Закон об избирательных правах 1965 года

| |

| Длинное название | Закон о принудительном исполнении пятнадцатой поправки к Конституции Соединенных Штатов и для других целей. |

|---|---|

| Сокращения (разговорный) | ПРОСИТЬ |

| Прозвища | Закон об избирательных правах |

| Принят | 89- й Конгресс США |

| Эффективный | 6 августа 1965 г. |

| Цитаты | |

| Публичное право | Паб. L. 89–110 |

| Statutes at Large | 79 Stat. 437 |

| Codification | |

| Titles amended | Title 52—Voting and Elections |

| U.S.C. sections created | |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| Major amendments | |

| |

| United States Supreme Court cases | |

List | |

Закон об избирательных правах 1965 года является знаковым законодательным актом в Соединенных Штатах , который запрещает расовую дискриминацию при голосовании . [ 7 ] [ 8 ] Он был подписан президентом Линдоном Б. Джонсоном в разгар движения за гражданские права 6 августа 1965 года, а позже Конгресс пять раз вносил поправки в закон, чтобы расширить его защиту. [ 7 ] Закон, призванный обеспечить соблюдение избирательных прав, защищенных Четырнадцатой и Пятнадцатой поправками к Конституции Соединенных Штатов , стремился обеспечить право голоса расовым меньшинствам на всей территории страны, особенно на Юге . По данным Министерства юстиции США , этот закон считается наиболее эффективным федеральным законодательством о гражданских правах , когда-либо принятым в стране. [ 9 ] Национальное управление архивов и документации заявило: «Закон об избирательных правах 1965 года стал наиболее значительным законодательным изменением в отношениях между федеральным правительством и правительством штата в области голосования со времен периода реконструкции после гражданской войны ». [ 10 ]

The act contains numerous provisions that regulate elections. The act's "general provisions" provide nationwide protections for voting rights. Section 2 is a general provision that prohibits state and local government from imposing any voting rule that "results in the denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen to vote on account of race or color" or membership in a language minority group.[11] Other general provisions specifically outlaw literacy tests and similar devices that were historically used to disenfranchise racial minorities. The act also contains "special provisions" that apply to only certain jurisdictions. A core special provision is the Section 5 preclearance requirement, which prohibited certain jurisdictions from implementing any change affecting voting without first receiving confirmation from the U.S. attorney general or the U.S. District Court for D.C. that the change does not discriminate against protected minorities.[12] Еще одно специальное положение требует, чтобы юрисдикции, в которых проживает значительное количество языковых меньшинств, предоставляли двуязычные избирательные бюллетени и другие избирательные материалы.

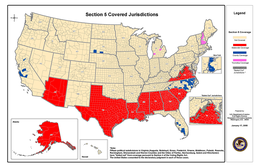

Section 5 and most other special provisions applied to jurisdictions encompassed by the "coverage formula" prescribed in Section 4(b). The coverage formula was originally designed to encompass jurisdictions that engaged in egregious voting discrimination in 1965, and Congress updated the formula in 1970 and 1975. In Shelby County v. Holder (2013), the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the coverage formula as unconstitutional, reasoning that it was obsolete.[13] The court did not strike down Section 5, but without a coverage formula, Section 5 is unenforceable.[14] The jurisdictions which had previously been covered by the coverage formula massively increased the rate of voter registration purges after the Shelby decision.[15]

In 2021, the Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee Supreme Court ruling reinterpreted Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, substantially weakening it.[16][11] The ruling interpreted the "totality of circumstances" language of Section 2 to mean that it does not generally prohibit voting rules that have disparate impact on the groups that it sought to protect, including a rule blocked under Section 5 before the Court inactivated that section in Shelby County v. Holder.[16][11] In particular, the ruling held that fears of election fraud could justify such rules, even without evidence that any such fraud had occurred in the past or that the new rule would make elections safer.[11]

Research shows that the Act had successfully and massively increased voter turnout and voter registrations, in particular among black people.[17][18][19][20] The Act has also been linked to concrete outcomes, such as greater public goods provision (such as public education) for areas with higher black population shares, more members of Congress who vote for civil rights-related legislation, and greater Black representation in local offices.[21][22][23]

Background

[edit]As initially ratified, the United States Constitution granted each state complete discretion to determine voter qualifications for its residents.[24][25]: 50 After the Civil War, the three Reconstruction Amendments were ratified and limited this discretion. The Thirteenth Amendment (1865) prohibits slavery "except as a punishment for crime"; the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) grants citizenship to anyone "born or naturalized in the United States" and guarantees every person due process and equal protection rights; and the Fifteenth Amendment (1870) provides that "[t]he right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude." These Amendments also empower Congress to enforce their provisions through "appropriate legislation".[26]

To enforce the Reconstruction Amendments, Congress passed the Enforcement Acts in the 1870s. The acts criminalized the obstruction of a citizen's voting rights and provided for federal supervision of the electoral process, including voter registration.[27]: 310 However, in 1875 the Supreme Court struck down parts of the legislation as unconstitutional in United States v. Cruikshank and United States v. Reese.[28]: 97 After the Reconstruction Era ended in 1877, enforcement of these laws became erratic, and in 1894, Congress repealed most of their provisions.[27]: 310

Southern states generally sought to disenfranchise racial minorities during and after Reconstruction. From 1868 to 1888, electoral fraud and violence throughout the South suppressed the African-American vote.[29] From 1888 to 1908, Southern states legalized disenfranchisement by enacting Jim Crow laws; they amended their constitutions and passed legislation to impose various voting restrictions, including literacy tests, poll taxes, property-ownership requirements, moral character tests, requirements that voter registration applicants interpret particular documents, and grandfather clauses that allowed otherwise-ineligible persons to vote if their grandfathers voted (which excluded many African Americans whose grandfathers had been slaves or otherwise ineligible).[27][29] During this period, the Supreme Court generally upheld efforts to discriminate against racial minorities. In Giles v. Harris (1903), the court held that regardless of the Fifteenth Amendment, the judiciary did not have the remedial power to force states to register racial minorities to vote.[28]: 100

Prior to the enactment of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 there were several efforts to stop the disenfranchisement of black voters by Southern states,.[7] Besides the above-mentioned literacy tests and poll taxes other bureaucratic restrictions were used to deny them the right to vote. African Americans also "risked harassment, intimidation, economic reprisals, and physical violence when they tried to register or vote. As a result, very few African Americans were registered voters, and they had very little, if any, political power, either locally or nationally."[30] In the 1950s the Civil Rights Movement increased pressure on the federal government to protect the voting rights of racial minorities. In 1957, Congress passed the first civil rights legislation since Reconstruction: the Civil Rights Act of 1957. This legislation authorized the attorney general to sue for injunctive relief on behalf of persons whose Fifteenth Amendment rights were denied, created the Civil Rights Division within the Department of Justice to enforce civil rights through litigation, and created the Commission on Civil Rights to investigate voting rights deprivations. Further protections were enacted in the Civil Rights Act of 1960, which allowed federal courts to appoint referees to conduct voter registration in jurisdictions that engaged in voting discrimination against racial minorities.[9]

Although these acts helped empower courts to remedy violations of federal voting rights, strict legal standards made it difficult for the Department of Justice to successfully pursue litigation. For example, to win a discrimination lawsuit against a state that maintained a literacy test, the department needed to prove that the rejected voter-registration applications of racial minorities were comparable to the accepted applications of whites. This involved comparing thousands of applications in each of the state's counties in a process that could last months. The department's efforts were further hampered by resistance from local election officials, who would claim to have misplaced the voter registration records of racial minorities, remove registered racial minorities from the electoral rolls, and resign so that voter registration ceased. Moreover, the department often needed to appeal lawsuits several times before the judiciary provided relief because many federal district court judges opposed racial minority suffrage. Thus, between 1957 and 1964, the African-American voter registration rate in the South increased only marginally even though the department litigated 71 voting rights lawsuits.[28]: 514 Efforts to stop the disfranchisement by the Southern states had achieved only modest success overall and in some areas had proved almost entirely ineffectual, because the "Department of Justice's efforts to eliminate discriminatory election practices by litigation on a case-by-case basis had been unsuccessful in opening up the registration process; as soon as one discriminatory practice or procedure was proven to be unconstitutional and enjoined, a new one would be substituted in its place and litigation would have to commence anew."[7]

Congress responded to rampant discrimination against racial minorities in public accommodations and government services by passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The act included some voting rights protections; it required registrars to equally administer literacy tests in writing to each voter and to accept applications that contained minor errors, and it created a rebuttable presumption that persons with a sixth-grade education were sufficiently literate to vote.[25]: 97 [31][32] However, despite lobbying from civil rights leaders, the Act did not prohibit most forms of voting discrimination.[33]: 253 President Lyndon B. Johnson recognized this, and shortly after the 1964 elections in which Democrats gained overwhelming majorities in both chambers of Congress, he privately instructed Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach to draft "the goddamndest, toughest voting rights act that you can".[25]: 48–50 However, Johnson did not publicly push for the legislation at the time; his advisers warned him of political costs for vigorously pursuing a voting rights bill so soon after Congress had passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and Johnson was concerned that championing voting rights would endanger his Great Society reforms by angering Southern Democrats in Congress.[25]: 47–48, 50–52

Following the 1964 elections, civil rights organizations such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) pushed for federal action to protect the voting rights of racial minorities.[33]: 254–255 Their efforts culminated in protests in Alabama, particularly in the city of Selma, where County Sheriff Jim Clark's police force violently resisted African-American voter registration efforts. Speaking about the voting rights push in Selma, James Forman of SNCC said: "Our strategy, as usual, was to force the U.S. government to intervene in case there were arrests—and if they did not intervene, that inaction would once again prove the government was not on our side and thus intensify the development of a mass consciousness among blacks. Our slogan for this drive was 'One Man, One Vote.'"[33]: 255

In January 1965, Martin Luther King Jr., James Bevel,[34][35] and other civil rights leaders organized several peaceful demonstrations in Selma, which were violently attacked by police and white counter-protesters. Throughout January and February, these protests received national media coverage and drew attention to the issue of voting rights. King and other demonstrators were arrested during a march on February 1 for violating an anti-parade ordinance; this inspired similar marches in the following days, causing hundreds more to be arrested.[33]: 259–261 On February 4, civil rights leader Malcolm X gave a militant speech in Selma in which he said that many African Americans did not support King's nonviolent approach;[33]: 262 he later privately said that he wanted to frighten whites into supporting King.[25]: 69 The next day, King was released and a letter he wrote addressing voting rights, "Letter From A Selma Jail", appeared in The New York Times.[33]: 262

With increasing national attention focused on Selma and voting rights, President Johnson reversed his decision to delay voting rights legislation. On February 6, he announced he would send a proposal to Congress.[25]: 69 Johnson did not reveal the proposal's content or disclose when it would come before Congress.[33]: 264

On February 18 in Marion, Alabama, state troopers violently broke up a nighttime voting-rights march during which officer James Bonard Fowler shot and killed young African-American protester Jimmie Lee Jackson, who was unarmed and protecting his mother.[33]: 265 [36] Spurred by this event, and at the initiation of Bevel,[33]: 267 [34][35][37]: 81–86 on March 7 SCLC and SNCC began the first of the Selma to Montgomery marches, in which Selma residents intended to march to Alabama's capital, Montgomery, to highlight voting rights issues and present Governor George Wallace with their grievances. On the first march, demonstrators were stopped by state and county police on horseback at the Edmund Pettus Bridge near Selma. The police shot tear gas into the crowd and trampled protesters. Televised footage of the scene, which became known as "Bloody Sunday", generated outrage across the country.[28]: 515 A second march was held on March 9, which became known as "Turnaround Tuesday". That evening, three white Unitarian ministers who participated in the march were attacked on the street and beaten with clubs by four Ku Klux Klan members.[38] The worst injured was Reverend James Reeb from Boston, who died on Thursday, March 11.[39]

In the wake of the events in Selma, President Johnson, addressing a televised joint session of Congress on March 15, called on legislators to enact expansive voting rights legislation. In his speech, he used the words "we shall overcome", adopting the rallying cry of the civil rights movement.[33]: 278 [40] The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was introduced in Congress two days later while civil rights leaders, now under the protection of federal troops, led a march of 25,000 people from Selma to Montgomery.[28]: 516 [33]: 279, 282

Legislative history

[edit]Efforts to eliminate discriminatory election practices by litigation on a case-by-case basis by the United States Department of Justice had been unsuccessful and existing federal anti-discrimination laws were not sufficient to overcome the resistance by state officials to enforcement of the 15th Amendment. Against this backdrop Congress came to the conclusion that a new comprehensive federal bill was necessary to break the grip of state disfranchisement.[7] The United States Supreme Court explained this in South Carolina v. Katzenbach (1966) with the following words:

In recent years, Congress has repeatedly tried to cope with the problem by facilitating case-by-case litigation against voting discrimination. The Civil Rights Act of 1957 authorized the Attorney General to seek injunctions against public and private interference with the right to vote on racial grounds. Perfecting amendments in the Civil Rights Act of 1960 permitted the joinder of States as parties defendant, gave the Attorney General access to local voting records, and authorized courts to register voters in areas of systematic discrimination. Title I of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 expedited the hearing of voting cases before three-judge courts and outlawed some of the tactics used to disqualify Negroes from voting in federal elections. Despite the earnest efforts of the Justice Department and of many federal judges, these new laws have done little to cure the problem of voting discrimination. [...] The previous legislation has proved ineffective for a number of reasons. Voting suits are unusually onerous to prepare, sometimes requiring as many as 6,000 man-hours spent combing through registration records in preparation for trial. Litigation has been exceedingly slow, in part because of the ample opportunities for delay afforded voting officials and others involved in the proceedings. Even when favorable decisions have finally been obtained, some of the States affected have merely switched to discriminatory devices not covered by the federal decrees, or have enacted difficult new tests designed to prolong the existing disparity between white and Negro registration. Alternatively, certain local officials have defied and evaded court orders or have simply closed their registration offices to freeze the voting rolls. The provision of the 1960 law authorizing registration by federal officers has had little impact on local maladministration, because of its procedural complexities.[41]

In South Carolina v. Katzenbach (1966) the Supreme Court also held that Congress had the power to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965 under its Enforcement Powers stemming from the Fifteenth Amendment:

Congress exercised its authority under the Fifteenth Amendment in an inventive manner when it enacted the Voting Rights Act of 1965. First: the measure prescribes remedies for voting discrimination which go into effect without any need for prior adjudication. This was clearly a legitimate response to the problem, for which there is ample precedent under other constitutional provisions. See Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U. S. 294, 379 U. S. 302–304; United States v. Darby, 312 U. S. 100, 312 U. S. 120–121. Congress had found that case-by-case litigation was inadequate to combat widespread and persistent discrimination in voting, because of the inordinate amount of time and energy required to overcome the obstructionist tactics invariably encountered in these lawsuits. After enduring nearly a century of systematic resistance to the Fifteenth Amendment, Congress might well decide to shift the advantage of time and inertia from the perpetrators of the evil to its victims. [...] Second: the Act intentionally confines these remedies to a small number of States and political subdivisions which, in most instances, were familiar to Congress by name. This, too, was a permissible method of dealing with the problem. Congress had learned that substantial voting discrimination presently occurs in certain sections of the country, and it knew no way of accurately forecasting whether the evil might spread elsewhere in the future. In acceptable legislative fashion, Congress chose to limit its attention to the geographic areas where immediate action seemed necessary. See McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U. S. 420, 366 U. S. 427; Salsburg v. Maryland, 346 U. S. 545, 346 U. S. 550–554. The doctrine of the equality of States, invoked by South Carolina, does not bar this approach, for that doctrine applies only to the terms upon which States are admitted to the Union, and not to the remedies for local evils which have subsequently appeared. See Coyle v. Smith, 221 U. S. 559, and cases cited therein.[42]

Original bill

[edit]

Senate

[edit]The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was introduced in Congress on March 17, 1965, as S. 1564, and it was jointly sponsored by Senate majority leader Mike Mansfield (D-MT) and Senate minority leader Everett Dirksen (R-IL), both of whom had worked with Attorney General Katzenbach to draft the bill's language.[43] Although Democrats held two-thirds of the seats in both chambers of Congress after the 1964 Senate elections,[25]: 49 Johnson worried that Southern Democrats would filibuster the legislation because they had opposed other civil rights efforts. He enlisted Dirksen to help gain Republican support. Dirksen did not originally intend to support voting rights legislation so soon after supporting the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but he expressed willingness to accept "revolutionary" legislation after learning about the police violence against marchers in Selma on Bloody Sunday.[25]: 95–96 Given Dirksen's key role in helping Katzenbach draft the legislation, it became known informally as the "Dirksenbach" bill.[25]: 96 After Mansfield and Dirksen introduced the bill, 64 additional senators agreed to cosponsor it,[25]: 150 with a total 46 Democratic and 20 Republican cosponsors.[44]

The bill contained several special provisions that targeted certain state and local governments: a "coverage formula" that determined which jurisdictions were subject to the Act's other special provisions ("covered jurisdictions"); a "preclearance" requirement that prohibited covered jurisdictions from implementing changes to their voting procedures without first receiving approval from the U.S. attorney general or the U.S. District Court for D.C. that the changes were not discriminatory; and the suspension of "tests or devices", such as literacy tests, in covered jurisdictions. The bill also authorized the assignment of federal examiners to register voters, and of federal observers to monitor elections, to covered jurisdictions that were found to have engaged in egregious discrimination. The bill set these special provisions to expire after five years.[27]: 319–320 [28]: 520, 524 [45]: 5–6

The scope of the coverage formula was a matter of contentious congressional debate. The coverage formula reached a jurisdiction if (1) the jurisdiction maintained a "test or device" on November 1, 1964, and (2) less than 50 percent of the jurisdiction's voting-age residents either were registered to vote on November 1, 1964, or cast a ballot in the November 1964 presidential election.[27]: 317 This formula reached few jurisdictions outside the Deep South. To appease legislators who felt that the bill unfairly targeted Southern jurisdictions, the bill included a general prohibition on racial discrimination in voting that applied nationwide.[46]: 1352 The bill also included provisions allowing a covered jurisdiction to "bail out" of coverage by proving in federal court that it had not used a "test or device" for a discriminatory purpose or with a discriminatory effect during the 5 years preceding its bailout request.[45]: 6 Additionally, the bill included a "bail in" provision under which federal courts could subject discriminatory non-covered jurisdictions to remedies contained in the special provisions.[47][48]: 2006–2007

The bill was first considered by the Senate Judiciary Committee, whose chair, Senator James Eastland (D-MS), opposed the legislation with several other Southern senators on the committee. To prevent the bill from dying in committee, Mansfield proposed a motion to require the Judiciary Committee to report the bill out of committee by April 9, which the Senate overwhelmingly passed by a vote of 67 to 13.[25]: 150 [44] During the committee's consideration of the bill, Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA) led an effort to amend the bill to prohibit poll taxes. Although the Twenty-fourth Amendment—which banned the use of poll taxes in federal elections— was ratified a year earlier, Johnson's administration and the bill's sponsors did not include a provision in the voting rights bill banning poll taxes in state elections because they feared courts would strike down the legislation as unconstitutional.[28]: 521 [33]: 285 Additionally, by excluding poll taxes from the definition of "tests or devices", the coverage formula did not reach Texas or Arkansas, mitigating opposition from those two states' influential congressional delegations.[28]: 521 Nonetheless, with the support of liberal committee members, Kennedy's amendment to prohibit poll taxes passed by a 9–4 vote. In response, Dirksen offered an amendment that exempted from the coverage formula any state that had at least 60 percent of its eligible residents registered to vote or that had a voter turnout that surpassed the national average in the preceding presidential election. This amendment, which effectively exempted all states from coverage except Mississippi, passed during a committee meeting in which three liberal members were absent. Dirksen offered to drop the amendment if the poll tax ban were removed. Ultimately, the bill was reported out of committee on April 9 by a 12–4 vote without a recommendation.[25]: 152–153

On April 22, the full Senate started debating the bill. Dirksen spoke first on the bill's behalf, saying that "legislation is needed if the unequivocal mandate of the Fifteenth Amendment ... is to be enforced and made effective, and if the Declaration of Independence is to be made truly meaningful."[25]: 154 Senator Strom Thurmond (D-SC) retorted that the bill would lead to "despotism and tyranny", and Senator Sam Ervin (D-NC) argued that the bill was unconstitutional because it deprived states of their right under Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution to establish voter qualifications and because the bill's special provisions targeted only certain jurisdictions. On May 6, Ervin offered an amendment to abolish the coverage formula's automatic trigger and instead allow federal judges to appoint federal examiners to administer voter registration. This amendment overwhelmingly failed, with 42 Democrats and 22 Republicans voting against it.[25]: 154–156 After lengthy debate, Ted Kennedy's amendment to prohibit poll taxes also failed 49–45 on May 11.[44] However, the Senate agreed to include a provision authorizing the attorney general to sue any jurisdiction, covered or non-covered, to challenge its use of poll taxes.[33]: 156–157 [45]: 2 An amendment offered by Senator Robert F. Kennedy (D-NY) to enfranchise English-illiterate citizens who had attained at least a sixth-grade education in a non-English-speaking school also passed by 48–19. Southern legislators offered a series of amendments to weaken the bill, all of which failed.[25]: 159

On May 25, the Senate voted for cloture by a 70–30 vote, thus overcoming the threat of filibuster and limiting further debate on the bill.[49] On May 26, the Senate passed the bill by a 77–19 vote (Democrats 47–16, Republicans 30–2); only senators representing Southern states voted against it.[25]: 161 [50]

House of Representatives

[edit]Emanuel Celler (D-NY), Chair of the House Judiciary Committee, introduced the Voting Rights Act in the House of Representatives on March 19, 1965, as H.R. 6400.[44] The House Judiciary Committee was the first committee to consider the bill. The committee's ranking Republican, William McCulloch (R-OH), generally supported expanding voting rights, but he opposed both the poll tax ban and the coverage formula, and he led opposition to the bill in committee. The committee eventually approved the bill on May 12, but it did not file its committee report until June 1.[25]: 162 The bill included two amendments from subcommittee: a penalty for private persons who interfered with the right to vote and a prohibition of all poll taxes. The poll tax prohibition gained Speaker of the House John McCormack's support. The bill was next considered by the Rules Committee, whose chair, Howard W. Smith (D-VA), opposed the bill and delayed its consideration until June 24, when Celler initiated proceedings to have the bill discharged from committee.[44] Under pressure from the bill's proponents, Smith allowed the bill to be released a week later, and the full House started debating the bill on July 6.[25]: 163

To defeat the Voting Rights Act, McCulloch introduced an alternative bill, H.R. 7896. It would have allowed the attorney general to appoint federal registrars after receiving 25 serious complaints of discrimination against a jurisdiction, and it would have imposed a nationwide ban on literacy tests for persons who could prove they attained a sixth-grade education. McCulloch's bill was co-sponsored by House minority leader Gerald Ford (R-MI) and supported by Southern Democrats as an alternative to the Voting Rights Act.[25]: 162–164 The Johnson administration viewed H.R. 7896 as a serious threat to passing the Voting Rights Act. However, support for H.R. 7896 dissipated after William M. Tuck (D-VA) publicly said he preferred H.R. 7896 because the Voting Rights Act would legitimately ensure that African Americans could vote. His statement alienated most supporters of H.R. 7896, and the bill failed on the House floor by a 171–248 vote on July 9.[51] Later that night, the House passed the Voting Rights Act by a 333–85 vote (Democrats 221–61, Republicans 112–24).[25]: 163–165 [44][52]

Conference committee

[edit]The chambers appointed a conference committee to resolve differences between the House and Senate versions of the bill. A major contention concerned the poll tax provisions; the Senate version allowed the attorney general to sue states that used poll taxes to discriminate, while the House version outright banned all poll taxes. Initially, the committee members were stalemated. To help broker a compromise, Attorney General Katzenbach drafted legislative language explicitly asserting that poll taxes were unconstitutional and instructed the Department of Justice to sue the states that maintained poll taxes. To assuage concerns of liberal committee members that this provision was not strong enough, Katzenbach enlisted the help of Martin Luther King Jr., who gave his support to the compromise. King's endorsement ended the stalemate, and on July 29, the conference committee reported its version out of committee.[25]: 166–167 The House approved this conference report version of the bill on August 3 by a 328–74 vote (Democrats 217–54, Republicans 111–20),[53] and the Senate passed it on August 4 by a 79–18 vote (Democrats 49–17, Republicans 30–1).[25]: 167 [54][55] On August 6, President Johnson signed the Act into law with King, Rosa Parks, John Lewis, and other civil rights leaders in attendance at the signing ceremony.[25]: 168

Amendments

[edit]

Congress enacted major amendments to the Act in 1970, 1975, 1982, 1992, and 2006. Each amendment coincided with an impending expiration of some or all of the Act's special provisions. Originally set to expire by 1970, Congress repeatedly reauthorized the special provisions in recognition of continuing voting discrimination.[25]: 209–210 [45]: 6–8 Congress extended the coverage formula and special provisions tied to it, such as the Section 5 preclearance requirement, for five years in 1970, seven years in 1975, and 25 years in both 1982 and 2006. In 1970 and 1975, Congress also expanded the reach of the coverage formula by supplementing it with new 1968 and 1972 trigger dates. Coverage was further enlarged in 1975 when Congress expanded the meaning of "tests or devices" to encompass any jurisdiction that provided English-only election information, such as ballots, if the jurisdiction had a single language minority group that constituted more than five percent of the jurisdiction's voting-age citizens. These expansions brought numerous jurisdictions into coverage, including many outside of the South.[56] To ease the burdens of the reauthorized special provisions, Congress liberalized the bailout procedure in 1982 by allowing jurisdictions to escape coverage by complying with the Act and affirmatively acting to expand minority political participation.[28]: 523

In addition to reauthorizing the original special provisions and expanding coverage, Congress amended and added several other provisions to the Act. For instance, Congress expanded the original ban on "tests or devices" to apply nationwide in 1970, and in 1975, Congress made the ban permanent.[45]: 6–9 Separately, in 1975 Congress expanded the Act's scope to protect language minorities from voting discrimination. Congress defined "language minority" to mean "persons who are American Indian, Asian American, Alaskan Natives or of Spanish heritage."[57] Congress amended various provisions, such as the preclearance requirement and Section 2's general prohibition of discriminatory voting laws, to prohibit discrimination against language minorities.[58]: 199 Congress also enacted a bilingual election requirement in Section 203, which requires election officials in certain jurisdictions with large numbers of English-illiterate language minorities to provide ballots and voting information in the language of the language minority group. Originally set to expire after 10 years, Congress reauthorized Section 203 in 1982 for seven years, expanded and reauthorized it in 1992 for 15 years, and reauthorized it in 2006 for 25 years.[59]: 19–21, 25, 49 The bilingual election requirements have remained controversial, with proponents arguing that bilingual assistance is necessary to enable recently naturalized citizens to vote and opponents arguing that the bilingual election requirements constitute costly unfunded mandates.[59]: 26

Several of the amendments responded to judicial rulings with which Congress disagreed. In 1982, Congress amended the Act to overturn the Supreme Court case Mobile v. Bolden (1980), which held that the general prohibition of voting discrimination prescribed in Section 2 prohibited only purposeful discrimination. Congress responded by expanding Section 2 to explicitly ban any voting practice that had a discriminatory effect, regardless of whether the practice was enacted or operated for a discriminatory purpose. The creation of this "results test" shifted the majority of vote dilution litigation brought under the Act from preclearance lawsuits to Section 2 lawsuits.[28]: 644–645 In 2006, Congress amended the Act to overturn two Supreme Court cases: Reno v. Bossier Parish School Board (2000),[60] which interpreted the Section 5 preclearance requirement to prohibit only voting changes that were enacted or maintained for a "retrogressive" discriminatory purpose instead of any discriminatory purpose, and Georgia v. Ashcroft (2003),[61] which established a broader test for determining whether a redistricting plan had an impermissible effect under Section 5 than assessing only whether a minority group could elect its preferred candidates.[62]: 207–208 Since the Supreme Court struck down the coverage formula as unconstitutional in Shelby County v. Holder (2013), several bills have been introduced in Congress to create a new coverage formula and amend various other provisions; none of these bills have passed.[63][64][65]

Provisions

[edit]

The act contains two types of provisions: "general provisions", which apply nationwide, and "special provisions", which apply to only certain states and local governments.[66]: 1 "The Voting Rights Act was aimed at the subtle, as well as the obvious, state regulations which have the effect of denying citizens their right to vote because of their race. Moreover, compatible with the decisions of this Court, the Act gives a broad interpretation to the right to vote, recognizing that voting includes "all action necessary to make a vote effective." 79 Stat. 445, 42 U.S.C. § 19731(c)(1) (1969 ed., Supp. I). See Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U. S. 533, 377 U. S. 555 (1964)."[67] Most provisions are designed to protect the voting rights of racial and language minorities. The term "language minority" means "persons who are American Indian, Asian American, Alaskan Natives or of Spanish heritage."[57] The act's provisions have been colored by numerous judicial interpretations and congressional amendments.

General provisions

[edit]General prohibition of discriminatory voting laws

[edit]Section 2 prohibits any jurisdiction from implementing a "voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure ... in a manner which results in a denial or abridgement of the right ... to vote on account of race," color, or language minority status.[59]: 37 [68] Section 2 of the law contains two separate protections against voter discrimination for laws which, in contrast to Section 5 of the law, are already implemented.[69][70] The first protection is a prohibition of intentional discrimination based on race or color in voting. The second protection is a prohibition of election practices that result in the denial or abridgment of the right to vote based on race or color.[69][70][71][72] If the violation of the second protection is intentional, then this violation is also a violation of the Fifteenth Amendment.[71] The Supreme Court has allowed private plaintiffs to sue to enforce these prohibitions.[73]: 138 [74] In Mobile v. Bolden (1980), the Supreme Court held that as originally enacted in 1965, Section 2 simply restated the Fifteenth Amendment and thus prohibited only those voting laws that were intentionally enacted or maintained for a discriminatory purpose.[75]: 60–61 [76][69][7][77] In 1982, Congress amended Section 2 to create a "results" test,[78] which prohibits any voting law that has a discriminatory effect irrespective of whether the law was intentionally enacted or maintained for a discriminatory purpose.[79][80]: 3 [69][7][77] The 1982 amendments stipulated that the results test does not guarantee protected minorities a right to proportional representation.[81] In Thornburg v. Gingles (1986) the United States Supreme Court explained with respect to the 1982 amendment for section 2 that the "essence of a Section 2 claim is that a certain electoral law, practice, or structure interacts with social and historical conditions to cause an inequality in the opportunities enjoyed by black and white voters to elect their preferred representatives."[82] The United States Department of Justice declared that section 2 is not only a permanent and nationwide-applying prohibition against discrimination in voting to any voting standard, practice, or procedure that results in the denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen to vote on account of race, color, or membership in a language minority group, but also a prohibition for state and local officials to adopt or maintain voting laws or procedures that purposefully discriminate on the basis of race, color, or membership in a language minority group.[82]

The United States Supreme Court expressed its views regarding Section 2 and its amendment from 1982 in Chisom v. Roemer (1991).[83] Under the amended statute, proof of intent is no longer required to prove a § 2 violation. Now plaintiffs can prevail under § 2 by demonstrating that a challenged election practice has resulted in the denial or abridgement of the right to vote based on color or race. Congress not only incorporated the results test in the paragraph that formerly constituted the entire § 2, but also designated that paragraph as subsection (a) and added a new subsection (b) to make clear that an application of the results test requires an inquiry into "the totality of the circumstances." Section 2(a) adopts a results test, thus providing that proof of discriminatory intent is no longer necessary to establish any violation of the section. Section 2(b) provides guidance about how the results test is to be applied.[84] There is a statutory framework to determine whether a jurisdiction's election law violates the general prohibition from Section 2 in its amended form:[85]

Section 2 prohibits voting practices that “result[] in a denial or abridgment of the right * * * to vote on account of race or color [or language-minority status],” and it states that such a result “is established” if a jurisdiction’s “political processes * * * are not equally open” to members of such a group “in that [they] have less opportunity * * * to participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice.” 52 U.S.C. 10301. [...] Subsection (b) states in relevant part: A violation of subsection (a) is established if, based on the totality of circumstances, it is shown that the political processes leading to nomination or election in the State or political subdivision are not equally open to participation by members of a class of citizens protected by subsection (a) in that its members have less opportunity than other members of the electorate to participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice.[86][87]

The Office of the Arizona Attorney general stated with respect to the framework to determine whether a jurisdiction's election law violates the general prohibition from Section 2 in its amended form and the reason for the adoption of Section 2 in its amended form:

To establish a violation of amended Section 2, the plaintiff must prove,“based on the totality of circumstances,” that the State’s “political processes” are “not equally open to participation by members” of a protected class, “in that its members have less opportunity than other members of the electorate to participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice.” § 10301(b). That is the “result” that amended Section 2 prohibits: “less opportunity than other members of the electorate,” viewing the State’s “political processes” as a whole. The new language was crafted as a compromise designed to eliminate the need for direct evidence of discriminatory intent, which is often difficult to obtain, but without embracing an unqualified “disparate impact” test that would invalidate many legitimate voting procedures. S. REP. NO. 97–417, at 28–29, 31–32, 99 (1982)[88][87]

In Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee (2021) the United States Supreme Court introduced the means to review Section 2 challenges.[89][90] The slip opinion stated in its Syllabus section in this regard that "The Court declines in these cases to announce a test to govern all VRA [Section 2] challenges to rules that specify the time, place, or manner for casting ballots. It is sufficient for present purposes to identify certain guideposts that lead to the Court's decision in these cases."[91] The Court laid out these guideposts used to evaluate the state regulations in context of Section 2, which included: the size of the burden created by the rule, the degree which the rule deviates from past practices, the size of the racial imbalance, and the overall level of opportunity afforded voters in considering all election rules.[92][90][72]

When determining whether a jurisdiction's election law violates the general prohibition from Section 2 of the VRA, courts have relied on factors enumerated in the Senate Judiciary Committee report associated with the 1982 amendments ("Senate Factors"), including:[82]

- The history of official discrimination in the jurisdiction that affects the right to vote;

- The degree to which voting in the jurisdiction is racially polarized;

- The extent of the jurisdiction's use of majority vote requirements, unusually large electoral districts, prohibitions on bullet voting, and other devices that tend to enhance the opportunity for voting discrimination;

- Whether minority candidates are denied access to the jurisdiction's candidate slating processes, if any;

- The extent to which the jurisdiction's minorities are discriminated against in socioeconomic areas, such as education, employment, and health;

- Whether overt or subtle racial appeals in campaigns exist;

- The extent to which minority candidates have won elections;

- The degree that elected officials are unresponsive to the concerns of the minority group; and

- Whether the policy justification for the challenged law is tenuous.

The report indicates not all or a majority of these factors need to exist for an electoral device to result in discrimination, and it also indicates that this list is not exhaustive, allowing courts to consider additional evidence at their discretion.[76][81]: 344 [93]: 28–29

No right is more precious in a free country than that of having a voice in the election of those who make the laws under which, as good citizens, we must live. Other rights, even the most basic, are illusory if the right to vote is undermined. Our Constitution leaves no room for classification of people in a way that unnecessarily abridges this right.

— Justice Black on the right to vote as the foundation of democracy in Wesberry v. Sanders (1964).[94]

Section 2 prohibits two types of discrimination: "vote denial", in which a person is denied the opportunity to cast a ballot or to have their vote properly counted, and "vote dilution",[95][96]: 2–6 in which the strength or effectiveness of a person's vote is diminished.[97]: 691–692 Most Section 2 litigation has concerned vote dilution, especially claims that a jurisdiction's redistricting plan or use of at-large/multimember elections prevents minority voters from casting sufficient votes to elect their preferred candidates.[97]: 708–709 An at-large election can dilute the votes cast by minority voters by allowing a cohesive majority group to win every legislative seat in the jurisdiction.[98]: 221 Redistricting plans can be gerrymandered to dilute votes cast by minorities by "packing" high numbers of minority voters into a small number of districts or "cracking" minority groups by placing small numbers of minority voters into a large number of districts.[99]

In Thornburg v. Gingles (1986), the Supreme Court used the term "vote dilution through submergence" to describe claims that a jurisdiction's use of an at-large/multimember election system or gerrymandered redistricting plan diluted minority votes, and it established a legal framework for assessing such claims under Section 2.[a] Under the Gingles test, plaintiffs must show the existence of three preconditions:

- The racial or language minority group "is sufficiently numerous and compact to form a majority in a single-member district";

- The minority group is "politically cohesive" (meaning its members tend to vote similarly); and

- The "majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it ... usually to defeat the minority's preferred candidate."[101]: 50–51

The first precondition is known as the "compactness" requirement and concerns whether a majority-minority district can be created. The second and third preconditions are collectively known as the "racially polarized voting" or "racial bloc voting" requirement, and they concern whether the voting patterns of the different racial groups are different from each other. If a plaintiff proves these preconditions exist, then the plaintiff must additionally show, using the remaining Senate Factors and other evidence, that under the "totality of the circumstances", the jurisdiction's redistricting plan or use of at-large or multimember elections diminishes the ability of the minority group to elect candidates of its choice.[81]: 344–345

Subsequent litigation further defined the contours of these "vote dilution through submergence" claims. In Bartlett v. Strickland (2009),[102] the Supreme Court held that the first Gingles precondition can be satisfied only if a district can be drawn in which the minority group comprises a majority of voting-age citizens. This means that plaintiffs cannot succeed on a submergence claim in jurisdictions where the size of the minority group, despite not being large enough to comprise a majority in a district, is large enough for its members to elect their preferred candidates with the help of "crossover" votes from some members of the majority group.[103][104]: A2 In contrast, the Supreme Court has not addressed whether different protected minority groups can be aggregated to satisfy the Gingles preconditions as a coalition, and lower courts have split on the issue.[b]

The Supreme Court provided additional guidance on the "totality of the circumstances" test in Johnson v. De Grandy (1994).[100] The court emphasized that the existence of the three Gingles preconditions may be insufficient to prove liability for vote dilution through submergence if other factors weigh against such a determination, especially in lawsuits challenging redistricting plans. In particular, the court held that even where the three Gingles preconditions are satisfied, a jurisdiction is unlikely to be liable for vote dilution if its redistricting plan contains a number of majority-minority districts that is proportional to the minority group's population size. The decision thus clarified that Section 2 does not require jurisdictions to maximize the number of majority-minority districts.[110] The opinion also distinguished the proportionality of majority-minority districts, which allows minorities to have a proportional opportunity to elect their candidates of choice, from the proportionality of election results, which Section 2 explicitly does not guarantee to minorities.[100]: 1013–1014

An issue regarding the third Gingles precondition remains unresolved. In Gingles, the Supreme Court split as to whether plaintiffs must prove that the majority racial group votes as a bloc specifically because its members are motivated to vote based on racial considerations and not other considerations that may overlap with race, such as party affiliation. A plurality of justices said that requiring such proof would violate Congress's intent to make Section 2 a "results" test, but Justice White maintained that the proof was necessary to show that an electoral scheme results in racial discrimination.[111]: 555–557 Since Gingles, lower courts have split on the issue.[c]

The right to vote freely for the candidate of one's choice is of the essence of a democratic society, and any restrictions on that right strike at the heart of representative government. And the right of suffrage can be denied by a debasement or dilution of the weight of a citizen's vote just as effectively as by wholly prohibiting the free exercise of the franchise. [...] Undoubtedly, the right of suffrage is a fundamental matter in a free and democratic society. Especially since the right to exercise the franchise in a free and unimpaired manner is preservative of other basic civil and political rights, any alleged infringement of the right of citizens to vote must be carefully and meticulously scrutinized.

— Chief Justice Earl Warren on the right to vote as the foundation of democracy in Reynolds v. Sims (1964).[115]

Although most Section 2 litigation has involved claims of vote dilution through submergence,[97]: 708–709 courts also have addressed other types of vote dilution under this provision. In Holder v. Hall (1994),[116] the Supreme Court held that claims that minority votes are diluted by the small size of a governing body, such as a one-person county commission, may not be brought under Section 2. A plurality of the court reasoned that no uniform, non-dilutive "benchmark" size for a governing body exists, making relief under Section 2 impossible.[117] Another type of vote dilution may result from a jurisdiction's requirement that a candidate be elected by a majority vote. A majority-vote requirement may cause a minority group's candidate of choice, who would have won the election with a simple plurality of votes, to lose after a majority of voters unite behind another candidate in a runoff election. The Supreme Court has not addressed whether such claims may be brought under Section 2, and lower courts have reached different conclusions on the issue.[d]

In addition to claims of vote dilution, courts have considered vote denial claims brought under Section 2. The Supreme Court, in Richardson v. Ramirez (1974),[120] held that felony disenfranchisement laws cannot violate Section 2 because, among other reasons, Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment permits such laws.[28]: 756–757 A federal district court in Mississippi held that a "dual registration" system that requires a person to register to vote separately for state elections and local elections may violate Section 2 if the system has a racially disparate impact in light of the Senate Factors.[28]: 754 [121] Starting in 2013, lower federal courts began to consider various challenges to voter ID laws brought under Section 2.[122]

Specific prohibitions

[edit]The act contains several specific prohibitions on conduct that may interfere with a person's ability to cast an effective vote. One of these prohibitions is prescribed in Section 201, which prohibits any jurisdiction from requiring a person to comply with any "test or device" to register to vote or cast a ballot. The term "test or device" is defined as literacy tests, educational or knowledge requirements, proof of good moral character, and requirements that a person be vouched for when voting.[123] Before the Act's enactment, these devices were the primary tools used by jurisdictions to prevent racial minorities from voting.[124] Originally, the Act suspended tests or devices temporarily in jurisdictions covered by the Section 4(b) coverage formula, but Congress subsequently expanded the prohibition to the entire country and made it permanent.[45]: 6–9 Relatedly, Section 202 prohibits jurisdictions from imposing any "durational residency requirement" that requires persons to have lived in the jurisdiction for more than 30 days before being eligible to vote in a presidential election.[125]: 353

Several further protections for voters are contained in Section 11. Section 11(a) prohibits any person acting under color of law from refusing or failing to allow a qualified person to vote or to count a qualified voter's ballot. Similarly, Section 11(b) prohibits any person from intimidating, harassing, or coercing another person for voting or attempting to vote.[59] Two provisions in Section 11 address voter fraud: Section 11(c) prohibits people from knowingly submitting a false voter registration application to vote in a federal election, and Section 11(e) prohibits voting twice in a federal election.[126][127]: 360

Finally, under Section 208, a jurisdiction may not prevent anyone who is English-illiterate or has a disability from being accompanied into the ballot box by an assistant of the person's choice. The only exceptions are that the assistant may not be an agent of the person's employer or union.[58]: 221

Bail-in

[edit]Section 3(c) contains a "bail-in" or "pocket trigger" process by which jurisdictions that fall outside the coverage formula of Section 4(b) may become subject to preclearance. Under this provision, if a jurisdiction has racially discriminated against voters in violation of the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments, a court may order the jurisdiction to have future changes to its election laws preapproved by the federal government.[48]: 2006–2007 Because courts have interpreted the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to prohibit only intentional discrimination, a court may bail in a jurisdiction only if the plaintiff proves that the jurisdiction enacted or operated a voting practice to purposely discriminate.[48]: 2009

Section 3(c) contains its own preclearance language and differs from Section 5 preclearance in several ways. Unlike Section 5 preclearance, which applies to a covered jurisdiction until such time as the jurisdiction may bail out of coverage under Section 4(a), bailed-in jurisdictions remain subject to preclearance for as long as the court orders. Moreover, the court may require the jurisdiction to preclear only particular types of voting changes. For example, the bail-in of New Mexico in 1984 applied for 10 years and required preclearance of only redistricting plans. This differs from Section 5 preclearance, which requires a covered jurisdiction to preclear all of its voting changes.[48]: 2009–2010 [128]

During the Act's early history, Section 3(c) was little used; no jurisdictions were bailed in until 1975. Between 1975 and 2013, 18 jurisdictions were bailed in, including 16 local governments and the states of Arkansas and New Mexico.[129]: 1a–2a Although the Supreme Court held the Section 4(b) coverage formula unconstitutional in Shelby County v. Holder (2013), it did not hold Section 3(c) unconstitutional. Therefore, jurisdictions may continue to be bailed-in and subjected to Section 3(c) preclearance.[13][130] In the months following Shelby County, courts began to consider requests by the attorney general and other plaintiffs to bail in the states of Texas and North Carolina,[131] and in January 2014 a federal court bailed in Evergreen, Alabama.[132]

A more narrow bail-in process pertaining to federal observer certification is prescribed in Section 3(a). Under this provision, a federal court may certify a non-covered jurisdiction to receive federal observers if the court determines that the jurisdiction violated the voting rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments. Jurisdictions certified to receive federal observers under Section 3(a) are not subject to preclearance.[133]: 236–237

Special provisions

[edit]Coverage formula

[edit]

Section 4(b) contains a "coverage formula" that determines which states and local governments may be subjected to the Act's other special provisions (except for the Section 203(c) bilingual election requirements, which fall under a different formula). Congress intended for the coverage formula to encompass the most pervasively discriminatory jurisdictions. A jurisdiction is covered by the formula if:

- As of November 1, 1964, 1968, or 1972, the jurisdiction used a "test or device" to restrict the opportunity to register and vote; and

- Less than half of the jurisdiction's eligible citizens were registered to vote on November 1, 1964, 1968, or 1972; or less than half of eligible citizens voted in the presidential election of November 1964, 1968, or 1972.

As originally enacted, the coverage formula contained only November 1964 triggering dates; subsequent revisions to the law supplemented it with the additional triggering dates of November 1968 and November 1972, which brought more jurisdictions into coverage.[56] For purposes of the coverage formula, the term "test or device" includes the same four devices prohibited nationally by Section 201—literacy tests, educational or knowledge requirements, proof of good moral character, and requirements that a person be vouched for when voting—and one further device defined in Section 4(f)(3): in jurisdictions where more than five percent of the citizen voting age population are members of a single language minority group, any practice or requirement by which registration or election materials are provided only in English. The types of jurisdictions that the coverage formula applies to include states and "political subdivisions" of states.[58]: 207–208 Section 14(c)(2) defines "political subdivision" to mean any county, parish, or "other subdivision of a State which conducts registration for voting."[134]

As Congress added new triggering dates to the coverage formula, new jurisdictions were brought into coverage. The 1965 coverage formula included the whole of Alabama, Alaska, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Virginia; and some subdivisions (mostly counties) in Arizona, Hawaii, Idaho, and North Carolina.[56] The 1968 coverage resulted in the partial coverage of Alaska, Arizona, California, Connecticut, Idaho, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, and Wyoming. Connecticut, Idaho, Maine, Massachusetts, and Wyoming filed successful "bailout" lawsuits, as also provided by section 4.[56] The 1972 coverage covered the whole of Alaska, Arizona, and Texas, and parts of California, Florida, Michigan, New York, North Carolina, and South Dakota.[56]

The special provisions of the Act were initially due to expire in 1970, and Congress renewed them for another five years. In 1975, the Act's special provisions were extended for another seven years. In 1982, the coverage formula was extended again, this time for 25 years, but no changes were made to the coverage formula, and in 2006, the coverage formula was again extended for 25 years.[56]

Throughout its history, the coverage formula remained controversial because it singled out certain jurisdictions for scrutiny, most of which were in the Deep South. In Shelby County v. Holder (2013), the Supreme Court declared the coverage formula unconstitutional because the criteria used were outdated and thus violated principles of equal state sovereignty and federalism.[13][135][136] The other special provisions that are dependent on the coverage formula, such as the Section 5 preclearance requirement, remain valid law. However, without a valid coverage formula, these provisions are unenforceable.[14][137]

Preclearance requirement

[edit]Section 5[138] requires that covered jurisdictions receive federal approval, known as "preclearance", before implementing changes to their election laws. A covered jurisdiction has the burden of proving that the change does not have the purpose or effect of discriminating on the basis of race or language minority status; if the jurisdiction fails to meet this burden, the federal government will deny preclearance and the jurisdiction's change will not go into effect. The Supreme Court broadly interpreted Section 5's scope in Allen v. State Board of Election (1969),[139] holding that any change in a jurisdiction's voting practices, even if minor, must be submitted for preclearance.[140] The court also held that if a jurisdiction fails to have its voting change precleared, private plaintiffs may sue the jurisdiction in the plaintiff's local district court before a three-judge panel.[e] In these Section 5 "enforcement actions", a court considers whether the jurisdiction made a covered voting change, and if so, whether the change had been precleared. If the jurisdiction improperly failed to obtain preclearance, the court will order the jurisdiction to obtain preclearance before implementing the change. However, the court may not consider the merits of whether the change should be approved.[12][73]: 128–129 [139]: 556 [142]: 23

Jurisdictions may seek preclearance through either an "administrative preclearance" process or a "judicial preclearance" process. If a jurisdiction seeks administrative preclearance, the attorney general will consider whether the proposed change has a discriminatory purpose or effect. After the jurisdiction submits the proposed change, the attorney general has 60 days to interpose an objection to it. The 60-day period may be extended an additional 60 days if the jurisdiction later submits additional information. If the attorney general interposes an objection, then the change is not precleared and may not be implemented.[143]: 90–92 The attorney general's decision is not subject to judicial review,[144] but if the attorney general interposes an objection, the jurisdiction may independently seek judicial preclearance, and the court may disregard the attorney general's objection at its discretion.[28]: 559 If a jurisdiction seeks judicial preclearance, it must file a declaratory judgment action against the attorney general in the U.S. District Court for D.C. A three-judge panel will consider whether the voting change has a discriminatory purpose or effect, and the losing party may appeal directly to the Supreme Court.[145] Private parties may intervene in judicial preclearance lawsuits.[61]: 476–477 [143]: 90

In several cases, the Supreme Court has addressed the meaning of "discriminatory effect" and "discriminatory purpose" for Section 5 purposes. In Beer v. United States (1976),[146] the court held that for a voting change to have a prohibited discriminatory effect, it must result in "retrogression" (backsliding). Under this standard, a voting change that causes discrimination, but does not result in more discrimination than before the change was made, cannot be denied preclearance for having a discriminatory effect.[147]: 283–284 For example, replacing a poll tax with an equally expensive voter registration fee is not a "retrogressive" change because it causes equal discrimination, not more.[148]: 695 Relying on the Senate report for the Act, the court reasoned that the retrogression standard was the correct interpretation of the term "discriminatory effect" because Section 5's purpose is " 'to insure that [the gains thus far achieved in minority political participation] shall not be destroyed through new [discriminatory] procedures' ".[146]: 140–141 The retrogression standard applies irrespective of whether the voting change allegedly causes vote denial or vote dilution.[147]: 311

In 2003, the Supreme Court held in Georgia v. Ashcroft[61] that courts should not determine that a new redistricting plan has a retrogressive effect solely because the plan decreases the number of minority-majority districts. The court emphasized that judges should analyze various other factors under the "totality of the circumstances", such as whether the redistricting plan increases the number of "influence districts" in which a minority group is large enough to influence (but not decide) election outcomes. In 2006, Congress overturned this decision by amending Section 5 to explicitly state that "diminishing the ability [of a protected minority] to elect their preferred candidates of choice denies or abridges the right to vote within the meaning of" Section 5.[149] Uncertainty remains as to what this language precisely means and how courts may interpret it.[28]: 551–552, 916

Before 2000, the "discriminatory purpose" prong of Section 5 was understood to mean any discriminatory purpose, which is the same standard used to determine whether discrimination is unconstitutional. In Reno v. Bossier Parish (Bossier Parish II) (2000),[60] the Supreme Court extended the retrogression standard, holding that for a voting change to have a "discriminatory purpose" under Section 5, the change must have been implemented for a retrogressive purpose. Therefore, a voting change intended to discriminate against a protected minority was permissible under Section 5 so long as the change was not intended to increase existing discrimination.[147]: 277–278 This change significantly reduced the number of instances in which preclearance was denied based on discriminatory purpose. In 2006, Congress overturned Bossier Parish II by amending Section 5 to explicitly define "purpose" to mean "any discriminatory purpose."[62]: 199–200, 207 [150]

Federal examiners and observers

[edit]Until the 2006 amendments to the Act,[59]: 50 Section 6 allowed the appointment of "federal examiners" to oversee certain jurisdictions' voter registration functions. Federal examiners could be assigned to a covered jurisdiction if the attorney general certified that

- The Department of Justice received 20 or more meritorious complaints that the covered jurisdiction denied its residents the right to vote based on race or language minority status; or

- The assignment of federal examiners was otherwise necessary to enforce the voting rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments.[133]: 235–236

Federal examiners had the authority to register voters, examine voter registration applications, and maintain voter rolls.[133]: 237 The goal of the federal examiner provision was to prevent jurisdictions from denying protected minorities the right to vote by engaging in discriminatory behavior in the voter registration process, such as refusing to register qualified applicants, purging qualified voters from the voter rolls, and limiting the hours during which persons could register. Federal examiners were used extensively in the years following the Act's enactment, but their importance waned over time; 1983 was the last year that a federal examiner registered a person to vote. In 2006, Congress repealed the provision.[133]: 238–239

Under the Act's original framework, in any jurisdiction certified for federal examiners, the attorney general could additionally require the appointment of "federal observers". By 2006, the federal examiner provision was used solely as a means to appoint federal observers.[133]: 239 When Congress repealed the federal examiner provision in 2006, Congress amended Section 8 to allow for the assignment of federal observers to jurisdictions that satisfied the same certification criteria that had been used to appoint federal examiners.[59]: 50

Federal observers are tasked with observing poll worker and voter conduct at polling places during an election and observing election officials tabulate the ballots.[133]: 248 The goal of the federal observer provision is to facilitate minority voter participation by deterring and documenting instances of discriminatory conduct in the election process, such as election officials denying qualified minority persons the right to cast a ballot, intimidation or harassment of voters on election day, or improper vote counting.[133]: 231–235 Discriminatory conduct that federal observers document may also serve as evidence in subsequent enforcement lawsuits.[133]: 233 Between 1965 and the Supreme Court's 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder to strike down the coverage formula, the attorney general certified 153 local governments across 11 states.[151] Because of time and resource constraints, federal observers are not assigned to every certified jurisdiction for every election.[133]: 230 Separate provisions allow for a certified jurisdiction to "bail out" of its certification.[151]

Bailout

[edit]Under Section 4(a), a covered jurisdiction may seek exemption from coverage through a process called "bailout."[56] To achieve an exemption, a covered jurisdiction must obtain a declaratory judgment from a three-judge panel of the District Court for D.C. that the jurisdiction is eligible to bail out.[12][56] As originally enacted, a covered jurisdiction was eligible to bail out if it had not used a test or device with a discriminatory purpose or effect during the 5 years preceding its bailout request.[45]: 22, 33–34 Therefore, a jurisdiction that requested to bail out in 1967 would have needed to prove that it had not misused a test or device since at least 1962. Until 1970, this effectively required a covered jurisdiction to prove that it had not misused a test or device since before the Act was enacted five years earlier in 1965,[45]: 6 making it impossible for many covered jurisdictions to bail out.[45]: 27 However, Section 4(a) also prohibited covered jurisdictions from using tests or devices in any manner, discriminatory or otherwise; hence, under the original act, a covered jurisdiction would become eligible for bailout in 1970 by simply complying with this requirement. But in the course of amending the Act in 1970 and 1975 to extend the special provisions, Congress also extended the period of time that a covered jurisdiction must not have misused a test or device to 10 years and then to 17 years, respectively.[45]: 7, 9 These extensions continued the effect of requiring jurisdictions to prove that they had not misused a test or device since before the Act's enactment in 1965.

In 1982, Congress amended Section 4(a) to make bailout easier to achieve in two ways. First, Congress provided that if a state is covered, local governments in that state may bail out even if the state is ineligible to bail out.[56] Second, Congress liberalized the eligibility criteria by replacing the 17-year requirement with a new standard, allowing a covered jurisdiction to bail out by proving that in the 10 years preceding its bailout request:

- The jurisdiction did not use a test or device with a discriminatory purpose or effect;

- No court determined that the jurisdiction denied or abridged the right to vote based on racial or language minority status;

- The jurisdiction complied with the preclearance requirement;

- The federal government did not assign federal examiners to the jurisdiction;

- The jurisdiction abolished discriminatory election practices; and

- The jurisdiction took affirmative steps to eliminate voter intimidation and expand voting opportunities for protected minorities.

Additionally, Congress required jurisdictions seeking bailout to produce evidence of minority registration and voting rates, including how these rates have changed over time and in comparison to the registration and voting rates of the majority. If the court determines that the covered jurisdiction is eligible for bailout, it will enter a declaratory judgment in the jurisdiction's favor. The court will retain jurisdiction for the following 10 years and may order the jurisdiction back into coverage if the jurisdiction subsequently engages in voting discrimination.[45][56][59]: 22–23 [152]

The 1982 amendment to the bailout eligibility standard went into effect on August 5, 1984.[56] Between that date and 2013, 196 jurisdictions bailed out of coverage through 38 bailout actions; in each instance, the attorney general consented to the bailout request.[129]: 54 Between that date and 2009, all jurisdictions that bailed out were located in Virginia.[56] In 2009, a municipal utility jurisdiction in Texas bailed out after the Supreme Court's opinion in Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District No. 1 v. Holder (2009),[153] which held that local governments that do not register voters have the ability to bail out.[154] After this ruling, jurisdictions succeeded in at least 20 bailout actions before the Supreme Court held in Shelby County v. Holder (2013) that the coverage formula was unconstitutional.[129]: 54

Separate provisions allow a covered jurisdiction that has been certified to receive federal observers to bail out of its certification alone. Under Section 13, the attorney general may terminate the certification of a jurisdiction if 1) more than 50 percent of the jurisdiction's minority voting age population is registered to vote, and 2) there is no longer reasonable cause to believe that residents may experience voting discrimination. Alternatively, the District Court for D.C. may order the certification terminated.[133]: 237, 239 [151]

Bilingual election requirements

[edit]Two provisions require certain jurisdictions to provide election materials to voters in multiple languages: Section 4(f)(4) and Section 203(c). A jurisdiction covered by either provision must provide all materials related to an election—such as voter registration materials, ballots, notices, and instructions—in the language of any applicable language minority group residing in the jurisdiction.[58]: 209 Language minority groups protected by these provisions include Asian Americans, Hispanics, Native Americans, and Native Alaskans.[155] Congress enacted the provisions to break down language barriers and combat pervasive language discrimination against the protected groups.[58]: 200, 209

Section 4(f)(4) applies to any jurisdiction encompassed by the Section 4(b) coverage formula where more than five percent of the citizen voting age population are members of a single language minority group. Section 203(c) contains a formula that is separate from the Section 4(b) coverage formula, and therefore jurisdictions covered solely by 203(c) are not subject to the Act's other special provisions, such as preclearance. The Section 203(c) formula encompasses jurisdictions where the following conditions exist:

- A single language minority is present that has an English-illiteracy rate higher than the national average; and

- Either:

- The number of "limited-English proficient" members of the language minority group is at least 10,000 voting-age citizens or large enough to comprise at least five percent of the jurisdiction's voting-age citizen population; or

- The jurisdiction is a political subdivision that contains an Indian reservation, and more than five percent of the jurisdiction's American Indian or Alaska Native voting-age citizens are members of a single language minority and are limited-English proficient.[58]: 223–224

Раздел 203 (b) определяет «ограниченное владение английским языком» как «неспособного говорить или понимать английский язык достаточно адекватно, чтобы участвовать в избирательном процессе». [58]: 223 Определение того, какие юрисдикции удовлетворяют критериям раздела 203 (c), происходит один раз в десять лет после завершения десятилетней переписи населения; в это время в действие могут вступить новые юрисдикции, в то время как действие других юрисдикций может быть прекращено. Кроме того, в соответствии с разделом 203(d) юрисдикция может «отказаться» от действия раздела 203(c), доказав в федеральном суде, что ни в одной группе языковых меньшинств в пределах юрисдикции уровень неграмотности по английскому языку не превышает национальный уровень неграмотности. [ 58 ] : 226 После переписи 2010 года 150 юрисдикций в 25 штатах подпадали под действие раздела 203(c), включая охват штатов Калифорнии, Техаса и Флориды. [ 156 ]

Влияние

[ редактировать ]