 | Alamogordo | Otero | 31,248 | ||||||

| 10 | Carlsbad | Eddy | 28,774 | ||||||

Demographics

[edit]Population

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 61,547 | — | |

| 1860 | 93,516 | 51.9% | |

| 1870 | 91,874 | −1.8% | |

| 1880 | 119,565 | 30.1% | |

| 1890 | 160,282 | 34.1% | |

| 1900 | 195,310 | 21.9% | |

| 1910 | 327,301 | 67.6% | |

| 1920 | 360,350 | 10.1% | |

| 1930 | 423,317 | 17.5% | |

| 1940 | 531,818 | 25.6% | |

| 1950 | 681,187 | 28.1% | |

| 1960 | 951,023 | 39.6% | |

| 1970 | 1,016,000 | 6.8% | |

| 1980 | 1,302,894 | 28.2% | |

| 1990 | 1,515,069 | 16.3% | |

| 2000 | 1,819,046 | 20.1% | |

| 2010 | 2,059,179 | 13.2% | |

| 2020 | 2,117,522 | 2.8% | |

| Source: 1910–2020[127] | |||

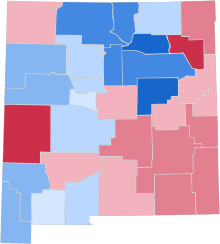

The 2020 census recorded a population of 2,117,522, an increase of 2.8% from 2,059,179 in the 2010 census.[128] This was the lowest rate of growth in the western U.S. after Wyoming, and among the slowest nationwide.[129] By comparison, between 2000 and 2010, New Mexico's population increased by 11.7% from 1,819,046—among the fastest growth rates in the country.[130] A report commissioned in 2021 by the New Mexico Legislature attributed the state's slow growth to a negative net migration rate, particularly among those 18 or younger, and to a 19% decline in the birth rate.[129] However, growth among Hispanics and Native Americans remained healthy.[131]

The U.S. Census Bureau estimated a slight decrease in population, with 3,333 fewer people from July 2021 to July 2022.[132] This was attributed to deaths exceeding births by roughly 5,000, with net migration mitigating the loss by 1,389.[132]

More than half of New Mexicans (51.4%) were born in the state; 37.9% were born in another state; 1.1% were born in either Puerto Rico, an island territory, or abroad to at least one American parent; and 9.4% were foreign born (compared to a national average of roughly 12%).[133] Almost a quarter of the population (22.7%) was under the age of 18, and the state's median age of 38.4 is slightly above the national average of 38.2. New Mexico's somewhat older population is partly reflective of its popularity among retirees: It ranked as the most popular retirement destination in 2018,[134] with an estimated 42% of new residents being retired.[135]

Hispanics and Latinos constitute nearly half of all residents (49.3%), giving New Mexico the highest proportion of Hispanic ancestry among the fifty states. This broad classification includes descendants of Spanish colonists who settled between the 16th and 18th centuries as well as recent immigrants from Latin America (particularly Mexico and Central America).

From 2000 to 2010, the number of persons in poverty increased to 400,779, or approximately one-fifth of the population.[130] The 2020 census recorded a slightly reduced poverty rate of 18.2%, albeit the third highest among U.S. states, compared to a national average of 10.5%. Poverty disproportionately affects minorities, with about one-third of African Americans and Native Americans living in poverty, compared with less than a fifth of whites and roughly a tenth of Asians; likewise, New Mexico ranks 49th among states for education equality by race and 32nd for its racial gap in income.[136]

New Mexico's population is among the most difficult to count, according to the Center for Urban Research at the City University of New York, due to the state's size, sparse population, and numerous isolated communities.[129] Likewise, the Census Bureau estimated that roughly 43% of the state's population (about 900,000 people) live in such "hard-to-count" areas.[129] In response, the New Mexico government invested heavily in public outreach to increase census participation, resulting in a final tally that exceeded earlier estimates and outperformed several neighboring states.[137]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 2,560 homeless people in New Mexico.[138][139]

Birth data

[edit]The majority of live births in New Mexico are to Hispanic whites, with Hispanics of any race consistently accounting for over half of all live births since 2013.

| Race | 2013[140] | 2014[141] | 2015[142] | 2016[143] | 2017[144] | 2018[145] | 2019[146] | 2020[147] | 2021[148] | 2022[149] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White[Note 5] | 21,325 (80.9%) | 21,161 (81.2%) | 21,183 (82.0%) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| > Non-Hispanic White | 7,428 (28.2%) | 7,222 (27.7%) | 7,157 (27.7%) | 7,004 (28.4%) | 6,522 (27.4%) | 6,450 (28.0%) | 6,218 (27.1%) | 5,872 (26.8%) | 5,754 (26.9%) | 5,531 (25.6%) |

| Native American | 3,763 (14.3%) | 3,581 (13.7%) | 3,452 (13.4%) | 2,827 (11.4%) | 2,694 (11.3%) | 2,603 (11.3%) | 2,643 (11.5%) | 2,434 (11.1%) | 2,152 (10.1%) | 2,240 (10.4%) |

| Black | 669 (2.5%) | 732 (2.8%) | 664 (2.6%) | 354 (1.4%) | 387 (1.6%) | 387 (1.7%) | 355 (1.5%) | 403 (1.8%) | 372 (1.7%) | 403 (1.9%) |

| Asian | 597 (2.3%) | 578 (2.2%) | 517 (2.0%) | 425 (1.7%) | 420 (1.8%) | 409 (1.8%) | 392 (1.7%) | 410 (1.8%) | 351 (1.6%) | 412 (1.9%) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 14,402 (54.6%) | 14,449 (55.5%) | 14,431 (55.9%) | 13,639 (55.2%) | 13,362 (56.2%) | 12,783 (55.4%) | 12,924 (56.3%) | 12,406 (56.6%) | 12,354 (57.7%) | 12,617 (58.4%) |

| Total | 26,354 (100%) | 26,052 (100%) | 25,816 (100%) | 24,692 (100%) | 23,767 (100%) | 23,039 (100%) | 22,960 (100%) | 21,903 (100%) | 21,391 (100%) | 21,614 (100%) |

Race and ethnicity

[edit]

New Mexico is one of seven "majority-minority" states where non-Hispanic whites constitute less than half the population.[150] As early as 1940, roughly half the population was estimated to be nonwhite.[151] Before becoming a state in 1912, New Mexico was among the few U.S. territories that was predominately nonwhite, which contributed to its delayed admission into the Union.[152]

The largest ethnic group is Hispanic and Latino Americans; according to the 2020 census they account for nearly half the state's population, at 47.7%; they include Hispanos descended from pre-United States settlers and more recent successions of Mexican Americans.[153]

New Mexico has the fourth largest Native American community in the U.S., at over 200,000; comprising roughly one-tenth of all residents, this is the second largest population by percentage after Alaska.[154][155] New Mexico is also the only state besides Alaska where indigenous people have maintained a stable proportion of the population for over a century: In 1890, Native Americans made up 9.4% of New Mexico's population, almost the same percentage as in 2020.[156] By contrast, during that same period, neighboring Arizona went from one-third indigenous to less than 5%.[156]

New Mexico's population consists of many mestizo Indo-Hispano groups, including Hispanos of Oasisamerican descent and Indigenous Mexican American with Mesoamerican ancestry.[157][158]

| Racial composition | 1970[159] | 1990[159] | 2000[160] | 2010[161] | 2020[162] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic or Latino | 37.4% | 38.2% | 42.1% | 46.3% | 47.7% |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 53.8% | 50.4% | 44.7% | 40.5% | 36.5% |

| Native | 7.2% | 8.9% | 9.5% | 9.4% | 10.0% |

| Black | 1.9% | 2.0% | 1.9% | 2.1% | 2.1% |

| Asian | 0.2% | 0.9% | 1.1% | 1.4% | 1.8% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

– | – | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Other | 0.6% | 12.6% | 17.0% | 15.0% | 15.0% |

| Two or more races | – | – | 3.6% | 3.7% | 19.9% |

According to the 2022 American Community Survey,[163][164][165] the most commonly claimed ancestry groups in New Mexico were:

- Mexican (32.8%)

- Other Hispanic (Hispano/Spanish) (15.3%)

- English (8.0%)

- German (7.9%)

- Irish (6.4%)

- Navajo (6.3%)

- Pueblo (2.4%)

Census data from 2020 found that 19.9% of the population identifies as multiracial/mixed-race, a population larger than the Native American, Black, Asian and NHPI population groups.[162] Almost 90% of the multiracial population in New Mexico identifies as Hispanic or Latino.[166]

Immigration

[edit]A little over 9% of New Mexican residents are foreign-born, and an additional 6.0% of U.S.-born residents live with at least one immigrant parent.[167] The proportion of foreign-born residents is below the national average of 13.7%, and New Mexico was the only state to see a decline in its immigrant population between 2012 and 2022.[168]

In 2018, the top countries of origin for New Mexico's immigrants were Mexico, the Philippines, India, Germany and Cuba.[169] As of 2021, the vast majority of immigrants in the state came from Mexico (67.6%), followed by the Philippines (3.1%) and Germany (2.4%).[167]

Notwithstanding their relatively small population, immigrants play a disproportionately large role in New Mexico's economy, accounting for almost one-eighth (12.5%) of the labor force,15% of entrepreneurs, and 19.1% of personal care aides, as well as 9.1% of workers in STEM fields.[167]

Languages

[edit]| English only | 64% |

|---|---|

| Spanish | 28% |

| Navajo | 4% |

| Others | 4% |

New Mexico ranks third after California and Texas in the number of multilingual residents.[170] According to the 2010 U.S. census, 28.5% of the population age 5 and older speak Spanish at home, while 3.5% speak Navajo.[171] Some speakers of New Mexican Spanish are descendants of pre-18th century Spanish settlers.[172] Contrary to popular belief, New Mexican Spanish is not an archaic form of 17th-century Castilian Spanish; though some archaic elements exist, linguistic research has determined that the dialect "is neither more Iberian nor more archaic" than other varieties spoken in the Americas.[173][174] Nevertheless, centuries of isolation during the colonial period insulated the New Mexican dialect from "standard" Spanish, leading to the preservation of older vocabulary as well as its own innovations.[175][176]

Besides Navajo, which is also spoken in Arizona, several other Native American languages are spoken by smaller groups in New Mexico, most of which are endemic to the state. Native New Mexican languages include Mescalero Apache, Jicarilla Apache, Tewa, Southern Tiwa, Northern Tiwa, Towa, Keres (Eastern and Western), and Zuni. Mescalero and Jicarilla Apache are closely related Southern Athabaskan languages, and both are also related to Navajo. Tewa, the Tiwa languages, and Towa belong to the Kiowa-Tanoan language family, and thus all descend from a common ancestor. Keres and Zuni are language isolates with no relatives outside of New Mexico.

Official language

[edit]New Mexico's original state constitution of 1911 required all laws be published in both English and Spanish for twenty years after ratification;[177] this requirement was renewed in 1931 and 1943,[178] with some sources stating the state was officially bilingual until 1953.[179] Nonetheless, the current constitution does not declare any language "official".[180] While Spanish was permitted in the legislature until 1935, all state officials are required to have a good knowledge of English; consequently, some analysts argue that New Mexico cannot be considered a bilingual state, since not all laws are published in both languages.[178]

However, the state legislature remains constitutionally empowered to publish laws in English and Spanish and to appropriate funds for translation. Whenever a referendum to approve an amendment to the New Mexican constitution is held, the ballots must be printed in both English and Spanish.[181] Certain legal notices must be published in both English and Spanish as well, and the state maintains a list of newspapers for Spanish publication.[182]

With regard to the judiciary, witnesses and defendants have the right to testify in either of the two languages, and monolingual speakers of Spanish have the same right to be considered for jury duty as do speakers of English.[180][183] In public education, the state has the constitutional obligation to provide bilingual education and Spanish-speaking instructors in school districts where the majority of students are Hispanophone.[180] The constitution also provides that all state citizens who speak neither English nor Spanish have a right to vote, hold public office, and serve on juries.[184]

In 1989, New Mexico became the first of only four states to officially adopt the English Plus resolution, which supports acceptance of non-English languages.[185] In 1995, the state adopted an official bilingual song, "New Mexico – Mi Lindo Nuevo México".[186]: 75, 81 In 2008, New Mexico was the first state to officially adopt a Navajo textbook for use in public schools.[187]

Religion

[edit]Religious self-identification, per Public Religion Research Institute's 2022 American Values Survey[188]

Like most U.S. states, New Mexico is predominantly Christian, with Roman Catholicism and Protestantism each constituting roughly a third of the population. According to Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA), the largest denominations in 2010 were the Catholic Church (684,941 members); the Southern Baptist Convention (113,452); The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (67,637), and the United Methodist Church (36,424).[189] Approximately one-fifth of residents are unaffiliated with any religion, which includes atheists, agnostics, deists. A 2020 study by the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) determined 67% of the population were Christian, with Roman Catholics constituting the largest denominational group.[190] In 2022, the PRRI estimated 63% of the population were Christian.[191]

Roman Catholicism is deeply rooted in New Mexico's history and culture, going back to its settlement by the Spanish in the early 17th century. The oldest Christian church in the continental U.S., and the third oldest in any U.S. state or territory, is the San Miguel Mission in Santa Fe, which was built in 1610. Within the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, New Mexico belongs to the ecclesiastical province of Santa Fe. The state has three ecclesiastical districts:[192] the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, the Diocese of Gallup, and the Diocese of Las Cruces.[193] Evangelicalism and nondenominational Christianity have seen growth in the state since the late 20th century: The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association has hosted numerous events in New Mexico,[194][195] and Albuquerque has several megachurches, which have numerous satellite locations in the state, including Calvary of Albuquerque, Legacy Church, and Sagebrush Church.[196]

New Mexico has been a leading center of the New Age movement since at least the 1960s, attracting adherents from across the country.[197] The state's "thriving New Age network" encompasses various schools of alternative medicine, Holistic Health, psychic healing, and new religions, as well as festivals, pilgrimage sites, spiritual retreats, and communes.[198][199] New Mexico's Japanese American community has influenced the state's religious heritage, with Shinto and Zen represented by Kagyu Shenpen Kunchab, Kōbun Chino Otogawa, Upaya Institute and Zen Center.[200] Likewise, Holism is represented in New Mexico, as are associated faiths such as Buddhism and Seventh-day Adventism;[201][202] a Tibetan Buddhist temple is located at Zuni Mountain Stupa in Grants.

Religious education, art, broadcasting, media exist across religions and faiths in New Mexico, including KHAC, KXXQ, Dar al-Islam, and Intermountain Jewish News. Christian schools in New Mexico are encouraged to receive educational accreditation, and among them are the University of the Southwest, St. Pius High School, Hope Christian, Sandia View Academy, St. Michael's High School, Las Cruces Catholic School, St. Bonaventure Indian School, and Rehoboth Christian School. Albuquerque's growing media sector has made it a popular hub for several national Christian media institutions, such as Trinity Broadcasting Network's KNAT-TV. Christian artistic expression includes the gospel tradition within New Mexico music,[203] and contemporary Christian music such as KLYT radio station.[204] Several indigenous and Christian religious sites are registered and protected as part of regional and global cultural heritage.[205][206]

Reflecting centuries of successive migrations and settlements, New Mexico has developed a distinct syncretic folk religion that is centered on Puebloan traditions and Hispano folk Catholicism, with some elements of Diné Bahaneʼ, Apache, Protestant, and Evangelical faiths.[207] This unique religious tradition is sometimes referred to as "Pueblo Christianity" or "Placita Christianity", referring to both the Pueblos and Hispanic town squares.[208] Customs and practices include the maintenance of acequias,[209] Pueblo and Territorial Style churches,[209] ceremonial dances such as the matachines,[210][211] religious artistic expression of kachinas and santos,[212] religious holidays celebrating saints such as Pueblo Feast Days,[213] Christmas traditions of bizcochitos and farolitos or luminarias,[214][215] and pilgrimages like that of El Santuario de Chimayo.[216] The luminaria tradition is a cultural hallmark of the Pueblos and Hispanos of New Mexico and a part of the state's distinct heritage. The luminaria custom has spread nationwide, both as a Christmas tradition as well as for other events. New Mexico's distinctive faith tradition is believed to reflect the religious naturalism of the state's indigenous and Hispano peoples, who constitute a pseudo ethnoreligious group.[217]

New Mexico's leadership within otherwise disparate traditions such as Christianity, the Native American Church, and New Age movements has been linked to its remote and ancient indigenous spirituality, which emphasized sacred connections to nature, and its over 300 years of syncretized Pueblo and Hispano religious and folk customs.[197][198] The state's remoteness has likewise been cited as attracting and fostering communities seeking the freedom to practice or cultivate new beliefs.[198] Global spiritual leaders including Billy Graham and Dalai Lama, along with community leaders of Hispanic and Latino Americans and indigenous peoples of the North American Southwest, have remarked on New Mexico being a sacred space.[218][219][220]

According to a 2017 survey by the Pew Research Center, New Mexico ranks 18th among the 50 U.S. states in religiosity, 63% of respondents stating they believe in God with certainty, with an additional 20% being fairly certain of the existence of God, while 59% considering religion to be important in their lives and another 20% believe it to be somewhat important.[221] Among its population in 2022, 31% were unaffiliated.[191]

Economy

[edit]This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (June 2024) |

Oil and gas production, the entertainment industry, high tech scientific research, tourism, and government spending are important drivers of the state economy.[222] The state government has an elaborate system of tax credits and technical assistance to promote job growth and business investment, especially in new technologies.[223]

As of 2021, New Mexico's gross domestic product was over $95 billion,[224] compared to roughly $80 billion in 2010.[225] State GDP peaked in 2019 at nearly $99 billion but declined in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, the per capita personal income was slightly over $45,800, compared to $31,474 in 2007;[226] it was the third lowest in the country after West Virginia and Mississippi.[227] The percentage of persons below the poverty level has largely plateaued in the 21st century, from 18.4% in 2005 to 18.2% in 2021.[228][229]

Traditionally dependent on resource extraction, ranching, and railroad transportation, New Mexico has increasingly shifted towards services, high-end manufacturing, and tourism.[230][231] Since 2017, the state has seen a steady rise in the number of annual visitors, culminating in a record-breaking 39.2 million tourists in 2021, which had a total economic income of $10 billion.[232] New Mexico has also seen greater investment in media and scientific research.

Oil and gas

[edit]New Mexico is the second largest crude oil and ninth largest natural gas producer in the United States;[233] it overtook North Dakota in oil production in July 2021 and is expected to continue expanding.[234] The Permian and San Juan Basins, which are located partly in New Mexico, account for some of these natural resources. In 2000 the value of oil and gas produced was $8.2 billion,[235] and in 2006, New Mexico accounted for 3.4% of the crude oil, 8.5% of the dry natural gas, and 10.2% of the natural gas liquids produced in the United States.[236] However, the boom in hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling since the mid-2010s led to a large increase in the production of crude oil from the Permian Basin and other U.S. sources; these developments allowed the United States to again become the world's largest producer of crude oil by 2018.[237][238][239][240] New Mexico's oil and gas operations contribute to the state's above-average release of the greenhouse gas methane, including from a national methane hot spot in the Four Corners area.[241][242][243][244]

In common with other states in the Western U.S., New Mexico receives royalties from the sale of federally owned land to oil and gas companies.[245] It has the highest proportion of federal land with oil and gas, as well as the most lucrative: since the last amendment to the U.S. Mineral Leasing Act in 1987, New Mexico had by far the lowest percent of land sold for the minimum statutory amount of $2 per acre, at just 3%; by contrast, all of Arizona's federal land was sold at the lowest rate, followed by Oregon at 98% and Nevada at 84%.[245] The state had the fourth-highest total acreage sold to the oil and gas industry, at about 1.1 million acres, and the second-highest number of acres currently leased fossil fuel production, at 4.3 million acres, after Wyoming's 9.2 million acres; only 11 percent of these lands, or 474,121 acres, are idle, which is the lowest among Western states.[245] Nevertheless, New Mexico has had recurring disputes and discussions with the U.S. government concerning management and revenue rights over federal land.[246]

Arts and entertainment

[edit]

Reflecting the artistic traditions of the American Southwest, New Mexican art has its origins in the folk arts of the indigenous and Hispanic peoples in the region. Pueblo pottery, Navajo rugs, and Hispano religious icons like kachinas and santos are recognized in the global art world.[247] Georgia O'Keeffe's presence brought international attention to the Santa Fe art scene, and today the city has several notable art establishments and many commercial art galleries along Canyon Road.[248] As the birthplace of William Hanna, and the residence of Chuck Jones, the state also connections to the animation industry.[249][250]

New Mexico provides financial incentives for film production, including tax credits valued at 25–40% of eligible in-state spending.[251][252] A program enacted in 2019 provides benefits to media companies that commit to investing in the state for at least a decade and that use local talent, crew, and businesses.[253] According to the New Mexico Film Office, in 2022, film and television expenditures reached the highest recorded level at over $855 million, compared to $624 million the previous year.[254] During fiscal years 2020–2023, the total direct economic impact from the film tax credit was $2.36 million. In 2018, Netflix chose New Mexico for its first U.S. production hub, pledging to spend over $1 billion over the next decade to create one of the largest film studios in North America at Albuquerque Studios.[255] NBCUniversal followed suit in 2021 with the opening of its own television film studio in the city, committing to spend $500 million in direct production and employ 330 full-time equivalent local jobs over the next decade.[253] Albuquerque is consistently recognized by MovieMaker magazine as one of the top "big cities" in North America to live and work as a filmmaker, and the only city to earn No. 1 for four consecutive years (2019–2022); in 2024, it placed second, after Toronto.[256]

Country music record labels have a presence in the state, following the former success of Warner Western.[257][258][259][260][261] During the 1950s to 1960s, Glen Campbell, The Champs, Johnny Duncan, Carolyn Hester, Al Hurricane, Waylon Jennings, Eddie Reeves, and J. D. Souther recorded on equipment by Norman Petty at Clovis. Norman Petty's recording studio was a part of the rock and roll and rockabilly movement of the 1950s, with the distinctive "Route 66 Rockabilly" stylings of Buddy Holly and The Fireballs.[262] Albuquerque has been referred to as the "Chicano Nashville" due to the popularity of regional Mexican and Western music artists from the region.[263] A heritage style of country music, called New Mexico music, is widely popular throughout the southwestern U.S.; outlets for these artists include the radio station KANW, Los 15 Grandes de Nuevo México music awards, and Al Hurricane Jr. hosts Hurricane Fest to honor his father's music legacy.[264][265][266]

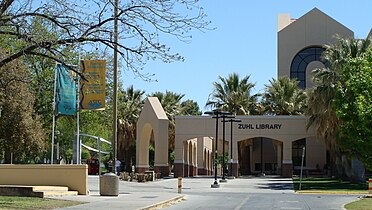

Technology

[edit]New Mexico is part of the larger Rio Grande Technology Corridor, an emerging alternative to Silicon Valley[267] consisting of clusters of science and technology institutions stretching from southwestern Colorado to the Gulf of Mexico.[268] The constituent New Mexico Technology Corridor, centered primarily around Albuquerque, hosts a constellation of high technology and scientific research entities, which include federal facilities such as Sandia National Laboratories, Los Alamos National Laboratory, and the Very Large Array; private companies such as Intel, HP, and Facebook; and academic institutions such as the University of New Mexico (UNM), New Mexico State University (NMSU), and New Mexico Tech.[269][270][76][271][272] Most of these entities form part of an "ecosystem" that links their researchers and resources with private capital, often through initiatives of local, state, and federal governments.[273]

New Mexico has been a science and technology hub since at least the mid-20th century, following heavy federal government investment during the Second World War. Los Alamos was the site of Project Y, the laboratory responsible for designing and developing the world's first atomic bomb for the Manhattan Project. Horticulturist Fabián García developed several new varieties of peppers and other crops at what is now NMSU, which is also a leading space grant college. Robert H. Goddard, credited with ushering the space age, conducted many of his early rocketry tests in Roswell. Astronomer Clyde Tombaugh of Las Cruces discovered Pluto in neighboring Arizona. Personal computer company MITS, which was founded in Albuquerque in 1969, brought about the "microcomputer revolution" with the development of the first commercially successful microcomputer, the Altair 8800; two of its employees, Paul Allen and Bill Gates, later founded Microsoft in the city in 1975.[274][275][276] Multinational technology company Intel, which has had operations in Rio Rancho since 1980, opened its Fab 9 factory in the city in January 2024, part of its commitment to invest $3.5 billion in expanding its operations in the state; it is the company's first high-volume semiconductor operation and the only U.S. factory producing the world's most advanced packaging solutions at scale.[277]