История Индии

| История Индии |

|---|

|

| Хронология |

| История Южной Азии |

|---|

|

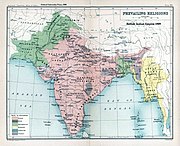

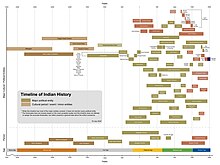

Анатомически современные люди впервые прибыли на Индийский субконтинент между 73 000 и 55 000 лет назад. [ 1 ] Самые ранние известные человеческие останки в Южной Азии датируются 30 000 лет назад. Оседлый образ жизни начался в Южной Азии около 7000 г. до н. э.; [ 2 ] к 4500 г. до н. э. распространилась оседлая жизнь, [ 2 ] и постепенно превратилась в цивилизацию долины Инда , которая процветала между 2500 г. до н. э. и 1900 г. до н. э. на территории современного Пакистана и северо-западной Индии. В начале второго тысячелетия до нашей эры постоянная засуха привела к тому, что население долины Инда переселилось из крупных городских центров в деревни. Индоарийские племена переселились в Пенджаб из Средней Азии в результате нескольких волн миграции . Ведический период ведического народа северной Индии (1500–500 гг. до н. э.) ознаменовался составлением обширных сборников гимнов ( Вед ). Социальная структура была слабо стратифицирована через систему варн , включенную в высокоразвитую современную систему Джати . Пастушеские и кочевые индоарии распространились из Пенджаба на равнину Ганга . Около 600 г. до н. э. возникла новая межрегиональная культура; затем мелкие вожди ( джанапада ) были объединены в более крупные государства ( махаджанапада ). Произошла вторая урбанизация, сопровождавшаяся появлением новых аскетических движений и религиозных концепций. [ 3 ] включая возникновение джайнизма и буддизма . Последняя была синтезирована с существовавшими ранее религиозными культурами субконтинента, дав начало индуизму .

Чандрагупта Маурья сверг империю Нанда и основал первую великую империю в древней Индии — Империю Маурьев . Индийский король Маурьев Ашока широко известен своим историческим признанием буддизма и попытками распространить ненасилие и мир по всей своей империи. Империя Маурьев рухнула в 185 г. до н.э. после убийства тогдашнего императора Брихадратхи его генералом Пушьямитрой Шунгой . Сюнга образовала Империю Шунга на севере и северо-востоке субконтинента, в то время как Греко-Бактрийское царство претендовало на северо-запад и основало Индо-Греческое царство . Различные части Индии находились под властью многочисленных династий, в том числе Империи Гуптов , в IV-VI веках нашей эры. Этот период, когда наблюдается индуистское религиозное и интеллектуальное возрождение, известен как классический или золотой век Индии . Аспекты индийской цивилизации, управления, культуры и религии распространились на большую часть Азии, что привело к созданию в регионе индианизированных королевств, образовавших Великая Индия . [ 4 ] [ 5 ] Самым значительным событием между VII и XI веками была Трехсторонняя борьба, сосредоточенная в Каннаудже . В Южной Индии с середины пятого века наблюдался рост множества имперских держав. Династия Чола завоевала южную Индию в 11 веке. В период раннего средневековья индийская математика , включая индуистские цифры , повлияла на развитие математики и астрономии в арабском мире , включая создание индуистско -арабской системы счисления . [ 6 ]

Исламские завоевания совершили ограниченные вторжения в современный Афганистан и Синд еще в 8 веке. [ 7 ] за которым последовали вторжения Махмуда Газни . [ 8 ] Делийский султанат среднеазиатскими турками в 1206 году индианизированными был основан . [ 9 ] [ 10 ] [ 11 ] [ 12 ] Они правили большей частью северного Индийского субконтинента в начале 14 века. Им правили многочисленные тюркские , афганские и индийские династии, в том числе турко-монгольская индианизированная династия Туглаков. [ 13 ] но пришел в упадок в конце 14 века после вторжения Тимура. [ 14 ] и стал свидетелем появления султанатов малва , Гуджарата и Бахмани , последний из которых распался в 1518 году на пять султанатов Декана . Богатый Бенгальский султанат также стал крупной державой, просуществовавшей более трех столетий. [ 15 ] В этот период возникли многочисленные сильные индуистские королевства, в частности Империя Виджаянагара и государства Раджпутов , которые сыграли значительную роль в формировании культурного и политического ландшафта Индии.

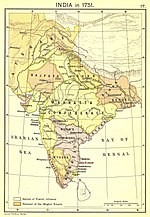

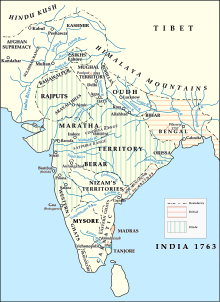

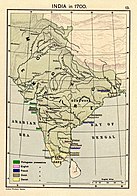

Ранний современный период начался в 16 веке, когда Империя Великих Моголов завоевала большую часть Индийского субконтинента. [ 16 ] сигнализируя о протоиндустриализации , становясь крупнейшей мировой экономикой и производственной державой. [ 17 ] [ 18 ] [ 19 ] В начале 18 века Моголы пережили постепенный упадок, во многом из-за растущей мощи маратхов , которые взяли под свой контроль обширные регионы Индийского субконтинента. [ 20 ] [ 21 ] Ост -Индская компания , действуя как суверенная сила от имени британского правительства , в период с середины XVIII до середины XIX веков постепенно приобрела контроль над огромными территориями Индии. Политика правления компаний в Индии привела к Индийскому восстанию 1857 года . Впоследствии Индией управляла непосредственно британская корона в составе британского владычества . После Первой мировой войны начал общенациональную борьбу за независимость Индийский национальный конгресс во главе с Махатмой Ганди . Позже Всеиндийская мусульманская лига будет выступать за создание отдельного национального государства с мусульманским большинством . Британско-Индийская империя была разделена в августе 1947 года на Доминион Индия и Доминион Пакистан , каждый из которых получил свою независимость.

Доисторическая эпоха (до 3300 г. до н.э.)

Этот раздел содержит слишком много или слишком длинные цитаты . ( июль 2021 г. ) |

Палеолит

По оценкам, экспансия гомининов из Африки достигла Индийского субконтинента примерно два миллиона лет назад, а возможно, уже 2,2 миллиона лет назад. [ 25 ] [ 26 ] [ 27 ] Эта датировка основана на известном присутствии Homo erectus в Индонезии 1,8 миллиона лет назад и в Восточной Азии 1,36 миллиона лет назад, а также на открытии каменных орудий в Ривате в Пакистане . [ 26 ] [ 28 ] Хотя были заявлены некоторые более старые открытия, предполагаемые даты, основанные на датировке речных отложений , не были проверены независимо. [ 27 ] [ 29 ]

Самые старые ископаемые останки гоминидов на Индийском субконтиненте — это останки Homo erectus или Homo heidelbergensis из долины Нармада в центральной Индии, они датируются примерно полумиллионом лет назад. [ 26 ] [ 29 ] Заявлялись о более старых находках окаменелостей, но они считаются ненадежными. [ 29 ] Обзоры археологических данных показали, что заселение Индийского субконтинента гомининами было спорадическим примерно до 700 000 лет назад и было географически широко распространено примерно 250 000 лет назад. [ 29 ] [ 27 ]

По словам исторического демографа Южной Азии Тима Дайсона:

Современные люди — Homo sapiens — возникли в Африке. Затем, с перерывами, где-то между 60 000 и 80 000 лет назад, их крошечные группы начали проникать на северо-запад Индийского субконтинента. Кажется вероятным, что первоначально они пришли через побережье. Практически достоверно, что Homo sapiens существовал на субконтиненте 55 000 лет назад, хотя самые ранние окаменелости, которые были найдены, датируются всего лишь примерно 30 000 лет назад. [ 30 ]

По словам Майкла Д. Петральи и Бриджит Олчин :

Данные Y-хромосомы и Мт-ДНК подтверждают колонизацию Южной Азии современными людьми, происходящими из Африки. ... Даты слияния большинства неевропейских популяций в среднем составляют 73–55 тыс. лет назад. [ 31 ]

Историк Южной Азии Майкл Х. Фишер утверждает:

По оценкам ученых, первое успешное расширение ареала Homo sapiens за пределы Африки и Аравийского полуострова произошло от 80 000 до 40 000 лет назад, хотя, возможно, и до этого имели место неудачные эмиграции. Некоторые из их потомков в каждом поколении все больше расширяли ареал человечества, распространяясь на каждую обитаемую землю, с которой они сталкивались. Один человеческий канал пролегал вдоль теплых и плодородных прибрежных земель Персидского залива и северной части Индийского океана. В конце концов, между 75 000 и 35 000 лет назад в Индию проникли различные племена. [ 32 ]

Археологические данные были интерпретированы как предполагающие присутствие анатомически современных людей на Индийском субконтиненте 78 000–74 000 лет назад. [ 33 ] хотя эта интерпретация оспаривается. [ 34 ] [ 35 ] Заселение Южной Азии современными людьми, первоначально находившимися в различных формах изоляции в качестве охотников-собирателей, превратило ее в чрезвычайно разнообразную страну, уступающую только Африке по генетическому разнообразию человека. [ 36 ]

По словам Тима Дайсона:

Генетические исследования способствовали познанию предыстории народов субконтинента и в других отношениях. В частности, уровень генетического разнообразия в регионе чрезвычайно высок. Действительно, только население Африки генетически более разнообразно. В связи с этим существуют убедительные доказательства событий «основателей» на субконтиненте. Под этим подразумеваются обстоятельства, при которых подгруппа, например племя, происходит от небольшого числа «исходных» особей. Кроме того, по сравнению с большинством регионов мира, жители субконтинента относительно отличаются тем, что практикуют сравнительно высокий уровень эндогамии. [ 36 ]

неолит

Оседлая жизнь возникла на субконтиненте на западных окраинах аллювия реки Инд примерно 9000 лет назад, постепенно превратившись в цивилизацию долины Инда третьего тысячелетия до нашей эры. [ 2 ] [ 37 ] По словам Тима Дайсона: «7000 лет назад сельское хозяйство прочно утвердилось в Белуджистане… [и] медленно распространилось на восток, в долину Инда». Майкл Фишер добавляет: [ 38 ]

Самый ранний обнаруженный пример... устоявшегося, оседлого земледельческого общества находится в Мехргархе, на холмах между перевалом Болан и равниной Инда (сегодня в Пакистане) (см. карту 3.1). Уже с 7000 г. до н.э. местные общины начали вкладывать больше труда в подготовку земли, а также отбор, посадку, уход и сбор урожая конкретных зерновых культур. Они также одомашнили животных, в том числе овец, коз, свиней и волов (как горбатого зебу [ Bos indicus ], так и негорбатого [ Bos taurus ]). Например, кастрация быков превратила их в основном из источников мяса в одомашненных тягловых животных. [ 38 ]

Бронзовый век (ок. 3300 – ок. 1800 до н. э.)

Цивилизация долины Инда

Бронзовый век на Индийском субконтиненте начался около 3300 г. до н.э. [ нужна ссылка ] Регион долины Инда был одной из трех ранних колыбелей цивилизации Старого Света ; Цивилизация долины Инда была самой обширной, [ 39 ] и на пике своего развития население могло превышать пять миллионов человек. [ 40 ]

Цивилизация была сосредоточена в первую очередь на территории современного Пакистана, в бассейне реки Инд и, во вторую очередь, в бассейне реки Гаггар-Хакра . Зрелая цивилизация Инда процветала примерно с 2600 по 1900 год до нашей эры, положив начало городской цивилизации на Индийском субконтиненте. В его состав входили такие города, как Хараппа , Ганверивал и Мохенджо-Даро в современном Пакистане, а также Дхолавира , Калибанган , Рахигархи и Лотал в современной Индии.

Жители древней долины реки Инд — хараппцы — разработали новые методы металлургии и ремесла, производили медь, бронзу, свинец и олово. [ 42 ] Цивилизация известна своими кирпичными городами и придорожной дренажной системой и, как полагают, имела какую-то муниципальную организацию. Цивилизация также разработала письменность Инда , самую раннюю из древних индийских письменностей , которая в настоящее время не расшифрована. [ 43 ] По этой причине хараппский язык не засвидетельствован напрямую, а его принадлежность неясна. [ 44 ]

После распада цивилизации долины Инда жители мигрировали из долин рек Инд и Гаггар-Хакра в сторону гималайских предгорий бассейна Ганга-Ямуны. [ 45 ]

Культура цветной керамики охры

Во 2-м тысячелетии до нашей эры культура керамики цвета охры существовала в регионе Ганга-Ямуна-Доаб. Это были сельские поселения с земледелием и охотой. Они использовали медные инструменты, такие как топоры, копья, стрелы и мечи, и имели домашних животных. [ 47 ]

Железный век ( ок. 1800–200 гг. до н. э.)

Ведический период ( ок. 1500–600 до н.э.)

Начиная с. В 1900 году до нашей эры индоарийские племена переселились в Пенджаб из Центральной Азии в результате нескольких волн миграции . [ 48 ] [ 49 ] Ведический период – это когда Веды были составлены из литургических гимнов индоарийского народа . Ведическая культура была расположена в части северо-западной Индии, в то время как другие части Индии имели особую культурную самобытность. В этот период многие регионы Индийского субконтинента перешли от энеолита к железному веку . [ 50 ]

Ведическая культура описана в текстах Вед , до сих пор священных для индусов, которые устно сочинялись и передавались на ведическом санскрите . Веды — одни из древнейших дошедших до нас текстов в Индии. [ 51 ] Ведический период, продолжавшийся примерно с 1500 по 500 год до нашей эры. [ 52 ] [ 53 ] внес вклад в развитие нескольких культурных аспектов Индийского субконтинента.

Ведическое общество

Историки проанализировали Веды и установили наличие ведической культуры в Пенджабе и верхней части Гангской равнины . [ 50 ] Дерево Пипал и корова были освящены ко времени Атхарва Веды . [ 55 ] Многие из концепций индийской философии, поддержанных позже, например, дхарма , уходят своими корнями в ведические предшественники. [ 56 ]

Раннее ведическое общество описано в Ригведе , старейшем ведическом тексте, который, как полагают, был составлен во 2-м тысячелетии до нашей эры. [ 57 ] [ 58 ] в северо-западной части Индийского субконтинента. [ 59 ] В это время арийское общество состояло преимущественно из племенных и скотоводческих групп, в отличие от заброшенной хараппской урбанизации. [ 60 ] Раннее индоарийское присутствие, вероятно, частично соответствует культуре керамики цвета охры в археологическом контексте. [ 61 ] [ 62 ]

В конце периода Ригведы арийское общество распространилось из северо-западного региона Индийского субконтинента на западную равнину Ганга . Оно становилось все более сельскохозяйственным и было социально организовано вокруг иерархии четырех варн , или социальных классов. Эта социальная структура характеризовалась как синкретизмом с местными культурами северной Индии, так и [ 63 ] но также, в конечном итоге, путем исключения некоторых коренных народов, называя их занятия нечистыми. [ 64 ] В этот период многие из предыдущих небольших племенных единиц и вождеств начали объединяться в джанападас (монархические государства государственного уровня). [ 65 ]

Санскритские эпосы

В этот период были написаны санскритские эпопеи «Рамаяна» и «Махабхарата» . [ 66 ] Махабхарата остается самым длинным стихотворением в мире. [ 67 ] Историки раньше постулировали «эпическую эпоху» как среду этих двух эпических поэм, но теперь признают, что тексты прошли несколько стадий развития на протяжении веков. [ 68 ] Считается, что существующие тексты этих эпосов относятся к постведической эпохе, между ок. 400 г. до н.э. и 400 г. н.э. [ 68 ] [ 69 ]

Джанападас

Железный век на Индийском субконтиненте, примерно с 1200 г. до н.э. до 6-го века до н.э., определяется возникновением Джанападов, которые представляют собой королевства , республики и королевства , в частности, королевства железного века Куру , Панчала , Косала и Видеха . [ 70 ] [ 71 ]

Королевство Куру ( ок. 1200–450 до н.э.) было первым обществом государственного уровня ведического периода, соответствующим началу железного века на северо-западе Индии, около 1200–800 до н.э. [ 72 ] а также с составом Атхарваведы . [ 73 ] Государство Куру организовало сборники ведических гимнов и разработало ритуал шраута для поддержания общественного порядка. [ 73 ] Двумя ключевыми фигурами государства Куру были царь Парикшит и его преемник Джанамеджая , которые превратили это царство в доминирующую политическую, социальную и культурную державу северной Индии. [ 73 ] Когда царство Куру пришло в упадок, центр ведической культуры переместился к их восточным соседям, царству Панчала. [ 73 ] Археологическая культура PGW на северо-востоке Индии (расписная серая посуда), которая процветала в регионах Харьяна и западном Уттар-Прадеше примерно с 1100 по 600 год до нашей эры. [ 61 ] Считается, что он соответствует королевствам Куру и Панчала . [ 73 ] [ 74 ]

В поздневедический период царство Видеха возникло как новый центр ведической культуры, расположенный еще дальше на Востоке (на территории нынешних штатов Непал и Бихар ); [ 62 ] достиг своего выдающегося положения при царе Джанаке , чей двор обеспечивал покровительство браминам мудрецам и философам- , таким как Яджнавалкья , Аруни и Гарги Вачакнави . [ 75 ] Более поздняя часть этого периода соответствует консолидации все более крупных государств и королевств, называемых Махаджанападас , по всей Северной Индии.

Вторая урбанизация ( ок. 600–200 гг. До н.э.)

В период между 800 и 200 годами до нашей эры сформировалось движение Шрамана , из которого возникли джайнизм и буддизм . В этот период были написаны первые Упанишады . После 500 г. до н.э. произошла так называемая «вторая урбанизация». [ примечание 1 ] началось с возникновения новых городских поселений на равнине Ганга. [ 76 ] Основы «второй урбанизации» были заложены до 600 г. до н.э. в культуре расписной серой посуды на равнинах Гаггар-Хакра и Верхний Ганг; хотя большинство участков PGW были небольшими фермерскими деревнями, «несколько десятков» участков PGW в конечном итоге превратились в относительно крупные поселения, которые можно охарактеризовать как города, самые крупные из которых были укреплены рвами или рвами и насыпями из насыпанной земли с деревянными частоколами. [ 77 ]

Равнина Центрального Ганга, где Магадха приобрела известность, составив основу Империи Маурьев , была отдельной культурной областью. [ 78 ] с новыми государствами, возникшими после 500 г. до н.э. [ 79 ] [ 80 ] На него повлияла ведическая культура. [ 81 ] но заметно отличался от региона Куру-Панчала. [ 78 ] «Это была область самого раннего известного выращивания риса в Южной Азии, и к 1800 году до нашей эры здесь проживало развитое неолитическое население, связанное с местами Чиранд и Чечар». [ 82 ] В этом регионе процветали шраманические движения, зародились джайнизм и буддизм. [ 76 ]

Буддизм и джайнизм

Период между 800 г. до н.э. и 400 г. до н.э. стал свидетелем создания самых ранних Упанишад . [ 83 ] [ 84 ] [ 85 ] которые составляют теоретическую основу классического индуизма и известны также как Веданта (заключение Вед ) . [ 86 ]

Растущая урбанизация Индии в VII и VI веках до нашей эры привела к возникновению новых аскетических или «движений шрамана», которые бросили вызов ортодоксальности ритуалов. [ 83 ] Махавира ( ок. 599–527 до н. э.), сторонник джайнизма , и Гаутама Будда ( ок. 563–483 до н. э.), основатель буддизма, были наиболее выдающимися иконами этого движения. Шрамана породила концепцию цикла рождения и смерти, концепцию сансары и концепцию освобождения. [ 87 ] Будда нашел Срединный путь , который смягчил крайний аскетизм , присущий религиям шрамана . [ 88 ]

Примерно в то же время Махавира (24-й Тиртханкара в джайнизме) пропагандировал теологию, которая позже стала джайнизмом. [ 89 ] Однако джайнская ортодоксальность считает, что учение Тиртханкаров предшествует всем известным временам, а ученые полагают, что Паршванатха (ок. 872 – ок. 772 до н. э.), получивший статус 23-го Тиртханкара , был исторической фигурой. Считается, что Веды задокументировали несколько Тиртханкаров и аскетический орден, подобный движению Шрамана . [ 90 ]

Махаджанападас

Период с ок. 600 г. до н.э. – ок. 300 г. до н. э. стал свидетелем возникновения Махаджанапад , шестнадцати могущественных и обширных королевств и олигархических республик . Эти Махаджанапады развивались и процветали в поясе, простирающемся от Гандхары на северо-западе до Бенгалии в восточной части Индийского субконтинента и включавшего части трансвиндхийского региона . [ 91 ] Древние буддийские тексты , такие как Ангуттара Никайя , [ 92 ] часто упоминайте эти шестнадцать великих царств и республик — Анга , Ассака , Аванти , Чеди , Гандхара , Каши , Камбоджа , Косала , Куру , Магадха , Малла , Матсья (или Мачча), Панчала , Сурасена , Вриджи и Ватса . Этот период стал свидетелем второго крупного подъема урбанизма в Индии после цивилизации долины Инда . [ 93 ]

Ранние «республики» или Ганасангха , [ 94 ] Такие, как Шакьяс , Колияс , Маллакас и Личчавис , имели республиканское правительство. Ганасангха , [ 94 ] такие как Маллаки с центром в городе Кусинагара и Лига Ваджика с центром в городе Вайшали , существовали еще в 6 веке до нашей эры и сохранялись в некоторых областях до 4 века нашей эры. [ 95 ] Самым известным кланом среди правящих конфедеративных кланов Ваджи Махаджанапады были Личчави . [ 96 ]

Этот период в археологическом контексте соответствует культуре Северной чернополированной посуды . Эта культура, особенно сосредоточенная на равнине Центрального Ганга, но также распространившаяся на обширные территории северного и центрального Индийского субконтинента, характеризуется появлением крупных городов с массивными укреплениями, значительным ростом населения, усилением социального расслоения, широкими торговыми сетями, строительством. общественной архитектуры и водных каналов, специализированных ремесленных производств, системы весов, монет с перфорацией и введения письменности в форме шрифтов Брахми и Харости . [ 97 ] [ 98 ] Языком дворянства в то время был санскрит , а языки основного населения северной Индии назывались пракритами .

многие из шестнадцати королевств объединились в четыре основных Ко времени Гаутамы Будды . Этими четырьмя были Ватса, Аванти, Косала и Магадха. [ 93 ]

Ранние династии Магадхи

Магадха сформировал одно из шестнадцати Махаджанапад ( санскрит : «Великие Царства») или королевств в древней Индии . Ядром королевства была область Бихара к югу от Ганга ; его первой столицей была Раджагриха (современный Раджгир), затем Паталипутра (современная Патна ). Магадха расширилась и включила большую часть Бихара и Бенгалии после завоевания Личчави и Анги соответственно. [ 99 ] за ним следует большая часть восточного Уттар-Прадеша и Ориссы. Древнее королевство Магадха часто упоминается в джайнских и буддийских текстах. Он также упоминается в Рамаяне , Махабхарате и Пуранах . [ 100 ] Самое раннее упоминание о народе Магадха встречается в Атхарва-веде, где они упоминаются наряду с ангами , гандхарами и муджаватами. Магадха сыграла важную роль в развитии джайнизма и буддизма . Республиканские общины (такие как община Раджакумара) объединены в королевство Магадха. В деревнях были свои собрания под руководством местных вождей, называемых Грамаками. Их администрация была разделена на исполнительные, судебные и военные функции.

В ранних источниках, из буддийского Палийского канона , джайнских агам и индуистских Пуран , упоминается, что Магадха правила династией Прадьота и династией Харьянка ( ок. 544–413 до н.э.) в течение примерно 200 лет, ок. 600–413 гг. до н.э. Король Бимбисара из династии Харьянка вел активную и экспансивную политику, завоевав Ангу на территории нынешнего восточного Бихара и Западной Бенгалии . Царь Бимбисара был свергнут и убит своим сыном, принцем Аджаташатру , продолжавшим экспансионистскую политику Магадхи. В этот период Гаутама Будда , основатель буддизма, прожил большую часть своей жизни в королевстве Магадха. Он достиг просветления в Бодх-Гайе , произнес свою первую проповедь в Сарнатхе , а первый буддийский совет был проведен в Раджгрихе. [ 101 ] Династия Харьянка была свергнута династией Шайшунага ( ок. 413–345 до н. э.). Последний правитель Сишунаги, Каласока, был убит Махападмой Нандой в 345 г. до н. э., первым из так называемых Девяти Нанд (Махападма Нанда и его восемь сыновей).

Империя Нанда и кампания Александра

Империя Нанда ( ок. 345–322 гг. до н.э.) на пике своего развития простиралась от Бенгалии на востоке до Пенджаба на западе и на юг до хребта Виндхья . [ 102 ] Династия Нанда строила свою деятельность на фундаменте, заложенном их предшественниками Харьянка и Сишунага . [ 103 ] Империя Нанда построила огромную армию, состоящую из 200 000 пехоты , 20 000 кавалерии , 2 000 боевых колесниц и 3 000 боевых слонов (по самым низким оценкам). [ 104 ] [ 105 ]

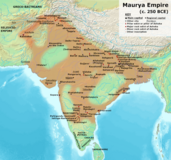

Империя Маурьев

Империя Маурьев (322–185 гг. до н. э.) объединила большую часть Индийского субконтинента в одно государство и была крупнейшей империей, когда-либо существовавшей на Индийском субконтиненте. [ 106 ] В наибольшей степени Империя Маурьев простиралась на север до естественных границ Гималаев и на восток до территории нынешнего Ассама . На западе она простиралась за пределы современного Пакистана, до гор Гиндукуш на территории современного Афганистана. Империя была основана Чандрагуптой Маурья при помощи Чанакьи ( Каутильи ) в Магадхе (в современном Бихаре ), когда он сверг Империю Нанда . [ 107 ]

Чандрагупта быстро расширил свою власть на запад, через центральную и западную Индию, и к 317 г. до н. э. империя полностью оккупировала северо-запад Индии. Империя Маурьев победила Селевка I , основателя Империи Селевкидов , во время войны Селевкидов и Маурьев , таким образом получив дополнительную территорию к западу от реки Инд. Сын Чандрагупты Биндусара взошел на престол около 297 г. до н.э. К тому времени, когда он умер в c. В 272 г. до н.э. большая часть Индийского субконтинента находилась под сюзеренитетом Маурьев. Однако регион Калинга (около современной Одиши ) оставался вне контроля Маурьев, возможно, мешая торговле с югом. [ 108 ]

На смену Биндусаре пришел Ашока , правление которого продолжалось до его смерти примерно в 232 г. до н.э. [ 109 ] Его кампания против калинганцев примерно в 260 г. до н. э., хотя и была успешной, привела к огромным человеческим жертвам и страданиям. Это побудило Ашоку избегать насилия и впоследствии принять буддизм. [ 108 ] Империя начала приходить в упадок после его смерти, и последний правитель Маурьев, Брихадратха , был убит Пушьямитрой Шунгой , чтобы основать Империю Шунга . [ 109 ]

При Чандрагупте Маурье и его преемниках внутренняя и внешняя торговля, сельское хозяйство и экономическая деятельность процветали и расширялись по всей Индии благодаря созданию единой эффективной системы финансов, управления и безопасности. Маурья построили Великую магистраль , одну из старейших и самых длинных главных дорог Азии, соединяющую Индийский субконтинент с Центральной Азией. [ 110 ] После Калингской войны Империя пережила почти полвека мира и безопасности под властью Ашоки. Индия Маурьев также переживала эпоху социальной гармонии, религиозных преобразований и расширения научных знаний. Принятие Чандрагуптой Маурья джайнизма способствовало социальному и религиозному обновлению и реформам во всем его обществе, в то время как принятие Ашокой буддизма, как говорят, стало основой господства социального и политического мира и ненасилия во всей Индии. [ нужна ссылка ] Ашока спонсировал буддийские миссии в Шри-Ланку , Юго-Восточную Азию , Западную Азию , Северную Африку и Средиземноморскую Европу . [ 111 ]

« Арташастра », написанная Чанакьей , и « Эдикты Ашоки» являются основными письменными источниками времен Маурьев. Археологически этот период приходится на эпоху северной чернополированной посуды . Империя Маурьев была основана на современной и эффективной экономике и обществе, в котором продажа товаров строго регулировалась правительством. [ 112 ] Хотя в обществе Маурьев не было банковского дела, ростовщичество было обычным явлением. Обнаружено значительное количество письменных записей о рабстве, что позволяет предположить его распространенность. [ 113 ] В этот период на юге Индии была разработана высококачественная сталь под названием Wootz , которая позже экспортировалась в Китай и Аравию. [ 114 ]

Период кровотечения

В период Сангама тамильская литература процветала с III века до нашей эры по IV век нашей эры. Три тамильские династии, известные под общим названием « Три коронованных короля Тамилакама » : династия Чера , династия Чола и династия Пандья , правили частями южной Индии. [ 116 ]

Литература Сангама посвящена истории, политике, войнам и культуре тамильского народа этого периода. [ 117 ] В отличие от санскритских писателей, которые в основном были браминами, писатели сангама происходили из разных классов и социального происхождения и в основном не были браминами. [ 118 ]

Около ок. 300 г. до н. э. – ок. 200 г. н.э. была составлена «Патупатту» , антология из десяти книжных сборников среднего размера, которая считается частью литературы Сангама ; составление восьми антологий поэтических произведений «Эттутогай», а также составление восемнадцати второстепенных поэтических произведений «Патиенкиёкканакку» ; в то время как Толкаппиям , самая ранняя грамматическая работа на тамильском языке, была разработана. [ 119 ] Кроме того, в период Сангама два из пяти великих эпосов тамильской литературы были написаны . Иланго Адигал написал Силаппатикарам , нерелигиозное произведение, вращающееся вокруг Каннаги . [ 120 ] и Манимекалай , составленный Читалаем Чатанаром , является продолжением Силаппатикарама и рассказывает историю дочери Ковалана и Мадхави , которая стала буддийским бхикхуни . [ 121 ] [ 122 ]

Классический период (ок. 200 г. до н.э. – ок. 650 г. н.э.)

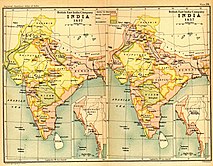

-

Древняя Индия во время возникновения империи Шунга с севера, династии Сатавахана из Декана , а также династии Пандьян и династии Чола из южной части Индии .

-

Великая Чайтья в пещерах Карла . Святыни создавались в период со 2 века до нашей эры по 5 век нашей эры.

-

Пещеры Удаягири и Кхандагири являются домом для надписи Хатигумфа , которая была сделана при Кхаравеле , тогдашнем императоре Калинги из Махамегавахана. династии

Время между Империей Маурьев в 3 веке до нашей эры и концом Империи Гуптов в 6 веке нашей эры называется «классическим» периодом Индии. [ 125 ] Империя Гуптов (4–6 века) считается «золотым веком» индуизма, хотя в эти века Индией правило множество королевств. Кроме того, литература сангама процветала с III века до нашей эры по III век нашей эры на юге Индии. [ 126 ] По оценкам , в этот период экономика Индии была крупнейшей в мире, на ее долю приходилось от одной трети до одной четверти мирового богатства, с 1 по 1000 год нашей эры. [ 127 ] [ 128 ]

Ранний классический период (ок. 200 г. до н.э. – ок. 320 г. н.э.)

Итак, Империя

Шунга произошли из Магадхи и контролировали большие территории центрального и восточного Индийского субконтинента примерно с 187 по 78 год до нашей эры. Династию основал Пушьямитра Шунга , свергнувший последнего императора Маурьев . Ее столицей была Паталипутра , но более поздние императоры, такие как Бхагабхадра , также держали двор в Видише , современном Беснагаре . [ 129 ]

Пушьямитра Шунга правил 36 лет, и ему наследовал его сын Агнимитра . Было десять правителей Сюнга. Однако после смерти Агнимитры империя быстро распалась; [ 130 ] надписи и монеты указывают на то, что большая часть северной и центральной Индии состояла из небольших королевств и городов-государств, независимых от какой-либо гегемонии Шунга. [ 131 ] Империя известна своими многочисленными войнами как с иностранными, так и с местными державами. Они воевали с династией Махамегавахана из Калинга , династией Сатавахана из Декана , индо-греками и, возможно, с Панчалами и Митрами из Матхуры .

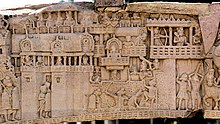

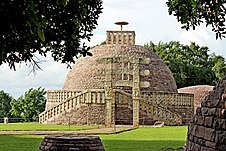

Искусство, образование, философия и другие формы обучения процветали в этот период, включая архитектурные памятники, такие как Ступа в Бхархуте и знаменитая Великая Ступа в Санчи . Правители Сюнга помогли установить традицию королевской поддержки образования и искусства. Сценарий, используемый империей, был вариантом Брахми и использовался для написания санскрита . Империя Сюнга сыграла важную роль в покровительстве индийской культуре в то время, когда происходили некоторые из наиболее важных событий в индуистской мысли.

Империя Сатавахана

Шатаваханы были основаны в Амаравати в Андхра-Прадеше, а также в Джуннаре ( Пуна ) и Пратистане ( Пайтхане ) в Махараштре . Территория империи охватывала большую часть Индии, начиная с I века до нашей эры. Сатаваханы начинали как феодалы династии Маурьев , но после ее упадка провозгласили независимость.

Сатаваханы известны своим покровительством индуизму и буддизму, в результате чего были созданы буддийские памятники от Эллоры ( объект всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО ) до Амаравати . Они были одним из первых индийских штатов, выпустивших монеты с тиснением своих правителей. Они сформировали культурный мост и сыграли жизненно важную роль в торговле, а также в передаче идей и культуры на Индо-Гангскую равнину и обратно на южную оконечность Индии.

Им пришлось конкурировать с империей Шунга , а затем с династией Канва в Магадхе, чтобы установить свое правление. Позже они сыграли решающую роль в защите значительной части Индии от иностранных захватчиков, таких как саки , яваны и пехлевы . их борьба с западными кшатрапами В частности, долгое время продолжалась . Известные правители династии Сатавахана Гаутамипутра Сатакарни и Шри Ягья Сатакарни смогли победить иностранных захватчиков, таких как западные кшатрапы , и остановить их экспансию. В III веке нашей эры империя была разделена на более мелкие государства. [ 132 ]

Торговля и путешествия в Индию

Торговля специями в Керале привлекала в Индию торговцев со всего Старого Света. на юго-западе Индии , прибрежный порт Музирис зарекомендовал себя как крупный центр торговли специями еще в 3000 году до нашей эры Согласно шумерским записям . Еврейские торговцы прибыли в Кочи , Керала, Индия, еще в 562 году до нашей эры. [ 133 ] Греко -римский мир , за которым следовала торговля по маршруту благовоний и маршруту Рим-Индия . [ 134 ] Во 2 веке до нашей эры греческие и индийские корабли встречались для торговли в арабских портах, таких как Аден . [ 135 ] В течение первого тысячелетия морские пути в Индию контролировались индийцами и эфиопами , которые стали морской торговой державой Красного моря .

Индийские купцы, занимавшиеся торговлей специями, привезли индийскую кухню в Юго-Восточную Азию, где смеси специй и карри стали популярны у коренных жителей. [ 136 ] Буддизм проник в Китай по Шелковому пути в I или II веке нашей эры. [ 137 ] Индуистские и буддийские религиозные учреждения Южной и Юго-Восточной Азии стали центрами производства и торговли по мере накопления капитала, пожертвованного покровителями. Они занимались управлением имениями, ремеслами и торговлей. Буддизм, в частности, распространялся наряду с морской торговлей, продвигая грамотность, искусство и использование монет. [ 138 ]

Kushan Empire

Кушанская империя расширилась за пределы территории нынешнего Афганистана на северо-запад Индийского субконтинента под руководством своего первого императора Куджулы Кадфиза Примерно в середине I века нашей эры . Кушаны, возможно, были тохароязычным племенем. [ 139 ] одна из пяти ветвей конфедерации Юэчжи . [ 140 ] [ 141 ] Ко времени правления его внука Канишки Великого империя распространилась и охватила большую часть Афганистана . [ 142 ] а затем северные части Индийского субконтинента. [ 143 ]

Император Канишка был великим покровителем буддизма; однако по мере того, как кушаны расширялись на юг, божества их более поздней чеканки стали отражать новое индуистское большинство. [ 144 ] [ 145 ] Историк Винсент Смит сказал о Канишке:

Он сыграл роль второго Ашоки в истории буддизма. [ 146 ]

Империя связала морскую торговлю в Индийском океане с торговлей по Шелковому пути через долину Инда, поощряя торговлю на дальние расстояния, особенно между Китаем и Римом . Кушаны привнесли новые тенденции в зарождающееся и расцветающее искусство Гандхары и искусство Матхуры , достигшее своего пика во время правления Кушанов. [ 147 ] Период мира под властью Кушанов известен как Пакс Кушана . К III веку их империя в Индии распадалась, и последним известным великим императором был Васудева I. [ 148 ] [ 149 ]

Классический период (ок. 320–650 гг. Н. Э.)

Империя Гуптов

Период Гуптов был отмечен культурным творчеством, особенно в области литературы, архитектуры, скульптуры и живописи. [ 150 ] Период Гуптов породил таких ученых, как Калидаса , Арьябхата , Варахамихира , Вишну Шарма и Ватьсияна . Период Гуптов стал водоразделом индийской культуры: Гупты совершали ведические жертвоприношения, чтобы узаконить свое правление, но они также покровительствовали буддизму, альтернативе брахманской ортодоксальности. Военные подвиги первых трёх правителей — Чандрагупты I , Самудрагупты и Чандрагупты II — привели под их руководство большую часть Индии. [151] Science and political administration reached new heights during the Gupta era. Strong trade ties also made the region an important cultural centre and established it as a base that would influence nearby kingdoms and regions.[152][153] Период мира под властью Гупты известен как Пакс Гупта .

The latter Guptas successfully resisted the northwestern kingdoms until the arrival of the Alchon Huns, who established themselves in Afghanistan by the first half of the 5th century CE, with their capital at Bamiyan.[154] However, much of the southern India including Deccan were largely unaffected by these events.[155][156]

Vakataka Empire

The Vākāṭaka Empire originated from the Deccan in the mid-third century CE. Their state is believed to have extended from the southern edges of Malwa and Gujarat in the north to the Tungabhadra River in the south as well as from the Arabian Sea in the western to the edges of Chhattisgarh in the east. They were the most important successors of the Satavahanas in the Deccan, contemporaneous with the Guptas in northern India and succeeded by the Vishnukundina dynasty.

The Vakatakas are noted for having been patrons of the arts, architecture and literature. The rock-cut Buddhist viharas and chaityas of Ajanta Caves (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) were built under the patronage of Vakataka emperor, Harishena.[157][158]

-

Buddhist monks praying in front of the Dagoba of Chaitya Cave 26 of the Ajanta Caves.

-

Buddhist "Chaitya Griha" or prayer hall, with a seated Buddha, Cave 26 of the Ajanta Caves.

-

Many foreign ambassadors, representatives, and travelers are included as devotees attending the Buddha's descent from Trayastrimsa Heaven; painting from Cave 17 of the Ajanta Caves.

Kamarupa Kingdom

Samudragupta's 4th-century Allahabad pillar inscription mentions Kamarupa (Western Assam)[159] and Davaka (Central Assam)[160] as frontier kingdoms of the Gupta Empire. Davaka was later absorbed by Kamarupa, which grew into a large kingdom that spanned from Karatoya river to near present Sadiya and covered the entire Brahmaputra valley, North Bengal, parts of Bangladesh and, at times Purnea and parts of West Bengal.[161]

Ruled by three dynasties Varmanas (c. 350–650 CE), Mlechchha dynasty (c. 655–900 CE) and Kamarupa-Palas (c. 900–1100 CE), from their capitals in present-day Guwahati (Pragjyotishpura), Tezpur (Haruppeswara) and North Gauhati (Durjaya) respectively. All three dynasties claimed their descent from Narakasura.[citation needed] In the reign of the Varman king, Bhaskar Varman (c. 600–650 CE), the Chinese traveller Xuanzang visited the region and recorded his travels. Later, after weakening and disintegration (after the Kamarupa-Palas), the Kamarupa tradition was somewhat extended until c. 1255 CE by the Lunar I (c. 1120–1185 CE) and Lunar II (c. 1155–1255 CE) dynasties.[162] The Kamarupa kingdom came to an end in the middle of the 13th century when the Khen dynasty under Sandhya of Kamarupanagara (North Guwahati), moved his capital to Kamatapur (North Bengal) after the invasion of Muslim Turks, and established the Kamata kingdom.[163]

Pallava Empire

The Pallavas, during the 4th to 9th centuries were, alongside the Guptas of the North, great patronisers of Sanskrit development in the South of the Indian subcontinent. The Pallava reign saw the first Sanskrit inscriptions in a script called Grantha.[164] Early Pallavas had different connexions to Southeast Asian countries. The Pallavas used Dravidian architecture to build some very important Hindu temples and academies in Mamallapuram, Kanchipuram and other places; their rule saw the rise of great poets. The practice of dedicating temples to different deities came into vogue followed by fine artistic temple architecture and sculpture style of Vastu Shastra.[165]

Pallavas reached the height of power during the reign of Mahendravarman I (571–630 CE) and Narasimhavarman I (630–668 CE) and dominated the Telugu and northern parts of the Tamil region until the end of the 9th century.[166]

Kadamba Empire

Kadambas originated from Karnataka, was founded by Mayurasharma in 345 CE which at later times showed the potential of developing into imperial proportions. King Mayurasharma defeated the armies of Pallavas of Kanchi possibly with help of some native tribes. The Kadamba fame reached its peak during the rule of Kakusthavarma, a notable ruler with whom the kings of Gupta Dynasty of northern India cultivated marital alliances. The Kadambas were contemporaries of the Western Ganga Dynasty and together they formed the earliest native kingdoms to rule the land with absolute autonomy. The dynasty later continued to rule as a feudatory of larger Kannada empires, the Chalukya and the Rashtrakuta empires, for over five hundred years during which time they branched into minor dynasties (Kadambas of Goa, Kadambas of Halasi and Kadambas of Hangal).

Empire of Harsha

Harsha ruled northern India from 606 to 647 CE. He was the son of Prabhakarvardhana and the younger brother of Rajyavardhana, who were members of the Vardhana dynasty and ruled Thanesar, in present-day Haryana.

After the downfall of the prior Gupta Empire in the middle of the 6th century, North India reverted to smaller republics and monarchical states. The power vacuum resulted in the rise of the Vardhanas of Thanesar, who began uniting the republics and monarchies from the Punjab to central India. After the death of Harsha's father and brother, representatives of the empire crowned Harsha emperor in April 606 CE, giving him the title of Maharaja.[168] At the peak, his Empire covered much of North and Northwestern India, extended East until Kamarupa, and South until Narmada River; and eventually made Kannauj (in present Uttar Pradesh) his capital, and ruled until 647 CE.[169]

The peace and prosperity that prevailed made his court a centre of cosmopolitanism, attracting scholars, artists and religious visitors.[169] During this time, Harsha converted to Buddhism from Surya worship.[170] The Chinese traveller Xuanzang visited the court of Harsha and wrote a very favourable account of him, praising his justice and generosity.[169] His biography Harshacharita ("Deeds of Harsha") written by Sanskrit poet Banabhatta, describes his association with Thanesar and the palace with a two-storied Dhavalagriha (White Mansion).[171][172]

Early medieval period (mid 6th – c. 1200)

Early medieval India began after the end of the Gupta Empire in the 6th century CE.[125] This period also covers the "Late Classical Age" of Hinduism, which began after the collapse of the Empire of Harsha in the 7th century,[173] and ended in the 13th century with the rise of the Delhi Sultanate in Northern India;[174] the beginning of Imperial Kannauj, leading to the Tripartite struggle; and the end of the Later Cholas with the death of Rajendra Chola III in 1279 in Southern India; however some aspects of the Classical period continued until the fall of the Vijayanagara Empire in the south around the 17th century.

From the fifth century to the thirteenth, Śrauta sacrifices declined, and initiatory traditions of Buddhism, Jainism or more commonly Shaivism, Vaishnavism and Shaktism expanded in royal courts.[175] This period produced some of India's finest art, considered the epitome of classical development, and the development of the main spiritual and philosophical systems which continued to be in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.

In the 7th century, Kumārila Bhaṭṭa formulated his school of Mimamsa philosophy and defended the position on Vedic rituals against Buddhist attacks. Scholars note Bhaṭṭa's contribution to the decline of Buddhism in India.[176] In the 8th century, Adi Shankara travelled across the Indian subcontinent to propagate and spread the doctrine of Advaita Vedanta, which he consolidated; and is credited with unifying the main characteristics of the current thoughts in Hinduism.[177][178][179] He was a critic of both Buddhism and Minamsa school of Hinduism;[180][181][182][183] and founded mathas (monasteries) for the spread and development of Advaita Vedanta.[184] Muhammad bin Qasim's invasion of Sindh (modern Pakistan) in 711 witnessed further decline of Buddhism.[185]

From the 8th to the 10th century, three dynasties contested for control of northern India: the Gurjara Pratiharas of Malwa, the Palas of Bengal, and the Rashtrakutas of the Deccan. The Sena dynasty would later assume control of the Pala Empire; the Gurjara Pratiharas fragmented into various states, notably the Kingdom of Malwa, the Kingdom of Bundelkhand, the Kingdom of Dahala, the Tomaras of Haryana, and the Kingdom of Sambhar, these states were some of the earliest Rajput kingdoms;[186] while the Rashtrakutas were annexed by the Western Chalukyas.[187] During this period, the Chaulukya dynasty emerged; the Chaulukyas constructed the Dilwara Temples, Modhera Sun Temple, Rani ki vav[188] in the style of Māru-Gurjara architecture, and their capital Anhilwara (modern Patan, Gujarat) was one of the largest cities in the Indian subcontinent, with the population estimated at 100,000 in c. 1000.

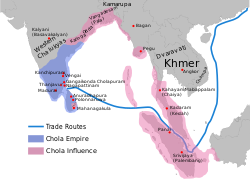

The Chola Empire emerged as a major power during the reign of Raja Raja Chola I and Rajendra Chola I who successfully invaded parts of Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka in the 11th century.[189] Lalitaditya Muktapida (r. 724–760 CE) was an emperor of the Kashmiri Karkoṭa dynasty, which exercised influence in northwestern India from 625 until 1003, and was followed by Lohara dynasty. Kalhana in his Rajatarangini credits king Lalitaditya with leading an aggressive military campaign in Northern India and Central Asia.[190][191][192]

The Hindu Shahi dynasty ruled portions of eastern Afghanistan, northern Pakistan, and Kashmir from the mid-7th century to the early 11th century. While in Odisha, the Eastern Ganga Empire rose to power; noted for the advancement of Hindu architecture, most notable being Jagannath Temple and Konark Sun Temple, as well as being patrons of art and literature.

-

Martand Sun Temple Central shrine, dedicated to the deity Surya, and built by the third ruler of the Karkota dynasty, Lalitaditya Muktapida, in the 8th century

-

Konark Sun Temple at Konark, Orissa, built by Narasimhadeva I (1238–1264) of the Eastern Ganga dynasty

Chalukya Empire

The Chalukya Empire ruled large parts of southern and central India between the 6th and the 12th centuries, as three related yet individual dynasties. The earliest dynasty, known as the "Badami Chalukyas", ruled from Vatapi (modern Badami) from the middle of the 6th century. The Badami Chalukyas began to assert their independence at the decline of the Kadamba kingdom of Banavasi and rapidly rose to prominence during the reign of Pulakeshin II. The rule of the Chalukyas marks an important milestone in the history of South India and a golden age in the history of Karnataka. The political atmosphere in South India shifted from smaller kingdoms to large empires with the ascendancy of Badami Chalukyas. A Southern India-based kingdom took control and consolidated the entire region between the Kaveri and the Narmada Rivers. The rise of this empire saw the birth of efficient administration, overseas trade and commerce and the development of new style of architecture called "Chalukyan architecture". The Chalukya dynasty ruled parts of southern and central India from Badami in Karnataka between 550 and 750, and then again from Kalyani between 970 and 1190.

-

Galaganatha Temple at Pattadakal complex (UNESCO World Heritage) is an example of Badami Chalukya architecture

-

8th century Durga temple exterior view at Aihole complex. It includes Hindu, Buddhist and Jain temples and monuments

Rashtrakuta Empire

Founded by Dantidurga around 753,[193] the Rashtrakuta Empire ruled from its capital at Manyakheta for almost two centuries.[194] At its peak, the Rashtrakutas ruled from the Ganges-Yamuna Doab in the north to Cape Comorin in the south, a fruitful time of architectural and literary achievements.[195][196]

The early rulers of this dynasty were Hindu, but the later rulers were strongly influenced by Jainism.[197] Govinda III and Amoghavarsha were the most famous of the long line of able administrators produced by the dynasty. Amoghavarsha was also an author and wrote Kavirajamarga, the earliest known Kannada work on poetics.[194][198] Architecture reached a milestone in the Dravidian style, the finest example of which is seen in the Kailasanath Temple at Ellora. Other important contributions are the Kashivishvanatha temple and the Jain Narayana temple at Pattadakal in Karnataka.

The Arab traveller Suleiman described the Rashtrakuta Empire as one of the four great Empires of the world.[199] The Rashtrakuta period marked the beginning of the golden age of southern Indian mathematics. The great south Indian mathematician Mahāvīra had a huge impact on medieval south Indian mathematicians.[200] The Rashtrakuta rulers also patronised men of letters in a variety of languages.[194]

Gurjara-Pratihara Empire

The Gurjara-Pratiharas were instrumental in containing Arab armies moving east of the Indus River. Nagabhata I defeated the Arab army under Junaid and Tamin during the Umayyad campaigns in India.[201] Under Nagabhata II, the Gurjara-Pratiharas became the most powerful dynasty in northern India. He was succeeded by his son Ramabhadra, who ruled briefly before being succeeded by his son, Mihira Bhoja. Under Bhoja and his successor Mahendrapala I, the Pratihara Empire reached its peak of prosperity and power. By the time of Mahendrapala, its territory stretched from the border of Sindh in the west to Bihar in the east and from the Himalayas in the north to around the Narmada River in the south.[202] The expansion triggered a tripartite power struggle with the Rashtrakuta and Pala empires for control of the Indian subcontinent.

By the end of the 10th century, several feudatories of the empire took advantage of the temporary weakness of the Gurjara-Pratiharas to declare their independence, notably the Kingdom of Malwa, the Kingdom of Bundelkhand, the Tomaras of Haryana, and the Kingdom of Sambhar[203] and the Kingdom of Dahala.[citation needed]

-

Sculptures near Teli ka Mandir, Gwalior Fort

-

Jainism-related cave monuments and statues carved into the rock face inside Siddhachal Caves, Gwalior Fort

-

Ghateshwara Mahadeva temple at Baroli Temples complex. Complex of eight temples, built by the Gurjara-Pratiharas, within a walled enclosure

Gahadavala dynasty

Gahadavala dynasty ruled parts of the present-day Indian states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, during 11th and 12th centuries. Their capital was located at Varanasi.[205]

Khayaravala dynasty

The Khayaravala dynasty, ruled parts of the present-day Indian states of Bihar and Jharkhand, during 11th and 12th centuries. Their capital was located at Khayaragarh in Shahabad district. Pratapdhavala and Shri Pratapa were king of the dynasty.[206]

Pala Empire

The Pala Empire was founded by Gopala I.[207][208][209] It was ruled by a Buddhist dynasty from Bengal. The Palas reunified Bengal after the fall of Shashanka's Gauda Kingdom.[210]

The Palas were followers of the Mahayana and Tantric schools of Buddhism,[211] they also patronised Shaivism and Vaishnavism.[212] The empire reached its peak under Dharmapala and Devapala. Dharmapala is believed to have conquered Kanauj and extended his sway up to the farthest limits of India in the north-west.[212]

The Pala Empire can be considered as the golden era of Bengal.[213] Dharmapala founded the Vikramashila and revived Nalanda,[212] considered one of the first great universities in recorded history. Nalanda reached its height under the patronage of the Pala Empire.[213][214] The Palas also built many viharas. They maintained close cultural and commercial ties with countries of Southeast Asia and Tibet. Sea trade added greatly to the prosperity of the Pala Empire.

Cholas

Medieval Cholas rose to prominence during the middle of the 9th century and established the greatest empire South India had seen.[215] They successfully united the South India under their rule and through their naval strength extended their influence in the Southeast Asian countries such as Srivijaya.[189] Under Rajaraja Chola I and his successors Rajendra Chola I, Rajadhiraja Chola, Virarajendra Chola and Kulothunga Chola I the dynasty became a military, economic and cultural power in South Asia and South-East Asia.[216][217] Rajendra Chola I's navies occupied the sea coasts from Burma to Vietnam,[218] the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, the Lakshadweep (Laccadive) islands, Sumatra, and the Malay Peninsula. The power of the new empire was proclaimed to the eastern world by the expedition to the Ganges which Rajendra Chola I undertook and by the occupation of cities of the maritime empire of Srivijaya in Southeast Asia, as well as by the repeated embassies to China.[219]

They dominated the political affairs of Sri Lanka for over two centuries through repeated invasions and occupation. They also had continuing trade contacts with the Arabs and the Chinese empire.[220] Rajaraja Chola I and his son Rajendra Chola I gave political unity to the whole of Southern India and established the Chola Empire as a respected sea power.[221] Under the Cholas, the South India reached new heights of excellence in art, religion and literature. In all of these spheres, the Chola period marked the culmination of movements that had begun in an earlier age under the Pallavas. Monumental architecture in the form of majestic temples and sculpture in stone and bronze reached a finesse never before achieved in India.[222]

-

The granite gopuram (tower) of Brihadeeswarar Temple, 1010

-

Chariot detail at Airavatesvara Temple built by Rajaraja Chola II in the 12th century

-

The pyramidal structure above the sanctum at Brihadisvara Temple.

-

Brihadeeswara Temple Entrance Gopurams at Thanjavur

Western Chalukya Empire

The Western Chalukya Empire ruled most of the western Deccan, South India, between the 10th and 12th centuries.[224] Vast areas between the Narmada River in the north and Kaveri River in the south came under Chalukya control.[224] During this period the other major ruling families of the Deccan, the Hoysalas, the Seuna Yadavas of Devagiri, the Kakatiya dynasty and the Southern Kalachuris, were subordinates of the Western Chalukyas and gained their independence only when the power of the Chalukya waned during the latter half of the 12th century.[225]

The Western Chalukyas developed an architectural style known today as a transitional style, an architectural link between the style of the early Chalukya dynasty and that of the later Hoysala empire. Most of its monuments are in the districts bordering the Tungabhadra River in central Karnataka. Well known examples are the Kasivisvesvara Temple at Lakkundi, the Mallikarjuna Temple at Kuruvatti, the Kallesvara Temple at Bagali, Siddhesvara Temple at Haveri, and the Mahadeva Temple at Itagi.[226] This was an important period in the development of fine arts in Southern India, especially in literature as the Western Chalukya kings encouraged writers in the native language of Kannada, and Sanskrit like the philosopher and statesman Basava and the great mathematician Bhāskara II.[227][228]

-

Ornate entrance to the closed hall from the south at Kalleshvara Temple at Bagali

-

Shrine wall relief, molding frieze and miniature decorative tower in Mallikarjuna Temple at Kuruvatti

-

Rear view showing lateral entrances of the Mahadeva Temple at Itagi

Late medieval period (c. 1200–1526)

The late medieval period is marked by repeated invasions of the Muslim Central Asian nomadic clans,[229][230] the rule of the Delhi sultanate, and by the growth of other dynasties and empires, built upon military technology of the Sultanate.[231] It turned from a turkic Monopoly to an Indianized Indo-Muslim polity [9][232][233][234]

Delhi Sultanate

The Delhi Sultanate was a series of successive Islamic states based in Delhi, ruled by several dynasties of Turkic, Indic[235][236],Turko-Indian[237] and Pashtun origins.[238] It ruled large parts of the Indian subcontinent from the 13th to the early 16th century.[239] In the 12th and 13th centuries, Central Asian Turks invaded parts of northern India and established the Delhi Sultanate in the former Hindu holdings.[240] The subsequent Mamluk dynasty of Delhi managed to conquer large areas of northern India, while the Khalji dynasty conquered most of central India while forcing the principal Hindu kingdoms of South India to become vassal states.[239]

The Sultanate ushered in a period of Indian cultural renaissance. The resulting "Indo-Muslim" fusion of cultures left lasting syncretic monuments in architecture, music, literature, religion, and clothing. It is surmised that the language of Urdu was born during the Delhi Sultanate period. The Delhi Sultanate is the only Indo-Islamic empire to enthrone one of the few female rulers in India, Razia Sultana (1236–1240).

While initially disruptive due to the passing of power from native Indian elites to Turkic Muslim, Indic muslim and Pashtun muslim elites, the Delhi Sultanate was responsible for integrating the Indian subcontinent into a growing world system, drawing India into a wider international network, which had a significant impact on Indian culture and society.[241] However, the Delhi Sultanate also caused large-scale destruction and desecration of temples in the Indian subcontinent.[242]

The Mongol invasions of India were successfully repelled by the Delhi Sultanate during the rule of Alauddin Khalji. A major factor in their success was their Turkic Mamluk slave army, who were highly skilled in the same style of nomadic cavalry warfare as the Mongols. It is possible that the Mongol Empire may have expanded into India were it not for the Delhi Sultanate's role in repelling them.[243] By repeatedly repulsing the Mongol raiders,[244] the sultanate saved India from the devastation visited on West and Central Asia. Soldiers from that region and learned men and administrators fleeing Mongol invasions of Iran migrated into the subcontinent, thereby creating a syncretic Indo-Islamic culture in the north.[243]

A Turco-Mongol conqueror in Central Asia, Timur (Tamerlane), attacked the reigning Sultan Nasir-u Din Mehmud of the Tughlaq dynasty in the north Indian city of Delhi.[245] The Sultan's army was defeated on 17 December 1398. Timur entered Delhi and the city was sacked, destroyed, and left in ruins after Timur's army had killed and plundered for three days and nights. He ordered the whole city to be sacked except for the sayyids, scholars, and the "other Muslims" (artists); 100,000 war prisoners were put to death in one day.[246] The Sultanate suffered significantly from the sacking of Delhi. Though revived briefly under the Lodi dynasty, it was but a shadow of the former.

-

Qutb Minar, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, whose construction was begun by Qutb ud-Din Aibak, the first Sultan of Delhi.

Vijayanagara Empire

The Vijayanagara Empire was established in 1336 by Harihara I and his brother Bukka Raya I of Sangama Dynasty,[247] which originated as a political heir of the Hoysala Empire, Kakatiya Empire,[248] and the Pandyan Empire.[249] The empire rose to prominence as a culmination of attempts by the south Indian powers to ward off Islamic invasions by the end of the 13th century. It lasted until 1646, although its power declined after a major military defeat in 1565 by the combined armies of the Deccan sultanates. The empire is named after its capital city of Vijayanagara, whose ruins surround present day Hampi, now a World Heritage Site in Karnataka, India.[250]

In the first two decades after the founding of the empire, Harihara I gained control over most of the area south of the Tungabhadra river and earned the title of Purvapaschima Samudradhishavara ("master of the eastern and western seas"). By 1374 Bukka Raya I, successor to Harihara I, had defeated the chiefdom of Arcot, the Reddys of Kondavidu, and the Sultan of Madurai and had gained control over Goa in the west and the Tungabhadra-Krishna doab in the north.[251][252]

Harihara II, the second son of Bukka Raya I, further consolidated the kingdom beyond the Krishna River and brought the whole of South India under the Vijayanagara umbrella.[253] The next ruler, Deva Raya I, emerged successful against the Gajapatis of Odisha and undertook important works of fortification and irrigation.[254] Italian traveller Niccolo de Conti wrote of him as the most powerful ruler of India.[255] Deva Raya II succeeded to the throne in 1424 and was possibly the most capable of the Sangama Dynasty rulers.[256] He quelled rebelling feudal lords as well as the Zamorin of Calicut and Quilon in the south. He invaded the island of Sri Lanka and became overlord of the kings of Burma at Pegu and Tanasserim.[257][258][259]

The Vijayanagara Emperors were tolerant of all religions and sects, as writings by foreign visitors show.[260] The kings used titles such as Gobrahamana Pratipalanacharya (literally, "protector of cows and Brahmins") and Hindurayasuratrana (lit, "upholder of Hindu faith") that testified to their intention of protecting Hinduism and yet were at the same time staunchly Islamicate in their court ceremonials and dress.[261] The empire's founders, Harihara I and Bukka Raya I, were devout Shaivas (worshippers of Shiva), but made grants to the Vaishnava order of Sringeri with Vidyaranya as their patron saint, and designated Varaha (an avatar of Vishnu) as their emblem.[262] Nobles from Central Asia's Timurid kingdoms also came to Vijayanagara.[263] The later Saluva and Tuluva kings were Vaishnava by faith, but worshipped at the feet of Lord Virupaksha (Shiva) at Hampi as well as Lord Venkateshwara (Vishnu) at Tirupati.[264] A Sanskrit work, Jambavati Kalyanam by King Krishnadevaraya, called Lord Virupaksha Karnata Rajya Raksha Mani ("protective jewel of Karnata Empire").[265] The kings patronised the saints of the dvaita order (philosophy of dualism) of Madhvacharya at Udupi.[266]

-

Photograph of the ruins of the Vijayanagara Empire at Hampi, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1868[267]

-

Gajashaala, or elephant's stable, was built by the Vijayanagar rulers for their war elephants.[268]

-

Vijayanagara marketplace at Hampi, along with the sacred tank located on the side of Krishna temple.

-

Stone temple car in Vitthala Temple at Hampi

The empire's legacy includes many monuments spread over South India, the best known of which is the group at Hampi. The previous temple building traditions in South India came together in the Vijayanagara Architecture style. The mingling of all faiths and vernaculars inspired architectural innovation of Hindu temple construction. South Indian mathematics flourished under the protection of the Vijayanagara Empire in Kerala. The south Indian mathematician Madhava of Sangamagrama founded the famous Kerala School of Astronomy and Mathematics in the 14th century which produced a lot of great south Indian mathematicians like Parameshvara, Nilakantha Somayaji and Jyeṣṭhadeva.[269] Efficient administration and vigorous overseas trade brought new technologies such as water management systems for irrigation.[270] The empire's patronage enabled fine arts and literature to reach new heights in Kannada, Telugu, Tamil, and Sanskrit, while Carnatic music evolved into its current form.[271]

Vijayanagara went into decline after the defeat in the Battle of Talikota (1565). After the death of Aliya Rama Raya in the Battle of Talikota, Tirumala Deva Raya started the Aravidu dynasty, moved and founded a new capital of Penukonda to replace the destroyed Hampi, and attempted to reconstitute the remains of Vijayanagara Empire.[272] Tirumala abdicated in 1572, dividing the remains of his kingdom to his three sons, and pursued a religious life until his death in 1578. The Aravidu dynasty successors ruled the region but the empire collapsed in 1614, and the final remains ended in 1646, from continued wars with the Bijapur sultanate and others.[273][274][275] During this period, more kingdoms in South India became independent and separate from Vijayanagara. These include the Mysore Kingdom, Keladi Nayaka, Nayaks of Madurai, Nayaks of Tanjore, Nayakas of Chitradurga and Nayak Kingdom of Gingee – all of which declared independence and went on to have a significant impact on the history of South India in the coming centuries.[273]

Other kingdoms

-

Vijaya Stambha (Tower of Victory).

-

Temple inside Chittorgarh fort

-

Man Singh (Manasimha) palace at the Gwalior fort

-

Chinese manuscript Tribute Giraffe with Attendant, depicting a giraffe presented by Bengali envoys in the name of Sultan Saifuddin Hamza Shah of Bengal to the Yongle Emperor of Ming China

-

Mahmud Gawan Madrasa was built by Mahmud Gawan, the Wazir of the Bahmani Sultanate as the centre of religious as well as secular education

For two and a half centuries from the mid-13th century, politics in Northern India was dominated by the Delhi Sultanate, and in Southern India by the Vijayanagar Empire. However, there were other regional powers present as well. After fall of Pala Empire, the Chero dynasty ruled much of Eastern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Jharkhand from the 12th to the 18th centuries.[276][277][278] The Reddy dynasty successfully defeated the Delhi Sultanate and extended their rule from Cuttack in the north to Kanchi in the south, eventually being absorbed into the expanding Vijayanagara Empire.[279]

In the north, the Rajput kingdoms remained the dominant force in Western and Central India. The Mewar dynasty under Maharana Hammir defeated and captured Muhammad Tughlaq with the Bargujars as his main allies. Tughlaq had to pay a huge ransom and relinquish all of Mewar's lands. After this event, the Delhi Sultanate did not attack Chittor for a few hundred years. The Rajputs re-established their independence, and Rajput states were established as far east as Bengal and north into teh Punjab. The Tomaras established themselves at Gwalior, and Man Singh Tomar reconstructed the Gwalior Fort.[280] During this period, Mewar emerged as the leading Rajput state; and Rana Kumbha expanded his kingdom at the expense of the Sultanates of Malwa and Gujarat.[280][281] The next great Rajput ruler, Rana Sanga of Mewar, became the principal player in Northern India. His objectives grew in scope – he planned to conquer Delhi. But, his defeat in the Battle of Khanwa consolidated the new Mughal dynasty in India.[280] The Mewar dynasty under Maharana Udai Singh II faced further defeat by Mughal emperor Akbar, with their capital Chittor being captured. Due to this event, Udai Singh II founded Udaipur, which became the new capital of the Mewar kingdom. His son, Maharana Pratap of Mewar, firmly resisted the Mughals. Akbar sent many missions against him. He survived to ultimately gain control of all of Mewar, excluding the Chittor Fort.[282]

In the south, the Bahmani Sultanate in the Deccan, born from a rebellion in 1347 against the Tughlaq dynasty,[283] was the chief rival of Vijayanagara, and frequently created difficulties for them.[284] Starting in 1490, the Bahmani Sultanate's governors revolted, their independent states composing the five Deccan sultanates; Ahmadnagar declared independence, followed by Bijapur and Berar in the same year; Golkonda became independent in 1518 and Bidar in 1528.[285] Although generally rivals, they allied against the Vijayanagara Empire in 1565, permanently weakening Vijayanagar in the Battle of Talikota.[286][287]

In the East, the Gajapati Kingdom remained a strong regional power to reckon with, associated with a high point in the growth of regional culture and architecture. Under Kapilendradeva, Gajapatis became an empire stretching from the lower Ganga in the north to the Kaveri in the south.[288] In Northeast India, the Ahom Kingdom was a major power for six centuries;[289][290] led by Lachit Borphukan, the Ahoms decisively defeated the Mughal army at the Battle of Saraighat during the Ahom-Mughal conflicts.[291] Further east in Northeastern India was the Kingdom of Manipur, which ruled from their seat of power at Kangla Fort and developed a sophisticated Hindu Gaudiya Vaishnavite culture.[292][293][294]

The Sultanate of Bengal was the dominant power of the Ganges–Brahmaputra Delta, with a network of mint towns spread across the region. It was a Sunni Muslim monarchy with Indo-Turkic, Arab, Abyssinian and Bengali Muslim elites. The sultanate was known for its religious pluralism where non-Muslim communities co-existed peacefully. The Bengal Sultanate had a circle of vassal states, including Odisha in the southwest, Arakan in the southeast, and Tripura in the east. In the early 16th century, the Bengal Sultanate reached the peak of its territorial growth with control over Kamrup and Kamata in the northeast and Jaunpur and Bihar in the west. It was reputed as a thriving trading nation and one of Asia's strongest states. The Bengal Sultanate was described by contemporary European and Chinese visitors as a relatively prosperous kingdom and the "richest country to trade with". The Bengal Sultanate left a strong architectural legacy. Buildings from the period show foreign influences merged into a distinct Bengali style. The Bengal Sultanate was also the largest and most prestigious authority among the independent medieval Muslim-ruled states in the history of Bengal. Its decline began with an interregnum by the Suri Empire, followed by Mughal conquest and disintegration into petty kingdoms.

Bhakti movement and Sikhism

The Bhakti movement refers to the theistic devotional trend that emerged in medieval Hinduism[295] and later revolutionised in Sikhism.[296] It originated in the seventh-century south India (now parts of Tamil Nadu and Kerala), and spread northwards.[295] It swept over east and north India from the 15th century onwards, reaching its zenith between the 15th and 17th century.[297]

- The Bhakti movement regionally developed around different gods and goddesses, such as Vaishnavism (Vishnu), Shaivism (Shiva), Shaktism (Shakti goddesses), and Smartism.[298][299][300] The movement was inspired by many poet-saints, who championed a wide range of philosophical positions ranging from theistic dualism of Dvaita to absolute monism of Advaita Vedanta.[301][302]

- Sikhism is a monotheistic and panentheistic religion based on the spiritual teachings of Guru Nanak, the first Guru,[303] and the ten successive Sikh gurus. After the death of the tenth Guru, Guru Gobind Singh, the Sikh scripture, Guru Granth Sahib, became the literal embodiment of the eternal, impersonal Guru, where the scripture's word serves as the spiritual guide for Sikhs.[304][305][306]

- Buddhism in India flourished in the Himalayan kingdoms of Namgyal Kingdom in Ladakh, Sikkim Kingdom in Sikkim, and Chutia Kingdom in Arunachal Pradesh of the Late medieval period.

-

Rang Ghar, built by Pramatta Singha in Ahom kingdom's capital Rangpur, is one of the earliest pavilions of outdoor stadia in the Indian subcontinent

-

Chittor Fort is the largest fort on the Indian subcontinent; it is one of the six Hill Forts of Rajasthan

-

Ranakpur Jain temple was built in the 15th century with the support of the Rajput state of Mewar

-

Gol Gumbaz built by the Bijapur Sultanate, has the second largest pre-modern dome in the world after the Byzantine Hagia Sophia

Early modern period (1526–1858)

The early modern period of Indian history is dated from 1526 to 1858, corresponding to the rise and fall of the Mughal Empire, which inherited from the Timurid Renaissance. During this age India's economy expanded, relative peace was maintained and arts were patronised. This period witnessed the further development of Indo-Islamic architecture;[307][308] the growth of Marathas and Sikhs enabled them to rule significant regions of India in the waning days of the Mughal empire.[16] With the discovery of the Cape route in the 1500s, the first Europeans to arrive by sea and establish themselves, were the Portuguese in Goa and Bombay.[309]

Mughal Empire

In 1526, Babur swept across the Khyber Pass and established the Mughal Empire, which at its zenith covered much of South Asia.[311] However, his son Humayun was defeated by the Afghan warrior Sher Shah Suri in 1540, and Humayun was forced to retreat to Kabul. After Sher Shah's death, his son Islam Shah Suri and his Hindu general Hemu Vikramaditya established secular rule in North India from Delhi until 1556, when Akbar (r. 1556–1605), grandson of Babur, defeated Hemu in the Second Battle of Panipat on 6 November 1556 after winning Battle of Delhi. Akbar tried to establish a good relationship with the Hindus. Akbar declared "Amari" or non-killing of animals in the holy days of Jainism. He rolled back the jizya tax for non-Muslims. The Mughal emperors married local royalty, allied themselves with local maharajas, and attempted to fuse their Turko-Persian culture with ancient Indian styles, creating a unique Indo-Persian culture and Indo-Saracenic architecture.

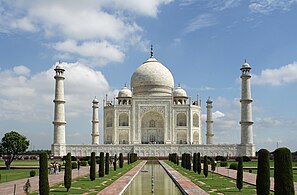

Akbar married a Rajput princess, Mariam-uz-Zamani, and they had a son, Jahangir (r. 1605–1627).[312] Jahangir followed his father's policy. The Mughal dynasty ruled most of the Indian subcontinent by 1600. The reign of Shah Jahan (r. 1628–1658) was the golden age of Mughal architecture. He erected several large monuments, the most famous of which is the Taj Mahal at Agra.

It was one of the largest empires to have existed in the Indian subcontinent,[313] and surpassed China to become the world's largest economic power, controlling 24.4% of the world economy,[314] and the world leader in manufacturing,[315] producing 25% of global industrial output.[316] The economic and demographic upsurge was stimulated by Mughal agrarian reforms that intensified agricultural production,[317] and a relatively high degree of urbanisation.[318]

-

Fatehpur Sikri, near Agra, showing Buland Darwaza, the complex built by Akbar, the third Mughal emperor

-

Red Fort, Delhi, constructed in the year 1648

The Mughal Empire reached the zenith of its territorial expanse during the reign of Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707), under whose reign India surpassed Qing China as the world's largest economy.[319][320] Aurangzeb was less tolerant than his predecessors, reintroducing the jizya tax and destroying several historical temples, while at the same time building more Hindu temples than he destroyed,[321] employing significantly more Hindus in his imperial bureaucracy than his predecessors, and advancing administrators based on ability rather than religion.[322] However, he is often blamed for the erosion of the tolerant syncretic tradition of his predecessors, as well as increasing religious controversy and centralisation. The English East India Company suffered a defeat in the Anglo-Mughal War.[323][324]

The Mughals suffered several blows due to invasions from Marathas, Rajputs, Jats and Afghans. In 1737, the Maratha general Bajirao of the Maratha Empire invaded and plundered Delhi. Under the general Amir Khan Umrao Al Udat, the Mughal Emperor sent 8,000 troops to drive away the 5,000 Maratha cavalry soldiers. Baji Rao easily routed the novice Mughal general. In 1737, in the final defeat of Mughal Empire, the commander-in-chief of the Mughal Army, Nizam-ul-mulk, was routed at Bhopal by the Maratha army. This essentially brought an end to the Mughal Empire.[citation needed] While Bharatpur State under Jat ruler Suraj Mal, overran the Mughal garrison at Agra and plundered the city.[325] In 1739, Nader Shah, emperor of Iran, defeated the Mughal army at the Battle of Karnal.[326] After this victory, Nader captured and sacked Delhi, carrying away treasures including the Peacock Throne.[327] Mughal rule was further weakened by constant native Indian resistance; Banda Singh Bahadur led the Sikh Khalsa against Mughal religious oppression; Hindu Rajas of Bengal, Pratapaditya and Raja Sitaram Ray revolted; and Maharaja Chhatrasal, of Bundela Rajputs, fought the Mughals and established the Panna State.[328] The Mughal dynasty was reduced to puppet rulers by 1757. Vadda Ghalughara took place under the Muslim provincial government based at Lahore to wipe out the Sikhs, with 30,000 Sikhs being killed, an offensive that had begun with the Mughals, with the Chhota Ghallughara,[329] and lasted several decades under its Muslim successor states.[330]

Maratha Empire

The Maratha kingdom was founded and consolidated by Chatrapati Shivaji.[331] However, the credit for making the Marathas formidable power nationally goes to Peshwa (chief minister) Bajirao I. Historian K.K. Datta wrote that Bajirao I "may very well be regarded as the second founder of the Maratha Empire".[332]

In the early 18th century, under the Peshwas, the Marathas consolidated and ruled over much of South Asia. The Marathas are credited to a large extent for ending Mughal rule in India.[333][334][335] In 1737, the Marathas defeated a Mughal army in their capital, in the Battle of Delhi. The Marathas continued their military campaigns against the Mughals, Nizam, Nawab of Bengal and the Durrani Empire to further extend their boundaries. At its peak, the domain of the Marathas encompassed most of the Indian subcontinent.[336] The Marathas even attempted to capture Delhi and discussed putting Vishwasrao Peshwa on the throne there in place of the Mughal emperor.[337]

The Maratha empire at its peak stretched from Tamil Nadu in the south,[338] to Peshawar (modern-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan[339] [note 2]) in the north, and Bengal in the east. The Northwestern expansion of the Marathas was stopped after the Third Battle of Panipat (1761). However, the Maratha authority in the north was re-established within a decade under Peshwa Madhavrao I.[341]