Моисей

Моисей | |

|---|---|

Моза | |

Моисей с таблетками закона (1624) Гвидо Рене | |

| Born | |

| Died | |

| Nationality | Egyptian Israelite |

| Known for | Law of Moses and Torah Important prophet in Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Baháʼí Faith, Druze Faith, Rastafari, and Samaritanism |

| Spouse(s) | Zipporah Unnamed Cushite woman[1] |

| Children | |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | |

Моисей [ Примечание 1 ] был еврейским пророком, учителем и лидером, [ 2 ] Согласно Авраамической традиции. Он считается самым важным пророком в иудаизме [ 3 ] [ 4 ] и самаританство и один из самых важных пророков в христианстве , исламе , вере Бахаʼ и других религиях Авраама . По словам Библии , и Корана , [ 5 ] Моисей был лидером израильтян и законодателя , ( первые пять которым приписывается пророческое авторство Торы книг Библии). [ 6 ]

Согласно книге Исход , Моисей родился в то время, когда его народ, израильтяне, порабощенное меньшинство, увеличивались в населении, и, как следствие, египетский фараон обеспокоен, что они могут объединиться с . врагами Египта [ 7 ] Еврейская мать Моисея, Джохебед , тайно спрятала его, когда фараон приказал убить всех новорожденных ивритских мальчиков, чтобы уменьшить население израильтян. Через дочь фараона ребенок был усыновлен в качестве подкидыша из Нила и вырос с египетской королевской семьей. После убийства египетского рабовладельческого мастера, который избивал иврит, Моисей бежал через Красное море в Мидиайан , где он столкнулся с ангелом Господа , [8] Говоря с ним из горящего куста на горе Хореб , которую он считал горой Божьей.

God sent Moses back to Egypt to demand the release of the Israelites from slavery. Moses said that he could not speak eloquently,[9] so God allowed Aaron, his elder brother,[10] to become his spokesperson. After the Ten Plagues, Moses led the Exodus of the Israelites out of Egypt and across the Red Sea, after which they based themselves at Mount Sinai, where Moses received the Ten Commandments. After 40 years of wandering in the desert, Moses died on Mount Nebo at the age of 120, within sight of the Promised Land.[11]

The majority of scholars see the biblical Moses as a legendary figure, while retaining the possibility that Moses or a Moses-like figure existed in the 13th century BCE.[12][13][14][15][16] Rabbinical Judaism calculated a lifespan of Moses corresponding to 1391–1271 BCE;[17] Jerome suggested 1592 BCE,[18] and James Ussher suggested 1571 BCE as his birth year.[19][note 2] The Egyptian name "Moses" is mentioned in ancient Egyptian literature.[22][23] In the writing of Jewish historian Josephus, ancient Egyptian historian Manetho is quoted writing of a treasonous ancient Egyptian priest, Osarseph, who renamed himself Moses and led a successful coup against the presiding pharaoh, subsequently ruling Egypt for years until the pharaoh regained power and expelled Osarseph and his supporters.[24][25][26]

Moses has often been portrayed in Christian art and literature, for instance in Michelangelo's Moses and in works at a number of US government buildings. In the medieval and Renaissance period, he is frequently shown as having small horns, as the result of a mistranslation in the Latin Vulgate bible, which nevertheless at times could reflect Christian ambivalence or have overtly antisemitic connotations.

Etymology of name

The Egyptian root msy ('child of') or mose has been considered as a possible etymology,[27] arguably an abbreviation of a theophoric name with the god’s name omitted. The suffix mose appears in Egyptian pharaohs’ names like Thutmose ('born of Thoth') and Ramose ('born of Ra').[28] One of the Egyptian names of Ramesses was Ra-mesesu mari-Amon, meaning “born of Ra, beloved of Amon” (he was also called Usermaatre Setepenre, meaning “Keeper of light and harmony, strong in light, elect of Re”). Linguist Abraham Yahuda, based on the spelling given in the Tanakh, argues that it combines "water" or "seed" and "pond, expanse of water," thus yielding the sense of "child of the Nile" (mw-š).[29]

The biblical account of Moses' birth provides him with a folk etymology to explain the ostensible meaning of his name.[28][30] He is said to have received it from the Pharaoh's daughter: "he became her son. She named him Moses [מֹשֶׁה, Mōše], saying, 'I drew him out [מְשִׁיתִֽהוּ, mǝšīṯīhū] of the water'."[31][32] This explanation links it to the Semitic root משׁה, m-š-h, meaning "to draw out".[32][33] The eleventh-century Tosafist Isaac b. Asher haLevi noted that the princess names him the active participle 'drawer-out' (מֹשֶׁה, mōše), not the passive participle 'drawn-out' (נִמְשֶׁה, nīmše), in effect prophesying that Moses would draw others out (of Egypt); this has been accepted by some scholars.[34][35]

The Hebrew etymology in the Biblical story may reflect an attempt to cancel out traces of Moses' Egyptian origins.[35] The Egyptian character of his name was recognized as such by ancient Jewish writers like Philo and Josephus.[35] Philo linked Moses' name (Ancient Greek: Μωϋσῆς, romanized: Mōysēs, lit. 'Mōusês') to the Egyptian (Coptic) word for 'water' (môu, μῶυ), in reference to his finding in the Nile and the biblical folk etymology.[note 3] Josephus, in his Antiquities of the Jews, claims that the second element, -esês, meant 'those who are saved'. The problem of how an Egyptian princess (who, according to the Biblical account found in the book of Exodus, gave him the name "Moses") could have known Hebrew puzzled medieval Jewish commentators like Abraham ibn Ezra and Hezekiah ben Manoah. Hezekiah suggested she either converted to the Jewish religion or took a tip from Jochebed (Moses' mother).[36][37][38] The Egyptian princess who named Moses is not named in the book of Exodus. However, she was known to Josephus as Thermutis (identified as Tharmuth),[32] and some within Jewish tradition have tried to identify her with a "daughter of Pharaoh" in 1 Chronicles 4:17 named Bithiah,[39] but others note that this is unlikely since there is no textual indication that this daughter of Pharaoh is the same one who named Moses.[39]

Ibn Ezra gave two possibilities for the name of Moses: he believed that it was either a translation of the Egyptian name instead of a transliteration or that the Pharaoh's daughter was able to speak Hebrew.[40][41]

Kenneth Kitchen argues that the Hebrew etymology is most likely correct, as the sounds in the Hebrew m-š-h do not correspond to the pronunciation of Egyptian msy in the relevant time period.[42]

Biblical narrative

Prophet and deliverer of Israel

The Israelites had settled in the Land of Goshen in the time of Joseph and Jacob, but a new Pharaoh arose who oppressed the children of Israel. At this time Moses was born to his father Amram, son (or descendant) of Kehath the Levite, who entered Egypt with Jacob's household; his mother was Jochebed (also Yocheved), who was kin to Kehath. Moses had one older (by seven years) sister, Miriam, and one older (by three years) brother, Aaron.[44] Pharaoh had commanded that all male Hebrew children born would be drowned in the river Nile, but Moses' mother placed him in an ark and concealed the ark in the bulrushes by the riverbank, where the baby was discovered and adopted by Pharaoh's daughter, and raised as an Egyptian. One day, after Moses had reached adulthood, he killed an Egyptian who was beating a Hebrew. Moses, in order to escape Pharaoh's death penalty, fled to Midian (a desert country south of Judah), where he married Zipporah.[45]

There, on Mount Horeb, God appeared to Moses as a burning bush, revealed to Moses his name YHWH (probably pronounced Yahweh)[46] and commanded him to return to Egypt and bring his chosen people (Israel) out of bondage and into the Promised Land (Canaan).[47][48] During the journey, God tried to kill Moses for failing to circumcise his son,[49] but Zipporah saved his life. Moses returned to carry out God's command, but God caused the Pharaoh to refuse, and only after God had subjected Egypt to ten plagues did Pharaoh relent. Moses led the Israelites to the border of Egypt, but their God hardened the Pharaoh's heart once more, so that he could destroy Pharaoh and his army at the Red Sea Crossing as a sign of his power to Israel and the nations.[50]

After defeating the Amalekites in Rephidim,[51] Moses led the Israelites to Mount Sinai, where he was given the Ten Commandments from God, written on stone tablets. However, since Moses remained a long time on the mountain, some of the people feared that he might be dead, so they made a statue of a golden calf and worshipped it, thus disobeying and angering God and Moses. Moses, out of anger, broke the tablets, and later ordered the elimination of those who had worshiped the golden statue, which was melted down and fed to the idolaters.[52] God again wrote the ten commandments on a new set of tablets. Later at Mount Sinai, Moses and the elders entered into a covenant, by which Israel would become the people of YHWH, obeying his laws, and YHWH would be their god. Moses delivered the laws of God to Israel, instituted the priesthood under the sons of Moses' brother Aaron, and destroyed those Israelites who fell away from his worship. In his final act at Sinai, God gave Moses instructions for the Tabernacle, the mobile shrine by which he would travel with Israel to the Promised Land.[53]

From Sinai, Moses led the Israelites to the Desert of Paran on the border of Canaan. From there he sent twelve spies into the land. The spies returned with samples of the land's fertility but warned that its inhabitants were giants. The people were afraid and wanted to return to Egypt, and some rebelled against Moses and against God. Moses told the Israelites that they were not worthy to inherit the land, and would wander the wilderness for forty years until the generation who had refused to enter Canaan had died, so that it would be their children who would possess the land.[54] Later on, Korah was punished for leading a revolt against Moses.

When the forty years had passed, Moses led the Israelites east around the Dead Sea to the territories of Edom and Moab. There they escaped the temptation of idolatry, conquered the lands of Og and Sihon in Transjordan, received God's blessing through Balaam the prophet, and massacred the Midianites, who by the end of the Exodus journey had become the enemies of the Israelites due to their notorious role in enticing the Israelites to sin against God. Moses was twice given notice that he would die before entry to the Promised Land: in Numbers 27:13,[55] once he had seen the Promised Land from a viewpoint on Mount Abarim, and again in Numbers 31:1[56] once battle with the Midianites had been won.

On the banks of the Jordan River, in sight of the land, Moses assembled the tribes. After recalling their wanderings, he delivered God's laws by which they must live in the land, sang a song of praise and pronounced a blessing on the people, and passed his authority to Joshua, under whom they would possess the land. Moses then went up Mount Nebo, looked over the Promised Land spread out before him, and died, at the age of one hundred and twenty:

So Moses the servant of the LORD died there in the land of Moab according to the word of the LORD. And He buried him in the valley in the land of Moab, opposite Beth-peor; but no man knows his burial place to this day. (Deuteronomy 34:5–6, Amplified Bible)

Lawgiver of Israel

Moses is honoured among Jews today as the "lawgiver of Israel", and he delivers several sets of laws in the course of the four books. The first is the Covenant Code,[57] the terms of the covenant which God offers to the Israelites at Mount Sinai. Embedded in the covenant are the Decalogue (the Ten Commandments, Exodus 20:1–17),[58] and the Book of the Covenant (Exodus 20:22–23:19).[59][60] The entire Book of Leviticus constitutes a second body of law, the Book of Numbers begins with yet another set, and the Book of Deuteronomy another.[citation needed]

Moses has traditionally been regarded as the author of those four books and the Book of Genesis, which together comprise the Torah, the first section of the Hebrew Bible.[61]

Historicity

Scholars hold different opinions on the historicity of Moses.[62][63] For instance, according to William G. Dever, the modern scholarly consensus is that the biblical person of Moses is largely mythical while also holding that "a Moses-like figure may have existed somewhere in the southern Transjordan in the mid-late 13th century B.C." and that "archeology can do nothing" to prove or confirm either way.[63][13] Some scholars, such as Konrad Schmid and Jens Schröter, consider Moses a historical figure.[64] According to Solomon Nigosian, there are actually three prevailing views among biblical scholars: one is that Moses is not a historical figure, another view strives to anchor the decisive role he played in Israelite religion, and a third that argues there are elements of both history and legend from which "these issues are hotly debated unresolved matters among scholars".[62] According to Brian Britt, there is divide amongst scholars when discussing matters on Moses that threatens gridlock.[65] According to the official Torah commentary for Conservative Judaism, it is irrelevant if the historical Moses existed, calling him "the folkloristic, national hero".[66][67]

Jan Assmann argues that it cannot be known if Moses ever lived because there are no traces of him outside tradition.[68] Though the names of Moses and others in the biblical narratives are Egyptian and contain genuine Egyptian elements, no extrabiblical sources point clearly to Moses.[69][70][15] No references to Moses appear in any Egyptian sources prior to the 4th century BCE, long after he is believed to have lived. No contemporary Egyptian sources mention Moses, or the events of Exodus–Deuteronomy, nor has any archaeological evidence been discovered in Egypt or the Sinai wilderness to support the story in which he is the central figure.[71] David Adams Leeming states that Moses is a mythic hero and the central figure in Hebrew mythology.[72] The Oxford Companion to the Bible states that the historicity of Moses is the most reasonable (albeit not unbiased) assumption to be made about him as his absence would leave a vacuum that cannot be explained away.[73] Oxford Biblical Studies states that although few modern scholars are willing to support the traditional view that Moses himself wrote the five books of the Torah, there are certainly those who regard the leadership of Moses as too firmly based in Israel's corporate memory to be dismissed as pious fiction.[15]

The story of Moses' discovery follows a familiar motif in ancient Near Eastern mythological accounts of the ruler who rises from humble origins.[74][75] For example, in the account of the origin of Sargon of Akkad (23rd century BCE):

My mother, the high priestess, conceived; in secret she bore me

She set me in a basket of rushes, with bitumen she sealed my lid

She cast me into the river which rose over me.[76]

Moses' story, like those of the other patriarchs, most likely had a substantial oral prehistory[77][failed verification] (he is mentioned in the Book of Jeremiah[78] and the Book of Isaiah[79]). The earliest mention of him is vague, in the Book of Hosea[80] and his name is apparently ancient, as the tradition found in Exodus gives it a folk etymology.[28][33] Nevertheless, the Torah was completed by combining older traditional texts with newly-written ones.[81] Isaiah,[82] written during the Exile (i.e., in the first half of the 6th century BCE), testifies to tension between the people of Judah and the returning post-Exilic Jews (the "gôlâ"), stating that God is the father of Israel and that Israel's history begins with the Exodus and not with Abraham.[83] The conclusion to be inferred from this and similar evidence (e.g., the Book of Ezra and the Book of Nehemiah) is that the figure of Moses and the story of the Exodus must have been preeminent among the people of Judah at the time of the Exile and after, serving to support their claims to the land in opposition to those of the returning exiles.[83]

A theory developed by Cornelis Tiele in 1872, which has proved influential, argued that Yahweh was a Midianite god, introduced to the Israelites by Moses, whose father-in-law Jethro was a Midianite priest.[84] It was to such a Moses that Yahweh reveals his real name, hidden from the Patriarchs who knew him only as El Shaddai.[85] Against this view is the modern consensus that most of the Israelites were native to Palestine.[86][87][88][89] Martin Noth argued that the Pentateuch uses the figure of Moses, originally linked to legends of a Transjordan conquest, as a narrative bracket or late redactional device to weld together four of the five, originally independent, themes of that work.[90][91] Manfred Görg[92] and Rolf Krauss,[93] the latter in a somewhat sensationalist manner,[94] have suggested that the Moses story is a distortion or transmogrification of the historical pharaoh Amenmose (c. 1200 BCE), who was dismissed from office and whose name was later simplified to msy (Mose). Aidan Dodson regards this hypothesis as "intriguing, but beyond proof".[95] Rudolf Smend argues that the two details about Moses that were most likely to be historical are his name, of Egyptian origin, and his marriage to a Midianite woman, details which seem unlikely to have been invented by the Israelites; in Smend's view, all other details given in the biblical narrative are too mythically charged to be seen as accurate data.[96]

The name King Mesha of Moab has been linked to that of Moses. Mesha also is associated with narratives of an exodus and a conquest, and several motifs in stories about him are shared with the Exodus tale and that regarding Israel's war with Moab (2 Kings 3). Moab rebels against oppression, like Moses, leads his people out of Israel, as Moses does from Egypt, and his first-born son is slaughtered at the wall of Kir-hareseth as the firstborn of Israel are condemned to slaughter in the Exodus story, in what Calvinist theologian Peter Leithart described as "an infernal Passover that delivers Mesha while wrath burns against his enemies".[97]

An Egyptian version of the tale that crosses over with the Moses story is found in Manetho who, according to the summary in Josephus, wrote that a certain Osarseph, a Heliopolitan priest, became overseer of a band of lepers, when Amenophis, following indications by Amenhotep, son of Hapu, had all the lepers in Egypt quarantined in order to cleanse the land so that he might see the gods. The lepers are bundled into Avaris, the former capital of the Hyksos, where Osarseph prescribes for them everything forbidden in Egypt, while proscribing everything permitted in Egypt. They invite the Hyksos to reinvade Egypt, rule with them for 13 years – Osarseph then assumes the name Moses – and are then driven out.[98]

Other Egyptian figures which have been postulated as candidates for a historical Moses-like figure include the princes Ahmose-ankh and Ramose, who were sons of pharaoh Ahmose I, or a figure associated with the family of pharaoh Thutmose III.[99][100] Israel Knohl has proposed to identify Moses with Irsu, a Shasu who, according to Papyrus Harris I and the Elephantine Stele, took power in Egypt with the support of "Asiatics" (people from the Levant) after the death of Queen Twosret; after coming to power, Irsu and his supporters disrupted Egyptian rituals, "treating the gods like the people" and halting offerings to the Egyptian deities. They were eventually defeated and expelled by the new Pharaoh Setnakhte and, while fleeing, they abandoned large quantities of gold and silver they had stolen from the temples.[23]

Hellenistic literature

Non-biblical writings about Jews, with references to the role of Moses, first appear at the beginning of the Hellenistic period, from 323 BCE to about 146 BCE. Shmuel notes that "a characteristic of this literature is the high honour in which it holds the peoples of the East in general and some specific groups among these peoples."[101]

In addition to the Judeo-Roman or Judeo-Hellenic historians Artapanus, Eupolemus, Josephus, and Philo, a few non-Jewish historians including Hecataeus of Abdera (quoted by Diodorus Siculus), Alexander Polyhistor, Manetho, Apion, Chaeremon of Alexandria, Tacitus and Porphyry also make reference to him. The extent to which any of these accounts rely on earlier sources is unknown.[102] Moses also appears in other religious texts such as the Mishnah (c. 200 CE) and the Midrash (200–1200 CE).[103]

The figure of Osarseph in Hellenistic historiography is a renegade Egyptian priest who leads an army of lepers against the pharaoh and is finally expelled from Egypt, changing his name to Moses.[104]

Hecataeus

The earliest existing reference to Moses in Greek literature occurs in the Egyptian history of Hecataeus of Abdera (4th century BCE). All that remains of his description of Moses are two references made by Diodorus Siculus, wherein, writes historian Arthur Droge, he "describes Moses as a wise and courageous leader who left Egypt and colonized Judaea".[105] Among the many accomplishments described by Hecataeus, Moses had founded cities, established a temple and religious cult, and issued laws:

After the establishment of settled life in Egypt in early times, which took place, according to the mythical account, in the period of the gods and heroes, the first ... to persuade the multitudes to use written laws was Mneves, a man not only great of soul but also in his life the most public-spirited of all lawgivers whose names are recorded.[105]

Droge also points out that this statement by Hecataeus was similar to statements made subsequently by Eupolemus.[105]

Artapanus

The Jewish historian Artapanus of Alexandria (2nd century BCE) portrayed Moses as a cultural hero, alien to the Pharaonic court. According to theologian John Barclay, the Moses of Artapanus "clearly bears the destiny of the Jews, and in his personal, cultural and military splendor, brings credit to the whole Jewish people".[106]

Jealousy of Moses' excellent qualities induced Chenephres to send him with unskilled troops on a military expedition to Ethiopia, where he won great victories. After having built the city of Hermopolis, he taught the people the value of the ibis as a protection against the serpents, making the bird the sacred guardian spirit of the city; then he introduced circumcision. After his return to Memphis, Moses taught the people the value of oxen for agriculture, and the consecration of the same by Moses gave rise to the cult of Apis. Finally, after having escaped another plot by killing the assailant sent by the king, Moses fled to Arabia, where he married the daughter of Raguel [Jethro], the ruler of the district.[107]

Artapanus goes on to relate how Moses returns to Egypt with Aaron, and is imprisoned, but miraculously escapes through the name of YHWH in order to lead the Exodus. This account further testifies that all Egyptian temples of Isis thereafter contained a rod, in remembrance of that used for Moses' miracles. He describes Moses as 80 years old, "tall and ruddy, with long white hair, and dignified".[108]

Some historians, however, point out the "apologetic nature of much of Artapanus' work",[109] with his addition of extra-biblical details, such as his references to Jethro: the non-Jewish Jethro expresses admiration for Moses' gallantry in helping his daughters, and chooses to adopt Moses as his son.[110]

Strabo

Strabo, a Greek historian, geographer and philosopher, in his Geographica (c. 24 CE), wrote in detail about Moses, whom he considered to be an Egyptian who deplored the situation in his homeland, and thereby attracted many followers who respected the deity. He writes, for example, that Moses opposed the picturing of the deity in the form of man or animal, and was convinced that the deity was an entity which encompassed everything – land and sea:[111]

35. An Egyptian priest named Moses, who possessed a portion of the country called the Lower Egypt, being dissatisfied with the established institutions there, left it and came to Judaea with a large body of people who worshipped the Divinity. He declared and taught that the Egyptians and Africans entertained erroneous sentiments, in representing the Divinity under the likeness of wild beasts and cattle of the field; that the Greeks also were in error in making images of their gods after the human form. For God [said he] may be this one thing which encompasses us all, land and sea, which we call heaven, or the universe, or the nature of things....

36. By such doctrine Moses persuaded a large body of right-minded persons to accompany him to the place where Jerusalem now stands.[112]

In Strabo's writings of the history of Judaism as he understood it, he describes various stages in its development: from the first stage, including Moses and his direct heirs; to the final stage where "the Temple of Jerusalem continued to be surrounded by an aura of sanctity". Strabo's "positive and unequivocal appreciation of Moses' personality is among the most sympathetic in all ancient literature."[113] His portrayal of Moses is said to be similar to the writing of Hecataeus who "described Moses as a man who excelled in wisdom and courage".[113]

Egyptologist Jan Assmann concludes that Strabo was the historian "who came closest to a construction of Moses' religion as monotheistic and as a pronounced counter-religion." It recognized "only one divine being whom no image can represent ... [and] the only way to approach this god is to live in virtue and in justice."[114]

Tacitus

The Roman historian Tacitus (c. 56–120 CE) refers to Moses by noting that the Jewish religion was monotheistic and without a clear image. His primary work, wherein he describes Jewish philosophy, is his Histories (c. 100), where, according to 18th-century translator and Irish dramatist Arthur Murphy, as a result of the Jewish worship of one God, "pagan mythology fell into contempt".[115] Tacitus states that, despite various opinions current in his day regarding the Jews' ethnicity, most of his sources are in agreement that there was an Exodus from Egypt. By his account, the Pharaoh Bocchoris, suffering from a plague, banished the Jews in response to an oracle of the god Zeus-Amun.

A motley crowd was thus collected and abandoned in the desert. While all the other outcasts lay idly lamenting, one of them, named Moses, advised them not to look for help to gods or men, since both had deserted them, but to trust rather in themselves, and accept as divine the guidance of the first being, by whose aid they should get out of their present plight.[116]

In this version, Moses and the Jews wander through the desert for only six days, capturing the Holy Land on the seventh.[116]

Longinus

The Septuagint, the Greek version of the Hebrew Bible, impressed the pagan author of the famous classical book of literary criticism, On the Sublime, traditionally attributed to Longinus. The date of composition is unknown, but it is commonly assigned to the late 1st century C.E.[117]

The writer quotes Genesis in a "style which presents the nature of the deity in a manner suitable to his pure and great being", but he does not mention Moses by name, calling him 'no chance person' (οὐχ ὁ τυχὼν ἀνήρ) but "the Lawgiver" (θεσμοθέτης, thesmothete) of the Jews, a term that puts him on a par with Lycurgus and Minos.[118] Aside from a reference to Cicero, Moses is the only non-Greek writer quoted in the work; contextually he is put on a par with Homer[110] and he is described "with far more admiration than even Greek writers who treated Moses with respect, such as Hecataeus and Strabo".[119]

Josephus

In Josephus' (37 – c. 100 CE) Antiquities of the Jews, Moses is mentioned throughout. For example, Book VIII Ch. IV, describes Solomon's Temple, also known as the First Temple, at the time the Ark of the Covenant was first moved into the newly built temple:

When King Solomon had finished these works, these large and beautiful buildings, and had laid up his donations in the temple, and all this in the interval of seven years, and had given a demonstration of his riches and alacrity therein; ... he also wrote to the rulers and elders of the Hebrews, and ordered all the people to gather themselves together to Jerusalem, both to see the temple which he had built, and to remove the ark of God into it; and when this invitation of the whole body of the people to come to Jerusalem was everywhere carried abroad, ... The Feast of Tabernacles happened to fall at the same time, which was kept by the Hebrews as a most holy and most eminent feast. So they carried the ark and the tabernacle which Moses had pitched, and all the vessels that were for ministration to the sacrifices of God, and removed them to the temple. ... Now the ark contained nothing else but those two tables of stone that preserved the ten commandments, which God spake to Moses in Mount Sinai, and which were engraved upon them ...[120]

According to Feldman, Josephus also attaches particular significance to Moses' possession of the "cardinal virtues of wisdom, courage, temperance, and justice". He also includes piety as an added fifth virtue. In addition, he "stresses Moses' willingness to undergo toil and his careful avoidance of bribery. Like Plato's philosopher-king, Moses excels as an educator."[121]

Numenius

Numenius, a Greek philosopher who was a native of Apamea, in Syria, wrote during the latter half of the 2nd century CE. Historian Kennieth Guthrie writes that "Numenius is perhaps the only recognized Greek philosopher who explicitly studied Moses, the prophets, and the life of Jesus".[122] He describes his background:

Numenius was a man of the world; he was not limited to Greek and Egyptian mysteries, but talked familiarly of the myths of Brahmins and Magi. It is however his knowledge and use of the Hebrew scriptures which distinguished him from other Greek philosophers. He refers to Moses simply as "the prophet", exactly as for him Homer is the poet. Plato is described as a Greek Moses.[123]

Justin Martyr

The Christian saint and religious philosopher Justin Martyr (103–165 CE) drew the same conclusion as Numenius, according to other experts. Theologian Paul Blackham notes that Justin considered Moses to be "more trustworthy, profound and truthful because he is older than the Greek philosophers."[124] He quotes him:

I will begin, then, with our first prophet and lawgiver, Moses ... that you may know that, of all your teachers, whether sages, poets, historians, philosophers, or lawgivers, by far the oldest, as the Greek histories show us, was Moses, who was our first religious teacher.[124]

Abrahamic religions

Moses | |

|---|---|

Moses striking the rock, 1630 by Pieter de Grebber | |

| Prophet, Saint, Seer, Lawgiver, Apostle to Pharaoh, Reformer, God-seer | |

| Born | Goshen, Lower Egypt |

| Died | Mount Nebo, Moab |

| Venerated in | Christianity Islam Judaism Baháʼí Faith Druze Faith Rastafari Samaritanism |

| Feast | September 4, July 20 and April 14 in Eastern Orthodox Church and Catholic Church |

| Attributes | Ten Commandments (in Christianity and Judaism) |

Judaism

Most of what is known about Moses from the Bible comes from the books of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.[125] The majority of scholars consider the compilation of these books to go back to the Persian period, 538–332 BCE, but based on earlier written and oral traditions.[126][127] There is a wealth of stories and additional information about Moses in the Jewish apocrypha and in the genre of rabbinical exegesis known as Midrash, as well as in the primary works of the Jewish oral law, the Mishnah and the Talmud. Moses is also given a number of bynames in Jewish tradition. The Midrash identifies Moses as one of seven biblical personalities who were called by various names.[128][clarification needed] Moses' other names were Jekuthiel (by his mother), Heber (by his father), Jered (by Miriam), Avi Zanoah (by Aaron), Avi Gedor (by Kohath), Avi Soco (by his wet-nurse), Shemaiah ben Nethanel (by people of Israel).[129] Moses is also attributed the names Toviah (as a first name), and Levi (as a family name) (Vayikra Rabbah 1:3), Heman,[130] Mechoqeiq (lawgiver),[131] and Ehl Gav Ish (Numbers 12:3).[132] In another exegesis, Moses had ascended to the first heaven until the seventh, even visited Paradise and Hell alive, after he saw the divine vision in Mount Horeb.[133]

Jewish historians who lived at Alexandria, such as Eupolemus, attributed to Moses the feat of having taught the Phoenicians their alphabet,[134] similar to legends of Thoth. Artapanus of Alexandria explicitly identified Moses not only with Thoth/Hermes, but also with the Greek figure Musaeus (whom he called "the teacher of Orpheus") and ascribed to him the division of Egypt into 36 districts, each with its own liturgy. He named the princess who adopted Moses as Merris, wife of Pharaoh Chenephres.[135]

Jewish tradition considers Moses to be the greatest prophet who ever lived.[133][136] Despite his importance, Judaism stresses that Moses was a human being, and is therefore not to be worshipped.[citation needed] Only God is worthy of worship in Judaism.[citation needed]

To Orthodox Jews, Moses is called Moshe Rabbenu, 'Eved HaShem, Avi haNeviim zya"a: "Our Leader Moshe, Servant of God, Father of all the Prophets (may his merit shield us, amen)". In the orthodox view, Moses received not only the Torah, but also the revealed (written and oral) and the hidden (the 'hokhmat nistar) teachings, which gave Judaism the Zohar of the Rashbi, the Torah of the Ari haQadosh and all that is discussed in the Heavenly Yeshiva between the Ramhal and his masters.[citation needed]

Arising in part from his age of death (120 years, according to Deuteronomy 34:7) and that "his eye had not dimmed, and his vigor had not diminished", the phrase "may you live to 120" has become a common blessing among Jews (120 is stated as the maximum age for all of Noah's descendants in Genesis 6:3).

Christianity

Moses is mentioned more often in the New Testament than any other Old Testament figure. For Christians, Moses is often a symbol of God's law, as reinforced and expounded on in the teachings of Jesus. New Testament writers often compared Jesus' words and deeds with Moses' to explain Jesus' mission. In Acts 7:39–43, 51–53, for example, the rejection of Moses by the Jews who worshipped the golden calf is likened to the rejection of Jesus by the Jews that continued in traditional Judaism.[137][138]

Moses also figures in several of Jesus' messages. When he met the Pharisee Nicodemus at night in the third chapter of the Gospel of John, he compared Moses' lifting up of the bronze serpent in the wilderness, which any Israelite could look at and be healed, to his own lifting up (by his death and resurrection) for the people to look at and be healed. In the sixth chapter, Jesus responded to the people's claim that Moses provided them manna in the wilderness by saying that it was not Moses, but God, who provided. Calling himself the "bread of life", Jesus stated that he was provided to feed God's people.[139]

Moses, along with Elijah, is presented as meeting with Jesus in all three Synoptic Gospels of the Transfiguration of Jesus in Matthew 17, Mark 9, and Luke 9. In Matthew 23, in what is the first attested use of a phrase referring to this rabbinical usage (the Graeco-Aramaic קתדרא דמשה), Jesus refers to the scribes and the Pharisees, in a passage critical of them, as having seated themselves "on the chair of Moses" (Greek: Ἐπὶ τῆς Μωϋσέως καθέδρας, epì tēs Mōüséōs kathédras)[140][141]

His relevance to modern Christianity has not diminished. Moses is considered to be a saint by several churches; and is commemorated as a prophet in the respective Calendars of Saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Roman Catholic Church, and the Lutheran churches on September 4. In Eastern Orthodox liturgics for September 4, Moses is commemorated as the "Holy Prophet and God-seer Moses, on Mount Nebo".[142][143][note 4] The Orthodox Church also commemorates him on the Sunday of the Forefathers, two Sundays before the Nativity.[145] Moses is also commemorated on July 20 with Aaron, Elias (Elijah) and Eliseus (Elisha)[146] and on April 14 with all saint Sinai monks.[147]

The Armenian Apostolic Church commemorates him as one of the Holy Forefathers in their Calendar of Saints on July 30.[148]

Catholicism

In Catholicism Moses is seen as a type of Jesus Christ. Justus Knecht writes:

Through Moses God instituted the Old Law, on which account he is called the mediator of the Old Law. As such, Moses was a striking type of Jesus Christ, who instituted the New Law. Moses, as a child, was condemned to death by a cruel king, and was saved in a wonderful way; Jesus Christ was condemned by Herod, and also wonderfully saved. Moses forsook the king's court so as to help his persecuted brethren; the Son of God left the glory of heaven to save us sinners. Moses prepared himself in the desert for his vocation, freed his people from slavery, and proved his divine mission by great miracles; Jesus Christ proved by still greater miracles that He was the only begotten Son of God. Moses was the advocate of his people; Jesus was our advocate with His Father on the Cross, and is eternally so in heaven. Moses was the law-giver of his people and announced to them the word of God: Jesus Christ is the supreme law-giver, and not only announced God's word, but is Himself the Eternal Word made flesh. Moses was the leader of the people to the Promised Land: Jesus is our leader on our journey to heaven.[149]

Mormonism

Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (colloquially called Mormons) generally view Moses in the same way that other Christians do. However, in addition to accepting the biblical account of Moses, Mormons include Selections from the Book of Moses as part of their scriptural canon.[150] This book is believed to be the translated writings of Moses and is included in the Pearl of Great Price.[151]

Latter-day Saints are also unique in believing that Moses was taken to heaven without having tasted death (translated). In addition, Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery stated that on April 3, 1836, Moses appeared to them in the Kirtland Temple (located in Kirtland, Ohio) in a glorified, immortal, physical form and bestowed upon them the "keys of the gathering of Israel from the four parts of the earth, and the leading of the ten tribes from the land of the north".[152]

Islam

| Part of a series on |

| Musa |

|---|

|

|

Moses is mentioned more in the Quran than any other individual and his life is narrated and recounted more than that of any other Islamic prophet.[153] Islamically, Moses is described in ways which parallel the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[154] Like Muhammad, Moses is defined in the Quran as both prophet (nabi) and messenger (rasul), the latter term indicating that he was one of those prophets who brought a book and law to his people.[155][156]

Most of the key events in Moses' life which are narrated in the Bible are to be found dispersed through the different chapters (suwar) of the Quran, with a story about meeting the Quranic figure Khidr which is not found in the Bible.[153]

In the Moses' story narrated by the Quran, Jochebed is commanded by God to place Moses in a coffin[157] and cast him on the waters of the Nile, thus abandoning him completely to God's protection.[153][158] The Pharaoh's wife Asiya, not his daughter, found Moses floating in the waters of the Nile. She convinced the Pharaoh to keep him as their son because they were not blessed with any children.[159][160][161]

The Quran's account emphasizes Moses' mission to invite the Pharaoh to accept God's divine message[162] as well as give salvation to the Israelites.[153][163] According to the Quran, Moses encourages the Israelites to enter Canaan, but they are unwilling to fight the Canaanites, fearing certain defeat. Moses responds by pleading to Allah that he and his brother Aaron be separated from the rebellious Israelites, after which the Israelites are made to wander for 40 years.[164]

One of the hadith, or traditional narratives about Muhammad's life, describes a meeting in heaven between Moses and Muhammad, which resulted in Muslims observing 5 daily prayers.[165] Huston Smith says this was "one of the crucial events in Muhammad's life".[166]

According to some Islamic tradition, Moses is buried at Maqam El-Nabi Musa, near Jericho.[167]

Baháʼí Faith

Moses is one of the most important of God's messengers in the Baháʼí Faith, being designated a Manifestation of God.[168] An epithet of Moses in Baháʼí scriptures is the "One Who Conversed with God".[169]

According to the Baháʼí Faith, Bahá'u'lláh, the founder of the faith, is the one who spoke to Moses from the burning bush.[170]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá has highlighted the fact that Moses, like Abraham, had none of the makings of a great man of history, but through God's assistance he was able to achieve many great things. He is described as having been "for a long time a shepherd in the wilderness", of having had a stammer, and of being "much hated and detested" by Pharaoh and the ancient Egyptians of his time. He is said to have been raised in an oppressive household, and to have been known, in Egypt, as a man who had committed murder – though he had done so in order to prevent an act of cruelty.[171]

Nevertheless, like Abraham, through the assistance of God, he achieved great things and gained renown even beyond the Levant. Chief among these achievements was the freeing of his people, the Hebrews, from bondage in Egypt and leading "them to the Holy Land". He is viewed as the one who bestowed on Israel "the religious and the civil law" which gave them "honour among all nations", and which spread their fame to different parts of the world.[171]

Furthermore, through the law, Moses is believed to have led the Hebrews "to the highest possible degree of civilization at that period". 'Abdul'l-Bahá asserts that the ancient Greek philosophers regarded "the illustrious men of Israel as models of perfection". Chief among these philosophers, he says, was Socrates who "visited Syria, and took from the children of Israel the teachings of the Unity of God and of the immortality of the soul".[171]

Moses is further seen as paving the way for Bahá'u'lláh and his ultimate revelation, and as a teacher of truth, whose teachings were in line with the customs of his time.[172]

Druze faith

Moses is considered an important prophet of God in the Druze faith, being among the seven prophets who appeared in different periods of history.[173][174]

Legacy in politics and law

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (May 2018) |

In a metaphorical sense in the Christian tradition, a "Moses" has been referred to as the leader who delivers the people from a terrible situation. Among the Presidents of the United States known to have used the symbolism of Moses were Harry S. Truman, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama, who referred to his supporters as "the Moses generation".[175]

In subsequent years, theologians linked the Ten Commandments with the formation of early democracy. Scottish theologian William Barclay described them as "the universal foundation of all things ... the law without which nationhood is impossible. ... Our society is founded upon it."[176] Pope Francis addressed the United States Congress in 2015 stating that all people need to "keep alive their sense of unity by means of just legislation ... [and] the figure of Moses leads us directly to God and thus to the transcendent dignity of the human being".[177]

In United States history

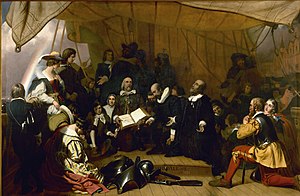

Pilgrims

References to Moses were used by the Puritans, who relied on the story of Moses to give meaning and hope to the lives of Pilgrims seeking religious and personal freedom in North America. John Carver was the first governor of Plymouth colony and first signer of the Mayflower Compact, which he wrote in 1620 during the ship Mayflower's three-month voyage. He inspired the Pilgrims with a "sense of earthly grandeur and divine purpose", notes historian Jon Meacham,[178] and was called the "Moses of the Pilgrims".[179] Early American writer James Russell Lowell noted the similarity of the founding of America by the Pilgrims to that of ancient Israel by Moses:

Рядом с беглецами, которых Моисей вывел из Египта, небольшой груз изгостей, приземленных в Плимуте, суждено повлиять на будущее мира. Духовная жажда человечества на протяжении веков была утолена на ивритских фонтанах; Но воплощение в человеческих институтах истин, произнесенных Сыном Человеческого восемнадцати веков назад, должна была быть в основном работой пуританской мысли и пуританской самоотверженности. ... если их муниципальные правила немного ударяют иудаизм, но не может быть более благородной цели или более практической мудрости, чем их; ибо это должно было сделать закон человека живым аналогом закона Божьего, в их высшей концепции его. [ 180 ]

После смерти Карвера в следующем году Уильям Брэдфорд стал губернатором. Он боялся, что оставшиеся паломники не выживут на трудностях новой земли, причем половина их людей уже погибла в течение нескольких месяцев после прибытия. Брэдфорд вызвал символ Моисея ослабленным и отчаянным паломникам, чтобы помочь успокоить их и дать им надежду: «Насилие сломает все. Где кроткий и скромный дух Моисея?» [ 181 ] Уильям Дж. Девер объясняет отношение паломников: «Мы считали себя« новым Израилем », особенно мы в Америке. И по этой причине мы знали, кто мы, во что мы верили и ценили, и во что наша« Явная судьба ' был." [ 182 ] [ 183 ]

Отцы -основатели Соединенных Штатов

4 июля 1776 года, сразу после того, как заявление о независимости была официально принята, Континентальный конгресс спросил Джона Адамса , Томаса Джефферсона и Бенджамина Франклина , чтобы спроектировать печать, которая будет четко представлять символ для новых Соединенных Штатов. Они выбрали символ Моисея, ведущего израильтян к свободе. [ 184 ]

После смерти Джорджа Вашингтона в 1799 году две трети его восхваления называли его «Моисеем Америки», и один оратор сказал, что «Вашингтон был для нас таким же, как и Моисей для детей Израиля». [ 185 ]

Бенджамин Франклин, в 1788 году, увидел трудности, с которыми сталкивались некоторые из недавно независимых американских государств при формировании правительства, и предположил, что до тех пор, пока не может быть согласован новый кодекс законов, они должны регулироваться «законами Моисея», как содержится в Ветхом Завете. [ 186 ] Он оправдал свое предложение, объяснив, что законы работали в библейские времена: « Высшее существо ... спасла их от рабства многими чудесами, исполняемыми его слугой Моисей, он лично доставил этот избранного слуги, в присутствии Вся нация, конституция и кодекс законов для их соблюдения ». [ 187 ]

Джон Адамс , 2 -й президент Соединенных Штатов , заявил, почему он полагался на законы Моисея из -за греческой философии за создание Конституции Соединенных Штатов : «Как я люблю, уважаю и восхищаюсь греками, я полагаю, что Евреи сделали больше просветить и цивизовать мир. [ 178 ] Шведский историк Хьюго Валентин приписывал Моисея «первым, чтобы провозглашать права человека ». [ 188 ]

Рабство и гражданские права

Подземный железнодорожный дирижер и гражданской войны в американской гражданской войне ветеран Харриет Тубман были названы «Моисей» из -за ее различных миссий по освобождению и перевозке сбежавших порабощенных людей в свободу в свободных штатах Соединенных Штатов . [ 189 ] [ 190 ]

Историк Глэдис Л. Найт описывает, как лидеры, которые появились во время и после того периода, когда рабство было законным, часто олицетворяли символ Моисея. «Символ Моисея расширял возможности в том смысле, что он служил усилению потребности в свободе». [ 191 ] Поэтому, когда Авраам Линкольн был убит в 1865 году после принятия поправки в Конституцию, запрещающую рабство , чернокожие американцы сказали, что потеряли «своего Моисея». [ 192 ] Биограф Линкольна Чарльз Карлтон Коффин пишет: «Миллионы, которых Авраам Линкольн, избавленный из рабства, когда -либо сравнивает его с Моисеем, избавителем Израиля». [ 193 ]

В 1960 -х годах главной фигурой в движении за гражданские права был Мартин Лютер Кинг -младший , которого называли «современным Моисеем» и часто упоминали Моисея в своих выступлениях: «Борьба Моисея, борьба его преданных последователей как Они стремились выйти из Египта. [ 194 ]

Культурные изображения и ссылки

Искусство

Моисей часто появляется в христианском искусстве, а частная часовня Папы, Сикстинская часовня , имеет большую последовательность из шести фресков жизни Моисея на южной стене, напротив сет с жизнью Христа . Они были нарисованы в 1481–82 гг. Группой в основном флорентийских художников, включая Сандро Боттичелли и Пьетро Перугино .

Из -за двусмысленности в ивритском словом קֶרֶן (керен), что означает как рог, так и луча или луча, в Библейского Лица латинском переводе Иерома в Вильгате Моисея описывается как Cornutam («рогатый») при спуска с горы Синай с таблетками. , Моисей обычно показывается в западном искусстве до эпохи Возрождения с небольшими рогами , которые, по крайней мере, служили удобным идентифицирующим атрибутом. [ 195 ] По крайней мере, в некоторых из этих изображений, вероятно, было предназначено антисемитное значение, [ 196 ] Например, на Херефорд Маппа Мунди . [ 197 ]

С пророком Илайджей он является необходимой фигурой в трансфигурации Иисуса в христианском искусстве , предмете с долгой историей в восточном православном искусстве. Он появляется в искусстве Западной Церкви с 10 -го века и был особенно популярен между 1475 и 1535 годами. [ 198 ]

Статуя Микеланджело

( Микеланджело Статуя Моисея 1513–1515), в церкви Сан -Пьетро в Винколи , Рим , является одной из самых знакомых статуй в мире. Рога, которые скульптор, включенный в голову Моисея, являются результатом неправильного перевода еврейской Библии в латинскую библию Вульгата, с которой Микеланджело был знаком. Еврейское слово, взятое из исхода, означает либо «рог», либо «облучение». Эксперты Археологического института Америки показывают, что этот термин использовался, когда Моисей «вернулся к своему народу после того, как увидел, как большая часть славы Господа могло бы стоять», а его лицо «отражало сияние». [ 199 ] Более того, в раннем еврейском искусстве Моисей часто «показаны с лучами, выходящими из его головы». [ 200 ]

Описание правительственных зданий США

Моисей изображен в нескольких правительственных зданиях США из -за его наследия как законодателя. В Библиотеке Конгресса стоит большая статуя Моисея вместе со статуей Апостола Павла . Моисей является одним из двадцати трех законодателей, изображенных в мраморных барельфах в Палате Палаты представителей США в Капитолии Соединенных Штатов . В обзоре мемориальной доски говорится: «Моисей (ок. 1350–1250 гг. До н.э.) Еврейский пророк и законодатель; превратил странствующих людей в нацию; получили десять заповедей». [ 201 ]

Остальные 22 фигуры имеют свои профили, обращенные к Моисею, что является единственным барельем, обращенным вперед. [ 202 ] [ 203 ]

Моисей появляется восемь раз в резьбе, которые звонят в потолок Большого Зала Верховного суда . Его лицо представлено вместе с другими древними фигурами, такими как Соломон , греческий Бог Зевс и римская богиня мудрости, Минерва . Восточный фронтон здания Верховного суда изображает Моисея, держащего две таблетки. Таблетки, представляющие десять заповедей, можно найти вырезанными в дверях дуба в зале суда, на рамке поддержки бронзовых ворот зала суда, а также в библиотеке. Спорный образ - это тот, который находится непосредственно над главным судьей Соединенных Штатов . В центре 40-футовой резьбы по испанской мраморной резьбе находится таблетка, демонстрируя римские цифры I до x, с некоторыми числами частично скрыты. [ 204 ]

Литература

- Сигмунд Фрейд в своей последней книге « и монотеизм» в 1939 году постулировал, что Моисей был египетским дворянином, который придерживался монотеизма Ахнатена Моисей . После теории, предложенной современным библейским критиком , Фрейд полагал, что Моисей был убит в пустыне, создавая коллективное чувство патрицидовой вины, которое с тех пор лежит в основе иудаизма. «Иудаизм был религией Отца, христианство стало религией Сына», - написал он. Возможное египетское происхождение Моисея и его послания получило значительное научное внимание. [ 205 ] [ страница необходима ] [ 206 ] [ Полная цитата необходима ] Противники этой точки зрения отмечают, что религия Торы, кажется, отличается от атенизма во всем, кроме центральной особенности преданности единому Богу, [ 207 ] Хотя это противостояло различным аргументам, например, указывая на сходство между гимном с Атеном и Псалом 104 . [ 205 ] [ страница необходима ] [ 208 ] Интерпретация Фрейда исторического Моисея не очень хорошо принята среди историков и считается псевдогисторией многими. [ 209 ] [ страница необходима ]

- Томаса Манна Новелла «Таблицы закона» (1944) - это пересказ истории Исхода из Египта с Моисеем в качестве главного героя. [ 210 ]

- WG Hardy Роман «Все трубы» звучали (1942) рассказывает выдуманную жизнь Моисея. [ 211 ]

- Orson Scott Card Новые каменные столы (1997) - это роман жизни Моисея. [ 212 ]

Фильм и телевидение

- Моисей был изображен Теодором Робертсом в Сесиле Б. Демилле в 1923 году , «Десять заповедей» . Моисей также появился в качестве центрального персонажа в римейке 1956 года, также снятым Демиллом и назвал «Десять заповедей» , в которых его изобразил Чарлтон Хестон , который имел заметное сходство с статуей Микеланджело. был Телевизионный римейк выпущен в 2006 году. [ 213 ] [ 214 ]

- Берт Ланкастер сыграл Моисея в телевизионном мини -сериале 1975 года. Моисей Законодатель .

- В 1981 году фильма» « История мирового 1981 года, часть I , Моисей был изображен Мел Брукс .

- В 1995 году сэр Бен Кингсли изобразил Моисея в телевизионном фильме 1995 года «Моисей» , созданный британскими и итальянскими производственными компаниями.

- Моисей появился в качестве центрального персонажа в «Принц Египта» анимационном фильме 1998 года «Принц Египта» . Его говорящий голос был предоставлен Вэл Килмер , а американский певец Евангелия и тенор Амик Байрам обеспечил свой поющий голос.

- Бен Кингсли был рассказчиком анимационного фильма 2007 года «Десять заповедей» .

- В на мини -сериале битвах 2009 года Британс Б.К. Моисей был изображен Каззи Луи Церегино .

- В телевизионной мини -сериале 2013 года Библия Моисей был изображен Уильямом Хьюстоном .

- В седере-мазохизме , анимационном фильме «Нины Пейли » 2018 года , Моисей появляется как один из ключевых персонажей в переосмыслении « Книга Исхода» . [ 215 ] [ 216 ]

- Кристиан Бэйл изобразил Моисея в фильме Ридли Скотта 2014 года «Исход: боги и царей» , в которых Моисея и Рамса II были подняты Сети I как двоюродные братья.

- Бразильский библейский теленовел 2016 года. Десять заповедей бразильский актер Гильерма Винтер изображает . Моисея

Критика Моисея

В конце восемнадцатого века деист Томас Пейн подробно прокомментировал законы Моисея в эпоху разума (1794, 1795 и 1807). Пейн считал, что Моисей является «отвратительным злодеем » и приводил числа 31 в качестве примера его «неправомерных злодеяний». [ 217 ] В проходе после того, как израильская армия вернулась из завоевания Мидиана , Моисей приказывает убийство мадианитян, за исключением девственных девушек, которые должны были храниться для израильтян.

Вы спасли всех женщин в живых? Вот, это заставило детей Израиля через адвокат Балаама совершить посягательство против Господа в вопросе Пеота , и среди собрания Господа была чума. Следовательно, убейте каждого мужчину среди маленьких и убивайте каждую женщину, которая известна мужчину, лежа с ним; Но все женщины-дети, которые не знали мужчины, лежа с ним , сохраняют для себя.

- Числа 31 [ 218 ]

что история - это «мощная басня похоти Раввин Джоэл Гроссман утверждал , и предательство », и что исполнение женщин Моисея было символическим осуждением тех, кто стремится превратить пол и желание в злые цели. [ 219 ] Он говорит, что женщины -мидианиты «использовали свою сексуальную привлекательность, чтобы отвергнуть израильтянских мужчин от [Яхвех] Бога и поклонения Баале Перу [другого ханаанитскому богу]». [ 219 ] Раввин Гроссман утверждает, что геноцид всех мидианитовых невиргинальных женщин, в том числе тех, кто не соблазнил еврейских мужчин, был справедливым, потому что у некоторых из них был секс по «неправильным причинам». [ 219 ] Алан Левин, специалист по образованию в реформе , также предположил, что историю следует воспринимать как предостерегающая история , чтобы «предупредить последовательные поколения евреев, чтобы следить за своим собственным идолопоклонным поведением». [ 220 ] Часам Софер подчеркивает, что эта война не велась по воле Моисея, но его командовал Бог как акт мести против женщин -мидианитовых женщин, [ 221 ] Кто, согласно библейскому отчету, соблазнил израильтян и привел их к греху. Лингвист Кит Аллан заметил: «Произведение Бога или нет, это военное поведение, которое было бы оштуован сегодня и может привести к судебному разбирательству военных преступлений ». [ 222 ]

Моисей также был предметом большой феминистской критики. Обименное библейское ученое Ньяша Джуниор утверждал, что Моисей может быть объектом феминистского расследования. [ 223 ]

Смотрите также

- Шестая и седьмая книга Моисея

- Таблица пророков Авраамовых религий

- Тарбис , по словам Иосифа , жены Моисея

- Еврейская мифология

- Дети Моисея

- Рабство в древнем Египте

Примечания

- ^ / ˈ m oʊ z ɪ z , - z ɪ s / ; Библейский иврит : Моисей , Романизированный: Моше ; Также известный как Моше или Моше Раббейн Мишнайский : , горит Моисей иврит . ( Сириас : ܡܫ , Романизированный : Мараше ; Арабский : مُ arch еты , романизированный : m'sā ; Древний греческий : внешний вид , романизированный : mōÿsş

- ^ Святой Августин записывает имена королей, когда Моисей родился в городе Божий :

Когда Сапрус царствовал как четырнадцатый царь Ассирии , а Ортополис - двенадцатый Сисион , а Криас - пятый из Аргоса , Моисей родился в Египте, ...

— [ 20 ]Ортополис царствовал как 12 -й король Сисиона в течение 63 лет, с 1596 по 1533 г. до н.э.; и Criasus царствовал как 5 -й король Аргоса в течение 54 лет, с 1637 по 1583 г. до н.э. [ 21 ]

- ^

После того, как название Моисея Моисею в воде воды воды;

«С тех пор, как он был взят из воды, принцесса дала ему имя, полученное из этого, и назвал его Моисей, потому что Мо - это египетское слово для воды».

- Филон Александрии , де Вита Мос , I: 4: 17. - Колсон, Ф.Х., транс. 1935. На Аврааме. На Джозеф. На Моисее , ( Классическая библиотека Loeb 289). Кембридж, Массачусетс: издательство Гарвардского университета . С. 284–85. - ^ Согласно Православному Менаону , 4 сентября был день, когда Моисей увидел страну обещания . [ 144 ]

Ссылки

- ^ Наполнитель, элад. «Моисей и женщина Кушита: классические интерпретации и аллегория Филона» . Thetorah.com . Получено 11 мая 2019 года .

- ^ Бигл, Дьюи М. (2024) [1999]. "Моисей" . Encyclopædia Britannica .

- ^ «Второзаконие 34:10» . www.sefaria.org . Получено 2024-05-22 .

- ^ Маймонид , 13 принципов веры , 7 -й принцип .

- ^ "Моисей" . Оксфордские исламские исследования . Архивировано из оригинала 17 апреля 2021 года . Получено 6 декабря 2020 года .

- ^ Девер, Уильям Г. (2001). «Получение в« Истории истории » . Что знали библейские писатели, и когда они это узнали?: Что археология может рассказать нам о реальности древнего Израиля . Гранд -Рапидс, Мичиган и Кембридж, Великобритания : Wm. Б. Eerdmans . С. 97–102. ISBN 978-0-8028-2126-3 Полем OCLC 46394298 .

- ^ Исход 1:10

- ^ Дуглас К. Стюарт (2006). Исход: экзегетическая и богословская экспозиция Священного Писания . B & H Publishing Group. С. 110–13.

- ^ Исход 4:10

- ^ Исход 7: 7

- ^ Куглер, Гили (декабрь 2018 г.). Шепард, Дэвид; Tiemeyer, Lena-Sofia (ред.). «Моисей умер, и люди пошли дальше: скрытое повествование в Второзаконии». Журнал для изучения Ветхого Завета . 43 (2). SAGE Publications : 191–204. doi : 10.1177/0309089217711030 . ISSN 1476-6728 . S2CID 171688935 .

- ^ Nigosian, SA (1993). «Моисей, как они его видели». Ветер Testamentum . 43 (3): 339–350. doi : 10.1163/156853393x00160 . ISSN 0042-4935 .

Три взгляда, основанные на анализе источников или историческом критическом методе, по-видимому, преобладают среди библейских ученых. Во -первых, ряд ученых, таких как Мейер и Холшер, стремятся лишить Моисея все прерогативы, приписываемые ему, отрицая что -либо историческую ценность о его личности или роль, которую он играл в израильской религии. Во -вторых, другие ученые, .... диаметрально противостоять первой точке зрения и стремиться закрепить Моисея решающую роль, которую он играл в израильской религии в твердой обстановке. И в -третьих, те, кто занимает среднюю позицию ... определяют твердую историческую идентификацию Моисея из надстройки более поздних легендарных акций ... необходимо сказать, что эти вопросы горячо обсуждаются неразрешенные вопросы среди ученых. Таким образом, попытка отделить исторический от неисторических элементов в Торе дала мало, если таковые имеются, положительные результаты, касающиеся фигуры Моисея или той роли, которую он играл в израильской религии. Неудивительно, что Дж. Ван Шетерс пришел к выводу, что «поиск исторического Моисея - бесполезное упражнение. Теперь он принадлежит только к легенде

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Девер, Уильям Г. (2001). Что знали библейские писатели, и когда они это узнали?: Что археология может рассказать нам о реальности древнего Израиля . Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. п. 99. ISBN 978-0-8028-2126-3 Полем

Моисейская фигура, возможно, существовала где-то в южном Трансджордане в середине 13-го века, где многие ученые считают библейские традиции, касающиеся Бога Яхве.

- ^ Бигл, Дьюи (5 июля 2023 г.). "Моисей" . Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в "Моисей" . Оксфордские библейские исследования онлайн .

- ^ Миллер II, Роберт Д. (25 ноября 2013 г.). Освещение Моисея: история приема от Исхода до эпохи Возрождения . Брилль стр. 21, 24. ISBN 978-90-04-25854-9 Полем

Ван Сетерс пришел к выводу: «Поиск исторического Моисея - бесполезное упражнение. Теперь он принадлежит только к легенде. ... «Ничто из этого не означает, что нет исторического Моисея и что сказки не включают историческую информацию. Но в Пятикнижии история стала мемориалом. Мемориал пересматривает историю, восхищает память и делает миф из истории.

- ^ Простой Олам Раббах [ Полная цитата необходима ]

- ^ ( 4 Chronicon -го века) дает 1592 год за рождение Моисея

- ^ 17-го века Хронология USSHER рассчитывается 1571 г. до н.э. ( Анналы мира , 1658 г. Параграф 164)

- ^ Святой Августин . Город Божий . Книга XVIII. ГЛАВА 8 - КТО БЫЛИ ЦЕЛИ, КОГДА МОСЕССОВ, И ЧТОГОМ ГОГАМ стали поклоняться тогда.

- ^ Hoeh, Herman L (1967), сборник мировой истории (диссертация), Vol. 1, факультет Амбассадора, Высшая школа богословия, 1962 .

- ^ «Давайте послушаем это от фараонов: египетская история Моисея» . Музей еврейского народа . 7 апреля 2020 года . Получено 8 июня 2024 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный «Исход: история истории - thetorah.com» . Thetorah.com . Получено 2021-07-01 .

- ^ Грюн, Эрих С. (1998). «Использование и злоупотребление истории Исхода» . Еврейская история . 12 (1). Спрингер: 93–122. doi : 10.1007/bf02335457 . ISSN 0334-701X . JSTOR 20101326 . Получено 8 июня 2024 года .

- ^ Фельдман, Луи Х. (1998). «Ответы: изменили ли евреи рассказ об исходе?» Полем Еврейская история . 12 (1). Springer: 123–127. doi : 10.1007/bf02335458 . ISSN 0334-701X . JSTOR 20101327 . Получено 8 июня 2024 года .

- ^ «Моисей вылечен от проказы» . Еврейская Библия ежеквартально . 12 сентября 2016 года . Получено 8 июня 2024 года .

- ^ Дэвис 2020 , с. 181.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Хейс, Кристофер Б. (2014). Скрытые богатства: источник для сравнительного изучения еврейской Библии и Древнего Ближнего Востока . Пресвитерианская издательская корпорация . п. 116. ISBN 978-0-664-23701-1 .

- ^ Ulmer, Rivka. 2009. Египетские культурные иконы в Мидраш . де Грюйтер . п. 269

- ^ Наоми Э. Пасачфф, Роберт Дж. Литтман (2005), Краткая история еврейского народа , Rowman & Littlefield, p. 5

- ^ Исход 2:10

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Maciá, Lorena Miralles. 2014. «Идея язычника библейского характера посредством фиктивных биографических отчетов: случай Битиа, дочери фараона, матери Моисея, согласно раввинским интерпретациям» . С. 145–175 в C. Cordoni и G. Langer (Eds.), Нарратология, герменевтика и мидраш: еврейские, христианские и мусульманские повествования от поздней античности до современного времени . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Dozeman 2009 , с. 81–82.

- ^ "Рива на Торе, Исход 2: 10: 1" . Сефария . Получено 2021-03-14 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Greifenhagen, Franz V. 2003. Египет на идеологической карте Пятикнижия: создание библейской идентичности Израиля . Блумсбери. С. 60ff [62] N.65. [63].

- ^ Шурпин, Иегуда. Моисей - еврейское или египетское имя? Полем Chabad.org .

- ^ Салкин, Джеффри К. (2008). Праведные язычники в еврейской Библии: древние образцы для подражания для священных отношений . Еврейские огни . С. 47ff [54].

- ^ Харрис, Морис Д. 2012. Моисей: незнакомец среди нас . WIPF и Stock . С. 22–24.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Сколний, Бенджамин Эдидин . 2005. Если египтяне утонули в Красном море, где находятся колесницы фараона?: Изучение исторического измерения Библии . Университетская пресса Америки . п. 82

- ^ "Имена дочери Фараона Моисея? На иврите?" Полем Thetorah.com . Получено 2022-04-18 .

- ^ Данзингер, Ю. Элизер (2008-01-20). "Как было настоящее имя Моше?" Полем Chabad.org . Получено 5 мая 2022 года .

- ^ Кеннет А. Кухня, о надежности Ветхого Завета (2003), стр. 296–97: «Его имя широко считается египетским, и его форма слишком часто неверно истолкована библейскими учеными. Он часто приравнивается к Египетское слово «MS» (Mose), означающее «ребенок», и заявило, что является аббревиатурой имени, составленного с именем божества, чье имя было опущено. -Ма, HOR-MOSE и так далее. -Класс Мозей (из Храма Птаха в Мемфисе), под рамс. Скорее всего, это не египетский Semitic 's' (simekh) появляется как «TJ» на египетском. И наоборот, египетский «sh» = иврит 'sh', и наоборот. Лучше признать, что его собственная мать назвала ребенка (Исход 2: 10b) в форме, изначально озвучивая «Машу», «один вытянутый» (который стал «Моше», «Тот, кто вытягивает», т.е. его люди из рабства, когда он привел их). В Египте четырнадцатого/тринадцатого века «Мозей» был фактически произносится «Масу», и поэтому вполне возможно, что молодой иврит Машу был назван Масу его египетскими спутниками; Но это словесный каламбур, а не заимствование в любом случае ».

- ^ МакКлинток, Джон ; Джеймс, Стронг (1882). " Моисей ". Циклопедия библейской, богословской и церковной литературы . Тол. VI Ме-нев. Нью -Йорк: Harper & Brothers. С. 677–87.

- ^ Согласно Мането, место его рождения было в древнем городе Хелиополис . [ 43 ]

- ^ Исход 2:21

- ^ Исход 3:14

- ^ Исход 8: 1

- ^ Шмидт, Натаниэль (февраль 1896 г.). «Моисей: его возраст и его работа. II». Библейский мир . 7 (2): 105–19 [108]. doi : 10.1086/471808 . S2CID 222445896 .

Это был призыв Пророка. Это был настоящий экстатический опыт, подобно опыту Давида под бака-деревом, Илией на горе, Исаия в храме, Иезекииль на Кхебаре, Иисус в Иордании, Павл на дороге Дамаск. Это была вечная загадка божественного касания человека.

- ^ Исход 4: 24-26

- ^ Гинцберг, Луи (1909). Легенды евреев , том III: Глава I (перевод Генриетты Шолд) Филадельфия: еврейское публикационное общество.

- ^ Трим, Чарли (сентябрь 2019 г.). Шепард, Дэвид; Tiemeyer, Lena-Sofia (ред.). «Персонал Бога и рука Моисея: битва против амалекитов как поворотный момент в роли божественного воина» . Журнал для изучения Ветхого Завета . 44 (1). Sage Publications : 198–214. doi : 10.1177/0309089218778588 . ISSN 1476-6728 .

- ^ Рад, Герхард фон; Хансон, KC; Нил, Стивен (2012). Моисей . Кембридж: Джеймс Кларк. ISBN 978-0-227-17379-4 Полем Получено 2017-06-09 .

- ^ Гинцберг, Луи (1909). Легенды евреев (PDF) . Тол. III: символическая значимость скинии. Перевод Шолда, Генриетта. Филадельфия: еврейское публикационное общество.

- ^ Гинцберг, Луи (1909). Легенды евреев (PDF) . Тол. III: наказанная неблагодарность. Перевод Шолда, Генриетта. Филадельфия: еврейское публикационное общество.

- ^ Числа 27:13

- ^ Числа 31: 1

- ^ Исход 20: 19-23: 33

- ^ Исход 20: 1-17

- ^ Исход 20: 22-23: 19

- ^ Гамильтон 2011 , с. XXV.

- ^ Робинсон, Джордж (2008). Основная Тора: Полное руководство по пяти книгам Моисея . Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. п. 97. ISBN 978-0-307-48437-6 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Nigosian, SA (1993). «Моисей, как они его видели». Ветер Testamentum . 43 (3): 339–350. doi : 10.1163/156853393x00160 .

Три взгляда, основанные на анализе источников или историческом критическом методе, по-видимому, преобладают среди библейских ученых. Во -первых, ряд ученых, таких как Мейер и Холшер, стремятся лишить Моисея все прерогативы, приписываемые ему, отрицая что -либо историческую ценность о его личности или роль, которую он играл в израильской религии. Во -вторых, другие ученые, ... Диаметрически противостоят первым взглядам и стремится закрепить Моисея решающую роль, которую он играл в израильской религии в твердой обстановке. И в -третьих, те, кто занимает среднюю позицию ... определяют твердую историческую идентификацию Моисея из надстройки более поздних легендарных акций ... Излишне говорить, что эти вопросы горячо обсуждаются неразрешенные вопросы среди ученых. Таким образом, попытка отделить исторический от неисторических элементов в Торе дала мало, если таковые имеются, положительные результаты, касающиеся фигуры Моисея или той роли, которую он играл в израильской религии. Неудивительно, что Дж. Ван Шетерс пришел к выводу, что «поиск исторического Моисея - бесполезное упражнение. Теперь он принадлежит только к легенде.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Девер, Уильям Г. (1993). «Что осталось от дома, который построил Олбрайт?». Библейский археолог . 56 (1). Университет Чикагской Прессы: 25–35. doi : 10.2307/3210358 . ISSN 0006-0895 . JSTOR 3210358 . S2CID 166003641 .

Подавляющий научный консенсус сегодня заключается в том, что Моисей - мифическая фигура

- ^ Шмид, Конрад; Schröter, Jens (2021). Создание Библии: от первых фрагментов до священного Писания . Гарвардский университет издательство. п. 44. ISBN 978-0-674-24838-0 Полем

Моисей был, по всей вероятности, исторической фигурой

- ^ Бритт, Брайан (2004). «Миф Моисея, за пределами библейской истории» . Библия и интерпретация . Университет Аризоны.

- ^ Гарфинкель, Стивен (2001). «Моисей: человек Израиля, человек Божий» . В Либере, Дэвид Л.; Дорфф, Эллиот Н.; Харлоу, Жюль; Дорфф, Rppen; Fishbane, Michael A.; Еврейское публикационное общество; Объединенная синагога консервативного иудаизма; Раввинская сборка; Гроссман, Сьюзен; Кушнер, Гарольд С.; Поток, Хаим (ред.). עץ חים: Тора и комментарий . Библейская серия JPS (на иврите). Еврейское публикационное общество. п. 1414. ISBN 978-0-8276-0712-5 Полем Получено 13 января 2022 года .

Таким образом, вопрос, который нужно задать при понимании Торы на его собственных условиях, не в том случае, если бы жил Моисей, а то, что его жизнь передает в Саге Израиля. [...] Типично для фольклористского, национального героя, Моисей успешно выдерживает [...]

- ^ Массинг, Майкл (9 марта 2002 г.). «Новая Тора для современных умов» . New York Times . Архивировано из оригинала 27 марта 2010 года . Получено 1 сентября 2022 года .

- ^ Ассманн, Ян (1998-10-15). Моисей Египтянин . Гарвардский университет издательство. с. 2, 11. ISBN 978-0-674-58739-7 Полем

Мы не можем быть уверены, что Моисей когда -либо жил, потому что нет следов его существования вне традиции [с. 2] ... Я даже не задам вопрос - давай, ответьте на него - был ли Моисей египетским, или ивритом, или мидианитом. Этот вопрос касается исторического Моисея и, таким образом, относится к истории. Я обеспокоен Моисеем как фигурой памяти. Как фигура памяти, Моисей Египтянин радикально отличается от Моисея иврита или библейского Моисея.

- ^ Девер, Уильям (17 ноября 2008 г.). «Археология еврейской Библии» . Новая Пбс.

«Моисей» - это египетское имя. Некоторые из других имен в повествованиях являются египетскими, и есть подлинные египетские элементы. Но никто не нашел текст или артефакт в самом Египте или даже в Синае, который имеет какую -либо прямую связь. Это не значит, что этого не произошло. Но я думаю, что это означает, что то, что произошло, было довольно скромным. И библейские писатели расширили историю.

- ^ Мур, Меган Бишоп; Келл, Брэд Э. (2011-05-17). Библейская история и прошлое Израиля: изменение изучения Библии и истории . Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. С. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-8028-6260-0 Полем

... нет внебиблейского исходного значения явно для Моисея, ...

- ^ Meyers 2005 , с. 5–6.

- ^ Leeming, David (2005-11-17). Оксфордский компаньон мировой мифологии . Oxford University Press USA. ISBN 978-0-19-515669-0 .

- ^ "Исход,". Исход, книга (онлайн) . Издательство Оксфордского университета. 2004. ISBN 978-0-19-504645-8 - через www.oxfordreference.com.

Историчность Моисея - самое разумное предположение о нем. Нет никакого жизнеспособного аргумента, почему Моисея следует рассматривать как художественную литературу благочестивой необходимости. Его удаление с места начала Израиля как теократической общины оставило бы вакуум, который просто нельзя объяснить.

- ^ Куган, Майкл Дэвид; Куган, Майкл Д. (2001). Оксфордская история библейского мира . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-513937-2 Полем

Многие из этих форм не являются и не должны рассматриваться, исторически основанные; Например, повествование о рождении Моисея построено на фольклорных мотивах, найденных во всем древнем мире.

- ^ Рандсбург, Гэри А. (2006). «Моисей как равен фараону» . В Бекмане, Гэри М.; Льюис, Теодор Дж. (Ред.). Текст, артефакт и образ: раскрытие древней израильской религии . Коричневые иудаические исследования. п. 204. ISBN 978-1-930675-28-5 .

- ^ Финлей, Тимоти Д. (2005). Жанр отчета о рождении в еврейской Библии . Исследование на Ветхий Завет. Том 12. Мохр Сибек. п. 236. ISBN 978-3-16-148745-3 .

- ^ Питард, Уэйн Т. (2001). «До Израиля: Сирия-Палестина в бронзовом веке» . В Кугане, Майкл Д. (ред.). Оксфордская история библейского мира . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 27. ISBN 9780195139372 .

- ^ Иеремия 15: 1

- ^ Исаия 63: 11–12

- ^ Осия 12:13

- ^ Карр, Дэвид М.; Конвей, Коллин М. (2010). Введение в Библию: священные тексты и имперские контексты . Нью -Йорк: Уайли . п. 193. ISBN 9781405167383 .

- ^ Исаия 63:16

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Будет 2009 , с.

- ^ Судьи 1: 16–3: 11 ; Числа 10:29 ; Исход 6: 2–3

- ^ Смит, Марк С. (2002). Ранняя история Бога: Яхве и другие божества в древнем Израиле . Wm. Б. Eerdmans. п. 34. ISBN 978-0-8028-3972-5 .

- ^ Ван дер Тёрн, Карел; Бекинг, Боб; Ван дер Хорст, Питер Виллем, ред. (1999). Словарь божеств и демонов в Библии (2 -е изд.). Wm. Б. Eerdmans. п. 912. ISBN 978-0-8028-2491-2 .

- ^ Grabbe, Lester L. (23 февраля 2017 г.). Древний Израиль: Что мы знаем и как мы его знаем?: Пересмотренное издание . Bloomsbury Publishing. п. 36. ISBN 978-0-567-67044-1 Полем

Впечатление, которое есть сейчас, заключается в том, что дебаты успокоились. Хотя они, кажется, не признают это, минималисты одержали победу во многих отношениях. То есть большинство ученых отвергают историчность «патриархального периода», рассматривают поселение как в основном состоит из коренных жителей Ханаана и осторожны с ранней монархией. Исход отклоняется или предполагается, что он основан на событии, сильно отличающемся от библейского счета. С другой стороны, не существует широко распространенного отклонения библейского текста как исторического источника, который можно найти среди основных минималистов. Есть мало, если таковые имеются, максималисты (определяемые как те, кто принимает библейский текст, если он не может быть абсолютно опровергнут) в основной стипендии, только на более фундаменталистских полосах.

- ^ Killebrew, Ann E. (2020). «Раннее происхождение Израиля, поселения и этногенез» . В Келле, Брэд Э.; Strawn, Brent A. (ред.). Оксфордский справочник исторических книг еврейской Библии . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 86. ISBN 978-0-19-007411-1 .

- ^ Фауст, Авраам (2023). «Рождение Израиля» . В Хойленде, Роберт Дж.; Уильямсон, HGM (ред.). Оксфордская история Святой Земли . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 28. ISBN 978-0-19-288687-3 .

- ^ Coats, George W. (1988). Моисей: героический человек, человек Божий . A & C Black. С. 10 и далее (стр. 11 Олбрайт, с. 29–30, нет). ISBN 9780567594204 .

- ^ Отто, Экарт (2006). Моисей: История и Легенда [ Моисей: История и Легенда ] (на немецком языке). Ч. Бек. С. ISBN 978-3-406-53600-7 .

- ^ Görg, Manfred (2000). «Моисей - имя, имени и имена. Попытка исторического подхода». В Отто, Э. (ред.). Пизда. Египет и Ветхий Завет (на немецком языке). Штутгарт: Верлаг Католическая Библия.

- ^ Краусс, Рольф (2001). Моисейная головоломка: по стопам библейского изобретения (на немецком языке). Мюнхен: Ульштейн.

- ^ Ассманн, январь (2 февраля 2002 г.). «Он парлас как египтолог в течение дня, а ночью он разрывает Библию» . Франкфуртер Allgemeine Zeitung (на немецком языке).

- ^ Додсон, Эйдан (2010). Отравленное наследие: падение 19 -й египетской династии . Американский университет в Каир Пресс. п. 72. ISBN 978-1-61797-071-9 .

- ^ Сменд, Рудольф (1995). «Моисей как историческая фигура» [Моисей как историческая фигура] (PDF) . Исторический журнал . 260 : 1–19. Doi : 10.1524/hzhz.1995.260.jg.1 . S2CID 164459862 .

- ^ Leithart, Peter J. (2006). 1 и 2 короли . Brazos Press. С. 178ff [181–82]. ISBN 9781587431258 .