Право-либертарианство

| Часть серии о |

| Капитализм |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarianism |

|---|

Право-либертарианство , [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] [ 4 ] также известный как либертарианский капитализм , [ 5 ] или правое либертарианство , [ 1 ] [ 6 ] Это либертарианская политическая философия , которая поддерживает капиталистические права собственности и защищает рыночное распределение природных ресурсов и частной собственности . [ 7 ] Термин «правое либертарианство» используется для обозначения этого класса взглядов на природу собственности и капитала. [ 8 ] от левого либертарианства , типа либертарианства, сочетающего в себе собственность на себя с антиавторитарным подходом к собственности и доходам. [ 9 ] В отличие от социалистического либертарианства, [ 3 ] Правое либертарианство поддерживает капитализм свободного рынка . [ 1 ] Как и большинство форм либертарианства, он поддерживает гражданские свободы . [ 1 ] особенно естественное право , [ 10 ] отрицательные права , [ 11 ] принцип ненападения , [ 12 ] и крупный разворот современного государства всеобщего благосостояния . [ 13 ] Практикующие правого либертарианства обычно не называют себя этим термином и часто возражают против него.

Right-libertarian political thought is characterized by the strict priority given to liberty, with the need to maximize the realm of individual freedom and minimize the scope of public authority.[14] Right-libertarians typically see the state as the principal threat to liberty. This anti-statism differs from anarchist doctrines in that it is based upon strong individualism that places less emphasis on human sociability or cooperation.[2][14][15] Right-libertarian philosophy is also rooted in the ideas of individual rights and laissez-faire economics. The right-libertarian theory of individual rights generally follows the homestead principle and the labor theory of property, stressing self-ownership and that people have an absolute right to the property that their labor produces.[14] Economically, right-libertarians make no distinction between capitalism and free markets and view any attempt to dictate the market process as counterproductive, emphasizing the mechanisms and self-regulating nature of the market whilst portraying government intervention and attempts to redistribute wealth as invariably unnecessary and counter-productive.[14] Although all right-libertarians oppose government intervention, there is a division between anarcho-capitalists, who view the state as an unnecessary evil and want property rights protected without statutory law through market-generated tort, contract and property law; and minarchists, who support the need for a minimal state, often referred to as a night-watchman state, to provide its citizens with courts, military, and police.[16]

Like libertarians of all varieties, right-libertarians refer to themselves simply as libertarians.[2][16][6] Being the most common type of libertarianism in the United States,[3] right-libertarianism has become the most common referent of libertarianism[17][18] there since the late 20th century while historically and elsewhere[19][20][21][22][23][24] it continues to be widely used to refer to anti-state forms of socialism such as anarchism[25][26][27][28] and more generally libertarian communism/libertarian Marxism and libertarian socialism.[19][29] Around the time of Murray Rothbard, who popularized the term libertarian in the United States during the 1960s, anarcho-capitalist movements started calling themselves libertarian, leading to the rise of the term right-libertarian to distinguish them. Rothbard himself acknowledged the co-opting of the term and boasted of its "capture [...] from the enemy".[19]

Definition

[edit]

People described as being left-libertarian or right-libertarian generally tend to call themselves simply libertarians and refer to their philosophy as libertarianism. In light of this, some authors and political scientists classify the forms of libertarianism into two groups,[30][31] namely left-libertarianism and right-libertarianism,[1][2][16][3][6] to distinguish libertarian views on the nature of property and capital.[8]

The term libertarian was first used by late Enlightenment freethinkers, referring to those who believed in free will, as opposed to necessity, a now-disused philosophy that posited a kind of determinism.[32] The word libertarian is first recorded in 1789 coined by the British historian William Belsham, in a discussion against free will from the author's deterministic point of view.[33][34] This debate between libertarianism in a philosophical-metaphysical sense and determinism would continue into the early nineteenth century, especially in the field of Protestant theology.[35] The Merriam-Webster Dictionary, in English, attests to this ancient use of the word libertarian by describing its meaning as "an advocate of the doctrine of free will "and, taking a broad definition, also says that he is" a person who holds the principles of individual freedom especially in thought and action ".[36]

Many decades later, libertarian was a term used by the French libertarian communist Joseph Déjacque[25][26][37][38][39] to mean a form of left-wing politics that has been frequently used to refer to anarchism[2][21][25][26] and libertarian socialism[23] since the mid- to late 19th century.[27][28] With the modern development of right-libertarian ideologies such as anarcho-capitalism and minarchism co-opting[19][20][22] the term libertarian in the mid-20th century to instead advocate laissez-faire capitalism and strong private property rights such as in land, infrastructure and natural resources,[40] the terms left-libertarianism and right-libertarianism have been used more often as to differentiate between the two.[2][16] Socialist libertarianism[41] has been included within a broad left-libertarianism[42][43][44] while right-libertarianism mainly refers to laissez-faire capitalism such as Murray Rothbard's anarcho-capitalism and Robert Nozick's minarchism.[2][16][6]

Right-libertarianism has been described as combining individual freedom and opposition to the state, with strong support for free markets and private property. Property rights have been the issue that has divided libertarian philosophies. According to Jennifer Carlson, right-libertarianism is the dominant form of libertarianism in the United States. Right-libertarians "see strong private property rights as the basis for freedom and thus are—to quote the title of Brian Doherty's text on libertarianism in the United States—"Radicals for Capitalism".[3]

Herbert Kitschelt and Anthony J. McGann contrast right-libertarianism—"a strategy that combines pro-market positions with opposition to hierarchical authority, support of unconventional political participation, and endorsement of feminism and of environmentalism"—with right-authoritarianism.[45][46]

Mark Bevir holds that there are three types of libertarianism, namely left, right and consequentialist libertarianism as promoted by Friedrich Hayek.[47]

According to contemporary American libertarian Walter Block, left-libertarians and right-libertarians agree with certain libertarian premises, but "where [they] differ is in terms of the logical implications of these founding axioms".[48] Although some libertarians may reject the political spectrum, especially the left–right political spectrum,[1] right-libertarianism and several right-oriented strands of libertarianism in the United States have been described as being right-wing,[49] New Right,[50][51][52][53] radical right[45][46] and reactionary.[13][54]

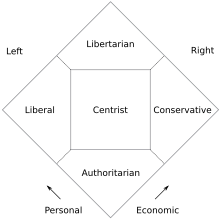

American libertarian activist and politician David Nolan, the principal founder of the Libertarian Party, developed what is now known as the Nolan Chart to replace the traditional left-right political spectrum. The Nolan Chart has been used by several modern American libertarians and right-libertarians who reject the traditional political spectrum for its lack of inclusivity and see themselves as north-of-center. It is used in an effort to quantify typical libertarian views that support both free markets and social liberties and reject what they see as restrictions on economic and personal freedom imposed by the left and the right, respectively,[55] although this latter point has been criticized.[56] Other libertarians reject the separation of personal and economic liberty or argue that the Nolan Chart gives no weight to foreign policy.[57]

Since the resurgence of neoliberalism in the 1970s, right-libertarianism has spread beyond North America via think tanks and political parties.[58][59][60] In the United States, libertarianism is increasingly viewed as this capitalist free-market position.[2][16][6][3]

Terminology

[edit]As a term, right-libertarianism is used by some political analysts, academics and media sources, especially in the United States, to describe the libertarian philosophy which is supportive of free-market capitalism and strong right to property, in addition to supporting limited government and self-ownership,[61] being contrasted with left-wing views which do not support the former. In most of the world, this particular political position is mostly known as classical liberalism, economic liberalism and neoliberalism.[62] It is mainly associated with right-wing politics, support for free markets and private ownership of capital goods. Furthermore, it is usually contrasted with similar ideologies such as social democracy and social liberalism which generally favor alternative forms of capitalism such as mixed economies, state capitalism and welfare capitalism.[63][64]

Peter Vallentyne writes that libertarianism, defined as being about self-ownership, is not a right-wing doctrine in the context of the typical left–right political spectrum because on social issues it tends to be left-wing, opposing laws restricting consensual sexual relationships between or drug use by adults as well as laws imposing religious views or practices and compulsory military service. He defines right-libertarianism as holding that unowned natural resources "may be appropriated by the first person who discovers them, mixes her labor with them, or merely claims them—without the consent of others, and with little or no payment to them". He contrasts this with left-libertarianism, where such "unappropriated natural resources belong to everyone in some egalitarian manner".[18] Similarly, Charlotte and Lawrence Becker maintain that right-libertarianism most often refers to the political position that because natural resources are originally unowned, they may be appropriated at will by private parties without the consent of, or owing to, others.[65]

Samuel Edward Konkin III, who characterized agorism as a form of left-libertarianism[66][67] and strategic branch of left-wing market anarchism,[68] defined right-libertarianism as an "activist, organization, publication or tendency which supports parliamentarianism exclusively as a strategy for reducing or abolishing the state, typically opposes Counter-Economics, either opposes the Libertarian Party or works to drag it right and prefers coalitions with supposedly 'free-market' conservatives".[69]

Anthony Gregory maintains that libertarianism "can refer to any number of varying and at times mutually exclusive political orientations". While holding that the important distinction for libertarians is not left or right, but whether they are "government apologists who use libertarian rhetoric to defend state aggression", he describes right-libertarianism as having and maintaining interest in economic freedom, preferring a conservative lifestyle, viewing private business as a "great victim of the state" and favoring a non-interventionist foreign policy, sharing the Old Right's "opposition to empire".[70]

Old Right

[edit]Murray Rothbard, whose writings and personal influence helped create some strands of right-libertarianism,[71] wrote about the Old Right in the United States, a loose coalition of individuals formed in the 1930s to oppose the New Deal at home and military interventionism abroad, that they "did not describe or think of themselves as conservatives: they wanted to repeal and overthrow, not conserve".[72] Bill Kauffman has also written about such "old right libertarians".[73] Peter Marshall dates right-libertarianism and anarcho-capitalism in particular back to the Old Right and as being popularized again by the New Right.[52]

Individuals who are seen in this Old Right libertarian tradition[72][74][75] include Frank Chodorov,[76][77] John T. Flynn,[78][79] Garet Garrett,[80][81] Rose Wilder Lane,[82][83] H. L. Mencken,[84] Albert Jay Nock[85][86][87] and Isabel Paterson.[88][89] What those thinkers had in common was opposition to the rise of the managerial state during the Progressive Era and its expansion in connection with the New Deal and the Fair Deal whilst challenging imperialism and military interventionism.[90] However, Old Right was a label about which many or most of these figures might have been skeptical as most thought of themselves effectively as classical liberals rather than the national defense and social conservatism of thinkers associated with the later movement conservatism, with Chodorov famously writing: "As for me, I will punch anyone who calls me a conservative in the nose. I am a radical".[91][92][93] Their opposition and resistance to the state approached philosophical anarchism with Nock and amounted to statelessness in Chodorov's case.[73] On the other hand, Lew Rockwell and Jeffrey Tucker identifies the Old Right as being culturally conservative, arguing that "[v]igorous social authority—as embodied in the family, church, and other mediating institutions—is a bedrock of the virtuous society" and that "[t]he egalitarian ethic is morally reprehensible and destructive of private property and social authority".[94]

While libertarian was popularized by the libertarian socialist Benjamin Tucker around the late 1870s and early 1880s,[95] H. L. Mencken and Albert Jay Nock were the first prominent figures in the United States to describe themselves as libertarian as a synonym for liberal. They believed that Franklin D. Roosevelt had co-opted the word liberal for his New Deal policies which they opposed and used libertarian to signify their allegiance to classical liberalism, individualism and limited government.[96]

In the 1960s, Rothbard started publishing Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought, believing that the left–right political spectrum had gone "entirely askew" since conservatives were sometimes more statist than liberals and tried to reach out to leftists and go beyond left and right.[97] In 1971, Rothbard wrote about right-libertarianism which he described as supporting free trade, property rights and self-ownership.[1] Rothbard would later describe it as anarcho-capitalism[98][99][100] and paleolibertarianism.[101][102]

Philosophy

[edit]| This article is part of a series on |

| Libertarianism in the United States |

|---|

|

Right-libertarianism developed in the United States in the mid-20th century from the works of European liberal writers such as John Locke, Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises and is the most popular conception of libertarianism in the United States today.[3][103] It is commonly referred to as a continuation or radicalization of classical liberalism.[32][104] The most important of these early right-libertarian philosophers were modern American libertarians such as Robert Nozick and Murray Rothbard.[2]

Although often sharing the left-libertarian advocacy for social freedom, right-libertarians also value capitalism while rejecting institutions that intervene the free market on the grounds that such interventions represent unnecessary coercion of individuals and therefore a violation of their economic freedom.[105] Anarcho-capitalists[106][107] seek complete elimination of the state in favor of private defense agencies while minarchists defend night-watchman states which maintain only those functions of government necessary to safeguard natural rights, understood in terms of self-ownership or autonomy.[108]

Right-libertarians are economic liberals of either the Austrian School (majority) or the Chicago school of economics (minority) and support laissez-faire capitalism which they define as the free market in opposition to state capitalism and interventionism.[109] Right-libertarianism and its individualism have been discussed as part of the New Right[52][53] in relation to neoliberalism and Thatcherism.[51] In the 20th century, New Right liberal conservatism influenced by right-libertarianism marginalized other forms of conservatism.[110]

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy describes right-libertarian philosophy as follows:

Libertarianism is often thought of as 'right-wing' doctrine. This, however, is mistaken for at least two reasons. First, on social—rather than economic—issues, libertarianism tends to be 'left-wing'. It opposes laws that restrict consensual and private sexual relationships between adults (e.g., gay-sex, non-marital sex, and deviant sex), laws that restrict drug use, laws that impose religious views or practices on individuals, and compulsory military service. Second, in addition to the better-known version of libertarianism—right-libertarianism—, there is also a version known as 'left-libertarianism. Both endorse full self-ownership, but they differ with respect to the powers agents have to appropriate unappropriated natural resources (land, air, water, etc.).[18]

Right-libertarians are distinguished from left-libertarians by their relation to property and capital. While both left-libertarianism and right-libertarianism share general antipathy towards power by a government authority, the latter exempts power wielded through free-market capitalism. Historically, libertarians such as Herbert Spencer and Max Stirner supported the protection of an individual's freedom from powers of government and private ownership. While condemning governmental encroachment on personal liberties, right-libertarians support freedoms on the basis of their agreement with private property rights and the abolishment of public amenities is a common theme in right-libertarian writings.[8][111]

While associated with free-market capitalism, right-libertarianism is not opposed in principle to voluntary egalitarianism and socialism.[112][113] However, right-libertarians believe that their advocated economic system would prove superior and that people would prefer it to socialism.[114][115] For Nozick, it does not imply support of capitalism, but merely that capitalism is compatible with libertarianism,[116] something which is rejected by anti-capitalist libertarians.[117][118][119][120]

According to Stephen Metcalf, Nozick expressed serious misgivings about capitalism, going so far as to reject much of the foundations of the theory on the grounds that personal freedom can sometimes only be fully actualized via a collectivist politics and that wealth is at times justly redistributed via taxation to protect the freedom of the many from the potential tyranny of an overly selfish and powerful few.[121] Nozick suggested that citizens who are opposed to wealth redistribution which fund programs they object to should be able to opt-out by supporting alternative government-approved charities with an added 5% surcharge.[122] Nonetheless, Nozick did not stop from self-identifying as a libertarian in a broad sense[123] and Julian Sanchez has argued that his views simply became more nuanced.[124]

Non-aggression principle

[edit]The non-aggression principle (NAP) is often described as the foundation of several present-day libertarian philosophies, including right-libertarianism.[125][126][127][128][129] The NAP is a moral stance which forbids actions that are inconsistent with capitalist private property and property rights. It defines aggression and initiation of force as violation of these rights. The NAP and property rights are closely linked since what constitutes aggression depends on what it is considered to be one's property.[130] The principle has been used rhetorically to oppose policies such as military drafts, taxation and victimless crime laws.[5]

Property rights

[edit]While there is debate on whether right-libertarianism and left-libertarianism or socialist libertarianism "represent distinct ideologies as opposed to variations on a theme", right-libertarianism is most in favor of capitalist private property and property rights.[131] Right-libertarians maintain that unowned natural resources "may be appropriated by the first person who discovers them, mixes his labor with them, or merely claims them—without the consent of others, and with little or no payment to them". This contrasts with left-libertarianism in which "unappropriated natural resources belong to everyone in some egalitarian manner".[132] Right-libertarians believe that natural resources are originally unowned and therefore private parties may appropriate them at will without the consent of, or owing to, others (e.g. a land value tax).[133]

Right-libertarians are also referred to as propertarians because they hold that societies in which private property rights are enforced are the only ones that are both ethical and lead to the best possible outcomes.[134] They generally support free-market capitalism and are not opposed to any concentrations of economic power, provided it occurs through non-coercive means.[135]

State

[edit]

There is a debate amongst right-libertarians as to whether or not the state is legitimate. While anarcho-capitalists advocate its abolition, minarchists support minimal states, often referred to as night-watchman states. Minarchists maintain that the state is necessary for the protection of individuals from aggression, breach of contract, fraud and theft. They believe the only legitimate governmental institutions are courts, military and police, although some expand this list to include the executive and legislative branches, fire departments and prisons. These minarchists justify the state on the grounds that it is the logical consequence of adhering to the non-aggression principle.[136][137][138] Some minarchists argue that a state is inevitable, believing anarchy to be futile.[139] Others argue that anarchy is immoral because it implies that the non-aggression principle is optional and not sufficient to enforce the non-aggression principle because the enforcement of laws under anarchy is open to competition.[140][page needed] Another common justification is that private defense agencies and court firms would tend to represent the interests of those who pay them enough.[141]

Right-libertarians such as anarcho-capitalists argue that the state violates the non-aggression principle by its nature because governments use force against those who have not stolen or vandalized private property, assaulted anyone, or committed fraud.[142][143] Others argue that monopolies tend to be corrupt and inefficient and that private defense and court agencies would have to have a good reputation to stay in business. Linda and Morris Tannehill argue that no coercive monopoly of force can arise on a truly free market and that a government's citizenry can desert them in favor of a competent protection and defense agency.[144]

Philosopher Moshe Kroy argues that the disagreement between anarcho-capitalists who adhere to Murray Rothbard's view of human consciousness and the nature of values and minarchists who adhere to Ayn Rand's view of human consciousness and the nature of values over whether or not the state is moral is not due to a disagreement over the correct interpretation of a mutually held ethical stance. He argues that the disagreement between these two groups is instead the result of their disagreement over the nature of human consciousness and that each group is making the correct interpretation of their differing premises. According to Kroy, these two groups are not making any errors with respect to deducing the correct interpretation of any ethical stance because they do not hold the same ethical stance.[145]

Taxation as theft

[edit]The idea of taxation as theft is a viewpoint found in a number of political philosophies. Under this view, government transgresses property rights by enforcing compulsory tax collection.[146][147] Right-libertarians see taxation as a violation of the non-aggression principle.[148]

Schools of thought

[edit]Anarcho-capitalism

[edit]

Anarcho-capitalism advocates the elimination of centralized states in favor of capitalism,[149][150][151] contracts, free markets, individual sovereignty, private property, the right-libertarian interpretation of self-ownership and voluntaryism. In the absence of statute, anarcho-capitalists hold that society tends to contractually self-regulate and civilize through participation in the free market which they describe as a voluntary society.[152][153] In an anarcho-capitalist society, courts, law enforcement and all other security services would be provided by privately funded competitors rather than through taxation and money would be privately and competitively provided in an open market.[154] Under anarcho-capitalism, personal and economic activities would be regulated by private law rather than through politics.[155] Anarcho-capitalists support wage labour[156] and believe that neither protection of person and property nor victim compensation requires a state.[52] Autarchism promotes the principles of individualism, the moral ideology of individual liberty and self-reliance whilst rejecting compulsory government and supporting the elimination of government in favor of ruling oneself to the exclusion of rule by others.

The most well-known version of anarcho-capitalism was formulated in the mid-20th century by Austrian School economist and paleolibertarian Murray Rothbard.[157] Widely regarded as its founder,[158] Rothbard combined the free-market approach from the Austrian School with the human rights views and a rejection of the state from 19th-century American individualist anarchists and mutualists such as Lysander Spooner and Benjamin Tucker, although rejecting their anti-capitalism and socialist economics, along with the labor theory of value and the normative implications they derived from it.[159] In Rothbardian anarcho-capitalism, exemplified in For a New Liberty, there would first be the implementation of a mutually agreed-upon libertarian "legal code which would be generally accepted and which the courts would pledge themselves to follow".[160] This legal code would recognize contracts, individual sovereignty, private property, self-ownership, and tort law as part of the principle of non-aggression[161] In the tradition following David D. Friedman, exemplified in The Machinery of Freedom, anarcho-capitalists do not rely upon the idea of natural law or natural rights (deontological libertarianism) and follow consequentialist libertarianism, presenting economic justifications for a free-market capitalist society.[162]

While some authors consider anarcho-capitalism a form of individualist anarchism, many others disagree with this as individualist anarchism is largely socialistic.[163][164][165] Rothbard argued that individualist anarchism is different from anarcho-capitalism and other capitalist theories due to the individualist anarchists retaining the labor theory of value and socialist economics.[166] Many anarchist activists and scholars deny that anarcho-capitalism is a form of anarchism, or that capitalism is compatible with anarchism,[165] regarding it instead as right-libertarian.[2][16][6] Anarcho-capitalists are distinguished from anarchists and minarchists. The latter advocate a night-watchman state limited to protecting individuals from aggression and enforcing private property.[140] On the other hand, anarchists support personal property (defined in terms of possession and use, i.e. mutualist usufruct)[167][168] and oppose capital concentration, interest, monopoly, private ownership of productive property such as the means of production (capital, land and the means of labor), profit, rent, usury and wage slavery which are viewed as inherent to capitalism.[169][170] Anarchism's emphasis on anti-capitalism, egalitarianism and for the extension of community and individuality sets it apart from anarcho-capitalism and other types of right-libertarianism.[171][172][173][174]

Ruth Kinna writes that anarcho-capitalism is a term coined by Rothbard to describe "a commitment to unregulated private property and laissez-faire economics, prioritizing the liberty-rights of individuals, unfettered by government regulation, to accumulate, consume and determine the patterns of their lives as they see fit". According to Kinna, anarcho-capitalists "will sometimes label themselves market anarchists because they recognize the negative connotations of 'capitalism'. But the literatures of anarcho-capitalism draw on classical liberal theory, particularly the Austrian School—Friedrich von Hayek and Ludwig von Mises—rather than recognizable anarchist traditions. Ayn Rand's laissez-faire, anti-government, corporate philosophy—Objectivism—is sometimes associated with anarcho-capitalism".[175] Other scholars similarly associate anarcho-capitalism with anti-state liberal schools such as neo-classical liberalism, radical neoliberalism and right-libertarianism.[2][16][3][6][176] Anarcho-capitalism is usually seen as part of the New Right.[53][177]

Conservative libertarianism

[edit]

Conservative libertarianism combines laissez-faire economics and conservative values. It advocates the greatest possible economic liberty and the least possible government regulation of social life whilst harnessing this to traditionalist conservatism, emphasizing authority and duty.[178]

Conservative libertarianism prioritizes liberty as its main emphasis, promoting free expression, freedom of choice and laissez-faire capitalism to achieve cultural and social conservative ends whilst rejecting liberal social engineering.[179] This can also be understood as promoting civil society through conservative institutions and authority such as education, family, fatherland and religion in the quest of libertarian ends for less state power.[180]

In the United States, conservative libertarianism combines conservatism and libertarianism, representing the conservative wing of libertarianism and vice versa. Fusionism combines traditionalist and social conservatism with laissez-faire economics.[181] This is most closely associated with Frank Meyer.[182] Hans-Hermann Hoppe is a cultural conservative right-libertarian, whose belief in the rights of property owners to establish private covenant communities, from which homosexuals and political dissidents may be "physically removed",[183] has proven particularly divisive.[184][185][186][187] Hoppe also garnered controversy due to his support for restrictive limits on immigration which critics argue is at odds with libertarianism.[188]

Minarchism

[edit]Within right-libertarian philosophy, minarchism[189] is supportive of a night-watchman state, a model of a state whose only functions are to provide its citizens with courts, military and police, protecting them from aggression, breach of contract, fraud and theft whilst enforcing property laws.[136][137][138] 19th-century Britain has been described by historian Charles Townshend as standard-bearer of this form of government among European countries.[190]

As a term, night-watchman state (German: Nachtwächterstaat) was coined by German socialist Ferdinand Lassalle, an advocate of social-democratic state socialism, to criticize the bourgeois state.[191] Austrian School economist Ludwig von Mises, a classical liberal who greatly influenced right-libertarianism, later opined that Lassalle tried to make limited government look ridiculous, but that it was no more ridiculous than governments that concerned themselves with "the preparation of sauerkraut, with the manufacture of trouser buttons, or with the publication of newspapers".[192]

Robert Nozick, a right-libertarian advocate of minarchism, received a National Book Award in category Philosophy and Religion for his book Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974),[193] where he argued that only a minimal state limited to the narrow functions of protection against "force, fraud, theft, and administering courts of law" could be justified without violating people's rights.[194][195]

Neo-classical liberalism

[edit]

Traditionally, liberalism's primary emphasis was placed on securing the freedom of the individual by limiting the power of the government and maximizing the power of free market forces. As a political philosophy, it advocated civil liberties under the rule of law, with an emphasis on economic freedom. Closely related to economic liberalism, it developed in the early 19th century, emerging as a response to urbanization and to the Industrial Revolution in Europe and the United States.[196][197][198][199] It advocated a limited government and held a belief in laissez-faire economic policy.[197][198][200]

Built on ideas that had already arisen by the end of the 18th century such as selected ideas of John Locke,[201] Adam Smith, Thomas Robert Malthus, Jean-Baptiste Say and David Ricardo, it drew on classical economics and economic ideas as espoused by Smith in The Wealth of Nations and stressed the belief in progress,[202] natural law[203] and utilitarianism.[204] These liberals were more suspicious than conservatives of all but the most minimal government and adopted Thomas Hobbes's theory of government, believing government had been created by individuals to protect themselves from one another.[205] The term classical liberalism was applied in retrospect to distinguish earlier 19th-century liberalism from the newer social liberalism.[206]

Neoliberalism emerged in the era following World War II during which social liberalism was the mainstream form of liberalism while Keynesianism and social democracy were the dominant ideologies in the Western world. It was led by neoclassical economists such as Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, who advocated the reduction of the state and a return to classical liberalism, hence the term neo-classical liberalism,[207] not to be confused with the more left-leaning neoclassical liberalism,[208][209] an American bleeding-heart libertarian school originating in Arizona.[208] However, it did accept some aspects of social liberalism such as some degree of welfare provision by the state, but on a greatly reduced scale. Hayek and Friedman used the term classical liberalism to refer to their ideas, but others use the term to refer to all liberalism before the 20th century, not to designate any particular set of political views and therefore see all modern developments as being by definition not classical.[210]

In the late 19th century, classical liberalism developed into neo-classical liberalism which argued for government to be as small as possible to allow the exercise of individual freedom. In its most extreme form, neo-classical liberalism advocated social Darwinism.[211] Right-libertarianism has been influenced by these schools of liberalism. It has been commonly referred to as a continuation or radicalization of classical liberalism[210][32][104][212] and referred to as neo-classical liberalism.[211]

Neolibertarianism

[edit]The concept of neolibertarianism gained a small following in the mid-2000s[213] among right-leaning commentators who distinguished themselves from neoconservatives by their support for individual liberties[214] and from libertarians by their support for foreign interventionism.[213]

Paleolibertarianism

[edit]

Paleolibertarianism was developed by American libertarian theorists Murray Rothbard and Lew Rockwell. Combining conservative cultural values and social philosophy with a libertarian opposition to government intervention,[215] it overlaps with paleoconservatism.[216][217]

In the United States, paleolibertarianism is a controversial current due its connections to the alt-right[185][186][187] and the Tea Party movement.[218][219] Besides their anti-gun control stance in regard to gun laws and politics in support of the right to keep and bear arms, these movements, especially the Old Right and paleoconservatism, are united by an anti-leftist stance.[216][220] In the essay "Right-Wing Populism: A Strategy for the Paleo Movement", Rothbard reflected on the ability of paleolibertarians to engage in an "outreach to rednecks" founded on libertarianism and social conservatism.[221] He cited former Louisiana State Representative David Duke and former United States Senator Joseph McCarthy as models for the new movement.[217]

In Europe, paleolibertarianism has some significant overlap with right-wing populism. Former European Union-parliamentarian Janusz Korwin-Mikke from KORWiN supports both laissez-faire economics and anti-immigration and anti-feminist positions.[222][223][224]

Propertarianism

[edit]Propertarianism advocates the replacement of states with contractual relationships. Propertarian ideals are most commonly cited to advocate for a state or other governance body whose main or only job is to enforce contracts and private property.[225][226]

Propertarianism is generally considered right-libertarian[175] because it "reduce[s] all human rights to rights of property, beginning with the natural right of self-ownership".[227]

As a term, propertarian appears to have been coined in 1963 by Edward Cain, who wrote:

Since their use of the word "liberty" refers almost exclusively to property, it would be helpful if we had some other word, such as "propertarian", to describe them. [...] Novelist Ayn Rand is not a conservative at all but claims to be very relevant. She is a radical capitalist, and is the closest to what I mean by a propertarian.[228]

Comparison to Classical Liberalism

[edit]Some forms of right-libertarianism are an outgrowth or as a variant of classical liberal thought.[210] With other forms of right-libertarianism there are significant differences. Edwin Van de Haar argues that "confusingly, in the United States the term libertarianism is sometimes also used for or by classical liberals. But this erroneously masks the differences between them".[229] Classical liberalism refuses to give priority to liberty over order and therefore does not exhibit the hostility to the state which is the defining feature of libertarianism.[14] As such, right-libertarians believe classical liberals favor too much state involvement,[230] arguing that they do not have enough respect for individual property rights and lack sufficient trust in the workings of the free market and its spontaneous order leading to support of a much larger state.[230] Right-libertarians also disagree with classical liberals as being too supportive of central banks and monetarist policies.[231]

By country

[edit]Since the 1970s, right-libertarianism has spread beyond the United States.[59][60] With the foundation of the Libertarian Party in 1971,[232][233] many countries followed the example and led to the creation of libertarian parties advocating this type of libertarianism, along with classical liberalism, economic liberalism and neoliberalism, around the world, including the United Kingdom,[234] Israel[235][236][237][238] and South Africa.[239] Internationally, the majority of those libertarian parties are grouped within the International Alliance of Libertarian Parties.[240][241][242][243] There also exists the European Party for Individual Liberty at the European level.[244]

Murray Rothbard was the founder and co-founder of a number of right-libertarian and right-libertarian-leaning journals and organizations. Rothbard was the founder of the Center for Libertarian Studies in 1976, the Journal of Libertarian Studies and co-founder of the Mises Institute in 1982,[245] including the founding in 1987 of the Mises Institute's Review of Austrian Economics, a heterodox economics[246] journal later renamed the Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics.[247]

United Kingdom

[edit]In the United Kingdom, right-libertarianism emerged and became more prominent in British politics after the 1980s neoliberalism and the economic liberalism of the premiership of Margaret Thatcher, albeit not as prominent as in the United States during the 1970s and the presidency of Republican Ronald Reagan during the 1980s.[248]

Prominent British right-libertarians include former director of the Libertarian Alliance Sean Gabb and philosopher Stephen R. L. Clark, who are seen as rightists. Gabb has called himself "a man of the right"[249] and Clark self-identifies as an "anarcho-conservative".[250][251] Gabb has also articulated a libertarian defense of the British Empire.[252] At the same time, Gabb has given a generally appreciative commentary of left-libertarian Kevin Carson's work on organization theory[253] and Clark has supported animal rights, gender inclusiveness and non-judgmental attitude toward some unconventional sexual arrangements.[254][255][256][257]

Apart from the Libertarian Party, there is also a right-libertarian faction of the mainstream Conservative Party that espouses Thatcherism.[258]

United States

[edit]| This article is part of a series on |

| Libertarianism in the United States |

|---|

|

Right-libertarianism is the dominant form and better known version of libertarianism in the United States,[3][17] especially when compared with left-libertarianism.[18] Robert Nozick and Murray Rothbard have been described as the most noted advocate of this type of libertarianism.[2][16][6] Unlike Rothbard, who argued for the abolition of the state,[259] Nozick argued for a night-watchman state.[193] To this day, there remains a division between anarcho-capitalists that advocate its abolition and minarchists who support a night-watchman state.[16] According to Nozick, only such a minimal state could be justified without violating people's rights. Nozick argued that a night-watchman state provides a framework that allows for any political system that respects fundamental individual rights and therefore morally justifies the existence of a state.[194][195]

Already a radical classical liberal and anti-interventionist strongly influenced by the Old Right, especially its opposition to the managerial state whilst being more unequivocally anti-war and anti-imperialist,[260] Rothbard had become the doyen of right-libertarianism.[261][262] Before his departure from the New Left, with which he helped build for a few years a relationship with other libertarians, Rothbard considered liberalism and libertarianism to be left-wing, radical and revolutionary whereas conservatism to be right-wing, reactionary and counter-revolutionary. As for socialism, especially state socialism, Rothbard argued that it was not the opposite of libertarianism, but rather that it pursued liberal ends through conservative means, putting it in the political center.[263][264] By the time of his death in 1995,[265] Rothbard had involved the segment of the libertarian movement loyal to him in an alliance with the growing paleoconservative movement,[266][267] seen by many observers, libertarian and otherwise, as flirting with racism and social reaction.[185][186][187] Suggesting that libertarians needed a new cultural profile that would make them more acceptable to social and cultural conservatives, Rothbard criticized the tendency of proponents of libertarianism to appeal to "'free spirits,' to people who don't want to push other people around, and who don't want to be pushed around themselves" in contrast to "the bulk of Americans", who "might well be tight-assed conformists, who want to stamp out drugs in their vicinity, kick out people with strange dress habits." While emphasizing that it was relevant as a matter of strategy, Rothbard argued that the failure to pitch the libertarian message to Middle America might result in the loss of "the tight-assed majority".[268]

At least partly reflective of some of the social and cultural concerns that lay beneath Rothbard's outreach to paleoconservatives is paleolibertarianism.[269] In an early statement of this position, Lew Rockwell and Jeffrey Tucker arguing for a specifically Christian libertarianism.[94] Later, Rockwell would no longer consider himself a "paleolibertarian" and was "happy with the term libertarian."[270] While distancing himself from the paleolibertarian alliance strategy, Rockwell affirmed paleoconservatives for their "work on the immigration issue" and maintained that "porous borders in Texas and California" could be seen as "reducing liberty, not increasing it, through a form of publicly subsidized right to trespass."[271]

Hans-Hermann Hoppe argued that "libertarians must be conservatives."[272] Hoppe acknowledged what he described as "the importance, under clearly stated circumstances, of discriminating against communists, democrats, and habitual advocates of alternative, non-family centered lifestyles, including homosexuals."[273][274] He disagreed with Walter Block[275] and argued that libertarianism need not be seen as requiring open borders.[276] Hoppe attributed "open border enthusiasm" to "egalitarianism".[277] While defending market anarchy in preference to both, Hoppe argued for the superiority of monarchy to democracy by maintaining that monarchs are likely to be better stewards of the territory they claim to own than are democratic politicians, whose time horizons may be shorter.[278]

Defending the fusion of traditionalist conservatism with libertarianism and rejecting the view that libertarianism means support for a liberal culture, Edward Feser implies that a central issue for those who share his viewpoint is "the preservation of traditional morality—particularly traditional sexual morality, with its idealization of marriage and its insistence that sexual activity be confined within the bounds of that institution, but also a general emphasis on dignity and temperance over self-indulgence and dissolute living."[279]

California Governor Ronald Reagan appealed to right-libertarians in a 1975 interview with Reason by stating to "believe the very heart and soul of conservatism is libertarianism."[280] However, President Reagan, Reaganomics and policies of the Reagan administration have been criticized by libertarians, including right-libertarians such as Rothbard,[281][282] who argued that the Reagan presidency has been "a disaster for libertarianism in the United States"[283] and Reagan himself was "a dramatic failure".[284] Among other reasons, this was because Reagan turned the United States' big trade deficit into debt and the United States became a debtor nation for the first time since World War I under Reagan.[285][286] Ron Paul was one of the first elected officials in the nation to support Reagan's presidential campaign[287] and actively campaigned for Reagan in 1976 and 1980.[284] Paul quickly became disillusioned with the Reagan administration's policies after Reagan's election in 1980 and later recalled being the only Republican to vote against the Reagan budget proposals in 1981,[288][289] aghast that "in 1977, Jimmy Carter proposed a budget with a $38 billion deficit, and every Republican in the House voted against it. In 1981, Reagan proposed a budget with a $45 billion deficit—which turned out to be $113 billion—and Republicans were cheering his great victory. They were living in a storybook land."[287] Paul expressed his disgust with the political culture of both major parties in a speech delivered in 1984 upon resigning from the House of Representatives to prepare for a failed run for the Senate and eventually apologized to his libertarian friends for having supported Reagan.[289] By 1987, Paul was ready to sever all ties to the Republican Party as explained in a blistering resignation letter.[284] While affiliated with both Libertarian and Republican parties at different times, Paul stated to have always been a libertarian at heart.[288][289]

Walter Block identifies Feser, Hoppe, and Paul as "right-libertarians".[48] Rothbard's outreach to conservatives was partly triggered by his perception of negative reactions within the Libertarian Party to Ron Paul 1988 presidential campaign because of Paul's conservative appearance and his discomfort with abortion. Nonetheless, Paul himself did not make cultural issues central to his public persona during his 2008 and 2012 presidential campaigns for the Republican presidential nomination and focused on a simple message of support for personal freedom and civil liberties, commitment to fiscal discipline and opposition to war,[290] although he did continue to take what some regarded as a conservative position regarding immigration, arguing for some restrictions on cross-border freedom of movement.[291]

Paul's fellow libertarian anti-militarist Justin Raimondo, a co-founder of Antiwar.com, described himself as a "conservative paleolibertarian". Unlike Feser and Rockwell, Raimondo's Reclaiming the American Right argued for a resurgence of Old Right political attitudes and did not focus on the social and cultural issues that are of central importance to Feser and Rockwell.[292]

Free State Project

[edit]One of the most prominent groups dedicated to promulgating and instituting right-libertarian values is the Free State Project. The Free State Project is an activist libertarian movement formed in 2001. It is working to bring libertarians to the state of New Hampshire to protect and advance liberty. As of July 2022[update], the project website showed that 19,988 people have pledged to move and 6,232 people identified as Free Staters in New Hampshire.[293]

Free State Project participants interact with the political landscape in New Hampshire in various ways. In 2017, there were 17 Free Staters in the New Hampshire House of Representatives,[294] and in 2021, the New Hampshire Liberty Alliance, which ranks bills and elected representatives based on their adherence to what they see as libertarian principles, scored 150 (out of 380 rated) representatives as "A−" or above rated representatives.[295] Participants also engage with other like-minded activist groups such as Rebuild New Hampshire,[296] Young Americans for Liberty,[297] and Americans for Prosperity.[298]

Criticism

[edit]Criticism of right-libertarianism includes ethical, economic, environmental, pragmatic and philosophical concerns,[299][300][301][302][303][304][305] including the view that it has no explicit theory of liberty.[103] It has been argued that laissez-faire capitalism[5] does not necessarily produce the best or most efficient outcome,[303][306] nor does its philosophy of individualism and policies of deregulation prevent the abuse of natural resources.[307]

Use of the NAP as a justification for right-libertarianism has been criticized as circular reasoning and as a rhetorical obfuscation of the coercive nature of right-libertarian property law enforcement,[5] with critics arguing that the principle redefines aggression in their own terms.[299][300][301][302][303][304][305]

Jeffrey H. Reiman criticized right-libertarians' support of private property, arguing that "the holders of large amounts of property have great power to dictate the terms upon which others work for them and thus in effect the power to 'force' others to be resources for them".[5]

See also

[edit]- Anarchism and capitalism

- Conservative liberalism

- Constitutionalism

- Criticism of democracy

- Debates within libertarianism

- Fiscal conservatism

- Free banking

- Freedom of association

- Issues in anarchism

- Labor mobility

- Market fundamentalism

- Objectivist movement

- Outline of libertarianism

- Patriot movement

- Republican Liberty Caucus

- Sovereign citizen movement

References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Rothbard, Murray (1 March 1971). "The Left and Right Within Libertarianism" Archived 1 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine. WIN: Peace and Freedom Through Nonviolent Action. 7 (4): 6–10. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Goodway, David (2006). Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow: Left-Libertarian Thought and British Writers from William Morris to Colin Ward. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. p. 4 Archived 7 February 2024 at the Wayback Machine. "The problem with the term 'libertarian' is that it is now also used by the Right. [...] In its moderate form, right libertarianism embraces laissez-faire liberals like Robert Nozick who call for a minimal State, and in its extreme form, anarcho-capitalists like Murray Rothbard and David Friedman who entirely repudiate the role of the State and look to the market as a means of ensuring social order".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Carlson, Jennifer D. (2012). "Libertarianism". In Miller, Wilburn R., ed. The Social History of Crime and Punishment in America. London: Sage Publications. p. 1006 Archived 7 February 2024 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 1412988764.

- ^ Wündisch 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Reiman, Jeffrey H. (2005). "The Fallacy of Libertarian Capitalism". Ethics. 10 (1): 85–95. doi:10.1086/292300. JSTOR 2380706. S2CID 170927490.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Newman 2010, p. 53 "It is important to distinguish between anarchism and certain strands of right-wing libertarianism which at times go by the same name (for example, Murray Rothbard's anarcho-capitalism). There is a complex debate within this tradition between those like Robert Nozick, who advocate a 'minimal state', and those like Rothbard who want to do away with the state altogether and allow all transactions to be governed by the market alone. From an anarchist perspective, however, both positions—the minimal state (minarchist) and the no-state ('anarchist') positions—neglect the problem of economic domination; in other words, they neglect the hierarchies, oppressions, and forms of exploitation that would inevitably arise in laissez-faire 'free' market. [...] Anarchism, therefore, has no truck with this right-wing libertarianism, not only because it neglects economic inequality and domination, but also because in practice (and theory) it is highly inconsistent and contradictory. The individual freedom invoked by right-wing libertarians is only narrow economic freedom within the constraints of a capitalist market, which, as anarchists show, is no freedom at all.

- ^ Kymlicka 2005, p. 516: "Right-wing libertarians argue that the right of self-ownership entails the right to appropriate unequal parts of the external world, such as unequal amounts of land."

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Francis, Mark (December 1983). "Human Rights and Libertarians". Australian Journal of Politics & History. 29 (3): 462–472. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8497.1983.tb00212.x. ISSN 0004-9522.

- ^ Vallentyne 2007, p. 6. "The best-known versions of libertarianism are right-libertarian theories, which hold that agents have a very strong moral power to acquire full private property rights in external things. Left-libertarians, by contrast, holds that natural resources (e.g., space, land, minerals, air, and water) belong to everyone in some egalitarian manner and thus cannot be appropriated without the consent of, or significant payment to, the members of society."

- ^ Miller, Fred (15 August 2008). "Natural Law". The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Sterba, James P. (October 1994). "From Liberty to Welfare". Ethics. Cambridge: Blackwell. 105 (1): 237–241.

- ^ "What you should know about the Non-Aggression Principle". Learnliberty.org. 24 February 2017. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Baradat 2015, p. 31.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Heywood 2004, p. 337.

- ^ Newman 2010, p. 43: "It is important to distinguish between anarchism and certain strands of right-wing libertarianism which at times go by the same name (for example, Murray Rothbard's anarcho-capitalism). There is a complex debate within this tradition between those like Robert Nozick, who advocate a 'minimal state', and those like Rothbard who want to do away with the state altogether and allow all transactions to be governed by the market alone. From an anarchist perspective, however, both positions—the minimal state (minarchist) and the no-state ('anarchist') positions—neglect the problem of economic domination; in other words, they neglect the hierarchies, oppressions, and forms of exploitation that would inevitably arise in a laissez-faire 'free' market. [...] Anarchism, therefore, has no truck with this right-wing libertarianism, not only because it neglects economic inequality and domination, but also because in practice (and theory) it is highly inconsistent and contradictory. The individual freedom invoked by right-wing libertarians is only narrow economic freedom within the constraints of a capitalist market, which, as anarchists show, is no freedom at all."

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Marshall, Peter (2008). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: Harper Perennial. p. 565. "The problem with the term 'libertarian' is that it is now also used by the Right. [...] In its moderate form, right libertarianism embraces laissez-faire liberals like Robert Nozick who call for a minimal State, and in its extreme form, anarcho-capitalists like Murray Rothbard and David Friedman who entirely repudiate the role of the State and look to the market as a means of ensuring social order".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Beltrán, Miquel (1989). "Libertarismo y deber. Una reflexión sobre la ética de Nozick" [Libertarianism and duty. A reflection on Nozick's ethics]. Revista de ciencias sociales (in Spanish). 91: 123–128. ISSN 0210-0223. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Vallentyne, Peter (20 July 2010). "Libertarianism" Archived 8 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Rothbard, Murray (2009) [2007]. The Betrayal of the American Right (PDF). Mises Institute. p. 83. ISBN 978-1610165013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

One gratifying aspect of our rise to some prominence is that, for the first time in my memory, we, 'our side,' had captured a crucial word from the enemy. 'Libertarians' had long been simply a polite word for left-wing anarchists, that is for anti-private property anarchists, either of the communist or syndicalist variety. But now we had taken it over.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bookchin, Murray (January 1986). "The Greening of Politics: Toward a New Kind of Political Practice" Archived 1 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Green Perspectives: Newsletter of the Green Program Project (1). "We have permitted cynical political reactionaries and the spokesmen of large corporations to pre-empt these basic libertarian American ideals. We have permitted them not only to become the specious voice of these ideals such that individualism has been used to justify egotism; the pursuit of happiness to justify greed, and even our emphasis on local and regional autonomy has been used to justify parochialism, insularism, and exclusivity—often against ethnic minorities and so-called deviant individuals. We have even permitted these reactionaries to stake out a claim to the word libertarian, a word, in fact, that was literally devised in the 1890s in France by Elisée Reclus as a substitute for the word anarchist, which the government had rendered an illegal expression for identifying one's views. The propertarians, in effect—acolytes of Ayn Rand, the earth mother of greed, egotism, and the virtues of property—have appropriated expressions and traditions that should have been expressed by radicals but were willfully neglected because of the lure of European and Asian traditions of socialism, socialisms that are now entering into decline in the very countries in which they originated".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nettlau, Max (1996). A Short History of Anarchism. London: Freedom Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0900384899. OCLC 37529250.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fernandez, Frank (2001). Cuban Anarchism. The History of a Movement[permanent dead link]. Sharp Press. p. 9. "Thus, in the United States, the once exceedingly useful term "libertarian" has been hijacked by egotists who are in fact enemies of liberty in the full sense of the word."

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Week Online Interviews Chomsky". Z Magazine. 23 February 2002. "The term libertarian as used in the US means something quite different from what it meant historically and still means in the rest of the world. Historically, the libertarian movement has been the anti-statist wing of the socialist movement. In the US, which is a society much more dominated by business, the term has a different meaning. It means eliminating or reducing state controls, mainly controls over private tyrannies. Libertarians in the US don't say let's get rid of corporations. It is a sort of ultra-rightism."

- ^ Ward, Colin (2004). Anarchism: A Very Short Introduction Archived 7 February 2024 at the Wayback Machine. Oxford University Press. p. 62. "For a century, anarchists have used the word 'libertarian' as a synonym for 'anarchist', both as a noun and an adjective. The celebrated anarchist journal Le Libertaire was founded in 1896. However, much more recently the word has been appropriated by various American free-market philosophers."

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Graham, Robert, ed. (2005). Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas. Vol. 1. Montreal: Black Rose Books. §17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Marshall, Peter (2009). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. p. 641. "The word 'libertarian' has long been associated with anarchism and has been used repeatedly throughout this work. The term originally denoted a person who upheld the doctrine of the freedom of the will; in this sense, Godwin was not a 'libertarian', but a 'necessitarian'. It came however to be applied to anyone who approved of liberty in general. In anarchist circles, it was first used by Joseph Déjacque as the title of his anarchist journal Le Libertaire, Journal du Mouvement Social published in New York in 1858. At the end of the last century, the anarchist Sebastien Faure took up the word, to stress the difference between anarchists and authoritarian socialists".

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Anarchist FAQ Editorial Collective (11 December 2008). "150 years of Libertarian" Archived 17 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Anarchist Writers. The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Редакционный коллектив The Anarchist FAQ (17 мая 2017 г.). «160 лет либертарианцу». Архивировано 25 апреля 2020 года в Wayback Machine . Писатели-анархисты . Анархистский FAQ . Проверено 31 января 2020 г.

- ^ Маршалл, Питер (2009). Требуя невозможного: история анархизма . п. 641. Архивировано 30 сентября 2020 года в Wayback Machine . «В течение долгого времени слово «либертарианец» было взаимозаменяемым во Франции с «анархизмом», но в последние годы его значение стало более двойственным. Некоторые анархисты, такие как Даниэль Герен, будут называть себя «либертарианскими социалистами», отчасти для того, чтобы избежать негативного подтекста, все еще связанного с анархизмом, и отчасти для того, чтобы подчеркнуть место анархизма в социалистической традиции. Даже марксисты «Новых левых», такие как Е. П. Томпсон, называют себя «либертарианцами», чтобы отличить себя от тех авторитарных социалистов и коммунистов, которые верят в революционную диктатуру и авангардные партии».

- ^ Лонг, Джозеф. В (1996). «К либертарианской теории классов». Социальная философия и политика . 15 (2): 310. «Когда я говорю о «либертарианстве» [...], я имею в виду все три этих очень разных движения. Можно возразить, что LibCap [либертарианский капитализм], LibSoc [либертарианский социализм] и LibPop [либертарианский капитализм] популизм] слишком отличаются друг от друга, чтобы их можно было рассматривать как аспекты единой точки зрения, но они имеют общее — или, по крайней мере, пересекающееся — интеллектуальное происхождение».

- ^ Карлсон, Дженнифер Д. (2012). «Либертарианство». В Миллер, Уилберн Р., изд. Социальная история преступлений и наказаний в Америке . Лондон: Публикации Sage. п. 1006. Архивировано 30 сентября 2020 года в Wayback Machine . ISBN 1412988764 . «В либертарианской мысли существует три основных лагеря: правое либертарианство, социалистическое либертарианство и левое либертарианство; степень, в которой они представляют собой отдельные идеологии, а не вариации на тему, оспаривается учеными».

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Вооз, Давид (1998). Либертарианство: учебник для начинающих . Свободная пресса. стр. 22–26.

- ^ Уильям Белшам, «Очерки», напечатано для К. Дилли, 1789 г.; оригинал из Мичиганского университета, оцифрован 21 мая 2007 г.

- ^ Уильям Белшам (1752–1827). Архивировано 8 января 2015 года в Wayback Machine . Информационный философ. El primer uso de la palabra se encuentra en el primer ensayo llamado « О свободе и необходимости». Архивировано 28 июля 2021 года в Wayback Machine (1789 г.): «Или где разница между либертарианцем, который говорит, что разум выбирает мотив; и Несессариан, который утверждает, что мотив определяет разум, если воля является необходимым результатом всех предшествующих обстоятельств?»

- ^ Джаред Спаркс, Сборник эссе и трактатов по теологии от разных авторов с биографическими и критическими примечаниями , публикация Оливера Эверетта, 13 Корнхилл, 1824 г. (версия, «Сочинения доктора Когана», 205).

- ^ Определение слова «либертарианец» в словаре Merriam-Webster. Архивировано 5 мая 2021 года в Wayback Machine . Первое известное использование слова «либертарианец»: 1789 год, в значении, определенном в смысле 1.

- ^ Дежак, Жозеф (1857). «О мужчине и женщине – Письмо П. Ж. Прудону». Архивировано 17 сентября 2019 г. в Wayback Machine (на французском языке).

- ^ Мутон, Жан Клод. «Le Libertaire, Journal du Social Mouvement» (на французском языке). Архивировано из оригинала 16 мая 2011 года . Проверено 16 июля 2019 г.

- ^ Вудкок, Джордж (1962). Анархизм: история либертарианских идей и движений . Книги Меридиана. п. 280. «Он называл себя «социальным поэтом» и опубликовал два тома сильно дидактических стихов — «Лазаринцы» и «Нивельские Пиренеи». В Нью-Йорке с 1858 по 1861 год он редактировал анархистскую газету под названием « Le Libertaire, Journal du Mouvement Social », на страницах которого он напечатал в виде сериала свое видение анархической утопии под названием «L'Humanisphére».

- ^ Хусейн, Сайед Б. (2004). Энциклопедия капитализма. Том. II: HR . Нью-Йорк: Факты о File Inc., с. 492. ИСБН 0816052247 . Архивировано из оригинала 7 февраля 2024 года . Проверено 15 ноября 2019 г. .

В современном мире политические идеологии во многом определяются их отношением к капитализму. Марксисты хотят его свергнуть, либералы — резко ограничить его, консерваторы — умерить его. Тех, кто утверждает, что капитализм — это превосходная экономическая система, несправедливо оклеветанная и практически не нуждающаяся в корректирующей государственной политике, обычно называют либертарианцами.

- ^ Карлсон, Дженнифер Д. (2012). «Либертарианство». В Миллер, Уилберн Р., изд. Социальная история преступлений и наказаний в Америке . Лондон: Публикации Sage. п. 1006. ISBN 1412988764 . «В либертарианской мысли существует три основных лагеря: правое либертарианство, социалистическое либертарианство и левое либертарианство. [...] [С] социалистические либертарианцы [...] выступают за одновременную отмену как правительства, так и капитализма».

- ^ Букчин, Мюррей; Биль, Джанет (1997). Читатель Мюррея Букчина . Касселл. п. 170 ISBN 0304338737 .

- ^ Хикс, Стивен В.; Шеннон, Дэниел Э. (2003). Американский журнал экономики и социологии . Паб Блэквелл. п. 612.

- ^ «Анархизм». В Гаусе, Джеральд Ф.; Д'Агостино, Фред, ред. (2012). Путеводитель Рутледжа по социальной и политической философии . п. 227.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Китшельт, Герберт; Макганн, Энтони Дж. (1997) [1995]. Радикальные правые в Западной Европе : сравнительный анализ . Издательство Мичиганского университета. п. 27. Архивировано 11 октября 2023 года в Wayback Machine . ISBN 978-0472084418 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мадде, Кас (2016). Популистские радикальные правые: читатель. Архивировано 4 августа 2020 года в Wayback Machine (1-е изд.). Рутледж. ISBN 978-1138673861 .

- ^ Бевир, Марк, изд. (2010). Энциклопедия политической теории . Публикации Сейджа. п. 811. Архивировано 11 октября 2023 года в Wayback Machine . ISBN 978-1412958653 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Блок, Уолтер (2010). «Либертарианство уникально и не принадлежит ни правым, ни левым: критика взглядов Лонга, Холкомба и Бадена слева, Хоппе, Фезера и Пола справа». Архивировано 13 мая 2014 года в Wayback Machine . Журнал либертарианских исследований . 22 . стр. 127–170.

- ^ Робин, Кори (2011). Реакционный разум: консерватизм от Эдмунда Бёрка до Сары Пэйлин . Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 15–16 . ISBN 978-0199793747 .

- ^ Хармель, Роберт; Гибсон, Рэйчел К. (июнь 1995 г.). «Право-либертарианские партии и «новые ценности»: пересмотр». Скандинавские политические исследования . 18 (июль 1993 г.): 97–118. дои : 10.1111/j.1467-9477.1995.tb00157.x .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Робинсон, Эмили; и др. (2017). «Рассказывая истории о послевоенной Британии: популярный индивидуализм и «кризис» 1970-х годов». Архивировано 3 августа 2020 года в Wayback Machine . Британская история двадцатого века . 28 (2): 268–304.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Маршалл, Питер (2008). Требуя невозможного: история анархизма . «Новые правые и анархо-капитализм». Архивировано 19 апреля 2021 года в Wayback Machine . Лондон: Харпер Многолетник. ISBN 978-1604860641 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Винсент, Эндрю (2009). Современные политические идеологии (3-е изд.). Хобокен: Джон Уайли и сыновья. п. 66. ИСБН 978-1444311051 .

Кого отнести к «Новым правым», остается загадкой. Обычно его рассматривают как смесь традиционного либерального консерватизма, австрийской либеральной экономической теории Людвинга фон Мизеса и Хайека), крайнего либертарианства (анархо-капитализма) и грубого популизма.

- ↑ Макманус, Мэтт (26 мая 2019 г.). «Классические либералы» и альтернативные правые» Архивировано 21 октября 2021 года в Wayback Machine . Мерион Уэст . Получено 17 июня 2020 года. консервативно-реакционные позиции. [...] Второй способ, которым люди склонны интерпретировать классический либерализм и либертарианство, - это идеология, которая является строго негалитарной. Они склонны поддерживать его, потому что видят общество как конкурентное объединение, в котором выдающиеся личности поднимаются на вершину благодаря своим заслугам и усилиям. Хотя они идентифицируют себя как классические либералы и либертарианцы, эти люди склонны ограничиваться желанием, чтобы капиталистический рынок проводил различие между высшими и низшими, распределяя награды и почести в соответствии с экономическим вкладом. Но если эти люди поверят, что система все больше вознаграждает недостойных, они могут вдохновиться на радикализацию и двигаться дальше к крайностям, предлагаемым альтернативными правыми доктринами».

- ^ «О викторине». Архивировано 31 марта 2020 года в Wayback Machine . Сторонники самоуправления. Проверено 18 января 2020 г.

- ^ Миттел, Брайан Патрик (2007). Восемь способов управлять страной: новый и показательный взгляд на левых и правых . Издательская группа Гринвуд. стр. 7–8. ISBN 978-0275993580 . Архивировано из оригинала 7 февраля 2024 года . Проверено 2 ноября 2020 г.

- ^ Хьюберт, Джейкоб Х. (2010). Либертарианство сегодня . Санта-Барбара, Калифорния: Прегер. стр. 22–24 . ISBN 978-0313377556 . OCLC 655885097 .

- ↑ Вооз, Давид (21 ноября 1998 г.). «Предисловие к японскому изданию книги «Либертарианство: учебник для начинающих». Архивировано 21 сентября 2011 года в Wayback Machine . Институт Катона . Проверено 25 января 2020 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Грегори, Энтони (24 апреля 2007 г.). «Реальная мировая политика и радикальное либертарианство» . LewRockwell.com. Архивировано 18 июня 2015 года в Wayback Machine . Проверено 25 января 2020 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Телес, Стивен; Кенни, Дэниел А. «Распространение информации: распространение американского консерватизма в Европе и за ее пределами». В Копстене, Джеффри; Стейнмо, Свен, ред. (2007). Растут?: Америка и Европа в XXI веке. Архивировано 7 февраля 2024 года в Wayback Machine . Издательство Кембриджского университета . стр. 136–169.

- ^ Валлентайн 2007 , стр. 187–205.

- ^ Боас, Тейлор С.; Ганс-Морс, Джордан (2009). «Неолиберализм: от новой либеральной философии к антилиберальному лозунгу». Исследования в области сравнительного международного развития . 44 (2): 151–152. два : 10.1007/s12116-009-9040-5 .

- ^ Кнапп, Эндрю; Райт, Винсент (2006). Правительство и политика Франции . Рутледж. ISBN 978-0415357326 .

- ^ Джон, Дэвид К. (21 ноября 2003 г.). «Истоки современного американского консервативного движения» . Фонд наследия. Архивировано из оригинала 8 марта 2010 года . Проверено 13 мая 2010 г.

- ^ Беккер, Шарлотта Б.; Беккер, Лоуренс К. (2001). Энциклопедия этики . 3 . Тейлор и Фрэнсис США. п. 1562. Архивировано 11 октября 2023 года в Wayback Machine . ISBN 978-0415936750 .

- ^ «Разрушение государства ради развлечения и прибыли с 1969 года: интервью с иконой либертарианства Сэмюэлем Эдвардом Конкиным III (он же SEK3)». Архивировано 7 сентября 2021 года в Wayback Machine . Spaz.org. Проверено 15 марта 2020 г.

- ^ Д'Амато, Дэвид С. (27 ноября 2018 г.). «Активизм черного рынка: Сэмюэл Эдвард Конкин III и агоризм». Архивировано 16 ноября 2018 года в Wayback Machine . Либертарианство.орг. Проверено 21 ноября 2019 г.

- ^ Конкин III, Сэмюэл Эдвард. «Агористический букварь» (PDF) . Kopubco.com. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 11 марта 2022 года . Проверено 15 марта 2020 г.

- ^ Конкин III, Сэмюэл Эдвард (1983). «Новый либертарианский манифест» . Агоризм.eu.org. Архивировано 27 апреля 2022 года в Wayback Machine . Проверено 4 мая 2022 года.

- ↑ Грегори, Энтони (21 декабря 2006 г.). «Левые, правые, умеренные и радикальные» . LewRockwell.com. Архивировано 25 декабря 2014 года в Wayback Machine . 25 января 2020 г.

- ^ Миллер, Дэвид , изд. (1991). Энциклопедия политической мысли Блэквелла . Издательство Блэквелл. п. 290. ИСБН 0631179445 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Ротбард, Мюррей (2007). Предательство американских правых. Архивировано 16 октября 2014 года в Wayback Machine . Оберн, Алабама: Институт Мизеса . п. xi. ISBN 978-1479229512 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Кауфман, Билл (18 мая 2009 г.). «Найдено причина». Архивировано 27 октября 2020 года в Wayback Machine . Американский консерватор . Проверено 15 марта 2020 г.

- ^ Радош, Рональд (1975). Пророки справа: профили консервативных критиков американского глобализма . Нью-Йорк, Нью-Йорк: Саймон.

- ^ Раймондо, Джастин (2008). Возвращение американских правых: утраченное наследие консервативного движения (2-е изд.). Уилмингтон, Делавэр: ISI.

- ^ Ходоров, Франк (1962). Не в ногу: автобиография индивидуалиста . Нью-Йорк, Нью-Йорк: Девин-Адэр.

- ^ Гамильтон, Чарльз Х. (1980). Беглые очерки: Избранные сочинения Фрэнка Ходорова . Индианаполис, Индиана: Свобода.

- ^ Флинн, Джон Т. (1973) [1944]. Пока мы маршируем: резкое обвинение в приходе внутреннего фашизма в Америку . Нью-Йорк, Нью-Йорк: Свободная жизнь.

- ^ Мозер, Джон (2005). Правый поворот: Джон Т. Флинн и трансформация американского либерализма . Нью-Йорк, Нью-Йорк: Издательство Нью-Йоркского университета.

- ^ Райант, Карл (1989). Пророк прибыли: Гарет Гаррет (1878–1954) . Селинсгроув, Пенсильвания: Издательство Университета Саскуэханна.

- ^ Рэмси, Брюс (2008). Несанкционированный голос: Гарет Гаррет, журналист старых правых . Колдуэлл, Индиана: Кэкстон.

- ^ Уайлдер Лейн, Роуз (2006) [1936]. Дайте мне свободу . Уайтфиш, Монтана: Кессинджер.

- ^ Уайлдер Лейн, Роуз (2007) [1943]. Открытие свободы: борьба человека с властью . Оберн, Алабама: Институт Мизеса.

- ^ Менкен, HL (1961). Письма Х. Л. Менкена . Кнофп. стр. XIII, 189.

- ^ Нок, Альберт Джей (1935). Наш враг – государство . Нью-Йорк: Морроу.

- ^ Нок, Альберт Джей (июнь 1936 г.). «Работа Исайи». Atlantic Monthly (157): 641–649.

- ^ Нок, Альберт Джей (1943). Мемуары лишнего человека . Нью-Йорк: Харпер.

- ^ Патерсон, Изабель (1993). Бог машины . Нью-Брансуик, Нью-Джерси: Сделка.

- ^ Кокс, Стивен Д. (2004). Женщина и динамо: Изабель Патерсон и идея Америки . Нью-Брансуик, Нью-Джерси: Сделка.

- ^ Кауфман, Билл (2008). Это не моя Америка: долгая и благородная история антивоенного консерватизма и среднеамериканского антиимпериализма . Нью-Йорк, Нью-Йорк: Метрополитен.

- ↑ Ходоров, Франк (6 октября 1956 г.). «Письмо в редакцию». Национальное обозрение . 2 (20): 23.

- ^ Гамильтон, Чарльз Х. (1981). "Введение". Беглые очерки: Сборник избранных сочинений Фрэнка Ходорова . п. 29.

- ^ Ротбард, Мюррей (2007). Предательство американских правых. Архивировано 16 октября 2014 года в Wayback Machine . Оберн, Алабама: Институт Мизеса . п. 165. ISBN 978-1479229512 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Роквелл, Лью ; Такер, Джеффри (28 мая 1990 г.). «Айн Рэнд мертва». Архивировано 3 августа 2020 года в Wayback Machine . Национальное обозрение . стр. 35–36. Проверено 16 марта 2020 г.

- ^ Коменья, Энтони; Гомес, Камилло (3 октября 2018 г.). «Либертарианство тогда и сейчас». Архивировано 3 августа 2020 года в Wayback Machine . Либертарианство . Институт Катона. «[...] Бенджамин Такер был первым американцем, который действительно начал использовать термин «либертарианец» в качестве самоидентификатора где-то в конце 1870-х или начале 1880-х годов». Проверено 3 августа 2020 г.

- ^ Бернс, Дженнифер (2009). Богиня рынка: Айн Рэнд и американские правые . Нью-Йорк: Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 309. ИСБН 978-0195324877 .

- ^ Раймондо, Джастин (2000). Враг государства: жизнь Мюррея Н. Ротбарда . «За пределами левого и правого». Книги Прометея . п. 159. ISBN 978-1573928090 .

- ^ Ротбард, Мюррей (17 августа 2007 г.). «Флойд Артур «Балди» Харпер, RIP» . Мизес Ежедневно . Институт Мизеса. Архивировано из оригинала 13 декабря 2011 года . Проверено 15 марта 2020 г.

- ^ Д'Агостино, Фред; Гаус, Джеральд (2012). Компаньон Routledge по социальной и политической философии . Рутледж. п. 225. ИСБН 978-0415874564 .