Кришна

| Кришна | |

|---|---|

Бог защиты, сострадания, нежности и любви, [ 1 ] Господь йогов [ 2 ] [ 3 ] Высшее Существо ( кришнаизм ) | |

| Член Дашаватара | |

Статуя Кришны в храме Шри Мариамман, Сингапур | |

| Другие имена | Ачьюта , Дамодара , Гопала , Гопинатх , Говинда , Кешава , Мадхава , Радха Рамана , Васудева |

| Деванагари | Кришна |

| Санскритская транслитерация | Кришна |

| Принадлежность |

|

| Обитель | |

| Мантра | |

| Оружие | |

| Битвы | Курукшетра Война (Махабхарата) |

| День | Среда |

| Устанавливать | Гаруда |

| Тексты | |

| Пол | Мужской |

| Фестивали | |

| Генеалогия | |

| Рождение Аватара | Матхура , Сурасена (современный Уттар-Прадеш , Индия) [ 6 ] |

| Аватар конец | Бхалка , Саураштра (современный Веравал , Гуджарат, Индия) [ 7 ] |

| Родители | |

| Братья и сестры |

|

| Супруги | [ примечание 2 ] |

| Дети | [ примечание 1 ] |

| Dashavatara Sequence | |

|---|---|

| Predecessor | Rama |

| Successor | Buddha |

Кришна ( / ˈ k r ɪ ʃ n ə / ; [ 12 ] Санскрит : कृष्ण, IAST : Kṛṣṇa [ˈkr̩ʂɳɐ] ) — главное божество в индуизме . Ему поклоняются как восьмому аватару Вишну , а также как Верховному Богу . Самостоятельному [ 13 ] Он бог защиты, сострадания, нежности и любви; [ 14 ] [ 1 ] и широко почитается среди индуистских божеств. [ 15 ] День рождения Кришны индуисты отмечают каждый год в Кришна Джанмаштами по лунно-солнечному индуистскому календарю , который приходится на конец августа или начало сентября по григорианскому календарю . [ 16 ] [ 17 ] [ 18 ]

Анекдоты и рассказы о жизни Кришны обычно называются Кришна-лила . Он является центральной фигурой в «Махабхарате» , «Бхагавата-пуране» , «Брахма-вайварта-пуране » и « Бхагавад-гите» , а также упоминается во многих индуистских философских , теологических и мифологических текстах. [ 19 ] Они изображают его в разных ракурсах: как крестника, проказника, образцового любовника, божественного героя и вселенского высшего существа. [ 20 ] Его иконография отражает эти легенды и изображает его на разных этапах его жизни, например, младенцем, который ест масло, мальчиком, играющим на флейте , мальчиком с Радхой или в окружении преданных женщин, или дружелюбным возничим, дающим советы Арджуне . [ 21 ]

Имя и синонимы Кришны восходят к 1-го тысячелетия до нашей эры . литературе и культам [ 22 ] В некоторых суб-традициях, таких как кришнаизм , Кришне поклоняются как Верховному Богу и Сваям Бхагавану (Самому Богу). Эти субтрадиции возникли в контексте движения бхакти средневековой эпохи . [ 23 ] [ 24 ] Литература, связанная с Кришной, вдохновила множество исполнительских искусств, таких как танец Бхаратанатьям , Катхакали , Кучипуди , Одисси и танец Манипури . [ 25 ] [ 26 ] Он является паниндуистским богом, но особенно почитается в некоторых местах, например, во Вриндаване в Уттар-Прадеше. [ 27 ] Дварка и Джунагад в Гуджарате; аспект Джаганнатхи Одише в ; , Маяпуре в Западной Бенгалии [ 23 ] [ 28 ] [ 29 ] в форме Витхобы в Пандхарпуре , Махараштре, Шринатджи в Натхдваре в Раджастхане, [ 23 ] [ 30 ] Удупи Кришна в Карнатаке , [ 31 ] Партхасарати в Тамил Наду и в Аранмуле , Керала, и Гурувайораппан в Гурувайоре в Керале. [ 32 ] С 1960-х годов поклонение Кришне распространилось также на западный мир и в Африку, во многом благодаря работе Международного общества сознания Кришны (ИСККОН). [ 33 ]

Имена и эпитеты

Имя «Кришна» происходит от санскритского слова «Кришна» , которое в первую очередь является прилагательным, означающим «черный», «темный» или «темно-синий». [ 34 ] Убывающая луна называется Кришна Пакша , что соответствует прилагательному, означающему «темнеющий». [ 34 ]

Как имя Вишну , Кришна указан как 57-е имя в Вишну Сахасранаме . Судя по его имени, Кришна часто изображается в идолах чернокожим или синекожим. Кришна также известен под другими именами, эпитетами и титулами , которые отражают его многочисленные связи и качества. Среди наиболее распространенных имен — Мохан «чародей»; Говинда «главный пастух», [ 35 ] Кеев «шутник» и Гопала «Защитник Го», что означает «душа» или «коровы». [ 36 ] [ 37 ] Некоторые имена Кришны имеют региональное значение; Джаганнатха , найденный в индуистском храме Пури , является популярным воплощением в штате Одиша и близлежащих регионах восточной Индии . [ 38 ] [ 39 ] [ 40 ]

Историко-литературные источники

Традиция Кришны, по-видимому, представляет собой объединение нескольких независимых божеств древней Индии, самым ранним из которых было засвидетельствовано свидетельство о Васудеве . [ 41 ] Васудева был богом-героем племени Вришни , принадлежащим к героям Вришни , поклонение которым засвидетельствовано с 5–6 веков до нашей эры в трудах Панини , а со 2 века до нашей эры в эпиграфике со столбом Гелиодора . [ 41 ] Считается, что в какой-то момент племя Вришни слилось с племенем Ядавов/Абхирасов, чьего собственного бога-героя звали Кришна. [ 41 ] Васудева и Кришна слились в единое божество, которое появляется в Махабхарате , и их начали отождествлять с Вишну в Махабхарате и Бхагавад-Гите . [ 41 ] Примерно в IV веке нашей эры другая традиция, культ Гопала-Кришны из Абхиров, защитника скота, также была поглощена традицией Кришны. [ 41 ]

Ранние эпиграфические источники

Изображение в чеканке (2 век до н.э.)

Around 180 BCE, the Indo-Greek king Agathocles issued some coinage (discovered in Ai-Khanoum, Afghanistan) bearing images of deities that are now interpreted as being related to Vaisnava imagery in India.[45][46] The deities displayed on the coins appear to be Saṃkarṣaṇa-Balarama with attributes consisting of the Gada mace and the plow, and Vāsudeva-Krishna with attributes of the Shankha (conch) and the Sudarshana Chakra wheel.[45][47] According to Bopearachchi, the headdress of the deity is actually a misrepresentation of a shaft with a half-moon parasol on top (chattra).[45]

Inscriptions

The Heliodorus Pillar, a stone pillar with a Brahmi script inscription, was discovered by colonial era archaeologists in Besnagar (Vidisha, in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh). Based on the internal evidence of the inscription, it has been dated to between 125 and 100 BCE and is now known after Heliodorus – an Indo-Greek who served as an ambassador of the Greek king Antialcidas to a regional Indian king, Kasiputra Bhagabhadra.[45][48] The Heliodorus pillar inscription is a private religious dedication of Heliodorus to "Vāsudeva", an early deity and another name for Krishna in the Indian tradition. It states that the column was constructed by "the Bhagavata Heliodorus" and that it is a "Garuda pillar" (both are Vishnu-Krishna-related terms). Additionally, the inscription includes a Krishna-related verse from chapter 11.7 of the Mahabharata stating that the path to immortality and heaven is to correctly live a life of three virtues: self-temperance (damah), generosity (cagah or tyaga), and vigilance (apramadah).[48][50][51] The Heliodorus pillar site was fully excavated by archaeologists in the 1960s. The effort revealed the brick foundations of a much larger ancient elliptical temple complex with a sanctum, mandapas, and seven additional pillars.[52][53] The Heliodorus pillar inscriptions and the temple are among the earliest known evidence of Krishna-Vasudeva devotion and Vaishnavism in ancient India.[54][45][55]

The Heliodorus inscription is not isolated evidence. The Hathibada Ghosundi Inscriptions, all located in the state of Rajasthan and dated by modern methodology to the 1st century BCE, mention Saṃkarṣaṇa and Vāsudeva, also mention that the structure was built for their worship in association with the supreme deity Narayana. These four inscriptions are notable for being some of the oldest-known Sanskrit inscriptions.[56]

A Mora stone slab found at the Mathura-Vrindavan archaeological site in Uttar Pradesh, held now in the Mathura Museum, has a Brahmi inscription. It is dated to the 1st century CE and mentions the five Vrishni heroes, otherwise known as Saṃkarṣaṇa, Vāsudeva, Pradyumna, Aniruddha, and Samba.[57][58][59]

The inscriptional record for Vāsudeva starts in the 2nd century BCE with the coinage of Agathocles and the Heliodorus pillar, but the name of Krishna appears rather later in epigraphy. At the Chilas II archaeological site dated to the first half of the 1st-century CE in northwest Pakistan, near the Afghanistan border, are engraved two males, along with many Buddhist images nearby. The larger of the two males held a plough and club in his two hands. The artwork also has an inscription with it in Kharosthi script, which has been deciphered by scholars as Rama-Krsna, and interpreted as an ancient depiction of the two brothers, Balarama and Krishna.[60][61]

The first known depiction of the life of Krishna himself comes relatively late, with a relief found in Mathura, and dated to the 1st–2nd century CE.[62] This fragment seems to show Vasudeva, Krishna's father, carrying baby Krishna in a basket across the Yamuna.[62] The relief shows at one end a seven-hooded Naga crossing a river, where a makara crocodile is thrashing around, and at the other end a person seemingly holding a basket over his head.[62]

Literary sources

Mahabharata

The earliest text containing detailed descriptions of Krishna as a personality is the epic Mahabharata, which depicts Krishna as an incarnation of Vishnu.[63] Krishna is central to many of the main stories of the epic. The eighteen chapters of the sixth book (Bhishma Parva) of the epic that constitute the Bhagavad Gita contain the advice of Krishna to Arjuna on the battlefield.

During the ancient times that the Bhagavad Gita was composed in, Krishna was widely seen as an avatar of Vishnu rather than an individual deity, yet he was immensely powerful and almost everything in the universe other than Vishnu was "somehow present in the body of Krishna".[64] Krishna had "no beginning or end", "fill[ed] space", and every god but Vishnu was seen as ultimately him, including Brahma, "storm gods, sun gods, bright gods", light gods, "and gods of ritual."[64] Other forces also existed in his body, such as "hordes of varied creatures" that included "celestial serpents."[64] He is also "the essence of humanity."[64]

The Harivamsa, a later appendix to the Mahabharata, contains a detailed version of Krishna's childhood and youth.[65]

Other sources

The Chandogya Upanishad (verse III.xvii.6) mentions Krishna in Krishnaya Devakiputraya as a student of the sage Ghora of the Angirasa family. Ghora is identified with Neminatha, the twenty-second tirthankara in Jainism, by some scholars.[66] This phrase, which means "To Krishna the son of Devaki", has been mentioned by scholars such as Max Müller[67] as a potential source of fables and Vedic lore about Krishna in the Mahabharata and other ancient literature – only potential because this verse could have been interpolated into the text,[67] or the Krishna Devakiputra, could be different from the deity Krishna.[68] These doubts are supported by the fact that the much later age Sandilya Bhakti Sutras, a treatise on Krishna,[69] cites later age compilations such as the Narayana Upanishad but never cites this verse of the Chandogya Upanishad. Other scholars disagree that the Krishna mentioned along with Devaki in the ancient Upanishad is unrelated to the later Hindu god of the Bhagavad Gita fame. For example, Archer states that the coincidence of the two names appearing together in the same Upanishad verse cannot be dismissed easily.[70]

Yāska's Nirukta, an etymological dictionary published around the 6th century BCE, contains a reference to the Shyamantaka jewel in the possession of Akrura, a motif from the well-known Puranic story about Krishna.[71] Shatapatha Brahmana and Aitareya-Aranyaka associate Krishna with his Vrishni origins.[72]

In Ashṭādhyāyī, authored by the ancient grammarian Pāṇini (probably belonged to the 5th or 6th century BCE), Vāsudeva and Arjuna, as recipients of worship, are referred to together in the same sutra.[73][74][75]

Megasthenes, a Greek ethnographer and an ambassador of Seleucus I to the court of Chandragupta Maurya towards the end of 4th century BCE, made reference to Herakles in his famous work Indica. This text is now lost to history, but was quoted in secondary literature by later Greeks such as Arrian, Diodorus, and Strabo.[76] According to these texts, Megasthenes mentioned that the Sourasenoi tribe of India, who worshipped Herakles, had two major cities named Methora and Kleisobora, and a navigable river named the Jobares. According to Edwin Bryant, a professor of Indian religions known for his publications on Krishna, "there is little doubt that the Sourasenoi refers to the Shurasenas, a branch of the Yadu dynasty to which Krishna belonged".[76] The word Herakles, states Bryant, is likely a Greek phonetic equivalent of Hari-Krishna, as is Methora of Mathura, Kleisobora of Krishnapura, and the Jobares of Jamuna. Later, when Alexander the Great launched his campaign in the northwest Indian subcontinent, his associates recalled that the soldiers of Porus were carrying an image of Herakles.[76]

The Buddhist Pali canon and the Ghata-Jâtaka (No. 454) polemically mention the devotees of Vâsudeva and Baladeva. These texts have many peculiarities and may be a garbled and confused version of the Krishna legends.[77] The texts of Jainism mention these tales as well, also with many peculiarities and different versions, in their legends about Tirthankaras. This inclusion of Krishna-related legends in ancient Buddhist and Jaina literature suggests that Krishna theology was existent and important in the religious landscape observed by non-Hindu traditions of ancient India.[78][79]

The ancient Sanskrit grammarian Patanjali in his Mahabhashya makes several references to Krishna and his associates found in later Indian texts. In his commentary on Pāṇini's verse 3.1.26, he also uses the word Kamsavadha or the "killing of Kamsa", an important part of the legends surrounding Krishna.[76][80]

Puranas

Many Puranas tell Krishna's life story or some highlights from it. Two Puranas, the Bhagavata Purana and the Vishnu Purana, contain the most elaborate telling of Krishna's story,[81] but the life stories of Krishna in these and other texts vary, and contain significant inconsistencies.[82][83] The Bhagavata Purana consists of twelve books subdivided into 332 chapters, with a cumulative total of between 16,000 and 18,000 verses depending on the version.[84][85] The tenth book of the text, which contains about 4,000 verses (~25%) and is dedicated to legends about Krishna, has been the most popular and widely studied part of this text.[86][87]

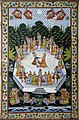

Iconography

Krishna is represented in the Indian traditions in many ways, but with some common features.[88] His iconography typically depicts him with black, dark, or blue skin, like Vishnu.[89] However, ancient and medieval reliefs and stone-based arts depict him in the natural color of the material out of which he is formed, both in India and in southeast Asia.[90][91] In some texts, his skin is poetically described as the color of Jambul (Jamun, a purple-colored fruit).[92]

Krishna is often depicted wearing a peacock-feather wreath or crown, and playing the bansuri (Indian flute).[93][94] In this form, he is usually shown standing with one leg bent in front of the other in the Tribhanga posture. He is sometimes accompanied by cows or a calf, which symbolise the divine herdsman Govinda. Alternatively, he is shown as a romantic young boy with the gopis (milkmaids), often making music or playing pranks.[95]

In other icons, he is a part of battlefield scenes of the epic Mahabharata. He is shown as a charioteer, notably when he is addressing the Pandava prince Arjuna, symbolically reflecting the events that led to the Bhagavad Gita – a scripture of Hinduism. In these popular depictions, Krishna appears in the front as the charioteer, either as a counsel listening to Arjuna or as the driver of the chariot while Arjuna aims his arrows in the battlefield of Kurukshetra.[97][98]

Alternate icons of Krishna show him as a baby (Bala Krishna, the child Krishna), a toddler crawling on his hands and knees, a dancing child, or an innocent-looking child playfully stealing or consuming butter (Makkan Chor),[99] holding Laddu in his hand (Laddu Gopal)[100][101] or as a cosmic infant sucking his toe while floating on a banyan leaf during the Pralaya (the cosmic dissolution) observed by sage Markandeya.[102] Regional variations in the iconography of Krishna are seen in his different forms, such as Jaganatha in Odisha, Vithoba in Maharashtra,[103] Shrinathji in Rajasthan[104] and Guruvayoorappan in Kerala.[105]

Guidelines for the preparation of Krishna icons in design and architecture are described in medieval-era Sanskrit texts on Hindu temple arts such as Vaikhanasa agama, Vishnu dharmottara, Brihat samhita, and Agni Purana.[106] Similarly, early medieval-era Tamil texts also contain guidelines for sculpting Krishna and Rukmini. Several statues made according to these guidelines are in the collections of the Government Museum, Chennai.[107]

Krishna iconography forms an important element in the figural sculpture on 17th–19th century terracotta temples of Bengal. In many temples, the stories of Krishna are depicted on a long series of narrow panels along the base of the facade. In other temples, the important Krishnalila episodes are depicted on large brick panels above the entrance arches or on the walls surrounding the entrance.[108]

Life and legends

This summary is an account based on literary details from the Mahābhārata, the Harivamsa, the Bhagavata Purana, and the Vishnu Purana. The scenes from the narrative are set in ancient India, mostly in the present states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, Haryana, Delhi, and Gujarat. The legends about Krishna's life are called Krishna charitas (IAST: Kṛṣṇacaritas).[109]

Birth

In the Padma Purana, Vishnu states that he will be born among the Abhiras in his eighth incarnation.[110]

In the Krishna Charitas, Krishna is born to Devaki and her husband, Vasudeva, of the Yadava clan in Mathura.[111][page needed] Devaki's brother is a tyrant named Kamsa. At Devaki's wedding, according to Puranic legends, Kamsa is told by fortune tellers that a child of Devaki would kill him. Sometimes, it is depicted as an akashvani announcing Kamsa's death. Kamsa arranges to kill all of Devaki's children. When Krishna is born, Vasudeva secretly carries the infant Krishna away across the Yamuna, and exchanges him with Yashoda's daughter. When Kamsa tries to kill the newborn, the exchanged baby appears as the Hindu goddess Yogamaya, warning him that his death has arrived in his kingdom, and then disappears, according to the legends in the Puranas. Krishna grows up with Nanda and his wife, Yashoda, near modern-day Mathura.[112][113][114] Two of Krishna's siblings also survive, namely Balarama and Subhadra, according to these legends.[115] The day of the birth of Krishna is celebrated as Krishna Janmashtami.

Childhood and youth

The legends of Krishna's childhood and youth describe him as a cow-herder, a mischievous boy whose pranks earn him the nickname Makhan Chor (butter thief), and a protector who steals the hearts of the people in both Gokul and Vrindavana. The texts state, for example, that Krishna lifts the Govardhana hill to protect the inhabitants of Vrindavana from devastating rains and floods.[116]

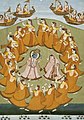

Other legends describe him as an enchanter and playful lover of the gopis (milkmaids) of Vrindavana, especially Radha. These metaphor-filled love stories are known as the Rasa lila and were romanticized in the poetry of Jayadeva, author of the Gita Govinda. They are also central to the development of the Krishna bhakti traditions worshiping Radha Krishna.[117]

Krishna's childhood illustrates the Hindu concept of Lila, playing for fun and enjoyment and not for sport or gain. His interaction with the gopis at the rasa dance or Rasa-lila is an example. Krishna plays his flute and the gopis come immediately, from whatever they were doing, to the banks of the Yamuna River and join him in singing and dancing. Even those who could not physically be there join him through meditation. He is the spiritual essence and the love-eternal in existence, the gopis metaphorically represent the prakṛti matter and the impermanent body.[118]: 256

This Lila is a constant theme in the legends of Krishna's childhood and youth. Even when he is battling with a serpent to protect others, he is described in Hindu texts as if he were playing a game.[118]: 255 This quality of playfulness in Krishna is celebrated during festivals as Rasa-Lila and Janmashtami, where Hindus in some regions such as Maharashtra playfully mimic his legends, such as by making human gymnastic pyramids to break open handis (clay pots) hung high in the air to "steal" butter or buttermilk, spilling it all over the group.[118]: 253–261

Adulthood

Krishna legends then describe his return to Mathura. He overthrows and kills the tyrant king, his maternal uncle Kamsa/Kansa after quelling several assassination attempts by Kamsa. He reinstates Kamsa's father, Ugrasena, as the king of the Yadavas and becomes a leading prince at the court.[120] In one version of the Krishna story, as narrated by Shanta Rao, Krishna after Kamsa's death leads the Yadavas to the newly built city of Dwaraka. Thereafter Pandavas rise. Krishna befriends Arjuna and the other Pandava princes of the Kuru kingdom. Krishna plays a key role in the Mahabharata.[121]

The Bhagavata Purana describes eight wives of Krishna that appear in sequence as Rukmini, Satyabhama, Jambavati, Kalindi, Mitravinda, Nagnajiti (also called Satya), Bhadra and Lakshmana (also called Madra).[122] This has been interpreted as a metaphor where each of the eight wives signifies a different aspect of him.[123] Vaishnava texts mention all Gopis as wives of Krishna, but this is understood as spiritual symbolism of devotional relationship and Krishna's complete loving devotion to each and everyone devoted to him.[124]

In Krishna-related Hindu traditions, he is most commonly seen with Radha. All of his wives and his lover Radha are considered in the Hindu tradition to be the avatars of the goddess Lakshmi, the consort of Vishnu.[125][11] Gopis are considered as Lakshmi's or Radha's manifestations.[11][126]

Kurukshetra War and Bhagavad Gita

According to the epic poem Mahabharata, Krishna becomes Arjuna's charioteer for the Kurukshetra War, but on the condition that he personally will not raise any weapon. Upon arrival at the battlefield and seeing that the enemies are his family, his grandfather, and his cousins and loved ones, Arjuna is moved and says his heart will not allow him to fight and kill others. He would rather renounce the kingdom and put down his Gandiva (Arjuna's bow). Krishna then advises him about the nature of life, ethics, and morality when one is faced with a war between good and evil, the impermanence of matter, the permanence of the soul and the good, duties and responsibilities, the nature of true peace and bliss and the different types of yoga to reach this state of bliss and inner liberation. This conversation between Krishna and Arjuna is presented as a discourse called the Bhagavad Gita.[127][128][129]

Death and ascension

It is stated in the Indian texts that the legendary Kurukshetra War led to the death of all the hundred sons of Gandhari. After Duryodhana's death, Krishna visits Gandhari to offer his condolences when Gandhari and Dhritarashtra visited Kurukshetra, as stated in Stree Parva. Feeling that Krishna deliberately did not put an end to the war, in a fit of rage and sorrow, Gandhari said, "Thou were indifferent to the Kurus and the Pandavas whilst they slew each other. Therefore, O Govinda, thou shalt be the slayer of thy own kinsmen!" According to the Mahabharata, a fight breaks out at a festival among the Yadavas, who end up killing each other. Mistaking the sleeping Krishna for a deer, a hunter named Jara shoots an arrow towards Krishna's foot that fatally injures him. Krishna forgives Jara and dies.[130][7][131] The pilgrimage (tirtha) site of Bhalka in Gujarat marks the location where Krishna is believed to have died. It is also known as Dehotsarga, states Diana L. Eck, a term that literally means the place where Krishna "gave up his body".[7] The Bhagavata Purana in Book 11, Chapter 31 states that after his death, Krishna returned to his transcendent abode directly because of his yogic concentration. Waiting gods such as Brahma and Indra were unable to trace the path Krishna took to leave his human incarnation and return to his abode.[132][133]

Versions and interpretations

There are numerous versions of Krishna's life story, of which three are most studied: the Harivamsa, the Bhagavata Purana, and the Vishnu Purana.[134] They share the basic storyline but vary significantly in their specifics, details, and styles.[135] The most original composition, the Harivamsa is told in a realistic style that describes Krishna's life as a poor herder but weaves in poetic and allusive fantasy. It ends on a triumphal note, not with the death of Krishna.[136] Differing in some details, the fifth book of the Vishnu Purana moves away from Harivamsa realism and embeds Krishna in mystical terms and eulogies.[137] The Vishnu Purana manuscripts exist in many versions.[138]

The tenth and eleventh books of the Bhagavata Purana are widely considered to be a poetic masterpiece, full of imagination and metaphors, with no relation to the realism of pastoral life found in the Harivamsa. Krishna's life is presented as a cosmic play (Lila), where his youth is set as a princely life with his foster father Nanda portrayed as a king.[139] Krishna's life is closer to that of a human being in Harivamsa, but is a symbolic universe in the Bhagavata Purana, where Krishna is within the universe and beyond it, as well as the universe itself, always.[140] The Bhagavata Purana manuscripts also exist in many versions, in numerous Indian languages.[141][86]

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu is considered as the incarnation of Krishna in Gaudiya Vaishnavism and by the ISKCON community.[142][143][144]

Proposed datings and historicity

The date of Krishna's birth is celebrated every year as Janmashtami.[145][page needed]

According to Guy Beck, "most scholars of Hinduism and Indian history accept the historicity of Krishna – that he was a real male person, whether human or divine, who lived on Indian soil by at least 1000 BCE and interacted with many other historical persons within the cycles of the epic and puranic histories." Yet, Beck also notes that there is an "enormous number of contradictions and discrepancies surrounding the chronology of Krishna's life as depicted in the Sanskrit canon".[146]

Some scholars believe that, among others, the detailed description of Krishna’s peace mission in the 5th Book of the Mahabharata (Udyogaparvan) is likely to be based on real events. The epic’s translator J.A.B. van Buitenen in this context assumes “that there was some degree of verisimilitude in the Mahabharata’s depictions of life.”[147]

Philosophy and theology

A wide range of theological and philosophical ideas are presented through Krishna in Hindu texts. The teachings of the Bhagavad Gita can be considered, according to Friedhelm Hardy, as the first Krishnaite system of theology.[23]

Ramanuja, a Hindu theologian and philosopher whose works were influential in Bhakti movement,[148] presented him in terms of qualified monism, or nondualism (namely Vishishtadvaita school).[149] Madhvacharya, a philosopher whose works led to the founding of Haridasa tradition of Vaishnavism,[150] presented Krishna in the framework of dualism (Dvaita).[151] Bhedabheda – a group of schools, which teaches that the individual self is both different and not different from the ultimate reality – predates the positions of monism and dualism. Among medieval Bhedabheda thinkers are Nimbarkacharya, who founded the Kumara Sampradaya (Dvaitadvaita philosophical school),[152] and Jiva Goswami, a saint from Gaudiya Vaishnava school,[153] who described Krishna theology in terms of Bhakti yoga and Achintya Bheda Abheda.[154] Krishna theology is presented in a pure monism (Shuddhadvaita) framework by Vallabha Acharya, the founder of Pushti sect of Vaishnavism.[155][156] Madhusudana Sarasvati, an India philosopher,[157] presented Krishna theology in nondualism-monism framework (Advaita Vedanta), while Adi Shankara, credited with unifying and establishing the main currents of thought in Hinduism,[158][159][160] mentioned Krishna in his early eighth-century discussions on Panchayatana puja.[161]

The Bhagavata Purana synthesizes an Advaita, Samkhya, and Yoga framework for Krishna, but it does so through loving devotion to Krishna.[162][163][164] Bryant describes the synthesis of ideas in Bhagavata Purana as:

The philosophy of the Bhagavata is a mixture of Vedanta terminology, Samkhyan metaphysics, and devotionalized Yoga praxis. (...) The tenth book promotes Krishna as the highest absolute personal aspect of godhead – the personality behind the term Ishvara and the ultimate aspect of Brahman.

— Edwin Bryant, Krishna: A Sourcebook[4]

While Sheridan and Pintchman both affirm Bryant's view, the latter adds that the Vedantic view emphasized in the Bhagavata is non-dualist with a difference. In conventional nondual Vedanta, all reality is interconnected and one, the Bhagavata posits that the reality is interconnected and plural.[165][166]

Across the various theologies and philosophies, the common theme presents Krishna as the essence and symbol of divine love, with human life and love as a reflection of the divine. The longing and love-filled legends of Krishna and the gopis, his playful pranks as a baby,[167] as well as his later dialogues with other figures, are philosophically treated as metaphors for the human longing for the divine and for meaning, and the play between the universals and the human soul.[168][169][170] Krishna's lila is a theology of love-play. According to John Koller, "love is presented not simply as a means to salvation, it is the highest life". Human love is God's love.[171]

Other texts that include Krishna such as the Bhagavad Gita have attracted numerous bhasya (commentaries) in the Hindu traditions.[172] Though only a part of the Hindu epic Mahabharata, it has functioned as an independent spiritual guide. It allegorically raises the ethical and moral dilemmas of human life through Krishna and Arjuna. It then presents a spectrum of answers, addressing the ideological questions on human freedoms, choices, and responsibilities towards self and others.[172][173] This Krishna dialogue has attracted numerous interpretations, from being a metaphor for inner human struggle that teaches non-violence to being a metaphor for outer human struggle that advocates a rejection of quietism and persecution.[172][173][174]

Madhusudana Sarasvati, known for his contributions to classical Advaita Vedanta, was also a devout follower of Krishna and expressed his devotion in various verses within his works, notably in his Bhagavad Gita commentary, Bhagavad Gita Gudarthadipika. In his works, Krishna is often interpreted as representing nirguna Brahman, leading to a transtheistic understanding of deity, where Krishna symbolizes the nondual Self, embodying Being, Consciousness, and Bliss, and the pure Existence underlying all.[175]

Influence

Vaishnavism

The worship of Krishna is part of Vaishnavism, a major tradition within Hinduism. Krishna is considered a full avatar of Vishnu, or one with Vishnu himself.[176] However, the exact relationship between Krishna and Vishnu is complex and diverse,[177] with Krishna of Krishnaite sampradayas considered an independent deity and supreme.[23][178] Vaishnavas accept many incarnations of Vishnu, but Krishna is particularly important. Their theologies are generally centered either on Vishnu or an avatar such as Krishna as supreme. The terms Krishnaism and Vishnuism have sometimes been used to distinguish the two, the former implying that Krishna is the transcendent Supreme Being. [179] Some scholars, as Friedhelm Hardy, do not define Krishnaism as a sub-order or offshoot of Vaishnavism, considering it a parallel and no less ancient current of Hinduism.[23]

All Vaishnava traditions recognise Krishna as the eighth avatar of Vishnu; others identify Krishna with Vishnu, while Krishnaite traditions such as Gaudiya Vaishnavism,[180][181] Ekasarana Dharma, Mahanam Sampraday, Nimbarka Sampradaya and the Vallabha Sampradaya regard Krishna as the Svayam Bhagavan, the original form of Lord or the same as the concept of Brahman in Hinduism.[5][182][183][184][185] Gitagovinda of Jayadeva considers Krishna to be the supreme lord while the ten incarnations are his forms. Swaminarayan, the founder of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya, also worshipped Krishna as God himself. "Greater Krishnaism" corresponds to the second and dominant phase of Vaishnavism, revolving around the cults of the Vasudeva, Krishna, and Gopala of the late Vedic period.[186] Today the faith has a significant following outside of India as well.[187]

Early traditions

The deity Krishna-Vasudeva (kṛṣṇa vāsudeva "Krishna, the son of Vasudeva Anakadundubhi") is historically one of the earliest forms of worship in Krishnaism and Vaishnavism.[22][71] It is believed to be a significant tradition of the early history of Krishna religion in antiquity.[188] Thereafter, there was an amalgamation of various similar traditions. These include ancient Bhagavatism, the cult of Gopala, of "Krishna Govinda" (cow-finding Krishna), of Balakrishna (baby Krishna) and of "Krishna Gopivallabha[189]" (Krishna the lover).[190][191] According to Andre Couture, the Harivamsa contributed to the synthesis of various figures as aspects of Krishna.[192]

Already in the early Middle Ages, Jagannathism (a.k.a. Odia Vaishnavism) originated as the cult of the god Jagannath (lit. ''Lord of the Universe'') – an abstract form of Krishna.[193] Jagannathism was a regional temple-centered version of Krishnaism,[23] where Jagannath is understood as a principal god, Purushottama and Para Brahman, but can also be regarded as a non-sectarian syncretic Vaishnavite and all-Hindu cult.[194] According to the Vishnudharma Purana (c. 4th century), Krishna is woshipped in the form of Purushottama in Odia (Odisha).[195] The notable Jagannath temple in Puri, Odisha has been particularly significant within the tradition since about 800 CE.[196]

Bhakti tradition

The use of the term bhakti, meaning devotion, is not confined to any one deity. However, Krishna is an important and popular focus of the devotionalism tradition within Hinduism, particularly among the Vaishnava Krishnaite sects.[180][197] Devotees of Krishna subscribe to the concept of lila, meaning 'divine play', as the central principle of the universe. It is a form of bhakti yoga, one of three types of yoga discussed by Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita.[181][198][199]

Indian subcontinent

The bhakti movements devoted to Krishna became prominent in southern India in the 7th to 9th centuries CE. The earliest works included those of the Alvar saints of Tamil Nadu.[200] A major collection of their works is the Divya Prabandham. Alvar Andal's popular collection of songs Tiruppavai, in which she conceives of herself as a gopi, is the most famous of the oldest works in this genre.[201][202][203]

The movement originated in South India during the 7th century CE, spreading northwards from Tamil Nadu through Karnataka and Maharashtra; by the 15th century, it was established in Bengal and northern India.[204] Early Krishnaite Bhakti pioneers included Nimbarkacharya (12th or 13th century CE),[152][205][note 3] but most emerged later, including Vallabhacharya (15th century CE) and Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. They started their own schools, namely Nimbarka Sampradaya, Vallabha Sampradaya, and Gaudiya Vaishnavism, with Krishna and Radha as the supreme gods. In addition, since the 15th century, flourished Tantric variety of Krishnaism, Vaishnava-Sahajiya, is linked to the Bengali poet Chandidas.[206]

In the Deccan, particularly in Maharashtra, saint poets of the Warkari sect such as Dnyaneshwar, Namdev, Janabai, Eknath, and Tukaram promoted the worship of Vithoba,[103] a local form of Krishna, from the 13th to 18th century.[20] Before the Warkari tradition, Krishna devotion became well established in Maharashtra due to the rise of the Mahanubhava Sampradaya founded by Sarvajna Chakradhara.[207] The Pranami Sampradaya emerged in the 17th century in Gujarat, based on the Krishna-focussed syncretist Hindu-Islamic teachings of Devchandra Maharaj and his famous successor, Mahamati Prannath.[208] In southern India, Purandara Dasa and Kanakadasa of Karnataka composed songs devoted to the Krishna image of Udupi. Rupa Goswami of Gaudiya Vaishnavism has compiled a comprehensive summary of bhakti called Bhakti-rasamrita-sindhu.[197]

In South India, the acharyas of the Sri Sampradaya have written reverently about Krishna in most of their works, including the Tiruppavai by Andal[209] and Gopalavimshati by Vedanta Desika.[210]

Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Kerala states have many major Krishna temples, and Janmashtami is one of the widely celebrated festivals in South India.[211]

Outside Asia

By 1965, the Krishna-bhakti movement had spread outside India after Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (as instructed by his guru, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura) travelled from his homeland in West Bengal to New York City. A year later, in 1966, after gaining many followers, he was able to form the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), popularly known as the Hare Krishna movement. The purpose of this movement was to write about Krishna in English and to share the Gaudiya Vaishnava philosophy with people in the Western world by spreading the teachings of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. In the biographies of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, the mantra he received when he was given diksha or initiation in Gaya was the six-word verse of the Kali-Santarana Upanishad, namely "Hare Krishna Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna Hare Hare; Hare Rama Hare Rama, Rama Rama Hare Hare". In the Gaudiya tradition, it is the maha-mantra, or great mantra, about Krishna bhakti.[212][213] Its chanting was known as hari-nama sankirtana.[214]

The maha-mantra gained the attention of George Harrison and John Lennon of the Beatles fame,[215] and Harrison produced a 1969 recording of the mantra by devotees from the London Radha Krishna Temple.[216] Titled "Hare Krishna Mantra", the song reached the top twenty on the UK music charts and was also successful in West Germany and Czechoslovakia.[215][217] The mantra of the Upanishad thus helped bring Bhaktivedanta and ISKCON ideas about Krishna into the West.[215] ISKCON has built many Krishna temples in the West, as well as other locations such as South Africa.[218]

Southeast Asia

Krishna is found in Southeast Asian history and art, but to a far lesser extent than Shiva, Durga, Nandi, Agastya, and Buddha. In temples (candi) of the archaeological sites in hilly volcanic Java, Indonesia, temple reliefs do not portray his pastoral life or his role as the erotic lover, nor do the historic Javanese Hindu texts.[221] Rather, either his childhood or the life as a king and Arjuna's companion have been more favored. The most elaborate temple arts of Krishna is found in a series of Krsnayana reliefs in the Prambanan Hindu temple complex near Yogyakarta. These are dated to the 9th century CE.[221][222][223] Krishna remained a part of the Javanese cultural and theological fabric through the 14th century, as evidenced by the 14th-century Penataran reliefs along with those of the Hindu god Rama in east Java, before Islam replaced Buddhism and Hinduism on the island.[224]

The medieval era arts of Vietnam and Cambodia feature Krishna. The earliest surviving sculptures and reliefs are from the 6th and 7th centuries, and these include Vaishnavism iconography.[219] According to John Guy, the curator and director of Southeast Asian arts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Krishna Govardhana art from 6th/7th-century Vietnam at Danang, and 7th-century Cambodia at Phnom Da cave in Angkor Borei, are some of the most sophisticated of this era.[219]

Krishna's iconography has also been found in Thailand, along with those of Surya and Vishnu. For example, a large number of sculptures and icons have been found in the Si Thep and Klangnai sites in the Phetchabun region of northern Thailand. These are dated to about the 7th and 8th centuries, from both the Funan and Zhenla period archaeological sites.[225]

Performance arts

Dance and culture

Indian dance and music theatre traces its origins and techniques to the ancient Sama Veda and Natyasastra texts.[226][227] The stories enacted and the numerous choreographic themes are inspired by the legends in Hindu texts, including Krishna-related literature such as Harivamsa and Bhagavata Purana.[228]

The Krishna stories have played a key role in the history of Indian theatre, music, and dance, particularly through the tradition of Rasaleela. These are dramatic enactments of Krishna's childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. One common scene involves Krishna playing flute in Rasa Leela, only to be heard by certain gopis (cowherd maidens), which is theologically supposed to represent divine call only heard by certain enlightened beings.[229] Some of the text's legends have inspired secondary theatre literature such as the eroticism in Gita Govinda.[230]

Krishna-related literature such as the Bhagavata Purana accords a metaphysical significance to the performances and treats them as a religious ritual, infusing daily life with spiritual meaning, thus representing a good, honest, happy life. Similarly, Krishna-inspired performances aim to cleanse the hearts of faithful actors and listeners. Singing, dancing, and performing any part of Krishna Lila is an act of remembering the dharma in the text, as a form of para bhakti (supreme devotion). To remember Krishna at any time and in any art, asserts the text, is to worship the good and the divine.[231]

Classical dance styles such as Kathak, Odissi, Manipuri, Kuchipudi and Bharatanatyam in particular are known for their Krishna-related performances.[232] Krisnattam (Krishnattam) traces its origins to Krishna legends, and is linked to another major classical Indian dance form called Kathakali.[233] Bryant summarizes the influence of Krishna stories in the Bhagavata Purana as, "[it] has inspired more derivative literature, poetry, drama, dance, theatre and art than any other text in the history of Sanskrit literature, with the possible exception of the Ramayana.[25][234]

The Palliyodam, a type of large boat built and used by Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple in Kerala for the annual water processions of Uthrattathi Jalamela and Valla Sadhya has the legend that it was designed by Krishna and were made to look like Sheshanaga, the serpent on which Vishnu rests.[235]

In popular culture

Films

- In the 1933 Bengali film Radha Krishna, Radha was portrayed by Shreemati Lakshmi.[236]

- In the 1957 Telugu-Tamil film Mayabazar, the 1966, 1967 and 1971 Telugu films Sri Krishna Tulabharam, Sri Krishnavataram and Sri Krishna Vijayamu respectively, Krishna was portrayed by N. T. Rama Rao.[237][238][239]

- In the 1971 Hindi film Shri Krishna Leela, Radha was portrayed by Sachin.[240]

- In the 1986 Hindi film Krishna-Krishna, Krishna was portrayed by Biswajeet.

- In the 2012 Hindi animated film Krishna Aur Kans, Radha was voiced by Prachi Save Saathi.[241]

Television

- In B. R. Chopra's 1988 series Mahabharat, Krishna was portrayed by Nitish Bharadwaj.[242]

- In Ramanand Sagar's 1993 series Shri Krishna, Krishna was portrayed by Sarvadaman D. Banerjee, Swapnil Joshi and Ashok Kumar Balkrishnan.[243]

- In the 2008 series Jai Shri Krishna, Krishna was portrayed by Meghan Jadhav, Dhriti Bhatia and Pinky Rajput.

- In the 2008 series Kahaani Hamaaray Mahaabhaarat Ki, Krishna was portrayed by Mrunal Jain.[244]

- In the 2011 series Dwarkadheesh Bhagwan Shree Krishn and the 2019 series Dwarkadheesh Bhagwan Shree Krishn – Sarvkala Sampann, Krishna was portrayed by Vishal Karwal.

- In the 2013 series Mahabharat , Krishna was portrayed by Saurabh Raj Jain.[245]

- In the 2017 series Vithu Mauli, Krishna was portrayed by Ajinkya Raut.

- In the 2017 series Paramavatar Shri Krishna, Krishna was portrayed by Sudeep Sahir and Nirnay Samadhiya.[246]

- In the 2018 series RadhaKrishn, Krishna was portrayed by Sumedh Mudgalkar and Himanshu Soni.[247]

- In the 2019 series Shrimad Bhagwat Mahapuran, Krishna was portrayed by Rajneesh Duggal.[248]

- In the 2021 series Jai Kanhaiya Lal Ki, Krishna was portrayed by Hazel Gaur.[249]

- In the 2022 series Brij Ke Gopal, Krishna was portrayed by Paras Arora.[250]

Temples

- Ambalappuzha Sree Krishna Swamy Temple

- Banke Bihari Temple, Vrindavan

- Dwarkadhish Temple, Dwarka

- Govind Dev Ji Temple, Jaipur

- Guruvayur Temple, Kerala

- ISKCON Temples

- Jagannath Temple, Puri

- Kantajew Temple, Bangladesh

- Krishna Janmasthan Temple Complex, Mathura

- Madan Mohan Temple, Karauli

- Parthasarathy Temple, Chennai

- Prem Mandir, Vrindavan

- Pushtimarg Haveli-Temples

- Radha Damodar Temple, Junagadh

- Radha Damodar Temple, Vrindavan

- Radha Krishna Vivah Sthali, Bhandirvan

- Radha Madan Mohan Temple, Vrindavan

- Radha Madhab Temple, Bishnupur

- Radha Raman Temple, Vrindavan

- Radha Vallabh Temple, Vrindavan

- Rajagopalaswamy Temple, Mannargudi

- Ranchodrai Temple, Dakor

- Shree Govindajee Temple, Imphal

- Sri Kunj Bihari Temple, Malaysia

- Swaminarayan Temples

- Trichambaram Temple, Thaliparamba

- Udupi Sri Krishna Matha

- Vithoba Temple, Pandarpur

Outside Hinduism

Jainism

The Jainism tradition lists 63 Śalākāpuruṣa or notable figures which, amongst others, includes the twenty-four Tirthankaras (spiritual teachers) and nine sets of triads. One of these triads is Krishna as the Vasudeva, Balarama as the Baladeva, and Jarasandha as the Prati-Vasudeva. In each age of the Jain cyclic time is born a Vasudeva with an elder brother termed the Baladeva. Between the triads, Baladeva upholds the principle of non-violence, a central idea of Jainism. The villain is the Prati-vasudeva, who attempts to destroy the world. To save the world, Vasudeva-Krishna has to forsake the non-violence principle and kill the Prati-Vasudeva.[251] The stories of these triads can be found in the Harivamsa Purana (8th century CE) of Jinasena (not be confused with its namesake, the addendum to Mahābhārata) and the Trishashti-shalakapurusha-charita of Hemachandra.[252][253]

The story of Krishna's life in the Puranas of Jainism follows the same general outline as those in the Hindu texts, but in details, they are very different: they include Jain Tirthankaras as figures in the story, and generally are polemically critical of Krishna, unlike the versions found in the Mahabharata, the Bhagavata Purana, and the Vishnu Purana.[254] For example, Krishna loses battles in the Jain versions, and his gopis and his clan of Yadavas die in a fire created by an ascetic named Dvaipayana. Similarly, after dying from the hunter Jara's arrow, the Jaina texts state Krishna goes to the third hell in Jain cosmology, while his brother is said to go to the sixth heaven.[255]

Vimalasuri is attributed to be the author of the Jain version of the Harivamsa Purana, but no manuscripts have been found that confirm this. It is likely that later Jain scholars, probably Jinasena of the 8th century, wrote a complete version of Krishna legends in the Jain tradition and credited it to the ancient Vimalasuri.[256] Partial and older versions of the Krishna story are available in Jain literature, such as in the Antagata Dasao of the Svetambara Agama tradition.[256]

In other Jain texts, Krishna is stated to be a cousin of the twenty-second Tirthankara, Neminatha. The Jain texts state that Neminatha taught Krishna all the wisdom that he later gave to Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita. According to Jeffery D. Long, a professor of religion known for his publications on Jainism, this connection between Krishna and Neminatha has been a historic reason for Jains to accept, read, and cite the Bhagavad Gita as a spiritually important text, celebrate Krishna-related festivals, and intermingle with Hindus as spiritual cousins.[257]

Buddhism

The story of Krishna occurs in the Jataka tales in Buddhism.[258] The Vidhurapandita Jataka mentions Madhura (Sanskrit: Mathura), the Ghata Jataka mentions Kamsa, Devagabbha (Sk: Devaki), Upasagara or Vasudeva, Govaddhana (Sk: Govardhana), Baladeva (Balarama), and Kanha or Kesava (Sk: Krishna, Keshava).[259][260]

Like the Jain versions of the Krishna legends, the Buddhist versions such as one in Ghata Jataka follow the general outline of the story,[261] but are different from the Hindu versions as well.[259][78] For example, the Buddhist legend describes Devagabbha (Devaki) to have been isolated in a palace built upon a pole after she is born, so no future husband could reach her. Krishna's father similarly is described as a powerful king, but who meets up with Devagabbha anyway, and to whom Kamsa gives away his sister Devagabbha in marriage. The siblings of Krishna are not killed by Kamsa, though he tries. In the Buddhist version of the legend, all of Krishna's siblings grow to maturity.[262]

Krishna and his siblings' capital becomes Dvaravati. The Arjuna and Krishna interaction is missing in the Jataka version. A new legend is included, wherein Krishna laments in uncontrollable sorrow when his son dies, and a Ghatapandita feigns madness to teach Krishna a lesson.[263] The Jataka tale also includes internecine destruction among his siblings after they all get drunk. Krishna also dies in the Buddhist legend by the hand of a hunter named Jara, but while he is traveling to a frontier city. Mistaking Krishna for a pig, Jara throws a spear that fatally pierces his feet, causing Krishna great pain and then his death.[262]

At the end of this Ghata-Jataka discourse, the Buddhist text declares that Sariputta, one of the revered disciples of the Buddha in the Buddhist tradition, was incarnated as Krishna in his previous life to learn lessons on grief from the Buddha in his prior rebirth:

Then he [Master] declared the Truths and identified the Birth: "At that time, Ananda was Rohineyya, Sariputta was Vasudeva [Krishna], the followers of the Buddha were the other persons, and I myself was Ghatapandita."

— Jataka Tale No. 454, Translator: W. H. D. Rouse[264]

While the Buddhist Jataka texts co-opt Krishna-Vasudeva and make him a student of the Buddha in his previous life,[264] the Hindu texts co-opt the Buddha and make him an avatar of Vishnu.[265][266] In Chinese Buddhism, Taoism and Chinese folk religion, the figure of Krishna has been amalgamated and merged with that of Nalakuvara to influence the formation of the god Nezha, who has taken on iconographic characteristics of Krishna such as being presented as a divine god-child and slaying a nāga in his youth.[267][268]

Other

Krishna's life is written about in "Krishna Avtar" of the Chaubis Avtar, a composition in Dasam Granth traditionally and historically attributed to Sikh Guru Gobind Singh.[269]

Within the Sikh-derived 19th-century Radha Soami movement, the followers of its founder Shiv Dayal Singh used to consider him the Living Master and incarnation of God (Krishna/Vishnu).[note 4]

Baháʼís believe that Krishna was a "Manifestation of God", or one in a line of prophets who have revealed the Word of God progressively for a gradually maturing humanity. In this way, Krishna shares an exalted station with Abraham, Moses, Zoroaster, Buddha, Muhammad, Jesus, the Báb, and the founder of the Baháʼí Faith, Bahá'u'lláh.[271][272]

Ahmadiyya, a 20th-century Islamic movement, consider Krishna as one of their ancient prophets.[273][274][275] Ghulam Ahmad stated that he was himself a prophet in the likeness of prophets such as Krishna, Jesus, and Muhammad,[276] who had come to earth as a latter-day reviver of religion and morality.

Krishna worship or reverence has been adopted by several new religious movements since the 19th century, and he is sometimes a member of an eclectic pantheon in occult texts, along with Greek, Buddhist, biblical, and even historical figures.[277] For instance, Édouard Schuré, an influential figure in perennial philosophy and occult movements, considered Krishna a Great Initiate, while Theosophists regard Krishna as an incarnation of Maitreya (one of the Masters of the Ancient Wisdom), the most important spiritual teacher for humanity along with Buddha.[278][279]

Krishna was canonised by Aleister Crowley and is recognised as a saint of Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica in the Gnostic Mass of Ordo Templi Orientis.[280][281]

Explanatory notes

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

- ^ The number of Krishna's children varies from one interpretation to another. According to some scriptures like the Bhagavata Purana, Krishna had 10 children from each of his wives (16,008 wives and 160,080 children)[9]

- ^ Radha is seen as Krishna's lover-consort (although in some beliefs Radha is considered to be Krishna's married consort). On the other hand, Rukmini and others are already married to him. Krishna had eight chief wives, known as Ashtabharyas. Regional texts vary in the identity of Krishna's wives (consorts), some presenting them as Rukmini, some as Radha, all gopis, and some identifying all as different aspects or manifestations of Devi Lakshmi.[10][11]

- ^ "The first Kṛṣṇaite sampradāya was developed by Nimbārka."[23]

- ^ "Various branches of Radhasoami have argued about the incarnationalism of Satguru (Lane, 1981). Guru Maharaj Ji has accepted it and identifies with Krishna and other incarnations of Vishnu."[270]

References

Citations

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bryant & Ekstrand 2004, pp. 20–25, quote: "Three Dimensions of Krishna's Divinity (...) divine majesty and supremacy, (...) divine tenderness and intimacy, (...) compassion and protection., (..., p. 24) Krishna as the God of Love".

- ^ Swami Sivananda (1964). Sri Krishna. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 4.

- ^ "Krishna the Yogeshwara". The Hindu. 12 September 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bryant 2007, p. 114.

- ^ Jump up to: a b K. Klostermaier (1997). The Charles Strong Trust Lectures, 1972–1984. Crotty, Robert B. Brill Academic Pub. p. 109. ISBN 978-90-04-07863-5.

(...) After attaining to fame eternal, he again took up his real nature as Brahman. The most important among Visnu's avataras is undoubtedly Krsna, the black one, also called Syama. For his worshippers he is not an avatara in the usual sense, but Svayam Bhagavan, the Lord himself.

- ^ Raychaudhuri 1972, p. 124

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Diana L. Eck (2012). India: A Sacred Geography. Harmony. pp. 380–381. ISBN 978-0-385-53190-0., Quote: "Krishna was shot through the foot, hand, and heart by the single arrow of a hunter named Jara. Krishna was reclining there, so they say, and Jara mistook his reddish foot for a deer and released his arrow. There Krishna died."

- ^ Naravane, Vishwanath S. (1987). A Companion to Indian Mythology: Hindu, Buddhist & Jaina. Thinker's Library, Technical Publishing House.

- ^ Sinha, Purnendu Narayana (1950). A Study of the Bhagavata Purana: Or, Esoteric Hinduism. Library of Alexandria. ISBN 978-1-4655-2506-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b John Stratton Hawley, Donna Marie Wulff (1982). The Divine Consort: Rādhā and the Goddesses of India. Motilal Banarsidass Publisher. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-89581-102-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bryant 2007, p. 443.

- ^ "Krishna". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ "Krishna". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 26 June 2023.

- ^ Ben-Ami Scharfstein (1993). Ineffability: The Failure of Words in Philosophy and Religion. State University of New York Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-7914-1347-0.

- ^ Freda Matchett (2001). Krishna, Lord Or Avatara?. Psychology Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-7007-1281-6.

- ^ "Krishna". World History Encyclopedia.

- ^ "Krishna Janmashtami". International Society for Krishna Consciousness. 31 August 2022.

- ^ James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 314–315. ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8.

- ^ Richard Thompson, Ph.D. (December 1994). "Reflections on the Relation Between Religion and Modern Rationalism". Archived from the original on 4 January 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mahony, W. K. (1987). "Perspectives on Krsna's Various Personalities". History of Religions. 26 (3): 333–335. doi:10.1086/463085. ISSN 0018-2710. JSTOR 1062381. S2CID 164194548. Quote: "Krsna's various appearances as a divine hero, alluring god child, cosmic prankster, perfect lover, and universal supreme being (...)".

- ^ Knott 2000, pp. 15, 36, 56

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hein, Norvin (1986). "A Revolution in Kṛṣṇaism: The Cult of Gopāla". History of Religions. 25 (4): 296–317. doi:10.1086/463051. JSTOR 1062622. S2CID 162049250.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Hardy 1987, pp. 387–392.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ravi Gupta and Kenneth Valpey (2013), The Bhagavata Purana, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231149990, pp. 185–200

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bryant 2007, p. 118.

- ^ Jump up to: a b ML Varadpande (1987), History of Indian Theatre, Vol 1, Abhinav, ISBN 978-8170172215, pp. 98–99

- ^ Hawley 2020.

- ^ Miśra 2005.

- ^ J. Gordon Melton (2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-Clio. pp. 330–331. ISBN 978-1-59884-205-0.

- ^ Cynthia Packert (2010). The Art of Loving Krishna: Ornamentation and Devotion. Indiana University Press. pp. 5, 70–71, 181–187. ISBN 978-0-253-22198-8.

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 3.

- ^ Lavanya Vemsani (2016). Krishna in History, Thought, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-1-61069-211-3.

- ^ Selengut, Charles (1996). "Charisma and Religious Innovation: Prabhupada and the Founding of ISKCON". ISKCON Communications Journal. 4 (2). Archived from the original on 10 July 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b *Monier Williams Sanskrit–English Dictionary (2008 revision) Archived 18 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Apte Sanskrit–English Dictionary Archived 16 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Monier Monier Williams, Go-vinda, Sanskrit English Dictionary and Etymology, Oxford University Press, p. 336, 3rd column

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 17

- ^ Hiltebeitel, Alf (2001). Rethinking the Mahābhārata: a reader's guide to the education of the dharma king. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 251–253, 256, 259. ISBN 978-0-226-34054-8.

- ^ B. M. Misra (2007). Orissa: Shri Krishna Jagannatha: the Mushali parva from Sarala's Mahabharata. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514891-6.

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 139.

- ^ For the historic Jagannath temple in Ranchi, Jharkhand see: Francis Bradley Bradley-Birt (1989). Chota Nagpur, a Little-known Province of the Empire. Asian Educational Services (Orig: 1903). pp. 61–64. ISBN 978-81-206-1287-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Flood 1996, pp. 119–120

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. pp. 436–438. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- ^ Osmund Bopearachchi, Emergence of Viṣṇu and Śiva Images in India: Numismatic and Sculptural Evidence, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Srinivasan, Doris (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. Brill. p. 215. ISBN 978-90-04-10758-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Osmund Bopearachchi (2016). "Emergence of Viṣṇu and Śiva Images in India: Numismatic and Sculptural Evidence".

- ^ Audouin, Rémy, and Paul Bernard, "Trésor de monnaies indiennes et indo-grecques d'Aï Khanoum (Afghanistan). II. Les monnaies indo-grecques." Revue numismatique 6, no. 16 (1974), pp. 6–41 (in French).

- ^ Nilakanth Purushottam Joshi, Iconography of Balarāma, Abhinav Publications, 1979, p. 22

- ^ Jump up to: a b c F. R. Allchin; George Erdosy (1995). The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States. Cambridge University Press. pp. 309–310. ISBN 978-0-521-37695-2.

- ^ L. A. Waddell (1914), Besnagar Pillar Inscription B Re-Interpreted, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1031–1037

- ^ Richard Salomon (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 265–267. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

- ^ Benjamín Preciado-Solís (1984). The Kṛṣṇa Cycle in the Purāṇas: Themes and Motifs in a Heroic Saga. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-89581-226-1.

- ^ Khare 1967.

- ^ Irwin 1974, pp. 169–176 with Figure 2 and 3.

- ^ Susan V Mishra & Himanshu P Ray 2017, p. 5.

- ^ Burjor Avari (2016). India: The Ancient Past: A History of the Indian Subcontinent from C. 7000 BCE to CE 1200. Routledge. pp. 165–167. ISBN 978-1-317-23673-3.

- ^ Richard Salomon (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the Other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-19-509984-3.

- ^ Manohar Laxman Varadpande (1982). Krishna Theatre in India. Abhinav Publications. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-81-7017-151-5.

- ^ Barnett, Lionel David (1922). Hindu Gods and Heroes: Studies in the History of the Religion of India. J. Murray. p. 93.

- ^ Puri, B. N. (1968). India in the Time of Patanjali. Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 51: The coins of Rajuvula have been recovered from the Sultanpur District...the Brahmi inscription on the Mora stone slab, now in the Mathura Museum,

- ^ Doris Srinivasan (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. Broll Academic. pp. 214–215 with footnotes. ISBN 90-04-10758-4.

- ^ Jason Neelis (2010). Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange Within and Beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia. Btill Academic. pp. 271–272. ISBN 978-90-04-18159-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bhattacharya, Sunil Kumar (1996). Krishna-cult in Indian Art. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 27. ISBN 978-81-7533-001-6.

- ^ Wendy Doniger (2008). "Britannica: Mahabharata". encyclopedia. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Armstrong, Karen (1996). A History of God: The 4000-year Quest of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0-679-42600-4.

- ^ Морис Винтерниц (1981), История индийской литературы , Vol. 1, Дели, Мотилал Банарсидасс, ISBN 978-0836408010 , стр. 426–431

- ^ Натубхай Шах 2004 , с. 23.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Макс Мюллер, Чандогья Упанишад 3.16–3.17 , Упанишады, Часть I, Oxford University Press, стр. 50–53 со сносками.

- ^ Эдвин Брайант и Мария Экстранд (2004), Движение Харе Кришна , издательство Колумбийского университета, ISBN 978-0231122566 , стр. 33–34 с примечанием 3.

- ^ Сандилья Бхакти Сутра СС Риши (переводчик), Шри Гаудия Матх (Мадрас)

- ^ WG Archer (2004), Любовь Кришны в индийской живописи и поэзии , Дувр, ISBN 978-0486433714 , с. 5

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брайант 2007 , с. 4

- ^ Сунил Кумар Бхаттачарья Культ Кришны в индийском искусстве . 1996 MD Publications Pvt. ООО ISBN 81-7533-001-5 стр. 128: Сатха-патха-брахман и Айтарейя- араньяка со ссылкой на первую главу.

- ^ [1] Архивировано 17 февраля 2012 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ Пан. IV. 3. 98, Васудеварджунабхьям вун. См. Бхандаркар, Вайшнавизм и Шиваизм, с. 3 и JRAS 1910, с. 168. Сутра 95, чуть выше, по-видимому, указывает на бхакти, веру или преданность, испытываемую к этому Васудеве.

- ^ Сунил Кумар Бхаттачарья Культ Кришны в индийском искусстве . 1996 MD Publications Pvt. ООО ISBN 81-7533-001-5 стр. 1

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Брайант 2007 , с. 5.

- ^ Брайант 2007 , стр. 5–6.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брайант 2007 , с. 6.

- ^ Хемачандра Абхидханачинтамани, Эд. Бетлингк и Риен, с. 128, и перевод Антагада Дасао, сделанный Барнеттом, стр. 13–15, 67–82.

- ^ Гопал, Мадан (1990). КС Гаутам (ред.). Индия сквозь века . Отдел публикаций Министерства информации и радиовещания правительства Индии. п. 73 .

- ^ Элкман, С.М.; Госвами, Дж. (1986). «Таттвасандарбха» Дживы Госвамина: исследование философского и сектантского развития движения Гаудия-вайшнавов . Мотилал Банарсидасс.

- ^ Роше 1986 , стр. 18, 49–53, 245–249.

- ^ Грегори Бейли (2003). Арвинд Шарма (ред.). Изучение индуизма . Издательство Университета Южной Каролины. стр. 141–142. ISBN 978-1-57003-449-7 .

- ^ Барбара Холдридж (2015), Бхакти и воплощение, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415670708 , стр. 109–110

- ^ Ричард Томпсон (2007), Космология Бхагавата Пураны «Тайны Священной Вселенной» , Мотилал Банарсидасс, ISBN 978-8120819191

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брайант 2007 , с. 112.

- ^ Матчетт 2001 , стр. 127–137.

- ^ Арчер 2004 , Кришна живописи.

- ^ Т. Ричард Блертон (1993). Индуистское искусство . Издательство Гарвардского университета. стр. 133–134. ISBN 978-0-674-39189-5 .

- ^ Гай, Джон (2014). Затерянные королевства: индуистско-буддийская скульптура ранней Юго-Восточной Азии . Метрополитен-музей. стр. 222–223. ISBN 978-1-58839-524-5 .

- ^ [а] Кулер, Ричард М. (1978). «Скульптура, Царство и Триада Пном Да». Артибус Азия . 40 (1): 29–40. дои : 10.2307/3249812 . JSTOR 3249812 . ;

[b] Бертран Порт (2006), «Статуя Говардхана Пном Да Кришна из Национального музея Пномпеня». УДАЯ, Журнал кхмерских исследований, том 7, стр. 199–205 - ^ Вишванатха, Чакраварти Тхакур (2011). Сарартха-дарсини ( Бхану Свами изд. ). Шри Вайкунта Энтерпрайзис. п. 790. ИСБН 978-81-89564-13-1 .

- ^ Американская энциклопедия . [sl]: Гролье. 1988. с. 589 . ISBN 978-0-7172-0119-8 .

- ^ Бентон, Уильям (1974). Новая Британская энциклопедия Британская энциклопедия. п. 885. ИСБН 978-0-85229-290-7 .

- ^ Харл, Джей Си (1994). Искусство и архитектура Индийского субконтинента . Нью-Хейвен, Коннектикут: Издательство Йельского университета . п. 410 . ISBN 978-0-300-06217-5 .

Рисунок 327. Манаку, посланник Радхи, описывающий Кришну, стоящего с девушками-коровницами, гопи из Басохли.

- ^ Диана Л. Эк (1982). Банарас, Город Света . Издательство Колумбийского университета. стр. 66–67. ISBN 978-0-231-11447-9 .

- ^ Ариэль Глюклих (2008). Шаги Вишну: индуистская культура в исторической перспективе . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 106. ИСБН 978-0-19-971825-2 .

- ^ Т. А. Гопинатха Рао (1993). Элементы индуистской иконографии . Мотилал Банарсидасс. стр. 210–212. ISBN 978-81-208-0878-2 .

- ^ Джон Стрэттон Хоули (2014). Кришна, Похититель масла . Издательство Принстонского университета. стр. 3–8. ISBN 978-1-4008-5540-7 .

- ^ Хойберг, Дейл; Рамчандани, Инду (2000). Студенческая Британика Индия . Популярный Пракашан. п. 251. ИСБН 978-0-85229-760-5 .

- ^ Сатсварупа дас Госвами (1998). Качества Шри Кришны . GNPress. п. 152. ИСБН 978-0-911233-64-3 .

- ^ Стюарт Кэри Уэлч (1985). Индия: Искусство и культура, 1300–1900 гг . Метрополитен-музей. п. 58. ИСБН 978-0-03-006114-1 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Витхоба рассматривается не только как форма Кришны. Некоторые также считают его именем Вишну, Шивы и Гаутамы Будды, согласно различным традициям. Видеть: Келкар, Ашок Р. (2001) [1992]. « Шри-Виттал: Эк Махасаманвай (маратхи) Р. К. Дере» . Энциклопедия индийской литературы . Том. 5. Сахитья Академия . п. 4179. ИСБН 978-8126012213 . Проверено 20 сентября 2008 г. и Мокаши, нарисованный Балкришной; Энгблом, Филип К. (1987). Палкхи: паломничество в Пандхарпур - перевод из книги на маратхи «Палахи» Филипа К. Энгблома . Олбани: Издательство Государственного университета Нью-Йорка . п. 35. ISBN 978-0-88706-461-6 .

- ^ Трина Лайонс (2004). Художники Натхдвары: практика живописи в Раджастане . Издательство Университета Индианы. стр. 16–22. ISBN 978-0-253-34417-5 .

- ^ Куниссери Рамакришнер Вайдьянатан (1992). Шри Кришна, Господь Гуруваюра . Бхаратия Видья Бхаван. стр. 2–5.

- ^ Т. А. Гопинатха Рао (1993). Элементы индуистской иконографии . Мотилал Банарсидасс. стр. 201–204. ISBN 978-81-208-0878-2 .

- ^ Т. А. Гопинатха Рао (1993). Элементы индуистской иконографии . Мотилал Банарсидасс. стр. 204–208. ISBN 978-81-208-0878-2 .

- ^ Амит Гуха, Кришналила в терракотовых храмах , заархивировано из оригинала 2 января 2021 года , получено 2 января 2021 года.

- ^ Матчетт 2001 , с. 145.

- ^ Сингх, Апиндер (2009). История древней и раннесредневековой Индии: от каменного века до XII века (PB) . Пирсон Индия. п. 438. ИСБН 978-93-325-6996-6 .

- ^ Стихи Шурадаса . Публикации Абхинава. 1999. ISBN 978-8170173694 .

- ^ «Яшода и Кришна» . Metmuseum.org. 10 октября 2011 года. Архивировано из оригинала 13 октября 2008 года . Проверено 23 октября 2011 г.

- ^ Санги, Ашвин (2012). Ключ Кришны . Ченнаи: Вестленд. п. Ключ7. ISBN 978-9381626689 . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г. [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Лок Нат Сони (2000). Скот и палка: этнографический профиль раутов Чхаттисгарха . Антропологическое исследование Индии, Правительство Индии, Министерство туризма и культуры, Департамент культуры, Дели: Антропологическое исследование Индии, Правительство Индии, Министерство туризма и культуры, Департамент культуры, 2000 г. Оригинал из Мичиганского университета. п. 16. ISBN 978-8185579573 .

- ^ Брайант 2007 , стр. 124–130, 224.

- ^ Линн Гибсон (1999). Энциклопедия мировых религий Мерриам-Вебстера . Мерриам-Вебстер. п. 503.

- ^ Швейг, генеральный директор (2005). Танец божественной любви: Раса-лила Кришны из «Бхагавата-пураны», классической индийской священной истории любви . Издательство Принстонского университета , Принстон, Нью-Джерси; Оксфорд. ISBN 978-0-691-11446-0 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Ларген, Кристин Джонстон (2011). Бог в игре: взгляд на Бога через призму юного Кришны . Индия: Уайли-Блэквелл. ISBN 978-1608330188 . OCLC 1030901369 .

- ^ «Кришна Раджаманнар со своими женами Рукмини и Сатьябхамой и его скакуном Гарудой | Коллекции LACMA» . Collections.lacma.org. Архивировано из оригинала 16 июля 2014 года . Проверено 23 сентября 2014 г.

- ^ Брайант 2007 , с. 290

- ^ Рао, Шанта Рамешвар (2005). Кришна . Нью-Дели: Ориент Лонгман. п. 108. ИСБН 978-8125026969 .

- ^ D Деннис Хадсон (2008). Тело Бога: Императорский дворец Кришны в Канчипураме восьмого века: Императорский дворец Кришны в Канчипураме восьмого века . Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 263–264. ISBN 978-0-19-970902-1 . Проверено 28 марта 2013 г.

- ^ D Деннис Хадсон (2008). Тело Бога: Императорский дворец Кришны в Канчипураме восьмого века: Императорский дворец Кришны в Канчипураме восьмого века . Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 102–103, 263–273. ISBN 978-0-19-970902-1 . Проверено 28 марта 2013 г.

- ^ Джордж Мейсон Уильямс (2008). Справочник по индуистской мифологии . Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 188, 222. ISBN. 978-0-19-533261-2 . Проверено 10 марта 2013 г.

- ^ Розен 2006 , с. 136

- ^ Джон Стрэттон Хоули, Донна Мари Вульф (1982). Божественная супруга: Радха и богини Индии Издательство Мотилал Банарсидасс. п. 12. ISBN 978-0-89581-102-8 . Цитата: «Региональные тексты различаются по личности жены (супруги) Кришны: некоторые представляют ее как Рукмини, некоторые — как Радху, некоторые — как Сваминиджи, некоторые добавляют всех гопи , а некоторые определяют все как различные аспекты или проявления одной Деви Лакшми. ."

- ^ Кришна в Бхагавад-Гите, Роберт Н. Майнор в Брайанте, 2007 , стр. 77–79.

- ^ Джинин Д. Фаулер (2012). Бхагавад-гита: текст и комментарии для студентов . Сассекс Академик Пресс. стр. 1–7. ISBN 978-1-84519-520-5 .

- ^ Экнат Ишваран (2007). Бхагавад-гита: (Классика индийской духовности) . Нилгири Пресс. стр. 21–59. ISBN 978-1-58638-019-9 .

- ^ Брайант 2007 , с. 148

- ^ Мани, Веттам (1975). Пураническая энциклопедия: обширный словарь с особым упором на эпическую и пураническую литературу . Дели: Мотилал Банарсидасс. п. 429 . ISBN 978-0-8426-0822-0 .

- ^ Брайант 2003 , с. 417-418.

- ^ Ларген, Кристин Джонстон (2011). Младенец Кришна, Младенец Христос: Сравнительная теология спасения . Книги Орбис. п. 44. ИСБН 978-1-60833-018-8 .

- ^ Матчетт 2001 , стр. 9–14, 145–149.

- ^ Бенджамин Прешес-Солис (1984). Цикл Кришны в Пуранах: темы и мотивы героической саги . Мотилал Банарсидасс. п. 40. ИСБН 978-0-89581-226-1 . , Цитата: «В течение четырех или пяти столетий [примерно в начале нашей эры] мы встречаемся с нашими основными источниками информации, причем все в разных версиях. Махабхарата, Харивамса, Вишну Пурана, Гхата Джатака и Все Бала Чарита появляются между первым и пятым веками нашей эры, и каждый из них представляет собой традицию цикла Кришны, отличную от других».

- ^ Матчетт 2001 , стр. 44–49, 63–64, 145.

- ^ Матчетт 2001 , стр. 89–104, 146.

- ^ Роше 1986 , стр. 18, 245–249.

- ^ Матчетт 2001 , стр. 108–115, 146–147.

- ^ Матчетт 2001 , стр. 145–149.

- ^ Роше 1986 , стр. 138–149.

- ^ «Гаура Пурнима Махотсава Международного общества сознания Кришны (ИСККОН)» . Город: Гувахати. Сентинелассам . 18 марта 2019 года . Проверено 30 января 2020 г.

- ^ «Альфред Форд выполняет миссию по финансированию крупнейшего храма» . Город: Хайдарабад. Телангана сегодня . 14 октября 2019 г. Проверено 30 января 2020 г.

- ^ Бенджамин Э. Зеллер (2010), Пророки и протоны , издательство Нью-Йоркского университета, ISBN 978-0814797211 , стр. 77–79

- ^ Нотт 2000 .

- ^ Бек, Гай (2012). Альтернативные Кришны: региональные и народные вариации индуистского божества . Сани Пресс. стр. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-7914-8341-1 .

- ^ ДЖАБ ван Бютенен, Махабхарата , том. 3, Чикагский университет, 1978 г., стр. 134.

- ^ Герман Кульке; Дитмар Ротермунд (2004). История Индии . Рутледж. п. 149. ИСБН 978-0-415-32920-0 .

- ^ Брайант 2007 , стр. 329–334 (Фрэнсис X Клуни).

- ^ Шарма; Б. Н. Кришнамурти (2000). История школы веданты Двайта и ее литературы . Мотилал Банарсидасс. стр. 514–516. ISBN 978-8120815759 .

- ^ Брайант 2007 , стр. 358–365 (Дипак Сарма).

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Рамнараче 2014 .

- ^ Трипурари, Свами. «Жизнь Шри Дживы Госвами» . Гармонист . Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2013 года.

- ^ Брайант 2007 , стр. 373–378 (Сатьянараяна дас).

- ^ Джиндел, Раджендра (1976). Культура священного города: социологическое исследование Натхдвары . Популярный Пракашан. стр. 34, 37. ISBN. 978-8171540402 .

- ^ Брайант 2007 , стр. 479–480 (Ричард Барз).

- ^ Уильям Р. Пинч (1996). «Монахи-солдаты и воинствующие садху» . В Дэвиде Ладдене (ред.). Соперничество с нацией . Издательство Пенсильванского университета. стр. 148–150. ISBN 978-0-8122-1585-4 .

- ^ Йоханнес де Круйф и Аджая Саху (2014), Индийский транснационализм в Интернете: новые взгляды на диаспору , ISBN 978-1-4724-1913-2 , с. 105, Цитата: «Другими словами, согласно аргументации Ади Шанкары, философия Адвайта Веданты стояла над всеми другими формами индуизма и заключала их в себе. Это тогда объединило индуизм; (...) Еще одно важное начинание Ади Шанкары, которое способствовало объединению индуизма основание им ряда монашеских центров».

- ^ Шанкара , Студенческая энциклопедия Британской энциклопедии - Индия (2000), Том 4, Издательство Британской энциклопедии (Великобритания), ISBN 978-0-85229-760-5 , с. 379, Цитата: «Шанкарачарья, философ и богослов, наиболее известный представитель философской школы Адвайта Веданта, из чьих доктрин произошли основные течения современной индийской мысли»;

Дэвид Кристал (2004), Энциклопедия Пингвинов, Penguin Books, стр. 1353, Цитата: «[Шанкара] является самым известным представителем школы индуистской философии Адвайта Веданта и источником основных течений современной индуистской мысли». - ^ Кристоф Жафрело (1998), Индуистское националистическое движение в Индии , издательство Колумбийского университета, ISBN 978-0-231-10335-0 , с. 2, Цитата: «Основным течением индуизма – если не единственным – которое формализовалось таким образом, что приближается к церковной структуре, было течение Шанкары».

- ^ Брайант 2007 , стр. 313–318 (Лэнс Нельсон).

- ^ Шеридан 1986 , стр. 1–2, 17–25.

- ^ Кумар Дас 2006 , стр. 172–173.

- ^ Браун 1983 , стр. 553–557.

- ^ Трейси Пинчман (1994), Возвышение Богини в индуистской традиции , State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791421123 , стр. 132–134

- ^ Шеридан 1986 , стр. 17–21.

- ^ Джон Стрэттон Хоули (2014). Кришна, Похититель масла . Издательство Принстонского университета. стр. 10, 170. ISBN. 978-1-4008-5540-7 .

- ^ Кришна: индуистское божество , Британская энциклопедия (2015)

- ^ Джон М. Коллер (2016). Индийский путь: введение в философию и религию Индии . Рутледж. стр. 210–215. ISBN 978-1-315-50740-8 .

- ^ Водевиль, Ч. (1962). «Эволюция символики любви в бхагаватизме». Журнал Американского восточного общества . 82 (1): 31–40. дои : 10.2307/595976 . JSTOR 595976 .

- ^ Джон М. Коллер (2016). Индийский путь: введение в философию и религию Индии . Рутледж. п. 210. ИСБН 978-1-315-50740-8 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Хуан Маскаро (1962). Бхагавад Гита . Пингвины. стр. XXVI–XXVIII. ISBN 978-0-14-044918-1 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Джордж Фейерштейн; Бренда Фейерштейн (2011). Бхагавад-гита: новый перевод . Публикации Шамбалы. стр. ix – xi. ISBN 978-1-59030-893-6 .

- ^ Николас Ф. Гир (2004). Достоинство ненасилия: от Гаутамы до Ганди . Издательство Государственного университета Нью-Йорка. стр. 36–40. ISBN 978-0-7914-5949-2 .

- ^ Брайант 2007 , с. 315.

- ^ Джон Доусон (2003). Классический словарь индуистской мифологии и религии, географии, истории и литературы . Издательство Кессинджер. п. 361. ИСБН 978-0-7661-7589-1 . [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ См. Бек, Гай, «Введение» в Beck 2005 , стр. 1–18.

- ^ Нотт 2000 , с. 55

- ^ Наводнение 1996 , с. 117.