Эдинбург

Edinburgh

Dùn Èideann | |

|---|---|

| City of Edinburgh | |

Skyline of Central Edinburgh, with the Dugald Stewart Monument (forefront) and Edinburgh Castle (background) | |

|

| |

| Nicknames: "Auld Reekie", "Edina", "Athens of the North" | |

| Motto(s): | |

Edinburgh locality within the City of Edinburgh council area | |

| Coordinates: 55°57′12″N 03°11′21″W / 55.95333°N 3.18917°W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | City of Edinburgh |

| Lieutenancy area | Edinburgh |

| Founded | Before 7th century AD |

| Burgh Charter | 1124 |

| City status | 1633[3] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Unitary authority |

| • Governing body | The City of Edinburgh Council |

| • Lord Provost of Edinburgh | Robert Aldridge |

| • MSPs |

|

| • MPs |

|

| Area | |

| • Locality | 46 sq mi (119 km2) |

| • Urban | 49 sq mi (126 km2) |

| • Council area[6] | 102 sq mi (263 km2) |

| Elevation | 154 ft (47 m) |

| Population | |

| • Locality | 506,520 |

| • Density | 11,000/sq mi (4,300/km2) |

| • Urban | 530,990 |

| • Urban density | 11,000/sq mi (4,200/km2) |

| • Metro | 901,455 |

| • Council area | 514,990[disputed – discuss] |

| • Council area density | 5,060/sq mi (1,955/km2) |

| • Language(s) | English Scots |

| GDP | |

| • Council area | £31.802 billion (2022) |

| • Per head | £60,764 (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC±0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| Postcode areas | |

| Area code | 0131 |

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-EDH |

| ONS code | S12000036 |

| OS grid reference | NT275735 |

| NUTS 3 | UKM25 |

| Primary Airport | Edinburgh Airport |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Old and New Towns of Edinburgh |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv |

| Reference | 728 |

| Inscription | 1995 (19th Session) |

| Official name | The Forth Bridge |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iv |

| Reference | 1485 |

| Inscription | 2015 (39th Session) |

| Edinburgh |

|---|

|

Edinburgh (/ˈɛdɪnbərə/ ED-in-bər-ə,[12][13][14] Scots: [ˈɛdɪnbʌrə]; Scottish Gaelic: Dùn Èideann [t̪un ˈeːtʲən̪ˠ]) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth estuary and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh had a population of 506,520 in mid-2020,[8] making it the second-most populous city in Scotland and the seventh-most populous in the United Kingdom. The wider metropolitan area has a population of 912,490.[15]

Recognised as the capital of Scotland since at least the 15th century, Edinburgh is the seat of the Scottish Government, the Scottish Parliament, the highest courts in Scotland, and the Palace of Holyroodhouse, the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. It is also the annual venue of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. The city has long been a centre of education, particularly in the fields of medicine, Scottish law, literature, philosophy, the sciences and engineering. The University of Edinburgh, founded in 1582 and now one of three in the city, is considered one of the best research institutions in the world. It is the second-largest financial centre in the United Kingdom, the fourth largest in Europe, and the thirteenth largest internationally.[16]

The city is a cultural centre, and is the home of institutions including the National Museum of Scotland, the National Library of Scotland and the Scottish National Gallery.[17] The city is also known for the Edinburgh International Festival and the Fringe, the latter being the world's largest annual international arts festival. Historic sites in Edinburgh include Edinburgh Castle, the Palace of Holyroodhouse, the churches of St. Giles, Greyfriars and the Canongate, and the extensive Georgian New Town built in the 18th/19th centuries. Edinburgh's Old Town and New Town together are listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site,[18] which has been managed by Edinburgh World Heritage since 1999. The city's historical and cultural attractions have made it the UK's second-most visited tourist destination, attracting 4.9 million visits, including 2.4 million from overseas in 2018.[19][20]

Edinburgh is governed by the City of Edinburgh Council, a unitary authority. The City of Edinburgh council area had an estimated population of 514,990 in mid-2021,[9] and includes outlying towns and villages which are not part of Edinburgh proper. The city is in the Lothian region and was historically part of the shire of Midlothian (also called Edinburghshire).

Etymology

[edit]"Edin", the root of the city's name, derives from Eidyn, the name for the region in Cumbric, the Brittonic Celtic language formerly spoken there. The name's meaning is unknown.[21] The district of Eidyn was centred on the stronghold of Din Eidyn, the dun or hillfort of Eidyn.[21] This stronghold is believed to have been located at Castle Rock,[citation needed] now the site of Edinburgh Castle. A siege of Din Eidyn by Oswald, king of the Angles of Northumbria in 638 marked the beginning of three centuries of Germanic influence in south east Scotland that laid the foundations for the development of Scots, before the town was ultimately subsumed in 954 by the kingdom known to the English as Scotland.[22] As the language shifted from Cumbric to Northumbrian Old English and then Scots, the Brittonic din in Din Eidyn was replaced by burh, producing Edinburgh. In Scottish Gaelic din becomes dùn, producing modern Dùn Èideann.[21][23]

Nicknames

[edit]

The city is affectionately nicknamed Auld Reekie,[24][25] Scots for Old Smoky, for the views from the country of the smoke-covered Old Town. A note in a collection of the works of the poet, Allan Ramsay, explains, "Auld Reeky...A name the country people give Edinburgh, from the cloud of smoke or reek that is always impending over it."[26] In Walter Scott's 1820 novel The Abbot, a character observes that "yonder stands Auld Reekie—you may see the smoke hover over her at twenty miles' distance".[27] In 1898, Thomas Carlyle comments on the phenomenon: "Smoke cloud hangs over old Edinburgh, for, ever since Aeneas Silvius's time and earlier, the people have the art, very strange to Aeneas, of burning a certain sort of black stones, and Edinburgh with its chimneys is called 'Auld Reekie' by the country people".[28] The 19th-century historian Robert Chambers asserted that the sobriquet could not be traced before the reign of Charles II in the late 17th century. He attributed the name to a Fife laird, Durham of Largo, who regulated the bedtime of his children by the smoke rising above Edinburgh from the fires of the tenements. "It's time now bairns, to tak' the beuks, and gang to our beds, for yonder's Auld Reekie, I see, putting on her nicht -cap!".[29]

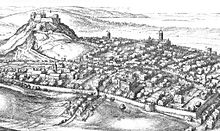

Edinburgh has been popularly called the Athens of the North since the early 19th century.[30] References to Athens, such as Athens of Britain and Modern Athens, had been made as early as the 1760s. The similarities were seen to be topographical but also intellectual. Edinburgh's Castle Rock reminded returning grand tourists of the Athenian Acropolis, as did aspects of the neoclassical architecture and layout of New Town.[30] Both cities had flatter, fertile agricultural land sloping down to a port several miles away (respectively, Leith and Piraeus). Intellectually, the Scottish Enlightenment, with its humanist and rationalist outlook, was influenced by Ancient Greek philosophy.[31] In 1822, artist Hugh William Williams organized an exhibition that showed his paintings of Athens alongside views of Edinburgh, and the idea of a direct parallel between both cities quickly caught the popular imagination.[32] When plans were drawn up in the early 19th century to architecturally develop Calton Hill, the design of the National Monument directly copied Athens' Parthenon.[33] Tom Stoppard's character Archie of Jumpers said, perhaps playing on Reykjavík meaning "smoky bay", that the "Reykjavík of the South" would be more appropriate.[34]

The city has also been known by several Latin names, such as Edinburgum, while the adjectival forms Edinburgensis and Edinensis are used in educational and scientific contexts.[35][36]

Edina is a late 18th-century poetical form used by the Scots poets Robert Fergusson and Robert Burns. "Embra" or "Embro" are colloquialisms from the same time,[37] as in Robert Garioch's Embro to the Ploy.[38]

Ben Jonson described it as "Britaine's other eye",[39] and Sir Walter Scott referred to it as "yon Empress of the North".[40] Robert Louis Stevenson, also a son of the city, wrote that Edinburgh "is what Paris ought to be".[41]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

The earliest known human habitation in the Edinburgh area was at Cramond, where evidence was found of a Mesolithic camp site dated to c. 8500 BC.[42] Traces of later Bronze Age and Iron Age settlements have been found on Castle Rock, Arthur's Seat, Craiglockhart Hill and the Pentland Hills.[43]

When the Romans arrived in Lothian at the end of the 1st century AD, they found a Brittonic Celtic tribe whose name they recorded as the Votadini.[44] The Votadini transitioned into the Gododdin kingdom in the Early Middle Ages, with Eidyn serving as one of the kingdom's districts. During this period, the Castle Rock site, thought to have been the stronghold of Din Eidyn, emerged as the kingdom's major centre.[45] The medieval poem Y Gododdin describes a war band from across the Brittonic world who gathered in Eidyn before a fateful raid; this may describe a historical event around AD 600.[46][47][48]

In 638, the Gododdin stronghold was besieged by forces loyal to King Oswald of Northumbria, and around this time control of Lothian passed to the Angles. Their influence continued for the next three centuries until around 950, when, during the reign of Indulf, son of Constantine II, the "burh" (fortress), named in the 10th-century Pictish Chronicle as oppidum Eden,[49] was abandoned to the Scots. It thenceforth remained, for the most part, under their jurisdiction.[50]

The royal burgh was founded by King David I in the early 12th century on land belonging to the Crown, though the date of its charter is unknown.[51] The first documentary evidence of the medieval burgh is a royal charter, c. 1124–1127, by King David I granting a toft in burgo meo de Edenesburg to the Priory of Dunfermline.[52] The shire of Edinburgh seems to have also been created in the reign of David I, possibly covering all of Lothian at first, but by 1305 the eastern and western parts of Lothian had become Haddingtonshire and Linlithgowshire, leaving Edinburgh as the county town of a shire covering the central part of Lothian, which was called Edinburghshire or Midlothian (the latter name being an informal, but commonly used, alternative until the county's name was legally changed in 1947).[53][54]

Edinburgh was largely under English control from 1291 to 1314 and from 1333 to 1341, during the Wars of Scottish Independence. When the English invaded Scotland in 1298, Edward I of England chose not to enter Edinburgh but passed by it with his army.[55]

In the middle of the 14th century, the French chronicler Jean Froissart described it as the capital of Scotland (c. 1365), and James III (1451–88) referred to it in the 15th century as "the principal burgh of our kingdom".[56] In 1482 James III "granted and perpetually confirmed to the said Provost, Bailies, Clerk, Council, and Community, and their successors, the office of Sheriff within the Burgh for ever, to be exercised by the Provost for the time as Sheriff, and by the Bailies for the time as Sheriffsdepute conjunctly and severally; with full power to hold Courts, to punish transgressors not only by banishment but by death, to appoint officers of Court, and to do everything else appertaining to the office of Sheriff; as also to apply to their own proper use the fines and escheats arising out of the exercise of the said office."[57] Despite being burnt by the English in 1544, Edinburgh continued to develop and grow,[58] and was at the centre of events in the 16th-century Scottish Reformation[59] and 17th-century Wars of the Covenant.[60] In 1582, Edinburgh's town council was given a royal charter by King James VI permitting the establishment of a university;[61] founded as Tounis College (Town's College), the institution developed into the University of Edinburgh, which contributed to Edinburgh's central intellectual role in subsequent centuries.[62]

17th century

[edit]

In 1603, King James VI of Scotland succeeded to the English throne, uniting the crowns of Scotland and England in a personal union known as the Union of the Crowns, though Scotland remained, in all other respects, a separate kingdom.[63] In 1638, King Charles I's attempt to introduce Anglican church forms in Scotland encountered stiff Presbyterian opposition culminating in the conflicts of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.[64] Subsequent Scottish support for Charles Stuart's restoration to the throne of England resulted in Edinburgh's occupation by Oliver Cromwell's Commonwealth of England forces – the New Model Army – in 1650.[65]

In the 17th century, Edinburgh's boundaries were still defined by the city's defensive town walls. As a result, the city's growing population was accommodated by increasing the height of the houses. Buildings of 11 storeys or more were common,[66] and have been described as forerunners of the modern-day skyscraper.[67][68] Most of these old structures were replaced by the predominantly Victorian buildings seen in today's Old Town. In 1611 an act of parliament created the High Constables of Edinburgh to keep order in the city, thought to be the oldest statutory police force in the world.[69]

18th century

[edit]

Following the Treaty of Union in 1706, the Parliaments of England and Scotland passed Acts of Union in 1706 and 1707 respectively, uniting the two kingdoms in the Kingdom of Great Britain effective from 1 May 1707.[70] As a consequence, the Parliament of Scotland merged with the Parliament of England to form the Parliament of Great Britain, which sat at Westminster in London. The Union was opposed by many Scots, resulting in riots in the city.[71]

By the first half of the 18th century, Edinburgh was described as one of Europe's most densely populated, overcrowded and unsanitary towns.[72][73] Visitors were struck by the fact that the social classes shared the same urban space, even inhabiting the same tenement buildings; although here a form of social segregation did prevail, whereby shopkeepers and tradesmen tended to occupy the cheaper-to-rent cellars and garrets, while the more well-to-do professional classes occupied the more expensive middle storeys.[74]

During the Jacobite rising of 1745, Edinburgh was briefly occupied by the Jacobite "Highland Army" before its march into England.[75] After its eventual defeat at Culloden, there followed a period of reprisals and pacification, largely directed at the rebellious clans.[76] In Edinburgh, the Town Council, keen to emulate London by initiating city improvements and expansion to the north of the castle,[77] reaffirmed its belief in the Union and loyalty to the Hanoverian monarch George III by its choice of names for the streets of the New Town: for example, Rose Street and Thistle Street; and for the royal family, George Street, Queen Street, Hanover Street, Frederick Street and Princes Street (in honour of George's two sons).[78] The consistently geometric layout of the plan for the extension of Edinburgh was the result of a major competition in urban planning staged by the Town Council in 1766.[79]

In the second half of the century, the city was at the heart of the Scottish Enlightenment,[80] when thinkers like David Hume, Adam Smith, James Hutton and Joseph Black were familiar figures in its streets. Edinburgh became a major intellectual centre, earning it the nickname "Athens of the North" because of its many neo-classical buildings and reputation for learning, recalling ancient Athens.[81] In the 18th-century novel The Expedition of Humphry Clinker by Tobias Smollett one character describes Edinburgh as a "hotbed of genius".[82] Edinburgh was also a major centre for the Scottish book trade. The highly successful London bookseller Andrew Millar was apprenticed there to James McEuen.[83]

From the 1770s onwards, the professional and business classes gradually deserted the Old Town in favour of the more elegant "one-family" residences of the New Town, a migration that changed the city's social character. According to the foremost historian of this development, "Unity of social feeling was one of the most valuable heritages of old Edinburgh, and its disappearance was widely and properly lamented."[84]

19th and 20th centuries

[edit]

Despite an enduring myth to the contrary,[85] Edinburgh became an industrial centre[86] with its traditional industries of printing, brewing and distilling continuing to grow in the 19th century and joined by new industries such as rubber works, engineering works and others. By 1821, Edinburgh had been overtaken by Glasgow as Scotland's largest city.[87] The city centre between Princes Street and George Street became a major commercial and shopping district, a development partly stimulated by the arrival of railways in the 1840s. The Old Town became an increasingly dilapidated, overcrowded slum with high mortality rates.[88] Improvements carried out under Lord Provost William Chambers in the 1860s began the transformation of the area into the predominantly Victorian Old Town seen today.[89] More improvements followed in the early 20th century as a result of the work of Patrick Geddes,[90] but relative economic stagnation during the two world wars and beyond saw the Old Town deteriorate further before major slum clearance in the 1960s and 1970s began to reverse the process. University building developments which transformed the George Square and Potterrow areas proved highly controversial.[91]

Since the 1990s a new "financial district", including the Edinburgh International Conference Centre, has grown mainly on demolished railway property to the west of the castle, stretching into Fountainbridge, a run-down 19th-century industrial suburb which has undergone radical change since the 1980s with the demise of industrial and brewery premises. This ongoing development has enabled Edinburgh to maintain its place as the United Kingdom's second largest financial and administrative centre after London.[92][93] Financial services now account for a third of all commercial office space in the city.[94] The development of Edinburgh Park, a new business and technology park covering 38 acres (15 ha), 4 mi (6 km) west of the city centre, has also contributed to the District Council's strategy for the city's major economic regeneration.[94]

In 1998, the Scotland Act, which came into force the following year, established a devolved Scottish Parliament and Scottish Executive (renamed the Scottish Government since September 2007[95]). Both based in Edinburgh, they are responsible for governing Scotland while reserved matters such as defence, foreign affairs and some elements of income tax remain the responsibility of the Parliament of the United Kingdom in London.[96]

21st century

[edit]In 2022, Edinburgh was affected by the 2022 Scotland bin strikes.[97] In 2023, Edinburgh became the first capital city in Europe to sign the global Plant Based Treaty, which was introduced at COP26 in 2021 in Glasgow.[98] Green Party councillor Steve Burgess introduced the treaty. The Scottish Countryside Alliance and other farming groups called the treaty "anti-farming".[99]

Geography

[edit]Location

[edit]Situated in Scotland's Central Belt, Edinburgh lies on the southern shore of the Firth of Forth. The city centre is 2+1⁄2 mi (4.0 km) southwest of the shoreline of Leith and 26 mi (42 km) inland, as the crow flies, from the east coast of Scotland and the North Sea at Dunbar.[100] While the early burgh grew up near the prominent Castle Rock, the modern city is often said to be built on seven hills, namely Calton Hill, Corstorphine Hill, Craiglockhart Hill, Braid Hill, Blackford Hill, Arthur's Seat and the Castle Rock,[101] giving rise to allusions to the seven hills of Rome.[102]

Cityscape

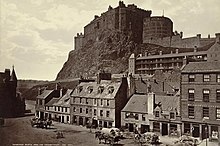

[edit]Occupying a narrow gap between the Firth of Forth to the north and the Pentland Hills and their outrunners to the south, the city sprawls over a landscape which is the product of early volcanic activity and later periods of intensive glaciation. [103]: 64–65 Igneous activity between 350 and 400 million years ago, coupled with faulting, led to the creation of tough basalt volcanic plugs, which predominate over much of the area.[103]: 64–65 One such example is the Castle Rock which forced the advancing ice sheet to divide, sheltering the softer rock and forming a 1 mi-long (1.6 km) tail of material to the east, thus creating a distinctive crag and tail formation.[103]: 64–65 Glacial erosion on the north side of the crag gouged a deep valley later filled by the now drained Nor Loch. These features, along with another hollow on the rock's south side, formed an ideal natural strongpoint upon which Edinburgh Castle was built.[103]: 64–65 Similarly, Arthur's Seat is the remains of a volcano dating from the Carboniferous period, which was eroded by a glacier moving west to east during the ice age.[103]: 64–65 Erosive action such as plucking and abrasion exposed the rocky crags to the west before leaving a tail of deposited glacial material swept to the east.[104] This process formed the distinctive Salisbury Crags, a series of teschenite cliffs between Arthur's Seat and the location of the early burgh.[105] The residential areas of Marchmont and Bruntsfield are built along a series of drumlin ridges south of the city centre, which were deposited as the glacier receded.[103]: 64–65

Other prominent landforms such as Calton Hill and Corstorphine Hill are also products of glacial erosion.[103]: 64–65 The Braid Hills and Blackford Hill are a series of small summits to the south of the city centre that command expansive views looking northwards over the urban area to the Firth of Forth.[103]: 64–65

Edinburgh is drained by the river named the Water of Leith, which rises at the Colzium Springs in the Pentland Hills and runs for 18 miles (29 km) through the south and west of the city, emptying into the Firth of Forth at Leith.[106] The nearest the river gets to the city centre is at Dean Village on the north-western edge of the New Town, where a deep gorge is spanned by Thomas Telford's Dean Bridge, built in 1832 for the road to Queensferry. The Water of Leith Walkway is a mixed-use trail that follows the course of the river for 19.6 km (12.2 mi) from Balerno to Leith.[107]

Excepting the shoreline of the Firth of Forth, Edinburgh is encircled by a green belt, designated in 1957, which stretches from Dalmeny in the west to Prestongrange in the east.[108] With an average width of 3.2 km (2 mi) the principal objectives of the green belt were to contain the outward expansion of the city and to prevent the agglomeration of urban areas.[108] Expansion affecting the green belt is strictly controlled but developments such as Edinburgh Airport and the Royal Highland Showground at Ingliston lie within the zone.[108] Similarly, suburbs such as Juniper Green and Balerno are situated on green belt land.[108] One feature of the Edinburgh green belt is the inclusion of parcels of land within the city which are designated green belt, even though they do not connect with the peripheral ring. Examples of these independent wedges of green belt include Holyrood Park and Corstorphine Hill.[108]

Areas

[edit]

Early settlements

[edit]Edinburgh includes former towns and villages that retain much of their original character as settlements in existence before they were absorbed into the expanding city of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.[109] Many areas, such as Dalry, contain residences that are multi-occupancy buildings known as tenements, although the more southern and western parts of the city have traditionally been less built-up with a greater number of detached and semi-detached villas.[110]

The historic centre of Edinburgh is divided in two by the broad green swathe of Princes Street Gardens. To the south, the view is dominated by Edinburgh Castle, built high on Castle Rock, and the long sweep of the Old Town descending towards Holyrood Palace. To the north lie Princes Street and the New Town.

The West End includes the financial district, with insurance and banking offices as well as the Edinburgh International Conference Centre.

Old and New Towns

[edit]Edinburgh's Old and New Towns were listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995 in recognition of the unique character of the Old Town with its medieval street layout and the planned Georgian New Town, including the adjoining Dean Village and Calton Hill areas. There are over 4,500 listed buildings within the city,[18] a higher proportion relative to area than any other city in the United Kingdom.

The castle is perched on top of a rocky crag (the remnant of an extinct volcano) and the Royal Mile runs down the crest of a ridge from it terminating at Holyrood Palace. Minor streets (called closes or wynds) lie on either side of the main spine forming a herringbone pattern.[111] Due to space restrictions imposed by the narrowness of this landform, the Old Town became home to some of the earliest "high rise" residential buildings. Multi-storey dwellings known as lands were the norm from the 16th century onwards with ten and eleven storeys being typical and one even reaching fourteen or fifteen storeys.[112] Numerous vaults below street level were inhabited to accommodate the influx of incomers, particularly Irish immigrants, during the Industrial Revolution. The street has several fine public buildings such as St Giles' Cathedral, the City Chambers and the Law Courts. Other places of historical interest nearby are Greyfriars Kirkyard and Mary King's Close. The Grassmarket, running deep below the castle is connected by the steep double terraced Victoria Street. The street layout is typical of the old quarters of many Northern European cities.

The New Town was an 18th-century solution to the problem of an increasingly crowded city which had been confined to the ridge sloping down from the castle. In 1766 a competition to design a "New Town" was won by James Craig, a 27-year-old architect.[113] The plan was a rigid, ordered grid, which fitted in well with Enlightenment ideas of rationality. The principal street was to be George Street, running along the natural ridge to the north of what became known as the "Old Town". To either side of it are two other main streets: Princes Street and Queen Street. Princes Street has become Edinburgh's main shopping street and now has few of its Georgian buildings in their original state. The three main streets are connected by a series of streets running perpendicular to them. The east and west ends of George Street are terminated by St Andrew Square and Charlotte Square respectively. The latter, designed by Robert Adam, influenced the architectural style of the New Town into the early 19th century.[114] Bute House, the official residence of the First Minister of Scotland, is on the north side of Charlotte Square.[115]

The hollow between the Old and New Towns was formerly the Nor Loch, which was created for the town's defence but came to be used by the inhabitants for dumping their sewage. It was drained by the 1820s as part of the city's northward expansion. Craig's original plan included an ornamental canal on the site of the loch,[78] but this idea was abandoned.[116] Soil excavated while laying the foundations of buildings in the New Town was dumped on the site of the loch to create the slope connecting the Old and New Towns known as The Mound.

In the middle of the 19th century the National Gallery of Scotland and Royal Scottish Academy Building were built on The Mound, and tunnels for the railway line between Haymarket and Waverley stations were driven through it.

Southside

[edit]The Southside is a residential part of the city, which includes the districts of St Leonards, Marchmont, Morningside, Newington, Sciennes, the Grange and Blackford. The Southside is broadly analogous to the area covered formerly by the Burgh Muir, and was developed as a residential area after the opening of the South Bridge in the 1780s. The Southside is particularly popular with families (many state and private schools are here), young professionals and students (the central University of Edinburgh campus is based around George Square just north of Marchmont and the Meadows), and Napier University (with major campuses around Merchiston and Morningside). The area is also well provided with hotel and "bed and breakfast" accommodation for visiting festival-goers. These districts often feature in works of fiction. For example, Church Hill in Morningside, was the home of Muriel Spark's Miss Jean Brodie,[117] and Ian Rankin's Inspector Rebus lives in Marchmont and works in St Leonards.[118]

Leith

[edit]

Leith was historically the port of Edinburgh, an arrangement of unknown date that was confirmed by the royal charter Robert the Bruce granted to the city in 1329.[119] The port developed a separate identity from Edinburgh, which to some extent it still retains, and it was a matter of great resentment when the two burghs merged in 1920 into the City of Edinburgh.[120] Even today the parliamentary seat is known as "Edinburgh North and Leith". The loss of traditional industries and commerce (the last shipyard closed in 1983) resulted in economic decline.[121] The Edinburgh Waterfront development has transformed old dockland areas from Leith to Granton into residential areas with shopping and leisure facilities and helped rejuvenate the area. With the redevelopment, Edinburgh has gained the business of cruise liner companies which now provide cruises to Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands.

The coastal suburb of Portobello is characterised by Georgian villas, Victorian tenements, a beach and promenade and cafés, bars, restaurants and independent shops. There are rowing and sailing clubs, a restored Victorian swimming pool, and Victorian Turkish baths.

Urban area

[edit]The urban area of Edinburgh is almost entirely within the City of Edinburgh Council boundary, merging with Musselburgh in East Lothian. Towns within easy reach of the city boundary include Inverkeithing, Haddington, Tranent, Prestonpans, Dalkeith, Bonnyrigg, Loanhead, Penicuik, Broxburn, Livingston and Dunfermline. Edinburgh lies at the heart of the Edinburgh & South East Scotland City region with a population in 2014 of 1,339,380.[122][123]

Climate

[edit]Like most of Scotland, Edinburgh has a cool temperate maritime climate (Cfb) which, despite its northerly latitude, is milder than places which lie at similar latitudes such as Moscow and Labrador.[124] The city's proximity to the sea mitigates any large variations in temperature or extremes of climate. Winter daytime temperatures rarely fall below freezing while summer temperatures are moderate, rarely exceeding 22 °C (72 °F).[124] The highest temperature recorded in the city was 31.6 °C (88.9 °F) on 25 July 2019[124] at Gogarbank, beating the previous record of 31 °C (88 °F) on 4 August 1975 at Edinburgh Airport.[125] The lowest temperature recorded in recent years was −14.6 °C (5.7 °F) during December 2010 at Gogarbank.[126]

Given Edinburgh's position between the coast and hills, it is renowned as "the windy city", with the prevailing wind direction coming from the south-west, which is often associated with warm, unstable air from the North Atlantic Current that can give rise to rainfall – although considerably less than cities to the west, such as Glasgow.[124] Rainfall is distributed fairly evenly throughout the year.[124] Winds from an easterly direction are usually drier but considerably colder, and may be accompanied by haar, a persistent coastal fog. Vigorous Atlantic depressions, known as European windstorms, can affect the city between October and April.[124]

Located slightly north of the city centre, the weather station at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) has been an official weather station for the Met Office since 1956. The Met Office operates its own weather station at Gogarbank on the city's western outskirts, near Edinburgh Airport.[127] This slightly inland station has a slightly wider temperature span between seasons, is cloudier and somewhat wetter, but differences are minor.

Temperature and rainfall records have been kept at the Royal Observatory since 1764.[128]

| Climate data for Edinburgh (RBGE),[a] elevation: 23 m (75 ft), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1960–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.0 (59.0) |

15.2 (59.4) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

27.8 (82.0) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.4 (88.5) |

26.7 (80.1) |

24.4 (75.9) |

20.6 (69.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

31.6 (88.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.3 (45.1) |

8.0 (46.4) |

9.7 (49.5) |

12.2 (54.0) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.4 (63.3) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.1 (66.4) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.4 (56.1) |

9.9 (49.8) |

7.3 (45.1) |

13.0 (55.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.5 (40.1) |

4.8 (40.6) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

13.7 (56.7) |

15.4 (59.7) |

15.3 (59.5) |

13.3 (55.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

4.5 (40.1) |

9.5 (49.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.7 (35.1) |

1.7 (35.1) |

2.9 (37.2) |

4.7 (40.5) |

7.1 (44.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

11.5 (52.7) |

9.7 (49.5) |

6.7 (44.1) |

3.8 (38.8) |

1.6 (34.9) |

6.1 (43.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −15.5 (4.1) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

1.1 (34.0) |

4.4 (39.9) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

−15.5 (4.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 64.7 (2.55) |

53.1 (2.09) |

48.5 (1.91) |

40.8 (1.61) |

47.6 (1.87) |

66.2 (2.61) |

72.1 (2.84) |

71.6 (2.82) |

54.9 (2.16) |

75.7 (2.98) |

65.3 (2.57) |

67.4 (2.65) |

727.7 (28.65) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 12.4 | 9.8 | 9.8 | 8.6 | 9.6 | 10.4 | 11.5 | 10.4 | 9.9 | 11.7 | 11.7 | 12.3 | 128.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 55.2 | 82.2 | 117.3 | 157.3 | 194.7 | 161.8 | 169.9 | 160.0 | 130.1 | 99.4 | 72.1 | 49.2 | 1,449.1 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Source: Met Office,[129] KNMI[130] and Weather Atlas[131] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Edinburgh (Gogarbank),[b] elevation: 57 m (187 ft), 1991–2020 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.9 (44.4) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.3 (48.7) |

12.0 (53.6) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.2 (66.6) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.2 (55.8) |

9.5 (49.1) |

7.0 (44.6) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

13.4 (56.1) |

15.2 (59.4) |

15.1 (59.2) |

13.1 (55.6) |

9.8 (49.6) |

6.6 (43.9) |

4.2 (39.6) |

9.3 (48.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.5 (34.7) |

1.6 (34.9) |

2.7 (36.9) |

4.3 (39.7) |

6.7 (44.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.0 (51.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

6.5 (43.7) |

3.6 (38.5) |

1.4 (34.5) |

5.8 (42.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 73.0 (2.87) |

61.1 (2.41) |

52.5 (2.07) |

45.9 (1.81) |

50.2 (1.98) |

68.8 (2.71) |

71.9 (2.83) |

74.7 (2.94) |

55.2 (2.17) |

82.7 (3.26) |

73.7 (2.90) |

74.9 (2.95) |

784.3 (30.88) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 13.3 | 10.7 | 10.3 | 9.2 | 10.8 | 11.1 | 11.4 | 11.2 | 10.5 | 13.0 | 12.9 | 13.1 | 137.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 47.4 | 77.5 | 111.0 | 147.7 | 189.5 | 159.4 | 160.9 | 145.7 | 125.5 | 94.1 | 66.9 | 37.8 | 1,363.4 |

| Source: Met Office[132] | |||||||||||||

Demography

[edit]Current

[edit]

The most recent official population estimates (2020) are 506,520 for the locality (includes Currie),[8] 530,990 for the Edinburgh settlement (includes Musselburgh).[8]

Edinburgh has a high proportion of young adults, with 19.5% of the population in their 20s (exceeded only by Aberdeen) and 15.2% in their 30s which is the highest in Scotland. The proportion of Edinburgh's population born in the UK fell from 92% to 84% between 2001 and 2011, while the proportion of White Scottish-born fell from 78% to 70%. Of those Edinburgh residents born in the UK, 335,000 or 83% were born in Scotland, with 58,000 or 14% being born in England.[133]

| Ethnic Group | 1991[134][135] | 2001[136][137] | 2011[136][137] | 2022[138] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| White: Total | 409,044 | 97.64% | 430,369 | 95.9% | 437,167 | 91.7% | 436,742 | 84.9% |

| White: Scottish | – | – | 354,053 | 78.9% | 334,987 | 70.2% | 298,533 | 58.0% |

| White: Other British | – | – | 51,407 | 11.4% | 56,132 | 11.7% | 69,829 | 13.6% |

| White: Irish | 5,518 | 1.31% | 6,470 | 1.4% | 8,603 | 1.8% | 10,326 | 2.0% |

| White: Gypsy/Traveller[note 1] | – | – | – | – | 388 | – | 256 | – |

| White: Polish[note 1] | – | – | – | – | 12,820 | 2.68% | 16,351 | 3.18% |

| White: Other | – | – | 18,439 | 4.1% | 24,237 | 5.1% | 41,449 | 8.1% |

| Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British: Total | 6,979 | 1.66% | 11,600 | 2.5% | 26,264 | 5.5% | 44,070 | 8.6% |

| Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British: Indian | 1,176 | 0.28% | 2,384 | 0.53% | 6,470 | 1.35% | 12,414 | 2.41% |

| Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British: Pakistani | 2,625 | 0.62% | 3,928 | 0.87% | 5,858 | 1.22% | 7,454 | 1.45% |

| Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British: Bangladeshi | 328 | – | 636 | 0.14% | 1,277 | 0.26% | 2,685 | 0.52% |

| Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British: Chinese | 1,940 | 0.46% | 3,532 | 0.78% | 8,076 | 1.69% | 15,076 | 2.93% |

| Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British: Asian Other | 910 | 0.21% | 1,201 | 0.26% | 4,583 | 0.96% | 6,441 | 1.25% |

| Black, Black Scottish or Black British[note 2] | 1,171 | 0.3% | 1,577 | 0.3% | 5,505 | 1.2% | 10,881 | 2.1% |

| African: Total | 603 | - | 1,285 | 0.2% | 4,474 | 0.9% | 9,462 | 1.84% |

| African: African, African Scottish or African British | 603 | – | 1,285 | 0.2% | 4,364 | 0.91% | 809 | 0.16% |

| African: Other African | – | – | – | – | 110 | – | 8,653 | 1.68% |

| Caribbean or Black: Total | 568 | – | 292 | – | 1,031 | 0.2% | 1,419 | 0.3% |

| Caribbean | 175 | – | 292 | – | 505 | 0.1% | 477 | 0.1% |

| Black | – | – | – | – | 403 | – | 80 | – |

| Caribbean or Black: Other | 393 | – | – | – | 123 | – | 862 | 0.17% |

| Mixed or multiple ethnic groups: Total | – | – | 2,776 | 0.6% | 4,087 | 0.8% | 12,882 | 2.5% |

| Other: Total | 1,720 | 0.41% | 2,047 | 0.45% | 3,603 | 0.8% | 9,966 | 1.9% |

| Other: Arab[note 1] | – | – | – | – | 2,500 | 0.52% | 4,119 | 0.8% |

| Other: Any other ethnic group | 1,720 | 0.41% | 2,047 | 0.45% | 1,103 | 0.23% | 5,849 | 1.14% |

| Total: | 418,914 | 100% | 448,624 | 100% | 476,626 | 100% | 514,543 | 100% |

Some 16,000 people or 3.2% of the city's population are of Polish descent. 77,800 people or 15.1% of Edinburgh's population class themselves as Non-White which is an increase from 8.2% in 2011 and 4% in 2001. Of the Non-White population, the largest group by far are Asian, totalling about 44 thousand people. Within the Asian population, people of Chinese descent are now the largest sub-group, with 15,076 people, amounting to about 2.9% of the city's total population. The city's population of Indian descent amounts to 12,414 (2.4% of the total population), while there are some 7,454 of Pakistani descent (1.5% of the total population). Although they account for only 2,685 people or 0.5% of the city's population, Edinburgh has the highest number and proportion of people of Bangladeshi descent in Scotland. Close to 12,000 people were born in African countries (2.3% of the total population) and over 13,000 in the Americas. With the notable exception of Inner London, Edinburgh has a higher number of people born in the United States (over 6,500) than any other city in the UK.[138]

The proportion of people residing in Edinburgh born outside the UK was 23.5% in 2022, compared with 15.9% in 2011 and 8.3% in 2001. Below are the largest overseas-born groups in Edinburgh according to the 2022 census, alongside the two previous censuses.

| Place of birth | 2022[139] | 2011[140] | 2001[141] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13,842 | 11,651 | 416 | |

| 9,445 | 4,888 | 1,733 | |

| 8,229 | 4,188 | 978 | |

| 6,539 | 3,715 | 2,184 | |

| 4,885 | 1,716 | 1,257 | |

| 4,837 | 2,011 | 1,058 | |

| 4,774 | 4,743 | 3,324 | |

| 3,843 | 3,526 | 2,760 | |

| 3,556 | 1,622 | 1,416 | |

| 3,220 | 2,472 | 1,663 | |

| 2,978 | 1,186 | 231 | |

| 2,973 | 2,039 | 1,412 | |

| 2,464 | 1,824 | 1,331 | |

| 2,377 | 992 | 575 | |

| 2,189 | 2,086 | 2,012 | |

| 2,079 | 1,760 | 1,332 | |

| Overall – all overseas-born | 120,978 | 75,698 | 37,420 |

Historical

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1801 | 82,560 | — |

| 1811 | 102,987 | +24.7% |

| 1821 | 138,235 | +34.2% |

| 1831 | 161,909 | +17.1% |

| 1841 | 166,450 | +2.8% |

| 1851 | 193,929 | +16.5% |

| 1901 | 303,638 | +56.6% |

| 1911 | 320,318 | +5.5% |

| 1921 | 420,264 | +31.2% |

| 1931 | 439,010 | +4.5% |

| 1951 | 466,761 | +6.3% |

| Source: [142] | ||

A census by the Edinburgh presbytery in 1592 recorded a population of 8,003 adults spread equally north and south of the High Street which runs along the spine of the ridge sloping down from the Castle.[143] In the 18th and 19th centuries, the population expanded rapidly, rising from 49,000 in 1751 to 136,000 in 1831, primarily due to migration from rural areas.[103]: 9 As the population grew, problems of overcrowding in the Old Town, particularly in the cramped tenements that lined the present day Royal Mile and the Cowgate, were exacerbated.[103]: 9 Poor sanitary arrangements resulted in a high incidence of disease,[103]: 9 with outbreaks of cholera occurring in 1832, 1848 and 1866.[144]

The construction of the New Town from 1767 onwards witnessed the migration of the professional and business classes from the difficult living conditions in the Old Town to the lower density, higher quality surroundings taking shape on land to the north. [145] Expansion southwards from the Old Town saw more tenements being built in the 19th century, giving rise to Victorian suburbs such as Dalry, Newington, Marchmont and Bruntsfield.[145]

Early 20th-century population growth coincided with lower-density suburban development. As the city expanded to the south and west, detached and semi-detached villas with large gardens replaced tenements as the predominant building style. Nonetheless, the 2001 census revealed that over 55% of Edinburgh's population were still living in tenements or blocks of flats, a figure in line with other Scottish cities, but much higher than other British cities, and even central London.[146]

From the early to mid 20th century, the growth in population, together with slum clearance in the Old Town and other areas, such as Dumbiedykes, Leith, and Fountainbridge, led to the creation of new estates such as Stenhouse and Saughton, Craigmillar and Niddrie, Pilton and Muirhouse, Piershill, and Sighthill.[147]

Religion

[edit]

In 2018, the Church of Scotland had 20,956 members in 71 congregations in the Presbytery of Edinburgh.[149] Its most prominent church is St Giles' on the Royal Mile, first dedicated in 1243 but believed to date from before the 12th century.[150] Saint Giles is historically the patron saint of Edinburgh.[151] St Cuthbert's, situated at the west end of Princes Street Gardens in the shadow of Edinburgh Castle and St Giles' can lay claim to being the oldest Christian sites in the city,[152] though the present St Cuthbert's, designed by Hippolyte Blanc, was dedicated in 1894.[153]

Other Church of Scotland churches include Greyfriars Kirk, the Canongate Kirk, The New Town Church and the Barclay Church. The Church of Scotland Offices are in Edinburgh,[154] as is the Assembly Hall where the annual General Assembly is held.[155]

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of St Andrews and Edinburgh has 27 parishes across the city.[156] The Archbishop of St Andrews and Edinburgh has his official residence in Greenhill,[157] the diocesan offices are in nearby Marchmont,[158] and its cathedral is St Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh. The Diocese of Edinburgh of the Scottish Episcopal Church has over 50 churches, half of them in the city.[159] Its centre is the late 19th-century Gothic style St Mary's Cathedral in the West End's Palmerston Place.[160] Orthodox Christianity is represented by Pan, Romanian and Russian Orthodox churches, including St Andrew's Orthodox Church, part of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Thyateira and Great Britain.[161] There are several independent churches in the city, both Catholic and Protestant, including Charlotte Chapel, Carrubbers Christian Centre, Bellevue Chapel and Sacred Heart.[162] There are also churches belonging to Quakers, Christadelphians,[163] Seventh-day Adventists, Church of Christ, Scientist, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) and Elim Pentecostal Church.

Muslims have several places of worship across the city. Edinburgh Central Mosque, the largest Islamic place of worship, is located in Potterrow on the city's Southside, near Bristo Square. Construction was largely financed by a gift from King Fahd of Saudi Arabia[164] and was completed in 1998.[165] There is also an Ahmadiyya Muslim community.[166]

The first recorded presence of a Jewish community in Edinburgh dates back to the late 18th century.[167] Edinburgh's Orthodox synagogue, opened in 1932, is in Salisbury Road and can accommodate a congregation of 2000. A Liberal Jewish congregation also meets in the city.

A Sikh gurdwara and a Hindu mandir are located in Leith.[168][169] The city also has a Brahma Kumaris centre in the Polwarth area.[170]

The Edinburgh Buddhist Centre, run by the Triratna Buddhist Community, formerly situated in Melville Terrace, now runs sessions at the Healthy Life Centre, Bread Street.[171] Other Buddhist traditions are represented by groups which meet in the capital: the Community of Interbeing (followers of Thich Nhat Hanh), Rigpa, Samye Dzong, Theravadin, Pure Land and Shambala. There is a Sōtō Zen Priory in Portobello[172] and a Theravadin Thai Buddhist Monastery in Slateford Road.[173]

Edinburgh is home to a Baháʼí community,[174] and a Theosophical Society meets in Great King Street.[175]

Edinburgh has an Inter-Faith Association.[176]

Edinburgh has over 39 graveyards and cemeteries, many of which are listed and of historical character, including several former church burial grounds.[177] Examples include Old Calton Burial Ground, Greyfriars Kirkyard and Dean Cemetery.[178][179][180]

Economy

[edit]

Edinburgh has the strongest economy of any city in the United Kingdom outside London and the highest percentage of professionals in the UK with 43% of the population holding a degree-level or professional qualification.[181] According to the Centre for International Competitiveness, it is the most competitive large city in the United Kingdom.[182] It also has the highest gross value added per employee of any city in the UK outside London, measuring £57,594 in 2010.[183] It was named European Best Large City of the Future for Foreign Direct Investment and Best Large City for Foreign Direct Investment Strategy in the Financial Times magazine in 2012.[184]

As the centre of Scotland's government and legal system, the public sector plays a central role in Edinburgh's economy. Many departments of the Scottish Government are in the city, including the headquarters of the government at St Andrew's House, the official residence of the First Minister at Bute House and Scottish Government offices at Victoria Quay. Other major sectors across the city include administrative and support services, the education sector, public administration and defence, the health and social care sector, scientific and technical services, and construction and manufacturing.[185] When the £1.3bn Edinburgh & South East Scotland City Region Deal[186] was signed in 2018, the region's Gross Value Added (GVA) contribution to the Scottish economy was cited as £33bn, or 33% of the country's output. The City Region Deal funds a range of "Data Driven Innovation" hubs which are using data to innovate in the region, recognising the region's strengths in technology and data science, the growing importance of the data economy, and the need to tackle the digital skills gap, as a route to social and economic prosperity.[187][188][189]

Tourism is also an important element in the city's economy. As a World Heritage Site, tourists visit historical sites such as Edinburgh Castle, the Palace of Holyroodhouse and the Old and New Towns. Their numbers are augmented in August each year during the Edinburgh Festivals, which attracts 4.4 million visitors,[190] and generates over £100M for the local economy.[191] In March 2010, unemployment in Edinburgh was comparatively low at 3.6%, and it remains consistently below the Scottish average of 4.5%.[190] In 2022 Edinburgh was the second most visited city in the United Kingdom, behind London, by overseas visitors.[192]

Culture

[edit]Festivals and celebrations

[edit]Edinburgh festivals

[edit]

The city hosts a series of festivals that run between the end of July and early September each year. The best known of these events are the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, the Edinburgh International Festival, the Edinburgh Military Tattoo, the Edinburgh Art Festival and the Edinburgh International Book Festival.[193]

The longest established of these festivals is the Edinburgh International Festival, which was first held in 1947[194] and consists mainly of a programme of high-profile theatre productions and classical music performances, featuring international directors, conductors, theatre companies and orchestras.[195]

This has since been overtaken in size by the Edinburgh Fringe which began as a programme of marginal acts alongside the "official" Festival and has become the world's largest performing arts festival. In 2017, nearly 3400 different shows were staged in 300 venues across the city.[196][197] Comedy has become one of the mainstays of the Fringe, with numerous well-known comedians getting their first 'break' there, often by being chosen to receive the Edinburgh Comedy Award.[198] The Edinburgh Military Tattoo, occupies the Castle Esplanade every night for three weeks each August, with massed pipe bands and military bands drawn from around the world. Performances end with a short fireworks display.

As well as the summer festivals, many other festivals are held during the rest of the year, including the Edinburgh International Film Festival[199] and Edinburgh International Science Festival.[200]

The summer of 2020 was the first time in its 70-year history that the Edinburgh festival was not run, being cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[201] This affected many of the tourist-focused businesses in Edinburgh which depend on the various festivals over summer to return an annual profit.[202]

Edinburgh's Hogmanay

[edit]

The annual Edinburgh Hogmanay celebration was originally an informal street party focused on the Tron Kirk in the Old Town's High Street. Since 1993, it has been officially organised with the focus moved to Princes Street. In 1996, over 300,000 people attended, leading to ticketing of the main street party in later years up to a limit of 100,000 tickets.[203] Hogmanay now covers four days of processions, concerts and fireworks, with the street party beginning on Hogmanay. Alternative tickets are available for entrance into the Princes Street Gardens concert and Cèilidh, where well-known artists perform and ticket holders can participate in traditional Scottish cèilidh dancing. The event attracts thousands of people from all over the world.[203]

Beltane and other festivals

[edit]On the night of 30 April the Beltane Fire Festival takes place on Calton Hill, involving a procession followed by scenes inspired by pagan old spring fertility celebrations.[204] At the beginning of October each year the Dussehra Hindu Festival is also held on Calton Hill.[205]

Music, theatre and film

[edit]

Outside the Festival season, Edinburgh supports several theatres and production companies. The Royal Lyceum Theatre has its own company, while the King's Theatre, Edinburgh Festival Theatre and Edinburgh Playhouse stage large touring shows. The Traverse Theatre presents a more contemporary repertoire. Amateur theatre companies productions are staged at the Bedlam Theatre, Church Hill Theatre and King's Theatre among others.[206]

The Usher Hall is Edinburgh's premier venue for classical music, as well as occasional popular music concerts.[207] It was the venue for the Eurovision Song Contest 1972. Other halls staging music and theatre include The Hub, the Assembly Rooms and the Queen's Hall. The Scottish Chamber Orchestra is based in Edinburgh.[208]

Edinburgh has one repertory cinema, The Cameo, and formerly, the Edinburgh Filmhouse as well as the independent Dominion Cinema and a range of multiplexes.[209]

Edinburgh has a healthy popular music scene. Occasionally large concerts are staged at Murrayfield and Meadowbank, while mid-sized events take place at smaller venues such as 'The Corn Exchange', 'The Liquid Rooms' and 'The Bongo Club'. In 2010, PRS for Music listed Edinburgh among the UK's top ten 'most musical' cities.[210] Several city pubs are well known for their live performances of folk music. They include 'Sandy Bell's' in Forrest Road, 'Captain's Bar' in South College Street and 'Whistlebinkies' in South Bridge.

Like many other cities in the UK, numerous nightclub venues host Electronic dance music events.[211]

Edinburgh is home to a flourishing group of contemporary composers such as Nigel Osborne, Peter Nelson, Lyell Cresswell, Hafliði Hallgrímsson, Edward Harper, Robert Crawford, Robert Dow and John McLeod. McLeod's music is heard regularly on BBC Radio 3 and throughout the UK.[212]

Media

[edit]Newspapers

[edit]The main local newspaper is the Edinburgh Evening News. It is owned and published alongside its sister titles The Scotsman and Scotland on Sunday by JPIMedia.[213] Student newspapers include, The Journal Scotland wide Universities, and The Student University of Edinburgh which was founded in 1887. Community newspapers include The Spurtle from Broughton, Spokes Bulletin, and The Edinburgh Reporter.

Radio

[edit]The city has many commercial radio stations including Forth 1, a station which broadcasts mainstream chart music, Greatest Hits Edinburgh on DAB which plays classic hits and Edge Radio.[214] Capital Scotland and Heart Scotland also have transmitters covering Edinburgh. Along with the UK national radio stations, BBC Radio Scotland and the Gaelic language service BBC Radio nan Gàidheal are also broadcast. DAB digital radio is broadcast over two local multiplexes. BFBS Radio broadcasts from studios on the base at Dreghorn Barracks across the city on 98.5FM as part of its UK Bases network. Small scale DAB started October 2022 with numerous community stations on board.

Television

[edit]Television, along with most radio services, is broadcast to the city from the Craigkelly transmitting station situated in Fife on the opposite side of the Firth of Forth[215] and the Black Hill transmitting station in North Lanarkshire to the west.

There are no television stations based in the city. Edinburgh Television existed in the late 1990s to early 2003[216] and STV Edinburgh existed from 2015 to 2018.[217][218]

Museums, libraries and galleries

[edit]

Edinburgh has many museums and libraries. These include the National Museum of Scotland, the National Library of Scotland, National War Museum, the Museum of Edinburgh, Surgeons' Hall Museum, the Writers' Museum, the Museum of Childhood and Dynamic Earth. The Museum on The Mound has exhibits on money and banking.[219]

Edinburgh Zoo, covering 82 acres (33 ha) on Corstorphine Hill, is the second most visited paid tourist attraction in Scotland,[220] and was previously home to two giant pandas, Tian Tian and Yang Guang, on loan from the People's Republic of China. Edinburgh is also home to The Royal Yacht Britannia, decommissioned in 1997 and now a five-star visitor attraction and evening events venue permanently berthed at Ocean Terminal.

Edinburgh contains Scotland's three National Galleries of Art as well as numerous smaller art galleries.[221] The national collection is housed in the Scottish National Gallery, located on The Mound, comprising the linked National Gallery of Scotland building and the Royal Scottish Academy building. Contemporary collections are shown in the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art which occupies a split site at Belford. The Scottish National Portrait Gallery on Queen Street focuses on portraits and photography.

The council-owned City Art Centre in Market Street mounts regular art exhibitions. Across the road, The Fruitmarket Gallery offers world-class exhibitions of contemporary art, featuring work by British and international artists with both emerging and established international reputations.[222]

The city hosts several of Scotland's galleries and organisations dedicated to contemporary visual art. Significant strands of this infrastructure include Creative Scotland, Edinburgh College of Art, Talbot Rice Gallery (University of Edinburgh), Collective Gallery (based at the City Observatory) and the Edinburgh Annuale.

There are also many small private shops/galleries that provide space to showcase works from local artists.[223]

Shopping

[edit]The locale around Princes Street is the main shopping area in the city centre, with souvenir shops, chain stores such as Boots the Chemist, Edinburgh Woollen Mill, and H&M.[224] George Street, north of Princes Street, has several upmarket shops and independent stores.[224] At the east end of Princes Street, the redeveloped St James Quarter opened its doors in June 2021,[225] while next to the Balmoral Hotel and Waverley Station is Waverley Market. Multrees Walk is a pedestrian shopping district, dominated by the presence of Harvey Nichols, and other names including Louis Vuitton, Mulberry and Michael Kors.[224]

Edinburgh also has substantial retail parks outside the city centre. These include The Gyle Shopping Centre and Hermiston Gait in the west of the city, Cameron Toll Shopping Centre, Straiton Retail Park (actually just outside the city, in Midlothian) and Fort Kinnaird in the south and east, and Ocean Terminal in the north on the Leith waterfront.[226]

Government and politics

[edit]Government

[edit]

Following local government reorganisation in 1996, the City of Edinburgh Council constitutes one of the 32 council areas of Scotland.[227] Like all other local authorities of Scotland, the council has powers over most matters of local administration such as housing, planning, local transport, parks, economic development and regeneration.[228] The council comprises 63 elected councillors, returned from 17 multi-member electoral wards in the city.[229] Following the 2007 City of Edinburgh Council election the incumbent Labour Party lost majority control of the council after 23 years to a Liberal Democrat/SNP coalition.[230]

After the 2017 election, the SNP and Labour formed a coalition administration, which lasted until the next election in 2022. The 2022 City of Edinburgh Council election resulted in the most politically balanced council in the UK, with 19 SNP, 13 Labour, 12 Liberal Democrat, 10 Green and 9 Conservative councillors. A minority Labour administration was formed, being voted in by Scottish Conservative and Scottish Liberal Democrat councillors. The SNP and Greens presented a coalition agreement, but could not command majority support in the council. This caused controversy amongst the Scottish Labour Party group for forming an administration supported by Conservatives and led to the suspension of two Labour councillors on the council for abstaining on the vote to approve the new administration.[231] The city's coat of arms was registered by the Lord Lyon King of Arms in 1732.[232]

Politics

[edit]Edinburgh, like all of Scotland, is represented in the Scottish Parliament, situated in the Holyrood area of the city. For electoral purposes, the city is divided into six constituencies which, along with 3 seats outside of the city, form part of the Lothian region.[233] Each constituency elects one Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP) by the first past the post system of election, and the region elects seven additional MSPs to produce a result based on a form of proportional representation.[233]

As of the 2021 election, the Scottish National Party have four MSPs: Ash Denham for Edinburgh Eastern, Ben Macpherson for Edinburgh Northern and Leith and Gordon MacDonald for Edinburgh Pentlands and Angus Robertson for Edinburgh Central constituencies. Alex Cole-Hamilton, the Leader of the Scottish Liberal Democrats represents Edinburgh Western and Daniel Johnson of the Scottish Labour Party represents Edinburgh Southern constituency. In addition, the city is also represented by seven regional MSPs representing the Lothian electoral region: The Conservatives have three regional MSPs: Jeremy Balfour, Miles Briggs and Sue Webber, Labour have two regional MSPs: Sarah Boyack and Foysol Choudhury; two Scottish Green regional MSPs were elected: Green's Co-Leader Lorna Slater and Alison Johnstone. However, following her election as the Presiding Officer of the 6th Session of the Scottish Parliament on 13 May 2021, Alison Johnstone has abided by the established parliamentary convention for speakers and renounced all affiliation with her former political party for the duration of her term as Presiding Officer. So she presently sits as an independent MSP for the Lothians Region.[citation needed]

Edinburgh is also represented in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom by five Members of Parliament. The city is divided into Edinburgh North and Leith, Edinburgh East, Edinburgh South, Edinburgh South West, and Edinburgh West,[234] each constituency electing one member by the first past the post system. Since the 2019 UK General election, Edinburgh is represented by three Scottish National Party MPs (Deirdre Brock, Edinburgh North and Leith/Tommy Sheppard, Edinburgh East/Joanna Cherry, Edinburgh South West), one Liberal Democrat MP in Edinburgh West (Christine Jardine) and one Labour MP in Edinburgh South (Ian Murray).

Transport

[edit]Air

[edit]

Edinburgh Airport is Scotland's busiest airport and the principal international gateway to the capital, handling over 14.7 million passengers; it was also the sixth-busiest airport in the United Kingdom by total passengers in 2019.[235][236] In anticipation of rising passenger numbers, the former operator of the airport BAA outlined a draft masterplan in 2011 to provide for the expansion of the airfield and the terminal building. In June 2012, Global Infrastructure Partners purchased the airport for £807 million.[237] The possibility of building a second runway to cope with an increased number of aircraft movements has also been mooted.[238]

Buses

[edit]

Travel in Edinburgh is undertaken predominantly by bus. Lothian Buses, the successor company to Edinburgh Corporation Transport Department, operate the majority of city bus services within the city and to surrounding suburbs, with the most routes running via Princes Street. Services further afield operate from the Edinburgh Bus Station off St Andrew Square and Waterloo Place and are operated mainly by Stagecoach East Scotland, Scottish Citylink, National Express Coaches and Borders Buses.

Lothian Buses and McGill's Scotland East operate the city's branded public tour buses. The night bus service and airport buses are mainly operated by Lothian Buses link.[239] In 2019, Lothian Buses recorded 124.2 million passenger journeys.[240]

To tackle traffic congestion, Edinburgh is now served by six park & ride sites on the periphery of the city at Sheriffhall (in Midlothian), Ingliston, Riccarton, Inverkeithing (in Fife), Newcraighall and Straiton (in Midlothian). A referendum of Edinburgh residents in February 2005 rejected a proposal to introduce congestion charging in the city. [241]

Railway

[edit]

Edinburgh Waverley is the second-busiest railway station in Scotland, with only Glasgow Central handling more passengers. On the evidence of passenger entries and exits between April 2015 and March 2016, Edinburgh Waverley is the fifth-busiest station outside London; it is also the UK's second biggest station in terms of the number of platforms and area size.[242] Waverley is the terminus for most trains arriving from London King's Cross and the departure point for many rail services within Scotland operated by ScotRail.

To the west of the city centre lies Haymarket station, which is an important commuter stop. Opened in 2003, Edinburgh Park station serves the Gyle business park in the west of the city and the nearby Gogarburn headquarters of the Royal Bank of Scotland. The Edinburgh Crossrail route connects Edinburgh Park with Haymarket, Edinburgh Waverley and the suburban stations of Brunstane and Newcraighall in the east of the city.[243] There are also commuter lines to Edinburgh Gateway, South Gyle and Dalmeny, the latter serving South Queensferry by the Forth Bridges, and to Wester Hailes and Curriehill in the south-west of the city.

Trams

[edit]

Edinburgh Trams became operational on 31 May 2014. The city had been without a tram system since Edinburgh Corporation Tramways ceased on 16 November 1956.[244] Following parliamentary approval in 2007, construction began in early 2008. The first stage of the project was expected to be completed by July 2011[245] but, following delays caused by extra utility work and a long-running contractual dispute between the council and the main contractor, Bilfinger SE, the project was rescheduled.[246][247][248] The line opened in 2014 but had been cut short to 8.7 mi (14.0 km) in length, running from Edinburgh Airport To York Place in the east end of the city.

The line was later extended north onto Leith and Newhaven opening a further eight stops to passengers in June 2023. The York Place stop was replaced by a new island stop at Picardy Place. The original plan would have seen a second line run from Haymarket through Ravelston and Craigleith to Granton Square on the Waterfront Edinburgh.This was shelved in 2011 but is now once again under consideration, as is another line potentially linking the south of the city and the Bioquarter.[249] There were also long-term plans for lines running west from the airport to Ratho and Newbridge and another connecting Granton to Newhaven via Lower Granton Road. Lothian Buses and Edinburgh Trams are both owned and operated by Transport for Edinburgh.

Despite its modern transport links, in January 2021 Edinburgh was named the most congested city in the UK for the fourth year running, though has since fallen to 7th place in 2022 [250][251]

Education

[edit]Schools

[edit]There are 18 nursery, 94 primary and 23 secondary schools administered by the City of Edinburgh Council.[252] Edinburgh is home to The Royal High School, one of the oldest schools in the country and the world. The city also has several independent, fee-paying schools including Edinburgh Academy, Fettes College, George Heriot's School, George Watson's College, Merchiston Castle School, Stewart's Melville College and The Mary Erskine School. In 2009, the proportion of pupils attending independent schools was 24.2%, far above the Scottish national average of just over 7% and higher than in any other region of Scotland.[253] In August 2013, the City of Edinburgh Council opened the city's first stand-alone Gaelic primary school, Bun-sgoil Taobh na Pàirce.[254]

College and university

[edit]

There are three universities in Edinburgh: the University of Edinburgh, Heriot-Watt University and Edinburgh Napier University.

Established by royal charter in 1583, the University of Edinburgh is one of Scotland's ancient universities and is the fourth oldest in the country after St Andrews, Glasgow and Aberdeen.[255] Originally centred on Old College the university expanded to premises on The Mound, the Royal Mile and George Square.[255] Today, the King's Buildings in the south of the city contain most of the schools within the College of Science and Engineering. In 2002, the medical school moved to purpose built accommodation adjacent to the new Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh at Little France. The university is placed 16th in the QS World University Rankings for 2022.[256]

Heriot-Watt University is based at the Riccarton campus in the west of Edinburgh. Originally established in 1821, as the world's first mechanics' institute, it was granted university status by royal charter in 1966. It has other campuses in the Scottish Borders, Orkney, United Arab Emirates and Putrajaya in Malaysia. It takes the name Heriot-Watt from Scottish inventor James Watt and Scottish philanthropist and goldsmith George Heriot. Heriot-Watt University has been named International University of the Year by The Times and Sunday Times Good University Guide 2018. In the latest Research Excellence Framework, it was ranked overall in the Top 25% of UK universities and 1st in Scotland for research impact.

Edinburgh Napier University was originally founded as the Napier College, which was renamed Napier Polytechnic in 1986 and gained university status in 1992.[257] Edinburgh Napier University has campuses in the south and west of the city, including the former Merchiston Tower and Craiglockhart Hydropathic.[257] It is home to the Screen Academy Scotland.

Queen Margaret University was located in Edinburgh before it moved to a new campus just outside the city boundary on the edge of Musselburgh in 2008.[258] Until 2012, further education colleges in the city included Jewel and Esk College (incorporating Leith Nautical College founded in 1903), Telford College, opened in 1968, and Stevenson College, opened in 1970. These have now been amalgamated to form Edinburgh College. Scotland's Rural College also has a campus in south Edinburgh. Other institutions include the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh and the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh which were established by royal charter in 1506 and 1681 respectively. The Trustees Drawing Academy of Edinburgh, founded in 1760, became the Edinburgh College of Art in 1907.[259]

Healthcare

[edit]

The main NHS Lothian hospitals serving the Edinburgh area are the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, which includes the University of Edinburgh Medical School, and the Western General Hospital,[260] which has a large cancer treatment centre and nurse-led Minor Injuries Clinic.[261] The Royal Edinburgh Hospital in Morningside specialises in mental health. The Royal Hospital for Children and Young People, colloquially referred to as the Sick Kids, is a specialist paediatrics hospital.

There are two private hospitals: Murrayfield Hospital in the west of the city and Shawfair Hospital in the south; both are owned by Spire Healthcare.[260]

Sport

[edit]Football

[edit]Men's

[edit]Edinburgh has four football clubs that play in the Scottish Professional Football League (SPFL): Heart of Midlothian, founded in 1874, Hibernian, founded in 1875, Edinburgh City F.C., founded in 1966 and Spartans, founded in 1951.

Heart of Midlothian and Hibernian are known locally as "Hearts" and "Hibs", respectively. Both play in the Scottish Premiership.[262] They are the oldest city rivals in Scotland and the Edinburgh derby is one of the oldest derby matches in world football. Both clubs have won the Scottish league championship four times. Hearts have won the Scottish Cup eight times and the Scottish League Cup four times. Hibs have won the Scottish Cup and the Scottish League Cup three times each. Edinburgh City were promoted to Scottish League Two in the 2015–16 season, becoming the first club to win promotion to the SPFL via the pyramid system playoffs.

Edinburgh was also home to four other former Scottish Football League clubs: the original Edinburgh City (founded in 1928), Leith Athletic, Meadowbank Thistle and St Bernard's. Meadowbank Thistle played at Meadowbank Stadium until 1995, when the club moved to Livingston and became Livingston F.C. The Scottish national team has very occasionally played at Easter Road and Tynecastle, although its normal home stadium is Hampden Park in Glasgow. St Bernard's' New Logie Green was used to host the 1896 Scottish Cup Final, the only time the match has been played outside Glasgow.[263]

The city also plays host to Lowland Football League clubs Civil Service Strollers, Edinburgh University and Spartans, as well as East of Scotland League clubs Craigroyston, Edinburgh United, Heriot-Watt University, Leith Athletic, Lothian Thistle Hutchison Vale, and Tynecastle.

Women's

[edit]In women's football, Hearts, Hibs and Spartans play in the SWPL 1.[264] Hutchison Vale and Boroughmuir Thistle play in the SWPL 2.[265]

Rugby

[edit]The Scotland national rugby union team play at Murrayfield Stadium, and the professional Edinburgh Rugby team play at the nextdoor Edinburgh Rugby Stadium; both are owned by the Scottish Rugby Union and are also used for other events, including music concerts. Murrayfield is the largest capacity stadium in Scotland, seating 67,144 spectators.[266] Edinburgh is also home to Scottish Premiership teams Boroughmuir RFC, Currie RFC, the Edinburgh Academicals, Heriot's Rugby Club and Watsonians RFC.[267]

The Edinburgh Academicals ground at Raeburn Place was the location of the world's first international rugby game on 27 March 1871, between Scotland and England.[268]

Rugby league is represented by the Edinburgh Eagles who play in the Rugby League Conference Scotland Division. Murrayfield Stadium has hosted the Magic Weekend where all Super League matches are played in the stadium over one weekend.

-

Edinburgh Marathon

-

Murrayfield Ice Rink

Other sports

[edit]The Scottish cricket team, which represents Scotland internationally, play their home matches at the Grange cricket club.[269]

The Edinburgh Capitals are the latest of a succession of ice hockey clubs in the Scottish capital. Previously Edinburgh was represented by the Murrayfield Racers (2018), the original Murrayfield Racers (who folded in 1996) and the Edinburgh Racers. The club play their home games at the Murrayfield Ice Rink and have competed in the eleven-team professional Scottish National League (SNL) since the 2018–19 season.[270]

Next door to Murrayfield Ice Rink is a 7-sheeter dedicated curling facility where curling is played from October to March each season.

Caledonia Pride are the only women's professional basketball team in Scotland. Established in 2016, the team compete in the UK wide Women's British Basketball League and play their home matches at the Oriam National Performance Centre. Edinburgh also has several men's basketball teams within the Scottish National League. Boroughmuir Blaze, City of Edinburgh Kings and Edinburgh Lions all compete in Division 1 of the National League, and Pleasance B.C. compete in Division 2.

The Edinburgh Diamond Devils is a baseball club which won its first Scottish Championship in 1991 as the "Reivers". 1992 saw the team repeat the achievement, becoming the first team to do so in league history. The same year saw the start of their first youth team, the Blue Jays. The club adopted its present name in 1999.[271]

Edinburgh has also hosted national and international sports events including the World Student Games, the 1970 British Commonwealth Games,[272] the 1986 Commonwealth Games[272] and the inaugural 2000 Commonwealth Youth Games.[273] For the 1970 Games the city built Olympic standard venues and facilities including Meadowbank Stadium and the Royal Commonwealth Pool. The Pool underwent refurbishment in 2012 and hosted the Diving competition in the 2014 Commonwealth Games which were held in Glasgow.[274]

In American football, the Scottish Claymores played WLAF/NFL Europe games at Murrayfield, including their World Bowl 96 victory. From 1995 to 1997 they played all their games there, from 1998 to 2000 they split their home matches between Murrayfield and Glasgow's Hampden Park, then moved to Glasgow full-time, with one final Murrayfield appearance in 2002.[275] The city's most successful non-professional team are the Edinburgh Wolves who play at Meadowbank Stadium.[276]