United States

United States of America | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "In God We Trust"[1] Other traditional mottos:[2] | |

| Anthem: "The Star-Spangled Banner"[3] | |

| Capital | Washington, D.C. 38°53′N 77°1′W / 38.883°N 77.017°W |

| Largest city | New York City 40°43′N 74°0′W / 40.717°N 74.000°W |

| Official languages | None at the federal level[a] |

| National language | English[b] |

| Ethnic groups | By race:

By origin:

|

| Religion (2023)[7] |

|

| Demonym(s) | American[c][8] |

| Government | Federal presidential republic |

| Joe Biden | |

| Kamala Harris | |

| Mike Johnson | |

| John Roberts | |

| Legislature | Congress |

| Senate | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Independence from Great Britain | |

| July 4, 1776 | |

| March 1, 1781 | |

| September 3, 1783 | |

| June 21, 1788 | |

| Area | |

• Total area | 3,796,742 sq mi (9,833,520 km2)[9][d] (3rd) |

• Water (%) | 7.0[10] (2010) |

• Land area | 3,531,905 sq mi (9,147,590 km2) (3rd) |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | |

• 2020 census | |

• Density | 87/sq mi (33.6/km2) (185th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2022) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | very high (20th) |

| Currency | U.S. dollar ($) (USD) |

| Time zone | UTC−4 to −12, +10, +11 |

• Summer (DST) | UTC−4 to −10[g] |

| Date format | mm/dd/yyyy[h] |

| Driving side | right[i] |

| Calling code | +1 |

| ISO 3166 code | US |

| Internet TLD | .us[16] |

The United States of America (USA or U.S.A.), commonly known as the United States (US or U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal union of 50 states, which also includes its federal capital district of Washington, D.C., and 326 Indian reservations.[j] The 48 contiguous states are bordered by Canada to the north and Mexico to the south. The State of Alaska is non-contiguous and lies to the northwest, while the State of Hawaii is an archipelago in the Pacific Ocean. The United States also asserts sovereignty over five major unincorporated island territories and various uninhabited islands.[k] The country has the world's third-largest land area,[d] second-largest exclusive economic zone, and third-largest population, exceeding 334 million.[l]

Paleo-Indians migrated across the Bering land bridge more than 12,000 years ago, and went on to form various civilizations and societies. British colonization led to the first settlement of the Thirteen Colonies in Virginia in 1607. Clashes with the British Crown over taxation and political representation sparked the American Revolution, with the Second Continental Congress formally declaring independence on July 4, 1776. Following its victory in the 1775–1783 Revolutionary War, the country continued to expand across North America. As more states were admitted, sectional division over slavery led to the secession of the Confederate States of America, which fought the remaining states of the Union during the 1861–1865 American Civil War. With the Union's victory and preservation, slavery was abolished nationally. By 1890, the United States had established itself as a great power. After Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the U.S. entered World War II. The aftermath of the war left the U.S. and the Soviet Union as the world's two superpowers and led to the Cold War, during which both countries engaged in a struggle for ideological dominance and international influence. Following the Soviet Union's collapse and the end of the Cold War in 1991, the U.S. emerged as the world's sole superpower, wielding significant geopolitical influence globally.

The U.S. national government is a presidential constitutional federal republic and liberal democracy with three separate branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. It has a bicameral national legislature composed of the House of Representatives, a lower house based on population; and the Senate, an upper house based on equal representation for each state. Substantial autonomy is given to the states and several territories, with a political culture promoting liberty, equality, individualism, personal autonomy, and limited government.

One of the world's most developed countries, the United States has had the largest nominal GDP since about 1890 and accounted for 15% of the global economy in 2023.[m] It possesses by far the largest amount of wealth of any country and has the highest disposable household income per capita among OECD countries. The U.S. ranks among the world's highest in economic competitiveness, productivity, innovation, human rights, and higher education. Its hard power and cultural influence have a global reach. The U.S. is a founding member of the World Bank, Organization of American States, NATO, and United Nations,[n] as well as a permanent member of the UN Security Council.

Etymology

The first documented use of the phrase "United States of America" is a letter from January 2, 1776. Stephen Moylan, a Continental Army aide to General George Washington, wrote to Joseph Reed, Washington's aide-de-camp, seeking to go "with full and ample powers from the United States of America to Spain" to seek assistance in the Revolutionary War effort.[21][22] The first known public usage is an anonymous essay published in the Williamsburg newspaper, The Virginia Gazette, on April 6, 1776.[23][24][25] By June 1776, the "United States of America" appeared in the Articles of Confederation[26][27] and the Declaration of Independence.[26] The Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776.[28]

History

Indigenous peoples

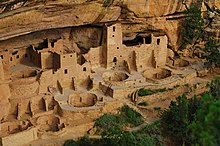

The first inhabitants of North America migrated from Siberia across the Bering land bridge about 12,000 years ago;[30][31] the Clovis culture, which appeared around 11,000 BC, is believed to be the first widespread culture in the Americas.[32][33] Over time, indigenous North American cultures grew increasingly sophisticated, and some, such as the Mississippian culture, developed agriculture, architecture, and complex societies.[34] In the post-archaic period, the Mississippian cultures were located in the midwestern, eastern, and southern regions, and the Algonquian in the Great Lakes region and along the Eastern Seaboard, while the Hohokam culture and Ancestral Puebloans inhabited the southwest.[35] Native population estimates of what is now the United States before the arrival of European immigrants range from around 500,000[36][37] to nearly 10 million.[37][38]

European settlement (from 1492) and the Thirteen Colonies (1607–1776)

Christopher Columbus began exploring the Caribbean for Spain in 1492, leading to Spanish-speaking settlements and missions from Puerto Rico and Florida to New Mexico and California.[39][40][41] France established its own settlements along the Mississippi River and Gulf of Mexico.[42] British colonization of the East Coast began with the Virginia Colony (1607) and Plymouth Colony (1620).[43][44] The Mayflower Compact and the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut established precedents for representative self-governance and constitutionalism that would develop throughout the American colonies.[45][46] While European settlers in what is now the United States experienced conflicts with Native Americans, they also engaged in trade, exchanging European tools for food and animal pelts.[47][o] Relations ranged from close cooperation to warfare and massacres. The colonial authorities often pursued policies that forced Native Americans to adopt European lifestyles, including conversion to Christianity.[51][52] Along the eastern seaboard, settlers trafficked African slaves through the Atlantic slave trade.[53]

The original Thirteen Colonies[p] that would later found the United States were administered by Great Britain,[54] and had local governments with elections open to most white male property owners.[55][56] The colonial population grew rapidly, eclipsing Native American populations;[57] by the 1770s, the natural increase of the population was such that only a small minority of Americans had been born overseas.[58] The colonies' distance from Britain allowed for the development of self-governance,[59] and the First Great Awakening, a series of Christian revivals, fueled colonial interest in religious liberty.[60]

American Revolution and the early republic (1776–1815)

After winning the French and Indian War, Britain began to assert greater control over local colonial affairs, resulting in colonial political resistance; one of the primary colonial grievances was a denial of their rights as Englishmen, particularly the right to representation in the British government that taxed them. In 1774, the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia, and passed the Continental Association, a colonial boycott of British goods that proved effective. The British attempt to then disarm the colonists resulted in the 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord, igniting the American Revolutionary War. At the Second Continental Congress, the colonies appointed George Washington commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, and created a committee led by Thomas Jefferson to draft the Declaration of Independence, which was adopted on July 4, 1776, two days after passing the Lee Resolution to create an independent nation.[61] The political values of the American Revolution included liberty, inalienable individual rights; and the sovereignty of the people;[62] supporting republicanism and rejecting monarchy, aristocracy, and all hereditary political power; civic virtue; and vilification of political corruption.[63] The Founding Fathers of the United States, who included George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, John Jay, James Madison, Thomas Paine, John Adams and many others, were inspired by Greco-Roman, Renaissance, and Enlightenment philosophies and ideas.[64][65]

After the British surrender at the siege of Yorktown in 1781 American sovereignty was internationally recognized by the Treaty of Paris (1783), through which the U.S. gained territory stretching west to the Mississippi River, north to present-day Canada, and south to Spanish Florida.[66] The Articles of Confederation were ratified in 1781 and established a decentralized government that operated until 1789.[61] The Northwest Ordinance (1787) established the precedent by which the country's territory would expand with the admission of new states, rather than the expansion of existing states.[67] The U.S. Constitution was drafted at the 1787 Constitutional Convention to overcome the limitations of the Articles. It went into effect in 1789, creating a federal republic governed by three separate branches that together ensured a system of checks and balances.[68] George Washington was elected the country's first president under the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights was adopted in 1791 to allay skeptics' concerns about the power of the more centralized government.[69][70] His resignation as commander-in-chief after the Revolution and later refusal to run for a third term established the precedent of peaceful transfer of power and supremacy of civil authority.[71][72]

Westward expansion and Civil War (1815–1865)

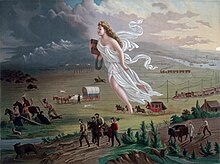

The Louisiana Purchase (1803) from France nearly doubled the territory of the United States.[73][74] Lingering issues with Britain remained, leading to the War of 1812, which was fought to a draw.[75][76] Spain ceded Florida and its Gulf Coast territory in 1819.[77] In the late 18th century, American settlers began to expand westward, many with a sense of manifest destiny.[78][79] The Missouri Compromise attempted to balance desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it, admitting Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state and declared a policy of prohibiting slavery in the remaining Louisiana Purchase lands north of the 36°30′ parallel.[80] As Americans expanded further into land inhabited by Native Americans, the federal government often applied policies of Indian removal or assimilation.[81][82] Organized displacements prompted a long series of American Indian Wars west of the Mississippi.[83][84] The Republic of Texas was annexed in 1845,[85] and the 1846 Oregon Treaty led to U.S. control of the present-day American Northwest.[86] Victory in the Mexican–American War resulted in the 1848 Mexican Cession of California and much of the present-day American Southwest.[78][87] Issues of slavery in the new territories acquired were temporarily resolved by the Compromise of 1850.[88][89]

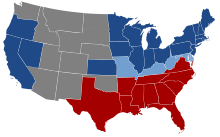

During the colonial period, slavery had been legal in the American colonies, though the practice began to be significantly questioned during the American Revolution.[90] States in the North enacted abolition laws,[91] though support for slavery strengthened in Southern states, as inventions such as the cotton gin made the institution increasingly profitable for Southern elites.[92][93][94] This sectional conflict regarding slavery culminated in the American Civil War (1861–1865).[95][96] Eleven slave states seceded and formed the Confederate States of America, while the other states remained in the Union.[97][98] War broke out in April 1861 after the Confederates bombarded Fort Sumter.[99][100] After the January 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, many freed slaves joined the Union Army.[101] The war began to turn in the Union's favor following the 1863 Siege of Vicksburg and Battle of Gettysburg, and the Confederacy surrendered in 1865 after the Union's victory in the Battle of Appomattox Court House.[102] The Reconstruction era followed the war. After the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, Reconstruction Amendments were passed to protect the rights of African Americans. National infrastructure, including transcontinental telegraph and railroads, spurred growth in the American frontier.[103]

Post–Civil War era (1865–1917)

From 1865 through 1917 an unprecedented stream of immigrants arrived in the United States, including 24.4 million from Europe.[106] Most came through the port of New York City, and New York City and other large cities on the East Coast became home to large Jewish, Irish, and Italian populations, while many Germans and Central Europeans moved to the Midwest. At the same time, about one million French Canadians migrated from Quebec to New England.[107] During the Great Migration, millions of African Americans left the rural South for urban areas in the North.[108] Alaska was purchased from Russia in 1867.[109]

The Compromise of 1877 effectively ended Reconstruction and white supremacists took local control of Southern politics.[110][111] African Americans endured a period of heightened, overt racism following Reconstruction, a time often called the nadir of American race relations.[112][113] A series of Supreme Court decisions, including Plessy v. Ferguson, emptied the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments of their force, allowing Jim Crow laws in the South to remain unchecked, sundown towns in the Midwest, and segregation in communities across the country, which would be reinforced by the policy of redlining later adopted by the federal Home Owners' Loan Corporation.[114]

An explosion of technological advancement accompanied by the exploitation of cheap immigrant labor[115] led to rapid economic development during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, allowing the United States to outpace the economies of England, France, and Germany combined.[116][117] This fostered the amassing of power by a few prominent industrialists, largely by their formation of trusts and monopolies to prevent competition.[118] Tycoons led the nation's expansion in the railroad, petroleum, and steel industries. The United States emerged as a pioneer of the automotive industry.[119] These changes were accompanied by significant increases in economic inequality, slum conditions, and social unrest, creating the environment for labor unions to begin to flourish.[120][121][122] This period eventually ended with the advent of the Progressive Era, which was characterized by significant reforms.[123][124]

Pro-American elements in Hawaii overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy; the islands were annexed in 1898. That same year, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam were ceded to the U.S. by Spain after the latter's defeat in the Spanish–American War. (The Philippines was granted full independence from the U.S. on July 4, 1946, following World War II. Puerto Rico and Guam have remained U.S. territories.)[125] American Samoa was acquired by the United States in 1900 after the Second Samoan Civil War.[126] The U.S. Virgin Islands were purchased from Denmark in 1917.[127]

Rise as a superpower (1917–1945)

The United States entered World War I alongside the Allies of World War I, helping to turn the tide against the Central Powers.[128] In 1920, a constitutional amendment granted nationwide women's suffrage.[129] During the 1920s and '30s, radio for mass communication and the invention of early television transformed communications nationwide.[130] The Wall Street Crash of 1929 triggered the Great Depression, which President Franklin D. Roosevelt responded to with the New Deal, a series of sweeping programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations.[131][132]

Initially neutral during World War II, the U.S. began supplying war materiel to the Allies of World War II in March 1941 and entered the war in December after the Empire of Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor.[133][134] The U.S. developed the first nuclear weapons and used them against the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, ending the war.[135][136] The United States was one of the "Four Policemen" who met to plan the post-war world, alongside the United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and China.[137][138] The U.S. emerged relatively unscathed from the war, with even greater economic power and international political influence.[139]

Cold War (1945–1991)

After World War II, the United States entered the Cold War, where geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union led the two countries to dominate world affairs.[140] The U.S. engaged in regime change against governments perceived to be aligned with the Soviet Union, and competed in the Space Race, culminating in the first crewed Moon landing in 1969.[141][142][143][144] Domestically, the U.S. experienced economic growth, urbanization, and population growth following World War II.[145] The civil rights movement emerged, with Martin Luther King Jr. becoming a prominent leader in the early 1960s.[146] The Great Society plan of President Lyndon Johnson's administration resulted in groundbreaking and broad-reaching laws, policies and a constitutional amendment to counteract some of the worst effects of lingering institutional racism.[147] The counterculture movement in the U.S. brought significant social changes, including the liberalization of attitudes toward recreational drug use and sexuality. It also encouraged open defiance of the military draft (leading to the end of conscription in 1973) and wide opposition to U.S. intervention in Vietnam (with the U.S. totally withdrawing in 1975).[148][149][150] The societal shift in the roles of women partly resulted in large increases in female labor participation in the 1970s, and by 1985 the majority of women aged 16 and older were employed.[151] The late 1980s and early 1990s saw the collapse of the Warsaw Pact and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which marked the end of the Cold War and solidified the U.S. as the world's sole superpower.[152][153][154][155]

Contemporary (1991–present)

The 1990s saw the longest recorded economic expansion in American history, a dramatic decline in crime, and advances in technology, with the World Wide Web, the evolution of the Pentium microprocessor in accordance with Moore's law, rechargeable lithium-ion batteries, the first gene therapy trial, and cloning all emerging and improved upon throughout the decade. The Human Genome Project was formally launched in 1990, while Nasdaq became the first stock market in the United States to trade online in 1998.[156]

In the Gulf War of 1991, an American-led international coalition of states expelled an Iraqi invasion force that had occupied neighboring Kuwait.[157] The September 11 attacks on the United States in 2001 by the pan-Islamist militant organization al-Qaeda led to the war on terror, and subsequent military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq.[158][159] The cultural impact of the attacks was profound and long-lasting.

The U.S. housing bubble culminated in 2007 with the Great Recession, the largest economic contraction since the Great Depression.[160] Coming to a head in the 2010s, political polarization increased as sociopolitical debates on cultural issues dominated politics.[161][162][163] This polarization was capitalized upon in the January 2021 Capitol attack, when a mob of insurrectionists entered the U.S. Capitol and attempted to prevent the peaceful transfer of power.[164]

Geography

The United States is the world's third-largest country by total area behind Russia and Canada.[d][165][166] The 48 contiguous states and the District of Columbia occupy a combined area of 3,119,885 square miles (8,080,470 km2).[167][168] The coastal plain of the Atlantic seaboard gives way to inland forests and rolling hills in the Piedmont plateau region.[169]

The Appalachian Mountains and the Adirondack massif separate the East Coast from the Great Lakes and the grasslands of the Midwest.[170] The Mississippi River System, the world's fourth-longest river system, runs predominantly north–south through the heart of the country. The flat and fertile prairie of the Great Plains stretches to the west, interrupted by a highland region in the southeast.[170]

The Rocky Mountains, west of the Great Plains, extend north to south across the country, peaking at over 14,000 feet (4,300 m) in Colorado.[171] Farther west are the rocky Great Basin and Chihuahua, Sonoran, and Mojave deserts.[172] In the northwest corner of Arizona, carved by the Colorado River over millions of years, is the Grand Canyon, a steep-sided canyon and popular tourist destination known for its overwhelming visual size and intricate, colorful landscape.

The Sierra Nevada and Cascade mountain ranges run close to the Pacific coast. The lowest and highest points in the contiguous United States are in the State of California,[173] about 84 miles (135 km) apart.[174] At an elevation of 20,310 feet (6,190.5 m), Alaska's Denali is the highest peak in the country and continent.[175] Active volcanoes are common throughout Alaska's Alexander and Aleutian Islands, and Hawaii consists of volcanic islands. The supervolcano underlying Yellowstone National Park in the Rocky Mountains, the Yellowstone Caldera, is the continent's largest volcanic feature.[176] In 2021, the United States had 8% of global permanent meadows and pastures and 10% of cropland.[177]

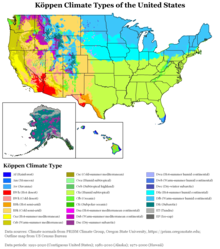

Climate

With its large size and geographic variety, the United States includes most climate types. East of the 100th meridian, the climate ranges from humid continental in the north to humid subtropical in the south.[178] The western Great Plains are semi-arid. Many mountainous areas of the American West have an alpine climate. The climate is arid in the Southwest, Mediterranean in coastal California, and oceanic in coastal Oregon, Washington, and southern Alaska. Most of Alaska is subarctic or polar. Hawaii, the southern tip of Florida and U.S. territories in the Caribbean and Pacific are tropical.[179]

States bordering the Gulf of Mexico are prone to hurricanes, and most of the world's tornadoes occur in the country, mainly in Tornado Alley.[180] Overall, the United States receives more high-impact extreme weather incidents than any other country.[181][182] Extreme weather became more frequent in the U.S. in the 21st century, with three times the number of reported heat waves as in the 1960s. In the American Southwest, droughts became more persistent and more severe.[183]

Biodiversity and conservation

The U.S. is one of 17 megadiverse countries containing large numbers of endemic species: about 17,000 species of vascular plants occur in the contiguous United States and Alaska, and over 1,800 species of flowering plants are found in Hawaii, few of which occur on the mainland.[185] The United States is home to 428 mammal species, 784 birds, 311 reptiles, 295 amphibians,[186] and around 91,000 insect species.[187]

There are 63 national parks, and hundreds of other federally managed parks, forests, and wilderness areas, managed by the National Park Service and other agencies.[188] About 28% of the country's land is publicly owned and federally managed,[189] primarily in the western states.[190] Most of this land is protected, though some is leased for commercial use, and less than one percent is used for military purposes.[191][192]

Environmental issues in the United States include debates on non-renewable resources and nuclear energy, air and water pollution, biodiversity, logging and deforestation,[193][194] and climate change.[195][196] The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is the federal agency charged with addressing most environmental-related issues.[197] The idea of wilderness has shaped the management of public lands since 1964, with the Wilderness Act.[198] The Endangered Species Act of 1973 provides a way to protect threatened and endangered species and their habitats. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service implements and enforces the Act.[199] In 2024, the U.S. ranked 34th among 180 countries in the Environmental Performance Index.[200] The country joined the Paris Agreement on climate change in 2016 and has many other environmental commitments.[201]

Government and politics

The United States is a federal republic of 50 states and a federal district, Washington, D.C. It also asserts sovereignty over five unincorporated territories and several uninhabited island possessions.[202][203] The world's oldest surviving federation,[204] the U.S. has the world's oldest national constitution still in effect (from March 4, 1789). Its presidential system of government has been adopted, in whole or in part, by many newly independent nations following decolonization.[205] It is a liberal representative democracy "in which majority rule is tempered by minority rights protected by law."[206] The Constitution of the United States serves as the country's supreme legal document, also establishing the structure and responsibilities of the national federal government and its relationship with the individual states.[207]

According to V-Dem Institute's 2023 Human Rights Index, the United States ranks among the highest in the world for human rights.[208]

National government

Composed of three branches, all headquartered in Washington, D.C., the federal government is the national government of the United States. It is regulated by a strong system of checks and balances.[209]

- The U.S. Congress, a bicameral legislature, made up of the Senate and the House of Representatives, makes federal law, declares war, approves treaties, has the power of the purse,[210] and has the power of impeachment.[211] The Senate has 100 members (2 from each state), elected for a six-year term. The House of Representatives has 435 members, each elected for a two-year term; all representatives serve one congressional district of equivalent population.[212] The Congress also organizes a collection of committees, each of which handles a specific task or duty. Appointment to a committee enables a member to develop specialized knowledge of the matters under its purview. The various committees monitor ongoing governmental operations, identify issues suitable for legislative review, gather and evaluate information, and recommend courses of action to the U.S. Congress, including but not limited to new legislation. The two major political parties have appointment power in deciding each committee's membership. Committee chairs are assigned to a member of the majority party.

- The U.S. president is the commander-in-chief of the military and chief executive of the federal government, with the ability to veto legislative bills in the U.S. Congress before they ever become law. However, vetoes are subject to congressional override after a vote of two-thirds of the Senate. The president appoints the members of the Cabinet, subject to Senate approval, and names other officials who administer and enforce federal laws through their respective agencies.[213] The president also has clemency power for federal crimes and can issue pardons, thus reversing the decision of the court. Finally, the president has the right to issue expansive "executive orders", subject to judicial review, in a number of policy areas. Candidates for president campaign with a vice-presidential running mate. Both candidates are elected together, or defeated together, in a presidential election. Unlike other votes in American politics, this is technically an indirect election in which the winner will be determined by the U.S. Electoral College. There, votes are officially cast by individual electors selected by their state legislature.[214] In practice, however, each of the 50 states chooses a group of presidential electors who are required to confirm the winner of their state's popular vote. This group of electors equals their state's number of U.S. representatives, plus two more electors for the two U.S. senators the state sends to Congress. (The District of Columbia, with no representatives or senators, is allocated three electoral votes.) Both the president and the vice president serve a four-year term, and the president may be reelected to the office only once, for one additional four-year term.[q]

- The U.S. federal judiciary, whose judges are all appointed for life by the president with Senate approval, consists primarily of the U.S. Supreme Court, the U.S. courts of appeals, and the U.S. district courts. The U.S. Supreme Court interprets laws and overturn those they find unconstitutional.[215] The Supreme Court has nine members led by the Chief Justice of the United States. The members are appointed by the sitting president when a vacancy becomes available.[216] In a number of ways the federal court system operates differently than state courts. For civil cases that is apparent in the types of cases that can be heard in the federal system. Their limited jurisdiction restricts them to cases authorized by the United States Constitution or federal statutes. In criminal cases, states may only bring criminal prosecutions in state courts, and the federal government may only bring criminal prosecutions in federal court. The first level in the federal courts is federal district court for any case under "original jurisdiction", such as federal statutes, the Constitution, or treaties. There are twelve federal circuits that divide the country into different regions for federal appeals courts. After a federal district court has decided a case, it can then be appealed to a United States court of appeal. The next and highest court in the system is the Supreme Court of the United States. It has the power to decide appeals on all cases brought in federal court or those brought in state court but dealing with federal law. Unlike circuit court appeals, however, the Supreme Court is usually not required to hear the appeal. A "petition for writ of certiorari" may be submitted to the court, asking it to hear the case. If it is granted, the Supreme Court will take briefs and conduct oral arguments. If it is not granted, the opinion of the lower court stands. Certiorari is not often granted, and less than 1% of appeals to the Supreme Court are actually heard by it. Usually, the Court only hears cases when there are conflicting decisions across the nation on a particular issue, or when there is an obvious error in a case.

The three-branch system is known as the presidential system, in contrast to the parliamentary system, where the executive is part of the legislative body. Many countries around the world imitated this aspect of the 1789 Constitution of the United States, especially in the Americas.[217]

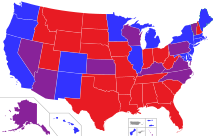

Political parties

The Constitution is silent on political parties. However, they developed independently in the 18th century with the Federalist and Anti-Federalist parties.[218] Since then, the United States has operated as a de facto two-party system, though the parties in that system have been different at different times.[219] The two main national parties are presently the Democratic and the Republican. The former is perceived as relatively liberal in its political platform while the latter is perceived as relatively conservative.[220]

Subdivisions

In the American federal system, sovereign powers are shared between two levels of elected government: national and state. People in the states are also represented by local elected governments, which are administrative divisions of the states.[221] States are subdivided into counties or county equivalents, and further divided into municipalities. The District of Columbia is a federal district that contains the capital of the United States, the city of Washington.[222] The territories and the District of Columbia are administrative divisions of the federal government.[223] Federally recognized tribes govern 326 Indian reservations.[224]

Foreign relations

The United States has an established structure of foreign relations, and it has the world's second-largest diplomatic corps as of 2024[update]. It is a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council,[225] and home to the United Nations headquarters.[226] The United States is a member of the G7,[227] G20,[228] and OECD intergovernmental organizations.[229] Almost all countries have embassies and many have consulates (official representatives) in the country. Likewise, nearly all countries host formal diplomatic missions with the United States, except Iran,[230] North Korea,[231] and Bhutan.[232] Though Taiwan does not have formal diplomatic relations with the U.S., it maintains close unofficial relations.[233] The United States regularly supplies Taiwan with military equipment to deter potential Chinese aggression.[234] Its geopolitical attention also turned to the Indo-Pacific when the United States joined the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue with Australia, India, and Japan.[235]

The United States has a "Special Relationship" with the United Kingdom[236] and strong ties with Canada,[237] Australia,[238] New Zealand,[239] the Philippines,[240] Japan,[241] South Korea,[242] Israel,[243] and several European Union countries (France, Italy, Germany, Spain, and Poland).[244] The U.S. works closely with its NATO allies on military and national security issues, and with countries in the Americas through the Organization of American States and the United States–Mexico–Canada Free Trade Agreement. In South America, Colombia is traditionally considered to be the closest ally of the United States.[245] The U.S. exercises full international defense authority and responsibility for Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and Palau through the Compact of Free Association.[246] It has increasingly conducted strategic cooperation with India,[247] but its ties with China have steadily deteriorated.[248][249] Since 2014, the U.S. has become a key ally of Ukraine;[250] it has also provided the country with significant military equipment and other support in response to Russia's 2022 invasion.[251]

Military

The president is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces and appoints its leaders, the secretary of defense and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The Department of Defense, which is headquartered at the Pentagon near Washington, D.C., administers five of the six service branches, which are made up of the U.S. Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, and Space Force.[252] The Coast Guard is administered by the Department of Homeland Security in peacetime and can be transferred to the Department of the Navy in wartime.[253]

The United States spent $916 billion on its military in 2023, which is by far the largest amount of any country, making up 37% of global military spending and accounting for 3.4% of the country's GDP.[254][255] The U.S. has 42% of the world's nuclear weapons, the second-largest share after Russia.[256]

The United States has the third-largest combined armed forces in the world, behind the Chinese People's Liberation Army and Indian Armed Forces.[257] The military operates about 800 bases and facilities abroad,[258] and maintains deployments greater than 100 active duty personnel in 25 foreign countries.[259]

Law enforcement and criminal justice

There are about 18,000 U.S. police agencies from local to national level in the United States.[260] Law in the United States is mainly enforced by local police departments and sheriff departments in their municipal or county jurisdictions. The state police departments have authority in their respective state, and federal agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the U.S. Marshals Service have national jurisdiction and specialized duties, such as protecting civil rights, national security and enforcing U.S. federal courts' rulings and federal laws.[261] State courts conduct most civil and criminal trials,[262] and federal courts handle designated crimes and appeals of state court decisions.[263]

There is no unified "criminal justice system" in the United States. The American prison system is actually one of significant heterogeneity, with thousands of systems operating across federal, state, local, and Native American tribal levels. In 2023, there were a reported "1,566 state prisons, 98 federal prisons, 3,116 local jails, 1,323 juvenile correctional facilities, 181 immigrant detention facilities, and 80 Indian country jails, as well as military prisons, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and prisons in the U.S."[264][citation needed] Despite disparate systems of confinement, four main institutions dominate: federal prisons, state prisons, local jails, and juvenile correctional facilities.[265] Federal prisons are run by the U.S. Bureau of Prisons and hold people who have been convicted of federal crimes, including pretrial detainees.[265] State prisons, run by the official department of correction of each state, hold sentenced people serving prison time (usually longer than one year) for felony offenses.[265] Local jails are county or municipal facilities that incarcerate defendants prior to trial; they also hold those serving short sentences (typically under a year).[265] Juvenile correctional facilities are operated by local or state governments and serve as longer-term placements for any minor adjudicated as delinquent and ordered by a judge to be confined.[266]

As of January 2023, the United States has the sixth-highest per capita incarceration rate in the world—531 people per 100,000 inhabitants—and the largest prison and jail population in the world, with almost 2 million people incarcerated.[267][268][269] An analysis of the World Health Organization Mortality Database from 2010 showed U.S. homicide rates "were 7 times higher than in other high-income countries, driven by a gun homicide rate that was 25 times higher".[270]

Economy

The U.S. has been the world's largest economy nominally since about 1890.[273] The 2023 nominal U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) of more than $27 trillion was the highest in the world, constituting over 25% of the global economy or 15% at purchasing power parity (PPP).[274][13] From 1983 to 2008, U.S. real compounded annual GDP growth was 3.3%, compared to a 2.3% weighted average for the rest of the Group of Seven.[275] The country ranks first in the world by nominal GDP,[276] second when adjusted for purchasing power parities (PPP),[13] and ninth by PPP-adjusted GDP per capita.[13] It possesses the highest disposable household income per capita among OECD countries.[277] As of February 2024, the total federal government debt was $34.4 trillion.[278]

Of the world's 500 largest companies, 136 are headquartered in the U.S. as of 2023[279]—the highest number of any country.[280] The U.S. dollar is the currency most used in international transactions and is the world's foremost reserve currency, backed by the country's dominant economy, its military, the petrodollar system, and its linked eurodollar and large U.S. treasuries market.[271] Several countries use it as their official currency, and in others it is the de facto currency.[281][282] It has free trade agreements with several countries, including the USMCA.[283] The U.S. ranked second in the Global Competitiveness Report in 2019, after Singapore.[284] Although the United States has reached a post-industrial level of development[285] and is often described as having a service economy,[285][286] it still remains a major industrial power.[287] As of 2021[update], the U.S. is the second-largest manufacturing country after China.[288]

New York City is the world's principal financial center[290][291] and the epicenter of the world's largest metropolitan economy.[292] The New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq, both located in New York City, are the world's two largest stock exchanges by market capitalization and trade volume.[293][294] The United States is at or near the forefront of technological advancement and innovation[295] in many economic fields, especially in artificial intelligence; computers; pharmaceuticals; and medical, aerospace and military equipment.[296] The country's economy is fueled by abundant natural resources, a well-developed infrastructure, and high productivity.[297] The largest U.S. trading partners are the European Union, Mexico, Canada, China, Japan, South Korea, the United Kingdom, Vietnam, India, and Taiwan.[298] The United States is the world's largest importer and the second-largest exporter.[r] It is by far the world's largest exporter of services.[301]

Americans have the highest average household and employee income among OECD member states,[302] and the fourth-highest median household income,[303] up from sixth-highest in 2013.[304] With personal consumption expenditures of over $18.5 trillion in 2023,[305] the U.S. has a heavily consumer-driven economy and is by far the world's largest consumer market.[306] Wealth in the United States is highly concentrated; the richest 10% of the adult population own 72% of the country's household wealth, while the bottom 50% own just 2%.[307] Income inequality in the U.S. remains at record highs,[308] with the top fifth of earners taking home more than half of all income[309] and giving the U.S. one of the widest income distributions among OECD members.[310][311] The U.S. ranks first in the number of dollar billionaires and millionaires, with 735 billionaires and nearly 22 million millionaires as of 2023.[312] There were about 582,500 sheltered and unsheltered homeless persons in the U.S. in 2022, with 60% staying in an emergency shelter or transitional housing program.[313] In 2022, 6.4 million children experienced food insecurity.[314] Feeding America estimates that around one in five, or approximately 13 million, children experience hunger in the U.S. and do not know where they will get their next meal or when.[315] As of 2022,[update] 37.9 million people, or 11.5% of the U.S. population, were living in poverty.[316]

The United States has a smaller welfare state and redistributes less income through government action than most other high-income countries.[317][318] It is the only advanced economy that does not guarantee its workers paid vacation nationally[319] and is one of a few countries in the world without federal paid family leave as a legal right.[320] The United States has a higher percentage of low-income workers than almost any other developed country, largely because of a weak collective bargaining system and lack of government support for at-risk workers.[321]

Science, technology and energy

The United States has been a leader in technological innovation since the late 19th century and scientific research since the mid-20th century.[322] Methods for producing interchangeable parts and the establishment of a machine tool industry enabled the large-scale manufacturing of U.S. consumer products in the late 19th century.[323] By the early 20th century, factory electrification, the introduction of the assembly line, and other labor-saving techniques created the system of mass production.[324] The United States is widely considered to be the leading country in the development of artificial intelligence technology[325][326][327] and maintains a space program since the late 1950s, with plans for long-term habitation of the Moon.[328]

In 2022, the United States was the country with the second-highest number of published scientific papers.[329] As of 2021, the U.S. ranked second by the number of patent applications, and third by trademark and industrial design applications.[330] In 2023, the United States ranked third in the Global Innovation Index.[331] The U.S. has the highest total research and development expenditure of any country[332] and ranks ninth as a percentage of GDP.[333] In 2023, the United States was ranked as the second most technologically advanced country in the world by Global Finance.[334]

As of 2023[update], the United States receives approximately 84% of its energy from fossil fuel and the largest source of the country's energy came from petroleum (38%), followed by natural gas (36%), renewable sources (9%), coal (9%), and nuclear power (9%).[335][336] The United States constitutes less than 4% of the world's population, but consumes around 16% of the world's energy.[337] The U.S. ranks as the second-highest emitter of greenhouse gases.[338]

Transportation

Personal transportation in the United States is dominated by automobiles,[340][341] which operate on a network of 4 million miles (6.4 million kilometers) of public roads, making it the longest network in the world.[342][343] The Oldsmobile Curved Dash and the Ford Model T, both American cars, are considered the first mass-produced[344] and mass-affordable[345] cars, respectively. As of 2023, the United States is the second-largest manufacturer of motor vehicles[346] and is home to Tesla, the world's most valuable car company.[347] American automotive company General Motors held the title of the world's best-selling automaker from 1931 to 2008.[348] The American automotive industry is the world's second-largest automobile market by sales, having been overtaken by China in 2010,[349] and the U.S. has the highest vehicle ownership per capita in the world,[350] with 910 vehicles per 1000 people.[351] By value, the U.S. was the world's largest importer and third-largest exporter of cars in 2022.[352] The United States' rail transport network, the longest network in the world,[353] handles mostly freight.[354][355]

The American civil airline industry is entirely privately owned and has been largely deregulated since 1978, while most major airports are publicly owned.[356] The three largest airlines in the world by passengers carried are U.S.-based; American Airlines is number one after its 2013 acquisition by US Airways.[357] Of the world's 50 busiest passenger airports, 16 are in the United States, including the top five and the busiest, Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport.[358][359] As of 2022[update], there are 19,969 airports in the U.S., of which 5,193 are designated as "public use", including for general aviation and other activities.[360]

Of the fifty busiest container ports, four are located in the United States, of which the busiest is the Port of Los Angeles.[361] The country's inland waterways are the world's fifth-longest, and total 41,009 km (25,482 mi).[362]

Demographics

Population

| State | Population (millions) |

|---|---|

| California | |

| Texas | |

| Florida | |

| New York | |

| Pennsylvania | |

| Illinois | |

| Ohio | |

| Georgia | |

| North Carolina | |

| Michigan |

The U.S. Census Bureau reported 331,449,281 residents as of April 1, 2020,[s][365] making the United States the third-most-populous country in the world, after China and India.[366] According to the Bureau's U.S. Population Clock, on July 1, 2024, the U.S. population had a net gain of one person every 16 seconds, or about 5400 people per day.[367] In 2023, 51% of Americans age 15 and over were married, 6% were widowed, 10% were divorced, and 34% had never been married.[368] In 2023, the total fertility rate for the U.S. stood at 1.6 children per woman,[369] and, at 23%, it had the world's highest rate of children living in single-parent households in 2019.[370]

The United States has a diverse population; 37 ancestry groups have more than one million members.[371] White Americans with ancestry from Europe, the Middle East or North Africa form the largest racial and ethnic group at 57.8% of the United States population.[372][373] Hispanic and Latino Americans form the second-largest group and are 18.7% of the United States population. African Americans constitute the country's third-largest ancestry group and are 12.1% of the total U.S. population.[371] Asian Americans are the country's fourth-largest group, composing 5.9% of the United States population. The country's 3.7 million Native Americans account for about 1%,[371] and some 574 native tribes are recognized by the federal government.[374] In 2022, the median age of the United States population was 38.9 years.[375]

Language

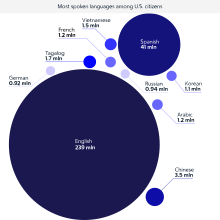

While many languages are spoken in the United States, English is by far the most commonly spoken and written.[376] Although there is no official language at the federal level, some laws, such as U.S. naturalization requirements, standardize English, and most states have declared it the official language.[377] Three states and four U.S. territories have recognized local or indigenous languages in addition to English, including Hawaii (Hawaiian),[378] Alaska (twenty Native languages),[t][379] South Dakota (Sioux),[380] American Samoa (Samoan), Puerto Rico (Spanish), Guam (Chamorro), and the Northern Mariana Islands (Carolinian and Chamorro). In total, 169 Native American languages are spoken in the United States.[381] In Puerto Rico, Spanish is more widely spoken than English.[382]

According to the American Community Survey in 2010, some 229 million people out of the total U.S. population of 308 million spoke only English at home. About 37 million spoke Spanish at home, making it the second most commonly used language. Other languages spoken at home by one million people or more include Chinese (2.8 million), Tagalog (1.6 million), Vietnamese (1.4 million), French (1.3 million), Korean (1.1 million), and German (1 million).[383]

Immigration

America's immigrant population of nearly 51 million is by far the world's largest in absolute terms.[384][385] In 2022, there were 87.7 million immigrants and U.S.-born children of immigrants in the United States, accounting for nearly 27% of the overall U.S. population.[386] In 2017, out of the U.S. foreign-born population, some 45% (20.7 million) were naturalized citizens, 27% (12.3 million) were lawful permanent residents, 6% (2.2 million) were temporary lawful residents, and 23% (10.5 million) were unauthorized immigrants.[387] In 2019, the top countries of origin for immigrants were Mexico (24% of immigrants), India (6%), China (5%), the Philippines (4.5%), and El Salvador (3%).[388] In fiscal year 2022, over one million immigrants (most of whom entered through family reunification) were granted legal residence.[389] The United States led the world in refugee resettlement for decades, admitting more refugees than the rest of the world combined.[390]

Religion

Religious affiliation in the U.S., according to a 2023 Gallup poll:[7]

The First Amendment guarantees the free exercise of religion in the country and forbids Congress from passing laws respecting its establishment.[391][392] Religious practice is widespread, among the most diverse in the world,[393] and profoundly vibrant.[394] The country has the world's largest Christian population.[395] Other notable faiths include Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, many New Age movements, and Native American religions.[396] Religious practice varies significantly by region.[397] "Ceremonial deism" is common in American culture.[398]

The overwhelming majority of Americans believe in a higher power or spiritual force, engage in spiritual practices such as prayer, and consider themselves religious or spiritual.[399][400] In the "Bible Belt", located within the Southern United States, evangelical Protestantism plays a significant role culturally, whereas New England and the Western United States tend to be more secular.[397] Mormonism—a Restorationist movement, whose members migrated westward from Missouri and Illinois under the leadership of Brigham Young in 1847 after the assassination of Joseph Smith[401]—remains the predominant religion in Utah to this day.[402]

Urbanization

About 82% of Americans live in urban areas, including suburbs;[165] about half of those reside in cities with populations over 50,000.[403] In 2022, 333 incorporated municipalities had populations over 100,000, nine cities had more than one million residents, and four cities—New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Houston—had populations exceeding two million.[404] Many U.S. metropolitan populations are growing rapidly, particularly in the South and West.[405]

Largest metropolitan areas in the United States

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

New York  Los Angeles |

1 | New York | Northeast | 19,498,249 | 11 | Boston | Northeast | 4,919,179 |  Chicago  Dallas–Fort Worth |

| 2 | Los Angeles | West | 12,799,100 | 12 | Riverside–San Bernardino | West | 4,688,053 | ||

| 3 | Chicago | Midwest | 9,262,825 | 13 | San Francisco | West | 4,566,961 | ||

| 4 | Dallas–Fort Worth | South | 8,100,037 | 14 | Detroit | Midwest | 4,342,304 | ||

| 5 | Houston | South | 7,510,253 | 15 | Seattle | West | 4,044,837 | ||

| 6 | Atlanta | South | 6,307,261 | 16 | Minneapolis–Saint Paul | Midwest | 3,712,020 | ||

| 7 | Washington, D.C. | South | 6,304,975 | 17 | Tampa–St. Petersburg | South | 3,342,963 | ||

| 8 | Philadelphia | Northeast | 6,246,160 | 18 | San Diego | West | 3,269,973 | ||

| 9 | Miami | South | 6,183,199 | 19 | Denver | West | 3,005,131 | ||

| 10 | Phoenix | West | 5,070,110 | 20 | Baltimore | South | 2,834,316 | ||

Health

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), average American life expectancy at birth was 77.5 years in 2022 (74.8 years for men and 80.2 years for women). This was a gain of 1.1 years from 76.4 years in 2021, but the CDC noted that the new average "didn't fully offset the loss of 2.4 years between 2019 and 2021". The health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and higher overall mortality due to opioid overdoses and suicides were held mostly responsible for the previous drop in life expectancy.[410] The same report stated that the 2022 gains in average U.S. life expectancy were especially significant for men, Hispanics, and American Indian–Alaskan Native people (AIAN). Starting in 1998, the life expectancy in the U.S. fell behind that of other wealthy industrialized countries, and Americans' "health disadvantage" gap has been increasing ever since.[411] The U.S. has one of the highest suicide rates among high-income countries.[412] Approximately one-third of the U.S. adult population is obese and another third is overweight.[413] The U.S. healthcare system far outspends that of any other country, measured both in per capita spending and as a percentage of GDP, but attains worse healthcare outcomes when compared to peer countries for reasons that are debated.[414] The United States is the only developed country without a system of universal healthcare, and a significant proportion of the population that does not carry health insurance.[415] Government-funded healthcare coverage for the poor (Medicaid) and for those age 65 and older (Medicare) is available to Americans who meet the programs' income or age qualifications. In 2010, former President Obama passed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.[u][416] Abortion in the United States is not federally protected, and is illegal or restricted in 18 states.[417]

Education

American primary and secondary education (known in the U.S. as K-12, "kindergarten through 12th grade") is decentralized. It is operated by state, territorial, and sometimes municipal governments and regulated by the U.S. Department of Education. In general, children are required to attend school or an approved homeschool from the age of five or six (kindergarten or first grade) until they are 18 years old. This often brings students through the 12th grade, the final year of a U.S. high school, but some states and territories allow them to leave school earlier, at age 16 or 17.[419] The U.S. spends more on education per student than any country in the world,[420] an average of $18,614 per year per public elementary and secondary school student in 2020–2021.[421] Among Americans age 25 and older, 92.2% graduated from high school, 62.7% attended some college, 37.7% earned a bachelor's degree, and 14.2% earned a graduate degree.[422] The U.S. literacy rate is near-universal.[165][423] The country has the most Nobel Prize winners of any country, with 411 (having won 413 awards).[424][425]

U.S. tertiary or higher education has earned a global reputation. Many of the world's top universities, as listed by various ranking organizations, are in the United States, including 19 of the top 25.[426][427] American higher education is dominated by state university systems, although the country's many private universities and colleges enroll about 20% of all American students. Local community colleges generally offer coursework and degree programs covering the first two years of college study. They often have more open admission policies, shorter academic programs, and lower tuition.[428]

As for public expenditures on higher education, the U.S. spends more per student than the OECD average, and Americans spend more than all nations in combined public and private spending.[429] Colleges and universities directly funded by the federal government do not charge tuition and are limited to military personnel and government employees, including: the U.S. service academies, the Naval Postgraduate School, and military staff colleges. Despite some student loan forgiveness programs in place,[430] student loan debt increased by 102% between 2010 and 2020,[431] and exceeded $1.7 trillion as of 2022.[432]

Culture and society

Americans have traditionally been characterized by a unifying political belief in an "American Creed" emphasizing consent of the governed, liberty, equality under the law, democracy, social equality, property rights, and a preference for limited government.[434][435] Culturally, the country has been described as having the values of individualism and personal autonomy,[436][437] as well as having a strong work ethic,[438] competitiveness,[439] and voluntary altruism towards others.[440][441][442] According to a 2016 study by the Charities Aid Foundation, Americans donated 1.44% of total GDP to charity—the highest rate in the world by a large margin.[443] The United States is home to a wide variety of ethnic groups, traditions, and values.[444][445] It has acquired significant cultural and economic soft power.[446][447]

Nearly all present Americans or their ancestors came from Europe, Africa, or Asia (the "Old World") within the past five centuries.[448] Mainstream American culture is a Western culture largely derived from the traditions of European immigrants with influences from many other sources, such as traditions brought by slaves from Africa.[449] More recent immigration from Asia and especially Latin America has added to a cultural mix that has been described as a homogenizing melting pot, and a heterogeneous salad bowl, with immigrants contributing to, and often assimilating into, mainstream American culture. The American Dream, or the perception that Americans enjoy high social mobility, plays a key role in attracting immigrants.[450][451] Whether this perception is accurate has been a topic of debate.[452][453][454] While mainstream culture holds that the United States is a classless society,[455] scholars identify significant differences between the country's social classes, affecting socialization, language, and values.[456][457] Americans tend to greatly value socioeconomic achievement, but being ordinary or average is promoted by some as a noble condition as well.[458]

The United States is considered to have the strongest protections of free speech of any country under the First Amendment,[459] which protects flag desecration, hate speech, blasphemy, and lese-majesty as forms of protected expression.[460][461][462] A 2016 Pew Research Center poll found that Americans were the most supportive of free expression of any polity measured.[463] They are the "most supportive of freedom of the press and the right to use the Internet without government censorship."[464] The U.S. is a socially progressive country[465] with permissive attitudes surrounding human sexuality.[466] LGBT rights in the United States are advanced by global standards.[466][467][468]

Literature

Colonial American authors were influenced by John Locke and various other Enlightenment philosophers.[470][471] The American Revolutionary Period (1765–1783) is notable for the political writings of Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Paine, and Thomas Jefferson. Shortly before and after the Revolutionary War, the newspaper rose to prominence, filling a demand for anti-British national literature.[472][473] An early novel is William Hill Brown's The Power of Sympathy, published in 1791. Writer and critic John Neal in the early- to mid-nineteenth century helped advance America toward a unique literature and culture by criticizing predecessors such as Washington Irving for imitating their British counterparts, and by influencing writers such as Edgar Allan Poe[474], who took American poetry and short fiction in new directions. Ralph Waldo Emerson and Margaret Fuller pioneered the influential Transcendentalism movement;[475][476] Henry David Thoreau, author of Walden, was influenced by this movement. The conflict surrounding abolitionism inspired writers, like Harriet Beecher Stowe, and authors of slave narratives, such as Frederick Douglass. Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter (1850) explored the dark side of American history, as did Herman Melville's Moby-Dick (1851). Major American poets of the nineteenth century American Renaissance include Walt Whitman, Melville, and Emily Dickinson.[477][478] Mark Twain was the first major American writer to be born in the West. Henry James achieved international recognition with novels like The Portrait of a Lady (1881). As literacy rates rose, periodicals published more stories centered around industrial workers, women, and the rural poor.[479][480] Naturalism, regionalism, and realism were the major literary movements of the period.[481][482]

While modernism generally took on an international character, modernist authors working within the United States more often rooted their work in specific regions, peoples, and cultures.[483] Following the Great Migration to northern cities, African-American and black West Indian authors of the Harlem Renaissance developed an independent tradition of literature that rebuked a history of inequality and celebrated black culture. An important cultural export during the Jazz Age, these writings were a key influence on Négritude, a philosophy emerging in the 1930s among francophone writers of the African diaspora.[484][485] In the 1950s, an ideal of homogeneity led many authors to attempt to write the Great American Novel,[486] while the Beat Generation rejected this conformity, using styles that elevated the impact of the spoken word over mechanics to describe drug use, sexuality, and the failings of society.[487][488] Contemporary literature is more pluralistic than in previous eras, with the closest thing to a unifying feature being a trend toward self-conscious experiments with language.[489] As of 2024 there have been 12 American laureates for the Nobel Prize in literature.[490]

Mass media

Media is broadly uncensored, with the First Amendment providing significant protections, as reiterated in New York Times Co. v. United States.[459] The four major broadcasters in the U.S. are the National Broadcasting Company (NBC), Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), American Broadcasting Company (ABC), and Fox Broadcasting Company (FOX). The four major broadcast television networks are all commercial entities. Cable television offers hundreds of channels catering to a variety of niches.[491] As of 2021[update], about 83% of Americans over age 12 listen to broadcast radio, while about 40% listen to podcasts.[492] As of 2020[update], there were 15,460 licensed full-power radio stations in the U.S. according to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).[493] Much of the public radio broadcasting is supplied by NPR, incorporated in February 1970 under the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967.[494]

U.S. newspapers with a global reach and reputation include The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and USA Today.[495] About 800 publications are produced in Spanish.[496][497] With few exceptions, newspapers are privately owned, either by large chains such as Gannett or McClatchy, which own dozens or even hundreds of newspapers; by small chains that own a handful of papers; or, in an increasingly rare situation, by individuals or families. Major cities often have alternative newspapers to complement the mainstream daily papers, such as The Village Voice in New York City and LA Weekly in Los Angeles. The five most popular websites used in the U.S. are Google, YouTube, Amazon, Yahoo!, and Facebook—all of them American-owned.[498]

As of 2022[update], the video game market of the United States is the world's largest by revenue.[499] There are 444 publishers, developers, and hardware companies in California alone.[500]

Theater

The United States is well known for its theater. Mainstream theater in the United States derives from the old European theatrical tradition and has been heavily influenced by the British theater.[501] By the middle of the 19th century America had created new distinct dramatic forms in the Tom Shows, the showboat theater and the minstrel show.[502] The central hub of the American theater scene is Manhattan, with its divisions of Broadway, off-Broadway, and off-off-Broadway.[503]

Many movie and television stars have gotten their big break working in New York productions. Outside New York City, many cities have professional regional or resident theater companies that produce their own seasons. The biggest-budget theatrical productions are musicals. U.S. theater has an active community theater culture.[504]

The Tony Awards recognizes excellence in live Broadway theater and are presented at an annual ceremony in Manhattan. The awards are given for Broadway productions and performances. One is also given for regional theater. Several discretionary non-competitive awards are given as well, including a Special Tony Award, the Tony Honors for Excellence in Theatre, and the Isabelle Stevenson Award.[505]

Visual arts

In the visual arts, the Hudson River School was a mid-19th-century movement in the tradition of European naturalism. The 1913 Armory Show in New York City, an exhibition of European modernist art, shocked the public and transformed the U.S. art scene.[507]

Georgia O'Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, and others experimented with new and individualistic styles, which would become known as American modernism. Major artistic movements such as the abstract expressionism of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning and the pop art of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein developed largely in the United States. Major photographers include Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, Dorothea Lange, Edward Weston, James Van Der Zee, Ansel Adams, and Gordon Parks.[508]

The tide of modernism and then postmodernism has brought global fame to American architects, including Frank Lloyd Wright, Philip Johnson, and Frank Gehry.[509] The Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan is the largest art museum in the United States.[510]

Music

American folk music encompasses numerous music genres, variously known as traditional music, traditional folk music, contemporary folk music, or roots music. Many traditional songs have been sung within the same family or folk group for generations, and sometimes trace back to such origins as the British Isles, mainland Europe, or Africa.[511] The rhythmic and lyrical styles of African-American music in particular have influenced American music.[512] Banjos were brought to America through the slave trade. Minstrel shows incorporating the instrument into their acts led to its increased popularity and widespread production in the 19th century.[513][514] The electric guitar, first invented in the 1930s, and mass-produced by the 1940s, had an enormous influence on popular music, in particular due to the development of rock and roll.[515]

Elements from folk idioms such as the blues and old-time music were adopted and transformed into popular genres with global audiences. Jazz grew from blues and ragtime in the early 20th century, developing from the innovations and recordings of composers such as W.C. Handy and Jelly Roll Morton. Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington increased its popularity early in the 20th century.[516] Country music developed in the 1920s,[517] rock and roll in the 1930s,[515] and bluegrass[518] and rhythm and blues in the 1940s.[519] In the 1960s, Bob Dylan emerged from the folk revival to become one of the country's most celebrated songwriters.[520] The musical forms of punk and hip hop both originated in the United States in the 1970s.[521]

The United States has the world's largest music market with a total retail value of $15.9 billion in 2022.[522] Most of the world's major record companies are based in the U.S.; they are represented by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).[523] Mid-20th-century American pop stars, such as Frank Sinatra[524] and Elvis Presley,[525] became global celebrities and best-selling music artists,[516] as have artists of the late 20th century, such as Michael Jackson,[526] Madonna,[527] Whitney Houston,[528] and Prince,[529] and the early 21st century, such as Taylor Swift and Beyoncé.[530]

Fashion

The United States, along with China, collectively accounts for the majority of global apparel demand. Apart from professional business attire, American fashion is eclectic and predominantly informal. Americans' diverse cultural roots are reflected in their clothing; however, sneakers, jeans, T-shirts, and baseball caps are emblematic of American styles.[531] New York, with its fashion week, is considered to be one of the "Big Four" global fashion capitals, along with Paris, Milan, and London. A study demonstrated that general proximity to Manhattan's Garment District has been synonymous with American fashion since its inception in the early 20th century.[532]

The headquarters of many designer labels reside in Manhattan. Labels cater to niche markets, such as pre teens. There has been a trend in the United States fashion towards sustainable clothing.[533] New York Fashion Week is one of the most influential fashion weeks in the world, and occurs twice a year;[534] while the annual Met Gala in Manhattan is commonly known as the fashion world's "biggest night".[535][536]

Cinema

The U.S. film industry has a worldwide influence and following. Hollywood, a district in northern Los Angeles, the nation's second-most populous city, is also metonymous for the American filmmaking industry.[537][538][539] The major film studios of the United States are the primary source of the most commercially successful and most ticket-selling movies in the world.[540][541] Since the early 20th century, the U.S. film industry has largely been based in and around Hollywood, although in the 21st century an increasing number of films are not made there, and film companies have been subject to the forces of globalization.[542] The Academy Awards, popularly known as the Oscars, have been held annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences since 1929,[543] and the Golden Globe Awards have been held annually since January 1944.[544]

The industry enjoyed its golden years, in what is commonly referred to as the "Golden Age of Hollywood", from the early sound period until the early 1960s,[545] with screen actors such as John Wayne and Marilyn Monroe becoming iconic figures.[546][547] In the 1970s, "New Hollywood", or the "Hollywood Renaissance",[548] was defined by grittier films influenced by French and Italian realist pictures of the post-war period.[549] The 21st century was marked by the rise of American streaming platforms, which came to rival traditional cinema.[550][551]

Cuisine

Early settlers were introduced by Native Americans to foods such as turkey, sweet potatoes, corn, squash, and maple syrup. Of the most enduring and pervasive examples are variations of the native dish called succotash. Early settlers and later immigrants combined these with foods they were familiar with, such as wheat flour,[552] beef, and milk, to create a distinctive American cuisine.[553][554] New World crops, especially pumpkin, corn, potatoes, and turkey as the main course are part of a shared national menu on Thanksgiving, when many Americans prepare or purchase traditional dishes to celebrate the occasion.[555]

Characteristic American dishes such as apple pie, fried chicken, doughnuts, french fries, macaroni and cheese, ice cream, pizza, hamburgers, and hot dogs derive from the recipes of various immigrant groups.[556][557][558][559] Mexican dishes such as burritos and tacos preexisted the United States in areas later annexed from Mexico, and adaptations of Chinese cuisine as well as pasta dishes freely adapted from Italian sources are all widely consumed.[560] American chefs have had a significant impact on society both domestically and internationally. In 1946, the Culinary Institute of America was founded by Katharine Angell and Frances Roth. This would become the United States' most prestigious culinary school, where many of the most talented American chefs would study prior to successful careers.[561][562]

The United States restaurant industry was projected at $899 billion in sales for 2020,[563][564] and employed more than 15 million people, representing 10% of the nation's workforce directly.[563] It is the country's second-largest private employer and the third-largest employer overall.[264][565] The United States is home to over 220 Michelin Star-rated restaurants, 70 of which are in New York City alone.[566] Wine has been produced in what is now the United States since the 1500s, with the first widespread production beginning in what is now New Mexico in 1628.[567][568][569] In the modern U.S., wine production is undertaken in all fifty states, with California producing 84 percent of all U.S. wine. With more than 1,100,000 acres (4,500 km2) under vine, the United States is the fourth-largest wine producing country in the world, after Italy, Spain, and France.[570][571]

The American fast-food industry developed alongside the nation's car culture.[572] American restaurants developed the drive-in format in the 1920s, which they began to replace with the drive-through format by the 1940s.[573][574] American fast-food restaurant chains, such as McDonald's,[575][576] Kentucky Fried Chicken, and many others, have numerous outlets around the world.[577]

Sports

The most popular spectator sports in the U.S. are American football, basketball, baseball, soccer, and ice hockey.[578] While most major U.S. sports such as baseball and American football have evolved out of European practices, basketball, volleyball, skateboarding, and snowboarding are American inventions, many of which have become popular worldwide.[579] Lacrosse and surfing arose from Native American and Native Hawaiian activities that predate European contact.[580] The market for professional sports in the United States was approximately $69 billion in July 2013, roughly 50% larger than that of all of Europe, the Middle East, and Africa combined.[581]

American football is by several measures the most popular spectator sport in the United States;[582] the National Football League has the highest average attendance of any sports league in the world, and the Super Bowl is watched by tens of millions globally.[583] However, baseball has been regarded as the U.S. "national sport" since the late 19th century. After American football, the next four most popular professional team sports are basketball, baseball, soccer, and ice hockey. Their premier leagues are, respectively, the National Basketball Association, Major League Baseball, Major League Soccer, and the National Hockey League. The most-watched individual sports in the U.S. are golf and auto racing, particularly NASCAR and IndyCar.[584][585]

On the collegiate level, earnings for the member institutions exceed $1 billion annually,[586] and college football and basketball attract large audiences, as the NCAA March Madness tournament and the College Football Playoff are some of the most watched national sporting events.[587] In the U.S., the intercollegiate sports level serves as a feeder system for professional sports. This differs greatly from practices in nearly all other countries, where publicly and privately funded sports organizations serve this function.[588]

Eight Olympic Games have taken place in the United States. The 1904 Summer Olympics in St. Louis, Missouri, were the first-ever Olympic Games held outside of Europe.[589] The Olympic Games will be held in the U.S. for a ninth time when Los Angeles hosts the 2028 Summer Olympics. U.S. athletes have won a total of 2,968 medals (1,179 gold) at the Olympic Games, the most of any country.[590][591][592]