санскрит

| санскрит | |

|---|---|

| Санскрит , сашкрита , санскрит , saṃskṛtam | |

|

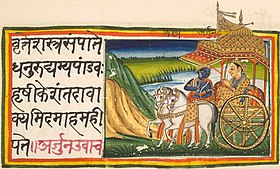

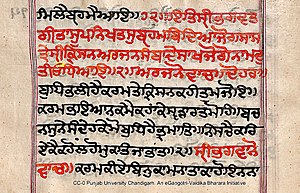

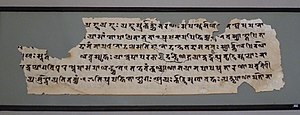

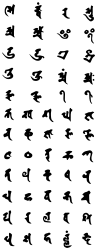

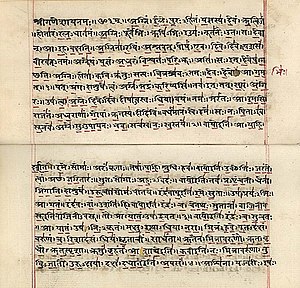

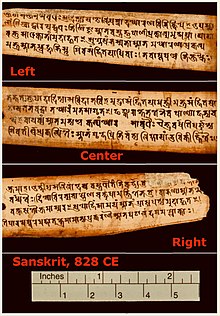

(Верх) Иллюстрированная санскритская рукопись 19-го века из Bhagavad Gita , [ 1 ] составлен c. 400 - 200 до н.э. [ 2 ] [ 3 ] (внизу) Печана 175-го годовщины третьего старейшего санскритского колледжа, санскритского колледжа, Калькутта . 1791. | |

| Произношение | [ˈSɐ̃skr̩tɐm] |

| Область | Южная Азия (собственная Индия) , индийская Юго -Восточная Азия , Большой Тибет , Большая Монголия , Центральная Азия (ранее). |

| Эпоха | в 1500–600 гг. До н.э. (ведический санскрит); [ 4 ] 700 г. до н.э. - 1350 г. н.э. (классический санскрит) [ 5 ] |

| Возрождение | Нет известных носителей санскрита. [ 6 ] [ 7 ] [ 8 ] [ 9 ] [ 10 ] [ 11 ] |

Индоевропейский

| |

Ранняя форма | |

| |

| Официальный статус | |

Официальный язык в |

|

Признанное меньшинство Язык в | Южная Африка (защищенный язык) [ 14 ] |

| Языковые коды | |

| ISO 639-1 | sa |

| ISO 639-2 | san |

| ISO 639-3 | san - Инклюзивный код Отдельные коды: cls - Классический санскрит vsn - Ведический санскрит |

| Глотолог | sans1269 |

Санскрит ( / ˈ s æ n s k r ɪ t / ; атрибутивно संस्कृत- , saṃskṛta- ; [ 15 ] [ 16 ] Номинально санскрит , Saṃskṛtam , IPA: [ˈsɐ̃skr̩tɐm] [ 17 ] [ B ] ) является классическим языком, принадлежащим индоарийской ветви индоевропейских языков . [ 19 ] [ 20 ] [ 21 ] Это возникло в Южной Азии после того, как его предшественники диффундировали там с северо -запада в позднем бронзовом веке . [ 22 ] [ 23 ] Санскрит - это язык индуизма священный , язык классической индуистской философии и исторических текстов буддизма и джайнизма . Это был язык связей в древней и средневековой Южной Азии, а после передачи индуистской и буддийской культуры в Юго -Восточную Азию, Восточную Азию и Центральную Азию в раннюю средневековую эпоху он стал языком религии и высокой культуры , а также политических элит в некоторых из этих регионов. [ 24 ] [ 25 ] В результате санскрит оказал длительное влияние на языки Южной Азии, Юго -Восточной Азии и Восточной Азии, особенно в их формальных и изученных словари. [ 26 ]

Санскрит обычно означает несколько старых индоарийских сортов языка. [ 27 ] [ 28 ] Наиболее архаичным из них является ведический санскрит , обнаруженный в Ригведе , коллекция из 1028 гимнов, составленных между 1500 г. до н.э. до 1200 г. до н.э. индоарийскими племенами, мигрирующими на восток из того, что сегодня является Афганистаном по всему северному Пакистану и в северо-западной Индии. [ 29 ] [ 30 ] Ведический санскрит взаимодействовал с ранее существовавшими древними языками субконтинента, поглощая названия недавно встречающихся растений и животных; Кроме того, древние дравидийские языки повлияли на фонологию и синтаксис Санскрита. [ 31 ] Санскрит также может более узко относиться к классическому санскриту , утонченной и стандартизированной грамматической форме, которая появилась в середине 1-го тысячелетия до н.э. и была кодифицирована в наиболее полной из древних грамматов, [ C ] Ашадхьяй ( « восемь глав») Панини . [ 32 ] Величайший драматург на санскрите, Калидаса , написал на классическом санскрите, а основы современной арифметики впервые были описаны на классическом санскрите. [ D ] [ 33 ] Однако два основных санскритских эпопея, Махабхарата и Рамаяна , были составлены в ряде устных регистров рассказывания историй, называемых эпическим санскритом , который использовался в северной Индии между 400 г. до н.э. до 300 г. н.э., и примерно современный с классическим санскритом. [ 34 ] В течение следующих веков санскрит стал традиционным, перестал быть изученным как родной язык и в конечном итоге перестал развиваться как живой язык. [ 9 ]

Гимны Ригведы особенно похожи на самые архаичные стихи иранских и греческих языковых семей Гатх Старого Авестана и Илиада Гомера , . [ 35 ] Поскольку Ригведа была перорально передана методами запоминания исключительной сложности, строгости и верности, [ 36 ] [ 37 ] как единственный текст без вариантов чтений, [ 38 ] Его сохраненный архаичный синтаксис и морфология имеют жизненно важное значение для реконструкции прото-индоевропейского языка общего предка . [ 35 ] Санскрит не имеет подтвержденного нативного сценария: с рутины 1-го миллинда К.Е., он был написан в различных брахмских сценариях и в современную эпоху чаще всего в Деванагари . [ А ] [ 12 ] [ 13 ]

Статус санскрита, функция и место в культурном наследии Индии признаются его включением в конституцию Индии восьмого языков графика . [ 39 ] [ 40 ] Однако, несмотря на попытки возрождения, [ 8 ] [ 41 ] В Индии нет носителей первого языка санскрита. [ 8 ] [ 10 ] [ 42 ] В каждой из недавних переписей Индии в десятилетнем возрасте несколько тысяч граждан сообщили о санскрите, чтобы быть их родным языком, [ E ] Но считается, что цифры означают желание быть согласованным с престижем языка. [ 6 ] [ 7 ] [ 8 ] [ 43 ] Санскрит преподавался в традиционных гурукулах с древних времен; Это широко преподается сегодня на уровне средней школы. Самым старым санскритским колледжем является санскритский колледж Бенареса, основанный в 1791 году во время правления Ост -Индской компании . [ 44 ] Санскрит по -прежнему широко используется в качестве церемониального и ритуального языка в индуистских и буддийских гимнах и песнопениях .

Этимология и номенклатура

На санскрите словесное прилагательное Sáṃskṛta - это составное слово, состоящее из Sáṃ («вместе, хорошо, хорошо, совершенствовано») и kṛta - («сделано, сформировано, работа»). [ 45 ] [ 46 ] Это означает работу, которая была «хорошо подготовлена, чистой и совершенной, отполированной, священной». [ 47 ] [ 48 ] [ 49 ] По словам Бидермана, совершенство контекстуально упоминается в этимологическом происхождении слова, это его тональный, чем семантические квадраты. Звуковая и устная передача были высоко ценными качествами в древней Индии, и ее мудрецы уточняли алфавит, структуру слов и ее требовательную грамматику в «коллекцию звуков, своего рода возвышенную музыкальную плесень» как интегральный язык, который они называли санскритом . [ 46 ] Начиная с позднего ведического периода , штат Аннет Вилке и Оливер Моубус, резонируя звук и его музыкальные основы привлекли к «исключительно большому количеству лингвистической, философской и религиозной литературы» в Индии. Звук был визуализирован как «проникающее все творение», еще одно представление самого мира; «таинственный магнит» индуистской мысли. Поиск совершенства в мышлении и цель освобождения были среди измерений священного звука, и общая нить, которая сотворила все идеи и вдохновения вместе, стал поиском того, что древние индейцы считали совершенным языком, «фоноцентрическая эпистема» санскрита. [ 50 ] [ 51 ]

Санскрит как язык конкурировал с многочисленными, менее точными местными индийскими языками, называемыми пракритными языками ( Prākṛta - ). Термин Prakrta буквально означает «оригинальный, естественный, нормальный, бесхитросный», заявляет Франклин Саутворт . [ 52 ] Взаимосвязь между пракритом и санскритом встречается в индийских текстах, датированных 1 -м тысячелетием. Патаньяли признал, что Пракрит - это первое язык, один инстинктивно принятый каждым ребенком со всеми его недостатками, а затем приводит к проблемам толкования и недопонимания. Очищающая структура санскритского языка устраняет эти недостатки. Например, в раннем санскритском грамматике говорится , что многого на языках пракрита этимологически укоренено на санскрите, но включает в себя «потерю звуков» и коррупции, которые являются результатом «игнорирования грамматики». Да'ин признал, что в пракрите есть слова и запутанные структуры, которые процветают независимо от санскрита. Эта точка зрения найдена в написании Бхарата Муни , автора древнего текста Natya Shastra . Ранний джайнский ученый Намисадху признал разницу, но не согласился с тем, что язык пракрита был коррупцией санскрита. Намисадху заявил, что пракритский язык был Пурвамом («Пришло раньше, происхождение») и что это было естественно для детей, в то время как санскрит был уточнением пракрита посредством «очищения грамматикой». [ 53 ]

История

Происхождение и развитие

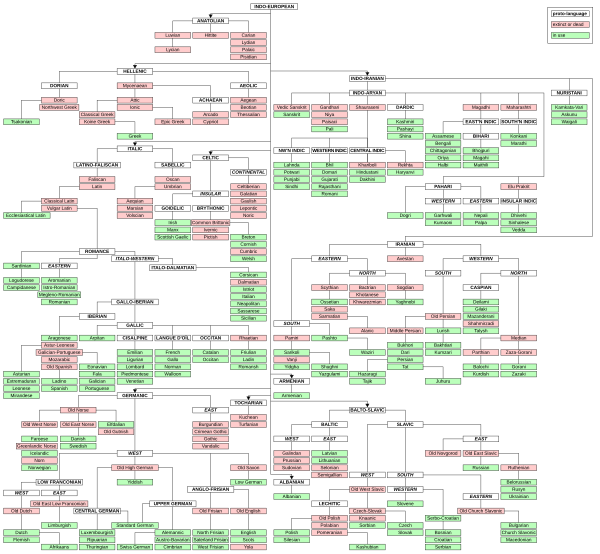

Санскрит принадлежит индоевропейскому семейству языков . Это один из трех самых ранних древних задокументированных языков, возникших из общего корневого языка, который теперь называется прото-индоевропейским : [ 19 ] [ 20 ] [ 21 ]

- Ведический санскрит ( ок. 1500–500 гг. До н.э.).

- Микенский греческий ( ок. 1450 г. до н.э.) [ 54 ] и древнегреческий ( ок. 750–400 гг. До н.э.).

- Хетт ( ок. 1750–1200 гг. До н.э.).

Другие индоевропейские языки, отдаленно связанные с санскритом, включают архаичный и классический латынь ( ок. 600 г. до н.э.-100 г. н.э., курсивные языки ), готический (архаичный германский язык , ок. 350 г. н.э. ), старый норвеж ( ок. 200 г. и после), Старый Авестан ( ок. Конец 2 тысячелетия до н.э. [ 55 ] ) и младший аван ( ок. 900 г. до н.э.). [ 20 ] [ 21 ] Ближайшие древние родственники ведического санскрита на индоевропейских языках-это нулевые языки, найденные в отдаленном индуистском регионе северо-восточного Афганистана и северо-западных Гималаев, [ 21 ] [ 56 ] [ 57 ] а также вымерший авенст и старый персидский - оба являются иранскими языками . [ 58 ] [ 59 ] [ 60 ] Санскрит принадлежит группе Satem индоевропейских языков.

Ученые колониальной эры, знакомые с латинскими и греческими, были поражены сходством санскритского языка, как в его словарном, так и в грамматике, к классическим языкам Европы. В Оксфордском введении в прото-индоевропейский и прото-индоевропейский мир Мэллори и Адамс иллюстрируют сходство со следующими примерами родственных форм [ 61 ] (С добавлением старого английского для дальнейшего сравнения):

| Около | Английский | Старый английский | латинский | Греческий | санскрит | Глоссарий |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Пчела | мать | Mōdor | Матер | бросить | Материнский | мать |

| *Ph₂tḗr | отец | кормление | отец | потребитель | питар | отец |

| * Bʰʰtēr | брат | хрупкий | брат | прорех | Бхратар- | брат |

| * Sinkōrr | сестра | грубая | сестра | эор | Свасар | сестра |

| *Suhnús | сын | презентация | - | гипо | Сунду- | сын |

| *dʰugh₂tḗr | дочь | Дохтор | - | Thugáckeccar | Duhitar | дочь |

| *gʷṓws | корова | хоар | бродяга | Бур | Ган- | корова |

| *demh₂- | Ручная, древесина | Там древесина | дом | доми- | леди | Дом, ручный, строительство |

Соответствия предполагают некоторые общие корни и исторические связи между некоторыми из далеких крупных древних языков мира. [ f ]

Теория индоарийских миграций разделяемые санскритом и другими индоевропейски объясняет общие черты , начало 2 тысячелетия до н.э. Доказательства такой теории включают тесную связь между индо-иранскими языками и балтийскими и славянскими языками , словарным обменом с не-индоевропейскими уральскими языками и природой заветных индоевропейских слов для флоры и фауны. [ 63 ]

Предыстория индоарийских языков, предшествующих ведическому санскрите, неясна, и различные гипотезы ставят его на довольно широкий предел. По словам Томаса Берроу, на основе взаимосвязи между различными индоевропейскими языками происхождение всех этих языков может быть в том, что сейчас является центральной или восточной Европой, в то время как индоиранская группа, возможно, возникла в центральной России. [ 64 ] Иранские и индоарийские ветви разделялись довольно рано. Это индоарийская филиал, которая переехала в восточный Иран, а затем на юг в Южную Азию в первой половине 2-го тысячелетия до н.э. Оказавшись в древней Индии, индоарийский язык претерпел быстрые лингвистические изменения и превратился в ведический санскритский язык. [ 65 ]

Ведический санскрит

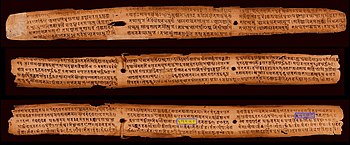

Преклассическая форма санскрита известна как ведический санскрит . Самым ранним подтвержденным санскритским текстом является Ригведа , индуистское писание с середины до конца второго тысячелетия до н.э. Никакие письменные записи из такого раннего периода не сохранились, если вообще когда -либо существовали, но ученые, как правило, уверены, что устная передача текстов является надежной: это церемониальная литература, где точное фонетическое выражение и его сохранение были частью исторической традиции Полем [ 66 ] [ 67 ] [ 68 ]

Однако некоторые ученые предположили, что оригинальная ṛ-veda отличалась некоторыми фундаментальными способами в фонологии по сравнению с единственной выжившей версией, доступной для нас. В частности, ретрофлексные согласные не существовали как естественную часть самого раннего ведического языка, [ 69 ] и что они развивались в столетия после завершения композиции, и в качестве постепенного бессознательного процесса во время пероральной передачи поколениями покорных. [ Цитация необходима ]

Основным источником этого аргумента является внутреннее свидетельство текста, которое выдает нестабильность явления ретрофлексии, причем те же фразы имеют ретрофлексию, вызванную песком, в некоторых частях, но не других. [ 70 ] Это принимается наряду с доказательствами противоречий, например, в отрывках Aitareya-storakyaka (700 г. до н. [ 71 ]

Ṛg-veda-это коллекция книг, созданная несколькими авторами. Эти авторы представляли разные поколения, а мандалас от 2 до 7 - самые старые, в то время как мандалы 1 и 10 являются относительно самыми молодыми. [ 72 ] [ 73 ] Тем не менее, ведический санскрит в этих книгах Аг-Веды «вряд ли представляет какое-либо диалектическое разнообразие», заявляет Луи Рену -индолог, известный своей стипендией санскритской литературы и в частности, Аг-Веды. По словам Рену, это подразумевает, что ведический санскритский язык имел «установленную лингвистическую паттерн» ко второй половине второго тысячелетия до н.э. [ 74 ] Помимо ṛg-veda, древняя литература в ведическом санскрите, которая выжила в современную эпоху, включают Самаведа , Яджурведа , Атхарваведа , а также встроенные и слоистые ведические тексты, такие как Брахманы , Араняки и ранние Упанишады . [ 66 ] Эти ведические документы отражают диалекты санскрита, найденные в различных частях северо -западного, северного и восточно -индийского субконтинента. [ 75 ] [ 76 ]

По словам Майкла Витцеля, ведический санскрит был разговорным языком полукомадических арийцев, которые временно обосновались в одном месте, поддерживали стада крупного рогатого скота, практиковали ограниченное сельское хозяйство и через некоторое время, перемещенные поездами фургонов, которые они называли Грамой . [ 77 ] [ 78 ] Ведический санскритский язык или тесно связанный индоевропейский вариант был признан за пределами древней Индии о чем свидетельствует « Договор Митанни » между древним хиттетом и народом Митанни, вырезанного в скале, в регионе, в котором теперь есть части Сирии и Турции. [ 79 ] [ G ] Части этого договора, такие как имена князей Митанни и технические термины, связанные с обучением лошадей, по причинам, не понятыми, находятся в ранних формах ведического санскрита. Договор также вызывает боги Варуна, Митра, Индра и Насатия, которые можно найти в самых ранних слоях ведической литературы. [ 79 ] [ 81 ]

О брихаспати, когда давая имена

Сначала они изложили начало языка,

Их самый превосходный и безупречный секрет

был обнажен через любовь,

Когда мудрые сформировали язык со своим разумом,

Очистить его как зерно с виндовым вентилятором,

Тогда друзья знали дружбу -

благоприятный знак на их языке.

Ведический санскрит, обнаруженный в ṛg-veda, явно более архаичен, чем другие ведические тексты, и во многих отношениях ригведный язык особенно похож на те, которые встречаются в архаичных текстах старого Зороастрийского Гатхаса Гомера и Илиады и Одисси . [ 83 ] По словам Стефани В. Джеймисона и Джоэла П. Бреретона-индологов, известных своим переводом Аг-Веды-ведической санскритской литературы, «явно унаследованной» от индоиранской и индоевропейской времена, такие как социальные структуры, как роль поэта и священники, экономика патронажа, фразовые уравнения и некоторые поэтические счетчики. [ 84 ] [ H ] Несмотря на то, что существуют сходства, штат Джейсон и Бреретон, существуют также различия между ведическим санскритом, старым авеняном и микенской греческой литературой. Например, в отличие от санскритских сравнений в Аг-Веду, старому авеняну Гатхас не хватает совместимости, и это редко встречается в более поздней версии языка. Греческий греческий год, как санскрит Аг-Ведика, широко использует риски, но они структурно очень разные. [ 86 ]

Классический санскрит

Ранняя ведическая форма санскритского языка была гораздо менее гомогенной по сравнению с классическим санскритом, как определено грамматиками примерно на середину 1-го тысячелетия до н.э. По словам Ричарда Гомбриха - индолога и ученого санскрита, пали и буддийских исследований - архаичный ведический санскрит, обнаруженный в Ригведе , уже развивался в ведический период, о чем свидетельствует в более поздней ведической литературе. Гомбрих утверждает, что язык в ранних Упанишадах индуизма и поздней ведической литературы приближается к классическому санскриту, в то время как архаичный ведический санскрит, который стал временем Будды , стал неразрешимым для всех, кроме древних индийских мудрецов. [ 87 ]

Формализация санскритского языка приписывается Панини , наряду с комментарием Патанджали Махабхагья и Катьяны, в котором предшествовал работа Патаньжали. [ 88 ] Панини сочинил Aṣṭādhyāyī («грамматику восьми глазей»). В столетии, в котором он жил, неясно и обсуждается, но его работа, как правило, считается, что когда -нибудь между 6 и 4 -м веками до н.э. [ 89 ] [ 90 ] [ 91 ]

Ашадхьяй был не первым описанием санскритской грамматики, но это самое раннее, которое выжило полностью, и кульминацией длинной грамматической традиции , которая, по словам Фортсона, является «одним из интеллектуальных чудес древнего мира». [ 92 ] Панини цитирует десяти ученых о фонологических и грамматических аспектах санскритского языка перед ним, а также о вариантах использования санскрита в разных регионах Индии. [ 93 ] Десять ведических ученых, которых он цитирует, - это Иекинали, Каиньяпа , Гарга, Галава, Какравармана, Бхарадвая , Шакнаяна, Шакалья, Сенака и Спхайана. [ 94 ] [ 95 ] Ашадхьяй Панини стал основой Вьякараны, Веданги . [ 93 ]

В Ашадхьяйи язык наблюдается таким образом, который не имеет параллельно среди греческих или латинских грамматов. Грамматика Панини, согласно Рену и Филлиозату, является классикой, которая определяет лингвистическое выражение и устанавливает стандарт для санскритского языка. [ 96 ] Панини использовал технический металлический язык, состоящий из синтаксиса, морфологии и лексикона. Этот металлический язык организован в соответствии с серией мета-правил, некоторые из которых явно указаны, в то время как другие могут быть выведены. [ 97 ] Несмотря на различия в анализе современной лингвистики, работа Панини была признана ценной и наиболее продвинутым анализом лингвистики до двадцатого века. [ 92 ]

Комплексная и научная теория грамматики Панини традиционно принимается, чтобы отметить начало классического санскрита. [ 98 ] Его систематический трактат вдохновил и сделал санскрит выдающимся индийским языком обучения и литературы в течение двух тысячелетий. [ 99 ] Неясно, написал ли сам Панини свой трактат или он устно создал подробный и сложный трактат, а затем передал его через своих учеников. Современная стипендия в целом признает, что он знал о форме письма, основанной на ссылках на такие слова, как Липи («Скрипт») и Липикара («писец») в разделе 3.2 Ахадхьяй . [ 100 ] [ 101 ] [ 102 ] [ я ]

Классический санскритский язык, формализованный Панини, государства Рену, является «не обнищанным языком», скорее, это «контролируемый и сдержанный язык, из которого были исключены архаизм и ненужные формальные альтернативы». [ 109 ] Классическая форма языка упростила правила Сандхи , но сохранила различные аспекты ведического языка, добавляя строгость и гибкость, чтобы у него были достаточные средства для выражения мыслей, а также «способны реагировать на будущее. диверсифицированная литература », по словам Рену. структуры ведического санскрита Панини включил многочисленные «необязательные правила» за пределами бахуламской , чтобы уважать свободу и творческий подход, чтобы отдельные авторы, разделенные географией или временем Санскритский язык. [ 110 ]

Фонетические различия между ведическим санскритом и классическим санскритом, как выяснены из текущего состояния выжившей литературы, [ 71 ] являются незначительными по сравнению с интенсивными изменениями, которые должны были произойти в преведический период между прото-индоарийским языком и ведическим санскритом. [ 111 ] Заметные различия между ведическим и классическим санскритом включают в себя многоэтапную грамматику и грамматические категории, а также различия в акценте, семантик и синтаксис. [ 112 ] Существуют также некоторые различия между тем, как заканчиваются некоторые существительные и глаголы, а также правила Sandhi , как внутренние, так и внешние. [ 112 ] Довольно много слов, найденных на раннем ведическом санскритском языке, никогда не встречаются в позднем ведическом санскритском или классической санскритской литературе, в то время как некоторые слова имеют разные и новые значения в классическом санскрите, когда контекстуально сравниваются с ранней ведической санскритской литературой. [ 112 ]

Артур Макдонелл был среди ученых ранней колониальной эры, которые суммировали некоторые различия между ведическим и классическим санскритом. [ 112 ] [ 113 ] Луи Рену опубликовал на французском языке в 1956 году более обширное обсуждение сходства, различий и эволюции ведического санскрита в ведический период, а затем к классическому санскриту, а также его взгляды на историю. Эта работа была переведена Джагбансом Балбиром. [ 114 ]

Санскрит и пракрит

Мандавр каменной надпись Яшодхармана-Вишнувардхана , 532 г. н.э. [ 115 ]

Самое раннее известное использование слова Saṃskṛta (санскрит), в контексте речи или языка, встречается в стихах 5.28.17–19 Рамаяны . [ 16 ] За пределами изученной сферы письменного классического санскрита, народные разговорные диалекты ( пракриты ) продолжали развиваться. Санскрит сосуществовал с множеством других пракритских языков древней Индии. Пракритские языки Индии также имеют древние корни, и некоторые санскритские ученые называли эти апабхрамса , буквально «избалованными». [ 116 ] [ 117 ] Ведическая литература включает в себя слова, чьи фонетический эквивалент не встречается на других индоевропейских языках , а которые встречаются на региональных языках пракрита, что делает вероятным, что взаимодействие, обмен словами и идеями началось в начале индийской истории. Поскольку индийская мысль диверсифицировала и бросила вызов более ранним убеждениям в индуизме, особенно в форме буддизма и джайнизма , языки пракрита, такие как пали в буддизме и ардхамагаджи в джайнизме, соревновались с санскритом в древние времена. [ 118 ] [ 119 ] [ 120 ] Тем не менее, утверждает Пол Дандас , ученый джайнизма, эти древние языки пракрита «имели примерно такую же связь с санскритом, как и средневековые итальянцы, с латыни». [ 120 ] Индийская традиция утверждает, что Будда и Махавира предпочитали пракритский язык, чтобы каждый мог его понять. Однако такие ученые, как Dundas, подвергли сомнению эту гипотезу. Они утверждают, что нет никаких доказательств для этого, и любые доказательства, которые доступны, предполагают, что к началу общей эпохи едва ли кто -либо, кроме изученных монахов, имел способность понимать старые языки пракрита, такие как Ардхамагадхи . [ 120 ]

Ученые колониальной эры задавались вопросом, был ли санскрит когда -либо разговорным языком или просто литературным языком. [ 121 ] Ученые не согласны в своих ответах. В разделе западных ученых говорится, что санскрит никогда не был разговорным языком, в то время как другие и особенно большинство индийских ученых заявляют наоборот. [ 122 ] Те, кто подтверждает санскрит, что были народным языком, указывают на необходимость того, чтобы санскрит был разговорным языком для устной традиции , которая сохранила огромное количество санскритских рукописей из древней Индии. Во -вторых, они утверждают, что текстовые доказательства в работах Яксы, Панини и Патанаджали подтверждают, что классический санскрит в их эпоху был языком, на котором говорится ( Бхаша ) культурным и образованным. Некоторые сутры излагают варианты форм разговорного санскрита по сравнению с написанным санскритом. [ 122 ] Китайский буддийский паломник в 7-м веке Сюансанг упомянул в своих мемуарах, что на санскрите были проведены официальные философские дебаты в Индии, а не на местном языке этого региона. [ 122 ]

По словам санскритского лингвиста-профессора Мадхава Дешпанде, санскрит был разговорным языком в разговорной форме к середине 1-го тысячелетия до н.э., который сосуществовал с более формальной, грамматически правильной формой литературного санскрита. [ 123 ] Это, утверждает Дешпанде, верно для современных языков, где говорят и понимаются разговорные неверные приближения и диалекты языка, а также более «утонченные, сложные и грамматически точные» формы того же языка, обнаруженные в литературных произведениях. [ 123 ] Индийская традиция, штат Winternitz (1996), предпочитала обучение и использование нескольких языков с древних времен. Санскрит был разговорным языком в образованных и элитных классах, но это был также язык, который, как следует из которых было понят в более широком круге общества, потому что широко популярные народные эпосы и истории, такие как Рамаяна , Махабхарата , Бхагавата Пурана , Панчатантра . и многие другие тексты находятся на санскритском языке [ 124 ] Таким образом, классическим санскритом с его точной грамматикой был язык индийских ученых и образованных классов, в то время как другие общались с приблизительными или неграмотными его вариантами, а также с другими индийскими языками. [ 123 ] Таким образом, санскрит, как ученый язык древней Индии, существовал вместе с местными пракритами. [ 123 ] Многие санскритские драмы указывают на то, что язык сосуществовал с местными пракритами. Города Варанаси , Пайтан , Пуна и Канчипурам были центрами классического санскритского обучения и общественных дебатов до прибытия колониальной эры. [ 125 ]

По словам Ламотты (1976), индологов и ученых буддизма, санскрит стал доминирующим литературным и надписным языком из -за его точности в общении. Это было, утверждает Ламотта, идеальный инструмент для представления идей, и как знание санскрита умножалось, так и его распространение и влияние. [ 126 ] Санскрит был принят добровольно как средство высокой культуры, искусства и глубоких идей. Поллок не согласен с Ламоттой, но соглашается с тем, что влияние санскрита превратился в то, что он называет «санскритским космополисом» над регионом, в который включали всю Южную Азию и большую часть Юго -Восточной Азии. На санскритском языке Cosmopolis процветал за пределами Индии с 300 до 1300 г. н.э. [ 127 ]

Сегодня считается, что Кашмири - самый близкий язык к санскрите. [ 128 ] [ 129 ] [ 130 ]

Дравидийское влияние на санскрит

Рейнель упоминает, что не только дравидийские языки заимствованы на санскритском словаре, но они также повлияли на санскрит на более глубоких уровнях структуры, например, в области фонологии, где индоарьянские ретрофлексы были приписаны дравидийскому влиянию ». [ 131 ] Точно так же Ференк Руцка утверждает, что все основные сдвиги в индоарийской фонетике в течение двух тысячелетий могут быть связаны с постоянным влиянием дравидийского языка с аналогичной фонетической структурой на тамильский. [ 132 ] Hock et al. цитируя Джордж Харт, что на санскрите было влияние старого тамильского тамильца . [ 133 ] Харт сравнил старый тамильский и классический санскрит, чтобы прийти к выводу, что существует общий язык, из которого эти функции были получены - «как тамильский, так и санскрит вывели их общие соглашения, счетчики и методы из общего источника, потому что это ясно, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что, что они Никто не заимствовал непосредственно у другого ". [ 134 ]

Reinöhl далее утверждает, что существует симметричная связь между дравидийскими языками, такими как каннада или тамильский, с индоарийскими языками, такими как бенгальские или хинди, тогда как те же отношения не найдены для неарийских языков, например, персидских или английских: английский: английский: английский: английский: английский: английский: английский или английский: те же отношения не найден

Предложение на дравидийском языке, таком как тамильский или каннада, становится обычно хорошим бенгальским или хинди, заменяя бенгальские или хинди эквиваленты на дравидийские слова и формы, не изменяя порядок слова; Но то же самое невозможно при превращении персидского или английского приговора на неарийский язык.

- Reinöhl [ 131 ]

Шульман упоминает, что «дравидийские нефинитовые вербальные формы (называемые винайеккамом на тамильском языке) сформировали использование санскритских нефинитовых глаголов (первоначально полученных из перегибаемых форм действия существительных в ведике). Этот особенно веский случай возможного влияния на санскрита - один из Из многих предметов синтаксической ассимиляции, не в последнюю очередь среди них большой репертуар морфологической модальности и аспекта, которые, как только кто -то знает, можно найти, можно найти повсюду в классическом и постклассическом санскрите ». [ 135 ]

Основное влияние дравидийца на санскрит, как было сосредоточено, было сконцентрировано в временном запасе между поздним ведическим периодом и кристаллизацией классического санскрита. Как и в этот период индоарийские племена еще не вступили в контакт с жителями юга субконтинента, это говорит о значительном присутствии дравидийских носителей в Северной Индии (центральная гангская равнина и классика Мадхьядеша), которые сыграли важную роль в этом Влияние субстрата на санскрит. [ 136 ]

Влияние

Экспадиционные рукописи на санскрите более 30 миллионов, в сто раз на греческом и латинском комбинировали, что составляет наибольшее культурное наследие, которое любая цивилизация произвела до изобретения типографии.

- Предисловие санскритской вычислительной лингвистики (2009), Giard Has, Amba Culkarni и Peter Scharm [ 137 ] [ 138 ] [ J ]

Санскрит был преобладающим языком индуистских текстов, охватывающих богатую традицию философских и религиозных текстов, а также поэзии, музыки, драмы , научных , технических и других. [ 140 ] [ 141 ] Это преобладающий язык одной из крупнейших коллекций исторических рукописей. Самые ранние известные надписи на санскрите-с 1-го века до нашей эры, такие как надпись Айодхья Дхана и Госунди-Хатибада (Читторгарх) . [ 142 ]

Несмотря на то, что санскрит разработал и воспитывался учеными православных школ индуизма, был языком некоторых ключевых литературных произведений и теологии гетеродоксальных школ индийских философий, таких как буддизм и джайнизм. [ 143 ] [ 144 ] Структура и возможности классического санскритского языка запускали древние индийские спекуляции о «природе и функции языка», какова отношения между словами и их значениями в контексте сообщества ораторов, являются ли эти отношения объективными или субъективными, обнаруженными, обнаруженными Или создается, как люди учатся и относятся к окружающему миру через язык и о пределах языка? [ 143 ] [ 145 ] Они размышляли о роли языка, онтологическом статусе рисования словесных изображений через звук и необходимость в правилах, чтобы он мог служить средством для сообщества ораторов, разделенных географией или временем, делиться и понимать глубокие идеи друг от друга. [ 145 ] [ k ] Эти спекуляции стали особенно важными для Мимашсы и Ньяя -школ индуистской философии, а затем для буддизма Веданты и Махаяны, заявляет Фрит Стаал - ученый лингвистику с акцентом на индийскую философию и санскритс. [ 143 ] Несмотря на то, что доминирующий язык индуистских текстов написан в ряде различных сценариев, был санскритом. Это или гибридная форма санскрита стала предпочтительным языком стипендии буддизма Махаяны; [ 148 ] Например, один из ранних и влиятельных буддийских философов, Нагарджуна (~ 200 г. н.э.), использовал классический санскрит в качестве языка для своих текстов. [ 149 ] Согласно Рену, санскрит играл ограниченную роль в традиции трювы (ранее известной как Хинаяна), но пережившие работы пракритов имеют сомнительную подлинность. Некоторые из канонических фрагментов ранних буддийских традиций, обнаруженных в 20 -м веке, предполагают, что ранние буддийские традиции использовали несовершенный и достаточно хороший санскрит, иногда с синтаксисом пали, утверждает Рену. Махасахгика . и Махавасту, в их поздних формах Хинойны, использовали гибридный санскрит для их литературы [ 150 ] Санскрит был также языком некоторых из самых старых выживших, авторитетных и много следовал философским произведениям джайнизма, таких как Tattvartha Sutra , Umaswati . [ L ] [ 152 ]

Санскритский язык был одним из основных средств для передачи знаний и идей в истории азиатской истории. Индийские тексты на санскрите уже находились в Китае к 402 годам н . [ 156 ] Сюанзанг , еще один китайский буддийский паломник, выучил санскрит в Индии и донес 657 санскритских текстов в Китай в 7 -м веке, где он создал крупный центр обучения и языкового перевода под покровительством императора Тайзонга. [ 157 ] [ 158 ] К началу 1 -го тысячелетия н.э. санскрит распространил буддийские и индуистские идеи в Юго -Восточную Азию, [ 159 ] части Восточной Азии [ 160 ] и Центральная Азия. [ 161 ] Он был принят как язык высокой культуры и предпочтительный язык некоторыми местными правящими элитами в этих регионах. [ 162 ] Согласно Далай -ламе , санскритский язык - это родительский язык, который находится в основе многих современных языков Индии, и тот, который продвигал индийскую мысль в другие далекие страны. В тибетском буддизме говорится, что далай-лама на санскритском языке был уважаемым и называется Legjar Lhai-ka или «элегантный язык богов». Это было средством передачи «глубокой мудрости буддийской философии» в Тибет. [ 163 ]

На санскритском языке создал пан-индоарийский доступ к информации и знаниям в древние и средневековые времена, в отличие от пракритских языков, которые были поняты только на региональном уровне. [ 125 ] [ 166 ] Это создало культурную связь по всему субконтиненту. [ 166 ] Поскольку местные языки и диалекты развивались и диверсифицированы, санскрит служил общим языком. [ 166 ] Он связывал ученых из отдаленных частей Южной Азии, таких как Тамил Наду и Кашмир, государства Дешпанде, а также из разных областей исследований, хотя должны были быть различия в его произношении, учитывая родной язык соответствующих ораторов. На санскритском языке собрались люди, говорящие на индо-саринец, особенно его элитные ученые. [ 125 ] Некоторые из этих ученых индийской истории на региональном уровне производили местный санскрит, чтобы охватить более широкую аудиторию, о чем свидетельствуют тексты, обнаруженные в Раджастхане, Гуджарате и Махараштре. Как только аудитория познакомилась с легкой концерной версией санскрита, заинтересованные в разговорной санскрите с более продвинутым классическим санскритом. Ритуалы и церемонии обрядов прохождения были и по-прежнему остаются другими случаями, когда широкий спектр людей слышат санскрит, и иногда присоединяются к некоторым санскритским словам, таким как нама . [ 125 ]

Классический санскрит - это стандартный регистр , изложенная в грамматике Панини , около четвертого века до нашей эры. [ 167 ] Его положение в культурах Большой Индии сродни латинскому и древнегреческому греческому языку в Европе. Санскрит значительно повлиял на большинство современных языков индийского субконтинента , особенно на языках северного, западного, центрального и восточно -индийского субконтинента. [ 168 ] [ 169 ] [ 170 ]

Отклонить

Санскрит отказался от начала и после 13 -го века. [ 127 ] [ 171 ] Это совпадает с началом исламских вторжений в Южную Азию для создания, а затем расширяет мусульманское правление в форме султанатов, а затем Империю Моголов . [ 172 ] Шелдон Поллок характеризует упадок санскрита как долгосрочные «культурные, социальные и политические изменения». Он отклоняет идею о том, что санскрит отказался от «борьбы с варварскими захватчиками», и подчеркивает такие факторы, как растущая привлекательность народного языка для литературного выражения. [ 173 ]

С падением Кашмира около 13 -го века, ведущий центр санскритского литературного творчества, санскритская литература исчезла, исчезла, исчезла, [ 174 ] Возможно, в «пожарах, которые периодически охватывали столицу Кашмира» или «Монгольское вторжение 1320 года», штат Поллок. [ 175 ] Санскритская литература, которая когда -то была широко распространена из северо -западных областей субконтинента, остановилась после 12 -го века. [ 176 ] Поскольку индуистские королевства упали на востоке и Южной Индии, такие как Великая Империя Виджаянагара , тоже был санскрит. [ 174 ] Были исключения и короткие периоды имперской поддержки санскрита, в основном сконцентрированные во время правления толерантного императора Моголов Акбар . [ 177 ] Мусульманские правители покровительствовали ближневосточному языку и сценариям, найденным в Персии и Аравии, и индейцы лингвистически адаптировались к этой персидзии, чтобы получить работу с мусульманскими правителями. [ 178 ] Индуистские правители, такие как Шиваджи Империи Маратхи , изменили процесс, переадируя санскрит и повторно утвердив свою социально-лингвистическую идентичность. [ 178 ] [ 179 ] [ 180 ] После того, как исламское правление распалось в Южной Азии, и началась эпоха колониального правления, санскрит вновь появился, но в форме «призрачного существования» в таких регионах, как Бенгалия. Этот упадок был результатом «политических институтов и гражданского духа», которые не поддерживали историческую санскритскую литературную культуру [ 174 ] и неспособность новой санскритской литературы ассимилировать в изменяющуюся культурную и политическую среду. [ 173 ]

Шелдон Поллок заявляет, что каким -то важным образом «санскрит мертв ». [ 181 ] После 12 -го века санскритские литературные произведения были сведены к «повторному взору и пересмотрам» идей, уже изучаемых, и любое творчество было ограничено гимнами и стихами. Это контрастировало с предыдущими 1500 годами, когда «великие эксперименты в моральном и эстетическом воображении» ознаменовали индийскую стипендию с использованием классического санскрита, утверждает Поллок. [ 176 ]

Ученые утверждают, что санскритский язык не умер, а только снизился. Юрген Хенер не согласен с Поллоком, обнаружив свои аргументы элегантными, но «часто произвольными». По словам Ханеншер, снижение или региональное отсутствие творческой и инновационной литературы представляет собой негативное доказательство гипотезы Поллока, но это не положительные доказательства. Более внимательный взгляд на санскрит в истории Индии после 12 -го века предполагает, что санскрит выжил, несмотря на шансы. По словам Ханеншер, [ 182 ]

На более общественном уровне утверждение о том, что санскрит является мертвым языком, вводит в заблуждение, потому что санскрит явно не такой мертв Язык в наиболее распространенном использовании термина. Представление Поллока о «смерти санскрита» остается в этом неясном сфере между академическими кругами и общественным мнением, когда он говорит, что «большинство наблюдателей согласятся с тем, что каким -то важным образом санскрит мертв». [ 174 ]

Ученый для санскритского языка Мориз Винтерниц , санскрит никогда не был мертвым языком, и он все еще жив, хотя его распространенность меньше, чем древние и средневековые времена. Санскрит остается неотъемлемой частью индуистских журналов, фестивалей, игр Рамлилы, драмы, ритуалов и обрядов. [ 183 ] Точно так же Брайан Хэтчер утверждает, что «метафоры исторического разрыва» Поллока недействительны, что существует достаточно доказательств того, что санскрит был очень жив в узких ограничениях выживших индуистских королевств между 13 и 18 веками, а также его почтение и традиции продолжается. [ 184 ]

Ханенер утверждает, что современные работы на санскрите игнорируются либо их «современность». [ 185 ]

По словам Роберта П. Голдмана и Салли Сазерленд, санскрит не является ни «мертвым», ни «живым» в обычном смысле. Это особый, вневременный язык, который живет в многочисленных рукописях, ежедневных песнопениях и церемониальных чтениях, языке наследия , который индийцы контекстуально приправляют, и который некоторые практикуют. [ 186 ]

Когда англичане ввели английский в Индию в 19 -м веке, знание санскритской и древней литературы продолжало процветать, поскольку изучение санскрита превратился из более традиционного стиля в форму аналитического и сравнительного стипендии, отражающего исследование Европы. [ 187 ]

Современные индоарийские языки

Соотношение санскрита с пракритскими языками, особенно современной формой индийских языков, является сложной и охватывает около 3500 лет, говорится, что Колин Масика - лингвист, специализирующийся на южноазиатских языках. Частью сложности является отсутствие достаточного текстового, археологического и эпиграфического доказательства древних языков пракрита с редкими исключениями, такими как пали, что приводит к тенденции к анахронистическим ошибкам. [ 188 ] Санскритские и пракритские языки могут быть разделены на старые индоарийцы (1500 г. до н.э.-600 г. до н. , средний или второй, и поздние эволюционные подстанции. [ 188 ]

Ведический санскрит принадлежит к ранней старой индоарийской стадии, а классический санскрит к более поздней индоарийской стадии. Доказательства того, что пракриты, такие как пали (буддизм, буддизм, магадхи, Махараштри, сингальский, саурасени и ния (гандхари), появляются в средней индоарской сцене в двух версиях и более формалированных-это может быть размещен в раннем и среднем возрастах периода 600 г. до н.э. - 1000 г. н.э. [ 188 ] Два литературных индоарийских языка могут быть прослежены до поздней средней индоарийской стадии, и это апабхрамса и элу (литературная форма сингальцев ). Многочисленные северные, центральные, восточные и западные индийские языки, такие как хинди, гуджарати, синдхи, пенджаби, кашмири, непали, брадж, Авадхи, бенгальский, ассамский, ария, маратхи и другие, принадлежат новой индоологической сцене. [ 188 ]

Существует обширное совпадение в словаре, фонетике и других аспектах этих новых индоарийских языков с санскритом, но он не является ни универсальным, ни идентичен на языках. Скорее всего, они появились из синтеза древних санскритских языковых традиций и примесей различных региональных диалектов. У каждого языка есть некоторые уникальные и регионально творческие аспекты, с неясным происхождением. Пракритские языки имеют грамматическую структуру, но, как и ведический санскрит, он гораздо менее строгий, чем классический санскрит. В то время как корни всех пракритских языков могут находиться на ведическом санскрите и, в конечном счете, на прото-индоарийском языке, их структурные детали варьируются от классического санскрита. [ 28 ] [ 188 ] Ученые общепризнаются и широко распространены в Индии, что современные индоарийские языки , такие как бенгальские, гуджарати, хинди и пенджаби, являются потомками санскритского языка. [ 189 ] [ 190 ] [ 191 ] Санскрит, Государства -бордо, можно описать как «родной язык почти всех языков Северной Индии». [ 192 ]

Географическое распределение

Историческое присутствие на санскритском языке подтверждается широкой географией за пределами Южной Азии. Надписи и литературные данные свидетельствуют о том, что санскритский язык уже был принят в Юго -Восточной Азии и Центральной Азии в 1 -м тысячелетии н.э. через монахов, религиозных паломников и торговцев. [ 193 ] [ 194 ] [ 195 ]

Южная Азия была географическим диапазоном крупнейшей коллекции древних и до 18-го века санскритских рукописей и надписей. [ 139 ] Помимо древней Индии, в Китае были обнаружены значительные коллекции санскритских рукописей и надписей (особенно в тибетских монастырях), [ 196 ] [ 197 ] Мьянма , [ 198 ] Индонезия , [ 199 ] Камбоджа , [ 200 ] Лаос , [ 201 ] Вьетнам , [ 202 ] Таиланд , [ 203 ] и Малайзия . [ 201 ] Санскритские надписи, рукописи или ее остатки, в том числе некоторые из самых старых известных санскритских написанных текстов, были обнаружены в сухих высоких пустынях и горных местах, таких как в Непале, [ 204 ] [ 205 ] [ м ] Тибет, [ 197 ] [ 206 ] Афганистан, [ 207 ] [ 208 ] Монголия, [ 209 ] Узбекистан, [ 210 ] Туркменистан, Таджикистан, [ 210 ] и Казахстан. [ 211 ] Некоторые санскритские тексты и надписи также были обнаружены в Корее и Японии. [ 212 ] [ 213 ] [ 214 ]

Официальный статус

В Индии санскрит входит в число 22 официальных языков Индии в восьмом графике в Конституции . [ 215 ] В 2010 году Уттаракханд стал первым штатом в Индии, который сделал санскрит своим вторым официальным языком. [ 216 ] В 2019 году Химачал -Прадеш сделал санскрит своим вторым официальным языком, став вторым штатом в Индии, который сделал это. [ 217 ]

Фонология

Санскрит разделяет много прото-индоевропейских фонологических особенностей, хотя в нем есть больший инвентарь различных фонем. Согласная система такая же, хотя она систематически увеличила инвентаризацию различных звуков. Например, санскрит добавил безмолвную аспирированную «tʰ», к безмолвному «T», озвучил «D» и озвученные аспирированные «dʰ», найденные на языках пирога. [ 218 ]

Наиболее значимым и отличительным фонологическим развитием на санскрите является слияние гласного. [ 218 ] Короткий *e , *o и *a , все сливается как ( अ) на санскрите, в то время как длинная *ē , *ō и *ā , все сливается так долго ā (आ). Сравните санскрит наман с латинскими номанами . Эти слияния произошли очень рано и значительно повлияли на морфологическую систему санскрита. [ 218 ] Некоторые фонологические разработки в ИТ отражают те, кто на других языках пирога. Например, лабиовелары объединились с простыми веларами, как и на других языках Satem. Вторичная палатализация полученных сегментов является более тщательной и систематической на санскрите. [ 218 ] Например, в отличие от потери морфологической ясности из -за сокращения гласных, которое встречается на ранних греческих и связанных с этим юго -востоке Европейского языка, санскрит развернут *y , *w и *s, мешающие для обеспечения морфологической ясности. [ 218 ]

Гласные

Кардинальные гласные ( svaras ) i (इ), u (उ), a (अ) различают длину на санскрите. [ 219 ] [ 220 ] Короткий A (अ) на санскрите является более близким гласным, чем ā, эквивалентный Schwa. Средние гласные ē (ए) и ō (ओ) на санскрите являются монофтхонгизациями индоиранских дифтонов *ai и *au . Старый иранский язык сохранился *AI и *Au . [ 219 ] Санскритские гласные по своей сути длинные, хотя часто транскрибируются E и O без диаклита. Вокалическая жидкость r̥ на санскрите - это слияние пирога *r̥ и *l̥ . Длинный r̥ - это инновация, и он используется в нескольких аналогично генерируемых морфологических категориях. [ 219 ] [ 221 ] [ 222 ]

| Независимая форма | Яст / Iso |

НАСИЛИЕ | Независимая форма | Яст/ Iso |

НАСИЛИЕ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Канхья ( Горта ) |

А | а | / ɐ / | Приходить | и au | / ː / | ||

| Талавья ( Платальный ) |

Агл | я | / я / | Эн | отметка | /я/ | ||

| шезлонья ( Губ ) |

U | в | / u / | Он | грудь | /Люк ̐/ | ||

| Только мурдха ( Ретрофлекс ) |

Ряд | ṛ / r̥ | / Гид / | Ведущий | окислитель / сульрус | / R̩ː / | ||

| dantya ( Зуб ) |

L. | ḷ / l̥ | / l̩ / | ( 4 ) | ( ḹ / l̥̄ ) [ O ] | / L̩ː / | ||

| Канхаталавья (Палатогуттура) |

А | eВойдите | / ː / | Да | это | /ɑj/ | ||

| Канхошхья (Labioguttural) |

О! | o / | / oː / | О | В | /ɑw/ | ||

| (Согласные аллофоны) | ं | ṃ / / [ 225 ] | / ◌̃ / | ः | час [ 226 ] | /час/ |

По словам Масики, санскрит имеет четыре традиционных полугол., С помощью которых были классифицированы «по морфофонемическим причинам, жидкости: y, r, l и v; то есть, так как y и v были несиллабиками, соответствующими i, u, u, так и были R, L по отношению к R̥ и L̥ ". [ 227 ] Северо -западный, центральный и восточный санскритский диалекты испытывали историческую путаницу между «R» и «L». Панинианская система, которая последовала за центральным диалектом, сохранила различие, вероятно, из -за почтения к ведическому санскриту, который отличил «R» и «L». Тем не менее, северо -западный диалект имел только «R», в то время как восточный диалект, вероятно, имел только «L», заявляет Масика. Таким образом, литературные произведения из разных частей древней Индии кажутся непоследовательными в использовании «R» и «L», что приводит к дублетам, которые иногда семантически дифференцированы. [ 227 ]

Согласные

Санскрит обладает симметричной согласной структурой фонем, основанной на том, как сформулирован звук, хотя фактическое использование этих звуков скрывает отсутствие параллелизма в кажущейся симметрии, возможно, из исторических изменений в языке. [ 228 ]

| sparśa (Plosive) |

anunāsika (Nasal) |

antastha (Approximant) |

ūṣman/saṃgharṣhī (Fricative) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voicing → | aghoṣa | ghoṣa | aghoṣa | |||||||||||

| Aspiration → | alpaprāṇa | mahāprāṇa | alpaprāṇa | mahāprāṇa | alpaprāṇa | mahāprāṇa | ||||||||

| kaṇṭhya (Guttural) |

क | ka [k] |

ख | kha [kʰ] |

ग | ga [ɡ] |

घ | gha [ɡʱ] |

ङ | ṅa [ŋ] |

ह | ha [ɦ] |

||

| tālavya (Palatal) |

च | ca [t͜ɕ] |

छ | cha [t͜ɕʰ] |

ज | ja [d͜ʑ] |

झ | jha [d͜ʑʱ] |

ञ | ña [ɲ] |

य | ya [j] |

श | śa [ɕ] |

| mūrdhanya (Retroflex) |

ट | ṭa [ʈ] |

ठ | ṭha [ʈʰ] |

ड | ḍa [ɖ] |

ढ | ḍha [ɖʱ] |

ण | ṇa [ɳ] |

र | ra [ɾ] |

ष | ṣa [ʂ] |

| dantya (Dental) |

त | ta [t] |

थ | tha [tʰ] |

द | da [d] |

ध | dha [dʱ] |

न | na [n] |

ल | la [l] |

स | sa [s] |

| oṣṭhya (Labial) |

प | pa [p] |

फ | pha [pʰ] |

ब | ba [b] |

भ | bha [bʱ] |

म | ma [m] |

व | va [ʋ] |

||

Sanskrit had a series of retroflex stops originating as conditioned alternants of dentals, albeit by Sanskrit they had become phonemic.[228]

Regarding the palatal plosives, the pronunciation is a matter of debate. In contemporary attestation, the palatal plosives are a regular series of palatal stops, supported by most Sanskrit sandhi rules. However, the reflexes in descendant languages, as well as a few of the sandhi rules regarding ch, could suggest an affricate pronunciation.

jh was a marginal phoneme in Sanskrit, hence its phonology is more difficult to reconstruct; it was more commonly employed in the Middle Indo-Aryan languages as a result of phonological processes resulting in the phoneme.

The palatal nasal is a conditioned variant of n occurring next to palatal obstruents.[228] The anusvara that Sanskrit deploys is a conditioned alternant of postvocalic nasals, under certain sandhi conditions.[229] Its visarga is a word-final or morpheme-final conditioned alternant of s and r under certain sandhi conditions.[229]

The system of Sanskrit Sounds

[The] order of Sanskrit sounds works along three principles: it goes from simple to complex; it goes from the back to the front of the mouth; and it groups similar sounds together. [...] Among themselves, both the vowels and consonants are ordered according to where in the mouth they are pronounced, going from back to front.

— A. M. Ruppel, The Cambridge Introduction to Sanskrit[230]

The voiceless aspirated series is also an innovation in Sanskrit but is significantly rarer than the other three series.[228]

While the Sanskrit language organizes sounds for expression beyond those found in the PIE language, it retained many features found in the Iranian and Balto-Slavic languages. An example of a similar process in all three is the retroflex sibilant ʂ being the automatic product of dental s following i, u, r, and k.[229]

Phonological alternations, sandhi rules

Sanskrit deploys extensive phonological alternations on different linguistic levels through sandhi rules (literally, the rules of "putting together, union, connection, alliance"), similar to the English alteration of "going to" as gonna.[231] The Sanskrit language accepts such alterations within it, but offers formal rules for the sandhi of any two words next to each other in the same sentence or linking two sentences. The external sandhi rules state that similar short vowels coalesce into a single long vowel, while dissimilar vowels form glides or undergo diphthongization.[231] Among the consonants, most external sandhi rules recommend regressive assimilation for clarity when they are voiced. These rules ordinarily apply at compound seams and morpheme boundaries.[231] In Vedic Sanskrit, the external sandhi rules are more variable than in Classical Sanskrit.[232]

The internal sandhi rules are more intricate and account for the root and the canonical structure of the Sanskrit word. These rules anticipate what are now known as the Bartholomae's law and Grassmann's law. For example, states Jamison, the "voiceless, voiced, and voiced aspirated obstruents of a positional series regularly alternate with each other (p ≈ b ≈ bh; t ≈ d ≈ dh, etc.; note, however, c ≈ j ≈ h), such that, for example, a morpheme with an underlying voiced aspirate final may show alternants with all three stops under differing internal sandhi conditions".[233] The velar series (k, g, gʰ) alternate with the palatal series (c, j, h), while the structural position of the palatal series is modified into a retroflex cluster when followed by dental. This rule creates two morphophonemically distinct series from a single palatal series.[233]

Vocalic alternations in the Sanskrit morphological system is termed "strengthening", and called guṇa and vr̥ddhi in the preconsonantal versions. There is an equivalence to terms deployed in Indo-European descriptive grammars, wherein Sanskrit's unstrengthened state is same as the zero-grade, guṇa corresponds to normal-grade, while vr̥ddhi is same as the lengthened-state.[234] The qualitative ablaut is not found in Sanskrit just like it is absent in Iranian, but Sanskrit retains quantitative ablaut through vowel strengthening.[234] The transformations between unstrengthened to guṇa is prominent in the morphological system, states Jamison, while vr̥ddhi is a particularly significant rule when adjectives of origin and appurtenance are derived. The manner in which this is done slightly differs between the Vedic and the Classical Sanskrit.[234][235]

Sanskrit grants a very flexible syllable structure, where they may begin or end with vowels, be single consonants or clusters. Similarly, the syllable may have an internal vowel of any weight. Vedic Sanskrit shows traces of following the Sievers–Edgerton law, but Classical Sanskrit does not.[citation needed] Vedic Sanskrit has a pitch accent system (inherited from Proto-Indo-European) which was acknowledged by Pāṇini, states Jamison; but in his Classical Sanskrit the accents disappear.[236] Most Vedic Sanskrit words have one accent. However, this accent is not phonologically predictable, states Jamison.[236] It can fall anywhere in the word and its position often conveys morphological and syntactic information.[236] The presence of an accent system in Vedic Sanskrit is evidenced from the markings in the Vedic texts. This is important because of Sanskrit's connection to the PIE languages and comparative Indo-European linguistics.[237]

Sanskrit, like most early Indo-European languages, lost the so-called "laryngeal consonants (cover-symbol *H) present in the Proto-Indo-European", states Jamison.[236] This significantly affected the evolutionary path of the Sanskrit phonology and morphology, particularly in the variant forms of roots.[238]

Pronunciation

Because Sanskrit is not anyone's native language, it does not have a fixed pronunciation. People tend to pronounce it as they do their native language. The articles on Hindustani, Marathi, Nepali, Oriya and Bengali phonology will give some indication of the variation that is encountered. When Sanskrit was a spoken language, its pronunciation varied regionally and also over time. Nonetheless, Panini described the sound system of Sanskrit well enough that people have a fairly good idea of what he intended.

| Transcription | Goldman (2002)[p] |

Cardona (2003)[240] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | ɐ | ɐ | |

| ā | aː | aː | |

| i | ɪ | ɪ | |

| ī | iː | iː | |

| u | ʊ | ʊ | |

| ū | uː | uː | |

| r̥ | ɽɪ | ɽɪ | ᵊɾᵊ or ᵊɽᵊ[q] |

| r̥̄ | ɽiː | ɽiː?[r] | ?[r] |

| l̥ | lɪ | ?[s] | [t] |

| ē | eː | eː | eː |

| ai | ai | ai | ɐi or ɛi |

| ō | oː | oː | oː |

| au | au | au | ɐu or ɔu |

| aṃ | ɐ̃, ɐɴ | ɐ̃, ɐɴ[u] | |

| aḥ | ɐh | ɐhɐ[v] | ɐh |

| k | k | k | |

| kh | kʰ | kʰ | |

| g | ɡ | ɡ | |

| gh | ɡʱ | ɡʱ | |

| ṅ | ŋ | ŋ | |

| h | ɦ | ɦ | ɦ |

| c | t͡ɕ | t͡ɕ | |

| ch | t͡ɕʰ | t͡ɕʰ | |

| j | d͡ʑ | d͡ʑ | |

| jh | d͡ʑʱ | d͡ʑʱ | |

| ñ | n | n | |

| y | j | j | j |

| ś | ɕ | ɕ | ɕ |

| ṭ | t̠ | t̠ | |

| ṭh | t̠ʰ | t̠ʰ | |

| ḍ | d̠ | d̠ | |

| ḍh | d̠ʱ | d̠ʱ | |

| ṇ | n̠ | n̠ | |

| r | ɾ | ɾ | ɾ̪, ɾ or ɽ |

| ṣ | s̠ | s̠ | ʂ |

| t | t̪ | t̪ | |

| th | t̪ʰ | t̪ʰ | |

| d | d̪ | d̪ | |

| dh | d̪ʱ | d̪ʱ | |

| n | n̪ | n̪ | |

| l | l | l | l̪ |

| s | s | s | s̪ |

| p | p | p | |

| ph | pʰ | pʰ | |

| b | b | b | |

| bh | bʱ | bʱ | |

| m | m | m | |

| v | ʋ | ʋ | ʋ |

| stress | (ante)pen- ultimate[w] |

Morphology

The basis of Sanskrit morphology is the root, states Jamison, "a morpheme bearing lexical meaning".[241] The verbal and nominal stems of Sanskrit words are derived from this root through the phonological vowel-gradation processes, the addition of affixes, verbal and nominal stems. It then adds an ending to establish the grammatical and syntactic identity of the stem. According to Jamison, the "three major formal elements of the morphology are (i) root, (ii) affix, and (iii) ending; and they are roughly responsible for (i) lexical meaning, (ii) derivation, and (iii) inflection respectively".[242]

A Sanskrit word has the following canonical structure:[241]

0-n + Ending

0–1

The root structure has certain phonological constraints. Two of the most important constraints of a "root" is that it does not end in a short "a" (अ) and that it is monosyllabic.[241] In contrast, the affixes and endings commonly do. The affixes in Sanskrit are almost always suffixes, with exceptions such as the augment "a-" added as prefix to past tense verb forms and the "-na/n-" infix in single verbal present class, states Jamison.[241]

Sanskrit verbs have the following canonical structure:[243]

Tense-Aspect + Suffix

Mood + Ending

Personal-Number-Voice

According to Ruppel, verbs in Sanskrit express the same information as other Indo-European languages such as English.[244] Sanskrit verbs describe an action or occurrence or state, its embedded morphology informs as to "who is doing it" (person or persons), "when it is done" (tense) and "how it is done" (mood, voice). The Indo-European languages differ in the detail. For example, the Sanskrit language attaches the affixes and ending to the verb root, while the English language adds small independent words before the verb. In Sanskrit, these elements co-exist within the word.[244][x]

| Sanskrit word equivalent | ||

|---|---|---|

| English expression | IAST/ISO | Devanagari |

| you carry | bharasi | भरसि |

| they carry | bharanti | भरन्ति |

| you will carry | bhariṣyasi | भरिष्यसि |

Both verbs and nouns in Sanskrit are either thematic or athematic, states Jamison.[246] Guna (strengthened) forms in the active singular regularly alternate in athematic verbs. The finite verbs of Classical Sanskrit have the following grammatical categories: person, number, voice, tense-aspect, and mood. According to Jamison, a portmanteau morpheme generally expresses the person-number-voice in Sanskrit, and sometimes also the ending or only the ending. The mood of the word is embedded in the affix.[246]

These elements of word architecture are the typical building blocks in Classical Sanskrit, but in Vedic Sanskrit these elements fluctuate and are unclear. For example, in the Rigveda preverbs regularly occur in tmesis, states Jamison, which means they are "separated from the finite verb".[241] This indecisiveness is likely linked to Vedic Sanskrit's attempt to incorporate accent. With nonfinite forms of the verb and with nominal derivatives thereof, states Jamison, "preverbs show much clearer univerbation in Vedic, both by position and by accent, and by Classical Sanskrit, tmesis is no longer possible even with finite forms".[241]

While roots are typical in Sanskrit, some words do not follow the canonical structure.[242] A few forms lack both inflection and root. Many words are inflected (and can enter into derivation) but lack a recognizable root. Examples from the basic vocabulary include kinship terms such as mātar- (mother), nas- (nose), śvan- (dog). According to Jamison, pronouns and some words outside the semantic categories also lack roots, as do the numerals. Similarly, the Sanskrit language is flexible enough to not mandate inflection.[242]

The Sanskrit words can contain more than one affix that interact with each other. Affixes in Sanskrit can be athematic as well as thematic, according to Jamison.[247] Athematic affixes can be alternating. Sanskrit deploys eight cases, namely nominative, accusative, instrumental, dative, ablative, genitive, locative, vocative.[247]

Stems, that is "root + affix", appear in two categories in Sanskrit: vowel stems and consonant stems. Unlike some Indo-European languages such as Latin or Greek, according to Jamison, "Sanskrit has no closed set of conventionally denoted noun declensions". Sanskrit includes a fairly large set of stem-types.[248] The linguistic interaction of the roots, the phonological segments, lexical items and the grammar for the Classical Sanskrit consist of four Paninian components. These, states Paul Kiparsky, are the Astadhyaayi, a comprehensive system of 4,000 grammatical rules, of which a small set are frequently used; Sivasutras, an inventory of anubandhas (markers) that partition phonological segments for efficient abbreviations through the pratyharas technique; Dhatupatha, a list of 2,000 verbal roots classified by their morphology and syntactic properties using diacritic markers, a structure that guides its writing systems; and, the Ganapatha, an inventory of word groups, classes of lexical systems.[249] There are peripheral adjuncts to these four, such as the Unadisutras, which focus on irregularly formed derivatives from the roots.[249]

Sanskrit morphology is generally studied in two broad fundamental categories: the nominal forms and the verbal forms. These differ in the types of endings and what these endings mark in the grammatical context.[242] Pronouns and nouns share the same grammatical categories, though they may differ in inflection. Verb-based adjectives and participles are not formally distinct from nouns. Adverbs are typically frozen case forms of adjectives, states Jamison, and "nonfinite verbal forms such as infinitives and gerunds also clearly show frozen nominal case endings".[242]

Tense and voice

The Sanskrit language includes five tenses: present, future, past imperfect, past aorist and past perfect.[245] It outlines three types of voices: active, passive and the middle.[245] The middle is also referred to as the mediopassive, or more formally in Sanskrit as parasmaipada (word for another) and atmanepada (word for oneself).[243]

| Active | Middle (Mediopassive) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

| 1st person | -mi | -vas | -mas | -e | -vahe | -mahe |

| 2nd person | -si | -thas | -tha | -se | -āthe | -dhve |

| 3rd person | -ti | -tas | -anti | -te | -āte | -ante |

The paradigm for the tense-aspect system in Sanskrit is the three-way contrast between the "present", the "aorist" and the "perfect" architecture.[250] Vedic Sanskrit is more elaborate and had several additional tenses. For example, the Rigveda includes perfect and a marginal pluperfect. Classical Sanskrit simplifies the "present" system down to two tenses, the perfect and the imperfect, while the "aorist" stems retain the aorist tense and the "perfect" stems retain the perfect and marginal pluperfect.[250] The classical version of the language has elaborate rules for both voice and the tense-aspect system to emphasize clarity, and this is more elaborate than in other Indo-European languages. The evolution of these systems can be seen from the earliest layers of the Vedic literature to the late Vedic literature.[251]

Number, person

Sanskrit recognizes three numbers—singular, dual, and plural.[247] The dual is a fully functioning category, used beyond naturally paired objects such as hands or eyes, extending to any collection of two. The elliptical dual is notable in the Vedic Sanskrit, according to Jamison, where a noun in the dual signals a paired opposition.[247] Illustrations include dyāvā (literally, "the two heavens" for heaven-and-earth), mātarā (literally, "the two mothers" for mother-and-father).[247] A verb may be singular, dual or plural, while the person recognized in the language are forms of "I", "you", "he/she/it", "we" and "they".[245]

There are three persons in Sanskrit: first, second and third.[243] Sanskrit uses the 3×3 grid formed by the three numbers and the three persons parameters as the paradigm and the basic building block of its verbal system.[251]

Gender, mood

The Sanskrit language incorporates three genders: feminine, masculine and neuter.[247] All nouns have inherent gender. With some exceptions, personal pronouns have no gender. Exceptions include demonstrative and anaphoric pronouns.[247] Derivation of a word is used to express the feminine. Two most common derivations come from feminine-forming suffixes, the -ā- (आ, Rādhā) and -ī- (ई, Rukmīnī). The masculine and neuter are much simpler, and the difference between them is primarily inflectional.[247][252] Similar affixes for the feminine are found in many Indo-European languages, states Burrow, suggesting links of the Sanskrit to its PIE heritage.[253]

Pronouns in Sanskrit include the personal pronouns of the first and second persons, unmarked for gender, and a larger number of gender-distinguishing pronouns and adjectives.[246] Examples of the former include ahám (first singular), vayám (first plural) and yūyám (second plural). The latter can be demonstrative, deictic or anaphoric.[246] Both the Vedic and Classical Sanskrit share the sá/tám pronominal stem, and this is the closest element to a third person pronoun and an article in the Sanskrit language, states Jamison.[246]

Indicative, potential and imperative are the three mood forms in Sanskrit.[245]

Prosody, metre

The Sanskrit language formally incorporates poetic metres.[254] By the late Vedic era, this developed into a field of study; it was central to the composition of the Hindu literature, including the later Vedic texts. This study of Sanskrit prosody is called chandas, and is considered one of the six Vedangas, or limbs of Vedic studies.[254][255]

Sanskrit prosody includes linear and non-linear systems.[256] The system started off with seven major metres, according to Annette Wilke and Oliver Moebus, called the "seven birds" or "seven mouths of Brihaspati", and each had its own rhythm, movements and aesthetics wherein a non-linear structure (aperiodicity) was mapped into a four verse polymorphic linear sequence.[256] A syllable in Sanskrit is classified as either laghu (light) or guru (heavy). This classification is based on a matra (literally, "count, measure, duration"), and typically a syllable that ends in a short vowel is a light syllable, while those that end in consonant, anusvara or visarga are heavy. The classical Sanskrit found in Hindu scriptures such as the Bhagavad Gita and many texts are so arranged that the light and heavy syllables in them follow a rhythm, though not necessarily a rhyme.[257][258][aa]

Sanskrit metres include those based on a fixed number of syllables per verse, and those based on fixed number of morae per verse.[260] The Vedic Sanskrit employs fifteen metres, of which seven are common, and the most frequent are three (8-, 11- and 12-syllable lines).[261] The Classical Sanskrit deploys both linear and non-linear metres, many of which are based on syllables and others based on diligently crafted verses based on repeating numbers of morae (matra per foot).[261]

There is no word without metre,

nor is there any metre without words.

— Natya Shastra[262]

Metre and rhythm is an important part of the Sanskrit language. It may have played a role in helping preserve the integrity of the message and Sanskrit texts. The verse perfection in the Vedic texts such as the verse Upanishads[ab] and post-Vedic Smṛti texts are rich in prosody. This feature of the Sanskrit language led some Indologists from the 19th century onwards to identify suspected portions of texts where a line or sections are off the expected metre.[263][264][ac]

The metre-feature of the Sanskrit language embeds another layer of communication to the listener or reader. A change in metres has been a tool of literary architecture and an embedded code to inform the reciter and audience that it marks the end of a section or chapter.[268] Each section or chapter of these texts uses identical metres, rhythmically presenting their ideas and making it easier to remember, recall and check for accuracy.[268] Authors coded a hymn's end by frequently using a verse of a metre different from that used in the hymn's body.[268] However, Hindu tradition does not use the Gayatri metre to end a hymn or composition, possibly because it has enjoyed a special level of reverence in Hinduism.[268]

Writing system

The early history of writing Sanskrit and other languages in ancient India is a problematic topic despite a century of scholarship, states Richard Salomon – an epigraphist and Indologist specializing in Sanskrit and Pali literature.[269] The earliest possible script from South Asia is from the Indus Valley civilization (3rd/2nd millennium BCE), but this script – if it is a script – remains undeciphered. If any scripts existed in the Vedic period, they have not survived. Scholars generally accept that Sanskrit was spoken in an oral society, and that an oral tradition preserved the extensive Vedic and Classical Sanskrit literature.[270] Other scholars such as Jack Goody argue that the Vedic Sanskrit texts are not the product of an oral society, basing this view by comparing inconsistencies in the transmitted versions of literature from various oral societies such as the Greek (Greco-Sanskrit), Serbian, and other cultures. This minority of scholars argue that the Vedic literature is too consistent and vast to have been composed and transmitted orally across generations, without having been written down.[271][272][273]

Lipi is the term in Sanskrit which means "writing, letters, alphabet". It contextually refers to scripts, the art or any manner of writing or drawing.[100] The term, in the sense of a writing system, appears in some of the earliest Buddhist, Hindu, and Jaina texts. Pāṇini's Astadhyayi, composed sometime around the 5th or 4th century BCE, for example, mentions lipi in the context of a writing script and education system in his times, but he does not name the script.[100][101][274] Several early Buddhist and Jaina texts, such as the Lalitavistara Sūtra and Pannavana Sutta include lists of numerous writing scripts in ancient India.[ad] The Buddhist texts list the sixty four lipi that the Buddha knew as a child, with the Brahmi script topping the list. "The historical value of this list is however limited by several factors", states Salomon. The list may be a later interpolation.[276][ae] The Jain canonical texts such as the Pannavana Sutta – probably older than the Buddhist texts – list eighteen writing systems, with the Brahmi topping the list and Kharotthi (Kharoshthi) listed as fourth. The Jaina text elsewhere states that the "Brahmi is written in 18 different forms", but the details are lacking.[278] However, the reliability of these lists has been questioned and the empirical evidence of writing systems in the form of Sanskrit or Prakrit inscriptions dated prior to the 3rd century BCE has not been found. If the ancient surfaces for writing Sanskrit were palm leaves, tree bark and cloth – the same as those in later times – these have not survived.[279][af] According to Salomon, many find it difficult to explain the "evidently high level of political organization and cultural complexity" of ancient India without a writing system for Sanskrit and other languages.[279][ag]

The oldest datable writing systems for Sanskrit are the Brāhmī script, the related Kharoṣṭhī script and the Brahmi derivatives.[282][283] The Kharosthi was used in the northwestern part of South Asia and it became extinct, while the Brahmi was used all over the subcontinent along with regional scripts such as Old Tamil.[284] Of these, the earliest records in the Sanskrit language are in Brahmi, a script that later evolved into numerous related Indic scripts for Sanskrit, along with Southeast Asian scripts (Burmese, Thai, Lao, Khmer, others) and many extinct Central Asian scripts such as those discovered along with the Kharosthi in the Tarim Basin of western China and in Uzbekistan.[285] The most extensive inscriptions that have survived into the modern era are the rock edicts and pillar inscriptions of the 3rd century BCE Mauryan emperor Ashoka, but these are not in Sanskrit.[286][ah]

Scripts

Over the centuries, and across countries, a number of scripts have been used to write Sanskrit.

Brahmi script

The Brahmi script for writing Sanskrit is a "modified consonant-syllabic" script. The graphic syllable is its basic unit, and this consists of a consonant with or without diacritic modifications.[283] Since the vowel is an integral part of the consonants, and given the efficiently compacted, fused consonant cluster morphology for Sanskrit words and grammar, the Brahmi and its derivative writing systems deploy ligatures, diacritics and relative positioning of the vowel to inform the reader how the vowel is related to the consonant and how it is expected to be pronounced for clarity.[283][288][aj] This feature of Brahmi and its modern Indic script derivatives makes it difficult to classify it under the main script types used for the writing systems for most of the world's languages, namely logographic, syllabic and alphabetic.[283]

The Brahmi script evolved into "a vast number of forms and derivatives", states Richard Salomon, and in theory, Sanskrit "can be represented in virtually any of the main Brahmi-based scripts and in practice it often is".[289] From the ancient times, it has been written in numerous regional scripts in South and Southeast Asia. Most of these are descendants of the Brahmi script.[ak] The earliest datable varnamala Brahmi alphabet system, found in later Sanskrit texts, is from the 2nd century BCE, in the form of a terracotta plaque found in Sughana, Haryana. It shows a "schoolboy's writing lessons", states Salomon.[291][292]

Nagari script

| Devanāgarī |

|---|

|

Many modern era manuscripts are written and available in the Nagari script, whose form is attestable to the 1st millennium CE.[293] The Nagari script is the ancestor of Devanagari (north India), Nandinagari (south India) and other variants. The Nāgarī script was in regular use by 7th century CE, and had fully evolved into Devanagari and Nandinagari[294] scripts by about the end of the first millennium of the common era.[295][296] The Devanagari script, states Banerji, became more popular for Sanskrit in India since about the 18th century.[297] However, Sanskrit does have special historical connection to the Nagari script as attested by the epigraphical evidence.[298]

The Nagari script has been thought of as a northern Indic script for Sanskrit as well as the regional languages such as Hindi, Marathi, and Nepali. However, it has had a "supra-local" status as evidenced by 1st-millennium CE epigraphy and manuscripts discovered all over India and as far as Sri Lanka, Burma, Indonesia, and in its parent form, called the Siddhamatrka script, found in manuscripts of East Asia.[299] The Sanskrit and Balinese languages Sanur inscription on Belanjong pillar of Bali (Indonesia), dated to about 914 CE, is in part in the Nagari script.[300]

The Nagari script used for Classical Sanskrit has the fullest repertoire of characters consisting of fourteen vowels and thirty three consonants. For Vedic Sanskrit, it has two more allophonic consonantal characters (the intervocalic ळ ḷa, and ळ्ह ḷha).[299] To communicate phonetic accuracy, it also includes several modifiers such as the anusvara dot and the visarga double dot, punctuation symbols and others such as the halanta sign.[299]

Other writing systems

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmi script and its descendants |

Other scripts such as Gujarati, Bangla-Assamese, Odia and major south Indian scripts, states Salomon, "have been and often still are used in their proper territories for writing Sanskrit".[293] These and many Indian scripts look different to the untrained eye, but the differences between Indic scripts is "mostly superficial and they share the same phonetic repertoire and systemic features", states Salomon.[301] They all have essentially the same set of eleven to fourteen vowels and thirty-three consonants as established by the Sanskrit language and attestable in the Brahmi script. Further, a closer examination reveals that they all have the similar basic graphic principles, the same varnamala (literally, "garland of letters") alphabetic ordering following the same logical phonetic order, easing the work of historic skilled scribes writing or reproducing Sanskrit works across South Asia.[302][al] The Sanskrit language written in some Indic scripts exaggerate angles or round shapes, but this serves only to mask the underlying similarities. Nagari script favours symmetry set with squared outlines and right angles. In contrast, Sanskrit written in the Bengali script emphasizes the acute angles while the neighbouring Odia script emphasizes rounded shapes and uses cosmetically appealing "umbrella-like curves" above the script symbols.[304]

In the south, where Dravidian languages predominate, scripts used for Sanskrit include the Kannada, Telugu, Malayalam and Grantha alphabets.

Transliteration schemes, Romanisation