Избирательное право женщин

| Часть серии о |

| Женщины в обществе |

|---|

|

| Часть серии о |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

Избирательное право женщин – это право женщин голосовать на выборах . В начале 18 века некоторые люди стремились изменить законы о голосовании, чтобы позволить женщинам голосовать. Либеральные политические партии продолжат предоставлять женщинам право голоса, увеличивая число потенциальных избирателей этих партий. Национальные и международные организации, созданные для координации усилий по обеспечению женского голосования, особенно Международный союз избирательного права женщин (основан в 1904 году в Берлине , Германия). [1]

За последние столетия произошло несколько случаев, когда женщинам выборочно давали, а затем лишали права голоса. В Швеции условное избирательное право женщин действовало в эпоху Свободы (1718–1772), а также в революционном и в начале независимости Нью-Джерси (1776–1807) в США. [2] [3]

The first territory to continuously allow women to vote to this present day is the Pitcairn Islands since 1838. The Kingdom of Hawai'i, which originally had universal suffrage in 1840, rescinded this in 1852 and was subsequently annexed by the United States in 1898. In the years after 1869, a number of provinces held by the British and Russian empires conferred women's suffrage, and some of these became sovereign nations at a later point, like New Zealand, Australia, and Finland. Several states and territories of the United States, such as Wyoming (1869) and Utah (1870), also granted women the right to vote. Women who owned property gained the right to vote in the Isle of Man in 1881, and in 1893, women in the then self-governing[4] British colony of New Zealand were granted the right to vote. In Australia, the colony of South Australia conferred voter rights on all women from 1894, and the right to stand for Parliament from 1895, while the Australian Federal Parliament conferred the right to vote and stand for election in 1902 (although it allowed for the exclusion of "aboriginal natives").[5][6] Prior to independence, in the Russian Grand Duchy of Finland, women gained equal suffrage, with both the right to vote and to stand as candidates in 1906.[7][8][9] Most major Western powers extended voting rights to women in the interwar period, including Canada (1917), Germany (1918), the United Kingdom (1918 for some women, 1928 for all women), Austria, the Netherlands (1919) and the United States (1920).[10] Notable exceptions in Europe were France, where women could not vote until 1944, Greece (equal voting rights for women did not exist there until 1952, although, since 1930, literate women were able to vote in local elections), and Switzerland (where, since 1971, women could vote at the federal level, and between 1959 and 1990, women got the right to vote at the local canton level). The last European jurisdictions to give women the right to vote were Liechtenstein in 1984 and the Swiss canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden at the local level in 1990,[11] with the Vatican City being an absolute elective monarchy (the electorate of the Holy See, the conclave, is composed of male cardinals, rather than Vatican citizens). In some cases of direct democracy, such as Swiss cantons governed by Landsgemeinden, objections to expanding the suffrage claimed that logistical limitations, and the absence of secret ballot, made it impractical as well as unnecessary; others, such as Appenzell Ausserrhoden, instead abolished the system altogether for both women and men.[12][13][14]

Leslie Hume argues that the First World War changed the popular mood:

The women's contribution to the war effort challenged the notion of women's physical and mental inferiority and made it more difficult to maintain that women were, both by constitution and temperament, unfit to vote. If women could work in munitions factories, it seemed both ungrateful and illogical to deny them a place in the voting booth. But the vote was much more than simply a reward for war work; the point was that women's participation in the war helped to dispel the fears that surrounded women's entry into the public arena.[15]

Pre-WWI opponents of women's suffrage such as the Women's National Anti-Suffrage League cited women's relative inexperience in military affairs. They claimed that since women were the majority of the population, women should vote in local elections, but due to a lack of experience in military affairs, they asserted that it would be dangerous to allow them to vote in national elections.[16]

Extended political campaigns by women and their supporters were necessary to gain legislation or constitutional amendments for women's suffrage. In many countries, limited suffrage for women was granted before universal suffrage for men; for instance, literate women or property owners were granted suffrage before all men received it. The United Nations encouraged women's suffrage in the years following World War II, and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (1979) identifies it as a basic right with 189 countries currently being parties to this convention.

History

[edit]

Before the 19th century

[edit]In ancient Athens, often cited as the birthplace of democracy, only adult male citizens who owned land were permitted to vote.[citation needed] Through subsequent centuries, Europe was ruled by monarchs, though various forms of parliament arose at different times. The high rank ascribed to abbesses within the Catholic Church permitted some women the right to sit and vote at national assemblies – as with various high-ranking abbesses in Medieval Germany, who were ranked among the independent princes of the empire. Their Protestant successors enjoyed the same privilege almost into modern times.[17]

Marie Guyart, a French nun who worked with the First Nations people of Canada during the 17th century, wrote in 1654 regarding the suffrage practices of Iroquois women: "These female chieftains are women of standing amongst the savages, and they have a deciding vote in the councils. They make decisions there like their male counterparts, and it is they who even delegated as first ambassadors to discuss peace."[18] The Iroquois, like many First Nations in North America,[citation needed] had a matrilineal kinship system. Property and descent were passed through the female line. Women elders voted on hereditary male chiefs and could depose them.

The first independent country to introduce women's suffrage was arguably Sweden. In Sweden, conditional women's suffrage was in effect during the Age of Liberty (1718–1772).[2]

In 1756, Lydia Taft became the first legal woman voter in colonial America. This occurred under British rule in the Massachusetts Colony.[20] In a New England town meeting in Uxbridge, Massachusetts, she voted on at least three occasions.[21] Unmarried white women who owned property could vote in New Jersey from 1776 to 1807.[22]

In the 1792 elections in Sierra Leone, then a new British colony, all heads of household could vote and one-third were ethnic African women.[23]

Other early instances of women's suffrage include the Corsican Republic (1755), the Pitcairn Islands (1838), the Isle of Man (1881), and Franceville (1889–1890), but some of these operated only briefly as independent states and others were not clearly independent.

19th century

[edit]The female descendants of the Bounty mutineers who lived on Pitcairn Islands could vote from 1838. This right was transferred after they resettled in 1856 to Norfolk Island (now an Australian external territory).[24]

The emergence of modern democracy generally began with male citizens obtaining the right to vote in advance of female citizens, except in the Kingdom of Hawai'i, where universal suffrage was introduced in 1840 without mention of sex; however, a constitutional amendment in 1852 rescinded female voting and put property qualifications on male voting.[25]

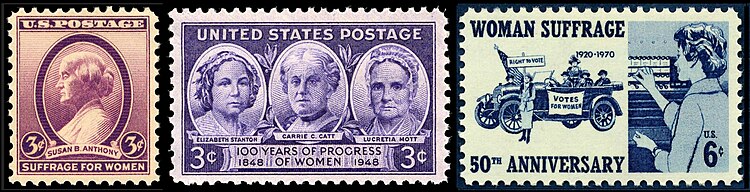

The seed for the first Woman's Rights Convention in the United States in Seneca Falls, New York, was planted in 1840, when Elizabeth Cady Stanton met Lucretia Mott at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. The conference refused to seat Mott and other women delegates from the U.S. because of their sex. In 1851, Stanton met temperance worker Susan B. Anthony, and shortly the two would be joined in the long struggle to secure the vote for women in the U.S. In 1868 Anthony encouraged working women from the printing and sewing trades in New York, who were excluded from men's trade unions, to form Working Women's Associations. As a delegate to the National Labor Congress in 1868, Anthony persuaded the committee on female labor to call for votes for women and equal pay for equal work. The men at the conference deleted the reference to the vote.[26] In the US, women in the Wyoming Territory were permitted to both vote and stand for office in 1869.[27] Subsequent American suffrage groups often disagreed on tactics, with the National American Woman Suffrage Association arguing for a state-by-state campaign and the National Woman's Party focusing on an amendment to the U.S. Constitution.[28][29][30]

The 1840 constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaii established a House of Representatives, but did not specify who was eligible to participate in the election of it. Some academics have argued that this omission enabled women to vote in the first elections, in which votes were cast by means of signatures on petitions; but this interpretation remains controversial.[31] The second constitution of 1852 specified that suffrage was restricted to males over twenty years-old.[25]

In 1849, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, in Italy, was the first European state to have a law that provided for the vote of women, for administrative elections, taking up a tradition that was already informally sometimes present in Italy.

The 1853 Constitution of the province of Vélez in the Republic of New Granada, modern day Colombia, allowed for married women, or women older than the age of 21, the right to vote within the province. However, this law was subsequently annulled by the Supreme Court of the Republic, arguing that the citizens of the province could not have more rights than those already guaranteed to the citizens of the other provinces of the country, thus eliminating female suffrage from this province in 1856.[32][33][34]

In 1881 the Isle of Man, an internally self-governing dependent territory of the British Crown, enfranchised women property owners. With this it provided the first action for women's suffrage within the British Isles.[24]

The Pacific commune of Franceville (now Port Vila, Vanuatu), maintained independence from 1889 to 1890, becoming the first self-governing nation to adopt universal suffrage without distinction of sex or color, although only white males were permitted to hold office.[35]

For countries that have their origins in self-governing colonies but later became independent nations in the 20th century, the Colony of New Zealand was the first to acknowledge women's right to vote in 1893, largely due to a movement led by Kate Sheppard. The British protectorate of Cook Islands rendered the same right in 1893 as well.[36] Another British colony in the same decade, South Australia, followed in 1894, enacting laws which not only extended voting to women, but also made women eligible to stand for election to its parliament at the next vote in 1895.[19]

20th century

[edit]

Following the federation of the British colonies in Australia in 1901, the new federal government enacted the Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902 which allowed female British subjects to vote and stand for election on the same terms as men. However, many indigenous Australians remained excluded from voting federally until 1962.[37]

The first place in Europe to introduce women's suffrage was the Grand Duchy of Finland in 1906, and it also became the first place in continental Europe to implement racially-equal suffrage for women.[7][8] As a result of the 1907 parliamentary elections, Finland's voters elected 19 women as the first female members of a representative parliament. This was one of many self-governing actions in the Russian autonomous province that led to conflict with the Russian governor of Finland, ultimately leading to the creation of the Finnish nation in 1917.

In the years before World War I, women in Norway also won the right to vote. During WWI, Denmark, Russia, Germany, and Poland also recognized women's right to vote.

Canada gave right to vote to some white women in 1917; women getting vote on same basis as men in 1920, that is, men and women of certain races or status being excluded from voting until 1960, when universal adult suffrage was achieved.[38]

The Representation of the People Act 1918 saw British women over 30 gain the vote. Dutch women won the passive vote (allowed to run for parliament) after a revision of the Dutch Constitution in 1917 and the active vote (electing representatives) in 1919, and American women on August 26, 1920, with the passage of the 19th Amendment (the Voting Rights Act of 1965 secured voting rights for racial minorities). Irish women won the same voting rights as men in the Irish Free State constitution, 1922. In 1928, British women won suffrage on the same terms as men, that is, for ages 21 and older. The suffrage of Turkish women was introduced in 1930 for local elections and in 1934 for national elections.

As the 19th Amendment passed and fully gave women the right to the vote, there were other contributors that made this happen. One of which being Alice Paul as she helped sealed the path of this right for women in the 1920s.

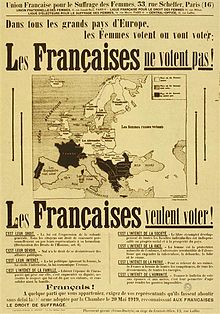

By the time French women were granted the suffrage in July 1944 by Charles de Gaulle's government in exile, by a vote of 51 for, 16 against,[39] France had been for about a decade the only Western country that did not at least allow women's suffrage at municipal elections.[40]

Voting rights for women were introduced into international law by the United Nations' Human Rights Commission, whose elected chair was Eleanor Roosevelt. In 1948 the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; Article 21 stated: "(1) Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives. (3) The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures."

The United Nations General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Political Rights of Women, which went into force in 1954, enshrining the equal rights of women to vote, hold office, and access public services as set out by national laws.

21st century

[edit]One of the most recent jurisdictions to acknowledge women's full right to vote was Bhutan in 2008 (its first national elections).[41] Most recently, King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia let Saudi women vote and run for office for the first time in the 2015 local elections.[42][43]

Suffrage movements

[edit]

The suffrage movement was a broad one, made up of women and men with a wide range of views. In terms of diversity, the greatest achievement of the 20th-century woman suffrage movement was its extremely broad class base.[44] One major division, especially in Britain, was between suffragists, who sought to create change constitutionally, and suffragettes, led by English political activist Emmeline Pankhurst, who in 1903 formed the more militant Women's Social and Political Union.[45] Pankhurst would not be satisfied with anything but action on the question of women's enfranchisement, with "deeds, not words" the organization's motto.[46][47]

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott were the first two women in America to organize the women's rights convention in July 1848. Susan B. Anthony later joined the movement and helped form the National Woman's Suffrage Association (NWSA) in May 1869. Their goal was to change the 15th Amendment because it did not mention nor include women which is why the NWSA protested against it. Around the same time, there was also another group of women who supported the 15th amendment and they called themselves American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). The American Women Suffrage Association was founded by Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe, and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who were more focused on gaining access at a local level.[48] The two groups united became one and called themselves the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).[48]

Throughout the world, the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), which was established in the United States in 1873, campaigned for women's suffrage, in addition to ameliorating the condition of prostitutes.[49][50] Under the leadership of Frances Willard, "the WCTU became the largest women's organization of its day and is now the oldest continuing women's organization in the United States."[51]

There was also a diversity of views on a "woman's place". Suffragist themes often included the notions that women were naturally kinder and more concerned about children and the elderly. As Kraditor shows, it was often assumed that women voters would have a civilizing effect on politics, opposing domestic violence, liquor, and emphasizing cleanliness and community. An opposing theme, Kraditor argues, held that women had the same moral standards. They should be equal in every way and that there was no such thing as a woman's "natural role".[52][53]

For Black women in the United States, achieving suffrage was a way to counter the disfranchisement of the men of their race.[54] Despite this discouragement, black suffragists continued to insist on their equal political rights. Starting in the 1890s, African American women began to assert their political rights aggressively from within their own clubs and suffrage societies.[55] "If white American women, with all their natural and acquired advantages, need the ballot," argued Adella Hunt Logan of Tuskegee, Alabama, "how much more do black Americans, male and female, need the strong defense of a vote to help secure their right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness?"[54]

Explanations for suffrage extensions

[edit]Scholars have proposed different theories for variations in the timing of women's suffrage across countries. These explanations include the activism of social movements, cultural diffusion and normative change, the electoral calculations of political parties, and the occurrence of major wars.[56][57] According to Adam Przeworski, women's suffrage tends to be extended in the aftermath of major wars.[56]

Impact

[edit]Scholars have linked women's suffrage to subsequent economic growth,[58] the rise of the welfare state,[59][60][61] and less interstate conflict.[62]

Timeline

[edit]Timeline of National elections |

|---|

By continent

[edit]Africa

[edit]Egypt

[edit]The struggle for women's suffrage in Egypt first sparked from the nationalist 1919 Revolution in which women of all classes took to the streets in protest against the British occupation. The struggle was led by several Egyptian women's rights pioneers in the first half of the 20th century through protest, journalism, and lobbying, through women's organizations, primarily the Egyptian Feminist Union (EFU). President Gamal Abdel-Nasser supported women's suffrage in 1956 after they were denied the vote under the British occupation.[122]

Liberia

[edit]In 1920, the women's movement organized in the National Liberian Women's Social and Political Movement, who campaigned without success for women's suffrage, followed by the Liberia Women's League and the Liberian Women's Social and Political Movement,[123] and in 1946, limited suffrage was finally introduced for women of the privileged Libero-American elite, and expanded to universal women's suffrage in 1951.[124]

Sierra Leone

[edit]One of the first occasions when women were able to vote was in the elections of the Nova Scotian settlers at Freetown. In the 1792 elections, all heads of household could vote and one-third were ethnic African women.[125]Women won the right to vote in Sierra Leone in 1930.[126]

South Africa

[edit]The campaign for women's suffrage was conducted largely by the Women's Enfranchisement Association of the Union, which was founded in 1911.[127]

The franchise was extended to white women 21 years or older by the Women's Enfranchisement Act, 1930. The first general election at which women could vote was the 1933 election. At that election Leila Reitz (wife of Deneys Reitz) was elected as the first female MP, representing Parktown for the South African Party. The limited voting rights available to non-white men in the Cape Province and Natal (Transvaal and the Orange Free State practically denied all non-whites the right to vote, and had also done so to white foreign nationals when independent in the 1800s) were not extended to women, and were themselves progressively eliminated between 1936 and 1968.

The right to vote for the Transkei Legislative Assembly, established in 1963 for the Transkei bantustan, was granted to all adult citizens of the Transkei, including women. Similar provision was made for the Legislative Assemblies created for other bantustans. All adult coloured citizens were eligible to vote for the Coloured Persons Representative Council, which was established in 1968 with limited legislative powers; the council was however abolished in 1980. Similarly, all adult Indian citizens were eligible to vote for the South African Indian Council in 1981. In 1984 the Tricameral Parliament was established, and the right to vote for the House of Representatives and House of Delegates was granted to all adult Coloured and Indian citizens, respectively.

In 1994 the bantustans and the Tricameral Parliament were abolished and the right to vote for the National Assembly was granted to all adult citizens.

Southern Rhodesia

[edit]Southern Rhodesian white women won the vote in 1919 and Ethel Tawse Jollie (1875–1950) was elected to the Southern Rhodesia legislature 1920–1928, the first woman to sit in any national Commonwealth Parliament outside Westminster. The influx of women settlers from Britain proved a decisive factor in the 1922 referendum that rejected annexation by a South Africa increasingly under the sway of traditionalist Afrikaner Nationalists in favor of Rhodesian Home Rule or "responsible government". Black Rhodesian males qualified for the vote in 1923 (based only upon property, assets, income, and literacy). It is unclear when the first black woman qualified for the vote.

Asia

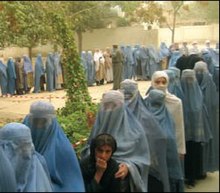

[edit]Afghanistan

[edit]

Women were granted suffrage in 1964,[63][64][65] and have been able to vote in Afghanistan since 1965 (except during Taliban rule, 1996–2001, when no elections were held).[128] As of 2009[update], women have been casting fewer ballots in part due to being unaware of their voting rights.[129] In the 2014 election, Afghanistan's elected president pledged to bring women equal rights.[130]

Bangladesh

[edit]Bangladesh was (mostly) the province of Bengal in British India until 1947 when it became part of Pakistan. It became an independent nation in 1971. Women have had equal suffrage since 1947, and they have reserved seats in parliament. Bangladesh is notable in that since 1991, two women, namely Sheikh Hasina and Begum Khaleda Zia, have served terms as the country's Prime Minister continuously. Women have traditionally played a minimal role in politics beyond the anomaly of the two leaders; few used to run against men; few have been ministers. Recently, however, women have become more active in politics, with several prominent ministerial posts given to women and women participating in national, district and municipal elections against men and winning on several occasions. Choudhury and Hasanuzzaman argue that the strong patriarchal traditions of Bangladesh explain why women are so reluctant to stand up in politics.[131]

China

[edit]The fight for women's suffrage in China was organized when Tang Qunying founded the women's suffrage organization Nüzi chanzheng tongmenghui, to ensure that women's suffrage would be included in the first Constitution drafted after the abolition of the Chinese monarchy in 1911–1912.[132] A short but intense period of campaigning was ended with failure in 1914.

In the following period, local governments in China introduced women's suffrage in their own territories, such as Hunan and Guangdong in 1921 and Sichuan in 1923.[133]

Women's suffrage was included by the Kuomintang Government in the Constitution of 1936,[134] but because of the war, the reform could not be enacted until after the war and was finally introduced in 1947.[134]

India

[edit]Women in India were allowed to vote right from the first general elections after the independence of India in 1947 unlike during the British rule who resisted allowing women to vote.[135] The Women's Indian Association (WIA) was founded in 1917. It sought votes for women and the right to hold legislative office on the same basis as men. These positions were endorsed by the main political groupings, the Indian National Congress.[136] British and Indian feminists combined in 1918 to publish a magazine Stri Dharma that featured international news from a feminist perspective.[137] In 1919 in the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms, the British set up provincial legislatures which had the power to grant women's suffrage. Madras in 1921 granted votes to wealthy and educated women, under the same terms that applied to men. The other provinces followed, but not the princely states (which did not have votes for men either, being monarchies).[136] In Bengal province, the provincial assembly rejected it in 1921 but Southard shows an intense campaign produced victory in 1921. Success in Bengal depended on middle class Indian women, who emerged from a fast-growing urban elite. The women leaders in Bengal linked their crusade to a moderate nationalist agenda, by showing how they could participate more fully in nation-building by having voting power. They carefully avoided attacking traditional gender roles by arguing that traditions could coexist with political modernization.[138]

Whereas wealthy and educated women in Madras were granted voting right in 1921, in Punjab the Sikhs granted women equal voting rights in 1925, irrespective of their educational qualifications or being wealthy or poor. This happened when the Gurdwara Act of 1925 was approved. The original draft of the Gurdwara Act sent by the British to the Sharomani Gurdwara Prabhandak Committee (SGPC) did not include Sikh women, but the Sikhs inserted the clause without the women having to ask for it. Equality of women with men is enshrined in the Guru Granth Sahib, the sacred scripture of the Sikh faith.

In the Government of India Act 1935 the British Raj set up a system of separate electorates and separate seats for women. Most women's leaders opposed segregated electorates and demanded adult franchise. In 1931 the Congress promised universal adult franchise when it came to power. It enacted equal voting rights for both men and women in 1947.[136]

Indonesia

[edit]Indonesia granted women voting rights for municipal councils in 1905. Only men who could read and write could vote, which excluded many non-European males. At the time, the literacy rate for males was 11% and for females 2%. The main group that pressed for women's suffrage in Indonesia was the Dutch Vereeninging voor Vrouwenkiesrecht (VVV-Women's Suffrage Association), founded in the Netherlands in 1894. VVV tried to attract Indonesian members, but had very limited success because the leaders of the organization had little skill in relating to even the educated class of Indonesians. When they eventually did connect somewhat with women, they failed to sympathize with them and ended up alienating many well-educated Indonesians. In 1918, the first national representative body, the Volksraad, was formed which still excluded women from voting. Indigenous women did not organize until the Perikatan Perempuan Indonesia (PPI, Indonesian Women Association) in 1928. In 1935, the colonial administration used its power of nomination to appoint a European woman to the Volksraad. In 1938, women gained the right to be elected to urban representative institutions, which led to some Indonesian and European women entering municipal councils. Eventually, only European women and municipal councils could vote,[clarification needed] excluding all other women and local councils. In September 1941, the Volksraad extended the vote to women of all races. Finally, in November 1941, the right to vote for municipal councils was granted to all women on a similar basis to men (subject to property and educational qualifications).[139]

Iran

[edit]

Women's suffrage had been expressly excluded in the Iranian Constitution of 1906 and a women's rights movement had been organized, which supported women's suffrage.

In 1942, the Women’s party of Iran (Ḥezb-e zanān-e Īrān) was founded to work to introduce the reform, and in 1944, the women's group of the Tudeh Party of Iran, the Democratic Society of Women (Jāmeʿa-ye demokrāt-e zanān) put forward a suggestion of women's suffrage in the Parliament, which was however blocked by the Islamic conservatives.[140] In 1956, a new campaign for women's suffrage was launched by the New Path Society (Jamʿīyat-e rāh-e now), the Association of Women Lawyers (Anjoman-e zanān-e ḥoqūqdān) and the League of Women Supporters of Human Rights (Jamʿīyat-e zanān-e ṭarafdār-e ḥoqūq-e bašar).[140]

After this, the reform was actively supported by the Shah and included as a part of his modernization program, the White Revolution. A referendum in January 1963 overwhelmingly approved by voters gave women the right to vote, a right previously denied to them under the Iranian Constitution of 1906 pursuant to Chapter 2, Article 3.[128][dead link]

Israel

[edit]Women have had full suffrage since the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948.

The first (and as of 2023, the only) woman to be elected Prime Minister of Israel was Golda Meir in 1969.

Japan

[edit]

Although women were allowed to vote in some prefectures in 1880, women's suffrage was enacted at a national level in 1945 with the end of the world war.[141]

The campaign for women's suffrage started in 1923, when the women's umbrella organization Tokyo Rengo Fujinkai was founded and created several sub groups to address different women's issues, one of whom, Fusen Kakutoku Domei (FKD), was to work for the introduction of women's suffrage and political rights.[142] The campaign was gradually reduced due to difficulties in the 1930s fascist era; the FKD was banned after the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese war, and women's suffrage could not be introduced until it was incorporated in the new constitution after the war.[143]

Korea

[edit]South Korean people, including South Korean women, were universally granted the vote in 1948.[144]

Kuwait

[edit]When voting was first introduced in Kuwait in 1985, Kuwaiti women had the right to vote.[145] The right was later removed. In May 2005, the Kuwaiti parliament re-granted female suffrage.[146]

Lebanon

[edit]The women's movement organized in Lebanon with the creation of the Syrian-Lebanese Women's Union in 1924; it split into the Women's Union under Ibtihaj Qaddoura and the Lebanese Women Solidarity Association under Laure Thabet in 1946. The women's movement united again when the two biggest women's organizations, the Lebanese Women's Union and the Christian Women's Solidarity Association created the Lebanese Council of Women in 1952 to campaign for women's suffrage, a task that finally succeeded, after an intense campaign.[147]

Pakistan

[edit]Pakistan was part of British Raj until 1947, when it became independent. Women received full suffrage in 1947. Muslim women leaders from all classes actively supported the Pakistan movement in the mid-1940s. Their movement was led by wives and other relatives of leading politicians. Women were sometimes organized into large-scale public demonstrations.In November 1988, Benazir Bhutto became the first Muslim woman to be elected as prime minister of a Muslim country.[148]

Philippines

[edit]

The Philippines was one of the first countries in Asia to grant women the right to vote.[149] The women's movement organized in the early 20th-century in organizations such as the Asociacion Feminista Filipina (1904) the Society for the Advancement of Women (SAW) and the Asociaction Feminist Ilonga, who campaigned for women's suffrage and other rights for gender equality.[150] Suffrage for Filipinas was achieved following an all-female, special plebiscite held on April 30, 1937. 447,725 – some ninety percent – voted in favour of women's suffrage against 44,307 who voted no. In compliance with the 1935 Constitution, the National Assembly passed a law which extended the right of suffrage to women, which remains to this day.[151][149]

Saudi Arabia

[edit]In late September 2011, King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz al-Saud declared that women would be able to vote and run for office starting in 2015. That applies to the municipal councils, which are the kingdom's only semi-elected bodies. Half of the seats on municipal councils are elective, and the councils have few powers.[152] The council elections have been held since 2005 (the first time they were held before that was the 1960s).[153][154] Saudi women did first vote and first run for office in December 2015, for those councils.[155] Salma bint Hizab al-Oteibi became the first elected female politician in Saudi Arabia in December 2015, when she won a seat on the council in Madrakah in Mecca province.[156] In all, the December 2015 election in Saudi Arabia resulted in twenty women being elected to municipal councils.[157]

The king declared in 2011 that women would be eligible to be appointed to the Shura Council, an unelected body that issues advisory opinions on national policy.[158] '"This is great news," said Saudi writer and women's rights activist Wajeha al-Huwaider. "Women's voices will finally be heard. Now it is time to remove other barriers like not allowing women to drive cars and not being able to function, to live a normal life without male guardians."' Robert Lacey, author of two books about the kingdom, said, "This is the first positive, progressive speech out of the government since the Arab Spring.... First the warnings, then the payments, now the beginnings of solid reform." The king made the announcement in a five-minute speech to the Shura Council.[153] In January 2013, King Abdullah issued two royal decrees, granting women thirty seats on the council, and stating that women must always hold at least a fifth of the seats on the council.[159] According to the decrees, the female council members must be "committed to Islamic Shariah disciplines without any violations" and be "restrained by the religious veil".[159] The decrees also said that the female council members would be entering the council building from special gates, sit in seats reserved for women and pray in special worshipping places.[159] Earlier, officials said that a screen would separate genders and an internal communications network would allow men and women to communicate.[159] Women first joined the council in 2013, holding a total of thirty seats.[160][161] There are two Saudi royal women among these thirty female members of the assembly, Sara bint Faisal Al Saud and Moudi bint Khalid Al Saud.[162] Furthermore, in 2013 three women were named as deputy chairpersons of three committees: Thurayya Obeid was named deputy chairwoman of the human rights and petitions committee, Zainab Abu Talib, deputy chairwoman of the information and cultural committee, and Lubna Al Ansari, deputy chairwoman of the health affairs and environment committee.[160]

Sri Lanka

[edit]In 1931, Sri Lanka (at that time Ceylon) became one of the first Asian countries to allow voting rights to women over the age of 21 without any restrictions. Since then, women have enjoyed a significant presence in the Sri Lankan political arena.

The women's movement organized on Sri Lanka under the Ceylon Women's Union in 1904, and from 1925, the Mallika Kulangana Samitiya and then the Women's Franchise Union (WFU) campaigned successfully for the introduction of women's suffrage, which was achieved in 1931.[163]

The zenith of this favourable condition to women has been the 1960 July General Elections, in which Ceylon elected the world's first female prime minister, Sirimavo Bandaranaike. She became the world's first democratically elected female head of government. Her daughter, Chandrika Kumaratunga also became the Prime Minister later in 1994, and the same year she was elected as the Executive president of Sri Lanka, making her the fourth woman in the world to be elected president, and the first female executive president.

Thailand

[edit]The Ministry of Interior's Local Administrative Act of May 1897 (Phraraachabanyat 1897 [BE 2440]) granted municipal suffrage in the election of village leader to all villagers “whose house or houseboat was located in that village,” and explicitly included women voters who met the qualifications.[164] This was a part of the far-reaching administrative reforms enacted by King Chulalongkorn (r. 1868–1919), in his efforts to protect Thai sovereignty.[164]

In the new constitution introduced after the Siamese revolution of 1932, which transformed Siam from an absolute monarchy to a parliamentary constitutional monarchy, women were granted the right to vote and run for office.[165] This reform was enacted without any prior activism in favor of women's suffrage and was followed by a number of reforms in women's rights, and it has been suggested that the reform was part of an effort by Pridi Bhanomyong to put Thailand on equal political terms with modern Western powers and establish diplomatic recognition by those as a modern nation.[165] The new right was used for the first time in 1933, and the first female MPs were elected in 1949.

Europe

[edit]

In Europe, the last two countries to enact women's suffrage were Switzerland and Liechtenstein. In Switzerland, women gained the right to vote in federal elections in 1971;[166] but in the canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden women obtained the right to vote on local issues only in 1991, when the canton was forced to do so by the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland.[167] In Liechtenstein, women were given the right to vote by the women's suffrage referendum of 1984. Three prior referendums held in 1968, 1971 and 1973 had failed to secure women's right to vote.[168]

Albania

[edit]Albania introduced a limited and conditional form of women's suffrage in 1920, and subsequently provided full voting rights in 1945.[169]

Andorra

[edit]The Principality of Andorra introduced women's suffrage in 1970 (third last in Europa), though Andorra did not have a democratic constitution until 1993.[170]

In 1969, 3708 signatures demanding women's suffrage and eligibility was presented to the Andorra Council Parliament. In April 1970, women's suffrage was introduced after a vote with 10 votes for and eight against, while however eligibility was voted down.[171] Women's eligibility was introduced on 5 September 1973.[171] The first woman became MP in 1984.

Austria

[edit]After the breakdown of the Habsburg monarchy in 1918, Austria granted the general, equal, direct and secret right to vote to all citizens, regardless of sex, through the change of the electoral code in December 1918.[73] The first elections in which women participated were the February 1919 Constituent Assembly elections.[172]

Azerbaijan

[edit]Universal voting rights were recognized in Azerbaijan in 1918 by the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic.[75] Thus, making Azerbaijan the first Muslim-majority country to enfranchise women.[173] This early commitment to women's rights was part of a broader movement towards secularization and modernization in the country.

Belgium

[edit]

A revision of the constitution in October 1921 (it changed art. 47 of the Constitution of Belgium of 1831) introduced the general right to vote according to the "one man, one vote" principle. Art. 47 allowed widows of World War I to vote at the national level as well.[174] The introduction of women's suffrage was already put onto the agenda at the time, by means of including an article in the constitution that allowed approval of women's suffrage by special law (meaning it needed a 2/3 majority to pass).[175] Belgian socialists opposed the women's suffrage, fearing their conservative leanings and their "domination" by the clergy.[176] This happened on March 27, 1948. In Belgium, voting is compulsory.

Bulgaria

[edit]Bulgaria left Ottoman rule in 1878. Although the first adopted constitution, the Tarnovo Constitution (1879), gave women equal election rights, in fact women were disenfranchised, not allowed to vote and to be elected. The Bulgarian Women's Union was an umbrella organization of the 27 local women's organisations that had been established in Bulgaria since 1878. It was founded as a reply to the limitations of women's education and access to university studies in the 1890s, with the goal to further women's intellectual development and participation, arranged national congresses and used Zhenski glas as its organ. However, they had limited success, and women were allowed to vote and to be elected only after when Communist rule was established.

Croatia

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2016) |

Czech Republic

[edit]In the former Bohemia, taxpaying women and women in "learned profession[s]" were allowed to vote by proxy and made eligible to the legislative body in 1864.[177] The first Czech female MP was elected to the Diet of Bohemia in 1912. The Declaration of Independence of the Czechoslovak Nation from October 18, 1918, declared that "our democracy shall rest on universal suffrage. Women shall be placed on equal footing with men, politically, socially, and culturally," and women were appointed to the Revolutionary National Assembly (parliament) on November 13, 1918. On June 15, 1919, women voted in local elections for the first time. Women were guaranteed equal voting rights by the constitution of the Czechoslovak Republic in February 1920 and were able to vote for the parliament for the first time in April 1920.[178]

Cyprus

[edit]Cyprus had no organized women's movement until the mid-20th century and no activism in favor of women's suffrage, which was introduced in the new constitution of 1961 after the liberation from Britain, simply because women's suffrage had at that point came to be regarded as a given thing in international democratic standard.[179]

Denmark

[edit]

In Denmark, the Danish Women's Society (DK) debated, and informally supported, women's suffrage from 1884, but it did not support it publicly until in 1887, when it supported the suggestion of the parliamentarian Fredrik Bajer to grant women municipal suffrage.[180] In 1886, in response to the perceived overcautious attitude of DK in the question of women suffrage, Matilde Bajer founded the Kvindelig Fremskridtsforening (or KF, 1886–1904) to deal exclusively with the right to suffrage, both in municipal and national elections, and it 1887, the Danish women publicly demanded the right for women's suffrage for the first time through the KF. However, as the KF was very much involved with worker's rights and pacifist activity, the question of women's suffrage was in fact not given full attention, which led to the establishment of the strictly women's suffrage movement Kvindevalgretsforeningen (1889–1897).[180] In 1890, the KF and the Kvindevalgretsforeningen united with five women's trade worker's unions to found the De samlede Kvindeforeninger, and through this form, an active women's suffrage campaign was arranged through agitation and demonstration. However, after having been met by compact resistance, the Danish suffrage movement almost discontinued with the dissolution of the De samlede Kvindeforeninger in 1893.[180]

In 1898, an umbrella organization, the Danske Kvindeforeningers Valgretsforbund or DKV was founded and became a part of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA).[180] In 1907, the Landsforbundet for Kvinders Valgret (LKV) was founded by Elna Munch, Johanne Rambusch and Marie Hjelmer in reply to what they considered to be the much too careful attitude of the Danish Women's Society. The LKV originated from a local suffrage association in Copenhagen, and like its rival DKV, it successfully organized other such local associations nationally.[180]

Women won the right to vote in municipal elections on April 20, 1908. However it was not until June 5, 1915 that they were allowed to vote in Rigsdag elections.[181]

Estonia

[edit]Estonia gained its independence in 1918 with the Estonian War of Independence. However, the first official elections were held in 1917. These were the elections of temporary council (i.e. Maapäev), which ruled Estonia from 1917 to 1919. Since then, women have had the right to vote.

The parliament elections were held in 1920. After the elections, two women got into the parliament – history teacher Emma Asson and journalist Alma Ostra-Oinas. Estonian parliament is called Riigikogu and during the First Republic of Estonia it used to have 100 seats.

Finland

[edit]

The area that in 1809 became Finland had been a group of integral provinces of the Kingdom of Sweden for over 600 years. Thus, women in Finland were allowed to vote during the Swedish Age of Liberty (1718–1772), during which conditional suffrage was granted to tax-paying female members of guilds.[182] However, this right was controversial. In Vaasa, there was opposition against women participating in the town hall discussing political issues, as this was not seen as their right place, and women's suffrage appears to have been opposed in practice in some parts of the realm: when Anna Elisabeth Baer and two other women petitioned to vote in Turku in 1771, they were not allowed to do so by town officials.[183]

The predecessor state of modern Finland, the Grand Duchy of Finland, was part of the Russian Empire from 1809 to 1917 and enjoyed a high degree of autonomy. In 1863, taxpaying women were granted municipal suffrage in the countryside, and in 1872, the same reform was implemented in the cities.[177] The issue of women's suffrage was first raised by the women's movement when it organized in the Finnish Women's Association (1884), and the first organization exclusively devoted to the issue of suffrage was Naisasialiitto Unioni (1892).[184]

In 1906, Finland became the first province in the world to implement racially-equal women's suffrage, unlike Australia in 1902. Finland also elected the world's first female members of parliament the following year.[7][8] In 1907, the first general election in Finland that had been open to women took place. Nineteen women were elected which was less than 10% of the total members of parliament. The successful women included Lucina Hagman, Miina Sillanpää, Anni Huotari, Hilja Pärssinen, Hedvig Gebhard, Ida Aalle, Mimmi Kanervo, Eveliina Ala-Kulju, Hilda Käkikoski, Liisi Kivioja, Sandra Lehtinen, Dagmar Neovius, Maria Raunio, Alexandra Gripenberg, Iida Vemmelpuu, Maria Laine, Jenny Nuotio and Hilma Räsänen. Many had expected more. A few women realised that the women of Finland needed to seize this opportunity and organisation and education would be required. Newly elected MPs Lucina Hagman and Maikki Friberg together with Olga Oinola, Aldyth Hultin, Mathilda von Troil, Ellinor Ingman-Ivalo, Sofia Streng and Olga Österberg founded the Finnish Women's Association's first branch in Helsinki.[185] Miina Sillanpää became Finland's first female government minister in 1926.[186]

France

[edit]The April 21, 1944 ordinance of the French Committee of National Liberation, confirmed in October 1944 by the French provisional government, extended the suffrage to French women.[187][188] The first elections with female participation were the municipal elections of April 29, 1945 and the parliamentary elections of October 21, 1945. "Indigenous Muslim" women in French Algeria also known as Colonial Algeria, had to wait until a July 3, 1958, decree.[189][190] Although several countries had started extending suffrage to women from the end of the 19th century, France was one of the last countries to do so in Europe. In fact, the Napoleonic Code declares the legal and political incapacity of women, which blocked attempts to give women political rights.[191] First feminist claims started emerging during the French Revolution in 1789. Condorcet expressed his support for women's right to vote in an article published in Journal de la Société de 1789, but his project failed.[192] After World War I, French women continued demanding political rights, and despite the Chamber of Deputies being in favor, the Senate continuously refused to analyze the law proposal.[192] Socialists, and more generally, the political left repeatedly opposed the right to vote for women because they feared their more conservative preferences and their "domination" by priests.[191][176] It was only after World War II that women were granted political rights.

Georgia

[edit]Upon its declaration of independence on May 26, 1918, in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, the Democratic Republic of Georgia extended suffrage to its female citizens. The women of Georgia first exercised their right to vote in the 1919 legislative election.[193]

Germany

[edit]Women were granted the right to vote and be elected from November 12, 1918. The Weimar Constitution established a "new" Germany after the end of World War I and extended the right to vote to all citizens above the age of 20, with some exceptions.[128]

Greece

[edit]Greece had universal suffrage since its independence in 1832, but this suffrage excluded women. The first proposal to give Greek women the right to vote was made on May 19, 1922, by a member of parliament, supported by then Prime Minister Dimitrios Gounaris, during a constitutional convention.[194] The proposal garnered a narrow majority of those present when it was first proposed, but failed to get the broad 80% support needed to add it to the constitution.[194] In 1925 consultations began again, and a law was passed allowing women the right to vote in local elections, provided they were 30 years of age and had attended at least primary education.[194] The law remained unenforced, until feminist movements within the civil service lobbied the government to enforce it in December 1927 and March 1929.[194] Women were allowed to vote on a local level for the first time in the Thessaloniki local elections, on December 14, 1930, where 240 women exercised their right to do so.[194] Women's turnout remained low, at only around 15,000 in the national local elections of 1934, despite women being a narrow majority of the population of 6.8 million.[194] Women could not stand for election, despite a proposal made by Interior minister Ioannis Rallis, which was contested in the courts; the courts ruled that the law only gave women "a limited franchise" and struck down any lists where women were listed as candidates for local councils.[194] Misogyny was rampant in that era; Emmanuel Rhoides is quoted as having said that "two professions are fit for women: housewife and prostitute". Another misogynistic "argument" employed against women's right to vote was that "during menstruation women are loony and in a frantic psychological state, and since they may be menstruating at the time of the elections, they can't vote".[195]

On a national level women over 18 voted for the first time in April 1944 for the National Council, a legislative body set up by the National Liberation Front resistance movement. Ultimately, women won the legal right to vote and run for office on May 28, 1952. Eleni Skoura, again from Thessaloniki, became the first woman elected to the Hellenic Parliament in 1953, with the conservative Greek Rally, when she won a by-election against another female opponent.[196] Women were finally able to participate in the 1956 election, with two more women becoming members of parliament; Lina Tsaldari, wife of former Prime Minister Panagis Tsaldaris, won the most votes of any candidate in the country and became the first female minister in Greece under the conservative National Radical Union government of Konstantinos Karamanlis.[196]

No woman has been elected Prime Minister of Greece, but Vassiliki Thanou-Christophilou served as the country's first female prime minister, heading a caretaker government, between August 27 and September 21, 2015. The first woman to lead a major political party was Aleka Papariga, who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of Greece from 1991 to 2013.

Hungary

[edit]In Hungary, although it was already planned in 1818,[citation needed] the first occasion when women could vote was the elections held in January 1920.

Iceland

[edit]Iceland was under Danish rule until 1944. Icelandic women acquired full voting rights along with Danish women in 1915.

Ireland

[edit]From 1918, with the rest of the United Kingdom, women in Ireland could vote at age 30 with property qualifications or in university constituencies, while men could vote at age 21 with no qualification. From separation in 1922, the Irish Free State gave equal voting rights to men and women. ["All citizens of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) without distinction of sex, who have reached the age of twenty-one years and who comply with the provisions of the prevailing electoral laws, shall have the right to vote for members of Dáil Eireann, and to take part in the Referendum and Initiative."][197] Promises of equal rights from the Proclamation were embraced in the Constitution in 1922, the year Irish women achieved full voting rights. However, over the next ten years, laws were introduced that eliminated women's rights from serving on juries, working after marriage, and working in industry. The 1937 Constitution and Taoiseach Éamon de Valera’s conservative leadership further stripped women of their previously granted rights.[198] As well, though the 1937 Constitution guarantees women the right to vote and to nationality and citizenship on an equal basis with men, it also contains a provision, Article 41.2, which states:

1° [...] the State recognises that by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved.2° The State shall, therefore, endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.

Isle of Man

[edit]In 1881, The Isle of Man (in the British Isles but not part of the United Kingdom) passed a law giving the vote to single and widowed women who passed a property qualification. This was to vote in elections for the House of Keys, in the Island's parliament, Tynwald. This was extended to universal suffrage for men and women in 1919.[199]

Italy

[edit]In Italy, women's suffrage was not introduced following World War I, but upheld by Socialist and Fascist activists and partly introduced on a local or municipal level by Benito Mussolini's government in 1925.[200] In April 1945, the provisional government led by the Italian Resistance decreed the universal enfranchisement of women in Italy, allowing for the immediate appointment of women to public office, of which the first was Elena Fischli Dreher.[201] In the 1946 election, all Italians simultaneously voted for the Constituent Assembly and for a referendum about keeping Italy a monarchy or creating a republic instead. Elections were not held in the Julian March and South Tyrol because they were under Allied occupation.

The new version of article 51 Constitution recognizes equal opportunities in electoral lists.[202]

Liechtenstein

[edit]- See also Women's suffrage in Liechtenstein

In Liechtenstein, women's suffrage was granted via referendum in 1984.[203]

Luxembourg

[edit]In Luxembourg, Marguerite Thomas-Clement spoke in favour of women suffrage in public debate through articles in the press in 1917–19; however, there was never any organized women suffrage movement in Luxembourg, as women suffrage was included without debate in the new democratic constitution of 1919.

Malta

[edit]Malta was a British colony, but when women's suffrage was finally introduced in Great Britain in 1918, this had not been included in the 1921 Constitution on Malta, when Malta was given its own parliament, although the Labour Party did support the reform.[204] In 1931, Mabel Strickland, assistant secretary of Constitution Party, delivered a petition signed by 428 to the Royal Commission on Maltese Affairs requesting women's suffrage without success.[204]

However, there had been no organized movement for women's suffrage on Malta. In 1944 the Women of Malta Association was founded by Josephine Burns de Bono and Helen Buhagiar. The purpose was to work for the inclusion of women's suffrage in the new Malta constitution, which was to be introduced in 1947 and which was at that time prepared in parliament.[204] The Women of Malta Association was officially registered as a labor union, in order to give its representatives the right to speak in parliament.[204] The Catholic church as well as the Nationalist Party opposed women's suffrage with the argument that suffrage would be an unnecessary burden for women who had family and household to occupy them.[204] The Labour Party as well as the labour movement in general supported the reform.[204] An argument was that women paid taxes and should therefore also vote to decide what to do with them. Women's suffrage was approved with the votes 145 to 137.[204] However, this did not include women's right to be elected to political office, and the Women of Malta Association therefore continued the campaign to include also this right. The debate continued with the same supporters and opponents, and the same arguments for and against, until this right was approved as well.

Women's suffrage and right to be elected to political office were included in the MacMichael Constitution, which was finally introduced on September 5, 1947. A politician at the time commented that the reform had been possible only because of women's participation in the war effort during the World War II.[204]

Monaco

[edit]Monaco introduced women's suffrage in 1962, as the fourth last in Europe. In Monaco, Women's suffrage was not introduced after a long campaign – although supported by the Union of Monegasque Women, itself only founded in 1958[205] – but was introduced as a part of the new Constitution, alongside Parliamentarism, an independent court system and a number of other legal and political reforms.[206]

Netherlands

[edit]

Women were granted the right to vote in the Netherlands on August 9, 1919.[128] In 1917, a constitutional reform already allowed women to be electable. However, even though women's right to vote was approved in 1919, this only took effect from January 1, 1920.

The women's suffrage movement in the Netherlands was led by three women: Aletta Jacobs, Wilhelmina Drucker and Annette Versluys-Poelman. In 1889, Wilhelmina Drucker founded a women's movement called Vrije Vrouwen Vereeniging (Free Women's Union) and it was from this movement that the campaign for women's suffrage in the Netherlands emerged. This movement got a lot of support from other countries, especially from the women's suffrage movement in England. In 1906 the movement wrote an open letter to the Queen pleading for women's suffrage. When this letter was rejected, in spite of popular support, the movement organised several demonstrations and protests in favor of women's suffrage. This movement was of great significance for women's suffrage in the Netherlands.[207]

Norway

[edit]

Liberal politician Gina Krog was the leading campaigner for women's suffrage in Norway from the 1880s. She founded the Norwegian Association for Women's Rights and the National Association for Women's Suffrage to promote this cause. Members of these organisations were politically well-connected and well organised and in a few years gradually succeeded in obtaining equal rights for women. Middle-class women won the right to vote in municipal elections in 1901 and parliamentary elections in 1907. Universal suffrage for women in municipal elections was introduced in 1910, and in 1913 a motion on universal suffrage for women was adopted unanimously by the Norwegian parliament (Stortinget).[208] Norway thus became the first independent country to introduce women's suffrage.[209]

Poland

[edit]Regaining independence in 1918 following the 123-year period of partition and foreign rule,[210] Poland immediately granted women the right to vote and be elected as of November 28, 1918.[128]

The first women elected to the Sejm in 1919 were: Gabriela Balicka, Jadwiga Dziubińska, Irena Kosmowska, Maria Moczydłowska, Zofia Moraczewska, Anna Piasecka, Zofia Sokolnicka, and Franciszka Wilczkowiakowa.[211][212]

Portugal

[edit]Carolina Beatriz Ângelo was the first Portuguese woman to vote, in the Constituent National Assembly election of 1911,[213] taking advantage of a loophole in the country's electoral law.

In 1931, during the Estado Novo regime, women were allowed to vote for the first time, but only if they had a high school or university degree, while men had only to be able to read and write. In 1946 a new electoral law enlarged the possibility of female vote, but still with some differences regarding men. A law from 1968 claimed to establish "equality of political rights for men and women", but a few electoral rights were reserved for men. After the Carnation Revolution, women were granted full and equal electoral rights in 1976.[98][99]

Romania

[edit]The timeline of granting women's suffrage in Romania was gradual and complex, due to the turbulent historical period when it happened. The concept of universal suffrage for all men was introduced in 1918,[214] and reinforced by the 1923 Constitution of Romania. Although this constitution opened the way for the possibility of women's suffrage too (Article 6),[215] this did not materialize: the Electoral Law of 1926 did not grant women the right to vote, maintaining all male suffrage.[216] Starting in 1929, women who met certain qualifications were allowed to vote in local elections.[216] After the Constitution from 1938 (elaborated under Carol II of Romania who sought to implement an authoritarian regime) the voting rights were extended to women for national elections by the Electoral Law 1939,[217] but both women and men had restrictions, and in practice these restrictions affected women more than men (the new restrictions on men also meant that men lost their previous universal suffrage). Although women could vote, they could be elected only to the Senate and not to the Chamber of Deputies (Article 4 (c)).[217] (the Senate was later abolished in 1940). Due to the historical context of the time, which included the dictatorship of Ion Antonescu, there were no elections in Romania between 1940 and 1946. In 1946, Law no. 560 gave full equal rights to men and women to vote and to be elected in the Chamber of Deputies; and women voted in the 1946 Romanian general election.[218] The Constitution of 1948 gave women and men equal civil and political rights (Article 18).[219] Until the collapse of communism in 1989, all the candidates were chosen by the Romanian Communist Party, and civil rights were merely symbolic under this authoritarian regime.[220]

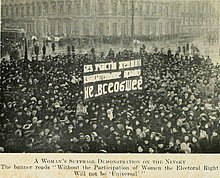

Russia

[edit]Despite initial apprehension against enfranchising women for the right to vote for the upcoming Constituent Assembly election, the League for Women's Equality and other suffragists rallied throughout the year of 1917 for the right to vote. After much pressure (including a 40,000-strong march on the Tauride Palace), on July 20, 1917, the Provisional Government enfranchised women with the right to vote.[221]

San Marino

[edit]San Marino introduced women's suffrage in 1959,[98] following the 1957 constitutional crisis known as Fatti di Rovereta. It was however only in 1973 that women obtained the right to stand for election.[98]

Spain

[edit]

During the Miguel Primo de Rivera regime (1923–1930) only women who were considered heads of household were allowed to vote in local elections, but there were none at that time. Women's suffrage was officially adopted in 1931 despite the opposition of Margarita Nelken and Victoria Kent, two female MPs (both members of the Republican Radical-Socialist Party), who argued that women in Spain at that moment lacked social and political education enough to vote responsibly because they would be unduly influenced by Catholic priests.[176] Most Spanish Republicans at the time held the same view.[176] The other female MP at the time, Clara Campoamor of the liberal Radical Party, was a strong advocate of women's suffrage and she was the one leading the Parliament's affirmative vote. During the Franco regime in the "organic democracy" type of elections called "referendums" (Franco's regime was dictatorial) women over 21 were allowed to vote without distinction.[222] From 1976, during the Spanish transition to democracy women fully exercised the right to vote and be elected to office.

Sweden

[edit]

During the Age of Liberty (1718–1772), Sweden had conditional women's suffrage.[2] Until the reform of 1865, the local elections consisted of mayoral elections in the cities, and elections of parish vicars in the countryside parishes. The Sockenstämma was the local parish council who handled local affairs, in which the parish vicar presided and the local peasantry assembled and voted, an informally regulated process in which women are reported to have participated already in the 17th century.[223] The national elections consisted of the election of the representations to the Riksdag of the Estates.

Suffrage was gender neutral and therefore applied to women as well as men if they filled the qualifications of a voting citizen.[2] These qualifications were changed during the course of the 18th-century, as well as the local interpretation of the credentials, affecting the number of qualified voters: the qualifications also differed between cities and countryside, as well as local or national elections.[2]

Initially, the right to vote in local city elections (mayoral elections) was granted to every burgher, which was defined as a taxpaying citizen with a guild membership.[2] Women as well as men were members of guilds, which resulted in women's suffrage for a limited number of women.[2]In 1734, suffrage in both national and local elections, in cities as well as countryside, was granted to every property owning taxpaying citizen of legal majority.[2] This extended suffrage to all taxpaying property owning women whether guild members or not, but excluded married women and the majority of unmarried women, as married women were defined as legal minors, and unmarried women were minors unless they applied for legal majority by royal dispensation, while widowed and divorced women were of legal majority.[2] The 1734 reform increased the participation of women in elections from 55 to 71 percent.[2]

Between 1726 and 1742, women voted in 17 of 31 examined mayoral elections.[2] Reportedly, some women voters in mayoral elections preferred to appoint a male to vote for them by proxy in the city hall because they found it embarrassing to do so in person, which was cited as a reason to abolish women's suffrage by its opponents.[2] The custom to appoint to vote by proxy was however used also by males, and it was in fact common for men, who were absent or ill during elections, to appoint their wives to vote for them.[2] In Vaasa in Finland (then a Swedish province), there was opposition against women participating in the town hall discussing political issues as this was not seen as their right place, and women's suffrage appears to have been opposed in practice in some parts of the realm: when Anna Elisabeth Baer and two other women petitioned to vote in Åbo in 1771, they were not allowed to do so by town officials.[183]

In 1758, women were excluded from mayoral elections by a new regulation by which they could no longer be defined as burghers, but women's suffrage was kept in the national elections as well as the countryside parish elections.[2] Women participated in all of the eleven national elections held up until 1757.[2] In 1772, women's suffrage in national elections was abolished by demand from the burgher estate. Women's suffrage was first abolished for taxpaying unmarried women of legal majority, and then for widows.[2]However, the local interpretation of the prohibition of women's suffrage varied, and some cities continued to allow women to vote: in Kalmar, Växjö, Västervik, Simrishamn, Ystad, Åmål, Karlstad, Bergslagen, Dalarna and Norrland, women were allowed to continue to vote despite the 1772 ban, while in Lund, Uppsala, Skara, Åbo, Gothenburg and Marstrand, women were strictly barred from the vote after 1772.[2]

While women's suffrage was banned in the mayoral elections in 1758 and in the national elections in 1772, no such bar was ever introduced in the local elections in the countryside, where women therefore continued to vote in the local parish elections of vicars.[2] In a series of reforms in 1813–1817, unmarried women of legal majority, "Unmarried maiden, who has been declared of legal majority", were given the right to vote in the sockestämma (local parish council, the predecessor of the communal and city councils), and the kyrkoråd (local church councils).[224]

In 1823, a suggestion was raised by the mayor of Strängnäs to reintroduce women's suffrage for taxpaying women of legal majority (unmarried, divorced and widowed women) in the mayoral elections, and this right was reintroduced in 1858.[223]

In 1862, tax-paying women of legal majority (unmarried, divorced and widowed women) were again allowed to vote in municipal elections, making Sweden the first country in the world to grant women the right to vote.[177] This was after the introduction of a new political system, where a new local authority was introduced: the communal municipal council. The right to vote in municipal elections applied only to people of legal majority, which excluded married women, as they were juridically under the guardianship of their husbands. In 1884 the suggestion to grant women the right to vote in national elections was initially voted down in Parliament.[225] During the 1880s, the Married Woman's Property Rights Association had a campaign to encourage the female voters, qualified to vote in accordance with the 1862 law, to use their vote and increase the participation of women voters in the elections, but there was yet no public demand for women's suffrage among women. In 1888, the temperance activist Emilie Rathou became the first woman in Sweden to demand the right for women's suffrage in a public speech.[226] In 1899, a delegation from the Fredrika Bremer Association presented a suggestion of women's suffrage to prime minister Erik Gustaf Boström. The delegation was headed by Agda Montelius, accompanied by Gertrud Adelborg, who had written the demand. This was the first time the Swedish women's movement themselves had officially presented a demand for suffrage.

In 1902 the Swedish Society for Woman Suffrage was founded, supported by the Social Democratic women's Clubs.[227] In 1906 the suggestion of women's suffrage was voted down in parliament again.[228] In 1909, the right to vote in municipal elections were extended to also include married women.[229] The same year, women were granted eligibility for election to municipal councils,[229] and in the following 1910–11 municipal elections, forty women were elected to different municipal councils,[228] Gertrud Månsson being the first. In 1914 Emilia Broomé became the first woman in the legislative assembly.[230]

The right to vote in national elections was not returned to women until 1919, and was practiced again in the election of 1921, for the first time in 150 years.[182]

After the 1921 election, the first women were elected to Swedish Parliament after women's suffrage were Kerstin Hesselgren in the Upper chamber and Nelly Thüring (Social Democrat), Agda Östlund (Social Democrat) Elisabeth Tamm (liberal) and Bertha Wellin (Conservative) in the Lower chamber. Karin Kock-Lindberg became the first female government minister, and in 1958, Ulla Lindström became the first acting prime minister.[231]

Switzerland

[edit]A referendum on women's suffrage was held on February 1, 1959. The majority of Switzerland's men (67%) voted against it, but in some French-speaking cantons women obtained the vote.[232] The first Swiss woman to hold political office, Trudy Späth-Schweizer, was elected to the municipal government of Riehen in 1958.[233]

Switzerland was the last Western republic to grant women's suffrage; they gained the right to vote in federal elections in 1971 after a second referendum that year.[232] In 1991 following a decision by the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland, Appenzell Innerrhoden became the last Swiss canton to grant women the vote on local issues.[167]

The first female member of the seven-member Swiss Federal Council, Elisabeth Kopp, served from 1984 to 1989. Ruth Dreifuss, the second female member, served from 1993 to 1999, and was the first female President of the Swiss Confederation for the year 1999. From September 22, 2010, until December 31, 2011, the highest political executive of the Swiss Confederation had a majority of female councillors (4 of 7); for the three years 2010, 2011, and 2012 Switzerland was presided by female presidency for three years in a row; the latest one was for the year 2017.[234]

Turkey

[edit]

In Turkey, Atatürk, the founding president of the republic, led a secularist cultural and legal transformation supporting women's rights including voting and being elected. Women won the right to vote in municipal elections on March 20, 1930. Women's suffrage was achieved for parliamentary elections on December 5, 1934, through a constitutional amendment. Turkish women, who participated in parliamentary elections for the first time on February 8, 1935, obtained 18 seats.

In the early republic, when Atatürk ran a one-party state, his party picked all candidates. A small percentage of seats were set aside for women, so naturally those female candidates won. When multi-party elections began in the 1940s, the share of women in the legislature fell, and the 4% share of parliamentary seats gained in 1935 was not reached again until 1999. In the parliament of 2011, women hold about 9% of the seats. Nevertheless, Turkish women gained the right to vote a decade or more before women in such Western European countries as France, Italy, and Belgium – a mark of Atatürk's far-reaching social changes.[235]

Tansu Çiller served as the 22nd prime minister of Turkey and the first female prime minister of Turkey from 1993 to 1996. She was elected to the parliament in 1991 general elections and she became prime minister on June 25, 1993, when her cabinet was approved by the parliament.

United Kingdom

[edit]

The campaign for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland gained momentum throughout the early part of the 19th century, as women became increasingly politically active, particularly during the campaigns to reform suffrage in the United Kingdom. John Stuart Mill, elected to Parliament in 1865 and an open advocate of female suffrage (about to publish The Subjection of Women), campaigned for an amendment to the Reform Act 1832 to include female suffrage.[236] Roundly defeated in an all-male parliament under a Conservative government, the issue of women's suffrage came to the fore.

Until the 1832 Reform Act specified "male persons", a few women had been able to vote in parliamentary elections through property ownership, although this was rare.[237] In local government elections, women lost the right to vote under the Municipal Corporations Act 1835. Unmarried women ratepayers received the right to vote in the Municipal Franchise Act 1869. This right was confirmed in the Local Government Act 1894 and extended to include some married women.[238][239][240][241] By 1900, more than 1 million women were registered to vote in local government elections in England.[238]

In 1881, the Isle of Man (in the British Isles but not part of the United Kingdom) passed a law giving the vote to single and widowed women who passed a property qualification. This was to vote in elections for the House of Keys, in the Island's parliament, Tynwald. This was extended to universal suffrage for men and women in 1919.[242]

During the later half of the 19th century, a number of campaign groups for women's suffrage in national elections were formed in an attempt to lobby members of parliament and gain support. In 1897, seventeen of these groups came together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), who held public meetings, wrote letters to politicians and published various texts.[243] In 1907 the NUWSS organized its first large procession.[243] This march became known as the Mud March as over 3,000 women trudged through the streets of London from Hyde Park to Exeter Hall to advocate women's suffrage.[244]