Свадьба

| Часть серии о |

| Антропология родства |

|---|

|

| Social anthropology Cultural anthropology |

Relationships (Outline) |

|---|

Брак , также называемый супружеством или браком , представляет собой культурно и часто юридически признанный союз между людьми, называемыми супругами . Он устанавливает права и обязанности между ними, а также между ними и их детьми (если таковые имеются), а также между ними и их родственниками . [1] Это почти культурная универсалия , [2] но определение брака варьируется в зависимости от культуры и религии , а также с течением времени. Обычно это институт , в котором межличностные отношения, обычно сексуальные признаются или одобряются . В некоторых культурах брак рекомендуется или считается обязательным перед началом сексуальной активности . Церемония бракосочетания называется свадьбой , а частный брак иногда называют побегом .

Around the world, there has been a general trend towards ensuring equal rights for women and ending discrimination and harassment against couples who are interethnic, interracial, interfaith, interdenominational, interclass, intercommunity, transnational, and same-sex as well as immigrant couples, couples with an immigrant spouse, and other minority couples. Debates persist regarding the legal status of married women, leniency towards violence within marriage, customs such as dowry and bride price, marriageable age, and criminalization of premarital and extramarital sex. Individuals may marry for several reasons, including legal, social, libidinal, emotional, financial, spiritual, cultural, economic, political, religious, sexual, and romantic purposes. In some areas of the world, arranged marriage, forced marriage, polygyny marriage, polyandry marriage, group marriage, coverture marriage, child marriage, cousin marriage, sibling marriage, teenage marriage, avunculate marriage, incestuous marriage, and bestiality marriage are practiced and legally permissible, while others areas outlaw them to protect human rights.[3][improper synthesis?] Female age at marriage has proven to be a strong indicator for female autonomy and is continuously used by economic history research.[4]

Marriage can be recognized by a state, an organization, a religious authority, a tribal group, a local community, or peers. It is often viewed as a contract. A religious marriage ceremony is performed by a religious institution to recognize and create the rights and obligations intrinsic to matrimony in that religion. Religious marriage is known variously as sacramental marriage in Christianity (especially Catholicism), nikah in Islam, nissuin in Judaism, and various other names in other faith traditions, each with their own constraints as to what constitutes, and who can enter into, a valid religious marriage.

Etymology

The word "marriage" appeared around 1300 and likely descended from the Old French "mariage" of the 12th Century and the Vulgar Latin "maritaticum" of the 11th Century, ultimately tracing to the Latin "maritatus", past participle of "maritare".[5] The adjective marīt-us -a, -um meaning matrimonial or nuptial could also be used in the masculine form as a noun for "husband" and in the feminine form for "wife".[6] The related word "matrimony" derives from the Old French word matremoine, which appears around 1300 CE and ultimately derives from Latin mātrimōnium, which combines the two concepts: mater meaning "mother" and the suffix -monium signifying "action, state, or condition".[7]

Definitions

Anthropologists have proposed several competing definitions of marriage in an attempt to encompass the wide variety of marital practices observed across cultures.[8] Even within Western culture, "definitions of marriage have careened from one extreme to another and everywhere in between" (as Evan Gerstmann has put it).[9]

Relation recognized by custom or law

In The History of Human Marriage (1891), Edvard Westermarck defined marriage as "a more or less durable connection between male and female lasting beyond the mere act of propagation till after the birth of the offspring."[10] In The Future of Marriage in Western Civilization (1936), he rejected his earlier definition, instead provisionally defining marriage as "a relation of one or more men to one or more women that is recognized by custom or law".[11]

Legitimacy of offspring

The anthropological handbook Notes and Queries (1951) defined marriage as "a union between a man and a woman such that children born to the woman are the recognized legitimate offspring of both partners."[12] In recognition of a practice by the Nuer people of Sudan allowing women to act as a husband in certain circumstances (the ghost marriage), Kathleen Gough suggested modifying this to "a woman and one or more other persons."[13]

In an analysis of marriage among the Nayar, a polyandrous society in India, Gough found that the group lacked a husband role in the conventional sense. The husband role, unitary in the west, was instead divided between a non-resident "social father" of the woman's children, and her lovers, who were the actual procreators. None of these men had legal rights to the woman's child. This forced Gough to disregard sexual access as a key element of marriage and to define it in terms of legitimacy of offspring alone: marriage is "a relationship established between a woman and one or more other persons, which provides a child born to the woman under circumstances not prohibited by the rules of relationship, is accorded full birth-status rights common to normal members of his society or social stratum."[14]

Economic anthropologist Duran Bell has criticized the legitimacy-based definition on the basis that some societies do not require marriage for legitimacy. He argued that a legitimacy-based definition of marriage is circular in societies where illegitimacy has no other legal or social implications for a child other than the mother being unmarried.[8]

Collection of rights

Edmund Leach criticized Gough's definition for being too restrictive in terms of recognized legitimate offspring and suggested that marriage be viewed in terms of the different types of rights it serves to establish. In a 1955 article in Man, Leach argued that no one definition of marriage applied to all cultures. He offered a list of ten rights associated with marriage, including sexual monopoly and rights with respect to children, with specific rights differing across cultures. Those rights, according to Leach, included:

- "To establish a legal father of a woman's children.

- To establish a legal mother of a man's children.

- To give the husband a monopoly in the wife's sexuality.

- To give the wife a monopoly in the husband's sexuality.

- To give the husband partial or monopolistic rights to the wife's domestic and other labor services.

- To give the wife partial or monopolistic rights to the husband's domestic and other labor services.

- To give the husband partial or total control over property belonging or potentially accruing to the wife.

- To give the wife partial or total control over property belonging or potentially accruing to the husband.

- To establish a joint fund of property – a partnership – for the benefit of the children of the marriage.

- To establish a socially significant 'relationship of affinity' between the husband and his wife's brothers."[15]

Right of sexual access

In a 1997 article in Current Anthropology, Duran Bell describes marriage as "a relationship between one or more men (male or female) in severalty to one or more women that provides those men with a demand-right of sexual access within a domestic group and identifies women who bear the obligation of yielding to the demands of those specific men." In referring to "men in severalty", Bell is referring to corporate kin groups such as lineages which, in having paid bride price, retain a right in a woman's offspring even if her husband (a lineage member) deceases (Levirate marriage). In referring to "men (male or female)", Bell is referring to women within the lineage who may stand in as the "social fathers" of the wife's children born of other lovers. (See Nuer "ghost marriage".)[8]

Types

Monogamy

Monogamy is a form of marriage in which an individual has only one spouse during their lifetime or at any one time (serial monogamy).

Anthropologist Jack Goody's comparative study of marriage around the world utilizing the Ethnographic Atlas found a strong correlation between intensive plough agriculture, dowry and monogamy. This pattern was found in a broad swath of Eurasian societies from Japan to Ireland. The majority of Sub-Saharan African societies that practice extensive hoe agriculture, in contrast, show a correlation between "bride price" and polygamy.[17] A further study drawing on the Ethnographic Atlas showed a statistical correlation between increasing size of the society, the belief in "high gods" to support human morality, and monogamy.[18]

In the countries which do not permit polygamy, a person who marries in one of those countries a person while still being lawfully married to another commits the crime of bigamy. In all cases, the second marriage is considered legally null and void. Besides the second and subsequent marriages being void, the bigamist is also liable to other penalties, which also vary between jurisdictions.

Serial monogamy

Governments that support monogamy may allow easy divorce. In a number of Western countries, divorce rates approach 50%. Those who remarry do so usually no more than three times.[19] Divorce and remarriage can thus result in "serial monogamy", i.e. having multiple marriages but only one legal spouse at a time. This can be interpreted as a form of plural mating, as are those societies dominated by female-headed families in the Caribbean, Mauritius and Brazil where there is frequent rotation of unmarried partners. In all, these account for 16 to 24% of the "monogamous" category.[20]

Serial monogamy creates a new kind of relative, the "ex-". The "ex-wife", for example, may remain an active part of her "ex-husband's" or "ex-wife's" life, as they may be tied together by transfers of resources (alimony, child support), or shared child custody. Bob Simpson notes that in the British case, serial monogamy creates an "extended family" – a number of households tied together in this way, including mobile children (possible exes may include an ex-wife, an ex-brother-in-law, etc., but not an "ex-child"). These "unclear families" do not fit the mould of the monogamous nuclear family. As a series of connected households, they come to resemble the polygynous model of separate households maintained by mothers with children, tied by a male to whom they are married or divorced.[21]

Polygamy

Polygamy is a marriage which includes more than two spouses.[22] When a man is married to more than one wife at a time, the relationship is called polygyny, and there is no marriage bond between the wives; and when a woman is married to more than one husband at a time, it is called polyandry, and there is no marriage bond between the husbands. If a marriage includes multiple husbands or wives, it can be called group marriage.[22]

A molecular genetic study of global human genetic diversity argued that sexual polygyny was typical of human reproductive patterns until the shift to sedentary farming communities approximately 10,000 to 5,000 years ago in Europe and Asia, and more recently in Africa and the Americas.[23] As noted above, Anthropologist Jack Goody's comparative study of marriage around the world utilizing the Ethnographic Atlas found that the majority of Sub-Saharan African societies that practice extensive hoe agriculture show a correlation between "Bride price" and polygamy.[17] A survey of other cross-cultural samples has confirmed that the absence of the plough was the only predictor of polygamy, although other factors such as high male mortality in warfare (in non-state societies) and pathogen stress (in state societies) had some impact.[24]

Marriages are classified according to the number of legal spouses an individual has. The suffix "-gamy" refers specifically to the number of spouses, as in bi-gamy (two spouses, generally illegal in most nations), and poly-gamy (more than one spouse).

Societies show variable acceptance of polygamy as a cultural ideal and practice. According to the Ethnographic Atlas, of 1,231 societies noted, 186 were monogamous; 453 had occasional polygyny; 588 had more frequent polygyny, and 4 had polyandry.[25] However, as Miriam Zeitzen writes, social tolerance for polygamy is different from the practice of polygamy, since it requires wealth to establish multiple households for multiple wives. The actual practice of polygamy in a tolerant society may actually be low, with the majority of aspirant polygamists practicing monogamous marriage. Tracking the occurrence of polygamy is further complicated in jurisdictions where it has been banned, but continues to be practiced (de facto polygamy).[26]

Zeitzen also notes that Western perceptions of African society and marriage patterns are biased by "contradictory concerns of nostalgia for traditional African culture versus critique of polygamy as oppressive to women or detrimental to development."[26] Polygamy has been condemned as being a form of human rights abuse, with concerns arising over domestic abuse, forced marriage, and neglect. The vast majority of the world's countries, including virtually all of the world's developed nations, do not permit polygamy. There have been calls[by whom?] for the abolition of polygamy in developing countries.[citation needed]

Polygyny

Polygyny usually grants wives equal status, although the husband may have personal preferences. One type of de facto polygyny is concubinage, where only one woman gets a wife's rights and status, while other women remain legal house mistresses.

Although a society may be classified as polygynous, not all marriages in it necessarily are; monogamous marriages may in fact predominate. It is to this flexibility that Anthropologist Robin Fox attributes its success as a social support system: "This has often meant – given the imbalance in the sex ratios, the higher male infant mortality, the shorter life span of males, the loss of males in wartime, etc. – that often women were left without financial support from husbands. To correct this condition, females had to be killed at birth, remain single, become prostitutes, or be siphoned off into celibate religious orders. Polygynous systems have the advantage that they can promise, as did the Mormons, a home and family for every woman."[27]

Nonetheless, polygyny is a gender issue which offers men asymmetrical benefits. In some cases, there is a large age discrepancy (as much as a generation) between a man and his youngest wife, compounding the power differential between the two. Tensions not only exist between genders, but also within genders; senior and junior men compete for wives, and senior and junior wives in the same household may experience radically different life conditions, and internal hierarchy. Several studies have suggested that the wive's relationship with other women, including co-wives and husband's female kin, are more critical relationships than that with her husband for her productive, reproductive and personal achievement.[28] In some societies, the co-wives are relatives, usually sisters, a practice called sororal polygyny; the pre-existing relationship between the co-wives is thought to decrease potential tensions within the marriage.[29]

Fox argues that "the major difference between polygyny and monogamy could be stated thus: while plural mating occurs in both systems, under polygyny several unions may be recognized as being legal marriages while under monogamy only one of the unions is so recognized. Often, however, it is difficult to draw a hard and fast line between the two."[30]

As polygamy in Africa is increasingly subject to legal limitations, a variant form of de facto (as opposed to legal or de jure) polygyny is being practiced in urban centers. Although it does not involve multiple (now illegal) formal marriages, the domestic and personal arrangements follow old polygynous patterns. The de facto form of polygyny is found in other parts of the world as well (including some Mormon sects and Muslim families in the United States).[31]In some societies such as the Lovedu of South Africa, or the Nuer of the Sudan, aristocratic women may become female 'husbands.' In the Lovedu case, this female husband may take a number of polygamous wives. This is not a lesbian relationship, but a means of legitimately expanding a royal lineage by attaching these wives' children to it. The relationships are considered polygynous, not polyandrous, because the female husband is in fact assuming masculine gendered political roles.[29]

Religious groups have differing views on the legitimacy of polygyny. It is allowed in Islam and Confucianism. Judaism and Christianity have mentioned practices involving polygyny in the past, however, outright religious acceptance of such practices was not addressed until its rejection in later passages. They do explicitly prohibit polygyny today.

Polyandry

Polyandry is notably more rare than polygyny, though less rare than the figure commonly cited in the Ethnographic Atlas (1980) which listed only those polyandrous societies found in the Himalayan Mountains. More recent studies have found 53 societies outside the 28 found in the Himalayans which practice polyandry.[32] It is most common in egalitarian societies marked by high male mortality or male absenteeism. It is associated with partible paternity, the cultural belief that a child can have more than one father.[33]

The explanation for polyandry in the Himalayan Mountains is related to the scarcity of land; the marriage of all brothers in a family to the same wife (fraternal polyandry) allows family land to remain intact and undivided. If every brother married separately and had children, family land would be split into unsustainable small plots. In Europe, this was prevented through the social practice of impartible inheritance (the dis-inheriting of most siblings, some of whom went on to become celibate monks and priests).[34]

Plural marriage

Group marriage (also known as multi-lateral marriage) is a form of polyamory in which more than two persons form a family unit, with all the members of the group marriage being considered to be married to all the other members of the group marriage, and all members of the marriage share parental responsibility for any children arising from the marriage.[35] No country legally condones group marriages, neither under the law nor as a common law marriage, but historically it has been practiced by some cultures of Polynesia, Asia, Papua New Guinea and the Americas – as well as in some intentional communities and alternative subcultures such as the Oneida Perfectionists in up-state New York. Of the 250 societies reported by the American anthropologist George Murdock in 1949, only the Kaingang of Brazil had any group marriages at all.[36]

Child marriage

A child marriage is a marriage where one or both spouses are under the age of 18.[37][38] It is related to child betrothal and teenage pregnancy.

Child marriage was common throughout history, even up until the 1900s in the United States, where in 1880 CE, in the state of Delaware, the age of consent for marriage was 7 years old.[39] Still, in 2017, over half of the 50 United States have no explicit minimum age to marry and several states set the age as low as 14.[40] Today it is condemned by international human rights organizations.[41][42] Child marriages are often arranged between the families of the future bride and groom, sometimes as soon as the girl is born.[41] However, in the late 1800s in England and the United States, feminist activists began calling for raised age of consent laws, which was eventually handled in the 1920s, having been raised to 16–18.[43]

Child marriages can also occur in the context of bride kidnapping.[41]

In the year 1552 CE, John Somerford and Jane Somerford Brereton were both married at the ages of 3 and 2, respectively. Twelve years later, in 1564, John filed for divorce.[44]

While child marriage is observed for both boys and girls, the overwhelming majority of child spouses are girls.[45] In many cases, only one marriage-partner is a child, usually the female, due to the importance placed upon female virginity.[41] Causes of child marriage include poverty, bride price, dowry, laws that allow child marriages, religious and social pressures, regional customs, fear of remaining unmarried, and perceived inability of women to work for money.

Today, child marriages are widespread in parts of the world; being most common in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, with more than half of the girls in some countries in those regions being married before 18.[41] The incidence of child marriage has been falling in most parts of the world. In developed countries, child marriage is outlawed or restricted.

Girls who marry before 18 are at greater risk of becoming victims of domestic violence, than those who marry later, especially when they are married to a much older man.[42]

Same-sex and third-gender marriages

Several kinds of same-sex marriages have been documented in Indigenous and lineage-based cultures. In the Americas, We'wha (Zuni), was a lhamana (male individuals who, at least some of the time, dress and live in the roles usually filled by women in that culture); a respected artist, We'wha served as an emissary of the Zuni to Washington, where he met President Grover Cleveland.[46] We'wha had at least one husband who was generally recognized as such.[47]

While it is a relatively new practice to grant same-sex couples the same form of legal marital recognition as commonly granted to mixed-sex couples, there is some history of recorded same-sex unions around the world.[48] Ancient Greek same-sex relationships were like modern companionate marriages, unlike their different-sex marriages in which the spouses had few emotional ties, and the husband had freedom to engage in outside sexual liaisons. The Codex Theodosianus (C. Th. 9.7.3) issued in 438 CE imposed severe penalties or death on same-sex relationships,[49] but the exact intent of the law and its relation to social practice is unclear, as only a few examples of same-sex relationships in that culture exist.[50] Same-sex unions were celebrated in some regions of China, such as Fujian.[51] Possibly the earliest documented same-sex wedding in Latin Christendom occurred in Rome, Italy, at the San Giovanni a Porta Latina basilica in 1581.[52]

Temporary marriages

Several cultures have practised temporary and conditional marriages. Examples include the Celtic practice of handfasting and fixed-term marriages in the Muslim community. Pre-Islamic Arabs practiced a form of temporary marriage that carries on today in the practice of Nikah mut'ah, a fixed-term marriage contract. The Islamic prophet Muhammad sanctioned a temporary marriage – sigheh in Iran and muta'a in Iraq – which can provide a legitimizing cover for sex workers.[53] The same forms of temporary marriage have been used in Egypt, Lebanon and Iran to make the donation of a human ova legal for in vitro fertilisation; a woman cannot, however, use this kind of marriage to obtain a sperm donation.[54] Muslim controversies related to Nikah Mut'ah have resulted in the practice being confined mostly to Shi'ite communities. The matrilineal Mosuo of China practice what they call "walking marriage".

Cohabitation

In some jurisdictions cohabitation, in certain circumstances, may constitute a common-law marriage, an unregistered partnership, or otherwise provide the unmarried partners with various rights and responsibilities; and in some countries, the laws recognize cohabitation in lieu of institutional marriage for taxation and social security benefits. This is the case, for example, in Australia.[55] Cohabitation may be an option pursued as a form of resistance to traditional institutionalized marriage. However, in this context, some nations reserve the right to define the relationship as marital, or otherwise to regulate the relation, even if the relation has not been registered with the state or a religious institution.[56]

Conversely, institutionalized marriages may not involve cohabitation. In some cases, couples living together do not wish to be recognized as married. This may occur because pension or alimony rights are adversely affected; because of taxation considerations; because of immigration issues, or for other reasons. Such marriages have also been increasingly common in Beijing. Guo Jianmei, director of the center for women's studies at Beijing University, told a Newsday correspondent, "Walking marriages reflect sweeping changes in Chinese society." A "walking marriage" refers to a type of temporary marriage formed by the Mosuo of China, in which male partners live elsewhere and make nightly visits.[57] A similar arrangement in Saudi Arabia, called misyar marriage, also involves the husband and wife living separately but meeting regularly.[58]

Partner selection

There is wide cross-cultural variation in the social rules governing the selection of a partner for marriage. There is variation in the degree to which partner selection is an individual decision by the partners or a collective decision by the partners' kin groups, and there is variation in the rules regulating which partners are valid choices.

The United Nations World Fertility Report of 2003 reports that 89% of all people get married before age forty-nine.[60] The percent of women and men who marry before age forty-nine drops to nearly 50% in some nations and reaches near 100% in other nations.[61]

In other cultures with less strict rules governing the groups from which a partner can be chosen the selection of a marriage partner may involve either the couple going through a selection process of courtship or the marriage may be arranged by the couple's parents or an outside party, a matchmaker.

Age difference

Some people want to marry a person that is older or younger than they. This may impact marital stability[62] and partners with more than a 10-year gap in age tend to experience social disapproval[63] In addition, older women (older than 35) have increased health risks when getting pregnant.[64]

Social status and wealth

Some people want to marry a person with higher or lower status than them. Others want to marry people who have similar status. In many societies, women marry men who are of higher social status.[65] There are marriages where each party has sought a partner of similar status. There are other marriages in which the man is older than the woman.[66]

Some persons also wish to engage in transactional relationship for money rather than love (thus a type of marriage of convenience). Such people are sometimes referred to as gold diggers. Separate property systems can however be used to prevent property of being passed on to partners after divorce or death.

Higher income men are more likely to marry and less likely to divorce. High income women are more likely to divorce.[67]

The incest taboo, exogamy and endogamy

Societies have often placed restrictions on marriage to relatives, though the degree of prohibited relationship varies widely. Marriages between parents and children, or between full siblings, with few exceptions,[68][69][70][71][72][73][74] have been considered incest and forbidden. However, marriages between more distant relatives have been much more common, with one estimate being that 80% of all marriages in history have been between second cousins or closer.[75] This proportion has fallen dramatically, but still, more than 10% of all marriages are believed to be between people who are second cousins or more closely related.[76] In the United States, such marriages are now highly stigmatized, and laws ban most or all first-cousin marriage in 30 states. Specifics vary: in South Korea, historically it was illegal to marry someone with the same last name and same ancestral line.[77]

An Avunculate marriage is a marriage that occurs between an uncle and his niece or between an aunt and her nephew. Such marriages are illegal in most countries due to incest restrictions. However, a small number of countries have legalized it, including Argentina, Australia, Austria, Malaysia,[78] and Russia.[79]

In various societies, the choice of partner is often limited to suitable persons from specific social groups. In some societies the rule is that a partner is selected from an individual's own social group – endogamy, this is often the case in class- and caste-based societies. But in other societies a partner must be chosen from a different group than one's own – exogamy, this may be the case in societies practicing totemic religion where society is divided into several exogamous totemic clans, such as most Aboriginal Australian societies. In other societies a person is expected to marry their cross-cousin, a woman must marry her father's sister's son and a man must marry his mother's brother's daughter – this is often the case if either a society has a rule of tracing kinship exclusively through patrilineal or matrilineal descent groups as among the Akan people of West Africa. Another kind of marriage selection is the levirate marriage in which widows are obligated to marry their husband's brother, mostly found in societies where kinship is based on endogamous clan groups.

Religion has commonly weighed in on the matter of which relatives, if any, are allowed to marry. Relations may be by consanguinity or affinity, meaning by blood or by marriage. On the marriage of cousins, Catholic policy has evolved from initial acceptance, through a long period of general prohibition, to the contemporary requirement for a dispensation.[80] Islam has always allowed it, while Hindu texts vary widely.[81][82]

Prescriptive marriage

In a wide array of lineage-based societies with a classificatory kinship system, potential spouses are sought from a specific class of relative as determined by a prescriptive marriage rule. This rule may be expressed by anthropologists using a "descriptive" kinship term, such as a "man's mother's brother's daughter" (also known as a "cross-cousin"). Such descriptive rules mask the participant's perspective: a man should marry a woman from his mother's lineage. Within the society's kinship terminology, such relatives are usually indicated by a specific term which sets them apart as potentially marriageable. Pierre Bourdieu notes, however, that very few marriages ever follow the rule, and that when they do so, it is for "practical kinship" reasons such as the preservation of family property, rather than the "official kinship" ideology.[83]

Insofar as regular marriages following prescriptive rules occur, lineages are linked together in fixed relationships; these ties between lineages may form political alliances in kinship dominated societies.[84] French structural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss developed alliance theory to account for the "elementary" kinship structures created by the limited number of prescriptive marriage rules possible.[85]

A pragmatic (or 'arranged') marriage is made easier by formal procedures of family or group politics. A responsible authority sets up or encourages the marriage; they may, indeed, engage a professional matchmaker to find a suitable spouse for an unmarried person. The authority figure could be parents, family, a religious official, or a group consensus. In some cases, the authority figure may choose a match for purposes other than marital harmony.[86]

Forced marriage

A forced marriage is a marriage in which one or both of the parties is married against their will. Forced marriages continue to be practiced in parts of the world, especially in South Asia and Africa. The line between forced marriage and consensual marriage may become blurred, because the social norms of these cultures dictate that one should never oppose the desire of one's parents/relatives in regard to the choice of a spouse; in such cultures, it is not necessary for violence, threats, intimidation etc. to occur, the person simply "consents" to the marriage even if they do not want it, out of the implied social pressure and duty. The customs of bride price and dowry, that exist in parts of the world, can lead to buying and selling people into marriage.[87][88]

In some societies, ranging from Central Asia to the Caucasus to Africa, the custom of bride kidnapping still exists, in which a woman is captured by a man and his friends. Sometimes this covers an elopement, but sometimes it depends on sexual violence. In previous times, raptio was a larger-scale version of this, with groups of women captured by groups of men, sometimes in war; the most famous example is The Rape of the Sabine Women, which provided the first citizens of Rome with their wives.

Other marriage partners are more or less imposed on an individual. For example, widow inheritance provides a widow with another man from her late husband's brothers.

In rural areas of India, child marriage is practiced, with parents often arranging the wedding, sometimes even before the child is born.[89] This practice was made illegal under the Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929.

Economic considerations

The financial aspects of marriage vary between cultures and have changed over time.

In some cultures, dowries and bride wealth continue to be required today. In both cases, the financial arrangements are usually made between the groom (or his family) and the bride's family; with the bride often not being involved in the negotiations, and often not having a choice in whether to participate in the marriage.

In Early modern Britain, the social status of the couple was supposed to be equal. After the marriage, all the property (called "fortune") and expected inheritances of the wife belonged to the husband.

Dowry

A dowry is "a process whereby parental property is distributed to a daughter at her marriage (i.e. inter vivos) rather than at the holder's death (mortis causa)… A dowry establishes some variety of conjugal fund, the nature of which may vary widely. This fund ensures her support (or endowment) in widowhood and eventually goes to provide for her sons and daughters."[90]

In some cultures, especially in countries such as Turkey, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Morocco, Nepal, dowries continue to be expected. In India, thousands of dowry-related deaths have taken place on yearly basis,[91][92] to counter this problem, several jurisdictions have enacted laws restricting or banning dowry (see Dowry law in India). In Nepal, dowry was made illegal in 2009.[93] Some authors believe that the giving and receiving of dowry reflects the status and even the effort to climb high in social hierarchy.[94]

Dower

Direct Dowry contrasts with bride wealth, which is paid by the groom or his family to the bride's parents, and with indirect dowry (or dower), which is property given to the bride herself by the groom at the time of marriage and which remains under her ownership and control.[95]

In the Jewish tradition, the rabbis in ancient times insisted on the marriage couple entering into a prenuptial agreement, called a ketubah. Besides other things, the ketubah provided for an amount to be paid by the husband in the event of a divorce or his estate in the event of his death. This amount was a replacement of the biblical dower or bride price, which was payable at the time of the marriage by the groom to the father of the bride.[96] This innovation was put in place because the biblical bride price created a major social problem: many young prospective husbands could not raise the bride price at the time when they would normally be expected to marry. So, to enable these young men to marry, the rabbis, in effect, delayed the time that the amount would be payable, when they would be more likely to have the sum. It may also be noted that both the dower and the ketubah amounts served the same purpose: the protection for the wife should her support cease, either by death or divorce. The only difference between the two systems was the timing of the payment. It is the predecessor to the wife's present-day entitlement to maintenance in the event of the breakup of marriage, and family maintenance in the event of the husband not providing adequately for the wife in his will. Another function performed by the ketubah amount was to provide a disincentive for the husband contemplating divorcing his wife: he would need to have the amount to be able to pay to the wife.

Morning gifts, which might also be arranged by the bride's father rather than the bride, are given to the bride herself; the name derives from the Germanic tribal custom of giving them the morning after the wedding night. She might have control of this morning gift during the lifetime of her husband, but is entitled to it when widowed. If the amount of her inheritance is settled by law rather than agreement, it may be called dower. Depending on legal systems and the exact arrangement, she may not be entitled to dispose of it after her death, and may lose the property if she remarries. Morning gifts were preserved for centuries in morganatic marriage, a union where the wife's inferior social status was held to prohibit her children from inheriting a noble's titles or estates. In this case, the morning gift would support the wife and children. Another legal provision for widowhood was jointure, in which property, often land, would be held in joint tenancy, so that it would automatically go to the widow on her husband's death.

Islamic tradition has similar practices. A 'mahr', either immediate or deferred, is the woman's portion of the groom's wealth (divorce) or estate (death). These amounts are usually set on the basis of the groom's own and family wealth and incomes, but in some parts these are set very high so as to provide a disincentive for the groom exercising the divorce, or the husband's family 'inheriting' a large portion of the estate, especially if there are no male offspring from the marriage. In some countries, including Iran, the mahr or alimony can amount to more than a man can ever hope to earn, sometimes up to US$1,000,000 (4000 official Iranian gold coins). If the husband cannot pay the mahr, either in case of a divorce or on demand, according to the current laws in Iran, he will have to pay it by installments. Failure to pay the mahr might even lead to imprisonment.[97]

Bridewealth

Bridewealth is a common practice in parts of Southeast Asia (Thailand, Cambodia), parts of Central Asia, and in much of sub-Saharan Africa. It is also known as brideprice although this has fallen in disfavor as it implies the purchase of the bride. Bridewealth is the amount of money or property or wealth paid by the groom or his family to the parents of a woman upon the marriage of their daughter to the groom. In anthropological literature, bride price has often been explained as payment made to compensate the bride's family for the loss of her labor and fertility. In some cases, bridewealth is a means by which the groom's family's ties to the children of the union are recognized.

Taxation

In some countries a married person or couple benefits from various taxation advantages not available to a single person. For example, spouses may be allowed to average their combined incomes. This is advantageous to a married couple with disparate incomes. To compensate for this, countries may provide a higher tax bracket for the averaged income of a married couple. While income averaging might still benefit a married couple with a stay-at-home spouse, such averaging would cause a married couple with roughly equal personal incomes to pay more total tax than they would as two single persons. In the United States, this is called the marriage penalty.[98]

When the rates applied by the tax code are not based income averaging, but rather on the sum of individuals' incomes, higher rates will usually apply to each individual in a two-earner households in a progressive tax systems. This is most often the case with high-income taxpayers and is another situation called a marriage penalty.[99]

Conversely, when progressive tax is levied on the individual with no consideration for the partnership, dual-income couples fare much better than single-income couples with similar household incomes. The effect can be increased when the welfare system treats the same income as a shared income thereby denying welfare access to the non-earning spouse. Such systems apply in Australia and Canada, for example.[100]

Post-marital residence

In many Western cultures, marriage usually leads to the formation of a new household comprising the married couple, with the married couple living together in the same home, often sharing the same bed, but in some other cultures this is not the tradition.[101] Among the Minangkabau of West Sumatra, residency after marriage is matrilocal, with the husband moving into the household of his wife's mother.[102] Residency after marriage can also be patrilocal or avunculocal. In these cases, married couples may not form an independent household, but remain part of an extended family household.

Early theories explaining the determinants of postmarital residence[103] connected it with the sexual division of labor. However, to date, cross-cultural tests of this hypothesis using worldwide samples have failed to find any significant relationship between these two variables. However, Korotayev's tests show that the female contribution to subsistence does correlate significantly with matrilocal residence in general. However, this correlation is masked by a general polygyny factor.

Although, in different-sex marriages, an increase in the female contribution to subsistence tends to lead to matrilocal residence, it also tends simultaneously to lead to general non-sororal polygyny which effectively destroys matrilocality. If this polygyny factor is controlled (e.g., through a multiple regression model), division of labor turns out to be a significant predictor of postmarital residence. Thus, Murdock's hypotheses regarding the relationships between the sexual division of labor and postmarital residence were basically correct, though[104] the actual relationships between those two groups of variables are more complicated than he expected.[105][106]

There has been a trend toward the neolocal residence in western societies.[107]

Law

| Family law |

|---|

| Family |

Marriage laws refer to the legal requirements which determine the validity of a marriage, which vary considerably between countries. Article 16 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares that:

1. Men and women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion, have the right to marry and to found a family. They are entitled to equal rights as to marriage, during marriage and at its dissolution.

2. Marriage shall be entered into only with the free and full consent of the intending spouses.3. The family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.

Rights and obligations

A marriage bestows rights and obligations on the married parties, and sometimes on relatives as well, being the sole mechanism for the creation of affinal ties (in-laws). These may include, depending on jurisdiction:

- Giving one spouse or his/her family control over the other spouse's sexual services, labor, and property.

- Giving one spouse responsibility for the other's debts.

- Giving one spouse visitation rights when the other is incarcerated or hospitalized.

- Giving one spouse control over the other's affairs when the other is incapacitated.

- Establishing the second legal guardian of a parent's child.

- Establishing a joint fund of property for the benefit of children.

- Establishing a relationship between the families of the spouses.

These rights and obligations vary considerably between societies, and between groups within society.[108] These might include arranged marriages, family obligations, the legal establishment of a nuclear family unit, the legal protection of children and public declaration of commitment.[109][110]

Property regime

In many countries today, each marriage partner has the choice of keeping his or her property separate or combining properties. In the latter case, called community property, when the marriage ends by divorce each owns half. In lieu of a will or trust, property owned by the deceased generally is inherited by the surviving spouse.

In some legal systems, the partners in a marriage are "jointly liable" for the debts of the marriage. This has a basis in a traditional legal notion called the "Doctrine of Necessities" whereby, in a heterosexual marriage, a husband was responsible to provide necessary things for his wife. Where this is the case, one partner may be sued to collect a debt for which they did not expressly contract. Critics of this practice note that debt collection agencies can abuse this by claiming an unreasonably wide range of debts to be expenses of the marriage. The cost of defense and the burden of proof is then placed on the non-contracting party to prove that the expense is not a debt of the family. The respective maintenance obligations, both during and eventually after a marriage, are regulated in most jurisdictions; alimony is one such method.

Restrictions

Marriage is an institution that is historically filled with restrictions. From age, to race, to social status, to consanguinity, to gender, restrictions are placed on marriage by society for reasons of benefiting the children, passing on healthy genes, maintaining cultural values, or because of prejudice and fear. Almost all cultures that recognize marriage also recognize adultery as a violation of the terms of marriage.[111]

Age

Most jurisdictions set a minimum age for marriage; that is, a person must attain a certain age to be legally allowed to marry. This age may depend on circumstances, for instance exceptions from the general rule may be permitted if the parents of a young person express their consent and/or if a court decides that said marriage is in the best interest of the young person (often this applies in cases where a girl is pregnant). Although most age restrictions are in place in order to prevent children from being forced into marriages, especially to much older partners – marriages which can have negative education and health related consequences, and lead to child sexual abuse and other forms of violence[112] – such child marriages remain common in parts of the world. According to the UN, child marriages are most common in rural sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. The ten countries with the highest rates of child marriage are: Niger (75%), Chad, Central African Republic, Bangladesh, Guinea, Mozambique, Mali, Burkina Faso, South Sudan, and Malawi.[113]

Kinship

To prohibit incest and eugenic reasons, marriage laws have set restrictions for relatives to marry. Direct blood relatives are usually prohibited to marry, while for branch line relatives, laws are wary.[114][115]

Kinship relations through marriage is also called "affinity", relationships that arise in one's group of origin, can also be called one's descent group. Some cultures in kinship relationships may be considered to extend out to those who they have economic or political relationships with; or other forms of social connections. Within some cultures they may lead you back to gods[116] or animal ancestors (totems). This can be conceived of on a more or less literal basis.

Race

Laws banning "race-mixing" were enforced in certain North American jurisdictions from 1691[117] until 1967, in Nazi Germany (the Nuremberg Laws) from 1935 until 1945, and in South Africa during most part of the apartheid era (1949–1985). All these laws primarily banned marriage between persons of different racially or ethnically defined groups, which was termed "amalgamation" or "miscegenation" in the U.S. The laws in Nazi Germany and many of the U.S. states, as well as South Africa, also banned sexual relations between such individuals.

In the United States, laws in some but not all of the states prohibited the marriage of whites and blacks, and in many states also the intermarriage of whites with Native Americans or Asians.[118] In the U.S., such laws were known as anti-miscegenation laws. From 1913 until 1948, 30 out of the then 48 states enforced such laws.[119] Although an "Anti-Miscegenation Amendment" to the United States Constitution was proposed in 1871, in 1912–1913, and in 1928,[120][121] no nationwide law against racially mixed marriages was ever enacted. In 1967, the Supreme Court of the United States unanimously ruled in Loving v. Virginia that anti-miscegenation laws are unconstitutional. With this ruling, these laws were no longer in effect in the remaining 16 states that still had them.

The Nazi ban on interracial marriage and interracial sex was enacted in September 1935 as part of the Nuremberg Laws, the Gesetz zum Schutze des deutschen Blutes und der deutschen Ehre (The Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour). The Nuremberg Laws classified Jews as a race and forbade marriage and extramarital sexual relations at first with people of Jewish descent, but was later ended to the "Gypsies, Negroes or their bastard offspring" and people of "German or related blood".[122] Such relations were marked as Rassenschande (lit. "race-disgrace") and could be punished by imprisonment (usually followed by deportation to a concentration camp) and even by death.

South Africa under apartheid also banned interracial marriage. The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act, 1949 prohibited marriage between persons of different races, and the Immorality Act of 1950 made sexual relations with a person of a different race a crime.

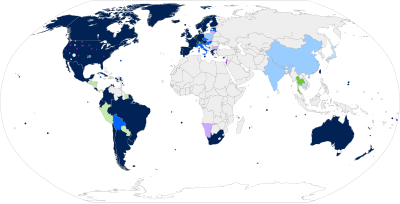

Sex

Same-sex marriage is legally performed and recognized in countries such as Andorra, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Denmark, Ecuador, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, the Netherlands,[a] New Zealand,[b] Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, the United Kingdom,[c] the United States,[d] and Uruguay. Israel recognizes same-sex marriages entered into abroad as full marriages.

The introduction of same-sex marriage has varied by jurisdiction, being variously accomplished through legislative change to marriage law, a court ruling based on constitutional guarantees of equality, or by direct popular vote (via ballot initiative or referendum). The recognition of same-sex marriage is considered to be a human right and a civil right as well as a political, social, and religious issue.[123] The most prominent supporters of same-sex marriage are human rights and civil rights organizations as well as the medical and scientific communities, while the most prominent opponents are religious groups. Various faith communities around the world support same-sex marriage, while many religious groups oppose it. Polls consistently show continually rising support for the recognition of same-sex marriage in all developed democracies and in some developing democracies.[124]

The establishment of recognition in law for the marriages of same-sex couples is one of the most prominent objectives of the LGBT rights movement.

Number of spouses

- In India, Malaysia, Philippines and Singapore polygamy is only legal for Muslims.

- In Nigeria and South Africa, polygamous marriages under customary law and for Muslims are legally recognized.

- In Mauritius, polygamous unions have no legal recognition. Muslim men may, however, "marry" up to four women, but they do not have the legal status of wives.

Polygyny is widely practiced in mostly Muslim and African countries.[125][126] In the Middle Eastern region, Israel, Turkey and Tunisia are notable exceptions.[127]

In most other jurisdictions, polygamy is illegal. For example, In the United States, polygamy is illegal in all 50 states.[128]

In the late-19th century, citizens of the self-governing territory of what is present-day Utah were forced by the United States federal government to abandon the practice of polygamy through the vigorous enforcement of several Acts of Congress, and eventually complied. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints formally abolished the practice in 1890, in a document labeled 'The Manifesto' (see Latter Day Saint polygamy in the late-19th century).[129] Among American Muslims, a small minority of around 50,000 to 100,000 people are estimated to live in families with a husband maintaining an illegal polygamous relationship.[128]

Several countries such as India and Sri Lanka,[130] permit only their Islamic citizens to practice polygamy. Some Indians have converted to Islam in order to bypass such legal restrictions.[131] Predominantly Christian nations usually do not allow polygamous unions, with a handful of exceptions being the Republic of the Congo, Uganda, and Zambia.

State recognition

When a marriage is performed and carried out by a government institution in accordance with the marriage laws of the jurisdiction, without religious content, it is a civil marriage. Civil marriage recognizes and creates the rights and obligations intrinsic to matrimony in the eyes of the state. Some countries do not recognize locally performed religious marriage on its own, and require a separate civil marriage for official purposes. Conversely, civil marriage does not exist in some countries governed by a religious legal system, such as Saudi Arabia, where marriages contracted abroad might not be recognized if they were contracted contrary to Saudi interpretations of Islamic religious law. In countries governed by a mixed secular-religious legal system, such as Lebanon and Israel, locally performed civil marriage does not exist within the country, which prevents interfaith and various other marriages that contradict religious laws from being entered into in the country; however, civil marriages performed abroad may be recognized by the state even if they conflict with religious laws. For example, in the case of recognition of marriage in Israel, this includes recognition of not only interfaith civil marriages performed abroad, but also overseas same-sex civil marriages.

In various jurisdictions, a civil marriage may take place as part of the religious marriage ceremony, although they are theoretically distinct. Some jurisdictions allow civil marriages in circumstances which are notably not allowed by particular religions, such as same-sex marriages or civil unions.

The opposite case may happen as well. Partners may not have full juridical acting capacity and churches may have less strict limits than the civil jurisdictions. This particularly applies to minimum age, or physical infirmities.[citation needed]

It is possible for two people to be recognized as married by a religious or other institution, but not by the state, and hence without the legal rights and obligations of marriage; or to have a civil marriage deemed invalid and sinful by a religion. Similarly, a couple may remain married in religious eyes after a civil divorce.

Most sovereign states and other jurisdictions limit legally recognized marriage to opposite-sex couples and a diminishing number of these permit polygyny marriage, polyandry marriage, group marriage, coverture marriage, arranged marriages, forced marriages, child marriages, cousin marriages, sibling marriages, teenage marriages, avunculate marriages, incestuous marriages, and bestiality marriages. In modern times, a growing number of countries, primarily developed democracies, have lifted bans on, and have established legal recognition for, equal rights for women and the marriages of interethnic, interracial, interfaith, interdenominational, interclass, intercommunity, transnational, and same-sex couples as well as immigrant couples, couples with an immigrant spouse, and other minority couples. In some areas, child marriages and polygamy may occur in spite of national laws against the practice.

Marriage license, civil ceremony and registration

A marriage is usually formalized at a wedding or marriage ceremony. The ceremony may be officiated either by a religious official, by a government official or by a state approved celebrant. In various European and Latin American countries, any religious ceremony must be held separately from the required civil ceremony. Some countries – such as Belgium, Bulgaria, France, the Netherlands, Romania and Turkey[132] – require that a civil ceremony take place before any religious one. In some countries – notably the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Norway, and Spain – both ceremonies can be held together; the officiant at the religious and civil ceremony also serving as agent of the state to perform the civil ceremony. To avoid any implication that the state is "recognizing" a religious marriage (which is prohibited in some countries) – the "civil" ceremony is said to be taking place at the same time as the religious ceremony. Often this involves simply signing a register during the religious ceremony. If the civil element of the religious ceremony is omitted, the marriage ceremony is not recognized as a marriage by government under the law.

Some countries, such as Australia, permit marriages to be held in private and at any location; others, including England and Wales, require that the civil ceremony be conducted in a place open to the public and specially sanctioned by law for the purpose. In England, the place of marriage formerly had to be a church or register office, but this was extended to any public venue with the necessary licence. An exception can be made in the case of marriage by special emergency license (UK: licence), which is normally granted only when one of the parties is terminally ill. Rules about where and when persons can marry vary from place to place. Some regulations require one of the parties to reside within the jurisdiction of the register office (formerly parish).

Each religious authority has rules for the manner in which marriages are to be conducted by their officials and members. Where religious marriages are recognised by the state, the officiator must also conform with the law of the jurisdiction.

Common-law marriage

In a small number of jurisdictions marriage relationships may be created by the operation of the law alone.[133] Unlike the typical ceremonial marriage with legal contract, wedding ceremony, and other details, a common-law marriage may be called "marriage by habit and repute (cohabitation)." A de facto common-law marriage without a license or ceremony is legally binding in some jurisdictions but has no legal consequence in others.[133]

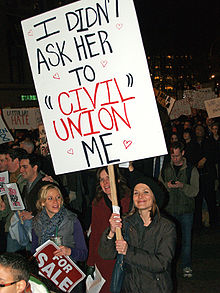

Civil unions

A civil union, also referred to as a civil partnership, is a legally recognized form of partnership similar to marriage. Beginning with Denmark in 1989, civil unions under one name or another have been established by law in several countries in order to provide same-sex couples rights, benefits, and responsibilities similar (in some countries, identical) to opposite-sex civil marriage. In some jurisdictions, such as Brazil, New Zealand, Uruguay, Ecuador, France and the U.S. states of Hawaii and Illinois, civil unions are also open to opposite-sex couples.

"Marriage of convenience"

Sometimes people marry to take advantage of a certain situation, sometimes called a marriage of convenience or a sham marriage. In 2003, over 180,000 immigrants were admitted to the U.S. as spouses of U.S. citizens;[135] more were admitted as fiancés of US citizens for the purpose of being married within 90 days. These marriages had a diverse range of motives, including obtaining permanent residency, securing an inheritance that has a marriage clause, or to enroll in health insurance, among many others. While all marriages have a complex combination of conveniences motivating the parties to marry, a marriage of convenience is one that is devoid of normal reasons to marry. In certain countries like Singapore sham marriages are punishable criminal offences.[136]

Contemporary legal and human rights criticisms of marriage

People have proposed arguments against marriage for reasons that include political, philosophical and religious criticisms; concerns about the divorce rate; individual liberty and gender equality; questioning the necessity of having a personal relationship sanctioned by government or religious authorities; or the promotion of celibacy for religious or philosophical reasons. Research has found that unhappily married couples are at 3–25 times the risk of developing clinical depression.[137][138][139]

Power and gender roles

Historically, in most cultures, married women had very few rights of their own, being considered, along with the family's children, the property of the husband; as such, they could not own or inherit property, or represent themselves legally (see, for example, coverture). Since the late 19th century, in some (primarily Western) countries, marriage has undergone gradual legal changes, aimed at improving the rights of the wife. These changes included giving wives legal identities of their own, abolishing the right of husbands to physically discipline their wives, giving wives property rights, liberalizing divorce laws, providing wives with reproductive rights of their own, and requiring a wife's consent when sexual relations occur. In the 21st century, there continue to be controversies regarding the legal status of married women, legal acceptance of or leniency towards violence within marriage (especially sexual violence), traditional marriage customs such as dowry and bride price, forced marriage, marriageable age, and criminalization of consensual behaviors such as premarital and extramarital sex.

Feminist theory approaches opposite-sex marriage as an institution traditionally rooted in patriarchy that promotes male superiority and power over women. This power dynamic conceptualizes men as "the provider operating in the public sphere" and women as "the caregivers operating within the private sphere".[141] "Theoretically, women ... [were] defined as the property of their husbands .... The adultery of a woman was always treated with more severity than that of a man."[142] "[F]eminist demands for a wife's control over her own property were not met [in parts of Britain] until ... [laws were passed in the late 19th century]."[143]

Traditional heterosexual marriage imposed an obligation of the wife to be sexually available for her husband and an obligation of the husband to provide material/financial support for the wife. Numerous philosophers, feminists and other academic figures have commented on this throughout history, condemning the hypocrisy of legal and religious authorities in regard to sexual issues; pointing to the lack of choice of a woman in regard to controlling her own sexuality; and drawing parallels between marriage, an institution promoted as sacred, and prostitution, widely condemned and vilified (though often tolerated as a "necessary evil"). Mary Wollstonecraft, in the 18th century, described marriage as "legal prostitution".[144] Emma Goldman wrote in 1910: "To the moralist prostitution does not consist so much in the fact that the woman sells her body, but rather that she sells it out of wedlock".[145] Bertrand Russell in his book Marriage and Morals wrote that: "Marriage is for woman the commonest mode of livelihood, and the total amount of undesired sex endured by women is probably greater in marriage than in prostitution."[146] Angela Carter in Nights at the Circus wrote: "What is marriage but prostitution to one man instead of many?"[147]

Some critics object to what they see as propaganda in relation to marriage – from the government, religious organizations, the media – which aggressively promote marriage as a solution for all social problems; such propaganda includes, for instance, marriage promotion in schools, where children, especially girls, are bombarded with positive information about marriage, being presented only with the information prepared by authorities.[148][149]

The performance of dominant gender roles by men and submissive gender roles by women influence the power dynamic of a heterosexual marriage.[150] In some American households, women internalize gender role stereotypes and often assimilate into the role of "wife", "mother", and "caretaker" in conformity to societal norms and their male partner. Author bell hooks states "within the family structure, individuals learn to accept sexist oppression as 'natural' and are primed to support other forms of oppression, including heterosexist domination."[151] "[T]he cultural, economic, political and legal supremacy of the husband" was "[t]raditional ... under English law".[152] This patriarchal dynamic is contrasted with a conception of egalitarian or peer marriage in which power and labour are divided equally, and not according to gender roles.[141]

In the US, studies have shown that, despite egalitarian ideals being common, less than half of respondents viewed their opposite-sex relationships as equal in power, with unequal relationships being more commonly dominated by the male partner.[153] Studies also show that married couples find the highest level of satisfaction in egalitarian relationships and lowest levels of satisfaction in wife dominate relationships.[153] In recent years, egalitarian or peer marriages have been receiving increasing focus and attention politically, economically and culturally in a number of countries, including the United States.

Extra-marital sex

Different societies demonstrate variable tolerance of extramarital sex. The Standard Cross-Cultural Sample describes the occurrence of extramarital sex by gender in over 50 pre-industrial cultures.[155][156] The occurrence of extramarital sex by men is described as "universal" in 6 cultures, "moderate" in 29 cultures, "occasional" in 6 cultures, and "uncommon" in 10 cultures. The occurrence of extramarital sex by women is described as "universal" in 6 cultures, "moderate" in 23 cultures, "occasional" in 9 cultures, and "uncommon" in 15 cultures. Three studies using nationally representative samples in the United States found that between 10 and 15% of women and 20–25% of men engage in extramarital sex.[157][158][159]

Many of the world's major religions look with disfavor on sexual relations outside marriage.[160] In some non-secular Islamic countries, there are criminal penalties for sexual intercourse before marriage.[161] Sexual relations by a married person with someone other than his/her spouse is known as adultery. Adultery is considered in many jurisdictions to be a crime and grounds for divorce.

In some countries, such as Saudi Arabia, Pakistan,[162] Afghanistan,[163][164] Iran,[164] Kuwait,[165] Maldives,[166] Morocco,[167] Oman,[168] Mauritania,[169] United Arab Emirates,[170][171] Sudan,[172] Yemen,[173] any form of sexual activity outside marriage is illegal.

In some parts of the world, women and girls accused of having sexual relations outside marriage are at risk of becoming victims of honor killings committed by their families.[174][175] In 2011 several people were sentenced to death by stoning after being accused of adultery in Iran, Somalia, Afghanistan, Sudan, Mali and Pakistan.[176][177][178][179][180][181][182][183][184] Practices such as honor killings and stoning continue to be supported by mainstream politicians and other officials in some countries. In Pakistan, after the 2008 Balochistan honour killings in which five women were killed by tribesmen of the Umrani Tribe of Balochistan, Pakistani Federal Minister for Postal Services Israr Ullah Zehri defended the practice; he said:[185] "These are centuries-old traditions, and I will continue to defend them. Only those who indulge in immoral acts should be afraid."[186]

Sexual violence

An issue that is a serious concern regarding marriage and which has been the object of international scrutiny is that of sexual violence within marriage. Throughout much of the history, in most cultures, sex in marriage was considered a 'right', that could be taken by force (often by a man from a woman), if 'denied'. As the concept of human rights started to develop in the 20th century, and with the arrival of second-wave feminism, such views, and laws, have become less widely held.[187]

The legal and social concept of marital rape has developed in most industrialized countries in the mid- to late 20th century; in many other parts of the world it is not recognized as a form of abuse, socially or legally. Several countries in Eastern Europe and Scandinavia made marital rape illegal before 1970, and other countries in Western Europe and the English-speaking Western world outlawed it in the 1980s and 1990s. In England and Wales, marital rape was made illegal in 1991. Although marital rape is being increasingly criminalized in developing countries too, cultural, religious, and traditional ideologies about "conjugal rights" remain very strong in many parts of the world; and even where countries may have adequate laws against rape in marriage, these laws may rarely be enforced.[188]

Apart from the issue of rape committed against one's spouse, marriage is, in many parts of the world, closely connected with other forms of sexual violence: in some places, like Morocco, unmarried girls and women who are raped are often forced by their families to marry their rapist. Because being the victim of rape and losing virginity carry extreme social stigma, and the victims are deemed to have their "reputation" tarnished, a marriage with the rapist is arranged. This is claimed to be in the advantage of both the victim – who does not remain unmarried and does not lose social status – and of the rapist, who avoids punishment. In 2012, after a Moroccan 16-year-old girl committed suicide after having been forced by her family to marry her rapist and enduring further abuse by the rapist after they married, there have been protests from activists against this practice which is common in Morocco.[189]

In some societies, the very high social and religious importance of marital fidelity, especially female fidelity, has as result the criminalization of adultery, often with harsh penalties such as stoning or flogging; as well as leniency towards punishment of violence related to infidelity (such as honor killings).[190] In the 21st century, criminal laws against adultery have become controversial with international organizations calling for their abolition.[191][192] Opponents of adultery laws argue that these laws are a major contributor to discrimination and violence against women, as they are enforced selectively mostly against women; that they prevent women from reporting sexual violence; and that they maintain social norms which justify violent crimes committed against women by husbands, families and communities. A Joint Statement by the United Nations Working Group on discrimination against women in law and in practice states that "Adultery as a criminal offence violates women's human rights".[192] Some human rights organizations argue that the criminalization of adultery also violates internationally recognized protections for private life, as it represents an arbitrary interference with an individual's privacy, which is not permitted under international law.[193]

Laws, human rights and gender status

The laws surrounding heterosexual marriage in many countries have come under international scrutiny because they contradict international standards of human rights; institutionalize violence against women, child marriage and forced marriage; require the permission of a husband for his wife to work in a paid job, sign legal documents, file criminal charges against someone, sue in civil court etc.; sanction the use by husbands of violence to "discipline" their wives; and discriminate against women in divorce.[194][195][196]

Such things were legal even in many Western countries until recently: for instance, in France, married women obtained the right to work without their husband's permission in 1965,[197][198][199] and in West Germany women obtained this right in 1977 (by comparison women in East Germany had many more rights).[200][201] In Spain, during Franco's era, a married woman needed her husband's consent, referred to as the permiso marital, for almost all economic activities, including employment, ownership of property, and even traveling away from home; the permiso marital was abolished in 1975.[202]

An absolute submission of a wife to her husband is accepted as natural in many parts of the world, for instance surveys by UNICEF have shown that the percentage of women aged 15–49 who think that a husband is justified in hitting or beating his wife under certain circumstances is as high as 90% in Afghanistan and Jordan, 87% in Mali, 86% in Guinea and Timor-Leste, 81% in Laos, 80% in Central African Republic.[203] Detailed results from Afghanistan show that 78% of women agree with a beating if the wife "goes out without telling him [the husband]" and 76% agree "if she argues with him".[204]

Throughout history, and still today in many countries, laws have provided for extenuating circumstances, partial or complete defenses, for men who killed their wives due to adultery, with such acts often being seen as crimes of passion and being covered by legal defenses such as provocation or defense of family honor.[205]

Right and ability to divorce

While international law and conventions recognize the need for consent for entering a marriage – namely that people cannot be forced to get married against their will – the right to obtain a divorce is not recognized; therefore holding a person in a marriage against their will (if such person has consented to entering in it) is not considered a violation of human rights, with the issue of divorce being left at the appreciation of individual states.[206]

In the EU, the last country to allow divorce was Malta, in 2011. Around the world, the only countries to forbid divorce are Philippines and Vatican City,[207] although in practice in many countries which use a fault-based divorce system obtaining a divorce is very difficult. The ability to divorce, in law and practice, has been and continues to be a controversial issue in many countries, and public discourse involves different ideologies such as feminism, social conservatism, religious interpretations.[208]

Dowry and bridewealth

In recent years, the customs of dowry and bride price have received international criticism for inciting conflicts between families and clans; contributing to violence against women; promoting materialism; increasing property crimes (where men steal goods such as cattle in order to be able to pay the bride price); and making it difficult for poor people to marry. African women's rights campaigners advocate the abolishing of bride price, which they argue is based on the idea that women are a form of property which can be bought.[209] Bride price has also been criticized for contributing to child trafficking as impoverished parents sell their young daughters to rich older men.[210] A senior Papua New Guinea police officer has called for the abolishing of bride price arguing that it is one of the main reasons for the mistreatment of women in that country.[211] The opposite practice of dowry has been linked to a high level of violence (see Dowry death) and to crimes such as extortion.[212]

Children born outside marriage

Historically, and still in many countries, children born outside marriage suffered severe social stigma and discrimination. In England and Wales, such children were known as bastards and whoresons.

There are significant differences between world regions in regard to the social and legal position of non-marital births, ranging from being fully accepted and uncontroversial to being severely stigmatized and discriminated.[214][215]

The 1975 European Convention on the Legal Status of Children Born out of Wedlock protects the rights of children born to unmarried parents.[216] The convention states, among others, that: "The father and mother of a child born out of wedlock shall have the same obligation to maintain the child as if it were born in wedlock" and that "A child born out of wedlock shall have the same right of succession in the estate of its father and its mother and of a member of its father's or mother's family, as if it had been born in wedlock."[217]

While in most Western countries legal inequalities between children born inside and outside marriage have largely been abolished, this is not the case in some parts of the world.

The legal status of an unmarried father differs greatly from country to country. Without voluntary formal recognition of the child by the father, in most cases there is a need of due process of law in order to establish paternity. In some countries however, unmarried cohabitation of a couple for a specific period of time does create a presumption of paternity similar to that of formal marriage. This is the case in Australia.[218] Under what circumstances can a paternity action be initiated, the rights and responsibilities of a father once paternity has been established (whether he can obtain parental responsibility and whether he can be forced to support the child) as well as the legal position of a father who voluntarily acknowledges the child, vary widely by jurisdiction. A special situation arises when a married woman has a child by a man other than her husband. Some countries, such as Israel, refuse to accept a legal challenge of paternity in such a circumstance, in order to avoid the stigmatization of the child (see Mamzer, a concept under Jewish law). In 2010, the European Court of Human Rights ruled in favor of a German man who had fathered twins with a married woman, granting him right of contact with the twins, despite the fact that the mother and her husband had forbidden him to see the children.[219]